User login

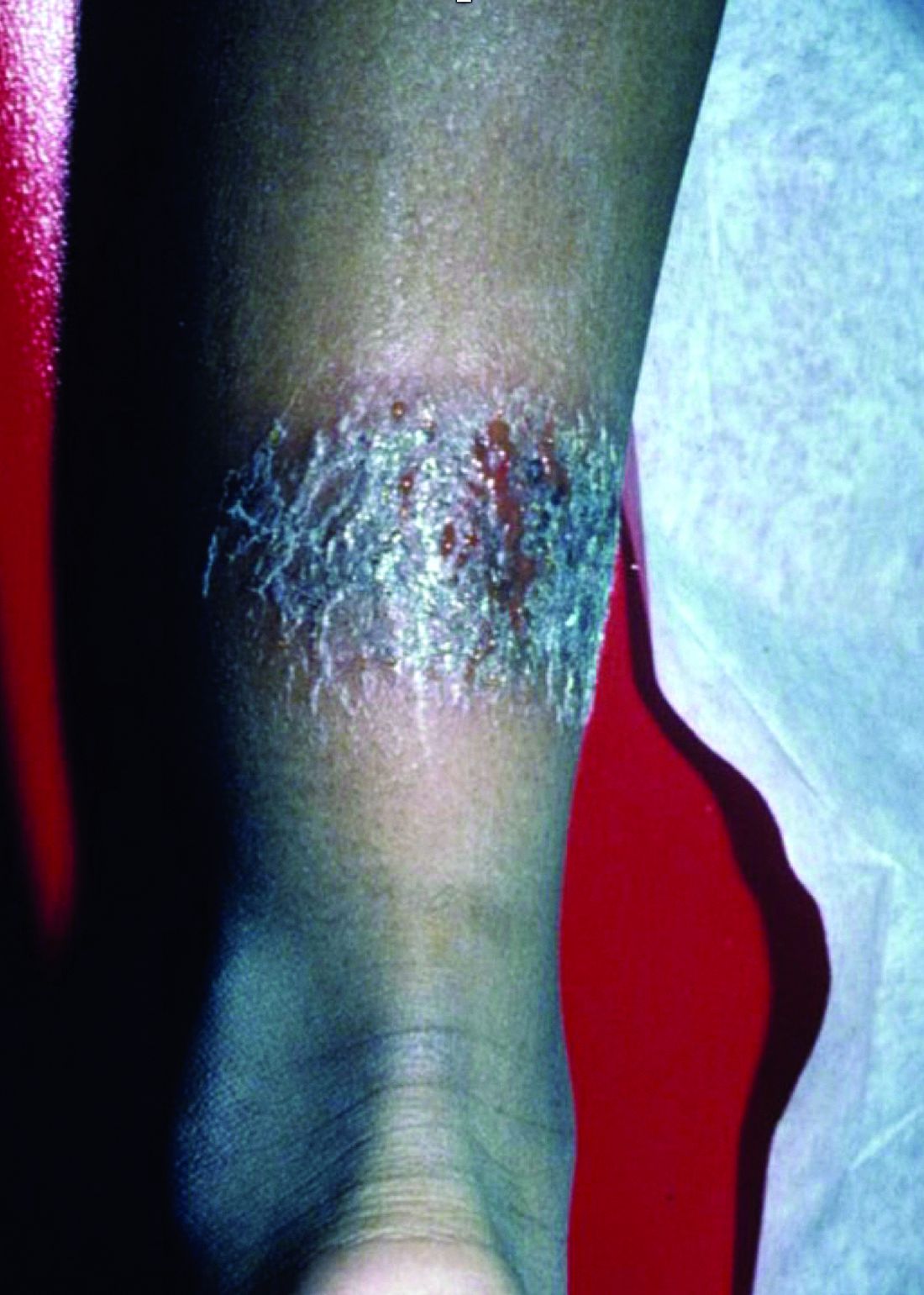

Intense stinging and burning, followed by the development of skin lesions minutes after exposure to a plant

Urticaria from stinging nettle

The stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) is a plant that grows in the United States, Eurasia, Northern Africa, and some parts of South America. It is commonly found in patches along hiking trails and near streams. The leaves are green with a characteristic tapered tip and bear tiny spines or hairs. The spines contain substances such as histamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine. Within seconds of contact with the stinging nettle, sharp stinging and burning will occur. Urticaria and pruritus may appear a few minutes later and may last up to 24 hours. The plant is eaten in some parts of the world and has been used as medicine.

The wood nettle (Laportea canadensis) is a relative of the stinging nettle that often grows in woodlands. Like the stinging nettle, the wood nettle leaves are covered with spines that sting when they come into contact with skin. However, the leaves are shorter and more oval shaped that the stinging nettle, and they lack the tapered tip that is characteristic for the stinging nettle. The reaction from the wood nettle is generally milder than that of the stinging nettle.

Plants can illicit different types of reactions in the skin: urticaria (immunologic and toxin mediated), irritant dermatitis (mechanical and chemical), phototoxic dermatitis (phytophotodermatitis), and allergic contact dermatitis. where anyone coming into contact with the hairs of the plant can be affected. Previous sensitization is not required. The reaction usually occurs immediately after exposure.

The allergic contact dermatitis seen with toxicodendron (poison ivy and poison sumac) appears 48 hours after exposure of a previously sensitized person to the plant. This type of delayed hypersensitivity reaction is known as cell-mediated hypersensitivity. Generally, no reaction is elicited upon the first exposure to the allergen. In fact, it may take years of exposure to allergens for someone to develop an allergic contact dermatitis.

The poison ivy plant can grow anywhere and is characteristically found in “leaves of three.” Skin reactions are often appear as linearly-arranged vesicles a few days after the exposure to the urushiol chemical in the sap of the plant. Poison sumac has red stems with 7-12 green, smooth leaves, and causes a similar skin reaction as poison ivy. It typically grows in wet areas.

Most stings are self-limited. Topical corticosteroid creams may be used if needed.

This case and photo were submitted by Susannah McClain, MD, of Three Rivers Dermatology in Coraopolis, Pa., and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Urticaria from stinging nettle

The stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) is a plant that grows in the United States, Eurasia, Northern Africa, and some parts of South America. It is commonly found in patches along hiking trails and near streams. The leaves are green with a characteristic tapered tip and bear tiny spines or hairs. The spines contain substances such as histamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine. Within seconds of contact with the stinging nettle, sharp stinging and burning will occur. Urticaria and pruritus may appear a few minutes later and may last up to 24 hours. The plant is eaten in some parts of the world and has been used as medicine.

The wood nettle (Laportea canadensis) is a relative of the stinging nettle that often grows in woodlands. Like the stinging nettle, the wood nettle leaves are covered with spines that sting when they come into contact with skin. However, the leaves are shorter and more oval shaped that the stinging nettle, and they lack the tapered tip that is characteristic for the stinging nettle. The reaction from the wood nettle is generally milder than that of the stinging nettle.

Plants can illicit different types of reactions in the skin: urticaria (immunologic and toxin mediated), irritant dermatitis (mechanical and chemical), phototoxic dermatitis (phytophotodermatitis), and allergic contact dermatitis. where anyone coming into contact with the hairs of the plant can be affected. Previous sensitization is not required. The reaction usually occurs immediately after exposure.

The allergic contact dermatitis seen with toxicodendron (poison ivy and poison sumac) appears 48 hours after exposure of a previously sensitized person to the plant. This type of delayed hypersensitivity reaction is known as cell-mediated hypersensitivity. Generally, no reaction is elicited upon the first exposure to the allergen. In fact, it may take years of exposure to allergens for someone to develop an allergic contact dermatitis.

The poison ivy plant can grow anywhere and is characteristically found in “leaves of three.” Skin reactions are often appear as linearly-arranged vesicles a few days after the exposure to the urushiol chemical in the sap of the plant. Poison sumac has red stems with 7-12 green, smooth leaves, and causes a similar skin reaction as poison ivy. It typically grows in wet areas.

Most stings are self-limited. Topical corticosteroid creams may be used if needed.

