User login

Make the Diagnosis - March 2020

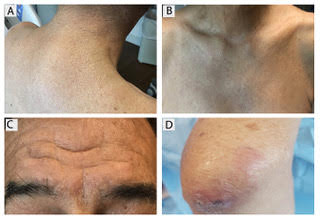

The patient’s biopsy showed sparse and grouped and slightly enlarged atypical stained mononuclear cells in mostly perifollicular areas with focal epidermotropism. CD30 staining was positive. She responded to potent topical steroids.

The etiology of LyP is unknown. It is unclear whether the proliferation of T-cells is a benign and chronic disorder, or an indolent T-cell malignancy.

In addition, 10% of LyP cases are associated with anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides), or Hodgkin lymphoma. Borderline cases are those that overlap LyP and lymphoma.

Patients typically present with crops of asymptomatic erythematous to brown papules that may become pustular, vesicular, or necrotic. Lesions tend to resolve within 2-8 weeks with or without scarring. The trunk and extremities are commonly affected. The condition tends to be chronic over months to years. The waxing and waning course is characteristic of LyP. Constitutional symptoms are generally absent in cases not associated with systemic disease.

Histopathologic examination reveals a dense wedge-shaped dermal infiltrate of atypical lymphocytes along with numerous eosinophils and neutrophils. Epidermotropism may be present and lymphocytes stain positive for CD30+. Vessels in the dermis may exhibit fibrin deposition and red blood cell extravasation. Histologically, LyP can be classified as Type A to E. These subtypes are determined by the size and type of atypical cells, location and amount of infiltrate, and staining of CD30 and CD8.

The differential diagnosis of LyP includes pityriasis lichenoides, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, folliculitis, arthropod assault, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and leukemia cutis. Treatment is symptomatic. Mild forms of LyP can many times be managed with superpotent topical corticosteroids. Bexarotene gel has been used for early lesions. For more widespread or persistent disease, intralesional corticosteroids, phototherapy (UVB or PUVA), tetracycline antibiotics, and methotrexate have been reported to be effective. Refractory cases may respond to interferon alpha or oral bexarotene. Routine evaluations are recommended as patients may be at increased risk for the development of lymphoma.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

The patient’s biopsy showed sparse and grouped and slightly enlarged atypical stained mononuclear cells in mostly perifollicular areas with focal epidermotropism. CD30 staining was positive. She responded to potent topical steroids.

The etiology of LyP is unknown. It is unclear whether the proliferation of T-cells is a benign and chronic disorder, or an indolent T-cell malignancy.

In addition, 10% of LyP cases are associated with anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides), or Hodgkin lymphoma. Borderline cases are those that overlap LyP and lymphoma.

Patients typically present with crops of asymptomatic erythematous to brown papules that may become pustular, vesicular, or necrotic. Lesions tend to resolve within 2-8 weeks with or without scarring. The trunk and extremities are commonly affected. The condition tends to be chronic over months to years. The waxing and waning course is characteristic of LyP. Constitutional symptoms are generally absent in cases not associated with systemic disease.

Histopathologic examination reveals a dense wedge-shaped dermal infiltrate of atypical lymphocytes along with numerous eosinophils and neutrophils. Epidermotropism may be present and lymphocytes stain positive for CD30+. Vessels in the dermis may exhibit fibrin deposition and red blood cell extravasation. Histologically, LyP can be classified as Type A to E. These subtypes are determined by the size and type of atypical cells, location and amount of infiltrate, and staining of CD30 and CD8.

The differential diagnosis of LyP includes pityriasis lichenoides, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, folliculitis, arthropod assault, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and leukemia cutis. Treatment is symptomatic. Mild forms of LyP can many times be managed with superpotent topical corticosteroids. Bexarotene gel has been used for early lesions. For more widespread or persistent disease, intralesional corticosteroids, phototherapy (UVB or PUVA), tetracycline antibiotics, and methotrexate have been reported to be effective. Refractory cases may respond to interferon alpha or oral bexarotene. Routine evaluations are recommended as patients may be at increased risk for the development of lymphoma.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

The patient’s biopsy showed sparse and grouped and slightly enlarged atypical stained mononuclear cells in mostly perifollicular areas with focal epidermotropism. CD30 staining was positive. She responded to potent topical steroids.

The etiology of LyP is unknown. It is unclear whether the proliferation of T-cells is a benign and chronic disorder, or an indolent T-cell malignancy.

In addition, 10% of LyP cases are associated with anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides), or Hodgkin lymphoma. Borderline cases are those that overlap LyP and lymphoma.

Patients typically present with crops of asymptomatic erythematous to brown papules that may become pustular, vesicular, or necrotic. Lesions tend to resolve within 2-8 weeks with or without scarring. The trunk and extremities are commonly affected. The condition tends to be chronic over months to years. The waxing and waning course is characteristic of LyP. Constitutional symptoms are generally absent in cases not associated with systemic disease.

Histopathologic examination reveals a dense wedge-shaped dermal infiltrate of atypical lymphocytes along with numerous eosinophils and neutrophils. Epidermotropism may be present and lymphocytes stain positive for CD30+. Vessels in the dermis may exhibit fibrin deposition and red blood cell extravasation. Histologically, LyP can be classified as Type A to E. These subtypes are determined by the size and type of atypical cells, location and amount of infiltrate, and staining of CD30 and CD8.

The differential diagnosis of LyP includes pityriasis lichenoides, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, folliculitis, arthropod assault, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and leukemia cutis. Treatment is symptomatic. Mild forms of LyP can many times be managed with superpotent topical corticosteroids. Bexarotene gel has been used for early lesions. For more widespread or persistent disease, intralesional corticosteroids, phototherapy (UVB or PUVA), tetracycline antibiotics, and methotrexate have been reported to be effective. Refractory cases may respond to interferon alpha or oral bexarotene. Routine evaluations are recommended as patients may be at increased risk for the development of lymphoma.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

February 2020

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is a type of cutaneous lupus erythematosus that may occur independently of or in combination with systemic lupus erythematosus. About 10%-15% of patients with SCLE will develop systemic lupus erythematosus. White females are more typically affected.

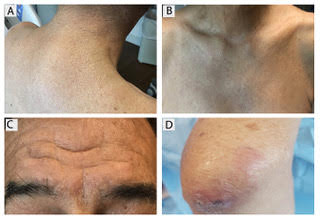

SCLE lesions often present as scaly, annular, or polycyclic scaly patches and plaques with central clearing. They may appear psoriasiform. They heal without atrophy or scarring but may leave dyspigmentation. Follicular plugging is absent. Lesions generally occur on sun exposed areas such as the neck, V of the chest, and upper extremities. Up to 75% of patients may exhibit associated symptoms such as photosensitivity, oral ulcers, and arthritis. Less than 20% of patients will develop internal disease, including nephritis and pulmonary disease. Symptoms of Sjögren’s syndrome and SCLE may overlap in some patients, and will portend higher risk for internal disease.

The differential diagnosis includes eczema, psoriasis, dermatophytosis, granuloma annulare, and erythema annulare centrifugum. Histology reveals epidermal atrophy and keratinocyte apoptosis, with a superficial and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis. Interface changes at the dermal-epidermal junction can be seen. Direct immunofluorescence of lesional skin is positive in one-third of cases, often revealing granular deposits of IgG and IgM at the dermal-epidermal junction and around hair follicles (called the lupus-band test). Serology in SCLE may reveal a positive antinuclear antigen test, as well as positive Ro/SSA antigen. Other lupus serologies such as La/SSB, dsDNA, antihistone, and Sm antibodies may be positive, but are less commonly seen.

