User login

National poll shows ‘concerning’ impact of COVID on Americans’ mental health

Concern and anxiety around COVID-19 remains high among Americans, with more people reporting mental health effects from the pandemic this year than last, and parents concerned about the mental health of their children, results of a new poll by the American Psychiatric Association show. Although the overall level of anxiety has decreased from last year’s APA poll, “the degree to which anxiety still reigns is concerning,” APA President Jeffrey Geller, MD, MPH, told this news organization.

The results of the latest poll were presented at the American Psychiatric Association 2021 annual meeting and based on an online survey conducted March 26 to April 5 among a sample of 1,000 adults aged 18 years or older.

Serious mental health hit

In the new poll, about 4 in 10 Americans (41%) report they are more anxious than last year, down from just over 60%.

Young adults aged 18-29 years (49%) and Hispanic/Latinos (50%) are more likely to report being more anxious now than a year ago. Those 65 or older (30%) are less apt to say they feel more anxious than last year.

The latest poll also shows that Americans are more anxious about family and loved ones getting COVID-19 (64%) than about catching the virus themselves (49%).

Concern about family and loved ones contracting COVID-19 has increased since last year’s poll (conducted September 2020), rising from 56% then to 64% now. Hispanic/Latinx individuals (73%) and African American/Black individuals (76%) are more anxious about COVID-19 than White people (59%).

In the new poll, 43% of adults report the pandemic has had a serious impact on their mental health, up from 37% in 2020. Younger adults are more apt than older adults to report serious mental health effects.

Slightly fewer Americans report the pandemic is affecting their day-to-day life now as compared to a year ago, in ways such as problems sleeping (19% down from 22%), difficulty concentrating (18% down from 20%), and fighting more with loved ones (16% down from 17%).

The percentage of adults consuming more alcohol or other substances/drugs than normal increased slightly since last year (14%-17%). Additionally, 33% of adults (40% of women) report gaining weight during the pandemic.

Call to action

More than half of adults (53%) with children report they are concerned about the mental state of their children and almost half (48%) report the pandemic has caused mental health problems for one or more of their children, including minor problems for 29% and major problems for 19%.

More than a quarter (26%) of parents have sought professional mental health help for their children because of the pandemic.

; 23% received help from a primary care professional, 18% from a psychiatrist, 15% from a psychologist, 13% from a therapist, 10% from a social worker, and 10% from a school counselor or school psychologist.

More than 1 in 5 parents reported difficulty scheduling appointments for their child with a mental health professional.

“This poll shows that, even as vaccines become more widespread, Americans are still worried about the mental state of their children,” Dr. Geller said in a news release.

“This is a call to action for policymakers, who need to remember that, in our COVID-19 recovery, there’s no health without mental health,” he added.

Just over three-quarters (76%) of those surveyed say they have been or intend to get vaccinated; 22% say they don’t intend to get vaccinated; and 2% didn’t know.

For those who do not intend to get vaccinated, the primary concern (53%) is about side effects of the vaccine. Other reasons for not getting vaccinated include believing the vaccine is not effective (31%), believing the makers of the vaccine aren’t being honest about what’s in it (27%), and fear/anxiety about needles (12%).

Resiliency a finite resource

Reached for comment, Samoon Ahmad, MD, professor in the department of psychiatry, New York University, said it’s not surprising that Americans are still suffering more anxiety than normal.

“The Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey has shown that anxiety and depression levels have remained higher than normal since the pandemic began. That 43% of adults now say that the pandemic has had a serious impact on their mental health seems in line with what that survey has been reporting for over a year,” Dr. Ahmad, who serves as unit chief of inpatient psychiatry at Bellevue Hospital Center in New York, said in an interview.

He believes there are several reasons why anxiety levels remain high. One reason is something he’s noticed among his patients for years. “Most people struggle with anxiety especially at night when the noise and distractions of contemporary life fade away. This is the time of introspection,” he explained.

“Quarantine has been kind of like a protracted night because the distractions that are common in the so-called ‘rat race’ have been relatively muted for the past 14 months. I believe this has caused what you might call ‘forced introspection,’ and that this is giving rise to feelings of anxiety as people use their time alone to reassess their careers and their social lives and really begin to fret about some of the decisions that have led them to this point in their lives,” said Dr. Ahmad.

The other finding in the APA survey – that people are more concerned about their loved ones catching the virus than they were a year ago – is also not surprising, Dr. Ahmad said.

“Even though we seem to have turned a corner in the United States and the worst of the pandemic is behind us, the surge that went from roughly November through March of this year was more wide-reaching geographically than previous waves, and I think this made the severity of the virus far more real to people who lived in communities that had been spared severe outbreaks during the surges that we saw in the spring and summer of 2020,” Dr. Ahmad told this news organization.

“There’s also heightened concern over variants and the efficacy of the vaccine in treating these variants. Those who have families in other countries where the virus is surging, such as India or parts of Latin America, are likely experiencing additional stress and anxiety too,” he noted.

While the new APA poll findings are not surprising, they still are “deeply concerning,” Dr. Ahmad said.

“Resiliency is a finite resource, and people can only take so much stress before their mental health begins to suffer. For most people, this is not going to lead to some kind of overdramatic nervous breakdown. Instead, one may notice that they are more irritable than they once were, that they’re not sleeping particularly well, or that they have a nagging sense of discomfort and stress when doing activities that they used to think of as normal,” like taking a trip to the grocery store, meeting up with friends, or going to work, Dr. Ahmad said.

“Overcoming this kind of anxiety and reacclimating ourselves to social situations is going to take more time for some people than others, and that is perfectly natural,” said Dr. Ahmad, founder of the Integrative Center for Wellness in New York.

“I don’t think it’s wise to try to put a limit on what constitutes a normal amount of time to readjust, and I think everyone in the field of mental health needs to avoid pathologizing any lingering sense of unease. No one needs to be medicated or diagnosed with a mental illness because they are nervous about going into public spaces in the immediate aftermath of a pandemic. We need to show a lot of patience and encourage people to readjust at their own pace for the foreseeable future,” Dr. Ahmad said.

Dr. Geller and Dr. Ahmad have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Concern and anxiety around COVID-19 remains high among Americans, with more people reporting mental health effects from the pandemic this year than last, and parents concerned about the mental health of their children, results of a new poll by the American Psychiatric Association show. Although the overall level of anxiety has decreased from last year’s APA poll, “the degree to which anxiety still reigns is concerning,” APA President Jeffrey Geller, MD, MPH, told this news organization.

The results of the latest poll were presented at the American Psychiatric Association 2021 annual meeting and based on an online survey conducted March 26 to April 5 among a sample of 1,000 adults aged 18 years or older.

Serious mental health hit

In the new poll, about 4 in 10 Americans (41%) report they are more anxious than last year, down from just over 60%.

Young adults aged 18-29 years (49%) and Hispanic/Latinos (50%) are more likely to report being more anxious now than a year ago. Those 65 or older (30%) are less apt to say they feel more anxious than last year.

The latest poll also shows that Americans are more anxious about family and loved ones getting COVID-19 (64%) than about catching the virus themselves (49%).

Concern about family and loved ones contracting COVID-19 has increased since last year’s poll (conducted September 2020), rising from 56% then to 64% now. Hispanic/Latinx individuals (73%) and African American/Black individuals (76%) are more anxious about COVID-19 than White people (59%).

In the new poll, 43% of adults report the pandemic has had a serious impact on their mental health, up from 37% in 2020. Younger adults are more apt than older adults to report serious mental health effects.

Slightly fewer Americans report the pandemic is affecting their day-to-day life now as compared to a year ago, in ways such as problems sleeping (19% down from 22%), difficulty concentrating (18% down from 20%), and fighting more with loved ones (16% down from 17%).

The percentage of adults consuming more alcohol or other substances/drugs than normal increased slightly since last year (14%-17%). Additionally, 33% of adults (40% of women) report gaining weight during the pandemic.

Call to action

More than half of adults (53%) with children report they are concerned about the mental state of their children and almost half (48%) report the pandemic has caused mental health problems for one or more of their children, including minor problems for 29% and major problems for 19%.

More than a quarter (26%) of parents have sought professional mental health help for their children because of the pandemic.

; 23% received help from a primary care professional, 18% from a psychiatrist, 15% from a psychologist, 13% from a therapist, 10% from a social worker, and 10% from a school counselor or school psychologist.

More than 1 in 5 parents reported difficulty scheduling appointments for their child with a mental health professional.

“This poll shows that, even as vaccines become more widespread, Americans are still worried about the mental state of their children,” Dr. Geller said in a news release.

