User login

Vegetative Sacral Plaque in a Patient With Human Immunodeficiency Virus

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Vegetans

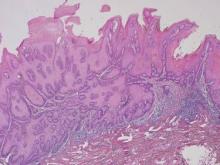

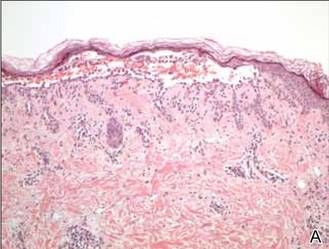

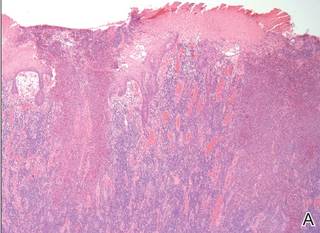

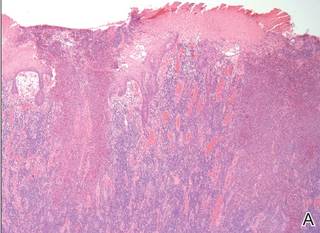

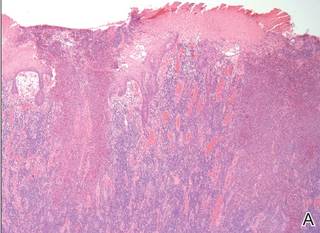

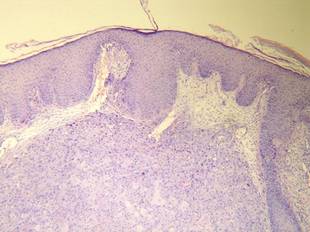

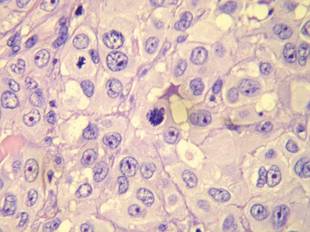

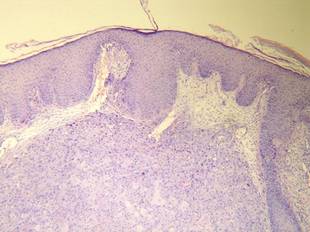

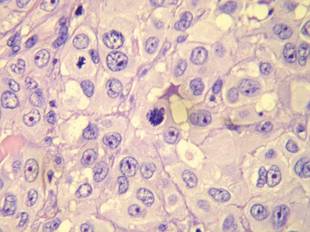

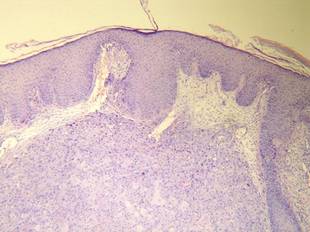

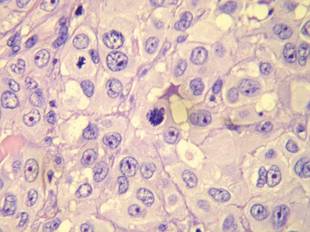

Histopathologic examination using hematoxylin and eosin stain demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with granulation tissue, ulceration, and abundant exudate joined by a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate that included a myriad of eosinophils (Figure, A). At higher power (Figure, B), many single and multinucleate acantholytic keratinocytes showed ground-glass nuclei and peripheral margination of chromatin within zones of ulceration and crust. Viral culture and direct fluorescent antibody assay identified herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2. Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with herpes simplex vegetans. He was initially treated with oral acyclovir and then oral famciclovir but showed minimal improvement. Eventually, he was referred to surgery and the mass was totally excised with clear margins and no evidence of underlying malignancy.

|

| Histopathology revealed marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, ulceration, and a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate (A)(H&E, original magnification ×20). Many multinucleate acantholytic keratinocytes with ground-glass nuclei and peripheral margination of chromatin were shown (B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

Herpes simplex virus is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections, with a notably increased incidence and prevalence among individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.1 Although typical HSV manifestation in immunocompetent patients includes clustered vesicles and/or ulcerations, immunocompromised patients may have unusual presentations, such as persistent and extensive ulcerations or nodular hyperkeratotic lesions.2,3 Herpes vegetans, a term used to describe these atypical exophytic lesions, rarely has been reported in literature, but its presence should raise suspicion for possible underlying immunocompromise. The pathogenesis behind the hypertrophic nature of these lesions is not well understood, but it is postulated that the immune dysregulation from concomitant HIV and HSV infection plays a role.2 Overproduction of tumor necrosis factor and IL-6 by HIV-infected dermal dendritic cells causes an increase in antiapoptotic factors within the epidermis, resulting in enhanced keratinocyte proliferation and clinical hyperkeratosis.2,4

The differential diagnosis for herpes vegetans is somewhat broad, owing to the verrucous and often eroded appearance of the lesions. Biopsy and cultures can be obtained to differentiate from condyloma acuminatum, condyloma latum (secondary syphilis), pyoderma vegetans, pemphigus vegetans, granuloma inguinale, extraintestinal Crohn disease, deep fungal infections, cutaneous tuberculosis, and malignancy.2-4 Histopathology shows epithelial hyperplasia and ulceration with scattered multinucleate keratinocytes, usually at the periphery of the ulcer, and intranuclear inclusions typical of HSV. In addition, a dense dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils is usually present beneath the base of the ulcer.2,4

Treatment options for herpes vegetans are limited due to the high prevalence of acyclovir-resistant (ACV-R) HSV-2 strains in HIV patients. Valacyclovir and penciclovir have been largely ineffective against ACV-R HSV due to their dependence on the same enzyme—thymidine kinase—involved in the mechanism of acyclovir resistance. Intravenous foscarnet and cidofovir have shown efficacy against ACV-R virus, but concerns of nephrotoxicity have limited their use over prolonged intervals.5 Castelo-Soccio et al6 reported promising results with intralesional cidofovir. This route of administration provides the advantage of increased bioavailability with reduced risk for nephrotoxicity.6 Finally, surgical resection may be considered for refractory lesions to circumvent the toxicity from systemically administered drugs.3

- Severson JL, Tyring SK. Relation between herpes simplex viruses and human immunodeficiency virus infections. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1393-1397.

- Patel AB, Rosen T. Herpes vegetans as a sign of HIV infection. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:6.

- Chung VQ, Parker DC, Parker SR. Surgical excision for vegetative herpes simplex virus infection. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1374-1379.

- Beasley KL, Cooley GE, Kao GF, et al. Herpes simplex vegetans: atypical genital herpes infection in a patient with common variable immunodeficiency. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(5, pt 2):860-863.

- Chilukuri S, Rosen T. Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:311-320.

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Vegetans

Histopathologic examination using hematoxylin and eosin stain demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with granulation tissue, ulceration, and abundant exudate joined by a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate that included a myriad of eosinophils (Figure, A). At higher power (Figure, B), many single and multinucleate acantholytic keratinocytes showed ground-glass nuclei and peripheral margination of chromatin within zones of ulceration and crust. Viral culture and direct fluorescent antibody assay identified herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2. Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with herpes simplex vegetans. He was initially treated with oral acyclovir and then oral famciclovir but showed minimal improvement. Eventually, he was referred to surgery and the mass was totally excised with clear margins and no evidence of underlying malignancy.

|

| Histopathology revealed marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, ulceration, and a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate (A)(H&E, original magnification ×20). Many multinucleate acantholytic keratinocytes with ground-glass nuclei and peripheral margination of chromatin were shown (B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

Herpes simplex virus is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections, with a notably increased incidence and prevalence among individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.1 Although typical HSV manifestation in immunocompetent patients includes clustered vesicles and/or ulcerations, immunocompromised patients may have unusual presentations, such as persistent and extensive ulcerations or nodular hyperkeratotic lesions.2,3 Herpes vegetans, a term used to describe these atypical exophytic lesions, rarely has been reported in literature, but its presence should raise suspicion for possible underlying immunocompromise. The pathogenesis behind the hypertrophic nature of these lesions is not well understood, but it is postulated that the immune dysregulation from concomitant HIV and HSV infection plays a role.2 Overproduction of tumor necrosis factor and IL-6 by HIV-infected dermal dendritic cells causes an increase in antiapoptotic factors within the epidermis, resulting in enhanced keratinocyte proliferation and clinical hyperkeratosis.2,4

The differential diagnosis for herpes vegetans is somewhat broad, owing to the verrucous and often eroded appearance of the lesions. Biopsy and cultures can be obtained to differentiate from condyloma acuminatum, condyloma latum (secondary syphilis), pyoderma vegetans, pemphigus vegetans, granuloma inguinale, extraintestinal Crohn disease, deep fungal infections, cutaneous tuberculosis, and malignancy.2-4 Histopathology shows epithelial hyperplasia and ulceration with scattered multinucleate keratinocytes, usually at the periphery of the ulcer, and intranuclear inclusions typical of HSV. In addition, a dense dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils is usually present beneath the base of the ulcer.2,4

