User login

How to Advise Medical Students Interested in Dermatology: A Survey of Academic Dermatology Mentors

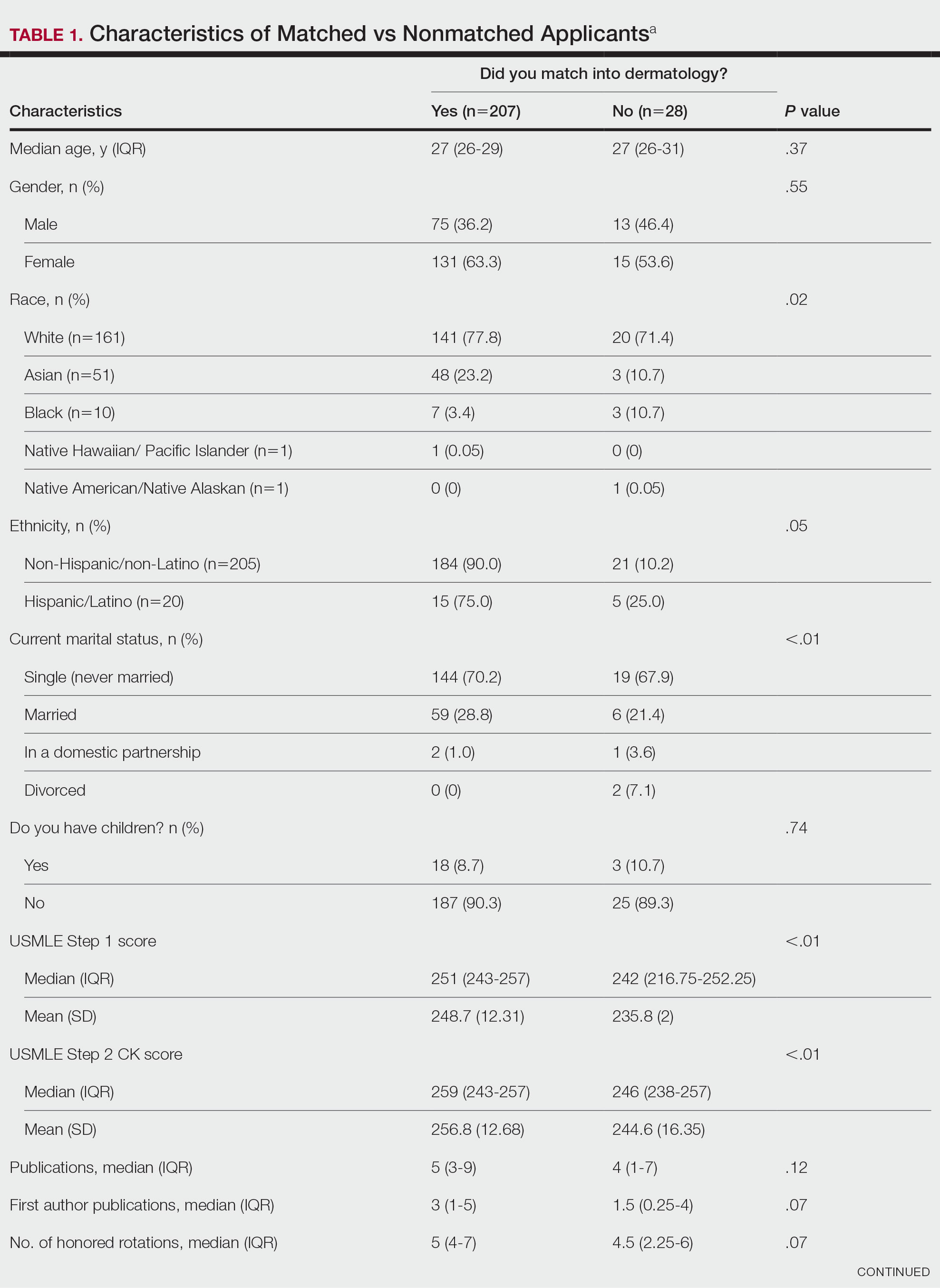

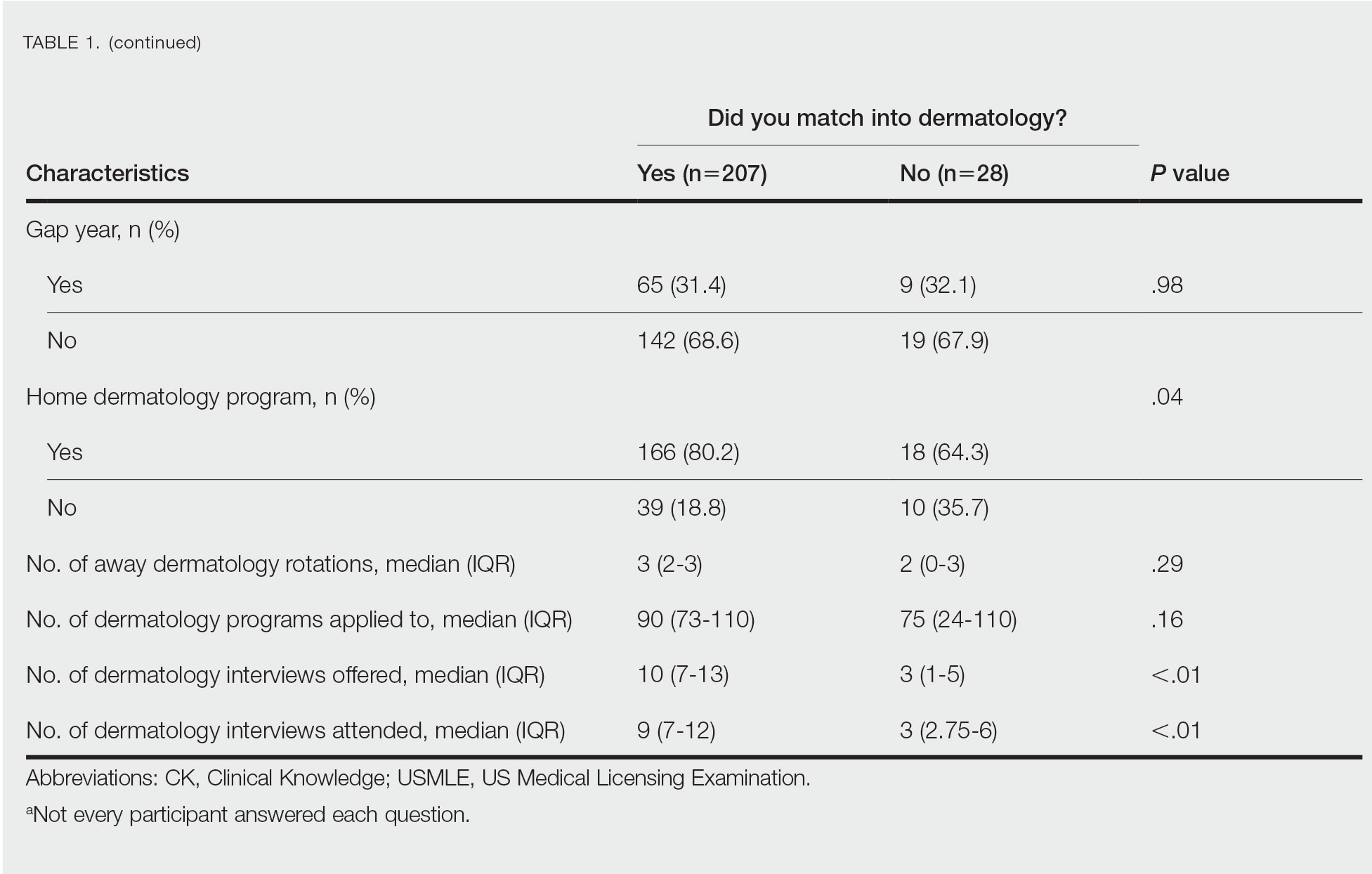

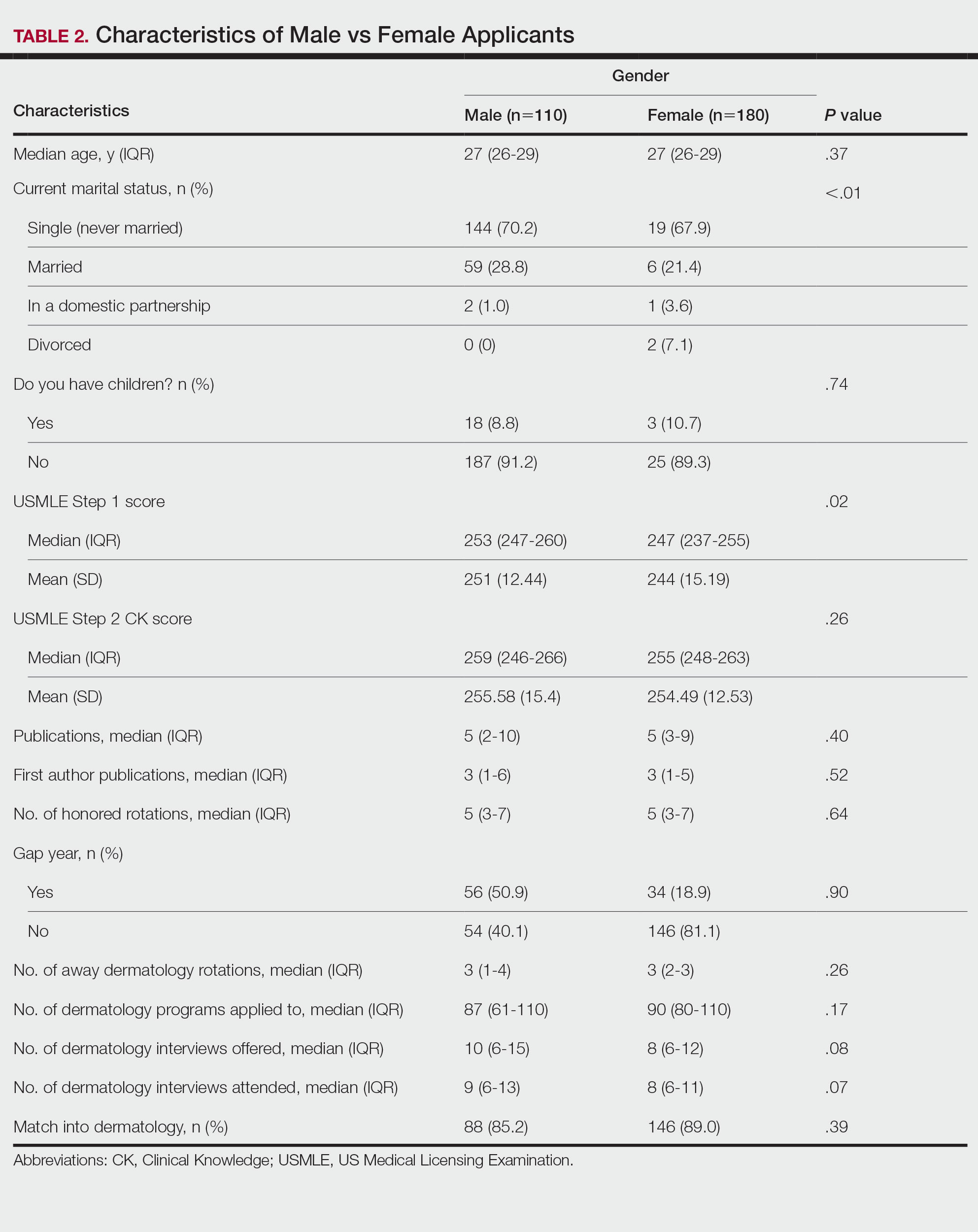

Dermatology remains one of the most competitive specialties in medicine. In 2022, there were 851 applicants (613 doctor of medicine seniors, 85 doctor of osteopathic medicine seniors) for 492 postgraduate year (PGY) 2 positions.1 During the 2022 application season, the average matched dermatology candidate had 7.2 research experiences; 20.9 abstracts, presentations, or publications; 11 volunteer experiences; and a US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 2 Clinical Knowledge score of 257.1 With hopes of matching into such a competitive field, students often seek advice from academic dermatology mentors. Such advice may substantially differ based on each mentor and may or may not be evidence based.

We sought to analyze the range of advice given to medical students applying to dermatology residency programs via a survey to members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) with the intent to help applicants and mentors understand how letters of intent, letters of recommendation (LORs), and Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) supplemental applications are used by dermatology programs nationwide.

