User login

Are aging physicians a burden?

The evaluation of physicians with alleged cognitive decline

As forensic evaluators, we are often asked to review and assess the cognition of aging colleagues. The premise often involves a minor mistake, a poor choice of words, or a lapse in judgment. A physician gets reported for having difficulty using a new electronic form, forgetting the dose of a brand new medication, or getting upset in a public setting. Those behaviors often lead to mandatory psychiatric evaluations. Those requirements are often perceived by the provider as an insult, and betrayal by peers despite many years of dedicated work.

Interestingly, we have noticed many independent evaluators and hospital administrators using this opportunity to send many of our colleagues to pasture. There seems to be an unspoken rule among some forensic evaluators that physicians should represent some form of apex of humanity, beyond reproach, and beyond any fault. Those evaluators will point to any mistake on cognitive scales as proof that the aging physician is no longer safe to practice.1 Forgetting that Jill is from Illinois in the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination test or how to copy a three-dimensional cube on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment can cost someone their license.2 We are also aware of some evaluators even taking the step further and opining that physicians not only need to score adequately but also demonstrate cognition significantly above average to maintain their privileges.

There is certainly significant appeal in setting a high bar for physicians. In many ways, physicians are characterized in society by their astuteness, intelligence, and high ethical standards. Patients place their lives in the hands of physicians and should trust that those physicians have the cognitive tools to heal them. It could almost seem evident that physicians should have high IQs, score perfectly on screening tools for dementia, and complete a mandatory psychiatric evaluation without any reproach. Yet the reality is often more complex.

We have two main concerns about the idea that we should be intransigent with aging physicians. The first one is the vast differential diagnosis for minor mistakes. An aging physician refusing to comply with a new form or yelling at a clerk once when asked to learn a new electronic medical record are inappropriate though not specific assessments for dementia. Similarly, having significant difficulty learning a new electronic medical record system more often is a sign of ageism rather than cognitive impairment. Subsequently, when arriving for their evaluation, forgetting the date is a common sign of anxiety. A relatable analogy would be to compare the mistake with a medical student forgetting part of the anatomy while questioning by an attending during surgery. Imagine such medical students being referred to mandatory psychiatric evaluation when failing to answer a question during rounds.

In our practice, the most common reason for those minor mistakes during our clinical evaluation is anxiety. After all, patients who present for problems completely unrelated to cognitive decline make similar mistakes. Psychological stressors in physicians require no introduction. The concept is so prevalent and pervasive that it has its own name, “burnout.” Imagine having dedicated most of one’s life to a profession then being enumerated a list of complaints, having one’s privileges put on hold, then being told to complete an independent psychiatric evaluation. If burnout is in part caused by a lack of control, unclear job expectations, rapidly changing models of health care, and dysfunctional workplace dynamics, imagine the consequence of such a referral.

The militant evaluator will use jargon to vilify the reviewed physician. If the physician complains too voraciously, he will be described as having signs of frontotemporal dementia. If the physician comes with a written list of rebuttals, he will be described as having memory problems requiring aids. If the physician is demoralized and quiet, he will be described as being withdrawn and apathetic. If the physician refuses to use or has difficulty with new forms or electronic systems, he will be described as having “impaired executive function,” an ominous term that surely should not be associated with a practicing physician.

The second concern arises from problems with the validity and use of diagnoses like mild cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI is considered to be a transition stage when one maintains “normal activities of daily living, and normal general cognitive function.”3 The American Psychiatric Association Textbook of Psychiatry mentions that there are “however, many cases of nonprogressive MCI.” Should a disorder with generally normal cognition and unclear progression to a more severe disorder require one to be dispensed of their privileges? Should any disorder trump an assessment of functioning?

It is our experience that many if not most physicians’ practice of medicine is not a job but a profession that defines who they are. As such, their occupational habits are an overly repeated and ingrained series of maneuvers analogous to so-called muscle memory. This kind of ritualistic pattern is precisely the kind of cognition that may persist as one starts to have some deficits. This requires the evaluator to be particularly sensitive and cognizant that one may still be able to perform professionally despite some mild but notable deficits. While it is facile to diagnose someone with MCI and justify removing their license, a review of their actual clinical skills is, despite being more time consuming, more pertinent to the evaluation.

In practice, we find that many cases lie in a gray area, which is hard to define. Physicians may come to our office for an evaluation after having said something odd at work. Maybe they misdosed a medication on one occasion. Maybe they wrote the wrong year on a chart. However, if the physician was 30 years old, would we consider any one of those incidents significant? As a psychiatrist rather than a physician practicing the specialty in review, it is particularly hard and sometimes unwise to condone or sanction individual incidents.

Evaluators find solace in neuropsychological testing. However the relevance to the safety of patients is unclear. Many of those tests end up being a simple proxy for age. A physicians’ ability to sort words or cards at a certain speed might correlate to cognitive performance but has unclear significance to the ability to care for patients. Using such tests becomes a de facto age limit on the practice of medicine. It seems essential to expand and refine our repertoire of evaluation tools for the assessment of physicians. As when we perform capacity evaluation in the hospital, we enlist the assistance of the treating team in understanding the questions being asked for a patient, medical boards could consider creating independent multidisciplinary teams where psychiatry has a seat along with the relevant specialties of the evaluee. Likewise, the assessment would benefit from a broad review of the physicians’ general practice rather than the more typical review of one or two incidents.

We are promoting a more individualized approach by medical boards to the many issues of the aging physician. Retiring is no longer the dream of older physicians, but rather working in the suitable position where their contributions, clinical experience, and wisdom are positive contributions to patient care. Furthermore, we encourage medical boards to consider more nuanced decisions. A binary approach fits few cases that we see. Surgeons are a prime example of this. A surgeon in the early stages of Parkinsonism may be unfit to perform surgery but very capable of continuing to contribute to the well-being of patients in other forms of clinical work, including postsurgical care that doesn’t involve physical dexterity. Similarly, medical boards could consider other forms of partial restrictions, including a ban on procedures, a ban on hospital privileges, as well as required supervision or working in teams. Accumulated clinical wisdom allows older physicians to be excellent mentors and educators for younger doctors. There is no simple method to predict which physicians may have the early stages of a progressive dementia, and which may have a stable MCI. A yearly reevaluation if there are no further complaints, is the best approach to determine progression of cognitive problems.

Few crises like the current COVID-19 pandemic can better remind us of the importance of the place of medicine in society. Many states have encouraged retired physicians to contribute their knowledge and expertise, putting themselves in particular risk because of their age. It is a good time to be reminded that we owe them significant respect and care when deciding to remove their license. We are encouraged by the diligent efforts of medical boards in supervising our colleagues but warn against zealot evaluators who use this opportunity to force physicians into retirement. We also encourage medical boards to expand their tools and approaches when facing such cases, as mislabeled cognitive diagnoses can be an easy scapegoat of a poor understanding of the more important psychological and biological factors in the evaluation.

References

1. Tariq SH et al. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:900-10.

2. Nasreddine Z. mocatest.org. Version 2004 Nov 7.

3. Hales RE et al. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. Washington: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2014.

Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Among his writings in chapter 7 in the book “Critical Psychiatry: Controversies and Clinical Implications” (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019). He has no disclosures.

Dr. Abrams is a forensic psychiatrist and attorney in San Diego. He is an expert in addictionology, behavioral toxicology, psychopharmacology and correctional mental health. He holds a teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego. Among his writings are chapters about competency in national textbooks. Dr. Abrams has no disclosures.

