User login

Paclitaxel Drug-Drug Interactions in the Military Health System

Background

Paclitaxel was first derived from the bark of the yew tree (Taxus brevifolia). It was discovered as part of a National Cancer Institute program screen of plants and natural products with putative anticancer activity during the 1960s.1-9 Paclitaxel works by suppressing spindle microtube dynamics, which results in the blockage of the metaphase-anaphase transitions, inhibition of mitosis, and induction of apoptosis in a broad spectrum of cancer cells. Paclitaxel also displayed additional anticancer activities, including the suppression of cell proliferation and antiangiogenic effects. However, since the growth of normal body cells may also be affected, other adverse effects (AEs) will also occur.8-18

Two different chemotherapy drugs contain paclitaxel—paclitaxel and nab-paclitaxel—and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recognizes them as separate entities.19-21 Taxol (paclitaxel) was approved by the FDA in 1992 for treating advanced ovarian cancer.20 It has since been approved for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer, AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma (as an orphan drug), non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and cervical cancers (in combination withbevacizumab) in 1994, 1997, 1999, and 2014, respectively.21 Since 2002, a generic version of Taxol, known as paclitaxel injectable, has been FDA-approved from different manufacturers. According to the National Cancer Institute, a combination of carboplatin and Taxol is approved to treat carcinoma of unknown primary, cervical, endometrial, NSCLC, ovarian, and thymoma cancers.19 Abraxane (nab-paclitaxel) was FDA-approved to treat metastatic breast cancer in 2005. It was later approved for first-line treatment of advanced NSCLC and late-stage pancreatic cancer in 2012 and 2013, respectively. In 2018 and 2020, both Taxol and Abraxane were approved for first-line treatment of metastatic squamous cell NSCLC in combination with carboplatin and pembrolizumab and metastatic triple-negative breast cancer in combination with pembrolizumab, respectively.22-26 In 2019, Abraxane was approved with atezolizumab to treat metastatic triple-negative breast cancer, but this approval was withdrawn in 2021. In 2022, a generic version of Abraxane, known as paclitaxel protein-bound, was released in the United States. Furthermore, paclitaxel-containing formulations also are being studied in the treatment of other types of cancer.19-32

One of the main limitations of paclitaxel is its low solubility in water, which complicates its drug supply. To distribute this hydrophobic anticancer drug efficiently, paclitaxel is formulated and administered to patients via polyethoxylated castor oil or albumin-bound (nab-paclitaxel). However, polyethoxylated castor oil induces complement activation and is the cause of common hypersensitivity reactions related to paclitaxel use.2,17,33-38 Therefore, many alternatives to polyethoxylated castor oil have been researched.

Since 2000, new paclitaxel formulations have emerged using nanomedicine techniques. The difference between these formulations is the drug vehicle. Different paclitaxel-based nanotechnological vehicles have been developed and approved, such as albumin-based nanoparticles, polymeric lipidic nanoparticles, polymeric micelles, and liposomes, with many others in clinical trial phases.3,37 Albumin-based nanoparticles have a high response rate (33%), whereas the response rate for polyethoxylated castor oil is 25% in patients with metastatic breast cancer.33,39-52 The use of paclitaxel dimer nanoparticles also has been proposed as a method for increasing drug solubility.33,53

Paclitaxel is metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzymes 2C8 and 3A4. When administering paclitaxel with known inhibitors, inducers, or substrates of CYP2C8 or CYP3A4, caution is required.19-22 Regulations for CYP research were not issued until 2008, so potential interactions between paclitaxel and other drugs have not been extensively evaluated in clinical trials. A study of 12 kinase inhibitors showed strong inhibition of CYP2C8 and/or CYP3A4 pathways by these inhibitors, which could alter the ratio of paclitaxel metabolites in vivo, leading to clinically relevant changes.54 Differential metabolism has been linked to paclitaxel-induced neurotoxicity in patients with cancer.55 Nonetheless, variants in the CYP2C8, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and ABCB1 genes do not account for significant interindividual variability in paclitaxel pharmacokinetics.56 In liver microsomes, losartan inhibited paclitaxel metabolism when used at concentrations > 50 µmol/L.57 Many drug-drug interaction (DDI) studies of CYP2C8 and CYP3A4 have shown similar results for paclitaxel.58-64

The goals of this study are to investigate prescribed drugs used with paclitaxel and determine patient outcomes through several Military Health System (MHS) databases. The investigation focused on (1) the functions of paclitaxel; (2) identifying AEs that patients experienced; (3) evaluating differences when paclitaxel is used alone vs concomitantly and between the completed vs discontinued treatment groups; (4) identifying all drugs used during paclitaxel treatment; and (5) evaluating DDIs with antidepressants (that have an FDA boxed warning and are known to have DDIs confirmed in previous publications) and other drugs.65-67

The Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, institutionalreview board approved the study protocol and ensured compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act as an exempt protocol. The Joint Pathology Center (JPC) of the US Department of Defense (DoD) Cancer Registry Program and MHS data experts from the Comprehensive Ambulatory/Professional Encounter Record (CAPER) and the Pharmacy Data Transaction Service (PDTS) provided data for the analysis.

METHODS

The DoD Cancer Registry Program was established in 1986 and currently contains data from 1998 to 2024. CAPER and PDTS are part of the MHS Data Repository/Management Analysis and Reporting Tool database. Each observation in the CAPER record represents an ambulatory encounter at a military treatment facility (MTF). CAPER includes data from 2003 to 2024.

Each observation in the PDTS record represents a prescription filled for an MHS beneficiary at an MTF through the TRICARE mail-order program or a US retail pharmacy. Missing from this record are prescriptions filled at international civilian pharmacies and inpatient pharmacy prescriptions. The MHS Data Repository PDTS record is available from 2002 to 2024. The legacy Composite Health Care System is being replaced by GENESIS at MTFs.

Data Extraction Design

The study design involved a cross-sectional analysis. We requested data extraction for paclitaxel from 1998 to 2022. Data from the DoD Cancer Registry Program were used to identify patients who received cancer treatment. Once patients were identified, the CAPER database was searched for diagnoses to identify other health conditions, whereas the PDTS database was used to populate a list of prescription medications filled during chemotherapy treatment.

Data collected from the JPC included cancer treatment, cancer information, demographics, and physicians’ comments on AEs. Collected data from the MHS include diagnosis and filled prescription history from initiation to completion of the therapy period (or 2 years after the diagnosis date). For the analysis of the DoD Cancer Registry Program and CAPER databases, we used all collected data without excluding any. When analyzing PDTS data, we excluded patients with PDTS data but without a record of paclitaxel being filled, or medications filled outside the chemotherapy period (by evaluating the dispensed date and day of supply).

Data Extraction Analysis

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program Coding and Staging Manual 2016 and the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition, 1st revision, were used to decode disease and cancer types.68,69 Data sorting and analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel. The percentage for the total was calculated by using the number of patients or data available within the paclitaxel groups divided by the total number of patients or data variables. The subgroup percentage was calculated by using the number of patients or data available within the subgroup divided by the total number of patients in that subgroup.

In alone vs concomitant and completed vs discontinued treatment groups, a 2-tailed, 2-sample z test was used to statistical significance (P < .05) using a statistics website.70 Concomitant was defined as paclitaxel taken with other antineoplastic agent(s) before, after, or at the same time as cancer therapy. For the retrospective data analysis, physicians’ notes with a period, comma, forward slash, semicolon, or space between medication names were interpreted as concurrent, whereas plus (+), minus/plus (-/+), or “and” between drug names that were dispensed on the same day were interpreted as combined with known common combinations: 2 drugs (DM886 paclitaxel and carboplatin and DM881-TC-1 paclitaxel and cisplatin) or 3 drugs (DM887-ACT doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and paclitaxel). Completed treatment was defined as paclitaxel as the last medication the patient took without recorded AEs; switching or experiencing AEs was defined as discontinued treatment.

RESULTS

The JPC provided 702 entries for 687 patients with a mean age of 56 years (range, 2 months to 88 years) who were treated with paclitaxel from March 1996 to October 2021. Fifteen patients had duplicate entries because they had multiple cancer sites or occurrences. There were 623 patients (89%) who received paclitaxel for FDA-approved indications. The most common types of cancer identified were 344 patients with breast cancer (49%), 91 patients with lung cancer (13%), 79 patients with ovarian cancer (11%), and 75 patients with endometrial cancer (11%) (Table 1). Seventy-nine patients (11%) received paclitaxel for cancers that were not for FDA-approved indications, including 19 for cancers of the fallopian tube (3%) and 17 for esophageal cancer (2%) (Table 2).

