User login

Slow-growing, Asymptomatic, Annular Plaques on the Bilateral Palms

The Diagnosis: Circumscribed Palmar Hypokeratosis

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a rare, benign, acquired dermatosis that was first described by Pérez et al1 in 2002 and is characterized by annular plaques with an atrophic center and hyperkeratotic edges. Classically, the lesions present on the thenar and hypothenar eminences of the palms.2 The condition predominantly affects women (4:1 ratio), with a mean age of onset of 65 years.3

Although the pathogenesis of circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is unknown, local trauma generally is considered to be the causative factor. Other hypotheses include human papillomaviruses 4 and 6 infection and primary abnormal keratinization in the epidermis.3 Immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated increased expression of keratin 16 and Ki-67 in cutaneous lesions, which is postulated to be responsible for keratinocyte fragility associated with epidermal hyperproliferation. Other reported cases have shown diminished keratin 9, keratin 2e, and connexin 26 expression, which normally are abundant in the acral epidermis. Abnormal expression of antigens associated with epidermal proliferation and differentiation also have been reported,3 suggesting that there is an altered regulation of the cutaneous desquamation process.

Histologically, circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is characterized by an abrupt reduction in the stratum corneum (Figure), forming a step between the lesion and the perilesional normal skin.2,3 The clinical appearance of erythema is due to visualization of dermal blood circulation in the area of corneal thinning and is not a result of vasodilation. The dermis is uninvolved, and inflammation is absent. The differential diagnosis includes psoriasis, Bowen disease, porokeratosis, and dermatophytosis.3

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a chronic condition, and there are no known reports of development of malignancy. Treatment is not required but may include cryotherapy; topical therapy with corticosteroids, retinoids, urea, and calcipotriene; and photodynamic therapy. Circumscribed hypokeratosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of palmar lesions.

- Pérez A, Rütten A, Gold R, et al. Circumscribed palmar or plantar hypokeratosis: a distinctive epidermal malformation of the palms or soles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:21-27.

- Mitkov M, Balagula Y, Lockshin B. Case report: circumscribed plantar hypokeratosis. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E203-E205.

- Rocha L, Nico M. Circumscribed palmoplantar hypokeratosis: report of two Brazilian cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:623-626.

The Diagnosis: Circumscribed Palmar Hypokeratosis

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a rare, benign, acquired dermatosis that was first described by Pérez et al1 in 2002 and is characterized by annular plaques with an atrophic center and hyperkeratotic edges. Classically, the lesions present on the thenar and hypothenar eminences of the palms.2 The condition predominantly affects women (4:1 ratio), with a mean age of onset of 65 years.3

Although the pathogenesis of circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is unknown, local trauma generally is considered to be the causative factor. Other hypotheses include human papillomaviruses 4 and 6 infection and primary abnormal keratinization in the epidermis.3 Immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated increased expression of keratin 16 and Ki-67 in cutaneous lesions, which is postulated to be responsible for keratinocyte fragility associated with epidermal hyperproliferation. Other reported cases have shown diminished keratin 9, keratin 2e, and connexin 26 expression, which normally are abundant in the acral epidermis. Abnormal expression of antigens associated with epidermal proliferation and differentiation also have been reported,3 suggesting that there is an altered regulation of the cutaneous desquamation process.

Histologically, circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is characterized by an abrupt reduction in the stratum corneum (Figure), forming a step between the lesion and the perilesional normal skin.2,3 The clinical appearance of erythema is due to visualization of dermal blood circulation in the area of corneal thinning and is not a result of vasodilation. The dermis is uninvolved, and inflammation is absent. The differential diagnosis includes psoriasis, Bowen disease, porokeratosis, and dermatophytosis.3

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a chronic condition, and there are no known reports of development of malignancy. Treatment is not required but may include cryotherapy; topical therapy with corticosteroids, retinoids, urea, and calcipotriene; and photodynamic therapy. Circumscribed hypokeratosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of palmar lesions.

The Diagnosis: Circumscribed Palmar Hypokeratosis

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a rare, benign, acquired dermatosis that was first described by Pérez et al1 in 2002 and is characterized by annular plaques with an atrophic center and hyperkeratotic edges. Classically, the lesions present on the thenar and hypothenar eminences of the palms.2 The condition predominantly affects women (4:1 ratio), with a mean age of onset of 65 years.3

Although the pathogenesis of circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is unknown, local trauma generally is considered to be the causative factor. Other hypotheses include human papillomaviruses 4 and 6 infection and primary abnormal keratinization in the epidermis.3 Immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated increased expression of keratin 16 and Ki-67 in cutaneous lesions, which is postulated to be responsible for keratinocyte fragility associated with epidermal hyperproliferation. Other reported cases have shown diminished keratin 9, keratin 2e, and connexin 26 expression, which normally are abundant in the acral epidermis. Abnormal expression of antigens associated with epidermal proliferation and differentiation also have been reported,3 suggesting that there is an altered regulation of the cutaneous desquamation process.

Histologically, circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is characterized by an abrupt reduction in the stratum corneum (Figure), forming a step between the lesion and the perilesional normal skin.2,3 The clinical appearance of erythema is due to visualization of dermal blood circulation in the area of corneal thinning and is not a result of vasodilation. The dermis is uninvolved, and inflammation is absent. The differential diagnosis includes psoriasis, Bowen disease, porokeratosis, and dermatophytosis.3

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a chronic condition, and there are no known reports of development of malignancy. Treatment is not required but may include cryotherapy; topical therapy with corticosteroids, retinoids, urea, and calcipotriene; and photodynamic therapy. Circumscribed hypokeratosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of palmar lesions.

- Pérez A, Rütten A, Gold R, et al. Circumscribed palmar or plantar hypokeratosis: a distinctive epidermal malformation of the palms or soles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:21-27.

- Mitkov M, Balagula Y, Lockshin B. Case report: circumscribed plantar hypokeratosis. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E203-E205.

- Rocha L, Nico M. Circumscribed palmoplantar hypokeratosis: report of two Brazilian cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:623-626.

- Pérez A, Rütten A, Gold R, et al. Circumscribed palmar or plantar hypokeratosis: a distinctive epidermal malformation of the palms or soles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:21-27.

- Mitkov M, Balagula Y, Lockshin B. Case report: circumscribed plantar hypokeratosis. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E203-E205.

- Rocha L, Nico M. Circumscribed palmoplantar hypokeratosis: report of two Brazilian cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:623-626.

A 77-year-old woman presented with slow-growing, asymptomatic, annular plaques on the bilateral palms of many years' duration. There was no history of trauma or local infection. Prior treatment with over-the-counter creams was unsuccessful. A 3-mm punch biopsy of the lesion on the right palm was performed.

