User login

Review of 3 Comprehensive Anki Flash Card Decks for Dermatology Residents

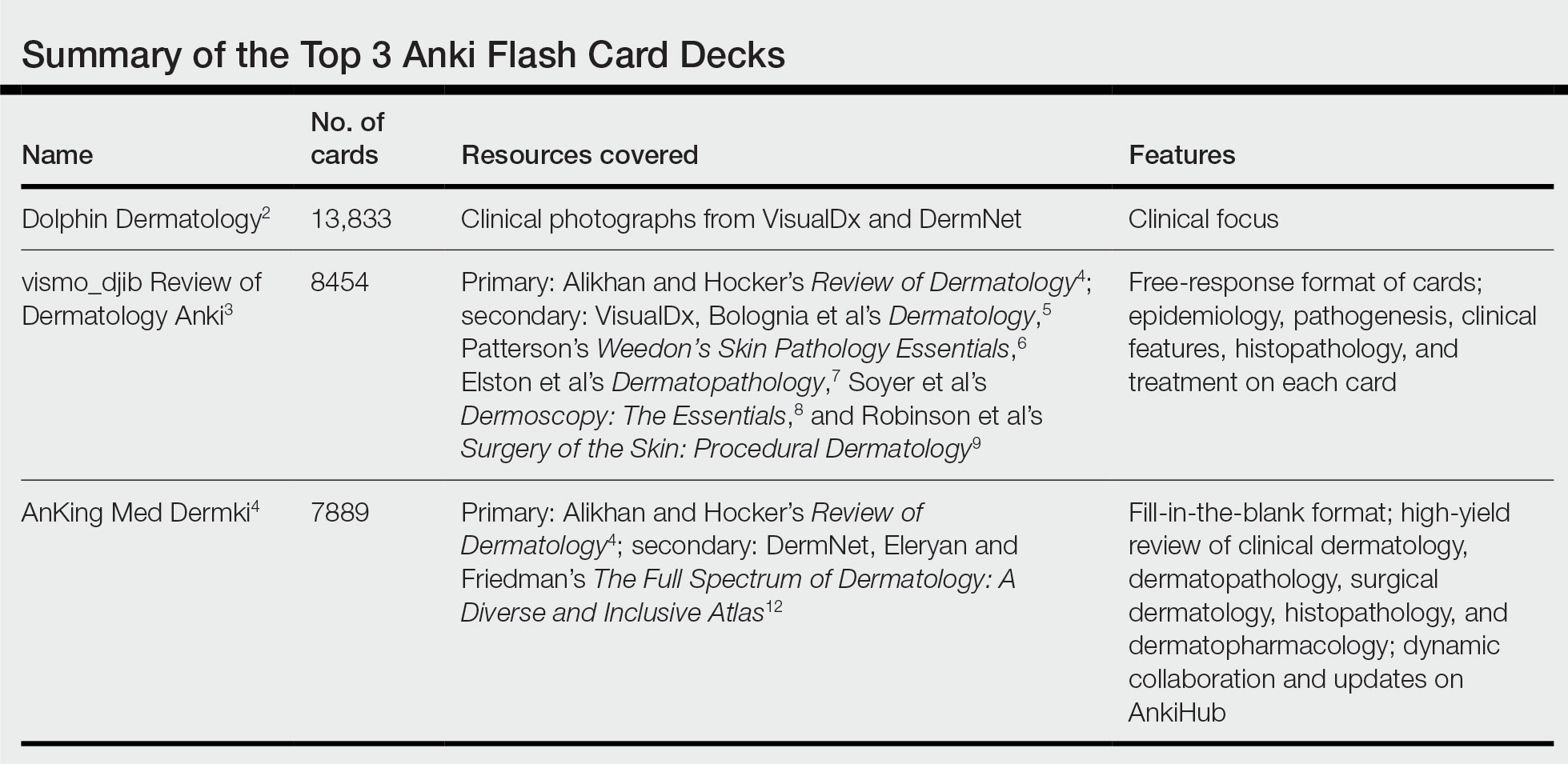

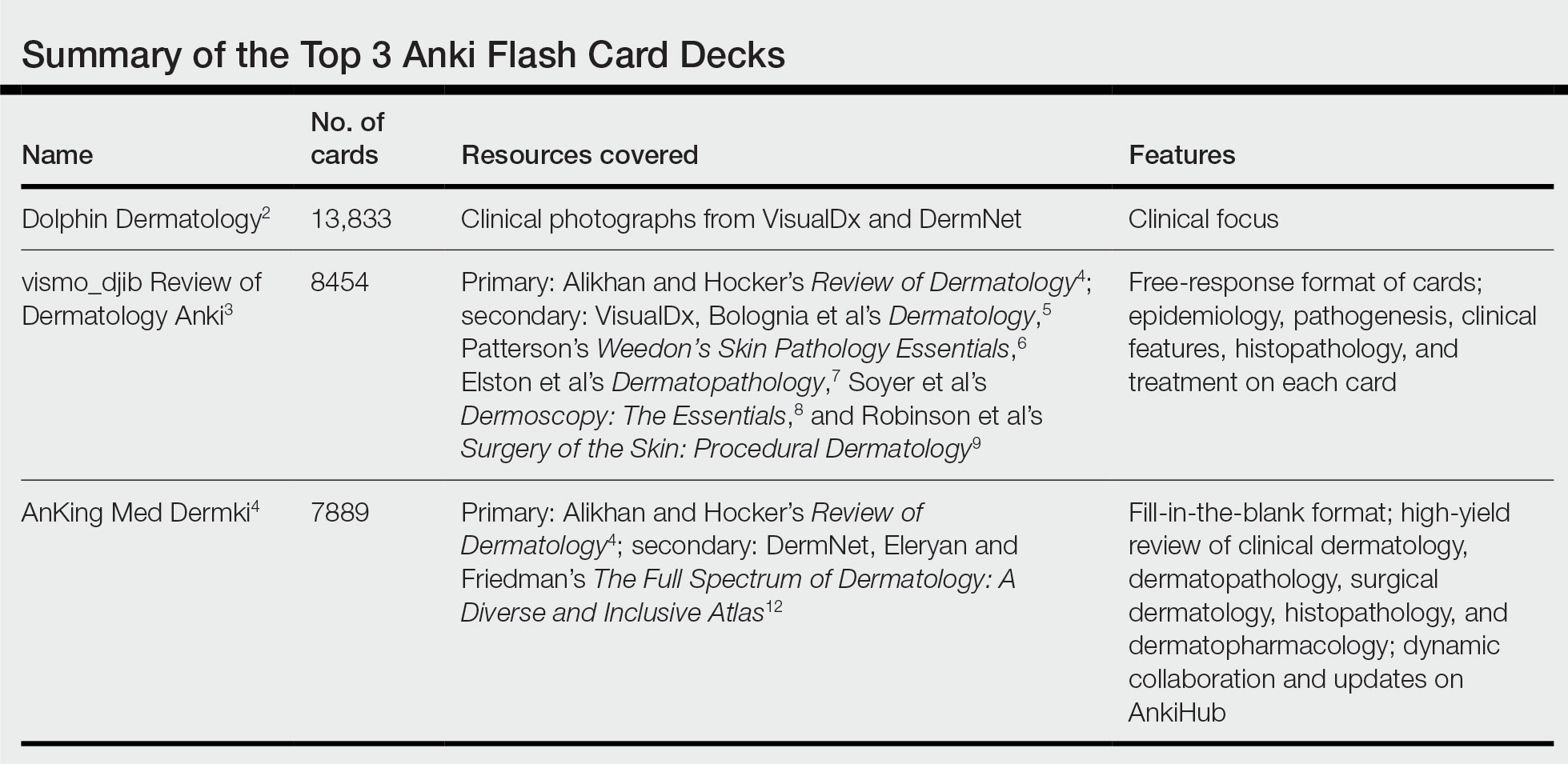

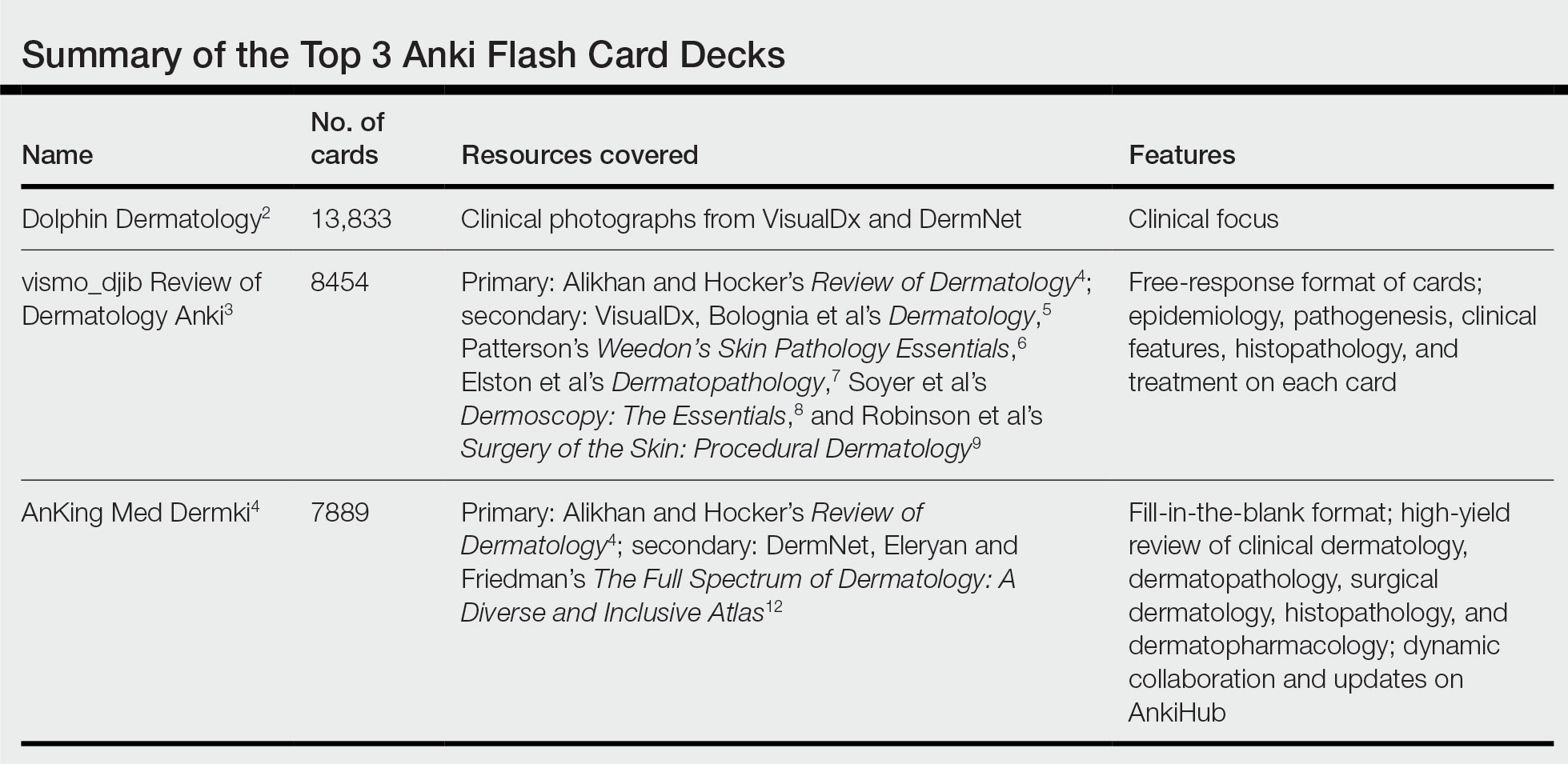

Similar to medical school, residency is a time to drink out of the proverbial firehose of knowledge. Along with clinical duties, there is a plethora of information ranging from clinical management decisions to boards fodder that dermatology residents are expected to know, leaving residents to adopt study habits from medical school. Flash cards remain a popular study tool in the medical education community. The use of Anki, a web-based and mobile flash card application (app) that features custom and premade flash card decks made and shared by users, has become increasingly popular. In a 2021 study, Lu et al1 found that Anki flash card usage was associated with higher US Medical Licensing Examination scores. Herein, I provide an updated review of the top 3 most comprehensive premade Anki decks for dermatology residents, per my assessment.

COMPREHENSIVE DERMATOLOGY DECKS

Dolphin Dermatology

- Creator: Reddit user, Unknown2

- Date created: December 2020

- Last updated: April 2022

- Number of cards: 13,833

- Resources covered: Photographs of common dermatologic diagnoses from online sources such as VisualDx (https://www.visualdx.com/) and DermNet (https://dermnetnz.org/).

- Format of cards: One image or factoid per card.

- Card tags (allow separation of Anki decks into subcategories): Each general dermatology card is tagged by the diagnosis name. Pediatric dermatology cards are tagged by affected body location.

