User login

FDA approves first generic albuterol inhaler

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first generic of Proventil HFA (albuterol sulfate) metered-dose inhaler, 90 mcg/inhalation, according to a release from the agency. This inhaler is indicated for prevention of bronchospasm in patients aged 4 years and older. Specifically, these are patients with reversible obstructive airway disease or exercise-induced bronchospasm.

“The FDA recognizes the increased demand for albuterol products during the novel coronavirus pandemic,” said FDA Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD.

The most common side effects include upper respiratory tract infection, rhinitis, nausea, vomiting, rapid heart rate, tremor, and nervousness.

This approval comes as part of FDA’s efforts to guide industry through the development process of generic products, according to the release. Complex combination products – such as this inhaler, which comprises both medication and a delivery system – can be more challenging to develop than solid oral dosage forms, such as tablets.

The FDA released a draft guidance in March 2020 specific to proposed generic albuterol sulfate metered-dose inhalers, including drug products referencing Proventil HFA. As with other similar guidances, it details the steps companies need to take in developing generics in order to submit complete applications for those products. The full news release regarding this approval is available on the FDA website.

This article was updated 4/8/20.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first generic of Proventil HFA (albuterol sulfate) metered-dose inhaler, 90 mcg/inhalation, according to a release from the agency. This inhaler is indicated for prevention of bronchospasm in patients aged 4 years and older. Specifically, these are patients with reversible obstructive airway disease or exercise-induced bronchospasm.

“The FDA recognizes the increased demand for albuterol products during the novel coronavirus pandemic,” said FDA Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD.

The most common side effects include upper respiratory tract infection, rhinitis, nausea, vomiting, rapid heart rate, tremor, and nervousness.

This approval comes as part of FDA’s efforts to guide industry through the development process of generic products, according to the release. Complex combination products – such as this inhaler, which comprises both medication and a delivery system – can be more challenging to develop than solid oral dosage forms, such as tablets.

The FDA released a draft guidance in March 2020 specific to proposed generic albuterol sulfate metered-dose inhalers, including drug products referencing Proventil HFA. As with other similar guidances, it details the steps companies need to take in developing generics in order to submit complete applications for those products. The full news release regarding this approval is available on the FDA website.

This article was updated 4/8/20.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first generic of Proventil HFA (albuterol sulfate) metered-dose inhaler, 90 mcg/inhalation, according to a release from the agency. This inhaler is indicated for prevention of bronchospasm in patients aged 4 years and older. Specifically, these are patients with reversible obstructive airway disease or exercise-induced bronchospasm.

“The FDA recognizes the increased demand for albuterol products during the novel coronavirus pandemic,” said FDA Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD.

The most common side effects include upper respiratory tract infection, rhinitis, nausea, vomiting, rapid heart rate, tremor, and nervousness.

This approval comes as part of FDA’s efforts to guide industry through the development process of generic products, according to the release. Complex combination products – such as this inhaler, which comprises both medication and a delivery system – can be more challenging to develop than solid oral dosage forms, such as tablets.

The FDA released a draft guidance in March 2020 specific to proposed generic albuterol sulfate metered-dose inhalers, including drug products referencing Proventil HFA. As with other similar guidances, it details the steps companies need to take in developing generics in order to submit complete applications for those products. The full news release regarding this approval is available on the FDA website.

This article was updated 4/8/20.

Asthma: Newer Tx options mean more targeted therapy

Recent advances in our understanding of asthma pathophysiology have led to the development of new treatment approaches to this chronic respiratory condition, which affects 25 million Americans or nearly 8% of the population.1 As a result, asthma treatment options have expanded from just simple inhalers and corticosteroids to include

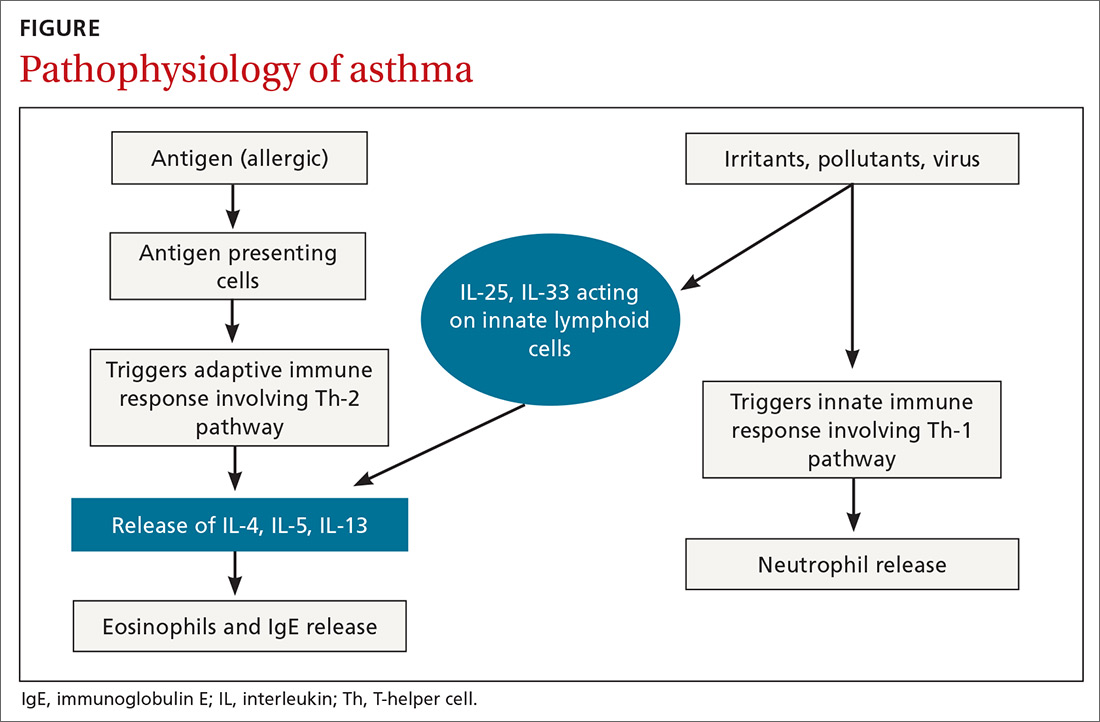

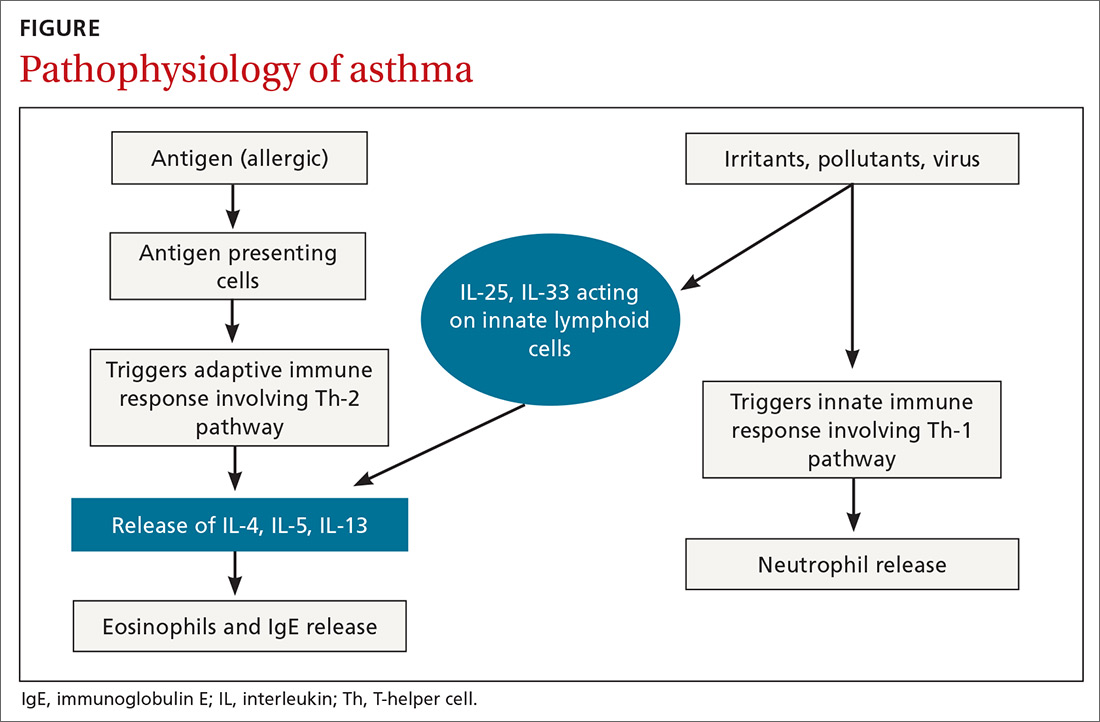

The pathophysiology of asthma provides key targets for therapy

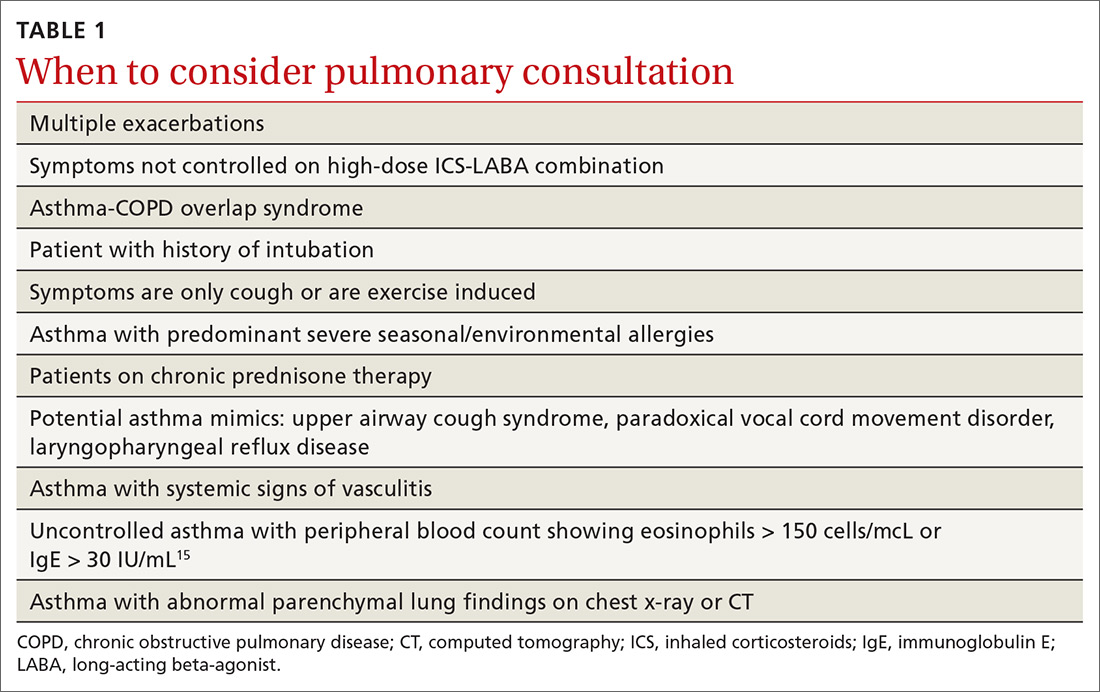

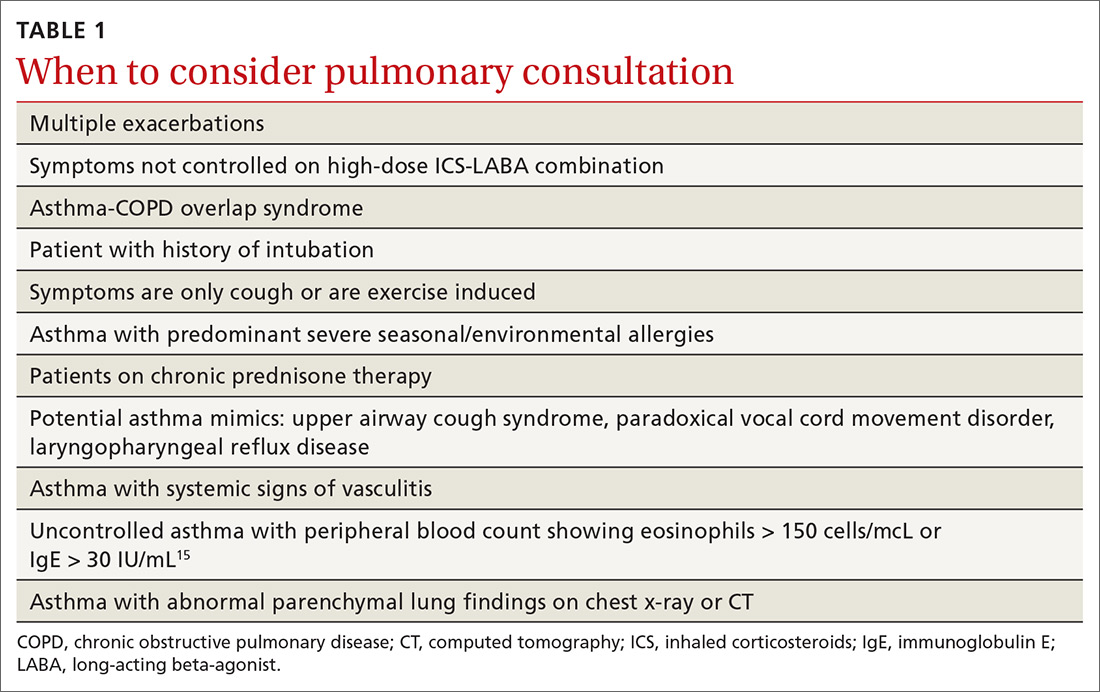

There are 2 basic phenotypes of asthma—neutrophilic predominant and eosinophilic predominant—and 3 key components to its pathophysiology2:

