User login

Sublingual buprenorphine plus buprenorphine XR for opioid use disorder

Mr. L, age 31, presents to the emergency department (ED) with somnolence after sustaining an arm laceration at work. While in the ED, Mr. L explains he has opioid use disorder (OUD) and last week received an initial 300 mg injection of extended-release buprenorphine (BUP-XR). Due to ongoing opioid cravings, he took nonprescribed fentanyl and alprazolam before work.

The ED clinicians address Mr. L’s arm injury and transfer him to the hospital’s low-threshold outpatient addiction clinic for further assessment and management. There, he is prescribed sublingual buprenorphine/naloxone (SL-BUP) 8 mg/2 mg daily as needed for 1 week to address ongoing opioid cravings, and is encouraged to return for another visit the following week.

The United States continues to struggle with the overdose crisis, largely fueled by illicitly manufactured opioids such as fentanyl.1 Opioid agonist and partial agonist treatments such as methadone and buprenorphine decrease the risk of death in individuals with OUD by up to 50%.2 While methadone has a history of proven effectiveness for OUD, accessibility is fraught with barriers (eg, patients must attend an opioid treatment program daily to receive a dose, pharmacies are unable to dispense methadone for OUD).

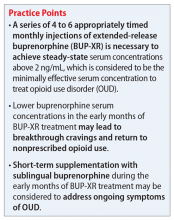

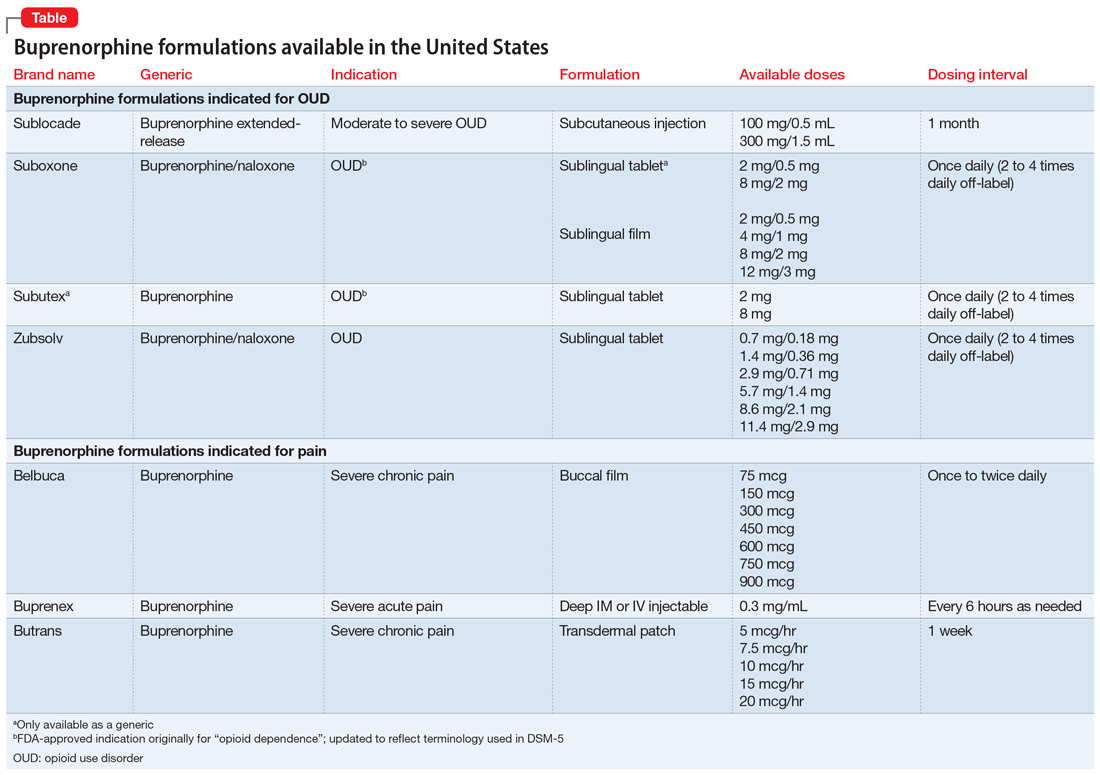

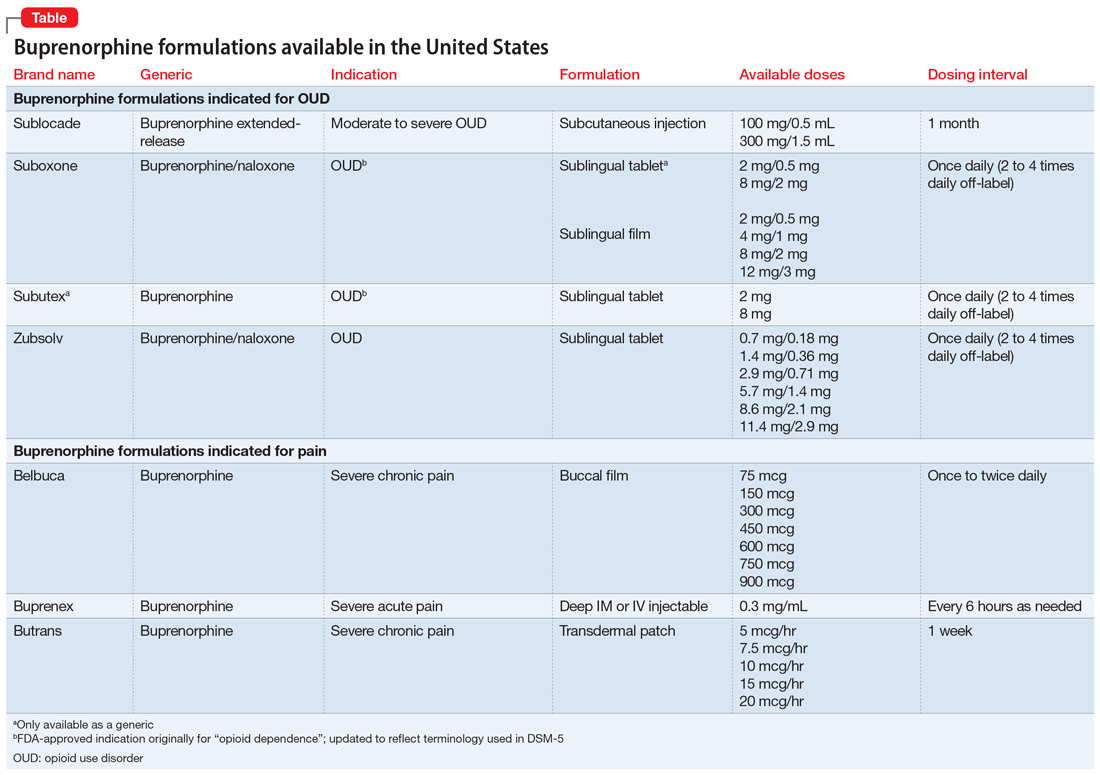

Buprenorphine has been shown to decrease opioid cravings while limiting euphoria due to its partial—as opposed to full—agonist activity.3 Several buprenorphine formulations are available (Table). Buprenorphine presents an opportunity to treat OUD like other chronic illnesses. In accordance with the US Department of Health and Human Services Practice Guideline (2021), any clinician can obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine in any treatment setting, and patients can receive the medication at a pharmacy.4

However, many patients have barriers to consistent daily dosing of buprenorphine due to strict clinic/prescriber requirements, transportation difficulties, continued cravings, and other factors. BUP-XR, a buprenorphine injection administered once a month, may address several of these concerns, most notably the potential for better suppression of cravings by delivering a consistent level of buprenorphine over the course of 28 days.5 Since BUP-XR was FDA-approved in 2017, questions remain whether it can adequately quell opioid cravings in early treatment months prior to steady-state concentration.

This article addresses whether clinicians should consider supplemental SL-BUP in addition to BUP-XR during early treatment months and/or prior to steady-state.

Pharmacokinetics of BUP-XR

BUP-XR is administered by subcutaneous injection via an ATRIGEL delivery system (BUP-XR; Albany Molecular Research, Burlington, Massachusetts).6 Upon injection, approximately 7% of the buprenorphine dose dissipates with the solvent, leading to maximum concentration approximately 24 hours post-dose. The remaining dose hardens to create a depot that elutes buprenorphine gradually over 28 days.7

Continue to: Buprenorphine requires...

