User login

Cancer risk assessment from family history: Gaps in primary care practice

OBJECTIVE: To determine whether an adequate amount of family history is being collected and recorded by family practitioners to appropriately identify patients at increased risk for cancer.

STUDY DESIGN: Retrospective chart audit.

POPULATION: Charts from 500 randomly chosen patients, 40 to 60 years of age, were audited. Of those charts, 400 were from a large academic family practice and 50 charts each were from 2 small community family practices in the greater Philadelphia area.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: General features of family history taking were recorded, including presence of a family history and date when recorded, evidence of updated family history data, and presence of a genogram. Cancer features recorded included mention of family history of cancer or colon polyps and, if positive, identification of which relative was affected, site of cancer, and age of diagnosis or death.

RESULTS: Most charts (89%) had some family history information recorded, and 55% listed a family history of cancer, either positive or negative. Of the 356 relatives affected with cancer, an age of diagnosis was documented in only 8%; of 183 first-degree relatives with cancer, only 7% had a documented age of diagnosis. Two percent of all charts had any mention of a family history of colon polyps. Sixty-five percent of family histories were recorded at the first visit, and only 35% had any updated family history information.

CONCLUSIONS: The number and type of family histories currently being recorded by family practitioners are not adequate to fully assess familial risk of cancer. New strategies will need to be developed to better prepare providers for risk-based clinical decision making.

Taking a family history is a significant component of providing comprehensive primary care because family history provides key psychosocial and medical risk information.1,2 As our understanding of the genetic basis for disease grows, obtaining an accurate and complete family history is likely to gain increasing relevance as a vital source of data to guide counseling and testing. Patients who have a first-degree relative with a colon neoplasm or prostate cancer are advised to screen differently from those who do not.3 Failure to gather accurate or complete family data prevents the clinician from providing advice that is consistent with screening guidelines. Understanding how primary care clinicians gather family history data is necessary to identify gaps in current performance and to develop strategies to bridge these gaps.

Several studies have used physician self-report to assess the current level of taking a family history in primary care. In 1 study, 90% of surveyed physicians stated that they obtain a family history of cancer from their patients, with 77% to 80% inquiring about a family history of colorectal cancer in their patients who are at least 40 years of age.3 In another study, 63% to 85% of responding physicians reported obtaining a family history of cancer from 76% to 100% of their patients.5 Respondents in 1 study reported obtaining family histories of colorectal cancer in only 30.7% of patients, breast cancer in 48.4% of patients, and coronary disease and hypertension in 94.3% of patients.6 However, data on actual performance of family history taking are sparse.7,8 The physicians in the Direct Observation of Primary Care study obtained a family history during 51% of new visits and 22% of established visits. A genogram was present in 11% of charts, and documentation of a family history of breast cancer or colorectal cancer was found in 40% of charts. Further analysis from this study showed that providers who more frequently obtained and recorded family history information performed more preventive care services for their patients.9

First-degree relatives of cancer patients appear to be interested in and receptive to information about their risk and in the possibility of genetic counseling.10-14 In fact, many patients overestimate their likelihood of getting cancer based on family history10; primary care providers thus have the opportunity to counsel and relieve anxiety in their patients. Family history is an important tool to define risk and guide referral, counseling, and testing.

This article presents the findings of a descriptive study of the review of 500 charts from 3 different family practice offices. We documented general family history components and completeness related to a family history of cancer, including whether enough family history information was collected to appropriately identify patients at increased risk for cancer.

Methods

Data were collected from 500 patient charts from 3 family practice offices in the greater Philadelphia area. Patients who were in the practice for at least 1 year, made a minimum of 2 visits between June 1, 1997 and June 1, 2000, and were between the ages of 40 and 60 years at 1 of those visits were included. Fifty charts were selected by using a random starting point at each of 2 small (1 to 3 providers) private practices, and 400 charts were randomly selected from all eligible charts in a large academic practice (more than 60 providers). The large practice had nearly 1500 patients who fit the selection criteria, and the total population did not differ from the random sample in mean age, sex, or race (P < .05). Total population characteristics were not available for the 2 smaller practices.

Family history data were collected from progress notes and designated family history spaces on flow sheets or chart covers. Family histories consisting only of “none” or “noncontributory” were counted only when they clearly referred to a specific condition. Family births or deaths recorded in a psychosocial context also were not counted as part of the family history unless death from a specific disease was mentioned. The first dated family history was considered to be first for the purpose of this study. Date of birth, race, sex, current primary care provider, if any, and the date first seen in the practice were recorded. The current primary care provider was determined by the physician seen for the majority of recent visits and/or notations in the chart at acute visits. Data collected for the primary care providers included practice site, sex, level of training, and years in practice. Variables collected from family history information included: date of first family history; date of most recent family history; presence of a genogram, presence of a patient-completed family history self-questionnaire; whether any mention was made, positive or negative, of cancer or colon polyps; and whether there was a positive family history of cancer or colon polyps. For individuals with a positive family history of cancer or colon polyps, all details recorded in the chart were abstracted; these included site of cancer or polyp, relationship to patient, age at diagnosis, and age at death. The data were entered into an Access 97 database and stored separately from chart number identifiers. All analyses and tests were done in SAS version 6.12.

Results

Demographic data from the 500 patients whose charts were audited are presented in Table 1. Ninety-seven percent of patients had a primary care provider, which included 60 physicians and 3 nurse practitioners. No significant associations were seen with practice site, sex, or level of training of the provider and the presence of family history information in the chart.

Most patients (89%) had some family history information in the chart and 63% had a genogram. This did not differ by sex or race of the patient. Fifty-seven percent of patients supplied family history information at the first visit to the office; 59% of these patients had no family history data recorded on subsequent visits. Only 31% of charts had updated family history information Table 2. For patients who had been in the same practice for at least 5 years and had some family history in the chart, 20% had some updated information within the past 3 years.

Of the 500 charts, 276 (55%) recorded a family history of cancer, positive or negative. Two hundred fifteen patients (43%) had a positive family history of cancer, with a total of 356 relatives affected. The site of cancer was listed for 88% of all family member cancers, with breast, colon, lung, and prostate being the most common cancer locations. The specific relative was identified in 92% of cases, with most being first (51%) or second (37%) degree. Although degree of relative and cancer location were usually recorded, age at diagnosis was listed for only 8% of affected relatives, and age at death was identified for 19% of relatives with cancer.

For patients with affected first-degree relatives, the group with the greatest clinical significance, primary care providers identified the location of the cancer in 93% of cases but listed the ages at diagnosis and death in only 7% and 31%, respectively Table 3. Only 7 medical records (1.4%) had any mention of a family history of polyps; of these, 5 (1%) were positive. None listed an age at diagnosis. Five patients in our study met the American Society of Clinical Oncology criteria to be evaluated for genetic breast and ovarian cancer syndrome, and no patients met the criteria for hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer.

The 2 community practices intermittently used patient self-administered medical intake questionnaires. In our sample, 31 of 500 patients (6%) had a questionnaire in the chart. All patients who completed questionnaires had family history data in their charts. Use of a questionnaire was associated with a greater likelihood that the physician recorded the age of diagnosis for a relative with cancer, although this did not reach significance (20% vs 7%).

Discussion

Despite our finding that providers are documenting family histories in most charts, very few are recording the age of diagnosis in relatives diagnosed with cancer. Age of diagnosis plays a critical role in determining screening recommendations and identifying patients with possible genetic syndromes. For example, the Amsterdam criteria used to identify families with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer include knowing whether 1 of 3 relatives with colorectal cancer was diagnosed at younger than 50 years. Breast and ovarian cancer syndrome should be suspected when breast and/or ovarian cancer is diagnosed in 2 first-degree relatives younger than 50 years.15

Most physicians obtain family histories at initial visits. If the patient’s initial visit is for symptom- or disease-related care, an opportunity to gather family history data may be lost. New tools to consistently capture comprehensive family history data at this first visit may be beneficial. Patient self-administered intake questionnaires may prove valuable in this respect, but only 6% of charts in our study contained such a questionnaire, so we cannot draw conclusions about its impact. We did observe a trend toward gathering more complete family history data in patients who used a questionnaire.

