User login

Antipsychotic shows benefit for Alzheimer’s agitation

SAN FRANCISCO – In a widely anticipated report,

Members of a panel of dementia specialists here at the 15th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference said that the results were encouraging. But they also noted that the available data make it difficult to understand the impact of the drug on the day-to-day life on patients.

“I’d like to be able to translate that into something else to understand the risk benefit calculus,” said neurologist and neuroscientist Alireza Atri, MD, PhD, of Banner Sun Health Research Institute in Phoenix. “How does it affect the patients themselves, their quality of life, and the family members and their burden?”

Currently, there’s no Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for agitation in AD.

In 2015, the FDA approved brexpiprazole, an oral medication, as a treatment for schizophrenia and an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD). It is an expensive drug with an average retail price per GoodRx of $1,582 per month, and no generic is available.

Researchers released the results of a trio of phase 3 clinical trials at CTAD that examined various doses of brexpiprazole. The results of the first two trials had been released earlier in 2018.

Three trials

All trials were multicenter, 12-week, randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled.

Study participants were aged 55-90 years, had probable AD diagnoses, and had agitation per various scales. The average age in the groups was 74 years, 56.0%-61.7% were women, and 94.3%-98.1% were White.

The first trial examined two fixed doses (1 mg/d, n = 137; and 2 mg/d, n = 140) or placebo (n = 136). “The study initially included a 0.5 mg/day arm,” the researchers reported, “which was removed in a protocol amendment, and patients randomized to that arm were not included in efficacy analyses.”

The second trial looked at a flexible dose (0.5-2 mg/d, n = 133) or placebo (n = 137).

In a CTAD presentation, Nanco Hefting of Lundbeck, a codeveloper of the drug, said that the researchers learned from the first two trials that 2 mg/d might be an appropriate dose, and the FDA recommended they also examine 3 mg/day. As a result, the third trial examined two fixed doses (2 mg/d, n = 75; 3 mg/d, n = 153; or placebo, n = 117).

In the third trial, both the placebo and drug groups improved per a measurement of agitation; those in the drug group improved somewhat more.

The mean change in baseline on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory scale – the primary endpoint – was –5.32 for the 2-mg/d and 3-mg/d groups vs. placebo (P = .0026); the score in the placebo group fell by about 18 and by about 22 in the drug group.

The key secondary endpoint was an improvement from baseline to week 12 in the Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI-S) score related to agitation. Compared with the placebo group, this score was –0.27 in the drug group (P = .0078). Both scores hovered around –1.0.

Safety data show the percentage of treatment-emergent events ranged from 45.9% in the placebo group to 49.0%-56.8% for brexpiprazole in the three trials. The percentage of these events leading to discontinuation was 6.3% among those receiving the drug and 3.4% in the placebo group.

University of Exeter dementia researcher Clive Ballard, MD, MB ChB, one of the panelists who discussed the research after the CTAD presentation, praised the trials as “well-conducted” and said that he was pleased that subjects in institutions were included. “It’s not an easy environment to do trials in. They should be really commended for doing for doing that.”

But he echoed fellow panelist Dr. Atri by noting that more data are needed to understand how well the drug works. “I would like to see the effect sizes and a little bit more detail to understand the clinical meaningfulness of that level of benefit.”

What’s next? A spokeswoman for Otsuka, a codeveloper of brexpiprazole, said that it hopes to hear in 2023 about a supplemental new drug application that was filed in November 2022.

Otsuka and Lundbeck funded the research. Mr. Hefting is an employee of Lundbeck, and several other authors work for Lundbeck or Otsuka. The single non-employee author reports various disclosures. Disclosures for Dr. Atri and Dr. Ballard were not provided.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN FRANCISCO – In a widely anticipated report,

Members of a panel of dementia specialists here at the 15th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference said that the results were encouraging. But they also noted that the available data make it difficult to understand the impact of the drug on the day-to-day life on patients.

“I’d like to be able to translate that into something else to understand the risk benefit calculus,” said neurologist and neuroscientist Alireza Atri, MD, PhD, of Banner Sun Health Research Institute in Phoenix. “How does it affect the patients themselves, their quality of life, and the family members and their burden?”

Currently, there’s no Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for agitation in AD.

In 2015, the FDA approved brexpiprazole, an oral medication, as a treatment for schizophrenia and an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD). It is an expensive drug with an average retail price per GoodRx of $1,582 per month, and no generic is available.

Researchers released the results of a trio of phase 3 clinical trials at CTAD that examined various doses of brexpiprazole. The results of the first two trials had been released earlier in 2018.

Three trials

All trials were multicenter, 12-week, randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled.

Study participants were aged 55-90 years, had probable AD diagnoses, and had agitation per various scales. The average age in the groups was 74 years, 56.0%-61.7% were women, and 94.3%-98.1% were White.

The first trial examined two fixed doses (1 mg/d, n = 137; and 2 mg/d, n = 140) or placebo (n = 136). “The study initially included a 0.5 mg/day arm,” the researchers reported, “which was removed in a protocol amendment, and patients randomized to that arm were not included in efficacy analyses.”

The second trial looked at a flexible dose (0.5-2 mg/d, n = 133) or placebo (n = 137).

In a CTAD presentation, Nanco Hefting of Lundbeck, a codeveloper of the drug, said that the researchers learned from the first two trials that 2 mg/d might be an appropriate dose, and the FDA recommended they also examine 3 mg/day. As a result, the third trial examined two fixed doses (2 mg/d, n = 75; 3 mg/d, n = 153; or placebo, n = 117).

In the third trial, both the placebo and drug groups improved per a measurement of agitation; those in the drug group improved somewhat more.

The mean change in baseline on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory scale – the primary endpoint – was –5.32 for the 2-mg/d and 3-mg/d groups vs. placebo (P = .0026); the score in the placebo group fell by about 18 and by about 22 in the drug group.

The key secondary endpoint was an improvement from baseline to week 12 in the Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI-S) score related to agitation. Compared with the placebo group, this score was –0.27 in the drug group (P = .0078). Both scores hovered around –1.0.

Safety data show the percentage of treatment-emergent events ranged from 45.9% in the placebo group to 49.0%-56.8% for brexpiprazole in the three trials. The percentage of these events leading to discontinuation was 6.3% among those receiving the drug and 3.4% in the placebo group.

University of Exeter dementia researcher Clive Ballard, MD, MB ChB, one of the panelists who discussed the research after the CTAD presentation, praised the trials as “well-conducted” and said that he was pleased that subjects in institutions were included. “It’s not an easy environment to do trials in. They should be really commended for doing for doing that.”

But he echoed fellow panelist Dr. Atri by noting that more data are needed to understand how well the drug works. “I would like to see the effect sizes and a little bit more detail to understand the clinical meaningfulness of that level of benefit.”

What’s next? A spokeswoman for Otsuka, a codeveloper of brexpiprazole, said that it hopes to hear in 2023 about a supplemental new drug application that was filed in November 2022.

Otsuka and Lundbeck funded the research. Mr. Hefting is an employee of Lundbeck, and several other authors work for Lundbeck or Otsuka. The single non-employee author reports various disclosures. Disclosures for Dr. Atri and Dr. Ballard were not provided.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN FRANCISCO – In a widely anticipated report,

Members of a panel of dementia specialists here at the 15th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference said that the results were encouraging. But they also noted that the available data make it difficult to understand the impact of the drug on the day-to-day life on patients.

“I’d like to be able to translate that into something else to understand the risk benefit calculus,” said neurologist and neuroscientist Alireza Atri, MD, PhD, of Banner Sun Health Research Institute in Phoenix. “How does it affect the patients themselves, their quality of life, and the family members and their burden?”

Currently, there’s no Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for agitation in AD.

In 2015, the FDA approved brexpiprazole, an oral medication, as a treatment for schizophrenia and an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD). It is an expensive drug with an average retail price per GoodRx of $1,582 per month, and no generic is available.