Buprenorphine requires ≥70% mu-opioid receptor (MOR) occupancy to effectively suppress symptoms of craving and withdrawal in patients with OUD. Buprenorphine serum concentration correlates significantly with MOR occupancy, such that concentrations of 2 to 3 ng/mL are acknowledged as baseline minimums for clinical efficacy.8

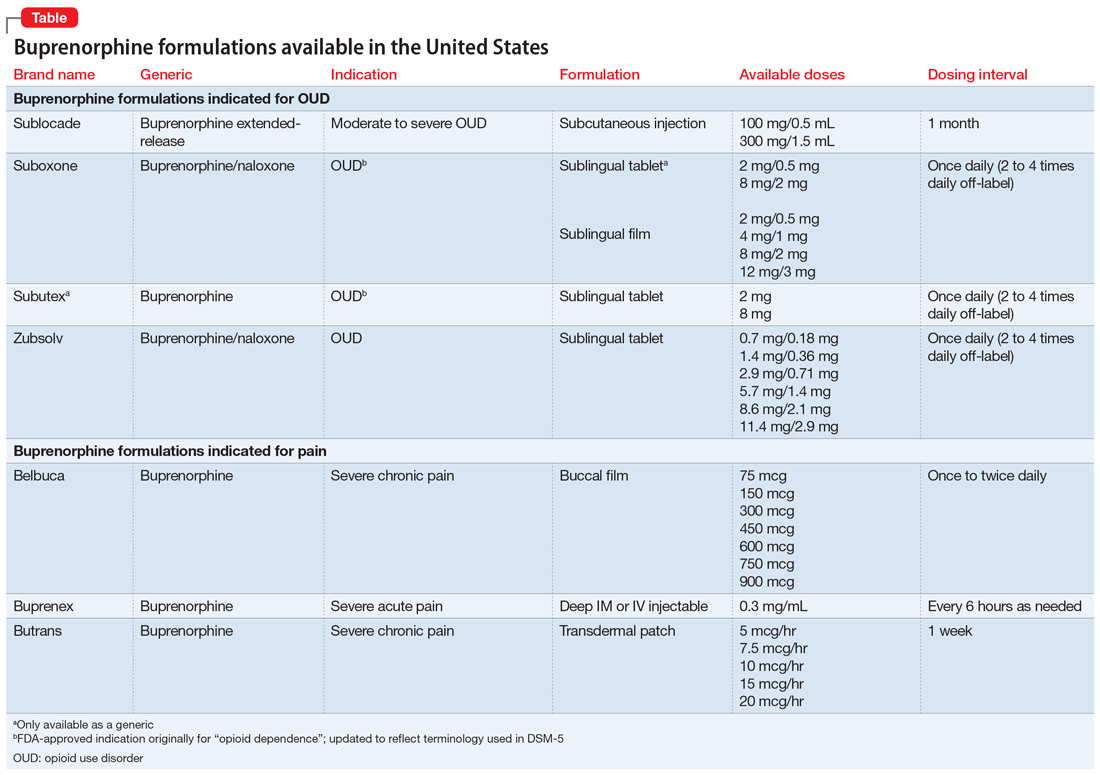

BUP-XR is administered in 1 of 2 dosing regimens. In both, 2 separate 300 mg doses are administered 28 days apart during Month 1 and Month 2, followed by maintenance doses of either 300 mg (300/300 mg dosing regimen) or 100 mg (300/100 mg dosing regimen) every 28 days thereafter. Combined Phase II and Phase III data analyzing serum concentrations of BUP-XR across both dosing regimens revealed that, for most patients, there is a noticeable period during Month 1 and Month 2 when serum concentrations fall below 2 ng/mL.7 Steady-state concentrations of both regimens develop after 4 to 6 appropriately timed injections, providing average steady-state serum concentrations in Phase II and Phase III trials of 6.54 ng/mL for the 300/300 mg dosing regimen and 3.00 ng/mL for 300/100 mg dosing regimen.7

Real-world experiences with BUP-XR

The theoretical need for supplementation has been voiced in practice. A case series by Peckham et al9 noted that 55% (n = 22) of patients required SL-BUP supplementation for up to 120 days after the first BUP-XR injection to quell cravings and reduce nonprescribed opioid use.

The RECOVER trial by Ling et al10 demonstrated the importance of the first 2 months of BUP-XR therapy in the overall treatment success for patients with OUD. In this analysis, patients maintained on BUP-XR for 12 months reported a 75% likelihood of abstinence, compared to 24% for patients receiving 0 to 2 months of BUP-XR treatment. Other benefits included improved employment status and reduced depression rates. This trial did not specifically discuss supplemental SL-BUP or subthreshold concentrations of buprenorphine during early months.10

Individualized treatment should be based on OUD symptoms

While BUP-XR was designed to continuously deliver at least 2 ng/mL of buprenorphine, serum concentrations are labile during the first 2 months of treatment. This may result in breakthrough OUD symptoms, particularly withdrawal or opioid cravings. Additionally, due to individual variability, some patients may still experience serum concentrations below 2 ng/mL after Month 2 and until steady-state is achieved between Month 4 and Month 6.7

Continue to: Beyond a theoretical...

Beyond a theoretical need for supplementation with SL-BUP, there is limited information regarding optimal dosing, dosage intervals, or length of supplementation. Therefore, clear guidance is not available at this time, and treatment should be individualized based on subjective and objective OUD symptoms.

What also remains unknown are potential barriers patients may face in receiving 2 concurrent buprenorphine prescriptions. BUP-XR, administered in a health care setting, can be obtained 2 ways. A clinician can directly order the medication from the distributor to be administered via buy-and-bill. An alternate option requires the clinician to send a prescription to an appropriately credentialed pharmacy that will ship patient-specific orders directly to the clinic. Despite this, most SL-BUP prescriptions are billed and dispensed from community pharmacies. At the insurance level, there is risk the prescription claim will be rejected for duplication of therapy, which may require additional collaboration between the prescribing clinician, pharmacist, and insurance representative to ensure patients have access to the medication.

Pending studies and approvals may also provide greater guidance and flexibility in decision-making for patients with OUD. The CoLAB study currently underway in Australia is examining the efficacy and outcomes of an intermediate dose (200 mg) of BUP-XR and will also allow for supplemental SL-BUP doses.11 Additionally, an alternative BUP-XR formulation, Brixadi, currently in use in the European Union as Buvidal, has submitted an application for FDA approval in the United States. The application indicates that Brixadi will be available with a wider range of doses and at both weekly and monthly intervals. Approval has been delayed due to deficiencies in the United States–based third-party production facilities. It is unclear how the FDA and manufacturer plan to proceed.12

Short-term supplementation with SL-BUP during early the months of treatment with BUP-XR should be considered to control OUD symptoms and assist with patient retention. Once steady-state is achieved, trough concentrations of buprenorphine are not expected to drop below 2 ng/mL with continued on-time maintenance doses and thus, supplementation can likely cease.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. L is seen in the low-threshold outpatient clinic 1 week after his ED visit. His arm laceration is healing well, and he is noticeably more alert and engaged. Each morning this week, he awakes with cravings, sweating, and anxiety. These symptoms alleviate after he takes SL-BUP. Mr. L’s clinician gives him a copy of the Subjective Opioid Withdrawal Scale so he can assess his withdrawal symptoms each morning and provide this data at follow-up appointments. Mr. L and his clinician decide to meet weekly until his next injection to continue assessing his current supplemental dose, symptoms, and whether there should be additional adjustments to his treatment plan.

Related Resources

- Cho J, Bhimani J, Patel M, et al. Substance abuse among older adults: a growing problem. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(3):14-20.

- Verma S. Opioid use disorder in adolescents: an overview. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(2):12-14,16-21.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Buprenorphine • Sublocade, Subutex

Buprenorphine/naloxone • Suboxone, Zubsolv

Methadone • Methadose

1. Mattson CL, Tanz LJ, Quinn K, et al. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths - United States, 2013-2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(6):202-207. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4

2. Ma J, Bao YP, Wang RJ, et al. Effects of medication-assisted treatment on mortality among opioids users: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(12):1868-1883. doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0094-5

3. Coe MA, Lofwall MR, Walsh SL. Buprenorphine pharmacology review: update on transmucosal and long-acting formulations. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):93-103. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000457

4. Becerra X. Practice Guidelines for the Administration of Buprenorphine for Treating Opioid Use Disorder. US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2021:22439-22440. FR Document 2021-08961. Accessed April 5, 2021. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/04/28/2021-08961/practice-guidelines-for-the-administration-of-buprenorphine-for-treating-opioid-use-disorder

5. Haight BR, Learned SM, Laffont CM, et al. Efficacy and safety of a monthly buprenorphine depot injection for opioid use disorder: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10173):778-790. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32259-1

6. Sublocade [package insert]. North Chesterfield, VA: Indivior Inc; 2021.

7. Jones AK, Ngaimisi E, Gopalakrishnan M, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of a monthly buprenorphine depot injection for the treatment of opioid use disorder: a combined analysis of phase II and phase III trials. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2021;60(4):527-540. doi:10.1007/s40262-020-00957-0

8. Greenwald MK, Comer SD, Fiellin DA. Buprenorphine maintenance and mu-opioid receptor availability in the treatment of opioid use disorder: implications for clinical use and policy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;144:1-11. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.07.035

9. Peckham AM, Kehoe LG, Gray JR, et al. Real-world outcomes with extended-release buprenorphine (XR-BUP) in a low threshold bridge clinic: a retrospective case series. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;126:108316. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108316

10. Ling W, Nadipelli VR, Aldridge AP, et al. Recovery from opioid use disorder (OUD) after monthly long-acting buprenorphine treatment: 12-month longitudinal outcomes from RECOVER, an observational study. J Addict Med. 2020;14(5):e233-e240. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000647

11. Larance B, Byrne M, Lintzeris N, et al. Open-label, multicentre, single-arm trial of monthly injections of depot buprenorphine in people with opioid dependence: protocol for the CoLAB study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(7):e034389. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034389

12. Braeburn receives new Complete Response Letter for Brixadi in the US. News release. News Powered by Cision. December 15, 2021. Accessed April 13, 2022. https://news.cision.com/camurus-ab/r/braeburn-receives-new-complete-response-letter-for-brixadi-in-the-us,c3473281

Mr. L, age 31, presents to the emergency department (ED) with somnolence after sustaining an arm laceration at work. While in the ED, Mr. L explains he has opioid use disorder (OUD) and last week received an initial 300 mg injection of extended-release buprenorphine (BUP-XR). Due to ongoing opioid cravings, he took nonprescribed fentanyl and alprazolam before work.

