User login

Republican-controlled House votes to repeal ACA

Once again, the Republican-controlled House voted to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

But for the first time, this bill – H.R. 596 – could get a vote in the Republican-controlled Senate, something that did not happen for the 56 bills to repeal or dismantle the health reform law while Democrats controlled that chamber.

H.R. 596 passed the House on Feb. 3 by a 239-186 vote, with three Republicans voting against repeal and no Democrats voting for it. The bill calls for the repeal of the ACA and directs the Congressional committees with jurisdiction over health care to draft replacement legislation.

President Obama has vowed repeatedly to veto any legislation that repeals the health care reform law.

Debate preceding the vote focused on the usual arguments, with Republicans asserting the ACA has increased health insurance costs and premiums while serving as a job killer.

During debate on the House floor, Rep. Gary Palmer (R-Ala.) argued that 4 years after passage of the law, 41 million people are still without health insurance, and that premiums “have skyrocketed,” with some seeing increases as high as 78%. He added that there are “millions of people out of full-time work and millions more forced into part-time jobs.”

Democrats praised the growth in covered lives, as well as the slowdown in growth of Medicare costs in calling on members to vote against the bill.

Rep. Lois Capps (D-Calif.) noted that a repeal vote “will actually take health insurance away from millions of Americans,” adding that the ACA “is not perfect and there are clear areas where we could work together to build on and improve this law, but today’s repeal vote would turn back time, reverting back to a system everyone agreed was broken.”

Democrats also complained that the bill did not go through regular order through the committee hearing and markup process, but rather went straight to the floor for a vote with no amendments allowed to be introduced during the debate.

Once again, the Republican-controlled House voted to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

But for the first time, this bill – H.R. 596 – could get a vote in the Republican-controlled Senate, something that did not happen for the 56 bills to repeal or dismantle the health reform law while Democrats controlled that chamber.

H.R. 596 passed the House on Feb. 3 by a 239-186 vote, with three Republicans voting against repeal and no Democrats voting for it. The bill calls for the repeal of the ACA and directs the Congressional committees with jurisdiction over health care to draft replacement legislation.

President Obama has vowed repeatedly to veto any legislation that repeals the health care reform law.

Debate preceding the vote focused on the usual arguments, with Republicans asserting the ACA has increased health insurance costs and premiums while serving as a job killer.

During debate on the House floor, Rep. Gary Palmer (R-Ala.) argued that 4 years after passage of the law, 41 million people are still without health insurance, and that premiums “have skyrocketed,” with some seeing increases as high as 78%. He added that there are “millions of people out of full-time work and millions more forced into part-time jobs.”

Democrats praised the growth in covered lives, as well as the slowdown in growth of Medicare costs in calling on members to vote against the bill.

Rep. Lois Capps (D-Calif.) noted that a repeal vote “will actually take health insurance away from millions of Americans,” adding that the ACA “is not perfect and there are clear areas where we could work together to build on and improve this law, but today’s repeal vote would turn back time, reverting back to a system everyone agreed was broken.”

Democrats also complained that the bill did not go through regular order through the committee hearing and markup process, but rather went straight to the floor for a vote with no amendments allowed to be introduced during the debate.

Once again, the Republican-controlled House voted to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

But for the first time, this bill – H.R. 596 – could get a vote in the Republican-controlled Senate, something that did not happen for the 56 bills to repeal or dismantle the health reform law while Democrats controlled that chamber.

H.R. 596 passed the House on Feb. 3 by a 239-186 vote, with three Republicans voting against repeal and no Democrats voting for it. The bill calls for the repeal of the ACA and directs the Congressional committees with jurisdiction over health care to draft replacement legislation.

President Obama has vowed repeatedly to veto any legislation that repeals the health care reform law.

Debate preceding the vote focused on the usual arguments, with Republicans asserting the ACA has increased health insurance costs and premiums while serving as a job killer.

During debate on the House floor, Rep. Gary Palmer (R-Ala.) argued that 4 years after passage of the law, 41 million people are still without health insurance, and that premiums “have skyrocketed,” with some seeing increases as high as 78%. He added that there are “millions of people out of full-time work and millions more forced into part-time jobs.”

Democrats praised the growth in covered lives, as well as the slowdown in growth of Medicare costs in calling on members to vote against the bill.

Rep. Lois Capps (D-Calif.) noted that a repeal vote “will actually take health insurance away from millions of Americans,” adding that the ACA “is not perfect and there are clear areas where we could work together to build on and improve this law, but today’s repeal vote would turn back time, reverting back to a system everyone agreed was broken.”

Democrats also complained that the bill did not go through regular order through the committee hearing and markup process, but rather went straight to the floor for a vote with no amendments allowed to be introduced during the debate.

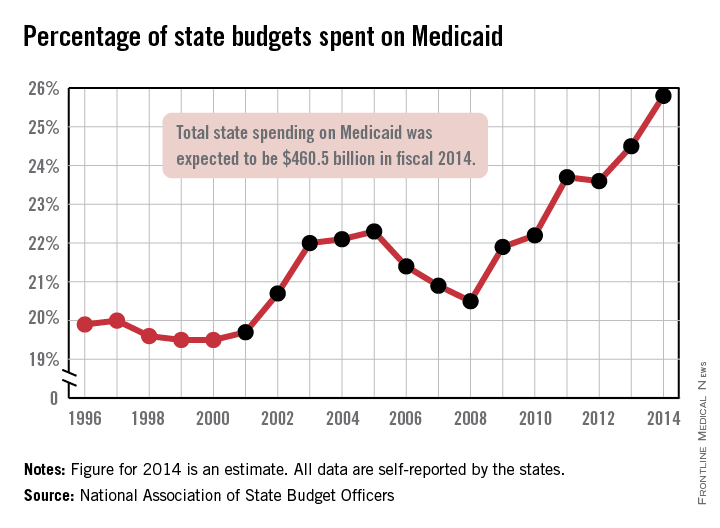

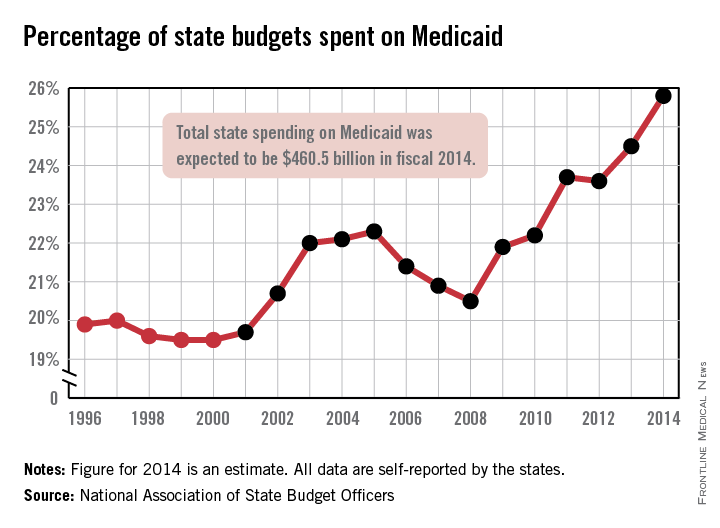

Medicaid’s share of state budgets was nearly 26% in 2014

States spent more than a quarter of their budgets on Medicaid for the first time in 2014, with the total share estimated at 25.8% by the National Association of State Budget Officers.

That 25.8% represents expenditures of $460.5 billion, excluding administration costs – an increase of 11.3% over 2013. Medicaid was the single largest component of total state spending last year, NASBO noted in its annual State Expenditure Report, and has been every year since 2009.

State funding for Medicaid increased by 2.7% in 2014, while the federal share of funding went up by an estimated 17.8%, compared with 2013. Medicaid enrollment was projected to increase by 8.3% across all states in 2014 after going up 1.5% in 2013; it is expected to increase by 13.2% in fiscal 2015, NASBO said.

