User login

Nurse Responses to Physiologic Monitor Alarms on a General Pediatric Unit

Alarms from bedside continuous physiologic monitors (CPMs) occur frequently in children’s hospitals and can lead to harm. Recent studies conducted in children’s hospitals have identified alarm rates of up to 152 alarms per patient per day outside of the intensive care unit,1-3 with as few as 1% of alarms being considered clinically important.4 Excessive alarms have been linked to alarm fatigue, when providers become desensitized to and may miss alarms indicating impending patient deterioration. Alarm fatigue has been identified by national patient safety organizations as a patient safety concern given the risk of patient harm.5-7 Despite these concerns, CPMs are routinely used: up to 48% of pediatric patients in nonintensive care units at children’s hospitals are monitored.2

Although the low number of alarms that receive responses has been well-described,8,9 the reasons why clinicians do or do not respond to alarms are unclear. A study conducted in an adult perioperative unit noted prolonged nurse response times for patients with high alarm rates.10 A second study conducted in the pediatric inpatient setting demonstrated a dose-response effect and noted progressively prolonged nurse response times with increased rates of nonactionable alarms.4,11 Findings from another study suggested that underlying factors are highly complex and may be a result of excessive alarms, clinician characteristics, and working conditions (eg, workload and unit noise level).12 Evidence also suggests that humans have difficulty distinguishing the importance of alarms in situations where multiple alarm tones are used, a common scenario in hospitals.

An enhanced understanding of why nurses respond to alarms in daily practice will inform intervention development and improvement work. In the long term, this information could help improve systems for monitoring pediatric inpatients that are less prone to issues with alarm fatigue. The objective of this qualitative study, which employed structured observation, was to describe how bedside nurses think about and act upon bedside monitor alarms in a general pediatric inpatient unit.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This prospective observational study took place on a 48-bed hospital medicine unit at a large, freestanding children’s hospital with >650 beds and >19,000 annual admissions. General Electric (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) physiologic monitors (models Dash 3000, 4000, and 5000) were used at the time of the study, and nurses could be notified of monitor alarms in four ways: First, an in-room auditory alarm sounds. Second, a light positioned above the door outside of each patient room blinks for alarms that are at a “warning” or “critical level” (eg ventricular tachycardia or low oxygen saturation). Third, audible alarms occur at the unit’s central monitoring station. Lastly, another staff member can notify the patient’s nurse via in-person conversion or secure smart phone communication. On the study unit, CPMs are initiated and discontinued through a physician order.

This study was reviewed and approved by the hospital’s institutional review board.

Study Population

We used a purposive recruitment strategy to enroll bedside nurses working on general hospital medicine units, stratified to ensure varying levels of experience and primary shifts (eg, day vs night). We planned to conduct approximately two observations with each participating nurse and to continue collecting data until we could no longer identify new insights in terms of responses to alarms (ie, thematic saturation15). Observations were targeted to cover times of day that coincided with increased rates of distraction. These times included just prior to and after the morning and evening change of shifts (7:00

Data Sources

Prior to data collection, the research team, which consisted of physicians, bedside nurses, research coordinators, and a human factors expert, created a system for categorizing alarm responses. Categories for observed responses were based on the location and corresponding action taken. Initial categories were developed a priori from existing literature and expanded through input from the multidisciplinary study team, then vetted with bedside staff, and finally pilot tested through >4 hours of observations, thus producing the final categories. These categories were entered into a work-sampling program (WorkStudy by Quetech Ltd., Waterloo, Ontario, Canada) to facilitate quick data recording during observations.

The hospital uses a central alarm collection software (BedMasterEx by Anandic Medical Systems, Feuerthalen, Switzerland), which permitted the collection of date, time, trigger (eg, high heart rate), and level (eg, crisis, warning) of the generated CPM alarms. Alarms collected are based on thresholds preset at the bedside monitor. The central collection software does not differentiate between accurate (eg, correctly representing the physiologic state of the patient) and inaccurate alarms.

Observation Procedure

At the time of observation, nurse demographic information (eg, primary shift worked and years working as a nurse) was obtained. A brief preobservation questionnaire was administered to collect patient information (eg, age and diagnosis) and the nurses’ perspectives on the necessity of monitors for each monitored patient in his/her care.

The observer shadowed the nurse for a two-hour block of his/her shift. During this time, nurses were instructed to “think aloud” as they responded to alarms (eg, “I notice the oxygen saturation monitor alarming off, but the probe has fallen off”). A trained observer (AML or KMT) recorded responses verbalized by the nurse and his/her reaction by selecting the appropriate category using the work-sampling software. Data were also collected on the vital sign associated with the alarm (eg, heart rate). Moreover, the observer kept written notes to provide context for electronically recorded data. Alarms that were not verbalized by the nurse were not counted. Similarly, alarms that were noted outside of the room by the nurse were not classified by vital sign unless the nurse confirmed with the bedside monitor. Observers did not adjudicate the accuracy of the alarms. The session was stopped if monitors were discontinued during the observation period. Alarm data generated by the bedside monitor were pulled for each patient room after observations were completed.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to assess the percentage of each nurse response category and each alarm type (eg, heart rate and respiratory rate). The observed alarm rate was calculated by taking the total number of observed alarms (ie, alarms noted by the nurse) divided by the total number of patient-hours observed. The monitor-generated alarm rate was calculated by taking the total number of alarms from the bedside-alarm generated data divided by the number of patient-hours observed.

Electronically recorded observations using the work-sampling program were cross-referenced with hand-written field notes to assess for any discrepancies or identify relevant events not captured by the program. Three study team members (AML, KMT, and ACS) reviewed each observation independently and compared field notes to ensure accurate categorization. Discrepancies were referred to the larger study group in cases of uncertainty.

RESULTS

Nine nurses had monitored patients during the available observations and participated in 19 observation sessions, which included 35 monitored patients for a total of 61.3 patient-hours of observation. Nurses were observed for a median of two times each (range 1-4). The median number of monitored patients during a single observation session was two (range 1-3). Observed nurses were female with a median of eight years of experience (range 0.5-26 years). Patients represented a broad range of age categories and were hospitalized with a variety of diagnoses (Table). Nurses, when queried at the start of the observation, felt that monitors were necessary for 29 (82.9%) of the observed patients given either patient condition or unit policy.

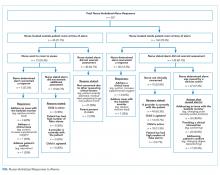

A total of 207 observed nurse responses to alarms occurred during the study period for a rate of 3.4 responses per patient per hour. Of the total number of responses, 45 (21.7%) were noted outside of a patient room, and in 15 (33.3%) the nurse chose to go to the room. The other 162 were recorded when the nurse was present in the room when the alarm activated. Of the 177 in-person nurse responses, 50 were related to a pulse oximetry alarm, 66 were related to a heart rate alarm, and 61 were related to a respiratory rate alarm. The most common observed in-person response to an alarm involved the nurse judging that no intervention was necessary (n = 152, 73.1%). Only 14 (7% of total responses) observed in-person responses involved a clinical intervention, such as suctioning or titrating supplemental oxygen. Findings are summarized in the Figure and describe nurse-verbalized reasons to further assess (or not) and then whether the nurse chose to take action (or not) after an alarm.

Alarm data were available for 17 of the 19 observation periods during the study. Technical issues with the central alarm collection software precluded alarm data collection for two of the observation sessions. A total of 483 alarms were recorded on bedside monitors during those 17 observation periods or 8.8 alarms per patient per hour, which was equivalent to 211.2 alarms per patient-day. A total of 175 observed responses were collected during these 17 observation periods. This number of responses was 36% of the number we would have expected on the basis of the alarm count from the central alarm software.