Airway inflammation. Asthma is mediated through either a type 1 T-helper (Th-1) cell or a type 2 T-helper (Th-2) cell response, the pathways of which have a fair amount of overlap (FIGURE). In the neutrophilic-predominant phenotype, irritants, pollutants, and viruses trigger an innate Th-1 cell–mediated pathway that leads to subsequent neutrophil release. This asthma phenotype responds poorly to standard asthma therapy.2-4

In the eosinophilic-predominant phenotype, environmental allergic antigens induce a Th-2 cell–mediated response in the airways of patients with asthma.5-7 This creates a downstream effect on the release of interleukins (IL) including IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. IL-4 triggers immunoglobulin (Ig) E release, which subsequently induces mast cells to release inflammatory cytokines, while IL-5 and IL-13 are responsible for eosinophilic response. These cytokines and eosinophils induce airway hyperresponsiveness, remodeling, and mucus production. Through repeated exposure, chronic inflammation develops and subsequently causes structural changes related to increased smooth muscle mass, goblet cell hyperplasia, and thickening of lamina reticularis.8,9 Understanding of this pathobiological pathway has led to the development of anti-IgE and anti-IL-5 drugs (to be discussed shortly).

Airway obstruction. Early asthmatic response is due to acute bronchoconstriction secondary to IgE; this is followed by airway edema occurring 6 to 24 hours after an acute event (called late asthmatic response). The obstruction is worsened by an overproduction of mucus, which may take weeks to resolve.10 Longstanding inflammation can lead to structural changes and reduced airflow reversibility.

Bronchial hyperresponsiveness is induced by various forms of allergens, pollutants, or viral upper respiratory infections. Sympathetic control in the airway is mediated via beta-2 adrenoceptors expressed on airway smooth muscle, which are responsible for the effect of bronchodilation in response to albuterol.11,12 Cholinergic pathways may further contribute to bronchial hyperresponsiveness and form the basis for the efficacy of anticholinergic therapy.12,13

What we’ve learned about asthma can inform treatment decisions

Presentation may vary, as asthma has many forms including cough-variant asthma and exercise-induced asthma. Airflow limitation is typically identified through spirometry and characterized by reduced (< 70% in adults) forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) or bronchodilator response positivity (an increase in post-bronchodilator FEV1 > 12% or FVC > 200 mL from baseline).2 If spirometry is not diagnostic but suspicion for asthma remains, bronchial provocation testing or exercise challenge testing may be needed.

Continue to: Additional diagnostic considerations...

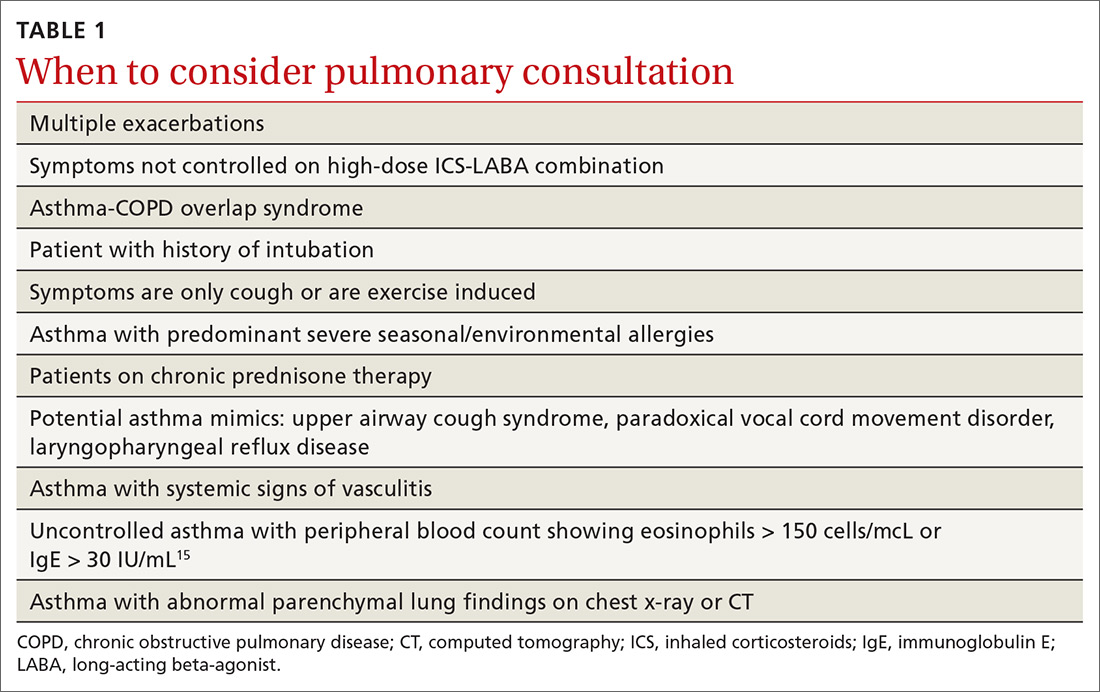

Additional diagnostic considerations may impact the treatment plan for patients with asthma:

Asthma and COPD. A history of smoking is a key factor in the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)—but many patients with asthma are also smokers. This subgroup may have asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS). It is important to determine whether these patients are asthma predominant or COPD predominant, because appropriate first-line treatment will differ. Patients who are COPD predominant demonstrate reduced diffusion capacity (DLCO) and abnormal PaCO2 on arterial blood gas. They also may show more structural damage on chest computed tomography (CT) than patients with asthma do. Asthma-predominant patients are more likely to have eosinophilia.14

Patients with severe persistent asthma or frequent exacerbations, or those receiving step-up therapy, may require additional serologic testing. Specialized testing for IgE and eosinophil count, as well as a sensitized allergy panel, may help clinicians in selecting specific biological therapies for treatment of severe asthma (further discussion to follow). We recommend using a serum allergy panel, as it is a quick and easy way to identify patients with extrinsic allergies, whereas skin-based testing is often time consuming and may require referral to a specialist.2,5,15

Aspergillus. An additional consideration is testing for Aspergillus antibodies. Aspergillus is a ubiquitous fungus found in the airways of humans. In patients with asthma, however, it can trigger an intense inflammatory response known as allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. ABPA is not an infection. It should be considered in patients who have lived in a damp, old housing environment with possible mold exposure. Treatment of ABPA involves oral corticosteroids; there are varying reports of efficacy with voriconazole or itraconazole as suppressive therapy or steroid-sparing treatment.16-18

