User login

Debunking Psoriasis Myths: Which Psoriasis Therapies Can Be Used in Pregnant Women?

Myth: Psoriasis Treatments Should Not Be Used During Pregnancy

It is likely that dermatologists will encounter female patients with psoriasis who are pregnant or wish to become pregnant during the course of their psoriasis treatment. Earlier this year Porter et al evaluated several psoriasis therapies and discussed their safety for patients with psoriasis during pregnancy. Because psoriasis is a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes, control of disease prior to and during pregnancy may optimize maternal and fetal health, according to the authors. As a result, they outlined the following treatment recommendations:

- Consider anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α agents over IL-12/IL-23 and IL-17 inhibitors.

- Anti–TNF-α agents can be used during the first half of pregnancy.

- Longer-term use of anti–TNF-α agents during pregnancy can be considered depending on psoriasis disease severity.

- If biologic therapy is required during pregnancy, use certolizumab because it does not cross the placenta in significant amounts; etanercept also may be a reasonable alternative.

- Babies born to mothers who are continually treated with biologic agents should not be administered live vaccinations for at least 6 months after birth due to the increased risk of infection; inactive vaccinations can be administered according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines.

- Breastfeeding by mothers currently treated with anti–TNF-α agents is generally considered safe.

- Cotreatment with methotrexate and a biologic agent should be avoided.

However, the National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines for treating psoriasis in pregnant or breastfeeding women advise that topical treatments are the first choice of treatment, particularly moisturizers and emollients. Limited use of low- to moderate-potency topical steroids appears to be safe, but women should avoid applying topical steroids to the breasts. Second-line treatment is narrowband UVB phototherapy; if narrowband UVB is not available, use broadband UVB. Breastfeeding women should avoid psoralen plus UVA. The foundation also advises that systemic and biologic drugs should be avoided while pregnant or breastfeeding unless there is a clear medical need. Childbearing women should avoid oral retinoids, methotrexate, and cyclosporine due to a link to birth defects. A useful table of US Food and Drug Administration–approved psoriasis treatments and their category for use by pregnant and breastfeeding women is available online. Specifically, drugs that should absolutely be avoided in this patient population include acitretin, methotrexate, and tazarotene.

For some patients, discontinuing therapy may not be practical. Dermatologists should be prepared to weigh the risks and benefits of treatment to advise patients appropriately. According to Dr. Jeffrey M. Weinberg’s pearls for treating psoriasis in pregnant women in Cutis, “Most biologic therapies are pregnancy category B. We still use these drugs with caution in the setting of pregnancy. If a pregnant patient does wish to continue a biologic therapy, close monitoring and enrollment in a pregnancy registry would be good options.”

RELATED ARTICLE: How to Manage Psoriasis Safely in Pregnant Women

More research is necessary; however, pregnant women often are excluded from clinical trials. Therefore, adverse outcomes should be reported to registries such as the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists or others sponsored by drug manufacturers, which will aid in understanding the effects of psoriasis treatments in pregnant and breastfeeding women.

Expert Commentary

The treatment of psoriasis in pregnancy should be approached in a thoughtful manner. While we always want to minimize therapeutic interventions in pregnant individuals, we also want to maintain control of a disease such as psoriasis. As outlined in this article, there is good amount of flexibility in terms of therapies available to us. It is important to discuss the situation carefully, including the benefits and risks, with the patient and the obstetric professionals, in order to design the optimal regimen for each individual.

—Jeffrey M. Weinberg (New York, New York)

FDA determinations for pregnant and nursing women. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/pregnancy/fda-determinations. Accessed December 4, 2017.

Porter ML, Lockwood SJ, Kimball AB. Update on biologic safety for patients with psoriasis during pregnancy. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:21-25.

Psoriasis and pregnancy: treatment options, psoriatic arthritis, and genetics. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/pregnancy. Accessed December 4, 2017.

Weinberg JM. Treating psoriasis in pregnant women. Cutis. 2015;96:80.

Myth: Psoriasis Treatments Should Not Be Used During Pregnancy

It is likely that dermatologists will encounter female patients with psoriasis who are pregnant or wish to become pregnant during the course of their psoriasis treatment. Earlier this year Porter et al evaluated several psoriasis therapies and discussed their safety for patients with psoriasis during pregnancy. Because psoriasis is a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes, control of disease prior to and during pregnancy may optimize maternal and fetal health, according to the authors. As a result, they outlined the following treatment recommendations:

- Consider anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α agents over IL-12/IL-23 and IL-17 inhibitors.

- Anti–TNF-α agents can be used during the first half of pregnancy.

- Longer-term use of anti–TNF-α agents during pregnancy can be considered depending on psoriasis disease severity.

- If biologic therapy is required during pregnancy, use certolizumab because it does not cross the placenta in significant amounts; etanercept also may be a reasonable alternative.

- Babies born to mothers who are continually treated with biologic agents should not be administered live vaccinations for at least 6 months after birth due to the increased risk of infection; inactive vaccinations can be administered according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines.

- Breastfeeding by mothers currently treated with anti–TNF-α agents is generally considered safe.

- Cotreatment with methotrexate and a biologic agent should be avoided.

However, the National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines for treating psoriasis in pregnant or breastfeeding women advise that topical treatments are the first choice of treatment, particularly moisturizers and emollients. Limited use of low- to moderate-potency topical steroids appears to be safe, but women should avoid applying topical steroids to the breasts. Second-line treatment is narrowband UVB phototherapy; if narrowband UVB is not available, use broadband UVB. Breastfeeding women should avoid psoralen plus UVA. The foundation also advises that systemic and biologic drugs should be avoided while pregnant or breastfeeding unless there is a clear medical need. Childbearing women should avoid oral retinoids, methotrexate, and cyclosporine due to a link to birth defects. A useful table of US Food and Drug Administration–approved psoriasis treatments and their category for use by pregnant and breastfeeding women is available online. Specifically, drugs that should absolutely be avoided in this patient population include acitretin, methotrexate, and tazarotene.

For some patients, discontinuing therapy may not be practical. Dermatologists should be prepared to weigh the risks and benefits of treatment to advise patients appropriately. According to Dr. Jeffrey M. Weinberg’s pearls for treating psoriasis in pregnant women in Cutis, “Most biologic therapies are pregnancy category B. We still use these drugs with caution in the setting of pregnancy. If a pregnant patient does wish to continue a biologic therapy, close monitoring and enrollment in a pregnancy registry would be good options.”

RELATED ARTICLE: How to Manage Psoriasis Safely in Pregnant Women

More research is necessary; however, pregnant women often are excluded from clinical trials. Therefore, adverse outcomes should be reported to registries such as the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists or others sponsored by drug manufacturers, which will aid in understanding the effects of psoriasis treatments in pregnant and breastfeeding women.

Expert Commentary

The treatment of psoriasis in pregnancy should be approached in a thoughtful manner. While we always want to minimize therapeutic interventions in pregnant individuals, we also want to maintain control of a disease such as psoriasis. As outlined in this article, there is good amount of flexibility in terms of therapies available to us. It is important to discuss the situation carefully, including the benefits and risks, with the patient and the obstetric professionals, in order to design the optimal regimen for each individual.

—Jeffrey M. Weinberg (New York, New York)

Myth: Psoriasis Treatments Should Not Be Used During Pregnancy

It is likely that dermatologists will encounter female patients with psoriasis who are pregnant or wish to become pregnant during the course of their psoriasis treatment. Earlier this year Porter et al evaluated several psoriasis therapies and discussed their safety for patients with psoriasis during pregnancy. Because psoriasis is a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes, control of disease prior to and during pregnancy may optimize maternal and fetal health, according to the authors. As a result, they outlined the following treatment recommendations:

- Consider anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α agents over IL-12/IL-23 and IL-17 inhibitors.

- Anti–TNF-α agents can be used during the first half of pregnancy.

- Longer-term use of anti–TNF-α agents during pregnancy can be considered depending on psoriasis disease severity.

- If biologic therapy is required during pregnancy, use certolizumab because it does not cross the placenta in significant amounts; etanercept also may be a reasonable alternative.

- Babies born to mothers who are continually treated with biologic agents should not be administered live vaccinations for at least 6 months after birth due to the increased risk of infection; inactive vaccinations can be administered according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines.

- Breastfeeding by mothers currently treated with anti–TNF-α agents is generally considered safe.

- Cotreatment with methotrexate and a biologic agent should be avoided.

However, the National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines for treating psoriasis in pregnant or breastfeeding women advise that topical treatments are the first choice of treatment, particularly moisturizers and emollients. Limited use of low- to moderate-potency topical steroids appears to be safe, but women should avoid applying topical steroids to the breasts. Second-line treatment is narrowband UVB phototherapy; if narrowband UVB is not available, use broadband UVB. Breastfeeding women should avoid psoralen plus UVA. The foundation also advises that systemic and biologic drugs should be avoided while pregnant or breastfeeding unless there is a clear medical need. Childbearing women should avoid oral retinoids, methotrexate, and cyclosporine due to a link to birth defects. A useful table of US Food and Drug Administration–approved psoriasis treatments and their category for use by pregnant and breastfeeding women is available online. Specifically, drugs that should absolutely be avoided in this patient population include acitretin, methotrexate, and tazarotene.