Researchers released the results of a trio of phase 3 clinical trials at CTAD that examined various doses of brexpiprazole. The results of the first two trials had been released earlier in 2018.

Three trials

All trials were multicenter, 12-week, randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled.

Study participants were aged 55-90 years, had probable AD diagnoses, and had agitation per various scales. The average age in the groups was 74 years, 56.0%-61.7% were women, and 94.3%-98.1% were White.

The first trial examined two fixed doses (1 mg/d, n = 137; and 2 mg/d, n = 140) or placebo (n = 136). “The study initially included a 0.5 mg/day arm,” the researchers reported, “which was removed in a protocol amendment, and patients randomized to that arm were not included in efficacy analyses.”

The second trial looked at a flexible dose (0.5-2 mg/d, n = 133) or placebo (n = 137).

In a CTAD presentation, Nanco Hefting of Lundbeck, a codeveloper of the drug, said that the researchers learned from the first two trials that 2 mg/d might be an appropriate dose, and the FDA recommended they also examine 3 mg/day. As a result, the third trial examined two fixed doses (2 mg/d, n = 75; 3 mg/d, n = 153; or placebo, n = 117).

In the third trial, both the placebo and drug groups improved per a measurement of agitation; those in the drug group improved somewhat more.

The mean change in baseline on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory scale – the primary endpoint – was –5.32 for the 2-mg/d and 3-mg/d groups vs. placebo (P = .0026); the score in the placebo group fell by about 18 and by about 22 in the drug group.

The key secondary endpoint was an improvement from baseline to week 12 in the Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI-S) score related to agitation. Compared with the placebo group, this score was –0.27 in the drug group (P = .0078). Both scores hovered around –1.0.

Safety data show the percentage of treatment-emergent events ranged from 45.9% in the placebo group to 49.0%-56.8% for brexpiprazole in the three trials. The percentage of these events leading to discontinuation was 6.3% among those receiving the drug and 3.4% in the placebo group.

University of Exeter dementia researcher Clive Ballard, MD, MB ChB, one of the panelists who discussed the research after the CTAD presentation, praised the trials as “well-conducted” and said that he was pleased that subjects in institutions were included. “It’s not an easy environment to do trials in. They should be really commended for doing for doing that.”

But he echoed fellow panelist Dr. Atri by noting that more data are needed to understand how well the drug works. “I would like to see the effect sizes and a little bit more detail to understand the clinical meaningfulness of that level of benefit.”

What’s next? A spokeswoman for Otsuka, a codeveloper of brexpiprazole, said that it hopes to hear in 2023 about a supplemental new drug application that was filed in November 2022.

Otsuka and Lundbeck funded the research. Mr. Hefting is an employee of Lundbeck, and several other authors work for Lundbeck or Otsuka. The single non-employee author reports various disclosures. Disclosures for Dr. Atri and Dr. Ballard were not provided.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT CTAD 2022

Mindfulness, exercise strike out in memory trial

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

We are coming to the end of the year, which always makes me think about getting older. Much like the search for the fountain of youth, many promising leads have ultimately led to dead ends. And yet, I had high hopes for a trial that focused on two cornerstones of wellness – exercise and mindfulness – to address the subjective loss of memory that comes with aging. Alas, meditation and exercise do not appear to be the fountain of youth.

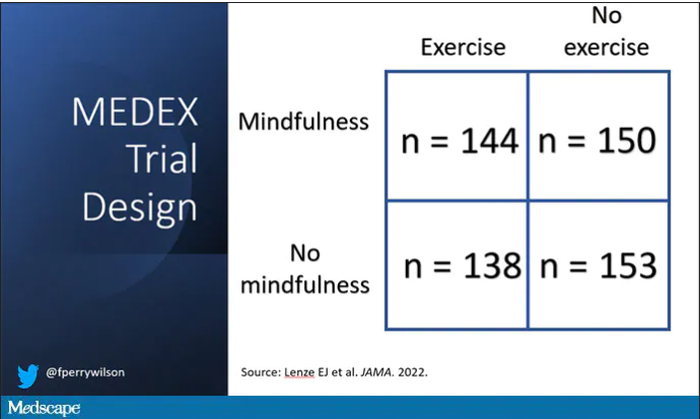

I’m talking about this study, appearing in JAMA, known as the MEDEX trial.

It’s a clever design: a 2 x 2 factorial randomized trial where participants could be randomized to a mindfulness intervention, an exercise intervention, both, or neither.

In this manner, you can test multiple hypotheses exploiting a shared control group. Or as a mentor of mine used to say, you get two trials for the price of one and a half.

The participants were older adults, aged 65-84, living in the community. They had to be relatively sedentary at baseline and not engaging in mindfulness practices. They had to subjectively report some memory or concentration issues but had to be cognitively intact, based on a standard dementia screening test. In other words, these are your average older people who are worried that they aren’t as sharp as they used to be.

The interventions themselves were fairly intense. The exercise group had instructor-led sessions for 90 minutes twice a week for the first 6 months of the study, once a week thereafter. And participants were encouraged to exercise at home such that they had a total of 300 minutes of weekly exercise.

The mindfulness program was characterized by eight weekly classes of 2.5 hours each as well as a half-day retreat to teach the tenets of mindfulness and meditation, with monthly refreshers thereafter. Participants were instructed to meditate for 60 minutes a day in addition to the classes.

For the 144 people who were randomized to both meditation and exercise, this trial amounted to something of a part-time job. So you might think that adherence to the interventions was low, but apparently that’s not the case. Attendance to the mindfulness classes was over 90%, and over 80% for the exercise classes. And diary-based reporting of home efforts was also pretty good.

The control group wasn’t left to their own devices. Recognizing that the community aspect of exercise or mindfulness classes might convey a benefit independent of the actual exercise or mindfulness, the control group met on a similar schedule to discuss health education, but no mention of exercise or mindfulness occurred in that setting.

The primary outcome was change in memory and executive function scores across a battery of neuropsychologic testing, but the story is told in just a few pictures.

Memory scores improved in all three groups – mindfulness, exercise, and health education – over time. Cognitive composite score improved in all three groups similarly. There was no synergistic effect of mindfulness and exercise either. Basically, everyone got a bit better.

But the study did way more than look at scores on tests. Researchers used MRI to measure brain anatomic outcomes as well. And the surprising thing is that virtually none of these outcomes were different between the groups either.

Hippocampal volume decreased a bit in all the groups. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex volume was flat. There was no change in scores measuring tasks of daily living.

When you see negative results like this, right away you worry that the intervention wasn’t properly delivered. Were these people really exercising and meditating? Well, the authors showed that individuals randomized to exercise, at least, had less sleep latency, greater aerobic fitness, and greater strength. So we know something was happening.

They then asked, would the people in the exercise group with the greatest changes in those physiologic parameters show some improvement in cognitive parameters? In other words, we know you were exercising because you got stronger and are sleeping better; is your memory better? The answer? Surprisingly, still no. Even in that honestly somewhat cherry-picked group, the interventions had no effect.

Could it be that the control was inappropriate, that the “health education” intervention was actually so helpful that it obscured the benefits of exercise and meditation? After all, cognitive scores did improve in all groups. The authors doubt it. They say they think the improvement in cognitive scores reflects the fact that patients had learned a bit about how to take the tests. This is pretty common in the neuropsychiatric literature.

So here we are and I just want to say, well, shoot. This is not the result I wanted. And I think the reason I’m so disappointed is because aging and the loss of cognitive faculties that comes with aging are just sort of scary. We are all looking for some control over that fear, and how nice it would be to be able to tell ourselves not to worry – that we won’t have those problems as we get older because we exercise, or meditate, or drink red wine, or don’t drink wine, or whatever. And while I have no doubt that staying healthier physically will keep you healthier mentally, it may take more than one simple thing to move the needle.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

We are coming to the end of the year, which always makes me think about getting older. Much like the search for the fountain of youth, many promising leads have ultimately led to dead ends. And yet, I had high hopes for a trial that focused on two cornerstones of wellness – exercise and mindfulness – to address the subjective loss of memory that comes with aging. Alas, meditation and exercise do not appear to be the fountain of youth.