Several drugs may cause SCLE, such as hydrochlorothiazide, terbinafine, ACE inhibitors, NSAIDs, calcium-channel blockers, interferons, anticonvulsants, griseofulvin, penicillamine, spironolactone, tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors, and statins. Discontinuing the offending medications may clear the lesions, but not always.

Treatment includes sunscreen and avoidance of sun exposure. Potent topical corticosteroids are helpful. If systemic treatment is indicated, antimalarials are first line.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is a type of cutaneous lupus erythematosus that may occur independently of or in combination with systemic lupus erythematosus. About 10%-15% of patients with SCLE will develop systemic lupus erythematosus. White females are more typically affected.

SCLE lesions often present as scaly, annular, or polycyclic scaly patches and plaques with central clearing. They may appear psoriasiform. They heal without atrophy or scarring but may leave dyspigmentation. Follicular plugging is absent. Lesions generally occur on sun exposed areas such as the neck, V of the chest, and upper extremities. Up to 75% of patients may exhibit associated symptoms such as photosensitivity, oral ulcers, and arthritis. Less than 20% of patients will develop internal disease, including nephritis and pulmonary disease. Symptoms of Sjögren’s syndrome and SCLE may overlap in some patients, and will portend higher risk for internal disease.

The differential diagnosis includes eczema, psoriasis, dermatophytosis, granuloma annulare, and erythema annulare centrifugum. Histology reveals epidermal atrophy and keratinocyte apoptosis, with a superficial and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis. Interface changes at the dermal-epidermal junction can be seen. Direct immunofluorescence of lesional skin is positive in one-third of cases, often revealing granular deposits of IgG and IgM at the dermal-epidermal junction and around hair follicles (called the lupus-band test). Serology in SCLE may reveal a positive antinuclear antigen test, as well as positive Ro/SSA antigen. Other lupus serologies such as La/SSB, dsDNA, antihistone, and Sm antibodies may be positive, but are less commonly seen.

Several drugs may cause SCLE, such as hydrochlorothiazide, terbinafine, ACE inhibitors, NSAIDs, calcium-channel blockers, interferons, anticonvulsants, griseofulvin, penicillamine, spironolactone, tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors, and statins. Discontinuing the offending medications may clear the lesions, but not always.

Treatment includes sunscreen and avoidance of sun exposure. Potent topical corticosteroids are helpful. If systemic treatment is indicated, antimalarials are first line.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is a type of cutaneous lupus erythematosus that may occur independently of or in combination with systemic lupus erythematosus. About 10%-15% of patients with SCLE will develop systemic lupus erythematosus. White females are more typically affected.

SCLE lesions often present as scaly, annular, or polycyclic scaly patches and plaques with central clearing. They may appear psoriasiform. They heal without atrophy or scarring but may leave dyspigmentation. Follicular plugging is absent. Lesions generally occur on sun exposed areas such as the neck, V of the chest, and upper extremities. Up to 75% of patients may exhibit associated symptoms such as photosensitivity, oral ulcers, and arthritis. Less than 20% of patients will develop internal disease, including nephritis and pulmonary disease. Symptoms of Sjögren’s syndrome and SCLE may overlap in some patients, and will portend higher risk for internal disease.

The differential diagnosis includes eczema, psoriasis, dermatophytosis, granuloma annulare, and erythema annulare centrifugum. Histology reveals epidermal atrophy and keratinocyte apoptosis, with a superficial and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis. Interface changes at the dermal-epidermal junction can be seen. Direct immunofluorescence of lesional skin is positive in one-third of cases, often revealing granular deposits of IgG and IgM at the dermal-epidermal junction and around hair follicles (called the lupus-band test). Serology in SCLE may reveal a positive antinuclear antigen test, as well as positive Ro/SSA antigen. Other lupus serologies such as La/SSB, dsDNA, antihistone, and Sm antibodies may be positive, but are less commonly seen.

Several drugs may cause SCLE, such as hydrochlorothiazide, terbinafine, ACE inhibitors, NSAIDs, calcium-channel blockers, interferons, anticonvulsants, griseofulvin, penicillamine, spironolactone, tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors, and statins. Discontinuing the offending medications may clear the lesions, but not always.

Treatment includes sunscreen and avoidance of sun exposure. Potent topical corticosteroids are helpful. If systemic treatment is indicated, antimalarials are first line.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Rash on hands and feet

Lichenoid dermatoses are a heterogeneous group of diseases with varying clinical presentations. The term “lichenoid” refers to the popular lesions of certain skin disorders of which lichen planus (LP) is the prototype. The papules are shiny, flat topped, polygonal, of different sizes, and occur in clusters creating a pattern that resembles lichen growing on a rock. Lichenoid eruptions are quite common in children and can result from many different origins. In most instances the precise mechanism of disease is not known, although it is usually believed to be immunologic in nature. Certain disorders are common in children, whereas others more often affect the adult population.

Lichen striatus, lichen nitidus (LN), and lichen spinulosus are lichenoid lesions that are more common in children than adults.

LN – as seen in the patient described here – is an uncommon benign inflammatory skin disease, primarily of children. Individual lesions are sharply demarcated, pinpoint to pinhead sized, round or polygonal, and strikingly monomorphous in nature. The papules are usually flesh colored, however, the color varies from yellow and brown to violet hues depending on the background color of the patient’s skin. This variation in color is in contrast with LP which is characteristically violaceous. The surfaces of the papules are flat, shiny, and slightly elevated. They may have a fine scale or a hyperkeratotic plug. The lesions tend to occur in groups, primarily on the abdomen, chest, glans penis, and upper extremities. The Koebner phenomenon is observed and is a hallmark for the disorder. LN is generally asymptomatic, unlike LP, which is exceedingly pruritic.

The cause of LN is unknown; however, it has been proposed that LN, in particular generalized LN, may be associated with immune alterations in the patient. The course of LN is slowly progressive with a tendency toward remission. The lesions can remain stationary for years; however, they sometimes disappear spontaneously and completely.

The differential diagnosis of LN beyond the entities discussed above includes frictional lichenoid eruption, lichenoid drug eruption, LP, and keratosis pilaris.

LP is the classic lichenoid eruption. It is rare in children and occurs most frequently in individuals aged 30-60 years. LP usually manifests as an extremely pruritic eruption of flat-topped polygonal and violaceous papules that often have fine linear white scales known as Wickham striae. The distribution is usually bilateral and symmetric with most of the papules and plaques located on the legs, flexor wrists, neck, and genitalia. The lesions may exhibit the Koebner phenomenon, appearing in a linear pattern along the site of a scratch. Generally, in childhood cases there is reported itching, and oral and nail lesions are less common.

Frictional lichenoid eruption occurs in childhood. The lesions consist of lichenoid papules with regular borders 1-2 mm in diameter that generally are asymptomatic, although they may be mildly pruritic. The papules are found in a very characteristic distribution with almost exclusive involvement of the backs of the hands, fingers, elbows, and knees with occasional involvement of the extensor forearms and cheeks. This disorder occurs in predisposed children who have been exposed to significant frictional force during play, and typically resolves spontaneously after removal of the stimulus.

Keratosis pilaris is a rash that usually is found on the outer areas of the upper arms, upper thighs, buttocks, and cheeks. It consists of small bumps that are flesh colored to red. The bumps generally don’t hurt or itch.