For some patients, discontinuing therapy may not be practical. Dermatologists should be prepared to weigh the risks and benefits of treatment to advise patients appropriately. According to Dr. Jeffrey M. Weinberg’s pearls for treating psoriasis in pregnant women in Cutis, “Most biologic therapies are pregnancy category B. We still use these drugs with caution in the setting of pregnancy. If a pregnant patient does wish to continue a biologic therapy, close monitoring and enrollment in a pregnancy registry would be good options.”

RELATED ARTICLE: How to Manage Psoriasis Safely in Pregnant Women

More research is necessary; however, pregnant women often are excluded from clinical trials. Therefore, adverse outcomes should be reported to registries such as the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists or others sponsored by drug manufacturers, which will aid in understanding the effects of psoriasis treatments in pregnant and breastfeeding women.

Expert Commentary

The treatment of psoriasis in pregnancy should be approached in a thoughtful manner. While we always want to minimize therapeutic interventions in pregnant individuals, we also want to maintain control of a disease such as psoriasis. As outlined in this article, there is good amount of flexibility in terms of therapies available to us. It is important to discuss the situation carefully, including the benefits and risks, with the patient and the obstetric professionals, in order to design the optimal regimen for each individual.

—Jeffrey M. Weinberg (New York, New York)

FDA determinations for pregnant and nursing women. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/pregnancy/fda-determinations. Accessed December 4, 2017.

Porter ML, Lockwood SJ, Kimball AB. Update on biologic safety for patients with psoriasis during pregnancy. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:21-25.

Psoriasis and pregnancy: treatment options, psoriatic arthritis, and genetics. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/pregnancy. Accessed December 4, 2017.

Weinberg JM. Treating psoriasis in pregnant women. Cutis. 2015;96:80.

FDA determinations for pregnant and nursing women. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/pregnancy/fda-determinations. Accessed December 4, 2017.

Porter ML, Lockwood SJ, Kimball AB. Update on biologic safety for patients with psoriasis during pregnancy. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:21-25.

Psoriasis and pregnancy: treatment options, psoriatic arthritis, and genetics. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/pregnancy. Accessed December 4, 2017.

Weinberg JM. Treating psoriasis in pregnant women. Cutis. 2015;96:80.

Oral and Injectable Medications for Psoriasis: Benefits and Downsides Requiring Patient Support

Approximately three-quarters of respondents indicated that they have used oral or injectable medications (eg, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, apremilast, biologics) to control their psoriasis, according to a public meeting hosted by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to hear patient perspectives on psoriasis. Approximately 70 psoriasis patients or patient representatives attended the meeting in person and others attended through a live webcast.

Patients universally spoke about the benefits of their current treatments, especially the biologics, but variable experiences regarding the effectiveness of the therapies were reported, ranging from excellent improvement, to improvement that lasted only a few months, to a near-complete clearance. However, limitations to these therapies also were mentioned, which are areas where dermatologists can provide counseling and alternatives. For example, treatments were reported to be effective in clearing cutaneous psoriasis symptoms such as flaking and scaling, but pruritus, burning, and pain were still problematic and mostly limited to areas where the cutaneous symptoms had been located.

Other treatment downsides that dermatologists should discuss with patients are side effects, including fatigue, nausea, fluctuations in weight, increased facial hair growth, nosebleeds, increased blood pressure, headaches, and palpitations, according to the patients present at the meeting. Patients also expressed concern about immune compromise from the biologics. Others reported concerns that the treatments addressed specific psoriasis symptoms but led to worsening of other symptoms or development of new conditions such as uveitis and psoriatic arthritis. The burden of treatment infusions or required blood work also were discussed. These are areas in which dermatologists may be best suited to provide more patient education or support when prescribing these therapies. The National Psoriasis Foundation’s Patient Navigation Center is a tool for patients to access information and interact with members of the psoriasis patient community.

The psoriasis public meeting in March 2016 was the FDA’s 18th patient-focused drug development meeting. The FDA sought this information to have a greater understanding of the burden of psoriasis on patients and the treatments currently used to treat psoriasis and its symptoms. This information will help guide the FDA as they consider future drug approvals.

Approximately three-quarters of respondents indicated that they have used oral or injectable medications (eg, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, apremilast, biologics) to control their psoriasis, according to a public meeting hosted by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to hear patient perspectives on psoriasis. Approximately 70 psoriasis patients or patient representatives attended the meeting in person and others attended through a live webcast.

Patients universally spoke about the benefits of their current treatments, especially the biologics, but variable experiences regarding the effectiveness of the therapies were reported, ranging from excellent improvement, to improvement that lasted only a few months, to a near-complete clearance. However, limitations to these therapies also were mentioned, which are areas where dermatologists can provide counseling and alternatives. For example, treatments were reported to be effective in clearing cutaneous psoriasis symptoms such as flaking and scaling, but pruritus, burning, and pain were still problematic and mostly limited to areas where the cutaneous symptoms had been located.

Other treatment downsides that dermatologists should discuss with patients are side effects, including fatigue, nausea, fluctuations in weight, increased facial hair growth, nosebleeds, increased blood pressure, headaches, and palpitations, according to the patients present at the meeting. Patients also expressed concern about immune compromise from the biologics. Others reported concerns that the treatments addressed specific psoriasis symptoms but led to worsening of other symptoms or development of new conditions such as uveitis and psoriatic arthritis. The burden of treatment infusions or required blood work also were discussed. These are areas in which dermatologists may be best suited to provide more patient education or support when prescribing these therapies. The National Psoriasis Foundation’s Patient Navigation Center is a tool for patients to access information and interact with members of the psoriasis patient community.

The psoriasis public meeting in March 2016 was the FDA’s 18th patient-focused drug development meeting. The FDA sought this information to have a greater understanding of the burden of psoriasis on patients and the treatments currently used to treat psoriasis and its symptoms. This information will help guide the FDA as they consider future drug approvals.

Approximately three-quarters of respondents indicated that they have used oral or injectable medications (eg, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, apremilast, biologics) to control their psoriasis, according to a public meeting hosted by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to hear patient perspectives on psoriasis. Approximately 70 psoriasis patients or patient representatives attended the meeting in person and others attended through a live webcast.

Patients universally spoke about the benefits of their current treatments, especially the biologics, but variable experiences regarding the effectiveness of the therapies were reported, ranging from excellent improvement, to improvement that lasted only a few months, to a near-complete clearance. However, limitations to these therapies also were mentioned, which are areas where dermatologists can provide counseling and alternatives. For example, treatments were reported to be effective in clearing cutaneous psoriasis symptoms such as flaking and scaling, but pruritus, burning, and pain were still problematic and mostly limited to areas where the cutaneous symptoms had been located.

Other treatment downsides that dermatologists should discuss with patients are side effects, including fatigue, nausea, fluctuations in weight, increased facial hair growth, nosebleeds, increased blood pressure, headaches, and palpitations, according to the patients present at the meeting. Patients also expressed concern about immune compromise from the biologics. Others reported concerns that the treatments addressed specific psoriasis symptoms but led to worsening of other symptoms or development of new conditions such as uveitis and psoriatic arthritis. The burden of treatment infusions or required blood work also were discussed. These are areas in which dermatologists may be best suited to provide more patient education or support when prescribing these therapies. The National Psoriasis Foundation’s Patient Navigation Center is a tool for patients to access information and interact with members of the psoriasis patient community.

The psoriasis public meeting in March 2016 was the FDA’s 18th patient-focused drug development meeting. The FDA sought this information to have a greater understanding of the burden of psoriasis on patients and the treatments currently used to treat psoriasis and its symptoms. This information will help guide the FDA as they consider future drug approvals.

Debunking Actinic Keratosis Myths: Do All Actinic Keratoses Progress to Squamous Cell Carcinoma?

Myth: Hypertrophic actinic keratoses are more likely to progress to squamous cell carcinoma

Actinic keratosis (AK) indicates cumulative UV exposure and is the initial lesion in the majority of invasive cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). However, most AKs do not progress to invasive SCC and it currently is not possible to clinically or histopathologically determine which AK lesions will progress to SCC.

The rates of progression of individual AK lesions to SCC vary. In 2011, Feldman and Fleischer summarized 6 studies of 560 to 6691 patients with AK. The AK progression to SCC was found to range from 0.075% per year per lesion to 14% over 5 years.

Criscione et al found that the risk of progression of AK to primary SCC was 0.60% at 1 year and 2.57% at 4 years. In this study, 187 primary SCCs were diagnosed after enrollment, with 65% arising in previously clinically diagnosed and documented AKs. Therefore, although the authors noted low risks of progression of AK to SCC, they observed that the majority of SCCs arose from AKs.

The risk for progression of AK to invasive SCC with the potential for metastasis warrants treatment of AK with lesion- or field-directed therapy or a combined approach when indicated. Dermatologists also should monitor AK patients closely.