The evaluation of physicians with alleged cognitive decline

The evaluation of physicians with alleged cognitive decline

As forensic evaluators, we are often asked to review and assess the cognition of aging colleagues. The premise often involves a minor mistake, a poor choice of words, or a lapse in judgment. A physician gets reported for having difficulty using a new electronic form, forgetting the dose of a brand new medication, or getting upset in a public setting. Those behaviors often lead to mandatory psychiatric evaluations. Those requirements are often perceived by the provider as an insult, and betrayal by peers despite many years of dedicated work.

Interestingly, we have noticed many independent evaluators and hospital administrators using this opportunity to send many of our colleagues to pasture. There seems to be an unspoken rule among some forensic evaluators that physicians should represent some form of apex of humanity, beyond reproach, and beyond any fault. Those evaluators will point to any mistake on cognitive scales as proof that the aging physician is no longer safe to practice.1 Forgetting that Jill is from Illinois in the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination test or how to copy a three-dimensional cube on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment can cost someone their license.2 We are also aware of some evaluators even taking the step further and opining that physicians not only need to score adequately but also demonstrate cognition significantly above average to maintain their privileges.

There is certainly significant appeal in setting a high bar for physicians. In many ways, physicians are characterized in society by their astuteness, intelligence, and high ethical standards. Patients place their lives in the hands of physicians and should trust that those physicians have the cognitive tools to heal them. It could almost seem evident that physicians should have high IQs, score perfectly on screening tools for dementia, and complete a mandatory psychiatric evaluation without any reproach. Yet the reality is often more complex.

We have two main concerns about the idea that we should be intransigent with aging physicians. The first one is the vast differential diagnosis for minor mistakes. An aging physician refusing to comply with a new form or yelling at a clerk once when asked to learn a new electronic medical record are inappropriate though not specific assessments for dementia. Similarly, having significant difficulty learning a new electronic medical record system more often is a sign of ageism rather than cognitive impairment. Subsequently, when arriving for their evaluation, forgetting the date is a common sign of anxiety. A relatable analogy would be to compare the mistake with a medical student forgetting part of the anatomy while questioning by an attending during surgery. Imagine such medical students being referred to mandatory psychiatric evaluation when failing to answer a question during rounds.

In our practice, the most common reason for those minor mistakes during our clinical evaluation is anxiety. After all, patients who present for problems completely unrelated to cognitive decline make similar mistakes. Psychological stressors in physicians require no introduction. The concept is so prevalent and pervasive that it has its own name, “burnout.” Imagine having dedicated most of one’s life to a profession then being enumerated a list of complaints, having one’s privileges put on hold, then being told to complete an independent psychiatric evaluation. If burnout is in part caused by a lack of control, unclear job expectations, rapidly changing models of health care, and dysfunctional workplace dynamics, imagine the consequence of such a referral.

The militant evaluator will use jargon to vilify the reviewed physician. If the physician complains too voraciously, he will be described as having signs of frontotemporal dementia. If the physician comes with a written list of rebuttals, he will be described as having memory problems requiring aids. If the physician is demoralized and quiet, he will be described as being withdrawn and apathetic. If the physician refuses to use or has difficulty with new forms or electronic systems, he will be described as having “impaired executive function,” an ominous term that surely should not be associated with a practicing physician.

The second concern arises from problems with the validity and use of diagnoses like mild cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI is considered to be a transition stage when one maintains “normal activities of daily living, and normal general cognitive function.”3 The American Psychiatric Association Textbook of Psychiatry mentions that there are “however, many cases of nonprogressive MCI.” Should a disorder with generally normal cognition and unclear progression to a more severe disorder require one to be dispensed of their privileges? Should any disorder trump an assessment of functioning?

It is our experience that many if not most physicians’ practice of medicine is not a job but a profession that defines who they are. As such, their occupational habits are an overly repeated and ingrained series of maneuvers analogous to so-called muscle memory. This kind of ritualistic pattern is precisely the kind of cognition that may persist as one starts to have some deficits. This requires the evaluator to be particularly sensitive and cognizant that one may still be able to perform professionally despite some mild but notable deficits. While it is facile to diagnose someone with MCI and justify removing their license, a review of their actual clinical skills is, despite being more time consuming, more pertinent to the evaluation.

In practice, we find that many cases lie in a gray area, which is hard to define. Physicians may come to our office for an evaluation after having said something odd at work. Maybe they misdosed a medication on one occasion. Maybe they wrote the wrong year on a chart. However, if the physician was 30 years old, would we consider any one of those incidents significant? As a psychiatrist rather than a physician practicing the specialty in review, it is particularly hard and sometimes unwise to condone or sanction individual incidents.

Evaluators find solace in neuropsychological testing. However the relevance to the safety of patients is unclear. Many of those tests end up being a simple proxy for age. A physicians’ ability to sort words or cards at a certain speed might correlate to cognitive performance but has unclear significance to the ability to care for patients. Using such tests becomes a de facto age limit on the practice of medicine. It seems essential to expand and refine our repertoire of evaluation tools for the assessment of physicians. As when we perform capacity evaluation in the hospital, we enlist the assistance of the treating team in understanding the questions being asked for a patient, medical boards could consider creating independent multidisciplinary teams where psychiatry has a seat along with the relevant specialties of the evaluee. Likewise, the assessment would benefit from a broad review of the physicians’ general practice rather than the more typical review of one or two incidents.

We are promoting a more individualized approach by medical boards to the many issues of the aging physician. Retiring is no longer the dream of older physicians, but rather working in the suitable position where their contributions, clinical experience, and wisdom are positive contributions to patient care. Furthermore, we encourage medical boards to consider more nuanced decisions. A binary approach fits few cases that we see. Surgeons are a prime example of this. A surgeon in the early stages of Parkinsonism may be unfit to perform surgery but very capable of continuing to contribute to the well-being of patients in other forms of clinical work, including postsurgical care that doesn’t involve physical dexterity. Similarly, medical boards could consider other forms of partial restrictions, including a ban on procedures, a ban on hospital privileges, as well as required supervision or working in teams. Accumulated clinical wisdom allows older physicians to be excellent mentors and educators for younger doctors. There is no simple method to predict which physicians may have the early stages of a progressive dementia, and which may have a stable MCI. A yearly reevaluation if there are no further complaints, is the best approach to determine progression of cognitive problems.

Few crises like the current COVID-19 pandemic can better remind us of the importance of the place of medicine in society. Many states have encouraged retired physicians to contribute their knowledge and expertise, putting themselves in particular risk because of their age. It is a good time to be reminded that we owe them significant respect and care when deciding to remove their license. We are encouraged by the diligent efforts of medical boards in supervising our colleagues but warn against zealot evaluators who use this opportunity to force physicians into retirement. We also encourage medical boards to expand their tools and approaches when facing such cases, as mislabeled cognitive diagnoses can be an easy scapegoat of a poor understanding of the more important psychological and biological factors in the evaluation.

References

1. Tariq SH et al. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:900-10.

2. Nasreddine Z. mocatest.org. Version 2004 Nov 7.

3. Hales RE et al. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. Washington: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2014.

Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Among his writings in chapter 7 in the book “Critical Psychiatry: Controversies and Clinical Implications” (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019). He has no disclosures.

Dr. Abrams is a forensic psychiatrist and attorney in San Diego. He is an expert in addictionology, behavioral toxicology, psychopharmacology and correctional mental health. He holds a teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego. Among his writings are chapters about competency in national textbooks. Dr. Abrams has no disclosures.

As forensic evaluators, we are often asked to review and assess the cognition of aging colleagues. The premise often involves a minor mistake, a poor choice of words, or a lapse in judgment. A physician gets reported for having difficulty using a new electronic form, forgetting the dose of a brand new medication, or getting upset in a public setting. Those behaviors often lead to mandatory psychiatric evaluations. Those requirements are often perceived by the provider as an insult, and betrayal by peers despite many years of dedicated work.

