User login

Improving the Transition of Intravenous to Enteral Antibiotics in Pediatric Patients with Pneumonia or Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

Intravenous (IV) antibiotics are commonly used in hospitalized pediatric patients to treat bacterial infections. Antimicrobial stewardship guidelines published by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommend institutions develop a systematic plan to convert from IV to enteral antibiotics, as early transition may reduce healthcare costs, decrease length of stay (LOS), and avoid prolonged IV access complications1 such as extravasation, thrombosis, and catheter-associated infections.2-5

Pediatric patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and mild skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI) may not require IV antibiotics, even if the patient is hospitalized.6 Although national guidelines for pediatric CAP and SSTI recommend IV antibiotics for hospitalized patients, these guidelines state that mild infections may be treated with enteral antibiotics and emphasize discontinuation of IV antibiotics when the patient meets discharge criteria.7,8 Furthermore, several enteral antibiotics used for the treatment of CAP and SSTI, such as cephalexin and clindamycin,9 have excellent bioavailability (>90%) or can achieve sufficient concentrations to attain the pharmacodynamic target (ie, amoxicillin and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole).10,11 Nonetheless, the guidelines do not explicitly outline criteria regarding the transition from IV to enteral antibiotics.7,8

At our institution, patients admitted to Hospital Medicine (HM) often remained on IV antibiotics until discharge. Data review revealed that antibiotic treatment of CAP and SSTI posed the greatest opportunity for early conversion to enteral therapy based on the high frequency of admissions and the ability of commonly used enteral antibiotics to attain pharmacodynamic targets. We sought to change practice culture by decoupling transition to enteral antibiotics from discharge and use administration of other enteral medications as an objective indicator for transition. Our aim was to increase the proportion of enterally administered antibiotic doses for HM patients aged >60 days admitted with uncomplicated CAP or SSTI from 44% to 75% in eight months.

METHODS

Context

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) is a large, urban, academic hospital. The HM division has 45 attendings and admits >8,000 general pediatric patients annually. The five HM teams at the main campus consist of attendings, fellows, residents, and medical students. One HM team serves as the resident quality improvement (QI) team where residents collaborate in a longitudinal study under the guidance of QI-trained coaches. The focus of this QI initiative was determined by resident consensus and aligned with a high-value care curriculum.12

To identify the target patient population, we investigated IV antimicrobials frequently used in HM patients. Ampicillin and clindamycin are commonly used IV antibiotics, most frequently corresponding with the diagnoses of CAP and SSTI, respectively, accounting for half of all antibiotic use on the HM service. Amoxicillin, the enteral equivalent of ampicillin, can achieve sufficient concentrations to attain the pharmacodynamic target at infection sites, and clindamycin has high bioavailability, making them ideal options for early transition. Our institution’s robust antimicrobial stewardship program has published local guidelines on using amoxicillin as the enteral antibiotic of choice for uncomplicated CAP, but it does not provide guidance on the timing of transition for either CAP or SSTI; the clinical team makes this decision.

HM attendings were surveyed to determine the criteria used to transition from IV to enteral antibiotics for patients with CAP or SSTI. The survey illustrated practice variability with providers using differing clinical criteria to signal the timing of transition. Additionally, only 49% of respondents (n = 37) rated themselves as “very comfortable” with residents making autonomous decisions to transition to enteral antibiotics. We chose to use the administration of other enteral medications, instead of discharge readiness, as an objective indicator of a patient’s readiness to transition to enteral antibiotics, given the low-risk patient population and the ability of the enteral antibiotics commonly used for CAP and SSTI to achieve pharmacodynamic targets.

The study population included patients aged >60 days admitted to HM with CAP or SSTI treated with any antibiotic. We excluded patients with potential complications or significant progression of their disease process, including patients with parapneumonic effusions or chest tubes, patients who underwent bronchoscopy, and patients with osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, or preseptal or orbital cellulitis. Past medical history and clinical status on admission were not used to exclude patients.

Interventions

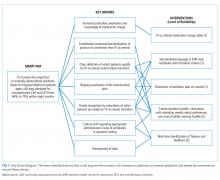

Our multidisciplinary team, formed in January 2017, included HM attendings, HM fellows, pediatric residents, a critical care attending, a pharmacy resident, and an antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist. Under the guidance of QI coaches, the residents on the HM QI team developed and tested all interventions on their team and then determined which interventions would spread to the other four teams. The nursing director of our primary HM unit disseminated project updates to bedside nurses. A simplified failure mode and effects analysis identified areas for improvement and potential interventions. Interventions focused on the following key drivers (Figure 1): increased prescriber awareness of medication charge, standardization of conversion from IV to enteral antibiotics, clear definition of the patients ready for transition, ongoing evaluation of the antimicrobial plan, timely recognition by prescribers of patients ready for transition, culture shift regarding the appropriate administration route in the inpatient setting, and transparency of data. The team implemented sequential Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles13 to test the interventions.

Charge Table

To improve knowledge about the increased charge for commonly used IV medications compared with enteral formulations, a table comparing relative charges was shared during monthly resident morning conferences and at an HM faculty meeting. The table included charge comparisons between ampicillin and amoxicillin and IV and enteral clindamycin.

Standardized Language in Electronic Health Record (EHR) Antibiotic Plan on Rounds

Standardized language to document antibiotic transition plans was added to admission and progress note templates in the EHR. The standard template prompted residents to (1) define clinical transition criteria, (2) discuss attending comfort with transition overnight (based on survey results), and (3) document patient preference of solid or liquid dosage forms. Plans were reviewed and updated daily. We hypothesized that since residents use the information in the daily progress notes, including assessments and plans, to present on rounds, inclusion of the transition criteria in the note would prompt transition plan discussions.

Communication Bundle

To promote early transition to enteral antibiotics, we standardized the discussion about antibiotic transition between residents and attendings. During a weekly preexisting meeting, the resident QI team reviewed preferences for transitions with the new service attending. By identifying attending preferences early, residents were able to proactively transition patients who met the criteria (eg, antibiotic transition in the evening instead of waiting until morning rounds). This discussion also provided an opportunity to engage service attendings in the QI efforts, which were also shared at HM faculty meetings quarterly.

Recognizing that in times of high census, discussion of patient plans may be abbreviated during rounds, residents were asked to identify all patients on IV antibiotics while reviewing patient medication orders prior to rounds. As part of an existing daily prerounds huddle to discuss rounding logistics, residents listed all patients on IV antibiotics and discussed which patients were ready for transition. If patients could not be transitioned immediately, the team identified the transition criteria.

At preexisting evening huddles between overnight shift HM residents and the evening HM attending, residents identified patients who were prescribed IV antibiotics and discussed readiness for enteral transition. If a patient could be transitioned overnight, enteral antibiotic orders were placed. Overnight residents were also encouraged to review the transition criteria with families upon admission.

Real-time Identification of Failures and Feedback

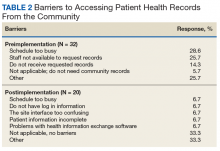

For two weeks, the EHR was queried daily to identify patients admitted for uncomplicated CAP and SSTI who were on antibiotics as well as other enteral medications. A failure was defined as an IV antibiotic dose given to a patient who was administered any enteral medication. Residents on the QI team approached residents on other HM teams whenever patients were identified as a failed transition to learn about failure reasons.

Study of the Interventions

Data for HM patients who met the inclusion criteria were collected weekly from January 2016 through June 2018 via EHR query. We initially searched for diagnoses that fit under the disease categories of pneumonia and SSTI in the EHR, which generated a list of International Classification of Disease-9 and -10 Diagnosis codes (Appendix Figure 1). The query identified patients based on these codes and reported whether the identified patients took a dose of any enteral medication, excluding nystatin, sildenafil, tacrolimus, and mouthwashes, which are commonly continued during NPO status due to no need for absorption or limited parenteral options. It also reported the ordered route of administration for the queried antibiotics (Appendix Figure 1).

