User login

Patient with a breast mass: Why did she pursue litigation?

CASE: After routine mammography results, DCIS found

A 49-year-old woman (G2 P2002) with a history of fibrocystic breast disease presented with a left breast mass that she found a month ago on self-examination. The patient faithfully had obtained routine mammograms since age 40. This year, after reporting the mass and with spot films obtained as recommended by the radiologist, a new cluster of microcalcifications was identified on the report: “spot compression” assessment identified a 3-cm mass and noted “s/p breast augmentation.”

The radiologist interpreted the spot films to be benign. His report stated that “15% of breast cancers are not detected by mammogram and breast self-exam is recommended monthly from 40 years of age.”

The gynecologist recommended a 6-month follow up. When the patient complied, the radiologist’s report again noted calcifications believed to be nonmalignant. Six months later, the patient presented with bloody nipple discharge from her left breast with apparent “eczema-like” lesions on the areola. The patient noted that her “left implant felt different.”

The patient’s surgical history included breast augmentation “years ago.” Her family history was negative for breast cancer. Her medications included hormone therapy (conjugated estrogens 0.625 mg with medroxyprogesterone acetate 2.5 mg daily) for vaginal atrophy. Other medical conditions included irritable bowel syndrome (managed with diet), anxiety and mood swings (for which she was taking sertraline), decreased libido, and irregular vaginal bleeding (after the patient refused endometrial sampling, she was switched to oral contraceptives to address the problem). In addition, her hypertension was being treated with hydrochlorothiazide.

At the gynecologist’s suggestion, a dermatology consultation was obtained.

The dermatologist gave a diagnosis of Paget disease with high-grade ductal carcinoma-in-situ (DCIS). The interval from screening mammogram to DCIS diagnosis had been 8 months. The dermatologist referred the patient to a breast surgeon. A discussion ensued between the breast surgeon and the dermatologist concerning the difficulty of making a diagnosis of breast cancer in a woman with breast augmentation.

The patient underwent modified radical mastectomy, and histopathology revealed DCIS with clear margins; lymph nodes were negative.

The patient filed a malpractice suit against the gynecologist related to the delayed breast mass evaluation and management. She remained upset that when she called the gynecologist’s office to convey her concerns regarding the left nipple discharge and implant concerns, “she was blown off.” She felt there was a clear “failure to communicate on critical matters of her health.” She alleged that the gynecologist, not the dermatologist, should have referred her to a breast surgeon.

WHAT 'S THE VERDICT?

In the end, the patient decided not to pursue the lawsuit.

Related article:

Who is liable when a surgical error occurs?

Medical considerations

Breast cancer is the most common female malignancy, with 232,340 cases occurring annually in the United States. It is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in US women.1 For this case discussion, we review the role of breast cancer screening, including breast self-examination and mammography.

Is breast self-examination recommended?

Recently, medical care has evolved from “breast self-examination” (BSE) to “breast self-awareness.”2 The concept of BSE and concerns about it stem in part from “the Shanghai study.”3 In this prospective randomized trial, 266,064 female textile workers were randomly assigned to “rigorous and repetitive training in BSE” versus no instruction and no BSE performance. The former group had twice as many breast biopsies than the latter group (2,761 biopsies in the BSE group vs 1,505 in the control group). There was no difference in the number of breast cancers diagnosed among the groups—864 in the BSE group and 896 in the control group (relative risk [RR], 0.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.88–1.06; P = .47). Other studies also support lack of efficacy regarding BSE.4

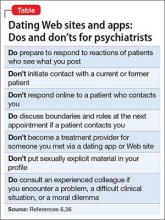

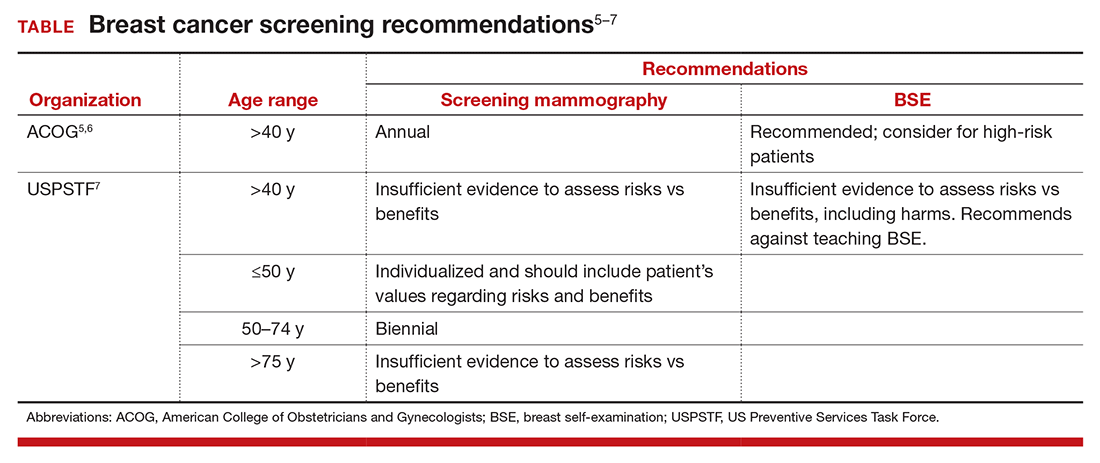

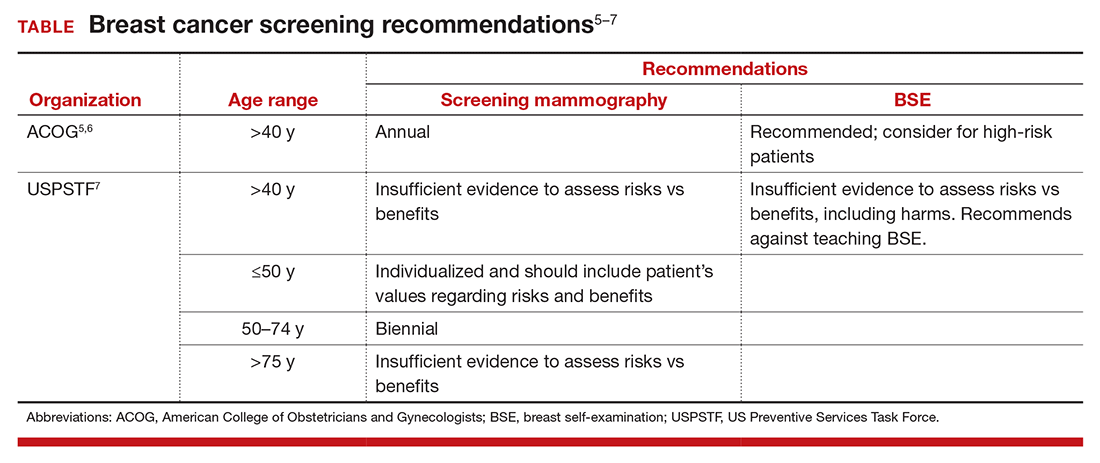

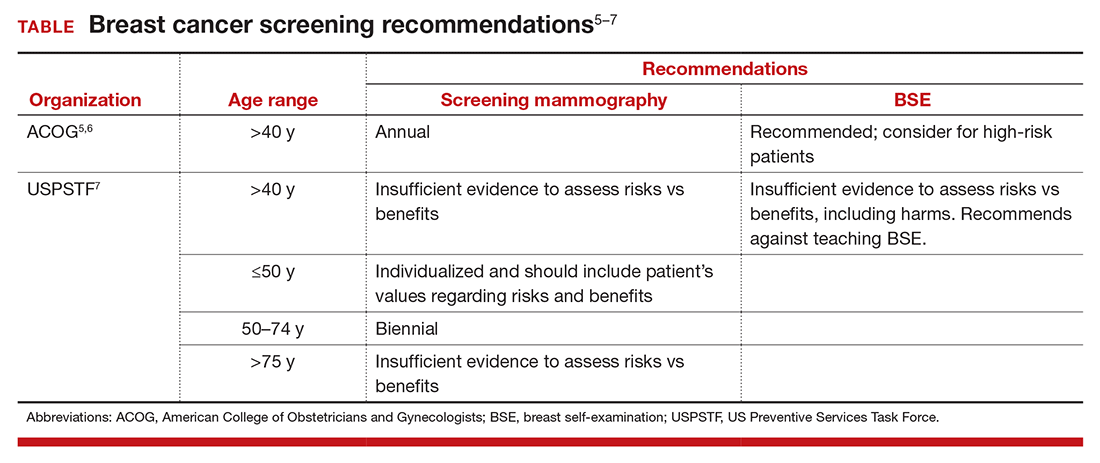

The potential for psychological harm, unnecessary biopsy, and additional imaging in association with false-positive findings is a concern2 (TABLE). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) states, “breast self-examination may be appropriate for certain high-risk populations and for other women who chose to follow this approach.”2,5,6 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines say that there is “insufficient evidence to assess risks vs benefits, including harms,” and recommends against teaching BSE.7 The American Cancer Society puts BSE in the “optional” category.2,8

