User login

Daily Recap: Lifestyle vs. genes in breast cancer showdown; Big pharma sues over insulin affordability law

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Lifestyle choices may reduce breast cancer risk regardless of genetics

A “favorable” lifestyle was associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer even among women at high genetic risk for the disease in a study of more than 90,000 women, researchers reported.

The findings suggest that, regardless of genetic risk, women may be able to reduce their risk of developing breast cancer by getting adequate levels of exercise; maintaining a healthy weight; and limiting or eliminating use of alcohol, oral contraceptives, and hormone replacement therapy.

“These data should empower patients that they can impact on their overall health and reduce the risk of developing breast cancer,” said William Gradishar, MD, who was not invovled with the study. Read more.

Primary care practices may lose $68K per physician this year

Primary care practices stand to lose almost $68,000 per full-time physician this year as COVID-19 causes care delays and cancellations, researchers estimate. And while some outpatient care has started to rebound to near baseline appointment levels, other ambulatory specialties remain dramatically down from prepandemic rates.

Dermatology and rheumatology visits have recovered, but some specialties have cumulative deficits that are particularly concerning. For example, pediatric visits were down by 47% in the 3 months since March 15, and pulmonology visits were down 45% in that time.

This primary care estimate is without a potential second wave of COVID-19, noted Sanjay Basu, MD, director of research and population health at Collective Health in San Francisco, and colleagues.

“We expect ongoing turbulent times, so having a prospective payment could unleash the capacity for primary care practices to be creative in the way they care for their patients,” Daniel Horn, MD, director of population health and quality at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in an interview. Read more.

Big pharma sues to block Minnesota insulin affordability law

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers Association (PhRMA) is suing the state of Minnesota in an attempt to overturn a law that requires insulin makers to provide an emergency supply to individuals free of charge.

In the July 1 filing, PhRMA’s attorneys said the law is unconstitutional. It “order[s] pharmaceutical manufacturers to give insulin to state residents, on the state’s prescribed terms, at no charge to the recipients and without compensating the manufacturers in any way.”

The state has estimated that as many as 30,000 Minnesotans would be eligible for free insulin in the first year of the program. The drugmakers strenuously objected, noting that would mean they would “be compelled to provide 173,800 monthly supplies of free insulin” just in the first year.

“There is nothing in the U.S. Constitution that prevents states from saving the lives of its citizens who are in imminent danger,” said Mayo Clinic hematologist S. Vincent Rajkumar, MD. “The only motives for this lawsuit in my opinion are greed and the worry that other states may also choose to put lives of patients ahead of pharma profits.” Read more.

Despite guidelines, kids get opioids & steroids for pneumonia, sinusitis

A significant percentage of children receive opioids and systemic corticosteroids for pneumonia and sinusitis despite guidelines, according to an analysis of 2016 Medicaid data from South Carolina.

Prescriptions for these drugs were more likely after visits to EDs than after ambulatory visits, researchers reported in Pediatrics.

“Each of the 828 opioid and 2,737 systemic steroid prescriptions in the data set represent a potentially inappropriate prescription,” wrote Karina G. Phang, MD, MPH, of Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pa., and colleagues. “These rates appear excessive given that the use of these medications is not supported by available research or recommended in national guidelines.” Read more.

Study supports changing classification of RCC

The definition of stage IV renal cell carcinoma (RCC) should be expanded to include lymph node–positive stage III disease, according to a population-level cohort study published in Cancer.

While patients with lymph node–negative stage III disease had superior overall survival at 5 years, survival rates were similar between patients with node–positive stage III disease and stage IV disease. This supports reclassifying stage III node-positive RCC to stage IV, according to researchers.

“Prior institutional studies have indicated that, among patients with stage III disease, those with lymph node disease have worse oncologic outcomes and experience survival that is similar to that of patients with American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage IV disease,” wrote Arnav Srivastava, MD, of Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, New Brunswick, and colleagues. Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Lifestyle choices may reduce breast cancer risk regardless of genetics

A “favorable” lifestyle was associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer even among women at high genetic risk for the disease in a study of more than 90,000 women, researchers reported.

The findings suggest that, regardless of genetic risk, women may be able to reduce their risk of developing breast cancer by getting adequate levels of exercise; maintaining a healthy weight; and limiting or eliminating use of alcohol, oral contraceptives, and hormone replacement therapy.

“These data should empower patients that they can impact on their overall health and reduce the risk of developing breast cancer,” said William Gradishar, MD, who was not invovled with the study. Read more.

Primary care practices may lose $68K per physician this year

Primary care practices stand to lose almost $68,000 per full-time physician this year as COVID-19 causes care delays and cancellations, researchers estimate. And while some outpatient care has started to rebound to near baseline appointment levels, other ambulatory specialties remain dramatically down from prepandemic rates.

Dermatology and rheumatology visits have recovered, but some specialties have cumulative deficits that are particularly concerning. For example, pediatric visits were down by 47% in the 3 months since March 15, and pulmonology visits were down 45% in that time.

This primary care estimate is without a potential second wave of COVID-19, noted Sanjay Basu, MD, director of research and population health at Collective Health in San Francisco, and colleagues.

“We expect ongoing turbulent times, so having a prospective payment could unleash the capacity for primary care practices to be creative in the way they care for their patients,” Daniel Horn, MD, director of population health and quality at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in an interview. Read more.

Big pharma sues to block Minnesota insulin affordability law

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers Association (PhRMA) is suing the state of Minnesota in an attempt to overturn a law that requires insulin makers to provide an emergency supply to individuals free of charge.

In the July 1 filing, PhRMA’s attorneys said the law is unconstitutional. It “order[s] pharmaceutical manufacturers to give insulin to state residents, on the state’s prescribed terms, at no charge to the recipients and without compensating the manufacturers in any way.”

The state has estimated that as many as 30,000 Minnesotans would be eligible for free insulin in the first year of the program. The drugmakers strenuously objected, noting that would mean they would “be compelled to provide 173,800 monthly supplies of free insulin” just in the first year.

“There is nothing in the U.S. Constitution that prevents states from saving the lives of its citizens who are in imminent danger,” said Mayo Clinic hematologist S. Vincent Rajkumar, MD. “The only motives for this lawsuit in my opinion are greed and the worry that other states may also choose to put lives of patients ahead of pharma profits.” Read more.

Despite guidelines, kids get opioids & steroids for pneumonia, sinusitis

A significant percentage of children receive opioids and systemic corticosteroids for pneumonia and sinusitis despite guidelines, according to an analysis of 2016 Medicaid data from South Carolina.

Prescriptions for these drugs were more likely after visits to EDs than after ambulatory visits, researchers reported in Pediatrics.

“Each of the 828 opioid and 2,737 systemic steroid prescriptions in the data set represent a potentially inappropriate prescription,” wrote Karina G. Phang, MD, MPH, of Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pa., and colleagues. “These rates appear excessive given that the use of these medications is not supported by available research or recommended in national guidelines.” Read more.

Study supports changing classification of RCC

The definition of stage IV renal cell carcinoma (RCC) should be expanded to include lymph node–positive stage III disease, according to a population-level cohort study published in Cancer.

While patients with lymph node–negative stage III disease had superior overall survival at 5 years, survival rates were similar between patients with node–positive stage III disease and stage IV disease. This supports reclassifying stage III node-positive RCC to stage IV, according to researchers.

“Prior institutional studies have indicated that, among patients with stage III disease, those with lymph node disease have worse oncologic outcomes and experience survival that is similar to that of patients with American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage IV disease,” wrote Arnav Srivastava, MD, of Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, New Brunswick, and colleagues. Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Lifestyle choices may reduce breast cancer risk regardless of genetics

A “favorable” lifestyle was associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer even among women at high genetic risk for the disease in a study of more than 90,000 women, researchers reported.

The findings suggest that, regardless of genetic risk, women may be able to reduce their risk of developing breast cancer by getting adequate levels of exercise; maintaining a healthy weight; and limiting or eliminating use of alcohol, oral contraceptives, and hormone replacement therapy.

“These data should empower patients that they can impact on their overall health and reduce the risk of developing breast cancer,” said William Gradishar, MD, who was not invovled with the study. Read more.

Primary care practices may lose $68K per physician this year

Primary care practices stand to lose almost $68,000 per full-time physician this year as COVID-19 causes care delays and cancellations, researchers estimate. And while some outpatient care has started to rebound to near baseline appointment levels, other ambulatory specialties remain dramatically down from prepandemic rates.

Dermatology and rheumatology visits have recovered, but some specialties have cumulative deficits that are particularly concerning. For example, pediatric visits were down by 47% in the 3 months since March 15, and pulmonology visits were down 45% in that time.

This primary care estimate is without a potential second wave of COVID-19, noted Sanjay Basu, MD, director of research and population health at Collective Health in San Francisco, and colleagues.

“We expect ongoing turbulent times, so having a prospective payment could unleash the capacity for primary care practices to be creative in the way they care for their patients,” Daniel Horn, MD, director of population health and quality at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in an interview. Read more.

Big pharma sues to block Minnesota insulin affordability law

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers Association (PhRMA) is suing the state of Minnesota in an attempt to overturn a law that requires insulin makers to provide an emergency supply to individuals free of charge.

In the July 1 filing, PhRMA’s attorneys said the law is unconstitutional. It “order[s] pharmaceutical manufacturers to give insulin to state residents, on the state’s prescribed terms, at no charge to the recipients and without compensating the manufacturers in any way.”

The state has estimated that as many as 30,000 Minnesotans would be eligible for free insulin in the first year of the program. The drugmakers strenuously objected, noting that would mean they would “be compelled to provide 173,800 monthly supplies of free insulin” just in the first year.

“There is nothing in the U.S. Constitution that prevents states from saving the lives of its citizens who are in imminent danger,” said Mayo Clinic hematologist S. Vincent Rajkumar, MD. “The only motives for this lawsuit in my opinion are greed and the worry that other states may also choose to put lives of patients ahead of pharma profits.” Read more.

