User login

Milestone Match Day sees record highs; soar in DO applicants

Unifying allopathic (MD) and osteopathic (DO) applicants for the first time in a single matching program, 2020’s Match Day results underscored the continuing growth of DOs in the field, boosting numbers in primary care medicine and the Match as a whole.

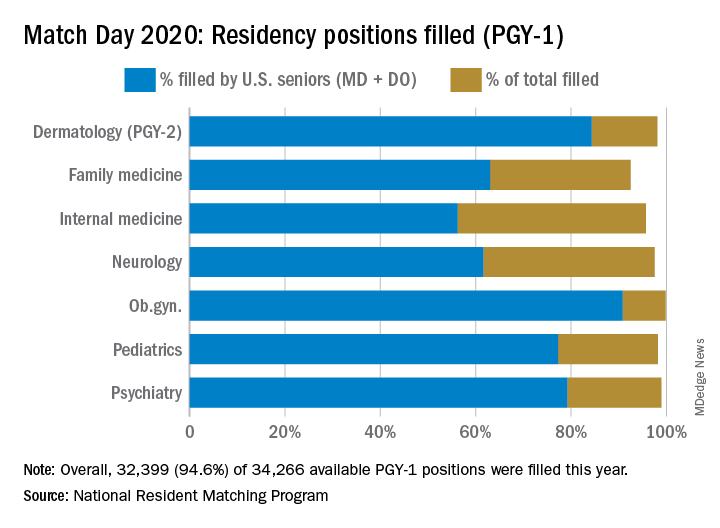

The 2020 Main Residency Match bested 2019’s record as the largest in the history of the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP), with 40,084 applicants submitting program choices for 37,256 positions. This compares with 38,376 applicants vying for 35,185 positions last year.

It’s the seventh consecutive year in which overall match numbers are up, according to the NRMP. Although the number of applicants increased, so did the number of positions, resulting in a slight drop in the percent of positions filled during 2019-2020.

Available first-year (PGY-1) positions rose to 34,266, an increase of 2,072 (6.4%) over 2019. “This was, in part, due to the last migration of osteopathic program positions into the Main Residency Match,” Donna L. Lamb, DHSc, NRMP president and CEO, said in an interview. An agreement the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, American Osteopathic Association and American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine reached in 2014 recognized ACGME as the primary accrediting body for graduate medical education programs by 2020.

This led to the first single match for U.S. MD and DO senior students and graduates and the inclusion of DO senior students as sponsored applicants in 2020, Dr. Lamb noted.

Gains, trends in 2020 match

Growth in U.S. DO senior participation also pushed this year’s Match to record highs. There were 6,581 U.S. DO medical school seniors who submitted rank order lists, 1,103 more than in 2019. Among those seniors, 90.7% matched to PGY-1 positions, driving the match rate for U.S. DO seniors up 2.6 percentage points from 2019.

Since 2016, the number of U.S. DO seniors seeking positions has risen by 3,599 or 120%. “Of course, the number of U.S. MD seniors who submitted program choices was also record-high: 19,326, an increase of 401 over 2019. The 93.7% match rate to first-year positions for this group has remained very consistent for many years,” Dr. Lamb said.

Among individual specialties, the NRMP reported extremely high fill rates for dermatology, medicine-emergency medicine, neurological surgery, physical medicine and rehabilitation (categorical), integrated plastic surgery, and thoracic surgery. Other competitive specialties included medicine-pediatrics, orthopedic surgery, otolaryngology, and vascular surgery.

Participation of international medical school students and graduates (IMGs) went up in 2020, breaking a 3-year cycle of decline. More than 61% matched to first-year positions, 2.5 percentage points higher than 2019 – and the highest match rate since 1990. “IMGs generally are having the most success matching to primary care specialties, including internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics,” Dr. Lamb said.

Primary care benefits from DO growth

DO candidates also helped drive up the numbers in primary care.

Internal medicine offered 8,697 categorical positions, 581 more than in 2019, reflecting a fill rate of 95.7%. More than 40% of these slots were filled by U.S. MD seniors, a category that’s seen decreases over the last 5 years, due in part to administrative and financial burdens associated with primary care internal medicine.

“In addition, the steady growth of internal medicine has increased the overall number of training positions available, and with the growth of other specialties in parallel, it has also likely had some effect on decreasing the percentage of U.S. graduates entering the field,” Phil Masters, MD, vice president of membership and global engagement at the American College of Physicians, said in an interview.

However, fill rates for U.S. DO seniors reached 16% in 2020, a notable rise from 6.9% in 2016. “As the number of osteopathic trainees increases, we are happy that more are choosing internal medicine as a career path,” Dr. Masters said, adding that the slightly different training and practice orientation of osteopathic physicians “complements that of their allopathic colleagues, and add richness to the many different practice settings that internal medicine encompasses.”

A record number of DO seniors also matched in family medicine (1,392), accounting for nearly 30% of all applicants. The single match led to an important net increase in filled family medicine residency positions, Clif Knight, MD, senior vice president for education at the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in an interview.

Overall, family medicine filled 92.5% of its 4,662 positions, 555 more than in 2019. The results show that family medicine and primary care are on solid footing, Dr. Knight said. “We are excited that the number of filled family medicine residency positions increased from last year. This is important as we work to meet the significant primary care workforce shortage,” he added.

In other specialties:

- Pediatrics filled more than 98% of its 2,864 categorical positions, 17 more than in 2019. U.S. MD seniors filled 1,731 (60.4%) of those slots. “We’re very excited about our newly matched pediatricians,” Sara “Sally” H. Goza, MD, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, said in an interview. “The coronavirus outbreak has shown us how valuable the pediatric workforce is and how much we’re needed.’’

- Dermatology offered 478 positions, achieving a fill rate of 98.1%. “Looking at our own program’s Match results, I feel very satisfied that we are accomplishing our specific aim to serve rural populations and to create a diverse workforce in dermatology,” Erik Stratman, MD, an expert on dermatologic education in U.S. medical schools/residency programs, and a member of the American Academy of Dermatology, said in an interview. “It’s nice to see the fruits of the specialty’s expanding efforts to get the right people in the specialty who reflect those populations we serve.”

- Obstetrics-gynecology offered 1,433 first-year positions – 48 more than in 2019 – achieving a fill rate of 99.8%, with U.S. MD seniors filling more than 75% of those slots.

- Neurology filled more than 97.5% of 682 offered positions in 2020. However, U.S. MD seniors represented just under half of those filled positions (46.5%).

- Psychiatry offered 1,858 positions in 2020, achieving an overall fill rate of 98.9%, 61.2% for U.S. MD seniors.

- Emergency Medicine filled 99.5% of the 2,665 positions offered this year. In this profession, the U.S. MD fill rate was 64.3%. These new interns are sorely needed at a time when EM physicians are on the front lines of a pandemic, Hannah R. Hughes, MD, president of the Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association, said in an interview.

Unifying allopathic (MD) and osteopathic (DO) applicants for the first time in a single matching program, 2020’s Match Day results underscored the continuing growth of DOs in the field, boosting numbers in primary care medicine and the Match as a whole.

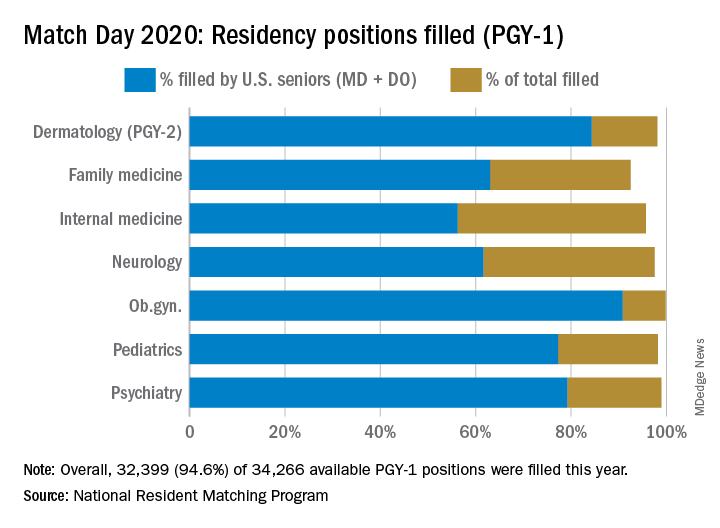

The 2020 Main Residency Match bested 2019’s record as the largest in the history of the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP), with 40,084 applicants submitting program choices for 37,256 positions. This compares with 38,376 applicants vying for 35,185 positions last year.