There were no patients transferred to the intensive care unit during the observation period. Nurses who chose not to respond to alarms outside the room most often cited the brevity of the alarm or other reassuring contextual details, such as that a family member was in the room to notify them if anything was truly wrong, that another member of the medical team was with the patient, or that they had recently assessed the patient and thought likely the alarm did not require any action. During three observations, the observed nurse cited the presence of family in the patient’s room in their decision not to conduct further assessment in response to the alarm, noting that the parent would be able to notify the nurse if something required attention. On two occasions in which a nurse had multiple monitored patients, the observed nurse noted that if the other monitored patients were alarming and she happened to be in another patient’s room, she would not be able to hear them. Four nurses cited policy as the reason a patient was on monitors (eg, patient was on respiratory support at night for obstructive sleep apnea).

DISCUSSION

We characterized responses to physiologic monitor alarms by a group of nurses with a range of experience levels. We found that most nurse responses to alarms in continuously monitored general pediatric patients involved no intervention, and further assessment was often not conducted for alarms that occurred outside of the room if the nurse noted otherwise reassuring clinical context. Observed responses occurred for 36% of alarms during the study period when compared with bedside monitor-alarm generated data. Overall, only 14 clinical interventions were noted among the observed responses. Nurses noted that they felt the monitors were necessary for 82.9% of monitored patients because of the clinical context or because of unit policy.

Our study findings highlight some potential contradictions in the current widespread use of CPMs in general pediatric units and how clinicians respond to them in practice.2 First, while nurses reported that monitors were necessary for most of their patients, participating nurses deemed few alarms clinically actionable and often chose not to further assess when they noted alarms outside of the room. This is in line with findings from prior studies suggesting that clinicians overvalue the contribution of monitoring systems to patient safety.

Our findings provide a novel understanding of previously observed phenomena, such as long response times or nonresponses in settings with high alarm rates.4,10 Similar to that in a prior study conducted in the pediatric setting,11 alarms with an observed response constituted a minority of the total alarms that occurred in our study. This finding has previously been attributed to mental fatigue, caregiver apathy, and desensitization.8 However, even though a minority of observed responses in our study included an intervention, the nurse had a rationale for why the alarm did or did not need a response. This behavior and the verbalized rationale indicate that in his/her opinion, not responding to the alarm was clinically appropriate. Study participants also reflected on the difficulties of responding to alarms given the monitor system setup, in which they may not always be capable of hearing alarms for their patients. Without data from nurses regarding the alarms that had no observed response, we can only speculate; however, based on our findings, each of these factors could contribute to nonresponse. Finally, while high numbers of false alarms have been posited as an underlying cause of alarm fatigue, we noted that a majority of nonresponse was reported to be related to other clinical factors. This relationship suggests that from the nurse’s perspective, a more applicable framework for understanding alarms would be based on clinical actionability4 over physiologic accuracy.

In total, our findings suggest that a multifaceted approach will be necessary to improve alarm response rates. These interventions should include adjusting parameters such that alarms are highly likely to indicate a need for intervention coupled with educational interventions addressing clinician knowledge of the alarm system and bias about the actionability of alarms may improve response rates. Changes in the monitoring system setup such that nurses can easily be notified when alarms occur may also be indicated, in addition to formally engaging patients and families around response to alarms. Although secondary notification systems (eg, alarms transmitted to individual clinician’s devices) are one solution, the utilization of these systems needs to be balanced with the risks of contributing to existing alarm fatigue and the need to appropriately tailor monitoring thresholds and strategies to patients.

Our study has several limitations. First, nurses may have responded in a way they perceive to be socially desirable, and studies using in-person observers are also prone to a Hawthorne-like effect,19-21 where the nurse may have tried to respond more frequently to alarms than usual during observations. However, given that the majority of bedside alarms did not receive a response and a substantial number of responses involved no action, these effects were likely weak. Second, we were unable to assess which alarms were accurately reflecting the patient’s physiologic status and which were not; we were also unable to link observed alarm response to monitor-recorded alarms. Third, despite the use of silent observers and an actual, rather than a simulated, clinical setting, by virtue of the data collection method we likely captured a more deliberate thought process (so-called System 2 thinking)22 rather than the subconscious processes that may predominate when nurses respond to alarms in the course of clinical care (System 1 thinking).22 Despite this limitation, our study findings, which reflect a nurse’s in-the-moment thinking, remain relevant to guiding the improvement of monitoring systems, and the development of nurse-facing interventions and education. Finally, we studied a small, purposive sample of nurses at a single hospital. Our study sample impacts the generalizability of our results and precluded a detailed analysis of the effect of nurse- and patient-level variables.

CONCLUSION

We found that nurses often deemed that no response was necessary for CPM alarms. Nurses cited contextual factors, including the duration of alarms and the presence of other providers or parents in their decision-making. Few (7%) of the alarm responses in our study included a clinical intervention. The number of observed alarm responses constituted roughly a third of the alarms recorded by bedside CPMs during the study. This result supports concerns about the nurse’s capacity to hear and process all CPM alarms given system limitations and a heavy clinical workload. Subsequent steps should include staff education, reducing overall alarm rates with appropriate monitor use and actionable alarm thresholds, and ensuring that patient alarms are easily recognizable for frontline staff.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by the Place Outcomes Research Award from the Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation. Dr. Brady is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality under Award Number K08HS23827. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

1. Schondelmeyer AC, Bonafide CP, Goel VV, et al. The frequency of physiologic monitor alarms in a children’s hospital. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):796-798. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2612.

2. Schondelmeyer AC, Brady PW, Goel VV, et al. Physiologic monitor alarm rates at 5 children’s hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(6):396-398. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2918.

3. Schondelmeyer AC, Brady PW, Sucharew H, et al. The impact of reduced pulse oximetry use on alarm frequency. Hosp Pediatr. In press. PubMed

4. Bonafide CP, Lin R, Zander M, et al. Association between exposure to nonactionable physiologic monitor alarms and response time in a children’s hospital. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):345-351. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2331.

5. Siebig S, Kuhls S, Imhoff M, et al. Intensive care unit alarms--how many do we need? Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2):451-456. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cb0888.

6. Sendelbach S, Funk M. Alarm fatigue: a patient safety concern. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2013;24(4):378-386. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCI.0b013e3182a903f9.

7. Sendelbach S. Alarm fatigue. Nurs Clin North Am. 2012;47(3):375-382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnur.2012.05.009.

8. Cvach M. Monitor alarm fatigue: an integrative review. Biomed Instrum Technol. 2012;46(4):268-277. https://doi.org/10.2345/0899-8205-46.4.268.

9. Paine CW, Goel VV, Ely E, et al. Systematic review of physiologic monitor alarm characteristics and pragmatic interventions to reduce alarm frequency. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(2):136-144. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2520.

10. Voepel-Lewis T, Parker ML, Burke CN, et al. Pulse oximetry desaturation alarms on a general postoperative adult unit: a prospective observational study of nurse response time. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(10):1351-1358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.02.006.

11. Bonafide CP, Localio AR, Holmes JH, et al. Video analysis of factors associated With response time to physiologic monitor alarms in a children’s hospital. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(6):524-531. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.5123.

12. Deb S, Claudio D. Alarm fatigue and its influence on staff performance. IIE Trans Healthc Syst Eng. 2015;5(3):183-196. https://doi.org/10.1080/19488300.2015.1062065.

13. Mondor TA, Hurlburt J, Thorne L. Categorizing sounds by pitch: effects of stimulus similarity and response repetition. Percept Psychophys. 2003;65(1):107-114. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03194787.

14. Mondor TA, Finley GA. The perceived urgency of auditory warning alarms used in the hospital operating room is inappropriate. Can J Anaesth. 2003;50(3):221-228. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03017788.

