User login

Prostate Cancer Surveillance After Radiation Therapy in a National Delivery System (FULL)

Guideline concordance with PSA surveillance among veterans treated with definitiveradiation therapy was generally high, but opportunities may exist to improve surveillance among select groups.

Guidelines recommend prostate-specific antigen (PSA) surveillance among men treated with definitive radiation therapy (RT) for prostate cancer. Specifically, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends testing every 6 to 12 months for 5 years and annually thereafter (with no specific stopping period specified), while the American Urology Association recommends testing for at least 10 years, with the frequency to be determined by the risk of relapse and patient preferences for monitoring.1,2 Salvage treatments exist for men with localized recurrence identified early through PSA testing, so adherence to follow-up guidelines is important for quality prostate cancer survivorship care.1,2

However, few studies focus on adherence to PSA surveillance following radiation therapy. Posttreatment surveillance among surgical patients is generally high, but sociodemographic disparities exist. Racial and ethnic minorities and unmarried men are less likely to undergo guideline concordant surveillance than is the general population, potentially preventing effective salvage therapy.3,4 A recent Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) study on posttreatment surveillance included radiation therapy patients but did not examine the impact of younger age, concurrent androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), or treatment facility (ie, diagnosed and treated at the same vs different facilities, with the latter including a separate VA facility or the community) on surveillance patterns.5 The latter is particularly relevant given increasing efforts to coordinate care outside the VA delivery system supported by the 2018 VA Maintaining Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act. Furthermore, these patient, treatment, and delivery system factors may each uniquely contribute to whether patients receive guideline-recommended PSA surveillance after prostate cancer treatment.

For these reasons, we conducted a study to better understand determinants of adherence to guideline-recommended PSA surveillance among veterans undergoing definitive radiation therapy with or without concurrent ADT. Our study uniquely included both elderly and nonelderly patients as well as investigated relationships between treatment at or away from the diagnosing facility. Although we found high overall levels of adherence to PSA surveillance, our findings do offer insights into determinants associated with worse adherence and provide opportunities to improve prostate cancer survivorship care after RT.

Methods

This study population included men with biopsy-proven nonmetastatic incident prostate cancer diagnosed between January 2005 and December 2008, with follow-up through 2012, identified using the VA Central Cancer Registry. We included men who underwent definitive RT with or without concurrent ADT injections, determined using the VA pharmacy files. We excluded men with a prior diagnosis of prostate or other malignancy (given the presence of other malignancies might affect life expectancy and surveillance patterns), hospice enrollment within 30 days, diagnosis at autopsy, and those treated with radical prostatectomy. We extracted cancer registry data, including biopsy Gleason score, pretreatment PSA level, clinical tumor stage, and whether RT was delivered at the patient’s diagnosing facility. For the latter, we used data on radiation location coded by the tumor registrar. We also collected demographic information, including age at diagnosis, race, ethnicity, marital status, and ZIP code. We used diagnosis codes to determine Charlson comorbidity scores similar to prior studies.6-8

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was receipt of guideline concordant annual PSA surveillance in the initial 5 years following RT. We used laboratory files within the VA Corporate Data Warehouse to identify the date and value for each PSA test after RT for the entire cohort. Specifically, we defined the surveillance period as 60 days after initiation of RT through December 31, 2012. We defined guideline concordance as receiving at least 1 PSA test for each 12-month period after RT.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize our cohort of veterans with prostate cancer treated with RT with or without concurrent ADT. To handle missing data, we performed multiple imputation, generating 10 imputations using all baseline clinical and demographic variables, year of diagnosis, and the regional VA network (ie, the Veterans Integrated Services Network [VISN]) for each patient.

Next, we calculated the annual guideline concordance rate for each year of follow-up for each patient, for the overall cohort, as well as by age, race/ethnicity, and concurrent ADT use. We examined bivariable relationships between guideline concordance and baseline demographic, clinical, and delivery system factors, including year of diagnosis and whether patients were treated at the diagnosing facility, using multilevel logistic regression modeling to account for clustering at the patient level.

Analyses were performed using Stata Version 15 (College Station, TX). We considered a 2-sided P value of < .05 as statistically significant. This study was approved by the VA Ann Arbor Health Care System Institution Review Board.

Results

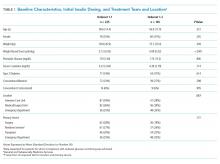

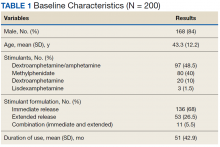

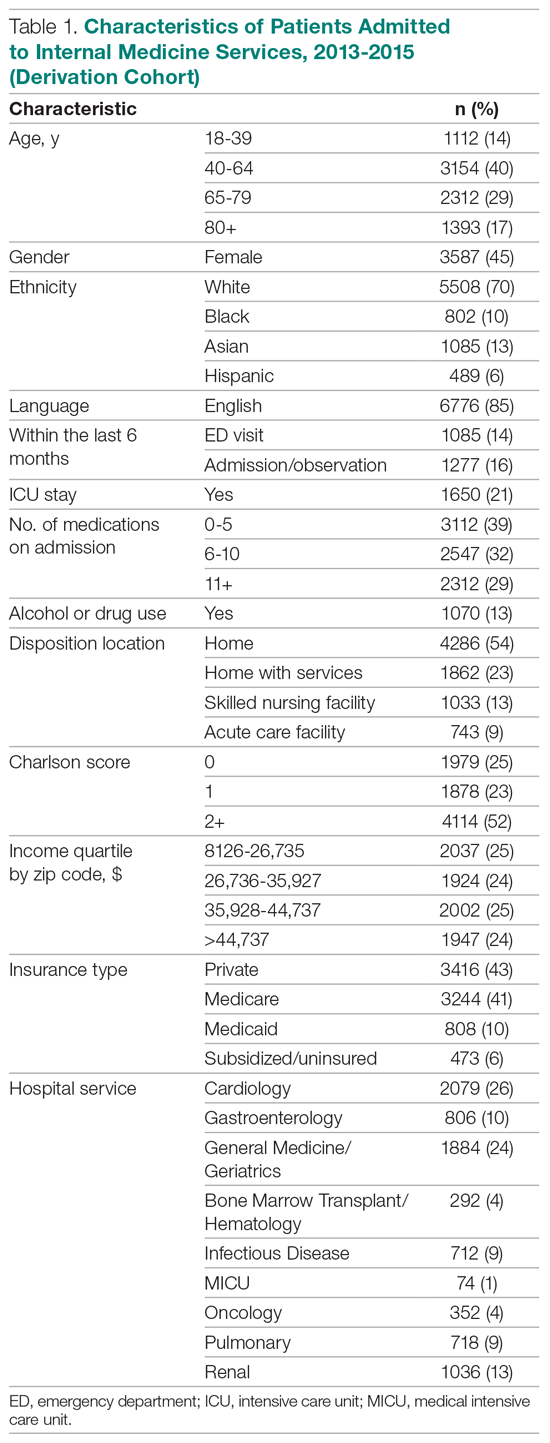

We evaluated annual PSA surveillance for 15,538 men treated with RT with or without concurrent ADT (Table 1).

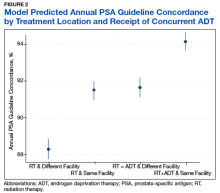

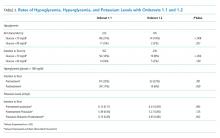

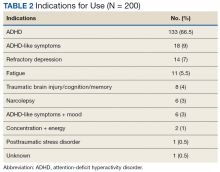

On unadjusted analysis, annual guideline concordance was less common among patients who were at the extremes of age, white, had Gleason 6 disease, PSA ≤ 10 ng/mL, did not receive concurrent ADT, and were treated away from their diagnosing facility (P < .05) (data not shown). We did find slight differences in patient characteristics based on whether patients were treated at their diagnosing facility (Table 2).

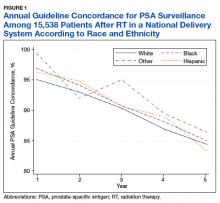

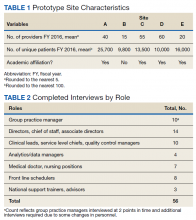

Overall, we found annual guideline concordance was initially very high, though declined slightly over the study period. For example, guideline concordance dropped from 96% in year 1 to 85% in year 5, with an average patient-level guideline concordance of 91% during the study period. We found minimal differences in annual surveillance after RT by race/ethnicity (Figure 1).