Interestingly, we have noticed many independent evaluators and hospital administrators using this opportunity to send many of our colleagues to pasture. There seems to be an unspoken rule among some forensic evaluators that physicians should represent some form of apex of humanity, beyond reproach, and beyond any fault. Those evaluators will point to any mistake on cognitive scales as proof that the aging physician is no longer safe to practice.1 Forgetting that Jill is from Illinois in the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination test or how to copy a three-dimensional cube on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment can cost someone their license.2 We are also aware of some evaluators even taking the step further and opining that physicians not only need to score adequately but also demonstrate cognition significantly above average to maintain their privileges.

There is certainly significant appeal in setting a high bar for physicians. In many ways, physicians are characterized in society by their astuteness, intelligence, and high ethical standards. Patients place their lives in the hands of physicians and should trust that those physicians have the cognitive tools to heal them. It could almost seem evident that physicians should have high IQs, score perfectly on screening tools for dementia, and complete a mandatory psychiatric evaluation without any reproach. Yet the reality is often more complex.

We have two main concerns about the idea that we should be intransigent with aging physicians. The first one is the vast differential diagnosis for minor mistakes. An aging physician refusing to comply with a new form or yelling at a clerk once when asked to learn a new electronic medical record are inappropriate though not specific assessments for dementia. Similarly, having significant difficulty learning a new electronic medical record system more often is a sign of ageism rather than cognitive impairment. Subsequently, when arriving for their evaluation, forgetting the date is a common sign of anxiety. A relatable analogy would be to compare the mistake with a medical student forgetting part of the anatomy while questioning by an attending during surgery. Imagine such medical students being referred to mandatory psychiatric evaluation when failing to answer a question during rounds.

In our practice, the most common reason for those minor mistakes during our clinical evaluation is anxiety. After all, patients who present for problems completely unrelated to cognitive decline make similar mistakes. Psychological stressors in physicians require no introduction. The concept is so prevalent and pervasive that it has its own name, “burnout.” Imagine having dedicated most of one’s life to a profession then being enumerated a list of complaints, having one’s privileges put on hold, then being told to complete an independent psychiatric evaluation. If burnout is in part caused by a lack of control, unclear job expectations, rapidly changing models of health care, and dysfunctional workplace dynamics, imagine the consequence of such a referral.

The militant evaluator will use jargon to vilify the reviewed physician. If the physician complains too voraciously, he will be described as having signs of frontotemporal dementia. If the physician comes with a written list of rebuttals, he will be described as having memory problems requiring aids. If the physician is demoralized and quiet, he will be described as being withdrawn and apathetic. If the physician refuses to use or has difficulty with new forms or electronic systems, he will be described as having “impaired executive function,” an ominous term that surely should not be associated with a practicing physician.

The second concern arises from problems with the validity and use of diagnoses like mild cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI is considered to be a transition stage when one maintains “normal activities of daily living, and normal general cognitive function.”3 The American Psychiatric Association Textbook of Psychiatry mentions that there are “however, many cases of nonprogressive MCI.” Should a disorder with generally normal cognition and unclear progression to a more severe disorder require one to be dispensed of their privileges? Should any disorder trump an assessment of functioning?

It is our experience that many if not most physicians’ practice of medicine is not a job but a profession that defines who they are. As such, their occupational habits are an overly repeated and ingrained series of maneuvers analogous to so-called muscle memory. This kind of ritualistic pattern is precisely the kind of cognition that may persist as one starts to have some deficits. This requires the evaluator to be particularly sensitive and cognizant that one may still be able to perform professionally despite some mild but notable deficits. While it is facile to diagnose someone with MCI and justify removing their license, a review of their actual clinical skills is, despite being more time consuming, more pertinent to the evaluation.

In practice, we find that many cases lie in a gray area, which is hard to define. Physicians may come to our office for an evaluation after having said something odd at work. Maybe they misdosed a medication on one occasion. Maybe they wrote the wrong year on a chart. However, if the physician was 30 years old, would we consider any one of those incidents significant? As a psychiatrist rather than a physician practicing the specialty in review, it is particularly hard and sometimes unwise to condone or sanction individual incidents.

Evaluators find solace in neuropsychological testing. However the relevance to the safety of patients is unclear. Many of those tests end up being a simple proxy for age. A physicians’ ability to sort words or cards at a certain speed might correlate to cognitive performance but has unclear significance to the ability to care for patients. Using such tests becomes a de facto age limit on the practice of medicine. It seems essential to expand and refine our repertoire of evaluation tools for the assessment of physicians. As when we perform capacity evaluation in the hospital, we enlist the assistance of the treating team in understanding the questions being asked for a patient, medical boards could consider creating independent multidisciplinary teams where psychiatry has a seat along with the relevant specialties of the evaluee. Likewise, the assessment would benefit from a broad review of the physicians’ general practice rather than the more typical review of one or two incidents.

We are promoting a more individualized approach by medical boards to the many issues of the aging physician. Retiring is no longer the dream of older physicians, but rather working in the suitable position where their contributions, clinical experience, and wisdom are positive contributions to patient care. Furthermore, we encourage medical boards to consider more nuanced decisions. A binary approach fits few cases that we see. Surgeons are a prime example of this. A surgeon in the early stages of Parkinsonism may be unfit to perform surgery but very capable of continuing to contribute to the well-being of patients in other forms of clinical work, including postsurgical care that doesn’t involve physical dexterity. Similarly, medical boards could consider other forms of partial restrictions, including a ban on procedures, a ban on hospital privileges, as well as required supervision or working in teams. Accumulated clinical wisdom allows older physicians to be excellent mentors and educators for younger doctors. There is no simple method to predict which physicians may have the early stages of a progressive dementia, and which may have a stable MCI. A yearly reevaluation if there are no further complaints, is the best approach to determine progression of cognitive problems.

Few crises like the current COVID-19 pandemic can better remind us of the importance of the place of medicine in society. Many states have encouraged retired physicians to contribute their knowledge and expertise, putting themselves in particular risk because of their age. It is a good time to be reminded that we owe them significant respect and care when deciding to remove their license. We are encouraged by the diligent efforts of medical boards in supervising our colleagues but warn against zealot evaluators who use this opportunity to force physicians into retirement. We also encourage medical boards to expand their tools and approaches when facing such cases, as mislabeled cognitive diagnoses can be an easy scapegoat of a poor understanding of the more important psychological and biological factors in the evaluation.

References

1. Tariq SH et al. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:900-10.

2. Nasreddine Z. mocatest.org. Version 2004 Nov 7.

3. Hales RE et al. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. Washington: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2014.

Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Among his writings in chapter 7 in the book “Critical Psychiatry: Controversies and Clinical Implications” (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019). He has no disclosures.

Dr. Abrams is a forensic psychiatrist and attorney in San Diego. He is an expert in addictionology, behavioral toxicology, psychopharmacology and correctional mental health. He holds a teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego. Among his writings are chapters about competency in national textbooks. Dr. Abrams has no disclosures.

