User login

Asymptomatic Soft Tumor on the Forearm

The Diagnosis: Aneurysmal Dermatofibroma

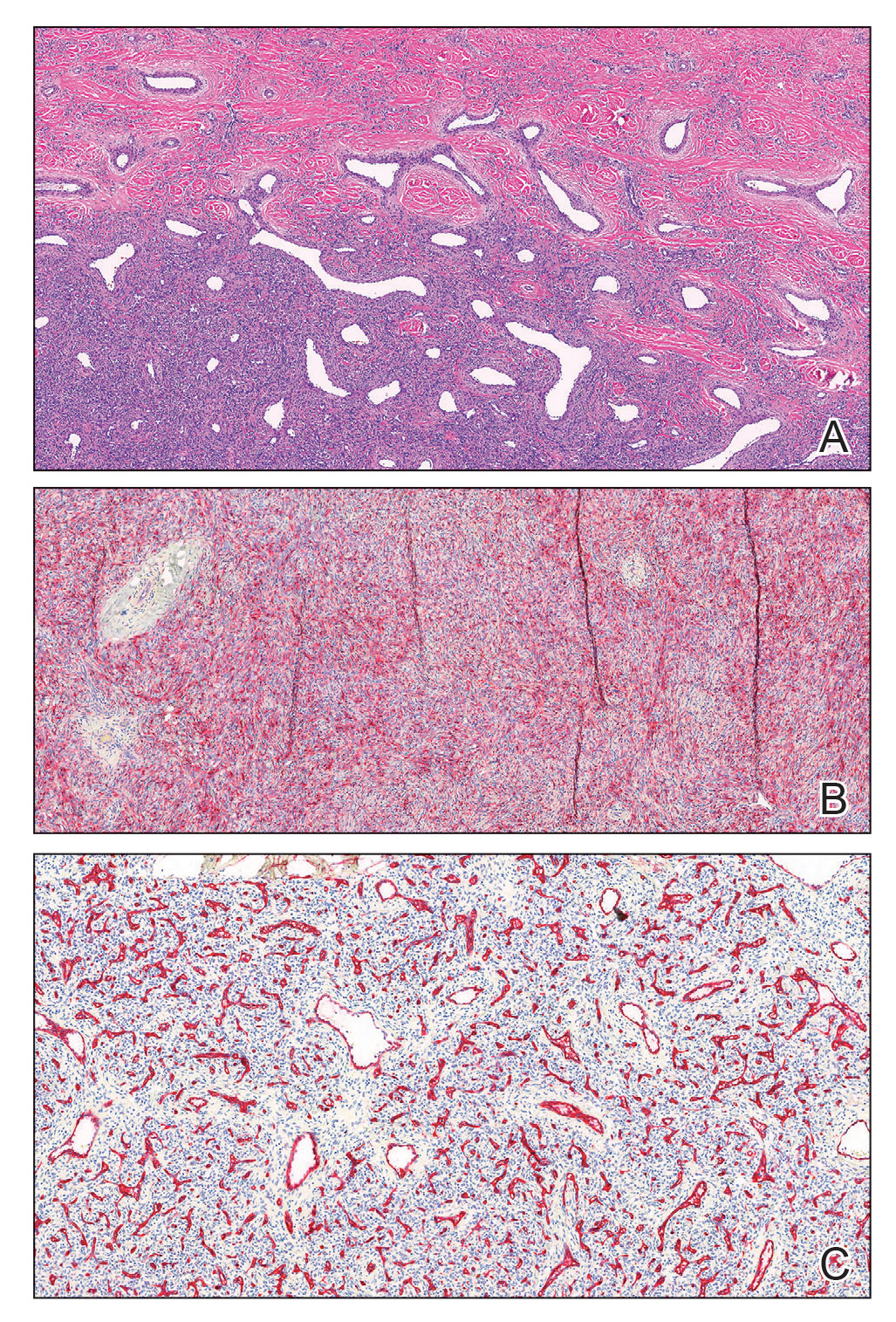

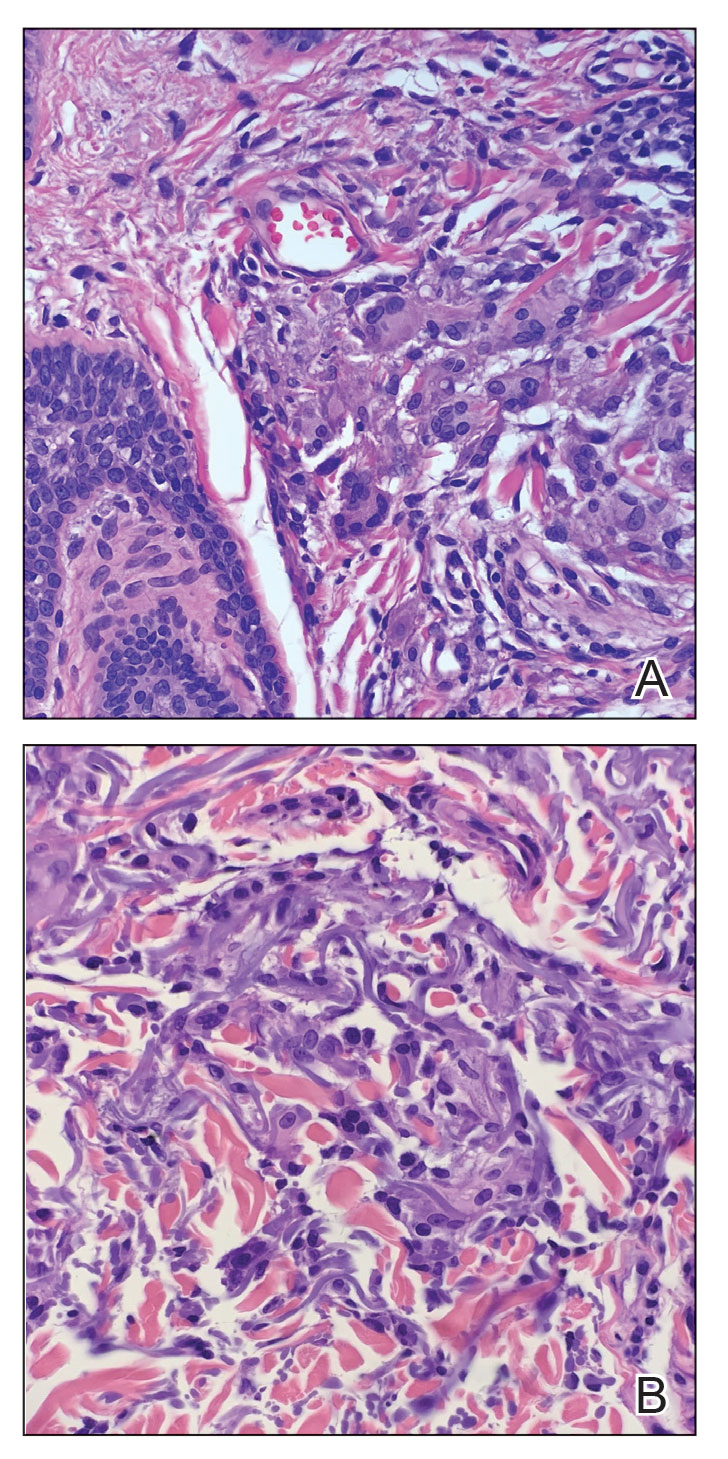

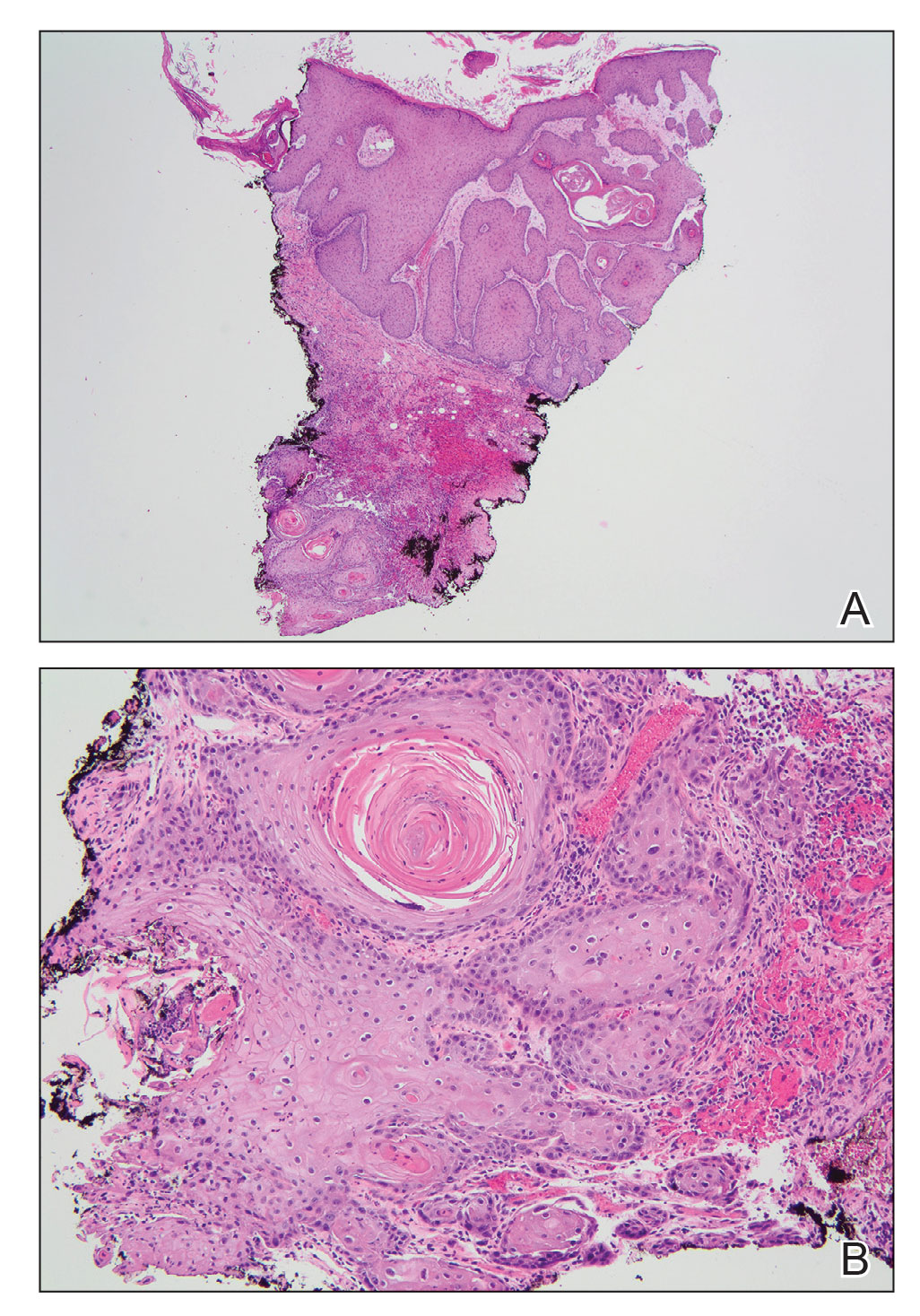

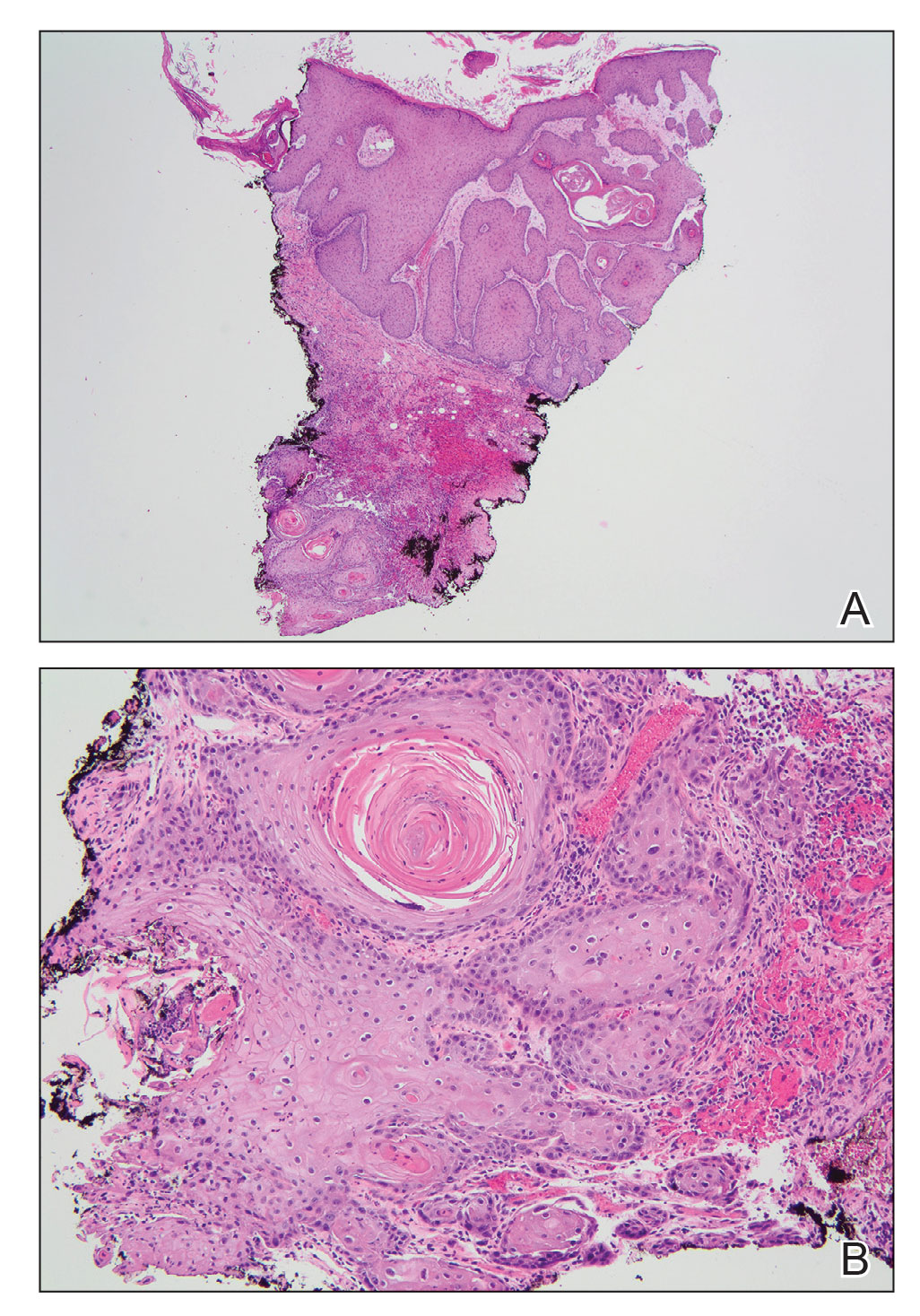

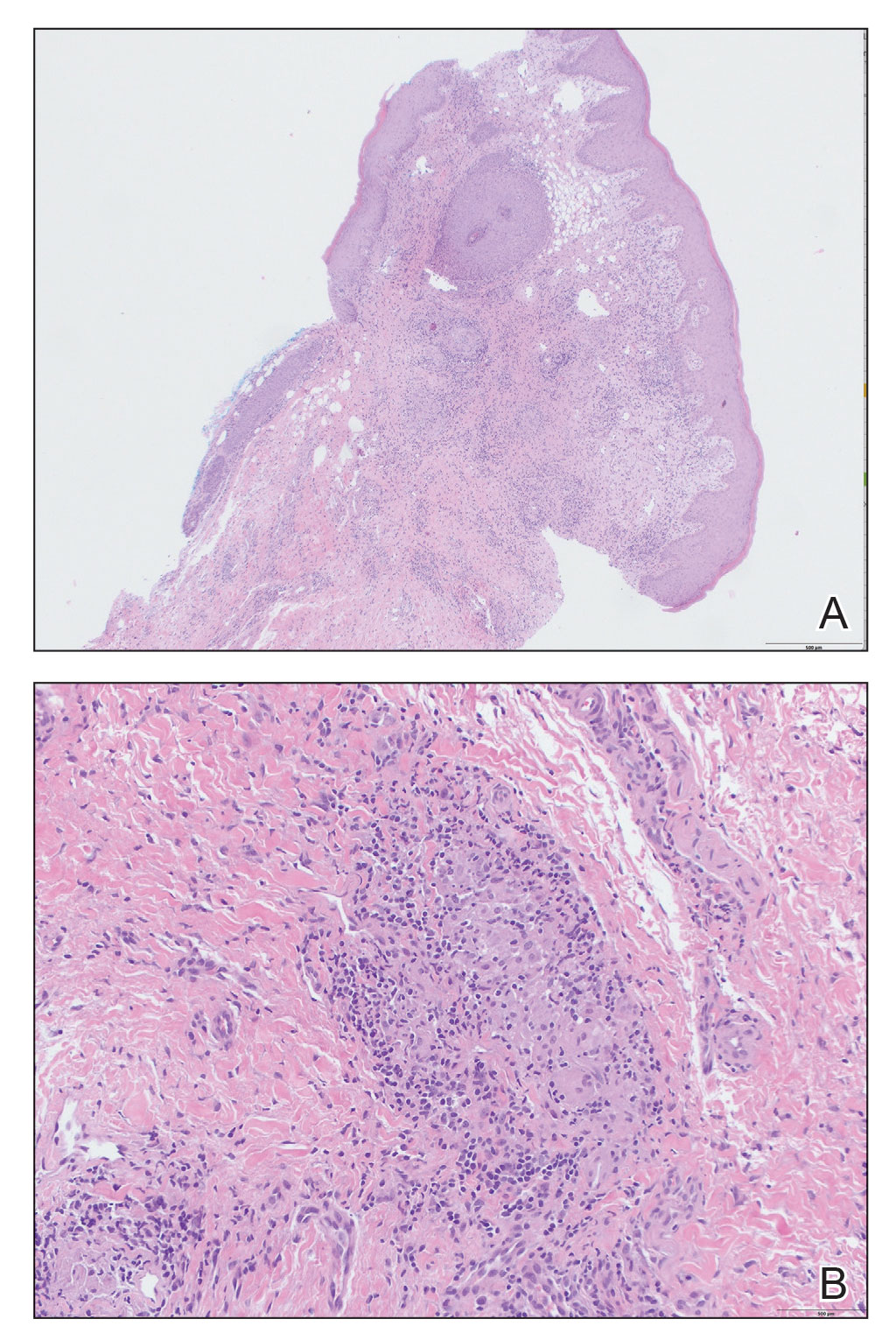

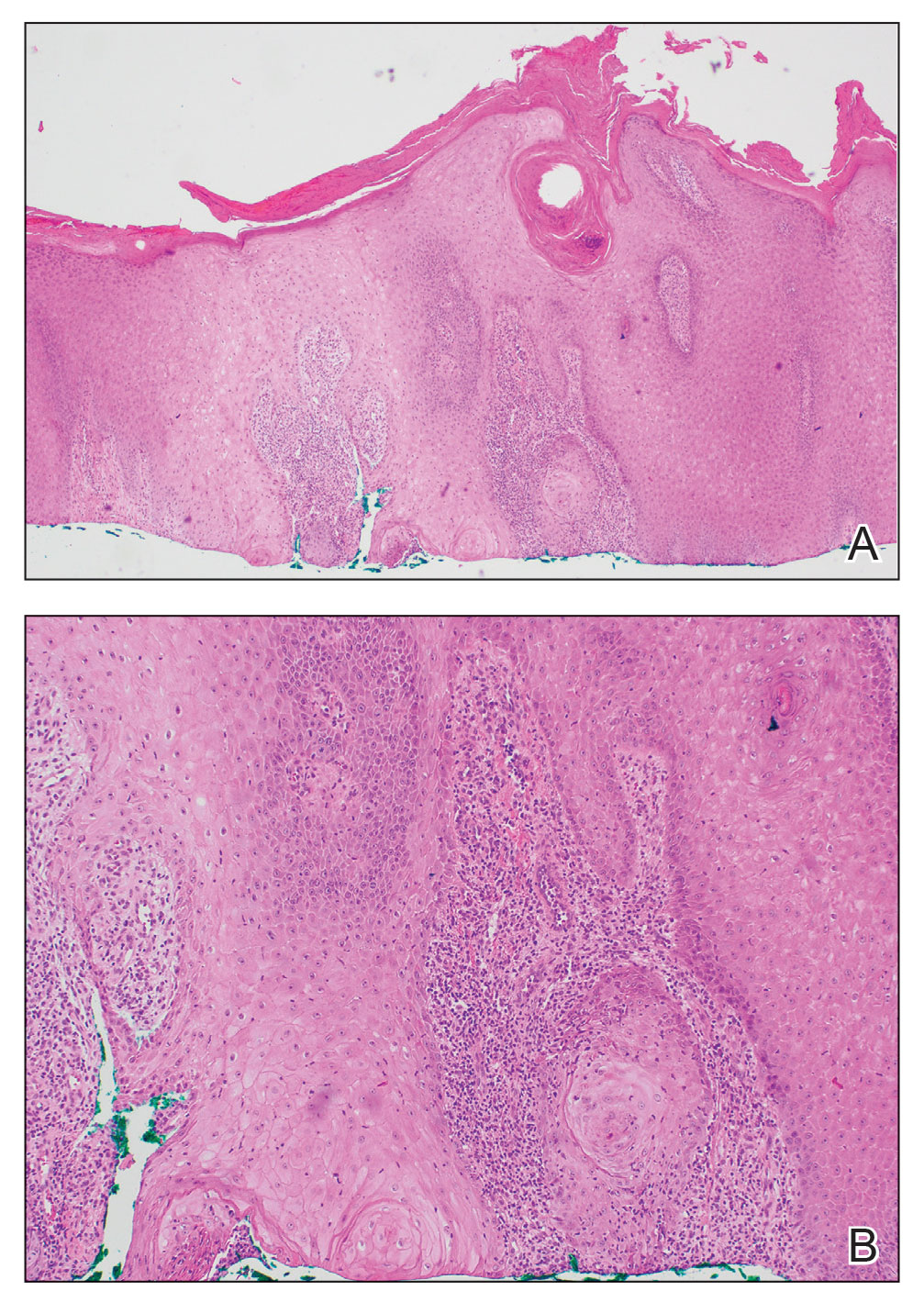

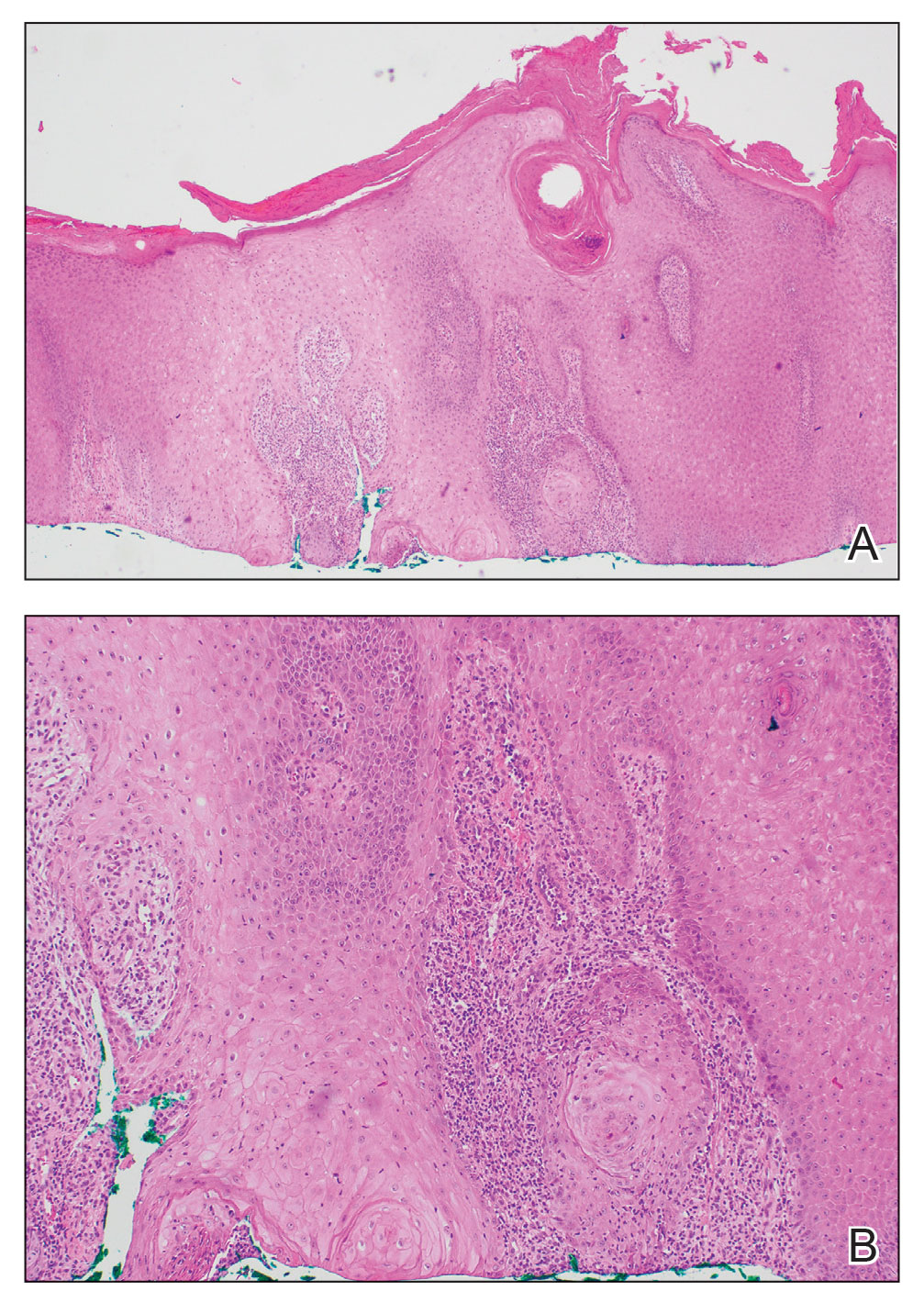

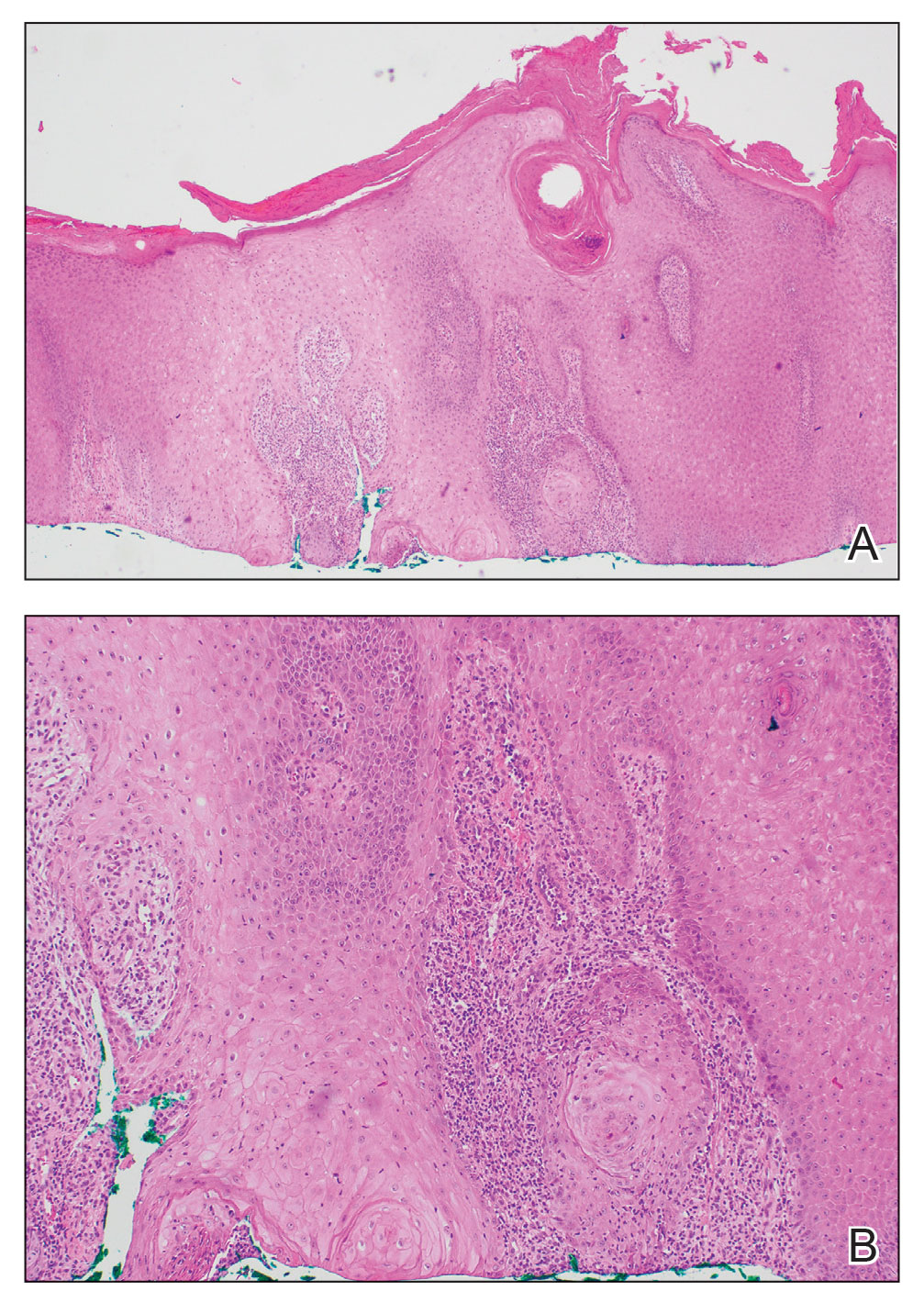

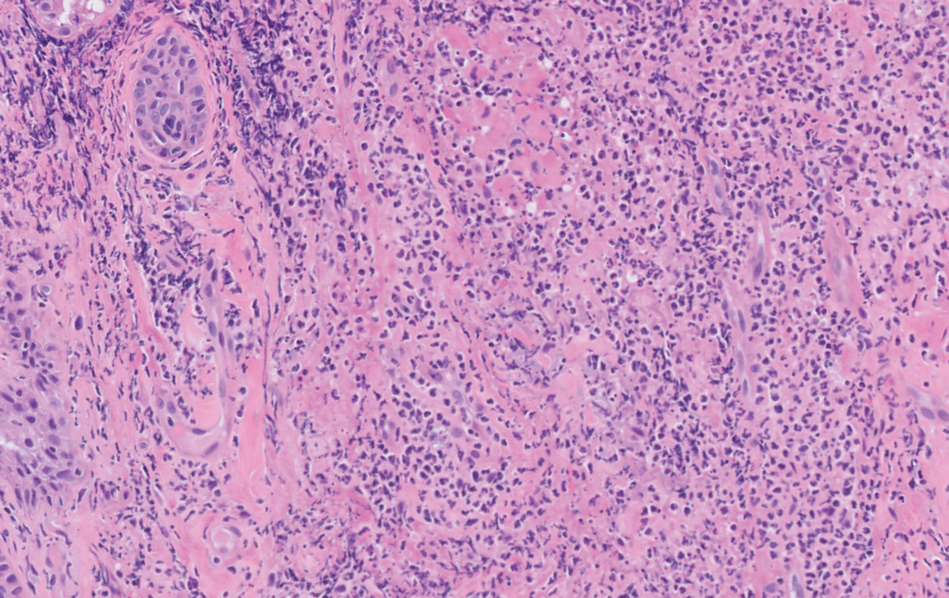

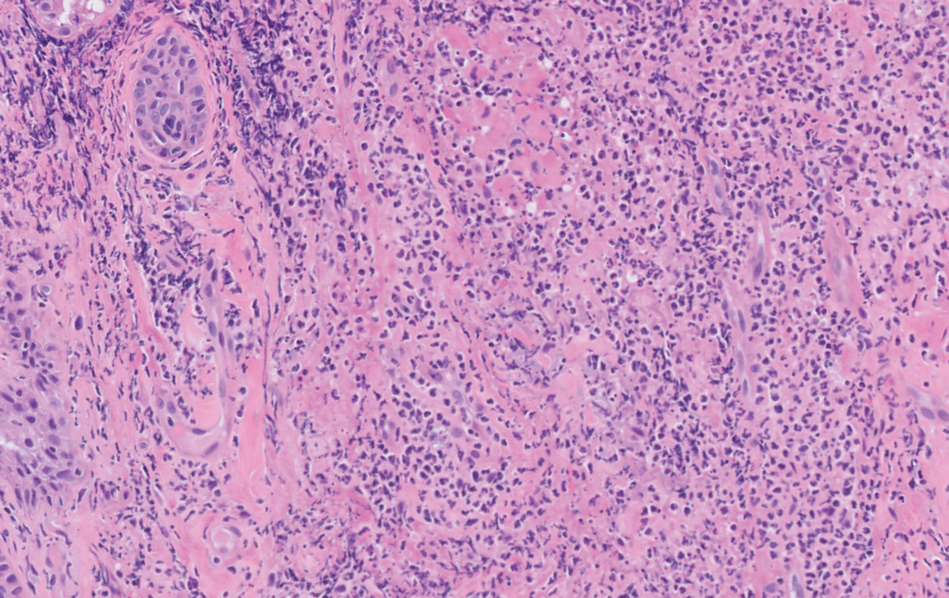

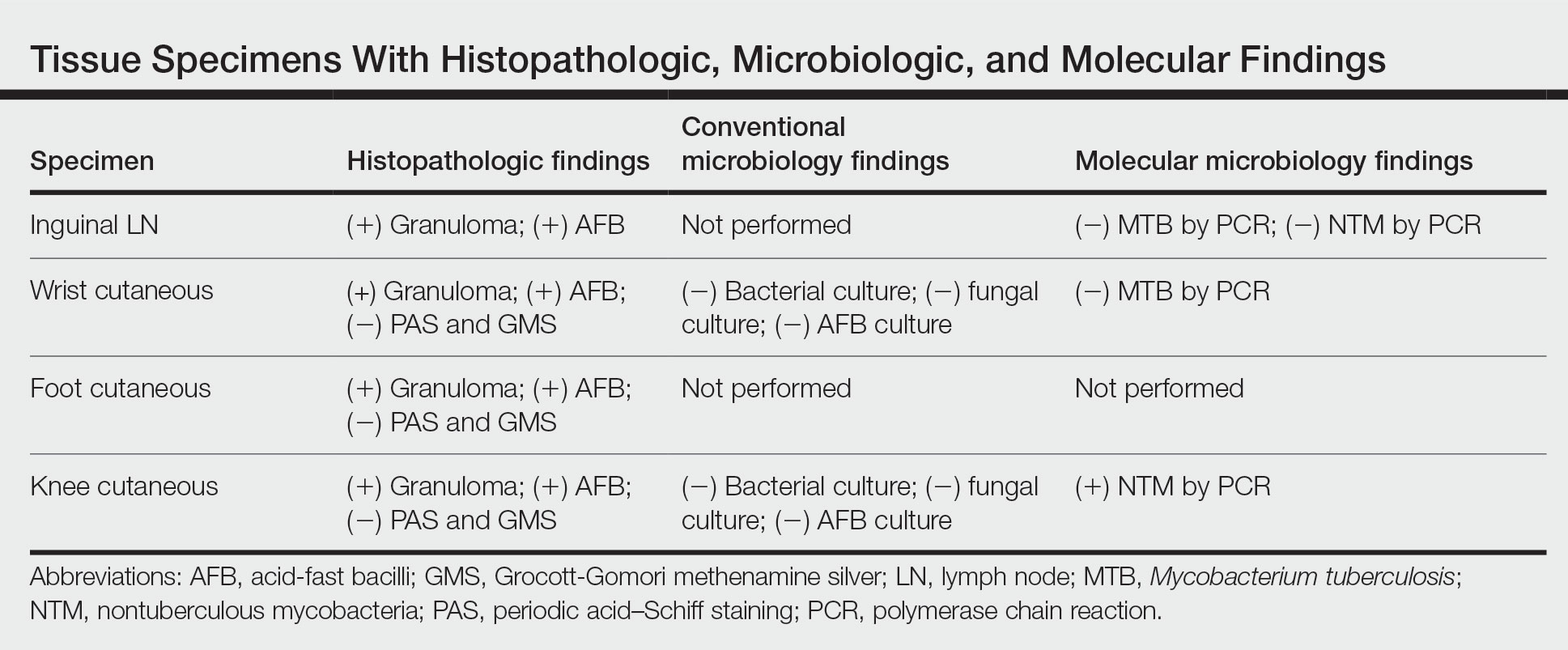

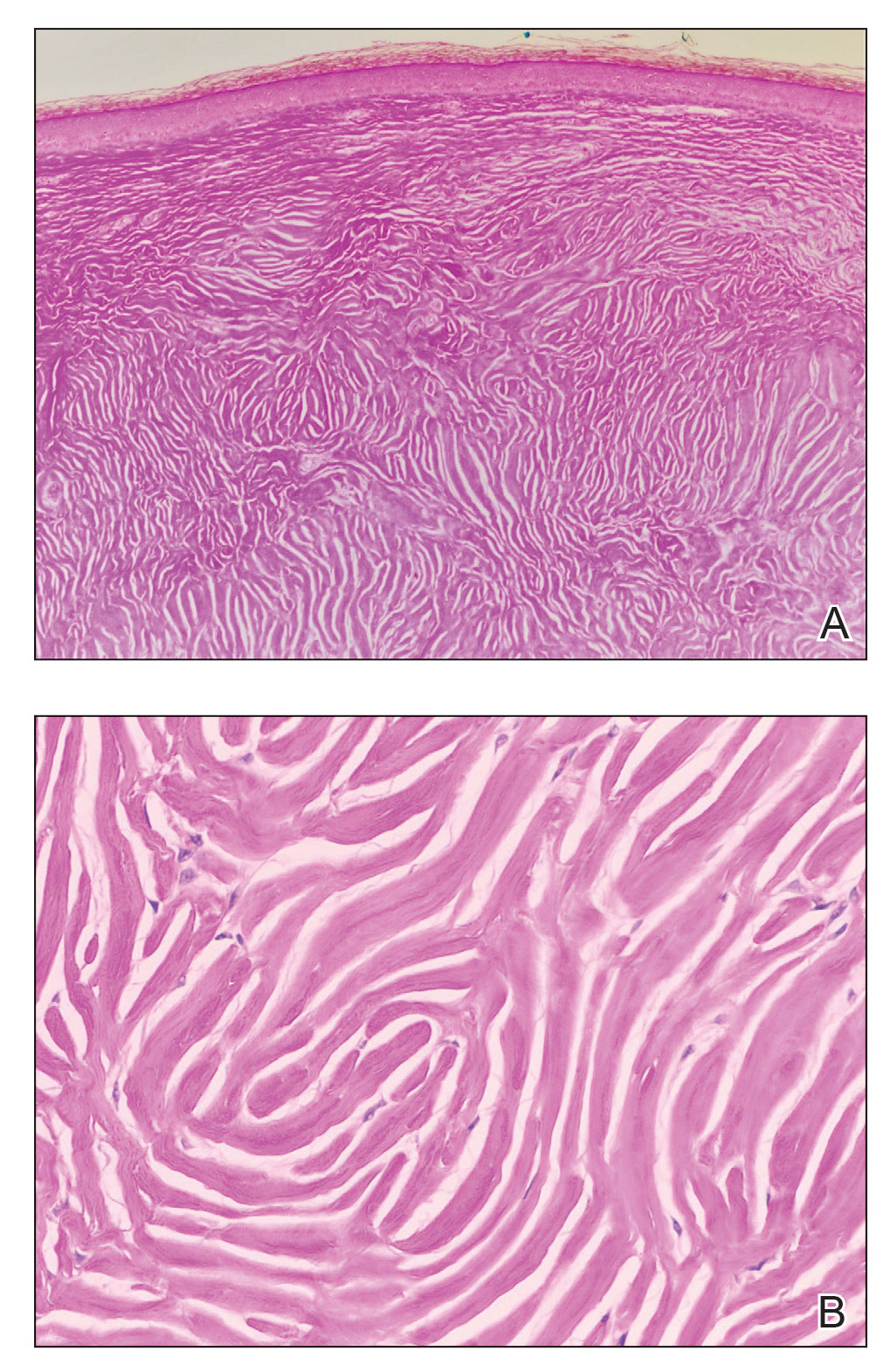

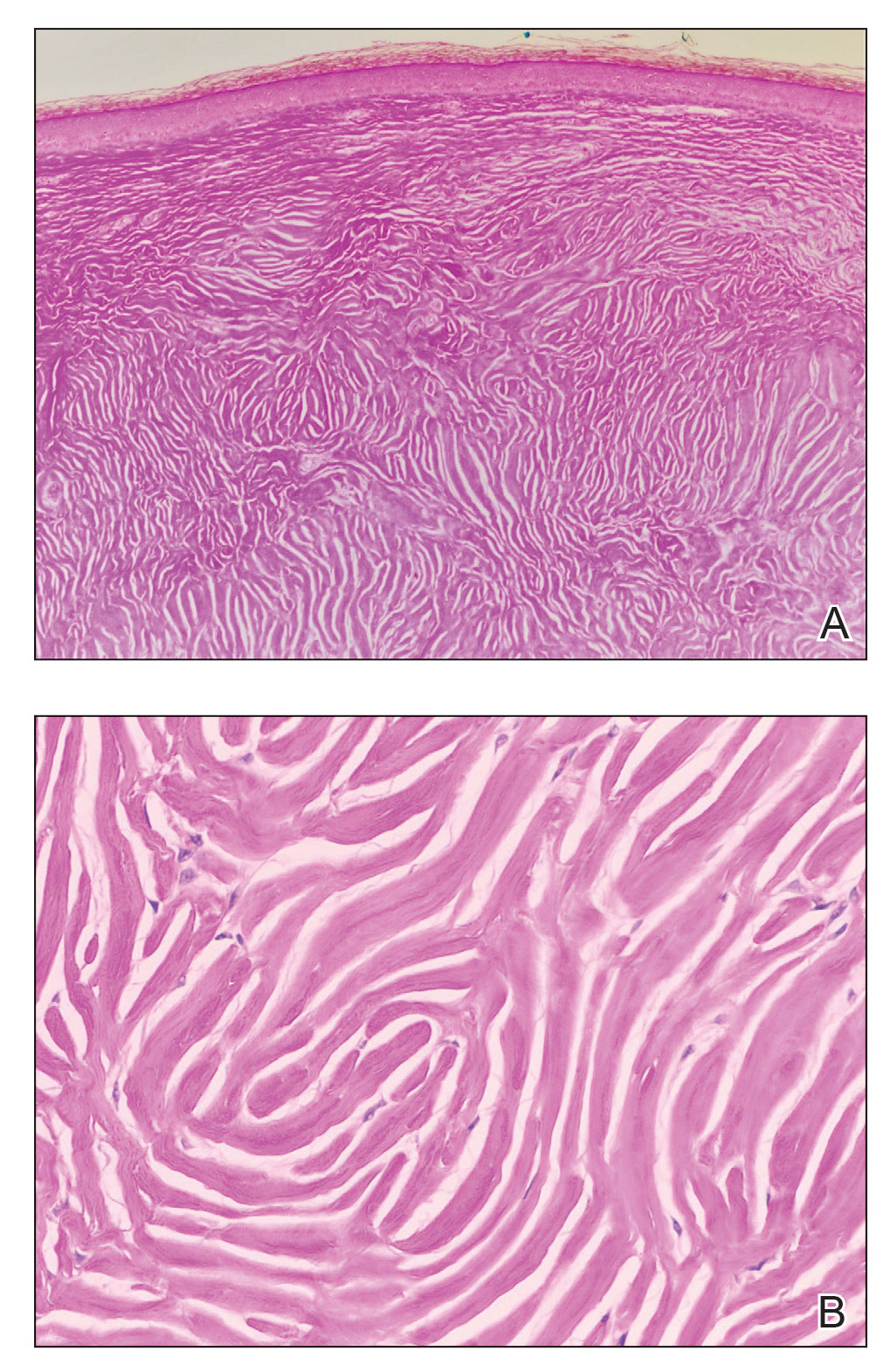

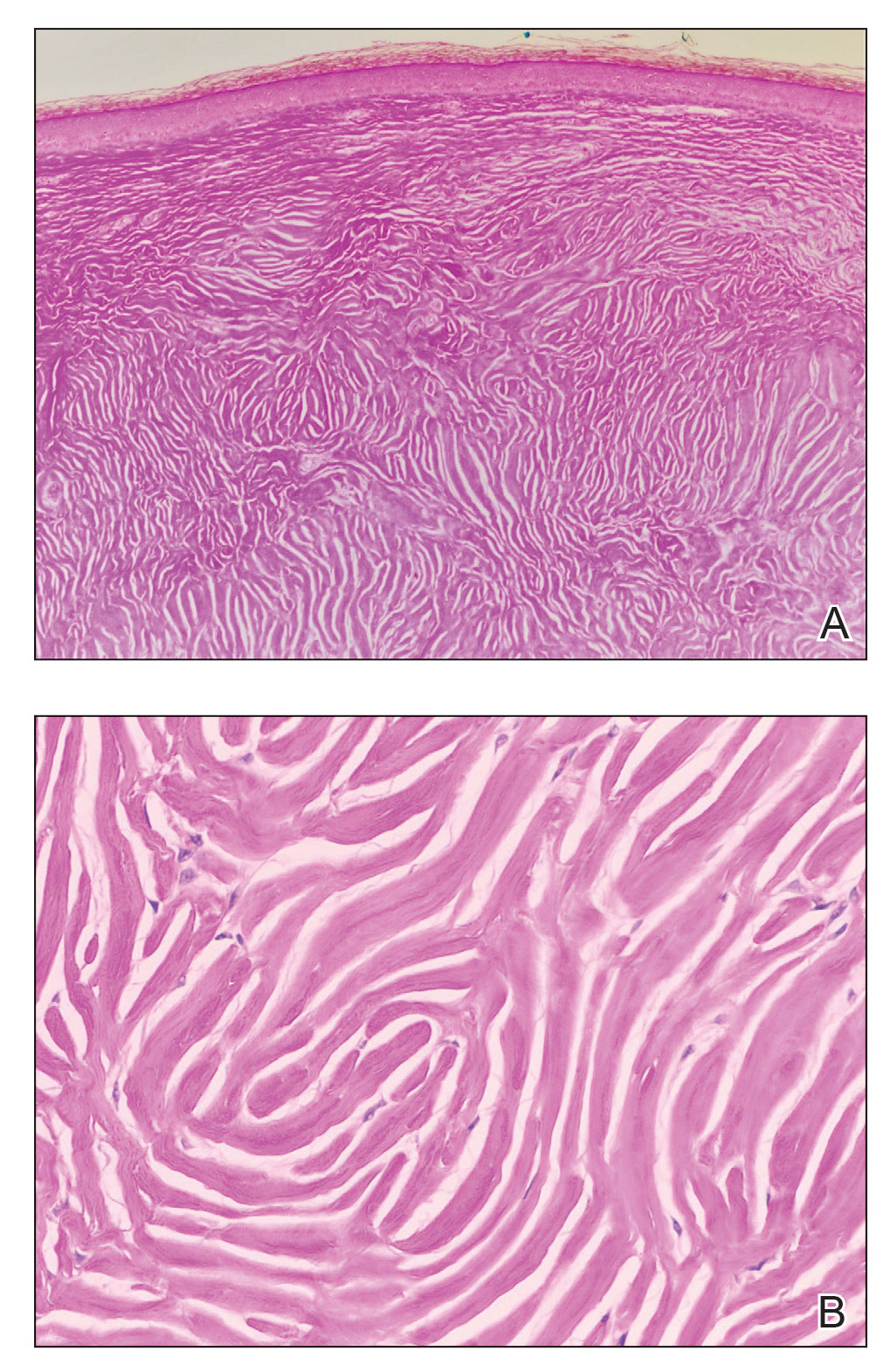

A shave biopsy of the entire tumor was performed at the initial visit. Histologic examination with hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a fibrohistiocytic infiltrate containing cleftlike cavernous spaces lined by epithelial cells (Figure, A). Immunohistochemical staining revealed factor XIIIa expression on fibrohistiocytic cells (Figure, B). CD34 was expressed on vascular endothelial cells, but it failed to highlight the fibrohistiocytic space (Figure, C). Overall, these findings supported the diagnosis of aneurysmal dermatofibroma. The lesion healed without complications, and the patient was counseled on the risk for recurrence. He was offered localized excision but opted for conservative management without excision and close follow-up and monitoring.

Dermatofibromas are common benign cutaneous nodules that often are asymptomatic and occur on the extremities. Dermatofibromas also are known as cutaneous fibrous histiocytomas and have numerous histologic variants. Aneurysmal dermatofibroma (also called aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma) is a rare histologic variant of dermatofibroma presenting as a slow-growing exophytic tumor that can be purple, red, brown, or blue. Although classic dermatofibromas typically constitute a straightforward diagnosis, aneurysmal dermatofibromas often are more challenging to clinically differentiate from other cutaneous neoplasms. Additionally, due to the exophytic nature and larger size (0.5–4.0 cm), aneurysmal dermatofibromas do not exhibit the characteristic dimple (Fitzpatrick) sign found in many dermatofibromas. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas are 10 times more likely to recur than classic dermatofibromas.1-4

Aneurysmal dermatofibromas can mimic other cutaneous neoplasms, some indolent and others more aggressive. Similar to aneurysmal dermatofibromas, solitary neurofibromas and nevi lipomatosus can appear as asymptomatic exophytic nodules with a similar spectrum of color and indolent clinical courses. In nevus lipomatosus, the dermis is almost entirely replaced by mature adipose tissue.5 Solitary neurofibromas represent a proliferation of neuromesenchymal cells with haphazardly arranged, wavy nuclei characteristic of nerve cells.6 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans can be distinguished from aneurysmal dermatofibroma by lack of factor XIIIa expression and diffuse positivity for CD34.7 Finally, aneurysmal dermatofibromas may resemble vascular tumors such as nodular Kaposi sarcoma. Kaposi sarcoma can be differentiated from an aneurysmal dermatofibroma by the presence of characteristic vascular wrapping, the absence of fibrohistiocytic cells, and expression of human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1.1,8 Although aneurysmal dermatofibromas are of low malignant potential, they are associated with a higher rate of recurrence compared to common dermatofibromas.9 Definitive treatment involves complete excision with follow-up to ensure no signs of recurrence.10 Incomplete excision can increase the likelihood of recurrence, especially for larger aneurysmal dermatofibromas. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas are one of the subtypes of dermatofibromas that may extend into the subcutaneous tissue. Han et al2 found that 77.8% of aneurysmal dermatofibromas extended into subcutaneous tissue. Recognizing the clinical and pathological features of this rare subtype of dermatofibroma can aid dermatologists in appropriate recognition and management.