- Advantages: As you may glean by the sheer number of flash cards, this deck is a comprehensive review of clinical dermatology. Most cards feature clinical vignettes with clinical photographs of a dermatologic condition or histologic slide and ask what the diagnosis may be. It features photographs of pathology on a range of skin tones and many different images of each diagnosis. This is a great deck for residents who need to study clinical photographs of dermatologic diagnoses.

- Disadvantages: This deck does not cover dermatopathology, basic science, treatment options, or pharmacology in depth. Additionally, is difficult to find a link to download this resource.

- At the time of publication of this article, users are unable to download this deck.

vismo_djib’s Review of Dermatology Anki

- Creator: Reddit user vismo_djib3

- Date created: June 2020

- Last updated: February 2022

- Number of cards: 8454

- Resources covered: Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology4 is the main resource with supplemental images from VisualDx, Bolognia et al’s Dermatology,5 Patterson’s Weedon’s Skin Pathology Essentials,6 Elston et al’s Dermatopathology,7 Soyer et al’s Dermoscopy: The Essentials,8 and Robinson et al’s Surgery of the Skin: Procedural Dermatology.9

- Format of cards: Cards mostly feature a diagnosis with color-coded categories including epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical features, histopathology, and treatment.

- Card tags (allow separation of Anki decks into subcategories): Cards are tagged with chapter numbers from Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology.4

- Advantages: This impressive comprehensive review of dermatology is a great option for residents studying for the American Board of Dermatology CORE examinations and users looking to solidify the information in Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology,4 a frequently used resource among dermatology residents. It currently is my favorite deck because it features holistic information on diagnosis, epidemiology, pathogenesis, histopathology, and treatment with excellent clinical photographs.

- Disadvantages: For some purposes, this deck may be too lofty. For maximum benefit, it may require user customization including separating cards by tag and other add-ons that allow only 1 card per note, which will separate the information on each card into smaller increments. The mostly free-response format and lengthy slides may make it difficult to practice recall.

AnKingMed Dermki

- Creator: Reddit user AnKingMed10,11

- Date created: April 2023

- Last updated: This deck features a dynamic add-on and collaboration application called AnkiHub, which allows for real-time updates. At the time this article was written, the deck was last updated on June 19, 2023.

- Number of cards: 7889

- Resources covered: Currently 75% of Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology4 with supplemental images from DermNet and Eleryan and Friedman’s The Full Spectrum of Dermatology: A Diverse and Inclusive Atlas.12

- Format of cards: Cards are in a fill-in-the-blank format.

- Card tags (allow separation of Anki decks into subcategories): Cards are tagged by chapter number and subsection of Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology.4

- Advantages: As the newest contribution to the dermatology Anki card compendium, this deck is up to date, innovative, and dynamic. It features an optional add-on application—AnkiHub—which allows users to keep up with live updates and collaborations. The deck features a fill-in-the-blank format that may be preferred to a free-response format for information recall. It features Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology,4 which is a high-yield review of clinical dermatology, dermatopathology, surgical dermatology, pharmacology, and histopathology for dermatology residents.

- Disadvantages: The deck is still currently in a development phase, covering 75% of Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology4 with plans to add the remaining 25%. The add-on to access the most up-to-date version of the flashcards requires a paid monthly or annual subscription; however, the creator announced they will release periodic free updates of the deck.

Final Thoughts

As a collaborative platform, new flash card decks are always being added to Anki. This article is not comprehensive of all dermatologic flash card decks available. There are decks better suited for medical students covering topics such as the American Academy of Dermatology Basic Dermatology Curriculum, UWorld United States Medical Licensing Examination dermatology, and dermatology in internal medicine. Furthermore, specific study tools in dermatology may have their own accompanying Anki decks (ie, The Grenz Zone podcast, Dermnemonics). Flash cards can be a valuable study tool to trainees in medicine, and residents are immensely grateful to our peers who make them for our use.

- Lu M, Farhat JH, Beck Dallaghan GL. Enhanced learning and retention of medical knowledge using the mobile flash card application Anki. Med Sci Educ. 2021;31:1975-1981. doi:10.1007/s40670-021-01386-9

- Unknown. Dolphin Dermatology. Reddit website. Accessed July 19, 2023. https://www.reddit.com/r/medicalschoolanki/comments/116jbpc/dolphin_derm/

- vismo_djib. Review of dermatology Anki. Reddit website. Published June 13, 2020. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.reddit.com/r/DermApp/comments/h8gz3d/review_of_dermatology_anki/

- Alikhan A, Hocker TLH. Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2016.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017.

- Patterson JW. Weedon’s Skin Pathology Essentials. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2016.

- Elston D, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013.

- Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, et al. Dermoscopy: The Essentials. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011.

- Robinson JK, Hanke CW, Siegel DM, et al. Surgery of the Skin: Procedural Dermatology. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2014.

- AnKingMed. Dermki: dermatology residency Anki deck. Reddit website. Published April 8, 2023. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.reddit.com/r/medicalschoolanki/comments/12fo9ji/dermki_dermatology_residency_anki_deck/

- Dermki deck for Dermatology Residents. Notion website. Accessed July 10, 2023. https://ankingmed.notion.site/Dermki-deck-for-Dermatology-Residents-9e0b8d8abc2a4bf7941903d80e5b01a2

- Eleryan M, Friedman A. The Full Spectrum of Dermatology: A Diverse and Inclusive Atlas. Sanovaworks; 2021.

Similar to medical school, residency is a time to drink out of the proverbial firehose of knowledge. Along with clinical duties, there is a plethora of information ranging from clinical management decisions to boards fodder that dermatology residents are expected to know, leaving residents to adopt study habits from medical school. Flash cards remain a popular study tool in the medical education community. The use of Anki, a web-based and mobile flash card application (app) that features custom and premade flash card decks made and shared by users, has become increasingly popular. In a 2021 study, Lu et al1 found that Anki flash card usage was associated with higher US Medical Licensing Examination scores. Herein, I provide an updated review of the top 3 most comprehensive premade Anki decks for dermatology residents, per my assessment.

COMPREHENSIVE DERMATOLOGY DECKS

Dolphin Dermatology

- Creator: Reddit user, Unknown2

- Date created: December 2020

- Last updated: April 2022

- Number of cards: 13,833

- Resources covered: Photographs of common dermatologic diagnoses from online sources such as VisualDx (https://www.visualdx.com/) and DermNet (https://dermnetnz.org/).

- Format of cards: One image or factoid per card.

- Card tags (allow separation of Anki decks into subcategories): Each general dermatology card is tagged by the diagnosis name. Pediatric dermatology cards are tagged by affected body location.

- Advantages: As you may glean by the sheer number of flash cards, this deck is a comprehensive review of clinical dermatology. Most cards feature clinical vignettes with clinical photographs of a dermatologic condition or histologic slide and ask what the diagnosis may be. It features photographs of pathology on a range of skin tones and many different images of each diagnosis. This is a great deck for residents who need to study clinical photographs of dermatologic diagnoses.

- Disadvantages: This deck does not cover dermatopathology, basic science, treatment options, or pharmacology in depth. Additionally, is difficult to find a link to download this resource.

- At the time of publication of this article, users are unable to download this deck.

vismo_djib’s Review of Dermatology Anki

- Creator: Reddit user vismo_djib3

- Date created: June 2020

- Last updated: February 2022

- Number of cards: 8454

- Resources covered: Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology4 is the main resource with supplemental images from VisualDx, Bolognia et al’s Dermatology,5 Patterson’s Weedon’s Skin Pathology Essentials,6 Elston et al’s Dermatopathology,7 Soyer et al’s Dermoscopy: The Essentials,8 and Robinson et al’s Surgery of the Skin: Procedural Dermatology.9

- Format of cards: Cards mostly feature a diagnosis with color-coded categories including epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical features, histopathology, and treatment.

- Card tags (allow separation of Anki decks into subcategories): Cards are tagged with chapter numbers from Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology.4

- Advantages: This impressive comprehensive review of dermatology is a great option for residents studying for the American Board of Dermatology CORE examinations and users looking to solidify the information in Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology,4 a frequently used resource among dermatology residents. It currently is my favorite deck because it features holistic information on diagnosis, epidemiology, pathogenesis, histopathology, and treatment with excellent clinical photographs.

- Disadvantages: For some purposes, this deck may be too lofty. For maximum benefit, it may require user customization including separating cards by tag and other add-ons that allow only 1 card per note, which will separate the information on each card into smaller increments. The mostly free-response format and lengthy slides may make it difficult to practice recall.

AnKingMed Dermki

- Creator: Reddit user AnKingMed10,11

- Date created: April 2023

- Last updated: This deck features a dynamic add-on and collaboration application called AnkiHub, which allows for real-time updates. At the time this article was written, the deck was last updated on June 19, 2023.

- Number of cards: 7889

- Resources covered: Currently 75% of Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology4 with supplemental images from DermNet and Eleryan and Friedman’s The Full Spectrum of Dermatology: A Diverse and Inclusive Atlas.12

- Format of cards: Cards are in a fill-in-the-blank format.

- Card tags (allow separation of Anki decks into subcategories): Cards are tagged by chapter number and subsection of Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology.4

- Advantages: As the newest contribution to the dermatology Anki card compendium, this deck is up to date, innovative, and dynamic. It features an optional add-on application—AnkiHub—which allows users to keep up with live updates and collaborations. The deck features a fill-in-the-blank format that may be preferred to a free-response format for information recall. It features Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology,4 which is a high-yield review of clinical dermatology, dermatopathology, surgical dermatology, pharmacology, and histopathology for dermatology residents.

- Disadvantages: The deck is still currently in a development phase, covering 75% of Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology4 with plans to add the remaining 25%. The add-on to access the most up-to-date version of the flashcards requires a paid monthly or annual subscription; however, the creator announced they will release periodic free updates of the deck.

Final Thoughts

As a collaborative platform, new flash card decks are always being added to Anki. This article is not comprehensive of all dermatologic flash card decks available. There are decks better suited for medical students covering topics such as the American Academy of Dermatology Basic Dermatology Curriculum, UWorld United States Medical Licensing Examination dermatology, and dermatology in internal medicine. Furthermore, specific study tools in dermatology may have their own accompanying Anki decks (ie, The Grenz Zone podcast, Dermnemonics). Flash cards can be a valuable study tool to trainees in medicine, and residents are immensely grateful to our peers who make them for our use.

Similar to medical school, residency is a time to drink out of the proverbial firehose of knowledge. Along with clinical duties, there is a plethora of information ranging from clinical management decisions to boards fodder that dermatology residents are expected to know, leaving residents to adopt study habits from medical school. Flash cards remain a popular study tool in the medical education community. The use of Anki, a web-based and mobile flash card application (app) that features custom and premade flash card decks made and shared by users, has become increasingly popular. In a 2021 study, Lu et al1 found that Anki flash card usage was associated with higher US Medical Licensing Examination scores. Herein, I provide an updated review of the top 3 most comprehensive premade Anki decks for dermatology residents, per my assessment.

COMPREHENSIVE DERMATOLOGY DECKS

Dolphin Dermatology

- Creator: Reddit user, Unknown2

- Date created: December 2020

- Last updated: April 2022

- Number of cards: 13,833

- Resources covered: Photographs of common dermatologic diagnoses from online sources such as VisualDx (https://www.visualdx.com/) and DermNet (https://dermnetnz.org/).

- Format of cards: One image or factoid per card.

- Card tags (allow separation of Anki decks into subcategories): Each general dermatology card is tagged by the diagnosis name. Pediatric dermatology cards are tagged by affected body location.

- Advantages: As you may glean by the sheer number of flash cards, this deck is a comprehensive review of clinical dermatology. Most cards feature clinical vignettes with clinical photographs of a dermatologic condition or histologic slide and ask what the diagnosis may be. It features photographs of pathology on a range of skin tones and many different images of each diagnosis. This is a great deck for residents who need to study clinical photographs of dermatologic diagnoses.

- Disadvantages: This deck does not cover dermatopathology, basic science, treatment options, or pharmacology in depth. Additionally, is difficult to find a link to download this resource.

- At the time of publication of this article, users are unable to download this deck.

vismo_djib’s Review of Dermatology Anki

- Creator: Reddit user vismo_djib3

- Date created: June 2020

- Last updated: February 2022

- Number of cards: 8454

- Resources covered: Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology4 is the main resource with supplemental images from VisualDx, Bolognia et al’s Dermatology,5 Patterson’s Weedon’s Skin Pathology Essentials,6 Elston et al’s Dermatopathology,7 Soyer et al’s Dermoscopy: The Essentials,8 and Robinson et al’s Surgery of the Skin: Procedural Dermatology.9

- Format of cards: Cards mostly feature a diagnosis with color-coded categories including epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical features, histopathology, and treatment.

- Card tags (allow separation of Anki decks into subcategories): Cards are tagged with chapter numbers from Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology.4

- Advantages: This impressive comprehensive review of dermatology is a great option for residents studying for the American Board of Dermatology CORE examinations and users looking to solidify the information in Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology,4 a frequently used resource among dermatology residents. It currently is my favorite deck because it features holistic information on diagnosis, epidemiology, pathogenesis, histopathology, and treatment with excellent clinical photographs.