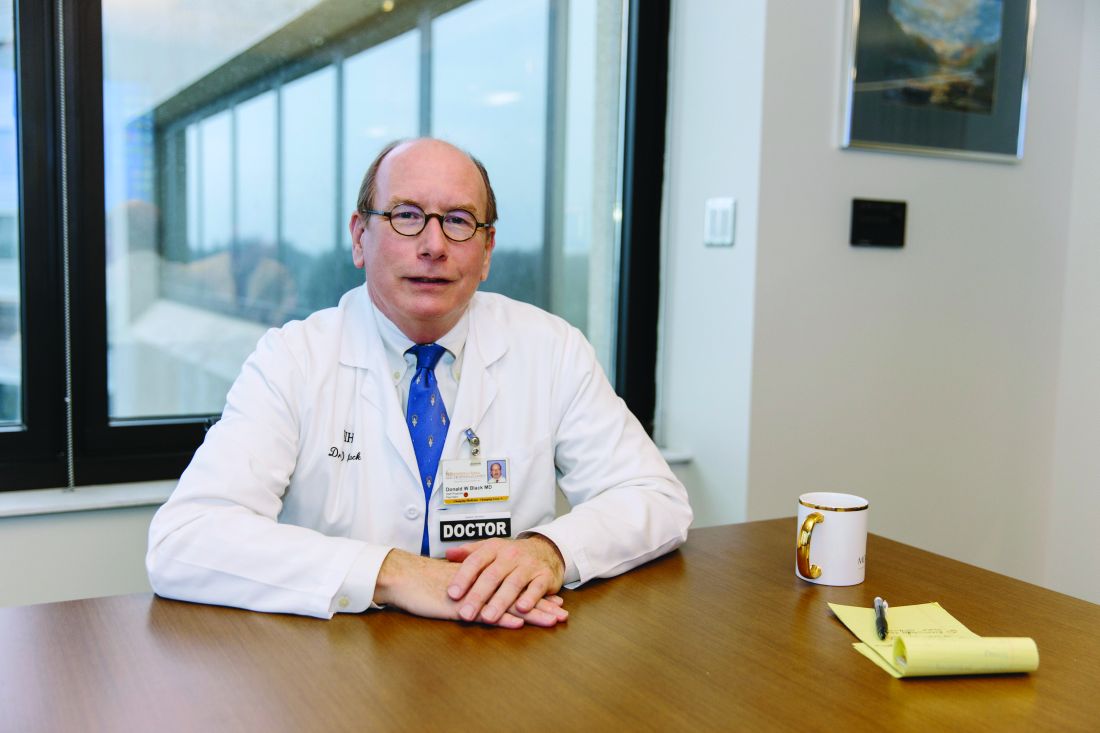

CDC data confirm mental health is suffering during COVID-19

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic continues to exact a huge toll on mental health in the United States, according to results of a survey released Aug. 13 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

During late June, about two in five U.S. adults surveyed said they were struggling with mental health or substance use. Younger adults, racial/ethnic minorities, essential workers, and those with preexisting psychiatric conditions were suffering the most.

“Addressing mental health disparities and preparing support systems to mitigate mental health consequences as the pandemic evolves will continue to be needed urgently,” write Rashon Lane, with the CDC COVID-19 Response Team, and colleagues in an article published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

During the period of June 24-30, 2020, 5,412 U.S. adults aged 18 and older completed online surveys that gauged mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation.

Overall, 40.9% of respondents reported having at least one adverse mental or behavioral health condition; 31% reported symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder; and 26% reported symptoms of a trauma- and stressor-related disorder related to the pandemic.

The prevalence of symptoms of anxiety disorder alone was roughly three times that reported in the second quarter of 2019, the authors noted.

In addition, , and nearly 11% reported having seriously considered suicide in the preceding 30 days.

Approximately twice as many respondents reported seriously considering suicide in the prior month compared with adults in the United States in 2018 (referring to the previous 12 months), the authors noted.

Suicidal ideation was significantly higher among younger respondents (aged 18-24 years, 26%), Hispanic persons (19%), non-Hispanic Black persons (15%), unpaid caregivers for adults (31%), and essential workers (22%).

The survey results are in line with recent data from Mental Health America, which indicate dramatic increases in depression, anxiety, and suicidality since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The “markedly elevated” prevalence of adverse mental and behavioral health conditions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic highlights the “broad impact of the pandemic and the need to prevent and treat these conditions,” the researchers wrote.

The survey also highlights populations at increased risk for psychological distress and unhealthy coping.

“Future studies should identify drivers of adverse mental and behavioral health during the COVID-19 pandemic and whether factors such as social isolation, absence of school structure, unemployment and other financial worries, and various forms of violence (e.g., physical, emotional, mental, or sexual abuse) serve as additional stressors,” they suggested.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic continues to exact a huge toll on mental health in the United States, according to results of a survey released Aug. 13 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

During late June, about two in five U.S. adults surveyed said they were struggling with mental health or substance use. Younger adults, racial/ethnic minorities, essential workers, and those with preexisting psychiatric conditions were suffering the most.

“Addressing mental health disparities and preparing support systems to mitigate mental health consequences as the pandemic evolves will continue to be needed urgently,” write Rashon Lane, with the CDC COVID-19 Response Team, and colleagues in an article published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

During the period of June 24-30, 2020, 5,412 U.S. adults aged 18 and older completed online surveys that gauged mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation.

Overall, 40.9% of respondents reported having at least one adverse mental or behavioral health condition; 31% reported symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder; and 26% reported symptoms of a trauma- and stressor-related disorder related to the pandemic.

The prevalence of symptoms of anxiety disorder alone was roughly three times that reported in the second quarter of 2019, the authors noted.

In addition, , and nearly 11% reported having seriously considered suicide in the preceding 30 days.

Approximately twice as many respondents reported seriously considering suicide in the prior month compared with adults in the United States in 2018 (referring to the previous 12 months), the authors noted.

Suicidal ideation was significantly higher among younger respondents (aged 18-24 years, 26%), Hispanic persons (19%), non-Hispanic Black persons (15%), unpaid caregivers for adults (31%), and essential workers (22%).

The survey results are in line with recent data from Mental Health America, which indicate dramatic increases in depression, anxiety, and suicidality since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The “markedly elevated” prevalence of adverse mental and behavioral health conditions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic highlights the “broad impact of the pandemic and the need to prevent and treat these conditions,” the researchers wrote.

The survey also highlights populations at increased risk for psychological distress and unhealthy coping.

“Future studies should identify drivers of adverse mental and behavioral health during the COVID-19 pandemic and whether factors such as social isolation, absence of school structure, unemployment and other financial worries, and various forms of violence (e.g., physical, emotional, mental, or sexual abuse) serve as additional stressors,” they suggested.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic continues to exact a huge toll on mental health in the United States, according to results of a survey released Aug. 13 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

During late June, about two in five U.S. adults surveyed said they were struggling with mental health or substance use. Younger adults, racial/ethnic minorities, essential workers, and those with preexisting psychiatric conditions were suffering the most.

“Addressing mental health disparities and preparing support systems to mitigate mental health consequences as the pandemic evolves will continue to be needed urgently,” write Rashon Lane, with the CDC COVID-19 Response Team, and colleagues in an article published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

During the period of June 24-30, 2020, 5,412 U.S. adults aged 18 and older completed online surveys that gauged mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation.

Overall, 40.9% of respondents reported having at least one adverse mental or behavioral health condition; 31% reported symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder; and 26% reported symptoms of a trauma- and stressor-related disorder related to the pandemic.

The prevalence of symptoms of anxiety disorder alone was roughly three times that reported in the second quarter of 2019, the authors noted.

In addition, , and nearly 11% reported having seriously considered suicide in the preceding 30 days.

Approximately twice as many respondents reported seriously considering suicide in the prior month compared with adults in the United States in 2018 (referring to the previous 12 months), the authors noted.

Suicidal ideation was significantly higher among younger respondents (aged 18-24 years, 26%), Hispanic persons (19%), non-Hispanic Black persons (15%), unpaid caregivers for adults (31%), and essential workers (22%).

The survey results are in line with recent data from Mental Health America, which indicate dramatic increases in depression, anxiety, and suicidality since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The “markedly elevated” prevalence of adverse mental and behavioral health conditions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic highlights the “broad impact of the pandemic and the need to prevent and treat these conditions,” the researchers wrote.