“Implementation of the Affordable Care Act has greatly increased the number of individuals served in the Medicaid program in 2014 and thereafter,” the report noted, adding that the ACA’s Medicaid eligibility expansion option is expected to “add approximately 18.3 million individuals by 2021.”

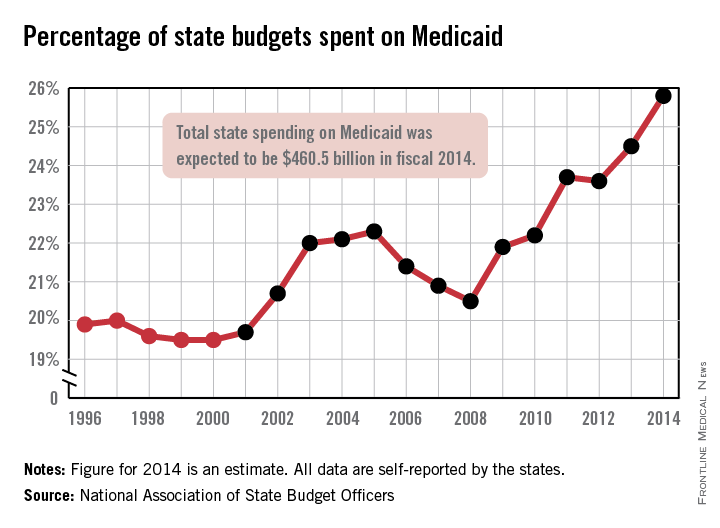

States spent more than a quarter of their budgets on Medicaid for the first time in 2014, with the total share estimated at 25.8% by the National Association of State Budget Officers.

That 25.8% represents expenditures of $460.5 billion, excluding administration costs – an increase of 11.3% over 2013. Medicaid was the single largest component of total state spending last year, NASBO noted in its annual State Expenditure Report, and has been every year since 2009.

State funding for Medicaid increased by 2.7% in 2014, while the federal share of funding went up by an estimated 17.8%, compared with 2013. Medicaid enrollment was projected to increase by 8.3% across all states in 2014 after going up 1.5% in 2013; it is expected to increase by 13.2% in fiscal 2015, NASBO said.

“Implementation of the Affordable Care Act has greatly increased the number of individuals served in the Medicaid program in 2014 and thereafter,” the report noted, adding that the ACA’s Medicaid eligibility expansion option is expected to “add approximately 18.3 million individuals by 2021.”

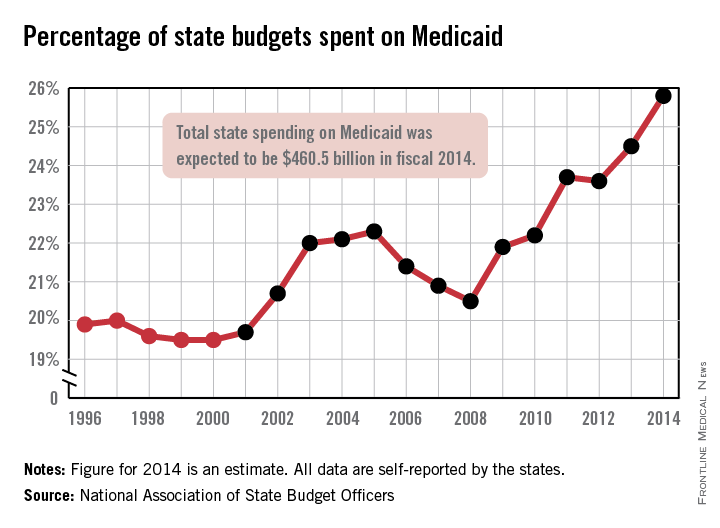

States spent more than a quarter of their budgets on Medicaid for the first time in 2014, with the total share estimated at 25.8% by the National Association of State Budget Officers.

That 25.8% represents expenditures of $460.5 billion, excluding administration costs – an increase of 11.3% over 2013. Medicaid was the single largest component of total state spending last year, NASBO noted in its annual State Expenditure Report, and has been every year since 2009.

State funding for Medicaid increased by 2.7% in 2014, while the federal share of funding went up by an estimated 17.8%, compared with 2013. Medicaid enrollment was projected to increase by 8.3% across all states in 2014 after going up 1.5% in 2013; it is expected to increase by 13.2% in fiscal 2015, NASBO said.

“Implementation of the Affordable Care Act has greatly increased the number of individuals served in the Medicaid program in 2014 and thereafter,” the report noted, adding that the ACA’s Medicaid eligibility expansion option is expected to “add approximately 18.3 million individuals by 2021.”

President’s budget would extend Medicaid pay bump, repeal SGR

President Barack Obama’s 2016 budget calls for extending the Medicaid pay bump for primary care physicians, improving access to health providers, and installing a permanent fix to Medicare’s Sustainable Growth Rate reimbursement formula.

The president outlined his nearly $4 trillion budget in a summary released Feb. 2 by the White House. The proposal includes extending increased payments for primary care services delivered by physicians who accept Medicaid through 2016, with modifications to expand provider eligibility. The president also wants to enhance training of primary care practitioners and other physicians in high-need specialties by providing $5.25 billion over 10 years to support 13,000 new medical school graduate residents through a new graduate medical education program.

In addition, the president is seeking the end of sequestration, the broad federal cuts triggered by the Budget Control Act of 2011. During a Feb. 2 news conference, the president stressed that the deficit reduction achieved during his presidency – a reported cut of two-thirds – makes his budget proposals possible.

“We can afford to make these investments, while remaining fiscally responsible,” President Obama said during the conference. “In fact, we would be making a critical error if we avoided making these investments.”

The president’s budget includes a number of recommendations that would cut billions in Medicare funding over the next 10 years.

The budget would reduce the projected growth of Medicare payments for graduate medical education by $16 billion, while saving more than $100 billion by reducing inflation updates for providers who treat Medicare beneficiaries after they leave the hospital. Meanwhile, improving payment accuracy for the Medicare Advantage program would result in $43 billion in savings over 10 years, according to the plan.

The proposal also seeks to extend funding for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) through 2019 and give states the option to streamline eligibility determinations for children in Medicaid and CHIP.

The president said he wants to accelerate physician participation in high-quality and efficient health care delivery systems by repealing the SGR and reforming Medicare physician payments consistent with recent bipartisan legislation. Obama also suggested extending increased Medicaid payments to primary care physicians through 2016 at a cost of $6.3 billion.

Other medical and public health care proposals include:

• Directing more than $100 million to reduce abuse of prescription opioids and $4.2 billion to the Health Center Program to expand services to an additional 1 million patients.

• Funding increases for every state to expand existing prescription drug monitoring programs, and funding increases for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to decrease the rates of inappropriate prescription drug abuse.

• An increase of more than $550 million above 2015 enacted levels across the federal government to prevent, detect, and control illness and death related to infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

• More than $500 million to enhance the advanced development of next-generation medical countermeasures against chemical, biologic, radiologic, and nuclear threats.

• A 6% spending increase in medical research and development to fuel programs such as the Precision Medicine Initiative and the Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative.

• Increased access to generic drugs by stopping companies from entering into anticompetitive deals intended to block consumer access to generics.

The administration contends the budget will trim the deficit by $1.8 trillion over the next decade, primarily because of health, tax, and immigration reforms. That includes $400 billion in health savings that would grow over time – raising about $1 trillion in the second decade and extending the Medicare hospital insurance trust fund solvency by about 5 years, the president said.

Republican lawmakers criticized the budget proposal, calling it a repeat of past failures.

“Today President Obama laid out a plan for more taxes, more spending, and more of the Washington gridlock that has failed middle-class families,” House Speaker John Boehner (R-Ohio) said in a statement. “It may be Groundhog Day, but the American people can’t afford a repeat of the same old top-down policies of the past. Like the president’s previous budgets, this plan never balances – ever.”

