User login

Single bivalent COVID booster is enough for now: CDC

“If you have completed your updated booster dose, you are currently up to date. There is not a recommendation to get another updated booster dose,” the CDC website now explains.

In January, the nation’s expert COVID panel recommended that the United States move toward an annual COVID booster shot in the fall, similar to the annual flu shot, that targets the most widely circulating strains of the virus. Recent studies have shown that booster strength wanes after a few months, spurring discussions of whether people at high risk of getting a severe case of COVID may need more than one annual shot.

September was the last time a new booster dose was recommended, when, at the time, the bivalent booster was released, offering new protection against Omicron variants of the virus. Health officials’ focus is now shifting from preventing infections to reducing the likelihood of severe ones, the San Francisco Chronicle reported.

“The bottom line is that there is some waning of protection for those who got boosters more than six months ago and haven’t had an intervening infection,” said Bob Wachter, MD, head of the University of California–San Francisco’s department of medicine, according to the Chronicle. “But the level of protection versus severe infection continues to be fairly high, good enough that people who aren’t at super high risk are probably fine waiting until a new booster comes out in the fall.”

The Wall Street Journal reported recently that many people have been asking their doctors to give them another booster, which is not authorized by the Food and Drug Administration.

About 8 in 10 people in the United States got the initial set of COVID-19 vaccines, which were first approved in August 2021. But just 16.4% of people in the United States have gotten the latest booster that was released in September, CDC data show.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

“If you have completed your updated booster dose, you are currently up to date. There is not a recommendation to get another updated booster dose,” the CDC website now explains.

In January, the nation’s expert COVID panel recommended that the United States move toward an annual COVID booster shot in the fall, similar to the annual flu shot, that targets the most widely circulating strains of the virus. Recent studies have shown that booster strength wanes after a few months, spurring discussions of whether people at high risk of getting a severe case of COVID may need more than one annual shot.

September was the last time a new booster dose was recommended, when, at the time, the bivalent booster was released, offering new protection against Omicron variants of the virus. Health officials’ focus is now shifting from preventing infections to reducing the likelihood of severe ones, the San Francisco Chronicle reported.

“The bottom line is that there is some waning of protection for those who got boosters more than six months ago and haven’t had an intervening infection,” said Bob Wachter, MD, head of the University of California–San Francisco’s department of medicine, according to the Chronicle. “But the level of protection versus severe infection continues to be fairly high, good enough that people who aren’t at super high risk are probably fine waiting until a new booster comes out in the fall.”

The Wall Street Journal reported recently that many people have been asking their doctors to give them another booster, which is not authorized by the Food and Drug Administration.

About 8 in 10 people in the United States got the initial set of COVID-19 vaccines, which were first approved in August 2021. But just 16.4% of people in the United States have gotten the latest booster that was released in September, CDC data show.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

“If you have completed your updated booster dose, you are currently up to date. There is not a recommendation to get another updated booster dose,” the CDC website now explains.

In January, the nation’s expert COVID panel recommended that the United States move toward an annual COVID booster shot in the fall, similar to the annual flu shot, that targets the most widely circulating strains of the virus. Recent studies have shown that booster strength wanes after a few months, spurring discussions of whether people at high risk of getting a severe case of COVID may need more than one annual shot.

September was the last time a new booster dose was recommended, when, at the time, the bivalent booster was released, offering new protection against Omicron variants of the virus. Health officials’ focus is now shifting from preventing infections to reducing the likelihood of severe ones, the San Francisco Chronicle reported.

“The bottom line is that there is some waning of protection for those who got boosters more than six months ago and haven’t had an intervening infection,” said Bob Wachter, MD, head of the University of California–San Francisco’s department of medicine, according to the Chronicle. “But the level of protection versus severe infection continues to be fairly high, good enough that people who aren’t at super high risk are probably fine waiting until a new booster comes out in the fall.”

The Wall Street Journal reported recently that many people have been asking their doctors to give them another booster, which is not authorized by the Food and Drug Administration.

About 8 in 10 people in the United States got the initial set of COVID-19 vaccines, which were first approved in August 2021. But just 16.4% of people in the United States have gotten the latest booster that was released in September, CDC data show.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

FDA approves OTC naloxone, but will cost be a barrier?

Greater access to the drug should mean more lives saved. However, it’s unclear how much the nasal spray will cost and whether pharmacies will stock the product openly on shelves.

Currently, major pharmacy chains such as CVS and Walgreens make naloxone available without prescription, but consumers have to ask a pharmacist to dispense the drug.

“The major question is what is it going to cost,” Brian Hurley, MD, MBA, president-elect of the American Society of Addiction Medicine, said in an interview. “In order for people to access it they have to be able to afford it.”

“We won’t accomplish much if people can’t afford to buy Narcan,” said Chuck Ingoglia, president and CEO of the National Council for Mental Wellbeing, in a statement. Still, he applauded the FDA.

“No single approach will end overdose deaths but making Narcan easy to obtain and widely available likely will save countless lives annually,” he said.

“The timeline for availability and price of this OTC product is determined by the manufacturer,” the FDA said in a statement.

Commissioner Robert M. Califf, MD, called for the drug’s manufacturer to “make accessibility to the product a priority by making it available as soon as possible and at an affordable price.”

Emergent BioSolutions did not comment on cost. It said in a statement that the spray “will be available on U.S. shelves and at online retailers by the late summer,” after it has adapted Narcan for direct-to-consumer use, including more consumer-oriented packaging.

Naloxone’s cost varies, depending on geographic location and whether it is generic. According to GoodRX, a box containing two doses of generic naloxone costs $31-$100, depending on location and coupon availability.

A two-dose box of Narcan costs $135-$140. Emergent reported a 14% decline in naloxone sales in 2022 – to $373.7 million – blaming it in part on the introduction of generic formulations.

Dr. Hurley said he expects those who purchase Narcan at a drug store will primarily already be shopping there. It may or may not be those who most often experience overdose, such as people leaving incarceration or experiencing homelessness.

Having Narcan available over-the-counter “is an important supplement but it doesn’t replace the existing array of naloxone distribution programs,” Dr. Hurley said.

The FDA has encouraged naloxone manufacturers to seek OTC approval for the medication since at least 2019, when it designed a model label for a theoretical OTC product.

In November, the agency said it had determined that some naloxone products had the potential to be safe and effective for OTC use and again urged drugmakers to seek such an approval.

Emergent BioSolutions was the first to pursue OTC approval, but another manufacturer – the nonprofit Harm Reduction Therapeutics – is awaiting approval of its application to sell its spray directly to consumers.

Scott Gottlieb, MD, who was the FDA commissioner from 2017 to 2019, said in a tweet that more work needed to be done.

“This regulatory move should be followed by a strong push by elected officials to support wider deployment of Narcan, getting more doses into the hands of at risk households and frontline workers,” he tweeted.

Mr. Ingoglia said that “Narcan represents a second chance. By giving people a second chance, we also give them an opportunity to enter treatment if they so choose. You can’t recover if you’re dead, and we shouldn’t turn our backs on those who may choose a pathway to recovery that includes treatment.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Greater access to the drug should mean more lives saved. However, it’s unclear how much the nasal spray will cost and whether pharmacies will stock the product openly on shelves.

Currently, major pharmacy chains such as CVS and Walgreens make naloxone available without prescription, but consumers have to ask a pharmacist to dispense the drug.

“The major question is what is it going to cost,” Brian Hurley, MD, MBA, president-elect of the American Society of Addiction Medicine, said in an interview. “In order for people to access it they have to be able to afford it.”

“We won’t accomplish much if people can’t afford to buy Narcan,” said Chuck Ingoglia, president and CEO of the National Council for Mental Wellbeing, in a statement. Still, he applauded the FDA.

“No single approach will end overdose deaths but making Narcan easy to obtain and widely available likely will save countless lives annually,” he said.

“The timeline for availability and price of this OTC product is determined by the manufacturer,” the FDA said in a statement.

Commissioner Robert M. Califf, MD, called for the drug’s manufacturer to “make accessibility to the product a priority by making it available as soon as possible and at an affordable price.”