Is there a middle of the road strategy? Perhaps. The concept of breast-awareness was developed so that women understand how their breasts look and feel.2,5 The concept does not advocate monthly BSE. The Mayo Clinic reported that, of 592 breast cancers, 57% were detected following abnormal screening mammography, 30% by BSE and 14% by clinical examination by a clinician. Furthermore, 38% of women with a palpable abnormality had a normal mammogram within the preceding 13 months.9 McBride and colleagues aptly addressed this: “Healthcare providers can educate their patients that breast awareness, in essence, is a two-step process. First, it requires that women be familiar with their breasts and aware of new changes and, second, have an understanding of the implications of these changes which includes informing their health care provider promptly.”10 The concept of “know what is normal for you” as conveyed by The Susan G. Komen Foundation succinctly encourages communication with patients.2,11

Mammography

The latest technique in mammography is digital or 3D mammography, also known as tomosynthesis. The technique is similar to 2D mammography with the addition of digital cameras. A study published in the radiology literature noted that the 2 methods were equivalent.12 One possible advantage of 3D mammography is that the 3D images are stored in computer files and are more easily incorporated into the electronic medical record.

What about mammography after breast augmentation?

While breast augmentation is not associated with an increase in breast cancer,13 mammography following breast augmentation can be more difficult to interpret and may result in a delay in diagnosis. In a prospective study of asymptomatic women who were diagnosed with breast cancer, 137 had augmentation and 685 did not. Miglioretti and colleagues noted that the sensitivity of screening mammography was lower in the augmentation cohort.14 To enhance accuracy, breast implant displacement views (in which the breast tissue is pulled forward and the implant is displaced posteriorly to improve visualization) have been recommended.15 A retrospective review provides data reporting no effect on interpretation of mammograms following augmentation.16 The American Cancer Society recommends the same screening for women with implants as without implants, starting at age 40 years.17

Paget disease of the breast

Paget disease of the breast was first described by Sir James Paget in 1874. He also defined Paget disease of extramammary tissue, bone, vulva, and penis. Paget disease of the breast is a rare type of cancer in which the skin and nipple are involved frequently in association with DCIS or invasive breast cancer. The skin has an eczema-like appearance. Characteristic Paget (malignant) cells are large with clear cytoplasm (clear halo) and eccentric, hyperchromatic nuclei throughout the dermis. Assessment includes mammography and biopsy with immunohistochemical staining. Treatment varies by case and can include lumpectomy or mastectomy and chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy. Medications, including tamoxifen and anastrazole, have been recommended. Prognosis depends on nodal involvement. The disease is more common in women older than age 50.18

Related article:

The medicolegal considerations of interacting with your patients online

Legal issues: What was the gynecologist’s obligation?

The question remains, did the gynecologist have an obligation to obtain diagnostic mammography and ultrasound of the breast? Would it have been prudent for immediate referral to a breast surgeon? These are critical questions.

Negligence and the standard of care

The malpractice lawsuit against this gynecologist is based on negligence. In essence, it is a claim that the management provided fell below a standard of care that would be given by a reasonably careful and prudent gynecologist under the circumstances. This generally means that the care was less than the profession itself would find acceptable. Here the claim is essentially a diagnostic error claim, a common basis of malpractice.19 The delay in diagnosing breast cancer is a leading cause of malpractice claims against gynecologists.20,21

It is axiomatic that not all bad outcomes are the result of error, and not all errors are a result of an unacceptable standard of care. It is only bad outcomes resulting from careless or negligent errors that give rise to malpractice. But malpractice claims are often filed without knowing whether or not there was negligence—and, as we will see, many of those claims are without merit.

Was there negligence?

Ordinarily the plaintiff/patient must demonstrate that the care by the physician fell below the standard of care and, as a result, the patient suffered an injury. Stated another way, the plaintiff must show that the physician’s actions were unreasonable given all of the circumstances. In this case, the plaintiff must demonstrate that the gynecologist’s care was not appropriate. Failure to refer to another physician or provide additional testing is likely to be the major claim for negligence or inappropriate care.

Did that negligence cause injury?

Even if the plaintiff can demonstrate that the care was negligent, to prevail the plaintiff must also demonstrate that that negligence caused the injury—and that might be difficult.

What injury was caused by the delay in discovering the cancer? It did not apparently lead to the patient’s death. Can it be proven that the delay clearly shortened the patient’s life expectancy or required additional expensive and painful treatment? That may be difficult to demonstrate.

Causation. The causation factor could appear in many cancer or similar medical cases. On one hand, causation is a critical matter, but on the other hand, delay in treating cancer might have a very adverse effect on patients.

In recent years, about half the states have solved this dilemma by recognizing the concept of “loss of chance.”22 Essentially, this means that the health care provider, by delaying treatment, diminished the possibility that the patient would survive or recover fully.

There are significant variations among states in the loss-of-chance concept, many being quite technical.22 Thus, it is possible that a delay that reduced the chance of recovery or survival could be the injury and causal connection between the injury and the negligence. Even in states that recognize the loss-of-chance concept, the patient still must prove loss of chance.

Lessons learned from this case study

- Breast self-awareness has replaced (substituted) breast self-examination

- ACOG recommends breast mammography beginning at age 40 years

- Breast augmentation affects mammographic interpretation

- Prehaps if better communication had been provided initially, the patient would not have sought legal counsel or filed a weak suit

Related article:

Is the smartphone recording while the patient is under anesthesia?

Is this a strong malpractice case?

In the case presented here, it is not clear that the patient could show a meaningful loss of chance. If there is a delay in the breast cancer diagnosis, tumor doubling time would be an issue. While it is impossible to assess growth rate when a breast cancer is in its preclinical microscopic stage, doubling time can be 100 to 200 days. Therefore, it would take 20 years for the tumor to reach a 1- to 2-cm diameter. A log-normal distribution has been suggested for determining tumor growth.23

Although the facts in this case are sketchy, this does not look like a strong malpractice case. Given the expense, difficulty, and length of time it takes to pursue a malpractice case (especially for someone battling cancer), an obvious question is: Why would a patient file a lawsuit in these circumstances? There is no single answer to that, but the hope of getting rich is unlikely a primary motivation. Ironically, many malpractice cases are filed in which there was no error (or at least no negligent error).24

The search for what really happened, or why the bad event happened, is key. In other circumstances, it may be a desire for revenge or to protect other patients from similar bad results. Studies repeatedly have shown a somewhat limited correlation between negligent error and the decision to file a malpractice claim.24–26 In this case, the patient’s sense of being “blown off” during a particularly difficult time may represent the reason why she filed a malpractice lawsuit. Communication gaffes and poor physician-patient relationships undoubtedly contribute to medical malpractice claims.27,28 Improving communication with patients probably improves care, but it also almost certainly reduces the risk of a malpractice claim.29

Why a lawyer would accept this case is also unclear, but that is an issue for another day. Also for another day is the issue of product liability concerning breast implants. Those legal issues and related liability, primarily directed to the manufacturers of the implants, are interesting topics. They are also complex and will be the subject of a future article.

Finally, the patient’s decision to not pursue her lawsuit does not come as a surprise. A relatively small percentage of malpractice claims result in any meaningful financial recovery for the plaintiff. Few cases go to trial, and of those that do result in a verdict, about 75% of the verdicts are in favor of the physician.25,30 Many cases just fade away, either because the plaintiff never pursues them or because they are dismissed by a court at an early stage. Nonetheless, for the physician, even winning a malpractice case is disruptive and difficult. So in addition to ensuring careful, quality, and up-to-date care, a physician should seek to maintain good relationships and communication with patients to reduce the probability of even weak lawsuits being filed.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11–30.

