User login

An Algorithm for Managing Spitting Sutures

Practice Gap

It is well established that surgical complications and a poor scar outcome can have a remarkable impact on patient satisfaction.1 A common complication following dermatologic surgery is suture spitting, in which a buried suture is extruded through the skin surface. When repairing a cutaneous defect following dermatologic surgery, absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures are placed under the skin surface to approximate wound edges, eliminate dead space, and reduce tension on the edges of the wound, improving the cosmetic outcomes.

Absorbable sutures constitute most buried sutures in cutaneous surgery and can be made of natural or synthetic fibers.2 Absorbable sutures made from synthetic fibers are degraded by hydrolysis, in which water breaks down polymer chains of the suture filament. Natural absorbable sutures are composed of mammalian collagen; they are broken down by the enzymatic process of proteolysis.

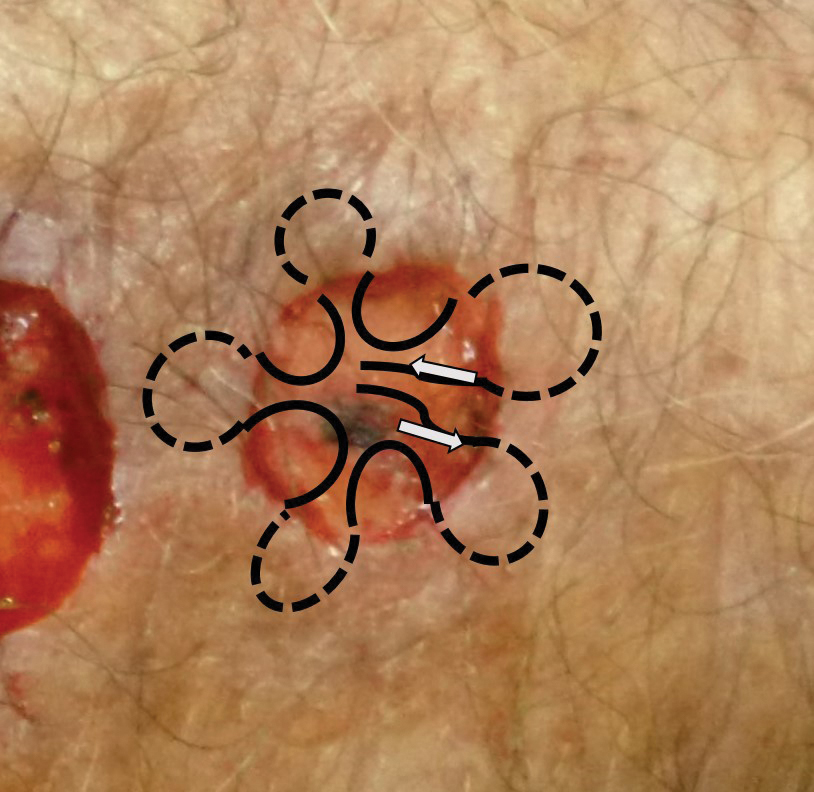

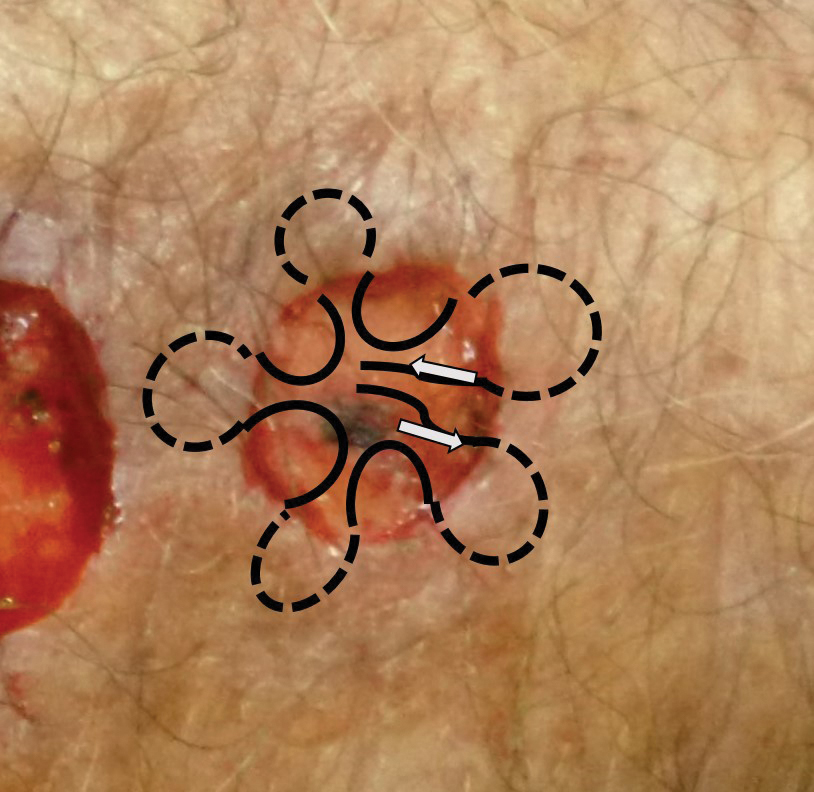

Tensile strength is lost long before a suture is fully absorbed. Although synthetic fibers have, in general, higher tensile strength and generate less tissue inflammation, they take much longer to absorb.2 During absorption, in some cases, a buried suture is pushed to the surface and extrudes along the wound edge or scar, which is known as spitting3 (Figure 1).

Suture spitting typically occurs in the 2-week to 3-month postoperative period. However, with the use of long-lasting absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures, spitting can occur several months or years postoperatively. Spitting sutures often are associated with surrounding erythema, edema, discharge, and a foreign-body sensation4—symptoms that can be highly distressing to the patient and can lead to postoperative infection or stitch abscess.3

Herein, we review techniques that can decrease the risk for suture spitting, and we present a stepwise approach to managing this common problem.

The Technique

Choice of suture material for buried sutures can influence the risk of spitting.

Factors Impacting Increased Spitting

The 3 most common absorbable sutures in dermatologic surgery include poliglecaprone 25, polyglactin 910, and polydioxanone; of them, polyglactin 910 has been found to have a higher rate of spitting than poliglecaprone 25 and polydioxanone.2 However, because complete absorption of polydioxanone can take as long as 8 months, this suture might “spit” much later than polyglactin 910 or poliglecaprone 25, which typically are fully hydrolyzed by 3 and 4 months, respectively.2 Placing sutures superficially in the dermis has been found to increase the rate of spitting.5 Throwing more knots per closure also has been found to increase the rate of spitting.5

How to Decrease Spitting

Careful choice of suture material and proper depth of suture placement might decrease the risk for spitting in dermatologic surgery. Furthermore, if polyglactin 910 or a long-lasting suture is to be used, sutures should be placed deeply.

What to Do If Sutures Spit

When a suture has begun to spit, the extruding foreign material needs to be removed and the surgical site assessed for infection or abscess. Exposed suture material typically can be removed with forceps without local anesthesia. In some cases, fine-tipped Bishop-Harmon tissue forceps or jewelers forceps might be required.

If the suture cannot be removed completely, it should be trimmed as short as possible. This can be accomplished by pulling on the exposed end of the suture, tenting the skin, and trimming it as close as possible to the surface. Once the foreign material is removed, assessment for signs of infection is paramount.

How to Manage Infection—Postoperative infection associated with a spitting suture can take the form of a periwound cellulitis or stitch abscess.3 A stitch abscess can reflect a sterile inflammatory response to the buried suture or a true infection4; the former is more common.3 In the event of an infected stitch abscess, provide warm compresses, obtain specimens for culture, and prescribe antibiotics after the spitting suture has been removed. Incision and drainage also might be required if notable fluctuance is present.