15. Fusch PI, Ness LR. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qual Rep; 20(9), 2015:1408-1416.

16. Najafi N, Auerbach A. Use and outcomes of telemetry monitoring on a medicine service. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1349-1350. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3163.

17. Estrada CA, Rosman HS, Prasad NK, et al. Role of telemetry monitoring in the non-intensive care unit. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76(12):960-965. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9149(99)80270-7.

18. Khan A, Furtak SL, Melvin P et al. Parent-reported errors and adverse events in hospitalized children. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(4):e154608.https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4608.

19. Adair JG. The Hawthorne effect: a reconsideration of the methodological artifact. J Appl Psychol. 1984;69(2):334-345. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.69.2.334.

20. Kovacs-Litman A, Wong K, Shojania KG, et al. Do physicians clean their hands? Insights from a covert observational study. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):862-864. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2632.

21. Wolfe F, Michaud K. The Hawthorne effect, sponsored trials, and the overestimation of treatment effectiveness. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(11):2216-2220. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.100497.

22. Kahneman D. Thinking, Fast and Slow. 1st Pbk. ed. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2013.

Alarms from bedside continuous physiologic monitors (CPMs) occur frequently in children’s hospitals and can lead to harm. Recent studies conducted in children’s hospitals have identified alarm rates of up to 152 alarms per patient per day outside of the intensive care unit,1-3 with as few as 1% of alarms being considered clinically important.4 Excessive alarms have been linked to alarm fatigue, when providers become desensitized to and may miss alarms indicating impending patient deterioration. Alarm fatigue has been identified by national patient safety organizations as a patient safety concern given the risk of patient harm.5-7 Despite these concerns, CPMs are routinely used: up to 48% of pediatric patients in nonintensive care units at children’s hospitals are monitored.2

Although the low number of alarms that receive responses has been well-described,8,9 the reasons why clinicians do or do not respond to alarms are unclear. A study conducted in an adult perioperative unit noted prolonged nurse response times for patients with high alarm rates.10 A second study conducted in the pediatric inpatient setting demonstrated a dose-response effect and noted progressively prolonged nurse response times with increased rates of nonactionable alarms.4,11 Findings from another study suggested that underlying factors are highly complex and may be a result of excessive alarms, clinician characteristics, and working conditions (eg, workload and unit noise level).12 Evidence also suggests that humans have difficulty distinguishing the importance of alarms in situations where multiple alarm tones are used, a common scenario in hospitals.

An enhanced understanding of why nurses respond to alarms in daily practice will inform intervention development and improvement work. In the long term, this information could help improve systems for monitoring pediatric inpatients that are less prone to issues with alarm fatigue. The objective of this qualitative study, which employed structured observation, was to describe how bedside nurses think about and act upon bedside monitor alarms in a general pediatric inpatient unit.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This prospective observational study took place on a 48-bed hospital medicine unit at a large, freestanding children’s hospital with >650 beds and >19,000 annual admissions. General Electric (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) physiologic monitors (models Dash 3000, 4000, and 5000) were used at the time of the study, and nurses could be notified of monitor alarms in four ways: First, an in-room auditory alarm sounds. Second, a light positioned above the door outside of each patient room blinks for alarms that are at a “warning” or “critical level” (eg ventricular tachycardia or low oxygen saturation). Third, audible alarms occur at the unit’s central monitoring station. Lastly, another staff member can notify the patient’s nurse via in-person conversion or secure smart phone communication. On the study unit, CPMs are initiated and discontinued through a physician order.

This study was reviewed and approved by the hospital’s institutional review board.

Study Population

We used a purposive recruitment strategy to enroll bedside nurses working on general hospital medicine units, stratified to ensure varying levels of experience and primary shifts (eg, day vs night). We planned to conduct approximately two observations with each participating nurse and to continue collecting data until we could no longer identify new insights in terms of responses to alarms (ie, thematic saturation15). Observations were targeted to cover times of day that coincided with increased rates of distraction. These times included just prior to and after the morning and evening change of shifts (7:00

Data Sources

Prior to data collection, the research team, which consisted of physicians, bedside nurses, research coordinators, and a human factors expert, created a system for categorizing alarm responses. Categories for observed responses were based on the location and corresponding action taken. Initial categories were developed a priori from existing literature and expanded through input from the multidisciplinary study team, then vetted with bedside staff, and finally pilot tested through >4 hours of observations, thus producing the final categories. These categories were entered into a work-sampling program (WorkStudy by Quetech Ltd., Waterloo, Ontario, Canada) to facilitate quick data recording during observations.

The hospital uses a central alarm collection software (BedMasterEx by Anandic Medical Systems, Feuerthalen, Switzerland), which permitted the collection of date, time, trigger (eg, high heart rate), and level (eg, crisis, warning) of the generated CPM alarms. Alarms collected are based on thresholds preset at the bedside monitor. The central collection software does not differentiate between accurate (eg, correctly representing the physiologic state of the patient) and inaccurate alarms.

Observation Procedure

At the time of observation, nurse demographic information (eg, primary shift worked and years working as a nurse) was obtained. A brief preobservation questionnaire was administered to collect patient information (eg, age and diagnosis) and the nurses’ perspectives on the necessity of monitors for each monitored patient in his/her care.

The observer shadowed the nurse for a two-hour block of his/her shift. During this time, nurses were instructed to “think aloud” as they responded to alarms (eg, “I notice the oxygen saturation monitor alarming off, but the probe has fallen off”). A trained observer (AML or KMT) recorded responses verbalized by the nurse and his/her reaction by selecting the appropriate category using the work-sampling software. Data were also collected on the vital sign associated with the alarm (eg, heart rate). Moreover, the observer kept written notes to provide context for electronically recorded data. Alarms that were not verbalized by the nurse were not counted. Similarly, alarms that were noted outside of the room by the nurse were not classified by vital sign unless the nurse confirmed with the bedside monitor. Observers did not adjudicate the accuracy of the alarms. The session was stopped if monitors were discontinued during the observation period. Alarm data generated by the bedside monitor were pulled for each patient room after observations were completed.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to assess the percentage of each nurse response category and each alarm type (eg, heart rate and respiratory rate). The observed alarm rate was calculated by taking the total number of observed alarms (ie, alarms noted by the nurse) divided by the total number of patient-hours observed. The monitor-generated alarm rate was calculated by taking the total number of alarms from the bedside-alarm generated data divided by the number of patient-hours observed.

Electronically recorded observations using the work-sampling program were cross-referenced with hand-written field notes to assess for any discrepancies or identify relevant events not captured by the program. Three study team members (AML, KMT, and ACS) reviewed each observation independently and compared field notes to ensure accurate categorization. Discrepancies were referred to the larger study group in cases of uncertainty.

RESULTS

Nine nurses had monitored patients during the available observations and participated in 19 observation sessions, which included 35 monitored patients for a total of 61.3 patient-hours of observation. Nurses were observed for a median of two times each (range 1-4). The median number of monitored patients during a single observation session was two (range 1-3). Observed nurses were female with a median of eight years of experience (range 0.5-26 years). Patients represented a broad range of age categories and were hospitalized with a variety of diagnoses (Table). Nurses, when queried at the start of the observation, felt that monitors were necessary for 29 (82.9%) of the observed patients given either patient condition or unit policy.

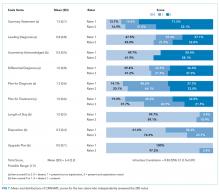

A total of 207 observed nurse responses to alarms occurred during the study period for a rate of 3.4 responses per patient per hour. Of the total number of responses, 45 (21.7%) were noted outside of a patient room, and in 15 (33.3%) the nurse chose to go to the room. The other 162 were recorded when the nurse was present in the room when the alarm activated. Of the 177 in-person nurse responses, 50 were related to a pulse oximetry alarm, 66 were related to a heart rate alarm, and 61 were related to a respiratory rate alarm. The most common observed in-person response to an alarm involved the nurse judging that no intervention was necessary (n = 152, 73.1%). Only 14 (7% of total responses) observed in-person responses involved a clinical intervention, such as suctioning or titrating supplemental oxygen. Findings are summarized in the Figure and describe nurse-verbalized reasons to further assess (or not) and then whether the nurse chose to take action (or not) after an alarm.