- Mark K, Temkin S, Terplan M. Breast self-awareness: the evidence behind the euphemism. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(4):734–745.

- Thomas D, Gao D, Self S, et al. Randomized trial of breast self-examination in Shanghai: methodology and preliminary results. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89(5):355–365.

- Jones S. Regular self-examination or clinical examination for early detection of breast cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(6):1219.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 122. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Practice-Bulletins/Committee-on-Practice-Bulletins-Gynecology/Breast-Cancer-Screening. Published August 2011; reaffirmed 2014. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- ACOG Statement on breast cancer screening guidelines. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Statements/2016/ACOG-Statement-on-Breast-Cancer-Screening-Guidelines. Published January 11, 2016. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- Final Recommendation Statement: Breast Cancer: Screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force web site. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/breast-cancer-screening1. Published September 2016. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- American Cancer Society recommendations for early breast cancer detection in women without breast symptoms. American Cancer Society website. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/breastcancer/moreinformation/breastcancerearlydetection/breast-cancer-early-detection-acs-recs. Updated October 20, 2015. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- Mathis K, Hoskin T, Boughey J, et al. Palpable presentation of breast cancer persists in the era of screening mammography. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(3):314–318.

- MacBride M, Pruthi S, Bevers T. The evolution of breast self-examination to breast awareness. Breast J. 2012;18(6):641–643.

- Susan G. Komen Foundation. Breast self-awareness messages. http://ww5.komen.org/Breastcancer/Breastselfawareness.html. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- DelTurco MR, Mantellini P, Ciatto S, et al. Full-field digital versus screen-film mammography: comparative accuracy in concurrent screening cohorts. AJR. 2007;189(4):860–866.

- Susan G. Koman Foundation. Factors that do not increase breast cancer risk: Breast implants. https://ww5.komen.org/BreastCancer/FactorsThatDoNotIncreaseRisk.html. Updated October 28, 2016. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- Miglioretti D, Rutter, C, Geller B, et al. Effect of breast augmentation on the accuracy of mammography and cancer characteristics. JAMA. 2004;291(4):442–450.

- Eklund GW, Busby RC, Miller SH, Job JS. Improved imaging of the augmented breast. Am J Roentgenol. 1988;151(3):469–473.

- Kam K, Lee E, Pairwan S, et al. The effect of breast implants on mammogram outcomes. Am Surg. 2015;81(10):1053–1056.

- American Cancer Society. Mammograms and other imaging tests. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/003178-pdf.pdf. Revised April 25, 2016. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- Dalberg K, Hellborg H, Warnberg F. Paget’s disease of the nipple in a population based cohort. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;111(2):313–319.

- Saber Tehrani A, Lee H, Mathews S, et al. 25-year summary of US malpractice claims for diagnostic errors 1986–2010: an analysis from the National Practitioner Data Bank. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(8):672–680.

- White AA, Pichert JW, Bledsoe SH, Irwin C, Entman SS. Cause and effect analysis of closed claims in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 pt 1):1031–1038.

- Ward CJ, Green VL. Risk management and medico-legal issues in breast cancer. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;59(2):439–446.

- Guest L, Schap D, Tran T. The “Loss of Chance” rule as a special category of damages in medical malpractice: a state-by-state analysis. J Legal Econ. 2015;21(2):53–107.

- Kuroishi T, Tominaga S, Morimoto T, et al. Tumor growth rate and prognosis of breast cancer mainly detected by mass screening. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1990;81(5):454–462.

- Localio AR, Lawthers AG, Brennan TA, et al. Relation between malpractice claims and adverse events due to negligence: results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study III. N Engl J Medicine. 1991;325(4):245–251.

- Gandhi TK, Kachalia A, Thomas EJ, et al. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the ambulatory setting: a study of closed malpractice claims. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(7):488–496.

- Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(19):2024–2033.

- Huntington B, Kuhn N. Communication gaffes: a root cause of malpractice claims. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2003;16(2):157–161.

- Moore PJ, Adler NE, Robertson PA. Medical malpractice: the effect of doctor-patient relations on medical patient perceptions and malpractice intentions. West J Med. 2000;173(4):244–250.

- Hickson GB, Jenkins AD. Identifying and addressing communication failures as a means of reducing unnecessary malpractice claims. NC Med J. 2007;68(5):362–364.

- Jena AB, Chandra A, Lakdawalla D, Seabury S. Outcomes of medical malpractice litigation against US physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(11):892–894.

CASE: After routine mammography results, DCIS found

A 49-year-old woman (G2 P2002) with a history of fibrocystic breast disease presented with a left breast mass that she found a month ago on self-examination. The patient faithfully had obtained routine mammograms since age 40. This year, after reporting the mass and with spot films obtained as recommended by the radiologist, a new cluster of microcalcifications was identified on the report: “spot compression” assessment identified a 3-cm mass and noted “s/p breast augmentation.”

The radiologist interpreted the spot films to be benign. His report stated that “15% of breast cancers are not detected by mammogram and breast self-exam is recommended monthly from 40 years of age.”

The gynecologist recommended a 6-month follow up. When the patient complied, the radiologist’s report again noted calcifications believed to be nonmalignant. Six months later, the patient presented with bloody nipple discharge from her left breast with apparent “eczema-like” lesions on the areola. The patient noted that her “left implant felt different.”

The patient’s surgical history included breast augmentation “years ago.” Her family history was negative for breast cancer. Her medications included hormone therapy (conjugated estrogens 0.625 mg with medroxyprogesterone acetate 2.5 mg daily) for vaginal atrophy. Other medical conditions included irritable bowel syndrome (managed with diet), anxiety and mood swings (for which she was taking sertraline), decreased libido, and irregular vaginal bleeding (after the patient refused endometrial sampling, she was switched to oral contraceptives to address the problem). In addition, her hypertension was being treated with hydrochlorothiazide.

At the gynecologist’s suggestion, a dermatology consultation was obtained.

The dermatologist gave a diagnosis of Paget disease with high-grade ductal carcinoma-in-situ (DCIS). The interval from screening mammogram to DCIS diagnosis had been 8 months. The dermatologist referred the patient to a breast surgeon. A discussion ensued between the breast surgeon and the dermatologist concerning the difficulty of making a diagnosis of breast cancer in a woman with breast augmentation.

The patient underwent modified radical mastectomy, and histopathology revealed DCIS with clear margins; lymph nodes were negative.

The patient filed a malpractice suit against the gynecologist related to the delayed breast mass evaluation and management. She remained upset that when she called the gynecologist’s office to convey her concerns regarding the left nipple discharge and implant concerns, “she was blown off.” She felt there was a clear “failure to communicate on critical matters of her health.” She alleged that the gynecologist, not the dermatologist, should have referred her to a breast surgeon.

WHAT 'S THE VERDICT?

In the end, the patient decided not to pursue the lawsuit.

Related article:

Who is liable when a surgical error occurs?

Medical considerations

Breast cancer is the most common female malignancy, with 232,340 cases occurring annually in the United States. It is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in US women.1 For this case discussion, we review the role of breast cancer screening, including breast self-examination and mammography.

Is breast self-examination recommended?

Recently, medical care has evolved from “breast self-examination” (BSE) to “breast self-awareness.”2 The concept of BSE and concerns about it stem in part from “the Shanghai study.”3 In this prospective randomized trial, 266,064 female textile workers were randomly assigned to “rigorous and repetitive training in BSE” versus no instruction and no BSE performance. The former group had twice as many breast biopsies than the latter group (2,761 biopsies in the BSE group vs 1,505 in the control group). There was no difference in the number of breast cancers diagnosed among the groups—864 in the BSE group and 896 in the control group (relative risk [RR], 0.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.88–1.06; P = .47). Other studies also support lack of efficacy regarding BSE.4

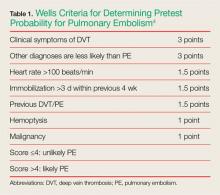

The potential for psychological harm, unnecessary biopsy, and additional imaging in association with false-positive findings is a concern2 (TABLE). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) states, “breast self-examination may be appropriate for certain high-risk populations and for other women who chose to follow this approach.”2,5,6 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines say that there is “insufficient evidence to assess risks vs benefits, including harms,” and recommends against teaching BSE.7 The American Cancer Society puts BSE in the “optional” category.2,8

Is there a middle of the road strategy? Perhaps. The concept of breast-awareness was developed so that women understand how their breasts look and feel.2,5 The concept does not advocate monthly BSE. The Mayo Clinic reported that, of 592 breast cancers, 57% were detected following abnormal screening mammography, 30% by BSE and 14% by clinical examination by a clinician. Furthermore, 38% of women with a palpable abnormality had a normal mammogram within the preceding 13 months.9 McBride and colleagues aptly addressed this: “Healthcare providers can educate their patients that breast awareness, in essence, is a two-step process. First, it requires that women be familiar with their breasts and aware of new changes and, second, have an understanding of the implications of these changes which includes informing their health care provider promptly.”10 The concept of “know what is normal for you” as conveyed by The Susan G. Komen Foundation succinctly encourages communication with patients.2,11

Mammography

The latest technique in mammography is digital or 3D mammography, also known as tomosynthesis. The technique is similar to 2D mammography with the addition of digital cameras. A study published in the radiology literature noted that the 2 methods were equivalent.12 One possible advantage of 3D mammography is that the 3D images are stored in computer files and are more easily incorporated into the electronic medical record.