Methods

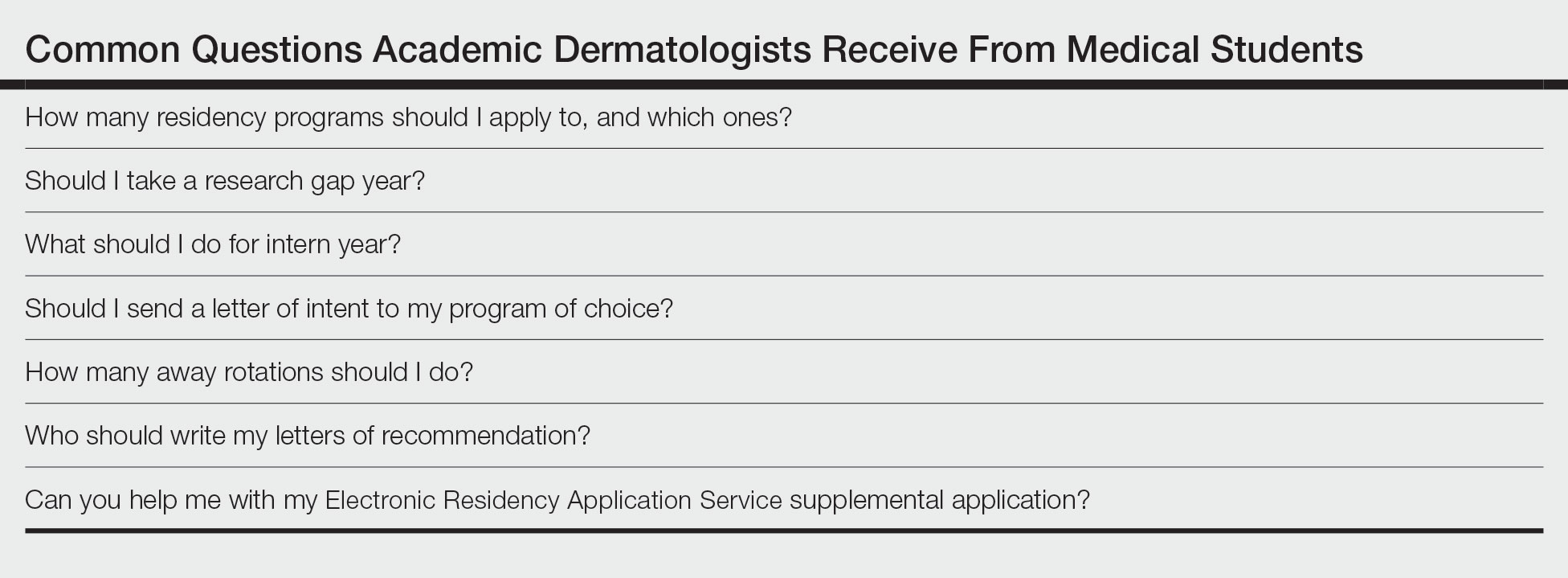

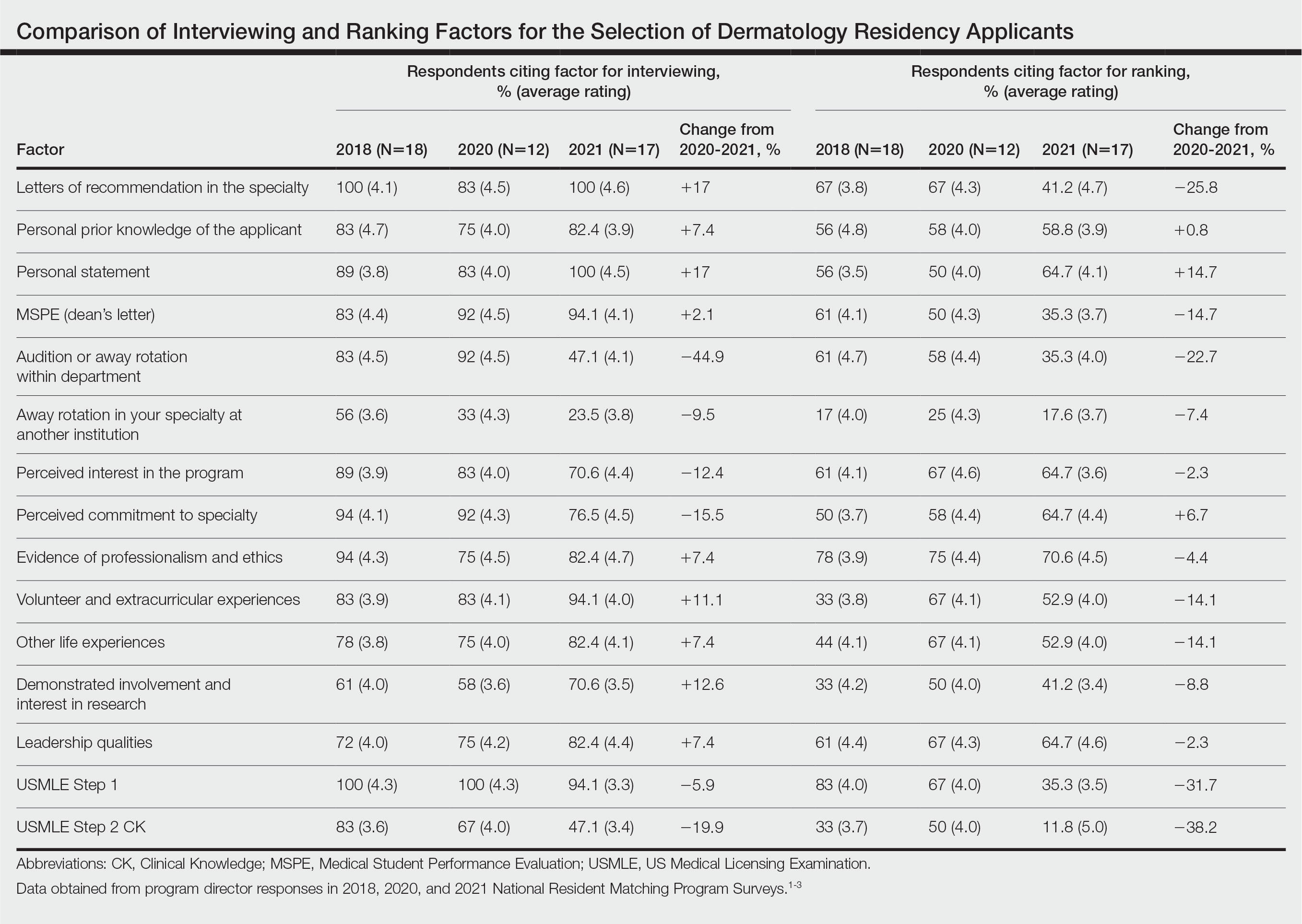

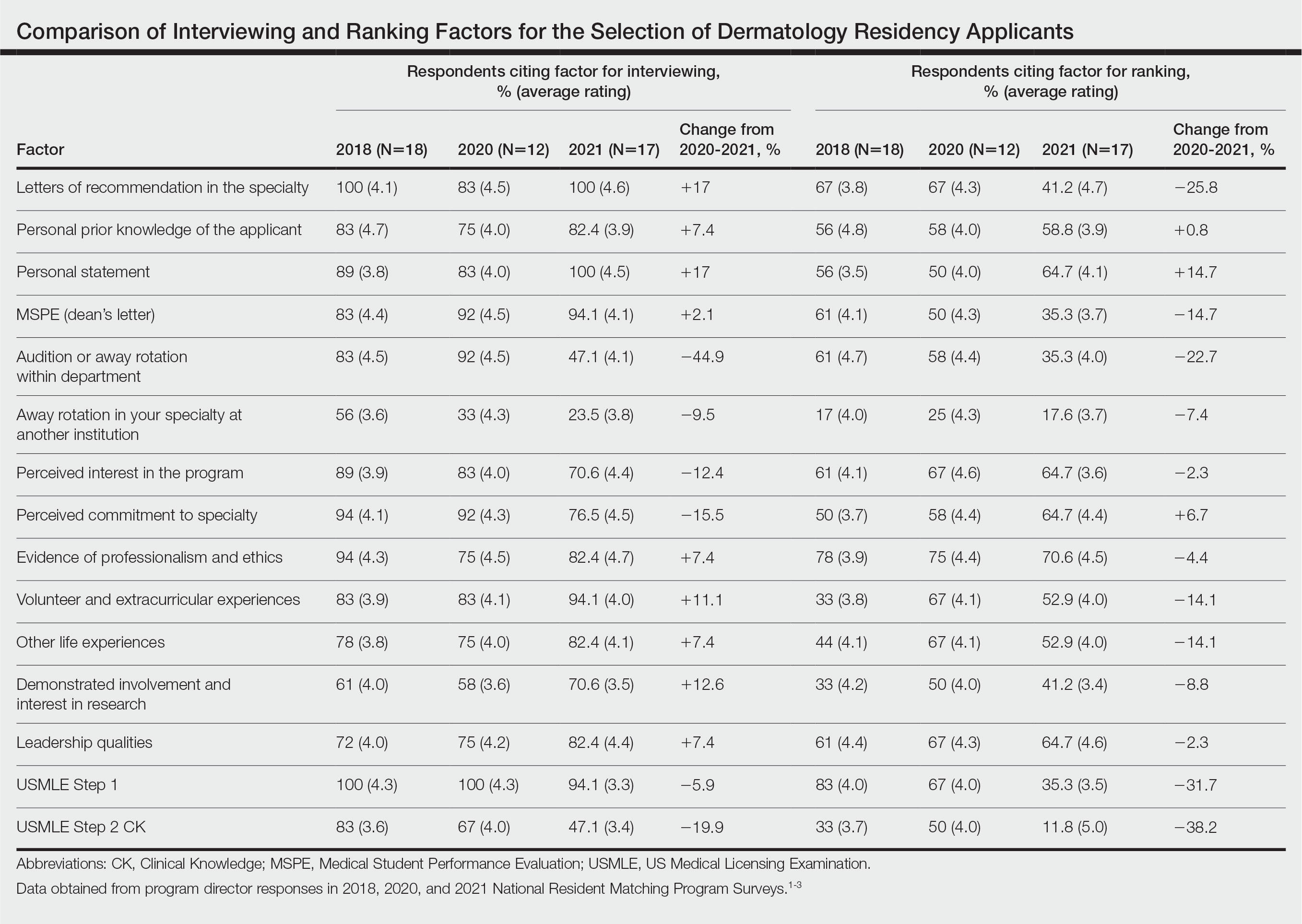

The study was reviewed by The Ohio State University institutional review board and was deemed exempt. A branching-logic survey with common questions from medical students while applying to dermatology residency programs (Table) was sent to all members of APD through the email listserve. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at The Ohio State University (Columbus, Ohio) to ensure data security.

The survey was distributed from August 28, 2022, to September 12, 2022. A total of 101 surveys were returned from 646 listserve members (15.6%). Given the branching-logic questions, differing numbers of responses were collected for each question. Descriptive statistics were utilized to analyze and report the results.

Results

Residency Program Number—Members of the APD were asked if they recommend students apply to a certain number of programs, and if so, how many programs. Of members who responded, 62.2% (61/98) either always (22.4% [22/98]) or sometimes (40.2% [39/97]) suggested students apply to a certain number of programs. When mentors made a recommendation, 54.1% (33/61) recommended applying to 59 or fewer programs, with only 9.8% (6/61) recommending students apply to 80 or more programs.

Gap Year—We queried mentors about their recommendations for a research gap year and asked which applicants should pursue this extra year. Our survey found that 74.5% of mentors (73/98) almost always (4.1% [4/98]) or sometimes (70.4% [69/98]) recommended a research gap year, most commonly for those applicants with a strong research interest (71.8% [51/71]). Other reasons mentors recommended a dedicated research year during medical school included low USMLE Step scores (50.7% [36/71]), low grades (45.1% [32/71]), little research (46.5% [33/71]), and no home program (43.7% [31/71]).

Internship Choices—Our survey results indicated that nearly two-thirds (63.3% [62/98]) of mentors did not give applicants a recommendation on type of internship (PGY-1). If a recommendation was given, academic dermatologists more commonly recommended an internal medicine preliminary year (29.6% [29/98]) over a transitional year (7.1% [7/98]).