Getting a handle on an ever-expanding asthma Tx arsenal

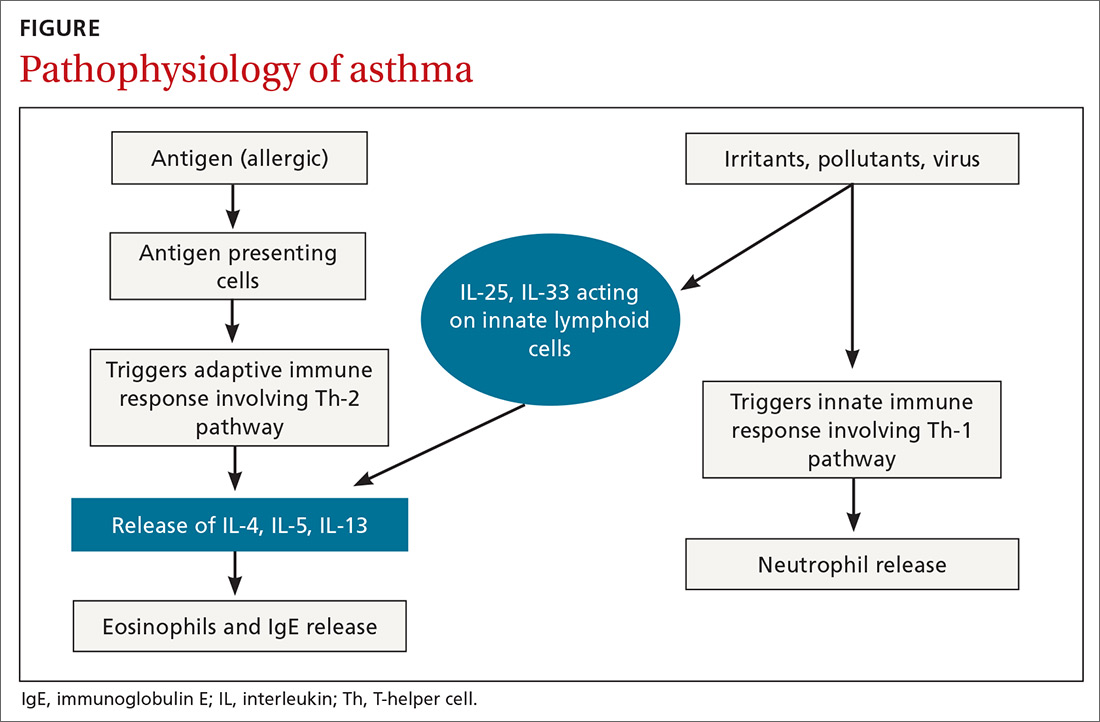

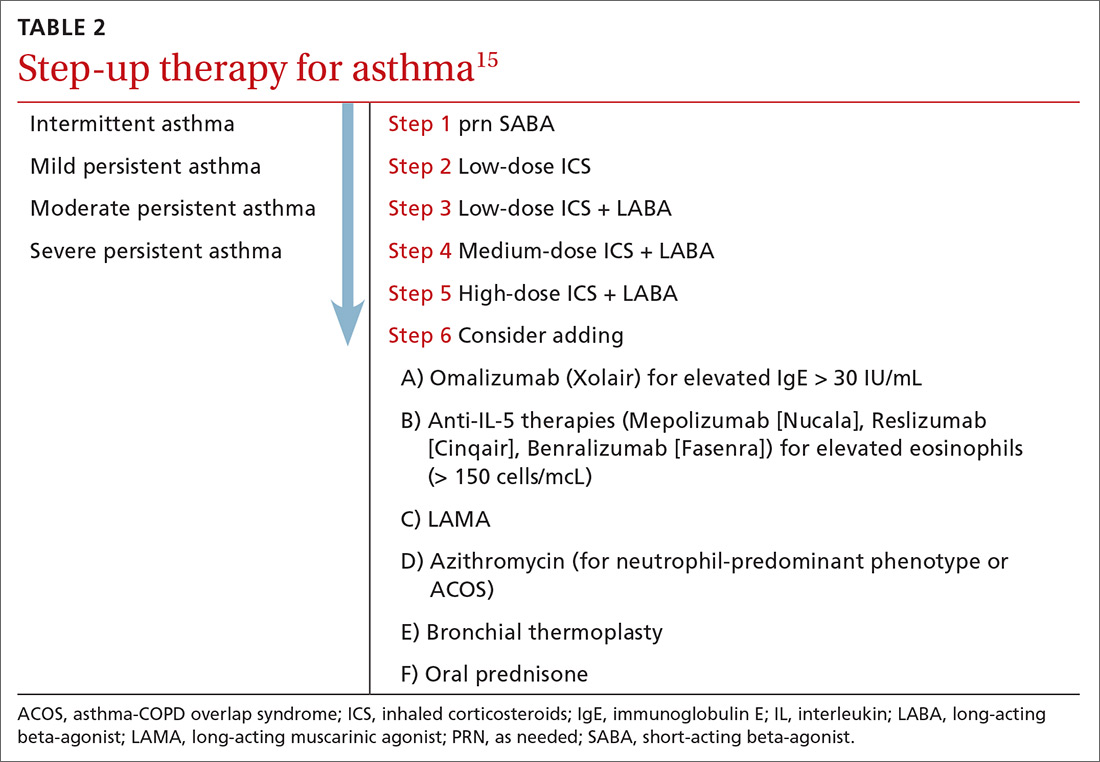

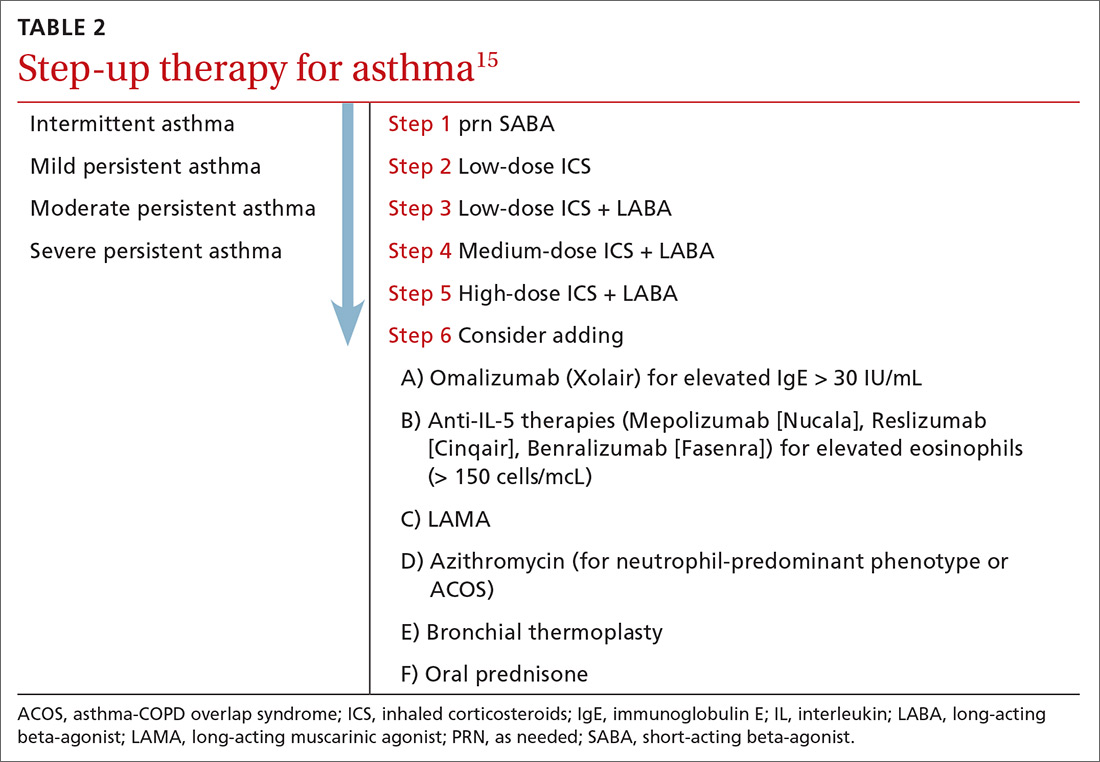

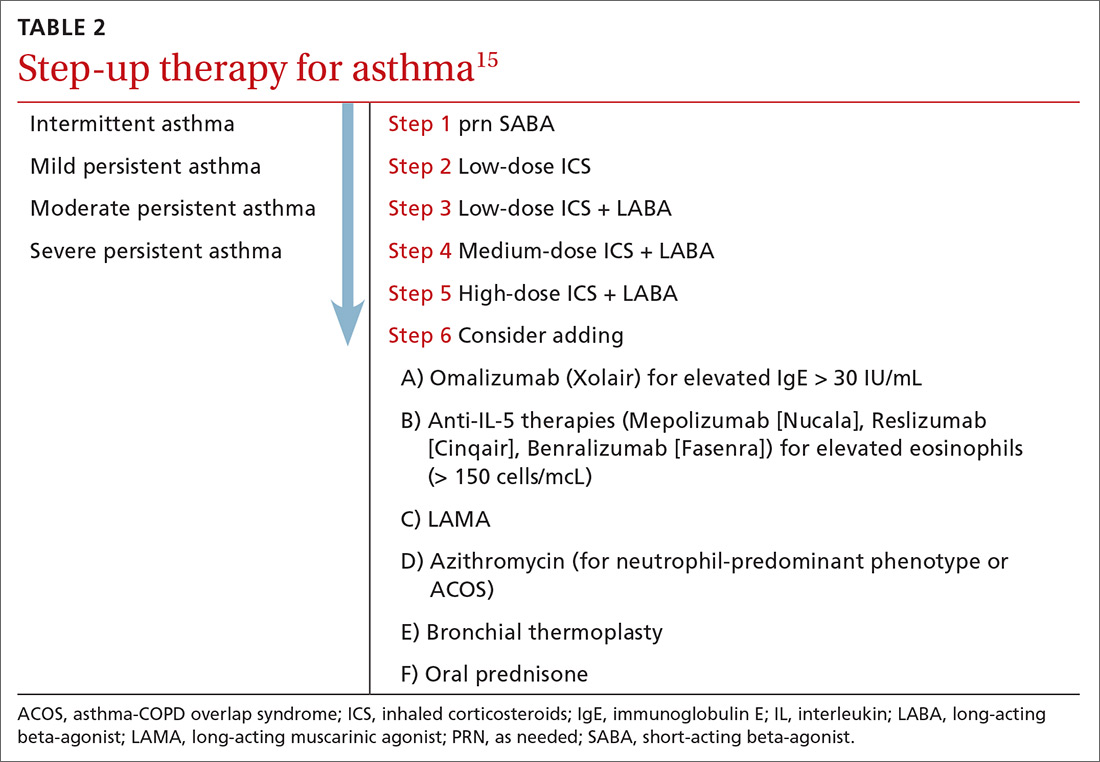

The goals of asthma treatment are symptom control and risk minimization. Treatment choices are dictated in part by disease severity (mild, moderate, severe) and classification (intermittent, persistent). Asthma therapy is traditionally described as step-up and step-down; TABLE 2 summarizes available pharmacotherapy for asthma and provides a framework for add-on therapy as the disease advances.

Continue to: Over the past decade...

Over the past decade, a number of therapeutic options have been introduced or added to the pantheon of asthma treatment.

Inhaled medications

This category includes inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), which are recommended for use alone or in combination with long-acting beta-agonists (LABA) or with long-acting

ICS is the first choice for long-term control of persistent asthma.2 Its molecular effects include activating anti-inflammatory genes, switching off inflammatory genes, and inhibiting inflammatory cells, combined with enhancement of beta-2-adrenergic receptor expression. The cumulative effect is reduction in airway responsiveness in asthma patients.19-22

LABAs are next in line in the step-up, step-down model of symptom management. LABAs should not be prescribed as stand-alone therapy in patients with asthma, as they have received a black box warning from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for an increase in asthma-related death23—a concern that has not been demonstrated with the combination of ICS-LABA.

LABAs cause smooth muscle relaxation in the lungs.24 There are 3 combination products currently available: once-daily fluticasone furoate/vilanterol (Breo), twice-daily fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (Advair), and twice-daily budesonide/formoterol (Symbicort).

Continue to: Once-daily fluticasone furoate/vilanterol...

Once-daily fluticasone furoate/vilanterol has been shown to improve mean FEV1.25 In a 24-week, open-label, multicenter randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of all 3 combination ICS-LABAs, preliminary results indicated that—at least in a tightly controlled setting—once-daily fluticasone furoate/vilanterol provides asthma control similar to the twice-daily combinations and is well tolerated.26

Two ultra-long-acting (24-hour) LABAs, olodaterol (Striverdi Respimat) and indacaterol (Arcapta Neohaler), are being studied for possible use in asthma treatment. In a phase 2 trial investigating therapy for moderate-to-severe persistent asthma, 24-hour FEV1 improved with olodeaterol when compared to placebo.27

Another ongoing clinical trial is studying the effects of ultra-long-acting bronchodilator therapy (olodaterol vs combination olodaterol/tiotropium) in asthma patients who smoke and who are already using ICS (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02682862). Indacaterol has been shown to be effective in the treatment of moderate-to-severe asthma in a once-a-day dosing regimen.28 However, when compared to mometasone alone, a combination of indacaterol and mometasone demonstrated no statistically significant reduction in time to serious exacerbation.29

The LAMA tiotropium is recommended as add-on therapy for patients whose asthma is uncontrolled despite use of low-dose ICS-LABA or as an alternative to high-dose ICS-LABA, per Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 2019 guidelines.15

Tiotropium induces bronchodilation by selectively inhibiting the action of acetylcholine at muscarinic (M) receptors in bronchial smooth muscles; it has a longer duration of action because of its slower dissociation from receptor types M1 and M3.30 Tiotropium respimat (Spiriva, Tiova) has been approved for COPD for many years; in 2013, it was shown to prevent worsening of symptomatic asthma and increase time to first severe exacerbation.13 The FDA subsequently approved tiotropium as an add-on treatment for patients with uncontrolled asthma despite use of ICS-LABA.

Continue to: Glycopyrronium bromide...

Glycopyrronium bromide (glycopyrrolate, multiple brand names) and umeclidinium (Incruse Ellipta) are LAMAs that are approved for COPD treatment but have not yet been approved for patients who have asthma only.31

Biological therapies

In the past few years, improved understanding of asthma’s pathophysiology has led to the development of biological therapy for severe asthma. This therapy is directed at Th-2 inflammatory pathways (FIGURE) and targets various inflammatory markers, such as IgE, IL-5, and eosinophils.

Biologicals are not the first-line therapy for the management of severe asthma. Ideal candidates for this therapy are patients who have exhausted other forms of severe asthma treatment, including ICS-LABA, LAMA, leukotriene receptor antagonists, and mucus-clearing agents. Patients with frequent exacerbations who need continuous steroids or need steroids at least twice a year should be considered for biologicals.32