- Disadvantages: For some purposes, this deck may be too lofty. For maximum benefit, it may require user customization including separating cards by tag and other add-ons that allow only 1 card per note, which will separate the information on each card into smaller increments. The mostly free-response format and lengthy slides may make it difficult to practice recall.

AnKingMed Dermki

- Creator: Reddit user AnKingMed10,11

- Date created: April 2023

- Last updated: This deck features a dynamic add-on and collaboration application called AnkiHub, which allows for real-time updates. At the time this article was written, the deck was last updated on June 19, 2023.

- Number of cards: 7889

- Resources covered: Currently 75% of Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology4 with supplemental images from DermNet and Eleryan and Friedman’s The Full Spectrum of Dermatology: A Diverse and Inclusive Atlas.12

- Format of cards: Cards are in a fill-in-the-blank format.

- Card tags (allow separation of Anki decks into subcategories): Cards are tagged by chapter number and subsection of Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology.4

- Advantages: As the newest contribution to the dermatology Anki card compendium, this deck is up to date, innovative, and dynamic. It features an optional add-on application—AnkiHub—which allows users to keep up with live updates and collaborations. The deck features a fill-in-the-blank format that may be preferred to a free-response format for information recall. It features Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology,4 which is a high-yield review of clinical dermatology, dermatopathology, surgical dermatology, pharmacology, and histopathology for dermatology residents.

- Disadvantages: The deck is still currently in a development phase, covering 75% of Alikhan and Hocker’s Review of Dermatology4 with plans to add the remaining 25%. The add-on to access the most up-to-date version of the flashcards requires a paid monthly or annual subscription; however, the creator announced they will release periodic free updates of the deck.

Final Thoughts

As a collaborative platform, new flash card decks are always being added to Anki. This article is not comprehensive of all dermatologic flash card decks available. There are decks better suited for medical students covering topics such as the American Academy of Dermatology Basic Dermatology Curriculum, UWorld United States Medical Licensing Examination dermatology, and dermatology in internal medicine. Furthermore, specific study tools in dermatology may have their own accompanying Anki decks (ie, The Grenz Zone podcast, Dermnemonics). Flash cards can be a valuable study tool to trainees in medicine, and residents are immensely grateful to our peers who make them for our use.

- Lu M, Farhat JH, Beck Dallaghan GL. Enhanced learning and retention of medical knowledge using the mobile flash card application Anki. Med Sci Educ. 2021;31:1975-1981. doi:10.1007/s40670-021-01386-9

- Unknown. Dolphin Dermatology. Reddit website. Accessed July 19, 2023. https://www.reddit.com/r/medicalschoolanki/comments/116jbpc/dolphin_derm/

- vismo_djib. Review of dermatology Anki. Reddit website. Published June 13, 2020. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.reddit.com/r/DermApp/comments/h8gz3d/review_of_dermatology_anki/

- Alikhan A, Hocker TLH. Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2016.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017.

- Patterson JW. Weedon’s Skin Pathology Essentials. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2016.

- Elston D, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013.

- Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, et al. Dermoscopy: The Essentials. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011.

- Robinson JK, Hanke CW, Siegel DM, et al. Surgery of the Skin: Procedural Dermatology. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2014.

- AnKingMed. Dermki: dermatology residency Anki deck. Reddit website. Published April 8, 2023. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.reddit.com/r/medicalschoolanki/comments/12fo9ji/dermki_dermatology_residency_anki_deck/

- Dermki deck for Dermatology Residents. Notion website. Accessed July 10, 2023. https://ankingmed.notion.site/Dermki-deck-for-Dermatology-Residents-9e0b8d8abc2a4bf7941903d80e5b01a2

- Eleryan M, Friedman A. The Full Spectrum of Dermatology: A Diverse and Inclusive Atlas. Sanovaworks; 2021.

- Lu M, Farhat JH, Beck Dallaghan GL. Enhanced learning and retention of medical knowledge using the mobile flash card application Anki. Med Sci Educ. 2021;31:1975-1981. doi:10.1007/s40670-021-01386-9

- Unknown. Dolphin Dermatology. Reddit website. Accessed July 19, 2023. https://www.reddit.com/r/medicalschoolanki/comments/116jbpc/dolphin_derm/

- vismo_djib. Review of dermatology Anki. Reddit website. Published June 13, 2020. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.reddit.com/r/DermApp/comments/h8gz3d/review_of_dermatology_anki/

- Alikhan A, Hocker TLH. Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2016.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017.

- Patterson JW. Weedon’s Skin Pathology Essentials. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2016.

- Elston D, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013.

- Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, et al. Dermoscopy: The Essentials. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011.

- Robinson JK, Hanke CW, Siegel DM, et al. Surgery of the Skin: Procedural Dermatology. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2014.

- AnKingMed. Dermki: dermatology residency Anki deck. Reddit website. Published April 8, 2023. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.reddit.com/r/medicalschoolanki/comments/12fo9ji/dermki_dermatology_residency_anki_deck/

- Dermki deck for Dermatology Residents. Notion website. Accessed July 10, 2023. https://ankingmed.notion.site/Dermki-deck-for-Dermatology-Residents-9e0b8d8abc2a4bf7941903d80e5b01a2

- Eleryan M, Friedman A. The Full Spectrum of Dermatology: A Diverse and Inclusive Atlas. Sanovaworks; 2021.

Resident Pearl

- Publicly available Anki flashcard decks may aid dermatology residents in mastering the learning objectives required during training.

A pivot in training: My path to reproductive psychiatry

In March 2020, as I was wheeling my patient into the operating room to perform a Caesarean section, covered head-to-toe in COVID personal protective equipment, my phone rang. It was Jody Schindelheim, MD, Director of the Psychiatry Residency Program at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, calling to offer me a PGY-2 spot in their program.

As COVID upended the world, I was struggling with my own major change. My path had been planned since before medical school: I would grind through a 4-year OB/GYN residency, complete a fellowship, and establish myself as a reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialist. My personal statement emphasized my dream that no woman should be made to feel useless based on infertility. OB/GYN, genetics, and ultrasound were my favorite rotations at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx.

However, 6 months into my OB/GYN intern year, I grew curious about the possibility of a future in reproductive psychiatry and women’s mental health. This decision was not easy. As someone who loved the adrenaline rush of delivering babies and performing surgery, I had paid little attention to psychiatry in medical school. However, my experience in gynecologic oncology in January 2020 made me realize my love of stories and trauma-informed care. I recall a woman, cachectic with only days left to live due to ovarian cancer, talking to me about her trauma and the power of her lifelong partner. Another woman, experiencing complications from chemotherapy to treat fallopian tube cancer, shared about her coping skill of chair yoga.

Fulfilling an unmet need

As I spent time with these 2 women and heard their stories, I felt compelled to help them with these psychological challenges. As a gynecologist, I addressed their physical needs, but not their personal needs. I spoke to many psychiatrists, including reproductive psychiatrists, in New York, who shared their stories and taught me about the prevalence of postpartum depression and psychosis. After caring for hundreds of pregnant and postpartum women in the Bronx, I thought about the unmet need for women’s mental health and how this career change could still fulfill my purpose of helping women feel empowered regardless of their fertility status.

In the inpatient and outpatient settings at Tufts, I have loved hearing my patients’ stories and providing continuity of care with medical management and therapy. My mentors in reproductive psychiatry inspired me to create the Reproductive Psychiatry Trainee Interest Group (https://www.repropsychtrainees.com), a national group for the burgeoning field that now has more than 650 members. With monthly lectures, journal clubs, and book clubs, I have surrounded myself with like-minded individuals who love learning about the perinatal, postpartum, and perimenopausal experiences.

As I prepare to begin a full-time faculty position in psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, I know I have found my joy and my calling. I once feared the life of a psychiatrist would be too sedentary for someone accustomed to the pace of OB/GYN. Now I know that my patients’ stories are all the motivation I need.

In March 2020, as I was wheeling my patient into the operating room to perform a Caesarean section, covered head-to-toe in COVID personal protective equipment, my phone rang. It was Jody Schindelheim, MD, Director of the Psychiatry Residency Program at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, calling to offer me a PGY-2 spot in their program.

As COVID upended the world, I was struggling with my own major change. My path had been planned since before medical school: I would grind through a 4-year OB/GYN residency, complete a fellowship, and establish myself as a reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialist. My personal statement emphasized my dream that no woman should be made to feel useless based on infertility. OB/GYN, genetics, and ultrasound were my favorite rotations at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx.

However, 6 months into my OB/GYN intern year, I grew curious about the possibility of a future in reproductive psychiatry and women’s mental health. This decision was not easy. As someone who loved the adrenaline rush of delivering babies and performing surgery, I had paid little attention to psychiatry in medical school. However, my experience in gynecologic oncology in January 2020 made me realize my love of stories and trauma-informed care. I recall a woman, cachectic with only days left to live due to ovarian cancer, talking to me about her trauma and the power of her lifelong partner. Another woman, experiencing complications from chemotherapy to treat fallopian tube cancer, shared about her coping skill of chair yoga.

Fulfilling an unmet need

As I spent time with these 2 women and heard their stories, I felt compelled to help them with these psychological challenges. As a gynecologist, I addressed their physical needs, but not their personal needs. I spoke to many psychiatrists, including reproductive psychiatrists, in New York, who shared their stories and taught me about the prevalence of postpartum depression and psychosis. After caring for hundreds of pregnant and postpartum women in the Bronx, I thought about the unmet need for women’s mental health and how this career change could still fulfill my purpose of helping women feel empowered regardless of their fertility status.

In the inpatient and outpatient settings at Tufts, I have loved hearing my patients’ stories and providing continuity of care with medical management and therapy. My mentors in reproductive psychiatry inspired me to create the Reproductive Psychiatry Trainee Interest Group (https://www.repropsychtrainees.com), a national group for the burgeoning field that now has more than 650 members. With monthly lectures, journal clubs, and book clubs, I have surrounded myself with like-minded individuals who love learning about the perinatal, postpartum, and perimenopausal experiences.

As I prepare to begin a full-time faculty position in psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, I know I have found my joy and my calling. I once feared the life of a psychiatrist would be too sedentary for someone accustomed to the pace of OB/GYN. Now I know that my patients’ stories are all the motivation I need.

In March 2020, as I was wheeling my patient into the operating room to perform a Caesarean section, covered head-to-toe in COVID personal protective equipment, my phone rang. It was Jody Schindelheim, MD, Director of the Psychiatry Residency Program at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, calling to offer me a PGY-2 spot in their program.

As COVID upended the world, I was struggling with my own major change. My path had been planned since before medical school: I would grind through a 4-year OB/GYN residency, complete a fellowship, and establish myself as a reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialist. My personal statement emphasized my dream that no woman should be made to feel useless based on infertility. OB/GYN, genetics, and ultrasound were my favorite rotations at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx.

However, 6 months into my OB/GYN intern year, I grew curious about the possibility of a future in reproductive psychiatry and women’s mental health. This decision was not easy. As someone who loved the adrenaline rush of delivering babies and performing surgery, I had paid little attention to psychiatry in medical school. However, my experience in gynecologic oncology in January 2020 made me realize my love of stories and trauma-informed care. I recall a woman, cachectic with only days left to live due to ovarian cancer, talking to me about her trauma and the power of her lifelong partner. Another woman, experiencing complications from chemotherapy to treat fallopian tube cancer, shared about her coping skill of chair yoga.

Fulfilling an unmet need

As I spent time with these 2 women and heard their stories, I felt compelled to help them with these psychological challenges. As a gynecologist, I addressed their physical needs, but not their personal needs. I spoke to many psychiatrists, including reproductive psychiatrists, in New York, who shared their stories and taught me about the prevalence of postpartum depression and psychosis. After caring for hundreds of pregnant and postpartum women in the Bronx, I thought about the unmet need for women’s mental health and how this career change could still fulfill my purpose of helping women feel empowered regardless of their fertility status.

In the inpatient and outpatient settings at Tufts, I have loved hearing my patients’ stories and providing continuity of care with medical management and therapy. My mentors in reproductive psychiatry inspired me to create the Reproductive Psychiatry Trainee Interest Group (https://www.repropsychtrainees.com), a national group for the burgeoning field that now has more than 650 members. With monthly lectures, journal clubs, and book clubs, I have surrounded myself with like-minded individuals who love learning about the perinatal, postpartum, and perimenopausal experiences.

As I prepare to begin a full-time faculty position in psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, I know I have found my joy and my calling. I once feared the life of a psychiatrist would be too sedentary for someone accustomed to the pace of OB/GYN. Now I know that my patients’ stories are all the motivation I need.

