User login

How much would you bet on a diagnosis?

“You have psoriasis,” I say all the time. I mean it when I say it, of course. But I don’t always to the same degree. Sometimes I’m trying to say, “You probably have psoriasis.” Other times I mean, “You most definitely have psoriasis.” I rarely use those terms though.

One 36-year-old man with a flaky scalp and scaly elbows wasn’t satisfied with my assessment. His dad has psoriasis. So does his older brother. He was in to see me to find out if he had psoriasis too. “Probably” was what I gave him. He pushed back, “What percent chance?” That’s a good question — must be an engineer. I’m unsure.

With the exception of the poker players, our species is notoriously bad at probabilities. We’re wired to notice the significance of events, but terrible at understanding their likelihood. This is salient in lottery ticket holders and some NFL offensive coordinators who persist despite very long odds of things working out. It’s also reflected in the language we use. Rarely do we say, there’s a sixty percent chance something will happen. Rather, we say, “it’s likely.” There are two problems here. One, we often misjudge the actual probability of something occurring and two, the terms we use are subjective and differences in interpretation can lead to misunderstandings.

Let’s take a look. A 55-year-old man with a chronic eczematous rash on his trunk and extremities is getting worse despite dupilumab. He recently had night sweats. Do you think he has atopic dermatitis or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma? If you had to place a $100 bet, would you change your answer? Immanuel Kant thinks you would. In his “Critique of Pure Reason,” the German philosopher proposes that betting helps clarify the mind, an antidote to brashness. The example Kant uses is of a physician who observes a patient and concludes he has phthisis (tuberculosis), but we really don’t know if the physician is confident. Kant proposes that if he had to bet on his conclusion, then we’d have insight into just how convinced he is of phthisis. So, what’s your bet?

If you’re a bad poker player, then you might bet he has cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. However, not having any additional information, the smart call is atopic dermatitis, which has a base rate 1000-fold higher than CTCL. It is therefore more probable to be eczema even in a case that worsens despite dupilumab or with recent night sweats, both of which could be a result of common variables such as weather and COVID. Failure to account for the base rate is a mistake we physicians sometimes make. Economists rarely do. Try to think like one before answering a likelihood question.

If you think about it, “probably” means something different even to me, depending on the situation. I might say I’ll probably go to Montana this summer and I’ll probably retire at 65. The actual likelihoods might be 95% and 70%. That’s a big difference. What about between probably and likely? Or possibly and maybe? Do they mean the same to you as to the person you’re speaking with? For much of the work we do, precise likelihoods aren’t critical. Yet, it can be important in decision making and in discussing probabilities, such as the risk of hepatitis on terbinafine or of melanoma recurrence after Mohs.

I told my patient “I say about a 70% chance you have psoriasis. I could do a biopsy today to confirm.” He thought for a second and asked, “What is the chance it’s psoriasis if the biopsy shows it?” “Eighty six percent,” I replied.

Seemed like a good bet to me.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at [email protected].

“You have psoriasis,” I say all the time. I mean it when I say it, of course. But I don’t always to the same degree. Sometimes I’m trying to say, “You probably have psoriasis.” Other times I mean, “You most definitely have psoriasis.” I rarely use those terms though.

One 36-year-old man with a flaky scalp and scaly elbows wasn’t satisfied with my assessment. His dad has psoriasis. So does his older brother. He was in to see me to find out if he had psoriasis too. “Probably” was what I gave him. He pushed back, “What percent chance?” That’s a good question — must be an engineer. I’m unsure.

With the exception of the poker players, our species is notoriously bad at probabilities. We’re wired to notice the significance of events, but terrible at understanding their likelihood. This is salient in lottery ticket holders and some NFL offensive coordinators who persist despite very long odds of things working out. It’s also reflected in the language we use. Rarely do we say, there’s a sixty percent chance something will happen. Rather, we say, “it’s likely.” There are two problems here. One, we often misjudge the actual probability of something occurring and two, the terms we use are subjective and differences in interpretation can lead to misunderstandings.

Let’s take a look. A 55-year-old man with a chronic eczematous rash on his trunk and extremities is getting worse despite dupilumab. He recently had night sweats. Do you think he has atopic dermatitis or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma? If you had to place a $100 bet, would you change your answer? Immanuel Kant thinks you would. In his “Critique of Pure Reason,” the German philosopher proposes that betting helps clarify the mind, an antidote to brashness. The example Kant uses is of a physician who observes a patient and concludes he has phthisis (tuberculosis), but we really don’t know if the physician is confident. Kant proposes that if he had to bet on his conclusion, then we’d have insight into just how convinced he is of phthisis. So, what’s your bet?

If you’re a bad poker player, then you might bet he has cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. However, not having any additional information, the smart call is atopic dermatitis, which has a base rate 1000-fold higher than CTCL. It is therefore more probable to be eczema even in a case that worsens despite dupilumab or with recent night sweats, both of which could be a result of common variables such as weather and COVID. Failure to account for the base rate is a mistake we physicians sometimes make. Economists rarely do. Try to think like one before answering a likelihood question.

If you think about it, “probably” means something different even to me, depending on the situation. I might say I’ll probably go to Montana this summer and I’ll probably retire at 65. The actual likelihoods might be 95% and 70%. That’s a big difference. What about between probably and likely? Or possibly and maybe? Do they mean the same to you as to the person you’re speaking with? For much of the work we do, precise likelihoods aren’t critical. Yet, it can be important in decision making and in discussing probabilities, such as the risk of hepatitis on terbinafine or of melanoma recurrence after Mohs.

I told my patient “I say about a 70% chance you have psoriasis. I could do a biopsy today to confirm.” He thought for a second and asked, “What is the chance it’s psoriasis if the biopsy shows it?” “Eighty six percent,” I replied.

Seemed like a good bet to me.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at [email protected].

“You have psoriasis,” I say all the time. I mean it when I say it, of course. But I don’t always to the same degree. Sometimes I’m trying to say, “You probably have psoriasis.” Other times I mean, “You most definitely have psoriasis.” I rarely use those terms though.

One 36-year-old man with a flaky scalp and scaly elbows wasn’t satisfied with my assessment. His dad has psoriasis. So does his older brother. He was in to see me to find out if he had psoriasis too. “Probably” was what I gave him. He pushed back, “What percent chance?” That’s a good question — must be an engineer. I’m unsure.

With the exception of the poker players, our species is notoriously bad at probabilities. We’re wired to notice the significance of events, but terrible at understanding their likelihood. This is salient in lottery ticket holders and some NFL offensive coordinators who persist despite very long odds of things working out. It’s also reflected in the language we use. Rarely do we say, there’s a sixty percent chance something will happen. Rather, we say, “it’s likely.” There are two problems here. One, we often misjudge the actual probability of something occurring and two, the terms we use are subjective and differences in interpretation can lead to misunderstandings.

Let’s take a look. A 55-year-old man with a chronic eczematous rash on his trunk and extremities is getting worse despite dupilumab. He recently had night sweats. Do you think he has atopic dermatitis or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma? If you had to place a $100 bet, would you change your answer? Immanuel Kant thinks you would. In his “Critique of Pure Reason,” the German philosopher proposes that betting helps clarify the mind, an antidote to brashness. The example Kant uses is of a physician who observes a patient and concludes he has phthisis (tuberculosis), but we really don’t know if the physician is confident. Kant proposes that if he had to bet on his conclusion, then we’d have insight into just how convinced he is of phthisis. So, what’s your bet?

If you’re a bad poker player, then you might bet he has cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. However, not having any additional information, the smart call is atopic dermatitis, which has a base rate 1000-fold higher than CTCL. It is therefore more probable to be eczema even in a case that worsens despite dupilumab or with recent night sweats, both of which could be a result of common variables such as weather and COVID. Failure to account for the base rate is a mistake we physicians sometimes make. Economists rarely do. Try to think like one before answering a likelihood question.

If you think about it, “probably” means something different even to me, depending on the situation. I might say I’ll probably go to Montana this summer and I’ll probably retire at 65. The actual likelihoods might be 95% and 70%. That’s a big difference. What about between probably and likely? Or possibly and maybe? Do they mean the same to you as to the person you’re speaking with? For much of the work we do, precise likelihoods aren’t critical. Yet, it can be important in decision making and in discussing probabilities, such as the risk of hepatitis on terbinafine or of melanoma recurrence after Mohs.