Alarm data were available for 17 of the 19 observation periods during the study. Technical issues with the central alarm collection software precluded alarm data collection for two of the observation sessions. A total of 483 alarms were recorded on bedside monitors during those 17 observation periods or 8.8 alarms per patient per hour, which was equivalent to 211.2 alarms per patient-day. A total of 175 observed responses were collected during these 17 observation periods. This number of responses was 36% of the number we would have expected on the basis of the alarm count from the central alarm software.

There were no patients transferred to the intensive care unit during the observation period. Nurses who chose not to respond to alarms outside the room most often cited the brevity of the alarm or other reassuring contextual details, such as that a family member was in the room to notify them if anything was truly wrong, that another member of the medical team was with the patient, or that they had recently assessed the patient and thought likely the alarm did not require any action. During three observations, the observed nurse cited the presence of family in the patient’s room in their decision not to conduct further assessment in response to the alarm, noting that the parent would be able to notify the nurse if something required attention. On two occasions in which a nurse had multiple monitored patients, the observed nurse noted that if the other monitored patients were alarming and she happened to be in another patient’s room, she would not be able to hear them. Four nurses cited policy as the reason a patient was on monitors (eg, patient was on respiratory support at night for obstructive sleep apnea).

DISCUSSION

We characterized responses to physiologic monitor alarms by a group of nurses with a range of experience levels. We found that most nurse responses to alarms in continuously monitored general pediatric patients involved no intervention, and further assessment was often not conducted for alarms that occurred outside of the room if the nurse noted otherwise reassuring clinical context. Observed responses occurred for 36% of alarms during the study period when compared with bedside monitor-alarm generated data. Overall, only 14 clinical interventions were noted among the observed responses. Nurses noted that they felt the monitors were necessary for 82.9% of monitored patients because of the clinical context or because of unit policy.

Our study findings highlight some potential contradictions in the current widespread use of CPMs in general pediatric units and how clinicians respond to them in practice.2 First, while nurses reported that monitors were necessary for most of their patients, participating nurses deemed few alarms clinically actionable and often chose not to further assess when they noted alarms outside of the room. This is in line with findings from prior studies suggesting that clinicians overvalue the contribution of monitoring systems to patient safety.

Our findings provide a novel understanding of previously observed phenomena, such as long response times or nonresponses in settings with high alarm rates.4,10 Similar to that in a prior study conducted in the pediatric setting,11 alarms with an observed response constituted a minority of the total alarms that occurred in our study. This finding has previously been attributed to mental fatigue, caregiver apathy, and desensitization.8 However, even though a minority of observed responses in our study included an intervention, the nurse had a rationale for why the alarm did or did not need a response. This behavior and the verbalized rationale indicate that in his/her opinion, not responding to the alarm was clinically appropriate. Study participants also reflected on the difficulties of responding to alarms given the monitor system setup, in which they may not always be capable of hearing alarms for their patients. Without data from nurses regarding the alarms that had no observed response, we can only speculate; however, based on our findings, each of these factors could contribute to nonresponse. Finally, while high numbers of false alarms have been posited as an underlying cause of alarm fatigue, we noted that a majority of nonresponse was reported to be related to other clinical factors. This relationship suggests that from the nurse’s perspective, a more applicable framework for understanding alarms would be based on clinical actionability4 over physiologic accuracy.

In total, our findings suggest that a multifaceted approach will be necessary to improve alarm response rates. These interventions should include adjusting parameters such that alarms are highly likely to indicate a need for intervention coupled with educational interventions addressing clinician knowledge of the alarm system and bias about the actionability of alarms may improve response rates. Changes in the monitoring system setup such that nurses can easily be notified when alarms occur may also be indicated, in addition to formally engaging patients and families around response to alarms. Although secondary notification systems (eg, alarms transmitted to individual clinician’s devices) are one solution, the utilization of these systems needs to be balanced with the risks of contributing to existing alarm fatigue and the need to appropriately tailor monitoring thresholds and strategies to patients.

Our study has several limitations. First, nurses may have responded in a way they perceive to be socially desirable, and studies using in-person observers are also prone to a Hawthorne-like effect,19-21 where the nurse may have tried to respond more frequently to alarms than usual during observations. However, given that the majority of bedside alarms did not receive a response and a substantial number of responses involved no action, these effects were likely weak. Second, we were unable to assess which alarms were accurately reflecting the patient’s physiologic status and which were not; we were also unable to link observed alarm response to monitor-recorded alarms. Third, despite the use of silent observers and an actual, rather than a simulated, clinical setting, by virtue of the data collection method we likely captured a more deliberate thought process (so-called System 2 thinking)22 rather than the subconscious processes that may predominate when nurses respond to alarms in the course of clinical care (System 1 thinking).22 Despite this limitation, our study findings, which reflect a nurse’s in-the-moment thinking, remain relevant to guiding the improvement of monitoring systems, and the development of nurse-facing interventions and education. Finally, we studied a small, purposive sample of nurses at a single hospital. Our study sample impacts the generalizability of our results and precluded a detailed analysis of the effect of nurse- and patient-level variables.

CONCLUSION

We found that nurses often deemed that no response was necessary for CPM alarms. Nurses cited contextual factors, including the duration of alarms and the presence of other providers or parents in their decision-making. Few (7%) of the alarm responses in our study included a clinical intervention. The number of observed alarm responses constituted roughly a third of the alarms recorded by bedside CPMs during the study. This result supports concerns about the nurse’s capacity to hear and process all CPM alarms given system limitations and a heavy clinical workload. Subsequent steps should include staff education, reducing overall alarm rates with appropriate monitor use and actionable alarm thresholds, and ensuring that patient alarms are easily recognizable for frontline staff.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by the Place Outcomes Research Award from the Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation. Dr. Brady is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality under Award Number K08HS23827. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Alarms from bedside continuous physiologic monitors (CPMs) occur frequently in children’s hospitals and can lead to harm. Recent studies conducted in children’s hospitals have identified alarm rates of up to 152 alarms per patient per day outside of the intensive care unit,1-3 with as few as 1% of alarms being considered clinically important.4 Excessive alarms have been linked to alarm fatigue, when providers become desensitized to and may miss alarms indicating impending patient deterioration. Alarm fatigue has been identified by national patient safety organizations as a patient safety concern given the risk of patient harm.5-7 Despite these concerns, CPMs are routinely used: up to 48% of pediatric patients in nonintensive care units at children’s hospitals are monitored.2

Although the low number of alarms that receive responses has been well-described,8,9 the reasons why clinicians do or do not respond to alarms are unclear. A study conducted in an adult perioperative unit noted prolonged nurse response times for patients with high alarm rates.10 A second study conducted in the pediatric inpatient setting demonstrated a dose-response effect and noted progressively prolonged nurse response times with increased rates of nonactionable alarms.4,11 Findings from another study suggested that underlying factors are highly complex and may be a result of excessive alarms, clinician characteristics, and working conditions (eg, workload and unit noise level).12 Evidence also suggests that humans have difficulty distinguishing the importance of alarms in situations where multiple alarm tones are used, a common scenario in hospitals.

