User login

Emerging research shows link between suicidality, ‘high-potency’ cannabis products

Number of suicides positive for marijuana on rise soared among Colorado youth

In the days since recreational sales of marijuana became legal in Colorado in January 2014, concerning trends have emerged among the state’s young cannabis users.

According to a report from the Rocky Mountain High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, between 2014 and 2017, the number of suicides positive for marijuana increased 250% among those aged 10-19 years (from 4 to 14) and 22% among those aged 20 and older (from 118 to 144). “Other states are seeing something similar, and there is an emerging research showing a relationship between suicidality and the use of marijuana, especially high-potency products that are available in legalized markets,” Paula D. Riggs, MD, reported during an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association.

During that same 3-year time span, the proportion of Colorado youth aged 12 years and older who used marijuana in the past month jumped by 45%, which is more than 85% above the national average. “Similarly, among college-age students, we’ve seen an 18% increase in past-month marijuana use, which is 60% above the national average,” said Dr. Riggs, professor and vice chair of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Among adolescents, state health officials have observed a 5% increase in the proportion of those who used marijuana in the past month, which is more than 54% above the national average. “But a concerning trend is that we’re seeing an increase in the use of concentrates such as dabs and waxes,” she said. “That’s worrisome in terms of exposure to high-potency products.”

In other findings, 48% of young marijuana users reported going to work high (40% at least once per week), and there has been a 170% increase in youth ED urgent care visits for marijuana-related illnesses such as cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome or first-episode psychosis. State health officials have also observed a 148% increase in marijuana-related hospitalizations.

According to Dr. Riggs, who also directs the University of Colorado’s division of addiction science, prevention, and treatment, the average marijuana joint in the 1960s contained about 3% tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), a level that crept up to the 4%-6% range in 2002. In today’s postlegalization era, the average joint now contains 13%-23% THC. “What’s concerning is that the concentrates – the dabs, waxes, shatter, and butane hash oils – contain upward of 70%-95% THC,” Dr. Riggs said. “Those are highly potent products that represent about 25% of the market share now. That’s a very big concern because the higher the potency the cannabis product used, the greater the abuse liability and addictive potential.”

The use of high-potency products also doubles the risk of developing generalized anxiety disorder, triples the risk of tobacco dependence, doubles the risk of other illicit substance disorders, and it at least quadruples the risk of developing first-episode psychosis in young people. “So, when you’re taking a cannabis use history, it’s important to ask patients about the potency of the products being used,” she said.

In the 2019 Monitoring the Future survey, 12% of U.S. 8th graders self-reported marijuana use in the past year and 7% in the past month, compared with 29% and 18% of 10th graders, respectively. Self-reported use by 12th graders was even more elevated (36% in the past year and 29% in the past month). “The concern is, this survey doesn’t really capture what’s happening with marijuana concentrates,” Dr. Riggs said.

A survey of Colorado youth conducted by the state’s Department of Public Health and Environment found that the percentage of students who reported using concentrated forms of marijuana has risen steadily in recent years and now stands at roughly 34%. “The use of edibles has also crept up,” said Dr. Riggs, who noted that marijuana dispensaries in Colorado outnumber Starbucks locations and McDonald’s restaurants. “You might not think that’s particularly concerning, except that the use of edibles is even more associated with onset of psychosis than other forms. This is probably because when you eat a marijuana product, you can’t control the exposure or the dose that you’re ingesting. We need to be concerned about these trends.”

European studies report that 30%-50% of new cases of first-onset psychosis are attributed to high-potency cannabis. “There is a dose-response relationship between cannabis and psychosis,” Dr. Riggs said. “That is, the frequency and duration of cannabis use, or the use of high-potency products, and the age of onset, are strongly associated with the risk of first-episode psychosis.

Researchers have known for some time that alterations in the endocannabinoid system are associated with psychosis independent of cannabis exposure. “Dysregulation of that endocannabinoid system occurs in patients at all stages of the psychosis continuum,” she continued. “It also means that the endocannabinoid system is a potential therapeutic target for psychosis.”

According to Dr. Riggs, THC exposure acutely increases dopamine in the ventral striatum and it can produce transient psychotomimetic effects in clinical and nonclinical populations. Genetic differences in the dopaminergic system can also interact with cannabis use to increase the risk of psychosis.

“For example, the COMT (catechol-O-methyltransferase) breaks down catecholamines such as dopamine in the prefrontal cortex,” she explained. “If you have a COMT gene polymorphism, that increases your risk of developing psychosis due to increased levels of dopamine signaling.”

She emphasized the importance of clinicians to understand that the age of cannabis use onset, the duration, frequency, and THC potency is related to the psychosis risk and worse prognosis. The earlier the initiation of marijuana use, the greater potential for first-episode psychosis. “Those who continue using cannabis after a first-episode psychosis have greater severity of psychotic illness and more treatment resistance, and they’re less likely to engage or be compliant with treatment recommendations,” Dr. Riggs said. “So, Because if they resume cannabis use, this can turn into a more chronic psychotic disorder.”

She added that, while insufficient evidence exists to determine whether cannabis plays a causal role in the development of schizophrenia or not, mounting evidence suggests that cannabis use may precipitate earlier onset of schizophrenia in those with other risk factors for the disorder. “There is considerable evidence that cannabis use increases the risk of psychosis in a dose-related manner, especially with an onset before age 16,” Dr. Riggs said. “However, this does not mean that cannabis is safe for young adults. Cannabis-induced psychotic symptoms often develop during young adulthood and may become chronic.”

Dr. Riggs disclosed that she had received grant funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. She is also executive director for Encompass, which provides integrated treatment for adolescents and young adults.

Number of suicides positive for marijuana on rise soared among Colorado youth

Number of suicides positive for marijuana on rise soared among Colorado youth

In the days since recreational sales of marijuana became legal in Colorado in January 2014, concerning trends have emerged among the state’s young cannabis users.

According to a report from the Rocky Mountain High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, between 2014 and 2017, the number of suicides positive for marijuana increased 250% among those aged 10-19 years (from 4 to 14) and 22% among those aged 20 and older (from 118 to 144). “Other states are seeing something similar, and there is an emerging research showing a relationship between suicidality and the use of marijuana, especially high-potency products that are available in legalized markets,” Paula D. Riggs, MD, reported during an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association.

During that same 3-year time span, the proportion of Colorado youth aged 12 years and older who used marijuana in the past month jumped by 45%, which is more than 85% above the national average. “Similarly, among college-age students, we’ve seen an 18% increase in past-month marijuana use, which is 60% above the national average,” said Dr. Riggs, professor and vice chair of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Among adolescents, state health officials have observed a 5% increase in the proportion of those who used marijuana in the past month, which is more than 54% above the national average. “But a concerning trend is that we’re seeing an increase in the use of concentrates such as dabs and waxes,” she said. “That’s worrisome in terms of exposure to high-potency products.”

In other findings, 48% of young marijuana users reported going to work high (40% at least once per week), and there has been a 170% increase in youth ED urgent care visits for marijuana-related illnesses such as cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome or first-episode psychosis. State health officials have also observed a 148% increase in marijuana-related hospitalizations.

According to Dr. Riggs, who also directs the University of Colorado’s division of addiction science, prevention, and treatment, the average marijuana joint in the 1960s contained about 3% tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), a level that crept up to the 4%-6% range in 2002. In today’s postlegalization era, the average joint now contains 13%-23% THC. “What’s concerning is that the concentrates – the dabs, waxes, shatter, and butane hash oils – contain upward of 70%-95% THC,” Dr. Riggs said. “Those are highly potent products that represent about 25% of the market share now. That’s a very big concern because the higher the potency the cannabis product used, the greater the abuse liability and addictive potential.”

The use of high-potency products also doubles the risk of developing generalized anxiety disorder, triples the risk of tobacco dependence, doubles the risk of other illicit substance disorders, and it at least quadruples the risk of developing first-episode psychosis in young people. “So, when you’re taking a cannabis use history, it’s important to ask patients about the potency of the products being used,” she said.

In the 2019 Monitoring the Future survey, 12% of U.S. 8th graders self-reported marijuana use in the past year and 7% in the past month, compared with 29% and 18% of 10th graders, respectively. Self-reported use by 12th graders was even more elevated (36% in the past year and 29% in the past month). “The concern is, this survey doesn’t really capture what’s happening with marijuana concentrates,” Dr. Riggs said.