There are no clear guidelines regarding when to update a family history. We arbitrarily chose 3 years as a reasonable period for primary care providers to explore changes in family history status. Updating at any subsequent visit was recorded for 35% of patient charts in which a family history was initially taken. It is not clear that primary care providers are documenting changes in family history in any systematic way. Opportunistic updating likely occurs when a new diagnosis of serious disease in a close family member produces anxiety, stress, or concern in the patient. The value of updating family history and the ideal interval to reexamine family history are unknown.

Several conditions would need to be met for family history updating to have value. (1) A close relative must have developed an important illness in the interval since the last family history was recorded or the update must discover family information that was previously missed. (2) The illness must have a familial component that affects the estimate of the risk of the identified patient. (3) The clinician would need to be aware of the updated information. (4) The clinician must change recommendations to the patient based on this new information. Discovering a new family history of colonic neoplasm satisfies these conditions. Process measures that have the potential to improve updating include adding an update of family history as an item on a preventive care flow sheet or using periodic self-administered patient questionnaires. Whether adequate improvements in health care would occur to justify these changes in process will need to be studied. If any updating has value, determining the appropriate intervals for systematic updates deserves attention.

Charts in this study included a genogram 63% of the time, a significant increase over the 11% noted in the Direct Observation of Primary Care study.9 This discrepancy may be explained by differences in practice types because 1 study suggested a higher genogram use in academic medical centers than in community practices.16 The genogram has been cited as an attractive and efficient way to document family history,17,18 but over one fourth of the charts that contained family history in our study used the more cumbersome narrative form. Many geneticists predict that our ability to apply genetic testing will grow dramatically over the next decade. Optimal application of this new knowledge will rely on the health care system’s capacity to accurately identify risk based on assessment of family history. The 3-generation pedigree is likely to be a key tool in finding individuals who may benefit from testing. However, there is currently no standardized education in family history taking in many undergraduate and graduate medical education programs.19

Although patients with a first-degree relative with a history of polyps diagnosed at younger than 60 years are considered to be at increased risk for colorectal cancer,3 providers infrequently asked about a family history of polyps. This may reflect a recent finding that only 36% of primary care providers recommend screening at the age of 40 years for their patients with a family history of polyps in relatives younger than 60 years.20 In fact, family history data do not consistently influence behavior: in the same study, gastroenterologists asked about a family history of polyps 93% of the time, but only 37% recommended earlier screening in those with such a history.

The study is limited in its use of only 3 primary care practices, 1 of which was a large academic family practice. However, because the charts of 63 different clinicians were represented, a range of educational backgrounds and personal philosophies toward family history taking was included. Most patients (97%) had a clearly identified primary care provider and patients had been members of the practice for an average of 7.6 years. The sample was specifically chosen to review the charts of individuals who had been enrolled in the same practice for at least 1 year. This may explain the higher rates of family history taking found in this study compared with previously published studies. Given that the vast majority of charts did contain some family history, it is even more compelling that age at diagnosis of cancer was inadequately recorded. This study reflected only what was documented in the patient chart and not direct observation of physician behavior regarding the family history. It is likely that physicians are not recording all responses to inquiries about family history, although the extent of this underreporting is unknown.

CONCLUSION

Findings in this chart review study are consistent with previous work showing that the quantity and type of family history currently being recorded in primary care charts are not adequate to fully assess familial risk. Bridging the gap between recommendations and actual practice will demand interventions to alter primary care practice or the introduction of new models to gather and analyze family data. Further research is also needed to evaluate the impact of improved family history taking on health care costs and outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Howard Rabinowitz, MD, for providing helpful suggestions in the development and execution of this project and Aliza Mansolino for the preparation of the manuscript.

1. Brownson RC, Davis JR, Simms SG, Kern TG, Harmon RG. Cancer control knowledge and priorities among primary care physicians. J Cancer Educ 1993;8:35-41.

2. Emery J, Rose P. Expanding the role of the family history in primary care (editorial). Br J Gen Pract 1999;49(441):260-1.

3. Smith RA, von Eschenbach AC, Wender RC, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer: update of early detection guidelines for prostate, colorectal, and endometrial cancers. CA Cancer J Clin 2001;51:38-75.

4. Polednak AP. Screening for colorectal cancer by primary-care physicians in Long Island (New York) and Connecticut. Cancer Detect Prev 1989;13:301-9.

5. Acton RT, Burst NM, Casebeer L, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of Alabama’s primary care physicians regarding cancer genetics. Acad Med 2000;75:850-2.

6. Summerton N, Garrood PV. The family history in family practice: a questionnaire study. Fam Pract 1997;14:285-8.

7. Del Mar C, Lowe JB, Adkins P, Arnold E. What is the quality of general practitioner records in Australia? Aust Fam Phys 1996;suppl 1:S21-5.

8. Medalie JH, Zyzanski SJ, Langa D, Stange KC. The family in family practice: is it a reality?. J Fam Pract 1998;46:390-6.

9. Medalie JH, Zyzanski SJ, Goodwin MA, Stange KC. Two physician styles of focusing on the family. J Fam Pract 2000;49:209-15.

10. de Bock GH, Perk DC, Oosterwijk JC, Hageman GC, Kievit J, Springer MP. Women worried about their familial breast cancer risk-a study on genetic advice in general practice. Fam Pract 1997;14:40-3.

11. Graham ID, Logan DM, Hughes-Benzie R, et al. How interested is the public in genetic testing for colon cancer susceptibility? Report of a cross-sectional population survey. Cancer Prev Control 1998;2:167-72.

12. Bosompra K, Flynn BS, Ashikaga T, Rairikar CJ, Worden JK, Solomon LJ. Likelihood of undergoing genetic testing for cancer risk: a population-based study. Prev Med 2000;30:155-66.

13. Kinney AY, Choi YA, DeVellis B, Kobetz E, Millikan RC, Sandler RS. Interest in genetic testing among first-degree relatives of colorectal cancer patients. Am J Prev Med 2000;18:249-52.

14. Petersen GM, Larkin E, Codori AM, et al. Attitudes toward colon cancer gene testing: survey of relatives of colon cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1999;8(4 pt 2):337-44.

15. Statement of the American Society of Clinical Oncology: genetic testing for cancer susceptibility, adopted on February 20, 1996. J Clin Oncol 1996;14:1730-6.

16. Rogers J, Halloway R. Completion rate and reliability of the self-administered genogram. Fam Pract 1990;7:149-51.

17. Rogers J, Durkin M, Kelly K. The family genogram: an underutilized clinical tool. N J Med 1985;82:887-92.

18. Rogers J, Durkin M. The semi-structured genogram interview: I. Protocol, II. Evaluation. Fam Syst Med 1984;2:176-87.

19. Shore WB, Wilkie HA, Croughan-Minihane M. Family of origin genograms: evaluation of a teaching program for medical students. Fam Med 1994;26:238-43.

20. Physicians lax in screening patients with family history of adenomatous polyps. Reuters Health 2000;May 22.

Address reprint requests to Randa Sifri, MD, Department of Family Medicine, 1015 Walnut Street, Suite 401, Philadelphia, PA 19107. E-mail: [email protected].

To submit a letter to the editor on this topic, click here: [email protected].

OBJECTIVE: To determine whether an adequate amount of family history is being collected and recorded by family practitioners to appropriately identify patients at increased risk for cancer.

