User login

A trainee’s path to fighting addiction

When I came to this country, even before my current residency, I launched my addiction psychiatry career by researching nicotine addiction in schizophrenia patients. Those early experiences gave me a greater understanding of the health concerns and life experiences of people with addictions – and those more likely to develop them.

So imagine my excitement when I first became acquainted with the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry (AAAP). I first learned about the AAAP, its mission, and activities at the 2017 American Psychiatric Association’s annual meeting in San Diego.

Getting in and involved

After returning to New York, I took those next steps and joined up, which opened the AAAP gates so I could receive its newsletters and submission calls, gain access to resources such as The American Journal on Addictions, survey the various joinable task forces, as well as discover who might be available to me as a mentor as part of the AAAP’s mentor-mentee program.

Sometime during my third-year residency training, I received a member-email advertising the AAAP 28th Annual Meeting and Scientific Symposium, and soon after that, received another email calling for research submissions to be presented there, as well as an invitation to apply for a trainee travel scholarship that would defray the cost for and allow its fellows to attend the meeting in San Diego. That alone was enticing enough to apply. But even more enticing was the opportunity to showcase the addiction work I had been doing during my residency, as well as to meet other members at various levels of the AAAP to determine whether I wanted to become more involved.

Pursuing experiences

I did not think twice about applying for the poster presentation and the travel scholarship. The AAAP’s online application forms for both were easy to understand and very well structured, which greatly helped me with filling out and formatting my applications. Taking the initiative toward even these first AAAP offerings brought more positive echoes. I was thrilled when the poster I proposed was accepted, mostly because it would give me the chance to present my recent addiction psych work from a higher platform. A few weeks later, I was thrilled again when I received an AAAP email congratulating me on being awarded the San Diego 28th annual meeting travel scholarship, which would waive the annual membership and conference registration fees, in addition to defraying my travel costs. Pacific breezes, here I come. And there I went. (Thanks to my extremely supportive training director, who first nominated me for the award.)

On the ground at 2017 AAAP

The 28th AAAP annual meeting opened on a balmy December Thursday, and that’s the day I arrived. I attended many addiction workshops and symposiums, which featured premier figures in addiction psychiatry. Of the numerous trainee-specific events I attended, the most informative was the “Fellowship Forum: Exploring the Field of Addiction Psychiatry.” At this forum, I learned the true benefits of doing an addiction psychiatry fellowship, while meeting many of the fellowship program directors of top institutions. Having them all under one “roof” made it easy to compare and contrast the specific training they offered.

Then came what were, for me, major highlights of the AAAP 2017. After I delivered my poster presentation and shared my research, I was able to receive very close, constructive feedback from the field’s most experienced professionals. And, finally, I met my AAAP mentors face to face: Dr. Amy Yule of Harvard Medical School, Boston; Dr. Thomas Penders, of East Carolina University, Greenville, N.C.; and Dr. Cornel Stanciu of Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H.

One AAAP trainee’s takeaways

All AAAP trainees, fellows, presenters leave the meeting with their own conclusions, but my biggest takeaways were:

- Regarding barriers to buprenorphine, emerging research supports similar efficacy for long-acting injectable naltrexone.

- Various protocols for rapid implementation of naltrexone are being used, and these allow for smoother transition and shorter “washout” periods.

- We should not overlook the effects of tobacco use in our patient population – and should address it aggressively, regardless of psychiatric comorbidities.

- The cannabinoid CBD receptors that exist on the dopamine pathway strengthen and complicate their relationship with psychosis.

- , especially in rural and remote settings. The body of evidence supporting its efficacy is expanding.

- Synthetic cannabinoids are prevalent, and toxidromes exist – yet, trainees are not current on these.

The challenges facing those of us dedicated to fighting addiction have never been greater. I would urge more trainees and psychiatrists to join the AAAP in light of the opioid crisis and the potential fallout tied to marijuana legalization. I am grateful to have the opportunity to join my colleagues in this fight. Becoming part of the AAAP has led to a highly rewarding, career-enriching experience.

This article was updated 1/17/17.

Dr. Ahmed is a third-year resident in the department of psychiatry at Nassau University Medical Center, East Meadow, New York. Besides addiction psychiatry, his interests include public social psychiatry, health care policy, health disparities, and mental health stigma. Dr. Ahmed is a member of the American Psychiatric Association, the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, and the American Association for Social Psychiatry.

When I came to this country, even before my current residency, I launched my addiction psychiatry career by researching nicotine addiction in schizophrenia patients. Those early experiences gave me a greater understanding of the health concerns and life experiences of people with addictions – and those more likely to develop them.

So imagine my excitement when I first became acquainted with the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry (AAAP). I first learned about the AAAP, its mission, and activities at the 2017 American Psychiatric Association’s annual meeting in San Diego.

Getting in and involved

After returning to New York, I took those next steps and joined up, which opened the AAAP gates so I could receive its newsletters and submission calls, gain access to resources such as The American Journal on Addictions, survey the various joinable task forces, as well as discover who might be available to me as a mentor as part of the AAAP’s mentor-mentee program.

Sometime during my third-year residency training, I received a member-email advertising the AAAP 28th Annual Meeting and Scientific Symposium, and soon after that, received another email calling for research submissions to be presented there, as well as an invitation to apply for a trainee travel scholarship that would defray the cost for and allow its fellows to attend the meeting in San Diego. That alone was enticing enough to apply. But even more enticing was the opportunity to showcase the addiction work I had been doing during my residency, as well as to meet other members at various levels of the AAAP to determine whether I wanted to become more involved.

Pursuing experiences

I did not think twice about applying for the poster presentation and the travel scholarship. The AAAP’s online application forms for both were easy to understand and very well structured, which greatly helped me with filling out and formatting my applications. Taking the initiative toward even these first AAAP offerings brought more positive echoes. I was thrilled when the poster I proposed was accepted, mostly because it would give me the chance to present my recent addiction psych work from a higher platform. A few weeks later, I was thrilled again when I received an AAAP email congratulating me on being awarded the San Diego 28th annual meeting travel scholarship, which would waive the annual membership and conference registration fees, in addition to defraying my travel costs. Pacific breezes, here I come. And there I went. (Thanks to my extremely supportive training director, who first nominated me for the award.)

On the ground at 2017 AAAP

The 28th AAAP annual meeting opened on a balmy December Thursday, and that’s the day I arrived. I attended many addiction workshops and symposiums, which featured premier figures in addiction psychiatry. Of the numerous trainee-specific events I attended, the most informative was the “Fellowship Forum: Exploring the Field of Addiction Psychiatry.” At this forum, I learned the true benefits of doing an addiction psychiatry fellowship, while meeting many of the fellowship program directors of top institutions. Having them all under one “roof” made it easy to compare and contrast the specific training they offered.

Then came what were, for me, major highlights of the AAAP 2017. After I delivered my poster presentation and shared my research, I was able to receive very close, constructive feedback from the field’s most experienced professionals. And, finally, I met my AAAP mentors face to face: Dr. Amy Yule of Harvard Medical School, Boston; Dr. Thomas Penders, of East Carolina University, Greenville, N.C.; and Dr. Cornel Stanciu of Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H.

One AAAP trainee’s takeaways

All AAAP trainees, fellows, presenters leave the meeting with their own conclusions, but my biggest takeaways were:

- Regarding barriers to buprenorphine, emerging research supports similar efficacy for long-acting injectable naltrexone.

- Various protocols for rapid implementation of naltrexone are being used, and these allow for smoother transition and shorter “washout” periods.

- We should not overlook the effects of tobacco use in our patient population – and should address it aggressively, regardless of psychiatric comorbidities.

- The cannabinoid CBD receptors that exist on the dopamine pathway strengthen and complicate their relationship with psychosis.

- , especially in rural and remote settings. The body of evidence supporting its efficacy is expanding.

- Synthetic cannabinoids are prevalent, and toxidromes exist – yet, trainees are not current on these.

The challenges facing those of us dedicated to fighting addiction have never been greater. I would urge more trainees and psychiatrists to join the AAAP in light of the opioid crisis and the potential fallout tied to marijuana legalization. I am grateful to have the opportunity to join my colleagues in this fight. Becoming part of the AAAP has led to a highly rewarding, career-enriching experience.

This article was updated 1/17/17.

Dr. Ahmed is a third-year resident in the department of psychiatry at Nassau University Medical Center, East Meadow, New York. Besides addiction psychiatry, his interests include public social psychiatry, health care policy, health disparities, and mental health stigma. Dr. Ahmed is a member of the American Psychiatric Association, the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, and the American Association for Social Psychiatry.

When I came to this country, even before my current residency, I launched my addiction psychiatry career by researching nicotine addiction in schizophrenia patients. Those early experiences gave me a greater understanding of the health concerns and life experiences of people with addictions – and those more likely to develop them.

So imagine my excitement when I first became acquainted with the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry (AAAP). I first learned about the AAAP, its mission, and activities at the 2017 American Psychiatric Association’s annual meeting in San Diego.

Getting in and involved

After returning to New York, I took those next steps and joined up, which opened the AAAP gates so I could receive its newsletters and submission calls, gain access to resources such as The American Journal on Addictions, survey the various joinable task forces, as well as discover who might be available to me as a mentor as part of the AAAP’s mentor-mentee program.

Sometime during my third-year residency training, I received a member-email advertising the AAAP 28th Annual Meeting and Scientific Symposium, and soon after that, received another email calling for research submissions to be presented there, as well as an invitation to apply for a trainee travel scholarship that would defray the cost for and allow its fellows to attend the meeting in San Diego. That alone was enticing enough to apply. But even more enticing was the opportunity to showcase the addiction work I had been doing during my residency, as well as to meet other members at various levels of the AAAP to determine whether I wanted to become more involved.

Pursuing experiences

I did not think twice about applying for the poster presentation and the travel scholarship. The AAAP’s online application forms for both were easy to understand and very well structured, which greatly helped me with filling out and formatting my applications. Taking the initiative toward even these first AAAP offerings brought more positive echoes. I was thrilled when the poster I proposed was accepted, mostly because it would give me the chance to present my recent addiction psych work from a higher platform. A few weeks later, I was thrilled again when I received an AAAP email congratulating me on being awarded the San Diego 28th annual meeting travel scholarship, which would waive the annual membership and conference registration fees, in addition to defraying my travel costs. Pacific breezes, here I come. And there I went. (Thanks to my extremely supportive training director, who first nominated me for the award.)