Communication of Interest Via a Letter of Intent—We asked mentors if they recommended applicants send a letter of intent and conversely if receiving a letter of intent impacted their rank list. Nearly half (48.5% [47/97]) of mentors indicated they did not recommend sending a letter of intent, with only 15.5% (15/97) of mentors regularly recommending this practice. Additionally, 75.8% of mentors indicated that a letter of intent never (42.1% [40/95]) or rarely (33.7% [32/95]) impacted their rank list.

Rotation Choices—We queried mentors if they recommended students complete away rotations, and if so, how many rotations did they recommend. We found that 85.9% (85/99) of mentors recommended students complete an away rotation; 63.1% (53/84) of them recommended performing 2 away rotations, and 14.3% (12/84) of respondents recommended students complete 3 away rotations. More than a quarter of mentors (27.1% [23/85]) indicated their home medical schools limited the number of away rotations a medical student could complete in any 1 specialty, and 42.4% (36/85) of respondents were unsure if such a limitation existed.

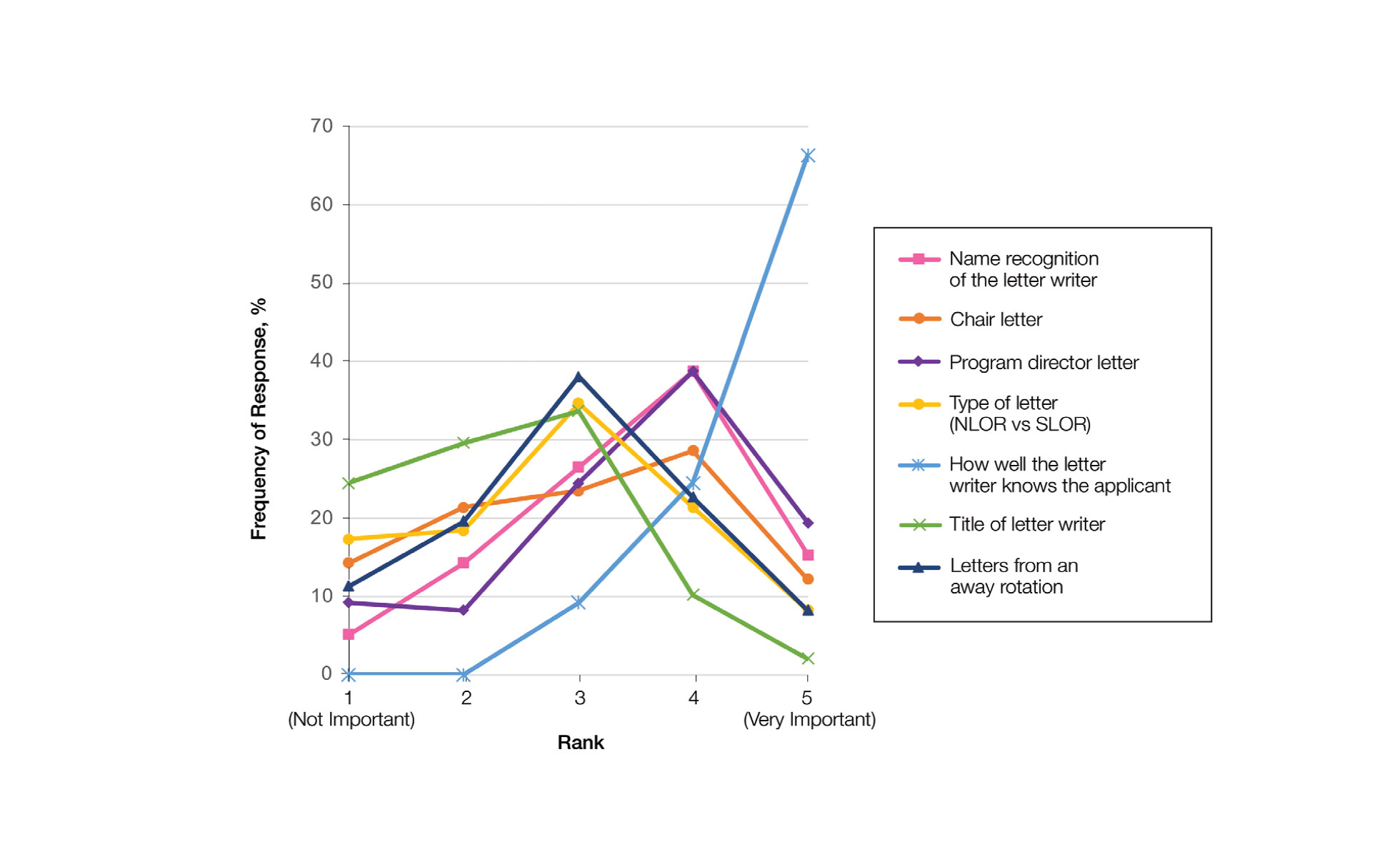

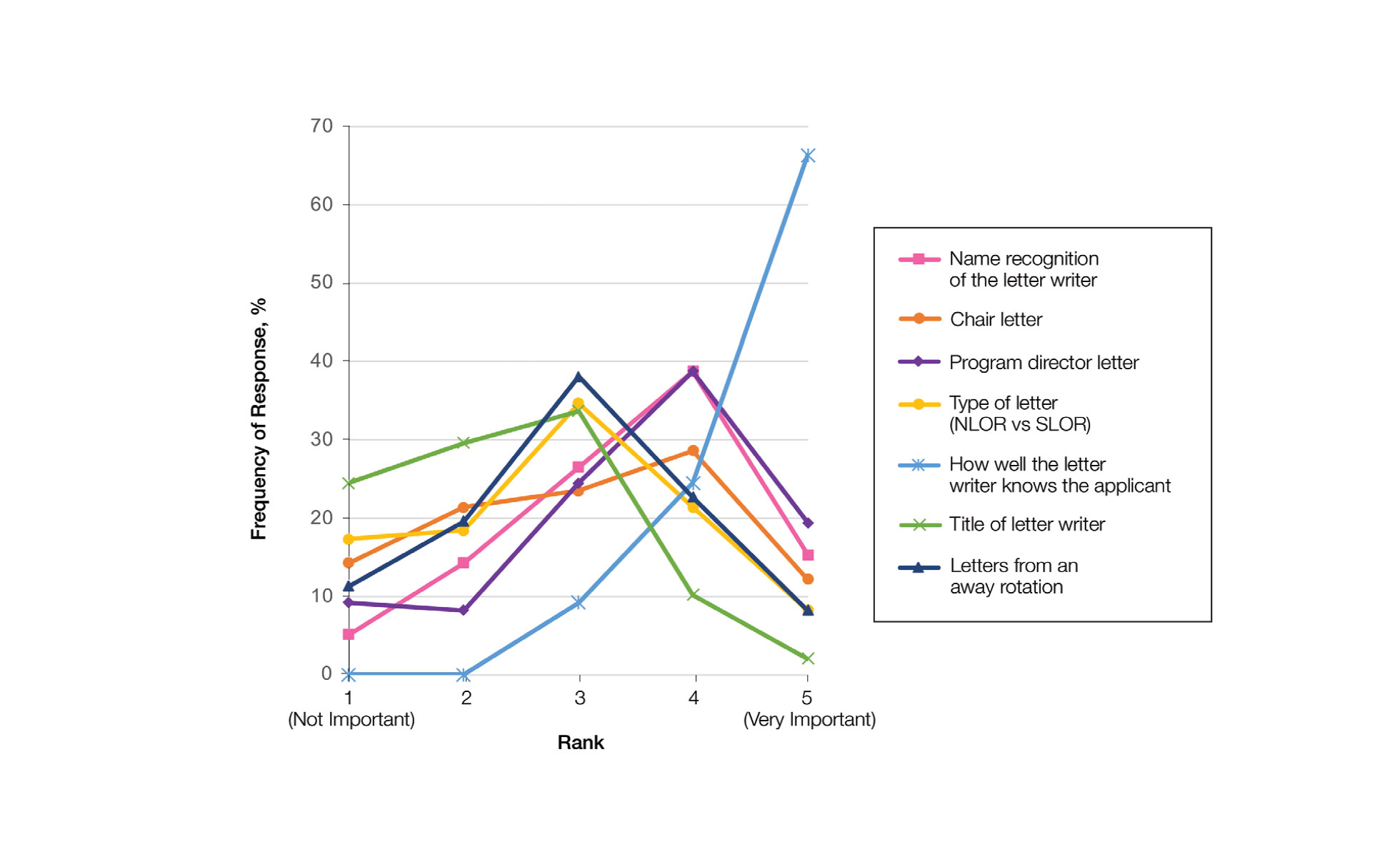

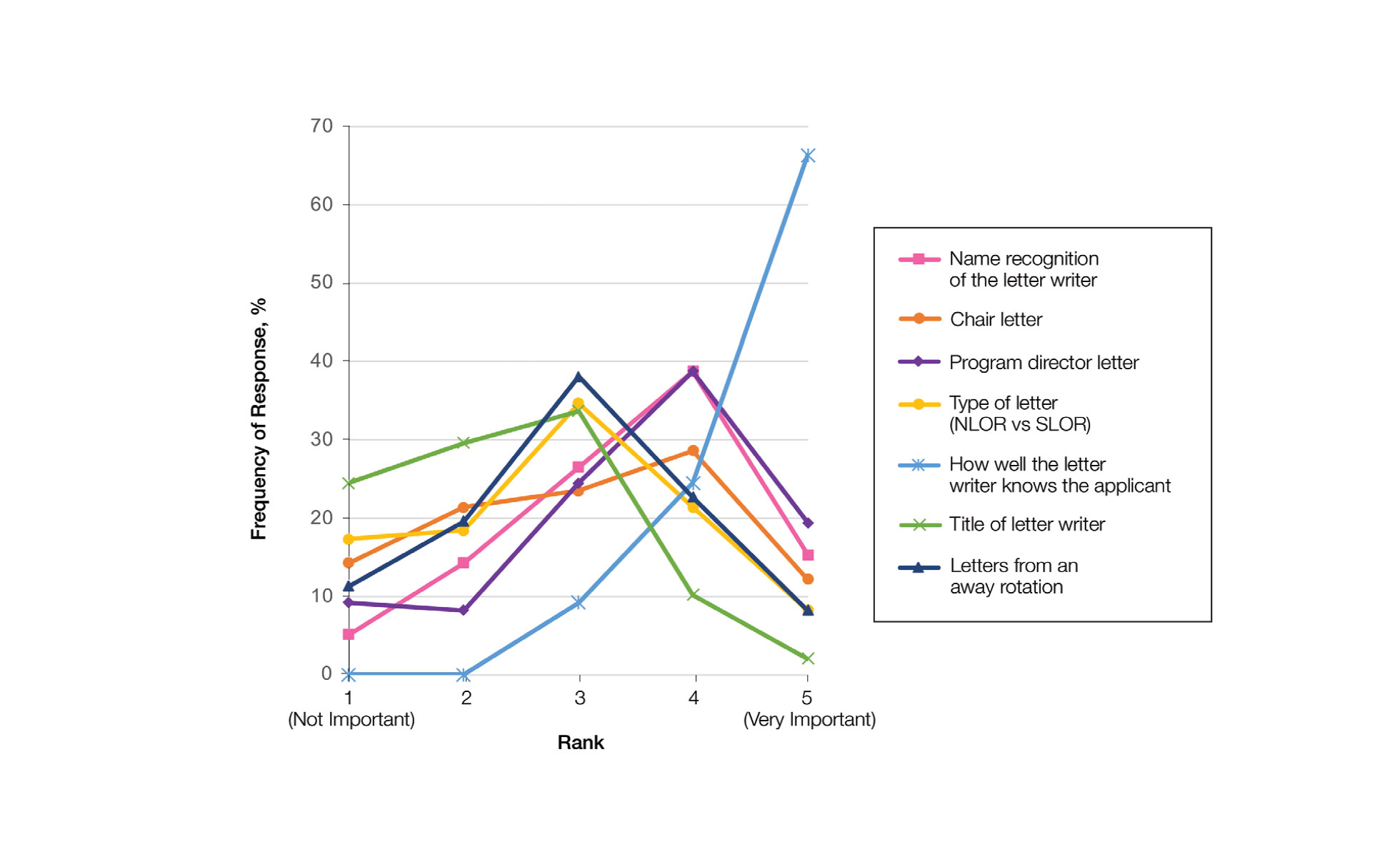

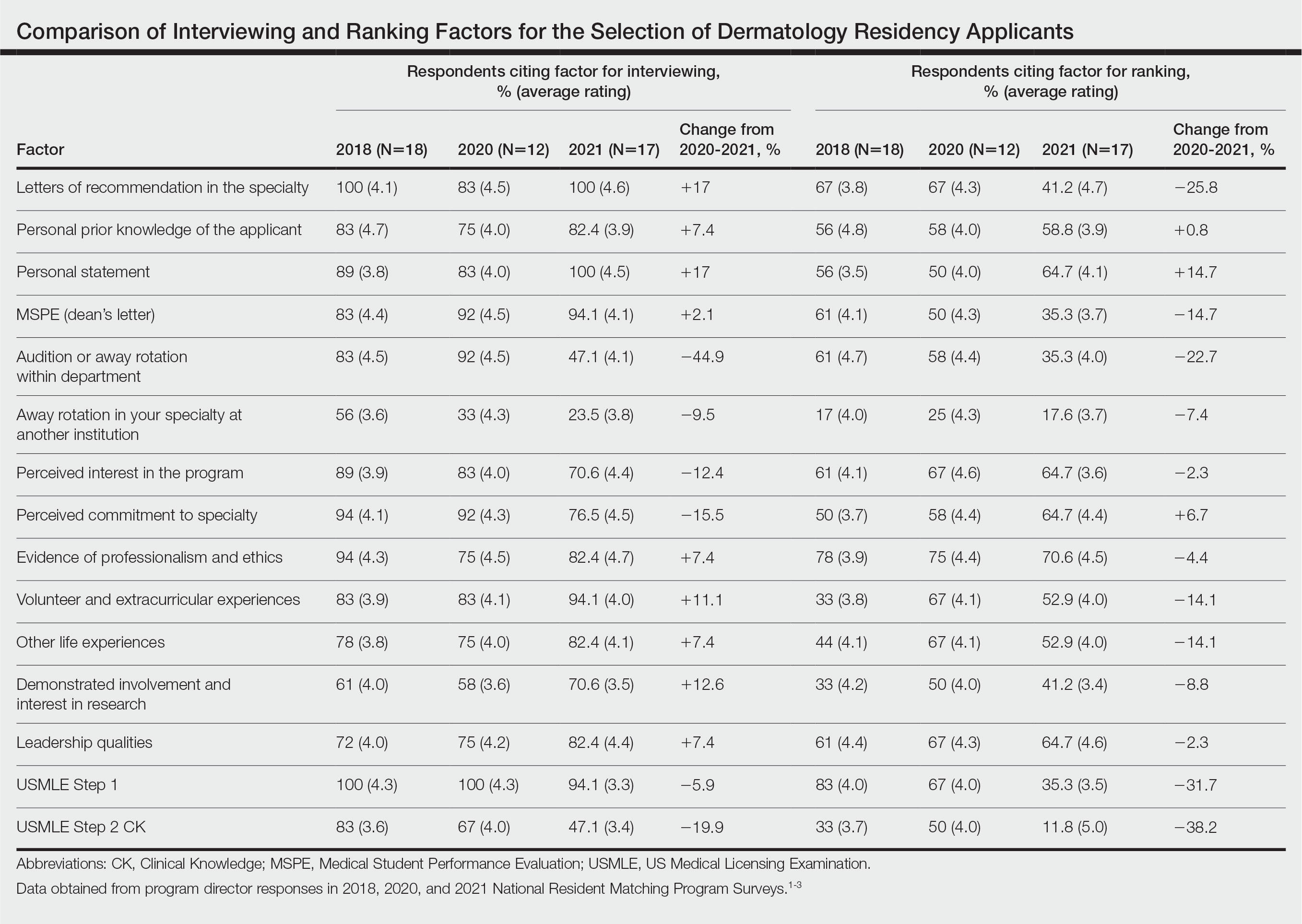

Letters of Recommendation—Our survey asked respondents to rank various factors on a 5-point scale (1=not important; 5=very important) when deciding who should write the students’ LORs. Mentors indicated that the most important factor for letter-writer selection was how well the letter writer knows the applicant, with 90.8% (89/98) of mentors rating the importance of this quality as a 4 or 5 (Figure). More than half of respondents rated the name recognition of the letter writer and program director letter as a 4 or 5 in importance (54.1% [53/98] and 58.2% [57/98], respectively). Type of letter (standardized vs nonstandardized), title of letter writer, letters from an away rotation, and chair letter scored lower, with fewer than half of mentors rating these as a 4 or 5 in importance.

Supplemental Application—When asked about the 2022 application cycle, respondents of our survey reported that the supplemental application was overall more important in deciding which applicants to interview vs which to rank highly. Prior experiences were important (ranked 4 or 5) for 58.8% (57/97) of respondents in choosing applicants to interview, and 49.4% (48/97) of respondents thought prior experiences were important for ranking. Similarly, 34.0% (33/97) of mentors indicated geographic preference was important (ranked 4 or 5) for interview compared with only 23.8% (23/97) for ranking. Finally, 57.7% (56/97) of our survey respondents denoted that program signals were important or very important in choosing which applicants to interview, while 32.0% (31/97) indicated that program signals were important in ranking applicants.

Comment

Residency Programs: Which Ones, and How Many?—The number of applications for dermatology residency programs has increased 33.9% from 2010 to 2019.2 The American Association of Medical Colleges Apply Smart data from 2013 to 2017 indicate that dermatology applicants arrive at a point of diminishing return between 37 and 62 applications, with variation within that range based on USMLE Step 1 score,3 and our data support this with nearly two-thirds of dermatology advisors recommending students apply within this range. Despite this data, dermatology residency applicants applied to more programs over the last decade (64.8 vs 77.0),2 likely to maximize their chance of matching.

Research Gap Years During Medical School—Prior research has shown that nearly half of faculty indicated that a research year during medical school can distinguish similar applicants, and close to 25% of applicants completed a research gap year.4,5 However, available data indicate that taking a research gap year has no effect on match rate or number of interview invites but does correlate with match rates at the highest ranked dermatology residency programs.6-8

Our data indicate that the most commonly recommended reason for a research gap year was an applicants’ strong interest in research. However, nearly half of dermatology mentors recommended research years during medical school for reasons other than an interest in research. As research gap years increase in popularity, future research is needed to confirm the consequence of this additional year and which applicants, if any, will benefit from such a year.

Preferences for Intern Year—Prior research suggests that dermatology residency program directors favor PGY-1 preliminary medicine internships because of the rigor of training.9,10 Our data continue to show a preference for internal medicine preliminary years over transitional years. However, given nearly two-thirds of dermatology mentors do not give applicants any recommendations on PGY-1 year, this preference may be fading.

Letters of Intent Not Recommended—Research in 2022 found that 78.8% of dermatology applicants sent a letter of intent communicating a plan to rank that program number 1, with nearly 13% sending such a letter to more than 1 program.11 With nearly half of mentors in our survey actively discouraging this process and more than 75% of mentors not utilizing this letter, the APD issued a brief statement on the 2022-2023 application cycle stating, “Post-interview communication of preference—including ‘letters of intent’ and thank you letters—should not be sent to programs. These types of communication are typically not used by residency programs in decision-making and lead to downstream pressures on applicants.”12

Away Rotations—Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, data demonstrated that nearly one-third of dermatology applicants (29%) matched at their home institution, and nearly one-fifth (18%) matched where they completed an away rotation.13 In-person away rotations were eliminated in 2020 and restricted to 1 away rotation in 2021. Restrictions regarding away rotations were removed in 2022. Our data indicate that dermatology mentors strongly supported an away rotation, with more than half of them recommending at least 2 away rotations.