Expert Commentary

It’s a myth that hypertrophic lesions are more likely to turn into SCC. In fact, it’s the lesions with follicular extension that are more likely to progress to SCC. These may be hypertrophic or atrophic or simple AKs. The genetics of AKs that become hypertrophic may be different from those that become invasive. These lesions may be more likely to first grow outward before becoming invasive.

—Gary Goldenberg (New York, New York)

Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, et al. Actinic keratoses: natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention trial. Cancer. 2009;115:2523-2530.

Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr. Progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma revisited: clinical and treatment implications. Cutis. 2011;87:201-207.

Pandey S, Mercer SE, Dallas K, et al. Evaluation of the prognostic significance of follicular extension in actinic keratoses. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:25-28.

Myth: Hypertrophic actinic keratoses are more likely to progress to squamous cell carcinoma

Actinic keratosis (AK) indicates cumulative UV exposure and is the initial lesion in the majority of invasive cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). However, most AKs do not progress to invasive SCC and it currently is not possible to clinically or histopathologically determine which AK lesions will progress to SCC.

The rates of progression of individual AK lesions to SCC vary. In 2011, Feldman and Fleischer summarized 6 studies of 560 to 6691 patients with AK. The AK progression to SCC was found to range from 0.075% per year per lesion to 14% over 5 years.

Criscione et al found that the risk of progression of AK to primary SCC was 0.60% at 1 year and 2.57% at 4 years. In this study, 187 primary SCCs were diagnosed after enrollment, with 65% arising in previously clinically diagnosed and documented AKs. Therefore, although the authors noted low risks of progression of AK to SCC, they observed that the majority of SCCs arose from AKs.

The risk for progression of AK to invasive SCC with the potential for metastasis warrants treatment of AK with lesion- or field-directed therapy or a combined approach when indicated. Dermatologists also should monitor AK patients closely.

Expert Commentary

It’s a myth that hypertrophic lesions are more likely to turn into SCC. In fact, it’s the lesions with follicular extension that are more likely to progress to SCC. These may be hypertrophic or atrophic or simple AKs. The genetics of AKs that become hypertrophic may be different from those that become invasive. These lesions may be more likely to first grow outward before becoming invasive.

—Gary Goldenberg (New York, New York)

Myth: Hypertrophic actinic keratoses are more likely to progress to squamous cell carcinoma

Actinic keratosis (AK) indicates cumulative UV exposure and is the initial lesion in the majority of invasive cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). However, most AKs do not progress to invasive SCC and it currently is not possible to clinically or histopathologically determine which AK lesions will progress to SCC.

The rates of progression of individual AK lesions to SCC vary. In 2011, Feldman and Fleischer summarized 6 studies of 560 to 6691 patients with AK. The AK progression to SCC was found to range from 0.075% per year per lesion to 14% over 5 years.

Criscione et al found that the risk of progression of AK to primary SCC was 0.60% at 1 year and 2.57% at 4 years. In this study, 187 primary SCCs were diagnosed after enrollment, with 65% arising in previously clinically diagnosed and documented AKs. Therefore, although the authors noted low risks of progression of AK to SCC, they observed that the majority of SCCs arose from AKs.

The risk for progression of AK to invasive SCC with the potential for metastasis warrants treatment of AK with lesion- or field-directed therapy or a combined approach when indicated. Dermatologists also should monitor AK patients closely.

Expert Commentary

It’s a myth that hypertrophic lesions are more likely to turn into SCC. In fact, it’s the lesions with follicular extension that are more likely to progress to SCC. These may be hypertrophic or atrophic or simple AKs. The genetics of AKs that become hypertrophic may be different from those that become invasive. These lesions may be more likely to first grow outward before becoming invasive.

—Gary Goldenberg (New York, New York)

Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, et al. Actinic keratoses: natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention trial. Cancer. 2009;115:2523-2530.

Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr. Progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma revisited: clinical and treatment implications. Cutis. 2011;87:201-207.

Pandey S, Mercer SE, Dallas K, et al. Evaluation of the prognostic significance of follicular extension in actinic keratoses. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:25-28.

Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, et al. Actinic keratoses: natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention trial. Cancer. 2009;115:2523-2530.

Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr. Progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma revisited: clinical and treatment implications. Cutis. 2011;87:201-207.

Pandey S, Mercer SE, Dallas K, et al. Evaluation of the prognostic significance of follicular extension in actinic keratoses. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:25-28.

Debunking Acne Myths: Does Back Acne Need to Be Treated?

Myth: Back acne will clear on its own

Patients with back acne may not seek treatment options because they assume it will clear on its own; however, deep painful lesions typically require treatment by a dermatologist. Mild to moderate cases may respond to less aggressive over-the-counter treatments but also may benefit from a combination of topical and systemic antibiotic therapies. According to James Q. Del Rosso, MD, a dermatologist in Las Vegas, Nevada, “Many dermatologists believe that truncal acne vulgaris warrants use of systemic antibiotic therapy, which may not necessarily be the case, especially in patients presenting with mild to moderate acne severity.” Cases of deep inflammatory acne on the back often warrant using systemic therapies such as oral isotretinoin. These severe cases may be less responsive to standard therapies and may require repeated treatment.

Although back acne is not as cosmetically visible as facial acne, it has been associated with sexual and bodily self-consciousness in both males and females. Preliminary data from one study showed that 78% of patients with truncal acne (n=141) on the back and/or chest indicated they were definitely interested in treatment, but truncal acne was not mentioned by these patients without direct inquiry from a physician. As a result, it may be beneficial for dermatologists to ask acne patients about lesions presenting on the back and inform them that treatment options are available.

Treatment application also is a consideration for back acne. Benzoyl peroxide cleanser/wash formulations are convenient, and the foam formulation of clindamycin phosphate allows for easy use due to its spreadability, rapid penetration, and lack of residue and fabric bleaching.

It is important to inform patients that back acne can flare even during active treatment. Patients should be instructed to wear loose-fitting clothes made of cotton or other sweat-wicking fabrics when working out and to shower and change clothes immediately after. Sheets and pillowcases should be changed regularly to avoid exposure to dead skin cells and bacteria, which can exacerbate acne on the back. Backpacks and handbags also can rub against the skin on the back, causing acne to flare. As an alternative, patients should be encouraged to carry handheld bags or bags with shoulder straps to avoid irritation of the skin on the back.

Back acne: how to see clearer skin. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/back-acne-how-to-see-clearer-skin. Accessed October 30, 2017.

Del Rosso JQ. Management of truncal acne vulgaris: current perspectives on treatment. Cutis. 2006;77:285-289.

Dunn LK, O’Neill JL, Feldman SR. Acne in adolescents: quality of life, self-esteem, mood, and psychological disorders. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

Hassan J, Grogan S, Clark-Carter D, et al. The individual health burden of acne: appearance-related distress in male and female adolescents and adults with back, chest and facial acne. J Health Psychol. 2009;14:1105-11118.

Myth: Back acne will clear on its own

Patients with back acne may not seek treatment options because they assume it will clear on its own; however, deep painful lesions typically require treatment by a dermatologist. Mild to moderate cases may respond to less aggressive over-the-counter treatments but also may benefit from a combination of topical and systemic antibiotic therapies. According to James Q. Del Rosso, MD, a dermatologist in Las Vegas, Nevada, “Many dermatologists believe that truncal acne vulgaris warrants use of systemic antibiotic therapy, which may not necessarily be the case, especially in patients presenting with mild to moderate acne severity.” Cases of deep inflammatory acne on the back often warrant using systemic therapies such as oral isotretinoin. These severe cases may be less responsive to standard therapies and may require repeated treatment.

Although back acne is not as cosmetically visible as facial acne, it has been associated with sexual and bodily self-consciousness in both males and females. Preliminary data from one study showed that 78% of patients with truncal acne (n=141) on the back and/or chest indicated they were definitely interested in treatment, but truncal acne was not mentioned by these patients without direct inquiry from a physician. As a result, it may be beneficial for dermatologists to ask acne patients about lesions presenting on the back and inform them that treatment options are available.

Treatment application also is a consideration for back acne. Benzoyl peroxide cleanser/wash formulations are convenient, and the foam formulation of clindamycin phosphate allows for easy use due to its spreadability, rapid penetration, and lack of residue and fabric bleaching.

It is important to inform patients that back acne can flare even during active treatment. Patients should be instructed to wear loose-fitting clothes made of cotton or other sweat-wicking fabrics when working out and to shower and change clothes immediately after. Sheets and pillowcases should be changed regularly to avoid exposure to dead skin cells and bacteria, which can exacerbate acne on the back. Backpacks and handbags also can rub against the skin on the back, causing acne to flare. As an alternative, patients should be encouraged to carry handheld bags or bags with shoulder straps to avoid irritation of the skin on the back.

Myth: Back acne will clear on its own

Patients with back acne may not seek treatment options because they assume it will clear on its own; however, deep painful lesions typically require treatment by a dermatologist. Mild to moderate cases may respond to less aggressive over-the-counter treatments but also may benefit from a combination of topical and systemic antibiotic therapies. According to James Q. Del Rosso, MD, a dermatologist in Las Vegas, Nevada, “Many dermatologists believe that truncal acne vulgaris warrants use of systemic antibiotic therapy, which may not necessarily be the case, especially in patients presenting with mild to moderate acne severity.” Cases of deep inflammatory acne on the back often warrant using systemic therapies such as oral isotretinoin. These severe cases may be less responsive to standard therapies and may require repeated treatment.