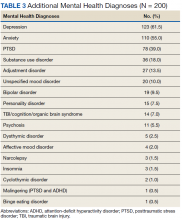

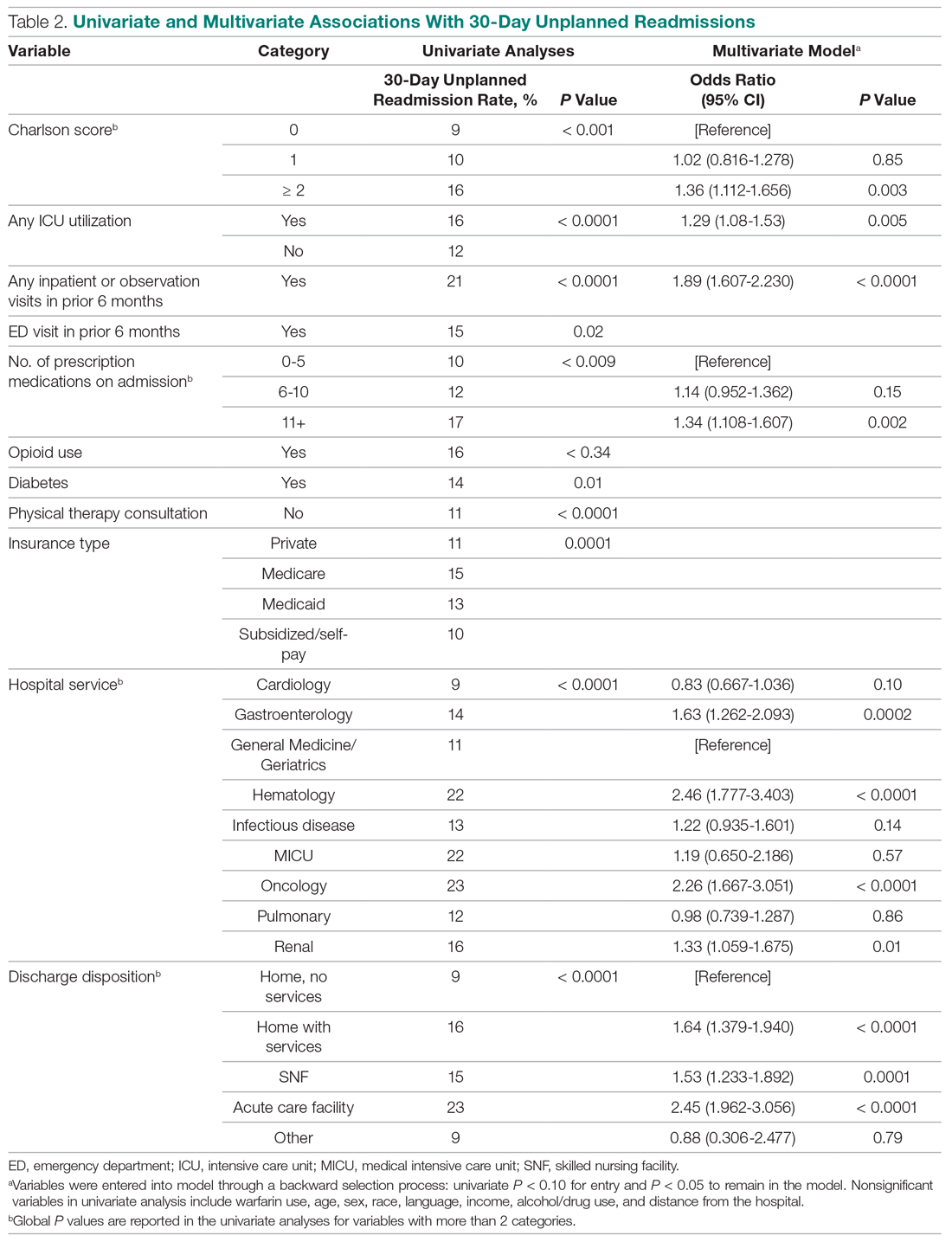

On multilevel multivariable analysis to adjust for clustering at the patient level, we found that race and PSA level were no longer significant predictors of annual surveillance (Table 3).

Discussion

We investigated adherence to guideline-recommended annual surveillance PSA testing in a national cohort of veterans treated with definitive RT for prostate cancer. We found guideline concordance was initially high and decreased slightly over time. We also found guideline concordance with PSA surveillance varied based on a number of clinical and delivery system factors, including marital status, rurality, receipt of concurrent ADT, as well as whether the veteran was treated at his diagnosing facility. Taken together, these overall results are promising, however, also point to unique considerations for some patient groups and potentially those treated in the community.

Our finding of lower guideline concordance among nonmarried patients is consistent with prior research, including our study of patients undergoing surgery for prostate cancer.4 Addressing surveillance in this population is important, as they may have less social support than do their married counterparts. We also found surveillance was lower at the extremes of age, which may be appropriate in elderly patients with limited life expectancy but is concerning for younger men with low competing mortality risks.7 Future work should explore whether younger patients experience barriers to care, including employment challenges, as these men are at greatest risk of cancer progression if recurrence goes undetected.

Although rural patients are less likely to undergo definitive prostate cancer treatment, possibly reflecting barriers to care, in our study, surveillance was actually higher among this population than that for urban patients.9 This could reflect the VA’s success in connecting rural patients to appropriate services despite travel distances to maintain quality of cancer care.10 Given annual PSA surveillance is relatively infrequent and not particularly resource intensive, these high surveillance rates might not apply to patients with cancers who need more frequent survivorship care, such as those with head and neck cancer. Future work should examine why surveillance rates among urban patients might be slightly lower, as living in a metropolitan area does not equate to the absence of barriers to survivorship care, especially for veterans who may not be able to take time off from work or have transportation barriers.

We found guideline concordance was higher among patients with higher Gleason scores, which is important given their higher likelihood of failure. However, low- and intermediate-risk patients also are at risk for treatment failure, so annual PSA surveillance should be optimized in this population unless future studies support the safety and feasibility of less frequent surveillance.10-13 Our finding of increased surveillance in patients who receive concurrent ADT may relate to the increased frequency of survivorship care given the need for injections, often every 3 to 6 months. Future studies might examine whether surveillance decreases in this population once they complete their short or long-term ADT, typically given for a maximum of 3 years.

A particularly relevant finding given recent VA policy changes includes lower guideline concordance for patients receiving RT at a different facility than where they were diagnosed. One possible explanation is that a proportion of patients treated outside of their home facilities use Medicare or private insurance and may have surveillance performed outside of the VA, which would not have been captured in our study.14 However, it remains plausible that there are challenges related to coordination and fragmentation of survivorship care for veterans who receive care at separate VA facilities or receive their initial treatment in the community.15 Future studies can help quantify how much this difference is driven by diagnosis and treatment at separate VA sites vs treatment outside of the VA, as different strategies might be necessary to improve surveillance in these 2 populations. Moreover, electronic health record-based tracking has been proposed as a strategy to identify patients who have not received guideline concordant PSA surveillance.14 This strategy may help increase guideline concordance regardless of initial treatment location if VA survivorship care is intended.

Although our study examined receipt of PSA testing, it did not examine whether patients are physically seen back in radiation oncology clinics, or whether their PSAs have been reviewed by radiation oncology providers. Although many surgical patients return to primary care providers for PSA surveillance, surveillance after RT is more complex and likely best managed in the initial years by radiation oncologists. Unlike the postoperative setting in which the definition of PSA failure is straightforward at > 0.2 ng/mL, the definition of treatment failure after RT is more complicated as described below.

For patients who did not receive concurrent ADT, failure is defined as a PSA nadir + 2 ng/mL, which first requires establishing the nadir using the first few postradiation PSA values.15 It becomes even more complex in the setting of ADT as it causes PSA suppression even in the absence of RT due to testosterone suppression.2 At the conclusion of ADT (short term 4-6 months or long term 18-36 months), the PSA may rise as testosterone recovers.15,16 This is not necessarily indicative of treatment failure, as some normal PSA-producing prostatic tissue may remain after treatment. Given these complexities, ongoing survivorship care with radiation oncology is recommended at least in the short term.

Physical visits are a challenge for some patients undergoing prostate cancer surveillance after treatment. Therefore, exploring the safety and feasibility of automated PSA tracking15 and strategies for increasing utilization of telemedicine, including clinical video telehealth appointments that are already used for survivorship and other urologic care in a number of VA clinics, represents opportunities to systematically provide highest quality survivorship care in VA.17,18

Conclusion

Most veterans receive guideline concordant PSA surveillance after RT for prostate cancer. Nonetheless, at the beginning of treatment, providers should screen veterans for risk factors for loss to follow-up (eg, care at a different or non-VA facility), discuss geographic, financial, and other barriers, and plan to leverage existing VA resources (eg, travel support) to continue to achieve high-quality PSA surveillance and survivorship care. Future research should investigate ways to take advantage of the VA’s robust electronic health record system and telemedicine infrastructure to further optimize prostate cancer survivorship care and PSA surveillance particularly among vulnerable patient groups and those treated outside of their diagnosing facility.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: VA HSR&D Career Development Award: 2 (CDA 12−171) and NCI R37 R37CA222885 (TAS).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.

1. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: prostate cancer v4.2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. Updated August 15, 2018. Accessed January 23, 2019.

2. Sanda MG, Chen RC, Crispino T, et al. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO guideline. https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer-clinically-localized-(2017). Published 2017. Accessed January 22,2019.

3. Zeliadt SB, Penson DF, Albertsen PC, Concato J, Etzioni RD. Race independently predicts prostate specific antigen testing frequency following a prostate carcinoma diagnosis. Cancer. 2003;98(3):496-503.

4. Trantham LC, Nielsen ME, Mobley LR, Wheeler SB, Carpenter WR, Biddle AK. Use of prostate-specific antigen testing as a disease surveillance tool following radical prostatectomy. Cancer. 2013;119(19):3523-3530.

5. Shi Y, Fung KZ, John Boscardin W, et al. Individualizing PSA monitoring among older prostate cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):602-604.

6. Chapman C, Burns J, Caram M, Zaslavsky A, Tsodikov A, Skolarus TA. Multilevel predictors of surveillance PSA guideline concordance after radical prostatectomy: a national Veterans Affairs study. Paper presented at: Association of VA Hematology/Oncology Annual Meeting;

September 28-30, 2018; Chicago, IL. Abstract 34. https://www.mdedge.com/fedprac/avaho/article/175094/prostate-cancer/multilevel-predictors-surveillance-psa-guideline. Accessed January 22, 2019.

7. Kirk PS, Borza T, Caram MEV, et al. Characterising potential bone scan overuse amongst men treated with radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2018. [Epub ahead of print.]

8. Kirk PS, Borza T, Shahinian VB, et al. The implications of baseline bone-health assessment at initiation of androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2018;121(4):558-564.

9. Baldwin LM, Andrilla CH, Porter MP, Rosenblatt RA, Patel S, Doescher MP. Treatment of early-stage prostate cancer among rural and urban patients. Cancer. 2013;119(16):3067-3075.

10. Skolarus TA, Chan S, Shelton JB, et al. Quality of prostate cancer care among rural men in the Veterans Health Administration. Cancer. 2013;119(20):3629-3635.

11. Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al; ProtecT Study Group. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1415-1424.

