User login

Debunking Acne Myths: Is Itching a Symptom of Acne?

Myth: Itching is not a symptom of acne

Acne vulgaris typically is not considered to be a pruritic disease; however, many patients experience itching, which leads them to scratch their acne lesions, causing secondary bacterial infections and subsequent scarring, hypopigmentation, or hyperpigmentation of the involved skin. Although itching rarely is mentioned as a clinical feature of acne, pruritus can be an important contributory factor to the burden of disability and impaired quality of life in acne patients of all ages, and acne itching may be an important target for therapy.

In a descriptive study of 120 consecutive acne patients in Singapore, itch was found to be a common (70% of patients) and debilitating symptom of acne. The majority of patients (83%) reported itch at noon with severity that was comparable to a mosquito bite, and the most common physical descriptor was tickling (68%). Common aggravating factors included sweat (71%), heat (62%), and stress (31%). Fifty-five percent of patients said itching had a negative impact on their mood, and 52% reported that they had scratched or rubbed the affected area.

A study of 108 adolescents with acne limited to the face yielded half who reported itching within acne lesions. The presence of itching was unrelated to age, gender, where they lived, positive family history, or acne severity. In most patients, pruritus appeared relatively infrequently and for a short period of time: 7.4% reported itching every day, 24.1% on a weekly basis, 29.6% at least once a month, and 37.7% even less frequently. Itch episodes lasted less than 1 minute in most participants. However, 31.5% of participants sought medical treatment to reduce itching. The most important factors aggravating the intensity of itching were sweat, stress, physical effort, heat, fatigue, and dry air, respectively.

Regarding the impact of acne itching on quality of life, 29.6% of participants felt depressed and 1.8% were anxious because of their itching. Some participants also noted that itching caused difficulties in falling asleep and awakening from itching.

The pathogenesis of localized itching in acne could be connected with the change in pH of the microenvironment of the acne follicle, providing an optimal environment for the production of histamine or histaminelike products by Propionibacterium acnes. Pruritus also may be a complication of certain acne therapies. Increased awareness among patients of this potential side effect may be helpful in preventing the unnecessary discontinuation of an otherwise effective acne therapy. Understanding factors that may aggravate itching in acne lesions also may be helpful to patients.

Lim YL, Chan YH, Yosipovitch G, et al. Pruritus is a common and significant symptom of acne [published online July 8, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1332-1336.

Reich A, Trybucka K, Tracinska A, et al. Acne itch: do acne patients suffer from itching? Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:38-42.

Myth: Itching is not a symptom of acne

Acne vulgaris typically is not considered to be a pruritic disease; however, many patients experience itching, which leads them to scratch their acne lesions, causing secondary bacterial infections and subsequent scarring, hypopigmentation, or hyperpigmentation of the involved skin. Although itching rarely is mentioned as a clinical feature of acne, pruritus can be an important contributory factor to the burden of disability and impaired quality of life in acne patients of all ages, and acne itching may be an important target for therapy.

In a descriptive study of 120 consecutive acne patients in Singapore, itch was found to be a common (70% of patients) and debilitating symptom of acne. The majority of patients (83%) reported itch at noon with severity that was comparable to a mosquito bite, and the most common physical descriptor was tickling (68%). Common aggravating factors included sweat (71%), heat (62%), and stress (31%). Fifty-five percent of patients said itching had a negative impact on their mood, and 52% reported that they had scratched or rubbed the affected area.

A study of 108 adolescents with acne limited to the face yielded half who reported itching within acne lesions. The presence of itching was unrelated to age, gender, where they lived, positive family history, or acne severity. In most patients, pruritus appeared relatively infrequently and for a short period of time: 7.4% reported itching every day, 24.1% on a weekly basis, 29.6% at least once a month, and 37.7% even less frequently. Itch episodes lasted less than 1 minute in most participants. However, 31.5% of participants sought medical treatment to reduce itching. The most important factors aggravating the intensity of itching were sweat, stress, physical effort, heat, fatigue, and dry air, respectively.

Regarding the impact of acne itching on quality of life, 29.6% of participants felt depressed and 1.8% were anxious because of their itching. Some participants also noted that itching caused difficulties in falling asleep and awakening from itching.

The pathogenesis of localized itching in acne could be connected with the change in pH of the microenvironment of the acne follicle, providing an optimal environment for the production of histamine or histaminelike products by Propionibacterium acnes. Pruritus also may be a complication of certain acne therapies. Increased awareness among patients of this potential side effect may be helpful in preventing the unnecessary discontinuation of an otherwise effective acne therapy. Understanding factors that may aggravate itching in acne lesions also may be helpful to patients.

Myth: Itching is not a symptom of acne

Acne vulgaris typically is not considered to be a pruritic disease; however, many patients experience itching, which leads them to scratch their acne lesions, causing secondary bacterial infections and subsequent scarring, hypopigmentation, or hyperpigmentation of the involved skin. Although itching rarely is mentioned as a clinical feature of acne, pruritus can be an important contributory factor to the burden of disability and impaired quality of life in acne patients of all ages, and acne itching may be an important target for therapy.

In a descriptive study of 120 consecutive acne patients in Singapore, itch was found to be a common (70% of patients) and debilitating symptom of acne. The majority of patients (83%) reported itch at noon with severity that was comparable to a mosquito bite, and the most common physical descriptor was tickling (68%). Common aggravating factors included sweat (71%), heat (62%), and stress (31%). Fifty-five percent of patients said itching had a negative impact on their mood, and 52% reported that they had scratched or rubbed the affected area.

A study of 108 adolescents with acne limited to the face yielded half who reported itching within acne lesions. The presence of itching was unrelated to age, gender, where they lived, positive family history, or acne severity. In most patients, pruritus appeared relatively infrequently and for a short period of time: 7.4% reported itching every day, 24.1% on a weekly basis, 29.6% at least once a month, and 37.7% even less frequently. Itch episodes lasted less than 1 minute in most participants. However, 31.5% of participants sought medical treatment to reduce itching. The most important factors aggravating the intensity of itching were sweat, stress, physical effort, heat, fatigue, and dry air, respectively.

Regarding the impact of acne itching on quality of life, 29.6% of participants felt depressed and 1.8% were anxious because of their itching. Some participants also noted that itching caused difficulties in falling asleep and awakening from itching.

The pathogenesis of localized itching in acne could be connected with the change in pH of the microenvironment of the acne follicle, providing an optimal environment for the production of histamine or histaminelike products by Propionibacterium acnes. Pruritus also may be a complication of certain acne therapies. Increased awareness among patients of this potential side effect may be helpful in preventing the unnecessary discontinuation of an otherwise effective acne therapy. Understanding factors that may aggravate itching in acne lesions also may be helpful to patients.

Lim YL, Chan YH, Yosipovitch G, et al. Pruritus is a common and significant symptom of acne [published online July 8, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1332-1336.

Reich A, Trybucka K, Tracinska A, et al. Acne itch: do acne patients suffer from itching? Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:38-42.

Lim YL, Chan YH, Yosipovitch G, et al. Pruritus is a common and significant symptom of acne [published online July 8, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1332-1336.

Reich A, Trybucka K, Tracinska A, et al. Acne itch: do acne patients suffer from itching? Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:38-42.

Knotless Arthroscopic Reduction and Internal Fixation of a Displaced Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tibial Eminence Avulsion Fracture

Take-Home Points

- Technique provides optimal fixation while simultaneously protecting open growth plates.

- Self tensioning feature insures both optimal ACL tension and fracture reduction.

- No need for future hardware removal.

- 10Cross suture configuration optimizes strength of fixation for highly consistent results.

- Use fluoroscopy to avoid violation of tibial physis.

Generally occurring in the 8- to 14-year-old population, tibial eminence avulsion (TEA) fractures are a common variant of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) ruptures and represent 2% to 5% of all knee injuries in skeletally immature individuals.1,2 Compared with adults, children likely experience this anomaly more often because of the weakness of their incompletely ossified tibial plateau relative to the strength of their native ACL.3

The open repair techniques that have been described have multiple disadvantages, including open incisions, difficult visualization of the fracture owing to the location of the fat pad, and increased risk for arthrofibrosis. Arthroscopic fixation is considered the treatment of choice for TEA fractures because it allows for direct visualization of injury, accurate reduction of fracture fragments, removal of loose fragments, and easy treatment of associated soft-tissue injuries.4-6Several fixation techniques for ACL-TEA fractures were recently described: arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation (ARIF) with Kirschner wires,7 cannulated screws,4 the Meniscus Arrow device (Bionx Implants),8 pull-out sutures,9,10 bioabsorbable nails,11 Herbert screws,12 TightRope fixation (Arthrex),13 and various other rotator cuff and meniscal repair systems.14,15 These approaches tend to have good outcomes for TEA fractures, but there are risks associated with ACL tensioning and potential tibial growth plate violation or hardware problems. Likewise, there are no studies with large numbers of patients treated with these new techniques, so the optimal method of reduction and fixation is still unknown.