Further research is needed to determine the effect numerous away rotations have on minimizing students’ exposure to other specialties outside their chosen field. Additionally, further studies are needed to determine the impact away rotations have on economically disadvantaged students, students without home programs, and students with families. In an effort to standardize the number of away rotations, the APD issued a statement for the 2023-2024 application cycle indicating that dermatology applicants should limit away rotations to 2 in-person electives. Students without a home dermatology program could consider completing up to 3 electives.14

Who Should Write LORs?—Research in 2014 demonstrated that LORs were very important in determining applicants to interview, with a strong preference for LORs from academic dermatologists and colleagues.15 Our data strongly indicated applicants should predominantly ask for letters from writers who know them well. The majority of mentors did not give value to the rank of the letter writer (eg, assistant professor, associate professor, professor), type of letter, chair letters, or letters from an away rotation. These data may help alleviate stress many students feel as they search for letter writers.

How is the Supplemental Application Used?—In 2022, the ERAS supplemental application was introduced, which allowed applicants to detail 5 meaningful experiences, describe impactful life challenges, and indicate preferences for geographic region. Dermatology residency applicants also were able to choose 3 residency programs to signal interest in that program. Our data found that the supplemental application was utilized predominantly to select applicants to interview, which is in line with the Association of American Medical Colleges’ and APD guidelines indicating that this tool is solely meant to assist with application review.16 Further research and data will hopefully inform approaches to best utilize the ERAS supplemental application data.

Limitations—Our data were limited by response rate and sample size, as only academic dermatologists belonging to the APD were queried. Additionally, we did not track personal information of the mentors, so more than 1 mentor may have responded from a single institution, making it possible that our data may not be broadly applicable to all institutions.

Conclusion

Although there is no algorithmic method of advising medical students who are interested in dermatology, our survey data help to describe the range of advice currently given to students, which can improve and guide future recommendations. Additionally, some of our data demonstrate a discrepancy between mentor advice and current medical student practice for the number of applications and use of a letter of intent. We hope our data will assist academic dermatology mentors in the provision of advice to mentees as well as inform organizations seeking to create standards and official recommendations regarding aspects of the application process.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2022 Main Residency Match. May 2022. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/2022-Main-Match-Results-and-Data_Final.pdf

- Secrest AM, Coman GC, Swink JM, et al. Limiting residency applications to dermatology benefits nearly everyone. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:30-32.

- Apply smart for residency. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/apply-smart-residency

- Shamloul N, Grandhi R, Hossler E. Perceived importance of dermatology research fellowships. Presented at: Dermatology Teachers Exchange Group; October 3, 2020.

- Runge M, Jairath NK, Renati S, et al. Pursuit of a research year or dual degree by dermatology residency applicants: a cross-sectional study. Cutis. 2022;109:E12-E13.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role of race and ethnicity in the dermatology applicant match process. J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;113:666-670.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap years play in a successful dermatology match. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:226-230.

- Ramachandran V, Nguyen HY, Dao H Jr. Does it match? analyzing self-reported online dermatology match data to charting outcomes in the Match. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030/qt4604h1w4.

- Hopkins C, Jalali O, Guffey D, et al. A survey of dermatology residents and program directors assessing the transition to dermatology residency. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Center). 2021;34:59-62.

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, Rinderknecht FA, et al. Current perspectives of and potential reforms to the dermatology residency application process: a nationwide survey of program directors and applicants. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:595-601.

- Association of Professors of Dermatology. Residency Program Directors Section. Updated Information Regarding the 2022-2023 Application Cycle. Updated October 18, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2023. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20statement%20on%202022-2023%20application%20cycle_updated%20Oct.pdf

- Narang J, Morgan F, Eversman A, et al. Trends in geographic and home program preferences in the dermatology residency match: a retrospective cohort analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:645-647.

- Association of Professors of Dermatology Residency Program Directors Section. Recommendations Regarding Away Electives. Updated December 14, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2022. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20recommendations%20on%20away%20rotations%202023-2024.pdf

- Kaffenberger BH, Kaffenberger JA, Zirwas MJ. Academic dermatologists’ views on the value of residency letters of recommendation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:395-396.

- Supplemental ERAS Application: Guide for Residency Program. Association of American Medical Colleges; June 2022.

Dermatology remains one of the most competitive specialties in medicine. In 2022, there were 851 applicants (613 doctor of medicine seniors, 85 doctor of osteopathic medicine seniors) for 492 postgraduate year (PGY) 2 positions.1 During the 2022 application season, the average matched dermatology candidate had 7.2 research experiences; 20.9 abstracts, presentations, or publications; 11 volunteer experiences; and a US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 2 Clinical Knowledge score of 257.1 With hopes of matching into such a competitive field, students often seek advice from academic dermatology mentors. Such advice may substantially differ based on each mentor and may or may not be evidence based.