It’s the seventh consecutive year in which overall match numbers are up, according to the NRMP. Although the number of applicants increased, so did the number of positions, resulting in a slight drop in the percent of positions filled during 2019-2020.

Available first-year (PGY-1) positions rose to 34,266, an increase of 2,072 (6.4%) over 2019. “This was, in part, due to the last migration of osteopathic program positions into the Main Residency Match,” Donna L. Lamb, DHSc, NRMP president and CEO, said in an interview. An agreement the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, American Osteopathic Association and American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine reached in 2014 recognized ACGME as the primary accrediting body for graduate medical education programs by 2020.

This led to the first single match for U.S. MD and DO senior students and graduates and the inclusion of DO senior students as sponsored applicants in 2020, Dr. Lamb noted.

Gains, trends in 2020 match

Growth in U.S. DO senior participation also pushed this year’s Match to record highs. There were 6,581 U.S. DO medical school seniors who submitted rank order lists, 1,103 more than in 2019. Among those seniors, 90.7% matched to PGY-1 positions, driving the match rate for U.S. DO seniors up 2.6 percentage points from 2019.

Since 2016, the number of U.S. DO seniors seeking positions has risen by 3,599 or 120%. “Of course, the number of U.S. MD seniors who submitted program choices was also record-high: 19,326, an increase of 401 over 2019. The 93.7% match rate to first-year positions for this group has remained very consistent for many years,” Dr. Lamb said.

Among individual specialties, the NRMP reported extremely high fill rates for dermatology, medicine-emergency medicine, neurological surgery, physical medicine and rehabilitation (categorical), integrated plastic surgery, and thoracic surgery. Other competitive specialties included medicine-pediatrics, orthopedic surgery, otolaryngology, and vascular surgery.

Participation of international medical school students and graduates (IMGs) went up in 2020, breaking a 3-year cycle of decline. More than 61% matched to first-year positions, 2.5 percentage points higher than 2019 – and the highest match rate since 1990. “IMGs generally are having the most success matching to primary care specialties, including internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics,” Dr. Lamb said.

Primary care benefits from DO growth

DO candidates also helped drive up the numbers in primary care.

Internal medicine offered 8,697 categorical positions, 581 more than in 2019, reflecting a fill rate of 95.7%. More than 40% of these slots were filled by U.S. MD seniors, a category that’s seen decreases over the last 5 years, due in part to administrative and financial burdens associated with primary care internal medicine.

“In addition, the steady growth of internal medicine has increased the overall number of training positions available, and with the growth of other specialties in parallel, it has also likely had some effect on decreasing the percentage of U.S. graduates entering the field,” Phil Masters, MD, vice president of membership and global engagement at the American College of Physicians, said in an interview.

However, fill rates for U.S. DO seniors reached 16% in 2020, a notable rise from 6.9% in 2016. “As the number of osteopathic trainees increases, we are happy that more are choosing internal medicine as a career path,” Dr. Masters said, adding that the slightly different training and practice orientation of osteopathic physicians “complements that of their allopathic colleagues, and add richness to the many different practice settings that internal medicine encompasses.”

A record number of DO seniors also matched in family medicine (1,392), accounting for nearly 30% of all applicants. The single match led to an important net increase in filled family medicine residency positions, Clif Knight, MD, senior vice president for education at the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in an interview.

Overall, family medicine filled 92.5% of its 4,662 positions, 555 more than in 2019. The results show that family medicine and primary care are on solid footing, Dr. Knight said. “We are excited that the number of filled family medicine residency positions increased from last year. This is important as we work to meet the significant primary care workforce shortage,” he added.

In other specialties:

- Pediatrics filled more than 98% of its 2,864 categorical positions, 17 more than in 2019. U.S. MD seniors filled 1,731 (60.4%) of those slots. “We’re very excited about our newly matched pediatricians,” Sara “Sally” H. Goza, MD, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, said in an interview. “The coronavirus outbreak has shown us how valuable the pediatric workforce is and how much we’re needed.’’

- Dermatology offered 478 positions, achieving a fill rate of 98.1%. “Looking at our own program’s Match results, I feel very satisfied that we are accomplishing our specific aim to serve rural populations and to create a diverse workforce in dermatology,” Erik Stratman, MD, an expert on dermatologic education in U.S. medical schools/residency programs, and a member of the American Academy of Dermatology, said in an interview. “It’s nice to see the fruits of the specialty’s expanding efforts to get the right people in the specialty who reflect those populations we serve.”

- Obstetrics-gynecology offered 1,433 first-year positions – 48 more than in 2019 – achieving a fill rate of 99.8%, with U.S. MD seniors filling more than 75% of those slots.

- Neurology filled more than 97.5% of 682 offered positions in 2020. However, U.S. MD seniors represented just under half of those filled positions (46.5%).

- Psychiatry offered 1,858 positions in 2020, achieving an overall fill rate of 98.9%, 61.2% for U.S. MD seniors.

- Emergency Medicine filled 99.5% of the 2,665 positions offered this year. In this profession, the U.S. MD fill rate was 64.3%. These new interns are sorely needed at a time when EM physicians are on the front lines of a pandemic, Hannah R. Hughes, MD, president of the Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association, said in an interview.

Unifying allopathic (MD) and osteopathic (DO) applicants for the first time in a single matching program, 2020’s Match Day results underscored the continuing growth of DOs in the field, boosting numbers in primary care medicine and the Match as a whole.

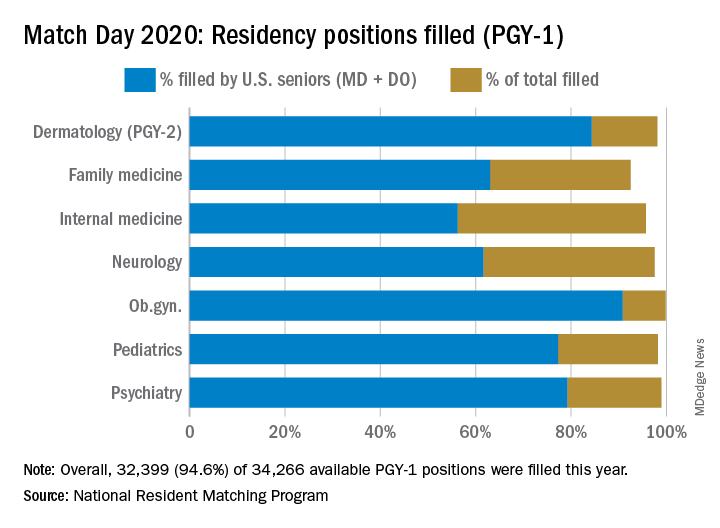

The 2020 Main Residency Match bested 2019’s record as the largest in the history of the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP), with 40,084 applicants submitting program choices for 37,256 positions. This compares with 38,376 applicants vying for 35,185 positions last year.

It’s the seventh consecutive year in which overall match numbers are up, according to the NRMP. Although the number of applicants increased, so did the number of positions, resulting in a slight drop in the percent of positions filled during 2019-2020.

Available first-year (PGY-1) positions rose to 34,266, an increase of 2,072 (6.4%) over 2019. “This was, in part, due to the last migration of osteopathic program positions into the Main Residency Match,” Donna L. Lamb, DHSc, NRMP president and CEO, said in an interview. An agreement the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, American Osteopathic Association and American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine reached in 2014 recognized ACGME as the primary accrediting body for graduate medical education programs by 2020.

