User login

Continuity Visits by Primary Care Physicians Could Benefit Inpatients

Hospital medicine leaders have long acknowledged the disconnects in medical care that occur at discharge. The demand for greater efficiency in hospital-based care is what has driven the hospitalist movement and its inexorable growth the past two decades.

Efforts to overcome discontinuity of care have included more timely discharge summaries, phone calls to primary care physicians (PCPs) and specialists at the time of discharge, and hospitalist-staffed post-discharge clinics. In a 2002 article, Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, and Steven Pantilat, MD, SFHM, of the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), suggested that PCPs make continuity visits to the hospital once or twice to maintain their involvement and help coordinate the care of their patients.1

A new “Perspectives” piece in The New England Journal of Medicine proposes that PCPs act as medical consultants to the hospitalist team while their patients are in the hospital, making a consulting visit “within 12 to 18 hours after admission to provide support and continuity to them and their families.”2 Authors Allan Goroll, MD, MACP, and Daniel Hunt, MD, propose that the PCP be asked to write a succinct consultation note in the hospital chart, highlighting key elements of the patient’s history and recent tests—with the goal of complementing and informing the hospitalist’s admission workup and care plan—while being paid as a consultant.

“It’s a fairly straightforward proposal,” says Dr. Hunt, chief of the hospital medicine unit at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston. “We’re not looking for PCPs to take care of every aspect of inpatient care. It’s really just to bring in the PCP’s expertise and nuanced understanding of the patient at a vulnerable time for the patient.”

The idea might seem a little ironic given the fact that hospitalists were created in part to relieve busy PCPs from having to visit the hospital. But some see it as a way forward.

“I wouldn’t call it a step backward,” says Joseph Ming Wah Li, MD, SFHM, FACP, director of the hospital medicine program at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston and a former SHM president. “Is it feasible? Realistically, in most settings today, I don’t think it is. But I would love it. I don’t really know enough about the patients I take care of in the hospital.”

The Barrier of “Not Enough Time”

Dr. Hunt says the biggest barrier to this proposal is the time that PCPs would have to carve out to make physical trips to the hospital.

“That ultimately comes down to reimbursement,” he says.

MGH, which is well situated with medical practices in or near the main hospital building, has piloted an approach similar to the NEJM proposal with a primary care group that comes in to see its patients in the first day or two after admission and then again on the day before discharge.

“But they are essentially doing it out of the goodness of their hearts,” Dr. Hunt explains. “What we’ve seen from this experiment are much better transitions of care and much better decision making around big decisions, such as end-of-life care or surgical interventions.”

Hospitalists at MGH and the PCPs spent a year and a half talking through the specifics of how their arrangement would work.

“We made a commitment, as hospitalists, to communicate directly by phone with the PCPs,” he says. “That commitment lasted about a week, and then we quickly converted to a daily e-mail. That works, because both parties are communicating substantial information in these e-mails.”

Dr. Hunt says the key is recognizing the “huge” value PCPs bring to an inpatient stay. And, while physical trips to the hospital or e-mails might not work for every hospitalist or PCP, the connecting of information and insight is often worth the investment.

“There are other ways [to communicate], such as video conferencing and Skype, where doctors could participate more efficiently in the care of their hospitalized patients,” he says, adding that hospitalists should reach out to PCPs, both when a patient enters the hospital and as part of a larger discussion about how to improve communication and continuity of care.

The PCP Perspective

Boston internist Gila Kriegel, MD, might seem like a throwback. She says she wants to visit her patients when they are in the hospital, if at all possible. In fact, hospitalists in Boston say Dr. Kriegel allows them to take care of her patients “almost begrudgingly.”

“She is so involved in their care,” Dr. Li says. “She tells me everything I need to know about them. She’d be here every day if she weren’t juggling other responsibilities.”

A PCP since 1986, Dr. Kriegel’s story illustrates the complexities of an evolving healthcare system. She’s based in an academic setting, which she calls a “kind of ivory tower.”

“But I was fortunate in 1989, after my first son was born and I went part-time, to have a colleague who offered to see my inpatients on the days I wasn’t working,” she explains. “Then a woman colleague of mine also went part-time, and we agreed to cross-cover for each other.”

Eventually, Dr. Kriegel was approached by Dr. Li’s hospitalist group, which offered to manage her hospitalized patients.

“For the first six months to a year, I’d go see my patients in the hospital on a social visit. I’d even write notes in the chart, until they told me, ‘You are not responsible for the care in the hospital. The hospitalist is,’” she recalls. “For me, it was a big loss to stop going to the hospital. Most PCPs I know like seeing their patients through the course of the illness.”

Then again, she also admits how difficult it is to see her patients in the hospital.

Still, she managed to stay connected. “When I stopped going to see my patients, I asked the hospital staff to give me the patient’s bedside phone number, and I’d call them in the hospital to let them know I was up on what was happening,” she says.

Technology, coincidentally, inserted a barrier: She wasn’t able to access hospitalists’ daily notes in the BIDMC electronic health records. That’s when Dr. Kriegel began e-mailing the hospitalists. In the end, even that form of communication wasn’t fully satisfying.

“The current system requires me to do the outreach,” she explains. “If you ask hospitalists about communication, they’d say they’re already doing it. But a discharge summary isn’t the same as knowing in real time what’s happening with my patients.”

“I’d love to make virtual visits to the patient in the hospital, by phone or computer link—even more so if I could get paid for my time. But I want to stay involved.”

Ripe for Innovation

Dr. Wachter, chief of hospital medicine at UCSF, who writes an HM-focused blog [wachtersworld.com], says the continuity visit is a good idea but also understands the difficulties in the new healthcare paradigm.

“It’s not easy to work out the logistics, and it depends on the geography,” he says. “We also need to be considering telemedicine. But something to enhance continuity is ripe for innovation.”

He says consultation or continuity visits offer ways to improve care with a relatively small expenditure.

“We still see a few PCPs come in when their patients are hospitalized. It’s very reassuring to their patients,” he says. “For the complicated cases where an ongoing relationship matters, those encounters are fabulous.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

References

Hospital medicine leaders have long acknowledged the disconnects in medical care that occur at discharge. The demand for greater efficiency in hospital-based care is what has driven the hospitalist movement and its inexorable growth the past two decades.

Efforts to overcome discontinuity of care have included more timely discharge summaries, phone calls to primary care physicians (PCPs) and specialists at the time of discharge, and hospitalist-staffed post-discharge clinics. In a 2002 article, Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, and Steven Pantilat, MD, SFHM, of the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), suggested that PCPs make continuity visits to the hospital once or twice to maintain their involvement and help coordinate the care of their patients.1

A new “Perspectives” piece in The New England Journal of Medicine proposes that PCPs act as medical consultants to the hospitalist team while their patients are in the hospital, making a consulting visit “within 12 to 18 hours after admission to provide support and continuity to them and their families.”2 Authors Allan Goroll, MD, MACP, and Daniel Hunt, MD, propose that the PCP be asked to write a succinct consultation note in the hospital chart, highlighting key elements of the patient’s history and recent tests—with the goal of complementing and informing the hospitalist’s admission workup and care plan—while being paid as a consultant.

