User login

Inframammary Macerated Erosion

The Diagnosis: Hailey-Hailey Disease (Benign Familial Chronic Pemphigus)

Our patient had a long-standing history of Hailey-Hailey disease, as confirmed by multiple prior skin biopsies at outside institutions as well as our affiliated site. He began treatment with oral doxycycline 50 mg twice daily for 2 weeks, triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily to the affected region, and aluminum acetate solution soaks and chlorhexidine wash daily along with petroleum jelly, which resulted in good control of the disease. The differential diagnosis of eroded plaques, particularly in the axillary, crural, and inframammary folds, is broad and includes candidiasis, inverse psoriasis, contact dermatitis, dermatophyte infection, pemphigus vegetans or foliaceus, and granular parakeratosis.

Hailey-Hailey disease is a genetic disorder with a prevalence of 1 in 50,000 individuals. Most patients develop symptoms during the second or third decades of life.1 Hailey-Hailey disease exhibits an autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance secondary to mutation in the human ATP2C1 gene, which codes for the ATPase secretory pathway of the Ca2+ transporting pump type 1 (SPCA1) localized in the Golgi apparatus.2 Altered SPCA1 protein reduces concentration of Ca2+ within the Golgi lumen, which in turn impairs the processing of junctional proteins needed for normal cell-to-cell adhesion.1

Clinically, Hailey-Hailey disease is characterized by vesicular or erosive plaques that have a predilection for intertriginous areas of the body.1 The primary lesions often are flaccid vesicles that easily rupture, leaving behind crusted erosions that spread peripherally. The lesions also can appear as macerated plaques resembling torn tissue paper, as in our case. Friction, heat, and sweat exacerbate the disease. Complications occur from secondary bacterial, fungal, and viral colonization. Malodor and vegetations can indicate bacterial or fungal infections and can lead to persistence of skin lesions. Herpes simplex virus infections can exacerbate preexisting lesions.3 Hailey-Hailey disease of the anogenital region also can be complicated by infection with oncogenic strains of human papillomavirus and lead to cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.4

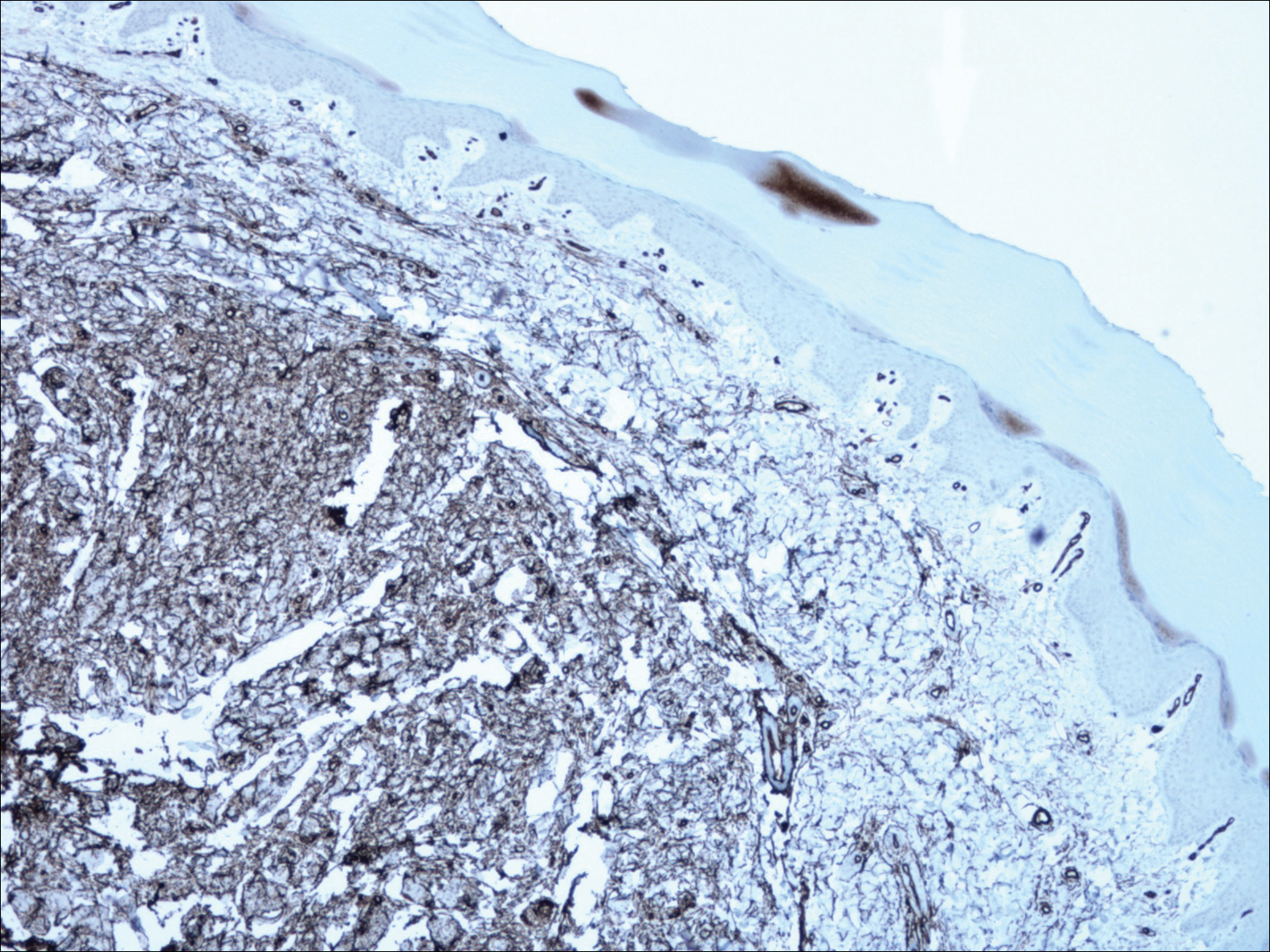

Hailey-Hailey disease histologically appears as suprabasal and intraepidermal keratinocyte acantholysis,5 which typically is widespread in the epidermis, with large areas of dyscohesion with a dilapidated brick wall-like appearance.1 In more chronic lesions, epidermal hyperplasia, parakeratosis, and focal crusts may be observed. A moderate perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate can be observed in the superficial dermis. Direct immunofluorescence typically is negative.

Topical corticosteroids and antimicrobials are first-line therapies that often only provide temporary suppression. When the disease is refractory to topical therapies, intralesional corticosteroids may be attempted. There is no strong evidence to support the use of systemic therapy, aside from antimicrobial agents (eg, doxycycline) for the use of superinfections. In severe cases, immunomodulating therapies such as prednisone, cyclosporine, methotrexate, dapsone, alefacept, and oral retinoids may be effective.6-8 Surgical therapy also can be considered for recalcitrant disease, including wide excision and grafting, though these techniques can be associated with morbidity.9

Superficial ablative techniques including dermabrasion, laser therapy with CO2 and erbium-doped YAG, photodynamic therapy, and electron beam radiation have been shown to be effective modalities in severe cases.5,9-11 It has been hypothesized that keratinocytes expressing the molecular defect are ablated, while the surrounding normal adnexal epithelium can regenerate normal epithelium. It also is thought that dermal fibrosis leads to better support of the diseased epidermis and decreases the risk for ulceration and fissuring.9

- Hohl D. Darier disease and Hailey-Hailey disease. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:887-896.

- Micaroni M, Giacchetti G, Plebani R, et al. ATP2C1 gene mutations in Hailey-Hailey disease and possible roles of SPCA1 isoforms in membrane trafficking. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:E2259.

- Peppiatt T, Keefe M,White JE. Hailey-Hailey disease--exacerbation by herpes simplex virus and patch tests. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:201-202.

- Chen MY, Chiu HC, Su LH, et al. Presence of human papillomavirus type 6 DNA in the perineal verrucoid lesions of Hailey-Hailey disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1356-1357.

- Graham PM, Melkonian A, Fivenson D. Familial benign chronic pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease) treated with electron beam radiation. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:159-161.

- Berth-Jones J, Smith SG, Graham-Brown RA, et al. Benign familial chronic pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease) responds to cyclosporin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:70-72.

- Sire DJ, Johnson BL. Benign familial chronic pemphigus treated with dapsone. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:262-265.

- Hunt MJ, Salisbury EL, Painter DM. Vesiculobullous Hailey-Hailey disease: successful treatment with oral retinoids. Australas J Dermatol. 1996;37:196-198.

- Ortiz AE, Zachary CB. Laser therapy for Hailey-Hailey disease: review of the literature and a case report. Dermatol Reports. 2011;3:E28.

- Don PC, Carney PS, Lynch WS, et al. Carbon dioxide laserabrasion: a new approach to management of familial benign chronic pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease). J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1987;13:1187-1194.

- Beier C, Kaufmann R. Efficacy of erbium:YAG laser ablation in Darier disease and Hailey-Hailey disease. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:423-427.

The Diagnosis: Hailey-Hailey Disease (Benign Familial Chronic Pemphigus)

Our patient had a long-standing history of Hailey-Hailey disease, as confirmed by multiple prior skin biopsies at outside institutions as well as our affiliated site. He began treatment with oral doxycycline 50 mg twice daily for 2 weeks, triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily to the affected region, and aluminum acetate solution soaks and chlorhexidine wash daily along with petroleum jelly, which resulted in good control of the disease. The differential diagnosis of eroded plaques, particularly in the axillary, crural, and inframammary folds, is broad and includes candidiasis, inverse psoriasis, contact dermatitis, dermatophyte infection, pemphigus vegetans or foliaceus, and granular parakeratosis.

Hailey-Hailey disease is a genetic disorder with a prevalence of 1 in 50,000 individuals. Most patients develop symptoms during the second or third decades of life.1 Hailey-Hailey disease exhibits an autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance secondary to mutation in the human ATP2C1 gene, which codes for the ATPase secretory pathway of the Ca2+ transporting pump type 1 (SPCA1) localized in the Golgi apparatus.2 Altered SPCA1 protein reduces concentration of Ca2+ within the Golgi lumen, which in turn impairs the processing of junctional proteins needed for normal cell-to-cell adhesion.1

Clinically, Hailey-Hailey disease is characterized by vesicular or erosive plaques that have a predilection for intertriginous areas of the body.1 The primary lesions often are flaccid vesicles that easily rupture, leaving behind crusted erosions that spread peripherally. The lesions also can appear as macerated plaques resembling torn tissue paper, as in our case. Friction, heat, and sweat exacerbate the disease. Complications occur from secondary bacterial, fungal, and viral colonization. Malodor and vegetations can indicate bacterial or fungal infections and can lead to persistence of skin lesions. Herpes simplex virus infections can exacerbate preexisting lesions.3 Hailey-Hailey disease of the anogenital region also can be complicated by infection with oncogenic strains of human papillomavirus and lead to cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.4

Hailey-Hailey disease histologically appears as suprabasal and intraepidermal keratinocyte acantholysis,5 which typically is widespread in the epidermis, with large areas of dyscohesion with a dilapidated brick wall-like appearance.1 In more chronic lesions, epidermal hyperplasia, parakeratosis, and focal crusts may be observed. A moderate perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate can be observed in the superficial dermis. Direct immunofluorescence typically is negative.

Topical corticosteroids and antimicrobials are first-line therapies that often only provide temporary suppression. When the disease is refractory to topical therapies, intralesional corticosteroids may be attempted. There is no strong evidence to support the use of systemic therapy, aside from antimicrobial agents (eg, doxycycline) for the use of superinfections. In severe cases, immunomodulating therapies such as prednisone, cyclosporine, methotrexate, dapsone, alefacept, and oral retinoids may be effective.6-8 Surgical therapy also can be considered for recalcitrant disease, including wide excision and grafting, though these techniques can be associated with morbidity.9

Superficial ablative techniques including dermabrasion, laser therapy with CO2 and erbium-doped YAG, photodynamic therapy, and electron beam radiation have been shown to be effective modalities in severe cases.5,9-11 It has been hypothesized that keratinocytes expressing the molecular defect are ablated, while the surrounding normal adnexal epithelium can regenerate normal epithelium. It also is thought that dermal fibrosis leads to better support of the diseased epidermis and decreases the risk for ulceration and fissuring.9

The Diagnosis: Hailey-Hailey Disease (Benign Familial Chronic Pemphigus)

Our patient had a long-standing history of Hailey-Hailey disease, as confirmed by multiple prior skin biopsies at outside institutions as well as our affiliated site. He began treatment with oral doxycycline 50 mg twice daily for 2 weeks, triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily to the affected region, and aluminum acetate solution soaks and chlorhexidine wash daily along with petroleum jelly, which resulted in good control of the disease. The differential diagnosis of eroded plaques, particularly in the axillary, crural, and inframammary folds, is broad and includes candidiasis, inverse psoriasis, contact dermatitis, dermatophyte infection, pemphigus vegetans or foliaceus, and granular parakeratosis.

Hailey-Hailey disease is a genetic disorder with a prevalence of 1 in 50,000 individuals. Most patients develop symptoms during the second or third decades of life.1 Hailey-Hailey disease exhibits an autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance secondary to mutation in the human ATP2C1 gene, which codes for the ATPase secretory pathway of the Ca2+ transporting pump type 1 (SPCA1) localized in the Golgi apparatus.2 Altered SPCA1 protein reduces concentration of Ca2+ within the Golgi lumen, which in turn impairs the processing of junctional proteins needed for normal cell-to-cell adhesion.1

Clinically, Hailey-Hailey disease is characterized by vesicular or erosive plaques that have a predilection for intertriginous areas of the body.1 The primary lesions often are flaccid vesicles that easily rupture, leaving behind crusted erosions that spread peripherally. The lesions also can appear as macerated plaques resembling torn tissue paper, as in our case. Friction, heat, and sweat exacerbate the disease. Complications occur from secondary bacterial, fungal, and viral colonization. Malodor and vegetations can indicate bacterial or fungal infections and can lead to persistence of skin lesions. Herpes simplex virus infections can exacerbate preexisting lesions.3 Hailey-Hailey disease of the anogenital region also can be complicated by infection with oncogenic strains of human papillomavirus and lead to cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.4

Hailey-Hailey disease histologically appears as suprabasal and intraepidermal keratinocyte acantholysis,5 which typically is widespread in the epidermis, with large areas of dyscohesion with a dilapidated brick wall-like appearance.1 In more chronic lesions, epidermal hyperplasia, parakeratosis, and focal crusts may be observed. A moderate perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate can be observed in the superficial dermis. Direct immunofluorescence typically is negative.