Painful Nonhealing Vulvar and Perianal Erosions

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

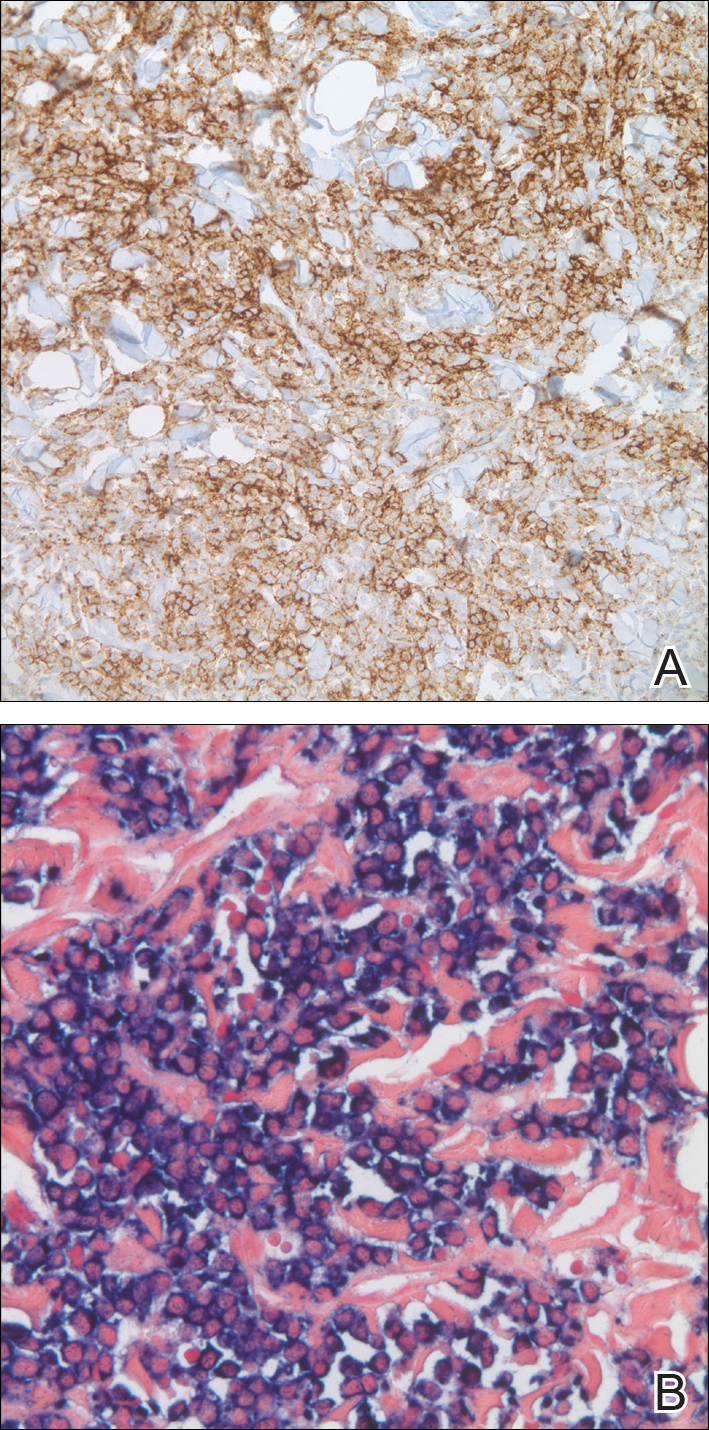

A punch biopsy of the vulvar skin revealed epidermal hyperplasia with moderate spongiosis and exocytosis of lymphocytes and neutrophils in the epidermis. A brisk mixed inflammatory infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleate foreign body-type giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils in a granulomatous pattern also were present in the dermis (Figure). Periodic acid-Schiff and acid-fast bacillus stains were negative. Given the history of Crohn disease (CD) and the characteristic dermal noncaseating granulomas on histology, the patient was diagnosed with cutaneous CD.

Although the patient was offered a topical corticosteroid, she deferred topical therapy. Given the lack of response to adalimumab, the gastroenterology department switched the patient to a treatment of infliximab 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks. Azathioprine was discontinued and the patient was switched to intramuscular methotrexate 25 mg/mL weekly. Slow reepithelialization of the vulvar and perianal erosions occurred on this regimen.

Although CD has numerous cutaneous features, cutaneous CD, also known as metastatic CD, is the rarest cutaneous manifestation of CD.1 This disease process is characterized by noncaseating granulomatous cutaneous lesions that are not contiguous with the affected gastrointestinal tract.2 The pathogenesis of cutaneous CD is unknown. Young adults tend to be more predisposed to developing cutaneous CD, likely due to the age distribution of CD.3

Cutaneous CD commonly presents in patients with a well-established history of gastrointestinal CD but occasionally can be the presenting sign of CD.1 The most common sites of involvement are the legs, vulva, penis, trunk, face, and intertriginous areas. Cutaneous CD findings can be divided into 2 subgroups: genital and nongenital lesions. Genital findings involve ulceration, erythema, edema, and fissuring of the vulva, labia, clitoris, scrotum, penis, and perineum. Nongenital cutaneous manifestations include ulcers; erythematous papules, plaques, and nodules; abscesslike lesions; and lichenoid papules.4,5 The severity of cutaneous lesions does not correlate to the severity of gastrointestinal disease; however, colon involvement is more common in patients with cutaneous CD.6

Histologically, cutaneous CD presents as noncaseating granulomatous inflammation in the papillary and reticular dermis. These granulomas consist of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells with a lymphocytic infiltrate.5

Given the rarity of cutaneous CD, treatment approach is based on anecdotal evidence from case reports and case series. For a single lesion or localized disease, topical superpotent or intralesional steroids are recommended for initial therapy.3 Oral metronidazole also is an effective treatment and can be combined with topical or intralesional steroids.7 For disseminated disease, systemic corticosteroids have shown efficacy.3 Other reported treatment options include oral corticosteroids, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, infliximab, and adalimumab. If monotherapy fails, combination therapy may be needed. Surgical debridement may be attempted if medical therapy fails but is complicated by wound dehiscence and disease recurrence.3

Although genital ulcers can be a presentation of Behçet disease and genital herpes infection, genital nodules and plaques are not typical for these 2 diseases. Also, the patient did not have oral ulcers, which is a common feature of Behçet disease. Genital sarcoidosis is extremely rare, and cutaneous CD was more likely given the patient's medical history. Finally, Jacquet dermatitis is more common in children, and patients with this condition typically have history of fecal and urinary incontinence.

- Teixeira M, Machado S, Lago P, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1074-1076.

- Stingeni L, Neve D, Bassotti G, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease successfully treated with adalimumab [published online Sep 15, 2015]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2016;30:E72-E74.

- Kurtzman DJ, Jones T, Fangru L, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review and approach to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:804-813.

- Hagen JW, Swoger JM, Grandinetti LM. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:417-431.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review [published online June 19, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Thrash B, Patel M, Shah KR, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease, part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:211.e1-211.e33.

- Abide JM. Metastatic Crohn disease: clearance with metronidazole. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:448-449.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

A punch biopsy of the vulvar skin revealed epidermal hyperplasia with moderate spongiosis and exocytosis of lymphocytes and neutrophils in the epidermis. A brisk mixed inflammatory infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleate foreign body-type giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils in a granulomatous pattern also were present in the dermis (Figure). Periodic acid-Schiff and acid-fast bacillus stains were negative. Given the history of Crohn disease (CD) and the characteristic dermal noncaseating granulomas on histology, the patient was diagnosed with cutaneous CD.

Although the patient was offered a topical corticosteroid, she deferred topical therapy. Given the lack of response to adalimumab, the gastroenterology department switched the patient to a treatment of infliximab 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks. Azathioprine was discontinued and the patient was switched to intramuscular methotrexate 25 mg/mL weekly. Slow reepithelialization of the vulvar and perianal erosions occurred on this regimen.

Although CD has numerous cutaneous features, cutaneous CD, also known as metastatic CD, is the rarest cutaneous manifestation of CD.1 This disease process is characterized by noncaseating granulomatous cutaneous lesions that are not contiguous with the affected gastrointestinal tract.2 The pathogenesis of cutaneous CD is unknown. Young adults tend to be more predisposed to developing cutaneous CD, likely due to the age distribution of CD.3

Cutaneous CD commonly presents in patients with a well-established history of gastrointestinal CD but occasionally can be the presenting sign of CD.1 The most common sites of involvement are the legs, vulva, penis, trunk, face, and intertriginous areas. Cutaneous CD findings can be divided into 2 subgroups: genital and nongenital lesions. Genital findings involve ulceration, erythema, edema, and fissuring of the vulva, labia, clitoris, scrotum, penis, and perineum. Nongenital cutaneous manifestations include ulcers; erythematous papules, plaques, and nodules; abscesslike lesions; and lichenoid papules.4,5 The severity of cutaneous lesions does not correlate to the severity of gastrointestinal disease; however, colon involvement is more common in patients with cutaneous CD.6

Histologically, cutaneous CD presents as noncaseating granulomatous inflammation in the papillary and reticular dermis. These granulomas consist of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells with a lymphocytic infiltrate.5

Given the rarity of cutaneous CD, treatment approach is based on anecdotal evidence from case reports and case series. For a single lesion or localized disease, topical superpotent or intralesional steroids are recommended for initial therapy.3 Oral metronidazole also is an effective treatment and can be combined with topical or intralesional steroids.7 For disseminated disease, systemic corticosteroids have shown efficacy.3 Other reported treatment options include oral corticosteroids, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, infliximab, and adalimumab. If monotherapy fails, combination therapy may be needed. Surgical debridement may be attempted if medical therapy fails but is complicated by wound dehiscence and disease recurrence.3

Although genital ulcers can be a presentation of Behçet disease and genital herpes infection, genital nodules and plaques are not typical for these 2 diseases. Also, the patient did not have oral ulcers, which is a common feature of Behçet disease. Genital sarcoidosis is extremely rare, and cutaneous CD was more likely given the patient's medical history. Finally, Jacquet dermatitis is more common in children, and patients with this condition typically have history of fecal and urinary incontinence.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

A punch biopsy of the vulvar skin revealed epidermal hyperplasia with moderate spongiosis and exocytosis of lymphocytes and neutrophils in the epidermis. A brisk mixed inflammatory infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleate foreign body-type giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils in a granulomatous pattern also were present in the dermis (Figure). Periodic acid-Schiff and acid-fast bacillus stains were negative. Given the history of Crohn disease (CD) and the characteristic dermal noncaseating granulomas on histology, the patient was diagnosed with cutaneous CD.