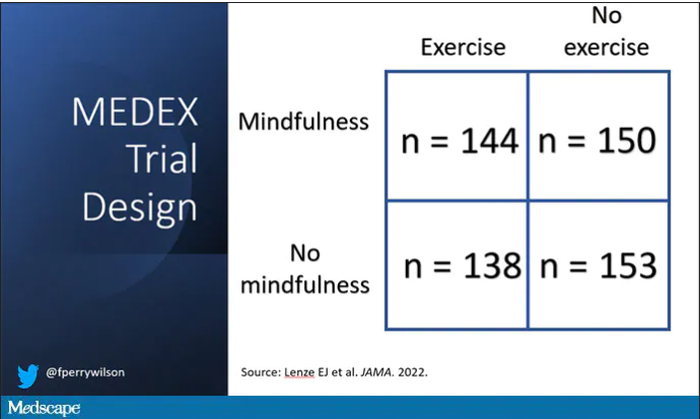

I’m talking about this study, appearing in JAMA, known as the MEDEX trial.

It’s a clever design: a 2 x 2 factorial randomized trial where participants could be randomized to a mindfulness intervention, an exercise intervention, both, or neither.

In this manner, you can test multiple hypotheses exploiting a shared control group. Or as a mentor of mine used to say, you get two trials for the price of one and a half.

The participants were older adults, aged 65-84, living in the community. They had to be relatively sedentary at baseline and not engaging in mindfulness practices. They had to subjectively report some memory or concentration issues but had to be cognitively intact, based on a standard dementia screening test. In other words, these are your average older people who are worried that they aren’t as sharp as they used to be.

The interventions themselves were fairly intense. The exercise group had instructor-led sessions for 90 minutes twice a week for the first 6 months of the study, once a week thereafter. And participants were encouraged to exercise at home such that they had a total of 300 minutes of weekly exercise.

The mindfulness program was characterized by eight weekly classes of 2.5 hours each as well as a half-day retreat to teach the tenets of mindfulness and meditation, with monthly refreshers thereafter. Participants were instructed to meditate for 60 minutes a day in addition to the classes.

For the 144 people who were randomized to both meditation and exercise, this trial amounted to something of a part-time job. So you might think that adherence to the interventions was low, but apparently that’s not the case. Attendance to the mindfulness classes was over 90%, and over 80% for the exercise classes. And diary-based reporting of home efforts was also pretty good.

The control group wasn’t left to their own devices. Recognizing that the community aspect of exercise or mindfulness classes might convey a benefit independent of the actual exercise or mindfulness, the control group met on a similar schedule to discuss health education, but no mention of exercise or mindfulness occurred in that setting.

The primary outcome was change in memory and executive function scores across a battery of neuropsychologic testing, but the story is told in just a few pictures.

Memory scores improved in all three groups – mindfulness, exercise, and health education – over time. Cognitive composite score improved in all three groups similarly. There was no synergistic effect of mindfulness and exercise either. Basically, everyone got a bit better.

But the study did way more than look at scores on tests. Researchers used MRI to measure brain anatomic outcomes as well. And the surprising thing is that virtually none of these outcomes were different between the groups either.

Hippocampal volume decreased a bit in all the groups. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex volume was flat. There was no change in scores measuring tasks of daily living.

When you see negative results like this, right away you worry that the intervention wasn’t properly delivered. Were these people really exercising and meditating? Well, the authors showed that individuals randomized to exercise, at least, had less sleep latency, greater aerobic fitness, and greater strength. So we know something was happening.

They then asked, would the people in the exercise group with the greatest changes in those physiologic parameters show some improvement in cognitive parameters? In other words, we know you were exercising because you got stronger and are sleeping better; is your memory better? The answer? Surprisingly, still no. Even in that honestly somewhat cherry-picked group, the interventions had no effect.

Could it be that the control was inappropriate, that the “health education” intervention was actually so helpful that it obscured the benefits of exercise and meditation? After all, cognitive scores did improve in all groups. The authors doubt it. They say they think the improvement in cognitive scores reflects the fact that patients had learned a bit about how to take the tests. This is pretty common in the neuropsychiatric literature.

So here we are and I just want to say, well, shoot. This is not the result I wanted. And I think the reason I’m so disappointed is because aging and the loss of cognitive faculties that comes with aging are just sort of scary. We are all looking for some control over that fear, and how nice it would be to be able to tell ourselves not to worry – that we won’t have those problems as we get older because we exercise, or meditate, or drink red wine, or don’t drink wine, or whatever. And while I have no doubt that staying healthier physically will keep you healthier mentally, it may take more than one simple thing to move the needle.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

We are coming to the end of the year, which always makes me think about getting older. Much like the search for the fountain of youth, many promising leads have ultimately led to dead ends. And yet, I had high hopes for a trial that focused on two cornerstones of wellness – exercise and mindfulness – to address the subjective loss of memory that comes with aging. Alas, meditation and exercise do not appear to be the fountain of youth.

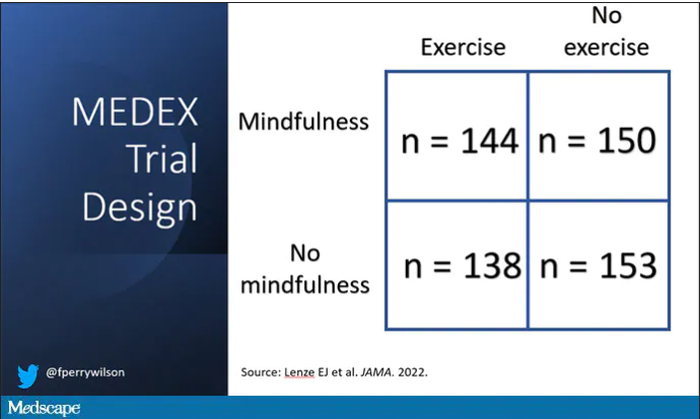

I’m talking about this study, appearing in JAMA, known as the MEDEX trial.

It’s a clever design: a 2 x 2 factorial randomized trial where participants could be randomized to a mindfulness intervention, an exercise intervention, both, or neither.

In this manner, you can test multiple hypotheses exploiting a shared control group. Or as a mentor of mine used to say, you get two trials for the price of one and a half.

The participants were older adults, aged 65-84, living in the community. They had to be relatively sedentary at baseline and not engaging in mindfulness practices. They had to subjectively report some memory or concentration issues but had to be cognitively intact, based on a standard dementia screening test. In other words, these are your average older people who are worried that they aren’t as sharp as they used to be.

The interventions themselves were fairly intense. The exercise group had instructor-led sessions for 90 minutes twice a week for the first 6 months of the study, once a week thereafter. And participants were encouraged to exercise at home such that they had a total of 300 minutes of weekly exercise.

The mindfulness program was characterized by eight weekly classes of 2.5 hours each as well as a half-day retreat to teach the tenets of mindfulness and meditation, with monthly refreshers thereafter. Participants were instructed to meditate for 60 minutes a day in addition to the classes.

For the 144 people who were randomized to both meditation and exercise, this trial amounted to something of a part-time job. So you might think that adherence to the interventions was low, but apparently that’s not the case. Attendance to the mindfulness classes was over 90%, and over 80% for the exercise classes. And diary-based reporting of home efforts was also pretty good.

The control group wasn’t left to their own devices. Recognizing that the community aspect of exercise or mindfulness classes might convey a benefit independent of the actual exercise or mindfulness, the control group met on a similar schedule to discuss health education, but no mention of exercise or mindfulness occurred in that setting.