The lack of symptoms and spontaneous healing have rendered treatment unnecessary in most cases. LN generally is self-limiting, thus treatment may not be necessary. However, topical treatment with mid- to high-potency corticosteroids has hastened resolution of lesions in some children, as have topical dinitrochlorobenzene and systemic treatment with psoralens, astemizole, etretinate, and psoralen-UVA.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Bhatti is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego. Neither Dr. Eichenfield nor Dr. Bhatti has any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

Pickert A. Cutis. 2012 Sep;90(3):E1-3. https://mdedge-files-live.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/files/s3fs-public/Document/September-2017/0900300E1.pdf Tziotzios C et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Nov;79(5):789-804. Tilly JJ et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Oct;51(4):606-24.

Lichenoid dermatoses are a heterogeneous group of diseases with varying clinical presentations. The term “lichenoid” refers to the popular lesions of certain skin disorders of which lichen planus (LP) is the prototype. The papules are shiny, flat topped, polygonal, of different sizes, and occur in clusters creating a pattern that resembles lichen growing on a rock. Lichenoid eruptions are quite common in children and can result from many different origins. In most instances the precise mechanism of disease is not known, although it is usually believed to be immunologic in nature. Certain disorders are common in children, whereas others more often affect the adult population.

Lichen striatus, lichen nitidus (LN), and lichen spinulosus are lichenoid lesions that are more common in children than adults.

LN – as seen in the patient described here – is an uncommon benign inflammatory skin disease, primarily of children. Individual lesions are sharply demarcated, pinpoint to pinhead sized, round or polygonal, and strikingly monomorphous in nature. The papules are usually flesh colored, however, the color varies from yellow and brown to violet hues depending on the background color of the patient’s skin. This variation in color is in contrast with LP which is characteristically violaceous. The surfaces of the papules are flat, shiny, and slightly elevated. They may have a fine scale or a hyperkeratotic plug. The lesions tend to occur in groups, primarily on the abdomen, chest, glans penis, and upper extremities. The Koebner phenomenon is observed and is a hallmark for the disorder. LN is generally asymptomatic, unlike LP, which is exceedingly pruritic.

The cause of LN is unknown; however, it has been proposed that LN, in particular generalized LN, may be associated with immune alterations in the patient. The course of LN is slowly progressive with a tendency toward remission. The lesions can remain stationary for years; however, they sometimes disappear spontaneously and completely.

The differential diagnosis of LN beyond the entities discussed above includes frictional lichenoid eruption, lichenoid drug eruption, LP, and keratosis pilaris.

LP is the classic lichenoid eruption. It is rare in children and occurs most frequently in individuals aged 30-60 years. LP usually manifests as an extremely pruritic eruption of flat-topped polygonal and violaceous papules that often have fine linear white scales known as Wickham striae. The distribution is usually bilateral and symmetric with most of the papules and plaques located on the legs, flexor wrists, neck, and genitalia. The lesions may exhibit the Koebner phenomenon, appearing in a linear pattern along the site of a scratch. Generally, in childhood cases there is reported itching, and oral and nail lesions are less common.

Frictional lichenoid eruption occurs in childhood. The lesions consist of lichenoid papules with regular borders 1-2 mm in diameter that generally are asymptomatic, although they may be mildly pruritic. The papules are found in a very characteristic distribution with almost exclusive involvement of the backs of the hands, fingers, elbows, and knees with occasional involvement of the extensor forearms and cheeks. This disorder occurs in predisposed children who have been exposed to significant frictional force during play, and typically resolves spontaneously after removal of the stimulus.

Keratosis pilaris is a rash that usually is found on the outer areas of the upper arms, upper thighs, buttocks, and cheeks. It consists of small bumps that are flesh colored to red. The bumps generally don’t hurt or itch.

The lack of symptoms and spontaneous healing have rendered treatment unnecessary in most cases. LN generally is self-limiting, thus treatment may not be necessary. However, topical treatment with mid- to high-potency corticosteroids has hastened resolution of lesions in some children, as have topical dinitrochlorobenzene and systemic treatment with psoralens, astemizole, etretinate, and psoralen-UVA.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Bhatti is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego. Neither Dr. Eichenfield nor Dr. Bhatti has any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

Pickert A. Cutis. 2012 Sep;90(3):E1-3. https://mdedge-files-live.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/files/s3fs-public/Document/September-2017/0900300E1.pdf Tziotzios C et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Nov;79(5):789-804. Tilly JJ et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Oct;51(4):606-24.

Lichenoid dermatoses are a heterogeneous group of diseases with varying clinical presentations. The term “lichenoid” refers to the popular lesions of certain skin disorders of which lichen planus (LP) is the prototype. The papules are shiny, flat topped, polygonal, of different sizes, and occur in clusters creating a pattern that resembles lichen growing on a rock. Lichenoid eruptions are quite common in children and can result from many different origins. In most instances the precise mechanism of disease is not known, although it is usually believed to be immunologic in nature. Certain disorders are common in children, whereas others more often affect the adult population.

Lichen striatus, lichen nitidus (LN), and lichen spinulosus are lichenoid lesions that are more common in children than adults.

LN – as seen in the patient described here – is an uncommon benign inflammatory skin disease, primarily of children. Individual lesions are sharply demarcated, pinpoint to pinhead sized, round or polygonal, and strikingly monomorphous in nature. The papules are usually flesh colored, however, the color varies from yellow and brown to violet hues depending on the background color of the patient’s skin. This variation in color is in contrast with LP which is characteristically violaceous. The surfaces of the papules are flat, shiny, and slightly elevated. They may have a fine scale or a hyperkeratotic plug. The lesions tend to occur in groups, primarily on the abdomen, chest, glans penis, and upper extremities. The Koebner phenomenon is observed and is a hallmark for the disorder. LN is generally asymptomatic, unlike LP, which is exceedingly pruritic.

The cause of LN is unknown; however, it has been proposed that LN, in particular generalized LN, may be associated with immune alterations in the patient. The course of LN is slowly progressive with a tendency toward remission. The lesions can remain stationary for years; however, they sometimes disappear spontaneously and completely.

The differential diagnosis of LN beyond the entities discussed above includes frictional lichenoid eruption, lichenoid drug eruption, LP, and keratosis pilaris.

LP is the classic lichenoid eruption. It is rare in children and occurs most frequently in individuals aged 30-60 years. LP usually manifests as an extremely pruritic eruption of flat-topped polygonal and violaceous papules that often have fine linear white scales known as Wickham striae. The distribution is usually bilateral and symmetric with most of the papules and plaques located on the legs, flexor wrists, neck, and genitalia. The lesions may exhibit the Koebner phenomenon, appearing in a linear pattern along the site of a scratch. Generally, in childhood cases there is reported itching, and oral and nail lesions are less common.

Frictional lichenoid eruption occurs in childhood. The lesions consist of lichenoid papules with regular borders 1-2 mm in diameter that generally are asymptomatic, although they may be mildly pruritic. The papules are found in a very characteristic distribution with almost exclusive involvement of the backs of the hands, fingers, elbows, and knees with occasional involvement of the extensor forearms and cheeks. This disorder occurs in predisposed children who have been exposed to significant frictional force during play, and typically resolves spontaneously after removal of the stimulus.

Keratosis pilaris is a rash that usually is found on the outer areas of the upper arms, upper thighs, buttocks, and cheeks. It consists of small bumps that are flesh colored to red. The bumps generally don’t hurt or itch.