The survey also highlights populations at increased risk for psychological distress and unhealthy coping.

“Future studies should identify drivers of adverse mental and behavioral health during the COVID-19 pandemic and whether factors such as social isolation, absence of school structure, unemployment and other financial worries, and various forms of violence (e.g., physical, emotional, mental, or sexual abuse) serve as additional stressors,” they suggested.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Chloroquine linked to serious psychiatric side effects

Chloroquine may be associated with serious psychiatric side effects, even in patients with no family or personal history of psychiatric disorders, a new review suggests.

In a letter to the editor published online July 28 in The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, the authors summarize data from several studies published as far back as 1993 and as recently as May 2020.

“In addition to previously reported side effects, chloroquine could also induce psychiatric side effects which are polymorphic and can persist even after stopping the drug,” lead author Florence Gressier, MD, PhD, CESP, Inserm, department of psychiatry, Le Kremlin Bicêtre, France, said in an interview.

“In COVID-19 patients who may still be [undergoing treatment] with chloroquine, close psychiatric assessment and monitoring should be performed,” she said.

Heated controversy

Following findings of a small French study that suggested efficacy in lowering the viral load in patients with COVID-19, President Donald Trump expressed optimism regarding the role of hydroxychloroquine in treating COVID-19, calling it a “game changer”.

Other studies, however, have called into question both the efficacy and the safety of hydroxychloroquine in treating COVID-19. On June 15, the Food and Drug Administration revoked the emergency use authorization it had given in March to chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19.

Nevertheless, hydroxychloroquine continues to be prescribed for COVID-19. For example, an article that appeared in Click2Houston on June 15 quoted the chief medical officer of Houston’s United Memorial Center as saying he plans to continue prescribing hydroxychloroquine for patients with COVID-19 until he finds a better alternative.

As discussed in a Medscape expert commentary, a group of physicians who held a “white coat summit” in front of the U.S. Supreme Court building promoted the use of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19. The video of their summit was retweeted by President Trump and garnered millions of views before it was taken down by Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube.

Sudden onset

For the new review, “we wanted to alert the public and practitioners on the potentially psychiatric risks induced by chloroquine, as it could be taken as self-medication or potentially still prescribed,” Dr. Gressier said.

“We think the format of the letter to the editor allows information to be provided in a concise and clear manner,” she added.

According to the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System database, 12% of reported adverse events (520 of 4,336) following the use of chloroquine that occurred between the fourth quarter of 2012 and the fourth quarter of 2019 were neuropsychiatric. These events included amnesia, delirium, hallucinations, depression, and loss of consciousness, the authors write.

The researchers acknowledged that the incidence of psychiatric adverse effects associated with the use of chloroquine is “unclear in the absence of high-quality, randomized placebo-controlled trials of its safety.” Nevertheless, they pointed out that there have been reports of insomnia and depression when the drug was used as prophylaxis against malaria .

Moreover, some case series or case reports describe symptoms such as depression, anxiety, agitation, violent outburst, suicidal ideation, and psychosis in patients who have been treated with chloroquine for malaria, lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis .

“In contrast to many other psychoses, chloroquine psychosis may be more affective and include prominent visual hallucinations, symptoms of derealization, and disorders of thought, with preserved insight,” the authors wrote.

They noted that the frequency of symptoms does not appear to be connected to the cumulative dose or the duration of treatment, and the onset of psychosis or other adverse effects is usually “sudden.”

In addition, they warn that the drug’s psychiatric effects may go unnoticed, especially because COVID-19 itself has been associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms, making it hard to distinguish between symptoms caused by the illness and those caused by the drug.

Although the psychiatric symptoms typically occur early after treatment initiation, some “subtle” symptoms might persist after stopping the drug, possibly owing to its “extremely long” half-life, the authors stated.

Dr. Gressier noted that practicing clinicians should look up reports about self-medication with chloroquine “and warn their patients about the risk induced by chloroquine.”

Safe but ‘not benign’

Nilanjana Bose, MD, MBA, a rheumatologist at the Rheumatology Center of Houston, said she uses hydroxychloroquine “all the time” in clinical practice to treat patients with rheumatic conditions.

“I cannot comment on whether it [hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine] is a potential prophylactic or treatment for COVID-19, but I can say that, from a safety point of view, as a rheumatologist who uses hydroxychloroquine at a dose of 400 mg/day, I do not think we need to worry about serious [psychiatric] side effects,” Dr. Bose said in an interview.

Because clinicians are trying all types of possible treatments for COVID-19, “if this medication has possible efficacy, it is a great medicine from a rheumatologic perspective and is safe,” she added.

Nevertheless, the drug is “not benign, and regular side effects will be there, and of course, higher doses will cause more side effects,” said Dr. Bose, who was not involved in authoring the letter.

She counsels patients about potential psychiatric side effects of hydroxychloroquine because some of her patients have complained about irritability, worsening anxiety and depression, and difficulty sleeping.

Be wary

James “Jimmy” Potash, MD, MPH, Henry Phipps Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, said in an interview that the “take-home message of this letter is that serious psychiatric effects, psychotic illness in particular,” can occur in individuals who take chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine.

In addition, “these are potentially very concerning side effects that psychiatrists should be aware of,” noted Dr. Potash, department director and psychiatrist-in-chief at Johns Hopkins.

He said that one of his patients who had been “completely psychiatrically healthy” took chloroquine prophylactically prior to traveling overseas. After she began taking the drug, she had an episode of mania that resolved once she discontinued the medication and received treatment for the mania.

“If you add potential psychiatric side effects to the other side effects that can result from these medications, that adds up to a pretty important reason to be wary of taking them, particularly for the indication of COVID-19, where the level of evidence that it helps in any way is still quite weak,” Dr. Potash said.

In an interview, Remington Nevin, MD, MPH, DrPH, executive director at the Quinism Foundation, White River Junction, Vt., a nonprofit organization that supports and promotes education and research on disorders caused by poisoning by quinoline drugs; and faculty associate in the department of mental health at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, said that the authors of the letter “are to be commended for their efforts in raising awareness of the potentially lasting and disabling psychiatric effects of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, which, as with similar effects from other synthetic quinoline antimalarials, have occasionally been overlooked or misattributed to other conditions.”

He added: “I have proposed that the chronic neuropsychiatric effects of this class of drug are best considered not as side effects but as signs and symptoms of a disorder known as chronic quinoline encephalopathy caused by poisoning of the central nervous system.”

Dr. Gressier and the other letter authors, Dr. Bose, and Dr. Potash have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Nevin has been retained as a consultant and expert witness in legal cases involving claims of adverse effects from quinoline antimalarial drugs.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Chloroquine may be associated with serious psychiatric side effects, even in patients with no family or personal history of psychiatric disorders, a new review suggests.

In a letter to the editor published online July 28 in The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, the authors summarize data from several studies published as far back as 1993 and as recently as May 2020.

“In addition to previously reported side effects, chloroquine could also induce psychiatric side effects which are polymorphic and can persist even after stopping the drug,” lead author Florence Gressier, MD, PhD, CESP, Inserm, department of psychiatry, Le Kremlin Bicêtre, France, said in an interview.

“In COVID-19 patients who may still be [undergoing treatment] with chloroquine, close psychiatric assessment and monitoring should be performed,” she said.

Heated controversy

Following findings of a small French study that suggested efficacy in lowering the viral load in patients with COVID-19, President Donald Trump expressed optimism regarding the role of hydroxychloroquine in treating COVID-19, calling it a “game changer”.

Other studies, however, have called into question both the efficacy and the safety of hydroxychloroquine in treating COVID-19. On June 15, the Food and Drug Administration revoked the emergency use authorization it had given in March to chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19.