Liberal groups, such as the Center for American Progress, praised the budget proposal.

“President Obama’s budget lays out a detailed agenda to create good jobs, raise wages, and help working families achieve middle-class security,” Carmel Martin, the center’s executive vice president, said in a statement. “Rather than stumbling through a series of unnecessary manufactured crises or clinging to failed austerity measures such as sequestration, Congress has an opportunity to work with President Obama to build an economy that works for everyone, not just the wealthy few.”

On Twitter @legal_med

President Barack Obama’s 2016 budget calls for extending the Medicaid pay bump for primary care physicians, improving access to health providers, and installing a permanent fix to Medicare’s Sustainable Growth Rate reimbursement formula.

The president outlined his nearly $4 trillion budget in a summary released Feb. 2 by the White House. The proposal includes extending increased payments for primary care services delivered by physicians who accept Medicaid through 2016, with modifications to expand provider eligibility. The president also wants to enhance training of primary care practitioners and other physicians in high-need specialties by providing $5.25 billion over 10 years to support 13,000 new medical school graduate residents through a new graduate medical education program.

In addition, the president is seeking the end of sequestration, the broad federal cuts triggered by the Budget Control Act of 2011. During a Feb. 2 news conference, the president stressed that the deficit reduction achieved during his presidency – a reported cut of two-thirds – makes his budget proposals possible.

“We can afford to make these investments, while remaining fiscally responsible,” President Obama said during the conference. “In fact, we would be making a critical error if we avoided making these investments.”

The president’s budget includes a number of recommendations that would cut billions in Medicare funding over the next 10 years.

The budget would reduce the projected growth of Medicare payments for graduate medical education by $16 billion, while saving more than $100 billion by reducing inflation updates for providers who treat Medicare beneficiaries after they leave the hospital. Meanwhile, improving payment accuracy for the Medicare Advantage program would result in $43 billion in savings over 10 years, according to the plan.

The proposal also seeks to extend funding for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) through 2019 and give states the option to streamline eligibility determinations for children in Medicaid and CHIP.

The president said he wants to accelerate physician participation in high-quality and efficient health care delivery systems by repealing the SGR and reforming Medicare physician payments consistent with recent bipartisan legislation. Obama also suggested extending increased Medicaid payments to primary care physicians through 2016 at a cost of $6.3 billion.

Other medical and public health care proposals include:

• Directing more than $100 million to reduce abuse of prescription opioids and $4.2 billion to the Health Center Program to expand services to an additional 1 million patients.

• Funding increases for every state to expand existing prescription drug monitoring programs, and funding increases for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to decrease the rates of inappropriate prescription drug abuse.

• An increase of more than $550 million above 2015 enacted levels across the federal government to prevent, detect, and control illness and death related to infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

• More than $500 million to enhance the advanced development of next-generation medical countermeasures against chemical, biologic, radiologic, and nuclear threats.

• A 6% spending increase in medical research and development to fuel programs such as the Precision Medicine Initiative and the Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative.

• Increased access to generic drugs by stopping companies from entering into anticompetitive deals intended to block consumer access to generics.

The administration contends the budget will trim the deficit by $1.8 trillion over the next decade, primarily because of health, tax, and immigration reforms. That includes $400 billion in health savings that would grow over time – raising about $1 trillion in the second decade and extending the Medicare hospital insurance trust fund solvency by about 5 years, the president said.

Republican lawmakers criticized the budget proposal, calling it a repeat of past failures.

“Today President Obama laid out a plan for more taxes, more spending, and more of the Washington gridlock that has failed middle-class families,” House Speaker John Boehner (R-Ohio) said in a statement. “It may be Groundhog Day, but the American people can’t afford a repeat of the same old top-down policies of the past. Like the president’s previous budgets, this plan never balances – ever.”

Liberal groups, such as the Center for American Progress, praised the budget proposal.

“President Obama’s budget lays out a detailed agenda to create good jobs, raise wages, and help working families achieve middle-class security,” Carmel Martin, the center’s executive vice president, said in a statement. “Rather than stumbling through a series of unnecessary manufactured crises or clinging to failed austerity measures such as sequestration, Congress has an opportunity to work with President Obama to build an economy that works for everyone, not just the wealthy few.”

On Twitter @legal_med

President Barack Obama’s 2016 budget calls for extending the Medicaid pay bump for primary care physicians, improving access to health providers, and installing a permanent fix to Medicare’s Sustainable Growth Rate reimbursement formula.

The president outlined his nearly $4 trillion budget in a summary released Feb. 2 by the White House. The proposal includes extending increased payments for primary care services delivered by physicians who accept Medicaid through 2016, with modifications to expand provider eligibility. The president also wants to enhance training of primary care practitioners and other physicians in high-need specialties by providing $5.25 billion over 10 years to support 13,000 new medical school graduate residents through a new graduate medical education program.

In addition, the president is seeking the end of sequestration, the broad federal cuts triggered by the Budget Control Act of 2011. During a Feb. 2 news conference, the president stressed that the deficit reduction achieved during his presidency – a reported cut of two-thirds – makes his budget proposals possible.

“We can afford to make these investments, while remaining fiscally responsible,” President Obama said during the conference. “In fact, we would be making a critical error if we avoided making these investments.”

The president’s budget includes a number of recommendations that would cut billions in Medicare funding over the next 10 years.

The budget would reduce the projected growth of Medicare payments for graduate medical education by $16 billion, while saving more than $100 billion by reducing inflation updates for providers who treat Medicare beneficiaries after they leave the hospital. Meanwhile, improving payment accuracy for the Medicare Advantage program would result in $43 billion in savings over 10 years, according to the plan.

The proposal also seeks to extend funding for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) through 2019 and give states the option to streamline eligibility determinations for children in Medicaid and CHIP.

The president said he wants to accelerate physician participation in high-quality and efficient health care delivery systems by repealing the SGR and reforming Medicare physician payments consistent with recent bipartisan legislation. Obama also suggested extending increased Medicaid payments to primary care physicians through 2016 at a cost of $6.3 billion.

Other medical and public health care proposals include:

• Directing more than $100 million to reduce abuse of prescription opioids and $4.2 billion to the Health Center Program to expand services to an additional 1 million patients.

• Funding increases for every state to expand existing prescription drug monitoring programs, and funding increases for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to decrease the rates of inappropriate prescription drug abuse.

• An increase of more than $550 million above 2015 enacted levels across the federal government to prevent, detect, and control illness and death related to infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

• More than $500 million to enhance the advanced development of next-generation medical countermeasures against chemical, biologic, radiologic, and nuclear threats.

• A 6% spending increase in medical research and development to fuel programs such as the Precision Medicine Initiative and the Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative.

• Increased access to generic drugs by stopping companies from entering into anticompetitive deals intended to block consumer access to generics.

The administration contends the budget will trim the deficit by $1.8 trillion over the next decade, primarily because of health, tax, and immigration reforms. That includes $400 billion in health savings that would grow over time – raising about $1 trillion in the second decade and extending the Medicare hospital insurance trust fund solvency by about 5 years, the president said.

Republican lawmakers criticized the budget proposal, calling it a repeat of past failures.

“Today President Obama laid out a plan for more taxes, more spending, and more of the Washington gridlock that has failed middle-class families,” House Speaker John Boehner (R-Ohio) said in a statement. “It may be Groundhog Day, but the American people can’t afford a repeat of the same old top-down policies of the past. Like the president’s previous budgets, this plan never balances – ever.”

Liberal groups, such as the Center for American Progress, praised the budget proposal.

“President Obama’s budget lays out a detailed agenda to create good jobs, raise wages, and help working families achieve middle-class security,” Carmel Martin, the center’s executive vice president, said in a statement. “Rather than stumbling through a series of unnecessary manufactured crises or clinging to failed austerity measures such as sequestration, Congress has an opportunity to work with President Obama to build an economy that works for everyone, not just the wealthy few.”

