User login

Cannabis use causes spike in ED visits

Cannabis users had a 22% increased risk of an emergency department (ED) visit or hospitalization compared to nonusers, as determined from data from more than 30,000 individuals.

Although cannabis contains compounds similar to tobacco, “data published on the association between cannabis smoking and airways health have been contradictory,” and whether smoking cannabis increases a user’s risk of developing acute respiratory illness remains unclear, wrote Nicholas T. Vozoris, MD, of the University of Toronto, and colleagues.

In a study published in BMJ Open Respiratory Research, the investigators reviewed national health records data from 35,114 individuals aged 12-65 years for the period January 2009 to December 2015. Of these persons, 4,807 of the 6,425 who reported cannabis use in the past year were matched with 10,395 never-users who served as controls. The mean age of the study population at the index date was 35 years, and 42% were women; demographics were similar between users and control persons.

Overall, the odds of respiratory-related emergency department visits or hospitalizations were not significantly different between the cannabis users and the control persons (3.6% vs. 3.9%; odds ratio, 0.91). However, cannabis users had significantly greater odds of all-cause ED visits or hospitalizations (30.0% vs. 26.0%; OR, 1.22). All-cause mortality was 0.2% for both groups.

Respiratory problems were the second-highest reason for all-cause visits, the researchers noted. The lack of a difference in respiratory-related visits between cannabis users and nonusers conflicts somewhat with previous studies on this topic, which were limited, the researchers noted in their discussion.

The negative results also might stem from factors for which the researchers could not adjust, including insufficient cannabis smoke exposure among users in the study population, noninhalational cannabis use, which is less likely to have a respiratory effect, and possible secondhand exposure among control persons.

“It is also possible that our analysis might have been insufficiently powered to detect a significant signal with respect to the primary outcome,” they noted.

However, after the researchers controlled for multiple variables, the risk of an equally important morbidity outcome, all-cause ED visits or hospitalizations, was significantly greater among cannabis users than among control individuals, and respiratory reasons were the second most common cause for ED visits and hospitalizations in the all-cause outcome, they emphasized.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the retrospective and observational design and the inability to control for all confounding variables, the researchers noted. Other limitations include the use of self-reports and potential for bias, the inability to perform dose-response analysis, and the high number of infrequent cannabis users in the study population.

However, the results suggest that cannabis use is associated with an increased risk of serious health events and should be discouraged, although more research is needed to confirm the current study findings, they concluded.

Consider range of causes for cannabis emergency visits

“With growing numbers of states legalizing recreational use of cannabis, it’s important to understand whether cannabis use is associated with increased emergency department visits,” Robert D. Glatter, MD, an emergency medicine physician at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, told this news organization.

Previous studies have shown an association between increased ED visits and cannabis use in states, especially with edibles, where cannabis is legal, and “the current study reinforces the elevated risk of ED visits along with hospitalizations,” he said.

“While the researchers found no increased risk of respiratory-related complaints among users compared to the general population, there was an associated increase in ED visits and hospitalizations, which is important to understand,” said Dr. Glatter, who was not involved in the study.

“While this observational study found that the incidence of respiratory complaints was not significantly different among frequent users of cannabis, the increased odds that cannabis users would require evaluation in the emergency room or even hospitalization was still apparent even after the investigators controlled for such factors as use of alcohol, tobacco, illicit drug use, or other mental health–related disorders,” Dr. Glatter noted.

“That said, it’s a bit surprising that with the continued popularity of vaping, especially among teens, there was still not any appreciable or significant increase in respiratory complaints observed. Beyond this finding, I was not surprised by the overall conclusions of the current study, as we continue to see an elevated number of patients presenting to the ED with adverse events related to cannabis use.”

Dr. Glatter noted that “the majority of patients we see in the ED are associated with use of edibles, since it takes longer for the person to feel the effects, leading the user to consume more of the product up front, with delayed effects lasting up to 12 hours. This is what gets people into trouble and leads to toxicity of cannabis, or ‘overdoses,’ “ he explained.

When consuming edible cannabis products, “[p]eople need to begin at low dosages and not take additional gummies up front, since it can take up to 2 or even 3 hours in some cases to feel the initial effects. With the drug’s effects lasting up to 12 hours, it’s especially important to avoid operating any motor vehicles, bicycles, or scooters, since reaction time is impaired, as well as overall judgment, balance, and fine motor skills,” Dr. Glatter said.

Cannabis can land users in the ED for a range of reasons, said Dr. Glatter. “According to the study, 15% of the emergency room visits and hospitalizations were due to acute trauma, 14% due to respiratory issues, and 13% to gastrointestinal illnesses. These effects were seen in first-time users but not those with chronic use, according to the study inclusion criteria.”

Cannabis use could result in physical injuries through “impaired judgment, coordination, combined with an altered state of consciousness or generalized drowsiness, that could contribute to an increase in motor vehicle collisions, along with an increased risk for falls leading to lacerations, fractures, contusions, or bruising,” said Dr. Glatter. “Cannabis may also lead to an altered sense of perception related to interactions with others, resulting in feelings of anxiety or restlessness culminating in physical altercations and other injuries.”

The current study indicates the need for understanding the potential physical and psychological effects of cannabis use, he said.

“Additional research is needed to better understand the relative percentage cases related to edibles vs. inhalation presenting to the ED,” he noted. “There is no question that edibles continue to present significant dangers for those who don’t read labels or remain poorly informed regarding their dosing as a result of delayed onset and longer duration,” he said. To help reduce risk of toxicity, the concept of a “high lasting 12-15 hours, as with edibles, as opposed to 3-4 hours from inhalation must be clearly stated on packaging and better communicated with users, as the toxicity with edibles is more often from lack of prior knowledge about onset of effects related to dosing.”

In addition, the “potential for psychosis to develop with more chronic cannabis use, along with cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome should be on every clinician’s radar,” Dr. Glatter emphasized.

“The bottom line is that as more states legalize the use of cannabis, it’s vital to also implement comprehensive public education efforts to provide users with the reported risks associated with not only inhalation (vaping or flower) but also edibles, which account for an increasingly greater percentage of ED visits and associated adverse effects,” he said.

The study was supported by the Lung Association–Ontario, as well as by grants from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Long-Term Care. The researchers and Dr. Glatter have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cannabis users had a 22% increased risk of an emergency department (ED) visit or hospitalization compared to nonusers, as determined from data from more than 30,000 individuals.

Although cannabis contains compounds similar to tobacco, “data published on the association between cannabis smoking and airways health have been contradictory,” and whether smoking cannabis increases a user’s risk of developing acute respiratory illness remains unclear, wrote Nicholas T. Vozoris, MD, of the University of Toronto, and colleagues.

In a study published in BMJ Open Respiratory Research, the investigators reviewed national health records data from 35,114 individuals aged 12-65 years for the period January 2009 to December 2015. Of these persons, 4,807 of the 6,425 who reported cannabis use in the past year were matched with 10,395 never-users who served as controls. The mean age of the study population at the index date was 35 years, and 42% were women; demographics were similar between users and control persons.

Overall, the odds of respiratory-related emergency department visits or hospitalizations were not significantly different between the cannabis users and the control persons (3.6% vs. 3.9%; odds ratio, 0.91). However, cannabis users had significantly greater odds of all-cause ED visits or hospitalizations (30.0% vs. 26.0%; OR, 1.22). All-cause mortality was 0.2% for both groups.

Respiratory problems were the second-highest reason for all-cause visits, the researchers noted. The lack of a difference in respiratory-related visits between cannabis users and nonusers conflicts somewhat with previous studies on this topic, which were limited, the researchers noted in their discussion.

The negative results also might stem from factors for which the researchers could not adjust, including insufficient cannabis smoke exposure among users in the study population, noninhalational cannabis use, which is less likely to have a respiratory effect, and possible secondhand exposure among control persons.

“It is also possible that our analysis might have been insufficiently powered to detect a significant signal with respect to the primary outcome,” they noted.

However, after the researchers controlled for multiple variables, the risk of an equally important morbidity outcome, all-cause ED visits or hospitalizations, was significantly greater among cannabis users than among control individuals, and respiratory reasons were the second most common cause for ED visits and hospitalizations in the all-cause outcome, they emphasized.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the retrospective and observational design and the inability to control for all confounding variables, the researchers noted. Other limitations include the use of self-reports and potential for bias, the inability to perform dose-response analysis, and the high number of infrequent cannabis users in the study population.

However, the results suggest that cannabis use is associated with an increased risk of serious health events and should be discouraged, although more research is needed to confirm the current study findings, they concluded.

Consider range of causes for cannabis emergency visits

“With growing numbers of states legalizing recreational use of cannabis, it’s important to understand whether cannabis use is associated with increased emergency department visits,” Robert D. Glatter, MD, an emergency medicine physician at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, told this news organization.