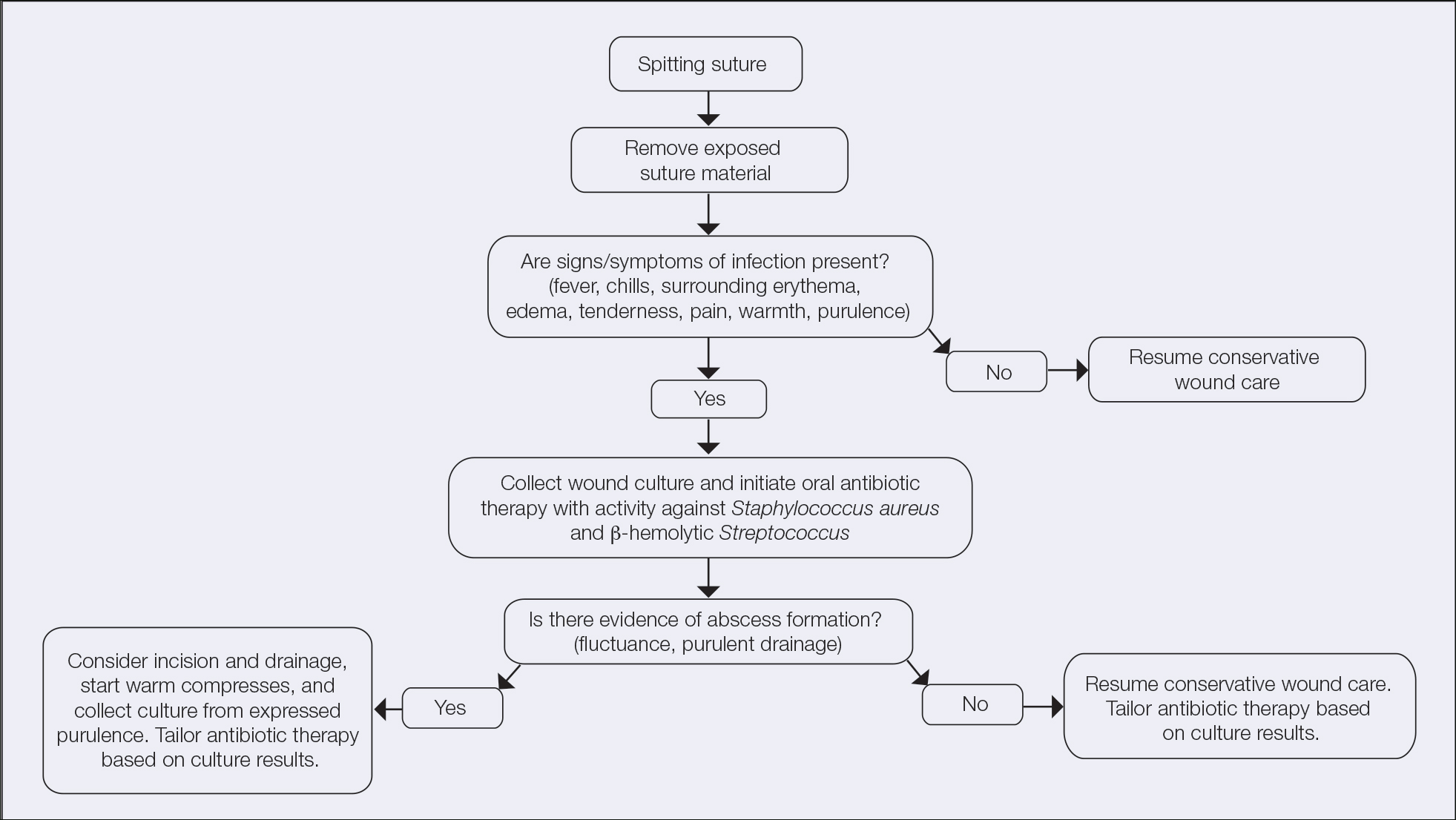

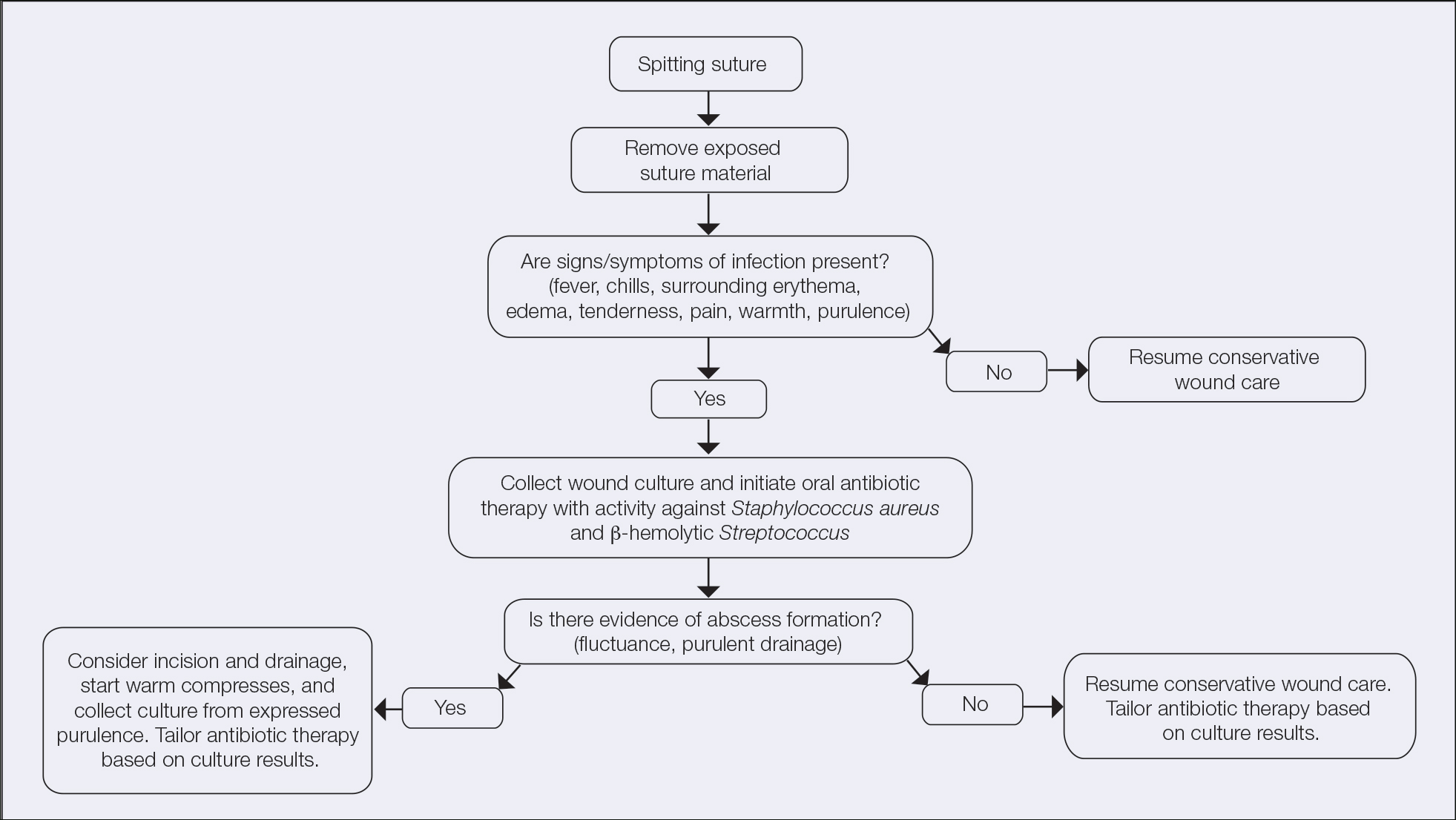

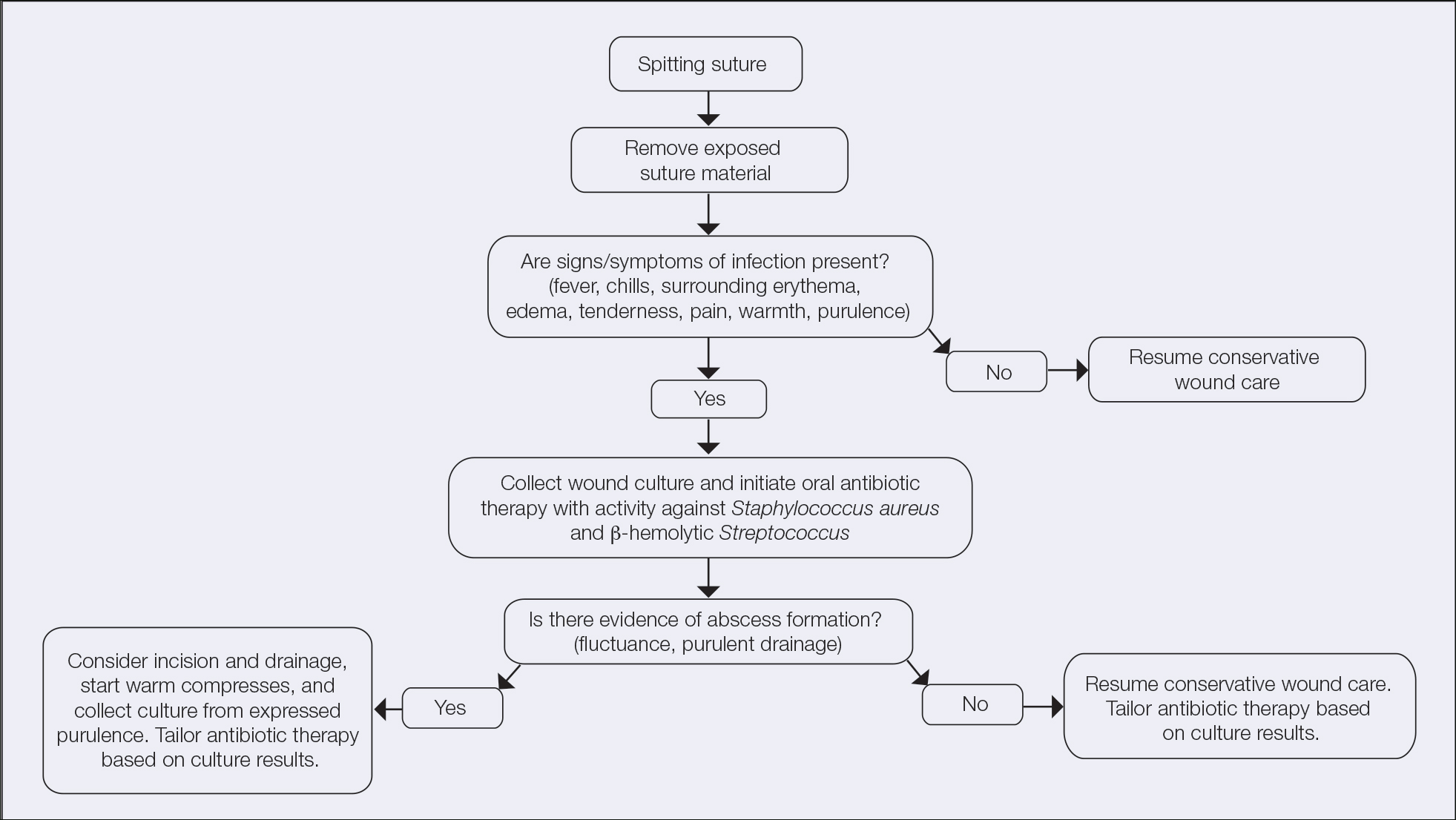

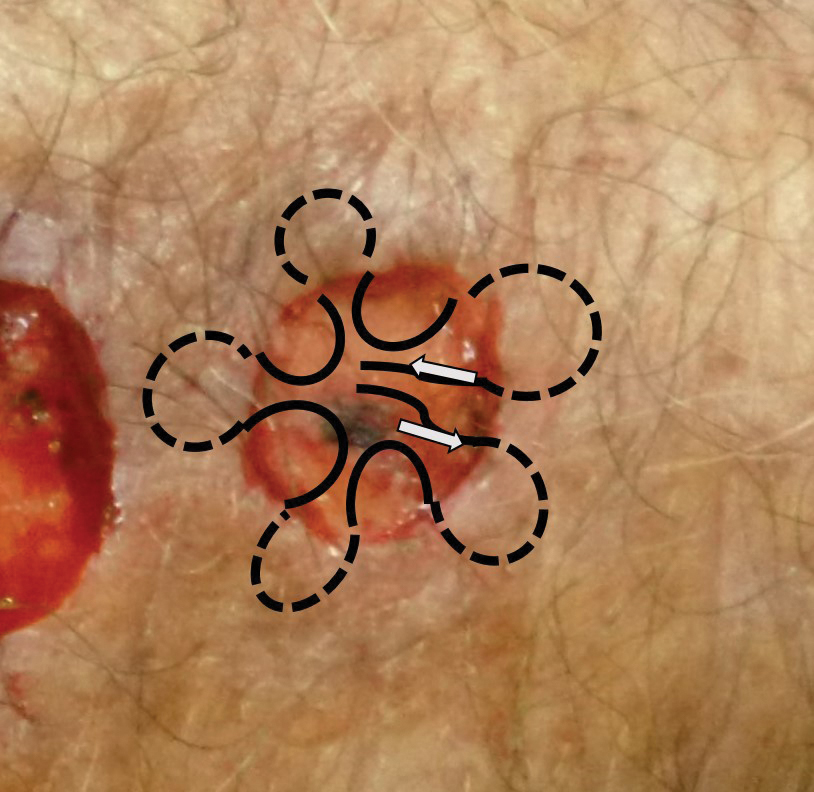

It is crucial for dermatologic surgeons to identify and manage these complications. Figure 2 illustrates an algorithmic approach to managing spitting sutures.

Practical Implications

Spitting sutures are a common occurrence following dermatologic surgery that can lead to remarkable patient distress. Fortunately, in the absence of superimposed infection, spitting sutures have not been shown to worsen outcomes of healing and scarring.5 Nevertheless, it is important to identify and appropriately treat this common complication. The simple algorithm we provide (Figure 2) aids in cutaneous surgery by providing a straightforward approach to managing spitting sutures and their complications.

- Balaraman B, Geddes ER, Friedman PM. Best reconstructive techniques: improving the final scar. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 10):S265-S275. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000496

- Yag-Howard C. Sutures, needles, and tissue adhesives: a review for dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40(suppl 9):S3-S15. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452738.23278.2d

- Gloster HM. Complications in Cutaneous Surgery. Springer; 2011.

- Slutsky JB, Fosko ST. Complications in Mohs surgery. In: Berlin A, ed. Mohs and Cutaneous Surgery: Maximizing Aesthetic Outcomes. CRC Press; 2015:55-89.

- Kim B, Sgarioto M, Hewitt D, et al. Scar outcomes in dermatological surgery. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:48-51. doi:10.1111/ajd.12570

Practice Gap

It is well established that surgical complications and a poor scar outcome can have a remarkable impact on patient satisfaction.1 A common complication following dermatologic surgery is suture spitting, in which a buried suture is extruded through the skin surface. When repairing a cutaneous defect following dermatologic surgery, absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures are placed under the skin surface to approximate wound edges, eliminate dead space, and reduce tension on the edges of the wound, improving the cosmetic outcomes.

Absorbable sutures constitute most buried sutures in cutaneous surgery and can be made of natural or synthetic fibers.2 Absorbable sutures made from synthetic fibers are degraded by hydrolysis, in which water breaks down polymer chains of the suture filament. Natural absorbable sutures are composed of mammalian collagen; they are broken down by the enzymatic process of proteolysis.

Tensile strength is lost long before a suture is fully absorbed. Although synthetic fibers have, in general, higher tensile strength and generate less tissue inflammation, they take much longer to absorb.2 During absorption, in some cases, a buried suture is pushed to the surface and extrudes along the wound edge or scar, which is known as spitting3 (Figure 1).

Suture spitting typically occurs in the 2-week to 3-month postoperative period. However, with the use of long-lasting absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures, spitting can occur several months or years postoperatively. Spitting sutures often are associated with surrounding erythema, edema, discharge, and a foreign-body sensation4—symptoms that can be highly distressing to the patient and can lead to postoperative infection or stitch abscess.3

Herein, we review techniques that can decrease the risk for suture spitting, and we present a stepwise approach to managing this common problem.

The Technique

Choice of suture material for buried sutures can influence the risk of spitting.

Factors Impacting Increased Spitting

The 3 most common absorbable sutures in dermatologic surgery include poliglecaprone 25, polyglactin 910, and polydioxanone; of them, polyglactin 910 has been found to have a higher rate of spitting than poliglecaprone 25 and polydioxanone.2 However, because complete absorption of polydioxanone can take as long as 8 months, this suture might “spit” much later than polyglactin 910 or poliglecaprone 25, which typically are fully hydrolyzed by 3 and 4 months, respectively.2 Placing sutures superficially in the dermis has been found to increase the rate of spitting.5 Throwing more knots per closure also has been found to increase the rate of spitting.5

How to Decrease Spitting

Careful choice of suture material and proper depth of suture placement might decrease the risk for spitting in dermatologic surgery. Furthermore, if polyglactin 910 or a long-lasting suture is to be used, sutures should be placed deeply.

What to Do If Sutures Spit

When a suture has begun to spit, the extruding foreign material needs to be removed and the surgical site assessed for infection or abscess. Exposed suture material typically can be removed with forceps without local anesthesia. In some cases, fine-tipped Bishop-Harmon tissue forceps or jewelers forceps might be required.

If the suture cannot be removed completely, it should be trimmed as short as possible. This can be accomplished by pulling on the exposed end of the suture, tenting the skin, and trimming it as close as possible to the surface. Once the foreign material is removed, assessment for signs of infection is paramount.