In this article, we describe a new ARIF technique that involves 2 absorbable anchors with adjustable suture-tensioning technology. This technique optimizes reduction and helps surgeons avoid proximal tibial physeal damage, procedure-related morbidity, and additional surgery.

Case Report

History

The patient, an 8-year-old boy, sustained a noncontact twisting injury of the left knee during a cutting maneuver in a flag football game. He experienced immediate pain and subsequent swelling. Clinical examination revealed a moderate effusion with motion limitations secondary to swelling and irritability. The patient’s Lachman test result was 2+. Pivot shift testing was not possible because of guarding. The knee was stable to varus and valgus stress at 0° and 30° of flexion. Limited knee flexion prohibited placement of the patient in the position needed for anterior and posterior drawer testing. His patella was stable on lateral stress testing at 20° of flexion with no apprehension. Neurovascular status was intact throughout the lower extremity.

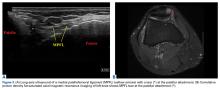

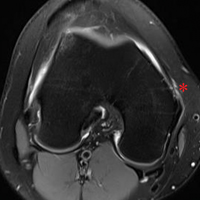

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs showed a minimally displaced Meyers-McKeever type II TEA fracture (Figures 1A, 1B).

After discussing potential treatment options with the parents, Dr. Smith proceeded with arthroscopic surgery for definitive reduction and internal fixation of the patient’s left knee displaced ACL-TEA fracture. The new adjustable suture-tensioning fixation technique was used. The patient’s guardian provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Examination Under Anesthesia

Examination with the patient under general anesthesia revealed 3+ Lachman, 2+ pivot shift with foot in internal and external rotation, and 1+ anterior drawer with foot in neutral and internal rotation. The knee was stable to varus and valgus stress testing.

Surgical Technique

Proper patient positioning and padding of bony prominences were ensured, and the limb was sterilely prepared and draped.

Given the young age of the patient, it was imperative to avoid the open proximal tibial growth plate. The surgical plan for stabilization involved use of two 3.0-mm BioComposite Knotless SutureTak anchors (Arthrex). This anchor configuration is based on a No. 2 FiberWire suture shuttled through itself to create a locking splice mechanism that allows for adjustable tensioning. The anchors were placed on each side of the tibial bony avulsion site with two No. 2 FiberWire sutures and were then crossed about the avulsion fracture fragment in an “x-type” configuration to secure the ACL back down to the bony bed.

First, a curette was used to débride fibrous tissue on the underside of the fracture fragment and on the fracture bed. Minimal amounts of cancellous bone were débrided from the tibial fracture bed to optimize fracture reduction by slightly recessing the fracture fragment to ensure optimal ACL tensioning (Figure 5).

Next, from the accessory superior medial portal, the end of the wire that had been passed through the medial aspect of the bony avulsion was retrieved through the lateral portal. This wire was used to shuttle the repair suture from the laterally positioned SutureTak anchor over and through the medial aspect of the bony fragment out of the accessory superior medial (Figure 7).

Follow-Up

Two weeks after surgery, the patient returned to clinic for suture removal. Four weeks after surgery, radiographs confirmed anatomical reduction of the TEA fracture, and outpatient physical therapy (range-of-motion exercises as tolerated) and isometric quadriceps strengthening were instituted. Twelve weeks after surgery, examination revealed full knee motion, negative Lachman and pivot shift test results, and residual quadriceps muscle atrophy, and radiographs confirmed complete fracture healing with maintenance of a normal proximal tibial growth plate (Figures 10A, 10B).

Discussion

The highlight of this case is the simplicity of an excellent reduction of a displaced ACL-TEA fracture. Minimally invasive absorbable implants did not violate the proximal tibial physis, and the unique adjustable suture-tensioning technology allowed the degree of reduction and ACL tension to be “dialed in.” SutureTak implants have strong No. 2 FiberWire suture for excellent stability with an overall small suture load, and their small size avoids the risk of violating the proximal tibial physis and avoids potential growth disturbances.

Despite the obvious risks it poses to the open proximal tibial physis, surgical reduction of Meyers-McKeever type II and type III fractures is the norm for restoring ACL stability. Screws and suture fixation are the most common and reliable methods of TEA fracture reduction.16,17 In recent systematic reviews, however, Osti and colleagues17 and Gans and colleagues18 noted there is not enough evidence to warrant a “gold standard” in pediatric tibial avulsion cases.

Other fixation methods for TEA fractures must be investigated. Anderson and colleagues19 described the biomechanics of 4 different physeal-sparing avulsion fracture reduction techniques: an ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) suture-suture button, a suture anchor, a polydioxanone suture-suture button, and screw fixation. Using techniques described by Kocher and colleagues,4 Berg,20 Mah and colleagues,21 Vega and colleagues,22 and Lu and colleagues,23 Anderson and colleagues19 reduced TEA fractures in skeletally immature porcine knees. Compared with suture anchors, UHMWPE suture-suture buttons provided biomechanically superior cyclic and load-to-failure results as well as more consistent fixation.

Screw fixation has shown good results but has disadvantages. Incorrect positioning of a screw can lead to impingement and articular cartilage damage, and screw removal may be needed if discomfort at the fixation site persists.24,25 Likewise, screws generally are an option only for large fracture fragments, as there is an inherent risk of fracturing small TEA fractures, which can be common in skeletally immature patients.

Brunner and colleagues26 recently found that TEA fracture repair with absorbable sutures and distal bone bridge fixation yielded 3-month radiographic and clinical healing rates similar to those obtained with nonabsorbable sutures tied around a screw. However, other authors have reported growth disturbances with use of a similar technique, owing to a disturbance of the open proximal tibial growth plate.9 In that regard, a major advantage of this new knotless suturing technique is that distal fixation is not necessary.

The minimally invasive TEA fraction reduction technique described in this article has 6 advantages: It provides excellent fixation while avoiding proximal tibial growth plate injury; the degree of tensioning is easily controlled during reduction; it uses strong suture instead of metal screws or pins; the reduction construct is low-profile; distal fixation is unnecessary; and implant removal is unnecessary, thus limiting subsequent surgical intervention. With respect to long-term outcomes, however, it is not known how this procedure will compare with other commonly used ARIF methods in physeal-sparing techniques for TEA fracture fixation.

This case report highlights a novel pediatric displaced ACL-TEA fracture reduction technique that allows for adjustable reduction and resultant ACL tensioning with excellent strong suture fixation without violating the proximal tibial physis, which could make it invaluable in the surgical treatment of this injury in skeletally immature patients.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(4):203-208. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Eiskjaer S, Larsen ST, Schmidt MB. The significance of hemarthrosis of the knee in children. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1988;107(2):96-98.

2. Luhmann SJ. Acute traumatic knee effusions in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23(2):199-202.

3. Woo SL, Hollis JM, Adams DJ, Lyon RM, Takai S. Tensile properties of the human femur-anterior cruciate ligament-tibia complex. The effects of specimen age and orientation. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(3):217-225.

4. Kocher MS, Foreman ES, Micheli LJ. Laxity and functional outcome after arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation of displaced tibial spine fractures in children. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(10):1085-1090.

5. Lubowitz JH, Elson WS, Guttmann D. Part II: arthroscopic treatment of tibial plateau fractures: intercondylar eminence avulsion fractures. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(1):86-92.

6. Vargas B, Lutz N, Dutoit M, Zambelli PY. Nonunion after fracture of the anterior tibial spine: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2009;18(2):90-92.

7. Sommerfeldt DW. Arthroscopically assisted internal fixation of avulsion fractures of the anterior cruciate ligament during childhood and adolescence [in German]. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2008;20(4-5):310-320.