I told my patient “I say about a 70% chance you have psoriasis. I could do a biopsy today to confirm.” He thought for a second and asked, “What is the chance it’s psoriasis if the biopsy shows it?” “Eighty six percent,” I replied.

Seemed like a good bet to me.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at [email protected].

Cutting Across the Bias

On a recent rainy afternoon I was speed skimming through the pile of publications sitting on the floor next to my Grampy’s chair. A bright patch of color jumped off the gray background of the printed page forcing me to pause and consider the content.

In the right upper corner was a photograph of an attractive Black woman nursing her baby. Her bare arms suggested she might be slightly overweight. She wore a simple off-white head wrap and smiled broadly as she played with her infant’s fingers. The image was a reproduction of a WIC poster encouraging women to take advantage of the program’s breastfeeding support services. The accompanying article from American Academy of Pediatrics offered ten strategies for achieving breastfeeding equity.

I must admit that I tend to shy away from discussions of equity because I’ve seldom found them very informative. However, the engaging image of this Black woman breastfeeding led me to read beyond the title.

The first of the strategies listed was “Check you biases.” I will certainly admit to having biases. We all have biases and see and interpret the world through lenses ground and tinted by our experiences and the environment we have inhabited. In the case of breastfeeding, I wasn’t sure where my biases lay. Maybe one of mine is reflected in a hesitancy to actively promote exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months. I prefer a more nuanced approach adjusted to the unique needs and limitations of each family. But I decided to chase down the Implicit Association Test (IAT) suggested in the article. I couldn’t make that link work, but found a long list of subjects on the Harvard Implicit Association Test website. None dealt with breastfeeding, so I chose the one described as Black/White.

If, like me, you have never had your implicit biases assessed by taking an IAT, you might find it interesting. Probably took me about 15 minutes using my laptop. There are a lot of demographic questions then some rapid-fire exercises in which you must provide your first response to a barrage of photos of faces and words. At times I sensed that the test makers were trying to trick me into making associations that I didn’t want to make by the order in which the exercises were presented. At the end I was told that I was a little slow in associating Black faces with positive words.

I’m not sure what this means. After doing a little internet searching I learned that one of the criticisms of the IAT is that, while it may hint at a bias, it is really more important whether you cut with or across that bias. If I acknowledge that where and how I grew up may have left me with some implicit biases, it is more important that I make a strong and honest effort to act independently of those biases.

In full disclosure I must tell you that there was one Black girl in my high school of a thousand students. I have lived and practiced in Maine for 50 years. At less than 2%, we are sixth from the bottom in Black population among other states. However, in the last 5 or 6 years here in Brunswick we have welcomed a large infusion of asylum seekers who come predominantly from Black African countries.

Skimming through the rest of the article, I found it hard to argue with the remaining nine recommendations for promoting breastfeeding, although most of them we not terribly applicable to small community practices. The photo of the Black woman nursing her baby at the top of the page remains as the primary message. The fact that I was drawn to that image is a testament to several of my biases and another example of a picture being worth far more than a thousand words.

I suspect that I’m not alone in appreciating the uniqueness of that image. Until recently, the standard photos of a mother breastfeeding have used trim White women as their models. I suspect and hope this poster will be effective in encouraging Black women to nurse. I urge you all to hang it in your office as a reminder to you and your staff of your biases and assumptions. Don’t bother to take the Implicit Association Test unless you’re retired and have 15 minutes to burn on a rainy afternoon.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

On a recent rainy afternoon I was speed skimming through the pile of publications sitting on the floor next to my Grampy’s chair. A bright patch of color jumped off the gray background of the printed page forcing me to pause and consider the content.

In the right upper corner was a photograph of an attractive Black woman nursing her baby. Her bare arms suggested she might be slightly overweight. She wore a simple off-white head wrap and smiled broadly as she played with her infant’s fingers. The image was a reproduction of a WIC poster encouraging women to take advantage of the program’s breastfeeding support services. The accompanying article from American Academy of Pediatrics offered ten strategies for achieving breastfeeding equity.

I must admit that I tend to shy away from discussions of equity because I’ve seldom found them very informative. However, the engaging image of this Black woman breastfeeding led me to read beyond the title.

The first of the strategies listed was “Check you biases.” I will certainly admit to having biases. We all have biases and see and interpret the world through lenses ground and tinted by our experiences and the environment we have inhabited. In the case of breastfeeding, I wasn’t sure where my biases lay. Maybe one of mine is reflected in a hesitancy to actively promote exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months. I prefer a more nuanced approach adjusted to the unique needs and limitations of each family. But I decided to chase down the Implicit Association Test (IAT) suggested in the article. I couldn’t make that link work, but found a long list of subjects on the Harvard Implicit Association Test website. None dealt with breastfeeding, so I chose the one described as Black/White.

If, like me, you have never had your implicit biases assessed by taking an IAT, you might find it interesting. Probably took me about 15 minutes using my laptop. There are a lot of demographic questions then some rapid-fire exercises in which you must provide your first response to a barrage of photos of faces and words. At times I sensed that the test makers were trying to trick me into making associations that I didn’t want to make by the order in which the exercises were presented. At the end I was told that I was a little slow in associating Black faces with positive words.

I’m not sure what this means. After doing a little internet searching I learned that one of the criticisms of the IAT is that, while it may hint at a bias, it is really more important whether you cut with or across that bias. If I acknowledge that where and how I grew up may have left me with some implicit biases, it is more important that I make a strong and honest effort to act independently of those biases.

In full disclosure I must tell you that there was one Black girl in my high school of a thousand students. I have lived and practiced in Maine for 50 years. At less than 2%, we are sixth from the bottom in Black population among other states. However, in the last 5 or 6 years here in Brunswick we have welcomed a large infusion of asylum seekers who come predominantly from Black African countries.

Skimming through the rest of the article, I found it hard to argue with the remaining nine recommendations for promoting breastfeeding, although most of them we not terribly applicable to small community practices. The photo of the Black woman nursing her baby at the top of the page remains as the primary message. The fact that I was drawn to that image is a testament to several of my biases and another example of a picture being worth far more than a thousand words.

I suspect that I’m not alone in appreciating the uniqueness of that image. Until recently, the standard photos of a mother breastfeeding have used trim White women as their models. I suspect and hope this poster will be effective in encouraging Black women to nurse. I urge you all to hang it in your office as a reminder to you and your staff of your biases and assumptions. Don’t bother to take the Implicit Association Test unless you’re retired and have 15 minutes to burn on a rainy afternoon.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

On a recent rainy afternoon I was speed skimming through the pile of publications sitting on the floor next to my Grampy’s chair. A bright patch of color jumped off the gray background of the printed page forcing me to pause and consider the content.

In the right upper corner was a photograph of an attractive Black woman nursing her baby. Her bare arms suggested she might be slightly overweight. She wore a simple off-white head wrap and smiled broadly as she played with her infant’s fingers. The image was a reproduction of a WIC poster encouraging women to take advantage of the program’s breastfeeding support services. The accompanying article from American Academy of Pediatrics offered ten strategies for achieving breastfeeding equity.

I must admit that I tend to shy away from discussions of equity because I’ve seldom found them very informative. However, the engaging image of this Black woman breastfeeding led me to read beyond the title.

The first of the strategies listed was “Check you biases.” I will certainly admit to having biases. We all have biases and see and interpret the world through lenses ground and tinted by our experiences and the environment we have inhabited. In the case of breastfeeding, I wasn’t sure where my biases lay. Maybe one of mine is reflected in a hesitancy to actively promote exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months. I prefer a more nuanced approach adjusted to the unique needs and limitations of each family. But I decided to chase down the Implicit Association Test (IAT) suggested in the article. I couldn’t make that link work, but found a long list of subjects on the Harvard Implicit Association Test website. None dealt with breastfeeding, so I chose the one described as Black/White.

If, like me, you have never had your implicit biases assessed by taking an IAT, you might find it interesting. Probably took me about 15 minutes using my laptop. There are a lot of demographic questions then some rapid-fire exercises in which you must provide your first response to a barrage of photos of faces and words. At times I sensed that the test makers were trying to trick me into making associations that I didn’t want to make by the order in which the exercises were presented. At the end I was told that I was a little slow in associating Black faces with positive words.

I’m not sure what this means. After doing a little internet searching I learned that one of the criticisms of the IAT is that, while it may hint at a bias, it is really more important whether you cut with or across that bias. If I acknowledge that where and how I grew up may have left me with some implicit biases, it is more important that I make a strong and honest effort to act independently of those biases.