The ED clinicians address Mr. L’s arm injury and transfer him to the hospital’s low-threshold outpatient addiction clinic for further assessment and management. There, he is prescribed sublingual buprenorphine/naloxone (SL-BUP) 8 mg/2 mg daily as needed for 1 week to address ongoing opioid cravings, and is encouraged to return for another visit the following week.

The United States continues to struggle with the overdose crisis, largely fueled by illicitly manufactured opioids such as fentanyl.1 Opioid agonist and partial agonist treatments such as methadone and buprenorphine decrease the risk of death in individuals with OUD by up to 50%.2 While methadone has a history of proven effectiveness for OUD, accessibility is fraught with barriers (eg, patients must attend an opioid treatment program daily to receive a dose, pharmacies are unable to dispense methadone for OUD).

Buprenorphine has been shown to decrease opioid cravings while limiting euphoria due to its partial—as opposed to full—agonist activity.3 Several buprenorphine formulations are available (Table). Buprenorphine presents an opportunity to treat OUD like other chronic illnesses. In accordance with the US Department of Health and Human Services Practice Guideline (2021), any clinician can obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine in any treatment setting, and patients can receive the medication at a pharmacy.4

However, many patients have barriers to consistent daily dosing of buprenorphine due to strict clinic/prescriber requirements, transportation difficulties, continued cravings, and other factors. BUP-XR, a buprenorphine injection administered once a month, may address several of these concerns, most notably the potential for better suppression of cravings by delivering a consistent level of buprenorphine over the course of 28 days.5 Since BUP-XR was FDA-approved in 2017, questions remain whether it can adequately quell opioid cravings in early treatment months prior to steady-state concentration.

This article addresses whether clinicians should consider supplemental SL-BUP in addition to BUP-XR during early treatment months and/or prior to steady-state.

Pharmacokinetics of BUP-XR

BUP-XR is administered by subcutaneous injection via an ATRIGEL delivery system (BUP-XR; Albany Molecular Research, Burlington, Massachusetts).6 Upon injection, approximately 7% of the buprenorphine dose dissipates with the solvent, leading to maximum concentration approximately 24 hours post-dose. The remaining dose hardens to create a depot that elutes buprenorphine gradually over 28 days.7

Continue to: Buprenorphine requires...

Buprenorphine requires ≥70% mu-opioid receptor (MOR) occupancy to effectively suppress symptoms of craving and withdrawal in patients with OUD. Buprenorphine serum concentration correlates significantly with MOR occupancy, such that concentrations of 2 to 3 ng/mL are acknowledged as baseline minimums for clinical efficacy.8

BUP-XR is administered in 1 of 2 dosing regimens. In both, 2 separate 300 mg doses are administered 28 days apart during Month 1 and Month 2, followed by maintenance doses of either 300 mg (300/300 mg dosing regimen) or 100 mg (300/100 mg dosing regimen) every 28 days thereafter. Combined Phase II and Phase III data analyzing serum concentrations of BUP-XR across both dosing regimens revealed that, for most patients, there is a noticeable period during Month 1 and Month 2 when serum concentrations fall below 2 ng/mL.7 Steady-state concentrations of both regimens develop after 4 to 6 appropriately timed injections, providing average steady-state serum concentrations in Phase II and Phase III trials of 6.54 ng/mL for the 300/300 mg dosing regimen and 3.00 ng/mL for 300/100 mg dosing regimen.7

Real-world experiences with BUP-XR

The theoretical need for supplementation has been voiced in practice. A case series by Peckham et al9 noted that 55% (n = 22) of patients required SL-BUP supplementation for up to 120 days after the first BUP-XR injection to quell cravings and reduce nonprescribed opioid use.

The RECOVER trial by Ling et al10 demonstrated the importance of the first 2 months of BUP-XR therapy in the overall treatment success for patients with OUD. In this analysis, patients maintained on BUP-XR for 12 months reported a 75% likelihood of abstinence, compared to 24% for patients receiving 0 to 2 months of BUP-XR treatment. Other benefits included improved employment status and reduced depression rates. This trial did not specifically discuss supplemental SL-BUP or subthreshold concentrations of buprenorphine during early months.10

Individualized treatment should be based on OUD symptoms

While BUP-XR was designed to continuously deliver at least 2 ng/mL of buprenorphine, serum concentrations are labile during the first 2 months of treatment. This may result in breakthrough OUD symptoms, particularly withdrawal or opioid cravings. Additionally, due to individual variability, some patients may still experience serum concentrations below 2 ng/mL after Month 2 and until steady-state is achieved between Month 4 and Month 6.7

Continue to: Beyond a theoretical...

Beyond a theoretical need for supplementation with SL-BUP, there is limited information regarding optimal dosing, dosage intervals, or length of supplementation. Therefore, clear guidance is not available at this time, and treatment should be individualized based on subjective and objective OUD symptoms.

What also remains unknown are potential barriers patients may face in receiving 2 concurrent buprenorphine prescriptions. BUP-XR, administered in a health care setting, can be obtained 2 ways. A clinician can directly order the medication from the distributor to be administered via buy-and-bill. An alternate option requires the clinician to send a prescription to an appropriately credentialed pharmacy that will ship patient-specific orders directly to the clinic. Despite this, most SL-BUP prescriptions are billed and dispensed from community pharmacies. At the insurance level, there is risk the prescription claim will be rejected for duplication of therapy, which may require additional collaboration between the prescribing clinician, pharmacist, and insurance representative to ensure patients have access to the medication.

Pending studies and approvals may also provide greater guidance and flexibility in decision-making for patients with OUD. The CoLAB study currently underway in Australia is examining the efficacy and outcomes of an intermediate dose (200 mg) of BUP-XR and will also allow for supplemental SL-BUP doses.11 Additionally, an alternative BUP-XR formulation, Brixadi, currently in use in the European Union as Buvidal, has submitted an application for FDA approval in the United States. The application indicates that Brixadi will be available with a wider range of doses and at both weekly and monthly intervals. Approval has been delayed due to deficiencies in the United States–based third-party production facilities. It is unclear how the FDA and manufacturer plan to proceed.12

Short-term supplementation with SL-BUP during early the months of treatment with BUP-XR should be considered to control OUD symptoms and assist with patient retention. Once steady-state is achieved, trough concentrations of buprenorphine are not expected to drop below 2 ng/mL with continued on-time maintenance doses and thus, supplementation can likely cease.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. L is seen in the low-threshold outpatient clinic 1 week after his ED visit. His arm laceration is healing well, and he is noticeably more alert and engaged. Each morning this week, he awakes with cravings, sweating, and anxiety. These symptoms alleviate after he takes SL-BUP. Mr. L’s clinician gives him a copy of the Subjective Opioid Withdrawal Scale so he can assess his withdrawal symptoms each morning and provide this data at follow-up appointments. Mr. L and his clinician decide to meet weekly until his next injection to continue assessing his current supplemental dose, symptoms, and whether there should be additional adjustments to his treatment plan.

Related Resources

- Cho J, Bhimani J, Patel M, et al. Substance abuse among older adults: a growing problem. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(3):14-20.

- Verma S. Opioid use disorder in adolescents: an overview. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(2):12-14,16-21.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Buprenorphine • Sublocade, Subutex

Buprenorphine/naloxone • Suboxone, Zubsolv

Methadone • Methadose

Mr. L, age 31, presents to the emergency department (ED) with somnolence after sustaining an arm laceration at work. While in the ED, Mr. L explains he has opioid use disorder (OUD) and last week received an initial 300 mg injection of extended-release buprenorphine (BUP-XR). Due to ongoing opioid cravings, he took nonprescribed fentanyl and alprazolam before work.