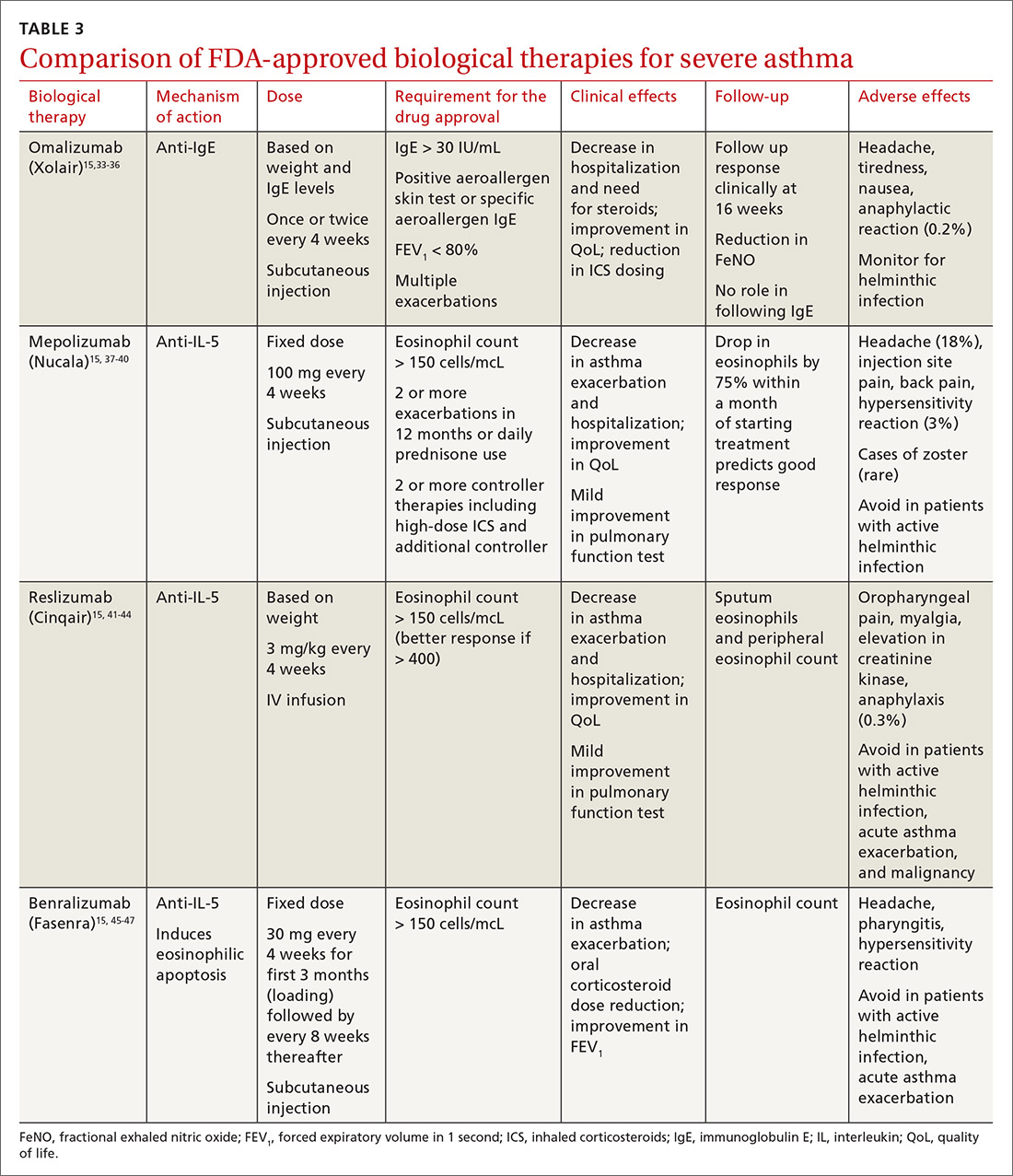

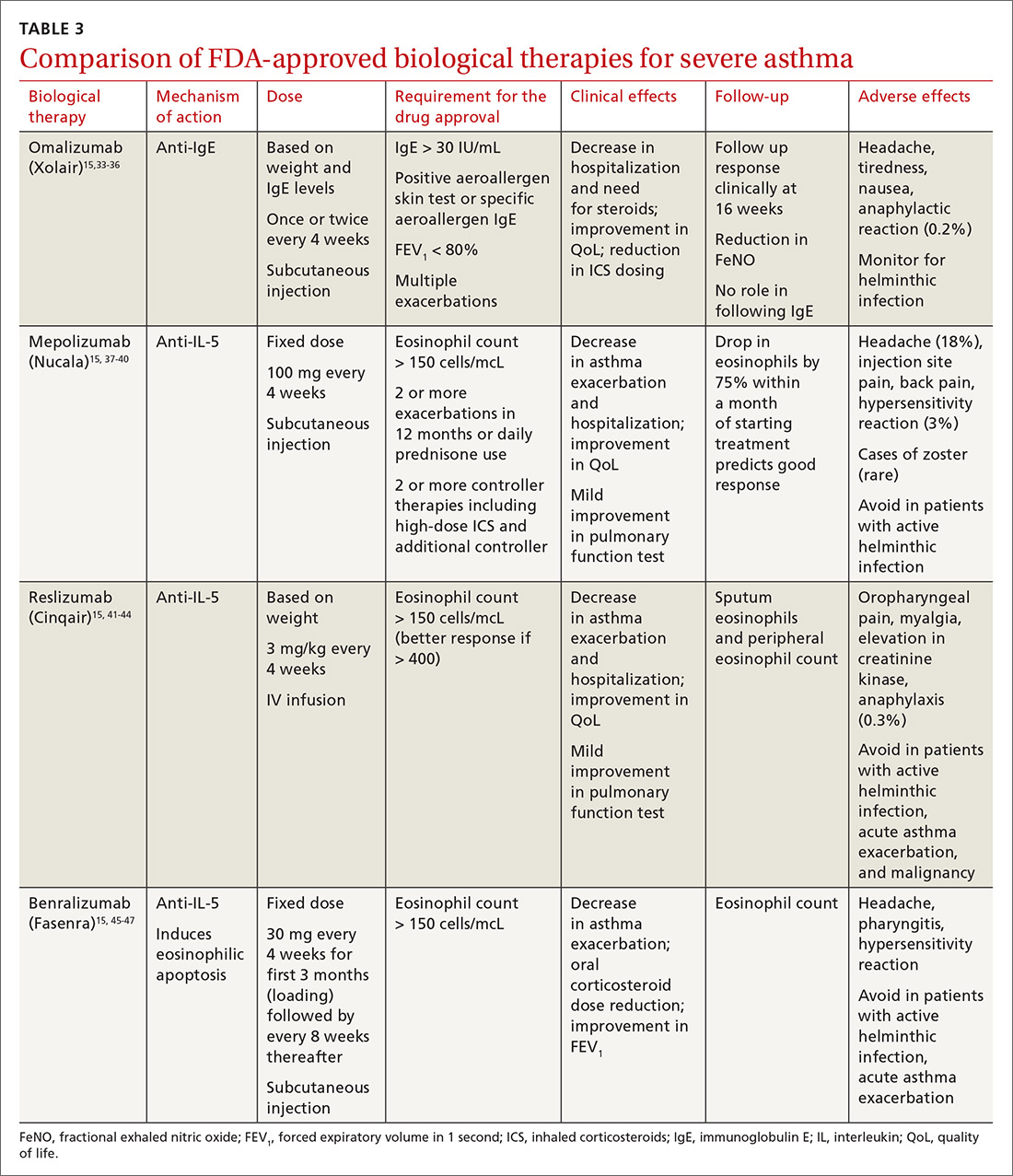

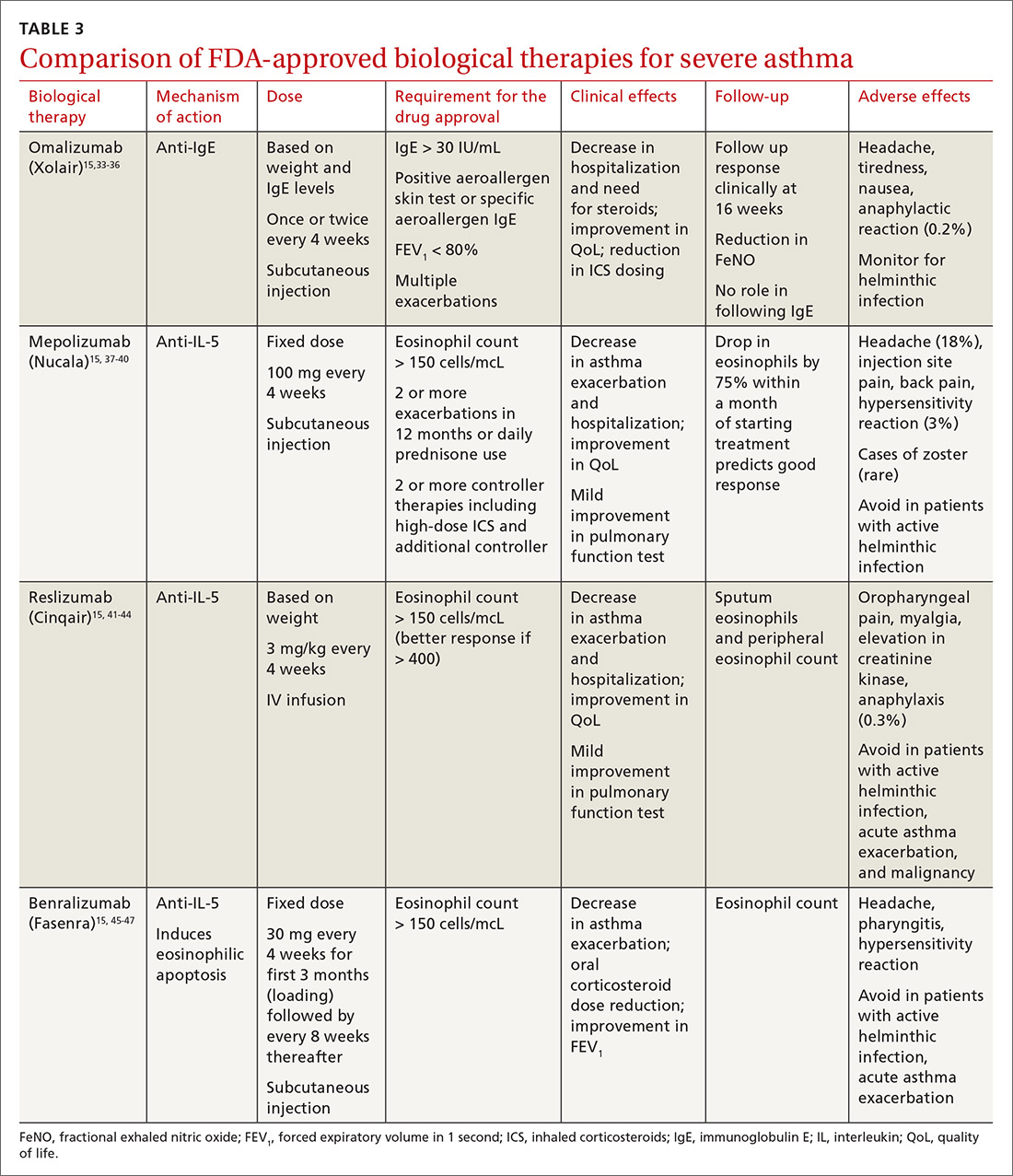

All biological therapies must be administered in a clinical setting, as they carry risk for anaphylaxis. TABLE 315,33-47 summarizes all approved biologicals for the management of severe asthma.

Anti-IgE therapy. Omalizumab (Xolair) was the first approved biological therapy for severe asthma (in 2003). It is a recombinant humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds to free IgE and down regulates the inflammatory cascade. It is therefore best suited for patients with early-onset allergic asthma with a high IgE count. The dose and frequency (once or twice per month) of omalizumab are based on IgE levels and patient weight. Omalizumab reduces asthma exacerbation (up to 45%) and hospitalization (up to 85%).34 Omalizumab also reduces the need for high-dose ICS-LABA therapy and improves quality of life (QoL).33,34

Continue to: Its efficacy and safety...

Its efficacy and safety have been proven outside the clinical trial setting. Treatment response should be assessed over a 3- to 4-month period, using fractional exhalation of nitric oxide (FeNO); serial measurement of IgE levels is not recommended for this purpose. Once started, treatment should be considered long term, as discontinuation of treatment has been shown to lead to recurrence of symptoms and exacerbation.35,36 Of note, the GINA guidelines recommend omalizumab over prednisone as add-on therapy for severe persistent asthma.15

Anti-IL-5 therapy. IL-5 is the main cytokine for growth, differentiation, and activation of eosinophils in the Th-2-mediated inflammatory cascade. Mepolizumab, reslizumab, and benralizumab are 3 FDA-approved anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibody therapies for severe eosinophilic asthma. Mepolizumab has been the most commonly studied anti-IL-5 therapy, while benralizumab, the latest of the 3, has a unique property of inducing eosinophilic apoptosis. There has been no direct comparison of the different anti-IL-5 therapies.

Mepolizumab (Nucala) is a mouse anti-human monoclonal antibody that binds to IL-5 and prevents it from binding to IL-5 receptors on the eosinophil surface. Mepolizumab should be considered in patients with a peripheral eosinophil count > 150 cells/mcL; it has shown a trend of greater benefit in patients with a very high eosinophil count (75% reduction in exacerbation with blood eosinophil count > 500 cells/mcL compared to 56% exacerbation reduction with blood eosinophil count > 150 cells/mcL).37

Mepolizumab has consistently been shown to reduce asthma exacerbation (by about 50%) and emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalization (60%), when compared with placebo in clinical trials.37,38 It also reduces the need for oral corticosteroids, an effect sustained for up to 52 weeks.39,40 The Mepolizumab adjUnctive therapy in subjects with Severe eosinophiliC Asthma (MUSCA) study showed that mepolizumab was associated with significant improvement of health-related QoL, lung function, and asthma symptoms in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma.38

GINA guidelines recommend mepolizumab as an add-on therapy for severe asthma. Mepolizumab is given as a fixed dose of 100 mg every 4 weeks. A 300-mg dose has also been approved for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Monitoring with serial eosinophils might be of value in determining the efficacy of the drug. Mepolizumab is currently in clinical trials for a broad spectrum of diseases, including COPD, hyper-eosinophilic syndrome, and ABPA.

Continue to: Reslizumab (Cinqair)...