Treatment options for herpes vegetans are limited due to the high prevalence of acyclovir-resistant (ACV-R) HSV-2 strains in HIV patients. Valacyclovir and penciclovir have been largely ineffective against ACV-R HSV due to their dependence on the same enzyme—thymidine kinase—involved in the mechanism of acyclovir resistance. Intravenous foscarnet and cidofovir have shown efficacy against ACV-R virus, but concerns of nephrotoxicity have limited their use over prolonged intervals.5 Castelo-Soccio et al6 reported promising results with intralesional cidofovir. This route of administration provides the advantage of increased bioavailability with reduced risk for nephrotoxicity.6 Finally, surgical resection may be considered for refractory lesions to circumvent the toxicity from systemically administered drugs.3

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Vegetans

Histopathologic examination using hematoxylin and eosin stain demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with granulation tissue, ulceration, and abundant exudate joined by a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate that included a myriad of eosinophils (Figure, A). At higher power (Figure, B), many single and multinucleate acantholytic keratinocytes showed ground-glass nuclei and peripheral margination of chromatin within zones of ulceration and crust. Viral culture and direct fluorescent antibody assay identified herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2. Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with herpes simplex vegetans. He was initially treated with oral acyclovir and then oral famciclovir but showed minimal improvement. Eventually, he was referred to surgery and the mass was totally excised with clear margins and no evidence of underlying malignancy.

|

| Histopathology revealed marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, ulceration, and a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate (A)(H&E, original magnification ×20). Many multinucleate acantholytic keratinocytes with ground-glass nuclei and peripheral margination of chromatin were shown (B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

Herpes simplex virus is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections, with a notably increased incidence and prevalence among individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.1 Although typical HSV manifestation in immunocompetent patients includes clustered vesicles and/or ulcerations, immunocompromised patients may have unusual presentations, such as persistent and extensive ulcerations or nodular hyperkeratotic lesions.2,3 Herpes vegetans, a term used to describe these atypical exophytic lesions, rarely has been reported in literature, but its presence should raise suspicion for possible underlying immunocompromise. The pathogenesis behind the hypertrophic nature of these lesions is not well understood, but it is postulated that the immune dysregulation from concomitant HIV and HSV infection plays a role.2 Overproduction of tumor necrosis factor and IL-6 by HIV-infected dermal dendritic cells causes an increase in antiapoptotic factors within the epidermis, resulting in enhanced keratinocyte proliferation and clinical hyperkeratosis.2,4

The differential diagnosis for herpes vegetans is somewhat broad, owing to the verrucous and often eroded appearance of the lesions. Biopsy and cultures can be obtained to differentiate from condyloma acuminatum, condyloma latum (secondary syphilis), pyoderma vegetans, pemphigus vegetans, granuloma inguinale, extraintestinal Crohn disease, deep fungal infections, cutaneous tuberculosis, and malignancy.2-4 Histopathology shows epithelial hyperplasia and ulceration with scattered multinucleate keratinocytes, usually at the periphery of the ulcer, and intranuclear inclusions typical of HSV. In addition, a dense dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils is usually present beneath the base of the ulcer.2,4

Treatment options for herpes vegetans are limited due to the high prevalence of acyclovir-resistant (ACV-R) HSV-2 strains in HIV patients. Valacyclovir and penciclovir have been largely ineffective against ACV-R HSV due to their dependence on the same enzyme—thymidine kinase—involved in the mechanism of acyclovir resistance. Intravenous foscarnet and cidofovir have shown efficacy against ACV-R virus, but concerns of nephrotoxicity have limited their use over prolonged intervals.5 Castelo-Soccio et al6 reported promising results with intralesional cidofovir. This route of administration provides the advantage of increased bioavailability with reduced risk for nephrotoxicity.6 Finally, surgical resection may be considered for refractory lesions to circumvent the toxicity from systemically administered drugs.3

- Severson JL, Tyring SK. Relation between herpes simplex viruses and human immunodeficiency virus infections. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1393-1397.

- Patel AB, Rosen T. Herpes vegetans as a sign of HIV infection. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:6.

- Chung VQ, Parker DC, Parker SR. Surgical excision for vegetative herpes simplex virus infection. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1374-1379.

- Beasley KL, Cooley GE, Kao GF, et al. Herpes simplex vegetans: atypical genital herpes infection in a patient with common variable immunodeficiency. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(5, pt 2):860-863.

- Chilukuri S, Rosen T. Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:311-320.

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126.

- Severson JL, Tyring SK. Relation between herpes simplex viruses and human immunodeficiency virus infections. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1393-1397.

- Patel AB, Rosen T. Herpes vegetans as a sign of HIV infection. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:6.

- Chung VQ, Parker DC, Parker SR. Surgical excision for vegetative herpes simplex virus infection. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1374-1379.

- Beasley KL, Cooley GE, Kao GF, et al. Herpes simplex vegetans: atypical genital herpes infection in a patient with common variable immunodeficiency. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(5, pt 2):860-863.

- Chilukuri S, Rosen T. Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:311-320.

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126.

A 53-year-old man presented to our clinic with a sacral mass that had progressively enlarged over 2 years. The patient reported occasional oozing from the mass as well as pain when laying flat but denied fever or other symptoms. His medical history was remarkable for human immunodeficiency virus infection with variable adherence to a highly active antiretroviral therapy regimen. At the time of presentation, the patient had a CD4 lymphocyte count of 78 cells/mm3 (reference range, 500–1400 cells/mm3) and a viral load of 290 copies/mL (reference range, 0 copies/mL). Physical examination revealed a 10-cm discrete, moist and pink, exophytic plaque on the sacrum with superficial erosions. The plaque was nontender and without associated lymphadenopathy. The skin and mucous membranes were otherwise clear. A cutaneous biopsy specimen was obtained from the tumor and sent for histopathologic analysis.

What Is Your Diagnosis? Idiopathic Guttate Hypomelanosis

The Diagnosis: Idiopathic Guttate Hypomelanosis

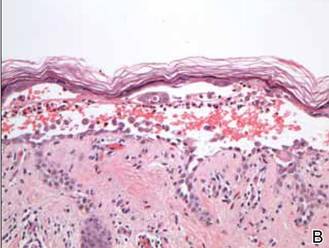

A biopsy of the largest lesion from the left leg superior to the lateral malleolus was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed solar elastosis, diminished number of focal melanocytes and pigment within keratinocytes compared to uninvolved skin, and presence of hyperkeratosis with flattening of rete ridges. The clinical presentation along with histopathologic analysis confirmed a diagnosis of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis (IGH). The lesions were treated with short-exposure cryotherapy, which resulted in partial repigmentation after several treatments.

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis is a common but underreported condition in elderly patients that usually presents with small, discrete, asymptomatic, hypopigmented macules. The frequency of IGH increases with age.1 Frequency of the condition is much lower in patients aged 21 to 30 years and does not exceed 7%. Lesions of IGH have a predilection for sun-exposed areas such as the arms and legs but rarely can be seen on the face and trunk. Facial lesions of IGH are more frequently reported in women.1 The size of lesions can be up to 1.5 cm in diameter. The condition generally is self-limited, but some patients may express aesthetic concerns. Rare cases of IGH in children have been associated with prolonged sun exposure.2

The etiology of IGH is unknown but an association with sun exposure has been noted. Patients with IGH frequently show other signs of photoaging, such as numerous seborrheic keratoses, solar lentigines, xeroses, freckles, and actinic keratoses.1 Short-term exposure to UVB radiation and psoralen plus UVA therapy has been shown to cause IGH in patients with chronic diseases such as mycosis fungoides.3-5 One small study that examined renal transplant recipients determined an association between HLA-DQ3 antigens and IGH, whereas HLA-DR8 antigens were not identified in any patients with IGH, indicating it may have some advantage in preventing the development of IGH.6 Shin et al1 reported that IGH was prevalent among patients who regularly traumatized their skin by scrubbing.