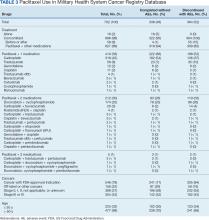

There were 477 patients (68%) aged > 50 years. A total of 304 patients (43%) had a stage III or IV cancer diagnosis and 398 (57%) had stage II or lower (combination of data for stages 0, I, and II; not applicable; and unknown) cancer diagnosis. For systemic treatment, 16 patients (2%) were treated with paclitaxel alone and 686 patients (98%) received paclitaxel concomitantly with additional chemotherapy: 59 patients (9%) in the before or after group, 410 patients (58%) had a 2-drug combination, 212 patients (30%) had a 3-drug combination, and 5 patients (1%) had a 4-drug combination. In addition, for doublet therapies, paclitaxel combined with carboplatin, trastuzumab, gemcitabine, or cisplatin had more patients (318, 58, 12, and 11, respectively) than other combinations (≤ 4 patients). For triplet therapies, paclitaxel combined withdoxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide or carboplatin plus bevacizumab had more patients (174 and 20, respectively) than other combinations, including quadruplet therapies (≤ 4 patients) (Table 3).

Patients were more likely to discontinue paclitaxel if they received concomitant treatment. None of the 16 patients receiving paclitaxel monotherapy experienced AEs, whereas 364 of 686 patients (53%) treated concomitantly discontinued (P < .001). Comparisons of 1 drug vs combination (2 to 4 drugs) and use for treating cancers that were FDA-approved indications vs off-label use were significant (P < .001), whereas comparisons of stage II or lower vs stage III and IV cancer and of those aged ≤ 50 years vs aged > 50 years were not significant (P = .50 andP = .30, respectively) (Table 4).

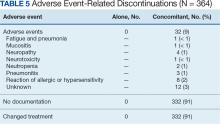

Among the 364 patients who had concomitant treatment and had discontinued their treatment, 332 (91%) switched treatments with no AEs documented and 32 (9%) experienced fatigue with pneumonia, mucositis, neuropathy, neurotoxicity, neutropenia, pneumonitis, allergic or hypersensitivity reaction, or an unknown AE. Patients who discontinued treatment because of unknown AEs had a physician’s note that detailed progressive disease, a significant decline in performance status, and another unknown adverse effect due to a previous sinus tract infection and infectious colitis (Table 5).

Management Analysis and Reporting Tool Database

MHS data analysts provided data on diagnoses for 639 patients among 687 submitteddiagnoses, with 294 patients completing and 345 discontinuing paclitaxel treatment. Patients in the completed treatment group had 3 to 258 unique health conditions documented, while patients in the discontinued treatment group had 4 to 181 unique health conditions documented. The MHS reported 3808 unique diagnosis conditions for the completed group and 3714 for the discontinued group (P = .02).

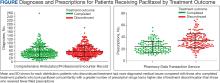

The mean (SD) number of diagnoses was 51 (31) for the completed and 55 (28) for the discontinued treatment groups (Figure). Among 639 patients who received paclitaxel, the top 5 diagnoses were administrative, including encounters for other administrative examinations; antineoplastic chemotherapy; administrative examination for unspecified; other specified counseling; and adjustment and management of vascular access device. The database does not differentiate between administrative and clinically significant diagnoses.

MHS data analysts provided data for 336 of 687 submitted patients who were prescribed paclitaxel; 46 patients had no PDTS data, and 305 patients had PDTS data without paclitaxel, Taxol, or Abraxane dispensed. Medications that were filled outside the chemotherapy period were removed by evaluating the dispensed date and day of supply. Among these 336 patients, 151 completed the treatment and 185 discontinued, with 14 patients experiencing documented AEs. Patients in the completed treatment group filled 9 to 56 prescriptions while patients in the discontinued treatment group filled 6 to 70 prescriptions.Patients in the discontinued group filled more prescriptions than those who completed treatment: 793 vs 591, respectively (P = .34).

The mean (SD) number of filled prescription drugs was 24 (9) for the completed and 34 (12) for the discontinued treatment group. The 5 most filled prescriptions with paclitaxel from 336 patients with PDTS data were dexamethasone (324 prescriptions with 14 recorded AEs), diphenhydramine (296 prescriptions with 12 recorded AEs), ondansetron (277 prescriptions with 11 recorded AEs), prochlorperazine (265 prescriptions with 12 recorded AEs), and sodium chloride (232 prescriptions with 11 recorded AEs).

DISCUSSION

As a retrospective review, this study is more limited in the strength of its conclusions when compared to randomized control trials. The DoD Cancer Registry Program only contains information about cancer types, stages, treatment regimens, and physicians’ notes. Therefore, noncancer drugs are based solely on the PDTS database. In most cases, physicians' notes on AEs were not detailed. There was no distinction between initial vs later lines of therapy and dosage reductions. The change in status or appearance of a new medical condition did not indicate whether paclitaxel caused the changes to develop or directly worsen a pre-existing condition. The PDTS records prescriptions filled, but that may not reflect patients taking prescriptions.

Paclitaxel

Paclitaxel has a long list of both approved and off-label uses in malignancies as a primary agent and in conjunction with other drugs. The FDA prescribing information for Taxol and Abraxane was last updated in April 2011 and September 2020, respectively.20,21 The National Institutes of Health National Library of Medicine has the current update for paclitaxel on July 2023.19,22 Thus, the prescribed information for paclitaxel referenced in the database may not always be up to date. The combinations of paclitaxel with bevacizumab, carboplatin, or carboplatin and pembrolizumab were not in the Taxol prescribing information. Likewise, a combination of nab-paclitaxel with atezolizumab or carboplatin and pembrolizumab is missing in the Abraxane prescribing information.22-27

The generic name is not the same as a generic drug, which may have slight differences from the brand name product.71 The generic drug versions of Taxol and Abraxane have been approved by the FDA as paclitaxel injectable and paclitaxel-protein bound, respectively. There was a global shortage of nab-paclitaxel from October 2021 to June 2022 because of a manufacturing problem.72 During this shortage, data showed similar comments from physician documents that treatment switched to Taxol due to the Abraxane shortage.

Of 336 patients in the PDTS database with dispensed paclitaxel prescriptions, 276 received paclitaxel (year dispensed, 2013-2022), 27 received Abraxane (year dispensed, 2013-2022), 47 received Taxol (year dispensed, 2004-2015), 8 received both Abraxane and paclitaxel, and 6 received both Taxol and paclitaxel. Based on this information, it appears that the distinction between the drugs was not made in the PDTS until after 2015, 10 years after Abraxane received FDA approval. Abraxane was prescribed in the MHS in 2013, 8 years after FDA approval. There were a few comparison studies of Abraxane and Taxol.73-76

Safety and effectiveness in pediatric patients have not been established for paclitaxel. According to the DoD Cancer Registry Program, the youngest patient was aged 2 months. In 2021, this patient was diagnosed with corpus uteri and treated with carboplatin and Taxol in course 1; in course 2, the patient reacted to Taxol; in course 3, Taxol was replaced with Abraxane; in courses 4 to 7, the patient was treated with carboplatin only.

Discontinued Treatment

Ten patients had prescribed Taxol that was changed due to AEs: 1 was switched to Abraxane and atezolizumab, 3 switched to Abraxane, 2 switched to docetaxel, 1 switched to doxorubicin, and 3 switched to pembrolizumab (based on physician’s comments). Of the 10 patients, 7 had Taxol reaction, 2 experienced disease progression, and 1 experienced high programmed death–ligand 1 expression (this patient with breast cancer was switched to Abraxane and atezolizumab during the accelerated FDA approval phase for atezolizumab, which was later revoked). Five patients were treated with carboplatin and Taxol for cancer of the anal canal (changed to pembrolizumab after disease progression), lung not otherwise specified (changed to carboplatin and pembrolizumab due to Taxol reaction), lower inner quadrant of the breast (changed to doxorubicin due to hypersensitivity reaction), corpus uteri (changed to Abraxane due to Taxol reaction), and ovary (changed to docetaxel due to Taxol reaction). Three patients were treated with doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and Taxol for breast cancer; 2 patients with breast cancer not otherwise specified switched to Abraxane due to cardiopulmonary hypersensitivity and Taxol reaction and 1 patient with cancer of the upper outer quadrant of the breast changed to docetaxel due to allergic reaction. One patient, who was treated with paclitaxel, ifosfamide, and cisplatin for metastasis of the lower lobe of the lung and kidney cancer, experienced complications due to infectious colitis (treated with ciprofloxacin) and then switched to pembrolizumab after the disease progressed. These AEs are known in paclitaxel medical literature on paclitaxel AEs.19-24,77-81

Combining 2 or more treatments to target cancer-inducing or cell-sustaining pathways is a cornerstone of chemotherapy.82-84 Most combinations are given on the same day, but some are not. For 3- or 4-drug combinations, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide were given first, followed by paclitaxel with or withouttrastuzumab, carboplatin, or pembrolizumab. Only 16 patients (2%) were treated with paclitaxel alone; therefore, the completed and discontinued treatment groups are mostly concomitant treatment. As a result, the comparisons of the completed and discontinued treatment groups were almost the same for the diagnosis. The PDTS data have a better result because 2 exclusion criteria were applied before narrowing the analysis down to paclitaxel treatment specifically.