Emergent BioSolutions did not comment on cost. It said in a statement that the spray “will be available on U.S. shelves and at online retailers by the late summer,” after it has adapted Narcan for direct-to-consumer use, including more consumer-oriented packaging.

Naloxone’s cost varies, depending on geographic location and whether it is generic. According to GoodRX, a box containing two doses of generic naloxone costs $31-$100, depending on location and coupon availability.

A two-dose box of Narcan costs $135-$140. Emergent reported a 14% decline in naloxone sales in 2022 – to $373.7 million – blaming it in part on the introduction of generic formulations.

Dr. Hurley said he expects those who purchase Narcan at a drug store will primarily already be shopping there. It may or may not be those who most often experience overdose, such as people leaving incarceration or experiencing homelessness.

Having Narcan available over-the-counter “is an important supplement but it doesn’t replace the existing array of naloxone distribution programs,” Dr. Hurley said.

The FDA has encouraged naloxone manufacturers to seek OTC approval for the medication since at least 2019, when it designed a model label for a theoretical OTC product.

In November, the agency said it had determined that some naloxone products had the potential to be safe and effective for OTC use and again urged drugmakers to seek such an approval.

Emergent BioSolutions was the first to pursue OTC approval, but another manufacturer – the nonprofit Harm Reduction Therapeutics – is awaiting approval of its application to sell its spray directly to consumers.

Scott Gottlieb, MD, who was the FDA commissioner from 2017 to 2019, said in a tweet that more work needed to be done.

“This regulatory move should be followed by a strong push by elected officials to support wider deployment of Narcan, getting more doses into the hands of at risk households and frontline workers,” he tweeted.

Mr. Ingoglia said that “Narcan represents a second chance. By giving people a second chance, we also give them an opportunity to enter treatment if they so choose. You can’t recover if you’re dead, and we shouldn’t turn our backs on those who may choose a pathway to recovery that includes treatment.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Greater access to the drug should mean more lives saved. However, it’s unclear how much the nasal spray will cost and whether pharmacies will stock the product openly on shelves.

Currently, major pharmacy chains such as CVS and Walgreens make naloxone available without prescription, but consumers have to ask a pharmacist to dispense the drug.

“The major question is what is it going to cost,” Brian Hurley, MD, MBA, president-elect of the American Society of Addiction Medicine, said in an interview. “In order for people to access it they have to be able to afford it.”

“We won’t accomplish much if people can’t afford to buy Narcan,” said Chuck Ingoglia, president and CEO of the National Council for Mental Wellbeing, in a statement. Still, he applauded the FDA.

“No single approach will end overdose deaths but making Narcan easy to obtain and widely available likely will save countless lives annually,” he said.

“The timeline for availability and price of this OTC product is determined by the manufacturer,” the FDA said in a statement.

Commissioner Robert M. Califf, MD, called for the drug’s manufacturer to “make accessibility to the product a priority by making it available as soon as possible and at an affordable price.”

Emergent BioSolutions did not comment on cost. It said in a statement that the spray “will be available on U.S. shelves and at online retailers by the late summer,” after it has adapted Narcan for direct-to-consumer use, including more consumer-oriented packaging.

Naloxone’s cost varies, depending on geographic location and whether it is generic. According to GoodRX, a box containing two doses of generic naloxone costs $31-$100, depending on location and coupon availability.

A two-dose box of Narcan costs $135-$140. Emergent reported a 14% decline in naloxone sales in 2022 – to $373.7 million – blaming it in part on the introduction of generic formulations.

Dr. Hurley said he expects those who purchase Narcan at a drug store will primarily already be shopping there. It may or may not be those who most often experience overdose, such as people leaving incarceration or experiencing homelessness.

Having Narcan available over-the-counter “is an important supplement but it doesn’t replace the existing array of naloxone distribution programs,” Dr. Hurley said.

The FDA has encouraged naloxone manufacturers to seek OTC approval for the medication since at least 2019, when it designed a model label for a theoretical OTC product.

In November, the agency said it had determined that some naloxone products had the potential to be safe and effective for OTC use and again urged drugmakers to seek such an approval.

Emergent BioSolutions was the first to pursue OTC approval, but another manufacturer – the nonprofit Harm Reduction Therapeutics – is awaiting approval of its application to sell its spray directly to consumers.

Scott Gottlieb, MD, who was the FDA commissioner from 2017 to 2019, said in a tweet that more work needed to be done.

“This regulatory move should be followed by a strong push by elected officials to support wider deployment of Narcan, getting more doses into the hands of at risk households and frontline workers,” he tweeted.

Mr. Ingoglia said that “Narcan represents a second chance. By giving people a second chance, we also give them an opportunity to enter treatment if they so choose. You can’t recover if you’re dead, and we shouldn’t turn our backs on those who may choose a pathway to recovery that includes treatment.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID led to rise in pregnancy-related deaths: New research

The rise in deaths was most pronounced among Black mothers.

In 2021, 1,205 women died from pregnancy-related causes, making the year one of the worst for maternal mortality in U.S. history, according to newly released data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Maternal mortality is defined as occurring during pregnancy, at delivery, or soon after delivery.

COVID was the driver of the increased death rate, according to a study published in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology. The researchers noted that unvaccinated pregnant people are more likely to get severe COVID, and that prenatal and postnatal care were disrupted during the early part of the pandemic. From July 2021 to March 2023, the rate of women being vaccinated before pregnancy has risen from 22% to 70%, CDC data show.

Maternal mortality rates jumped the most among Black women, who in 2021 had a maternal mortality rate of nearly 70 deaths per 100,000 live births, which was 2.6 times the rate for White women.

Existing risks based on a mother’s age also increased from 2020 to 2021. The maternal mortality rates by age in 2021 per 100,000 live births were:

- 20.4 for women under age 25.

- 31.3 for women ages 25 to 39.

- 138.5 for women ages 40 and older.

Iffath Abbasi Hoskins, MD, FACOG, president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, called the situation “stunning” and “preventable.”

The findings “send a resounding message that maternal health and evidence-based efforts to eliminate racial health inequities need to be, and remain, a top public health priority,” Dr. Hoskins said in a statement.

“The COVID-19 pandemic had a dramatic and tragic effect on maternal death rates, but we cannot let that fact obscure that there was – and still is – already a maternal mortality crisis to compound,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The rise in deaths was most pronounced among Black mothers.

In 2021, 1,205 women died from pregnancy-related causes, making the year one of the worst for maternal mortality in U.S. history, according to newly released data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Maternal mortality is defined as occurring during pregnancy, at delivery, or soon after delivery.

COVID was the driver of the increased death rate, according to a study published in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology. The researchers noted that unvaccinated pregnant people are more likely to get severe COVID, and that prenatal and postnatal care were disrupted during the early part of the pandemic. From July 2021 to March 2023, the rate of women being vaccinated before pregnancy has risen from 22% to 70%, CDC data show.

Maternal mortality rates jumped the most among Black women, who in 2021 had a maternal mortality rate of nearly 70 deaths per 100,000 live births, which was 2.6 times the rate for White women.

Existing risks based on a mother’s age also increased from 2020 to 2021. The maternal mortality rates by age in 2021 per 100,000 live births were:

- 20.4 for women under age 25.

- 31.3 for women ages 25 to 39.

- 138.5 for women ages 40 and older.

Iffath Abbasi Hoskins, MD, FACOG, president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, called the situation “stunning” and “preventable.”

The findings “send a resounding message that maternal health and evidence-based efforts to eliminate racial health inequities need to be, and remain, a top public health priority,” Dr. Hoskins said in a statement.

“The COVID-19 pandemic had a dramatic and tragic effect on maternal death rates, but we cannot let that fact obscure that there was – and still is – already a maternal mortality crisis to compound,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The rise in deaths was most pronounced among Black mothers.

In 2021, 1,205 women died from pregnancy-related causes, making the year one of the worst for maternal mortality in U.S. history, according to newly released data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Maternal mortality is defined as occurring during pregnancy, at delivery, or soon after delivery.

COVID was the driver of the increased death rate, according to a study published in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology. The researchers noted that unvaccinated pregnant people are more likely to get severe COVID, and that prenatal and postnatal care were disrupted during the early part of the pandemic. From July 2021 to March 2023, the rate of women being vaccinated before pregnancy has risen from 22% to 70%, CDC data show.