How to Manage Infection—Postoperative infection associated with a spitting suture can take the form of a periwound cellulitis or stitch abscess.3 A stitch abscess can reflect a sterile inflammatory response to the buried suture or a true infection4; the former is more common.3 In the event of an infected stitch abscess, provide warm compresses, obtain specimens for culture, and prescribe antibiotics after the spitting suture has been removed. Incision and drainage also might be required if notable fluctuance is present.

It is crucial for dermatologic surgeons to identify and manage these complications. Figure 2 illustrates an algorithmic approach to managing spitting sutures.

Practical Implications

Spitting sutures are a common occurrence following dermatologic surgery that can lead to remarkable patient distress. Fortunately, in the absence of superimposed infection, spitting sutures have not been shown to worsen outcomes of healing and scarring.5 Nevertheless, it is important to identify and appropriately treat this common complication. The simple algorithm we provide (Figure 2) aids in cutaneous surgery by providing a straightforward approach to managing spitting sutures and their complications.

Practice Gap

It is well established that surgical complications and a poor scar outcome can have a remarkable impact on patient satisfaction.1 A common complication following dermatologic surgery is suture spitting, in which a buried suture is extruded through the skin surface. When repairing a cutaneous defect following dermatologic surgery, absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures are placed under the skin surface to approximate wound edges, eliminate dead space, and reduce tension on the edges of the wound, improving the cosmetic outcomes.

Absorbable sutures constitute most buried sutures in cutaneous surgery and can be made of natural or synthetic fibers.2 Absorbable sutures made from synthetic fibers are degraded by hydrolysis, in which water breaks down polymer chains of the suture filament. Natural absorbable sutures are composed of mammalian collagen; they are broken down by the enzymatic process of proteolysis.

Tensile strength is lost long before a suture is fully absorbed. Although synthetic fibers have, in general, higher tensile strength and generate less tissue inflammation, they take much longer to absorb.2 During absorption, in some cases, a buried suture is pushed to the surface and extrudes along the wound edge or scar, which is known as spitting3 (Figure 1).

Suture spitting typically occurs in the 2-week to 3-month postoperative period. However, with the use of long-lasting absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures, spitting can occur several months or years postoperatively. Spitting sutures often are associated with surrounding erythema, edema, discharge, and a foreign-body sensation4—symptoms that can be highly distressing to the patient and can lead to postoperative infection or stitch abscess.3

Herein, we review techniques that can decrease the risk for suture spitting, and we present a stepwise approach to managing this common problem.

The Technique

Choice of suture material for buried sutures can influence the risk of spitting.

Factors Impacting Increased Spitting

The 3 most common absorbable sutures in dermatologic surgery include poliglecaprone 25, polyglactin 910, and polydioxanone; of them, polyglactin 910 has been found to have a higher rate of spitting than poliglecaprone 25 and polydioxanone.2 However, because complete absorption of polydioxanone can take as long as 8 months, this suture might “spit” much later than polyglactin 910 or poliglecaprone 25, which typically are fully hydrolyzed by 3 and 4 months, respectively.2 Placing sutures superficially in the dermis has been found to increase the rate of spitting.5 Throwing more knots per closure also has been found to increase the rate of spitting.5

How to Decrease Spitting

Careful choice of suture material and proper depth of suture placement might decrease the risk for spitting in dermatologic surgery. Furthermore, if polyglactin 910 or a long-lasting suture is to be used, sutures should be placed deeply.

What to Do If Sutures Spit

When a suture has begun to spit, the extruding foreign material needs to be removed and the surgical site assessed for infection or abscess. Exposed suture material typically can be removed with forceps without local anesthesia. In some cases, fine-tipped Bishop-Harmon tissue forceps or jewelers forceps might be required.

If the suture cannot be removed completely, it should be trimmed as short as possible. This can be accomplished by pulling on the exposed end of the suture, tenting the skin, and trimming it as close as possible to the surface. Once the foreign material is removed, assessment for signs of infection is paramount.

How to Manage Infection—Postoperative infection associated with a spitting suture can take the form of a periwound cellulitis or stitch abscess.3 A stitch abscess can reflect a sterile inflammatory response to the buried suture or a true infection4; the former is more common.3 In the event of an infected stitch abscess, provide warm compresses, obtain specimens for culture, and prescribe antibiotics after the spitting suture has been removed. Incision and drainage also might be required if notable fluctuance is present.

It is crucial for dermatologic surgeons to identify and manage these complications. Figure 2 illustrates an algorithmic approach to managing spitting sutures.

Practical Implications

Spitting sutures are a common occurrence following dermatologic surgery that can lead to remarkable patient distress. Fortunately, in the absence of superimposed infection, spitting sutures have not been shown to worsen outcomes of healing and scarring.5 Nevertheless, it is important to identify and appropriately treat this common complication. The simple algorithm we provide (Figure 2) aids in cutaneous surgery by providing a straightforward approach to managing spitting sutures and their complications.

- Balaraman B, Geddes ER, Friedman PM. Best reconstructive techniques: improving the final scar. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 10):S265-S275. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000496

- Yag-Howard C. Sutures, needles, and tissue adhesives: a review for dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40(suppl 9):S3-S15. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452738.23278.2d

- Gloster HM. Complications in Cutaneous Surgery. Springer; 2011.

- Slutsky JB, Fosko ST. Complications in Mohs surgery. In: Berlin A, ed. Mohs and Cutaneous Surgery: Maximizing Aesthetic Outcomes. CRC Press; 2015:55-89.

- Kim B, Sgarioto M, Hewitt D, et al. Scar outcomes in dermatological surgery. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:48-51. doi:10.1111/ajd.12570

- Balaraman B, Geddes ER, Friedman PM. Best reconstructive techniques: improving the final scar. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 10):S265-S275. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000496

- Yag-Howard C. Sutures, needles, and tissue adhesives: a review for dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40(suppl 9):S3-S15. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452738.23278.2d

- Gloster HM. Complications in Cutaneous Surgery. Springer; 2011.

- Slutsky JB, Fosko ST. Complications in Mohs surgery. In: Berlin A, ed. Mohs and Cutaneous Surgery: Maximizing Aesthetic Outcomes. CRC Press; 2015:55-89.

- Kim B, Sgarioto M, Hewitt D, et al. Scar outcomes in dermatological surgery. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:48-51. doi:10.1111/ajd.12570

Wound Healing on the Dorsal Hands: An Intrapatient Comparison of Primary Closure, Purse-String Closure, and Secondary Intention

Practice Gap

Many cutaneous surgery wounds can be closed primarily; however, in certain cases, other repair options might be appropriate and should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis with input from the patient. Defects on the dorsal aspect of the hands—where nonmelanoma skin cancer is common and reserve tissue is limited—often heal by secondary intention with good cosmetic and functional results. Patients often express a desire to reduce the time spent in the surgical suite and restrictions on postoperative activity, making secondary intention healing more appealing. An additional advantage is obviation of the need to remove additional tissue in the form of Burow triangles, which would lead to a longer wound. The major disadvantage of secondary intention healing is longer time to wound maturity; we often minimize this disadvantage with purse-string closure to decrease the size of the wound defect, which can be done quickly and without removing additional tissue.

The Technique

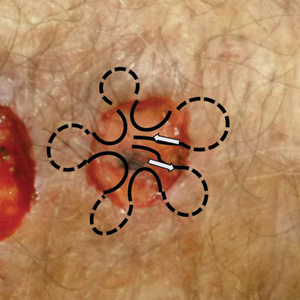

An elderly man had 3 nonmelanoma skin cancers—all on the dorsal aspect of the left hand—that were treated on the same day, leaving 3 similar wound defects after Mohs micrographic surgery. The wound defects (distal to proximal) measured 12 mm, 12 mm, and 10 mm in diameter (Figure 1) and were repaired by primary closure, secondary intention, and purse-string circumferential closure, respectively. Purse-string closure1 was performed with a 4-0 polyglactin 901 suture and left to heal without external sutures (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows the 3 types of repairs immediately following closure. All wounds healed with excellent and essentially equivalent cosmetic results, with excellent patient satisfaction at 6-month follow-up (Figure 4).

Practical Implications

Our case illustrates different modalities of wound repair during precisely the same time frame and essentially on the same location. Skin of the dorsal hand often is tight; depending on the size of the defect, large primary closure can be tedious to perform, can lead to increased wound tension and risk of dehiscence, and can be uncomfortable for the patient during healing. However, primary closure typically will lead to faster healing.

Secondary intention healing and purse-string closure require less surgery and therefore cost less; these modalities yield similar cosmesis and satisfaction. In the appropriate context, secondary intention has been highlighted as a suitable alternative to primary closure2-4; in our experience (and that of others5), patient satisfaction is not diminished with healing by secondary intention. Purse-string closure also can minimize wound size and healing time.

For small shallow wounds on the dorsal hand, dermatologic surgeons should have confidence that secondary intention healing, with or without wound reduction using purse-string repair, likely will lead to acceptable cosmetic and functional results. Of course, repair should be tailored to the circumstances and wishes of the individual patient.

- Peled IJ, Zagher U, Wexler MR. Purse-string suture for reduction and closure of skin defects. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;14:465-469. doi:10.1097/00000637-198505000-00012

- Zitelli JA. Secondary intention healing: an alternative to surgical repair. Clin Dermatol. 1984;2:92-106. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(84)90031-2

- Fazio MJ, Zitelli JA. Principles of reconstruction following excision of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:601-616. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(95)00099-2

- Bosley R, Leithauser L, Turner M, et al. The efficacy of second-intention healing in the management of defects on the dorsal surface of the hands and fingers after Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:647-653. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02258.x

- Stebbins WG, Gusev J, Higgins HW 2nd, et al. Evaluation of patient satisfaction with second intention healing versus primary surgical closure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:865-867.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.019

Practice Gap

Many cutaneous surgery wounds can be closed primarily; however, in certain cases, other repair options might be appropriate and should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis with input from the patient. Defects on the dorsal aspect of the hands—where nonmelanoma skin cancer is common and reserve tissue is limited—often heal by secondary intention with good cosmetic and functional results. Patients often express a desire to reduce the time spent in the surgical suite and restrictions on postoperative activity, making secondary intention healing more appealing. An additional advantage is obviation of the need to remove additional tissue in the form of Burow triangles, which would lead to a longer wound. The major disadvantage of secondary intention healing is longer time to wound maturity; we often minimize this disadvantage with purse-string closure to decrease the size of the wound defect, which can be done quickly and without removing additional tissue.

The Technique

An elderly man had 3 nonmelanoma skin cancers—all on the dorsal aspect of the left hand—that were treated on the same day, leaving 3 similar wound defects after Mohs micrographic surgery. The wound defects (distal to proximal) measured 12 mm, 12 mm, and 10 mm in diameter (Figure 1) and were repaired by primary closure, secondary intention, and purse-string circumferential closure, respectively. Purse-string closure1 was performed with a 4-0 polyglactin 901 suture and left to heal without external sutures (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows the 3 types of repairs immediately following closure. All wounds healed with excellent and essentially equivalent cosmetic results, with excellent patient satisfaction at 6-month follow-up (Figure 4).

Practical Implications

Our case illustrates different modalities of wound repair during precisely the same time frame and essentially on the same location. Skin of the dorsal hand often is tight; depending on the size of the defect, large primary closure can be tedious to perform, can lead to increased wound tension and risk of dehiscence, and can be uncomfortable for the patient during healing. However, primary closure typically will lead to faster healing.

Secondary intention healing and purse-string closure require less surgery and therefore cost less; these modalities yield similar cosmesis and satisfaction. In the appropriate context, secondary intention has been highlighted as a suitable alternative to primary closure2-4; in our experience (and that of others5), patient satisfaction is not diminished with healing by secondary intention. Purse-string closure also can minimize wound size and healing time.

For small shallow wounds on the dorsal hand, dermatologic surgeons should have confidence that secondary intention healing, with or without wound reduction using purse-string repair, likely will lead to acceptable cosmetic and functional results. Of course, repair should be tailored to the circumstances and wishes of the individual patient.

Practice Gap

Many cutaneous surgery wounds can be closed primarily; however, in certain cases, other repair options might be appropriate and should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis with input from the patient. Defects on the dorsal aspect of the hands—where nonmelanoma skin cancer is common and reserve tissue is limited—often heal by secondary intention with good cosmetic and functional results. Patients often express a desire to reduce the time spent in the surgical suite and restrictions on postoperative activity, making secondary intention healing more appealing. An additional advantage is obviation of the need to remove additional tissue in the form of Burow triangles, which would lead to a longer wound. The major disadvantage of secondary intention healing is longer time to wound maturity; we often minimize this disadvantage with purse-string closure to decrease the size of the wound defect, which can be done quickly and without removing additional tissue.