The lack of symptoms and spontaneous healing have rendered treatment unnecessary in most cases. LN generally is self-limiting, thus treatment may not be necessary. However, topical treatment with mid- to high-potency corticosteroids has hastened resolution of lesions in some children, as have topical dinitrochlorobenzene and systemic treatment with psoralens, astemizole, etretinate, and psoralen-UVA.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Bhatti is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego. Neither Dr. Eichenfield nor Dr. Bhatti has any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

Pickert A. Cutis. 2012 Sep;90(3):E1-3. https://mdedge-files-live.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/files/s3fs-public/Document/September-2017/0900300E1.pdf Tziotzios C et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Nov;79(5):789-804. Tilly JJ et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Oct;51(4):606-24.

A 9-year-old healthy Kuwaiti male with no significant past medical history presents with a rash on his hands and feet that has been present for 3 years.

His mother reports that he has been seen by dermatologists in various countries and was last seen by a dermatologist in Kuwait 3 years ago. At that time, he was told that it was dryness and advised to not shower daily. Since then he has been taking showers three times weekly and using Cetaphil once weekly without improvement. He was seen by his pediatrician 6 months ago, diagnosed with xerosis, and was given hydrocortisone 2.5% to use twice daily, again without any improvement.

The rash is not itchy, and he has no oral lesions or nail involvement. Exam revealed lichenoid papules on bilateral dorsal hands and feet, bilateral upper arms, bilateral axilla, lower abdomen, and left upper chest.

Make the Diagnosis

A skin biopsy of one of the lesions showed granulomatous inflammation composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, and giant cells around hair follicles with negative mycobacterium stains and fungal stains, consistent with granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Tissue cultures from a skin biopsy for aerobic bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungus all were negative.

The patient initially was treated with erythromycin, but after 2 weeks, he reported abdominal pain and nausea and was unable to tolerate the medication. He was switched to clarithromycin, which he took for 6 weeks with clearance of the lesions.

A year later, some of the lesions recurred. He was treated again with clarithromycin and the lesions resolved.

Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis (CGPD) is a benign skin eruption that occurs in prepubertal children. It also has been called facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption (FACE), and it tends to occur most commonly in children of darker skin types.1 but there are some cases reported of extra facial involvement.2 The lesions usually are not symptomatic, and they are more common in boys. The cause of this condition is not known, but possible triggers could include prior exposure to topical and systemic corticosteroids, as well as exposure to certain allergens such as formaldehyde.1

In histopathology, the lesions are characterized by granulomatous infiltrates around the hair follicles and the upper dermis. The granulomas are formed of macrophages, lymphocytes, and giant cell, as were seen in our patient.3

Several conditions can look very similar to CGPD; these include sarcoidosis, lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei (LMDF), and granulomatous rosacea.

Sarcoidosis is a rare condition in children, and the lesions can be similar to the ones seen in our patient. Patients with sarcoidosis usually present with other systemic symptoms including fever, weight loss, respiratory symptoms, and fatigue; none of these were seen in our patient. Under the microscope, the lesions are characterized by “naked granulomas” instead of the inflammatory granulomas seen on our patient.

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei is a rare inflammatory skin condition commonly seen in young adults and is thought to be a variant of rosacea. It is characterized by skin-color to pink to yellow dome-shaped papules on the central face. Histologically, the lesions present as dermal epithelioid cell granulomas with central necrosis and surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate with multinucleate giant cells.4

Granulomatous rosacea and CGPD are considered two separate entities. Granulomatous rosacea tends to have a more chronic course, is not that common in children, and clinically presents with pustules, papules, and cysts around the eyes and cheeks.

Infectious processes like tuberculosis and fungal infections were ruled out in our patient with cultures and histopathology. Allergic contact dermatitis on the face can present with skin-color to pink papules, but they usually are very pruritic and improve with topical corticosteroids, while these medications can worsen CGPD.

CGPD can be a self-limiting condition. When mild, it can be treated with topical metronidazole, topical erythromycin, topical clindamycin solution, or pimecrolimus. Our patient failed treatment with pimecrolimus. For severe presentations, oral tetracyclines, erythromycin, and other macrolides, metronidazole, and oral isotretinoin can help clear the lesions.5

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Ann Dermatol. 2011 Aug;23(3):386-8.

2. Int J Dermatol. 2007 Feb;46(2):143-5.

3. J Cutan Med Surg. 2009 Feb 28;13(2):115-8.

4. An Bras Dermatol. 2017 Nov-Dec;92(6):851-3.

5. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018 Jan-Feb; 9(1):68-70.

A skin biopsy of one of the lesions showed granulomatous inflammation composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, and giant cells around hair follicles with negative mycobacterium stains and fungal stains, consistent with granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Tissue cultures from a skin biopsy for aerobic bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungus all were negative.

The patient initially was treated with erythromycin, but after 2 weeks, he reported abdominal pain and nausea and was unable to tolerate the medication. He was switched to clarithromycin, which he took for 6 weeks with clearance of the lesions.

A year later, some of the lesions recurred. He was treated again with clarithromycin and the lesions resolved.

Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis (CGPD) is a benign skin eruption that occurs in prepubertal children. It also has been called facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption (FACE), and it tends to occur most commonly in children of darker skin types.1 but there are some cases reported of extra facial involvement.2 The lesions usually are not symptomatic, and they are more common in boys. The cause of this condition is not known, but possible triggers could include prior exposure to topical and systemic corticosteroids, as well as exposure to certain allergens such as formaldehyde.1

In histopathology, the lesions are characterized by granulomatous infiltrates around the hair follicles and the upper dermis. The granulomas are formed of macrophages, lymphocytes, and giant cell, as were seen in our patient.3

Several conditions can look very similar to CGPD; these include sarcoidosis, lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei (LMDF), and granulomatous rosacea.

Sarcoidosis is a rare condition in children, and the lesions can be similar to the ones seen in our patient. Patients with sarcoidosis usually present with other systemic symptoms including fever, weight loss, respiratory symptoms, and fatigue; none of these were seen in our patient. Under the microscope, the lesions are characterized by “naked granulomas” instead of the inflammatory granulomas seen on our patient.

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei is a rare inflammatory skin condition commonly seen in young adults and is thought to be a variant of rosacea. It is characterized by skin-color to pink to yellow dome-shaped papules on the central face. Histologically, the lesions present as dermal epithelioid cell granulomas with central necrosis and surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate with multinucleate giant cells.4

Granulomatous rosacea and CGPD are considered two separate entities. Granulomatous rosacea tends to have a more chronic course, is not that common in children, and clinically presents with pustules, papules, and cysts around the eyes and cheeks.

Infectious processes like tuberculosis and fungal infections were ruled out in our patient with cultures and histopathology. Allergic contact dermatitis on the face can present with skin-color to pink papules, but they usually are very pruritic and improve with topical corticosteroids, while these medications can worsen CGPD.

CGPD can be a self-limiting condition. When mild, it can be treated with topical metronidazole, topical erythromycin, topical clindamycin solution, or pimecrolimus. Our patient failed treatment with pimecrolimus. For severe presentations, oral tetracyclines, erythromycin, and other macrolides, metronidazole, and oral isotretinoin can help clear the lesions.5

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Ann Dermatol. 2011 Aug;23(3):386-8.

2. Int J Dermatol. 2007 Feb;46(2):143-5.

3. J Cutan Med Surg. 2009 Feb 28;13(2):115-8.

4. An Bras Dermatol. 2017 Nov-Dec;92(6):851-3.

5. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018 Jan-Feb; 9(1):68-70.

A skin biopsy of one of the lesions showed granulomatous inflammation composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, and giant cells around hair follicles with negative mycobacterium stains and fungal stains, consistent with granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Tissue cultures from a skin biopsy for aerobic bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungus all were negative.