Antidepressants and Other Drugs

Drug response can vary from person to person and can lead to treatment failure related to AEs. One major factor in drug metabolism is CYP.85 CYP2C8 is the major pathway for paclitaxel and CYP3A4 is the minor pathway. When evaluating the noncancer drugs, there were no reports of CYP2C8 inhibition or induction. Over the years, many DDI warnings have been issued for paclitaxel with different drugs in various electronic resources.

Oncologists follow guidelines to prevent DDIs, as paclitaxel is known to have severe, moderate, and minor interactions with other drugs. Among 687 patients, 261 (38%) were prescribed any of 14 antidepressants. Eight of these antidepressants (amitriptyline, citalopram, desipramine, doxepin, venlafaxine, escitalopram, nortriptyline, and trazodone) are metabolized, 3 (mirtazapine, sertraline, and fluoxetine) are metabolized and inhibited, 2 (bupropion and duloxetine) are neither metabolized nor inhibited, and 1 (paroxetine) is inhibited by CYP3A4. Duloxetine, venlafaxine, and trazodone were more commonly dispensed (84, 78, and 42 patients, respectively) than others (≤ 33 patients).

Of 32 patients with documented AEs,14 (44%) had 168 dispensed drugs in the PDTS database. Six patients (19%) were treated with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel for breast cancer; 6 (19%) were treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel for cancer of the lung (n = 3), corpus uteri (n = 2), and ovary (n = 1); 1 patient (3%) was treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel, then switched to carboplatin, bevacizumab, and paclitaxel, and then completed treatment with carboplatin and paclitaxel for an unspecified female genital cancer; and 1 patient (3%) was treated with cisplatin, ifosfamide, and paclitaxel for metastasis of the lower lobe lung and kidney cancer.

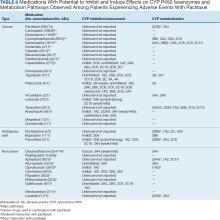

The 14 patients with PDTS data had 18 cancer drugs dispensed. Eleven had moderate interaction reports and 7 had no interaction reports. A total of 165 noncancer drugs were dispensed, of which 3 were antidepressants and had no interactions reported, 8 had moderate interactions reported, and 2 had minor interactions with Taxol and Abraxane, respectively (Table 6).86-129

Of 3 patients who were dispensed bupropion, nortriptyline, or paroxetine, 1 patient with breast cancer was treated with doxorubicin andcyclophosphamide, followed by paclitaxel with bupropion, nortriptyline, pegfilgrastim,dexamethasone, and 17 other noncancer drugs that had no interaction report dispensed during paclitaxel treatment. Of 2 patients with lung cancer, 1 patient was treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel with nortriptyline, dexamethasone, and 13 additional medications, and the second patient was treated with paroxetine, cimetidine, dexamethasone, and 12 other medications. Patients were dispensed up to6 noncancer medications on the same day as paclitaxel administration to control the AEs, not including the prodrugs filled before the treatments. Paroxetine and cimetidine have weak inhibition, and dexamethasone has weak induction of CYP3A4. Therefore, while 1:1 DDIs might have little or no effect with weak inhibit/induce CYP3A4 drugs, 1:1:1 or more combinations could have a different outcome (confirmed in previous publications).65-67

Dispensed on the same day may not mean taken at the same time. One patient experienced an AE with dispensed 50 mg losartan, carboplatin plus paclitaxel, dexamethasone, and 6 other noncancer drugs. Losartan inhibits paclitaxel, which can lead to negative AEs.57,66,67 However, there were no blood or plasma samples taken to confirm the losartan was taken at the same time as the paclitaxel given this was not a clinical trial.

Conclusions

This retrospective study discusses the use of paclitaxel in the MHS and the potential DDIs associated with it. The study population consisted mostly of active-duty personnel, who are required to be healthy or have controlled or nonactive medical diagnoses and be physically fit. This group is mixed with dependents and retirees that are more reflective of the average US population. As a result, this patient population is healthier than the general population, with a lower prevalence of common illnesses such as diabetes and obesity. The study aimed to identify drugs used alongside paclitaxel treatment. While further research is needed to identify potential DDIs among patients who experienced AEs, in vitro testing will need to be conducted before confirming causality. The low number of AEs experienced by only 32 of 702 patients (5%), with no deaths during paclitaxel treatment, indicates that the drug is generally well tolerated. Although this study cannot conclude that concomitant use with noncancer drugs led to the discontinuation of paclitaxel, we can conclude that there seems to be no significant DDIsidentified between paclitaxel and antidepressants. This comprehensive overview provides clinicians with a complete picture of paclitaxel use for 27 years (1996-2022), enabling them to make informed decisions about paclitaxel treatment.

Acknowledgments

The Department of Research Program funds at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center supported this protocol. We sincerely appreciate the contribution of data extraction from the Joint Pathology Center teams (Francisco J. Rentas, John D. McGeeney, Beatriz A. Hallo, and Johnny P. Beason) and the MHS database personnel (Maj Ryan Costantino, Brandon E. Jenkins, and Alexander G. Rittel). We gratefully thank you for the protocol support from the Department of Research programs: CDR Martin L. Boese, CDR Wesley R. Campbell, Maj. Abhimanyu Chandel, CDR Ling Ye, Chelsea N. Powers, Yaling Zhou, Elizabeth Schafer, Micah Stretch, Diane Beaner, and Adrienne Woodard.

1. American Chemical Society. Discovery of camptothecin and taxol. acs.org. Accessed June 4, 2024. https://www.acs.org/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/camptothecintaxol.html

2. Bocci G, Di Paolo A, Danesi R. The pharmacological bases of the antiangiogenic activity of paclitaxel. Angiogenesis. 2013;16(3):481-492. doi:10.1007/s10456-013-9334-0.

3. Meštrovic T. Paclitaxel history. News Medical Life Sciences. Updated March 11, 2023. Accessed June 4, 2024. https://www.news-medical.net/health/Paclitaxel-History.aspx

4. Rowinsky EK, Donehower RC. Paclitaxel (taxol). N Engl J Med. 1995;332(15):1004-1014. doi:10.1056/NEJM199504133321507

5. Walsh V, Goodman J. The billion dollar molecule: Taxol in historical and theoretical perspective. Clio Med. 2002;66:245-267. doi:10.1163/9789004333499_013

6. Perdue RE, Jr, Hartwell JL. The search for plant sources of anticancer drugs. Morris Arboretum Bull. 1969;20:35-53.

7. Wall ME, Wani MC. Camptothecin and taxol: discovery to clinic—thirteenth Bruce F. Cain Memorial Award lecture. Cancer Res. 1995;55:753-760.

8. Wani MC, Taylor HL, Wall ME, Coggon P, McPhail AT. Plant antitumor agents. VI. The isolation and structure of taxol, a novel antileukemic and antitumor agent from taxus brevifolia. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93(9):2325-2327. doi:10.1021/ja00738a045

9. Weaver BA. How taxol/paclitaxel kills cancer cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25(18):2677-2681. doi:10.1091/mbc.E14-04-0916

10. Chen JG, Horwitz SB. Differential mitotic responses to microtubule-stabilizing and-destabilizing drugs. Cancer Res. 2002;62(7):1935-1938.

11. Singh S, Dash AK. Paclitaxel in cancer treatment: perspectives and prospects of its delivery challenges. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2009;26(4):333-372. doi:10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v26.i4.10

12. Schiff PB, Fant J, Horwitz SB. Promotion of microtubule assembly in vitro by taxol. Nature. 1979;277(5698):665-667. doi:10.1038/277665a0

13. Fuchs DA, Johnson RK. Cytologic evidence that taxol, an antineoplastic agent from taxus brevifolia, acts as a mitotic spindle poison. Cancer Treat Rep. 1978;62(8):1219-1222.

14. Walsh V, Goodman J. From taxol to taxol: the changing identities and ownership of an anti-cancer drug. Med Anthropol. 2002;21(3-4):307-336. doi:10.1080/01459740214074

15. Walsh V, Goodman J. Cancer chemotherapy, biodiversity, public and private property: the case of the anti-cancer drug taxol. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(9):1215-1225. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00161-6

16. Jordan MA, Wendell K, Gardiner S, Derry WB, Copp H, Wilson L. Mitotic block induced in HeLa cells by low concentrations of paclitaxel (taxol) results in abnormal mitotic exit and apoptotic cell death. Cancer Res. 1996;56(4):816-825.