The Technique

An elderly man had 3 nonmelanoma skin cancers—all on the dorsal aspect of the left hand—that were treated on the same day, leaving 3 similar wound defects after Mohs micrographic surgery. The wound defects (distal to proximal) measured 12 mm, 12 mm, and 10 mm in diameter (Figure 1) and were repaired by primary closure, secondary intention, and purse-string circumferential closure, respectively. Purse-string closure1 was performed with a 4-0 polyglactin 901 suture and left to heal without external sutures (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows the 3 types of repairs immediately following closure. All wounds healed with excellent and essentially equivalent cosmetic results, with excellent patient satisfaction at 6-month follow-up (Figure 4).

Practical Implications

Our case illustrates different modalities of wound repair during precisely the same time frame and essentially on the same location. Skin of the dorsal hand often is tight; depending on the size of the defect, large primary closure can be tedious to perform, can lead to increased wound tension and risk of dehiscence, and can be uncomfortable for the patient during healing. However, primary closure typically will lead to faster healing.

Secondary intention healing and purse-string closure require less surgery and therefore cost less; these modalities yield similar cosmesis and satisfaction. In the appropriate context, secondary intention has been highlighted as a suitable alternative to primary closure2-4; in our experience (and that of others5), patient satisfaction is not diminished with healing by secondary intention. Purse-string closure also can minimize wound size and healing time.

For small shallow wounds on the dorsal hand, dermatologic surgeons should have confidence that secondary intention healing, with or without wound reduction using purse-string repair, likely will lead to acceptable cosmetic and functional results. Of course, repair should be tailored to the circumstances and wishes of the individual patient.

- Peled IJ, Zagher U, Wexler MR. Purse-string suture for reduction and closure of skin defects. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;14:465-469. doi:10.1097/00000637-198505000-00012

- Zitelli JA. Secondary intention healing: an alternative to surgical repair. Clin Dermatol. 1984;2:92-106. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(84)90031-2

- Fazio MJ, Zitelli JA. Principles of reconstruction following excision of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:601-616. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(95)00099-2

- Bosley R, Leithauser L, Turner M, et al. The efficacy of second-intention healing in the management of defects on the dorsal surface of the hands and fingers after Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:647-653. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02258.x

- Stebbins WG, Gusev J, Higgins HW 2nd, et al. Evaluation of patient satisfaction with second intention healing versus primary surgical closure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:865-867.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.019

- Peled IJ, Zagher U, Wexler MR. Purse-string suture for reduction and closure of skin defects. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;14:465-469. doi:10.1097/00000637-198505000-00012

- Zitelli JA. Secondary intention healing: an alternative to surgical repair. Clin Dermatol. 1984;2:92-106. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(84)90031-2

- Fazio MJ, Zitelli JA. Principles of reconstruction following excision of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:601-616. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(95)00099-2

- Bosley R, Leithauser L, Turner M, et al. The efficacy of second-intention healing in the management of defects on the dorsal surface of the hands and fingers after Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:647-653. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02258.x

- Stebbins WG, Gusev J, Higgins HW 2nd, et al. Evaluation of patient satisfaction with second intention healing versus primary surgical closure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:865-867.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.019

Reconstruction Technique for Defects of the Cutaneous and Mucosal Lip: V-to-flying-Y Closure

Practice Gap

Reconstruction of a lip defect poses challenges to the dermatologic surgeon. The lip is a free margin, where excess tension can cause noticeable distortion in facial aesthetics. Distortion of that free margin might not only disrupt the appearance of the lip but affect function by impairing oral competency and mobility; therefore, when choosing a method of reconstruction, the surgeon must take free margin distortion into account. Misalignment of the vermilion border upon reconstruction will cause a poor aesthetic result in the absence of free margin distortion. When a surgical defect involves more than one cosmetic subunit of the lip, great care must be taken to repair each subunit individually to achieve the best cosmetic and functional results.

The suitability of traditional approaches to reconstruction of a defect that crosses the vermilion border—healing by secondary intention, primary linear repair, full-thickness wedge repair, partial-thickness wedge repair, and combined cutaneous and mucosal advancement1—depends on the depth of the lesion.