A survey of Colorado youth conducted by the state’s Department of Public Health and Environment found that the percentage of students who reported using concentrated forms of marijuana has risen steadily in recent years and now stands at roughly 34%. “The use of edibles has also crept up,” said Dr. Riggs, who noted that marijuana dispensaries in Colorado outnumber Starbucks locations and McDonald’s restaurants. “You might not think that’s particularly concerning, except that the use of edibles is even more associated with onset of psychosis than other forms. This is probably because when you eat a marijuana product, you can’t control the exposure or the dose that you’re ingesting. We need to be concerned about these trends.”

European studies report that 30%-50% of new cases of first-onset psychosis are attributed to high-potency cannabis. “There is a dose-response relationship between cannabis and psychosis,” Dr. Riggs said. “That is, the frequency and duration of cannabis use, or the use of high-potency products, and the age of onset, are strongly associated with the risk of first-episode psychosis.

Researchers have known for some time that alterations in the endocannabinoid system are associated with psychosis independent of cannabis exposure. “Dysregulation of that endocannabinoid system occurs in patients at all stages of the psychosis continuum,” she continued. “It also means that the endocannabinoid system is a potential therapeutic target for psychosis.”

According to Dr. Riggs, THC exposure acutely increases dopamine in the ventral striatum and it can produce transient psychotomimetic effects in clinical and nonclinical populations. Genetic differences in the dopaminergic system can also interact with cannabis use to increase the risk of psychosis.

“For example, the COMT (catechol-O-methyltransferase) breaks down catecholamines such as dopamine in the prefrontal cortex,” she explained. “If you have a COMT gene polymorphism, that increases your risk of developing psychosis due to increased levels of dopamine signaling.”

She emphasized the importance of clinicians to understand that the age of cannabis use onset, the duration, frequency, and THC potency is related to the psychosis risk and worse prognosis. The earlier the initiation of marijuana use, the greater potential for first-episode psychosis. “Those who continue using cannabis after a first-episode psychosis have greater severity of psychotic illness and more treatment resistance, and they’re less likely to engage or be compliant with treatment recommendations,” Dr. Riggs said. “So, Because if they resume cannabis use, this can turn into a more chronic psychotic disorder.”

She added that, while insufficient evidence exists to determine whether cannabis plays a causal role in the development of schizophrenia or not, mounting evidence suggests that cannabis use may precipitate earlier onset of schizophrenia in those with other risk factors for the disorder. “There is considerable evidence that cannabis use increases the risk of psychosis in a dose-related manner, especially with an onset before age 16,” Dr. Riggs said. “However, this does not mean that cannabis is safe for young adults. Cannabis-induced psychotic symptoms often develop during young adulthood and may become chronic.”

Dr. Riggs disclosed that she had received grant funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. She is also executive director for Encompass, which provides integrated treatment for adolescents and young adults.

In the days since recreational sales of marijuana became legal in Colorado in January 2014, concerning trends have emerged among the state’s young cannabis users.

According to a report from the Rocky Mountain High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, between 2014 and 2017, the number of suicides positive for marijuana increased 250% among those aged 10-19 years (from 4 to 14) and 22% among those aged 20 and older (from 118 to 144). “Other states are seeing something similar, and there is an emerging research showing a relationship between suicidality and the use of marijuana, especially high-potency products that are available in legalized markets,” Paula D. Riggs, MD, reported during an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association.

During that same 3-year time span, the proportion of Colorado youth aged 12 years and older who used marijuana in the past month jumped by 45%, which is more than 85% above the national average. “Similarly, among college-age students, we’ve seen an 18% increase in past-month marijuana use, which is 60% above the national average,” said Dr. Riggs, professor and vice chair of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Among adolescents, state health officials have observed a 5% increase in the proportion of those who used marijuana in the past month, which is more than 54% above the national average. “But a concerning trend is that we’re seeing an increase in the use of concentrates such as dabs and waxes,” she said. “That’s worrisome in terms of exposure to high-potency products.”

In other findings, 48% of young marijuana users reported going to work high (40% at least once per week), and there has been a 170% increase in youth ED urgent care visits for marijuana-related illnesses such as cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome or first-episode psychosis. State health officials have also observed a 148% increase in marijuana-related hospitalizations.

According to Dr. Riggs, who also directs the University of Colorado’s division of addiction science, prevention, and treatment, the average marijuana joint in the 1960s contained about 3% tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), a level that crept up to the 4%-6% range in 2002. In today’s postlegalization era, the average joint now contains 13%-23% THC. “What’s concerning is that the concentrates – the dabs, waxes, shatter, and butane hash oils – contain upward of 70%-95% THC,” Dr. Riggs said. “Those are highly potent products that represent about 25% of the market share now. That’s a very big concern because the higher the potency the cannabis product used, the greater the abuse liability and addictive potential.”

The use of high-potency products also doubles the risk of developing generalized anxiety disorder, triples the risk of tobacco dependence, doubles the risk of other illicit substance disorders, and it at least quadruples the risk of developing first-episode psychosis in young people. “So, when you’re taking a cannabis use history, it’s important to ask patients about the potency of the products being used,” she said.

In the 2019 Monitoring the Future survey, 12% of U.S. 8th graders self-reported marijuana use in the past year and 7% in the past month, compared with 29% and 18% of 10th graders, respectively. Self-reported use by 12th graders was even more elevated (36% in the past year and 29% in the past month). “The concern is, this survey doesn’t really capture what’s happening with marijuana concentrates,” Dr. Riggs said.

A survey of Colorado youth conducted by the state’s Department of Public Health and Environment found that the percentage of students who reported using concentrated forms of marijuana has risen steadily in recent years and now stands at roughly 34%. “The use of edibles has also crept up,” said Dr. Riggs, who noted that marijuana dispensaries in Colorado outnumber Starbucks locations and McDonald’s restaurants. “You might not think that’s particularly concerning, except that the use of edibles is even more associated with onset of psychosis than other forms. This is probably because when you eat a marijuana product, you can’t control the exposure or the dose that you’re ingesting. We need to be concerned about these trends.”

European studies report that 30%-50% of new cases of first-onset psychosis are attributed to high-potency cannabis. “There is a dose-response relationship between cannabis and psychosis,” Dr. Riggs said. “That is, the frequency and duration of cannabis use, or the use of high-potency products, and the age of onset, are strongly associated with the risk of first-episode psychosis.

Researchers have known for some time that alterations in the endocannabinoid system are associated with psychosis independent of cannabis exposure. “Dysregulation of that endocannabinoid system occurs in patients at all stages of the psychosis continuum,” she continued. “It also means that the endocannabinoid system is a potential therapeutic target for psychosis.”

According to Dr. Riggs, THC exposure acutely increases dopamine in the ventral striatum and it can produce transient psychotomimetic effects in clinical and nonclinical populations. Genetic differences in the dopaminergic system can also interact with cannabis use to increase the risk of psychosis.

“For example, the COMT (catechol-O-methyltransferase) breaks down catecholamines such as dopamine in the prefrontal cortex,” she explained. “If you have a COMT gene polymorphism, that increases your risk of developing psychosis due to increased levels of dopamine signaling.”

She emphasized the importance of clinicians to understand that the age of cannabis use onset, the duration, frequency, and THC potency is related to the psychosis risk and worse prognosis. The earlier the initiation of marijuana use, the greater potential for first-episode psychosis. “Those who continue using cannabis after a first-episode psychosis have greater severity of psychotic illness and more treatment resistance, and they’re less likely to engage or be compliant with treatment recommendations,” Dr. Riggs said. “So, Because if they resume cannabis use, this can turn into a more chronic psychotic disorder.”

She added that, while insufficient evidence exists to determine whether cannabis plays a causal role in the development of schizophrenia or not, mounting evidence suggests that cannabis use may precipitate earlier onset of schizophrenia in those with other risk factors for the disorder. “There is considerable evidence that cannabis use increases the risk of psychosis in a dose-related manner, especially with an onset before age 16,” Dr. Riggs said. “However, this does not mean that cannabis is safe for young adults. Cannabis-induced psychotic symptoms often develop during young adulthood and may become chronic.”

Dr. Riggs disclosed that she had received grant funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. She is also executive director for Encompass, which provides integrated treatment for adolescents and young adults.

FROM NPA 2021

Vaccine may blunt effects of deadly synthetic opioids

New experimental vaccines could stop the worst effects of synthetic fentanyl and carfentanil, two drugs that have been major drivers of the opioid epidemic in the United States, according to a new study published in ACS Chemical Biology on Feb. 3, 2021.

