User login

How to Avoid Data Breaches, HIPAA Violations When Posting Patients’ Protected Health Information Online

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, YouTube, blogs, webpages, Google+, LinkedIn. What do all of these social media outlets have in common? Each can get physicians in trouble under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), state privacy laws, and state medical laws, to name a few. It seems that all too often, news outlets are reporting data breaches generated in the medical community, many of which arise out of physicians’ use of social media, and most of which could have been avoided.

Physicians should be aware of the intersection of social media—both for personal and professional use—and HIPAA and state laws. Even an inadvertent, seemingly innocuous disclosure of a patient’s protected health information (PHI) through social media can be problematic.

PHI is defined under HIPAA, in part, as health information that (i) is created or received by a physician, (ii) relates to the health or condition of an individual, (iii) identifies the individual (or with respect to which there is a reasonable basis to believe the information can be used to identify the individual), and (iv) is transmitted by or maintained in electronic media, or transmitted or maintained in another form or medium. Under HIPAA, a physician may use and disclose PHI for “treatment, payment, or healthcare operations.” Generally, using or disclosing PHI through social media does not qualify as treatment, payment, or healthcare operations. If a physician were to use or disclose a patient’s PHI without permission, this would be a violation of HIPAA—and likely state law as well.

In order to use or disclose a patient’s PHI without obtaining the patient’s consent, a physician must de-identify the information so that the information does not identify the patient and there is no reasonable basis to believe that the information can be used to identify the patient. One option under HIPAA is to retain an expert to determine “that the risk is very small that the information could be used, alone or in combination with other reasonably available information, by an anticipated recipient to identify an individual who is the subject of the information.” Alternatively, and more commonly, a physician seeking to use or disclose patient PHI can remove the following identifiers from the PHI:

- Names;

- Geographic information;

- Dates (e.g. birth date, admission date, discharge date, date of death);

- Telephone numbers;

- Fax numbers;

- E-mail addresses;

- Social Security numbers;

- Medical record numbers;

- Health plan beneficiary numbers;

- Account numbers;

- Certificate/license numbers;

- Vehicle identifiers and serial numbers, including license plate numbers;

- Device identifiers and serial numbers;

- URLs;

- IP address numbers;

- Biometric identifiers (e.g. finger and voice prints);

- Full-face photographic images and any comparable images; and

- Other unique identifying numbers, characteristics, or codes.

Identifier #18 is the most difficult to comply with in light of the significant amount of personal information available on the Internet, particularly through search engines like Google. Inputting even a small amount of information into a search engine will generate relevant “hits” that make it increasingly difficult to comply with the de-identification standards under HIPAA. Even if the first 17 identifiers are carefully removed, the broadness of #18 can turn a seemingly harmless post on social media into a patient privacy violation.

Do not let the following examples be you:

Example 1: An ED physician in Rhode Island was fired, lost her hospital medical staff privileges, and was reprimanded by the Rhode Island Board of Medical Licensure and Discipline for posting information about a trauma patient on her personal Facebook page. According to the Rhode Island Board of Medical Licensure and Discipline, “[She] did not use patient names and had no intention to reveal any confidential patient information. However, because of the nature of one person’s injury … the patient was identified by unauthorized third parties. As soon as it was brought to [her] attention that this had occurred, [she] deleted her Facebook account.” Despite the physician leaving out all information she thought might make the patient identifiable, she apparently did not omit enough.

Example 2: An OB-GYN in St. Louis took to Facebook to complain about her frustration with a patient: “So I have a patient who has chosen to either no-show or be late (sometimes hours) for all of her prenatal visits, ultrasounds, and NSTs. She is now 3 hours late for her induction. May I show up late to her delivery?” Another physician then commented on this post: “If it’s elective, it’d be canceled!” The OB-GYN at issue then responded: “Here is the explanation why I have put up with it/not cancelled induction: prior stillbirth.”

Although the OB-GYN did not reveal the patient’s name, controversy erupted after someone posted a screenshot of the post and response comments to the hospital’s Facebook page. The hospital issued a statement indicating that its privacy compliance staff did not find the posting to be a breach of privacy, but the hospital added it would use this opportunity to educate its staff about the appropriate use of social media. Many believe this physician got off too easy.

The penalties for patient privacy violations (or even alleged patient privacy violations) are multifaceted. Not only can the federal government impose civil and criminal sanctions under HIPAA on the physician and his/her affiliated parties (e.g. physician’s employer), but states can also impose penalties. State-imposed penalties for patient privacy violations vary from state to state. Additionally, the patient may sue the violating physician and his/her affiliated parties for privacy violations. Although HIPAA does not afford patients the right to bring a private cause of action against a physician, state law often does grant patients such a right. Also, state medical boards often have the right to impose penalties, monetary and non-monetary, on a physician for privacy violations. These can include suspension or termination of medical licensure.

Recent reports indicate that people who “like,” “share,” “re-tweet,” or comment on inappropriate social media posts are also getting reprimanded. Finally, the reputational harm associated with an inappropriate post on social media is immeasurable, especially in light of the availability of information on the Internet. Unfortunately, when the physicians described above enter their names in a search engine, they do not see their professional accomplishments and prestigious educations; instead, their top hits are news articles reporting on their inappropriate posts.

Post with caution.

Steven M. Harris, Esq., is a nationally recognized healthcare attorney and a member of the law firm McDonald Hopkins LLC in Chicago. Write to him at [email protected].

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, YouTube, blogs, webpages, Google+, LinkedIn. What do all of these social media outlets have in common? Each can get physicians in trouble under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), state privacy laws, and state medical laws, to name a few. It seems that all too often, news outlets are reporting data breaches generated in the medical community, many of which arise out of physicians’ use of social media, and most of which could have been avoided.

Physicians should be aware of the intersection of social media—both for personal and professional use—and HIPAA and state laws. Even an inadvertent, seemingly innocuous disclosure of a patient’s protected health information (PHI) through social media can be problematic.

PHI is defined under HIPAA, in part, as health information that (i) is created or received by a physician, (ii) relates to the health or condition of an individual, (iii) identifies the individual (or with respect to which there is a reasonable basis to believe the information can be used to identify the individual), and (iv) is transmitted by or maintained in electronic media, or transmitted or maintained in another form or medium. Under HIPAA, a physician may use and disclose PHI for “treatment, payment, or healthcare operations.” Generally, using or disclosing PHI through social media does not qualify as treatment, payment, or healthcare operations. If a physician were to use or disclose a patient’s PHI without permission, this would be a violation of HIPAA—and likely state law as well.

In order to use or disclose a patient’s PHI without obtaining the patient’s consent, a physician must de-identify the information so that the information does not identify the patient and there is no reasonable basis to believe that the information can be used to identify the patient. One option under HIPAA is to retain an expert to determine “that the risk is very small that the information could be used, alone or in combination with other reasonably available information, by an anticipated recipient to identify an individual who is the subject of the information.” Alternatively, and more commonly, a physician seeking to use or disclose patient PHI can remove the following identifiers from the PHI:

- Names;

- Geographic information;

- Dates (e.g. birth date, admission date, discharge date, date of death);

- Telephone numbers;

- Fax numbers;

- E-mail addresses;

- Social Security numbers;

- Medical record numbers;

- Health plan beneficiary numbers;

- Account numbers;

- Certificate/license numbers;

- Vehicle identifiers and serial numbers, including license plate numbers;

- Device identifiers and serial numbers;

- URLs;

- IP address numbers;

- Biometric identifiers (e.g. finger and voice prints);

- Full-face photographic images and any comparable images; and

- Other unique identifying numbers, characteristics, or codes.

Identifier #18 is the most difficult to comply with in light of the significant amount of personal information available on the Internet, particularly through search engines like Google. Inputting even a small amount of information into a search engine will generate relevant “hits” that make it increasingly difficult to comply with the de-identification standards under HIPAA. Even if the first 17 identifiers are carefully removed, the broadness of #18 can turn a seemingly harmless post on social media into a patient privacy violation.