Although the patient was offered a topical corticosteroid, she deferred topical therapy. Given the lack of response to adalimumab, the gastroenterology department switched the patient to a treatment of infliximab 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks. Azathioprine was discontinued and the patient was switched to intramuscular methotrexate 25 mg/mL weekly. Slow reepithelialization of the vulvar and perianal erosions occurred on this regimen.

Although CD has numerous cutaneous features, cutaneous CD, also known as metastatic CD, is the rarest cutaneous manifestation of CD.1 This disease process is characterized by noncaseating granulomatous cutaneous lesions that are not contiguous with the affected gastrointestinal tract.2 The pathogenesis of cutaneous CD is unknown. Young adults tend to be more predisposed to developing cutaneous CD, likely due to the age distribution of CD.3

Cutaneous CD commonly presents in patients with a well-established history of gastrointestinal CD but occasionally can be the presenting sign of CD.1 The most common sites of involvement are the legs, vulva, penis, trunk, face, and intertriginous areas. Cutaneous CD findings can be divided into 2 subgroups: genital and nongenital lesions. Genital findings involve ulceration, erythema, edema, and fissuring of the vulva, labia, clitoris, scrotum, penis, and perineum. Nongenital cutaneous manifestations include ulcers; erythematous papules, plaques, and nodules; abscesslike lesions; and lichenoid papules.4,5 The severity of cutaneous lesions does not correlate to the severity of gastrointestinal disease; however, colon involvement is more common in patients with cutaneous CD.6

Histologically, cutaneous CD presents as noncaseating granulomatous inflammation in the papillary and reticular dermis. These granulomas consist of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells with a lymphocytic infiltrate.5

Given the rarity of cutaneous CD, treatment approach is based on anecdotal evidence from case reports and case series. For a single lesion or localized disease, topical superpotent or intralesional steroids are recommended for initial therapy.3 Oral metronidazole also is an effective treatment and can be combined with topical or intralesional steroids.7 For disseminated disease, systemic corticosteroids have shown efficacy.3 Other reported treatment options include oral corticosteroids, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, infliximab, and adalimumab. If monotherapy fails, combination therapy may be needed. Surgical debridement may be attempted if medical therapy fails but is complicated by wound dehiscence and disease recurrence.3

Although genital ulcers can be a presentation of Behçet disease and genital herpes infection, genital nodules and plaques are not typical for these 2 diseases. Also, the patient did not have oral ulcers, which is a common feature of Behçet disease. Genital sarcoidosis is extremely rare, and cutaneous CD was more likely given the patient's medical history. Finally, Jacquet dermatitis is more common in children, and patients with this condition typically have history of fecal and urinary incontinence.

- Teixeira M, Machado S, Lago P, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1074-1076.

- Stingeni L, Neve D, Bassotti G, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease successfully treated with adalimumab [published online Sep 15, 2015]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2016;30:E72-E74.

- Kurtzman DJ, Jones T, Fangru L, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review and approach to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:804-813.

- Hagen JW, Swoger JM, Grandinetti LM. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:417-431.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review [published online June 19, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Thrash B, Patel M, Shah KR, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease, part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:211.e1-211.e33.

- Abide JM. Metastatic Crohn disease: clearance with metronidazole. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:448-449.

- Teixeira M, Machado S, Lago P, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1074-1076.

- Stingeni L, Neve D, Bassotti G, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease successfully treated with adalimumab [published online Sep 15, 2015]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2016;30:E72-E74.

- Kurtzman DJ, Jones T, Fangru L, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review and approach to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:804-813.

- Hagen JW, Swoger JM, Grandinetti LM. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:417-431.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review [published online June 19, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Thrash B, Patel M, Shah KR, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease, part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:211.e1-211.e33.

- Abide JM. Metastatic Crohn disease: clearance with metronidazole. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:448-449.

A 38-year-old woman with a history of Crohn disease presented with painful nonhealing vulvar and perianal erosions of 6 months' duration. The erosions developed 4 months after discontinuing adalimumab for a planned surgery. During this time, the patient also had an exacerbation of Crohn colitis and developed an anal fistula. Prior to this break in adalimumab, the patient's Crohn disease was well controlled on adalimumab 40 mg every 2 weeks, azathioprine 100 mg daily, and mesalamine 4.8 g daily. Despite restarting adalimumab and therapy with multiple antibiotics (ie, metronidazole, ciprofloxacin), the erosions persisted. On physical examination erythematous plaques and nodules were present at the vulvar (top) and perianal (bottom) skin. In addition, well-demarcated erosions measuring 20 mm and 80 mm were present on the vulvar and perianal skin, respectively. Human immunodeficiency virus screening and rapid plasma reagin were negative.

Scaly Annular and Concentric Plaques

The Diagnosis: Annular Psoriasis

Because the patient's history was nonconcordant with the clinical appearance, a 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from a lesion on the left hip. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections demonstrated mild irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with discrete mounds of parakeratin (Figure 1A). Higher power revealed numerous neutrophils entrapped within focal scale crusts (Figure 1B). Periodic acid-Schiff stain for fungus demonstrated no hyphal elements or yeast forms in the stratum corneum. These histopathology findings were consistent with the diagnosis of annular psoriasis.

The manifestation of psoriasis may take many forms, ranging from classic plaques to pustular eruptions--either annular or generalized--and erythroderma. Primarily annular plaque-type psoriasis without pustules, however, remains an uncommon finding.1 Psoriatic plaques may become annular or arcuate with central clearing from partial treatment with topical medications, though our patient reported annular plaques prior to any treatment. His presentation was notably different than annular pustular psoriasis in that there were no pustules in the leading edge, and there was no trailing scale, which is typical of annular pustular psoriasis.

Topical triamcinolone prescribed at the initial presentation to the dermatology department helped with pruritus, but due to the large body surface area involved, methotrexate later was initiated. After a 10-mg test dose of methotrexate and titration to 15 mg weekly, dramatic improvement in the rash was noted after 8 weeks. As the rash resolved, only faint hyperpigmented patches remained (Figure 2).

Erythema gyratum repens is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome that presents with annular scaly plaques with concentric circles with a wood grain-like appearance. The borders can advance up to 1 cm daily and show nonspecific findings on histopathology.2 Due to the observation that approximately 80% of cases of erythema gyratum repens were associated with an underlying malignancy, most often of the lung,3 this diagnosis was entertained given our patient's clinical presentation.

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) historically has been divided into 2 forms: superficial and deep.4 Both present with slowly expanding, annular, pink plaques. Superficial EAC demonstrates parakeratosis and trailing scale and has not been proven to be associated with other systemic diseases, while deep EAC has infiltrated borders without scale, and many cases of EAC may represent annular forms of tumid lupus.4 Inflammatory cells may cuff vessels tightly, resulting in so-called coat sleeve infiltrate in superficial EAC. Along with trailing scale, this finding suggests the diagnosis. It has been argued that EAC is not an entity on its own and should prompt evaluation for lupus erythematosus, dermatitis, hypersensitivity to tinea pedis, and Lyme disease in appropriate circumstances.5

Tinea corporis always should be considered when evaluating annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Diagnosis and treatment are straightforward when hyphae are found on microscopy of skin scrapings or seen on periodic acid-Schiff stains of formalin-fixed tissue. Tinea imbricata presents with an interesting morphology and appears more ornate or cerebriform than tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. It is caused by infection with Trichophyton circumscriptum and occurs in certain regions in the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America, making the diagnosis within the United States unlikely for a patient who has not traveled to these areas.6

Erythema chronicum migrans is diagnostic of Lyme disease infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, and solitary lesions occur surrounding the site of a tick bite in the majority of patients. Only 20% of patients will develop multiple lesions consistent with erythema chronicum migrans due to multiple tick bites, spirochetemia, or lymphatic spread.7 Up to one-third of patients are unaware that they were bitten by a tick. In endemic areas, this diagnosis must be entertained in any patient presenting with an annular rash, as treatment may prevent notable morbidity.