During several experiments in mice, the vaccines prevented respiratory depression, which is the main cause of overdose deaths. The vaccines also reduced the amount of drug that was distributed to the brain. Once in the brain, synthetic opioids prompt the body to slow down breathing, and when too much of the drug is consumed, breathing can stop.

“Synthetic opioids are not only extremely deadly but also addictive and easy to manufacture, making them a formidable public health threat, especially when the coronavirus crisis is negatively impacting mental health,” Kim Janda, PhD, a chemist at Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif., who developed the vaccines, said in a statement.

Fentanyl is up to 100 times stronger than morphine, and carfentanil, which is often used by veterinarians to sedate large animals such as elephants, is up to 10,000 times stronger than morphine. Carfentanil isn’t as well-known as a street drug, but it’s being used more often as an additive in heroin and cocaine.

“We’ve shown it is possible to prevent these unnecessary deaths by eliciting antibodies that stop the drug from reaching the brain,” he said.

The vaccines could be used in emergency situations to treat overdoses and as a therapy for those with substance abuse disorders, Dr. Janda said. In addition, the vaccines could protect military officers who are exposed to opioids as chemical weapons, and they may also help opioid-sniffing police dogs to train for the job.

The vaccines are still in the early stages of testing, but looking at the latest data “brings us hope that this approach will work to treat a number of opioid-related maladies,” Dr. Janda said.

In December, the CDC reported that more than 81,000 drug overdose deaths happened in the United States between May 2019 and May 2020, which was the highest number ever recorded in a 12-month period. Synthetic opioids, particularly illegally created fentanyl, were to blame.

“Unfortunately, currently battling a pandemic,” Dr. Janda said. “We look forward to continuing our vaccine research and translating it to the clinic, where we can begin to make an impact on the opioid crisis.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New experimental vaccines could stop the worst effects of synthetic fentanyl and carfentanil, two drugs that have been major drivers of the opioid epidemic in the United States, according to a new study published in ACS Chemical Biology on Feb. 3, 2021.

During several experiments in mice, the vaccines prevented respiratory depression, which is the main cause of overdose deaths. The vaccines also reduced the amount of drug that was distributed to the brain. Once in the brain, synthetic opioids prompt the body to slow down breathing, and when too much of the drug is consumed, breathing can stop.

“Synthetic opioids are not only extremely deadly but also addictive and easy to manufacture, making them a formidable public health threat, especially when the coronavirus crisis is negatively impacting mental health,” Kim Janda, PhD, a chemist at Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif., who developed the vaccines, said in a statement.

Fentanyl is up to 100 times stronger than morphine, and carfentanil, which is often used by veterinarians to sedate large animals such as elephants, is up to 10,000 times stronger than morphine. Carfentanil isn’t as well-known as a street drug, but it’s being used more often as an additive in heroin and cocaine.

“We’ve shown it is possible to prevent these unnecessary deaths by eliciting antibodies that stop the drug from reaching the brain,” he said.

The vaccines could be used in emergency situations to treat overdoses and as a therapy for those with substance abuse disorders, Dr. Janda said. In addition, the vaccines could protect military officers who are exposed to opioids as chemical weapons, and they may also help opioid-sniffing police dogs to train for the job.

The vaccines are still in the early stages of testing, but looking at the latest data “brings us hope that this approach will work to treat a number of opioid-related maladies,” Dr. Janda said.

In December, the CDC reported that more than 81,000 drug overdose deaths happened in the United States between May 2019 and May 2020, which was the highest number ever recorded in a 12-month period. Synthetic opioids, particularly illegally created fentanyl, were to blame.

“Unfortunately, currently battling a pandemic,” Dr. Janda said. “We look forward to continuing our vaccine research and translating it to the clinic, where we can begin to make an impact on the opioid crisis.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New experimental vaccines could stop the worst effects of synthetic fentanyl and carfentanil, two drugs that have been major drivers of the opioid epidemic in the United States, according to a new study published in ACS Chemical Biology on Feb. 3, 2021.

During several experiments in mice, the vaccines prevented respiratory depression, which is the main cause of overdose deaths. The vaccines also reduced the amount of drug that was distributed to the brain. Once in the brain, synthetic opioids prompt the body to slow down breathing, and when too much of the drug is consumed, breathing can stop.

“Synthetic opioids are not only extremely deadly but also addictive and easy to manufacture, making them a formidable public health threat, especially when the coronavirus crisis is negatively impacting mental health,” Kim Janda, PhD, a chemist at Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif., who developed the vaccines, said in a statement.

Fentanyl is up to 100 times stronger than morphine, and carfentanil, which is often used by veterinarians to sedate large animals such as elephants, is up to 10,000 times stronger than morphine. Carfentanil isn’t as well-known as a street drug, but it’s being used more often as an additive in heroin and cocaine.

“We’ve shown it is possible to prevent these unnecessary deaths by eliciting antibodies that stop the drug from reaching the brain,” he said.

The vaccines could be used in emergency situations to treat overdoses and as a therapy for those with substance abuse disorders, Dr. Janda said. In addition, the vaccines could protect military officers who are exposed to opioids as chemical weapons, and they may also help opioid-sniffing police dogs to train for the job.

The vaccines are still in the early stages of testing, but looking at the latest data “brings us hope that this approach will work to treat a number of opioid-related maladies,” Dr. Janda said.

In December, the CDC reported that more than 81,000 drug overdose deaths happened in the United States between May 2019 and May 2020, which was the highest number ever recorded in a 12-month period. Synthetic opioids, particularly illegally created fentanyl, were to blame.

“Unfortunately, currently battling a pandemic,” Dr. Janda said. “We look forward to continuing our vaccine research and translating it to the clinic, where we can begin to make an impact on the opioid crisis.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As demand for mental health care spikes, budget ax set to strike

When the pandemic hit, health officials in Montana’s Beaverhead County had barely begun to fill a hole left by the 2017 closure of the local public assistance office, mental health clinic, chemical dependency center and job placement office after the state’s last budget shortfall.

Now, those health officials worry more cuts are coming, even as they brace for a spike in demand for substance abuse and mental health services. That would be no small challenge in a poor farming and ranching region where stigma often prevents people from admitting they need help, said Katherine Buckley-Patton, who chairs the county’s Mental Health Local Advisory Council.

“I find it very challenging to find the words that will not make one of my hard-nosed cowboys turn around and walk away,” Ms. Buckley-Patton said.

States across the U.S. are still stinging after businesses closed and millions of people lost jobs because of COVID-related shutdowns and restrictions. Meanwhile, the pandemic has led to a dramatic increase in the number of people who say their mental health has suffered, rising from one in three people in March to more than half of people polled by KFF in July. (KHN is an editorially independent program of KFF.)

The full extent of the mental health crisis and the demand for behavioral health services may not be known until after the pandemic is over, mental health experts said. That could add costs that budget writers haven’t anticipated.

“It usually takes a while before people feel comfortable seeking care from a specialty behavioral health organization,” said Chuck Ingoglia, president and CEO of the nonprofit National Council for Behavioral Health in Washington, D.C. “We are not likely to see the results of that either in terms of people seeking care – or suicide rates going up – until we’re on the other side of the pandemic.”

Last year, states slashed agency budgets, froze pay, furloughed workers, borrowed money, and tapped into rainy-day funds to make ends meet. Health programs, often among the most expensive part of a state’s budget, were targeted for cuts in several states even as health officials led efforts to stem the spread of the coronavirus.

This year, the outlook doesn’t seem quite so bleak, partly because of relief packages passed by Congress last spring and in December that buoyed state economies. Another major advantage was that income increased or held steady for people with well-paying jobs and investment income, which boosted states’ tax revenues even as millions of lower-income workers were laid off.

“It has turned out to be not as bad as it might have been in terms of state budgets,” said Mike Leachman, vice president for state fiscal policy for the nonpartisan Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

But many states still face cash shortfalls that will be made worse if additional federal aid doesn’t come, Mr. Leachman said. President Joe Biden has pledged to push through Congress a $1.9 billion relief package that includes aid to states, while congressional Republicans are proposing a package worth about a third of that amount. States are banking on federal help.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, predicted his state would have to plug a $15 billion deficit with spending cuts and tax increases if a fresh round of aid doesn’t materialize. Some states, such as New Jersey, borrowed to make their budgets whole, and they’re going to have to start paying that money back. Tourism states such as Hawaii and energy-producing states such as Alaska and Wyoming continue to face grim economic outlooks with oil, gas, and coal prices down and tourists cutting back on travel, Mr. Leachman said.