The primary outcome was change in memory and executive function scores across a battery of neuropsychologic testing, but the story is told in just a few pictures.

Memory scores improved in all three groups – mindfulness, exercise, and health education – over time. Cognitive composite score improved in all three groups similarly. There was no synergistic effect of mindfulness and exercise either. Basically, everyone got a bit better.

But the study did way more than look at scores on tests. Researchers used MRI to measure brain anatomic outcomes as well. And the surprising thing is that virtually none of these outcomes were different between the groups either.

Hippocampal volume decreased a bit in all the groups. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex volume was flat. There was no change in scores measuring tasks of daily living.

When you see negative results like this, right away you worry that the intervention wasn’t properly delivered. Were these people really exercising and meditating? Well, the authors showed that individuals randomized to exercise, at least, had less sleep latency, greater aerobic fitness, and greater strength. So we know something was happening.

They then asked, would the people in the exercise group with the greatest changes in those physiologic parameters show some improvement in cognitive parameters? In other words, we know you were exercising because you got stronger and are sleeping better; is your memory better? The answer? Surprisingly, still no. Even in that honestly somewhat cherry-picked group, the interventions had no effect.

Could it be that the control was inappropriate, that the “health education” intervention was actually so helpful that it obscured the benefits of exercise and meditation? After all, cognitive scores did improve in all groups. The authors doubt it. They say they think the improvement in cognitive scores reflects the fact that patients had learned a bit about how to take the tests. This is pretty common in the neuropsychiatric literature.

So here we are and I just want to say, well, shoot. This is not the result I wanted. And I think the reason I’m so disappointed is because aging and the loss of cognitive faculties that comes with aging are just sort of scary. We are all looking for some control over that fear, and how nice it would be to be able to tell ourselves not to worry – that we won’t have those problems as we get older because we exercise, or meditate, or drink red wine, or don’t drink wine, or whatever. And while I have no doubt that staying healthier physically will keep you healthier mentally, it may take more than one simple thing to move the needle.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Noninvasive laser therapy tied to improved short-term memory

Investigators compared the effect of 1,064 nm of tPBM delivered over a 12-minute session to the right PFC vs. three other treatment arms: delivery of the same intervention to the left PFC, delivery of the intervention at a lower frequency, and a sham intervention.

All participants were shown a series of items prior to the intervention and asked to recall them after the intervention. Those who received tPBM 1,064 nm to the right PFC showed a superior performance of up to 25% in the memory tasks compared with the other groups.

Patients with attention-related conditions, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, “could benefit from this type of treatment, which is safe, simple, and noninvasive, with no side effects,” coinvestigator Dongwei Li, a visiting PhD student at the Centre for Human Brain Health, University of Birmingham, England, said in a news release.

The findings were published online in Science Advances.

Differing wavelengths

The researchers note that “in the past decades,” noninvasive brain stimulation technology using transcranial application of direct or alternating electrical or magnetic fields “has been proven to be useful” in the improvement of working memory (WM).

When applied to the right PFC, tPBM has been shown to improve accuracy and speed of reaction time in WM tasks and improvements in “high-order cognitive functions,” such as sustained attention, emotion, and executive functions.

The investigators wanted to assess the impact of tPBM applied to different parts of the brain and at different wavelengths. They conducted four double-blind, sham-controlled experiments encompassing 90 neurotypical college students (mean age, 22 years). Each student participated in only one of the four experiments.

All completed two different tPBM sessions, separated by a week, in which sham and active tPBM were compared. Two different types of change-detection memory tasks were given: one requiring participants to remember the orientation of a series of items before and after the intervention and one other requiring them to remember the color of the items (experiments 1 and 2).

A series of follow-up experiments focused on comparing different wavelengths (1,064 nm vs. 852 nm) and different stimulation sites (right vs. left PFC; experiments 3 and 4).

EEG recordings were obtained during the intervention and the memory tasks.

Each experiment consisted of one active tPBM session and one sham tPBM session, with sessions consisting of 12 minutes of laser light (or sham) intervention. These sessions were conducted on the first and the seventh day; then, on the eighth day, participants were asked to report (or guess) which session was the active tPBM session.

Stimulating astrocytes

Results showed that, compared with sham tPBM, there was an improvement in WM capacity and scores by the 1,064 nm intervention in the orientation as well as the color task.

Participants who received the targeted treatment were able to remember between four and five test objects, whereas those with the treatment variations were only able to remember between three and four objects.

“These results support the hypothesis that 1,064 nm tPBM on the right PFC enhances WM capacity,” the investigators wrote.

They also found improvements in WM in participants receiving tPBM vs. sham regardless of whether their performance in the WM task was at a low or high level. This finding held true in both the orientation and the color tasks.

“Therefore, participants with good and poor WM capacity improved after 1,064 nm tPBM,” the researchers noted.

In addition, participants were unable to guess or report whether they had received sham or active tPBM.

EEG monitoring showed changes in brain activity that predicted the improvements in memory performance. In particular, 1,064 tPBM applied to the right PFC increased occipitoparietal contralateral delay activity (CDA), with CDA mediating the WM improvement.

This is “consistent with previous research that CDA is indicative of the number of maintained objects in visual working memory,” the investigators wrote.

Pearson correlation analyses showed that the differences in CDA set-size effects between active and sham session “correlated positively” with the behavioral differences between these sessions. For the orientation task, the r was 0.446 (P < .04); and for the color task, the r was .563 (P < .02).

No similar improvements were found with the 852 nm tPBM.

“We need further research to understand exactly why the tPBM is having this positive effect,” coinvestigator Ole Jensen, PhD, professor in translational neuroscience and codirector of the Centre for Human Brain Health, said in the release.

“It’s possible that the light is stimulating the astrocytes – the powerplants – in the nerve cells within the PFC, and this has a positive effect on the cells’ efficiency,” he noted.

Dr. Jensen added that his team “will also be investigating how long the effects might last. Clearly, if these experiments are to lead to a clinical intervention, we will need to see long-lasting benefits.”

Beneficial cognitive, emotional effects

Commenting for this news organization, Francisco Gonzalez-Lima, PhD, professor in the department of psychology, University of Texas at Austin, called the study “well done.”

Dr. Gonzalez-Lima was one of the first researchers to demonstrate that 1,064 nm transcranial infrared laser stimulation “produces beneficial cognitive and emotional effects in humans, including improving visual working memory,” he said.

The current study “reported an additional brain effect linked to the improved visual working memory that consists of an EEG-derived response, which is a new finding,” noted Dr. Gonzales-Lima, who was not involved with the new research.

He added that the same laser method “has been found by the Gonzalez-Lima lab to be effective at improving cognition in older adults and depressed and bipolar patients.”

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China, and the National Defence Basic Scientific Research Program of China. The investigators and Dr. Gonzalez-Lima report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators compared the effect of 1,064 nm of tPBM delivered over a 12-minute session to the right PFC vs. three other treatment arms: delivery of the same intervention to the left PFC, delivery of the intervention at a lower frequency, and a sham intervention.

All participants were shown a series of items prior to the intervention and asked to recall them after the intervention. Those who received tPBM 1,064 nm to the right PFC showed a superior performance of up to 25% in the memory tasks compared with the other groups.

Patients with attention-related conditions, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, “could benefit from this type of treatment, which is safe, simple, and noninvasive, with no side effects,” coinvestigator Dongwei Li, a visiting PhD student at the Centre for Human Brain Health, University of Birmingham, England, said in a news release.

The findings were published online in Science Advances.

Differing wavelengths

The researchers note that “in the past decades,” noninvasive brain stimulation technology using transcranial application of direct or alternating electrical or magnetic fields “has been proven to be useful” in the improvement of working memory (WM).

When applied to the right PFC, tPBM has been shown to improve accuracy and speed of reaction time in WM tasks and improvements in “high-order cognitive functions,” such as sustained attention, emotion, and executive functions.