STUDY DESIGN: Retrospective chart audit.

POPULATION: Charts from 500 randomly chosen patients, 40 to 60 years of age, were audited. Of those charts, 400 were from a large academic family practice and 50 charts each were from 2 small community family practices in the greater Philadelphia area.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: General features of family history taking were recorded, including presence of a family history and date when recorded, evidence of updated family history data, and presence of a genogram. Cancer features recorded included mention of family history of cancer or colon polyps and, if positive, identification of which relative was affected, site of cancer, and age of diagnosis or death.

RESULTS: Most charts (89%) had some family history information recorded, and 55% listed a family history of cancer, either positive or negative. Of the 356 relatives affected with cancer, an age of diagnosis was documented in only 8%; of 183 first-degree relatives with cancer, only 7% had a documented age of diagnosis. Two percent of all charts had any mention of a family history of colon polyps. Sixty-five percent of family histories were recorded at the first visit, and only 35% had any updated family history information.

CONCLUSIONS: The number and type of family histories currently being recorded by family practitioners are not adequate to fully assess familial risk of cancer. New strategies will need to be developed to better prepare providers for risk-based clinical decision making.

Taking a family history is a significant component of providing comprehensive primary care because family history provides key psychosocial and medical risk information.1,2 As our understanding of the genetic basis for disease grows, obtaining an accurate and complete family history is likely to gain increasing relevance as a vital source of data to guide counseling and testing. Patients who have a first-degree relative with a colon neoplasm or prostate cancer are advised to screen differently from those who do not.3 Failure to gather accurate or complete family data prevents the clinician from providing advice that is consistent with screening guidelines. Understanding how primary care clinicians gather family history data is necessary to identify gaps in current performance and to develop strategies to bridge these gaps.

Several studies have used physician self-report to assess the current level of taking a family history in primary care. In 1 study, 90% of surveyed physicians stated that they obtain a family history of cancer from their patients, with 77% to 80% inquiring about a family history of colorectal cancer in their patients who are at least 40 years of age.3 In another study, 63% to 85% of responding physicians reported obtaining a family history of cancer from 76% to 100% of their patients.5 Respondents in 1 study reported obtaining family histories of colorectal cancer in only 30.7% of patients, breast cancer in 48.4% of patients, and coronary disease and hypertension in 94.3% of patients.6 However, data on actual performance of family history taking are sparse.7,8 The physicians in the Direct Observation of Primary Care study obtained a family history during 51% of new visits and 22% of established visits. A genogram was present in 11% of charts, and documentation of a family history of breast cancer or colorectal cancer was found in 40% of charts. Further analysis from this study showed that providers who more frequently obtained and recorded family history information performed more preventive care services for their patients.9

First-degree relatives of cancer patients appear to be interested in and receptive to information about their risk and in the possibility of genetic counseling.10-14 In fact, many patients overestimate their likelihood of getting cancer based on family history10; primary care providers thus have the opportunity to counsel and relieve anxiety in their patients. Family history is an important tool to define risk and guide referral, counseling, and testing.

This article presents the findings of a descriptive study of the review of 500 charts from 3 different family practice offices. We documented general family history components and completeness related to a family history of cancer, including whether enough family history information was collected to appropriately identify patients at increased risk for cancer.

Methods

Data were collected from 500 patient charts from 3 family practice offices in the greater Philadelphia area. Patients who were in the practice for at least 1 year, made a minimum of 2 visits between June 1, 1997 and June 1, 2000, and were between the ages of 40 and 60 years at 1 of those visits were included. Fifty charts were selected by using a random starting point at each of 2 small (1 to 3 providers) private practices, and 400 charts were randomly selected from all eligible charts in a large academic practice (more than 60 providers). The large practice had nearly 1500 patients who fit the selection criteria, and the total population did not differ from the random sample in mean age, sex, or race (P < .05). Total population characteristics were not available for the 2 smaller practices.

Family history data were collected from progress notes and designated family history spaces on flow sheets or chart covers. Family histories consisting only of “none” or “noncontributory” were counted only when they clearly referred to a specific condition. Family births or deaths recorded in a psychosocial context also were not counted as part of the family history unless death from a specific disease was mentioned. The first dated family history was considered to be first for the purpose of this study. Date of birth, race, sex, current primary care provider, if any, and the date first seen in the practice were recorded. The current primary care provider was determined by the physician seen for the majority of recent visits and/or notations in the chart at acute visits. Data collected for the primary care providers included practice site, sex, level of training, and years in practice. Variables collected from family history information included: date of first family history; date of most recent family history; presence of a genogram, presence of a patient-completed family history self-questionnaire; whether any mention was made, positive or negative, of cancer or colon polyps; and whether there was a positive family history of cancer or colon polyps. For individuals with a positive family history of cancer or colon polyps, all details recorded in the chart were abstracted; these included site of cancer or polyp, relationship to patient, age at diagnosis, and age at death. The data were entered into an Access 97 database and stored separately from chart number identifiers. All analyses and tests were done in SAS version 6.12.

Results

Demographic data from the 500 patients whose charts were audited are presented in Table 1. Ninety-seven percent of patients had a primary care provider, which included 60 physicians and 3 nurse practitioners. No significant associations were seen with practice site, sex, or level of training of the provider and the presence of family history information in the chart.

Most patients (89%) had some family history information in the chart and 63% had a genogram. This did not differ by sex or race of the patient. Fifty-seven percent of patients supplied family history information at the first visit to the office; 59% of these patients had no family history data recorded on subsequent visits. Only 31% of charts had updated family history information Table 2. For patients who had been in the same practice for at least 5 years and had some family history in the chart, 20% had some updated information within the past 3 years.

Of the 500 charts, 276 (55%) recorded a family history of cancer, positive or negative. Two hundred fifteen patients (43%) had a positive family history of cancer, with a total of 356 relatives affected. The site of cancer was listed for 88% of all family member cancers, with breast, colon, lung, and prostate being the most common cancer locations. The specific relative was identified in 92% of cases, with most being first (51%) or second (37%) degree. Although degree of relative and cancer location were usually recorded, age at diagnosis was listed for only 8% of affected relatives, and age at death was identified for 19% of relatives with cancer.

For patients with affected first-degree relatives, the group with the greatest clinical significance, primary care providers identified the location of the cancer in 93% of cases but listed the ages at diagnosis and death in only 7% and 31%, respectively Table 3. Only 7 medical records (1.4%) had any mention of a family history of polyps; of these, 5 (1%) were positive. None listed an age at diagnosis. Five patients in our study met the American Society of Clinical Oncology criteria to be evaluated for genetic breast and ovarian cancer syndrome, and no patients met the criteria for hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer.

The 2 community practices intermittently used patient self-administered medical intake questionnaires. In our sample, 31 of 500 patients (6%) had a questionnaire in the chart. All patients who completed questionnaires had family history data in their charts. Use of a questionnaire was associated with a greater likelihood that the physician recorded the age of diagnosis for a relative with cancer, although this did not reach significance (20% vs 7%).

Discussion

Despite our finding that providers are documenting family histories in most charts, very few are recording the age of diagnosis in relatives diagnosed with cancer. Age of diagnosis plays a critical role in determining screening recommendations and identifying patients with possible genetic syndromes. For example, the Amsterdam criteria used to identify families with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer include knowing whether 1 of 3 relatives with colorectal cancer was diagnosed at younger than 50 years. Breast and ovarian cancer syndrome should be suspected when breast and/or ovarian cancer is diagnosed in 2 first-degree relatives younger than 50 years.15

Most physicians obtain family histories at initial visits. If the patient’s initial visit is for symptom- or disease-related care, an opportunity to gather family history data may be lost. New tools to consistently capture comprehensive family history data at this first visit may be beneficial. Patient self-administered intake questionnaires may prove valuable in this respect, but only 6% of charts in our study contained such a questionnaire, so we cannot draw conclusions about its impact. We did observe a trend toward gathering more complete family history data in patients who used a questionnaire.