Cross-sectional Analysis of Matched Dermatology Residency Applicants Without US Home Programs

To the Editor:

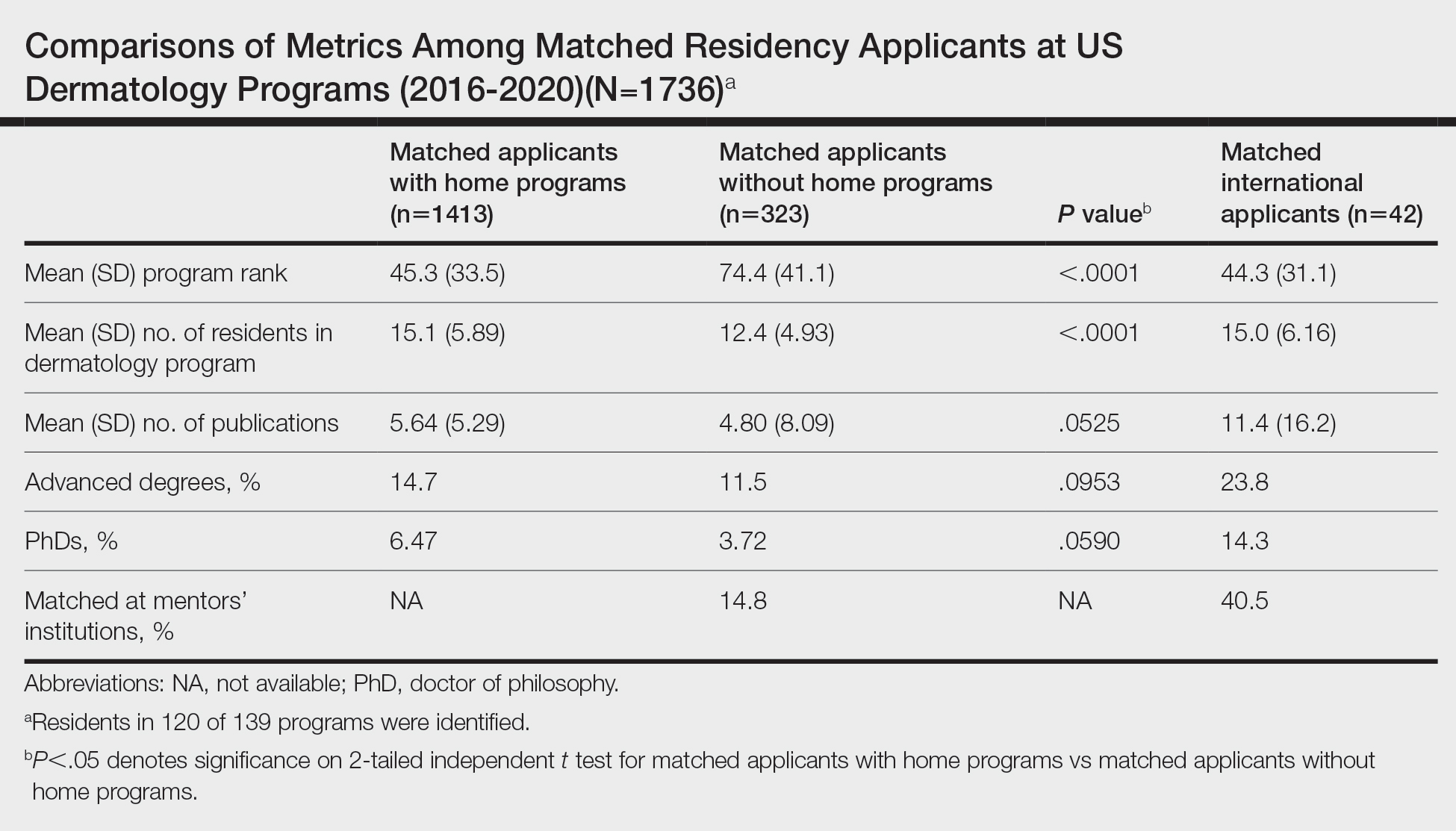

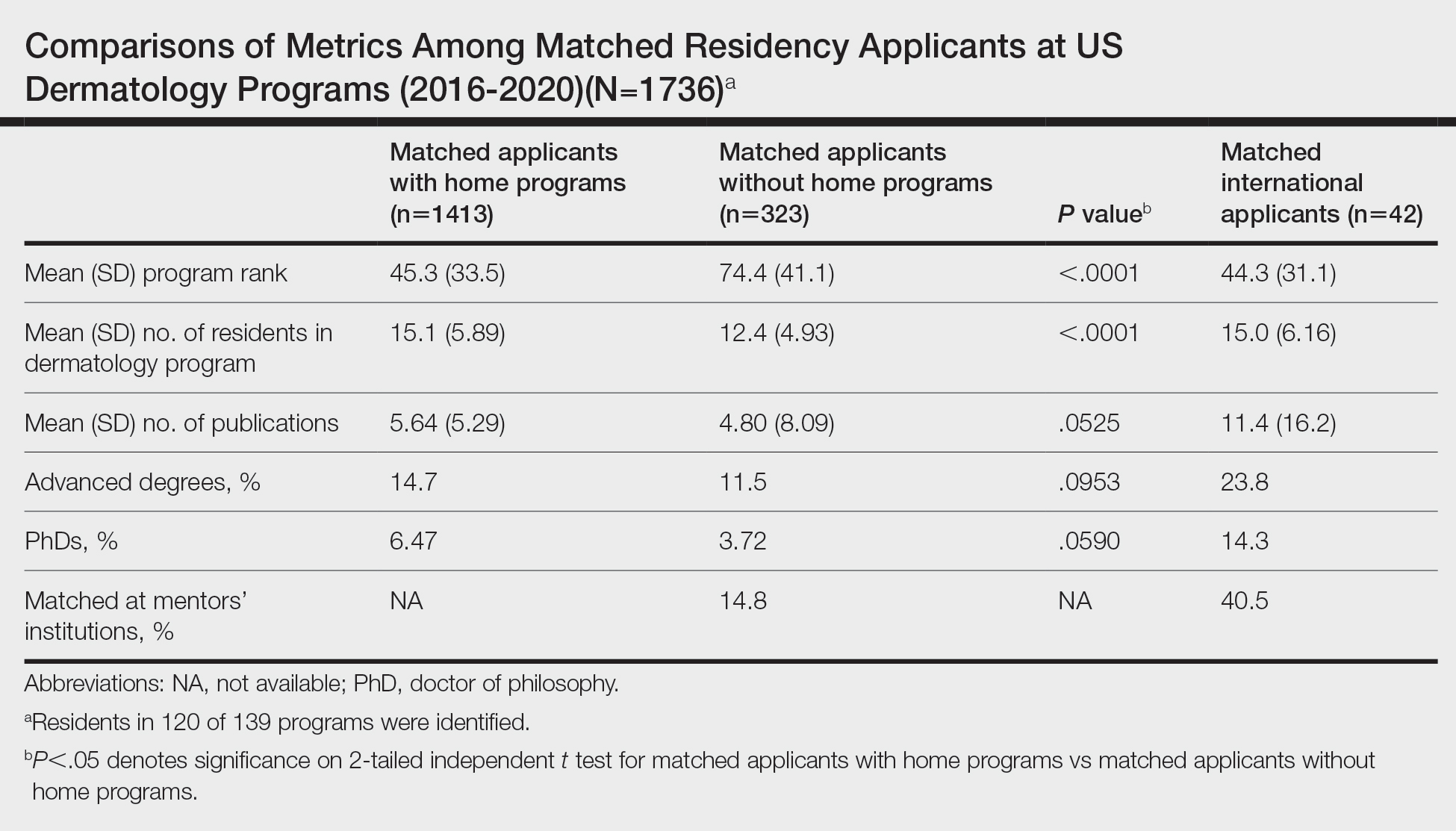

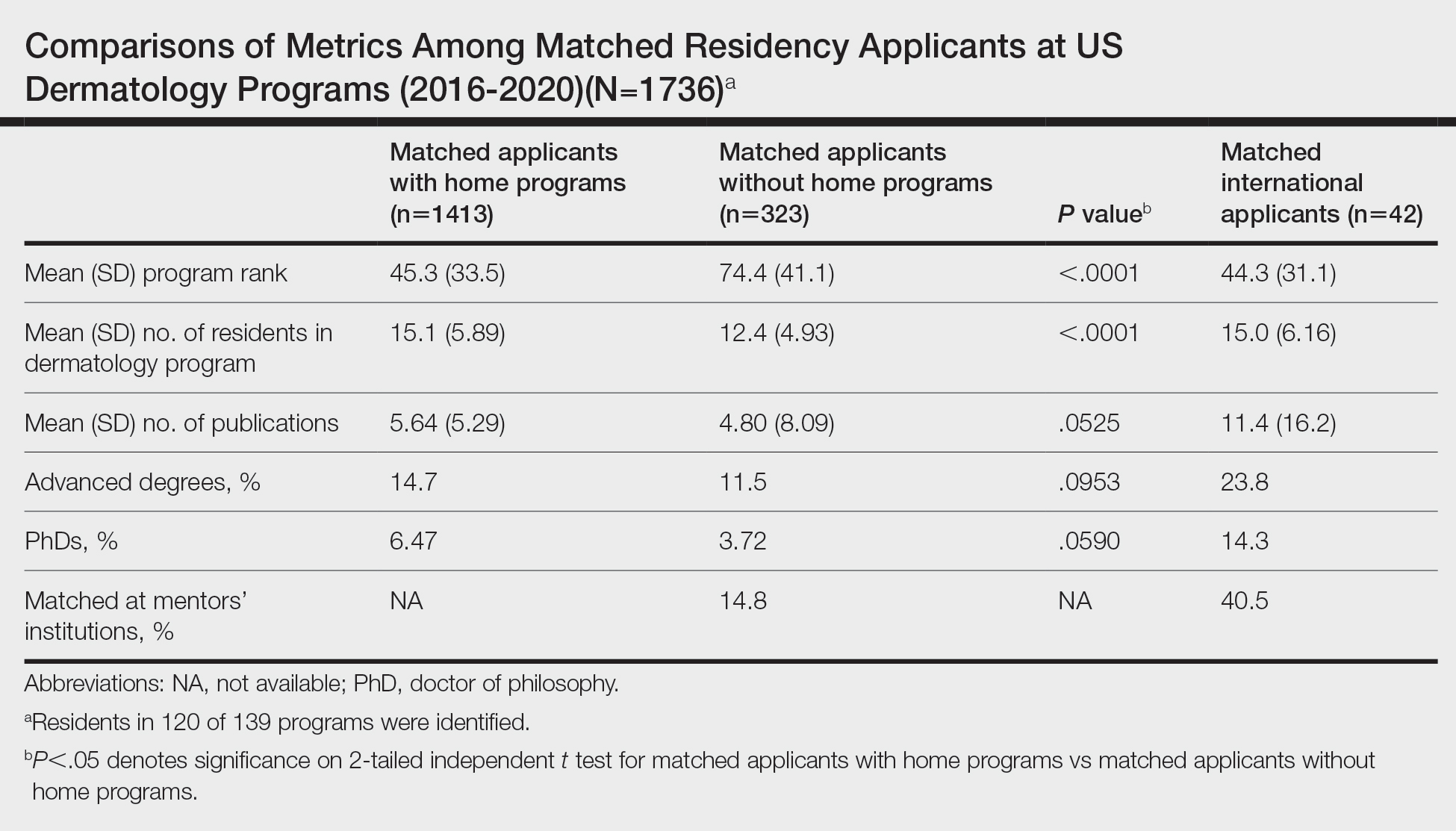

Dermatology is one of the most competitive residencies for matching, with a 57.5% match rate in 2022.1 Our prior study of research-mentor relationships among matched dermatology applicants corroborated the importance of home programs (HPs) and program connections.2 Therefore, our current objective was to compare profiles of matched dermatology applicants without HPs vs those with HPs.

We searched websites of 139 dermatology programs nationwide and found 1736 matched applicants from 2016 to 2020; of them, 323 did not have HPs. We determined program rank by research output using Doximity Residency Navigator (https://www.doximity.com/residency/). Advanced degrees (ADs) of applicants were identified using program websites and LinkedIn. A PubMed search was conducted for number of articles published by each applicant before September 15 of their match year. For applicants without HPs, we identified the senior author on each publication. The senior author publishing with an applicant most often was considered the research mentor. Two-tailed independent t tests and χ2 tests were used to determine statistical significance (P<.05).

On average, matched applicants without HPs matched in lower-ranked (74.4) and smaller (12.4) programs compared with matched applicants with HPs (45.3 [P<.0001] and 15.1 [P<.0001], respectively)(eTable). The mean number of publications was similar between matched applicants with HPs and without HPs (5.64 and 4.80, respectively; P=.0525) as well as the percentage with ADs (14.7% and 11.5%, respectively; P=.0953). Overall, 14.8% of matched applicants without HPs matched at their mentors’ institutions.

Data were obtained for matched international applicants as a subset of non-HP applicants. Despite attending medical schools without associated HPs in the United States, international applicants matched at similarly ranked (44.3) and sized (15.0) programs, on average, compared with HP applicants. The mean number of publications was higher for international applicants (11.4) vs domestic applicants (5.33). International applicants more often had ADs (23.8%) and 60.1% of them held doctor of philosophy degrees. Overall, 40.5% of international applicants matched at their mentors’ institutions.