“This is a call to action for policymakers, who need to remember that, in our COVID-19 recovery, there’s no health without mental health,” he added.

Just over three-quarters (76%) of those surveyed say they have been or intend to get vaccinated; 22% say they don’t intend to get vaccinated; and 2% didn’t know.

For those who do not intend to get vaccinated, the primary concern (53%) is about side effects of the vaccine. Other reasons for not getting vaccinated include believing the vaccine is not effective (31%), believing the makers of the vaccine aren’t being honest about what’s in it (27%), and fear/anxiety about needles (12%).

Resiliency a finite resource

Reached for comment, Samoon Ahmad, MD, professor in the department of psychiatry, New York University, said it’s not surprising that Americans are still suffering more anxiety than normal.

“The Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey has shown that anxiety and depression levels have remained higher than normal since the pandemic began. That 43% of adults now say that the pandemic has had a serious impact on their mental health seems in line with what that survey has been reporting for over a year,” Dr. Ahmad, who serves as unit chief of inpatient psychiatry at Bellevue Hospital Center in New York, said in an interview.

He believes there are several reasons why anxiety levels remain high. One reason is something he’s noticed among his patients for years. “Most people struggle with anxiety especially at night when the noise and distractions of contemporary life fade away. This is the time of introspection,” he explained.

“Quarantine has been kind of like a protracted night because the distractions that are common in the so-called ‘rat race’ have been relatively muted for the past 14 months. I believe this has caused what you might call ‘forced introspection,’ and that this is giving rise to feelings of anxiety as people use their time alone to reassess their careers and their social lives and really begin to fret about some of the decisions that have led them to this point in their lives,” said Dr. Ahmad.

The other finding in the APA survey – that people are more concerned about their loved ones catching the virus than they were a year ago – is also not surprising, Dr. Ahmad said.

“Even though we seem to have turned a corner in the United States and the worst of the pandemic is behind us, the surge that went from roughly November through March of this year was more wide-reaching geographically than previous waves, and I think this made the severity of the virus far more real to people who lived in communities that had been spared severe outbreaks during the surges that we saw in the spring and summer of 2020,” Dr. Ahmad told this news organization.

“There’s also heightened concern over variants and the efficacy of the vaccine in treating these variants. Those who have families in other countries where the virus is surging, such as India or parts of Latin America, are likely experiencing additional stress and anxiety too,” he noted.

While the new APA poll findings are not surprising, they still are “deeply concerning,” Dr. Ahmad said.

“Resiliency is a finite resource, and people can only take so much stress before their mental health begins to suffer. For most people, this is not going to lead to some kind of overdramatic nervous breakdown. Instead, one may notice that they are more irritable than they once were, that they’re not sleeping particularly well, or that they have a nagging sense of discomfort and stress when doing activities that they used to think of as normal,” like taking a trip to the grocery store, meeting up with friends, or going to work, Dr. Ahmad said.

“Overcoming this kind of anxiety and reacclimating ourselves to social situations is going to take more time for some people than others, and that is perfectly natural,” said Dr. Ahmad, founder of the Integrative Center for Wellness in New York.

“I don’t think it’s wise to try to put a limit on what constitutes a normal amount of time to readjust, and I think everyone in the field of mental health needs to avoid pathologizing any lingering sense of unease. No one needs to be medicated or diagnosed with a mental illness because they are nervous about going into public spaces in the immediate aftermath of a pandemic. We need to show a lot of patience and encourage people to readjust at their own pace for the foreseeable future,” Dr. Ahmad said.

Dr. Geller and Dr. Ahmad have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Concern and anxiety around COVID-19 remains high among Americans, with more people reporting mental health effects from the pandemic this year than last, and parents concerned about the mental health of their children, results of a new poll by the American Psychiatric Association show. Although the overall level of anxiety has decreased from last year’s APA poll, “the degree to which anxiety still reigns is concerning,” APA President Jeffrey Geller, MD, MPH, told this news organization.

The results of the latest poll were presented at the American Psychiatric Association 2021 annual meeting and based on an online survey conducted March 26 to April 5 among a sample of 1,000 adults aged 18 years or older.

Serious mental health hit

In the new poll, about 4 in 10 Americans (41%) report they are more anxious than last year, down from just over 60%.

Young adults aged 18-29 years (49%) and Hispanic/Latinos (50%) are more likely to report being more anxious now than a year ago. Those 65 or older (30%) are less apt to say they feel more anxious than last year.

The latest poll also shows that Americans are more anxious about family and loved ones getting COVID-19 (64%) than about catching the virus themselves (49%).

Concern about family and loved ones contracting COVID-19 has increased since last year’s poll (conducted September 2020), rising from 56% then to 64% now. Hispanic/Latinx individuals (73%) and African American/Black individuals (76%) are more anxious about COVID-19 than White people (59%).

In the new poll, 43% of adults report the pandemic has had a serious impact on their mental health, up from 37% in 2020. Younger adults are more apt than older adults to report serious mental health effects.

Slightly fewer Americans report the pandemic is affecting their day-to-day life now as compared to a year ago, in ways such as problems sleeping (19% down from 22%), difficulty concentrating (18% down from 20%), and fighting more with loved ones (16% down from 17%).

The percentage of adults consuming more alcohol or other substances/drugs than normal increased slightly since last year (14%-17%). Additionally, 33% of adults (40% of women) report gaining weight during the pandemic.

Call to action

More than half of adults (53%) with children report they are concerned about the mental state of their children and almost half (48%) report the pandemic has caused mental health problems for one or more of their children, including minor problems for 29% and major problems for 19%.

More than a quarter (26%) of parents have sought professional mental health help for their children because of the pandemic.

; 23% received help from a primary care professional, 18% from a psychiatrist, 15% from a psychologist, 13% from a therapist, 10% from a social worker, and 10% from a school counselor or school psychologist.

More than 1 in 5 parents reported difficulty scheduling appointments for their child with a mental health professional.

“This poll shows that, even as vaccines become more widespread, Americans are still worried about the mental state of their children,” Dr. Geller said in a news release.

“This is a call to action for policymakers, who need to remember that, in our COVID-19 recovery, there’s no health without mental health,” he added.

Just over three-quarters (76%) of those surveyed say they have been or intend to get vaccinated; 22% say they don’t intend to get vaccinated; and 2% didn’t know.

For those who do not intend to get vaccinated, the primary concern (53%) is about side effects of the vaccine. Other reasons for not getting vaccinated include believing the vaccine is not effective (31%), believing the makers of the vaccine aren’t being honest about what’s in it (27%), and fear/anxiety about needles (12%).

Resiliency a finite resource

Reached for comment, Samoon Ahmad, MD, professor in the department of psychiatry, New York University, said it’s not surprising that Americans are still suffering more anxiety than normal.

“The Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey has shown that anxiety and depression levels have remained higher than normal since the pandemic began. That 43% of adults now say that the pandemic has had a serious impact on their mental health seems in line with what that survey has been reporting for over a year,” Dr. Ahmad, who serves as unit chief of inpatient psychiatry at Bellevue Hospital Center in New York, said in an interview.

He believes there are several reasons why anxiety levels remain high. One reason is something he’s noticed among his patients for years. “Most people struggle with anxiety especially at night when the noise and distractions of contemporary life fade away. This is the time of introspection,” he explained.

“Quarantine has been kind of like a protracted night because the distractions that are common in the so-called ‘rat race’ have been relatively muted for the past 14 months. I believe this has caused what you might call ‘forced introspection,’ and that this is giving rise to feelings of anxiety as people use their time alone to reassess their careers and their social lives and really begin to fret about some of the decisions that have led them to this point in their lives,” said Dr. Ahmad.

The other finding in the APA survey – that people are more concerned about their loved ones catching the virus than they were a year ago – is also not surprising, Dr. Ahmad said.

“Even though we seem to have turned a corner in the United States and the worst of the pandemic is behind us, the surge that went from roughly November through March of this year was more wide-reaching geographically than previous waves, and I think this made the severity of the virus far more real to people who lived in communities that had been spared severe outbreaks during the surges that we saw in the spring and summer of 2020,” Dr. Ahmad told this news organization.

“There’s also heightened concern over variants and the efficacy of the vaccine in treating these variants. Those who have families in other countries where the virus is surging, such as India or parts of Latin America, are likely experiencing additional stress and anxiety too,” he noted.

While the new APA poll findings are not surprising, they still are “deeply concerning,” Dr. Ahmad said.

“Resiliency is a finite resource, and people can only take so much stress before their mental health begins to suffer. For most people, this is not going to lead to some kind of overdramatic nervous breakdown. Instead, one may notice that they are more irritable than they once were, that they’re not sleeping particularly well, or that they have a nagging sense of discomfort and stress when doing activities that they used to think of as normal,” like taking a trip to the grocery store, meeting up with friends, or going to work, Dr. Ahmad said.