On the ground at 2017 AAAP

The 28th AAAP annual meeting opened on a balmy December Thursday, and that’s the day I arrived. I attended many addiction workshops and symposiums, which featured premier figures in addiction psychiatry. Of the numerous trainee-specific events I attended, the most informative was the “Fellowship Forum: Exploring the Field of Addiction Psychiatry.” At this forum, I learned the true benefits of doing an addiction psychiatry fellowship, while meeting many of the fellowship program directors of top institutions. Having them all under one “roof” made it easy to compare and contrast the specific training they offered.

Then came what were, for me, major highlights of the AAAP 2017. After I delivered my poster presentation and shared my research, I was able to receive very close, constructive feedback from the field’s most experienced professionals. And, finally, I met my AAAP mentors face to face: Dr. Amy Yule of Harvard Medical School, Boston; Dr. Thomas Penders, of East Carolina University, Greenville, N.C.; and Dr. Cornel Stanciu of Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H.

One AAAP trainee’s takeaways

All AAAP trainees, fellows, presenters leave the meeting with their own conclusions, but my biggest takeaways were:

- Regarding barriers to buprenorphine, emerging research supports similar efficacy for long-acting injectable naltrexone.

- Various protocols for rapid implementation of naltrexone are being used, and these allow for smoother transition and shorter “washout” periods.

- We should not overlook the effects of tobacco use in our patient population – and should address it aggressively, regardless of psychiatric comorbidities.

- The cannabinoid CBD receptors that exist on the dopamine pathway strengthen and complicate their relationship with psychosis.

- , especially in rural and remote settings. The body of evidence supporting its efficacy is expanding.

- Synthetic cannabinoids are prevalent, and toxidromes exist – yet, trainees are not current on these.

The challenges facing those of us dedicated to fighting addiction have never been greater. I would urge more trainees and psychiatrists to join the AAAP in light of the opioid crisis and the potential fallout tied to marijuana legalization. I am grateful to have the opportunity to join my colleagues in this fight. Becoming part of the AAAP has led to a highly rewarding, career-enriching experience.

This article was updated 1/17/17.

Dr. Ahmed is a third-year resident in the department of psychiatry at Nassau University Medical Center, East Meadow, New York. Besides addiction psychiatry, his interests include public social psychiatry, health care policy, health disparities, and mental health stigma. Dr. Ahmed is a member of the American Psychiatric Association, the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, and the American Association for Social Psychiatry.

Pediatric Leg Ulcers: Going Out on a Limb for the Diagnosis

Compared to the adult population with a prevalence of lower extremity ulcers reaching approximately 1% to 2%, pediatric leg ulcers are much less common and require dermatologists to think outside the box for differential diagnoses.1 Although the most common types of lower extremity ulcers in the adult population include venous leg ulcers, arterial ulcers, and diabetic foot ulcers, the etiology for pediatric ulcers is vastly different, and thus these statistics cannot be extrapolated to this younger group. Additionally, scant research has been conducted to construct a systemic algorithm for helping these patients. In 1998, Dangoisse and Song2 concluded that juvenile leg ulcers secondary to causes other than trauma are uncommon, with the infectious origin fairly frequent; however, they stated further workup should be pursued to investigate for underlying vascular, metabolic, hematologic, and immunologic disorders. They also added that an infectious etiology must be ruled out with foremost priority, and a subsequent biopsy could assist in the ultimate diagnosis.2

To further investigate pediatric leg ulcers and their unique causes, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE published from 1995 to present was performed using the term pediatric leg ulcers. The search yielded approximately 100 relevant articles. The search generated more than 47 different causes of leg ulcers and produced unusual etiologies such as trophic ulcers of Lesch-Nyhan syndrome, ulcers secondary to disabling pansclerotic morphea of childhood, dracunculiasis, and dengue hemorrhagic fever, among others.3-6 The articles were further divided into 4 categories to better characterize the causes—hematologic, infectious, genodermatoses, and autoimmune—which are reviewed here.

Hematologic Causes

Hematologic causes predominated in this juvenile arena, with sickle cell disease specifically comprising the vast majority of causes of pediatric leg ulcers.7,8 Sickle cell disease is a chronic disease with anemia and sickling crises contributing to a myriad of health problems. In a 13-year study following 44 patients with sickle cell disease, Silva et al8 found that leg ulcers affected approximately 5% of pediatric patients; however, the authors noted that this statistic may underestimate the accurate prevalence, as the ulcers typically affect older children and their study population was a younger distribution. The lesions manifest as painful, well-demarcated ulcers with surrounding hyperpigmentation mimicking venous ulcers.9 The ulcers may be readily diagnosed if the history is known, and it is critical to maximize care of these lesions, as they may heal at least 10 times slower than venous leg ulcers and frequently recur, with the vast majority recurring in less than 1 year. Furthermore, the presence of leg ulcers in sickle cell disease may be associated with increased hemolysis and pulmonary hypertension, demonstrating the severity of disease in these patients.10 Local wound care is the mainstay of therapy including compression, leg elevation, and adjuvant wound dressings. Systemic therapies such as hydroxyurea, zinc supplementation, pentoxifylline, and transfusion therapy may be pursued in refractory cases, though an ideal systemic regimen is still under exploration.9,10 Other major hematologic abnormalities leading to leg ulcers included additional causes of anemia, such as thalassemia and hereditary spherocytosis. These patients additionally were treated with local wound care to maximize healing.11,12

Infectious Causes

Infectious causes of pediatric ulcers were much more varied with a myriad of etiologies such as ulcers from ecthyma gangrenosum caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa to leishmaniasis and tularemia. The most commonly reported infection causing leg ulcers in the pediatric literature was Mycobacterium ulcerans, which led to the characteristic Buruli ulcer; however, this infection is likely grossly overrepresented, as more common etiologies are underreported; the geographic location for a Buruli ulcer also is important, as cases are rare in the United States.13,14 A Buruli ulcer presents as a well-defined, painless, chronic skin ulceration and most commonly affects children.15 Exposure to stagnant water in tropical climates is thought to play a role in the pathogenesis of this slow-growing, acid-fast bacillus. The bacteria produces a potent cytotoxin called mycolactone, which then induces tissue necrosis and ulceration, leading to the clinical manifestations of disease.15 The ulcers may heal spontaneously; however, up to 15% can be associated with osteomyelitis; treatment includes surgical excision and prolonged antibiotics.14 Given the numerous additional causes of pediatric leg ulcers harboring infections, it is critical to be cognizant of the travel history and immune status of the patient. The infectious cause of leg ulcers likely predominates, making a biopsy with culture necessary in any nonhealing wound in this population prior to pursuing further workup.

Genodermatoses

A number of genodermatoses also contribute to persistent wounds in the pediatric population; specifically, genodermatoses that predispose to neuropathies and decreased pain sensation, which affect the child’s ability to detect sensation in the lower extremities, can result in inadvertent trauma leading to refractory wounds. For example, hereditary, sensory, and autonomic neuropathies are rare disorders causing progressive distal sensory loss, leading to ulcerations, osteomyelitis, arthritis, and even amputation.16 Hereditary, sensory, and autonomic neuropathies are further categorized into several different types; however, the unifying theme of diminished sensation is the culprit for troublesome wounds. Therapeutic endeavors to maximize preventative care with orthotics are vital in allaying recurrent wounds in these patients. Another uncommon hereditary disorder that promotes poor wound healing is caused by an inborn error of collagen synthesis. Prolidase deficiency is an autosomal-recessive condition resulting in characteristic facies, recurrent infections, and recalcitrant leg ulcerations due to impaired collagen formation.17 More than 50% of affected patients experience leg ulcers comprised of irregular borders with prominent granulation tissue. Treatment is aimed at restoring collagen synthesis and optimizing wound healing with the use of topical proline, glycine, and even growth hormone to promote repair.18 Additional genodermatoses predisposing to leg ulcerations include Lesch-Nyhan syndrome due to self-mutilating behaviors and epidermolysis bullosa due to impaired barrier and a decreased ability to repair cutaneous defects.

Autoimmune Causes

Although a much smaller category, ulcers due to autoimmune etiologies were reported in the literature. Fibrosing disorders including morphea and scleroderma can cause extensive disease in severe cases. Disabling pansclerotic morphea of childhood can cause sclerosis that extends into muscle, fascia, and even bone, resulting in contractures and ulcerations.4 The initial areas of involvement are the arms and legs, followed by spread to the trunk and head and neck area.4 Immunosuppressant therapy is needed to halt disease progression. Pediatric cases of systemic lupus erythematosus also have been associated with digital ulcers. One case was thought to be due to vasculitis,19 and another resulted from peripheral gangrene in association with Raynaud phenomenon.20 Albeit rare, it is important to consider autoimmune connective tissue diseases when faced with recurrent wounds and to search for additional symptoms that might yield the underlying diagnosis.

Conclusion

Pediatric leg ulcers are a relatively uncommon phenomenon; however, the etiologies are vastly different than adult leg ulcers and require careful contemplation surrounding the cardinal etiology. The main categories of disease in pediatric leg ulcers after trauma include hematologic abnormalities, infection, genodermatoses, and autoimmune diseases. The evaluation requires obtaining a thorough history and physical examination, including pertinent family histories for associated inheritable disorders. If the clinical picture remains elusive and the ulceration fails conservative management, a biopsy with tissue culture may be necessary to rule out an infectious etiology.

- Morton LM, Phillips TJ. Wound healing and treating wounds: differential diagnosis and evaluation of chronic wounds. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:589-605.

- Dangoisse C, Song M. Particular aspects of ulcers in children [in French]. Rev Med Brux. 1998;18:241-244.

- Kesiktas E, Gencel E, Acarturk S. Lesch-Nyhan syndrome: reconstruction of a calcaneal defect with a sural flap. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2006;40:117-119.

- Kura MM, Jindal SR. Disabling pansclerotic morphea of childhood with extracutaneous manifestations. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:159.

- Spring M, Spearman P. Dracunculiasis: report of an imported case in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:749-750.

- Vitug MR, Dayrit JF, Oblepias MS, et al. Group A streptococcal septic vasculitis in a child with dengue hemorrhagic fever. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1458-1461.

- Adegoke SA, Adeodu OO, Adekile AD. Sickle cell disease clinical phenotypes in children from South-Western Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2015;18:95-101.

- Silva IV, Reis AF, Palaré MJ, et al. Sickle cell disease in children: chronic complications and search of predictive factors for adverse outcomes. Eur J Haematol. 2015;94:157-161.

- Trent JT, Kirsner RS. Leg ulcers in sickle cell disease. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2004;17:410-416.