Our study suggests that matched dermatology applicants with and without HPs had similar achievements, on average, for the number of publications and percentage with ADs. However, non-HP applicants matched at lower-ranked programs than HP applicants. Therefore, applicants without HPs should strongly consider cultivating program connections, especially if they desire to match at higher-ranked dermatology programs. To illustrate, the rate of matching at research mentors’ institutions was approximately 3-times higher for international applicants than non-HP applicants overall. Despite the disadvantages of applying as international applicants, they were able to match at substantially higher-ranked dermatology programs than non-HP applicants. International applicants may have a longer time investment—the number of years from obtaining their medical degree or US medical license to matching—giving them time to produce quality research and develop meaningful relationships at an institution. Additionally, our prior study of the top 25 dermatology residencies showed that 26.2% of successful applicants matched at their research mentors’ institutions, with almost half of this subset matching at their HPs, where their mentors also practiced.2 Because of the potential benefits of having program connections, applicants without HPs should seek dermatology research mentors, especially via highly beneficial in-person networking opportunities (eg, away rotations, conferences) that had previously been limited during the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Formal mentorship programs giving priority to students without HPs recently have been developed, which only begins to address the inequities in the dermatology residency application process.4

Study limitations include lack of resident information on 15 program websites, missed publications due to applicant name changes, not accounting for abstracts and posters, and inability to collect data on unmatched applicants.

We hope that our study alleviates some concerns that applicants without HPs may have regarding applying for dermatology residency and encourages those with a genuine interest in dermatology to pursue the specialty, provided they find a strong research mentor. Residency programs should be cognizant of the unique challenges that non-HP applicants face for matching.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2022 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; May 2022. Accessed May 30, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11 /2022-Main-Match-Results-and-Data-Final-Revised.pdf

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wilson BN, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of scholarly work and mentor relationships in matched dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1437-1439.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Specialty recommendations on away rotations for 2021-22 academic year. Accessed May 24, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/researching-residency-programs -and-building-application-strategy/specialty-response-covid-19

- derminterest Instagram page. DIGA is excited for the second year of our mentor-mentee program! Mentors are dermatology residents. Please keep in mind due to the current circumstances, dermatology residency 2021-2022 applicants without home programs will be prioritized as mentees. Please refrain from signing up if you were paired with a faculty mentor for the APD-DIGA Mentorship Program in May 2021. Contact @suryasweetie123 only if you have specific questions, otherwise all information is on our website and the link is here. Link is below and in our bio! #DIGA #derm #mentee #residencyapplication. Accessed May 24, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CSrq0exMchY/

To the Editor:

Dermatology is one of the most competitive residencies for matching, with a 57.5% match rate in 2022.1 Our prior study of research-mentor relationships among matched dermatology applicants corroborated the importance of home programs (HPs) and program connections.2 Therefore, our current objective was to compare profiles of matched dermatology applicants without HPs vs those with HPs.

We searched websites of 139 dermatology programs nationwide and found 1736 matched applicants from 2016 to 2020; of them, 323 did not have HPs. We determined program rank by research output using Doximity Residency Navigator (https://www.doximity.com/residency/). Advanced degrees (ADs) of applicants were identified using program websites and LinkedIn. A PubMed search was conducted for number of articles published by each applicant before September 15 of their match year. For applicants without HPs, we identified the senior author on each publication. The senior author publishing with an applicant most often was considered the research mentor. Two-tailed independent t tests and χ2 tests were used to determine statistical significance (P<.05).

On average, matched applicants without HPs matched in lower-ranked (74.4) and smaller (12.4) programs compared with matched applicants with HPs (45.3 [P<.0001] and 15.1 [P<.0001], respectively)(eTable). The mean number of publications was similar between matched applicants with HPs and without HPs (5.64 and 4.80, respectively; P=.0525) as well as the percentage with ADs (14.7% and 11.5%, respectively; P=.0953). Overall, 14.8% of matched applicants without HPs matched at their mentors’ institutions.

Data were obtained for matched international applicants as a subset of non-HP applicants. Despite attending medical schools without associated HPs in the United States, international applicants matched at similarly ranked (44.3) and sized (15.0) programs, on average, compared with HP applicants. The mean number of publications was higher for international applicants (11.4) vs domestic applicants (5.33). International applicants more often had ADs (23.8%) and 60.1% of them held doctor of philosophy degrees. Overall, 40.5% of international applicants matched at their mentors’ institutions.

Our study suggests that matched dermatology applicants with and without HPs had similar achievements, on average, for the number of publications and percentage with ADs. However, non-HP applicants matched at lower-ranked programs than HP applicants. Therefore, applicants without HPs should strongly consider cultivating program connections, especially if they desire to match at higher-ranked dermatology programs. To illustrate, the rate of matching at research mentors’ institutions was approximately 3-times higher for international applicants than non-HP applicants overall. Despite the disadvantages of applying as international applicants, they were able to match at substantially higher-ranked dermatology programs than non-HP applicants. International applicants may have a longer time investment—the number of years from obtaining their medical degree or US medical license to matching—giving them time to produce quality research and develop meaningful relationships at an institution. Additionally, our prior study of the top 25 dermatology residencies showed that 26.2% of successful applicants matched at their research mentors’ institutions, with almost half of this subset matching at their HPs, where their mentors also practiced.2 Because of the potential benefits of having program connections, applicants without HPs should seek dermatology research mentors, especially via highly beneficial in-person networking opportunities (eg, away rotations, conferences) that had previously been limited during the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Formal mentorship programs giving priority to students without HPs recently have been developed, which only begins to address the inequities in the dermatology residency application process.4

Study limitations include lack of resident information on 15 program websites, missed publications due to applicant name changes, not accounting for abstracts and posters, and inability to collect data on unmatched applicants.

We hope that our study alleviates some concerns that applicants without HPs may have regarding applying for dermatology residency and encourages those with a genuine interest in dermatology to pursue the specialty, provided they find a strong research mentor. Residency programs should be cognizant of the unique challenges that non-HP applicants face for matching.

To the Editor:

Dermatology is one of the most competitive residencies for matching, with a 57.5% match rate in 2022.1 Our prior study of research-mentor relationships among matched dermatology applicants corroborated the importance of home programs (HPs) and program connections.2 Therefore, our current objective was to compare profiles of matched dermatology applicants without HPs vs those with HPs.

We searched websites of 139 dermatology programs nationwide and found 1736 matched applicants from 2016 to 2020; of them, 323 did not have HPs. We determined program rank by research output using Doximity Residency Navigator (https://www.doximity.com/residency/). Advanced degrees (ADs) of applicants were identified using program websites and LinkedIn. A PubMed search was conducted for number of articles published by each applicant before September 15 of their match year. For applicants without HPs, we identified the senior author on each publication. The senior author publishing with an applicant most often was considered the research mentor. Two-tailed independent t tests and χ2 tests were used to determine statistical significance (P<.05).

On average, matched applicants without HPs matched in lower-ranked (74.4) and smaller (12.4) programs compared with matched applicants with HPs (45.3 [P<.0001] and 15.1 [P<.0001], respectively)(eTable). The mean number of publications was similar between matched applicants with HPs and without HPs (5.64 and 4.80, respectively; P=.0525) as well as the percentage with ADs (14.7% and 11.5%, respectively; P=.0953). Overall, 14.8% of matched applicants without HPs matched at their mentors’ institutions.

Data were obtained for matched international applicants as a subset of non-HP applicants. Despite attending medical schools without associated HPs in the United States, international applicants matched at similarly ranked (44.3) and sized (15.0) programs, on average, compared with HP applicants. The mean number of publications was higher for international applicants (11.4) vs domestic applicants (5.33). International applicants more often had ADs (23.8%) and 60.1% of them held doctor of philosophy degrees. Overall, 40.5% of international applicants matched at their mentors’ institutions.

Our study suggests that matched dermatology applicants with and without HPs had similar achievements, on average, for the number of publications and percentage with ADs. However, non-HP applicants matched at lower-ranked programs than HP applicants. Therefore, applicants without HPs should strongly consider cultivating program connections, especially if they desire to match at higher-ranked dermatology programs. To illustrate, the rate of matching at research mentors’ institutions was approximately 3-times higher for international applicants than non-HP applicants overall. Despite the disadvantages of applying as international applicants, they were able to match at substantially higher-ranked dermatology programs than non-HP applicants. International applicants may have a longer time investment—the number of years from obtaining their medical degree or US medical license to matching—giving them time to produce quality research and develop meaningful relationships at an institution. Additionally, our prior study of the top 25 dermatology residencies showed that 26.2% of successful applicants matched at their research mentors’ institutions, with almost half of this subset matching at their HPs, where their mentors also practiced.2 Because of the potential benefits of having program connections, applicants without HPs should seek dermatology research mentors, especially via highly beneficial in-person networking opportunities (eg, away rotations, conferences) that had previously been limited during the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Formal mentorship programs giving priority to students without HPs recently have been developed, which only begins to address the inequities in the dermatology residency application process.4

Study limitations include lack of resident information on 15 program websites, missed publications due to applicant name changes, not accounting for abstracts and posters, and inability to collect data on unmatched applicants.

We hope that our study alleviates some concerns that applicants without HPs may have regarding applying for dermatology residency and encourages those with a genuine interest in dermatology to pursue the specialty, provided they find a strong research mentor. Residency programs should be cognizant of the unique challenges that non-HP applicants face for matching.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2022 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; May 2022. Accessed May 30, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11 /2022-Main-Match-Results-and-Data-Final-Revised.pdf

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wilson BN, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of scholarly work and mentor relationships in matched dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1437-1439.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Specialty recommendations on away rotations for 2021-22 academic year. Accessed May 24, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/researching-residency-programs -and-building-application-strategy/specialty-response-covid-19

- derminterest Instagram page. DIGA is excited for the second year of our mentor-mentee program! Mentors are dermatology residents. Please keep in mind due to the current circumstances, dermatology residency 2021-2022 applicants without home programs will be prioritized as mentees. Please refrain from signing up if you were paired with a faculty mentor for the APD-DIGA Mentorship Program in May 2021. Contact @suryasweetie123 only if you have specific questions, otherwise all information is on our website and the link is here. Link is below and in our bio! #DIGA #derm #mentee #residencyapplication. Accessed May 24, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CSrq0exMchY/

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2022 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; May 2022. Accessed May 30, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11 /2022-Main-Match-Results-and-Data-Final-Revised.pdf

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wilson BN, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of scholarly work and mentor relationships in matched dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1437-1439.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Specialty recommendations on away rotations for 2021-22 academic year. Accessed May 24, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/researching-residency-programs -and-building-application-strategy/specialty-response-covid-19

- derminterest Instagram page. DIGA is excited for the second year of our mentor-mentee program! Mentors are dermatology residents. Please keep in mind due to the current circumstances, dermatology residency 2021-2022 applicants without home programs will be prioritized as mentees. Please refrain from signing up if you were paired with a faculty mentor for the APD-DIGA Mentorship Program in May 2021. Contact @suryasweetie123 only if you have specific questions, otherwise all information is on our website and the link is here. Link is below and in our bio! #DIGA #derm #mentee #residencyapplication. Accessed May 24, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CSrq0exMchY/

Practice Points

- Our study suggests that matched dermatology applicants with and without home programs (HPs) had similar achievements, on average, for number of publications and holding advanced degrees.

- Because of the potential benefits of having program connections for matching in dermatology, applicants without HPs should seek dermatology research mentors.

Guidelines on Away Rotations in Dermatology Programs

Medical students often perform away rotations (also called visiting electives) to gain exposure to educational experiences in a particular specialty, learn about a program, and show interest in a certain program. Away rotations also allow applicants to meet and form relationships with mentors and faculty outside of their home institution. For residency programs, away rotations provide an opportunity for a holistic review of applicants by allowing program directors to get to know potential residency applicants and assess their performance in the clinical environment and among the program’s team. In a National Resident Matching Program survey, program directors (n=17) reported that prior knowledge of an applicant is an important factor in selecting applicants to interview (82.4%) and rank (58.8%).1

In this article, we discuss the importance of away rotations in dermatology and provide an overview of the Organization of Program Director Associations (OPDA) and Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) guidelines for away rotations.

Importance of the Away Rotation in the Match

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, 86.7% of dermatology applicants (N=345) completed one or more away rotations (mean, 2.7) in 2020.2 Winterton et al3 reported that 47% of dermatology applicants (N=45) matched at a program where they completed an away rotation. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of applicants matching to their home program was reported as 26.7% (N=641), which jumped to 40.3% (N=231) in the 2020-2021 cycle.4 Given that the majority of dermatology applicants reportedly match either at their home program or at programs where they completed an away rotation, the benefits of away rotations are high, particularly in a competitive specialty such as dermatology and particularly for applicants without a dermatology program at their home institution. However, it must be acknowledged that correlation does not necessarily mean causation, as away rotations have not necessarily been shown to increase applicants’ chances of matching for the most competitive specialties.5

OPDA Guidelines for Away Rotations

In 2021, the Coalition of Physician Accountability’s Undergraduate Medical Education-Graduate Medical Education Review Committee recommended creating a workgroup to explore the function and value of away rotations for medical students, programs, and institutions, with a particular focus on issues of equity (eg, accessibility, assessment, opportunity) for underrepresented in medicine students and those with financial disadvantages.6 The OPDA workgroup evaluated the advantages and disadvantages of away rotations across specialties. The disadvantages included that away rotations may decrease resources to students at their own institution, particularly if faculty time and energy are funneled/dedicated to away rotators instead of internal rotators, and may impart bias into the recruitment process. Additionally, there is a consideration of equity given the considerable cost and time commitment of travel and housing for students at another institution. In 2022, the estimated cost of an away rotation in dermatology ranged from $1390 to $5500 per rotation.7 Visiting scholarships may be available at some institutions but typically are reserved for underrepresented in medicine students.8 Virtual rotations offered at some programs offset the cost-prohibitiveness of an in-person away rotation; however, they are not universally offered and may be limited in allowing for meaningful interactions between students and program faculty and residents.