Clinical Presentation

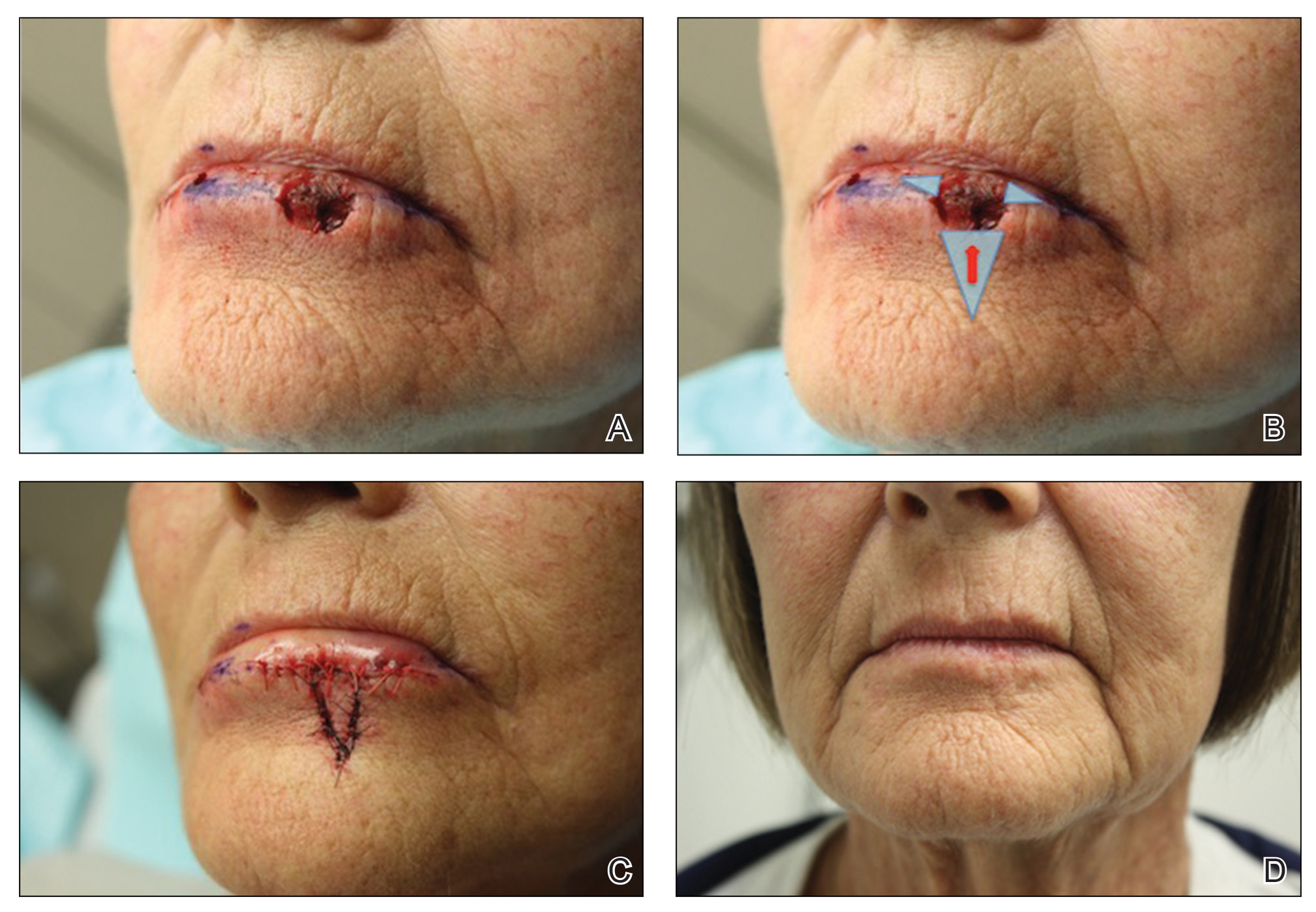

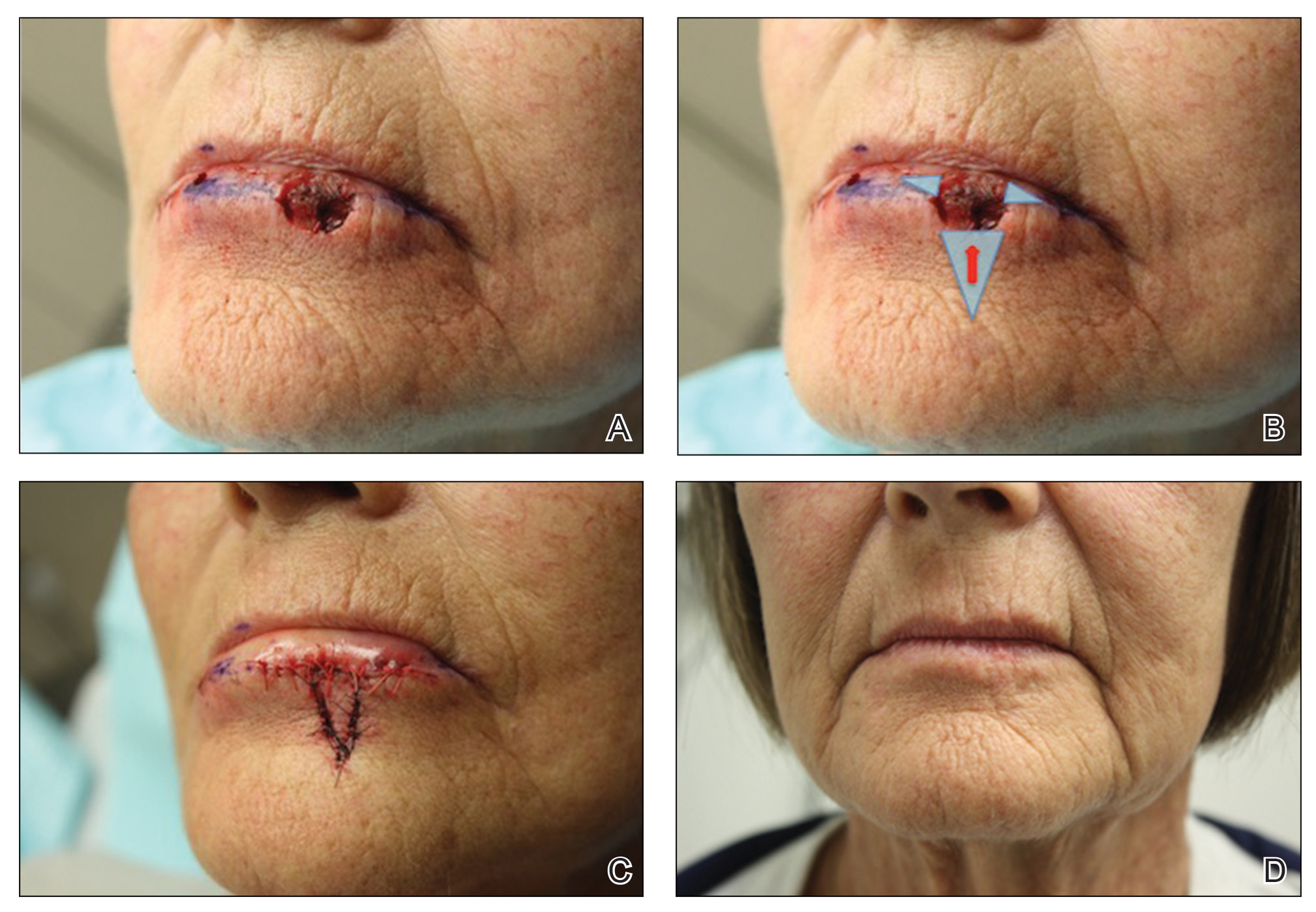

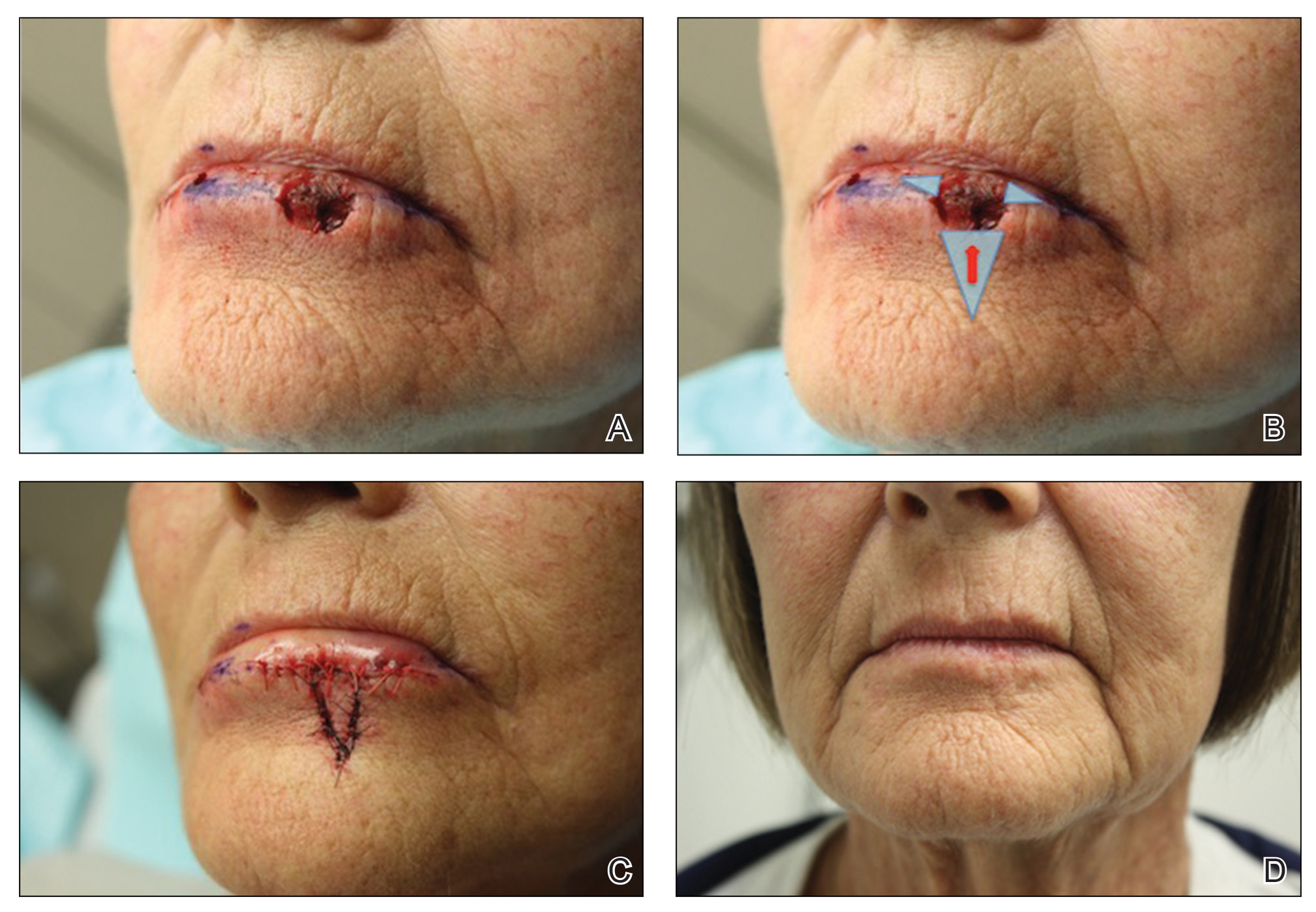

A 66-year-old woman with a 4×6-mm, invasive, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the left lower lip was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery. Removal of the tumor required 2 stages to obtain clear margins, leaving a 1.0×1.2-cm defect that crossed the vermilion border (Figure, A). How would you repair this defect?

Selecting a Technique to Close the Surgical Defect

For this patient, we had several options to consider in approaching closure, including several that we rejected. Because the defect crossed cosmetic subunit boundaries, healing by secondary intention was avoided, as it would cause contraction, obliterate the vermilion border, and result in poor functional and cosmetic results. We decided against primary closure, even with careful attention to reapproximation of the vermilion border, because the width of the defect would have required a large Burow triangle that extended into the oral cavity. For defects less than one-third the width of the lip, full-thickness wedge repair can yield excellent cosmetic results but, in this case, would decrease the oral aperture and was deemed too extensive a procedure for a relatively shallow defect.2

Instead, we chose to perform repair with V to Y advancement of skin below the cutaneous defect, up to the location of the absent vermilion border, combined with small, horizontal, linear closure of the mucosal portion of the defect. This approach is a variation of a repair described by Jin et al,3 who described using 2 opposing V-Y advancement flaps to repair defects of the lip. This repair has provided excellent cosmetic results for a small series of our patients, preserving the oral aperture and maintaining the important aesthetic location of the vermilion border. In addition, the technique makes it unnecessary for the patient to undergo a much larger repair, such as a full- or partial-thickness wedge when the initial defect is relatively shallow.

Closure Technique

It is essential to properly outline the vermilion border of the lip before initiating the repair, ideally before any infiltration of local anesthesia if the surgeon anticipates that tumor extirpation might cross the vermilion border.

Repair

Closing then proceeds as follows:

• The cutaneous portion of the defect is drawn out in standard V to Y fashion, carrying the incision through the dermis and into subcutaneous tissue. The pedicle of the flap is maintained at the base of the island, serving as the blood supply to the flap.

• The periphery of the flap and surrounding tissue is undermined to facilitate movement superiorly into the cutaneous portion of the defect.

• A single buried vertical mattress suture can be placed at the advancing border of the island, holding it in place at the anticipated location of the vermilion border. The secondary defect created by the advancing V is closed to help push the island into place and prevent downward tension on the free margin of the lip.

• The remaining defect of the vermilion lip is closed by removing Burow triangles at the horizontal edges on each side of the remaining defect (Figure, B). The triangles are removed completely within the mucosal lip, with the inferior edge of the triangle placed at the vermilion border.

• The defect is closed in a primary linear horizontal fashion, using buried vertical mattress sutures and cutaneous approximation.

The final appearance of the sutured defect yields a small lateral extension at the superior edge of the V to Y closure, giving the appearance of wings on the Y, prompting us to term the closure V-to-flying-Y (Figure, C).

Although the limited portion of the mucosal lip that is closed in this fashion might appear thinner than the remaining lip, it generally yields a cosmetically acceptable result in the properly selected patient. Our experience also has shown an improvement in this difference in the months following repair. A full mucosal advancement flap might result in a more uniform appearance of the lower lip, but it is a larger and more difficult procedure for the patient to endure. Additionally, a full mucosal advancement flap risks uniformly creating a much thinner lip.

Postoperative Course

Sutures were removed 1 week postoperatively. Proper location of the vermilion border, without distortion of the free margin, was demonstrated. At 11-month follow-up, excellent cosmetic and functional results were noted (Figure, D).

Practice Implications

This repair (1) demonstrates an elegant method of closing a relatively shallow defect that crosses the vermilion border and (2) allows the surgeon to address each cosmetic subunit individually. We have found that this repair provides excellent cosmetic and functional results, with little morbidity.

The lip is a common site of nonmelanoma squamous cell carcinoma. Poorly planned closing after excision of the tumor risks notable impairment of function or cosmetic distortion. When a defect of the lip crosses cosmetic subunits, it is helpful to repair each subunit individually. V-to-flying-Y closure is an effective method to close defects that cross the vermilion border, resulting in well-preserved cosmetic appearance and function.

- Ishii LE, Byrne PJ. Lip reconstruction. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2009;17:445-453. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2009.05.007

- Sebben JE. Wedge resection of the lip: minimizing problems. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1985;11:60-64. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1985.tb02892.x

- Jin X, Teng L, Zhang C, et al. Reconstruction of partial-thickness vermilion defects with a mucosal V-Y advancement flap based on the orbicularis oris muscle. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:472-476. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2010.07.017

Practice Gap

Reconstruction of a lip defect poses challenges to the dermatologic surgeon. The lip is a free margin, where excess tension can cause noticeable distortion in facial aesthetics. Distortion of that free margin might not only disrupt the appearance of the lip but affect function by impairing oral competency and mobility; therefore, when choosing a method of reconstruction, the surgeon must take free margin distortion into account. Misalignment of the vermilion border upon reconstruction will cause a poor aesthetic result in the absence of free margin distortion. When a surgical defect involves more than one cosmetic subunit of the lip, great care must be taken to repair each subunit individually to achieve the best cosmetic and functional results.

The suitability of traditional approaches to reconstruction of a defect that crosses the vermilion border—healing by secondary intention, primary linear repair, full-thickness wedge repair, partial-thickness wedge repair, and combined cutaneous and mucosal advancement1—depends on the depth of the lesion.

Clinical Presentation

A 66-year-old woman with a 4×6-mm, invasive, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the left lower lip was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery. Removal of the tumor required 2 stages to obtain clear margins, leaving a 1.0×1.2-cm defect that crossed the vermilion border (Figure, A). How would you repair this defect?

Selecting a Technique to Close the Surgical Defect

For this patient, we had several options to consider in approaching closure, including several that we rejected. Because the defect crossed cosmetic subunit boundaries, healing by secondary intention was avoided, as it would cause contraction, obliterate the vermilion border, and result in poor functional and cosmetic results. We decided against primary closure, even with careful attention to reapproximation of the vermilion border, because the width of the defect would have required a large Burow triangle that extended into the oral cavity. For defects less than one-third the width of the lip, full-thickness wedge repair can yield excellent cosmetic results but, in this case, would decrease the oral aperture and was deemed too extensive a procedure for a relatively shallow defect.2

Instead, we chose to perform repair with V to Y advancement of skin below the cutaneous defect, up to the location of the absent vermilion border, combined with small, horizontal, linear closure of the mucosal portion of the defect. This approach is a variation of a repair described by Jin et al,3 who described using 2 opposing V-Y advancement flaps to repair defects of the lip. This repair has provided excellent cosmetic results for a small series of our patients, preserving the oral aperture and maintaining the important aesthetic location of the vermilion border. In addition, the technique makes it unnecessary for the patient to undergo a much larger repair, such as a full- or partial-thickness wedge when the initial defect is relatively shallow.

Closure Technique

It is essential to properly outline the vermilion border of the lip before initiating the repair, ideally before any infiltration of local anesthesia if the surgeon anticipates that tumor extirpation might cross the vermilion border.

Repair

Closing then proceeds as follows:

• The cutaneous portion of the defect is drawn out in standard V to Y fashion, carrying the incision through the dermis and into subcutaneous tissue. The pedicle of the flap is maintained at the base of the island, serving as the blood supply to the flap.

• The periphery of the flap and surrounding tissue is undermined to facilitate movement superiorly into the cutaneous portion of the defect.

• A single buried vertical mattress suture can be placed at the advancing border of the island, holding it in place at the anticipated location of the vermilion border. The secondary defect created by the advancing V is closed to help push the island into place and prevent downward tension on the free margin of the lip.

• The remaining defect of the vermilion lip is closed by removing Burow triangles at the horizontal edges on each side of the remaining defect (Figure, B). The triangles are removed completely within the mucosal lip, with the inferior edge of the triangle placed at the vermilion border.

• The defect is closed in a primary linear horizontal fashion, using buried vertical mattress sutures and cutaneous approximation.

The final appearance of the sutured defect yields a small lateral extension at the superior edge of the V to Y closure, giving the appearance of wings on the Y, prompting us to term the closure V-to-flying-Y (Figure, C).

Although the limited portion of the mucosal lip that is closed in this fashion might appear thinner than the remaining lip, it generally yields a cosmetically acceptable result in the properly selected patient. Our experience also has shown an improvement in this difference in the months following repair. A full mucosal advancement flap might result in a more uniform appearance of the lower lip, but it is a larger and more difficult procedure for the patient to endure. Additionally, a full mucosal advancement flap risks uniformly creating a much thinner lip.

Postoperative Course

Sutures were removed 1 week postoperatively. Proper location of the vermilion border, without distortion of the free margin, was demonstrated. At 11-month follow-up, excellent cosmetic and functional results were noted (Figure, D).

Practice Implications

This repair (1) demonstrates an elegant method of closing a relatively shallow defect that crosses the vermilion border and (2) allows the surgeon to address each cosmetic subunit individually. We have found that this repair provides excellent cosmetic and functional results, with little morbidity.

The lip is a common site of nonmelanoma squamous cell carcinoma. Poorly planned closing after excision of the tumor risks notable impairment of function or cosmetic distortion. When a defect of the lip crosses cosmetic subunits, it is helpful to repair each subunit individually. V-to-flying-Y closure is an effective method to close defects that cross the vermilion border, resulting in well-preserved cosmetic appearance and function.

Practice Gap

Reconstruction of a lip defect poses challenges to the dermatologic surgeon. The lip is a free margin, where excess tension can cause noticeable distortion in facial aesthetics. Distortion of that free margin might not only disrupt the appearance of the lip but affect function by impairing oral competency and mobility; therefore, when choosing a method of reconstruction, the surgeon must take free margin distortion into account. Misalignment of the vermilion border upon reconstruction will cause a poor aesthetic result in the absence of free margin distortion. When a surgical defect involves more than one cosmetic subunit of the lip, great care must be taken to repair each subunit individually to achieve the best cosmetic and functional results.

The suitability of traditional approaches to reconstruction of a defect that crosses the vermilion border—healing by secondary intention, primary linear repair, full-thickness wedge repair, partial-thickness wedge repair, and combined cutaneous and mucosal advancement1—depends on the depth of the lesion.

Clinical Presentation

A 66-year-old woman with a 4×6-mm, invasive, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the left lower lip was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery. Removal of the tumor required 2 stages to obtain clear margins, leaving a 1.0×1.2-cm defect that crossed the vermilion border (Figure, A). How would you repair this defect?