17. Picard M, Castells MC. Re-visiting hypersensitivity reactions to taxanes: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015;49(2):177-191. doi:10.1007/s12016-014-8416-0

18. Zasadil LM, Andersen KA, Yeum D, et al. Cytotoxicity of paclitaxel in breast cancer is due to chromosome missegregation on multipolar spindles. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:229ra243. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3007965

19. National Cancer Institute. Carboplatin-Taxol. Published May 30, 2012. Updated March 22, 2023. Accessed June 4, 2024. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/drugs/carboplatin-taxol

20. Taxol (paclitaxel). Prescribing information. Bristol-Myers Squibb; 2011. Accessed June 4, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/020262s049lbl.pdf

21. Abraxane (paclitaxel). Prescribing information. Celgene Corporation; 2021. Accessed June 4, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/021660s047lbl.pdf

22. Awosika AO, Farrar MC, Jacobs TF. Paclitaxel. StatPearls. Updated November 18, 2023. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536917/

23. Gerriets V, Kasi A. Bevacizumab. StatPearls. Updated September 1, 2022. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482126/

24. American Cancer Society. Chemotherapy for endometrial cancer. Updated March 27, 2019. Accessed June 4, 2024. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/endometrial-cancer/treating/chemotherapy.html

25. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves pembrolizumab in combination with chemotherapy for first-line treatment of metastatic squamous NSCLC. October 30, 2018. Updated December 14, 2018. Accessed June 4, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/fda-approves-pembrolizumab-combination-chemotherapy-first-line-treatment-metastatic-squamous-nsclc

26. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA grants accelerated approval to pembrolizumab for locally recurrent unresectable or metastatic triple negative breast cancer. November 13, 2020. Accessed June 4, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-pembrolizumab-locally-recurrent-unresectable-or-metastatic-triple

27. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves atezolizumab for PD-L1 positive unresectable locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast. March 8, 2019. Updated March 18, 2019. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/fda-approves-atezolizumab-pd-l1-positive-unresectable-locally-advanced-or-metastatic-triple-negative

28. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA issues alert about efficacy and potential safety concerns with atezolizumab in combination with paclitaxel for treatment of breast cancer. September 8, 2020. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-issues-alert-about-efficacy-and-potential-safety-concerns-atezolizumab-combination-paclitaxel

29. Tan AR. Chemoimmunotherapy: still the standard of care for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. ASCO Daily News. February 23, 2022. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://dailynews.ascopubs.org/do/chemoimmunotherapy-still-standard-care-metastatic-triple-negative-breast-cancer

30. McGuire WP, Rowinsky EK, Rosenshein NB, et al. Taxol: a unique antineoplastic agent with significant activity in advanced ovarian epithelial neoplasms. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111(4):273-279. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-111-4-273

31. Milas L, Hunter NR, Kurdoglu B, et al. Kinetics of mitotic arrest and apoptosis in murine mammary and ovarian tumors treated with taxol. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1995;35(4):297-303. doi:10.1007/BF00689448

32. Searle J, Collins DJ, Harmon B, Kerr JF. The spontaneous occurrence of apoptosis in squamous carcinomas of the uterine cervix. Pathology. 1973;5(2):163-169. doi:10.3109/00313027309060831

33. Gallego-Jara J, Lozano-Terol G, Sola-Martínez RA, Cánovas-Díaz M, de Diego Puente T. A compressive review about taxol®: history and future challenges. Molecules. 2020;25(24):5986. doi:10.3390/molecules25245986

34. Bernabeu E, Cagel M, Lagomarsino E, Moretton M, Chiappetta DA. Paclitaxel: What has been done and the challenges remain ahead. Int J Pharm. 2017;526(1-2):474-495. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.05.016

35. Nehate C, Jain S, Saneja A, et al. Paclitaxel formulations: challenges and novel delivery options. Curr Drug Deliv. 2014;11(6):666-686. doi:10.2174/1567201811666140609154949

36. Gelderblom H, Verweij J, Nooter K, Sparreboom A, Cremophor EL. The drawbacks and advantages of vehicle selection for drug formulation. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(13):1590-1598. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00171-x

37. Chowdhury MR, Moshikur RM, Wakabayashi R, et al. In vivo biocompatibility, pharmacokinetics, antitumor efficacy, and hypersensitivity evaluation of ionic liquid-mediated paclitaxel formulations. Int J Pharm. 2019;565:219-226. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.05.020

38. Borgå O, Henriksson R, Bjermo H, Lilienberg E, Heldring N, Loman N. Maximum tolerated dose and pharmacokinetics of paclitaxel micellar in patients with recurrent malignant solid tumours: a dose-escalation study. Adv Ther. 2019;36(5):1150-1163. doi:10.1007/s12325-019-00909-6

39. Rouzier R, Rajan R, Wagner P, et al. Microtubule-associated protein tau: a marker of paclitaxel sensitivity in breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(23):8315-8320. doi:10.1073/pnas.0408974102

40. Choudhury H, Gorain B, Tekade RK, Pandey M, Karmakar S, Pal TK. Safety against nephrotoxicity in paclitaxel treatment: oral nanocarrier as an effective tool in preclinical evaluation with marked in vivo antitumor activity. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2017;91:179-189. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2017.10.023

41. Barkat MA, Beg S, Pottoo FH, Ahmad FJ. Nanopaclitaxel therapy: an evidence based review on the battle for next-generation formulation challenges. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2019;14(10):1323-1341. doi:10.2217/nnm-2018-0313

42. Sofias AM, Dunne M, Storm G, Allen C. The battle of “nano” paclitaxel. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;122:20-30. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2017.02.003

43. Yang N, Wang C, Wang J, et al. Aurora inase a stabilizes FOXM1 to enhance paclitaxel resistance in triple-negative breast cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(9):6442-6453. doi:10.1111/jcmm.14538

44. Chowdhury MR, Moshikur RM, Wakabayashi R, et al. Ionic-liquid-based paclitaxel preparation: a new potential formulation for cancer treatment. Mol Pharm. 2018;15(16):2484-2488. doi:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.8b00305

45. Chung HJ, Kim HJ, Hong ST. Tumor-specific delivery of a paclitaxel-loading HSA-haemin nanoparticle for cancer treatment. Nanomedicine. 2020;23:102089. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2019.102089

46. Ye L, He J, Hu Z, et al. Antitumor effect and toxicity of lipusu in rat ovarian cancer xenografts. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;52:200-206. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2012.11.004

47. Ma WW, Lam ET, Dy GK, et al. A pharmacokinetic and dose-escalating study of paclitaxel injection concentrate for nano-dispersion (PICN) alone and with arboplatin in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2557. doi:10.1200/jco.2013.31.15_suppl.2557

48. Micha JP, Goldstein BH, Birk CL, Rettenmaier MA, Brown JV. Abraxane in the treatment of ovarian cancer: the absence of hypersensitivity reactions. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100(2):437-438. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.09.012

49. Ingle SG, Pai RV, Monpara JD, Vavia PR. Liposils: an effective strategy for stabilizing paclitaxel loaded liposomes by surface coating with silica. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2018;122:51-63. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2018.06.025

50. Abriata JP, Turatti RC, Luiz MT, et al. Development, characterization and biological in vitro assays of paclitaxel-loaded PCL polymeric nanoparticles. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2019;96:347-355. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2018.11.035

51. Hu J, Fu S, Peng Q, et al. Paclitaxel-loaded polymeric nanoparticles combined with chronomodulated chemotherapy on lung cancer: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Int J Pharm. 2017;516(1-2):313-322. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.11.047

52. Dranitsaris G, Yu B, Wang L, et al. Abraxane® vs Taxol® for patients with advanced breast cancer: a prospective time and motion analysis from a chinese health care perspective. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2016;22(2):205-211. doi:10.1177/1078155214556008

53. Pei Q, Hu X, Liu S, Li Y, Xie Z, Jing X. Paclitaxel dimers assembling nanomedicines for treatment of cervix carcinoma. J Control Release. 2017;254:23-33. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.03.391

54. Wang Y, Wang M, Qi H, et al. Pathway-dependent inhibition of paclitaxel hydroxylation by kinase inhibitors and assessment of drug-drug interaction potentials. Drug Metab Dispos. 2014;42(4):782-795. doi:10.1124/dmd.113.053793

55. Shen F, Jiang G, Philips S, et al. Cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (POR) associated with severe paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy in patients of european ancestry from ECOG-ACRIN E5103. Clin Cancer Res. 2023;29(13):2494-2500. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-2431