Topical corticosteroids and antimicrobials are first-line therapies that often only provide temporary suppression. When the disease is refractory to topical therapies, intralesional corticosteroids may be attempted. There is no strong evidence to support the use of systemic therapy, aside from antimicrobial agents (eg, doxycycline) for the use of superinfections. In severe cases, immunomodulating therapies such as prednisone, cyclosporine, methotrexate, dapsone, alefacept, and oral retinoids may be effective.6-8 Surgical therapy also can be considered for recalcitrant disease, including wide excision and grafting, though these techniques can be associated with morbidity.9

Superficial ablative techniques including dermabrasion, laser therapy with CO2 and erbium-doped YAG, photodynamic therapy, and electron beam radiation have been shown to be effective modalities in severe cases.5,9-11 It has been hypothesized that keratinocytes expressing the molecular defect are ablated, while the surrounding normal adnexal epithelium can regenerate normal epithelium. It also is thought that dermal fibrosis leads to better support of the diseased epidermis and decreases the risk for ulceration and fissuring.9

- Hohl D. Darier disease and Hailey-Hailey disease. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:887-896.

- Micaroni M, Giacchetti G, Plebani R, et al. ATP2C1 gene mutations in Hailey-Hailey disease and possible roles of SPCA1 isoforms in membrane trafficking. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:E2259.

- Peppiatt T, Keefe M,White JE. Hailey-Hailey disease--exacerbation by herpes simplex virus and patch tests. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:201-202.

- Chen MY, Chiu HC, Su LH, et al. Presence of human papillomavirus type 6 DNA in the perineal verrucoid lesions of Hailey-Hailey disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1356-1357.

- Graham PM, Melkonian A, Fivenson D. Familial benign chronic pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease) treated with electron beam radiation. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:159-161.

- Berth-Jones J, Smith SG, Graham-Brown RA, et al. Benign familial chronic pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease) responds to cyclosporin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:70-72.

- Sire DJ, Johnson BL. Benign familial chronic pemphigus treated with dapsone. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:262-265.

- Hunt MJ, Salisbury EL, Painter DM. Vesiculobullous Hailey-Hailey disease: successful treatment with oral retinoids. Australas J Dermatol. 1996;37:196-198.

- Ortiz AE, Zachary CB. Laser therapy for Hailey-Hailey disease: review of the literature and a case report. Dermatol Reports. 2011;3:E28.

- Don PC, Carney PS, Lynch WS, et al. Carbon dioxide laserabrasion: a new approach to management of familial benign chronic pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease). J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1987;13:1187-1194.

- Beier C, Kaufmann R. Efficacy of erbium:YAG laser ablation in Darier disease and Hailey-Hailey disease. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:423-427.

- Hohl D. Darier disease and Hailey-Hailey disease. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:887-896.

- Micaroni M, Giacchetti G, Plebani R, et al. ATP2C1 gene mutations in Hailey-Hailey disease and possible roles of SPCA1 isoforms in membrane trafficking. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:E2259.

- Peppiatt T, Keefe M,White JE. Hailey-Hailey disease--exacerbation by herpes simplex virus and patch tests. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:201-202.

- Chen MY, Chiu HC, Su LH, et al. Presence of human papillomavirus type 6 DNA in the perineal verrucoid lesions of Hailey-Hailey disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1356-1357.

- Graham PM, Melkonian A, Fivenson D. Familial benign chronic pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease) treated with electron beam radiation. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:159-161.

- Berth-Jones J, Smith SG, Graham-Brown RA, et al. Benign familial chronic pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease) responds to cyclosporin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:70-72.

- Sire DJ, Johnson BL. Benign familial chronic pemphigus treated with dapsone. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:262-265.

- Hunt MJ, Salisbury EL, Painter DM. Vesiculobullous Hailey-Hailey disease: successful treatment with oral retinoids. Australas J Dermatol. 1996;37:196-198.

- Ortiz AE, Zachary CB. Laser therapy for Hailey-Hailey disease: review of the literature and a case report. Dermatol Reports. 2011;3:E28.

- Don PC, Carney PS, Lynch WS, et al. Carbon dioxide laserabrasion: a new approach to management of familial benign chronic pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease). J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1987;13:1187-1194.

- Beier C, Kaufmann R. Efficacy of erbium:YAG laser ablation in Darier disease and Hailey-Hailey disease. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:423-427.

An 81-year-old man presented with a painful erosion in the left inframammary region of 2 weeks' duration. He described the lesion as pruritic and burning. He reported having prior similar episodes in the bilateral groin, axilla, and lower abdomen that often were malodorous. Use of triamcinolone cream 0.1% up to 4 times daily resulted in little relief of the erosion. Of note, the patient reported therapies for prior sites had included oral doxycycline 50 mg twice daily, clobetasol cream, and clindamycin solution, which provided limited relief but eventual resolution. Application of cold aluminum acetate solution compresses for 5 minutes daily irritated the skin even further and led to bleeding at the affected sites. The patient's father had a history of similar skin lesions.