“It’s a fairly straightforward proposal,” says Dr. Hunt, chief of the hospital medicine unit at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston. “We’re not looking for PCPs to take care of every aspect of inpatient care. It’s really just to bring in the PCP’s expertise and nuanced understanding of the patient at a vulnerable time for the patient.”

The idea might seem a little ironic given the fact that hospitalists were created in part to relieve busy PCPs from having to visit the hospital. But some see it as a way forward.

“I wouldn’t call it a step backward,” says Joseph Ming Wah Li, MD, SFHM, FACP, director of the hospital medicine program at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston and a former SHM president. “Is it feasible? Realistically, in most settings today, I don’t think it is. But I would love it. I don’t really know enough about the patients I take care of in the hospital.”

The Barrier of “Not Enough Time”

Dr. Hunt says the biggest barrier to this proposal is the time that PCPs would have to carve out to make physical trips to the hospital.

“That ultimately comes down to reimbursement,” he says.

MGH, which is well situated with medical practices in or near the main hospital building, has piloted an approach similar to the NEJM proposal with a primary care group that comes in to see its patients in the first day or two after admission and then again on the day before discharge.

“But they are essentially doing it out of the goodness of their hearts,” Dr. Hunt explains. “What we’ve seen from this experiment are much better transitions of care and much better decision making around big decisions, such as end-of-life care or surgical interventions.”

Hospitalists at MGH and the PCPs spent a year and a half talking through the specifics of how their arrangement would work.

“We made a commitment, as hospitalists, to communicate directly by phone with the PCPs,” he says. “That commitment lasted about a week, and then we quickly converted to a daily e-mail. That works, because both parties are communicating substantial information in these e-mails.”

Dr. Hunt says the key is recognizing the “huge” value PCPs bring to an inpatient stay. And, while physical trips to the hospital or e-mails might not work for every hospitalist or PCP, the connecting of information and insight is often worth the investment.

“There are other ways [to communicate], such as video conferencing and Skype, where doctors could participate more efficiently in the care of their hospitalized patients,” he says, adding that hospitalists should reach out to PCPs, both when a patient enters the hospital and as part of a larger discussion about how to improve communication and continuity of care.

The PCP Perspective

Boston internist Gila Kriegel, MD, might seem like a throwback. She says she wants to visit her patients when they are in the hospital, if at all possible. In fact, hospitalists in Boston say Dr. Kriegel allows them to take care of her patients “almost begrudgingly.”

“She is so involved in their care,” Dr. Li says. “She tells me everything I need to know about them. She’d be here every day if she weren’t juggling other responsibilities.”

A PCP since 1986, Dr. Kriegel’s story illustrates the complexities of an evolving healthcare system. She’s based in an academic setting, which she calls a “kind of ivory tower.”

“But I was fortunate in 1989, after my first son was born and I went part-time, to have a colleague who offered to see my inpatients on the days I wasn’t working,” she explains. “Then a woman colleague of mine also went part-time, and we agreed to cross-cover for each other.”

Eventually, Dr. Kriegel was approached by Dr. Li’s hospitalist group, which offered to manage her hospitalized patients.

“For the first six months to a year, I’d go see my patients in the hospital on a social visit. I’d even write notes in the chart, until they told me, ‘You are not responsible for the care in the hospital. The hospitalist is,’” she recalls. “For me, it was a big loss to stop going to the hospital. Most PCPs I know like seeing their patients through the course of the illness.”

Then again, she also admits how difficult it is to see her patients in the hospital.

Still, she managed to stay connected. “When I stopped going to see my patients, I asked the hospital staff to give me the patient’s bedside phone number, and I’d call them in the hospital to let them know I was up on what was happening,” she says.

Technology, coincidentally, inserted a barrier: She wasn’t able to access hospitalists’ daily notes in the BIDMC electronic health records. That’s when Dr. Kriegel began e-mailing the hospitalists. In the end, even that form of communication wasn’t fully satisfying.

“The current system requires me to do the outreach,” she explains. “If you ask hospitalists about communication, they’d say they’re already doing it. But a discharge summary isn’t the same as knowing in real time what’s happening with my patients.”

“I’d love to make virtual visits to the patient in the hospital, by phone or computer link—even more so if I could get paid for my time. But I want to stay involved.”

Ripe for Innovation

Dr. Wachter, chief of hospital medicine at UCSF, who writes an HM-focused blog [wachtersworld.com], says the continuity visit is a good idea but also understands the difficulties in the new healthcare paradigm.

“It’s not easy to work out the logistics, and it depends on the geography,” he says. “We also need to be considering telemedicine. But something to enhance continuity is ripe for innovation.”

He says consultation or continuity visits offer ways to improve care with a relatively small expenditure.

“We still see a few PCPs come in when their patients are hospitalized. It’s very reassuring to their patients,” he says. “For the complicated cases where an ongoing relationship matters, those encounters are fabulous.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

References

Hospital medicine leaders have long acknowledged the disconnects in medical care that occur at discharge. The demand for greater efficiency in hospital-based care is what has driven the hospitalist movement and its inexorable growth the past two decades.

Efforts to overcome discontinuity of care have included more timely discharge summaries, phone calls to primary care physicians (PCPs) and specialists at the time of discharge, and hospitalist-staffed post-discharge clinics. In a 2002 article, Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, and Steven Pantilat, MD, SFHM, of the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), suggested that PCPs make continuity visits to the hospital once or twice to maintain their involvement and help coordinate the care of their patients.1

A new “Perspectives” piece in The New England Journal of Medicine proposes that PCPs act as medical consultants to the hospitalist team while their patients are in the hospital, making a consulting visit “within 12 to 18 hours after admission to provide support and continuity to them and their families.”2 Authors Allan Goroll, MD, MACP, and Daniel Hunt, MD, propose that the PCP be asked to write a succinct consultation note in the hospital chart, highlighting key elements of the patient’s history and recent tests—with the goal of complementing and informing the hospitalist’s admission workup and care plan—while being paid as a consultant.

“It’s a fairly straightforward proposal,” says Dr. Hunt, chief of the hospital medicine unit at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston. “We’re not looking for PCPs to take care of every aspect of inpatient care. It’s really just to bring in the PCP’s expertise and nuanced understanding of the patient at a vulnerable time for the patient.”

The idea might seem a little ironic given the fact that hospitalists were created in part to relieve busy PCPs from having to visit the hospital. But some see it as a way forward.

“I wouldn’t call it a step backward,” says Joseph Ming Wah Li, MD, SFHM, FACP, director of the hospital medicine program at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston and a former SHM president. “Is it feasible? Realistically, in most settings today, I don’t think it is. But I would love it. I don’t really know enough about the patients I take care of in the hospital.”

The Barrier of “Not Enough Time”

Dr. Hunt says the biggest barrier to this proposal is the time that PCPs would have to carve out to make physical trips to the hospital.

“That ultimately comes down to reimbursement,” he says.

MGH, which is well situated with medical practices in or near the main hospital building, has piloted an approach similar to the NEJM proposal with a primary care group that comes in to see its patients in the first day or two after admission and then again on the day before discharge.

“But they are essentially doing it out of the goodness of their hearts,” Dr. Hunt explains. “What we’ve seen from this experiment are much better transitions of care and much better decision making around big decisions, such as end-of-life care or surgical interventions.”

Hospitalists at MGH and the PCPs spent a year and a half talking through the specifics of how their arrangement would work.