We sought to analyze the range of advice given to medical students applying to dermatology residency programs via a survey to members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) with the intent to help applicants and mentors understand how letters of intent, letters of recommendation (LORs), and Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) supplemental applications are used by dermatology programs nationwide.

Methods

The study was reviewed by The Ohio State University institutional review board and was deemed exempt. A branching-logic survey with common questions from medical students while applying to dermatology residency programs (Table) was sent to all members of APD through the email listserve. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at The Ohio State University (Columbus, Ohio) to ensure data security.

The survey was distributed from August 28, 2022, to September 12, 2022. A total of 101 surveys were returned from 646 listserve members (15.6%). Given the branching-logic questions, differing numbers of responses were collected for each question. Descriptive statistics were utilized to analyze and report the results.

Results

Residency Program Number—Members of the APD were asked if they recommend students apply to a certain number of programs, and if so, how many programs. Of members who responded, 62.2% (61/98) either always (22.4% [22/98]) or sometimes (40.2% [39/97]) suggested students apply to a certain number of programs. When mentors made a recommendation, 54.1% (33/61) recommended applying to 59 or fewer programs, with only 9.8% (6/61) recommending students apply to 80 or more programs.

Gap Year—We queried mentors about their recommendations for a research gap year and asked which applicants should pursue this extra year. Our survey found that 74.5% of mentors (73/98) almost always (4.1% [4/98]) or sometimes (70.4% [69/98]) recommended a research gap year, most commonly for those applicants with a strong research interest (71.8% [51/71]). Other reasons mentors recommended a dedicated research year during medical school included low USMLE Step scores (50.7% [36/71]), low grades (45.1% [32/71]), little research (46.5% [33/71]), and no home program (43.7% [31/71]).

Internship Choices—Our survey results indicated that nearly two-thirds (63.3% [62/98]) of mentors did not give applicants a recommendation on type of internship (PGY-1). If a recommendation was given, academic dermatologists more commonly recommended an internal medicine preliminary year (29.6% [29/98]) over a transitional year (7.1% [7/98]).

Communication of Interest Via a Letter of Intent—We asked mentors if they recommended applicants send a letter of intent and conversely if receiving a letter of intent impacted their rank list. Nearly half (48.5% [47/97]) of mentors indicated they did not recommend sending a letter of intent, with only 15.5% (15/97) of mentors regularly recommending this practice. Additionally, 75.8% of mentors indicated that a letter of intent never (42.1% [40/95]) or rarely (33.7% [32/95]) impacted their rank list.

Rotation Choices—We queried mentors if they recommended students complete away rotations, and if so, how many rotations did they recommend. We found that 85.9% (85/99) of mentors recommended students complete an away rotation; 63.1% (53/84) of them recommended performing 2 away rotations, and 14.3% (12/84) of respondents recommended students complete 3 away rotations. More than a quarter of mentors (27.1% [23/85]) indicated their home medical schools limited the number of away rotations a medical student could complete in any 1 specialty, and 42.4% (36/85) of respondents were unsure if such a limitation existed.

Letters of Recommendation—Our survey asked respondents to rank various factors on a 5-point scale (1=not important; 5=very important) when deciding who should write the students’ LORs. Mentors indicated that the most important factor for letter-writer selection was how well the letter writer knows the applicant, with 90.8% (89/98) of mentors rating the importance of this quality as a 4 or 5 (Figure). More than half of respondents rated the name recognition of the letter writer and program director letter as a 4 or 5 in importance (54.1% [53/98] and 58.2% [57/98], respectively). Type of letter (standardized vs nonstandardized), title of letter writer, letters from an away rotation, and chair letter scored lower, with fewer than half of mentors rating these as a 4 or 5 in importance.

Supplemental Application—When asked about the 2022 application cycle, respondents of our survey reported that the supplemental application was overall more important in deciding which applicants to interview vs which to rank highly. Prior experiences were important (ranked 4 or 5) for 58.8% (57/97) of respondents in choosing applicants to interview, and 49.4% (48/97) of respondents thought prior experiences were important for ranking. Similarly, 34.0% (33/97) of mentors indicated geographic preference was important (ranked 4 or 5) for interview compared with only 23.8% (23/97) for ranking. Finally, 57.7% (56/97) of our survey respondents denoted that program signals were important or very important in choosing which applicants to interview, while 32.0% (31/97) indicated that program signals were important in ranking applicants.

Comment

Residency Programs: Which Ones, and How Many?—The number of applications for dermatology residency programs has increased 33.9% from 2010 to 2019.2 The American Association of Medical Colleges Apply Smart data from 2013 to 2017 indicate that dermatology applicants arrive at a point of diminishing return between 37 and 62 applications, with variation within that range based on USMLE Step 1 score,3 and our data support this with nearly two-thirds of dermatology advisors recommending students apply within this range. Despite this data, dermatology residency applicants applied to more programs over the last decade (64.8 vs 77.0),2 likely to maximize their chance of matching.

Research Gap Years During Medical School—Prior research has shown that nearly half of faculty indicated that a research year during medical school can distinguish similar applicants, and close to 25% of applicants completed a research gap year.4,5 However, available data indicate that taking a research gap year has no effect on match rate or number of interview invites but does correlate with match rates at the highest ranked dermatology residency programs.6-8

Our data indicate that the most commonly recommended reason for a research gap year was an applicants’ strong interest in research. However, nearly half of dermatology mentors recommended research years during medical school for reasons other than an interest in research. As research gap years increase in popularity, future research is needed to confirm the consequence of this additional year and which applicants, if any, will benefit from such a year.

Preferences for Intern Year—Prior research suggests that dermatology residency program directors favor PGY-1 preliminary medicine internships because of the rigor of training.9,10 Our data continue to show a preference for internal medicine preliminary years over transitional years. However, given nearly two-thirds of dermatology mentors do not give applicants any recommendations on PGY-1 year, this preference may be fading.

Letters of Intent Not Recommended—Research in 2022 found that 78.8% of dermatology applicants sent a letter of intent communicating a plan to rank that program number 1, with nearly 13% sending such a letter to more than 1 program.11 With nearly half of mentors in our survey actively discouraging this process and more than 75% of mentors not utilizing this letter, the APD issued a brief statement on the 2022-2023 application cycle stating, “Post-interview communication of preference—including ‘letters of intent’ and thank you letters—should not be sent to programs. These types of communication are typically not used by residency programs in decision-making and lead to downstream pressures on applicants.”12

Away Rotations—Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, data demonstrated that nearly one-third of dermatology applicants (29%) matched at their home institution, and nearly one-fifth (18%) matched where they completed an away rotation.13 In-person away rotations were eliminated in 2020 and restricted to 1 away rotation in 2021. Restrictions regarding away rotations were removed in 2022. Our data indicate that dermatology mentors strongly supported an away rotation, with more than half of them recommending at least 2 away rotations.

Further research is needed to determine the effect numerous away rotations have on minimizing students’ exposure to other specialties outside their chosen field. Additionally, further studies are needed to determine the impact away rotations have on economically disadvantaged students, students without home programs, and students with families. In an effort to standardize the number of away rotations, the APD issued a statement for the 2023-2024 application cycle indicating that dermatology applicants should limit away rotations to 2 in-person electives. Students without a home dermatology program could consider completing up to 3 electives.14

Who Should Write LORs?—Research in 2014 demonstrated that LORs were very important in determining applicants to interview, with a strong preference for LORs from academic dermatologists and colleagues.15 Our data strongly indicated applicants should predominantly ask for letters from writers who know them well. The majority of mentors did not give value to the rank of the letter writer (eg, assistant professor, associate professor, professor), type of letter, chair letters, or letters from an away rotation. These data may help alleviate stress many students feel as they search for letter writers.

How is the Supplemental Application Used?—In 2022, the ERAS supplemental application was introduced, which allowed applicants to detail 5 meaningful experiences, describe impactful life challenges, and indicate preferences for geographic region. Dermatology residency applicants also were able to choose 3 residency programs to signal interest in that program. Our data found that the supplemental application was utilized predominantly to select applicants to interview, which is in line with the Association of American Medical Colleges’ and APD guidelines indicating that this tool is solely meant to assist with application review.16 Further research and data will hopefully inform approaches to best utilize the ERAS supplemental application data.

Limitations—Our data were limited by response rate and sample size, as only academic dermatologists belonging to the APD were queried. Additionally, we did not track personal information of the mentors, so more than 1 mentor may have responded from a single institution, making it possible that our data may not be broadly applicable to all institutions.

Conclusion

Although there is no algorithmic method of advising medical students who are interested in dermatology, our survey data help to describe the range of advice currently given to students, which can improve and guide future recommendations. Additionally, some of our data demonstrate a discrepancy between mentor advice and current medical student practice for the number of applications and use of a letter of intent. We hope our data will assist academic dermatology mentors in the provision of advice to mentees as well as inform organizations seeking to create standards and official recommendations regarding aspects of the application process.

Dermatology remains one of the most competitive specialties in medicine. In 2022, there were 851 applicants (613 doctor of medicine seniors, 85 doctor of osteopathic medicine seniors) for 492 postgraduate year (PGY) 2 positions.1 During the 2022 application season, the average matched dermatology candidate had 7.2 research experiences; 20.9 abstracts, presentations, or publications; 11 volunteer experiences; and a US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 2 Clinical Knowledge score of 257.1 With hopes of matching into such a competitive field, students often seek advice from academic dermatology mentors. Such advice may substantially differ based on each mentor and may or may not be evidence based.

We sought to analyze the range of advice given to medical students applying to dermatology residency programs via a survey to members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) with the intent to help applicants and mentors understand how letters of intent, letters of recommendation (LORs), and Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) supplemental applications are used by dermatology programs nationwide.

Methods

The study was reviewed by The Ohio State University institutional review board and was deemed exempt. A branching-logic survey with common questions from medical students while applying to dermatology residency programs (Table) was sent to all members of APD through the email listserve. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at The Ohio State University (Columbus, Ohio) to ensure data security.

The survey was distributed from August 28, 2022, to September 12, 2022. A total of 101 surveys were returned from 646 listserve members (15.6%). Given the branching-logic questions, differing numbers of responses were collected for each question. Descriptive statistics were utilized to analyze and report the results.

Results

Residency Program Number—Members of the APD were asked if they recommend students apply to a certain number of programs, and if so, how many programs. Of members who responded, 62.2% (61/98) either always (22.4% [22/98]) or sometimes (40.2% [39/97]) suggested students apply to a certain number of programs. When mentors made a recommendation, 54.1% (33/61) recommended applying to 59 or fewer programs, with only 9.8% (6/61) recommending students apply to 80 or more programs.

Gap Year—We queried mentors about their recommendations for a research gap year and asked which applicants should pursue this extra year. Our survey found that 74.5% of mentors (73/98) almost always (4.1% [4/98]) or sometimes (70.4% [69/98]) recommended a research gap year, most commonly for those applicants with a strong research interest (71.8% [51/71]). Other reasons mentors recommended a dedicated research year during medical school included low USMLE Step scores (50.7% [36/71]), low grades (45.1% [32/71]), little research (46.5% [33/71]), and no home program (43.7% [31/71]).

Internship Choices—Our survey results indicated that nearly two-thirds (63.3% [62/98]) of mentors did not give applicants a recommendation on type of internship (PGY-1). If a recommendation was given, academic dermatologists more commonly recommended an internal medicine preliminary year (29.6% [29/98]) over a transitional year (7.1% [7/98]).

Communication of Interest Via a Letter of Intent—We asked mentors if they recommended applicants send a letter of intent and conversely if receiving a letter of intent impacted their rank list. Nearly half (48.5% [47/97]) of mentors indicated they did not recommend sending a letter of intent, with only 15.5% (15/97) of mentors regularly recommending this practice. Additionally, 75.8% of mentors indicated that a letter of intent never (42.1% [40/95]) or rarely (33.7% [32/95]) impacted their rank list.