Maternal mortality rates jumped the most among Black women, who in 2021 had a maternal mortality rate of nearly 70 deaths per 100,000 live births, which was 2.6 times the rate for White women.

Existing risks based on a mother’s age also increased from 2020 to 2021. The maternal mortality rates by age in 2021 per 100,000 live births were:

- 20.4 for women under age 25.

- 31.3 for women ages 25 to 39.

- 138.5 for women ages 40 and older.

Iffath Abbasi Hoskins, MD, FACOG, president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, called the situation “stunning” and “preventable.”

The findings “send a resounding message that maternal health and evidence-based efforts to eliminate racial health inequities need to be, and remain, a top public health priority,” Dr. Hoskins said in a statement.

“The COVID-19 pandemic had a dramatic and tragic effect on maternal death rates, but we cannot let that fact obscure that there was – and still is – already a maternal mortality crisis to compound,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FDA approves new formulation of Hyrimoz adalimumab biosimilar

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a citrate-free, 100 mg/mL formulation of the biosimilar adalimumab-adaz (Hyrimoz), according to a statement from manufacturer Sandoz.

Hyrimoz, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blocker that is biosimilar to its reference product Humira, was approved by the FDA in 2018 at a concentration of 50 mg/mL for rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and plaque psoriasis. The high-concentration formula is indicated for these same conditions.

Sandoz said that it intends to launch the citrate-free formulation in the United States on July 1. It will be one of up to nine other adalimumab biosimilars that are expected to launch in July. On January 31, Amjevita (adalimumab-atto) became the first adalimumab biosimilar to launch in the United States.

The current label for Hyrimoz contains a black box warning emphasizing certain risks, notably the increased risk for serious infections, such as tuberculosis or sepsis, and an increased risk of malignancy, particularly lymphomas.

Adverse effects associated with Hyrimoz with an incidence greater than 10% include upper respiratory infections and sinusitis, injection-site reactions, headache, and rash.

The approval for the high-concentration formulation was based on data from a phase 1 pharmacokinetics bridging study that compared Hyrimoz 50 mg/mL and citrate-free Hyrimoz 100 mg/mL.

“This study met all of the primary objectives, demonstrating comparable pharmacokinetics and showing similar safety and immunogenicity of the Hyrimoz 50 mg/mL and Hyrimoz [100 mg/mL],” according to Sandoz, a division of Novartis.

The approval for Hyrimoz 50 mg/mL in 2018 was based on preclinical and clinical research comparing Hyrimoz and Humira. In a phase 3 trial published in the British Journal of Dermatology, which included adults with clinically stable but active moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis, Hyrimoz and Humira showed a similar percentage of patients met the primary endpoint of a 75% reduction or more in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 75) score at 16 weeks, compared with baseline (66.8% and 65%, respectively).

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a citrate-free, 100 mg/mL formulation of the biosimilar adalimumab-adaz (Hyrimoz), according to a statement from manufacturer Sandoz.

Hyrimoz, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blocker that is biosimilar to its reference product Humira, was approved by the FDA in 2018 at a concentration of 50 mg/mL for rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and plaque psoriasis. The high-concentration formula is indicated for these same conditions.

Sandoz said that it intends to launch the citrate-free formulation in the United States on July 1. It will be one of up to nine other adalimumab biosimilars that are expected to launch in July. On January 31, Amjevita (adalimumab-atto) became the first adalimumab biosimilar to launch in the United States.

The current label for Hyrimoz contains a black box warning emphasizing certain risks, notably the increased risk for serious infections, such as tuberculosis or sepsis, and an increased risk of malignancy, particularly lymphomas.

Adverse effects associated with Hyrimoz with an incidence greater than 10% include upper respiratory infections and sinusitis, injection-site reactions, headache, and rash.

The approval for the high-concentration formulation was based on data from a phase 1 pharmacokinetics bridging study that compared Hyrimoz 50 mg/mL and citrate-free Hyrimoz 100 mg/mL.

“This study met all of the primary objectives, demonstrating comparable pharmacokinetics and showing similar safety and immunogenicity of the Hyrimoz 50 mg/mL and Hyrimoz [100 mg/mL],” according to Sandoz, a division of Novartis.

The approval for Hyrimoz 50 mg/mL in 2018 was based on preclinical and clinical research comparing Hyrimoz and Humira. In a phase 3 trial published in the British Journal of Dermatology, which included adults with clinically stable but active moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis, Hyrimoz and Humira showed a similar percentage of patients met the primary endpoint of a 75% reduction or more in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 75) score at 16 weeks, compared with baseline (66.8% and 65%, respectively).

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a citrate-free, 100 mg/mL formulation of the biosimilar adalimumab-adaz (Hyrimoz), according to a statement from manufacturer Sandoz.

Hyrimoz, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blocker that is biosimilar to its reference product Humira, was approved by the FDA in 2018 at a concentration of 50 mg/mL for rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and plaque psoriasis. The high-concentration formula is indicated for these same conditions.

Sandoz said that it intends to launch the citrate-free formulation in the United States on July 1. It will be one of up to nine other adalimumab biosimilars that are expected to launch in July. On January 31, Amjevita (adalimumab-atto) became the first adalimumab biosimilar to launch in the United States.

The current label for Hyrimoz contains a black box warning emphasizing certain risks, notably the increased risk for serious infections, such as tuberculosis or sepsis, and an increased risk of malignancy, particularly lymphomas.

Adverse effects associated with Hyrimoz with an incidence greater than 10% include upper respiratory infections and sinusitis, injection-site reactions, headache, and rash.

The approval for the high-concentration formulation was based on data from a phase 1 pharmacokinetics bridging study that compared Hyrimoz 50 mg/mL and citrate-free Hyrimoz 100 mg/mL.

“This study met all of the primary objectives, demonstrating comparable pharmacokinetics and showing similar safety and immunogenicity of the Hyrimoz 50 mg/mL and Hyrimoz [100 mg/mL],” according to Sandoz, a division of Novartis.

The approval for Hyrimoz 50 mg/mL in 2018 was based on preclinical and clinical research comparing Hyrimoz and Humira. In a phase 3 trial published in the British Journal of Dermatology, which included adults with clinically stable but active moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis, Hyrimoz and Humira showed a similar percentage of patients met the primary endpoint of a 75% reduction or more in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 75) score at 16 weeks, compared with baseline (66.8% and 65%, respectively).

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Prostate cancer drug shortage leaves some with uncertainty

according to the Food and Drug Administration.

The therapy lutetium Lu 177 vipivotide tetraxetan (Pluvicto), approved in March 2022, will remain in limited supply until the drug’s manufacturer, Novartis, can ramp up production of the drug over the next 12 months.

In a letter in February, Novartis said it is giving priority to patients who have already started the regimen so they can “appropriately complete their course of therapy.” The manufacturer will not be taking any orders for new patients over the next 4-6 months, as they work to increase supply.

“We are operating our production site at full capacity to treat as many patients as possible, as quickly as possible,” Novartis said. “However, with a nuclear medicine like Pluvicto, there is no backup supply that we can draw from when we experience a delay.”

Pluvicto is currently made in small batches in the company’s manufacturing facility in Italy. The drug only has a 5-day window to reach its intended patient, after which time it cannot be used. Any disruption in the production or shipping process can create a delay.

Novartis said the facility in Italy is currently operating at full capacity and the company is “working to increase production capacity and supply” of the drug over the next 12 months at two new manufacturing sites in the United States.

The company also encountered supply problems with Pluvicto in 2022 after quality issues were discovered in the manufacturing process.

Currently, patients who are waiting for their first dose of Pluvicto will need to be rescheduled. The manufacturer will be reaching out to health care professionals with options for rescheduling.

Jonathan McConathy, MD, PhD, told The Wall Street Journal that “people will die from this shortage, for sure.”

Dr. McConathy, a radiologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham who has consulted for Novartis, explained that some patients who would have benefited from the drug likely won’t receive it in time.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to the Food and Drug Administration.

The therapy lutetium Lu 177 vipivotide tetraxetan (Pluvicto), approved in March 2022, will remain in limited supply until the drug’s manufacturer, Novartis, can ramp up production of the drug over the next 12 months.

