User login

Itchy Papules and Plaques on the Dorsal Hands

The Diagnosis: Neutrophilic Dermatosis of the Dorsal Hands

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH) is considered to be an uncommon localized variant of Sweet syndrome (SS). The term pustular vasculitis originally was used to describe this condition by Strutton et al1 in 1995 due to the presence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histology. In 2000, Galaria et al2 suggested this eruption was a localized variant of SS based on clinical presentations that demonstrated associated fever and lack of necrotizing vasculitis and proposed the term neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands to describe the condition. Cases of similar cutaneous eruptions on the hands associated with fever, leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and leukocytoclasis have since been reported.3-5 Some authors have concluded that these eruptions, previously termed atypical pyoderma gangrenosum and pustular vasculitis of the hands, represent a single disease entity and should be designated as NDDH.3,4

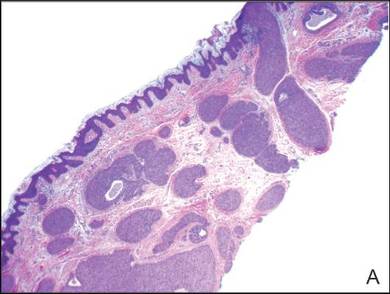

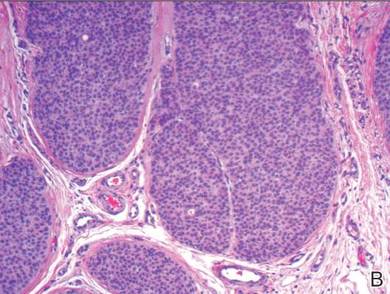

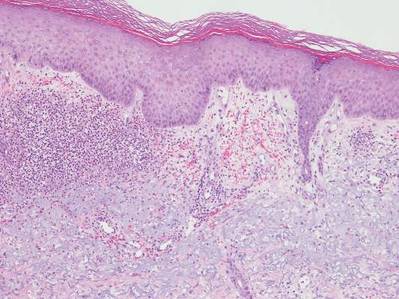

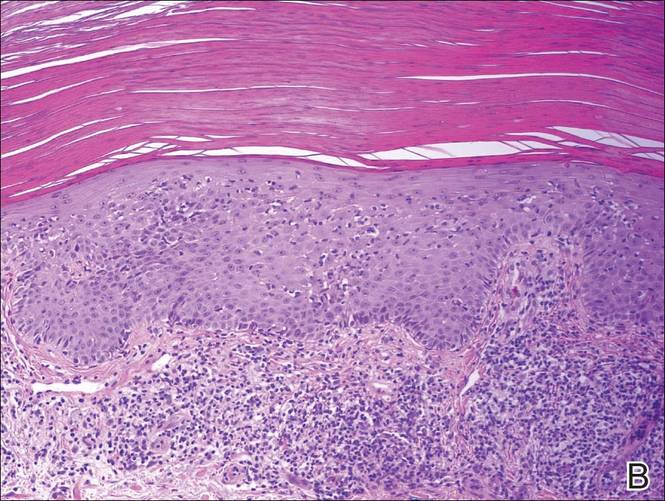

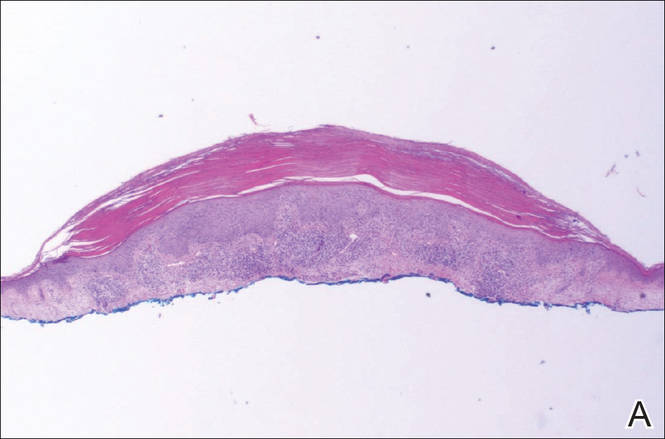

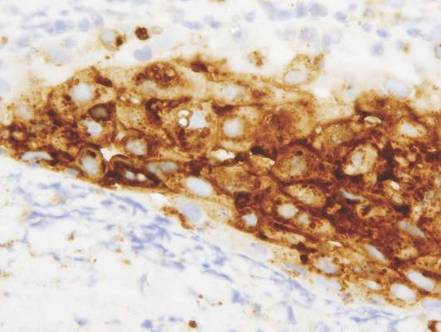

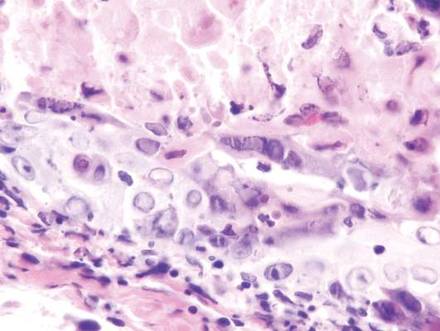

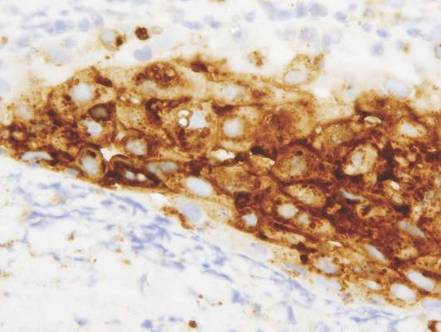

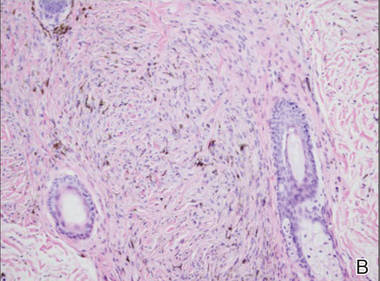

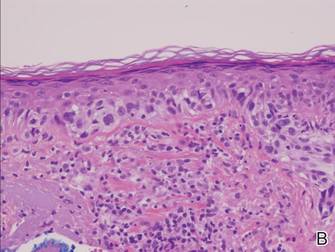

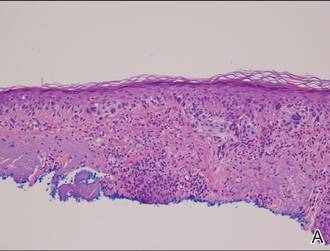

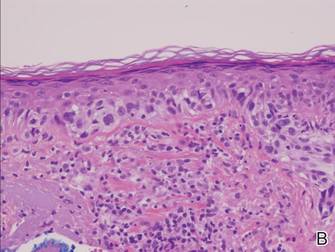

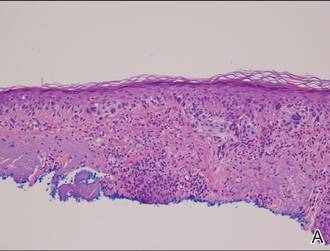

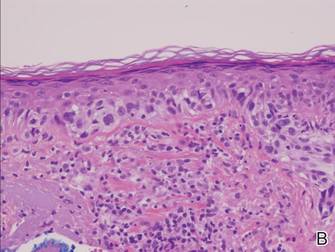

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands characteristically presents with hemorrhagic pustular ulcerations limited to or predominantly located on the dorsal hands, as seen in our patient. Histopathologically, NDDH demonstrates a neutrophil-predominant infiltrate of the upper dermis and marked papillary dermal edema; a punch biopsy specimen from our patient was consistent with these features (Figure). Two punch biopsies were performed and were negative for fungus and acid-fast bacteria and positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Vasculitis, if present, is more commonly seen in eruptions of longer duration (ie, months to years) and is thought to be secondary to the dense neutrophilic infiltrate and not a primary vasculitis.3,6,7 Similar to classic SS, NDDH is inherently responsive to corticosteroid therapy. Successful treatment also has been reported with dapsone, colchicine, sulfapyridine, potassium iodide, intralesional and topical corticosteroids, and topical tacrolimus.2-8 Oral minocycline has shown variable results.3,4

Numerous case series have demonstrated that a majority of cases of NDDH are associated with hematologic or solid organ malignancies, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), inflammatory bowel disease, or other underlying systemic diseases.3,5,9 It is important for dermatologists to recognize NDDH, distinguish it from localized infection, and perform the appropriate workup (eg, basic laboratory tests [complete blood count, complete metabolic panel], age-appropriate malignancy screening, colonoscopy, bone marrow biopsy) to exclude associated systemic diseases.

Our patient demonstrated characteristic clinical and histopathologic findings of NDDH in association with early MDS and possible common bile duct (CBD) malignancy. The lesions showed a rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy. The initial differential diagnoses included NDDH or other neutrophilic dermatosis, phototoxic drug eruption, and atypical mycobacterial or fungal infection (cultures were negative in our patient). Physical examination and histopathologic findings along with the patient’s clinical course and rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy supported the diagnosis of NDDH. Our patient’s multiple comorbidities, including macrocytic anemia, MDS, and potential CBD malignancy, presented a therapeutic challenge. Oral dapsone, an ideal steroid-sparing agent for neutrophilic dermatoses including NDDH, was avoided given its associated hematologic side effects including hemolysis, methemoglobinemia, and possible agranulocytosis. To date, the patient has not received any further treatment for MDS or the CBD mass and continues regular follow-up with hematology, gastroenterology, and dermatology.

This case highlights the importance of including NDDH in the differential diagnosis of papules and plaques on the hands, especially in patients with known malignancies, and emphasizes the association of neutrophilic dermatoses with malignancy and systemic disease.

- Strutton G, Weedon D, Robertson I. Pustular vasculitis of the hands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:192-198.