Despite guidelines, kids get opioids & steroids for pneumonia, sinusitis

A significant percentage of children receive opioids and systemic corticosteroids for pneumonia and sinusitis despite guidelines, according to an analysis of 2016 Medicaid data from South Carolina.

Prescriptions for these drugs were more likely after visits to EDs than after ambulatory visits, researchers reported in Pediatrics.

“Each of the 828 opioid and 2,737 systemic steroid prescriptions in the data set represent a potentially inappropriate prescription,” wrote Karina G. Phang, MD, MPH, of Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pa., and colleagues. “These rates appear excessive given that the use of these medications is not supported by available research or recommended in national guidelines.” Read more.

Study supports changing classification of RCC

The definition of stage IV renal cell carcinoma (RCC) should be expanded to include lymph node–positive stage III disease, according to a population-level cohort study published in Cancer.

While patients with lymph node–negative stage III disease had superior overall survival at 5 years, survival rates were similar between patients with node–positive stage III disease and stage IV disease. This supports reclassifying stage III node-positive RCC to stage IV, according to researchers.

“Prior institutional studies have indicated that, among patients with stage III disease, those with lymph node disease have worse oncologic outcomes and experience survival that is similar to that of patients with American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage IV disease,” wrote Arnav Srivastava, MD, of Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, New Brunswick, and colleagues. Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

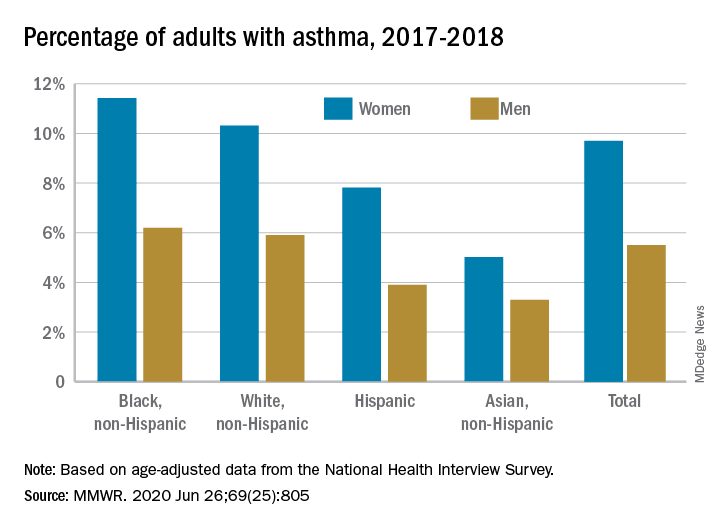

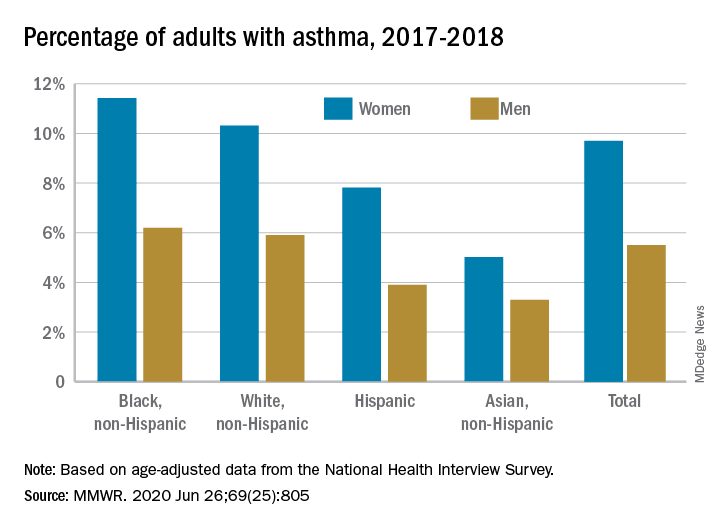

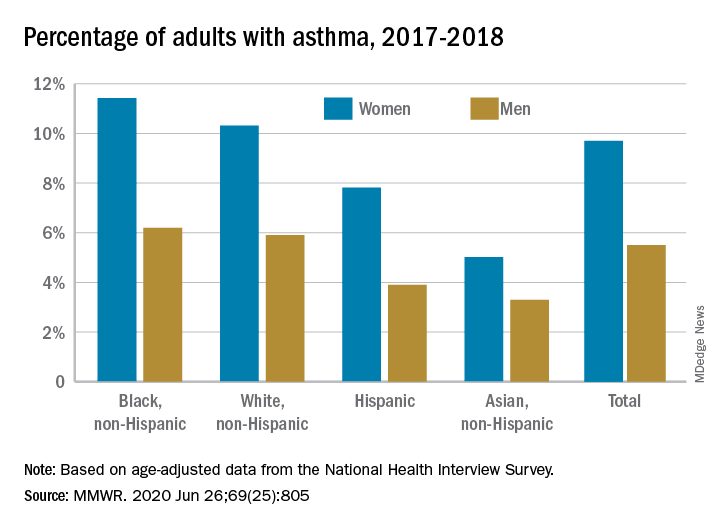

Black women at highest risk for asthma

Women are much more likely than men to have asthma, and , according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Among all women aged 18 years and older, 9.7% reported that they currently had asthma in 2017-2018, compared with 5.5% of men, based on age-adjusted data from the National Health Interview Survey.

The proportion of black, non-Hispanic women with asthma, however, was even higher, at 11.4%. White non-Hispanic women were next at 10.3%, followed by Hispanic (7.8%) and Asian (5.0%) women, the CDC reported June 26 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The same pattern held for men: 6.2% of black men had asthma in 2017-2018, compared with 5.9% of whites, 3.9% of Hispanics, and 3.3% of Asian men, the CDC said.

SOURCE: MMWR. 2020 Jun 26;69(25):805.

Women are much more likely than men to have asthma, and , according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Among all women aged 18 years and older, 9.7% reported that they currently had asthma in 2017-2018, compared with 5.5% of men, based on age-adjusted data from the National Health Interview Survey.

The proportion of black, non-Hispanic women with asthma, however, was even higher, at 11.4%. White non-Hispanic women were next at 10.3%, followed by Hispanic (7.8%) and Asian (5.0%) women, the CDC reported June 26 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The same pattern held for men: 6.2% of black men had asthma in 2017-2018, compared with 5.9% of whites, 3.9% of Hispanics, and 3.3% of Asian men, the CDC said.

SOURCE: MMWR. 2020 Jun 26;69(25):805.

Women are much more likely than men to have asthma, and , according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Among all women aged 18 years and older, 9.7% reported that they currently had asthma in 2017-2018, compared with 5.5% of men, based on age-adjusted data from the National Health Interview Survey.

The proportion of black, non-Hispanic women with asthma, however, was even higher, at 11.4%. White non-Hispanic women were next at 10.3%, followed by Hispanic (7.8%) and Asian (5.0%) women, the CDC reported June 26 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The same pattern held for men: 6.2% of black men had asthma in 2017-2018, compared with 5.9% of whites, 3.9% of Hispanics, and 3.3% of Asian men, the CDC said.

SOURCE: MMWR. 2020 Jun 26;69(25):805.

FROM MMWR

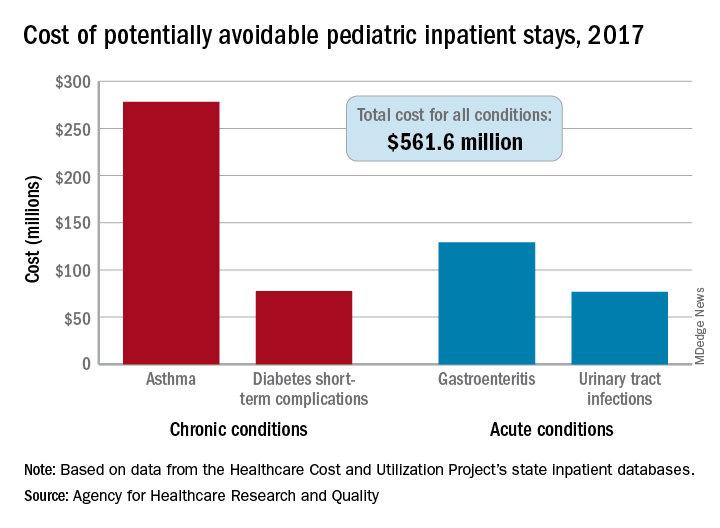

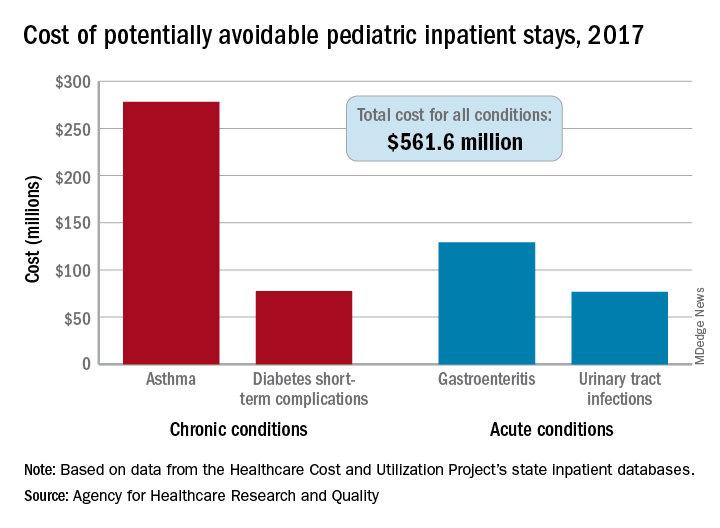

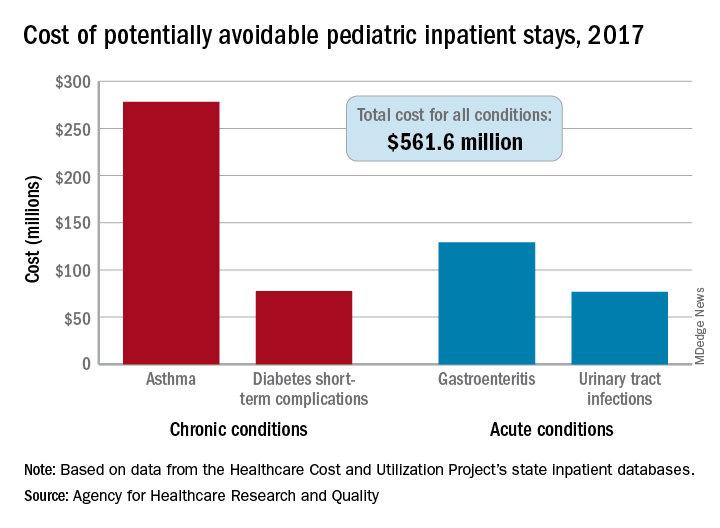

Asthma leads spending on avoidable pediatric inpatient stays

according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The cost of potentially avoidable visits for asthma that year was $278 million, versus $284 million combined for the other three conditions “that evidence suggests may be avoidable, in part, through timely and quality primary and preventive care,” Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and H. Joanna Jiang, PhD, said in an AHRQ statistical brief.