“Overcoming this kind of anxiety and reacclimating ourselves to social situations is going to take more time for some people than others, and that is perfectly natural,” said Dr. Ahmad, founder of the Integrative Center for Wellness in New York.

“I don’t think it’s wise to try to put a limit on what constitutes a normal amount of time to readjust, and I think everyone in the field of mental health needs to avoid pathologizing any lingering sense of unease. No one needs to be medicated or diagnosed with a mental illness because they are nervous about going into public spaces in the immediate aftermath of a pandemic. We need to show a lot of patience and encourage people to readjust at their own pace for the foreseeable future,” Dr. Ahmad said.

Dr. Geller and Dr. Ahmad have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA OKs higher-dose naloxone nasal spray for opioid overdose

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a higher-dose naloxone hydrochloride nasal spray (Kloxxado) for the emergency treatment of known or suspected opioid overdose, as manifested by respiratory and/or central nervous system depression.

Kloxxado delivers 8 mg of naloxone into the nasal cavity, which is twice as much as the 4 mg of naloxone contained in Narcan nasal spray.

When administered quickly, naloxone can counter opioid overdose effects, usually within minutes. A higher dose of naloxone provides an additional option for the treatment of opioid overdoses, the FDA said in a news release.

“This approval meets another critical need in combating opioid overdose,” Patrizia Cavazzoni, MD, director, FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the release.

“Addressing the opioid crisis is a top priority for the FDA, and we will continue our efforts to increase access to naloxone and place this important medicine in the hands of those who need it most,” said Dr. Cavazzoni.

In a company news release announcing the approval, manufacturer Hikma Pharmaceuticals noted that a recent survey of community organizations in which the 4-mg naloxone nasal spray had been distributed showed that for 34% of attempted reversals, two or more doses of naloxone were used.

A separate study found that the percentage of overdose-related emergency medical service calls in the United States that led to the administration of multiple doses of naloxone increased to 21% during the period of 2013-2016, which represents a 43% increase over 4 years.

“The approval of Kloxxado is an important step in providing patients, friends, and family members – as well as the public health community – with an important new option for treating opioid overdose,” Brian Hoffmann, president of Hikma Generics, said in the release.

The FDA approved Kloxxado through the 505(b)(2) regulatory pathway, which allows the agency to refer to previous findings of safety and efficacy for an already-approved product, as well as to review findings from further studies of the product.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a higher-dose naloxone hydrochloride nasal spray (Kloxxado) for the emergency treatment of known or suspected opioid overdose, as manifested by respiratory and/or central nervous system depression.

Kloxxado delivers 8 mg of naloxone into the nasal cavity, which is twice as much as the 4 mg of naloxone contained in Narcan nasal spray.

When administered quickly, naloxone can counter opioid overdose effects, usually within minutes. A higher dose of naloxone provides an additional option for the treatment of opioid overdoses, the FDA said in a news release.

“This approval meets another critical need in combating opioid overdose,” Patrizia Cavazzoni, MD, director, FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the release.

“Addressing the opioid crisis is a top priority for the FDA, and we will continue our efforts to increase access to naloxone and place this important medicine in the hands of those who need it most,” said Dr. Cavazzoni.

In a company news release announcing the approval, manufacturer Hikma Pharmaceuticals noted that a recent survey of community organizations in which the 4-mg naloxone nasal spray had been distributed showed that for 34% of attempted reversals, two or more doses of naloxone were used.

A separate study found that the percentage of overdose-related emergency medical service calls in the United States that led to the administration of multiple doses of naloxone increased to 21% during the period of 2013-2016, which represents a 43% increase over 4 years.

“The approval of Kloxxado is an important step in providing patients, friends, and family members – as well as the public health community – with an important new option for treating opioid overdose,” Brian Hoffmann, president of Hikma Generics, said in the release.

The FDA approved Kloxxado through the 505(b)(2) regulatory pathway, which allows the agency to refer to previous findings of safety and efficacy for an already-approved product, as well as to review findings from further studies of the product.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a higher-dose naloxone hydrochloride nasal spray (Kloxxado) for the emergency treatment of known or suspected opioid overdose, as manifested by respiratory and/or central nervous system depression.

Kloxxado delivers 8 mg of naloxone into the nasal cavity, which is twice as much as the 4 mg of naloxone contained in Narcan nasal spray.

When administered quickly, naloxone can counter opioid overdose effects, usually within minutes. A higher dose of naloxone provides an additional option for the treatment of opioid overdoses, the FDA said in a news release.

“This approval meets another critical need in combating opioid overdose,” Patrizia Cavazzoni, MD, director, FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the release.

“Addressing the opioid crisis is a top priority for the FDA, and we will continue our efforts to increase access to naloxone and place this important medicine in the hands of those who need it most,” said Dr. Cavazzoni.

In a company news release announcing the approval, manufacturer Hikma Pharmaceuticals noted that a recent survey of community organizations in which the 4-mg naloxone nasal spray had been distributed showed that for 34% of attempted reversals, two or more doses of naloxone were used.

A separate study found that the percentage of overdose-related emergency medical service calls in the United States that led to the administration of multiple doses of naloxone increased to 21% during the period of 2013-2016, which represents a 43% increase over 4 years.

“The approval of Kloxxado is an important step in providing patients, friends, and family members – as well as the public health community – with an important new option for treating opioid overdose,” Brian Hoffmann, president of Hikma Generics, said in the release.

The FDA approved Kloxxado through the 505(b)(2) regulatory pathway, which allows the agency to refer to previous findings of safety and efficacy for an already-approved product, as well as to review findings from further studies of the product.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The cloudy role of cannabis as a neuropsychiatric treatment

Although the healing properties of cannabis have been touted for millennia, research into its potential neuropsychiatric applications truly began to take off in the 1990s following the discovery of the cannabinoid system in the brain. This led to speculation that cannabis could play a therapeutic role in regulating dopamine, serotonin, and other neurotransmitters and offer a new means of treating various ailments.

At the same time, efforts to liberalize marijuana laws have successfully played out in several nations, including the United States, where, as of April 29, 36 states provide some access to cannabis. These dual tracks – medical and political – have made cannabis an increasingly accepted part of the cultural fabric.

Yet with this development has come a new quandary for clinicians. Medical cannabis has been made widely available to patients and has largely outpaced the clinical evidence, leaving it unclear how and for which indications it should be used.

The many forms of medical cannabis

Cannabis is a genus of plants that includes marijuana (Cannabis sativa) and hemp. These plants contain over 100 compounds, including terpenes, flavonoids, and – most importantly for medicinal applications – cannabinoids.