56. Henningsson A, Marsh S, Loos WJ, et al. Association of CYP2C8, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and ABCB1 polymorphisms with the pharmacokinetics of paclitaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(22):8097-8104. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1152

57. Mukai Y, Senda A, Toda T, et al. Drug-drug interaction between losartan and paclitaxel in human liver microsomes with different CYP2C8 genotypes. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;116(6):493-498. doi:10.1111/bcpt.12355

58. Kawahara B, Faull KF, Janzen C, Mascharak PK. Carbon monoxide inhibits cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP3A4/2C8 in human breast cancer cells, increasing sensitivity to paclitaxel. J Med Chem. 2021;64(12):8437-8446. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00404

59. Cresteil T, Monsarrat B, Dubois J, Sonnier M, Alvinerie P, Gueritte F. Regioselective metabolism of taxoids by human CYP3A4 and 2C8: structure-activity relationship. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30(4):438-445. doi:10.1124/dmd.30.4.438

60. Taniguchi R, Kumai T, Matsumoto N, et al. Utilization of human liver microsomes to explain individual differences in paclitaxel metabolism by CYP2C8 and CYP3A4. J Pharmacol Sci. 2005;97(1):83-90. doi:10.1254/jphs.fp0040603

61. Nakayama A, Tsuchiya K, Xu L, Matsumoto T, Makino T. Drug-interaction between paclitaxel and goshajinkigan extract and its constituents. J Nat Med. 2022;76(1):59-67. doi:10.1007/s11418-021-01552-8

62. Monsarrat B, Chatelut E, Royer I, et al. Modification of paclitaxel metabolism in a cancer patient by induction of cytochrome P450 3A4. Drug Metab Dispos. 1998;26(3):229-233.

63. Walle T. Assays of CYP2C8- and CYP3A4-mediated metabolism of taxol in vivo and in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1996;272:145-151. doi:10.1016/s0076-6879(96)72018-9

64. Hanioka N, Matsumoto K, Saito Y, Narimatsu S. Functional characterization of CYP2C8.13 and CYP2C8.14: catalytic activities toward paclitaxel. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;107(1):565-569. doi:10.1111/j.1742-7843.2010.00543.x

65. Luong TT, Powers CN, Reinhardt BJ, Weina PJ. Pre-clinical drug-drug interactions (DDIs) of gefitinib with/without losartan and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): citalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine. Curr Res Pharmacol Drug Discov. 2022;3:100112. doi:10.1016/j.crphar.2022.100112

66. Luong TT, McAnulty MJ, Evers DL, Reinhardt BJ, Weina PJ. Pre-clinical drug-drug interaction (DDI) of gefitinib or erlotinib with Cytochrome P450 (CYP) inhibiting drugs, fluoxetine and/or losartan. Curr Res Toxicol. 2021;2:217-224. doi:10.1016/j.crtox.2021.05.006

67. Luong TT, Powers CN, Reinhardt BJ, et al. Retrospective evaluation of drug-drug interactions with erlotinib and gefitinib use in the military health system. Fed Pract. 2023;40(suppl 3):S24-S34. doi:10.12788/fp.0401

68. Adamo M, Dickie L, Ruhl J. SEER program coding and staging manual 2016. National Cancer Institute. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/manuals/2016/SPCSM_2016_maindoc.pdf

69. World Health Organization. International classification of diseases for oncology (ICD-O) 3rd ed, 1st revision. World Health Organization; 2013. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/96612

70. Z score calculator for 2 population proportions. Social science statistics. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.socscistatistics.com/tests/ztest/default2.aspx

71. US Food and Drug Administration. Generic drugs: question & answers. FDA.gov. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/frequently-asked-questions-popular-topics/generic-drugs-questions-answers

72. Oura M, Saito H, Nishikawa Y. Shortage of nab-paclitaxel in Japan and around the world: issues in global information sharing. JMA J. 2023;6(2):192-195. doi:10.31662/jmaj.2022-0179

73. Yuan H, Guo H, Luan X, et al. Albumin nanoparticle of paclitaxel (abraxane) decreases while taxol increases breast cancer stem cells in treatment of triple negative breast cancer. Mol Pharm. 2020;17(7):2275-2286. doi:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.9b01221

74. Dranitsaris G, Yu B, Wang L, et al. Abraxane® versus Taxol® for patients with advanced breast cancer: a prospective time and motion analysis from a Chinese health care perspective. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2016;22(2):205-211. doi:10.1177/1078155214556008

75. Gradishar WJ, Tjulandin S, Davidson N, et al. Phase III trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel compared with polyethylated castor oil-based paclitaxel in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(31):7794-7803. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.04.

76. Liu M, Liu S, Yang L, Wang S. Comparison between nab-paclitaxel and solvent-based taxanes as neoadjuvant therapy in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):118. doi:10.1186/s12885-021-07831-7

77. Rowinsky EK, Eisenhauer EA, Chaudhry V, Arbuck SG, Donehower RC. Clinical toxicities encountered with paclitaxel (taxol). Semin Oncol. 1993;20(4 Suppl 3):1-15.

78. Banerji A, Lax T, Guyer A, Hurwitz S, Camargo CA Jr, Long AA. Management of hypersensitivity reactions to carboplatin and paclitaxel in an outpatient oncology infusion center: a 5-year review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(4):428-433. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2014.04.010

79. Staff NP, Fehrenbacher JC, Caillaud M, Damaj MI, Segal RA, Rieger S. Pathogenesis of paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy: a current review of in vitro and in vivo findings using rodent and human model systems. Exp Neurol. 2020;324:113121. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.113121

80. Postma TJ, Vermorken JB, Liefting AJ, Pinedo HM, Heimans JJ. Paclitaxel-induced neuropathy. Ann Oncol. 1995;6(5):489-494. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a059220

81. Liu JM, Chen YM, Chao Y, et al. Paclitaxel-induced severe neuropathy in patients with previous radiotherapy to the head and neck region. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88(14):1000-1002. doi:10.1093/jnci/88.14.1000-a

82. Bayat Mokhtari R, Homayouni TS, Baluch N, et al. Combination therapy in combating cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(23):38022-38043. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.16723

83. Blagosklonny MV. Analysis of FDA approved anticancer drugs reveals the future of cancer therapy. Cell Cycle. 2004;3(8):1035-1042.

84. Yap TA, Omlin A, de Bono JS. Development of therapeutic combinations targeting major cancer signaling pathways. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(12):1592-1605. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.37.6418

85. Gilani B, Cassagnol M. Biochemistry, Cytochrome P450. StatPearls. Updated April 24, 2023. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557698/

86. LiverTox: clinical and research information on drug-induced liver injury; 2012. Carboplatin. Updated September 15, 2020. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548565/

87. Carboplatin. Prescribing information. Teva Parenteral Medicines; 2012. Accessed June 5, 204. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/077139Orig1s016lbl.pdf

88. Johnson-Arbor K, Dubey R. Doxorubicin. StatPearls. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459232/

89. Doxorubicin hydrochloride injection. Prescribing information. Pfizer; 2019. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/050467s078,050629s030lbl.pdf

90. Gor, PP, Su, HI, Gray, RJ, et al. Cyclophosphamide-metabolizing enzyme polymorphisms and survival outcomes after adjuvant chemotherapy for node-positive breast cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(3):R26. doi:10.1186/bcr2570

91. Cyclophosphamide. Prescribing information. Ingenus Pharmaceuticals; 2020. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/212501s000lbl.pdf

92. Gemcitabine. Prescribing information. Hospira; 2019. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/200795Orig1s010lbl.pdf

93. Ifex (ifosfamide). Prescribing information. Baxter; 2012. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/019763s017lbl.pdf

94. Cisplatin. Prescribing information. WG Critical Care; 2019. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/018057s089lbl.pdf

95. Gerriets V, Kasi A. Bevacizumab. StatPearls. Updated August 28, 2023. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482126/

96. Avastin (bevacizumab). Prescribing information. Genentech; 2022. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata .fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/125085s340lbl.pdf

97. Keytruda (pembrolizumab). Prescribing information. Merck; 2021. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/125514s096lbl.pdf

97. Keytruda (pembrolizumab). Prescribing information. Merck; 2021. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/125514s096lbl.pdf

98. Dean L, Kane M. Capecitabine therapy and DPYD genotype. National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2012. Updated November 2, 2020. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK385155/

99. Xeloda (capecitabine). Prescribing information. Roche; 2000. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2000/20896lbl.pdf

100. Pemetrexed injection. Prescribing information. Fareva Unterach; 2022. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/214657s000lbl.pdf

101. Topotecan Injection. Prescribing information. Zydus Hospira Oncology; 2014. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/200582s001lbl.pdf

102. Ibrance (palbociclib). Prescribing information. Pfizer; 2019. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/207103s008lbl.pdf

103. Navelbine (vinorelbine) injection. Prescribing information. Pierre Fabre Médicament; 2020. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/020388s037lbl.pdf

104. LiverTox: clinical and research information on drug-induced liver injury; 2012. Letrozole. Updated July 25, 2017. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548381/

105. Femara (letrozole). Prescribing information. Novartis; 2014. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/020726s027lbl.pdf

106. Soltamox (tamoxifen citrate). Prescribing information. Rosemont Pharmaceuticals; 2018. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/021807s005lbl.pdf

107. LiverTox: clinical and research information on drug-induced liver injury; 2012. Anastrozole. Updated July 25, 2017. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548189/

108. Grimm SW, Dyroff MC. Inhibition of human drug metabolizing cytochromes P450 by anastrozole, a potent and selective inhibitor of aromatase. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25(5):598-602.