The ED clinicians address Mr. L’s arm injury and transfer him to the hospital’s low-threshold outpatient addiction clinic for further assessment and management. There, he is prescribed sublingual buprenorphine/naloxone (SL-BUP) 8 mg/2 mg daily as needed for 1 week to address ongoing opioid cravings, and is encouraged to return for another visit the following week.

The United States continues to struggle with the overdose crisis, largely fueled by illicitly manufactured opioids such as fentanyl.1 Opioid agonist and partial agonist treatments such as methadone and buprenorphine decrease the risk of death in individuals with OUD by up to 50%.2 While methadone has a history of proven effectiveness for OUD, accessibility is fraught with barriers (eg, patients must attend an opioid treatment program daily to receive a dose, pharmacies are unable to dispense methadone for OUD).

Buprenorphine has been shown to decrease opioid cravings while limiting euphoria due to its partial—as opposed to full—agonist activity.3 Several buprenorphine formulations are available (Table). Buprenorphine presents an opportunity to treat OUD like other chronic illnesses. In accordance with the US Department of Health and Human Services Practice Guideline (2021), any clinician can obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine in any treatment setting, and patients can receive the medication at a pharmacy.4

However, many patients have barriers to consistent daily dosing of buprenorphine due to strict clinic/prescriber requirements, transportation difficulties, continued cravings, and other factors. BUP-XR, a buprenorphine injection administered once a month, may address several of these concerns, most notably the potential for better suppression of cravings by delivering a consistent level of buprenorphine over the course of 28 days.5 Since BUP-XR was FDA-approved in 2017, questions remain whether it can adequately quell opioid cravings in early treatment months prior to steady-state concentration.

This article addresses whether clinicians should consider supplemental SL-BUP in addition to BUP-XR during early treatment months and/or prior to steady-state.

Pharmacokinetics of BUP-XR

BUP-XR is administered by subcutaneous injection via an ATRIGEL delivery system (BUP-XR; Albany Molecular Research, Burlington, Massachusetts).6 Upon injection, approximately 7% of the buprenorphine dose dissipates with the solvent, leading to maximum concentration approximately 24 hours post-dose. The remaining dose hardens to create a depot that elutes buprenorphine gradually over 28 days.7

Continue to: Buprenorphine requires...

Buprenorphine requires ≥70% mu-opioid receptor (MOR) occupancy to effectively suppress symptoms of craving and withdrawal in patients with OUD. Buprenorphine serum concentration correlates significantly with MOR occupancy, such that concentrations of 2 to 3 ng/mL are acknowledged as baseline minimums for clinical efficacy.8

BUP-XR is administered in 1 of 2 dosing regimens. In both, 2 separate 300 mg doses are administered 28 days apart during Month 1 and Month 2, followed by maintenance doses of either 300 mg (300/300 mg dosing regimen) or 100 mg (300/100 mg dosing regimen) every 28 days thereafter. Combined Phase II and Phase III data analyzing serum concentrations of BUP-XR across both dosing regimens revealed that, for most patients, there is a noticeable period during Month 1 and Month 2 when serum concentrations fall below 2 ng/mL.7 Steady-state concentrations of both regimens develop after 4 to 6 appropriately timed injections, providing average steady-state serum concentrations in Phase II and Phase III trials of 6.54 ng/mL for the 300/300 mg dosing regimen and 3.00 ng/mL for 300/100 mg dosing regimen.7

Real-world experiences with BUP-XR

The theoretical need for supplementation has been voiced in practice. A case series by Peckham et al9 noted that 55% (n = 22) of patients required SL-BUP supplementation for up to 120 days after the first BUP-XR injection to quell cravings and reduce nonprescribed opioid use.

The RECOVER trial by Ling et al10 demonstrated the importance of the first 2 months of BUP-XR therapy in the overall treatment success for patients with OUD. In this analysis, patients maintained on BUP-XR for 12 months reported a 75% likelihood of abstinence, compared to 24% for patients receiving 0 to 2 months of BUP-XR treatment. Other benefits included improved employment status and reduced depression rates. This trial did not specifically discuss supplemental SL-BUP or subthreshold concentrations of buprenorphine during early months.10

Individualized treatment should be based on OUD symptoms

While BUP-XR was designed to continuously deliver at least 2 ng/mL of buprenorphine, serum concentrations are labile during the first 2 months of treatment. This may result in breakthrough OUD symptoms, particularly withdrawal or opioid cravings. Additionally, due to individual variability, some patients may still experience serum concentrations below 2 ng/mL after Month 2 and until steady-state is achieved between Month 4 and Month 6.7

Continue to: Beyond a theoretical...

Beyond a theoretical need for supplementation with SL-BUP, there is limited information regarding optimal dosing, dosage intervals, or length of supplementation. Therefore, clear guidance is not available at this time, and treatment should be individualized based on subjective and objective OUD symptoms.

What also remains unknown are potential barriers patients may face in receiving 2 concurrent buprenorphine prescriptions. BUP-XR, administered in a health care setting, can be obtained 2 ways. A clinician can directly order the medication from the distributor to be administered via buy-and-bill. An alternate option requires the clinician to send a prescription to an appropriately credentialed pharmacy that will ship patient-specific orders directly to the clinic. Despite this, most SL-BUP prescriptions are billed and dispensed from community pharmacies. At the insurance level, there is risk the prescription claim will be rejected for duplication of therapy, which may require additional collaboration between the prescribing clinician, pharmacist, and insurance representative to ensure patients have access to the medication.

Pending studies and approvals may also provide greater guidance and flexibility in decision-making for patients with OUD. The CoLAB study currently underway in Australia is examining the efficacy and outcomes of an intermediate dose (200 mg) of BUP-XR and will also allow for supplemental SL-BUP doses.11 Additionally, an alternative BUP-XR formulation, Brixadi, currently in use in the European Union as Buvidal, has submitted an application for FDA approval in the United States. The application indicates that Brixadi will be available with a wider range of doses and at both weekly and monthly intervals. Approval has been delayed due to deficiencies in the United States–based third-party production facilities. It is unclear how the FDA and manufacturer plan to proceed.12

Short-term supplementation with SL-BUP during early the months of treatment with BUP-XR should be considered to control OUD symptoms and assist with patient retention. Once steady-state is achieved, trough concentrations of buprenorphine are not expected to drop below 2 ng/mL with continued on-time maintenance doses and thus, supplementation can likely cease.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. L is seen in the low-threshold outpatient clinic 1 week after his ED visit. His arm laceration is healing well, and he is noticeably more alert and engaged. Each morning this week, he awakes with cravings, sweating, and anxiety. These symptoms alleviate after he takes SL-BUP. Mr. L’s clinician gives him a copy of the Subjective Opioid Withdrawal Scale so he can assess his withdrawal symptoms each morning and provide this data at follow-up appointments. Mr. L and his clinician decide to meet weekly until his next injection to continue assessing his current supplemental dose, symptoms, and whether there should be additional adjustments to his treatment plan.

Related Resources

- Cho J, Bhimani J, Patel M, et al. Substance abuse among older adults: a growing problem. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(3):14-20.

- Verma S. Opioid use disorder in adolescents: an overview. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(2):12-14,16-21.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Buprenorphine • Sublocade, Subutex

Buprenorphine/naloxone • Suboxone, Zubsolv

Methadone • Methadose

1. Mattson CL, Tanz LJ, Quinn K, et al. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths - United States, 2013-2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(6):202-207. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4

2. Ma J, Bao YP, Wang RJ, et al. Effects of medication-assisted treatment on mortality among opioids users: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(12):1868-1883. doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0094-5

3. Coe MA, Lofwall MR, Walsh SL. Buprenorphine pharmacology review: update on transmucosal and long-acting formulations. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):93-103. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000457

4. Becerra X. Practice Guidelines for the Administration of Buprenorphine for Treating Opioid Use Disorder. US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2021:22439-22440. FR Document 2021-08961. Accessed April 5, 2021. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/04/28/2021-08961/practice-guidelines-for-the-administration-of-buprenorphine-for-treating-opioid-use-disorder

5. Haight BR, Learned SM, Laffont CM, et al. Efficacy and safety of a monthly buprenorphine depot injection for opioid use disorder: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10173):778-790. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32259-1

6. Sublocade [package insert]. North Chesterfield, VA: Indivior Inc; 2021.

7. Jones AK, Ngaimisi E, Gopalakrishnan M, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of a monthly buprenorphine depot injection for the treatment of opioid use disorder: a combined analysis of phase II and phase III trials. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2021;60(4):527-540. doi:10.1007/s40262-020-00957-0

8. Greenwald MK, Comer SD, Fiellin DA. Buprenorphine maintenance and mu-opioid receptor availability in the treatment of opioid use disorder: implications for clinical use and policy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;144:1-11. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.07.035

9. Peckham AM, Kehoe LG, Gray JR, et al. Real-world outcomes with extended-release buprenorphine (XR-BUP) in a low threshold bridge clinic: a retrospective case series. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;126:108316. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108316