The 2016 calendar year established our baseline to account for seasonal variability. Data were reported weekly and reviewed to evaluate the impact of PDSA cycles and inform new interventions.

Measures

Our process measure was the total number of enteral antibiotic doses divided by all antibiotic doses in patients receiving any enteral medication. We reasoned that if patients were well enough to take medications enterally, they could be given an enteral antibiotic that is highly bioavailable or readily achieves concentrations that attain pharmacodynamic targets. This practice change was a culture shift, decoupling the switch to enteral antibiotics from discharge readiness. Our EHR query reported only the antibiotic doses given to patients who took an enteral medication on the day of antibiotic administration and excluded patients who received only IV medications.

Outcome measures included antimicrobial costs per patient encounter using average wholesale prices, which were reported in our EHR query, and LOS. To ensure that transitions of IV to enteral antibiotics were not negatively impacting patient outcomes, patient readmissions within seven days served as a balancing measure.

Analysis

An annotated statistical process control p-chart tracked the impact of interventions on the proportion of antibiotic doses that were enterally administered during hospitalization. An x-bar and an s-chart tracked the impact of interventions on antimicrobial costs per patient encounter and on LOS. A p-chart and an encounters-between g-chart were used to evaluate the impact of our interventions on readmissions. Control chart rules for identifying special cause were used for center line shifts.14

Ethical Considerations

This study was part of a larger study of the residency high-value care curriculum,12 which was deemed exempt by the CCHMC IRB.

RESULTS

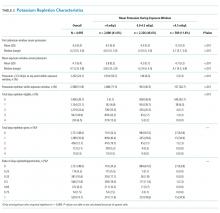

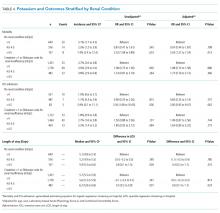

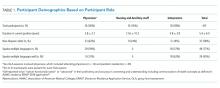

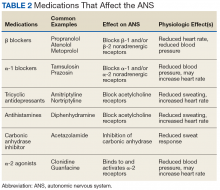

The baseline data collected included 372 patients and the postintervention period in 2017 included 326 patients (Table). Approximately two-thirds of patients had a diagnosis of CAP.

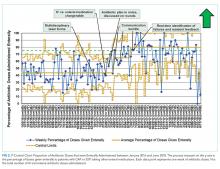

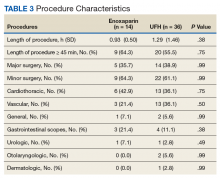

The percentage of antibiotic doses given enterally increased from 44% to 80% within eight months (Figure 2). When studying the impact of interventions, residents on the HM QI team found that the standard EHR template added to daily notes did not consistently prompt residents to discuss antibiotic plans and thus was abandoned. Initial improvement coincided with standardizing discussions between residents and attendings regarding transitions. Furthermore, discussion of all patients on IV antibiotics during the prerounds huddle allowed for reliable, daily communication about antibiotic plans and was subsequently spread to and adopted by all HM teams. The percentage of enterally administered antibiotic doses increased to >75% after the evening huddle, which involved all HM teams, and real-time identification of failures on all HM teams with provider feedback. Despite variability when the total number of antibiotic doses prescribed per week was low (<10), we demonstrated sustainability for 11 months (Figure 2), during which the prerounds and evening huddle discussions were continued and an updated control chart was shown monthly to residents during their educational conferences.

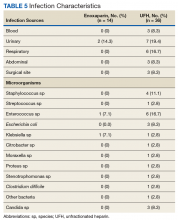

Residents on the QI team spoke directly with other HM residents when there were missed opportunities for transition. Based on these discussions and intermittent chart reviews, common reasons for failure to transition in patients with CAP included admission for failed outpatient enteral treatment, recent evaluation by critical care physicians for possible transfer to the intensive care unit, and difficulty weaning oxygen. For patients with SSTI, hand abscesses requiring drainage by surgery and treatment failure with other antibiotics constituted many of the IV antibiotic doses given to patients on enteral medications.

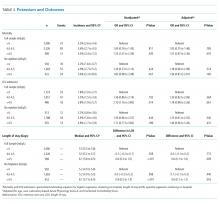

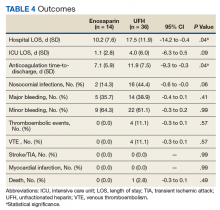

Antimicrobial costs per patient encounter decreased by 70% over one year; the shift in costs coincided with the second shift in our process measure (Appendix Figure 2A). Based on an estimate of 350 patients admitted per year for uncomplicated CAP or SSTI, this translates to an annual cost savings of approximately $29,000. The standard deviation of costs per patient encounter decreased by 84% (Appendix Figure 2B), suggesting a decrease in the variability of prescribing practices.

The average LOS in our patient population prior to intervention was 2.1 days and did not change (Appendix Figure 2C), but the standard deviation decreased by >50% (Appendix Figure 2D). There was no shift in the mean seven-day readmission rate or the number of encounters between readmissions (2.6% and 26, respectively; Appendix Figure 3). In addition, the hospital billing department did not identify an increase in insurance denials related to the route of antibiotic administration.

DISCUSSION

Summary

Using improvement science, we promoted earlier transition to enteral antibiotics for children hospitalized with uncomplicated CAP and SSTI by linking the decision for transition to the ability to take other enteral medications, rather than to discharge readiness. We increased the percentage of enterally administered antibiotic doses in this patient population from 44% to 80% in eight months. Although we did not observe a decrease in LOS as previously noted in a cost analysis study comparing pediatric patients with CAP treated with oral antibiotics versus those treated with IV antibiotics,15 we did find a decrease in LOS variability and in antimicrobial costs to our patients. These cost savings did not include potential savings from nursing or pharmacy labor. In addition, we noted a decrease in the variability in antibiotic prescribing practice, which demonstrates provider ability and willingness to couple antibiotic route transition to an objective characteristic (administration of other enteral medications).

A strength of our study was that residents, the most frequent prescribers of antibiotics on our HM service, were highly involved in the QI initiative, including defining the SMART aim, identifying key drivers, developing interventions, and completing sequential PDSA cycles. Under the guidance of QI-trained coaches, residents developed feasible interventions and assessed their success in real time. Consistent with other studies,16,17 resident buy-in and involvement led to the success of our improvement study.

Interpretation

Despite emerging evidence regarding the timing of transition to enteral antibiotics, several factors impeded early transition at our institution, including physician culture, variable practice habits, and hospital workflow. Evidence supports the use of enteral antibiotics in immunocompetent children hospitalized for uncomplicated CAP who do not have chronic lung disease, are not in shock, and have oxygen saturations >85%.6 Although existing literature suggests that in pediatric patients admitted for SSTIs not involving the eye or bone, IV antibiotics may be transitioned when clinical improvement, evidenced by a reduction in fever or erythema, is noted,6 enteral antibiotics that achieve appropriate concentrations to attain pharmacodynamic targets should have the same efficacy as that of IV antibiotics.9 Using the criterion of administration of any medication enterally to identify a patient’s readiness to transition, we were able to overcome practice variation among providers who may have differing opinions of what constitutes clinical improvement. Of note, new evidence is emerging on predictors of enteral antibiotic treatment failure in patients with CAP and SSTI to guide transition timing, but these studies have largely focused on the adult population or were performed in the outpatient and emergency department (ED) settings.18,19 Regardless, the stable number of encounters between readmissions in our patient population likely indicates that treatment failure in these patients was rare.