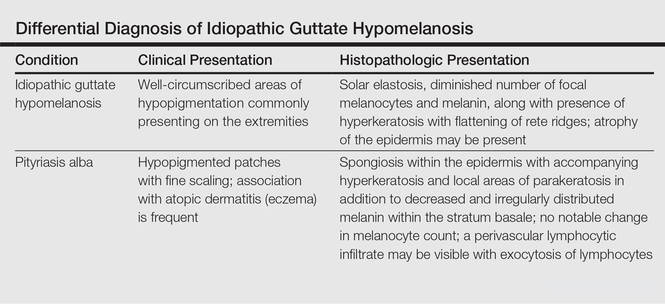

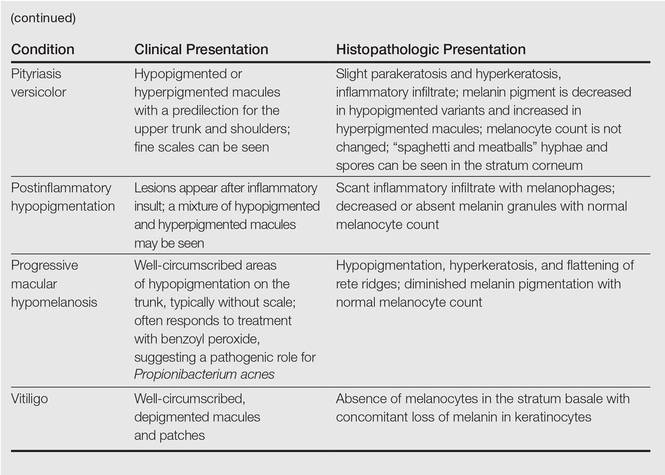

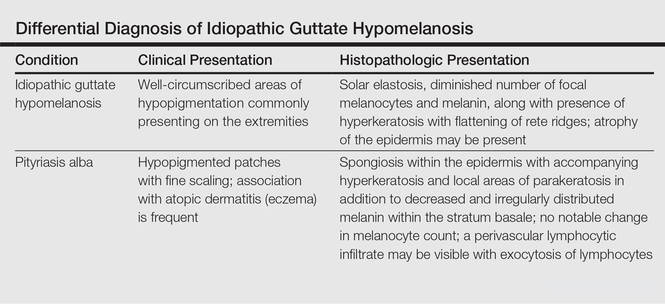

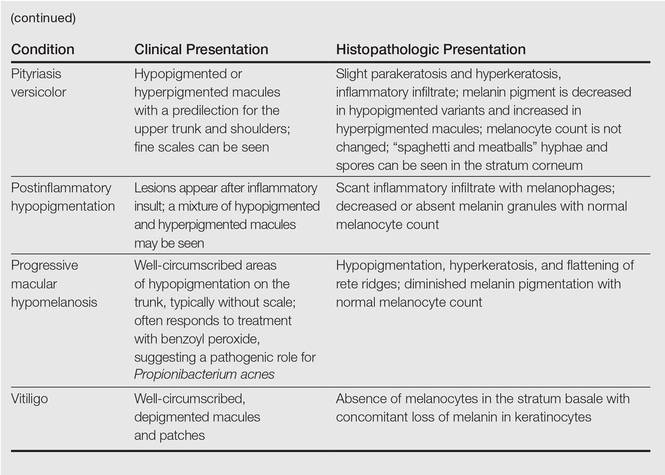

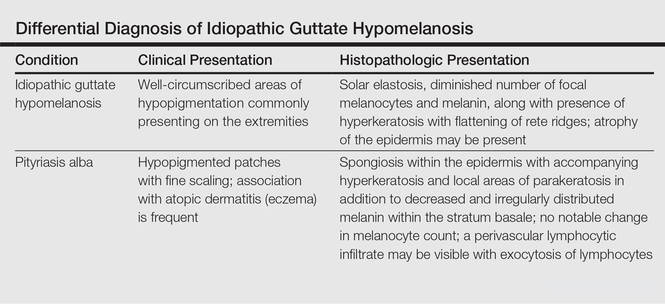

Clinically, IGH should be differentiated from other conditions characterized by hypopigmentation, such as pityriasis alba, pityriasis versicolor, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, progressive macular hypomelanosis, and vitiligo. Aside from clinical examination, histopathologic studies are helpful in making a definitive diagnosis. The differential diagnosis of IGH is presented in the Table.

Histopathology of IGH lesions usually reveals slight atrophy of the epidermis with flattening of rete ridges and concomitant hyperkeratosis. A thickened stratum granulosum also has been noted in lesions of IGH.2 The diminished number of melanocytes and melanin pigment granules along with hyperkeratosis both appear to contribute to the hypopigmentation noted in IGH.7 Ultrastructural studies of lesions of IGH can confirm melanocytic degeneration and a decreased number of melanosomes in melanocytes and keratinocytes.2,8

There is no uniformly effective treatment of IGH. Topical application of tacrolimus and tretinoin have shown efficacy in repigmenting IGH lesions.8,9 Short-exposure cryotherapy with a duration of 3 to 5 seconds, localized chemical peels, and/or local dermabrasion can be helpful.10-12 CO2 lasers also have demonstrated promising results.13

- Shin MK, Jeong KH, Oh IH, et al. Clinical features of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis in 646 subjects and association with other aspects of photoaging. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:798-805.

- Kim SK, Kim EH, Kang HY, et al. Comprehensive understanding of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: clinical and histopathological correlation. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:162-166.

- Friedland R, David M, Feinmesser M, et al. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis-like lesions in patients with mycosis fungoides: a new adverse effect of phototherapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1026-1030.

- Kaya TI, Yazici AC, Tursen U, et al. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: idiopathic or ultraviolet induced? Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2005;21:270-271.

- Loquai C, Metze D, Nashan D, et al. Confetti-like lesions with hyperkeratosis: a novel ultraviolet-induced hypomelanotic disorder? Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:190-193.

- Arrunategui A, Trujillo RA, Marulanda MP, et al. HLA-DQ3 is associated with idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis, whereas HLA-DR8 is not, in a group of renal transplant patients. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:744-747.

- Wallace ML, Grichnik JM, Prieto VG, et al. Numbers and differentiation status of melanocytes in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. J Cutan Pathol. 1998;25:375-379.

- Ortonne JP, Perrot H. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. ultrastructural study. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:664-668.

- Rerknimitr P, Disphanurat W, Achariyakul M. Topical tacrolimus significantly promotes repigmentation in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:460-464.

- Pagnoni A, Kligman AM, Sadiq I, et al. Hypopigmented macules of photodamaged skin and their treatment with topical tretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:305-310.

- Kumarasinghe SP. 3-5 second cryotherapy is effective in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. J Dermatol. 2004;31:457-459.

- Hexsel DM. Treatment of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis by localized superficial dermabrasion. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:917-918.

- Shin J, Kim M, Park SH, et al. The effect of fractional carbon dioxide lasers on idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: a preliminary study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:e243-e246.

The Diagnosis: Idiopathic Guttate Hypomelanosis

A biopsy of the largest lesion from the left leg superior to the lateral malleolus was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed solar elastosis, diminished number of focal melanocytes and pigment within keratinocytes compared to uninvolved skin, and presence of hyperkeratosis with flattening of rete ridges. The clinical presentation along with histopathologic analysis confirmed a diagnosis of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis (IGH). The lesions were treated with short-exposure cryotherapy, which resulted in partial repigmentation after several treatments.

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis is a common but underreported condition in elderly patients that usually presents with small, discrete, asymptomatic, hypopigmented macules. The frequency of IGH increases with age.1 Frequency of the condition is much lower in patients aged 21 to 30 years and does not exceed 7%. Lesions of IGH have a predilection for sun-exposed areas such as the arms and legs but rarely can be seen on the face and trunk. Facial lesions of IGH are more frequently reported in women.1 The size of lesions can be up to 1.5 cm in diameter. The condition generally is self-limited, but some patients may express aesthetic concerns. Rare cases of IGH in children have been associated with prolonged sun exposure.2

The etiology of IGH is unknown but an association with sun exposure has been noted. Patients with IGH frequently show other signs of photoaging, such as numerous seborrheic keratoses, solar lentigines, xeroses, freckles, and actinic keratoses.1 Short-term exposure to UVB radiation and psoralen plus UVA therapy has been shown to cause IGH in patients with chronic diseases such as mycosis fungoides.3-5 One small study that examined renal transplant recipients determined an association between HLA-DQ3 antigens and IGH, whereas HLA-DR8 antigens were not identified in any patients with IGH, indicating it may have some advantage in preventing the development of IGH.6 Shin et al1 reported that IGH was prevalent among patients who regularly traumatized their skin by scrubbing.

Clinically, IGH should be differentiated from other conditions characterized by hypopigmentation, such as pityriasis alba, pityriasis versicolor, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, progressive macular hypomelanosis, and vitiligo. Aside from clinical examination, histopathologic studies are helpful in making a definitive diagnosis. The differential diagnosis of IGH is presented in the Table.

Histopathology of IGH lesions usually reveals slight atrophy of the epidermis with flattening of rete ridges and concomitant hyperkeratosis. A thickened stratum granulosum also has been noted in lesions of IGH.2 The diminished number of melanocytes and melanin pigment granules along with hyperkeratosis both appear to contribute to the hypopigmentation noted in IGH.7 Ultrastructural studies of lesions of IGH can confirm melanocytic degeneration and a decreased number of melanosomes in melanocytes and keratinocytes.2,8

There is no uniformly effective treatment of IGH. Topical application of tacrolimus and tretinoin have shown efficacy in repigmenting IGH lesions.8,9 Short-exposure cryotherapy with a duration of 3 to 5 seconds, localized chemical peels, and/or local dermabrasion can be helpful.10-12 CO2 lasers also have demonstrated promising results.13

The Diagnosis: Idiopathic Guttate Hypomelanosis

A biopsy of the largest lesion from the left leg superior to the lateral malleolus was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed solar elastosis, diminished number of focal melanocytes and pigment within keratinocytes compared to uninvolved skin, and presence of hyperkeratosis with flattening of rete ridges. The clinical presentation along with histopathologic analysis confirmed a diagnosis of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis (IGH). The lesions were treated with short-exposure cryotherapy, which resulted in partial repigmentation after several treatments.

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis is a common but underreported condition in elderly patients that usually presents with small, discrete, asymptomatic, hypopigmented macules. The frequency of IGH increases with age.1 Frequency of the condition is much lower in patients aged 21 to 30 years and does not exceed 7%. Lesions of IGH have a predilection for sun-exposed areas such as the arms and legs but rarely can be seen on the face and trunk. Facial lesions of IGH are more frequently reported in women.1 The size of lesions can be up to 1.5 cm in diameter. The condition generally is self-limited, but some patients may express aesthetic concerns. Rare cases of IGH in children have been associated with prolonged sun exposure.2

The etiology of IGH is unknown but an association with sun exposure has been noted. Patients with IGH frequently show other signs of photoaging, such as numerous seborrheic keratoses, solar lentigines, xeroses, freckles, and actinic keratoses.1 Short-term exposure to UVB radiation and psoralen plus UVA therapy has been shown to cause IGH in patients with chronic diseases such as mycosis fungoides.3-5 One small study that examined renal transplant recipients determined an association between HLA-DQ3 antigens and IGH, whereas HLA-DR8 antigens were not identified in any patients with IGH, indicating it may have some advantage in preventing the development of IGH.6 Shin et al1 reported that IGH was prevalent among patients who regularly traumatized their skin by scrubbing.