This case and photo were submitted by Susannah McClain, MD, of Three Rivers Dermatology in Coraopolis, Pa., and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Urticaria from stinging nettle

The stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) is a plant that grows in the United States, Eurasia, Northern Africa, and some parts of South America. It is commonly found in patches along hiking trails and near streams. The leaves are green with a characteristic tapered tip and bear tiny spines or hairs. The spines contain substances such as histamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine. Within seconds of contact with the stinging nettle, sharp stinging and burning will occur. Urticaria and pruritus may appear a few minutes later and may last up to 24 hours. The plant is eaten in some parts of the world and has been used as medicine.

The wood nettle (Laportea canadensis) is a relative of the stinging nettle that often grows in woodlands. Like the stinging nettle, the wood nettle leaves are covered with spines that sting when they come into contact with skin. However, the leaves are shorter and more oval shaped that the stinging nettle, and they lack the tapered tip that is characteristic for the stinging nettle. The reaction from the wood nettle is generally milder than that of the stinging nettle.

Plants can illicit different types of reactions in the skin: urticaria (immunologic and toxin mediated), irritant dermatitis (mechanical and chemical), phototoxic dermatitis (phytophotodermatitis), and allergic contact dermatitis. where anyone coming into contact with the hairs of the plant can be affected. Previous sensitization is not required. The reaction usually occurs immediately after exposure.

The allergic contact dermatitis seen with toxicodendron (poison ivy and poison sumac) appears 48 hours after exposure of a previously sensitized person to the plant. This type of delayed hypersensitivity reaction is known as cell-mediated hypersensitivity. Generally, no reaction is elicited upon the first exposure to the allergen. In fact, it may take years of exposure to allergens for someone to develop an allergic contact dermatitis.

The poison ivy plant can grow anywhere and is characteristically found in “leaves of three.” Skin reactions are often appear as linearly-arranged vesicles a few days after the exposure to the urushiol chemical in the sap of the plant. Poison sumac has red stems with 7-12 green, smooth leaves, and causes a similar skin reaction as poison ivy. It typically grows in wet areas.

Most stings are self-limited. Topical corticosteroid creams may be used if needed.

This case and photo were submitted by Susannah McClain, MD, of Three Rivers Dermatology in Coraopolis, Pa., and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

A 2-month-old infant with a scalp rash that appeared after birth

With the perinatal history of prolonged labor and prolonged rupture of membranes, the diagnosis of halo scalp ring was made. This occurs secondary to prolonged pressure of the baby’s scalp with the mother’s pelvic bones, uterus, or cervical area, which causes decreased blood flow to the area, secondary ischemic damage, and in some cases scarring and hair loss.1

The degree of involvement is variable as some babies have mild alopecia and others have severe full-thickness necrosis and scarring. These lesions also can present with associated caput succedaneum and scalp molding, but these were not seen in our patient. Predisposing factors for halo scalp ring include caput succedaneum, prolonged or difficult labor, premature or prolonged rupture of membranes, vaginal delivery, vertex presentation, first delivery, as well as prematurity.2 On physical examination, a semicircular patch of alopecia with associated scarring, crusting, or erythema can be seen in some more severe cases.

The differential diagnosis includes aplasia cutis. In aplasia cutis, there is congenital loss of skin on the affected areas. The scalp usually is affected, but these lesions can occur in any other part of the body. Most patients with aplasia cutis have no other findings, but there are cases that can be associated with other cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, or central nervous system abnormalities. Neonatal lupus also can present with scarring lesions on the scalp, but they usually present a little after birth, mainly affecting the face. The mothers of this children usually have a diagnosis of connective tissue disease and may have positive antibodies to Sjögren’s syndrome antibody A, Sjögren’s syndrome antibody B, or antiribonucleoprotein antibody. Seborrheic dermatitis does not cause scarring alopecia. The lesions present as waxy scaly plaques on the scalp, erythematous waxy plaques behind the ears, face, and folds. Some patients can have hair loss secondary to the inflammation, but the hair grows back once the inflammation is controlled. Dissecting cellulitis is a type of scarring alopecia seen in pubescent and adult individuals. No cases of neonatal dissecting cellulitis have been described.

Halo scalp ring is not associated with any other systemic symptoms or syndromes. Extensive imaging and systemic work-up are not required unless the baby presents with other neurologic symptoms. The areas can be treated with petrolatum and observation as most lesions resolve.

In cases of extensive areas of scarring alopecia, referral to a plastic surgeon can be made to consider tissue expanders or scar revision prior to the child starting school if the lesions are causing psychological stressors.

The true prevalence of this condition is unknown. We believe halo ring alopecia is sometimes not diagnosed, and as lesions tend to resolve, most cases go unreported.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(7):673.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009 Nov-Dec;26(6):706-8.

3. Dermatol Online J. 2016 Nov 15;22(11).pii:13030/qt7rt592tz.

With the perinatal history of prolonged labor and prolonged rupture of membranes, the diagnosis of halo scalp ring was made. This occurs secondary to prolonged pressure of the baby’s scalp with the mother’s pelvic bones, uterus, or cervical area, which causes decreased blood flow to the area, secondary ischemic damage, and in some cases scarring and hair loss.1

The degree of involvement is variable as some babies have mild alopecia and others have severe full-thickness necrosis and scarring. These lesions also can present with associated caput succedaneum and scalp molding, but these were not seen in our patient. Predisposing factors for halo scalp ring include caput succedaneum, prolonged or difficult labor, premature or prolonged rupture of membranes, vaginal delivery, vertex presentation, first delivery, as well as prematurity.2 On physical examination, a semicircular patch of alopecia with associated scarring, crusting, or erythema can be seen in some more severe cases.

The differential diagnosis includes aplasia cutis. In aplasia cutis, there is congenital loss of skin on the affected areas. The scalp usually is affected, but these lesions can occur in any other part of the body. Most patients with aplasia cutis have no other findings, but there are cases that can be associated with other cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, or central nervous system abnormalities. Neonatal lupus also can present with scarring lesions on the scalp, but they usually present a little after birth, mainly affecting the face. The mothers of this children usually have a diagnosis of connective tissue disease and may have positive antibodies to Sjögren’s syndrome antibody A, Sjögren’s syndrome antibody B, or antiribonucleoprotein antibody. Seborrheic dermatitis does not cause scarring alopecia. The lesions present as waxy scaly plaques on the scalp, erythematous waxy plaques behind the ears, face, and folds. Some patients can have hair loss secondary to the inflammation, but the hair grows back once the inflammation is controlled. Dissecting cellulitis is a type of scarring alopecia seen in pubescent and adult individuals. No cases of neonatal dissecting cellulitis have been described.

Halo scalp ring is not associated with any other systemic symptoms or syndromes. Extensive imaging and systemic work-up are not required unless the baby presents with other neurologic symptoms. The areas can be treated with petrolatum and observation as most lesions resolve.

In cases of extensive areas of scarring alopecia, referral to a plastic surgeon can be made to consider tissue expanders or scar revision prior to the child starting school if the lesions are causing psychological stressors.

The true prevalence of this condition is unknown. We believe halo ring alopecia is sometimes not diagnosed, and as lesions tend to resolve, most cases go unreported.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(7):673.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009 Nov-Dec;26(6):706-8.

3. Dermatol Online J. 2016 Nov 15;22(11).pii:13030/qt7rt592tz.

With the perinatal history of prolonged labor and prolonged rupture of membranes, the diagnosis of halo scalp ring was made. This occurs secondary to prolonged pressure of the baby’s scalp with the mother’s pelvic bones, uterus, or cervical area, which causes decreased blood flow to the area, secondary ischemic damage, and in some cases scarring and hair loss.1

The degree of involvement is variable as some babies have mild alopecia and others have severe full-thickness necrosis and scarring. These lesions also can present with associated caput succedaneum and scalp molding, but these were not seen in our patient. Predisposing factors for halo scalp ring include caput succedaneum, prolonged or difficult labor, premature or prolonged rupture of membranes, vaginal delivery, vertex presentation, first delivery, as well as prematurity.2 On physical examination, a semicircular patch of alopecia with associated scarring, crusting, or erythema can be seen in some more severe cases.