- Delaney KM, Axelrod KC, Buscetta A, et al. Leg ulcers in sickle cell disease: current patterns and practices. Hemoglobin. 2013;37:325-332.

- Matta B, Abbas O, Maakaron J, et al. Leg ulcers in patients with B-thalassemia intermedia: a single centre’s experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1245-1250.

- Giraldi S, Abbage KT, Marinoni LP, et al. Leg ulcer in hereditary spherocytosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:427-428.

- Journeau P, Fitoussi F, Jehanno P, et al. Buruli’s ulcer: three cases diagnosed and treated in France. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2003;12: 229-232.

- Raghunathan PL, Whitney EA, Asamoa K, et al. Risk factors for Buruli ulcer disease (Mycobacterium ulcerans infection): results from a case-control study in Ghana. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1445-1453.

- Buruli ulcer (Mycobacterium ulcerans infection). World Health Organization website. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs199/en/. Updated February 2017. Accessed December 19, 2017.

- 16. Rao AG. Painless ulcers and fissures of toes: hereditary sensory neuropathy, not leprosy. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:121.

- Adışen E, Erduran FB, Ezqü FS, et al. A rare cause of lower extremity ulcers: prolidase deficiency. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2016;15:86-91.

- Trent JT, Kirsner RS. Leg ulcers secondary to prolidase deficiency. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2004;17:468-472.

- Olivieri AN, Mellos A, Duilio C, et al. Refractory vasculitis ulcer of the toe in adolescent suffering from systemic lupus erythematosus treated successfully with hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Ital J Pediatr. 2010;36:72.

- Ziaee V, Yeganeh MH, Moradinejad MH. Peripheral gangrene: a rare presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus in a child. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:337-340.

Compared to the adult population with a prevalence of lower extremity ulcers reaching approximately 1% to 2%, pediatric leg ulcers are much less common and require dermatologists to think outside the box for differential diagnoses.1 Although the most common types of lower extremity ulcers in the adult population include venous leg ulcers, arterial ulcers, and diabetic foot ulcers, the etiology for pediatric ulcers is vastly different, and thus these statistics cannot be extrapolated to this younger group. Additionally, scant research has been conducted to construct a systemic algorithm for helping these patients. In 1998, Dangoisse and Song2 concluded that juvenile leg ulcers secondary to causes other than trauma are uncommon, with the infectious origin fairly frequent; however, they stated further workup should be pursued to investigate for underlying vascular, metabolic, hematologic, and immunologic disorders. They also added that an infectious etiology must be ruled out with foremost priority, and a subsequent biopsy could assist in the ultimate diagnosis.2

To further investigate pediatric leg ulcers and their unique causes, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE published from 1995 to present was performed using the term pediatric leg ulcers. The search yielded approximately 100 relevant articles. The search generated more than 47 different causes of leg ulcers and produced unusual etiologies such as trophic ulcers of Lesch-Nyhan syndrome, ulcers secondary to disabling pansclerotic morphea of childhood, dracunculiasis, and dengue hemorrhagic fever, among others.3-6 The articles were further divided into 4 categories to better characterize the causes—hematologic, infectious, genodermatoses, and autoimmune—which are reviewed here.

Hematologic Causes

Hematologic causes predominated in this juvenile arena, with sickle cell disease specifically comprising the vast majority of causes of pediatric leg ulcers.7,8 Sickle cell disease is a chronic disease with anemia and sickling crises contributing to a myriad of health problems. In a 13-year study following 44 patients with sickle cell disease, Silva et al8 found that leg ulcers affected approximately 5% of pediatric patients; however, the authors noted that this statistic may underestimate the accurate prevalence, as the ulcers typically affect older children and their study population was a younger distribution. The lesions manifest as painful, well-demarcated ulcers with surrounding hyperpigmentation mimicking venous ulcers.9 The ulcers may be readily diagnosed if the history is known, and it is critical to maximize care of these lesions, as they may heal at least 10 times slower than venous leg ulcers and frequently recur, with the vast majority recurring in less than 1 year. Furthermore, the presence of leg ulcers in sickle cell disease may be associated with increased hemolysis and pulmonary hypertension, demonstrating the severity of disease in these patients.10 Local wound care is the mainstay of therapy including compression, leg elevation, and adjuvant wound dressings. Systemic therapies such as hydroxyurea, zinc supplementation, pentoxifylline, and transfusion therapy may be pursued in refractory cases, though an ideal systemic regimen is still under exploration.9,10 Other major hematologic abnormalities leading to leg ulcers included additional causes of anemia, such as thalassemia and hereditary spherocytosis. These patients additionally were treated with local wound care to maximize healing.11,12

Infectious Causes

Infectious causes of pediatric ulcers were much more varied with a myriad of etiologies such as ulcers from ecthyma gangrenosum caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa to leishmaniasis and tularemia. The most commonly reported infection causing leg ulcers in the pediatric literature was Mycobacterium ulcerans, which led to the characteristic Buruli ulcer; however, this infection is likely grossly overrepresented, as more common etiologies are underreported; the geographic location for a Buruli ulcer also is important, as cases are rare in the United States.13,14 A Buruli ulcer presents as a well-defined, painless, chronic skin ulceration and most commonly affects children.15 Exposure to stagnant water in tropical climates is thought to play a role in the pathogenesis of this slow-growing, acid-fast bacillus. The bacteria produces a potent cytotoxin called mycolactone, which then induces tissue necrosis and ulceration, leading to the clinical manifestations of disease.15 The ulcers may heal spontaneously; however, up to 15% can be associated with osteomyelitis; treatment includes surgical excision and prolonged antibiotics.14 Given the numerous additional causes of pediatric leg ulcers harboring infections, it is critical to be cognizant of the travel history and immune status of the patient. The infectious cause of leg ulcers likely predominates, making a biopsy with culture necessary in any nonhealing wound in this population prior to pursuing further workup.

Genodermatoses

A number of genodermatoses also contribute to persistent wounds in the pediatric population; specifically, genodermatoses that predispose to neuropathies and decreased pain sensation, which affect the child’s ability to detect sensation in the lower extremities, can result in inadvertent trauma leading to refractory wounds. For example, hereditary, sensory, and autonomic neuropathies are rare disorders causing progressive distal sensory loss, leading to ulcerations, osteomyelitis, arthritis, and even amputation.16 Hereditary, sensory, and autonomic neuropathies are further categorized into several different types; however, the unifying theme of diminished sensation is the culprit for troublesome wounds. Therapeutic endeavors to maximize preventative care with orthotics are vital in allaying recurrent wounds in these patients. Another uncommon hereditary disorder that promotes poor wound healing is caused by an inborn error of collagen synthesis. Prolidase deficiency is an autosomal-recessive condition resulting in characteristic facies, recurrent infections, and recalcitrant leg ulcerations due to impaired collagen formation.17 More than 50% of affected patients experience leg ulcers comprised of irregular borders with prominent granulation tissue. Treatment is aimed at restoring collagen synthesis and optimizing wound healing with the use of topical proline, glycine, and even growth hormone to promote repair.18 Additional genodermatoses predisposing to leg ulcerations include Lesch-Nyhan syndrome due to self-mutilating behaviors and epidermolysis bullosa due to impaired barrier and a decreased ability to repair cutaneous defects.

Autoimmune Causes

Although a much smaller category, ulcers due to autoimmune etiologies were reported in the literature. Fibrosing disorders including morphea and scleroderma can cause extensive disease in severe cases. Disabling pansclerotic morphea of childhood can cause sclerosis that extends into muscle, fascia, and even bone, resulting in contractures and ulcerations.4 The initial areas of involvement are the arms and legs, followed by spread to the trunk and head and neck area.4 Immunosuppressant therapy is needed to halt disease progression. Pediatric cases of systemic lupus erythematosus also have been associated with digital ulcers. One case was thought to be due to vasculitis,19 and another resulted from peripheral gangrene in association with Raynaud phenomenon.20 Albeit rare, it is important to consider autoimmune connective tissue diseases when faced with recurrent wounds and to search for additional symptoms that might yield the underlying diagnosis.

Conclusion

Pediatric leg ulcers are a relatively uncommon phenomenon; however, the etiologies are vastly different than adult leg ulcers and require careful contemplation surrounding the cardinal etiology. The main categories of disease in pediatric leg ulcers after trauma include hematologic abnormalities, infection, genodermatoses, and autoimmune diseases. The evaluation requires obtaining a thorough history and physical examination, including pertinent family histories for associated inheritable disorders. If the clinical picture remains elusive and the ulceration fails conservative management, a biopsy with tissue culture may be necessary to rule out an infectious etiology.

Compared to the adult population with a prevalence of lower extremity ulcers reaching approximately 1% to 2%, pediatric leg ulcers are much less common and require dermatologists to think outside the box for differential diagnoses.1 Although the most common types of lower extremity ulcers in the adult population include venous leg ulcers, arterial ulcers, and diabetic foot ulcers, the etiology for pediatric ulcers is vastly different, and thus these statistics cannot be extrapolated to this younger group. Additionally, scant research has been conducted to construct a systemic algorithm for helping these patients. In 1998, Dangoisse and Song2 concluded that juvenile leg ulcers secondary to causes other than trauma are uncommon, with the infectious origin fairly frequent; however, they stated further workup should be pursued to investigate for underlying vascular, metabolic, hematologic, and immunologic disorders. They also added that an infectious etiology must be ruled out with foremost priority, and a subsequent biopsy could assist in the ultimate diagnosis.2

To further investigate pediatric leg ulcers and their unique causes, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE published from 1995 to present was performed using the term pediatric leg ulcers. The search yielded approximately 100 relevant articles. The search generated more than 47 different causes of leg ulcers and produced unusual etiologies such as trophic ulcers of Lesch-Nyhan syndrome, ulcers secondary to disabling pansclerotic morphea of childhood, dracunculiasis, and dengue hemorrhagic fever, among others.3-6 The articles were further divided into 4 categories to better characterize the causes—hematologic, infectious, genodermatoses, and autoimmune—which are reviewed here.