Although back acne is not as cosmetically visible as facial acne, it has been associated with sexual and bodily self-consciousness in both males and females. Preliminary data from one study showed that 78% of patients with truncal acne (n=141) on the back and/or chest indicated they were definitely interested in treatment, but truncal acne was not mentioned by these patients without direct inquiry from a physician. As a result, it may be beneficial for dermatologists to ask acne patients about lesions presenting on the back and inform them that treatment options are available.

Treatment application also is a consideration for back acne. Benzoyl peroxide cleanser/wash formulations are convenient, and the foam formulation of clindamycin phosphate allows for easy use due to its spreadability, rapid penetration, and lack of residue and fabric bleaching.

It is important to inform patients that back acne can flare even during active treatment. Patients should be instructed to wear loose-fitting clothes made of cotton or other sweat-wicking fabrics when working out and to shower and change clothes immediately after. Sheets and pillowcases should be changed regularly to avoid exposure to dead skin cells and bacteria, which can exacerbate acne on the back. Backpacks and handbags also can rub against the skin on the back, causing acne to flare. As an alternative, patients should be encouraged to carry handheld bags or bags with shoulder straps to avoid irritation of the skin on the back.

Back acne: how to see clearer skin. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/back-acne-how-to-see-clearer-skin. Accessed October 30, 2017.

Del Rosso JQ. Management of truncal acne vulgaris: current perspectives on treatment. Cutis. 2006;77:285-289.

Dunn LK, O’Neill JL, Feldman SR. Acne in adolescents: quality of life, self-esteem, mood, and psychological disorders. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

Hassan J, Grogan S, Clark-Carter D, et al. The individual health burden of acne: appearance-related distress in male and female adolescents and adults with back, chest and facial acne. J Health Psychol. 2009;14:1105-11118.

Back acne: how to see clearer skin. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/back-acne-how-to-see-clearer-skin. Accessed October 30, 2017.

Del Rosso JQ. Management of truncal acne vulgaris: current perspectives on treatment. Cutis. 2006;77:285-289.

Dunn LK, O’Neill JL, Feldman SR. Acne in adolescents: quality of life, self-esteem, mood, and psychological disorders. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

Hassan J, Grogan S, Clark-Carter D, et al. The individual health burden of acne: appearance-related distress in male and female adolescents and adults with back, chest and facial acne. J Health Psychol. 2009;14:1105-11118.

Debunking Actinic Keratosis Myths: Are Patients With Darker Skin At Risk for Actinic Keratoses?

Myth: Actinic keratoses are only seen in patients with lighter skin

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are precancerous lesions that may turn into squamous cell carcinoma if left untreated. UV rays cause AKs, either from outdoor sun exposure or tanning beds. According to the American Academy of Dermatology, AKs are more likely to develop in patients 40 years or older with fair skin; hair color that is naturally blonde or red; eye color that is naturally blue, green, or hazel; skin that freckles or burns when in the sun; a weakened immune system; and occupations involving substances that contain polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons such as coal or tar.

A 2007 study compared the most common diagnoses among patients of different racial and ethnic groups in New York City. Alexis et al found that AK was in the top 10 diagnoses in white patients but not for black patients. They postulated that photoprotective factors in darkly pigmented skin such as larger and more numerous melanosomes that contain more melanin and are more dispersed throughout the epidermis result in a lower incidence of skin cancers in the skin of color (SOC) population.

RELATED ARTICLE: Common Dermatologic Disorders in Skin of Color: A Comparative Practice Survey

However, a recent skin cancer awareness study in Cutis reported that even though SOC populations have lower incidences of skin cancer such as melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma, they exhibit higher death rates. Furthermore, black individuals are more likely to present with advanced-stage melanoma and acral lentiginous melanomas compared to white individuals. Kailas et al stated, “Overall, SOC patients have the poorest skin cancer prognosis, and the data suggest that the reason for this paradox is delayed diagnosis.” They evaluated several knowledge-based interventions for increasing skin cancer awareness, knowledge, and protective behaviors in SOC populations, including the use of visuals such as photographs to allow SOC patients to visualize different skin tones, educational interventions in another language, and pamphlets.

Dermatologists should be aware that education of SOC patients is important to eradicate the common misconception that these patients do not have to worry about AKs and other skin cancers. Remind these patients that they need to protect their skin from the sun, just as patients with fair skin do. Further research in the dermatology community should focus on educational interventions that will help increase knowledge regarding skin cancer in SOC populations.

Expert Commentary

Although more common in patients with lighter skin, actinic keratosis and skin cancer can be seen in patients of all skin types. Many patients are unaware of this risk and do not use sunscreen and other sun-protective measures. We, as a specialty, have to educate our patients and the public of the risk for actinic keratosis and skin cancer in all skin types.

—Gary Goldenberg, MD (New York, New York)

Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

American Academy of Dermatology. Actinic keratosis. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/actinic-keratosis. Accessed October 17, 2017.

Kailas A, Botwin AL, Pritchett EN, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of knowledge-based interventions in increasing skin cancer awareness, knowledge, and protective behaviors in skin of color populations. Cutis. 2017;100:235-240.

Myth: Actinic keratoses are only seen in patients with lighter skin

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are precancerous lesions that may turn into squamous cell carcinoma if left untreated. UV rays cause AKs, either from outdoor sun exposure or tanning beds. According to the American Academy of Dermatology, AKs are more likely to develop in patients 40 years or older with fair skin; hair color that is naturally blonde or red; eye color that is naturally blue, green, or hazel; skin that freckles or burns when in the sun; a weakened immune system; and occupations involving substances that contain polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons such as coal or tar.

A 2007 study compared the most common diagnoses among patients of different racial and ethnic groups in New York City. Alexis et al found that AK was in the top 10 diagnoses in white patients but not for black patients. They postulated that photoprotective factors in darkly pigmented skin such as larger and more numerous melanosomes that contain more melanin and are more dispersed throughout the epidermis result in a lower incidence of skin cancers in the skin of color (SOC) population.

RELATED ARTICLE: Common Dermatologic Disorders in Skin of Color: A Comparative Practice Survey

However, a recent skin cancer awareness study in Cutis reported that even though SOC populations have lower incidences of skin cancer such as melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma, they exhibit higher death rates. Furthermore, black individuals are more likely to present with advanced-stage melanoma and acral lentiginous melanomas compared to white individuals. Kailas et al stated, “Overall, SOC patients have the poorest skin cancer prognosis, and the data suggest that the reason for this paradox is delayed diagnosis.” They evaluated several knowledge-based interventions for increasing skin cancer awareness, knowledge, and protective behaviors in SOC populations, including the use of visuals such as photographs to allow SOC patients to visualize different skin tones, educational interventions in another language, and pamphlets.

Dermatologists should be aware that education of SOC patients is important to eradicate the common misconception that these patients do not have to worry about AKs and other skin cancers. Remind these patients that they need to protect their skin from the sun, just as patients with fair skin do. Further research in the dermatology community should focus on educational interventions that will help increase knowledge regarding skin cancer in SOC populations.

Expert Commentary

Although more common in patients with lighter skin, actinic keratosis and skin cancer can be seen in patients of all skin types. Many patients are unaware of this risk and do not use sunscreen and other sun-protective measures. We, as a specialty, have to educate our patients and the public of the risk for actinic keratosis and skin cancer in all skin types.

—Gary Goldenberg, MD (New York, New York)

Myth: Actinic keratoses are only seen in patients with lighter skin

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are precancerous lesions that may turn into squamous cell carcinoma if left untreated. UV rays cause AKs, either from outdoor sun exposure or tanning beds. According to the American Academy of Dermatology, AKs are more likely to develop in patients 40 years or older with fair skin; hair color that is naturally blonde or red; eye color that is naturally blue, green, or hazel; skin that freckles or burns when in the sun; a weakened immune system; and occupations involving substances that contain polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons such as coal or tar.

A 2007 study compared the most common diagnoses among patients of different racial and ethnic groups in New York City. Alexis et al found that AK was in the top 10 diagnoses in white patients but not for black patients. They postulated that photoprotective factors in darkly pigmented skin such as larger and more numerous melanosomes that contain more melanin and are more dispersed throughout the epidermis result in a lower incidence of skin cancers in the skin of color (SOC) population.

RELATED ARTICLE: Common Dermatologic Disorders in Skin of Color: A Comparative Practice Survey

However, a recent skin cancer awareness study in Cutis reported that even though SOC populations have lower incidences of skin cancer such as melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma, they exhibit higher death rates. Furthermore, black individuals are more likely to present with advanced-stage melanoma and acral lentiginous melanomas compared to white individuals. Kailas et al stated, “Overall, SOC patients have the poorest skin cancer prognosis, and the data suggest that the reason for this paradox is delayed diagnosis.” They evaluated several knowledge-based interventions for increasing skin cancer awareness, knowledge, and protective behaviors in SOC populations, including the use of visuals such as photographs to allow SOC patients to visualize different skin tones, educational interventions in another language, and pamphlets.