The differential diagnosis includes aplasia cutis. In aplasia cutis, there is congenital loss of skin on the affected areas. The scalp usually is affected, but these lesions can occur in any other part of the body. Most patients with aplasia cutis have no other findings, but there are cases that can be associated with other cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, or central nervous system abnormalities. Neonatal lupus also can present with scarring lesions on the scalp, but they usually present a little after birth, mainly affecting the face. The mothers of this children usually have a diagnosis of connective tissue disease and may have positive antibodies to Sjögren’s syndrome antibody A, Sjögren’s syndrome antibody B, or antiribonucleoprotein antibody. Seborrheic dermatitis does not cause scarring alopecia. The lesions present as waxy scaly plaques on the scalp, erythematous waxy plaques behind the ears, face, and folds. Some patients can have hair loss secondary to the inflammation, but the hair grows back once the inflammation is controlled. Dissecting cellulitis is a type of scarring alopecia seen in pubescent and adult individuals. No cases of neonatal dissecting cellulitis have been described.

Halo scalp ring is not associated with any other systemic symptoms or syndromes. Extensive imaging and systemic work-up are not required unless the baby presents with other neurologic symptoms. The areas can be treated with petrolatum and observation as most lesions resolve.

In cases of extensive areas of scarring alopecia, referral to a plastic surgeon can be made to consider tissue expanders or scar revision prior to the child starting school if the lesions are causing psychological stressors.

The true prevalence of this condition is unknown. We believe halo ring alopecia is sometimes not diagnosed, and as lesions tend to resolve, most cases go unreported.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(7):673.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009 Nov-Dec;26(6):706-8.

3. Dermatol Online J. 2016 Nov 15;22(11).pii:13030/qt7rt592tz.

A 2-month-old male is referred to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of persistent seborrheic dermatitis. The mother reports that he presented with a rash on his scalp a few days after birth. She has been treating the crusted areas with clotrimazole and hydrocortisone and has noted improvement on the crusting, but now is worried that there is some scarring. The affected areas are not bleeding or tender. There are no other rashes elsewhere in the body.

He was born at 36 weeks from a 35-year-old gravida 1 para 0 woman with adequate prenatal care. The mother was diagnosed with preeclampsia and was induced. She had a prolonged labor and had premature rupture of membranes. The baby was delivered via cesarean section because of failure to progress and fetal distress; forceps, vacuum, and a scalp probe were not used during delivery. He was admitted to the neonatal unit for 5 days for sepsis work-up and respiratory distress. No intubation was needed.

Besides the preeclampsia, the mother denied any other medical conditions and was not taking any medications. He has met all developmental milestones for his age. He has no history of seizures.

On physical exam, there are semicircular patches of alopecia on the scalp. Some areas have pink, rubbery plaques with loss of hair follicles. On the frontal scalp, there are waxy plaques.

There is a blanchable violaceous patch on the occiput and there are some erythematous papules on the cheeks.

An asymptomatic reddish-brown plaque in a healthy adult man

Chromosomal translocation abnormalities in the tumor cells involving chromosomes 17 and 22 resulting in the fusion gene COL1A1-PDGFB have been reported in DFSP. This translocation causes an overproduction of the protein platelet-derived growth factor, resulting in tumor growth.

Lesions are most common in the trunk and proximal extremities. Less commonly, the head and neck may be involved. Lesions present as painless slow-growing red-brown nodules that may become painful as they enlarge. The differential diagnosis for early DFSP includes large dermatofibroma, keloid, dermatomyofibroma, and morphea. DFSP in childhood tends to appear more atrophic. It may be difficult to diagnose DFSP if the initial biopsy is superficial. If clinical suspicion is high, rebiopsy, ideally into the fat, is recommended.

Histologically, there is a cellular proliferation of thin spindled fibroblasts and collagen in the dermis that extend into the fat, often in a multilayered pattern. Adnexal structures can be obliterated. Fibroblasts may form a cartwheel or storiform pattern. There is mild cytologic atypia. Fibrosarcomatous change may signal increased risk of metastasis. CD34 is often positive and factor XIIIa is negative, unlike in dermatofibroma, which is opposite. Forms of DFSP that can be seen histologically include atrophic DFSP (flat rather than nodular), myxoid DFSP, and pigmented DFSP (also known as Bednar tumor).

DFSP can have irregular shapes with extensions into the fat. Subsequently, DFSP has a high recurrence rate with traditional surgical removal. Mohs surgery is now the treatment of choice. Recurrent tumors should be resected. As metastasis is rare, further work-up is not routinely indicated unless history and physical examination warrant it. Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec), which targets the platelet-derived growth factor receptor, has been tried with patients with inoperable or metastatic DFSP with some success. Radiation may also be used as an adjuvant after surgery. Regular follow-up exams with examination of the surgical site for possible recurrence should be performed every 6-12 months.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Chromosomal translocation abnormalities in the tumor cells involving chromosomes 17 and 22 resulting in the fusion gene COL1A1-PDGFB have been reported in DFSP. This translocation causes an overproduction of the protein platelet-derived growth factor, resulting in tumor growth.

Lesions are most common in the trunk and proximal extremities. Less commonly, the head and neck may be involved. Lesions present as painless slow-growing red-brown nodules that may become painful as they enlarge. The differential diagnosis for early DFSP includes large dermatofibroma, keloid, dermatomyofibroma, and morphea. DFSP in childhood tends to appear more atrophic. It may be difficult to diagnose DFSP if the initial biopsy is superficial. If clinical suspicion is high, rebiopsy, ideally into the fat, is recommended.

Histologically, there is a cellular proliferation of thin spindled fibroblasts and collagen in the dermis that extend into the fat, often in a multilayered pattern. Adnexal structures can be obliterated. Fibroblasts may form a cartwheel or storiform pattern. There is mild cytologic atypia. Fibrosarcomatous change may signal increased risk of metastasis. CD34 is often positive and factor XIIIa is negative, unlike in dermatofibroma, which is opposite. Forms of DFSP that can be seen histologically include atrophic DFSP (flat rather than nodular), myxoid DFSP, and pigmented DFSP (also known as Bednar tumor).

DFSP can have irregular shapes with extensions into the fat. Subsequently, DFSP has a high recurrence rate with traditional surgical removal. Mohs surgery is now the treatment of choice. Recurrent tumors should be resected. As metastasis is rare, further work-up is not routinely indicated unless history and physical examination warrant it. Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec), which targets the platelet-derived growth factor receptor, has been tried with patients with inoperable or metastatic DFSP with some success. Radiation may also be used as an adjuvant after surgery. Regular follow-up exams with examination of the surgical site for possible recurrence should be performed every 6-12 months.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Chromosomal translocation abnormalities in the tumor cells involving chromosomes 17 and 22 resulting in the fusion gene COL1A1-PDGFB have been reported in DFSP. This translocation causes an overproduction of the protein platelet-derived growth factor, resulting in tumor growth.

Lesions are most common in the trunk and proximal extremities. Less commonly, the head and neck may be involved. Lesions present as painless slow-growing red-brown nodules that may become painful as they enlarge. The differential diagnosis for early DFSP includes large dermatofibroma, keloid, dermatomyofibroma, and morphea. DFSP in childhood tends to appear more atrophic. It may be difficult to diagnose DFSP if the initial biopsy is superficial. If clinical suspicion is high, rebiopsy, ideally into the fat, is recommended.

Histologically, there is a cellular proliferation of thin spindled fibroblasts and collagen in the dermis that extend into the fat, often in a multilayered pattern. Adnexal structures can be obliterated. Fibroblasts may form a cartwheel or storiform pattern. There is mild cytologic atypia. Fibrosarcomatous change may signal increased risk of metastasis. CD34 is often positive and factor XIIIa is negative, unlike in dermatofibroma, which is opposite. Forms of DFSP that can be seen histologically include atrophic DFSP (flat rather than nodular), myxoid DFSP, and pigmented DFSP (also known as Bednar tumor).