Hematologic Causes

Hematologic causes predominated in this juvenile arena, with sickle cell disease specifically comprising the vast majority of causes of pediatric leg ulcers.7,8 Sickle cell disease is a chronic disease with anemia and sickling crises contributing to a myriad of health problems. In a 13-year study following 44 patients with sickle cell disease, Silva et al8 found that leg ulcers affected approximately 5% of pediatric patients; however, the authors noted that this statistic may underestimate the accurate prevalence, as the ulcers typically affect older children and their study population was a younger distribution. The lesions manifest as painful, well-demarcated ulcers with surrounding hyperpigmentation mimicking venous ulcers.9 The ulcers may be readily diagnosed if the history is known, and it is critical to maximize care of these lesions, as they may heal at least 10 times slower than venous leg ulcers and frequently recur, with the vast majority recurring in less than 1 year. Furthermore, the presence of leg ulcers in sickle cell disease may be associated with increased hemolysis and pulmonary hypertension, demonstrating the severity of disease in these patients.10 Local wound care is the mainstay of therapy including compression, leg elevation, and adjuvant wound dressings. Systemic therapies such as hydroxyurea, zinc supplementation, pentoxifylline, and transfusion therapy may be pursued in refractory cases, though an ideal systemic regimen is still under exploration.9,10 Other major hematologic abnormalities leading to leg ulcers included additional causes of anemia, such as thalassemia and hereditary spherocytosis. These patients additionally were treated with local wound care to maximize healing.11,12

Infectious Causes

Infectious causes of pediatric ulcers were much more varied with a myriad of etiologies such as ulcers from ecthyma gangrenosum caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa to leishmaniasis and tularemia. The most commonly reported infection causing leg ulcers in the pediatric literature was Mycobacterium ulcerans, which led to the characteristic Buruli ulcer; however, this infection is likely grossly overrepresented, as more common etiologies are underreported; the geographic location for a Buruli ulcer also is important, as cases are rare in the United States.13,14 A Buruli ulcer presents as a well-defined, painless, chronic skin ulceration and most commonly affects children.15 Exposure to stagnant water in tropical climates is thought to play a role in the pathogenesis of this slow-growing, acid-fast bacillus. The bacteria produces a potent cytotoxin called mycolactone, which then induces tissue necrosis and ulceration, leading to the clinical manifestations of disease.15 The ulcers may heal spontaneously; however, up to 15% can be associated with osteomyelitis; treatment includes surgical excision and prolonged antibiotics.14 Given the numerous additional causes of pediatric leg ulcers harboring infections, it is critical to be cognizant of the travel history and immune status of the patient. The infectious cause of leg ulcers likely predominates, making a biopsy with culture necessary in any nonhealing wound in this population prior to pursuing further workup.

Genodermatoses

A number of genodermatoses also contribute to persistent wounds in the pediatric population; specifically, genodermatoses that predispose to neuropathies and decreased pain sensation, which affect the child’s ability to detect sensation in the lower extremities, can result in inadvertent trauma leading to refractory wounds. For example, hereditary, sensory, and autonomic neuropathies are rare disorders causing progressive distal sensory loss, leading to ulcerations, osteomyelitis, arthritis, and even amputation.16 Hereditary, sensory, and autonomic neuropathies are further categorized into several different types; however, the unifying theme of diminished sensation is the culprit for troublesome wounds. Therapeutic endeavors to maximize preventative care with orthotics are vital in allaying recurrent wounds in these patients. Another uncommon hereditary disorder that promotes poor wound healing is caused by an inborn error of collagen synthesis. Prolidase deficiency is an autosomal-recessive condition resulting in characteristic facies, recurrent infections, and recalcitrant leg ulcerations due to impaired collagen formation.17 More than 50% of affected patients experience leg ulcers comprised of irregular borders with prominent granulation tissue. Treatment is aimed at restoring collagen synthesis and optimizing wound healing with the use of topical proline, glycine, and even growth hormone to promote repair.18 Additional genodermatoses predisposing to leg ulcerations include Lesch-Nyhan syndrome due to self-mutilating behaviors and epidermolysis bullosa due to impaired barrier and a decreased ability to repair cutaneous defects.

Autoimmune Causes

Although a much smaller category, ulcers due to autoimmune etiologies were reported in the literature. Fibrosing disorders including morphea and scleroderma can cause extensive disease in severe cases. Disabling pansclerotic morphea of childhood can cause sclerosis that extends into muscle, fascia, and even bone, resulting in contractures and ulcerations.4 The initial areas of involvement are the arms and legs, followed by spread to the trunk and head and neck area.4 Immunosuppressant therapy is needed to halt disease progression. Pediatric cases of systemic lupus erythematosus also have been associated with digital ulcers. One case was thought to be due to vasculitis,19 and another resulted from peripheral gangrene in association with Raynaud phenomenon.20 Albeit rare, it is important to consider autoimmune connective tissue diseases when faced with recurrent wounds and to search for additional symptoms that might yield the underlying diagnosis.

Conclusion

Pediatric leg ulcers are a relatively uncommon phenomenon; however, the etiologies are vastly different than adult leg ulcers and require careful contemplation surrounding the cardinal etiology. The main categories of disease in pediatric leg ulcers after trauma include hematologic abnormalities, infection, genodermatoses, and autoimmune diseases. The evaluation requires obtaining a thorough history and physical examination, including pertinent family histories for associated inheritable disorders. If the clinical picture remains elusive and the ulceration fails conservative management, a biopsy with tissue culture may be necessary to rule out an infectious etiology.

- Morton LM, Phillips TJ. Wound healing and treating wounds: differential diagnosis and evaluation of chronic wounds. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:589-605.

- Dangoisse C, Song M. Particular aspects of ulcers in children [in French]. Rev Med Brux. 1998;18:241-244.

- Kesiktas E, Gencel E, Acarturk S. Lesch-Nyhan syndrome: reconstruction of a calcaneal defect with a sural flap. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2006;40:117-119.

- Kura MM, Jindal SR. Disabling pansclerotic morphea of childhood with extracutaneous manifestations. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:159.

- Spring M, Spearman P. Dracunculiasis: report of an imported case in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:749-750.

- Vitug MR, Dayrit JF, Oblepias MS, et al. Group A streptococcal septic vasculitis in a child with dengue hemorrhagic fever. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1458-1461.

- Adegoke SA, Adeodu OO, Adekile AD. Sickle cell disease clinical phenotypes in children from South-Western Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2015;18:95-101.

- Silva IV, Reis AF, Palaré MJ, et al. Sickle cell disease in children: chronic complications and search of predictive factors for adverse outcomes. Eur J Haematol. 2015;94:157-161.

- Trent JT, Kirsner RS. Leg ulcers in sickle cell disease. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2004;17:410-416.

- Delaney KM, Axelrod KC, Buscetta A, et al. Leg ulcers in sickle cell disease: current patterns and practices. Hemoglobin. 2013;37:325-332.

- Matta B, Abbas O, Maakaron J, et al. Leg ulcers in patients with B-thalassemia intermedia: a single centre’s experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1245-1250.

- Giraldi S, Abbage KT, Marinoni LP, et al. Leg ulcer in hereditary spherocytosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:427-428.

- Journeau P, Fitoussi F, Jehanno P, et al. Buruli’s ulcer: three cases diagnosed and treated in France. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2003;12: 229-232.

- Raghunathan PL, Whitney EA, Asamoa K, et al. Risk factors for Buruli ulcer disease (Mycobacterium ulcerans infection): results from a case-control study in Ghana. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1445-1453.

- Buruli ulcer (Mycobacterium ulcerans infection). World Health Organization website. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs199/en/. Updated February 2017. Accessed December 19, 2017.

- 16. Rao AG. Painless ulcers and fissures of toes: hereditary sensory neuropathy, not leprosy. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:121.

- Adışen E, Erduran FB, Ezqü FS, et al. A rare cause of lower extremity ulcers: prolidase deficiency. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2016;15:86-91.

- Trent JT, Kirsner RS. Leg ulcers secondary to prolidase deficiency. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2004;17:468-472.

- Olivieri AN, Mellos A, Duilio C, et al. Refractory vasculitis ulcer of the toe in adolescent suffering from systemic lupus erythematosus treated successfully with hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Ital J Pediatr. 2010;36:72.

- Ziaee V, Yeganeh MH, Moradinejad MH. Peripheral gangrene: a rare presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus in a child. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:337-340.

- Morton LM, Phillips TJ. Wound healing and treating wounds: differential diagnosis and evaluation of chronic wounds. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:589-605.

- Dangoisse C, Song M. Particular aspects of ulcers in children [in French]. Rev Med Brux. 1998;18:241-244.

- Kesiktas E, Gencel E, Acarturk S. Lesch-Nyhan syndrome: reconstruction of a calcaneal defect with a sural flap. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2006;40:117-119.

- Kura MM, Jindal SR. Disabling pansclerotic morphea of childhood with extracutaneous manifestations. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:159.

- Spring M, Spearman P. Dracunculiasis: report of an imported case in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:749-750.

- Vitug MR, Dayrit JF, Oblepias MS, et al. Group A streptococcal septic vasculitis in a child with dengue hemorrhagic fever. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1458-1461.

- Adegoke SA, Adeodu OO, Adekile AD. Sickle cell disease clinical phenotypes in children from South-Western Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2015;18:95-101.

- Silva IV, Reis AF, Palaré MJ, et al. Sickle cell disease in children: chronic complications and search of predictive factors for adverse outcomes. Eur J Haematol. 2015;94:157-161.

- Trent JT, Kirsner RS. Leg ulcers in sickle cell disease. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2004;17:410-416.

- Delaney KM, Axelrod KC, Buscetta A, et al. Leg ulcers in sickle cell disease: current patterns and practices. Hemoglobin. 2013;37:325-332.

- Matta B, Abbas O, Maakaron J, et al. Leg ulcers in patients with B-thalassemia intermedia: a single centre’s experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1245-1250.

- Giraldi S, Abbage KT, Marinoni LP, et al. Leg ulcer in hereditary spherocytosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:427-428.

- Journeau P, Fitoussi F, Jehanno P, et al. Buruli’s ulcer: three cases diagnosed and treated in France. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2003;12: 229-232.

- Raghunathan PL, Whitney EA, Asamoa K, et al. Risk factors for Buruli ulcer disease (Mycobacterium ulcerans infection): results from a case-control study in Ghana. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1445-1453.

- Buruli ulcer (Mycobacterium ulcerans infection). World Health Organization website. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs199/en/. Updated February 2017. Accessed December 19, 2017.

- 16. Rao AG. Painless ulcers and fissures of toes: hereditary sensory neuropathy, not leprosy. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:121.

- Adışen E, Erduran FB, Ezqü FS, et al. A rare cause of lower extremity ulcers: prolidase deficiency. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2016;15:86-91.

- Trent JT, Kirsner RS. Leg ulcers secondary to prolidase deficiency. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2004;17:468-472.