- Galaria NA, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Kligman D, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: pustular vasculitis revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:870-874.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM. Neutrophilic dermatosis (pustular vasculitis) of the dorsal hands. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:361-365.

- Weening RH, Bruce AJ, McEvoy MT, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: four new cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:95-102.

- Malone JC, Slone SP, Wills-Frank LA, et al. Vascular inflammation (vasculitis) in Sweet syndrome: a clinicopathologic study of 28 biopsy specimens from 21 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:345-349.

- Cohen PR. Skin lesions of Sweet syndrome and its dorsal hand variant contain vasculitis: an oxymoron or an epiphenomenon? Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:400-403.

- Del Pozo J, Sacristán F, Martínez W, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: presentation of eight cases and review of the literature. J Dermatol. 2007;34:243-247.

- Callen JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:409-419.

The Diagnosis: Neutrophilic Dermatosis of the Dorsal Hands

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH) is considered to be an uncommon localized variant of Sweet syndrome (SS). The term pustular vasculitis originally was used to describe this condition by Strutton et al1 in 1995 due to the presence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histology. In 2000, Galaria et al2 suggested this eruption was a localized variant of SS based on clinical presentations that demonstrated associated fever and lack of necrotizing vasculitis and proposed the term neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands to describe the condition. Cases of similar cutaneous eruptions on the hands associated with fever, leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and leukocytoclasis have since been reported.3-5 Some authors have concluded that these eruptions, previously termed atypical pyoderma gangrenosum and pustular vasculitis of the hands, represent a single disease entity and should be designated as NDDH.3,4

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands characteristically presents with hemorrhagic pustular ulcerations limited to or predominantly located on the dorsal hands, as seen in our patient. Histopathologically, NDDH demonstrates a neutrophil-predominant infiltrate of the upper dermis and marked papillary dermal edema; a punch biopsy specimen from our patient was consistent with these features (Figure). Two punch biopsies were performed and were negative for fungus and acid-fast bacteria and positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Vasculitis, if present, is more commonly seen in eruptions of longer duration (ie, months to years) and is thought to be secondary to the dense neutrophilic infiltrate and not a primary vasculitis.3,6,7 Similar to classic SS, NDDH is inherently responsive to corticosteroid therapy. Successful treatment also has been reported with dapsone, colchicine, sulfapyridine, potassium iodide, intralesional and topical corticosteroids, and topical tacrolimus.2-8 Oral minocycline has shown variable results.3,4

Numerous case series have demonstrated that a majority of cases of NDDH are associated with hematologic or solid organ malignancies, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), inflammatory bowel disease, or other underlying systemic diseases.3,5,9 It is important for dermatologists to recognize NDDH, distinguish it from localized infection, and perform the appropriate workup (eg, basic laboratory tests [complete blood count, complete metabolic panel], age-appropriate malignancy screening, colonoscopy, bone marrow biopsy) to exclude associated systemic diseases.

Our patient demonstrated characteristic clinical and histopathologic findings of NDDH in association with early MDS and possible common bile duct (CBD) malignancy. The lesions showed a rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy. The initial differential diagnoses included NDDH or other neutrophilic dermatosis, phototoxic drug eruption, and atypical mycobacterial or fungal infection (cultures were negative in our patient). Physical examination and histopathologic findings along with the patient’s clinical course and rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy supported the diagnosis of NDDH. Our patient’s multiple comorbidities, including macrocytic anemia, MDS, and potential CBD malignancy, presented a therapeutic challenge. Oral dapsone, an ideal steroid-sparing agent for neutrophilic dermatoses including NDDH, was avoided given its associated hematologic side effects including hemolysis, methemoglobinemia, and possible agranulocytosis. To date, the patient has not received any further treatment for MDS or the CBD mass and continues regular follow-up with hematology, gastroenterology, and dermatology.

This case highlights the importance of including NDDH in the differential diagnosis of papules and plaques on the hands, especially in patients with known malignancies, and emphasizes the association of neutrophilic dermatoses with malignancy and systemic disease.

The Diagnosis: Neutrophilic Dermatosis of the Dorsal Hands

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH) is considered to be an uncommon localized variant of Sweet syndrome (SS). The term pustular vasculitis originally was used to describe this condition by Strutton et al1 in 1995 due to the presence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histology. In 2000, Galaria et al2 suggested this eruption was a localized variant of SS based on clinical presentations that demonstrated associated fever and lack of necrotizing vasculitis and proposed the term neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands to describe the condition. Cases of similar cutaneous eruptions on the hands associated with fever, leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and leukocytoclasis have since been reported.3-5 Some authors have concluded that these eruptions, previously termed atypical pyoderma gangrenosum and pustular vasculitis of the hands, represent a single disease entity and should be designated as NDDH.3,4

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands characteristically presents with hemorrhagic pustular ulcerations limited to or predominantly located on the dorsal hands, as seen in our patient. Histopathologically, NDDH demonstrates a neutrophil-predominant infiltrate of the upper dermis and marked papillary dermal edema; a punch biopsy specimen from our patient was consistent with these features (Figure). Two punch biopsies were performed and were negative for fungus and acid-fast bacteria and positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Vasculitis, if present, is more commonly seen in eruptions of longer duration (ie, months to years) and is thought to be secondary to the dense neutrophilic infiltrate and not a primary vasculitis.3,6,7 Similar to classic SS, NDDH is inherently responsive to corticosteroid therapy. Successful treatment also has been reported with dapsone, colchicine, sulfapyridine, potassium iodide, intralesional and topical corticosteroids, and topical tacrolimus.2-8 Oral minocycline has shown variable results.3,4

Numerous case series have demonstrated that a majority of cases of NDDH are associated with hematologic or solid organ malignancies, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), inflammatory bowel disease, or other underlying systemic diseases.3,5,9 It is important for dermatologists to recognize NDDH, distinguish it from localized infection, and perform the appropriate workup (eg, basic laboratory tests [complete blood count, complete metabolic panel], age-appropriate malignancy screening, colonoscopy, bone marrow biopsy) to exclude associated systemic diseases.

Our patient demonstrated characteristic clinical and histopathologic findings of NDDH in association with early MDS and possible common bile duct (CBD) malignancy. The lesions showed a rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy. The initial differential diagnoses included NDDH or other neutrophilic dermatosis, phototoxic drug eruption, and atypical mycobacterial or fungal infection (cultures were negative in our patient). Physical examination and histopathologic findings along with the patient’s clinical course and rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy supported the diagnosis of NDDH. Our patient’s multiple comorbidities, including macrocytic anemia, MDS, and potential CBD malignancy, presented a therapeutic challenge. Oral dapsone, an ideal steroid-sparing agent for neutrophilic dermatoses including NDDH, was avoided given its associated hematologic side effects including hemolysis, methemoglobinemia, and possible agranulocytosis. To date, the patient has not received any further treatment for MDS or the CBD mass and continues regular follow-up with hematology, gastroenterology, and dermatology.

This case highlights the importance of including NDDH in the differential diagnosis of papules and plaques on the hands, especially in patients with known malignancies, and emphasizes the association of neutrophilic dermatoses with malignancy and systemic disease.

- Strutton G, Weedon D, Robertson I. Pustular vasculitis of the hands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:192-198.

- Galaria NA, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Kligman D, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: pustular vasculitis revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:870-874.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM. Neutrophilic dermatosis (pustular vasculitis) of the dorsal hands. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:361-365.

- Weening RH, Bruce AJ, McEvoy MT, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: four new cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:95-102.

- Malone JC, Slone SP, Wills-Frank LA, et al. Vascular inflammation (vasculitis) in Sweet syndrome: a clinicopathologic study of 28 biopsy specimens from 21 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:345-349.

- Cohen PR. Skin lesions of Sweet syndrome and its dorsal hand variant contain vasculitis: an oxymoron or an epiphenomenon? Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:400-403.

- Del Pozo J, Sacristán F, Martínez W, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: presentation of eight cases and review of the literature. J Dermatol. 2007;34:243-247.

- Callen JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:409-419.

- Strutton G, Weedon D, Robertson I. Pustular vasculitis of the hands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:192-198.

- Galaria NA, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Kligman D, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: pustular vasculitis revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:870-874.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM. Neutrophilic dermatosis (pustular vasculitis) of the dorsal hands. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:361-365.

- Weening RH, Bruce AJ, McEvoy MT, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: four new cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:95-102.

- Malone JC, Slone SP, Wills-Frank LA, et al. Vascular inflammation (vasculitis) in Sweet syndrome: a clinicopathologic study of 28 biopsy specimens from 21 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:345-349.

- Cohen PR. Skin lesions of Sweet syndrome and its dorsal hand variant contain vasculitis: an oxymoron or an epiphenomenon? Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:400-403.

- Del Pozo J, Sacristán F, Martínez W, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: presentation of eight cases and review of the literature. J Dermatol. 2007;34:243-247.

- Callen JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:409-419.

A 69-year-old man presented with tender, itchy papules and plaques on the bilateral dorsal hands of 2 months’ duration. The plaques had started as small papules that gradually enlarged and then became ulcerated. The patient denied prior trauma or constitutional symptoms. Laboratory testing revealed macrocytic anemia, thrombocytosis, and hypoalbuminemia. A complete blood count and complete metabolic panel were otherwise unremarkable. A recent bone marrow biopsy for macrocytic anemia performed prior to the current presentation suggested early myelodysplastic syndrome, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography revealed a large mass in the common bile duct that was suspicious for malignancy. Two punch biopsies were performed and were negative for fungus and acid-fast bacteria and positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Treatment with topical clobetasol 0.05% twice daily was initiated with complete healing of the plaques on the hands after 2 weeks of use; however, the patient continued to develop new ulcerated papulonodules distally.