Those three other conditions are diabetes short-term complications, gastroenteritis, and urinary tract infections (UTIs). Neonatal stays were excluded from the analysis, Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Dr. Jiang of the AHRQ noted.

The state inpatient databases of the AHRQ’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project included 1.4 million inpatient stays among children aged 3 months to 17 years in 2017, of which 8% (108,300) were deemed potentially preventable. Hospital charges for the preventable stays came to $561.6 million, or 3% of the $20 billion in total costs for all nonneonatal stays, they said.

Rates of potentially avoidable stays for asthma (159 per 100,000 population), gastroenteritis (90 per 100,000), and UTIs (41 per 100,000) were highest for children aged 0-4 years and generally decreased with age, but diabetes stays increased with age, rising from 12 per 100,000 in children aged 5-9 years to 38 per 100,000 for those 15-17 years old, the researchers said.

Black children had a much higher rate of potentially avoidable stays for asthma (218 per 100,000) than did Hispanic children (74), Asian/Pacific Islander children (46), or white children (43), but children classified as other race/ethnicity were higher still: 380 per 100,000. Rates for children classified as other race/ethnicity were highest for the other three conditions as well, they reported.

Comparisons by sex for the four conditions ended up in a 2-2 tie: Girls had higher rates for diabetes (28 vs. 23) and UTIs (35 vs. 8), and boys had higher rates for asthma (96 vs. 67) and gastroenteritis (38 vs. 35), Dr. McDermott and Dr. Jiang reported.

SOURCE: McDermott KW, Jiang HJ. HCUP Statistical Brief #259. June 2020.

according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The cost of potentially avoidable visits for asthma that year was $278 million, versus $284 million combined for the other three conditions “that evidence suggests may be avoidable, in part, through timely and quality primary and preventive care,” Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and H. Joanna Jiang, PhD, said in an AHRQ statistical brief.

Those three other conditions are diabetes short-term complications, gastroenteritis, and urinary tract infections (UTIs). Neonatal stays were excluded from the analysis, Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Dr. Jiang of the AHRQ noted.

The state inpatient databases of the AHRQ’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project included 1.4 million inpatient stays among children aged 3 months to 17 years in 2017, of which 8% (108,300) were deemed potentially preventable. Hospital charges for the preventable stays came to $561.6 million, or 3% of the $20 billion in total costs for all nonneonatal stays, they said.

Rates of potentially avoidable stays for asthma (159 per 100,000 population), gastroenteritis (90 per 100,000), and UTIs (41 per 100,000) were highest for children aged 0-4 years and generally decreased with age, but diabetes stays increased with age, rising from 12 per 100,000 in children aged 5-9 years to 38 per 100,000 for those 15-17 years old, the researchers said.

Black children had a much higher rate of potentially avoidable stays for asthma (218 per 100,000) than did Hispanic children (74), Asian/Pacific Islander children (46), or white children (43), but children classified as other race/ethnicity were higher still: 380 per 100,000. Rates for children classified as other race/ethnicity were highest for the other three conditions as well, they reported.

Comparisons by sex for the four conditions ended up in a 2-2 tie: Girls had higher rates for diabetes (28 vs. 23) and UTIs (35 vs. 8), and boys had higher rates for asthma (96 vs. 67) and gastroenteritis (38 vs. 35), Dr. McDermott and Dr. Jiang reported.

SOURCE: McDermott KW, Jiang HJ. HCUP Statistical Brief #259. June 2020.

according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The cost of potentially avoidable visits for asthma that year was $278 million, versus $284 million combined for the other three conditions “that evidence suggests may be avoidable, in part, through timely and quality primary and preventive care,” Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and H. Joanna Jiang, PhD, said in an AHRQ statistical brief.

Those three other conditions are diabetes short-term complications, gastroenteritis, and urinary tract infections (UTIs). Neonatal stays were excluded from the analysis, Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Dr. Jiang of the AHRQ noted.

The state inpatient databases of the AHRQ’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project included 1.4 million inpatient stays among children aged 3 months to 17 years in 2017, of which 8% (108,300) were deemed potentially preventable. Hospital charges for the preventable stays came to $561.6 million, or 3% of the $20 billion in total costs for all nonneonatal stays, they said.

Rates of potentially avoidable stays for asthma (159 per 100,000 population), gastroenteritis (90 per 100,000), and UTIs (41 per 100,000) were highest for children aged 0-4 years and generally decreased with age, but diabetes stays increased with age, rising from 12 per 100,000 in children aged 5-9 years to 38 per 100,000 for those 15-17 years old, the researchers said.

Black children had a much higher rate of potentially avoidable stays for asthma (218 per 100,000) than did Hispanic children (74), Asian/Pacific Islander children (46), or white children (43), but children classified as other race/ethnicity were higher still: 380 per 100,000. Rates for children classified as other race/ethnicity were highest for the other three conditions as well, they reported.

Comparisons by sex for the four conditions ended up in a 2-2 tie: Girls had higher rates for diabetes (28 vs. 23) and UTIs (35 vs. 8), and boys had higher rates for asthma (96 vs. 67) and gastroenteritis (38 vs. 35), Dr. McDermott and Dr. Jiang reported.

SOURCE: McDermott KW, Jiang HJ. HCUP Statistical Brief #259. June 2020.

Kids with food allergies the newest victims of COVID-19?

Food insecurity is not knowing how you will get your next meal. This pandemic has led to a lot of it, especially as a result of massive unemployment. Now imagine being in that situation with a food-allergic child. It would be frightening.

There is always a level of anxiety for parents of food-allergic children, but the Food and Drug Administration–mandated labeling of food allergens has helped to allay some of those concerns. Shopping can feel safer, even if it’s not foolproof.

Now, that fear for the safety of food-allergic children is going to be compounded by the FDA’s latest announcement, made at the behest of the food industry.

Disruptions in the food supply chain caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have created some problems for the food industry. The industry sought – and received – relief from the FDA; they are now allowing some ingredient substitutions without mandating a change in labeling. These changes were made without opportunity for public comment, according to the FDA, because of the exigency of the situation. Furthermore, the changes may stay in effect for an indeterminate period of time after the pandemic is deemed under control.

Labeling of gluten and the major eight allergens (peanuts, tree nuts, milk, eggs, soy, wheat, fish, and crustacean shellfish) cannot change under the new guidelines. The FDA also advised “consideration” of major food allergens recognized in other countries (sesame, celery, lupin, buckwheat, molluscan shellfish, and mustard). Of these, lupin is known to cross-react with peanut, and sesame seed allergy is increasingly prevalent. In fact, the FDA has considered adding it to the list of major allergens.

Meanwhile, according to this temporary FDA policy, substitutions should be limited to no more than 2% of the weight of the final product unless it is a variety of the same ingredient. The example provided is substitution of one type of mushroom for another, but even that could be an issue for the rare patient. And what if this is misinterpreted – as will surely happen somewhere – and one seed is substituted for another?

A friend of mine is a pediatrician and mother of a child who is allergic to sesame, peanuts, tree nuts, and garbanzo beans. Naturally, she had grave concerns about these changes. She also wondered what the liability would be for the food manufacturing company in the current situation despite the FDA notice, which seems like a valid point. It is worth noting that, at the very top of this FDA notice, are the words “contains nonbinding recommendations,” so manufacturers may want to think twice about how they approach this. A minority of companies have pledged to relabel foods if necessary. Meanwhile, without any alert in advance, it is now up to patients and their physicians to sort out the attendant risks.

The FDA should have advised or mandated that food manufacturers give notice to online and physical retailers of ingredient changes. A simple sign in front of a display or alert online would be a very reasonable solution and pose no burden to those involved. It should be self-evident that mistakes always happen, especially under duress, and that the loosening of these regulations will have unintended consequences. To the severe problem of food insecurity, we can add one more concern for the parents of allergic children: food-allergen insecurity.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Food insecurity is not knowing how you will get your next meal. This pandemic has led to a lot of it, especially as a result of massive unemployment. Now imagine being in that situation with a food-allergic child. It would be frightening.

There is always a level of anxiety for parents of food-allergic children, but the Food and Drug Administration–mandated labeling of food allergens has helped to allay some of those concerns. Shopping can feel safer, even if it’s not foolproof.

Now, that fear for the safety of food-allergic children is going to be compounded by the FDA’s latest announcement, made at the behest of the food industry.

Disruptions in the food supply chain caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have created some problems for the food industry. The industry sought – and received – relief from the FDA; they are now allowing some ingredient substitutions without mandating a change in labeling. These changes were made without opportunity for public comment, according to the FDA, because of the exigency of the situation. Furthermore, the changes may stay in effect for an indeterminate period of time after the pandemic is deemed under control.