In full disclosure I must tell you that there was one Black girl in my high school of a thousand students. I have lived and practiced in Maine for 50 years. At less than 2%, we are sixth from the bottom in Black population among other states. However, in the last 5 or 6 years here in Brunswick we have welcomed a large infusion of asylum seekers who come predominantly from Black African countries.

Skimming through the rest of the article, I found it hard to argue with the remaining nine recommendations for promoting breastfeeding, although most of them we not terribly applicable to small community practices. The photo of the Black woman nursing her baby at the top of the page remains as the primary message. The fact that I was drawn to that image is a testament to several of my biases and another example of a picture being worth far more than a thousand words.

I suspect that I’m not alone in appreciating the uniqueness of that image. Until recently, the standard photos of a mother breastfeeding have used trim White women as their models. I suspect and hope this poster will be effective in encouraging Black women to nurse. I urge you all to hang it in your office as a reminder to you and your staff of your biases and assumptions. Don’t bother to take the Implicit Association Test unless you’re retired and have 15 minutes to burn on a rainy afternoon.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Oncologists Sound the Alarm About Rise of White Bagging

For years, oncologist John DiPersio, MD, PhD, had faced frustrating encounters with insurers that only cover medications through a process called white bagging.

Instead of the traditional buy-and-bill pathway where oncologists purchase specialty drugs, such as infusion medications, directly from the distributor or manufacturer, white bagging requires physicians to receive these drugs from a specialty pharmacy.

On its face, the differences may seem minor. However, as Dr. DiPersio knows well, the consequences for oncologists and patients are not.

That is why Dr. DiPersio’s cancer center does not allow white bagging.

And when insurers refuse to reconsider the white bagging policy, his cancer team is left with few options.

“Sometimes, we have to redirect patients to other places,” said Dr. DiPersio, a bone marrow transplant specialist at Siteman Cancer Center, Washington University, St. Louis.

In emergency instances where patients cannot wait, Dr. DiPersio’s team will administer their own stock of a drug. In such cases, “we accept the fact that by not allowing white bagging, there may be nonpayment. We take the hit as far as cost.”

Increasingly, white bagging mandates are becoming harder for practices to avoid.

In a 2021 survey, 87% of Association of Community Cancer Centers members said white bagging has become an insurer mandate for some of their patients.

A 2023 analysis from Adam J. Fein, PhD, of Drug Channels Institute, Philadelphia, found that white bagging accounted for 17% of infused oncology product sourcing from clinics and 38% from hospital outpatient departments, up from 15% to 28% in 2019. Another practice called brown bagging, where specialty pharmacies send drugs directly to patients, creates many of the same issues but is much less prevalent than white bagging.

This change reflects “the broader battle over oncology margins” and insurers’ “attempts to shift costs to providers, patients, and manufacturers,” Dr. Fein wrote in his 2023 report.

White Bagging: Who Benefits?

At its core, white bagging changes how drugs are covered and reimbursed. Under buy and bill, drugs fall under a patient’s medical benefit. Oncologists purchase drugs directly from the manufacturer or distributor and receive reimbursement from the insurance company for both the cost of the drug as well as for administering it to patients.

Under white bagging, drugs fall under a patient’s pharmacy benefit. In these instances, a specialty pharmacy prepares the infusion ahead of time and ships it directly to the physician’s office or clinic. Because oncologists do not purchase the drug directly, they cannot bill insurers for it; instead, the pharmacy receives reimbursement for the drug and the provider is reimbursed for administering it.

Insurance companies argue that white bagging reduces patients’ out-of-pocket costs “by preventing hospitals and physicians from charging exorbitant fees to buy and store specialty medicines themselves,” according to advocacy group America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP).

Data from AHIP suggested that hospitals mark up the price of cancer drugs considerably, charging about twice as much as a specialty pharmacy, and that physician’s offices also charge about 23% more. However, these figures highlight how much insurers are billed, not necessarily how much patients ultimately pay.

Other evidence shows that white bagging raises costs for patients while reducing reimbursement for oncologists and saving insurance companies money.

A recent analysis in JAMA Network Open, which looked at 50 cancer drugs associated with the highest total spending from the 2020 Medicare Part B, found that mean insurance payments to providers were more than $2000 lower for drugs distributed under bagging than traditional buy and bill: $7405 vs $9547 per patient per month. Investigators found the same pattern in median insurance payments: $5746 vs $6681. Patients also paid more out-of-pocket each month with bagging vs buy and bill: $315 vs $145.

For patients with private insurance, “out-of-pocket costs were higher under bagging practice than the traditional buy-and-bill practice,” said lead author Ya-Chen Tina Shih, PhD, a professor in the department of radiation oncology at UCLA Health, Los Angeles.

White bagging is entirely for the profit of health insurers, specialty pharmacies, and pharmacy benefit managers, the middlemen who negotiate drug prices on behalf of payers.

Many people may not realize the underlying money-making strategies behind white bagging, explained Ted Okon, executive director for Community Oncology Alliance, which opposes the practice. Often, an insurer, pharmacy benefit manager, and mail order pharmacy involved in the process are all affiliated with the same corporation. In such cases, an insurer has a financial motive to control the source of medications and steer business to its affiliated pharmacies, Mr. Okon said.

When a single corporation owns numerous parts of the drug supply chain, insurers end up having “sway over what drug to use and then how the patient is going to get it,” Mr. Okon said. If the specialty pharmacy is a 340B contract pharmacy, it likely also receives a sizable discount on the drug and can make more money through white bagging.

Dangerous to Patients?

On the safety front, proponents of white bagging say the process is safe and efficient.

Specialty pharmacies are used only for prescription drugs that can be safely delivered, said AHIP spokesman David Allen.

In addition to having the same supply chain safety requirements as any other dispensing pharmacy, “specialty pharmacies also must meet additional safety requirements for specialty drugs” to ensure “the safe storage, handling, and dispensing of the drugs,” Mr. Allen explained.

However, oncologists argue that white bagging can be dangerous.

With white bagging, specialty pharmacies send a specified dose to practices, which does not allow practices to source and mix the drug themselves or make essential last-minute dose-related changes — something that happens every day in the clinic, said Debra Patt, MD, PhD, MBA, executive vice president for policy and strategy for Texas Oncology, Dallas.

White bagging also increases the risk for drug contamination, results in drug waste if the medication can’t be used, and can create delays in care.

Essentially, white bagging takes control away from oncologists and makes patient care more unpredictable and complex, explained Dr. Patt, president of the Texas Society of Clinical Oncology, Rockville, Maryland.

Dr. Patt, who does not allow white bagging in her practice, recalled a recent patient with metastatic breast cancer who came to the clinic for trastuzumab deruxtecan. The patient had been experiencing acute abdominal pain. After an exam and CT, Dr. Patt found the breast cancer had grown and moved into the patient’s liver.

“I had to discontinue that plan and change to a different chemotherapy,” she said. “If we had white bagged, that would have been a waste of several thousand dollars. Also, the patient would have to wait for the new medication to be white bagged, a delay that would be at least a week and the patient would have to come back at another time.”

When asked about the safety concerns associated with white bagging, Lemrey “Al” Carter, MS, PharmD, RPh, executive director of the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP), said the NABP “acknowledges that all these issues exist.

“It is unfortunate if patient care or costs are negatively impacted,” Dr. Carter said, adding that “boards of pharmacy can investigate if they are made aware of safety concerns at the pharmacy level. If a violation of the pharmacy laws or rules is found, boards can take action.”

More Legislation to Prevent Bagging

As white bagging mandates from insurance companies ramp up, more practices and states are banning it.

In the Association of Community Cancer Centers’ 2021 survey, 59% of members said their cancer program or practice does not allow white bagging.

At least 15 states have introduced legislation that restricts and/or prohibits white and brown bagging practices, according to a 2023 report by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Some of the proposed laws would restrict mandates by stipulating that physicians are reimbursed at the contracted amount for clinician-administered drugs, whether obtained from a pharmacy or the manufacturer.

Louisiana, Vermont, and Minnesota were the first to enact anti–white bagging laws. Louisiana’s law, for example, enacted in 2021, bans white bagging and requires insurers to reimburse providers for physician-administered drugs if obtained from out-of-network pharmacies.