Erythematous Scaly Papules on the Shins and Calves

The Diagnosis: Hyperkeratosis Lenticularis Perstans

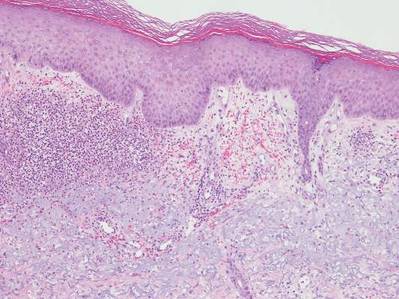

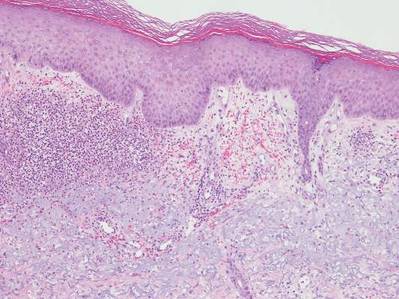

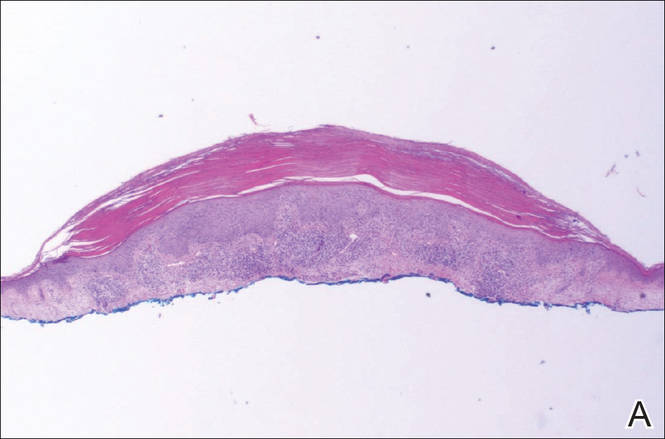

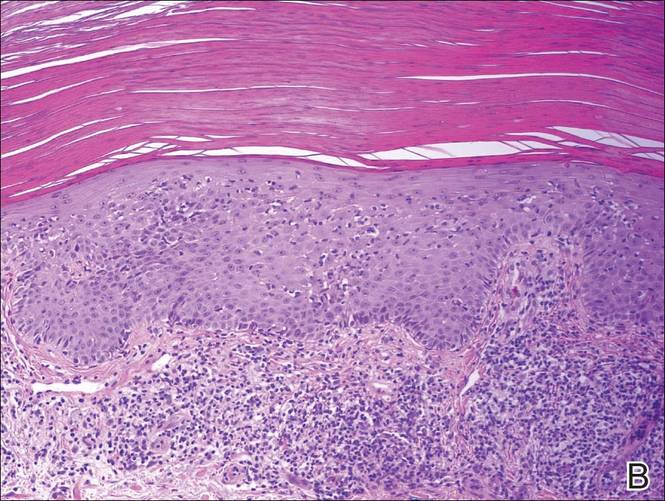

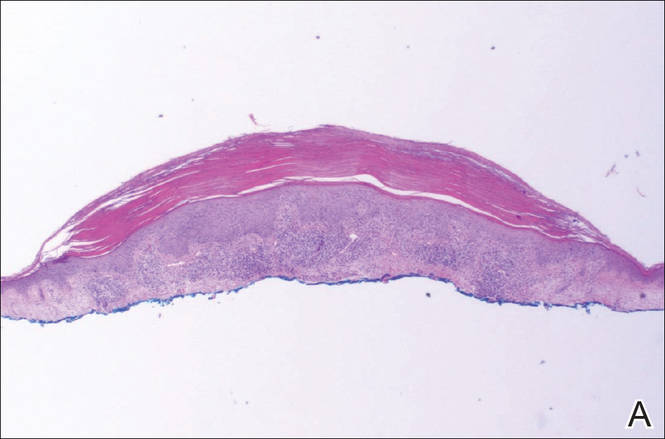

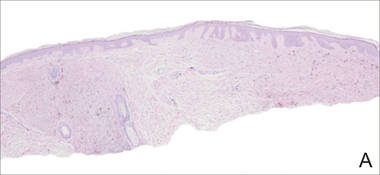

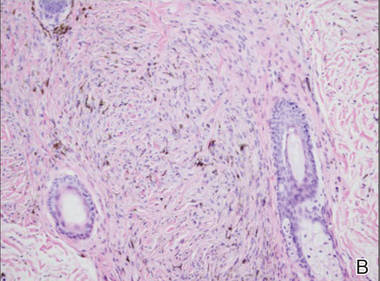

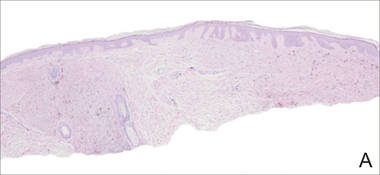

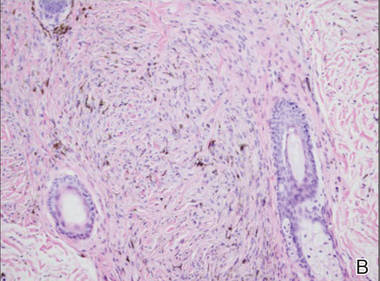

A shave biopsy of a lesion on the right leg was performed. Histopathology revealed a discrete papule with overlying compact hyperkeratosis. There was parakeratosis with an absent granular layer and a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate within the papillary dermis (Figure). Given the clinical context, these changes were consistent with a diagnosis of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (HLP), also known as Flegel disease.

The patient was started on tretinoin cream 0.1% nightly for 3 months and triamcinolone ointment 0.1% as needed for pruritus but showed no clinical response. Given the benign nature of the condition and because the lesions were asymptomatic, additional treatment options were not pursued.

Originally described by Flegel1 in 1958, HLP is a rare skin disorder commonly seen in white individuals with onset in the fourth or fifth decades of life.1,2 While most cases are sporadic,3-6 HLP also has been associated with autosomal dominant inheritance.7-10

Patients with HLP typically present with multiple 1- to 5-mm reddish-brown, hyperkeratotic, scaly papules that reveal a moist, erythematous base with pinpoint bleeding upon removal of the scale. Lesions usually are distributed symmetrically and most commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the lower legs and dorsal feet.1,2,7 Lesions also may appear on the extensor surfaces of the arms, pinna, periocular region, antecubital and popliteal fossae, and oral mucosa and also may present as pits on the palms and soles.2,4,7,8 Furthermore, unilateral and localized variants of HLP have been described.11,12 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans usually is asymptomatic but can present with mild pruritus or burning.3,5,13

The etiology and pathogenesis of HLP are unknown. Exposure to UV light has been implicated as an inciting factor14; however, reports of spontaneous resolution in the summer13 and upon treatment with psoralen plus UVA therapy15 make the role of UV light unclear. Furthermore, investigators disagree as to whether the primary pathogenic event in HLP is an inflammatory process or one of abnormal keratinization.1,3,7,10 Fernandez-Flores and Manjon16 suggested HLP is an inflammatory process with periods of exacerbations and remissions after finding mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils arranged in different strata in the stratum corneum.

Histologically, compact hyperkeratosis usually is noted, often with associated parakeratosis, epidermal atrophy with thinning or absence of the granular layer, and a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.1-3 Histopathologic differences between recent-onset versus longstanding lesions have been found, with old lesions lacking an inflammatory infiltrate.3 Furthermore, new lesions often show abnormalities in quantity and/or morphology of membrane-coating granules, also known as Odland bodies, in keratinocytes on electron microscopy,3,10,17 while old lesions do not.3 Odland bodies are involved in normal desquamation, leading some to speculate on their role in HLP.10 Currently, it is unclear whether abnormalities in these organelles cause the retention hyperkeratosis seen in HLP or if such abnormalities are a secondary phenomenon.3,17

There are questionable associations between HLP and diabetes mellitus type 2, hyperthyroidism, basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin, and gastrointestinal malignancy.4,9,18 Our patient had a history of basal cell carcinoma on the face, diet-controlled diabetes mellitus, and hypothyroidism. Given the high prevalence of these diseases in the general population, however, it is difficult to ascertain whether a true association with HLP exists.

While HLP can slowly progress to involve additional body sites, it is overall a benign condition that does not require treatment. Therapeutic options are based on case reports, with no single treatment showing a consistent response. From review of the literature, therapies that have been most effective include dermabrasion, excision,19 topical 5-fluorouracil,2,17,20 and oral retinoids.8 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans generally is resistant to topical steroids, retinoids, and vitamin D3 analogs, although success with betamethasone dipropionate,5 isotretinoin

gel 0.05%,11 and calcipotriol have been reported.6 A case of HLP with clinical response to psoralen plus UVA therapy also has been described.15

- Flegel H. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Hautarzt. 1958;9:363-364.

- Pearson LH, Smith JG, Chalker DK. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:190-195.

- Ando K, Hattori H, Yamauchi Y. Histopathological differences between early and old lesions of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:122-126.

- Fernández-Crehuet P, Rodríguez-Rey E, Ríos-Martín JJ, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans, or Flegel disease, with palmoplantar involvement. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:157-159.

- Sterneberg-Vos H, van Marion AM, Frank J, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease)—successful treatment with topical corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:38-41.

- Bayramgürler D, Apaydin R, Dökmeci S, et al. Flegel’s disease: treatment with topical calcipotriol. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:161-162.

- Price ML, Jones EW, MacDonald DM. A clinicopathological study of Flegel’s disease (hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans). Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:681-691.

- Krishnan A, Kar S. Photoletter to the editor: hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease) with unusual clinical presentation. response to isotretinoin therapy. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:93-95.

- Beveridge GW, Langlands AO. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans associated with tumours of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:453-458.