Dermatologists should be aware that education of SOC patients is important to eradicate the common misconception that these patients do not have to worry about AKs and other skin cancers. Remind these patients that they need to protect their skin from the sun, just as patients with fair skin do. Further research in the dermatology community should focus on educational interventions that will help increase knowledge regarding skin cancer in SOC populations.

Expert Commentary

Although more common in patients with lighter skin, actinic keratosis and skin cancer can be seen in patients of all skin types. Many patients are unaware of this risk and do not use sunscreen and other sun-protective measures. We, as a specialty, have to educate our patients and the public of the risk for actinic keratosis and skin cancer in all skin types.

—Gary Goldenberg, MD (New York, New York)

Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

American Academy of Dermatology. Actinic keratosis. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/actinic-keratosis. Accessed October 17, 2017.

Kailas A, Botwin AL, Pritchett EN, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of knowledge-based interventions in increasing skin cancer awareness, knowledge, and protective behaviors in skin of color populations. Cutis. 2017;100:235-240.

Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

American Academy of Dermatology. Actinic keratosis. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/actinic-keratosis. Accessed October 17, 2017.

Kailas A, Botwin AL, Pritchett EN, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of knowledge-based interventions in increasing skin cancer awareness, knowledge, and protective behaviors in skin of color populations. Cutis. 2017;100:235-240.

Debunking Acne Myths: Does Popping Pimples Resolve Acne Faster?

Myth: Popping pimples resolves acne faster

Acne patients may be compelled to squeeze or pop their pimples at home thinking it will clear their acne faster, but they should be advised that doing so without using the proper technique can actually make the condition worse.

When over-the-counter or prescription acne medications take too long to work, some patients may use their fingernails or even a physical instrument (eg, tweezers) to clear the contents of the pimple; however, this process often produces lesions that are inflamed and far more visible, slower to heal, and more likely to scar than lesions progressing through the natural disease course. According to the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD), unwanted side effects of popping pimples can include permanent acne scars, more noticeable and/or painful acne lesions, and infection from bacteria on the hands.

The AAD promotes that dermatologists know how to remove bothersome acne lesions safely. Also, the AAD guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris reported that comedo removal may be helpful for lesions resistant to other therapies. Acne extraction may be offered when standard treatments fail and involves the use of sterile instruments to clear comedones and microcomedones. For single lesions that are particularly painful, dermatologists may opt to inject the lesion with a corticosteroid to reduce inflammation, speed healing, and decrease the risk of scarring; the strength of this recommendation is level C, according to the AAD acne guidelines work group. Finally, incision and drainage using a sterile needle or surgical blade can be used to open and clear the contents of large or painful pimples, nodules, and cysts.

These procedures are not first-line acne therapies. To minimize the appearance of acne lesions and promote clearance while waiting to see results from prescribed treatment regimens, patients should be advised to keep their hands away from their face and avoid picking at lesions, to apply ice to painful lesions to reduce inflammation and relieve pain, and to be patient with the acne treatment prescribed by a dermatologist. If patients are prone to picking their acne lesions, a more aggressive approach to treatment may be necessary, as a reduced number of inflammatory lesions leaves the patient with fewer spots to manipulate.

Pimple popping: why only a dermatologist should do it. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/pimple-popping-why-only-a-dermatologist-should-do-it. Accessed October 11, 2017.

Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.

Myth: Popping pimples resolves acne faster

Acne patients may be compelled to squeeze or pop their pimples at home thinking it will clear their acne faster, but they should be advised that doing so without using the proper technique can actually make the condition worse.

When over-the-counter or prescription acne medications take too long to work, some patients may use their fingernails or even a physical instrument (eg, tweezers) to clear the contents of the pimple; however, this process often produces lesions that are inflamed and far more visible, slower to heal, and more likely to scar than lesions progressing through the natural disease course. According to the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD), unwanted side effects of popping pimples can include permanent acne scars, more noticeable and/or painful acne lesions, and infection from bacteria on the hands.

The AAD promotes that dermatologists know how to remove bothersome acne lesions safely. Also, the AAD guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris reported that comedo removal may be helpful for lesions resistant to other therapies. Acne extraction may be offered when standard treatments fail and involves the use of sterile instruments to clear comedones and microcomedones. For single lesions that are particularly painful, dermatologists may opt to inject the lesion with a corticosteroid to reduce inflammation, speed healing, and decrease the risk of scarring; the strength of this recommendation is level C, according to the AAD acne guidelines work group. Finally, incision and drainage using a sterile needle or surgical blade can be used to open and clear the contents of large or painful pimples, nodules, and cysts.

These procedures are not first-line acne therapies. To minimize the appearance of acne lesions and promote clearance while waiting to see results from prescribed treatment regimens, patients should be advised to keep their hands away from their face and avoid picking at lesions, to apply ice to painful lesions to reduce inflammation and relieve pain, and to be patient with the acne treatment prescribed by a dermatologist. If patients are prone to picking their acne lesions, a more aggressive approach to treatment may be necessary, as a reduced number of inflammatory lesions leaves the patient with fewer spots to manipulate.

Myth: Popping pimples resolves acne faster

Acne patients may be compelled to squeeze or pop their pimples at home thinking it will clear their acne faster, but they should be advised that doing so without using the proper technique can actually make the condition worse.

When over-the-counter or prescription acne medications take too long to work, some patients may use their fingernails or even a physical instrument (eg, tweezers) to clear the contents of the pimple; however, this process often produces lesions that are inflamed and far more visible, slower to heal, and more likely to scar than lesions progressing through the natural disease course. According to the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD), unwanted side effects of popping pimples can include permanent acne scars, more noticeable and/or painful acne lesions, and infection from bacteria on the hands.

The AAD promotes that dermatologists know how to remove bothersome acne lesions safely. Also, the AAD guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris reported that comedo removal may be helpful for lesions resistant to other therapies. Acne extraction may be offered when standard treatments fail and involves the use of sterile instruments to clear comedones and microcomedones. For single lesions that are particularly painful, dermatologists may opt to inject the lesion with a corticosteroid to reduce inflammation, speed healing, and decrease the risk of scarring; the strength of this recommendation is level C, according to the AAD acne guidelines work group. Finally, incision and drainage using a sterile needle or surgical blade can be used to open and clear the contents of large or painful pimples, nodules, and cysts.

These procedures are not first-line acne therapies. To minimize the appearance of acne lesions and promote clearance while waiting to see results from prescribed treatment regimens, patients should be advised to keep their hands away from their face and avoid picking at lesions, to apply ice to painful lesions to reduce inflammation and relieve pain, and to be patient with the acne treatment prescribed by a dermatologist. If patients are prone to picking their acne lesions, a more aggressive approach to treatment may be necessary, as a reduced number of inflammatory lesions leaves the patient with fewer spots to manipulate.

Pimple popping: why only a dermatologist should do it. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/pimple-popping-why-only-a-dermatologist-should-do-it. Accessed October 11, 2017.

Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.

Pimple popping: why only a dermatologist should do it. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/pimple-popping-why-only-a-dermatologist-should-do-it. Accessed October 11, 2017.

Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.

Optical Coherence Tomography in Dermatology

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a noninvasive imaging technique that is cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration as a 510(k) class II regulatory device to visualize biological tissues in vivo and in real time.1-3 In July 2017, OCT received 2 category III Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes from the American Medical Association—0470T and 0471T—enabling physicians to report and track the usage of this emerging imaging method.4 Category III CPT codes remain investigational and therefore are not easily reimbursed by insurance.5 The goal of OCT manufacturers and providers within the next 5 years is to upgrade to category I coding before the present codes are archived. Although documented advantages of OCT include its unique ability to effectively differentiate and monitor skin lesions throughout nonsurgical treatment as well as to efficiently delineate presurgical margins, additional research reporting its efficacy may facilitate the coding conversion and encourage greater usage of OCT technology. We present a brief review of OCT imaging in dermatology, including its indications and limitations.

