User login

Painful Nodules With a Crawling Sensation

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Furuncular Myiasis

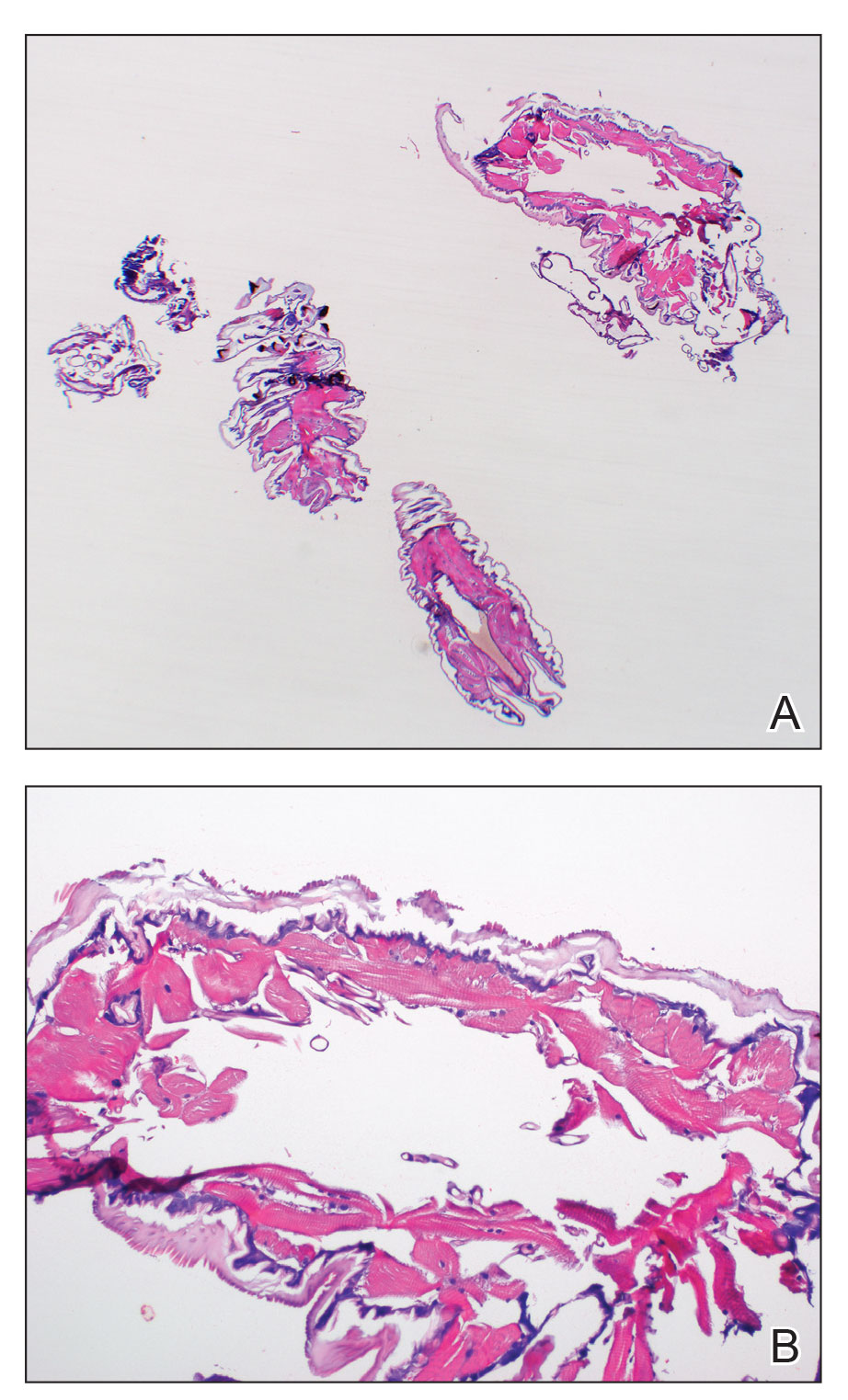

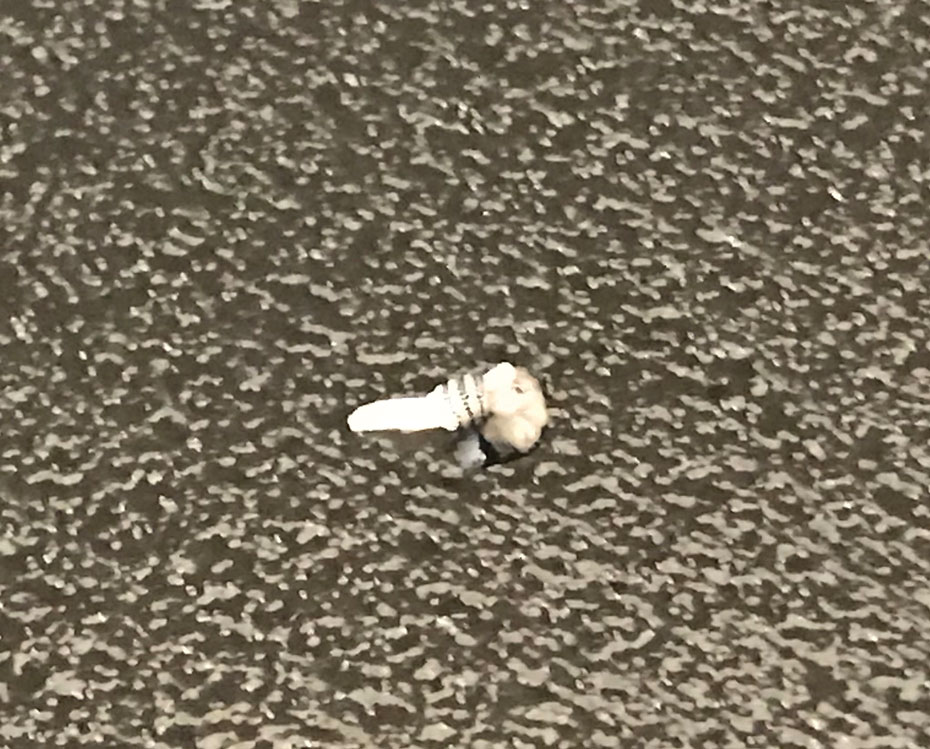

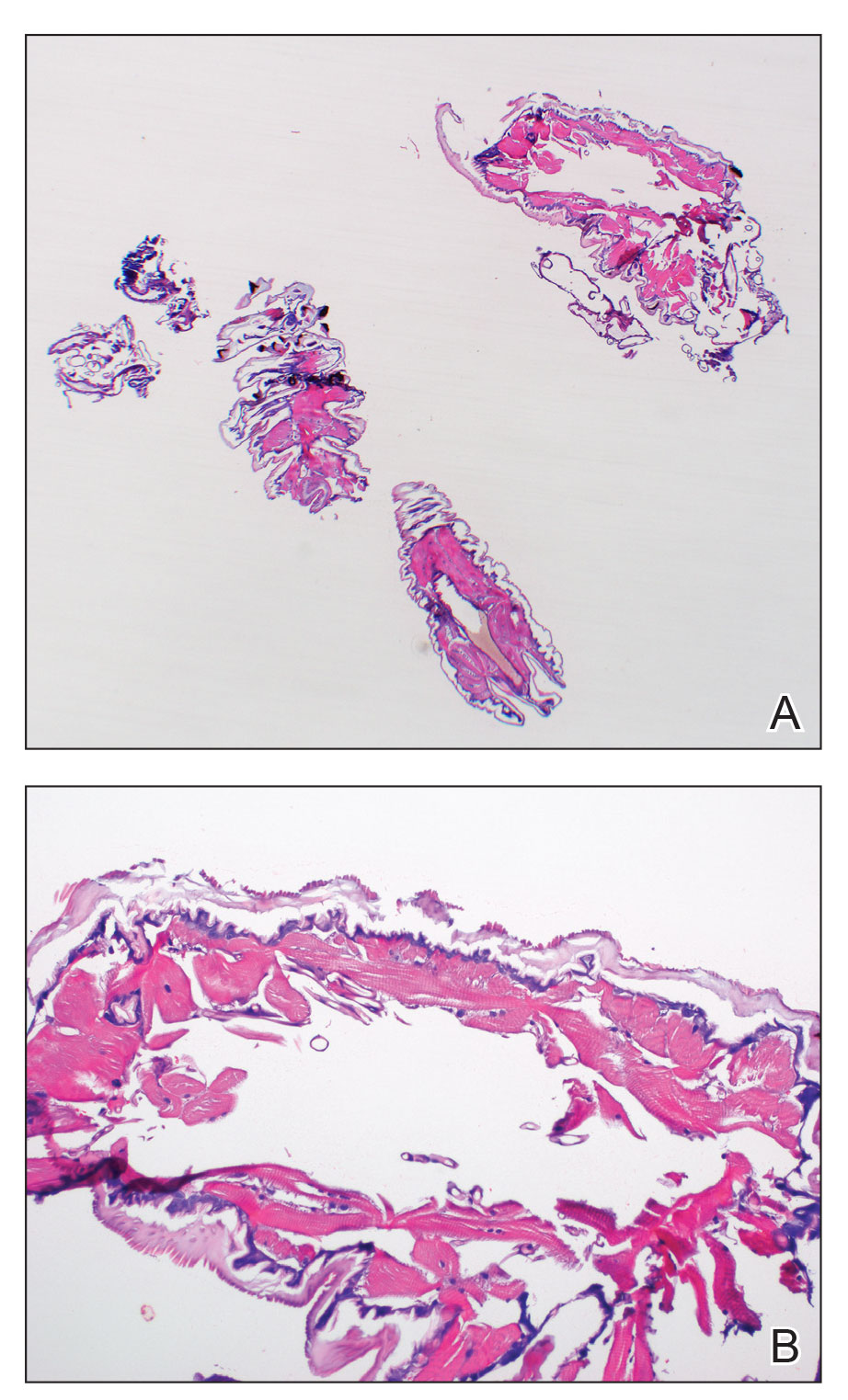

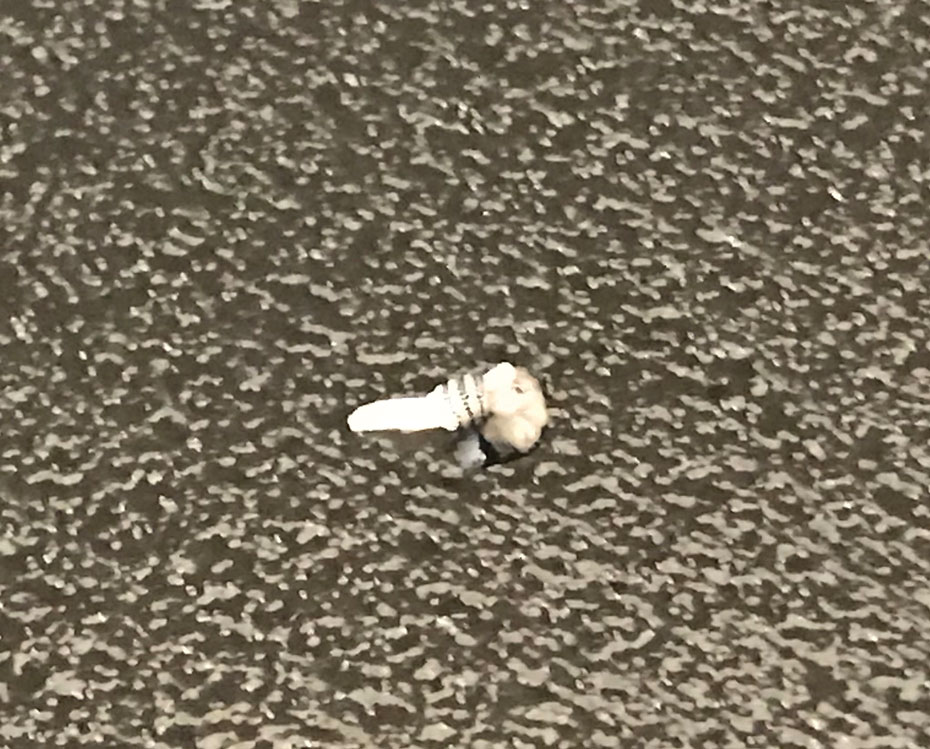

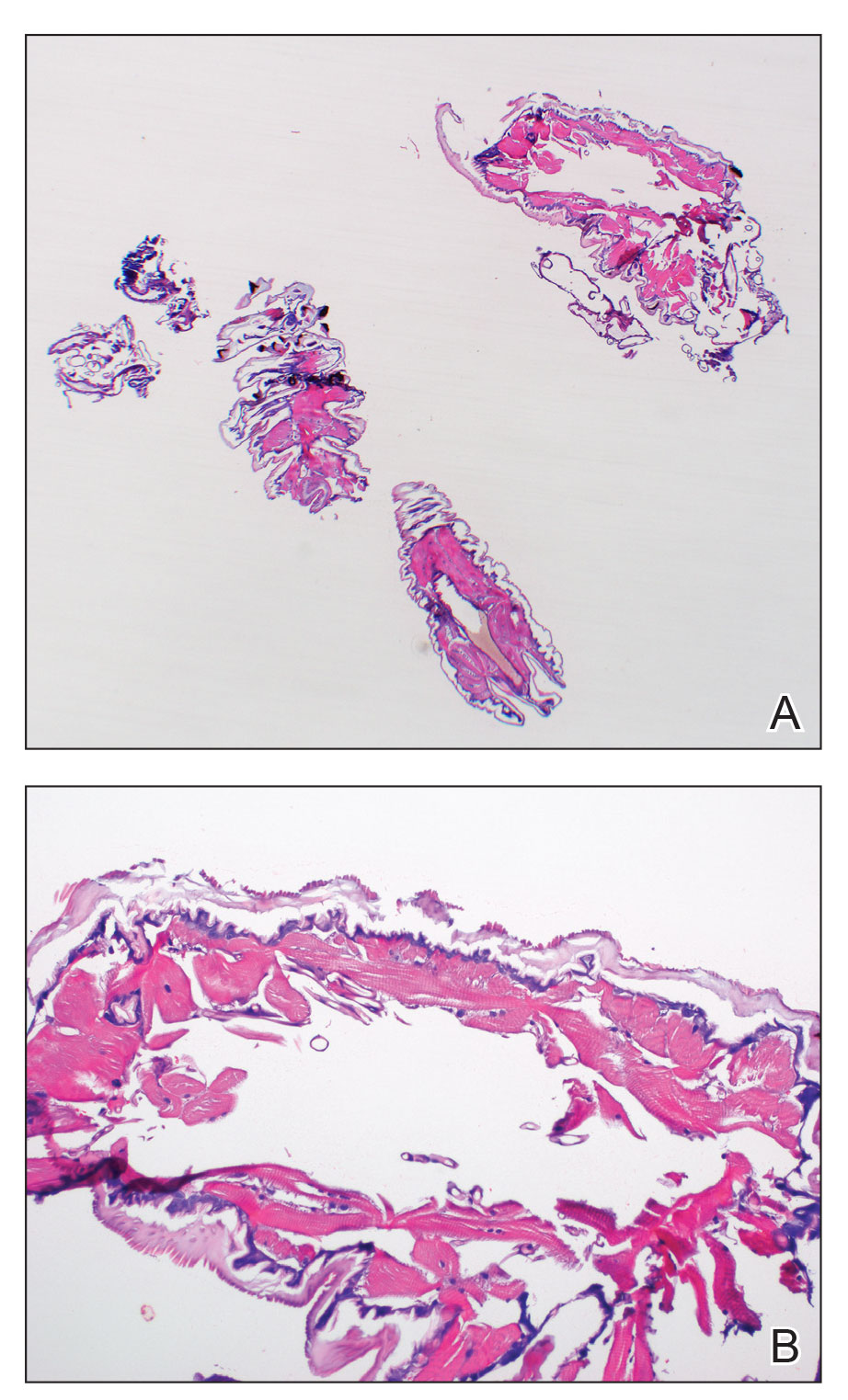

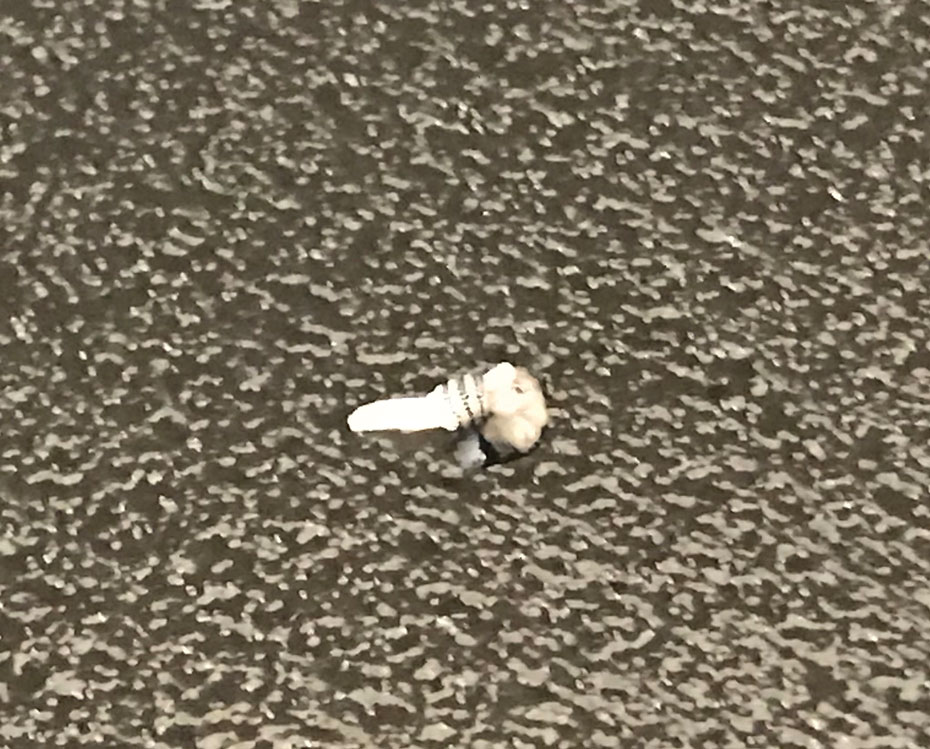

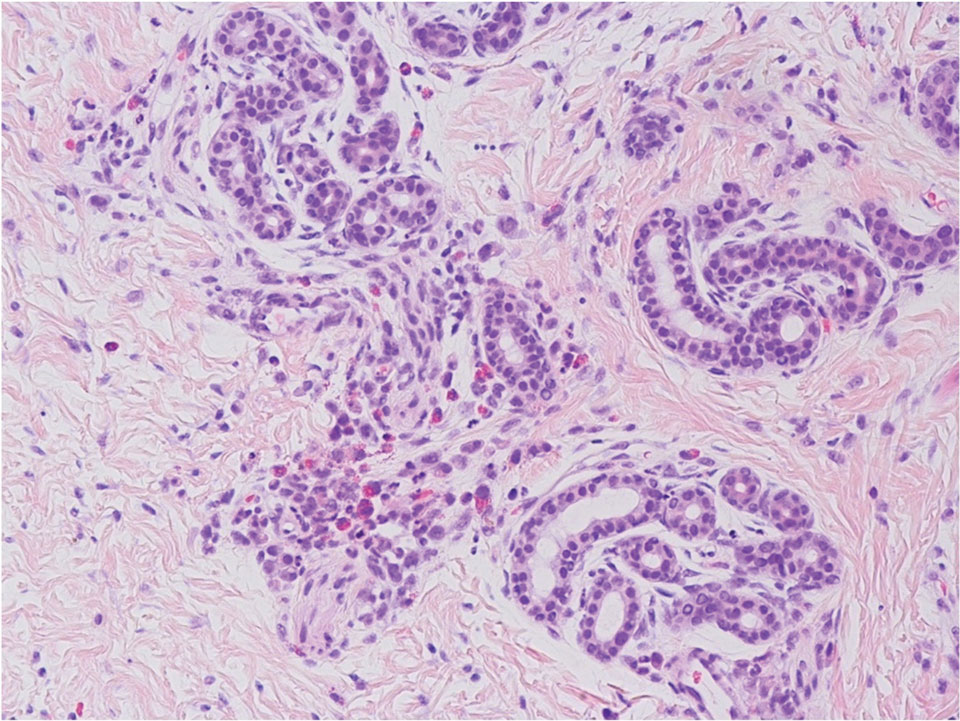

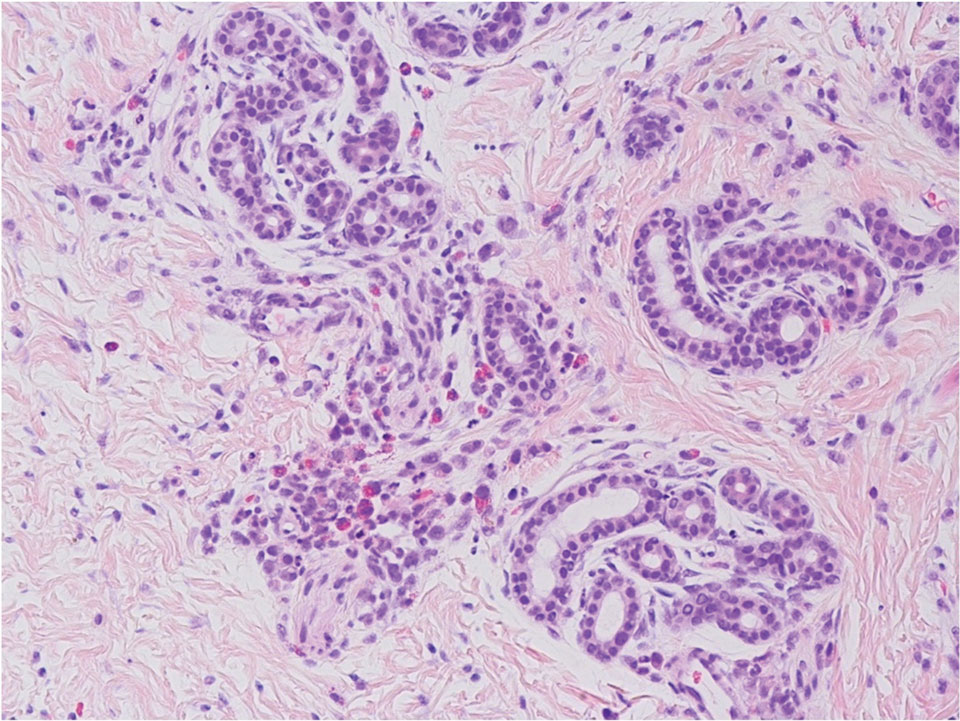

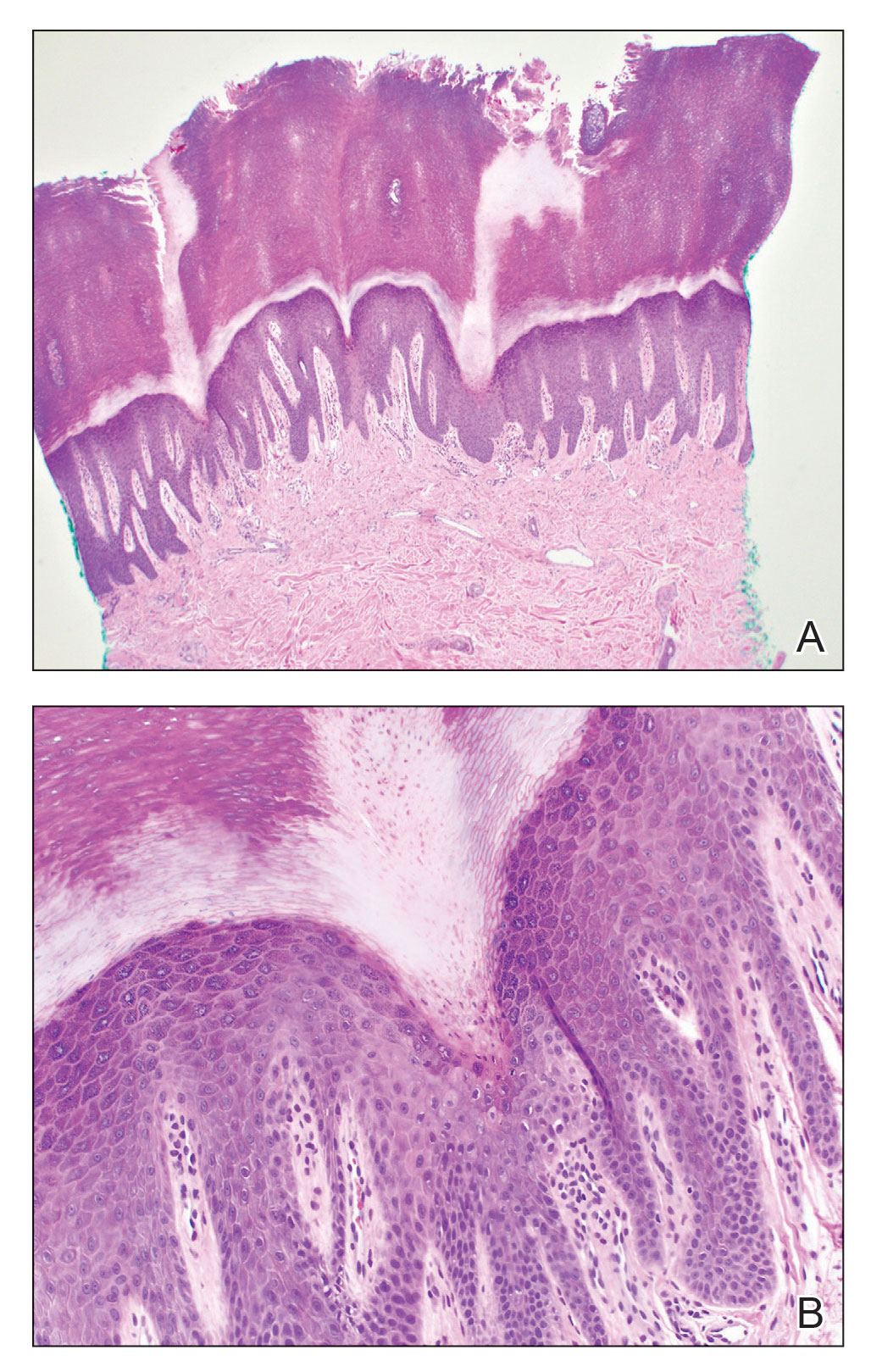

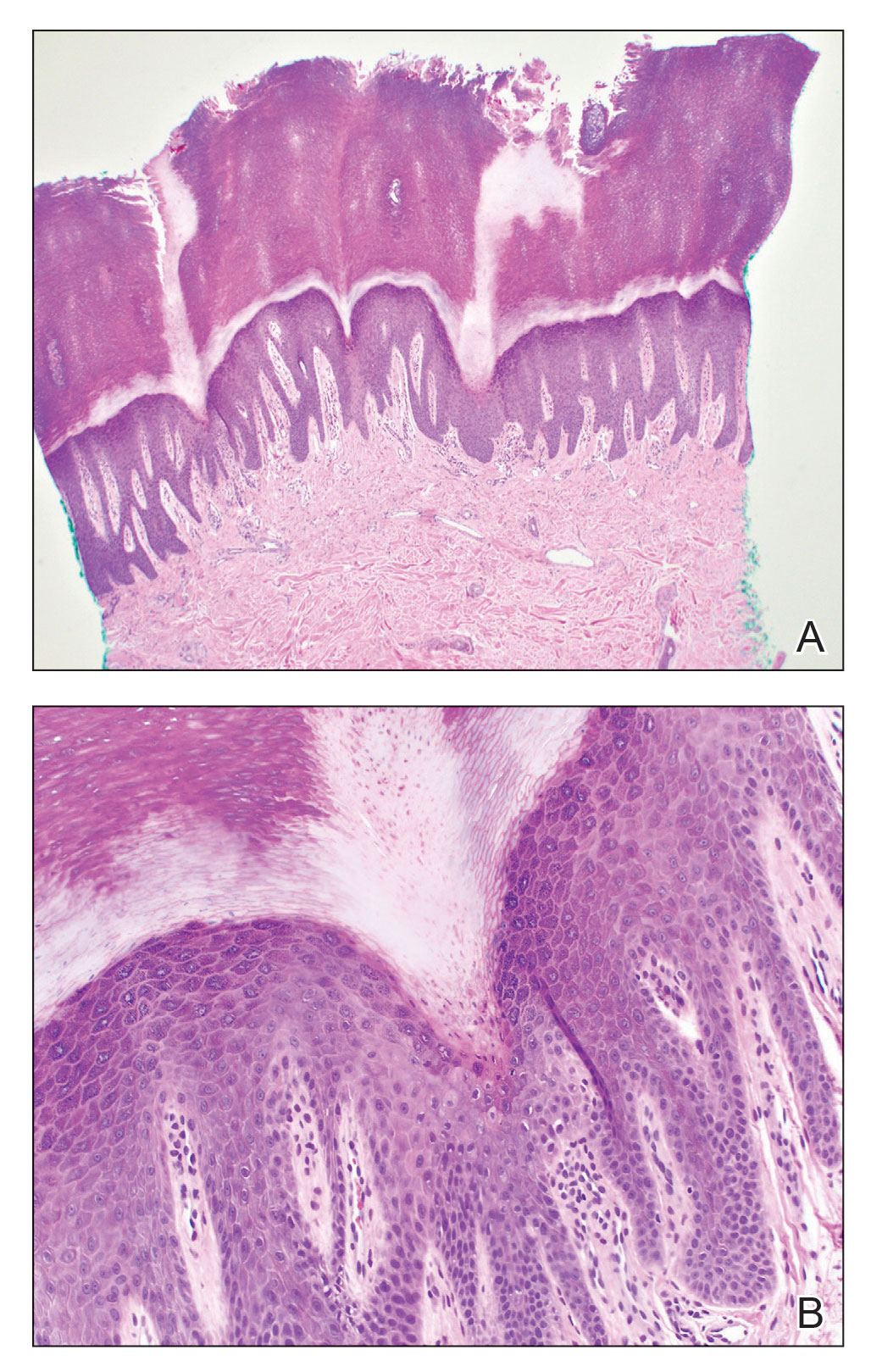

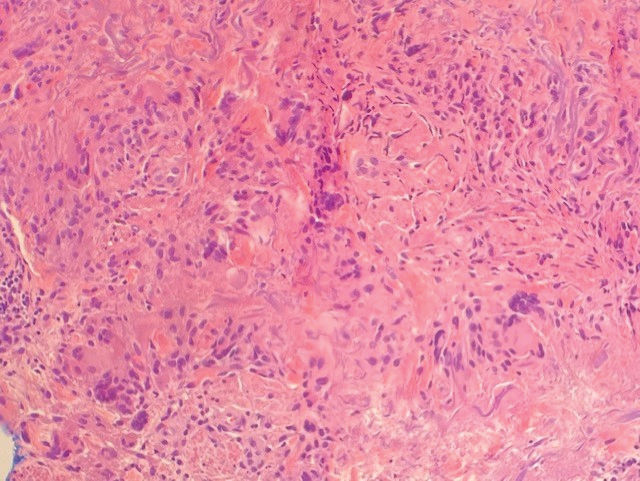

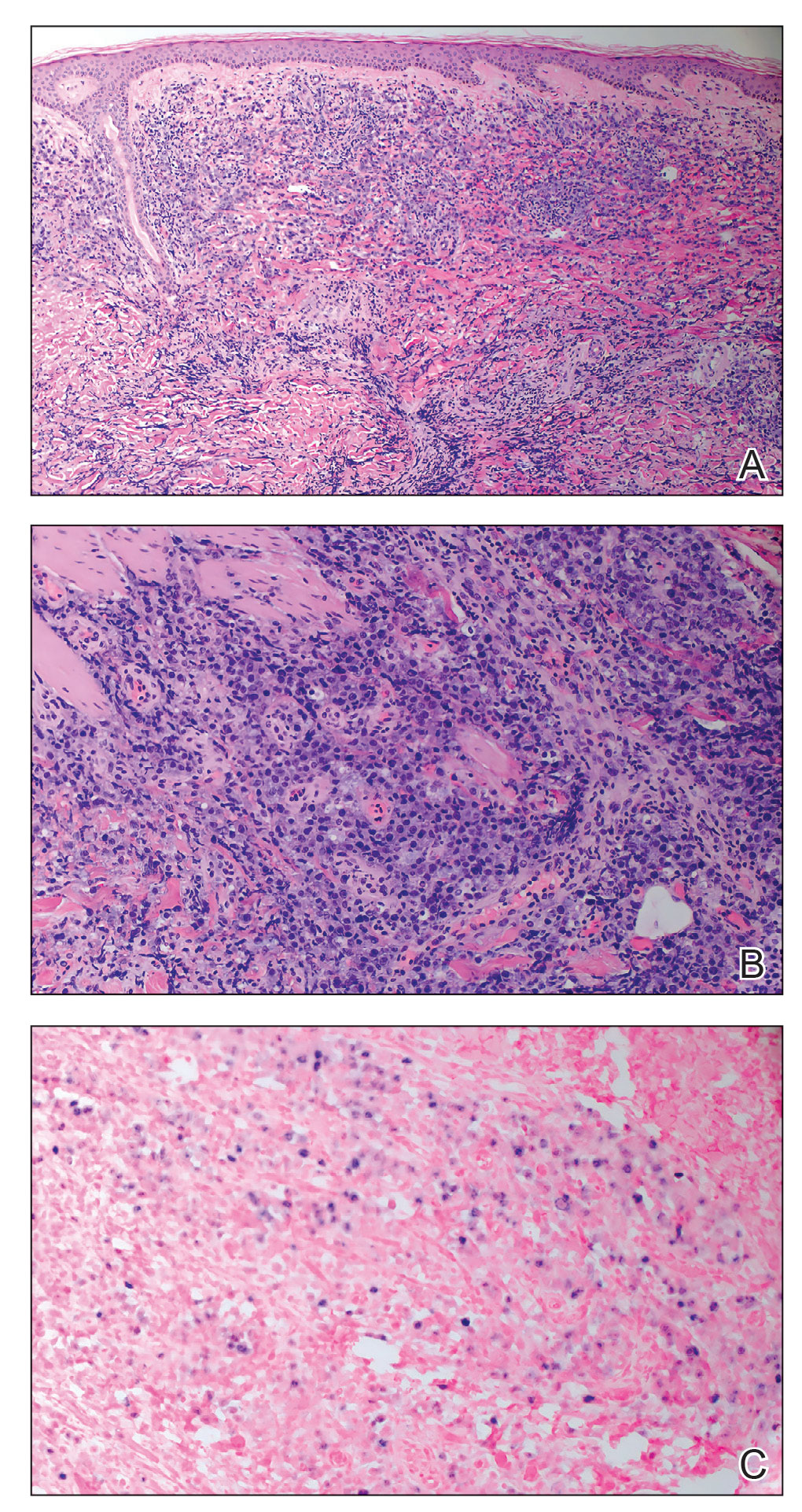

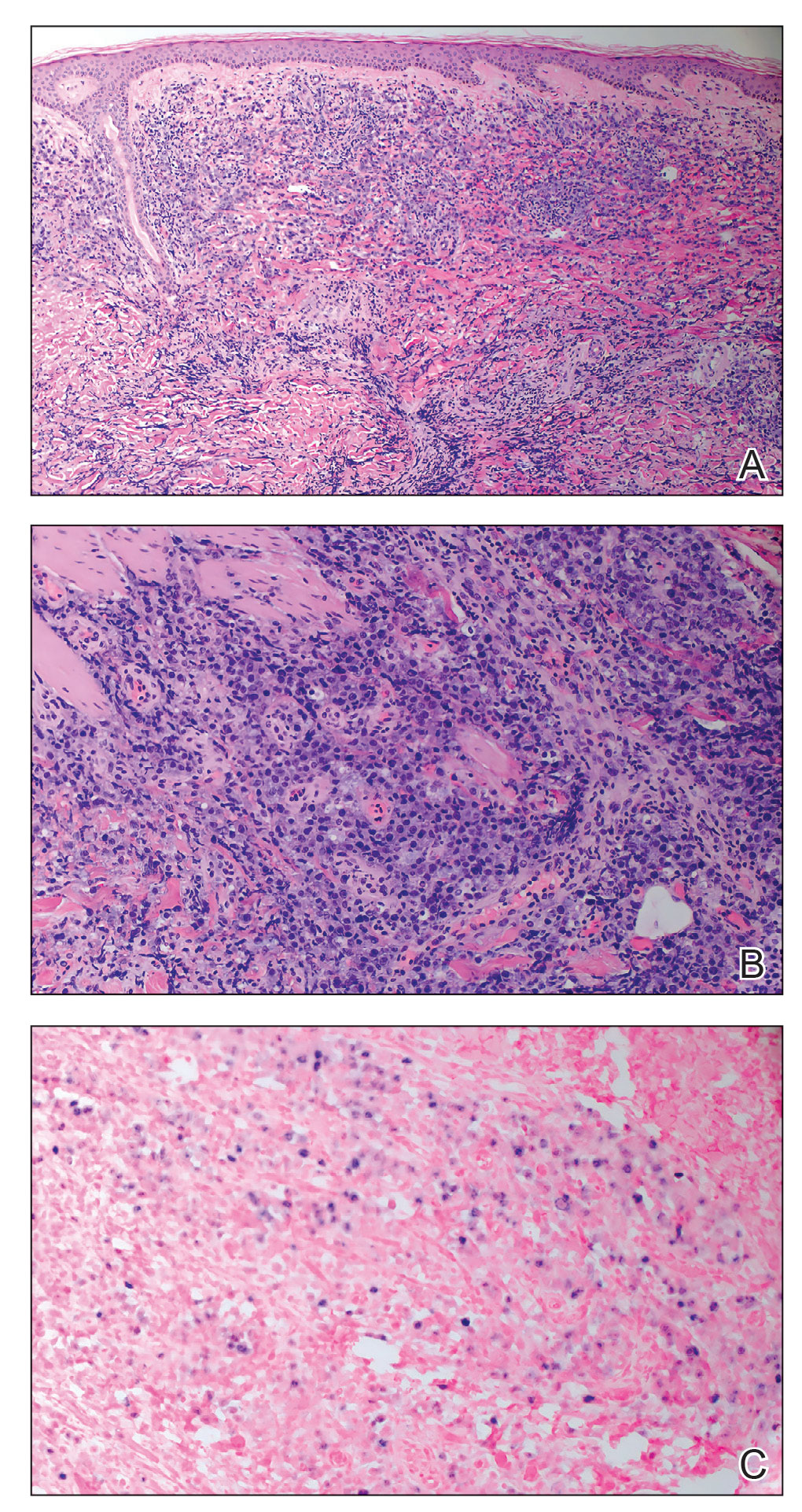

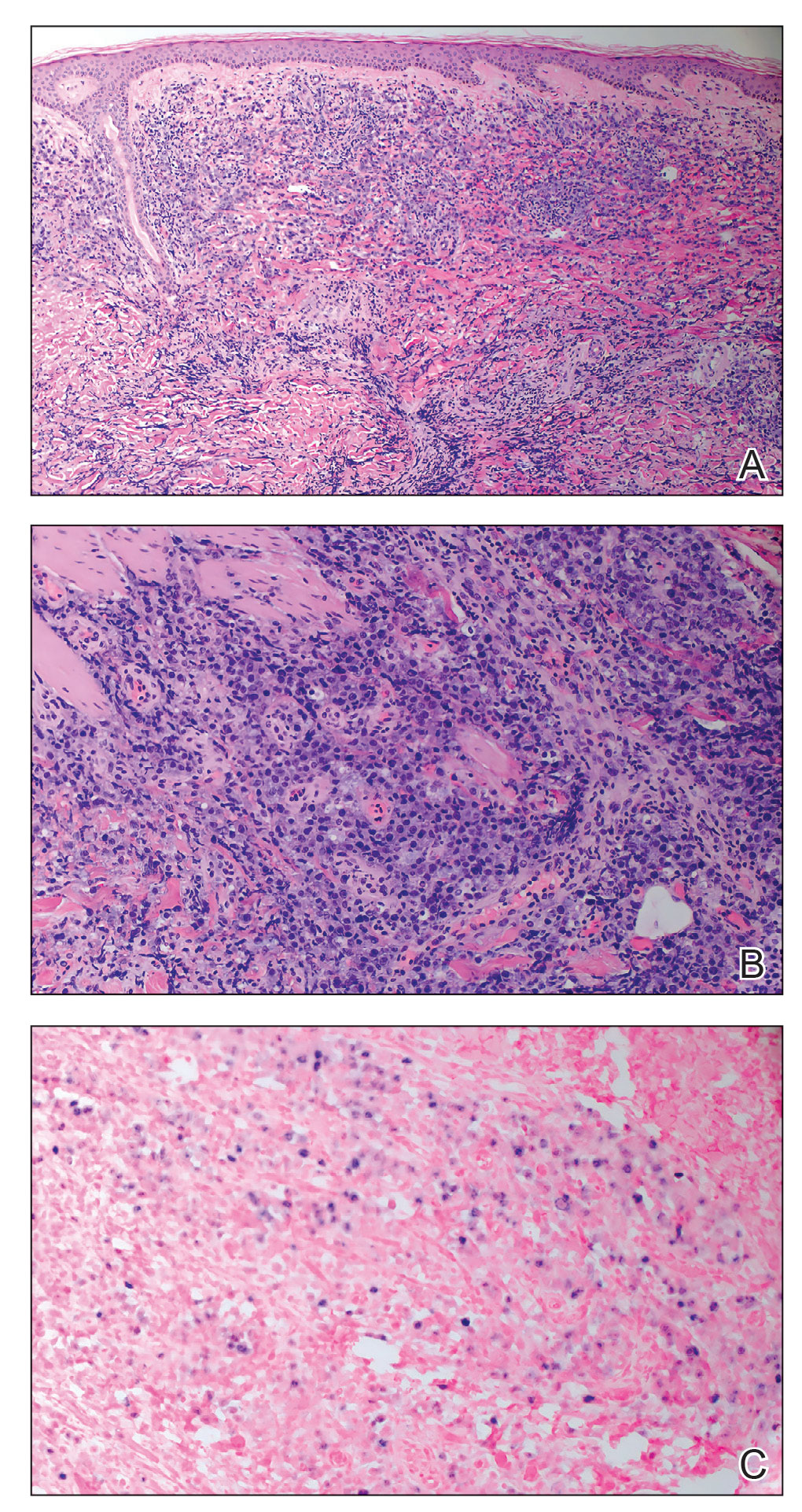

Histopathology of the punch biopsy showed an undulating chitinous exoskeleton and pigmented spines (setae) protruding from the exoskeleton with associated superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrates on hematoxylin and eosin stain (Figure 1). Live insect larvae were observed and extracted, which immediately relieved the crawling sensation (Figure 2). Light microscopy of the larva showed a row of hooks surrounding a tapered body with a head attached anteriorly (Figure 3).

Myiasis is a parasitic infestation of the dipterous fly’s larvae in the host organ and tissue. There are 5 types of myiasis based on the location of the infestation: wound myiasis occurs with egg infestations on an open wound; furuncular myiasis results from egg placement by penetration of healthy skin by a mosquito vector; plaque myiasis comprises the placement of eggs on clothing through several maggots and flies; creeping myiasis involves the Gasterophilus fly delivering the larva intradermally; and body cavity myiasis may develop in the orbit, nasal cavity, urogenital system, and gastrointestinal tract.1-3

Furuncular myiasis infestation occurs via a complex life cycle in which mosquitoes act as a vector and transfer the eggs to the human or animal host.1-3 Botfly larvae then penetrate the skin and reside within the subdermis to mature. Adults then emerge after 1 month to repeat the cycle.1 Dermatobia hominis and Cordylobia anthropophaga are the most common causes of furuncular myiasis.2,3 