Labeling of gluten and the major eight allergens (peanuts, tree nuts, milk, eggs, soy, wheat, fish, and crustacean shellfish) cannot change under the new guidelines. The FDA also advised “consideration” of major food allergens recognized in other countries (sesame, celery, lupin, buckwheat, molluscan shellfish, and mustard). Of these, lupin is known to cross-react with peanut, and sesame seed allergy is increasingly prevalent. In fact, the FDA has considered adding it to the list of major allergens.

Meanwhile, according to this temporary FDA policy, substitutions should be limited to no more than 2% of the weight of the final product unless it is a variety of the same ingredient. The example provided is substitution of one type of mushroom for another, but even that could be an issue for the rare patient. And what if this is misinterpreted – as will surely happen somewhere – and one seed is substituted for another?

A friend of mine is a pediatrician and mother of a child who is allergic to sesame, peanuts, tree nuts, and garbanzo beans. Naturally, she had grave concerns about these changes. She also wondered what the liability would be for the food manufacturing company in the current situation despite the FDA notice, which seems like a valid point. It is worth noting that, at the very top of this FDA notice, are the words “contains nonbinding recommendations,” so manufacturers may want to think twice about how they approach this. A minority of companies have pledged to relabel foods if necessary. Meanwhile, without any alert in advance, it is now up to patients and their physicians to sort out the attendant risks.

The FDA should have advised or mandated that food manufacturers give notice to online and physical retailers of ingredient changes. A simple sign in front of a display or alert online would be a very reasonable solution and pose no burden to those involved. It should be self-evident that mistakes always happen, especially under duress, and that the loosening of these regulations will have unintended consequences. To the severe problem of food insecurity, we can add one more concern for the parents of allergic children: food-allergen insecurity.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Food insecurity is not knowing how you will get your next meal. This pandemic has led to a lot of it, especially as a result of massive unemployment. Now imagine being in that situation with a food-allergic child. It would be frightening.

There is always a level of anxiety for parents of food-allergic children, but the Food and Drug Administration–mandated labeling of food allergens has helped to allay some of those concerns. Shopping can feel safer, even if it’s not foolproof.

Now, that fear for the safety of food-allergic children is going to be compounded by the FDA’s latest announcement, made at the behest of the food industry.

Disruptions in the food supply chain caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have created some problems for the food industry. The industry sought – and received – relief from the FDA; they are now allowing some ingredient substitutions without mandating a change in labeling. These changes were made without opportunity for public comment, according to the FDA, because of the exigency of the situation. Furthermore, the changes may stay in effect for an indeterminate period of time after the pandemic is deemed under control.

Labeling of gluten and the major eight allergens (peanuts, tree nuts, milk, eggs, soy, wheat, fish, and crustacean shellfish) cannot change under the new guidelines. The FDA also advised “consideration” of major food allergens recognized in other countries (sesame, celery, lupin, buckwheat, molluscan shellfish, and mustard). Of these, lupin is known to cross-react with peanut, and sesame seed allergy is increasingly prevalent. In fact, the FDA has considered adding it to the list of major allergens.

Meanwhile, according to this temporary FDA policy, substitutions should be limited to no more than 2% of the weight of the final product unless it is a variety of the same ingredient. The example provided is substitution of one type of mushroom for another, but even that could be an issue for the rare patient. And what if this is misinterpreted – as will surely happen somewhere – and one seed is substituted for another?

A friend of mine is a pediatrician and mother of a child who is allergic to sesame, peanuts, tree nuts, and garbanzo beans. Naturally, she had grave concerns about these changes. She also wondered what the liability would be for the food manufacturing company in the current situation despite the FDA notice, which seems like a valid point. It is worth noting that, at the very top of this FDA notice, are the words “contains nonbinding recommendations,” so manufacturers may want to think twice about how they approach this. A minority of companies have pledged to relabel foods if necessary. Meanwhile, without any alert in advance, it is now up to patients and their physicians to sort out the attendant risks.

The FDA should have advised or mandated that food manufacturers give notice to online and physical retailers of ingredient changes. A simple sign in front of a display or alert online would be a very reasonable solution and pose no burden to those involved. It should be self-evident that mistakes always happen, especially under duress, and that the loosening of these regulations will have unintended consequences. To the severe problem of food insecurity, we can add one more concern for the parents of allergic children: food-allergen insecurity.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

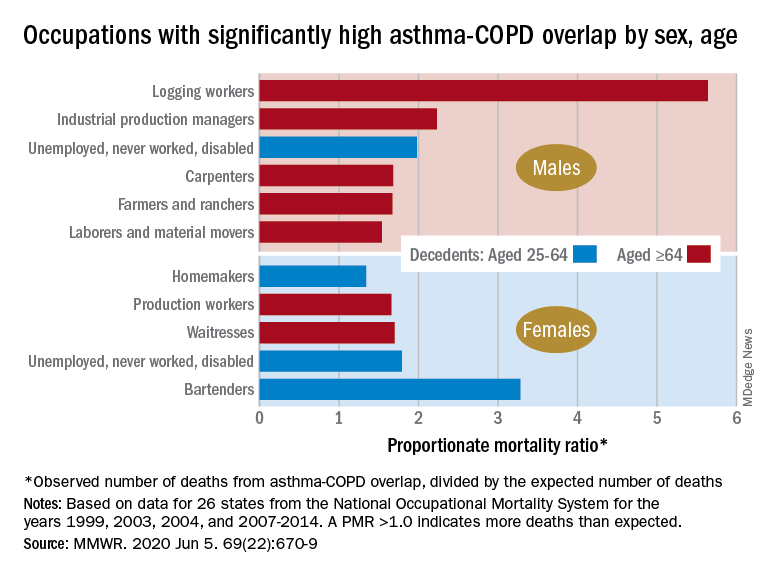

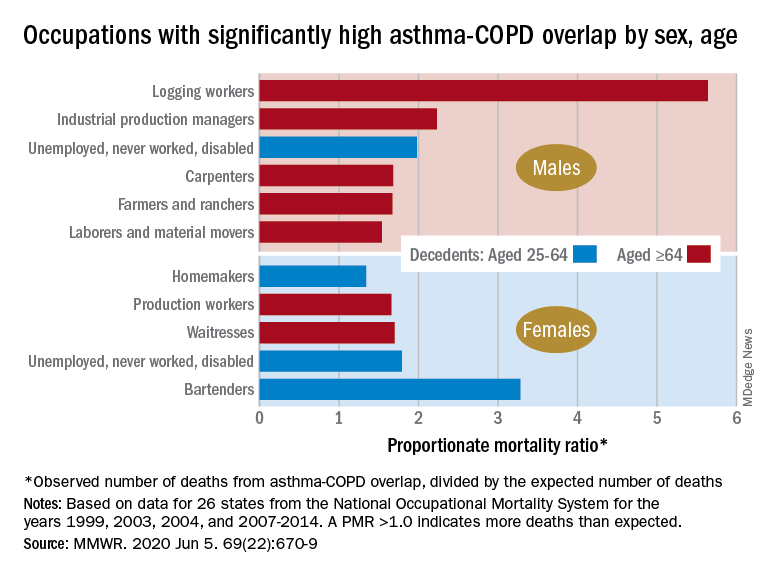

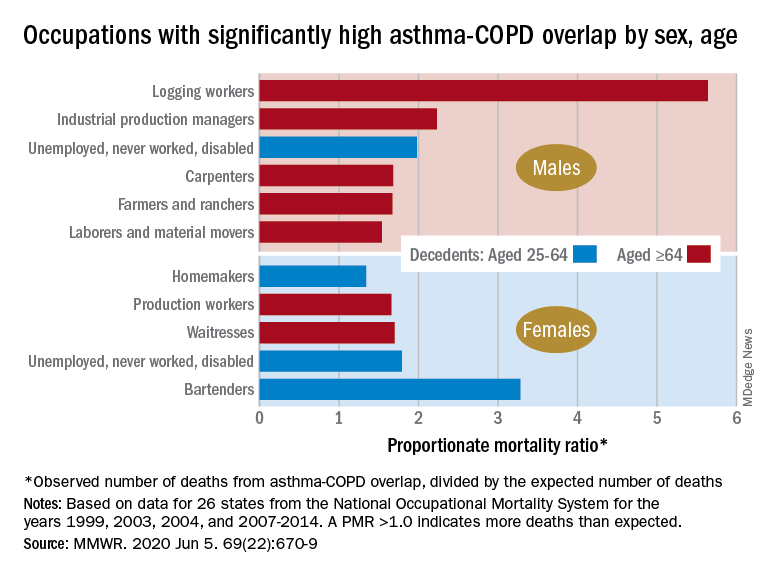

By the numbers: Asthma-COPD overlap deaths

Death rates for combined asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease declined during 1999-2016, but the risk remains higher among women, compared with men, and in certain occupations, according to a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There is also an association between mortality and nonworking status among adults aged 25-64 years, which “suggests that asthma-COPD overlap might be associated with substantial morbidity,” Katelynn E. Dodd, MPH, and associates at the CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. “These patients have been reported to have worse health outcomes than do those with asthma or COPD alone.”

For females with asthma-COPD overlap, the age-adjusted death rate among adults aged 25 years and older dropped from 7.71 per million in 1999 to 4.01 in 2016, with corresponding rates of 6.70 and 3.01 per million for males, they reported.

In 1999-2016, a total of 18,766 U.S. decedents aged ≥25 years had both asthma and COPD assigned as the underlying or contributing cause of death (12,028 women and 6,738 men), for an overall death rate of 5.03 per million persons (women, 5.59; men, 4.30), data from the National Vital Statistics System show.

Additional analysis, based on the calculation of proportionate mortality ratios (PMRs), also showed that mortality varied by occupational status and age for both males and females, the investigators said, noting that workplace exposures, such as dusts and secondhand smoke, are known to cause both asthma and COPD.

The PMR represents the observed number of deaths from asthma-COPD overlap in a specified industry or occupation, divided by the expected number of deaths, so a value over 1.0 indicates that there were more deaths associated with the condition than expected, Ms. Dodd and her associates explained.