- Guill C, Hoang M, Carder K. Primary annular plaque-type psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:15-18.

- Boyd A, Neldner K, Menter A. Erythema gyratum repens: a paraneoplastic eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:757-762.

- Kawakami T, Saito R. Erythema gyratum repens unassociated with underlying malignancy. J Dermatol. 1995;22:587-589.

- Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

- Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does notrepresent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

- Bonifaz A, Vázquez-González D. Tinea imbricata in the Americas. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:106-111.

- Müllegger R, Glatz M. Skin manifestations of Lyme borreliosis: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:355-368.

The Diagnosis: Annular Psoriasis

Because the patient's history was nonconcordant with the clinical appearance, a 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from a lesion on the left hip. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections demonstrated mild irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with discrete mounds of parakeratin (Figure 1A). Higher power revealed numerous neutrophils entrapped within focal scale crusts (Figure 1B). Periodic acid-Schiff stain for fungus demonstrated no hyphal elements or yeast forms in the stratum corneum. These histopathology findings were consistent with the diagnosis of annular psoriasis.

The manifestation of psoriasis may take many forms, ranging from classic plaques to pustular eruptions--either annular or generalized--and erythroderma. Primarily annular plaque-type psoriasis without pustules, however, remains an uncommon finding.1 Psoriatic plaques may become annular or arcuate with central clearing from partial treatment with topical medications, though our patient reported annular plaques prior to any treatment. His presentation was notably different than annular pustular psoriasis in that there were no pustules in the leading edge, and there was no trailing scale, which is typical of annular pustular psoriasis.

Topical triamcinolone prescribed at the initial presentation to the dermatology department helped with pruritus, but due to the large body surface area involved, methotrexate later was initiated. After a 10-mg test dose of methotrexate and titration to 15 mg weekly, dramatic improvement in the rash was noted after 8 weeks. As the rash resolved, only faint hyperpigmented patches remained (Figure 2).

Erythema gyratum repens is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome that presents with annular scaly plaques with concentric circles with a wood grain-like appearance. The borders can advance up to 1 cm daily and show nonspecific findings on histopathology.2 Due to the observation that approximately 80% of cases of erythema gyratum repens were associated with an underlying malignancy, most often of the lung,3 this diagnosis was entertained given our patient's clinical presentation.

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) historically has been divided into 2 forms: superficial and deep.4 Both present with slowly expanding, annular, pink plaques. Superficial EAC demonstrates parakeratosis and trailing scale and has not been proven to be associated with other systemic diseases, while deep EAC has infiltrated borders without scale, and many cases of EAC may represent annular forms of tumid lupus.4 Inflammatory cells may cuff vessels tightly, resulting in so-called coat sleeve infiltrate in superficial EAC. Along with trailing scale, this finding suggests the diagnosis. It has been argued that EAC is not an entity on its own and should prompt evaluation for lupus erythematosus, dermatitis, hypersensitivity to tinea pedis, and Lyme disease in appropriate circumstances.5

Tinea corporis always should be considered when evaluating annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Diagnosis and treatment are straightforward when hyphae are found on microscopy of skin scrapings or seen on periodic acid-Schiff stains of formalin-fixed tissue. Tinea imbricata presents with an interesting morphology and appears more ornate or cerebriform than tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. It is caused by infection with Trichophyton circumscriptum and occurs in certain regions in the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America, making the diagnosis within the United States unlikely for a patient who has not traveled to these areas.6

Erythema chronicum migrans is diagnostic of Lyme disease infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, and solitary lesions occur surrounding the site of a tick bite in the majority of patients. Only 20% of patients will develop multiple lesions consistent with erythema chronicum migrans due to multiple tick bites, spirochetemia, or lymphatic spread.7 Up to one-third of patients are unaware that they were bitten by a tick. In endemic areas, this diagnosis must be entertained in any patient presenting with an annular rash, as treatment may prevent notable morbidity.

The Diagnosis: Annular Psoriasis

Because the patient's history was nonconcordant with the clinical appearance, a 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from a lesion on the left hip. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections demonstrated mild irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with discrete mounds of parakeratin (Figure 1A). Higher power revealed numerous neutrophils entrapped within focal scale crusts (Figure 1B). Periodic acid-Schiff stain for fungus demonstrated no hyphal elements or yeast forms in the stratum corneum. These histopathology findings were consistent with the diagnosis of annular psoriasis.

The manifestation of psoriasis may take many forms, ranging from classic plaques to pustular eruptions--either annular or generalized--and erythroderma. Primarily annular plaque-type psoriasis without pustules, however, remains an uncommon finding.1 Psoriatic plaques may become annular or arcuate with central clearing from partial treatment with topical medications, though our patient reported annular plaques prior to any treatment. His presentation was notably different than annular pustular psoriasis in that there were no pustules in the leading edge, and there was no trailing scale, which is typical of annular pustular psoriasis.

Topical triamcinolone prescribed at the initial presentation to the dermatology department helped with pruritus, but due to the large body surface area involved, methotrexate later was initiated. After a 10-mg test dose of methotrexate and titration to 15 mg weekly, dramatic improvement in the rash was noted after 8 weeks. As the rash resolved, only faint hyperpigmented patches remained (Figure 2).

Erythema gyratum repens is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome that presents with annular scaly plaques with concentric circles with a wood grain-like appearance. The borders can advance up to 1 cm daily and show nonspecific findings on histopathology.2 Due to the observation that approximately 80% of cases of erythema gyratum repens were associated with an underlying malignancy, most often of the lung,3 this diagnosis was entertained given our patient's clinical presentation.

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) historically has been divided into 2 forms: superficial and deep.4 Both present with slowly expanding, annular, pink plaques. Superficial EAC demonstrates parakeratosis and trailing scale and has not been proven to be associated with other systemic diseases, while deep EAC has infiltrated borders without scale, and many cases of EAC may represent annular forms of tumid lupus.4 Inflammatory cells may cuff vessels tightly, resulting in so-called coat sleeve infiltrate in superficial EAC. Along with trailing scale, this finding suggests the diagnosis. It has been argued that EAC is not an entity on its own and should prompt evaluation for lupus erythematosus, dermatitis, hypersensitivity to tinea pedis, and Lyme disease in appropriate circumstances.5

Tinea corporis always should be considered when evaluating annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Diagnosis and treatment are straightforward when hyphae are found on microscopy of skin scrapings or seen on periodic acid-Schiff stains of formalin-fixed tissue. Tinea imbricata presents with an interesting morphology and appears more ornate or cerebriform than tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. It is caused by infection with Trichophyton circumscriptum and occurs in certain regions in the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America, making the diagnosis within the United States unlikely for a patient who has not traveled to these areas.6

Erythema chronicum migrans is diagnostic of Lyme disease infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, and solitary lesions occur surrounding the site of a tick bite in the majority of patients. Only 20% of patients will develop multiple lesions consistent with erythema chronicum migrans due to multiple tick bites, spirochetemia, or lymphatic spread.7 Up to one-third of patients are unaware that they were bitten by a tick. In endemic areas, this diagnosis must be entertained in any patient presenting with an annular rash, as treatment may prevent notable morbidity.

- Guill C, Hoang M, Carder K. Primary annular plaque-type psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:15-18.

- Boyd A, Neldner K, Menter A. Erythema gyratum repens: a paraneoplastic eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:757-762.

- Kawakami T, Saito R. Erythema gyratum repens unassociated with underlying malignancy. J Dermatol. 1995;22:587-589.

- Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

- Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does notrepresent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

- Bonifaz A, Vázquez-González D. Tinea imbricata in the Americas. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:106-111.