- Burr DM, Peterson WA, Peterson MW. Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Am Osteopath. June 2018;40. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.aocd.org/resource/resmgr/jaocd/contents/volume40/40-04.pdf

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee JHK, et al. A clinical and histopathological study of 122 cases of dermatofibroma (benign fibrous histiocytoma). Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:185-192.

- Morariu SH, Suciu M, Vartolomei MD, et al. Aneurysmal dermatofibroma mimicking both clinical and dermoscopic malignant melanoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:1221-1224.

- Calonje E, Fletcher CDM. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathological analysis of 40 cases of a tumour frequently misdiagnosed as a vascular neoplasm. Histopathology. 1995;26:323-331.

- Pujani M, Choudhury M, Garg T, et al. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis: a rare cutaneous hamartoma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:109-110.

- Strike SA, Puhaindran ME. Nerve tumors of the upper extremity. Clin Plast Surg. 2019;46:347-350.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Farhood AI. Dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: differential expression of CD34 and factor XIIIa. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:573-574.

- Kandal S, Ozmen S, Demir HY, et al. Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma of the skin: a rare variant of dermatofibroma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:2050-2051.

- Hornick JL. Cutaneous soft tissue tumors: how do we make sense of fibrous and “fibrohistiocytic” tumors with confusing names and similar appearances? Mod Pathol. 2020;33:56-65.