- Olivieri AN, Mellos A, Duilio C, et al. Refractory vasculitis ulcer of the toe in adolescent suffering from systemic lupus erythematosus treated successfully with hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Ital J Pediatr. 2010;36:72.

- Ziaee V, Yeganeh MH, Moradinejad MH. Peripheral gangrene: a rare presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus in a child. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:337-340.

Vesiculobullous and Pustular Diseases in Newborns

Vesiculobullous eruptions in neonates can readily generate anxiety from parents/guardians and pediatricians over both infectious and noninfectious causes. The role of the dermatology resident is critical to help diminish fear over common vesicular presentations or to escalate care in rarer situations if a more obscure or ominous diagnosis is clouding the patient’s clinical presentation and well-being. This article summarizes both common and uncommon vesiculobullous neonatal diseases to augment precise and efficient diagnoses in this vulnerable patient population.

Steps for Evaluating a Vesiculopustular Eruption

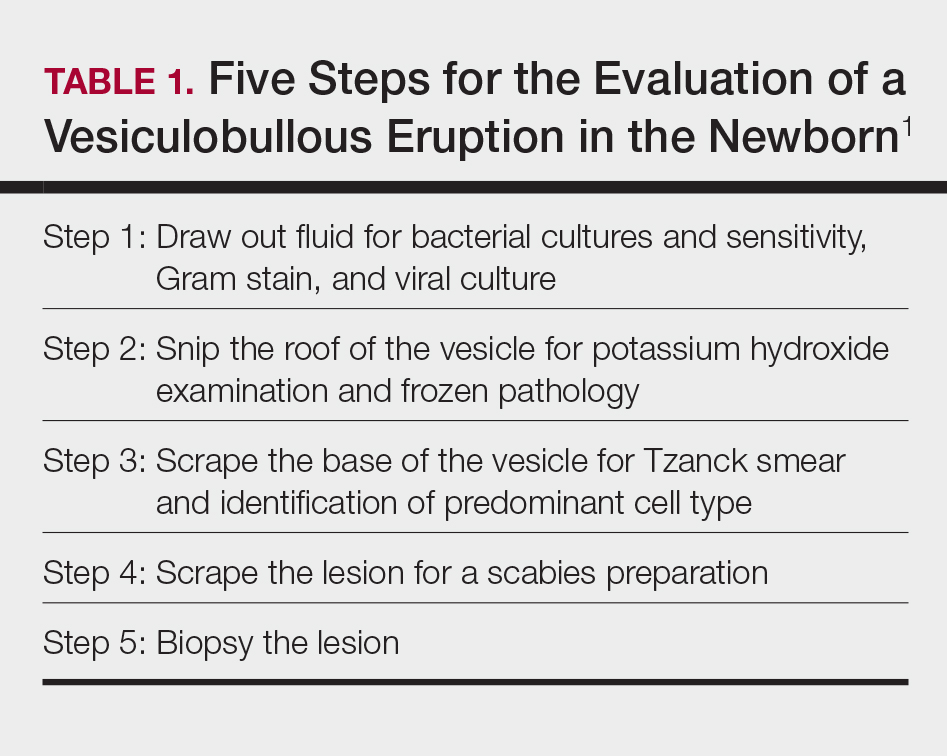

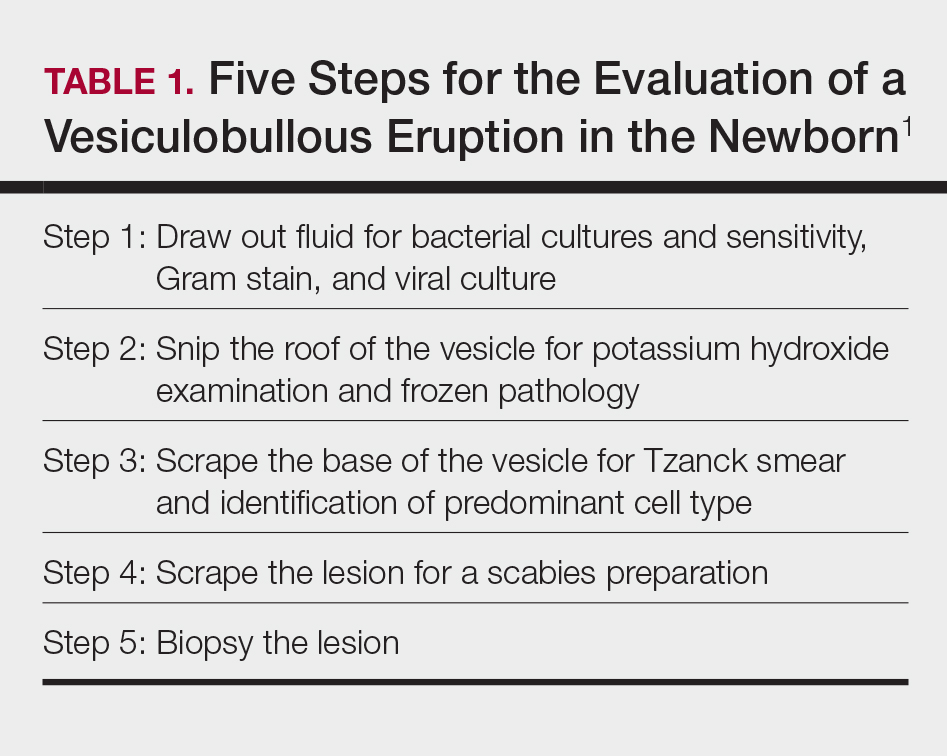

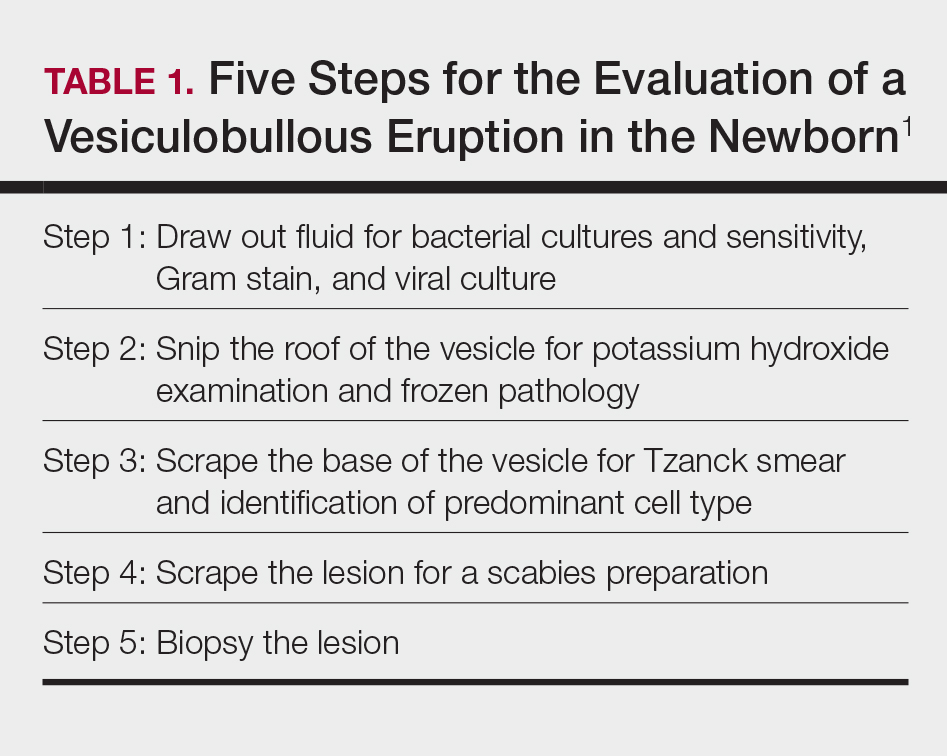

Receiving a consultation for a newborn with widespread vesicles can be a daunting scenario for a dermatology resident. Fear of missing an ominous diagnosis or aggressively treating a newborn for an erroneous infection when the diagnosis is actually a benign presentation can lead to an anxiety-provoking situation. Additionally, performing a procedure on a newborn can cause personal uneasiness. Dr. Lawrence A. Schachner, an eminent pediatric dermatologist at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine (Miami, Florida), recently lectured on 5 key steps (Table 1) for the evaluation of a vesiculobullous eruption in the newborn to maximize the accuracy of diagnosis and patient care.1

First, draw out the fluid from the vesicle to send for bacterial and viral culture as well as Gram stain. Second, snip the roof of the vesicle to perform potassium hydroxide examination for yeast or fungi and frozen pathology when indicated. Third, use the base of the vesicle to obtain cells for a Tzanck smear to identify the predominant cell infiltrate, such as multinucleated giant cells in herpes simplex virus or eosinophils in erythema toxicum neonatorum (ETN). Fourth, a mineral oil preparation can be performed on several lesions, especially if a burrow is observed, to rule out bullous scabies in the appropriate clinical presentation. Lastly, a perilesional or lesional punch biopsy can be performed if the above steps have not yet clinched the diagnosis.2 By utilizing these steps, the resident efficiently utilizes 1 lesion to narrow down a formidable differential list of bullous disorders in the newborn.