Furuncular myiasis commonly presents in travelers that are returning from tropical countries. Initially, an itching erythematous papule develops. After the larvae mature, they can appear as boil-like lesions with a small central punctum.1-3 Dermoscopy can be utilized for visualization of different larvae anatomy such as a furuncularlike lesion, spines, and posterior breathing spiracle from the central punctum.4

Our patient’s recent travel to the Amazon in Brazil, clinical history, and histopathologic findings ruled out other differential diagnoses such as cutaneous larva migrans, gnathostomiasis, loiasis, and tungiasis.

Treatment is curative with the extraction of the intact larva from the nodule. Localized skin anesthetic injection can be used to bulge the larva outward for easier extraction. A single dose of ivermectin 15 mg can treat the parasitic infestation of myiasis.1-3

- John DT, Petri WA, Markell EK, et al. Markell and Voge’s Medical Parasitology. 9th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2006.

- Caissie R, Beaulieu F, Giroux M, et al. Cutaneous myiasis: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:560-568.

- Lachish T, Marhoom E, Mumcuoglu KY, et al. Myiasis in travelers. J Travel Med. 2015;22:232-236.

- Mello C, Magalhães R. Triangular black dots in dermoscopy of furuncular myiasis. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;12:49-50.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Furuncular Myiasis

Histopathology of the punch biopsy showed an undulating chitinous exoskeleton and pigmented spines (setae) protruding from the exoskeleton with associated superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrates on hematoxylin and eosin stain (Figure 1). Live insect larvae were observed and extracted, which immediately relieved the crawling sensation (Figure 2). Light microscopy of the larva showed a row of hooks surrounding a tapered body with a head attached anteriorly (Figure 3).