- Das A, Das A, Bandyopadhyay D, et al. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma presenting as a giant acrochordon on thigh. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:436.

The Diagnosis: Aneurysmal Dermatofibroma

A shave biopsy of the entire tumor was performed at the initial visit. Histologic examination with hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a fibrohistiocytic infiltrate containing cleftlike cavernous spaces lined by epithelial cells (Figure, A). Immunohistochemical staining revealed factor XIIIa expression on fibrohistiocytic cells (Figure, B). CD34 was expressed on vascular endothelial cells, but it failed to highlight the fibrohistiocytic space (Figure, C). Overall, these findings supported the diagnosis of aneurysmal dermatofibroma. The lesion healed without complications, and the patient was counseled on the risk for recurrence. He was offered localized excision but opted for conservative management without excision and close follow-up and monitoring.

Dermatofibromas are common benign cutaneous nodules that often are asymptomatic and occur on the extremities. Dermatofibromas also are known as cutaneous fibrous histiocytomas and have numerous histologic variants. Aneurysmal dermatofibroma (also called aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma) is a rare histologic variant of dermatofibroma presenting as a slow-growing exophytic tumor that can be purple, red, brown, or blue. Although classic dermatofibromas typically constitute a straightforward diagnosis, aneurysmal dermatofibromas often are more challenging to clinically differentiate from other cutaneous neoplasms. Additionally, due to the exophytic nature and larger size (0.5–4.0 cm), aneurysmal dermatofibromas do not exhibit the characteristic dimple (Fitzpatrick) sign found in many dermatofibromas. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas are 10 times more likely to recur than classic dermatofibromas.1-4

Aneurysmal dermatofibromas can mimic other cutaneous neoplasms, some indolent and others more aggressive. Similar to aneurysmal dermatofibromas, solitary neurofibromas and nevi lipomatosus can appear as asymptomatic exophytic nodules with a similar spectrum of color and indolent clinical courses. In nevus lipomatosus, the dermis is almost entirely replaced by mature adipose tissue.5 Solitary neurofibromas represent a proliferation of neuromesenchymal cells with haphazardly arranged, wavy nuclei characteristic of nerve cells.6 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans can be distinguished from aneurysmal dermatofibroma by lack of factor XIIIa expression and diffuse positivity for CD34.7 Finally, aneurysmal dermatofibromas may resemble vascular tumors such as nodular Kaposi sarcoma. Kaposi sarcoma can be differentiated from an aneurysmal dermatofibroma by the presence of characteristic vascular wrapping, the absence of fibrohistiocytic cells, and expression of human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1.1,8 Although aneurysmal dermatofibromas are of low malignant potential, they are associated with a higher rate of recurrence compared to common dermatofibromas.9 Definitive treatment involves complete excision with follow-up to ensure no signs of recurrence.10 Incomplete excision can increase the likelihood of recurrence, especially for larger aneurysmal dermatofibromas. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas are one of the subtypes of dermatofibromas that may extend into the subcutaneous tissue. Han et al2 found that 77.8% of aneurysmal dermatofibromas extended into subcutaneous tissue. Recognizing the clinical and pathological features of this rare subtype of dermatofibroma can aid dermatologists in appropriate recognition and management.

The Diagnosis: Aneurysmal Dermatofibroma

A shave biopsy of the entire tumor was performed at the initial visit. Histologic examination with hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a fibrohistiocytic infiltrate containing cleftlike cavernous spaces lined by epithelial cells (Figure, A). Immunohistochemical staining revealed factor XIIIa expression on fibrohistiocytic cells (Figure, B). CD34 was expressed on vascular endothelial cells, but it failed to highlight the fibrohistiocytic space (Figure, C). Overall, these findings supported the diagnosis of aneurysmal dermatofibroma. The lesion healed without complications, and the patient was counseled on the risk for recurrence. He was offered localized excision but opted for conservative management without excision and close follow-up and monitoring.

Dermatofibromas are common benign cutaneous nodules that often are asymptomatic and occur on the extremities. Dermatofibromas also are known as cutaneous fibrous histiocytomas and have numerous histologic variants. Aneurysmal dermatofibroma (also called aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma) is a rare histologic variant of dermatofibroma presenting as a slow-growing exophytic tumor that can be purple, red, brown, or blue. Although classic dermatofibromas typically constitute a straightforward diagnosis, aneurysmal dermatofibromas often are more challenging to clinically differentiate from other cutaneous neoplasms. Additionally, due to the exophytic nature and larger size (0.5–4.0 cm), aneurysmal dermatofibromas do not exhibit the characteristic dimple (Fitzpatrick) sign found in many dermatofibromas. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas are 10 times more likely to recur than classic dermatofibromas.1-4

Aneurysmal dermatofibromas can mimic other cutaneous neoplasms, some indolent and others more aggressive. Similar to aneurysmal dermatofibromas, solitary neurofibromas and nevi lipomatosus can appear as asymptomatic exophytic nodules with a similar spectrum of color and indolent clinical courses. In nevus lipomatosus, the dermis is almost entirely replaced by mature adipose tissue.5 Solitary neurofibromas represent a proliferation of neuromesenchymal cells with haphazardly arranged, wavy nuclei characteristic of nerve cells.6 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans can be distinguished from aneurysmal dermatofibroma by lack of factor XIIIa expression and diffuse positivity for CD34.7 Finally, aneurysmal dermatofibromas may resemble vascular tumors such as nodular Kaposi sarcoma. Kaposi sarcoma can be differentiated from an aneurysmal dermatofibroma by the presence of characteristic vascular wrapping, the absence of fibrohistiocytic cells, and expression of human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1.1,8 Although aneurysmal dermatofibromas are of low malignant potential, they are associated with a higher rate of recurrence compared to common dermatofibromas.9 Definitive treatment involves complete excision with follow-up to ensure no signs of recurrence.10 Incomplete excision can increase the likelihood of recurrence, especially for larger aneurysmal dermatofibromas. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas are one of the subtypes of dermatofibromas that may extend into the subcutaneous tissue. Han et al2 found that 77.8% of aneurysmal dermatofibromas extended into subcutaneous tissue. Recognizing the clinical and pathological features of this rare subtype of dermatofibroma can aid dermatologists in appropriate recognition and management.

- Burr DM, Peterson WA, Peterson MW. Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Am Osteopath. June 2018;40. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.aocd.org/resource/resmgr/jaocd/contents/volume40/40-04.pdf

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee JHK, et al. A clinical and histopathological study of 122 cases of dermatofibroma (benign fibrous histiocytoma). Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:185-192.

- Morariu SH, Suciu M, Vartolomei MD, et al. Aneurysmal dermatofibroma mimicking both clinical and dermoscopic malignant melanoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:1221-1224.

- Calonje E, Fletcher CDM. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathological analysis of 40 cases of a tumour frequently misdiagnosed as a vascular neoplasm. Histopathology. 1995;26:323-331.

- Pujani M, Choudhury M, Garg T, et al. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis: a rare cutaneous hamartoma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:109-110.

- Strike SA, Puhaindran ME. Nerve tumors of the upper extremity. Clin Plast Surg. 2019;46:347-350.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Farhood AI. Dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: differential expression of CD34 and factor XIIIa. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:573-574.

- Kandal S, Ozmen S, Demir HY, et al. Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma of the skin: a rare variant of dermatofibroma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:2050-2051.

- Hornick JL. Cutaneous soft tissue tumors: how do we make sense of fibrous and “fibrohistiocytic” tumors with confusing names and similar appearances? Mod Pathol. 2020;33:56-65.

- Das A, Das A, Bandyopadhyay D, et al. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma presenting as a giant acrochordon on thigh. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:436.

- Burr DM, Peterson WA, Peterson MW. Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Am Osteopath. June 2018;40. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.aocd.org/resource/resmgr/jaocd/contents/volume40/40-04.pdf

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee JHK, et al. A clinical and histopathological study of 122 cases of dermatofibroma (benign fibrous histiocytoma). Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:185-192.

- Morariu SH, Suciu M, Vartolomei MD, et al. Aneurysmal dermatofibroma mimicking both clinical and dermoscopic malignant melanoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:1221-1224.

- Calonje E, Fletcher CDM. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathological analysis of 40 cases of a tumour frequently misdiagnosed as a vascular neoplasm. Histopathology. 1995;26:323-331.

- Pujani M, Choudhury M, Garg T, et al. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis: a rare cutaneous hamartoma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:109-110.

- Strike SA, Puhaindran ME. Nerve tumors of the upper extremity. Clin Plast Surg. 2019;46:347-350.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Farhood AI. Dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: differential expression of CD34 and factor XIIIa. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:573-574.

- Kandal S, Ozmen S, Demir HY, et al. Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma of the skin: a rare variant of dermatofibroma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:2050-2051.

- Hornick JL. Cutaneous soft tissue tumors: how do we make sense of fibrous and “fibrohistiocytic” tumors with confusing names and similar appearances? Mod Pathol. 2020;33:56-65.

- Das A, Das A, Bandyopadhyay D, et al. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma presenting as a giant acrochordon on thigh. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:436.

A 43-year-old Black man with no notable medical history presented to our clinic with a progressively enlarging tumor on the right forearm of 12 months’ duration. Despite its progressive growth, the tumor was asymptomatic. Physical examination of the right forearm revealed a 3.7×3.0-cm, well-circumscribed, exophytic tumor with a mildly erythematous hue, scaly surface, and rubbery consistency. There was no surrounding erythema, edema, localized lymphadenopathy, or concurrent lymphedema.

Periorbital Orange Spots

The Diagnosis: Orange Palpebral Spots

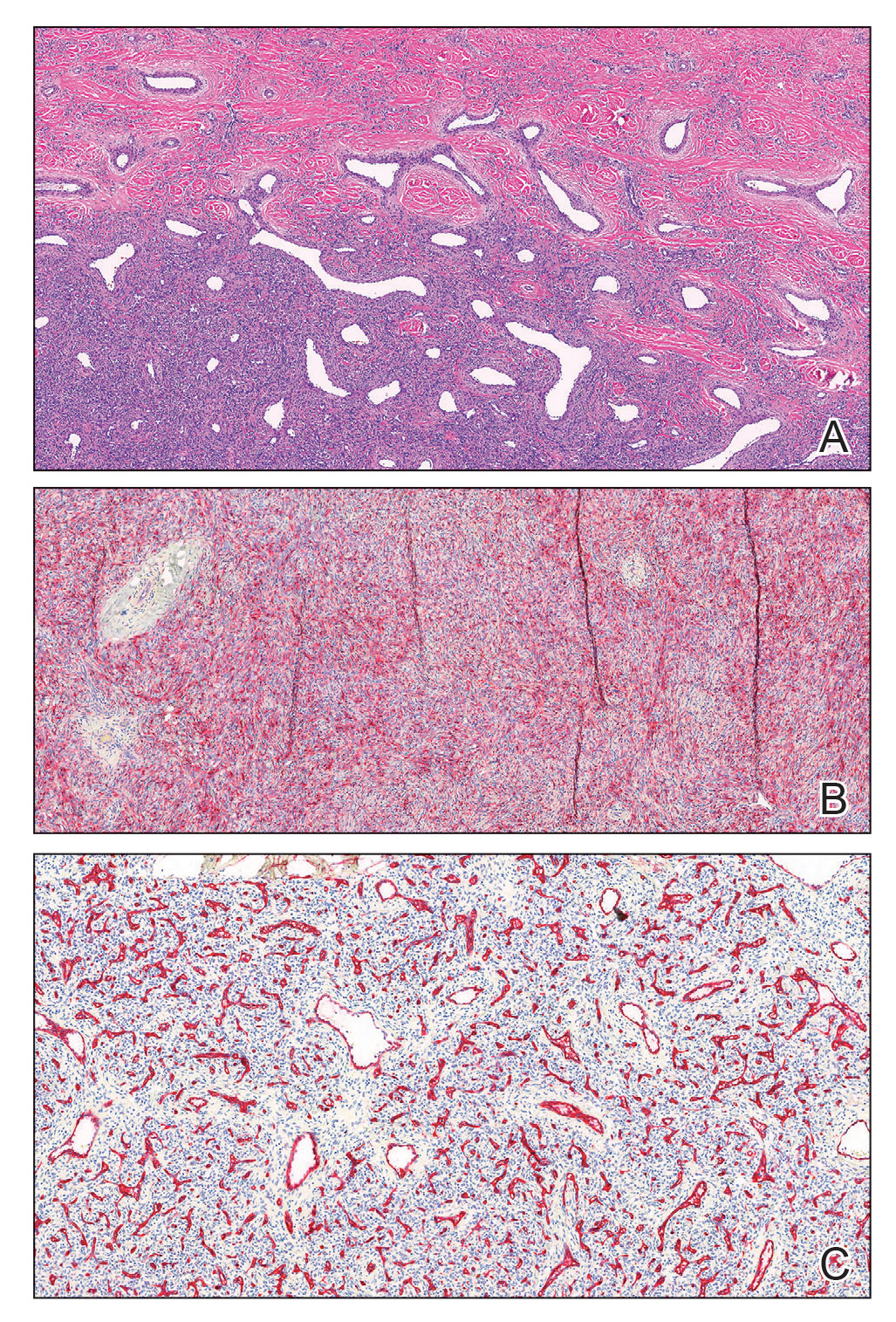

The clinical presentation of our patient was consistent with a diagnosis of orange palpebral spots (OPSs), an uncommon discoloration that most often appears in White patients in the fifth or sixth decades of life. Orange palpebral spots were first described in 2008 by Assouly et al1 in 27 patients (23 females and 4 males). In 2015, Belliveau et al2 expanded the designation to yellow-orange palpebral spots because they felt the term more fully expressed the color variations depicted in their patients; however, this term more frequently is used in ophthalmology.

Orange palpebral spots commonly appear as asymptomatic, yellow-orange, symmetric lesions with a predilection for the recessed areas of the superior eyelids but also can present on the canthi and inferior eyelids. The discolorations are more easily visible on fair skin and have been reported to measure from 10 to 15 mm in the long axis.3 Assouly et al1 described the orange spots as having indistinct margins, with borders similar to “sand on a sea shore.” Orange palpebral spots can be a persistent discoloration, and there are no reports of spontaneous regression. No known association with malignancy or systemic illness has been reported.

Case reports of OPSs describe histologic similarities between specimens, including increased adipose tissue and pigment-laden macrophages in the superficial dermis.2 The pigmented deposits sometimes may be found in the basal keratinocytes of the epidermis and turn black with Fontana-Masson stain.1 No inflammatory infiltrates, necrosis, or xanthomization are characteristically found. Stains for iron, mucin, and amyloid also have been negative.2

The cause of pigmentation in OPSs is unknown; however, lipofuscin deposits and high-situated adipocytes in the reticular dermis colored by carotenoids have been proposed as possible mechanisms.1 No unifying cause for pigmentation in the serum (eg, cholesterol, triglycerides, thyroid-stimulating hormone, free retinol, vitamin E, carotenoids) was found in 11 of 27 patients with OPSs assessed by Assouly et al.1 In one case, lipofuscin, a degradation product of lysosomes, was detected by microscopic autofluorescence in the superficial dermis. However, lipofuscin typically is a breakdown product associated with aging, and OPSs have been present in patients as young as 28 years.1 Local trauma related to eye rubbing is another theory that has been proposed due to the finding of melanin in the superficial dermis. However, the absence of hemosiderin deposits as well as the extensive duration of the discolorations makes local trauma a less likely explanation for the etiology of OPSs.2

The clinical differential diagnosis for OPSs includes xanthelasma, jaundice, and carotenoderma. Xanthelasma presents as elevated yellow plaques usually found over the medial aspect of the eyes. In contrast, OPSs are nonelevated with both orange and yellow hues typically present. Histologic samples of xanthelasma are characterized by lipid-laden macrophages (foam cells) in the dermis in contrast to the adipose tissue seen in OPSs that has not been phagocytized.1,2 The lack of scleral icterus made jaundice an unlikely diagnosis in our patient. Bilirubin elevations substantial enough to cause skin discoloration also would be expected to discolor the conjunctiva. In carotenoderma, carotenoids are deposited in the sweat and sebum of the stratum corneum with the orange pigmentation most prominent in regions of increased sweating such as the palms, soles, and nasolabial folds.4 Our patient’s lack of discoloration in places other than the periorbital region made carotenoderma less likely.

In the study by Assouly et al,1 10 of 11 patients who underwent laboratory analysis self-reported eating a diet rich in fruit and vegetables, though no standardized questionnaire was given. One patient was found to have an elevated vitamin E level, and in 5 cases there was an elevated level of β-cryptoxanthin. The significance of these elevations in such a small minority is unknown, and increased β-cryptoxanthin has been attributed to increased consumption of citrus fruits during the winter season. Our patient reported ingesting a daily oral supplement rich in carotenoids that constituted 60% of the daily value of vitamin E including mixed tocopherols as well as 90% of the daily value of vitamin A with many sources of carotenoids including beta-carotenes, lutein/zeaxanthin, lycopene, and astaxanthin. An invasive biopsy was not taken in this case, as OPSs largely are diagnosed clinically. Greater awareness and recognition of OPSs may help to identify common underlying causes for this unique diagnosis.

- Assouly P, Cavelier-Balloy B, Dupré T. Orange palpebral spots. Dermatology. 2008;216:166-170.

- Belliveau MJ, Odashiro AN, Harvey JT. Yellow-orange palpebral spots. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2139-2140.

- Kluger N, Guillot B. Bilateral orange discoloration of the upper eyelids: a quiz. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:211-212.