“We made a commitment, as hospitalists, to communicate directly by phone with the PCPs,” he says. “That commitment lasted about a week, and then we quickly converted to a daily e-mail. That works, because both parties are communicating substantial information in these e-mails.”

Dr. Hunt says the key is recognizing the “huge” value PCPs bring to an inpatient stay. And, while physical trips to the hospital or e-mails might not work for every hospitalist or PCP, the connecting of information and insight is often worth the investment.

“There are other ways [to communicate], such as video conferencing and Skype, where doctors could participate more efficiently in the care of their hospitalized patients,” he says, adding that hospitalists should reach out to PCPs, both when a patient enters the hospital and as part of a larger discussion about how to improve communication and continuity of care.

The PCP Perspective

Boston internist Gila Kriegel, MD, might seem like a throwback. She says she wants to visit her patients when they are in the hospital, if at all possible. In fact, hospitalists in Boston say Dr. Kriegel allows them to take care of her patients “almost begrudgingly.”

“She is so involved in their care,” Dr. Li says. “She tells me everything I need to know about them. She’d be here every day if she weren’t juggling other responsibilities.”

A PCP since 1986, Dr. Kriegel’s story illustrates the complexities of an evolving healthcare system. She’s based in an academic setting, which she calls a “kind of ivory tower.”

“But I was fortunate in 1989, after my first son was born and I went part-time, to have a colleague who offered to see my inpatients on the days I wasn’t working,” she explains. “Then a woman colleague of mine also went part-time, and we agreed to cross-cover for each other.”

Eventually, Dr. Kriegel was approached by Dr. Li’s hospitalist group, which offered to manage her hospitalized patients.

“For the first six months to a year, I’d go see my patients in the hospital on a social visit. I’d even write notes in the chart, until they told me, ‘You are not responsible for the care in the hospital. The hospitalist is,’” she recalls. “For me, it was a big loss to stop going to the hospital. Most PCPs I know like seeing their patients through the course of the illness.”

Then again, she also admits how difficult it is to see her patients in the hospital.

Still, she managed to stay connected. “When I stopped going to see my patients, I asked the hospital staff to give me the patient’s bedside phone number, and I’d call them in the hospital to let them know I was up on what was happening,” she says.

Technology, coincidentally, inserted a barrier: She wasn’t able to access hospitalists’ daily notes in the BIDMC electronic health records. That’s when Dr. Kriegel began e-mailing the hospitalists. In the end, even that form of communication wasn’t fully satisfying.

“The current system requires me to do the outreach,” she explains. “If you ask hospitalists about communication, they’d say they’re already doing it. But a discharge summary isn’t the same as knowing in real time what’s happening with my patients.”

“I’d love to make virtual visits to the patient in the hospital, by phone or computer link—even more so if I could get paid for my time. But I want to stay involved.”

Ripe for Innovation

Dr. Wachter, chief of hospital medicine at UCSF, who writes an HM-focused blog [wachtersworld.com], says the continuity visit is a good idea but also understands the difficulties in the new healthcare paradigm.

“It’s not easy to work out the logistics, and it depends on the geography,” he says. “We also need to be considering telemedicine. But something to enhance continuity is ripe for innovation.”

He says consultation or continuity visits offer ways to improve care with a relatively small expenditure.

“We still see a few PCPs come in when their patients are hospitalized. It’s very reassuring to their patients,” he says. “For the complicated cases where an ongoing relationship matters, those encounters are fabulous.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

References

Service Distinction Crucial for Medical Claim Submissions

Hospitalists often are tasked with coordinating and overseeing patient care throughout a hospitalization. Depending on the care model and the availability of varying specialists, a patient could see several specialists throughout the stay, and even during a single day. A recurring issue for many hospitalists is justifying the medical necessity of their services, because payers do not want to reimburse overlapping care (i.e., multiple providers caring for the same patient problem) when more than one physician provides care on the same service date.

Payers often consider two key principles before reimbursing multiple visits on the same date:1

- Does the patient’s condition warrant the services of more than one physician?

- Are the individual services provided by each physician reasonable and necessary?

Consider the following example: A 65-year-old female patient is admitted with a hip fracture (820.8) after slipping on the ice outside her home. The patient also has hypertension (401.1) and type II diabetes (250.00). The surgeon manages the patient’s peri-operative course for the fracture, while the hospitalist manages the patient’s medical issues.

Payers must be sure that the services of one physician do not duplicate those provided by another.1 For the above scenario, it is imperative that the hospitalist understand which services are considered the surgeon’s responsibility. The global surgical package includes payment for the surgical procedure and the completion of its corresponding facility-required paperwork (e.g. pre-operative history and physical exam, operative consent forms, pre-operative orders), in addition to the following services:2

- Pre-operative visits after making the decision for surgery beginning one day prior to surgery;

- All additional post-operative medical or surgical services provided by the surgeon related to complications but not requiring additional trips to the operating room;

- Post-operative visits by the surgeon related to recovery from surgery, including but not limited to dressing changes, local incisional care, removal of cutaneous sutures and staples, line removals, changes and removal of tracheostomy tubes, and discharge services; and

- Post-operative pain management provided by the surgeon.

Another physician who performs any component of the global package will not receive separate payment unless the surgeon is willing to forego a portion of the payment. For example, a hospitalist admits a patient who has no other identifiable medical conditions aside from the problem prompting surgery. The hospitalist’s role may be dictated by facility policy—quality of care or risk reduction, for example—and administrative requirements (history and physical exam, discharge services, coordination of care) rather than what a payer would perceive as necessary “medical” management. Similarly, if the hospitalist’s post-op care is limited to ordering routine post-op labs or maintaining appropriate pain management, the hospitalist’s service will likely be denied as incidental to the surgical package.

Remember, if the hospitalist’s claim is submitted and paid, it doesn’t mean that the payer won’t retract the payment upon review if an erroneous payment is suspected. A payer review may be triggered when the diagnosis listed on the hospitalist’s claim matches the diagnosis listed on the surgeon’s claim (e.g. 820.8). If too many claims are considered “not medically necessary” due to overlapping care, hospitalists may need to negotiate other terms of payment with the facility to recoup unpaid time and effort when involved in this type of care.

When more than one medical condition exists and several physicians participate in the patient’s care, medical necessity is easily established for each physician. Each physician manages the condition related to his/her expertise. In the above example, the surgeon cares for the patient’s fracture, while the hospitalist oversees diabetes and hypertension management. Service distinction is crucial during the claim submission process. The hospitalist should report a subsequent hospital care code (99231-99233) with a primary diagnosis corresponding to his/her specialty-related care (i.e., 9923x with 250.00, 401.1).3

When more specialists are involved, claim submission becomes more complex. A cardiologist who was also involved in patient management would report his or her service using 401.1. When a different primary diagnosis is assigned to the visit code to indicate the reason for each physician’s involvement, all claims are more likely to be paid.4 As long as the hospitalist maintains care over one of the patients’ conditions, concurrent care is justified.