Rising healthcare costs have led to concerns around sustainability of the healthcare system;20,21 tackling overuse in clinical practice, as in our study, is one mitigation strategy. Several studies have used QI methods to facilitate the provision of high-value care through the decrease of continuous monitor overuse and extraneous ordering of electrolytes.22,23 Our QI study adds to the high-value care literature by safely decreasing the use of IV antibiotics. One retrospective study demonstrated that a one-day decrease in the use of IV antibiotics in pneumonia resulted in decreased costs without an increase in readmissions, similar to our findings.24 In adults, QI initiatives aimed at improving early transition of antibiotics utilized electronic trigger tools.25,26 Fischer et al. used active orders for scheduled enteral medications or an enteral diet as indication that a patient’s IV medications could be converted to enteral form.26

Our work is not without limitations. The list of ICD-9 and -10 codes used to query the EHR did not capture all diagnoses that would be considered as uncomplicated CAP or SSTI. However, we included an extensive list of diagnoses to ensure that the majority of patients meeting our inclusion criteria were captured. Our process measure did not account for patients on IV antibiotics who were not administered other enteral medications but tolerating an enteral diet. These patients were not identified in our EHR query and were not included in our process measure as a failure. However, in latter interventions, residents identified all patients on IV antibiotics, so that patients not identified by our EHR query benefited from our work. Furthermore, this QI study was conducted at a single institution and several interventions took advantage of preexisting structured huddles and a resident QI curriculum, which may not exist at other institutions. Our study does highlight that engaging frontline providers, such as residents, to review antibiotic orders consistently and question the appropriateness of the administration route is key to making incremental changes in prescribing practices.

CONCLUSIONS

Through a partnership between HM and Pharmacy and with substantial resident involvement, we improved the transition of IV antibiotics in patients with CAP or SSTI by increasing the percentage of enterally administered antibiotic doses and reducing antimicrobial costs and variability in antibiotic prescribing practices. This work illustrates how reducing overuse of IV antibiotics promotes high-value care and aligns with initiatives to prevent avoidable harm.27 Our work highlights that standardized discussions about medication orders to create consensus around enteral antibiotic transitions, real-time feedback, and challenging the status quo can influence practice habits and effect change.

Next steps include testing automated methods to notify providers of opportunities for transition from IV to enteral antibiotics through embedded clinical decision support, a method similar to the electronic trigger tools used in adult QI studies.25,26 Since our prerounds huddle includes identifying all patients on IV antibiotics, studying the transition to enteral antibiotics and its effect on prescribing practices in other diagnoses (ie, urinary tract infection and osteomyelitis) may contribute to spreading these efforts. Partnering with our ED colleagues may be an important next step, as several patients admitted to HM on IV antibiotics are given their first dose in the ED.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the faculty of the James M. Anderson Center for Health Systems Excellence Intermediate Improvement Science Series for their guidance in the planning of this project. The authors would also like to thank Ms. Ursula Bradshaw and Mr. Michael Ponti-Zins for obtaining the hospital data on length of stay and readmissions. The authors acknowledge Dr. Philip Hagedorn for his assistance with the software that queries the electronic health record and Dr. Laura Brower and Dr. Joanna Thomson for their assistance with statistical analysis. The authors are grateful to all the residents and coaches on the QI Hospital Medicine team who contributed ideas on study design and interventions.

1. Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE, Jr, et al. Infectious diseases society of America and the society for healthcare epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(2):159-177. https://doi.org/10.1086/510393.

2. Shah SS, Srivastava R, Wu S, et al. Intravenous Versus oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of complicated pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2016;138(6). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1692.

3. Keren R, Shah SS, Srivastava R, et al. Comparative effectiveness of intravenous vs oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of acute osteomyelitis in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(2):120-128. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.2822.

4. Jumani K, Advani S, Reich NG, Gosey L, Milstone AM. Risk factors for peripherally inserted central venous catheter complications in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(5):429-435.https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.775.

5. Zaoutis T, Localio AR, Leckerman K, et al. Prolonged intravenous therapy versus early transition to oral antimicrobial therapy for acute osteomyelitis in children. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):636-642. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-0596.

6. McMullan BJ, Andresen D, Blyth CC, et al. Antibiotic duration and timing of the switch from intravenous to oral route for bacterial infections in children: systematic review and guidelines. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(8):e139-e152. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30024-X.

7. Bradley JS, Byington CL, Shah SS, et al. The management of community-acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(7):e25-e76. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cir531.

8. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Executive summary: practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):147-159. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu444.

9. MacGregor RR, Graziani AL. Oral administration of antibiotics: a rational alternative to the parenteral route. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24(3):457-467. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinids/24.3.457.

10. Downes KJ, Hahn A, Wiles J, Courter JD, Vinks AA. Dose optimisation of antibiotics in children: application of pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics in paediatrics. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014;43(3):223-230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.11.006.

11. Autmizguine J, Melloni C, Hornik CP, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in infants and children. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(1):e01813-e01817. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01813-17.

12. Dewan M, Herrmann LE, Tchou MJ, et al. Development and evaluation of high-value pediatrics: a high-value care pediatric resident curriculum. Hosp Pediatr. 2018;8(12):785-792. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2018-0115

13. Langley GJ, Moen RD, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. New Jersey, US: John Wiley & Sons; 2009.

14. Benneyan JC. Use and interpretation of statistical quality control charts. Int J Qual Health Care. 1998;10(1):69-73. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/10.1.69.

15. Lorgelly PK, Atkinson M, Lakhanpaul M, et al. Oral versus i.v. antibiotics for community-acquired pneumonia in children: a cost-minimisation analysis. Eur Respir J. 2010;35(4):858-864. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00087209.

16. Vidyarthi AR, Green AL, Rosenbluth G, Baron RB. Engaging residents and fellows to improve institution-wide quality: the first six years of a novel financial incentive program. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):460-468. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000159.

17. Stinnett-Donnelly JM, Stevens PG, Hood VL. Developing a high value care programme from the bottom up: a programme of faculty-resident improvement projects targeting harmful or unnecessary care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(11):901-908. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004546.

18. Peterson D, McLeod S, Woolfrey K, McRae A. Predictors of failure of empiric outpatient antibiotic therapy in emergency department patients with uncomplicated cellulitis. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(5):526-531. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12371.

19. Yadav K, Suh KN, Eagles D, et al. Predictors of oral antibiotic treatment failure for non-purulent skin and soft tissue infections in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2018;20(S1):S24-S25. https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2018.114.

20. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Healthcare costs unsustainable in advanced economies without reform. http://www.oecd.org/health/healthcarecostsunsustainableinadvancedeconomieswithoutreform.htm. Accessed June 28, 2018; 2015.

21. Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513-1516. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.362.

22. Schondelmeyer AC, Simmons JM, Statile AM, et al. Using quality improvement to reduce continuous pulse oximetry use in children with wheezing. Pediatrics. 2015;135(4):e1044-e1051. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2295.

23. Tchou MJ, Tang Girdwood S, Wormser B, et al. Reducing electrolyte testing in hospitalized children by using quality improvement methods. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3187.

24. Christensen EW, Spaulding AB, Pomputius WF, Grapentine SP. Effects of hospital practice patterns for antibiotic administration for pneumonia on hospital lengths of stay and costs. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2019;8(2):115-121. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpids/piy003.

25. Berrevoets MAH, Pot JHLW, Houterman AE, et al. An electronic trigger tool to optimise intravenous to oral antibiotic switch: a controlled, interrupted time series study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017;6:81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-017-0239-3.

26. Fischer MA, Solomon DH, Teich JM, Avorn J. Conversion from intravenous to oral medications: assessment of a computerized intervention for hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(21):2585-2589. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.163.21.2585.