Among female decedents, the occupation with the highest PMR that was statistically significant was bartending at 3.28. For men, the highest significant PMR, 5.64, occurred in logging workers. Those rates, however, only applied to one of the two age groups: 25-64 years in women and ≥65 in men, based on data from the National Occupational Mortality Surveillance, which included information from 26 states for the years 1999, 2003, 2004, and 2007-2014.

Occupationally speaking, the one area of common ground between males and females was lack of occupation. PMRs for those aged 25-64 years “were significantly elevated among men (1.98) and women (1.79) who were unemployed, never worked, or were disabled workers,” they said. PMRs were elevated for nonworking older males and females but were not significant.

The elevated PMRs suggest “that asthma-COPD overlap might be associated with substantial morbidity resulting in loss of employment [because] retired and unemployed persons might have left the workforce because of severe asthma or COPD,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Dodd KE et al. MMWR. 2020 Jun 5. 69(22):670-9.

Death rates for combined asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease declined during 1999-2016, but the risk remains higher among women, compared with men, and in certain occupations, according to a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There is also an association between mortality and nonworking status among adults aged 25-64 years, which “suggests that asthma-COPD overlap might be associated with substantial morbidity,” Katelynn E. Dodd, MPH, and associates at the CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. “These patients have been reported to have worse health outcomes than do those with asthma or COPD alone.”

For females with asthma-COPD overlap, the age-adjusted death rate among adults aged 25 years and older dropped from 7.71 per million in 1999 to 4.01 in 2016, with corresponding rates of 6.70 and 3.01 per million for males, they reported.

In 1999-2016, a total of 18,766 U.S. decedents aged ≥25 years had both asthma and COPD assigned as the underlying or contributing cause of death (12,028 women and 6,738 men), for an overall death rate of 5.03 per million persons (women, 5.59; men, 4.30), data from the National Vital Statistics System show.

Additional analysis, based on the calculation of proportionate mortality ratios (PMRs), also showed that mortality varied by occupational status and age for both males and females, the investigators said, noting that workplace exposures, such as dusts and secondhand smoke, are known to cause both asthma and COPD.

The PMR represents the observed number of deaths from asthma-COPD overlap in a specified industry or occupation, divided by the expected number of deaths, so a value over 1.0 indicates that there were more deaths associated with the condition than expected, Ms. Dodd and her associates explained.

Among female decedents, the occupation with the highest PMR that was statistically significant was bartending at 3.28. For men, the highest significant PMR, 5.64, occurred in logging workers. Those rates, however, only applied to one of the two age groups: 25-64 years in women and ≥65 in men, based on data from the National Occupational Mortality Surveillance, which included information from 26 states for the years 1999, 2003, 2004, and 2007-2014.

Occupationally speaking, the one area of common ground between males and females was lack of occupation. PMRs for those aged 25-64 years “were significantly elevated among men (1.98) and women (1.79) who were unemployed, never worked, or were disabled workers,” they said. PMRs were elevated for nonworking older males and females but were not significant.

The elevated PMRs suggest “that asthma-COPD overlap might be associated with substantial morbidity resulting in loss of employment [because] retired and unemployed persons might have left the workforce because of severe asthma or COPD,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Dodd KE et al. MMWR. 2020 Jun 5. 69(22):670-9.

Death rates for combined asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease declined during 1999-2016, but the risk remains higher among women, compared with men, and in certain occupations, according to a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There is also an association between mortality and nonworking status among adults aged 25-64 years, which “suggests that asthma-COPD overlap might be associated with substantial morbidity,” Katelynn E. Dodd, MPH, and associates at the CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. “These patients have been reported to have worse health outcomes than do those with asthma or COPD alone.”

For females with asthma-COPD overlap, the age-adjusted death rate among adults aged 25 years and older dropped from 7.71 per million in 1999 to 4.01 in 2016, with corresponding rates of 6.70 and 3.01 per million for males, they reported.

In 1999-2016, a total of 18,766 U.S. decedents aged ≥25 years had both asthma and COPD assigned as the underlying or contributing cause of death (12,028 women and 6,738 men), for an overall death rate of 5.03 per million persons (women, 5.59; men, 4.30), data from the National Vital Statistics System show.

Additional analysis, based on the calculation of proportionate mortality ratios (PMRs), also showed that mortality varied by occupational status and age for both males and females, the investigators said, noting that workplace exposures, such as dusts and secondhand smoke, are known to cause both asthma and COPD.

The PMR represents the observed number of deaths from asthma-COPD overlap in a specified industry or occupation, divided by the expected number of deaths, so a value over 1.0 indicates that there were more deaths associated with the condition than expected, Ms. Dodd and her associates explained.

Among female decedents, the occupation with the highest PMR that was statistically significant was bartending at 3.28. For men, the highest significant PMR, 5.64, occurred in logging workers. Those rates, however, only applied to one of the two age groups: 25-64 years in women and ≥65 in men, based on data from the National Occupational Mortality Surveillance, which included information from 26 states for the years 1999, 2003, 2004, and 2007-2014.

Occupationally speaking, the one area of common ground between males and females was lack of occupation. PMRs for those aged 25-64 years “were significantly elevated among men (1.98) and women (1.79) who were unemployed, never worked, or were disabled workers,” they said. PMRs were elevated for nonworking older males and females but were not significant.

The elevated PMRs suggest “that asthma-COPD overlap might be associated with substantial morbidity resulting in loss of employment [because] retired and unemployed persons might have left the workforce because of severe asthma or COPD,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Dodd KE et al. MMWR. 2020 Jun 5. 69(22):670-9.

FROM MMWR

Prolonged azithromycin Tx for asthma?

In “Asthma: Newer Tx options mean more targeted therapy” (J Fam Pract. 2020;65:135-144), Rali et al recommend azithromycin as an add-on therapy to ICS-LABA for a select group of patients with uncontrolled persistent asthma (neutrophilic phenotype)—a Grade C recommendation. However, the best available evidence demonstrates that azithromycin is equally efficacious for uncontrolled persistent eosinophilic asthma.1,2 Thus, family physicians need not refer patients for bronchoscopy to identify the inflammatory “phenotype.”

An important unanswered question is whether azithromycin needs to be administered continuously. Emerging evidence indicates that some patients may experience prolonged benefit after time-limited azithromycin treatment. This suggests that the mechanism of action, which has been described as anti-inflammatory, is (at least in part) antimicrobial.3

For azithromycin-treated asthma patients who experience a significant clinical response after 3 to 6 months of treatment, I recommend that the prescribing clinician try taking the patient off azithromycin to assess whether clinical improvement persists or wanes. Nothing is lost, and much is gained, by this approach; patients who relapse can resume azithromycin, and patients who remain improved are spared exposure to an unnecessary and prolonged treatment.

David L. Hahn, MD, MS

Madison, WI

1. Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, et al. Effect of azithromycin on asthma exacerbations and quality of life in adults with persistent uncontrolled asthma (AMAZES): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390: 659-668.

2. Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, et al. Efficacy of azithromycin in severe asthma from the AMAZES randomised trial. ERJ Open Res. 2019;5.

3. Hahn D. When guideline treatment of asthma fails, consider a macrolide antibiotic. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:536-545.

In “Asthma: Newer Tx options mean more targeted therapy” (J Fam Pract. 2020;65:135-144), Rali et al recommend azithromycin as an add-on therapy to ICS-LABA for a select group of patients with uncontrolled persistent asthma (neutrophilic phenotype)—a Grade C recommendation. However, the best available evidence demonstrates that azithromycin is equally efficacious for uncontrolled persistent eosinophilic asthma.1,2 Thus, family physicians need not refer patients for bronchoscopy to identify the inflammatory “phenotype.”

An important unanswered question is whether azithromycin needs to be administered continuously. Emerging evidence indicates that some patients may experience prolonged benefit after time-limited azithromycin treatment. This suggests that the mechanism of action, which has been described as anti-inflammatory, is (at least in part) antimicrobial.3

For azithromycin-treated asthma patients who experience a significant clinical response after 3 to 6 months of treatment, I recommend that the prescribing clinician try taking the patient off azithromycin to assess whether clinical improvement persists or wanes. Nothing is lost, and much is gained, by this approach; patients who relapse can resume azithromycin, and patients who remain improved are spared exposure to an unnecessary and prolonged treatment.

David L. Hahn, MD, MS

Madison, WI

In “Asthma: Newer Tx options mean more targeted therapy” (J Fam Pract. 2020;65:135-144), Rali et al recommend azithromycin as an add-on therapy to ICS-LABA for a select group of patients with uncontrolled persistent asthma (neutrophilic phenotype)—a Grade C recommendation. However, the best available evidence demonstrates that azithromycin is equally efficacious for uncontrolled persistent eosinophilic asthma.1,2 Thus, family physicians need not refer patients for bronchoscopy to identify the inflammatory “phenotype.”

An important unanswered question is whether azithromycin needs to be administered continuously. Emerging evidence indicates that some patients may experience prolonged benefit after time-limited azithromycin treatment. This suggests that the mechanism of action, which has been described as anti-inflammatory, is (at least in part) antimicrobial.3

For azithromycin-treated asthma patients who experience a significant clinical response after 3 to 6 months of treatment, I recommend that the prescribing clinician try taking the patient off azithromycin to assess whether clinical improvement persists or wanes. Nothing is lost, and much is gained, by this approach; patients who relapse can resume azithromycin, and patients who remain improved are spared exposure to an unnecessary and prolonged treatment.

David L. Hahn, MD, MS

Madison, WI

1. Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, et al. Effect of azithromycin on asthma exacerbations and quality of life in adults with persistent uncontrolled asthma (AMAZES): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390: 659-668.

2. Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, et al. Efficacy of azithromycin in severe asthma from the AMAZES randomised trial. ERJ Open Res. 2019;5.

3. Hahn D. When guideline treatment of asthma fails, consider a macrolide antibiotic. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:536-545.

1. Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, et al. Effect of azithromycin on asthma exacerbations and quality of life in adults with persistent uncontrolled asthma (AMAZES): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390: 659-668.

2. Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, et al. Efficacy of azithromycin in severe asthma from the AMAZES randomised trial. ERJ Open Res. 2019;5.

3. Hahn D. When guideline treatment of asthma fails, consider a macrolide antibiotic. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:536-545.

Food allergies in children less frequent than expected

The prevalence was as low as 1.4% and as high as 3.8% using different research methods, and most likely falls somewhere in between. The findings were “considerably lower” than the 16% rate based on parental reports of symptoms such as rash, itching, or diarrhea, Linus Grabenhenrich, MD, MPH, and colleagues reported in Allergy.

In addition, peanut and hazelnut allergens were most common among the 223 children with a positive skin prick allergy assay. A total 5.6% tested sensitive to peanuts and 5.2% to hazelnuts.

Previous research reports of pediatric food allergy prevalence were largely single-center studies with heterogeneous designs, the researchers noted. These prior protocols make comparisons across countries challenging.

In search of a more definitive answer, Dr. Grabenhenrich, of the Robert Koch-Institut in Berlin, and colleagues evaluated 238 children. This group was about 10% of 2,288 children with parental face-to-face interviews and/or skin prick testing from a birth cohort in Germany, Greece, Iceland, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, and United Kingdom called the EuroPrevall-iFAAM.

All participants had suspected food allergies, and the mean age at follow-up was 8 years. A total 46 children participated in a double-blind, placebo-controlled oral food allergy challenge (DBPCFC). “Most of the positively challenged children reacted only mildly or moderately, except for five children with severe signs or symptoms during DBPCFC,” Dr. Grabenhenrich and associates noted.

A food allergy to at least one allergen was confirmed in 17 children out of 2,097 who completed assessment. This yielded an average raw prevalence of 0.8% across all eight countries. The estimated 1.4%-3.8% food allergy prevalence was based on adjusted analyses that extrapolated findings to all children with questionnaire data or who completed an eligibility assessment.

“Considerable attrition” in all stages of the assessment was a potential limitation. In addition, 192 parents refused to participate in the DBPCFC food challenge component of the research. Studying a birth cohort across European countries was a study strength.

The European Commission supported this study. Dr. Grabenhenrich had no relevant disclosures. Some coauthors reported various ties to pharmaceutical and food companies.

SOURCE: Grabenhenrich L et al. Allergy. 2020 Mar 27. doi: 10.1111/all.14290.

The prevalence was as low as 1.4% and as high as 3.8% using different research methods, and most likely falls somewhere in between. The findings were “considerably lower” than the 16% rate based on parental reports of symptoms such as rash, itching, or diarrhea, Linus Grabenhenrich, MD, MPH, and colleagues reported in Allergy.

In addition, peanut and hazelnut allergens were most common among the 223 children with a positive skin prick allergy assay. A total 5.6% tested sensitive to peanuts and 5.2% to hazelnuts.

Previous research reports of pediatric food allergy prevalence were largely single-center studies with heterogeneous designs, the researchers noted. These prior protocols make comparisons across countries challenging.

In search of a more definitive answer, Dr. Grabenhenrich, of the Robert Koch-Institut in Berlin, and colleagues evaluated 238 children. This group was about 10% of 2,288 children with parental face-to-face interviews and/or skin prick testing from a birth cohort in Germany, Greece, Iceland, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, and United Kingdom called the EuroPrevall-iFAAM.

All participants had suspected food allergies, and the mean age at follow-up was 8 years. A total 46 children participated in a double-blind, placebo-controlled oral food allergy challenge (DBPCFC). “Most of the positively challenged children reacted only mildly or moderately, except for five children with severe signs or symptoms during DBPCFC,” Dr. Grabenhenrich and associates noted.

A food allergy to at least one allergen was confirmed in 17 children out of 2,097 who completed assessment. This yielded an average raw prevalence of 0.8% across all eight countries. The estimated 1.4%-3.8% food allergy prevalence was based on adjusted analyses that extrapolated findings to all children with questionnaire data or who completed an eligibility assessment.

“Considerable attrition” in all stages of the assessment was a potential limitation. In addition, 192 parents refused to participate in the DBPCFC food challenge component of the research. Studying a birth cohort across European countries was a study strength.

The European Commission supported this study. Dr. Grabenhenrich had no relevant disclosures. Some coauthors reported various ties to pharmaceutical and food companies.

SOURCE: Grabenhenrich L et al. Allergy. 2020 Mar 27. doi: 10.1111/all.14290.

The prevalence was as low as 1.4% and as high as 3.8% using different research methods, and most likely falls somewhere in between. The findings were “considerably lower” than the 16% rate based on parental reports of symptoms such as rash, itching, or diarrhea, Linus Grabenhenrich, MD, MPH, and colleagues reported in Allergy.

In addition, peanut and hazelnut allergens were most common among the 223 children with a positive skin prick allergy assay. A total 5.6% tested sensitive to peanuts and 5.2% to hazelnuts.

Previous research reports of pediatric food allergy prevalence were largely single-center studies with heterogeneous designs, the researchers noted. These prior protocols make comparisons across countries challenging.

In search of a more definitive answer, Dr. Grabenhenrich, of the Robert Koch-Institut in Berlin, and colleagues evaluated 238 children. This group was about 10% of 2,288 children with parental face-to-face interviews and/or skin prick testing from a birth cohort in Germany, Greece, Iceland, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, and United Kingdom called the EuroPrevall-iFAAM.

All participants had suspected food allergies, and the mean age at follow-up was 8 years. A total 46 children participated in a double-blind, placebo-controlled oral food allergy challenge (DBPCFC). “Most of the positively challenged children reacted only mildly or moderately, except for five children with severe signs or symptoms during DBPCFC,” Dr. Grabenhenrich and associates noted.

A food allergy to at least one allergen was confirmed in 17 children out of 2,097 who completed assessment. This yielded an average raw prevalence of 0.8% across all eight countries. The estimated 1.4%-3.8% food allergy prevalence was based on adjusted analyses that extrapolated findings to all children with questionnaire data or who completed an eligibility assessment.

“Considerable attrition” in all stages of the assessment was a potential limitation. In addition, 192 parents refused to participate in the DBPCFC food challenge component of the research. Studying a birth cohort across European countries was a study strength.

The European Commission supported this study. Dr. Grabenhenrich had no relevant disclosures. Some coauthors reported various ties to pharmaceutical and food companies.

SOURCE: Grabenhenrich L et al. Allergy. 2020 Mar 27. doi: 10.1111/all.14290.

FROM ALLERGY

Does vitamin D supplementation reduce asthma exacerbations?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