Because these physicians are in different specialties and different provider groups, most payers do not require the modifier 25 (separately identifiable evaluation/management [E/M] service on the same day as a procedure or other service) with the visit code; however, some managed care payers may have a general claim edit that pays the first claim and denies the second unless modifier 25 is appended to the concurrent E/M visit code (i.e., 99232-25) as an attestation that the service is distinct from any other provider’s service that day, despite claim submission under different tax identification numbers. This may not be identified until the claim is rejected or denied. If appropriate modifier use does not yield payment, appeal the denied concurrent care claims with supporting documentation from each physician visit, if possible. This demonstrates each physician’s contribution to care.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Chapter 15—Covered Medical and Other Health Services. Section 30.E. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/Downloads/bp102c15.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12—Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners. Section 40.A. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2015.

- American Medical Association. Current Procedural Terminology 2015 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12—Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners. Section 30.6.9.C. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12—Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners. Section 30.6.5. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 26—Completing and Processing Form CMS-1500 Data Set. Section 10.8.2. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c26.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2015.

Hospitalists often are tasked with coordinating and overseeing patient care throughout a hospitalization. Depending on the care model and the availability of varying specialists, a patient could see several specialists throughout the stay, and even during a single day. A recurring issue for many hospitalists is justifying the medical necessity of their services, because payers do not want to reimburse overlapping care (i.e., multiple providers caring for the same patient problem) when more than one physician provides care on the same service date.

Payers often consider two key principles before reimbursing multiple visits on the same date:1

- Does the patient’s condition warrant the services of more than one physician?

- Are the individual services provided by each physician reasonable and necessary?

Consider the following example: A 65-year-old female patient is admitted with a hip fracture (820.8) after slipping on the ice outside her home. The patient also has hypertension (401.1) and type II diabetes (250.00). The surgeon manages the patient’s peri-operative course for the fracture, while the hospitalist manages the patient’s medical issues.

Payers must be sure that the services of one physician do not duplicate those provided by another.1 For the above scenario, it is imperative that the hospitalist understand which services are considered the surgeon’s responsibility. The global surgical package includes payment for the surgical procedure and the completion of its corresponding facility-required paperwork (e.g. pre-operative history and physical exam, operative consent forms, pre-operative orders), in addition to the following services:2

- Pre-operative visits after making the decision for surgery beginning one day prior to surgery;

- All additional post-operative medical or surgical services provided by the surgeon related to complications but not requiring additional trips to the operating room;

- Post-operative visits by the surgeon related to recovery from surgery, including but not limited to dressing changes, local incisional care, removal of cutaneous sutures and staples, line removals, changes and removal of tracheostomy tubes, and discharge services; and

- Post-operative pain management provided by the surgeon.

Another physician who performs any component of the global package will not receive separate payment unless the surgeon is willing to forego a portion of the payment. For example, a hospitalist admits a patient who has no other identifiable medical conditions aside from the problem prompting surgery. The hospitalist’s role may be dictated by facility policy—quality of care or risk reduction, for example—and administrative requirements (history and physical exam, discharge services, coordination of care) rather than what a payer would perceive as necessary “medical” management. Similarly, if the hospitalist’s post-op care is limited to ordering routine post-op labs or maintaining appropriate pain management, the hospitalist’s service will likely be denied as incidental to the surgical package.

Remember, if the hospitalist’s claim is submitted and paid, it doesn’t mean that the payer won’t retract the payment upon review if an erroneous payment is suspected. A payer review may be triggered when the diagnosis listed on the hospitalist’s claim matches the diagnosis listed on the surgeon’s claim (e.g. 820.8). If too many claims are considered “not medically necessary” due to overlapping care, hospitalists may need to negotiate other terms of payment with the facility to recoup unpaid time and effort when involved in this type of care.

When more than one medical condition exists and several physicians participate in the patient’s care, medical necessity is easily established for each physician. Each physician manages the condition related to his/her expertise. In the above example, the surgeon cares for the patient’s fracture, while the hospitalist oversees diabetes and hypertension management. Service distinction is crucial during the claim submission process. The hospitalist should report a subsequent hospital care code (99231-99233) with a primary diagnosis corresponding to his/her specialty-related care (i.e., 9923x with 250.00, 401.1).3

When more specialists are involved, claim submission becomes more complex. A cardiologist who was also involved in patient management would report his or her service using 401.1. When a different primary diagnosis is assigned to the visit code to indicate the reason for each physician’s involvement, all claims are more likely to be paid.4 As long as the hospitalist maintains care over one of the patients’ conditions, concurrent care is justified.

Because these physicians are in different specialties and different provider groups, most payers do not require the modifier 25 (separately identifiable evaluation/management [E/M] service on the same day as a procedure or other service) with the visit code; however, some managed care payers may have a general claim edit that pays the first claim and denies the second unless modifier 25 is appended to the concurrent E/M visit code (i.e., 99232-25) as an attestation that the service is distinct from any other provider’s service that day, despite claim submission under different tax identification numbers. This may not be identified until the claim is rejected or denied. If appropriate modifier use does not yield payment, appeal the denied concurrent care claims with supporting documentation from each physician visit, if possible. This demonstrates each physician’s contribution to care.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Chapter 15—Covered Medical and Other Health Services. Section 30.E. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/Downloads/bp102c15.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12—Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners. Section 40.A. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2015.

- American Medical Association. Current Procedural Terminology 2015 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12—Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners. Section 30.6.9.C. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12—Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners. Section 30.6.5. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 26—Completing and Processing Form CMS-1500 Data Set. Section 10.8.2. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c26.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2015.

Hospitalists often are tasked with coordinating and overseeing patient care throughout a hospitalization. Depending on the care model and the availability of varying specialists, a patient could see several specialists throughout the stay, and even during a single day. A recurring issue for many hospitalists is justifying the medical necessity of their services, because payers do not want to reimburse overlapping care (i.e., multiple providers caring for the same patient problem) when more than one physician provides care on the same service date.

Payers often consider two key principles before reimbursing multiple visits on the same date:1

- Does the patient’s condition warrant the services of more than one physician?

- Are the individual services provided by each physician reasonable and necessary?

Consider the following example: A 65-year-old female patient is admitted with a hip fracture (820.8) after slipping on the ice outside her home. The patient also has hypertension (401.1) and type II diabetes (250.00). The surgeon manages the patient’s peri-operative course for the fracture, while the hospitalist manages the patient’s medical issues.

Payers must be sure that the services of one physician do not duplicate those provided by another.1 For the above scenario, it is imperative that the hospitalist understand which services are considered the surgeon’s responsibility. The global surgical package includes payment for the surgical procedure and the completion of its corresponding facility-required paperwork (e.g. pre-operative history and physical exam, operative consent forms, pre-operative orders), in addition to the following services:2

- Pre-operative visits after making the decision for surgery beginning one day prior to surgery;

- All additional post-operative medical or surgical services provided by the surgeon related to complications but not requiring additional trips to the operating room;

- Post-operative visits by the surgeon related to recovery from surgery, including but not limited to dressing changes, local incisional care, removal of cutaneous sutures and staples, line removals, changes and removal of tracheostomy tubes, and discharge services; and

- Post-operative pain management provided by the surgeon.

Another physician who performs any component of the global package will not receive separate payment unless the surgeon is willing to forego a portion of the payment. For example, a hospitalist admits a patient who has no other identifiable medical conditions aside from the problem prompting surgery. The hospitalist’s role may be dictated by facility policy—quality of care or risk reduction, for example—and administrative requirements (history and physical exam, discharge services, coordination of care) rather than what a payer would perceive as necessary “medical” management. Similarly, if the hospitalist’s post-op care is limited to ordering routine post-op labs or maintaining appropriate pain management, the hospitalist’s service will likely be denied as incidental to the surgical package.