Do not let the following examples be you:

Example 1: An ED physician in Rhode Island was fired, lost her hospital medical staff privileges, and was reprimanded by the Rhode Island Board of Medical Licensure and Discipline for posting information about a trauma patient on her personal Facebook page. According to the Rhode Island Board of Medical Licensure and Discipline, “[She] did not use patient names and had no intention to reveal any confidential patient information. However, because of the nature of one person’s injury … the patient was identified by unauthorized third parties. As soon as it was brought to [her] attention that this had occurred, [she] deleted her Facebook account.” Despite the physician leaving out all information she thought might make the patient identifiable, she apparently did not omit enough.

Example 2: An OB-GYN in St. Louis took to Facebook to complain about her frustration with a patient: “So I have a patient who has chosen to either no-show or be late (sometimes hours) for all of her prenatal visits, ultrasounds, and NSTs. She is now 3 hours late for her induction. May I show up late to her delivery?” Another physician then commented on this post: “If it’s elective, it’d be canceled!” The OB-GYN at issue then responded: “Here is the explanation why I have put up with it/not cancelled induction: prior stillbirth.”

Although the OB-GYN did not reveal the patient’s name, controversy erupted after someone posted a screenshot of the post and response comments to the hospital’s Facebook page. The hospital issued a statement indicating that its privacy compliance staff did not find the posting to be a breach of privacy, but the hospital added it would use this opportunity to educate its staff about the appropriate use of social media. Many believe this physician got off too easy.

The penalties for patient privacy violations (or even alleged patient privacy violations) are multifaceted. Not only can the federal government impose civil and criminal sanctions under HIPAA on the physician and his/her affiliated parties (e.g. physician’s employer), but states can also impose penalties. State-imposed penalties for patient privacy violations vary from state to state. Additionally, the patient may sue the violating physician and his/her affiliated parties for privacy violations. Although HIPAA does not afford patients the right to bring a private cause of action against a physician, state law often does grant patients such a right. Also, state medical boards often have the right to impose penalties, monetary and non-monetary, on a physician for privacy violations. These can include suspension or termination of medical licensure.

Recent reports indicate that people who “like,” “share,” “re-tweet,” or comment on inappropriate social media posts are also getting reprimanded. Finally, the reputational harm associated with an inappropriate post on social media is immeasurable, especially in light of the availability of information on the Internet. Unfortunately, when the physicians described above enter their names in a search engine, they do not see their professional accomplishments and prestigious educations; instead, their top hits are news articles reporting on their inappropriate posts.

Post with caution.

Steven M. Harris, Esq., is a nationally recognized healthcare attorney and a member of the law firm McDonald Hopkins LLC in Chicago. Write to him at [email protected].

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, YouTube, blogs, webpages, Google+, LinkedIn. What do all of these social media outlets have in common? Each can get physicians in trouble under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), state privacy laws, and state medical laws, to name a few. It seems that all too often, news outlets are reporting data breaches generated in the medical community, many of which arise out of physicians’ use of social media, and most of which could have been avoided.

Physicians should be aware of the intersection of social media—both for personal and professional use—and HIPAA and state laws. Even an inadvertent, seemingly innocuous disclosure of a patient’s protected health information (PHI) through social media can be problematic.

PHI is defined under HIPAA, in part, as health information that (i) is created or received by a physician, (ii) relates to the health or condition of an individual, (iii) identifies the individual (or with respect to which there is a reasonable basis to believe the information can be used to identify the individual), and (iv) is transmitted by or maintained in electronic media, or transmitted or maintained in another form or medium. Under HIPAA, a physician may use and disclose PHI for “treatment, payment, or healthcare operations.” Generally, using or disclosing PHI through social media does not qualify as treatment, payment, or healthcare operations. If a physician were to use or disclose a patient’s PHI without permission, this would be a violation of HIPAA—and likely state law as well.

In order to use or disclose a patient’s PHI without obtaining the patient’s consent, a physician must de-identify the information so that the information does not identify the patient and there is no reasonable basis to believe that the information can be used to identify the patient. One option under HIPAA is to retain an expert to determine “that the risk is very small that the information could be used, alone or in combination with other reasonably available information, by an anticipated recipient to identify an individual who is the subject of the information.” Alternatively, and more commonly, a physician seeking to use or disclose patient PHI can remove the following identifiers from the PHI:

- Names;

- Geographic information;

- Dates (e.g. birth date, admission date, discharge date, date of death);

- Telephone numbers;

- Fax numbers;

- E-mail addresses;

- Social Security numbers;

- Medical record numbers;

- Health plan beneficiary numbers;

- Account numbers;

- Certificate/license numbers;

- Vehicle identifiers and serial numbers, including license plate numbers;

- Device identifiers and serial numbers;

- URLs;

- IP address numbers;

- Biometric identifiers (e.g. finger and voice prints);

- Full-face photographic images and any comparable images; and

- Other unique identifying numbers, characteristics, or codes.

Identifier #18 is the most difficult to comply with in light of the significant amount of personal information available on the Internet, particularly through search engines like Google. Inputting even a small amount of information into a search engine will generate relevant “hits” that make it increasingly difficult to comply with the de-identification standards under HIPAA. Even if the first 17 identifiers are carefully removed, the broadness of #18 can turn a seemingly harmless post on social media into a patient privacy violation.

Do not let the following examples be you:

Example 1: An ED physician in Rhode Island was fired, lost her hospital medical staff privileges, and was reprimanded by the Rhode Island Board of Medical Licensure and Discipline for posting information about a trauma patient on her personal Facebook page. According to the Rhode Island Board of Medical Licensure and Discipline, “[She] did not use patient names and had no intention to reveal any confidential patient information. However, because of the nature of one person’s injury … the patient was identified by unauthorized third parties. As soon as it was brought to [her] attention that this had occurred, [she] deleted her Facebook account.” Despite the physician leaving out all information she thought might make the patient identifiable, she apparently did not omit enough.

Example 2: An OB-GYN in St. Louis took to Facebook to complain about her frustration with a patient: “So I have a patient who has chosen to either no-show or be late (sometimes hours) for all of her prenatal visits, ultrasounds, and NSTs. She is now 3 hours late for her induction. May I show up late to her delivery?” Another physician then commented on this post: “If it’s elective, it’d be canceled!” The OB-GYN at issue then responded: “Here is the explanation why I have put up with it/not cancelled induction: prior stillbirth.”

Although the OB-GYN did not reveal the patient’s name, controversy erupted after someone posted a screenshot of the post and response comments to the hospital’s Facebook page. The hospital issued a statement indicating that its privacy compliance staff did not find the posting to be a breach of privacy, but the hospital added it would use this opportunity to educate its staff about the appropriate use of social media. Many believe this physician got off too easy.

The penalties for patient privacy violations (or even alleged patient privacy violations) are multifaceted. Not only can the federal government impose civil and criminal sanctions under HIPAA on the physician and his/her affiliated parties (e.g. physician’s employer), but states can also impose penalties. State-imposed penalties for patient privacy violations vary from state to state. Additionally, the patient may sue the violating physician and his/her affiliated parties for privacy violations. Although HIPAA does not afford patients the right to bring a private cause of action against a physician, state law often does grant patients such a right. Also, state medical boards often have the right to impose penalties, monetary and non-monetary, on a physician for privacy violations. These can include suspension or termination of medical licensure.

Recent reports indicate that people who “like,” “share,” “re-tweet,” or comment on inappropriate social media posts are also getting reprimanded. Finally, the reputational harm associated with an inappropriate post on social media is immeasurable, especially in light of the availability of information on the Internet. Unfortunately, when the physicians described above enter their names in a search engine, they do not see their professional accomplishments and prestigious educations; instead, their top hits are news articles reporting on their inappropriate posts.