This led to the first single match for U.S. MD and DO senior students and graduates and the inclusion of DO senior students as sponsored applicants in 2020, Dr. Lamb noted.

Gains, trends in 2020 match

Growth in U.S. DO senior participation also pushed this year’s Match to record highs. There were 6,581 U.S. DO medical school seniors who submitted rank order lists, 1,103 more than in 2019. Among those seniors, 90.7% matched to PGY-1 positions, driving the match rate for U.S. DO seniors up 2.6 percentage points from 2019.

Since 2016, the number of U.S. DO seniors seeking positions has risen by 3,599 or 120%. “Of course, the number of U.S. MD seniors who submitted program choices was also record-high: 19,326, an increase of 401 over 2019. The 93.7% match rate to first-year positions for this group has remained very consistent for many years,” Dr. Lamb said.

Among individual specialties, the NRMP reported extremely high fill rates for dermatology, medicine-emergency medicine, neurological surgery, physical medicine and rehabilitation (categorical), integrated plastic surgery, and thoracic surgery. Other competitive specialties included medicine-pediatrics, orthopedic surgery, otolaryngology, and vascular surgery.

Participation of international medical school students and graduates (IMGs) went up in 2020, breaking a 3-year cycle of decline. More than 61% matched to first-year positions, 2.5 percentage points higher than 2019 – and the highest match rate since 1990. “IMGs generally are having the most success matching to primary care specialties, including internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics,” Dr. Lamb said.

Primary care benefits from DO growth

DO candidates also helped drive up the numbers in primary care.

Internal medicine offered 8,697 categorical positions, 581 more than in 2019, reflecting a fill rate of 95.7%. More than 40% of these slots were filled by U.S. MD seniors, a category that’s seen decreases over the last 5 years, due in part to administrative and financial burdens associated with primary care internal medicine.

“In addition, the steady growth of internal medicine has increased the overall number of training positions available, and with the growth of other specialties in parallel, it has also likely had some effect on decreasing the percentage of U.S. graduates entering the field,” Phil Masters, MD, vice president of membership and global engagement at the American College of Physicians, said in an interview.

However, fill rates for U.S. DO seniors reached 16% in 2020, a notable rise from 6.9% in 2016. “As the number of osteopathic trainees increases, we are happy that more are choosing internal medicine as a career path,” Dr. Masters said, adding that the slightly different training and practice orientation of osteopathic physicians “complements that of their allopathic colleagues, and add richness to the many different practice settings that internal medicine encompasses.”

A record number of DO seniors also matched in family medicine (1,392), accounting for nearly 30% of all applicants. The single match led to an important net increase in filled family medicine residency positions, Clif Knight, MD, senior vice president for education at the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in an interview.

Overall, family medicine filled 92.5% of its 4,662 positions, 555 more than in 2019. The results show that family medicine and primary care are on solid footing, Dr. Knight said. “We are excited that the number of filled family medicine residency positions increased from last year. This is important as we work to meet the significant primary care workforce shortage,” he added.

In other specialties:

- Pediatrics filled more than 98% of its 2,864 categorical positions, 17 more than in 2019. U.S. MD seniors filled 1,731 (60.4%) of those slots. “We’re very excited about our newly matched pediatricians,” Sara “Sally” H. Goza, MD, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, said in an interview. “The coronavirus outbreak has shown us how valuable the pediatric workforce is and how much we’re needed.’’

- Dermatology offered 478 positions, achieving a fill rate of 98.1%. “Looking at our own program’s Match results, I feel very satisfied that we are accomplishing our specific aim to serve rural populations and to create a diverse workforce in dermatology,” Erik Stratman, MD, an expert on dermatologic education in U.S. medical schools/residency programs, and a member of the American Academy of Dermatology, said in an interview. “It’s nice to see the fruits of the specialty’s expanding efforts to get the right people in the specialty who reflect those populations we serve.”

- Obstetrics-gynecology offered 1,433 first-year positions – 48 more than in 2019 – achieving a fill rate of 99.8%, with U.S. MD seniors filling more than 75% of those slots.

- Neurology filled more than 97.5% of 682 offered positions in 2020. However, U.S. MD seniors represented just under half of those filled positions (46.5%).

- Psychiatry offered 1,858 positions in 2020, achieving an overall fill rate of 98.9%, 61.2% for U.S. MD seniors.

- Emergency Medicine filled 99.5% of the 2,665 positions offered this year. In this profession, the U.S. MD fill rate was 64.3%. These new interns are sorely needed at a time when EM physicians are on the front lines of a pandemic, Hannah R. Hughes, MD, president of the Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association, said in an interview.

DIY masks: Worth the risk? Researchers are conflicted

In the midst of the rapidly spreading COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals and clinics are running out of masks. Health care workers are going online to beg for more, the hashtags #GetMePPE and #WeNeedPPE are trending on Twitter, and some hospitals have even put out public calls for mask donations. Health providers are working scared: They know that the moment the masks run out, they’re at increased risk for disease. So instead of waiting for mask shipments that may be weeks off, some people are making their own.

Using a simple template, they cut green surgical sheeting into half-moons, which they pin and sew before attaching elastic straps. Deaconess Health System in Evansville, Indiana, has posted instructions for fabric masks on their website and asked the public to step up and sew.

Elsewhere, health care workers have turned to diapers, maxi pads and other products to create masks. Social media channels are full of tips and sewing patterns. It’s an innovative strategy that is also contentious. Limited evidence suggests that homemade masks can offer some protection. But the DIY approach has also drawn criticism for providing a false sense of security, potentially putting wearers at risk.

The conflict points to an immediate need for more protective equipment, says Christopher Friese, PhD, RN, professor of nursing and public health at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Also needed, he says, are new ideas for reducing strain on limited supplies, like adopting gear from other industries and finding innovative ways to provide care so that less protective gear is needed.

“We don’t want clinicians inventing and ‘MacGyvering’ their own device because we don’t want to put them at risk if we can avoid it,” says Friese, referring to the TV character who could build and assemble a vast array of tools/devices. “We have options that have been tested, and we have experience, maybe not in health care, but in other settings. We want to try that first before that frontline doctor, nurse, respiratory therapist decides to take matters into their own hands.

Increasingly, though, health care workers are finding they have no other choice — something even the CDC has acknowledged. In new guidelines, the agency recommends a bandanna, scarf, or other type of covering in cases where face masks are not available.

N95 respirators or surgical masks?

There are two main types of masks generally used in health care. N95 respirators filter out 95% of airborne particles, including bacteria and viruses. The lighter surgical or medical face masks are made to prevent spit and mucous from getting on patients or equipment.

Both types reduce rates of infection among health care workers, though comparisons (at least for influenza) have yet to show that one is superior to the other. One 2020 review by Chinese researchers, for example, analyzed six randomly controlled trials that included more than 9000 participants and found no added benefits of N95 masks over ordinary surgical masks for health care providers treating patients with the flu.

But COVID-19 is not influenza, and evidence suggests it may require more intensive protection, says Friese, who coauthored a blog post for JAMA about the country’s unpreparedness for protecting health care workers during a pandemic. The virus can linger in the air for hours, suggesting that N95 respirators are health care providers’ best option when treating infected patients.

The problem is there’s not enough to go around — of either mask type. In a March 5 survey, National Nurses United reported that just 30% of more than 6500 US respondents said their organizations had enough PPE to respond to a surge in patients. Another 38% did not know if their organizations were prepared. In a tweet, Friese estimated that 12% of nurses and other providers are at risk from reusing equipment or using equipment that is not backed by evidence.

Physicians and providers around the world have been sharing strategies online for how to make their own masks. Techniques vary, as do materials and plans for how to use the homemade equipment. At Phoebe Putney Health, DIY masks are intended to be worn over N95 respirators and then disposed of so that the respirators can be reused more safely, says Amanda Clements, the hospital’s public relations coordinator. Providers might also wear them to greet people at the front door.