On Twitter @legal_med

How Hospitalist Groups Make Time for Leadership

Negotiating salaries. Improving patient flow. Increasing patient satisfaction. Reducing readmissions. Championing quality improvement efforts. Planning strategically. Handling schedule issues. Dealing with coverage issues. Working on Ebola preparation. Being on call 24 hours a day for an urgent concern from hospital administration or a hospitalist.

Hospitalist group leaders often feel they are pulled in multiple directions all at once and find that a day off really is not a day off. Leaders often are asked to take on additional responsibilities and might wonder whether they are given sufficient protected time. Leaders of larger HM groups might ask whether adding an associate chief would help cover the administrative workload. Or they may be asking whether hospitalist group leaders should receive a premium in salary, above that of other hospitalists in the group.

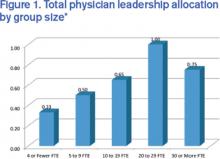

These are questions the State of Hospital Medicine Report (SOHM) attempts to answer. Although there is significant variation that is dependent on many factors (i.e., group size, academic status, and whether or not the practice is part of a larger multi-site group), the 2014 SOHM found that the median total full-time equivalent (FTE) allocation for physician administration/leadership for HMGs serving adults was just 0.60. The highest-ranking physician leader most commonly had 0.25 to 0.35 FTE protected for administrative responsibilities. And the median compensation premium for group leaders was 15%.

One leadership challenge is that administrative work never stops. Group leaders often find themselves having to come in for meetings before or after night shifts. Leaders sometimes feel that the 0.30 FTE allocated for administrative responsibilities actually requires the workload of a full-time position. Yet, like other hospitalists, leaders typically work a significant number of consecutive clinical shifts to ensure continuity of care for patients, which can make juggling administrative work challenging.

Additionally, group leaders often carry a significant clinical workload. (Read about Team Hospitalist’s newest member and her split leadership-clinical roles) I would argue that this is a good thing, important for many reasons, including maintaining clinical skills, understanding the nature of work and challenges on the front lines, and being able to facilitate quality improvement efforts. Further, group leaders often are perceived to be team players by other hospitalists when they work a wide variety of shifts on all days of the week. Many programs face staffing challenges, and leaders might work extra shifts when other hospitalists are unable to fill them.

Certainly group leaders face significant challenges, but the position also comes with many rewards. Satisfaction comes from improving the program for all hospitalists in a group, from gains in hospital efficiency or flow, from systems improvements to ensure patient safety or improve patient outcomes, and from being respected by hospital administration as well as other hospitalists in the group. With a good understanding of hospital finances and patient flow, some hospitalist group leaders advance to other roles in hospital administration, such as CMO or CEO.

Although there may be no one-size-fits-all answer for the right amount of protected time or salary for group leaders, leaders clearly play a challenging but essential role in bringing value to both hospitals and hospitalist groups.

For more data from the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine Report, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

Dr. Huang is associate chief of the division of hospital medicine and associate clinical professor at the University of California San Diego. He is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Negotiating salaries. Improving patient flow. Increasing patient satisfaction. Reducing readmissions. Championing quality improvement efforts. Planning strategically. Handling schedule issues. Dealing with coverage issues. Working on Ebola preparation. Being on call 24 hours a day for an urgent concern from hospital administration or a hospitalist.

Hospitalist group leaders often feel they are pulled in multiple directions all at once and find that a day off really is not a day off. Leaders often are asked to take on additional responsibilities and might wonder whether they are given sufficient protected time. Leaders of larger HM groups might ask whether adding an associate chief would help cover the administrative workload. Or they may be asking whether hospitalist group leaders should receive a premium in salary, above that of other hospitalists in the group.

These are questions the State of Hospital Medicine Report (SOHM) attempts to answer. Although there is significant variation that is dependent on many factors (i.e., group size, academic status, and whether or not the practice is part of a larger multi-site group), the 2014 SOHM found that the median total full-time equivalent (FTE) allocation for physician administration/leadership for HMGs serving adults was just 0.60. The highest-ranking physician leader most commonly had 0.25 to 0.35 FTE protected for administrative responsibilities. And the median compensation premium for group leaders was 15%.

One leadership challenge is that administrative work never stops. Group leaders often find themselves having to come in for meetings before or after night shifts. Leaders sometimes feel that the 0.30 FTE allocated for administrative responsibilities actually requires the workload of a full-time position. Yet, like other hospitalists, leaders typically work a significant number of consecutive clinical shifts to ensure continuity of care for patients, which can make juggling administrative work challenging.

Additionally, group leaders often carry a significant clinical workload. (Read about Team Hospitalist’s newest member and her split leadership-clinical roles) I would argue that this is a good thing, important for many reasons, including maintaining clinical skills, understanding the nature of work and challenges on the front lines, and being able to facilitate quality improvement efforts. Further, group leaders often are perceived to be team players by other hospitalists when they work a wide variety of shifts on all days of the week. Many programs face staffing challenges, and leaders might work extra shifts when other hospitalists are unable to fill them.

Certainly group leaders face significant challenges, but the position also comes with many rewards. Satisfaction comes from improving the program for all hospitalists in a group, from gains in hospital efficiency or flow, from systems improvements to ensure patient safety or improve patient outcomes, and from being respected by hospital administration as well as other hospitalists in the group. With a good understanding of hospital finances and patient flow, some hospitalist group leaders advance to other roles in hospital administration, such as CMO or CEO.

Although there may be no one-size-fits-all answer for the right amount of protected time or salary for group leaders, leaders clearly play a challenging but essential role in bringing value to both hospitals and hospitalist groups.

For more data from the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine Report, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

Dr. Huang is associate chief of the division of hospital medicine and associate clinical professor at the University of California San Diego. He is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Negotiating salaries. Improving patient flow. Increasing patient satisfaction. Reducing readmissions. Championing quality improvement efforts. Planning strategically. Handling schedule issues. Dealing with coverage issues. Working on Ebola preparation. Being on call 24 hours a day for an urgent concern from hospital administration or a hospitalist.

Hospitalist group leaders often feel they are pulled in multiple directions all at once and find that a day off really is not a day off. Leaders often are asked to take on additional responsibilities and might wonder whether they are given sufficient protected time. Leaders of larger HM groups might ask whether adding an associate chief would help cover the administrative workload. Or they may be asking whether hospitalist group leaders should receive a premium in salary, above that of other hospitalists in the group.

These are questions the State of Hospital Medicine Report (SOHM) attempts to answer. Although there is significant variation that is dependent on many factors (i.e., group size, academic status, and whether or not the practice is part of a larger multi-site group), the 2014 SOHM found that the median total full-time equivalent (FTE) allocation for physician administration/leadership for HMGs serving adults was just 0.60. The highest-ranking physician leader most commonly had 0.25 to 0.35 FTE protected for administrative responsibilities. And the median compensation premium for group leaders was 15%.

One leadership challenge is that administrative work never stops. Group leaders often find themselves having to come in for meetings before or after night shifts. Leaders sometimes feel that the 0.30 FTE allocated for administrative responsibilities actually requires the workload of a full-time position. Yet, like other hospitalists, leaders typically work a significant number of consecutive clinical shifts to ensure continuity of care for patients, which can make juggling administrative work challenging.

Additionally, group leaders often carry a significant clinical workload. (Read about Team Hospitalist’s newest member and her split leadership-clinical roles) I would argue that this is a good thing, important for many reasons, including maintaining clinical skills, understanding the nature of work and challenges on the front lines, and being able to facilitate quality improvement efforts. Further, group leaders often are perceived to be team players by other hospitalists when they work a wide variety of shifts on all days of the week. Many programs face staffing challenges, and leaders might work extra shifts when other hospitalists are unable to fill them.