Post with caution.

Steven M. Harris, Esq., is a nationally recognized healthcare attorney and a member of the law firm McDonald Hopkins LLC in Chicago. Write to him at [email protected].

Jury Finds Fault With Midwife’s Care

During her pregnancy, a Wisconsin woman received care from a nurse-midwife. In late July 2001, misoprostol was administered to induce labor. The woman was admitted to the hospital in active labor at approximately 2 pm. She was 6 cm dilated. Dilation arrested three times, and then there was a two-hour failure to dilate.

The nurse-midwife then tried putting the mother in a water-birthing tub to stimulate contractions, without success. Oxytocin was then administered. Immediately thereafter, the patient developed uterine hyperstimulation, and the fetal heart rate strip showed late decelerations, indicative of fetal distress.

Despite these abnormalities, the nurse-midwife continued increasing oxytocin throughout labor, which continued for about 12 hours. The oxytocin dose exceeded the hospital’s recommended protocols. The patient reached a point at which she was having strong contractions every 1.5 min. Full dilation was not reached until 10:38 pm.

Around midnight, the electronic fetal monitor allegedly showed an abnormal heart pattern, with decelerations with almost every contraction. The mother was allowed to continue with labor, and the fetal monitoring equipment was removed at 1:26 am so the mother could be placed in the water-birthing tub again. Nurses took the fetal heart rate during this time and recorded it as normal.

When the child was delivered at approximately 2 am, she had a heart rate of 80 beats/min; she was apneic, cyanotic, and virtually lifeless. Apgar scores were recorded as 1 at one minute and 3 at five minutes. Arterial blood gas/pH was 7.165.

An attending physician was called and arrived within 20 min. The infant was resuscitated, intubated, and transferred to another hospital. A CT scan taken at 56 hours of life was read as normal. An MRl at nine months was also read as normal.

The child was subsequently diagnosed as having cerebral palsy. She requires a walker for ambulation and has arm and leg impairments and significant cognitive deficits, necessitating 24-hour assistance.

The plaintiff claimed that if oxytocin had been discontinued, she would have reached full dilation hours earlier than she did. She also claimed that a cesarean delivery or operative vaginal delivery should have been performed when the fetal monitor indicated an abnormal heart pattern. (She contended that the “normal” heart rate recorded around this time was actually the maternal heart rate.)

The parties did not dispute that the infant had experienced a hypoxic/ischemic event but disagreed on when it occurred. The plaintiff claimed that the ischemic event occurred during delivery. The defendants claimed that it occurred in utero prior to delivery. The plaintiff also disputed the MRI findings, which the plaintiff argued showed significant brain injury.

On the next page: Outcome >>

OUTCOME

A jury found the nurse-midwife 80% at fault and the hospital 20% at fault. The jury awarded $13.5 million to the child and $100,000 to the plaintiff. An additional $110,000 in past medical expenses was added to the verdict.

COMMENT

Obstetrics/midwifery accounts for a significant percentage of malpractice cases filed and monetary damages awarded. In this case, a substantial $13.5 million verdict was awarded, with 80% of the verdict against the midwife for inappropriate use of oxytocin and failure to refer for cesarean delivery.

A detailed discussion of obstetric management is beyond the scope of this article (in part because we don’t have access to much data, including fetal heart rate tracings). However, there are a few points to consider.

First, consider surgical options when appropriate. Without doubt, operative delivery by cesarean section is overused for all the wrong reasons. Some mothers, families, and clinicians strongly desire a more natural childbirth and strive to create such an experience—forgoing traditional medications and anesthesia. Often, this is perfectly safe, reasonable, and preferable.

However, if the perinatal course is rocky, it is wise to monitor closely and adopt a collaborative approach. When prenatal screening suggests a difficult delivery, exercise caution and have a fallback plan. Known high-risk deliveries should have a team approach from the outset, with all assets available to bedside on short notice.

While operative delivery is overused, it shouldn’t be demonized either. When genuinely needed, it can be lifesaving. Some patients do not want a cesarean delivery, and both the patient and the clinician may equate operative delivery with personal failure. However, that view may present a barrier to calling for consultation when it is genuinely needed.

For natural childbirth enthusiasts, think of the surgical delivery option as sealed in a glass case. Break that glass for all the right reasons: to preserve life or avoid significant fetal morbidity. Discuss the indications for surgical management ahead of time, so the mother is not surprised by a sudden rush to the operating room, feeling frightened and out of control.

It is recognized that patients and clinicians have firmly held beliefs, and opinions are strong on this subject. Patients have a right to self-determination and to select the birthing experience that will suit them best. Yet there is tension because jurors will expect a clinician to fully communicate known risks to patients and use all available resources to safeguard the mother and fetus at all times. In this case, the jury concluded that the midwife failed to refer for cesarean delivery after about 10 hours of labor, when the fetal heart rate pattern was nonreassuring. One of the plaintiff’s expert witnesses who criticized the defendant midwife’s care was herself a highly regarded midwife.

Continued on the next page >>

Second, use oxytocin carefully, slowing or stopping it when required. While we do not have access to the fetal heart rate monitor strips in this case, we do know that the plaintiff met her burden of proof and persuaded the jurors that the midwife inappropriately increased the drug in the setting of uterine hyperstimulation, with evidence of fetal distress. It seems surprising that the allegedly “normal” pattern recorded at 1:26 am could have been the maternal heart rate—but apparently, the jurors were convinced of this.

Third, when a facility has a medication protocol, follow it unless there is good cause not to. Medication protocols can be useful to establish operating guidelines and reduce medication errors. But they can also shackle clinicians by substituting tables and algorithms for clinical judgment. Problems arise when a protocol is sidestepped, and the clinician is raked over the coals for failing to adhere. If your facility has protocols that are important to your practice, read the documentation. Learn it, know it, live it.

If you operate outside a protocol, and your case goes to trial, the expert witness defending your care will be forced to take on both the plaintiff’s allegations and your own facility’s recommendations. The plaintiff’s closing argument will include a variation of “Mr. A did not even bother to follow his hospital’s own rules.” This argument is easy for jurors to understand, and many will reach a finding of negligence based on this fact alone. If you disagree with the protocol, or it is not reflective of your actual practice, either clinician practice or the protocol must be changed. Do not routinely circumvent protocols without good reason.

Ideally, protocols should be constructed to give clinicians flexibility based on clinical judgment and patient response. If you have a role in forming a protocol, consider advocating for less rigidity and allowing for professional judgment. If the protocol is rigid, be sure that everyone understands it and that it can be strictly followed in a real world practice environment. Put plainly, don’t install a set of rules you can’t live with—it is professionally constraining and legally risky.

IN SUM

From a legal standpoint, it is not safe to completely discard surgical delivery; when needed, it is required. Patients given oxytocin must be monitored closely, and the drug should be discontinued in the setting of uterine hyperactivity with fetal distress. Follow medication protocols or change them—but whatever you do, don’t ignore them.

During her pregnancy, a Wisconsin woman received care from a nurse-midwife. In late July 2001, misoprostol was administered to induce labor. The woman was admitted to the hospital in active labor at approximately 2 pm. She was 6 cm dilated. Dilation arrested three times, and then there was a two-hour failure to dilate.

The nurse-midwife then tried putting the mother in a water-birthing tub to stimulate contractions, without success. Oxytocin was then administered. Immediately thereafter, the patient developed uterine hyperstimulation, and the fetal heart rate strip showed late decelerations, indicative of fetal distress.

Despite these abnormalities, the nurse-midwife continued increasing oxytocin throughout labor, which continued for about 12 hours. The oxytocin dose exceeded the hospital’s recommended protocols. The patient reached a point at which she was having strong contractions every 1.5 min. Full dilation was not reached until 10:38 pm.