- Müllegger R, Glatz M. Skin manifestations of Lyme borreliosis: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:355-368.

- Guill C, Hoang M, Carder K. Primary annular plaque-type psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:15-18.

- Boyd A, Neldner K, Menter A. Erythema gyratum repens: a paraneoplastic eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:757-762.

- Kawakami T, Saito R. Erythema gyratum repens unassociated with underlying malignancy. J Dermatol. 1995;22:587-589.

- Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

- Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does notrepresent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

- Bonifaz A, Vázquez-González D. Tinea imbricata in the Americas. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:106-111.

- Müllegger R, Glatz M. Skin manifestations of Lyme borreliosis: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:355-368.

A healthy 23-year-old man presented for evaluation of an enlarging annular pruritic rash of 1.5 years' duration. Treatment with ciclopirox cream 0.77%, calcipotriene cream 0.005%, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, fluticasone cream 0.05%, and halobetasol cream 0.05% prescribed by an outside physician provided only modest temporary improvement. The patient reported no history of travel outside of western New York, camping, tick bites, or medications. He denied any joint swelling or morning stiffness. Physical examination revealed multiple 4- to 6-cm pink, annular, scaly plaques with central clearing on the abdomen (top) and thighs. A few 1-cm pink scaly patches were present on the back (bottom), and few 2- to 3-mm pink scaly papules were noted on the extensor aspects of the elbows and forearms. A potassium hydroxide examination revealed no hyphal elements or yeast forms.

Red-Brown Plaque on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Wells Syndrome

A punch biopsy taken from the perimeter of the lesion demonstrated mild spongiosis overlying a dense nodular to diffuse infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and numerous eosinophils, some involving underlying fat lobules (Figure, A and B). In some areas, eosinophilic degeneration of collagen bundles surrounded by a rim of histiocytes, "flame features," were observed (Figure C). The clinical and histological features were consistent with Wells syndrome (WS), also known as eosinophilic cellulitis. Given the localized mild nature of the disease, the patient was started on a midpotency topical corticosteroid.

Wells syndrome is a rare inflammatory condition characterized by clinical polymorphism, suggestive histologic findings, and a recurrent course.1,2 This condition is especially rare in children.3,4 Caputo et al1 described 7 variants in their case series of 19 patients: classic plaque-type variant (the most common clinical presentation in children); annular granuloma-like (the most common clinical presentation in adults); urticarialike; bullous; papulonodular; papulovesicular; and fixed drug eruption-like. Wells syndrome is thought to result from excess production of IL-5 in response to a hypersensitivity reaction to an exogenous or endogenous circulating antigen.3,4 Increased levels of IL-5 enhance eosinophil accumulation in the skin, degranulation, and subsequent tissue destruction.3,4 Reported triggers include insect bites, viral and bacterial infections, drug eruptions, recent vaccination, and paraphenylenediamine in henna tattoos.3-7 Additionally, WS has been reported in the setting of gastrointestinal pathologies, such as celiac disease and ulcerative colitis, and with asthma exacerbations.8,9 However, in half of pediatric cases, no trigger can be identified.7

Clinically, WS presents with pruritic, mildly tender plaques.7 Lesions may be localized or diffuse and range from mild annular or circinate plaques with infiltrated borders to cellulitic-appearing lesions that are occasionally associated with bullae.5,6 Patients often report prodromal symptoms of burning and pruritus.5,6 Lesions rapidly progress over 2 to 3 days, pass through a blue grayish discoloration phase, and gradually resolve over 2 to 8 weeks.5,6,10 Although patients generally heal without scarring, WS lesions have been described to resolve with atrophy and hyperpigmentation resembling morphea.5-7 Additionally, patients typically experience a relapsing remitting course over months to years with eventual spontaneous resolution.1,5 Patients also may experience systemic symptoms including fever, lymphadenopathy, and arthralgia, though they do not develop more widespread systemic manifestations.2,3,7

Diagnosis of WS is based on clinicopathologic correlation. Histopathology of WS lesions demonstrates 3 phases. The acute phase demonstrates edema of the superficial and mid dermis with a dense dermal eosinophilic infiltrate.1,6,10 The subacute granulomatous phase demonstrates flame figures in the dermis.1,2,6,7,10 Flame figures consist of palisading groups of eosinophils and histiocytes around a core of degenerating basophilic collagen bundles associated with major basic protein.1,2,6,7,10 Finally, in the resolution phase, eosinophils gradually disappear while histiocytes and giant cells persist, forming microgranulomas.1,2,10 Notably, no vasculitis is observed and direct immunofluorescence is negative.3,7 Although flame figures are suggestive of WS, they are not pathognomonic and are observed in other conditions including Churg-Strauss syndrome, parasitic and fungal infections, herpes gestationis, bullous pemphigoid, and follicular mucinosis.2,5

Wells syndrome is a self-resolving and benign condition.1,10 Physicians are recommended to gather a complete history including review of medications and vaccinations; a history of insect bites, infections, and asthma; laboratory workup consisting of a complete blood cell count with differential and stool samples for ova and parasites; and a skin biopsy if the diagnosis is unclear.7 Identification and treatment of underlying causes often results in resolution.6 Systemic corticosteroids frequently are used in both adult and pediatric patients, though practitioners should consider alternative treatments when recurrences occur to avoid steroid side effects.3,6 Midpotency topical corticosteroids present a safe alternative to systemic corticosteroids in the pediatric population, especially in cases of localized WS without systemic symptoms.3 Other medications reported in the literature include cyclosporine, dapsone, antimalarial medications, and azathioprine.6 Despite appropriate therapy, patients and physicians should anticipate recurrence over months to years.1,6

- Caputo R, Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

- Smith SM, Kiracofe EA, Clark LN, et al. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome with cutaneous manifestations and flame figures: a spectrum of eosinophilic dermatoses whose features overlap with Wells' syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:910-914.

- Gilliam AE, Bruckner AL, Howard RM, et al. Bullous "cellulitis" with eosinophilia: case report and review of Wells' syndrome in childhood. Pediatrics. 2005;116:E149-E155.

- Nacaroglu HT, Celegen M, Karkıner CS, et al. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells' syndrome) caused by a temporary henna tattoo. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:322-324.

- Heelan K, Ryan JF, Shear NH, et al. Wells syndrome (eosinophilic cellulitis): proposed diagnostic criteria and a literature review of the drug-induced variant. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2013;7:113-120.

- Sinno H, Lacroix JP, Lee J, et al. Diagnosis and management of eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells' syndrome): a case series and literature review. Can J Plast Surg. 2012;20:91-97.

- Cherng E, McClung AA, Rosenthal HM, et al. Wells' syndrome associated with parvovirus in a 5-year-old boy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:762-764.

- Eren M, Açikalin M. A case report of Wells' syndrome in a celiac patient. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2010;21:172-174.

- Cruz MJ, Mota A, Baudrier T, et al. Recurrent Wells' syndrome associated with allergic asthma exacerbation. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:154-156.

- Van der Straaten S, Wojciechowski M, Salgado R, et al. Eosinophilic cellulitis or Wells' syndrome in a 6-year-old child. Eur J Pediatr. 2006;165:197-198.

The Diagnosis: Wells Syndrome

A punch biopsy taken from the perimeter of the lesion demonstrated mild spongiosis overlying a dense nodular to diffuse infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and numerous eosinophils, some involving underlying fat lobules (Figure, A and B). In some areas, eosinophilic degeneration of collagen bundles surrounded by a rim of histiocytes, "flame features," were observed (Figure C). The clinical and histological features were consistent with Wells syndrome (WS), also known as eosinophilic cellulitis. Given the localized mild nature of the disease, the patient was started on a midpotency topical corticosteroid.