Selecting a Technique to Close the Surgical Defect

For this patient, we had several options to consider in approaching closure, including several that we rejected. Because the defect crossed cosmetic subunit boundaries, healing by secondary intention was avoided, as it would cause contraction, obliterate the vermilion border, and result in poor functional and cosmetic results. We decided against primary closure, even with careful attention to reapproximation of the vermilion border, because the width of the defect would have required a large Burow triangle that extended into the oral cavity. For defects less than one-third the width of the lip, full-thickness wedge repair can yield excellent cosmetic results but, in this case, would decrease the oral aperture and was deemed too extensive a procedure for a relatively shallow defect.2

Instead, we chose to perform repair with V to Y advancement of skin below the cutaneous defect, up to the location of the absent vermilion border, combined with small, horizontal, linear closure of the mucosal portion of the defect. This approach is a variation of a repair described by Jin et al,3 who described using 2 opposing V-Y advancement flaps to repair defects of the lip. This repair has provided excellent cosmetic results for a small series of our patients, preserving the oral aperture and maintaining the important aesthetic location of the vermilion border. In addition, the technique makes it unnecessary for the patient to undergo a much larger repair, such as a full- or partial-thickness wedge when the initial defect is relatively shallow.

Closure Technique

It is essential to properly outline the vermilion border of the lip before initiating the repair, ideally before any infiltration of local anesthesia if the surgeon anticipates that tumor extirpation might cross the vermilion border.

Repair

Closing then proceeds as follows:

• The cutaneous portion of the defect is drawn out in standard V to Y fashion, carrying the incision through the dermis and into subcutaneous tissue. The pedicle of the flap is maintained at the base of the island, serving as the blood supply to the flap.

• The periphery of the flap and surrounding tissue is undermined to facilitate movement superiorly into the cutaneous portion of the defect.

• A single buried vertical mattress suture can be placed at the advancing border of the island, holding it in place at the anticipated location of the vermilion border. The secondary defect created by the advancing V is closed to help push the island into place and prevent downward tension on the free margin of the lip.

• The remaining defect of the vermilion lip is closed by removing Burow triangles at the horizontal edges on each side of the remaining defect (Figure, B). The triangles are removed completely within the mucosal lip, with the inferior edge of the triangle placed at the vermilion border.

• The defect is closed in a primary linear horizontal fashion, using buried vertical mattress sutures and cutaneous approximation.

The final appearance of the sutured defect yields a small lateral extension at the superior edge of the V to Y closure, giving the appearance of wings on the Y, prompting us to term the closure V-to-flying-Y (Figure, C).

Although the limited portion of the mucosal lip that is closed in this fashion might appear thinner than the remaining lip, it generally yields a cosmetically acceptable result in the properly selected patient. Our experience also has shown an improvement in this difference in the months following repair. A full mucosal advancement flap might result in a more uniform appearance of the lower lip, but it is a larger and more difficult procedure for the patient to endure. Additionally, a full mucosal advancement flap risks uniformly creating a much thinner lip.

Postoperative Course

Sutures were removed 1 week postoperatively. Proper location of the vermilion border, without distortion of the free margin, was demonstrated. At 11-month follow-up, excellent cosmetic and functional results were noted (Figure, D).

Practice Implications

This repair (1) demonstrates an elegant method of closing a relatively shallow defect that crosses the vermilion border and (2) allows the surgeon to address each cosmetic subunit individually. We have found that this repair provides excellent cosmetic and functional results, with little morbidity.

The lip is a common site of nonmelanoma squamous cell carcinoma. Poorly planned closing after excision of the tumor risks notable impairment of function or cosmetic distortion. When a defect of the lip crosses cosmetic subunits, it is helpful to repair each subunit individually. V-to-flying-Y closure is an effective method to close defects that cross the vermilion border, resulting in well-preserved cosmetic appearance and function.

- Ishii LE, Byrne PJ. Lip reconstruction. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2009;17:445-453. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2009.05.007

- Sebben JE. Wedge resection of the lip: minimizing problems. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1985;11:60-64. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1985.tb02892.x

- Jin X, Teng L, Zhang C, et al. Reconstruction of partial-thickness vermilion defects with a mucosal V-Y advancement flap based on the orbicularis oris muscle. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:472-476. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2010.07.017

- Ishii LE, Byrne PJ. Lip reconstruction. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2009;17:445-453. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2009.05.007

- Sebben JE. Wedge resection of the lip: minimizing problems. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1985;11:60-64. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1985.tb02892.x

- Jin X, Teng L, Zhang C, et al. Reconstruction of partial-thickness vermilion defects with a mucosal V-Y advancement flap based on the orbicularis oris muscle. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:472-476. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2010.07.017

High-Potency Topical Steroid Treatment of Multiple Keratoacanthomas Associated With Prurigo Nodularis

Practice Gap

Multiple keratoacanthomas (KAs) of the legs often are a challenge to treat, especially when these lesions appear within a field of prurigo nodules. Multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis is a rarer finding; more often, the condition is reported on the lower limbs of elderly women with actinically damaged skin.1,2 At times, it can be difficult to distinguish between KA and prurigo nodularis in these patients, who often report notable pruritus and might have associated eczematous dermatitis.2

Keratoacanthomas often are treated with aggressive modalities, such as Mohs micrographic surgery, excision, and electrodesiccation and curettage. Some patients are hesitant to undergo surgical treatment, however, preferring a less invasive approach. Trauma from these aggressive modalities also can be associated with recurrence of existing lesions or development of new KAs, possibly related to stimulation of a local inflammatory response and upregulation of helper T cells.2-4

Acitretin and other systemic retinoids often are considered first-line therapy for multiple KAs. Cyclosporine has been added as adjunctive treatment in cases associated with prurigo nodularis or eczematous dermatitis1,2; however, these treatments have a high rate of discontinuation because of adverse effects, including transaminitis, xerostomia, alopecia (acitretin), and renal toxicity (cyclosporine).2

Another treatment option for patients with coexisting KA and prurigo nodularis is intralesional corticosteroids, often administered in combination with systemic retinoids.3 Topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) has been used successfully for KA, but topical treatment options are limited if 5-FU fails. Topical imiquimod and cryotherapy are thought to be of little benefit, and the appearance of new KA within imiquimod and cryotherapy treatment fields has been reported.1,2 Topical corticosteroids have been used as an adjuvant therapy for multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms keratoacanthoma and steroid and keratoacanthoma and prurigo nodularis yielded no published reports of successful use of topical corticosteroids as monotherapy.2

The Technique

For patients who want to continue topical treatment of coexisting KA and prurigo nodularis after topical 5-FU fails, we have found success applying a high-potency topical corticosteroid to affected areas under occlusion nightly for 6 to 8 weeks. This treatment not only leads to resolution of KA but also simultaneously treats prurigo nodules that might be clinically difficult to distinguish from KA in some presentations. This regimen has been implemented in our practice with remarkable reduction of KA burden and relief of pruritus.