Remember, if the hospitalist’s claim is submitted and paid, it doesn’t mean that the payer won’t retract the payment upon review if an erroneous payment is suspected. A payer review may be triggered when the diagnosis listed on the hospitalist’s claim matches the diagnosis listed on the surgeon’s claim (e.g. 820.8). If too many claims are considered “not medically necessary” due to overlapping care, hospitalists may need to negotiate other terms of payment with the facility to recoup unpaid time and effort when involved in this type of care.

When more than one medical condition exists and several physicians participate in the patient’s care, medical necessity is easily established for each physician. Each physician manages the condition related to his/her expertise. In the above example, the surgeon cares for the patient’s fracture, while the hospitalist oversees diabetes and hypertension management. Service distinction is crucial during the claim submission process. The hospitalist should report a subsequent hospital care code (99231-99233) with a primary diagnosis corresponding to his/her specialty-related care (i.e., 9923x with 250.00, 401.1).3

When more specialists are involved, claim submission becomes more complex. A cardiologist who was also involved in patient management would report his or her service using 401.1. When a different primary diagnosis is assigned to the visit code to indicate the reason for each physician’s involvement, all claims are more likely to be paid.4 As long as the hospitalist maintains care over one of the patients’ conditions, concurrent care is justified.

Because these physicians are in different specialties and different provider groups, most payers do not require the modifier 25 (separately identifiable evaluation/management [E/M] service on the same day as a procedure or other service) with the visit code; however, some managed care payers may have a general claim edit that pays the first claim and denies the second unless modifier 25 is appended to the concurrent E/M visit code (i.e., 99232-25) as an attestation that the service is distinct from any other provider’s service that day, despite claim submission under different tax identification numbers. This may not be identified until the claim is rejected or denied. If appropriate modifier use does not yield payment, appeal the denied concurrent care claims with supporting documentation from each physician visit, if possible. This demonstrates each physician’s contribution to care.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Chapter 15—Covered Medical and Other Health Services. Section 30.E. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/Downloads/bp102c15.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12—Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners. Section 40.A. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2015.

- American Medical Association. Current Procedural Terminology 2015 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12—Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners. Section 30.6.9.C. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12—Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners. Section 30.6.5. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 26—Completing and Processing Form CMS-1500 Data Set. Section 10.8.2. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c26.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2015.

Academic Hospitalist Groups Lag Behind in Admissions, Discharges

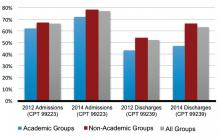

In 2012, SHM reported increasing numbers of hospital encounters coded for high-level evaluation and management services, as reported by the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) survey respondents. The 2014 SOHM report shows a solid continuation of this trend, with high-level CPT codes predominating in admission and discharge services by wider margins than ever before.

The 2014 report provides CPT code data from 173 hospitalist groups, who reported the number of inpatient admissions with CPT codes corresponding to Level 1, Level 2, or Level 3. Inpatient discharges have codes corresponding to either Level 1 or Level 2.

Compared to 2012, Level 3 admissions (CPT 99223) increased by 14% in 2014 and now account for 77% of all admissions (see Figure 1). Level 2 discharges (CPT 99239) have increased by 17% since 2012 and now account for 63% of discharges.

In 2014, SOHM added CPT code distribution data for observation care. Observation admissions and inpatient and observation subsequent care are also reported as Level 1, 2, or 3 by the corresponding CPT codes. Observation discharges, which have only one code level, are also reported, in addition to the three levels of same-day admit/discharge encounters.

The rate of Level 3 CPT codes reported for observation admissions, which was 72%, roughly approximated that of inpatient admissions. For subsequent care, Level 2 accounts for the majority of both observation and inpatient codes.

Despite the general predominance of Level 3 admissions and now Level 2 inpatient discharges, not all hospitalist groups deal equally in these higher billing evaluation and management services. Groups in the West region previously dominated the high-level encounters in both admissions and discharges; in 2014, the South took the lead in high-level admissions.

One factor that has consistently signaled lower rates of high-level coding, however, is academic status. A likely reason, as alluded to in a previous “Survey Insights” column, relates to the fact that residents’ time is not billable. This is particularly important in the discharge coding, in which the higher Level 2 code is strictly based on the statement by an attending that discharge services were personally provided for more than 30 minutes. Understandably, this happens less often when a resident’s education includes providing discharge services.

If attending face-to-face time is a major factor in the discharge coding differential, it does not explain where academic groups are missing the boat on the admission side, where residents’ documentation is incorporated by attendings—and can have a substantial effect on accurate billing. This assumes that academic groups are not treating far fewer sick patients, less comprehensively, across the board.

In my own public academic hospital, I see reviewing the required elements of the history and physical examination (H&P) as survival for our hospital and our mission, as well as an opportunity to educate residents simultaneously in patient interviewing skills and system-based practice.

But before I get too far into waxing altruistic, let me recognize another factor suggested by the SOHM report: I am not 100% salaried. That means thorough documentation and accurate coding directly impact my personal compensation.

The 2014 SOHM report shows, as it did in 2012, an inverse correlation between high-level admissions and percent salaried compensation. Although this relationship remains less clear in follow-ups and discharges, perhaps hospitalists pay more attention to coding criteria when it’s bread on the table…and if time permits.

Dr. Creamer is medical director of the short-stay unit at MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

In 2012, SHM reported increasing numbers of hospital encounters coded for high-level evaluation and management services, as reported by the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) survey respondents. The 2014 SOHM report shows a solid continuation of this trend, with high-level CPT codes predominating in admission and discharge services by wider margins than ever before.

The 2014 report provides CPT code data from 173 hospitalist groups, who reported the number of inpatient admissions with CPT codes corresponding to Level 1, Level 2, or Level 3. Inpatient discharges have codes corresponding to either Level 1 or Level 2.

Compared to 2012, Level 3 admissions (CPT 99223) increased by 14% in 2014 and now account for 77% of all admissions (see Figure 1). Level 2 discharges (CPT 99239) have increased by 17% since 2012 and now account for 63% of discharges.

In 2014, SOHM added CPT code distribution data for observation care. Observation admissions and inpatient and observation subsequent care are also reported as Level 1, 2, or 3 by the corresponding CPT codes. Observation discharges, which have only one code level, are also reported, in addition to the three levels of same-day admit/discharge encounters.

The rate of Level 3 CPT codes reported for observation admissions, which was 72%, roughly approximated that of inpatient admissions. For subsequent care, Level 2 accounts for the majority of both observation and inpatient codes.

Despite the general predominance of Level 3 admissions and now Level 2 inpatient discharges, not all hospitalist groups deal equally in these higher billing evaluation and management services. Groups in the West region previously dominated the high-level encounters in both admissions and discharges; in 2014, the South took the lead in high-level admissions.

One factor that has consistently signaled lower rates of high-level coding, however, is academic status. A likely reason, as alluded to in a previous “Survey Insights” column, relates to the fact that residents’ time is not billable. This is particularly important in the discharge coding, in which the higher Level 2 code is strictly based on the statement by an attending that discharge services were personally provided for more than 30 minutes. Understandably, this happens less often when a resident’s education includes providing discharge services.