RELATED VIDEO: Imaging Overview: Report From the Mount Sinai Fall Symposium

Types of OCT

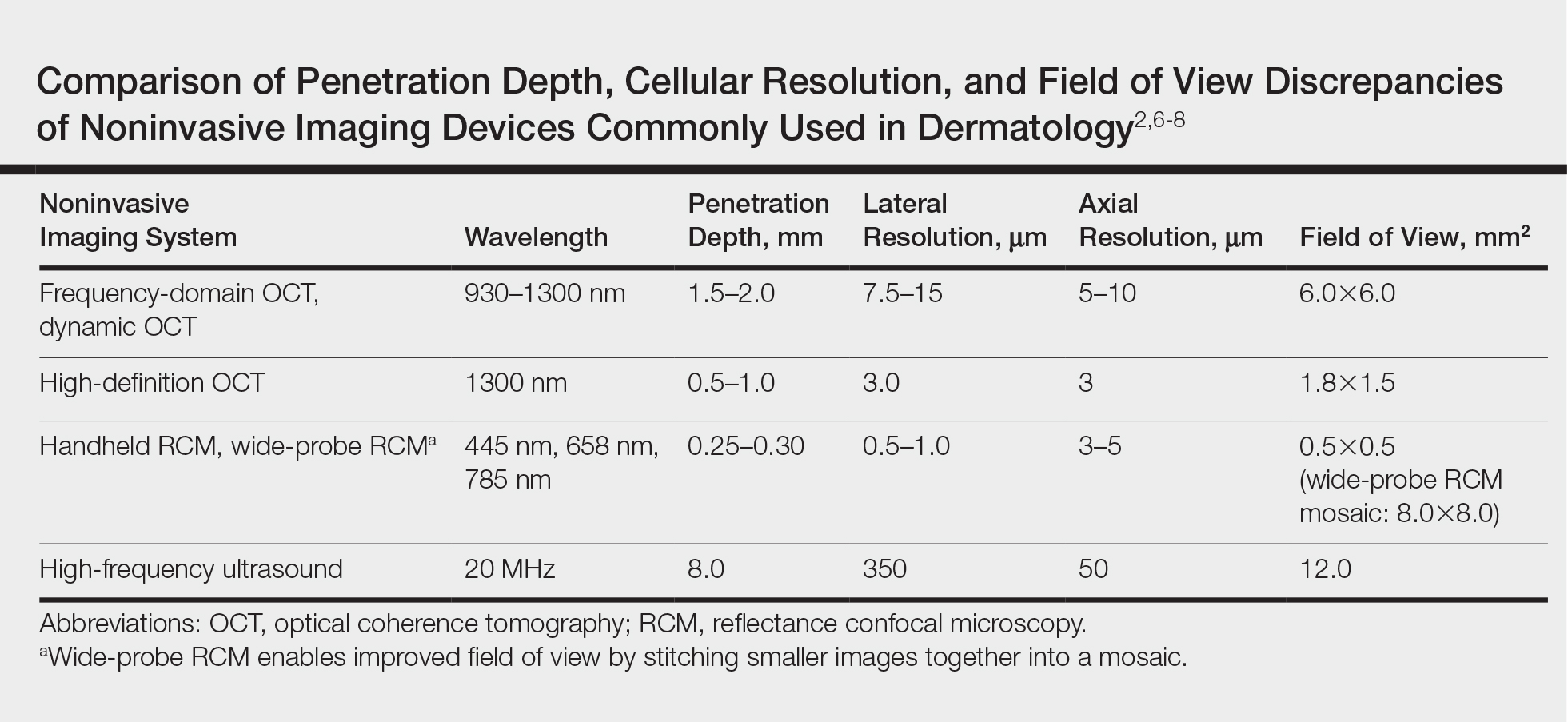

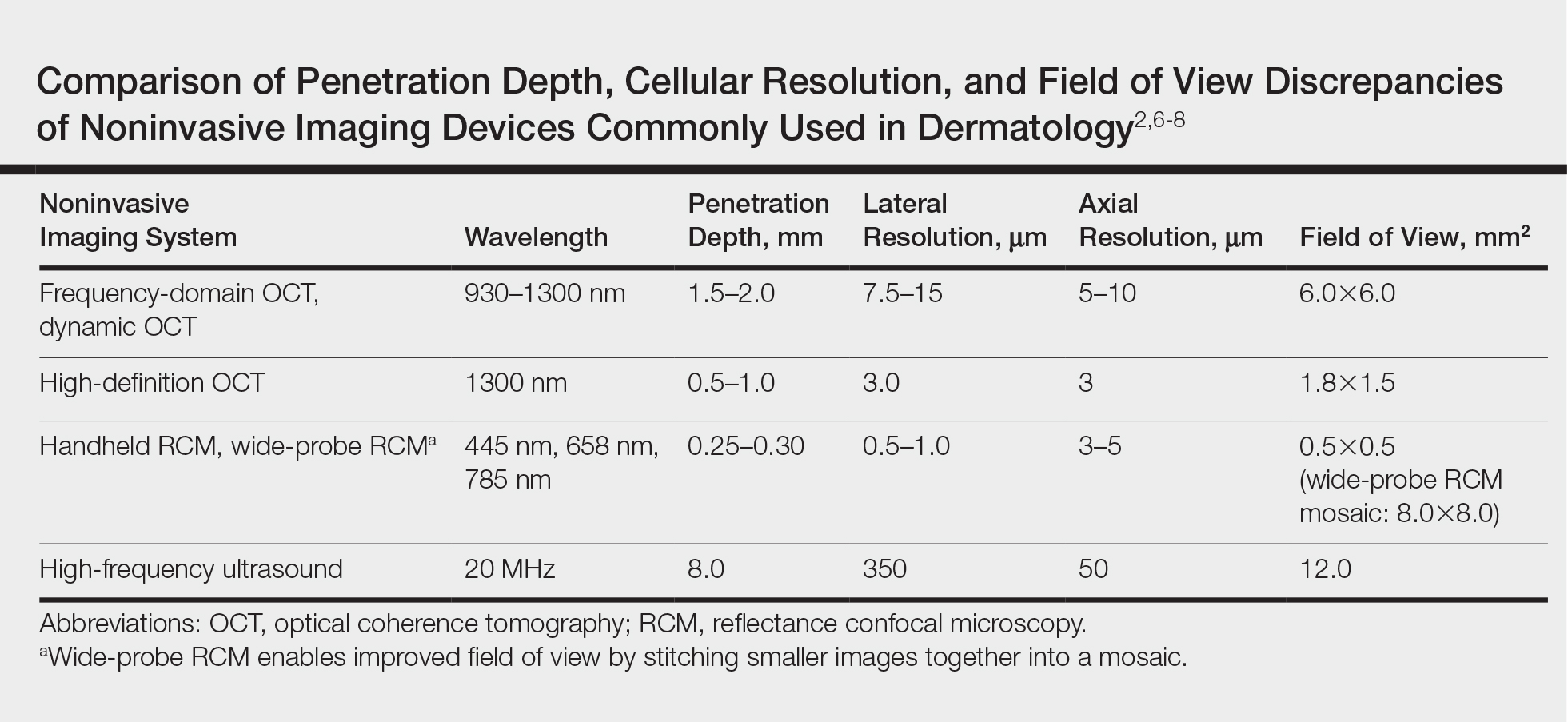

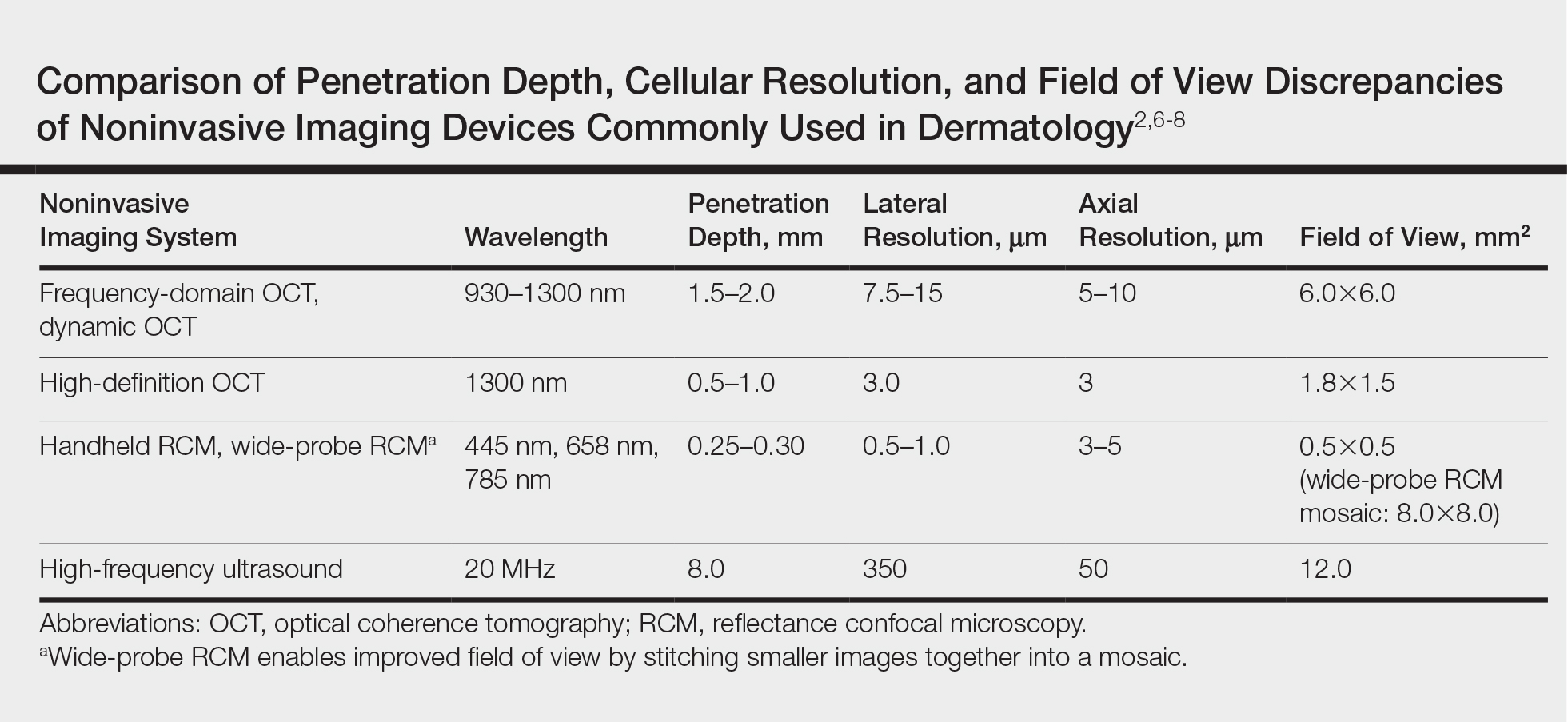

Optical coherence tomography, based on the principle of low-coherence interferometry, uses infrared light to extract fine details from within highly scattering turbid media to visualize the subsurface of the skin.2 Since its introduction for use in dermatology, OCT has been used to study skin in both the research and clinical settings.2,3 Current OCT devices on the market are mobile and easy to use in a busy dermatology practice. The Table reviews the most commonly used noninvasive imaging tools for the skin, depicting the inverse relationship between penetration depth and cellular resolution as well as field of view discrepancies.2,6-8 Optical coherence tomography technology collects cross-sectional (vertical) images similar to histology and en face (horizontal) images similar to reflective confocal microscopy (RCM) of skin areas with adequate cellular resolution and without compromising penetration depth as well as a field of view comparable to the probe aperture contacting the skin.

RELATED VIDEO: Noninvasive Imaging: Report From the Mount Sinai Fall Symposium

Conventional OCT

Due to multiple simultaneous beams, conventional frequency-domain OCT (FD-OCT) provides enhanced lateral resolution of 7.5 to 15 µm and axial resolution of 5 to 10 µm with a field of view of 6.0×6.0 mm2 and depth of 1.5 to 2.0 mm.2,6,8 Conventional FD-OCT detects architectural details within tissue with better cellular clarity than high-frequency ultrasound and better depth than RCM, yet FD-OCT is not sufficient to distinguish individual cells.

Dynamic OCT

The recent development of dynamic OCT (D-OCT) software based on speckle-variance has the added ability to visualize the skin microvasculature and therefore detect blood vessels and their distribution within specific lesions. This angiographic variant of FD-OCT detects motion corresponding to blood flow in the images and may enhance diagnostic accuracy, particularly in the differentiation of nevi and malignant melanomas.8-11

High-Definition OCT

High-definition OCT (HD-OCT), a hybrid of RCM and FD-OCT, provides improved optical resolution of 3 μm for both lateral and axial imaging approaching a resolution similar to RCM making it possible to visualize individual cells, though at the expense of lower penetration depth of 0.5 to 1.0 mm and reduced field of view of 1.8×1.5 mm2 to FD-OCT. High-definition OCT combines 2 different views to produce a 3-dimensional image for additional data interpretation (Table).7,8,12

Current CPT Guidelines

Two category III CPT codes—0470T and 0471T—allow the medical community to collect and track the usage of the emerging OCT technology. Code 0470T is used for microstructural and morphological skin imaging, specifically acquisition, interpretation, and reading of the images. Code 0471T is used for each additional skin lesion imaged.4

Current Procedural Terminology category III codes remain investigational in contrast to the permanent category I codes. Reimbursement for CPT III codes is difficult because it is not generally an accepted service covered by insurance.5 The goal within the next 5 years is to convert to category I CPT codes, meanwhile the CPT III codes should encourage increased utilization of OCT technology.

Indications for OCT

Depiction of Healthy Versus Diseased Skin

Optical coherence tomography is a valuable tool in visualizing normal skin morphology including principal skin layers, namely the dermis, epidermis, and dermoepidermal junction, as well as structures such as hair follicles, blood vessels, and glands.2,13 The OCT images show architectural changes of the skin layers and can be used to differentiate abnormal from normal tissue in vivo.2

Diagnosis and Treatment Monitoring of Skin Cancers

Optical coherence tomography is well established for use in the diagnosis and management of nonmelanoma skin cancers and to determine clinical end points of nonsurgical treatment without the need for skin biopsy. Promising diagnostic criteria have been developed for nonmelanoma skin cancers including basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma, as well as premalignant actinic keratoses using FD-OCT and the newer D-OCT and HD-OCT devices.9-17 For example, FD-OCT offers improved diagnosis of lesions suspicious for BCC, the most common type of skin cancer, showing improved sensitivity (79%–96%) and specificity (75%–96%) when compared with clinical assessment and dermoscopy alone.12,14 Typical OCT features differentiating BCC from other lesions include hyporeflective ovoid nests with a dark rim and an alteration of the dermoepidermal junction. In addition to providing a good diagnostic overview of skin, OCT devices show promise in monitoring the effects of treatment on primary and recurrent lesions.14-16

In Vivo Excision Planning