What about mammography after breast augmentation?

While breast augmentation is not associated with an increase in breast cancer,13 mammography following breast augmentation can be more difficult to interpret and may result in a delay in diagnosis. In a prospective study of asymptomatic women who were diagnosed with breast cancer, 137 had augmentation and 685 did not. Miglioretti and colleagues noted that the sensitivity of screening mammography was lower in the augmentation cohort.14 To enhance accuracy, breast implant displacement views (in which the breast tissue is pulled forward and the implant is displaced posteriorly to improve visualization) have been recommended.15 A retrospective review provides data reporting no effect on interpretation of mammograms following augmentation.16 The American Cancer Society recommends the same screening for women with implants as without implants, starting at age 40 years.17

Paget disease of the breast

Paget disease of the breast was first described by Sir James Paget in 1874. He also defined Paget disease of extramammary tissue, bone, vulva, and penis. Paget disease of the breast is a rare type of cancer in which the skin and nipple are involved frequently in association with DCIS or invasive breast cancer. The skin has an eczema-like appearance. Characteristic Paget (malignant) cells are large with clear cytoplasm (clear halo) and eccentric, hyperchromatic nuclei throughout the dermis. Assessment includes mammography and biopsy with immunohistochemical staining. Treatment varies by case and can include lumpectomy or mastectomy and chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy. Medications, including tamoxifen and anastrazole, have been recommended. Prognosis depends on nodal involvement. The disease is more common in women older than age 50.18

Related article:

The medicolegal considerations of interacting with your patients online

Legal issues: What was the gynecologist’s obligation?

The question remains, did the gynecologist have an obligation to obtain diagnostic mammography and ultrasound of the breast? Would it have been prudent for immediate referral to a breast surgeon? These are critical questions.

Negligence and the standard of care

The malpractice lawsuit against this gynecologist is based on negligence. In essence, it is a claim that the management provided fell below a standard of care that would be given by a reasonably careful and prudent gynecologist under the circumstances. This generally means that the care was less than the profession itself would find acceptable. Here the claim is essentially a diagnostic error claim, a common basis of malpractice.19 The delay in diagnosing breast cancer is a leading cause of malpractice claims against gynecologists.20,21

It is axiomatic that not all bad outcomes are the result of error, and not all errors are a result of an unacceptable standard of care. It is only bad outcomes resulting from careless or negligent errors that give rise to malpractice. But malpractice claims are often filed without knowing whether or not there was negligence—and, as we will see, many of those claims are without merit.

Was there negligence?

Ordinarily the plaintiff/patient must demonstrate that the care by the physician fell below the standard of care and, as a result, the patient suffered an injury. Stated another way, the plaintiff must show that the physician’s actions were unreasonable given all of the circumstances. In this case, the plaintiff must demonstrate that the gynecologist’s care was not appropriate. Failure to refer to another physician or provide additional testing is likely to be the major claim for negligence or inappropriate care.

Did that negligence cause injury?

Even if the plaintiff can demonstrate that the care was negligent, to prevail the plaintiff must also demonstrate that that negligence caused the injury—and that might be difficult.

What injury was caused by the delay in discovering the cancer? It did not apparently lead to the patient’s death. Can it be proven that the delay clearly shortened the patient’s life expectancy or required additional expensive and painful treatment? That may be difficult to demonstrate.

Causation. The causation factor could appear in many cancer or similar medical cases. On one hand, causation is a critical matter, but on the other hand, delay in treating cancer might have a very adverse effect on patients.

In recent years, about half the states have solved this dilemma by recognizing the concept of “loss of chance.”22 Essentially, this means that the health care provider, by delaying treatment, diminished the possibility that the patient would survive or recover fully.

There are significant variations among states in the loss-of-chance concept, many being quite technical.22 Thus, it is possible that a delay that reduced the chance of recovery or survival could be the injury and causal connection between the injury and the negligence. Even in states that recognize the loss-of-chance concept, the patient still must prove loss of chance.

Lessons learned from this case study

- Breast self-awareness has replaced (substituted) breast self-examination

- ACOG recommends breast mammography beginning at age 40 years

- Breast augmentation affects mammographic interpretation

- Prehaps if better communication had been provided initially, the patient would not have sought legal counsel or filed a weak suit

Related article:

Is the smartphone recording while the patient is under anesthesia?

Is this a strong malpractice case?

In the case presented here, it is not clear that the patient could show a meaningful loss of chance. If there is a delay in the breast cancer diagnosis, tumor doubling time would be an issue. While it is impossible to assess growth rate when a breast cancer is in its preclinical microscopic stage, doubling time can be 100 to 200 days. Therefore, it would take 20 years for the tumor to reach a 1- to 2-cm diameter. A log-normal distribution has been suggested for determining tumor growth.23

Although the facts in this case are sketchy, this does not look like a strong malpractice case. Given the expense, difficulty, and length of time it takes to pursue a malpractice case (especially for someone battling cancer), an obvious question is: Why would a patient file a lawsuit in these circumstances? There is no single answer to that, but the hope of getting rich is unlikely a primary motivation. Ironically, many malpractice cases are filed in which there was no error (or at least no negligent error).24

The search for what really happened, or why the bad event happened, is key. In other circumstances, it may be a desire for revenge or to protect other patients from similar bad results. Studies repeatedly have shown a somewhat limited correlation between negligent error and the decision to file a malpractice claim.24–26 In this case, the patient’s sense of being “blown off” during a particularly difficult time may represent the reason why she filed a malpractice lawsuit. Communication gaffes and poor physician-patient relationships undoubtedly contribute to medical malpractice claims.27,28 Improving communication with patients probably improves care, but it also almost certainly reduces the risk of a malpractice claim.29

Why a lawyer would accept this case is also unclear, but that is an issue for another day. Also for another day is the issue of product liability concerning breast implants. Those legal issues and related liability, primarily directed to the manufacturers of the implants, are interesting topics. They are also complex and will be the subject of a future article.

Finally, the patient’s decision to not pursue her lawsuit does not come as a surprise. A relatively small percentage of malpractice claims result in any meaningful financial recovery for the plaintiff. Few cases go to trial, and of those that do result in a verdict, about 75% of the verdicts are in favor of the physician.25,30 Many cases just fade away, either because the plaintiff never pursues them or because they are dismissed by a court at an early stage. Nonetheless, for the physician, even winning a malpractice case is disruptive and difficult. So in addition to ensuring careful, quality, and up-to-date care, a physician should seek to maintain good relationships and communication with patients to reduce the probability of even weak lawsuits being filed.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE: After routine mammography results, DCIS found

A 49-year-old woman (G2 P2002) with a history of fibrocystic breast disease presented with a left breast mass that she found a month ago on self-examination. The patient faithfully had obtained routine mammograms since age 40. This year, after reporting the mass and with spot films obtained as recommended by the radiologist, a new cluster of microcalcifications was identified on the report: “spot compression” assessment identified a 3-cm mass and noted “s/p breast augmentation.”

The radiologist interpreted the spot films to be benign. His report stated that “15% of breast cancers are not detected by mammogram and breast self-exam is recommended monthly from 40 years of age.”

The gynecologist recommended a 6-month follow up. When the patient complied, the radiologist’s report again noted calcifications believed to be nonmalignant. Six months later, the patient presented with bloody nipple discharge from her left breast with apparent “eczema-like” lesions on the areola. The patient noted that her “left implant felt different.”