Some evidence suggests that homemade masks can help in a pinch, at least for some illnesses. For a 2013 study by researchers in the UK, volunteers made surgical masks from cotton T-shirts, then put them on and coughed into a chamber that measured how much bacterial content got through. The team also assessed the aerosol-filtering ability of a variety of household materials, including scarfs, antimicrobial pillowcases, vacuum-cleaner bags, and tea towels. They tested each material with an aerosol containing two types of bacteria similar in size to influenza.

Commercial surgical masks performed three times better than homemade ones in the filtration test. Surgical masks worked twice as well at blocking droplets on the cough test. But all the makeshift materials — which also included silk, linen, and regular pillowcases — blocked some microbes. Vacuum-cleaner bags blocked the most bacteria, but their stiffness and thickness made them unsuitable for use as masks, the researchers reported. Tea towels showed a similar pattern. But pillowcases and cotton T-shirts were stretchy enough to fit well, thereby reducing the particles that could get through or around them.

Homemade masks should be used only as a last resort if commercial masks become unavailable, the researchers concluded. “Probably something is better than nothing for trained health care workers — for droplet contact avoidance, if nothing else,” says Anna Davies, BSc, a research facilitator at the University of Cambridge, UK, who is a former public health microbiologist and one of the study’s authors.

She recommends that members of the general public donate any stockpiles they have to health care workers, and make their own if they want masks for personal use. She is working with collaborators in the US to develop guidance for how best to do it.

“If people are quarantined and looking for something worthwhile to do, it probably wouldn’t be the worst thing to apply themselves to,” she wrote by email. “My suggestion would be for something soft and cotton, ideally with a bit of stretch (although it’s a pain to sew), and in two layers, marked ‘inside’ and ‘outside.’ ”

The idea that something is better than nothing was also the conclusion of a 2008 study by researchers in the Netherlands and the US. The study enlisted 28 healthy individuals who performed a variety of tasks while wearing N95 masks, surgical masks, or homemade masks sewn from teacloths. Effectiveness varied among individuals, but over a 90-second period, N95 masks worked best, with 25 times more protection than surgical masks and about 50 times more protection than homemade ones. Surgical masks were twice as effective as homemade masks. But the homemade masks offered at least some protection against large droplets.

Researchers emphasize that it’s not yet clear whether those findings are applicable to aerosolized COVID-19. In an influenza pandemic, at least, the authors posit that homemade masks could reduce transmission for the general public enough for some immunity to build. “It is important not to focus on a single intervention in case of a pandemic,” the researchers write, “but to integrate all effective interventions for optimal protection.”

For health care workers on the frontlines of COVID-19, Friese says, homemade masks might do more than nothing but they also might not work. Instead, he would rather see providers using construction or nuclear-engineering masks. And his best suggestion is something many providers are already doing: reducing physical contact with patients through telemedicine and other creative solutions, which is cutting down the overwhelming need for PPE.

Homemade mask production emphasizes the urgent need for more supplies, Friese adds.

“The government needs to step up and do a variety of things to increase production, and that needs to happen now, immediately,” he says. “We don’t we don’t want our clinicians to have to come up with these decisions.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the midst of the rapidly spreading COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals and clinics are running out of masks. Health care workers are going online to beg for more, the hashtags #GetMePPE and #WeNeedPPE are trending on Twitter, and some hospitals have even put out public calls for mask donations. Health providers are working scared: They know that the moment the masks run out, they’re at increased risk for disease. So instead of waiting for mask shipments that may be weeks off, some people are making their own.

Using a simple template, they cut green surgical sheeting into half-moons, which they pin and sew before attaching elastic straps. Deaconess Health System in Evansville, Indiana, has posted instructions for fabric masks on their website and asked the public to step up and sew.

Elsewhere, health care workers have turned to diapers, maxi pads and other products to create masks. Social media channels are full of tips and sewing patterns. It’s an innovative strategy that is also contentious. Limited evidence suggests that homemade masks can offer some protection. But the DIY approach has also drawn criticism for providing a false sense of security, potentially putting wearers at risk.

The conflict points to an immediate need for more protective equipment, says Christopher Friese, PhD, RN, professor of nursing and public health at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Also needed, he says, are new ideas for reducing strain on limited supplies, like adopting gear from other industries and finding innovative ways to provide care so that less protective gear is needed.

“We don’t want clinicians inventing and ‘MacGyvering’ their own device because we don’t want to put them at risk if we can avoid it,” says Friese, referring to the TV character who could build and assemble a vast array of tools/devices. “We have options that have been tested, and we have experience, maybe not in health care, but in other settings. We want to try that first before that frontline doctor, nurse, respiratory therapist decides to take matters into their own hands.

Increasingly, though, health care workers are finding they have no other choice — something even the CDC has acknowledged. In new guidelines, the agency recommends a bandanna, scarf, or other type of covering in cases where face masks are not available.

N95 respirators or surgical masks?

There are two main types of masks generally used in health care. N95 respirators filter out 95% of airborne particles, including bacteria and viruses. The lighter surgical or medical face masks are made to prevent spit and mucous from getting on patients or equipment.

Both types reduce rates of infection among health care workers, though comparisons (at least for influenza) have yet to show that one is superior to the other. One 2020 review by Chinese researchers, for example, analyzed six randomly controlled trials that included more than 9000 participants and found no added benefits of N95 masks over ordinary surgical masks for health care providers treating patients with the flu.

But COVID-19 is not influenza, and evidence suggests it may require more intensive protection, says Friese, who coauthored a blog post for JAMA about the country’s unpreparedness for protecting health care workers during a pandemic. The virus can linger in the air for hours, suggesting that N95 respirators are health care providers’ best option when treating infected patients.

The problem is there’s not enough to go around — of either mask type. In a March 5 survey, National Nurses United reported that just 30% of more than 6500 US respondents said their organizations had enough PPE to respond to a surge in patients. Another 38% did not know if their organizations were prepared. In a tweet, Friese estimated that 12% of nurses and other providers are at risk from reusing equipment or using equipment that is not backed by evidence.

Physicians and providers around the world have been sharing strategies online for how to make their own masks. Techniques vary, as do materials and plans for how to use the homemade equipment. At Phoebe Putney Health, DIY masks are intended to be worn over N95 respirators and then disposed of so that the respirators can be reused more safely, says Amanda Clements, the hospital’s public relations coordinator. Providers might also wear them to greet people at the front door.

Some evidence suggests that homemade masks can help in a pinch, at least for some illnesses. For a 2013 study by researchers in the UK, volunteers made surgical masks from cotton T-shirts, then put them on and coughed into a chamber that measured how much bacterial content got through. The team also assessed the aerosol-filtering ability of a variety of household materials, including scarfs, antimicrobial pillowcases, vacuum-cleaner bags, and tea towels. They tested each material with an aerosol containing two types of bacteria similar in size to influenza.

Commercial surgical masks performed three times better than homemade ones in the filtration test. Surgical masks worked twice as well at blocking droplets on the cough test. But all the makeshift materials — which also included silk, linen, and regular pillowcases — blocked some microbes. Vacuum-cleaner bags blocked the most bacteria, but their stiffness and thickness made them unsuitable for use as masks, the researchers reported. Tea towels showed a similar pattern. But pillowcases and cotton T-shirts were stretchy enough to fit well, thereby reducing the particles that could get through or around them.

Homemade masks should be used only as a last resort if commercial masks become unavailable, the researchers concluded. “Probably something is better than nothing for trained health care workers — for droplet contact avoidance, if nothing else,” says Anna Davies, BSc, a research facilitator at the University of Cambridge, UK, who is a former public health microbiologist and one of the study’s authors.

She recommends that members of the general public donate any stockpiles they have to health care workers, and make their own if they want masks for personal use. She is working with collaborators in the US to develop guidance for how best to do it.

