User login

Thymectomy improves clinical outcomes for myasthenia gravis

Thymectomy improved 3-year clinical outcomes and proved superior to medical therapy for mild to severe nonthymomatous myasthenia gravis, according to a report published online Aug. 11 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Compared with standard prednisone therapy, thymectomy plus prednisone decreased the number and severity of symptoms, allowed the lowering of steroid doses, decreased the number and length of hospitalizations for disease exacerbations, reduced the need for immunosuppressive agents, and improved health-related quality of life in an international, randomized clinical trial, said Gil I. Wolfe, MD, of the department of neurology, State University of New York at Buffalo and his associates.

Until now, thymectomy was known to be beneficial in some cases of myasthenia gravis “but with widely varying rates of clinical improvement or remission.” And the success of immunotherapy has raised the question of whether an invasive surgery is necessary. Data from randomized, controlled studies have been sparse.

Moreover, thymectomy rarely causes adverse effects, but “the procedure can cost up to $80,000 and can be associated with operative complications that need to be weighed against benefits.” In comparison, medical therapy with glucocorticoids and other immunosuppressive agents is less invasive but is definitely associated with adverse events, including some that are life threatening, and negatively impacts quality of life, the investigators said.

To address the lack of randomized controlled trial data, they assessed 3-year outcomes in 126 patients treated at 67 medical centers in 18 countries during a 6-year period. The study participants were aged 18-65 years, had a disease duration of less than 5 years at enrollment (median duration, 1 year), and had class II (mild generalized disease) to class IV (severe generalized disease) myasthenia gravis. These patients were randomly assigned to undergo thymectomy and receive standard prednisone therapy (66 participants) or to receive standard prednisone alone (60 participants).

Thymectomy was performed using a median sternotomy “with the goal of an en bloc resection of all mediastinal tissue that could anatomically contain gross or microscopic thymus.”

At follow-up, time-weighted average scores on the Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis scale were significantly lower by 2.85 points, indicating improved clinical status, in the thymectomy group than in the control group. Time-weighted average prednisone dose also was significantly lower, at an average alternate-day dose of 44 mg in the thymectomy group and 60 mg in the control group, Dr. Wolfe and his associates said (N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602489).

On a measure of treatment-related complications, scores favored thymectomy with regard to the number of patients with symptoms, the total number of symptoms, and the distress level related to symptoms throughout the study period. Fewer patients in the thymectomy group required hospitalization for exacerbations of myasthenia gravis (9% vs. 37%), and the mean cumulative number of hospital days was lower with thymectomy (8.4 vs. 19.2).

In addition, scores on the Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living scale favored thymectomy (2.24 vs. 3.41). Fewer patients in the thymectomy group required azathioprine (17% vs. 0.48%). And the percentage of patients who reported having minimal manifestations of the disease at 3 years was significantly higher with thymectomy (67%) than with prednisone alone (47%).

This study was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Muscular Dystrophy Association, and the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America and received no commercial support. Dr. Wolfe reported ties to Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Alpha Cancer Technologies, Argenx, Baxalta, CSL Behring, Grifols, and UCB, and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Landmark trial establishes effectiveness of thymectomy in myasthenia gravis

One of the many challenges of treating patients with myasthenia gravis (MG) is the fluctuating nature of symptoms and deficits. The neurologist or neuromuscular specialist must decide whether the disease is truly worsening, whether the patient is experiencing more pronounced symptoms from intercurrent illness or the effects of a medication known to affect the neuromuscular junction adversely, or whether the patient is concerned that there might be worsening disease when all objective measures indicate stability. These factors make treatment decisions more difficult in MG than for many other neuromuscular disorders.

Similarly, researchers considering a trial investigating treatment efficacy in MG face the complex issues of disease fluctuation in cohorts of individuals with the disease, varying levels of corticosteroid and immunosuppressant doses in different MG patients, and thorny ethical dilemmas in providing accepted therapies but not withholding effective treatments from those in need.

Dr. Wolfe and his colleagues demonstrate that they have navigated these treacherous waters. They have succeeded in completing a landmark controlled clinical trial which establishes the effectiveness of transsternal thymectomy with adjuvant corticosteroid therapy in nonthymomatous MG vs. oral prednisone without surgery. While this international 36-center trial managed to recruit 126 subjects over a 6-year period, using sound inclusion and exclusion criteria and a meticulous trial design, the number of patients is not sufficient to allow for as robust a subgroup analysis for age, gender, and a variety of clinical variables reflecting severity of disease as would have been hoped for by the MG community.