In a letter in February, Novartis said it is giving priority to patients who have already started the regimen so they can “appropriately complete their course of therapy.” The manufacturer will not be taking any orders for new patients over the next 4-6 months, as they work to increase supply.

“We are operating our production site at full capacity to treat as many patients as possible, as quickly as possible,” Novartis said. “However, with a nuclear medicine like Pluvicto, there is no backup supply that we can draw from when we experience a delay.”

Pluvicto is currently made in small batches in the company’s manufacturing facility in Italy. The drug only has a 5-day window to reach its intended patient, after which time it cannot be used. Any disruption in the production or shipping process can create a delay.

Novartis said the facility in Italy is currently operating at full capacity and the company is “working to increase production capacity and supply” of the drug over the next 12 months at two new manufacturing sites in the United States.

The company also encountered supply problems with Pluvicto in 2022 after quality issues were discovered in the manufacturing process.

Currently, patients who are waiting for their first dose of Pluvicto will need to be rescheduled. The manufacturer will be reaching out to health care professionals with options for rescheduling.

Jonathan McConathy, MD, PhD, told The Wall Street Journal that “people will die from this shortage, for sure.”

Dr. McConathy, a radiologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham who has consulted for Novartis, explained that some patients who would have benefited from the drug likely won’t receive it in time.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to the Food and Drug Administration.

The therapy lutetium Lu 177 vipivotide tetraxetan (Pluvicto), approved in March 2022, will remain in limited supply until the drug’s manufacturer, Novartis, can ramp up production of the drug over the next 12 months.

In a letter in February, Novartis said it is giving priority to patients who have already started the regimen so they can “appropriately complete their course of therapy.” The manufacturer will not be taking any orders for new patients over the next 4-6 months, as they work to increase supply.

“We are operating our production site at full capacity to treat as many patients as possible, as quickly as possible,” Novartis said. “However, with a nuclear medicine like Pluvicto, there is no backup supply that we can draw from when we experience a delay.”

Pluvicto is currently made in small batches in the company’s manufacturing facility in Italy. The drug only has a 5-day window to reach its intended patient, after which time it cannot be used. Any disruption in the production or shipping process can create a delay.

Novartis said the facility in Italy is currently operating at full capacity and the company is “working to increase production capacity and supply” of the drug over the next 12 months at two new manufacturing sites in the United States.

The company also encountered supply problems with Pluvicto in 2022 after quality issues were discovered in the manufacturing process.

Currently, patients who are waiting for their first dose of Pluvicto will need to be rescheduled. The manufacturer will be reaching out to health care professionals with options for rescheduling.

Jonathan McConathy, MD, PhD, told The Wall Street Journal that “people will die from this shortage, for sure.”

Dr. McConathy, a radiologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham who has consulted for Novartis, explained that some patients who would have benefited from the drug likely won’t receive it in time.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cases of potentially deadly fungus jump 200%: CDC

prompting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to issue a warning to health care facilities about the rising threat.

C. auris is a yeast that spreads easily from touching it on a surface like a countertop. It can also spread from person to person. It isn’t a threat to healthy people, but people in hospitals and nursing homes are at a heightened risk because they might have weakened immune systems or be using invasive medical devices that can introduce the fungus inside their bodies. When C. auris progresses to causing an infection that reaches the brain, blood, or lungs, more than one in three people die.

The worrying increase was detailed in the journal Annals of Internal Medicine. In 2021, cases reached a count of 3,270 with an active infection, and 7,413 cases showed the fungus was present but hadn’t caused an infection. Infection counts were up 95% over the previous year, and the fungus showed up on screenings three times as often. The number of cases resistant to medication also tripled.

The CDC called the figures “alarming,” noting that the fungus was only detected in the United States in 2016.

“The timing of this increase and findings from public health investigations suggest C. auris spread may have worsened due to strain on health care and public health systems during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the CDC explained in a news release.

Another potential reason for the jump could be that screening for C. auris has simply increased and it’s being found more often because it’s being looked for more often. But researchers believe that, even with the increase in testing, the reported counts are underestimated. That’s because even though screening has increased, health care providers still aren’t looking for the presence of the fungus as often as the CDC would like.

“The rapid rise and geographic spread of cases is concerning and emphasizes the need for continued surveillance, expanded lab capacity, quicker diagnostic tests, and adherence to proven infection prevention and control,” said study author Meghan Lyman, MD, a CDC epidemiologist in Atlanta, in a statement.

Cases of C. auris continued to rise in 2022, the CDC said. A map on the agency’s website of reported cases from 2022 shows it was found in more than half of U.S. states, with the highest counts occurring in California, Florida, Illinois, Nevada, New York, and Texas. The fungus is a problem worldwide and is listed among the most threatening treatment-resistant fungi by the World Health Organization.

The study authors concluded that screening capacity for the fungus needs to be expanded nationwide so that when C. auris is detected, measures can be taken to prevent its spread.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

prompting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to issue a warning to health care facilities about the rising threat.

C. auris is a yeast that spreads easily from touching it on a surface like a countertop. It can also spread from person to person. It isn’t a threat to healthy people, but people in hospitals and nursing homes are at a heightened risk because they might have weakened immune systems or be using invasive medical devices that can introduce the fungus inside their bodies. When C. auris progresses to causing an infection that reaches the brain, blood, or lungs, more than one in three people die.

The worrying increase was detailed in the journal Annals of Internal Medicine. In 2021, cases reached a count of 3,270 with an active infection, and 7,413 cases showed the fungus was present but hadn’t caused an infection. Infection counts were up 95% over the previous year, and the fungus showed up on screenings three times as often. The number of cases resistant to medication also tripled.

The CDC called the figures “alarming,” noting that the fungus was only detected in the United States in 2016.

“The timing of this increase and findings from public health investigations suggest C. auris spread may have worsened due to strain on health care and public health systems during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the CDC explained in a news release.

Another potential reason for the jump could be that screening for C. auris has simply increased and it’s being found more often because it’s being looked for more often. But researchers believe that, even with the increase in testing, the reported counts are underestimated. That’s because even though screening has increased, health care providers still aren’t looking for the presence of the fungus as often as the CDC would like.

“The rapid rise and geographic spread of cases is concerning and emphasizes the need for continued surveillance, expanded lab capacity, quicker diagnostic tests, and adherence to proven infection prevention and control,” said study author Meghan Lyman, MD, a CDC epidemiologist in Atlanta, in a statement.

Cases of C. auris continued to rise in 2022, the CDC said. A map on the agency’s website of reported cases from 2022 shows it was found in more than half of U.S. states, with the highest counts occurring in California, Florida, Illinois, Nevada, New York, and Texas. The fungus is a problem worldwide and is listed among the most threatening treatment-resistant fungi by the World Health Organization.

The study authors concluded that screening capacity for the fungus needs to be expanded nationwide so that when C. auris is detected, measures can be taken to prevent its spread.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

prompting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to issue a warning to health care facilities about the rising threat.

C. auris is a yeast that spreads easily from touching it on a surface like a countertop. It can also spread from person to person. It isn’t a threat to healthy people, but people in hospitals and nursing homes are at a heightened risk because they might have weakened immune systems or be using invasive medical devices that can introduce the fungus inside their bodies. When C. auris progresses to causing an infection that reaches the brain, blood, or lungs, more than one in three people die.

The worrying increase was detailed in the journal Annals of Internal Medicine. In 2021, cases reached a count of 3,270 with an active infection, and 7,413 cases showed the fungus was present but hadn’t caused an infection. Infection counts were up 95% over the previous year, and the fungus showed up on screenings three times as often. The number of cases resistant to medication also tripled.

The CDC called the figures “alarming,” noting that the fungus was only detected in the United States in 2016.

“The timing of this increase and findings from public health investigations suggest C. auris spread may have worsened due to strain on health care and public health systems during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the CDC explained in a news release.

Another potential reason for the jump could be that screening for C. auris has simply increased and it’s being found more often because it’s being looked for more often. But researchers believe that, even with the increase in testing, the reported counts are underestimated. That’s because even though screening has increased, health care providers still aren’t looking for the presence of the fungus as often as the CDC would like.