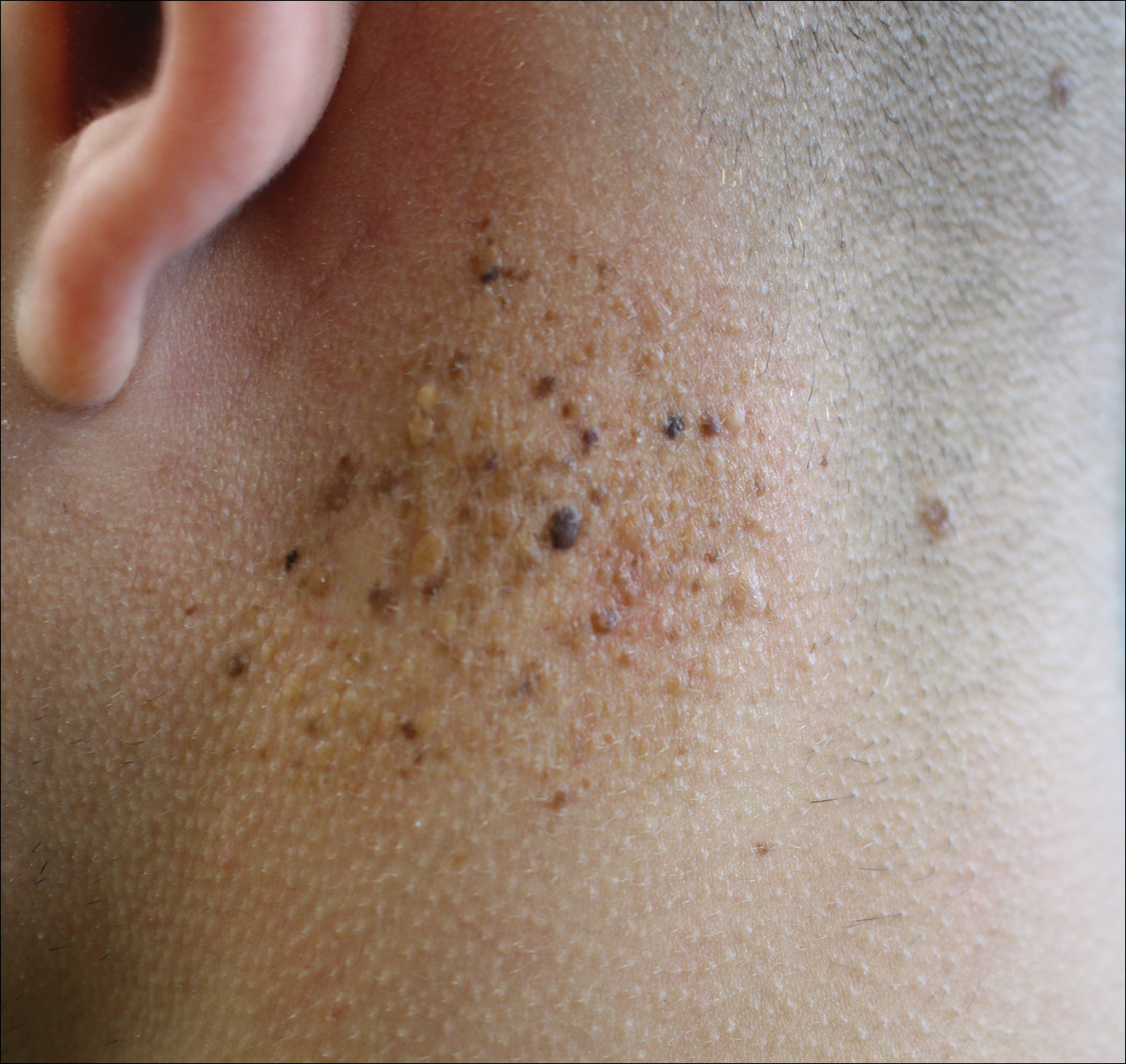

Agminated Papules on the Neck

The Diagnosis: Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum

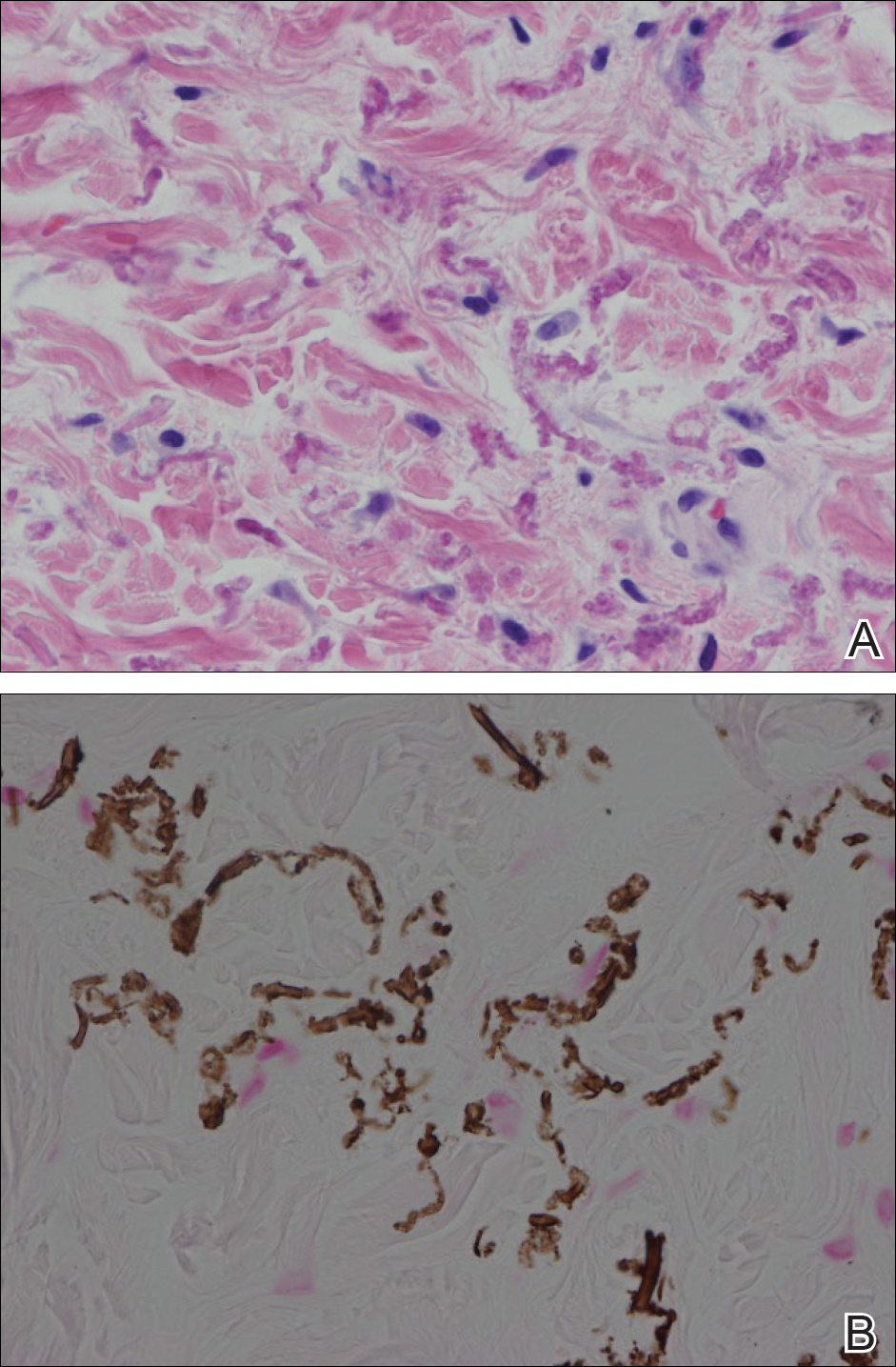

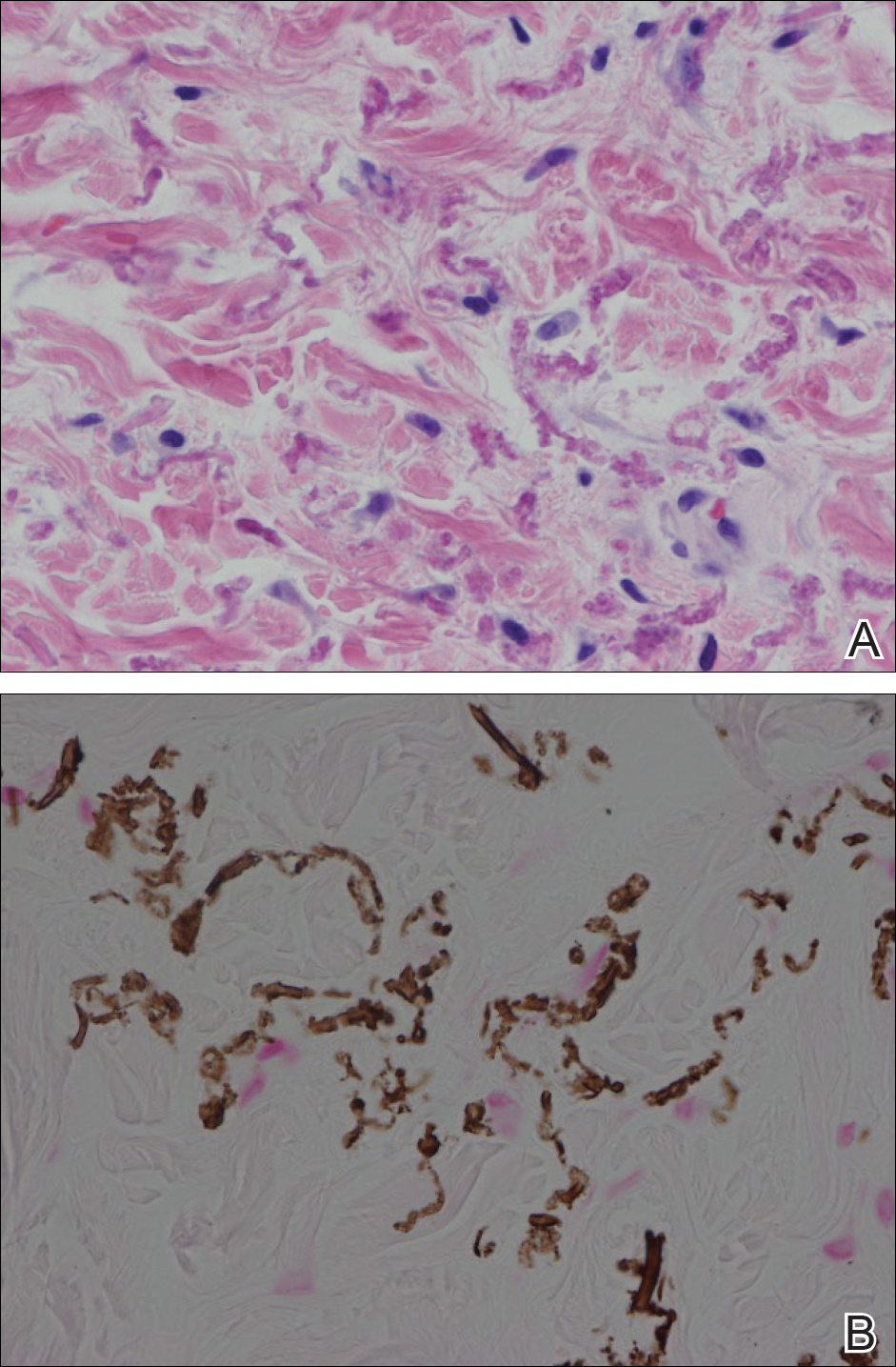

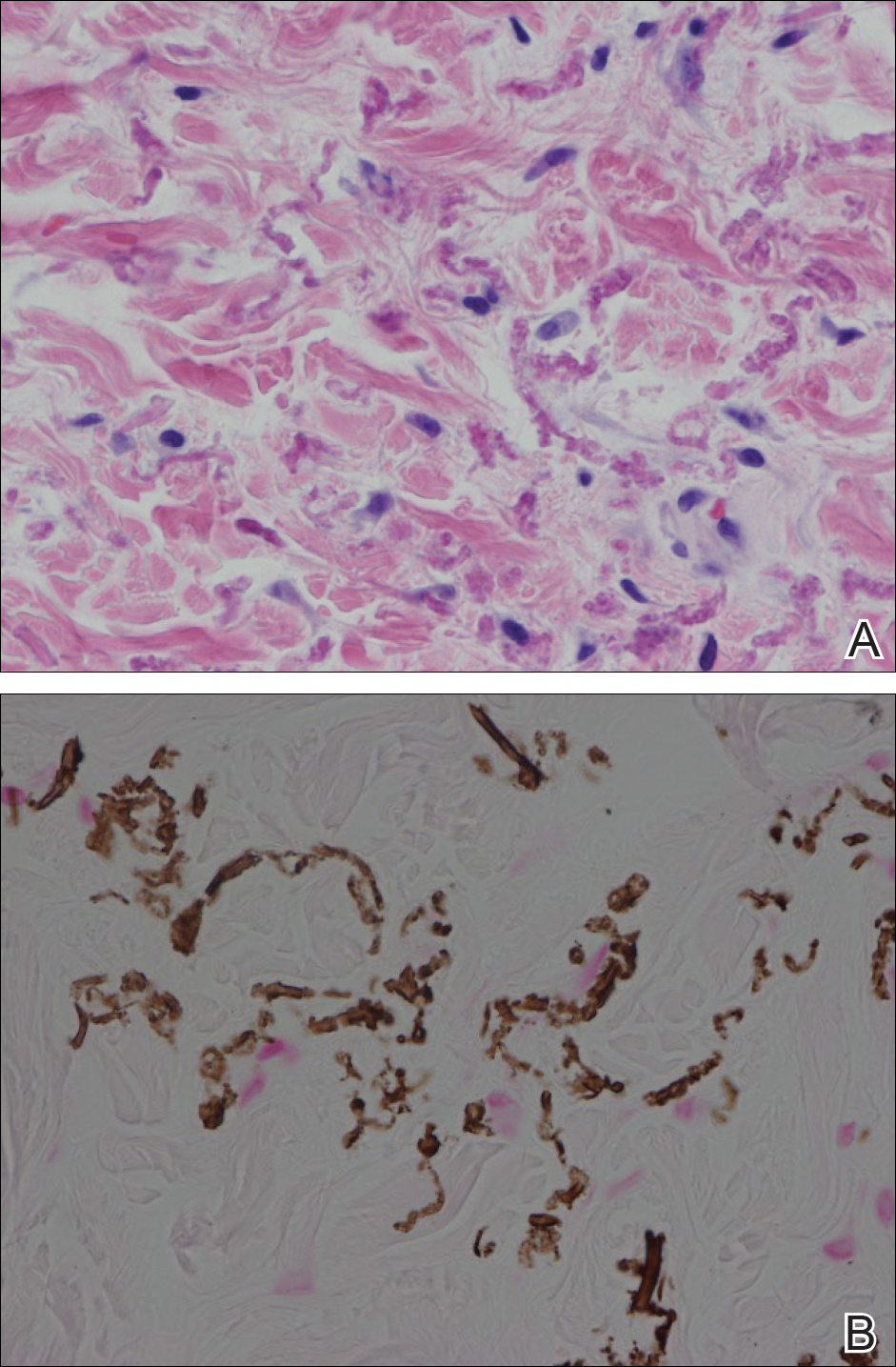

Histopathology showed abnormal curled frayed elastic fibers in the mid dermis (Figure, A); von Kossa stain was positive for calcified and fragmented elastic fibers (Figure, B). Based on clinical and histological findings, a diagnosis of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) was made.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is a rare multisystem heterogeneous genetic disorder that causes abnormal mineralization and fragmentation of tissue elastin fibers. Clinically, accumulation of mineralized elastin fibers leads to soft tissue calcification and late-onset pathology in the dermis, retinal Bruch membrane, and medial layers of large- and medium-sized arterial walls.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is an autosomal-recessive disease associated with more than 300 loss mutations in the ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 6 gene, ABCC6.1,2 However, PXE clinically is characterized by wide variability in clinical progression and outcome as well as phenotypic overlap with other disorders such as generalized arterial calcification of infancy. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum affects an estimated 1 in 25,000 to 100,000 individuals with a female preponderance (2:1 ratio).1-3 Age of onset typically is in the second to third decades of life, with 80% of cases demonstrating skin manifestations before 20 years of age.2,3

The first and most benign finding often is the appearance of small soft asymptomatic yellow papules with a plucked chicken skin-like appearance that occur on the flexural areas such as the neck, axilla, antecubital, popliteal, inguinal, and periumbilical areas. These papules may progress to irregularly shaped, yellowish plaques with a leathery appearance; mucous membranes, often occurring on the inner aspect of the lower lips, also may be involved. More severe abdominal striae also may affect some but not all women with PXE. Histologic examination demonstrates swollen, clumped, and fragmented elastin fibers with calcium deposits in the mid dermis. Elastin-specific stains such as orcein and calcium-specific stains such as the von Kossa stain aid in the diagnosis.

Vision impairment subsequently develops in 50% to 70% of patients, with severe vision loss in 3% to 8% of patients.4,5 Ophthalmologic examination identifies characteristic angioid streaks (ie, gray lines radiating from the optic disk) and subretinal hemorrhages caused by brittle new vessel formation.

Bleeding complications, especially from the gastrointestinal tract, caused by arterial wall fragility may affect 10% of PXE patients.5 Although bleeding complications also may affect the genitourinary system, the risk for fetal loss or adverse reproductive outcomes is considered low.6 More insidiously, progressive arterial calcification and peripheral arterial disease contribute to accelerated atherosclerosis, causing earlier presentations of claudication, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, and hypertension by the third and fourth decades of life.

Management of PXE is limited. Primary care providers should be attentive to cardiovascular screening for coronary and peripheral arterial disease. Patients should receive regular eye examinations, and choroidal neovascularization should be aggressively treated with photocoagulation, photodynamic therapy, and vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors.1,3

Collagenous fibromas are slow-growing tumors but are histologically distinct, showing fibrous or myxoid connective tissue arising within adipose tissue. Cutaneous leiomyomas may be solitary or grouped, often painful papules composed histologically of bundles of smooth muscle. Cutaneous sclerosis in sclerosing mesenteritis is a rare cutaneous manifestation of an internal disorder and presents as asymptomatic indurated subcutaneous nodules but histologically is distinctive, demonstrating sclerosis with fat necrosis. Xanthoma disseminatum is a rare form of histiocytosis that commonly presents as hundreds of small yellowish brown or reddish brown papules symmetrically distributed on the face, trunk, and intertriginous areas.

On follow-up within a year after initial presentation, our patient was found to have early subtle angioid streaks on ophthalmologic examination with no vision loss. A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed and showed no cardiac abnormalities. Her pregnancy was complicated by intrauterine growth retardation in the third trimester; however, the patient delivered a healthy-appearing 2835 g neonate (10th percentile for gestational age) at 39 weeks of gestations via an uncomplicated cesarean delivery.

- Uitto J, Bercovitch L, Terry SF, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: progress in diagnostics and research towards treatment: summary of the 2010 PXE International Research Meeting. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:1517-1526.

- Li Q, Jiang Q, Pfendner E, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: clinical phenotypes, molecular genetics and putative pathomechanisms. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:1-11.

- Finger RP, Charbel Issa P, Ladewig MS, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: genetics, clinical manifestations and therapeutic approaches. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54:272-285.

- Li Y, Cui Y, Zhao H, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: a review of 86 cases in China. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2014;3:75-78.

- Laube S, Moss C. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:754-756.

- Bercovitch L, Leroux T, Terry S, et al. Pregnancy and obstetrical outcomes in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:1011-1018.

The Diagnosis: Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum

Histopathology showed abnormal curled frayed elastic fibers in the mid dermis (Figure, A); von Kossa stain was positive for calcified and fragmented elastic fibers (Figure, B). Based on clinical and histological findings, a diagnosis of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) was made.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is a rare multisystem heterogeneous genetic disorder that causes abnormal mineralization and fragmentation of tissue elastin fibers. Clinically, accumulation of mineralized elastin fibers leads to soft tissue calcification and late-onset pathology in the dermis, retinal Bruch membrane, and medial layers of large- and medium-sized arterial walls.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is an autosomal-recessive disease associated with more than 300 loss mutations in the ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 6 gene, ABCC6.1,2 However, PXE clinically is characterized by wide variability in clinical progression and outcome as well as phenotypic overlap with other disorders such as generalized arterial calcification of infancy. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum affects an estimated 1 in 25,000 to 100,000 individuals with a female preponderance (2:1 ratio).1-3 Age of onset typically is in the second to third decades of life, with 80% of cases demonstrating skin manifestations before 20 years of age.2,3

The first and most benign finding often is the appearance of small soft asymptomatic yellow papules with a plucked chicken skin-like appearance that occur on the flexural areas such as the neck, axilla, antecubital, popliteal, inguinal, and periumbilical areas. These papules may progress to irregularly shaped, yellowish plaques with a leathery appearance; mucous membranes, often occurring on the inner aspect of the lower lips, also may be involved. More severe abdominal striae also may affect some but not all women with PXE. Histologic examination demonstrates swollen, clumped, and fragmented elastin fibers with calcium deposits in the mid dermis. Elastin-specific stains such as orcein and calcium-specific stains such as the von Kossa stain aid in the diagnosis.

Vision impairment subsequently develops in 50% to 70% of patients, with severe vision loss in 3% to 8% of patients.4,5 Ophthalmologic examination identifies characteristic angioid streaks (ie, gray lines radiating from the optic disk) and subretinal hemorrhages caused by brittle new vessel formation.

Bleeding complications, especially from the gastrointestinal tract, caused by arterial wall fragility may affect 10% of PXE patients.5 Although bleeding complications also may affect the genitourinary system, the risk for fetal loss or adverse reproductive outcomes is considered low.6 More insidiously, progressive arterial calcification and peripheral arterial disease contribute to accelerated atherosclerosis, causing earlier presentations of claudication, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, and hypertension by the third and fourth decades of life.

Management of PXE is limited. Primary care providers should be attentive to cardiovascular screening for coronary and peripheral arterial disease. Patients should receive regular eye examinations, and choroidal neovascularization should be aggressively treated with photocoagulation, photodynamic therapy, and vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors.1,3

Collagenous fibromas are slow-growing tumors but are histologically distinct, showing fibrous or myxoid connective tissue arising within adipose tissue. Cutaneous leiomyomas may be solitary or grouped, often painful papules composed histologically of bundles of smooth muscle. Cutaneous sclerosis in sclerosing mesenteritis is a rare cutaneous manifestation of an internal disorder and presents as asymptomatic indurated subcutaneous nodules but histologically is distinctive, demonstrating sclerosis with fat necrosis. Xanthoma disseminatum is a rare form of histiocytosis that commonly presents as hundreds of small yellowish brown or reddish brown papules symmetrically distributed on the face, trunk, and intertriginous areas.

On follow-up within a year after initial presentation, our patient was found to have early subtle angioid streaks on ophthalmologic examination with no vision loss. A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed and showed no cardiac abnormalities. Her pregnancy was complicated by intrauterine growth retardation in the third trimester; however, the patient delivered a healthy-appearing 2835 g neonate (10th percentile for gestational age) at 39 weeks of gestations via an uncomplicated cesarean delivery.