Nonetheless, this paper sets the use of thymectomy in nonthymomatous MG on firmer ground going forward. The investigators will doubtless be presenting further data from the trial, including clinical-pathologic correlates and other relevant novel observations. In addition, Wolfe et al. have opened the door for future trials of thymectomy in MG to address such issues as the benefits vs. risks of performing the operation via the traditional transsternal vs. alternative non–sternal splitting approaches.

Benn E. Smith, MD, is an associate professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz. and is the director of the sensory laboratory there. Dr. Smith is on the Editorial Advisory Board of Clinical Neurology News.

End to an 80-year controversy

These findings from Wolfe et al. end an 80-year controversy over the effectiveness of thymectomy for patients with myasthenia gravis.

Perhaps the most important benefit for patients is that even when they require prednisone following the surgery, they can take lower doses, endure fewer glucocorticoid-related symptoms, and experience less distress from those symptoms than patients who don’t undergo thymectomy.

Unfortunately, the study results cannot offer further clarity regarding patient selection for thymectomy. The patient population in this trial was so small that subgroup analyses couldn’t allow conclusions regarding the relative effectiveness of thymectomy in men vs. women or younger vs. older patients.

Allan H. Ropper, MD, is in the department of neurology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. His financial disclosures are available at NEJM.org. Dr. Ropper made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Wolfe’s report (N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1607953).

Landmark trial establishes effectiveness of thymectomy in myasthenia gravis

One of the many challenges of treating patients with myasthenia gravis (MG) is the fluctuating nature of symptoms and deficits. The neurologist or neuromuscular specialist must decide whether the disease is truly worsening, whether the patient is experiencing more pronounced symptoms from intercurrent illness or the effects of a medication known to affect the neuromuscular junction adversely, or whether the patient is concerned that there might be worsening disease when all objective measures indicate stability. These factors make treatment decisions more difficult in MG than for many other neuromuscular disorders.

Similarly, researchers considering a trial investigating treatment efficacy in MG face the complex issues of disease fluctuation in cohorts of individuals with the disease, varying levels of corticosteroid and immunosuppressant doses in different MG patients, and thorny ethical dilemmas in providing accepted therapies but not withholding effective treatments from those in need.

Dr. Wolfe and his colleagues demonstrate that they have navigated these treacherous waters. They have succeeded in completing a landmark controlled clinical trial which establishes the effectiveness of transsternal thymectomy with adjuvant corticosteroid therapy in nonthymomatous MG vs. oral prednisone without surgery. While this international 36-center trial managed to recruit 126 subjects over a 6-year period, using sound inclusion and exclusion criteria and a meticulous trial design, the number of patients is not sufficient to allow for as robust a subgroup analysis for age, gender, and a variety of clinical variables reflecting severity of disease as would have been hoped for by the MG community.

Nonetheless, this paper sets the use of thymectomy in nonthymomatous MG on firmer ground going forward. The investigators will doubtless be presenting further data from the trial, including clinical-pathologic correlates and other relevant novel observations. In addition, Wolfe et al. have opened the door for future trials of thymectomy in MG to address such issues as the benefits vs. risks of performing the operation via the traditional transsternal vs. alternative non–sternal splitting approaches.

Benn E. Smith, MD, is an associate professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz. and is the director of the sensory laboratory there. Dr. Smith is on the Editorial Advisory Board of Clinical Neurology News.

End to an 80-year controversy

These findings from Wolfe et al. end an 80-year controversy over the effectiveness of thymectomy for patients with myasthenia gravis.

Perhaps the most important benefit for patients is that even when they require prednisone following the surgery, they can take lower doses, endure fewer glucocorticoid-related symptoms, and experience less distress from those symptoms than patients who don’t undergo thymectomy.

Unfortunately, the study results cannot offer further clarity regarding patient selection for thymectomy. The patient population in this trial was so small that subgroup analyses couldn’t allow conclusions regarding the relative effectiveness of thymectomy in men vs. women or younger vs. older patients.