Even states with a relatively rosy economic outlook are being cautious. In Colorado, for example, Democratic Gov. Jared Polis proposed a budget that restores the cuts made last year to Medicaid and substance abuse programs. But health providers are doubtful the legislature will approve any significant spending increases in this economy.

“Everybody right now is just trying to protect and make sure we don’t have additional cuts,” said Doyle Forrestal, CEO of the Colorado Behavioral Healthcare Council.

That’s also what Ms. Buckley-Patton wants for Montana’s Beaverhead County, where most of the 9,400 residents live in poverty or earn low incomes.

She led the county’s effort to recover from the loss in 2017 of a wide range of behavioral health services, along with offices to help poor people receive Medicaid health services, plus cash and food assistance.

Through persuasive grant writing and donations coaxed from elected officials, Ms. Buckley-Patton and her team secured office space, equipment, and a part-time employee for a resource center that’s open once a week in the county in the southwestern corner of the state, she said. They also convinced the state health department to send two people every other week on a 120-mile round trip from the Butte office to help county residents with their Medicaid and public assistance applications.

But now Ms. Buckley-Patton worries even those modest gains will be threatened in this year’s budget. Montana is one of the few states with a budget on a 2-year cycle, so this is the first time lawmakers have had to craft a spending plan since the pandemic began.

Revenue forecasts predict healthy tax collections over the next 2 years.

In January, at the start of the legislative session, the panel in charge of building the state health department’s budget proposed starting with nearly $1 billion in cuts. The panel’s chairperson, Republican Rep. Matt Regier, pledged to add back programs and services on their merits during the months-long budget process.

It’s a strategy Ms. Buckley-Patton worries will lead to a net loss of funding for Beaverhead County, which covers more land than Connecticut.

“I have grave concerns about this legislative session,” she said. “We’re not digging out of the hole; we’re only going deeper.”

Republicans, who are in control of the Montana House, Senate, and governor’s office for the first time in 16 years, are considering reducing the income tax level for the state’s top earners. Such a measure that could affect state revenue in an uncertain economy has some observers concerned, particularly when an increased need for health services is expected.

“Are legislators committed to building back up that budget in a way that works for communities and for health providers, or are we going to see tax cuts that reduce revenue that put us yet again in another really tight budget?” asked Heather O’Loughlin, codirector of the Montana Budget and Policy Center.

Mary Windecker, executive director of the Behavioral Health Alliance of Montana, said that health providers across the state are still clawing back from more than $100 million in budget cuts in 2017, and that she worries more cuts are on the horizon.

But one bright spot, she said, is a proposal by new Gov. Greg Gianforte to create a fund that would put $23 million a year toward community substance abuse prevention and treatment programs. It would be partially funded by tax revenue the state will receive from recreational marijuana, which voters approved in November, with sales to begin next year.

Ms. Windecker cautioned, though, that mental health and substance use are linked, and the governor and lawmakers should plan with that in mind.

“In the public’s mind, there’s drug addicts and there’s the mentally ill,” she said. “Quite often, the same people who have a substance use disorder are using it to treat a mental health issue that is underlying that substance use. So, you can never split the two out.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

When the pandemic hit, health officials in Montana’s Beaverhead County had barely begun to fill a hole left by the 2017 closure of the local public assistance office, mental health clinic, chemical dependency center and job placement office after the state’s last budget shortfall.

Now, those health officials worry more cuts are coming, even as they brace for a spike in demand for substance abuse and mental health services. That would be no small challenge in a poor farming and ranching region where stigma often prevents people from admitting they need help, said Katherine Buckley-Patton, who chairs the county’s Mental Health Local Advisory Council.

“I find it very challenging to find the words that will not make one of my hard-nosed cowboys turn around and walk away,” Ms. Buckley-Patton said.

States across the U.S. are still stinging after businesses closed and millions of people lost jobs because of COVID-related shutdowns and restrictions. Meanwhile, the pandemic has led to a dramatic increase in the number of people who say their mental health has suffered, rising from one in three people in March to more than half of people polled by KFF in July. (KHN is an editorially independent program of KFF.)

The full extent of the mental health crisis and the demand for behavioral health services may not be known until after the pandemic is over, mental health experts said. That could add costs that budget writers haven’t anticipated.

“It usually takes a while before people feel comfortable seeking care from a specialty behavioral health organization,” said Chuck Ingoglia, president and CEO of the nonprofit National Council for Behavioral Health in Washington, D.C. “We are not likely to see the results of that either in terms of people seeking care – or suicide rates going up – until we’re on the other side of the pandemic.”

Last year, states slashed agency budgets, froze pay, furloughed workers, borrowed money, and tapped into rainy-day funds to make ends meet. Health programs, often among the most expensive part of a state’s budget, were targeted for cuts in several states even as health officials led efforts to stem the spread of the coronavirus.

This year, the outlook doesn’t seem quite so bleak, partly because of relief packages passed by Congress last spring and in December that buoyed state economies. Another major advantage was that income increased or held steady for people with well-paying jobs and investment income, which boosted states’ tax revenues even as millions of lower-income workers were laid off.

“It has turned out to be not as bad as it might have been in terms of state budgets,” said Mike Leachman, vice president for state fiscal policy for the nonpartisan Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

But many states still face cash shortfalls that will be made worse if additional federal aid doesn’t come, Mr. Leachman said. President Joe Biden has pledged to push through Congress a $1.9 billion relief package that includes aid to states, while congressional Republicans are proposing a package worth about a third of that amount. States are banking on federal help.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, predicted his state would have to plug a $15 billion deficit with spending cuts and tax increases if a fresh round of aid doesn’t materialize. Some states, such as New Jersey, borrowed to make their budgets whole, and they’re going to have to start paying that money back. Tourism states such as Hawaii and energy-producing states such as Alaska and Wyoming continue to face grim economic outlooks with oil, gas, and coal prices down and tourists cutting back on travel, Mr. Leachman said.

Even states with a relatively rosy economic outlook are being cautious. In Colorado, for example, Democratic Gov. Jared Polis proposed a budget that restores the cuts made last year to Medicaid and substance abuse programs. But health providers are doubtful the legislature will approve any significant spending increases in this economy.

“Everybody right now is just trying to protect and make sure we don’t have additional cuts,” said Doyle Forrestal, CEO of the Colorado Behavioral Healthcare Council.

That’s also what Ms. Buckley-Patton wants for Montana’s Beaverhead County, where most of the 9,400 residents live in poverty or earn low incomes.

She led the county’s effort to recover from the loss in 2017 of a wide range of behavioral health services, along with offices to help poor people receive Medicaid health services, plus cash and food assistance.

Through persuasive grant writing and donations coaxed from elected officials, Ms. Buckley-Patton and her team secured office space, equipment, and a part-time employee for a resource center that’s open once a week in the county in the southwestern corner of the state, she said. They also convinced the state health department to send two people every other week on a 120-mile round trip from the Butte office to help county residents with their Medicaid and public assistance applications.

But now Ms. Buckley-Patton worries even those modest gains will be threatened in this year’s budget. Montana is one of the few states with a budget on a 2-year cycle, so this is the first time lawmakers have had to craft a spending plan since the pandemic began.

Revenue forecasts predict healthy tax collections over the next 2 years.

In January, at the start of the legislative session, the panel in charge of building the state health department’s budget proposed starting with nearly $1 billion in cuts. The panel’s chairperson, Republican Rep. Matt Regier, pledged to add back programs and services on their merits during the months-long budget process.

It’s a strategy Ms. Buckley-Patton worries will lead to a net loss of funding for Beaverhead County, which covers more land than Connecticut.

“I have grave concerns about this legislative session,” she said. “We’re not digging out of the hole; we’re only going deeper.”

Republicans, who are in control of the Montana House, Senate, and governor’s office for the first time in 16 years, are considering reducing the income tax level for the state’s top earners. Such a measure that could affect state revenue in an uncertain economy has some observers concerned, particularly when an increased need for health services is expected.

“Are legislators committed to building back up that budget in a way that works for communities and for health providers, or are we going to see tax cuts that reduce revenue that put us yet again in another really tight budget?” asked Heather O’Loughlin, codirector of the Montana Budget and Policy Center.

Mary Windecker, executive director of the Behavioral Health Alliance of Montana, said that health providers across the state are still clawing back from more than $100 million in budget cuts in 2017, and that she worries more cuts are on the horizon.

But one bright spot, she said, is a proposal by new Gov. Greg Gianforte to create a fund that would put $23 million a year toward community substance abuse prevention and treatment programs. It would be partially funded by tax revenue the state will receive from recreational marijuana, which voters approved in November, with sales to begin next year.