DFSP can have irregular shapes with extensions into the fat. Subsequently, DFSP has a high recurrence rate with traditional surgical removal. Mohs surgery is now the treatment of choice. Recurrent tumors should be resected. As metastasis is rare, further work-up is not routinely indicated unless history and physical examination warrant it. Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec), which targets the platelet-derived growth factor receptor, has been tried with patients with inoperable or metastatic DFSP with some success. Radiation may also be used as an adjuvant after surgery. Regular follow-up exams with examination of the surgical site for possible recurrence should be performed every 6-12 months.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

A 3-year-old is brought to the clinic for evaluation of a localized, scaling inflamed lesion on the left leg

Nummular dermatitis, or nummular eczema, is an inflammatory skin condition that is considered to be a distinctive form of idiopathic eczema, while the term also is used to describe lesional morphology associated with other conditions.

The term nummular derives from the Latin word for “coin,” as lesions are commonly annular plaques. Lesions of nummular dermatitis can be single or multiple. The typical distribution involves the extremities and, although less common, it can affect the trunk as well.

Nummular dermatitis may be associated with atopic dermatitis, or it can be an isolated condition.1 While the pathogenesis is uncertain, instigating factors include xerotic skin, insect bites, or scratches or scrapes.1Staphylococcus infection or colonization, contact allergies to metals such as nickel and less commonly mercury, sensitivity to formaldehyde or medicines such as neomycin, and sensitization to an environmental aeroallergen (such as Candida albicans, dust mites) are considered risk factors.2

The diagnosis of nummular dermatitis is clinical. Laboratory testing and/or biopsy generally are not necessary, although a bacterial culture can be considered in patients with exudative and/or crusted lesions to rule out impetigo as a primary process of secondary infection. In some cases, patch testing for allergic contact dermatitis may be useful.

The differential diagnosis of nummular dermatitis includes tinea corporis (ringworm), atopic dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, impetigo, and psoriasis. Tinea corporis usually presents as annular lesions with a distinct peripheral scaling, rather than the diffuse induration of nummular dermatitis. Potassium hydroxide preparation or fungal culture can identify tinea species. Nummular dermatitis may be seen in patients with atopic dermatitis, who should have typical history, morphology, and course consistent with standard diagnostic criteria. Allergic contact dermatitis can present with regional, localized eczematous plaques in areas exposed to contact allergens. Patterns of lesions in areas of contact and worsening with repeat exposures can be clues to this diagnosis. Impetigo can present with honey-colored crusted lesions and/or superficial erosions, or purulent pyoderma. Lesions can be single or multiple and generally appear less inflammatory than nummular dermatitis. Psoriasis lesions may be annular, are more common on extensor surfaces, and usually have more prominent overlying pinkish, silvery white or micaceous scale.

Management of nummular dermatitis requires strong anti-inflammatory medications, usually mid-potency or higher topical corticosteroids, along with moisturizers and limiting exposure to skin irritants. “Wet wraps,” with application of topical corticosteroids to wet skin with occlusive wet dressings can enhance response. Transition from higher strength topical corticosteroids to lower strength agents used intermittently can help achieve remission or cure. Management practices include less frequent bathing with lukewarm water, using hypoallergenic cleansers and detergents, and applying moisturizers frequently. If plaques do recur, they tend to do so in the same location and in some patients resolution may result in hyper or hypopigmentation. Refractory disease may be managed with intralesional steroid injections, or systemic medications such as methotrexate.3

Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Neither Dr. Tracy nor Dr. Eichenfield have any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012 Sep-Oct;29(5):580-3.

2. American Academy of Dermatology. Nummular Dermatitis Overview

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Sep;35(5):611-5.

Nummular dermatitis, or nummular eczema, is an inflammatory skin condition that is considered to be a distinctive form of idiopathic eczema, while the term also is used to describe lesional morphology associated with other conditions.

The term nummular derives from the Latin word for “coin,” as lesions are commonly annular plaques. Lesions of nummular dermatitis can be single or multiple. The typical distribution involves the extremities and, although less common, it can affect the trunk as well.

Nummular dermatitis may be associated with atopic dermatitis, or it can be an isolated condition.1 While the pathogenesis is uncertain, instigating factors include xerotic skin, insect bites, or scratches or scrapes.1Staphylococcus infection or colonization, contact allergies to metals such as nickel and less commonly mercury, sensitivity to formaldehyde or medicines such as neomycin, and sensitization to an environmental aeroallergen (such as Candida albicans, dust mites) are considered risk factors.2

The diagnosis of nummular dermatitis is clinical. Laboratory testing and/or biopsy generally are not necessary, although a bacterial culture can be considered in patients with exudative and/or crusted lesions to rule out impetigo as a primary process of secondary infection. In some cases, patch testing for allergic contact dermatitis may be useful.

The differential diagnosis of nummular dermatitis includes tinea corporis (ringworm), atopic dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, impetigo, and psoriasis. Tinea corporis usually presents as annular lesions with a distinct peripheral scaling, rather than the diffuse induration of nummular dermatitis. Potassium hydroxide preparation or fungal culture can identify tinea species. Nummular dermatitis may be seen in patients with atopic dermatitis, who should have typical history, morphology, and course consistent with standard diagnostic criteria. Allergic contact dermatitis can present with regional, localized eczematous plaques in areas exposed to contact allergens. Patterns of lesions in areas of contact and worsening with repeat exposures can be clues to this diagnosis. Impetigo can present with honey-colored crusted lesions and/or superficial erosions, or purulent pyoderma. Lesions can be single or multiple and generally appear less inflammatory than nummular dermatitis. Psoriasis lesions may be annular, are more common on extensor surfaces, and usually have more prominent overlying pinkish, silvery white or micaceous scale.

Management of nummular dermatitis requires strong anti-inflammatory medications, usually mid-potency or higher topical corticosteroids, along with moisturizers and limiting exposure to skin irritants. “Wet wraps,” with application of topical corticosteroids to wet skin with occlusive wet dressings can enhance response. Transition from higher strength topical corticosteroids to lower strength agents used intermittently can help achieve remission or cure. Management practices include less frequent bathing with lukewarm water, using hypoallergenic cleansers and detergents, and applying moisturizers frequently. If plaques do recur, they tend to do so in the same location and in some patients resolution may result in hyper or hypopigmentation. Refractory disease may be managed with intralesional steroid injections, or systemic medications such as methotrexate.3

Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Neither Dr. Tracy nor Dr. Eichenfield have any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012 Sep-Oct;29(5):580-3.

2. American Academy of Dermatology. Nummular Dermatitis Overview

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Sep;35(5):611-5.

Nummular dermatitis, or nummular eczema, is an inflammatory skin condition that is considered to be a distinctive form of idiopathic eczema, while the term also is used to describe lesional morphology associated with other conditions.

The term nummular derives from the Latin word for “coin,” as lesions are commonly annular plaques. Lesions of nummular dermatitis can be single or multiple. The typical distribution involves the extremities and, although less common, it can affect the trunk as well.

Nummular dermatitis may be associated with atopic dermatitis, or it can be an isolated condition.1 While the pathogenesis is uncertain, instigating factors include xerotic skin, insect bites, or scratches or scrapes.1Staphylococcus infection or colonization, contact allergies to metals such as nickel and less commonly mercury, sensitivity to formaldehyde or medicines such as neomycin, and sensitization to an environmental aeroallergen (such as Candida albicans, dust mites) are considered risk factors.2

The diagnosis of nummular dermatitis is clinical. Laboratory testing and/or biopsy generally are not necessary, although a bacterial culture can be considered in patients with exudative and/or crusted lesions to rule out impetigo as a primary process of secondary infection. In some cases, patch testing for allergic contact dermatitis may be useful.