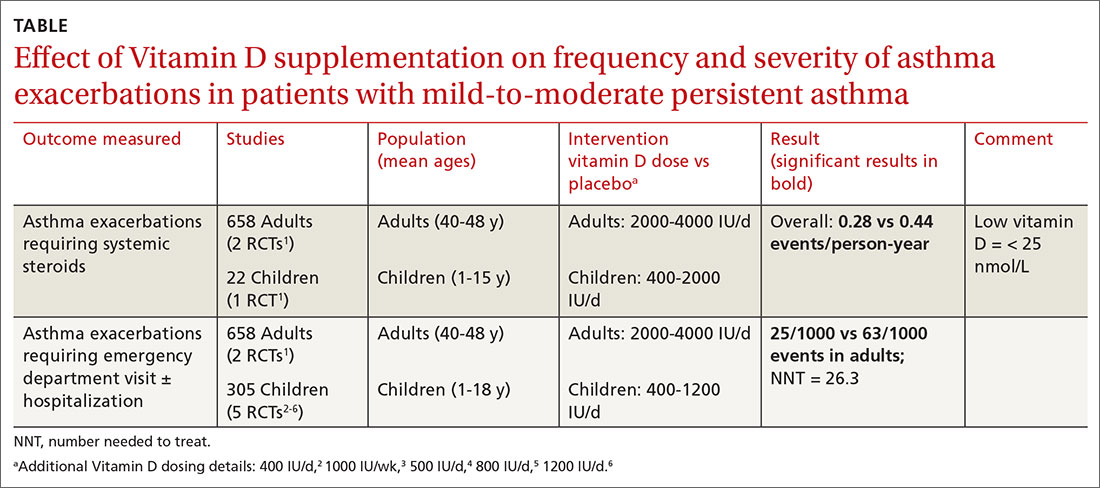

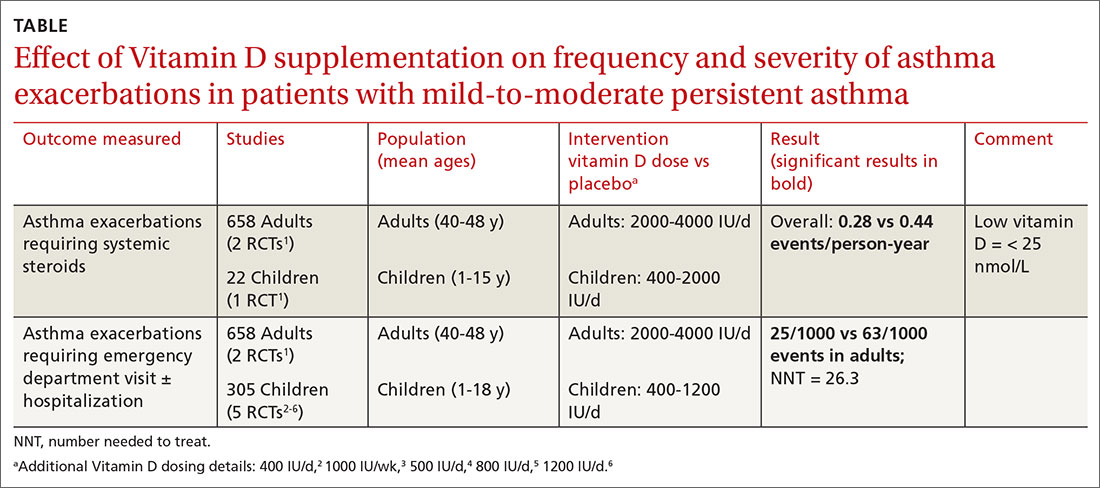

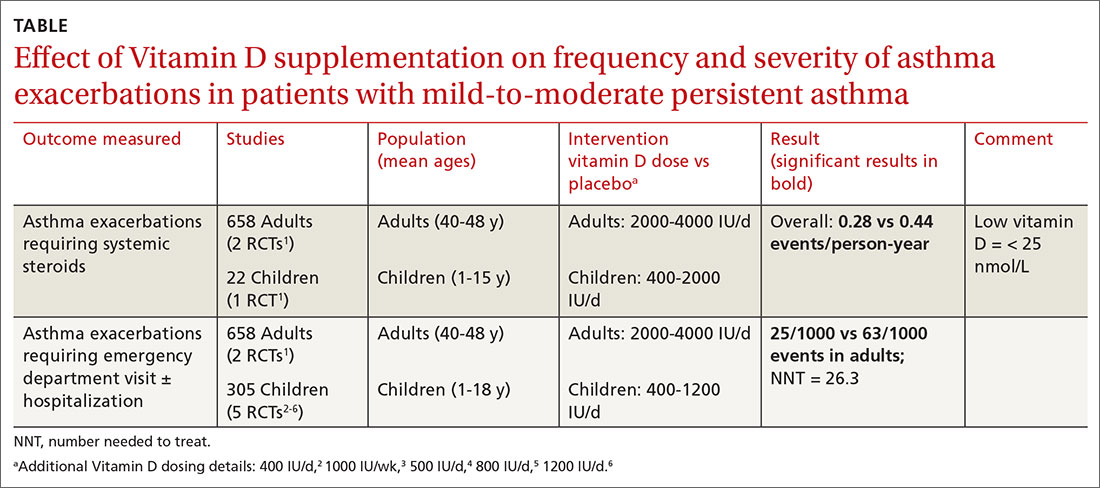

A Cochrane systematic review of vitamin D for managing asthma performed meta-analyses on RCTs that evaluated several outcomes.1 The review found improvement in the primary outcome of asthma exacerbations requiring systemic steroids, mainly in adult patients, and in the secondary outcomes of emergency department visits or hospitalization, in a mix of adults and children (TABLE1-6).

Most participants had mild-to-moderate asthma; trials lasted 4 to 12 months. Vitamin D dosage regimens varied, with a median daily dose of 900 IU/d (range, 400-4000 IU/d). Six RCTs were rated high-quality, and 1 had unclear risk of bias.

Supplementation reduced exacerbations in patients with low vitamin D levels

A subsequent (2017) systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the primary outcome of exacerbations requiring steroids7 included another study8 (in addition to the 6 RCTs in the Cochrane review).

When researchers reanalyzed individual participant data from the trials in the Cochrane review, plus the additional RCT, to include baseline vitamin D levels, they found that vitamin D supplementation reduced exacerbations overall (NNT = 7.7) and in patients with low baseline vitamin D levels (25[OH] vitamin D < 25 nmol/L; 92 participants in 3 RCTs; NNT = 4.3) but not in patients with higher baseline levels (764 participants in 6 RCTs). Vitamin D supplementation reduced the asthma exacerbation rate in patients with low baseline vitamin D levels (0.19 vs 0.42 events per participant-year; P = .046).

Smaller benefit found on ED visits and hospitalizations

The Cochrane review, with 2 RCTs with adults (n = 658)1 and 5 RCTs with children (n = 305),2-6 evaluated whether Vitamin D reduced the need for emergency department visits and hospitalization with asthma exacerbations; they found a smaller benefit (NNT = 26.3).

Effects on FEV1, daily asthma symptoms, and serious adverse effects

Several RCTs included in the 2017 meta-analysis found no effect of vitamin D supplementation on FEV1, daily asthma symptoms (evaluated with the standardized Asthma Control Test Score), or reported serious adverse events.2-6,9,10 No deaths occurred in any trial.

Additional findings in children from lower-quality studies

A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs evaluating vitamin D supplementation for children with asthma found11:

- moderate-quality evidence for decreased emergency department visits (1 RCT from India, 100 children ages 3 to 14 years, decrease not specified; P = .015);

- low-quality evidence for reduced exacerbations (6 RCTs [3 RCTs also in Cochrane review], 507 children ages 3 to 17 years; risk ratio = 0.41; 95% confidence interval, 0.27-0.63); and

- low-quality evidence for reduced standardized asthma symptom scores (6 RCTs [2 RCTs also in Cochrane review], 231 children ages 3 to 17 years; amount of reduction not listed; P = .01).

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

No published guidelines discuss using vitamin D in managing asthma. An American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) summary of the Cochrane systematic review recommends that family physicians await further studies and updated guidelines before recommending vitamin D for patients with asthma.12 The AAFP also points out that the Endocrine Society has recommended vitamin D supplementation for adults (1500-2000 IU/d) and children (at least 1000 IU/d) at risk for deficiency.

Editor's takeaway

In the meta-analyses highlighted here, researchers evaluated asthma patients with a wide range of ages, baseline vitamin D levels, and vitamin D supplementation protocols. Although vitamin D reduced asthma exacerbations requiring steroids overall, the effect was driven by 3 studies of patients with low baseline vitamin D levels. As a result, disentangling who might benefit the most remains a challenge. The conservative course for now is to manage asthma according to current guidelines and supplement vitamin D in patients at risk for, or with known, deficiency.

, , , . Vitamin D for the management of asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD011511.

2. Jensen M, Mailhot G, Alos N, et al. Vitamin D intervention in preschoolers with viral-induced asthma (DIVA): a pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2016;26:17:353.

, , , et al. Correlation of vitamin D with Foxp3 induction and steroid-sparing effect of immunotherapy in asthmatic children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109:329-335.

, , , et al. Vitamin D supplementation in children may prevent asthma exacerbation triggered by acute respiratory infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1294-1296.

, , , et al. Improved control of childhood asthma with low-dose, short-term vitamin D supplementation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Allergy. 2016;71:1001-1009.

, , , et al. Randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation to prevent seasonal influenza A in school children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1255-1260.

7. Joliffe DA, Greenberg L, Hooper RL, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent asthma exacerbations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 2017;5:881-890.

8. Kerley CP, Hutchinson K, Cormical L, et al. Vitamin D3 for uncontrolled childhood asthma: a pilot study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27:404-412.

, , , et al. Effect of vitamin D3 on asthma treatment failures in adults with symptomatic asthma and lower vitamin D levels: the VIDA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:2083-2091.

, , , et al. Double-blind multi-centre randomised controlled trial of vitamin D3 supplementation in adults with inhaled corticosteroid-treated asthma (ViDiAs). Thorax. 2015:70:451-457.

11. Riverin B, Maguire J, Li P. Vitamin D supplementation for childhood asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One. 2015;10:e0136841.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane systematic review of vitamin D for managing asthma performed meta-analyses on RCTs that evaluated several outcomes.1 The review found improvement in the primary outcome of asthma exacerbations requiring systemic steroids, mainly in adult patients, and in the secondary outcomes of emergency department visits or hospitalization, in a mix of adults and children (TABLE1-6).

Most participants had mild-to-moderate asthma; trials lasted 4 to 12 months. Vitamin D dosage regimens varied, with a median daily dose of 900 IU/d (range, 400-4000 IU/d). Six RCTs were rated high-quality, and 1 had unclear risk of bias.

Supplementation reduced exacerbations in patients with low vitamin D levels

A subsequent (2017) systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the primary outcome of exacerbations requiring steroids7 included another study8 (in addition to the 6 RCTs in the Cochrane review).

When researchers reanalyzed individual participant data from the trials in the Cochrane review, plus the additional RCT, to include baseline vitamin D levels, they found that vitamin D supplementation reduced exacerbations overall (NNT = 7.7) and in patients with low baseline vitamin D levels (25[OH] vitamin D < 25 nmol/L; 92 participants in 3 RCTs; NNT = 4.3) but not in patients with higher baseline levels (764 participants in 6 RCTs). Vitamin D supplementation reduced the asthma exacerbation rate in patients with low baseline vitamin D levels (0.19 vs 0.42 events per participant-year; P = .046).

Smaller benefit found on ED visits and hospitalizations

The Cochrane review, with 2 RCTs with adults (n = 658)1 and 5 RCTs with children (n = 305),2-6 evaluated whether Vitamin D reduced the need for emergency department visits and hospitalization with asthma exacerbations; they found a smaller benefit (NNT = 26.3).

Effects on FEV1, daily asthma symptoms, and serious adverse effects

Several RCTs included in the 2017 meta-analysis found no effect of vitamin D supplementation on FEV1, daily asthma symptoms (evaluated with the standardized Asthma Control Test Score), or reported serious adverse events.2-6,9,10 No deaths occurred in any trial.

Additional findings in children from lower-quality studies

A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs evaluating vitamin D supplementation for children with asthma found11:

- moderate-quality evidence for decreased emergency department visits (1 RCT from India, 100 children ages 3 to 14 years, decrease not specified; P = .015);

- low-quality evidence for reduced exacerbations (6 RCTs [3 RCTs also in Cochrane review], 507 children ages 3 to 17 years; risk ratio = 0.41; 95% confidence interval, 0.27-0.63); and

- low-quality evidence for reduced standardized asthma symptom scores (6 RCTs [2 RCTs also in Cochrane review], 231 children ages 3 to 17 years; amount of reduction not listed; P = .01).

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

No published guidelines discuss using vitamin D in managing asthma. An American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) summary of the Cochrane systematic review recommends that family physicians await further studies and updated guidelines before recommending vitamin D for patients with asthma.12 The AAFP also points out that the Endocrine Society has recommended vitamin D supplementation for adults (1500-2000 IU/d) and children (at least 1000 IU/d) at risk for deficiency.