“The rapid rise and geographic spread of cases is concerning and emphasizes the need for continued surveillance, expanded lab capacity, quicker diagnostic tests, and adherence to proven infection prevention and control,” said study author Meghan Lyman, MD, a CDC epidemiologist in Atlanta, in a statement.

Cases of C. auris continued to rise in 2022, the CDC said. A map on the agency’s website of reported cases from 2022 shows it was found in more than half of U.S. states, with the highest counts occurring in California, Florida, Illinois, Nevada, New York, and Texas. The fungus is a problem worldwide and is listed among the most threatening treatment-resistant fungi by the World Health Organization.

The study authors concluded that screening capacity for the fungus needs to be expanded nationwide so that when C. auris is detected, measures can be taken to prevent its spread.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

HIV testing still suboptimal

from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The reasons are complex and could jeopardize goals of ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030.

Patients and doctors alike face system challenges, including stigma, confidentiality concerns, racism, and inequitable access. Yet doctors, public health authorities, and even some patients agree that testing does work: In 2022, 81% of people diagnosed with HIV were linked to care within 30 days. Moreover, many patients are aware of where and how they wish to be tested. So, what would it take to achieve what ostensibly should be the lowest hanging fruit in the HIV care continuum?

“We didn’t look at the reasons for not testing,” Marc Pitasi, MPH, CDC epidemiologist and coauthor of the CDC study said in an interview. But “we found that the majority of people prefer the test in a clinical setting, so that’s a huge important piece of the puzzle,” he said.

The “never-tested” populations (4,334 of 6,072) in the study were predominantly aged 18-29 years (79.7%) and 50 years plus (78.1%). A total of 48% of never-tested adults also indicated that they had engaged in past-year risky behaviors (that is, injection drug use, treated for a sexually transmitted disease, exchanged sex/drugs for money, engaged in condomless anal sex, or had more than four sex partners). However, the difference between never-tested adults who live in EHE (Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S.)–designated jurisdictions (comprising 50 areas and 7 U.S. states responsible for more than 50% of new HIV infections) and those residing in non-EHE areas was only about 5 percentage points (69.1% vs. 74.5%, respectively), underscoring the need for broader engagement.

“There’s definitely a lack of testing across the board,” explained Lina Rosengren-Hovee, MD, MPH, MS, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “There are all sorts of biases on how we make decisions and how we stratify … and these heuristics that we have in our minds to identify who is at risk and who needs testing,” she said.

“If we just look at the need for HIV testing based on who is at risk, I think that we are always going to fall short.”

Conflicting priorities

Seventeen years have passed since the CDC recommended that HIV testing and screening be offered at least once to all people aged 13-64 years in a routine clinical setting, with an opt-out option and without a separate written consent. People at higher risk (sexually active gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men) should be rescreened at least annually.

These recommendations were subsequently reinforced by numerous organizations, including the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in 2013 and again in 2019, and the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2021.

But Dr. Rosengren-Hovee said that some clinicians remain unaware of the guidelines; for others, they’re usually not top-of-mind because of conflicting priorities.

This is especially true of pediatricians, who, despite data demonstrating that adolescents account for roughly 21% of new HIV diagnoses, rarely recognize or take advantage of HIV-testing opportunities during routine clinical visits.

“Pediatricians want to do the right thing for their patients but at the same time, they want to do the right thing on so many different fronts,” said Sarah Wood, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and attending physician of adolescent medicine at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Dr. Wood is coauthor of a study published in Implementation Science Communicationsexamining pediatrician perspectives on implementing HIV testing and prevention. Participants identified confidentiality and time constraints as the most important challenges across every step of their workflow, which in turn, influenced perceptions about patients’ perceived risks for acquiring HIV – perceptions that Dr. Wood believes can be overcome.

“We need to really push pediatricians (through guideline-making societies like AAP and USPSTF) that screening should be universal and not linked to sexual activity or pinned to behavior, so the offer of testing is a universal opt-out,” she said. Additionally, “we need to make it easier for pediatricians to order the test,” for example, “through an office rapid test … and a redesigned workflow that moves the conversation away from physicians and nurse practitioners to medical assistants.”

Dr. Wood also pointed out that any effort would require pediatricians and other types of providers to overcome discomfort around sexual health conversations, noting that, while pediatricians are ideally positioned to work with parents to do education around sexual health, training and impetus are needed.

A fractured system

A fractured, often ill-funded U.S. health care system might also be at play according to Scott Harris, MD, MPH, state health officer of the Alabama Department of Public Health in Montgomery, and Association of State and Territorial Health Officials’ Infectious Disease Policy Committee chair.

“There’s a general consensus among everyone in public health that [HIV testing] is an important issue that we’re not addressing as well as we’d like to,” he said.

Dr. Harris acknowledged that, while COVID diverted attention away from HIV, some states have prioritized HIV more than others.

“We don’t have a national public health program; we have a nationwide public health program,” he said. “Everyone’s different and has different responsibilities and authorities ... depending on where their funding streams come from.”

The White House recently announced that it proposed a measure in its Fiscal Year 2023 budget to increase funding for HIV a further $313 million to accelerate efforts to end HIV by 2030, also adding a mandatory program to increase preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) access. Without congressional approval, the measures are doomed to fail, leaving many states without the proper tools to enhance existing programs, and further painting overworked clinicians into a corner.

For patients, the ramifications are even greater.

“The majority of folks [in the CDC study] that were not tested said that if they were to get tested, they’d prefer to do that within the context of their primary care setting,” said Justin C. Smith, MS, MPH, director of the Campaign to End AIDS, Positive Impact Health Centers; a behavioral scientist at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health in Atlanta; and a member of the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS.

“When you create a more responsive system that really speaks to the needs that people are expressing, that can provide better outcomes,” Dr. Smith said.

“It’s vital that we create health care and public health interventions that change the dynamics ... and make sure that we’re designing systems with the people that we’re trying to serve at the center.”

Mr. Pitasi, Dr. Rosengren-Hovee, Dr. Wood, Dr. Harris, and Dr. Smith have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The reasons are complex and could jeopardize goals of ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030.

Patients and doctors alike face system challenges, including stigma, confidentiality concerns, racism, and inequitable access. Yet doctors, public health authorities, and even some patients agree that testing does work: In 2022, 81% of people diagnosed with HIV were linked to care within 30 days. Moreover, many patients are aware of where and how they wish to be tested. So, what would it take to achieve what ostensibly should be the lowest hanging fruit in the HIV care continuum?

“We didn’t look at the reasons for not testing,” Marc Pitasi, MPH, CDC epidemiologist and coauthor of the CDC study said in an interview. But “we found that the majority of people prefer the test in a clinical setting, so that’s a huge important piece of the puzzle,” he said.

The “never-tested” populations (4,334 of 6,072) in the study were predominantly aged 18-29 years (79.7%) and 50 years plus (78.1%). A total of 48% of never-tested adults also indicated that they had engaged in past-year risky behaviors (that is, injection drug use, treated for a sexually transmitted disease, exchanged sex/drugs for money, engaged in condomless anal sex, or had more than four sex partners). However, the difference between never-tested adults who live in EHE (Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S.)–designated jurisdictions (comprising 50 areas and 7 U.S. states responsible for more than 50% of new HIV infections) and those residing in non-EHE areas was only about 5 percentage points (69.1% vs. 74.5%, respectively), underscoring the need for broader engagement.

“There’s definitely a lack of testing across the board,” explained Lina Rosengren-Hovee, MD, MPH, MS, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “There are all sorts of biases on how we make decisions and how we stratify … and these heuristics that we have in our minds to identify who is at risk and who needs testing,” she said.

“If we just look at the need for HIV testing based on who is at risk, I think that we are always going to fall short.”

Conflicting priorities

Seventeen years have passed since the CDC recommended that HIV testing and screening be offered at least once to all people aged 13-64 years in a routine clinical setting, with an opt-out option and without a separate written consent. People at higher risk (sexually active gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men) should be rescreened at least annually.

These recommendations were subsequently reinforced by numerous organizations, including the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in 2013 and again in 2019, and the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2021.