Certainly group leaders face significant challenges, but the position also comes with many rewards. Satisfaction comes from improving the program for all hospitalists in a group, from gains in hospital efficiency or flow, from systems improvements to ensure patient safety or improve patient outcomes, and from being respected by hospital administration as well as other hospitalists in the group. With a good understanding of hospital finances and patient flow, some hospitalist group leaders advance to other roles in hospital administration, such as CMO or CEO.

Although there may be no one-size-fits-all answer for the right amount of protected time or salary for group leaders, leaders clearly play a challenging but essential role in bringing value to both hospitals and hospitalist groups.

For more data from the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine Report, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

Dr. Huang is associate chief of the division of hospital medicine and associate clinical professor at the University of California San Diego. He is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Time-Based Physician Services Require Proper Documentation

Providers typically rely on the “key components” (history, exam, medical decision-making) when documenting in the medical record, and they often misunderstand the use of time when selecting visit levels. Sometimes providers may report a lower service level than warranted because they didn’t feel that they spent the required amount of time with the patient; however, the duration of the visit is an ancillary factor and does not control the level of service to be billed unless more than 50% of the face-to-face time (for non-inpatient services) or more than 50% of the floor time (for inpatient services) is spent providing counseling or coordination of care (C/CC).1 In these instances, providers may choose to document only a brief history and exam, or none at all. They should update the medical decision-making based on the discussion.

Consider the hospitalization of an elderly patient who is newly diagnosed with diabetes. In addition to stabilizing the patient’s glucose levels and devising the appropriate care plan, the patient and/or caregivers also require extensive counseling regarding disease management, lifestyle modification, and medication regime. Coordination of care for outpatient programs and resources is also crucial. To make sure that this qualifies as a time-based service, ensure that the documentation contains the duration, the issues addressed, and the signature of the service provider.

Duration of Counseling and/or Coordination of Care

Time is not used for visit level selection if C/CC is minimal (<50%) or absent from the patient encounter. For inpatient services, total visit time is identified as provider face-to-face time (i.e., at the bedside) combined with time spent on the patient’s unit/floor performing services that are directly related to that patient, such as reviewing data, obtaining relevant patient information, and discussing the case with other involved healthcare providers.

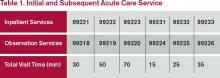

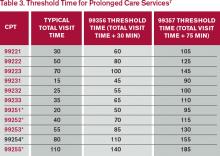

Time associated with activities performed in locations other than the patient’s unit/floor (e.g. reviewing current results or images from the physician’s office) is not allowable in calculating the total visit time. Time associated with teaching students/interns is also excluded, because this doesn’t reflect patient care activities. Once the provider documents all services rendered on a given calendar date, the provider selects the visit level that corresponds with the cumulative visit time documented in the chart (see Tables 1 and 2).

Issues Addressed

When counseling and/or coordination of care dominate more than 50% of the time a physician spends with a patient during an evaluation and management (E/M) service, then time may be considered as the controlling factor to qualify the E/M service for a particular level of care.2 The following must be documented in the patient’s medical record in order to report an E/M service based on time:

- The total length of time of the E/M visit;

- Evidence that more than half of the total length of time of the E/M visit was spent in counseling and coordinating of care; and

- The content of the counseling and coordination of care provided during the E/M visit.

History and exam, if performed or updated, should also be documented, along with the patient response or comprehension of information. An acceptable C/CC time entry may be noted as, “Total visit time = 35 minutes; > 50% spent counseling/coordinating care” or “20 of 35 minutes spent counseling/coordinating care.”

A payer may prefer one documentation style over another. It is always best to query payer policy and review local documentation standards to ensure compliance. Please remember that while this example constitutes the required elements for the notation of time, documentation must also include the details of counseling, care plan revisions, and any information that is pertinent to patient care and communication with other healthcare professionals.

Family Discussions

Family discussions are a typical event involved in taking care of patients and are appropriate to count as C/CC time. Special circumstances are considered when discussions must take place without the patient present. This type of counseling time is recognized but only counts towards C/CC time if the following criteria are met and documented:

- The patient is unable or clinically incompetent to participate in discussions;

- The time is spent on the unit/floor with the family members or surrogate decision makers obtaining a medical history, reviewing the patient’s condition or prognosis, or discussing treatment or limitation(s) of treatment; and

- The conversation bears directly on the management of the patient.3

Time cannot be counted if the discussion takes place in an area outside of the patient’s unit/floor (e.g. in the physician’s office) or if the time is spent counseling the family members through their grieving process.

It is fairly common for the family discussion to take place later in the day, after the physician has completed morning rounds. If the earlier encounter involved C/CC, the physician would report the cumulative time spent for that service date. If the earlier encounter was a typical patient assessment incorporating the components of an evaluation (i.e., history update and physical) and management (i.e., care plan review/revision) service, the meeting time may qualify for prolonged care services.

Service Provider

Be sure to count only the physician’s time spent in C/CC. Counseling time by the nursing staff, the social worker, or the resident cannot contribute toward the physician’s total visit time. When more than one physician is involved in services throughout the day, the physicians should select a level of service representative of the combined visits and submit the appropriate code for that level under one physician’s name.4

Consider the following example: The hospitalist takes a brief history about overnight events and reviews some of the pertinent information with the patient. He/she then leaves the room to coordinate the patient’s ongoing care in anticipation that the patient will be discharged over the next few days (25 minutes). The resident is asked to continue the assessment and counsel the patient on the patient’s current disease process (20 minutes).

In the above scenario, the hospitalist is only able to report 99232, because the time spent by the resident is “nonbillable time.”

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.1B. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Novitas Solutions, Inc. Frequently Asked Questions: Evaluation and Management Services (Part B). Available at: http://www.novitas-solutions.com/webcenter/faces/oracle/webcenter/page/scopedMD/sad78b265_6797_4ed0_a02f_81627913bc78/Page57.jspx?wc.contextURL=%2Fspaces%2FMedicareJH&wc.originURL=%2Fspaces%2FMedicareJH%2Fpage%2Fpagebyid&contentId=00005056&_afrLoop=1728453012371000#%40%3F_afrLoop%3D1728453012371000%26wc.originURL%3D%252Fspaces%252FMedicareJH%252Fpage%252Fpagebyid%26contentId%3D00005056%26wc.contextURL%3D%252Fspaces%252FMedicareJH%26_adf.ctrl-state%3D610bhasa4_134. Accessed on December 11, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare National Coverage Determinations Manual: Chapter 1, Part 1: Coverage Determinations, Section 70.1. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/ncd103c1_Part1.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.5. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Abraham M, Ahlman JT, Boudreau AJ, Connelly J, Levreau-Davis L. Current Procedural Terminology 2014 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2013:1-32.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.1C. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.15.1G. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf.

Providers typically rely on the “key components” (history, exam, medical decision-making) when documenting in the medical record, and they often misunderstand the use of time when selecting visit levels. Sometimes providers may report a lower service level than warranted because they didn’t feel that they spent the required amount of time with the patient; however, the duration of the visit is an ancillary factor and does not control the level of service to be billed unless more than 50% of the face-to-face time (for non-inpatient services) or more than 50% of the floor time (for inpatient services) is spent providing counseling or coordination of care (C/CC).1 In these instances, providers may choose to document only a brief history and exam, or none at all. They should update the medical decision-making based on the discussion.

Consider the hospitalization of an elderly patient who is newly diagnosed with diabetes. In addition to stabilizing the patient’s glucose levels and devising the appropriate care plan, the patient and/or caregivers also require extensive counseling regarding disease management, lifestyle modification, and medication regime. Coordination of care for outpatient programs and resources is also crucial. To make sure that this qualifies as a time-based service, ensure that the documentation contains the duration, the issues addressed, and the signature of the service provider.