12. Michalski JM, Moughan J, Purdy J, et al. Effect of standard vs dose-escalated radiation therapy for patients with intermediate-risk prostate cancer: the NRG Oncology RTOG 0126 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol.2018;4(6):e180039.

13. Chang MG, DeSotto K, Taibi P, Troeschel S. Development of a PSA tracking system for patients with prostate cancer following definitive radiotherapy to enhance rural health. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl 2):39-39.

14. Skolarus TA, Zhang Y, Hollenbeck BK. Understanding fragmentation of prostate cancer survivorship care: implications for cost and quality. Cancer. 2012;118(11):2837-2845.

15. Roach M, 3rd, Hanks G, Thames H Jr, et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(4):965-974.

16. Buyyounouski MK, Hanlon AL, Horwitz EM, Uzzo RG, Pollack A. Biochemical failure and the temporal kinetics of prostate-specific antigen after radiation therapy with androgen deprivation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61(5):1291-1298.

17. Chu S, Boxer R, Madison P, et al. Veterans Affairs telemedicine: bringing urologic care to remote clinics. Urology. 2015;86(2):255-260.

18. Safir IJ, Gabale S, David SA, et al. Implementation of a tele-urology program for outpatient hematuria referrals: initial results and patient satisfaction. Urology. 2016;97:33-39.

Guideline concordance with PSA surveillance among veterans treated with definitiveradiation therapy was generally high, but opportunities may exist to improve surveillance among select groups.

Guideline concordance with PSA surveillance among veterans treated with definitiveradiation therapy was generally high, but opportunities may exist to improve surveillance among select groups.

Guidelines recommend prostate-specific antigen (PSA) surveillance among men treated with definitive radiation therapy (RT) for prostate cancer. Specifically, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends testing every 6 to 12 months for 5 years and annually thereafter (with no specific stopping period specified), while the American Urology Association recommends testing for at least 10 years, with the frequency to be determined by the risk of relapse and patient preferences for monitoring.1,2 Salvage treatments exist for men with localized recurrence identified early through PSA testing, so adherence to follow-up guidelines is important for quality prostate cancer survivorship care.1,2

However, few studies focus on adherence to PSA surveillance following radiation therapy. Posttreatment surveillance among surgical patients is generally high, but sociodemographic disparities exist. Racial and ethnic minorities and unmarried men are less likely to undergo guideline concordant surveillance than is the general population, potentially preventing effective salvage therapy.3,4 A recent Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) study on posttreatment surveillance included radiation therapy patients but did not examine the impact of younger age, concurrent androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), or treatment facility (ie, diagnosed and treated at the same vs different facilities, with the latter including a separate VA facility or the community) on surveillance patterns.5 The latter is particularly relevant given increasing efforts to coordinate care outside the VA delivery system supported by the 2018 VA Maintaining Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act. Furthermore, these patient, treatment, and delivery system factors may each uniquely contribute to whether patients receive guideline-recommended PSA surveillance after prostate cancer treatment.

For these reasons, we conducted a study to better understand determinants of adherence to guideline-recommended PSA surveillance among veterans undergoing definitive radiation therapy with or without concurrent ADT. Our study uniquely included both elderly and nonelderly patients as well as investigated relationships between treatment at or away from the diagnosing facility. Although we found high overall levels of adherence to PSA surveillance, our findings do offer insights into determinants associated with worse adherence and provide opportunities to improve prostate cancer survivorship care after RT.

Methods

This study population included men with biopsy-proven nonmetastatic incident prostate cancer diagnosed between January 2005 and December 2008, with follow-up through 2012, identified using the VA Central Cancer Registry. We included men who underwent definitive RT with or without concurrent ADT injections, determined using the VA pharmacy files. We excluded men with a prior diagnosis of prostate or other malignancy (given the presence of other malignancies might affect life expectancy and surveillance patterns), hospice enrollment within 30 days, diagnosis at autopsy, and those treated with radical prostatectomy. We extracted cancer registry data, including biopsy Gleason score, pretreatment PSA level, clinical tumor stage, and whether RT was delivered at the patient’s diagnosing facility. For the latter, we used data on radiation location coded by the tumor registrar. We also collected demographic information, including age at diagnosis, race, ethnicity, marital status, and ZIP code. We used diagnosis codes to determine Charlson comorbidity scores similar to prior studies.6-8

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was receipt of guideline concordant annual PSA surveillance in the initial 5 years following RT. We used laboratory files within the VA Corporate Data Warehouse to identify the date and value for each PSA test after RT for the entire cohort. Specifically, we defined the surveillance period as 60 days after initiation of RT through December 31, 2012. We defined guideline concordance as receiving at least 1 PSA test for each 12-month period after RT.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize our cohort of veterans with prostate cancer treated with RT with or without concurrent ADT. To handle missing data, we performed multiple imputation, generating 10 imputations using all baseline clinical and demographic variables, year of diagnosis, and the regional VA network (ie, the Veterans Integrated Services Network [VISN]) for each patient.

Next, we calculated the annual guideline concordance rate for each year of follow-up for each patient, for the overall cohort, as well as by age, race/ethnicity, and concurrent ADT use. We examined bivariable relationships between guideline concordance and baseline demographic, clinical, and delivery system factors, including year of diagnosis and whether patients were treated at the diagnosing facility, using multilevel logistic regression modeling to account for clustering at the patient level.

Analyses were performed using Stata Version 15 (College Station, TX). We considered a 2-sided P value of < .05 as statistically significant. This study was approved by the VA Ann Arbor Health Care System Institution Review Board.

Results

We evaluated annual PSA surveillance for 15,538 men treated with RT with or without concurrent ADT (Table 1).

On unadjusted analysis, annual guideline concordance was less common among patients who were at the extremes of age, white, had Gleason 6 disease, PSA ≤ 10 ng/mL, did not receive concurrent ADT, and were treated away from their diagnosing facility (P < .05) (data not shown). We did find slight differences in patient characteristics based on whether patients were treated at their diagnosing facility (Table 2).

Overall, we found annual guideline concordance was initially very high, though declined slightly over the study period. For example, guideline concordance dropped from 96% in year 1 to 85% in year 5, with an average patient-level guideline concordance of 91% during the study period. We found minimal differences in annual surveillance after RT by race/ethnicity (Figure 1).

On multilevel multivariable analysis to adjust for clustering at the patient level, we found that race and PSA level were no longer significant predictors of annual surveillance (Table 3).

Discussion

We investigated adherence to guideline-recommended annual surveillance PSA testing in a national cohort of veterans treated with definitive RT for prostate cancer. We found guideline concordance was initially high and decreased slightly over time. We also found guideline concordance with PSA surveillance varied based on a number of clinical and delivery system factors, including marital status, rurality, receipt of concurrent ADT, as well as whether the veteran was treated at his diagnosing facility. Taken together, these overall results are promising, however, also point to unique considerations for some patient groups and potentially those treated in the community.

Our finding of lower guideline concordance among nonmarried patients is consistent with prior research, including our study of patients undergoing surgery for prostate cancer.4 Addressing surveillance in this population is important, as they may have less social support than do their married counterparts. We also found surveillance was lower at the extremes of age, which may be appropriate in elderly patients with limited life expectancy but is concerning for younger men with low competing mortality risks.7 Future work should explore whether younger patients experience barriers to care, including employment challenges, as these men are at greatest risk of cancer progression if recurrence goes undetected.

Although rural patients are less likely to undergo definitive prostate cancer treatment, possibly reflecting barriers to care, in our study, surveillance was actually higher among this population than that for urban patients.9 This could reflect the VA’s success in connecting rural patients to appropriate services despite travel distances to maintain quality of cancer care.10 Given annual PSA surveillance is relatively infrequent and not particularly resource intensive, these high surveillance rates might not apply to patients with cancers who need more frequent survivorship care, such as those with head and neck cancer. Future work should examine why surveillance rates among urban patients might be slightly lower, as living in a metropolitan area does not equate to the absence of barriers to survivorship care, especially for veterans who may not be able to take time off from work or have transportation barriers.

We found guideline concordance was higher among patients with higher Gleason scores, which is important given their higher likelihood of failure. However, low- and intermediate-risk patients also are at risk for treatment failure, so annual PSA surveillance should be optimized in this population unless future studies support the safety and feasibility of less frequent surveillance.10-13 Our finding of increased surveillance in patients who receive concurrent ADT may relate to the increased frequency of survivorship care given the need for injections, often every 3 to 6 months. Future studies might examine whether surveillance decreases in this population once they complete their short or long-term ADT, typically given for a maximum of 3 years.

A particularly relevant finding given recent VA policy changes includes lower guideline concordance for patients receiving RT at a different facility than where they were diagnosed. One possible explanation is that a proportion of patients treated outside of their home facilities use Medicare or private insurance and may have surveillance performed outside of the VA, which would not have been captured in our study.14 However, it remains plausible that there are challenges related to coordination and fragmentation of survivorship care for veterans who receive care at separate VA facilities or receive their initial treatment in the community.15 Future studies can help quantify how much this difference is driven by diagnosis and treatment at separate VA sites vs treatment outside of the VA, as different strategies might be necessary to improve surveillance in these 2 populations. Moreover, electronic health record-based tracking has been proposed as a strategy to identify patients who have not received guideline concordant PSA surveillance.14 This strategy may help increase guideline concordance regardless of initial treatment location if VA survivorship care is intended.

Although our study examined receipt of PSA testing, it did not examine whether patients are physically seen back in radiation oncology clinics, or whether their PSAs have been reviewed by radiation oncology providers. Although many surgical patients return to primary care providers for PSA surveillance, surveillance after RT is more complex and likely best managed in the initial years by radiation oncologists. Unlike the postoperative setting in which the definition of PSA failure is straightforward at > 0.2 ng/mL, the definition of treatment failure after RT is more complicated as described below.