The differential diagnosis of nummular dermatitis includes tinea corporis (ringworm), atopic dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, impetigo, and psoriasis. Tinea corporis usually presents as annular lesions with a distinct peripheral scaling, rather than the diffuse induration of nummular dermatitis. Potassium hydroxide preparation or fungal culture can identify tinea species. Nummular dermatitis may be seen in patients with atopic dermatitis, who should have typical history, morphology, and course consistent with standard diagnostic criteria. Allergic contact dermatitis can present with regional, localized eczematous plaques in areas exposed to contact allergens. Patterns of lesions in areas of contact and worsening with repeat exposures can be clues to this diagnosis. Impetigo can present with honey-colored crusted lesions and/or superficial erosions, or purulent pyoderma. Lesions can be single or multiple and generally appear less inflammatory than nummular dermatitis. Psoriasis lesions may be annular, are more common on extensor surfaces, and usually have more prominent overlying pinkish, silvery white or micaceous scale.

Management of nummular dermatitis requires strong anti-inflammatory medications, usually mid-potency or higher topical corticosteroids, along with moisturizers and limiting exposure to skin irritants. “Wet wraps,” with application of topical corticosteroids to wet skin with occlusive wet dressings can enhance response. Transition from higher strength topical corticosteroids to lower strength agents used intermittently can help achieve remission or cure. Management practices include less frequent bathing with lukewarm water, using hypoallergenic cleansers and detergents, and applying moisturizers frequently. If plaques do recur, they tend to do so in the same location and in some patients resolution may result in hyper or hypopigmentation. Refractory disease may be managed with intralesional steroid injections, or systemic medications such as methotrexate.3

Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Neither Dr. Tracy nor Dr. Eichenfield have any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012 Sep-Oct;29(5):580-3.

2. American Academy of Dermatology. Nummular Dermatitis Overview

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Sep;35(5):611-5.

On physical exam, he is noted to have a localized eczematous plaque with erythema and edema. Also, he is noted to have diffuse, fine xerosis of the bilateral lower extremities. His skin is otherwise nonremarkable.

A 56-year-old black woman presented with asymptomatic hypopigmented macules on her back, chest, face, and lateral arms

They often coalesce near the midline, and occasionally extend beyond the trunk to the arms, legs, head, or neck. PMH is more frequently diagnosed among black individuals, although it affects all races and ethnicities. The natural history of PMH can vary from stable and progressive disease, and may resolve spontaneously after a few years. The pathogenesis of PMH remains unknown. It has been proposed that the hypopigmentation is caused by decreased melanin production and altered melanosome dispersal in reaction to Propionibacterium acnes.

PMH must be distinguished from some of its clinical mimickers, including vitiligo, hypopigmented mycosis fungoides, tinea versicolor, and pityriasis alba. Potassium hydroxide preparations can be performed in the office to evaluate for tinea versicolor. An additional tool to aid in diagnosis is the use of a Wood’s light. The lesions of PMH characteristically show punctiform orange-red follicular fluorescence when exposed to a Wood’s light, indicating the presence of a porphyrin-producing organism, presumably P. acnes. A skin biopsy is necessary to rule out hypopigmented mycosis fungoides.

Skin biopsy of PMH typically reveals decreased melanin with a normal number of melanocytes. In our patient, a punch biopsy of the right lateral arm demonstrated minimally decreased density of epidermal melanocytes with dermal pigment incontinence. SOX10 immunohistochemical staining demonstrated scattered melanocytes in the epidermis. Preserved melanin within keratinocytes was noted.

In our patient, there was significant spread to the face, which is highly unusual and has only been documented in a few case series. There are no standard recommendations for definitive treatment of PMH. Topical antimicrobial therapies, such as clindamycin solution and benzoyl peroxide gel, have been beneficial in some studies. Tetracyclines, narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy, and even isotretinoin have had some reported success.

This case and photo were submitted by Mr. Franzetti, Dr. Rush, and Dr. Shalin of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

Donna Bilu Martin, MD, is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

They often coalesce near the midline, and occasionally extend beyond the trunk to the arms, legs, head, or neck. PMH is more frequently diagnosed among black individuals, although it affects all races and ethnicities. The natural history of PMH can vary from stable and progressive disease, and may resolve spontaneously after a few years. The pathogenesis of PMH remains unknown. It has been proposed that the hypopigmentation is caused by decreased melanin production and altered melanosome dispersal in reaction to Propionibacterium acnes.

PMH must be distinguished from some of its clinical mimickers, including vitiligo, hypopigmented mycosis fungoides, tinea versicolor, and pityriasis alba. Potassium hydroxide preparations can be performed in the office to evaluate for tinea versicolor. An additional tool to aid in diagnosis is the use of a Wood’s light. The lesions of PMH characteristically show punctiform orange-red follicular fluorescence when exposed to a Wood’s light, indicating the presence of a porphyrin-producing organism, presumably P. acnes. A skin biopsy is necessary to rule out hypopigmented mycosis fungoides.

Skin biopsy of PMH typically reveals decreased melanin with a normal number of melanocytes. In our patient, a punch biopsy of the right lateral arm demonstrated minimally decreased density of epidermal melanocytes with dermal pigment incontinence. SOX10 immunohistochemical staining demonstrated scattered melanocytes in the epidermis. Preserved melanin within keratinocytes was noted.

In our patient, there was significant spread to the face, which is highly unusual and has only been documented in a few case series. There are no standard recommendations for definitive treatment of PMH. Topical antimicrobial therapies, such as clindamycin solution and benzoyl peroxide gel, have been beneficial in some studies. Tetracyclines, narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy, and even isotretinoin have had some reported success.

This case and photo were submitted by Mr. Franzetti, Dr. Rush, and Dr. Shalin of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

Donna Bilu Martin, MD, is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

They often coalesce near the midline, and occasionally extend beyond the trunk to the arms, legs, head, or neck. PMH is more frequently diagnosed among black individuals, although it affects all races and ethnicities. The natural history of PMH can vary from stable and progressive disease, and may resolve spontaneously after a few years. The pathogenesis of PMH remains unknown. It has been proposed that the hypopigmentation is caused by decreased melanin production and altered melanosome dispersal in reaction to Propionibacterium acnes.

PMH must be distinguished from some of its clinical mimickers, including vitiligo, hypopigmented mycosis fungoides, tinea versicolor, and pityriasis alba. Potassium hydroxide preparations can be performed in the office to evaluate for tinea versicolor. An additional tool to aid in diagnosis is the use of a Wood’s light. The lesions of PMH characteristically show punctiform orange-red follicular fluorescence when exposed to a Wood’s light, indicating the presence of a porphyrin-producing organism, presumably P. acnes. A skin biopsy is necessary to rule out hypopigmented mycosis fungoides.

Skin biopsy of PMH typically reveals decreased melanin with a normal number of melanocytes. In our patient, a punch biopsy of the right lateral arm demonstrated minimally decreased density of epidermal melanocytes with dermal pigment incontinence. SOX10 immunohistochemical staining demonstrated scattered melanocytes in the epidermis. Preserved melanin within keratinocytes was noted.

In our patient, there was significant spread to the face, which is highly unusual and has only been documented in a few case series. There are no standard recommendations for definitive treatment of PMH. Topical antimicrobial therapies, such as clindamycin solution and benzoyl peroxide gel, have been beneficial in some studies. Tetracyclines, narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy, and even isotretinoin have had some reported success.

This case and photo were submitted by Mr. Franzetti, Dr. Rush, and Dr. Shalin of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

Donna Bilu Martin, MD, is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

A healthy 8-year-old boy presents with several skin-colored, round 1-3 mm papules on the nose, forehead, and cheeks

A shave biopsy of one of the lesions was performed that showed a proliferation of nests of basaloid cells on the dermis with palisading and rare vacuolated clear cell change. A rare ductal structure with luminal proteinaceous contents was noted. The findings were consistent with a trichoepithelioma.

Trichoepitheliomas are rare, benign, adnexal skin tumors that can start in early childhood or during puberty. The lesions are most commonly seen in girls as skin color papules on the face, and sometimes on the trunk and the neck. Trichoepitheliomas can appear as a benign single lesion nonfamilial form or as a familial form with multiple lesions.1 Brooke-Spiegler syndrome (BSS) is a rare autosomal dominant condition where affected individuals have multiple trichoepitheliomas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas. Depending on the predominant type of lesion, phenotypic variants include multiple familial trichoepithelioma type 1 and familial cylindromatosis.2 BSS is caused by mutations within CYLD, a tumor-suppressor gene located on chromosome 16q12-q13.3 Our patient presented only with trichoepitheliomas with no other lesions on the scalp, neck, or torso.