When the legislation passed, white bagging was just starting to enter the healthcare market in Louisiana, and the state wanted to act proactively, said Kathy W. Oubre, MS, CEO of the Pontchartrain Cancer Center, Covington, Louisiana, and president of the Coalition of Hematology and Oncology Practices, Mountain View, California.

“We recognized the growing concern around it,” Ms. Oubre said. The state legislature at the time included physicians and pharmacists who “really understood from a practice and patient perspective, the harm that policy could do.”

Ms. Oubre would like to see more legislation in other states and believes Louisiana’s law is a good model.

At the federal level, the American Hospital Association and American Society of Health-System Pharmacists have also urged the US Food and Drug Administration to take appropriate enforcement action to protect patients from white bagging.

Legislation that bars white bagging mandates is the most reasonable way to support timely and appropriate access to cancer care, Dr. Patt said. In the absence of such legislation, she said oncologists can only opt out of insurance contracts that may require the practice.

“That is a difficult position to put oncologists in,” she said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

For years, oncologist John DiPersio, MD, PhD, had faced frustrating encounters with insurers that only cover medications through a process called white bagging.

Instead of the traditional buy-and-bill pathway where oncologists purchase specialty drugs, such as infusion medications, directly from the distributor or manufacturer, white bagging requires physicians to receive these drugs from a specialty pharmacy.

On its face, the differences may seem minor. However, as Dr. DiPersio knows well, the consequences for oncologists and patients are not.

That is why Dr. DiPersio’s cancer center does not allow white bagging.

And when insurers refuse to reconsider the white bagging policy, his cancer team is left with few options.

“Sometimes, we have to redirect patients to other places,” said Dr. DiPersio, a bone marrow transplant specialist at Siteman Cancer Center, Washington University, St. Louis.

In emergency instances where patients cannot wait, Dr. DiPersio’s team will administer their own stock of a drug. In such cases, “we accept the fact that by not allowing white bagging, there may be nonpayment. We take the hit as far as cost.”

Increasingly, white bagging mandates are becoming harder for practices to avoid.

In a 2021 survey, 87% of Association of Community Cancer Centers members said white bagging has become an insurer mandate for some of their patients.

A 2023 analysis from Adam J. Fein, PhD, of Drug Channels Institute, Philadelphia, found that white bagging accounted for 17% of infused oncology product sourcing from clinics and 38% from hospital outpatient departments, up from 15% to 28% in 2019. Another practice called brown bagging, where specialty pharmacies send drugs directly to patients, creates many of the same issues but is much less prevalent than white bagging.

This change reflects “the broader battle over oncology margins” and insurers’ “attempts to shift costs to providers, patients, and manufacturers,” Dr. Fein wrote in his 2023 report.

White Bagging: Who Benefits?

At its core, white bagging changes how drugs are covered and reimbursed. Under buy and bill, drugs fall under a patient’s medical benefit. Oncologists purchase drugs directly from the manufacturer or distributor and receive reimbursement from the insurance company for both the cost of the drug as well as for administering it to patients.

Under white bagging, drugs fall under a patient’s pharmacy benefit. In these instances, a specialty pharmacy prepares the infusion ahead of time and ships it directly to the physician’s office or clinic. Because oncologists do not purchase the drug directly, they cannot bill insurers for it; instead, the pharmacy receives reimbursement for the drug and the provider is reimbursed for administering it.

Insurance companies argue that white bagging reduces patients’ out-of-pocket costs “by preventing hospitals and physicians from charging exorbitant fees to buy and store specialty medicines themselves,” according to advocacy group America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP).

Data from AHIP suggested that hospitals mark up the price of cancer drugs considerably, charging about twice as much as a specialty pharmacy, and that physician’s offices also charge about 23% more. However, these figures highlight how much insurers are billed, not necessarily how much patients ultimately pay.

Other evidence shows that white bagging raises costs for patients while reducing reimbursement for oncologists and saving insurance companies money.

A recent analysis in JAMA Network Open, which looked at 50 cancer drugs associated with the highest total spending from the 2020 Medicare Part B, found that mean insurance payments to providers were more than $2000 lower for drugs distributed under bagging than traditional buy and bill: $7405 vs $9547 per patient per month. Investigators found the same pattern in median insurance payments: $5746 vs $6681. Patients also paid more out-of-pocket each month with bagging vs buy and bill: $315 vs $145.

For patients with private insurance, “out-of-pocket costs were higher under bagging practice than the traditional buy-and-bill practice,” said lead author Ya-Chen Tina Shih, PhD, a professor in the department of radiation oncology at UCLA Health, Los Angeles.

White bagging is entirely for the profit of health insurers, specialty pharmacies, and pharmacy benefit managers, the middlemen who negotiate drug prices on behalf of payers.

Many people may not realize the underlying money-making strategies behind white bagging, explained Ted Okon, executive director for Community Oncology Alliance, which opposes the practice. Often, an insurer, pharmacy benefit manager, and mail order pharmacy involved in the process are all affiliated with the same corporation. In such cases, an insurer has a financial motive to control the source of medications and steer business to its affiliated pharmacies, Mr. Okon said.

When a single corporation owns numerous parts of the drug supply chain, insurers end up having “sway over what drug to use and then how the patient is going to get it,” Mr. Okon said. If the specialty pharmacy is a 340B contract pharmacy, it likely also receives a sizable discount on the drug and can make more money through white bagging.

Dangerous to Patients?

On the safety front, proponents of white bagging say the process is safe and efficient.

Specialty pharmacies are used only for prescription drugs that can be safely delivered, said AHIP spokesman David Allen.

In addition to having the same supply chain safety requirements as any other dispensing pharmacy, “specialty pharmacies also must meet additional safety requirements for specialty drugs” to ensure “the safe storage, handling, and dispensing of the drugs,” Mr. Allen explained.

However, oncologists argue that white bagging can be dangerous.

With white bagging, specialty pharmacies send a specified dose to practices, which does not allow practices to source and mix the drug themselves or make essential last-minute dose-related changes — something that happens every day in the clinic, said Debra Patt, MD, PhD, MBA, executive vice president for policy and strategy for Texas Oncology, Dallas.

White bagging also increases the risk for drug contamination, results in drug waste if the medication can’t be used, and can create delays in care.

Essentially, white bagging takes control away from oncologists and makes patient care more unpredictable and complex, explained Dr. Patt, president of the Texas Society of Clinical Oncology, Rockville, Maryland.

Dr. Patt, who does not allow white bagging in her practice, recalled a recent patient with metastatic breast cancer who came to the clinic for trastuzumab deruxtecan. The patient had been experiencing acute abdominal pain. After an exam and CT, Dr. Patt found the breast cancer had grown and moved into the patient’s liver.

“I had to discontinue that plan and change to a different chemotherapy,” she said. “If we had white bagged, that would have been a waste of several thousand dollars. Also, the patient would have to wait for the new medication to be white bagged, a delay that would be at least a week and the patient would have to come back at another time.”

When asked about the safety concerns associated with white bagging, Lemrey “Al” Carter, MS, PharmD, RPh, executive director of the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP), said the NABP “acknowledges that all these issues exist.

“It is unfortunate if patient care or costs are negatively impacted,” Dr. Carter said, adding that “boards of pharmacy can investigate if they are made aware of safety concerns at the pharmacy level. If a violation of the pharmacy laws or rules is found, boards can take action.”

More Legislation to Prevent Bagging

As white bagging mandates from insurance companies ramp up, more practices and states are banning it.

In the Association of Community Cancer Centers’ 2021 survey, 59% of members said their cancer program or practice does not allow white bagging.

At least 15 states have introduced legislation that restricts and/or prohibits white and brown bagging practices, according to a 2023 report by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Some of the proposed laws would restrict mandates by stipulating that physicians are reimbursed at the contracted amount for clinician-administered drugs, whether obtained from a pharmacy or the manufacturer.

Louisiana, Vermont, and Minnesota were the first to enact anti–white bagging laws. Louisiana’s law, for example, enacted in 2021, bans white bagging and requires insurers to reimburse providers for physician-administered drugs if obtained from out-of-network pharmacies.

When the legislation passed, white bagging was just starting to enter the healthcare market in Louisiana, and the state wanted to act proactively, said Kathy W. Oubre, MS, CEO of the Pontchartrain Cancer Center, Covington, Louisiana, and president of the Coalition of Hematology and Oncology Practices, Mountain View, California.