10. Ling W, Nadipelli VR, Aldridge AP, et al. Recovery from opioid use disorder (OUD) after monthly long-acting buprenorphine treatment: 12-month longitudinal outcomes from RECOVER, an observational study. J Addict Med. 2020;14(5):e233-e240. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000647

11. Larance B, Byrne M, Lintzeris N, et al. Open-label, multicentre, single-arm trial of monthly injections of depot buprenorphine in people with opioid dependence: protocol for the CoLAB study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(7):e034389. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034389

12. Braeburn receives new Complete Response Letter for Brixadi in the US. News release. News Powered by Cision. December 15, 2021. Accessed April 13, 2022. https://news.cision.com/camurus-ab/r/braeburn-receives-new-complete-response-letter-for-brixadi-in-the-us,c3473281

1. Mattson CL, Tanz LJ, Quinn K, et al. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths - United States, 2013-2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(6):202-207. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4

2. Ma J, Bao YP, Wang RJ, et al. Effects of medication-assisted treatment on mortality among opioids users: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(12):1868-1883. doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0094-5

3. Coe MA, Lofwall MR, Walsh SL. Buprenorphine pharmacology review: update on transmucosal and long-acting formulations. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):93-103. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000457

4. Becerra X. Practice Guidelines for the Administration of Buprenorphine for Treating Opioid Use Disorder. US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2021:22439-22440. FR Document 2021-08961. Accessed April 5, 2021. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/04/28/2021-08961/practice-guidelines-for-the-administration-of-buprenorphine-for-treating-opioid-use-disorder

5. Haight BR, Learned SM, Laffont CM, et al. Efficacy and safety of a monthly buprenorphine depot injection for opioid use disorder: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10173):778-790. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32259-1

6. Sublocade [package insert]. North Chesterfield, VA: Indivior Inc; 2021.

7. Jones AK, Ngaimisi E, Gopalakrishnan M, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of a monthly buprenorphine depot injection for the treatment of opioid use disorder: a combined analysis of phase II and phase III trials. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2021;60(4):527-540. doi:10.1007/s40262-020-00957-0

8. Greenwald MK, Comer SD, Fiellin DA. Buprenorphine maintenance and mu-opioid receptor availability in the treatment of opioid use disorder: implications for clinical use and policy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;144:1-11. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.07.035

9. Peckham AM, Kehoe LG, Gray JR, et al. Real-world outcomes with extended-release buprenorphine (XR-BUP) in a low threshold bridge clinic: a retrospective case series. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;126:108316. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108316

10. Ling W, Nadipelli VR, Aldridge AP, et al. Recovery from opioid use disorder (OUD) after monthly long-acting buprenorphine treatment: 12-month longitudinal outcomes from RECOVER, an observational study. J Addict Med. 2020;14(5):e233-e240. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000647

11. Larance B, Byrne M, Lintzeris N, et al. Open-label, multicentre, single-arm trial of monthly injections of depot buprenorphine in people with opioid dependence: protocol for the CoLAB study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(7):e034389. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034389

12. Braeburn receives new Complete Response Letter for Brixadi in the US. News release. News Powered by Cision. December 15, 2021. Accessed April 13, 2022. https://news.cision.com/camurus-ab/r/braeburn-receives-new-complete-response-letter-for-brixadi-in-the-us,c3473281

Safe supply programs aim to reduce drug overdose deaths

The Safer Alternatives for Emergency Response (SAFER) program provides a safe supply of substances to prevent drug overdose deaths, according to a new report.

The program has been operating in Vancouver, British Columbia, since April 2021. So far, the program has enrolled 58 participants who have reported benefits from having new options when other forms of treatment or harm reduction didn’t work. In addition, doctors who work with the program have reported increased medication adherence among the participants, as well as better chronic disease management.

Similar safe supply programs are being implemented or considered in other places across Canada. Since 2019, Health Canada has funded 18 safe supply pilot programs.

“When we look at the number of overdose deaths, it should be zero. These are preventable deaths,” author Christy Sutherland, MD, medical director at the PHS Community Services Society, Vancouver, which operates the SAFER program, told this news organization.

“As clinicians, we can see that the tools we have are working less because of prohibition. It drives the market to provide more potent and more dangerous options,” she said. “It’s critical that we disrupt the illicit market and provide medical solutions to keep people safe.”

The report was published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Safe supply programs

Between January 2016 and June 2021, more than 24,000 people died from opioid toxicity in Canada, according to the authors. A key driver of the ongoing public health crisis has been the introduction of illicit fentanyl and other dangerous substances into the unregulated drug supply.

In recent years, several harm-reduction options and substance use disorder treatment programs have been introduced in Canada to stem overdose deaths. However, they haven’t been sufficient, and the number of deaths continues to rise.

“In 2010, methadone worked, but now even high doses don’t keep people out of withdrawal due to the infiltration of fentanyl,” Dr. Sutherland said. “It’s clinically not working anymore. People are now going through benzodiazepine withdrawal and opiate withdrawal at the same time.”

The changes have led doctors to call for programs that provide legal and regulated sources of psychoactive substances, also known as “safe supply” programs. In particular, low-barrier and flexible options are necessary to meet the needs of various people in the community.

In Vancouver, the SAFER program provides medications that are prescribed off-label as substitutes to the illicit drug supply. A multidisciplinary team oversees the program, including doctors, nurses, pharmacists, social workers, and people who have experience living with substance use.

The program’s approach is akin to the use of medications as treatments for substance use disorder, such as opioid-agonist therapy. However,

Enrolled participants can access medications, including opioids such as hydromorphone and fentanyl, as a substitute for the unregulated substances that they consume. A notable aspect of SAFER is the offer of fentanyl – with a known potency and without dangerous adulterants found in the local drug supply.

Promoting participant autonomy

Given the increasing rate of overdose deaths involving stimulants in Canada, the program also offers prescribed psychostimulants, such as methylphenidate and dextroamphetamine.

The program focuses on harm reduction and promoting participant autonomy. SAFER doesn’t have a predetermined schedule for medication access, which allows participants to return as they need.

“Creating this program has required patience to change our practices,” Dr. Sutherland said. “As you learn more and do more, you’re always growing because you care about your patients and want to help them, especially vulnerable people with a high risk for death.”

The SAFER program is integrated into health care and social services, and participants have access to on-site primary care from clinicians trained in addiction medicine. The program is located alongside a low-barrier prevention site, where supplies such as syringes, take-home naloxone kits, and drug-checking services are available.

The SAFER program will undergo a scientific evaluation, led by two of the co-authors, which will include about 200 participants. During a 2-year period, the evaluation will assess whether the program reduces the risk for overdose deaths and supports access to primary care, harm reduction, and substance use disorder treatment. In addition, the researchers will analyze other key outcomes, such as fatal versus nonfatal overdoses, medication adherence, and the qualitative lived experience of participants.

The end of prohibition?

“We’ve had the same challenges with people buying illegal drugs on the street for almost 30 years, but about 5 years ago, that all changed when fentanyl became a prominent drug, and overdose deaths skyrocketed,” Mark Tyndall, MD, a public health professor at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said in an interview.

Dr. Tyndall is also executive director of the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control and executive director of MySafe Society, a safe supply program in Canada for those with opioid addiction. He is not involved in the SAFER program.

SAFER and MySafe Society are positioned as low-barrier programs, he said, meaning that the public health response is primarily focused on preventing deaths and helping people to get access to medication that won’t kill them. The idea is to meet people where they are today.

However, these programs still face major barriers, such as limitations from federal regulators and stigmas around illicit drugs and harm-reduction programs.

“These beliefs are entrenched, and it takes a long time to help people understand that prohibition means that dangerous drugs are on the street,” he said. “I don’t think way more people are using than 10 years ago, but there was a supply of heroin that was stable in potency back then, and people weren’t dying.”

Ultimately, Dr. Tyndall said, drug policy experts would like to create a regulated supply, similar to the supply of cannabis. The political and regulatory process may take much longer to catch up, but he believes that it’s the most ethical way to reduce overdose deaths and the unregulated drug supply.

“The harshest critics of harm reduction often go to the liquor store every weekend,” he said. “It’s going to be a long process before people think this way, but having fentanyl and other dangerous drugs on the street has signaled the end stage of prohibition.”

The SAFER program is operated by PHS Community Services Society in partnership with Vancouver Coastal Health and funded through Health Canada’s Substance Use and Addiction Program. Dr. Tyndall reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Safer Alternatives for Emergency Response (SAFER) program provides a safe supply of substances to prevent drug overdose deaths, according to a new report.

The program has been operating in Vancouver, British Columbia, since April 2021. So far, the program has enrolled 58 participants who have reported benefits from having new options when other forms of treatment or harm reduction didn’t work. In addition, doctors who work with the program have reported increased medication adherence among the participants, as well as better chronic disease management.

Similar safe supply programs are being implemented or considered in other places across Canada. Since 2019, Health Canada has funded 18 safe supply pilot programs.