Previous studies have shown an association between increased ED visits and cannabis use in states, especially with edibles, where cannabis is legal, and “the current study reinforces the elevated risk of ED visits along with hospitalizations,” he said.

“While the researchers found no increased risk of respiratory-related complaints among users compared to the general population, there was an associated increase in ED visits and hospitalizations, which is important to understand,” said Dr. Glatter, who was not involved in the study.

“While this observational study found that the incidence of respiratory complaints was not significantly different among frequent users of cannabis, the increased odds that cannabis users would require evaluation in the emergency room or even hospitalization was still apparent even after the investigators controlled for such factors as use of alcohol, tobacco, illicit drug use, or other mental health–related disorders,” Dr. Glatter noted.

“That said, it’s a bit surprising that with the continued popularity of vaping, especially among teens, there was still not any appreciable or significant increase in respiratory complaints observed. Beyond this finding, I was not surprised by the overall conclusions of the current study, as we continue to see an elevated number of patients presenting to the ED with adverse events related to cannabis use.”

Dr. Glatter noted that “the majority of patients we see in the ED are associated with use of edibles, since it takes longer for the person to feel the effects, leading the user to consume more of the product up front, with delayed effects lasting up to 12 hours. This is what gets people into trouble and leads to toxicity of cannabis, or ‘overdoses,’ “ he explained.

When consuming edible cannabis products, “[p]eople need to begin at low dosages and not take additional gummies up front, since it can take up to 2 or even 3 hours in some cases to feel the initial effects. With the drug’s effects lasting up to 12 hours, it’s especially important to avoid operating any motor vehicles, bicycles, or scooters, since reaction time is impaired, as well as overall judgment, balance, and fine motor skills,” Dr. Glatter said.

Cannabis can land users in the ED for a range of reasons, said Dr. Glatter. “According to the study, 15% of the emergency room visits and hospitalizations were due to acute trauma, 14% due to respiratory issues, and 13% to gastrointestinal illnesses. These effects were seen in first-time users but not those with chronic use, according to the study inclusion criteria.”

Cannabis use could result in physical injuries through “impaired judgment, coordination, combined with an altered state of consciousness or generalized drowsiness, that could contribute to an increase in motor vehicle collisions, along with an increased risk for falls leading to lacerations, fractures, contusions, or bruising,” said Dr. Glatter. “Cannabis may also lead to an altered sense of perception related to interactions with others, resulting in feelings of anxiety or restlessness culminating in physical altercations and other injuries.”

The current study indicates the need for understanding the potential physical and psychological effects of cannabis use, he said.

“Additional research is needed to better understand the relative percentage cases related to edibles vs. inhalation presenting to the ED,” he noted. “There is no question that edibles continue to present significant dangers for those who don’t read labels or remain poorly informed regarding their dosing as a result of delayed onset and longer duration,” he said. To help reduce risk of toxicity, the concept of a “high lasting 12-15 hours, as with edibles, as opposed to 3-4 hours from inhalation must be clearly stated on packaging and better communicated with users, as the toxicity with edibles is more often from lack of prior knowledge about onset of effects related to dosing.”

In addition, the “potential for psychosis to develop with more chronic cannabis use, along with cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome should be on every clinician’s radar,” Dr. Glatter emphasized.

“The bottom line is that as more states legalize the use of cannabis, it’s vital to also implement comprehensive public education efforts to provide users with the reported risks associated with not only inhalation (vaping or flower) but also edibles, which account for an increasingly greater percentage of ED visits and associated adverse effects,” he said.

The study was supported by the Lung Association–Ontario, as well as by grants from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Long-Term Care. The researchers and Dr. Glatter have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cannabis users had a 22% increased risk of an emergency department (ED) visit or hospitalization compared to nonusers, as determined from data from more than 30,000 individuals.

Although cannabis contains compounds similar to tobacco, “data published on the association between cannabis smoking and airways health have been contradictory,” and whether smoking cannabis increases a user’s risk of developing acute respiratory illness remains unclear, wrote Nicholas T. Vozoris, MD, of the University of Toronto, and colleagues.

In a study published in BMJ Open Respiratory Research, the investigators reviewed national health records data from 35,114 individuals aged 12-65 years for the period January 2009 to December 2015. Of these persons, 4,807 of the 6,425 who reported cannabis use in the past year were matched with 10,395 never-users who served as controls. The mean age of the study population at the index date was 35 years, and 42% were women; demographics were similar between users and control persons.

Overall, the odds of respiratory-related emergency department visits or hospitalizations were not significantly different between the cannabis users and the control persons (3.6% vs. 3.9%; odds ratio, 0.91). However, cannabis users had significantly greater odds of all-cause ED visits or hospitalizations (30.0% vs. 26.0%; OR, 1.22). All-cause mortality was 0.2% for both groups.

Respiratory problems were the second-highest reason for all-cause visits, the researchers noted. The lack of a difference in respiratory-related visits between cannabis users and nonusers conflicts somewhat with previous studies on this topic, which were limited, the researchers noted in their discussion.

The negative results also might stem from factors for which the researchers could not adjust, including insufficient cannabis smoke exposure among users in the study population, noninhalational cannabis use, which is less likely to have a respiratory effect, and possible secondhand exposure among control persons.

“It is also possible that our analysis might have been insufficiently powered to detect a significant signal with respect to the primary outcome,” they noted.

However, after the researchers controlled for multiple variables, the risk of an equally important morbidity outcome, all-cause ED visits or hospitalizations, was significantly greater among cannabis users than among control individuals, and respiratory reasons were the second most common cause for ED visits and hospitalizations in the all-cause outcome, they emphasized.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the retrospective and observational design and the inability to control for all confounding variables, the researchers noted. Other limitations include the use of self-reports and potential for bias, the inability to perform dose-response analysis, and the high number of infrequent cannabis users in the study population.

However, the results suggest that cannabis use is associated with an increased risk of serious health events and should be discouraged, although more research is needed to confirm the current study findings, they concluded.

Consider range of causes for cannabis emergency visits

“With growing numbers of states legalizing recreational use of cannabis, it’s important to understand whether cannabis use is associated with increased emergency department visits,” Robert D. Glatter, MD, an emergency medicine physician at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, told this news organization.

Previous studies have shown an association between increased ED visits and cannabis use in states, especially with edibles, where cannabis is legal, and “the current study reinforces the elevated risk of ED visits along with hospitalizations,” he said.

“While the researchers found no increased risk of respiratory-related complaints among users compared to the general population, there was an associated increase in ED visits and hospitalizations, which is important to understand,” said Dr. Glatter, who was not involved in the study.

“While this observational study found that the incidence of respiratory complaints was not significantly different among frequent users of cannabis, the increased odds that cannabis users would require evaluation in the emergency room or even hospitalization was still apparent even after the investigators controlled for such factors as use of alcohol, tobacco, illicit drug use, or other mental health–related disorders,” Dr. Glatter noted.

“That said, it’s a bit surprising that with the continued popularity of vaping, especially among teens, there was still not any appreciable or significant increase in respiratory complaints observed. Beyond this finding, I was not surprised by the overall conclusions of the current study, as we continue to see an elevated number of patients presenting to the ED with adverse events related to cannabis use.”

Dr. Glatter noted that “the majority of patients we see in the ED are associated with use of edibles, since it takes longer for the person to feel the effects, leading the user to consume more of the product up front, with delayed effects lasting up to 12 hours. This is what gets people into trouble and leads to toxicity of cannabis, or ‘overdoses,’ “ he explained.

When consuming edible cannabis products, “[p]eople need to begin at low dosages and not take additional gummies up front, since it can take up to 2 or even 3 hours in some cases to feel the initial effects. With the drug’s effects lasting up to 12 hours, it’s especially important to avoid operating any motor vehicles, bicycles, or scooters, since reaction time is impaired, as well as overall judgment, balance, and fine motor skills,” Dr. Glatter said.

Cannabis can land users in the ED for a range of reasons, said Dr. Glatter. “According to the study, 15% of the emergency room visits and hospitalizations were due to acute trauma, 14% due to respiratory issues, and 13% to gastrointestinal illnesses. These effects were seen in first-time users but not those with chronic use, according to the study inclusion criteria.”

Cannabis use could result in physical injuries through “impaired judgment, coordination, combined with an altered state of consciousness or generalized drowsiness, that could contribute to an increase in motor vehicle collisions, along with an increased risk for falls leading to lacerations, fractures, contusions, or bruising,” said Dr. Glatter. “Cannabis may also lead to an altered sense of perception related to interactions with others, resulting in feelings of anxiety or restlessness culminating in physical altercations and other injuries.”

The current study indicates the need for understanding the potential physical and psychological effects of cannabis use, he said.