Multiple trichoepitheliomas also can be seen in other syndromes including Rombo syndrome, which is characterized by basal cell carcinomas, milia, hypotrichosis, distal vasodilation, and atrophoderma vermiculata; none seen in our patient. Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome is an X-linked dominant condition in which affected individuals can present with multiple trichoepitheliomas, as well as milia, hypotrichosis, follicular atrophoderma, and basal cell carcinomas.

The differential diagnosis of skin color papules on the central face on a child should include acne, flat warts, and angiofibromas seen in tuberous sclerosis. Our patient’s lesions were monomorphous, and there were no comedones, pustules, or inflammatory papules characteristic of acne.

He had warts on his hands which could make it suspicious for the face lesions to be verrucous in nature. Flat warts also present as skin color papules, but characteristically are flat, not round and shiny as our patient’s lesions were. Angiofibromas, as seen in individuals with tuberous sclerosis, also can start at an early age in the same location as trichoepitheliomas in BSS, but clinically the lesions are pinker and redder rather than the skin-color, round shape papules characteristic of trichoepitheliomas. Patients may have other findings suggestive of tuberous sclerosis including confetti hypopigmentation, ash leaf spots, shagreen patch, and a history of seizures or developmental delay – none of which were present in our patient. Children with basal cell nevus syndrome can present with skin color to shiny telangiectatic papules (basal cell carcinomas) that can be single or multiple on the face, chest, and back. The lesions usually are not seen in clusters around the nose and central face as seen in patients with BSS. Patients with basal cell nevus syndrome can develop jaw bone cysts, brain tumors (medulloblastoma), and fibromas on the heart or ovaries, palmar pits and be macrocephalic.4

Trichoepitheliomas usually are treated surgically but other nonsurgical removing techniques include laser resurfacing, curettage, and electrocautery.5 Malignant transformation can occur in 5%-10% of the individuals and should be managed by a multidisciplinary team. Topical treatment with sirolimus previously has been reported to be effective in young patients.6

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Matiz at [email protected].

References

1. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2018 Jun;26(2):162-5.

2. Eur J Med Genet. 2015;58(5):271-8.

3. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36(11):868-74.

4. Int J Dermatol. 2016 Apr;55(4):367-75.

5. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(6):583-6.

6. Dermatol Ther. 2017 Mar. doi: 10.1111/dth.12458.

A shave biopsy of one of the lesions was performed that showed a proliferation of nests of basaloid cells on the dermis with palisading and rare vacuolated clear cell change. A rare ductal structure with luminal proteinaceous contents was noted. The findings were consistent with a trichoepithelioma.

Trichoepitheliomas are rare, benign, adnexal skin tumors that can start in early childhood or during puberty. The lesions are most commonly seen in girls as skin color papules on the face, and sometimes on the trunk and the neck. Trichoepitheliomas can appear as a benign single lesion nonfamilial form or as a familial form with multiple lesions.1 Brooke-Spiegler syndrome (BSS) is a rare autosomal dominant condition where affected individuals have multiple trichoepitheliomas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas. Depending on the predominant type of lesion, phenotypic variants include multiple familial trichoepithelioma type 1 and familial cylindromatosis.2 BSS is caused by mutations within CYLD, a tumor-suppressor gene located on chromosome 16q12-q13.3 Our patient presented only with trichoepitheliomas with no other lesions on the scalp, neck, or torso.

Multiple trichoepitheliomas also can be seen in other syndromes including Rombo syndrome, which is characterized by basal cell carcinomas, milia, hypotrichosis, distal vasodilation, and atrophoderma vermiculata; none seen in our patient. Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome is an X-linked dominant condition in which affected individuals can present with multiple trichoepitheliomas, as well as milia, hypotrichosis, follicular atrophoderma, and basal cell carcinomas.

The differential diagnosis of skin color papules on the central face on a child should include acne, flat warts, and angiofibromas seen in tuberous sclerosis. Our patient’s lesions were monomorphous, and there were no comedones, pustules, or inflammatory papules characteristic of acne.

He had warts on his hands which could make it suspicious for the face lesions to be verrucous in nature. Flat warts also present as skin color papules, but characteristically are flat, not round and shiny as our patient’s lesions were. Angiofibromas, as seen in individuals with tuberous sclerosis, also can start at an early age in the same location as trichoepitheliomas in BSS, but clinically the lesions are pinker and redder rather than the skin-color, round shape papules characteristic of trichoepitheliomas. Patients may have other findings suggestive of tuberous sclerosis including confetti hypopigmentation, ash leaf spots, shagreen patch, and a history of seizures or developmental delay – none of which were present in our patient. Children with basal cell nevus syndrome can present with skin color to shiny telangiectatic papules (basal cell carcinomas) that can be single or multiple on the face, chest, and back. The lesions usually are not seen in clusters around the nose and central face as seen in patients with BSS. Patients with basal cell nevus syndrome can develop jaw bone cysts, brain tumors (medulloblastoma), and fibromas on the heart or ovaries, palmar pits and be macrocephalic.4

Trichoepitheliomas usually are treated surgically but other nonsurgical removing techniques include laser resurfacing, curettage, and electrocautery.5 Malignant transformation can occur in 5%-10% of the individuals and should be managed by a multidisciplinary team. Topical treatment with sirolimus previously has been reported to be effective in young patients.6

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Matiz at [email protected].

References

1. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2018 Jun;26(2):162-5.

2. Eur J Med Genet. 2015;58(5):271-8.

3. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36(11):868-74.

4. Int J Dermatol. 2016 Apr;55(4):367-75.

5. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(6):583-6.

6. Dermatol Ther. 2017 Mar. doi: 10.1111/dth.12458.

A shave biopsy of one of the lesions was performed that showed a proliferation of nests of basaloid cells on the dermis with palisading and rare vacuolated clear cell change. A rare ductal structure with luminal proteinaceous contents was noted. The findings were consistent with a trichoepithelioma.

Trichoepitheliomas are rare, benign, adnexal skin tumors that can start in early childhood or during puberty. The lesions are most commonly seen in girls as skin color papules on the face, and sometimes on the trunk and the neck. Trichoepitheliomas can appear as a benign single lesion nonfamilial form or as a familial form with multiple lesions.1 Brooke-Spiegler syndrome (BSS) is a rare autosomal dominant condition where affected individuals have multiple trichoepitheliomas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas. Depending on the predominant type of lesion, phenotypic variants include multiple familial trichoepithelioma type 1 and familial cylindromatosis.2 BSS is caused by mutations within CYLD, a tumor-suppressor gene located on chromosome 16q12-q13.3 Our patient presented only with trichoepitheliomas with no other lesions on the scalp, neck, or torso.

Multiple trichoepitheliomas also can be seen in other syndromes including Rombo syndrome, which is characterized by basal cell carcinomas, milia, hypotrichosis, distal vasodilation, and atrophoderma vermiculata; none seen in our patient. Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome is an X-linked dominant condition in which affected individuals can present with multiple trichoepitheliomas, as well as milia, hypotrichosis, follicular atrophoderma, and basal cell carcinomas.

The differential diagnosis of skin color papules on the central face on a child should include acne, flat warts, and angiofibromas seen in tuberous sclerosis. Our patient’s lesions were monomorphous, and there were no comedones, pustules, or inflammatory papules characteristic of acne.