Ms. Windecker cautioned, though, that mental health and substance use are linked, and the governor and lawmakers should plan with that in mind.

“In the public’s mind, there’s drug addicts and there’s the mentally ill,” she said. “Quite often, the same people who have a substance use disorder are using it to treat a mental health issue that is underlying that substance use. So, you can never split the two out.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

When the pandemic hit, health officials in Montana’s Beaverhead County had barely begun to fill a hole left by the 2017 closure of the local public assistance office, mental health clinic, chemical dependency center and job placement office after the state’s last budget shortfall.

Now, those health officials worry more cuts are coming, even as they brace for a spike in demand for substance abuse and mental health services. That would be no small challenge in a poor farming and ranching region where stigma often prevents people from admitting they need help, said Katherine Buckley-Patton, who chairs the county’s Mental Health Local Advisory Council.

“I find it very challenging to find the words that will not make one of my hard-nosed cowboys turn around and walk away,” Ms. Buckley-Patton said.

States across the U.S. are still stinging after businesses closed and millions of people lost jobs because of COVID-related shutdowns and restrictions. Meanwhile, the pandemic has led to a dramatic increase in the number of people who say their mental health has suffered, rising from one in three people in March to more than half of people polled by KFF in July. (KHN is an editorially independent program of KFF.)

The full extent of the mental health crisis and the demand for behavioral health services may not be known until after the pandemic is over, mental health experts said. That could add costs that budget writers haven’t anticipated.

“It usually takes a while before people feel comfortable seeking care from a specialty behavioral health organization,” said Chuck Ingoglia, president and CEO of the nonprofit National Council for Behavioral Health in Washington, D.C. “We are not likely to see the results of that either in terms of people seeking care – or suicide rates going up – until we’re on the other side of the pandemic.”

Last year, states slashed agency budgets, froze pay, furloughed workers, borrowed money, and tapped into rainy-day funds to make ends meet. Health programs, often among the most expensive part of a state’s budget, were targeted for cuts in several states even as health officials led efforts to stem the spread of the coronavirus.

This year, the outlook doesn’t seem quite so bleak, partly because of relief packages passed by Congress last spring and in December that buoyed state economies. Another major advantage was that income increased or held steady for people with well-paying jobs and investment income, which boosted states’ tax revenues even as millions of lower-income workers were laid off.

“It has turned out to be not as bad as it might have been in terms of state budgets,” said Mike Leachman, vice president for state fiscal policy for the nonpartisan Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

But many states still face cash shortfalls that will be made worse if additional federal aid doesn’t come, Mr. Leachman said. President Joe Biden has pledged to push through Congress a $1.9 billion relief package that includes aid to states, while congressional Republicans are proposing a package worth about a third of that amount. States are banking on federal help.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, predicted his state would have to plug a $15 billion deficit with spending cuts and tax increases if a fresh round of aid doesn’t materialize. Some states, such as New Jersey, borrowed to make their budgets whole, and they’re going to have to start paying that money back. Tourism states such as Hawaii and energy-producing states such as Alaska and Wyoming continue to face grim economic outlooks with oil, gas, and coal prices down and tourists cutting back on travel, Mr. Leachman said.

Even states with a relatively rosy economic outlook are being cautious. In Colorado, for example, Democratic Gov. Jared Polis proposed a budget that restores the cuts made last year to Medicaid and substance abuse programs. But health providers are doubtful the legislature will approve any significant spending increases in this economy.

“Everybody right now is just trying to protect and make sure we don’t have additional cuts,” said Doyle Forrestal, CEO of the Colorado Behavioral Healthcare Council.

That’s also what Ms. Buckley-Patton wants for Montana’s Beaverhead County, where most of the 9,400 residents live in poverty or earn low incomes.

She led the county’s effort to recover from the loss in 2017 of a wide range of behavioral health services, along with offices to help poor people receive Medicaid health services, plus cash and food assistance.

Through persuasive grant writing and donations coaxed from elected officials, Ms. Buckley-Patton and her team secured office space, equipment, and a part-time employee for a resource center that’s open once a week in the county in the southwestern corner of the state, she said. They also convinced the state health department to send two people every other week on a 120-mile round trip from the Butte office to help county residents with their Medicaid and public assistance applications.

But now Ms. Buckley-Patton worries even those modest gains will be threatened in this year’s budget. Montana is one of the few states with a budget on a 2-year cycle, so this is the first time lawmakers have had to craft a spending plan since the pandemic began.

Revenue forecasts predict healthy tax collections over the next 2 years.

In January, at the start of the legislative session, the panel in charge of building the state health department’s budget proposed starting with nearly $1 billion in cuts. The panel’s chairperson, Republican Rep. Matt Regier, pledged to add back programs and services on their merits during the months-long budget process.

It’s a strategy Ms. Buckley-Patton worries will lead to a net loss of funding for Beaverhead County, which covers more land than Connecticut.

“I have grave concerns about this legislative session,” she said. “We’re not digging out of the hole; we’re only going deeper.”

Republicans, who are in control of the Montana House, Senate, and governor’s office for the first time in 16 years, are considering reducing the income tax level for the state’s top earners. Such a measure that could affect state revenue in an uncertain economy has some observers concerned, particularly when an increased need for health services is expected.

“Are legislators committed to building back up that budget in a way that works for communities and for health providers, or are we going to see tax cuts that reduce revenue that put us yet again in another really tight budget?” asked Heather O’Loughlin, codirector of the Montana Budget and Policy Center.

Mary Windecker, executive director of the Behavioral Health Alliance of Montana, said that health providers across the state are still clawing back from more than $100 million in budget cuts in 2017, and that she worries more cuts are on the horizon.

But one bright spot, she said, is a proposal by new Gov. Greg Gianforte to create a fund that would put $23 million a year toward community substance abuse prevention and treatment programs. It would be partially funded by tax revenue the state will receive from recreational marijuana, which voters approved in November, with sales to begin next year.

Ms. Windecker cautioned, though, that mental health and substance use are linked, and the governor and lawmakers should plan with that in mind.

“In the public’s mind, there’s drug addicts and there’s the mentally ill,” she said. “Quite often, the same people who have a substance use disorder are using it to treat a mental health issue that is underlying that substance use. So, you can never split the two out.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Minimizing Opioids After Joint Operation: Protocol to Decrease Postoperative Opioid Use After Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty

For decades, opioids have been a mainstay in the management of pain after total joint arthroplasty. In the past 10 years, however, opioid prescribing has come under increased scrutiny due to a rise in rates of opioid abuse, pill diversion, and opioid-related deaths.1,2 Opioids are associated with adverse effects, including nausea, vomiting, constipation, apathy, and respiratory depression, all of which influence arthroplasty outcomes and affect the patient experience. Although primary care groups account for nearly half of prescriptions written, orthopedic surgeons have the third highest per capita rate of opioid prescribing of all medical specialties.3,4 This puts orthopedic surgeons, particularly those who perform routine procedures, in an opportune but challenging position to confront this problem through novel pain management strategies.

Approximately 1 million total knee arthroplasties (TKAs) are performed in the US every year, and the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health system performs about 10,000 hip and knee joint replacements.5,6 There is no standardization of opioid prescribing in the postoperative period following these procedures, and studies have reported a wide variation in prescribing habits even within a single institution for a specific surgery.7 Patients who undergo TKA are at particularly high risk of long-term opioid use if they are on continuous opioids at the time of surgery; this is problematic in a VA patient population in which at least 16% of patients are prescribed opioids in a given year.8 Furthermore, veterans are twice as likely as nonveterans to die of an accidental overdose.9 Despite these risks, opioids remain a cornerstone of postoperative pain management both within and outside of the VA.10

In 2018, to limit unnecessary prescribing of opioid pain medication, the total joint service at the VA Portland Health Care System (VAPHCS) in Oregon implemented the Minimizing Opioids after Joint Operation (MOJO) postoperative pain protocol. The goal of the protocol was to reduce opioid use following TKA. The objectives were to provide safe, appropriate analgesia while allowing early mobilization and discharge without a concomitant increase in readmissions or emergency department (ED) visits. The purpose of this retrospective chart review was to compare the efficacy of the MOJO protocol with our historical experience and report our preliminary results.