“Additional research is needed to better understand the relative percentage cases related to edibles vs. inhalation presenting to the ED,” he noted. “There is no question that edibles continue to present significant dangers for those who don’t read labels or remain poorly informed regarding their dosing as a result of delayed onset and longer duration,” he said. To help reduce risk of toxicity, the concept of a “high lasting 12-15 hours, as with edibles, as opposed to 3-4 hours from inhalation must be clearly stated on packaging and better communicated with users, as the toxicity with edibles is more often from lack of prior knowledge about onset of effects related to dosing.”

In addition, the “potential for psychosis to develop with more chronic cannabis use, along with cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome should be on every clinician’s radar,” Dr. Glatter emphasized.

“The bottom line is that as more states legalize the use of cannabis, it’s vital to also implement comprehensive public education efforts to provide users with the reported risks associated with not only inhalation (vaping or flower) but also edibles, which account for an increasingly greater percentage of ED visits and associated adverse effects,” he said.

The study was supported by the Lung Association–Ontario, as well as by grants from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Long-Term Care. The researchers and Dr. Glatter have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Smoking cessation: Varenicline and the risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events

Mr. T, age 34, is a veteran who recently returned to civilian life. He presents to his local Veteran Affairs facility for transition of care. During active duty, he had been diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea, tobacco use disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) secondary to combat exposure, and insomnia. Mr. T says he wants to quit smoking; currently, he smokes 2 packs of cigarettes per day. The primary care clinician notes that Mr. T has uncontrolled PTSD symptoms and poor sleep, and refers him for an outpatient mental health appointment.

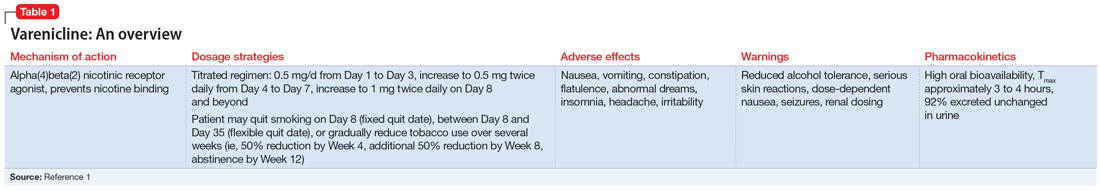

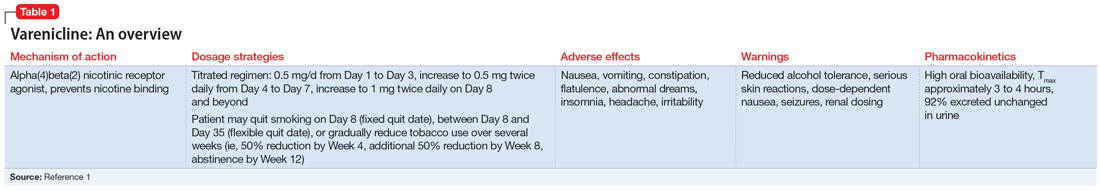

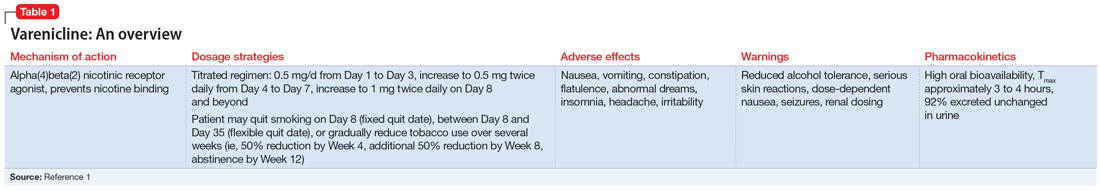

At the mental health appointment 3 weeks later, Mr. T asks about medications to quit smoking, specifically varenicline (Table 11). Mr. T’s PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 score is 52, which indicates severe PTSD symptomatology. He says he sees shadowy figures in his periphery every day, and worries they are spying on him. His wife reports Mr. T has had these symptoms for most of their 10-year marriage but has never been treated for them. After a discussion with the outpatient team, Mr. T says he is willing to engage in exposure therapy for PTSD, but he does not want to take any medications other than varenicline for smoking cessation.

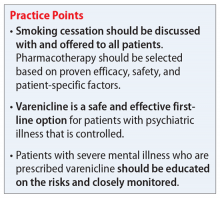

Cigarette smoke is a known carcinogen and risk factor for the development of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases and other comorbidities. People with severe mental illness (SMI) are 3 to 5 times more likely to smoke, and they often face multiple barriers to cessation, including low socioeconomic status and lack of support.2 Even when patients with SMI are provided appropriate behavioral and pharmacologic interventions, they often require more frequent monitoring and counseling, receive a longer duration of drug therapy, and experience lower smoking cessation rates than the general population.2

Current guidelines recommend nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion, varenicline, and behavioral support as first-line therapies for smoking cessation in patients with and without SMI.2 Evidence suggests that varenicline is more effective than other pharmacologic options; however, in 2009 a black-box warning was added to both varenicline and bupropion to highlight an increased risk of neuropsychiatric events in individuals with SMI.2 This led some clinicians to hesitate to prescribe varenicline or bupropion to patients with psychiatric illness. However, in 2016, the EAGLES trial evaluated the safety of varenicline, bupropion, and NRT in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders, and based on the findings, the black-box warning was removed.2