The Diagnosis: Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum

Histopathology showed abnormal curled frayed elastic fibers in the mid dermis (Figure, A); von Kossa stain was positive for calcified and fragmented elastic fibers (Figure, B). Based on clinical and histological findings, a diagnosis of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) was made.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is a rare multisystem heterogeneous genetic disorder that causes abnormal mineralization and fragmentation of tissue elastin fibers. Clinically, accumulation of mineralized elastin fibers leads to soft tissue calcification and late-onset pathology in the dermis, retinal Bruch membrane, and medial layers of large- and medium-sized arterial walls.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is an autosomal-recessive disease associated with more than 300 loss mutations in the ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 6 gene, ABCC6.1,2 However, PXE clinically is characterized by wide variability in clinical progression and outcome as well as phenotypic overlap with other disorders such as generalized arterial calcification of infancy. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum affects an estimated 1 in 25,000 to 100,000 individuals with a female preponderance (2:1 ratio).1-3 Age of onset typically is in the second to third decades of life, with 80% of cases demonstrating skin manifestations before 20 years of age.2,3

The first and most benign finding often is the appearance of small soft asymptomatic yellow papules with a plucked chicken skin-like appearance that occur on the flexural areas such as the neck, axilla, antecubital, popliteal, inguinal, and periumbilical areas. These papules may progress to irregularly shaped, yellowish plaques with a leathery appearance; mucous membranes, often occurring on the inner aspect of the lower lips, also may be involved. More severe abdominal striae also may affect some but not all women with PXE. Histologic examination demonstrates swollen, clumped, and fragmented elastin fibers with calcium deposits in the mid dermis. Elastin-specific stains such as orcein and calcium-specific stains such as the von Kossa stain aid in the diagnosis.

Vision impairment subsequently develops in 50% to 70% of patients, with severe vision loss in 3% to 8% of patients.4,5 Ophthalmologic examination identifies characteristic angioid streaks (ie, gray lines radiating from the optic disk) and subretinal hemorrhages caused by brittle new vessel formation.

Bleeding complications, especially from the gastrointestinal tract, caused by arterial wall fragility may affect 10% of PXE patients.5 Although bleeding complications also may affect the genitourinary system, the risk for fetal loss or adverse reproductive outcomes is considered low.6 More insidiously, progressive arterial calcification and peripheral arterial disease contribute to accelerated atherosclerosis, causing earlier presentations of claudication, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, and hypertension by the third and fourth decades of life.

Management of PXE is limited. Primary care providers should be attentive to cardiovascular screening for coronary and peripheral arterial disease. Patients should receive regular eye examinations, and choroidal neovascularization should be aggressively treated with photocoagulation, photodynamic therapy, and vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors.1,3

Collagenous fibromas are slow-growing tumors but are histologically distinct, showing fibrous or myxoid connective tissue arising within adipose tissue. Cutaneous leiomyomas may be solitary or grouped, often painful papules composed histologically of bundles of smooth muscle. Cutaneous sclerosis in sclerosing mesenteritis is a rare cutaneous manifestation of an internal disorder and presents as asymptomatic indurated subcutaneous nodules but histologically is distinctive, demonstrating sclerosis with fat necrosis. Xanthoma disseminatum is a rare form of histiocytosis that commonly presents as hundreds of small yellowish brown or reddish brown papules symmetrically distributed on the face, trunk, and intertriginous areas.

On follow-up within a year after initial presentation, our patient was found to have early subtle angioid streaks on ophthalmologic examination with no vision loss. A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed and showed no cardiac abnormalities. Her pregnancy was complicated by intrauterine growth retardation in the third trimester; however, the patient delivered a healthy-appearing 2835 g neonate (10th percentile for gestational age) at 39 weeks of gestations via an uncomplicated cesarean delivery.

- Uitto J, Bercovitch L, Terry SF, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: progress in diagnostics and research towards treatment: summary of the 2010 PXE International Research Meeting. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:1517-1526.

- Li Q, Jiang Q, Pfendner E, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: clinical phenotypes, molecular genetics and putative pathomechanisms. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:1-11.

- Finger RP, Charbel Issa P, Ladewig MS, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: genetics, clinical manifestations and therapeutic approaches. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54:272-285.

- Li Y, Cui Y, Zhao H, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: a review of 86 cases in China. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2014;3:75-78.

- Laube S, Moss C. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:754-756.

- Bercovitch L, Leroux T, Terry S, et al. Pregnancy and obstetrical outcomes in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:1011-1018.

- Uitto J, Bercovitch L, Terry SF, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: progress in diagnostics and research towards treatment: summary of the 2010 PXE International Research Meeting. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:1517-1526.

- Li Q, Jiang Q, Pfendner E, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: clinical phenotypes, molecular genetics and putative pathomechanisms. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:1-11.

- Finger RP, Charbel Issa P, Ladewig MS, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: genetics, clinical manifestations and therapeutic approaches. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54:272-285.

- Li Y, Cui Y, Zhao H, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: a review of 86 cases in China. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2014;3:75-78.

- Laube S, Moss C. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:754-756.

- Bercovitch L, Leroux T, Terry S, et al. Pregnancy and obstetrical outcomes in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:1011-1018.

A 24-year-old woman presented with a lesion on the neck of 3 months' duration. She noted occasional mild pruritus at the site but no other symptoms or similar lesions elsewhere. At the time of presentation, she was at 17 weeks of gestation without any complications. Her medical history was notable for hypertension, unspecified chest pain with a normal electrocardiogram, and 2 spontaneous abortions. She denied a personal or family history of notable cardiovascular or gastrointestinal tract diseases. Examination of the skin showed indurated 3- to 5-mm papules coalescing into a 3- to 4-cm plaque on the left posterolateral neck.