27. Schroeder AR, Harris SJ, Newman TB. Safely doing less: a missing component of the patient safety dialogue. Pediatrics. 2011;128(6):e1596-e1597. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2726.

Intravenous (IV) antibiotics are commonly used in hospitalized pediatric patients to treat bacterial infections. Antimicrobial stewardship guidelines published by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommend institutions develop a systematic plan to convert from IV to enteral antibiotics, as early transition may reduce healthcare costs, decrease length of stay (LOS), and avoid prolonged IV access complications1 such as extravasation, thrombosis, and catheter-associated infections.2-5

Pediatric patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and mild skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI) may not require IV antibiotics, even if the patient is hospitalized.6 Although national guidelines for pediatric CAP and SSTI recommend IV antibiotics for hospitalized patients, these guidelines state that mild infections may be treated with enteral antibiotics and emphasize discontinuation of IV antibiotics when the patient meets discharge criteria.7,8 Furthermore, several enteral antibiotics used for the treatment of CAP and SSTI, such as cephalexin and clindamycin,9 have excellent bioavailability (>90%) or can achieve sufficient concentrations to attain the pharmacodynamic target (ie, amoxicillin and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole).10,11 Nonetheless, the guidelines do not explicitly outline criteria regarding the transition from IV to enteral antibiotics.7,8

At our institution, patients admitted to Hospital Medicine (HM) often remained on IV antibiotics until discharge. Data review revealed that antibiotic treatment of CAP and SSTI posed the greatest opportunity for early conversion to enteral therapy based on the high frequency of admissions and the ability of commonly used enteral antibiotics to attain pharmacodynamic targets. We sought to change practice culture by decoupling transition to enteral antibiotics from discharge and use administration of other enteral medications as an objective indicator for transition. Our aim was to increase the proportion of enterally administered antibiotic doses for HM patients aged >60 days admitted with uncomplicated CAP or SSTI from 44% to 75% in eight months.

METHODS

Context

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) is a large, urban, academic hospital. The HM division has 45 attendings and admits >8,000 general pediatric patients annually. The five HM teams at the main campus consist of attendings, fellows, residents, and medical students. One HM team serves as the resident quality improvement (QI) team where residents collaborate in a longitudinal study under the guidance of QI-trained coaches. The focus of this QI initiative was determined by resident consensus and aligned with a high-value care curriculum.12

To identify the target patient population, we investigated IV antimicrobials frequently used in HM patients. Ampicillin and clindamycin are commonly used IV antibiotics, most frequently corresponding with the diagnoses of CAP and SSTI, respectively, accounting for half of all antibiotic use on the HM service. Amoxicillin, the enteral equivalent of ampicillin, can achieve sufficient concentrations to attain the pharmacodynamic target at infection sites, and clindamycin has high bioavailability, making them ideal options for early transition. Our institution’s robust antimicrobial stewardship program has published local guidelines on using amoxicillin as the enteral antibiotic of choice for uncomplicated CAP, but it does not provide guidance on the timing of transition for either CAP or SSTI; the clinical team makes this decision.

HM attendings were surveyed to determine the criteria used to transition from IV to enteral antibiotics for patients with CAP or SSTI. The survey illustrated practice variability with providers using differing clinical criteria to signal the timing of transition. Additionally, only 49% of respondents (n = 37) rated themselves as “very comfortable” with residents making autonomous decisions to transition to enteral antibiotics. We chose to use the administration of other enteral medications, instead of discharge readiness, as an objective indicator of a patient’s readiness to transition to enteral antibiotics, given the low-risk patient population and the ability of the enteral antibiotics commonly used for CAP and SSTI to achieve pharmacodynamic targets.

The study population included patients aged >60 days admitted to HM with CAP or SSTI treated with any antibiotic. We excluded patients with potential complications or significant progression of their disease process, including patients with parapneumonic effusions or chest tubes, patients who underwent bronchoscopy, and patients with osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, or preseptal or orbital cellulitis. Past medical history and clinical status on admission were not used to exclude patients.

Interventions

Our multidisciplinary team, formed in January 2017, included HM attendings, HM fellows, pediatric residents, a critical care attending, a pharmacy resident, and an antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist. Under the guidance of QI coaches, the residents on the HM QI team developed and tested all interventions on their team and then determined which interventions would spread to the other four teams. The nursing director of our primary HM unit disseminated project updates to bedside nurses. A simplified failure mode and effects analysis identified areas for improvement and potential interventions. Interventions focused on the following key drivers (Figure 1): increased prescriber awareness of medication charge, standardization of conversion from IV to enteral antibiotics, clear definition of the patients ready for transition, ongoing evaluation of the antimicrobial plan, timely recognition by prescribers of patients ready for transition, culture shift regarding the appropriate administration route in the inpatient setting, and transparency of data. The team implemented sequential Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles13 to test the interventions.

Charge Table

To improve knowledge about the increased charge for commonly used IV medications compared with enteral formulations, a table comparing relative charges was shared during monthly resident morning conferences and at an HM faculty meeting. The table included charge comparisons between ampicillin and amoxicillin and IV and enteral clindamycin.

Standardized Language in Electronic Health Record (EHR) Antibiotic Plan on Rounds

Standardized language to document antibiotic transition plans was added to admission and progress note templates in the EHR. The standard template prompted residents to (1) define clinical transition criteria, (2) discuss attending comfort with transition overnight (based on survey results), and (3) document patient preference of solid or liquid dosage forms. Plans were reviewed and updated daily. We hypothesized that since residents use the information in the daily progress notes, including assessments and plans, to present on rounds, inclusion of the transition criteria in the note would prompt transition plan discussions.

Communication Bundle

To promote early transition to enteral antibiotics, we standardized the discussion about antibiotic transition between residents and attendings. During a weekly preexisting meeting, the resident QI team reviewed preferences for transitions with the new service attending. By identifying attending preferences early, residents were able to proactively transition patients who met the criteria (eg, antibiotic transition in the evening instead of waiting until morning rounds). This discussion also provided an opportunity to engage service attendings in the QI efforts, which were also shared at HM faculty meetings quarterly.

Recognizing that in times of high census, discussion of patient plans may be abbreviated during rounds, residents were asked to identify all patients on IV antibiotics while reviewing patient medication orders prior to rounds. As part of an existing daily prerounds huddle to discuss rounding logistics, residents listed all patients on IV antibiotics and discussed which patients were ready for transition. If patients could not be transitioned immediately, the team identified the transition criteria.

At preexisting evening huddles between overnight shift HM residents and the evening HM attending, residents identified patients who were prescribed IV antibiotics and discussed readiness for enteral transition. If a patient could be transitioned overnight, enteral antibiotic orders were placed. Overnight residents were also encouraged to review the transition criteria with families upon admission.

Real-time Identification of Failures and Feedback

For two weeks, the EHR was queried daily to identify patients admitted for uncomplicated CAP and SSTI who were on antibiotics as well as other enteral medications. A failure was defined as an IV antibiotic dose given to a patient who was administered any enteral medication. Residents on the QI team approached residents on other HM teams whenever patients were identified as a failed transition to learn about failure reasons.

Study of the Interventions

Data for HM patients who met the inclusion criteria were collected weekly from January 2016 through June 2018 via EHR query. We initially searched for diagnoses that fit under the disease categories of pneumonia and SSTI in the EHR, which generated a list of International Classification of Disease-9 and -10 Diagnosis codes (Appendix Figure 1). The query identified patients based on these codes and reported whether the identified patients took a dose of any enteral medication, excluding nystatin, sildenafil, tacrolimus, and mouthwashes, which are commonly continued during NPO status due to no need for absorption or limited parenteral options. It also reported the ordered route of administration for the queried antibiotics (Appendix Figure 1).