The patient initially was treated with erythromycin, but after 2 weeks, he reported abdominal pain and nausea and was unable to tolerate the medication. He was switched to clarithromycin, which he took for 6 weeks with clearance of the lesions.

A year later, some of the lesions recurred. He was treated again with clarithromycin and the lesions resolved.

Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis (CGPD) is a benign skin eruption that occurs in prepubertal children. It also has been called facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption (FACE), and it tends to occur most commonly in children of darker skin types.1 but there are some cases reported of extra facial involvement.2 The lesions usually are not symptomatic, and they are more common in boys. The cause of this condition is not known, but possible triggers could include prior exposure to topical and systemic corticosteroids, as well as exposure to certain allergens such as formaldehyde.1

In histopathology, the lesions are characterized by granulomatous infiltrates around the hair follicles and the upper dermis. The granulomas are formed of macrophages, lymphocytes, and giant cell, as were seen in our patient.3

Several conditions can look very similar to CGPD; these include sarcoidosis, lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei (LMDF), and granulomatous rosacea.

Sarcoidosis is a rare condition in children, and the lesions can be similar to the ones seen in our patient. Patients with sarcoidosis usually present with other systemic symptoms including fever, weight loss, respiratory symptoms, and fatigue; none of these were seen in our patient. Under the microscope, the lesions are characterized by “naked granulomas” instead of the inflammatory granulomas seen on our patient.

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei is a rare inflammatory skin condition commonly seen in young adults and is thought to be a variant of rosacea. It is characterized by skin-color to pink to yellow dome-shaped papules on the central face. Histologically, the lesions present as dermal epithelioid cell granulomas with central necrosis and surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate with multinucleate giant cells.4

Granulomatous rosacea and CGPD are considered two separate entities. Granulomatous rosacea tends to have a more chronic course, is not that common in children, and clinically presents with pustules, papules, and cysts around the eyes and cheeks.

Infectious processes like tuberculosis and fungal infections were ruled out in our patient with cultures and histopathology. Allergic contact dermatitis on the face can present with skin-color to pink papules, but they usually are very pruritic and improve with topical corticosteroids, while these medications can worsen CGPD.

CGPD can be a self-limiting condition. When mild, it can be treated with topical metronidazole, topical erythromycin, topical clindamycin solution, or pimecrolimus. Our patient failed treatment with pimecrolimus. For severe presentations, oral tetracyclines, erythromycin, and other macrolides, metronidazole, and oral isotretinoin can help clear the lesions.5

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Ann Dermatol. 2011 Aug;23(3):386-8.

2. Int J Dermatol. 2007 Feb;46(2):143-5.

3. J Cutan Med Surg. 2009 Feb 28;13(2):115-8.

4. An Bras Dermatol. 2017 Nov-Dec;92(6):851-3.

5. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018 Jan-Feb; 9(1):68-70.

An 8-year-old African American male presented to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of a 3-month history of flesh-colored bumps on the face. According to the patient's mother, the lesions started with small pimple-like lesions around the nose and then spread to the whole face. Some lesions were crusty and somewhat itchy. He was treated with cephalexin and pimecrolimus with no improvement. The mother was very concerned because the lesions were close to the eyes and spreading.

He had no fevers, arthritis, or upper respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms. He recently came back from a trip to Africa to visit his family. No other family members were affected. He used some new soaps, sunscreens, and moisturizers while he was in Africa.

On physical examination, the boy was in no acute distress. He had multiple flesh-colored papules on the face, especially around the eyes, nose, and mouth, where some lesions appeared crusted. There were no other skin lesions elsewhere on his body. There was no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly.

Progressive, pruritic eruption of firm, skin-colored papules

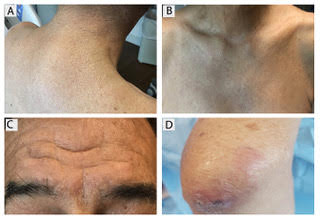

Scleromyxedema, or generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a primary cutaneous mucinosis with unknown pathogenesis characterized by generalized firm, skin-colored papules and is commonly associated with an underlying monoclonal gammopathy (usually Ig-gamma paraproteinemia).

Scleromyxedema may have associated internal involvement, including neurologic, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, renal, cardiovascular, ophthalmological, or musculoskeletal. Histopathology demonstrates mucin in the dermis seen with Alcian blue staining, proliferation of fibroblasts, and increased collagen deposition.

The condition is chronic and progressive. Intravenous immunoglobulin is considered first-line treatment. Thalidomide and corticosteroids have been reported to also be efficacious.

It is associated with hematologic disorders, including IgA monoclonal gammopathy, as well as myeloproliferative disorders, leukemia, infections, and inflammatory bowel disease. Although its pathophysiology is not well understood, vascular immune complex deposition, repetitive inflammation, and subsequent fibrosis may play a role. On histology, there is leukocytoclastic vasculitis with polymorphonuclear cell infiltrate and fibrin deposition in the superficial and mid-dermis and onion-skin fibrosis.

EED often self-resolves within 5-10 years, although it can become chronic and recurrent. Dapsone, niacinamide, antimalarials, NSAIDs, tetracyclines, corticosteroids, colchicine, and plasmapheresis are reported treatments. This patient’s EED was recalcitrant to prednisone and responded to colchicine.

Scleromyxedema and EED are both rare, distinct cutaneous entities associated with different underlying paraproteinemias and to the best of our knowledge, have not been previously reported to coexist in a single patient.

This case and the photos were submitted by Rachel Fayne, BA; Yumeng Li, MD, MS; Fabrizio Galimberti, MD, PhD; and Brian Morrison, MD, of the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery at the University of Miami.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Scleromyxedema, or generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a primary cutaneous mucinosis with unknown pathogenesis characterized by generalized firm, skin-colored papules and is commonly associated with an underlying monoclonal gammopathy (usually Ig-gamma paraproteinemia).

Scleromyxedema may have associated internal involvement, including neurologic, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, renal, cardiovascular, ophthalmological, or musculoskeletal. Histopathology demonstrates mucin in the dermis seen with Alcian blue staining, proliferation of fibroblasts, and increased collagen deposition.

The condition is chronic and progressive. Intravenous immunoglobulin is considered first-line treatment. Thalidomide and corticosteroids have been reported to also be efficacious.

It is associated with hematologic disorders, including IgA monoclonal gammopathy, as well as myeloproliferative disorders, leukemia, infections, and inflammatory bowel disease. Although its pathophysiology is not well understood, vascular immune complex deposition, repetitive inflammation, and subsequent fibrosis may play a role. On histology, there is leukocytoclastic vasculitis with polymorphonuclear cell infiltrate and fibrin deposition in the superficial and mid-dermis and onion-skin fibrosis.

EED often self-resolves within 5-10 years, although it can become chronic and recurrent. Dapsone, niacinamide, antimalarials, NSAIDs, tetracyclines, corticosteroids, colchicine, and plasmapheresis are reported treatments. This patient’s EED was recalcitrant to prednisone and responded to colchicine.

Scleromyxedema and EED are both rare, distinct cutaneous entities associated with different underlying paraproteinemias and to the best of our knowledge, have not been previously reported to coexist in a single patient.

This case and the photos were submitted by Rachel Fayne, BA; Yumeng Li, MD, MS; Fabrizio Galimberti, MD, PhD; and Brian Morrison, MD, of the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery at the University of Miami.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Scleromyxedema, or generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a primary cutaneous mucinosis with unknown pathogenesis characterized by generalized firm, skin-colored papules and is commonly associated with an underlying monoclonal gammopathy (usually Ig-gamma paraproteinemia).