The investigators wanted to assess the impact of tPBM applied to different parts of the brain and at different wavelengths. They conducted four double-blind, sham-controlled experiments encompassing 90 neurotypical college students (mean age, 22 years). Each student participated in only one of the four experiments.

All completed two different tPBM sessions, separated by a week, in which sham and active tPBM were compared. Two different types of change-detection memory tasks were given: one requiring participants to remember the orientation of a series of items before and after the intervention and one other requiring them to remember the color of the items (experiments 1 and 2).

A series of follow-up experiments focused on comparing different wavelengths (1,064 nm vs. 852 nm) and different stimulation sites (right vs. left PFC; experiments 3 and 4).

EEG recordings were obtained during the intervention and the memory tasks.

Each experiment consisted of one active tPBM session and one sham tPBM session, with sessions consisting of 12 minutes of laser light (or sham) intervention. These sessions were conducted on the first and the seventh day; then, on the eighth day, participants were asked to report (or guess) which session was the active tPBM session.

Stimulating astrocytes

Results showed that, compared with sham tPBM, there was an improvement in WM capacity and scores by the 1,064 nm intervention in the orientation as well as the color task.

Participants who received the targeted treatment were able to remember between four and five test objects, whereas those with the treatment variations were only able to remember between three and four objects.

“These results support the hypothesis that 1,064 nm tPBM on the right PFC enhances WM capacity,” the investigators wrote.

They also found improvements in WM in participants receiving tPBM vs. sham regardless of whether their performance in the WM task was at a low or high level. This finding held true in both the orientation and the color tasks.

“Therefore, participants with good and poor WM capacity improved after 1,064 nm tPBM,” the researchers noted.

In addition, participants were unable to guess or report whether they had received sham or active tPBM.

EEG monitoring showed changes in brain activity that predicted the improvements in memory performance. In particular, 1,064 tPBM applied to the right PFC increased occipitoparietal contralateral delay activity (CDA), with CDA mediating the WM improvement.

This is “consistent with previous research that CDA is indicative of the number of maintained objects in visual working memory,” the investigators wrote.

Pearson correlation analyses showed that the differences in CDA set-size effects between active and sham session “correlated positively” with the behavioral differences between these sessions. For the orientation task, the r was 0.446 (P < .04); and for the color task, the r was .563 (P < .02).

No similar improvements were found with the 852 nm tPBM.

“We need further research to understand exactly why the tPBM is having this positive effect,” coinvestigator Ole Jensen, PhD, professor in translational neuroscience and codirector of the Centre for Human Brain Health, said in the release.

“It’s possible that the light is stimulating the astrocytes – the powerplants – in the nerve cells within the PFC, and this has a positive effect on the cells’ efficiency,” he noted.

Dr. Jensen added that his team “will also be investigating how long the effects might last. Clearly, if these experiments are to lead to a clinical intervention, we will need to see long-lasting benefits.”

Beneficial cognitive, emotional effects

Commenting for this news organization, Francisco Gonzalez-Lima, PhD, professor in the department of psychology, University of Texas at Austin, called the study “well done.”

Dr. Gonzalez-Lima was one of the first researchers to demonstrate that 1,064 nm transcranial infrared laser stimulation “produces beneficial cognitive and emotional effects in humans, including improving visual working memory,” he said.

The current study “reported an additional brain effect linked to the improved visual working memory that consists of an EEG-derived response, which is a new finding,” noted Dr. Gonzales-Lima, who was not involved with the new research.

He added that the same laser method “has been found by the Gonzalez-Lima lab to be effective at improving cognition in older adults and depressed and bipolar patients.”

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China, and the National Defence Basic Scientific Research Program of China. The investigators and Dr. Gonzalez-Lima report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators compared the effect of 1,064 nm of tPBM delivered over a 12-minute session to the right PFC vs. three other treatment arms: delivery of the same intervention to the left PFC, delivery of the intervention at a lower frequency, and a sham intervention.

All participants were shown a series of items prior to the intervention and asked to recall them after the intervention. Those who received tPBM 1,064 nm to the right PFC showed a superior performance of up to 25% in the memory tasks compared with the other groups.

Patients with attention-related conditions, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, “could benefit from this type of treatment, which is safe, simple, and noninvasive, with no side effects,” coinvestigator Dongwei Li, a visiting PhD student at the Centre for Human Brain Health, University of Birmingham, England, said in a news release.

The findings were published online in Science Advances.

Differing wavelengths

The researchers note that “in the past decades,” noninvasive brain stimulation technology using transcranial application of direct or alternating electrical or magnetic fields “has been proven to be useful” in the improvement of working memory (WM).

When applied to the right PFC, tPBM has been shown to improve accuracy and speed of reaction time in WM tasks and improvements in “high-order cognitive functions,” such as sustained attention, emotion, and executive functions.

The investigators wanted to assess the impact of tPBM applied to different parts of the brain and at different wavelengths. They conducted four double-blind, sham-controlled experiments encompassing 90 neurotypical college students (mean age, 22 years). Each student participated in only one of the four experiments.

All completed two different tPBM sessions, separated by a week, in which sham and active tPBM were compared. Two different types of change-detection memory tasks were given: one requiring participants to remember the orientation of a series of items before and after the intervention and one other requiring them to remember the color of the items (experiments 1 and 2).

A series of follow-up experiments focused on comparing different wavelengths (1,064 nm vs. 852 nm) and different stimulation sites (right vs. left PFC; experiments 3 and 4).

EEG recordings were obtained during the intervention and the memory tasks.

Each experiment consisted of one active tPBM session and one sham tPBM session, with sessions consisting of 12 minutes of laser light (or sham) intervention. These sessions were conducted on the first and the seventh day; then, on the eighth day, participants were asked to report (or guess) which session was the active tPBM session.

Stimulating astrocytes

Results showed that, compared with sham tPBM, there was an improvement in WM capacity and scores by the 1,064 nm intervention in the orientation as well as the color task.

Participants who received the targeted treatment were able to remember between four and five test objects, whereas those with the treatment variations were only able to remember between three and four objects.

“These results support the hypothesis that 1,064 nm tPBM on the right PFC enhances WM capacity,” the investigators wrote.

They also found improvements in WM in participants receiving tPBM vs. sham regardless of whether their performance in the WM task was at a low or high level. This finding held true in both the orientation and the color tasks.

“Therefore, participants with good and poor WM capacity improved after 1,064 nm tPBM,” the researchers noted.

In addition, participants were unable to guess or report whether they had received sham or active tPBM.

EEG monitoring showed changes in brain activity that predicted the improvements in memory performance. In particular, 1,064 tPBM applied to the right PFC increased occipitoparietal contralateral delay activity (CDA), with CDA mediating the WM improvement.

This is “consistent with previous research that CDA is indicative of the number of maintained objects in visual working memory,” the investigators wrote.

Pearson correlation analyses showed that the differences in CDA set-size effects between active and sham session “correlated positively” with the behavioral differences between these sessions. For the orientation task, the r was 0.446 (P < .04); and for the color task, the r was .563 (P < .02).

No similar improvements were found with the 852 nm tPBM.

“We need further research to understand exactly why the tPBM is having this positive effect,” coinvestigator Ole Jensen, PhD, professor in translational neuroscience and codirector of the Centre for Human Brain Health, said in the release.

“It’s possible that the light is stimulating the astrocytes – the powerplants – in the nerve cells within the PFC, and this has a positive effect on the cells’ efficiency,” he noted.

Dr. Jensen added that his team “will also be investigating how long the effects might last. Clearly, if these experiments are to lead to a clinical intervention, we will need to see long-lasting benefits.”

Beneficial cognitive, emotional effects

Commenting for this news organization, Francisco Gonzalez-Lima, PhD, professor in the department of psychology, University of Texas at Austin, called the study “well done.”