“When we look at the number of overdose deaths, it should be zero. These are preventable deaths,” author Christy Sutherland, MD, medical director at the PHS Community Services Society, Vancouver, which operates the SAFER program, told this news organization.

“As clinicians, we can see that the tools we have are working less because of prohibition. It drives the market to provide more potent and more dangerous options,” she said. “It’s critical that we disrupt the illicit market and provide medical solutions to keep people safe.”

The report was published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Safe supply programs

Between January 2016 and June 2021, more than 24,000 people died from opioid toxicity in Canada, according to the authors. A key driver of the ongoing public health crisis has been the introduction of illicit fentanyl and other dangerous substances into the unregulated drug supply.

In recent years, several harm-reduction options and substance use disorder treatment programs have been introduced in Canada to stem overdose deaths. However, they haven’t been sufficient, and the number of deaths continues to rise.

“In 2010, methadone worked, but now even high doses don’t keep people out of withdrawal due to the infiltration of fentanyl,” Dr. Sutherland said. “It’s clinically not working anymore. People are now going through benzodiazepine withdrawal and opiate withdrawal at the same time.”

The changes have led doctors to call for programs that provide legal and regulated sources of psychoactive substances, also known as “safe supply” programs. In particular, low-barrier and flexible options are necessary to meet the needs of various people in the community.

In Vancouver, the SAFER program provides medications that are prescribed off-label as substitutes to the illicit drug supply. A multidisciplinary team oversees the program, including doctors, nurses, pharmacists, social workers, and people who have experience living with substance use.

The program’s approach is akin to the use of medications as treatments for substance use disorder, such as opioid-agonist therapy. However,

Enrolled participants can access medications, including opioids such as hydromorphone and fentanyl, as a substitute for the unregulated substances that they consume. A notable aspect of SAFER is the offer of fentanyl – with a known potency and without dangerous adulterants found in the local drug supply.

Promoting participant autonomy

Given the increasing rate of overdose deaths involving stimulants in Canada, the program also offers prescribed psychostimulants, such as methylphenidate and dextroamphetamine.

The program focuses on harm reduction and promoting participant autonomy. SAFER doesn’t have a predetermined schedule for medication access, which allows participants to return as they need.

“Creating this program has required patience to change our practices,” Dr. Sutherland said. “As you learn more and do more, you’re always growing because you care about your patients and want to help them, especially vulnerable people with a high risk for death.”

The SAFER program is integrated into health care and social services, and participants have access to on-site primary care from clinicians trained in addiction medicine. The program is located alongside a low-barrier prevention site, where supplies such as syringes, take-home naloxone kits, and drug-checking services are available.

The SAFER program will undergo a scientific evaluation, led by two of the co-authors, which will include about 200 participants. During a 2-year period, the evaluation will assess whether the program reduces the risk for overdose deaths and supports access to primary care, harm reduction, and substance use disorder treatment. In addition, the researchers will analyze other key outcomes, such as fatal versus nonfatal overdoses, medication adherence, and the qualitative lived experience of participants.

The end of prohibition?

“We’ve had the same challenges with people buying illegal drugs on the street for almost 30 years, but about 5 years ago, that all changed when fentanyl became a prominent drug, and overdose deaths skyrocketed,” Mark Tyndall, MD, a public health professor at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said in an interview.

Dr. Tyndall is also executive director of the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control and executive director of MySafe Society, a safe supply program in Canada for those with opioid addiction. He is not involved in the SAFER program.

SAFER and MySafe Society are positioned as low-barrier programs, he said, meaning that the public health response is primarily focused on preventing deaths and helping people to get access to medication that won’t kill them. The idea is to meet people where they are today.

However, these programs still face major barriers, such as limitations from federal regulators and stigmas around illicit drugs and harm-reduction programs.

“These beliefs are entrenched, and it takes a long time to help people understand that prohibition means that dangerous drugs are on the street,” he said. “I don’t think way more people are using than 10 years ago, but there was a supply of heroin that was stable in potency back then, and people weren’t dying.”

Ultimately, Dr. Tyndall said, drug policy experts would like to create a regulated supply, similar to the supply of cannabis. The political and regulatory process may take much longer to catch up, but he believes that it’s the most ethical way to reduce overdose deaths and the unregulated drug supply.

“The harshest critics of harm reduction often go to the liquor store every weekend,” he said. “It’s going to be a long process before people think this way, but having fentanyl and other dangerous drugs on the street has signaled the end stage of prohibition.”

The SAFER program is operated by PHS Community Services Society in partnership with Vancouver Coastal Health and funded through Health Canada’s Substance Use and Addiction Program. Dr. Tyndall reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Safer Alternatives for Emergency Response (SAFER) program provides a safe supply of substances to prevent drug overdose deaths, according to a new report.

The program has been operating in Vancouver, British Columbia, since April 2021. So far, the program has enrolled 58 participants who have reported benefits from having new options when other forms of treatment or harm reduction didn’t work. In addition, doctors who work with the program have reported increased medication adherence among the participants, as well as better chronic disease management.

Similar safe supply programs are being implemented or considered in other places across Canada. Since 2019, Health Canada has funded 18 safe supply pilot programs.

“When we look at the number of overdose deaths, it should be zero. These are preventable deaths,” author Christy Sutherland, MD, medical director at the PHS Community Services Society, Vancouver, which operates the SAFER program, told this news organization.

“As clinicians, we can see that the tools we have are working less because of prohibition. It drives the market to provide more potent and more dangerous options,” she said. “It’s critical that we disrupt the illicit market and provide medical solutions to keep people safe.”

The report was published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Safe supply programs

Between January 2016 and June 2021, more than 24,000 people died from opioid toxicity in Canada, according to the authors. A key driver of the ongoing public health crisis has been the introduction of illicit fentanyl and other dangerous substances into the unregulated drug supply.

In recent years, several harm-reduction options and substance use disorder treatment programs have been introduced in Canada to stem overdose deaths. However, they haven’t been sufficient, and the number of deaths continues to rise.

“In 2010, methadone worked, but now even high doses don’t keep people out of withdrawal due to the infiltration of fentanyl,” Dr. Sutherland said. “It’s clinically not working anymore. People are now going through benzodiazepine withdrawal and opiate withdrawal at the same time.”

The changes have led doctors to call for programs that provide legal and regulated sources of psychoactive substances, also known as “safe supply” programs. In particular, low-barrier and flexible options are necessary to meet the needs of various people in the community.

In Vancouver, the SAFER program provides medications that are prescribed off-label as substitutes to the illicit drug supply. A multidisciplinary team oversees the program, including doctors, nurses, pharmacists, social workers, and people who have experience living with substance use.

The program’s approach is akin to the use of medications as treatments for substance use disorder, such as opioid-agonist therapy. However,

Enrolled participants can access medications, including opioids such as hydromorphone and fentanyl, as a substitute for the unregulated substances that they consume. A notable aspect of SAFER is the offer of fentanyl – with a known potency and without dangerous adulterants found in the local drug supply.

Promoting participant autonomy

Given the increasing rate of overdose deaths involving stimulants in Canada, the program also offers prescribed psychostimulants, such as methylphenidate and dextroamphetamine.

The program focuses on harm reduction and promoting participant autonomy. SAFER doesn’t have a predetermined schedule for medication access, which allows participants to return as they need.

“Creating this program has required patience to change our practices,” Dr. Sutherland said. “As you learn more and do more, you’re always growing because you care about your patients and want to help them, especially vulnerable people with a high risk for death.”

The SAFER program is integrated into health care and social services, and participants have access to on-site primary care from clinicians trained in addiction medicine. The program is located alongside a low-barrier prevention site, where supplies such as syringes, take-home naloxone kits, and drug-checking services are available.

The SAFER program will undergo a scientific evaluation, led by two of the co-authors, which will include about 200 participants. During a 2-year period, the evaluation will assess whether the program reduces the risk for overdose deaths and supports access to primary care, harm reduction, and substance use disorder treatment. In addition, the researchers will analyze other key outcomes, such as fatal versus nonfatal overdoses, medication adherence, and the qualitative lived experience of participants.

The end of prohibition?

“We’ve had the same challenges with people buying illegal drugs on the street for almost 30 years, but about 5 years ago, that all changed when fentanyl became a prominent drug, and overdose deaths skyrocketed,” Mark Tyndall, MD, a public health professor at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said in an interview.

Dr. Tyndall is also executive director of the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control and executive director of MySafe Society, a safe supply program in Canada for those with opioid addiction. He is not involved in the SAFER program.

SAFER and MySafe Society are positioned as low-barrier programs, he said, meaning that the public health response is primarily focused on preventing deaths and helping people to get access to medication that won’t kill them. The idea is to meet people where they are today.

However, these programs still face major barriers, such as limitations from federal regulators and stigmas around illicit drugs and harm-reduction programs.

“These beliefs are entrenched, and it takes a long time to help people understand that prohibition means that dangerous drugs are on the street,” he said. “I don’t think way more people are using than 10 years ago, but there was a supply of heroin that was stable in potency back then, and people weren’t dying.”