The OPDA away rotation workgroup recommended that (1) each specialty publish guidelines regarding the necessity and number of recommended away rotations; (2) specialties publish explicit language regarding the use of program preference signals to programs where students rotated; (3) programs be transparent about the purpose and value of an away rotation, including explicitly stating whether a formal interview is guaranteed; and (4) the Association of American Medical Colleges create a repository of these specialty-specific recommendations.9

APD Guidelines for Away Rotations

In response to the OPDA recommendations, the APD Residency Program Directors Section developed dermatology-specific guidelines for away rotations and established guidelines in other specialties.10 The APD recommends completing up to 2 away rotations, or 3 for those without a home program, if desired. This number was chosen in acknowledgment of the importance of external program experiences, along with the recognition of the financial and time restrictions associated with away rotations as well as the limited number of spots for rotating students. Away rotations are not mandatory. The APD guidelines explain the purpose and value of an away rotation while also noting that these rotations do not necessarily guarantee a formal interview and recommending that programs be transparent about their policies on interview invitations, which may vary.10

Final Thoughts

Publishing specialty-specific guidelines on away rotations is one step toward streamlining the process as well as increasing transparency on the importance of these external program experiences in the application process and residency match. Ideally, away rotations provide a valuable educational experience in which students and program directors get to know each other in a mutually beneficial manner; however, away rotations are not required for securing an interview or matching at a program, and there also are recognized disadvantages to away rotations, particularly with regard to equity, that we must continue to weigh as a specialty. The APD will continue its collaborative work to evaluate our application processes to support a sustainable and equitable system.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results of the 2021 NRMP program director survey. Published August 2021. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2021-PD-Survey-Report-for-WWW.pdf

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Away rotations of U.S. medical school graduates by intended specialty, 2020 AAMC Medical School Graduation Questionnaire (GQ). Published September 24, 2020. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/media/9496/download

- Winterton M, Ahn J, Bernstein J. The prevalence and cost of medical student visiting rotations. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:291. doi:10.1186/s12909-016-0805-z

- Dowdle TS, Ryan MP, Wagner RF. Internal and geographic dermatology match trends in the age of COVID-19. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1364-1366. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.08.004

- Griffith M, DeMasi SC, McGrath AJ, et al. Time to reevaluate the away rotation: improving return on investment for students and schools. Acad Med. 2019;94:496-500. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002505

- Coalition for Physician Accountability. The Coalition for Physician Accountability’s Undergraduate Medication Education-Graduate Medical Education Review Committee (UGRC): recommendations for comprehensive improvement in the UME-GME transition. Published August 26, 2021. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://physicianaccountability.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/UGRC-Coalition-Report-FINAL.pdf

- Cucka B, Grant-Kels JM. Ethical implications of the high cost of medical student visiting dermatology rotations. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:539-540.

- Dahak S, Fernandez JM, Rosman IS. Funded dermatology visiting elective rotations for medical students who are underrepresented in medicine: a cross-sectional analysis [published online November 15, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:941-943.

- Council of Medical Specialty Societies. The Organization of Program Director Associations (OPDA): away rotations workgroup. Published July 26, 2022. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://cmss.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/OPDA-Work-Group-on-Away-Rotations-7.26.2022-1.pdf

- Association of Professors of Dermatology. Recommendations regarding away electives. Published December 14, 2022. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20recommendations%20on%20away%20rotations%202023-2024.pdf

Medical students often perform away rotations (also called visiting electives) to gain exposure to educational experiences in a particular specialty, learn about a program, and show interest in a certain program. Away rotations also allow applicants to meet and form relationships with mentors and faculty outside of their home institution. For residency programs, away rotations provide an opportunity for a holistic review of applicants by allowing program directors to get to know potential residency applicants and assess their performance in the clinical environment and among the program’s team. In a National Resident Matching Program survey, program directors (n=17) reported that prior knowledge of an applicant is an important factor in selecting applicants to interview (82.4%) and rank (58.8%).1

In this article, we discuss the importance of away rotations in dermatology and provide an overview of the Organization of Program Director Associations (OPDA) and Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) guidelines for away rotations.

Importance of the Away Rotation in the Match

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, 86.7% of dermatology applicants (N=345) completed one or more away rotations (mean, 2.7) in 2020.2 Winterton et al3 reported that 47% of dermatology applicants (N=45) matched at a program where they completed an away rotation. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of applicants matching to their home program was reported as 26.7% (N=641), which jumped to 40.3% (N=231) in the 2020-2021 cycle.4 Given that the majority of dermatology applicants reportedly match either at their home program or at programs where they completed an away rotation, the benefits of away rotations are high, particularly in a competitive specialty such as dermatology and particularly for applicants without a dermatology program at their home institution. However, it must be acknowledged that correlation does not necessarily mean causation, as away rotations have not necessarily been shown to increase applicants’ chances of matching for the most competitive specialties.5

OPDA Guidelines for Away Rotations

In 2021, the Coalition of Physician Accountability’s Undergraduate Medical Education-Graduate Medical Education Review Committee recommended creating a workgroup to explore the function and value of away rotations for medical students, programs, and institutions, with a particular focus on issues of equity (eg, accessibility, assessment, opportunity) for underrepresented in medicine students and those with financial disadvantages.6 The OPDA workgroup evaluated the advantages and disadvantages of away rotations across specialties. The disadvantages included that away rotations may decrease resources to students at their own institution, particularly if faculty time and energy are funneled/dedicated to away rotators instead of internal rotators, and may impart bias into the recruitment process. Additionally, there is a consideration of equity given the considerable cost and time commitment of travel and housing for students at another institution. In 2022, the estimated cost of an away rotation in dermatology ranged from $1390 to $5500 per rotation.7 Visiting scholarships may be available at some institutions but typically are reserved for underrepresented in medicine students.8 Virtual rotations offered at some programs offset the cost-prohibitiveness of an in-person away rotation; however, they are not universally offered and may be limited in allowing for meaningful interactions between students and program faculty and residents.

The OPDA away rotation workgroup recommended that (1) each specialty publish guidelines regarding the necessity and number of recommended away rotations; (2) specialties publish explicit language regarding the use of program preference signals to programs where students rotated; (3) programs be transparent about the purpose and value of an away rotation, including explicitly stating whether a formal interview is guaranteed; and (4) the Association of American Medical Colleges create a repository of these specialty-specific recommendations.9

APD Guidelines for Away Rotations

In response to the OPDA recommendations, the APD Residency Program Directors Section developed dermatology-specific guidelines for away rotations and established guidelines in other specialties.10 The APD recommends completing up to 2 away rotations, or 3 for those without a home program, if desired. This number was chosen in acknowledgment of the importance of external program experiences, along with the recognition of the financial and time restrictions associated with away rotations as well as the limited number of spots for rotating students. Away rotations are not mandatory. The APD guidelines explain the purpose and value of an away rotation while also noting that these rotations do not necessarily guarantee a formal interview and recommending that programs be transparent about their policies on interview invitations, which may vary.10

Final Thoughts

Publishing specialty-specific guidelines on away rotations is one step toward streamlining the process as well as increasing transparency on the importance of these external program experiences in the application process and residency match. Ideally, away rotations provide a valuable educational experience in which students and program directors get to know each other in a mutually beneficial manner; however, away rotations are not required for securing an interview or matching at a program, and there also are recognized disadvantages to away rotations, particularly with regard to equity, that we must continue to weigh as a specialty. The APD will continue its collaborative work to evaluate our application processes to support a sustainable and equitable system.

Medical students often perform away rotations (also called visiting electives) to gain exposure to educational experiences in a particular specialty, learn about a program, and show interest in a certain program. Away rotations also allow applicants to meet and form relationships with mentors and faculty outside of their home institution. For residency programs, away rotations provide an opportunity for a holistic review of applicants by allowing program directors to get to know potential residency applicants and assess their performance in the clinical environment and among the program’s team. In a National Resident Matching Program survey, program directors (n=17) reported that prior knowledge of an applicant is an important factor in selecting applicants to interview (82.4%) and rank (58.8%).1

In this article, we discuss the importance of away rotations in dermatology and provide an overview of the Organization of Program Director Associations (OPDA) and Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) guidelines for away rotations.

Importance of the Away Rotation in the Match

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, 86.7% of dermatology applicants (N=345) completed one or more away rotations (mean, 2.7) in 2020.2 Winterton et al3 reported that 47% of dermatology applicants (N=45) matched at a program where they completed an away rotation. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of applicants matching to their home program was reported as 26.7% (N=641), which jumped to 40.3% (N=231) in the 2020-2021 cycle.4 Given that the majority of dermatology applicants reportedly match either at their home program or at programs where they completed an away rotation, the benefits of away rotations are high, particularly in a competitive specialty such as dermatology and particularly for applicants without a dermatology program at their home institution. However, it must be acknowledged that correlation does not necessarily mean causation, as away rotations have not necessarily been shown to increase applicants’ chances of matching for the most competitive specialties.5

OPDA Guidelines for Away Rotations

In 2021, the Coalition of Physician Accountability’s Undergraduate Medical Education-Graduate Medical Education Review Committee recommended creating a workgroup to explore the function and value of away rotations for medical students, programs, and institutions, with a particular focus on issues of equity (eg, accessibility, assessment, opportunity) for underrepresented in medicine students and those with financial disadvantages.6 The OPDA workgroup evaluated the advantages and disadvantages of away rotations across specialties. The disadvantages included that away rotations may decrease resources to students at their own institution, particularly if faculty time and energy are funneled/dedicated to away rotators instead of internal rotators, and may impart bias into the recruitment process. Additionally, there is a consideration of equity given the considerable cost and time commitment of travel and housing for students at another institution. In 2022, the estimated cost of an away rotation in dermatology ranged from $1390 to $5500 per rotation.7 Visiting scholarships may be available at some institutions but typically are reserved for underrepresented in medicine students.8 Virtual rotations offered at some programs offset the cost-prohibitiveness of an in-person away rotation; however, they are not universally offered and may be limited in allowing for meaningful interactions between students and program faculty and residents.

The OPDA away rotation workgroup recommended that (1) each specialty publish guidelines regarding the necessity and number of recommended away rotations; (2) specialties publish explicit language regarding the use of program preference signals to programs where students rotated; (3) programs be transparent about the purpose and value of an away rotation, including explicitly stating whether a formal interview is guaranteed; and (4) the Association of American Medical Colleges create a repository of these specialty-specific recommendations.9

APD Guidelines for Away Rotations

In response to the OPDA recommendations, the APD Residency Program Directors Section developed dermatology-specific guidelines for away rotations and established guidelines in other specialties.10 The APD recommends completing up to 2 away rotations, or 3 for those without a home program, if desired. This number was chosen in acknowledgment of the importance of external program experiences, along with the recognition of the financial and time restrictions associated with away rotations as well as the limited number of spots for rotating students. Away rotations are not mandatory. The APD guidelines explain the purpose and value of an away rotation while also noting that these rotations do not necessarily guarantee a formal interview and recommending that programs be transparent about their policies on interview invitations, which may vary.10

Final Thoughts

Publishing specialty-specific guidelines on away rotations is one step toward streamlining the process as well as increasing transparency on the importance of these external program experiences in the application process and residency match. Ideally, away rotations provide a valuable educational experience in which students and program directors get to know each other in a mutually beneficial manner; however, away rotations are not required for securing an interview or matching at a program, and there also are recognized disadvantages to away rotations, particularly with regard to equity, that we must continue to weigh as a specialty. The APD will continue its collaborative work to evaluate our application processes to support a sustainable and equitable system.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results of the 2021 NRMP program director survey. Published August 2021. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2021-PD-Survey-Report-for-WWW.pdf

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Away rotations of U.S. medical school graduates by intended specialty, 2020 AAMC Medical School Graduation Questionnaire (GQ). Published September 24, 2020. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/media/9496/download

- Winterton M, Ahn J, Bernstein J. The prevalence and cost of medical student visiting rotations. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:291. doi:10.1186/s12909-016-0805-z

- Dowdle TS, Ryan MP, Wagner RF. Internal and geographic dermatology match trends in the age of COVID-19. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1364-1366. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.08.004

- Griffith M, DeMasi SC, McGrath AJ, et al. Time to reevaluate the away rotation: improving return on investment for students and schools. Acad Med. 2019;94:496-500. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002505

- Coalition for Physician Accountability. The Coalition for Physician Accountability’s Undergraduate Medication Education-Graduate Medical Education Review Committee (UGRC): recommendations for comprehensive improvement in the UME-GME transition. Published August 26, 2021. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://physicianaccountability.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/UGRC-Coalition-Report-FINAL.pdf

- Cucka B, Grant-Kels JM. Ethical implications of the high cost of medical student visiting dermatology rotations. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:539-540.