Around midnight, the electronic fetal monitor allegedly showed an abnormal heart pattern, with decelerations with almost every contraction. The mother was allowed to continue with labor, and the fetal monitoring equipment was removed at 1:26 am so the mother could be placed in the water-birthing tub again. Nurses took the fetal heart rate during this time and recorded it as normal.

When the child was delivered at approximately 2 am, she had a heart rate of 80 beats/min; she was apneic, cyanotic, and virtually lifeless. Apgar scores were recorded as 1 at one minute and 3 at five minutes. Arterial blood gas/pH was 7.165.

An attending physician was called and arrived within 20 min. The infant was resuscitated, intubated, and transferred to another hospital. A CT scan taken at 56 hours of life was read as normal. An MRl at nine months was also read as normal.

The child was subsequently diagnosed as having cerebral palsy. She requires a walker for ambulation and has arm and leg impairments and significant cognitive deficits, necessitating 24-hour assistance.

The plaintiff claimed that if oxytocin had been discontinued, she would have reached full dilation hours earlier than she did. She also claimed that a cesarean delivery or operative vaginal delivery should have been performed when the fetal monitor indicated an abnormal heart pattern. (She contended that the “normal” heart rate recorded around this time was actually the maternal heart rate.)

The parties did not dispute that the infant had experienced a hypoxic/ischemic event but disagreed on when it occurred. The plaintiff claimed that the ischemic event occurred during delivery. The defendants claimed that it occurred in utero prior to delivery. The plaintiff also disputed the MRI findings, which the plaintiff argued showed significant brain injury.

On the next page: Outcome >>

OUTCOME

A jury found the nurse-midwife 80% at fault and the hospital 20% at fault. The jury awarded $13.5 million to the child and $100,000 to the plaintiff. An additional $110,000 in past medical expenses was added to the verdict.

COMMENT

Obstetrics/midwifery accounts for a significant percentage of malpractice cases filed and monetary damages awarded. In this case, a substantial $13.5 million verdict was awarded, with 80% of the verdict against the midwife for inappropriate use of oxytocin and failure to refer for cesarean delivery.

A detailed discussion of obstetric management is beyond the scope of this article (in part because we don’t have access to much data, including fetal heart rate tracings). However, there are a few points to consider.

First, consider surgical options when appropriate. Without doubt, operative delivery by cesarean section is overused for all the wrong reasons. Some mothers, families, and clinicians strongly desire a more natural childbirth and strive to create such an experience—forgoing traditional medications and anesthesia. Often, this is perfectly safe, reasonable, and preferable.

However, if the perinatal course is rocky, it is wise to monitor closely and adopt a collaborative approach. When prenatal screening suggests a difficult delivery, exercise caution and have a fallback plan. Known high-risk deliveries should have a team approach from the outset, with all assets available to bedside on short notice.

While operative delivery is overused, it shouldn’t be demonized either. When genuinely needed, it can be lifesaving. Some patients do not want a cesarean delivery, and both the patient and the clinician may equate operative delivery with personal failure. However, that view may present a barrier to calling for consultation when it is genuinely needed.

For natural childbirth enthusiasts, think of the surgical delivery option as sealed in a glass case. Break that glass for all the right reasons: to preserve life or avoid significant fetal morbidity. Discuss the indications for surgical management ahead of time, so the mother is not surprised by a sudden rush to the operating room, feeling frightened and out of control.

It is recognized that patients and clinicians have firmly held beliefs, and opinions are strong on this subject. Patients have a right to self-determination and to select the birthing experience that will suit them best. Yet there is tension because jurors will expect a clinician to fully communicate known risks to patients and use all available resources to safeguard the mother and fetus at all times. In this case, the jury concluded that the midwife failed to refer for cesarean delivery after about 10 hours of labor, when the fetal heart rate pattern was nonreassuring. One of the plaintiff’s expert witnesses who criticized the defendant midwife’s care was herself a highly regarded midwife.

Continued on the next page >>

Second, use oxytocin carefully, slowing or stopping it when required. While we do not have access to the fetal heart rate monitor strips in this case, we do know that the plaintiff met her burden of proof and persuaded the jurors that the midwife inappropriately increased the drug in the setting of uterine hyperstimulation, with evidence of fetal distress. It seems surprising that the allegedly “normal” pattern recorded at 1:26 am could have been the maternal heart rate—but apparently, the jurors were convinced of this.

Third, when a facility has a medication protocol, follow it unless there is good cause not to. Medication protocols can be useful to establish operating guidelines and reduce medication errors. But they can also shackle clinicians by substituting tables and algorithms for clinical judgment. Problems arise when a protocol is sidestepped, and the clinician is raked over the coals for failing to adhere. If your facility has protocols that are important to your practice, read the documentation. Learn it, know it, live it.

If you operate outside a protocol, and your case goes to trial, the expert witness defending your care will be forced to take on both the plaintiff’s allegations and your own facility’s recommendations. The plaintiff’s closing argument will include a variation of “Mr. A did not even bother to follow his hospital’s own rules.” This argument is easy for jurors to understand, and many will reach a finding of negligence based on this fact alone. If you disagree with the protocol, or it is not reflective of your actual practice, either clinician practice or the protocol must be changed. Do not routinely circumvent protocols without good reason.

Ideally, protocols should be constructed to give clinicians flexibility based on clinical judgment and patient response. If you have a role in forming a protocol, consider advocating for less rigidity and allowing for professional judgment. If the protocol is rigid, be sure that everyone understands it and that it can be strictly followed in a real world practice environment. Put plainly, don’t install a set of rules you can’t live with—it is professionally constraining and legally risky.

IN SUM

From a legal standpoint, it is not safe to completely discard surgical delivery; when needed, it is required. Patients given oxytocin must be monitored closely, and the drug should be discontinued in the setting of uterine hyperactivity with fetal distress. Follow medication protocols or change them—but whatever you do, don’t ignore them.

During her pregnancy, a Wisconsin woman received care from a nurse-midwife. In late July 2001, misoprostol was administered to induce labor. The woman was admitted to the hospital in active labor at approximately 2 pm. She was 6 cm dilated. Dilation arrested three times, and then there was a two-hour failure to dilate.

The nurse-midwife then tried putting the mother in a water-birthing tub to stimulate contractions, without success. Oxytocin was then administered. Immediately thereafter, the patient developed uterine hyperstimulation, and the fetal heart rate strip showed late decelerations, indicative of fetal distress.

Despite these abnormalities, the nurse-midwife continued increasing oxytocin throughout labor, which continued for about 12 hours. The oxytocin dose exceeded the hospital’s recommended protocols. The patient reached a point at which she was having strong contractions every 1.5 min. Full dilation was not reached until 10:38 pm.

Around midnight, the electronic fetal monitor allegedly showed an abnormal heart pattern, with decelerations with almost every contraction. The mother was allowed to continue with labor, and the fetal monitoring equipment was removed at 1:26 am so the mother could be placed in the water-birthing tub again. Nurses took the fetal heart rate during this time and recorded it as normal.

When the child was delivered at approximately 2 am, she had a heart rate of 80 beats/min; she was apneic, cyanotic, and virtually lifeless. Apgar scores were recorded as 1 at one minute and 3 at five minutes. Arterial blood gas/pH was 7.165.

An attending physician was called and arrived within 20 min. The infant was resuscitated, intubated, and transferred to another hospital. A CT scan taken at 56 hours of life was read as normal. An MRl at nine months was also read as normal.

The child was subsequently diagnosed as having cerebral palsy. She requires a walker for ambulation and has arm and leg impairments and significant cognitive deficits, necessitating 24-hour assistance.

The plaintiff claimed that if oxytocin had been discontinued, she would have reached full dilation hours earlier than she did. She also claimed that a cesarean delivery or operative vaginal delivery should have been performed when the fetal monitor indicated an abnormal heart pattern. (She contended that the “normal” heart rate recorded around this time was actually the maternal heart rate.)