Wells syndrome is a rare inflammatory condition characterized by clinical polymorphism, suggestive histologic findings, and a recurrent course.1,2 This condition is especially rare in children.3,4 Caputo et al1 described 7 variants in their case series of 19 patients: classic plaque-type variant (the most common clinical presentation in children); annular granuloma-like (the most common clinical presentation in adults); urticarialike; bullous; papulonodular; papulovesicular; and fixed drug eruption-like. Wells syndrome is thought to result from excess production of IL-5 in response to a hypersensitivity reaction to an exogenous or endogenous circulating antigen.3,4 Increased levels of IL-5 enhance eosinophil accumulation in the skin, degranulation, and subsequent tissue destruction.3,4 Reported triggers include insect bites, viral and bacterial infections, drug eruptions, recent vaccination, and paraphenylenediamine in henna tattoos.3-7 Additionally, WS has been reported in the setting of gastrointestinal pathologies, such as celiac disease and ulcerative colitis, and with asthma exacerbations.8,9 However, in half of pediatric cases, no trigger can be identified.7

Clinically, WS presents with pruritic, mildly tender plaques.7 Lesions may be localized or diffuse and range from mild annular or circinate plaques with infiltrated borders to cellulitic-appearing lesions that are occasionally associated with bullae.5,6 Patients often report prodromal symptoms of burning and pruritus.5,6 Lesions rapidly progress over 2 to 3 days, pass through a blue grayish discoloration phase, and gradually resolve over 2 to 8 weeks.5,6,10 Although patients generally heal without scarring, WS lesions have been described to resolve with atrophy and hyperpigmentation resembling morphea.5-7 Additionally, patients typically experience a relapsing remitting course over months to years with eventual spontaneous resolution.1,5 Patients also may experience systemic symptoms including fever, lymphadenopathy, and arthralgia, though they do not develop more widespread systemic manifestations.2,3,7

Diagnosis of WS is based on clinicopathologic correlation. Histopathology of WS lesions demonstrates 3 phases. The acute phase demonstrates edema of the superficial and mid dermis with a dense dermal eosinophilic infiltrate.1,6,10 The subacute granulomatous phase demonstrates flame figures in the dermis.1,2,6,7,10 Flame figures consist of palisading groups of eosinophils and histiocytes around a core of degenerating basophilic collagen bundles associated with major basic protein.1,2,6,7,10 Finally, in the resolution phase, eosinophils gradually disappear while histiocytes and giant cells persist, forming microgranulomas.1,2,10 Notably, no vasculitis is observed and direct immunofluorescence is negative.3,7 Although flame figures are suggestive of WS, they are not pathognomonic and are observed in other conditions including Churg-Strauss syndrome, parasitic and fungal infections, herpes gestationis, bullous pemphigoid, and follicular mucinosis.2,5

Wells syndrome is a self-resolving and benign condition.1,10 Physicians are recommended to gather a complete history including review of medications and vaccinations; a history of insect bites, infections, and asthma; laboratory workup consisting of a complete blood cell count with differential and stool samples for ova and parasites; and a skin biopsy if the diagnosis is unclear.7 Identification and treatment of underlying causes often results in resolution.6 Systemic corticosteroids frequently are used in both adult and pediatric patients, though practitioners should consider alternative treatments when recurrences occur to avoid steroid side effects.3,6 Midpotency topical corticosteroids present a safe alternative to systemic corticosteroids in the pediatric population, especially in cases of localized WS without systemic symptoms.3 Other medications reported in the literature include cyclosporine, dapsone, antimalarial medications, and azathioprine.6 Despite appropriate therapy, patients and physicians should anticipate recurrence over months to years.1,6

The Diagnosis: Wells Syndrome

A punch biopsy taken from the perimeter of the lesion demonstrated mild spongiosis overlying a dense nodular to diffuse infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and numerous eosinophils, some involving underlying fat lobules (Figure, A and B). In some areas, eosinophilic degeneration of collagen bundles surrounded by a rim of histiocytes, "flame features," were observed (Figure C). The clinical and histological features were consistent with Wells syndrome (WS), also known as eosinophilic cellulitis. Given the localized mild nature of the disease, the patient was started on a midpotency topical corticosteroid.

Wells syndrome is a rare inflammatory condition characterized by clinical polymorphism, suggestive histologic findings, and a recurrent course.1,2 This condition is especially rare in children.3,4 Caputo et al1 described 7 variants in their case series of 19 patients: classic plaque-type variant (the most common clinical presentation in children); annular granuloma-like (the most common clinical presentation in adults); urticarialike; bullous; papulonodular; papulovesicular; and fixed drug eruption-like. Wells syndrome is thought to result from excess production of IL-5 in response to a hypersensitivity reaction to an exogenous or endogenous circulating antigen.3,4 Increased levels of IL-5 enhance eosinophil accumulation in the skin, degranulation, and subsequent tissue destruction.3,4 Reported triggers include insect bites, viral and bacterial infections, drug eruptions, recent vaccination, and paraphenylenediamine in henna tattoos.3-7 Additionally, WS has been reported in the setting of gastrointestinal pathologies, such as celiac disease and ulcerative colitis, and with asthma exacerbations.8,9 However, in half of pediatric cases, no trigger can be identified.7

Clinically, WS presents with pruritic, mildly tender plaques.7 Lesions may be localized or diffuse and range from mild annular or circinate plaques with infiltrated borders to cellulitic-appearing lesions that are occasionally associated with bullae.5,6 Patients often report prodromal symptoms of burning and pruritus.5,6 Lesions rapidly progress over 2 to 3 days, pass through a blue grayish discoloration phase, and gradually resolve over 2 to 8 weeks.5,6,10 Although patients generally heal without scarring, WS lesions have been described to resolve with atrophy and hyperpigmentation resembling morphea.5-7 Additionally, patients typically experience a relapsing remitting course over months to years with eventual spontaneous resolution.1,5 Patients also may experience systemic symptoms including fever, lymphadenopathy, and arthralgia, though they do not develop more widespread systemic manifestations.2,3,7

Diagnosis of WS is based on clinicopathologic correlation. Histopathology of WS lesions demonstrates 3 phases. The acute phase demonstrates edema of the superficial and mid dermis with a dense dermal eosinophilic infiltrate.1,6,10 The subacute granulomatous phase demonstrates flame figures in the dermis.1,2,6,7,10 Flame figures consist of palisading groups of eosinophils and histiocytes around a core of degenerating basophilic collagen bundles associated with major basic protein.1,2,6,7,10 Finally, in the resolution phase, eosinophils gradually disappear while histiocytes and giant cells persist, forming microgranulomas.1,2,10 Notably, no vasculitis is observed and direct immunofluorescence is negative.3,7 Although flame figures are suggestive of WS, they are not pathognomonic and are observed in other conditions including Churg-Strauss syndrome, parasitic and fungal infections, herpes gestationis, bullous pemphigoid, and follicular mucinosis.2,5

Wells syndrome is a self-resolving and benign condition.1,10 Physicians are recommended to gather a complete history including review of medications and vaccinations; a history of insect bites, infections, and asthma; laboratory workup consisting of a complete blood cell count with differential and stool samples for ova and parasites; and a skin biopsy if the diagnosis is unclear.7 Identification and treatment of underlying causes often results in resolution.6 Systemic corticosteroids frequently are used in both adult and pediatric patients, though practitioners should consider alternative treatments when recurrences occur to avoid steroid side effects.3,6 Midpotency topical corticosteroids present a safe alternative to systemic corticosteroids in the pediatric population, especially in cases of localized WS without systemic symptoms.3 Other medications reported in the literature include cyclosporine, dapsone, antimalarial medications, and azathioprine.6 Despite appropriate therapy, patients and physicians should anticipate recurrence over months to years.1,6

- Caputo R, Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

- Smith SM, Kiracofe EA, Clark LN, et al. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome with cutaneous manifestations and flame figures: a spectrum of eosinophilic dermatoses whose features overlap with Wells' syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:910-914.

- Gilliam AE, Bruckner AL, Howard RM, et al. Bullous "cellulitis" with eosinophilia: case report and review of Wells' syndrome in childhood. Pediatrics. 2005;116:E149-E155.

- Nacaroglu HT, Celegen M, Karkıner CS, et al. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells' syndrome) caused by a temporary henna tattoo. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:322-324.

- Heelan K, Ryan JF, Shear NH, et al. Wells syndrome (eosinophilic cellulitis): proposed diagnostic criteria and a literature review of the drug-induced variant. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2013;7:113-120.

- Sinno H, Lacroix JP, Lee J, et al. Diagnosis and management of eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells' syndrome): a case series and literature review. Can J Plast Surg. 2012;20:91-97.