An enhanced understanding of why nurses respond to alarms in daily practice will inform intervention development and improvement work. In the long term, this information could help improve systems for monitoring pediatric inpatients that are less prone to issues with alarm fatigue. The objective of this qualitative study, which employed structured observation, was to describe how bedside nurses think about and act upon bedside monitor alarms in a general pediatric inpatient unit.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This prospective observational study took place on a 48-bed hospital medicine unit at a large, freestanding children’s hospital with >650 beds and >19,000 annual admissions. General Electric (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) physiologic monitors (models Dash 3000, 4000, and 5000) were used at the time of the study, and nurses could be notified of monitor alarms in four ways: First, an in-room auditory alarm sounds. Second, a light positioned above the door outside of each patient room blinks for alarms that are at a “warning” or “critical level” (eg ventricular tachycardia or low oxygen saturation). Third, audible alarms occur at the unit’s central monitoring station. Lastly, another staff member can notify the patient’s nurse via in-person conversion or secure smart phone communication. On the study unit, CPMs are initiated and discontinued through a physician order.

This study was reviewed and approved by the hospital’s institutional review board.

Study Population

We used a purposive recruitment strategy to enroll bedside nurses working on general hospital medicine units, stratified to ensure varying levels of experience and primary shifts (eg, day vs night). We planned to conduct approximately two observations with each participating nurse and to continue collecting data until we could no longer identify new insights in terms of responses to alarms (ie, thematic saturation15). Observations were targeted to cover times of day that coincided with increased rates of distraction. These times included just prior to and after the morning and evening change of shifts (7:00

Data Sources

Prior to data collection, the research team, which consisted of physicians, bedside nurses, research coordinators, and a human factors expert, created a system for categorizing alarm responses. Categories for observed responses were based on the location and corresponding action taken. Initial categories were developed a priori from existing literature and expanded through input from the multidisciplinary study team, then vetted with bedside staff, and finally pilot tested through >4 hours of observations, thus producing the final categories. These categories were entered into a work-sampling program (WorkStudy by Quetech Ltd., Waterloo, Ontario, Canada) to facilitate quick data recording during observations.

The hospital uses a central alarm collection software (BedMasterEx by Anandic Medical Systems, Feuerthalen, Switzerland), which permitted the collection of date, time, trigger (eg, high heart rate), and level (eg, crisis, warning) of the generated CPM alarms. Alarms collected are based on thresholds preset at the bedside monitor. The central collection software does not differentiate between accurate (eg, correctly representing the physiologic state of the patient) and inaccurate alarms.

Observation Procedure

At the time of observation, nurse demographic information (eg, primary shift worked and years working as a nurse) was obtained. A brief preobservation questionnaire was administered to collect patient information (eg, age and diagnosis) and the nurses’ perspectives on the necessity of monitors for each monitored patient in his/her care.

The observer shadowed the nurse for a two-hour block of his/her shift. During this time, nurses were instructed to “think aloud” as they responded to alarms (eg, “I notice the oxygen saturation monitor alarming off, but the probe has fallen off”). A trained observer (AML or KMT) recorded responses verbalized by the nurse and his/her reaction by selecting the appropriate category using the work-sampling software. Data were also collected on the vital sign associated with the alarm (eg, heart rate). Moreover, the observer kept written notes to provide context for electronically recorded data. Alarms that were not verbalized by the nurse were not counted. Similarly, alarms that were noted outside of the room by the nurse were not classified by vital sign unless the nurse confirmed with the bedside monitor. Observers did not adjudicate the accuracy of the alarms. The session was stopped if monitors were discontinued during the observation period. Alarm data generated by the bedside monitor were pulled for each patient room after observations were completed.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to assess the percentage of each nurse response category and each alarm type (eg, heart rate and respiratory rate). The observed alarm rate was calculated by taking the total number of observed alarms (ie, alarms noted by the nurse) divided by the total number of patient-hours observed. The monitor-generated alarm rate was calculated by taking the total number of alarms from the bedside-alarm generated data divided by the number of patient-hours observed.

Electronically recorded observations using the work-sampling program were cross-referenced with hand-written field notes to assess for any discrepancies or identify relevant events not captured by the program. Three study team members (AML, KMT, and ACS) reviewed each observation independently and compared field notes to ensure accurate categorization. Discrepancies were referred to the larger study group in cases of uncertainty.

RESULTS

Nine nurses had monitored patients during the available observations and participated in 19 observation sessions, which included 35 monitored patients for a total of 61.3 patient-hours of observation. Nurses were observed for a median of two times each (range 1-4). The median number of monitored patients during a single observation session was two (range 1-3). Observed nurses were female with a median of eight years of experience (range 0.5-26 years). Patients represented a broad range of age categories and were hospitalized with a variety of diagnoses (Table). Nurses, when queried at the start of the observation, felt that monitors were necessary for 29 (82.9%) of the observed patients given either patient condition or unit policy.

A total of 207 observed nurse responses to alarms occurred during the study period for a rate of 3.4 responses per patient per hour. Of the total number of responses, 45 (21.7%) were noted outside of a patient room, and in 15 (33.3%) the nurse chose to go to the room. The other 162 were recorded when the nurse was present in the room when the alarm activated. Of the 177 in-person nurse responses, 50 were related to a pulse oximetry alarm, 66 were related to a heart rate alarm, and 61 were related to a respiratory rate alarm. The most common observed in-person response to an alarm involved the nurse judging that no intervention was necessary (n = 152, 73.1%). Only 14 (7% of total responses) observed in-person responses involved a clinical intervention, such as suctioning or titrating supplemental oxygen. Findings are summarized in the Figure and describe nurse-verbalized reasons to further assess (or not) and then whether the nurse chose to take action (or not) after an alarm.

Alarm data were available for 17 of the 19 observation periods during the study. Technical issues with the central alarm collection software precluded alarm data collection for two of the observation sessions. A total of 483 alarms were recorded on bedside monitors during those 17 observation periods or 8.8 alarms per patient per hour, which was equivalent to 211.2 alarms per patient-day. A total of 175 observed responses were collected during these 17 observation periods. This number of responses was 36% of the number we would have expected on the basis of the alarm count from the central alarm software.

There were no patients transferred to the intensive care unit during the observation period. Nurses who chose not to respond to alarms outside the room most often cited the brevity of the alarm or other reassuring contextual details, such as that a family member was in the room to notify them if anything was truly wrong, that another member of the medical team was with the patient, or that they had recently assessed the patient and thought likely the alarm did not require any action. During three observations, the observed nurse cited the presence of family in the patient’s room in their decision not to conduct further assessment in response to the alarm, noting that the parent would be able to notify the nurse if something required attention. On two occasions in which a nurse had multiple monitored patients, the observed nurse noted that if the other monitored patients were alarming and she happened to be in another patient’s room, she would not be able to hear them. Four nurses cited policy as the reason a patient was on monitors (eg, patient was on respiratory support at night for obstructive sleep apnea).

DISCUSSION

We characterized responses to physiologic monitor alarms by a group of nurses with a range of experience levels. We found that most nurse responses to alarms in continuously monitored general pediatric patients involved no intervention, and further assessment was often not conducted for alarms that occurred outside of the room if the nurse noted otherwise reassuring clinical context. Observed responses occurred for 36% of alarms during the study period when compared with bedside monitor-alarm generated data. Overall, only 14 clinical interventions were noted among the observed responses. Nurses noted that they felt the monitors were necessary for 82.9% of monitored patients because of the clinical context or because of unit policy.

Our study findings highlight some potential contradictions in the current widespread use of CPMs in general pediatric units and how clinicians respond to them in practice.2 First, while nurses reported that monitors were necessary for most of their patients, participating nurses deemed few alarms clinically actionable and often chose not to further assess when they noted alarms outside of the room. This is in line with findings from prior studies suggesting that clinicians overvalue the contribution of monitoring systems to patient safety.