Brown Papules on the Penis

The Diagnosis: Bowenoid Papulosis

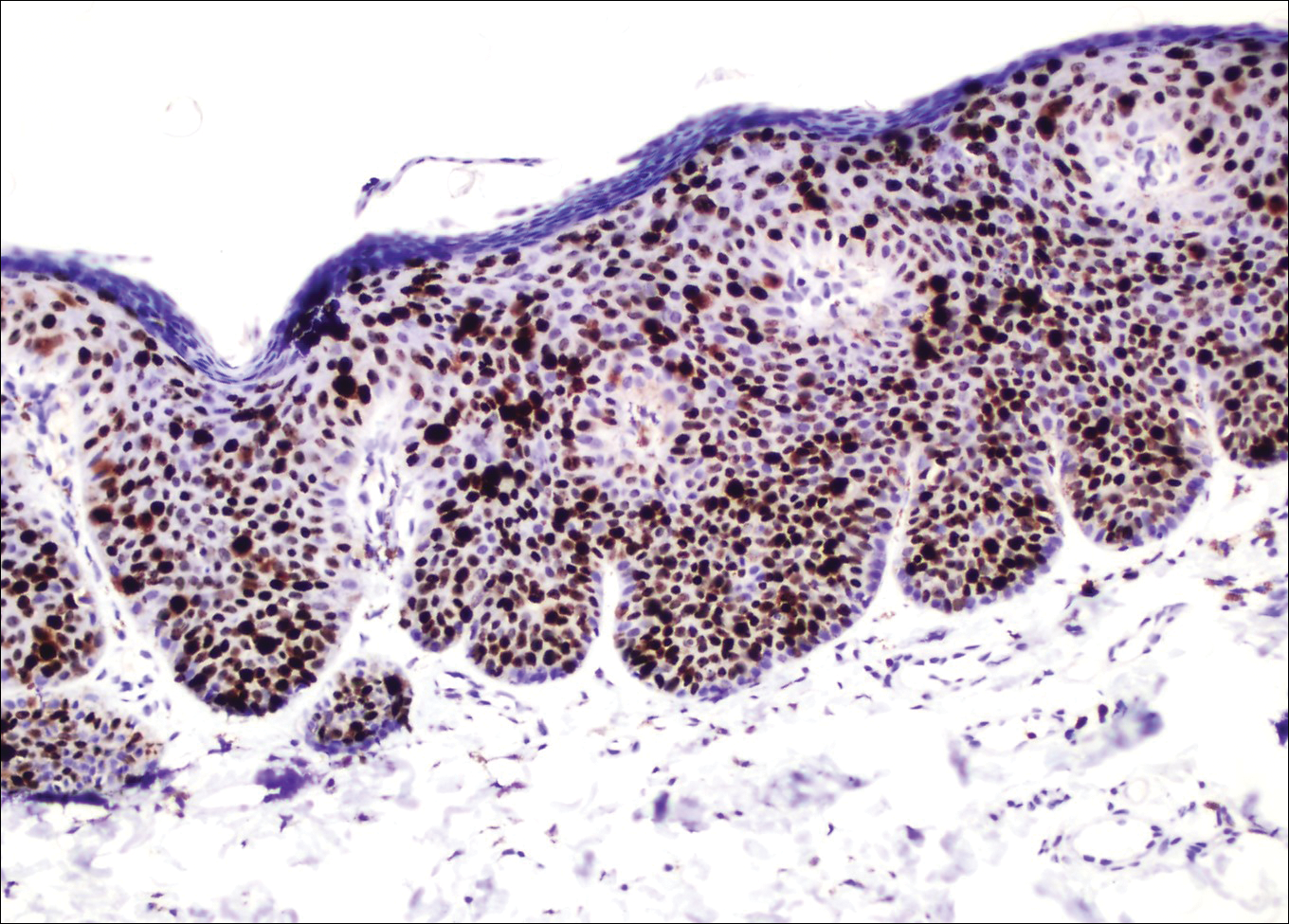

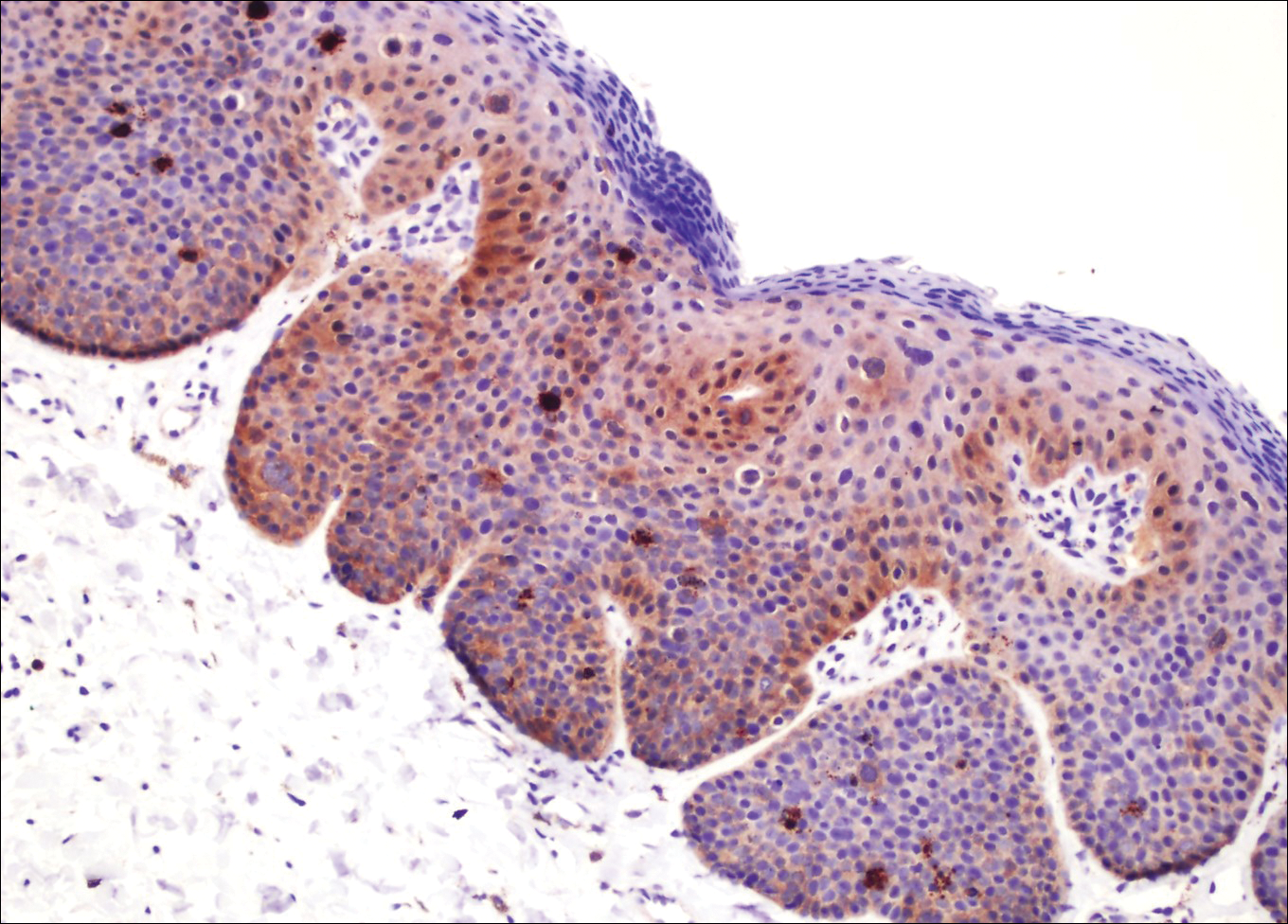

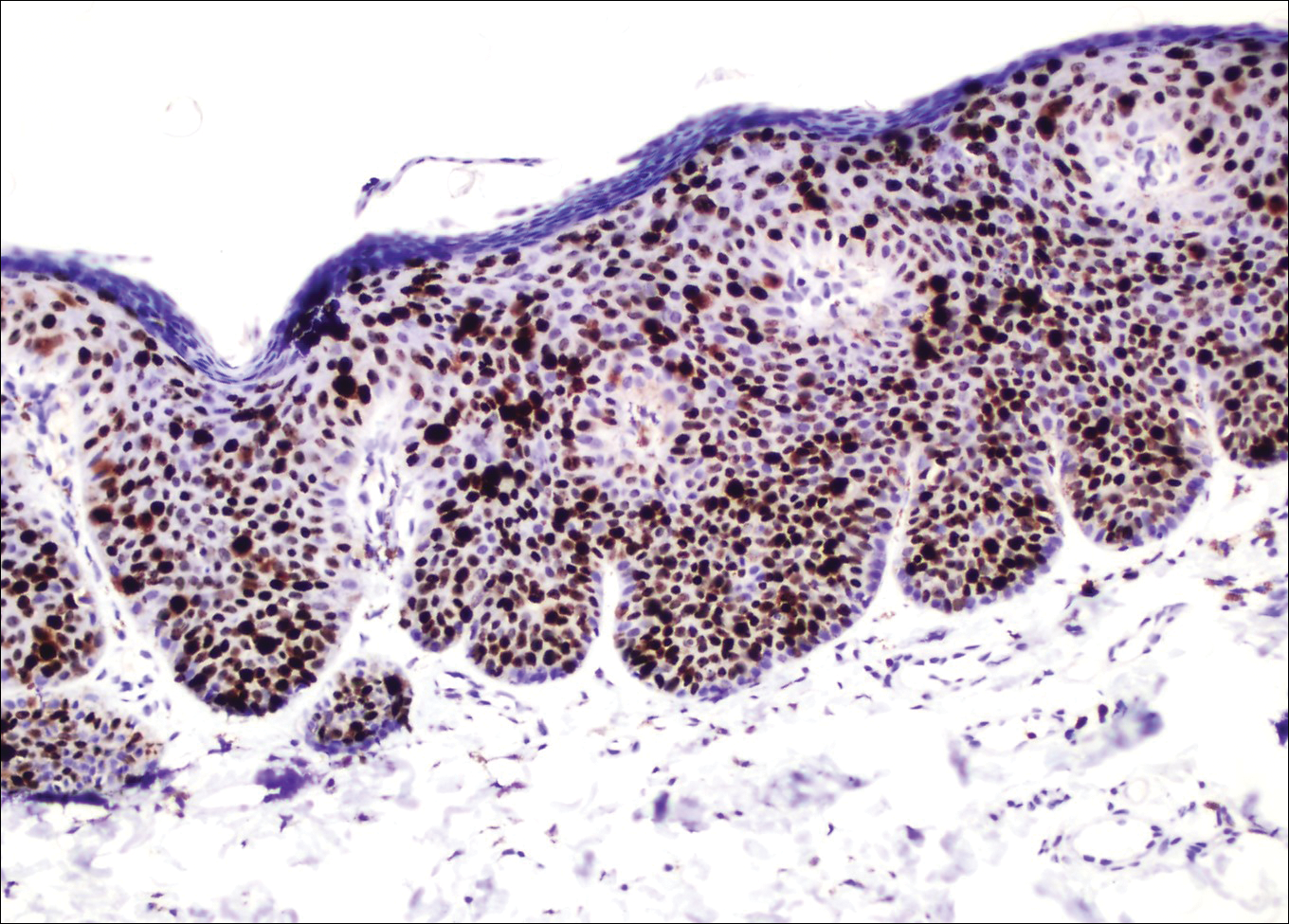

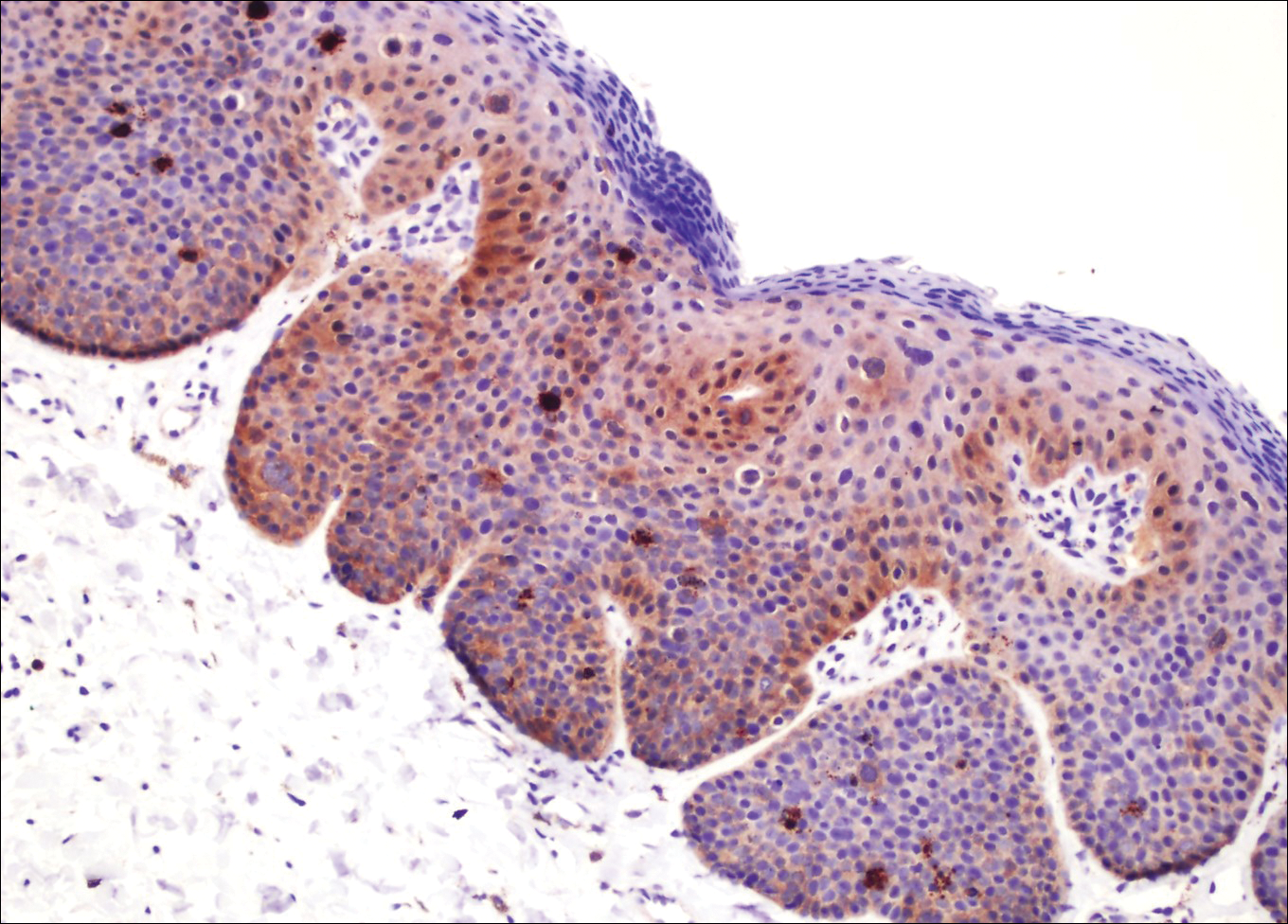

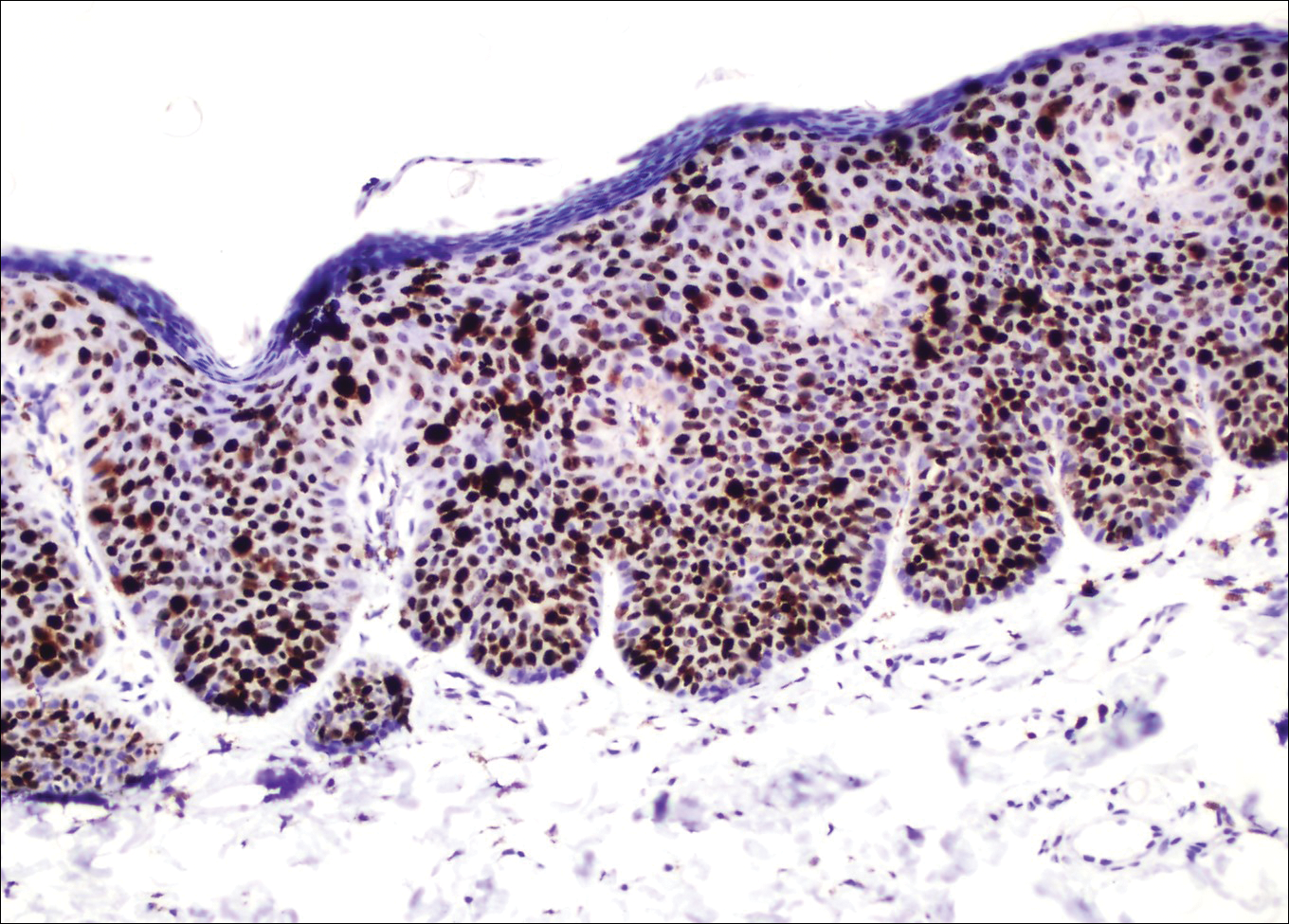

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from the active border of brown plaques on the dorsal penis. Histopathology revealed parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, loss of maturation in epithelium, and full-size atypia (Figure 1). Ki-67 index was 90% positive in the epidermis (Figure 2). Staining for p16 and human papillomavirus (HPV) screening was positive for HPV type 16 (Figure 3). Serologic tests for other sexually transmitted infections were negative. A diagnosis of penile bowenoid papulosis (BP) with grade 3 penile intraepithelial neoplasia was made, and treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) was initiated. Almost total regression was appreciated at 1-month follow-up (Figure 4), and he also was recurrence free at 1-year follow-up.

Penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), or penile squamous cell carcinoma in situ, is a rare disease with high morbidity and mortality rates. Clinically, PIN is comprised of a clinical spectrum including 3 different entities: erythroplasia of Queyrat, Bowen disease, and BP.1 Histologically, PIN also is classified into 3 subtypes according to histological depth of epidermal atypia.1

Bowenoid papulosis usually is characterized by multiple red-brown or flesh-colored papules that most commonly appear on the shaft or glans of the penis. Bowenoid papulosis frequently is associated with high-risk types of HPV, such as HPV type 16, and is sometimes difficult to differentiate clinically from pigmented condyloma acuminatum. The clinical lesions of BP usually are less papillomatous, smoother topped, more polymorphic, and more coalescent compared to common genital viral condyloma acuminatum.2 Bowenoid papulosis usually is seen in young (<30 years of age) sexually active men, unlike the patches or plaques of erythroplasia of Queyrat or Bowen disease, which are seen in older men aged 45 to 75 years. Bowenoid papulosis also has a lower malignancy potential than erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen disease.2

Penile melanosis, penile lentigo, and seborrheic keratosis comprise the differential diagnosis of dark spots on the penis and also should be kept in mind. Penile melanosis is the most common cause of dark spots on the penis. When the dark spots have irregular borders and change in color, they may be misdiagnosed as malignant lesions such as melanoma.3 In most cases, biopsy is indicated. Histologically, penile melanosis is characterized by hyperpigmentation of the basal cell layer with no melanocytic hyperplasia. Treatment is unnecessary in most cases.

Penile lentigo presents as small flat pigmented spots on the penile skin with clearly defined margins surrounded by normal-appearing skin. Histologically, it is characterized by hyperplasia of melanocytes above the basement membrane of the epidermis.3

Penile pigmented seborrheic keratosis is a rare clinical entity that can be easily misinterpreted as condyloma acuminatum. Histologically, it is characterized by basal cell hyperplasia with cystic formation in the thickened epidermis. Excisional biopsy may be the only way to rule out malignant disease.

Treatment options for PIN include cryotherapy, CO2 or Nd:YAG lasers, photodynamic therapy, topical 5-FU or imiquimod therapy, and surgical excision such as Mohs micrographic surgery.4-9 Although these therapeutic modalities usually are effective, recurrence is common.6 The patients' discomfort and poor cosmetic and functional outcomes from the surgical removal of lesions also present a challenge in treatment planning.

In our patient, we quickly achieved a good result with topical 5-FU, though the disease was in local advanced stage. It is important for clinicians to consider 5-FU as an effective treatment option for PIN before planning surgery.

- Deen K, Burdon-Jones D. Imiquimod in the treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia: an update. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:86-92.

- Porter WM, Francis N, Hawkins D, et al. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia: clinical spectrum and treatment of 35 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1159-1165.

- Fahmy M. Dermatological disease of the penis. In: Fahmy M. Congenital Anomalies of the Penis. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017:257-264.

- Shimizu A, Kato M, Ishikawa O. Bowenoid papulosis successfully treated with imiquimod 5% cream. J Dermatol. 2014;41:545-546.

- Lucky M, Murthy KV, Rogers B, et al. The treatment of penile carcinoma in situ (CIS) within a UK supra-regional network [published online December 15, 2014]. BJU Int. 2015;115:595-598.

- Alnajjar HM, Lam W, Bolgeri M, et al. Treatment of carcinoma in situ of the glans penis with topical chemotherapy agents. Eur Urol. 2012;62:923-928.

- Wang XL, Wang HW, Guo MX, et al. Combination of immunotherapy and photodynamic therapy in the treatment of bowenoid papulosis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2007;4:88-93.

- Zreik A, Rewhorn M, Vint R, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia [published online December 7, 2016]. Surgeon. 2017;15:321-324.

- Machan M, Brodland D, Zitelli J. Penile squamous cell carcinoma: penis-preserving treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:936-944.

The Diagnosis: Bowenoid Papulosis

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from the active border of brown plaques on the dorsal penis. Histopathology revealed parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, loss of maturation in epithelium, and full-size atypia (Figure 1). Ki-67 index was 90% positive in the epidermis (Figure 2). Staining for p16 and human papillomavirus (HPV) screening was positive for HPV type 16 (Figure 3). Serologic tests for other sexually transmitted infections were negative. A diagnosis of penile bowenoid papulosis (BP) with grade 3 penile intraepithelial neoplasia was made, and treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) was initiated. Almost total regression was appreciated at 1-month follow-up (Figure 4), and he also was recurrence free at 1-year follow-up.

Penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), or penile squamous cell carcinoma in situ, is a rare disease with high morbidity and mortality rates. Clinically, PIN is comprised of a clinical spectrum including 3 different entities: erythroplasia of Queyrat, Bowen disease, and BP.1 Histologically, PIN also is classified into 3 subtypes according to histological depth of epidermal atypia.1

Bowenoid papulosis usually is characterized by multiple red-brown or flesh-colored papules that most commonly appear on the shaft or glans of the penis. Bowenoid papulosis frequently is associated with high-risk types of HPV, such as HPV type 16, and is sometimes difficult to differentiate clinically from pigmented condyloma acuminatum. The clinical lesions of BP usually are less papillomatous, smoother topped, more polymorphic, and more coalescent compared to common genital viral condyloma acuminatum.2 Bowenoid papulosis usually is seen in young (<30 years of age) sexually active men, unlike the patches or plaques of erythroplasia of Queyrat or Bowen disease, which are seen in older men aged 45 to 75 years. Bowenoid papulosis also has a lower malignancy potential than erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen disease.2

Penile melanosis, penile lentigo, and seborrheic keratosis comprise the differential diagnosis of dark spots on the penis and also should be kept in mind. Penile melanosis is the most common cause of dark spots on the penis. When the dark spots have irregular borders and change in color, they may be misdiagnosed as malignant lesions such as melanoma.3 In most cases, biopsy is indicated. Histologically, penile melanosis is characterized by hyperpigmentation of the basal cell layer with no melanocytic hyperplasia. Treatment is unnecessary in most cases.

Penile lentigo presents as small flat pigmented spots on the penile skin with clearly defined margins surrounded by normal-appearing skin. Histologically, it is characterized by hyperplasia of melanocytes above the basement membrane of the epidermis.3

Penile pigmented seborrheic keratosis is a rare clinical entity that can be easily misinterpreted as condyloma acuminatum. Histologically, it is characterized by basal cell hyperplasia with cystic formation in the thickened epidermis. Excisional biopsy may be the only way to rule out malignant disease.

Treatment options for PIN include cryotherapy, CO2 or Nd:YAG lasers, photodynamic therapy, topical 5-FU or imiquimod therapy, and surgical excision such as Mohs micrographic surgery.4-9 Although these therapeutic modalities usually are effective, recurrence is common.6 The patients' discomfort and poor cosmetic and functional outcomes from the surgical removal of lesions also present a challenge in treatment planning.

In our patient, we quickly achieved a good result with topical 5-FU, though the disease was in local advanced stage. It is important for clinicians to consider 5-FU as an effective treatment option for PIN before planning surgery.

The Diagnosis: Bowenoid Papulosis

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from the active border of brown plaques on the dorsal penis. Histopathology revealed parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, loss of maturation in epithelium, and full-size atypia (Figure 1). Ki-67 index was 90% positive in the epidermis (Figure 2). Staining for p16 and human papillomavirus (HPV) screening was positive for HPV type 16 (Figure 3). Serologic tests for other sexually transmitted infections were negative. A diagnosis of penile bowenoid papulosis (BP) with grade 3 penile intraepithelial neoplasia was made, and treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) was initiated. Almost total regression was appreciated at 1-month follow-up (Figure 4), and he also was recurrence free at 1-year follow-up.

Penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), or penile squamous cell carcinoma in situ, is a rare disease with high morbidity and mortality rates. Clinically, PIN is comprised of a clinical spectrum including 3 different entities: erythroplasia of Queyrat, Bowen disease, and BP.1 Histologically, PIN also is classified into 3 subtypes according to histological depth of epidermal atypia.1

Bowenoid papulosis usually is characterized by multiple red-brown or flesh-colored papules that most commonly appear on the shaft or glans of the penis. Bowenoid papulosis frequently is associated with high-risk types of HPV, such as HPV type 16, and is sometimes difficult to differentiate clinically from pigmented condyloma acuminatum. The clinical lesions of BP usually are less papillomatous, smoother topped, more polymorphic, and more coalescent compared to common genital viral condyloma acuminatum.2 Bowenoid papulosis usually is seen in young (<30 years of age) sexually active men, unlike the patches or plaques of erythroplasia of Queyrat or Bowen disease, which are seen in older men aged 45 to 75 years. Bowenoid papulosis also has a lower malignancy potential than erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen disease.2

Penile melanosis, penile lentigo, and seborrheic keratosis comprise the differential diagnosis of dark spots on the penis and also should be kept in mind. Penile melanosis is the most common cause of dark spots on the penis. When the dark spots have irregular borders and change in color, they may be misdiagnosed as malignant lesions such as melanoma.3 In most cases, biopsy is indicated. Histologically, penile melanosis is characterized by hyperpigmentation of the basal cell layer with no melanocytic hyperplasia. Treatment is unnecessary in most cases.

Penile lentigo presents as small flat pigmented spots on the penile skin with clearly defined margins surrounded by normal-appearing skin. Histologically, it is characterized by hyperplasia of melanocytes above the basement membrane of the epidermis.3

Penile pigmented seborrheic keratosis is a rare clinical entity that can be easily misinterpreted as condyloma acuminatum. Histologically, it is characterized by basal cell hyperplasia with cystic formation in the thickened epidermis. Excisional biopsy may be the only way to rule out malignant disease.

Treatment options for PIN include cryotherapy, CO2 or Nd:YAG lasers, photodynamic therapy, topical 5-FU or imiquimod therapy, and surgical excision such as Mohs micrographic surgery.4-9 Although these therapeutic modalities usually are effective, recurrence is common.6 The patients' discomfort and poor cosmetic and functional outcomes from the surgical removal of lesions also present a challenge in treatment planning.

In our patient, we quickly achieved a good result with topical 5-FU, though the disease was in local advanced stage. It is important for clinicians to consider 5-FU as an effective treatment option for PIN before planning surgery.

- Deen K, Burdon-Jones D. Imiquimod in the treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia: an update. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:86-92.

- Porter WM, Francis N, Hawkins D, et al. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia: clinical spectrum and treatment of 35 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1159-1165.

- Fahmy M. Dermatological disease of the penis. In: Fahmy M. Congenital Anomalies of the Penis. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017:257-264.

- Shimizu A, Kato M, Ishikawa O. Bowenoid papulosis successfully treated with imiquimod 5% cream. J Dermatol. 2014;41:545-546.

- Lucky M, Murthy KV, Rogers B, et al. The treatment of penile carcinoma in situ (CIS) within a UK supra-regional network [published online December 15, 2014]. BJU Int. 2015;115:595-598.

- Alnajjar HM, Lam W, Bolgeri M, et al. Treatment of carcinoma in situ of the glans penis with topical chemotherapy agents. Eur Urol. 2012;62:923-928.

- Wang XL, Wang HW, Guo MX, et al. Combination of immunotherapy and photodynamic therapy in the treatment of bowenoid papulosis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2007;4:88-93.

- Zreik A, Rewhorn M, Vint R, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia [published online December 7, 2016]. Surgeon. 2017;15:321-324.

- Machan M, Brodland D, Zitelli J. Penile squamous cell carcinoma: penis-preserving treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:936-944.

- Deen K, Burdon-Jones D. Imiquimod in the treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia: an update. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:86-92.

- Porter WM, Francis N, Hawkins D, et al. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia: clinical spectrum and treatment of 35 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1159-1165.

- Fahmy M. Dermatological disease of the penis. In: Fahmy M. Congenital Anomalies of the Penis. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017:257-264.

- Shimizu A, Kato M, Ishikawa O. Bowenoid papulosis successfully treated with imiquimod 5% cream. J Dermatol. 2014;41:545-546.

- Lucky M, Murthy KV, Rogers B, et al. The treatment of penile carcinoma in situ (CIS) within a UK supra-regional network [published online December 15, 2014]. BJU Int. 2015;115:595-598.

- Alnajjar HM, Lam W, Bolgeri M, et al. Treatment of carcinoma in situ of the glans penis with topical chemotherapy agents. Eur Urol. 2012;62:923-928.

- Wang XL, Wang HW, Guo MX, et al. Combination of immunotherapy and photodynamic therapy in the treatment of bowenoid papulosis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2007;4:88-93.

- Zreik A, Rewhorn M, Vint R, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia [published online December 7, 2016]. Surgeon. 2017;15:321-324.

- Machan M, Brodland D, Zitelli J. Penile squamous cell carcinoma: penis-preserving treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:936-944.

A 32-year-old man presented to the outpatient clinic with reddish brown lesions on the penis of 5 months' duration. Dermatologic examination revealed multiple mildly infiltrated, bright reddish brown papules and plaques on the dorsal penis.