- Cherng E, McClung AA, Rosenthal HM, et al. Wells' syndrome associated with parvovirus in a 5-year-old boy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:762-764.

- Eren M, Açikalin M. A case report of Wells' syndrome in a celiac patient. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2010;21:172-174.

- Cruz MJ, Mota A, Baudrier T, et al. Recurrent Wells' syndrome associated with allergic asthma exacerbation. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:154-156.

- Van der Straaten S, Wojciechowski M, Salgado R, et al. Eosinophilic cellulitis or Wells' syndrome in a 6-year-old child. Eur J Pediatr. 2006;165:197-198.

- Caputo R, Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

- Smith SM, Kiracofe EA, Clark LN, et al. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome with cutaneous manifestations and flame figures: a spectrum of eosinophilic dermatoses whose features overlap with Wells' syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:910-914.

- Gilliam AE, Bruckner AL, Howard RM, et al. Bullous "cellulitis" with eosinophilia: case report and review of Wells' syndrome in childhood. Pediatrics. 2005;116:E149-E155.

- Nacaroglu HT, Celegen M, Karkıner CS, et al. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells' syndrome) caused by a temporary henna tattoo. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:322-324.

- Heelan K, Ryan JF, Shear NH, et al. Wells syndrome (eosinophilic cellulitis): proposed diagnostic criteria and a literature review of the drug-induced variant. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2013;7:113-120.

- Sinno H, Lacroix JP, Lee J, et al. Diagnosis and management of eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells' syndrome): a case series and literature review. Can J Plast Surg. 2012;20:91-97.

- Cherng E, McClung AA, Rosenthal HM, et al. Wells' syndrome associated with parvovirus in a 5-year-old boy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:762-764.

- Eren M, Açikalin M. A case report of Wells' syndrome in a celiac patient. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2010;21:172-174.

- Cruz MJ, Mota A, Baudrier T, et al. Recurrent Wells' syndrome associated with allergic asthma exacerbation. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:154-156.

- Van der Straaten S, Wojciechowski M, Salgado R, et al. Eosinophilic cellulitis or Wells' syndrome in a 6-year-old child. Eur J Pediatr. 2006;165:197-198.

A healthy 7-year-old boy presented with an enlarging hyperpigmented plaque on the anterior aspect of the lower left leg of 2 months' duration. His mother reported onset following a mosquito bite. Clotrimazole was used without improvement. His mother denied recent travel, similar lesions in close contacts, fever, asthma, and arthralgia. Physical examination revealed a 5.2 ×3-cm nonscaly, red-brown, ovoid, thin plaque with a slightly raised border.

Progressive Widespread Telangiectasias

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

Histopathologic examination revealed ectatic blood vessels lined with unremarkable endothelial cells and thickened, hyalinized vessel walls scattered within the papillary dermis (Figure 1). The epidermis was unremarkable. There was minimal associated inflammation and no extravasation of erythrocytes. The hyalinized material was weakly positive on periodic acid-Schiff staining (Figure 2) and negative on Congo red staining, which supported of a diagnosis of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV).

The patient previously had been given a suspected diagnosis of generalized essential telangiectasia by an outside dermatologist several years prior to the current presentation, as CCV had yet to be recognized as its own entity and therefore few cases had been described in the literature. She had a known history of obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus, which are associated with the condition. Multiple specialists concluded that the disease was too extensive for laser treatment. A review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE yielded no established treatment options.

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is a rare acquired microangiopathy involving the small vessels of the skin. Its clinical presentation is indistinguishable from that of generalized essential telangiectasia (GET). Patients generally present with asymptomatic, widespread, blanching, symmetric telangiectasias that classically begin on the legs and steadily progress upward with classic sparing of the face (Figure 3). Whereas GET has been reported to involve the oral and conjunctival mucosa, mucosal involvement is not typically observed in CCV and is considered to be a distinguishing factor between the 2 conditions.1,2 However, our patient reported oral symptoms, and oral erosions were seen on multiple physical examinations; therefore, ours is a rare case of mucosal involvement in conjunction with CCV. Given this finding, it is possible that more cases of CCV with mucosal involvement may exist but have been clinically misdiagnosed as GET.

First described by Salama and Rosenthal3 in 2000, CCV remains a rarely reported entity, with approximately 33 reported cases in the worldwide literature.2,4-7 The condition typically arises in adults with an equal predilection for males and females.2 The true incidence of CCV is unknown and likely is underreported given its close similarities to GET, which often is diagnosed clinically. The unique histopathologic finding of superficial ectatic vascular spaces with eosinophilic hyalinized vessel walls in CCV is key to distinguishing these similar entities, and even this finding can be subtle and is easily overlooked. Inflammation is sparse to absent. Deposited material is positive on periodic acid-Schiff and cytokeratin IV staining (representing reduplicated basement membrane-type collagen) and is diastase resistant. Smooth muscle actin staining is diminished or absent. Ultrastructural examination reveals reduplicated, laminated basement membrane; Luse bodies (abnormally long, widely spaced collagen fibers); and a decrease in or loss of pericytes. Of note, Luse bodies are nonspecific and their absence does not exclude a diagnosis of CCV.1

The etiology of CCV is unclear, and multiple pathogenetic mechanisms have been proposed. Ultimately, this entity is thought to arise from repeated endothelial cell damage, although the trigger for the endothelial cell injury is not completely understood. Diabetes mellitus sometimes is associated with microangiopathy and may be a confounding but not causative factor in some cases.1 Some investigators believe CCV is caused by a genetic defect that alters collagen production in the small vessels of the skin.5 Others have hypothesized that it is a secondary manifestation of an underlying disease or is associated with a medication; however, no disease or drug has been convincingly implicated in CCV.8

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is limited to the skin, with no known reports of systemic involvement in the literature.7 There are no recommended laboratory studies to aid in diagnosis.1 It is critical to exclude hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), as these patients can have life-threatening systemic involvement. Patients with CCV generally have no history of a bleeding diathesis, patients with HHT classically report recurrent epistaxis and gastrointestinal bleeding.7 A family history of HHT also is helpful for diagnosis, as the condition is autosomal dominant.1 Neither HHT or telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, which also can be included in the differential diagnosis, demonstrate vessel wall hyalinization.

Treatment options for CCV are limited. Basso et al6 reported notable improvement in a patient with CCV treated with a combined 595-nm pulsed dye laser and 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser and optimized pulsed light. In one patient, treatment with a 585-nm pulsed dye laser produced a blanching response, suggesting that this may be a potential treatment option.7 Treatment with sclerotherapy has been ineffective.2

It is critical for both dermatologists and dermatopathologists to recognize and report this newly described entity, as the unique finding of vessel wall hyalinization in CCV may be indicative of a certain pathogenetic mechanism and effective treatment avenue that has yet to be established due to the relatively few number of reports that currently exist in the literature.

- Burdick LM, Lohser S, Somach SC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare cutaneous microangiopathy. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:741-746.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and structural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Toda-Brito H, Resende C, Catorze G, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare cause of generalised cutaneous telangiectasia. BMJ Case Rep. 2015. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210635.

- Ma DL, Vano-Galvan S. Images in clinical medicine: cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:E14.

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111.

- Moteqi SI, Yasuda M, Yamanaka M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of first Japanese case and review of the literature. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:145-149.

- González Fernández D, Gómez Bernal S, Vivanco Allende B, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: description of two new cases in elderly women and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2012;225:1-8.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

Histopathologic examination revealed ectatic blood vessels lined with unremarkable endothelial cells and thickened, hyalinized vessel walls scattered within the papillary dermis (Figure 1). The epidermis was unremarkable. There was minimal associated inflammation and no extravasation of erythrocytes. The hyalinized material was weakly positive on periodic acid-Schiff staining (Figure 2) and negative on Congo red staining, which supported of a diagnosis of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV).

The patient previously had been given a suspected diagnosis of generalized essential telangiectasia by an outside dermatologist several years prior to the current presentation, as CCV had yet to be recognized as its own entity and therefore few cases had been described in the literature. She had a known history of obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus, which are associated with the condition. Multiple specialists concluded that the disease was too extensive for laser treatment. A review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE yielded no established treatment options.