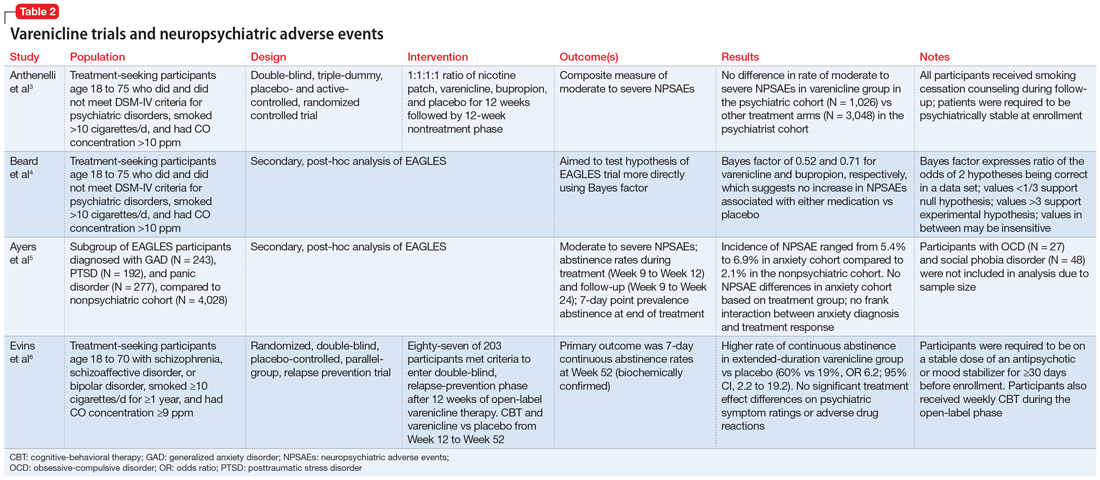

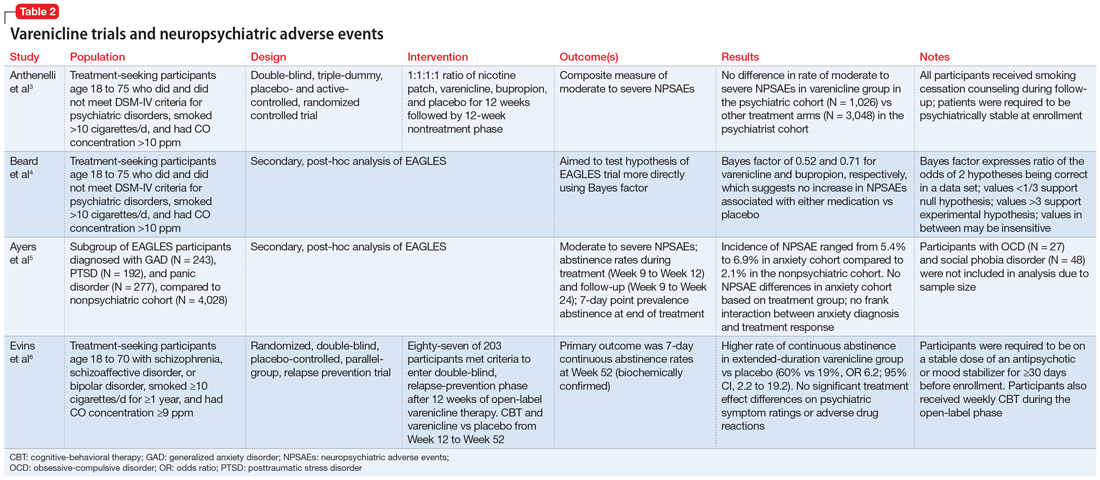

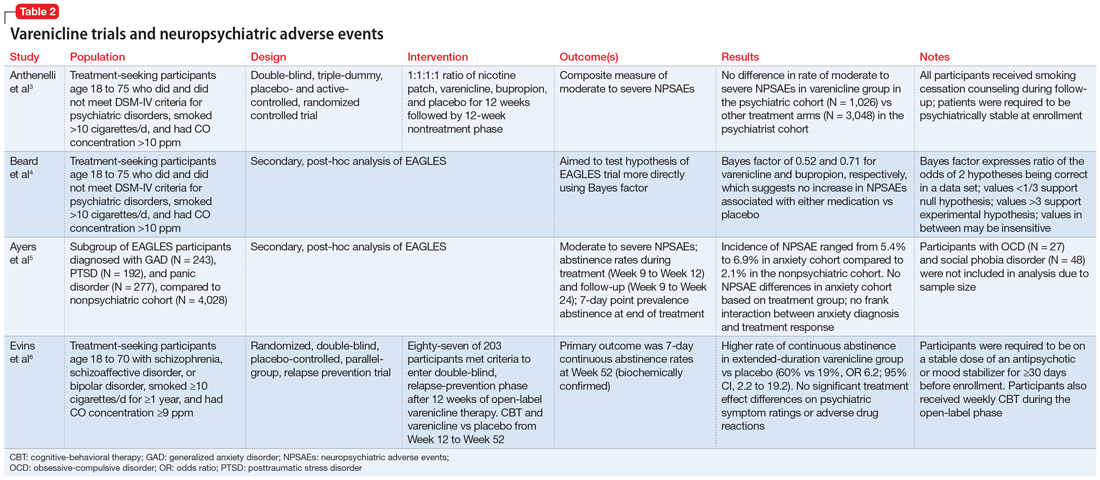

This article reviews the evidence regarding the use of varenicline and the risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events in patients with psychiatric illness. Table 23-6 provides a summary of each varenicline trial we discuss.

The EAGLES trial

EAGLES was a multicenter, multinational, randomized, double-blind, triple-dummy, placebo- and active-controlled trial of 8,144 individuals who received treatment for smoking cessation.3 The primary endpoint was the incidence of a composite measure of moderate to severe neuropsychiatric events (NPSAEs).3 Participants were split into psychiatric (N = 4,116) and nonpsychiatric (N = 4,028) cohorts and randomized into 4 treatment arms: varenicline 1 mg twice a day, bupropion 150 mg twice a day, nicotine patch 21 mg/d with taper, or placebo, all for 12 weeks with an additional 12 weeks of follow-up. All participants smoked ≥10 cigarettes per day. Individuals in the psychiatric cohort had to be psychiatrically stable (no exacerbations for 6 months and stable treatment for 3 months). Exclusionary diagnoses included psychotic disorders (except schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder), dementia, substance use (except nicotine), and personality disorders (except borderline personality disorder).2

The rates of moderate to severe NPSAEs in the varenicline groups were 1.25% (95% CI, 0.60 to 1.90) in the nonpsychiatric cohort and 6.42% (95% CI, 4.91 to 7.93) in the psychiatric cohort.3 However, when comparing the varenicline group of the psychiatric cohort to the other arms of the psychiatric cohort, there were no differences (bupropion 6.62% [95% CI, 5.09 to 8.15], nicotine patch 5.20% [95% CI, 3.84 to 6.56], placebo 4.83% [95% CI, 3.51 to 6.16], respectively). The primary efficacy endpoint was continuous abstinence rates (CAR) for Week 9 through Week 12. In the psychiatric cohort, varenicline was superior compared to placebo (odds ratio [OR] 3.24; 95% CI, 2.56 to 4.11), bupropion (OR 1.74; 95% CI, 1.41 to 2.14), and nicotine patch (OR 1.62; 95% CI, 1.32 to 1.99).3

Continue to: Further analysis of EAGLES

Further analysis of EAGLES

Beard et al4 used Bayes factor testing for additional analysis of EAGLES data to determine whether the data were insensitive to neuropsychiatric effects secondary to a lack of statistical power. In the psychiatric cohort, the varenicline and bupropion groups exhibited suggestive but not conclusive data that there was no increase in NPSAEs compared to placebo (Bayes factor 0.52 and 0.71, respectively).4

Another EAGLES analysis by Ayers et al5 evaluated participants with anxiety disorders (N = 712), including PTSD (N = 192), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (N = 243), and panic disorder (N = 277).Of those with PTSD who received varenicline, there were no statistically significant differences in CAR from Week 9 to Week 12 vs placebo.5 However, there was a significant difference in individuals with GAD (OR 4.53; 95% CI, 1.20 to 17.10), and panic disorder (OR 8.49; 95% CI, 1.57 to 45.78).5 In contrast to CAR from Week 9 to Week 12, 7-day point prevalence abstinence at Week 12 for participants with PTSD was significant (OR 4.04; 95% CI, 1.39 to 11.74) when comparing varenicline to placebo. Within the anxiety disorder cohort, there were no significant differences in moderate to severe NPSAE rates based on treatment group. Calculated risk differences comparing varenicline to placebo were: PTSD group -7.73 (95% CI, -21.95 to 6.49), GAD group 2.80 (95% CI, -6.63 to 12.23), and panic disorder group -0.18 (95% CI, -9.57 to 9.21).5

Other studies

Evins et al6 conducted a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the safety of varenicline maintenance therapy in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. To be deemed clinically stable, participants in this study needed to be taking a stable dose of an antipsychotic or mood-stabilizing agent(s) for ≥30 days, compared to the 3-month requirement of the EAGLES trial.3,6 Participants received 12 weeks of open-label varenicline; those who achieved abstinence (N = 87) entered the relapse-prevention phase and were randomized to varenicline 1 mg twice a day or placebo for 40 weeks. Of those who entered relapse-prevention, 5 in the placebo group and 2 in the varenicline group were psychiatrically hospitalized (risk ratio 0.45; 95% CI, 0.04 to 2.9).6 These researchers concluded that varenicline maintenance therapy prolonged abstinence rates with no significant increase in neuropsychiatric events.6

Although treatment options for smoking cessation have advanced, individuals with SMI are still disproportionately affected by the negative outcomes of cigarette smoking. Current literature suggests that varenicline does not confer an appreciable risk of neuropsychiatric events in otherwise stable patients and is the preferred first-line treatment. However, there is a gap in understanding the impact of this medication on individuals with unstable psychiatric illness. Health care professionals should be encouraged to use varenicline with careful monitoring for appropriate patients with psychiatric disorders as a standard of care to help them quit smoking.

CASE CONTINUED

After consulting with the psychiatric pharmacist and discussing the risks and benefits of varenicline, Mr. T is started on the appropriate titration schedule (Table 11). A pharmacist provides varenicline education, including the possibility of psychiatric adverse effects, and tells Mr. T to report any worsening psychiatric symptoms. Mr. T is scheduled for frequent follow-up visits to monitor possible adverse effects and his tobacco use. He says he understands the potential adverse effects of varenicline and agrees to frequent follow-up appointments while taking it.

Related Resources

- Leone FT, Zhang Y, Evers-Casey S, et al. Initiating pharmacologic treatment in tobacco-dependent adults. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(2):e5-e31. doi:10.1164/rccm.202005.1982ST

- Cieslak K, Freudenreich O. 4 Ways to help your patients with schizophrenia quit smoking. Current Psychiatry. 2018; 17(2):28,33.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Varenicline • Chantix

1. Chantix [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2019.

2. Sharma R, Alla K, Pfeffer D, et al. An appraisal of practice guidelines for smoking cessation in people with severe mental illness. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51(11):1106-1120. doi:10.1177/0004867417726176

3. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2507-2520. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)30272-0

4. Beard E, Jackson SE, Anthenelli RM, et al. Estimation of risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events from varenicline, bupropion and nicotine patch versus placebo: secondary analysis of results from the EAGLES trial using Bayes factors. Addiction. 2021;116(10):2816-2824. doi:10.1111/add.15440

5. Ayers CR, Heffner JL, Russ C, et al. Efficacy and safety of pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation in anxiety disorders: subgroup analysis of the randomized, active- and placebo-controlled EAGLES trial. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(3)247-260. doi:10.1002/da.22982

6. Evins AE, Cather C, Pratt SA, et al. Maintenance treatment with varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(2):145-154. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.285113

Mr. T, age 34, is a veteran who recently returned to civilian life. He presents to his local Veteran Affairs facility for transition of care. During active duty, he had been diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea, tobacco use disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) secondary to combat exposure, and insomnia. Mr. T says he wants to quit smoking; currently, he smokes 2 packs of cigarettes per day. The primary care clinician notes that Mr. T has uncontrolled PTSD symptoms and poor sleep, and refers him for an outpatient mental health appointment.