Clinically, IGH should be differentiated from other conditions characterized by hypopigmentation, such as pityriasis alba, pityriasis versicolor, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, progressive macular hypomelanosis, and vitiligo. Aside from clinical examination, histopathologic studies are helpful in making a definitive diagnosis. The differential diagnosis of IGH is presented in the Table.

Histopathology of IGH lesions usually reveals slight atrophy of the epidermis with flattening of rete ridges and concomitant hyperkeratosis. A thickened stratum granulosum also has been noted in lesions of IGH.2 The diminished number of melanocytes and melanin pigment granules along with hyperkeratosis both appear to contribute to the hypopigmentation noted in IGH.7 Ultrastructural studies of lesions of IGH can confirm melanocytic degeneration and a decreased number of melanosomes in melanocytes and keratinocytes.2,8

There is no uniformly effective treatment of IGH. Topical application of tacrolimus and tretinoin have shown efficacy in repigmenting IGH lesions.8,9 Short-exposure cryotherapy with a duration of 3 to 5 seconds, localized chemical peels, and/or local dermabrasion can be helpful.10-12 CO2 lasers also have demonstrated promising results.13

- Shin MK, Jeong KH, Oh IH, et al. Clinical features of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis in 646 subjects and association with other aspects of photoaging. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:798-805.

- Kim SK, Kim EH, Kang HY, et al. Comprehensive understanding of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: clinical and histopathological correlation. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:162-166.

- Friedland R, David M, Feinmesser M, et al. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis-like lesions in patients with mycosis fungoides: a new adverse effect of phototherapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1026-1030.

- Kaya TI, Yazici AC, Tursen U, et al. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: idiopathic or ultraviolet induced? Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2005;21:270-271.

- Loquai C, Metze D, Nashan D, et al. Confetti-like lesions with hyperkeratosis: a novel ultraviolet-induced hypomelanotic disorder? Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:190-193.

- Arrunategui A, Trujillo RA, Marulanda MP, et al. HLA-DQ3 is associated with idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis, whereas HLA-DR8 is not, in a group of renal transplant patients. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:744-747.

- Wallace ML, Grichnik JM, Prieto VG, et al. Numbers and differentiation status of melanocytes in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. J Cutan Pathol. 1998;25:375-379.

- Ortonne JP, Perrot H. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. ultrastructural study. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:664-668.

- Rerknimitr P, Disphanurat W, Achariyakul M. Topical tacrolimus significantly promotes repigmentation in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:460-464.

- Pagnoni A, Kligman AM, Sadiq I, et al. Hypopigmented macules of photodamaged skin and their treatment with topical tretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:305-310.

- Kumarasinghe SP. 3-5 second cryotherapy is effective in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. J Dermatol. 2004;31:457-459.

- Hexsel DM. Treatment of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis by localized superficial dermabrasion. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:917-918.

- Shin J, Kim M, Park SH, et al. The effect of fractional carbon dioxide lasers on idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: a preliminary study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:e243-e246.

- Shin MK, Jeong KH, Oh IH, et al. Clinical features of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis in 646 subjects and association with other aspects of photoaging. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:798-805.

- Kim SK, Kim EH, Kang HY, et al. Comprehensive understanding of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: clinical and histopathological correlation. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:162-166.

- Friedland R, David M, Feinmesser M, et al. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis-like lesions in patients with mycosis fungoides: a new adverse effect of phototherapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1026-1030.

- Kaya TI, Yazici AC, Tursen U, et al. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: idiopathic or ultraviolet induced? Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2005;21:270-271.

- Loquai C, Metze D, Nashan D, et al. Confetti-like lesions with hyperkeratosis: a novel ultraviolet-induced hypomelanotic disorder? Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:190-193.

- Arrunategui A, Trujillo RA, Marulanda MP, et al. HLA-DQ3 is associated with idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis, whereas HLA-DR8 is not, in a group of renal transplant patients. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:744-747.

- Wallace ML, Grichnik JM, Prieto VG, et al. Numbers and differentiation status of melanocytes in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. J Cutan Pathol. 1998;25:375-379.

- Ortonne JP, Perrot H. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. ultrastructural study. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:664-668.

- Rerknimitr P, Disphanurat W, Achariyakul M. Topical tacrolimus significantly promotes repigmentation in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:460-464.

- Pagnoni A, Kligman AM, Sadiq I, et al. Hypopigmented macules of photodamaged skin and their treatment with topical tretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:305-310.

- Kumarasinghe SP. 3-5 second cryotherapy is effective in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. J Dermatol. 2004;31:457-459.

- Hexsel DM. Treatment of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis by localized superficial dermabrasion. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:917-918.

- Shin J, Kim M, Park SH, et al. The effect of fractional carbon dioxide lasers on idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: a preliminary study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:e243-e246.

A 58-year-old man presented with disseminated, hypopigmented, asymptomatic lesions on the right arm (top) and left leg (bottom) that had been present for approximately 6 years. The patient reported that the lesions had become more visible and greater in number within the last year. Multiple circular hypopigmented macules of various sizes ranging from 1 to 3 mm in diameter were identified. No scaling was seen. Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable.

Painful Skin Lesions on the Hands Following Black Henna Application

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis to Para-phenylenediamine

To darken the color of henna and increase penetrance and staining, para-phenylenediamine (PPD) is added.1 Allergic contact dermatitis is the most common type of hypersensitivity to PPD.2 A retrospective study that examined severe adverse events from applying henna dyes in children found that angioedema of mucosal tissues was the most common severe adverse event; others included renal failure and shock.3

Black henna is associated with multiple cultural practices. For example, Indian weddings contain a henna decoration ceremony for the bride based on the belief that the longer the henna lasts, the longer the marriage lasts. Black henna is favored for this practice, as it lasts longer than red henna.

Henna (Lawsonia inermis) is a plant that contains the molecule lawsone (naphthoquinone). Lawsone has an intense affinity for keratin; as a result, lawsone is frequently added to temporary body tattoos and hair dyes to create a relatively permanent change in skin or hair color.4 Henna is mixed with hennotannic acid to release the lawsone from the plant. Lawsone and hennotannic acid rarely cause allergic reactions.1,5-7 Once applied to skin, henna takes a few hours to dry, and the resulting color is orange to red.8 Often, PPD is added to henna paste to create a black color, to speed up the drying process, and to increase its longevity.

Para-phenylenediamine has been repeatedly reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis. We describe a case of allergic contact dermatitis secondary to PPD in black henna. Our patient is a clear example that PPD is the allergen in black henna given that there was no reaction to the natural red henna tattoo that was applied at the same time to the palmar surfaces of the hands (Figure). Aside from the bullous reaction to black henna dye described here, other reported presentations include erythema multiforme–like and exudative erythema reactions.9,10

Contact dermatitis lesions from black henna dye can be treated with topical corticosteroids. Patients may develop residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation, leukoderma, keloids, or scars.1,11,12

- Onder M, Atahan CA, Oztas P, et al. Temporary henna tattoo reactions in children. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:577-579.

- Marcoux D, Couture-Trudel PM, Rboulet-Delmas G, et al. Sensitization to paraphenylenediame from a streetside temporary tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:498-502.

- Hashim S, Hamza Y, Yahia B, et al. Poisoning from henna dye and para-phenylenediamine mixtures in children in Khartoum. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1992;12:3-6.

- Hijji Y, Barare B, Zhang Y. Lawsone (2- hydroxy-1, 4-naphthoquinone) as a sensitive cyanide and acetate sensor. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 2012;169:106-112.

- Neri I, Guareschi E, Savoia F, et al. Childhood allergic contact dermatitis from henna tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:503-505.

- Evans CC, Fleming JD. Allergic contact dermatitis from a henna tattoo. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:627.

- Belhadjali H, Akkari H, Youssef M, et al. Bullous allergic contact dermatitis to pure henna in a 3-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:580-581.

- Najem N, Bagher Zadeh V. Allergic contact dermatitis to black henna. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2011;20:87-88.

- Sidwell RU, Francis ND, Basarab T, et al. Vesicular erythema multiforme-like reaction to para-phenylenediamine in a henna tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:201-204.

- Jovanovic DL, Slavkovic-Jovanovic MR. Allergic contact dermatitis from temporary henna tattoo. J Dermatol. 2009;36:63-65.

- Valsecchi R, Leghissa P, Di Landro A, et al. Persistent leukoderma after henna tattoo. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;56:108-109.

- Gunasti S, Aksungur VL. Severe inflammatory and keloidal, allergic reaction due to para-phenylenediamine in temporary tattoos. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:165-167.