8. Wouters DB, de Graaf JS, Hemmer PH, Burgerhof JG, Kramer WL. The arthroscopic treatment of displaced tibial spine fractures in children and adolescents using Meniscus Arrows®. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(5):736-739.

9. Ahn JH, Yoo JC. Clinical outcome of arthroscopic reduction and suture for displaced acute and chronic tibial spine fractures. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005;13(2):116-121.

10. Huang TW, Hsu KY, Cheng CY, et al. Arthroscopic suture fixation of tibial eminence avulsion fractures. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(11):1232-1238.

11. Liljeros K, Werner S, Janarv PM. Arthroscopic fixation of anterior tibial spine fractures with bioabsorbable nails in skeletally immature patients. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):923-928.

12. Wiegand N, Naumov I, Vamhidy L, Not LG. Arthroscopic treatment of tibial spine fracture in children with a cannulated Herbert screw. Knee. 2014;21(2):481-485.

13. Faivre B, Benea H, Klouche S, Lespagnol F, Bauer T, Hardy P. An original arthroscopic fixation of adult’s tibial eminence fractures using the Tightrope® device: a report of 8 cases and review of literature. Knee. 2014;21(4):833-839.

14. Kluemper CT, Snyder GM, Coats AC, Johnson DL, Mair SD. Arthroscopic suture fixation of tibial eminence fractures. Orthopedics. 2013;36(11):e1401-e1406.

15. Ochiai S, Hagino T, Watanabe Y, Senga S, Haro H. One strategy for arthroscopic suture fixation of tibial intercondylar eminence fractures using the Meniscal Viper Repair System. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2011;3:17.

16. Bogunovic L, Tarabichi M, Harris D, Wright R. Treatment of tibial eminence fractures: a systematic review. J Knee Surg. 2015;28(3):255-262.

17. Osti L, Buda M, Soldati F, Del Buono A, Osti R, Maffulli N. Arthroscopic treatment of tibial eminence fracture: a systematic review of different fixation methods. Br Med Bull. 2016;118(1):73-90.

18. Gans I, Baldwin KD, Ganley TJ. Treatment and management outcomes of tibial eminence fractures in pediatric patients: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(7):1743-1750.

19. Anderson CN, Nyman JS, McCullough KA, et al. Biomechanical evaluation of physeal-sparing fixation methods in tibial eminence fractures. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1586-1594.

20. Berg EE. Pediatric tibial eminence fractures: arthroscopic cannulated screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(3):328-331.

21. Mah JY, Otsuka NY, McLean J. An arthroscopic technique for the reduction and fixation of tibial-eminence fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 1996;16(1):119-121.

22. Vega JR, Irribarra LA, Baar AK, Iniguez M, Salgado M, Gana N. Arthroscopic fixation of displaced tibial eminence fractures: a new growth plate-sparing method. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(11):1239-1243.

23. Lu XW, Hu XP, Jin C, Zhu T, Ding Y, Dai LY. Reduction and fixation of the avulsion fracture of the tibial eminence using mini-open technique. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(11):1476-1480.

24. Bonin N, Jeunet L, Obert L, Dejour D. Adult tibial eminence fracture fixation: arthroscopic procedure using K-wire folded fixation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(7):857-862.

25. Senekovic V, Veselko M. Anterograde arthroscopic fixation of avulsion fractures of the tibial eminence with a cannulated screw: five-year results. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(1):54-61.

26. Brunner S, Vavken P, Kilger R, et al. Absorbable and non-absorbable suture fixation results in similar outcomes for tibial eminence fractures in children and adolescents. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(3):723-729.

Take-Home Points

- Technique provides optimal fixation while simultaneously protecting open growth plates.

- Self tensioning feature insures both optimal ACL tension and fracture reduction.

- No need for future hardware removal.

- 10Cross suture configuration optimizes strength of fixation for highly consistent results.

- Use fluoroscopy to avoid violation of tibial physis.

Generally occurring in the 8- to 14-year-old population, tibial eminence avulsion (TEA) fractures are a common variant of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) ruptures and represent 2% to 5% of all knee injuries in skeletally immature individuals.1,2 Compared with adults, children likely experience this anomaly more often because of the weakness of their incompletely ossified tibial plateau relative to the strength of their native ACL.3

The open repair techniques that have been described have multiple disadvantages, including open incisions, difficult visualization of the fracture owing to the location of the fat pad, and increased risk for arthrofibrosis. Arthroscopic fixation is considered the treatment of choice for TEA fractures because it allows for direct visualization of injury, accurate reduction of fracture fragments, removal of loose fragments, and easy treatment of associated soft-tissue injuries.4-6Several fixation techniques for ACL-TEA fractures were recently described: arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation (ARIF) with Kirschner wires,7 cannulated screws,4 the Meniscus Arrow device (Bionx Implants),8 pull-out sutures,9,10 bioabsorbable nails,11 Herbert screws,12 TightRope fixation (Arthrex),13 and various other rotator cuff and meniscal repair systems.14,15 These approaches tend to have good outcomes for TEA fractures, but there are risks associated with ACL tensioning and potential tibial growth plate violation or hardware problems. Likewise, there are no studies with large numbers of patients treated with these new techniques, so the optimal method of reduction and fixation is still unknown.

In this article, we describe a new ARIF technique that involves 2 absorbable anchors with adjustable suture-tensioning technology. This technique optimizes reduction and helps surgeons avoid proximal tibial physeal damage, procedure-related morbidity, and additional surgery.

Case Report

History

The patient, an 8-year-old boy, sustained a noncontact twisting injury of the left knee during a cutting maneuver in a flag football game. He experienced immediate pain and subsequent swelling. Clinical examination revealed a moderate effusion with motion limitations secondary to swelling and irritability. The patient’s Lachman test result was 2+. Pivot shift testing was not possible because of guarding. The knee was stable to varus and valgus stress at 0° and 30° of flexion. Limited knee flexion prohibited placement of the patient in the position needed for anterior and posterior drawer testing. His patella was stable on lateral stress testing at 20° of flexion with no apprehension. Neurovascular status was intact throughout the lower extremity.

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs showed a minimally displaced Meyers-McKeever type II TEA fracture (Figures 1A, 1B).

After discussing potential treatment options with the parents, Dr. Smith proceeded with arthroscopic surgery for definitive reduction and internal fixation of the patient’s left knee displaced ACL-TEA fracture. The new adjustable suture-tensioning fixation technique was used. The patient’s guardian provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Examination Under Anesthesia

Examination with the patient under general anesthesia revealed 3+ Lachman, 2+ pivot shift with foot in internal and external rotation, and 1+ anterior drawer with foot in neutral and internal rotation. The knee was stable to varus and valgus stress testing.

Surgical Technique

Proper patient positioning and padding of bony prominences were ensured, and the limb was sterilely prepared and draped.

Given the young age of the patient, it was imperative to avoid the open proximal tibial growth plate. The surgical plan for stabilization involved use of two 3.0-mm BioComposite Knotless SutureTak anchors (Arthrex). This anchor configuration is based on a No. 2 FiberWire suture shuttled through itself to create a locking splice mechanism that allows for adjustable tensioning. The anchors were placed on each side of the tibial bony avulsion site with two No. 2 FiberWire sutures and were then crossed about the avulsion fracture fragment in an “x-type” configuration to secure the ACL back down to the bony bed.

First, a curette was used to débride fibrous tissue on the underside of the fracture fragment and on the fracture bed. Minimal amounts of cancellous bone were débrided from the tibial fracture bed to optimize fracture reduction by slightly recessing the fracture fragment to ensure optimal ACL tensioning (Figure 5).

Next, from the accessory superior medial portal, the end of the wire that had been passed through the medial aspect of the bony avulsion was retrieved through the lateral portal. This wire was used to shuttle the repair suture from the laterally positioned SutureTak anchor over and through the medial aspect of the bony fragment out of the accessory superior medial (Figure 7).

Follow-Up

Two weeks after surgery, the patient returned to clinic for suture removal. Four weeks after surgery, radiographs confirmed anatomical reduction of the TEA fracture, and outpatient physical therapy (range-of-motion exercises as tolerated) and isometric quadriceps strengthening were instituted. Twelve weeks after surgery, examination revealed full knee motion, negative Lachman and pivot shift test results, and residual quadriceps muscle atrophy, and radiographs confirmed complete fracture healing with maintenance of a normal proximal tibial growth plate (Figures 10A, 10B).