109. Arimidex (anastrozole). Prescribing information. AstraZeneca; 2010. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/020541s026lbl.pdf

110. Megace (megestrol acetate). Prescribing information. Endo Pharmaceuticals; 2018. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/021778s024lbl.pdf

111. Imfinzi (durvalumab). Prescribing information. AstraZeneca; 2020. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/761069s018lbl.pdf

112. Merwar G, Gibbons JR, Hosseini SA, et al. Nortriptyline. StatPearls. Updated June 5, 2023. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482214/

113. Pamelor (nortriptyline HCl). Prescribing information. Patheon Inc.; 2012. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/018012s029,018013s061lbl.pdf

114. Wellbutrin (bupropion hydrochloride). Prescribing information. GlaxoSmithKline; 2017. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/018644s052lbl.pdf

115. Paxil (paroxetine). Prescribing information. Apotex Inc.; 2021. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/020031s077lbl.pdf

116. Johnson DB, Lopez MJ, Kelley B. Dexamethasone. StatPearls. Updated May 2, 2023. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482130/

117. Hemady (dexamethasone). Prescribing information. Dexcel Pharma; 2019. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/211379s000lbl.pdf

118. Parker SD, King N, Jacobs TF. Pegfilgrastim. StatPearls. Updated May 9, 2024. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532893/

119. Fylnetra (pegfilgrastim-pbbk). Prescribing information. Kashiv BioSciences; 2022. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/761084s000lbl.pdf

120. Emend (aprepitant). Prescribing information. Merck; 2015. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/207865lbl.pdf

121. Lipitor (atorvastatin calcium). Prescribing information. Viatris Specialty; 2022. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/020702Orig1s079correctedlbl.pdf

122. Cipro (ciprofloxacin hydrochloride). Prescribing information. Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2020. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/019537s090,020780s047lbl.pdf

123. Pino MA, Azer SA. Cimetidine. StatPearls. Updated March 6, 2023. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544255/

124. Tagament (Cimetidine). Prescribing information. Mylan; 2020. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/020238Orig1s024lbl.pdf

125. Neupogen (filgrastim). Prescribing information. Amgen Inc.; 2015. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/103353s5184lbl.pdf

126. Flagyl (metronidazole). Prescribing information. Pfizer; 2013. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/020334s008lbl.pdf

127. Zymaxid (gatifloxacin ophthalmic solution). Prescribing information. Allergan; 2016. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/022548s002lbl.pdf

128. Macrobid (nitrofurantoin monohydrate). Prescribing information. Procter and Gamble Pharmaceutical Inc.; 2009. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/020064s019lbl.pdf

129. Hyzaar (losartan). Prescribing information. Merck; 2020. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/020387s067lbl.pdf

Background

Paclitaxel was first derived from the bark of the yew tree (Taxus brevifolia). It was discovered as part of a National Cancer Institute program screen of plants and natural products with putative anticancer activity during the 1960s.1-9 Paclitaxel works by suppressing spindle microtube dynamics, which results in the blockage of the metaphase-anaphase transitions, inhibition of mitosis, and induction of apoptosis in a broad spectrum of cancer cells. Paclitaxel also displayed additional anticancer activities, including the suppression of cell proliferation and antiangiogenic effects. However, since the growth of normal body cells may also be affected, other adverse effects (AEs) will also occur.8-18

Two different chemotherapy drugs contain paclitaxel—paclitaxel and nab-paclitaxel—and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recognizes them as separate entities.19-21 Taxol (paclitaxel) was approved by the FDA in 1992 for treating advanced ovarian cancer.20 It has since been approved for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer, AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma (as an orphan drug), non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and cervical cancers (in combination withbevacizumab) in 1994, 1997, 1999, and 2014, respectively.21 Since 2002, a generic version of Taxol, known as paclitaxel injectable, has been FDA-approved from different manufacturers. According to the National Cancer Institute, a combination of carboplatin and Taxol is approved to treat carcinoma of unknown primary, cervical, endometrial, NSCLC, ovarian, and thymoma cancers.19 Abraxane (nab-paclitaxel) was FDA-approved to treat metastatic breast cancer in 2005. It was later approved for first-line treatment of advanced NSCLC and late-stage pancreatic cancer in 2012 and 2013, respectively. In 2018 and 2020, both Taxol and Abraxane were approved for first-line treatment of metastatic squamous cell NSCLC in combination with carboplatin and pembrolizumab and metastatic triple-negative breast cancer in combination with pembrolizumab, respectively.22-26 In 2019, Abraxane was approved with atezolizumab to treat metastatic triple-negative breast cancer, but this approval was withdrawn in 2021. In 2022, a generic version of Abraxane, known as paclitaxel protein-bound, was released in the United States. Furthermore, paclitaxel-containing formulations also are being studied in the treatment of other types of cancer.19-32

One of the main limitations of paclitaxel is its low solubility in water, which complicates its drug supply. To distribute this hydrophobic anticancer drug efficiently, paclitaxel is formulated and administered to patients via polyethoxylated castor oil or albumin-bound (nab-paclitaxel). However, polyethoxylated castor oil induces complement activation and is the cause of common hypersensitivity reactions related to paclitaxel use.2,17,33-38 Therefore, many alternatives to polyethoxylated castor oil have been researched.

Since 2000, new paclitaxel formulations have emerged using nanomedicine techniques. The difference between these formulations is the drug vehicle. Different paclitaxel-based nanotechnological vehicles have been developed and approved, such as albumin-based nanoparticles, polymeric lipidic nanoparticles, polymeric micelles, and liposomes, with many others in clinical trial phases.3,37 Albumin-based nanoparticles have a high response rate (33%), whereas the response rate for polyethoxylated castor oil is 25% in patients with metastatic breast cancer.33,39-52 The use of paclitaxel dimer nanoparticles also has been proposed as a method for increasing drug solubility.33,53

Paclitaxel is metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzymes 2C8 and 3A4. When administering paclitaxel with known inhibitors, inducers, or substrates of CYP2C8 or CYP3A4, caution is required.19-22 Regulations for CYP research were not issued until 2008, so potential interactions between paclitaxel and other drugs have not been extensively evaluated in clinical trials. A study of 12 kinase inhibitors showed strong inhibition of CYP2C8 and/or CYP3A4 pathways by these inhibitors, which could alter the ratio of paclitaxel metabolites in vivo, leading to clinically relevant changes.54 Differential metabolism has been linked to paclitaxel-induced neurotoxicity in patients with cancer.55 Nonetheless, variants in the CYP2C8, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and ABCB1 genes do not account for significant interindividual variability in paclitaxel pharmacokinetics.56 In liver microsomes, losartan inhibited paclitaxel metabolism when used at concentrations > 50 µmol/L.57 Many drug-drug interaction (DDI) studies of CYP2C8 and CYP3A4 have shown similar results for paclitaxel.58-64

The goals of this study are to investigate prescribed drugs used with paclitaxel and determine patient outcomes through several Military Health System (MHS) databases. The investigation focused on (1) the functions of paclitaxel; (2) identifying AEs that patients experienced; (3) evaluating differences when paclitaxel is used alone vs concomitantly and between the completed vs discontinued treatment groups; (4) identifying all drugs used during paclitaxel treatment; and (5) evaluating DDIs with antidepressants (that have an FDA boxed warning and are known to have DDIs confirmed in previous publications) and other drugs.65-67

The Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, institutionalreview board approved the study protocol and ensured compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act as an exempt protocol. The Joint Pathology Center (JPC) of the US Department of Defense (DoD) Cancer Registry Program and MHS data experts from the Comprehensive Ambulatory/Professional Encounter Record (CAPER) and the Pharmacy Data Transaction Service (PDTS) provided data for the analysis.

METHODS

The DoD Cancer Registry Program was established in 1986 and currently contains data from 1998 to 2024. CAPER and PDTS are part of the MHS Data Repository/Management Analysis and Reporting Tool database. Each observation in the CAPER record represents an ambulatory encounter at a military treatment facility (MTF). CAPER includes data from 2003 to 2024.