There are no clear guidelines regarding when to update a family history. We arbitrarily chose 3 years as a reasonable period for primary care providers to explore changes in family history status. Updating at any subsequent visit was recorded for 35% of patient charts in which a family history was initially taken. It is not clear that primary care providers are documenting changes in family history in any systematic way. Opportunistic updating likely occurs when a new diagnosis of serious disease in a close family member produces anxiety, stress, or concern in the patient. The value of updating family history and the ideal interval to reexamine family history are unknown.

Several conditions would need to be met for family history updating to have value. (1) A close relative must have developed an important illness in the interval since the last family history was recorded or the update must discover family information that was previously missed. (2) The illness must have a familial component that affects the estimate of the risk of the identified patient. (3) The clinician would need to be aware of the updated information. (4) The clinician must change recommendations to the patient based on this new information. Discovering a new family history of colonic neoplasm satisfies these conditions. Process measures that have the potential to improve updating include adding an update of family history as an item on a preventive care flow sheet or using periodic self-administered patient questionnaires. Whether adequate improvements in health care would occur to justify these changes in process will need to be studied. If any updating has value, determining the appropriate intervals for systematic updates deserves attention.

Charts in this study included a genogram 63% of the time, a significant increase over the 11% noted in the Direct Observation of Primary Care study.9 This discrepancy may be explained by differences in practice types because 1 study suggested a higher genogram use in academic medical centers than in community practices.16 The genogram has been cited as an attractive and efficient way to document family history,17,18 but over one fourth of the charts that contained family history in our study used the more cumbersome narrative form. Many geneticists predict that our ability to apply genetic testing will grow dramatically over the next decade. Optimal application of this new knowledge will rely on the health care system’s capacity to accurately identify risk based on assessment of family history. The 3-generation pedigree is likely to be a key tool in finding individuals who may benefit from testing. However, there is currently no standardized education in family history taking in many undergraduate and graduate medical education programs.19

Although patients with a first-degree relative with a history of polyps diagnosed at younger than 60 years are considered to be at increased risk for colorectal cancer,3 providers infrequently asked about a family history of polyps. This may reflect a recent finding that only 36% of primary care providers recommend screening at the age of 40 years for their patients with a family history of polyps in relatives younger than 60 years.20 In fact, family history data do not consistently influence behavior: in the same study, gastroenterologists asked about a family history of polyps 93% of the time, but only 37% recommended earlier screening in those with such a history.

The study is limited in its use of only 3 primary care practices, 1 of which was a large academic family practice. However, because the charts of 63 different clinicians were represented, a range of educational backgrounds and personal philosophies toward family history taking was included. Most patients (97%) had a clearly identified primary care provider and patients had been members of the practice for an average of 7.6 years. The sample was specifically chosen to review the charts of individuals who had been enrolled in the same practice for at least 1 year. This may explain the higher rates of family history taking found in this study compared with previously published studies. Given that the vast majority of charts did contain some family history, it is even more compelling that age at diagnosis of cancer was inadequately recorded. This study reflected only what was documented in the patient chart and not direct observation of physician behavior regarding the family history. It is likely that physicians are not recording all responses to inquiries about family history, although the extent of this underreporting is unknown.

CONCLUSION

Findings in this chart review study are consistent with previous work showing that the quantity and type of family history currently being recorded in primary care charts are not adequate to fully assess familial risk. Bridging the gap between recommendations and actual practice will demand interventions to alter primary care practice or the introduction of new models to gather and analyze family data. Further research is also needed to evaluate the impact of improved family history taking on health care costs and outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Howard Rabinowitz, MD, for providing helpful suggestions in the development and execution of this project and Aliza Mansolino for the preparation of the manuscript.

OBJECTIVE: To determine whether an adequate amount of family history is being collected and recorded by family practitioners to appropriately identify patients at increased risk for cancer.

STUDY DESIGN: Retrospective chart audit.

POPULATION: Charts from 500 randomly chosen patients, 40 to 60 years of age, were audited. Of those charts, 400 were from a large academic family practice and 50 charts each were from 2 small community family practices in the greater Philadelphia area.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: General features of family history taking were recorded, including presence of a family history and date when recorded, evidence of updated family history data, and presence of a genogram. Cancer features recorded included mention of family history of cancer or colon polyps and, if positive, identification of which relative was affected, site of cancer, and age of diagnosis or death.

RESULTS: Most charts (89%) had some family history information recorded, and 55% listed a family history of cancer, either positive or negative. Of the 356 relatives affected with cancer, an age of diagnosis was documented in only 8%; of 183 first-degree relatives with cancer, only 7% had a documented age of diagnosis. Two percent of all charts had any mention of a family history of colon polyps. Sixty-five percent of family histories were recorded at the first visit, and only 35% had any updated family history information.

CONCLUSIONS: The number and type of family histories currently being recorded by family practitioners are not adequate to fully assess familial risk of cancer. New strategies will need to be developed to better prepare providers for risk-based clinical decision making.

Taking a family history is a significant component of providing comprehensive primary care because family history provides key psychosocial and medical risk information.1,2 As our understanding of the genetic basis for disease grows, obtaining an accurate and complete family history is likely to gain increasing relevance as a vital source of data to guide counseling and testing. Patients who have a first-degree relative with a colon neoplasm or prostate cancer are advised to screen differently from those who do not.3 Failure to gather accurate or complete family data prevents the clinician from providing advice that is consistent with screening guidelines. Understanding how primary care clinicians gather family history data is necessary to identify gaps in current performance and to develop strategies to bridge these gaps.

Several studies have used physician self-report to assess the current level of taking a family history in primary care. In 1 study, 90% of surveyed physicians stated that they obtain a family history of cancer from their patients, with 77% to 80% inquiring about a family history of colorectal cancer in their patients who are at least 40 years of age.3 In another study, 63% to 85% of responding physicians reported obtaining a family history of cancer from 76% to 100% of their patients.5 Respondents in 1 study reported obtaining family histories of colorectal cancer in only 30.7% of patients, breast cancer in 48.4% of patients, and coronary disease and hypertension in 94.3% of patients.6 However, data on actual performance of family history taking are sparse.7,8 The physicians in the Direct Observation of Primary Care study obtained a family history during 51% of new visits and 22% of established visits. A genogram was present in 11% of charts, and documentation of a family history of breast cancer or colorectal cancer was found in 40% of charts. Further analysis from this study showed that providers who more frequently obtained and recorded family history information performed more preventive care services for their patients.9

First-degree relatives of cancer patients appear to be interested in and receptive to information about their risk and in the possibility of genetic counseling.10-14 In fact, many patients overestimate their likelihood of getting cancer based on family history10; primary care providers thus have the opportunity to counsel and relieve anxiety in their patients. Family history is an important tool to define risk and guide referral, counseling, and testing.

This article presents the findings of a descriptive study of the review of 500 charts from 3 different family practice offices. We documented general family history components and completeness related to a family history of cancer, including whether enough family history information was collected to appropriately identify patients at increased risk for cancer.

Methods

Data were collected from 500 patient charts from 3 family practice offices in the greater Philadelphia area. Patients who were in the practice for at least 1 year, made a minimum of 2 visits between June 1, 1997 and June 1, 2000, and were between the ages of 40 and 60 years at 1 of those visits were included. Fifty charts were selected by using a random starting point at each of 2 small (1 to 3 providers) private practices, and 400 charts were randomly selected from all eligible charts in a large academic practice (more than 60 providers). The large practice had nearly 1500 patients who fit the selection criteria, and the total population did not differ from the random sample in mean age, sex, or race (P < .05). Total population characteristics were not available for the 2 smaller practices.