Discussion

The highlight of this case is the simplicity of an excellent reduction of a displaced ACL-TEA fracture. Minimally invasive absorbable implants did not violate the proximal tibial physis, and the unique adjustable suture-tensioning technology allowed the degree of reduction and ACL tension to be “dialed in.” SutureTak implants have strong No. 2 FiberWire suture for excellent stability with an overall small suture load, and their small size avoids the risk of violating the proximal tibial physis and avoids potential growth disturbances.

Despite the obvious risks it poses to the open proximal tibial physis, surgical reduction of Meyers-McKeever type II and type III fractures is the norm for restoring ACL stability. Screws and suture fixation are the most common and reliable methods of TEA fracture reduction.16,17 In recent systematic reviews, however, Osti and colleagues17 and Gans and colleagues18 noted there is not enough evidence to warrant a “gold standard” in pediatric tibial avulsion cases.

Other fixation methods for TEA fractures must be investigated. Anderson and colleagues19 described the biomechanics of 4 different physeal-sparing avulsion fracture reduction techniques: an ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) suture-suture button, a suture anchor, a polydioxanone suture-suture button, and screw fixation. Using techniques described by Kocher and colleagues,4 Berg,20 Mah and colleagues,21 Vega and colleagues,22 and Lu and colleagues,23 Anderson and colleagues19 reduced TEA fractures in skeletally immature porcine knees. Compared with suture anchors, UHMWPE suture-suture buttons provided biomechanically superior cyclic and load-to-failure results as well as more consistent fixation.

Screw fixation has shown good results but has disadvantages. Incorrect positioning of a screw can lead to impingement and articular cartilage damage, and screw removal may be needed if discomfort at the fixation site persists.24,25 Likewise, screws generally are an option only for large fracture fragments, as there is an inherent risk of fracturing small TEA fractures, which can be common in skeletally immature patients.

Brunner and colleagues26 recently found that TEA fracture repair with absorbable sutures and distal bone bridge fixation yielded 3-month radiographic and clinical healing rates similar to those obtained with nonabsorbable sutures tied around a screw. However, other authors have reported growth disturbances with use of a similar technique, owing to a disturbance of the open proximal tibial growth plate.9 In that regard, a major advantage of this new knotless suturing technique is that distal fixation is not necessary.

The minimally invasive TEA fraction reduction technique described in this article has 6 advantages: It provides excellent fixation while avoiding proximal tibial growth plate injury; the degree of tensioning is easily controlled during reduction; it uses strong suture instead of metal screws or pins; the reduction construct is low-profile; distal fixation is unnecessary; and implant removal is unnecessary, thus limiting subsequent surgical intervention. With respect to long-term outcomes, however, it is not known how this procedure will compare with other commonly used ARIF methods in physeal-sparing techniques for TEA fracture fixation.

This case report highlights a novel pediatric displaced ACL-TEA fracture reduction technique that allows for adjustable reduction and resultant ACL tensioning with excellent strong suture fixation without violating the proximal tibial physis, which could make it invaluable in the surgical treatment of this injury in skeletally immature patients.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(4):203-208. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

Take-Home Points

- Technique provides optimal fixation while simultaneously protecting open growth plates.

- Self tensioning feature insures both optimal ACL tension and fracture reduction.

- No need for future hardware removal.

- 10Cross suture configuration optimizes strength of fixation for highly consistent results.

- Use fluoroscopy to avoid violation of tibial physis.

Generally occurring in the 8- to 14-year-old population, tibial eminence avulsion (TEA) fractures are a common variant of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) ruptures and represent 2% to 5% of all knee injuries in skeletally immature individuals.1,2 Compared with adults, children likely experience this anomaly more often because of the weakness of their incompletely ossified tibial plateau relative to the strength of their native ACL.3

The open repair techniques that have been described have multiple disadvantages, including open incisions, difficult visualization of the fracture owing to the location of the fat pad, and increased risk for arthrofibrosis. Arthroscopic fixation is considered the treatment of choice for TEA fractures because it allows for direct visualization of injury, accurate reduction of fracture fragments, removal of loose fragments, and easy treatment of associated soft-tissue injuries.4-6Several fixation techniques for ACL-TEA fractures were recently described: arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation (ARIF) with Kirschner wires,7 cannulated screws,4 the Meniscus Arrow device (Bionx Implants),8 pull-out sutures,9,10 bioabsorbable nails,11 Herbert screws,12 TightRope fixation (Arthrex),13 and various other rotator cuff and meniscal repair systems.14,15 These approaches tend to have good outcomes for TEA fractures, but there are risks associated with ACL tensioning and potential tibial growth plate violation or hardware problems. Likewise, there are no studies with large numbers of patients treated with these new techniques, so the optimal method of reduction and fixation is still unknown.

In this article, we describe a new ARIF technique that involves 2 absorbable anchors with adjustable suture-tensioning technology. This technique optimizes reduction and helps surgeons avoid proximal tibial physeal damage, procedure-related morbidity, and additional surgery.

Case Report

History

The patient, an 8-year-old boy, sustained a noncontact twisting injury of the left knee during a cutting maneuver in a flag football game. He experienced immediate pain and subsequent swelling. Clinical examination revealed a moderate effusion with motion limitations secondary to swelling and irritability. The patient’s Lachman test result was 2+. Pivot shift testing was not possible because of guarding. The knee was stable to varus and valgus stress at 0° and 30° of flexion. Limited knee flexion prohibited placement of the patient in the position needed for anterior and posterior drawer testing. His patella was stable on lateral stress testing at 20° of flexion with no apprehension. Neurovascular status was intact throughout the lower extremity.

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs showed a minimally displaced Meyers-McKeever type II TEA fracture (Figures 1A, 1B).

After discussing potential treatment options with the parents, Dr. Smith proceeded with arthroscopic surgery for definitive reduction and internal fixation of the patient’s left knee displaced ACL-TEA fracture. The new adjustable suture-tensioning fixation technique was used. The patient’s guardian provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Examination Under Anesthesia

Examination with the patient under general anesthesia revealed 3+ Lachman, 2+ pivot shift with foot in internal and external rotation, and 1+ anterior drawer with foot in neutral and internal rotation. The knee was stable to varus and valgus stress testing.

Surgical Technique

Proper patient positioning and padding of bony prominences were ensured, and the limb was sterilely prepared and draped.

Given the young age of the patient, it was imperative to avoid the open proximal tibial growth plate. The surgical plan for stabilization involved use of two 3.0-mm BioComposite Knotless SutureTak anchors (Arthrex). This anchor configuration is based on a No. 2 FiberWire suture shuttled through itself to create a locking splice mechanism that allows for adjustable tensioning. The anchors were placed on each side of the tibial bony avulsion site with two No. 2 FiberWire sutures and were then crossed about the avulsion fracture fragment in an “x-type” configuration to secure the ACL back down to the bony bed.

First, a curette was used to débride fibrous tissue on the underside of the fracture fragment and on the fracture bed. Minimal amounts of cancellous bone were débrided from the tibial fracture bed to optimize fracture reduction by slightly recessing the fracture fragment to ensure optimal ACL tensioning (Figure 5).

Next, from the accessory superior medial portal, the end of the wire that had been passed through the medial aspect of the bony avulsion was retrieved through the lateral portal. This wire was used to shuttle the repair suture from the laterally positioned SutureTak anchor over and through the medial aspect of the bony fragment out of the accessory superior medial (Figure 7).

Follow-Up

Two weeks after surgery, the patient returned to clinic for suture removal. Four weeks after surgery, radiographs confirmed anatomical reduction of the TEA fracture, and outpatient physical therapy (range-of-motion exercises as tolerated) and isometric quadriceps strengthening were instituted. Twelve weeks after surgery, examination revealed full knee motion, negative Lachman and pivot shift test results, and residual quadriceps muscle atrophy, and radiographs confirmed complete fracture healing with maintenance of a normal proximal tibial growth plate (Figures 10A, 10B).

Discussion

The highlight of this case is the simplicity of an excellent reduction of a displaced ACL-TEA fracture. Minimally invasive absorbable implants did not violate the proximal tibial physis, and the unique adjustable suture-tensioning technology allowed the degree of reduction and ACL tension to be “dialed in.” SutureTak implants have strong No. 2 FiberWire suture for excellent stability with an overall small suture load, and their small size avoids the risk of violating the proximal tibial physis and avoids potential growth disturbances.