Myiasis is a parasitic infestation of the dipterous fly’s larvae in the host organ and tissue. There are 5 types of myiasis based on the location of the infestation: wound myiasis occurs with egg infestations on an open wound; furuncular myiasis results from egg placement by penetration of healthy skin by a mosquito vector; plaque myiasis comprises the placement of eggs on clothing through several maggots and flies; creeping myiasis involves the Gasterophilus fly delivering the larva intradermally; and body cavity myiasis may develop in the orbit, nasal cavity, urogenital system, and gastrointestinal tract.1-3

Furuncular myiasis infestation occurs via a complex life cycle in which mosquitoes act as a vector and transfer the eggs to the human or animal host.1-3 Botfly larvae then penetrate the skin and reside within the subdermis to mature. Adults then emerge after 1 month to repeat the cycle.1 Dermatobia hominis and Cordylobia anthropophaga are the most common causes of furuncular myiasis.2,3 Furuncular myiasis commonly presents in travelers that are returning from tropical countries. Initially, an itching erythematous papule develops. After the larvae mature, they can appear as boil-like lesions with a small central punctum.1-3 Dermoscopy can be utilized for visualization of different larvae anatomy such as a furuncularlike lesion, spines, and posterior breathing spiracle from the central punctum.4

Our patient’s recent travel to the Amazon in Brazil, clinical history, and histopathologic findings ruled out other differential diagnoses such as cutaneous larva migrans, gnathostomiasis, loiasis, and tungiasis.

Treatment is curative with the extraction of the intact larva from the nodule. Localized skin anesthetic injection can be used to bulge the larva outward for easier extraction. A single dose of ivermectin 15 mg can treat the parasitic infestation of myiasis.1-3

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Furuncular Myiasis

Histopathology of the punch biopsy showed an undulating chitinous exoskeleton and pigmented spines (setae) protruding from the exoskeleton with associated superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrates on hematoxylin and eosin stain (Figure 1). Live insect larvae were observed and extracted, which immediately relieved the crawling sensation (Figure 2). Light microscopy of the larva showed a row of hooks surrounding a tapered body with a head attached anteriorly (Figure 3).