At the mental health appointment 3 weeks later, Mr. T asks about medications to quit smoking, specifically varenicline (Table 11). Mr. T’s PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 score is 52, which indicates severe PTSD symptomatology. He says he sees shadowy figures in his periphery every day, and worries they are spying on him. His wife reports Mr. T has had these symptoms for most of their 10-year marriage but has never been treated for them. After a discussion with the outpatient team, Mr. T says he is willing to engage in exposure therapy for PTSD, but he does not want to take any medications other than varenicline for smoking cessation.

Cigarette smoke is a known carcinogen and risk factor for the development of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases and other comorbidities. People with severe mental illness (SMI) are 3 to 5 times more likely to smoke, and they often face multiple barriers to cessation, including low socioeconomic status and lack of support.2 Even when patients with SMI are provided appropriate behavioral and pharmacologic interventions, they often require more frequent monitoring and counseling, receive a longer duration of drug therapy, and experience lower smoking cessation rates than the general population.2

Current guidelines recommend nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion, varenicline, and behavioral support as first-line therapies for smoking cessation in patients with and without SMI.2 Evidence suggests that varenicline is more effective than other pharmacologic options; however, in 2009 a black-box warning was added to both varenicline and bupropion to highlight an increased risk of neuropsychiatric events in individuals with SMI.2 This led some clinicians to hesitate to prescribe varenicline or bupropion to patients with psychiatric illness. However, in 2016, the EAGLES trial evaluated the safety of varenicline, bupropion, and NRT in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders, and based on the findings, the black-box warning was removed.2

This article reviews the evidence regarding the use of varenicline and the risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events in patients with psychiatric illness. Table 23-6 provides a summary of each varenicline trial we discuss.

The EAGLES trial

EAGLES was a multicenter, multinational, randomized, double-blind, triple-dummy, placebo- and active-controlled trial of 8,144 individuals who received treatment for smoking cessation.3 The primary endpoint was the incidence of a composite measure of moderate to severe neuropsychiatric events (NPSAEs).3 Participants were split into psychiatric (N = 4,116) and nonpsychiatric (N = 4,028) cohorts and randomized into 4 treatment arms: varenicline 1 mg twice a day, bupropion 150 mg twice a day, nicotine patch 21 mg/d with taper, or placebo, all for 12 weeks with an additional 12 weeks of follow-up. All participants smoked ≥10 cigarettes per day. Individuals in the psychiatric cohort had to be psychiatrically stable (no exacerbations for 6 months and stable treatment for 3 months). Exclusionary diagnoses included psychotic disorders (except schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder), dementia, substance use (except nicotine), and personality disorders (except borderline personality disorder).2

The rates of moderate to severe NPSAEs in the varenicline groups were 1.25% (95% CI, 0.60 to 1.90) in the nonpsychiatric cohort and 6.42% (95% CI, 4.91 to 7.93) in the psychiatric cohort.3 However, when comparing the varenicline group of the psychiatric cohort to the other arms of the psychiatric cohort, there were no differences (bupropion 6.62% [95% CI, 5.09 to 8.15], nicotine patch 5.20% [95% CI, 3.84 to 6.56], placebo 4.83% [95% CI, 3.51 to 6.16], respectively). The primary efficacy endpoint was continuous abstinence rates (CAR) for Week 9 through Week 12. In the psychiatric cohort, varenicline was superior compared to placebo (odds ratio [OR] 3.24; 95% CI, 2.56 to 4.11), bupropion (OR 1.74; 95% CI, 1.41 to 2.14), and nicotine patch (OR 1.62; 95% CI, 1.32 to 1.99).3

Continue to: Further analysis of EAGLES

Further analysis of EAGLES

Beard et al4 used Bayes factor testing for additional analysis of EAGLES data to determine whether the data were insensitive to neuropsychiatric effects secondary to a lack of statistical power. In the psychiatric cohort, the varenicline and bupropion groups exhibited suggestive but not conclusive data that there was no increase in NPSAEs compared to placebo (Bayes factor 0.52 and 0.71, respectively).4

Another EAGLES analysis by Ayers et al5 evaluated participants with anxiety disorders (N = 712), including PTSD (N = 192), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (N = 243), and panic disorder (N = 277).Of those with PTSD who received varenicline, there were no statistically significant differences in CAR from Week 9 to Week 12 vs placebo.5 However, there was a significant difference in individuals with GAD (OR 4.53; 95% CI, 1.20 to 17.10), and panic disorder (OR 8.49; 95% CI, 1.57 to 45.78).5 In contrast to CAR from Week 9 to Week 12, 7-day point prevalence abstinence at Week 12 for participants with PTSD was significant (OR 4.04; 95% CI, 1.39 to 11.74) when comparing varenicline to placebo. Within the anxiety disorder cohort, there were no significant differences in moderate to severe NPSAE rates based on treatment group. Calculated risk differences comparing varenicline to placebo were: PTSD group -7.73 (95% CI, -21.95 to 6.49), GAD group 2.80 (95% CI, -6.63 to 12.23), and panic disorder group -0.18 (95% CI, -9.57 to 9.21).5

Other studies

Evins et al6 conducted a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the safety of varenicline maintenance therapy in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. To be deemed clinically stable, participants in this study needed to be taking a stable dose of an antipsychotic or mood-stabilizing agent(s) for ≥30 days, compared to the 3-month requirement of the EAGLES trial.3,6 Participants received 12 weeks of open-label varenicline; those who achieved abstinence (N = 87) entered the relapse-prevention phase and were randomized to varenicline 1 mg twice a day or placebo for 40 weeks. Of those who entered relapse-prevention, 5 in the placebo group and 2 in the varenicline group were psychiatrically hospitalized (risk ratio 0.45; 95% CI, 0.04 to 2.9).6 These researchers concluded that varenicline maintenance therapy prolonged abstinence rates with no significant increase in neuropsychiatric events.6

Although treatment options for smoking cessation have advanced, individuals with SMI are still disproportionately affected by the negative outcomes of cigarette smoking. Current literature suggests that varenicline does not confer an appreciable risk of neuropsychiatric events in otherwise stable patients and is the preferred first-line treatment. However, there is a gap in understanding the impact of this medication on individuals with unstable psychiatric illness. Health care professionals should be encouraged to use varenicline with careful monitoring for appropriate patients with psychiatric disorders as a standard of care to help them quit smoking.

CASE CONTINUED

After consulting with the psychiatric pharmacist and discussing the risks and benefits of varenicline, Mr. T is started on the appropriate titration schedule (Table 11). A pharmacist provides varenicline education, including the possibility of psychiatric adverse effects, and tells Mr. T to report any worsening psychiatric symptoms. Mr. T is scheduled for frequent follow-up visits to monitor possible adverse effects and his tobacco use. He says he understands the potential adverse effects of varenicline and agrees to frequent follow-up appointments while taking it.

Related Resources

- Leone FT, Zhang Y, Evers-Casey S, et al. Initiating pharmacologic treatment in tobacco-dependent adults. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(2):e5-e31. doi:10.1164/rccm.202005.1982ST

- Cieslak K, Freudenreich O. 4 Ways to help your patients with schizophrenia quit smoking. Current Psychiatry. 2018; 17(2):28,33.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Varenicline • Chantix

Mr. T, age 34, is a veteran who recently returned to civilian life. He presents to his local Veteran Affairs facility for transition of care. During active duty, he had been diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea, tobacco use disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) secondary to combat exposure, and insomnia. Mr. T says he wants to quit smoking; currently, he smokes 2 packs of cigarettes per day. The primary care clinician notes that Mr. T has uncontrolled PTSD symptoms and poor sleep, and refers him for an outpatient mental health appointment.

At the mental health appointment 3 weeks later, Mr. T asks about medications to quit smoking, specifically varenicline (Table 11). Mr. T’s PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 score is 52, which indicates severe PTSD symptomatology. He says he sees shadowy figures in his periphery every day, and worries they are spying on him. His wife reports Mr. T has had these symptoms for most of their 10-year marriage but has never been treated for them. After a discussion with the outpatient team, Mr. T says he is willing to engage in exposure therapy for PTSD, but he does not want to take any medications other than varenicline for smoking cessation.