The 2016 calendar year established our baseline to account for seasonal variability. Data were reported weekly and reviewed to evaluate the impact of PDSA cycles and inform new interventions.

Measures

Our process measure was the total number of enteral antibiotic doses divided by all antibiotic doses in patients receiving any enteral medication. We reasoned that if patients were well enough to take medications enterally, they could be given an enteral antibiotic that is highly bioavailable or readily achieves concentrations that attain pharmacodynamic targets. This practice change was a culture shift, decoupling the switch to enteral antibiotics from discharge readiness. Our EHR query reported only the antibiotic doses given to patients who took an enteral medication on the day of antibiotic administration and excluded patients who received only IV medications.

Outcome measures included antimicrobial costs per patient encounter using average wholesale prices, which were reported in our EHR query, and LOS. To ensure that transitions of IV to enteral antibiotics were not negatively impacting patient outcomes, patient readmissions within seven days served as a balancing measure.

Analysis

An annotated statistical process control p-chart tracked the impact of interventions on the proportion of antibiotic doses that were enterally administered during hospitalization. An x-bar and an s-chart tracked the impact of interventions on antimicrobial costs per patient encounter and on LOS. A p-chart and an encounters-between g-chart were used to evaluate the impact of our interventions on readmissions. Control chart rules for identifying special cause were used for center line shifts.14

Ethical Considerations

This study was part of a larger study of the residency high-value care curriculum,12 which was deemed exempt by the CCHMC IRB.

RESULTS

The baseline data collected included 372 patients and the postintervention period in 2017 included 326 patients (Table). Approximately two-thirds of patients had a diagnosis of CAP.

The percentage of antibiotic doses given enterally increased from 44% to 80% within eight months (Figure 2). When studying the impact of interventions, residents on the HM QI team found that the standard EHR template added to daily notes did not consistently prompt residents to discuss antibiotic plans and thus was abandoned. Initial improvement coincided with standardizing discussions between residents and attendings regarding transitions. Furthermore, discussion of all patients on IV antibiotics during the prerounds huddle allowed for reliable, daily communication about antibiotic plans and was subsequently spread to and adopted by all HM teams. The percentage of enterally administered antibiotic doses increased to >75% after the evening huddle, which involved all HM teams, and real-time identification of failures on all HM teams with provider feedback. Despite variability when the total number of antibiotic doses prescribed per week was low (<10), we demonstrated sustainability for 11 months (Figure 2), during which the prerounds and evening huddle discussions were continued and an updated control chart was shown monthly to residents during their educational conferences.

Residents on the QI team spoke directly with other HM residents when there were missed opportunities for transition. Based on these discussions and intermittent chart reviews, common reasons for failure to transition in patients with CAP included admission for failed outpatient enteral treatment, recent evaluation by critical care physicians for possible transfer to the intensive care unit, and difficulty weaning oxygen. For patients with SSTI, hand abscesses requiring drainage by surgery and treatment failure with other antibiotics constituted many of the IV antibiotic doses given to patients on enteral medications.

Antimicrobial costs per patient encounter decreased by 70% over one year; the shift in costs coincided with the second shift in our process measure (Appendix Figure 2A). Based on an estimate of 350 patients admitted per year for uncomplicated CAP or SSTI, this translates to an annual cost savings of approximately $29,000. The standard deviation of costs per patient encounter decreased by 84% (Appendix Figure 2B), suggesting a decrease in the variability of prescribing practices.

The average LOS in our patient population prior to intervention was 2.1 days and did not change (Appendix Figure 2C), but the standard deviation decreased by >50% (Appendix Figure 2D). There was no shift in the mean seven-day readmission rate or the number of encounters between readmissions (2.6% and 26, respectively; Appendix Figure 3). In addition, the hospital billing department did not identify an increase in insurance denials related to the route of antibiotic administration.

DISCUSSION

Summary

Using improvement science, we promoted earlier transition to enteral antibiotics for children hospitalized with uncomplicated CAP and SSTI by linking the decision for transition to the ability to take other enteral medications, rather than to discharge readiness. We increased the percentage of enterally administered antibiotic doses in this patient population from 44% to 80% in eight months. Although we did not observe a decrease in LOS as previously noted in a cost analysis study comparing pediatric patients with CAP treated with oral antibiotics versus those treated with IV antibiotics,15 we did find a decrease in LOS variability and in antimicrobial costs to our patients. These cost savings did not include potential savings from nursing or pharmacy labor. In addition, we noted a decrease in the variability in antibiotic prescribing practice, which demonstrates provider ability and willingness to couple antibiotic route transition to an objective characteristic (administration of other enteral medications).

A strength of our study was that residents, the most frequent prescribers of antibiotics on our HM service, were highly involved in the QI initiative, including defining the SMART aim, identifying key drivers, developing interventions, and completing sequential PDSA cycles. Under the guidance of QI-trained coaches, residents developed feasible interventions and assessed their success in real time. Consistent with other studies,16,17 resident buy-in and involvement led to the success of our improvement study.

Interpretation

Despite emerging evidence regarding the timing of transition to enteral antibiotics, several factors impeded early transition at our institution, including physician culture, variable practice habits, and hospital workflow. Evidence supports the use of enteral antibiotics in immunocompetent children hospitalized for uncomplicated CAP who do not have chronic lung disease, are not in shock, and have oxygen saturations >85%.6 Although existing literature suggests that in pediatric patients admitted for SSTIs not involving the eye or bone, IV antibiotics may be transitioned when clinical improvement, evidenced by a reduction in fever or erythema, is noted,6 enteral antibiotics that achieve appropriate concentrations to attain pharmacodynamic targets should have the same efficacy as that of IV antibiotics.9 Using the criterion of administration of any medication enterally to identify a patient’s readiness to transition, we were able to overcome practice variation among providers who may have differing opinions of what constitutes clinical improvement. Of note, new evidence is emerging on predictors of enteral antibiotic treatment failure in patients with CAP and SSTI to guide transition timing, but these studies have largely focused on the adult population or were performed in the outpatient and emergency department (ED) settings.18,19 Regardless, the stable number of encounters between readmissions in our patient population likely indicates that treatment failure in these patients was rare.

Rising healthcare costs have led to concerns around sustainability of the healthcare system;20,21 tackling overuse in clinical practice, as in our study, is one mitigation strategy. Several studies have used QI methods to facilitate the provision of high-value care through the decrease of continuous monitor overuse and extraneous ordering of electrolytes.22,23 Our QI study adds to the high-value care literature by safely decreasing the use of IV antibiotics. One retrospective study demonstrated that a one-day decrease in the use of IV antibiotics in pneumonia resulted in decreased costs without an increase in readmissions, similar to our findings.24 In adults, QI initiatives aimed at improving early transition of antibiotics utilized electronic trigger tools.25,26 Fischer et al. used active orders for scheduled enteral medications or an enteral diet as indication that a patient’s IV medications could be converted to enteral form.26

Our work is not without limitations. The list of ICD-9 and -10 codes used to query the EHR did not capture all diagnoses that would be considered as uncomplicated CAP or SSTI. However, we included an extensive list of diagnoses to ensure that the majority of patients meeting our inclusion criteria were captured. Our process measure did not account for patients on IV antibiotics who were not administered other enteral medications but tolerating an enteral diet. These patients were not identified in our EHR query and were not included in our process measure as a failure. However, in latter interventions, residents identified all patients on IV antibiotics, so that patients not identified by our EHR query benefited from our work. Furthermore, this QI study was conducted at a single institution and several interventions took advantage of preexisting structured huddles and a resident QI curriculum, which may not exist at other institutions. Our study does highlight that engaging frontline providers, such as residents, to review antibiotic orders consistently and question the appropriateness of the administration route is key to making incremental changes in prescribing practices.