Myiasis is a parasitic infestation of the dipterous fly’s larvae in the host organ and tissue. There are 5 types of myiasis based on the location of the infestation: wound myiasis occurs with egg infestations on an open wound; furuncular myiasis results from egg placement by penetration of healthy skin by a mosquito vector; plaque myiasis comprises the placement of eggs on clothing through several maggots and flies; creeping myiasis involves the Gasterophilus fly delivering the larva intradermally; and body cavity myiasis may develop in the orbit, nasal cavity, urogenital system, and gastrointestinal tract.1-3

Furuncular myiasis infestation occurs via a complex life cycle in which mosquitoes act as a vector and transfer the eggs to the human or animal host.1-3 Botfly larvae then penetrate the skin and reside within the subdermis to mature. Adults then emerge after 1 month to repeat the cycle.1 Dermatobia hominis and Cordylobia anthropophaga are the most common causes of furuncular myiasis.2,3 Furuncular myiasis commonly presents in travelers that are returning from tropical countries. Initially, an itching erythematous papule develops. After the larvae mature, they can appear as boil-like lesions with a small central punctum.1-3 Dermoscopy can be utilized for visualization of different larvae anatomy such as a furuncularlike lesion, spines, and posterior breathing spiracle from the central punctum.4

Our patient’s recent travel to the Amazon in Brazil, clinical history, and histopathologic findings ruled out other differential diagnoses such as cutaneous larva migrans, gnathostomiasis, loiasis, and tungiasis.

Treatment is curative with the extraction of the intact larva from the nodule. Localized skin anesthetic injection can be used to bulge the larva outward for easier extraction. A single dose of ivermectin 15 mg can treat the parasitic infestation of myiasis.1-3

- John DT, Petri WA, Markell EK, et al. Markell and Voge’s Medical Parasitology. 9th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2006.

- Caissie R, Beaulieu F, Giroux M, et al. Cutaneous myiasis: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:560-568.

- Lachish T, Marhoom E, Mumcuoglu KY, et al. Myiasis in travelers. J Travel Med. 2015;22:232-236.

- Mello C, Magalhães R. Triangular black dots in dermoscopy of furuncular myiasis. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;12:49-50.

- John DT, Petri WA, Markell EK, et al. Markell and Voge’s Medical Parasitology. 9th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2006.

- Caissie R, Beaulieu F, Giroux M, et al. Cutaneous myiasis: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:560-568.

- Lachish T, Marhoom E, Mumcuoglu KY, et al. Myiasis in travelers. J Travel Med. 2015;22:232-236.

- Mello C, Magalhães R. Triangular black dots in dermoscopy of furuncular myiasis. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;12:49-50.

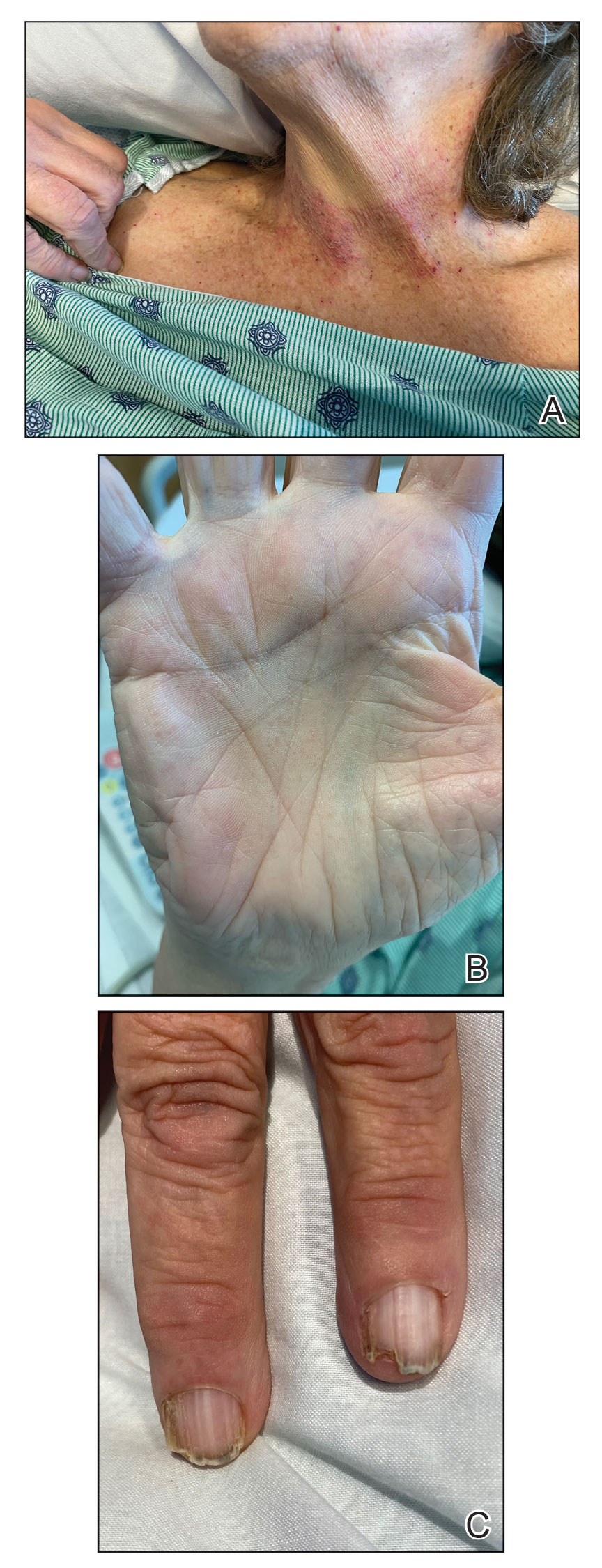

A 20-year-old man presented with progressively enlarging, painful lesions on the arm with a crawling sensation of 3 weeks’ duration. The lesions appeared after a recent trip to Brazil where he was hiking in the Amazon. He noted that the pain occurred suddenly and there was some serous drainage from the lesions. He denied any trauma to the area and reported no history of similar eruptions, treatments, or systemic symptoms. Physical examination revealed 2 tender erythematous nodules, each measuring 0.6 cm in diameter, with associated crust and a reported crawling sensation on the posterior aspect of the left arm. No drainage was seen. A punch biopsy was performed.

Scattered Red-Brown, Centrally Violaceous, Blanching Papules on an Infant

The Diagnosis: Neonatal-Onset Multisystem Inflammatory Disorder (NOMID)

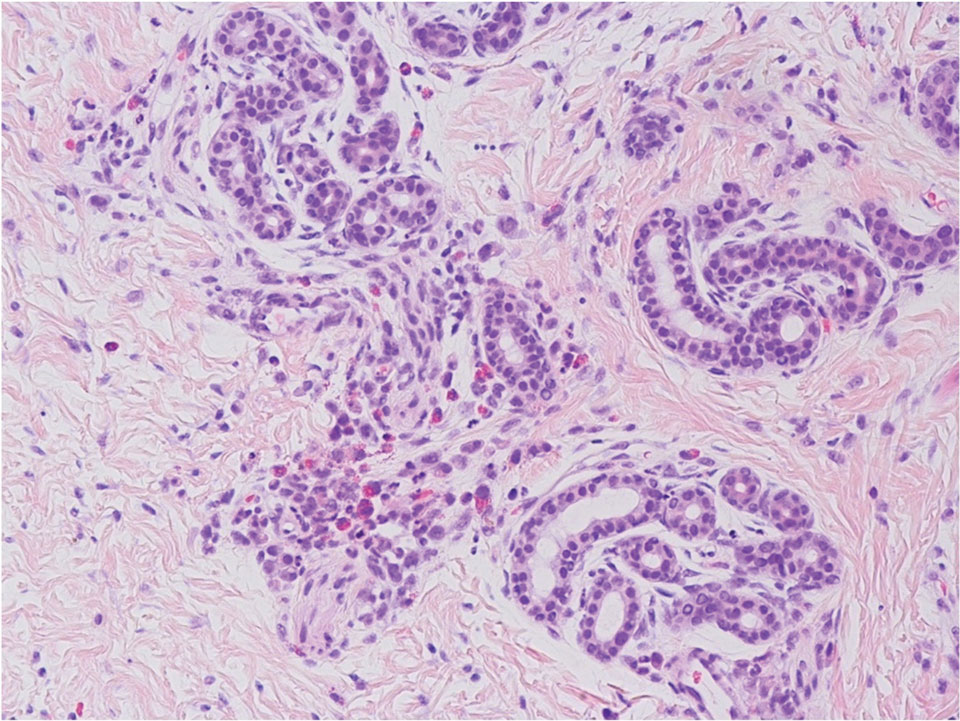

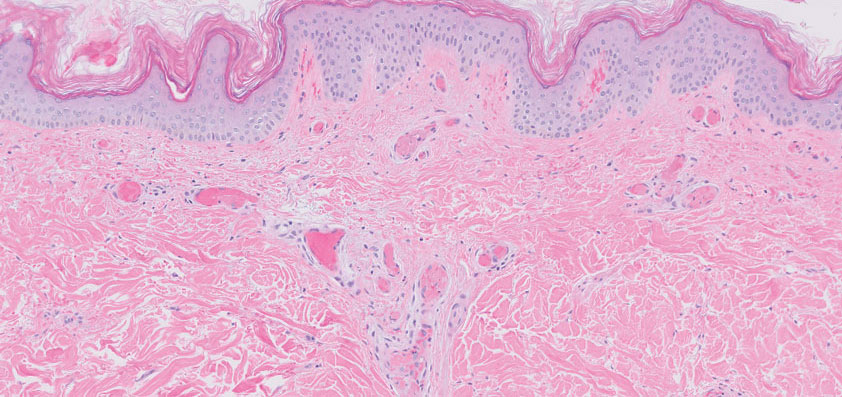

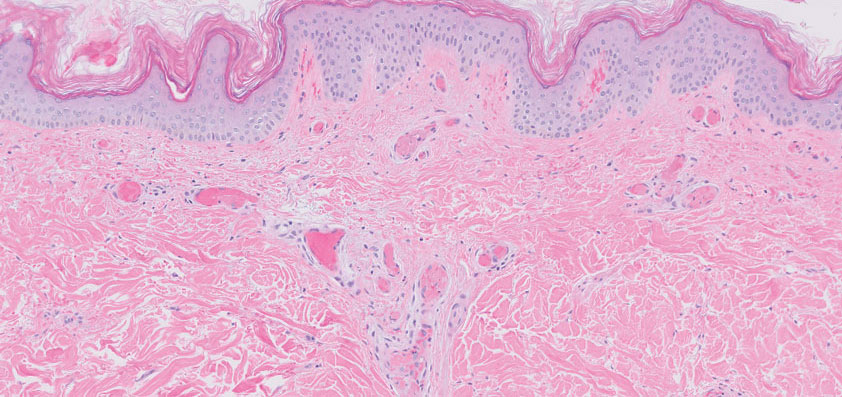

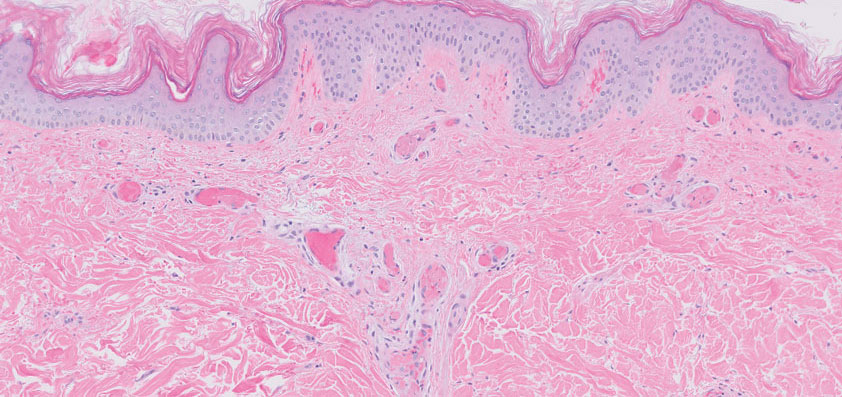

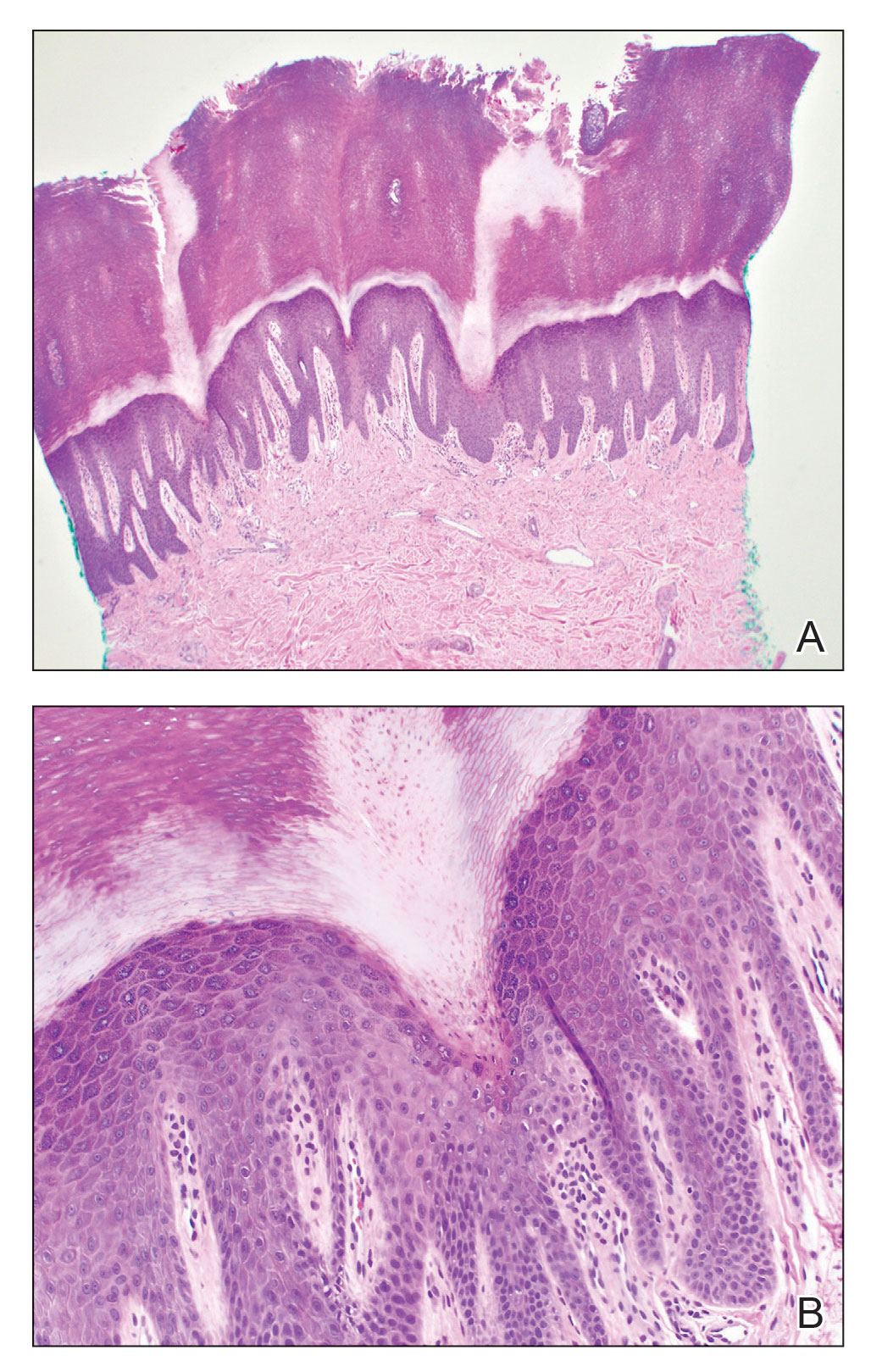

The punch biopsy demonstrated a predominantly deep but somewhat superficial, periadnexal, neutrophilic and eosinophilic infiltrate (Figure). The eruption resolved 3 days later with supportive treatment, including appropriate wound care. Genetic analysis revealed an autosomal-dominant NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 gene, NLRP3, de novo variant associated with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disorder (NOMID). Additional workup to characterize our patient’s inflammatory profile revealed elevated IL-18, CD3, CD4, S100A12, and S100A8/A9 levels. On day 48 of life, she was started on anakinra, an IL-1 inhibitor, at a dose of 1 mg/kg subcutaneously, which eventually was titrated to 10 mg/kg at hospital discharge. Hearing screenings were within normal limits.