But Dr. Rosengren-Hovee said that some clinicians remain unaware of the guidelines; for others, they’re usually not top-of-mind because of conflicting priorities.

This is especially true of pediatricians, who, despite data demonstrating that adolescents account for roughly 21% of new HIV diagnoses, rarely recognize or take advantage of HIV-testing opportunities during routine clinical visits.

“Pediatricians want to do the right thing for their patients but at the same time, they want to do the right thing on so many different fronts,” said Sarah Wood, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and attending physician of adolescent medicine at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Dr. Wood is coauthor of a study published in Implementation Science Communicationsexamining pediatrician perspectives on implementing HIV testing and prevention. Participants identified confidentiality and time constraints as the most important challenges across every step of their workflow, which in turn, influenced perceptions about patients’ perceived risks for acquiring HIV – perceptions that Dr. Wood believes can be overcome.

“We need to really push pediatricians (through guideline-making societies like AAP and USPSTF) that screening should be universal and not linked to sexual activity or pinned to behavior, so the offer of testing is a universal opt-out,” she said. Additionally, “we need to make it easier for pediatricians to order the test,” for example, “through an office rapid test … and a redesigned workflow that moves the conversation away from physicians and nurse practitioners to medical assistants.”

Dr. Wood also pointed out that any effort would require pediatricians and other types of providers to overcome discomfort around sexual health conversations, noting that, while pediatricians are ideally positioned to work with parents to do education around sexual health, training and impetus are needed.

A fractured system

A fractured, often ill-funded U.S. health care system might also be at play according to Scott Harris, MD, MPH, state health officer of the Alabama Department of Public Health in Montgomery, and Association of State and Territorial Health Officials’ Infectious Disease Policy Committee chair.

“There’s a general consensus among everyone in public health that [HIV testing] is an important issue that we’re not addressing as well as we’d like to,” he said.

Dr. Harris acknowledged that, while COVID diverted attention away from HIV, some states have prioritized HIV more than others.

“We don’t have a national public health program; we have a nationwide public health program,” he said. “Everyone’s different and has different responsibilities and authorities ... depending on where their funding streams come from.”

The White House recently announced that it proposed a measure in its Fiscal Year 2023 budget to increase funding for HIV a further $313 million to accelerate efforts to end HIV by 2030, also adding a mandatory program to increase preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) access. Without congressional approval, the measures are doomed to fail, leaving many states without the proper tools to enhance existing programs, and further painting overworked clinicians into a corner.

For patients, the ramifications are even greater.

“The majority of folks [in the CDC study] that were not tested said that if they were to get tested, they’d prefer to do that within the context of their primary care setting,” said Justin C. Smith, MS, MPH, director of the Campaign to End AIDS, Positive Impact Health Centers; a behavioral scientist at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health in Atlanta; and a member of the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS.

“When you create a more responsive system that really speaks to the needs that people are expressing, that can provide better outcomes,” Dr. Smith said.

“It’s vital that we create health care and public health interventions that change the dynamics ... and make sure that we’re designing systems with the people that we’re trying to serve at the center.”

Mr. Pitasi, Dr. Rosengren-Hovee, Dr. Wood, Dr. Harris, and Dr. Smith have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The reasons are complex and could jeopardize goals of ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030.

Patients and doctors alike face system challenges, including stigma, confidentiality concerns, racism, and inequitable access. Yet doctors, public health authorities, and even some patients agree that testing does work: In 2022, 81% of people diagnosed with HIV were linked to care within 30 days. Moreover, many patients are aware of where and how they wish to be tested. So, what would it take to achieve what ostensibly should be the lowest hanging fruit in the HIV care continuum?

“We didn’t look at the reasons for not testing,” Marc Pitasi, MPH, CDC epidemiologist and coauthor of the CDC study said in an interview. But “we found that the majority of people prefer the test in a clinical setting, so that’s a huge important piece of the puzzle,” he said.

The “never-tested” populations (4,334 of 6,072) in the study were predominantly aged 18-29 years (79.7%) and 50 years plus (78.1%). A total of 48% of never-tested adults also indicated that they had engaged in past-year risky behaviors (that is, injection drug use, treated for a sexually transmitted disease, exchanged sex/drugs for money, engaged in condomless anal sex, or had more than four sex partners). However, the difference between never-tested adults who live in EHE (Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S.)–designated jurisdictions (comprising 50 areas and 7 U.S. states responsible for more than 50% of new HIV infections) and those residing in non-EHE areas was only about 5 percentage points (69.1% vs. 74.5%, respectively), underscoring the need for broader engagement.

“There’s definitely a lack of testing across the board,” explained Lina Rosengren-Hovee, MD, MPH, MS, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “There are all sorts of biases on how we make decisions and how we stratify … and these heuristics that we have in our minds to identify who is at risk and who needs testing,” she said.

“If we just look at the need for HIV testing based on who is at risk, I think that we are always going to fall short.”

Conflicting priorities

Seventeen years have passed since the CDC recommended that HIV testing and screening be offered at least once to all people aged 13-64 years in a routine clinical setting, with an opt-out option and without a separate written consent. People at higher risk (sexually active gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men) should be rescreened at least annually.

These recommendations were subsequently reinforced by numerous organizations, including the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in 2013 and again in 2019, and the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2021.

But Dr. Rosengren-Hovee said that some clinicians remain unaware of the guidelines; for others, they’re usually not top-of-mind because of conflicting priorities.

This is especially true of pediatricians, who, despite data demonstrating that adolescents account for roughly 21% of new HIV diagnoses, rarely recognize or take advantage of HIV-testing opportunities during routine clinical visits.

“Pediatricians want to do the right thing for their patients but at the same time, they want to do the right thing on so many different fronts,” said Sarah Wood, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and attending physician of adolescent medicine at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Dr. Wood is coauthor of a study published in Implementation Science Communicationsexamining pediatrician perspectives on implementing HIV testing and prevention. Participants identified confidentiality and time constraints as the most important challenges across every step of their workflow, which in turn, influenced perceptions about patients’ perceived risks for acquiring HIV – perceptions that Dr. Wood believes can be overcome.

“We need to really push pediatricians (through guideline-making societies like AAP and USPSTF) that screening should be universal and not linked to sexual activity or pinned to behavior, so the offer of testing is a universal opt-out,” she said. Additionally, “we need to make it easier for pediatricians to order the test,” for example, “through an office rapid test … and a redesigned workflow that moves the conversation away from physicians and nurse practitioners to medical assistants.”

Dr. Wood also pointed out that any effort would require pediatricians and other types of providers to overcome discomfort around sexual health conversations, noting that, while pediatricians are ideally positioned to work with parents to do education around sexual health, training and impetus are needed.

A fractured system

A fractured, often ill-funded U.S. health care system might also be at play according to Scott Harris, MD, MPH, state health officer of the Alabama Department of Public Health in Montgomery, and Association of State and Territorial Health Officials’ Infectious Disease Policy Committee chair.

“There’s a general consensus among everyone in public health that [HIV testing] is an important issue that we’re not addressing as well as we’d like to,” he said.

Dr. Harris acknowledged that, while COVID diverted attention away from HIV, some states have prioritized HIV more than others.

“We don’t have a national public health program; we have a nationwide public health program,” he said. “Everyone’s different and has different responsibilities and authorities ... depending on where their funding streams come from.”

The White House recently announced that it proposed a measure in its Fiscal Year 2023 budget to increase funding for HIV a further $313 million to accelerate efforts to end HIV by 2030, also adding a mandatory program to increase preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) access. Without congressional approval, the measures are doomed to fail, leaving many states without the proper tools to enhance existing programs, and further painting overworked clinicians into a corner.

For patients, the ramifications are even greater.

“The majority of folks [in the CDC study] that were not tested said that if they were to get tested, they’d prefer to do that within the context of their primary care setting,” said Justin C. Smith, MS, MPH, director of the Campaign to End AIDS, Positive Impact Health Centers; a behavioral scientist at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health in Atlanta; and a member of the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS.

“When you create a more responsive system that really speaks to the needs that people are expressing, that can provide better outcomes,” Dr. Smith said.

“It’s vital that we create health care and public health interventions that change the dynamics ... and make sure that we’re designing systems with the people that we’re trying to serve at the center.”