Methods

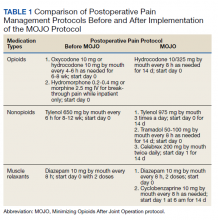

Institutional review board approval was obtained to retrospectively review the medical records of patients who had undergone TKA surgery during 2018 at VAPHCS. The MOJO protocol was composed of several simultaneous changes. The centerpiece of the new protocol was a drastic decrease in routine prescription of postoperative opioids (Table 1). Other changes included instructing patients to reduce the use of preoperative opioid pain medication 6 weeks before surgery with a goal of no opioid consumption, perform daily sets of preoperative exercises, and attend a preoperative consultation/education session with a nurse coordinator to emphasize early recovery and discharge. In patients with chronic use of opioid pain medication (particularly those for whom the medication had been prescribed for other sources of pain, such as lumbar back pain), the goal was daily opioid use of ≤ 30 morphine equivalent doses (MEDs). During the inpatient stay, we stopped prescribing prophylactic pain medication prior to physical therapy (PT).

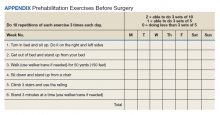

We encouraged preoperative optimization of muscle strength by giving instructions for 4 to 8 weeks of daily exercises (Appendix). We introduced perioperative adductor canal blocks (at the discretion of the anesthesia team) and transitioned to surgery without a tourniquet. Patients in both groups received intraoperative antibiotics and IV tranexamic acid (TXA); the MOJO group also received topical TXA.

Further patient care optimization included providing patients with a team-based approach, which consisted of nurse coordinators, physician assistants and nurse practitioners, residents, and the attending surgeon. Our team reviews the planned pain management protocol, perioperative expectations, criteria for discharge, and anticipated surgical outcomes with the patient during their preoperative visits. On postoperative day 1, these members round as a team to encourage patients in their immediate postoperative recovery and rehabilitation. During rounds, the team assesses whether the patient meets the criteria for discharge, adjusting the pain management protocol if necessary.

Changes in surgical technique included arthrotomy with electrocautery, minimizing traumatic dissection or resection of the synovial tissue, and intra-articular injection of a cocktail of ropivacaine 5 mg/mL 40 mL, epinephrine 1:1,000 0.5 mL, and methylprednisolone sodium 40 mg diluted with normal saline to a total volume of 120 mL.

The new routine was gradually implemented beginning January 2017 and fully implemented by July 2018. This study compared the first 20 consecutive patients undergoing primary TKA after July 2018 to the last 20 consecutive patients undergoing primary TKA prior to January 2017. Exclusion criteria included bilateral TKA, death before 90 days, and revision as the indication for surgery. The senior attending surgeon performed all surgeries using a standard midline approach. The majority of surgeries were performed using a cemented Vanguard total knee system (Zimmer Biomet); 4 patients in the historical group had a NexGen knee system, cementless monoblock tibial components (Zimmer Biomet); and 1 patient had a Logic knee system (Exactech). Surgical selection criteria for patients did not differ between groups.

Electronic health records were reviewed and data were abstracted. The data included demographic information (age, gender, body mass index [BMI], diagnosis, and procedure), surgical factors (American Society of Anesthesiologists score, Risk Assessment and Predictive Tool score, operative time, tourniquet time, estimated blood loss), hospital factors (length of stay [LOS], discharge location), postoperative pain scores (measured on postoperative day 1 and on day of discharge), and postdischarge events (90-day complications, telephone calls reporting pain, reoperations, returns to the ED, 90-day readmissions).

The primary outcome was the mean postoperative daily MED during the inpatient stay. Secondary outcomes included pain on postoperative day 1, pain at the time of discharge, LOS, hospital readmissions, and ED visits within 90 days of surgery. Because different opioid pain medications were used by patients postoperatively, all opioids were converted to MED prior to the final analysis. Collected patient data were de-identified prior to analysis.

Power analysis was conducted to determine whether the study had sufficient population size to reject the null hypothesis for the primary outcome measure. Because practitioners controlled postoperative opioid use, a Cohen’s d of 1.0 was used so that a very large effect size was needed to reach clinical significance. Statistical significance was set to 0.05, and patient groups were set at 20 patients each. This yielded an appropriate power of 0.87. Population characteristics were compared between groups using t tests and χ2 tests as appropriate. To analyze the primary outcome, comparisons were made between the 2 cohorts using 2-tailed t tests. Secondary outcomes were compared between groups using t tests or χ2 tests. All statistics were performed using R version 3.5.2. Power analysis was conducted using the package pwr.11 Statistical significance was set at