Rotation Choices—We queried mentors if they recommended students complete away rotations, and if so, how many rotations did they recommend. We found that 85.9% (85/99) of mentors recommended students complete an away rotation; 63.1% (53/84) of them recommended performing 2 away rotations, and 14.3% (12/84) of respondents recommended students complete 3 away rotations. More than a quarter of mentors (27.1% [23/85]) indicated their home medical schools limited the number of away rotations a medical student could complete in any 1 specialty, and 42.4% (36/85) of respondents were unsure if such a limitation existed.

Letters of Recommendation—Our survey asked respondents to rank various factors on a 5-point scale (1=not important; 5=very important) when deciding who should write the students’ LORs. Mentors indicated that the most important factor for letter-writer selection was how well the letter writer knows the applicant, with 90.8% (89/98) of mentors rating the importance of this quality as a 4 or 5 (Figure). More than half of respondents rated the name recognition of the letter writer and program director letter as a 4 or 5 in importance (54.1% [53/98] and 58.2% [57/98], respectively). Type of letter (standardized vs nonstandardized), title of letter writer, letters from an away rotation, and chair letter scored lower, with fewer than half of mentors rating these as a 4 or 5 in importance.

Supplemental Application—When asked about the 2022 application cycle, respondents of our survey reported that the supplemental application was overall more important in deciding which applicants to interview vs which to rank highly. Prior experiences were important (ranked 4 or 5) for 58.8% (57/97) of respondents in choosing applicants to interview, and 49.4% (48/97) of respondents thought prior experiences were important for ranking. Similarly, 34.0% (33/97) of mentors indicated geographic preference was important (ranked 4 or 5) for interview compared with only 23.8% (23/97) for ranking. Finally, 57.7% (56/97) of our survey respondents denoted that program signals were important or very important in choosing which applicants to interview, while 32.0% (31/97) indicated that program signals were important in ranking applicants.

Comment

Residency Programs: Which Ones, and How Many?—The number of applications for dermatology residency programs has increased 33.9% from 2010 to 2019.2 The American Association of Medical Colleges Apply Smart data from 2013 to 2017 indicate that dermatology applicants arrive at a point of diminishing return between 37 and 62 applications, with variation within that range based on USMLE Step 1 score,3 and our data support this with nearly two-thirds of dermatology advisors recommending students apply within this range. Despite this data, dermatology residency applicants applied to more programs over the last decade (64.8 vs 77.0),2 likely to maximize their chance of matching.

Research Gap Years During Medical School—Prior research has shown that nearly half of faculty indicated that a research year during medical school can distinguish similar applicants, and close to 25% of applicants completed a research gap year.4,5 However, available data indicate that taking a research gap year has no effect on match rate or number of interview invites but does correlate with match rates at the highest ranked dermatology residency programs.6-8

Our data indicate that the most commonly recommended reason for a research gap year was an applicants’ strong interest in research. However, nearly half of dermatology mentors recommended research years during medical school for reasons other than an interest in research. As research gap years increase in popularity, future research is needed to confirm the consequence of this additional year and which applicants, if any, will benefit from such a year.

Preferences for Intern Year—Prior research suggests that dermatology residency program directors favor PGY-1 preliminary medicine internships because of the rigor of training.9,10 Our data continue to show a preference for internal medicine preliminary years over transitional years. However, given nearly two-thirds of dermatology mentors do not give applicants any recommendations on PGY-1 year, this preference may be fading.

Letters of Intent Not Recommended—Research in 2022 found that 78.8% of dermatology applicants sent a letter of intent communicating a plan to rank that program number 1, with nearly 13% sending such a letter to more than 1 program.11 With nearly half of mentors in our survey actively discouraging this process and more than 75% of mentors not utilizing this letter, the APD issued a brief statement on the 2022-2023 application cycle stating, “Post-interview communication of preference—including ‘letters of intent’ and thank you letters—should not be sent to programs. These types of communication are typically not used by residency programs in decision-making and lead to downstream pressures on applicants.”12

Away Rotations—Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, data demonstrated that nearly one-third of dermatology applicants (29%) matched at their home institution, and nearly one-fifth (18%) matched where they completed an away rotation.13 In-person away rotations were eliminated in 2020 and restricted to 1 away rotation in 2021. Restrictions regarding away rotations were removed in 2022. Our data indicate that dermatology mentors strongly supported an away rotation, with more than half of them recommending at least 2 away rotations.

Further research is needed to determine the effect numerous away rotations have on minimizing students’ exposure to other specialties outside their chosen field. Additionally, further studies are needed to determine the impact away rotations have on economically disadvantaged students, students without home programs, and students with families. In an effort to standardize the number of away rotations, the APD issued a statement for the 2023-2024 application cycle indicating that dermatology applicants should limit away rotations to 2 in-person electives. Students without a home dermatology program could consider completing up to 3 electives.14

Who Should Write LORs?—Research in 2014 demonstrated that LORs were very important in determining applicants to interview, with a strong preference for LORs from academic dermatologists and colleagues.15 Our data strongly indicated applicants should predominantly ask for letters from writers who know them well. The majority of mentors did not give value to the rank of the letter writer (eg, assistant professor, associate professor, professor), type of letter, chair letters, or letters from an away rotation. These data may help alleviate stress many students feel as they search for letter writers.

How is the Supplemental Application Used?—In 2022, the ERAS supplemental application was introduced, which allowed applicants to detail 5 meaningful experiences, describe impactful life challenges, and indicate preferences for geographic region. Dermatology residency applicants also were able to choose 3 residency programs to signal interest in that program. Our data found that the supplemental application was utilized predominantly to select applicants to interview, which is in line with the Association of American Medical Colleges’ and APD guidelines indicating that this tool is solely meant to assist with application review.16 Further research and data will hopefully inform approaches to best utilize the ERAS supplemental application data.

Limitations—Our data were limited by response rate and sample size, as only academic dermatologists belonging to the APD were queried. Additionally, we did not track personal information of the mentors, so more than 1 mentor may have responded from a single institution, making it possible that our data may not be broadly applicable to all institutions.

Conclusion

Although there is no algorithmic method of advising medical students who are interested in dermatology, our survey data help to describe the range of advice currently given to students, which can improve and guide future recommendations. Additionally, some of our data demonstrate a discrepancy between mentor advice and current medical student practice for the number of applications and use of a letter of intent. We hope our data will assist academic dermatology mentors in the provision of advice to mentees as well as inform organizations seeking to create standards and official recommendations regarding aspects of the application process.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2022 Main Residency Match. May 2022. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/2022-Main-Match-Results-and-Data_Final.pdf

- Secrest AM, Coman GC, Swink JM, et al. Limiting residency applications to dermatology benefits nearly everyone. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:30-32.

- Apply smart for residency. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/apply-smart-residency

- Shamloul N, Grandhi R, Hossler E. Perceived importance of dermatology research fellowships. Presented at: Dermatology Teachers Exchange Group; October 3, 2020.

- Runge M, Jairath NK, Renati S, et al. Pursuit of a research year or dual degree by dermatology residency applicants: a cross-sectional study. Cutis. 2022;109:E12-E13.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role of race and ethnicity in the dermatology applicant match process. J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;113:666-670.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap years play in a successful dermatology match. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:226-230.

- Ramachandran V, Nguyen HY, Dao H Jr. Does it match? analyzing self-reported online dermatology match data to charting outcomes in the Match. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030/qt4604h1w4.

- Hopkins C, Jalali O, Guffey D, et al. A survey of dermatology residents and program directors assessing the transition to dermatology residency. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Center). 2021;34:59-62.

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, Rinderknecht FA, et al. Current perspectives of and potential reforms to the dermatology residency application process: a nationwide survey of program directors and applicants. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:595-601.

- Association of Professors of Dermatology. Residency Program Directors Section. Updated Information Regarding the 2022-2023 Application Cycle. Updated October 18, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2023. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20statement%20on%202022-2023%20application%20cycle_updated%20Oct.pdf

- Narang J, Morgan F, Eversman A, et al. Trends in geographic and home program preferences in the dermatology residency match: a retrospective cohort analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:645-647.

- Association of Professors of Dermatology Residency Program Directors Section. Recommendations Regarding Away Electives. Updated December 14, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2022. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20recommendations%20on%20away%20rotations%202023-2024.pdf

- Kaffenberger BH, Kaffenberger JA, Zirwas MJ. Academic dermatologists’ views on the value of residency letters of recommendation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:395-396.

- Supplemental ERAS Application: Guide for Residency Program. Association of American Medical Colleges; June 2022.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2022 Main Residency Match. May 2022. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/2022-Main-Match-Results-and-Data_Final.pdf

- Secrest AM, Coman GC, Swink JM, et al. Limiting residency applications to dermatology benefits nearly everyone. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:30-32.

- Apply smart for residency. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/apply-smart-residency

- Shamloul N, Grandhi R, Hossler E. Perceived importance of dermatology research fellowships. Presented at: Dermatology Teachers Exchange Group; October 3, 2020.

- Runge M, Jairath NK, Renati S, et al. Pursuit of a research year or dual degree by dermatology residency applicants: a cross-sectional study. Cutis. 2022;109:E12-E13.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role of race and ethnicity in the dermatology applicant match process. J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;113:666-670.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap years play in a successful dermatology match. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:226-230.

- Ramachandran V, Nguyen HY, Dao H Jr. Does it match? analyzing self-reported online dermatology match data to charting outcomes in the Match. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030/qt4604h1w4.

- Hopkins C, Jalali O, Guffey D, et al. A survey of dermatology residents and program directors assessing the transition to dermatology residency. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Center). 2021;34:59-62.

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, Rinderknecht FA, et al. Current perspectives of and potential reforms to the dermatology residency application process: a nationwide survey of program directors and applicants. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:595-601.

- Association of Professors of Dermatology. Residency Program Directors Section. Updated Information Regarding the 2022-2023 Application Cycle. Updated October 18, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2023. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20statement%20on%202022-2023%20application%20cycle_updated%20Oct.pdf

- Narang J, Morgan F, Eversman A, et al. Trends in geographic and home program preferences in the dermatology residency match: a retrospective cohort analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:645-647.

- Association of Professors of Dermatology Residency Program Directors Section. Recommendations Regarding Away Electives. Updated December 14, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2022. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20recommendations%20on%20away%20rotations%202023-2024.pdf

- Kaffenberger BH, Kaffenberger JA, Zirwas MJ. Academic dermatologists’ views on the value of residency letters of recommendation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:395-396.

- Supplemental ERAS Application: Guide for Residency Program. Association of American Medical Colleges; June 2022.

Practice Points

- Dermatology mentors recommend students apply to 60 or fewer programs, with only a small percentage of faculty routinely recommending students apply to more than 80 programs.

- Dermatology mentors strongly recommend that students should not send a letter of intent to programs, as it rarely is used in the ranking process.

- Dermatology mentors encourage students to ask for letters of recommendation from writers who know them the best, irrespective of the letter writer’s rank or title. The type of letter (standardized vs nonstandardized), chair letter, or letters from an away rotation do not hold as much importance.

The Evidence Behind Topical Hair Loss Remedies on TikTok

Hair loss is an exceedingly common chief concern in outpatient dermatology clinics. An estimated 50% of males and females will experience androgenetic alopecia.1 Approximately 2% of new dermatology outpatient visits in the United States and the United Kingdom are for alopecia areata, the second most common type of hair loss.2 As access to dermatology appointments remains an issue with some studies citing wait times ranging from 2 to 25 days for a dermatologic consultation, the ease of accessibility of medical information on social media continues to grow,3 which leaves many of our patients turning to social media as a first-line source of information. As dermatology resident physicians, it is essential to be aware of popular dermatologic therapies on social media so that we may provide evidence-based opinions to our patients.

Remedies for Hair Loss on Social Media

Many trends on hair loss therapies found on TikTok focus on natural remedies that are produced by ingredients accessible to patients at home and over the counter, which may increase the appeal due to ease of treatment.