For patients who did not receive concurrent ADT, failure is defined as a PSA nadir + 2 ng/mL, which first requires establishing the nadir using the first few postradiation PSA values.15 It becomes even more complex in the setting of ADT as it causes PSA suppression even in the absence of RT due to testosterone suppression.2 At the conclusion of ADT (short term 4-6 months or long term 18-36 months), the PSA may rise as testosterone recovers.15,16 This is not necessarily indicative of treatment failure, as some normal PSA-producing prostatic tissue may remain after treatment. Given these complexities, ongoing survivorship care with radiation oncology is recommended at least in the short term.

Physical visits are a challenge for some patients undergoing prostate cancer surveillance after treatment. Therefore, exploring the safety and feasibility of automated PSA tracking15 and strategies for increasing utilization of telemedicine, including clinical video telehealth appointments that are already used for survivorship and other urologic care in a number of VA clinics, represents opportunities to systematically provide highest quality survivorship care in VA.17,18

Conclusion

Most veterans receive guideline concordant PSA surveillance after RT for prostate cancer. Nonetheless, at the beginning of treatment, providers should screen veterans for risk factors for loss to follow-up (eg, care at a different or non-VA facility), discuss geographic, financial, and other barriers, and plan to leverage existing VA resources (eg, travel support) to continue to achieve high-quality PSA surveillance and survivorship care. Future research should investigate ways to take advantage of the VA’s robust electronic health record system and telemedicine infrastructure to further optimize prostate cancer survivorship care and PSA surveillance particularly among vulnerable patient groups and those treated outside of their diagnosing facility.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: VA HSR&D Career Development Award: 2 (CDA 12−171) and NCI R37 R37CA222885 (TAS).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.

Guidelines recommend prostate-specific antigen (PSA) surveillance among men treated with definitive radiation therapy (RT) for prostate cancer. Specifically, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends testing every 6 to 12 months for 5 years and annually thereafter (with no specific stopping period specified), while the American Urology Association recommends testing for at least 10 years, with the frequency to be determined by the risk of relapse and patient preferences for monitoring.1,2 Salvage treatments exist for men with localized recurrence identified early through PSA testing, so adherence to follow-up guidelines is important for quality prostate cancer survivorship care.1,2

However, few studies focus on adherence to PSA surveillance following radiation therapy. Posttreatment surveillance among surgical patients is generally high, but sociodemographic disparities exist. Racial and ethnic minorities and unmarried men are less likely to undergo guideline concordant surveillance than is the general population, potentially preventing effective salvage therapy.3,4 A recent Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) study on posttreatment surveillance included radiation therapy patients but did not examine the impact of younger age, concurrent androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), or treatment facility (ie, diagnosed and treated at the same vs different facilities, with the latter including a separate VA facility or the community) on surveillance patterns.5 The latter is particularly relevant given increasing efforts to coordinate care outside the VA delivery system supported by the 2018 VA Maintaining Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act. Furthermore, these patient, treatment, and delivery system factors may each uniquely contribute to whether patients receive guideline-recommended PSA surveillance after prostate cancer treatment.

For these reasons, we conducted a study to better understand determinants of adherence to guideline-recommended PSA surveillance among veterans undergoing definitive radiation therapy with or without concurrent ADT. Our study uniquely included both elderly and nonelderly patients as well as investigated relationships between treatment at or away from the diagnosing facility. Although we found high overall levels of adherence to PSA surveillance, our findings do offer insights into determinants associated with worse adherence and provide opportunities to improve prostate cancer survivorship care after RT.

Methods

This study population included men with biopsy-proven nonmetastatic incident prostate cancer diagnosed between January 2005 and December 2008, with follow-up through 2012, identified using the VA Central Cancer Registry. We included men who underwent definitive RT with or without concurrent ADT injections, determined using the VA pharmacy files. We excluded men with a prior diagnosis of prostate or other malignancy (given the presence of other malignancies might affect life expectancy and surveillance patterns), hospice enrollment within 30 days, diagnosis at autopsy, and those treated with radical prostatectomy. We extracted cancer registry data, including biopsy Gleason score, pretreatment PSA level, clinical tumor stage, and whether RT was delivered at the patient’s diagnosing facility. For the latter, we used data on radiation location coded by the tumor registrar. We also collected demographic information, including age at diagnosis, race, ethnicity, marital status, and ZIP code. We used diagnosis codes to determine Charlson comorbidity scores similar to prior studies.6-8

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was receipt of guideline concordant annual PSA surveillance in the initial 5 years following RT. We used laboratory files within the VA Corporate Data Warehouse to identify the date and value for each PSA test after RT for the entire cohort. Specifically, we defined the surveillance period as 60 days after initiation of RT through December 31, 2012. We defined guideline concordance as receiving at least 1 PSA test for each 12-month period after RT.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize our cohort of veterans with prostate cancer treated with RT with or without concurrent ADT. To handle missing data, we performed multiple imputation, generating 10 imputations using all baseline clinical and demographic variables, year of diagnosis, and the regional VA network (ie, the Veterans Integrated Services Network [VISN]) for each patient.

Next, we calculated the annual guideline concordance rate for each year of follow-up for each patient, for the overall cohort, as well as by age, race/ethnicity, and concurrent ADT use. We examined bivariable relationships between guideline concordance and baseline demographic, clinical, and delivery system factors, including year of diagnosis and whether patients were treated at the diagnosing facility, using multilevel logistic regression modeling to account for clustering at the patient level.

Analyses were performed using Stata Version 15 (College Station, TX). We considered a 2-sided P value of < .05 as statistically significant. This study was approved by the VA Ann Arbor Health Care System Institution Review Board.

Results

We evaluated annual PSA surveillance for 15,538 men treated with RT with or without concurrent ADT (Table 1).

On unadjusted analysis, annual guideline concordance was less common among patients who were at the extremes of age, white, had Gleason 6 disease, PSA ≤ 10 ng/mL, did not receive concurrent ADT, and were treated away from their diagnosing facility (P < .05) (data not shown). We did find slight differences in patient characteristics based on whether patients were treated at their diagnosing facility (Table 2).

Overall, we found annual guideline concordance was initially very high, though declined slightly over the study period. For example, guideline concordance dropped from 96% in year 1 to 85% in year 5, with an average patient-level guideline concordance of 91% during the study period. We found minimal differences in annual surveillance after RT by race/ethnicity (Figure 1).

On multilevel multivariable analysis to adjust for clustering at the patient level, we found that race and PSA level were no longer significant predictors of annual surveillance (Table 3).

Discussion

We investigated adherence to guideline-recommended annual surveillance PSA testing in a national cohort of veterans treated with definitive RT for prostate cancer. We found guideline concordance was initially high and decreased slightly over time. We also found guideline concordance with PSA surveillance varied based on a number of clinical and delivery system factors, including marital status, rurality, receipt of concurrent ADT, as well as whether the veteran was treated at his diagnosing facility. Taken together, these overall results are promising, however, also point to unique considerations for some patient groups and potentially those treated in the community.

Our finding of lower guideline concordance among nonmarried patients is consistent with prior research, including our study of patients undergoing surgery for prostate cancer.4 Addressing surveillance in this population is important, as they may have less social support than do their married counterparts. We also found surveillance was lower at the extremes of age, which may be appropriate in elderly patients with limited life expectancy but is concerning for younger men with low competing mortality risks.7 Future work should explore whether younger patients experience barriers to care, including employment challenges, as these men are at greatest risk of cancer progression if recurrence goes undetected.

Although rural patients are less likely to undergo definitive prostate cancer treatment, possibly reflecting barriers to care, in our study, surveillance was actually higher among this population than that for urban patients.9 This could reflect the VA’s success in connecting rural patients to appropriate services despite travel distances to maintain quality of cancer care.10 Given annual PSA surveillance is relatively infrequent and not particularly resource intensive, these high surveillance rates might not apply to patients with cancers who need more frequent survivorship care, such as those with head and neck cancer. Future work should examine why surveillance rates among urban patients might be slightly lower, as living in a metropolitan area does not equate to the absence of barriers to survivorship care, especially for veterans who may not be able to take time off from work or have transportation barriers.

We found guideline concordance was higher among patients with higher Gleason scores, which is important given their higher likelihood of failure. However, low- and intermediate-risk patients also are at risk for treatment failure, so annual PSA surveillance should be optimized in this population unless future studies support the safety and feasibility of less frequent surveillance.10-13 Our finding of increased surveillance in patients who receive concurrent ADT may relate to the increased frequency of survivorship care given the need for injections, often every 3 to 6 months. Future studies might examine whether surveillance decreases in this population once they complete their short or long-term ADT, typically given for a maximum of 3 years.

A particularly relevant finding given recent VA policy changes includes lower guideline concordance for patients receiving RT at a different facility than where they were diagnosed. One possible explanation is that a proportion of patients treated outside of their home facilities use Medicare or private insurance and may have surveillance performed outside of the VA, which would not have been captured in our study.14 However, it remains plausible that there are challenges related to coordination and fragmentation of survivorship care for veterans who receive care at separate VA facilities or receive their initial treatment in the community.15 Future studies can help quantify how much this difference is driven by diagnosis and treatment at separate VA sites vs treatment outside of the VA, as different strategies might be necessary to improve surveillance in these 2 populations. Moreover, electronic health record-based tracking has been proposed as a strategy to identify patients who have not received guideline concordant PSA surveillance.14 This strategy may help increase guideline concordance regardless of initial treatment location if VA survivorship care is intended.

Although our study examined receipt of PSA testing, it did not examine whether patients are physically seen back in radiation oncology clinics, or whether their PSAs have been reviewed by radiation oncology providers. Although many surgical patients return to primary care providers for PSA surveillance, surveillance after RT is more complex and likely best managed in the initial years by radiation oncologists. Unlike the postoperative setting in which the definition of PSA failure is straightforward at > 0.2 ng/mL, the definition of treatment failure after RT is more complicated as described below.