Specific Diagnoses

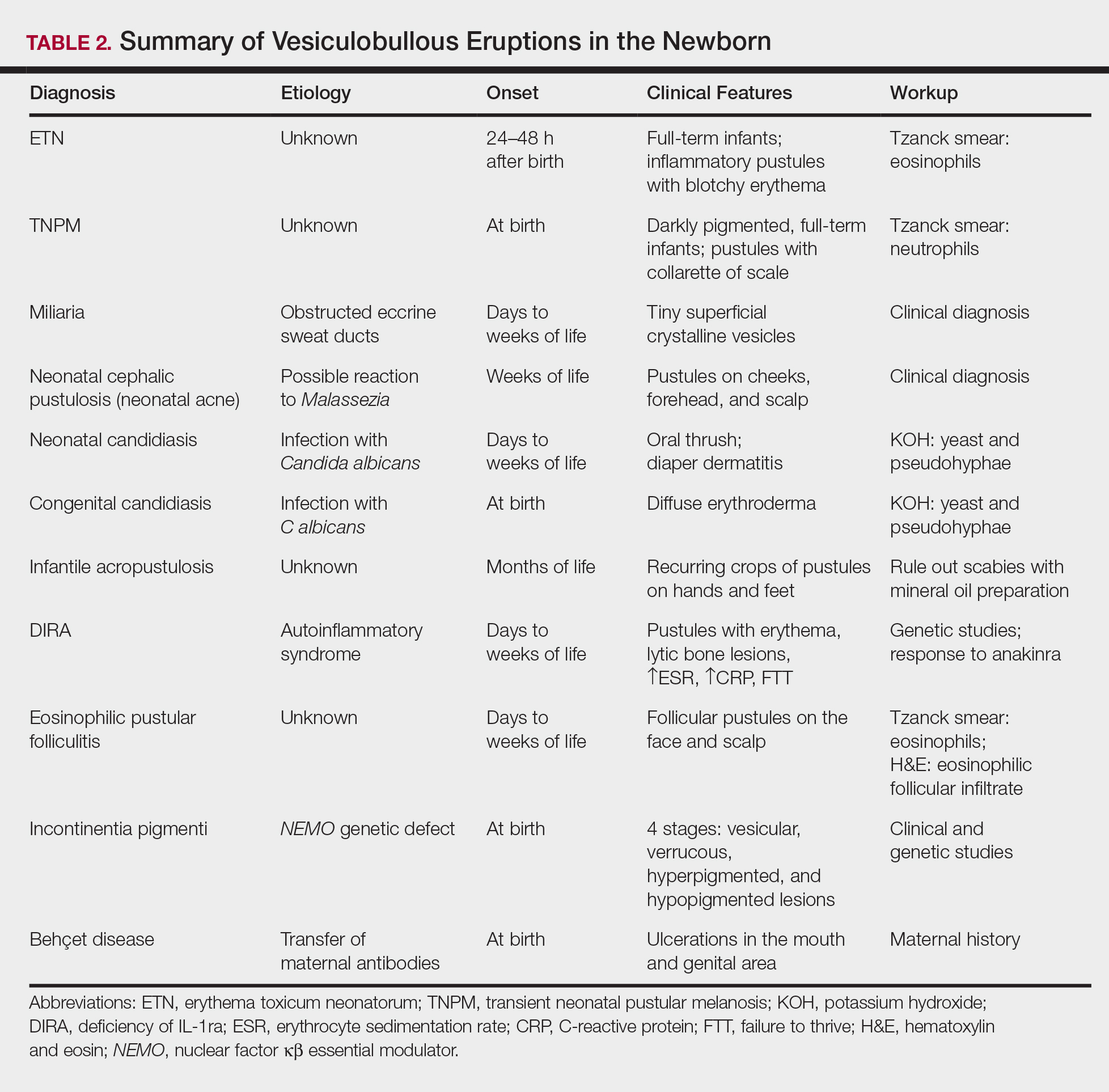

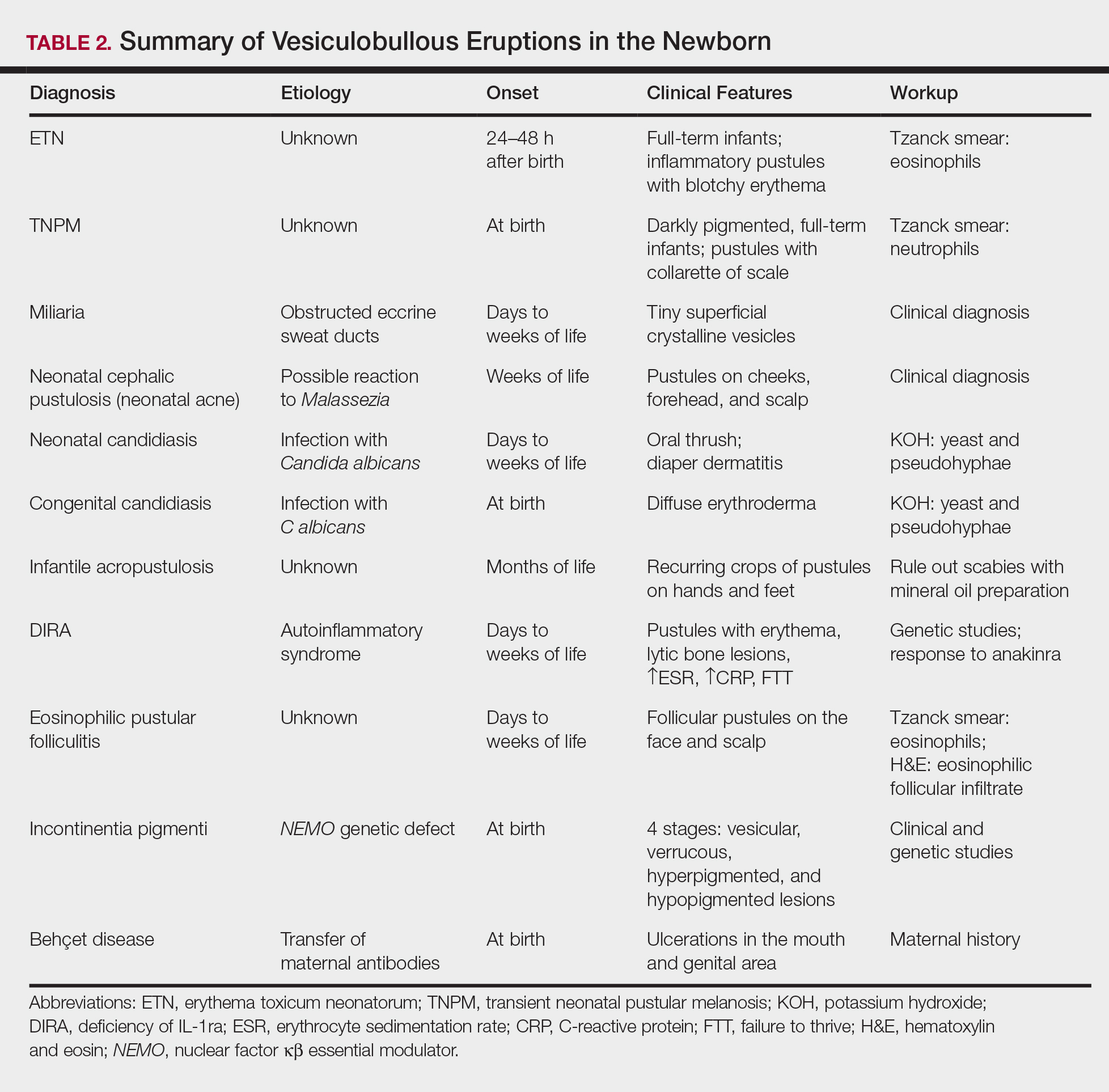

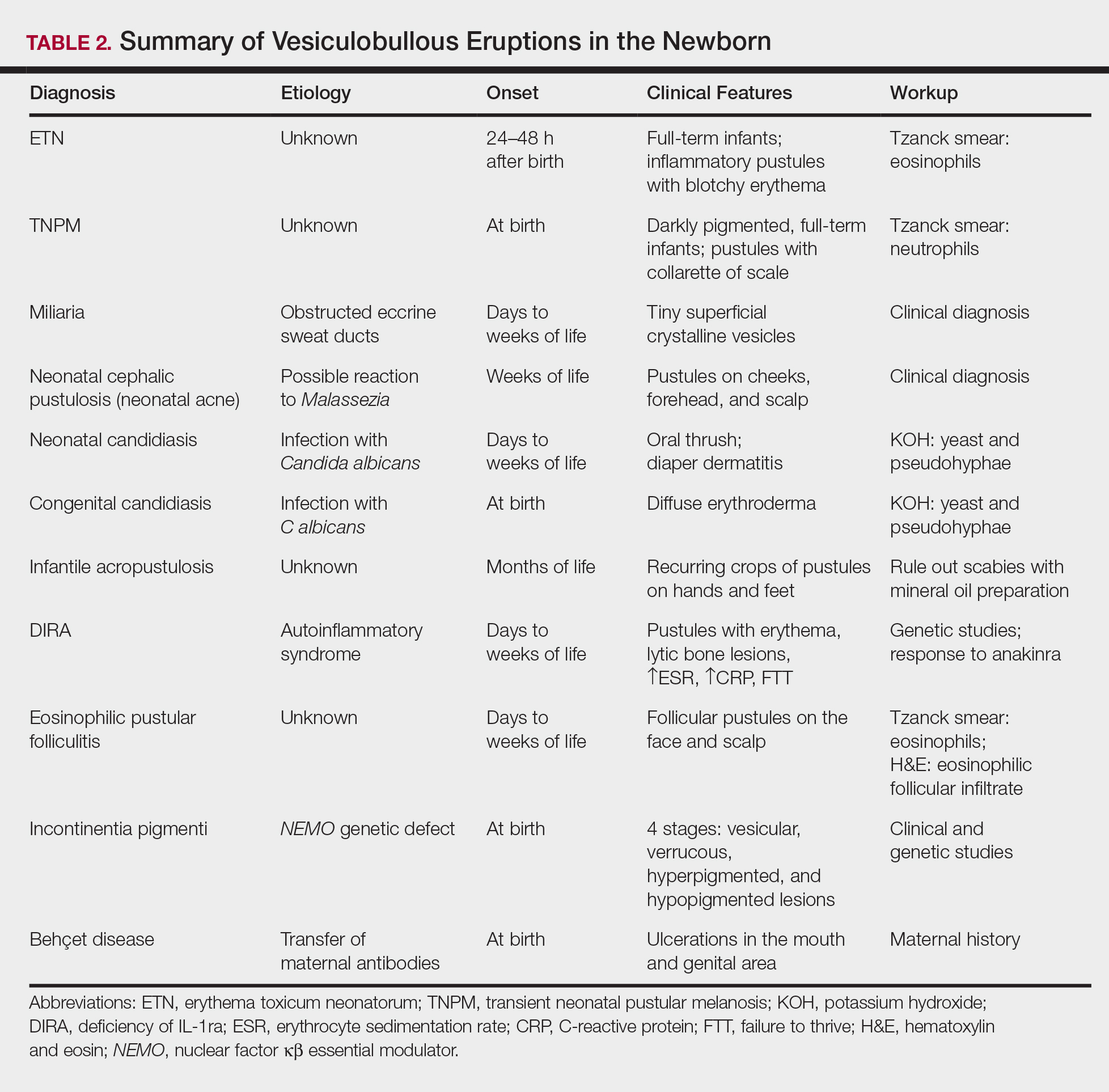

A number of common diagnoses can present during the newborn period and can usually be readily diagnosed by clinical manifestations alone; a summary of these eruptions is provided in Table 2. Erythema toxicum neonatorum is the most common pustular eruption in neonates and presents in up to 50% of full-term infants at days 1 to 2 of life. Inflammatory pustules surrounded by characteristic blotchy erythema are displayed on the face, trunk, arms, and legs, usually sparing the palms and soles.3 Erythema toxicum neonatorum typically is a clinical diagnosis; however, it can be confirmed by demonstrating the predominance of eosinophils on Tzanck smear.