“We recognized the growing concern around it,” Ms. Oubre said. The state legislature at the time included physicians and pharmacists who “really understood from a practice and patient perspective, the harm that policy could do.”

Ms. Oubre would like to see more legislation in other states and believes Louisiana’s law is a good model.

At the federal level, the American Hospital Association and American Society of Health-System Pharmacists have also urged the US Food and Drug Administration to take appropriate enforcement action to protect patients from white bagging.

Legislation that bars white bagging mandates is the most reasonable way to support timely and appropriate access to cancer care, Dr. Patt said. In the absence of such legislation, she said oncologists can only opt out of insurance contracts that may require the practice.

“That is a difficult position to put oncologists in,” she said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

For years, oncologist John DiPersio, MD, PhD, had faced frustrating encounters with insurers that only cover medications through a process called white bagging.

Instead of the traditional buy-and-bill pathway where oncologists purchase specialty drugs, such as infusion medications, directly from the distributor or manufacturer, white bagging requires physicians to receive these drugs from a specialty pharmacy.

On its face, the differences may seem minor. However, as Dr. DiPersio knows well, the consequences for oncologists and patients are not.

That is why Dr. DiPersio’s cancer center does not allow white bagging.

And when insurers refuse to reconsider the white bagging policy, his cancer team is left with few options.

“Sometimes, we have to redirect patients to other places,” said Dr. DiPersio, a bone marrow transplant specialist at Siteman Cancer Center, Washington University, St. Louis.

In emergency instances where patients cannot wait, Dr. DiPersio’s team will administer their own stock of a drug. In such cases, “we accept the fact that by not allowing white bagging, there may be nonpayment. We take the hit as far as cost.”

Increasingly, white bagging mandates are becoming harder for practices to avoid.

In a 2021 survey, 87% of Association of Community Cancer Centers members said white bagging has become an insurer mandate for some of their patients.

A 2023 analysis from Adam J. Fein, PhD, of Drug Channels Institute, Philadelphia, found that white bagging accounted for 17% of infused oncology product sourcing from clinics and 38% from hospital outpatient departments, up from 15% to 28% in 2019. Another practice called brown bagging, where specialty pharmacies send drugs directly to patients, creates many of the same issues but is much less prevalent than white bagging.

This change reflects “the broader battle over oncology margins” and insurers’ “attempts to shift costs to providers, patients, and manufacturers,” Dr. Fein wrote in his 2023 report.

White Bagging: Who Benefits?

At its core, white bagging changes how drugs are covered and reimbursed. Under buy and bill, drugs fall under a patient’s medical benefit. Oncologists purchase drugs directly from the manufacturer or distributor and receive reimbursement from the insurance company for both the cost of the drug as well as for administering it to patients.

Under white bagging, drugs fall under a patient’s pharmacy benefit. In these instances, a specialty pharmacy prepares the infusion ahead of time and ships it directly to the physician’s office or clinic. Because oncologists do not purchase the drug directly, they cannot bill insurers for it; instead, the pharmacy receives reimbursement for the drug and the provider is reimbursed for administering it.

Insurance companies argue that white bagging reduces patients’ out-of-pocket costs “by preventing hospitals and physicians from charging exorbitant fees to buy and store specialty medicines themselves,” according to advocacy group America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP).

Data from AHIP suggested that hospitals mark up the price of cancer drugs considerably, charging about twice as much as a specialty pharmacy, and that physician’s offices also charge about 23% more. However, these figures highlight how much insurers are billed, not necessarily how much patients ultimately pay.

Other evidence shows that white bagging raises costs for patients while reducing reimbursement for oncologists and saving insurance companies money.

A recent analysis in JAMA Network Open, which looked at 50 cancer drugs associated with the highest total spending from the 2020 Medicare Part B, found that mean insurance payments to providers were more than $2000 lower for drugs distributed under bagging than traditional buy and bill: $7405 vs $9547 per patient per month. Investigators found the same pattern in median insurance payments: $5746 vs $6681. Patients also paid more out-of-pocket each month with bagging vs buy and bill: $315 vs $145.

For patients with private insurance, “out-of-pocket costs were higher under bagging practice than the traditional buy-and-bill practice,” said lead author Ya-Chen Tina Shih, PhD, a professor in the department of radiation oncology at UCLA Health, Los Angeles.

White bagging is entirely for the profit of health insurers, specialty pharmacies, and pharmacy benefit managers, the middlemen who negotiate drug prices on behalf of payers.

Many people may not realize the underlying money-making strategies behind white bagging, explained Ted Okon, executive director for Community Oncology Alliance, which opposes the practice. Often, an insurer, pharmacy benefit manager, and mail order pharmacy involved in the process are all affiliated with the same corporation. In such cases, an insurer has a financial motive to control the source of medications and steer business to its affiliated pharmacies, Mr. Okon said.

When a single corporation owns numerous parts of the drug supply chain, insurers end up having “sway over what drug to use and then how the patient is going to get it,” Mr. Okon said. If the specialty pharmacy is a 340B contract pharmacy, it likely also receives a sizable discount on the drug and can make more money through white bagging.

Dangerous to Patients?

On the safety front, proponents of white bagging say the process is safe and efficient.

Specialty pharmacies are used only for prescription drugs that can be safely delivered, said AHIP spokesman David Allen.

In addition to having the same supply chain safety requirements as any other dispensing pharmacy, “specialty pharmacies also must meet additional safety requirements for specialty drugs” to ensure “the safe storage, handling, and dispensing of the drugs,” Mr. Allen explained.

However, oncologists argue that white bagging can be dangerous.

With white bagging, specialty pharmacies send a specified dose to practices, which does not allow practices to source and mix the drug themselves or make essential last-minute dose-related changes — something that happens every day in the clinic, said Debra Patt, MD, PhD, MBA, executive vice president for policy and strategy for Texas Oncology, Dallas.

White bagging also increases the risk for drug contamination, results in drug waste if the medication can’t be used, and can create delays in care.

Essentially, white bagging takes control away from oncologists and makes patient care more unpredictable and complex, explained Dr. Patt, president of the Texas Society of Clinical Oncology, Rockville, Maryland.

Dr. Patt, who does not allow white bagging in her practice, recalled a recent patient with metastatic breast cancer who came to the clinic for trastuzumab deruxtecan. The patient had been experiencing acute abdominal pain. After an exam and CT, Dr. Patt found the breast cancer had grown and moved into the patient’s liver.

“I had to discontinue that plan and change to a different chemotherapy,” she said. “If we had white bagged, that would have been a waste of several thousand dollars. Also, the patient would have to wait for the new medication to be white bagged, a delay that would be at least a week and the patient would have to come back at another time.”

When asked about the safety concerns associated with white bagging, Lemrey “Al” Carter, MS, PharmD, RPh, executive director of the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP), said the NABP “acknowledges that all these issues exist.

“It is unfortunate if patient care or costs are negatively impacted,” Dr. Carter said, adding that “boards of pharmacy can investigate if they are made aware of safety concerns at the pharmacy level. If a violation of the pharmacy laws or rules is found, boards can take action.”

More Legislation to Prevent Bagging

As white bagging mandates from insurance companies ramp up, more practices and states are banning it.

In the Association of Community Cancer Centers’ 2021 survey, 59% of members said their cancer program or practice does not allow white bagging.

At least 15 states have introduced legislation that restricts and/or prohibits white and brown bagging practices, according to a 2023 report by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Some of the proposed laws would restrict mandates by stipulating that physicians are reimbursed at the contracted amount for clinician-administered drugs, whether obtained from a pharmacy or the manufacturer.

Louisiana, Vermont, and Minnesota were the first to enact anti–white bagging laws. Louisiana’s law, for example, enacted in 2021, bans white bagging and requires insurers to reimburse providers for physician-administered drugs if obtained from out-of-network pharmacies.

When the legislation passed, white bagging was just starting to enter the healthcare market in Louisiana, and the state wanted to act proactively, said Kathy W. Oubre, MS, CEO of the Pontchartrain Cancer Center, Covington, Louisiana, and president of the Coalition of Hematology and Oncology Practices, Mountain View, California.

“We recognized the growing concern around it,” Ms. Oubre said. The state legislature at the time included physicians and pharmacists who “really understood from a practice and patient perspective, the harm that policy could do.”

Ms. Oubre would like to see more legislation in other states and believes Louisiana’s law is a good model.