Our findings provide a novel understanding of previously observed phenomena, such as long response times or nonresponses in settings with high alarm rates.4,10 Similar to that in a prior study conducted in the pediatric setting,11 alarms with an observed response constituted a minority of the total alarms that occurred in our study. This finding has previously been attributed to mental fatigue, caregiver apathy, and desensitization.8 However, even though a minority of observed responses in our study included an intervention, the nurse had a rationale for why the alarm did or did not need a response. This behavior and the verbalized rationale indicate that in his/her opinion, not responding to the alarm was clinically appropriate. Study participants also reflected on the difficulties of responding to alarms given the monitor system setup, in which they may not always be capable of hearing alarms for their patients. Without data from nurses regarding the alarms that had no observed response, we can only speculate; however, based on our findings, each of these factors could contribute to nonresponse. Finally, while high numbers of false alarms have been posited as an underlying cause of alarm fatigue, we noted that a majority of nonresponse was reported to be related to other clinical factors. This relationship suggests that from the nurse’s perspective, a more applicable framework for understanding alarms would be based on clinical actionability4 over physiologic accuracy.

In total, our findings suggest that a multifaceted approach will be necessary to improve alarm response rates. These interventions should include adjusting parameters such that alarms are highly likely to indicate a need for intervention coupled with educational interventions addressing clinician knowledge of the alarm system and bias about the actionability of alarms may improve response rates. Changes in the monitoring system setup such that nurses can easily be notified when alarms occur may also be indicated, in addition to formally engaging patients and families around response to alarms. Although secondary notification systems (eg, alarms transmitted to individual clinician’s devices) are one solution, the utilization of these systems needs to be balanced with the risks of contributing to existing alarm fatigue and the need to appropriately tailor monitoring thresholds and strategies to patients.

Our study has several limitations. First, nurses may have responded in a way they perceive to be socially desirable, and studies using in-person observers are also prone to a Hawthorne-like effect,19-21 where the nurse may have tried to respond more frequently to alarms than usual during observations. However, given that the majority of bedside alarms did not receive a response and a substantial number of responses involved no action, these effects were likely weak. Second, we were unable to assess which alarms were accurately reflecting the patient’s physiologic status and which were not; we were also unable to link observed alarm response to monitor-recorded alarms. Third, despite the use of silent observers and an actual, rather than a simulated, clinical setting, by virtue of the data collection method we likely captured a more deliberate thought process (so-called System 2 thinking)22 rather than the subconscious processes that may predominate when nurses respond to alarms in the course of clinical care (System 1 thinking).22 Despite this limitation, our study findings, which reflect a nurse’s in-the-moment thinking, remain relevant to guiding the improvement of monitoring systems, and the development of nurse-facing interventions and education. Finally, we studied a small, purposive sample of nurses at a single hospital. Our study sample impacts the generalizability of our results and precluded a detailed analysis of the effect of nurse- and patient-level variables.

CONCLUSION

We found that nurses often deemed that no response was necessary for CPM alarms. Nurses cited contextual factors, including the duration of alarms and the presence of other providers or parents in their decision-making. Few (7%) of the alarm responses in our study included a clinical intervention. The number of observed alarm responses constituted roughly a third of the alarms recorded by bedside CPMs during the study. This result supports concerns about the nurse’s capacity to hear and process all CPM alarms given system limitations and a heavy clinical workload. Subsequent steps should include staff education, reducing overall alarm rates with appropriate monitor use and actionable alarm thresholds, and ensuring that patient alarms are easily recognizable for frontline staff.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by the Place Outcomes Research Award from the Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation. Dr. Brady is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality under Award Number K08HS23827. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

1. Schondelmeyer AC, Bonafide CP, Goel VV, et al. The frequency of physiologic monitor alarms in a children’s hospital. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):796-798. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2612.

2. Schondelmeyer AC, Brady PW, Goel VV, et al. Physiologic monitor alarm rates at 5 children’s hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(6):396-398. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2918.

3. Schondelmeyer AC, Brady PW, Sucharew H, et al. The impact of reduced pulse oximetry use on alarm frequency. Hosp Pediatr. In press. PubMed

4. Bonafide CP, Lin R, Zander M, et al. Association between exposure to nonactionable physiologic monitor alarms and response time in a children’s hospital. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):345-351. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2331.

5. Siebig S, Kuhls S, Imhoff M, et al. Intensive care unit alarms--how many do we need? Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2):451-456. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cb0888.

6. Sendelbach S, Funk M. Alarm fatigue: a patient safety concern. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2013;24(4):378-386. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCI.0b013e3182a903f9.

7. Sendelbach S. Alarm fatigue. Nurs Clin North Am. 2012;47(3):375-382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnur.2012.05.009.

8. Cvach M. Monitor alarm fatigue: an integrative review. Biomed Instrum Technol. 2012;46(4):268-277. https://doi.org/10.2345/0899-8205-46.4.268.

9. Paine CW, Goel VV, Ely E, et al. Systematic review of physiologic monitor alarm characteristics and pragmatic interventions to reduce alarm frequency. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(2):136-144. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2520.

10. Voepel-Lewis T, Parker ML, Burke CN, et al. Pulse oximetry desaturation alarms on a general postoperative adult unit: a prospective observational study of nurse response time. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(10):1351-1358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.02.006.

11. Bonafide CP, Localio AR, Holmes JH, et al. Video analysis of factors associated With response time to physiologic monitor alarms in a children’s hospital. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(6):524-531. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.5123.

12. Deb S, Claudio D. Alarm fatigue and its influence on staff performance. IIE Trans Healthc Syst Eng. 2015;5(3):183-196. https://doi.org/10.1080/19488300.2015.1062065.

13. Mondor TA, Hurlburt J, Thorne L. Categorizing sounds by pitch: effects of stimulus similarity and response repetition. Percept Psychophys. 2003;65(1):107-114. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03194787.

14. Mondor TA, Finley GA. The perceived urgency of auditory warning alarms used in the hospital operating room is inappropriate. Can J Anaesth. 2003;50(3):221-228. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03017788.

15. Fusch PI, Ness LR. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qual Rep; 20(9), 2015:1408-1416.

16. Najafi N, Auerbach A. Use and outcomes of telemetry monitoring on a medicine service. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1349-1350. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3163.

17. Estrada CA, Rosman HS, Prasad NK, et al. Role of telemetry monitoring in the non-intensive care unit. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76(12):960-965. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9149(99)80270-7.

18. Khan A, Furtak SL, Melvin P et al. Parent-reported errors and adverse events in hospitalized children. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(4):e154608.https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4608.

19. Adair JG. The Hawthorne effect: a reconsideration of the methodological artifact. J Appl Psychol. 1984;69(2):334-345. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.69.2.334.

20. Kovacs-Litman A, Wong K, Shojania KG, et al. Do physicians clean their hands? Insights from a covert observational study. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):862-864. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2632.

21. Wolfe F, Michaud K. The Hawthorne effect, sponsored trials, and the overestimation of treatment effectiveness. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(11):2216-2220. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.100497.

22. Kahneman D. Thinking, Fast and Slow. 1st Pbk. ed. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2013.

1. Schondelmeyer AC, Bonafide CP, Goel VV, et al. The frequency of physiologic monitor alarms in a children’s hospital. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):796-798. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2612.

2. Schondelmeyer AC, Brady PW, Goel VV, et al. Physiologic monitor alarm rates at 5 children’s hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(6):396-398. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2918.

3. Schondelmeyer AC, Brady PW, Sucharew H, et al. The impact of reduced pulse oximetry use on alarm frequency. Hosp Pediatr. In press. PubMed

4. Bonafide CP, Lin R, Zander M, et al. Association between exposure to nonactionable physiologic monitor alarms and response time in a children’s hospital. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):345-351. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2331.