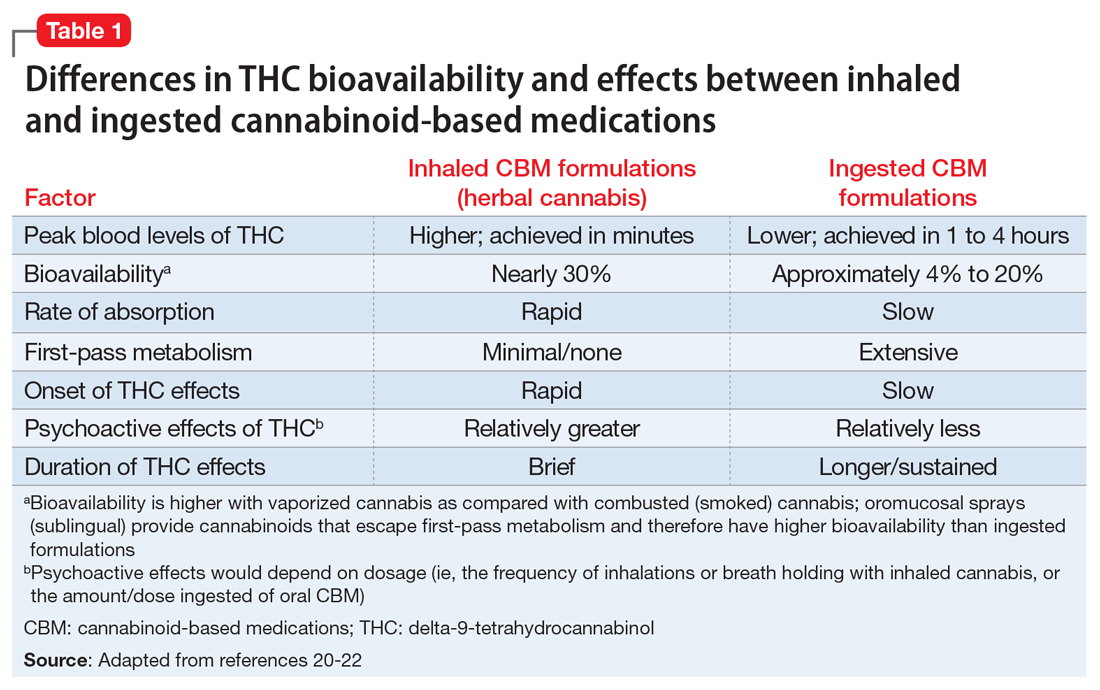

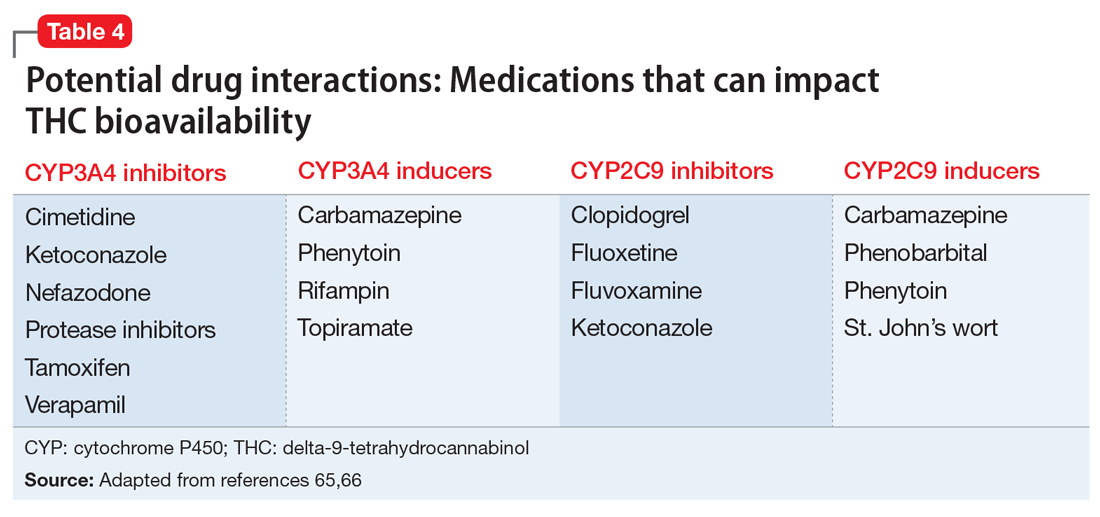

The most abundant cannabinoid in marijuana is the psychotropic delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which imparts the “high” sensation. The next most abundant cannabinoid is cannabidiol (CBD), which is the nonpsychotropic. THC and CBD are the most extensively studied cannabinoids, together and in isolation. Evidence suggests that other cannabinoids and terpenoids may also hold medical promise and that cannabis’ various compounds can work synergistically to produce a so-called entourage effect.

Patients walking into a typical medical cannabis dispensary will be faced with several plant-derived and synthetic options, which can differ considerably in terms of the ratios and amounts of THC and CBD they contain, as well in how they are consumed (i.e., via smoke, vapor, ingestion, topical administration, or oromucosal spray), all of which can alter their effects. Further complicating matters is the varying level of oversight each state and country has in how and whether they test for and accurately label products’ potency, cannabinoid content, and possible impurities.

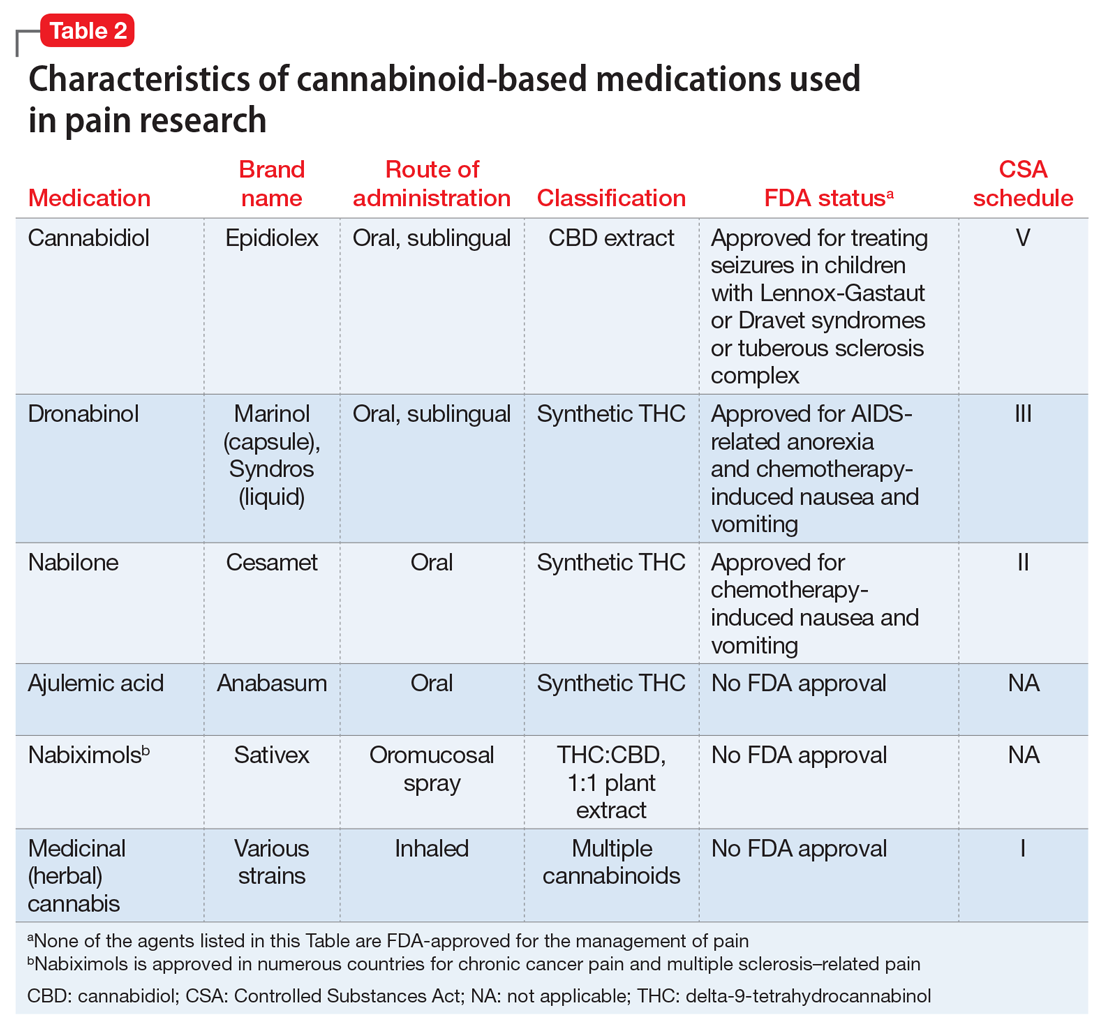

Medically authorized, prescription cannabis products go through an official regulatory review process, and indications/contraindications have been established for them. To date, the Food and Drug Administration has approved one cannabis-derived drug product – Epidiolex (purified CBD) – for the treatment of seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome or Dravet syndrome in patients aged 2 years and older. The FDA has also approved three synthetic cannabis-related drug products – Marinol, Syndros (or dronabinol, created from synthetic THC), and Cesamet (or nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid similar to THC) – all of which are indicated for treatment-related nausea and anorexia associated with weight loss in AIDS patients.

Surveys of medical cannabis consumers indicate that most people cannot distinguish between THC and CBD, so the first role that physicians find themselves in when recommending this treatment may be in helping patients navigate the volume of options.

Promising treatment for pain

Chronic pain is the leading reason patients seek out medical cannabis. It is also the indication that most researchers agree has the strongest evidence to support its use.

“In my mind, the most promising immediate use for medical cannabis is with THC for pain,” Diana M. Martinez, MD, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, New York, who specializes in addiction research, said in a recent MDedge podcast. “THC could be added to the armamentarium of pain medications that we use today.”

In a 2015 systematic literature review, researchers assessed 28 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) of the use of cannabinoids for chronic pain. They reported that a variety of formulations resulted in at least a 30% reduction in the odds of pain, compared with placebo. A meta-analysis of five RCTs involving patients with neuropathic pain found a 30% reduction in pain over placebo with inhaled, vaporized cannabis. Varying results have been reported in additional studies for this indication. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine concluded that there was a substantial body of evidence that cannabis is an effective treatment for chronic pain in adults.

The ongoing opioid epidemic has lent these results additional relevance.