Duration of Counseling and/or Coordination of Care

Time is not used for visit level selection if C/CC is minimal (<50%) or absent from the patient encounter. For inpatient services, total visit time is identified as provider face-to-face time (i.e., at the bedside) combined with time spent on the patient’s unit/floor performing services that are directly related to that patient, such as reviewing data, obtaining relevant patient information, and discussing the case with other involved healthcare providers.

Time associated with activities performed in locations other than the patient’s unit/floor (e.g. reviewing current results or images from the physician’s office) is not allowable in calculating the total visit time. Time associated with teaching students/interns is also excluded, because this doesn’t reflect patient care activities. Once the provider documents all services rendered on a given calendar date, the provider selects the visit level that corresponds with the cumulative visit time documented in the chart (see Tables 1 and 2).

Issues Addressed

When counseling and/or coordination of care dominate more than 50% of the time a physician spends with a patient during an evaluation and management (E/M) service, then time may be considered as the controlling factor to qualify the E/M service for a particular level of care.2 The following must be documented in the patient’s medical record in order to report an E/M service based on time:

- The total length of time of the E/M visit;

- Evidence that more than half of the total length of time of the E/M visit was spent in counseling and coordinating of care; and

- The content of the counseling and coordination of care provided during the E/M visit.

History and exam, if performed or updated, should also be documented, along with the patient response or comprehension of information. An acceptable C/CC time entry may be noted as, “Total visit time = 35 minutes; > 50% spent counseling/coordinating care” or “20 of 35 minutes spent counseling/coordinating care.”

A payer may prefer one documentation style over another. It is always best to query payer policy and review local documentation standards to ensure compliance. Please remember that while this example constitutes the required elements for the notation of time, documentation must also include the details of counseling, care plan revisions, and any information that is pertinent to patient care and communication with other healthcare professionals.

Family Discussions

Family discussions are a typical event involved in taking care of patients and are appropriate to count as C/CC time. Special circumstances are considered when discussions must take place without the patient present. This type of counseling time is recognized but only counts towards C/CC time if the following criteria are met and documented:

- The patient is unable or clinically incompetent to participate in discussions;

- The time is spent on the unit/floor with the family members or surrogate decision makers obtaining a medical history, reviewing the patient’s condition or prognosis, or discussing treatment or limitation(s) of treatment; and

- The conversation bears directly on the management of the patient.3

Time cannot be counted if the discussion takes place in an area outside of the patient’s unit/floor (e.g. in the physician’s office) or if the time is spent counseling the family members through their grieving process.

It is fairly common for the family discussion to take place later in the day, after the physician has completed morning rounds. If the earlier encounter involved C/CC, the physician would report the cumulative time spent for that service date. If the earlier encounter was a typical patient assessment incorporating the components of an evaluation (i.e., history update and physical) and management (i.e., care plan review/revision) service, the meeting time may qualify for prolonged care services.

Service Provider

Be sure to count only the physician’s time spent in C/CC. Counseling time by the nursing staff, the social worker, or the resident cannot contribute toward the physician’s total visit time. When more than one physician is involved in services throughout the day, the physicians should select a level of service representative of the combined visits and submit the appropriate code for that level under one physician’s name.4

Consider the following example: The hospitalist takes a brief history about overnight events and reviews some of the pertinent information with the patient. He/she then leaves the room to coordinate the patient’s ongoing care in anticipation that the patient will be discharged over the next few days (25 minutes). The resident is asked to continue the assessment and counsel the patient on the patient’s current disease process (20 minutes).

In the above scenario, the hospitalist is only able to report 99232, because the time spent by the resident is “nonbillable time.”

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.1B. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Novitas Solutions, Inc. Frequently Asked Questions: Evaluation and Management Services (Part B). Available at: http://www.novitas-solutions.com/webcenter/faces/oracle/webcenter/page/scopedMD/sad78b265_6797_4ed0_a02f_81627913bc78/Page57.jspx?wc.contextURL=%2Fspaces%2FMedicareJH&wc.originURL=%2Fspaces%2FMedicareJH%2Fpage%2Fpagebyid&contentId=00005056&_afrLoop=1728453012371000#%40%3F_afrLoop%3D1728453012371000%26wc.originURL%3D%252Fspaces%252FMedicareJH%252Fpage%252Fpagebyid%26contentId%3D00005056%26wc.contextURL%3D%252Fspaces%252FMedicareJH%26_adf.ctrl-state%3D610bhasa4_134. Accessed on December 11, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare National Coverage Determinations Manual: Chapter 1, Part 1: Coverage Determinations, Section 70.1. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/ncd103c1_Part1.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.5. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Abraham M, Ahlman JT, Boudreau AJ, Connelly J, Levreau-Davis L. Current Procedural Terminology 2014 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2013:1-32.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.1C. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.15.1G. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf.

Providers typically rely on the “key components” (history, exam, medical decision-making) when documenting in the medical record, and they often misunderstand the use of time when selecting visit levels. Sometimes providers may report a lower service level than warranted because they didn’t feel that they spent the required amount of time with the patient; however, the duration of the visit is an ancillary factor and does not control the level of service to be billed unless more than 50% of the face-to-face time (for non-inpatient services) or more than 50% of the floor time (for inpatient services) is spent providing counseling or coordination of care (C/CC).1 In these instances, providers may choose to document only a brief history and exam, or none at all. They should update the medical decision-making based on the discussion.

Consider the hospitalization of an elderly patient who is newly diagnosed with diabetes. In addition to stabilizing the patient’s glucose levels and devising the appropriate care plan, the patient and/or caregivers also require extensive counseling regarding disease management, lifestyle modification, and medication regime. Coordination of care for outpatient programs and resources is also crucial. To make sure that this qualifies as a time-based service, ensure that the documentation contains the duration, the issues addressed, and the signature of the service provider.

Duration of Counseling and/or Coordination of Care

Time is not used for visit level selection if C/CC is minimal (<50%) or absent from the patient encounter. For inpatient services, total visit time is identified as provider face-to-face time (i.e., at the bedside) combined with time spent on the patient’s unit/floor performing services that are directly related to that patient, such as reviewing data, obtaining relevant patient information, and discussing the case with other involved healthcare providers.

Time associated with activities performed in locations other than the patient’s unit/floor (e.g. reviewing current results or images from the physician’s office) is not allowable in calculating the total visit time. Time associated with teaching students/interns is also excluded, because this doesn’t reflect patient care activities. Once the provider documents all services rendered on a given calendar date, the provider selects the visit level that corresponds with the cumulative visit time documented in the chart (see Tables 1 and 2).

Issues Addressed

When counseling and/or coordination of care dominate more than 50% of the time a physician spends with a patient during an evaluation and management (E/M) service, then time may be considered as the controlling factor to qualify the E/M service for a particular level of care.2 The following must be documented in the patient’s medical record in order to report an E/M service based on time:

- The total length of time of the E/M visit;

- Evidence that more than half of the total length of time of the E/M visit was spent in counseling and coordinating of care; and

- The content of the counseling and coordination of care provided during the E/M visit.

History and exam, if performed or updated, should also be documented, along with the patient response or comprehension of information. An acceptable C/CC time entry may be noted as, “Total visit time = 35 minutes; > 50% spent counseling/coordinating care” or “20 of 35 minutes spent counseling/coordinating care.”

A payer may prefer one documentation style over another. It is always best to query payer policy and review local documentation standards to ensure compliance. Please remember that while this example constitutes the required elements for the notation of time, documentation must also include the details of counseling, care plan revisions, and any information that is pertinent to patient care and communication with other healthcare professionals.

Family Discussions

Family discussions are a typical event involved in taking care of patients and are appropriate to count as C/CC time. Special circumstances are considered when discussions must take place without the patient present. This type of counseling time is recognized but only counts towards C/CC time if the following criteria are met and documented:

- The patient is unable or clinically incompetent to participate in discussions;

- The time is spent on the unit/floor with the family members or surrogate decision makers obtaining a medical history, reviewing the patient’s condition or prognosis, or discussing treatment or limitation(s) of treatment; and

- The conversation bears directly on the management of the patient.3

Time cannot be counted if the discussion takes place in an area outside of the patient’s unit/floor (e.g. in the physician’s office) or if the time is spent counseling the family members through their grieving process.