Despite the obvious risks it poses to the open proximal tibial physis, surgical reduction of Meyers-McKeever type II and type III fractures is the norm for restoring ACL stability. Screws and suture fixation are the most common and reliable methods of TEA fracture reduction.16,17 In recent systematic reviews, however, Osti and colleagues17 and Gans and colleagues18 noted there is not enough evidence to warrant a “gold standard” in pediatric tibial avulsion cases.

Other fixation methods for TEA fractures must be investigated. Anderson and colleagues19 described the biomechanics of 4 different physeal-sparing avulsion fracture reduction techniques: an ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) suture-suture button, a suture anchor, a polydioxanone suture-suture button, and screw fixation. Using techniques described by Kocher and colleagues,4 Berg,20 Mah and colleagues,21 Vega and colleagues,22 and Lu and colleagues,23 Anderson and colleagues19 reduced TEA fractures in skeletally immature porcine knees. Compared with suture anchors, UHMWPE suture-suture buttons provided biomechanically superior cyclic and load-to-failure results as well as more consistent fixation.

Screw fixation has shown good results but has disadvantages. Incorrect positioning of a screw can lead to impingement and articular cartilage damage, and screw removal may be needed if discomfort at the fixation site persists.24,25 Likewise, screws generally are an option only for large fracture fragments, as there is an inherent risk of fracturing small TEA fractures, which can be common in skeletally immature patients.

Brunner and colleagues26 recently found that TEA fracture repair with absorbable sutures and distal bone bridge fixation yielded 3-month radiographic and clinical healing rates similar to those obtained with nonabsorbable sutures tied around a screw. However, other authors have reported growth disturbances with use of a similar technique, owing to a disturbance of the open proximal tibial growth plate.9 In that regard, a major advantage of this new knotless suturing technique is that distal fixation is not necessary.

The minimally invasive TEA fraction reduction technique described in this article has 6 advantages: It provides excellent fixation while avoiding proximal tibial growth plate injury; the degree of tensioning is easily controlled during reduction; it uses strong suture instead of metal screws or pins; the reduction construct is low-profile; distal fixation is unnecessary; and implant removal is unnecessary, thus limiting subsequent surgical intervention. With respect to long-term outcomes, however, it is not known how this procedure will compare with other commonly used ARIF methods in physeal-sparing techniques for TEA fracture fixation.

This case report highlights a novel pediatric displaced ACL-TEA fracture reduction technique that allows for adjustable reduction and resultant ACL tensioning with excellent strong suture fixation without violating the proximal tibial physis, which could make it invaluable in the surgical treatment of this injury in skeletally immature patients.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(4):203-208. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Eiskjaer S, Larsen ST, Schmidt MB. The significance of hemarthrosis of the knee in children. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1988;107(2):96-98.

2. Luhmann SJ. Acute traumatic knee effusions in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23(2):199-202.

3. Woo SL, Hollis JM, Adams DJ, Lyon RM, Takai S. Tensile properties of the human femur-anterior cruciate ligament-tibia complex. The effects of specimen age and orientation. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(3):217-225.

4. Kocher MS, Foreman ES, Micheli LJ. Laxity and functional outcome after arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation of displaced tibial spine fractures in children. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(10):1085-1090.

5. Lubowitz JH, Elson WS, Guttmann D. Part II: arthroscopic treatment of tibial plateau fractures: intercondylar eminence avulsion fractures. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(1):86-92.

6. Vargas B, Lutz N, Dutoit M, Zambelli PY. Nonunion after fracture of the anterior tibial spine: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2009;18(2):90-92.

7. Sommerfeldt DW. Arthroscopically assisted internal fixation of avulsion fractures of the anterior cruciate ligament during childhood and adolescence [in German]. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2008;20(4-5):310-320.

8. Wouters DB, de Graaf JS, Hemmer PH, Burgerhof JG, Kramer WL. The arthroscopic treatment of displaced tibial spine fractures in children and adolescents using Meniscus Arrows®. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(5):736-739.

9. Ahn JH, Yoo JC. Clinical outcome of arthroscopic reduction and suture for displaced acute and chronic tibial spine fractures. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005;13(2):116-121.

10. Huang TW, Hsu KY, Cheng CY, et al. Arthroscopic suture fixation of tibial eminence avulsion fractures. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(11):1232-1238.

11. Liljeros K, Werner S, Janarv PM. Arthroscopic fixation of anterior tibial spine fractures with bioabsorbable nails in skeletally immature patients. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):923-928.

12. Wiegand N, Naumov I, Vamhidy L, Not LG. Arthroscopic treatment of tibial spine fracture in children with a cannulated Herbert screw. Knee. 2014;21(2):481-485.

13. Faivre B, Benea H, Klouche S, Lespagnol F, Bauer T, Hardy P. An original arthroscopic fixation of adult’s tibial eminence fractures using the Tightrope® device: a report of 8 cases and review of literature. Knee. 2014;21(4):833-839.

14. Kluemper CT, Snyder GM, Coats AC, Johnson DL, Mair SD. Arthroscopic suture fixation of tibial eminence fractures. Orthopedics. 2013;36(11):e1401-e1406.

15. Ochiai S, Hagino T, Watanabe Y, Senga S, Haro H. One strategy for arthroscopic suture fixation of tibial intercondylar eminence fractures using the Meniscal Viper Repair System. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2011;3:17.

16. Bogunovic L, Tarabichi M, Harris D, Wright R. Treatment of tibial eminence fractures: a systematic review. J Knee Surg. 2015;28(3):255-262.

17. Osti L, Buda M, Soldati F, Del Buono A, Osti R, Maffulli N. Arthroscopic treatment of tibial eminence fracture: a systematic review of different fixation methods. Br Med Bull. 2016;118(1):73-90.

18. Gans I, Baldwin KD, Ganley TJ. Treatment and management outcomes of tibial eminence fractures in pediatric patients: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(7):1743-1750.

19. Anderson CN, Nyman JS, McCullough KA, et al. Biomechanical evaluation of physeal-sparing fixation methods in tibial eminence fractures. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1586-1594.

20. Berg EE. Pediatric tibial eminence fractures: arthroscopic cannulated screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(3):328-331.

21. Mah JY, Otsuka NY, McLean J. An arthroscopic technique for the reduction and fixation of tibial-eminence fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 1996;16(1):119-121.

22. Vega JR, Irribarra LA, Baar AK, Iniguez M, Salgado M, Gana N. Arthroscopic fixation of displaced tibial eminence fractures: a new growth plate-sparing method. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(11):1239-1243.

23. Lu XW, Hu XP, Jin C, Zhu T, Ding Y, Dai LY. Reduction and fixation of the avulsion fracture of the tibial eminence using mini-open technique. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(11):1476-1480.

24. Bonin N, Jeunet L, Obert L, Dejour D. Adult tibial eminence fracture fixation: arthroscopic procedure using K-wire folded fixation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(7):857-862.

25. Senekovic V, Veselko M. Anterograde arthroscopic fixation of avulsion fractures of the tibial eminence with a cannulated screw: five-year results. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(1):54-61.

26. Brunner S, Vavken P, Kilger R, et al. Absorbable and non-absorbable suture fixation results in similar outcomes for tibial eminence fractures in children and adolescents. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(3):723-729.

1. Eiskjaer S, Larsen ST, Schmidt MB. The significance of hemarthrosis of the knee in children. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1988;107(2):96-98.

2. Luhmann SJ. Acute traumatic knee effusions in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23(2):199-202.

3. Woo SL, Hollis JM, Adams DJ, Lyon RM, Takai S. Tensile properties of the human femur-anterior cruciate ligament-tibia complex. The effects of specimen age and orientation. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(3):217-225.

4. Kocher MS, Foreman ES, Micheli LJ. Laxity and functional outcome after arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation of displaced tibial spine fractures in children. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(10):1085-1090.

5. Lubowitz JH, Elson WS, Guttmann D. Part II: arthroscopic treatment of tibial plateau fractures: intercondylar eminence avulsion fractures. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(1):86-92.

6. Vargas B, Lutz N, Dutoit M, Zambelli PY. Nonunion after fracture of the anterior tibial spine: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2009;18(2):90-92.

7. Sommerfeldt DW. Arthroscopically assisted internal fixation of avulsion fractures of the anterior cruciate ligament during childhood and adolescence [in German]. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2008;20(4-5):310-320.