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis to Para-phenylenediamine

To darken the color of henna and increase penetrance and staining, para-phenylenediamine (PPD) is added.1 Allergic contact dermatitis is the most common type of hypersensitivity to PPD.2 A retrospective study that examined severe adverse events from applying henna dyes in children found that angioedema of mucosal tissues was the most common severe adverse event; others included renal failure and shock.3

Black henna is associated with multiple cultural practices. For example, Indian weddings contain a henna decoration ceremony for the bride based on the belief that the longer the henna lasts, the longer the marriage lasts. Black henna is favored for this practice, as it lasts longer than red henna.

Henna (Lawsonia inermis) is a plant that contains the molecule lawsone (naphthoquinone). Lawsone has an intense affinity for keratin; as a result, lawsone is frequently added to temporary body tattoos and hair dyes to create a relatively permanent change in skin or hair color.4 Henna is mixed with hennotannic acid to release the lawsone from the plant. Lawsone and hennotannic acid rarely cause allergic reactions.1,5-7 Once applied to skin, henna takes a few hours to dry, and the resulting color is orange to red.8 Often, PPD is added to henna paste to create a black color, to speed up the drying process, and to increase its longevity.

Para-phenylenediamine has been repeatedly reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis. We describe a case of allergic contact dermatitis secondary to PPD in black henna. Our patient is a clear example that PPD is the allergen in black henna given that there was no reaction to the natural red henna tattoo that was applied at the same time to the palmar surfaces of the hands (Figure). Aside from the bullous reaction to black henna dye described here, other reported presentations include erythema multiforme–like and exudative erythema reactions.9,10

Contact dermatitis lesions from black henna dye can be treated with topical corticosteroids. Patients may develop residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation, leukoderma, keloids, or scars.1,11,12

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis to Para-phenylenediamine

To darken the color of henna and increase penetrance and staining, para-phenylenediamine (PPD) is added.1 Allergic contact dermatitis is the most common type of hypersensitivity to PPD.2 A retrospective study that examined severe adverse events from applying henna dyes in children found that angioedema of mucosal tissues was the most common severe adverse event; others included renal failure and shock.3

Black henna is associated with multiple cultural practices. For example, Indian weddings contain a henna decoration ceremony for the bride based on the belief that the longer the henna lasts, the longer the marriage lasts. Black henna is favored for this practice, as it lasts longer than red henna.

Henna (Lawsonia inermis) is a plant that contains the molecule lawsone (naphthoquinone). Lawsone has an intense affinity for keratin; as a result, lawsone is frequently added to temporary body tattoos and hair dyes to create a relatively permanent change in skin or hair color.4 Henna is mixed with hennotannic acid to release the lawsone from the plant. Lawsone and hennotannic acid rarely cause allergic reactions.1,5-7 Once applied to skin, henna takes a few hours to dry, and the resulting color is orange to red.8 Often, PPD is added to henna paste to create a black color, to speed up the drying process, and to increase its longevity.

Para-phenylenediamine has been repeatedly reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis. We describe a case of allergic contact dermatitis secondary to PPD in black henna. Our patient is a clear example that PPD is the allergen in black henna given that there was no reaction to the natural red henna tattoo that was applied at the same time to the palmar surfaces of the hands (Figure). Aside from the bullous reaction to black henna dye described here, other reported presentations include erythema multiforme–like and exudative erythema reactions.9,10

Contact dermatitis lesions from black henna dye can be treated with topical corticosteroids. Patients may develop residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation, leukoderma, keloids, or scars.1,11,12

- Onder M, Atahan CA, Oztas P, et al. Temporary henna tattoo reactions in children. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:577-579.

- Marcoux D, Couture-Trudel PM, Rboulet-Delmas G, et al. Sensitization to paraphenylenediame from a streetside temporary tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:498-502.

- Hashim S, Hamza Y, Yahia B, et al. Poisoning from henna dye and para-phenylenediamine mixtures in children in Khartoum. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1992;12:3-6.

- Hijji Y, Barare B, Zhang Y. Lawsone (2- hydroxy-1, 4-naphthoquinone) as a sensitive cyanide and acetate sensor. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 2012;169:106-112.

- Neri I, Guareschi E, Savoia F, et al. Childhood allergic contact dermatitis from henna tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:503-505.

- Evans CC, Fleming JD. Allergic contact dermatitis from a henna tattoo. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:627.

- Belhadjali H, Akkari H, Youssef M, et al. Bullous allergic contact dermatitis to pure henna in a 3-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:580-581.

- Najem N, Bagher Zadeh V. Allergic contact dermatitis to black henna. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2011;20:87-88.

- Sidwell RU, Francis ND, Basarab T, et al. Vesicular erythema multiforme-like reaction to para-phenylenediamine in a henna tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:201-204.

- Jovanovic DL, Slavkovic-Jovanovic MR. Allergic contact dermatitis from temporary henna tattoo. J Dermatol. 2009;36:63-65.

- Valsecchi R, Leghissa P, Di Landro A, et al. Persistent leukoderma after henna tattoo. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;56:108-109.

- Gunasti S, Aksungur VL. Severe inflammatory and keloidal, allergic reaction due to para-phenylenediamine in temporary tattoos. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:165-167.

- Onder M, Atahan CA, Oztas P, et al. Temporary henna tattoo reactions in children. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:577-579.

- Marcoux D, Couture-Trudel PM, Rboulet-Delmas G, et al. Sensitization to paraphenylenediame from a streetside temporary tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:498-502.

- Hashim S, Hamza Y, Yahia B, et al. Poisoning from henna dye and para-phenylenediamine mixtures in children in Khartoum. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1992;12:3-6.

- Hijji Y, Barare B, Zhang Y. Lawsone (2- hydroxy-1, 4-naphthoquinone) as a sensitive cyanide and acetate sensor. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 2012;169:106-112.

- Neri I, Guareschi E, Savoia F, et al. Childhood allergic contact dermatitis from henna tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:503-505.

- Evans CC, Fleming JD. Allergic contact dermatitis from a henna tattoo. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:627.

- Belhadjali H, Akkari H, Youssef M, et al. Bullous allergic contact dermatitis to pure henna in a 3-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:580-581.

- Najem N, Bagher Zadeh V. Allergic contact dermatitis to black henna. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2011;20:87-88.

- Sidwell RU, Francis ND, Basarab T, et al. Vesicular erythema multiforme-like reaction to para-phenylenediamine in a henna tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:201-204.

- Jovanovic DL, Slavkovic-Jovanovic MR. Allergic contact dermatitis from temporary henna tattoo. J Dermatol. 2009;36:63-65.

- Valsecchi R, Leghissa P, Di Landro A, et al. Persistent leukoderma after henna tattoo. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;56:108-109.

- Gunasti S, Aksungur VL. Severe inflammatory and keloidal, allergic reaction due to para-phenylenediamine in temporary tattoos. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:165-167.

A 14-year-old adolescent girl presented with painful skin lesions on the dorsal aspect of the hands of 10 days’ duration. She reported having received red henna tattoo on the palmar surface of the hands and black henna tattoo on the dorsal surface of the hands 1 day prior to development of the lesions. Within 1 day of receiving the tattoo, she developed pruritus, blisters, and pain on the dorsal aspect of the hands. The palms were unaffected. Physical examination revealed erythematous, brown to black bullae and crusts that followed the contours of the henna design on the dorsal aspect of the hands. There were orange and brown henna designs on the patient’s palms, but no erythema, bullae, or induration was noted.

Dry Scaly Rash

The Diagnosis: Phrynoderma

Phrynoderma, meaning “toad skin,” was first described by Nicholls1 in 1933 as a condition due to vitamin A deficiency and characterized by follicular hyperkeratosis. Since then, there has been debate in the literature over the etiology of phrynoderma, as studies have demonstrated different causes for this condition,2-5 which suggests that it is prudent to check several markers of nutritional status including vitamin A, vitamin B, vitamin E, and essential fatty acid studies.

Phrynoderma is most commonly seen in South and East Asia with relatively rare occurrences in the United States. Although it characteristically occurs in children and adolescents aged 5 to 15 years, almost all of the cases reported in the United States have occurred in adults.6,7 A clear gender predilection has not been established.7

Phrynoderma tends to favor the extensor surfaces. In particular, the elbows, thighs, and buttocks are the most commonly affected locations. The face is typically the last site to become involved. On physical examination of a patient with phrynoderma, there are various-sized, discrete, red-brown to flesh-colored papules with a conical keratotic follicular plug (Figure).3 The eruption is often asymptomatic, but mild pruritus may be reported.7 Additional signs of vitamin A deficiency may be present, including night blindness, hyperpigmentation, or xerosis. Patients with phrynoderma also may have evidence of other nutritional deficiencies, such as angular stomatitis, cheilitis, or glossitis. The differential diagnosis for a patient with this type of papular eruption may include pityriasis rubra pilaris, keratosis pilaris, lichen spinulosus, crusted scabies, and follicular lichen planus.7 History and clinical presentation can generally help to distinguish these diagnoses.