Mr. Pitasi, Dr. Rosengren-Hovee, Dr. Wood, Dr. Harris, and Dr. Smith have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

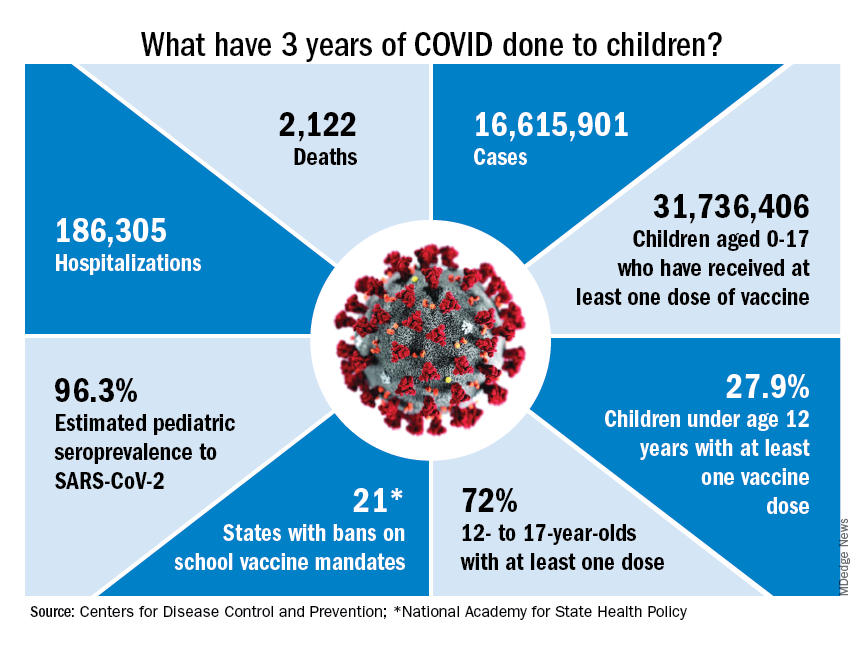

Children and COVID: A look back as the fourth year begins

With 3 years of the COVID-19 experience now past, it’s safe to say that SARS-CoV-2 changed American society in ways that could not have been predicted when the first U.S. cases were reported in January of 2020.

Who would have guessed back then that not one but two vaccines would be developed, approved, and widely distributed before the end of the year? Or that those vaccines would be rejected by large segments of the population on ideological grounds? Could anyone have predicted in early 2020 that schools in 21 states would be forbidden by law to require COVID-19 vaccination in students?

Vaccination is generally considered to be an activity of childhood, but that practice has been turned upside down with COVID-19. Among Americans aged 65 years and older, 95% have received at least one dose of vaccine, versus 27.9% of children younger than 12 years old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The vaccine situation for children mirrors that of the population as a whole. The oldest children have the highest vaccination rates, and the rates decline along with age: 72.0% of those aged 12-17 years have received at least one dose, compared with 39.8% of 5- to 11-year-olds, 10.5% of 2- to 4-year-olds, and 8.0% of children under age 2, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The youngest children were, of course, the last ones to be eligible for the vaccine, but their uptake has been much slower since emergency use was authorized in June of 2022. In the nearly 9 months since then, 9.5% of children aged 4 and under have received at least one dose, versus 66% of children aged 12-15 years in the first 9 months (May 2021 to March 2022).

Altogether, a total of 31.7 million, or 43%, of all children under age 18 had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine as of March 8, 2023, according to the most recent CDC data.

Incidence: Counting COVID

Vaccination and other prevention efforts have tried to stem the tide, but what has COVID actually done to children since the Trump administration declared a nationwide emergency on March 13, 2020?

- 16.6 million cases.

- 186,035 new hospital admissions.

- 2,122 deaths.

Even the proportion of total COVID cases in children, 17.2%, is less than might be expected, given their relatively undervaccinated status.

Seroprevalence estimates seem to support the undercounting of pediatric cases. A survey of commercial laboratories working with the CDC put the seroprevalance of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in children at 96.3% as of late 2022, based on tests of almost 27,000 specimens performed over an 8-week period from mid-October to mid-December. That would put the number of infected children at 65.7 million children.

Since Omicron

There has not been another major COVID-19 surge since the winter of 2021-2022, when the weekly rate of new cases reached 1,900 per 100,000 population in children aged 16-17 years in early January 2022 – the highest seen among children of any of the CDC’s age groups (0-4, 5-11, 12-15, 16-17) during the entire pandemic. Since the Omicron surge, the highest weekly rate was 221 per 100,000 during the week of May 15-21, again in 16- to 17-year-olds, the CDC reports.

The widely anticipated surge of COVID in the fall and winter of 2022 and 2023 – the so-called “tripledemic” involving influenza and respiratory syncytial virus – did not occur, possibly because so many Americans were vaccinated or previously infected, experts suggested. New-case rates, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations in children have continued to drop as winter comes to a close, CDC data show.

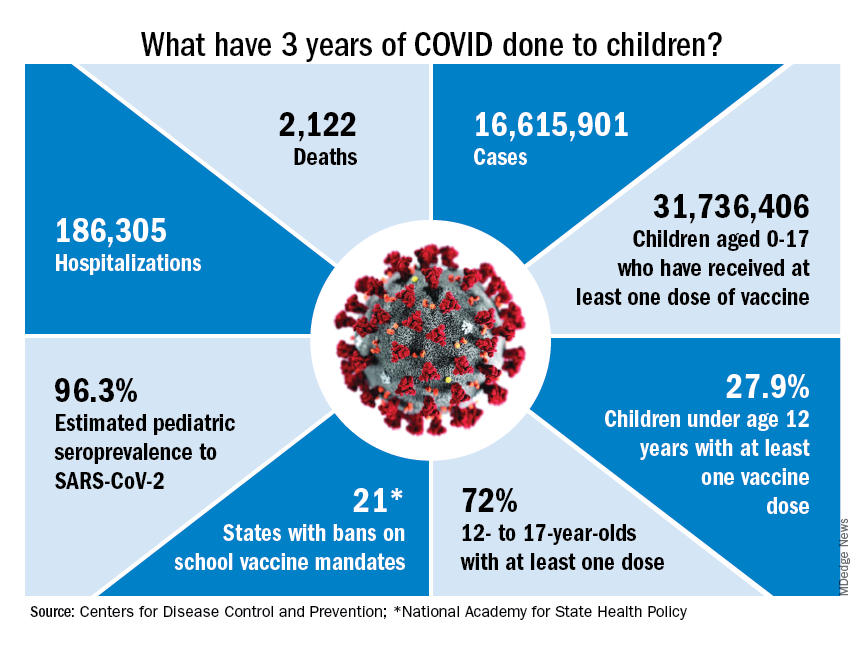

With 3 years of the COVID-19 experience now past, it’s safe to say that SARS-CoV-2 changed American society in ways that could not have been predicted when the first U.S. cases were reported in January of 2020.

Who would have guessed back then that not one but two vaccines would be developed, approved, and widely distributed before the end of the year? Or that those vaccines would be rejected by large segments of the population on ideological grounds? Could anyone have predicted in early 2020 that schools in 21 states would be forbidden by law to require COVID-19 vaccination in students?

Vaccination is generally considered to be an activity of childhood, but that practice has been turned upside down with COVID-19. Among Americans aged 65 years and older, 95% have received at least one dose of vaccine, versus 27.9% of children younger than 12 years old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The vaccine situation for children mirrors that of the population as a whole. The oldest children have the highest vaccination rates, and the rates decline along with age: 72.0% of those aged 12-17 years have received at least one dose, compared with 39.8% of 5- to 11-year-olds, 10.5% of 2- to 4-year-olds, and 8.0% of children under age 2, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The youngest children were, of course, the last ones to be eligible for the vaccine, but their uptake has been much slower since emergency use was authorized in June of 2022. In the nearly 9 months since then, 9.5% of children aged 4 and under have received at least one dose, versus 66% of children aged 12-15 years in the first 9 months (May 2021 to March 2022).

Altogether, a total of 31.7 million, or 43%, of all children under age 18 had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine as of March 8, 2023, according to the most recent CDC data.