Seeing this firsthand has caused Mark Steven Wallace, MD, a pain management specialist and chair of the division of pain medicine at the University of California San Diego Health, to reconsider offering cannabis to his patients.

“I think it’s probably more efficacious, just from my personal experience, and it’s a much lower risk of abuse and dependence than the opioids,” he said.

Dr. Wallace advised that clinicians who treat pain consider the ratios of cannabinoids.

“This is anecdotal, but we do find that with the combination of the two, CBD reduces the psychoactive effects of the THC. The ratios we use during the daytime range around 20 mg of CBD to 1 mg of THC,” he said.

In a recent secondary analysis of an RCT involving patients with painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy, Dr. Wallace and colleagues showed that THC’s effects appear to reverse themselves at a certain level.

“As the THC level goes up, the pain reduces until you reach about 16 ng/mL; then it starts going in the opposite direction, and pain will start to increase,” he said. “Even recreational cannabis users have reported that they avoid high doses because it’s very aversive. Using cannabis is all about, start low and go slow.”

A mixed bag for neurologic indications

There are relatively limited data on the use of medical cannabis for other neurologic conditions, and results have varied. For uses other than pain management, the evidence that does exist is strongest regarding epilepsy, said Daniel Freedman, DO, assistant professor of neurology at the University of Texas at Austin. He noted “multiple high-quality RCTs showing that pharmaceutical-grade CBD can reduce seizures associated with two particular epilepsy syndromes: Dravet Syndrome and Lennox Gastaut.”

These findings led to the FDA’s 2018 approval of Epidiolex for these syndromes. In earlier years, interest in CBD for pediatric seizures was largely driven by anecdotal parental reports of its benefits. NASEM’s 2017 overview on medical cannabis found evidence from subsequent RCTs in this indication to be insufficient. Clinicians who prescribe CBD for this indication must be vigilant because it can interact with several commonly used antiepileptic drugs.

Cannabinoid treatments have also shown success in alleviating muscle spasticity resulting from multiple sclerosis, most prominently in the form of nabiximols (Sativex), a standardized oralmucosal spray containing approximately equal quantities of THC and CBD. Nabiximols is approved in Europe but not in the United States. Moderate evidence supports the efficacy of these and other treatments over placebo in reducing muscle spasticity. Patient ratings of its effects tend to be higher than clinician assessment.

Parkinson’s disease has not yet been approved as an indication for treatment with cannabis or cannabinoids, yet a growing body of preclinical data suggests these could influence the dopaminergic system, said Carsten Buhmann, MD, from the department of neurology at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (Germany).

“In general, cannabinoids modulate basal-ganglia function on two levels which are especially relevant in Parkinson’s disease, i.e., the glutamatergic/dopaminergic synaptic neurotransmission and the corticostriatal plasticity,” he said. “Furthermore, activation of the endocannabinoid system might induce neuroprotective effects related to direct receptor-independent mechanisms, activation of anti-inflammatory cascades in glial cells via the cannabinoid receptor type 2, and antiglutamatergic antiexcitotoxic properties.”

Dr. Buhmann said that currently, clinical evidence is scarce, consisting of only four double-blind, placebo-controlled RCTs involving 49 patients. Various cannabinoids and methods of administering treatment were employed. Improvement was only observed in one of these RCTs, which found that the cannabinoid receptor agonist nabilone significantly reduced levodopa-induced dyskinesia for patients with Parkinson’s disease. Subjective data support a beneficial effect. In a nationwide survey of 1,348 respondents conducted by Dr. Buhmann and colleagues, the majority of medical cannabis users reported that it improved their symptoms (54% with oral CBD and 68% with inhaled THC-containing cannabis).

NASEM concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support the efficacy of medical cannabis for other neurologic conditions, including Tourette syndrome, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Huntington disease, dystonia, or dementia. A 2020 position statement from the American Academy of Neurology cited the lack of sufficient peer-reviewed research as the reason it could not currently support the use of cannabis for neurologic disorders.

Yet, according to Dr. Freedman, who served as a coauthor of the AAN position statement, this hasn’t stymied research interest in the topic. He’s seen a substantial uptick in studies of CBD over the past 2 years. “The body of evidence grows, but I still see many claims being made without evidence. And no one seems to care about all the negative trials.”

Cannabis as a treatment for, and cause of, psychiatric disorders

Mental health problems – such as anxiety, depression, and PTSD – are among the most common reasons patients seek out medical cannabis. There is an understandable interest in using cannabis and cannabinoids to treat psychiatric disorders. Preclinical studies suggest that the endocannabinoid system plays a prominent role in modulating feelings of anxiety, mood, and fear. As with opioids and chronic pain management, there is hope that medical cannabis may provide a means of reducing prescription anxiolytics and their associated risks.

The authors of the first systematic review (BMC Psychiatry. 2020 Jan 16;20[1]:24) of the use of medical cannabis for major psychiatric disorders noted that the current evidence was “encouraging, albeit embryonic.”

Meta-analyses have indicated a small but positive association between cannabis use and anxiety, although this may reflect the fact that patients with anxiety sought out this treatment. Given the risks for substance use disorders among patients with anxiety, CBD may present a more viable option. Positive results have been shown as treatment for generalized social anxiety disorder.

Limited but encouraging results have also been reported regarding the alleviation of PTSD symptoms with both cannabis and CBD, although the body of high-quality evidence hasn’t notably progressed since 2017, when NASEM declared that the evidence was insufficient. Supportive evidence is similarly lacking regarding the treatment of depression. Longitudinal studies suggest that cannabis use, particularly heavy use, may increase the risk of developing this disorder. Because THC is psychoactive, it is advised that it be avoided by patients at risk for psychotic disorders. However, CBD has yielded limited benefits for patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia and for young people at risk for psychosis.

The use of medical cannabis for psychiatric conditions requires a complex balancing act, inasmuch as these treatments may exacerbate the very problems they are intended to alleviate.

Marta Di Forti, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatric research at Kings College London, has been at the forefront of determining the mental health risks of continued cannabis use. In 2019, Dr. Di Forti developed the first and only Cannabis Clinic for Patients With Psychosis in London where she and her colleagues have continued to elucidate this connection.

Dr. Di Forti and colleagues have linked daily cannabis use to an increase in the risk of experiencing psychotic disorder, compared with never using it. That risk was further increased among users of high-potency cannabis (≥10% THC). The latter finding has troubling implications, because concentrations of THC have steadily risen since 1970. By contrast, CBD concentrations have remained generally stable. High-potency cannabis products are common in both recreational and medicinal settings.

“For somebody prescribing medicinal cannabis that has a ≥10% concentration of THC, I’d be particularly wary of the risk of psychosis,” said Dr. Di Forti. “If you’re expecting people to use a high content of THC daily to medicate pain or a chronic condition, you even more so need to be aware that this is a potential side effect.”

Dr. Di Forti noted that her findings come from a cohort of recreational users, most of whom were aged 18-35 years.

“There have actually not been studies developed from collecting data in this area from groups specifically using cannabis for medicinal rather than recreational purposes,” she said.

She added that she personally has no concerns about the use of medical cannabis but wants clinicians to be aware of the risk for psychosis, to structure their patient conversations to identify risk factors or family histories of psychosis, and to become knowledgeable in detecting the often subtle signs of its initial onset.

When cannabis-associated psychosis occurs, Dr. Di Forti said it is primarily treated with conventional means, such as antipsychotics and therapeutic interventions and by refraining from using cannabis. Achieving the latter goal can be a challenge for patients who are daily users of high-potency cannabis. Currently, there are no treatment options such as those offered to patients withdrawing from the use of alcohol or opioids. Dr. Di Forti and colleagues are currently researching a solution to that problem through the use of another medical cannabis, the oromucosal spray Sativex, which has been approved in the European Union.

The regulatory obstacles to clarifying cannabis’ role in medicine

That currently there is limited or no evidence to support the use of medical cannabis for the treatment of neuropsychiatric conditions points to the inherent difficulties in conducting high-level research in this area.

“There’s a tremendous shortage of reliable data, largely due to regulatory barriers,” said Dr. Martinez.

Since 1970, cannabis has been listed as a Schedule I drug that is illegal to prescribe (the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 removed hemp from such restrictions). The FDA has issued guidance for researchers who wish to investigate treatments using Cannabis sativa or its derivatives in which the THC content is greater than 0.3%. Such research requires regular interactions with several federal agencies, including the Drug Enforcement Administration.

“It’s impossible to do multicenter RCTs with large numbers of patients, because you can’t transport cannabis across state lines,” said Dr. Wallace.