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) consist of 3 rare, IL-1–associated, autoinflammatory disorders, including familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS), Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS), and NOMID (also known as chronic infantile neurologic cutaneous and articular syndrome). These conditions result from a sporadic or autosomal-dominant gain-of-function mutations in a single gene, NLRP3, on chromosome 1q44. NLRP3 encodes for cryopyrin, an important component of an IL-1 and IL-18 activating inflammasome.1 The most severe manifestation of CAPS is NOMID, which typically presents at birth as a migratory urticarial eruption, growth failure, myalgia, fever, and abnormal facial features, including frontal bossing, saddle-shaped nose, and protruding eyes.2 The illness also can manifest with hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, uveitis, sensorineural hearing loss, cerebral atrophy, and other neurologic manifestations.3 A diagnosis of chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature (CANDLE) syndrome was less likely given that our patient remained afebrile and did not show signs of lipodystrophy and persistent violaceous eyelid swelling. Both FCAS and MWS are less severe forms of CAPS when compared to NOMID. Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome was less likely given the absence of the typical periodic fever pattern associated with the condition and severity of our patient’s symptoms. Muckle-Wells syndrome typically presents in adolescence with symptoms of FCAS, painful urticarial plaques, and progressive sensorinueral hearing loss. Tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated periodic fever (TRAPS) usually is associated with episodic fevers, abdominal pain, periorbital edema, migratory erythema, and arthralgia.1,3,4

Diagnostic criteria for CAPS include elevated inflammatory markers and serum amyloid, plus at least 2 of the typical CAPS symptoms: urticarial rash, cold-triggered episodes, sensorineural hearing loss, musculoskeletal symptoms, chronic aseptic meningitis, and skeletal abnormalities.4 The sensitivity and specificity of these diagnostic criteria are 84% and 91%, respectively. Additional findings that can be seen but are not part of the diagnostic criteria include intermittent fever, transient joint swelling, bony overgrowths, uveitis, optic disc edema, impaired growth, and hepatosplenomegaly.5 Laboratory findings may reveal leukocytosis, eosinophilia, anemia, and/or thrombocytopenia.3,5

Genetic testing, skin biopsies, ophthalmic examinations, neuroimaging, joint radiography, cerebrospinal fluid tests, and hearing examinations can be performed for confirmation of diagnosis and evaluation of systemic complications.4 A skin biopsy may reveal a neutrophilic infiltrate. Ophthalmic examination can demonstrate uveitis and optic disk edema. Neuroimaging may reveal cerebral atrophy or ventricular dilation. Lastly, joint radiography can be used to evaluate for the presence of premature long bone ossification or osseous overgrowth.4

In summary, NOMID is a multisystemic disorder with cutaneous manifestations. Early recognition of this entity is important given the severe sequelae and available efficacious therapy. Dermatologists should be aware of these manifestations, as dermatologic consultation and a skin biopsy may aid in diagnosis.

- Lachmann HJ. Periodic fever syndromes. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2017;31:596-609. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2017.12.001

- Hull KM, Shoham N, Jin Chae J, et al. The expanding spectrum of systemic autoinflammatory disorders and their rheumatic manifestations. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:61-69. doi:10.1097/00002281-200301000-00011

- Ahmadi N, Brewer CC, Zalewski C, et al. Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes: otolaryngologic and audiologic manifestations. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:295-302. doi:10.1177/0194599811402296

- Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, Ozen S, Tyrrell PN, et al. Diagnostic criteria for cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS). Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:942-947. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209686

- Aksentijevich I, Nowak M, Mallah M, et al. De novo CIAS1 mutations, cytokine activation, and evidence for genetic heterogeneity in patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID): a new member of the expanding family of pyrinassociated autoinflammatory diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2002; 46:3340-3348. doi:10.1002/art.10688

The Diagnosis: Neonatal-Onset Multisystem Inflammatory Disorder (NOMID)

The punch biopsy demonstrated a predominantly deep but somewhat superficial, periadnexal, neutrophilic and eosinophilic infiltrate (Figure). The eruption resolved 3 days later with supportive treatment, including appropriate wound care. Genetic analysis revealed an autosomal-dominant NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 gene, NLRP3, de novo variant associated with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disorder (NOMID). Additional workup to characterize our patient’s inflammatory profile revealed elevated IL-18, CD3, CD4, S100A12, and S100A8/A9 levels. On day 48 of life, she was started on anakinra, an IL-1 inhibitor, at a dose of 1 mg/kg subcutaneously, which eventually was titrated to 10 mg/kg at hospital discharge. Hearing screenings were within normal limits.

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) consist of 3 rare, IL-1–associated, autoinflammatory disorders, including familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS), Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS), and NOMID (also known as chronic infantile neurologic cutaneous and articular syndrome). These conditions result from a sporadic or autosomal-dominant gain-of-function mutations in a single gene, NLRP3, on chromosome 1q44. NLRP3 encodes for cryopyrin, an important component of an IL-1 and IL-18 activating inflammasome.1 The most severe manifestation of CAPS is NOMID, which typically presents at birth as a migratory urticarial eruption, growth failure, myalgia, fever, and abnormal facial features, including frontal bossing, saddle-shaped nose, and protruding eyes.2 The illness also can manifest with hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, uveitis, sensorineural hearing loss, cerebral atrophy, and other neurologic manifestations.3 A diagnosis of chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature (CANDLE) syndrome was less likely given that our patient remained afebrile and did not show signs of lipodystrophy and persistent violaceous eyelid swelling. Both FCAS and MWS are less severe forms of CAPS when compared to NOMID. Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome was less likely given the absence of the typical periodic fever pattern associated with the condition and severity of our patient’s symptoms. Muckle-Wells syndrome typically presents in adolescence with symptoms of FCAS, painful urticarial plaques, and progressive sensorinueral hearing loss. Tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated periodic fever (TRAPS) usually is associated with episodic fevers, abdominal pain, periorbital edema, migratory erythema, and arthralgia.1,3,4

Diagnostic criteria for CAPS include elevated inflammatory markers and serum amyloid, plus at least 2 of the typical CAPS symptoms: urticarial rash, cold-triggered episodes, sensorineural hearing loss, musculoskeletal symptoms, chronic aseptic meningitis, and skeletal abnormalities.4 The sensitivity and specificity of these diagnostic criteria are 84% and 91%, respectively. Additional findings that can be seen but are not part of the diagnostic criteria include intermittent fever, transient joint swelling, bony overgrowths, uveitis, optic disc edema, impaired growth, and hepatosplenomegaly.5 Laboratory findings may reveal leukocytosis, eosinophilia, anemia, and/or thrombocytopenia.3,5

Genetic testing, skin biopsies, ophthalmic examinations, neuroimaging, joint radiography, cerebrospinal fluid tests, and hearing examinations can be performed for confirmation of diagnosis and evaluation of systemic complications.4 A skin biopsy may reveal a neutrophilic infiltrate. Ophthalmic examination can demonstrate uveitis and optic disk edema. Neuroimaging may reveal cerebral atrophy or ventricular dilation. Lastly, joint radiography can be used to evaluate for the presence of premature long bone ossification or osseous overgrowth.4

In summary, NOMID is a multisystemic disorder with cutaneous manifestations. Early recognition of this entity is important given the severe sequelae and available efficacious therapy. Dermatologists should be aware of these manifestations, as dermatologic consultation and a skin biopsy may aid in diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Neonatal-Onset Multisystem Inflammatory Disorder (NOMID)

The punch biopsy demonstrated a predominantly deep but somewhat superficial, periadnexal, neutrophilic and eosinophilic infiltrate (Figure). The eruption resolved 3 days later with supportive treatment, including appropriate wound care. Genetic analysis revealed an autosomal-dominant NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 gene, NLRP3, de novo variant associated with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disorder (NOMID). Additional workup to characterize our patient’s inflammatory profile revealed elevated IL-18, CD3, CD4, S100A12, and S100A8/A9 levels. On day 48 of life, she was started on anakinra, an IL-1 inhibitor, at a dose of 1 mg/kg subcutaneously, which eventually was titrated to 10 mg/kg at hospital discharge. Hearing screenings were within normal limits.

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) consist of 3 rare, IL-1–associated, autoinflammatory disorders, including familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS), Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS), and NOMID (also known as chronic infantile neurologic cutaneous and articular syndrome). These conditions result from a sporadic or autosomal-dominant gain-of-function mutations in a single gene, NLRP3, on chromosome 1q44. NLRP3 encodes for cryopyrin, an important component of an IL-1 and IL-18 activating inflammasome.1 The most severe manifestation of CAPS is NOMID, which typically presents at birth as a migratory urticarial eruption, growth failure, myalgia, fever, and abnormal facial features, including frontal bossing, saddle-shaped nose, and protruding eyes.2 The illness also can manifest with hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, uveitis, sensorineural hearing loss, cerebral atrophy, and other neurologic manifestations.3 A diagnosis of chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature (CANDLE) syndrome was less likely given that our patient remained afebrile and did not show signs of lipodystrophy and persistent violaceous eyelid swelling. Both FCAS and MWS are less severe forms of CAPS when compared to NOMID. Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome was less likely given the absence of the typical periodic fever pattern associated with the condition and severity of our patient’s symptoms. Muckle-Wells syndrome typically presents in adolescence with symptoms of FCAS, painful urticarial plaques, and progressive sensorinueral hearing loss. Tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated periodic fever (TRAPS) usually is associated with episodic fevers, abdominal pain, periorbital edema, migratory erythema, and arthralgia.1,3,4

Diagnostic criteria for CAPS include elevated inflammatory markers and serum amyloid, plus at least 2 of the typical CAPS symptoms: urticarial rash, cold-triggered episodes, sensorineural hearing loss, musculoskeletal symptoms, chronic aseptic meningitis, and skeletal abnormalities.4 The sensitivity and specificity of these diagnostic criteria are 84% and 91%, respectively. Additional findings that can be seen but are not part of the diagnostic criteria include intermittent fever, transient joint swelling, bony overgrowths, uveitis, optic disc edema, impaired growth, and hepatosplenomegaly.5 Laboratory findings may reveal leukocytosis, eosinophilia, anemia, and/or thrombocytopenia.3,5

Genetic testing, skin biopsies, ophthalmic examinations, neuroimaging, joint radiography, cerebrospinal fluid tests, and hearing examinations can be performed for confirmation of diagnosis and evaluation of systemic complications.4 A skin biopsy may reveal a neutrophilic infiltrate. Ophthalmic examination can demonstrate uveitis and optic disk edema. Neuroimaging may reveal cerebral atrophy or ventricular dilation. Lastly, joint radiography can be used to evaluate for the presence of premature long bone ossification or osseous overgrowth.4

In summary, NOMID is a multisystemic disorder with cutaneous manifestations. Early recognition of this entity is important given the severe sequelae and available efficacious therapy. Dermatologists should be aware of these manifestations, as dermatologic consultation and a skin biopsy may aid in diagnosis.

- Lachmann HJ. Periodic fever syndromes. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2017;31:596-609. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2017.12.001

- Hull KM, Shoham N, Jin Chae J, et al. The expanding spectrum of systemic autoinflammatory disorders and their rheumatic manifestations. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:61-69. doi:10.1097/00002281-200301000-00011

- Ahmadi N, Brewer CC, Zalewski C, et al. Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes: otolaryngologic and audiologic manifestations. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:295-302. doi:10.1177/0194599811402296

- Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, Ozen S, Tyrrell PN, et al. Diagnostic criteria for cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS). Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:942-947. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209686

- Aksentijevich I, Nowak M, Mallah M, et al. De novo CIAS1 mutations, cytokine activation, and evidence for genetic heterogeneity in patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID): a new member of the expanding family of pyrinassociated autoinflammatory diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2002; 46:3340-3348. doi:10.1002/art.10688

- Lachmann HJ. Periodic fever syndromes. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2017;31:596-609. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2017.12.001

- Hull KM, Shoham N, Jin Chae J, et al. The expanding spectrum of systemic autoinflammatory disorders and their rheumatic manifestations. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:61-69. doi:10.1097/00002281-200301000-00011

- Ahmadi N, Brewer CC, Zalewski C, et al. Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes: otolaryngologic and audiologic manifestations. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:295-302. doi:10.1177/0194599811402296

- Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, Ozen S, Tyrrell PN, et al. Diagnostic criteria for cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS). Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:942-947. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209686

- Aksentijevich I, Nowak M, Mallah M, et al. De novo CIAS1 mutations, cytokine activation, and evidence for genetic heterogeneity in patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID): a new member of the expanding family of pyrinassociated autoinflammatory diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2002; 46:3340-3348. doi:10.1002/art.10688

A 2-week-old infant girl was transferred to a specialty pediatric hospital where dermatology was consulted for evaluation of a diffuse eruption triggered by cold that was similar to an eruption present at birth. She was born at 31 weeks and 2 days’ gestation at an outside hospital via caesarean delivery. Early delivery was prompted by superimposed pre-eclampsia with severe hypertension after administration of antenatal steroids. At birth, the infant was cyanotic and apneic and had a documented skin eruption, according to the medical record. She had thrombocytopenia, elevated C-reactive protein, and an elevated temperature without fever. Extensive septic workup, including blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid cultures; herpes simplex virus and cytomegalovirus screening; and Toxoplasma polymerase chain reaction were negative. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed no evidence of intracranial congenital infection. Ampicillinsulbactam was initiated for presumed culture-negative sepsis. On day 2 of hospitalization, she developed conjunctival icterus, hepatomegaly, and jaundice. Direct hyperbilirubinemia; anemia; and elevated triglycerides, ferritin, and ammonia all were present. Coagulation studies were normal. Subsequent workup, including abdominal ultrasonography and hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scan, was concerning for biliary atresia. Despite appropriate treatment, her condition did not improve and she was transferred. Repeat abdominal ultrasonography on day 24 of life confirmed hepatomegaly but did not demonstrate other findings of biliary atresia. At the current presentation, physical examination revealed many scattered, redbrown and centrally violaceous, blanching papules measuring a few millimeters involving the trunk, arms, buttocks, and legs. A punch biopsy was obtained.