Generalized follicular, erythematous, and scaly papular eruption on the chest (A) and abdomen (B). |

Histopathology typically shows moderate hyperkeratosis with distension of the upper portion of the follicle by large keratotic plugs. Sebaceous glands are greatly reduced in size and may exhibit epithelial atrophy.8,9

A reduced serum vitamin A level can confirm the diagnosis of phrynoderma. Our patient’s laboratory results revealed a vitamin A value of 26 mg/100 dL (reference range, 38–106 mg/100 dL), consistent with his clinical presentation of phrynoderma. Other markers of nutritional status, including vitamins D, E, and K1, were all within reference range. Treatment consists of replacing the nutritional deficit. High doses of vitamin A, such as 200,000 to 500,000 IU daily for 3 to 5 days or daily doses of 2000 to 50,000 IU, can lead to resolution of the rash in 1 to 4 months.8,9 Our patient was started on 10,000 IU of oral vitamin A daily at discharge but unfortunately died a few months later.

Vitamin A has been shown to promote maturation and differentiation of the basal keratinocytes as they move up through the epidermis, which may in part explain why this treatment is effective.10 It is important to be aware of this condition when seeing a patient with follicular hyperkeratosis because even patients in developed countries with malnutrition due to diet or gastrointestinal disease may develop phrynoderma.

- Nicholls L. Phrynoderma: a condition due to vitamin deficiency. Indian Med Gazette. 1933;68:681-687.

- Bagchi K, Halder K, Chowdhury SR. The etiology of phrynoderma; histologic evidence. Am J Clin Nutr. 1959;7:251-258.

- Bleasel NR, Stapleton KM, Lee MS, et al. Vitamin A deficiency phrynoderma: due to malabsorption and inadequate diet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 2):322-324.

- Ghafoorunissa, Vidyasagar R, Krishnaswamy K. Phrynoderma: is it an EFA deficiency disease? Euro J Clin Nutr. 1988;42:29-39.

- Shrank AB. Phrynoderma. Br Med J. 1966;1:29-30.

- Maronn M, Allen DM, Esterly NB. Phrynoderma: a manifestation of vitamin A deficiency?…the rest of the story. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:60-63.

- Ragunatha S, Kumar VJ, Murugesh SB. A clinical study of 125 patients with phrynoderma. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:389-392.

- Neill SM, Pembroke AC, du-Vivier AWP, et al. Phrynoderma and perforating folliculitis due to vitamin A deficiency in a diabetic. J R Soc Med. 1988;81:171-172.

- Wechsler HL. Vitamin A deficiency following small-bowel bypass surgery for obesity. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:73-75.

- Logan WS. Vitamin A and keratinization. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:748-753.

The Diagnosis: Phrynoderma

Phrynoderma, meaning “toad skin,” was first described by Nicholls1 in 1933 as a condition due to vitamin A deficiency and characterized by follicular hyperkeratosis. Since then, there has been debate in the literature over the etiology of phrynoderma, as studies have demonstrated different causes for this condition,2-5 which suggests that it is prudent to check several markers of nutritional status including vitamin A, vitamin B, vitamin E, and essential fatty acid studies.

Phrynoderma is most commonly seen in South and East Asia with relatively rare occurrences in the United States. Although it characteristically occurs in children and adolescents aged 5 to 15 years, almost all of the cases reported in the United States have occurred in adults.6,7 A clear gender predilection has not been established.7

Phrynoderma tends to favor the extensor surfaces. In particular, the elbows, thighs, and buttocks are the most commonly affected locations. The face is typically the last site to become involved. On physical examination of a patient with phrynoderma, there are various-sized, discrete, red-brown to flesh-colored papules with a conical keratotic follicular plug (Figure).3 The eruption is often asymptomatic, but mild pruritus may be reported.7 Additional signs of vitamin A deficiency may be present, including night blindness, hyperpigmentation, or xerosis. Patients with phrynoderma also may have evidence of other nutritional deficiencies, such as angular stomatitis, cheilitis, or glossitis. The differential diagnosis for a patient with this type of papular eruption may include pityriasis rubra pilaris, keratosis pilaris, lichen spinulosus, crusted scabies, and follicular lichen planus.7 History and clinical presentation can generally help to distinguish these diagnoses.

Generalized follicular, erythematous, and scaly papular eruption on the chest (A) and abdomen (B). |

Histopathology typically shows moderate hyperkeratosis with distension of the upper portion of the follicle by large keratotic plugs. Sebaceous glands are greatly reduced in size and may exhibit epithelial atrophy.8,9

A reduced serum vitamin A level can confirm the diagnosis of phrynoderma. Our patient’s laboratory results revealed a vitamin A value of 26 mg/100 dL (reference range, 38–106 mg/100 dL), consistent with his clinical presentation of phrynoderma. Other markers of nutritional status, including vitamins D, E, and K1, were all within reference range. Treatment consists of replacing the nutritional deficit. High doses of vitamin A, such as 200,000 to 500,000 IU daily for 3 to 5 days or daily doses of 2000 to 50,000 IU, can lead to resolution of the rash in 1 to 4 months.8,9 Our patient was started on 10,000 IU of oral vitamin A daily at discharge but unfortunately died a few months later.

Vitamin A has been shown to promote maturation and differentiation of the basal keratinocytes as they move up through the epidermis, which may in part explain why this treatment is effective.10 It is important to be aware of this condition when seeing a patient with follicular hyperkeratosis because even patients in developed countries with malnutrition due to diet or gastrointestinal disease may develop phrynoderma.

The Diagnosis: Phrynoderma

Phrynoderma, meaning “toad skin,” was first described by Nicholls1 in 1933 as a condition due to vitamin A deficiency and characterized by follicular hyperkeratosis. Since then, there has been debate in the literature over the etiology of phrynoderma, as studies have demonstrated different causes for this condition,2-5 which suggests that it is prudent to check several markers of nutritional status including vitamin A, vitamin B, vitamin E, and essential fatty acid studies.

Phrynoderma is most commonly seen in South and East Asia with relatively rare occurrences in the United States. Although it characteristically occurs in children and adolescents aged 5 to 15 years, almost all of the cases reported in the United States have occurred in adults.6,7 A clear gender predilection has not been established.7

Phrynoderma tends to favor the extensor surfaces. In particular, the elbows, thighs, and buttocks are the most commonly affected locations. The face is typically the last site to become involved. On physical examination of a patient with phrynoderma, there are various-sized, discrete, red-brown to flesh-colored papules with a conical keratotic follicular plug (Figure).3 The eruption is often asymptomatic, but mild pruritus may be reported.7 Additional signs of vitamin A deficiency may be present, including night blindness, hyperpigmentation, or xerosis. Patients with phrynoderma also may have evidence of other nutritional deficiencies, such as angular stomatitis, cheilitis, or glossitis. The differential diagnosis for a patient with this type of papular eruption may include pityriasis rubra pilaris, keratosis pilaris, lichen spinulosus, crusted scabies, and follicular lichen planus.7 History and clinical presentation can generally help to distinguish these diagnoses.

Generalized follicular, erythematous, and scaly papular eruption on the chest (A) and abdomen (B). |

Histopathology typically shows moderate hyperkeratosis with distension of the upper portion of the follicle by large keratotic plugs. Sebaceous glands are greatly reduced in size and may exhibit epithelial atrophy.8,9

A reduced serum vitamin A level can confirm the diagnosis of phrynoderma. Our patient’s laboratory results revealed a vitamin A value of 26 mg/100 dL (reference range, 38–106 mg/100 dL), consistent with his clinical presentation of phrynoderma. Other markers of nutritional status, including vitamins D, E, and K1, were all within reference range. Treatment consists of replacing the nutritional deficit. High doses of vitamin A, such as 200,000 to 500,000 IU daily for 3 to 5 days or daily doses of 2000 to 50,000 IU, can lead to resolution of the rash in 1 to 4 months.8,9 Our patient was started on 10,000 IU of oral vitamin A daily at discharge but unfortunately died a few months later.

Vitamin A has been shown to promote maturation and differentiation of the basal keratinocytes as they move up through the epidermis, which may in part explain why this treatment is effective.10 It is important to be aware of this condition when seeing a patient with follicular hyperkeratosis because even patients in developed countries with malnutrition due to diet or gastrointestinal disease may develop phrynoderma.

- Nicholls L. Phrynoderma: a condition due to vitamin deficiency. Indian Med Gazette. 1933;68:681-687.

- Bagchi K, Halder K, Chowdhury SR. The etiology of phrynoderma; histologic evidence. Am J Clin Nutr. 1959;7:251-258.

- Bleasel NR, Stapleton KM, Lee MS, et al. Vitamin A deficiency phrynoderma: due to malabsorption and inadequate diet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 2):322-324.

- Ghafoorunissa, Vidyasagar R, Krishnaswamy K. Phrynoderma: is it an EFA deficiency disease? Euro J Clin Nutr. 1988;42:29-39.

- Shrank AB. Phrynoderma. Br Med J. 1966;1:29-30.

- Maronn M, Allen DM, Esterly NB. Phrynoderma: a manifestation of vitamin A deficiency?…the rest of the story. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:60-63.

- Ragunatha S, Kumar VJ, Murugesh SB. A clinical study of 125 patients with phrynoderma. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:389-392.

- Neill SM, Pembroke AC, du-Vivier AWP, et al. Phrynoderma and perforating folliculitis due to vitamin A deficiency in a diabetic. J R Soc Med. 1988;81:171-172.

- Wechsler HL. Vitamin A deficiency following small-bowel bypass surgery for obesity. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:73-75.

- Logan WS. Vitamin A and keratinization. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:748-753.