He had warts on his hands which could make it suspicious for the face lesions to be verrucous in nature. Flat warts also present as skin color papules, but characteristically are flat, not round and shiny as our patient’s lesions were. Angiofibromas, as seen in individuals with tuberous sclerosis, also can start at an early age in the same location as trichoepitheliomas in BSS, but clinically the lesions are pinker and redder rather than the skin-color, round shape papules characteristic of trichoepitheliomas. Patients may have other findings suggestive of tuberous sclerosis including confetti hypopigmentation, ash leaf spots, shagreen patch, and a history of seizures or developmental delay – none of which were present in our patient. Children with basal cell nevus syndrome can present with skin color to shiny telangiectatic papules (basal cell carcinomas) that can be single or multiple on the face, chest, and back. The lesions usually are not seen in clusters around the nose and central face as seen in patients with BSS. Patients with basal cell nevus syndrome can develop jaw bone cysts, brain tumors (medulloblastoma), and fibromas on the heart or ovaries, palmar pits and be macrocephalic.4

Trichoepitheliomas usually are treated surgically but other nonsurgical removing techniques include laser resurfacing, curettage, and electrocautery.5 Malignant transformation can occur in 5%-10% of the individuals and should be managed by a multidisciplinary team. Topical treatment with sirolimus previously has been reported to be effective in young patients.6

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Matiz at [email protected].

References

1. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2018 Jun;26(2):162-5.

2. Eur J Med Genet. 2015;58(5):271-8.

3. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36(11):868-74.

4. Int J Dermatol. 2016 Apr;55(4):367-75.

5. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(6):583-6.

6. Dermatol Ther. 2017 Mar. doi: 10.1111/dth.12458.

A white 8-year-old boy comes to our pediatric dermatology clinic with his mother for evaluation of acne. The lesions started about a year ago on his nose and now have spread to his cheeks. The bumps are not symptomatic. He has been applying over the counter salicylic acid and benzoyl peroxide gels with no help. The mother reports he has been growing well, denies any growth spurt, no axillary or genital hair or body odor noted.

None of the family members have a history of acne. The mother cannot recall any family members with similar lesions on the face. He has had some warts on his fingers for years and has been treated with over the counter salicylic acid. There is no family history of skin cancer.

On physical exam, he is a healthy young boy with several skin color, round papules 1-3 mm on the nose, forehead, and cheeks. There are no lesions on the scalp. He has abundant brown hair. He has few verrucous papules on the fingers. Axillary and genital hair is not noted. There is no body odor and he is Tanner stage I.

An 89-year-old woman presented with an ulceration overlying a cardiac pacemaker

Cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) – cardiac pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillators –are an established treatment for the management of cardiac dysrhythmias in millions of patients. Complications occur in up to 15%, some of which may present first to the dermatologist.

The differential (caused by local venous obstruction and pressure dermatitis), and impending skin erosion/device extrusion.

Erosion and extrusion is a major complication with significant morbidity and mortality. The two main causes are pressure necrosis and infection. Pressure necrosis is influenced by the size of the device, complexity of the connections, and technical skill with which the pacemaker chest wall pocket is created.

After extrusion, the pacemaker should be considered contaminated and removed, and the necrotic tissue debrided. If infected, a prolonged course of appropriate antibiotic therapy is indicated. A bacterial culture in the patient presented here was negative.

Pocket infection of CIEDs is rare and may manifest as erythema, tenderness, drainage, erosion, or pruritus above the site of the pacemaker, along with systemic symptoms and signs, including fever, chills, or malaise. Some may have just the systemic symptoms. Fewer than half of patients with CIED infection present within 1 year of their last procedure.

Ruptured epidermal cysts usually manifest as acute swelling, inflammation, and tenderness of previously long-standing asymptomatic epidermal cysts. There may be drainage of malodorous keratinous and purulent debris. They are typically not infected. Treatment includes incision and drainage for fluctuant lesions or intralesional corticosteroid injection for early, nonfluctuant cases.

Allergic contact dermatitis to metal may be seen with implantable devices. Patch testing to various metal allergens can be helpful in determining if any allergy is present.

This case and photo were submitted by Michael Stierstorfer, MD, East Penn Dermatology, North Wales, Pa.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) – cardiac pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillators –are an established treatment for the management of cardiac dysrhythmias in millions of patients. Complications occur in up to 15%, some of which may present first to the dermatologist.

The differential (caused by local venous obstruction and pressure dermatitis), and impending skin erosion/device extrusion.

Erosion and extrusion is a major complication with significant morbidity and mortality. The two main causes are pressure necrosis and infection. Pressure necrosis is influenced by the size of the device, complexity of the connections, and technical skill with which the pacemaker chest wall pocket is created.

After extrusion, the pacemaker should be considered contaminated and removed, and the necrotic tissue debrided. If infected, a prolonged course of appropriate antibiotic therapy is indicated. A bacterial culture in the patient presented here was negative.

Pocket infection of CIEDs is rare and may manifest as erythema, tenderness, drainage, erosion, or pruritus above the site of the pacemaker, along with systemic symptoms and signs, including fever, chills, or malaise. Some may have just the systemic symptoms. Fewer than half of patients with CIED infection present within 1 year of their last procedure.

Ruptured epidermal cysts usually manifest as acute swelling, inflammation, and tenderness of previously long-standing asymptomatic epidermal cysts. There may be drainage of malodorous keratinous and purulent debris. They are typically not infected. Treatment includes incision and drainage for fluctuant lesions or intralesional corticosteroid injection for early, nonfluctuant cases.

Allergic contact dermatitis to metal may be seen with implantable devices. Patch testing to various metal allergens can be helpful in determining if any allergy is present.

This case and photo were submitted by Michael Stierstorfer, MD, East Penn Dermatology, North Wales, Pa.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) – cardiac pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillators –are an established treatment for the management of cardiac dysrhythmias in millions of patients. Complications occur in up to 15%, some of which may present first to the dermatologist.

The differential (caused by local venous obstruction and pressure dermatitis), and impending skin erosion/device extrusion.

Erosion and extrusion is a major complication with significant morbidity and mortality. The two main causes are pressure necrosis and infection. Pressure necrosis is influenced by the size of the device, complexity of the connections, and technical skill with which the pacemaker chest wall pocket is created.

After extrusion, the pacemaker should be considered contaminated and removed, and the necrotic tissue debrided. If infected, a prolonged course of appropriate antibiotic therapy is indicated. A bacterial culture in the patient presented here was negative.

Pocket infection of CIEDs is rare and may manifest as erythema, tenderness, drainage, erosion, or pruritus above the site of the pacemaker, along with systemic symptoms and signs, including fever, chills, or malaise. Some may have just the systemic symptoms. Fewer than half of patients with CIED infection present within 1 year of their last procedure.

Ruptured epidermal cysts usually manifest as acute swelling, inflammation, and tenderness of previously long-standing asymptomatic epidermal cysts. There may be drainage of malodorous keratinous and purulent debris. They are typically not infected. Treatment includes incision and drainage for fluctuant lesions or intralesional corticosteroid injection for early, nonfluctuant cases.

Allergic contact dermatitis to metal may be seen with implantable devices. Patch testing to various metal allergens can be helpful in determining if any allergy is present.

This case and photo were submitted by Michael Stierstorfer, MD, East Penn Dermatology, North Wales, Pa.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

A 5-year-old boy with a papular rash on his arm

Lichen striatus (LS) is a common benign skin condition that presents in children between the ages of 5 and 15 years.1 The rash is typically unilateral and most frequently on the extremities, although it may appear on the face, trunk, or buttocks. The lesions start as pink or skin-colored asymptomatic papules in a linear orientation following the lines of Blaschko. There may be residual postinflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation which often improves within a few years.

Of note, there are subsets of lichen striatus: Hypopigmented lichen striatus with minimal papules has been termed “lichen striatus albus.” Nail lichen striatus may present as onycholysis or fissuring of nails, present as an isolated finding, or more commonly in association with concurrent affected skin. Nail lichen striatus typically resolves on its own, however there are case reports of improvement with intralesional steroids.2

There is no established etiology for LS. Autoimmune disease, viruses, immunizations, medications, and hypersensitivity reactions have been associated with triggering LS in various case reports, although strength of the associations is low. Children have been reported to have LS following scarlet fever and Candida vulvitis.3 Diagnosis usually is clinical, although biopsy may be helpful for histopathologic confirmation. No work-up for associated infections or conditions is warranted.