The patient’s surgical history included breast augmentation “years ago.” Her family history was negative for breast cancer. Her medications included hormone therapy (conjugated estrogens 0.625 mg with medroxyprogesterone acetate 2.5 mg daily) for vaginal atrophy. Other medical conditions included irritable bowel syndrome (managed with diet), anxiety and mood swings (for which she was taking sertraline), decreased libido, and irregular vaginal bleeding (after the patient refused endometrial sampling, she was switched to oral contraceptives to address the problem). In addition, her hypertension was being treated with hydrochlorothiazide.

At the gynecologist’s suggestion, a dermatology consultation was obtained.

The dermatologist gave a diagnosis of Paget disease with high-grade ductal carcinoma-in-situ (DCIS). The interval from screening mammogram to DCIS diagnosis had been 8 months. The dermatologist referred the patient to a breast surgeon. A discussion ensued between the breast surgeon and the dermatologist concerning the difficulty of making a diagnosis of breast cancer in a woman with breast augmentation.

The patient underwent modified radical mastectomy, and histopathology revealed DCIS with clear margins; lymph nodes were negative.

The patient filed a malpractice suit against the gynecologist related to the delayed breast mass evaluation and management. She remained upset that when she called the gynecologist’s office to convey her concerns regarding the left nipple discharge and implant concerns, “she was blown off.” She felt there was a clear “failure to communicate on critical matters of her health.” She alleged that the gynecologist, not the dermatologist, should have referred her to a breast surgeon.

WHAT 'S THE VERDICT?

In the end, the patient decided not to pursue the lawsuit.

Related article:

Who is liable when a surgical error occurs?

Medical considerations

Breast cancer is the most common female malignancy, with 232,340 cases occurring annually in the United States. It is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in US women.1 For this case discussion, we review the role of breast cancer screening, including breast self-examination and mammography.

Is breast self-examination recommended?

Recently, medical care has evolved from “breast self-examination” (BSE) to “breast self-awareness.”2 The concept of BSE and concerns about it stem in part from “the Shanghai study.”3 In this prospective randomized trial, 266,064 female textile workers were randomly assigned to “rigorous and repetitive training in BSE” versus no instruction and no BSE performance. The former group had twice as many breast biopsies than the latter group (2,761 biopsies in the BSE group vs 1,505 in the control group). There was no difference in the number of breast cancers diagnosed among the groups—864 in the BSE group and 896 in the control group (relative risk [RR], 0.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.88–1.06; P = .47). Other studies also support lack of efficacy regarding BSE.4

The potential for psychological harm, unnecessary biopsy, and additional imaging in association with false-positive findings is a concern2 (TABLE). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) states, “breast self-examination may be appropriate for certain high-risk populations and for other women who chose to follow this approach.”2,5,6 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines say that there is “insufficient evidence to assess risks vs benefits, including harms,” and recommends against teaching BSE.7 The American Cancer Society puts BSE in the “optional” category.2,8

Is there a middle of the road strategy? Perhaps. The concept of breast-awareness was developed so that women understand how their breasts look and feel.2,5 The concept does not advocate monthly BSE. The Mayo Clinic reported that, of 592 breast cancers, 57% were detected following abnormal screening mammography, 30% by BSE and 14% by clinical examination by a clinician. Furthermore, 38% of women with a palpable abnormality had a normal mammogram within the preceding 13 months.9 McBride and colleagues aptly addressed this: “Healthcare providers can educate their patients that breast awareness, in essence, is a two-step process. First, it requires that women be familiar with their breasts and aware of new changes and, second, have an understanding of the implications of these changes which includes informing their health care provider promptly.”10 The concept of “know what is normal for you” as conveyed by The Susan G. Komen Foundation succinctly encourages communication with patients.2,11

Mammography

The latest technique in mammography is digital or 3D mammography, also known as tomosynthesis. The technique is similar to 2D mammography with the addition of digital cameras. A study published in the radiology literature noted that the 2 methods were equivalent.12 One possible advantage of 3D mammography is that the 3D images are stored in computer files and are more easily incorporated into the electronic medical record.

What about mammography after breast augmentation?

While breast augmentation is not associated with an increase in breast cancer,13 mammography following breast augmentation can be more difficult to interpret and may result in a delay in diagnosis. In a prospective study of asymptomatic women who were diagnosed with breast cancer, 137 had augmentation and 685 did not. Miglioretti and colleagues noted that the sensitivity of screening mammography was lower in the augmentation cohort.14 To enhance accuracy, breast implant displacement views (in which the breast tissue is pulled forward and the implant is displaced posteriorly to improve visualization) have been recommended.15 A retrospective review provides data reporting no effect on interpretation of mammograms following augmentation.16 The American Cancer Society recommends the same screening for women with implants as without implants, starting at age 40 years.17

Paget disease of the breast

Paget disease of the breast was first described by Sir James Paget in 1874. He also defined Paget disease of extramammary tissue, bone, vulva, and penis. Paget disease of the breast is a rare type of cancer in which the skin and nipple are involved frequently in association with DCIS or invasive breast cancer. The skin has an eczema-like appearance. Characteristic Paget (malignant) cells are large with clear cytoplasm (clear halo) and eccentric, hyperchromatic nuclei throughout the dermis. Assessment includes mammography and biopsy with immunohistochemical staining. Treatment varies by case and can include lumpectomy or mastectomy and chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy. Medications, including tamoxifen and anastrazole, have been recommended. Prognosis depends on nodal involvement. The disease is more common in women older than age 50.18

Related article:

The medicolegal considerations of interacting with your patients online

Legal issues: What was the gynecologist’s obligation?

The question remains, did the gynecologist have an obligation to obtain diagnostic mammography and ultrasound of the breast? Would it have been prudent for immediate referral to a breast surgeon? These are critical questions.

Negligence and the standard of care

The malpractice lawsuit against this gynecologist is based on negligence. In essence, it is a claim that the management provided fell below a standard of care that would be given by a reasonably careful and prudent gynecologist under the circumstances. This generally means that the care was less than the profession itself would find acceptable. Here the claim is essentially a diagnostic error claim, a common basis of malpractice.19 The delay in diagnosing breast cancer is a leading cause of malpractice claims against gynecologists.20,21

It is axiomatic that not all bad outcomes are the result of error, and not all errors are a result of an unacceptable standard of care. It is only bad outcomes resulting from careless or negligent errors that give rise to malpractice. But malpractice claims are often filed without knowing whether or not there was negligence—and, as we will see, many of those claims are without merit.

Was there negligence?

Ordinarily the plaintiff/patient must demonstrate that the care by the physician fell below the standard of care and, as a result, the patient suffered an injury. Stated another way, the plaintiff must show that the physician’s actions were unreasonable given all of the circumstances. In this case, the plaintiff must demonstrate that the gynecologist’s care was not appropriate. Failure to refer to another physician or provide additional testing is likely to be the major claim for negligence or inappropriate care.

Did that negligence cause injury?

Even if the plaintiff can demonstrate that the care was negligent, to prevail the plaintiff must also demonstrate that that negligence caused the injury—and that might be difficult.

What injury was caused by the delay in discovering the cancer? It did not apparently lead to the patient’s death. Can it be proven that the delay clearly shortened the patient’s life expectancy or required additional expensive and painful treatment? That may be difficult to demonstrate.

Causation. The causation factor could appear in many cancer or similar medical cases. On one hand, causation is a critical matter, but on the other hand, delay in treating cancer might have a very adverse effect on patients.

In recent years, about half the states have solved this dilemma by recognizing the concept of “loss of chance.”22 Essentially, this means that the health care provider, by delaying treatment, diminished the possibility that the patient would survive or recover fully.

There are significant variations among states in the loss-of-chance concept, many being quite technical.22 Thus, it is possible that a delay that reduced the chance of recovery or survival could be the injury and causal connection between the injury and the negligence. Even in states that recognize the loss-of-chance concept, the patient still must prove loss of chance.

Lessons learned from this case study

- Breast self-awareness has replaced (substituted) breast self-examination

- ACOG recommends breast mammography beginning at age 40 years

- Breast augmentation affects mammographic interpretation

- Prehaps if better communication had been provided initially, the patient would not have sought legal counsel or filed a weak suit

Related article:

Is the smartphone recording while the patient is under anesthesia?