- Nicholls L. Phrynoderma: a condition due to vitamin deficiency. Indian Med Gazette. 1933;68:681-687.

- Bagchi K, Halder K, Chowdhury SR. The etiology of phrynoderma; histologic evidence. Am J Clin Nutr. 1959;7:251-258.

- Bleasel NR, Stapleton KM, Lee MS, et al. Vitamin A deficiency phrynoderma: due to malabsorption and inadequate diet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 2):322-324.

- Ghafoorunissa, Vidyasagar R, Krishnaswamy K. Phrynoderma: is it an EFA deficiency disease? Euro J Clin Nutr. 1988;42:29-39.

- Shrank AB. Phrynoderma. Br Med J. 1966;1:29-30.

- Maronn M, Allen DM, Esterly NB. Phrynoderma: a manifestation of vitamin A deficiency?…the rest of the story. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:60-63.

- Ragunatha S, Kumar VJ, Murugesh SB. A clinical study of 125 patients with phrynoderma. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:389-392.

- Neill SM, Pembroke AC, du-Vivier AWP, et al. Phrynoderma and perforating folliculitis due to vitamin A deficiency in a diabetic. J R Soc Med. 1988;81:171-172.

- Wechsler HL. Vitamin A deficiency following small-bowel bypass surgery for obesity. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:73-75.

- Logan WS. Vitamin A and keratinization. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:748-753.

A 22-year-old man with a history of severe mental retardation, a questionable diagnosis of cystic fibrosis, chronic abdominal pain, and a recent diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis was transferred from an outside hospital for worsening abdominal pain, lethargy, anasarca, anorexia, and constipation. An abdominal paracentesis and computed tomography scan of the abdomen were both negative for any acute processes. Blood cultures and paracentesis fluid cultures were negative. The dermatology section was consulted for a dry scaly rash of unknown duration. The eruption had not been treated, and the patient’s dermatologic history was otherwise unremarkable. On physical examination, the patient had a generalized follicular, erythematous, and scaly papular eruption with some areas of yellow-colored hyperkeratotic papules and plaques as well as scattered hemorrhagic crusts on the extensor surface of the right arm. He had normal oral mucosa and nails. The team was unable to gain consent for biopsy, but a blood test was obtained.

Diffuse Crusting of the Skin

The Diagnosis: Crusted Scabies

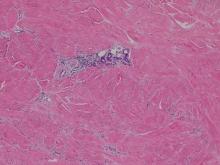

Approximately 1 year prior to presentation the patient completed a course of therapy comprised of repeat doses of ivermectin and permethrin for crusted scabies. He stated that the crusts had recurred shortly after treatment (Figure 1). The initial differential diagnosis included crusted scabies, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and psoriasis. Scraping from the interdigital web space (Figure 2) revealed multiple scabies mites, scabella, and ova (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with crusted scabies. Laboratory test results revealed a normal white blood cell count of 7300/μL, with an elevated eosinophil count of 1900/μL (reference range, <500/μL). Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1) was found to be positive. Serum protein electrophoresis showed a moderate polyclonal increase in gamma globulins. Treatment was promptly initiated with permethrin cream 5% applied to the whole body for a total of 2 treatments that were administered 7 days apart. Ivermectin also was started at 200 μg/kg and was given on days 1, 7, 14, and 29. Salicylic acid cream 25% was applied daily to help hasten resolution of the crusts.

|

|

Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 is endemic to Japan, Central and South America, the Middle East, and regions of Africa and the Caribbean.1 Multiple cases of HTLV-1 associated with crusted scabies have been reported in endemic areas.2-6 In the present case, we encountered a patient with crusted scabies and HTLV-1 in a nonendemic area.

Cases of HTLV-1 and crusted scabies have been reported in Brazil, Peru, and Central Australia.3,4,7 A retrospective study in Brazil showed a notable association between HTLV-1 infection and crusted scabies; of 23 patients with crusted scabies, 21 were HTLV-1 positive.3 In another small study from Peru, 23 patients with crusted scabies were tested for HTLV-1 and 16 (70%) were seropositive.4 Neither study had a control group for comparison; however, interestingly, the estimated seroprevalence in the general population (based on blood donors) is only 0.04% to 1% and 1.2% to 1.7% in Brazil and Peru, respectively, thus reinforcing the association between HTLV-1 and crusted scabies.1 Crusted scabies and HTLV-1 seropositivity acting as a predictor for adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) has been reported8 but not consistently.3 Our patient had abnormal serum protein electrophoresis findings. Although the results were not diagnostic of ATL, patients with HTLV-1 are at increased risk for ATL and the pres-ence of this virus is important to document when there is a high index of suspicion for ATL, as with crusted scabies.

Our patient resided in the northeastern United States and there was no evidence in support of underlying immunosuppression. This case of crusted scabies is unique because the patient was HTLV-1 positive without other underlying immunocompromise and he resided in a region where HTLV-1 is nonendemic. In light of these findings, the present case serves as a reminder to check for HTLV-1 infection in those patients with severe or crusted scabies and without an identifiable reason for immunosuppression, even if the patient resides in an area that is nonendemic for HTLV-1.

- Gessain A, Cassar O. Epidemiological aspects and world distribution of HTLV-1 infection. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:388.

- Nobre V, Guedes AC, Martins ML, et al. Dermatological findings in 3 generations of a family with a high prevalence of human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1 infection in Brazil. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1257-1263.

- Brites C, Weyll M, Pedroso C, et al. Severe and Norwegian scabies are strongly associated with retroviral (HIV-1/HTLV-1) infection in Bahia, Brazil. AIDS. 2002;16:1292-1293.

- Blas M, Bravo F, Castillo W, et al. Norwegian scabies in Peru: the impact of human T cell lymphotropic virus type I infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:855-857.

- Bergman JN, Dodd WA, Trotter MJ, et al. Crusted scabies in association with human T-cell lymphotropic virus 1. J Cutan Med Surg. 1999;3:148-152.

- Daisley H, Charles W, Suite M. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies as a pre-diagnostic indicator for HTLV-1 infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993;87:295.

- Mollison LC. HTLV-I and clinical disease correlates in central Australian aborigines. Med J Aust. 1994;160:238.

- del Giudice P, Sainte Marie D, Gérard Y, et al. Is crusted (Norwegian) scabies a marker of adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma in human T lymphotropic virus type I–seropositive patients? J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1090-1092.

The Diagnosis: Crusted Scabies

Approximately 1 year prior to presentation the patient completed a course of therapy comprised of repeat doses of ivermectin and permethrin for crusted scabies. He stated that the crusts had recurred shortly after treatment (Figure 1). The initial differential diagnosis included crusted scabies, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and psoriasis. Scraping from the interdigital web space (Figure 2) revealed multiple scabies mites, scabella, and ova (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with crusted scabies. Laboratory test results revealed a normal white blood cell count of 7300/μL, with an elevated eosinophil count of 1900/μL (reference range, <500/μL). Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1) was found to be positive. Serum protein electrophoresis showed a moderate polyclonal increase in gamma globulins. Treatment was promptly initiated with permethrin cream 5% applied to the whole body for a total of 2 treatments that were administered 7 days apart. Ivermectin also was started at 200 μg/kg and was given on days 1, 7, 14, and 29. Salicylic acid cream 25% was applied daily to help hasten resolution of the crusts.

|

|

Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 is endemic to Japan, Central and South America, the Middle East, and regions of Africa and the Caribbean.1 Multiple cases of HTLV-1 associated with crusted scabies have been reported in endemic areas.2-6 In the present case, we encountered a patient with crusted scabies and HTLV-1 in a nonendemic area.

Cases of HTLV-1 and crusted scabies have been reported in Brazil, Peru, and Central Australia.3,4,7 A retrospective study in Brazil showed a notable association between HTLV-1 infection and crusted scabies; of 23 patients with crusted scabies, 21 were HTLV-1 positive.3 In another small study from Peru, 23 patients with crusted scabies were tested for HTLV-1 and 16 (70%) were seropositive.4 Neither study had a control group for comparison; however, interestingly, the estimated seroprevalence in the general population (based on blood donors) is only 0.04% to 1% and 1.2% to 1.7% in Brazil and Peru, respectively, thus reinforcing the association between HTLV-1 and crusted scabies.1 Crusted scabies and HTLV-1 seropositivity acting as a predictor for adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) has been reported8 but not consistently.3 Our patient had abnormal serum protein electrophoresis findings. Although the results were not diagnostic of ATL, patients with HTLV-1 are at increased risk for ATL and the pres-ence of this virus is important to document when there is a high index of suspicion for ATL, as with crusted scabies.

Our patient resided in the northeastern United States and there was no evidence in support of underlying immunosuppression. This case of crusted scabies is unique because the patient was HTLV-1 positive without other underlying immunocompromise and he resided in a region where HTLV-1 is nonendemic. In light of these findings, the present case serves as a reminder to check for HTLV-1 infection in those patients with severe or crusted scabies and without an identifiable reason for immunosuppression, even if the patient resides in an area that is nonendemic for HTLV-1.