The parties did not dispute that the infant had experienced a hypoxic/ischemic event but disagreed on when it occurred. The plaintiff claimed that the ischemic event occurred during delivery. The defendants claimed that it occurred in utero prior to delivery. The plaintiff also disputed the MRI findings, which the plaintiff argued showed significant brain injury.

On the next page: Outcome >>

OUTCOME

A jury found the nurse-midwife 80% at fault and the hospital 20% at fault. The jury awarded $13.5 million to the child and $100,000 to the plaintiff. An additional $110,000 in past medical expenses was added to the verdict.

COMMENT

Obstetrics/midwifery accounts for a significant percentage of malpractice cases filed and monetary damages awarded. In this case, a substantial $13.5 million verdict was awarded, with 80% of the verdict against the midwife for inappropriate use of oxytocin and failure to refer for cesarean delivery.

A detailed discussion of obstetric management is beyond the scope of this article (in part because we don’t have access to much data, including fetal heart rate tracings). However, there are a few points to consider.

First, consider surgical options when appropriate. Without doubt, operative delivery by cesarean section is overused for all the wrong reasons. Some mothers, families, and clinicians strongly desire a more natural childbirth and strive to create such an experience—forgoing traditional medications and anesthesia. Often, this is perfectly safe, reasonable, and preferable.

However, if the perinatal course is rocky, it is wise to monitor closely and adopt a collaborative approach. When prenatal screening suggests a difficult delivery, exercise caution and have a fallback plan. Known high-risk deliveries should have a team approach from the outset, with all assets available to bedside on short notice.

While operative delivery is overused, it shouldn’t be demonized either. When genuinely needed, it can be lifesaving. Some patients do not want a cesarean delivery, and both the patient and the clinician may equate operative delivery with personal failure. However, that view may present a barrier to calling for consultation when it is genuinely needed.

For natural childbirth enthusiasts, think of the surgical delivery option as sealed in a glass case. Break that glass for all the right reasons: to preserve life or avoid significant fetal morbidity. Discuss the indications for surgical management ahead of time, so the mother is not surprised by a sudden rush to the operating room, feeling frightened and out of control.

It is recognized that patients and clinicians have firmly held beliefs, and opinions are strong on this subject. Patients have a right to self-determination and to select the birthing experience that will suit them best. Yet there is tension because jurors will expect a clinician to fully communicate known risks to patients and use all available resources to safeguard the mother and fetus at all times. In this case, the jury concluded that the midwife failed to refer for cesarean delivery after about 10 hours of labor, when the fetal heart rate pattern was nonreassuring. One of the plaintiff’s expert witnesses who criticized the defendant midwife’s care was herself a highly regarded midwife.

Continued on the next page >>

Second, use oxytocin carefully, slowing or stopping it when required. While we do not have access to the fetal heart rate monitor strips in this case, we do know that the plaintiff met her burden of proof and persuaded the jurors that the midwife inappropriately increased the drug in the setting of uterine hyperstimulation, with evidence of fetal distress. It seems surprising that the allegedly “normal” pattern recorded at 1:26 am could have been the maternal heart rate—but apparently, the jurors were convinced of this.

Third, when a facility has a medication protocol, follow it unless there is good cause not to. Medication protocols can be useful to establish operating guidelines and reduce medication errors. But they can also shackle clinicians by substituting tables and algorithms for clinical judgment. Problems arise when a protocol is sidestepped, and the clinician is raked over the coals for failing to adhere. If your facility has protocols that are important to your practice, read the documentation. Learn it, know it, live it.

If you operate outside a protocol, and your case goes to trial, the expert witness defending your care will be forced to take on both the plaintiff’s allegations and your own facility’s recommendations. The plaintiff’s closing argument will include a variation of “Mr. A did not even bother to follow his hospital’s own rules.” This argument is easy for jurors to understand, and many will reach a finding of negligence based on this fact alone. If you disagree with the protocol, or it is not reflective of your actual practice, either clinician practice or the protocol must be changed. Do not routinely circumvent protocols without good reason.

Ideally, protocols should be constructed to give clinicians flexibility based on clinical judgment and patient response. If you have a role in forming a protocol, consider advocating for less rigidity and allowing for professional judgment. If the protocol is rigid, be sure that everyone understands it and that it can be strictly followed in a real world practice environment. Put plainly, don’t install a set of rules you can’t live with—it is professionally constraining and legally risky.

IN SUM

From a legal standpoint, it is not safe to completely discard surgical delivery; when needed, it is required. Patients given oxytocin must be monitored closely, and the drug should be discontinued in the setting of uterine hyperactivity with fetal distress. Follow medication protocols or change them—but whatever you do, don’t ignore them.

Could ‘Rx: Pet therapy’ come back to bite you?

Dear Dr. Mossman,

My patient, Ms. A, asked me to write a letter to her landlord (who has a “no pets” policy) stating that she needed to keep her dog in her apartment for “therapeutic” purposes—to provide comfort and reduce her posttraumatic stress (PTSD) and anxiety. I hesitated. Could my written statement make me liable if her dog bit someone?

Submitted by “Dr. B”

Studies showing that animals can help outpatients manage psychiatric conditions have received a lot of publicity lately. As a result, more patients are asking physicians to provide documentation to support having pets in their apartments or letting their pets accompany them on planes and buses and at restaurants and shopping malls.

But sometimes, animals hurt people. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that dogs bite 4.5 million Americans each year and that one-fifth of dog bites cause injury that requires medical attention; in 2012, more than 27,000 dog-bite victims needed reconstructive surgery.1 If Dr. B writes a letter to support letting Ms. A keep a dog in her apartment, how likely is Dr. B to incur professional liability?

To answer this question, let’s examine:

• the history and background of “pet therapy”

• types of assistance animals

• potential liability for owners, landlords, and clinicians.

History and background

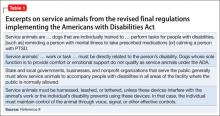

Using animals to improve hospitalized patients’ mental well-being dates back to the 18th century.2 In the late 1980s, medical publications began to document systematically how service dogs whose primary role was to help physically disabled individuals to navigate independently also provided social and emotional benefits.3-7 Since the 1990s, accessibility mandates in Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (Table 18) have led to the gradual acceptance of service animals in public places where their presence was previously frowned upon or prohibited.9,10

If service dogs help people with physical problems feel better, it only makes sense that dogs and other animals might lessen emotional ailments, too.11-13 Florence Nightingale and Sigmund Freud both recognized that involving pets in treatment reduced patients’ depression and anxiety,14 but credit for formally introducing animals into therapy usually goes to psychologist Boris Levinson, whose 1969 book described how his dog Jingles helped troubled children communicate.15 Over the past decade, using animals— trained and untrained—for psychological assistance has become an increasingly popular therapeutic maneuver for diverse mental disorders, including autism, anxiety, schizophrenia, and PTSD.16-19

Terminology

Because animals can provide many types of assistance and support, a variety of terms are used to refer to them: service animals, companion animals, therapy pets, and so on. In certain situations (including the one described by Dr. B), carefully delineating animals’ roles and functions can reduce confusion and misinterpretation by patients, health care professionals, policy makers, and regulators.

Parenti et al20 have proposed a “taxonomy” for assistance dogs based on variables that include:

• performing task related to a disability

• the skill level required of the dog

• who uses the dog

• applicable training standards

• legal protections for the dog and its handler.

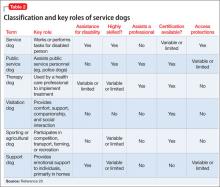

Table 220 summarizes this classification system and key variables that differentiate types of assistance dogs.

Certification

Health care facilities often require that visiting dogs have some form of “certification” that they are well behaved, and the ADA and many state statutes require that service dogs and some other animals be “certified” to perform their roles. Yet no federal or state statutes lay out explicit training standards or requirements for certification. Therapy Dogs International21 and Pet Partners22 are 2 organizations that provide certifications accepted by many agencies and organizations.