Cigarette smoke is a known carcinogen and risk factor for the development of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases and other comorbidities. People with severe mental illness (SMI) are 3 to 5 times more likely to smoke, and they often face multiple barriers to cessation, including low socioeconomic status and lack of support.2 Even when patients with SMI are provided appropriate behavioral and pharmacologic interventions, they often require more frequent monitoring and counseling, receive a longer duration of drug therapy, and experience lower smoking cessation rates than the general population.2

Current guidelines recommend nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion, varenicline, and behavioral support as first-line therapies for smoking cessation in patients with and without SMI.2 Evidence suggests that varenicline is more effective than other pharmacologic options; however, in 2009 a black-box warning was added to both varenicline and bupropion to highlight an increased risk of neuropsychiatric events in individuals with SMI.2 This led some clinicians to hesitate to prescribe varenicline or bupropion to patients with psychiatric illness. However, in 2016, the EAGLES trial evaluated the safety of varenicline, bupropion, and NRT in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders, and based on the findings, the black-box warning was removed.2

This article reviews the evidence regarding the use of varenicline and the risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events in patients with psychiatric illness. Table 23-6 provides a summary of each varenicline trial we discuss.

The EAGLES trial

EAGLES was a multicenter, multinational, randomized, double-blind, triple-dummy, placebo- and active-controlled trial of 8,144 individuals who received treatment for smoking cessation.3 The primary endpoint was the incidence of a composite measure of moderate to severe neuropsychiatric events (NPSAEs).3 Participants were split into psychiatric (N = 4,116) and nonpsychiatric (N = 4,028) cohorts and randomized into 4 treatment arms: varenicline 1 mg twice a day, bupropion 150 mg twice a day, nicotine patch 21 mg/d with taper, or placebo, all for 12 weeks with an additional 12 weeks of follow-up. All participants smoked ≥10 cigarettes per day. Individuals in the psychiatric cohort had to be psychiatrically stable (no exacerbations for 6 months and stable treatment for 3 months). Exclusionary diagnoses included psychotic disorders (except schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder), dementia, substance use (except nicotine), and personality disorders (except borderline personality disorder).2

The rates of moderate to severe NPSAEs in the varenicline groups were 1.25% (95% CI, 0.60 to 1.90) in the nonpsychiatric cohort and 6.42% (95% CI, 4.91 to 7.93) in the psychiatric cohort.3 However, when comparing the varenicline group of the psychiatric cohort to the other arms of the psychiatric cohort, there were no differences (bupropion 6.62% [95% CI, 5.09 to 8.15], nicotine patch 5.20% [95% CI, 3.84 to 6.56], placebo 4.83% [95% CI, 3.51 to 6.16], respectively). The primary efficacy endpoint was continuous abstinence rates (CAR) for Week 9 through Week 12. In the psychiatric cohort, varenicline was superior compared to placebo (odds ratio [OR] 3.24; 95% CI, 2.56 to 4.11), bupropion (OR 1.74; 95% CI, 1.41 to 2.14), and nicotine patch (OR 1.62; 95% CI, 1.32 to 1.99).3

Continue to: Further analysis of EAGLES

Further analysis of EAGLES

Beard et al4 used Bayes factor testing for additional analysis of EAGLES data to determine whether the data were insensitive to neuropsychiatric effects secondary to a lack of statistical power. In the psychiatric cohort, the varenicline and bupropion groups exhibited suggestive but not conclusive data that there was no increase in NPSAEs compared to placebo (Bayes factor 0.52 and 0.71, respectively).4

Another EAGLES analysis by Ayers et al5 evaluated participants with anxiety disorders (N = 712), including PTSD (N = 192), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (N = 243), and panic disorder (N = 277).Of those with PTSD who received varenicline, there were no statistically significant differences in CAR from Week 9 to Week 12 vs placebo.5 However, there was a significant difference in individuals with GAD (OR 4.53; 95% CI, 1.20 to 17.10), and panic disorder (OR 8.49; 95% CI, 1.57 to 45.78).5 In contrast to CAR from Week 9 to Week 12, 7-day point prevalence abstinence at Week 12 for participants with PTSD was significant (OR 4.04; 95% CI, 1.39 to 11.74) when comparing varenicline to placebo. Within the anxiety disorder cohort, there were no significant differences in moderate to severe NPSAE rates based on treatment group. Calculated risk differences comparing varenicline to placebo were: PTSD group -7.73 (95% CI, -21.95 to 6.49), GAD group 2.80 (95% CI, -6.63 to 12.23), and panic disorder group -0.18 (95% CI, -9.57 to 9.21).5

Other studies

Evins et al6 conducted a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the safety of varenicline maintenance therapy in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. To be deemed clinically stable, participants in this study needed to be taking a stable dose of an antipsychotic or mood-stabilizing agent(s) for ≥30 days, compared to the 3-month requirement of the EAGLES trial.3,6 Participants received 12 weeks of open-label varenicline; those who achieved abstinence (N = 87) entered the relapse-prevention phase and were randomized to varenicline 1 mg twice a day or placebo for 40 weeks. Of those who entered relapse-prevention, 5 in the placebo group and 2 in the varenicline group were psychiatrically hospitalized (risk ratio 0.45; 95% CI, 0.04 to 2.9).6 These researchers concluded that varenicline maintenance therapy prolonged abstinence rates with no significant increase in neuropsychiatric events.6

Although treatment options for smoking cessation have advanced, individuals with SMI are still disproportionately affected by the negative outcomes of cigarette smoking. Current literature suggests that varenicline does not confer an appreciable risk of neuropsychiatric events in otherwise stable patients and is the preferred first-line treatment. However, there is a gap in understanding the impact of this medication on individuals with unstable psychiatric illness. Health care professionals should be encouraged to use varenicline with careful monitoring for appropriate patients with psychiatric disorders as a standard of care to help them quit smoking.

CASE CONTINUED

After consulting with the psychiatric pharmacist and discussing the risks and benefits of varenicline, Mr. T is started on the appropriate titration schedule (Table 11). A pharmacist provides varenicline education, including the possibility of psychiatric adverse effects, and tells Mr. T to report any worsening psychiatric symptoms. Mr. T is scheduled for frequent follow-up visits to monitor possible adverse effects and his tobacco use. He says he understands the potential adverse effects of varenicline and agrees to frequent follow-up appointments while taking it.

Related Resources

- Leone FT, Zhang Y, Evers-Casey S, et al. Initiating pharmacologic treatment in tobacco-dependent adults. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(2):e5-e31. doi:10.1164/rccm.202005.1982ST

- Cieslak K, Freudenreich O. 4 Ways to help your patients with schizophrenia quit smoking. Current Psychiatry. 2018; 17(2):28,33.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Varenicline • Chantix

1. Chantix [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2019.

2. Sharma R, Alla K, Pfeffer D, et al. An appraisal of practice guidelines for smoking cessation in people with severe mental illness. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51(11):1106-1120. doi:10.1177/0004867417726176

3. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2507-2520. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)30272-0

4. Beard E, Jackson SE, Anthenelli RM, et al. Estimation of risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events from varenicline, bupropion and nicotine patch versus placebo: secondary analysis of results from the EAGLES trial using Bayes factors. Addiction. 2021;116(10):2816-2824. doi:10.1111/add.15440

5. Ayers CR, Heffner JL, Russ C, et al. Efficacy and safety of pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation in anxiety disorders: subgroup analysis of the randomized, active- and placebo-controlled EAGLES trial. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(3)247-260. doi:10.1002/da.22982

6. Evins AE, Cather C, Pratt SA, et al. Maintenance treatment with varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(2):145-154. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.285113

1. Chantix [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2019.

2. Sharma R, Alla K, Pfeffer D, et al. An appraisal of practice guidelines for smoking cessation in people with severe mental illness. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51(11):1106-1120. doi:10.1177/0004867417726176

3. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2507-2520. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)30272-0

4. Beard E, Jackson SE, Anthenelli RM, et al. Estimation of risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events from varenicline, bupropion and nicotine patch versus placebo: secondary analysis of results from the EAGLES trial using Bayes factors. Addiction. 2021;116(10):2816-2824. doi:10.1111/add.15440

5. Ayers CR, Heffner JL, Russ C, et al. Efficacy and safety of pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation in anxiety disorders: subgroup analysis of the randomized, active- and placebo-controlled EAGLES trial. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(3)247-260. doi:10.1002/da.22982

6. Evins AE, Cather C, Pratt SA, et al. Maintenance treatment with varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(2):145-154. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.285113

Mobile devices ‘addictive by design’: Obesity is one of many health effects

Wireless devices, like smart phones and tablets, appear to induce compulsive or even addictive use in many individuals, leading to adverse health consequences that are likely to be curtailed only through often difficult behavior modification, according to a pediatric endocrinologist’s take on the problem.

While the summary was based in part on the analysis of 234 published papers drawn from the medical literature, the lead author, Nidhi Gupta, MD, said the data reinforce her own clinical experience.