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is a rare acquired microangiopathy involving the small vessels of the skin. Its clinical presentation is indistinguishable from that of generalized essential telangiectasia (GET). Patients generally present with asymptomatic, widespread, blanching, symmetric telangiectasias that classically begin on the legs and steadily progress upward with classic sparing of the face (Figure 3). Whereas GET has been reported to involve the oral and conjunctival mucosa, mucosal involvement is not typically observed in CCV and is considered to be a distinguishing factor between the 2 conditions.1,2 However, our patient reported oral symptoms, and oral erosions were seen on multiple physical examinations; therefore, ours is a rare case of mucosal involvement in conjunction with CCV. Given this finding, it is possible that more cases of CCV with mucosal involvement may exist but have been clinically misdiagnosed as GET.

First described by Salama and Rosenthal3 in 2000, CCV remains a rarely reported entity, with approximately 33 reported cases in the worldwide literature.2,4-7 The condition typically arises in adults with an equal predilection for males and females.2 The true incidence of CCV is unknown and likely is underreported given its close similarities to GET, which often is diagnosed clinically. The unique histopathologic finding of superficial ectatic vascular spaces with eosinophilic hyalinized vessel walls in CCV is key to distinguishing these similar entities, and even this finding can be subtle and is easily overlooked. Inflammation is sparse to absent. Deposited material is positive on periodic acid-Schiff and cytokeratin IV staining (representing reduplicated basement membrane-type collagen) and is diastase resistant. Smooth muscle actin staining is diminished or absent. Ultrastructural examination reveals reduplicated, laminated basement membrane; Luse bodies (abnormally long, widely spaced collagen fibers); and a decrease in or loss of pericytes. Of note, Luse bodies are nonspecific and their absence does not exclude a diagnosis of CCV.1

The etiology of CCV is unclear, and multiple pathogenetic mechanisms have been proposed. Ultimately, this entity is thought to arise from repeated endothelial cell damage, although the trigger for the endothelial cell injury is not completely understood. Diabetes mellitus sometimes is associated with microangiopathy and may be a confounding but not causative factor in some cases.1 Some investigators believe CCV is caused by a genetic defect that alters collagen production in the small vessels of the skin.5 Others have hypothesized that it is a secondary manifestation of an underlying disease or is associated with a medication; however, no disease or drug has been convincingly implicated in CCV.8

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is limited to the skin, with no known reports of systemic involvement in the literature.7 There are no recommended laboratory studies to aid in diagnosis.1 It is critical to exclude hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), as these patients can have life-threatening systemic involvement. Patients with CCV generally have no history of a bleeding diathesis, patients with HHT classically report recurrent epistaxis and gastrointestinal bleeding.7 A family history of HHT also is helpful for diagnosis, as the condition is autosomal dominant.1 Neither HHT or telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, which also can be included in the differential diagnosis, demonstrate vessel wall hyalinization.

Treatment options for CCV are limited. Basso et al6 reported notable improvement in a patient with CCV treated with a combined 595-nm pulsed dye laser and 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser and optimized pulsed light. In one patient, treatment with a 585-nm pulsed dye laser produced a blanching response, suggesting that this may be a potential treatment option.7 Treatment with sclerotherapy has been ineffective.2

It is critical for both dermatologists and dermatopathologists to recognize and report this newly described entity, as the unique finding of vessel wall hyalinization in CCV may be indicative of a certain pathogenetic mechanism and effective treatment avenue that has yet to be established due to the relatively few number of reports that currently exist in the literature.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

Histopathologic examination revealed ectatic blood vessels lined with unremarkable endothelial cells and thickened, hyalinized vessel walls scattered within the papillary dermis (Figure 1). The epidermis was unremarkable. There was minimal associated inflammation and no extravasation of erythrocytes. The hyalinized material was weakly positive on periodic acid-Schiff staining (Figure 2) and negative on Congo red staining, which supported of a diagnosis of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV).

The patient previously had been given a suspected diagnosis of generalized essential telangiectasia by an outside dermatologist several years prior to the current presentation, as CCV had yet to be recognized as its own entity and therefore few cases had been described in the literature. She had a known history of obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus, which are associated with the condition. Multiple specialists concluded that the disease was too extensive for laser treatment. A review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE yielded no established treatment options.

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is a rare acquired microangiopathy involving the small vessels of the skin. Its clinical presentation is indistinguishable from that of generalized essential telangiectasia (GET). Patients generally present with asymptomatic, widespread, blanching, symmetric telangiectasias that classically begin on the legs and steadily progress upward with classic sparing of the face (Figure 3). Whereas GET has been reported to involve the oral and conjunctival mucosa, mucosal involvement is not typically observed in CCV and is considered to be a distinguishing factor between the 2 conditions.1,2 However, our patient reported oral symptoms, and oral erosions were seen on multiple physical examinations; therefore, ours is a rare case of mucosal involvement in conjunction with CCV. Given this finding, it is possible that more cases of CCV with mucosal involvement may exist but have been clinically misdiagnosed as GET.

First described by Salama and Rosenthal3 in 2000, CCV remains a rarely reported entity, with approximately 33 reported cases in the worldwide literature.2,4-7 The condition typically arises in adults with an equal predilection for males and females.2 The true incidence of CCV is unknown and likely is underreported given its close similarities to GET, which often is diagnosed clinically. The unique histopathologic finding of superficial ectatic vascular spaces with eosinophilic hyalinized vessel walls in CCV is key to distinguishing these similar entities, and even this finding can be subtle and is easily overlooked. Inflammation is sparse to absent. Deposited material is positive on periodic acid-Schiff and cytokeratin IV staining (representing reduplicated basement membrane-type collagen) and is diastase resistant. Smooth muscle actin staining is diminished or absent. Ultrastructural examination reveals reduplicated, laminated basement membrane; Luse bodies (abnormally long, widely spaced collagen fibers); and a decrease in or loss of pericytes. Of note, Luse bodies are nonspecific and their absence does not exclude a diagnosis of CCV.1

The etiology of CCV is unclear, and multiple pathogenetic mechanisms have been proposed. Ultimately, this entity is thought to arise from repeated endothelial cell damage, although the trigger for the endothelial cell injury is not completely understood. Diabetes mellitus sometimes is associated with microangiopathy and may be a confounding but not causative factor in some cases.1 Some investigators believe CCV is caused by a genetic defect that alters collagen production in the small vessels of the skin.5 Others have hypothesized that it is a secondary manifestation of an underlying disease or is associated with a medication; however, no disease or drug has been convincingly implicated in CCV.8

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is limited to the skin, with no known reports of systemic involvement in the literature.7 There are no recommended laboratory studies to aid in diagnosis.1 It is critical to exclude hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), as these patients can have life-threatening systemic involvement. Patients with CCV generally have no history of a bleeding diathesis, patients with HHT classically report recurrent epistaxis and gastrointestinal bleeding.7 A family history of HHT also is helpful for diagnosis, as the condition is autosomal dominant.1 Neither HHT or telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, which also can be included in the differential diagnosis, demonstrate vessel wall hyalinization.

Treatment options for CCV are limited. Basso et al6 reported notable improvement in a patient with CCV treated with a combined 595-nm pulsed dye laser and 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser and optimized pulsed light. In one patient, treatment with a 585-nm pulsed dye laser produced a blanching response, suggesting that this may be a potential treatment option.7 Treatment with sclerotherapy has been ineffective.2

It is critical for both dermatologists and dermatopathologists to recognize and report this newly described entity, as the unique finding of vessel wall hyalinization in CCV may be indicative of a certain pathogenetic mechanism and effective treatment avenue that has yet to be established due to the relatively few number of reports that currently exist in the literature.

- Burdick LM, Lohser S, Somach SC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare cutaneous microangiopathy. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:741-746.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and structural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Toda-Brito H, Resende C, Catorze G, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare cause of generalised cutaneous telangiectasia. BMJ Case Rep. 2015. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210635.

- Ma DL, Vano-Galvan S. Images in clinical medicine: cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:E14.

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111.

- Moteqi SI, Yasuda M, Yamanaka M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of first Japanese case and review of the literature. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:145-149.

- González Fernández D, Gómez Bernal S, Vivanco Allende B, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: description of two new cases in elderly women and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2012;225:1-8.

- Burdick LM, Lohser S, Somach SC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare cutaneous microangiopathy. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:741-746.