Family history data were collected from progress notes and designated family history spaces on flow sheets or chart covers. Family histories consisting only of “none” or “noncontributory” were counted only when they clearly referred to a specific condition. Family births or deaths recorded in a psychosocial context also were not counted as part of the family history unless death from a specific disease was mentioned. The first dated family history was considered to be first for the purpose of this study. Date of birth, race, sex, current primary care provider, if any, and the date first seen in the practice were recorded. The current primary care provider was determined by the physician seen for the majority of recent visits and/or notations in the chart at acute visits. Data collected for the primary care providers included practice site, sex, level of training, and years in practice. Variables collected from family history information included: date of first family history; date of most recent family history; presence of a genogram, presence of a patient-completed family history self-questionnaire; whether any mention was made, positive or negative, of cancer or colon polyps; and whether there was a positive family history of cancer or colon polyps. For individuals with a positive family history of cancer or colon polyps, all details recorded in the chart were abstracted; these included site of cancer or polyp, relationship to patient, age at diagnosis, and age at death. The data were entered into an Access 97 database and stored separately from chart number identifiers. All analyses and tests were done in SAS version 6.12.

Results

Demographic data from the 500 patients whose charts were audited are presented in Table 1. Ninety-seven percent of patients had a primary care provider, which included 60 physicians and 3 nurse practitioners. No significant associations were seen with practice site, sex, or level of training of the provider and the presence of family history information in the chart.

Most patients (89%) had some family history information in the chart and 63% had a genogram. This did not differ by sex or race of the patient. Fifty-seven percent of patients supplied family history information at the first visit to the office; 59% of these patients had no family history data recorded on subsequent visits. Only 31% of charts had updated family history information Table 2. For patients who had been in the same practice for at least 5 years and had some family history in the chart, 20% had some updated information within the past 3 years.

Of the 500 charts, 276 (55%) recorded a family history of cancer, positive or negative. Two hundred fifteen patients (43%) had a positive family history of cancer, with a total of 356 relatives affected. The site of cancer was listed for 88% of all family member cancers, with breast, colon, lung, and prostate being the most common cancer locations. The specific relative was identified in 92% of cases, with most being first (51%) or second (37%) degree. Although degree of relative and cancer location were usually recorded, age at diagnosis was listed for only 8% of affected relatives, and age at death was identified for 19% of relatives with cancer.

For patients with affected first-degree relatives, the group with the greatest clinical significance, primary care providers identified the location of the cancer in 93% of cases but listed the ages at diagnosis and death in only 7% and 31%, respectively Table 3. Only 7 medical records (1.4%) had any mention of a family history of polyps; of these, 5 (1%) were positive. None listed an age at diagnosis. Five patients in our study met the American Society of Clinical Oncology criteria to be evaluated for genetic breast and ovarian cancer syndrome, and no patients met the criteria for hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer.

The 2 community practices intermittently used patient self-administered medical intake questionnaires. In our sample, 31 of 500 patients (6%) had a questionnaire in the chart. All patients who completed questionnaires had family history data in their charts. Use of a questionnaire was associated with a greater likelihood that the physician recorded the age of diagnosis for a relative with cancer, although this did not reach significance (20% vs 7%).

Discussion

Despite our finding that providers are documenting family histories in most charts, very few are recording the age of diagnosis in relatives diagnosed with cancer. Age of diagnosis plays a critical role in determining screening recommendations and identifying patients with possible genetic syndromes. For example, the Amsterdam criteria used to identify families with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer include knowing whether 1 of 3 relatives with colorectal cancer was diagnosed at younger than 50 years. Breast and ovarian cancer syndrome should be suspected when breast and/or ovarian cancer is diagnosed in 2 first-degree relatives younger than 50 years.15

Most physicians obtain family histories at initial visits. If the patient’s initial visit is for symptom- or disease-related care, an opportunity to gather family history data may be lost. New tools to consistently capture comprehensive family history data at this first visit may be beneficial. Patient self-administered intake questionnaires may prove valuable in this respect, but only 6% of charts in our study contained such a questionnaire, so we cannot draw conclusions about its impact. We did observe a trend toward gathering more complete family history data in patients who used a questionnaire.

There are no clear guidelines regarding when to update a family history. We arbitrarily chose 3 years as a reasonable period for primary care providers to explore changes in family history status. Updating at any subsequent visit was recorded for 35% of patient charts in which a family history was initially taken. It is not clear that primary care providers are documenting changes in family history in any systematic way. Opportunistic updating likely occurs when a new diagnosis of serious disease in a close family member produces anxiety, stress, or concern in the patient. The value of updating family history and the ideal interval to reexamine family history are unknown.

Several conditions would need to be met for family history updating to have value. (1) A close relative must have developed an important illness in the interval since the last family history was recorded or the update must discover family information that was previously missed. (2) The illness must have a familial component that affects the estimate of the risk of the identified patient. (3) The clinician would need to be aware of the updated information. (4) The clinician must change recommendations to the patient based on this new information. Discovering a new family history of colonic neoplasm satisfies these conditions. Process measures that have the potential to improve updating include adding an update of family history as an item on a preventive care flow sheet or using periodic self-administered patient questionnaires. Whether adequate improvements in health care would occur to justify these changes in process will need to be studied. If any updating has value, determining the appropriate intervals for systematic updates deserves attention.

Charts in this study included a genogram 63% of the time, a significant increase over the 11% noted in the Direct Observation of Primary Care study.9 This discrepancy may be explained by differences in practice types because 1 study suggested a higher genogram use in academic medical centers than in community practices.16 The genogram has been cited as an attractive and efficient way to document family history,17,18 but over one fourth of the charts that contained family history in our study used the more cumbersome narrative form. Many geneticists predict that our ability to apply genetic testing will grow dramatically over the next decade. Optimal application of this new knowledge will rely on the health care system’s capacity to accurately identify risk based on assessment of family history. The 3-generation pedigree is likely to be a key tool in finding individuals who may benefit from testing. However, there is currently no standardized education in family history taking in many undergraduate and graduate medical education programs.19

Although patients with a first-degree relative with a history of polyps diagnosed at younger than 60 years are considered to be at increased risk for colorectal cancer,3 providers infrequently asked about a family history of polyps. This may reflect a recent finding that only 36% of primary care providers recommend screening at the age of 40 years for their patients with a family history of polyps in relatives younger than 60 years.20 In fact, family history data do not consistently influence behavior: in the same study, gastroenterologists asked about a family history of polyps 93% of the time, but only 37% recommended earlier screening in those with such a history.

The study is limited in its use of only 3 primary care practices, 1 of which was a large academic family practice. However, because the charts of 63 different clinicians were represented, a range of educational backgrounds and personal philosophies toward family history taking was included. Most patients (97%) had a clearly identified primary care provider and patients had been members of the practice for an average of 7.6 years. The sample was specifically chosen to review the charts of individuals who had been enrolled in the same practice for at least 1 year. This may explain the higher rates of family history taking found in this study compared with previously published studies. Given that the vast majority of charts did contain some family history, it is even more compelling that age at diagnosis of cancer was inadequately recorded. This study reflected only what was documented in the patient chart and not direct observation of physician behavior regarding the family history. It is likely that physicians are not recording all responses to inquiries about family history, although the extent of this underreporting is unknown.

CONCLUSION

Findings in this chart review study are consistent with previous work showing that the quantity and type of family history currently being recorded in primary care charts are not adequate to fully assess familial risk. Bridging the gap between recommendations and actual practice will demand interventions to alter primary care practice or the introduction of new models to gather and analyze family data. Further research is also needed to evaluate the impact of improved family history taking on health care costs and outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Howard Rabinowitz, MD, for providing helpful suggestions in the development and execution of this project and Aliza Mansolino for the preparation of the manuscript.