Ultimately, Dr. Tyndall said, drug policy experts would like to create a regulated supply, similar to the supply of cannabis. The political and regulatory process may take much longer to catch up, but he believes that it’s the most ethical way to reduce overdose deaths and the unregulated drug supply.

“The harshest critics of harm reduction often go to the liquor store every weekend,” he said. “It’s going to be a long process before people think this way, but having fentanyl and other dangerous drugs on the street has signaled the end stage of prohibition.”

The SAFER program is operated by PHS Community Services Society in partnership with Vancouver Coastal Health and funded through Health Canada’s Substance Use and Addiction Program. Dr. Tyndall reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE CANADIAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION JOURNAL

Video game obsession: Definitions and best treatments remain elusive

NEW ORLEANS – Research into video game addiction is turning up new insights, and some treatments seem to make a difference, according to addiction psychiatry experts speaking at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. Still, understanding remains limited amid a general lack of clarity about definitions, measurements, and the most effective treatment strategies.

“Video games have the potential to be uniquely addictive, and it’s difficult to come up with treatment modalities that you can use for kids who have access to these things 24/7 on their mobile phones or laptops,” psychiatrist James C. Sherer, MD, of NYU Langone Health, said during the May 22 session, “Internet Gaming Disorder: From Harmless Fun to Dependence,” at the meeting. “It makes treating this a really complicated endeavor.”

The number of people with so-called Internet gaming disorder is unknown, but video games remain wildly popular among adults and children of all genders. According to a 2021 survey by Common Sense Media, U.S. individuals aged 8-12 and 13-18 spent an average of 1:27 hours and 1:46 hours per day, respectively, playing video games.

“Video games are an extremely important part of normal social networking among kids, and there’s a huge amount of social pressure to be good,” Dr. Sherer said. “If you’re in a particularly affluent neighborhood, it’s not unheard of for a parent to hire a coach to make their kid good at a game like Fortnite so they impress the other kids.”

The 2013 edition of the DSM-5 doesn’t list Internet gaming disorder as a mental illness but suggests that the topic warrants more research and evaluation, Dr. Sherer said.

Why are video games so addicting? According to Dr. Sherer, they’re simply designed that way. Game manufacturers “employ psychologists and behaviorists whose only job is to look at the game and determine what colors and what sounds are most likely to make you spend a little bit extra.” And with the help of the Internet, video games have evolved over the past 40 years to encourage users to make multiple purchases on single games such as Candy Crush instead of simply buying, say, a single 1980s-style Atari cartridge.

According to Dr. Sherer, research suggests that video games place users into something called the “flow state,” which a recent review article published in Frontiers in Psychology describes as “a state of full task engagement that is accompanied with low-levels of self-referential thinking” and “highly relevant for human performance and well-being.”

Diagnosing gaming addiction

How can psychiatrists diagnose video gaming addiction? Dr. Sherer, who is himself a devoted gamer, advised against focusing too much on time spent gaming in determining whether a patient has a problem. Instead, keep in mind that excessive gaming can displace exercise and normal socialization, he said, and lead to worsening mood.

Rober Aziz, MD, also of NYU Langone Health, suggested asking these questions: What types of games do you play? How long do you spend playing? What’s your reason for playing? What’s the meaning of your character choices? Does this game interfere with school or work? Have you neglected your self-care to play more?

He recommends other questions, too: Have you tried to limit your play time without success? How uncomfortable do you get if you must stop in the middle of playing? Do you get agitated if servers go down unexpectedly?

“There’s actually a lot of parallel here to other addictions that we’re very familiar with,” he said.

According to Dr. Sherer, it’s helpful to know that children who have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder tend to struggle with gaming addiction the most. He highlighted a brain-scan study in the Journal of Attention Disorders that found that patients with gaming addiction and ADHD had less functional connectivity from the cortex to the subcortex compared to matched controls. But treatment helped increase connectivity in those with good prognoses.

The findings are “heartening,” he said. “Basically, if you’re treating ADHD, you’re treating Internet gaming disorder. And if you’re treating Internet gaming disorder, you’re treating ADHD.”

As for treatments, the speakers agreed that there is little research to point in the right direction regarding gaming addiction specifically.

According to Dr. Aziz, research has suggested that bupropion, methylphenidate, and escitalopram can be helpful. In terms of nondrug approaches, he recommends directing patients toward games that have distinct beginnings, middles, and ends instead of endlessly providing rewards. One such game is “Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild” on the Nintendo Switch platform, he said.

On the psychotherapy front, Dr. Aziz said, “reducing use rather than abstinence should be the treatment goal.” Research suggests that cognitive behavioral therapy may not help patients in the long term, he said. Other strategies, he said, include specific approaches known as “CBT for Internet addiction” and “motivational interviewing for Internet gaming disorder.”

Gaming addiction treatment centers have also popped up in the U.S., he said, and there’s now an organization called Gaming Addicts Anonymous.

The good news is that “there is a lot of active research that’s being done” into treating video game addiction, said psychiatrist Anil Thomas, MD, program director of the addiction psychiatry fellowship at NYU Langone Health and moderator of the APA session. “We just have to wait to see what the results are.”

NEW ORLEANS – Research into video game addiction is turning up new insights, and some treatments seem to make a difference, according to addiction psychiatry experts speaking at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. Still, understanding remains limited amid a general lack of clarity about definitions, measurements, and the most effective treatment strategies.

“Video games have the potential to be uniquely addictive, and it’s difficult to come up with treatment modalities that you can use for kids who have access to these things 24/7 on their mobile phones or laptops,” psychiatrist James C. Sherer, MD, of NYU Langone Health, said during the May 22 session, “Internet Gaming Disorder: From Harmless Fun to Dependence,” at the meeting. “It makes treating this a really complicated endeavor.”

The number of people with so-called Internet gaming disorder is unknown, but video games remain wildly popular among adults and children of all genders. According to a 2021 survey by Common Sense Media, U.S. individuals aged 8-12 and 13-18 spent an average of 1:27 hours and 1:46 hours per day, respectively, playing video games.

“Video games are an extremely important part of normal social networking among kids, and there’s a huge amount of social pressure to be good,” Dr. Sherer said. “If you’re in a particularly affluent neighborhood, it’s not unheard of for a parent to hire a coach to make their kid good at a game like Fortnite so they impress the other kids.”

The 2013 edition of the DSM-5 doesn’t list Internet gaming disorder as a mental illness but suggests that the topic warrants more research and evaluation, Dr. Sherer said.

Why are video games so addicting? According to Dr. Sherer, they’re simply designed that way. Game manufacturers “employ psychologists and behaviorists whose only job is to look at the game and determine what colors and what sounds are most likely to make you spend a little bit extra.” And with the help of the Internet, video games have evolved over the past 40 years to encourage users to make multiple purchases on single games such as Candy Crush instead of simply buying, say, a single 1980s-style Atari cartridge.

According to Dr. Sherer, research suggests that video games place users into something called the “flow state,” which a recent review article published in Frontiers in Psychology describes as “a state of full task engagement that is accompanied with low-levels of self-referential thinking” and “highly relevant for human performance and well-being.”

Diagnosing gaming addiction

How can psychiatrists diagnose video gaming addiction? Dr. Sherer, who is himself a devoted gamer, advised against focusing too much on time spent gaming in determining whether a patient has a problem. Instead, keep in mind that excessive gaming can displace exercise and normal socialization, he said, and lead to worsening mood.

Rober Aziz, MD, also of NYU Langone Health, suggested asking these questions: What types of games do you play? How long do you spend playing? What’s your reason for playing? What’s the meaning of your character choices? Does this game interfere with school or work? Have you neglected your self-care to play more?

He recommends other questions, too: Have you tried to limit your play time without success? How uncomfortable do you get if you must stop in the middle of playing? Do you get agitated if servers go down unexpectedly?

“There’s actually a lot of parallel here to other addictions that we’re very familiar with,” he said.

According to Dr. Sherer, it’s helpful to know that children who have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder tend to struggle with gaming addiction the most. He highlighted a brain-scan study in the Journal of Attention Disorders that found that patients with gaming addiction and ADHD had less functional connectivity from the cortex to the subcortex compared to matched controls. But treatment helped increase connectivity in those with good prognoses.

The findings are “heartening,” he said. “Basically, if you’re treating ADHD, you’re treating Internet gaming disorder. And if you’re treating Internet gaming disorder, you’re treating ADHD.”

As for treatments, the speakers agreed that there is little research to point in the right direction regarding gaming addiction specifically.

According to Dr. Aziz, research has suggested that bupropion, methylphenidate, and escitalopram can be helpful. In terms of nondrug approaches, he recommends directing patients toward games that have distinct beginnings, middles, and ends instead of endlessly providing rewards. One such game is “Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild” on the Nintendo Switch platform, he said.