Reslizumab (Cinqair) is a rat anti-human monoclonal antibody of the IgG4κ subtype that binds to a small region of IL-5 and subsequently blocks IL-5 from binding to the IL-5 receptor complex on the cell surface of eosinophils. It is currently approved for use as a 3-mg/kg IV infusion every 4 weeks. In large clinical trials,41-43 reslizumab decreased asthma exacerbation and improved QoL, asthma control, and lung function. Most of the study populations had an eosinophil count > 400 cells/mcL. A small study also suggested patients with severe eosinophilic asthma with prednisone dependency (10 mg/d) had better sputum eosinophilia suppression and asthma control with reslizumab when compared with mepolizumab.44

Benralizumab (Fasenra) is a humanized IgG1 anti-IL-5 receptor α monoclonal antibody derived from mice. It induces apoptosis of eosinophils and, to a lesser extent, of basophils.45 In clinical trials, it demonstrated a reduction in asthma exacerbation rate and improvement in prebronchodilator FEV1 and asthma symptoms.46,47 It does not need reconstitution, as the drug is dispensed as prefilled syringes with fixed non-weight-based dosing. Another potential advantage to benralizumab is that after the loading dose, subsequent doses are given every 8 weeks.

Bronchial thermoplasty

Bronchial thermoplasty (BT) is a novel nonpharmacologic intervention that entails the delivery of controlled radiofrequency-generated heat via a catheter inserted into the bronchial tree of the lungs through a flexible bronchoscope. The potential mechanism of action is reduction in airway smooth muscle mass and inflammatory markers.

Evidence for BT started with the Asthma Intervention Research (AIR) and Research in Severe Asthma (RISA) trials.48,49 In the AIR study, BT was shown to reduce the rate of mild exacerbations and improve morning peak expiratory flow and asthma scores at 12 months.48 In the RISA trial, BT resulted in improvements in Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ) score and need for rescue medication at 52 weeks, as well as a trend toward decrease in steroid use.49

However, these studies were criticized for not having a placebo group—an issue addressed in the AIR2 trial, which compared bronchial thermoplasty with a sham procedure. AIR2 demonstrated improvements in AQLQ score and a 32% reduction in severe exacerbations and 84% fewer ED visits in the post-treatment period (up to 1 year post treatment).50

Continue to: Both treatment groups...

Both treatment groups experienced an increase in respiratory adverse events: during the treatment period (up to 6 weeks post procedure), 16 subjects (8.4%) in the BT group required 19 hospitalizations for respiratory symptoms and 2 subjects (2%) in the sham group required 2 hospitalizations. A follow-up observational study involving a cohort of AIR2 patients demonstrated long-lasting effects of BT in asthma exacerbation frequency, ED visits, and stabilization of FEV1 for up to 5 years.51

The Post-market Post-FDA Approval Clinical Trial Evaluating Bronchial Thermoplasty in Severe Persistent Asthma (PAS2) showed similar beneficial effects of BT on asthma control despite enrolling subjects who may have had poorer asthma control in the “real world” setting.52

In summary, BT results in modest improvements in AQLQ scores and clinically worthwhile reductions in severe exacerbations and ED visits in the year post treatment, which may persist for up to 5 years. BT causes short-term increases in asthma-related morbidity, including hospital admissions. While there is encouraging data and the scope is increasing, BT remains limited to carefully selected (by a specialist) patients with severe asthma that is poorly controlled despite maximal inhaled therapy.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy for allergic disease is aimed at inducing immune tolerance to an allergen and alleviating allergic symptoms. This is done by administration of the allergen to which the patient is sensitive. There are 2 approaches: subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) and sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT; a dissolvable tablet under the tongue or an aqueous or liquid extract).

Immunotherapy is generally reserved for patients who have allergic symptoms with exposure to a trigger and evidence (through skin or serum testing) of specific IgE to that trigger, especially if there is poor response to pharmacotherapy and allergen avoidance. Overall, evidence in this field is limited: Most studies have included patients with mild asthma, and few studies have compared immunotherapy with pharmacologic therapy or used standardized outcomes, such as exacerbations.

Continue to: SCIT

SCIT. A 2010 Cochrane review concluded that SCIT reduces asthma symptoms and use of asthma medications and improves bronchial hyperreactivity. Adverse effects include uncommon anaphylactic reactions, which may be life-threatening.53

SLIT has advantages over SCIT as it can be administered by patients or caregivers, does not require injections, and carries a much lower risk for anaphylaxis. Modest benefits have been seen in adults and children, but there is concern about the design of many early studies.

A 2015 Cochrane review of SLIT in asthma recommended further research using validated scales and important outcomes for patients and decision makers so that SLIT can be properly assessed as a clinical treatment for asthma.54 A subsequently published study of SLIT for house dust mites (HDM) in patients with asthma and HDM allergic rhinitis demonstrated a modest reduction in use of ICS with high-dose SLIT.55

In another recent study, among adults with HDM allergy-related asthma not well controlled by ICS, the addition of HDM SLIT to maintenance medications improved time to first moderate-or-severe asthma exacerbation during ICS reduction.56 Additional studies are needed to assess long-term efficacy and safety. However, for patients who experience exacerbations despite use of a low-dose or medium-dose ICS-LABA combination, SLIT can now be considered as an add-on therapy.

Per the GINA guidelines, the potential benefits of allergen immunotherapy must be weighed against the risk for adverse effects, including anaphylaxis, and the inconvenience and cost of the prolonged course of therapy.15

Continue to: Azithromycin

Azithromycin

Macrolides have immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects in addition to their antibacterial effects. Maintenance treatment with macrolides such as azithromycin has been proven to be effective in chronic neutrophilic airway diseases (FIGURE). There have been attempts to assess whether this therapy can be useful in asthma management, as well. Some randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have shown conflicting results, and early studies were limited by lack of data, heterogeneous results, and inadequate study designs.

The AZithromycin Against pLacebo in Exacerbations of Asthma (AZALEA) study was a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in the United Kingdom among patients requiring emergency care for acute asthma exacerbations. Azithromycin added to standard care for asthma attacks did not result in clinical benefit.57 While azithromycin in acute exacerbation is not currently recommended, recent trials in outpatient settings have shown promise.

The AZIthromycin in Severe ASThma study (AZISAST) was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in subjects with exacerbation-prone severe asthma in Belgium. Low-dose azithromycin (250 mg 3 times a week) as an add-on treatment to combination ICS-LABA therapy for 6 months did not reduce the rate of severe asthma exacerbations or lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI). However, subjects with a non-eosinophilic variant (neutrophilic phenotype) experienced significant reduction in the rate of exacerbation and LRTI.58

The recently published Asthma and Macrolides: the AZithromycin Efficacy and Safety Study (AMAZES) shows promise for chronic azithromycin therapy as an add-on to medium-to-high-dose inhaled steroids and a long-acting bronchodilator in adults with uncontrolled persistent asthma. This was a large multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group trial in New Zealand and Australia. Patients were excluded if they had hearing impairment or abnormally prolonged QTc. Azithromycin at a dose of 500 mg 3 times a week for 48 months reduced asthma exacerbations and improved QoL compared to placebo. The effect was sustained between subgroups based on phenotypes (eosinophilic vs noneosinophilic; frequent exacerbators vs nonfrequent exacerbators) and even among those with symptom differences at baseline (eg, cough or sputum positivity). The rate of antibiotic courses for respiratory infectious episodes was significantly reduced in the azithromycin-treated group.59

The take-away: Chronic azithromycin might prove to be a useful agent in the long-term management of asthma patients whose disease is not well controlled on inhaled therapy. Further studies on mechanism and effects of prolonged antibiotic use will shed more light. For more information, see When guideline treatment of asthma fails, consider a macrolide antibiotic; http://bit.ly/2vDAWc6.

Continue to: A new era

A new era

We have entered an exciting era of asthma management, with the introduction of several novel modalities, such as biological therapy and bronchial thermoplasty, as well as use of known drugs such as macrolides, immunotherapy, and LAMA. This was made possible through a better understanding of the biological pathways of asthma. Asthma management has moved toward more personalized, targeted therapy based on asthma phenotypes.

It’s important to remember, however, that pharmacological and nonpharmacological aspects of management—including inhaler techniques, adherence to inhaler therapy, vaccinations, control of asthma triggers, and smoking cessation—remain the foundation of optimal asthma management and need to be aggressively addressed before embarking on advanced treatment options. Patients whose asthma is not well controlled with inhaled medications or who have frequent exacerbations (requiring use of steroids) should be comanaged by an expert asthma specialist to explore all possible therapies.

CORRESPONDENCE

Mayur Rali, MD, 995 Newbridge Road, Bellmore, NY 11710; [email protected]

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most recent national asthma data. Updated May 2019. www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm. Accessed March 6, 2020.

2. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert panel report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma—summary report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5 suppl):S94-S138.

3. Woodruff PG, Modrek B, Choy DF, et al. T-helper type 2-driven inflammation defines major subphenotypes of asthma [published correction appears in Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(8):796]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:388–395.

4. Fahy JV. Type 2 inflammation in asthma—present in most, absent in many. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:57–65.

5. Busse WW. Inflammation in asthma: the cornerstone of the disease and target of therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102(4 pt 2):S17-S22.

6. Lane SJ, Lee TH. Mast cell effector mechanisms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;98(5 pt 2):S67-S71.

7. Robinson DS, Bentley AM, Hartnell A, et al. Activated memory T helper cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with atopic asthma: relation to asthma symptoms, lung function, and bronchial responsiveness. Thorax. 1993;48:26-32.

8. Grigoraş A, Grigoraş CC, Giuşcă SE, et al. Remodeling of basement membrane in patients with asthma. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2016;57:115-119.

9. Huang SK, Xiao HQ, Kleine-Tebbe J, et al. IL-13 expression at the sites of allergen challenge in patients with asthma. J Immunol. 1995;155:2688-2694.

10. Hansbro PM, Starkey MR, Mattes J, et al. Pulmonary immunity during respiratory infections in early life and the development of severe asthma. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11 suppl 5:S297-S302.

11. Apter AJ, Reisine ST, Willard A, et al. The effect of inhaled albuterol in moderate to severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;98:295-301.

12. Peters SP, Kunselman SJ, Icitovic N, et al. Tiotropium bromide step-up therapy for adults with uncontrolled asthma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1715-1726.

13. Kerstjens HA, O’Byrne PM. Tiotropium for the treatment of asthma: a drug safety evaluation. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15:1115-1124.

14. Global Initiative for Asthma. Diagnosis of diseases of chronic air flow limitation: asthma, COPD and asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) 2014. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/GINA_GOLD_ACOS_2014-wms.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2020.

15. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Updated 2019. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/GINA-2019-main-report-June-2019-wms.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2020.

16. Khanbabaee G, Enayat J, Chavoshzadeh Z, et al. Serum level of specific IgG antibody for aspergillus and its association with severity of asthma in asthmatic children. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2012;59:43-50.

17. Agbetile J, Bourne M, Fairs A, et al. Effectiveness of voriconazole in the treatment of aspergillus fumigatus-associated asthma (EVITA3 study). J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:33-39.

18. Stevens DA, Schwartz HJ, Lee JY, et al. A randomized trial of itraconazole in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:756-762.

19. Barnes PJ. Glucocorticosteroids: current and future directions. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:29-43.

20. Oakley RH, Cidlowski JA. The biology of the glucocorticoid receptor: new signaling mechanisms in health and disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:1033-1044.

21. Barnes PJ. Scientific rationale for inhaled combination therapy with long-acting beta2-agonists and corticosteroids. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:182-191.

22. Newton R, Giembycz MA. Understanding how long-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonists enhance the clinical efficacy of inhaled corticosteroids in asthma—an update. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173:3405-3430.

23. Wijesinghe M, Perrin K, Harwood M, et al. The risk of asthma mortality with inhaled long acting beta-agonists. Postgrad Med J. 2008;84:467-472.

24. Cazzola M, Page CP, Rogliani P, et al. β2-agonist therapy in lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:690-696.

25. Bernstein DI, Bateman ED, Woodcock A, et al. Fluticasone furoate (FF)/vilanterol (100/25 mcg or 200/25 mcg) or FF (100 mcg) in persistent asthma. J Asthma. 2015;52:1073-1083.

26. Devillier P, Humbert M, Boye A, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily fluticasone furoate/vilanterol (FF/VI) versus twice-daily inhaled corticosteroids/long-acting β2-agonists (ICS/LABA) in patients with uncontrolled asthma: an open-label, randomized, controlled trial. Respir Med. 2018;141:111-120.

27. Beeh KM, LaForce C, Gahlemann M, et al. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study to investigate different dosing regimens of olodaterol delivered via Respimat(R) in patients with moderate to severe persistent asthma. Respir Res. 2015;16:87.

28. LaForce C, Alexander M, Deckelmann R, et al. Indacaterol provides sustained 24 h bronchodilation on once-daily dosing in asthma: a 7-day dose-ranging study. Allergy. 2008;63:103-111.