CONCLUSIONS

Through a partnership between HM and Pharmacy and with substantial resident involvement, we improved the transition of IV antibiotics in patients with CAP or SSTI by increasing the percentage of enterally administered antibiotic doses and reducing antimicrobial costs and variability in antibiotic prescribing practices. This work illustrates how reducing overuse of IV antibiotics promotes high-value care and aligns with initiatives to prevent avoidable harm.27 Our work highlights that standardized discussions about medication orders to create consensus around enteral antibiotic transitions, real-time feedback, and challenging the status quo can influence practice habits and effect change.

Next steps include testing automated methods to notify providers of opportunities for transition from IV to enteral antibiotics through embedded clinical decision support, a method similar to the electronic trigger tools used in adult QI studies.25,26 Since our prerounds huddle includes identifying all patients on IV antibiotics, studying the transition to enteral antibiotics and its effect on prescribing practices in other diagnoses (ie, urinary tract infection and osteomyelitis) may contribute to spreading these efforts. Partnering with our ED colleagues may be an important next step, as several patients admitted to HM on IV antibiotics are given their first dose in the ED.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the faculty of the James M. Anderson Center for Health Systems Excellence Intermediate Improvement Science Series for their guidance in the planning of this project. The authors would also like to thank Ms. Ursula Bradshaw and Mr. Michael Ponti-Zins for obtaining the hospital data on length of stay and readmissions. The authors acknowledge Dr. Philip Hagedorn for his assistance with the software that queries the electronic health record and Dr. Laura Brower and Dr. Joanna Thomson for their assistance with statistical analysis. The authors are grateful to all the residents and coaches on the QI Hospital Medicine team who contributed ideas on study design and interventions.

Intravenous (IV) antibiotics are commonly used in hospitalized pediatric patients to treat bacterial infections. Antimicrobial stewardship guidelines published by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommend institutions develop a systematic plan to convert from IV to enteral antibiotics, as early transition may reduce healthcare costs, decrease length of stay (LOS), and avoid prolonged IV access complications1 such as extravasation, thrombosis, and catheter-associated infections.2-5

Pediatric patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and mild skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI) may not require IV antibiotics, even if the patient is hospitalized.6 Although national guidelines for pediatric CAP and SSTI recommend IV antibiotics for hospitalized patients, these guidelines state that mild infections may be treated with enteral antibiotics and emphasize discontinuation of IV antibiotics when the patient meets discharge criteria.7,8 Furthermore, several enteral antibiotics used for the treatment of CAP and SSTI, such as cephalexin and clindamycin,9 have excellent bioavailability (>90%) or can achieve sufficient concentrations to attain the pharmacodynamic target (ie, amoxicillin and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole).10,11 Nonetheless, the guidelines do not explicitly outline criteria regarding the transition from IV to enteral antibiotics.7,8

At our institution, patients admitted to Hospital Medicine (HM) often remained on IV antibiotics until discharge. Data review revealed that antibiotic treatment of CAP and SSTI posed the greatest opportunity for early conversion to enteral therapy based on the high frequency of admissions and the ability of commonly used enteral antibiotics to attain pharmacodynamic targets. We sought to change practice culture by decoupling transition to enteral antibiotics from discharge and use administration of other enteral medications as an objective indicator for transition. Our aim was to increase the proportion of enterally administered antibiotic doses for HM patients aged >60 days admitted with uncomplicated CAP or SSTI from 44% to 75% in eight months.

METHODS

Context

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) is a large, urban, academic hospital. The HM division has 45 attendings and admits >8,000 general pediatric patients annually. The five HM teams at the main campus consist of attendings, fellows, residents, and medical students. One HM team serves as the resident quality improvement (QI) team where residents collaborate in a longitudinal study under the guidance of QI-trained coaches. The focus of this QI initiative was determined by resident consensus and aligned with a high-value care curriculum.12

To identify the target patient population, we investigated IV antimicrobials frequently used in HM patients. Ampicillin and clindamycin are commonly used IV antibiotics, most frequently corresponding with the diagnoses of CAP and SSTI, respectively, accounting for half of all antibiotic use on the HM service. Amoxicillin, the enteral equivalent of ampicillin, can achieve sufficient concentrations to attain the pharmacodynamic target at infection sites, and clindamycin has high bioavailability, making them ideal options for early transition. Our institution’s robust antimicrobial stewardship program has published local guidelines on using amoxicillin as the enteral antibiotic of choice for uncomplicated CAP, but it does not provide guidance on the timing of transition for either CAP or SSTI; the clinical team makes this decision.

HM attendings were surveyed to determine the criteria used to transition from IV to enteral antibiotics for patients with CAP or SSTI. The survey illustrated practice variability with providers using differing clinical criteria to signal the timing of transition. Additionally, only 49% of respondents (n = 37) rated themselves as “very comfortable” with residents making autonomous decisions to transition to enteral antibiotics. We chose to use the administration of other enteral medications, instead of discharge readiness, as an objective indicator of a patient’s readiness to transition to enteral antibiotics, given the low-risk patient population and the ability of the enteral antibiotics commonly used for CAP and SSTI to achieve pharmacodynamic targets.

The study population included patients aged >60 days admitted to HM with CAP or SSTI treated with any antibiotic. We excluded patients with potential complications or significant progression of their disease process, including patients with parapneumonic effusions or chest tubes, patients who underwent bronchoscopy, and patients with osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, or preseptal or orbital cellulitis. Past medical history and clinical status on admission were not used to exclude patients.

Interventions

Our multidisciplinary team, formed in January 2017, included HM attendings, HM fellows, pediatric residents, a critical care attending, a pharmacy resident, and an antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist. Under the guidance of QI coaches, the residents on the HM QI team developed and tested all interventions on their team and then determined which interventions would spread to the other four teams. The nursing director of our primary HM unit disseminated project updates to bedside nurses. A simplified failure mode and effects analysis identified areas for improvement and potential interventions. Interventions focused on the following key drivers (Figure 1): increased prescriber awareness of medication charge, standardization of conversion from IV to enteral antibiotics, clear definition of the patients ready for transition, ongoing evaluation of the antimicrobial plan, timely recognition by prescribers of patients ready for transition, culture shift regarding the appropriate administration route in the inpatient setting, and transparency of data. The team implemented sequential Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles13 to test the interventions.

Charge Table

To improve knowledge about the increased charge for commonly used IV medications compared with enteral formulations, a table comparing relative charges was shared during monthly resident morning conferences and at an HM faculty meeting. The table included charge comparisons between ampicillin and amoxicillin and IV and enteral clindamycin.

Standardized Language in Electronic Health Record (EHR) Antibiotic Plan on Rounds

Standardized language to document antibiotic transition plans was added to admission and progress note templates in the EHR. The standard template prompted residents to (1) define clinical transition criteria, (2) discuss attending comfort with transition overnight (based on survey results), and (3) document patient preference of solid or liquid dosage forms. Plans were reviewed and updated daily. We hypothesized that since residents use the information in the daily progress notes, including assessments and plans, to present on rounds, inclusion of the transition criteria in the note would prompt transition plan discussions.

Communication Bundle

To promote early transition to enteral antibiotics, we standardized the discussion about antibiotic transition between residents and attendings. During a weekly preexisting meeting, the resident QI team reviewed preferences for transitions with the new service attending. By identifying attending preferences early, residents were able to proactively transition patients who met the criteria (eg, antibiotic transition in the evening instead of waiting until morning rounds). This discussion also provided an opportunity to engage service attendings in the QI efforts, which were also shared at HM faculty meetings quarterly.