Retiform Purpura on the Lower Legs

The Diagnosis: Type I Cryoglobulinemia

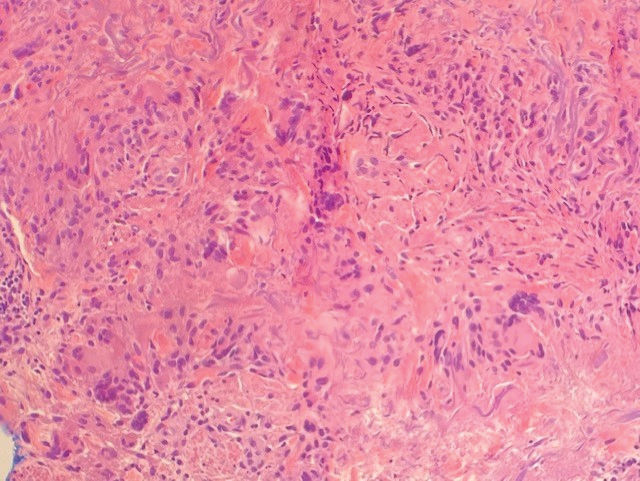

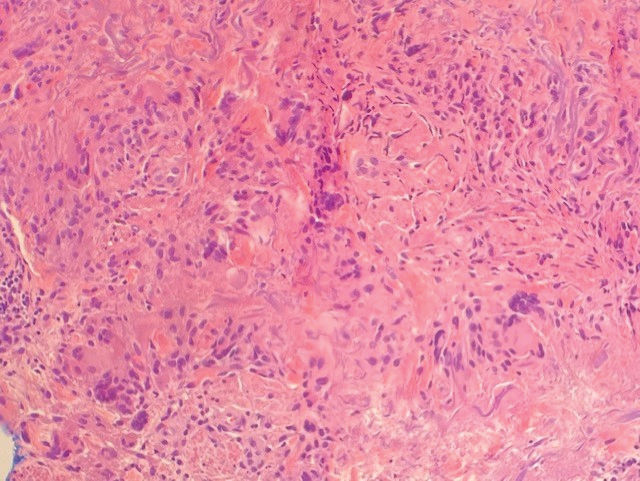

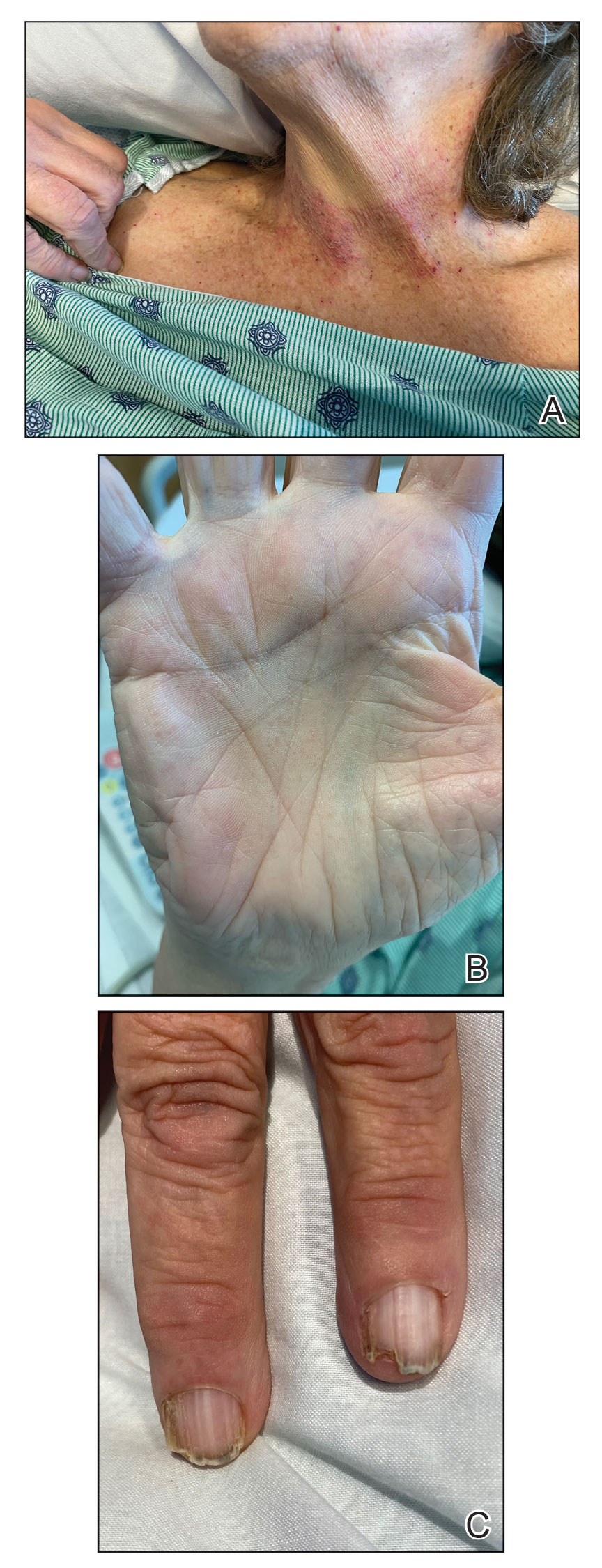

Retiform purpura with overlying necrosis subsequently developed over the course of a week following presentation (Figure 1). A skin biopsy showed fibrin thrombi and congestion of small- and medium-sized blood vessels, consistent with vasculopathy (Figure 2). Urinalysis revealed hematuria and proteinuria. A renal biopsy performed due to a continually elevated serum creatinine level revealed glomerulonephritis with numerous IgG1 lambda–restricted glomerular capillary hyaline thrombi, compatible with a lymphoproliferative disorder–associated type I cryoglobulinemia. A serum cryoglobulin immunofixation test confirmed type I cryoglobulinemia involving monoclonal IgG lambda. The combination of cutaneous, renal, and hematologic findings was consistent with type I cryoglobulinemia. A subsequent bone marrow biopsy demonstrated a CD20+ lambda–restricted plasma cell neoplasm. Initial treatment with high-dose corticosteroids followed by targeted treatment of the underlying hematologic condition with bortezomib, rituximab, and dexamethasone improved the skin disease.

Cryoglobulins are abnormal immunoglobulins that precipitate at temperatures below 37 °C. The persistent presence of cryoglobulins in the serum is termed cryoglobulinemia.1 Type I cryoglobulinemia is distinguished from mixed cryoglobulinemia—types II and III—by the presence of a single monoclonal immunoglobulin, typically IgM or IgG. It is associated with lymphoproliferative disorders, most commonly monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and B-cell malignancies such as Waldenström macroglobulinemia, multiple myeloma, or chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Histopathology shows occlusion of small vessel lumina with homogenous eosinophilic material containing the monoclonal cryoprecipitate.2 Disease manifestations are caused by small vessel occlusion, which leads to ischemia and tissue damage.

Retiform purpura, livedo reticularis/racemosa, and necrosis leading to ulcers are the most common cutaneous clinical findings. Extracutaneous signs include peripheral neuropathy, arthralgia, Raynaud phenomenon, and acrocyanosis. Renal involvement, most commonly glomerulonephritis with associated proteinuria, is noted in 14% to 20% of cases.3,4 An elevated cryocrit can lead to symptoms of hyperviscosity syndrome.2

Treatment is difficult and primarily is focused on addressing the underlying hematologic condition, which is responsible for synthesis of the cryoglobulin. Decreasing cryoglobulin production leads to decreased occlusion of blood vessels, thus alleviating the ischemia and skin damage. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance–related type I cryoglobulinemia initially is treated with corticosteroids followed by rituximab if a CD20+ B-cell clone is identified.2 Bortezomib is recommended for cases associated with Waldenström macroglobulinemia and cases associated with multiple myeloma with concurrent renal failure. In patients with neuropathy, a lenalidomide-based treatment can be employed. Patients should be instructed to keep extremities warm.2 Diabetic foot care guidelines should be followed to prevent wound complications. The differential diagnosis for type I cryoglobulinemia includes other causes of retiform purpura–like angioinvasive fungal infection, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, calciphylaxis, and livedoid vasculopathy.5 Angioinvasive fungal infections are caused by Candida, Aspergillus, and Mucorales species, as well as other hyaline molds. They typically occur in immunocompromised patients and invade the blood vessels via direct inoculation or dissemination.6 Patients present with retiform purpura but typically will be acutely ill with fevers and vital sign abnormalities. Histopathology with special stains often will identify the fungal organisms in the dermis or inside blood vessel walls with vessel wall destruction and hemorrhage.7 Accurate diagnosis is essential to selecting appropriate antifungal agents. If angioinvasive fungal infection is clinically suspected, treatment should begin before culture and histopathologic data are available.7

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome is an autoimmune thrombophilia that can occur as primary disease or in association with other autoimmune conditions, most commonly systemic lupus erythematosus. Diagnosis requires the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, such as lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody, anti–β2-glycoprotein-1 antibody, with arterial or venous thrombosis and/or recurrent pregnancy loss. Paraproteinemia is not seen. The most common cutaneous finding is livedo reticularis, with livedo racemosa being a more distinctive finding.8 Small vessel thrombosis is seen histopathologically. Treatment includes antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications. Patients with refractory disease may benefit from additional therapy with hydroxychloroquine or intravenous immunoglobulins.8

Calciphylaxis is a rare depositional vasculopathy that often occurs in patients with end-stage renal disease on dialysis. Patients present with painful and poor-healing skin lesions including indurated nodules, violaceous plaques, and retiform purpura that typically affect areas of high adiposity such as the thighs, abdomen, and buttocks.9 Ulceration and superimposed infections are common complications. Histopathologically, small dermal and subcutaneous vessels demonstrate calcification, microthrombosis, and fibrointimal hyperplasia.9 Wound management is critically important in patients with calciphylaxis. Treatment with intravenous sodium thiosulfate is typical, but prognosis remains poor. Although livedoid vasculopathy may present with retiform purpura in the ankles, paraproteinemia is not seen and patients frequently present with punched-out ulcerations that tend to heal into atrophie blanche.10 Livedoid vasculopathy has been associated with underlying hypercoagulable states, connective tissue diseases, and chronic venous hypertension. Hypercoagulability and endothelial cell damage contribute to the formation of fibrin thrombi in the superficial dermal blood vessels. Histopathology demonstrates thickening of vessel walls and intraluminal hyaline thrombi. Successful treatment in most cases is achieved with anticoagulation therapy, typically rivaroxaban, especially in patients with underlying hypercoagulability. Antiplatelet therapy also may be considered, while anabolic agents have been shown to be helpful in patients with connective tissue disease.10

- Desbois AC, Cacoub P, Saadoun D. Cryoglobulinemia: an update in 2019. Joint Bone Spine. 2019;86:707-713. doi:10.1016/j .jbspin.2019.01.016

- Muchtar E, Magen H, Gertz MA. How I treat cryoglobulinemia. Blood. 2017;129:289-298. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-09-719773

- Sidana S, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of patients with type 1 monoclonal cryoglobulinemia. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:668-673. doi:10.1002/ajh.24745

- Harel S, Mohr M, Jahn I, et al. Clinico-biological characteristics and treatment of type I monoclonal cryoglobulinaemia: a study of 64 cases. Br J Haematol. 2015;168:671-678. doi:10.1111/bjh.13196

- Georgesen C, Fox LP, Harp J. Retiform purpura: a diagnostic approach. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:783-796. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.112

- Shields BE, Rosenbach M, Brown-Joel Z, et al. Angioinvasive fungal infections impacting the skin: background, epidemiology, and clinical presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:869-880.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.059

- Berger AP, Ford BA, Brown-Joel Z, et al. Angioinvasive fungal infections impacting the skin: diagnosis, management, and complications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:883-898.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.058

- Negrini S, Pappalardo F, Murdaca G, et al. The antiphospholipid syndrome: from pathophysiology to treatment. Clin Exp Med. 2017;17:257-267. doi:10.1007/s10238-016-0430-5

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

- Georgesen C, Fox LP, Harp J. Retiform purpura: workup and therapeutic considerations in select conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:799-816. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.113

The Diagnosis: Type I Cryoglobulinemia

Retiform purpura with overlying necrosis subsequently developed over the course of a week following presentation (Figure 1). A skin biopsy showed fibrin thrombi and congestion of small- and medium-sized blood vessels, consistent with vasculopathy (Figure 2). Urinalysis revealed hematuria and proteinuria. A renal biopsy performed due to a continually elevated serum creatinine level revealed glomerulonephritis with numerous IgG1 lambda–restricted glomerular capillary hyaline thrombi, compatible with a lymphoproliferative disorder–associated type I cryoglobulinemia. A serum cryoglobulin immunofixation test confirmed type I cryoglobulinemia involving monoclonal IgG lambda. The combination of cutaneous, renal, and hematologic findings was consistent with type I cryoglobulinemia. A subsequent bone marrow biopsy demonstrated a CD20+ lambda–restricted plasma cell neoplasm. Initial treatment with high-dose corticosteroids followed by targeted treatment of the underlying hematologic condition with bortezomib, rituximab, and dexamethasone improved the skin disease.

Cryoglobulins are abnormal immunoglobulins that precipitate at temperatures below 37 °C. The persistent presence of cryoglobulins in the serum is termed cryoglobulinemia.1 Type I cryoglobulinemia is distinguished from mixed cryoglobulinemia—types II and III—by the presence of a single monoclonal immunoglobulin, typically IgM or IgG. It is associated with lymphoproliferative disorders, most commonly monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and B-cell malignancies such as Waldenström macroglobulinemia, multiple myeloma, or chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Histopathology shows occlusion of small vessel lumina with homogenous eosinophilic material containing the monoclonal cryoprecipitate.2 Disease manifestations are caused by small vessel occlusion, which leads to ischemia and tissue damage.

Retiform purpura, livedo reticularis/racemosa, and necrosis leading to ulcers are the most common cutaneous clinical findings. Extracutaneous signs include peripheral neuropathy, arthralgia, Raynaud phenomenon, and acrocyanosis. Renal involvement, most commonly glomerulonephritis with associated proteinuria, is noted in 14% to 20% of cases.3,4 An elevated cryocrit can lead to symptoms of hyperviscosity syndrome.2

Treatment is difficult and primarily is focused on addressing the underlying hematologic condition, which is responsible for synthesis of the cryoglobulin. Decreasing cryoglobulin production leads to decreased occlusion of blood vessels, thus alleviating the ischemia and skin damage. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance–related type I cryoglobulinemia initially is treated with corticosteroids followed by rituximab if a CD20+ B-cell clone is identified.2 Bortezomib is recommended for cases associated with Waldenström macroglobulinemia and cases associated with multiple myeloma with concurrent renal failure. In patients with neuropathy, a lenalidomide-based treatment can be employed. Patients should be instructed to keep extremities warm.2 Diabetic foot care guidelines should be followed to prevent wound complications. The differential diagnosis for type I cryoglobulinemia includes other causes of retiform purpura–like angioinvasive fungal infection, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, calciphylaxis, and livedoid vasculopathy.5 Angioinvasive fungal infections are caused by Candida, Aspergillus, and Mucorales species, as well as other hyaline molds. They typically occur in immunocompromised patients and invade the blood vessels via direct inoculation or dissemination.6 Patients present with retiform purpura but typically will be acutely ill with fevers and vital sign abnormalities. Histopathology with special stains often will identify the fungal organisms in the dermis or inside blood vessel walls with vessel wall destruction and hemorrhage.7 Accurate diagnosis is essential to selecting appropriate antifungal agents. If angioinvasive fungal infection is clinically suspected, treatment should begin before culture and histopathologic data are available.7

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome is an autoimmune thrombophilia that can occur as primary disease or in association with other autoimmune conditions, most commonly systemic lupus erythematosus. Diagnosis requires the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, such as lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody, anti–β2-glycoprotein-1 antibody, with arterial or venous thrombosis and/or recurrent pregnancy loss. Paraproteinemia is not seen. The most common cutaneous finding is livedo reticularis, with livedo racemosa being a more distinctive finding.8 Small vessel thrombosis is seen histopathologically. Treatment includes antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications. Patients with refractory disease may benefit from additional therapy with hydroxychloroquine or intravenous immunoglobulins.8

Calciphylaxis is a rare depositional vasculopathy that often occurs in patients with end-stage renal disease on dialysis. Patients present with painful and poor-healing skin lesions including indurated nodules, violaceous plaques, and retiform purpura that typically affect areas of high adiposity such as the thighs, abdomen, and buttocks.9 Ulceration and superimposed infections are common complications. Histopathologically, small dermal and subcutaneous vessels demonstrate calcification, microthrombosis, and fibrointimal hyperplasia.9 Wound management is critically important in patients with calciphylaxis. Treatment with intravenous sodium thiosulfate is typical, but prognosis remains poor. Although livedoid vasculopathy may present with retiform purpura in the ankles, paraproteinemia is not seen and patients frequently present with punched-out ulcerations that tend to heal into atrophie blanche.10 Livedoid vasculopathy has been associated with underlying hypercoagulable states, connective tissue diseases, and chronic venous hypertension. Hypercoagulability and endothelial cell damage contribute to the formation of fibrin thrombi in the superficial dermal blood vessels. Histopathology demonstrates thickening of vessel walls and intraluminal hyaline thrombi. Successful treatment in most cases is achieved with anticoagulation therapy, typically rivaroxaban, especially in patients with underlying hypercoagulability. Antiplatelet therapy also may be considered, while anabolic agents have been shown to be helpful in patients with connective tissue disease.10

The Diagnosis: Type I Cryoglobulinemia

Retiform purpura with overlying necrosis subsequently developed over the course of a week following presentation (Figure 1). A skin biopsy showed fibrin thrombi and congestion of small- and medium-sized blood vessels, consistent with vasculopathy (Figure 2). Urinalysis revealed hematuria and proteinuria. A renal biopsy performed due to a continually elevated serum creatinine level revealed glomerulonephritis with numerous IgG1 lambda–restricted glomerular capillary hyaline thrombi, compatible with a lymphoproliferative disorder–associated type I cryoglobulinemia. A serum cryoglobulin immunofixation test confirmed type I cryoglobulinemia involving monoclonal IgG lambda. The combination of cutaneous, renal, and hematologic findings was consistent with type I cryoglobulinemia. A subsequent bone marrow biopsy demonstrated a CD20+ lambda–restricted plasma cell neoplasm. Initial treatment with high-dose corticosteroids followed by targeted treatment of the underlying hematologic condition with bortezomib, rituximab, and dexamethasone improved the skin disease.