29. Beasley RW, Donohue JF, Mehta R, et al. Effect of once-daily indacaterol maleate/mometasone furoate on exacerbation risk in adolescent and adult asthma: a double-blind randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006131.

30. Aalbers R, Park HS. Positioning of long-acting muscarinic antagonists in the management of asthma. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2017;9:386-393.

31. Lee LA, Briggs A, Edwards LD, et al. A randomized, three-period crossover study of umeclidinium as monotherapy in adult patients with asthma. Respir Med. 2015;109:63-73.

32. Israel E, Reddel HK. Severe and difficult-to-treat asthma in adults. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:965-976.

33. Normansell R, Walker S, Milan SJ, et al. Omalizumab for asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(1):CD003559.

34. Hanania NA, Wenzel S, Rosen K, et al. Exploring the effects of omalizumab in allergic asthma: an analysis of biomarkers in the EXTRA study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:804-811.

35. Slavin RG, Ferioli C, Tannenbaum SJ, et al. Asthma symptom re-emergence after omalizumab withdrawal correlates well with increasing IgE and decreasing pharmacokinetic concentrations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:107-113.e3.

36. Ledford D, Busse W, Trzaskoma B, et al. A randomized multicenter study evaluating Xolair persistence of response after long-term therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:162-169.e2.

37. Ortega HG, Liu MC, Pavord ID, et al. Mepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1198-1207.

38. Chupp GL, Bradford ES, Albers FC, et al. Efficacy of mepolizumab add-on therapy on health-related quality of life and markers of asthma control in severe eosinophilic asthma (MUSCA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicentre, phase 3b trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5:390-400.

39. Lugogo N, Domingo C, Chanez P, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of mepolizumab in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma: a multi-center, open-label, phase IIIb study. Clin Ther. 2016;38:2058-2070.e1.

40. Bel EH, Wenzel SE, Thompson PJ, et al. Oral glucocorticoid-sparing effect of mepolizumab in eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1189-1197.

41. Castro M, Zangrilli J, Wechsler ME. Corrections. Reslizumab for inadequately controlled asthma with elevated blood eosinophil counts: results from two multicentre, parallel, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:e15.

42. Bjermer L, Lemiere C, Maspero J, et al. Reslizumab for inadequately controlled asthma with elevated blood eosinophil levels: a randomized phase 3 study. Chest. 2016;150:789-798.

43. Corren J, Weinstein S, Janka L, et al. Phase 3 study of reslizumab in patients with poorly controlled asthma: Effects across a broad range of eosinophil counts. Chest. 2016;150:799-810.

44. Mukherjee M, Aleman Paramo F, Kjarsgaard M, et al. Weight-adjusted intravenous reslizumab in severe asthma with inadequate response to fixed-dose subcutaneous mepolizumab. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:38-46.

45. Kolbeck R, Kozhich A, Koike M, et al. MEDI-563, a humanized anti-IL-5 receptor alpha mAb with enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity function. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:1344-1353.e2.

46. Bleecker ER, FitzGerald JM, Chanez P, et al. Efficacy and safety of benralizumab for patients with severe asthma uncontrolled with high-dosage inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting β2-agonists (SIROCCO): a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;388:2115-2127.

47. FitzGerald JM, Bleecker ER, Nair P, et al. Benralizumab, an anti-interleukin-5 receptor alpha monoclonal antibody, as add-on treatment for patients with severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma (CALIMA): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;388:2128-2141.

48. Cox G, Thomson NC, Rubin AS, et al. Asthma control during the year after bronchial thermoplasty. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1327-1337.

49. Pavord ID, Cox G, Thomson NC, et al. Safety and efficacy of bronchial thermoplasty in symptomatic, severe asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1185-1191.

50. Castro M, Rubin AS, Laviolette M, et al. Effectiveness and safety of bronchial thermoplasty in the treatment of severe asthma: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:116-124.

51. Wechsler ME, Laviolette M, Rubin AS, et al. Bronchial thermoplasty: Long-term safety and effectiveness in patients with severe persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:1295-1302.

52. Chupp G, Laviolette M, Cohn L, et al. Long-term outcomes of bronchial thermoplasty in subjects with severe asthma: A comparison of 3-year follow-up results from two prospective multicentre studies. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1700017.

53. Abramson MJ, Puy RM, Weiner JM. Injection allergen immunotherapy for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(8):CD001186.

54. Normansell R, Kew KM, Bridgman AL. Sublingual immunotherapy for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(8):CD011293.

55. Mosbech H, Deckelmann R, de Blay F, et al. Standardized quality (SQ) house dust mite sublingual immunotherapy tablet (ALK) reduces inhaled corticosteroid use while maintaining asthma control: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:568575.e7.

56. Virchow JC, Backer V, Kuna P, et al. Efficacy of a house dust mite sublingual allergen immunotherapy tablet in adults with allergic asthma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:1715-1725.

57. Johnston SL, Szigeti M, Cross M, et al. Azithromycin for acute exacerbations of asthma : the AZALEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1630-1637.

58. Brusselle GG, Vanderstichele C, Jordens P, et al. Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations in severe asthma (AZISAST): a multicentre randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Thorax. 2013;68:322-329.

59. Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, et al. Effect of azithromycin on asthma exacerbations and quality of life in adults with persistent uncontrolled asthma (AMAZES): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390:659-668.

Recent advances in our understanding of asthma pathophysiology have led to the development of new treatment approaches to this chronic respiratory condition, which affects 25 million Americans or nearly 8% of the population.1 As a result, asthma treatment options have expanded from just simple inhalers and corticosteroids to include

The pathophysiology of asthma provides key targets for therapy

There are 2 basic phenotypes of asthma—neutrophilic predominant and eosinophilic predominant—and 3 key components to its pathophysiology2:

Airway inflammation. Asthma is mediated through either a type 1 T-helper (Th-1) cell or a type 2 T-helper (Th-2) cell response, the pathways of which have a fair amount of overlap (FIGURE). In the neutrophilic-predominant phenotype, irritants, pollutants, and viruses trigger an innate Th-1 cell–mediated pathway that leads to subsequent neutrophil release. This asthma phenotype responds poorly to standard asthma therapy.2-4

In the eosinophilic-predominant phenotype, environmental allergic antigens induce a Th-2 cell–mediated response in the airways of patients with asthma.5-7 This creates a downstream effect on the release of interleukins (IL) including IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. IL-4 triggers immunoglobulin (Ig) E release, which subsequently induces mast cells to release inflammatory cytokines, while IL-5 and IL-13 are responsible for eosinophilic response. These cytokines and eosinophils induce airway hyperresponsiveness, remodeling, and mucus production. Through repeated exposure, chronic inflammation develops and subsequently causes structural changes related to increased smooth muscle mass, goblet cell hyperplasia, and thickening of lamina reticularis.8,9 Understanding of this pathobiological pathway has led to the development of anti-IgE and anti-IL-5 drugs (to be discussed shortly).

Airway obstruction. Early asthmatic response is due to acute bronchoconstriction secondary to IgE; this is followed by airway edema occurring 6 to 24 hours after an acute event (called late asthmatic response). The obstruction is worsened by an overproduction of mucus, which may take weeks to resolve.10 Longstanding inflammation can lead to structural changes and reduced airflow reversibility.

Bronchial hyperresponsiveness is induced by various forms of allergens, pollutants, or viral upper respiratory infections. Sympathetic control in the airway is mediated via beta-2 adrenoceptors expressed on airway smooth muscle, which are responsible for the effect of bronchodilation in response to albuterol.11,12 Cholinergic pathways may further contribute to bronchial hyperresponsiveness and form the basis for the efficacy of anticholinergic therapy.12,13

What we’ve learned about asthma can inform treatment decisions

Presentation may vary, as asthma has many forms including cough-variant asthma and exercise-induced asthma. Airflow limitation is typically identified through spirometry and characterized by reduced (< 70% in adults) forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) or bronchodilator response positivity (an increase in post-bronchodilator FEV1 > 12% or FVC > 200 mL from baseline).2 If spirometry is not diagnostic but suspicion for asthma remains, bronchial provocation testing or exercise challenge testing may be needed.

Continue to: Additional diagnostic considerations...

Additional diagnostic considerations may impact the treatment plan for patients with asthma:

Asthma and COPD. A history of smoking is a key factor in the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)—but many patients with asthma are also smokers. This subgroup may have asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS). It is important to determine whether these patients are asthma predominant or COPD predominant, because appropriate first-line treatment will differ. Patients who are COPD predominant demonstrate reduced diffusion capacity (DLCO) and abnormal PaCO2 on arterial blood gas. They also may show more structural damage on chest computed tomography (CT) than patients with asthma do. Asthma-predominant patients are more likely to have eosinophilia.14

Patients with severe persistent asthma or frequent exacerbations, or those receiving step-up therapy, may require additional serologic testing. Specialized testing for IgE and eosinophil count, as well as a sensitized allergy panel, may help clinicians in selecting specific biological therapies for treatment of severe asthma (further discussion to follow). We recommend using a serum allergy panel, as it is a quick and easy way to identify patients with extrinsic allergies, whereas skin-based testing is often time consuming and may require referral to a specialist.2,5,15

Aspergillus. An additional consideration is testing for Aspergillus antibodies. Aspergillus is a ubiquitous fungus found in the airways of humans. In patients with asthma, however, it can trigger an intense inflammatory response known as allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. ABPA is not an infection. It should be considered in patients who have lived in a damp, old housing environment with possible mold exposure. Treatment of ABPA involves oral corticosteroids; there are varying reports of efficacy with voriconazole or itraconazole as suppressive therapy or steroid-sparing treatment.16-18

Getting a handle on an ever-expanding asthma Tx arsenal

The goals of asthma treatment are symptom control and risk minimization. Treatment choices are dictated in part by disease severity (mild, moderate, severe) and classification (intermittent, persistent). Asthma therapy is traditionally described as step-up and step-down; TABLE 2 summarizes available pharmacotherapy for asthma and provides a framework for add-on therapy as the disease advances.

Continue to: Over the past decade...

Over the past decade, a number of therapeutic options have been introduced or added to the pantheon of asthma treatment.

Inhaled medications

This category includes inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), which are recommended for use alone or in combination with long-acting beta-agonists (LABA) or with long-acting

ICS is the first choice for long-term control of persistent asthma.2 Its molecular effects include activating anti-inflammatory genes, switching off inflammatory genes, and inhibiting inflammatory cells, combined with enhancement of beta-2-adrenergic receptor expression. The cumulative effect is reduction in airway responsiveness in asthma patients.19-22

LABAs are next in line in the step-up, step-down model of symptom management. LABAs should not be prescribed as stand-alone therapy in patients with asthma, as they have received a black box warning from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for an increase in asthma-related death23—a concern that has not been demonstrated with the combination of ICS-LABA.

LABAs cause smooth muscle relaxation in the lungs.24 There are 3 combination products currently available: once-daily fluticasone furoate/vilanterol (Breo), twice-daily fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (Advair), and twice-daily budesonide/formoterol (Symbicort).

Continue to: Once-daily fluticasone furoate/vilanterol...

Once-daily fluticasone furoate/vilanterol has been shown to improve mean FEV1.25 In a 24-week, open-label, multicenter randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of all 3 combination ICS-LABAs, preliminary results indicated that—at least in a tightly controlled setting—once-daily fluticasone furoate/vilanterol provides asthma control similar to the twice-daily combinations and is well tolerated.26

Two ultra-long-acting (24-hour) LABAs, olodaterol (Striverdi Respimat) and indacaterol (Arcapta Neohaler), are being studied for possible use in asthma treatment. In a phase 2 trial investigating therapy for moderate-to-severe persistent asthma, 24-hour FEV1 improved with olodeaterol when compared to placebo.27

Another ongoing clinical trial is studying the effects of ultra-long-acting bronchodilator therapy (olodaterol vs combination olodaterol/tiotropium) in asthma patients who smoke and who are already using ICS (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02682862). Indacaterol has been shown to be effective in the treatment of moderate-to-severe asthma in a once-a-day dosing regimen.28 However, when compared to mometasone alone, a combination of indacaterol and mometasone demonstrated no statistically significant reduction in time to serious exacerbation.29

The LAMA tiotropium is recommended as add-on therapy for patients whose asthma is uncontrolled despite use of low-dose ICS-LABA or as an alternative to high-dose ICS-LABA, per Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 2019 guidelines.15

Tiotropium induces bronchodilation by selectively inhibiting the action of acetylcholine at muscarinic (M) receptors in bronchial smooth muscles; it has a longer duration of action because of its slower dissociation from receptor types M1 and M3.30 Tiotropium respimat (Spiriva, Tiova) has been approved for COPD for many years; in 2013, it was shown to prevent worsening of symptomatic asthma and increase time to first severe exacerbation.13 The FDA subsequently approved tiotropium as an add-on treatment for patients with uncontrolled asthma despite use of ICS-LABA.