If attending face-to-face time is a major factor in the discharge coding differential, it does not explain where academic groups are missing the boat on the admission side, where residents’ documentation is incorporated by attendings—and can have a substantial effect on accurate billing. This assumes that academic groups are not treating far fewer sick patients, less comprehensively, across the board.

In my own public academic hospital, I see reviewing the required elements of the history and physical examination (H&P) as survival for our hospital and our mission, as well as an opportunity to educate residents simultaneously in patient interviewing skills and system-based practice.

But before I get too far into waxing altruistic, let me recognize another factor suggested by the SOHM report: I am not 100% salaried. That means thorough documentation and accurate coding directly impact my personal compensation.

The 2014 SOHM report shows, as it did in 2012, an inverse correlation between high-level admissions and percent salaried compensation. Although this relationship remains less clear in follow-ups and discharges, perhaps hospitalists pay more attention to coding criteria when it’s bread on the table…and if time permits.

Dr. Creamer is medical director of the short-stay unit at MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

In 2012, SHM reported increasing numbers of hospital encounters coded for high-level evaluation and management services, as reported by the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) survey respondents. The 2014 SOHM report shows a solid continuation of this trend, with high-level CPT codes predominating in admission and discharge services by wider margins than ever before.

The 2014 report provides CPT code data from 173 hospitalist groups, who reported the number of inpatient admissions with CPT codes corresponding to Level 1, Level 2, or Level 3. Inpatient discharges have codes corresponding to either Level 1 or Level 2.

Compared to 2012, Level 3 admissions (CPT 99223) increased by 14% in 2014 and now account for 77% of all admissions (see Figure 1). Level 2 discharges (CPT 99239) have increased by 17% since 2012 and now account for 63% of discharges.

In 2014, SOHM added CPT code distribution data for observation care. Observation admissions and inpatient and observation subsequent care are also reported as Level 1, 2, or 3 by the corresponding CPT codes. Observation discharges, which have only one code level, are also reported, in addition to the three levels of same-day admit/discharge encounters.

The rate of Level 3 CPT codes reported for observation admissions, which was 72%, roughly approximated that of inpatient admissions. For subsequent care, Level 2 accounts for the majority of both observation and inpatient codes.

Despite the general predominance of Level 3 admissions and now Level 2 inpatient discharges, not all hospitalist groups deal equally in these higher billing evaluation and management services. Groups in the West region previously dominated the high-level encounters in both admissions and discharges; in 2014, the South took the lead in high-level admissions.

One factor that has consistently signaled lower rates of high-level coding, however, is academic status. A likely reason, as alluded to in a previous “Survey Insights” column, relates to the fact that residents’ time is not billable. This is particularly important in the discharge coding, in which the higher Level 2 code is strictly based on the statement by an attending that discharge services were personally provided for more than 30 minutes. Understandably, this happens less often when a resident’s education includes providing discharge services.

If attending face-to-face time is a major factor in the discharge coding differential, it does not explain where academic groups are missing the boat on the admission side, where residents’ documentation is incorporated by attendings—and can have a substantial effect on accurate billing. This assumes that academic groups are not treating far fewer sick patients, less comprehensively, across the board.

In my own public academic hospital, I see reviewing the required elements of the history and physical examination (H&P) as survival for our hospital and our mission, as well as an opportunity to educate residents simultaneously in patient interviewing skills and system-based practice.

But before I get too far into waxing altruistic, let me recognize another factor suggested by the SOHM report: I am not 100% salaried. That means thorough documentation and accurate coding directly impact my personal compensation.

The 2014 SOHM report shows, as it did in 2012, an inverse correlation between high-level admissions and percent salaried compensation. Although this relationship remains less clear in follow-ups and discharges, perhaps hospitalists pay more attention to coding criteria when it’s bread on the table…and if time permits.

Dr. Creamer is medical director of the short-stay unit at MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

What Is the Appropriate Medical and Interventional Treatment for Hyperacute Ischemic Stroke?

Case

A 70-year-old woman was brought to the ED by ambulance with slurred speech after a fall. She arrived in the ED three hours and 29 minutes after the last time she was known to be normal. On initial examination, she had a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 13, with a left facial droop, left hemiplegia, and right gaze deviation. Her acute noncontrast head computed tomography (CT), CT angiogram, and CT perfusion scans are shown in Figure 1.

How should this patient’s acute stroke be managed at this time?

Overview

Pathophysiology/Epidemiology: Stroke is the fourth most common cause of death in the United States and the main cause of disability, resulting in substantial healthcare expenditures.1 Ischemic stroke accounts for about 85% of all stroke cases and has several subtypes. The most common causes of ischemic stroke are small vessel thrombosis, large vessel thromboembolism, and cardioembolism. Both small vessel thrombosis and large vessel thromboembolism often are related to typical atherosclerotic risk factors, and cardioembolism is most often related to atrial fibrillation/flutter.

Minimizing death and disability from stroke is dependent on prevention measures, as well as early response to the onset of symptoms. The typical patient loses 1.9 million neurons for every minute a stroke is untreated—hence the popular adage “Time is Brain.”2 Although the appropriate management and time window of stroke treatment have been somewhat controversial, the acuity of treatment is now undisputed. Intravenous thrombolysis with tPA, also known as alteplase, has been an FDA-approved treatment for stroke since 1996, yet, as of 2006, only 2.4% of patients hospitalized for ischemic stroke were treated with IV tPA.3

The etiology of stroke, in most cases, does not change management in the hyperacute period, when thrombolysis is appropriate regardless of etiology.

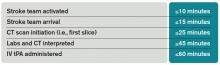

Timely evaluation: Although recognition of stroke symptoms by the public and pre-hospital management is a barrier in the treatment of acute stroke, this article will focus on appropriate ED and in-hospital treatment of stroke. Given the urgent need for management of acute ischemic stroke, it is critical that hospitals have an efficient process for identifying possible strokes and beginning treatment early. In order to accomplish these objectives, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) has established goals for time frames of evaluation and management of patients with stroke in the ED (see Table 1).4

The role of the hospitalist: Hospitalists can play critical roles both as part of a primary stroke team and in identifying missed strokes. Some acute stroke teams have included hospitalists due to their ability to help with medical management, identify mimics, and assess medical contraindications to thrombolytic therapy. In addition, hospitalists may be the first to recognize a stroke in the ED when evaluating a patient with symptoms confused with a medical condition, or when a stroke occurs in an inpatient. In both of these situations, as first responders, hospitalists have knowledge of stroke evaluation and treatment that is crucial in beginning the evaluation and triggering a stroke alert.

Diagnostic tools: The initial evaluation of a patient with a possible stroke includes a brief but thorough history of current symptoms, as well as past medical and medication histories. The most critical piece of information to obtain from patients, family members, or bystanders is the time of symptom onset, or the time the patient was last known normal, so that the options for treatment can be evaluated early.

After basic stabilization of ABCs—airway maintenance, breathing and ventilation, and circulation— a brief but thorough neurologic examination is critical to define severity of neurologic injury and to help localize injury. Some standardized tools help with rapid assessment, including the NIHSS. The NIHSS is a standardized and reproducible evaluation that can be performed by many different specialties and levels of healthcare providers and provides information about stroke severity, localization, and prognosis.5 NIHSS offers free online certification.