Each observation in the PDTS record represents a prescription filled for an MHS beneficiary at an MTF through the TRICARE mail-order program or a US retail pharmacy. Missing from this record are prescriptions filled at international civilian pharmacies and inpatient pharmacy prescriptions. The MHS Data Repository PDTS record is available from 2002 to 2024. The legacy Composite Health Care System is being replaced by GENESIS at MTFs.

Data Extraction Design

The study design involved a cross-sectional analysis. We requested data extraction for paclitaxel from 1998 to 2022. Data from the DoD Cancer Registry Program were used to identify patients who received cancer treatment. Once patients were identified, the CAPER database was searched for diagnoses to identify other health conditions, whereas the PDTS database was used to populate a list of prescription medications filled during chemotherapy treatment.

Data collected from the JPC included cancer treatment, cancer information, demographics, and physicians’ comments on AEs. Collected data from the MHS include diagnosis and filled prescription history from initiation to completion of the therapy period (or 2 years after the diagnosis date). For the analysis of the DoD Cancer Registry Program and CAPER databases, we used all collected data without excluding any. When analyzing PDTS data, we excluded patients with PDTS data but without a record of paclitaxel being filled, or medications filled outside the chemotherapy period (by evaluating the dispensed date and day of supply).

Data Extraction Analysis

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program Coding and Staging Manual 2016 and the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition, 1st revision, were used to decode disease and cancer types.68,69 Data sorting and analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel. The percentage for the total was calculated by using the number of patients or data available within the paclitaxel groups divided by the total number of patients or data variables. The subgroup percentage was calculated by using the number of patients or data available within the subgroup divided by the total number of patients in that subgroup.

In alone vs concomitant and completed vs discontinued treatment groups, a 2-tailed, 2-sample z test was used to statistical significance (P < .05) using a statistics website.70 Concomitant was defined as paclitaxel taken with other antineoplastic agent(s) before, after, or at the same time as cancer therapy. For the retrospective data analysis, physicians’ notes with a period, comma, forward slash, semicolon, or space between medication names were interpreted as concurrent, whereas plus (+), minus/plus (-/+), or “and” between drug names that were dispensed on the same day were interpreted as combined with known common combinations: 2 drugs (DM886 paclitaxel and carboplatin and DM881-TC-1 paclitaxel and cisplatin) or 3 drugs (DM887-ACT doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and paclitaxel). Completed treatment was defined as paclitaxel as the last medication the patient took without recorded AEs; switching or experiencing AEs was defined as discontinued treatment.

RESULTS

The JPC provided 702 entries for 687 patients with a mean age of 56 years (range, 2 months to 88 years) who were treated with paclitaxel from March 1996 to October 2021. Fifteen patients had duplicate entries because they had multiple cancer sites or occurrences. There were 623 patients (89%) who received paclitaxel for FDA-approved indications. The most common types of cancer identified were 344 patients with breast cancer (49%), 91 patients with lung cancer (13%), 79 patients with ovarian cancer (11%), and 75 patients with endometrial cancer (11%) (Table 1). Seventy-nine patients (11%) received paclitaxel for cancers that were not for FDA-approved indications, including 19 for cancers of the fallopian tube (3%) and 17 for esophageal cancer (2%) (Table 2).

There were 477 patients (68%) aged > 50 years. A total of 304 patients (43%) had a stage III or IV cancer diagnosis and 398 (57%) had stage II or lower (combination of data for stages 0, I, and II; not applicable; and unknown) cancer diagnosis. For systemic treatment, 16 patients (2%) were treated with paclitaxel alone and 686 patients (98%) received paclitaxel concomitantly with additional chemotherapy: 59 patients (9%) in the before or after group, 410 patients (58%) had a 2-drug combination, 212 patients (30%) had a 3-drug combination, and 5 patients (1%) had a 4-drug combination. In addition, for doublet therapies, paclitaxel combined with carboplatin, trastuzumab, gemcitabine, or cisplatin had more patients (318, 58, 12, and 11, respectively) than other combinations (≤ 4 patients). For triplet therapies, paclitaxel combined withdoxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide or carboplatin plus bevacizumab had more patients (174 and 20, respectively) than other combinations, including quadruplet therapies (≤ 4 patients) (Table 3).

Patients were more likely to discontinue paclitaxel if they received concomitant treatment. None of the 16 patients receiving paclitaxel monotherapy experienced AEs, whereas 364 of 686 patients (53%) treated concomitantly discontinued (P < .001). Comparisons of 1 drug vs combination (2 to 4 drugs) and use for treating cancers that were FDA-approved indications vs off-label use were significant (P < .001), whereas comparisons of stage II or lower vs stage III and IV cancer and of those aged ≤ 50 years vs aged > 50 years were not significant (P = .50 andP = .30, respectively) (Table 4).

Among the 364 patients who had concomitant treatment and had discontinued their treatment, 332 (91%) switched treatments with no AEs documented and 32 (9%) experienced fatigue with pneumonia, mucositis, neuropathy, neurotoxicity, neutropenia, pneumonitis, allergic or hypersensitivity reaction, or an unknown AE. Patients who discontinued treatment because of unknown AEs had a physician’s note that detailed progressive disease, a significant decline in performance status, and another unknown adverse effect due to a previous sinus tract infection and infectious colitis (Table 5).

Management Analysis and Reporting Tool Database

MHS data analysts provided data on diagnoses for 639 patients among 687 submitteddiagnoses, with 294 patients completing and 345 discontinuing paclitaxel treatment. Patients in the completed treatment group had 3 to 258 unique health conditions documented, while patients in the discontinued treatment group had 4 to 181 unique health conditions documented. The MHS reported 3808 unique diagnosis conditions for the completed group and 3714 for the discontinued group (P = .02).

The mean (SD) number of diagnoses was 51 (31) for the completed and 55 (28) for the discontinued treatment groups (Figure). Among 639 patients who received paclitaxel, the top 5 diagnoses were administrative, including encounters for other administrative examinations; antineoplastic chemotherapy; administrative examination for unspecified; other specified counseling; and adjustment and management of vascular access device. The database does not differentiate between administrative and clinically significant diagnoses.

MHS data analysts provided data for 336 of 687 submitted patients who were prescribed paclitaxel; 46 patients had no PDTS data, and 305 patients had PDTS data without paclitaxel, Taxol, or Abraxane dispensed. Medications that were filled outside the chemotherapy period were removed by evaluating the dispensed date and day of supply. Among these 336 patients, 151 completed the treatment and 185 discontinued, with 14 patients experiencing documented AEs. Patients in the completed treatment group filled 9 to 56 prescriptions while patients in the discontinued treatment group filled 6 to 70 prescriptions.Patients in the discontinued group filled more prescriptions than those who completed treatment: 793 vs 591, respectively (P = .34).

The mean (SD) number of filled prescription drugs was 24 (9) for the completed and 34 (12) for the discontinued treatment group. The 5 most filled prescriptions with paclitaxel from 336 patients with PDTS data were dexamethasone (324 prescriptions with 14 recorded AEs), diphenhydramine (296 prescriptions with 12 recorded AEs), ondansetron (277 prescriptions with 11 recorded AEs), prochlorperazine (265 prescriptions with 12 recorded AEs), and sodium chloride (232 prescriptions with 11 recorded AEs).

DISCUSSION

As a retrospective review, this study is more limited in the strength of its conclusions when compared to randomized control trials. The DoD Cancer Registry Program only contains information about cancer types, stages, treatment regimens, and physicians’ notes. Therefore, noncancer drugs are based solely on the PDTS database. In most cases, physicians' notes on AEs were not detailed. There was no distinction between initial vs later lines of therapy and dosage reductions. The change in status or appearance of a new medical condition did not indicate whether paclitaxel caused the changes to develop or directly worsen a pre-existing condition. The PDTS records prescriptions filled, but that may not reflect patients taking prescriptions.

Paclitaxel

Paclitaxel has a long list of both approved and off-label uses in malignancies as a primary agent and in conjunction with other drugs. The FDA prescribing information for Taxol and Abraxane was last updated in April 2011 and September 2020, respectively.20,21 The National Institutes of Health National Library of Medicine has the current update for paclitaxel on July 2023.19,22 Thus, the prescribed information for paclitaxel referenced in the database may not always be up to date. The combinations of paclitaxel with bevacizumab, carboplatin, or carboplatin and pembrolizumab were not in the Taxol prescribing information. Likewise, a combination of nab-paclitaxel with atezolizumab or carboplatin and pembrolizumab is missing in the Abraxane prescribing information.22-27

The generic name is not the same as a generic drug, which may have slight differences from the brand name product.71 The generic drug versions of Taxol and Abraxane have been approved by the FDA as paclitaxel injectable and paclitaxel-protein bound, respectively. There was a global shortage of nab-paclitaxel from October 2021 to June 2022 because of a manufacturing problem.72 During this shortage, data showed similar comments from physician documents that treatment switched to Taxol due to the Abraxane shortage.