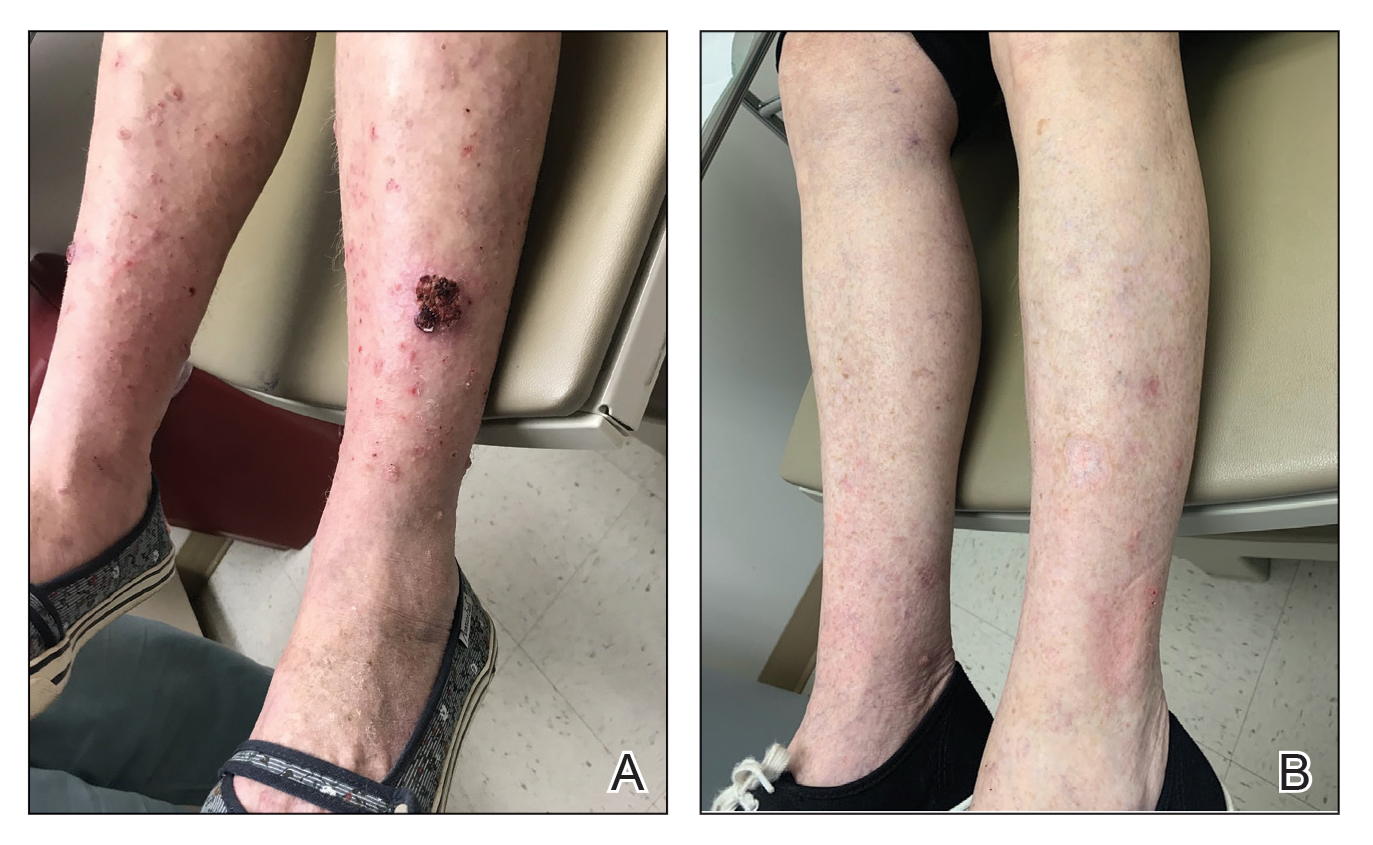

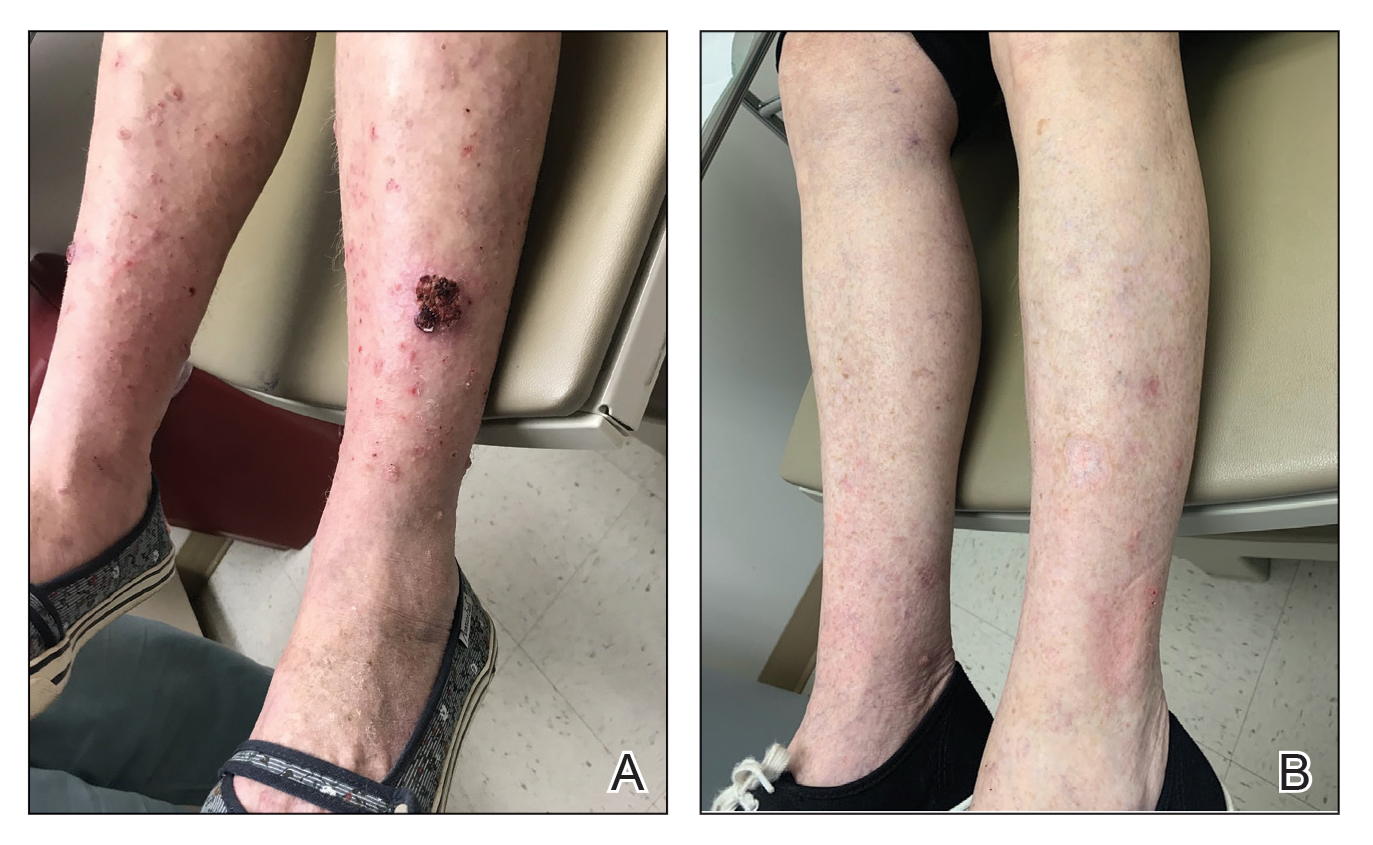

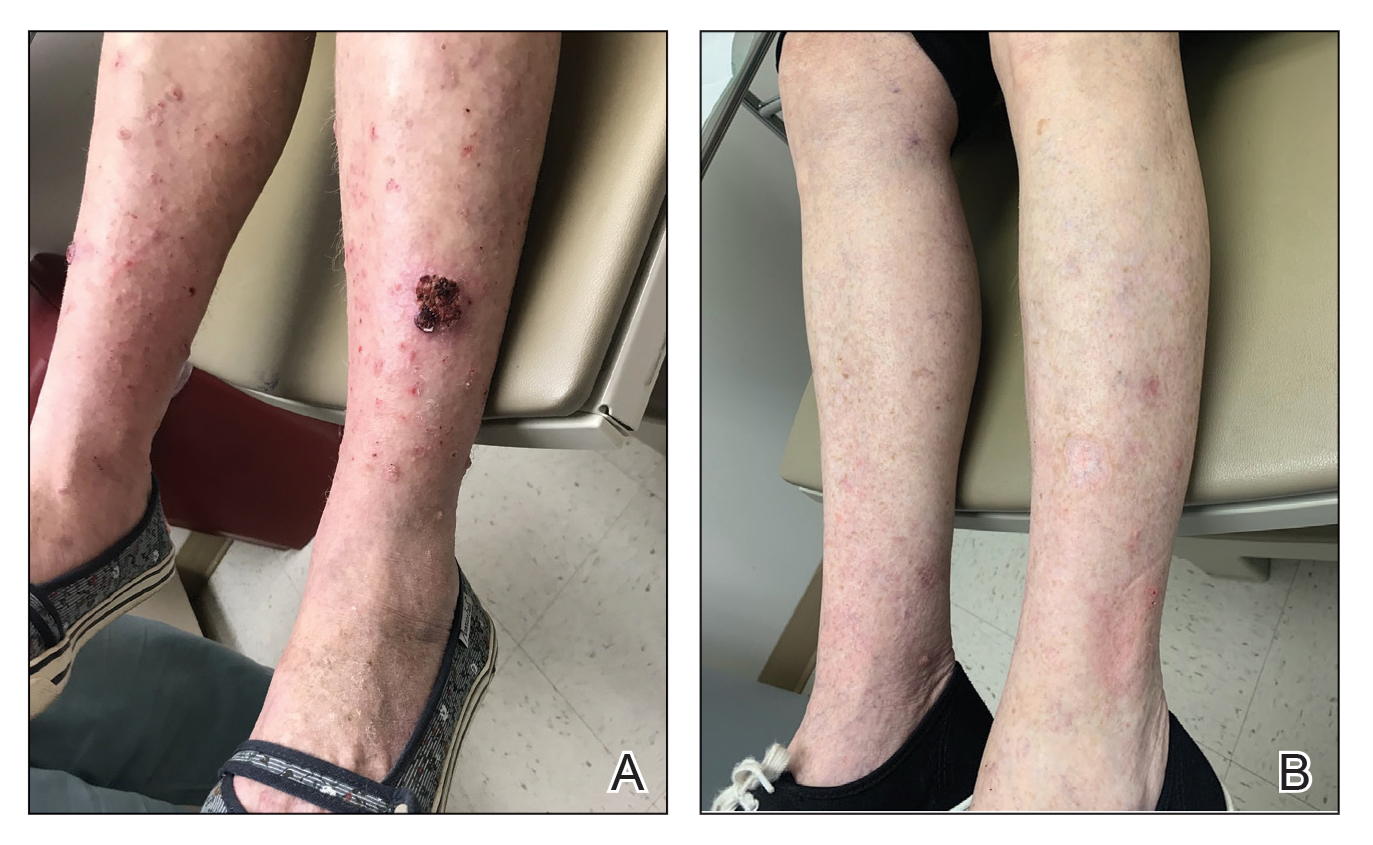

In a 68-year-old woman who was treated with this technique, multiple biopsies had shown KA (or well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma that appeared clinically as KA) on the shin (Figure, A) arising amid many lesions consistent with prurigo nodules. Topical 5-FU had failed, but the patient did not want to be treated with a more invasive modality, such as excision or injection.

Instead, we treated the patient with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% under occlusion nightly for 6 weeks. This strategy produced resolution of both KA and prurigo nodules (Figure, B). When lesions recurred after a few months, they were successfully re-treated with topical clobetasol under occlusion in a second 6-week course.

Practical Implications

Treatment of multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis can present a distinct challenge. For the subset of patients who want to pursue topical treatment, options reported in the literature are limited. We have found success treating multiple KAs and associated prurigo nodules with a high-potency topical corticosteroid under occlusion, with minimal or no adverse effects. We believe that a topical corticosteroid can be implemented easily in clinical practice before a more invasive surgical or intralesional modality is considered.

- Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): an update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1220-1233. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.033

- Wu TP, Miller K, Cohen DE, et al. Keratoacanthomas arising in association with prurigo nodules in pruritic, actinically damaged skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:426-430. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2013.03.035

- Sanders S, Busam KJ, Halpern AC, et al. Intralesional corticosteroid treatment of multiple eruptive keratoacanthomas: case report and review of a controversial therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:954-958. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02069.x

- Lee S, Coutts I, Ryan A, et al. Keratoacanthoma formation after skin grafting: a brief report and pathophysiological hypothesis. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E117-E119. doi:10.1111/ajd.12501

Practice Gap

Multiple keratoacanthomas (KAs) of the legs often are a challenge to treat, especially when these lesions appear within a field of prurigo nodules. Multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis is a rarer finding; more often, the condition is reported on the lower limbs of elderly women with actinically damaged skin.1,2 At times, it can be difficult to distinguish between KA and prurigo nodularis in these patients, who often report notable pruritus and might have associated eczematous dermatitis.2

Keratoacanthomas often are treated with aggressive modalities, such as Mohs micrographic surgery, excision, and electrodesiccation and curettage. Some patients are hesitant to undergo surgical treatment, however, preferring a less invasive approach. Trauma from these aggressive modalities also can be associated with recurrence of existing lesions or development of new KAs, possibly related to stimulation of a local inflammatory response and upregulation of helper T cells.2-4

Acitretin and other systemic retinoids often are considered first-line therapy for multiple KAs. Cyclosporine has been added as adjunctive treatment in cases associated with prurigo nodularis or eczematous dermatitis1,2; however, these treatments have a high rate of discontinuation because of adverse effects, including transaminitis, xerostomia, alopecia (acitretin), and renal toxicity (cyclosporine).2

Another treatment option for patients with coexisting KA and prurigo nodularis is intralesional corticosteroids, often administered in combination with systemic retinoids.3 Topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) has been used successfully for KA, but topical treatment options are limited if 5-FU fails. Topical imiquimod and cryotherapy are thought to be of little benefit, and the appearance of new KA within imiquimod and cryotherapy treatment fields has been reported.1,2 Topical corticosteroids have been used as an adjuvant therapy for multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms keratoacanthoma and steroid and keratoacanthoma and prurigo nodularis yielded no published reports of successful use of topical corticosteroids as monotherapy.2

The Technique

For patients who want to continue topical treatment of coexisting KA and prurigo nodularis after topical 5-FU fails, we have found success applying a high-potency topical corticosteroid to affected areas under occlusion nightly for 6 to 8 weeks. This treatment not only leads to resolution of KA but also simultaneously treats prurigo nodules that might be clinically difficult to distinguish from KA in some presentations. This regimen has been implemented in our practice with remarkable reduction of KA burden and relief of pruritus.

In a 68-year-old woman who was treated with this technique, multiple biopsies had shown KA (or well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma that appeared clinically as KA) on the shin (Figure, A) arising amid many lesions consistent with prurigo nodules. Topical 5-FU had failed, but the patient did not want to be treated with a more invasive modality, such as excision or injection.

Instead, we treated the patient with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% under occlusion nightly for 6 weeks. This strategy produced resolution of both KA and prurigo nodules (Figure, B). When lesions recurred after a few months, they were successfully re-treated with topical clobetasol under occlusion in a second 6-week course.

Practical Implications

Treatment of multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis can present a distinct challenge. For the subset of patients who want to pursue topical treatment, options reported in the literature are limited. We have found success treating multiple KAs and associated prurigo nodules with a high-potency topical corticosteroid under occlusion, with minimal or no adverse effects. We believe that a topical corticosteroid can be implemented easily in clinical practice before a more invasive surgical or intralesional modality is considered.

Practice Gap

Multiple keratoacanthomas (KAs) of the legs often are a challenge to treat, especially when these lesions appear within a field of prurigo nodules. Multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis is a rarer finding; more often, the condition is reported on the lower limbs of elderly women with actinically damaged skin.1,2 At times, it can be difficult to distinguish between KA and prurigo nodularis in these patients, who often report notable pruritus and might have associated eczematous dermatitis.2

Keratoacanthomas often are treated with aggressive modalities, such as Mohs micrographic surgery, excision, and electrodesiccation and curettage. Some patients are hesitant to undergo surgical treatment, however, preferring a less invasive approach. Trauma from these aggressive modalities also can be associated with recurrence of existing lesions or development of new KAs, possibly related to stimulation of a local inflammatory response and upregulation of helper T cells.2-4

Acitretin and other systemic retinoids often are considered first-line therapy for multiple KAs. Cyclosporine has been added as adjunctive treatment in cases associated with prurigo nodularis or eczematous dermatitis1,2; however, these treatments have a high rate of discontinuation because of adverse effects, including transaminitis, xerostomia, alopecia (acitretin), and renal toxicity (cyclosporine).2

Another treatment option for patients with coexisting KA and prurigo nodularis is intralesional corticosteroids, often administered in combination with systemic retinoids.3 Topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) has been used successfully for KA, but topical treatment options are limited if 5-FU fails. Topical imiquimod and cryotherapy are thought to be of little benefit, and the appearance of new KA within imiquimod and cryotherapy treatment fields has been reported.1,2 Topical corticosteroids have been used as an adjuvant therapy for multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms keratoacanthoma and steroid and keratoacanthoma and prurigo nodularis yielded no published reports of successful use of topical corticosteroids as monotherapy.2

The Technique

For patients who want to continue topical treatment of coexisting KA and prurigo nodularis after topical 5-FU fails, we have found success applying a high-potency topical corticosteroid to affected areas under occlusion nightly for 6 to 8 weeks. This treatment not only leads to resolution of KA but also simultaneously treats prurigo nodules that might be clinically difficult to distinguish from KA in some presentations. This regimen has been implemented in our practice with remarkable reduction of KA burden and relief of pruritus.

In a 68-year-old woman who was treated with this technique, multiple biopsies had shown KA (or well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma that appeared clinically as KA) on the shin (Figure, A) arising amid many lesions consistent with prurigo nodules. Topical 5-FU had failed, but the patient did not want to be treated with a more invasive modality, such as excision or injection.

Instead, we treated the patient with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% under occlusion nightly for 6 weeks. This strategy produced resolution of both KA and prurigo nodules (Figure, B). When lesions recurred after a few months, they were successfully re-treated with topical clobetasol under occlusion in a second 6-week course.