Dr. Gonzalez-Lima was one of the first researchers to demonstrate that 1,064 nm transcranial infrared laser stimulation “produces beneficial cognitive and emotional effects in humans, including improving visual working memory,” he said.

The current study “reported an additional brain effect linked to the improved visual working memory that consists of an EEG-derived response, which is a new finding,” noted Dr. Gonzales-Lima, who was not involved with the new research.

He added that the same laser method “has been found by the Gonzalez-Lima lab to be effective at improving cognition in older adults and depressed and bipolar patients.”

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China, and the National Defence Basic Scientific Research Program of China. The investigators and Dr. Gonzalez-Lima report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SCIENCE ADVANCES

Seizures in dementia hasten decline and death

NASHVILLE, TENN. – , according to a multicenter study presented at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“When we compared patients with seizures with those who did not have seizures, we found that patients with seizures were more likely to have more severe cognitive impairment; they were more likely to have physical dependence and so worse functional outcomes; and they also had higher mortality rates at a younger age,” lead study author Ifrah Zawar, MD, an assistant professor of neurology at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, said in an interview.

“The average age of mortality for seizure patients was around 72 years and the average age of mortality for nonseizure patients was around 79 years, so there was a 7- to 8-year difference in mortality,” she said.

Seizures make matters worse

The study analyzed data on 26,425 patients with dementia, 374 (1.4%) of whom had seizures, collected from 2005 to 2021 at 39 Alzheimer’s disease centers in the United States. Patients who had seizures were significantly younger when cognitive decline began (ages 62.9 vs. 68.4 years, P < .001) and died younger (72.99 vs. 79.72 years, P < .001).

The study also found a number of factors associated with active seizures, including a history of dominant Alzheimer’s disease mutation (odds ratio, 5.55; P < .001), stroke (OR, 3.17; P < .001), transient ischemic attack (OR, 1.72; P = .003), traumatic brain injury (OR, 1.92; P < .001), Parkinson’s disease (OR, 1.79; P = .025), active depression (OR, 1.61; P < .001) and lower education (OR, 0.97; P =.043).

After the study made adjustments for sex and other associated factors, it found that patients with seizures were still at a 76% higher risk of dying younger (hazard ratio, 1.76; P < .001).

The study also determined that patients with seizures had worse functional assessment scores and were more likely to be physically dependent on others (OR, 2.52; P < .001). Seizure patients also performed worse on Mini-Mental Status Examination (18.50 vs. 22.88; P < .001) and Clinical Dementia Rating-Sum of boxes (7.95 vs. 4.28; P < .001) after adjusting for age and duration of cognitive decline.

A tip for caregivers

Dr. Zawar acknowledged that differentiating seizures from transient bouts of confusion in people with dementia can be difficult for family members and caregivers, but she offered advice to help them do so. “If they notice any unusual confusion or any altered mentation which is episodic in nature,” she said, “they should bring it to the neurologist’s attention as early as possible, because there are studies that have shown the diagnosis of seizures is delayed, and if they are treated in time they can be well-controlled.” Electroencephalography can also confirm the presence of seizures, she added.

Double whammy

One limitation of this study is the lack of details on the types of seizures the participants had along with the inconsistency of EEGs performed on the study population. “In future studies, I would like to have more EEG data on the types of seizures and the frequency of seizures to assess these factors further,” Dr. Zawar said.

Having more detailed information on the seizures would make the findings more valuable, Andrew J. Cole, MD, director of the epilepsy service at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston said in an interview. “We know a lot about clinically apparent seizures, as witnessed by this paper, but we still don’t know a whole lot about clinically silent or cryptic or nighttime-only seizures that maybe no one would really recognize as such unless they were specifically looking for them, and this paper doesn’t address that issue,” he said.

While the finding that patients with other neurologic diseases have more seizures even if they also have Alzheimer’s disease isn’t “a huge surprise,” Dr. Cole added. “On the other hand, the paper is important because it shows us that in the course of having Alzheimer’s disease, having seizures also makes your outcome worse, the speed of progression faster, and it complicates the management and living with this disease, and they make that point quite clear.”

Dr. Zawar and Dr. Cole have no relevant disclosures.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – , according to a multicenter study presented at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“When we compared patients with seizures with those who did not have seizures, we found that patients with seizures were more likely to have more severe cognitive impairment; they were more likely to have physical dependence and so worse functional outcomes; and they also had higher mortality rates at a younger age,” lead study author Ifrah Zawar, MD, an assistant professor of neurology at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, said in an interview.

“The average age of mortality for seizure patients was around 72 years and the average age of mortality for nonseizure patients was around 79 years, so there was a 7- to 8-year difference in mortality,” she said.

Seizures make matters worse

The study analyzed data on 26,425 patients with dementia, 374 (1.4%) of whom had seizures, collected from 2005 to 2021 at 39 Alzheimer’s disease centers in the United States. Patients who had seizures were significantly younger when cognitive decline began (ages 62.9 vs. 68.4 years, P < .001) and died younger (72.99 vs. 79.72 years, P < .001).

The study also found a number of factors associated with active seizures, including a history of dominant Alzheimer’s disease mutation (odds ratio, 5.55; P < .001), stroke (OR, 3.17; P < .001), transient ischemic attack (OR, 1.72; P = .003), traumatic brain injury (OR, 1.92; P < .001), Parkinson’s disease (OR, 1.79; P = .025), active depression (OR, 1.61; P < .001) and lower education (OR, 0.97; P =.043).

After the study made adjustments for sex and other associated factors, it found that patients with seizures were still at a 76% higher risk of dying younger (hazard ratio, 1.76; P < .001).

The study also determined that patients with seizures had worse functional assessment scores and were more likely to be physically dependent on others (OR, 2.52; P < .001). Seizure patients also performed worse on Mini-Mental Status Examination (18.50 vs. 22.88; P < .001) and Clinical Dementia Rating-Sum of boxes (7.95 vs. 4.28; P < .001) after adjusting for age and duration of cognitive decline.

A tip for caregivers

Dr. Zawar acknowledged that differentiating seizures from transient bouts of confusion in people with dementia can be difficult for family members and caregivers, but she offered advice to help them do so. “If they notice any unusual confusion or any altered mentation which is episodic in nature,” she said, “they should bring it to the neurologist’s attention as early as possible, because there are studies that have shown the diagnosis of seizures is delayed, and if they are treated in time they can be well-controlled.” Electroencephalography can also confirm the presence of seizures, she added.

Double whammy

One limitation of this study is the lack of details on the types of seizures the participants had along with the inconsistency of EEGs performed on the study population. “In future studies, I would like to have more EEG data on the types of seizures and the frequency of seizures to assess these factors further,” Dr. Zawar said.

Having more detailed information on the seizures would make the findings more valuable, Andrew J. Cole, MD, director of the epilepsy service at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston said in an interview. “We know a lot about clinically apparent seizures, as witnessed by this paper, but we still don’t know a whole lot about clinically silent or cryptic or nighttime-only seizures that maybe no one would really recognize as such unless they were specifically looking for them, and this paper doesn’t address that issue,” he said.

While the finding that patients with other neurologic diseases have more seizures even if they also have Alzheimer’s disease isn’t “a huge surprise,” Dr. Cole added. “On the other hand, the paper is important because it shows us that in the course of having Alzheimer’s disease, having seizures also makes your outcome worse, the speed of progression faster, and it complicates the management and living with this disease, and they make that point quite clear.”

Dr. Zawar and Dr. Cole have no relevant disclosures.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – , according to a multicenter study presented at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“When we compared patients with seizures with those who did not have seizures, we found that patients with seizures were more likely to have more severe cognitive impairment; they were more likely to have physical dependence and so worse functional outcomes; and they also had higher mortality rates at a younger age,” lead study author Ifrah Zawar, MD, an assistant professor of neurology at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, said in an interview.