- Maharshak N, Shapiro J, Trau H. Carotenoderma—a review of the current literature. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:178-181.

The Diagnosis: Orange Palpebral Spots

The clinical presentation of our patient was consistent with a diagnosis of orange palpebral spots (OPSs), an uncommon discoloration that most often appears in White patients in the fifth or sixth decades of life. Orange palpebral spots were first described in 2008 by Assouly et al1 in 27 patients (23 females and 4 males). In 2015, Belliveau et al2 expanded the designation to yellow-orange palpebral spots because they felt the term more fully expressed the color variations depicted in their patients; however, this term more frequently is used in ophthalmology.

Orange palpebral spots commonly appear as asymptomatic, yellow-orange, symmetric lesions with a predilection for the recessed areas of the superior eyelids but also can present on the canthi and inferior eyelids. The discolorations are more easily visible on fair skin and have been reported to measure from 10 to 15 mm in the long axis.3 Assouly et al1 described the orange spots as having indistinct margins, with borders similar to “sand on a sea shore.” Orange palpebral spots can be a persistent discoloration, and there are no reports of spontaneous regression. No known association with malignancy or systemic illness has been reported.

Case reports of OPSs describe histologic similarities between specimens, including increased adipose tissue and pigment-laden macrophages in the superficial dermis.2 The pigmented deposits sometimes may be found in the basal keratinocytes of the epidermis and turn black with Fontana-Masson stain.1 No inflammatory infiltrates, necrosis, or xanthomization are characteristically found. Stains for iron, mucin, and amyloid also have been negative.2

The cause of pigmentation in OPSs is unknown; however, lipofuscin deposits and high-situated adipocytes in the reticular dermis colored by carotenoids have been proposed as possible mechanisms.1 No unifying cause for pigmentation in the serum (eg, cholesterol, triglycerides, thyroid-stimulating hormone, free retinol, vitamin E, carotenoids) was found in 11 of 27 patients with OPSs assessed by Assouly et al.1 In one case, lipofuscin, a degradation product of lysosomes, was detected by microscopic autofluorescence in the superficial dermis. However, lipofuscin typically is a breakdown product associated with aging, and OPSs have been present in patients as young as 28 years.1 Local trauma related to eye rubbing is another theory that has been proposed due to the finding of melanin in the superficial dermis. However, the absence of hemosiderin deposits as well as the extensive duration of the discolorations makes local trauma a less likely explanation for the etiology of OPSs.2

The clinical differential diagnosis for OPSs includes xanthelasma, jaundice, and carotenoderma. Xanthelasma presents as elevated yellow plaques usually found over the medial aspect of the eyes. In contrast, OPSs are nonelevated with both orange and yellow hues typically present. Histologic samples of xanthelasma are characterized by lipid-laden macrophages (foam cells) in the dermis in contrast to the adipose tissue seen in OPSs that has not been phagocytized.1,2 The lack of scleral icterus made jaundice an unlikely diagnosis in our patient. Bilirubin elevations substantial enough to cause skin discoloration also would be expected to discolor the conjunctiva. In carotenoderma, carotenoids are deposited in the sweat and sebum of the stratum corneum with the orange pigmentation most prominent in regions of increased sweating such as the palms, soles, and nasolabial folds.4 Our patient’s lack of discoloration in places other than the periorbital region made carotenoderma less likely.

In the study by Assouly et al,1 10 of 11 patients who underwent laboratory analysis self-reported eating a diet rich in fruit and vegetables, though no standardized questionnaire was given. One patient was found to have an elevated vitamin E level, and in 5 cases there was an elevated level of β-cryptoxanthin. The significance of these elevations in such a small minority is unknown, and increased β-cryptoxanthin has been attributed to increased consumption of citrus fruits during the winter season. Our patient reported ingesting a daily oral supplement rich in carotenoids that constituted 60% of the daily value of vitamin E including mixed tocopherols as well as 90% of the daily value of vitamin A with many sources of carotenoids including beta-carotenes, lutein/zeaxanthin, lycopene, and astaxanthin. An invasive biopsy was not taken in this case, as OPSs largely are diagnosed clinically. Greater awareness and recognition of OPSs may help to identify common underlying causes for this unique diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Orange Palpebral Spots

The clinical presentation of our patient was consistent with a diagnosis of orange palpebral spots (OPSs), an uncommon discoloration that most often appears in White patients in the fifth or sixth decades of life. Orange palpebral spots were first described in 2008 by Assouly et al1 in 27 patients (23 females and 4 males). In 2015, Belliveau et al2 expanded the designation to yellow-orange palpebral spots because they felt the term more fully expressed the color variations depicted in their patients; however, this term more frequently is used in ophthalmology.

Orange palpebral spots commonly appear as asymptomatic, yellow-orange, symmetric lesions with a predilection for the recessed areas of the superior eyelids but also can present on the canthi and inferior eyelids. The discolorations are more easily visible on fair skin and have been reported to measure from 10 to 15 mm in the long axis.3 Assouly et al1 described the orange spots as having indistinct margins, with borders similar to “sand on a sea shore.” Orange palpebral spots can be a persistent discoloration, and there are no reports of spontaneous regression. No known association with malignancy or systemic illness has been reported.

Case reports of OPSs describe histologic similarities between specimens, including increased adipose tissue and pigment-laden macrophages in the superficial dermis.2 The pigmented deposits sometimes may be found in the basal keratinocytes of the epidermis and turn black with Fontana-Masson stain.1 No inflammatory infiltrates, necrosis, or xanthomization are characteristically found. Stains for iron, mucin, and amyloid also have been negative.2

The cause of pigmentation in OPSs is unknown; however, lipofuscin deposits and high-situated adipocytes in the reticular dermis colored by carotenoids have been proposed as possible mechanisms.1 No unifying cause for pigmentation in the serum (eg, cholesterol, triglycerides, thyroid-stimulating hormone, free retinol, vitamin E, carotenoids) was found in 11 of 27 patients with OPSs assessed by Assouly et al.1 In one case, lipofuscin, a degradation product of lysosomes, was detected by microscopic autofluorescence in the superficial dermis. However, lipofuscin typically is a breakdown product associated with aging, and OPSs have been present in patients as young as 28 years.1 Local trauma related to eye rubbing is another theory that has been proposed due to the finding of melanin in the superficial dermis. However, the absence of hemosiderin deposits as well as the extensive duration of the discolorations makes local trauma a less likely explanation for the etiology of OPSs.2

The clinical differential diagnosis for OPSs includes xanthelasma, jaundice, and carotenoderma. Xanthelasma presents as elevated yellow plaques usually found over the medial aspect of the eyes. In contrast, OPSs are nonelevated with both orange and yellow hues typically present. Histologic samples of xanthelasma are characterized by lipid-laden macrophages (foam cells) in the dermis in contrast to the adipose tissue seen in OPSs that has not been phagocytized.1,2 The lack of scleral icterus made jaundice an unlikely diagnosis in our patient. Bilirubin elevations substantial enough to cause skin discoloration also would be expected to discolor the conjunctiva. In carotenoderma, carotenoids are deposited in the sweat and sebum of the stratum corneum with the orange pigmentation most prominent in regions of increased sweating such as the palms, soles, and nasolabial folds.4 Our patient’s lack of discoloration in places other than the periorbital region made carotenoderma less likely.

In the study by Assouly et al,1 10 of 11 patients who underwent laboratory analysis self-reported eating a diet rich in fruit and vegetables, though no standardized questionnaire was given. One patient was found to have an elevated vitamin E level, and in 5 cases there was an elevated level of β-cryptoxanthin. The significance of these elevations in such a small minority is unknown, and increased β-cryptoxanthin has been attributed to increased consumption of citrus fruits during the winter season. Our patient reported ingesting a daily oral supplement rich in carotenoids that constituted 60% of the daily value of vitamin E including mixed tocopherols as well as 90% of the daily value of vitamin A with many sources of carotenoids including beta-carotenes, lutein/zeaxanthin, lycopene, and astaxanthin. An invasive biopsy was not taken in this case, as OPSs largely are diagnosed clinically. Greater awareness and recognition of OPSs may help to identify common underlying causes for this unique diagnosis.

- Assouly P, Cavelier-Balloy B, Dupré T. Orange palpebral spots. Dermatology. 2008;216:166-170.

- Belliveau MJ, Odashiro AN, Harvey JT. Yellow-orange palpebral spots. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2139-2140.

- Kluger N, Guillot B. Bilateral orange discoloration of the upper eyelids: a quiz. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:211-212.

- Maharshak N, Shapiro J, Trau H. Carotenoderma—a review of the current literature. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:178-181.

- Assouly P, Cavelier-Balloy B, Dupré T. Orange palpebral spots. Dermatology. 2008;216:166-170.

- Belliveau MJ, Odashiro AN, Harvey JT. Yellow-orange palpebral spots. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2139-2140.

- Kluger N, Guillot B. Bilateral orange discoloration of the upper eyelids: a quiz. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:211-212.

- Maharshak N, Shapiro J, Trau H. Carotenoderma—a review of the current literature. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:178-181.

A 63-year-old White man with a history of melanoma presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of gradually worsening yellow discoloration around the eyes of 2 years’ duration. Physical examination revealed periorbital yellow-orange patches (top). The discolorations were nonelevated and nonpalpable. Dermoscopy revealed yellow blotches with sparing of the hair follicles (bottom). The remainder of the skin examination was unremarkable.

Annular Plaques Overlying Hyperpigmented Telangiectatic Patches on the Neck

The Diagnosis: Annular Elastolytic Giant Cell Granuloma

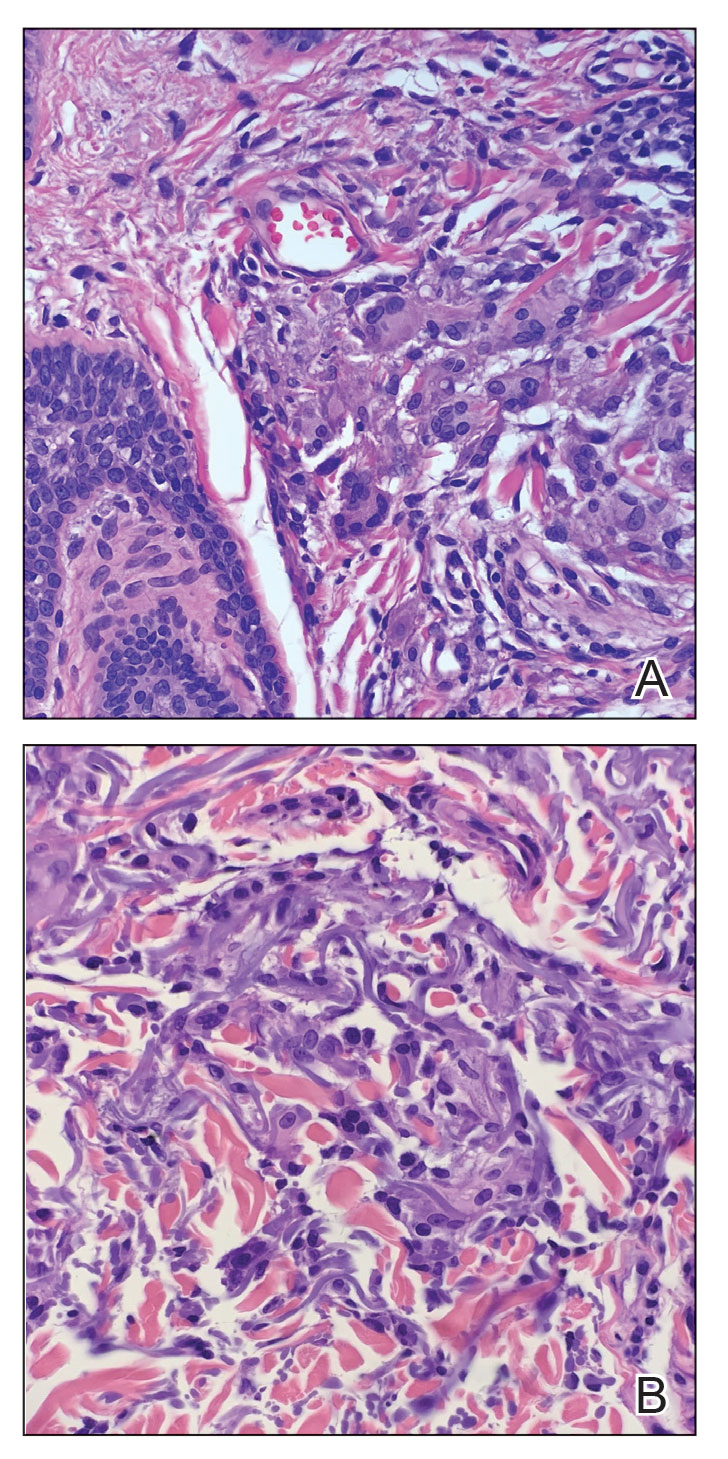

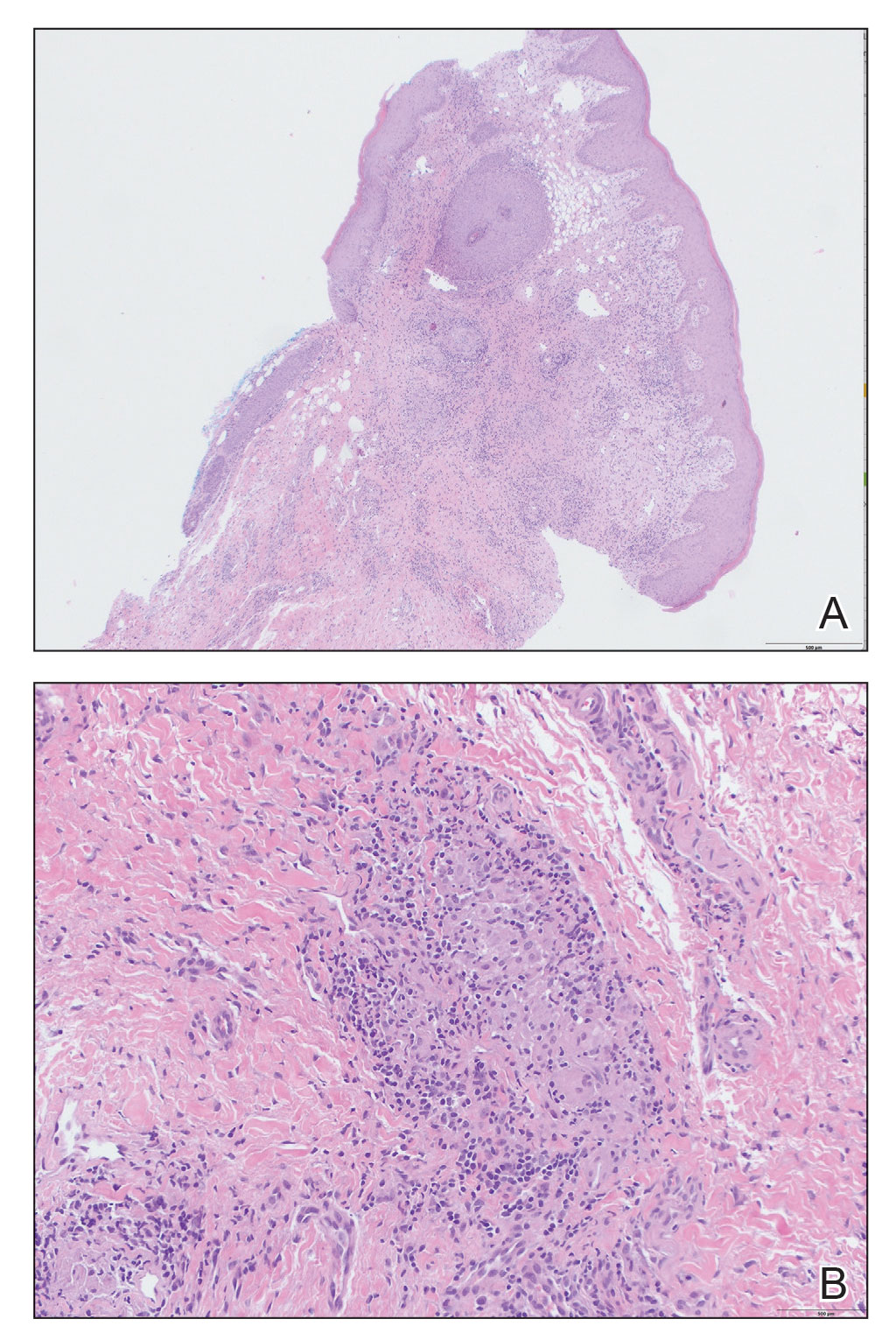

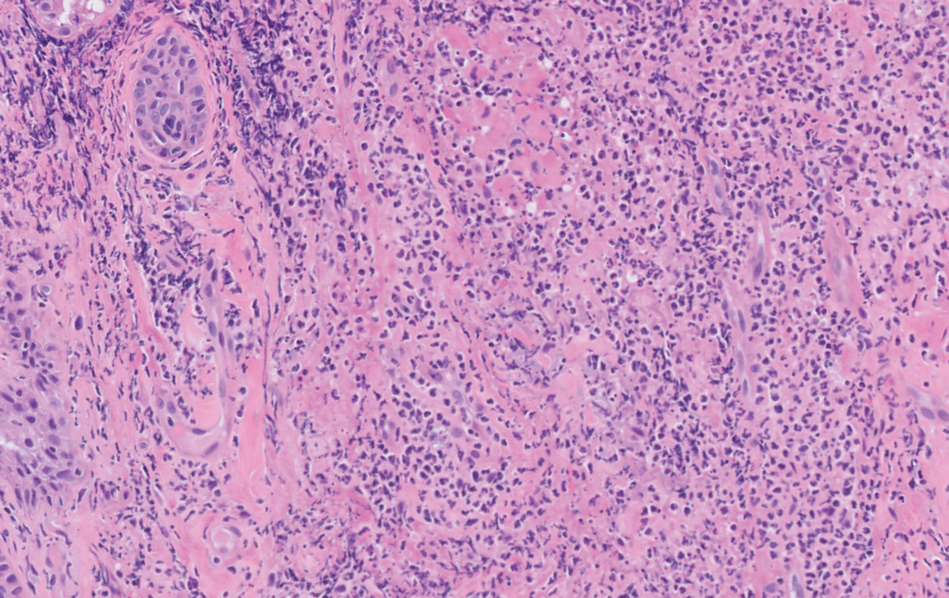

Histologic examination of the shave biopsies showed a granulomatous infiltrate of small lymphocytes, histiocytes, and multinucleated giant cells. The giant cells have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, with several also containing fragments of basophilic elastic fibers (elastophagocytosis)(Figure). Additionally, the granulomas revealed no signs of necrosis, making an infectious source unlikely, and examination under polarized light was negative for foreign material. These clinical and histologic findings were diagnostic for annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG).