Of 336 patients in the PDTS database with dispensed paclitaxel prescriptions, 276 received paclitaxel (year dispensed, 2013-2022), 27 received Abraxane (year dispensed, 2013-2022), 47 received Taxol (year dispensed, 2004-2015), 8 received both Abraxane and paclitaxel, and 6 received both Taxol and paclitaxel. Based on this information, it appears that the distinction between the drugs was not made in the PDTS until after 2015, 10 years after Abraxane received FDA approval. Abraxane was prescribed in the MHS in 2013, 8 years after FDA approval. There were a few comparison studies of Abraxane and Taxol.73-76

Safety and effectiveness in pediatric patients have not been established for paclitaxel. According to the DoD Cancer Registry Program, the youngest patient was aged 2 months. In 2021, this patient was diagnosed with corpus uteri and treated with carboplatin and Taxol in course 1; in course 2, the patient reacted to Taxol; in course 3, Taxol was replaced with Abraxane; in courses 4 to 7, the patient was treated with carboplatin only.

Discontinued Treatment

Ten patients had prescribed Taxol that was changed due to AEs: 1 was switched to Abraxane and atezolizumab, 3 switched to Abraxane, 2 switched to docetaxel, 1 switched to doxorubicin, and 3 switched to pembrolizumab (based on physician’s comments). Of the 10 patients, 7 had Taxol reaction, 2 experienced disease progression, and 1 experienced high programmed death–ligand 1 expression (this patient with breast cancer was switched to Abraxane and atezolizumab during the accelerated FDA approval phase for atezolizumab, which was later revoked). Five patients were treated with carboplatin and Taxol for cancer of the anal canal (changed to pembrolizumab after disease progression), lung not otherwise specified (changed to carboplatin and pembrolizumab due to Taxol reaction), lower inner quadrant of the breast (changed to doxorubicin due to hypersensitivity reaction), corpus uteri (changed to Abraxane due to Taxol reaction), and ovary (changed to docetaxel due to Taxol reaction). Three patients were treated with doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and Taxol for breast cancer; 2 patients with breast cancer not otherwise specified switched to Abraxane due to cardiopulmonary hypersensitivity and Taxol reaction and 1 patient with cancer of the upper outer quadrant of the breast changed to docetaxel due to allergic reaction. One patient, who was treated with paclitaxel, ifosfamide, and cisplatin for metastasis of the lower lobe of the lung and kidney cancer, experienced complications due to infectious colitis (treated with ciprofloxacin) and then switched to pembrolizumab after the disease progressed. These AEs are known in paclitaxel medical literature on paclitaxel AEs.19-24,77-81

Combining 2 or more treatments to target cancer-inducing or cell-sustaining pathways is a cornerstone of chemotherapy.82-84 Most combinations are given on the same day, but some are not. For 3- or 4-drug combinations, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide were given first, followed by paclitaxel with or withouttrastuzumab, carboplatin, or pembrolizumab. Only 16 patients (2%) were treated with paclitaxel alone; therefore, the completed and discontinued treatment groups are mostly concomitant treatment. As a result, the comparisons of the completed and discontinued treatment groups were almost the same for the diagnosis. The PDTS data have a better result because 2 exclusion criteria were applied before narrowing the analysis down to paclitaxel treatment specifically.

Antidepressants and Other Drugs

Drug response can vary from person to person and can lead to treatment failure related to AEs. One major factor in drug metabolism is CYP.85 CYP2C8 is the major pathway for paclitaxel and CYP3A4 is the minor pathway. When evaluating the noncancer drugs, there were no reports of CYP2C8 inhibition or induction. Over the years, many DDI warnings have been issued for paclitaxel with different drugs in various electronic resources.

Oncologists follow guidelines to prevent DDIs, as paclitaxel is known to have severe, moderate, and minor interactions with other drugs. Among 687 patients, 261 (38%) were prescribed any of 14 antidepressants. Eight of these antidepressants (amitriptyline, citalopram, desipramine, doxepin, venlafaxine, escitalopram, nortriptyline, and trazodone) are metabolized, 3 (mirtazapine, sertraline, and fluoxetine) are metabolized and inhibited, 2 (bupropion and duloxetine) are neither metabolized nor inhibited, and 1 (paroxetine) is inhibited by CYP3A4. Duloxetine, venlafaxine, and trazodone were more commonly dispensed (84, 78, and 42 patients, respectively) than others (≤ 33 patients).

Of 32 patients with documented AEs,14 (44%) had 168 dispensed drugs in the PDTS database. Six patients (19%) were treated with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel for breast cancer; 6 (19%) were treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel for cancer of the lung (n = 3), corpus uteri (n = 2), and ovary (n = 1); 1 patient (3%) was treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel, then switched to carboplatin, bevacizumab, and paclitaxel, and then completed treatment with carboplatin and paclitaxel for an unspecified female genital cancer; and 1 patient (3%) was treated with cisplatin, ifosfamide, and paclitaxel for metastasis of the lower lobe lung and kidney cancer.

The 14 patients with PDTS data had 18 cancer drugs dispensed. Eleven had moderate interaction reports and 7 had no interaction reports. A total of 165 noncancer drugs were dispensed, of which 3 were antidepressants and had no interactions reported, 8 had moderate interactions reported, and 2 had minor interactions with Taxol and Abraxane, respectively (Table 6).86-129

Of 3 patients who were dispensed bupropion, nortriptyline, or paroxetine, 1 patient with breast cancer was treated with doxorubicin andcyclophosphamide, followed by paclitaxel with bupropion, nortriptyline, pegfilgrastim,dexamethasone, and 17 other noncancer drugs that had no interaction report dispensed during paclitaxel treatment. Of 2 patients with lung cancer, 1 patient was treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel with nortriptyline, dexamethasone, and 13 additional medications, and the second patient was treated with paroxetine, cimetidine, dexamethasone, and 12 other medications. Patients were dispensed up to6 noncancer medications on the same day as paclitaxel administration to control the AEs, not including the prodrugs filled before the treatments. Paroxetine and cimetidine have weak inhibition, and dexamethasone has weak induction of CYP3A4. Therefore, while 1:1 DDIs might have little or no effect with weak inhibit/induce CYP3A4 drugs, 1:1:1 or more combinations could have a different outcome (confirmed in previous publications).65-67

Dispensed on the same day may not mean taken at the same time. One patient experienced an AE with dispensed 50 mg losartan, carboplatin plus paclitaxel, dexamethasone, and 6 other noncancer drugs. Losartan inhibits paclitaxel, which can lead to negative AEs.57,66,67 However, there were no blood or plasma samples taken to confirm the losartan was taken at the same time as the paclitaxel given this was not a clinical trial.

Conclusions

This retrospective study discusses the use of paclitaxel in the MHS and the potential DDIs associated with it. The study population consisted mostly of active-duty personnel, who are required to be healthy or have controlled or nonactive medical diagnoses and be physically fit. This group is mixed with dependents and retirees that are more reflective of the average US population. As a result, this patient population is healthier than the general population, with a lower prevalence of common illnesses such as diabetes and obesity. The study aimed to identify drugs used alongside paclitaxel treatment. While further research is needed to identify potential DDIs among patients who experienced AEs, in vitro testing will need to be conducted before confirming causality. The low number of AEs experienced by only 32 of 702 patients (5%), with no deaths during paclitaxel treatment, indicates that the drug is generally well tolerated. Although this study cannot conclude that concomitant use with noncancer drugs led to the discontinuation of paclitaxel, we can conclude that there seems to be no significant DDIsidentified between paclitaxel and antidepressants. This comprehensive overview provides clinicians with a complete picture of paclitaxel use for 27 years (1996-2022), enabling them to make informed decisions about paclitaxel treatment.

Acknowledgments

The Department of Research Program funds at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center supported this protocol. We sincerely appreciate the contribution of data extraction from the Joint Pathology Center teams (Francisco J. Rentas, John D. McGeeney, Beatriz A. Hallo, and Johnny P. Beason) and the MHS database personnel (Maj Ryan Costantino, Brandon E. Jenkins, and Alexander G. Rittel). We gratefully thank you for the protocol support from the Department of Research programs: CDR Martin L. Boese, CDR Wesley R. Campbell, Maj. Abhimanyu Chandel, CDR Ling Ye, Chelsea N. Powers, Yaling Zhou, Elizabeth Schafer, Micah Stretch, Diane Beaner, and Adrienne Woodard.

Background