Additionally, OCT is a helpful tool in delineating tumor margins prior to surgical resection to achieve optimal cosmesis. By detecting subclinical tumor extension, this preoperative technique has been shown to reduce the number of surgical stages. Pomerantz et al17 showed that mapping BCC tumor margins with OCT prior to Mohs micrographic surgery closely approximated the final surgical defects. Alawi et al18 showed that the OCT-defined lateral margins correctly indicated complete removal of tumors. These studies illustrate the ability of OCT to minimize the amount of skin excised without compromising the integrity of tumor-free borders. The use of ex vivo OCT to detect residual tumors is not recommended based on current studies.6,17,18

Diagnosis and Treatment Monitoring of Other Diseases

Further applications of OCT include diagnosis of noncancerous lesions such as nail conditions, scleroderma, psoriatic arthritis, blistering diseases, and vascular lesions, as well as assessment of skin moisture and hydration, burn depth, wound healing, skin atrophy, and UV damage.2 For example, Aldahan et al19 demonstrated the utility of D-OCT to identify structural and vascular features specific to nail psoriasis useful in the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of the condition.

Limitations of OCT

Resolution

Frequency-domain OCT enables the detection of architectural details within tissue, but its image resolution is not sufficient to distinguish individual cells, therefore restricting its use in evaluating pigmented benign and malignant lesions such as dysplastic nevi and melanomas. Higher-resolution RCM is superior for imaging these lesions, as its device can better evaluate microscopic structures. With the advent of D-OCT and HD-OCT, research is being conducted to assess their use in differentiating pigmented lesions.8,20 Schuh et al9 and Gambichler et al20 reported preliminary results indicating the utility of D-OCT and HD-OCT to differentiate dysplastic nevi from melanomas and melanoma in situ, respectively.

Depth Measurement

Another limitation is associated with measuring lesion depth for advanced tumors. Although the typical imaging depth of OCT is significantly deeper than most other noninvasive imaging modalities used on skin, imaging deep tumor margins and invasion is restricted.

Image Interpretation

Diagnostic imaging requires image interpretation leading to potential interobserver and intraobserver variation. Experienced observers in OCT more accurately differentiated normal from lesional skin compared to novices, which suggests that training could improve agreement.21,22

Reimbursement and Device Cost

Other practical limitations to widespread OCT utilization at this time include its initial laser device cost and lack of reimbursement. As such, large academic and research centers remain the primary sites to utilize these devices.

Future Directions

Optical coherence tomography complements other established noninvasive imaging tools allowing for real-time visualization of the skin without interfering with the tissue and offering images with a good balance of depth, resolution, and field of view. Although a single histology cut has superior cellular resolution to any imaging modality, OCT provides additional information that is not provided by a physical biopsy, given the multiple vertical sections of data. Optical coherence tomography is a useful diagnostic technique enabling patients to avoid unnecessary biopsies while increasing early lesion diagnosis. Furthermore, OCT helps to decrease repetitive biopsies throughout nonsurgical treatments. With the availability of newer technology such as D-OCT and HD-OCT, OCT will play an increasing role in patient management. Clinicians and researchers should work to convert from category III to category I CPT codes and obtain reimbursement for imaging, with the ultimate goal of increasing its use in clinical practice and improving patient care.

- Michelson Diagnostics secures CPT codes for optical coherence tomography imaging of skin [press release]. Maidstone, Kent, United Kingdom: Michelson Diagnostics; July 14, 2017. https://vivosight.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Press-Release-CPT-code-announcement-12-July-2017.pdf. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- Schmitz L, Reinhold U, Bierhoff E, et al. Optical coherence tomography: its role in daily dermatological practice. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:499-507.

- Hibler BP, Qi Q, Rossi AM. Current state of imaging in dermatology. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2016;35:2-8.

- Current Procedural Terminology 2018, Professional Edition. Chicago IL: American Medical Association; 2017.

- Current Procedural Terminology 2017, Professional Edition. Chicago IL: American Medical Association; 2016.

- Cheng HM, Guitera P. Systemic review of optical coherence tomography usage in the diagnosis and management of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1371-1380.

- Cao T, Tey HL. High-definition optical coherence tomography—an aid to clinical practice and research in dermatology. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:886-890.