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma is a rare chronic inflammatory disorder that classically presents on sun-exposed skin as annular plaques with elevated borders and atrophic centers.1-4 Histologically, AEGCG is characterized by diffuse granulomatous infiltrates composed of multinucleated giant cells, histiocytes, and lymphocytes in the dermis, along with phagocytosis of elastic fibers by multinucleated giant cells.5 The underlying etiology and pathogenesis of AEGCG remains unknown.6

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma commonly affects females aged 35 to 75 years; however, cases have been reported in the male and pediatric patient populations.1,2 Documented cases are known to last from 1 month to 10 years.7,8 Although the mechanisms underlying the development of AEGCG remain to be elucidated, studies have determined that the skin disorder is associated with sarcoidosis, molluscum contagiosum, amyloidosis, diabetes mellitus, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.9 Diabetes mellitus is the most common comorbidity associated with AEGCG, and it is theorized that diabetes contributes to the increased incidence of AEGCG in this population by inducing damage to elastic fibers in the skin.10 One study that examined 50 cases of AEGCG found that 38 patients had serum glucose levels evaluated, with 8 cases being subsequently diagnosed with diabetes mellitus and 6 cases with apparent impaired glucose tolerance, indicating that 37% of the sample population with AEGCG who were evaluated for metabolic disease were found to have definitive or latent type 2 diabetes mellitus.11 Although AEGCG is a rare disorder, a substantial number of patients diagnosed with AEGCG also have diabetes mellitus, making it important to consider screening all patients with AEGCG for diabetes given the ease and widely available resources to check glucose levels.

Actinic granuloma, granuloma annulare, atypical facial necrobiosis lipoidica, granuloma multiforme, secondary syphilis, tinea corporis, and erythema annulare centrifugum most commonly are included in the differential diagnosis with AEGCG; histopathology is the key determinant in discerning between these conditions.12 Our patient presented with typical annular plaques overlying hyperpigmented telangiectatic patches. With known type 2 diabetes mellitus and the clinical findings, granuloma annulare, erythema annulare centrifugum, and AEGCG remained high on the differential.

No standard of care exists for AEGCG due to its rare nature and tendency to spontaneously resolve. The most common first-line treatment includes topical and intralesional steroids, topical pimecrolimus, and the use of sunscreen and other sun-protective measures. UV radiation, specifically UVA, has been determined to be a causal factor for AEGCG by changing the antigenicity of elastic fibers and producing an immune response in individuals with fair skin.13 Further, resistant cases of AEGCG successfully have been treated with cyclosporine, systemic steroids, antimalarials, dapsone, and oral retinoids.14,15 Some studies reported partial regression or full resolution with topical tretinoin; adalimumab; clobetasol ointment; or a combination of corticosteroids, antihistamines, and hydroxychloroquine.2 Only 1 case series using sulfasalazine reported worsening symptoms after treatment initiation.16 Our patient deferred systemic medications and was treated with 4 weeks of topical triamcinolone followed by 4 weeks of topical tacrolimus with minimal improvement. At the time of diagnosis, our patient also was encouraged to use sun-protective measures. At 6-month follow-up, the lesions remained stable, and the decision was made to continue with photoprotection.

- Mistry AM, Patel R, Mistry M, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Cureus. 2020;12:E11456. doi:10.7759/cureus.11456

- Chen WT, Hsiao PF, Wu YH. Spectrum and clinical variants of giant cell elastolytic granuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:738-745. doi:10.1111/ijd.13502

- Raposo I, Mota F, Lobo I, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma: a “visible” diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt9rq3j927

- Klemke CD, Siebold D, Dippel E, et al. Generalised annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Dermatology. 2003;207:420-422. doi:10.1159/000074132

- Hassan R, Arunprasath P, Padmavathy L, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma in association with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:107-110. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.178087

- Kaya Erdog˘ an H, Arık D, Acer E, et al. Clinicopathological features of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma patients. Turkish J Dermatol. 2018;12:85-89.

- Can B, Kavala M, Türkog˘ lu Z, et al. Successful treatment of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with hydroxychloroquine. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:509-511. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2011.04941.x

- Arora S, Malik A, Patil C, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma: a report of 10 cases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6(suppl 1):S17-S20. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.171055

- Doulaveri G, Tsagroni E, Giannadaki M, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma in a 70-year-old woman. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:290-291. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01767.x

- Marmon S, O’Reilly KE, Fischer M, et al. Papular variant of annular elastolytic giant-cell granuloma. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:23.

- Aso Y, Izaki S, Teraki Y. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma associated with diabetes mellitus: a case report and review of the Japanese literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:917-919. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-2230.2011.04094.x

- Liu X, Zhang W, Liu Y, et al. A case of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma associated with syphilis. Case Rep Dermatol. 2018; 10:158-161. doi:10.1159/000489910

- Gutiérrez-González E, Pereiro M Jr, Toribio J. Elastolytic actinic giant cell granuloma. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:331-341. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.002

- de Oliveira FL, de Barros Silveira LK, Machado Ade M, et al. Hybrid clinical and histopathological pattern in annular lesions: an overlap between annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma and granuloma annulare? Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2012;2012:102915. doi:10.1155/2012/102915

- Wagenseller A, Larocca C, Vashi NA. Treatment of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with topical tretinoin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:699-700.

- Yang YW, Lehrer MD, Mangold AR, et al. Treatment of granuloma annulare and related granulomatous diseases with sulphasalazine: a series of 16 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:211-215. doi:10.1111/jdv.16356

The Diagnosis: Annular Elastolytic Giant Cell Granuloma

Histologic examination of the shave biopsies showed a granulomatous infiltrate of small lymphocytes, histiocytes, and multinucleated giant cells. The giant cells have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, with several also containing fragments of basophilic elastic fibers (elastophagocytosis)(Figure). Additionally, the granulomas revealed no signs of necrosis, making an infectious source unlikely, and examination under polarized light was negative for foreign material. These clinical and histologic findings were diagnostic for annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG).

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma is a rare chronic inflammatory disorder that classically presents on sun-exposed skin as annular plaques with elevated borders and atrophic centers.1-4 Histologically, AEGCG is characterized by diffuse granulomatous infiltrates composed of multinucleated giant cells, histiocytes, and lymphocytes in the dermis, along with phagocytosis of elastic fibers by multinucleated giant cells.5 The underlying etiology and pathogenesis of AEGCG remains unknown.6

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma commonly affects females aged 35 to 75 years; however, cases have been reported in the male and pediatric patient populations.1,2 Documented cases are known to last from 1 month to 10 years.7,8 Although the mechanisms underlying the development of AEGCG remain to be elucidated, studies have determined that the skin disorder is associated with sarcoidosis, molluscum contagiosum, amyloidosis, diabetes mellitus, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.9 Diabetes mellitus is the most common comorbidity associated with AEGCG, and it is theorized that diabetes contributes to the increased incidence of AEGCG in this population by inducing damage to elastic fibers in the skin.10 One study that examined 50 cases of AEGCG found that 38 patients had serum glucose levels evaluated, with 8 cases being subsequently diagnosed with diabetes mellitus and 6 cases with apparent impaired glucose tolerance, indicating that 37% of the sample population with AEGCG who were evaluated for metabolic disease were found to have definitive or latent type 2 diabetes mellitus.11 Although AEGCG is a rare disorder, a substantial number of patients diagnosed with AEGCG also have diabetes mellitus, making it important to consider screening all patients with AEGCG for diabetes given the ease and widely available resources to check glucose levels.

Actinic granuloma, granuloma annulare, atypical facial necrobiosis lipoidica, granuloma multiforme, secondary syphilis, tinea corporis, and erythema annulare centrifugum most commonly are included in the differential diagnosis with AEGCG; histopathology is the key determinant in discerning between these conditions.12 Our patient presented with typical annular plaques overlying hyperpigmented telangiectatic patches. With known type 2 diabetes mellitus and the clinical findings, granuloma annulare, erythema annulare centrifugum, and AEGCG remained high on the differential.

No standard of care exists for AEGCG due to its rare nature and tendency to spontaneously resolve. The most common first-line treatment includes topical and intralesional steroids, topical pimecrolimus, and the use of sunscreen and other sun-protective measures. UV radiation, specifically UVA, has been determined to be a causal factor for AEGCG by changing the antigenicity of elastic fibers and producing an immune response in individuals with fair skin.13 Further, resistant cases of AEGCG successfully have been treated with cyclosporine, systemic steroids, antimalarials, dapsone, and oral retinoids.14,15 Some studies reported partial regression or full resolution with topical tretinoin; adalimumab; clobetasol ointment; or a combination of corticosteroids, antihistamines, and hydroxychloroquine.2 Only 1 case series using sulfasalazine reported worsening symptoms after treatment initiation.16 Our patient deferred systemic medications and was treated with 4 weeks of topical triamcinolone followed by 4 weeks of topical tacrolimus with minimal improvement. At the time of diagnosis, our patient also was encouraged to use sun-protective measures. At 6-month follow-up, the lesions remained stable, and the decision was made to continue with photoprotection.

The Diagnosis: Annular Elastolytic Giant Cell Granuloma

Histologic examination of the shave biopsies showed a granulomatous infiltrate of small lymphocytes, histiocytes, and multinucleated giant cells. The giant cells have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, with several also containing fragments of basophilic elastic fibers (elastophagocytosis)(Figure). Additionally, the granulomas revealed no signs of necrosis, making an infectious source unlikely, and examination under polarized light was negative for foreign material. These clinical and histologic findings were diagnostic for annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG).

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma is a rare chronic inflammatory disorder that classically presents on sun-exposed skin as annular plaques with elevated borders and atrophic centers.1-4 Histologically, AEGCG is characterized by diffuse granulomatous infiltrates composed of multinucleated giant cells, histiocytes, and lymphocytes in the dermis, along with phagocytosis of elastic fibers by multinucleated giant cells.5 The underlying etiology and pathogenesis of AEGCG remains unknown.6

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma commonly affects females aged 35 to 75 years; however, cases have been reported in the male and pediatric patient populations.1,2 Documented cases are known to last from 1 month to 10 years.7,8 Although the mechanisms underlying the development of AEGCG remain to be elucidated, studies have determined that the skin disorder is associated with sarcoidosis, molluscum contagiosum, amyloidosis, diabetes mellitus, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.9 Diabetes mellitus is the most common comorbidity associated with AEGCG, and it is theorized that diabetes contributes to the increased incidence of AEGCG in this population by inducing damage to elastic fibers in the skin.10 One study that examined 50 cases of AEGCG found that 38 patients had serum glucose levels evaluated, with 8 cases being subsequently diagnosed with diabetes mellitus and 6 cases with apparent impaired glucose tolerance, indicating that 37% of the sample population with AEGCG who were evaluated for metabolic disease were found to have definitive or latent type 2 diabetes mellitus.11 Although AEGCG is a rare disorder, a substantial number of patients diagnosed with AEGCG also have diabetes mellitus, making it important to consider screening all patients with AEGCG for diabetes given the ease and widely available resources to check glucose levels.

Actinic granuloma, granuloma annulare, atypical facial necrobiosis lipoidica, granuloma multiforme, secondary syphilis, tinea corporis, and erythema annulare centrifugum most commonly are included in the differential diagnosis with AEGCG; histopathology is the key determinant in discerning between these conditions.12 Our patient presented with typical annular plaques overlying hyperpigmented telangiectatic patches. With known type 2 diabetes mellitus and the clinical findings, granuloma annulare, erythema annulare centrifugum, and AEGCG remained high on the differential.

No standard of care exists for AEGCG due to its rare nature and tendency to spontaneously resolve. The most common first-line treatment includes topical and intralesional steroids, topical pimecrolimus, and the use of sunscreen and other sun-protective measures. UV radiation, specifically UVA, has been determined to be a causal factor for AEGCG by changing the antigenicity of elastic fibers and producing an immune response in individuals with fair skin.13 Further, resistant cases of AEGCG successfully have been treated with cyclosporine, systemic steroids, antimalarials, dapsone, and oral retinoids.14,15 Some studies reported partial regression or full resolution with topical tretinoin; adalimumab; clobetasol ointment; or a combination of corticosteroids, antihistamines, and hydroxychloroquine.2 Only 1 case series using sulfasalazine reported worsening symptoms after treatment initiation.16 Our patient deferred systemic medications and was treated with 4 weeks of topical triamcinolone followed by 4 weeks of topical tacrolimus with minimal improvement. At the time of diagnosis, our patient also was encouraged to use sun-protective measures. At 6-month follow-up, the lesions remained stable, and the decision was made to continue with photoprotection.

- Mistry AM, Patel R, Mistry M, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Cureus. 2020;12:E11456. doi:10.7759/cureus.11456

- Chen WT, Hsiao PF, Wu YH. Spectrum and clinical variants of giant cell elastolytic granuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:738-745. doi:10.1111/ijd.13502

- Raposo I, Mota F, Lobo I, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma: a “visible” diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt9rq3j927

- Klemke CD, Siebold D, Dippel E, et al. Generalised annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Dermatology. 2003;207:420-422. doi:10.1159/000074132

- Hassan R, Arunprasath P, Padmavathy L, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma in association with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:107-110. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.178087

- Kaya Erdog˘ an H, Arık D, Acer E, et al. Clinicopathological features of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma patients. Turkish J Dermatol. 2018;12:85-89.

- Can B, Kavala M, Türkog˘ lu Z, et al. Successful treatment of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with hydroxychloroquine. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:509-511. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2011.04941.x

- Arora S, Malik A, Patil C, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma: a report of 10 cases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6(suppl 1):S17-S20. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.171055

- Doulaveri G, Tsagroni E, Giannadaki M, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma in a 70-year-old woman. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:290-291. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01767.x

- Marmon S, O’Reilly KE, Fischer M, et al. Papular variant of annular elastolytic giant-cell granuloma. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:23.

- Aso Y, Izaki S, Teraki Y. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma associated with diabetes mellitus: a case report and review of the Japanese literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:917-919. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-2230.2011.04094.x

- Liu X, Zhang W, Liu Y, et al. A case of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma associated with syphilis. Case Rep Dermatol. 2018; 10:158-161. doi:10.1159/000489910

- Gutiérrez-González E, Pereiro M Jr, Toribio J. Elastolytic actinic giant cell granuloma. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:331-341. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.002

- de Oliveira FL, de Barros Silveira LK, Machado Ade M, et al. Hybrid clinical and histopathological pattern in annular lesions: an overlap between annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma and granuloma annulare? Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2012;2012:102915. doi:10.1155/2012/102915

- Wagenseller A, Larocca C, Vashi NA. Treatment of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with topical tretinoin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:699-700.

- Yang YW, Lehrer MD, Mangold AR, et al. Treatment of granuloma annulare and related granulomatous diseases with sulphasalazine: a series of 16 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:211-215. doi:10.1111/jdv.16356

- Mistry AM, Patel R, Mistry M, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Cureus. 2020;12:E11456. doi:10.7759/cureus.11456

- Chen WT, Hsiao PF, Wu YH. Spectrum and clinical variants of giant cell elastolytic granuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:738-745. doi:10.1111/ijd.13502

- Raposo I, Mota F, Lobo I, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma: a “visible” diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt9rq3j927

- Klemke CD, Siebold D, Dippel E, et al. Generalised annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Dermatology. 2003;207:420-422. doi:10.1159/000074132

- Hassan R, Arunprasath P, Padmavathy L, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma in association with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:107-110. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.178087

- Kaya Erdog˘ an H, Arık D, Acer E, et al. Clinicopathological features of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma patients. Turkish J Dermatol. 2018;12:85-89.

- Can B, Kavala M, Türkog˘ lu Z, et al. Successful treatment of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with hydroxychloroquine. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:509-511. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2011.04941.x

- Arora S, Malik A, Patil C, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma: a report of 10 cases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6(suppl 1):S17-S20. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.171055

- Doulaveri G, Tsagroni E, Giannadaki M, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma in a 70-year-old woman. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:290-291. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01767.x

- Marmon S, O’Reilly KE, Fischer M, et al. Papular variant of annular elastolytic giant-cell granuloma. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:23.