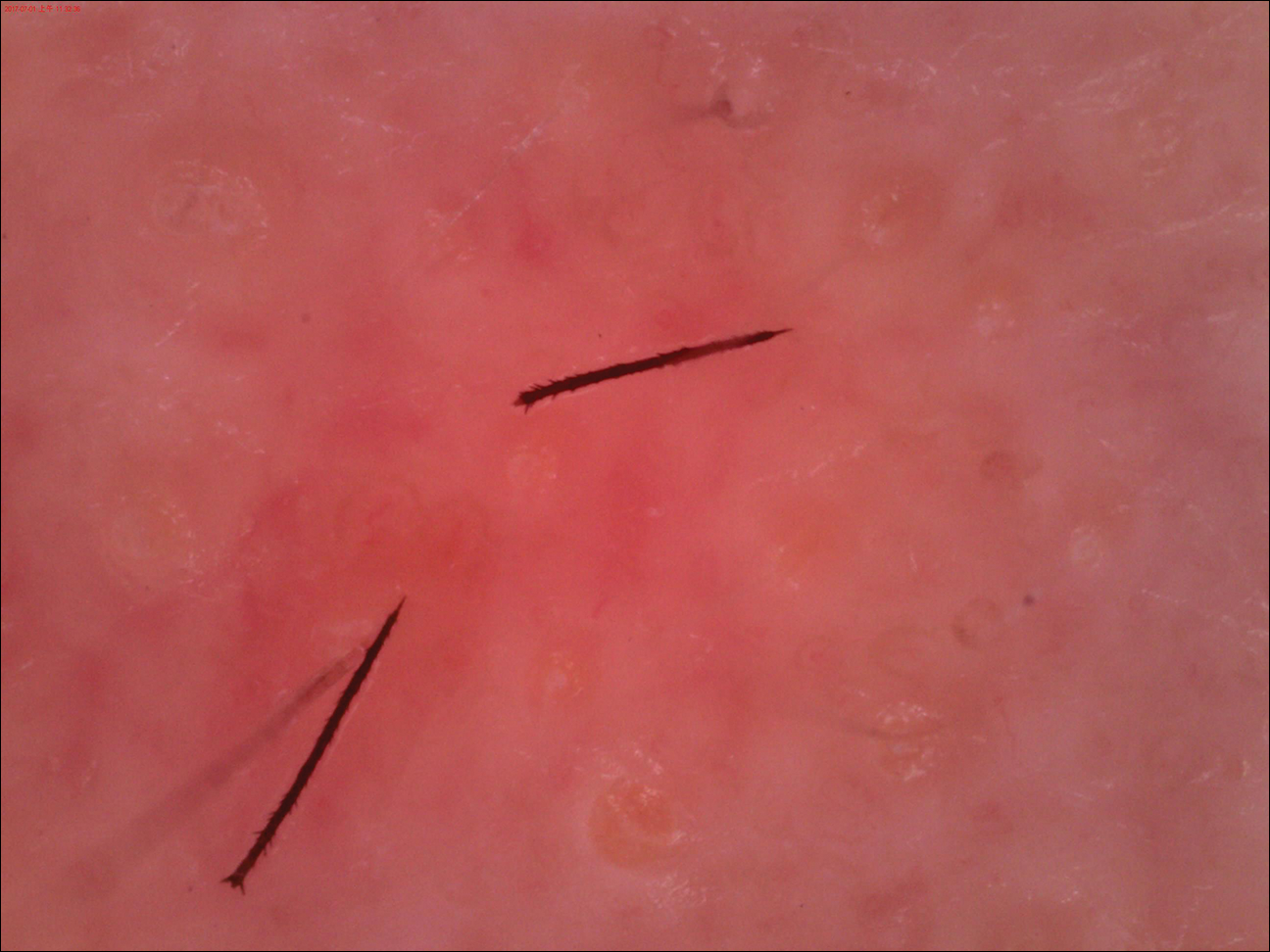

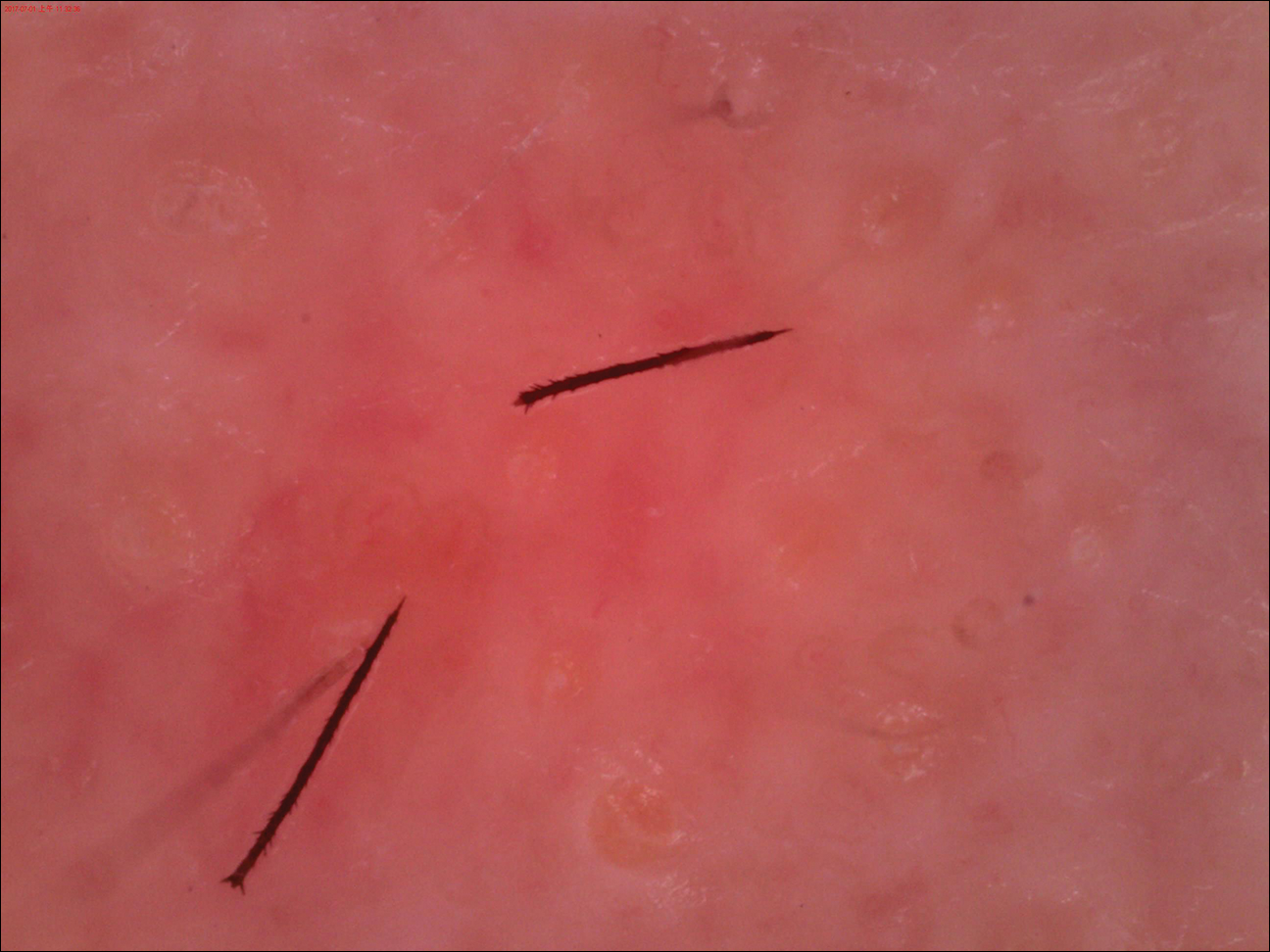

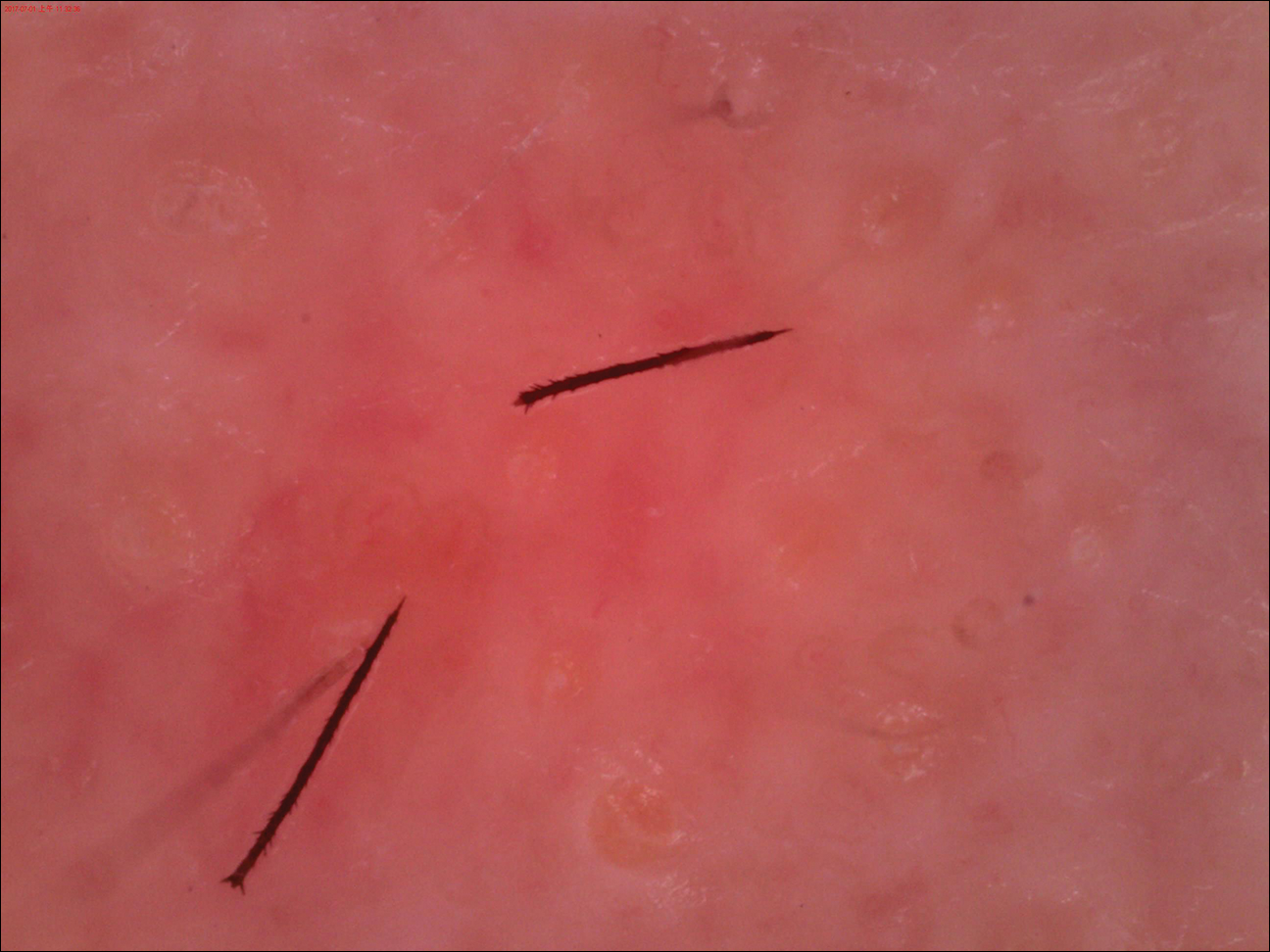

Agminated Heterogeneous Papules on the Neck

The Diagnosis: Eruptive Blue Nevus

All biopsies demonstrated similar histologic features, including an intradermal proliferation of heavily pigmented, spindle-shaped dendritic melanocytes (Figure). The dermal pigment was most pronounced in the grossly darker papules, and there was not a substantial amount of background pigmentation at the stratum basale. Cytologic atypia, foci of necrosis, and mitotic activity were absent from all sections. There was no definitive junctional component identified, no multinucleated giant cells, and there was no overlying epidermal aberration. With some background pigmentation seen histologically, nevus spilus was considered, but because this acute eruption occurred in a young adult without appreciable gross background hyperpigmentation, the clinical context led to a diagnosis of eruptive blue nevus. After communicating the findings to the patient, he declined further treatment.

Eruptive blue nevus is an exceptionally rare subtype of blue nevus with few cases reported since the 1940s.1-9 Generally, each case report found a triggering event that could possibly have precipitated the acute proliferation and evolution of nevi. Triggering events can include bullous processes such as erythema multiforme2 and Stevens-Johnson syndrome,3 severe sunburn,4 trauma,5 immunosuppression,6 and a variety of endocrinopathies. No such history could be identified in our patient, except the biopsy.

Common blue nevi are benign, usually congenital, well-circumscribed, solitary, blue-gray macules or papules. Half of blue nevi cases are found on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet but can present anywhere (eg, face, scalp, wrists, sacrum, buttocks). The blue-gray color appreciated clinically is attributed to the Tyndall effect, which occurs when long-wavelength light--red, orange, and yellow--is absorbed by the melanin deep in the dermis, while short-wavelength visible light--blue, violet, and indigo--is reflected with backscattering. On polarized dermoscopy, a homogeneous blue-gray hue is appreciated, but lighter segments may be present when collagen deposition is robust. Histopathologic findings confirm spindle-shaped dendritic melanocytes in the dermis without epidermal involvement. It generally is accepted that the etiology of these benign nevi is a failed migration of neural crest cells to the epidermis.10,11 Although the common blue nevus may be simple to diagnose, several subtypes have been described in the literature, including combined blue nevus, desmoplastic blue nevus, hypomelanotic/amelanotic blue nevus, and epithelioid blue nevus of Carney complex, and excluding a malignant process is of monumental importance.7,12

Biopsy is recommended for common blue nevi in the evaluation of newly acquired lesions, expansion of previously stable nevi, or for nevi larger than 10 mm in diameter. The nature of eruptive blue nevi warrants a biopsy to exclude melanoma or another malignant process. While the Becker nevus may manifest in adolescent males, it is clinically distinct from an eruptive blue nevus due to the size, relative homogeneity, and presence of hair within the lesion. Cutaneous amyloidosis may appear clinically similar to an eruptive blue nevus, but globular or amorphous material was not present in the papillary dermis of biopsied lesions in our patient. Since there was no cellular atypia or mitotic activity, melanoma and other malignancies were ruled out. Lastly, NAME syndrome by definition must include atrial myxomas, myxoid neurofibromas, and ephelides in addition to the nevi; however, our patient had only nevi and few ephelides. Once the diagnosis is established and benign nature confirmed, treatment is not necessarily required. If the patient elects to remove the lesion for aesthetic reasons, an excision into the subcutaneous fat is required to ensure complete removal of deep dermal melanocytes. Prior excisions of eruptive blue nevi have had no recurrence after more than 10 months.8,9

- Krause M, Bonnekoh B, Weisshaar E, et al. Coincidence of multiple, disseminated, tardive-eruptive blue nevi with cutis marmorata teleangiectatica congenita. Dermatology. 2000;200:134-138.

- Soltani K, Bernstein J, Lorincz A. Eruptive nevocytic nevi after erythema multiforme. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:503-505.

- Shoji T, Cockerell C, Koff A, et al. Eruptive melanocytic nevi after Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:337-339.

- Hendricks W. Eruptive blue nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:50-53.

- Kesty K, Zargari O. Eruptive blue nevi. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:198-201.

- Chen T, Kurwa H, Trotter M, et al. Agminated blue nevi in a patient with dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:52-53.

- Walsh M. Correspondence: eruptive disseminated blue naevi of the scalp. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:581-582.

- Nardini P, De Giorgi V, Massi D, et al. Eruptive disseminated blue naevi of the scalp. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:178-180.

- de Giorgi V, Massi D, Brunasso G, et al. Eruptive multiple blue nevi of the penis: a clinical dermoscopic pathologic case study. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:185-188.

- Zimmermann AH, Becker SA. Precursors of epidermal melanocytes in the negro fetus. In: Gordon M, ed. Pigment Cell Biology. New York, NY: Academic Press Inc; 1959:159-170.

- Leopold JG, Richards DB. The interrelationship of blue and common naevi. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1968;95:37-46.

- Zembowicz A, Phadke P. Blue nevi and variants: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:327-336.

The Diagnosis: Eruptive Blue Nevus

All biopsies demonstrated similar histologic features, including an intradermal proliferation of heavily pigmented, spindle-shaped dendritic melanocytes (Figure). The dermal pigment was most pronounced in the grossly darker papules, and there was not a substantial amount of background pigmentation at the stratum basale. Cytologic atypia, foci of necrosis, and mitotic activity were absent from all sections. There was no definitive junctional component identified, no multinucleated giant cells, and there was no overlying epidermal aberration. With some background pigmentation seen histologically, nevus spilus was considered, but because this acute eruption occurred in a young adult without appreciable gross background hyperpigmentation, the clinical context led to a diagnosis of eruptive blue nevus. After communicating the findings to the patient, he declined further treatment.

Eruptive blue nevus is an exceptionally rare subtype of blue nevus with few cases reported since the 1940s.1-9 Generally, each case report found a triggering event that could possibly have precipitated the acute proliferation and evolution of nevi. Triggering events can include bullous processes such as erythema multiforme2 and Stevens-Johnson syndrome,3 severe sunburn,4 trauma,5 immunosuppression,6 and a variety of endocrinopathies. No such history could be identified in our patient, except the biopsy.

Common blue nevi are benign, usually congenital, well-circumscribed, solitary, blue-gray macules or papules. Half of blue nevi cases are found on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet but can present anywhere (eg, face, scalp, wrists, sacrum, buttocks). The blue-gray color appreciated clinically is attributed to the Tyndall effect, which occurs when long-wavelength light--red, orange, and yellow--is absorbed by the melanin deep in the dermis, while short-wavelength visible light--blue, violet, and indigo--is reflected with backscattering. On polarized dermoscopy, a homogeneous blue-gray hue is appreciated, but lighter segments may be present when collagen deposition is robust. Histopathologic findings confirm spindle-shaped dendritic melanocytes in the dermis without epidermal involvement. It generally is accepted that the etiology of these benign nevi is a failed migration of neural crest cells to the epidermis.10,11 Although the common blue nevus may be simple to diagnose, several subtypes have been described in the literature, including combined blue nevus, desmoplastic blue nevus, hypomelanotic/amelanotic blue nevus, and epithelioid blue nevus of Carney complex, and excluding a malignant process is of monumental importance.7,12

Biopsy is recommended for common blue nevi in the evaluation of newly acquired lesions, expansion of previously stable nevi, or for nevi larger than 10 mm in diameter. The nature of eruptive blue nevi warrants a biopsy to exclude melanoma or another malignant process. While the Becker nevus may manifest in adolescent males, it is clinically distinct from an eruptive blue nevus due to the size, relative homogeneity, and presence of hair within the lesion. Cutaneous amyloidosis may appear clinically similar to an eruptive blue nevus, but globular or amorphous material was not present in the papillary dermis of biopsied lesions in our patient. Since there was no cellular atypia or mitotic activity, melanoma and other malignancies were ruled out. Lastly, NAME syndrome by definition must include atrial myxomas, myxoid neurofibromas, and ephelides in addition to the nevi; however, our patient had only nevi and few ephelides. Once the diagnosis is established and benign nature confirmed, treatment is not necessarily required. If the patient elects to remove the lesion for aesthetic reasons, an excision into the subcutaneous fat is required to ensure complete removal of deep dermal melanocytes. Prior excisions of eruptive blue nevi have had no recurrence after more than 10 months.8,9

The Diagnosis: Eruptive Blue Nevus

All biopsies demonstrated similar histologic features, including an intradermal proliferation of heavily pigmented, spindle-shaped dendritic melanocytes (Figure). The dermal pigment was most pronounced in the grossly darker papules, and there was not a substantial amount of background pigmentation at the stratum basale. Cytologic atypia, foci of necrosis, and mitotic activity were absent from all sections. There was no definitive junctional component identified, no multinucleated giant cells, and there was no overlying epidermal aberration. With some background pigmentation seen histologically, nevus spilus was considered, but because this acute eruption occurred in a young adult without appreciable gross background hyperpigmentation, the clinical context led to a diagnosis of eruptive blue nevus. After communicating the findings to the patient, he declined further treatment.

Eruptive blue nevus is an exceptionally rare subtype of blue nevus with few cases reported since the 1940s.1-9 Generally, each case report found a triggering event that could possibly have precipitated the acute proliferation and evolution of nevi. Triggering events can include bullous processes such as erythema multiforme2 and Stevens-Johnson syndrome,3 severe sunburn,4 trauma,5 immunosuppression,6 and a variety of endocrinopathies. No such history could be identified in our patient, except the biopsy.