“As a pediatric endocrinologist, the trend in smartphone-associated health disorders, such as obesity, sleep, and behavior issues, worries me,” Dr. Gupta, director of KAP Pediatric Endocrinology, Nashville, Tenn., said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Based on her search of the medical literature, the available data raise concern. In one study she cited, for example, each hour per day of screen time was found to translate into a body mass index increase of 0.5 to 0.7 kg/m2 (P < .001).

With this type of progressive rise in BMI comes prediabetes, dyslipidemia, and other metabolic disorders associated with major health risks, including cardiovascular disease. And there are others. Dr. Gupta cited data suggesting screen time before bed disturbs sleep, which has its own set of health risks.

“When I say health, it includes physical health, mental health, and emotional health,” said Dr. Gupta.

In the U.S. and other countries with a growing obesity epidemic, lack of physical activity and unhealthy eating are widely considered the major culprits. Excessive screen time contributes to both.

“When we are engaged with our devices, we are often snacking subconsciously and not very mindful that we are making unhealthy choices,” Dr. Gupta said.

The problem is that there is a vicious circle. Compulsive use of devices follows the same loop as other types of addictive behaviors, according to Dr. Gupta. She traced overuse of wireless devices to the dopaminergic system, which is a powerful neuroendocrine-mediated process of craving, response, and reward.

Like fat, sugar, and salt, which provoke a neuroendocrine reward signal, the chimes and buzzes of a cell phone provide their own cues for reward in the form of a dopamine surge. As a result, these become the “triggers of an irresistible and irrational urge to check our device that makes the dopamine go high in our brain,” Dr. Gupta explained.

Although the vicious cycle can be thwarted by turning off the device, Dr. Gupta characterized this as “impractical” when smartphones are so vital to daily communication. Rather, Dr. Gupta advocated a program of moderation, reserving the phone for useful tasks without succumbing to the siren song of apps that waste time.

The most conspicuous culprit is social media, which Dr. Gupta considers to be among the most Pavlovian triggers of cell phone addiction. However, she acknowledged that participation in social media has its justifications.

“I, myself, use social media for my own branding and marketing,” Dr. Gupta said.

The problem that users have is distinguishing between screen time that does and does not have value, according to Dr. Gupta. She indicated that many of those overusing their smart devices are being driven by the dopaminergic reward system, which is generally divorced from the real goals of life, such as personal satisfaction and activity that is rewarding monetarily or in other ways.

“I am not asking for these devices to be thrown out the window. I am advocating for moderation, balance, and real-life engagement,” Dr. Gupta said at the meeting, held in Atlanta and virtually.

She outlined a long list of practical suggestions, including turning off the alarms, chimes, and messages that engage the user into the vicious dopaminergic-reward system loop. She suggested mindfulness so that the user can distinguish between valuable device use and activity that is simply procrastination.

“The devices are designed to be addictive. They are designed to manipulate our brain,” she said. “Eliminate the reward. Let’s try to make our devices boring, unappealing, or enticing so that they only work as tools.”

The medical literature is filled with data that support the potential harms of excessive screen use, leading many others to make some of the same points. In 2017, Thomas N. Robinson, MD, professor of child health at Stanford (Calif.) University, reviewed data showing an association between screen media exposure and obesity in children and adolescents.

“This is an area crying out for more research,” Dr. Robinson said in an interview. The problem of screen time, sedentary behavior, and weight gain has been an issue since the television was invented, which was the point he made in his 2017 paper, but he agreed that the problem is only getting worse.

“Digital technology has become ubiquitous, touching nearly every aspect of people’s lives,” he said. Yet, as evidence grows that overuse of this technology can be harmful, it is creating a problem without a clear solution.

“There are few data about the efficacy of specific strategies to reduce harmful impacts of digital screen use,” he said.

While some of the solutions that Dr. Gupta described make sense, they are more easily described than executed. The dopaminergic reward system is strong and largely experienced subconsciously. Recruiting patients to recognize that dopaminergic rewards are not rewards in any true sense is already a challenge. Enlisting patients to take the difficult steps to avoid the behavioral cues might be even more difficult.

Dr. Gupta and Dr. Robinson report no potential conflicts of interest.

Wireless devices, like smart phones and tablets, appear to induce compulsive or even addictive use in many individuals, leading to adverse health consequences that are likely to be curtailed only through often difficult behavior modification, according to a pediatric endocrinologist’s take on the problem.

While the summary was based in part on the analysis of 234 published papers drawn from the medical literature, the lead author, Nidhi Gupta, MD, said the data reinforce her own clinical experience.

“As a pediatric endocrinologist, the trend in smartphone-associated health disorders, such as obesity, sleep, and behavior issues, worries me,” Dr. Gupta, director of KAP Pediatric Endocrinology, Nashville, Tenn., said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Based on her search of the medical literature, the available data raise concern. In one study she cited, for example, each hour per day of screen time was found to translate into a body mass index increase of 0.5 to 0.7 kg/m2 (P < .001).

With this type of progressive rise in BMI comes prediabetes, dyslipidemia, and other metabolic disorders associated with major health risks, including cardiovascular disease. And there are others. Dr. Gupta cited data suggesting screen time before bed disturbs sleep, which has its own set of health risks.

“When I say health, it includes physical health, mental health, and emotional health,” said Dr. Gupta.

In the U.S. and other countries with a growing obesity epidemic, lack of physical activity and unhealthy eating are widely considered the major culprits. Excessive screen time contributes to both.

“When we are engaged with our devices, we are often snacking subconsciously and not very mindful that we are making unhealthy choices,” Dr. Gupta said.

The problem is that there is a vicious circle. Compulsive use of devices follows the same loop as other types of addictive behaviors, according to Dr. Gupta. She traced overuse of wireless devices to the dopaminergic system, which is a powerful neuroendocrine-mediated process of craving, response, and reward.

Like fat, sugar, and salt, which provoke a neuroendocrine reward signal, the chimes and buzzes of a cell phone provide their own cues for reward in the form of a dopamine surge. As a result, these become the “triggers of an irresistible and irrational urge to check our device that makes the dopamine go high in our brain,” Dr. Gupta explained.

Although the vicious cycle can be thwarted by turning off the device, Dr. Gupta characterized this as “impractical” when smartphones are so vital to daily communication. Rather, Dr. Gupta advocated a program of moderation, reserving the phone for useful tasks without succumbing to the siren song of apps that waste time.

The most conspicuous culprit is social media, which Dr. Gupta considers to be among the most Pavlovian triggers of cell phone addiction. However, she acknowledged that participation in social media has its justifications.

“I, myself, use social media for my own branding and marketing,” Dr. Gupta said.

The problem that users have is distinguishing between screen time that does and does not have value, according to Dr. Gupta. She indicated that many of those overusing their smart devices are being driven by the dopaminergic reward system, which is generally divorced from the real goals of life, such as personal satisfaction and activity that is rewarding monetarily or in other ways.

“I am not asking for these devices to be thrown out the window. I am advocating for moderation, balance, and real-life engagement,” Dr. Gupta said at the meeting, held in Atlanta and virtually.

She outlined a long list of practical suggestions, including turning off the alarms, chimes, and messages that engage the user into the vicious dopaminergic-reward system loop. She suggested mindfulness so that the user can distinguish between valuable device use and activity that is simply procrastination.

“The devices are designed to be addictive. They are designed to manipulate our brain,” she said. “Eliminate the reward. Let’s try to make our devices boring, unappealing, or enticing so that they only work as tools.”

The medical literature is filled with data that support the potential harms of excessive screen use, leading many others to make some of the same points. In 2017, Thomas N. Robinson, MD, professor of child health at Stanford (Calif.) University, reviewed data showing an association between screen media exposure and obesity in children and adolescents.

“This is an area crying out for more research,” Dr. Robinson said in an interview. The problem of screen time, sedentary behavior, and weight gain has been an issue since the television was invented, which was the point he made in his 2017 paper, but he agreed that the problem is only getting worse.

“Digital technology has become ubiquitous, touching nearly every aspect of people’s lives,” he said. Yet, as evidence grows that overuse of this technology can be harmful, it is creating a problem without a clear solution.

“There are few data about the efficacy of specific strategies to reduce harmful impacts of digital screen use,” he said.

While some of the solutions that Dr. Gupta described make sense, they are more easily described than executed. The dopaminergic reward system is strong and largely experienced subconsciously. Recruiting patients to recognize that dopaminergic rewards are not rewards in any true sense is already a challenge. Enlisting patients to take the difficult steps to avoid the behavioral cues might be even more difficult.

Dr. Gupta and Dr. Robinson report no potential conflicts of interest.

Wireless devices, like smart phones and tablets, appear to induce compulsive or even addictive use in many individuals, leading to adverse health consequences that are likely to be curtailed only through often difficult behavior modification, according to a pediatric endocrinologist’s take on the problem.