Assistance Dogs International, an assistance animal advocacy group, has proposed “minimum standards” for training and deployment of service dogs. These include responding to basic obedience commands from the client in public and at home, being able to perform at least 3 tasks to mitigate the client’s disability, teaching the client about dog training and health care, and scheduled follow-ups for skill maintenance. Dogs also should be spayed or neutered, properly vaccinated, nonaggressive, clean, and continent in public places.23

Liability laws

Most U.S. jurisdictions make owners liable for animal-caused injuries, including injuries caused by service dogs.24 In many states (eg, Minnesota25), an owner can be liable for dog-bite injury even if the owner did nothing wrong and had no reason to suspect from prior behavior that the dog might bite someone. Other jurisdictions require evidence of owner negligence, or they allow liability only when bites occur off the owner’s premises26 or if the owner let the dog run loose.27 Many homeowners’ insurance policies include liability coverage for dog bites, and a few companies offer a special canine liability policy.

Landlords often try to bar tenants from having a dog, partly to avoid liability for dog bites. Most states have case law stating that, if a tenant’s apparently friendly dog bites someone, the landlord is not liable for the injury28,29; landlords can be liable only if they know about a dangerous dog and do nothing about it.30 In a recent decision, however, the Kentucky Supreme Court made landlords statutory owners with potential liability for dog bites if they give tenants permission to have dogs “on or about” the rental premises.31

Clinicians and liability

Asking tenants to provide documentation about their need for therapeutic pets has become standard operating procedure for landlords in many states, so Ms. A’s request to Dr. B sounds reasonable. But could Dr. B’s written statement lead to liability if Ms. A’s dog bit and injured someone else?

The best answer is, “It’s conceivable, but really unlikely.” Donna Vanderpool, MBA, JD, an author and attorney who develops and implements risk management services for psychiatrists, has not seen any claims or case reports on litigation blaming mental health clinicians for injury caused by emotional support pets after the clinicians had written a letter for housing purposes (oral and written communications, April 7-13, 2014).

Dr. B might wonder whether writing a letter for Ms. A would imply that he had evaluated the dog and Ms. A’s ability to control it. Psychiatrists don’t usually discuss—let alone evaluate—the temperament or behavior of their patients’ pets; even if they did they aren’t experts on pet training. Recognizing this, Dr. B’s letter could include a statement to the effect that he was not vouching for the dog’s behavior, but only for how the dog would help Ms. A.

Dr. B also might talk with Ms. A about her need for the dog and whether she had obtained appropriate certification, as discussed above. The ADA provisions pertaining to use and presence of service animals do not apply to dogs that are merely patients’ pets, notwithstanding the genuine emotional benefits that a dog’s companionship might provide. Stating that a patient needs an animal to treat an illness might be fraud if the doctor knew the pet was just a buddy.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists can expect that more and more patients will ask them for letters to support having pets accompany them at home or in public. Although liability seems unlikely, cautious psychiatrists can state in such letters that they have not evaluated the animal in question, only the potential benefits that the patient might derive from it.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing articles.

1. Dog Bites. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/ dog-bites/index.html. Updated October 25, 2013. Accessed April 22, 2014.

2. Serpell JA. Animal-assisted interventions in historical perspective. In Fine AH, ed. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2010:17-32.

3. Eddy J, Hart LA, Boltz RP. The effects of service dogs on social acknowledgments of people in wheelchairs. J Psychol. 1988;122(1):39-45.

4. Mader B, Hart LA, Bergin B. Social acknowledgments for children with disabilities: effects of service dogs. Child Dev. 1989;60(6):1529-1534.

5. Allen K, Blascovich J. The value of service dogs for people with severe ambulatory disabilities. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;275(13):1001-1006.

6. Camp MM. The use of service dogs as an adaptive strategy: a qualitative study. Am J Occup Ther. 2001;55(5):509-517.

7. Allen K, Shykoff BE, Izzo JL Jr. Pet ownership, but not ace inhibitor therapy, blunts home blood pressure responses to mental stress. Hypertension. 2001;38(4):815-820.

8. ADA requirements: service animals. United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division, Disability Rights Section Web site. http://www.ada.gov/service_ animals_2010.htm. Published September 15, 2010. Accessed April 22, 2014.

9. Eames E, Eames T. Interpreting legal mandates. Assistance dogs in medical facilities. Nurs Manage. 1997;28(6):49-51.

10. Houghtalen RP, Doody J. After the ADA: service dogs on inpatient psychiatric units. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1995;23(2):211-217.

11. Wenthold N, Savage TA. Ethical issues with service animals. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2007;14(2):68-74.

12. DiSalvo H, Haiduven D, Johnson N, et al. Who let the dogs out? Infection control did: utility of dogs in health care settings and infection control aspects. Am J Infect Control. 2006;34:301-307.

13. Collins DM, Fitzgerald SG, Sachs-Ericsson N, et al. Psychosocial well-being and community participation of service dog partners. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2006;1(1-2):41-48.

14. Coren S. Foreward. In: Fine AH, ed. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2010: xv-xviii.

15. Levinson BM, Mallon GP. Pet-oriented child psychotherapy. 2nd ed. Springfield IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, Ltd; 1997.

16. Esnayra J. Help from man’s best friend. Psychiatric service dogs are helping consumers deal with the symptoms of mental illness. Behav Healthc. 2007;27(7):30-32.

17. Barak Y, Savorai O, Mavashev S, et al. Animal-assisted therapy for elderly schizophrenic patients: a one year controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(4):439-442.

18. Burrows KE, Adams CL, Millman ST. Factors affecting behavior and welfare of service dogs for children with autism spectrum disorder. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2008;11(1):42-62.

19. Yount RA, Olmert MD, Lee MR. Service dog training program for treatment of posttraumatic stress in service members. US Army Med Dep J. 2012:63-69.

20. Parenti L, Foreman A, Meade BJ, et al. A revised taxonomy of assistance animals. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(6):745-756.

21. Testing Requirements. Therapy Dogs International. http:// www.tdi-dog.org/images/TestingBrochure.pdf. Accessed April 22, 2014.

22. How to become a registered therapy animal team. Pet Partners. http://www.petpartners.org/TAPinfo. Accessed April 22, 2014.

23. ADI Guide to Assistance Dog Laws. Assistance Dogs International. http://www.assistancedogsinternational. org/access-and-laws/adi-guide-to-assistance-dog-laws. Accessed April 22, 2014.

24. Id Stat §56-704.

25. Seim v Garavalia, 306 NW2d 806 (Minn 1981).

26. ME Rev Stat title 7, §3961.

27. Chadbourne v Kappaz, 2001 779 A2d 293 (DC App).

28. Stokes v Lyddy, 2002 75 (Conn App 252).

29. Georgianna v Gizzy, 483 NYS2d 892 (NY 1984).

30. Linebaugh v Hyndman, 516 A2d 638 (NJ 1986).

31. Benningfield v Zinsmeister, 367 SW3d 561 (Ky 2012).

Dear Dr. Mossman,

My patient, Ms. A, asked me to write a letter to her landlord (who has a “no pets” policy) stating that she needed to keep her dog in her apartment for “therapeutic” purposes—to provide comfort and reduce her posttraumatic stress (PTSD) and anxiety. I hesitated. Could my written statement make me liable if her dog bit someone?

Submitted by “Dr. B”

Studies showing that animals can help outpatients manage psychiatric conditions have received a lot of publicity lately. As a result, more patients are asking physicians to provide documentation to support having pets in their apartments or letting their pets accompany them on planes and buses and at restaurants and shopping malls.

But sometimes, animals hurt people. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that dogs bite 4.5 million Americans each year and that one-fifth of dog bites cause injury that requires medical attention; in 2012, more than 27,000 dog-bite victims needed reconstructive surgery.1 If Dr. B writes a letter to support letting Ms. A keep a dog in her apartment, how likely is Dr. B to incur professional liability?