- Frenk E, Tapernoux B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel): a biological model for keratinization occurring in the absence of Odland bodies? Dermatologica. 1976;153:253-262.

- Miranda-Romero A, Sánchez Sambucety P, Bajo del Pozo C, et al. Unilateral hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:655-657.

- Gutiérrez MC, Hasson A, Arias MD, et al. Localized hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). Cutis. 1991;48:201-204.

- Fathy S, Azadeh B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:120-121.

- Rosdahl I, Rosen K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans: report on two cases. Acta Derm Venerol. 1985;65:562-564.

- Cooper SM, George S. Flegel's disease treated with psoralen ultraviolet A. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:340-342.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Manjon JA. Morphological evidence of periodical exacerbation of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2009;17:16-19.

- Langer K, Zonzits E, Konrad K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). ultrastructural study of lesional and perilesional skin and therapeutic trial of topical tretinoin versus 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:812-816.

- Ishibashi A, Tsuboi R, Fujita K. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. associated with cancers of the digestive organs. J Dermatol. 1984;11:407-409.

- Cunha Filho RR, Almeida Jr HL. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S76-S77.

- Blaheta HJ, Metzler G, Rassner G, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease)—lack of response to treatment with tacalcitol and calcipotriol. Dermatology. 2001;202:255-258.

The Diagnosis: Hyperkeratosis Lenticularis Perstans

A shave biopsy of a lesion on the right leg was performed. Histopathology revealed a discrete papule with overlying compact hyperkeratosis. There was parakeratosis with an absent granular layer and a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate within the papillary dermis (Figure). Given the clinical context, these changes were consistent with a diagnosis of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (HLP), also known as Flegel disease.

The patient was started on tretinoin cream 0.1% nightly for 3 months and triamcinolone ointment 0.1% as needed for pruritus but showed no clinical response. Given the benign nature of the condition and because the lesions were asymptomatic, additional treatment options were not pursued.

Originally described by Flegel1 in 1958, HLP is a rare skin disorder commonly seen in white individuals with onset in the fourth or fifth decades of life.1,2 While most cases are sporadic,3-6 HLP also has been associated with autosomal dominant inheritance.7-10

Patients with HLP typically present with multiple 1- to 5-mm reddish-brown, hyperkeratotic, scaly papules that reveal a moist, erythematous base with pinpoint bleeding upon removal of the scale. Lesions usually are distributed symmetrically and most commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the lower legs and dorsal feet.1,2,7 Lesions also may appear on the extensor surfaces of the arms, pinna, periocular region, antecubital and popliteal fossae, and oral mucosa and also may present as pits on the palms and soles.2,4,7,8 Furthermore, unilateral and localized variants of HLP have been described.11,12 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans usually is asymptomatic but can present with mild pruritus or burning.3,5,13

The etiology and pathogenesis of HLP are unknown. Exposure to UV light has been implicated as an inciting factor14; however, reports of spontaneous resolution in the summer13 and upon treatment with psoralen plus UVA therapy15 make the role of UV light unclear. Furthermore, investigators disagree as to whether the primary pathogenic event in HLP is an inflammatory process or one of abnormal keratinization.1,3,7,10 Fernandez-Flores and Manjon16 suggested HLP is an inflammatory process with periods of exacerbations and remissions after finding mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils arranged in different strata in the stratum corneum.

Histologically, compact hyperkeratosis usually is noted, often with associated parakeratosis, epidermal atrophy with thinning or absence of the granular layer, and a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.1-3 Histopathologic differences between recent-onset versus longstanding lesions have been found, with old lesions lacking an inflammatory infiltrate.3 Furthermore, new lesions often show abnormalities in quantity and/or morphology of membrane-coating granules, also known as Odland bodies, in keratinocytes on electron microscopy,3,10,17 while old lesions do not.3 Odland bodies are involved in normal desquamation, leading some to speculate on their role in HLP.10 Currently, it is unclear whether abnormalities in these organelles cause the retention hyperkeratosis seen in HLP or if such abnormalities are a secondary phenomenon.3,17

There are questionable associations between HLP and diabetes mellitus type 2, hyperthyroidism, basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin, and gastrointestinal malignancy.4,9,18 Our patient had a history of basal cell carcinoma on the face, diet-controlled diabetes mellitus, and hypothyroidism. Given the high prevalence of these diseases in the general population, however, it is difficult to ascertain whether a true association with HLP exists.

While HLP can slowly progress to involve additional body sites, it is overall a benign condition that does not require treatment. Therapeutic options are based on case reports, with no single treatment showing a consistent response. From review of the literature, therapies that have been most effective include dermabrasion, excision,19 topical 5-fluorouracil,2,17,20 and oral retinoids.8 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans generally is resistant to topical steroids, retinoids, and vitamin D3 analogs, although success with betamethasone dipropionate,5 isotretinoin

gel 0.05%,11 and calcipotriol have been reported.6 A case of HLP with clinical response to psoralen plus UVA therapy also has been described.15

The Diagnosis: Hyperkeratosis Lenticularis Perstans

A shave biopsy of a lesion on the right leg was performed. Histopathology revealed a discrete papule with overlying compact hyperkeratosis. There was parakeratosis with an absent granular layer and a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate within the papillary dermis (Figure). Given the clinical context, these changes were consistent with a diagnosis of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (HLP), also known as Flegel disease.

The patient was started on tretinoin cream 0.1% nightly for 3 months and triamcinolone ointment 0.1% as needed for pruritus but showed no clinical response. Given the benign nature of the condition and because the lesions were asymptomatic, additional treatment options were not pursued.

Originally described by Flegel1 in 1958, HLP is a rare skin disorder commonly seen in white individuals with onset in the fourth or fifth decades of life.1,2 While most cases are sporadic,3-6 HLP also has been associated with autosomal dominant inheritance.7-10

Patients with HLP typically present with multiple 1- to 5-mm reddish-brown, hyperkeratotic, scaly papules that reveal a moist, erythematous base with pinpoint bleeding upon removal of the scale. Lesions usually are distributed symmetrically and most commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the lower legs and dorsal feet.1,2,7 Lesions also may appear on the extensor surfaces of the arms, pinna, periocular region, antecubital and popliteal fossae, and oral mucosa and also may present as pits on the palms and soles.2,4,7,8 Furthermore, unilateral and localized variants of HLP have been described.11,12 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans usually is asymptomatic but can present with mild pruritus or burning.3,5,13

The etiology and pathogenesis of HLP are unknown. Exposure to UV light has been implicated as an inciting factor14; however, reports of spontaneous resolution in the summer13 and upon treatment with psoralen plus UVA therapy15 make the role of UV light unclear. Furthermore, investigators disagree as to whether the primary pathogenic event in HLP is an inflammatory process or one of abnormal keratinization.1,3,7,10 Fernandez-Flores and Manjon16 suggested HLP is an inflammatory process with periods of exacerbations and remissions after finding mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils arranged in different strata in the stratum corneum.

Histologically, compact hyperkeratosis usually is noted, often with associated parakeratosis, epidermal atrophy with thinning or absence of the granular layer, and a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.1-3 Histopathologic differences between recent-onset versus longstanding lesions have been found, with old lesions lacking an inflammatory infiltrate.3 Furthermore, new lesions often show abnormalities in quantity and/or morphology of membrane-coating granules, also known as Odland bodies, in keratinocytes on electron microscopy,3,10,17 while old lesions do not.3 Odland bodies are involved in normal desquamation, leading some to speculate on their role in HLP.10 Currently, it is unclear whether abnormalities in these organelles cause the retention hyperkeratosis seen in HLP or if such abnormalities are a secondary phenomenon.3,17

There are questionable associations between HLP and diabetes mellitus type 2, hyperthyroidism, basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin, and gastrointestinal malignancy.4,9,18 Our patient had a history of basal cell carcinoma on the face, diet-controlled diabetes mellitus, and hypothyroidism. Given the high prevalence of these diseases in the general population, however, it is difficult to ascertain whether a true association with HLP exists.

While HLP can slowly progress to involve additional body sites, it is overall a benign condition that does not require treatment. Therapeutic options are based on case reports, with no single treatment showing a consistent response. From review of the literature, therapies that have been most effective include dermabrasion, excision,19 topical 5-fluorouracil,2,17,20 and oral retinoids.8 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans generally is resistant to topical steroids, retinoids, and vitamin D3 analogs, although success with betamethasone dipropionate,5 isotretinoin

gel 0.05%,11 and calcipotriol have been reported.6 A case of HLP with clinical response to psoralen plus UVA therapy also has been described.15

- Flegel H. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Hautarzt. 1958;9:363-364.

- Pearson LH, Smith JG, Chalker DK. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:190-195.

- Ando K, Hattori H, Yamauchi Y. Histopathological differences between early and old lesions of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:122-126.

- Fernández-Crehuet P, Rodríguez-Rey E, Ríos-Martín JJ, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans, or Flegel disease, with palmoplantar involvement. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:157-159.

- Sterneberg-Vos H, van Marion AM, Frank J, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease)—successful treatment with topical corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:38-41.

- Bayramgürler D, Apaydin R, Dökmeci S, et al. Flegel’s disease: treatment with topical calcipotriol. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:161-162.

- Price ML, Jones EW, MacDonald DM. A clinicopathological study of Flegel’s disease (hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans). Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:681-691.

- Krishnan A, Kar S. Photoletter to the editor: hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease) with unusual clinical presentation. response to isotretinoin therapy. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:93-95.

- Beveridge GW, Langlands AO. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans associated with tumours of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:453-458.

- Frenk E, Tapernoux B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel): a biological model for keratinization occurring in the absence of Odland bodies? Dermatologica. 1976;153:253-262.