For patients who did not receive concurrent ADT, failure is defined as a PSA nadir + 2 ng/mL, which first requires establishing the nadir using the first few postradiation PSA values.15 It becomes even more complex in the setting of ADT as it causes PSA suppression even in the absence of RT due to testosterone suppression.2 At the conclusion of ADT (short term 4-6 months or long term 18-36 months), the PSA may rise as testosterone recovers.15,16 This is not necessarily indicative of treatment failure, as some normal PSA-producing prostatic tissue may remain after treatment. Given these complexities, ongoing survivorship care with radiation oncology is recommended at least in the short term.

Physical visits are a challenge for some patients undergoing prostate cancer surveillance after treatment. Therefore, exploring the safety and feasibility of automated PSA tracking15 and strategies for increasing utilization of telemedicine, including clinical video telehealth appointments that are already used for survivorship and other urologic care in a number of VA clinics, represents opportunities to systematically provide highest quality survivorship care in VA.17,18

Conclusion

Most veterans receive guideline concordant PSA surveillance after RT for prostate cancer. Nonetheless, at the beginning of treatment, providers should screen veterans for risk factors for loss to follow-up (eg, care at a different or non-VA facility), discuss geographic, financial, and other barriers, and plan to leverage existing VA resources (eg, travel support) to continue to achieve high-quality PSA surveillance and survivorship care. Future research should investigate ways to take advantage of the VA’s robust electronic health record system and telemedicine infrastructure to further optimize prostate cancer survivorship care and PSA surveillance particularly among vulnerable patient groups and those treated outside of their diagnosing facility.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: VA HSR&D Career Development Award: 2 (CDA 12−171) and NCI R37 R37CA222885 (TAS).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.

1. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: prostate cancer v4.2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. Updated August 15, 2018. Accessed January 23, 2019.

2. Sanda MG, Chen RC, Crispino T, et al. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO guideline. https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer-clinically-localized-(2017). Published 2017. Accessed January 22,2019.

3. Zeliadt SB, Penson DF, Albertsen PC, Concato J, Etzioni RD. Race independently predicts prostate specific antigen testing frequency following a prostate carcinoma diagnosis. Cancer. 2003;98(3):496-503.

4. Trantham LC, Nielsen ME, Mobley LR, Wheeler SB, Carpenter WR, Biddle AK. Use of prostate-specific antigen testing as a disease surveillance tool following radical prostatectomy. Cancer. 2013;119(19):3523-3530.

5. Shi Y, Fung KZ, John Boscardin W, et al. Individualizing PSA monitoring among older prostate cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):602-604.

6. Chapman C, Burns J, Caram M, Zaslavsky A, Tsodikov A, Skolarus TA. Multilevel predictors of surveillance PSA guideline concordance after radical prostatectomy: a national Veterans Affairs study. Paper presented at: Association of VA Hematology/Oncology Annual Meeting;

September 28-30, 2018; Chicago, IL. Abstract 34. https://www.mdedge.com/fedprac/avaho/article/175094/prostate-cancer/multilevel-predictors-surveillance-psa-guideline. Accessed January 22, 2019.

7. Kirk PS, Borza T, Caram MEV, et al. Characterising potential bone scan overuse amongst men treated with radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2018. [Epub ahead of print.]

8. Kirk PS, Borza T, Shahinian VB, et al. The implications of baseline bone-health assessment at initiation of androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2018;121(4):558-564.

9. Baldwin LM, Andrilla CH, Porter MP, Rosenblatt RA, Patel S, Doescher MP. Treatment of early-stage prostate cancer among rural and urban patients. Cancer. 2013;119(16):3067-3075.

10. Skolarus TA, Chan S, Shelton JB, et al. Quality of prostate cancer care among rural men in the Veterans Health Administration. Cancer. 2013;119(20):3629-3635.

11. Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al; ProtecT Study Group. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1415-1424.

12. Michalski JM, Moughan J, Purdy J, et al. Effect of standard vs dose-escalated radiation therapy for patients with intermediate-risk prostate cancer: the NRG Oncology RTOG 0126 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol.2018;4(6):e180039.

13. Chang MG, DeSotto K, Taibi P, Troeschel S. Development of a PSA tracking system for patients with prostate cancer following definitive radiotherapy to enhance rural health. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl 2):39-39.

14. Skolarus TA, Zhang Y, Hollenbeck BK. Understanding fragmentation of prostate cancer survivorship care: implications for cost and quality. Cancer. 2012;118(11):2837-2845.

15. Roach M, 3rd, Hanks G, Thames H Jr, et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(4):965-974.

16. Buyyounouski MK, Hanlon AL, Horwitz EM, Uzzo RG, Pollack A. Biochemical failure and the temporal kinetics of prostate-specific antigen after radiation therapy with androgen deprivation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61(5):1291-1298.

17. Chu S, Boxer R, Madison P, et al. Veterans Affairs telemedicine: bringing urologic care to remote clinics. Urology. 2015;86(2):255-260.

18. Safir IJ, Gabale S, David SA, et al. Implementation of a tele-urology program for outpatient hematuria referrals: initial results and patient satisfaction. Urology. 2016;97:33-39.

1. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: prostate cancer v4.2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. Updated August 15, 2018. Accessed January 23, 2019.

2. Sanda MG, Chen RC, Crispino T, et al. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO guideline. https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer-clinically-localized-(2017). Published 2017. Accessed January 22,2019.

3. Zeliadt SB, Penson DF, Albertsen PC, Concato J, Etzioni RD. Race independently predicts prostate specific antigen testing frequency following a prostate carcinoma diagnosis. Cancer. 2003;98(3):496-503.

4. Trantham LC, Nielsen ME, Mobley LR, Wheeler SB, Carpenter WR, Biddle AK. Use of prostate-specific antigen testing as a disease surveillance tool following radical prostatectomy. Cancer. 2013;119(19):3523-3530.

5. Shi Y, Fung KZ, John Boscardin W, et al. Individualizing PSA monitoring among older prostate cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):602-604.

6. Chapman C, Burns J, Caram M, Zaslavsky A, Tsodikov A, Skolarus TA. Multilevel predictors of surveillance PSA guideline concordance after radical prostatectomy: a national Veterans Affairs study. Paper presented at: Association of VA Hematology/Oncology Annual Meeting;

September 28-30, 2018; Chicago, IL. Abstract 34. https://www.mdedge.com/fedprac/avaho/article/175094/prostate-cancer/multilevel-predictors-surveillance-psa-guideline. Accessed January 22, 2019.

7. Kirk PS, Borza T, Caram MEV, et al. Characterising potential bone scan overuse amongst men treated with radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2018. [Epub ahead of print.]

8. Kirk PS, Borza T, Shahinian VB, et al. The implications of baseline bone-health assessment at initiation of androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2018;121(4):558-564.

9. Baldwin LM, Andrilla CH, Porter MP, Rosenblatt RA, Patel S, Doescher MP. Treatment of early-stage prostate cancer among rural and urban patients. Cancer. 2013;119(16):3067-3075.

10. Skolarus TA, Chan S, Shelton JB, et al. Quality of prostate cancer care among rural men in the Veterans Health Administration. Cancer. 2013;119(20):3629-3635.

11. Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al; ProtecT Study Group. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1415-1424.

12. Michalski JM, Moughan J, Purdy J, et al. Effect of standard vs dose-escalated radiation therapy for patients with intermediate-risk prostate cancer: the NRG Oncology RTOG 0126 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol.2018;4(6):e180039.

13. Chang MG, DeSotto K, Taibi P, Troeschel S. Development of a PSA tracking system for patients with prostate cancer following definitive radiotherapy to enhance rural health. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl 2):39-39.

14. Skolarus TA, Zhang Y, Hollenbeck BK. Understanding fragmentation of prostate cancer survivorship care: implications for cost and quality. Cancer. 2012;118(11):2837-2845.

15. Roach M, 3rd, Hanks G, Thames H Jr, et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(4):965-974.

16. Buyyounouski MK, Hanlon AL, Horwitz EM, Uzzo RG, Pollack A. Biochemical failure and the temporal kinetics of prostate-specific antigen after radiation therapy with androgen deprivation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61(5):1291-1298.

17. Chu S, Boxer R, Madison P, et al. Veterans Affairs telemedicine: bringing urologic care to remote clinics. Urology. 2015;86(2):255-260.

18. Safir IJ, Gabale S, David SA, et al. Implementation of a tele-urology program for outpatient hematuria referrals: initial results and patient satisfaction. Urology. 2016;97:33-39.

Top research findings of 2018-2019 for clinical practice

In Part 1 of this article, published in

1. Han LKM, Aghajani M, Clark SL, et al. Epigenetic aging in major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):774-782.