Scleromyxedema may have associated internal involvement, including neurologic, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, renal, cardiovascular, ophthalmological, or musculoskeletal. Histopathology demonstrates mucin in the dermis seen with Alcian blue staining, proliferation of fibroblasts, and increased collagen deposition.

The condition is chronic and progressive. Intravenous immunoglobulin is considered first-line treatment. Thalidomide and corticosteroids have been reported to also be efficacious.

It is associated with hematologic disorders, including IgA monoclonal gammopathy, as well as myeloproliferative disorders, leukemia, infections, and inflammatory bowel disease. Although its pathophysiology is not well understood, vascular immune complex deposition, repetitive inflammation, and subsequent fibrosis may play a role. On histology, there is leukocytoclastic vasculitis with polymorphonuclear cell infiltrate and fibrin deposition in the superficial and mid-dermis and onion-skin fibrosis.

EED often self-resolves within 5-10 years, although it can become chronic and recurrent. Dapsone, niacinamide, antimalarials, NSAIDs, tetracyclines, corticosteroids, colchicine, and plasmapheresis are reported treatments. This patient’s EED was recalcitrant to prednisone and responded to colchicine.

Scleromyxedema and EED are both rare, distinct cutaneous entities associated with different underlying paraproteinemias and to the best of our knowledge, have not been previously reported to coexist in a single patient.

This case and the photos were submitted by Rachel Fayne, BA; Yumeng Li, MD, MS; Fabrizio Galimberti, MD, PhD; and Brian Morrison, MD, of the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery at the University of Miami.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Pink scaly rash on torso and extremities

Tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) inhibitors are therapeutic agents used to treat a variety of inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, as well as psoriasis of the skin (PSO) and psoriatic arthritis. In a 2017 systematic review, there were 216 reported cases of new-onset TNF-alpha inhibitor–induced psoriasis, with an estimated rate of 1 per 1,000. The cases thus far have had a wide range of presentations, the most common being plaque psoriasis, scalp psoriasis, as well as palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.1

A retrospective chart review study at Mayo clinic published in 2017 evaluated children younger than 19 years seen in 2003-2015 who developed new-onset or recurrent PSO with a history of inflammatory bowel disease being treated with anti-TNF-alpha therapy. The review showed variable latency in the development of PSO in these patients, although it typically occurred during inflammatory bowel disease remission.2 It is unclear whether there is an association between a personal or family history of psoriasis and development of these lesions.

TNF-alpha, interleukin (IL)–17) and interferon-alpha (IFN-alpha) are main cytokines that contribute to the development of psoriasis. The mechanism of action for paradoxical PSO/psoriasis in patients treated with anti-TNF is not clearly understood; however, many hypotheses are based on an imbalance between TNF-alpha and interferon-alpha – more specifically, an increased production of interferon-alpha. TNF-alpha inhibits the activity of plasmacytoid dendritic cells which are key producers of IFN-alpha. Because of this blockade, there is unopposed IFN-alpha production. Interferon-alpha allows for the expression of chemokines such as CXCR3, which favor T cells homing to the skin. IFN-alpha also stimulates and activates T cells to produce TNF-alpha and IL-17, which in turn sustains inflammatory mechanisms and allows for the development of psoriatic lesions.3

There are no universal management guidelines. Most of these patients’ treatment plans mirror standard psoriasis therapies while the main question remains the decision to continue the same anti-TNF therapy, change anti-TNF agents, or entirely switch classes of biologic or other systemic therapy. This decision in management requires several considerations: treatability of TNF-alpha inhibitor-induced psoriasis, the severity of background disease (i.e., rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, other systemic condition), and whether the underlying disease is well controlled on current therapy, as well as the consideration of possible loss in efficacy if a drug is discontinued and then restarted at a later date.4

A reasonable initial approach in patients with well-controlled underlying disease and mild skin eruption is to continue anti-TNF therapy and manage skin topically with topical corticosteroids and/or phototherapy. In patients that either do not have well-controlled underlying disease or moderate skin involvement, changing to an alternative anti-TNF or other agent may be reasonable, and requires coordinated care with involved specialists. In the 2017 pediatric review mentioned previously, nearly half of the patients required a change in their initial anti-TNF-alpha agent despite conventional skin-directed therapies, and one-third of patients discontinued all anti-TNF-alpha therapy because of PSO.2

The psoriasiform papulosquamous features of this case along with the history suggests the diagnosis. Pityriasis rosea would be highly atypical on the feet and with the duration of findings. Lichen planus and atopic dermatitis morphology are inconsistent with this eruption, and coxsackie viral infection would have a shorter course.

Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Feb;76(2):334-41.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017 May;34(3):253-60.

3. RMD Open. 2016 Jul 15;2(2):e000239.

4. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2019 Apr;4(2):70-80.

Tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) inhibitors are therapeutic agents used to treat a variety of inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, as well as psoriasis of the skin (PSO) and psoriatic arthritis. In a 2017 systematic review, there were 216 reported cases of new-onset TNF-alpha inhibitor–induced psoriasis, with an estimated rate of 1 per 1,000. The cases thus far have had a wide range of presentations, the most common being plaque psoriasis, scalp psoriasis, as well as palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.1

A retrospective chart review study at Mayo clinic published in 2017 evaluated children younger than 19 years seen in 2003-2015 who developed new-onset or recurrent PSO with a history of inflammatory bowel disease being treated with anti-TNF-alpha therapy. The review showed variable latency in the development of PSO in these patients, although it typically occurred during inflammatory bowel disease remission.2 It is unclear whether there is an association between a personal or family history of psoriasis and development of these lesions.

TNF-alpha, interleukin (IL)–17) and interferon-alpha (IFN-alpha) are main cytokines that contribute to the development of psoriasis. The mechanism of action for paradoxical PSO/psoriasis in patients treated with anti-TNF is not clearly understood; however, many hypotheses are based on an imbalance between TNF-alpha and interferon-alpha – more specifically, an increased production of interferon-alpha. TNF-alpha inhibits the activity of plasmacytoid dendritic cells which are key producers of IFN-alpha. Because of this blockade, there is unopposed IFN-alpha production. Interferon-alpha allows for the expression of chemokines such as CXCR3, which favor T cells homing to the skin. IFN-alpha also stimulates and activates T cells to produce TNF-alpha and IL-17, which in turn sustains inflammatory mechanisms and allows for the development of psoriatic lesions.3

There are no universal management guidelines. Most of these patients’ treatment plans mirror standard psoriasis therapies while the main question remains the decision to continue the same anti-TNF therapy, change anti-TNF agents, or entirely switch classes of biologic or other systemic therapy. This decision in management requires several considerations: treatability of TNF-alpha inhibitor-induced psoriasis, the severity of background disease (i.e., rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, other systemic condition), and whether the underlying disease is well controlled on current therapy, as well as the consideration of possible loss in efficacy if a drug is discontinued and then restarted at a later date.4

A reasonable initial approach in patients with well-controlled underlying disease and mild skin eruption is to continue anti-TNF therapy and manage skin topically with topical corticosteroids and/or phototherapy. In patients that either do not have well-controlled underlying disease or moderate skin involvement, changing to an alternative anti-TNF or other agent may be reasonable, and requires coordinated care with involved specialists. In the 2017 pediatric review mentioned previously, nearly half of the patients required a change in their initial anti-TNF-alpha agent despite conventional skin-directed therapies, and one-third of patients discontinued all anti-TNF-alpha therapy because of PSO.2

The psoriasiform papulosquamous features of this case along with the history suggests the diagnosis. Pityriasis rosea would be highly atypical on the feet and with the duration of findings. Lichen planus and atopic dermatitis morphology are inconsistent with this eruption, and coxsackie viral infection would have a shorter course.

Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Feb;76(2):334-41.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017 May;34(3):253-60.

3. RMD Open. 2016 Jul 15;2(2):e000239.

4. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2019 Apr;4(2):70-80.

Tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) inhibitors are therapeutic agents used to treat a variety of inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, as well as psoriasis of the skin (PSO) and psoriatic arthritis. In a 2017 systematic review, there were 216 reported cases of new-onset TNF-alpha inhibitor–induced psoriasis, with an estimated rate of 1 per 1,000. The cases thus far have had a wide range of presentations, the most common being plaque psoriasis, scalp psoriasis, as well as palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.1

A retrospective chart review study at Mayo clinic published in 2017 evaluated children younger than 19 years seen in 2003-2015 who developed new-onset or recurrent PSO with a history of inflammatory bowel disease being treated with anti-TNF-alpha therapy. The review showed variable latency in the development of PSO in these patients, although it typically occurred during inflammatory bowel disease remission.2 It is unclear whether there is an association between a personal or family history of psoriasis and development of these lesions.

TNF-alpha, interleukin (IL)–17) and interferon-alpha (IFN-alpha) are main cytokines that contribute to the development of psoriasis. The mechanism of action for paradoxical PSO/psoriasis in patients treated with anti-TNF is not clearly understood; however, many hypotheses are based on an imbalance between TNF-alpha and interferon-alpha – more specifically, an increased production of interferon-alpha. TNF-alpha inhibits the activity of plasmacytoid dendritic cells which are key producers of IFN-alpha. Because of this blockade, there is unopposed IFN-alpha production. Interferon-alpha allows for the expression of chemokines such as CXCR3, which favor T cells homing to the skin. IFN-alpha also stimulates and activates T cells to produce TNF-alpha and IL-17, which in turn sustains inflammatory mechanisms and allows for the development of psoriatic lesions.3

There are no universal management guidelines. Most of these patients’ treatment plans mirror standard psoriasis therapies while the main question remains the decision to continue the same anti-TNF therapy, change anti-TNF agents, or entirely switch classes of biologic or other systemic therapy. This decision in management requires several considerations: treatability of TNF-alpha inhibitor-induced psoriasis, the severity of background disease (i.e., rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, other systemic condition), and whether the underlying disease is well controlled on current therapy, as well as the consideration of possible loss in efficacy if a drug is discontinued and then restarted at a later date.4

A reasonable initial approach in patients with well-controlled underlying disease and mild skin eruption is to continue anti-TNF therapy and manage skin topically with topical corticosteroids and/or phototherapy. In patients that either do not have well-controlled underlying disease or moderate skin involvement, changing to an alternative anti-TNF or other agent may be reasonable, and requires coordinated care with involved specialists. In the 2017 pediatric review mentioned previously, nearly half of the patients required a change in their initial anti-TNF-alpha agent despite conventional skin-directed therapies, and one-third of patients discontinued all anti-TNF-alpha therapy because of PSO.2

The psoriasiform papulosquamous features of this case along with the history suggests the diagnosis. Pityriasis rosea would be highly atypical on the feet and with the duration of findings. Lichen planus and atopic dermatitis morphology are inconsistent with this eruption, and coxsackie viral infection would have a shorter course.

Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Feb;76(2):334-41.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017 May;34(3):253-60.

3. RMD Open. 2016 Jul 15;2(2):e000239.

4. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2019 Apr;4(2):70-80.

A 17-year-old male with a history of Crohn's disease, well controlled on infliximab, is seen for evaluation of a pink scaly rash on the torso, upper extremities, and lower extremities. The rash began 5 months previously and has been mostly asymptomatic. The patient denies pruritus or pain at the affected areas. There is no fever or drainage from any of the sites. The patient has not undergone any treatments. He does not have a personal or family history of chronic skin conditions.

On physical exam, he is noted to have numerous pink papules and plaques with overlying scale on his trunk, as well as the dorsal aspects of bilateral hands and the plantar surfaces of bilateral feet. His skin is otherwise unremarkable.

Asymptomatic hypopigmented macules and patches

, also known as Pityrosporum orbiculare or P. ovale. In its hyphal form, it produces skin lesions that appear as scaly, round or oval, hypopigmented, hyperpigmented, or pink macules or patches. Lesions are asymptomatic. The condition is more commonly seen in warm climates or during the summer months. Malassezia requires an oily environment for growth. Typically, TV appears in sebum-producing areas on the trunk. However, other sites may be affected such as the scalp, groin, and flexural areas. Infants may have facial lesions. Hypopigmentation may persist for months, even after lesions are treated, and takes time to resolve.

The differential diagnosis of hypopigmented lesions of tinea versicolor includes vitiligo, hypopigmented mycosis fungoides, progressive macular hypomelanosis (PMH), secondary syphilis, and pityriasis alba. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations can be performed in the office for TV to reveal short, thick fungal hyphae with multiple spores, often referred to as “spaghetti and meatballs.” Use of a Wood’s light may aid in diagnosis. In TV, lesions may fluoresce yellow-green in adjacent follicles, unlike PMH, which characteristically show orange-red follicular fluorescence. A skin biopsy is necessary to rule out hypopgimented mycosis fungoides or syphilis. Histologically in TV, hyphae and spores will be present in the stratum corneum or in hair follicles. These are readily seen with PAS or GMS (Grocott methenamine silver) stains. There is usually no inflammation and skin appears “normal.” A biopsy was performed in this patient that revealed PAS positive hyphae.

Treatment for TV can be topical or systemic. Antifungal azole shampoo or creams, selenium sulfide shampoo, sulfur preparations, and allylamine creams have all been reported as useful treatments. Oral itraconazole or fluconazole are often given as systemic treatments. Monthly or weekly topical therapy may help prevent relapse.

This case and the photos were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

, also known as Pityrosporum orbiculare or P. ovale. In its hyphal form, it produces skin lesions that appear as scaly, round or oval, hypopigmented, hyperpigmented, or pink macules or patches. Lesions are asymptomatic. The condition is more commonly seen in warm climates or during the summer months. Malassezia requires an oily environment for growth. Typically, TV appears in sebum-producing areas on the trunk. However, other sites may be affected such as the scalp, groin, and flexural areas. Infants may have facial lesions. Hypopigmentation may persist for months, even after lesions are treated, and takes time to resolve.

The differential diagnosis of hypopigmented lesions of tinea versicolor includes vitiligo, hypopigmented mycosis fungoides, progressive macular hypomelanosis (PMH), secondary syphilis, and pityriasis alba. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations can be performed in the office for TV to reveal short, thick fungal hyphae with multiple spores, often referred to as “spaghetti and meatballs.” Use of a Wood’s light may aid in diagnosis. In TV, lesions may fluoresce yellow-green in adjacent follicles, unlike PMH, which characteristically show orange-red follicular fluorescence. A skin biopsy is necessary to rule out hypopgimented mycosis fungoides or syphilis. Histologically in TV, hyphae and spores will be present in the stratum corneum or in hair follicles. These are readily seen with PAS or GMS (Grocott methenamine silver) stains. There is usually no inflammation and skin appears “normal.” A biopsy was performed in this patient that revealed PAS positive hyphae.

Treatment for TV can be topical or systemic. Antifungal azole shampoo or creams, selenium sulfide shampoo, sulfur preparations, and allylamine creams have all been reported as useful treatments. Oral itraconazole or fluconazole are often given as systemic treatments. Monthly or weekly topical therapy may help prevent relapse.