5. Siebig S, Kuhls S, Imhoff M, et al. Intensive care unit alarms--how many do we need? Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2):451-456. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cb0888.

6. Sendelbach S, Funk M. Alarm fatigue: a patient safety concern. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2013;24(4):378-386. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCI.0b013e3182a903f9.

7. Sendelbach S. Alarm fatigue. Nurs Clin North Am. 2012;47(3):375-382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnur.2012.05.009.

8. Cvach M. Monitor alarm fatigue: an integrative review. Biomed Instrum Technol. 2012;46(4):268-277. https://doi.org/10.2345/0899-8205-46.4.268.

9. Paine CW, Goel VV, Ely E, et al. Systematic review of physiologic monitor alarm characteristics and pragmatic interventions to reduce alarm frequency. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(2):136-144. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2520.

10. Voepel-Lewis T, Parker ML, Burke CN, et al. Pulse oximetry desaturation alarms on a general postoperative adult unit: a prospective observational study of nurse response time. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(10):1351-1358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.02.006.

11. Bonafide CP, Localio AR, Holmes JH, et al. Video analysis of factors associated With response time to physiologic monitor alarms in a children’s hospital. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(6):524-531. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.5123.

12. Deb S, Claudio D. Alarm fatigue and its influence on staff performance. IIE Trans Healthc Syst Eng. 2015;5(3):183-196. https://doi.org/10.1080/19488300.2015.1062065.

13. Mondor TA, Hurlburt J, Thorne L. Categorizing sounds by pitch: effects of stimulus similarity and response repetition. Percept Psychophys. 2003;65(1):107-114. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03194787.

14. Mondor TA, Finley GA. The perceived urgency of auditory warning alarms used in the hospital operating room is inappropriate. Can J Anaesth. 2003;50(3):221-228. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03017788.

15. Fusch PI, Ness LR. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qual Rep; 20(9), 2015:1408-1416.

16. Najafi N, Auerbach A. Use and outcomes of telemetry monitoring on a medicine service. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1349-1350. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3163.

17. Estrada CA, Rosman HS, Prasad NK, et al. Role of telemetry monitoring in the non-intensive care unit. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76(12):960-965. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9149(99)80270-7.

18. Khan A, Furtak SL, Melvin P et al. Parent-reported errors and adverse events in hospitalized children. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(4):e154608.https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4608.

19. Adair JG. The Hawthorne effect: a reconsideration of the methodological artifact. J Appl Psychol. 1984;69(2):334-345. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.69.2.334.

20. Kovacs-Litman A, Wong K, Shojania KG, et al. Do physicians clean their hands? Insights from a covert observational study. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):862-864. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2632.

21. Wolfe F, Michaud K. The Hawthorne effect, sponsored trials, and the overestimation of treatment effectiveness. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(11):2216-2220. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.100497.

22. Kahneman D. Thinking, Fast and Slow. 1st Pbk. ed. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2013.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Reducing Unneeded Clinical Variation in Sepsis and Heart Failure Care to Improve Outcomes and Reduce Cost: A Collaborative Engagement with Hospitalists in a MultiState System

Sepsis and heart failure are two common, costly, and deadly conditions. Among hospitalized Medicare patients, these conditions rank as the first and second most frequent principal diagnoses accounting for over $33 billion in spending across all payers.1 One-third to one-half of all hospital deaths are estimated to occur in patients with sepsis,2 and heart failure is listed as a contributing factor in over 10% of deaths in the United States.3

Previous research shows that evidence-based care decisions can impact the outcomes for these patients. For example, sepsis patients receiving intravenous fluids, blood cultures, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and lactate measurement within three hours of presentation have lower mortality rates.4 In heart failure, key interventions such as the appropriate use of ACE inhibitors, beta blockers, and referral to disease management programs reduce morbidity and mortality.5

However, rapid dissemination and adoption of evidence-based guidelines remain a challenge.6,7 Policy makers have introduced incentives and penalties to support adoption, with varying levels of success. After four years of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) penalties for hospitals with excess heart failure readmissions, only 21% performed well enough to avoid a penalty in 2017.8 CMS has been tracking sepsis bundle adherence as a core measure, but the rate in 2018 sat at just 54%.9 It is clear that new solutions are needed.10

AdventHealth (formerly Adventist Health System) is a growing, faith-based health system with hospitals across nine states. AdventHealth is a national leader in quality, safety, and patient satisfaction but is not immune to the challenges of delivering consistent, evidence-based care across an extensive network. To accelerate system-wide practice change, AdventHealth’s Office of Clinical Excellence (OCE) partnered with QURE Healthcare and Premier, Inc., to implement a physician engagement and care standardization collaboration involving nearly 100 hospitalists at eight facilities across five states.

This paper describes the results of the Adventist QURE Quality Project (AQQP), which used QURE’s validated, simulation-based measurement and feedback approach to engage hospitalists and standardize evidence-based practices for patients with sepsis and heart failure. We documented specific areas of variation identified in the simulations, how those practices changed through serial feedback, and the impact of those changes on real-world outcomes and costs.

METHODS

Setting

AdventHealth has its headquarters in Altamonte Springs, Florida. It has facilities in nine states, which includes 48 hospitals. The OCE is comprised of physician leaders, project managers, and data analysts who sponsored the project from July 2016 through July 2018.

Study Participants

AdventHealth hospitals were invited to enroll their hospitalists in AQQP; eight AdventHealth hospitals across five states, representing 91 physicians and 16 nurse practitioners/physician’s assistants (APPs), agreed to participate. Participants included both AdventHealth-employed providers and contracted hospitalist groups. Provider participation was voluntary and not tied to financial incentives; however, participants received Continuing Medical Education credit and, if applicable, Maintenance of Certification points through the American Board of Internal Medicine.

Quasi-experimental Design

We used AdventHealth hospitals not participating in AQQP as a quasi-experimental control group. We leveraged this to measure the impact of concurrent secular effects, such as order sets and other system-wide training, that could also improve practice and outcomes in our study.

Study Objectives and Approach

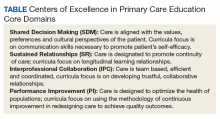

The explicit goals of AQQP were to (1) measure how sepsis and heart failure patients are cared for across AdventHealth using Clinical Performance and Value (CPV) case simulations, (2) provide a forum for hospitalists to discuss clinical variation, and (3) reduce unneeded variation to improve quality and reduce cost. QURE developed 12 CPV simulated patient cases (six sepsis and six heart failure cases) with case-specific evidenced-based scoring criteria tied to national and AdventHealth evidence-based guidelines. AdventHealth order sets were embedded in the cases and accessible by participants as they cared for their patients.

CPV vignettes are simulated patient cases administered online, and have been validated as an accurate and responsive measure of clinical decision-making in both ambulatory11-13 and inpatient settings.14,15 Cases take 20-30 minutes each to complete and simulate a typical clinical encounter: taking the medical history, performing a physical examination, ordering tests, making the diagnosis, implementing initial treatment, and outlining a follow-up plan. Each case has predefined, evidence-based scoring criteria for each care domain. Cases and scoring criteria were reviewed by AdventHealth hospitalist program leaders and physician leaders in OCE. Provider responses were double-scored by trained physician abstractors. Scores range from 0%-100%, with higher scores reflecting greater alignment with best practice recommendations.

In each round of the project, AQQP participants completed two CPV cases, received personalized online feedback reports on their care decisions, and met (at the various sites and via web conference) for a facilitated group discussion on areas of high group variation. The personal feedback reports included the participant’s case score compared to the group average, a list of high-priority personalized improvement opportunities, a summary of the cost of unneeded care items, and links to relevant references. The group discussions focused on six items of high variation. Six total rounds of CPV measurement and feedback were held, one every four months.