Incidence: Counting COVID

Vaccination and other prevention efforts have tried to stem the tide, but what has COVID actually done to children since the Trump administration declared a nationwide emergency on March 13, 2020?

- 16.6 million cases.

- 186,035 new hospital admissions.

- 2,122 deaths.

Even the proportion of total COVID cases in children, 17.2%, is less than might be expected, given their relatively undervaccinated status.

Seroprevalence estimates seem to support the undercounting of pediatric cases. A survey of commercial laboratories working with the CDC put the seroprevalance of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in children at 96.3% as of late 2022, based on tests of almost 27,000 specimens performed over an 8-week period from mid-October to mid-December. That would put the number of infected children at 65.7 million children.

Since Omicron

There has not been another major COVID-19 surge since the winter of 2021-2022, when the weekly rate of new cases reached 1,900 per 100,000 population in children aged 16-17 years in early January 2022 – the highest seen among children of any of the CDC’s age groups (0-4, 5-11, 12-15, 16-17) during the entire pandemic. Since the Omicron surge, the highest weekly rate was 221 per 100,000 during the week of May 15-21, again in 16- to 17-year-olds, the CDC reports.

The widely anticipated surge of COVID in the fall and winter of 2022 and 2023 – the so-called “tripledemic” involving influenza and respiratory syncytial virus – did not occur, possibly because so many Americans were vaccinated or previously infected, experts suggested. New-case rates, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations in children have continued to drop as winter comes to a close, CDC data show.

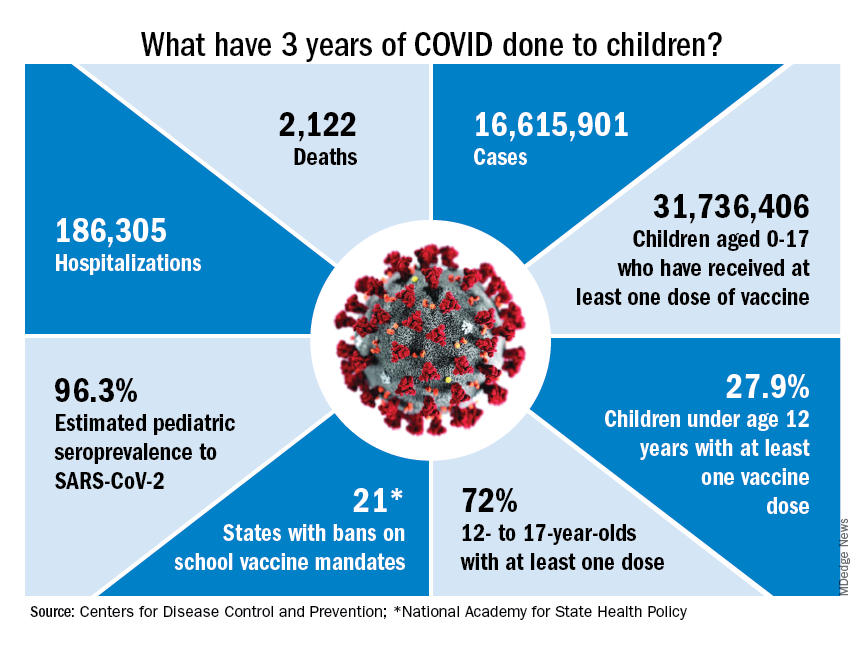

With 3 years of the COVID-19 experience now past, it’s safe to say that SARS-CoV-2 changed American society in ways that could not have been predicted when the first U.S. cases were reported in January of 2020.

Who would have guessed back then that not one but two vaccines would be developed, approved, and widely distributed before the end of the year? Or that those vaccines would be rejected by large segments of the population on ideological grounds? Could anyone have predicted in early 2020 that schools in 21 states would be forbidden by law to require COVID-19 vaccination in students?

Vaccination is generally considered to be an activity of childhood, but that practice has been turned upside down with COVID-19. Among Americans aged 65 years and older, 95% have received at least one dose of vaccine, versus 27.9% of children younger than 12 years old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The vaccine situation for children mirrors that of the population as a whole. The oldest children have the highest vaccination rates, and the rates decline along with age: 72.0% of those aged 12-17 years have received at least one dose, compared with 39.8% of 5- to 11-year-olds, 10.5% of 2- to 4-year-olds, and 8.0% of children under age 2, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The youngest children were, of course, the last ones to be eligible for the vaccine, but their uptake has been much slower since emergency use was authorized in June of 2022. In the nearly 9 months since then, 9.5% of children aged 4 and under have received at least one dose, versus 66% of children aged 12-15 years in the first 9 months (May 2021 to March 2022).

Altogether, a total of 31.7 million, or 43%, of all children under age 18 had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine as of March 8, 2023, according to the most recent CDC data.

Incidence: Counting COVID

Vaccination and other prevention efforts have tried to stem the tide, but what has COVID actually done to children since the Trump administration declared a nationwide emergency on March 13, 2020?

- 16.6 million cases.

- 186,035 new hospital admissions.

- 2,122 deaths.

Even the proportion of total COVID cases in children, 17.2%, is less than might be expected, given their relatively undervaccinated status.

Seroprevalence estimates seem to support the undercounting of pediatric cases. A survey of commercial laboratories working with the CDC put the seroprevalance of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in children at 96.3% as of late 2022, based on tests of almost 27,000 specimens performed over an 8-week period from mid-October to mid-December. That would put the number of infected children at 65.7 million children.

Since Omicron

There has not been another major COVID-19 surge since the winter of 2021-2022, when the weekly rate of new cases reached 1,900 per 100,000 population in children aged 16-17 years in early January 2022 – the highest seen among children of any of the CDC’s age groups (0-4, 5-11, 12-15, 16-17) during the entire pandemic. Since the Omicron surge, the highest weekly rate was 221 per 100,000 during the week of May 15-21, again in 16- to 17-year-olds, the CDC reports.

The widely anticipated surge of COVID in the fall and winter of 2022 and 2023 – the so-called “tripledemic” involving influenza and respiratory syncytial virus – did not occur, possibly because so many Americans were vaccinated or previously infected, experts suggested. New-case rates, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations in children have continued to drop as winter comes to a close, CDC data show.

FDA moves to stop the spread of illicit ‘tranq’ in the U.S.

The agency issued an import alert, which gives it the power to detain raw ingredients or bulk finished product if the shipments are suspected to be in violation of the law. Xylazine was first approved by the FDA in 1972 as a sedative and analgesic for use only in animals.

It is increasingly being detected and is usually mixed with fentanyl, cocaine, methamphetamine, and other illicit drugs. A January 2023 study by Nashville-based testing company Aegis Sciences found xylazine in 413 of about 60,000 urine samples and in 25 of 39 states that submitted tests. The vast majority of xylazine-positive samples also tested positive for fentanyl.

The FDA said it would continue to ensure the availability of xylazine for veterinary use, and the American Veterinary Medicine Association said in a statement that it “supports such efforts to combat illicit drug use.”

FDA Commissioner Robert M. Califf, MD, said in a statement that the agency “remains concerned about the increasing prevalence of xylazine mixed with illicit drugs, and this action is one part of broader efforts the agency is undertaking to address this issue.”

In November, the agency warned health care providers that because xylazine is not an opioid, the overdose reversal agent naloxone would not be effective. Xylazine acts as a central alpha-2-adrenergic receptor agonist in the brainstem, causing a rapid decrease in the release of norepinephrine and dopamine in the central nervous system. Its use can lead to central nervous system and respiratory depression, said the FDA.

Clinicians have scrambled to treat severe necrotic skin ulcerations that develop at injection sites.

Xylazine is relatively cheap and easy to access, said the Drug Enforcement Administration and Department of Justice in a November joint report. The drug is “readily available for purchase on other Internet sites in liquid and powder form, often with no association to the veterinary profession nor requirements to prove legitimate need,” said the Justice Department. A buyer can purchase xylazine powder online from Chinese suppliers for $6-$20 per kilogram, according to the report.

In 2021, xylazine-positive overdoses were highest in the South, which experienced a 1,127% increase from 2020, the Justice Department reported. The same year, there were 1,281 overdoses involving the substance in the Northeast and 351 in the Midwest.