At the federal level, the American Hospital Association and American Society of Health-System Pharmacists have also urged the US Food and Drug Administration to take appropriate enforcement action to protect patients from white bagging.

Legislation that bars white bagging mandates is the most reasonable way to support timely and appropriate access to cancer care, Dr. Patt said. In the absence of such legislation, she said oncologists can only opt out of insurance contracts that may require the practice.

“That is a difficult position to put oncologists in,” she said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

New Federal Rule for Prior Authorizations a ‘Major Win’ for Patients, Doctors

Physicians groups on January 17 hailed a new federal rule requiring health insurers to streamline and disclose more information about their prior authorization processes, saying it will improve patient care and reduce doctors’ administrative burden.

Health insurers participating in federal programs, including Medicare Advantage and Medicaid, must now respond to expedited prior authorization requests within 72 hours and other requests within 7 days under the long-awaited final rule, released on January 17 by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

Insurers also must include their reasons for denying a prior authorization request and will be required to publicly release data on denial and approval rates for medical treatment. They’ll also need to give patients more information about their decisions to deny care. Insurers must comply with some of the rule’s provisions by January 2026 and others by January 2027.

The final rule “is an important step forward” toward the Medical Group Management Association’s goal of reducing the overall volume of prior authorization requests, said Anders Gilberg, the group’s senior vice president for government affairs, in a statement.

“Only then will medical groups find meaningful reprieve from these onerous, ill-intentioned administrative requirements that dangerously impede patient care,” Mr. Gilberg said.

Health insurers have long lobbied against increased regulation of prior authorization, arguing that it’s needed to rein in healthcare costs and prevent unnecessary treatment.

“We appreciate CMS’s announcement of enforcement discretion that will permit plans to use one standard, rather than mixing and matching, to reduce costs and speed implementation,” said America’s Health Insurance Plans, an insurers’ lobbying group, in an unsigned statement. “However, we must remember that the CMS rule is only half the picture; the Office of the Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) should swiftly require vendors to build electronic prior authorization capabilities into the electronic health record so that providers can do their part, or plans will build a bridge to nowhere.”

The rule comes as health insurers have increasingly been criticized for onerous and time-consuming prior authorization procedures that physicians say unfairly delay or deny the medical treatment that their patients need. With federal legislation to rein in prior authorization overuse at a standstill, 30 states have introduced their own bills to address the problem. Regulators and lawsuits also have called attention to insurers’ increasing use of artificial intelligence and algorithms to deny claims without human review.

“Family physicians know firsthand how prior authorizations divert valuable time and resources away from direct patient care. We also know that these types of administrative requirements are driving physicians away from the workforce and worsening physician shortages,” said Steven P. Furr, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, in a statement praising the new rule.

Jesse M. Ehrenfeld, MD, MPH, president of the American Medical Association, called the final rule “ a major win” for patients and physicians, adding that its requirements for health insurers to integrate their prior authorization procedures into physicians’ electronic health records systems will also help make “the current time-consuming, manual workflow” more efficient.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physicians groups on January 17 hailed a new federal rule requiring health insurers to streamline and disclose more information about their prior authorization processes, saying it will improve patient care and reduce doctors’ administrative burden.

Health insurers participating in federal programs, including Medicare Advantage and Medicaid, must now respond to expedited prior authorization requests within 72 hours and other requests within 7 days under the long-awaited final rule, released on January 17 by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

Insurers also must include their reasons for denying a prior authorization request and will be required to publicly release data on denial and approval rates for medical treatment. They’ll also need to give patients more information about their decisions to deny care. Insurers must comply with some of the rule’s provisions by January 2026 and others by January 2027.

The final rule “is an important step forward” toward the Medical Group Management Association’s goal of reducing the overall volume of prior authorization requests, said Anders Gilberg, the group’s senior vice president for government affairs, in a statement.

“Only then will medical groups find meaningful reprieve from these onerous, ill-intentioned administrative requirements that dangerously impede patient care,” Mr. Gilberg said.

Health insurers have long lobbied against increased regulation of prior authorization, arguing that it’s needed to rein in healthcare costs and prevent unnecessary treatment.

“We appreciate CMS’s announcement of enforcement discretion that will permit plans to use one standard, rather than mixing and matching, to reduce costs and speed implementation,” said America’s Health Insurance Plans, an insurers’ lobbying group, in an unsigned statement. “However, we must remember that the CMS rule is only half the picture; the Office of the Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) should swiftly require vendors to build electronic prior authorization capabilities into the electronic health record so that providers can do their part, or plans will build a bridge to nowhere.”

The rule comes as health insurers have increasingly been criticized for onerous and time-consuming prior authorization procedures that physicians say unfairly delay or deny the medical treatment that their patients need. With federal legislation to rein in prior authorization overuse at a standstill, 30 states have introduced their own bills to address the problem. Regulators and lawsuits also have called attention to insurers’ increasing use of artificial intelligence and algorithms to deny claims without human review.

“Family physicians know firsthand how prior authorizations divert valuable time and resources away from direct patient care. We also know that these types of administrative requirements are driving physicians away from the workforce and worsening physician shortages,” said Steven P. Furr, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, in a statement praising the new rule.

Jesse M. Ehrenfeld, MD, MPH, president of the American Medical Association, called the final rule “ a major win” for patients and physicians, adding that its requirements for health insurers to integrate their prior authorization procedures into physicians’ electronic health records systems will also help make “the current time-consuming, manual workflow” more efficient.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physicians groups on January 17 hailed a new federal rule requiring health insurers to streamline and disclose more information about their prior authorization processes, saying it will improve patient care and reduce doctors’ administrative burden.

Health insurers participating in federal programs, including Medicare Advantage and Medicaid, must now respond to expedited prior authorization requests within 72 hours and other requests within 7 days under the long-awaited final rule, released on January 17 by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

Insurers also must include their reasons for denying a prior authorization request and will be required to publicly release data on denial and approval rates for medical treatment. They’ll also need to give patients more information about their decisions to deny care. Insurers must comply with some of the rule’s provisions by January 2026 and others by January 2027.

The final rule “is an important step forward” toward the Medical Group Management Association’s goal of reducing the overall volume of prior authorization requests, said Anders Gilberg, the group’s senior vice president for government affairs, in a statement.

“Only then will medical groups find meaningful reprieve from these onerous, ill-intentioned administrative requirements that dangerously impede patient care,” Mr. Gilberg said.

Health insurers have long lobbied against increased regulation of prior authorization, arguing that it’s needed to rein in healthcare costs and prevent unnecessary treatment.

“We appreciate CMS’s announcement of enforcement discretion that will permit plans to use one standard, rather than mixing and matching, to reduce costs and speed implementation,” said America’s Health Insurance Plans, an insurers’ lobbying group, in an unsigned statement. “However, we must remember that the CMS rule is only half the picture; the Office of the Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) should swiftly require vendors to build electronic prior authorization capabilities into the electronic health record so that providers can do their part, or plans will build a bridge to nowhere.”

The rule comes as health insurers have increasingly been criticized for onerous and time-consuming prior authorization procedures that physicians say unfairly delay or deny the medical treatment that their patients need. With federal legislation to rein in prior authorization overuse at a standstill, 30 states have introduced their own bills to address the problem. Regulators and lawsuits also have called attention to insurers’ increasing use of artificial intelligence and algorithms to deny claims without human review.

“Family physicians know firsthand how prior authorizations divert valuable time and resources away from direct patient care. We also know that these types of administrative requirements are driving physicians away from the workforce and worsening physician shortages,” said Steven P. Furr, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, in a statement praising the new rule.

Jesse M. Ehrenfeld, MD, MPH, president of the American Medical Association, called the final rule “ a major win” for patients and physicians, adding that its requirements for health insurers to integrate their prior authorization procedures into physicians’ electronic health records systems will also help make “the current time-consuming, manual workflow” more efficient.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Magic Wand Initiative Empowers Dermatologists to Innovate

NEW YORK – .

The program was founded in 2013 by two Harvard Medical School dermatologists, Lilit Garibyan, MD, PhD, the program director, and her mentor R. Rox Anderson MD, director of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Boston. It was based on the idea that clinicians are in a unique position to identify gaps in patient care and should be active in developing medical solutions to address those gaps.

“I truly believe that if we do a better job educating, training, and empowering our clinicians to become innovators, this will benefit patients and hospitals and physicians,” Dr. Garibyan said at the 26th annual Mount Sinai Winter Symposium — Advances in Medical and Surgical Dermatology.