The Diagnosis: Crusted Scabies

Approximately 1 year prior to presentation the patient completed a course of therapy comprised of repeat doses of ivermectin and permethrin for crusted scabies. He stated that the crusts had recurred shortly after treatment (Figure 1). The initial differential diagnosis included crusted scabies, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and psoriasis. Scraping from the interdigital web space (Figure 2) revealed multiple scabies mites, scabella, and ova (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with crusted scabies. Laboratory test results revealed a normal white blood cell count of 7300/μL, with an elevated eosinophil count of 1900/μL (reference range, <500/μL). Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1) was found to be positive. Serum protein electrophoresis showed a moderate polyclonal increase in gamma globulins. Treatment was promptly initiated with permethrin cream 5% applied to the whole body for a total of 2 treatments that were administered 7 days apart. Ivermectin also was started at 200 μg/kg and was given on days 1, 7, 14, and 29. Salicylic acid cream 25% was applied daily to help hasten resolution of the crusts.

|

|

Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 is endemic to Japan, Central and South America, the Middle East, and regions of Africa and the Caribbean.1 Multiple cases of HTLV-1 associated with crusted scabies have been reported in endemic areas.2-6 In the present case, we encountered a patient with crusted scabies and HTLV-1 in a nonendemic area.

Cases of HTLV-1 and crusted scabies have been reported in Brazil, Peru, and Central Australia.3,4,7 A retrospective study in Brazil showed a notable association between HTLV-1 infection and crusted scabies; of 23 patients with crusted scabies, 21 were HTLV-1 positive.3 In another small study from Peru, 23 patients with crusted scabies were tested for HTLV-1 and 16 (70%) were seropositive.4 Neither study had a control group for comparison; however, interestingly, the estimated seroprevalence in the general population (based on blood donors) is only 0.04% to 1% and 1.2% to 1.7% in Brazil and Peru, respectively, thus reinforcing the association between HTLV-1 and crusted scabies.1 Crusted scabies and HTLV-1 seropositivity acting as a predictor for adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) has been reported8 but not consistently.3 Our patient had abnormal serum protein electrophoresis findings. Although the results were not diagnostic of ATL, patients with HTLV-1 are at increased risk for ATL and the pres-ence of this virus is important to document when there is a high index of suspicion for ATL, as with crusted scabies.

Our patient resided in the northeastern United States and there was no evidence in support of underlying immunosuppression. This case of crusted scabies is unique because the patient was HTLV-1 positive without other underlying immunocompromise and he resided in a region where HTLV-1 is nonendemic. In light of these findings, the present case serves as a reminder to check for HTLV-1 infection in those patients with severe or crusted scabies and without an identifiable reason for immunosuppression, even if the patient resides in an area that is nonendemic for HTLV-1.

- Gessain A, Cassar O. Epidemiological aspects and world distribution of HTLV-1 infection. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:388.

- Nobre V, Guedes AC, Martins ML, et al. Dermatological findings in 3 generations of a family with a high prevalence of human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1 infection in Brazil. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1257-1263.

- Brites C, Weyll M, Pedroso C, et al. Severe and Norwegian scabies are strongly associated with retroviral (HIV-1/HTLV-1) infection in Bahia, Brazil. AIDS. 2002;16:1292-1293.

- Blas M, Bravo F, Castillo W, et al. Norwegian scabies in Peru: the impact of human T cell lymphotropic virus type I infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:855-857.

- Bergman JN, Dodd WA, Trotter MJ, et al. Crusted scabies in association with human T-cell lymphotropic virus 1. J Cutan Med Surg. 1999;3:148-152.

- Daisley H, Charles W, Suite M. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies as a pre-diagnostic indicator for HTLV-1 infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993;87:295.

- Mollison LC. HTLV-I and clinical disease correlates in central Australian aborigines. Med J Aust. 1994;160:238.

- del Giudice P, Sainte Marie D, Gérard Y, et al. Is crusted (Norwegian) scabies a marker of adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma in human T lymphotropic virus type I–seropositive patients? J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1090-1092.

- Gessain A, Cassar O. Epidemiological aspects and world distribution of HTLV-1 infection. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:388.

- Nobre V, Guedes AC, Martins ML, et al. Dermatological findings in 3 generations of a family with a high prevalence of human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1 infection in Brazil. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1257-1263.

- Brites C, Weyll M, Pedroso C, et al. Severe and Norwegian scabies are strongly associated with retroviral (HIV-1/HTLV-1) infection in Bahia, Brazil. AIDS. 2002;16:1292-1293.

- Blas M, Bravo F, Castillo W, et al. Norwegian scabies in Peru: the impact of human T cell lymphotropic virus type I infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:855-857.

- Bergman JN, Dodd WA, Trotter MJ, et al. Crusted scabies in association with human T-cell lymphotropic virus 1. J Cutan Med Surg. 1999;3:148-152.

- Daisley H, Charles W, Suite M. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies as a pre-diagnostic indicator for HTLV-1 infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993;87:295.

- Mollison LC. HTLV-I and clinical disease correlates in central Australian aborigines. Med J Aust. 1994;160:238.

- del Giudice P, Sainte Marie D, Gérard Y, et al. Is crusted (Norwegian) scabies a marker of adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma in human T lymphotropic virus type I–seropositive patients? J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1090-1092.

An 82-year-old white man who resided in the northeastern United States was admitted to the hospital for weakness. He was evaluated for diffuse crusting of the skin including the face. The patient reported a history of minimally itchy, generalized crusts of 10 years’ duration. He lived alone with one cat. His medications included fluticasone furoate, terazosin, and levothyroxine sodium. Human immunodeficiency virus screening was negative. A scraping was taken from one of the thick crusts within an interdigital web space.

What Is Your Diagnosis? Verrucous Carcinoma

An 81-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a nodule on the right labia majora that had been present for 1 year. She had a history of intertriginous psoriasis, and several biopsies were performed at an outside facility over the last 5 years that revealed psoriasis but were otherwise noncontributory. Physical examination revealed erythema and scaling on the buttocks with maceration in the intertriginous area (top) and the perineum associated with a verrucous nodule (bottom).

The Diagnosis: Verrucous Carcinoma

Biopsies of early lesions often may be difficult to interpret without clinicopathological correlation. Our patient’s tumor was associated with intertriginous psoriasis, which was the only abnormality previously noted on superficial biopsies performed at an outside facility. The patient was scheduled for an excisional biopsy due to the large tumor size and clinical suspicion that the prior biopsies were inadequate and failed to demonstrate the primary underlying pathology. Excisional biopsy of the verrucous tumor revealed epithelium composed of keratinocytes with glassy cytoplasm. Papillomatosis was noted along with an endophytic component of well-differentiated epithelial cells extending into the dermis in a bulbous pattern consistent with the verrucous carcinoma variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)(Figure). Verrucous carcinoma often requires correlation with both the clinical and histopathologic findings for definitive diagnosis, as keratinocytes often appear to be well differentiated.1

Verrucous carcinoma may begin as an innocuous papule that slowly grows into a large fungating tumor. Verrucous carcinomas typically are slow growing, exophytic, and low grade. The etiology of verrucous carcinoma is not clear, and the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is controversial.2 Best classified as a well-differentiated SCC, verrucous carcinoma rarely metastasizes but may invade adjacent tissues.

Differential diagnoses include a giant inflamed seborrheic keratosis, condyloma acuminatum, rupioid psoriasis, and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN). Although large and inflamed seborrheic keratoses may have squamous eddies that mimic SCC, seborrheic keratoses do not invade the dermis and typically have a well-circumscribed stuck-on appearance. Abnormal mitotic figures are not identified. Condylomas are genital warts caused by HPV infection that often are clustered, well circumscribed, and exophytic. Large lesions can be difficult to distinguish from verrucous carcinomas, and biopsy generally reveals koilocytes identified by perinuclear clearing and raisinlike nuclei. Immunohistochemical staining and in situ hybridization studies can be of value in diagnosis and in identifying those lesions that are at high risk for malignant transformation. High-risk condylomas are associated with HPV-16, HPV-18, HPV-31, HPV-33, HPV-35, and HPV-39, as well as other types, whereas low-risk condylomas are associated with HPV-6, HPV-11, HPV-42, and others.2 Differentiating squamous cell hyperplasia from squamous cell carcinoma in situ also can be aided by immunohistochemistry. Squamous cell hyperplasia is usually negative for INK4 p16Ink4A and p53 and exhibits variable Ki-67 staining. Differentiated squamous cell carcinoma in situ exhibits a profile that is p16Ink4A negative, Ki-67 positive, and exhibits variable p53 staining.3 Basaloid and warty intraepithelial neoplasia is consistently p16Ink4A positive, Ki-67 positive, and variably positive for p53.3 Therefore, p16 staining of high-grade areas is a useful biomarker that can help establish diagnosis of associated squamous cell carcinoma.4 The role of papillomaviruses in the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer is an area of active study, and research suggests that papillomaviruses may have a much greater role than previously suspected.5

At times, psoriasis may be markedly hyperkeratotic, clinically mimicking a verrucous neoplasm. This hyperkeratotic type of psoriasis is known as rupioid psoriasis. However, these psoriatic lesions are exophytic, are associated with spongiform pustules, and lack the atypia and endophytic pattern typically seen with verrucous carcinoma. An ILVEN also lacks atypia and an endophytic pattern and usually presents in childhood as a persistent linear plaque, rather than the verrucous plaque noted in our patient. Squamous cell carcinoma has been reported to arise in the setting of verrucoid ILVEN but is exceptionally uncommon.6