To answer this question, let’s examine:

• the history and background of “pet therapy”

• types of assistance animals

• potential liability for owners, landlords, and clinicians.

History and background

Using animals to improve hospitalized patients’ mental well-being dates back to the 18th century.2 In the late 1980s, medical publications began to document systematically how service dogs whose primary role was to help physically disabled individuals to navigate independently also provided social and emotional benefits.3-7 Since the 1990s, accessibility mandates in Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (Table 18) have led to the gradual acceptance of service animals in public places where their presence was previously frowned upon or prohibited.9,10

If service dogs help people with physical problems feel better, it only makes sense that dogs and other animals might lessen emotional ailments, too.11-13 Florence Nightingale and Sigmund Freud both recognized that involving pets in treatment reduced patients’ depression and anxiety,14 but credit for formally introducing animals into therapy usually goes to psychologist Boris Levinson, whose 1969 book described how his dog Jingles helped troubled children communicate.15 Over the past decade, using animals— trained and untrained—for psychological assistance has become an increasingly popular therapeutic maneuver for diverse mental disorders, including autism, anxiety, schizophrenia, and PTSD.16-19

Terminology

Because animals can provide many types of assistance and support, a variety of terms are used to refer to them: service animals, companion animals, therapy pets, and so on. In certain situations (including the one described by Dr. B), carefully delineating animals’ roles and functions can reduce confusion and misinterpretation by patients, health care professionals, policy makers, and regulators.

Parenti et al20 have proposed a “taxonomy” for assistance dogs based on variables that include:

• performing task related to a disability

• the skill level required of the dog

• who uses the dog

• applicable training standards

• legal protections for the dog and its handler.

Table 220 summarizes this classification system and key variables that differentiate types of assistance dogs.

Certification

Health care facilities often require that visiting dogs have some form of “certification” that they are well behaved, and the ADA and many state statutes require that service dogs and some other animals be “certified” to perform their roles. Yet no federal or state statutes lay out explicit training standards or requirements for certification. Therapy Dogs International21 and Pet Partners22 are 2 organizations that provide certifications accepted by many agencies and organizations.

Assistance Dogs International, an assistance animal advocacy group, has proposed “minimum standards” for training and deployment of service dogs. These include responding to basic obedience commands from the client in public and at home, being able to perform at least 3 tasks to mitigate the client’s disability, teaching the client about dog training and health care, and scheduled follow-ups for skill maintenance. Dogs also should be spayed or neutered, properly vaccinated, nonaggressive, clean, and continent in public places.23

Liability laws

Most U.S. jurisdictions make owners liable for animal-caused injuries, including injuries caused by service dogs.24 In many states (eg, Minnesota25), an owner can be liable for dog-bite injury even if the owner did nothing wrong and had no reason to suspect from prior behavior that the dog might bite someone. Other jurisdictions require evidence of owner negligence, or they allow liability only when bites occur off the owner’s premises26 or if the owner let the dog run loose.27 Many homeowners’ insurance policies include liability coverage for dog bites, and a few companies offer a special canine liability policy.

Landlords often try to bar tenants from having a dog, partly to avoid liability for dog bites. Most states have case law stating that, if a tenant’s apparently friendly dog bites someone, the landlord is not liable for the injury28,29; landlords can be liable only if they know about a dangerous dog and do nothing about it.30 In a recent decision, however, the Kentucky Supreme Court made landlords statutory owners with potential liability for dog bites if they give tenants permission to have dogs “on or about” the rental premises.31

Clinicians and liability

Asking tenants to provide documentation about their need for therapeutic pets has become standard operating procedure for landlords in many states, so Ms. A’s request to Dr. B sounds reasonable. But could Dr. B’s written statement lead to liability if Ms. A’s dog bit and injured someone else?

The best answer is, “It’s conceivable, but really unlikely.” Donna Vanderpool, MBA, JD, an author and attorney who develops and implements risk management services for psychiatrists, has not seen any claims or case reports on litigation blaming mental health clinicians for injury caused by emotional support pets after the clinicians had written a letter for housing purposes (oral and written communications, April 7-13, 2014).

Dr. B might wonder whether writing a letter for Ms. A would imply that he had evaluated the dog and Ms. A’s ability to control it. Psychiatrists don’t usually discuss—let alone evaluate—the temperament or behavior of their patients’ pets; even if they did they aren’t experts on pet training. Recognizing this, Dr. B’s letter could include a statement to the effect that he was not vouching for the dog’s behavior, but only for how the dog would help Ms. A.

Dr. B also might talk with Ms. A about her need for the dog and whether she had obtained appropriate certification, as discussed above. The ADA provisions pertaining to use and presence of service animals do not apply to dogs that are merely patients’ pets, notwithstanding the genuine emotional benefits that a dog’s companionship might provide. Stating that a patient needs an animal to treat an illness might be fraud if the doctor knew the pet was just a buddy.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists can expect that more and more patients will ask them for letters to support having pets accompany them at home or in public. Although liability seems unlikely, cautious psychiatrists can state in such letters that they have not evaluated the animal in question, only the potential benefits that the patient might derive from it.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing articles.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

My patient, Ms. A, asked me to write a letter to her landlord (who has a “no pets” policy) stating that she needed to keep her dog in her apartment for “therapeutic” purposes—to provide comfort and reduce her posttraumatic stress (PTSD) and anxiety. I hesitated. Could my written statement make me liable if her dog bit someone?

Submitted by “Dr. B”

Studies showing that animals can help outpatients manage psychiatric conditions have received a lot of publicity lately. As a result, more patients are asking physicians to provide documentation to support having pets in their apartments or letting their pets accompany them on planes and buses and at restaurants and shopping malls.

But sometimes, animals hurt people. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that dogs bite 4.5 million Americans each year and that one-fifth of dog bites cause injury that requires medical attention; in 2012, more than 27,000 dog-bite victims needed reconstructive surgery.1 If Dr. B writes a letter to support letting Ms. A keep a dog in her apartment, how likely is Dr. B to incur professional liability?

To answer this question, let’s examine:

• the history and background of “pet therapy”

• types of assistance animals

• potential liability for owners, landlords, and clinicians.

History and background

Using animals to improve hospitalized patients’ mental well-being dates back to the 18th century.2 In the late 1980s, medical publications began to document systematically how service dogs whose primary role was to help physically disabled individuals to navigate independently also provided social and emotional benefits.3-7 Since the 1990s, accessibility mandates in Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (Table 18) have led to the gradual acceptance of service animals in public places where their presence was previously frowned upon or prohibited.9,10

If service dogs help people with physical problems feel better, it only makes sense that dogs and other animals might lessen emotional ailments, too.11-13 Florence Nightingale and Sigmund Freud both recognized that involving pets in treatment reduced patients’ depression and anxiety,14 but credit for formally introducing animals into therapy usually goes to psychologist Boris Levinson, whose 1969 book described how his dog Jingles helped troubled children communicate.15 Over the past decade, using animals— trained and untrained—for psychological assistance has become an increasingly popular therapeutic maneuver for diverse mental disorders, including autism, anxiety, schizophrenia, and PTSD.16-19

Terminology

Because animals can provide many types of assistance and support, a variety of terms are used to refer to them: service animals, companion animals, therapy pets, and so on. In certain situations (including the one described by Dr. B), carefully delineating animals’ roles and functions can reduce confusion and misinterpretation by patients, health care professionals, policy makers, and regulators.

Parenti et al20 have proposed a “taxonomy” for assistance dogs based on variables that include:

• performing task related to a disability

• the skill level required of the dog

• who uses the dog

• applicable training standards

• legal protections for the dog and its handler.

Table 220 summarizes this classification system and key variables that differentiate types of assistance dogs.