Rosemary Oil—The top trends in hair loss remedies I have come across are rosemary oil and rosemary water. Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) has been known to possess antimicrobial and antioxidant properties but also has shown enhancement of microcapillary perfusion, which could explain its role in the prevention of hair loss and aiding hair growth in a similar mechanism to minoxidil.4,5 Unlike many other natural hair loss remedies, there are randomized controlled trials that assess the efficacy of rosemary oil for the treatment of hair loss. In a 2015 study of 100 patients with androgenetic alopecia, there was no statistically significant difference in mean hair count measured by microphotographic assessment after 6 months of treatment in 2 groups treated with either minoxidil solution 2% or rosemary oil, and both groups experienced a significant increase in hair count at 6 months (P<.05) compared with baseline and 3 months.6 Additionally, essential oils, including a mixture of thyme, rosemary, lavender, and cedarwood oils for alopecia were superior to placebo carrier oils in a posttreatment photographic assessment of their efficacy.7

Rice Water—The use of rice water and rice bran extract is a common hair care practice in Asia. Rice bran extract preparations have been shown in vivo to increase the number of anagen hair follicles as well as the number of anagen-related molecules in the dermal papillae.8,9 However, there are limited clinical data to support the use of rice water for hair growth.10

Onion Juice—Sharquie and Al-Obaidi11 conducted a study comparing crude onion juice to tap water in 38 patients with alopecia areata. They found that onion juice produced hair regrowth in significantly more patients than tap water (P<.0001).11 The mechanism of crude onion juice in hair growth is unknown; however, the induction of irritant or allergic contact dermatitis to components in crude onion juice may stimulate antigenic competition.12

Garlic Gel—Garlic gel, which is in the genus Allium, produces organosulfur compounds that provide antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory benefits.12 Additionally, in a double-blind randomized controlled trial, garlic powder was shown to increase cutaneous capillary perfusion.5 One study in 40 patients with alopecia areata demonstrated garlic gel 5% added to betamethasone valerate cream 0.1% was statistically superior to betamethasone alone in stimulating terminal hair growth (P=.001).13

Limitations and Downsides to Hair Loss Remedies on Social Media

Social media continues to be a prominent source of medical information for our patients, but most sources of hair content on social media are not board-certified dermatologists. A recent review of alopecia-related content found only 4% and 10% of posts were created by medical professionals on Instagram and TikTok, respectively, making misinformation extremely likely.14 Natural hair loss remedies contrived by TikTok have little clinical evidence to support their claims. Few data are available that compare these treatments to gold-standard hair loss therapies. Additionally, while some of these agents may be beneficial, the lack of standardized dosing may counteract these benefits. For example, videos on rosemary water advise the viewer to boil fresh rosemary sprigs in water and apply the solution to the hair daily with a spray bottle or apply cloves of garlic directly to the scalp, as opposed to a measured and standardized percentage. Some preparations may even induce harm to patients. Over-the-counter oils with added fragrances and natural compounds in onion and garlic may cause contact dermatitis. Finally, by using these products, patients may delay consultation with a board-certified dermatologist, leading to delays in applying evidence-based therapies targeted to specific hair loss subtypes while also incurring unnecessary expenses for these preparations.

Final Thoughts

Hair loss affects a notable portion of the population and is a common chief concern in dermatology clinics. Misinformation on social media continues to grow in prevalence. It is important to be aware of the hair loss remedies that are commonly touted to patients online and the evidence behind them.

- Ho CH, Sood T, Zito PM. Androgenetic alopecia. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- McMichael AJ, Pearce DJ, Wasserman D, et al. Alopecia in the United States: outpatient utilization and common prescribing patterns. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(2 suppl):S49-S51.

- Creadore A, Desai S, Li SJ, et al. Insurance acceptance, appointment wait time, and dermatologist access across practice types in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:181-188. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.5173

- Bassino E, Gasparri F, Munaron L. Protective role of nutritional plants containing flavonoids in hair follicle disruption: a review. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:523. doi:10.3390/ijms21020523

- Ezekwe N, King M, Hollinger JC. The use of natural ingredients in the treatment of alopecias with an emphasis on central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: a systematic review [published online August 1, 2020]. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:23-27.

- Panahi Y, Taghizadeh M, Marzony ET, et al. Rosemary oil vs minoxidil 2% for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia: a randomized comparative trial. Skinmed. 2015;13:15-21.

- Hay IC, Jamieson M, Ormerod AD. Randomized trial of aromatherapy. successful treatment for alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1349-1352. doi:10.1001/archderm.134.11.1349

- Choi JS, Jeon MH, Moon WS, et al. In vivo hair growth-promoting effect of rice bran extract prepared by supercritical carbon dioxide fluid. Biol Pharm Bull. 2014;37:44-53. doi:10.1248/bpb.b13-00528

- Kim YM, Kwon SJ, Jang HJ, et al. Rice bran mineral extract increases the expression of anagen-related molecules in human dermal papilla through wnt/catenin pathway. Food Nutr Res. 2017;61:1412792. doi:10.1080/16546628.2017.1412792

- Hashemi K, Pham C, Sung C, et al. A systematic review: application of rice products for hair growth. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:177-185. doi:10.36849/jdd.6345

- Sharquie KE, Al-Obaidi HK. Onion juice (Allium cepa L.), a new topical treatment for alopecia areata. J Dermatol. 2002;29:343-346. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2002.tb00277.x

- Hosking AM, Juhasz M, Atanaskova Mesinkovska N. Complementary and alternative treatments for alopecia: a comprehensive review. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:72-89. doi:10.1159/000492035

- Hajheydari Z, Jamshidi M, Akbari J, et al. Combination of topical garlic gel and betamethasone valerate cream in the treatment of localized alopecia areata: a double-blind randomized controlled study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:29-32. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.30648

- Laughter M, Anderson J, Kolla A, et al. An analysis of alopecia related content on Instagram and TikTok. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:1316-1321. doi:10.36849/JDD.6707

Hair loss is an exceedingly common chief concern in outpatient dermatology clinics. An estimated 50% of males and females will experience androgenetic alopecia.1 Approximately 2% of new dermatology outpatient visits in the United States and the United Kingdom are for alopecia areata, the second most common type of hair loss.2 As access to dermatology appointments remains an issue with some studies citing wait times ranging from 2 to 25 days for a dermatologic consultation, the ease of accessibility of medical information on social media continues to grow,3 which leaves many of our patients turning to social media as a first-line source of information. As dermatology resident physicians, it is essential to be aware of popular dermatologic therapies on social media so that we may provide evidence-based opinions to our patients.

Remedies for Hair Loss on Social Media

Many trends on hair loss therapies found on TikTok focus on natural remedies that are produced by ingredients accessible to patients at home and over the counter, which may increase the appeal due to ease of treatment.

Rosemary Oil—The top trends in hair loss remedies I have come across are rosemary oil and rosemary water. Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) has been known to possess antimicrobial and antioxidant properties but also has shown enhancement of microcapillary perfusion, which could explain its role in the prevention of hair loss and aiding hair growth in a similar mechanism to minoxidil.4,5 Unlike many other natural hair loss remedies, there are randomized controlled trials that assess the efficacy of rosemary oil for the treatment of hair loss. In a 2015 study of 100 patients with androgenetic alopecia, there was no statistically significant difference in mean hair count measured by microphotographic assessment after 6 months of treatment in 2 groups treated with either minoxidil solution 2% or rosemary oil, and both groups experienced a significant increase in hair count at 6 months (P<.05) compared with baseline and 3 months.6 Additionally, essential oils, including a mixture of thyme, rosemary, lavender, and cedarwood oils for alopecia were superior to placebo carrier oils in a posttreatment photographic assessment of their efficacy.7

Rice Water—The use of rice water and rice bran extract is a common hair care practice in Asia. Rice bran extract preparations have been shown in vivo to increase the number of anagen hair follicles as well as the number of anagen-related molecules in the dermal papillae.8,9 However, there are limited clinical data to support the use of rice water for hair growth.10

Onion Juice—Sharquie and Al-Obaidi11 conducted a study comparing crude onion juice to tap water in 38 patients with alopecia areata. They found that onion juice produced hair regrowth in significantly more patients than tap water (P<.0001).11 The mechanism of crude onion juice in hair growth is unknown; however, the induction of irritant or allergic contact dermatitis to components in crude onion juice may stimulate antigenic competition.12

Garlic Gel—Garlic gel, which is in the genus Allium, produces organosulfur compounds that provide antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory benefits.12 Additionally, in a double-blind randomized controlled trial, garlic powder was shown to increase cutaneous capillary perfusion.5 One study in 40 patients with alopecia areata demonstrated garlic gel 5% added to betamethasone valerate cream 0.1% was statistically superior to betamethasone alone in stimulating terminal hair growth (P=.001).13

Limitations and Downsides to Hair Loss Remedies on Social Media

Social media continues to be a prominent source of medical information for our patients, but most sources of hair content on social media are not board-certified dermatologists. A recent review of alopecia-related content found only 4% and 10% of posts were created by medical professionals on Instagram and TikTok, respectively, making misinformation extremely likely.14 Natural hair loss remedies contrived by TikTok have little clinical evidence to support their claims. Few data are available that compare these treatments to gold-standard hair loss therapies. Additionally, while some of these agents may be beneficial, the lack of standardized dosing may counteract these benefits. For example, videos on rosemary water advise the viewer to boil fresh rosemary sprigs in water and apply the solution to the hair daily with a spray bottle or apply cloves of garlic directly to the scalp, as opposed to a measured and standardized percentage. Some preparations may even induce harm to patients. Over-the-counter oils with added fragrances and natural compounds in onion and garlic may cause contact dermatitis. Finally, by using these products, patients may delay consultation with a board-certified dermatologist, leading to delays in applying evidence-based therapies targeted to specific hair loss subtypes while also incurring unnecessary expenses for these preparations.

Final Thoughts

Hair loss affects a notable portion of the population and is a common chief concern in dermatology clinics. Misinformation on social media continues to grow in prevalence. It is important to be aware of the hair loss remedies that are commonly touted to patients online and the evidence behind them.

Hair loss is an exceedingly common chief concern in outpatient dermatology clinics. An estimated 50% of males and females will experience androgenetic alopecia.1 Approximately 2% of new dermatology outpatient visits in the United States and the United Kingdom are for alopecia areata, the second most common type of hair loss.2 As access to dermatology appointments remains an issue with some studies citing wait times ranging from 2 to 25 days for a dermatologic consultation, the ease of accessibility of medical information on social media continues to grow,3 which leaves many of our patients turning to social media as a first-line source of information. As dermatology resident physicians, it is essential to be aware of popular dermatologic therapies on social media so that we may provide evidence-based opinions to our patients.

Remedies for Hair Loss on Social Media

Many trends on hair loss therapies found on TikTok focus on natural remedies that are produced by ingredients accessible to patients at home and over the counter, which may increase the appeal due to ease of treatment.

Rosemary Oil—The top trends in hair loss remedies I have come across are rosemary oil and rosemary water. Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) has been known to possess antimicrobial and antioxidant properties but also has shown enhancement of microcapillary perfusion, which could explain its role in the prevention of hair loss and aiding hair growth in a similar mechanism to minoxidil.4,5 Unlike many other natural hair loss remedies, there are randomized controlled trials that assess the efficacy of rosemary oil for the treatment of hair loss. In a 2015 study of 100 patients with androgenetic alopecia, there was no statistically significant difference in mean hair count measured by microphotographic assessment after 6 months of treatment in 2 groups treated with either minoxidil solution 2% or rosemary oil, and both groups experienced a significant increase in hair count at 6 months (P<.05) compared with baseline and 3 months.6 Additionally, essential oils, including a mixture of thyme, rosemary, lavender, and cedarwood oils for alopecia were superior to placebo carrier oils in a posttreatment photographic assessment of their efficacy.7

Rice Water—The use of rice water and rice bran extract is a common hair care practice in Asia. Rice bran extract preparations have been shown in vivo to increase the number of anagen hair follicles as well as the number of anagen-related molecules in the dermal papillae.8,9 However, there are limited clinical data to support the use of rice water for hair growth.10

Onion Juice—Sharquie and Al-Obaidi11 conducted a study comparing crude onion juice to tap water in 38 patients with alopecia areata. They found that onion juice produced hair regrowth in significantly more patients than tap water (P<.0001).11 The mechanism of crude onion juice in hair growth is unknown; however, the induction of irritant or allergic contact dermatitis to components in crude onion juice may stimulate antigenic competition.12

Garlic Gel—Garlic gel, which is in the genus Allium, produces organosulfur compounds that provide antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory benefits.12 Additionally, in a double-blind randomized controlled trial, garlic powder was shown to increase cutaneous capillary perfusion.5 One study in 40 patients with alopecia areata demonstrated garlic gel 5% added to betamethasone valerate cream 0.1% was statistically superior to betamethasone alone in stimulating terminal hair growth (P=.001).13

Limitations and Downsides to Hair Loss Remedies on Social Media

Social media continues to be a prominent source of medical information for our patients, but most sources of hair content on social media are not board-certified dermatologists. A recent review of alopecia-related content found only 4% and 10% of posts were created by medical professionals on Instagram and TikTok, respectively, making misinformation extremely likely.14 Natural hair loss remedies contrived by TikTok have little clinical evidence to support their claims. Few data are available that compare these treatments to gold-standard hair loss therapies. Additionally, while some of these agents may be beneficial, the lack of standardized dosing may counteract these benefits. For example, videos on rosemary water advise the viewer to boil fresh rosemary sprigs in water and apply the solution to the hair daily with a spray bottle or apply cloves of garlic directly to the scalp, as opposed to a measured and standardized percentage. Some preparations may even induce harm to patients. Over-the-counter oils with added fragrances and natural compounds in onion and garlic may cause contact dermatitis. Finally, by using these products, patients may delay consultation with a board-certified dermatologist, leading to delays in applying evidence-based therapies targeted to specific hair loss subtypes while also incurring unnecessary expenses for these preparations.