Transient neonatal pustular melanosis (TNPM) also presents in full-term infants; usually favors darkly pigmented neonates; and exhibits either pustules with a collarette of scale that lack surrounding erythema or with residual brown macules on the face, genitals, and acral surfaces. Postinflammatory pigmentary alteration on lesion clearance is another clue to diagnosis. Similarly, it is a clinical diagnosis but can be confirmed with a Tzanck smear demonstrating neutrophils as the major cell infiltrate.

In a prospective 1-year multicenter study performed by Reginatto et al,4 2831 neonates born in southern Brazil underwent a skin examination by a dermatologist within 72 hours of birth to characterize the prevalence and demographics of ETN and TNPM. They found a 21.3% (602 cases) prevalence of ETN compared to a 3.4% (97 cases) prevalence of TNPM, but they noted that most patients were white, and thus the diagnosis of TNPM likely is less prevalent in this group, as it favors darkly pigmented individuals. Additional predisposing factors associated with ETN were male gender, an Apgar score of 8 to 10 at 1 minute, non–neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) patients, and lack of gestational risk factors. The TNPM population was much smaller, though the authors were able to conclude that the disease also was correlated with healthy, non-NICU patients. The authors hypothesized that there may be a role of immune system maturity in the pathogenesis of ETN and thus dermatology residents should be aware of the setting of their consultation.4 A NICU consultation for ETN should raise suspicion, as ETN and TNPM favor healthy infants who likely are not residing in the NICU; we are reminded of the target populations for these disease processes.

Additional common causes of vesicular eruptions in neonates can likewise be diagnosed chiefly with clinical inspection. Miliaria presents with tiny superficial crystalline vesicles on the neck and back of newborns due to elevated temperature and resultant obstruction of the eccrine sweat ducts. Reassurance can be provided, as spontaneous resolution occurs with cooling and limitation of occlusive clothing and swaddling.2

Infants at a few weeks of life may present with a noncomedonal pustular eruption on the cheeks, forehead, and scalp commonly known as neonatal acne or neonatal cephalic pustulosis. The driving factor is thought to be an abnormal response to Malassezia and can be treated with ketoconazole cream or expectant management.2

Cutaneous candidiasis is the most common infectious cause of vesicles in the neonate and can present in 2 fashions. Neonatal candidiasis is common, presenting a week after birth and manifesting as oral thrush and red plaques with satellite pustules in the diaper area. Congenital candidiasis is due to infection in utero, presents prior to 1 week of life, exhibits diffuse erythroderma, and requires timely parenteral antifungals.5 Newborns and preterm infants are at higher risk for systemic disease, while full-term infants may experience a mild course of skin-limited lesions.

It is imperative to rule out other infectious etiologies in ill-appearing neonates with vesicles such as herpes simplex virus, bacterial infections, syphilis, and vertically transmitted TORCH (toxoplasmosis, other infections rubella, cytomegalovirus infection, and herpes simplex) diagnoses.6 Herpes simplex virus classically presents with grouped vesicles on an erythematous base; however, such characteristic lesions may be subtle in the newborn. The site of skin involvement usually is the area that first comes into contact with maternal lesions, such as the face for a newborn delivered in a cephalic presentation.2 It is critical to be cognizant of this diagnosis, as a delay in antiviral therapy can result in neurologic consequences due to disseminated disease.

If the clinical picture of vesiculobullous disease in the newborn is not as clear, less common causes must be considered. Infantile acropustulosis presents with recurring crops of pustules on the hands and feet at several months of age. The most common differential diagnosis is scabies; therefore, a mineral oil preparation should be performed to rule out this common mimicker. Potent topical corticosteroids are first-line therapy, and episodes generally resolve with time.

Another mimicker of pustules in neonates includes deficiency of IL-1ra, a rare entity described in 2009.7 Deficiency of IL-1ra is an autoinflammatory syndrome of skin and bone due to unopposed action of IL-1 with life-threatening inflammation; infants present with pustules, lytic bone lesions, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, and failure to thrive.8 The characteristic mutation was discovered when the infants dramatically responded to therapy with anakinra, an IL-1ra.

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis is an additional pustular dermatosis that manifests with lesions predominately in the head and neck area, and unlike the adult population, it usually is self-resolving and not associated with other comorbidities in newborns.2

Incontinentia pigmenti is an X-linked dominant syndrome due to a genetic mutation in NEMO, nuclear factor κβ essential modulator, which protects against apoptosis.3 Incontinentia pigmenti presents in newborn girls shortly after birth with vesicles in a blaschkoid distribution before evolving through 4 unique stages of vesicular lesions, verrucous lesions, hyperpigmentation, and ultimately resolves with residual hypopigmentation in the affected area.

Lastly, neonatal Behçet disease can present with vesicles in the mouth and genital region due to transfer of maternal antibodies. It is self-limiting in nature and would be readily diagnosed with a known maternal history, though judicious screening for infections may be needed in specific settings.2

Conclusion

In summary, a vast array of benign and worrisome dermatoses present in the neonatal period. A thorough history and physical examination, including the temporality of the lesions, the health status of the newborn, and the maternal history, can help delineate the diagnosis. The 5-step method presented can further elucidate the underlying mechanism and reduce an overwhelming differential diagnosis list by reviewing each finding yielded from each step. Dermatology residents should feel comfortable addressing this unique patient population to ameliorate unclear cutaneous diagnoses for pediatricians.

Acknowledgment

A special thank you to Lawrence A. Schachner, MD (Miami, Florida), for his help providing resources and guidance for this topic.

- Schachner L. Vesiculopustular dermatosis in neonates and infants. Lecture presented at: University of Miami Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery Grand Rounds; August 23, 2017; Miami, Florida.

- Eichenfield LF, Lee PW, Larraide M, et al. Neonatal skin and skin disorders. In: Schachner LA, Hansen RC, eds. Pediatric Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2011:299-373.

- Goddard DS, Gilliam AE, Frieden IJ. Vesiculobullous and erosive diseases in the newborn. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:523-537.

- Reginatto FP, Muller FM, Peruzzo J, et al. Epidemiology and predisposing factors for erythema toxicum neonatorum and transient neonatal pustular melanosis: a multicenter study [published online May 25, 2017]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:422-426.

- Aruna C, Seetharam K. Congenital candidiasis. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(suppl 1):S44-S47.

- O’Connor NR, McLaughlin MR, Ham P. Newborn skin: part I. common rashes. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:47-52.

- Reddy S, Jia S, Geoffrey R, et al. An autoinflammatory disease due to homozygous deletion of the IL1RN locus. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2438-2444.

- Minkis K, Aksentijevich I, Goldbach-Mansky R, et al. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist deficiency presenting as infantile pustulosis mimicking infantile pustular psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:747-752.

Vesiculobullous eruptions in neonates can readily generate anxiety from parents/guardians and pediatricians over both infectious and noninfectious causes. The role of the dermatology resident is critical to help diminish fear over common vesicular presentations or to escalate care in rarer situations if a more obscure or ominous diagnosis is clouding the patient’s clinical presentation and well-being. This article summarizes both common and uncommon vesiculobullous neonatal diseases to augment precise and efficient diagnoses in this vulnerable patient population.

Steps for Evaluating a Vesiculopustular Eruption

Receiving a consultation for a newborn with widespread vesicles can be a daunting scenario for a dermatology resident. Fear of missing an ominous diagnosis or aggressively treating a newborn for an erroneous infection when the diagnosis is actually a benign presentation can lead to an anxiety-provoking situation. Additionally, performing a procedure on a newborn can cause personal uneasiness. Dr. Lawrence A. Schachner, an eminent pediatric dermatologist at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine (Miami, Florida), recently lectured on 5 key steps (Table 1) for the evaluation of a vesiculobullous eruption in the newborn to maximize the accuracy of diagnosis and patient care.1

First, draw out the fluid from the vesicle to send for bacterial and viral culture as well as Gram stain. Second, snip the roof of the vesicle to perform potassium hydroxide examination for yeast or fungi and frozen pathology when indicated. Third, use the base of the vesicle to obtain cells for a Tzanck smear to identify the predominant cell infiltrate, such as multinucleated giant cells in herpes simplex virus or eosinophils in erythema toxicum neonatorum (ETN). Fourth, a mineral oil preparation can be performed on several lesions, especially if a burrow is observed, to rule out bullous scabies in the appropriate clinical presentation. Lastly, a perilesional or lesional punch biopsy can be performed if the above steps have not yet clinched the diagnosis.2 By utilizing these steps, the resident efficiently utilizes 1 lesion to narrow down a formidable differential list of bullous disorders in the newborn.

Specific Diagnoses

A number of common diagnoses can present during the newborn period and can usually be readily diagnosed by clinical manifestations alone; a summary of these eruptions is provided in Table 2. Erythema toxicum neonatorum is the most common pustular eruption in neonates and presents in up to 50% of full-term infants at days 1 to 2 of life. Inflammatory pustules surrounded by characteristic blotchy erythema are displayed on the face, trunk, arms, and legs, usually sparing the palms and soles.3 Erythema toxicum neonatorum typically is a clinical diagnosis; however, it can be confirmed by demonstrating the predominance of eosinophils on Tzanck smear.

Transient neonatal pustular melanosis (TNPM) also presents in full-term infants; usually favors darkly pigmented neonates; and exhibits either pustules with a collarette of scale that lack surrounding erythema or with residual brown macules on the face, genitals, and acral surfaces. Postinflammatory pigmentary alteration on lesion clearance is another clue to diagnosis. Similarly, it is a clinical diagnosis but can be confirmed with a Tzanck smear demonstrating neutrophils as the major cell infiltrate.

In a prospective 1-year multicenter study performed by Reginatto et al,4 2831 neonates born in southern Brazil underwent a skin examination by a dermatologist within 72 hours of birth to characterize the prevalence and demographics of ETN and TNPM. They found a 21.3% (602 cases) prevalence of ETN compared to a 3.4% (97 cases) prevalence of TNPM, but they noted that most patients were white, and thus the diagnosis of TNPM likely is less prevalent in this group, as it favors darkly pigmented individuals. Additional predisposing factors associated with ETN were male gender, an Apgar score of 8 to 10 at 1 minute, non–neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) patients, and lack of gestational risk factors. The TNPM population was much smaller, though the authors were able to conclude that the disease also was correlated with healthy, non-NICU patients. The authors hypothesized that there may be a role of immune system maturity in the pathogenesis of ETN and thus dermatology residents should be aware of the setting of their consultation.4 A NICU consultation for ETN should raise suspicion, as ETN and TNPM favor healthy infants who likely are not residing in the NICU; we are reminded of the target populations for these disease processes.