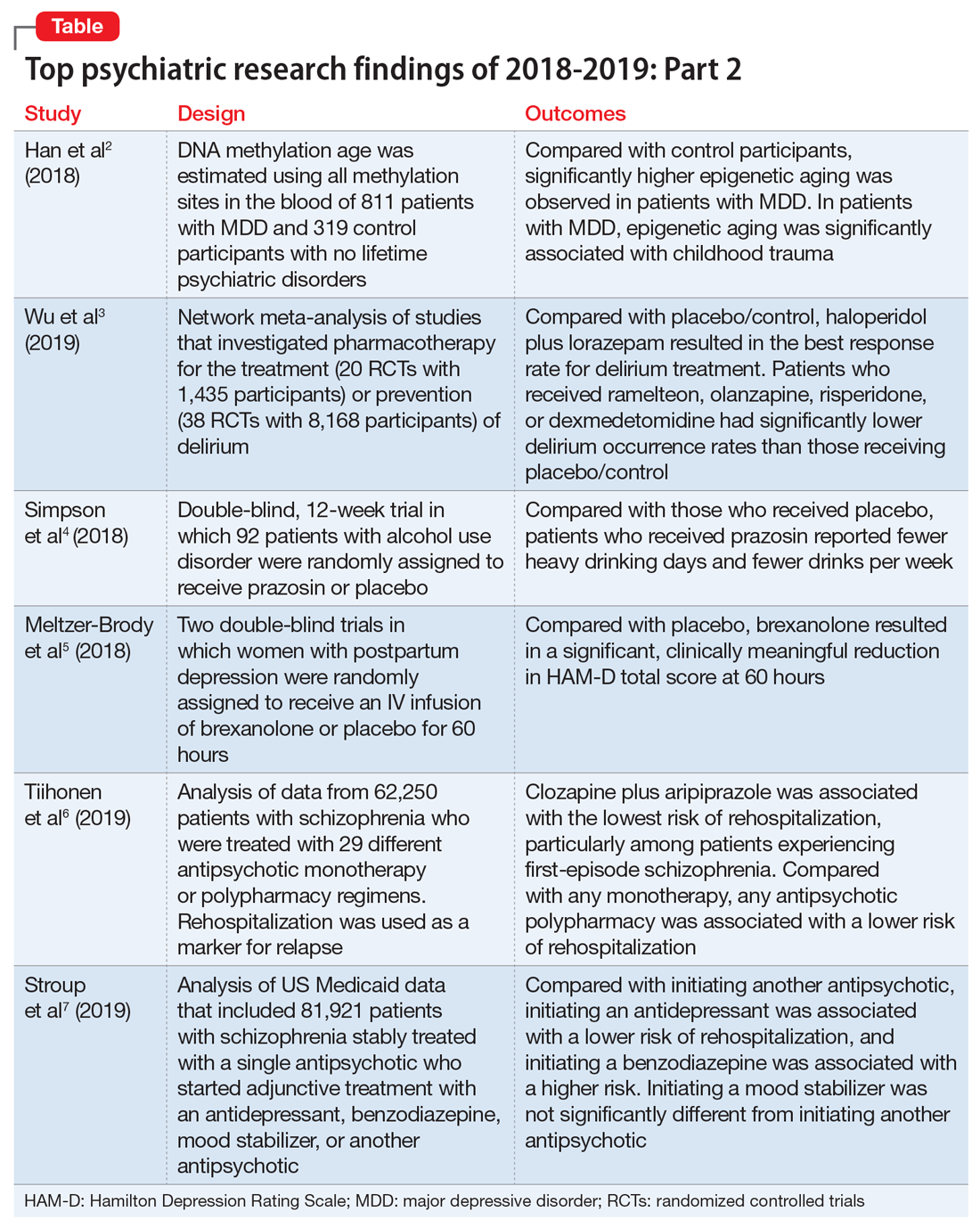

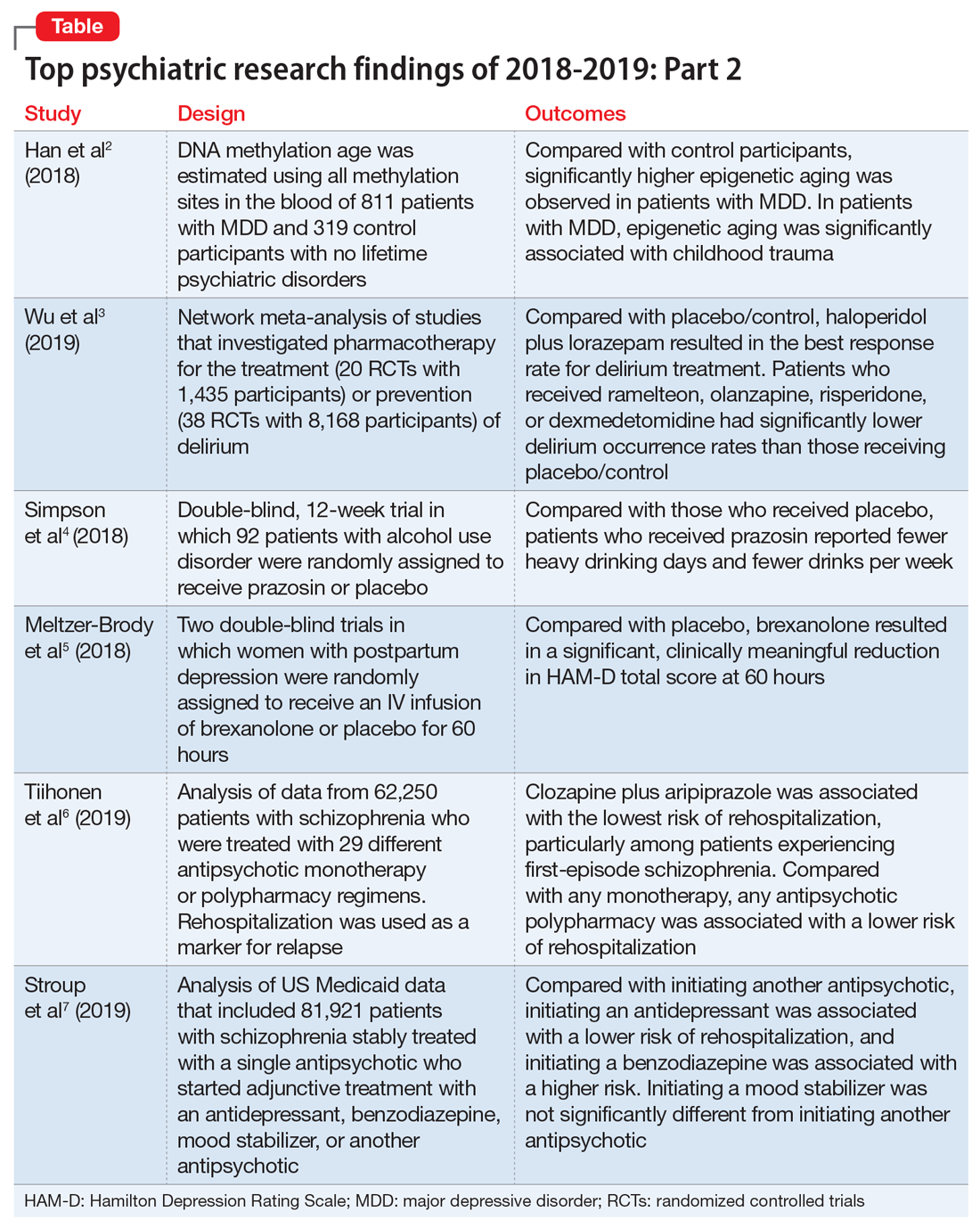

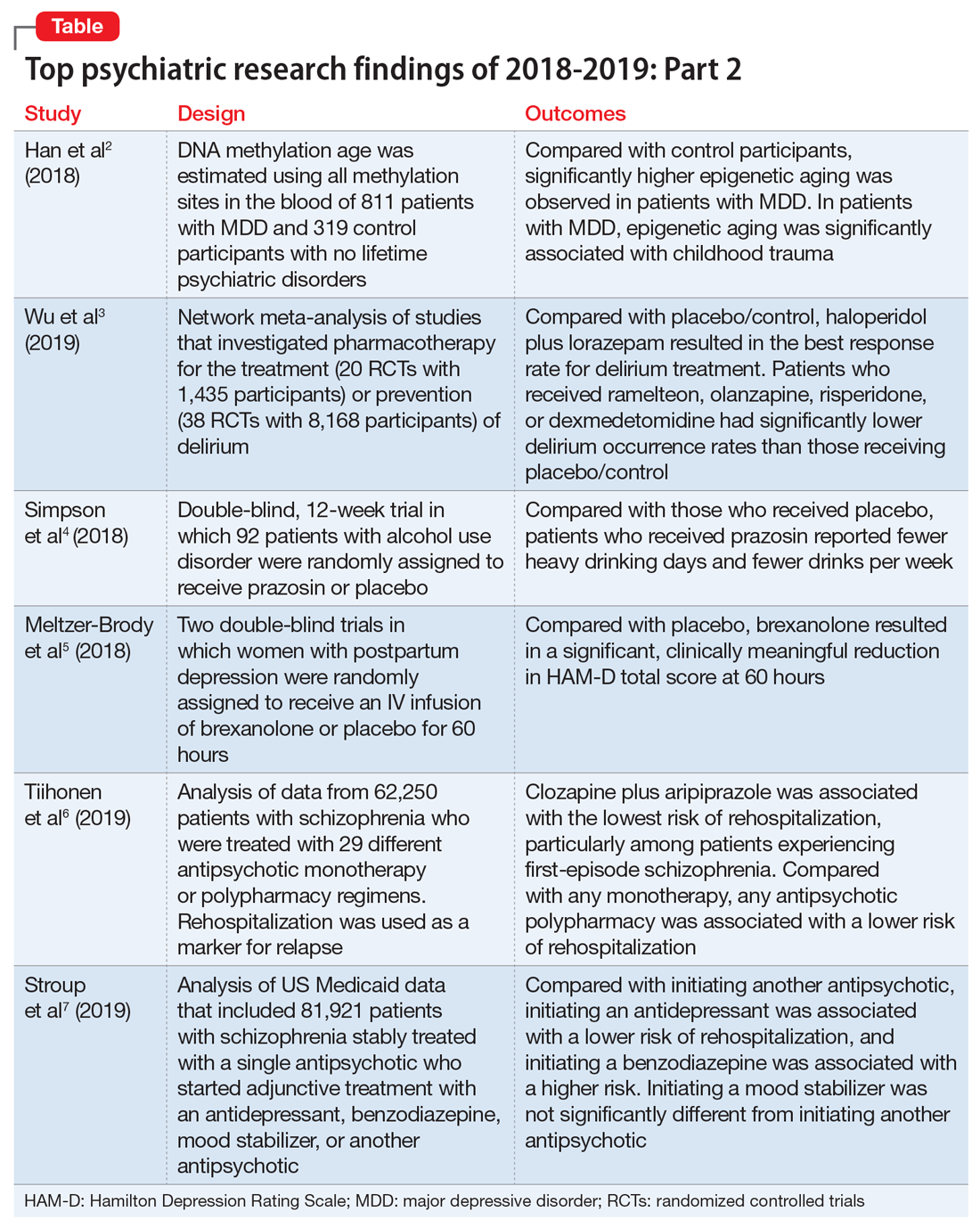

In light of the association of major depressive disorder (MDD) with an increased risk of aging-related diseases, Han et al2 examined whether MDD was associated with higher epigenetic aging in blood as measured by DNA methylation patterns. They also studied whether clinical characteristics of MDD had a further impact on these patterns, and whether the findings replicated in brain tissue. Many differentially methylated regions of our DNA tend to change as we age. Han et al2 used these age-sensitive differentially methylated regions to estimate chronological age, using DNA extracted from various tissues, including blood and brain.