“If people are quarantined and looking for something worthwhile to do, it probably wouldn’t be the worst thing to apply themselves to,” she wrote by email. “My suggestion would be for something soft and cotton, ideally with a bit of stretch (although it’s a pain to sew), and in two layers, marked ‘inside’ and ‘outside.’ ”

The idea that something is better than nothing was also the conclusion of a 2008 study by researchers in the Netherlands and the US. The study enlisted 28 healthy individuals who performed a variety of tasks while wearing N95 masks, surgical masks, or homemade masks sewn from teacloths. Effectiveness varied among individuals, but over a 90-second period, N95 masks worked best, with 25 times more protection than surgical masks and about 50 times more protection than homemade ones. Surgical masks were twice as effective as homemade masks. But the homemade masks offered at least some protection against large droplets.

Researchers emphasize that it’s not yet clear whether those findings are applicable to aerosolized COVID-19. In an influenza pandemic, at least, the authors posit that homemade masks could reduce transmission for the general public enough for some immunity to build. “It is important not to focus on a single intervention in case of a pandemic,” the researchers write, “but to integrate all effective interventions for optimal protection.”

For health care workers on the frontlines of COVID-19, Friese says, homemade masks might do more than nothing but they also might not work. Instead, he would rather see providers using construction or nuclear-engineering masks. And his best suggestion is something many providers are already doing: reducing physical contact with patients through telemedicine and other creative solutions, which is cutting down the overwhelming need for PPE.

Homemade mask production emphasizes the urgent need for more supplies, Friese adds.

“The government needs to step up and do a variety of things to increase production, and that needs to happen now, immediately,” he says. “We don’t we don’t want our clinicians to have to come up with these decisions.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the midst of the rapidly spreading COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals and clinics are running out of masks. Health care workers are going online to beg for more, the hashtags #GetMePPE and #WeNeedPPE are trending on Twitter, and some hospitals have even put out public calls for mask donations. Health providers are working scared: They know that the moment the masks run out, they’re at increased risk for disease. So instead of waiting for mask shipments that may be weeks off, some people are making their own.

Using a simple template, they cut green surgical sheeting into half-moons, which they pin and sew before attaching elastic straps. Deaconess Health System in Evansville, Indiana, has posted instructions for fabric masks on their website and asked the public to step up and sew.

Elsewhere, health care workers have turned to diapers, maxi pads and other products to create masks. Social media channels are full of tips and sewing patterns. It’s an innovative strategy that is also contentious. Limited evidence suggests that homemade masks can offer some protection. But the DIY approach has also drawn criticism for providing a false sense of security, potentially putting wearers at risk.

The conflict points to an immediate need for more protective equipment, says Christopher Friese, PhD, RN, professor of nursing and public health at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Also needed, he says, are new ideas for reducing strain on limited supplies, like adopting gear from other industries and finding innovative ways to provide care so that less protective gear is needed.

“We don’t want clinicians inventing and ‘MacGyvering’ their own device because we don’t want to put them at risk if we can avoid it,” says Friese, referring to the TV character who could build and assemble a vast array of tools/devices. “We have options that have been tested, and we have experience, maybe not in health care, but in other settings. We want to try that first before that frontline doctor, nurse, respiratory therapist decides to take matters into their own hands.

Increasingly, though, health care workers are finding they have no other choice — something even the CDC has acknowledged. In new guidelines, the agency recommends a bandanna, scarf, or other type of covering in cases where face masks are not available.

N95 respirators or surgical masks?

There are two main types of masks generally used in health care. N95 respirators filter out 95% of airborne particles, including bacteria and viruses. The lighter surgical or medical face masks are made to prevent spit and mucous from getting on patients or equipment.

Both types reduce rates of infection among health care workers, though comparisons (at least for influenza) have yet to show that one is superior to the other. One 2020 review by Chinese researchers, for example, analyzed six randomly controlled trials that included more than 9000 participants and found no added benefits of N95 masks over ordinary surgical masks for health care providers treating patients with the flu.

But COVID-19 is not influenza, and evidence suggests it may require more intensive protection, says Friese, who coauthored a blog post for JAMA about the country’s unpreparedness for protecting health care workers during a pandemic. The virus can linger in the air for hours, suggesting that N95 respirators are health care providers’ best option when treating infected patients.

The problem is there’s not enough to go around — of either mask type. In a March 5 survey, National Nurses United reported that just 30% of more than 6500 US respondents said their organizations had enough PPE to respond to a surge in patients. Another 38% did not know if their organizations were prepared. In a tweet, Friese estimated that 12% of nurses and other providers are at risk from reusing equipment or using equipment that is not backed by evidence.

Physicians and providers around the world have been sharing strategies online for how to make their own masks. Techniques vary, as do materials and plans for how to use the homemade equipment. At Phoebe Putney Health, DIY masks are intended to be worn over N95 respirators and then disposed of so that the respirators can be reused more safely, says Amanda Clements, the hospital’s public relations coordinator. Providers might also wear them to greet people at the front door.

Some evidence suggests that homemade masks can help in a pinch, at least for some illnesses. For a 2013 study by researchers in the UK, volunteers made surgical masks from cotton T-shirts, then put them on and coughed into a chamber that measured how much bacterial content got through. The team also assessed the aerosol-filtering ability of a variety of household materials, including scarfs, antimicrobial pillowcases, vacuum-cleaner bags, and tea towels. They tested each material with an aerosol containing two types of bacteria similar in size to influenza.

Commercial surgical masks performed three times better than homemade ones in the filtration test. Surgical masks worked twice as well at blocking droplets on the cough test. But all the makeshift materials — which also included silk, linen, and regular pillowcases — blocked some microbes. Vacuum-cleaner bags blocked the most bacteria, but their stiffness and thickness made them unsuitable for use as masks, the researchers reported. Tea towels showed a similar pattern. But pillowcases and cotton T-shirts were stretchy enough to fit well, thereby reducing the particles that could get through or around them.

Homemade masks should be used only as a last resort if commercial masks become unavailable, the researchers concluded. “Probably something is better than nothing for trained health care workers — for droplet contact avoidance, if nothing else,” says Anna Davies, BSc, a research facilitator at the University of Cambridge, UK, who is a former public health microbiologist and one of the study’s authors.

She recommends that members of the general public donate any stockpiles they have to health care workers, and make their own if they want masks for personal use. She is working with collaborators in the US to develop guidance for how best to do it.

“If people are quarantined and looking for something worthwhile to do, it probably wouldn’t be the worst thing to apply themselves to,” she wrote by email. “My suggestion would be for something soft and cotton, ideally with a bit of stretch (although it’s a pain to sew), and in two layers, marked ‘inside’ and ‘outside.’ ”

The idea that something is better than nothing was also the conclusion of a 2008 study by researchers in the Netherlands and the US. The study enlisted 28 healthy individuals who performed a variety of tasks while wearing N95 masks, surgical masks, or homemade masks sewn from teacloths. Effectiveness varied among individuals, but over a 90-second period, N95 masks worked best, with 25 times more protection than surgical masks and about 50 times more protection than homemade ones. Surgical masks were twice as effective as homemade masks. But the homemade masks offered at least some protection against large droplets.

Researchers emphasize that it’s not yet clear whether those findings are applicable to aerosolized COVID-19. In an influenza pandemic, at least, the authors posit that homemade masks could reduce transmission for the general public enough for some immunity to build. “It is important not to focus on a single intervention in case of a pandemic,” the researchers write, “but to integrate all effective interventions for optimal protection.”

For health care workers on the frontlines of COVID-19, Friese says, homemade masks might do more than nothing but they also might not work. Instead, he would rather see providers using construction or nuclear-engineering masks. And his best suggestion is something many providers are already doing: reducing physical contact with patients through telemedicine and other creative solutions, which is cutting down the overwhelming need for PPE.

Homemade mask production emphasizes the urgent need for more supplies, Friese adds.