8. Wouters DB, de Graaf JS, Hemmer PH, Burgerhof JG, Kramer WL. The arthroscopic treatment of displaced tibial spine fractures in children and adolescents using Meniscus Arrows®. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(5):736-739.

9. Ahn JH, Yoo JC. Clinical outcome of arthroscopic reduction and suture for displaced acute and chronic tibial spine fractures. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005;13(2):116-121.

10. Huang TW, Hsu KY, Cheng CY, et al. Arthroscopic suture fixation of tibial eminence avulsion fractures. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(11):1232-1238.

11. Liljeros K, Werner S, Janarv PM. Arthroscopic fixation of anterior tibial spine fractures with bioabsorbable nails in skeletally immature patients. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):923-928.

12. Wiegand N, Naumov I, Vamhidy L, Not LG. Arthroscopic treatment of tibial spine fracture in children with a cannulated Herbert screw. Knee. 2014;21(2):481-485.

13. Faivre B, Benea H, Klouche S, Lespagnol F, Bauer T, Hardy P. An original arthroscopic fixation of adult’s tibial eminence fractures using the Tightrope® device: a report of 8 cases and review of literature. Knee. 2014;21(4):833-839.

14. Kluemper CT, Snyder GM, Coats AC, Johnson DL, Mair SD. Arthroscopic suture fixation of tibial eminence fractures. Orthopedics. 2013;36(11):e1401-e1406.

15. Ochiai S, Hagino T, Watanabe Y, Senga S, Haro H. One strategy for arthroscopic suture fixation of tibial intercondylar eminence fractures using the Meniscal Viper Repair System. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2011;3:17.

16. Bogunovic L, Tarabichi M, Harris D, Wright R. Treatment of tibial eminence fractures: a systematic review. J Knee Surg. 2015;28(3):255-262.

17. Osti L, Buda M, Soldati F, Del Buono A, Osti R, Maffulli N. Arthroscopic treatment of tibial eminence fracture: a systematic review of different fixation methods. Br Med Bull. 2016;118(1):73-90.

18. Gans I, Baldwin KD, Ganley TJ. Treatment and management outcomes of tibial eminence fractures in pediatric patients: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(7):1743-1750.

19. Anderson CN, Nyman JS, McCullough KA, et al. Biomechanical evaluation of physeal-sparing fixation methods in tibial eminence fractures. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1586-1594.

20. Berg EE. Pediatric tibial eminence fractures: arthroscopic cannulated screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(3):328-331.

21. Mah JY, Otsuka NY, McLean J. An arthroscopic technique for the reduction and fixation of tibial-eminence fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 1996;16(1):119-121.

22. Vega JR, Irribarra LA, Baar AK, Iniguez M, Salgado M, Gana N. Arthroscopic fixation of displaced tibial eminence fractures: a new growth plate-sparing method. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(11):1239-1243.

23. Lu XW, Hu XP, Jin C, Zhu T, Ding Y, Dai LY. Reduction and fixation of the avulsion fracture of the tibial eminence using mini-open technique. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(11):1476-1480.

24. Bonin N, Jeunet L, Obert L, Dejour D. Adult tibial eminence fracture fixation: arthroscopic procedure using K-wire folded fixation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(7):857-862.

25. Senekovic V, Veselko M. Anterograde arthroscopic fixation of avulsion fractures of the tibial eminence with a cannulated screw: five-year results. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(1):54-61.

26. Brunner S, Vavken P, Kilger R, et al. Absorbable and non-absorbable suture fixation results in similar outcomes for tibial eminence fractures in children and adolescents. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(3):723-729.

A New Option for Glenoid Reconstruction in Recurrent Anterior Shoulder Instability

Take-Home Points

- Repair anterior bone defect on the glenoid related to recurrent anterior instability with preshaped, predrilled allograft.

- Avoid graft harvest complications related to coracoid (Latarjet) or iliac crest autograft.

- Simple guide system to allow for appropriate graft and screw placement.

- Soft tissues can be repaired to the allograft in predrilled suture holes either inside or outside of the graft

- Position the graft without step at the anterior glenoid.

Anteroinferior glenoid bone loss plays a significant role in recurrent glenohumeral instability. Arthroscopic capsulolabral reconstruction has been associated with a recurrence rate of 4% in the absence of significant glenoid bone loss but 67% in patients with either bone loss of more than 25% of the inferior glenoid diameter or an engaging Hill-Sachs lesion.1,2 Anteroinferior glenoid rim deficiency has been reported in up to 90% of cases of recurrent instability.3 Glenoid reconstruction is therefore recommended in patients with bone loss of more than 25% and in certain revision cases.4 Surgical strategies in these cases include coracoid transfer, iliac crest autograft, and allograft (osteochondral and iliac crest). These procedures all successfully restore stability of the glenohumeral joint. However, they carry the drawbacks of technical complexity with increased operative time or risk of neurovascular damage, or they create a nonanatomical reconstruction, which may contribute to subsequent instability arthropathy. In this article, we introduce a technique in which a preshaped allograft (Glenojet; Arthrosurface, Inc.) is used to match the contour of the glenoid defect. The graft is simple to insert and can reduce operative time.

Graft Preparation

The shaped human tissue cortical bone allograft is usually prepared from proximal or distal tibia or femur. There is no cartilage on the graft. It can be ordered in 2 sizes, 10 mm × 29 mm and 13 mm × 34 mm, for different amounts of bone loss. The more commonly used smaller graft reconstructs defects of 20% to 30% of the glenoid.

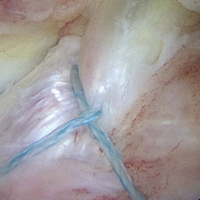

The sutures through this allograft can be prepared on the back table while the rest of the equipment is set up. Start by tying a No. 2 FiberWire (or equivalent) over a small thin object, such as a Freer elevator. Once the knot is secure, remove the Freer and trim the knot tails short. Thread another suture through the loop that has been created and pull to make the 2 tails even. Then thread these tails through one of the small holes of the graft, going from the flat side to the concave side. Pull the suture tails all the way through, including through the loop of the prior suture. The knot of the loop prevents the entire construct from pulling through. The suture tails are then able to slide as if attached to an anchor. Repeat these steps for the other 2 small holes to get a total of 3 sutures exiting the concave side of the graft (Figure 1). Alternatively, pass the suture the opposite way, if tying the capsule inside the graft is preferred.

Surgical Technique

A standard deltopectoral approach is used to expose the anterior glenoid. The subscapularis can either be split in line with its fibers or tenotomized with 1 cm to 2 cm attached to the tuberosity for later repair. In either instance, it is important to separate the muscle from the underlying capsule layer, as the capsule is what is directly repaired to the graft.

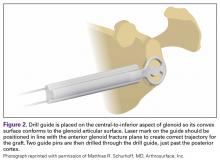

The capsule is carefully peeled off the anterior glenoid. A Fukuda or similar retractor may be used on the humerus, and a glenoid retractor is placed on the anterior glenoid, under the capsule and subscapularis, for optimal exposure. Once the anterior glenoid surface is exposed, the drill guide is placed flush against the surface of the glenoid.

The guide is removed. The cannulated reamer is introduced and advanced until the guide pin appears in the viewing window of the reamer and hits the stop—approximating the correct amount of bone to remove. This step is repeated for the second guide pin. Reaming flattens the anterior glenoid and allows for maximal stable apposition of the graft to the glenoid. The allograft is then inserted onto the pins in the correct orientation to match the surface of the native glenoid.

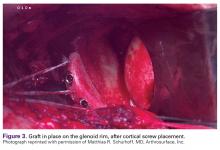

The length of the superior guide pin is measured with the depth gauge device. It is then removed, and the appropriate-length 3.5-mm cortical bone screw is inserted (alternatively, the guide pin is removed, and a standard depth gauge is used to measure screw length). Once the superior guide pin is secure, the process is repeated for the inferior guide pin (Figure 3).

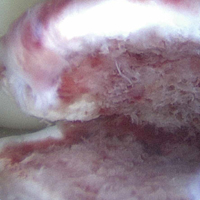

Once the graft is secure, the capsule is attached to the graft with the use of a free needle on the suture of the graft (Figure 4).