Study design

- As a part of the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA), this study included 811 patients with MDD and 319 control participants with no lifetime psychiatric disorders and low depressive symptoms (Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology score <14).

- Diagnosis of MDD and clinical characteristics were assessed by questionnaires and psychiatric interviews. Childhood trauma was assessed using the NEMESIS childhood trauma interview, which included a structured inventory of trauma exposure during childhood.

- DNA methylation age was estimated using all methylation sites in the blood of 811 patients with MDD and 319 control participants. The residuals of the DNA methylation age estimates regressed on chronological age were calculated to indicate epigenetic aging.

- Analyses were adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle, and health status.

- Postmortem brain samples of 74 patients with MDD and 64 control participants were used for replication.

Outcomes

- Significantly higher epigenetic aging was observed in patients with MDD compared with control participants (Cohen’s d = 0.18), which suggests that patients with MDD are biologically older than their corresponding chronological age. There was a significant dose effect with increasing symptom severity in the overall sample.

- In the MDD group, epigenetic aging was positively and significantly associated with childhood trauma.

- The case-control difference was replicated in an independent analysis of postmortem brain samples.

Conclusion

- These findings suggest that patients with MDD and people with a history of childhood trauma may biologically age relatively faster than those without MDD or childhood trauma. These findings may represent a biomarker of aging and might help identify patients who may benefit from early and intensive interventions to reduce the physical comorbidities of MDD.

- This study raises the possibility that MDD may be causally related to epigenetic age acceleration. However, it only points out the associations; there are other possible explanations for this correlation, including the possibility that a shared risk factor accounts for the observed association.

2. Wu YC, Tseng PT, Tu YK, et al. Association of delirium response and safety of pharmacological interventions for the management and prevention of delirium: a network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):526-535.

Delirium is common and often goes underdiagnosed. It is particularly prevalent among hospitalized geriatric patients. Several medications have been suggested to have a role in treating or preventing delirium. However, it remains uncertain which medications provide the best response rate, the lowest rate of delirium occurrence, and the best tolerability. In an attempt to find answers to these questions, Wu et al3 reviewed studies that evaluated the use of various medications used for delirium.

Study design

- Researchers conducted a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that investigated various pharmacologic agents used to treat or prevent delirium.

- Fifty-eight RCTs were included in the analyses. Of these, 20 RCTs with a total of 1,435 participants compared the outcomes of treatments of delirium, and 38 RCTs with a total of 8,168 participants examined prevention.

- A network meta-analysis was performed to determine if an agent or combinations of agents were superior to placebo or widely used medications.

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Haloperidol plus lorazepam provided the best response rate for treating delirium compared with placebo/control.

- For delirium prevention, patients who received ramelteon, olanzapine, risperidone, or dexmedetomidine had significantly lower delirium occurrence rates than those receiving placebo/control.

- None of the pharmacologic treatments were significantly associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality compared with placebo/control.

Conclusion

- Haloperidol plus lorazepam might be the best treatment and ramelteon the best preventive medicine for delirium. None of the pharmacologic interventions for treatment or prophylaxis increased all-cause mortality.

- However, network meta-analyses involve extrapolating treatment comparisons that are not made directly. As Blazer8 pointed out, both findings in this study (that haloperidol plus lorazepam is a unique intervention among the treatment trials and ramelteon is a unique intervention for prevention) seemed to be driven by 2 of the 58 studies that Wu et al3 examined.Wu et al3 also cautioned that both of these interventions needed to be further researched for efficacy.

3. Simpson TL, Saxon AJ, Stappenbeck C, et al. Double-blind randomized clinical trial of prazosin for alcohol use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1216-1224.

While some evidence suggests that elevated brain noradrenergic activity is involved in the initiation and maintenance of alcohol use disorder,9 current medications used to treat alcohol use disorder do not target brain noradrenergic pathways. In an RCT, Simpson et al4 tested prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic receptor antagonist, for the treatment of alcohol use disorder.

Study design

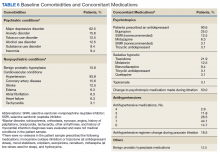

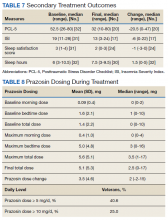

- In this 12-week double-blind study, 92 participants with alcohol use disorder were randomly assigned to receive prazosin or placebo. Individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder were excluded.

- Prazosin was titrated to a target dosing schedule of 4 mg in the morning, 4 mg in the afternoon, and 8 mg at bedtime by the end of Week 2. The behavioral platform was medical management. Participants provided daily data on their alcohol consumption.

- Generalized linear mixed-effects models were used to examine the impact of prazosin compared with placebo on number of drinks per week, number of drinking days per week, and number of heavy drinking days per week.

Outcomes

- Among the 80 participants who completed the titration period and were included in the primary analyses, prazosin was associated with self-reported fewer heavy drinking days, and fewer drinks per week (Palatino LT Std−8 vs Palatino LT Std−1.5 with placebo). Drinking days per week and craving showed no group differences.

- The rate of drinking and the probability of heavy drinking showed a greater decrease over time for participants receiving prazosin compared with those receiving placebo.

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- These findings of moderate reductions in heavy drinking days and drinks per week with prazosin suggest that prazosin may be a promising harm-reduction treatment for alcohol use disorder.

4. Meltzer-Brody S, Colquhoun H, Riesenberg R, et al. Brexanolone injection in post-partum depression: two multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1058-1070.

Postpartum depression is among the most common complications of childbirth. It can result in considerable suffering for mothers, children, and families. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) signaling has previously been reported to be involved in the pathophysiology of postpartum depression. Meltzer-Brody et al5 conducted 2 double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials comparing brexanolone with placebo in women with postpartum depression at 30 clinical research centers and specialized psychiatric units in the United States.

Study design

- Participants were women age 18 to 45, Palatino LT Std≤6 months postpartum at screening, with postpartum depression as indicated by a qualifying 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) score of ≥26 for Study 1 or 20 to 25 for Study 2.

- Of the 375 women who were screened simultaneously across both studies, 138 were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive a single IV injection of brexanolone, 90 μg/kg per hour (BRX90) (n = 45), brexanolone, 60 μg/kg per hour (BRX60) (n = 47), or placebo (n = 46) for 60 hours in Study 1, and 108 were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive BRX90 (n = 54) or placebo (n = 54) for 60 hours in Study 2.

- The primary efficacy endpoint was change in total score on the HAM-D from baseline to 60 hours. Patients were followed until Day 30.

Outcomes

- In Study 1, at 60 hours, the least-squares (LS) mean reduction in HAM-D total score from baseline was 19.5 points (standard error [SE] 1.2) in the BRX60 group and 17.7 points (SE 1.2) in the BRX90 group, compared with 14.0 points (SE 1.1) in the placebo group.

- In Study 2, at 60 hours, the LS mean reduction in HAM-D total score from baseline was 14.6 points (SE 0.8) in the BRX90 group compared with 12.1 points (SE 0.8) for the placebo group.

- In Study 1, one patient in the BRX60 group had 2 serious adverse events (suicidal ideation and intentional overdose attempt during follow-up). In Study 2, one patient in the BRX90 group had 2 serious adverse events (altered state of consciousness and syncope), which were considered treatment-related.

Conclusion

- Administration of brexanolone injection for postpartum depression resulted in significant, clinically meaningful reductions in HAM-D total score at 60 hours compared with placebo, with a rapid onset of action and durable treatment response during the study period. These results suggest that brexanolone injection has the potential to improve treatment options for women with this disorder.

Continue to: #5

5. Tiihonen J, Taipale H, Mehtälä J, et al. Association of antipsychotic polypharmacy vs monotherapy with psychiatric rehospitalization among adults with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):499-507.

In clinical practice, the use of multiple antipsychotic agents for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia is common but generally not recommended. The effectiveness of antipsychotic polypharmacy in preventing relapse of schizophrenia has not been established, and whether specific antipsychotic combinations are superior to monotherapies for maintenance treatment of schizophrenia is unknown. Tiihonen et al6 investigated the association of specific antipsychotic combinations with psychiatric rehospitalization, which was used as a marker for relapse.

Study design

- This study included 62,250 patients with schizophrenia, treated between January 1, 1996 and December 31, 2015, in a comprehensive, nationwide cohort in Finland. Overall, 31,257 individuals (50.2%) were men, and the median age was 45.6 (interquartile range, 34.6 to 57.9).

- Patients were receiving 29 different antipsychotic monotherapy or polypharmacy regimens.

- Researchers analyzed data from April 24 to June 15, 2018 using psychiatric rehospitalization as a marker for relapse. To minimize selection bias, rehospitalization risks were investigated using within-individual analyses.

- The main outcome was the hazard ratio (HR) for psychiatric rehospitalization during use of polypharmacy vs monotherapy by the same patient.

Outcomes

- Clozapine plus aripiprazole was associated with the lowest risk of psychiatric rehospitalization, with a difference of 14% (HR, .86; CI, .79 to .94) compared with clozapine monotherapy in the analysis that included all polypharmacy periods, and 18% (HR, .82; CI, .75 to .89) in the conservatively defined polypharmacy analysis that excluded periods <90 days.

- Among patients experiencing their first episode of schizophrenia, the differences between clozapine plus aripiprazole vs clozapine monotherapy were greater, with a difference of 22% in the analysis that included all polypharmacy periods, and 23% in the conservatively defined polypharmacy analysis.