Nevertheless, hydroxychloroquine continues to be prescribed for COVID-19. For example, an article that appeared in Click2Houston on June 15 quoted the chief medical officer of Houston’s United Memorial Center as saying he plans to continue prescribing hydroxychloroquine for patients with COVID-19 until he finds a better alternative.

As discussed in a Medscape expert commentary, a group of physicians who held a “white coat summit” in front of the U.S. Supreme Court building promoted the use of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19. The video of their summit was retweeted by President Trump and garnered millions of views before it was taken down by Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube.

Sudden onset

For the new review, “we wanted to alert the public and practitioners on the potentially psychiatric risks induced by chloroquine, as it could be taken as self-medication or potentially still prescribed,” Dr. Gressier said.

“We think the format of the letter to the editor allows information to be provided in a concise and clear manner,” she added.

According to the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System database, 12% of reported adverse events (520 of 4,336) following the use of chloroquine that occurred between the fourth quarter of 2012 and the fourth quarter of 2019 were neuropsychiatric. These events included amnesia, delirium, hallucinations, depression, and loss of consciousness, the authors write.

The researchers acknowledged that the incidence of psychiatric adverse effects associated with the use of chloroquine is “unclear in the absence of high-quality, randomized placebo-controlled trials of its safety.” Nevertheless, they pointed out that there have been reports of insomnia and depression when the drug was used as prophylaxis against malaria .

Moreover, some case series or case reports describe symptoms such as depression, anxiety, agitation, violent outburst, suicidal ideation, and psychosis in patients who have been treated with chloroquine for malaria, lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis .

“In contrast to many other psychoses, chloroquine psychosis may be more affective and include prominent visual hallucinations, symptoms of derealization, and disorders of thought, with preserved insight,” the authors wrote.

They noted that the frequency of symptoms does not appear to be connected to the cumulative dose or the duration of treatment, and the onset of psychosis or other adverse effects is usually “sudden.”

In addition, they warn that the drug’s psychiatric effects may go unnoticed, especially because COVID-19 itself has been associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms, making it hard to distinguish between symptoms caused by the illness and those caused by the drug.

Although the psychiatric symptoms typically occur early after treatment initiation, some “subtle” symptoms might persist after stopping the drug, possibly owing to its “extremely long” half-life, the authors stated.

Dr. Gressier noted that practicing clinicians should look up reports about self-medication with chloroquine “and warn their patients about the risk induced by chloroquine.”

Safe but ‘not benign’

Nilanjana Bose, MD, MBA, a rheumatologist at the Rheumatology Center of Houston, said she uses hydroxychloroquine “all the time” in clinical practice to treat patients with rheumatic conditions.

“I cannot comment on whether it [hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine] is a potential prophylactic or treatment for COVID-19, but I can say that, from a safety point of view, as a rheumatologist who uses hydroxychloroquine at a dose of 400 mg/day, I do not think we need to worry about serious [psychiatric] side effects,” Dr. Bose said in an interview.

Because clinicians are trying all types of possible treatments for COVID-19, “if this medication has possible efficacy, it is a great medicine from a rheumatologic perspective and is safe,” she added.

Nevertheless, the drug is “not benign, and regular side effects will be there, and of course, higher doses will cause more side effects,” said Dr. Bose, who was not involved in authoring the letter.

She counsels patients about potential psychiatric side effects of hydroxychloroquine because some of her patients have complained about irritability, worsening anxiety and depression, and difficulty sleeping.

Be wary

James “Jimmy” Potash, MD, MPH, Henry Phipps Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, said in an interview that the “take-home message of this letter is that serious psychiatric effects, psychotic illness in particular,” can occur in individuals who take chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine.

In addition, “these are potentially very concerning side effects that psychiatrists should be aware of,” noted Dr. Potash, department director and psychiatrist-in-chief at Johns Hopkins.

He said that one of his patients who had been “completely psychiatrically healthy” took chloroquine prophylactically prior to traveling overseas. After she began taking the drug, she had an episode of mania that resolved once she discontinued the medication and received treatment for the mania.

“If you add potential psychiatric side effects to the other side effects that can result from these medications, that adds up to a pretty important reason to be wary of taking them, particularly for the indication of COVID-19, where the level of evidence that it helps in any way is still quite weak,” Dr. Potash said.

In an interview, Remington Nevin, MD, MPH, DrPH, executive director at the Quinism Foundation, White River Junction, Vt., a nonprofit organization that supports and promotes education and research on disorders caused by poisoning by quinoline drugs; and faculty associate in the department of mental health at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, said that the authors of the letter “are to be commended for their efforts in raising awareness of the potentially lasting and disabling psychiatric effects of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, which, as with similar effects from other synthetic quinoline antimalarials, have occasionally been overlooked or misattributed to other conditions.”

He added: “I have proposed that the chronic neuropsychiatric effects of this class of drug are best considered not as side effects but as signs and symptoms of a disorder known as chronic quinoline encephalopathy caused by poisoning of the central nervous system.”

Dr. Gressier and the other letter authors, Dr. Bose, and Dr. Potash have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Nevin has been retained as a consultant and expert witness in legal cases involving claims of adverse effects from quinoline antimalarial drugs.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Chloroquine may be associated with serious psychiatric side effects, even in patients with no family or personal history of psychiatric disorders, a new review suggests.

In a letter to the editor published online July 28 in The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, the authors summarize data from several studies published as far back as 1993 and as recently as May 2020.

“In addition to previously reported side effects, chloroquine could also induce psychiatric side effects which are polymorphic and can persist even after stopping the drug,” lead author Florence Gressier, MD, PhD, CESP, Inserm, department of psychiatry, Le Kremlin Bicêtre, France, said in an interview.

“In COVID-19 patients who may still be [undergoing treatment] with chloroquine, close psychiatric assessment and monitoring should be performed,” she said.

Heated controversy

Following findings of a small French study that suggested efficacy in lowering the viral load in patients with COVID-19, President Donald Trump expressed optimism regarding the role of hydroxychloroquine in treating COVID-19, calling it a “game changer”.

Other studies, however, have called into question both the efficacy and the safety of hydroxychloroquine in treating COVID-19. On June 15, the Food and Drug Administration revoked the emergency use authorization it had given in March to chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19.

Nevertheless, hydroxychloroquine continues to be prescribed for COVID-19. For example, an article that appeared in Click2Houston on June 15 quoted the chief medical officer of Houston’s United Memorial Center as saying he plans to continue prescribing hydroxychloroquine for patients with COVID-19 until he finds a better alternative.

As discussed in a Medscape expert commentary, a group of physicians who held a “white coat summit” in front of the U.S. Supreme Court building promoted the use of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19. The video of their summit was retweeted by President Trump and garnered millions of views before it was taken down by Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube.

Sudden onset

For the new review, “we wanted to alert the public and practitioners on the potentially psychiatric risks induced by chloroquine, as it could be taken as self-medication or potentially still prescribed,” Dr. Gressier said.

“We think the format of the letter to the editor allows information to be provided in a concise and clear manner,” she added.

According to the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System database, 12% of reported adverse events (520 of 4,336) following the use of chloroquine that occurred between the fourth quarter of 2012 and the fourth quarter of 2019 were neuropsychiatric. These events included amnesia, delirium, hallucinations, depression, and loss of consciousness, the authors write.

The researchers acknowledged that the incidence of psychiatric adverse effects associated with the use of chloroquine is “unclear in the absence of high-quality, randomized placebo-controlled trials of its safety.” Nevertheless, they pointed out that there have been reports of insomnia and depression when the drug was used as prophylaxis against malaria .