Outcomes

Coracoid bone transfer or the Bristow-Latarjet technique has become more popular since bone loss was recognized as an important cause of failure of soft-tissue repair for anterior instability. This procedure, however, is not without complications. In a recent systematic review of 45 studies (1904 shoulders), Griesser and colleagues5 found an overall complication rate of 30% and a reoperation rate of 7%.

Given the potential complications of coracoid bone transfer, allograft reconstruction of the anteroinferior glenoid has become increasingly popular and proved successful at short- and medium-term follow-up. Allograft reconstruction avoids the drawbacks of traditional coracoid bone transfer—namely, high rates of neurovascular injury, and nonanatomical reconstruction with high rates of graft resorption and arthritis.5,6 At average 45-month follow-up after fresh distal tibia allograft reconstruction, Provencher and colleagues7 found an 89% radiographic union rate (average lysis, 3%), significantly improved patient-reported outcomes, and no recurrent instability. Similarly, in a study of iliac crest allograft reconstruction in 10 patients with an average 4-year follow-up, Mascarenhas and colleagues8 found an 80% radiographic union rate at 6 months, significantly improved patient-reported outcomes, and no recurrent shoulder instability.

The advantage of Glenojet over other allografts is that it is preshaped and predrilled and saves the surgeon the time and effort of preparing graft in the operating room. The surgical technologist can place the sutures before the patient enters the room. The 2 allograft sizes (10 mm × 29 mm, 13 mm × 34 mm) accommodate the spectrum of bone loss in glenoid deficiency, and graft contour fits the native glenoid well. So far we have implanted this allograft in 15 patients, and at short-term follow-up there are no known cases of recurrent instability.

The potential disadvantages of Glenojet are similar to those of other allografts. Care must be taken with retractor placement to avoid damaging the axillary and musculocutaneous nerves. There are concerns about graft union and subsequent resorption, but this will require long-term follow-up to determine. At 9-month follow-up, we had 1 fracture at the superior corner of the graft, which may have resulted from overtightening the screws in the graft, creating a stress concentration. After removal of this fragment arthroscopically, the patient has done very well clinically with no pain, instability and has returned to all activities. Although the graft does not have an articular surface, the capsular repair covers much of the articular side of the graft, and therefore we do not anticipate that the absence of articular cartilage will contribute to glenohumeral arthritis, though long-term follow-up is lacking. The other question many have is related to the lack of the sling effect since there is no conjoined tendon on the graft. Yamamoto and colleagues9 have reported that the conjoined tendon is the major stabilizing force at time zero in a cadaver model. However, other authors7,8 have successfully reconstructed glenoid defects in these difficult cases without the “sling effect” of the conjoined tendon with excellent clinical results. Our experience has been similar. It is likely that long-term studies will be necessary to answer this question. We have also done some cases with the tendon attached after releasing it from the coracoid, but the series is too small to make any comment about whether this is important or not.

The main limitation of this allograft technique is the lack of long-term outcome studies. However, short-term results are promising, and the ease of the procedure makes it an attractive option for either glenoid reconstruction of bony Bankart lesions or failed bone reconstruction, such as Bristow-Latarjet reconstruction.

Glenojetallograft is a new glenoid reconstruction option that is technically easy and simple to perform in cases of glenoid bone loss, while still creating an anatomical buttress with less surgical dissection than traditional coracoid bone transfer. Short-term outcomes are reassuring, though more research is needed for long-term graft follow-up and recurrent instability.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(4):199-202. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Burkhart SS, De Beer JF. Traumatic glenohumeral bone defects and their relationship to failure of arthroscopic Bankart repairs: significance of the inverted-pear glenoid and the humeral engaging Hill-Sachs lesion. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(7):677-694.

2. Rowe CR, Sakellarides HT. Factors related to recurrences of anterior dislocations of the shoulder. Clin Orthop. 1961;(20):40-48.

3. Piasecki DP, Verma NN, Romeo AA, Levine WN, Bach BR Jr, Provencher MT. Glenoid bone deficiency in recurrent anterior shoulder instability: diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(8):482-493.

4. Sayegh ET, Mascarenhas R, Chalmers PN, Cole BJ, Verma NN, Romeo AA. Allograft reconstruction for glenoid bone loss in glenohumeral instability: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(12):1642-1649.

5. Griesser MJ, Harris JD, McCoy BW, et al. Complications and re-operati ons after Bristow-Latarjet shoulder stabilization: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(2):286-292.

6. Young DC, Rockwood CA Jr. Complications of a failed Bristow procedure and their management. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(7):969-981.

7. Provencher MT, Frank RM, Golijanin P, et al. Distal tibia allograft glenoid reconstruction in recurrent anterior shoulder instability: clinical and radiographic outcomes. Arthroscopy. 2017;33(5):891-897.

8. Mascarenhas R, Raleigh E, McRae S, Leiter J, Saltzman B, MacDonald PB. Iliac crest allograft glenoid reconstruction for recurrent anterior shoulder instability in athletes: surgical technique and results. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2014;8(4):127-132.

9. Yamamoto N, Muraki T, An KN, et al. The stabilizing mechanism of the Latarjet procedure: a cadaveric study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(15):1390-1397.

Take-Home Points

- Repair anterior bone defect on the glenoid related to recurrent anterior instability with preshaped, predrilled allograft.

- Avoid graft harvest complications related to coracoid (Latarjet) or iliac crest autograft.

- Simple guide system to allow for appropriate graft and screw placement.

- Soft tissues can be repaired to the allograft in predrilled suture holes either inside or outside of the graft

- Position the graft without step at the anterior glenoid.

Anteroinferior glenoid bone loss plays a significant role in recurrent glenohumeral instability. Arthroscopic capsulolabral reconstruction has been associated with a recurrence rate of 4% in the absence of significant glenoid bone loss but 67% in patients with either bone loss of more than 25% of the inferior glenoid diameter or an engaging Hill-Sachs lesion.1,2 Anteroinferior glenoid rim deficiency has been reported in up to 90% of cases of recurrent instability.3 Glenoid reconstruction is therefore recommended in patients with bone loss of more than 25% and in certain revision cases.4 Surgical strategies in these cases include coracoid transfer, iliac crest autograft, and allograft (osteochondral and iliac crest). These procedures all successfully restore stability of the glenohumeral joint. However, they carry the drawbacks of technical complexity with increased operative time or risk of neurovascular damage, or they create a nonanatomical reconstruction, which may contribute to subsequent instability arthropathy. In this article, we introduce a technique in which a preshaped allograft (Glenojet; Arthrosurface, Inc.) is used to match the contour of the glenoid defect. The graft is simple to insert and can reduce operative time.

Graft Preparation

The shaped human tissue cortical bone allograft is usually prepared from proximal or distal tibia or femur. There is no cartilage on the graft. It can be ordered in 2 sizes, 10 mm × 29 mm and 13 mm × 34 mm, for different amounts of bone loss. The more commonly used smaller graft reconstructs defects of 20% to 30% of the glenoid.

The sutures through this allograft can be prepared on the back table while the rest of the equipment is set up. Start by tying a No. 2 FiberWire (or equivalent) over a small thin object, such as a Freer elevator. Once the knot is secure, remove the Freer and trim the knot tails short. Thread another suture through the loop that has been created and pull to make the 2 tails even. Then thread these tails through one of the small holes of the graft, going from the flat side to the concave side. Pull the suture tails all the way through, including through the loop of the prior suture. The knot of the loop prevents the entire construct from pulling through. The suture tails are then able to slide as if attached to an anchor. Repeat these steps for the other 2 small holes to get a total of 3 sutures exiting the concave side of the graft (Figure 1). Alternatively, pass the suture the opposite way, if tying the capsule inside the graft is preferred.

Surgical Technique

A standard deltopectoral approach is used to expose the anterior glenoid. The subscapularis can either be split in line with its fibers or tenotomized with 1 cm to 2 cm attached to the tuberosity for later repair. In either instance, it is important to separate the muscle from the underlying capsule layer, as the capsule is what is directly repaired to the graft.

The capsule is carefully peeled off the anterior glenoid. A Fukuda or similar retractor may be used on the humerus, and a glenoid retractor is placed on the anterior glenoid, under the capsule and subscapularis, for optimal exposure. Once the anterior glenoid surface is exposed, the drill guide is placed flush against the surface of the glenoid.