- At the aggregate level, any antipsychotic polypharmacy was associated with a 7% to 13% lower risk of psychiatric rehospitalization compared with any monotherapy.

- Clozapine was the only monotherapy among the 10 best treatments.

- Results on all-cause and somatic hospitalization, mortality, and other sensitivity analyses were in line with the primary outcomes.

Conclusion

- This study suggests that certain types of antipsychotic polypharmacy may reduce the risk of rehospitalization in patients with schizophrenia. Current treatment guidelines state that clinicians should prefer antipsychotic monotherapy and avoid polypharmacy. Tiihonen et al6 raise the question whether current treatment guidelines should continue to discourage antipsychotic polypharmacy in the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia.

- Despite the large administrative databases and sophisticated statistical methods used in this study, this approach has important limitations. As Goff10 points out, despite efforts to minimize bias, these results should be considered preliminary until confirmed by RCTs.

6. Stroup TS, Gerhard T, Crystal S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of adjunctive psychotropic medications in patients with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):508-515.

In routine clinical practice, patients with schizophrenia are often treated with combinations of antipsychotics and other psychotropic medications. However, there is little evidence about the comparative effectiveness of these adjunctive treatment strategies. Stroup et al7 investigated the comparative real-world effectiveness of adjunctive psychotropic treatments for patients with schizophrenia.

Continue to: Study design

Study design

- This comparative effectiveness study used US Medicaid data from January 1, 2001, to December 31, 2010. Data analysis was performed from January 1, 2017, to June 30, 2018.

- The study cohort included 81,921 adult outpatients diagnosed with schizophrenia with a mean age of 40.7 (range: 18 to 64), including 37,515 women (45.8%). All patients were stably treated with a single antipsychotic and then started on an adjunctive antidepressant (n = 31,117), benzodiazepine (n = 11,941), mood stabilizer (n = 12,849), or another antipsychotic (n = 26,014).

- Researchers used multinomial logistic regression models to estimate propensity scores to balance covariates across the 4 medication groups. Weighted Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to compare treatment outcomes during 365 days on an intention-to-treat basis.

- The main outcomes and measures included risk of hospitalization for a mental disorder (primary), emergency department (ED) visits for a mental disorder, and all-cause mortality.

Outcomes

- Compared with starting another antipsychotic, initiating use of an antidepressant was associated with a lower risk of psychiatric hospitalization, and initiating use of a benzodiazepine was associated with a higher risk. Initiating use of a mood stabilizer was not significantly different from initiating use of another antipsychotic.

- A similar pattern of associations was observed in psychiatric ED visits for initiating use of an antidepressant, benzodiazepine, or mood stabilizer.

- Initiating use of a mood stabilizer was associated with an increased risk of mortality.

Conclusion

- Compared with the addition of a second antipsychotic, adding an antidepressant was associated with substantially reduced rates of hospitalization, whereas adding a benzodiazepine was associated with a modest increase in the risk of hospitalization. While the addition of a mood stabilizer was not associated with a significant difference in the risk of hospitalization, it was associated with higher mortality.

- Despite the limitations associated with this study, the associations of benzodiazepines and mood stabilizers with poorer outcomes warrant clinical caution and further investigation.

Bottom Line

Significantly higher epigenetic aging has been observed in patients with major depressive disorder. Haloperidol plus lorazepam might be an effective treatment for delirium; and ramelteon may be effective for preventing delirium. Prazosin reduces heavy drinking in patients with alcohol use disorder. A 60-hour infusion of brexanolone can help alleviate postpartum depression. Clozapine plus aripiprazole reduces the risk of rehospitalization among patients with schizophrenia. Adding an antidepressant to an antipsychotic also can reduce the risk of rehospitalization among patients with schizophrenia.

Related Resources

- NEJM Journal Watch. www.jwatch.org.

- F1000 Prime. https://f1000.com/prime/home.

- BMJ Journals Evidence-Based Mental Health. https://ebmh.bmj.com.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Brexanolone • Zulresso

Clozapine • Clozaril

Dexmedetomidine • Precedex

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lorazepam • Ativan

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Prazosin • Minipress

Ramelteon • Rozerem

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. Saeed SA, Stanley JB. Top research findings of 2018-2019. First of 2 parts. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):13-18.

2. Han LKM, Aghajani M, Clark SL, et al. Epigenetic aging in major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):774-782.

3. Wu YC, Tseng PT, Tu YK, et al. Association of delirium response and safety of pharmacological interventions for the management and prevention of delirium: a network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):526-535.

4. Simpson TL, Saxon AJ, Stappenbeck C, et al. Double-blind randomized clinical trial of prazosin for alcohol use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1216-1224.

5. Meltzer-Brody S, Colquhoun H, Riesenberg R, et al. Brexanolone injection in post-partum depression: two multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1058-1070.

6. Tiihonen J, Taipale H, Mehtälä J, et al. Association of antipsychotic polypharmacy vs monotherapy with psychiatric rehospitalization among adults with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):499-507.

7. Stroup TS, Gerhard T, Crystal S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of adjunctive psychotropic medications in patients with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):508-515.

8. Blazer DG. Pharmacologic intervention for the treatment and prevention of delirium: looking beneath the modeling. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):472-473.

9. Koob GF. Brain stress systems in the amygdala and addiction. Brain Res. 2009;1293:61-75.

10. Goff DC. Can adjunctive pharmacotherapy reduce hospitalization in schizophrenia? Insights from administrative databases. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):468-469.

In Part 1 of this article, published in

1. Han LKM, Aghajani M, Clark SL, et al. Epigenetic aging in major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):774-782.

In light of the association of major depressive disorder (MDD) with an increased risk of aging-related diseases, Han et al2 examined whether MDD was associated with higher epigenetic aging in blood as measured by DNA methylation patterns. They also studied whether clinical characteristics of MDD had a further impact on these patterns, and whether the findings replicated in brain tissue. Many differentially methylated regions of our DNA tend to change as we age. Han et al2 used these age-sensitive differentially methylated regions to estimate chronological age, using DNA extracted from various tissues, including blood and brain.

Study design

- As a part of the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA), this study included 811 patients with MDD and 319 control participants with no lifetime psychiatric disorders and low depressive symptoms (Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology score <14).

- Diagnosis of MDD and clinical characteristics were assessed by questionnaires and psychiatric interviews. Childhood trauma was assessed using the NEMESIS childhood trauma interview, which included a structured inventory of trauma exposure during childhood.

- DNA methylation age was estimated using all methylation sites in the blood of 811 patients with MDD and 319 control participants. The residuals of the DNA methylation age estimates regressed on chronological age were calculated to indicate epigenetic aging.

- Analyses were adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle, and health status.

- Postmortem brain samples of 74 patients with MDD and 64 control participants were used for replication.

Outcomes

- Significantly higher epigenetic aging was observed in patients with MDD compared with control participants (Cohen’s d = 0.18), which suggests that patients with MDD are biologically older than their corresponding chronological age. There was a significant dose effect with increasing symptom severity in the overall sample.

- In the MDD group, epigenetic aging was positively and significantly associated with childhood trauma.

- The case-control difference was replicated in an independent analysis of postmortem brain samples.

Conclusion

- These findings suggest that patients with MDD and people with a history of childhood trauma may biologically age relatively faster than those without MDD or childhood trauma. These findings may represent a biomarker of aging and might help identify patients who may benefit from early and intensive interventions to reduce the physical comorbidities of MDD.

- This study raises the possibility that MDD may be causally related to epigenetic age acceleration. However, it only points out the associations; there are other possible explanations for this correlation, including the possibility that a shared risk factor accounts for the observed association.

2. Wu YC, Tseng PT, Tu YK, et al. Association of delirium response and safety of pharmacological interventions for the management and prevention of delirium: a network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):526-535.

Delirium is common and often goes underdiagnosed. It is particularly prevalent among hospitalized geriatric patients. Several medications have been suggested to have a role in treating or preventing delirium. However, it remains uncertain which medications provide the best response rate, the lowest rate of delirium occurrence, and the best tolerability. In an attempt to find answers to these questions, Wu et al3 reviewed studies that evaluated the use of various medications used for delirium.

Study design

- Researchers conducted a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that investigated various pharmacologic agents used to treat or prevent delirium.

- Fifty-eight RCTs were included in the analyses. Of these, 20 RCTs with a total of 1,435 participants compared the outcomes of treatments of delirium, and 38 RCTs with a total of 8,168 participants examined prevention.

- A network meta-analysis was performed to determine if an agent or combinations of agents were superior to placebo or widely used medications.

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Haloperidol plus lorazepam provided the best response rate for treating delirium compared with placebo/control.

- For delirium prevention, patients who received ramelteon, olanzapine, risperidone, or dexmedetomidine had significantly lower delirium occurrence rates than those receiving placebo/control.

- None of the pharmacologic treatments were significantly associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality compared with placebo/control.

Conclusion

- Haloperidol plus lorazepam might be the best treatment and ramelteon the best preventive medicine for delirium. None of the pharmacologic interventions for treatment or prophylaxis increased all-cause mortality.

- However, network meta-analyses involve extrapolating treatment comparisons that are not made directly. As Blazer8 pointed out, both findings in this study (that haloperidol plus lorazepam is a unique intervention among the treatment trials and ramelteon is a unique intervention for prevention) seemed to be driven by 2 of the 58 studies that Wu et al3 examined.Wu et al3 also cautioned that both of these interventions needed to be further researched for efficacy.

3. Simpson TL, Saxon AJ, Stappenbeck C, et al. Double-blind randomized clinical trial of prazosin for alcohol use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1216-1224.

While some evidence suggests that elevated brain noradrenergic activity is involved in the initiation and maintenance of alcohol use disorder,9 current medications used to treat alcohol use disorder do not target brain noradrenergic pathways. In an RCT, Simpson et al4 tested prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic receptor antagonist, for the treatment of alcohol use disorder.

Study design