“The average age of mortality for seizure patients was around 72 years and the average age of mortality for nonseizure patients was around 79 years, so there was a 7- to 8-year difference in mortality,” she said.

Seizures make matters worse

The study analyzed data on 26,425 patients with dementia, 374 (1.4%) of whom had seizures, collected from 2005 to 2021 at 39 Alzheimer’s disease centers in the United States. Patients who had seizures were significantly younger when cognitive decline began (ages 62.9 vs. 68.4 years, P < .001) and died younger (72.99 vs. 79.72 years, P < .001).

The study also found a number of factors associated with active seizures, including a history of dominant Alzheimer’s disease mutation (odds ratio, 5.55; P < .001), stroke (OR, 3.17; P < .001), transient ischemic attack (OR, 1.72; P = .003), traumatic brain injury (OR, 1.92; P < .001), Parkinson’s disease (OR, 1.79; P = .025), active depression (OR, 1.61; P < .001) and lower education (OR, 0.97; P =.043).

After the study made adjustments for sex and other associated factors, it found that patients with seizures were still at a 76% higher risk of dying younger (hazard ratio, 1.76; P < .001).

The study also determined that patients with seizures had worse functional assessment scores and were more likely to be physically dependent on others (OR, 2.52; P < .001). Seizure patients also performed worse on Mini-Mental Status Examination (18.50 vs. 22.88; P < .001) and Clinical Dementia Rating-Sum of boxes (7.95 vs. 4.28; P < .001) after adjusting for age and duration of cognitive decline.

A tip for caregivers

Dr. Zawar acknowledged that differentiating seizures from transient bouts of confusion in people with dementia can be difficult for family members and caregivers, but she offered advice to help them do so. “If they notice any unusual confusion or any altered mentation which is episodic in nature,” she said, “they should bring it to the neurologist’s attention as early as possible, because there are studies that have shown the diagnosis of seizures is delayed, and if they are treated in time they can be well-controlled.” Electroencephalography can also confirm the presence of seizures, she added.

Double whammy

One limitation of this study is the lack of details on the types of seizures the participants had along with the inconsistency of EEGs performed on the study population. “In future studies, I would like to have more EEG data on the types of seizures and the frequency of seizures to assess these factors further,” Dr. Zawar said.

Having more detailed information on the seizures would make the findings more valuable, Andrew J. Cole, MD, director of the epilepsy service at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston said in an interview. “We know a lot about clinically apparent seizures, as witnessed by this paper, but we still don’t know a whole lot about clinically silent or cryptic or nighttime-only seizures that maybe no one would really recognize as such unless they were specifically looking for them, and this paper doesn’t address that issue,” he said.

While the finding that patients with other neurologic diseases have more seizures even if they also have Alzheimer’s disease isn’t “a huge surprise,” Dr. Cole added. “On the other hand, the paper is important because it shows us that in the course of having Alzheimer’s disease, having seizures also makes your outcome worse, the speed of progression faster, and it complicates the management and living with this disease, and they make that point quite clear.”

Dr. Zawar and Dr. Cole have no relevant disclosures.

AT AES 2022

SSRI tied to improved cognition in comorbid depression, dementia

The results of the 12-week open-label, single-group study are positive, study investigator Michael Cronquist Christensen, MPA, DrPH, a director with the Lundbeck pharmaceutical company, told this news organization before presenting the results in a poster at the 15th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

“The study confirms earlier findings of improvement in both depressive symptoms and cognitive performance with vortioxetine in patients with depression and dementia and adds to this research that these clinical effects also extend to improvement in health-related quality of life and patients’ daily functioning,” Dr. Christensen said.

“It also demonstrates that patients with depression and comorbid dementia can be safely treated with 20 mg vortioxetine – starting dose of 5 mg for the first week and up-titration to 10 mg at day 8,” he added.

However, he reported that Lundbeck doesn’t plan to seek approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for a new indication. Vortioxetine received FDA approval in 2013 to treat MDD, but 3 years later the agency rejected an expansion of its indication to include cognitive dysfunction.

“Vortioxetine is approved for MDD, but the product can be used in patients with MDD who have other diseases, including other mental illnesses,” Dr. Christensen said.

Potential neurotransmission modulator

Vortioxetine is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and serotonin receptor modulator. According to Dr. Christensen, evidence suggests the drug’s receptor targets “have the potential to modulate neurotransmitter systems that are essential for regulation of cognitive function.”

The researchers recruited 83 individuals aged 55-85 with recurrent MDD that had started before the age of 55. All had MDD episodes within the previous 6 months and comorbid dementia for at least 6 months.

Of the participants, 65.9% were female. In addition, 42.7% had Alzheimer’s disease, 26.8% had mixed-type dementia, and the rest had other types of dementia.

The daily oral dose of vortioxetine started at 5 mg for up to week 1 and then was increased to 10 mg. It was then increased to 20 mg or decreased to 5 mg “based on investigator judgment and patient response.” The average daily dose was 12.3 mg.

In regard to the primary outcome, at week 12 (n = 70), scores on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) fell by a mean of –12.4 (.78, P < .0001), which researchers deemed to be a significant reduction in severe symptoms.

“A significant and clinically meaningful effect was observed from week 1,” the researchers reported.

“As a basis for comparison, we typically see an improvement around 13-14 points during 8 weeks of antidepressant treatment in adults with MDD who do not have dementia,” Dr. Christensen added.

More than a third of patients (35.7%) saw a reduction in MADRS score by more than 50% at week 12, and 17.2% were considered to have reached MDD depression remission, defined as a MADRS score at or under 10.

For secondary outcomes, the total Digit Symbol Substitution test score grew by 0.65 (standardized effect size) by week 12, showing significant improvement (P < .0001). In addition, participants improved on some other cognitive measures, and Dr. Christensen noted that “significant improvement was also observed in the patients’ health-related quality of life and daily functioning.”

A third of patients had drug-related treatment-emergent adverse events.

Vortioxetine is one of the most expensive antidepressants: It has a list price of $444 a month, and no generic version is currently available.

Small trial, open-label design

In a comment, Claire Sexton, DPhil, senior director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, said the study “reflects a valuable aspect of treatment research because of the close connection between depression and dementia. Depression is a known risk factor for dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, and those who have dementia may experience depression.”

She cautioned, however, that the trial was small and had an open-label design instead of the “gold standard” of a double-blinded trial with a control group.

The study was funded by Lundbeck, where Dr. Christensen is an employee. Another author is a Lundbeck employee, and a third author reported various disclosures. Dr. Sexton reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The results of the 12-week open-label, single-group study are positive, study investigator Michael Cronquist Christensen, MPA, DrPH, a director with the Lundbeck pharmaceutical company, told this news organization before presenting the results in a poster at the 15th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

“The study confirms earlier findings of improvement in both depressive symptoms and cognitive performance with vortioxetine in patients with depression and dementia and adds to this research that these clinical effects also extend to improvement in health-related quality of life and patients’ daily functioning,” Dr. Christensen said.

“It also demonstrates that patients with depression and comorbid dementia can be safely treated with 20 mg vortioxetine – starting dose of 5 mg for the first week and up-titration to 10 mg at day 8,” he added.

However, he reported that Lundbeck doesn’t plan to seek approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for a new indication. Vortioxetine received FDA approval in 2013 to treat MDD, but 3 years later the agency rejected an expansion of its indication to include cognitive dysfunction.

“Vortioxetine is approved for MDD, but the product can be used in patients with MDD who have other diseases, including other mental illnesses,” Dr. Christensen said.

Potential neurotransmission modulator

Vortioxetine is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and serotonin receptor modulator. According to Dr. Christensen, evidence suggests the drug’s receptor targets “have the potential to modulate neurotransmitter systems that are essential for regulation of cognitive function.”