Is this a strong malpractice case?

In the case presented here, it is not clear that the patient could show a meaningful loss of chance. If there is a delay in the breast cancer diagnosis, tumor doubling time would be an issue. While it is impossible to assess growth rate when a breast cancer is in its preclinical microscopic stage, doubling time can be 100 to 200 days. Therefore, it would take 20 years for the tumor to reach a 1- to 2-cm diameter. A log-normal distribution has been suggested for determining tumor growth.23

Although the facts in this case are sketchy, this does not look like a strong malpractice case. Given the expense, difficulty, and length of time it takes to pursue a malpractice case (especially for someone battling cancer), an obvious question is: Why would a patient file a lawsuit in these circumstances? There is no single answer to that, but the hope of getting rich is unlikely a primary motivation. Ironically, many malpractice cases are filed in which there was no error (or at least no negligent error).24

The search for what really happened, or why the bad event happened, is key. In other circumstances, it may be a desire for revenge or to protect other patients from similar bad results. Studies repeatedly have shown a somewhat limited correlation between negligent error and the decision to file a malpractice claim.24–26 In this case, the patient’s sense of being “blown off” during a particularly difficult time may represent the reason why she filed a malpractice lawsuit. Communication gaffes and poor physician-patient relationships undoubtedly contribute to medical malpractice claims.27,28 Improving communication with patients probably improves care, but it also almost certainly reduces the risk of a malpractice claim.29

Why a lawyer would accept this case is also unclear, but that is an issue for another day. Also for another day is the issue of product liability concerning breast implants. Those legal issues and related liability, primarily directed to the manufacturers of the implants, are interesting topics. They are also complex and will be the subject of a future article.

Finally, the patient’s decision to not pursue her lawsuit does not come as a surprise. A relatively small percentage of malpractice claims result in any meaningful financial recovery for the plaintiff. Few cases go to trial, and of those that do result in a verdict, about 75% of the verdicts are in favor of the physician.25,30 Many cases just fade away, either because the plaintiff never pursues them or because they are dismissed by a court at an early stage. Nonetheless, for the physician, even winning a malpractice case is disruptive and difficult. So in addition to ensuring careful, quality, and up-to-date care, a physician should seek to maintain good relationships and communication with patients to reduce the probability of even weak lawsuits being filed.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11–30.

- Mark K, Temkin S, Terplan M. Breast self-awareness: the evidence behind the euphemism. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(4):734–745.

- Thomas D, Gao D, Self S, et al. Randomized trial of breast self-examination in Shanghai: methodology and preliminary results. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89(5):355–365.

- Jones S. Regular self-examination or clinical examination for early detection of breast cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(6):1219.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 122. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Practice-Bulletins/Committee-on-Practice-Bulletins-Gynecology/Breast-Cancer-Screening. Published August 2011; reaffirmed 2014. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- ACOG Statement on breast cancer screening guidelines. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Statements/2016/ACOG-Statement-on-Breast-Cancer-Screening-Guidelines. Published January 11, 2016. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- Final Recommendation Statement: Breast Cancer: Screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force web site. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/breast-cancer-screening1. Published September 2016. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- American Cancer Society recommendations for early breast cancer detection in women without breast symptoms. American Cancer Society website. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/breastcancer/moreinformation/breastcancerearlydetection/breast-cancer-early-detection-acs-recs. Updated October 20, 2015. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- Mathis K, Hoskin T, Boughey J, et al. Palpable presentation of breast cancer persists in the era of screening mammography. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(3):314–318.

- MacBride M, Pruthi S, Bevers T. The evolution of breast self-examination to breast awareness. Breast J. 2012;18(6):641–643.

- Susan G. Komen Foundation. Breast self-awareness messages. http://ww5.komen.org/Breastcancer/Breastselfawareness.html. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- DelTurco MR, Mantellini P, Ciatto S, et al. Full-field digital versus screen-film mammography: comparative accuracy in concurrent screening cohorts. AJR. 2007;189(4):860–866.

- Susan G. Koman Foundation. Factors that do not increase breast cancer risk: Breast implants. https://ww5.komen.org/BreastCancer/FactorsThatDoNotIncreaseRisk.html. Updated October 28, 2016. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- Miglioretti D, Rutter, C, Geller B, et al. Effect of breast augmentation on the accuracy of mammography and cancer characteristics. JAMA. 2004;291(4):442–450.

- Eklund GW, Busby RC, Miller SH, Job JS. Improved imaging of the augmented breast. Am J Roentgenol. 1988;151(3):469–473.

- Kam K, Lee E, Pairwan S, et al. The effect of breast implants on mammogram outcomes. Am Surg. 2015;81(10):1053–1056.

- American Cancer Society. Mammograms and other imaging tests. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/003178-pdf.pdf. Revised April 25, 2016. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- Dalberg K, Hellborg H, Warnberg F. Paget’s disease of the nipple in a population based cohort. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;111(2):313–319.

- Saber Tehrani A, Lee H, Mathews S, et al. 25-year summary of US malpractice claims for diagnostic errors 1986–2010: an analysis from the National Practitioner Data Bank. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(8):672–680.

- White AA, Pichert JW, Bledsoe SH, Irwin C, Entman SS. Cause and effect analysis of closed claims in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 pt 1):1031–1038.

- Ward CJ, Green VL. Risk management and medico-legal issues in breast cancer. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;59(2):439–446.

- Guest L, Schap D, Tran T. The “Loss of Chance” rule as a special category of damages in medical malpractice: a state-by-state analysis. J Legal Econ. 2015;21(2):53–107.

- Kuroishi T, Tominaga S, Morimoto T, et al. Tumor growth rate and prognosis of breast cancer mainly detected by mass screening. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1990;81(5):454–462.

- Localio AR, Lawthers AG, Brennan TA, et al. Relation between malpractice claims and adverse events due to negligence: results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study III. N Engl J Medicine. 1991;325(4):245–251.

- Gandhi TK, Kachalia A, Thomas EJ, et al. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the ambulatory setting: a study of closed malpractice claims. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(7):488–496.

- Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(19):2024–2033.

- Huntington B, Kuhn N. Communication gaffes: a root cause of malpractice claims. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2003;16(2):157–161.

- Moore PJ, Adler NE, Robertson PA. Medical malpractice: the effect of doctor-patient relations on medical patient perceptions and malpractice intentions. West J Med. 2000;173(4):244–250.

- Hickson GB, Jenkins AD. Identifying and addressing communication failures as a means of reducing unnecessary malpractice claims. NC Med J. 2007;68(5):362–364.

- Jena AB, Chandra A, Lakdawalla D, Seabury S. Outcomes of medical malpractice litigation against US physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(11):892–894.

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11–30.

- Mark K, Temkin S, Terplan M. Breast self-awareness: the evidence behind the euphemism. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(4):734–745.

- Thomas D, Gao D, Self S, et al. Randomized trial of breast self-examination in Shanghai: methodology and preliminary results. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89(5):355–365.

- Jones S. Regular self-examination or clinical examination for early detection of breast cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(6):1219.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 122. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Practice-Bulletins/Committee-on-Practice-Bulletins-Gynecology/Breast-Cancer-Screening. Published August 2011; reaffirmed 2014. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- ACOG Statement on breast cancer screening guidelines. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Statements/2016/ACOG-Statement-on-Breast-Cancer-Screening-Guidelines. Published January 11, 2016. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- Final Recommendation Statement: Breast Cancer: Screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force web site. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/breast-cancer-screening1. Published September 2016. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- American Cancer Society recommendations for early breast cancer detection in women without breast symptoms. American Cancer Society website. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/breastcancer/moreinformation/breastcancerearlydetection/breast-cancer-early-detection-acs-recs. Updated October 20, 2015. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- Mathis K, Hoskin T, Boughey J, et al. Palpable presentation of breast cancer persists in the era of screening mammography. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(3):314–318.

- MacBride M, Pruthi S, Bevers T. The evolution of breast self-examination to breast awareness. Breast J. 2012;18(6):641–643.

- Susan G. Komen Foundation. Breast self-awareness messages. http://ww5.komen.org/Breastcancer/Breastselfawareness.html. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- DelTurco MR, Mantellini P, Ciatto S, et al. Full-field digital versus screen-film mammography: comparative accuracy in concurrent screening cohorts. AJR. 2007;189(4):860–866.