“The government needs to step up and do a variety of things to increase production, and that needs to happen now, immediately,” he says. “We don’t we don’t want our clinicians to have to come up with these decisions.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Match Day 2020: Online announcements replace celebrations, champagne

The third Friday in March usually marks a time when medical students across the United States participate in envelope-opening ceremonies with peers and family members. This year, the ruthless onslaught of coronavirus has forced residency programs to rethink their celebrations, leveraging social media platforms and other technologies to toast Match Day in cyberspace.

In the absence of ceremonies taking place due to restrictions on mass gatherings, “we anticipate that students may be more emotional than they expect,” Hannah R. Hughes, MD, president of the Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association (EMRA) said in an interview. To support these students on their journey to residency, EMRA has launched a social media campaign, asking medical students “to share with us their envelope-opening moments – either a selfie, photo, or video – that we can share with our online networks,” Dr. Hughes said.

EMRA is also asking program coordinators to forward photos and congratulatory messages to their new residents “so that we can share them with our networks at large,” she added.

Going virtual, it seems, has become the new norm.

At the University of California, San Francisco, the medical school decided to cancel its Match Day celebration for new interns, echoing many other programs across the United States. “We always send out a welcome email and make phone calls to all of our new interns,” said Rebecca Berman, MD, director of UCSF’s internal medicine residency program, which houses 63 medicine interns and 181 residents. Traditionally, the program has hosted the celebration for current residents. That, of course, had to change this year.

Current interns like to join in the fun, “since it means their internship is rapidly coming to a close,” said Dr. Berman, who at press time was considering a virtual toast via Zoom as a possible alternative. “These are difficult times for everyone, and we are doing our best to make our residents feel united and connected while they take care of patients in the era of social distancing.”

Melissa Held, MD, associate dean of medical student affairs at the University of Connecticut’s School of Medicine, Farmington, had been planning a celebration in the school’s academic rotunda with food and champagne. “Students typically come with their family members or significant others. The dean and I usually say a few words and then at noon, students get envelopes and can open them to find out where they matched for residency,” Dr. Held said. This year, the school will be uploading Match letters to its online system. Students can remotely find out where they matched at noon. “I plan to put together a slide show of pictures and congratulatory remarks from faculty and staff that will be sent to them around 11:30 a.m.,” Dr. Held said.

Mark Miceli, EdD, who oversees Match Day for the 130-plus medical students at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, is inviting faculty and staff to submit short videos of congratulations, which it will post on its student affairs Match Day Instagram account. Like other schools, it will share results with students in an email, said Dr. Miceli, assistant vice provost of student life. “This message will be more personalized to our school than the NRMP [National Resident Matching Program] message, and will also include links to our match stats, a map of our matched student locations, and a list of where folks matched,” he said.

Students can opt out of the list if they want to. The communications department has also provided templates for signs students can print out. “They can write in where they matched, and take pictures for social media. We are encouraging the use of various hashtags to help build a virtual community,” Dr. Miceli said.

In a state hit particularly hard by coronavirus, the University of Washington School of Medicine is spreading Match Day cheer through online meeting platforms and celebratory graphics. This five-state school, representing students from Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho, usually hosts several events across the different states and students have their pick of which to attend, according to Sarah Wood, associate director of student affairs.

In lieu of in-person events, some states are hosting a Zoom online celebration, others are using social media networking systems. “We’re inviting everyone to take part in an online event ... where we’ll do a slide show of photos that one of our students put together,” Ms. Wood said.

Students are disappointed in this change of plans, she said. To make things more festive, Ms. Wood is adding graphics such as fireworks and photos to the emails containing the Match results. “I want this to be more exciting for them than just a basic letter,” she said.

For now, Ms. Wood is trying to focus on the Match Day celebration, but admits that “my bigger fear is if we have to cancel graduation – and what that might look like.”

The third Friday in March usually marks a time when medical students across the United States participate in envelope-opening ceremonies with peers and family members. This year, the ruthless onslaught of coronavirus has forced residency programs to rethink their celebrations, leveraging social media platforms and other technologies to toast Match Day in cyberspace.

In the absence of ceremonies taking place due to restrictions on mass gatherings, “we anticipate that students may be more emotional than they expect,” Hannah R. Hughes, MD, president of the Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association (EMRA) said in an interview. To support these students on their journey to residency, EMRA has launched a social media campaign, asking medical students “to share with us their envelope-opening moments – either a selfie, photo, or video – that we can share with our online networks,” Dr. Hughes said.

EMRA is also asking program coordinators to forward photos and congratulatory messages to their new residents “so that we can share them with our networks at large,” she added.

Going virtual, it seems, has become the new norm.

At the University of California, San Francisco, the medical school decided to cancel its Match Day celebration for new interns, echoing many other programs across the United States. “We always send out a welcome email and make phone calls to all of our new interns,” said Rebecca Berman, MD, director of UCSF’s internal medicine residency program, which houses 63 medicine interns and 181 residents. Traditionally, the program has hosted the celebration for current residents. That, of course, had to change this year.

Current interns like to join in the fun, “since it means their internship is rapidly coming to a close,” said Dr. Berman, who at press time was considering a virtual toast via Zoom as a possible alternative. “These are difficult times for everyone, and we are doing our best to make our residents feel united and connected while they take care of patients in the era of social distancing.”

Melissa Held, MD, associate dean of medical student affairs at the University of Connecticut’s School of Medicine, Farmington, had been planning a celebration in the school’s academic rotunda with food and champagne. “Students typically come with their family members or significant others. The dean and I usually say a few words and then at noon, students get envelopes and can open them to find out where they matched for residency,” Dr. Held said. This year, the school will be uploading Match letters to its online system. Students can remotely find out where they matched at noon. “I plan to put together a slide show of pictures and congratulatory remarks from faculty and staff that will be sent to them around 11:30 a.m.,” Dr. Held said.

Mark Miceli, EdD, who oversees Match Day for the 130-plus medical students at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, is inviting faculty and staff to submit short videos of congratulations, which it will post on its student affairs Match Day Instagram account. Like other schools, it will share results with students in an email, said Dr. Miceli, assistant vice provost of student life. “This message will be more personalized to our school than the NRMP [National Resident Matching Program] message, and will also include links to our match stats, a map of our matched student locations, and a list of where folks matched,” he said.

Students can opt out of the list if they want to. The communications department has also provided templates for signs students can print out. “They can write in where they matched, and take pictures for social media. We are encouraging the use of various hashtags to help build a virtual community,” Dr. Miceli said.

In a state hit particularly hard by coronavirus, the University of Washington School of Medicine is spreading Match Day cheer through online meeting platforms and celebratory graphics. This five-state school, representing students from Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho, usually hosts several events across the different states and students have their pick of which to attend, according to Sarah Wood, associate director of student affairs.

In lieu of in-person events, some states are hosting a Zoom online celebration, others are using social media networking systems. “We’re inviting everyone to take part in an online event ... where we’ll do a slide show of photos that one of our students put together,” Ms. Wood said.

Students are disappointed in this change of plans, she said. To make things more festive, Ms. Wood is adding graphics such as fireworks and photos to the emails containing the Match results. “I want this to be more exciting for them than just a basic letter,” she said.

For now, Ms. Wood is trying to focus on the Match Day celebration, but admits that “my bigger fear is if we have to cancel graduation – and what that might look like.”

The third Friday in March usually marks a time when medical students across the United States participate in envelope-opening ceremonies with peers and family members. This year, the ruthless onslaught of coronavirus has forced residency programs to rethink their celebrations, leveraging social media platforms and other technologies to toast Match Day in cyberspace.

In the absence of ceremonies taking place due to restrictions on mass gatherings, “we anticipate that students may be more emotional than they expect,” Hannah R. Hughes, MD, president of the Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association (EMRA) said in an interview. To support these students on their journey to residency, EMRA has launched a social media campaign, asking medical students “to share with us their envelope-opening moments – either a selfie, photo, or video – that we can share with our online networks,” Dr. Hughes said.

EMRA is also asking program coordinators to forward photos and congratulatory messages to their new residents “so that we can share them with our networks at large,” she added.

Going virtual, it seems, has become the new norm.