Moreover, some case series or case reports describe symptoms such as depression, anxiety, agitation, violent outburst, suicidal ideation, and psychosis in patients who have been treated with chloroquine for malaria, lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis .

“In contrast to many other psychoses, chloroquine psychosis may be more affective and include prominent visual hallucinations, symptoms of derealization, and disorders of thought, with preserved insight,” the authors wrote.

They noted that the frequency of symptoms does not appear to be connected to the cumulative dose or the duration of treatment, and the onset of psychosis or other adverse effects is usually “sudden.”

In addition, they warn that the drug’s psychiatric effects may go unnoticed, especially because COVID-19 itself has been associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms, making it hard to distinguish between symptoms caused by the illness and those caused by the drug.

Although the psychiatric symptoms typically occur early after treatment initiation, some “subtle” symptoms might persist after stopping the drug, possibly owing to its “extremely long” half-life, the authors stated.

Dr. Gressier noted that practicing clinicians should look up reports about self-medication with chloroquine “and warn their patients about the risk induced by chloroquine.”

Safe but ‘not benign’

Nilanjana Bose, MD, MBA, a rheumatologist at the Rheumatology Center of Houston, said she uses hydroxychloroquine “all the time” in clinical practice to treat patients with rheumatic conditions.

“I cannot comment on whether it [hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine] is a potential prophylactic or treatment for COVID-19, but I can say that, from a safety point of view, as a rheumatologist who uses hydroxychloroquine at a dose of 400 mg/day, I do not think we need to worry about serious [psychiatric] side effects,” Dr. Bose said in an interview.

Because clinicians are trying all types of possible treatments for COVID-19, “if this medication has possible efficacy, it is a great medicine from a rheumatologic perspective and is safe,” she added.

Nevertheless, the drug is “not benign, and regular side effects will be there, and of course, higher doses will cause more side effects,” said Dr. Bose, who was not involved in authoring the letter.

She counsels patients about potential psychiatric side effects of hydroxychloroquine because some of her patients have complained about irritability, worsening anxiety and depression, and difficulty sleeping.

Be wary

James “Jimmy” Potash, MD, MPH, Henry Phipps Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, said in an interview that the “take-home message of this letter is that serious psychiatric effects, psychotic illness in particular,” can occur in individuals who take chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine.

In addition, “these are potentially very concerning side effects that psychiatrists should be aware of,” noted Dr. Potash, department director and psychiatrist-in-chief at Johns Hopkins.

He said that one of his patients who had been “completely psychiatrically healthy” took chloroquine prophylactically prior to traveling overseas. After she began taking the drug, she had an episode of mania that resolved once she discontinued the medication and received treatment for the mania.

“If you add potential psychiatric side effects to the other side effects that can result from these medications, that adds up to a pretty important reason to be wary of taking them, particularly for the indication of COVID-19, where the level of evidence that it helps in any way is still quite weak,” Dr. Potash said.

In an interview, Remington Nevin, MD, MPH, DrPH, executive director at the Quinism Foundation, White River Junction, Vt., a nonprofit organization that supports and promotes education and research on disorders caused by poisoning by quinoline drugs; and faculty associate in the department of mental health at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, said that the authors of the letter “are to be commended for their efforts in raising awareness of the potentially lasting and disabling psychiatric effects of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, which, as with similar effects from other synthetic quinoline antimalarials, have occasionally been overlooked or misattributed to other conditions.”

He added: “I have proposed that the chronic neuropsychiatric effects of this class of drug are best considered not as side effects but as signs and symptoms of a disorder known as chronic quinoline encephalopathy caused by poisoning of the central nervous system.”

Dr. Gressier and the other letter authors, Dr. Bose, and Dr. Potash have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Nevin has been retained as a consultant and expert witness in legal cases involving claims of adverse effects from quinoline antimalarial drugs.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Exploring cannabis use by older adults

Older Americans – people aged 65 or older – make up 15% of the U.S. population, according to the Census Bureau. By the end of this decade, or the year 2030, this proportion will increase to 21% – and all “baby boomers,” those born between 1946 and 1964, will be older than 65.1 Those demographic developments are occurring alongside a change in societal, legal, and public attitudes on cannabis.

Liberalization of cannabis laws across the United States allows for ever easier access to medicinal and recreational cannabis. Traditionally, cannabis use, its effects, and related considerations in the adolescent and young adult populations have commanded significant research attention. Cannabis use in older adults, however, is not as well studied.2 An exploration of trends in cannabis use by older adults and potential impact in terms of health is timely and important.

According to data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, cannabis use in adults aged 65 years and older appears to have been increasing steadily over the past 2 decades. Use among this group rose from 0.4% in 2006 and 2007, to 2.9% in 2015 and 2016.2 And, most recently, use climbed from 3.7% in 2017 to 4.2% in 2018.2

Cannabis use also has risen among other adults. For those aged 50-64, cannabis use increased from 2.8% in 2006-2007 to 4.8% in 2012-2013.2,3 Meanwhile, from 2015 to 2016, that number increased to 9.0%.3,4

Past-year cannabis use in the groups of those aged 50-64 and those aged 65 and older appears to be higher in individuals with mental health problems, alcohol use disorder, and nicotine dependence.5,6 Being male and being unmarried appear to be correlated with past-year cannabis use. Multimorbidity does not appear to be associated with past-year cannabis use. Those using cannabis tend to be long-term users and have first use at a much younger age, typically before age 21.

Older adults use cannabis for both recreational and perceived medical benefits. Arthritis, chronic back pain, anxiety, depression, relaxation, stress reduction, and enhancement in terms of creativity are all purported reasons for use. However, there is limited to no evidence for the efficacy of cannabis in helping with those conditions and purposes. Clinical trials have shown that cannabis can be beneficial in managing pain and nausea, but those trials have not been conducted in older adults.7,8

There is a real risk of cannabis use having a negative impact on the health of older adults. To begin with, the cannabis consumed today is significantly higher in potency than the cannabis that baby boomers were introduced to in their youth. The higher potency, combined with an age-related decline in function experienced by some older adults, makes them vulnerable to its known side effects, such as anxiety, dry mouth, tachycardia, high blood pressure, palpitations, wheezing, confusion, and dizziness.

Cannabis use is reported to bring a fourfold increase in cardiac events within the first hour of ingestion.9 Cognitive decline and memory impairment are well known adverse effects of cannabis use. Research has shown significant self-reported cognitive decline in older adults in relation to cannabis use.Cannabis metabolites are known to have an effect on cytochrome P450 enzymes, affecting the metabolism of medication, and increasing the susceptibility of older adults who use cannabis to adverse effects of polypharmacy. Finally, as research on emergency department visits by older adults shows, cannabis use can increase the risk of injury among this cohort.

As in the United States, cannabis use among older adults in Canada has increased significantly. The percentage of older adults who use cannabis in the Canadian province of Ontario, for example, reportedly doubled from 2005 to 2015. In response to this increase, and in anticipation of a rise in problematic use of cannabis and cannabis use disorder in older adults, the Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health (through financial support from Substance Use and Addictions Program of Health Canada) has created guidelines on the prevention, assessment, and management of cannabis use disorder in older adults.

In the absence of a set of guidelines specific to the United States, the recommendations made by the coalition should be helpful in the care of older Americans. Among other recommendations, the guidelines highlight the needs for primary care physicians to build a better knowledge base around the use of cannabis in older adults, to screen older adults for cannabis use, and to educate older adults and their families about the risk of cannabis use.9

Cannabis use is increasingly popular among older adults10 for both medicinal and recreational purposes. Research and data supporting its medical benefits are limited, and the potential of harm from its use among older adults is present and significant. Importantly, many older adults who use marijuana have co-occurring mental health issues and substance use disorder(s).