Recognizing that in times of high census, discussion of patient plans may be abbreviated during rounds, residents were asked to identify all patients on IV antibiotics while reviewing patient medication orders prior to rounds. As part of an existing daily prerounds huddle to discuss rounding logistics, residents listed all patients on IV antibiotics and discussed which patients were ready for transition. If patients could not be transitioned immediately, the team identified the transition criteria.

At preexisting evening huddles between overnight shift HM residents and the evening HM attending, residents identified patients who were prescribed IV antibiotics and discussed readiness for enteral transition. If a patient could be transitioned overnight, enteral antibiotic orders were placed. Overnight residents were also encouraged to review the transition criteria with families upon admission.

Real-time Identification of Failures and Feedback

For two weeks, the EHR was queried daily to identify patients admitted for uncomplicated CAP and SSTI who were on antibiotics as well as other enteral medications. A failure was defined as an IV antibiotic dose given to a patient who was administered any enteral medication. Residents on the QI team approached residents on other HM teams whenever patients were identified as a failed transition to learn about failure reasons.

Study of the Interventions

Data for HM patients who met the inclusion criteria were collected weekly from January 2016 through June 2018 via EHR query. We initially searched for diagnoses that fit under the disease categories of pneumonia and SSTI in the EHR, which generated a list of International Classification of Disease-9 and -10 Diagnosis codes (Appendix Figure 1). The query identified patients based on these codes and reported whether the identified patients took a dose of any enteral medication, excluding nystatin, sildenafil, tacrolimus, and mouthwashes, which are commonly continued during NPO status due to no need for absorption or limited parenteral options. It also reported the ordered route of administration for the queried antibiotics (Appendix Figure 1).

The 2016 calendar year established our baseline to account for seasonal variability. Data were reported weekly and reviewed to evaluate the impact of PDSA cycles and inform new interventions.

Measures

Our process measure was the total number of enteral antibiotic doses divided by all antibiotic doses in patients receiving any enteral medication. We reasoned that if patients were well enough to take medications enterally, they could be given an enteral antibiotic that is highly bioavailable or readily achieves concentrations that attain pharmacodynamic targets. This practice change was a culture shift, decoupling the switch to enteral antibiotics from discharge readiness. Our EHR query reported only the antibiotic doses given to patients who took an enteral medication on the day of antibiotic administration and excluded patients who received only IV medications.

Outcome measures included antimicrobial costs per patient encounter using average wholesale prices, which were reported in our EHR query, and LOS. To ensure that transitions of IV to enteral antibiotics were not negatively impacting patient outcomes, patient readmissions within seven days served as a balancing measure.

Analysis

An annotated statistical process control p-chart tracked the impact of interventions on the proportion of antibiotic doses that were enterally administered during hospitalization. An x-bar and an s-chart tracked the impact of interventions on antimicrobial costs per patient encounter and on LOS. A p-chart and an encounters-between g-chart were used to evaluate the impact of our interventions on readmissions. Control chart rules for identifying special cause were used for center line shifts.14

Ethical Considerations

This study was part of a larger study of the residency high-value care curriculum,12 which was deemed exempt by the CCHMC IRB.

RESULTS

The baseline data collected included 372 patients and the postintervention period in 2017 included 326 patients (Table). Approximately two-thirds of patients had a diagnosis of CAP.

The percentage of antibiotic doses given enterally increased from 44% to 80% within eight months (Figure 2). When studying the impact of interventions, residents on the HM QI team found that the standard EHR template added to daily notes did not consistently prompt residents to discuss antibiotic plans and thus was abandoned. Initial improvement coincided with standardizing discussions between residents and attendings regarding transitions. Furthermore, discussion of all patients on IV antibiotics during the prerounds huddle allowed for reliable, daily communication about antibiotic plans and was subsequently spread to and adopted by all HM teams. The percentage of enterally administered antibiotic doses increased to >75% after the evening huddle, which involved all HM teams, and real-time identification of failures on all HM teams with provider feedback. Despite variability when the total number of antibiotic doses prescribed per week was low (<10), we demonstrated sustainability for 11 months (Figure 2), during which the prerounds and evening huddle discussions were continued and an updated control chart was shown monthly to residents during their educational conferences.

Residents on the QI team spoke directly with other HM residents when there were missed opportunities for transition. Based on these discussions and intermittent chart reviews, common reasons for failure to transition in patients with CAP included admission for failed outpatient enteral treatment, recent evaluation by critical care physicians for possible transfer to the intensive care unit, and difficulty weaning oxygen. For patients with SSTI, hand abscesses requiring drainage by surgery and treatment failure with other antibiotics constituted many of the IV antibiotic doses given to patients on enteral medications.

Antimicrobial costs per patient encounter decreased by 70% over one year; the shift in costs coincided with the second shift in our process measure (Appendix Figure 2A). Based on an estimate of 350 patients admitted per year for uncomplicated CAP or SSTI, this translates to an annual cost savings of approximately $29,000. The standard deviation of costs per patient encounter decreased by 84% (Appendix Figure 2B), suggesting a decrease in the variability of prescribing practices.

The average LOS in our patient population prior to intervention was 2.1 days and did not change (Appendix Figure 2C), but the standard deviation decreased by >50% (Appendix Figure 2D). There was no shift in the mean seven-day readmission rate or the number of encounters between readmissions (2.6% and 26, respectively; Appendix Figure 3). In addition, the hospital billing department did not identify an increase in insurance denials related to the route of antibiotic administration.

DISCUSSION

Summary

Using improvement science, we promoted earlier transition to enteral antibiotics for children hospitalized with uncomplicated CAP and SSTI by linking the decision for transition to the ability to take other enteral medications, rather than to discharge readiness. We increased the percentage of enterally administered antibiotic doses in this patient population from 44% to 80% in eight months. Although we did not observe a decrease in LOS as previously noted in a cost analysis study comparing pediatric patients with CAP treated with oral antibiotics versus those treated with IV antibiotics,15 we did find a decrease in LOS variability and in antimicrobial costs to our patients. These cost savings did not include potential savings from nursing or pharmacy labor. In addition, we noted a decrease in the variability in antibiotic prescribing practice, which demonstrates provider ability and willingness to couple antibiotic route transition to an objective characteristic (administration of other enteral medications).

A strength of our study was that residents, the most frequent prescribers of antibiotics on our HM service, were highly involved in the QI initiative, including defining the SMART aim, identifying key drivers, developing interventions, and completing sequential PDSA cycles. Under the guidance of QI-trained coaches, residents developed feasible interventions and assessed their success in real time. Consistent with other studies,16,17 resident buy-in and involvement led to the success of our improvement study.

Interpretation

Despite emerging evidence regarding the timing of transition to enteral antibiotics, several factors impeded early transition at our institution, including physician culture, variable practice habits, and hospital workflow. Evidence supports the use of enteral antibiotics in immunocompetent children hospitalized for uncomplicated CAP who do not have chronic lung disease, are not in shock, and have oxygen saturations >85%.6 Although existing literature suggests that in pediatric patients admitted for SSTIs not involving the eye or bone, IV antibiotics may be transitioned when clinical improvement, evidenced by a reduction in fever or erythema, is noted,6 enteral antibiotics that achieve appropriate concentrations to attain pharmacodynamic targets should have the same efficacy as that of IV antibiotics.9 Using the criterion of administration of any medication enterally to identify a patient’s readiness to transition, we were able to overcome practice variation among providers who may have differing opinions of what constitutes clinical improvement. Of note, new evidence is emerging on predictors of enteral antibiotic treatment failure in patients with CAP and SSTI to guide transition timing, but these studies have largely focused on the adult population or were performed in the outpatient and emergency department (ED) settings.18,19 Regardless, the stable number of encounters between readmissions in our patient population likely indicates that treatment failure in these patients was rare.