The differential for linear papular lesions includes inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN), blaschkitis, or linear morphea. ILVEN is a hamartoma that usually is congenital or presents in early childhood; presents with linear or whorled, hyperkeratotic papules and plaque in similar linear “line of Blaschko” patterns; and represents cutaneous mosaicism. It is often difficult to differentiate between lichen striatus and ILVEN, however lichen striatus is not congenital, and is a self-limited condition. Under dermoscopy (polarized light systems) findings of LS more frequently demonstrate gray granular pigmentation. ILVEN is more frequently associated with cerebriform pattern.4 Blaschkitis is a term for a blaschkoid inflammation of the skin that presents with more eczematous findings and histology of spongiosis, unlike the lichenoid findings of LS. It is typically accompanied by noticeable pruritus and broader bands of involved area, and has older age of onset than LS. Linear morphea is a deeper inflammatory process of the dermis or subcutaneous fat, presenting with sclerotic skin, and typically has associated atrophy.

Treatment need not be pursued for lichen striatus because it is a benign condition. The lesions typically self-resolve without any residual scarring. If patients have associated pruritus then low- to midpotency topical steroids can be used for symptomatic relief.

Dr. Kaushik is with the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego, and Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. There are no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures for Dr. Kaushik or Dr. Eichenfield. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Gupta D, Mathes E. Lichen Striatus. (Levy ML ed.) 2019: UpToDate.

2. Dermatol Ther. 2018 Nov;31(6):e12713.

3. Int J Dermatol. 2018 Sep;57(9):1118-9.

4. J Dermatol. 2017 Dec;44(12):e355-6.

Lichen striatus (LS) is a common benign skin condition that presents in children between the ages of 5 and 15 years.1 The rash is typically unilateral and most frequently on the extremities, although it may appear on the face, trunk, or buttocks. The lesions start as pink or skin-colored asymptomatic papules in a linear orientation following the lines of Blaschko. There may be residual postinflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation which often improves within a few years.

Of note, there are subsets of lichen striatus: Hypopigmented lichen striatus with minimal papules has been termed “lichen striatus albus.” Nail lichen striatus may present as onycholysis or fissuring of nails, present as an isolated finding, or more commonly in association with concurrent affected skin. Nail lichen striatus typically resolves on its own, however there are case reports of improvement with intralesional steroids.2

There is no established etiology for LS. Autoimmune disease, viruses, immunizations, medications, and hypersensitivity reactions have been associated with triggering LS in various case reports, although strength of the associations is low. Children have been reported to have LS following scarlet fever and Candida vulvitis.3 Diagnosis usually is clinical, although biopsy may be helpful for histopathologic confirmation. No work-up for associated infections or conditions is warranted.

The differential for linear papular lesions includes inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN), blaschkitis, or linear morphea. ILVEN is a hamartoma that usually is congenital or presents in early childhood; presents with linear or whorled, hyperkeratotic papules and plaque in similar linear “line of Blaschko” patterns; and represents cutaneous mosaicism. It is often difficult to differentiate between lichen striatus and ILVEN, however lichen striatus is not congenital, and is a self-limited condition. Under dermoscopy (polarized light systems) findings of LS more frequently demonstrate gray granular pigmentation. ILVEN is more frequently associated with cerebriform pattern.4 Blaschkitis is a term for a blaschkoid inflammation of the skin that presents with more eczematous findings and histology of spongiosis, unlike the lichenoid findings of LS. It is typically accompanied by noticeable pruritus and broader bands of involved area, and has older age of onset than LS. Linear morphea is a deeper inflammatory process of the dermis or subcutaneous fat, presenting with sclerotic skin, and typically has associated atrophy.

Treatment need not be pursued for lichen striatus because it is a benign condition. The lesions typically self-resolve without any residual scarring. If patients have associated pruritus then low- to midpotency topical steroids can be used for symptomatic relief.

Dr. Kaushik is with the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego, and Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. There are no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures for Dr. Kaushik or Dr. Eichenfield. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Gupta D, Mathes E. Lichen Striatus. (Levy ML ed.) 2019: UpToDate.

2. Dermatol Ther. 2018 Nov;31(6):e12713.

3. Int J Dermatol. 2018 Sep;57(9):1118-9.

4. J Dermatol. 2017 Dec;44(12):e355-6.

Lichen striatus (LS) is a common benign skin condition that presents in children between the ages of 5 and 15 years.1 The rash is typically unilateral and most frequently on the extremities, although it may appear on the face, trunk, or buttocks. The lesions start as pink or skin-colored asymptomatic papules in a linear orientation following the lines of Blaschko. There may be residual postinflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation which often improves within a few years.

Of note, there are subsets of lichen striatus: Hypopigmented lichen striatus with minimal papules has been termed “lichen striatus albus.” Nail lichen striatus may present as onycholysis or fissuring of nails, present as an isolated finding, or more commonly in association with concurrent affected skin. Nail lichen striatus typically resolves on its own, however there are case reports of improvement with intralesional steroids.2

There is no established etiology for LS. Autoimmune disease, viruses, immunizations, medications, and hypersensitivity reactions have been associated with triggering LS in various case reports, although strength of the associations is low. Children have been reported to have LS following scarlet fever and Candida vulvitis.3 Diagnosis usually is clinical, although biopsy may be helpful for histopathologic confirmation. No work-up for associated infections or conditions is warranted.

The differential for linear papular lesions includes inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN), blaschkitis, or linear morphea. ILVEN is a hamartoma that usually is congenital or presents in early childhood; presents with linear or whorled, hyperkeratotic papules and plaque in similar linear “line of Blaschko” patterns; and represents cutaneous mosaicism. It is often difficult to differentiate between lichen striatus and ILVEN, however lichen striatus is not congenital, and is a self-limited condition. Under dermoscopy (polarized light systems) findings of LS more frequently demonstrate gray granular pigmentation. ILVEN is more frequently associated with cerebriform pattern.4 Blaschkitis is a term for a blaschkoid inflammation of the skin that presents with more eczematous findings and histology of spongiosis, unlike the lichenoid findings of LS. It is typically accompanied by noticeable pruritus and broader bands of involved area, and has older age of onset than LS. Linear morphea is a deeper inflammatory process of the dermis or subcutaneous fat, presenting with sclerotic skin, and typically has associated atrophy.

Treatment need not be pursued for lichen striatus because it is a benign condition. The lesions typically self-resolve without any residual scarring. If patients have associated pruritus then low- to midpotency topical steroids can be used for symptomatic relief.

Dr. Kaushik is with the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego, and Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. There are no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures for Dr. Kaushik or Dr. Eichenfield. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Gupta D, Mathes E. Lichen Striatus. (Levy ML ed.) 2019: UpToDate.

2. Dermatol Ther. 2018 Nov;31(6):e12713.

3. Int J Dermatol. 2018 Sep;57(9):1118-9.

4. J Dermatol. 2017 Dec;44(12):e355-6.

A 72-year-old white male with a history of psoriatic arthritis presented with a 1-year history of multiple, intermittently pruritic papules on his face and trunk

Scleromyxedema

area, characteristically involving the glabella and ears. In some patients, the skin may be intensely pruritic, but this is not a universal finding and varies considerably among patients. In addition to affecting the skin, scleromyxedema has variable multisystem effects on the gastrointestinal tract, and musculoskeletal, pulmonary, cardiovascular, renal, and central nervous systems. The most common symptoms are proximal muscle weakness, dysphagia, and dyspnea on exertion. Scleromyxedema can also be associated with a paraproteinemia, mainly immunoglobulin G-lambda type.

Scleromyxedema shares some features with other cutaneous diseases, and the main differential diagnosis includes localized scleromyxedema, also known as lichen myxedematosus. Lichen myxedematosus presents with waxy, firm papules and plaques. Systemic involvement and monoclonal gammopathy are characteristically absent. Scleroderma differs given the increase in fibrosis of cutaneous lesions, a higher percentage of Raynaud’s phenomenon, prominent lung disease, and autoantibodies.