At the University of California, San Francisco, the medical school decided to cancel its Match Day celebration for new interns, echoing many other programs across the United States. “We always send out a welcome email and make phone calls to all of our new interns,” said Rebecca Berman, MD, director of UCSF’s internal medicine residency program, which houses 63 medicine interns and 181 residents. Traditionally, the program has hosted the celebration for current residents. That, of course, had to change this year.

Current interns like to join in the fun, “since it means their internship is rapidly coming to a close,” said Dr. Berman, who at press time was considering a virtual toast via Zoom as a possible alternative. “These are difficult times for everyone, and we are doing our best to make our residents feel united and connected while they take care of patients in the era of social distancing.”

Melissa Held, MD, associate dean of medical student affairs at the University of Connecticut’s School of Medicine, Farmington, had been planning a celebration in the school’s academic rotunda with food and champagne. “Students typically come with their family members or significant others. The dean and I usually say a few words and then at noon, students get envelopes and can open them to find out where they matched for residency,” Dr. Held said. This year, the school will be uploading Match letters to its online system. Students can remotely find out where they matched at noon. “I plan to put together a slide show of pictures and congratulatory remarks from faculty and staff that will be sent to them around 11:30 a.m.,” Dr. Held said.

Mark Miceli, EdD, who oversees Match Day for the 130-plus medical students at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, is inviting faculty and staff to submit short videos of congratulations, which it will post on its student affairs Match Day Instagram account. Like other schools, it will share results with students in an email, said Dr. Miceli, assistant vice provost of student life. “This message will be more personalized to our school than the NRMP [National Resident Matching Program] message, and will also include links to our match stats, a map of our matched student locations, and a list of where folks matched,” he said.

Students can opt out of the list if they want to. The communications department has also provided templates for signs students can print out. “They can write in where they matched, and take pictures for social media. We are encouraging the use of various hashtags to help build a virtual community,” Dr. Miceli said.

In a state hit particularly hard by coronavirus, the University of Washington School of Medicine is spreading Match Day cheer through online meeting platforms and celebratory graphics. This five-state school, representing students from Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho, usually hosts several events across the different states and students have their pick of which to attend, according to Sarah Wood, associate director of student affairs.

In lieu of in-person events, some states are hosting a Zoom online celebration, others are using social media networking systems. “We’re inviting everyone to take part in an online event ... where we’ll do a slide show of photos that one of our students put together,” Ms. Wood said.

Students are disappointed in this change of plans, she said. To make things more festive, Ms. Wood is adding graphics such as fireworks and photos to the emails containing the Match results. “I want this to be more exciting for them than just a basic letter,” she said.

For now, Ms. Wood is trying to focus on the Match Day celebration, but admits that “my bigger fear is if we have to cancel graduation – and what that might look like.”

Clinicians petition government for national quarantine

Clinicians across the United States are petitioning the federal government to follow the lead of South Korea, China, and other nations by imposing an immediate nationwide quarantine to slow the inevitable spread of COVID-19. Without federal action, the creators say, their lives and the lives of their colleagues, patients, and families are being put at increased risk.

In addition to the quarantine, the petition, posted on the website Change.org, calls on U.S. leaders to institute emergency production and distribution of personal protective equipment for healthcare workers and to rapidly increase access to testing.

The petition – which garnered more than 40,000 signatures in just 12 hours and as of this writing was approaching 94,000 – was started by an apolitical Facebook group to focus attention on what members see as the most critical issues for clinicians: slowing the spread of the virus through a coast-to-coast quarantine, protection of medical personnel with adequate supplies of essential equipment, and widespread testing.

“We started this group last Friday out of the realization that clinicians needed information about the outbreak and weren’t getting it,” said coadministrator Jessica McIntyre, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Elliot Hospital in Manchester, N.H.

“We wanted to get ahead of it and connect with people before we were in the trenches experiencing it and to see what other programs were doing. From a local perspective, it has been really hard to see what people are doing in other states, especially when the protocols in our own states are changing every single day as we collect more information,” she said in an interview.

The Horse Has Bolted

A family medicine physician in Illinois helped launch the Facebook group. She asked that her name not be used but said in an interview that earlier actions may have prevented or at least delayed the need for the more draconian measures that her group is recommending.

“Clearly South Korea is one of the superstars as far as response has gone, but the concern we have in the United States is that we’re well beyond that point – we needed to be testing people over a month ago, in the hope of preventing a quarantine,” she said in an interview.

According to National Public Radio, as of March 13, South Korea had conducted 3,600 tests per million population, compared with five per million in the United States.

“I think the most concerning part is to see where Italy is now and where we are in comparison. Our ICUs have not yet overflowed, but I think we’re definitely looking at that in the next few weeks – hopefully longer, but I suspect that it will happen shortly,” she continued.

She cited work by Harvard University biostatistician Xihong Lin, PhD, that shows that when health authorities in Wuhan, China – widely cited as the epicenter of the global pandemic – cordoned off the city, the infection rate dropped from one person infecting 3.8 others to one infecting 1.25, thereby significantly slowing the rate of transmission.

“This is absolutely what we need to be doing,” she said.

Real News

Within 3 days of its creation, the online group had accrued more than 80,000 members with advanced medical training, including MDs, DOs, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and certified registered nurse anesthetists.

“A lot of us were already very busy with our day-to-day work outside of COVID-19, and I think a lot of us felt unsure about where to get the best information,” said coadministrator David Janssen, MD, a family medicine physician in group practice in Sioux Center, Iowa,

“If you turn on the TV, there’s a lot of politicizing of the issue, and there’s a lot of good information, but also a lot of bad information. When health care providers talk to other health care providers, that’s often how we get our information and how we learn,” he said in an interview.

The COVID-19 U.S. Physicians/APP Facebook group includes 20 volunteer moderators who handle hundreds of posts per hour from persons seeking information on the novel coronavirus, what to tell patients, and how to protect themselves.

“It’s been wonderful to see how providers have been helping other providers sort through issues. Teaching hospitals have their hands on the latest research, but a lot of people like myself are at small community hospitals, critical-access hospitals, where we may have a lot of questions but don’t necessarily have the answers readily available to us,” Dr. Janssen said.

Dr. Janssen said that his community of about 8,000 residents initially had only four COVID-19 testing kits, or one for every 2,000 people. The situation has since improved, and more tests are now available, he added.

Dr. McIntyre, Dr. Janssen, and the Illinois family physician have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinicians across the United States are petitioning the federal government to follow the lead of South Korea, China, and other nations by imposing an immediate nationwide quarantine to slow the inevitable spread of COVID-19. Without federal action, the creators say, their lives and the lives of their colleagues, patients, and families are being put at increased risk.

In addition to the quarantine, the petition, posted on the website Change.org, calls on U.S. leaders to institute emergency production and distribution of personal protective equipment for healthcare workers and to rapidly increase access to testing.

The petition – which garnered more than 40,000 signatures in just 12 hours and as of this writing was approaching 94,000 – was started by an apolitical Facebook group to focus attention on what members see as the most critical issues for clinicians: slowing the spread of the virus through a coast-to-coast quarantine, protection of medical personnel with adequate supplies of essential equipment, and widespread testing.

“We started this group last Friday out of the realization that clinicians needed information about the outbreak and weren’t getting it,” said coadministrator Jessica McIntyre, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Elliot Hospital in Manchester, N.H.

“We wanted to get ahead of it and connect with people before we were in the trenches experiencing it and to see what other programs were doing. From a local perspective, it has been really hard to see what people are doing in other states, especially when the protocols in our own states are changing every single day as we collect more information,” she said in an interview.

The Horse Has Bolted

A family medicine physician in Illinois helped launch the Facebook group. She asked that her name not be used but said in an interview that earlier actions may have prevented or at least delayed the need for the more draconian measures that her group is recommending.

“Clearly South Korea is one of the superstars as far as response has gone, but the concern we have in the United States is that we’re well beyond that point – we needed to be testing people over a month ago, in the hope of preventing a quarantine,” she said in an interview.