Rising healthcare costs have led to concerns around sustainability of the healthcare system;20,21 tackling overuse in clinical practice, as in our study, is one mitigation strategy. Several studies have used QI methods to facilitate the provision of high-value care through the decrease of continuous monitor overuse and extraneous ordering of electrolytes.22,23 Our QI study adds to the high-value care literature by safely decreasing the use of IV antibiotics. One retrospective study demonstrated that a one-day decrease in the use of IV antibiotics in pneumonia resulted in decreased costs without an increase in readmissions, similar to our findings.24 In adults, QI initiatives aimed at improving early transition of antibiotics utilized electronic trigger tools.25,26 Fischer et al. used active orders for scheduled enteral medications or an enteral diet as indication that a patient’s IV medications could be converted to enteral form.26

Our work is not without limitations. The list of ICD-9 and -10 codes used to query the EHR did not capture all diagnoses that would be considered as uncomplicated CAP or SSTI. However, we included an extensive list of diagnoses to ensure that the majority of patients meeting our inclusion criteria were captured. Our process measure did not account for patients on IV antibiotics who were not administered other enteral medications but tolerating an enteral diet. These patients were not identified in our EHR query and were not included in our process measure as a failure. However, in latter interventions, residents identified all patients on IV antibiotics, so that patients not identified by our EHR query benefited from our work. Furthermore, this QI study was conducted at a single institution and several interventions took advantage of preexisting structured huddles and a resident QI curriculum, which may not exist at other institutions. Our study does highlight that engaging frontline providers, such as residents, to review antibiotic orders consistently and question the appropriateness of the administration route is key to making incremental changes in prescribing practices.

CONCLUSIONS

Through a partnership between HM and Pharmacy and with substantial resident involvement, we improved the transition of IV antibiotics in patients with CAP or SSTI by increasing the percentage of enterally administered antibiotic doses and reducing antimicrobial costs and variability in antibiotic prescribing practices. This work illustrates how reducing overuse of IV antibiotics promotes high-value care and aligns with initiatives to prevent avoidable harm.27 Our work highlights that standardized discussions about medication orders to create consensus around enteral antibiotic transitions, real-time feedback, and challenging the status quo can influence practice habits and effect change.

Next steps include testing automated methods to notify providers of opportunities for transition from IV to enteral antibiotics through embedded clinical decision support, a method similar to the electronic trigger tools used in adult QI studies.25,26 Since our prerounds huddle includes identifying all patients on IV antibiotics, studying the transition to enteral antibiotics and its effect on prescribing practices in other diagnoses (ie, urinary tract infection and osteomyelitis) may contribute to spreading these efforts. Partnering with our ED colleagues may be an important next step, as several patients admitted to HM on IV antibiotics are given their first dose in the ED.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the faculty of the James M. Anderson Center for Health Systems Excellence Intermediate Improvement Science Series for their guidance in the planning of this project. The authors would also like to thank Ms. Ursula Bradshaw and Mr. Michael Ponti-Zins for obtaining the hospital data on length of stay and readmissions. The authors acknowledge Dr. Philip Hagedorn for his assistance with the software that queries the electronic health record and Dr. Laura Brower and Dr. Joanna Thomson for their assistance with statistical analysis. The authors are grateful to all the residents and coaches on the QI Hospital Medicine team who contributed ideas on study design and interventions.

1. Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE, Jr, et al. Infectious diseases society of America and the society for healthcare epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(2):159-177. https://doi.org/10.1086/510393.

2. Shah SS, Srivastava R, Wu S, et al. Intravenous Versus oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of complicated pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2016;138(6). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1692.

3. Keren R, Shah SS, Srivastava R, et al. Comparative effectiveness of intravenous vs oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of acute osteomyelitis in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(2):120-128. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.2822.

4. Jumani K, Advani S, Reich NG, Gosey L, Milstone AM. Risk factors for peripherally inserted central venous catheter complications in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(5):429-435.https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.775.

5. Zaoutis T, Localio AR, Leckerman K, et al. Prolonged intravenous therapy versus early transition to oral antimicrobial therapy for acute osteomyelitis in children. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):636-642. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-0596.

6. McMullan BJ, Andresen D, Blyth CC, et al. Antibiotic duration and timing of the switch from intravenous to oral route for bacterial infections in children: systematic review and guidelines. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(8):e139-e152. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30024-X.

7. Bradley JS, Byington CL, Shah SS, et al. The management of community-acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(7):e25-e76. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cir531.

8. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Executive summary: practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):147-159. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu444.

9. MacGregor RR, Graziani AL. Oral administration of antibiotics: a rational alternative to the parenteral route. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24(3):457-467. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinids/24.3.457.

10. Downes KJ, Hahn A, Wiles J, Courter JD, Vinks AA. Dose optimisation of antibiotics in children: application of pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics in paediatrics. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014;43(3):223-230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.11.006.

11. Autmizguine J, Melloni C, Hornik CP, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in infants and children. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(1):e01813-e01817. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01813-17.

12. Dewan M, Herrmann LE, Tchou MJ, et al. Development and evaluation of high-value pediatrics: a high-value care pediatric resident curriculum. Hosp Pediatr. 2018;8(12):785-792. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2018-0115

13. Langley GJ, Moen RD, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. New Jersey, US: John Wiley & Sons; 2009.

14. Benneyan JC. Use and interpretation of statistical quality control charts. Int J Qual Health Care. 1998;10(1):69-73. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/10.1.69.

15. Lorgelly PK, Atkinson M, Lakhanpaul M, et al. Oral versus i.v. antibiotics for community-acquired pneumonia in children: a cost-minimisation analysis. Eur Respir J. 2010;35(4):858-864. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00087209.

16. Vidyarthi AR, Green AL, Rosenbluth G, Baron RB. Engaging residents and fellows to improve institution-wide quality: the first six years of a novel financial incentive program. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):460-468. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000159.

17. Stinnett-Donnelly JM, Stevens PG, Hood VL. Developing a high value care programme from the bottom up: a programme of faculty-resident improvement projects targeting harmful or unnecessary care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(11):901-908. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004546.

18. Peterson D, McLeod S, Woolfrey K, McRae A. Predictors of failure of empiric outpatient antibiotic therapy in emergency department patients with uncomplicated cellulitis. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(5):526-531. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12371.

19. Yadav K, Suh KN, Eagles D, et al. Predictors of oral antibiotic treatment failure for non-purulent skin and soft tissue infections in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2018;20(S1):S24-S25. https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2018.114.

20. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Healthcare costs unsustainable in advanced economies without reform. http://www.oecd.org/health/healthcarecostsunsustainableinadvancedeconomieswithoutreform.htm. Accessed June 28, 2018; 2015.

21. Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513-1516. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.362.

22. Schondelmeyer AC, Simmons JM, Statile AM, et al. Using quality improvement to reduce continuous pulse oximetry use in children with wheezing. Pediatrics. 2015;135(4):e1044-e1051. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2295.

23. Tchou MJ, Tang Girdwood S, Wormser B, et al. Reducing electrolyte testing in hospitalized children by using quality improvement methods. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3187.

24. Christensen EW, Spaulding AB, Pomputius WF, Grapentine SP. Effects of hospital practice patterns for antibiotic administration for pneumonia on hospital lengths of stay and costs. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2019;8(2):115-121. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpids/piy003.

25. Berrevoets MAH, Pot JHLW, Houterman AE, et al. An electronic trigger tool to optimise intravenous to oral antibiotic switch: a controlled, interrupted time series study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017;6:81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-017-0239-3.