- Miranda-Romero A, Sánchez Sambucety P, Bajo del Pozo C, et al. Unilateral hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:655-657.

- Gutiérrez MC, Hasson A, Arias MD, et al. Localized hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). Cutis. 1991;48:201-204.

- Fathy S, Azadeh B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:120-121.

- Rosdahl I, Rosen K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans: report on two cases. Acta Derm Venerol. 1985;65:562-564.

- Cooper SM, George S. Flegel's disease treated with psoralen ultraviolet A. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:340-342.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Manjon JA. Morphological evidence of periodical exacerbation of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2009;17:16-19.

- Langer K, Zonzits E, Konrad K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). ultrastructural study of lesional and perilesional skin and therapeutic trial of topical tretinoin versus 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:812-816.

- Ishibashi A, Tsuboi R, Fujita K. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. associated with cancers of the digestive organs. J Dermatol. 1984;11:407-409.

- Cunha Filho RR, Almeida Jr HL. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S76-S77.

- Blaheta HJ, Metzler G, Rassner G, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease)—lack of response to treatment with tacalcitol and calcipotriol. Dermatology. 2001;202:255-258.

- Flegel H. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Hautarzt. 1958;9:363-364.

- Pearson LH, Smith JG, Chalker DK. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:190-195.

- Ando K, Hattori H, Yamauchi Y. Histopathological differences between early and old lesions of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:122-126.

- Fernández-Crehuet P, Rodríguez-Rey E, Ríos-Martín JJ, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans, or Flegel disease, with palmoplantar involvement. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:157-159.

- Sterneberg-Vos H, van Marion AM, Frank J, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease)—successful treatment with topical corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:38-41.

- Bayramgürler D, Apaydin R, Dökmeci S, et al. Flegel’s disease: treatment with topical calcipotriol. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:161-162.

- Price ML, Jones EW, MacDonald DM. A clinicopathological study of Flegel’s disease (hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans). Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:681-691.

- Krishnan A, Kar S. Photoletter to the editor: hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease) with unusual clinical presentation. response to isotretinoin therapy. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:93-95.

- Beveridge GW, Langlands AO. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans associated with tumours of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:453-458.

- Frenk E, Tapernoux B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel): a biological model for keratinization occurring in the absence of Odland bodies? Dermatologica. 1976;153:253-262.

- Miranda-Romero A, Sánchez Sambucety P, Bajo del Pozo C, et al. Unilateral hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:655-657.

- Gutiérrez MC, Hasson A, Arias MD, et al. Localized hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). Cutis. 1991;48:201-204.

- Fathy S, Azadeh B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:120-121.

- Rosdahl I, Rosen K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans: report on two cases. Acta Derm Venerol. 1985;65:562-564.

- Cooper SM, George S. Flegel's disease treated with psoralen ultraviolet A. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:340-342.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Manjon JA. Morphological evidence of periodical exacerbation of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2009;17:16-19.

- Langer K, Zonzits E, Konrad K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). ultrastructural study of lesional and perilesional skin and therapeutic trial of topical tretinoin versus 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:812-816.

- Ishibashi A, Tsuboi R, Fujita K. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. associated with cancers of the digestive organs. J Dermatol. 1984;11:407-409.

- Cunha Filho RR, Almeida Jr HL. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S76-S77.

- Blaheta HJ, Metzler G, Rassner G, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease)—lack of response to treatment with tacalcitol and calcipotriol. Dermatology. 2001;202:255-258.

What Is Your Diagnosis? Herpes Zoster

The Diagnosis: Herpes Zoster

Herpes zoster is a common infection that clinically presents with moderate to intense pain in the involved dermatome (1–3 days before the outbreak1) followed by a unilateral dermatomal eruption. The most common sites of involvement include the trunk (dermatomes T3–L2) and upper face (dermatome V1).2 Herpes zoster characteristically begins as erythematous macules and papules that progress to vesicles and sometimes pustules, which subsequently crust over (7–10 days after the initial outbreak).1 Regional lymphadenopathy is present in most cases. Due to the classic presentation of herpes zoster, clinical diagnosis is the mainstay for most cases. Although it can present in any age group, herpes zoster is most commonly associated with advancing age.3

During the course of primary varicella infection, the herpes virus spreads from infected lesions to the contiguous endings of sensory nerves and travels to the dorsal root ganglion cells where it remains latent.1 It is hypothesized that cell-mediated immunity suppresses viral activity and maintains viral latency. A decline in varicella zoster virus–specific cell-mediated immunity can result in reactivation of the latent virus.1 The virus is then transported to the skin from the dorsal root ganglion via myelinated nerves, which terminate at the isthmus of hair follicles, and subsequent infection of the folliculosebaceous unit occurs.4

Laboratory tests that can assist in the diagnosis of herpes zoster, especially atypical cases, include Tzanck smear and viral culture of the vesicle fluid.1 When vesicles are not present, biopsy of the lesion followed by immunohistochemical staining and polymerase chain reaction assay can aid in the diagnosis. The differential diagnosis for our patient included pseudolymphoma, herpes simplex virus, lymphomatoid papulosis, sarcoidosis, trigeminal trophic syndrome, and Sweet syndrome.

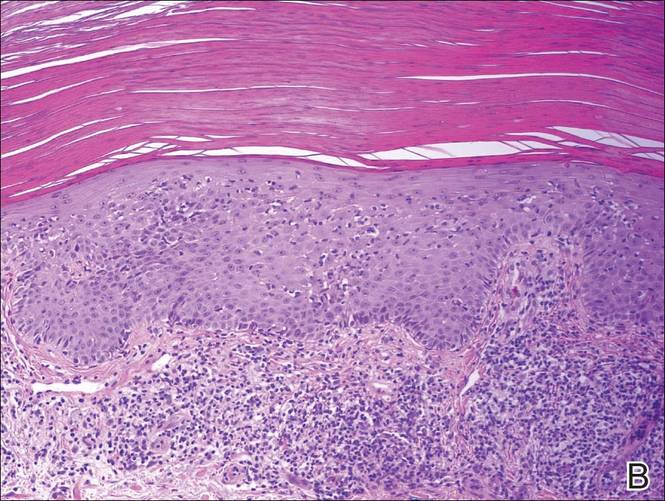

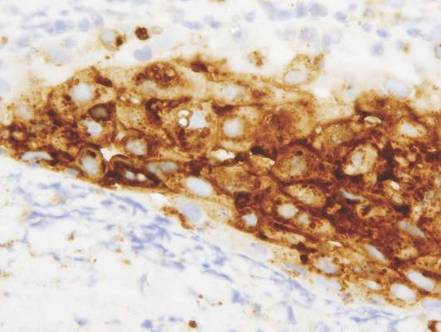

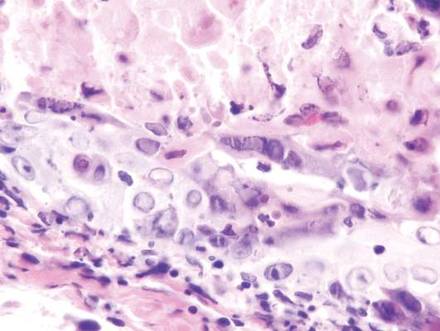

Vesicles were not present in our patient, but the dermatomal nature of the eruption and the pain she experienced made the clinical scenario suspicious for herpes zoster. A 4-mm punch biopsy of a single folliculosebaceous unit revealed herpetic, cytopathic features including prominent keratinocyte necrosis involving sebaceous, isthmic, and infundibular epithelium; ballooning of epithelial cells with steel gray nuclei; and multinucleation with nuclear molding (Figure 1). Strong nuclear and cytoplasmic staining was seen in the affected keratinocytes under anti–varicella zoster virus immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 2). Staining for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 was negative. Within days of starting valacyclovir 1000 mg (every 8 hours for 1 week), the patient’s symptoms resolved.

|

| |

|

|

Atypical presentations of herpes zoster (eg, presentations that are not completely dermatomal) are becoming more common. Herpetic infections should always be in the differential diagnosis for cutaneous ulcerations. Misdiagnosis of herpes zoster due to atypical features is common and can delay prompt and adequate treatment.

- Rockley PF, Tyring SK. Pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of varicella zoster virus infections. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:227-232.

- Chen TM, George S, Woodruff CA, et al. Clinical manifestations of varicella-zoster virus infection. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:267-282.

- Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:9-20.

- Walsh N, Boutilier R, Glasgow D, et al. Exclusive involvement of folliculosebaceous units by herpes: a reflection of early herpes zoster. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:189-194.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Zoster

Herpes zoster is a common infection that clinically presents with moderate to intense pain in the involved dermatome (1–3 days before the outbreak1) followed by a unilateral dermatomal eruption. The most common sites of involvement include the trunk (dermatomes T3–L2) and upper face (dermatome V1).2 Herpes zoster characteristically begins as erythematous macules and papules that progress to vesicles and sometimes pustules, which subsequently crust over (7–10 days after the initial outbreak).1 Regional lymphadenopathy is present in most cases. Due to the classic presentation of herpes zoster, clinical diagnosis is the mainstay for most cases. Although it can present in any age group, herpes zoster is most commonly associated with advancing age.3

During the course of primary varicella infection, the herpes virus spreads from infected lesions to the contiguous endings of sensory nerves and travels to the dorsal root ganglion cells where it remains latent.1 It is hypothesized that cell-mediated immunity suppresses viral activity and maintains viral latency. A decline in varicella zoster virus–specific cell-mediated immunity can result in reactivation of the latent virus.1 The virus is then transported to the skin from the dorsal root ganglion via myelinated nerves, which terminate at the isthmus of hair follicles, and subsequent infection of the folliculosebaceous unit occurs.4

Laboratory tests that can assist in the diagnosis of herpes zoster, especially atypical cases, include Tzanck smear and viral culture of the vesicle fluid.1 When vesicles are not present, biopsy of the lesion followed by immunohistochemical staining and polymerase chain reaction assay can aid in the diagnosis. The differential diagnosis for our patient included pseudolymphoma, herpes simplex virus, lymphomatoid papulosis, sarcoidosis, trigeminal trophic syndrome, and Sweet syndrome.