- Dahak S, Fernandez JM, Rosman IS. Funded dermatology visiting elective rotations for medical students who are underrepresented in medicine: a cross-sectional analysis [published online November 15, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:941-943.

- Council of Medical Specialty Societies. The Organization of Program Director Associations (OPDA): away rotations workgroup. Published July 26, 2022. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://cmss.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/OPDA-Work-Group-on-Away-Rotations-7.26.2022-1.pdf

- Association of Professors of Dermatology. Recommendations regarding away electives. Published December 14, 2022. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20recommendations%20on%20away%20rotations%202023-2024.pdf

- National Resident Matching Program. Results of the 2021 NRMP program director survey. Published August 2021. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2021-PD-Survey-Report-for-WWW.pdf

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Away rotations of U.S. medical school graduates by intended specialty, 2020 AAMC Medical School Graduation Questionnaire (GQ). Published September 24, 2020. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/media/9496/download

- Winterton M, Ahn J, Bernstein J. The prevalence and cost of medical student visiting rotations. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:291. doi:10.1186/s12909-016-0805-z

- Dowdle TS, Ryan MP, Wagner RF. Internal and geographic dermatology match trends in the age of COVID-19. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1364-1366. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.08.004

- Griffith M, DeMasi SC, McGrath AJ, et al. Time to reevaluate the away rotation: improving return on investment for students and schools. Acad Med. 2019;94:496-500. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002505

- Coalition for Physician Accountability. The Coalition for Physician Accountability’s Undergraduate Medication Education-Graduate Medical Education Review Committee (UGRC): recommendations for comprehensive improvement in the UME-GME transition. Published August 26, 2021. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://physicianaccountability.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/UGRC-Coalition-Report-FINAL.pdf

- Cucka B, Grant-Kels JM. Ethical implications of the high cost of medical student visiting dermatology rotations. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:539-540.

- Dahak S, Fernandez JM, Rosman IS. Funded dermatology visiting elective rotations for medical students who are underrepresented in medicine: a cross-sectional analysis [published online November 15, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:941-943.

- Council of Medical Specialty Societies. The Organization of Program Director Associations (OPDA): away rotations workgroup. Published July 26, 2022. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://cmss.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/OPDA-Work-Group-on-Away-Rotations-7.26.2022-1.pdf

- Association of Professors of Dermatology. Recommendations regarding away electives. Published December 14, 2022. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20recommendations%20on%20away%20rotations%202023-2024.pdf

Practice Points

- Away rotations are an important tool for both applicants and residency programs during the application process.

- The Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) recommends completing up to 2 external program experiences, or 3 if the student has no home program, ideally to be completed early in the fourth year of medical school prior to interview invitations.

- Away rotations may have considerable cost and time restrictions on applicants, which the APD recognizes and weighs in its recommendations. There may be program-specific scholarships and opportunities available to help with the cost of away rotations.

Interacting With Dermatology Patients Online: Private Practice vs Academic Institute Website Content

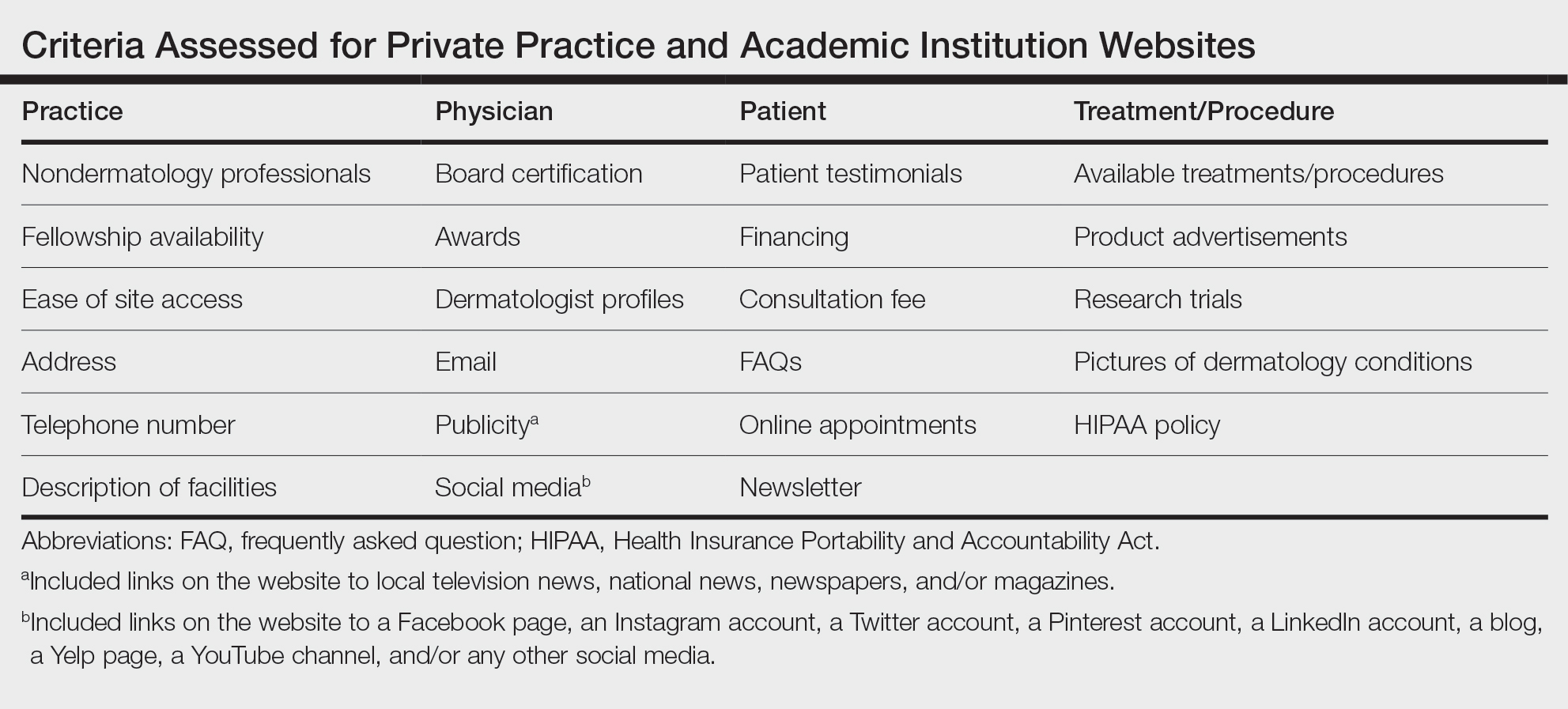

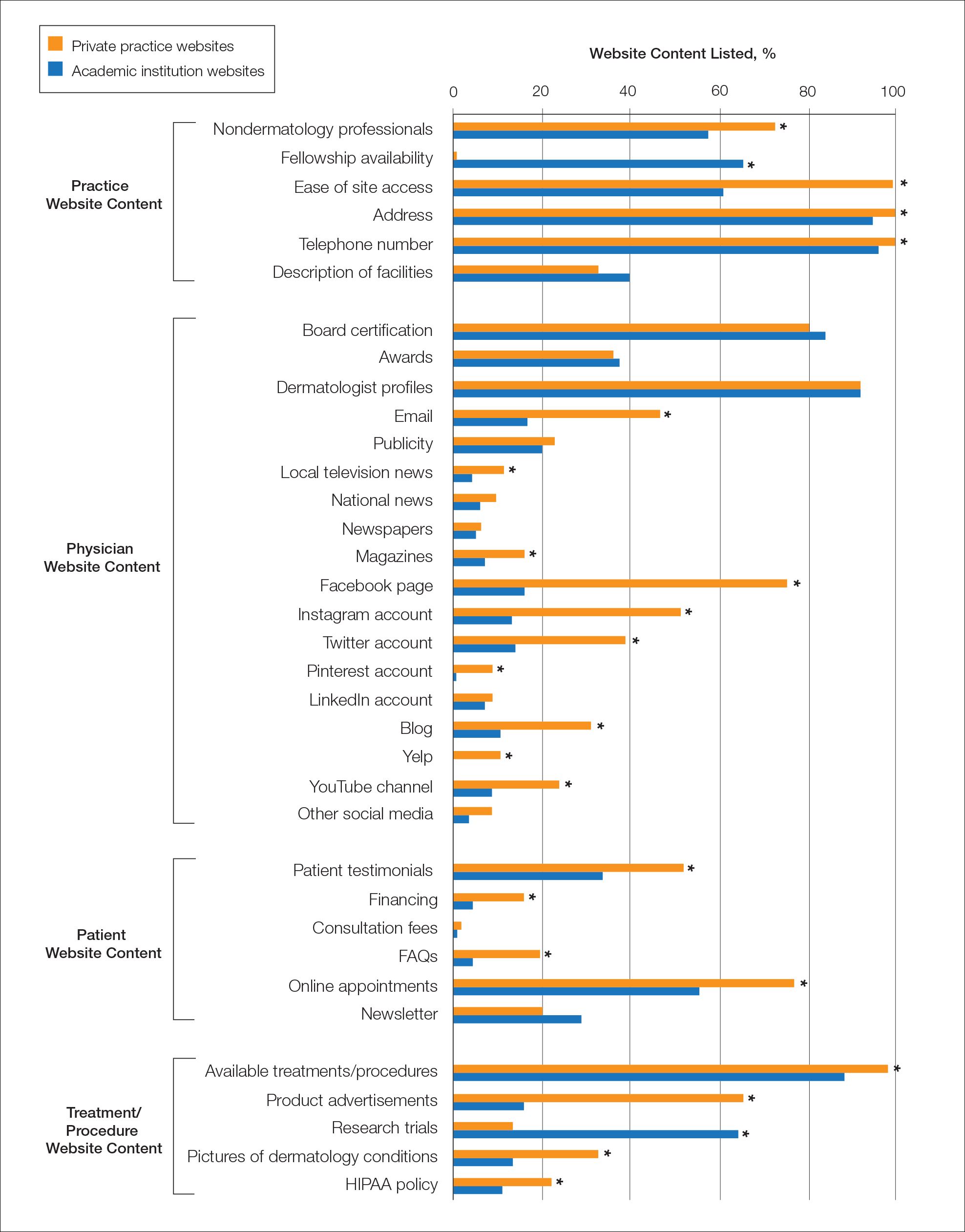

Patients are finding it easier to use online resources to discover health care providers who fit their personalized needs. In the United States, approximately 70% of individuals use the internet to find health care information, and 80% are influenced by the information presented to them on health care websites.1 Patients utilize the internet to better understand treatments offered by providers and their prices as well as how other patients have rated their experience. Providers in private practice also have noticed that many patients are referring themselves vs obtaining a referral from another provider.2 As a result, it is critical for practice websites to have information that is of value to their patients, including the unique qualities and treatments offered. The purpose of this study was to analyze the differences between the content presented on dermatology private practice websites and academic institutional websites.