Cryoglobulins are abnormal immunoglobulins that precipitate at temperatures below 37 °C. The persistent presence of cryoglobulins in the serum is termed cryoglobulinemia.1 Type I cryoglobulinemia is distinguished from mixed cryoglobulinemia—types II and III—by the presence of a single monoclonal immunoglobulin, typically IgM or IgG. It is associated with lymphoproliferative disorders, most commonly monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and B-cell malignancies such as Waldenström macroglobulinemia, multiple myeloma, or chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Histopathology shows occlusion of small vessel lumina with homogenous eosinophilic material containing the monoclonal cryoprecipitate.2 Disease manifestations are caused by small vessel occlusion, which leads to ischemia and tissue damage.

Retiform purpura, livedo reticularis/racemosa, and necrosis leading to ulcers are the most common cutaneous clinical findings. Extracutaneous signs include peripheral neuropathy, arthralgia, Raynaud phenomenon, and acrocyanosis. Renal involvement, most commonly glomerulonephritis with associated proteinuria, is noted in 14% to 20% of cases.3,4 An elevated cryocrit can lead to symptoms of hyperviscosity syndrome.2

Treatment is difficult and primarily is focused on addressing the underlying hematologic condition, which is responsible for synthesis of the cryoglobulin. Decreasing cryoglobulin production leads to decreased occlusion of blood vessels, thus alleviating the ischemia and skin damage. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance–related type I cryoglobulinemia initially is treated with corticosteroids followed by rituximab if a CD20+ B-cell clone is identified.2 Bortezomib is recommended for cases associated with Waldenström macroglobulinemia and cases associated with multiple myeloma with concurrent renal failure. In patients with neuropathy, a lenalidomide-based treatment can be employed. Patients should be instructed to keep extremities warm.2 Diabetic foot care guidelines should be followed to prevent wound complications. The differential diagnosis for type I cryoglobulinemia includes other causes of retiform purpura–like angioinvasive fungal infection, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, calciphylaxis, and livedoid vasculopathy.5 Angioinvasive fungal infections are caused by Candida, Aspergillus, and Mucorales species, as well as other hyaline molds. They typically occur in immunocompromised patients and invade the blood vessels via direct inoculation or dissemination.6 Patients present with retiform purpura but typically will be acutely ill with fevers and vital sign abnormalities. Histopathology with special stains often will identify the fungal organisms in the dermis or inside blood vessel walls with vessel wall destruction and hemorrhage.7 Accurate diagnosis is essential to selecting appropriate antifungal agents. If angioinvasive fungal infection is clinically suspected, treatment should begin before culture and histopathologic data are available.7

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome is an autoimmune thrombophilia that can occur as primary disease or in association with other autoimmune conditions, most commonly systemic lupus erythematosus. Diagnosis requires the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, such as lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody, anti–β2-glycoprotein-1 antibody, with arterial or venous thrombosis and/or recurrent pregnancy loss. Paraproteinemia is not seen. The most common cutaneous finding is livedo reticularis, with livedo racemosa being a more distinctive finding.8 Small vessel thrombosis is seen histopathologically. Treatment includes antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications. Patients with refractory disease may benefit from additional therapy with hydroxychloroquine or intravenous immunoglobulins.8

Calciphylaxis is a rare depositional vasculopathy that often occurs in patients with end-stage renal disease on dialysis. Patients present with painful and poor-healing skin lesions including indurated nodules, violaceous plaques, and retiform purpura that typically affect areas of high adiposity such as the thighs, abdomen, and buttocks.9 Ulceration and superimposed infections are common complications. Histopathologically, small dermal and subcutaneous vessels demonstrate calcification, microthrombosis, and fibrointimal hyperplasia.9 Wound management is critically important in patients with calciphylaxis. Treatment with intravenous sodium thiosulfate is typical, but prognosis remains poor. Although livedoid vasculopathy may present with retiform purpura in the ankles, paraproteinemia is not seen and patients frequently present with punched-out ulcerations that tend to heal into atrophie blanche.10 Livedoid vasculopathy has been associated with underlying hypercoagulable states, connective tissue diseases, and chronic venous hypertension. Hypercoagulability and endothelial cell damage contribute to the formation of fibrin thrombi in the superficial dermal blood vessels. Histopathology demonstrates thickening of vessel walls and intraluminal hyaline thrombi. Successful treatment in most cases is achieved with anticoagulation therapy, typically rivaroxaban, especially in patients with underlying hypercoagulability. Antiplatelet therapy also may be considered, while anabolic agents have been shown to be helpful in patients with connective tissue disease.10

- Desbois AC, Cacoub P, Saadoun D. Cryoglobulinemia: an update in 2019. Joint Bone Spine. 2019;86:707-713. doi:10.1016/j .jbspin.2019.01.016

- Muchtar E, Magen H, Gertz MA. How I treat cryoglobulinemia. Blood. 2017;129:289-298. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-09-719773

- Sidana S, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of patients with type 1 monoclonal cryoglobulinemia. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:668-673. doi:10.1002/ajh.24745

- Harel S, Mohr M, Jahn I, et al. Clinico-biological characteristics and treatment of type I monoclonal cryoglobulinaemia: a study of 64 cases. Br J Haematol. 2015;168:671-678. doi:10.1111/bjh.13196

- Georgesen C, Fox LP, Harp J. Retiform purpura: a diagnostic approach. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:783-796. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.112

- Shields BE, Rosenbach M, Brown-Joel Z, et al. Angioinvasive fungal infections impacting the skin: background, epidemiology, and clinical presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:869-880.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.059

- Berger AP, Ford BA, Brown-Joel Z, et al. Angioinvasive fungal infections impacting the skin: diagnosis, management, and complications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:883-898.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.058

- Negrini S, Pappalardo F, Murdaca G, et al. The antiphospholipid syndrome: from pathophysiology to treatment. Clin Exp Med. 2017;17:257-267. doi:10.1007/s10238-016-0430-5

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

- Georgesen C, Fox LP, Harp J. Retiform purpura: workup and therapeutic considerations in select conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:799-816. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.113

- Desbois AC, Cacoub P, Saadoun D. Cryoglobulinemia: an update in 2019. Joint Bone Spine. 2019;86:707-713. doi:10.1016/j .jbspin.2019.01.016

- Muchtar E, Magen H, Gertz MA. How I treat cryoglobulinemia. Blood. 2017;129:289-298. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-09-719773

- Sidana S, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of patients with type 1 monoclonal cryoglobulinemia. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:668-673. doi:10.1002/ajh.24745

- Harel S, Mohr M, Jahn I, et al. Clinico-biological characteristics and treatment of type I monoclonal cryoglobulinaemia: a study of 64 cases. Br J Haematol. 2015;168:671-678. doi:10.1111/bjh.13196

- Georgesen C, Fox LP, Harp J. Retiform purpura: a diagnostic approach. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:783-796. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.112

- Shields BE, Rosenbach M, Brown-Joel Z, et al. Angioinvasive fungal infections impacting the skin: background, epidemiology, and clinical presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:869-880.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.059

- Berger AP, Ford BA, Brown-Joel Z, et al. Angioinvasive fungal infections impacting the skin: diagnosis, management, and complications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:883-898.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.058

- Negrini S, Pappalardo F, Murdaca G, et al. The antiphospholipid syndrome: from pathophysiology to treatment. Clin Exp Med. 2017;17:257-267. doi:10.1007/s10238-016-0430-5

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

- Georgesen C, Fox LP, Harp J. Retiform purpura: workup and therapeutic considerations in select conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:799-816. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.113

A 58-year-old man presented with a petechial and purpuric rash limited to the lower extremities. He reported that the rash had been present for months but worsened acutely over the last 3 days with new-onset dark urine, joint pain, and edema limiting his ability to walk. Physical examination showed areas of violaceous macules and papules on the legs and dorsal feet in a reticular distribution. Laboratory findings were remarkable for an elevated serum creatinine level of 2.75 mg/dL (reference range, 0.70–1.30 mg/dL), and serum immunofixation revealed the presence of markedly elevated IgG lambda monoclonal proteins. He was afebrile and his vital signs were stable. Dermatology, nephrology, and rheumatology services were consulted.

Symmetric Palmoplantar Papules With a Keratotic Border

The Diagnosis: Porokeratosis Plantaris Palmaris et Disseminata

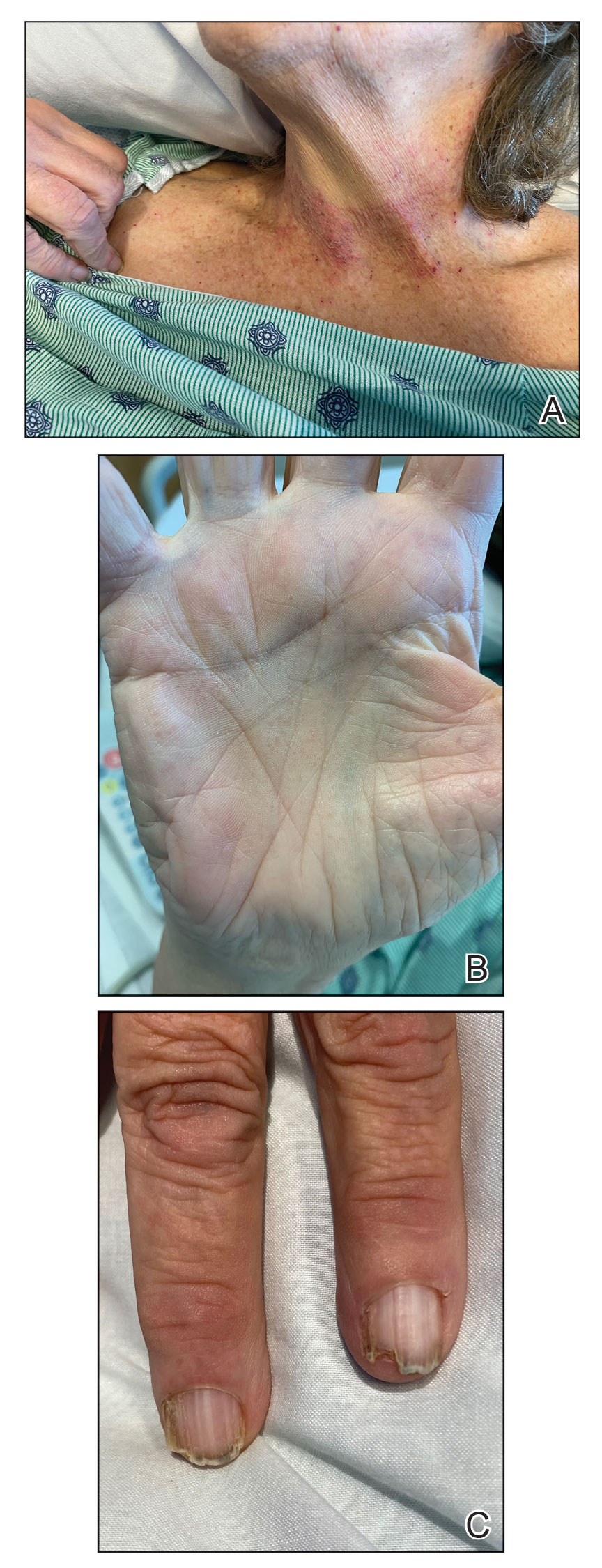

A 3-mm punch biopsy of the right upper arm showed incipient cornoid lamellae formation, pigment incontinence, and sparse dermal lymphocytic inflammation (Figure), suggestive of porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata (PPPD). The dermatopathologist recommended a second biopsy to confirm the diagnosis and to confirm that the lesions on the palms and soles also were suggestive of porokeratosis. A second 4-mm punch biopsy of the left palm was consistent with PPPD.

The risks of PPPD as a precancerous entity along with the benefits and side effects of the various management options were discussed with our patient. We recommended that he start low-dose isotretinoin (20 mg/d) due to the large body surface area affected, making focal and field treatments likely insufficient. However, our patient opted not to treat and did not return for follow-up.

Subtypes of porokeratosis, including disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP) and PPPD, are conditions that disrupt the normal maturation of keratin and present clinically with symmetric, crusted, annular papules.1 The signature but nonspecific histopathologic feature shared among the subtypes is the presence of a cornoid lamellae.2 Several triggers of porokeratosis have been proposed, including trauma and exposure to UV and ionizing radiation.2,3 The clinical variants of porokeratosis are important conditions to diagnose correctly because they portend a risk for Bowen disease and invasive squamous cell carcinoma and may indicate the presence of an underlying hematologic and/or solid organ malignancy.4 Management of porokeratosis is difficult, as treatments have shown limited efficacy and variable recurrence rates. Treatment options include focal, field, and systemic options, such as 5-fluorouracil, topical compound of cholesterol and lovastatin, isotretinoin, and acitretin.1,2

Porokeratoses may arise from gene mutations in the mevalonate pathway,5 which is essential for the production of cholesterol.6 Topical cholesterol alone has not been shown to improve porokeratosis, but the combination topical therapy of cholesterol and lovastatin is promising. It is theorized to deliver benefit by both providing the essential end product of the pathway and simultaneously reducing the number of potentially toxic intermediates.6

Porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata (also known as porokeratosis plantaris) is unique among the subtypes of porokeratosis in that its annular, red-pink, papular rash with scaling and a keratotic border tends to start distally, involving the palms and soles, and progresses proximally to the trunk with smaller lesions.1,7 This centripetal progression can take years, as was seen in our patient.1 The disease is uncommon, with a dearth of published reports on PPPD.2 However, case reports have shown that PPPD is strongly linked to family history and may have an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern. Penetrance is greater in men than in women, as PPPD is twice as common in men.8 Most cases of PPPD have been diagnosed in patients in their 20s and 30s, but Hartman et al9 reported a case wherein a patient was diagnosed with PPPD after 65 years of age, similar to our patient.

Although the lesions in DSAP can appear similar to those in PPPD, DSAP is more common among the family of porokeratotic conditions, affecting women twice as often as men, with a sporadic pattern of inheritance.2 These same features are present in some other types of porokeratosis but not PPPD. Furthermore, DSAP progresses proximally to distally but often with truncal sparing.2

Akin to PPPD, pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) often presents with palmoplantar keratoderma.10 There are at least 6 types of PRP with varying degrees of similarity to PPPD. However, in many cases PRP is associated with a background of diffuse erythema on the body with islands of spared skin. In addition, cases of PRP have been linked to extracutaneous findings such as ectropion and joint pain.11

Darier disease, especially the acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf variant, is more common in men and involves younger populations, as in PPPD.11 However, the crusted lesions seen in Darier disease frequently involve the skin folds. These intertriginous lesions may coalesce, mimicking warts in appearance, and are at risk for secondary infection. Nail findings in Darier disease also are distinct and include longitudinal white or red stripes running along the nail bed, in addition to V-shaped nicks at the nail tips.

Psoriasis can occur anywhere on the body and is associated with silver scaling atop a salmon-colored dermatitis.12 It results from aberrant proliferation of keratinocytes. Some distinguishing features of psoriasis include a disease course that waxes and wanes as well as pitting of the nails.

Although PPPD typically affects young adults, we presented a case of PPPD in an older man. Porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata in older adults may represent a delayed diagnosis, imply a broader range for the age of onset, or suggest its manifestation secondary to radiation treatment or another phenomenon. For example, our patient received 35 radiotherapy cycles for tongue cancer more than 5 years prior to the onset of PPPD.

- Irisawa R, Yamazaki M, Yamamoto T, et al. A case of porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:5.

- Vargas-Mora P, Morgado-Carrasco D, Fusta-Novell X. Porokeratosis: a review of its pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111:545-560.

- James AJ, Clarke LE, Elenitsas R, et al. Segmental porokeratosis after radiation therapy for follicular lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(2 suppl):S49-S50.

- Schena D, Papagrigoraki A, Frigo A, et al. Eruptive disseminated porokeratosis associated with internal malignancies: a case report. Cutis. 2010;85:156-159.