Final Thoughts

Hair loss affects a notable portion of the population and is a common chief concern in dermatology clinics. Misinformation on social media continues to grow in prevalence. It is important to be aware of the hair loss remedies that are commonly touted to patients online and the evidence behind them.

- Ho CH, Sood T, Zito PM. Androgenetic alopecia. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- McMichael AJ, Pearce DJ, Wasserman D, et al. Alopecia in the United States: outpatient utilization and common prescribing patterns. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(2 suppl):S49-S51.

- Creadore A, Desai S, Li SJ, et al. Insurance acceptance, appointment wait time, and dermatologist access across practice types in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:181-188. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.5173

- Bassino E, Gasparri F, Munaron L. Protective role of nutritional plants containing flavonoids in hair follicle disruption: a review. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:523. doi:10.3390/ijms21020523

- Ezekwe N, King M, Hollinger JC. The use of natural ingredients in the treatment of alopecias with an emphasis on central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: a systematic review [published online August 1, 2020]. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:23-27.

- Panahi Y, Taghizadeh M, Marzony ET, et al. Rosemary oil vs minoxidil 2% for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia: a randomized comparative trial. Skinmed. 2015;13:15-21.

- Hay IC, Jamieson M, Ormerod AD. Randomized trial of aromatherapy. successful treatment for alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1349-1352. doi:10.1001/archderm.134.11.1349

- Choi JS, Jeon MH, Moon WS, et al. In vivo hair growth-promoting effect of rice bran extract prepared by supercritical carbon dioxide fluid. Biol Pharm Bull. 2014;37:44-53. doi:10.1248/bpb.b13-00528

- Kim YM, Kwon SJ, Jang HJ, et al. Rice bran mineral extract increases the expression of anagen-related molecules in human dermal papilla through wnt/catenin pathway. Food Nutr Res. 2017;61:1412792. doi:10.1080/16546628.2017.1412792

- Hashemi K, Pham C, Sung C, et al. A systematic review: application of rice products for hair growth. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:177-185. doi:10.36849/jdd.6345

- Sharquie KE, Al-Obaidi HK. Onion juice (Allium cepa L.), a new topical treatment for alopecia areata. J Dermatol. 2002;29:343-346. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2002.tb00277.x

- Hosking AM, Juhasz M, Atanaskova Mesinkovska N. Complementary and alternative treatments for alopecia: a comprehensive review. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:72-89. doi:10.1159/000492035

- Hajheydari Z, Jamshidi M, Akbari J, et al. Combination of topical garlic gel and betamethasone valerate cream in the treatment of localized alopecia areata: a double-blind randomized controlled study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:29-32. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.30648

- Laughter M, Anderson J, Kolla A, et al. An analysis of alopecia related content on Instagram and TikTok. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:1316-1321. doi:10.36849/JDD.6707

- Ho CH, Sood T, Zito PM. Androgenetic alopecia. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- McMichael AJ, Pearce DJ, Wasserman D, et al. Alopecia in the United States: outpatient utilization and common prescribing patterns. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(2 suppl):S49-S51.

- Creadore A, Desai S, Li SJ, et al. Insurance acceptance, appointment wait time, and dermatologist access across practice types in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:181-188. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.5173

- Bassino E, Gasparri F, Munaron L. Protective role of nutritional plants containing flavonoids in hair follicle disruption: a review. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:523. doi:10.3390/ijms21020523

- Ezekwe N, King M, Hollinger JC. The use of natural ingredients in the treatment of alopecias with an emphasis on central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: a systematic review [published online August 1, 2020]. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:23-27.

- Panahi Y, Taghizadeh M, Marzony ET, et al. Rosemary oil vs minoxidil 2% for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia: a randomized comparative trial. Skinmed. 2015;13:15-21.

- Hay IC, Jamieson M, Ormerod AD. Randomized trial of aromatherapy. successful treatment for alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1349-1352. doi:10.1001/archderm.134.11.1349

- Choi JS, Jeon MH, Moon WS, et al. In vivo hair growth-promoting effect of rice bran extract prepared by supercritical carbon dioxide fluid. Biol Pharm Bull. 2014;37:44-53. doi:10.1248/bpb.b13-00528

- Kim YM, Kwon SJ, Jang HJ, et al. Rice bran mineral extract increases the expression of anagen-related molecules in human dermal papilla through wnt/catenin pathway. Food Nutr Res. 2017;61:1412792. doi:10.1080/16546628.2017.1412792

- Hashemi K, Pham C, Sung C, et al. A systematic review: application of rice products for hair growth. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:177-185. doi:10.36849/jdd.6345

- Sharquie KE, Al-Obaidi HK. Onion juice (Allium cepa L.), a new topical treatment for alopecia areata. J Dermatol. 2002;29:343-346. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2002.tb00277.x

- Hosking AM, Juhasz M, Atanaskova Mesinkovska N. Complementary and alternative treatments for alopecia: a comprehensive review. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:72-89. doi:10.1159/000492035

- Hajheydari Z, Jamshidi M, Akbari J, et al. Combination of topical garlic gel and betamethasone valerate cream in the treatment of localized alopecia areata: a double-blind randomized controlled study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:29-32. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.30648

- Laughter M, Anderson J, Kolla A, et al. An analysis of alopecia related content on Instagram and TikTok. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:1316-1321. doi:10.36849/JDD.6707

Resident Pearl

- With terabytes of information at their fingertips, patients often turn to social media for hair loss advice. Many recommended therapies lack evidence-based research, and some may even be harmful to patients or delay time to efficacious treatments.

Co-occurring psychogenic nonepileptic seizures and possible true seizures

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) are a physical manifestation of a psychological disturbance. They are characterized by episodes of altered subjective experience and movements that can resemble epilepsy, syncope, or other paroxysmal disorders, but are not caused by neuronal hypersynchronization or other epileptic semiology.

Patients with PNES may present to multiple clinicians and hospitals for assessment. Access to outside hospital records can be limited, which can lead to redundant testing and increased health care costs and burden. Additionally, repeat presentations can increase stigmatization of the patient and delay or prevent appropriate therapeutic management, which might exacerbate a patient’s underlying psychiatric condition and could be dangerous in a patient with a co-occurring true seizure disorder. Though obtaining and reviewing external medical records can be cumbersome, doing so may prevent unnecessary testing, guide medical treatment, and strengthen the patient-doctor therapeutic alliance.

In this article, I discuss our treatment team’s management of a patient with PNES who, based on our careful review of records from previous hospitalizations, may have had a co-occurring true seizure disorder.

Case report

Ms. M, age 31, has a medical history of anxiety, depression, first-degree atrioventricular block, type 2 diabetes, and PNES. She presented to the ED with witnessed seizure activity at home.

According to collateral information, earlier that day Ms. M said she felt like she was seizing and began mumbling, but returned to baseline within a few minutes. Later, she demonstrated intermittent upper and lower extremity shaking for more than 1 hour. At one point, Ms. M appeared to be not breathing. However, upon initiation of chest compressions, she began gasping for air and immediately returned to baseline.

In the ED, Ms. M demonstrated multiple seizure-like episodes every 5 minutes, each lasting 5 to 10 seconds. These episodes were described as thrashing of the bilateral limbs and head crossing midline with eyes closed. No urinary incontinence or tongue biting was observed. Following each episode, Ms. M was unresponsive to verbal or tactile stimuli but intermittently opened her eyes. Laboratory test results were notable for an elevated serum lactate and positive for cannabinoids on urine drug screen.

Ms. M expressed frustration when told that her seizures were psychogenic. She was adamant that she had a true seizure disorder, demanded testing, and threatened to leave against medical advice without it. She said her brother had epilepsy, and thus she knew how seizures present. The interview was complicated by Ms. M’s mistrust and Cluster B personality disorder traits, such as splitting staff into “good and bad.” Ultimately, she was able to be reassured and did not leave the hospital.

Continue to: The treatment team...

The treatment team reviewed external records from 2 hospitals, Hospital A and Hospital B. These records showed well-documented inpatient and outpatient Psychiatry and Neurology diagnoses of PNES and other conversion disorders. Her medications included

Ms. M’s first lifetime documented seizure occurred in May 2020, when she woke up with tongue biting, extremity shaking (laterality was unclear), and urinary incontinence followed by fatigue. She did not go to the hospital after this first episode. In June 2020, she presented and was admitted to Hospital A after similar seizure-like activity. While admitted and monitored on continuous EEG (cEEG), she had numerous events consistent with a nonepileptic etiology without a postictal state. A brain MRI was unremarkable, and Ms. M was diagnosed with PNES.

She presented to Hospital B in October 2020 reporting seizure-like activity. Hospital B reviewed Hospital A’s brain MRI and found right temporal lobe cortical dysplasia that was not noted in Hospital A’s MRI read. Ms. M again underwent cEEG while at Hospital B and had 2 recorded nonepileptic events. Interestingly, the cEEG demonstrated

Ms. M documented 3 seizure-like events between October and December 2020. She documented activity with and without full-body convulsions, some with laterality, some with loss of consciousness, and some preceded by an aura of impending doom. Ms. M was referred to psychotherapy and instructed to continue topiramate 100 mg every 12 hours for seizure prophylaxis.

Ms. M presented to Hospital B again in March 2022 reporting seizure-like activity. A brain MRI found cortical dysplasia in the right temporal lobe, consistent with the MRI at Hospital A in June 2020. cEEG was also repeated at Hospital B and was unremarkable. Oxcarbazepine 300 mg every 12 hours was added to Ms. M’s medications.

Ultimately, based on an external record review, our team (at Hospital C) concluded Ms. M had a possible true seizure co-occurrence with PNES. To avoid redundant testing, we did not repeat imaging or cEEG. Instead, we increased the patient’s oxcarbazepine to 450 mg every 12 hours, for both its effectiveness in temporal seizures and its mood-stabilizing properties. Moreover, in collecting our own data to draw a conclusion by a thorough record review, we gained Ms. M’s trust and strengthened the therapeutic alliance. She was agreeable to forgo more testing and continue outpatient follow-up with our hospital’s Neurology team.

Take-home points

Although PNES and true seizure disorder may not frequently co-occur, this case highlights the importance of clinician due diligence when evaluating a potential psychogenic illness, both for patient safety and clinician liability. By trusting our patients and drawing our own data-based conclusions, we can cultivate a safer and more satisfactory patient-clinician experience in the context of psychosomatic disorders.

1. Bajestan SN, LaFrance WC Jr. Clinical approaches to psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2016;14(4):422-431. doi:10.1176/appi.focus.20160020

2. Dickson JM, Dudhill H, Shewan J, et al. Cross-sectional study of the hospital management of adult patients with a suspected seizure (EPIC2). BMJ Open. 2017;7(7):e015696. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015696

3. Kutlubaev MA, Xu Y, Hackett ML, et al. Dual diagnosis of epilepsy and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: systematic review and meta-analysis of frequency, correlates, and outcomes. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;89:70-78. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.10.010

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) are a physical manifestation of a psychological disturbance. They are characterized by episodes of altered subjective experience and movements that can resemble epilepsy, syncope, or other paroxysmal disorders, but are not caused by neuronal hypersynchronization or other epileptic semiology.