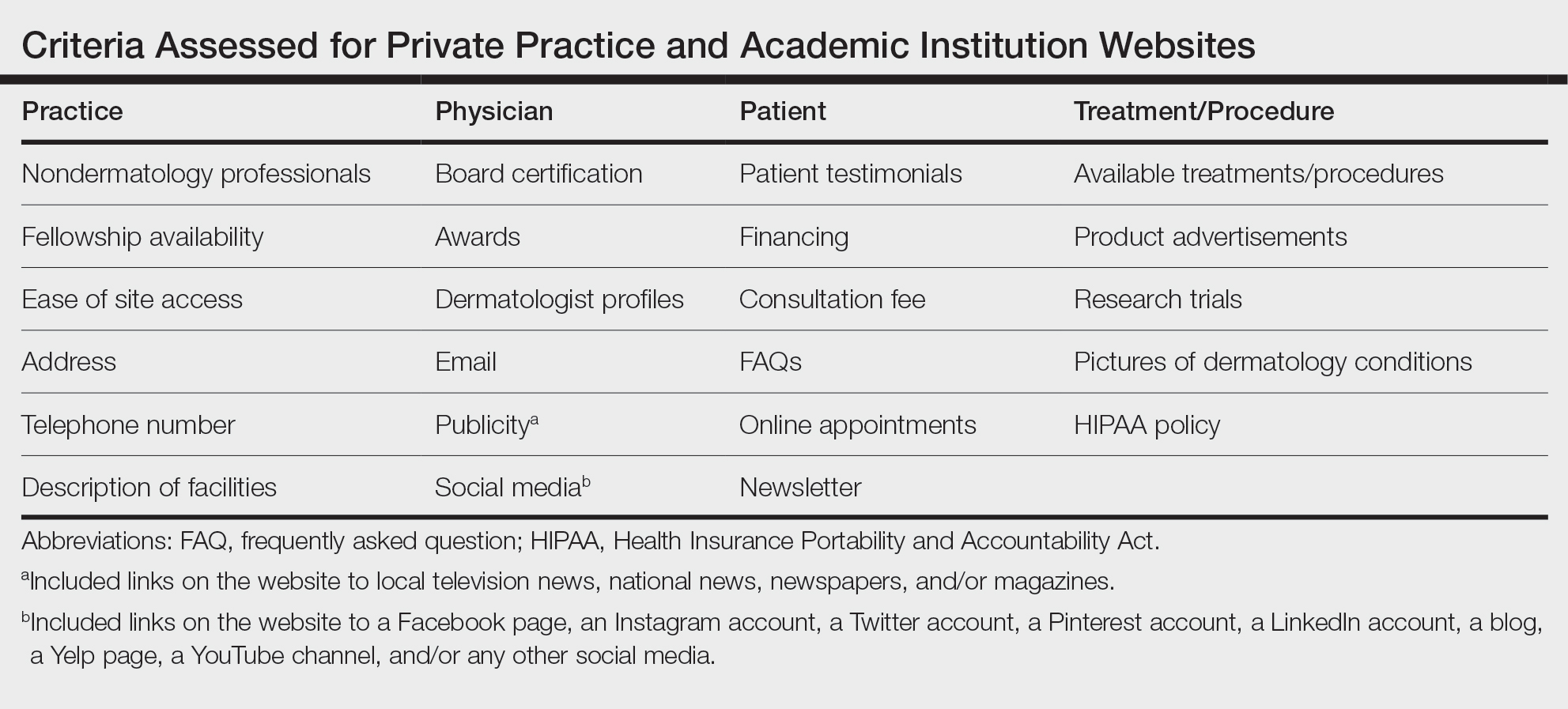

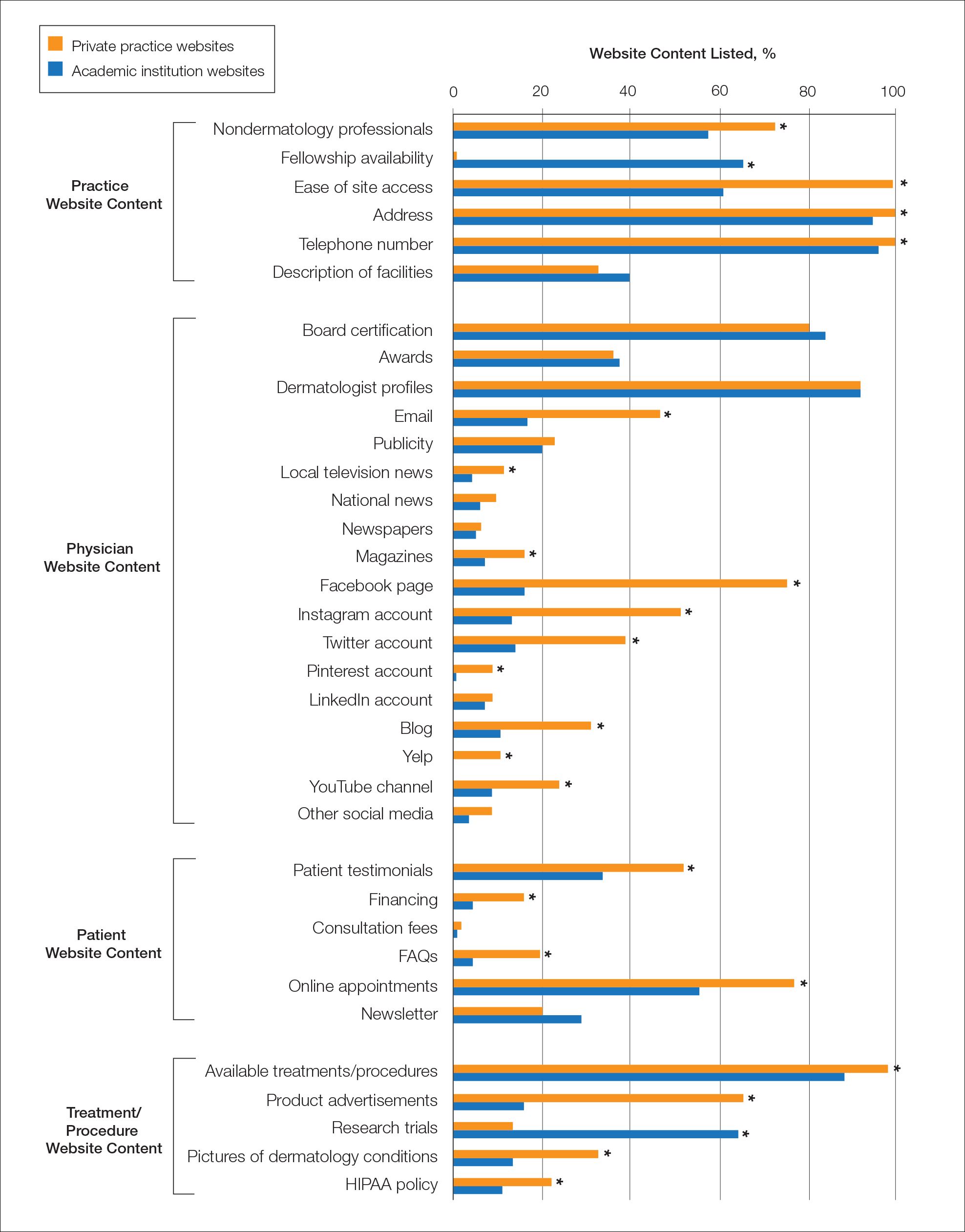

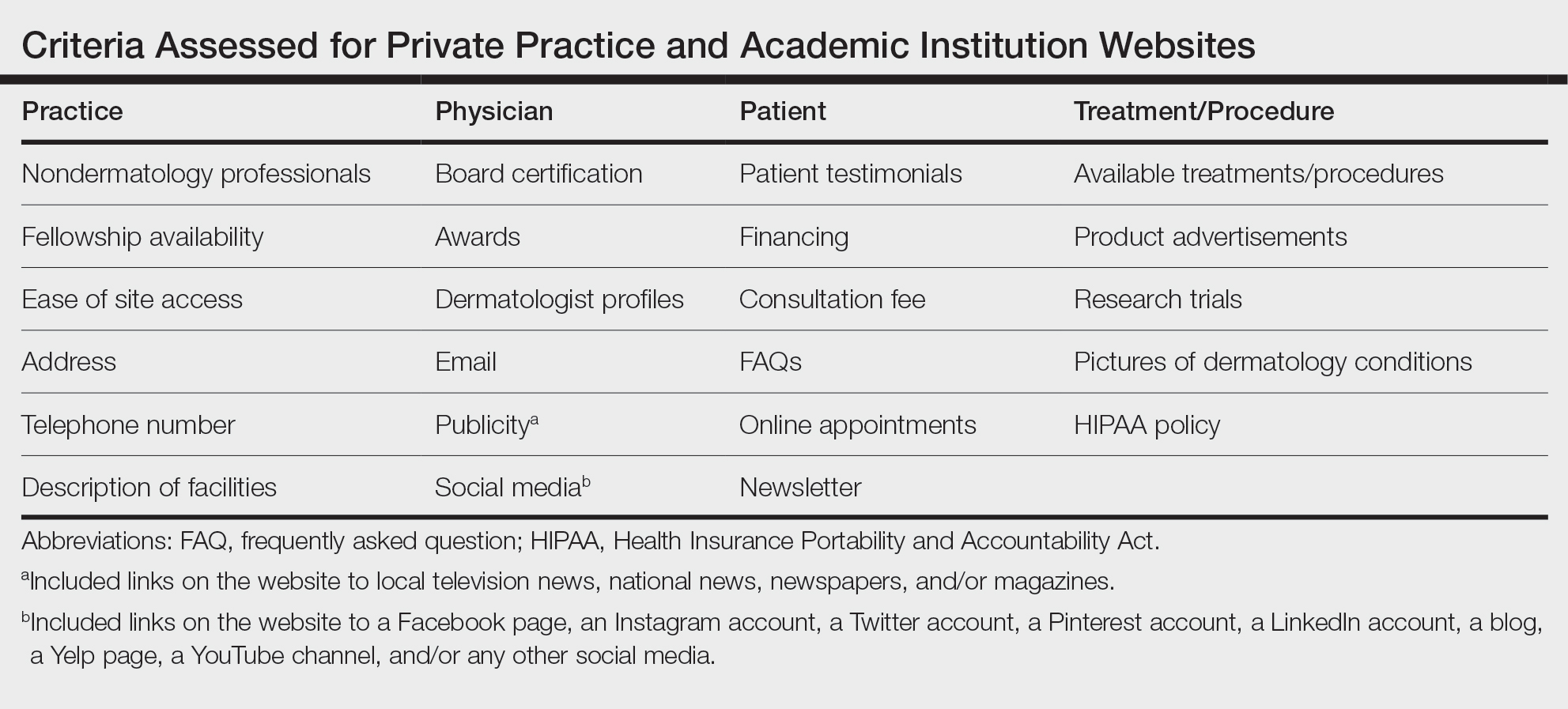

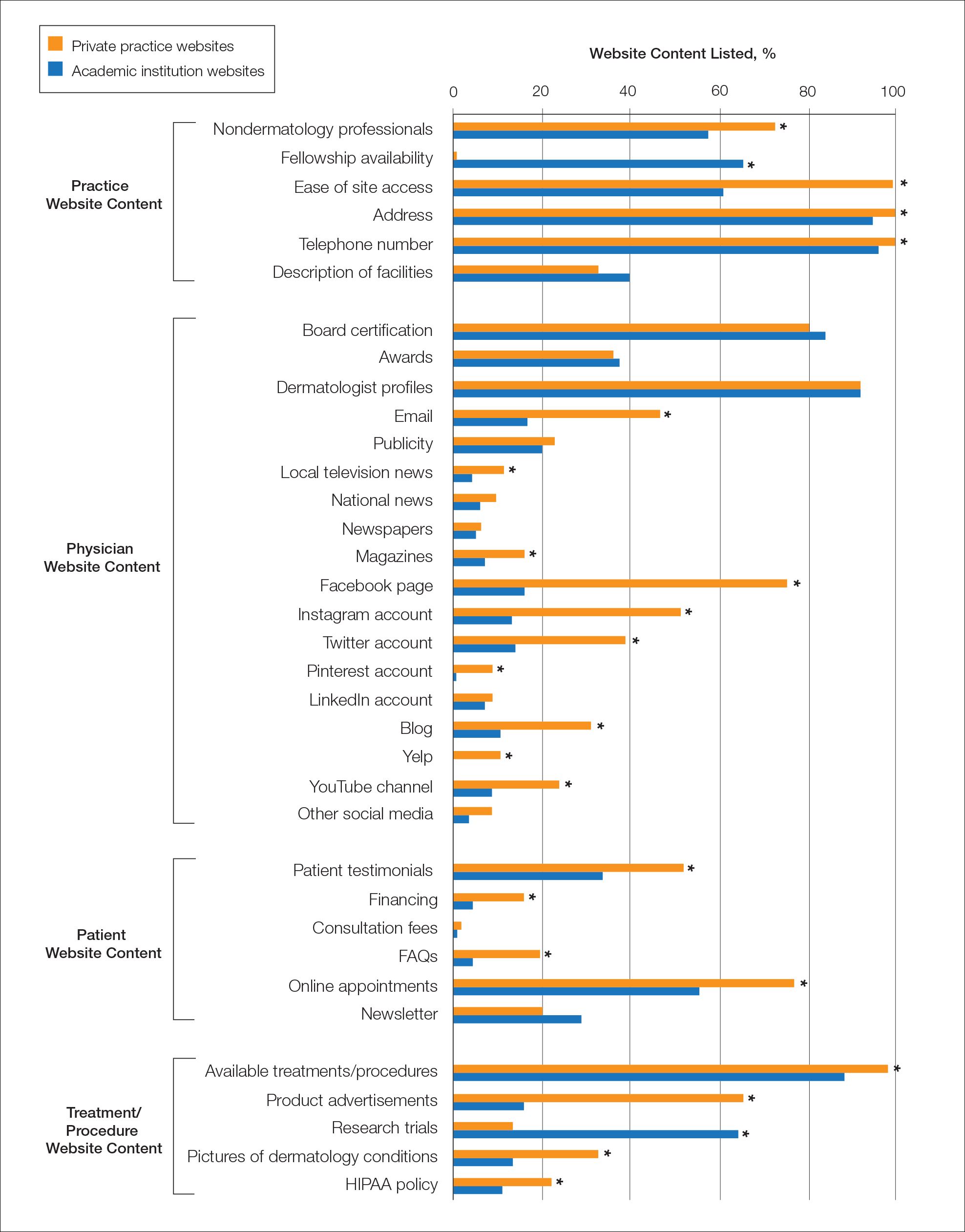

Methods