- Zhang Z, Li C, Wu F, et al. Genomic variations of the mevalonate pathway in porokeratosis. Elife. 2015;4:E06322. doi:10.7554/eLife.06322

- Atzmony L, Lim YH, Hamilton C, et al. Topical cholesterol/lovastatin for the treatment of porokeratosis: a pathogenesis-directed therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:123-131. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.043

- Guss SB, Osbourn RA, Lutzner MA. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris, et disseminata. a third type of porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:366-373.

- Kanitakis J. Porokeratoses: an update of clinical, aetiopathogenic and therapeutic features. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:533-544.

- Hartman R, Mandal R, Sanchez M, et al. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris, et disseminata. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:22.

- Suryawanshi H, Dhobley A, Sharma A, et al. Darier disease: a rare genodermatosis. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2017;21:321. doi:10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_170_16

- Eastham AB. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:404. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5030

- Nair PA, Badri T. Psoriasis. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated April 6, 2022. Accessed March 13, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448194/

The Diagnosis: Porokeratosis Plantaris Palmaris et Disseminata

A 3-mm punch biopsy of the right upper arm showed incipient cornoid lamellae formation, pigment incontinence, and sparse dermal lymphocytic inflammation (Figure), suggestive of porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata (PPPD). The dermatopathologist recommended a second biopsy to confirm the diagnosis and to confirm that the lesions on the palms and soles also were suggestive of porokeratosis. A second 4-mm punch biopsy of the left palm was consistent with PPPD.

The risks of PPPD as a precancerous entity along with the benefits and side effects of the various management options were discussed with our patient. We recommended that he start low-dose isotretinoin (20 mg/d) due to the large body surface area affected, making focal and field treatments likely insufficient. However, our patient opted not to treat and did not return for follow-up.

Subtypes of porokeratosis, including disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP) and PPPD, are conditions that disrupt the normal maturation of keratin and present clinically with symmetric, crusted, annular papules.1 The signature but nonspecific histopathologic feature shared among the subtypes is the presence of a cornoid lamellae.2 Several triggers of porokeratosis have been proposed, including trauma and exposure to UV and ionizing radiation.2,3 The clinical variants of porokeratosis are important conditions to diagnose correctly because they portend a risk for Bowen disease and invasive squamous cell carcinoma and may indicate the presence of an underlying hematologic and/or solid organ malignancy.4 Management of porokeratosis is difficult, as treatments have shown limited efficacy and variable recurrence rates. Treatment options include focal, field, and systemic options, such as 5-fluorouracil, topical compound of cholesterol and lovastatin, isotretinoin, and acitretin.1,2

Porokeratoses may arise from gene mutations in the mevalonate pathway,5 which is essential for the production of cholesterol.6 Topical cholesterol alone has not been shown to improve porokeratosis, but the combination topical therapy of cholesterol and lovastatin is promising. It is theorized to deliver benefit by both providing the essential end product of the pathway and simultaneously reducing the number of potentially toxic intermediates.6

Porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata (also known as porokeratosis plantaris) is unique among the subtypes of porokeratosis in that its annular, red-pink, papular rash with scaling and a keratotic border tends to start distally, involving the palms and soles, and progresses proximally to the trunk with smaller lesions.1,7 This centripetal progression can take years, as was seen in our patient.1 The disease is uncommon, with a dearth of published reports on PPPD.2 However, case reports have shown that PPPD is strongly linked to family history and may have an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern. Penetrance is greater in men than in women, as PPPD is twice as common in men.8 Most cases of PPPD have been diagnosed in patients in their 20s and 30s, but Hartman et al9 reported a case wherein a patient was diagnosed with PPPD after 65 years of age, similar to our patient.

Although the lesions in DSAP can appear similar to those in PPPD, DSAP is more common among the family of porokeratotic conditions, affecting women twice as often as men, with a sporadic pattern of inheritance.2 These same features are present in some other types of porokeratosis but not PPPD. Furthermore, DSAP progresses proximally to distally but often with truncal sparing.2

Akin to PPPD, pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) often presents with palmoplantar keratoderma.10 There are at least 6 types of PRP with varying degrees of similarity to PPPD. However, in many cases PRP is associated with a background of diffuse erythema on the body with islands of spared skin. In addition, cases of PRP have been linked to extracutaneous findings such as ectropion and joint pain.11

Darier disease, especially the acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf variant, is more common in men and involves younger populations, as in PPPD.11 However, the crusted lesions seen in Darier disease frequently involve the skin folds. These intertriginous lesions may coalesce, mimicking warts in appearance, and are at risk for secondary infection. Nail findings in Darier disease also are distinct and include longitudinal white or red stripes running along the nail bed, in addition to V-shaped nicks at the nail tips.

Psoriasis can occur anywhere on the body and is associated with silver scaling atop a salmon-colored dermatitis.12 It results from aberrant proliferation of keratinocytes. Some distinguishing features of psoriasis include a disease course that waxes and wanes as well as pitting of the nails.

Although PPPD typically affects young adults, we presented a case of PPPD in an older man. Porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata in older adults may represent a delayed diagnosis, imply a broader range for the age of onset, or suggest its manifestation secondary to radiation treatment or another phenomenon. For example, our patient received 35 radiotherapy cycles for tongue cancer more than 5 years prior to the onset of PPPD.

The Diagnosis: Porokeratosis Plantaris Palmaris et Disseminata

A 3-mm punch biopsy of the right upper arm showed incipient cornoid lamellae formation, pigment incontinence, and sparse dermal lymphocytic inflammation (Figure), suggestive of porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata (PPPD). The dermatopathologist recommended a second biopsy to confirm the diagnosis and to confirm that the lesions on the palms and soles also were suggestive of porokeratosis. A second 4-mm punch biopsy of the left palm was consistent with PPPD.

The risks of PPPD as a precancerous entity along with the benefits and side effects of the various management options were discussed with our patient. We recommended that he start low-dose isotretinoin (20 mg/d) due to the large body surface area affected, making focal and field treatments likely insufficient. However, our patient opted not to treat and did not return for follow-up.

Subtypes of porokeratosis, including disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP) and PPPD, are conditions that disrupt the normal maturation of keratin and present clinically with symmetric, crusted, annular papules.1 The signature but nonspecific histopathologic feature shared among the subtypes is the presence of a cornoid lamellae.2 Several triggers of porokeratosis have been proposed, including trauma and exposure to UV and ionizing radiation.2,3 The clinical variants of porokeratosis are important conditions to diagnose correctly because they portend a risk for Bowen disease and invasive squamous cell carcinoma and may indicate the presence of an underlying hematologic and/or solid organ malignancy.4 Management of porokeratosis is difficult, as treatments have shown limited efficacy and variable recurrence rates. Treatment options include focal, field, and systemic options, such as 5-fluorouracil, topical compound of cholesterol and lovastatin, isotretinoin, and acitretin.1,2

Porokeratoses may arise from gene mutations in the mevalonate pathway,5 which is essential for the production of cholesterol.6 Topical cholesterol alone has not been shown to improve porokeratosis, but the combination topical therapy of cholesterol and lovastatin is promising. It is theorized to deliver benefit by both providing the essential end product of the pathway and simultaneously reducing the number of potentially toxic intermediates.6

Porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata (also known as porokeratosis plantaris) is unique among the subtypes of porokeratosis in that its annular, red-pink, papular rash with scaling and a keratotic border tends to start distally, involving the palms and soles, and progresses proximally to the trunk with smaller lesions.1,7 This centripetal progression can take years, as was seen in our patient.1 The disease is uncommon, with a dearth of published reports on PPPD.2 However, case reports have shown that PPPD is strongly linked to family history and may have an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern. Penetrance is greater in men than in women, as PPPD is twice as common in men.8 Most cases of PPPD have been diagnosed in patients in their 20s and 30s, but Hartman et al9 reported a case wherein a patient was diagnosed with PPPD after 65 years of age, similar to our patient.

Although the lesions in DSAP can appear similar to those in PPPD, DSAP is more common among the family of porokeratotic conditions, affecting women twice as often as men, with a sporadic pattern of inheritance.2 These same features are present in some other types of porokeratosis but not PPPD. Furthermore, DSAP progresses proximally to distally but often with truncal sparing.2

Akin to PPPD, pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) often presents with palmoplantar keratoderma.10 There are at least 6 types of PRP with varying degrees of similarity to PPPD. However, in many cases PRP is associated with a background of diffuse erythema on the body with islands of spared skin. In addition, cases of PRP have been linked to extracutaneous findings such as ectropion and joint pain.11

Darier disease, especially the acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf variant, is more common in men and involves younger populations, as in PPPD.11 However, the crusted lesions seen in Darier disease frequently involve the skin folds. These intertriginous lesions may coalesce, mimicking warts in appearance, and are at risk for secondary infection. Nail findings in Darier disease also are distinct and include longitudinal white or red stripes running along the nail bed, in addition to V-shaped nicks at the nail tips.

Psoriasis can occur anywhere on the body and is associated with silver scaling atop a salmon-colored dermatitis.12 It results from aberrant proliferation of keratinocytes. Some distinguishing features of psoriasis include a disease course that waxes and wanes as well as pitting of the nails.

Although PPPD typically affects young adults, we presented a case of PPPD in an older man. Porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata in older adults may represent a delayed diagnosis, imply a broader range for the age of onset, or suggest its manifestation secondary to radiation treatment or another phenomenon. For example, our patient received 35 radiotherapy cycles for tongue cancer more than 5 years prior to the onset of PPPD.

- Irisawa R, Yamazaki M, Yamamoto T, et al. A case of porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:5.

- Vargas-Mora P, Morgado-Carrasco D, Fusta-Novell X. Porokeratosis: a review of its pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111:545-560.

- James AJ, Clarke LE, Elenitsas R, et al. Segmental porokeratosis after radiation therapy for follicular lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(2 suppl):S49-S50.

- Schena D, Papagrigoraki A, Frigo A, et al. Eruptive disseminated porokeratosis associated with internal malignancies: a case report. Cutis. 2010;85:156-159.

- Zhang Z, Li C, Wu F, et al. Genomic variations of the mevalonate pathway in porokeratosis. Elife. 2015;4:E06322. doi:10.7554/eLife.06322

- Atzmony L, Lim YH, Hamilton C, et al. Topical cholesterol/lovastatin for the treatment of porokeratosis: a pathogenesis-directed therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:123-131. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.043

- Guss SB, Osbourn RA, Lutzner MA. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris, et disseminata. a third type of porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:366-373.

- Kanitakis J. Porokeratoses: an update of clinical, aetiopathogenic and therapeutic features. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:533-544.

- Hartman R, Mandal R, Sanchez M, et al. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris, et disseminata. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:22.

- Suryawanshi H, Dhobley A, Sharma A, et al. Darier disease: a rare genodermatosis. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2017;21:321. doi:10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_170_16

- Eastham AB. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:404. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5030

- Nair PA, Badri T. Psoriasis. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated April 6, 2022. Accessed March 13, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448194/

- Irisawa R, Yamazaki M, Yamamoto T, et al. A case of porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:5.

- Vargas-Mora P, Morgado-Carrasco D, Fusta-Novell X. Porokeratosis: a review of its pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111:545-560.

- James AJ, Clarke LE, Elenitsas R, et al. Segmental porokeratosis after radiation therapy for follicular lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(2 suppl):S49-S50.

- Schena D, Papagrigoraki A, Frigo A, et al. Eruptive disseminated porokeratosis associated with internal malignancies: a case report. Cutis. 2010;85:156-159.

- Zhang Z, Li C, Wu F, et al. Genomic variations of the mevalonate pathway in porokeratosis. Elife. 2015;4:E06322. doi:10.7554/eLife.06322

- Atzmony L, Lim YH, Hamilton C, et al. Topical cholesterol/lovastatin for the treatment of porokeratosis: a pathogenesis-directed therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:123-131. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.043

- Guss SB, Osbourn RA, Lutzner MA. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris, et disseminata. a third type of porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:366-373.

- Kanitakis J. Porokeratoses: an update of clinical, aetiopathogenic and therapeutic features. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:533-544.

- Hartman R, Mandal R, Sanchez M, et al. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris, et disseminata. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:22.

- Suryawanshi H, Dhobley A, Sharma A, et al. Darier disease: a rare genodermatosis. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2017;21:321. doi:10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_170_16

- Eastham AB. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:404. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5030

- Nair PA, Badri T. Psoriasis. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated April 6, 2022. Accessed March 13, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448194/

A 67-year-old man presented to our office with a rash on the hands, feet, and periungual skin that began with wartlike growths many years prior and recently had started to involve the proximal arms and legs up to the thighs as well as the trunk. He had a medical history of essential hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He had an 18-year smoking history and had quit more than 25 years prior, with tongue cancer diagnosed more than 5 years prior that was treated with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation. The lesions occasionally were itchy but not painful. He also reported that his nails frequently split down the middle. He denied any oral lesions and was not using any treatments for the rash. He had no history of skin cancer or other skin conditions. His family history was unclear. Physical examination revealed annular red-pink scaling with a keratotic border on the soles of the feet, palms, and periungual skin. There also were small hyperpigmented papules on the arms, legs, thighs, and trunk over a background of dry and discolored skin, as well as dystrophy of all nails.

Annular Erythematous Plaques With Central Hypopigmentation on Sun-Exposed Skin

A biopsy showed a markedly elastotic dermis consisting of a palisading granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate and numerous multinucleated histiocytes (Figure). These histopathologic findings along with the clinical presentation confirmed a diagnosis of annular elastolytic granuloma (AEG). Treatment consisting of 3 months of oral minocycline, 2 months of oral doxycycline, and clobetasol ointment all failed. At that point, oral hydroxychloroquine was recommended. Our patient was lost to follow-up by dermatology, then subsequently was placed on hydroxychloroquine by rheumatology to treat both the osteoarthritis and AEG. A follow-up appointment with dermatology was planned for 3 months to monitor hydroxychloroquine treatment and monitor treatment progress; however, she did not follow-up or seek further treatment.

Annular elastolytic granuloma clinically is similar to granuloma annulare (GA), with both presenting as annular plaques surrounded by an elevated border.1 Although AEG clinically is distinct with hypopigmented atrophied plaque centers,2 a biopsy is required to confirm the lack of elastic tissue in zones of atrophy and the presence of multinucleated histiocytes.1,3 Lesions most commonly are seen clinically on sun-exposed areas in middle-aged White women; however, they rarely have been seen on frequently covered skin.4 Our case illustrates the striking photodistribution of AEG, especially on the posterior neck area. The clinical diagnoses of AEG, annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma, and GA in sun-exposed areas are synonymous and can be used interchangeably.5,6

Pathologies considered in the diagnosis of AEG include but are not limited to tinea corporis, annular lichen planus, erythema annulare centrifugum, and necrobiosis lipoidica. Scaling typically is absent in AEG, while tinea corporis presents with hyphae within the stratum corneum of the plaques.7 Papules along the periphery of annular lesions are more typical of annular lichen planus than AEG, and they tend to have a more purple hue.8 Erythema annulare centrifugum has annular erythematous plaques similar to those found in AEG but differs with scaling on the inner margins of these plaques. Histopathology presenting with a lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding vasculature and no indication of elastolytic degradation would further indicate a diagnosis of erythema annulare centrifugum.9 Histopathology showing necrobiosis, lipid depositions, and vascular wall thickenings is indicative of necrobiosis lipoidica.10

Similar to GA,11 the cause of AEG is idiopathic.2 Annular elastolytic granuloma and GA differ in the fact that elastin degradation is characteristic of AEG compared to collagen degradation in GA. It is suspected that elastin degradation in AEG patients is caused by an immune response triggering phagocytosis of elastin by multinucleated histiocytes.2 Actinic damage also is considered a possible cause of elastin fiber degradation in AEG.12 Granuloma annulare can be ruled out and the diagnosis of AEG confirmed with the absence of elastin fibers and mucin on pathology.13

Although there is no established first-line treatment of AEG, successful treatment has been achieved with antimalarial drugs paired with topical steroids.14 Treatment recommendations for AEG include minocycline, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, tranilast, and oral retinoids, as well as oral and topical steroids. In clinical cases where AEG occurs in the setting of a chronic disease such as diabetes mellitus, vascular occlusion, arthritis, or hypertension, treatment of underlying disease has been shown to resolve AEG symptoms.14