Results

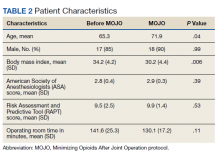

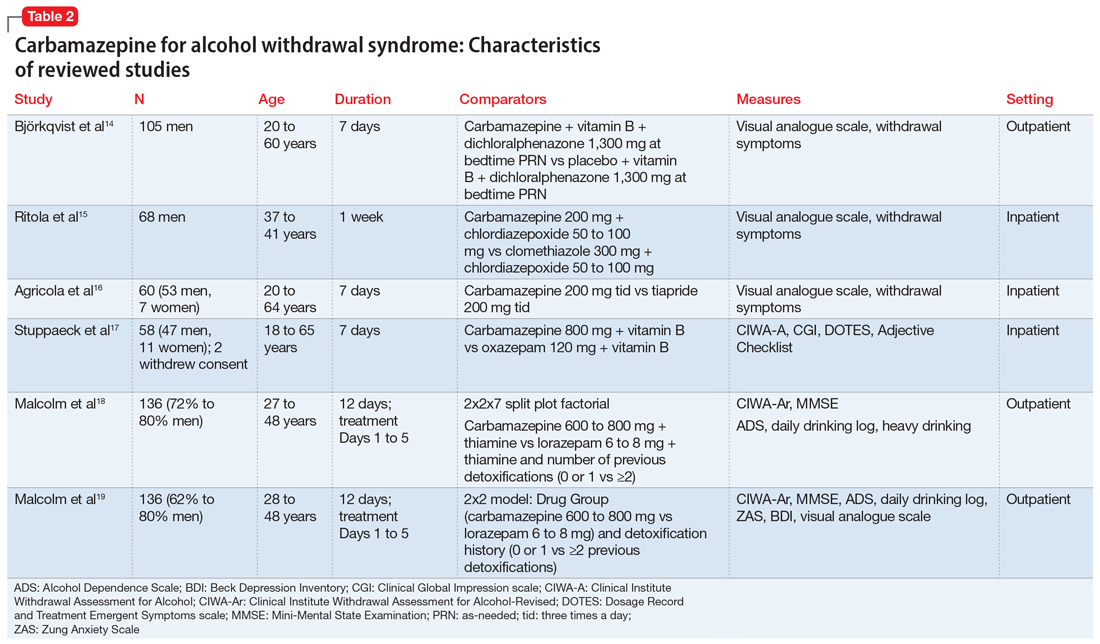

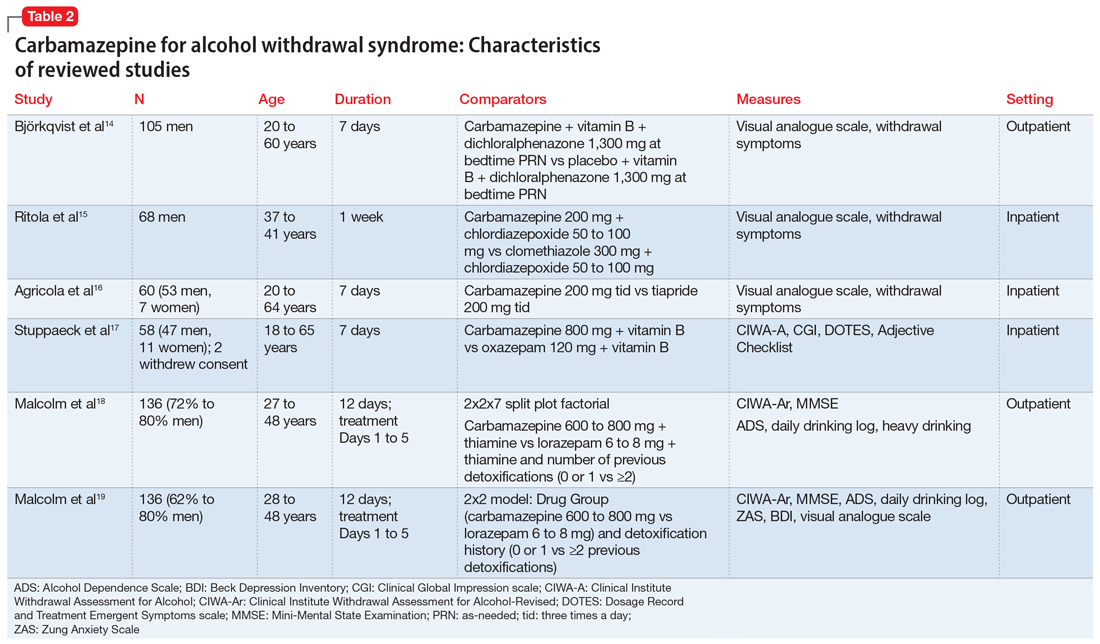

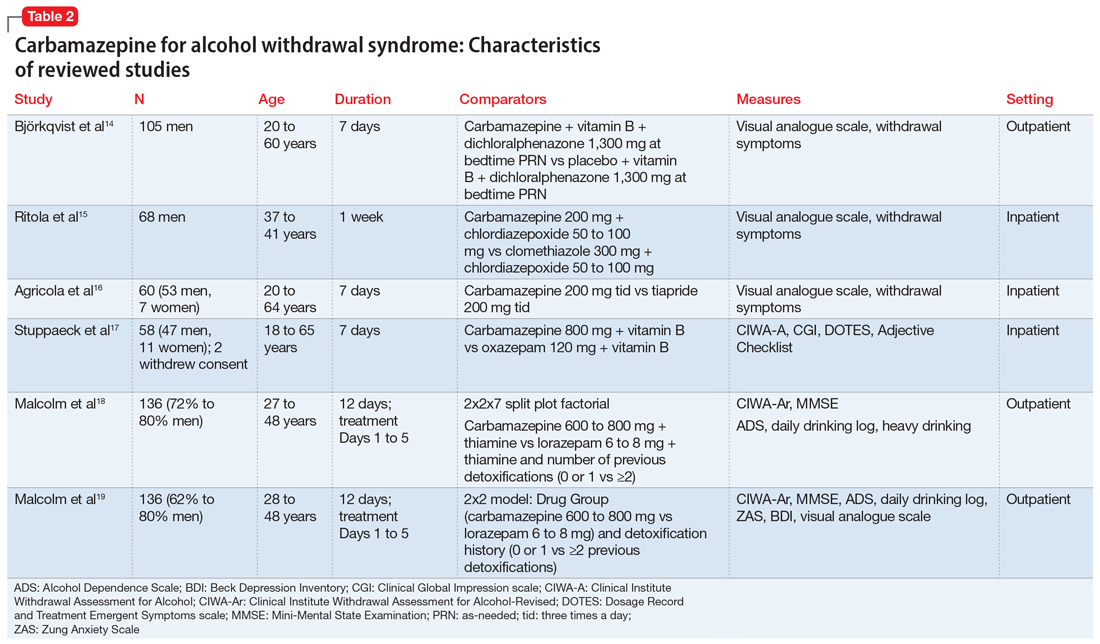

Forty patients met the inclusion criteria, evenly divided between those undergoing TKA before and after instituting the MOJO protocol (Table 2). A single patient in the MOJO group died and was excluded. A patient who underwent bilateral TKA also was excluded. Both groups reflected the male predominance of the VA patient population. MOJO patients tended to have lower BMIs (34 vs 30, P < .01). All patients indicated for surgery with preoperative opioid use were able to titrate down to their preoperative goal as verified by prescriptions filled at VA pharmacies. Twelve of the patients in the MOJO group received adductor canal blocks.

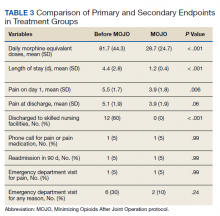

Results of t tests and χ2 tests comparing primary and secondary endpoints are listed in Table 3. Differences between the daily MEDs given in the historical and MOJO groups are shown. There were significant differences between the pre-MOJO and MOJO groups with regard to daily inpatient MEDs (82 mg vs 29 mg, P < .01) and total inpatient MEDs (306 mg vs 32 mg, P < .01). There was less self-reported pain on postoperative day 1 in the MOJO group (5.5 vs 3.9, P < .01), decreased LOS (4.4 days vs 1.2 days, P < .01), a trend toward fewer total ED visits (6 vs 2, P = .24), and fewer discharges to skilled nursing facilities (12 vs 0, P < .01). There were no blood transfusions in either group.

There were no readmissions due to uncontrolled pain. There was 1 readmission for shortness of breath in the MOJO group. The patient was discharged home the following day after ruling out thromboembolic and cardiovascular events. One patient from the control group was readmitted after missing a step on a staircase and falling. The patient sustained a quadriceps tendon rupture and underwent primary suture repair.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that a multimodal approach to significantly reduce postoperative opioid use in patients with TKA is possible without increasing readmissions or ED visits for pain control. The patients in the MOJO group had a faster recovery, earlier discharge, and less use of postoperative opioid medication. Our approach to postoperative pain management was divided into 2 main categories: patient optimization and surgical optimization.

Patient Selection

Besides the standard evaluation and optimization of patients’ medical conditions, identifying and optimizing at-risk patients before surgery was a critical component of our protocol. Managing postoperative pain in patients with prior opioid use is an intractable challenge in orthopedic surgery. Patients with a history of chronic pain and preoperative use of opioid medications remain at higher risk of postoperative chronic pain and persistent use of opioid medication despite no obvious surgical complications.8 In a sample of > 6,000 veterans who underwent TKA at VA hospitals in 2014, 57% of the patients with daily use of opioids in the 90 days before surgery remained on opioids 1 year after surgery (vs 2 % in patients not on long-term opioids).8 This relationship between pre- and postoperative opioid use also was dose dependent.12

Furthermore, those with high preoperative use may experience worse outcomes relative to the opioid naive population as measured by arthritis-specific pain indices.13 In a well-powered retrospective study of patients who underwent elective orthopedic procedures, preoperative opioid abuse or dependence (determined by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision diagnosis) increased inpatient mortality, aggregate morbidity, surgical site infection, myocardial infarction, and LOS.14 Preoperative opioid use also has been associated with increased risk of ED visits, readmission, infection, stiffness, and aseptic revision.15 In patients with TKA in the VA specifically, preoperative opioid use (> 3 months in the prior year) was associated with increased revision rates that were even higher than those for patients with diabetes mellitus.16

Patient Education

Based on this evidence, we instruct patients to reduce their preoperative opioid dosing to zero (for patients with joint pain) or < 30 MED (for patients using opioids for other reasons). Although preoperative reduction of opioid use has been shown to improve outcomes after TKA, pain subspecialty recommendations for patients with chronic opioid use recommend considering adjunctive therapies, including transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, cognitive behavioral therapy, gabapentin, or ketamine.17,18 Through patient education our team has been successful in decreasing preoperative opioid use without adding other drugs or modalities.

Patient Optimization

Preoperative patient optimization included 4 to 8 weeks of daily sets of physical activity instructions (prehab) to improve the musculoskeletal function. These instructions are given to patients 4 to 8 weeks before surgery and aim to improve the patient’s balance, mobility, and functional ability (Appendix). Meta-analysis has shown that patients who undergo preoperative PT have a small but statistically significant decrease in postoperative pain at 4 weeks, though this does not persist beyond that period.19

We did note a lower BMI in patients in the MOJO group. Though this has the potential to be a confounder, a study of BMI in > 4,000 patients who underwent joint replacement surgery has shown that BMI is not associated with differences in postoperative pain.20

Surgeon and Surgical-Related Variables

Patients in the MOJO group had increased use of adductor canal blocks. A 2017 meta-analysis of 12,530 patients comparing analgesic modalities found that peripheral nerve blocks targeting multiple nerves (eg, femoral/sciatic) decreased pain at rest, decreased opioid consumption, and improved range of motion postoperatively.21 Also, these were found to be superior to single nerve blocks, periarticular infiltration, and epidural blocks.21 However, major nerve and epidural blocks affecting the lower extremity may increase the risk of falls and prolong LOS.22,23 The preferred peripheral block at VAPHCS is a single shot ultrasound-guided adductor canal block before the induction of general or spinal anesthesia. A randomized controlled trial has demonstrated superiority of this block to the femoral nerve block with regard to postoperative quadriceps strength, conferring the theoretical advantage of decreased fall risk and ability to participate in immediate PT.24 Although we are unable to confirm an association between anesthetic modalities and opioid burden, our clinical impression is that blocks were effective at reducing immediate postoperative pain. However, among MOJO patients there were no differences in patients with and without blocks for either pain (4.2 vs 3.8, P = .69) or opioid consumption (28.8 vs 33.0, P = .72) after surgery, though our study was not powered to detect a difference in this restricted subgroup.