Vesicles were not present in our patient, but the dermatomal nature of the eruption and the pain she experienced made the clinical scenario suspicious for herpes zoster. A 4-mm punch biopsy of a single folliculosebaceous unit revealed herpetic, cytopathic features including prominent keratinocyte necrosis involving sebaceous, isthmic, and infundibular epithelium; ballooning of epithelial cells with steel gray nuclei; and multinucleation with nuclear molding (Figure 1). Strong nuclear and cytoplasmic staining was seen in the affected keratinocytes under anti–varicella zoster virus immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 2). Staining for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 was negative. Within days of starting valacyclovir 1000 mg (every 8 hours for 1 week), the patient’s symptoms resolved.

|

| |

|

|

Atypical presentations of herpes zoster (eg, presentations that are not completely dermatomal) are becoming more common. Herpetic infections should always be in the differential diagnosis for cutaneous ulcerations. Misdiagnosis of herpes zoster due to atypical features is common and can delay prompt and adequate treatment.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Zoster

Herpes zoster is a common infection that clinically presents with moderate to intense pain in the involved dermatome (1–3 days before the outbreak1) followed by a unilateral dermatomal eruption. The most common sites of involvement include the trunk (dermatomes T3–L2) and upper face (dermatome V1).2 Herpes zoster characteristically begins as erythematous macules and papules that progress to vesicles and sometimes pustules, which subsequently crust over (7–10 days after the initial outbreak).1 Regional lymphadenopathy is present in most cases. Due to the classic presentation of herpes zoster, clinical diagnosis is the mainstay for most cases. Although it can present in any age group, herpes zoster is most commonly associated with advancing age.3

During the course of primary varicella infection, the herpes virus spreads from infected lesions to the contiguous endings of sensory nerves and travels to the dorsal root ganglion cells where it remains latent.1 It is hypothesized that cell-mediated immunity suppresses viral activity and maintains viral latency. A decline in varicella zoster virus–specific cell-mediated immunity can result in reactivation of the latent virus.1 The virus is then transported to the skin from the dorsal root ganglion via myelinated nerves, which terminate at the isthmus of hair follicles, and subsequent infection of the folliculosebaceous unit occurs.4

Laboratory tests that can assist in the diagnosis of herpes zoster, especially atypical cases, include Tzanck smear and viral culture of the vesicle fluid.1 When vesicles are not present, biopsy of the lesion followed by immunohistochemical staining and polymerase chain reaction assay can aid in the diagnosis. The differential diagnosis for our patient included pseudolymphoma, herpes simplex virus, lymphomatoid papulosis, sarcoidosis, trigeminal trophic syndrome, and Sweet syndrome.

Vesicles were not present in our patient, but the dermatomal nature of the eruption and the pain she experienced made the clinical scenario suspicious for herpes zoster. A 4-mm punch biopsy of a single folliculosebaceous unit revealed herpetic, cytopathic features including prominent keratinocyte necrosis involving sebaceous, isthmic, and infundibular epithelium; ballooning of epithelial cells with steel gray nuclei; and multinucleation with nuclear molding (Figure 1). Strong nuclear and cytoplasmic staining was seen in the affected keratinocytes under anti–varicella zoster virus immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 2). Staining for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 was negative. Within days of starting valacyclovir 1000 mg (every 8 hours for 1 week), the patient’s symptoms resolved.

|

| |

|

|

Atypical presentations of herpes zoster (eg, presentations that are not completely dermatomal) are becoming more common. Herpetic infections should always be in the differential diagnosis for cutaneous ulcerations. Misdiagnosis of herpes zoster due to atypical features is common and can delay prompt and adequate treatment.

- Rockley PF, Tyring SK. Pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of varicella zoster virus infections. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:227-232.

- Chen TM, George S, Woodruff CA, et al. Clinical manifestations of varicella-zoster virus infection. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:267-282.

- Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:9-20.

- Walsh N, Boutilier R, Glasgow D, et al. Exclusive involvement of folliculosebaceous units by herpes: a reflection of early herpes zoster. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:189-194.

- Rockley PF, Tyring SK. Pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of varicella zoster virus infections. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:227-232.

- Chen TM, George S, Woodruff CA, et al. Clinical manifestations of varicella-zoster virus infection. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:267-282.

- Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:9-20.

- Walsh N, Boutilier R, Glasgow D, et al. Exclusive involvement of folliculosebaceous units by herpes: a reflection of early herpes zoster. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:189-194.

A 32-year-old woman with no remarkable medical history presented with a progressively worsening erythematous and edematous plaque on the right cheek of 8 days’ duration. She had previously been treated by her primary care physician with cephalexin for 3 days and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 2 days, which resulted in “flattening” of the plaque, but the lesion did not resolve. She was referred to our dermatology clinic for further evaluation. She denied any trauma to the cheek or scratching of the lesion. On physical examination, a 2-cm pink, erythematous, edematous plaque with a central eschar was noted on the right cheek with crusting of the right nasal wall.

Scaly Plaque With Pustules and Anonychia on the Middle Finger

The Diagnosis: Acrodermatitis Continua of Hallopeau

Acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau (ACH) is considered to be a form of acropustular psoriasis that presents as a sterile, pustular eruption initially affecting the fingertips and/or toes.1 The slow-growing pustules typically progress locally and can lead to onychodystrophy and/or osteolysis of the underlying bone.2,3 Most commonly affecting adult women, ACH often begins following local trauma to or infection of a single digit.4 As the disease progresses proximally, the small pustules burst, leaving a shiny, erythematous surface on which new pustules can develop. These pustules have a tendency to amalgamate, leading to the characteristic clinical finding of lakes of pus. Pustules frequently appear on the nail matrix and nail bed presenting as severe onychodystrophy and ultimately anonychia.5,6 Rarely, ACH can be associated with generalized pustular psoriasis as well as conjunctivitis, balanitis, and fissuring or annulus migrans of the tongue.2,7

Diagnosis can be established based on clinical findings, biopsy, and bacterial and fungal cultures revealing sterile pustules.8,9 Histologic findings are similar to those seen in pustular psoriasis, demonstrating subcorneal neutrophilic pustules, Munro microabscesses, and dilated blood vessels with lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.10

Due to the refractory nature of the disease, there are no recommended guidelines for treatment of ACH. Most successful treatment regimens consist of topical psoriasis medications combined with systemic psoriatic therapies such as cyclosporine, methotrexate, acitretin, or biologic therapy.8,11-16 Our patient achieved satisfactory clinical improvement with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily alternating with calcipotriene cream 0.005% twice daily.

- Suchanek J. Relation of Hallopeau’s acrodermatitis continua to psoriasis. Przegl Dermatol. 1951;1:165-181.

- Adam BA, Loh CL. Acropustulosis (acrodermatitis continua) with resorption of terminal phalanges. Med J Malaysia. 1972;27:30-32.

- Mrowietz U. Pustular eruptions of palms and soles. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LS, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007:215-218.

- Yerushalmi J, Grunwald MH, Hallel-Halevy D, et al. Chronic pustular eruption of the thumbs. diagnosis: acrodermatitis continue of Hallopeau (ACH). Arch Dermatol. 2000:136:925-930.

- Granelli U. Impetigo herpetiformis; acrodermatitis continue of Hallopeau and pustular psoriasis; etiology and pathogenesis and differential diagnosis. Minerva Dermatol. 1956;31:120-126.

- Mobini N, Toussaint S, Kamino H. Noninfectious erythematous, papular, and squamous diseases. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson B, et al, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2005:174-210.

- Radcliff-Crocker H. Diseases of the Skin: Their Descriptions, Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Philadelphia, PA: P. Blakiston, Son, & Co; 1888.

- Sehgal VN, Verma P, Sharma S, et al. Review: acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau: evolution of treatment options. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1195-1211.

- Post CF, Hopper ME. Dermatitis repens: a report of two cases with bacteriologic studies. AMA Arc Derm Syphilol. 1951;63:220-223.

- Sehgal VN, Sharma S. The significance of Gram’s stain smear, potassium hydroxide mount, culture and microscopic pathology in the diagnosis of acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Skinmed. 2011;9:260-261.

- Mosser G, Pillekamp H, Peter RU. Suppurative acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. a differential diagnosis of paronychia. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1998;123:386-390.

- Piquero-Casals J, Fonseca de Mello AP, Dal Coleto C, et al. Using oral tetracycline and topical betamethasone valerate to treat acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Cutis. 2002;70:106-108.

- Tsuji T, Nishimura M. Topically administered fluorouracil in acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:27-28.

- Van de Kerkhof PCM. In vivo effects of vitamin D3 analogs. J Dermatolog Treat. 1998;(suppl 3):S25-S29.

- Kokelj F, Plozzer C, Trevisan G. Uselessness of topical calcipotriol as monotherapy for acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:153.

- Schneider LA, Hinrichs R, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Phototherapy and photochemotherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:464-476.