- Aso Y, Izaki S, Teraki Y. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma associated with diabetes mellitus: a case report and review of the Japanese literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:917-919. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-2230.2011.04094.x

- Liu X, Zhang W, Liu Y, et al. A case of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma associated with syphilis. Case Rep Dermatol. 2018; 10:158-161. doi:10.1159/000489910

- Gutiérrez-González E, Pereiro M Jr, Toribio J. Elastolytic actinic giant cell granuloma. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:331-341. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.002

- de Oliveira FL, de Barros Silveira LK, Machado Ade M, et al. Hybrid clinical and histopathological pattern in annular lesions: an overlap between annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma and granuloma annulare? Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2012;2012:102915. doi:10.1155/2012/102915

- Wagenseller A, Larocca C, Vashi NA. Treatment of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with topical tretinoin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:699-700.

- Yang YW, Lehrer MD, Mangold AR, et al. Treatment of granuloma annulare and related granulomatous diseases with sulphasalazine: a series of 16 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:211-215. doi:10.1111/jdv.16356

A 58-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, nephrolithiasis, hypovitaminosis D, and hypercholesterolemia presented to our dermatology clinic for a follow-up total-body skin examination after a prior diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma on the vertex of the scalp. Physical examination revealed extensive photodamage and annular plaques overlying hyperpigmented telangiectatic patches on the dorsal portion of the neck. The eruption persisted for 1 year and failed to improve with clotrimazole cream. His medications included simvastatin, metformin, chlorthalidone, vitamin D, and tamsulosin. Two shave biopsies from the posterior neck were performed.

Chronic Ulcerative Lesion

The Diagnosis: Marjolin Ulcer

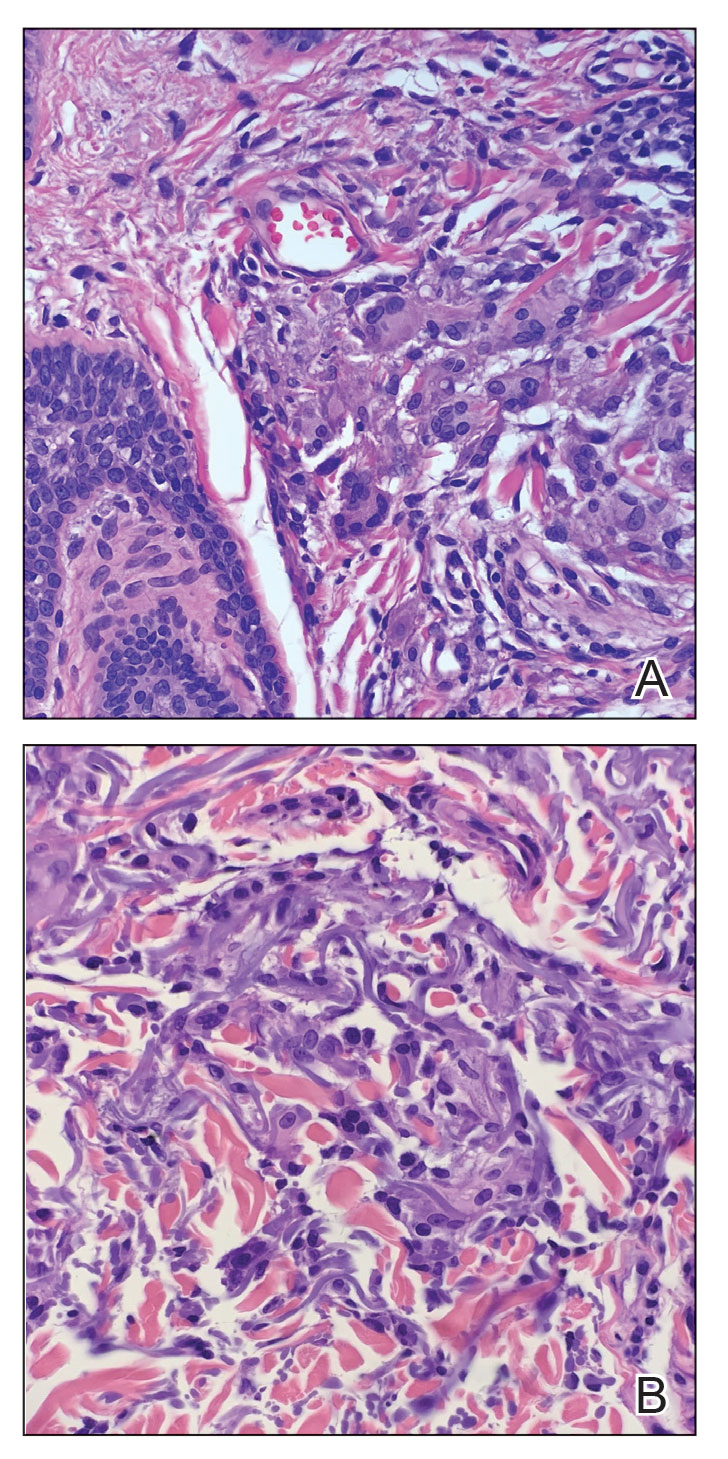

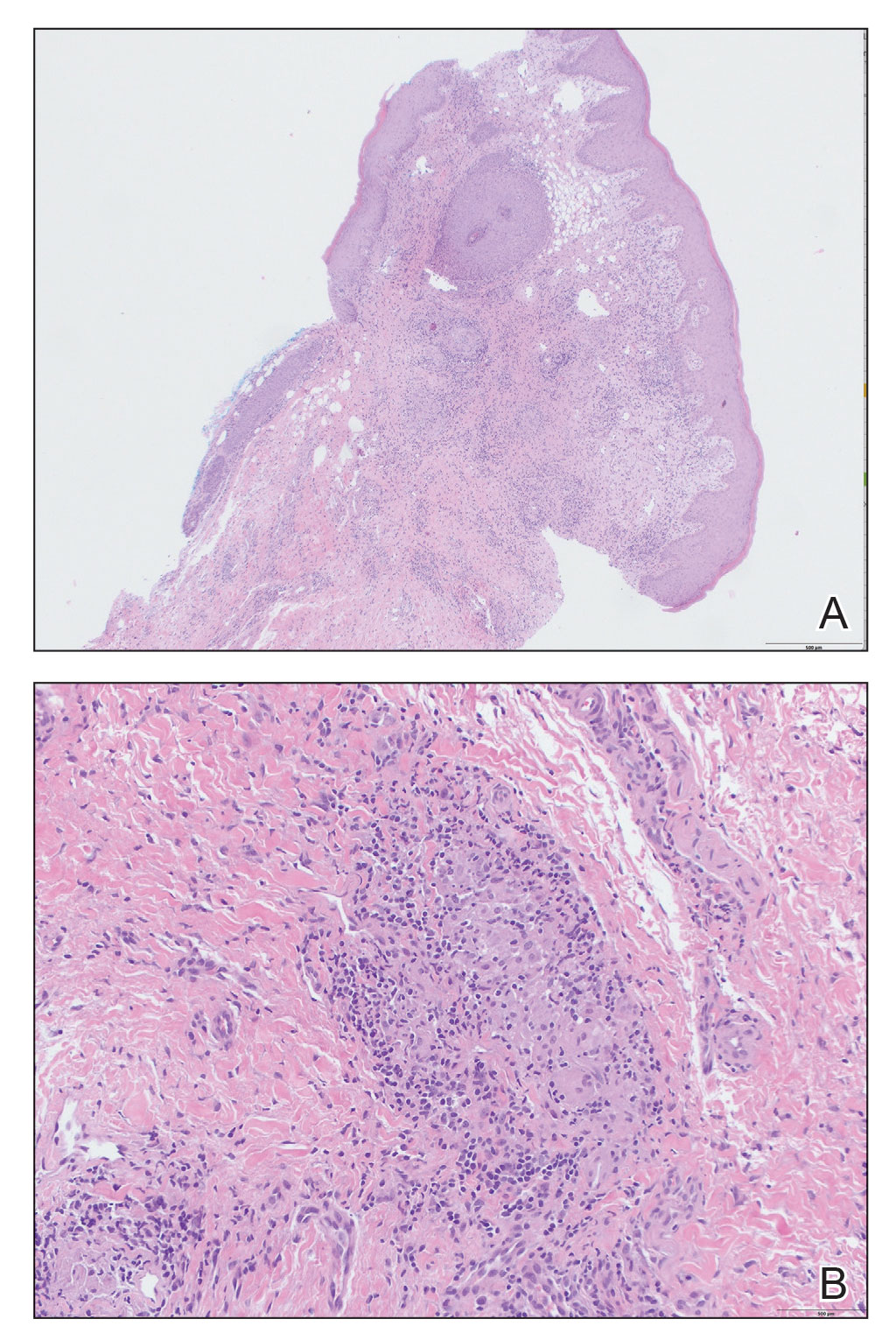

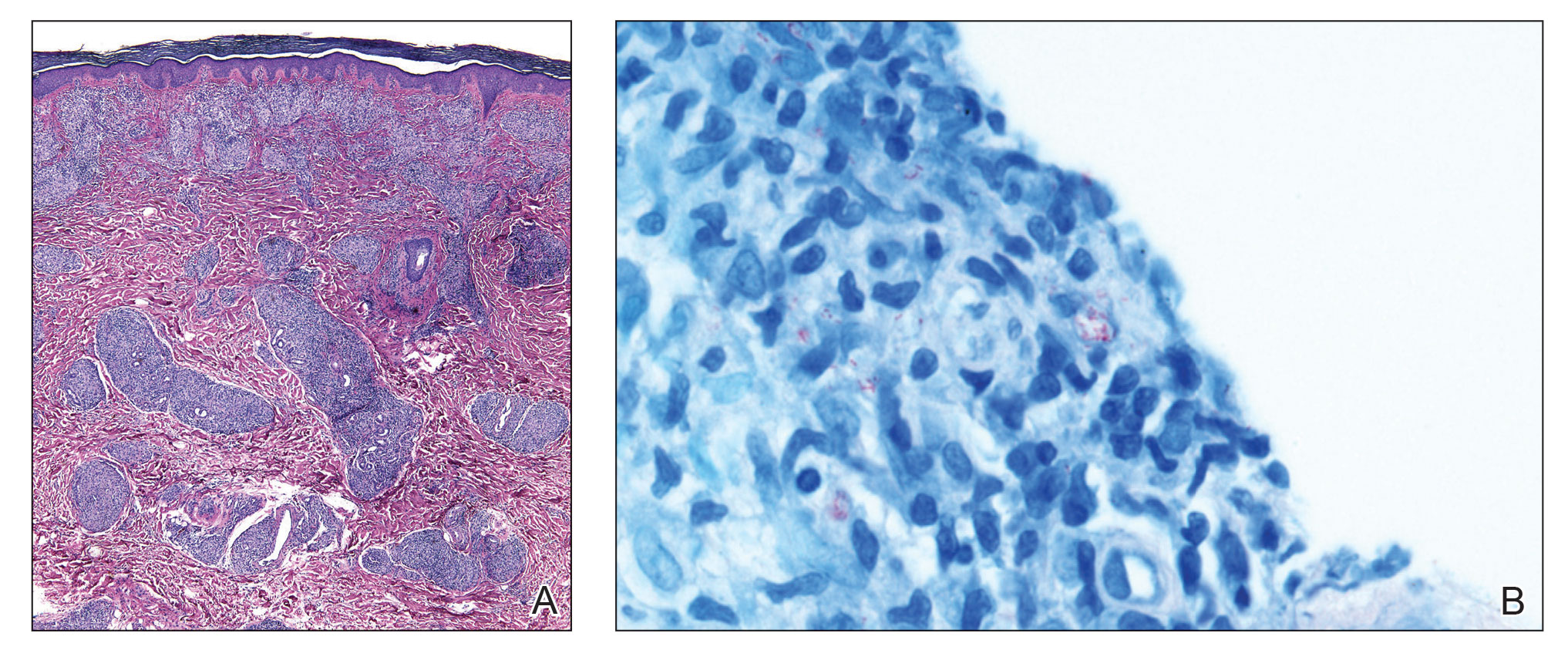

A skin biopsy during his prior hospital admission demonstrated an ulcer with granulation tissue and mixed inflammation, and the patient was discharged with close outpatient follow-up. Two repeat skin biopsies from the peripheral margin at the time of the outpatient follow-up confirmed an invasive, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (Figure), consistent with a Marjolin ulcer. Radiography demonstrated multiple left iliac chain and inguinal lymphadenopathies with extensive subcutaneous disease overlying the left medial tibia. After tumor board discussion, surgery was not recommended due to the size and likely penetration into the muscle. The patient began treatment with cemiplimab-rwlc, a PD-1 inhibitor. Within 4 cycles of treatment, he had improved pain and ambulation, and a 3-month follow-up positron emission tomography scan revealed decreased lymph node and cutaneous metabolic activity as well as clinical improvement.

Marjolin ulcers are rare and aggressive squamous cell carcinomas that arise from chronic wounds such as burn scars or pressure ulcers.1 Although an underlying well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma is the most common etiology, patients also may present with underlying basal cell carcinomas, melanomas, or angiosarcomas.2 The exact pathogenesis underlying the malignant degeneration is unclear but appears to be driven by chronic inflammation. Patients classically present with a nonhealing ulcer associated with raised, friable, or crusty borders, as well as surrounding scar tissue. There is a median latency of 30 years after the trauma, though acute transformation within 12 months of an injury is possible.3 The diagnosis is confirmed with a peripheral wound biopsy. Surgical excision with wide margins remains the most common and effective intervention, especially for localized disease.1 The addition of lymph node dissection remains controversial, but treatment decisions can be guided by radiographic staging.4

The prognosis of Marjolin ulcers remains poor, with a predicted 5-year survival rate ranging from 43% to 58%.1 Dermatologists and trainees should be aware of Marjolin ulcers, especially as a mimicker of other chronic ulcerating conditions. Among the differential diagnosis, ulcerative lichen planus is a condition that commonly affects the oral and genital regions; however, patients with erosive lichen planus may develop an increased risk for the subsequent development of squamous cell carcinoma in the region.5 Furthermore, arterial ulcers typically develop on the distal lower extremities with other signs of chronic ischemia, including absent peripheral pulses, atrophic skin, hair loss, and ankle-brachial indices less than 0.5. Conversely, a venous ulcer classically affects the medial malleolus and will have evidence of venous insufficiency, including stasis dermatitis and peripheral edema.6

- Iqbal FM, Sinha Y, Jaffe W. Marjolin’s ulcer: a rare entity with a call for early diagnosis [published online July 15, 2015]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-208176

- Kanth AM, Heiman AJ, Nair L, et al. Current trends in management of Marjolin’s ulcer: a systematic review. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42:144-151. doi:10.1093/jbcr/iraa128

- Copcu E. Marjolin’s ulcer: a preventable complication of burns? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:E156-E164. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a8082e

- Pekarek B, Buck S, Osher L. A comprehensive review on Marjolin’s ulcers: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Coll Certif Wound Spec. 2011; 3:60-64. doi:10.1016/j.jcws.2012.04.001

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Spentzouris G, Labropoulos N. The evaluation of lower-extremity ulcers. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2009;26:286-295. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1242204

The Diagnosis: Marjolin Ulcer

A skin biopsy during his prior hospital admission demonstrated an ulcer with granulation tissue and mixed inflammation, and the patient was discharged with close outpatient follow-up. Two repeat skin biopsies from the peripheral margin at the time of the outpatient follow-up confirmed an invasive, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (Figure), consistent with a Marjolin ulcer. Radiography demonstrated multiple left iliac chain and inguinal lymphadenopathies with extensive subcutaneous disease overlying the left medial tibia. After tumor board discussion, surgery was not recommended due to the size and likely penetration into the muscle. The patient began treatment with cemiplimab-rwlc, a PD-1 inhibitor. Within 4 cycles of treatment, he had improved pain and ambulation, and a 3-month follow-up positron emission tomography scan revealed decreased lymph node and cutaneous metabolic activity as well as clinical improvement.

Marjolin ulcers are rare and aggressive squamous cell carcinomas that arise from chronic wounds such as burn scars or pressure ulcers.1 Although an underlying well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma is the most common etiology, patients also may present with underlying basal cell carcinomas, melanomas, or angiosarcomas.2 The exact pathogenesis underlying the malignant degeneration is unclear but appears to be driven by chronic inflammation. Patients classically present with a nonhealing ulcer associated with raised, friable, or crusty borders, as well as surrounding scar tissue. There is a median latency of 30 years after the trauma, though acute transformation within 12 months of an injury is possible.3 The diagnosis is confirmed with a peripheral wound biopsy. Surgical excision with wide margins remains the most common and effective intervention, especially for localized disease.1 The addition of lymph node dissection remains controversial, but treatment decisions can be guided by radiographic staging.4

The prognosis of Marjolin ulcers remains poor, with a predicted 5-year survival rate ranging from 43% to 58%.1 Dermatologists and trainees should be aware of Marjolin ulcers, especially as a mimicker of other chronic ulcerating conditions. Among the differential diagnosis, ulcerative lichen planus is a condition that commonly affects the oral and genital regions; however, patients with erosive lichen planus may develop an increased risk for the subsequent development of squamous cell carcinoma in the region.5 Furthermore, arterial ulcers typically develop on the distal lower extremities with other signs of chronic ischemia, including absent peripheral pulses, atrophic skin, hair loss, and ankle-brachial indices less than 0.5. Conversely, a venous ulcer classically affects the medial malleolus and will have evidence of venous insufficiency, including stasis dermatitis and peripheral edema.6

The Diagnosis: Marjolin Ulcer

A skin biopsy during his prior hospital admission demonstrated an ulcer with granulation tissue and mixed inflammation, and the patient was discharged with close outpatient follow-up. Two repeat skin biopsies from the peripheral margin at the time of the outpatient follow-up confirmed an invasive, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (Figure), consistent with a Marjolin ulcer. Radiography demonstrated multiple left iliac chain and inguinal lymphadenopathies with extensive subcutaneous disease overlying the left medial tibia. After tumor board discussion, surgery was not recommended due to the size and likely penetration into the muscle. The patient began treatment with cemiplimab-rwlc, a PD-1 inhibitor. Within 4 cycles of treatment, he had improved pain and ambulation, and a 3-month follow-up positron emission tomography scan revealed decreased lymph node and cutaneous metabolic activity as well as clinical improvement.