Common blue nevi are benign, usually congenital, well-circumscribed, solitary, blue-gray macules or papules. Half of blue nevi cases are found on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet but can present anywhere (eg, face, scalp, wrists, sacrum, buttocks). The blue-gray color appreciated clinically is attributed to the Tyndall effect, which occurs when long-wavelength light--red, orange, and yellow--is absorbed by the melanin deep in the dermis, while short-wavelength visible light--blue, violet, and indigo--is reflected with backscattering. On polarized dermoscopy, a homogeneous blue-gray hue is appreciated, but lighter segments may be present when collagen deposition is robust. Histopathologic findings confirm spindle-shaped dendritic melanocytes in the dermis without epidermal involvement. It generally is accepted that the etiology of these benign nevi is a failed migration of neural crest cells to the epidermis.10,11 Although the common blue nevus may be simple to diagnose, several subtypes have been described in the literature, including combined blue nevus, desmoplastic blue nevus, hypomelanotic/amelanotic blue nevus, and epithelioid blue nevus of Carney complex, and excluding a malignant process is of monumental importance.7,12

Biopsy is recommended for common blue nevi in the evaluation of newly acquired lesions, expansion of previously stable nevi, or for nevi larger than 10 mm in diameter. The nature of eruptive blue nevi warrants a biopsy to exclude melanoma or another malignant process. While the Becker nevus may manifest in adolescent males, it is clinically distinct from an eruptive blue nevus due to the size, relative homogeneity, and presence of hair within the lesion. Cutaneous amyloidosis may appear clinically similar to an eruptive blue nevus, but globular or amorphous material was not present in the papillary dermis of biopsied lesions in our patient. Since there was no cellular atypia or mitotic activity, melanoma and other malignancies were ruled out. Lastly, NAME syndrome by definition must include atrial myxomas, myxoid neurofibromas, and ephelides in addition to the nevi; however, our patient had only nevi and few ephelides. Once the diagnosis is established and benign nature confirmed, treatment is not necessarily required. If the patient elects to remove the lesion for aesthetic reasons, an excision into the subcutaneous fat is required to ensure complete removal of deep dermal melanocytes. Prior excisions of eruptive blue nevi have had no recurrence after more than 10 months.8,9

- Krause M, Bonnekoh B, Weisshaar E, et al. Coincidence of multiple, disseminated, tardive-eruptive blue nevi with cutis marmorata teleangiectatica congenita. Dermatology. 2000;200:134-138.

- Soltani K, Bernstein J, Lorincz A. Eruptive nevocytic nevi after erythema multiforme. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:503-505.

- Shoji T, Cockerell C, Koff A, et al. Eruptive melanocytic nevi after Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:337-339.

- Hendricks W. Eruptive blue nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:50-53.

- Kesty K, Zargari O. Eruptive blue nevi. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:198-201.

- Chen T, Kurwa H, Trotter M, et al. Agminated blue nevi in a patient with dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:52-53.

- Walsh M. Correspondence: eruptive disseminated blue naevi of the scalp. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:581-582.

- Nardini P, De Giorgi V, Massi D, et al. Eruptive disseminated blue naevi of the scalp. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:178-180.

- de Giorgi V, Massi D, Brunasso G, et al. Eruptive multiple blue nevi of the penis: a clinical dermoscopic pathologic case study. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:185-188.

- Zimmermann AH, Becker SA. Precursors of epidermal melanocytes in the negro fetus. In: Gordon M, ed. Pigment Cell Biology. New York, NY: Academic Press Inc; 1959:159-170.

- Leopold JG, Richards DB. The interrelationship of blue and common naevi. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1968;95:37-46.

- Zembowicz A, Phadke P. Blue nevi and variants: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:327-336.

- Krause M, Bonnekoh B, Weisshaar E, et al. Coincidence of multiple, disseminated, tardive-eruptive blue nevi with cutis marmorata teleangiectatica congenita. Dermatology. 2000;200:134-138.

- Soltani K, Bernstein J, Lorincz A. Eruptive nevocytic nevi after erythema multiforme. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:503-505.

- Shoji T, Cockerell C, Koff A, et al. Eruptive melanocytic nevi after Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:337-339.

- Hendricks W. Eruptive blue nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:50-53.

- Kesty K, Zargari O. Eruptive blue nevi. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:198-201.

- Chen T, Kurwa H, Trotter M, et al. Agminated blue nevi in a patient with dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:52-53.

- Walsh M. Correspondence: eruptive disseminated blue naevi of the scalp. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:581-582.

- Nardini P, De Giorgi V, Massi D, et al. Eruptive disseminated blue naevi of the scalp. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:178-180.

- de Giorgi V, Massi D, Brunasso G, et al. Eruptive multiple blue nevi of the penis: a clinical dermoscopic pathologic case study. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:185-188.

- Zimmermann AH, Becker SA. Precursors of epidermal melanocytes in the negro fetus. In: Gordon M, ed. Pigment Cell Biology. New York, NY: Academic Press Inc; 1959:159-170.

- Leopold JG, Richards DB. The interrelationship of blue and common naevi. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1968;95:37-46.

- Zembowicz A, Phadke P. Blue nevi and variants: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:327-336.

A 19-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of several new dark papules on the neck of 1 year's duration. He denied any personal or family history of skin cancer, cardiac abnormalities, or endocrine dysfunction. He also denied any recent changes in health or use of medication. A biopsy was performed at the site 2 years prior for a single blue nevus, but the patient denied history of other trauma or cutaneous eruptions localized to the area. Physical examination revealed numerous dark brown, blue, white, and flesh-colored papules and macules agminated into a well-circumscribed plaque on the left posterolateral neck without background hyperpigmentation. The total area of the plaque was roughly 3×4 cm. There was no associated edema or erythema. Cardiac murmur, thyromegaly, exophthalmos, neurologic deficits, regional lymphadenopathy, and similar skin findings on other areas of the body were not appreciated. Three scouting punch biopsies were taken of the various morphologies present.

Telangiectatic Patch on the Neck

The Diagnosis: Unilateral Nevoid Telangiectasia

Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia (UNT) is an uncommon, or perhaps underreported, cutaneous condition involving telangiectatic patches in a unilateral dermatomal or blaschkoid pattern.1 The condition has been described as either congenital or acquired. Congenital UNT is thought to be a result of somatic mosaicism, whereby a mutation during embryogenesis leads to a distinct population of cells expressing the vascular malformation.1 Congenital UNT has been associated with Becker nevus, which also is thought to be a result of somatic mosaicism, further providing evidence for this theory, though it is unclear whether this finding is incidental.2 The acquired form often is associated with fluctuation of hormones, such as in pregnancy or with oral contraceptive initiation, as well as with hepatic disease as seen in our patient. However, there are many cases of acquired UNT with no implicated underlying disease, alcohol abuse, or hormonal changes, which calls into question if UNT is definitively an estrogen-related condition.3 One study demonstrated an increased level of estrogen and progesterone receptors in affected skin, which may have led to expression of the cutaneous changes at that site.4 More research is needed to elucidate this point, as other studies have not reproduced similar findings.

Congenital UNT occurs more commonly in males, whereas the acquired variant is seen more frequently in females. The third and fourth cervical dermatomes most often are involved.5 Most lesions persist without spontaneous resolution. Treatment options are limited and include pulsed dye laser treatment and makeup application to cover the telangiectatic patches. The main side effect seen with pulsed dye laser treatment is reversible pigmentary changes, with 1 report of textural skin change.6

A biopsy was deemed unnecessary for the clinical diagnosis in our patient because there was a clear explanation for the physical examination findings due to long-standing underlying liver disease. When biopsied, UNT characteristically demonstrates dilated dermal capillaries.5 Our patient elected not to pursue laser therapy but expressed interest in using makeup to camouflage the lesion.

The differential diagnosis includes acquired nevus flammeus, which typically is present on the face and often appears following mechanical or thermal trauma. Angioma serpiginosum most often occurs on the buttocks and legs as small red papules or puncta coalescing into a serpiginous linear arrangement. It often appears in childhood. Angiosarcoma is an aggressive malignancy that often occurs on the head and neck in elderly patients. It is associated with areas of long-standing lymphedema and often appears as a bruiselike lesion. Rosacea typically is not fixed in its clinical appearance and presents as transitory flushing of the head and neck with or without a history of acneform eruptions on the face. It typically is not unilateral.

- Wilkin JK. Unilateral dermatomal superficial telangiectasia. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:579-580.

- Karakaş M, Durdu M, Sönmezoğlu S, et al. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia. J Dermatol. 2004;31:109-112.

- Taskapan O, Harmanyeri Y, Sener O, et al. Acquired unilateral nevoid telangiectasia syndrome. Acta Derm Venereol. 1997;77:62-63.

- Uhlin SR, McCarty KS Jr. Unilateral nevoid telangiectatic syndrome: the role of estrogen and progesterone receptors. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:226-228.

- Derrow AE, Adams BB, Timani S, et al. Acquired unilateral nevoid telangiectasia in a 51-year-old female. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1331-1333.

- Sharma VK, Khandpur S. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia--response to pulsed dye laser. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:960-964.

The Diagnosis: Unilateral Nevoid Telangiectasia

Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia (UNT) is an uncommon, or perhaps underreported, cutaneous condition involving telangiectatic patches in a unilateral dermatomal or blaschkoid pattern.1 The condition has been described as either congenital or acquired. Congenital UNT is thought to be a result of somatic mosaicism, whereby a mutation during embryogenesis leads to a distinct population of cells expressing the vascular malformation.1 Congenital UNT has been associated with Becker nevus, which also is thought to be a result of somatic mosaicism, further providing evidence for this theory, though it is unclear whether this finding is incidental.2 The acquired form often is associated with fluctuation of hormones, such as in pregnancy or with oral contraceptive initiation, as well as with hepatic disease as seen in our patient. However, there are many cases of acquired UNT with no implicated underlying disease, alcohol abuse, or hormonal changes, which calls into question if UNT is definitively an estrogen-related condition.3 One study demonstrated an increased level of estrogen and progesterone receptors in affected skin, which may have led to expression of the cutaneous changes at that site.4 More research is needed to elucidate this point, as other studies have not reproduced similar findings.

Congenital UNT occurs more commonly in males, whereas the acquired variant is seen more frequently in females. The third and fourth cervical dermatomes most often are involved.5 Most lesions persist without spontaneous resolution. Treatment options are limited and include pulsed dye laser treatment and makeup application to cover the telangiectatic patches. The main side effect seen with pulsed dye laser treatment is reversible pigmentary changes, with 1 report of textural skin change.6

A biopsy was deemed unnecessary for the clinical diagnosis in our patient because there was a clear explanation for the physical examination findings due to long-standing underlying liver disease. When biopsied, UNT characteristically demonstrates dilated dermal capillaries.5 Our patient elected not to pursue laser therapy but expressed interest in using makeup to camouflage the lesion.

The differential diagnosis includes acquired nevus flammeus, which typically is present on the face and often appears following mechanical or thermal trauma. Angioma serpiginosum most often occurs on the buttocks and legs as small red papules or puncta coalescing into a serpiginous linear arrangement. It often appears in childhood. Angiosarcoma is an aggressive malignancy that often occurs on the head and neck in elderly patients. It is associated with areas of long-standing lymphedema and often appears as a bruiselike lesion. Rosacea typically is not fixed in its clinical appearance and presents as transitory flushing of the head and neck with or without a history of acneform eruptions on the face. It typically is not unilateral.

The Diagnosis: Unilateral Nevoid Telangiectasia

Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia (UNT) is an uncommon, or perhaps underreported, cutaneous condition involving telangiectatic patches in a unilateral dermatomal or blaschkoid pattern.1 The condition has been described as either congenital or acquired. Congenital UNT is thought to be a result of somatic mosaicism, whereby a mutation during embryogenesis leads to a distinct population of cells expressing the vascular malformation.1 Congenital UNT has been associated with Becker nevus, which also is thought to be a result of somatic mosaicism, further providing evidence for this theory, though it is unclear whether this finding is incidental.2 The acquired form often is associated with fluctuation of hormones, such as in pregnancy or with oral contraceptive initiation, as well as with hepatic disease as seen in our patient. However, there are many cases of acquired UNT with no implicated underlying disease, alcohol abuse, or hormonal changes, which calls into question if UNT is definitively an estrogen-related condition.3 One study demonstrated an increased level of estrogen and progesterone receptors in affected skin, which may have led to expression of the cutaneous changes at that site.4 More research is needed to elucidate this point, as other studies have not reproduced similar findings.

Congenital UNT occurs more commonly in males, whereas the acquired variant is seen more frequently in females. The third and fourth cervical dermatomes most often are involved.5 Most lesions persist without spontaneous resolution. Treatment options are limited and include pulsed dye laser treatment and makeup application to cover the telangiectatic patches. The main side effect seen with pulsed dye laser treatment is reversible pigmentary changes, with 1 report of textural skin change.6

A biopsy was deemed unnecessary for the clinical diagnosis in our patient because there was a clear explanation for the physical examination findings due to long-standing underlying liver disease. When biopsied, UNT characteristically demonstrates dilated dermal capillaries.5 Our patient elected not to pursue laser therapy but expressed interest in using makeup to camouflage the lesion.

The differential diagnosis includes acquired nevus flammeus, which typically is present on the face and often appears following mechanical or thermal trauma. Angioma serpiginosum most often occurs on the buttocks and legs as small red papules or puncta coalescing into a serpiginous linear arrangement. It often appears in childhood. Angiosarcoma is an aggressive malignancy that often occurs on the head and neck in elderly patients. It is associated with areas of long-standing lymphedema and often appears as a bruiselike lesion. Rosacea typically is not fixed in its clinical appearance and presents as transitory flushing of the head and neck with or without a history of acneform eruptions on the face. It typically is not unilateral.

- Wilkin JK. Unilateral dermatomal superficial telangiectasia. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:579-580.

- Karakaş M, Durdu M, Sönmezoğlu S, et al. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia. J Dermatol. 2004;31:109-112.

- Taskapan O, Harmanyeri Y, Sener O, et al. Acquired unilateral nevoid telangiectasia syndrome. Acta Derm Venereol. 1997;77:62-63.

- Uhlin SR, McCarty KS Jr. Unilateral nevoid telangiectatic syndrome: the role of estrogen and progesterone receptors. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:226-228.

- Derrow AE, Adams BB, Timani S, et al. Acquired unilateral nevoid telangiectasia in a 51-year-old female. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1331-1333.