According to National Public Radio, as of March 13, South Korea had conducted 3,600 tests per million population, compared with five per million in the United States.

“I think the most concerning part is to see where Italy is now and where we are in comparison. Our ICUs have not yet overflowed, but I think we’re definitely looking at that in the next few weeks – hopefully longer, but I suspect that it will happen shortly,” she continued.

She cited work by Harvard University biostatistician Xihong Lin, PhD, that shows that when health authorities in Wuhan, China – widely cited as the epicenter of the global pandemic – cordoned off the city, the infection rate dropped from one person infecting 3.8 others to one infecting 1.25, thereby significantly slowing the rate of transmission.

“This is absolutely what we need to be doing,” she said.

Real News

Within 3 days of its creation, the online group had accrued more than 80,000 members with advanced medical training, including MDs, DOs, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and certified registered nurse anesthetists.

“A lot of us were already very busy with our day-to-day work outside of COVID-19, and I think a lot of us felt unsure about where to get the best information,” said coadministrator David Janssen, MD, a family medicine physician in group practice in Sioux Center, Iowa,

“If you turn on the TV, there’s a lot of politicizing of the issue, and there’s a lot of good information, but also a lot of bad information. When health care providers talk to other health care providers, that’s often how we get our information and how we learn,” he said in an interview.

The COVID-19 U.S. Physicians/APP Facebook group includes 20 volunteer moderators who handle hundreds of posts per hour from persons seeking information on the novel coronavirus, what to tell patients, and how to protect themselves.

“It’s been wonderful to see how providers have been helping other providers sort through issues. Teaching hospitals have their hands on the latest research, but a lot of people like myself are at small community hospitals, critical-access hospitals, where we may have a lot of questions but don’t necessarily have the answers readily available to us,” Dr. Janssen said.

Dr. Janssen said that his community of about 8,000 residents initially had only four COVID-19 testing kits, or one for every 2,000 people. The situation has since improved, and more tests are now available, he added.

Dr. McIntyre, Dr. Janssen, and the Illinois family physician have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinicians across the United States are petitioning the federal government to follow the lead of South Korea, China, and other nations by imposing an immediate nationwide quarantine to slow the inevitable spread of COVID-19. Without federal action, the creators say, their lives and the lives of their colleagues, patients, and families are being put at increased risk.

In addition to the quarantine, the petition, posted on the website Change.org, calls on U.S. leaders to institute emergency production and distribution of personal protective equipment for healthcare workers and to rapidly increase access to testing.

The petition – which garnered more than 40,000 signatures in just 12 hours and as of this writing was approaching 94,000 – was started by an apolitical Facebook group to focus attention on what members see as the most critical issues for clinicians: slowing the spread of the virus through a coast-to-coast quarantine, protection of medical personnel with adequate supplies of essential equipment, and widespread testing.

“We started this group last Friday out of the realization that clinicians needed information about the outbreak and weren’t getting it,” said coadministrator Jessica McIntyre, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Elliot Hospital in Manchester, N.H.

“We wanted to get ahead of it and connect with people before we were in the trenches experiencing it and to see what other programs were doing. From a local perspective, it has been really hard to see what people are doing in other states, especially when the protocols in our own states are changing every single day as we collect more information,” she said in an interview.

The Horse Has Bolted

A family medicine physician in Illinois helped launch the Facebook group. She asked that her name not be used but said in an interview that earlier actions may have prevented or at least delayed the need for the more draconian measures that her group is recommending.

“Clearly South Korea is one of the superstars as far as response has gone, but the concern we have in the United States is that we’re well beyond that point – we needed to be testing people over a month ago, in the hope of preventing a quarantine,” she said in an interview.

According to National Public Radio, as of March 13, South Korea had conducted 3,600 tests per million population, compared with five per million in the United States.

“I think the most concerning part is to see where Italy is now and where we are in comparison. Our ICUs have not yet overflowed, but I think we’re definitely looking at that in the next few weeks – hopefully longer, but I suspect that it will happen shortly,” she continued.

She cited work by Harvard University biostatistician Xihong Lin, PhD, that shows that when health authorities in Wuhan, China – widely cited as the epicenter of the global pandemic – cordoned off the city, the infection rate dropped from one person infecting 3.8 others to one infecting 1.25, thereby significantly slowing the rate of transmission.

“This is absolutely what we need to be doing,” she said.

Real News

Within 3 days of its creation, the online group had accrued more than 80,000 members with advanced medical training, including MDs, DOs, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and certified registered nurse anesthetists.

“A lot of us were already very busy with our day-to-day work outside of COVID-19, and I think a lot of us felt unsure about where to get the best information,” said coadministrator David Janssen, MD, a family medicine physician in group practice in Sioux Center, Iowa,

“If you turn on the TV, there’s a lot of politicizing of the issue, and there’s a lot of good information, but also a lot of bad information. When health care providers talk to other health care providers, that’s often how we get our information and how we learn,” he said in an interview.

The COVID-19 U.S. Physicians/APP Facebook group includes 20 volunteer moderators who handle hundreds of posts per hour from persons seeking information on the novel coronavirus, what to tell patients, and how to protect themselves.

“It’s been wonderful to see how providers have been helping other providers sort through issues. Teaching hospitals have their hands on the latest research, but a lot of people like myself are at small community hospitals, critical-access hospitals, where we may have a lot of questions but don’t necessarily have the answers readily available to us,” Dr. Janssen said.

Dr. Janssen said that his community of about 8,000 residents initially had only four COVID-19 testing kits, or one for every 2,000 people. The situation has since improved, and more tests are now available, he added.

Dr. McIntyre, Dr. Janssen, and the Illinois family physician have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physicians and health systems can reduce fear around COVID-19

A message from a Chief Wellness Officer

We are at a time, unfortunately, of significant public uncertainty and fear of “the coronavirus.” Mixed and inaccurate messages from national leaders in the setting of delayed testing availability have heightened fears and impeded a uniformity in responses, medical and preventive.

Despite this, physicians, nurses, and other health professionals across the country, and in many other countries, have been addressing the medical realities of this pandemic in a way that should make every one of us health professionals proud – from the Chinese doctors and nurses to the Italian intensivists and primary care physicians throughout many countries who have treated patients suffering from, or fearful of, a novel disease with uncertain transmission characteristics and unpredictable clinical outcomes.

It is now time for physicians and other health providers in the United States to step up to the plate and model appropriate transmission-reducing behavior for the general public. This will help reduce the overall morbidity and mortality associated with this pandemic and let us return to a more normal lifestyle as soon as possible. Physicians need to be reassuring but realistic, and there are concrete steps that we can take to demonstrate to the general public that there is a way forward.

First the basic facts. The United States does not have enough intensive care beds or ventilators to handle a major pandemic. We will also have insufficient physicians and nurses if many are quarantined. The tragic experience in Italy, where patients are dying from lack of ventilators, intensive care facilities, and staff, must not be repeated here.

Many health systems are canceling or reducing outpatient appointments and increasingly using video and other telehealth technologies, especially for assessing and triaging people who believe that they may have become infected and are relatively asymptomatic. While all of the disruptions may seem unsettling, they are actually good news for those of us in healthcare. Efforts to “flatten the curve” will slow the infection spread and help us better manage patients who become critical.

So, what can physicians do?

- Make sure you are getting good information about the situation. Access reliable information and data that are widely available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the World Health Organization. Listen to professional news organizations, local and national. Pass this information to your patients and community.

- Obviously, when practicing clinically, follow all infection control protocols, which will inevitably change over time. Make it clear to your patients why you are following these protocols and procedures.

- Support and actively promote the public health responses to this pandemic. Systematic reviews of the evidence base have found that isolating ill persons, testing and tracing contacts, quarantining exposed persons, closing schools and workplaces, and avoiding crowding are more effective if implemented immediately, simultaneously (ie, school closures combined with teleworking for parents), and with high community compliance.