One of the seeds for the project was her own experience with cryolipolysis which involves topical cooling, a noninvasive method of removing subcutaneous fat for body contouring, which relies on conducting heat from subcutaneous fat across the skin and therefore, does not reach fat far from the dermis. With Dr. Anderson’s mentorship, she developed injectable cooling technology (ICT), a procedure where “ice slurry,” composed of normal saline and glycerol, is directly injected into adipose tissue, possibly leading to more efficient and effective cryolipolysis.

After nearly 10 years of animal studies at MGH, led by Dr. Garibyan as proof of concept trials, ice slurry (Coolio Therapy) recently received FDA breakthrough designation for long-term pain control and early-stage human trials of clinical applications are underway, she noted.

Magic Wand Program

In the Magic Wand program, participating physicians start by recording areas of unmet needs in their day-to-day practices, and in groups, engage in clinician-only brainstorming sessions to screen ideas, define problems, and generate lists of specifications and tools needed to address clinical problems. After working together to define challenges and possible solutions, they take their ideas to a development team, where scientists, engineers, regulatory experts, and industry professionals meet and help clinicians start pilot proof-of-concept projects, develop prototypes, and gain support for studies, followed by pilot feasibility studies.

Part of the project is the Virtual Magic Wand (VMW) Initiative, a 10-month online instructive and interactive course open to clinicians in the United States and Europe, designed to bring together dermatologists “interested in deeply understanding a dermatologic clinical problem worth solving,” according to Dr. Garibyan. Currently, there are more than 86 VMW scholars from 46 institutions, and military and private practice sites in the United States. The VMW was expanded to Europe in 2021 and there are plans to expand to Asia as well, she said.

The success of the program is not only attributed to its clinical methods but the fact that it provides a benefit to doctors at all stages of their careers, patients, and industry. “This is the only program that aims to engage in innovation from resident to full professor. We provide ideas that industry can then support and bring to market. Everyone including patients, doctors, and healthcare companies can benefit from active, engaged, and innovative physicians,” Dr. Garibyan said.

One of the success stories is that of Veradermics, a company founded by Kansas City dermatologist, Reid A. Waldman, MD, the company’s CEO, and Tim Durso, MD, the president, who met while participating in the VMW program in 2020, which eventually led them to start a company addressing an unmet need in dermatology, a kid-friendly treatment of warts.

In an interview with this news organization, Dr. Waldman explained how the program informed his company’s ethos. “Magic Wand Initiative is about identifying problems worth solving,” he said. At the company, “we find problems or unmet needs that are large enough to motivate prescribing changes, so we’ve really taken the philosophy I learned in the program into this company and building our portfolio.”

One of the first needs that Veradermics addressed was the fact that treatment for common warts, cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen, is painful and can frighten children, and, with a response rate of “at best, 50%,” Dr. Waldman said. Veradermics is in the process of creating a nearly painless, child-friendly wart treatment: an “immunostimulatory dissolvable microarray” patch that contains Candida antigen extract, which is currently being evaluated for treating warts in a phase 2 clinical trial started in 2023.

Although the Magic Wand Initiative was initially restricted to dermatologists at MGH, stories like that of Veradermics have made the program so popular that it has branched out to include anesthesiologists and otolaryngologists, as well as general and orthopedic surgeons at MGH, Dr. Garibyan said at the Mount Sinai meeting.

Dr. Garibyan disclosed that she is a cofounder of and has equity in Brixton Biosciences and EyeCool, and is a consultant for and/or investor in Brixton and Clarity Cosmetics. Royalties/inventorship are assigned to MGH.

NEW YORK – .

The program was founded in 2013 by two Harvard Medical School dermatologists, Lilit Garibyan, MD, PhD, the program director, and her mentor R. Rox Anderson MD, director of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Boston. It was based on the idea that clinicians are in a unique position to identify gaps in patient care and should be active in developing medical solutions to address those gaps.

“I truly believe that if we do a better job educating, training, and empowering our clinicians to become innovators, this will benefit patients and hospitals and physicians,” Dr. Garibyan said at the 26th annual Mount Sinai Winter Symposium — Advances in Medical and Surgical Dermatology.