It is fairly common for the family discussion to take place later in the day, after the physician has completed morning rounds. If the earlier encounter involved C/CC, the physician would report the cumulative time spent for that service date. If the earlier encounter was a typical patient assessment incorporating the components of an evaluation (i.e., history update and physical) and management (i.e., care plan review/revision) service, the meeting time may qualify for prolonged care services.

Service Provider

Be sure to count only the physician’s time spent in C/CC. Counseling time by the nursing staff, the social worker, or the resident cannot contribute toward the physician’s total visit time. When more than one physician is involved in services throughout the day, the physicians should select a level of service representative of the combined visits and submit the appropriate code for that level under one physician’s name.4

Consider the following example: The hospitalist takes a brief history about overnight events and reviews some of the pertinent information with the patient. He/she then leaves the room to coordinate the patient’s ongoing care in anticipation that the patient will be discharged over the next few days (25 minutes). The resident is asked to continue the assessment and counsel the patient on the patient’s current disease process (20 minutes).

In the above scenario, the hospitalist is only able to report 99232, because the time spent by the resident is “nonbillable time.”

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.1B. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Novitas Solutions, Inc. Frequently Asked Questions: Evaluation and Management Services (Part B). Available at: http://www.novitas-solutions.com/webcenter/faces/oracle/webcenter/page/scopedMD/sad78b265_6797_4ed0_a02f_81627913bc78/Page57.jspx?wc.contextURL=%2Fspaces%2FMedicareJH&wc.originURL=%2Fspaces%2FMedicareJH%2Fpage%2Fpagebyid&contentId=00005056&_afrLoop=1728453012371000#%40%3F_afrLoop%3D1728453012371000%26wc.originURL%3D%252Fspaces%252FMedicareJH%252Fpage%252Fpagebyid%26contentId%3D00005056%26wc.contextURL%3D%252Fspaces%252FMedicareJH%26_adf.ctrl-state%3D610bhasa4_134. Accessed on December 11, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare National Coverage Determinations Manual: Chapter 1, Part 1: Coverage Determinations, Section 70.1. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/ncd103c1_Part1.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.5. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Abraham M, Ahlman JT, Boudreau AJ, Connelly J, Levreau-Davis L. Current Procedural Terminology 2014 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2013:1-32.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.1C. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.15.1G. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf.

Malpractice Counsel

Traumatic Back Pain

An 84-year-old man with low-back pain following a motor vehicle crash was brought to the ED by emergency medical services (EMS). He had been the restrained driver, stopped at a traffic light, when he was struck from behind by a second vehicle.

In the ED, the patient only complained of low-back pain. He denied any radiation of pain or lower-extremity numbness or weakness. He also denied any head injury, loss of consciousness, neck pain, or abdominal pain. His past medical history was significant for hypertension, arthritis, and coronary artery disease.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were normal. The head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat (HEENT) examination was also normal; specifically, there was no tenderness to palpation of the cervical spine in the posterior midline. Regarding the cardiopulmonary examination, auscultation of the lungs revealed clear, bilateral breath sounds; the heart examination was normal. The patient had a soft abdomen, without tenderness, guarding, or rebound. His pelvis was stable, but he did exhibit some tenderness on palpation of the lower-thoracic and upper-lumbar spine. The neurological examination revealed normal motor strength and sensation in the lower extremities.

The emergency physician (EP) ordered X-rays of the thoracic and lumbar spine and a urinalysis. The films were interpreted by both the EP and radiologist as normal; the results of the urinalysis were also normal. The patient was diagnosed with a lower back strain secondary to the motor vehicle crash and was discharged home with an analgesic.

The next day, however, the patient began to complain of increased back pain and lower-extremity numbness and weakness. He was brought back to the same hospital ED where he was noted to have severe weakness of both lower extremities and decreased sensation to touch. Additional imaging was performed, which demonstrated a fracture of T11 with spinal cord impingement. He was taken to surgery, but unfortunately the injury was permanent, and the patient was left with lower-extremity paralysis and bowel and bladder incontinence.

The plaintiff sued the EP and the radiologist for not properly interpreting the initial X-rays. The defendants denied liability, asserting the patient’s injury was a result of the collision and that nothing could have prevented it. According to a published account, the jury returned a verdict finding the EP to be 40% at fault and the radiologist 60% at fault.

Discussion

Emergency physicians frequently manage patients experiencing pain or injury following a motor vehicle crash. If the patient is complaining of neck or back pain, the prehospital providers will immobilize the patient with a rigid cervical collar (ie, if neck pain is present) and a long backboard if pain anywhere along the spine is present (ie, cervical, thoracic, or lumbar).

When the initial airway, breathing, circulation, and disability assessment for the trauma patient is performed and found to be normal, a secondary examination should be performed. Trauma patients with back pain should be log-rolled onto their side, with spinal immobilization followed by visual inspection and palpation/percussion of the midline of the thoracic and lumbar spine. The presence of midline tenderness suggests an acute injury and the need to keep the patient immobilized. Patients should be removed off the backboard and onto the gurney mattress while immobilizing the spine. The standard hospital mattress provides acceptable spinal support.1

Historically, plain radiographs of the thoracic and lumbar spine have been the imaging test of choice in the initial evaluation of suspected traumatic spinal column injury. However, similar to cervical spine trauma, computed tomography (CT) is assuming a larger role in the evaluation of patients with suspected thoracic or lumbar spine injury. When thoracic and abdominal CT scans are performed to evaluate for possible chest or abdominal trauma, those images can be reformatted and used to reconstruct images of the thoracic and lumbar spine, significantly reducing radiation exposure.1 While CT is the gold standard imaging study for evaluation of bony or ligamentous injury of the spine, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the study of choice for patients with neurological deficits or suspected spinal cord injury.

This patient had a completely normal neurological examination at initial presentation, so there was no indication for an MRI. The bony injury to T11 must have been very subtle for both the EP and the radiologist to have missed it. Unfortunately, the jury appears to have used the standard of “perfection,” rather than the “reasonable and prudent physician” in judging that the injury should have been detected. This case serves as a reminder that EPs cannot rely on consulting specialists to consistently and reliably provide accurate information. Moreover, this case emphasizes the need to consider CT imaging of the spine in the evaluation of patients with severe back pain of traumatic origin when plain radiographs appear normal.

Hip-Reduction Problem

A 79-year-old man with left hip pain presented to the ED via EMS. The patient stated that when he had bent over to retrieve his dropped glasses, he experienced the immediate onset of left hip pain and fell to the floor. He was unable to get up on his own and called EMS. The patient had undergone total left hip replacement 1 month prior. At presentation, he complained only of severe pain in his left hip; he denied head injury, neck pain or stiffness, chest pain, or abdominal pain. His past medical history was significant for hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. The patient had no known drug allergies.

On physical examination, he was mildly tachycardic. His vital signs were: heart rate, 102 beats/minute; blood pressure, 156/88 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/minutes; and temperature, afebrile. His pulse oximetry was 98% on room air. The HEENT, lung, heart, and abdominal examinations were all normal. Standing at the foot of the bed, the patient had obvious shortening, internal rotation, and adduction of the left leg. The left knee was without tenderness or swelling. The neurovascular examination of the left lower extremity was completely normal.

Plain radiographs of the pelvis and left hip ordered by the EP demonstrated a posterior hip dislocation with intact hardware. The EP consulted the patient’s orthopedic physician, and both agreed the EP should attempt to reduce the dislocation in the ED. Using conscious sedation, the EP was able to reduce the dislocation, but postreduction films demonstrated a new fracture requiring orthopedic surgery. Unfortunately, the patient had a very difficult recovery, ultimately resulting in death.