Regulatory restrictions regarding medical cannabis vary considerably throughout the world (the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction provides a useful breakdown of this on their website). The lack of consistency in regulatory oversight acts as an impediment for conducting large-scale international multicenter studies on the topic.

Dr. Buhmann noted that, in Germany, cannabis has been broadly approved for treatment-resistant conditions with severe symptoms that impair quality of life. In addition, it is easy to be reimbursed for the use of cannabis as a medical treatment. These factors serve as disincentives for the funding of high-quality studies.

“It’s likely that no pharmaceutical company will do an expensive RCT to get an approval for Parkinson’s disease because it is already possible to prescribe medical cannabis of any type of THC-containing cannabinoid, dose, or route of application,” Dr. Buhmann said.

In the face of such restrictions and barriers, researchers are turning to ambitious real-world data projects to better understand medical cannabis’ efficacy and safety. A notable example is ProjectTwenty21, which is supported by the Royal College of Psychiatrists. The project is collecting outcomes of the use of medical cannabis among 20,000 U.K. patients whose conventional treatments of chronic pain, anxiety disorder, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, PTSD, substance use disorder, and Tourette syndrome failed.

Dr. Freedman noted that the continued lack of high-quality data creates a void that commercial interests fill with unfounded claims.

“The danger is that patients might abandon a medication or intervention backed by robust science in favor of something without any science or evidence behind it,” he said. “There is no reason not to expect the same level of data for claims about cannabis products as we would expect from pharmaceutical products.”

Getting to that point, however, will require that the authorities governing clinical trials begin to view cannabis as the research community does, as a possible treatment with potential value, rather than as an illicit drug that needs to be tamped down.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although the healing properties of cannabis have been touted for millennia, research into its potential neuropsychiatric applications truly began to take off in the 1990s following the discovery of the cannabinoid system in the brain. This led to speculation that cannabis could play a therapeutic role in regulating dopamine, serotonin, and other neurotransmitters and offer a new means of treating various ailments.

At the same time, efforts to liberalize marijuana laws have successfully played out in several nations, including the United States, where, as of April 29, 36 states provide some access to cannabis. These dual tracks – medical and political – have made cannabis an increasingly accepted part of the cultural fabric.

Yet with this development has come a new quandary for clinicians. Medical cannabis has been made widely available to patients and has largely outpaced the clinical evidence, leaving it unclear how and for which indications it should be used.

The many forms of medical cannabis

Cannabis is a genus of plants that includes marijuana (Cannabis sativa) and hemp. These plants contain over 100 compounds, including terpenes, flavonoids, and – most importantly for medicinal applications – cannabinoids.

The most abundant cannabinoid in marijuana is the psychotropic delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which imparts the “high” sensation. The next most abundant cannabinoid is cannabidiol (CBD), which is the nonpsychotropic. THC and CBD are the most extensively studied cannabinoids, together and in isolation. Evidence suggests that other cannabinoids and terpenoids may also hold medical promise and that cannabis’ various compounds can work synergistically to produce a so-called entourage effect.

Patients walking into a typical medical cannabis dispensary will be faced with several plant-derived and synthetic options, which can differ considerably in terms of the ratios and amounts of THC and CBD they contain, as well in how they are consumed (i.e., via smoke, vapor, ingestion, topical administration, or oromucosal spray), all of which can alter their effects. Further complicating matters is the varying level of oversight each state and country has in how and whether they test for and accurately label products’ potency, cannabinoid content, and possible impurities.

Medically authorized, prescription cannabis products go through an official regulatory review process, and indications/contraindications have been established for them. To date, the Food and Drug Administration has approved one cannabis-derived drug product – Epidiolex (purified CBD) – for the treatment of seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome or Dravet syndrome in patients aged 2 years and older. The FDA has also approved three synthetic cannabis-related drug products – Marinol, Syndros (or dronabinol, created from synthetic THC), and Cesamet (or nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid similar to THC) – all of which are indicated for treatment-related nausea and anorexia associated with weight loss in AIDS patients.

Surveys of medical cannabis consumers indicate that most people cannot distinguish between THC and CBD, so the first role that physicians find themselves in when recommending this treatment may be in helping patients navigate the volume of options.

Promising treatment for pain

Chronic pain is the leading reason patients seek out medical cannabis. It is also the indication that most researchers agree has the strongest evidence to support its use.

“In my mind, the most promising immediate use for medical cannabis is with THC for pain,” Diana M. Martinez, MD, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, New York, who specializes in addiction research, said in a recent MDedge podcast. “THC could be added to the armamentarium of pain medications that we use today.”

In a 2015 systematic literature review, researchers assessed 28 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) of the use of cannabinoids for chronic pain. They reported that a variety of formulations resulted in at least a 30% reduction in the odds of pain, compared with placebo. A meta-analysis of five RCTs involving patients with neuropathic pain found a 30% reduction in pain over placebo with inhaled, vaporized cannabis. Varying results have been reported in additional studies for this indication. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine concluded that there was a substantial body of evidence that cannabis is an effective treatment for chronic pain in adults.

The ongoing opioid epidemic has lent these results additional relevance.

Seeing this firsthand has caused Mark Steven Wallace, MD, a pain management specialist and chair of the division of pain medicine at the University of California San Diego Health, to reconsider offering cannabis to his patients.

“I think it’s probably more efficacious, just from my personal experience, and it’s a much lower risk of abuse and dependence than the opioids,” he said.

Dr. Wallace advised that clinicians who treat pain consider the ratios of cannabinoids.

“This is anecdotal, but we do find that with the combination of the two, CBD reduces the psychoactive effects of the THC. The ratios we use during the daytime range around 20 mg of CBD to 1 mg of THC,” he said.

In a recent secondary analysis of an RCT involving patients with painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy, Dr. Wallace and colleagues showed that THC’s effects appear to reverse themselves at a certain level.

“As the THC level goes up, the pain reduces until you reach about 16 ng/mL; then it starts going in the opposite direction, and pain will start to increase,” he said. “Even recreational cannabis users have reported that they avoid high doses because it’s very aversive. Using cannabis is all about, start low and go slow.”

A mixed bag for neurologic indications

There are relatively limited data on the use of medical cannabis for other neurologic conditions, and results have varied. For uses other than pain management, the evidence that does exist is strongest regarding epilepsy, said Daniel Freedman, DO, assistant professor of neurology at the University of Texas at Austin. He noted “multiple high-quality RCTs showing that pharmaceutical-grade CBD can reduce seizures associated with two particular epilepsy syndromes: Dravet Syndrome and Lennox Gastaut.”

These findings led to the FDA’s 2018 approval of Epidiolex for these syndromes. In earlier years, interest in CBD for pediatric seizures was largely driven by anecdotal parental reports of its benefits. NASEM’s 2017 overview on medical cannabis found evidence from subsequent RCTs in this indication to be insufficient. Clinicians who prescribe CBD for this indication must be vigilant because it can interact with several commonly used antiepileptic drugs.

Cannabinoid treatments have also shown success in alleviating muscle spasticity resulting from multiple sclerosis, most prominently in the form of nabiximols (Sativex), a standardized oralmucosal spray containing approximately equal quantities of THC and CBD. Nabiximols is approved in Europe but not in the United States. Moderate evidence supports the efficacy of these and other treatments over placebo in reducing muscle spasticity. Patient ratings of its effects tend to be higher than clinician assessment.

Parkinson’s disease has not yet been approved as an indication for treatment with cannabis or cannabinoids, yet a growing body of preclinical data suggests these could influence the dopaminergic system, said Carsten Buhmann, MD, from the department of neurology at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (Germany).

“In general, cannabinoids modulate basal-ganglia function on two levels which are especially relevant in Parkinson’s disease, i.e., the glutamatergic/dopaminergic synaptic neurotransmission and the corticostriatal plasticity,” he said. “Furthermore, activation of the endocannabinoid system might induce neuroprotective effects related to direct receptor-independent mechanisms, activation of anti-inflammatory cascades in glial cells via the cannabinoid receptor type 2, and antiglutamatergic antiexcitotoxic properties.”

Dr. Buhmann said that currently, clinical evidence is scarce, consisting of only four double-blind, placebo-controlled RCTs involving 49 patients. Various cannabinoids and methods of administering treatment were employed. Improvement was only observed in one of these RCTs, which found that the cannabinoid receptor agonist nabilone significantly reduced levodopa-induced dyskinesia for patients with Parkinson’s disease. Subjective data support a beneficial effect. In a nationwide survey of 1,348 respondents conducted by Dr. Buhmann and colleagues, the majority of medical cannabis users reported that it improved their symptoms (54% with oral CBD and 68% with inhaled THC-containing cannabis).