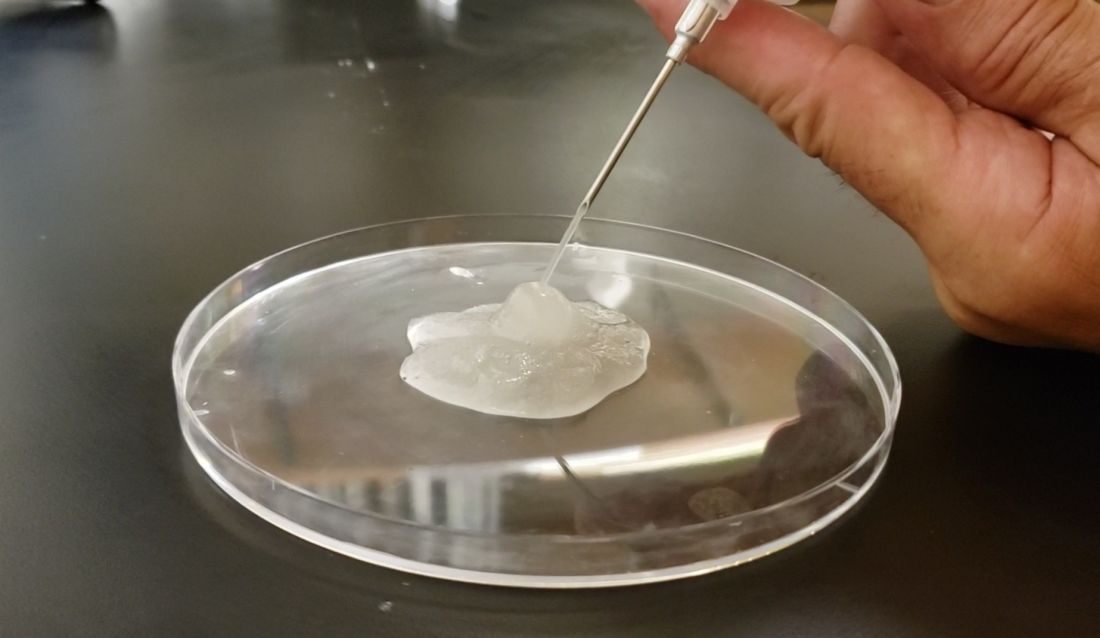

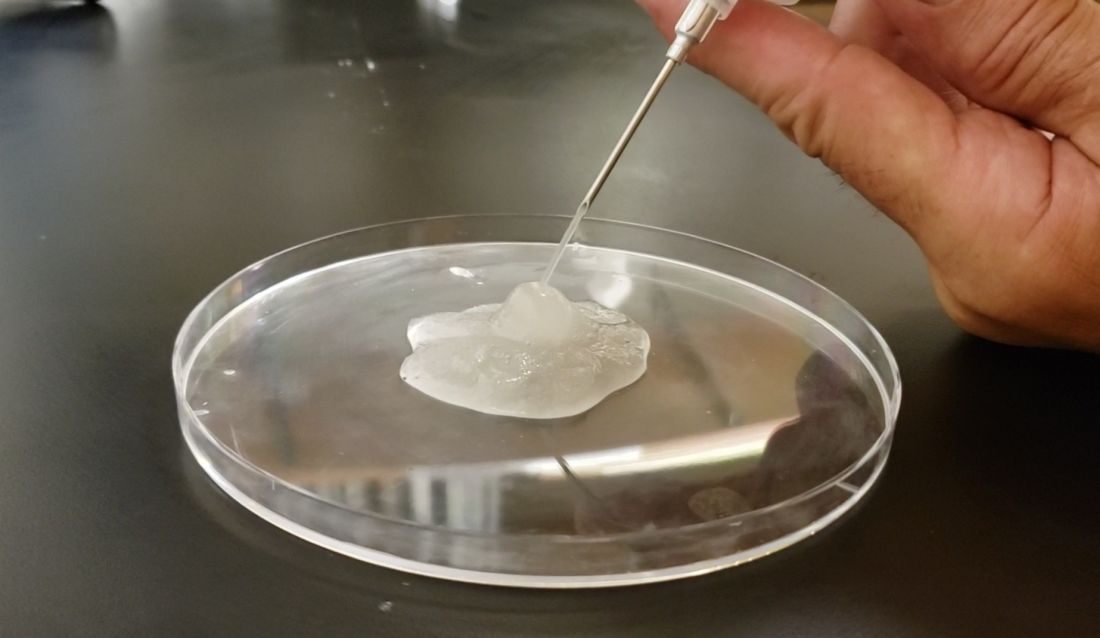

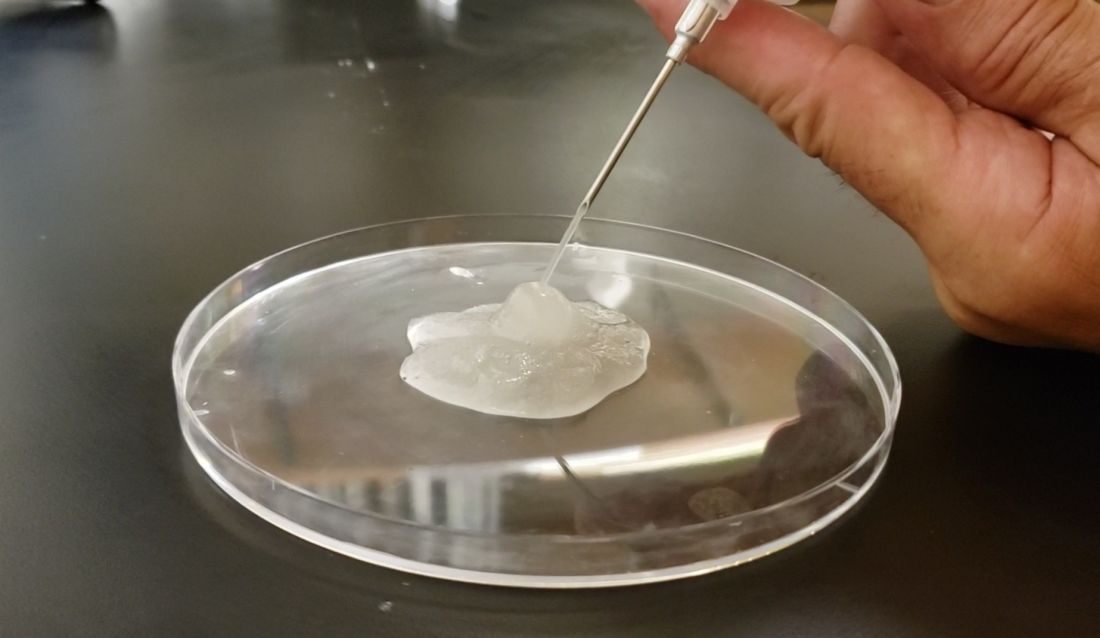

One of the seeds for the project was her own experience with cryolipolysis which involves topical cooling, a noninvasive method of removing subcutaneous fat for body contouring, which relies on conducting heat from subcutaneous fat across the skin and therefore, does not reach fat far from the dermis. With Dr. Anderson’s mentorship, she developed injectable cooling technology (ICT), a procedure where “ice slurry,” composed of normal saline and glycerol, is directly injected into adipose tissue, possibly leading to more efficient and effective cryolipolysis.

After nearly 10 years of animal studies at MGH, led by Dr. Garibyan as proof of concept trials, ice slurry (Coolio Therapy) recently received FDA breakthrough designation for long-term pain control and early-stage human trials of clinical applications are underway, she noted.

Magic Wand Program

In the Magic Wand program, participating physicians start by recording areas of unmet needs in their day-to-day practices, and in groups, engage in clinician-only brainstorming sessions to screen ideas, define problems, and generate lists of specifications and tools needed to address clinical problems. After working together to define challenges and possible solutions, they take their ideas to a development team, where scientists, engineers, regulatory experts, and industry professionals meet and help clinicians start pilot proof-of-concept projects, develop prototypes, and gain support for studies, followed by pilot feasibility studies.

Part of the project is the Virtual Magic Wand (VMW) Initiative, a 10-month online instructive and interactive course open to clinicians in the United States and Europe, designed to bring together dermatologists “interested in deeply understanding a dermatologic clinical problem worth solving,” according to Dr. Garibyan. Currently, there are more than 86 VMW scholars from 46 institutions, and military and private practice sites in the United States. The VMW was expanded to Europe in 2021 and there are plans to expand to Asia as well, she said.

The success of the program is not only attributed to its clinical methods but the fact that it provides a benefit to doctors at all stages of their careers, patients, and industry. “This is the only program that aims to engage in innovation from resident to full professor. We provide ideas that industry can then support and bring to market. Everyone including patients, doctors, and healthcare companies can benefit from active, engaged, and innovative physicians,” Dr. Garibyan said.

One of the success stories is that of Veradermics, a company founded by Kansas City dermatologist, Reid A. Waldman, MD, the company’s CEO, and Tim Durso, MD, the president, who met while participating in the VMW program in 2020, which eventually led them to start a company addressing an unmet need in dermatology, a kid-friendly treatment of warts.

In an interview with this news organization, Dr. Waldman explained how the program informed his company’s ethos. “Magic Wand Initiative is about identifying problems worth solving,” he said. At the company, “we find problems or unmet needs that are large enough to motivate prescribing changes, so we’ve really taken the philosophy I learned in the program into this company and building our portfolio.”

One of the first needs that Veradermics addressed was the fact that treatment for common warts, cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen, is painful and can frighten children, and, with a response rate of “at best, 50%,” Dr. Waldman said. Veradermics is in the process of creating a nearly painless, child-friendly wart treatment: an “immunostimulatory dissolvable microarray” patch that contains Candida antigen extract, which is currently being evaluated for treating warts in a phase 2 clinical trial started in 2023.

Although the Magic Wand Initiative was initially restricted to dermatologists at MGH, stories like that of Veradermics have made the program so popular that it has branched out to include anesthesiologists and otolaryngologists, as well as general and orthopedic surgeons at MGH, Dr. Garibyan said at the Mount Sinai meeting.

Dr. Garibyan disclosed that she is a cofounder of and has equity in Brixton Biosciences and EyeCool, and is a consultant for and/or investor in Brixton and Clarity Cosmetics. Royalties/inventorship are assigned to MGH.

NEW YORK – .

The program was founded in 2013 by two Harvard Medical School dermatologists, Lilit Garibyan, MD, PhD, the program director, and her mentor R. Rox Anderson MD, director of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Boston. It was based on the idea that clinicians are in a unique position to identify gaps in patient care and should be active in developing medical solutions to address those gaps.

“I truly believe that if we do a better job educating, training, and empowering our clinicians to become innovators, this will benefit patients and hospitals and physicians,” Dr. Garibyan said at the 26th annual Mount Sinai Winter Symposium — Advances in Medical and Surgical Dermatology.

One of the seeds for the project was her own experience with cryolipolysis which involves topical cooling, a noninvasive method of removing subcutaneous fat for body contouring, which relies on conducting heat from subcutaneous fat across the skin and therefore, does not reach fat far from the dermis. With Dr. Anderson’s mentorship, she developed injectable cooling technology (ICT), a procedure where “ice slurry,” composed of normal saline and glycerol, is directly injected into adipose tissue, possibly leading to more efficient and effective cryolipolysis.

After nearly 10 years of animal studies at MGH, led by Dr. Garibyan as proof of concept trials, ice slurry (Coolio Therapy) recently received FDA breakthrough designation for long-term pain control and early-stage human trials of clinical applications are underway, she noted.

Magic Wand Program

In the Magic Wand program, participating physicians start by recording areas of unmet needs in their day-to-day practices, and in groups, engage in clinician-only brainstorming sessions to screen ideas, define problems, and generate lists of specifications and tools needed to address clinical problems. After working together to define challenges and possible solutions, they take their ideas to a development team, where scientists, engineers, regulatory experts, and industry professionals meet and help clinicians start pilot proof-of-concept projects, develop prototypes, and gain support for studies, followed by pilot feasibility studies.

Part of the project is the Virtual Magic Wand (VMW) Initiative, a 10-month online instructive and interactive course open to clinicians in the United States and Europe, designed to bring together dermatologists “interested in deeply understanding a dermatologic clinical problem worth solving,” according to Dr. Garibyan. Currently, there are more than 86 VMW scholars from 46 institutions, and military and private practice sites in the United States. The VMW was expanded to Europe in 2021 and there are plans to expand to Asia as well, she said.