While the summary was based in part on the analysis of 234 published papers drawn from the medical literature, the lead author, Nidhi Gupta, MD, said the data reinforce her own clinical experience.

“As a pediatric endocrinologist, the trend in smartphone-associated health disorders, such as obesity, sleep, and behavior issues, worries me,” Dr. Gupta, director of KAP Pediatric Endocrinology, Nashville, Tenn., said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Based on her search of the medical literature, the available data raise concern. In one study she cited, for example, each hour per day of screen time was found to translate into a body mass index increase of 0.5 to 0.7 kg/m2 (P < .001).

With this type of progressive rise in BMI comes prediabetes, dyslipidemia, and other metabolic disorders associated with major health risks, including cardiovascular disease. And there are others. Dr. Gupta cited data suggesting screen time before bed disturbs sleep, which has its own set of health risks.

“When I say health, it includes physical health, mental health, and emotional health,” said Dr. Gupta.

In the U.S. and other countries with a growing obesity epidemic, lack of physical activity and unhealthy eating are widely considered the major culprits. Excessive screen time contributes to both.

“When we are engaged with our devices, we are often snacking subconsciously and not very mindful that we are making unhealthy choices,” Dr. Gupta said.

The problem is that there is a vicious circle. Compulsive use of devices follows the same loop as other types of addictive behaviors, according to Dr. Gupta. She traced overuse of wireless devices to the dopaminergic system, which is a powerful neuroendocrine-mediated process of craving, response, and reward.

Like fat, sugar, and salt, which provoke a neuroendocrine reward signal, the chimes and buzzes of a cell phone provide their own cues for reward in the form of a dopamine surge. As a result, these become the “triggers of an irresistible and irrational urge to check our device that makes the dopamine go high in our brain,” Dr. Gupta explained.

Although the vicious cycle can be thwarted by turning off the device, Dr. Gupta characterized this as “impractical” when smartphones are so vital to daily communication. Rather, Dr. Gupta advocated a program of moderation, reserving the phone for useful tasks without succumbing to the siren song of apps that waste time.

The most conspicuous culprit is social media, which Dr. Gupta considers to be among the most Pavlovian triggers of cell phone addiction. However, she acknowledged that participation in social media has its justifications.

“I, myself, use social media for my own branding and marketing,” Dr. Gupta said.

The problem that users have is distinguishing between screen time that does and does not have value, according to Dr. Gupta. She indicated that many of those overusing their smart devices are being driven by the dopaminergic reward system, which is generally divorced from the real goals of life, such as personal satisfaction and activity that is rewarding monetarily or in other ways.

“I am not asking for these devices to be thrown out the window. I am advocating for moderation, balance, and real-life engagement,” Dr. Gupta said at the meeting, held in Atlanta and virtually.

She outlined a long list of practical suggestions, including turning off the alarms, chimes, and messages that engage the user into the vicious dopaminergic-reward system loop. She suggested mindfulness so that the user can distinguish between valuable device use and activity that is simply procrastination.

“The devices are designed to be addictive. They are designed to manipulate our brain,” she said. “Eliminate the reward. Let’s try to make our devices boring, unappealing, or enticing so that they only work as tools.”

The medical literature is filled with data that support the potential harms of excessive screen use, leading many others to make some of the same points. In 2017, Thomas N. Robinson, MD, professor of child health at Stanford (Calif.) University, reviewed data showing an association between screen media exposure and obesity in children and adolescents.

“This is an area crying out for more research,” Dr. Robinson said in an interview. The problem of screen time, sedentary behavior, and weight gain has been an issue since the television was invented, which was the point he made in his 2017 paper, but he agreed that the problem is only getting worse.

“Digital technology has become ubiquitous, touching nearly every aspect of people’s lives,” he said. Yet, as evidence grows that overuse of this technology can be harmful, it is creating a problem without a clear solution.

“There are few data about the efficacy of specific strategies to reduce harmful impacts of digital screen use,” he said.

While some of the solutions that Dr. Gupta described make sense, they are more easily described than executed. The dopaminergic reward system is strong and largely experienced subconsciously. Recruiting patients to recognize that dopaminergic rewards are not rewards in any true sense is already a challenge. Enlisting patients to take the difficult steps to avoid the behavioral cues might be even more difficult.

Dr. Gupta and Dr. Robinson report no potential conflicts of interest.

FROM ENDO 2022

FDA orders Juul to stop selling E-cigarettes

The marketing denial order covers all the company’s products in the United States, which means Juul must stop distributing the products and remove everything on the market. That includes the Juul device and flavor replacement pods in the tobacco and menthol flavors.

“Today’s action is further progress on the FDA’s commitment to ensuring that all e-cigarette and electronic nicotine delivery system products currently being marketed to consumers meet our public health standards,” Robert Califf, MD, the FDA commissioner, said in the announcement.

“The agency has dedicated significant resources to review products from the companies that account for most of the U.S. market,” he said. “We recognize these make up a significant part of the available products and many have played a disproportionate role in the rise in youth vaping.”

The marketing denial order covers only the commercial distribution and retail sale of Juul’s products and doesn’t restrict consumer possession or use. The FDA “cannot and will not” enforce actions against consumers, the agency said.

The order comes after a 2-year review of the company’s application seeking authorization to continue selling non–fruit-flavored products, such as menthol and tobacco. The FDA determined the application “lacked sufficient evidence regarding the toxicological profile of the products to demonstrate that marketing of the products would be appropriate for the protection of the public health.”

Some of Juul’s study findings raised concerns because of “insufficient and conflicting data,” the FDA said, including potentially harmful chemicals leaching from the Juul liquid replacement pods.

“To date, the FDA has not received clinical information to suggest an immediate hazard associated with the use of the JUUL device or JUUL pods,” the agency said. “However, the [orders] issued today reflect FDA’s determination that there is insufficient evidence to assess the potential toxicological risks of using the JUUL products.”

Juul is expected to appeal the FDA’s decision, according to The New York Times.

In recent years, the FDA has reviewed marketing applications from Juul and other e-cigarette companies as anti-tobacco groups have called for new rules to limit products that led to a surge in youth vaping during the past decade. At the same time, advocates of e-cigarettes and nicotine-delivery devices have said the products help adult smokers to quit cigarettes and other tobacco products.

Juul, in particular, has been blamed for fueling the surge in underage vaping due to fruity flavors and hip marketing, according to The Wall Street Journal. The company removed sweet and fruity flavors from shelves in 2019 and has been trying to repair its reputation by limiting its marketing and focusing on adult cigarette smokers.

In 2020, all e-cigarette manufacturers in the United States were required to submit their products for FDA review to stay on the market, the newspaper reported. The agency has been weighing the potential benefits for adult cigarette smokers against the harms for young people.

The FDA banned the sale of fruit- and mint-flavored cartridges and juice pods in 2020, but menthol and tobacco-flavored products were left on the market, according to USA Today. In September 2021, the agency also banned the sale of hundreds of thousands of vaping and e-cigarette products but didn’t rule on Juul.

Meanwhile, the FDA has cleared Reynolds American and NJOY Holdings – two of Juul’s biggest rivals – to keep tobacco-flavored products on the market. Industry experts expected Juul to receive similar clearance, the Journal reported.

Juul, which was at the top of the U.S. e-cigarette market in 2018, has moved to second place behind Reynolds’s Vuse brand, the newspaper reported. The United States represents most of the company’s revenue, though its products are also available in Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Italy, and the Philippines.

Underage vaping has fallen in the United States since federal restrictions raised the legal purchase age for tobacco products to 21 and banned the sale of sweet and fruity cartridges, according to the Journal. Juul’s popularity has also dropped among youth, with other products such as Puff Bar, Vuse, and Smok becoming more popular among e-cigarette users in high school.

In a separate decision announced this week, the FDA is also moving forward with a plan to reduce the amount of nicotine in cigarettes. The decision, which has been years in the making, is aimed at prompting millions of cigarette users to quit smoking or switch to alternatives such as e-cigarettes, as well as limit the number of users who pick up smoking at an early age.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com .

The marketing denial order covers all the company’s products in the United States, which means Juul must stop distributing the products and remove everything on the market. That includes the Juul device and flavor replacement pods in the tobacco and menthol flavors.

“Today’s action is further progress on the FDA’s commitment to ensuring that all e-cigarette and electronic nicotine delivery system products currently being marketed to consumers meet our public health standards,” Robert Califf, MD, the FDA commissioner, said in the announcement.

“The agency has dedicated significant resources to review products from the companies that account for most of the U.S. market,” he said. “We recognize these make up a significant part of the available products and many have played a disproportionate role in the rise in youth vaping.”

The marketing denial order covers only the commercial distribution and retail sale of Juul’s products and doesn’t restrict consumer possession or use. The FDA “cannot and will not” enforce actions against consumers, the agency said.