Certification

Health care facilities often require that visiting dogs have some form of “certification” that they are well behaved, and the ADA and many state statutes require that service dogs and some other animals be “certified” to perform their roles. Yet no federal or state statutes lay out explicit training standards or requirements for certification. Therapy Dogs International21 and Pet Partners22 are 2 organizations that provide certifications accepted by many agencies and organizations.

Assistance Dogs International, an assistance animal advocacy group, has proposed “minimum standards” for training and deployment of service dogs. These include responding to basic obedience commands from the client in public and at home, being able to perform at least 3 tasks to mitigate the client’s disability, teaching the client about dog training and health care, and scheduled follow-ups for skill maintenance. Dogs also should be spayed or neutered, properly vaccinated, nonaggressive, clean, and continent in public places.23

Liability laws

Most U.S. jurisdictions make owners liable for animal-caused injuries, including injuries caused by service dogs.24 In many states (eg, Minnesota25), an owner can be liable for dog-bite injury even if the owner did nothing wrong and had no reason to suspect from prior behavior that the dog might bite someone. Other jurisdictions require evidence of owner negligence, or they allow liability only when bites occur off the owner’s premises26 or if the owner let the dog run loose.27 Many homeowners’ insurance policies include liability coverage for dog bites, and a few companies offer a special canine liability policy.

Landlords often try to bar tenants from having a dog, partly to avoid liability for dog bites. Most states have case law stating that, if a tenant’s apparently friendly dog bites someone, the landlord is not liable for the injury28,29; landlords can be liable only if they know about a dangerous dog and do nothing about it.30 In a recent decision, however, the Kentucky Supreme Court made landlords statutory owners with potential liability for dog bites if they give tenants permission to have dogs “on or about” the rental premises.31

Clinicians and liability

Asking tenants to provide documentation about their need for therapeutic pets has become standard operating procedure for landlords in many states, so Ms. A’s request to Dr. B sounds reasonable. But could Dr. B’s written statement lead to liability if Ms. A’s dog bit and injured someone else?

The best answer is, “It’s conceivable, but really unlikely.” Donna Vanderpool, MBA, JD, an author and attorney who develops and implements risk management services for psychiatrists, has not seen any claims or case reports on litigation blaming mental health clinicians for injury caused by emotional support pets after the clinicians had written a letter for housing purposes (oral and written communications, April 7-13, 2014).

Dr. B might wonder whether writing a letter for Ms. A would imply that he had evaluated the dog and Ms. A’s ability to control it. Psychiatrists don’t usually discuss—let alone evaluate—the temperament or behavior of their patients’ pets; even if they did they aren’t experts on pet training. Recognizing this, Dr. B’s letter could include a statement to the effect that he was not vouching for the dog’s behavior, but only for how the dog would help Ms. A.

Dr. B also might talk with Ms. A about her need for the dog and whether she had obtained appropriate certification, as discussed above. The ADA provisions pertaining to use and presence of service animals do not apply to dogs that are merely patients’ pets, notwithstanding the genuine emotional benefits that a dog’s companionship might provide. Stating that a patient needs an animal to treat an illness might be fraud if the doctor knew the pet was just a buddy.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists can expect that more and more patients will ask them for letters to support having pets accompany them at home or in public. Although liability seems unlikely, cautious psychiatrists can state in such letters that they have not evaluated the animal in question, only the potential benefits that the patient might derive from it.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing articles.

1. Dog Bites. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/ dog-bites/index.html. Updated October 25, 2013. Accessed April 22, 2014.

2. Serpell JA. Animal-assisted interventions in historical perspective. In Fine AH, ed. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2010:17-32.

3. Eddy J, Hart LA, Boltz RP. The effects of service dogs on social acknowledgments of people in wheelchairs. J Psychol. 1988;122(1):39-45.

4. Mader B, Hart LA, Bergin B. Social acknowledgments for children with disabilities: effects of service dogs. Child Dev. 1989;60(6):1529-1534.

5. Allen K, Blascovich J. The value of service dogs for people with severe ambulatory disabilities. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;275(13):1001-1006.

6. Camp MM. The use of service dogs as an adaptive strategy: a qualitative study. Am J Occup Ther. 2001;55(5):509-517.

7. Allen K, Shykoff BE, Izzo JL Jr. Pet ownership, but not ace inhibitor therapy, blunts home blood pressure responses to mental stress. Hypertension. 2001;38(4):815-820.

8. ADA requirements: service animals. United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division, Disability Rights Section Web site. http://www.ada.gov/service_ animals_2010.htm. Published September 15, 2010. Accessed April 22, 2014.

9. Eames E, Eames T. Interpreting legal mandates. Assistance dogs in medical facilities. Nurs Manage. 1997;28(6):49-51.

10. Houghtalen RP, Doody J. After the ADA: service dogs on inpatient psychiatric units. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1995;23(2):211-217.

11. Wenthold N, Savage TA. Ethical issues with service animals. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2007;14(2):68-74.

12. DiSalvo H, Haiduven D, Johnson N, et al. Who let the dogs out? Infection control did: utility of dogs in health care settings and infection control aspects. Am J Infect Control. 2006;34:301-307.

13. Collins DM, Fitzgerald SG, Sachs-Ericsson N, et al. Psychosocial well-being and community participation of service dog partners. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2006;1(1-2):41-48.

14. Coren S. Foreward. In: Fine AH, ed. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2010: xv-xviii.

15. Levinson BM, Mallon GP. Pet-oriented child psychotherapy. 2nd ed. Springfield IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, Ltd; 1997.

16. Esnayra J. Help from man’s best friend. Psychiatric service dogs are helping consumers deal with the symptoms of mental illness. Behav Healthc. 2007;27(7):30-32.

17. Barak Y, Savorai O, Mavashev S, et al. Animal-assisted therapy for elderly schizophrenic patients: a one year controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(4):439-442.

18. Burrows KE, Adams CL, Millman ST. Factors affecting behavior and welfare of service dogs for children with autism spectrum disorder. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2008;11(1):42-62.

19. Yount RA, Olmert MD, Lee MR. Service dog training program for treatment of posttraumatic stress in service members. US Army Med Dep J. 2012:63-69.

20. Parenti L, Foreman A, Meade BJ, et al. A revised taxonomy of assistance animals. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(6):745-756.

21. Testing Requirements. Therapy Dogs International. http:// www.tdi-dog.org/images/TestingBrochure.pdf. Accessed April 22, 2014.

22. How to become a registered therapy animal team. Pet Partners. http://www.petpartners.org/TAPinfo. Accessed April 22, 2014.

23. ADI Guide to Assistance Dog Laws. Assistance Dogs International. http://www.assistancedogsinternational. org/access-and-laws/adi-guide-to-assistance-dog-laws. Accessed April 22, 2014.

24. Id Stat §56-704.

25. Seim v Garavalia, 306 NW2d 806 (Minn 1981).

26. ME Rev Stat title 7, §3961.

27. Chadbourne v Kappaz, 2001 779 A2d 293 (DC App).

28. Stokes v Lyddy, 2002 75 (Conn App 252).

29. Georgianna v Gizzy, 483 NYS2d 892 (NY 1984).

30. Linebaugh v Hyndman, 516 A2d 638 (NJ 1986).

31. Benningfield v Zinsmeister, 367 SW3d 561 (Ky 2012).

1. Dog Bites. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/ dog-bites/index.html. Updated October 25, 2013. Accessed April 22, 2014.

2. Serpell JA. Animal-assisted interventions in historical perspective. In Fine AH, ed. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2010:17-32.

3. Eddy J, Hart LA, Boltz RP. The effects of service dogs on social acknowledgments of people in wheelchairs. J Psychol. 1988;122(1):39-45.

4. Mader B, Hart LA, Bergin B. Social acknowledgments for children with disabilities: effects of service dogs. Child Dev. 1989;60(6):1529-1534.