Patients who frequently had reported postoperative thigh pain prompted us to make changes in our surgical technique, performing TKA without use of a tourniquet. Tourniquet use has been associated with an increased risk of thigh pain after TKA by multiple authors.25,26 Postoperative thigh pain also is pressure dependent.27 In addition, its use may be associated with a slightly increased risk of thromboembolic events and delayed functional recovery.28,29

Because postoperative hemarthrosis is associated with more pain and reduced joint recovery function, we used topical TXA to reduce postoperative surgical site and joint hematoma. TXA (either oral, IV, or topical) during TKA is used to control postoperative bleeding primarily and decrease the need for transfusion without concomitant increase in thromboembolic events.30,31 Topical TXA may be more effective than IV, particularly in the immediate postoperative period.32 Although pain typically is not an endpoint in studies of TXA, a prospective study of 48 patients showed evidence that its use may be associated with decreased postoperative pain in the first 24 hours after surgery (though not after).33 Finally, the use of intra-articular injection has evolved in our clinical practice, but literature is lacking with regard to its efficacy; more studies are needed to determine its effect relative to no injection. We have not seen any benefits to using

Limitations

This is a nonrandomized retrospective single-institution study. Our study population is composed of mostly males with military experience and is not necessarily a representative sample of the general population eligible for joint arthroplasty. Our primary endpoint (reduction of opioid use postoperatively) also was a cornerstone of our intervention. To account for this, we set a very large effect size in our power analysis and evaluated multiple secondary endpoints to determine whether postoperative pain remained well controlled and complications/readmission minimized with our interventions. Because our intervention was multimodal, our study cannot make conclusions about the effect of a particular component of our treatment strategy. We did not measure or compare functional outcomes between both groups, which offers an opportunity for further research.

These limitations are balanced by several strengths. Our cohort was well controlled with respect to the dose and type of drug used. There is staff dedicated to postoperative telephone follow-up after discharge, and veterans are apt to seek care within the VA health care system, which improves case finding for complications and ED visits. No patients were lost to follow-up. Moreover, our drastic reduction in opioid use is promising enough to warrant reporting, while the broader orthopedic literature explores the relative impact of each variable.

Conclusions

The MOJO protocol has been effective for reducing postoperative opioid use after TKA without compromising effective pain management. The drastic reduction in the postoperative use of opioid pain medications and LOS have contributed to a cultural shift within our department, comprehensive team approach, multimodal pain management, and preoperative patient optimization. Further investigations are required to assess the impact of each intervention on observed outcomes. However, the framework and routines are applicable to other institutions and surgical specialties.

Acknowledgments

The authors recognize Derek Bond, MD, for his help in creating the MOJO acronym.

1. Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2017. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief No. 329. Published November 2018. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db329-h.pdf

2. Hedegaard H, Warner M, Miniño AM. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2016. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics NCHS data brief No. 294. Published December 2017. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db294.pdf

3. Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic–prescribing rates by specialty, U.S., 2007-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):409-413. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.020

4. Guy GP, Zhang K. Opioid prescribing by specialty and volume in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(5):e153-155. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.06.008

5. Kremers HM, Larson DR, Crowson CS, et al. Prevalence of total hip and knee replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surgery Am. 2015;17:1386-1397. doi:10.2106/JBJS.N.01141

6. Giori NJ, Amanatullah DF, Gupta S, Bowe T, Harris AHS. Risk reduction compared with access to care: quantifying the trade-off of enforcing a body mass index eligibility criterion for joint replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018; 4(100):539-545. doi:10.2106/JBJS.17.00120

7. Sabatino MJ, Kunkel ST, Ramkumar DB, Keeney BJ, Jevsevar DS. Excess opioid medication and variation in prescribing patterns following common orthopaedic procedures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(3):180-188. doi:10.2106/JBJS.17.00672

8. Hadlandsmyth K, Vander Weg MW, McCoy KD, Mosher HJ, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Lund BC. Risk for prolonged opioid use following total knee arthroplasty in veterans. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(1):119-123. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.08.022

9. Bohnert ASB, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1315-1321. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.370

10. Hall MJ, Schwartzman A, Zhang J, Liu X. Ambulatory surgery data from hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers: United States, 2010. Natl Health Stat Report. 2017(102):1-15.

11. Champely S. pwr: basic functions for power analysis. R package version 1.2-2; 2018. Accessed January 13, 2021. https://rdrr.io/cran/pwr/

12. Goesling J, Moser SE, Zaidi B, et al. Trends and predictors of opioid use after total knee and total hip arthroplasty. Pain. 2016;157(6):1259-1265. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000516

13. Smith SR, Bido J, Collins JE, Yang H, Katz JN, Losina E. Impact of preoperative opioid use on total knee arthroplasty outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(10):803-808. doi:10.2106/JBJS.16.01200

14. Menendez ME, Ring D, Bateman BT. Preoperative opioid misuse is associated with increased morbidity and mortality after elective orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(7):2402-412. doi:10.1007/s11999-015-4173-5

15. Cancienne JM, Patel KJ, Browne JA, Werner BC. Narcotic use and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(1):113-118. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.08.006

16. Ben-Ari A, Chansky H, Rozet I. Preoperative opioid use is associated with early revision after total knee arthroplasty: a study of male patients treated in the Veterans Affairs System. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(1):1-9. doi:10.2106/JBJS.16.00167

17. Nguyen L-CL, Sing DC, Bozic KJ. Preoperative reduction of opioid use before total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(suppl 9):282-287. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2016.01.068

18. Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131-157. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008

19. Wang L, Lee M, Zhang Z, Moodie J, Cheng D, Martin J. Does preoperative rehabilitation for patients planning to undergo joint replacement surgery improve outcomes? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e009857. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009857

20. Li W, Ayers DC, Lewis CG, Bowen TR, Allison JJ, Franklin PD. Functional gain and pain relief after total joint replacement according to obesity status. J Bone Joint Surg. 2017;99(14):1183-1189. doi:10.2106/JBJS.16.00960

21. Terkawi AS, Mavridis D, Sessler DI, et al. Pain management modalities after total knee arthroplasty: a network meta-analysis of 170 randomized controlled trials. Anesthesiology. 2017;126(5):923-937. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000001607

22. Ilfeld BM, Duke KB, Donohue MC. The association between lower extremity continuous peripheral nerve blocks and patient falls after knee and hip arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 2010;111(6):1552-1554. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181fb9507

23. Elkassabany NM, Antosh S, Ahmed M, et al. The risk of falls after total knee arthroplasty with the use of a femoral nerve block versus an adductor canal block. Anest Analg. 2016;122(5):1696-1703. doi:10.1213/ane.0000000000001237

24. Wang D, Yang Y, Li Q, et al. Adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block for total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40721. doi:10.1038/srep40721

25. Liu D, Graham D, Gillies K, Gillies RM. Effects of tourniquet use on quadriceps function and pain in total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2014;26(4):207-213. doi:10.5792/ksrr.2014.26.4.207

26. Abdel-Salam A, Eyres KS. Effects of tourniquet during total knee arthroplasty. A prospective randomised study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77(2):250-253.

27. Worland RL, Arredondo J, Angles F, Lopez-Jimenez F, Jessup DE. Thigh pain following tourniquet application in simultaneous bilateral total knee replacement arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12(8):848-852. doi:10.1016/s0883-5403(97)90153-4

28. Tai T-W, Lin C-J, Jou I-M, Chang C-W, Lai K-A, Yang C-Y. Tourniquet use in total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol, Arthrosc. 2011;19(7):1121-1130. doi:10.1007/s00167-010-1342-7

29. Jiang F-Z, Zhong H-M, Hong Y-C, Zhao G-F. Use of a tourniquet in total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Orthop Sci. 2015;20(21):110-123. doi:10.1007/s00776-014-0664-6

30. Alshryda S, Sarda P, Sukeik M, Nargol A, Blenkinsopp J, Mason JM. Tranexamic acid in total knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(12):1577-1585. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.93B12.26989

31. Panteli M, Papakostidis C, Dahabreh Z, Giannoudis PV. Topical tranexamic acid in total knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee. 2013;20(5):300-309. doi:10.1016/j.knee.2013.05.014

32. Wang J, Wang Q, Zhang X, Wang Q. Intra-articular application is more effective than intravenous application of tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(11):3385-3389. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.06.024

33. Guerreiro JPF, Badaro BS, Balbino JRM, Danieli MV, Queiroz AO, Cataneo DC. Application of tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty – prospective randomized trial. J Open Orthop J. 2017;11:1049-1057. doi:10.2174/1874325001711011049