This case and the photos were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

, also known as Pityrosporum orbiculare or P. ovale. In its hyphal form, it produces skin lesions that appear as scaly, round or oval, hypopigmented, hyperpigmented, or pink macules or patches. Lesions are asymptomatic. The condition is more commonly seen in warm climates or during the summer months. Malassezia requires an oily environment for growth. Typically, TV appears in sebum-producing areas on the trunk. However, other sites may be affected such as the scalp, groin, and flexural areas. Infants may have facial lesions. Hypopigmentation may persist for months, even after lesions are treated, and takes time to resolve.

The differential diagnosis of hypopigmented lesions of tinea versicolor includes vitiligo, hypopigmented mycosis fungoides, progressive macular hypomelanosis (PMH), secondary syphilis, and pityriasis alba. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations can be performed in the office for TV to reveal short, thick fungal hyphae with multiple spores, often referred to as “spaghetti and meatballs.” Use of a Wood’s light may aid in diagnosis. In TV, lesions may fluoresce yellow-green in adjacent follicles, unlike PMH, which characteristically show orange-red follicular fluorescence. A skin biopsy is necessary to rule out hypopgimented mycosis fungoides or syphilis. Histologically in TV, hyphae and spores will be present in the stratum corneum or in hair follicles. These are readily seen with PAS or GMS (Grocott methenamine silver) stains. There is usually no inflammation and skin appears “normal.” A biopsy was performed in this patient that revealed PAS positive hyphae.

Treatment for TV can be topical or systemic. Antifungal azole shampoo or creams, selenium sulfide shampoo, sulfur preparations, and allylamine creams have all been reported as useful treatments. Oral itraconazole or fluconazole are often given as systemic treatments. Monthly or weekly topical therapy may help prevent relapse.

This case and the photos were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Violaceous papules on calf & foot

that usually presents on the distal lower extremities or feet as red to violaceous papules, patches, and plaques.

Clinically, lesions may look similar to Kaposi sarcoma (KS). It is considered to be a variant of stasis dermatitis or severe chronic venous stasis with a more exuberant vascular proliferation of preexisting vasculature. Although the exact etiology is unknown, it is thought that chronic edema, increased venous pressure, and tissue hypoxia may induce fibroblast and vascular proliferation.

It has also been described in association with vascular anomalies, such as Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome, and Prader-Labhart-Willi syndrome, and is caused by arteriovenous fistulae. Paralysis of lower extremities and amputation stumps are predisposing factors.

KS has four clinical variants: classic KS, African endemic KS, KS in immunocompromised patients, and AIDS-related epidemic KS. All types are caused by the human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8). Violaceous lesions generally begin as macules and may progress to nodules or tumors.

Punch biopsies were performed in our patient. Histologically, thin-walled, dilated, capillary-like structures were present with a thin layer of surrounding pericytes with reactive fibrosis, hemorrhage, hemosiderin, and a scant chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. The endothelial cells did not show atypia or mitotic activity. Endothelial cells were positive for CD31, CD34, and CD99. Pericytes and some of the endothelial cells were positive for actin and negative for D2-40, desmin, and HHV-8. In KS, vessels appear like slitlike or jagged spaces lined by spindled endothelial cells. Mild cytologic atypia is usually present. Endothelial cells are characteristically plump. A distinguishing feature in KS is the “promontory sign,” in which new vessels protrude into the vascular space. CD34 is usually negative and HHV-8 is positive.

Acroangiodermatitis of Mali may improve when the underlying venous insufficiency is addressed with compression stockings, pumps, or vascular intervention. Laser ablation of individual lesions has been described in the literature. Dapsone, oral erythromycin, and topical corticosteroids have been reported as helpful in some patients.

This case and these photos were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

that usually presents on the distal lower extremities or feet as red to violaceous papules, patches, and plaques.

Clinically, lesions may look similar to Kaposi sarcoma (KS). It is considered to be a variant of stasis dermatitis or severe chronic venous stasis with a more exuberant vascular proliferation of preexisting vasculature. Although the exact etiology is unknown, it is thought that chronic edema, increased venous pressure, and tissue hypoxia may induce fibroblast and vascular proliferation.

It has also been described in association with vascular anomalies, such as Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome, and Prader-Labhart-Willi syndrome, and is caused by arteriovenous fistulae. Paralysis of lower extremities and amputation stumps are predisposing factors.

KS has four clinical variants: classic KS, African endemic KS, KS in immunocompromised patients, and AIDS-related epidemic KS. All types are caused by the human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8). Violaceous lesions generally begin as macules and may progress to nodules or tumors.

Punch biopsies were performed in our patient. Histologically, thin-walled, dilated, capillary-like structures were present with a thin layer of surrounding pericytes with reactive fibrosis, hemorrhage, hemosiderin, and a scant chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. The endothelial cells did not show atypia or mitotic activity. Endothelial cells were positive for CD31, CD34, and CD99. Pericytes and some of the endothelial cells were positive for actin and negative for D2-40, desmin, and HHV-8. In KS, vessels appear like slitlike or jagged spaces lined by spindled endothelial cells. Mild cytologic atypia is usually present. Endothelial cells are characteristically plump. A distinguishing feature in KS is the “promontory sign,” in which new vessels protrude into the vascular space. CD34 is usually negative and HHV-8 is positive.

Acroangiodermatitis of Mali may improve when the underlying venous insufficiency is addressed with compression stockings, pumps, or vascular intervention. Laser ablation of individual lesions has been described in the literature. Dapsone, oral erythromycin, and topical corticosteroids have been reported as helpful in some patients.

This case and these photos were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

that usually presents on the distal lower extremities or feet as red to violaceous papules, patches, and plaques.

Clinically, lesions may look similar to Kaposi sarcoma (KS). It is considered to be a variant of stasis dermatitis or severe chronic venous stasis with a more exuberant vascular proliferation of preexisting vasculature. Although the exact etiology is unknown, it is thought that chronic edema, increased venous pressure, and tissue hypoxia may induce fibroblast and vascular proliferation.

It has also been described in association with vascular anomalies, such as Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome, and Prader-Labhart-Willi syndrome, and is caused by arteriovenous fistulae. Paralysis of lower extremities and amputation stumps are predisposing factors.

KS has four clinical variants: classic KS, African endemic KS, KS in immunocompromised patients, and AIDS-related epidemic KS. All types are caused by the human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8). Violaceous lesions generally begin as macules and may progress to nodules or tumors.

Punch biopsies were performed in our patient. Histologically, thin-walled, dilated, capillary-like structures were present with a thin layer of surrounding pericytes with reactive fibrosis, hemorrhage, hemosiderin, and a scant chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. The endothelial cells did not show atypia or mitotic activity. Endothelial cells were positive for CD31, CD34, and CD99. Pericytes and some of the endothelial cells were positive for actin and negative for D2-40, desmin, and HHV-8. In KS, vessels appear like slitlike or jagged spaces lined by spindled endothelial cells. Mild cytologic atypia is usually present. Endothelial cells are characteristically plump. A distinguishing feature in KS is the “promontory sign,” in which new vessels protrude into the vascular space. CD34 is usually negative and HHV-8 is positive.

Acroangiodermatitis of Mali may improve when the underlying venous insufficiency is addressed with compression stockings, pumps, or vascular intervention. Laser ablation of individual lesions has been described in the literature. Dapsone, oral erythromycin, and topical corticosteroids have been reported as helpful in some patients.

This case and these photos were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.