- Susan G. Koman Foundation. Factors that do not increase breast cancer risk: Breast implants. https://ww5.komen.org/BreastCancer/FactorsThatDoNotIncreaseRisk.html. Updated October 28, 2016. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- Miglioretti D, Rutter, C, Geller B, et al. Effect of breast augmentation on the accuracy of mammography and cancer characteristics. JAMA. 2004;291(4):442–450.

- Eklund GW, Busby RC, Miller SH, Job JS. Improved imaging of the augmented breast. Am J Roentgenol. 1988;151(3):469–473.

- Kam K, Lee E, Pairwan S, et al. The effect of breast implants on mammogram outcomes. Am Surg. 2015;81(10):1053–1056.

- American Cancer Society. Mammograms and other imaging tests. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/003178-pdf.pdf. Revised April 25, 2016. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- Dalberg K, Hellborg H, Warnberg F. Paget’s disease of the nipple in a population based cohort. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;111(2):313–319.

- Saber Tehrani A, Lee H, Mathews S, et al. 25-year summary of US malpractice claims for diagnostic errors 1986–2010: an analysis from the National Practitioner Data Bank. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(8):672–680.

- White AA, Pichert JW, Bledsoe SH, Irwin C, Entman SS. Cause and effect analysis of closed claims in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 pt 1):1031–1038.

- Ward CJ, Green VL. Risk management and medico-legal issues in breast cancer. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;59(2):439–446.

- Guest L, Schap D, Tran T. The “Loss of Chance” rule as a special category of damages in medical malpractice: a state-by-state analysis. J Legal Econ. 2015;21(2):53–107.

- Kuroishi T, Tominaga S, Morimoto T, et al. Tumor growth rate and prognosis of breast cancer mainly detected by mass screening. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1990;81(5):454–462.

- Localio AR, Lawthers AG, Brennan TA, et al. Relation between malpractice claims and adverse events due to negligence: results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study III. N Engl J Medicine. 1991;325(4):245–251.

- Gandhi TK, Kachalia A, Thomas EJ, et al. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the ambulatory setting: a study of closed malpractice claims. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(7):488–496.

- Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(19):2024–2033.

- Huntington B, Kuhn N. Communication gaffes: a root cause of malpractice claims. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2003;16(2):157–161.

- Moore PJ, Adler NE, Robertson PA. Medical malpractice: the effect of doctor-patient relations on medical patient perceptions and malpractice intentions. West J Med. 2000;173(4):244–250.

- Hickson GB, Jenkins AD. Identifying and addressing communication failures as a means of reducing unnecessary malpractice claims. NC Med J. 2007;68(5):362–364.

- Jena AB, Chandra A, Lakdawalla D, Seabury S. Outcomes of medical malpractice litigation against US physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(11):892–894.

Malpractice Counsel: Missed Nodule

Case

A 48-year-old man presented to the ED with a 2-day history of cough and congestion. He described the cough as gradual in onset and, though initially nonproductive, it was now productive of green sputum. He denied fevers or chills, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, and complained of only mild shortness of breath. His medical history was significant for hypertension, which was well managed with daily lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide. He admitted to smoking one pack of cigarettes per day for the past 25 years, but denied alcohol or illicit drug use.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 112/64 mm Hg; heart rate, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and temperature, 98oF. Oxygen saturation was 97% on room air. The head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat examination was normal. Auscultation of the lungs revealed bilateral breath sounds with scattered, faint expiratory wheezing; the heart had a regular rate and rhythm, without murmurs, rubs, or gallops.

The emergency physician (EP) ordered posteroanterior and lateral chest X-rays (CXR), which he interpreted as normal. He also ordered an albuterol handheld nebulizer treatment for the patient. After the albuterol treatment, the patient felt he was breathing more easily. The frequency of his cough had also decreased following treatment and, on re-examination, he exhibited no wheezing and was given azithromycin 500 mg orally in the ED. The EP diagnosed the patient with acute bronchitis and discharged him home with an albuterol metered dose inhaler with a spacer, and a 4-day course of azithromycin. He also encouraged the patient to quit smoking.

The next day the radiologist’s official reading of the patient’s radiographs included the finding of a very small pulmonary nodule, which was seen only on the lateral X-ray. The radiologist recommended a repeat CXR or a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest in 6 months.

Unfortunately, the EP never saw this information, and the patient was not contacted regarding the abnormal radiology finding and the need for follow-up. Approximately 20 months later, the patient was diagnosed with lung cancer with metastasis to the thoracic spine and liver. Despite chemotherapy and radiation treatment, he died from the cancer.

The patient’s family brought a malpractice suit against the EP, stating that the cancer could have been successfully treated prior to any metastasis if the patient had been informed of the abnormal radiology findings at his ED visit 20 months prior. The EP argued that he never saw the official radiology report, and therefore had no knowledge of the need for follow-up. At trial, a jury verdict was returned in favor of the defendant.

Discussion

Unfortunately, some version of this scenario occurs on a frequent basis. While imaging studies account for the majority of such cases, the same situation can occur with abnormal laboratory results, body-fluid cultures, or pathology reports in which an abnormality is identified (eg, positive blood culture, missed fracture) but, for a myriad of reasons, the critical information does not get related to the patient.

Because of the episodic nature of the practice of emergency medicine (EM), a process must be in place to ensure any “positive” test results or findings discovered after patient discharge are reviewed and compared to the ED diagnosis, and that any “misses” result in notifying the patient and/or his or her primary care physician and arranging follow-up. In cases such as the one presented here, a system issue existed—one that was not due to any fault or oversight of the EP. Ideally, EM leadership should work closely with leadership from radiology and laboratory services and hospital risk management to develop such a process—one that will be effective every day, including weekends and holidays.

Missed fractures on radiographs are a common cause of malpractice litigation against EPs. In one review by Kachalia et al1 examining malpractice claims involving EPs, missed fractures on radiographs accounted for 19% (the most common) of the 79 missed diagnoses identified in their study.In a similar study by Karcz et al,2 missed fractures ranked second in frequency and dollars lost in malpractice cases against EPs in Massachusetts.

While missed lesions on CXR do not occur with the same frequency as missed fractures, the results are much more devastating when the lesion turns out to be malignant. Three common areas where such lesions are missed on CXR include: the apex of the lung, obscured by overlying clavicle and ribs; the retrocardiac region (as in the patient in this case); and the lung bases obscured by the diaphragm.

Emergency physicians are neither trained nor expected to identify every single abnormality—especially subtle radiographic abnormalities. This is why there are radiology overreads, and a system or process must be in place to ensure patients are informed of any positive findings and to arrange proper follow-up.

1. Kachalia A, Gandhi TK, Puopolo AL, et al. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the emergency department: a study of closed malpractice claims from 4 liability insurers. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(2):196-205.

2. Karcz A, Korn R, Burke MC, et al. Malpractice claims against emergency physicians in Massachusetts: 1975-1993. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14(4):341-345.

Case

A 48-year-old man presented to the ED with a 2-day history of cough and congestion. He described the cough as gradual in onset and, though initially nonproductive, it was now productive of green sputum. He denied fevers or chills, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, and complained of only mild shortness of breath. His medical history was significant for hypertension, which was well managed with daily lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide. He admitted to smoking one pack of cigarettes per day for the past 25 years, but denied alcohol or illicit drug use.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 112/64 mm Hg; heart rate, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and temperature, 98oF. Oxygen saturation was 97% on room air. The head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat examination was normal. Auscultation of the lungs revealed bilateral breath sounds with scattered, faint expiratory wheezing; the heart had a regular rate and rhythm, without murmurs, rubs, or gallops.

The emergency physician (EP) ordered posteroanterior and lateral chest X-rays (CXR), which he interpreted as normal. He also ordered an albuterol handheld nebulizer treatment for the patient. After the albuterol treatment, the patient felt he was breathing more easily. The frequency of his cough had also decreased following treatment and, on re-examination, he exhibited no wheezing and was given azithromycin 500 mg orally in the ED. The EP diagnosed the patient with acute bronchitis and discharged him home with an albuterol metered dose inhaler with a spacer, and a 4-day course of azithromycin. He also encouraged the patient to quit smoking.

The next day the radiologist’s official reading of the patient’s radiographs included the finding of a very small pulmonary nodule, which was seen only on the lateral X-ray. The radiologist recommended a repeat CXR or a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest in 6 months.