Often, our older patients learn about benefits and harms of cannabis from friends and the Internet rather than from physicians and other clinicians.9 We must do our part to make sure that older patients understand the potential negative health impact that cannabis can have on their health. Physicians should screen older adults for marijuana use. Building a better knowledge base around changing trends and views in/on the use and accessibility of cannabis will help physicians better address cannabis use in older adults.

Mr. Kaleka is a medical student in the class of 2021 at Central Michigan University College of Medicine, Mount Pleasant. He has no disclosures. Mr. Kaleka would like to thank his mentor, Furhut Janssen, DO, for her continued guidance and support in research on mental health in vulnerable populations.

References

1. Vespa J et al. Demographic turning points for the United States: Population projections for 2020 to 2060. Current Population Reports. Washington: U.S. Census Bureau. 2020 Feb.

2. Han BH et al. Addiction. 2016 Oct 21. doi: 10.1111/add.13670.

3. Han BH and Palamar JJ. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018 Oct;191:374-81.

4. Han BH and Palamar JJ. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Feb 4;180(4):609-11.

5. Choi NG et al. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2018;44(2):215-23.

6. Reynolds IR et al. J Am Griatr Soc. 2018 Nov;66(11):2167-71.

7. Ahmed AIA et al. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014 Feb;62(2):410-1.

8. Lum HD et al. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2019 Jan-Dec;5:2333721419843707.

9. Bertram JR et al. Can Geriatr J. 2020 Mar;23(1):135-42.

10. Baumbusch J and Yip IS. Clin Gerontol. 2020 Mar 29;1-7.

Older Americans – people aged 65 or older – make up 15% of the U.S. population, according to the Census Bureau. By the end of this decade, or the year 2030, this proportion will increase to 21% – and all “baby boomers,” those born between 1946 and 1964, will be older than 65.1 Those demographic developments are occurring alongside a change in societal, legal, and public attitudes on cannabis.

Liberalization of cannabis laws across the United States allows for ever easier access to medicinal and recreational cannabis. Traditionally, cannabis use, its effects, and related considerations in the adolescent and young adult populations have commanded significant research attention. Cannabis use in older adults, however, is not as well studied.2 An exploration of trends in cannabis use by older adults and potential impact in terms of health is timely and important.

According to data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, cannabis use in adults aged 65 years and older appears to have been increasing steadily over the past 2 decades. Use among this group rose from 0.4% in 2006 and 2007, to 2.9% in 2015 and 2016.2 And, most recently, use climbed from 3.7% in 2017 to 4.2% in 2018.2

Cannabis use also has risen among other adults. For those aged 50-64, cannabis use increased from 2.8% in 2006-2007 to 4.8% in 2012-2013.2,3 Meanwhile, from 2015 to 2016, that number increased to 9.0%.3,4

Past-year cannabis use in the groups of those aged 50-64 and those aged 65 and older appears to be higher in individuals with mental health problems, alcohol use disorder, and nicotine dependence.5,6 Being male and being unmarried appear to be correlated with past-year cannabis use. Multimorbidity does not appear to be associated with past-year cannabis use. Those using cannabis tend to be long-term users and have first use at a much younger age, typically before age 21.

Older adults use cannabis for both recreational and perceived medical benefits. Arthritis, chronic back pain, anxiety, depression, relaxation, stress reduction, and enhancement in terms of creativity are all purported reasons for use. However, there is limited to no evidence for the efficacy of cannabis in helping with those conditions and purposes. Clinical trials have shown that cannabis can be beneficial in managing pain and nausea, but those trials have not been conducted in older adults.7,8

There is a real risk of cannabis use having a negative impact on the health of older adults. To begin with, the cannabis consumed today is significantly higher in potency than the cannabis that baby boomers were introduced to in their youth. The higher potency, combined with an age-related decline in function experienced by some older adults, makes them vulnerable to its known side effects, such as anxiety, dry mouth, tachycardia, high blood pressure, palpitations, wheezing, confusion, and dizziness.

Cannabis use is reported to bring a fourfold increase in cardiac events within the first hour of ingestion.9 Cognitive decline and memory impairment are well known adverse effects of cannabis use. Research has shown significant self-reported cognitive decline in older adults in relation to cannabis use.Cannabis metabolites are known to have an effect on cytochrome P450 enzymes, affecting the metabolism of medication, and increasing the susceptibility of older adults who use cannabis to adverse effects of polypharmacy. Finally, as research on emergency department visits by older adults shows, cannabis use can increase the risk of injury among this cohort.

As in the United States, cannabis use among older adults in Canada has increased significantly. The percentage of older adults who use cannabis in the Canadian province of Ontario, for example, reportedly doubled from 2005 to 2015. In response to this increase, and in anticipation of a rise in problematic use of cannabis and cannabis use disorder in older adults, the Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health (through financial support from Substance Use and Addictions Program of Health Canada) has created guidelines on the prevention, assessment, and management of cannabis use disorder in older adults.

In the absence of a set of guidelines specific to the United States, the recommendations made by the coalition should be helpful in the care of older Americans. Among other recommendations, the guidelines highlight the needs for primary care physicians to build a better knowledge base around the use of cannabis in older adults, to screen older adults for cannabis use, and to educate older adults and their families about the risk of cannabis use.9

Cannabis use is increasingly popular among older adults10 for both medicinal and recreational purposes. Research and data supporting its medical benefits are limited, and the potential of harm from its use among older adults is present and significant. Importantly, many older adults who use marijuana have co-occurring mental health issues and substance use disorder(s).

Often, our older patients learn about benefits and harms of cannabis from friends and the Internet rather than from physicians and other clinicians.9 We must do our part to make sure that older patients understand the potential negative health impact that cannabis can have on their health. Physicians should screen older adults for marijuana use. Building a better knowledge base around changing trends and views in/on the use and accessibility of cannabis will help physicians better address cannabis use in older adults.

Mr. Kaleka is a medical student in the class of 2021 at Central Michigan University College of Medicine, Mount Pleasant. He has no disclosures. Mr. Kaleka would like to thank his mentor, Furhut Janssen, DO, for her continued guidance and support in research on mental health in vulnerable populations.

References

1. Vespa J et al. Demographic turning points for the United States: Population projections for 2020 to 2060. Current Population Reports. Washington: U.S. Census Bureau. 2020 Feb.

2. Han BH et al. Addiction. 2016 Oct 21. doi: 10.1111/add.13670.

3. Han BH and Palamar JJ. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018 Oct;191:374-81.

4. Han BH and Palamar JJ. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Feb 4;180(4):609-11.

5. Choi NG et al. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2018;44(2):215-23.

6. Reynolds IR et al. J Am Griatr Soc. 2018 Nov;66(11):2167-71.

7. Ahmed AIA et al. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014 Feb;62(2):410-1.

8. Lum HD et al. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2019 Jan-Dec;5:2333721419843707.

9. Bertram JR et al. Can Geriatr J. 2020 Mar;23(1):135-42.

10. Baumbusch J and Yip IS. Clin Gerontol. 2020 Mar 29;1-7.

Older Americans – people aged 65 or older – make up 15% of the U.S. population, according to the Census Bureau. By the end of this decade, or the year 2030, this proportion will increase to 21% – and all “baby boomers,” those born between 1946 and 1964, will be older than 65.1 Those demographic developments are occurring alongside a change in societal, legal, and public attitudes on cannabis.

Liberalization of cannabis laws across the United States allows for ever easier access to medicinal and recreational cannabis. Traditionally, cannabis use, its effects, and related considerations in the adolescent and young adult populations have commanded significant research attention. Cannabis use in older adults, however, is not as well studied.2 An exploration of trends in cannabis use by older adults and potential impact in terms of health is timely and important.