The guide is removed. The cannulated reamer is introduced and advanced until the guide pin appears in the viewing window of the reamer and hits the stop—approximating the correct amount of bone to remove. This step is repeated for the second guide pin. Reaming flattens the anterior glenoid and allows for maximal stable apposition of the graft to the glenoid. The allograft is then inserted onto the pins in the correct orientation to match the surface of the native glenoid.

The length of the superior guide pin is measured with the depth gauge device. It is then removed, and the appropriate-length 3.5-mm cortical bone screw is inserted (alternatively, the guide pin is removed, and a standard depth gauge is used to measure screw length). Once the superior guide pin is secure, the process is repeated for the inferior guide pin (Figure 3).

Once the graft is secure, the capsule is attached to the graft with the use of a free needle on the suture of the graft (Figure 4).

Outcomes

Coracoid bone transfer or the Bristow-Latarjet technique has become more popular since bone loss was recognized as an important cause of failure of soft-tissue repair for anterior instability. This procedure, however, is not without complications. In a recent systematic review of 45 studies (1904 shoulders), Griesser and colleagues5 found an overall complication rate of 30% and a reoperation rate of 7%.

Given the potential complications of coracoid bone transfer, allograft reconstruction of the anteroinferior glenoid has become increasingly popular and proved successful at short- and medium-term follow-up. Allograft reconstruction avoids the drawbacks of traditional coracoid bone transfer—namely, high rates of neurovascular injury, and nonanatomical reconstruction with high rates of graft resorption and arthritis.5,6 At average 45-month follow-up after fresh distal tibia allograft reconstruction, Provencher and colleagues7 found an 89% radiographic union rate (average lysis, 3%), significantly improved patient-reported outcomes, and no recurrent instability. Similarly, in a study of iliac crest allograft reconstruction in 10 patients with an average 4-year follow-up, Mascarenhas and colleagues8 found an 80% radiographic union rate at 6 months, significantly improved patient-reported outcomes, and no recurrent shoulder instability.

The advantage of Glenojet over other allografts is that it is preshaped and predrilled and saves the surgeon the time and effort of preparing graft in the operating room. The surgical technologist can place the sutures before the patient enters the room. The 2 allograft sizes (10 mm × 29 mm, 13 mm × 34 mm) accommodate the spectrum of bone loss in glenoid deficiency, and graft contour fits the native glenoid well. So far we have implanted this allograft in 15 patients, and at short-term follow-up there are no known cases of recurrent instability.

The potential disadvantages of Glenojet are similar to those of other allografts. Care must be taken with retractor placement to avoid damaging the axillary and musculocutaneous nerves. There are concerns about graft union and subsequent resorption, but this will require long-term follow-up to determine. At 9-month follow-up, we had 1 fracture at the superior corner of the graft, which may have resulted from overtightening the screws in the graft, creating a stress concentration. After removal of this fragment arthroscopically, the patient has done very well clinically with no pain, instability and has returned to all activities. Although the graft does not have an articular surface, the capsular repair covers much of the articular side of the graft, and therefore we do not anticipate that the absence of articular cartilage will contribute to glenohumeral arthritis, though long-term follow-up is lacking. The other question many have is related to the lack of the sling effect since there is no conjoined tendon on the graft. Yamamoto and colleagues9 have reported that the conjoined tendon is the major stabilizing force at time zero in a cadaver model. However, other authors7,8 have successfully reconstructed glenoid defects in these difficult cases without the “sling effect” of the conjoined tendon with excellent clinical results. Our experience has been similar. It is likely that long-term studies will be necessary to answer this question. We have also done some cases with the tendon attached after releasing it from the coracoid, but the series is too small to make any comment about whether this is important or not.

The main limitation of this allograft technique is the lack of long-term outcome studies. However, short-term results are promising, and the ease of the procedure makes it an attractive option for either glenoid reconstruction of bony Bankart lesions or failed bone reconstruction, such as Bristow-Latarjet reconstruction.

Glenojetallograft is a new glenoid reconstruction option that is technically easy and simple to perform in cases of glenoid bone loss, while still creating an anatomical buttress with less surgical dissection than traditional coracoid bone transfer. Short-term outcomes are reassuring, though more research is needed for long-term graft follow-up and recurrent instability.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(4):199-202. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

Take-Home Points

- Repair anterior bone defect on the glenoid related to recurrent anterior instability with preshaped, predrilled allograft.

- Avoid graft harvest complications related to coracoid (Latarjet) or iliac crest autograft.

- Simple guide system to allow for appropriate graft and screw placement.

- Soft tissues can be repaired to the allograft in predrilled suture holes either inside or outside of the graft

- Position the graft without step at the anterior glenoid.

Anteroinferior glenoid bone loss plays a significant role in recurrent glenohumeral instability. Arthroscopic capsulolabral reconstruction has been associated with a recurrence rate of 4% in the absence of significant glenoid bone loss but 67% in patients with either bone loss of more than 25% of the inferior glenoid diameter or an engaging Hill-Sachs lesion.1,2 Anteroinferior glenoid rim deficiency has been reported in up to 90% of cases of recurrent instability.3 Glenoid reconstruction is therefore recommended in patients with bone loss of more than 25% and in certain revision cases.4 Surgical strategies in these cases include coracoid transfer, iliac crest autograft, and allograft (osteochondral and iliac crest). These procedures all successfully restore stability of the glenohumeral joint. However, they carry the drawbacks of technical complexity with increased operative time or risk of neurovascular damage, or they create a nonanatomical reconstruction, which may contribute to subsequent instability arthropathy. In this article, we introduce a technique in which a preshaped allograft (Glenojet; Arthrosurface, Inc.) is used to match the contour of the glenoid defect. The graft is simple to insert and can reduce operative time.

Graft Preparation

The shaped human tissue cortical bone allograft is usually prepared from proximal or distal tibia or femur. There is no cartilage on the graft. It can be ordered in 2 sizes, 10 mm × 29 mm and 13 mm × 34 mm, for different amounts of bone loss. The more commonly used smaller graft reconstructs defects of 20% to 30% of the glenoid.

The sutures through this allograft can be prepared on the back table while the rest of the equipment is set up. Start by tying a No. 2 FiberWire (or equivalent) over a small thin object, such as a Freer elevator. Once the knot is secure, remove the Freer and trim the knot tails short. Thread another suture through the loop that has been created and pull to make the 2 tails even. Then thread these tails through one of the small holes of the graft, going from the flat side to the concave side. Pull the suture tails all the way through, including through the loop of the prior suture. The knot of the loop prevents the entire construct from pulling through. The suture tails are then able to slide as if attached to an anchor. Repeat these steps for the other 2 small holes to get a total of 3 sutures exiting the concave side of the graft (Figure 1). Alternatively, pass the suture the opposite way, if tying the capsule inside the graft is preferred.

Surgical Technique

A standard deltopectoral approach is used to expose the anterior glenoid. The subscapularis can either be split in line with its fibers or tenotomized with 1 cm to 2 cm attached to the tuberosity for later repair. In either instance, it is important to separate the muscle from the underlying capsule layer, as the capsule is what is directly repaired to the graft.

The capsule is carefully peeled off the anterior glenoid. A Fukuda or similar retractor may be used on the humerus, and a glenoid retractor is placed on the anterior glenoid, under the capsule and subscapularis, for optimal exposure. Once the anterior glenoid surface is exposed, the drill guide is placed flush against the surface of the glenoid.

The guide is removed. The cannulated reamer is introduced and advanced until the guide pin appears in the viewing window of the reamer and hits the stop—approximating the correct amount of bone to remove. This step is repeated for the second guide pin. Reaming flattens the anterior glenoid and allows for maximal stable apposition of the graft to the glenoid. The allograft is then inserted onto the pins in the correct orientation to match the surface of the native glenoid.

The length of the superior guide pin is measured with the depth gauge device. It is then removed, and the appropriate-length 3.5-mm cortical bone screw is inserted (alternatively, the guide pin is removed, and a standard depth gauge is used to measure screw length). Once the superior guide pin is secure, the process is repeated for the inferior guide pin (Figure 3).

Once the graft is secure, the capsule is attached to the graft with the use of a free needle on the suture of the graft (Figure 4).

Outcomes

Coracoid bone transfer or the Bristow-Latarjet technique has become more popular since bone loss was recognized as an important cause of failure of soft-tissue repair for anterior instability. This procedure, however, is not without complications. In a recent systematic review of 45 studies (1904 shoulders), Griesser and colleagues5 found an overall complication rate of 30% and a reoperation rate of 7%.