The patient’s estate sued the EP, stating he should have had the orthopedic physician reduce the dislocation. The defense argued that fracture is a known complication of reduction of a dislocated hip. A defense verdict was returned.

Discussion

Approximately 85% to 90% of hip dislocations are posterior; the remaining 10% are anterior. Posterior hip dislocations are a common complication following total hip-replacement surgery.1 Hip dislocation is a true orthopedic and time-dependent emergency. The longer the hip remains dislocated, the more likely complications are to occur, including osteonecrosis of the femoral head, arthritic degeneration of the hip joint, and long-term neurological sequelae.2 The treatment of posterior hip dislocation (without fracture) is closed reduction as quickly as possible, and preferably within 6 hours.3 As this case demonstrates, minimal forces can result in a hip dislocation following a total hip replacement. In healthy patients, however, significant forces (eg, high-speed motor vehicle crashes) are required to cause posterior hip dislocation.

Patients with a posterior hip dislocation will present in severe pain and an inability to ambulate. In most cases of posterior hip dislocation, the affected lower extremity will be visibly shortened, internally rotated, and adducted. The knee should always be examined for injury, as well as performance of a thorough neurovascular examination of the affected extremity.

Plain X-ray films will usually identify a posterior hip dislocation. On an anteroposterior pelvis X-ray, the femoral head will be seen outside and just superior to the acetabulum. Special attention should be made to the acetabulum to ensure a concomitant acetabular fracture is not missed.

Indications for closed reduction of a posterior hip dislocation include dislocation with or without neurological deficit and no associated fracture, or dislocation with an associated fracture if no neurological deficits are present.2 An open traumatic hip dislocation should only be reduced in the operating room.

It is certainly within the purview of the EP to attempt a closed reduction for a posterior hip dislocation if no contraindications exist. The patient will need to be sedated (ie, procedural sedation, conscious sedation, or moderate sedation) for any chance of success at reduction. While it is beyond the scope of this article to review the various techniques used to reduce a posterior hip dislocation, one of the guiding principles is that after two or three unsuccessful attempts by the EP to reduce the dislocation, no further attempts should be made and orthopedic surgery services should be consulted. This is because the risk of complications increases as the number of failed attempts increase.

It is unclear how many attempts the EP made in this case. Fracture is a known complication when attempting reduction for a hip dislocation, be it an orthopedic surgeon or an EP. It was certainly appropriate for the EP in this case to attempt closed reduction, given the importance of timely reduction.

Reference (Traumatic Back Pain)

- Baron BJ, McSherry KJ, Larson JL, Scalea TM. Spinal and spinal cord trauma In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Cline DM, Ma OJ, Cydulka RK, Meckler GD, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine—A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York: NY: McGraw Hill Medical; 2011:1709-1730.

(Hip-Reduction Problem)

- Dela Cruz JE, Sullivan DN, Varboncouer E, et al. Comparison of proceduralsedation for the reduction of dislocated total hip arthroplasty.West J Emerg Med. 2014:15(1):76-80.

- Davenport M. Joint reduction, hip dislocation, posterior. Medscape Web site. eMedicine.medscape.com/article/109225. Updated February 11, 2014. Accessed January 27, 2015.

- Steele MT, Stubbs AM. Hip and femur injuries. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Cline DM, Ma OJ, Cydulka RK, Meckler GD, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine—A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York: NY: McGraw Hill Medical; 2011:1848-1856.

Traumatic Back Pain

An 84-year-old man with low-back pain following a motor vehicle crash was brought to the ED by emergency medical services (EMS). He had been the restrained driver, stopped at a traffic light, when he was struck from behind by a second vehicle.

In the ED, the patient only complained of low-back pain. He denied any radiation of pain or lower-extremity numbness or weakness. He also denied any head injury, loss of consciousness, neck pain, or abdominal pain. His past medical history was significant for hypertension, arthritis, and coronary artery disease.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were normal. The head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat (HEENT) examination was also normal; specifically, there was no tenderness to palpation of the cervical spine in the posterior midline. Regarding the cardiopulmonary examination, auscultation of the lungs revealed clear, bilateral breath sounds; the heart examination was normal. The patient had a soft abdomen, without tenderness, guarding, or rebound. His pelvis was stable, but he did exhibit some tenderness on palpation of the lower-thoracic and upper-lumbar spine. The neurological examination revealed normal motor strength and sensation in the lower extremities.

The emergency physician (EP) ordered X-rays of the thoracic and lumbar spine and a urinalysis. The films were interpreted by both the EP and radiologist as normal; the results of the urinalysis were also normal. The patient was diagnosed with a lower back strain secondary to the motor vehicle crash and was discharged home with an analgesic.

The next day, however, the patient began to complain of increased back pain and lower-extremity numbness and weakness. He was brought back to the same hospital ED where he was noted to have severe weakness of both lower extremities and decreased sensation to touch. Additional imaging was performed, which demonstrated a fracture of T11 with spinal cord impingement. He was taken to surgery, but unfortunately the injury was permanent, and the patient was left with lower-extremity paralysis and bowel and bladder incontinence.

The plaintiff sued the EP and the radiologist for not properly interpreting the initial X-rays. The defendants denied liability, asserting the patient’s injury was a result of the collision and that nothing could have prevented it. According to a published account, the jury returned a verdict finding the EP to be 40% at fault and the radiologist 60% at fault.

Discussion

Emergency physicians frequently manage patients experiencing pain or injury following a motor vehicle crash. If the patient is complaining of neck or back pain, the prehospital providers will immobilize the patient with a rigid cervical collar (ie, if neck pain is present) and a long backboard if pain anywhere along the spine is present (ie, cervical, thoracic, or lumbar).

When the initial airway, breathing, circulation, and disability assessment for the trauma patient is performed and found to be normal, a secondary examination should be performed. Trauma patients with back pain should be log-rolled onto their side, with spinal immobilization followed by visual inspection and palpation/percussion of the midline of the thoracic and lumbar spine. The presence of midline tenderness suggests an acute injury and the need to keep the patient immobilized. Patients should be removed off the backboard and onto the gurney mattress while immobilizing the spine. The standard hospital mattress provides acceptable spinal support.1

Historically, plain radiographs of the thoracic and lumbar spine have been the imaging test of choice in the initial evaluation of suspected traumatic spinal column injury. However, similar to cervical spine trauma, computed tomography (CT) is assuming a larger role in the evaluation of patients with suspected thoracic or lumbar spine injury. When thoracic and abdominal CT scans are performed to evaluate for possible chest or abdominal trauma, those images can be reformatted and used to reconstruct images of the thoracic and lumbar spine, significantly reducing radiation exposure.1 While CT is the gold standard imaging study for evaluation of bony or ligamentous injury of the spine, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the study of choice for patients with neurological deficits or suspected spinal cord injury.

This patient had a completely normal neurological examination at initial presentation, so there was no indication for an MRI. The bony injury to T11 must have been very subtle for both the EP and the radiologist to have missed it. Unfortunately, the jury appears to have used the standard of “perfection,” rather than the “reasonable and prudent physician” in judging that the injury should have been detected. This case serves as a reminder that EPs cannot rely on consulting specialists to consistently and reliably provide accurate information. Moreover, this case emphasizes the need to consider CT imaging of the spine in the evaluation of patients with severe back pain of traumatic origin when plain radiographs appear normal.

Hip-Reduction Problem

A 79-year-old man with left hip pain presented to the ED via EMS. The patient stated that when he had bent over to retrieve his dropped glasses, he experienced the immediate onset of left hip pain and fell to the floor. He was unable to get up on his own and called EMS. The patient had undergone total left hip replacement 1 month prior. At presentation, he complained only of severe pain in his left hip; he denied head injury, neck pain or stiffness, chest pain, or abdominal pain. His past medical history was significant for hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. The patient had no known drug allergies.