Marjolin ulcers are rare and aggressive squamous cell carcinomas that arise from chronic wounds such as burn scars or pressure ulcers.1 Although an underlying well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma is the most common etiology, patients also may present with underlying basal cell carcinomas, melanomas, or angiosarcomas.2 The exact pathogenesis underlying the malignant degeneration is unclear but appears to be driven by chronic inflammation. Patients classically present with a nonhealing ulcer associated with raised, friable, or crusty borders, as well as surrounding scar tissue. There is a median latency of 30 years after the trauma, though acute transformation within 12 months of an injury is possible.3 The diagnosis is confirmed with a peripheral wound biopsy. Surgical excision with wide margins remains the most common and effective intervention, especially for localized disease.1 The addition of lymph node dissection remains controversial, but treatment decisions can be guided by radiographic staging.4

The prognosis of Marjolin ulcers remains poor, with a predicted 5-year survival rate ranging from 43% to 58%.1 Dermatologists and trainees should be aware of Marjolin ulcers, especially as a mimicker of other chronic ulcerating conditions. Among the differential diagnosis, ulcerative lichen planus is a condition that commonly affects the oral and genital regions; however, patients with erosive lichen planus may develop an increased risk for the subsequent development of squamous cell carcinoma in the region.5 Furthermore, arterial ulcers typically develop on the distal lower extremities with other signs of chronic ischemia, including absent peripheral pulses, atrophic skin, hair loss, and ankle-brachial indices less than 0.5. Conversely, a venous ulcer classically affects the medial malleolus and will have evidence of venous insufficiency, including stasis dermatitis and peripheral edema.6

- Iqbal FM, Sinha Y, Jaffe W. Marjolin’s ulcer: a rare entity with a call for early diagnosis [published online July 15, 2015]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-208176

- Kanth AM, Heiman AJ, Nair L, et al. Current trends in management of Marjolin’s ulcer: a systematic review. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42:144-151. doi:10.1093/jbcr/iraa128

- Copcu E. Marjolin’s ulcer: a preventable complication of burns? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:E156-E164. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a8082e

- Pekarek B, Buck S, Osher L. A comprehensive review on Marjolin’s ulcers: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Coll Certif Wound Spec. 2011; 3:60-64. doi:10.1016/j.jcws.2012.04.001

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Spentzouris G, Labropoulos N. The evaluation of lower-extremity ulcers. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2009;26:286-295. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1242204

- Iqbal FM, Sinha Y, Jaffe W. Marjolin’s ulcer: a rare entity with a call for early diagnosis [published online July 15, 2015]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-208176

- Kanth AM, Heiman AJ, Nair L, et al. Current trends in management of Marjolin’s ulcer: a systematic review. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42:144-151. doi:10.1093/jbcr/iraa128

- Copcu E. Marjolin’s ulcer: a preventable complication of burns? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:E156-E164. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a8082e

- Pekarek B, Buck S, Osher L. A comprehensive review on Marjolin’s ulcers: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Coll Certif Wound Spec. 2011; 3:60-64. doi:10.1016/j.jcws.2012.04.001

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Spentzouris G, Labropoulos N. The evaluation of lower-extremity ulcers. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2009;26:286-295. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1242204

A 46-year-old man with a history of a left leg burn during childhood that was unsuccessfully treated with multiple skin grafts presented as a hospital follow-up for outpatient management of an ulcer. The patient had an ulcer that gradually increased in size over 7 years. Over the course of 2 weeks prior to the hospital presentation, he noted increased pain and severe difficulty with ambulation but remained afebrile without other systemic symptoms. Prior to the outpatient follow-up, he had been admitted to the hospital where he underwent imaging, laboratory studies, and skin biopsy, as well as treatment with empiric vancomycin. Physical examination revealed a large undermined ulcer with an elevated peripheral margin and crusting on the left lower leg with surrounding chronic scarring.

Exophytic Firm Papulonodule on the Labia in a Patient With Nonspecific Gastrointestinal Symptoms

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

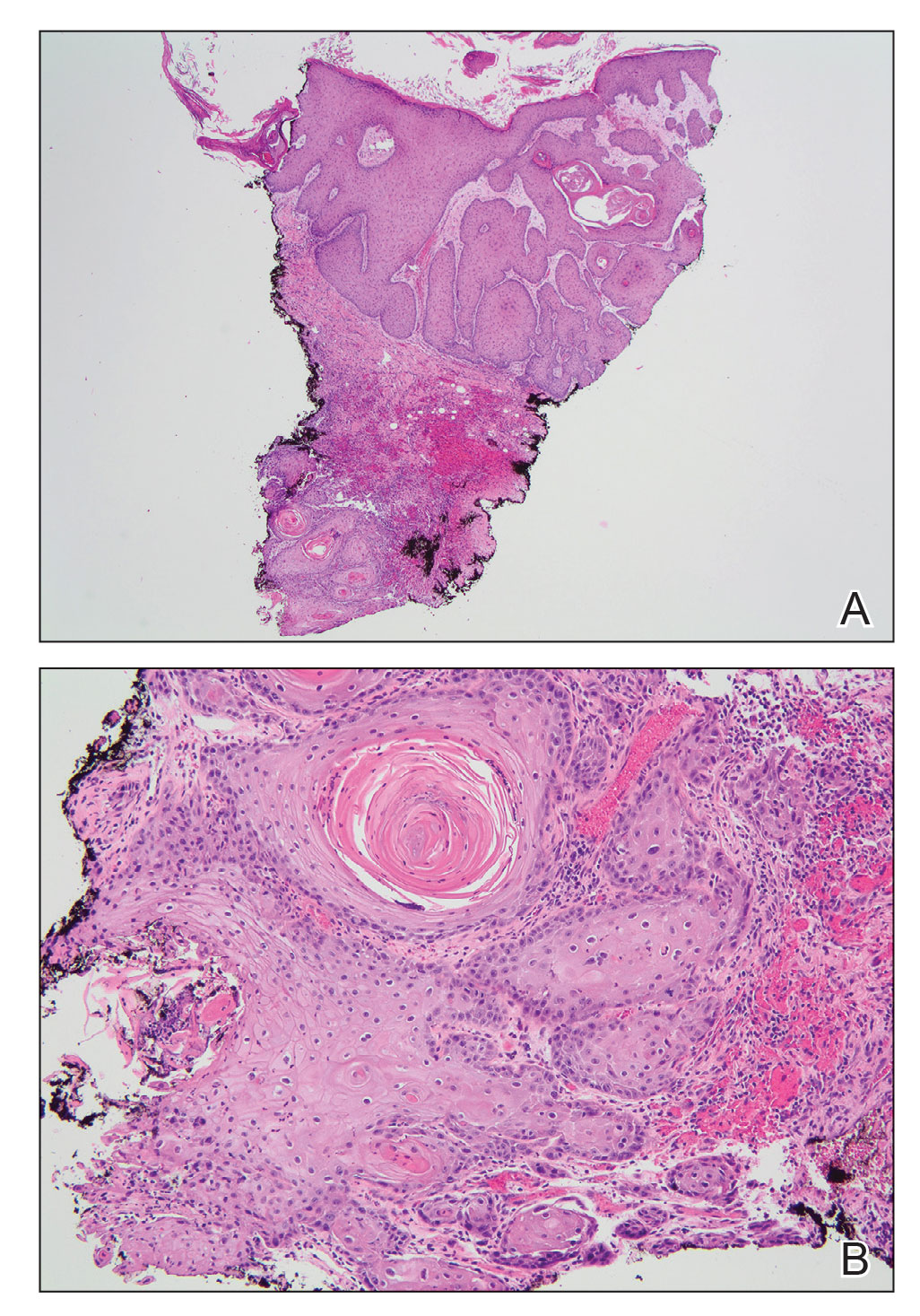

Kinyoun and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining of the labial biopsy were negative for mycobacteria and fungi, respectively. A complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, celiac disease serologies, stool occult blood, and stool calprotectin laboratory test results were within reference range. Magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis demonstrated an anal fissure extending from the anal verge at the 6 o’clock position, abnormal T2 bright signal in the skin of the buttocks and perineum extending to the labia, and mild mucosal enhancement of the rectal and anal mucosa. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and magnetic resonance elastography were unremarkable. Colonoscopy demonstrated scattered superficial erythematous patches and erosions in the rectum. Histologically, there was mild to moderately active colitis in the rectum with no evidence of chronicity. Given our patient’s labial edema and exophytic papulonodule (Figure 1) in the setting of nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and granulomatous dermatitis seen on pathology (Figure 2), she was diagnosed with cutaneous Crohn disease (CD).

In our patient, labial biopsy was necessary to definitively diagnose CD. Prior to biopsy of the lesion, our patient was diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation leading to an anal fissure and skin tag due to lack of laboratory, imaging, and colonoscopy findings commonly associated with CD. Her biopsy results and gastrointestinal symptoms made these diagnoses, as well as condyloma or a large sentinel skin tag, less likely.

Extraintestinal findings of CD, especially cutaneous manifestations, are relatively frequent and may be present in as many as 44% of patients.1,2 Cutaneous CD often is characterized based on pathogenic mechanisms as either reactive, associated, or CD specific. Reactive cutaneous manifestations include erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, and oral aphthae. Associated cutaneous manifestations include vitiligo, palmar erythema, and palmoplantar pustulosis.2 Crohn disease–specific manifestations, including genital or extragenital metastatic CD (MCD), fistulas, and oral involvement, are granulomatous in nature, similar to intestinal CD. Genital manifestations of MCD include edema, erythema, fissures, and/or ulceration of the vulva, penis, or scrotum. Labial swelling is the most common presenting symptom of MCD in females in both pediatric and adult age groups.2 Lymphedema, skin tags, and condylomalike growths also can be seen but are relatively less common.2

Given the labial edema, exophytic papulonodule, and granulomatous dermatitis seen on histopathology, our patient likely fit into the MCD category.2 In adults, most instances of MCD arise in the setting of well-established intestinal CD disease,3 whereas in children 86% of cases occur in patients without concurrent intestinal CD.2

Given the nonspecific and variable presentation of MCD, the differential diagnosis is broad. The differential diagnosis could include infectious etiologies such as condyloma acuminatum (human papillomavirus); syphilitic chancre; or mycobacterial, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic vulvovaginitis. Sexual abuse, sarcoidosis, Behçet disease, or hidradenitis suppurativa, among other diagnoses, also should be considered. Diagnostic workup should include biopsy of the lesion with special stains, polarizing microscopy, and tissue cultures.4 A thorough evaluation for gastrointestinal CD should be completed after diagnosis.3

The clinical course of vulvar CD can be unpredictable, with some cases healing spontaneously but most persisting despite treatment and sometimes prompting surgical removal.2,4 Early recognition is crucial, as long-standing MCD lesions can be therapy resistant.5 Due to the rarity of the condition and lack of data, there is a lack of treatment consensus for MCD. In 2014, the American Academy of Dermatology published treatment guidelines recommending superpotent topical steroids or topical tacrolimus as first-line therapy. Next-line therapy includes oral metronidazole, followed by prednisolone if still symptomatic.3 Treatment-resistant disease can warrant treatment with immunomodulators or tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors. Our patient was started on adalimumab; after just 2 months of therapy, the labial swelling decreased and the exophytic nodule was less firm and smaller.

Metastatic CD is a rare manifestation of cutaneous CD and can be present in the absence of gastrointestinal disease.3 This case demonstrates the importance of recognizing the cutaneous signs of CD and the necessity of lesional biopsy for the diagnosis of MCD, as our patient presented with nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and a diagnostic workup, including endoscopies, that proved inconclusive for the diagnosis of CD.

- Antonelli E, Bassotti G, Tramontana M, et al. Dermatological manifestations in inflammatory bowel diseases. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1-16. doi:10.3390/JCM10020364

- Schneider SL, Foster K, Patel D, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of metastatic Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:566-574. doi:10.1111/PDE.13565

- Kurtzman DJB, Jones T, Lian F, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a review and approach to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:804-813. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2014.04.002

- Barret M, De Parades V, Battistella M, et al. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:563-570. doi:10.1016/J.CROHNS.2013.10.009

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder [published online January 3, 2017]. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150. doi:10.1155/2017/8192150

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

Kinyoun and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining of the labial biopsy were negative for mycobacteria and fungi, respectively. A complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, celiac disease serologies, stool occult blood, and stool calprotectin laboratory test results were within reference range. Magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis demonstrated an anal fissure extending from the anal verge at the 6 o’clock position, abnormal T2 bright signal in the skin of the buttocks and perineum extending to the labia, and mild mucosal enhancement of the rectal and anal mucosa. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and magnetic resonance elastography were unremarkable. Colonoscopy demonstrated scattered superficial erythematous patches and erosions in the rectum. Histologically, there was mild to moderately active colitis in the rectum with no evidence of chronicity. Given our patient’s labial edema and exophytic papulonodule (Figure 1) in the setting of nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and granulomatous dermatitis seen on pathology (Figure 2), she was diagnosed with cutaneous Crohn disease (CD).

In our patient, labial biopsy was necessary to definitively diagnose CD. Prior to biopsy of the lesion, our patient was diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation leading to an anal fissure and skin tag due to lack of laboratory, imaging, and colonoscopy findings commonly associated with CD. Her biopsy results and gastrointestinal symptoms made these diagnoses, as well as condyloma or a large sentinel skin tag, less likely.

Extraintestinal findings of CD, especially cutaneous manifestations, are relatively frequent and may be present in as many as 44% of patients.1,2 Cutaneous CD often is characterized based on pathogenic mechanisms as either reactive, associated, or CD specific. Reactive cutaneous manifestations include erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, and oral aphthae. Associated cutaneous manifestations include vitiligo, palmar erythema, and palmoplantar pustulosis.2 Crohn disease–specific manifestations, including genital or extragenital metastatic CD (MCD), fistulas, and oral involvement, are granulomatous in nature, similar to intestinal CD. Genital manifestations of MCD include edema, erythema, fissures, and/or ulceration of the vulva, penis, or scrotum. Labial swelling is the most common presenting symptom of MCD in females in both pediatric and adult age groups.2 Lymphedema, skin tags, and condylomalike growths also can be seen but are relatively less common.2

Given the labial edema, exophytic papulonodule, and granulomatous dermatitis seen on histopathology, our patient likely fit into the MCD category.2 In adults, most instances of MCD arise in the setting of well-established intestinal CD disease,3 whereas in children 86% of cases occur in patients without concurrent intestinal CD.2

Given the nonspecific and variable presentation of MCD, the differential diagnosis is broad. The differential diagnosis could include infectious etiologies such as condyloma acuminatum (human papillomavirus); syphilitic chancre; or mycobacterial, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic vulvovaginitis. Sexual abuse, sarcoidosis, Behçet disease, or hidradenitis suppurativa, among other diagnoses, also should be considered. Diagnostic workup should include biopsy of the lesion with special stains, polarizing microscopy, and tissue cultures.4 A thorough evaluation for gastrointestinal CD should be completed after diagnosis.3

The clinical course of vulvar CD can be unpredictable, with some cases healing spontaneously but most persisting despite treatment and sometimes prompting surgical removal.2,4 Early recognition is crucial, as long-standing MCD lesions can be therapy resistant.5 Due to the rarity of the condition and lack of data, there is a lack of treatment consensus for MCD. In 2014, the American Academy of Dermatology published treatment guidelines recommending superpotent topical steroids or topical tacrolimus as first-line therapy. Next-line therapy includes oral metronidazole, followed by prednisolone if still symptomatic.3 Treatment-resistant disease can warrant treatment with immunomodulators or tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors. Our patient was started on adalimumab; after just 2 months of therapy, the labial swelling decreased and the exophytic nodule was less firm and smaller.

Metastatic CD is a rare manifestation of cutaneous CD and can be present in the absence of gastrointestinal disease.3 This case demonstrates the importance of recognizing the cutaneous signs of CD and the necessity of lesional biopsy for the diagnosis of MCD, as our patient presented with nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and a diagnostic workup, including endoscopies, that proved inconclusive for the diagnosis of CD.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

Kinyoun and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining of the labial biopsy were negative for mycobacteria and fungi, respectively. A complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, celiac disease serologies, stool occult blood, and stool calprotectin laboratory test results were within reference range. Magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis demonstrated an anal fissure extending from the anal verge at the 6 o’clock position, abnormal T2 bright signal in the skin of the buttocks and perineum extending to the labia, and mild mucosal enhancement of the rectal and anal mucosa. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and magnetic resonance elastography were unremarkable. Colonoscopy demonstrated scattered superficial erythematous patches and erosions in the rectum. Histologically, there was mild to moderately active colitis in the rectum with no evidence of chronicity. Given our patient’s labial edema and exophytic papulonodule (Figure 1) in the setting of nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and granulomatous dermatitis seen on pathology (Figure 2), she was diagnosed with cutaneous Crohn disease (CD).