NASEM concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support the efficacy of medical cannabis for other neurologic conditions, including Tourette syndrome, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Huntington disease, dystonia, or dementia. A 2020 position statement from the American Academy of Neurology cited the lack of sufficient peer-reviewed research as the reason it could not currently support the use of cannabis for neurologic disorders.

Yet, according to Dr. Freedman, who served as a coauthor of the AAN position statement, this hasn’t stymied research interest in the topic. He’s seen a substantial uptick in studies of CBD over the past 2 years. “The body of evidence grows, but I still see many claims being made without evidence. And no one seems to care about all the negative trials.”

Cannabis as a treatment for, and cause of, psychiatric disorders

Mental health problems – such as anxiety, depression, and PTSD – are among the most common reasons patients seek out medical cannabis. There is an understandable interest in using cannabis and cannabinoids to treat psychiatric disorders. Preclinical studies suggest that the endocannabinoid system plays a prominent role in modulating feelings of anxiety, mood, and fear. As with opioids and chronic pain management, there is hope that medical cannabis may provide a means of reducing prescription anxiolytics and their associated risks.

The authors of the first systematic review (BMC Psychiatry. 2020 Jan 16;20[1]:24) of the use of medical cannabis for major psychiatric disorders noted that the current evidence was “encouraging, albeit embryonic.”

Meta-analyses have indicated a small but positive association between cannabis use and anxiety, although this may reflect the fact that patients with anxiety sought out this treatment. Given the risks for substance use disorders among patients with anxiety, CBD may present a more viable option. Positive results have been shown as treatment for generalized social anxiety disorder.

Limited but encouraging results have also been reported regarding the alleviation of PTSD symptoms with both cannabis and CBD, although the body of high-quality evidence hasn’t notably progressed since 2017, when NASEM declared that the evidence was insufficient. Supportive evidence is similarly lacking regarding the treatment of depression. Longitudinal studies suggest that cannabis use, particularly heavy use, may increase the risk of developing this disorder. Because THC is psychoactive, it is advised that it be avoided by patients at risk for psychotic disorders. However, CBD has yielded limited benefits for patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia and for young people at risk for psychosis.

The use of medical cannabis for psychiatric conditions requires a complex balancing act, inasmuch as these treatments may exacerbate the very problems they are intended to alleviate.

Marta Di Forti, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatric research at Kings College London, has been at the forefront of determining the mental health risks of continued cannabis use. In 2019, Dr. Di Forti developed the first and only Cannabis Clinic for Patients With Psychosis in London where she and her colleagues have continued to elucidate this connection.

Dr. Di Forti and colleagues have linked daily cannabis use to an increase in the risk of experiencing psychotic disorder, compared with never using it. That risk was further increased among users of high-potency cannabis (≥10% THC). The latter finding has troubling implications, because concentrations of THC have steadily risen since 1970. By contrast, CBD concentrations have remained generally stable. High-potency cannabis products are common in both recreational and medicinal settings.

“For somebody prescribing medicinal cannabis that has a ≥10% concentration of THC, I’d be particularly wary of the risk of psychosis,” said Dr. Di Forti. “If you’re expecting people to use a high content of THC daily to medicate pain or a chronic condition, you even more so need to be aware that this is a potential side effect.”

Dr. Di Forti noted that her findings come from a cohort of recreational users, most of whom were aged 18-35 years.

“There have actually not been studies developed from collecting data in this area from groups specifically using cannabis for medicinal rather than recreational purposes,” she said.

She added that she personally has no concerns about the use of medical cannabis but wants clinicians to be aware of the risk for psychosis, to structure their patient conversations to identify risk factors or family histories of psychosis, and to become knowledgeable in detecting the often subtle signs of its initial onset.

When cannabis-associated psychosis occurs, Dr. Di Forti said it is primarily treated with conventional means, such as antipsychotics and therapeutic interventions and by refraining from using cannabis. Achieving the latter goal can be a challenge for patients who are daily users of high-potency cannabis. Currently, there are no treatment options such as those offered to patients withdrawing from the use of alcohol or opioids. Dr. Di Forti and colleagues are currently researching a solution to that problem through the use of another medical cannabis, the oromucosal spray Sativex, which has been approved in the European Union.

The regulatory obstacles to clarifying cannabis’ role in medicine

That currently there is limited or no evidence to support the use of medical cannabis for the treatment of neuropsychiatric conditions points to the inherent difficulties in conducting high-level research in this area.

“There’s a tremendous shortage of reliable data, largely due to regulatory barriers,” said Dr. Martinez.

Since 1970, cannabis has been listed as a Schedule I drug that is illegal to prescribe (the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 removed hemp from such restrictions). The FDA has issued guidance for researchers who wish to investigate treatments using Cannabis sativa or its derivatives in which the THC content is greater than 0.3%. Such research requires regular interactions with several federal agencies, including the Drug Enforcement Administration.

“It’s impossible to do multicenter RCTs with large numbers of patients, because you can’t transport cannabis across state lines,” said Dr. Wallace.

Regulatory restrictions regarding medical cannabis vary considerably throughout the world (the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction provides a useful breakdown of this on their website). The lack of consistency in regulatory oversight acts as an impediment for conducting large-scale international multicenter studies on the topic.

Dr. Buhmann noted that, in Germany, cannabis has been broadly approved for treatment-resistant conditions with severe symptoms that impair quality of life. In addition, it is easy to be reimbursed for the use of cannabis as a medical treatment. These factors serve as disincentives for the funding of high-quality studies.

“It’s likely that no pharmaceutical company will do an expensive RCT to get an approval for Parkinson’s disease because it is already possible to prescribe medical cannabis of any type of THC-containing cannabinoid, dose, or route of application,” Dr. Buhmann said.

In the face of such restrictions and barriers, researchers are turning to ambitious real-world data projects to better understand medical cannabis’ efficacy and safety. A notable example is ProjectTwenty21, which is supported by the Royal College of Psychiatrists. The project is collecting outcomes of the use of medical cannabis among 20,000 U.K. patients whose conventional treatments of chronic pain, anxiety disorder, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, PTSD, substance use disorder, and Tourette syndrome failed.

Dr. Freedman noted that the continued lack of high-quality data creates a void that commercial interests fill with unfounded claims.

“The danger is that patients might abandon a medication or intervention backed by robust science in favor of something without any science or evidence behind it,” he said. “There is no reason not to expect the same level of data for claims about cannabis products as we would expect from pharmaceutical products.”

Getting to that point, however, will require that the authorities governing clinical trials begin to view cannabis as the research community does, as a possible treatment with potential value, rather than as an illicit drug that needs to be tamped down.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although the healing properties of cannabis have been touted for millennia, research into its potential neuropsychiatric applications truly began to take off in the 1990s following the discovery of the cannabinoid system in the brain. This led to speculation that cannabis could play a therapeutic role in regulating dopamine, serotonin, and other neurotransmitters and offer a new means of treating various ailments.

At the same time, efforts to liberalize marijuana laws have successfully played out in several nations, including the United States, where, as of April 29, 36 states provide some access to cannabis. These dual tracks – medical and political – have made cannabis an increasingly accepted part of the cultural fabric.

Yet with this development has come a new quandary for clinicians. Medical cannabis has been made widely available to patients and has largely outpaced the clinical evidence, leaving it unclear how and for which indications it should be used.

The many forms of medical cannabis

Cannabis is a genus of plants that includes marijuana (Cannabis sativa) and hemp. These plants contain over 100 compounds, including terpenes, flavonoids, and – most importantly for medicinal applications – cannabinoids.

The most abundant cannabinoid in marijuana is the psychotropic delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which imparts the “high” sensation. The next most abundant cannabinoid is cannabidiol (CBD), which is the nonpsychotropic. THC and CBD are the most extensively studied cannabinoids, together and in isolation. Evidence suggests that other cannabinoids and terpenoids may also hold medical promise and that cannabis’ various compounds can work synergistically to produce a so-called entourage effect.

Patients walking into a typical medical cannabis dispensary will be faced with several plant-derived and synthetic options, which can differ considerably in terms of the ratios and amounts of THC and CBD they contain, as well in how they are consumed (i.e., via smoke, vapor, ingestion, topical administration, or oromucosal spray), all of which can alter their effects. Further complicating matters is the varying level of oversight each state and country has in how and whether they test for and accurately label products’ potency, cannabinoid content, and possible impurities.

Medically authorized, prescription cannabis products go through an official regulatory review process, and indications/contraindications have been established for them. To date, the Food and Drug Administration has approved one cannabis-derived drug product – Epidiolex (purified CBD) – for the treatment of seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome or Dravet syndrome in patients aged 2 years and older. The FDA has also approved three synthetic cannabis-related drug products – Marinol, Syndros (or dronabinol, created from synthetic THC), and Cesamet (or nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid similar to THC) – all of which are indicated for treatment-related nausea and anorexia associated with weight loss in AIDS patients.