On the psychotherapy front, Dr. Aziz said, “reducing use rather than abstinence should be the treatment goal.” Research suggests that cognitive behavioral therapy may not help patients in the long term, he said. Other strategies, he said, include specific approaches known as “CBT for Internet addiction” and “motivational interviewing for Internet gaming disorder.”

Gaming addiction treatment centers have also popped up in the U.S., he said, and there’s now an organization called Gaming Addicts Anonymous.

The good news is that “there is a lot of active research that’s being done” into treating video game addiction, said psychiatrist Anil Thomas, MD, program director of the addiction psychiatry fellowship at NYU Langone Health and moderator of the APA session. “We just have to wait to see what the results are.”

NEW ORLEANS – Research into video game addiction is turning up new insights, and some treatments seem to make a difference, according to addiction psychiatry experts speaking at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. Still, understanding remains limited amid a general lack of clarity about definitions, measurements, and the most effective treatment strategies.

“Video games have the potential to be uniquely addictive, and it’s difficult to come up with treatment modalities that you can use for kids who have access to these things 24/7 on their mobile phones or laptops,” psychiatrist James C. Sherer, MD, of NYU Langone Health, said during the May 22 session, “Internet Gaming Disorder: From Harmless Fun to Dependence,” at the meeting. “It makes treating this a really complicated endeavor.”

The number of people with so-called Internet gaming disorder is unknown, but video games remain wildly popular among adults and children of all genders. According to a 2021 survey by Common Sense Media, U.S. individuals aged 8-12 and 13-18 spent an average of 1:27 hours and 1:46 hours per day, respectively, playing video games.

“Video games are an extremely important part of normal social networking among kids, and there’s a huge amount of social pressure to be good,” Dr. Sherer said. “If you’re in a particularly affluent neighborhood, it’s not unheard of for a parent to hire a coach to make their kid good at a game like Fortnite so they impress the other kids.”

The 2013 edition of the DSM-5 doesn’t list Internet gaming disorder as a mental illness but suggests that the topic warrants more research and evaluation, Dr. Sherer said.

Why are video games so addicting? According to Dr. Sherer, they’re simply designed that way. Game manufacturers “employ psychologists and behaviorists whose only job is to look at the game and determine what colors and what sounds are most likely to make you spend a little bit extra.” And with the help of the Internet, video games have evolved over the past 40 years to encourage users to make multiple purchases on single games such as Candy Crush instead of simply buying, say, a single 1980s-style Atari cartridge.

According to Dr. Sherer, research suggests that video games place users into something called the “flow state,” which a recent review article published in Frontiers in Psychology describes as “a state of full task engagement that is accompanied with low-levels of self-referential thinking” and “highly relevant for human performance and well-being.”

Diagnosing gaming addiction

How can psychiatrists diagnose video gaming addiction? Dr. Sherer, who is himself a devoted gamer, advised against focusing too much on time spent gaming in determining whether a patient has a problem. Instead, keep in mind that excessive gaming can displace exercise and normal socialization, he said, and lead to worsening mood.

Rober Aziz, MD, also of NYU Langone Health, suggested asking these questions: What types of games do you play? How long do you spend playing? What’s your reason for playing? What’s the meaning of your character choices? Does this game interfere with school or work? Have you neglected your self-care to play more?

He recommends other questions, too: Have you tried to limit your play time without success? How uncomfortable do you get if you must stop in the middle of playing? Do you get agitated if servers go down unexpectedly?

“There’s actually a lot of parallel here to other addictions that we’re very familiar with,” he said.

According to Dr. Sherer, it’s helpful to know that children who have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder tend to struggle with gaming addiction the most. He highlighted a brain-scan study in the Journal of Attention Disorders that found that patients with gaming addiction and ADHD had less functional connectivity from the cortex to the subcortex compared to matched controls. But treatment helped increase connectivity in those with good prognoses.

The findings are “heartening,” he said. “Basically, if you’re treating ADHD, you’re treating Internet gaming disorder. And if you’re treating Internet gaming disorder, you’re treating ADHD.”

As for treatments, the speakers agreed that there is little research to point in the right direction regarding gaming addiction specifically.

According to Dr. Aziz, research has suggested that bupropion, methylphenidate, and escitalopram can be helpful. In terms of nondrug approaches, he recommends directing patients toward games that have distinct beginnings, middles, and ends instead of endlessly providing rewards. One such game is “Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild” on the Nintendo Switch platform, he said.

On the psychotherapy front, Dr. Aziz said, “reducing use rather than abstinence should be the treatment goal.” Research suggests that cognitive behavioral therapy may not help patients in the long term, he said. Other strategies, he said, include specific approaches known as “CBT for Internet addiction” and “motivational interviewing for Internet gaming disorder.”

Gaming addiction treatment centers have also popped up in the U.S., he said, and there’s now an organization called Gaming Addicts Anonymous.

The good news is that “there is a lot of active research that’s being done” into treating video game addiction, said psychiatrist Anil Thomas, MD, program director of the addiction psychiatry fellowship at NYU Langone Health and moderator of the APA session. “We just have to wait to see what the results are.”

AT APA 2022

Innovative med school curriculum could help curb the opioid epidemic

, new research suggests.

“Our study showed that implementing training for medical students about opioid use disorder and its treatment improves knowledge and understanding of clinical principles and may better prepare students to treat patients with this disorder,” study investigator Kimberly Hu, MD, psychiatry resident, Ohio State University, Columbus, told this news organization.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

The U.S. opioid epidemic claims thousands of lives every year, and there’s evidence it’s getting worse, said Dr. Hu. U.S. data from December 2020 to December 2021 show opioid-related deaths increased by almost 15%.

In 2019, about 70% of the nearly 71,000 drug overdose deaths in the United States involved opioids and now it exceeds 100,000 per year, said Dr. Hu. She noted 80% of heroin users report their addiction started with prescription opioids, data that she described as “pretty staggering.”

Although treatments such as buprenorphine are available for OUD, “insufficient access to medications for opioid use disorder remains a significant barrier for patients,” said Dr. Hu.

“Training the next generation of physicians across all specialties is one way that we can work to improve access to care and improve the health and well-being of our patients.”

The study, which is ongoing, included 405 3rd-year medical students at Ohio State. Researchers provided these students with in-person or virtual (during the pandemic) training in buprenorphine prescribing and in-person clinical experience.

Dr. Hu and her colleagues tested the students before and after the intervention and estimated improvement in knowledge (score 0-23) and approach to clinical management principles (1-5).

The investigators found a statistically significant increase in overall knowledge (from a mean total score of 18.34 to 19.32; P < .001). There was also a statistically significant increase in self-reported understanding of clinical management principles related to screening for and treating OUDs (from a mean of 3.12 to a mean of 4.02; P < .001).

An additional evaluation survey was completed by 162 students at the end of the program. About 83% of these students said they knew how to manage acute pain, 62% felt they knew how to manage chronic pain, and 77% agreed they knew how to screen a patient for OUD.

Dr. Hu noted 3rd-year medical students are a little over halfway through medical school, after which they will go into residency in various specialties. Providing them with this knowledge early on allows them to incorporate it as they continue their training, she said.

“If they are able to screen their patients in any specialty they eventually choose to go into, then they can help link these patients to resources early and make sure there aren’t patients who are slipping through the cracks.”

Worthwhile, important research

Howard Liu, MD, chair of the department of psychiatry at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, and incoming chair of the APA’s Council on Communications, applauded the study.

The proposed curriculum, he said, instills confidence in students and teaches important lessons they can apply no matter what field they choose.

Dr. Liu, who moderated a press briefing highlighting the study, noted every state is affected differently by the opioid epidemic, but the shortage of appropriate treatments for OUD is nationwide.

Commenting on the study, addiction specialist Elie G. Aoun, MD, of the division of law, medicine, and psychiatry at Columbia University, New York, said this research is “very worthwhile and important.”

He noted that attitudes about addiction need to change. When he taught medical students about substance use disorders, he was struck by some of their negative beliefs about addiction. For example, considering addicts as “junkies” who are “taking resources away” from what they perceive as more deserving patients.

Addiction has been ignored in medicine for too long, added Dr. Aoun. He noted the requirement for addiction training for psychiatry residents is 2 months while they spend 4 months learning internal medicine. “That makes no sense,” he said.

“And now with the opioid epidemic, we’re faced with the consequences of dismissing addiction for such a long time.”

A lack of understanding about addiction, and the “very limited number” of experienced people treating addictions, has contributed to the “huge problem” experts now face in treating addictions, said Dr. Aoun.

“So you want to approach this problem from as many different angles as you can.”

He praised the study for presenting “a framework to ‘medicalize’ the addiction model” for students. This, he said, will help them build empathy and see those with a substance use disorder as no different from other patients with medical conditions.

A curriculum such as the one presented by Dr. Hu and colleagues may spur more medical students into the addiction field, he said. “It may make them more willing to treat patients with addiction using evidence-based medicine rather than dismissing them.”

The study was supported by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.