1. Brownson RC, Davis JR, Simms SG, Kern TG, Harmon RG. Cancer control knowledge and priorities among primary care physicians. J Cancer Educ 1993;8:35-41.

2. Emery J, Rose P. Expanding the role of the family history in primary care (editorial). Br J Gen Pract 1999;49(441):260-1.

3. Smith RA, von Eschenbach AC, Wender RC, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer: update of early detection guidelines for prostate, colorectal, and endometrial cancers. CA Cancer J Clin 2001;51:38-75.

4. Polednak AP. Screening for colorectal cancer by primary-care physicians in Long Island (New York) and Connecticut. Cancer Detect Prev 1989;13:301-9.

5. Acton RT, Burst NM, Casebeer L, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of Alabama’s primary care physicians regarding cancer genetics. Acad Med 2000;75:850-2.

6. Summerton N, Garrood PV. The family history in family practice: a questionnaire study. Fam Pract 1997;14:285-8.

7. Del Mar C, Lowe JB, Adkins P, Arnold E. What is the quality of general practitioner records in Australia? Aust Fam Phys 1996;suppl 1:S21-5.

8. Medalie JH, Zyzanski SJ, Langa D, Stange KC. The family in family practice: is it a reality?. J Fam Pract 1998;46:390-6.

9. Medalie JH, Zyzanski SJ, Goodwin MA, Stange KC. Two physician styles of focusing on the family. J Fam Pract 2000;49:209-15.

10. de Bock GH, Perk DC, Oosterwijk JC, Hageman GC, Kievit J, Springer MP. Women worried about their familial breast cancer risk-a study on genetic advice in general practice. Fam Pract 1997;14:40-3.

11. Graham ID, Logan DM, Hughes-Benzie R, et al. How interested is the public in genetic testing for colon cancer susceptibility? Report of a cross-sectional population survey. Cancer Prev Control 1998;2:167-72.

12. Bosompra K, Flynn BS, Ashikaga T, Rairikar CJ, Worden JK, Solomon LJ. Likelihood of undergoing genetic testing for cancer risk: a population-based study. Prev Med 2000;30:155-66.

13. Kinney AY, Choi YA, DeVellis B, Kobetz E, Millikan RC, Sandler RS. Interest in genetic testing among first-degree relatives of colorectal cancer patients. Am J Prev Med 2000;18:249-52.

14. Petersen GM, Larkin E, Codori AM, et al. Attitudes toward colon cancer gene testing: survey of relatives of colon cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1999;8(4 pt 2):337-44.

15. Statement of the American Society of Clinical Oncology: genetic testing for cancer susceptibility, adopted on February 20, 1996. J Clin Oncol 1996;14:1730-6.

16. Rogers J, Halloway R. Completion rate and reliability of the self-administered genogram. Fam Pract 1990;7:149-51.

17. Rogers J, Durkin M, Kelly K. The family genogram: an underutilized clinical tool. N J Med 1985;82:887-92.

18. Rogers J, Durkin M. The semi-structured genogram interview: I. Protocol, II. Evaluation. Fam Syst Med 1984;2:176-87.

19. Shore WB, Wilkie HA, Croughan-Minihane M. Family of origin genograms: evaluation of a teaching program for medical students. Fam Med 1994;26:238-43.

20. Physicians lax in screening patients with family history of adenomatous polyps. Reuters Health 2000;May 22.

Address reprint requests to Randa Sifri, MD, Department of Family Medicine, 1015 Walnut Street, Suite 401, Philadelphia, PA 19107. E-mail: [email protected].

To submit a letter to the editor on this topic, click here: [email protected].

1. Brownson RC, Davis JR, Simms SG, Kern TG, Harmon RG. Cancer control knowledge and priorities among primary care physicians. J Cancer Educ 1993;8:35-41.

2. Emery J, Rose P. Expanding the role of the family history in primary care (editorial). Br J Gen Pract 1999;49(441):260-1.

3. Smith RA, von Eschenbach AC, Wender RC, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer: update of early detection guidelines for prostate, colorectal, and endometrial cancers. CA Cancer J Clin 2001;51:38-75.

4. Polednak AP. Screening for colorectal cancer by primary-care physicians in Long Island (New York) and Connecticut. Cancer Detect Prev 1989;13:301-9.

5. Acton RT, Burst NM, Casebeer L, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of Alabama’s primary care physicians regarding cancer genetics. Acad Med 2000;75:850-2.

6. Summerton N, Garrood PV. The family history in family practice: a questionnaire study. Fam Pract 1997;14:285-8.

7. Del Mar C, Lowe JB, Adkins P, Arnold E. What is the quality of general practitioner records in Australia? Aust Fam Phys 1996;suppl 1:S21-5.

8. Medalie JH, Zyzanski SJ, Langa D, Stange KC. The family in family practice: is it a reality?. J Fam Pract 1998;46:390-6.

9. Medalie JH, Zyzanski SJ, Goodwin MA, Stange KC. Two physician styles of focusing on the family. J Fam Pract 2000;49:209-15.

10. de Bock GH, Perk DC, Oosterwijk JC, Hageman GC, Kievit J, Springer MP. Women worried about their familial breast cancer risk-a study on genetic advice in general practice. Fam Pract 1997;14:40-3.

11. Graham ID, Logan DM, Hughes-Benzie R, et al. How interested is the public in genetic testing for colon cancer susceptibility? Report of a cross-sectional population survey. Cancer Prev Control 1998;2:167-72.

12. Bosompra K, Flynn BS, Ashikaga T, Rairikar CJ, Worden JK, Solomon LJ. Likelihood of undergoing genetic testing for cancer risk: a population-based study. Prev Med 2000;30:155-66.

13. Kinney AY, Choi YA, DeVellis B, Kobetz E, Millikan RC, Sandler RS. Interest in genetic testing among first-degree relatives of colorectal cancer patients. Am J Prev Med 2000;18:249-52.

14. Petersen GM, Larkin E, Codori AM, et al. Attitudes toward colon cancer gene testing: survey of relatives of colon cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1999;8(4 pt 2):337-44.

15. Statement of the American Society of Clinical Oncology: genetic testing for cancer susceptibility, adopted on February 20, 1996. J Clin Oncol 1996;14:1730-6.

16. Rogers J, Halloway R. Completion rate and reliability of the self-administered genogram. Fam Pract 1990;7:149-51.

17. Rogers J, Durkin M, Kelly K. The family genogram: an underutilized clinical tool. N J Med 1985;82:887-92.

18. Rogers J, Durkin M. The semi-structured genogram interview: I. Protocol, II. Evaluation. Fam Syst Med 1984;2:176-87.

19. Shore WB, Wilkie HA, Croughan-Minihane M. Family of origin genograms: evaluation of a teaching program for medical students. Fam Med 1994;26:238-43.

20. Physicians lax in screening patients with family history of adenomatous polyps. Reuters Health 2000;May 22.

Address reprint requests to Randa Sifri, MD, Department of Family Medicine, 1015 Walnut Street, Suite 401, Philadelphia, PA 19107. E-mail: [email protected].

To submit a letter to the editor on this topic, click here: [email protected].

Management of the low-grade abnormal Pap smear: What are women’s preferences?

- Any of several approaches may be used in managing women who have low-grade Pap smear abnormalities.

- Women’s preferences for a particular management approach to an abnormal Pap smear vary widely.

- Asking patients specific questions about their desire to avoid procedures and tolerance for uncertainty may help to clarify preferences.