Surveys of medical cannabis consumers indicate that most people cannot distinguish between THC and CBD, so the first role that physicians find themselves in when recommending this treatment may be in helping patients navigate the volume of options.

Promising treatment for pain

Chronic pain is the leading reason patients seek out medical cannabis. It is also the indication that most researchers agree has the strongest evidence to support its use.

“In my mind, the most promising immediate use for medical cannabis is with THC for pain,” Diana M. Martinez, MD, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, New York, who specializes in addiction research, said in a recent MDedge podcast. “THC could be added to the armamentarium of pain medications that we use today.”

In a 2015 systematic literature review, researchers assessed 28 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) of the use of cannabinoids for chronic pain. They reported that a variety of formulations resulted in at least a 30% reduction in the odds of pain, compared with placebo. A meta-analysis of five RCTs involving patients with neuropathic pain found a 30% reduction in pain over placebo with inhaled, vaporized cannabis. Varying results have been reported in additional studies for this indication. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine concluded that there was a substantial body of evidence that cannabis is an effective treatment for chronic pain in adults.

The ongoing opioid epidemic has lent these results additional relevance.

Seeing this firsthand has caused Mark Steven Wallace, MD, a pain management specialist and chair of the division of pain medicine at the University of California San Diego Health, to reconsider offering cannabis to his patients.

“I think it’s probably more efficacious, just from my personal experience, and it’s a much lower risk of abuse and dependence than the opioids,” he said.

Dr. Wallace advised that clinicians who treat pain consider the ratios of cannabinoids.

“This is anecdotal, but we do find that with the combination of the two, CBD reduces the psychoactive effects of the THC. The ratios we use during the daytime range around 20 mg of CBD to 1 mg of THC,” he said.

In a recent secondary analysis of an RCT involving patients with painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy, Dr. Wallace and colleagues showed that THC’s effects appear to reverse themselves at a certain level.

“As the THC level goes up, the pain reduces until you reach about 16 ng/mL; then it starts going in the opposite direction, and pain will start to increase,” he said. “Even recreational cannabis users have reported that they avoid high doses because it’s very aversive. Using cannabis is all about, start low and go slow.”

A mixed bag for neurologic indications

There are relatively limited data on the use of medical cannabis for other neurologic conditions, and results have varied. For uses other than pain management, the evidence that does exist is strongest regarding epilepsy, said Daniel Freedman, DO, assistant professor of neurology at the University of Texas at Austin. He noted “multiple high-quality RCTs showing that pharmaceutical-grade CBD can reduce seizures associated with two particular epilepsy syndromes: Dravet Syndrome and Lennox Gastaut.”

These findings led to the FDA’s 2018 approval of Epidiolex for these syndromes. In earlier years, interest in CBD for pediatric seizures was largely driven by anecdotal parental reports of its benefits. NASEM’s 2017 overview on medical cannabis found evidence from subsequent RCTs in this indication to be insufficient. Clinicians who prescribe CBD for this indication must be vigilant because it can interact with several commonly used antiepileptic drugs.

Cannabinoid treatments have also shown success in alleviating muscle spasticity resulting from multiple sclerosis, most prominently in the form of nabiximols (Sativex), a standardized oralmucosal spray containing approximately equal quantities of THC and CBD. Nabiximols is approved in Europe but not in the United States. Moderate evidence supports the efficacy of these and other treatments over placebo in reducing muscle spasticity. Patient ratings of its effects tend to be higher than clinician assessment.

Parkinson’s disease has not yet been approved as an indication for treatment with cannabis or cannabinoids, yet a growing body of preclinical data suggests these could influence the dopaminergic system, said Carsten Buhmann, MD, from the department of neurology at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (Germany).

“In general, cannabinoids modulate basal-ganglia function on two levels which are especially relevant in Parkinson’s disease, i.e., the glutamatergic/dopaminergic synaptic neurotransmission and the corticostriatal plasticity,” he said. “Furthermore, activation of the endocannabinoid system might induce neuroprotective effects related to direct receptor-independent mechanisms, activation of anti-inflammatory cascades in glial cells via the cannabinoid receptor type 2, and antiglutamatergic antiexcitotoxic properties.”

Dr. Buhmann said that currently, clinical evidence is scarce, consisting of only four double-blind, placebo-controlled RCTs involving 49 patients. Various cannabinoids and methods of administering treatment were employed. Improvement was only observed in one of these RCTs, which found that the cannabinoid receptor agonist nabilone significantly reduced levodopa-induced dyskinesia for patients with Parkinson’s disease. Subjective data support a beneficial effect. In a nationwide survey of 1,348 respondents conducted by Dr. Buhmann and colleagues, the majority of medical cannabis users reported that it improved their symptoms (54% with oral CBD and 68% with inhaled THC-containing cannabis).

NASEM concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support the efficacy of medical cannabis for other neurologic conditions, including Tourette syndrome, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Huntington disease, dystonia, or dementia. A 2020 position statement from the American Academy of Neurology cited the lack of sufficient peer-reviewed research as the reason it could not currently support the use of cannabis for neurologic disorders.

Yet, according to Dr. Freedman, who served as a coauthor of the AAN position statement, this hasn’t stymied research interest in the topic. He’s seen a substantial uptick in studies of CBD over the past 2 years. “The body of evidence grows, but I still see many claims being made without evidence. And no one seems to care about all the negative trials.”

Cannabis as a treatment for, and cause of, psychiatric disorders

Mental health problems – such as anxiety, depression, and PTSD – are among the most common reasons patients seek out medical cannabis. There is an understandable interest in using cannabis and cannabinoids to treat psychiatric disorders. Preclinical studies suggest that the endocannabinoid system plays a prominent role in modulating feelings of anxiety, mood, and fear. As with opioids and chronic pain management, there is hope that medical cannabis may provide a means of reducing prescription anxiolytics and their associated risks.

The authors of the first systematic review (BMC Psychiatry. 2020 Jan 16;20[1]:24) of the use of medical cannabis for major psychiatric disorders noted that the current evidence was “encouraging, albeit embryonic.”

Meta-analyses have indicated a small but positive association between cannabis use and anxiety, although this may reflect the fact that patients with anxiety sought out this treatment. Given the risks for substance use disorders among patients with anxiety, CBD may present a more viable option. Positive results have been shown as treatment for generalized social anxiety disorder.

Limited but encouraging results have also been reported regarding the alleviation of PTSD symptoms with both cannabis and CBD, although the body of high-quality evidence hasn’t notably progressed since 2017, when NASEM declared that the evidence was insufficient. Supportive evidence is similarly lacking regarding the treatment of depression. Longitudinal studies suggest that cannabis use, particularly heavy use, may increase the risk of developing this disorder. Because THC is psychoactive, it is advised that it be avoided by patients at risk for psychotic disorders. However, CBD has yielded limited benefits for patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia and for young people at risk for psychosis.

The use of medical cannabis for psychiatric conditions requires a complex balancing act, inasmuch as these treatments may exacerbate the very problems they are intended to alleviate.

Marta Di Forti, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatric research at Kings College London, has been at the forefront of determining the mental health risks of continued cannabis use. In 2019, Dr. Di Forti developed the first and only Cannabis Clinic for Patients With Psychosis in London where she and her colleagues have continued to elucidate this connection.

Dr. Di Forti and colleagues have linked daily cannabis use to an increase in the risk of experiencing psychotic disorder, compared with never using it. That risk was further increased among users of high-potency cannabis (≥10% THC). The latter finding has troubling implications, because concentrations of THC have steadily risen since 1970. By contrast, CBD concentrations have remained generally stable. High-potency cannabis products are common in both recreational and medicinal settings.

“For somebody prescribing medicinal cannabis that has a ≥10% concentration of THC, I’d be particularly wary of the risk of psychosis,” said Dr. Di Forti. “If you’re expecting people to use a high content of THC daily to medicate pain or a chronic condition, you even more so need to be aware that this is a potential side effect.”

Dr. Di Forti noted that her findings come from a cohort of recreational users, most of whom were aged 18-35 years.

“There have actually not been studies developed from collecting data in this area from groups specifically using cannabis for medicinal rather than recreational purposes,” she said.

She added that she personally has no concerns about the use of medical cannabis but wants clinicians to be aware of the risk for psychosis, to structure their patient conversations to identify risk factors or family histories of psychosis, and to become knowledgeable in detecting the often subtle signs of its initial onset.