- Schwartz M, Siegel DM, Markowitz O. Commentary on the diagnostic utility of non-invasive imaging devices for field cancerization. Exp Dermatol. 2016;25:855-856.

- Schuh S, Holmes J, Ulrich M, et al. Imaging blood vessel morphology in skin: dynamic optical coherence tomography as a novel potential diagnostic tool in dermatology. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:187-202.

- Themstrup L, Pellacani G, Welzel J, et al. In vivo microvascular imaging of cutaneous actinic keratosis, Bowen’s disease and squamous cell carcinoma using dynamic optical coherence tomography [published online May 14, 2017]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.14335.

- Markowitz O, Schwartz M, Minhas S, et al. DM. Speckle-variance optical coherence tomography: a novel approach to skin cancer characterization using vascular patterns. Dermatol Online J. 2016;18:22. pii:13030/qt7w10290r.

- Ulrich M, von Braunmuehl T, Kurzen H, et al. The sensitivity and specificity of optical coherence tomography for the assisted diagnosis of nonpigmented basal cell carcinoma: an observational study. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:428-435.

- Hussain AA, Themstrup L, Jemec GB. Optical coherence tomography in the diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol Res. 2015;307:1-10.

- Markowitz O, Schwartz M, Feldman E, et al. Evaluation of optical coherence tomography as a means of identifying earlier stage basal carcinomas while reducing the use of diagnostic biopsy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:14-20.

- Banzhaf CA, Themstrup L, Ring HC, et al. Optical coherence tomography imaging of non-melanoma skin cancer undergoing imiquimod therapy. Skin Res Technol. 2014;20:170-176.

- Themstrup L, Banzhaf CA, Mogensen M, et al. Optical coherence tomography imaging of non-melanoma skin cancer undergoing photodynamic therapy reveals subclinical residual lesions. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2014;11:7-12.

- Pomerantz R, Zell D, McKenzie G, et al. Optical coherence tomography used as a modality to delineate basal cell carcinoma prior to Mohs micrographic surgery. Case Rep Dermatol. 2011;3:212-218.

- Alawi SA, Kuck M, Wahrlich C, et al. Optical coherence tomography for presurgical margin assessment of non-melanoma skin cancer—a practical approach. Exp Dermatol. 2013;22:547-551.

- Aldahan AS, Chen LL, Fertig RM, et al. Vascular features of nail psoriasis using dynamic optical coherence tomography. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;2:102-108.

- Gambichler T, Plura I, Schmid-Wendtner M, et al. High-definition optical coherence tomography of melanocytic skin lesions. J Biophotonics. 2015;8:681-686.

- Mogensen M, Joergensen TM, Nurnberg BM, et al. Assessment of optical coherence tomography imaging in the diagnosis of non-melanoma skin cancer and benign lesions versus normal skin: observer-blinded evaluation by dermatologists. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:965-972.

- Olsen J, Themstrup L, De Carbalho N, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of optical coherence tomography in actinic keratosis and basal cell carcinoma. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2016;16:44-49.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a noninvasive imaging technique that is cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration as a 510(k) class II regulatory device to visualize biological tissues in vivo and in real time.1-3 In July 2017, OCT received 2 category III Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes from the American Medical Association—0470T and 0471T—enabling physicians to report and track the usage of this emerging imaging method.4 Category III CPT codes remain investigational and therefore are not easily reimbursed by insurance.5 The goal of OCT manufacturers and providers within the next 5 years is to upgrade to category I coding before the present codes are archived. Although documented advantages of OCT include its unique ability to effectively differentiate and monitor skin lesions throughout nonsurgical treatment as well as to efficiently delineate presurgical margins, additional research reporting its efficacy may facilitate the coding conversion and encourage greater usage of OCT technology. We present a brief review of OCT imaging in dermatology, including its indications and limitations.

RELATED VIDEO: Imaging Overview: Report From the Mount Sinai Fall Symposium

Types of OCT

Optical coherence tomography, based on the principle of low-coherence interferometry, uses infrared light to extract fine details from within highly scattering turbid media to visualize the subsurface of the skin.2 Since its introduction for use in dermatology, OCT has been used to study skin in both the research and clinical settings.2,3 Current OCT devices on the market are mobile and easy to use in a busy dermatology practice. The Table reviews the most commonly used noninvasive imaging tools for the skin, depicting the inverse relationship between penetration depth and cellular resolution as well as field of view discrepancies.2,6-8 Optical coherence tomography technology collects cross-sectional (vertical) images similar to histology and en face (horizontal) images similar to reflective confocal microscopy (RCM) of skin areas with adequate cellular resolution and without compromising penetration depth as well as a field of view comparable to the probe aperture contacting the skin.

RELATED VIDEO: Noninvasive Imaging: Report From the Mount Sinai Fall Symposium

Conventional OCT

Due to multiple simultaneous beams, conventional frequency-domain OCT (FD-OCT) provides enhanced lateral resolution of 7.5 to 15 µm and axial resolution of 5 to 10 µm with a field of view of 6.0×6.0 mm2 and depth of 1.5 to 2.0 mm.2,6,8 Conventional FD-OCT detects architectural details within tissue with better cellular clarity than high-frequency ultrasound and better depth than RCM, yet FD-OCT is not sufficient to distinguish individual cells.

Dynamic OCT

The recent development of dynamic OCT (D-OCT) software based on speckle-variance has the added ability to visualize the skin microvasculature and therefore detect blood vessels and their distribution within specific lesions. This angiographic variant of FD-OCT detects motion corresponding to blood flow in the images and may enhance diagnostic accuracy, particularly in the differentiation of nevi and malignant melanomas.8-11

High-Definition OCT

High-definition OCT (HD-OCT), a hybrid of RCM and FD-OCT, provides improved optical resolution of 3 μm for both lateral and axial imaging approaching a resolution similar to RCM making it possible to visualize individual cells, though at the expense of lower penetration depth of 0.5 to 1.0 mm and reduced field of view of 1.8×1.5 mm2 to FD-OCT. High-definition OCT combines 2 different views to produce a 3-dimensional image for additional data interpretation (Table).7,8,12

Current CPT Guidelines

Two category III CPT codes—0470T and 0471T—allow the medical community to collect and track the usage of the emerging OCT technology. Code 0470T is used for microstructural and morphological skin imaging, specifically acquisition, interpretation, and reading of the images. Code 0471T is used for each additional skin lesion imaged.4

Current Procedural Terminology category III codes remain investigational in contrast to the permanent category I codes. Reimbursement for CPT III codes is difficult because it is not generally an accepted service covered by insurance.5 The goal within the next 5 years is to convert to category I CPT codes, meanwhile the CPT III codes should encourage increased utilization of OCT technology.

Indications for OCT

Depiction of Healthy Versus Diseased Skin

Optical coherence tomography is a valuable tool in visualizing normal skin morphology including principal skin layers, namely the dermis, epidermis, and dermoepidermal junction, as well as structures such as hair follicles, blood vessels, and glands.2,13 The OCT images show architectural changes of the skin layers and can be used to differentiate abnormal from normal tissue in vivo.2

Diagnosis and Treatment Monitoring of Skin Cancers

Optical coherence tomography is well established for use in the diagnosis and management of nonmelanoma skin cancers and to determine clinical end points of nonsurgical treatment without the need for skin biopsy. Promising diagnostic criteria have been developed for nonmelanoma skin cancers including basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma, as well as premalignant actinic keratoses using FD-OCT and the newer D-OCT and HD-OCT devices.9-17 For example, FD-OCT offers improved diagnosis of lesions suspicious for BCC, the most common type of skin cancer, showing improved sensitivity (79%–96%) and specificity (75%–96%) when compared with clinical assessment and dermoscopy alone.12,14 Typical OCT features differentiating BCC from other lesions include hyporeflective ovoid nests with a dark rim and an alteration of the dermoepidermal junction. In addition to providing a good diagnostic overview of skin, OCT devices show promise in monitoring the effects of treatment on primary and recurrent lesions.14-16

In Vivo Excision Planning

Additionally, OCT is a helpful tool in delineating tumor margins prior to surgical resection to achieve optimal cosmesis. By detecting subclinical tumor extension, this preoperative technique has been shown to reduce the number of surgical stages. Pomerantz et al17 showed that mapping BCC tumor margins with OCT prior to Mohs micrographic surgery closely approximated the final surgical defects. Alawi et al18 showed that the OCT-defined lateral margins correctly indicated complete removal of tumors. These studies illustrate the ability of OCT to minimize the amount of skin excised without compromising the integrity of tumor-free borders. The use of ex vivo OCT to detect residual tumors is not recommended based on current studies.6,17,18

Diagnosis and Treatment Monitoring of Other Diseases

Further applications of OCT include diagnosis of noncancerous lesions such as nail conditions, scleroderma, psoriatic arthritis, blistering diseases, and vascular lesions, as well as assessment of skin moisture and hydration, burn depth, wound healing, skin atrophy, and UV damage.2 For example, Aldahan et al19 demonstrated the utility of D-OCT to identify structural and vascular features specific to nail psoriasis useful in the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of the condition.

Limitations of OCT

Resolution