The Diagnosis: Acrodermatitis Continua of Hallopeau

Acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau (ACH) is considered to be a form of acropustular psoriasis that presents as a sterile, pustular eruption initially affecting the fingertips and/or toes.1 The slow-growing pustules typically progress locally and can lead to onychodystrophy and/or osteolysis of the underlying bone.2,3 Most commonly affecting adult women, ACH often begins following local trauma to or infection of a single digit.4 As the disease progresses proximally, the small pustules burst, leaving a shiny, erythematous surface on which new pustules can develop. These pustules have a tendency to amalgamate, leading to the characteristic clinical finding of lakes of pus. Pustules frequently appear on the nail matrix and nail bed presenting as severe onychodystrophy and ultimately anonychia.5,6 Rarely, ACH can be associated with generalized pustular psoriasis as well as conjunctivitis, balanitis, and fissuring or annulus migrans of the tongue.2,7

Diagnosis can be established based on clinical findings, biopsy, and bacterial and fungal cultures revealing sterile pustules.8,9 Histologic findings are similar to those seen in pustular psoriasis, demonstrating subcorneal neutrophilic pustules, Munro microabscesses, and dilated blood vessels with lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.10

Due to the refractory nature of the disease, there are no recommended guidelines for treatment of ACH. Most successful treatment regimens consist of topical psoriasis medications combined with systemic psoriatic therapies such as cyclosporine, methotrexate, acitretin, or biologic therapy.8,11-16 Our patient achieved satisfactory clinical improvement with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily alternating with calcipotriene cream 0.005% twice daily.

The Diagnosis: Acrodermatitis Continua of Hallopeau

Acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau (ACH) is considered to be a form of acropustular psoriasis that presents as a sterile, pustular eruption initially affecting the fingertips and/or toes.1 The slow-growing pustules typically progress locally and can lead to onychodystrophy and/or osteolysis of the underlying bone.2,3 Most commonly affecting adult women, ACH often begins following local trauma to or infection of a single digit.4 As the disease progresses proximally, the small pustules burst, leaving a shiny, erythematous surface on which new pustules can develop. These pustules have a tendency to amalgamate, leading to the characteristic clinical finding of lakes of pus. Pustules frequently appear on the nail matrix and nail bed presenting as severe onychodystrophy and ultimately anonychia.5,6 Rarely, ACH can be associated with generalized pustular psoriasis as well as conjunctivitis, balanitis, and fissuring or annulus migrans of the tongue.2,7

Diagnosis can be established based on clinical findings, biopsy, and bacterial and fungal cultures revealing sterile pustules.8,9 Histologic findings are similar to those seen in pustular psoriasis, demonstrating subcorneal neutrophilic pustules, Munro microabscesses, and dilated blood vessels with lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.10

Due to the refractory nature of the disease, there are no recommended guidelines for treatment of ACH. Most successful treatment regimens consist of topical psoriasis medications combined with systemic psoriatic therapies such as cyclosporine, methotrexate, acitretin, or biologic therapy.8,11-16 Our patient achieved satisfactory clinical improvement with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily alternating with calcipotriene cream 0.005% twice daily.

- Suchanek J. Relation of Hallopeau’s acrodermatitis continua to psoriasis. Przegl Dermatol. 1951;1:165-181.

- Adam BA, Loh CL. Acropustulosis (acrodermatitis continua) with resorption of terminal phalanges. Med J Malaysia. 1972;27:30-32.

- Mrowietz U. Pustular eruptions of palms and soles. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LS, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007:215-218.

- Yerushalmi J, Grunwald MH, Hallel-Halevy D, et al. Chronic pustular eruption of the thumbs. diagnosis: acrodermatitis continue of Hallopeau (ACH). Arch Dermatol. 2000:136:925-930.

- Granelli U. Impetigo herpetiformis; acrodermatitis continue of Hallopeau and pustular psoriasis; etiology and pathogenesis and differential diagnosis. Minerva Dermatol. 1956;31:120-126.

- Mobini N, Toussaint S, Kamino H. Noninfectious erythematous, papular, and squamous diseases. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson B, et al, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2005:174-210.

- Radcliff-Crocker H. Diseases of the Skin: Their Descriptions, Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Philadelphia, PA: P. Blakiston, Son, & Co; 1888.

- Sehgal VN, Verma P, Sharma S, et al. Review: acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau: evolution of treatment options. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1195-1211.

- Post CF, Hopper ME. Dermatitis repens: a report of two cases with bacteriologic studies. AMA Arc Derm Syphilol. 1951;63:220-223.

- Sehgal VN, Sharma S. The significance of Gram’s stain smear, potassium hydroxide mount, culture and microscopic pathology in the diagnosis of acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Skinmed. 2011;9:260-261.

- Mosser G, Pillekamp H, Peter RU. Suppurative acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. a differential diagnosis of paronychia. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1998;123:386-390.

- Piquero-Casals J, Fonseca de Mello AP, Dal Coleto C, et al. Using oral tetracycline and topical betamethasone valerate to treat acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Cutis. 2002;70:106-108.

- Tsuji T, Nishimura M. Topically administered fluorouracil in acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:27-28.

- Van de Kerkhof PCM. In vivo effects of vitamin D3 analogs. J Dermatolog Treat. 1998;(suppl 3):S25-S29.

- Kokelj F, Plozzer C, Trevisan G. Uselessness of topical calcipotriol as monotherapy for acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:153.

- Schneider LA, Hinrichs R, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Phototherapy and photochemotherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:464-476.

- Suchanek J. Relation of Hallopeau’s acrodermatitis continua to psoriasis. Przegl Dermatol. 1951;1:165-181.

- Adam BA, Loh CL. Acropustulosis (acrodermatitis continua) with resorption of terminal phalanges. Med J Malaysia. 1972;27:30-32.

- Mrowietz U. Pustular eruptions of palms and soles. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LS, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007:215-218.

- Yerushalmi J, Grunwald MH, Hallel-Halevy D, et al. Chronic pustular eruption of the thumbs. diagnosis: acrodermatitis continue of Hallopeau (ACH). Arch Dermatol. 2000:136:925-930.

- Granelli U. Impetigo herpetiformis; acrodermatitis continue of Hallopeau and pustular psoriasis; etiology and pathogenesis and differential diagnosis. Minerva Dermatol. 1956;31:120-126.

- Mobini N, Toussaint S, Kamino H. Noninfectious erythematous, papular, and squamous diseases. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson B, et al, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2005:174-210.

- Radcliff-Crocker H. Diseases of the Skin: Their Descriptions, Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Philadelphia, PA: P. Blakiston, Son, & Co; 1888.

- Sehgal VN, Verma P, Sharma S, et al. Review: acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau: evolution of treatment options. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1195-1211.

- Post CF, Hopper ME. Dermatitis repens: a report of two cases with bacteriologic studies. AMA Arc Derm Syphilol. 1951;63:220-223.

- Sehgal VN, Sharma S. The significance of Gram’s stain smear, potassium hydroxide mount, culture and microscopic pathology in the diagnosis of acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Skinmed. 2011;9:260-261.

- Mosser G, Pillekamp H, Peter RU. Suppurative acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. a differential diagnosis of paronychia. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1998;123:386-390.

- Piquero-Casals J, Fonseca de Mello AP, Dal Coleto C, et al. Using oral tetracycline and topical betamethasone valerate to treat acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Cutis. 2002;70:106-108.

- Tsuji T, Nishimura M. Topically administered fluorouracil in acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:27-28.

- Van de Kerkhof PCM. In vivo effects of vitamin D3 analogs. J Dermatolog Treat. 1998;(suppl 3):S25-S29.

- Kokelj F, Plozzer C, Trevisan G. Uselessness of topical calcipotriol as monotherapy for acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:153.

- Schneider LA, Hinrichs R, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Phototherapy and photochemotherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:464-476.

A 69-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with a persistent rash on the right middle finger of 5 years’ duration (left). Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated scaly plaque with pustules and anonychia localized to the right middle finger (right). Fungal and bacterial cultures revealed sterile pustules. The patient was successfully treated with an occluded superpotent topical steroid alternating with a topical vitamin D analogue.

What Is Your Diagnosis? Tinea Corporis

The Diagnosis: Tinea Corporis

Although contact dermatitis from the metal on the back of the watch was suspected, many modern wrist watches are made with stainless steel rather than nickel, which is a common contact allergen; therefore, other diagnoses were considered in the differential including irritant contact dermatitis, psoriasis, and tinea infection. A potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was performed to rule out tinea infection. Unexpectedly, the KOH preparation was positive for fungal hyphae, confirming a diagnosis of tinea corporis. The patient was treated with clotrimazole cream 1% twice daily for 3 weeks during which time the rash completely resolved.

We present this case to stress the importance of performing KOH preparations even when the likelihood of tinea infection seems remote. At our institution, we teach our residents, “If it’s scaly, scrape it.” This adage has served us well. Tinea corporis may be mistaken for many other skin diseases, including eczema, psoriasis, and seborrheic dermatitis.1 A KOH preparation often is a helpful tool in confirming the diagnosis and should be performed when a dermatophyte infection is suspected. The KOH preparation is the most sensitive diagnostic test used to confirm dermatophyte infection, with 90% of infections showing positive results.2,3

Tinea infections may occur anywhere on the body, but areas that are prone to excessive heat and/or moisture are particularly susceptible.4 Dermatophyte infections typically present as annular, scaly, pruritic patches or plaques often with central clearing and an active border.1 In our patient, the lesion showed characteristics that were suggestive of a dermatophyte infection but was somewhat atypical in appearance, as it lacked central clearing (Figure). The 3 genera of dermatophytes—Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton—are common causes of fungal infections.2 The pathogenesis of dermatophytosis is the synthesis of keratinases that digest keratin and sustain the presence of the fungi. Local factors such as sweating and occlusion facilitate the activity of these organisms.2 In our case, the pathogenesis was believed to be due to the entrapment of moisture behind the patient’s watch, creating a favorable environment for fungal growth.

- Ely JW, Rosenfeld S, Seabury SM. Diagnosis and management of tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014:90:702-710.

- Wolff K, Saavedra AP, Fitzpatrick TB. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2013.