Continue to: Glycopyrronium bromide...

Glycopyrronium bromide (glycopyrrolate, multiple brand names) and umeclidinium (Incruse Ellipta) are LAMAs that are approved for COPD treatment but have not yet been approved for patients who have asthma only.31

Biological therapies

In the past few years, improved understanding of asthma’s pathophysiology has led to the development of biological therapy for severe asthma. This therapy is directed at Th-2 inflammatory pathways (FIGURE) and targets various inflammatory markers, such as IgE, IL-5, and eosinophils.

Biologicals are not the first-line therapy for the management of severe asthma. Ideal candidates for this therapy are patients who have exhausted other forms of severe asthma treatment, including ICS-LABA, LAMA, leukotriene receptor antagonists, and mucus-clearing agents. Patients with frequent exacerbations who need continuous steroids or need steroids at least twice a year should be considered for biologicals.32

All biological therapies must be administered in a clinical setting, as they carry risk for anaphylaxis. TABLE 315,33-47 summarizes all approved biologicals for the management of severe asthma.

Anti-IgE therapy. Omalizumab (Xolair) was the first approved biological therapy for severe asthma (in 2003). It is a recombinant humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds to free IgE and down regulates the inflammatory cascade. It is therefore best suited for patients with early-onset allergic asthma with a high IgE count. The dose and frequency (once or twice per month) of omalizumab are based on IgE levels and patient weight. Omalizumab reduces asthma exacerbation (up to 45%) and hospitalization (up to 85%).34 Omalizumab also reduces the need for high-dose ICS-LABA therapy and improves quality of life (QoL).33,34

Continue to: Its efficacy and safety...

Its efficacy and safety have been proven outside the clinical trial setting. Treatment response should be assessed over a 3- to 4-month period, using fractional exhalation of nitric oxide (FeNO); serial measurement of IgE levels is not recommended for this purpose. Once started, treatment should be considered long term, as discontinuation of treatment has been shown to lead to recurrence of symptoms and exacerbation.35,36 Of note, the GINA guidelines recommend omalizumab over prednisone as add-on therapy for severe persistent asthma.15

Anti-IL-5 therapy. IL-5 is the main cytokine for growth, differentiation, and activation of eosinophils in the Th-2-mediated inflammatory cascade. Mepolizumab, reslizumab, and benralizumab are 3 FDA-approved anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibody therapies for severe eosinophilic asthma. Mepolizumab has been the most commonly studied anti-IL-5 therapy, while benralizumab, the latest of the 3, has a unique property of inducing eosinophilic apoptosis. There has been no direct comparison of the different anti-IL-5 therapies.

Mepolizumab (Nucala) is a mouse anti-human monoclonal antibody that binds to IL-5 and prevents it from binding to IL-5 receptors on the eosinophil surface. Mepolizumab should be considered in patients with a peripheral eosinophil count > 150 cells/mcL; it has shown a trend of greater benefit in patients with a very high eosinophil count (75% reduction in exacerbation with blood eosinophil count > 500 cells/mcL compared to 56% exacerbation reduction with blood eosinophil count > 150 cells/mcL).37

Mepolizumab has consistently been shown to reduce asthma exacerbation (by about 50%) and emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalization (60%), when compared with placebo in clinical trials.37,38 It also reduces the need for oral corticosteroids, an effect sustained for up to 52 weeks.39,40 The Mepolizumab adjUnctive therapy in subjects with Severe eosinophiliC Asthma (MUSCA) study showed that mepolizumab was associated with significant improvement of health-related QoL, lung function, and asthma symptoms in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma.38

GINA guidelines recommend mepolizumab as an add-on therapy for severe asthma. Mepolizumab is given as a fixed dose of 100 mg every 4 weeks. A 300-mg dose has also been approved for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Monitoring with serial eosinophils might be of value in determining the efficacy of the drug. Mepolizumab is currently in clinical trials for a broad spectrum of diseases, including COPD, hyper-eosinophilic syndrome, and ABPA.

Continue to: Reslizumab (Cinqair)...

Reslizumab (Cinqair) is a rat anti-human monoclonal antibody of the IgG4κ subtype that binds to a small region of IL-5 and subsequently blocks IL-5 from binding to the IL-5 receptor complex on the cell surface of eosinophils. It is currently approved for use as a 3-mg/kg IV infusion every 4 weeks. In large clinical trials,41-43 reslizumab decreased asthma exacerbation and improved QoL, asthma control, and lung function. Most of the study populations had an eosinophil count > 400 cells/mcL. A small study also suggested patients with severe eosinophilic asthma with prednisone dependency (10 mg/d) had better sputum eosinophilia suppression and asthma control with reslizumab when compared with mepolizumab.44

Benralizumab (Fasenra) is a humanized IgG1 anti-IL-5 receptor α monoclonal antibody derived from mice. It induces apoptosis of eosinophils and, to a lesser extent, of basophils.45 In clinical trials, it demonstrated a reduction in asthma exacerbation rate and improvement in prebronchodilator FEV1 and asthma symptoms.46,47 It does not need reconstitution, as the drug is dispensed as prefilled syringes with fixed non-weight-based dosing. Another potential advantage to benralizumab is that after the loading dose, subsequent doses are given every 8 weeks.

Bronchial thermoplasty

Bronchial thermoplasty (BT) is a novel nonpharmacologic intervention that entails the delivery of controlled radiofrequency-generated heat via a catheter inserted into the bronchial tree of the lungs through a flexible bronchoscope. The potential mechanism of action is reduction in airway smooth muscle mass and inflammatory markers.

Evidence for BT started with the Asthma Intervention Research (AIR) and Research in Severe Asthma (RISA) trials.48,49 In the AIR study, BT was shown to reduce the rate of mild exacerbations and improve morning peak expiratory flow and asthma scores at 12 months.48 In the RISA trial, BT resulted in improvements in Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ) score and need for rescue medication at 52 weeks, as well as a trend toward decrease in steroid use.49

However, these studies were criticized for not having a placebo group—an issue addressed in the AIR2 trial, which compared bronchial thermoplasty with a sham procedure. AIR2 demonstrated improvements in AQLQ score and a 32% reduction in severe exacerbations and 84% fewer ED visits in the post-treatment period (up to 1 year post treatment).50

Continue to: Both treatment groups...

Both treatment groups experienced an increase in respiratory adverse events: during the treatment period (up to 6 weeks post procedure), 16 subjects (8.4%) in the BT group required 19 hospitalizations for respiratory symptoms and 2 subjects (2%) in the sham group required 2 hospitalizations. A follow-up observational study involving a cohort of AIR2 patients demonstrated long-lasting effects of BT in asthma exacerbation frequency, ED visits, and stabilization of FEV1 for up to 5 years.51

The Post-market Post-FDA Approval Clinical Trial Evaluating Bronchial Thermoplasty in Severe Persistent Asthma (PAS2) showed similar beneficial effects of BT on asthma control despite enrolling subjects who may have had poorer asthma control in the “real world” setting.52

In summary, BT results in modest improvements in AQLQ scores and clinically worthwhile reductions in severe exacerbations and ED visits in the year post treatment, which may persist for up to 5 years. BT causes short-term increases in asthma-related morbidity, including hospital admissions. While there is encouraging data and the scope is increasing, BT remains limited to carefully selected (by a specialist) patients with severe asthma that is poorly controlled despite maximal inhaled therapy.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy for allergic disease is aimed at inducing immune tolerance to an allergen and alleviating allergic symptoms. This is done by administration of the allergen to which the patient is sensitive. There are 2 approaches: subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) and sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT; a dissolvable tablet under the tongue or an aqueous or liquid extract).

Immunotherapy is generally reserved for patients who have allergic symptoms with exposure to a trigger and evidence (through skin or serum testing) of specific IgE to that trigger, especially if there is poor response to pharmacotherapy and allergen avoidance. Overall, evidence in this field is limited: Most studies have included patients with mild asthma, and few studies have compared immunotherapy with pharmacologic therapy or used standardized outcomes, such as exacerbations.

Continue to: SCIT

SCIT. A 2010 Cochrane review concluded that SCIT reduces asthma symptoms and use of asthma medications and improves bronchial hyperreactivity. Adverse effects include uncommon anaphylactic reactions, which may be life-threatening.53

SLIT has advantages over SCIT as it can be administered by patients or caregivers, does not require injections, and carries a much lower risk for anaphylaxis. Modest benefits have been seen in adults and children, but there is concern about the design of many early studies.

A 2015 Cochrane review of SLIT in asthma recommended further research using validated scales and important outcomes for patients and decision makers so that SLIT can be properly assessed as a clinical treatment for asthma.54 A subsequently published study of SLIT for house dust mites (HDM) in patients with asthma and HDM allergic rhinitis demonstrated a modest reduction in use of ICS with high-dose SLIT.55

In another recent study, among adults with HDM allergy-related asthma not well controlled by ICS, the addition of HDM SLIT to maintenance medications improved time to first moderate-or-severe asthma exacerbation during ICS reduction.56 Additional studies are needed to assess long-term efficacy and safety. However, for patients who experience exacerbations despite use of a low-dose or medium-dose ICS-LABA combination, SLIT can now be considered as an add-on therapy.

Per the GINA guidelines, the potential benefits of allergen immunotherapy must be weighed against the risk for adverse effects, including anaphylaxis, and the inconvenience and cost of the prolonged course of therapy.15

Continue to: Azithromycin

Azithromycin

Macrolides have immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects in addition to their antibacterial effects. Maintenance treatment with macrolides such as azithromycin has been proven to be effective in chronic neutrophilic airway diseases (FIGURE). There have been attempts to assess whether this therapy can be useful in asthma management, as well. Some randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have shown conflicting results, and early studies were limited by lack of data, heterogeneous results, and inadequate study designs.

The AZithromycin Against pLacebo in Exacerbations of Asthma (AZALEA) study was a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in the United Kingdom among patients requiring emergency care for acute asthma exacerbations. Azithromycin added to standard care for asthma attacks did not result in clinical benefit.57 While azithromycin in acute exacerbation is not currently recommended, recent trials in outpatient settings have shown promise.

The AZIthromycin in Severe ASThma study (AZISAST) was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in subjects with exacerbation-prone severe asthma in Belgium. Low-dose azithromycin (250 mg 3 times a week) as an add-on treatment to combination ICS-LABA therapy for 6 months did not reduce the rate of severe asthma exacerbations or lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI). However, subjects with a non-eosinophilic variant (neutrophilic phenotype) experienced significant reduction in the rate of exacerbation and LRTI.58

The recently published Asthma and Macrolides: the AZithromycin Efficacy and Safety Study (AMAZES) shows promise for chronic azithromycin therapy as an add-on to medium-to-high-dose inhaled steroids and a long-acting bronchodilator in adults with uncontrolled persistent asthma. This was a large multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group trial in New Zealand and Australia. Patients were excluded if they had hearing impairment or abnormally prolonged QTc. Azithromycin at a dose of 500 mg 3 times a week for 48 months reduced asthma exacerbations and improved QoL compared to placebo. The effect was sustained between subgroups based on phenotypes (eosinophilic vs noneosinophilic; frequent exacerbators vs nonfrequent exacerbators) and even among those with symptom differences at baseline (eg, cough or sputum positivity). The rate of antibiotic courses for respiratory infectious episodes was significantly reduced in the azithromycin-treated group.59

The take-away: Chronic azithromycin might prove to be a useful agent in the long-term management of asthma patients whose disease is not well controlled on inhaled therapy. Further studies on mechanism and effects of prolonged antibiotic use will shed more light. For more information, see When guideline treatment of asthma fails, consider a macrolide antibiotic; http://bit.ly/2vDAWc6.

Continue to: A new era

A new era

We have entered an exciting era of asthma management, with the introduction of several novel modalities, such as biological therapy and bronchial thermoplasty, as well as use of known drugs such as macrolides, immunotherapy, and LAMA. This was made possible through a better understanding of the biological pathways of asthma. Asthma management has moved toward more personalized, targeted therapy based on asthma phenotypes.

It’s important to remember, however, that pharmacological and nonpharmacological aspects of management—including inhaler techniques, adherence to inhaler therapy, vaccinations, control of asthma triggers, and smoking cessation—remain the foundation of optimal asthma management and need to be aggressively addressed before embarking on advanced treatment options. Patients whose asthma is not well controlled with inhaled medications or who have frequent exacerbations (requiring use of steroids) should be comanaged by an expert asthma specialist to explore all possible therapies.