The management of women who have low-grade cytologic abnormalities—including atypical squamous cells (ASC) and low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL)—is controversial.1-4 Without strong evidence favoring a single approach, some clinicians recommend immediate colposcopy to obtain a definitive diagnosis and to exclude the presence of a high-grade lesion, while others recommend observation with serial Pap smears, given the tendency for many low-grade lesions to regress spontaneously.5,6 Immediate colposcopy has the advantage of giving a patient a relatively rapid assessment of the nature and extent of her cervical dysplasia; however, the procedure is uncomfortable, and overall management may not be affected. Observation with serial Pap smears may avoid an invasive procedure, but it may also cause anxiety as time passes without a definitive diagnosis.

Eliciting and understanding patient preferences is an important part of clinical decision making. The clinician provides the best available information on the probability of clinical outcomes and the implications of each for the patient’s health. But only the patient knows what these outcomes mean to her well-being (also called “utility”).

Given the clinical disagreement over how to proceed with abnormal ASC and LSIL Pap smear results, the decision should be influenced by a patient’s preference, informed by knowledge of outcomes and costs of alternative approaches. It is unclear which approach women prefer, and whether women’s preferences for specific protocols are associated with sociodemographic characteristics. To understand better how women weigh these trade-offs, we evaluated the preferences of a diverse group of women for contrasting management approaches to the evaluation of a hypothetical low-grade abnormal Pap smear result.

Methods

Study population

Study participants were recruited from the waiting rooms of 5 family planning clinics in Northern California’s Central Valley. Women were eligible for the study if they were 18 years of age or older, or, if minors, they were emancipated and could thus provide informed consent. Potential subjects were excluded if they spoke neither English nor Spanish or if they had never had a Pap smear. The study protocol and informed consent procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of California, Davis, Human Subjects Committee.

Instruments and outcome measures

Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish. Information regarding demographic characteristics, level of education, past experiences with abnormal Pap smears and cervical cancer, and self-rated religiosity was collected with a self-administered questionnaire. The primary outcome measures were utilities (quantified preferences for specific health states) for 6 different scenarios. These were assessed by the standard gamble (SG) method, described in more detail below.7

Possible utility scores range from 0 to 1. A score of 0 represents immediate death; a score of 1 represents full (or ideal) health for the rest of one’s life. Because the scenarios under consideration in this study did not involve any meaningful level of risk of death, we expected utility scores for the scenarios to cluster toward the upper end of the scale. As a result, a measurement instrument based on an “immediate death” versus “full health” scale would be unable to discriminate between different scenarios. To avoid this problem, a scale was used in which the lower end point was a non-death state unambiguously less preferred than each of the scenarios under consideration.8 We used “invasive cervical cancer requiring hysterectomy” as the lower end point (utility of 0) contrasted with “full health with all normal Pap smears” (utility of 1) to generate the original score (SG Dys). In a separate standard gamble, subjects rated invasive cervical cancer versus immediate death (SG Ca), so that all utilities could be converted to the standard scale, using the formula: (1 – SG Ca) (SG Dys) + SG Ca.

The 6 scenarios rated in the study are shown in Table 1. The scenarios represent 3 sets of progressively more invasive interventions for a low-grade abnormal Pap smear: (1) resolution, representing spontaneous regression with treatment not required; (2) a low-grade abnormality requiring treatment with cryotherapy; (3) a more severe abnormality requiring a cervical cone biopsy. Following either spontaneous resolution or treatment, all scenarios assumed the abnormality was resolved. For each of the 3 results, a management strategy based on observation with serial Pap smears was applied in 1 instance, and a strategy of early colposcopy was applied in the other instance, resulting in 6 different pathways to the ultimate outcome; a normal Pap smear. The time frame for these scenarios was 18–36 months.

Trained interviewers used a standardized approach to elicit preferences from each subject. Subjects were read a description of all the procedures involved in the scenarios. Descriptions were accompanied by cards summarizing each procedure in pictures and words, and included information about the possibility of progression and spontaneous regression of the Pap smear abnormality. Subjects were encouraged to ask questions at any point during the interview. Procedure descriptions are available from the authors on request.

TABLE 1

Clinical scenarios classified by management approach and required treatment*

| Spontaneous resolution | Cryotherapy | Cone biopsy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observation | Pap smear: low-grade abnormal | Pap smear: low-grade abnormal | Pap smear: low-grade abnormal |

| ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |

| Pap smear: normal | Pap smear: low-grade abnormal | Pap smear: normal | |

| ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |

| 2 Pap smears every 6 months: normal | Pap smear: low-grade abnormal | Pap smear: normal | |

| ↓ | ↓ | ||

| Pap smear: low-grade abnormal | Pap smear: normal | ||

| ↓ | ↓ | ||

| Colposcopy and biopsy at 1 month | Colposcopy and biopsy at 1 month | ||

| ↓ | ↓ | ||

| Biopsy: low-grade abnormal | Biopsy: abnormal with ? ECC | ||

| ↓ | ↓ | ||

| Cryotherapy at 1 month | Cone biopsy at 1 month: moderately abnoramal cells | ||

| ↓ | ↓ | ||

| 3 Pap smears every 6 months: normal | Cure with cone biopsy | ||

| ↓ | |||

| 3 Pap smears every 6 months: normal | |||

| Early colposcopy | Pap smear: low-grade abnormal | Pap smear: low-grade abnormal | Pap smear: low-grade abnormal |

| ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |

| Colposcopy and biopsy at 1 month | Colposcopy and biopsy at 1 month | Colposcopy and biopsy at 1 month | |

| ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |

| Biopsy: normal | Biopsy: abnormal with ? ECC | Biopsy: abnormal with ? ECC | |

| ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |

| Second colposcopy and biopsy | Cone biopsy at 1 month | Cone biopsy at 1 month | |

| ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |

| Biopsy: normal | Biopsy: moderately abnormal | Biopsy: moderately abnormal | |

| ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |

| 2 Pap smears every 6 months: normal | Cure with cone biopsy | Cure with cone biopsy | |

| ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |

| Pap smear: low-grade abnormal | Colposcopy: normal | Colposcopy: normal | |

| ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |

| Colposcopy and biopsy at 1 month | 2 Pap smears every 6 months: normal | 2 Pap smears every 6 months: normal | |

| ↓ | |||

| Biopsy: low-grade abnormal | |||

| ↓ | |||

| Colposcopy: normal | |||

| ↓ | |||

| 2 Pap smears every 6 months: normal | |||

| *Intervals are 6 months unless specified otherwise. ECC, endocervical curettage. | |||

Standard gamble

Subjects were asked their preference between the certainty of the scenario under consideration and an uncertain prospect of either having cervical cancer treated by hysterectomy or full health. A probability wheel was used as visual aid.9 The probability of cervical cancer was altered until the subject was indifferent between the certain scenario and the uncertain prospect. Once all 6 scenarios had been scored, each subject was asked about her preference between the certainty of cervical cancer treated by hysterectomy and the uncertain prospect of immediate death or full health, using the same method.

At the end of the interview, both the subject and the interviewer completed evaluation forms including ratings of how well the subject understood the standard gamble rating exercises. Subject confusion was also defined a priori as those placing a higher utility on scenario 3 (observation for a long period followed by cone biopsy), which represented the longest period of uncertainty followed by the most invasive procedure, than on scenario 1 (a single mildly abnormal Pap smear evaluated by observation which then resolved spontaneously), which represented the absence of any invasive procedure.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated for ratings of each scenario for the entire group and with the confused subjects removed. Confused subjects included those who reported they found the interview “very confusing,” those who were recorded by the interviewer as finding the interview “very confusing,” and those whose rankings met the criteria for subject confusion, as described above. Means, standard deviations, medians, and percentiles were calculated for each scenario. The mean differences in adjusted standard gamble ratings between paired scenarios was evaluated using a t distribution. Multiple regression analyses were used to explore how much between-subject variation in the standard gamble scores was explained by the variables listed above.