Editor's takeaway

In the meta-analyses highlighted here, researchers evaluated asthma patients with a wide range of ages, baseline vitamin D levels, and vitamin D supplementation protocols. Although vitamin D reduced asthma exacerbations requiring steroids overall, the effect was driven by 3 studies of patients with low baseline vitamin D levels. As a result, disentangling who might benefit the most remains a challenge. The conservative course for now is to manage asthma according to current guidelines and supplement vitamin D in patients at risk for, or with known, deficiency.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane systematic review of vitamin D for managing asthma performed meta-analyses on RCTs that evaluated several outcomes.1 The review found improvement in the primary outcome of asthma exacerbations requiring systemic steroids, mainly in adult patients, and in the secondary outcomes of emergency department visits or hospitalization, in a mix of adults and children (TABLE1-6).

Most participants had mild-to-moderate asthma; trials lasted 4 to 12 months. Vitamin D dosage regimens varied, with a median daily dose of 900 IU/d (range, 400-4000 IU/d). Six RCTs were rated high-quality, and 1 had unclear risk of bias.

Supplementation reduced exacerbations in patients with low vitamin D levels

A subsequent (2017) systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the primary outcome of exacerbations requiring steroids7 included another study8 (in addition to the 6 RCTs in the Cochrane review).

When researchers reanalyzed individual participant data from the trials in the Cochrane review, plus the additional RCT, to include baseline vitamin D levels, they found that vitamin D supplementation reduced exacerbations overall (NNT = 7.7) and in patients with low baseline vitamin D levels (25[OH] vitamin D < 25 nmol/L; 92 participants in 3 RCTs; NNT = 4.3) but not in patients with higher baseline levels (764 participants in 6 RCTs). Vitamin D supplementation reduced the asthma exacerbation rate in patients with low baseline vitamin D levels (0.19 vs 0.42 events per participant-year; P = .046).

Smaller benefit found on ED visits and hospitalizations

The Cochrane review, with 2 RCTs with adults (n = 658)1 and 5 RCTs with children (n = 305),2-6 evaluated whether Vitamin D reduced the need for emergency department visits and hospitalization with asthma exacerbations; they found a smaller benefit (NNT = 26.3).

Effects on FEV1, daily asthma symptoms, and serious adverse effects

Several RCTs included in the 2017 meta-analysis found no effect of vitamin D supplementation on FEV1, daily asthma symptoms (evaluated with the standardized Asthma Control Test Score), or reported serious adverse events.2-6,9,10 No deaths occurred in any trial.

Additional findings in children from lower-quality studies

A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs evaluating vitamin D supplementation for children with asthma found11:

- moderate-quality evidence for decreased emergency department visits (1 RCT from India, 100 children ages 3 to 14 years, decrease not specified; P = .015);

- low-quality evidence for reduced exacerbations (6 RCTs [3 RCTs also in Cochrane review], 507 children ages 3 to 17 years; risk ratio = 0.41; 95% confidence interval, 0.27-0.63); and

- low-quality evidence for reduced standardized asthma symptom scores (6 RCTs [2 RCTs also in Cochrane review], 231 children ages 3 to 17 years; amount of reduction not listed; P = .01).

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

No published guidelines discuss using vitamin D in managing asthma. An American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) summary of the Cochrane systematic review recommends that family physicians await further studies and updated guidelines before recommending vitamin D for patients with asthma.12 The AAFP also points out that the Endocrine Society has recommended vitamin D supplementation for adults (1500-2000 IU/d) and children (at least 1000 IU/d) at risk for deficiency.

Editor's takeaway

In the meta-analyses highlighted here, researchers evaluated asthma patients with a wide range of ages, baseline vitamin D levels, and vitamin D supplementation protocols. Although vitamin D reduced asthma exacerbations requiring steroids overall, the effect was driven by 3 studies of patients with low baseline vitamin D levels. As a result, disentangling who might benefit the most remains a challenge. The conservative course for now is to manage asthma according to current guidelines and supplement vitamin D in patients at risk for, or with known, deficiency.

, , , . Vitamin D for the management of asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD011511.

2. Jensen M, Mailhot G, Alos N, et al. Vitamin D intervention in preschoolers with viral-induced asthma (DIVA): a pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2016;26:17:353.

, , , et al. Correlation of vitamin D with Foxp3 induction and steroid-sparing effect of immunotherapy in asthmatic children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109:329-335.

, , , et al. Vitamin D supplementation in children may prevent asthma exacerbation triggered by acute respiratory infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1294-1296.

, , , et al. Improved control of childhood asthma with low-dose, short-term vitamin D supplementation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Allergy. 2016;71:1001-1009.

, , , et al. Randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation to prevent seasonal influenza A in school children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1255-1260.

7. Joliffe DA, Greenberg L, Hooper RL, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent asthma exacerbations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 2017;5:881-890.

8. Kerley CP, Hutchinson K, Cormical L, et al. Vitamin D3 for uncontrolled childhood asthma: a pilot study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27:404-412.

, , , et al. Effect of vitamin D3 on asthma treatment failures in adults with symptomatic asthma and lower vitamin D levels: the VIDA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:2083-2091.

, , , et al. Double-blind multi-centre randomised controlled trial of vitamin D3 supplementation in adults with inhaled corticosteroid-treated asthma (ViDiAs). Thorax. 2015:70:451-457.

11. Riverin B, Maguire J, Li P. Vitamin D supplementation for childhood asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One. 2015;10:e0136841.

, , , . Vitamin D for the management of asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD011511.

2. Jensen M, Mailhot G, Alos N, et al. Vitamin D intervention in preschoolers with viral-induced asthma (DIVA): a pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2016;26:17:353.

, , , et al. Correlation of vitamin D with Foxp3 induction and steroid-sparing effect of immunotherapy in asthmatic children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109:329-335.

, , , et al. Vitamin D supplementation in children may prevent asthma exacerbation triggered by acute respiratory infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1294-1296.

, , , et al. Improved control of childhood asthma with low-dose, short-term vitamin D supplementation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Allergy. 2016;71:1001-1009.

, , , et al. Randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation to prevent seasonal influenza A in school children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1255-1260.

7. Joliffe DA, Greenberg L, Hooper RL, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent asthma exacerbations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 2017;5:881-890.

8. Kerley CP, Hutchinson K, Cormical L, et al. Vitamin D3 for uncontrolled childhood asthma: a pilot study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27:404-412.

, , , et al. Effect of vitamin D3 on asthma treatment failures in adults with symptomatic asthma and lower vitamin D levels: the VIDA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:2083-2091.

, , , et al. Double-blind multi-centre randomised controlled trial of vitamin D3 supplementation in adults with inhaled corticosteroid-treated asthma (ViDiAs). Thorax. 2015:70:451-457.

11. Riverin B, Maguire J, Li P. Vitamin D supplementation for childhood asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One. 2015;10:e0136841.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes, to some extent it does, and primarily in patients with low vitamin D levels. Supplementation reduces asthma exacerbations requiring systemic steroids by 30% overall in adults and children with mild-to-moderate asthma (number needed to treat [NNT] = 7.7). The outcome is driven by the effect in patients with vitamin D levels < 25 nmol/L (NNT = 4.3), however; supplementation doesn’t decrease exacerbations in patients with higher levels. Supplementation also reduces, by a smaller amount (NNT = 26.3), the odds of exacerbations requiring emergency department care or hospitalization (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

In children, vitamin D supplementation may also reduce exacerbations and improve symptom scores (SOR: C, low-quality RCTs).

Vitamin D doesn’t improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) or standardized asthma control test scores. Also, it isn’t associated with serious adverse effects (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs).

Omalizumab shown to improve chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps

The monoclonal antibody omalizumab, already approved to treat allergic asthma and urticaria, has been shown to improve symptoms of patients who have chronic rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps (CRSwNP), according to recent research released as an abstract from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology annual meeting. The AAAAI canceled the meeting and provided abstracts and access to presenters for press coverage.

“When you give this drug to patients who have nasal polyposis and concomitant asthma, you are effectively treating both the upper and lower airway disease components,” Jonathan Corren, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, said in an interview. “Typically, people with nasal polyp disease have worse nasal disease than people without asthma. In addition, asthma is also generally worse in patients with nasal polyposis,” he added.

Dr. Corren reported results of a subset of patients with corticosteroid-refractory CRSwNP and comorbid asthma enrolled in phase III, placebo-controlled, 24-week, trials of omalizumab, POLYP1 (n = 74) and POLYP2 (n = 77). The analysis excluded patients who were on oral steroids or high-dose steroid inhaler therapy so the effectiveness of omalizumab could be evaluated without interfering factors, Dr. Corren explained. As a result, the study population consisted of patients with mild to moderate asthma. Dr. Corren is also principal investigator of the POLYP1 trial.

The analysis compared changes in Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ) and sino-nasal outcome test (SNOT-22) measures after 24 weeks of treatment with those seen with placebo.

“With regard to asthma outcomes, we found there was a significant increase in the odds ratio that patients who received omalizumab would achieve a minimal, clinically important improvement in their asthma quality of life,” Dr. Corren said .

The study estimated the odds ratio for minimal clinically important difference in AQLQ at 24 weeks was 3.9 (95% confidence interval, 1.5-9.7; P = .0043), which Dr. Corren called “quite significant.” SNOT-22 scores showed a mean improvement of 23.3 from baseline to week 24, compared with a worsening of 8.4 in placebo (P = .0001).

Omalizumab is approved for treatment of perennial allergies and urticaria. Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps would be a third indication if the Food and Drug Administration approves it, Dr. Corren noted.

Genentech sponsored the subset analysis. Hoffmann-La Roche, Genentech’s parent company, is sponsor of the POLYP1 and POLYP2 trials. Dr. Corren disclosed financial relationships with Genentech.

SOURCE: Corren J et al. AAAAI, Session 4608, Abstract 813.

The monoclonal antibody omalizumab, already approved to treat allergic asthma and urticaria, has been shown to improve symptoms of patients who have chronic rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps (CRSwNP), according to recent research released as an abstract from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology annual meeting. The AAAAI canceled the meeting and provided abstracts and access to presenters for press coverage.