At the study’s conclusion, we administered a brief satisfaction survey, asking providers to rate various aspects of the project on a five-point Likert scale.

Data

The study used two primary data sources: (1) care decisions made in the CPV simulated cases and (2) patient-level utilization data from Premier Inc.’s QualityAdvisorTM (QA) data system. QA integrates quality, safety, and financial data from AdventHealth’s electronic medical record, claims data, charge master, and other resources. QualityAdvisor also calculates expected performance for critical measures, including cost per case and length of stay (LOS), based on a proprietary algorithm, which uses DRG classification, severity-of-illness, risk-of-mortality, and other patient risk factors. We pulled patient-level observed and expected data from AQQP qualifying physicians, defined as physicians participating in a majority of CPV measurement rounds. Of the 107 total hospitalists who participated, six providers did not participate in enough CPV rounds, and 22 providers left AdventHealth and could not be included in a patient-level impact analysis. These providers were replaced with 21 new hospitalists who were enrolled in the study and included in the CPV analysis but who did not have patient-level data before AQQP enrollment. Overall, 58 providers met the qualifying criteria to be included in the impact analysis. We compared their performance to a group of 96 hospitalists at facilities that were not participating in the project. Comparator facilities were selected based on quantitative measures of size and demographic matching the AQQP-facilities ensuring that both sets of hospitals (comparator and AQQP) exhibited similar levels of engagement with Advent- Health quality activities such as quality dashboard performance and order set usage. Baseline patient-level cost and LOS data covered from October 2015 to June 2016 and were re-measured annually throughout the project, from July 2016 to June 2018.

Statistical Analyses

We analyzed three primary outcomes: (1) general CPV-measured improvements in each round (scored against evidence-based scoring criteria); (2) disease-specific CPV improvements over each round; and (3) changes in patient-level outcomes and economic savings among AdventHealth pneumonia/sepsis and heart failure patients from the aforementioned improvements. We used Student’s t-test to analyze continuous outcome variables (including CPV, cost of care, and length of stay data) and Fisher’s exact test for binary outcome data. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 14.2 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics and Assessment

A total of 107 AdventHealth hospitalists participated in this study (Appendix Table 1). 78.1% of these providers rated the organization’s focus on quality and lowering unnecessary costs as either “good” or “excellent,” but 78.8% also reported that variation in care provided by the group was “moderate” to “very high”.

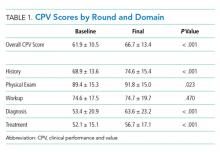

At baseline, we observed high variability in the care of pneumonia patients with sepsis (pneumonia/sepsis) and heart failure patients as measured by the care decisions obtained in the CPV cases. The overall quality score, which is a weighted average across all domains, averaged 61.9% ± 10.5% for the group (Table 1). Disaggregating scores by condition, we found an average overall score of 59.4% ± 10.9% for pneumonia/sepsis and 64.4% ± 9.4% for heart failure. The diagnosis and treatment domains, which require the most clinical judgment, had the lowest average domain scores of 53.4% ± 20.9% and 51.6% ± 15.1%, respectively.

Changes in CPV Scores

To determine the impact of serial measurement and feedback, we compared performance in the first two rounds of the project with the last two rounds. We found that overall CPV quality scores showed a 4.8%-point absolute improvement (P < .001; Table 1). We saw improvements in all care domains, and those increases were significant in all but the workup (P = .470); the most significant increase was in diagnostic accuracy (+19.1%; P < .001).

By condition, scores showed similar, statistically significant overall improvements: +4.4%-points for pneumonia/sepsis (P = .001) and +5.5%-points for heart failure (P < .001) driven by increases in the diagnosis and treatment domains. For example, providers increased appropriate identification of HF severity by 21.5%-points (P < .001) and primary diagnosis of pneumonia/sepsis by 3.6%-points (P = .385).

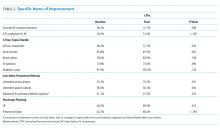

In the treatment domain, which included clinical decisions related to initial management and follow-up care, there were several specific improvements. For HF, we found that performing all the essential treatment elements—prescribing diuretics, ACE inhibitors and beta blockers for appropriate patients—improved by 13.9%-points (P = .038); ordering VTE prophylaxis increased more than threefold, from 16.6% to 51.0% (P < .001; Table 2). For pneumonia/sepsis patients, absolute adherence to all four elements of the 3-hour sepsis bundle improved by 11.7%-points (P = .034). We also saw a decrease in low-value diagnostic workup items for patient cases in which the guidelines suggest they are not needed, such as urinary antigen testing, which declined by 14.6%-points (P = .001) and sputum cultures, which declined 26.4%-points (P = .004). In addition, outlining an evidence-based discharge plan including a follow-up visit, patient education and medication reconciliation improved, especially for pneumonia/sepsis patients by 24.3%-points (P < .001).

Adherence to AdventHealth-preferred, evidence-based empiric antibiotic regimens was only 41.1% at baseline, but by the third round, adherence to preferred antibiotics had increased by 37% (P = .047). In the summer of 2017, after the third round, we updated scoring criteria for the cases to align with new AdventHealth-preferred antibiotic regimens. Not surprisingly, when the new antibiotic regimens were introduced, CPV-measured adherence to the new guidelines then regressed to nearly baseline levels (42.4%) as providers adjusted to the new recommendations. However, by the end of the final round, AdventHealth-preferred antibiotics orders improved by 12%.

Next, we explored whether the improvements seen were due to the best performers getting better, which was not the case. At baseline the bottom-half performers scored 10.7%-points less than top-half performers but, over the course of the study, we found that the bottom half performers had an absolute improvement nearly two times of those in the top half (+5.7%-points vs +2.9%-points; P = .006), indicating that these bottom performers were able to close the gap in quality-of-care provided. In particular, these bottom performers improved the accuracy of their primary diagnosis by 16.7%-points, compared to a 2.0%-point improvement for the top-half performers.

Patient-Level Impact on LOS and Cost Per Case

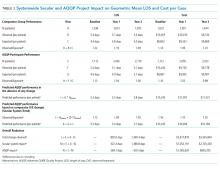

We took advantage of the quasi-experimental design, in which only a portion of AdventHealth facilities participated in the project, to compare patient-level results from AQQP-participating physicians against the engagement-matched cohort of hospitalists at nonparticipating AdventHealth facilities. We adjusted for potential differences in patient-level case mix between the two groups by comparing the observed/expected (O/E) LOS and cost per case ratios for pneumonia/sepsis and heart failure patients.

At baseline, AQQP-hospitalists performed better on geometric LOS versus the comparator group (O/E of 1.13 vs 1.22; P = .006) but at about the same on cost per case (O/E of 1.16 vs 1.14; P = .390). Throughout the project, as patient volumes and expected per patient costs rose for both groups, O/E ratios improved among both AQQP and non-AQQP providers.

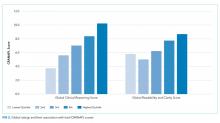

To set apart the contribution of system-wide improvements from the AQQP project-specific impacts, we applied the O/E improvement rates seen in the comparator group to the AQQP group baseline performance. We then compared that to the actual changes seen in the AQQP throughout the project to see if there was any additional benefit from the simulation measurement and feedback (Figure).

From baseline through year one of the project, the O/E LOS ratio decreased by 8.0% in the AQQP group (1.13 to 1.04; P = .004) and only 2.5% in the comparator group (1.22 to 1.19; P = .480), which is an absolute difference-in-difference of 0.06 LOS O/E. In year 1, these improvements represent a reduction in 892 patient days among patients cared for by AQQP-hospitalists of which 570 appear to be driven by the AQQP intervention and 322 attributable to secular system-wide improvements (Table 3). In year two, both groups continued to improve with the comparator group catching up to the AQQP group.