Practical Implications

Treatment of multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis can present a distinct challenge. For the subset of patients who want to pursue topical treatment, options reported in the literature are limited. We have found success treating multiple KAs and associated prurigo nodules with a high-potency topical corticosteroid under occlusion, with minimal or no adverse effects. We believe that a topical corticosteroid can be implemented easily in clinical practice before a more invasive surgical or intralesional modality is considered.

- Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): an update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1220-1233. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.033

- Wu TP, Miller K, Cohen DE, et al. Keratoacanthomas arising in association with prurigo nodules in pruritic, actinically damaged skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:426-430. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2013.03.035

- Sanders S, Busam KJ, Halpern AC, et al. Intralesional corticosteroid treatment of multiple eruptive keratoacanthomas: case report and review of a controversial therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:954-958. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02069.x

- Lee S, Coutts I, Ryan A, et al. Keratoacanthoma formation after skin grafting: a brief report and pathophysiological hypothesis. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E117-E119. doi:10.1111/ajd.12501

- Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): an update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1220-1233. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.033

- Wu TP, Miller K, Cohen DE, et al. Keratoacanthomas arising in association with prurigo nodules in pruritic, actinically damaged skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:426-430. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2013.03.035

- Sanders S, Busam KJ, Halpern AC, et al. Intralesional corticosteroid treatment of multiple eruptive keratoacanthomas: case report and review of a controversial therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:954-958. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02069.x

- Lee S, Coutts I, Ryan A, et al. Keratoacanthoma formation after skin grafting: a brief report and pathophysiological hypothesis. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E117-E119. doi:10.1111/ajd.12501

Hidden Basal Cell Carcinoma in the Intergluteal Crease

Practice Gap

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cancer, and its incidence is on the rise.1 The risk of this skin cancer is increased when there is a history of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or BCC.2 Basal cell carcinoma often is found in sun-exposed areas, most commonly due to a history of intense sunburn.3 Other risk factors include male gender and increased age.4

Eighty percent to 85% of BCCs present on the head and neck5; however, BCC also can occur in unusual locations. When BCC presents in areas such as the perianal region, it is found to be larger than when found in more common areas,6 likely because neoplasms in this sensitive area often are overlooked. Literature on BCC of the intergluteal crease is limited.7 Being educated on the existence of BCC in this sensitive area can aid proper diagnosis.

The Technique and Case

An 83-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for a suspicious lesion in the intergluteal crease that was tender to palpation with drainage. She first noticed this lesion and reported it to her primary care physician at a visit 6 months prior. The primary care physician did not pursue investigation of the lesion. One month later, the patient was seen by a gastroenterologist for the lesion and was referred to dermatology. The patient’s medical history included SCC and BCC on the face, both treated successfully with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Physical examination revealed a 2.6×1.1-cm, erythematous, nodular plaque in the coccygeal area of the intergluteal crease (Figure 1). A shave biopsy disclosed BCC, nodular type, ulcerated. Microscopically, there were nodular aggregates of basaloid cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and peripheral palisading, separated from mucinous stromal surroundings by artefactual clefts.

The initial differential diagnosis for this patient’s lesion included an ulcer or SCC. Basal cell carcinoma was not suspected due to the location and appearance of the lesion. The patient was successfully treated with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Practical Implications

Without thorough examination, this cancerous lesion would not have been seen (Figure 2). Therefore, it is important to practice thorough physical examination skills to avoid missing these cancers, particularly when examining a patient with a history of SCC or BCC. Furthermore, biopsy is recommended for suspicious lesions to rule out BCC.

Be careful not to get caught up in epidemiological or demographic considerations when making a diagnosis of this kind or when assessing the severity of a lesion. This patient, for instance, was female, which makes her less likely to present with BCC.8 Moreover, the cancer presented in a highly unlikely location for BCC, where there had not been significant sunburn.9 Patients and physicians should be educated about the incidence of BCC in unexpected areas; without a second and close look, this BCC could have been missed.

Final Thoughts

The literature continuously demonstrates the rarity of BCC in the intergluteal crease.10 However, when perianal BCC is properly identified and treated with local excision, prognosis is good.11 Basal cell carcinoma has been seen to arise in other sensitive locations; vulvar, nipple, and scrotal BCC neoplasms are among the uncommon locations where BCC has appeared.12 These areas are frequently—and easily—ignored. A total-body skin examination should be performed to ensure that these insidious-onset carcinomas are not overlooked to protect patients from the adverse consequences of untreated cancer.13

- Roewert-Huber J, Lange-Asschenfeldt B, Stockfleth E, et al. Epidemiology and aetiology of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(suppl 2):47-51.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Zanetti R, Rosso S, Martinez C, et al. Comparison of risk patterns in carcinoma and melanoma of the skin in men: a multi-centre case–case–control study. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:743-751.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Lorenzini M, Gatti S, Giannitrapani A. Giant basal cell carcinoma of the thoracic wall: a case report and review of the literature. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58:1007-1010.

- Lee HS, Kim SK. Basal cell carcinoma presenting as a perianal ulcer and treated with radiotherapy. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:212-214.

- Salih AM, Kakamad FH, Rauf GM. Basal cell carcinoma mimicking pilonidal sinus: a case report with literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;28:121-123.

- Scrivener Y, Grosshans E, Cribier B. Variations of basal cell carcinomas according to gender, age, location and histopathological subtype. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:41-47.

- Park J, Cho Y-S, Song K-H, et al. Basal cell carcinoma on the pubic area: report of a case and review of 19 Korean cases of BCC from non-sun-exposed areas. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:405-408.

- Damin DC, Rosito MA, Gus P, et al. Perianal basal cell carcinoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:26-28.

- Paterson CA, Young-Fadok TM, Dozois RR. Basal cell carcinoma of the perianal region: 20-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1200-1202.

- Mulvany NJ, Rayoo M, Allen DG. Basal cell carcinoma of the vulva: a case series. Pathology. 2012;44:528-533.

- Leonard D, Beddy D, Dozois EJ. Neoplasms of anal canal and perianal skin. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:54-63.

Practice Gap

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cancer, and its incidence is on the rise.1 The risk of this skin cancer is increased when there is a history of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or BCC.2 Basal cell carcinoma often is found in sun-exposed areas, most commonly due to a history of intense sunburn.3 Other risk factors include male gender and increased age.4

Eighty percent to 85% of BCCs present on the head and neck5; however, BCC also can occur in unusual locations. When BCC presents in areas such as the perianal region, it is found to be larger than when found in more common areas,6 likely because neoplasms in this sensitive area often are overlooked. Literature on BCC of the intergluteal crease is limited.7 Being educated on the existence of BCC in this sensitive area can aid proper diagnosis.

The Technique and Case

An 83-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for a suspicious lesion in the intergluteal crease that was tender to palpation with drainage. She first noticed this lesion and reported it to her primary care physician at a visit 6 months prior. The primary care physician did not pursue investigation of the lesion. One month later, the patient was seen by a gastroenterologist for the lesion and was referred to dermatology. The patient’s medical history included SCC and BCC on the face, both treated successfully with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Physical examination revealed a 2.6×1.1-cm, erythematous, nodular plaque in the coccygeal area of the intergluteal crease (Figure 1). A shave biopsy disclosed BCC, nodular type, ulcerated. Microscopically, there were nodular aggregates of basaloid cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and peripheral palisading, separated from mucinous stromal surroundings by artefactual clefts.

The initial differential diagnosis for this patient’s lesion included an ulcer or SCC. Basal cell carcinoma was not suspected due to the location and appearance of the lesion. The patient was successfully treated with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Practical Implications

Without thorough examination, this cancerous lesion would not have been seen (Figure 2). Therefore, it is important to practice thorough physical examination skills to avoid missing these cancers, particularly when examining a patient with a history of SCC or BCC. Furthermore, biopsy is recommended for suspicious lesions to rule out BCC.

Be careful not to get caught up in epidemiological or demographic considerations when making a diagnosis of this kind or when assessing the severity of a lesion. This patient, for instance, was female, which makes her less likely to present with BCC.8 Moreover, the cancer presented in a highly unlikely location for BCC, where there had not been significant sunburn.9 Patients and physicians should be educated about the incidence of BCC in unexpected areas; without a second and close look, this BCC could have been missed.

Final Thoughts

The literature continuously demonstrates the rarity of BCC in the intergluteal crease.10 However, when perianal BCC is properly identified and treated with local excision, prognosis is good.11 Basal cell carcinoma has been seen to arise in other sensitive locations; vulvar, nipple, and scrotal BCC neoplasms are among the uncommon locations where BCC has appeared.12 These areas are frequently—and easily—ignored. A total-body skin examination should be performed to ensure that these insidious-onset carcinomas are not overlooked to protect patients from the adverse consequences of untreated cancer.13

Practice Gap

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cancer, and its incidence is on the rise.1 The risk of this skin cancer is increased when there is a history of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or BCC.2 Basal cell carcinoma often is found in sun-exposed areas, most commonly due to a history of intense sunburn.3 Other risk factors include male gender and increased age.4

Eighty percent to 85% of BCCs present on the head and neck5; however, BCC also can occur in unusual locations. When BCC presents in areas such as the perianal region, it is found to be larger than when found in more common areas,6 likely because neoplasms in this sensitive area often are overlooked. Literature on BCC of the intergluteal crease is limited.7 Being educated on the existence of BCC in this sensitive area can aid proper diagnosis.

The Technique and Case

An 83-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for a suspicious lesion in the intergluteal crease that was tender to palpation with drainage. She first noticed this lesion and reported it to her primary care physician at a visit 6 months prior. The primary care physician did not pursue investigation of the lesion. One month later, the patient was seen by a gastroenterologist for the lesion and was referred to dermatology. The patient’s medical history included SCC and BCC on the face, both treated successfully with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Physical examination revealed a 2.6×1.1-cm, erythematous, nodular plaque in the coccygeal area of the intergluteal crease (Figure 1). A shave biopsy disclosed BCC, nodular type, ulcerated. Microscopically, there were nodular aggregates of basaloid cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and peripheral palisading, separated from mucinous stromal surroundings by artefactual clefts.

The initial differential diagnosis for this patient’s lesion included an ulcer or SCC. Basal cell carcinoma was not suspected due to the location and appearance of the lesion. The patient was successfully treated with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Practical Implications

Without thorough examination, this cancerous lesion would not have been seen (Figure 2). Therefore, it is important to practice thorough physical examination skills to avoid missing these cancers, particularly when examining a patient with a history of SCC or BCC. Furthermore, biopsy is recommended for suspicious lesions to rule out BCC.

Be careful not to get caught up in epidemiological or demographic considerations when making a diagnosis of this kind or when assessing the severity of a lesion. This patient, for instance, was female, which makes her less likely to present with BCC.8 Moreover, the cancer presented in a highly unlikely location for BCC, where there had not been significant sunburn.9 Patients and physicians should be educated about the incidence of BCC in unexpected areas; without a second and close look, this BCC could have been missed.

Final Thoughts

The literature continuously demonstrates the rarity of BCC in the intergluteal crease.10 However, when perianal BCC is properly identified and treated with local excision, prognosis is good.11 Basal cell carcinoma has been seen to arise in other sensitive locations; vulvar, nipple, and scrotal BCC neoplasms are among the uncommon locations where BCC has appeared.12 These areas are frequently—and easily—ignored. A total-body skin examination should be performed to ensure that these insidious-onset carcinomas are not overlooked to protect patients from the adverse consequences of untreated cancer.13

- Roewert-Huber J, Lange-Asschenfeldt B, Stockfleth E, et al. Epidemiology and aetiology of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(suppl 2):47-51.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Zanetti R, Rosso S, Martinez C, et al. Comparison of risk patterns in carcinoma and melanoma of the skin in men: a multi-centre case–case–control study. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:743-751.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Lorenzini M, Gatti S, Giannitrapani A. Giant basal cell carcinoma of the thoracic wall: a case report and review of the literature. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58:1007-1010.

- Lee HS, Kim SK. Basal cell carcinoma presenting as a perianal ulcer and treated with radiotherapy. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:212-214.

- Salih AM, Kakamad FH, Rauf GM. Basal cell carcinoma mimicking pilonidal sinus: a case report with literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;28:121-123.

- Scrivener Y, Grosshans E, Cribier B. Variations of basal cell carcinomas according to gender, age, location and histopathological subtype. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:41-47.

- Park J, Cho Y-S, Song K-H, et al. Basal cell carcinoma on the pubic area: report of a case and review of 19 Korean cases of BCC from non-sun-exposed areas. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:405-408.

- Damin DC, Rosito MA, Gus P, et al. Perianal basal cell carcinoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:26-28.

- Paterson CA, Young-Fadok TM, Dozois RR. Basal cell carcinoma of the perianal region: 20-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1200-1202.

- Mulvany NJ, Rayoo M, Allen DG. Basal cell carcinoma of the vulva: a case series. Pathology. 2012;44:528-533.

- Leonard D, Beddy D, Dozois EJ. Neoplasms of anal canal and perianal skin. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:54-63.