The researchers recruited 83 individuals aged 55-85 with recurrent MDD that had started before the age of 55. All had MDD episodes within the previous 6 months and comorbid dementia for at least 6 months.

Of the participants, 65.9% were female. In addition, 42.7% had Alzheimer’s disease, 26.8% had mixed-type dementia, and the rest had other types of dementia.

The daily oral dose of vortioxetine started at 5 mg for up to week 1 and then was increased to 10 mg. It was then increased to 20 mg or decreased to 5 mg “based on investigator judgment and patient response.” The average daily dose was 12.3 mg.

In regard to the primary outcome, at week 12 (n = 70), scores on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) fell by a mean of –12.4 (.78, P < .0001), which researchers deemed to be a significant reduction in severe symptoms.

“A significant and clinically meaningful effect was observed from week 1,” the researchers reported.

“As a basis for comparison, we typically see an improvement around 13-14 points during 8 weeks of antidepressant treatment in adults with MDD who do not have dementia,” Dr. Christensen added.

More than a third of patients (35.7%) saw a reduction in MADRS score by more than 50% at week 12, and 17.2% were considered to have reached MDD depression remission, defined as a MADRS score at or under 10.

For secondary outcomes, the total Digit Symbol Substitution test score grew by 0.65 (standardized effect size) by week 12, showing significant improvement (P < .0001). In addition, participants improved on some other cognitive measures, and Dr. Christensen noted that “significant improvement was also observed in the patients’ health-related quality of life and daily functioning.”

A third of patients had drug-related treatment-emergent adverse events.

Vortioxetine is one of the most expensive antidepressants: It has a list price of $444 a month, and no generic version is currently available.

Small trial, open-label design

In a comment, Claire Sexton, DPhil, senior director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, said the study “reflects a valuable aspect of treatment research because of the close connection between depression and dementia. Depression is a known risk factor for dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, and those who have dementia may experience depression.”

She cautioned, however, that the trial was small and had an open-label design instead of the “gold standard” of a double-blinded trial with a control group.

The study was funded by Lundbeck, where Dr. Christensen is an employee. Another author is a Lundbeck employee, and a third author reported various disclosures. Dr. Sexton reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The results of the 12-week open-label, single-group study are positive, study investigator Michael Cronquist Christensen, MPA, DrPH, a director with the Lundbeck pharmaceutical company, told this news organization before presenting the results in a poster at the 15th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

“The study confirms earlier findings of improvement in both depressive symptoms and cognitive performance with vortioxetine in patients with depression and dementia and adds to this research that these clinical effects also extend to improvement in health-related quality of life and patients’ daily functioning,” Dr. Christensen said.

“It also demonstrates that patients with depression and comorbid dementia can be safely treated with 20 mg vortioxetine – starting dose of 5 mg for the first week and up-titration to 10 mg at day 8,” he added.

However, he reported that Lundbeck doesn’t plan to seek approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for a new indication. Vortioxetine received FDA approval in 2013 to treat MDD, but 3 years later the agency rejected an expansion of its indication to include cognitive dysfunction.

“Vortioxetine is approved for MDD, but the product can be used in patients with MDD who have other diseases, including other mental illnesses,” Dr. Christensen said.

Potential neurotransmission modulator

Vortioxetine is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and serotonin receptor modulator. According to Dr. Christensen, evidence suggests the drug’s receptor targets “have the potential to modulate neurotransmitter systems that are essential for regulation of cognitive function.”

The researchers recruited 83 individuals aged 55-85 with recurrent MDD that had started before the age of 55. All had MDD episodes within the previous 6 months and comorbid dementia for at least 6 months.

Of the participants, 65.9% were female. In addition, 42.7% had Alzheimer’s disease, 26.8% had mixed-type dementia, and the rest had other types of dementia.

The daily oral dose of vortioxetine started at 5 mg for up to week 1 and then was increased to 10 mg. It was then increased to 20 mg or decreased to 5 mg “based on investigator judgment and patient response.” The average daily dose was 12.3 mg.

In regard to the primary outcome, at week 12 (n = 70), scores on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) fell by a mean of –12.4 (.78, P < .0001), which researchers deemed to be a significant reduction in severe symptoms.

“A significant and clinically meaningful effect was observed from week 1,” the researchers reported.

“As a basis for comparison, we typically see an improvement around 13-14 points during 8 weeks of antidepressant treatment in adults with MDD who do not have dementia,” Dr. Christensen added.

More than a third of patients (35.7%) saw a reduction in MADRS score by more than 50% at week 12, and 17.2% were considered to have reached MDD depression remission, defined as a MADRS score at or under 10.

For secondary outcomes, the total Digit Symbol Substitution test score grew by 0.65 (standardized effect size) by week 12, showing significant improvement (P < .0001). In addition, participants improved on some other cognitive measures, and Dr. Christensen noted that “significant improvement was also observed in the patients’ health-related quality of life and daily functioning.”

A third of patients had drug-related treatment-emergent adverse events.

Vortioxetine is one of the most expensive antidepressants: It has a list price of $444 a month, and no generic version is currently available.

Small trial, open-label design

In a comment, Claire Sexton, DPhil, senior director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, said the study “reflects a valuable aspect of treatment research because of the close connection between depression and dementia. Depression is a known risk factor for dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, and those who have dementia may experience depression.”

She cautioned, however, that the trial was small and had an open-label design instead of the “gold standard” of a double-blinded trial with a control group.

The study was funded by Lundbeck, where Dr. Christensen is an employee. Another author is a Lundbeck employee, and a third author reported various disclosures. Dr. Sexton reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CTAD 2022

How your voice could reveal hidden disease

: First during puberty, as the vocal cords thicken and the voice box migrates down the throat. Then a second time as aging causes structural changes that may weaken the voice.

But for some of us, there’s another voice shift, when a disease begins or when our mental health declines.

This is why more doctors are looking into voice as a biomarker – something that tells you that a disease is present.

Vital signs like blood pressure or heart rate “can give a general idea of how sick we are. But they’re not specific to certain diseases,” says Yael Bensoussan, MD, director of the University of South Florida, Tampa’s Health Voice Center and the coprincipal investigator for the National Institutes of Health’s Voice as a Biomarker of Health project.

“We’re learning that there are patterns” in voice changes that can indicate a range of conditions, including diseases of the nervous system and mental illnesses, she says.

Speaking is complicated, involving everything from the lungs and voice box to the mouth and brain. “A breakdown in any of those parts can affect the voice,” says Maria Powell, PhD, an assistant professor of otolaryngology (the study of diseases of the ear and throat) at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., who is working on the NIH project.

You or those around you may not notice the changes. But researchers say voice analysis as a standard part of patient care – akin to blood pressure checks or cholesterol tests – could help identify those who need medical attention earlier.

Often, all it takes is a smartphone – “something that’s cheap, off-the-shelf, and that everyone can use,” says Ariana Anderson, PhD, director of the University of California, Los Angeles, Laboratory of Computational Neuropsychology.

“You can provide voice data in your pajamas, on your couch,” says Frank Rudzicz, PhD, a computer scientist for the NIH project. “It doesn’t require very complicated or expensive equipment, and it doesn’t require a lot of expertise to obtain.” Plus, multiple samples can be collected over time, giving a more accurate picture of health than a single snapshot from, say, a cognitive test.

Over the next 4 years, the Voice as a Biomarker team will receive nearly $18 million to gather a massive amount of voice data. The goal is 20,000-30,000 samples, along with health data about each person being studied. The result will be a sprawling database scientists can use to develop algorithms linking health conditions to the way we speak.

For the first 2 years, new data will be collected exclusively via universities and high-volume clinics to control quality and accuracy. Eventually, people will be invited to submit their own voice recordings, creating a crowdsourced dataset. “Google, Alexa, Amazon – they have access to tons of voice data,” says Dr. Bensoussan. “But it’s not usable in a clinical way, because they don’t have the health information.”