Imaging: Early brain imaging and interpretation is another important piece of the acute evaluation of stroke. The most commonly used first-line imaging is noncontrast head CT, which is widely available and quickly performed. This type of imaging is sensitive for intracranial hemorrhage and can help distinguish nonvascular causes of symptoms such as tumor. CT is not sensitive for early signs of infarct, and, most often, initial CT findings are normal in early ischemic stroke. In patients who are candidates for intravenous fibrinolysis, ruling out hemorrhage is the main priority. Noncontrast head CT is the only imaging necessary to make decisions regarding IV thrombolytic treatment.

For further treatment decisions beyond IV tPA, intracranial and extracranial vascular imaging can help with decision making. All patients with stroke should have extracranial vascular imaging to help determine the etiology of stroke and evaluate the need for carotid endarterectomy or stenting for symptomatic stenosis in the days to weeks after stroke. More acutely, vascular imaging can be used to identify large vessel occlusions, in consideration of endovascular intervention (discussed in further detail below). CT angiography, magnetic resonance (MR) angiography, and conventional angiography are all options for evaluating the vasculature, though the first two are generally used as a noninvasive first step. Carotid ultrasound is often considered but only evaluates the extracranial anterior circulation; posterior circulation vessel abnormalities (like dissection) and intracranial abnormalities (like stenosis) may be missed. Although tPA decisions are not based upon these imaging modalities, secondary stroke prevention decisions may be altered by the findings.4

Perfusion imaging is the newest addition to acute stroke imaging, but its utility in guiding decision making remains unclear. Perfusion imaging provides hemodynamic information, ideally to identify areas of infarct versus ischemic penumbra, an area at risk of becoming ischemic. The use of perfusion imaging to identify good candidates for reperfusion (with IV tPA or with interventional techniques) is controversial.9 It is clear that perfusion imaging should not delay the time to treatment for IV tPA within the 4.5-hour window.

Windows: Current guidelines for administration of IV tPA for acute stroke are based in large part on two pivotal studies—the NINDS tPA Stroke Trial and the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study III (ECASS III).6,7 IV alteplase for the treatment of acute stroke was approved by the FDA in 1996 following publication of the NINDS tPA Stroke Trial. This placebo-controlled randomized trial of 624 patients within three hours of ischemic stroke onset found that treatment with IV alteplase improved the odds of minimal or no disability at three months by approximately 30%. The rate of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage was higher in the tPA group (6.4%) compared to the placebo group (0.6%), but mortality was not significantly different at three months. Though the benefit of IV tPA was clear in the three-hour window, subgroup analyses and further studies have clarified that treatment earlier in the window provides further benefit.

Given the difficulty of achieving treatment in short time windows, further studies have aimed to evaluate the utility of IV thrombolysis beyond the three-hour time window. While early studies found no clear benefit in extending the window, pooled analyses suggested a benefit in the three to 4.5-hour window, and ECASS III was designed to evaluate this window. This randomized placebo-controlled study used similar inclusion criteria to the NINDS study, with the exception of the time window, and excluded patients more than 80 years old, with large stroke (NIHSS score greater than 25), on anticoagulation (regardless of INR [international normalized ratio]), and with a history of prior stroke and diabetes. Again, in line with prior findings of time-dependent response to tPA, the study found that the IV tPA group were more likely than the placebo group to have good functional outcomes at three months, but the magnitude of this effect was lower than the one seen in the studies of the zero- to three-hour window. The rate of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage in the 4.5-hour window was 7.9% using the NINDS tPA Stroke Trial criteria.

The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) guidelines now recommend the use of IV tPA for patients within three hours of onset of ischemic stroke, with treatment initiated as quickly as possible (Class I; Level A). Although it has not been FDA approved, IV tPA treatment of eligible patients within the three to 4.5-hour window is recommended as Class I-Level B evidence with exclusions as in the ECASS study.4 Inclusion and exclusion criteria for tPA according to AHA/ASA guidelines can be found in Table 2.

IA thrombolysis/thrombectomy: Over the last two decades, there has been great interest in endovascular treatment of acute ischemic stroke and large advances in the numbers and types of treatments available. The FDA has approved multiple devices developed for mechanical thrombectomy based on their ability to recanalize vessels; however, to date, there is no clear evidence that thrombectomy improves patient outcomes. Several studies of endovascular therapy were recently published, including the Interventional Management of Stroke III (IMS 3) study, the Mechanical Retrieval and Recanalization of Stroke Clots using Embolectomy (MR RESCUE) study, and the SYNTHESIS Expansion study.8,9,10 None of these studies showed a benefit to endovascular treatment; however, critics have pointed out many flaws in these studies, including protracted time to treatment and patient selection. Furthermore, the most recent devices, like Solitaire and Trevo, were not used in most patients.

Three more recent trials found promising results for interventional treatment.11-13 The trials ranged from 70 to 500 patients with anterior circulation strokes with a large vessel occlusion; each study found a statistically significant improvement in functional independence at three months in the intervention group.12,13 Intravenous tPA was given in 72.7% to 100% of patients.11,12 Intervention to reperfusion was very quick in each study.

Some possible reasons for the more successful outcomes include the high proportion of newer devices for thrombectomy used and rapid treatment of symptoms, with symptom onset to groin puncture medians ranging from 185 minutes to 260 minutes.11,13 It remains clear that careful patient selection should occur, and those who are not candidates for intravenous therapy who present inside an appropriate time window could be considered. Time from symptom onset continues to be an important piece of making decisions about candidates for interventional treatment, but some advocate for the use of advanced imaging modalities, such as DWI imaging on MRI, or MR, or CT perfusion imaging, to help decide who could be a candidate.

Back to the Case

IV tPA was given to the patient 30 minutes after presentation. She met all inclusion and exclusion criteria for treatment and received the best-proven therapy for acute ischemic stroke. Due to her severe symptoms, the neurointerventional team was consulted for possible thrombectomy. This decision is controversial, as there is no proven benefit to intraarterial therapy. She was a possible candidate because of her time to presentation, large vessel occlusion, and substantial penumbra with CT imaging (see Figure 1).

About 20 minutes after treatment, she began to improve, now lifting her left arm and leg against gravity and showing less dysarthria. The decision was made to perform a conventional angiogram to reevaluate her blood vessels and to consider thrombectomy based upon the result. The majority of her middle cerebral artery had recanalized, so no further interventions were needed.

Bottom Line

Intravenous tPA (alteplase) is indicated for patients presenting within 4.5 hours of last known normal. Careful patient selection should occur if additional therapies are considered.

Drs. Poisson and Simpson are a neurohospitalists in the department of neurology at the University of Colorado Denver in Aurora.

References

- Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129(3):e28-e292.

- Saver JL. Time is brain–quantified. Stroke. 2006;37(1):263-266.

- Fang MC, Cutler DM, Rosen AB. Trends in thrombolytic use for ischemic stroke in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):406-409.

- Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP Jr, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(3):870-947. Lyden P, Raman R, Liu L, Emr M, Warren M, Marler

- J. National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale certification is reliable across multiple venues. Stroke. 2009;40(7):2507-2511.

- Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(24):1581-1587.

- Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(13):1317-1329. Broderick JP, Palesch YY, Demchuk AM, et al Endovascular therapy after intravenous t-PA versus t-PA alone for stroke. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(10):893-903.

- Kidwell CS, Jahan R, Gornbein J, et al. A trial of imaging selection and endovascular treatment for ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(10):914-923.

- Ciccone A, Valvassori L, Nichelatti M, et al. SYNTHESIS Expansion Investigators. Endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(10):904-913.

- Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(11):1019-1030.

- Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, et al. Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(11):1009-1018.

- Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS, Beumer D, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(1):11-20.

Case

A 70-year-old woman was brought to the ED by ambulance with slurred speech after a fall. She arrived in the ED three hours and 29 minutes after the last time she was known to be normal. On initial examination, she had a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 13, with a left facial droop, left hemiplegia, and right gaze deviation. Her acute noncontrast head computed tomography (CT), CT angiogram, and CT perfusion scans are shown in Figure 1.

How should this patient’s acute stroke be managed at this time?

Overview

Pathophysiology/Epidemiology: Stroke is the fourth most common cause of death in the United States and the main cause of disability, resulting in substantial healthcare expenditures.1 Ischemic stroke accounts for about 85% of all stroke cases and has several subtypes. The most common causes of ischemic stroke are small vessel thrombosis, large vessel thromboembolism, and cardioembolism. Both small vessel thrombosis and large vessel thromboembolism often are related to typical atherosclerotic risk factors, and cardioembolism is most often related to atrial fibrillation/flutter.

Minimizing death and disability from stroke is dependent on prevention measures, as well as early response to the onset of symptoms. The typical patient loses 1.9 million neurons for every minute a stroke is untreated—hence the popular adage “Time is Brain.”2 Although the appropriate management and time window of stroke treatment have been somewhat controversial, the acuity of treatment is now undisputed. Intravenous thrombolysis with tPA, also known as alteplase, has been an FDA-approved treatment for stroke since 1996, yet, as of 2006, only 2.4% of patients hospitalized for ischemic stroke were treated with IV tPA.3

The etiology of stroke, in most cases, does not change management in the hyperacute period, when thrombolysis is appropriate regardless of etiology.

Timely evaluation: Although recognition of stroke symptoms by the public and pre-hospital management is a barrier in the treatment of acute stroke, this article will focus on appropriate ED and in-hospital treatment of stroke. Given the urgent need for management of acute ischemic stroke, it is critical that hospitals have an efficient process for identifying possible strokes and beginning treatment early. In order to accomplish these objectives, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) has established goals for time frames of evaluation and management of patients with stroke in the ED (see Table 1).4

The role of the hospitalist: Hospitalists can play critical roles both as part of a primary stroke team and in identifying missed strokes. Some acute stroke teams have included hospitalists due to their ability to help with medical management, identify mimics, and assess medical contraindications to thrombolytic therapy. In addition, hospitalists may be the first to recognize a stroke in the ED when evaluating a patient with symptoms confused with a medical condition, or when a stroke occurs in an inpatient. In both of these situations, as first responders, hospitalists have knowledge of stroke evaluation and treatment that is crucial in beginning the evaluation and triggering a stroke alert.

Diagnostic tools: The initial evaluation of a patient with a possible stroke includes a brief but thorough history of current symptoms, as well as past medical and medication histories. The most critical piece of information to obtain from patients, family members, or bystanders is the time of symptom onset, or the time the patient was last known normal, so that the options for treatment can be evaluated early.

After basic stabilization of ABCs—airway maintenance, breathing and ventilation, and circulation— a brief but thorough neurologic examination is critical to define severity of neurologic injury and to help localize injury. Some standardized tools help with rapid assessment, including the NIHSS. The NIHSS is a standardized and reproducible evaluation that can be performed by many different specialties and levels of healthcare providers and provides information about stroke severity, localization, and prognosis.5 NIHSS offers free online certification.

Imaging: Early brain imaging and interpretation is another important piece of the acute evaluation of stroke. The most commonly used first-line imaging is noncontrast head CT, which is widely available and quickly performed. This type of imaging is sensitive for intracranial hemorrhage and can help distinguish nonvascular causes of symptoms such as tumor. CT is not sensitive for early signs of infarct, and, most often, initial CT findings are normal in early ischemic stroke. In patients who are candidates for intravenous fibrinolysis, ruling out hemorrhage is the main priority. Noncontrast head CT is the only imaging necessary to make decisions regarding IV thrombolytic treatment.

For further treatment decisions beyond IV tPA, intracranial and extracranial vascular imaging can help with decision making. All patients with stroke should have extracranial vascular imaging to help determine the etiology of stroke and evaluate the need for carotid endarterectomy or stenting for symptomatic stenosis in the days to weeks after stroke. More acutely, vascular imaging can be used to identify large vessel occlusions, in consideration of endovascular intervention (discussed in further detail below). CT angiography, magnetic resonance (MR) angiography, and conventional angiography are all options for evaluating the vasculature, though the first two are generally used as a noninvasive first step. Carotid ultrasound is often considered but only evaluates the extracranial anterior circulation; posterior circulation vessel abnormalities (like dissection) and intracranial abnormalities (like stenosis) may be missed. Although tPA decisions are not based upon these imaging modalities, secondary stroke prevention decisions may be altered by the findings.4

Perfusion imaging is the newest addition to acute stroke imaging, but its utility in guiding decision making remains unclear. Perfusion imaging provides hemodynamic information, ideally to identify areas of infarct versus ischemic penumbra, an area at risk of becoming ischemic. The use of perfusion imaging to identify good candidates for reperfusion (with IV tPA or with interventional techniques) is controversial.9 It is clear that perfusion imaging should not delay the time to treatment for IV tPA within the 4.5-hour window.

Windows: Current guidelines for administration of IV tPA for acute stroke are based in large part on two pivotal studies—the NINDS tPA Stroke Trial and the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study III (ECASS III).6,7 IV alteplase for the treatment of acute stroke was approved by the FDA in 1996 following publication of the NINDS tPA Stroke Trial. This placebo-controlled randomized trial of 624 patients within three hours of ischemic stroke onset found that treatment with IV alteplase improved the odds of minimal or no disability at three months by approximately 30%. The rate of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage was higher in the tPA group (6.4%) compared to the placebo group (0.6%), but mortality was not significantly different at three months. Though the benefit of IV tPA was clear in the three-hour window, subgroup analyses and further studies have clarified that treatment earlier in the window provides further benefit.

Given the difficulty of achieving treatment in short time windows, further studies have aimed to evaluate the utility of IV thrombolysis beyond the three-hour time window. While early studies found no clear benefit in extending the window, pooled analyses suggested a benefit in the three to 4.5-hour window, and ECASS III was designed to evaluate this window. This randomized placebo-controlled study used similar inclusion criteria to the NINDS study, with the exception of the time window, and excluded patients more than 80 years old, with large stroke (NIHSS score greater than 25), on anticoagulation (regardless of INR [international normalized ratio]), and with a history of prior stroke and diabetes. Again, in line with prior findings of time-dependent response to tPA, the study found that the IV tPA group were more likely than the placebo group to have good functional outcomes at three months, but the magnitude of this effect was lower than the one seen in the studies of the zero- to three-hour window. The rate of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage in the 4.5-hour window was 7.9% using the NINDS tPA Stroke Trial criteria.