Additional common causes of vesicular eruptions in neonates can likewise be diagnosed chiefly with clinical inspection. Miliaria presents with tiny superficial crystalline vesicles on the neck and back of newborns due to elevated temperature and resultant obstruction of the eccrine sweat ducts. Reassurance can be provided, as spontaneous resolution occurs with cooling and limitation of occlusive clothing and swaddling.2

Infants at a few weeks of life may present with a noncomedonal pustular eruption on the cheeks, forehead, and scalp commonly known as neonatal acne or neonatal cephalic pustulosis. The driving factor is thought to be an abnormal response to Malassezia and can be treated with ketoconazole cream or expectant management.2

Cutaneous candidiasis is the most common infectious cause of vesicles in the neonate and can present in 2 fashions. Neonatal candidiasis is common, presenting a week after birth and manifesting as oral thrush and red plaques with satellite pustules in the diaper area. Congenital candidiasis is due to infection in utero, presents prior to 1 week of life, exhibits diffuse erythroderma, and requires timely parenteral antifungals.5 Newborns and preterm infants are at higher risk for systemic disease, while full-term infants may experience a mild course of skin-limited lesions.

It is imperative to rule out other infectious etiologies in ill-appearing neonates with vesicles such as herpes simplex virus, bacterial infections, syphilis, and vertically transmitted TORCH (toxoplasmosis, other infections rubella, cytomegalovirus infection, and herpes simplex) diagnoses.6 Herpes simplex virus classically presents with grouped vesicles on an erythematous base; however, such characteristic lesions may be subtle in the newborn. The site of skin involvement usually is the area that first comes into contact with maternal lesions, such as the face for a newborn delivered in a cephalic presentation.2 It is critical to be cognizant of this diagnosis, as a delay in antiviral therapy can result in neurologic consequences due to disseminated disease.

If the clinical picture of vesiculobullous disease in the newborn is not as clear, less common causes must be considered. Infantile acropustulosis presents with recurring crops of pustules on the hands and feet at several months of age. The most common differential diagnosis is scabies; therefore, a mineral oil preparation should be performed to rule out this common mimicker. Potent topical corticosteroids are first-line therapy, and episodes generally resolve with time.

Another mimicker of pustules in neonates includes deficiency of IL-1ra, a rare entity described in 2009.7 Deficiency of IL-1ra is an autoinflammatory syndrome of skin and bone due to unopposed action of IL-1 with life-threatening inflammation; infants present with pustules, lytic bone lesions, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, and failure to thrive.8 The characteristic mutation was discovered when the infants dramatically responded to therapy with anakinra, an IL-1ra.

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis is an additional pustular dermatosis that manifests with lesions predominately in the head and neck area, and unlike the adult population, it usually is self-resolving and not associated with other comorbidities in newborns.2

Incontinentia pigmenti is an X-linked dominant syndrome due to a genetic mutation in NEMO, nuclear factor κβ essential modulator, which protects against apoptosis.3 Incontinentia pigmenti presents in newborn girls shortly after birth with vesicles in a blaschkoid distribution before evolving through 4 unique stages of vesicular lesions, verrucous lesions, hyperpigmentation, and ultimately resolves with residual hypopigmentation in the affected area.

Lastly, neonatal Behçet disease can present with vesicles in the mouth and genital region due to transfer of maternal antibodies. It is self-limiting in nature and would be readily diagnosed with a known maternal history, though judicious screening for infections may be needed in specific settings.2

Conclusion

In summary, a vast array of benign and worrisome dermatoses present in the neonatal period. A thorough history and physical examination, including the temporality of the lesions, the health status of the newborn, and the maternal history, can help delineate the diagnosis. The 5-step method presented can further elucidate the underlying mechanism and reduce an overwhelming differential diagnosis list by reviewing each finding yielded from each step. Dermatology residents should feel comfortable addressing this unique patient population to ameliorate unclear cutaneous diagnoses for pediatricians.

Acknowledgment

A special thank you to Lawrence A. Schachner, MD (Miami, Florida), for his help providing resources and guidance for this topic.

Vesiculobullous eruptions in neonates can readily generate anxiety from parents/guardians and pediatricians over both infectious and noninfectious causes. The role of the dermatology resident is critical to help diminish fear over common vesicular presentations or to escalate care in rarer situations if a more obscure or ominous diagnosis is clouding the patient’s clinical presentation and well-being. This article summarizes both common and uncommon vesiculobullous neonatal diseases to augment precise and efficient diagnoses in this vulnerable patient population.

Steps for Evaluating a Vesiculopustular Eruption

Receiving a consultation for a newborn with widespread vesicles can be a daunting scenario for a dermatology resident. Fear of missing an ominous diagnosis or aggressively treating a newborn for an erroneous infection when the diagnosis is actually a benign presentation can lead to an anxiety-provoking situation. Additionally, performing a procedure on a newborn can cause personal uneasiness. Dr. Lawrence A. Schachner, an eminent pediatric dermatologist at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine (Miami, Florida), recently lectured on 5 key steps (Table 1) for the evaluation of a vesiculobullous eruption in the newborn to maximize the accuracy of diagnosis and patient care.1

First, draw out the fluid from the vesicle to send for bacterial and viral culture as well as Gram stain. Second, snip the roof of the vesicle to perform potassium hydroxide examination for yeast or fungi and frozen pathology when indicated. Third, use the base of the vesicle to obtain cells for a Tzanck smear to identify the predominant cell infiltrate, such as multinucleated giant cells in herpes simplex virus or eosinophils in erythema toxicum neonatorum (ETN). Fourth, a mineral oil preparation can be performed on several lesions, especially if a burrow is observed, to rule out bullous scabies in the appropriate clinical presentation. Lastly, a perilesional or lesional punch biopsy can be performed if the above steps have not yet clinched the diagnosis.2 By utilizing these steps, the resident efficiently utilizes 1 lesion to narrow down a formidable differential list of bullous disorders in the newborn.

Specific Diagnoses

A number of common diagnoses can present during the newborn period and can usually be readily diagnosed by clinical manifestations alone; a summary of these eruptions is provided in Table 2. Erythema toxicum neonatorum is the most common pustular eruption in neonates and presents in up to 50% of full-term infants at days 1 to 2 of life. Inflammatory pustules surrounded by characteristic blotchy erythema are displayed on the face, trunk, arms, and legs, usually sparing the palms and soles.3 Erythema toxicum neonatorum typically is a clinical diagnosis; however, it can be confirmed by demonstrating the predominance of eosinophils on Tzanck smear.

Transient neonatal pustular melanosis (TNPM) also presents in full-term infants; usually favors darkly pigmented neonates; and exhibits either pustules with a collarette of scale that lack surrounding erythema or with residual brown macules on the face, genitals, and acral surfaces. Postinflammatory pigmentary alteration on lesion clearance is another clue to diagnosis. Similarly, it is a clinical diagnosis but can be confirmed with a Tzanck smear demonstrating neutrophils as the major cell infiltrate.

In a prospective 1-year multicenter study performed by Reginatto et al,4 2831 neonates born in southern Brazil underwent a skin examination by a dermatologist within 72 hours of birth to characterize the prevalence and demographics of ETN and TNPM. They found a 21.3% (602 cases) prevalence of ETN compared to a 3.4% (97 cases) prevalence of TNPM, but they noted that most patients were white, and thus the diagnosis of TNPM likely is less prevalent in this group, as it favors darkly pigmented individuals. Additional predisposing factors associated with ETN were male gender, an Apgar score of 8 to 10 at 1 minute, non–neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) patients, and lack of gestational risk factors. The TNPM population was much smaller, though the authors were able to conclude that the disease also was correlated with healthy, non-NICU patients. The authors hypothesized that there may be a role of immune system maturity in the pathogenesis of ETN and thus dermatology residents should be aware of the setting of their consultation.4 A NICU consultation for ETN should raise suspicion, as ETN and TNPM favor healthy infants who likely are not residing in the NICU; we are reminded of the target populations for these disease processes.

Additional common causes of vesicular eruptions in neonates can likewise be diagnosed chiefly with clinical inspection. Miliaria presents with tiny superficial crystalline vesicles on the neck and back of newborns due to elevated temperature and resultant obstruction of the eccrine sweat ducts. Reassurance can be provided, as spontaneous resolution occurs with cooling and limitation of occlusive clothing and swaddling.2

Infants at a few weeks of life may present with a noncomedonal pustular eruption on the cheeks, forehead, and scalp commonly known as neonatal acne or neonatal cephalic pustulosis. The driving factor is thought to be an abnormal response to Malassezia and can be treated with ketoconazole cream or expectant management.2

Cutaneous candidiasis is the most common infectious cause of vesicles in the neonate and can present in 2 fashions. Neonatal candidiasis is common, presenting a week after birth and manifesting as oral thrush and red plaques with satellite pustules in the diaper area. Congenital candidiasis is due to infection in utero, presents prior to 1 week of life, exhibits diffuse erythroderma, and requires timely parenteral antifungals.5 Newborns and preterm infants are at higher risk for systemic disease, while full-term infants may experience a mild course of skin-limited lesions.

It is imperative to rule out other infectious etiologies in ill-appearing neonates with vesicles such as herpes simplex virus, bacterial infections, syphilis, and vertically transmitted TORCH (toxoplasmosis, other infections rubella, cytomegalovirus infection, and herpes simplex) diagnoses.6 Herpes simplex virus classically presents with grouped vesicles on an erythematous base; however, such characteristic lesions may be subtle in the newborn. The site of skin involvement usually is the area that first comes into contact with maternal lesions, such as the face for a newborn delivered in a cephalic presentation.2 It is critical to be cognizant of this diagnosis, as a delay in antiviral therapy can result in neurologic consequences due to disseminated disease.

If the clinical picture of vesiculobullous disease in the newborn is not as clear, less common causes must be considered. Infantile acropustulosis presents with recurring crops of pustules on the hands and feet at several months of age. The most common differential diagnosis is scabies; therefore, a mineral oil preparation should be performed to rule out this common mimicker. Potent topical corticosteroids are first-line therapy, and episodes generally resolve with time.