- Levitt JO, Levitt BH, Akhavan A, et al. The sensitivity and specificity of potassium hydroxide smear and fungal culture relative to clinical assessment in the evaluation of tinea pedis: a pooled analysis (published online ahead of print June 22, 2010). Dermatol Res Pract. doi:10.1155/2010/764843.

- Gupta AK, Chaudhry M, Elewski B. Tinea corporis, tinea cruris, tinea nigra and piedra. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:395-400.

The Diagnosis: Tinea Corporis

Although contact dermatitis from the metal on the back of the watch was suspected, many modern wrist watches are made with stainless steel rather than nickel, which is a common contact allergen; therefore, other diagnoses were considered in the differential including irritant contact dermatitis, psoriasis, and tinea infection. A potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was performed to rule out tinea infection. Unexpectedly, the KOH preparation was positive for fungal hyphae, confirming a diagnosis of tinea corporis. The patient was treated with clotrimazole cream 1% twice daily for 3 weeks during which time the rash completely resolved.

We present this case to stress the importance of performing KOH preparations even when the likelihood of tinea infection seems remote. At our institution, we teach our residents, “If it’s scaly, scrape it.” This adage has served us well. Tinea corporis may be mistaken for many other skin diseases, including eczema, psoriasis, and seborrheic dermatitis.1 A KOH preparation often is a helpful tool in confirming the diagnosis and should be performed when a dermatophyte infection is suspected. The KOH preparation is the most sensitive diagnostic test used to confirm dermatophyte infection, with 90% of infections showing positive results.2,3

Tinea infections may occur anywhere on the body, but areas that are prone to excessive heat and/or moisture are particularly susceptible.4 Dermatophyte infections typically present as annular, scaly, pruritic patches or plaques often with central clearing and an active border.1 In our patient, the lesion showed characteristics that were suggestive of a dermatophyte infection but was somewhat atypical in appearance, as it lacked central clearing (Figure). The 3 genera of dermatophytes—Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton—are common causes of fungal infections.2 The pathogenesis of dermatophytosis is the synthesis of keratinases that digest keratin and sustain the presence of the fungi. Local factors such as sweating and occlusion facilitate the activity of these organisms.2 In our case, the pathogenesis was believed to be due to the entrapment of moisture behind the patient’s watch, creating a favorable environment for fungal growth.

The Diagnosis: Tinea Corporis

Although contact dermatitis from the metal on the back of the watch was suspected, many modern wrist watches are made with stainless steel rather than nickel, which is a common contact allergen; therefore, other diagnoses were considered in the differential including irritant contact dermatitis, psoriasis, and tinea infection. A potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was performed to rule out tinea infection. Unexpectedly, the KOH preparation was positive for fungal hyphae, confirming a diagnosis of tinea corporis. The patient was treated with clotrimazole cream 1% twice daily for 3 weeks during which time the rash completely resolved.

We present this case to stress the importance of performing KOH preparations even when the likelihood of tinea infection seems remote. At our institution, we teach our residents, “If it’s scaly, scrape it.” This adage has served us well. Tinea corporis may be mistaken for many other skin diseases, including eczema, psoriasis, and seborrheic dermatitis.1 A KOH preparation often is a helpful tool in confirming the diagnosis and should be performed when a dermatophyte infection is suspected. The KOH preparation is the most sensitive diagnostic test used to confirm dermatophyte infection, with 90% of infections showing positive results.2,3

Tinea infections may occur anywhere on the body, but areas that are prone to excessive heat and/or moisture are particularly susceptible.4 Dermatophyte infections typically present as annular, scaly, pruritic patches or plaques often with central clearing and an active border.1 In our patient, the lesion showed characteristics that were suggestive of a dermatophyte infection but was somewhat atypical in appearance, as it lacked central clearing (Figure). The 3 genera of dermatophytes—Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton—are common causes of fungal infections.2 The pathogenesis of dermatophytosis is the synthesis of keratinases that digest keratin and sustain the presence of the fungi. Local factors such as sweating and occlusion facilitate the activity of these organisms.2 In our case, the pathogenesis was believed to be due to the entrapment of moisture behind the patient’s watch, creating a favorable environment for fungal growth.

- Ely JW, Rosenfeld S, Seabury SM. Diagnosis and management of tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014:90:702-710.

- Wolff K, Saavedra AP, Fitzpatrick TB. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2013.

- Levitt JO, Levitt BH, Akhavan A, et al. The sensitivity and specificity of potassium hydroxide smear and fungal culture relative to clinical assessment in the evaluation of tinea pedis: a pooled analysis (published online ahead of print June 22, 2010). Dermatol Res Pract. doi:10.1155/2010/764843.

- Gupta AK, Chaudhry M, Elewski B. Tinea corporis, tinea cruris, tinea nigra and piedra. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:395-400.

- Ely JW, Rosenfeld S, Seabury SM. Diagnosis and management of tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014:90:702-710.

- Wolff K, Saavedra AP, Fitzpatrick TB. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2013.

- Levitt JO, Levitt BH, Akhavan A, et al. The sensitivity and specificity of potassium hydroxide smear and fungal culture relative to clinical assessment in the evaluation of tinea pedis: a pooled analysis (published online ahead of print June 22, 2010). Dermatol Res Pract. doi:10.1155/2010/764843.

- Gupta AK, Chaudhry M, Elewski B. Tinea corporis, tinea cruris, tinea nigra and piedra. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:395-400.

An 81-year-old woman presented with a 2-cm erythematous, scaly, pruritic rash on the left dorsal wrist localized to the skin under her watch. The patient first noticed the lesion 2 months prior. She moved the watch to the right wrist a few days prior to presentation and no symptoms developed in that location. No other areas of the skin were affected. She had no known allergies and was otherwise in good health.

Linear Bluish Black Papules on the Shoulder

The Diagnosis: Agminated Blue Nevus

Agminated blue nevus is a rare melanocytic nevus that characteristically presents as a group of multiple small, bluish papules occurring in a well-circumscribed area.1 It also has been referred to as a plaque-type nevus2,3 and an eruptive blue nevus.4 Originally described by Upshaw et al2 in 1947, agminated blue nevi may be congenital or arise in early childhood and almost always occur on the trunk. The skin between the papules often is unaffected or sometimes may show bluish or brown pigmentation.4 Agminated blue nevi usually are smaller than 10 cm in diameter; however, rare cases have measured up to 24 cm.1,4-6 The incidence of agminated blue nevi is 2 times higher in males than in females.1

|

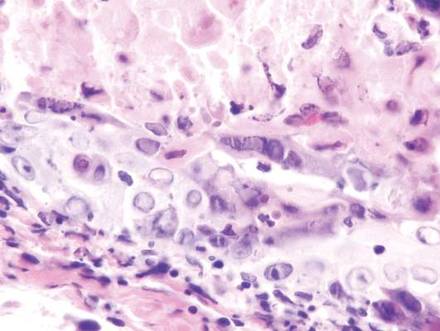

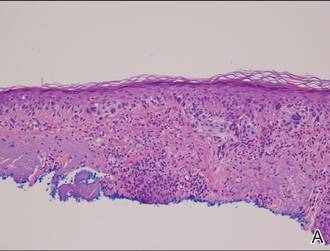

A biopsy of the lesion revealed pigmented dendritic melanocytes admixed with melanophages, forming fascicles and bundles (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10). In some areas the dermis was uninvolved. Higher magnification showed dendritic and epithelioid melanocytes extending down along the adnexal structures (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Histopathologically, agminated blue nevi typically demonstrate the features of common and/or cellular blue nevi. Cytologic atypia and mitoses are rare.1 The degree of cellularity and pigmentation of the lesions is variable, and the presence of subcutaneous cellular nodules also has been described.5

In our patient, histologic evaluation revealed foci of diffuse dermal spindle cell proliferation composed of heavily pigmented dendritic melanocytes admixed with melanophages in a fibrotic stroma (Figure, A). The dermis was uninvolved in some areas and the melanocytes were epithelioid and formed fascicles and bundles that extended down adnexal structures in other areas (Figure, B). Junctional involvement of melanocytes, cellular atypia, and mitoses were not identified. Our case demonstrated a combination of histologic findings of a cellular blue nevus as well as features reminiscent of a deep penetrating nevus. The differential diagnosis of agminated blue nevus includes agminated Spitz nevus arising in a speckled lentiginous nevus,7 dermal melanocytosis, melanoma, and pilar neurocristic hamartoma. Pilar neurocristic hamartomas may resemble plaque-type blue nevi; however, the former show a predilection for the scalp, histologically demonstrate features that overlap with blue nevi and congenital nevi, and are associated with neural structures that show Schwannian differentiation.8 Agminated blue nevi usually are characterized by a benign clinical course, but few cases describing malignant changes with development of malignant melanoma have been reported.9,10 Therefore, recognition of the clinical and histopathologic spectrum of agminated blue nevus is critical in order to avoid diagnostic pitfalls and confusion with melanoma.

- Vélez A, del-Río E, Martín-de-Hijas C, et al. Agminated blue nevi: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 1993;186:144-148.

- Upshaw BY, Ghormley RK, Montgomery H. Extensive blue nevus of Jadassohn-Tièche; report of a case. Surgery. 1947;22:761-765.

- Pittman JL, Fisher BK. Plaque-type blue nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1127-1128.

- Hendricks WM. Eruptive blue nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol.1981;4:50-53.

- Busam KJ, Woodruff JM, Erlandson RA, et al. Large plaque-type blue nevus with subcutaneous cellular nodules. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:92-99.

- Shenfield HT, Maize JC. Multiple and agminated blue nevi. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1980;6:725-728.

- Misago N, Narisawa Y, Kohda H. A combination of speckled lentiginous nevus with patch-type blue nevus. J Dermatol. 1993;20:643-647.