Unfortunately, the EP never saw this information, and the patient was not contacted regarding the abnormal radiology finding and the need for follow-up. Approximately 20 months later, the patient was diagnosed with lung cancer with metastasis to the thoracic spine and liver. Despite chemotherapy and radiation treatment, he died from the cancer.

The patient’s family brought a malpractice suit against the EP, stating that the cancer could have been successfully treated prior to any metastasis if the patient had been informed of the abnormal radiology findings at his ED visit 20 months prior. The EP argued that he never saw the official radiology report, and therefore had no knowledge of the need for follow-up. At trial, a jury verdict was returned in favor of the defendant.

Discussion

Unfortunately, some version of this scenario occurs on a frequent basis. While imaging studies account for the majority of such cases, the same situation can occur with abnormal laboratory results, body-fluid cultures, or pathology reports in which an abnormality is identified (eg, positive blood culture, missed fracture) but, for a myriad of reasons, the critical information does not get related to the patient.

Because of the episodic nature of the practice of emergency medicine (EM), a process must be in place to ensure any “positive” test results or findings discovered after patient discharge are reviewed and compared to the ED diagnosis, and that any “misses” result in notifying the patient and/or his or her primary care physician and arranging follow-up. In cases such as the one presented here, a system issue existed—one that was not due to any fault or oversight of the EP. Ideally, EM leadership should work closely with leadership from radiology and laboratory services and hospital risk management to develop such a process—one that will be effective every day, including weekends and holidays.

Missed fractures on radiographs are a common cause of malpractice litigation against EPs. In one review by Kachalia et al1 examining malpractice claims involving EPs, missed fractures on radiographs accounted for 19% (the most common) of the 79 missed diagnoses identified in their study.In a similar study by Karcz et al,2 missed fractures ranked second in frequency and dollars lost in malpractice cases against EPs in Massachusetts.

While missed lesions on CXR do not occur with the same frequency as missed fractures, the results are much more devastating when the lesion turns out to be malignant. Three common areas where such lesions are missed on CXR include: the apex of the lung, obscured by overlying clavicle and ribs; the retrocardiac region (as in the patient in this case); and the lung bases obscured by the diaphragm.

Emergency physicians are neither trained nor expected to identify every single abnormality—especially subtle radiographic abnormalities. This is why there are radiology overreads, and a system or process must be in place to ensure patients are informed of any positive findings and to arrange proper follow-up.

Case

A 48-year-old man presented to the ED with a 2-day history of cough and congestion. He described the cough as gradual in onset and, though initially nonproductive, it was now productive of green sputum. He denied fevers or chills, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, and complained of only mild shortness of breath. His medical history was significant for hypertension, which was well managed with daily lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide. He admitted to smoking one pack of cigarettes per day for the past 25 years, but denied alcohol or illicit drug use.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 112/64 mm Hg; heart rate, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and temperature, 98oF. Oxygen saturation was 97% on room air. The head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat examination was normal. Auscultation of the lungs revealed bilateral breath sounds with scattered, faint expiratory wheezing; the heart had a regular rate and rhythm, without murmurs, rubs, or gallops.

The emergency physician (EP) ordered posteroanterior and lateral chest X-rays (CXR), which he interpreted as normal. He also ordered an albuterol handheld nebulizer treatment for the patient. After the albuterol treatment, the patient felt he was breathing more easily. The frequency of his cough had also decreased following treatment and, on re-examination, he exhibited no wheezing and was given azithromycin 500 mg orally in the ED. The EP diagnosed the patient with acute bronchitis and discharged him home with an albuterol metered dose inhaler with a spacer, and a 4-day course of azithromycin. He also encouraged the patient to quit smoking.

The next day the radiologist’s official reading of the patient’s radiographs included the finding of a very small pulmonary nodule, which was seen only on the lateral X-ray. The radiologist recommended a repeat CXR or a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest in 6 months.

Unfortunately, the EP never saw this information, and the patient was not contacted regarding the abnormal radiology finding and the need for follow-up. Approximately 20 months later, the patient was diagnosed with lung cancer with metastasis to the thoracic spine and liver. Despite chemotherapy and radiation treatment, he died from the cancer.

The patient’s family brought a malpractice suit against the EP, stating that the cancer could have been successfully treated prior to any metastasis if the patient had been informed of the abnormal radiology findings at his ED visit 20 months prior. The EP argued that he never saw the official radiology report, and therefore had no knowledge of the need for follow-up. At trial, a jury verdict was returned in favor of the defendant.

Discussion

Unfortunately, some version of this scenario occurs on a frequent basis. While imaging studies account for the majority of such cases, the same situation can occur with abnormal laboratory results, body-fluid cultures, or pathology reports in which an abnormality is identified (eg, positive blood culture, missed fracture) but, for a myriad of reasons, the critical information does not get related to the patient.

Because of the episodic nature of the practice of emergency medicine (EM), a process must be in place to ensure any “positive” test results or findings discovered after patient discharge are reviewed and compared to the ED diagnosis, and that any “misses” result in notifying the patient and/or his or her primary care physician and arranging follow-up. In cases such as the one presented here, a system issue existed—one that was not due to any fault or oversight of the EP. Ideally, EM leadership should work closely with leadership from radiology and laboratory services and hospital risk management to develop such a process—one that will be effective every day, including weekends and holidays.

Missed fractures on radiographs are a common cause of malpractice litigation against EPs. In one review by Kachalia et al1 examining malpractice claims involving EPs, missed fractures on radiographs accounted for 19% (the most common) of the 79 missed diagnoses identified in their study.In a similar study by Karcz et al,2 missed fractures ranked second in frequency and dollars lost in malpractice cases against EPs in Massachusetts.

While missed lesions on CXR do not occur with the same frequency as missed fractures, the results are much more devastating when the lesion turns out to be malignant. Three common areas where such lesions are missed on CXR include: the apex of the lung, obscured by overlying clavicle and ribs; the retrocardiac region (as in the patient in this case); and the lung bases obscured by the diaphragm.

Emergency physicians are neither trained nor expected to identify every single abnormality—especially subtle radiographic abnormalities. This is why there are radiology overreads, and a system or process must be in place to ensure patients are informed of any positive findings and to arrange proper follow-up.

1. Kachalia A, Gandhi TK, Puopolo AL, et al. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the emergency department: a study of closed malpractice claims from 4 liability insurers. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(2):196-205.

2. Karcz A, Korn R, Burke MC, et al. Malpractice claims against emergency physicians in Massachusetts: 1975-1993. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14(4):341-345.

1. Kachalia A, Gandhi TK, Puopolo AL, et al. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the emergency department: a study of closed malpractice claims from 4 liability insurers. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(2):196-205.

2. Karcz A, Korn R, Burke MC, et al. Malpractice claims against emergency physicians in Massachusetts: 1975-1993. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14(4):341-345.

Claimed missteps lead to brain damage: $53M award

Claimed missteps lead to brain damage: $53M award

At 2:00 AM, a woman at 40 weeks’ gestation went to a hospital because she felt a decrease in fetal movement. At birth, the baby was not breathing. He was rushed to the neonatal intensive care unit where he was resuscitated and placed on life support. He remained in critical care for 4 weeks. The child has cerebral palsy and cannot walk, talk, or care for himself. He will need 24-hour care for the rest of his life.

PARENT’S CLAIM:

The lawsuit cited 20 alleged missteps by physicians and nurses, including failure to: react to abnormal fetal heart-rate patterns that indicated fetal distress, perform a timely cesarean delivery, and follow a chain of command. During the 12 hours that the mother was in labor at the hospital, nurses and physicians allegedly ignored her. Although the fetal heart-rate monitor showed fetal distress, the mother continued to lie unattended. At 12:40 PM, physicians called for cesarean delivery due to fetal distress, but it took an hour for the child to be born.

The negligence of the hospital staff and delay in delivery caused hypoxia, resulting in cerebral palsy. All medical records from the hospital’s neonatal clinic show that he suffered hypoxia at birth.

HOSPITAL’S DEFENSE:

The mother and child were treated for an infection, which is a recognized cause of cerebral palsy. The child was born with normal blood oxygen levels. His injury occurred before the mother came to the hospital.

VERDICT:

A $53 million Illinois verdict was returned. The hospital applied for a mistrial based on allegedly inflammatory comments by the prosecuting attorney, but that was dismissed.

Birth trauma: $2.75M settlement