CORRESPONDENCE

Mayur Rali, MD, 995 Newbridge Road, Bellmore, NY 11710; [email protected]

Recent advances in our understanding of asthma pathophysiology have led to the development of new treatment approaches to this chronic respiratory condition, which affects 25 million Americans or nearly 8% of the population.1 As a result, asthma treatment options have expanded from just simple inhalers and corticosteroids to include

The pathophysiology of asthma provides key targets for therapy

There are 2 basic phenotypes of asthma—neutrophilic predominant and eosinophilic predominant—and 3 key components to its pathophysiology2:

Airway inflammation. Asthma is mediated through either a type 1 T-helper (Th-1) cell or a type 2 T-helper (Th-2) cell response, the pathways of which have a fair amount of overlap (FIGURE). In the neutrophilic-predominant phenotype, irritants, pollutants, and viruses trigger an innate Th-1 cell–mediated pathway that leads to subsequent neutrophil release. This asthma phenotype responds poorly to standard asthma therapy.2-4

In the eosinophilic-predominant phenotype, environmental allergic antigens induce a Th-2 cell–mediated response in the airways of patients with asthma.5-7 This creates a downstream effect on the release of interleukins (IL) including IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. IL-4 triggers immunoglobulin (Ig) E release, which subsequently induces mast cells to release inflammatory cytokines, while IL-5 and IL-13 are responsible for eosinophilic response. These cytokines and eosinophils induce airway hyperresponsiveness, remodeling, and mucus production. Through repeated exposure, chronic inflammation develops and subsequently causes structural changes related to increased smooth muscle mass, goblet cell hyperplasia, and thickening of lamina reticularis.8,9 Understanding of this pathobiological pathway has led to the development of anti-IgE and anti-IL-5 drugs (to be discussed shortly).

Airway obstruction. Early asthmatic response is due to acute bronchoconstriction secondary to IgE; this is followed by airway edema occurring 6 to 24 hours after an acute event (called late asthmatic response). The obstruction is worsened by an overproduction of mucus, which may take weeks to resolve.10 Longstanding inflammation can lead to structural changes and reduced airflow reversibility.

Bronchial hyperresponsiveness is induced by various forms of allergens, pollutants, or viral upper respiratory infections. Sympathetic control in the airway is mediated via beta-2 adrenoceptors expressed on airway smooth muscle, which are responsible for the effect of bronchodilation in response to albuterol.11,12 Cholinergic pathways may further contribute to bronchial hyperresponsiveness and form the basis for the efficacy of anticholinergic therapy.12,13

What we’ve learned about asthma can inform treatment decisions

Presentation may vary, as asthma has many forms including cough-variant asthma and exercise-induced asthma. Airflow limitation is typically identified through spirometry and characterized by reduced (< 70% in adults) forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) or bronchodilator response positivity (an increase in post-bronchodilator FEV1 > 12% or FVC > 200 mL from baseline).2 If spirometry is not diagnostic but suspicion for asthma remains, bronchial provocation testing or exercise challenge testing may be needed.

Continue to: Additional diagnostic considerations...

Additional diagnostic considerations may impact the treatment plan for patients with asthma:

Asthma and COPD. A history of smoking is a key factor in the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)—but many patients with asthma are also smokers. This subgroup may have asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS). It is important to determine whether these patients are asthma predominant or COPD predominant, because appropriate first-line treatment will differ. Patients who are COPD predominant demonstrate reduced diffusion capacity (DLCO) and abnormal PaCO2 on arterial blood gas. They also may show more structural damage on chest computed tomography (CT) than patients with asthma do. Asthma-predominant patients are more likely to have eosinophilia.14

Patients with severe persistent asthma or frequent exacerbations, or those receiving step-up therapy, may require additional serologic testing. Specialized testing for IgE and eosinophil count, as well as a sensitized allergy panel, may help clinicians in selecting specific biological therapies for treatment of severe asthma (further discussion to follow). We recommend using a serum allergy panel, as it is a quick and easy way to identify patients with extrinsic allergies, whereas skin-based testing is often time consuming and may require referral to a specialist.2,5,15

Aspergillus. An additional consideration is testing for Aspergillus antibodies. Aspergillus is a ubiquitous fungus found in the airways of humans. In patients with asthma, however, it can trigger an intense inflammatory response known as allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. ABPA is not an infection. It should be considered in patients who have lived in a damp, old housing environment with possible mold exposure. Treatment of ABPA involves oral corticosteroids; there are varying reports of efficacy with voriconazole or itraconazole as suppressive therapy or steroid-sparing treatment.16-18

Getting a handle on an ever-expanding asthma Tx arsenal

The goals of asthma treatment are symptom control and risk minimization. Treatment choices are dictated in part by disease severity (mild, moderate, severe) and classification (intermittent, persistent). Asthma therapy is traditionally described as step-up and step-down; TABLE 2 summarizes available pharmacotherapy for asthma and provides a framework for add-on therapy as the disease advances.

Continue to: Over the past decade...

Over the past decade, a number of therapeutic options have been introduced or added to the pantheon of asthma treatment.

Inhaled medications

This category includes inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), which are recommended for use alone or in combination with long-acting beta-agonists (LABA) or with long-acting

ICS is the first choice for long-term control of persistent asthma.2 Its molecular effects include activating anti-inflammatory genes, switching off inflammatory genes, and inhibiting inflammatory cells, combined with enhancement of beta-2-adrenergic receptor expression. The cumulative effect is reduction in airway responsiveness in asthma patients.19-22

LABAs are next in line in the step-up, step-down model of symptom management. LABAs should not be prescribed as stand-alone therapy in patients with asthma, as they have received a black box warning from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for an increase in asthma-related death23—a concern that has not been demonstrated with the combination of ICS-LABA.

LABAs cause smooth muscle relaxation in the lungs.24 There are 3 combination products currently available: once-daily fluticasone furoate/vilanterol (Breo), twice-daily fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (Advair), and twice-daily budesonide/formoterol (Symbicort).

Continue to: Once-daily fluticasone furoate/vilanterol...

Once-daily fluticasone furoate/vilanterol has been shown to improve mean FEV1.25 In a 24-week, open-label, multicenter randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of all 3 combination ICS-LABAs, preliminary results indicated that—at least in a tightly controlled setting—once-daily fluticasone furoate/vilanterol provides asthma control similar to the twice-daily combinations and is well tolerated.26

Two ultra-long-acting (24-hour) LABAs, olodaterol (Striverdi Respimat) and indacaterol (Arcapta Neohaler), are being studied for possible use in asthma treatment. In a phase 2 trial investigating therapy for moderate-to-severe persistent asthma, 24-hour FEV1 improved with olodeaterol when compared to placebo.27

Another ongoing clinical trial is studying the effects of ultra-long-acting bronchodilator therapy (olodaterol vs combination olodaterol/tiotropium) in asthma patients who smoke and who are already using ICS (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02682862). Indacaterol has been shown to be effective in the treatment of moderate-to-severe asthma in a once-a-day dosing regimen.28 However, when compared to mometasone alone, a combination of indacaterol and mometasone demonstrated no statistically significant reduction in time to serious exacerbation.29

The LAMA tiotropium is recommended as add-on therapy for patients whose asthma is uncontrolled despite use of low-dose ICS-LABA or as an alternative to high-dose ICS-LABA, per Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 2019 guidelines.15

Tiotropium induces bronchodilation by selectively inhibiting the action of acetylcholine at muscarinic (M) receptors in bronchial smooth muscles; it has a longer duration of action because of its slower dissociation from receptor types M1 and M3.30 Tiotropium respimat (Spiriva, Tiova) has been approved for COPD for many years; in 2013, it was shown to prevent worsening of symptomatic asthma and increase time to first severe exacerbation.13 The FDA subsequently approved tiotropium as an add-on treatment for patients with uncontrolled asthma despite use of ICS-LABA.

Continue to: Glycopyrronium bromide...

Glycopyrronium bromide (glycopyrrolate, multiple brand names) and umeclidinium (Incruse Ellipta) are LAMAs that are approved for COPD treatment but have not yet been approved for patients who have asthma only.31

Biological therapies

In the past few years, improved understanding of asthma’s pathophysiology has led to the development of biological therapy for severe asthma. This therapy is directed at Th-2 inflammatory pathways (FIGURE) and targets various inflammatory markers, such as IgE, IL-5, and eosinophils.

Biologicals are not the first-line therapy for the management of severe asthma. Ideal candidates for this therapy are patients who have exhausted other forms of severe asthma treatment, including ICS-LABA, LAMA, leukotriene receptor antagonists, and mucus-clearing agents. Patients with frequent exacerbations who need continuous steroids or need steroids at least twice a year should be considered for biologicals.32

All biological therapies must be administered in a clinical setting, as they carry risk for anaphylaxis. TABLE 315,33-47 summarizes all approved biologicals for the management of severe asthma.

Anti-IgE therapy. Omalizumab (Xolair) was the first approved biological therapy for severe asthma (in 2003). It is a recombinant humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds to free IgE and down regulates the inflammatory cascade. It is therefore best suited for patients with early-onset allergic asthma with a high IgE count. The dose and frequency (once or twice per month) of omalizumab are based on IgE levels and patient weight. Omalizumab reduces asthma exacerbation (up to 45%) and hospitalization (up to 85%).34 Omalizumab also reduces the need for high-dose ICS-LABA therapy and improves quality of life (QoL).33,34

Continue to: Its efficacy and safety...

Its efficacy and safety have been proven outside the clinical trial setting. Treatment response should be assessed over a 3- to 4-month period, using fractional exhalation of nitric oxide (FeNO); serial measurement of IgE levels is not recommended for this purpose. Once started, treatment should be considered long term, as discontinuation of treatment has been shown to lead to recurrence of symptoms and exacerbation.35,36 Of note, the GINA guidelines recommend omalizumab over prednisone as add-on therapy for severe persistent asthma.15

Anti-IL-5 therapy. IL-5 is the main cytokine for growth, differentiation, and activation of eosinophils in the Th-2-mediated inflammatory cascade. Mepolizumab, reslizumab, and benralizumab are 3 FDA-approved anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibody therapies for severe eosinophilic asthma. Mepolizumab has been the most commonly studied anti-IL-5 therapy, while benralizumab, the latest of the 3, has a unique property of inducing eosinophilic apoptosis. There has been no direct comparison of the different anti-IL-5 therapies.

Mepolizumab (Nucala) is a mouse anti-human monoclonal antibody that binds to IL-5 and prevents it from binding to IL-5 receptors on the eosinophil surface. Mepolizumab should be considered in patients with a peripheral eosinophil count > 150 cells/mcL; it has shown a trend of greater benefit in patients with a very high eosinophil count (75% reduction in exacerbation with blood eosinophil count > 500 cells/mcL compared to 56% exacerbation reduction with blood eosinophil count > 150 cells/mcL).37

Mepolizumab has consistently been shown to reduce asthma exacerbation (by about 50%) and emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalization (60%), when compared with placebo in clinical trials.37,38 It also reduces the need for oral corticosteroids, an effect sustained for up to 52 weeks.39,40 The Mepolizumab adjUnctive therapy in subjects with Severe eosinophiliC Asthma (MUSCA) study showed that mepolizumab was associated with significant improvement of health-related QoL, lung function, and asthma symptoms in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma.38

GINA guidelines recommend mepolizumab as an add-on therapy for severe asthma. Mepolizumab is given as a fixed dose of 100 mg every 4 weeks. A 300-mg dose has also been approved for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Monitoring with serial eosinophils might be of value in determining the efficacy of the drug. Mepolizumab is currently in clinical trials for a broad spectrum of diseases, including COPD, hyper-eosinophilic syndrome, and ABPA.

Continue to: Reslizumab (Cinqair)...

Reslizumab (Cinqair) is a rat anti-human monoclonal antibody of the IgG4κ subtype that binds to a small region of IL-5 and subsequently blocks IL-5 from binding to the IL-5 receptor complex on the cell surface of eosinophils. It is currently approved for use as a 3-mg/kg IV infusion every 4 weeks. In large clinical trials,41-43 reslizumab decreased asthma exacerbation and improved QoL, asthma control, and lung function. Most of the study populations had an eosinophil count > 400 cells/mcL. A small study also suggested patients with severe eosinophilic asthma with prednisone dependency (10 mg/d) had better sputum eosinophilia suppression and asthma control with reslizumab when compared with mepolizumab.44