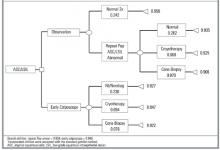

A simple decision tree (Figure 1) was constructed to contrast preferences for an observational approach vs early colposcopy. Outcome probabilities were derived from meta-analyses of the medical literature,5 from observational data obtained at the same Northern California family planning clinics,10 and, for cone biopsy outcomes, from expert opinion obtained using a modified Delphi process.11 Utilities were assigned to the decision tree based on the standard gamble results. Women having 2 consecutive low-grade abnormal Pap results followed by a normal Pap result were assigned the same utility value as that for women with a single abnormal result. Analysis of the tree, including 1-way and 2-way sensitivity analysis of key variables, was conducted with Data 3.5.

Results

One hundred seventy interviews were completed. Characteristics of the interview subjects are shown in Table 2. A total of 22 subjects were designated “confused.” Analyses including the confused subjects did not alter the pattern of results, but the range in responses was larger. All analyses are presented here with confused subjects removed (n = 148).

Median ratings with 25th–75th percentiles for the paired scenarios rated by the standard gamble are shown as box plots in Figure 2. Mean adjusted scores, standard deviations, and mean differences in scores between paired scenarios are shown in Table 3. Notable findings include the following. (1) For each scenario, the range of responses by either rating method was very large. (2) Mean differences in utilities for observation vs early colposcopy were small. (3) For the paired scenarios in which the outcome was spontaneous resolution, observation was preferred (P = .01); in the paired scenarios in which the outcome was cryotherapy, early colposcopy was preferred (P = .02). (4) In the multiple regression analyses for each scenario, age, education, ethnicity, religiosity, and having known someone with cervical cancer together explained only a small amount of the variability between subjects (range for R2, .09–.22).

The decision model with baseline probabilities is shown in Figure 1. The model was simplified to exclude the outcome of cervical cancer, which is a very rare outcome for women with ASC or LSIL cervical smears who have adequate follow-up.5 In the baseline analysis, the overall utility of early colposcopy was slightly favored over the overall utility of the observation approach (utility of observation = 0.932; utility of early colposcopy = 0.940).

Sensitivity analysis examines the effect of varying elements of the model on the outcome. In sensitivity analyses of probabilities, the early colposcopy branch was favored, but the differences were small. The maximum difference in utilities between branches was 0.012 in these sensitivity analyses. In 1-way sensitivity analysis of branch utilities, threshold utility values to favor the observation branch were 0.986 for spontaneous resolution after observation and 0.898 for early colposcopy. Threshold values for cryotherapy were 0.938 for observation and 0.938 for early colposcopy.

TABLE 2

Characteristics of study subjects (n = 170)

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Mean age (range), y | 26 (14–53) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 58 (34%) |

| High school | 77 (45%) |

| Some college | 35 (20%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| African American | 21 (12%) |

| Caucasian | 84 (49%) |

| Latina | 46 (27%) |

| Other | 21 (12%) |

| Interview language, Spanish | 15 (9%) |

| Prior colposcopy | 23 (14%) |

| Moderately or very religious | 64 (38%) |

| Knows someone with cervical cancer | 43 (25%) |

TABLE 3

Adjusted standard gamble values and paired differences* (n=148)

| Management Strategy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-term outcome | Observation Mean (SD) | Early colposcopy Mean (SD) | Difference | P value (2 sided) |

| Spontaneous resolution | .96 ±..13) | .93±.20) | .03 ±..15) | .01 |

| Cryotherapy | .93 ±..17) | .95 ±..14) | -.02 ±.11) | .02 |

| Cone biopsy | .91 ±..21) | .92 ±..16) | -.02 ±..17) | .23 |

| *Adjusted to scale so that immediate death had a utility of 0 and “full health with all normal Pap smears” had a utility of 1. | ||||

FIGURE 1Decision model comparing observation with early colposcopy *

FIGURE 2Distribution of individual utilities as assessed by the standard gamble*

Discussion

We found wide variation in women’s preferences for management approaches to a low-grade abnormal Pap smear result. The range of responses was very large and the variation between individuals rating the same scenario was substantially greater than the variation in mean ratings between different scenarios. Measured subject characteristics explained only a small proportion of the observed variation, indicating that other unmeasured factors contributed substantially to the variation. Although 25% of subjects stated they knew someone with cervical cancer, this high percentage seems improbable and more likely reflects knowledge of someone who had an abnormal Pap smear.

The decision model displayed a small preference for immediate colposcopy. This may be related to preference for quicker resolution of the concern about cancer, although it involves more procedures. Small changes in utilities for spontaneous resolution and cryotherapy influenced the model to prefer observation. For cryotherapy, these utility values were within 1 standard deviation of the mean.

Our finding of a wide variation in preferences is supported by other patient preference studies,12-14 including 2 on this subject. Ferris et al assessed triage preferences for the evaluation and management ASC and LSIL.13 They used a questionnaire with a sample of 968 women who presented for care at obstetrics and gynecology and family practice clinics. They found that more women preferred repeat Pap smear when the index smear was ASC, and more women preferred colposcopy when the index smear was LSIL. Among a group of 136 Canadian women with atypia or LSIL referred for colposcopy, Meana et al found that 64% preferred early colposcopy, while 17% preferred observation and 17% had no strong preference.14

The factors contributing to patient preferences are complex. Differences in preferences may be influenced by knowledge and understanding of the disease and possible interventions, risk aversion, access to services, socioeconomics, cultural background, and other factors. While 1 patient may be most interested in establishing a definitive diagnosis and undergoing treatment as soon as possible, another may place priority on avoiding invasive or uncomfortable procedures. How differences in patient preferences influence clinical choices is highlighted by the work of Kuppermann et al.15 These investigators found that utilities for outcomes of prenatal diagnostic testing predicted subsequent testing behavior.

Our findings are limited by our use of a convenience sample of women attending family planning clinics. They may not be representative of women’s preferences in general, or even those of women attending family planning clinics. Outcomes in our study were specified during the preference assessment process; in real decision making, the outcome is always unknown at the time the decision is made. We did not include HPV typing as an option in our clinical scenarios. While HPV typing may have a role for triage of ASC,6,16 it appears not to be useful in management of LSIL.17

Cost-effectiveness analysis would offer important information about which management approach might be favored in the context of resource allocation. For decision making by individual patients and doctors, however, decision analysis is often more relevant. In this case, the “preferred” decision is very sensitive to patient utilities, emphasizing the need for clear physician-patient communication.

Strengths of our study include the diversity of the subjects, the formal process for preference assessment, and the paired scenarios, which allow assessment of preferences for a single management decision, in which 2 separate paths lead to an equivalent ultimate outcome. Our findings are consistent with previous work showing that the sequence of events leading to an outcome will influence utilities for the outcome.18

Application to clinical practice

How might our findings be translated into clinical practice? In clinical situations where different approaches to management are unlikely to result in substantial outcome differences (a “toss-up”), patient preferences are a key aspect of the decision-making process.19 For women with lowgrade Pap abnormalities, several diagnostic options are available and no single option is strongly supported by evidence to offer better outcomes. Our study indicates that no single option is preferred by most women. Under these conditions, engaging the patient in the decision-making process may produce better health outcomes.20 Clinicians should anticipate highly varied preferences, and will need to adopt a flexible approach. Not all patients will want to be actively involved in the decision process, but the desire for information is nearly universal. Flexible use of the questions in Table 4 may help patients to define their preferences and will likely improve their satisfaction and adherence to the treatment plan.

TABLE 4

Questions for patients with an abnormal Pap smear

| What is your understanding of what it means for you to have an abnormal Pap smear showing _____________? |