Allan H. Ropper, MD, is in the department of neurology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. His financial disclosures are available at NEJM.org. Dr. Ropper made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Wolfe’s report (N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1607953).

Landmark trial establishes effectiveness of thymectomy in myasthenia gravis

One of the many challenges of treating patients with myasthenia gravis (MG) is the fluctuating nature of symptoms and deficits. The neurologist or neuromuscular specialist must decide whether the disease is truly worsening, whether the patient is experiencing more pronounced symptoms from intercurrent illness or the effects of a medication known to affect the neuromuscular junction adversely, or whether the patient is concerned that there might be worsening disease when all objective measures indicate stability. These factors make treatment decisions more difficult in MG than for many other neuromuscular disorders.

Similarly, researchers considering a trial investigating treatment efficacy in MG face the complex issues of disease fluctuation in cohorts of individuals with the disease, varying levels of corticosteroid and immunosuppressant doses in different MG patients, and thorny ethical dilemmas in providing accepted therapies but not withholding effective treatments from those in need.

Dr. Wolfe and his colleagues demonstrate that they have navigated these treacherous waters. They have succeeded in completing a landmark controlled clinical trial which establishes the effectiveness of transsternal thymectomy with adjuvant corticosteroid therapy in nonthymomatous MG vs. oral prednisone without surgery. While this international 36-center trial managed to recruit 126 subjects over a 6-year period, using sound inclusion and exclusion criteria and a meticulous trial design, the number of patients is not sufficient to allow for as robust a subgroup analysis for age, gender, and a variety of clinical variables reflecting severity of disease as would have been hoped for by the MG community.

Nonetheless, this paper sets the use of thymectomy in nonthymomatous MG on firmer ground going forward. The investigators will doubtless be presenting further data from the trial, including clinical-pathologic correlates and other relevant novel observations. In addition, Wolfe et al. have opened the door for future trials of thymectomy in MG to address such issues as the benefits vs. risks of performing the operation via the traditional transsternal vs. alternative non–sternal splitting approaches.

Benn E. Smith, MD, is an associate professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz. and is the director of the sensory laboratory there. Dr. Smith is on the Editorial Advisory Board of Clinical Neurology News.

End to an 80-year controversy

These findings from Wolfe et al. end an 80-year controversy over the effectiveness of thymectomy for patients with myasthenia gravis.

Perhaps the most important benefit for patients is that even when they require prednisone following the surgery, they can take lower doses, endure fewer glucocorticoid-related symptoms, and experience less distress from those symptoms than patients who don’t undergo thymectomy.

Unfortunately, the study results cannot offer further clarity regarding patient selection for thymectomy. The patient population in this trial was so small that subgroup analyses couldn’t allow conclusions regarding the relative effectiveness of thymectomy in men vs. women or younger vs. older patients.

Allan H. Ropper, MD, is in the department of neurology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. His financial disclosures are available at NEJM.org. Dr. Ropper made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Wolfe’s report (N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1607953).

Thymectomy improved 3-year clinical outcomes and proved superior to medical therapy for mild to severe nonthymomatous myasthenia gravis, according to a report published online Aug. 11 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Compared with standard prednisone therapy, thymectomy plus prednisone decreased the number and severity of symptoms, allowed the lowering of steroid doses, decreased the number and length of hospitalizations for disease exacerbations, reduced the need for immunosuppressive agents, and improved health-related quality of life in an international, randomized clinical trial, said Gil I. Wolfe, MD, of the department of neurology, State University of New York at Buffalo and his associates.

Until now, thymectomy was known to be beneficial in some cases of myasthenia gravis “but with widely varying rates of clinical improvement or remission.” And the success of immunotherapy has raised the question of whether an invasive surgery is necessary. Data from randomized, controlled studies have been sparse.

Moreover, thymectomy rarely causes adverse effects, but “the procedure can cost up to $80,000 and can be associated with operative complications that need to be weighed against benefits.” In comparison, medical therapy with glucocorticoids and other immunosuppressive agents is less invasive but is definitely associated with adverse events, including some that are life threatening, and negatively impacts quality of life, the investigators said.

To address the lack of randomized controlled trial data, they assessed 3-year outcomes in 126 patients treated at 67 medical centers in 18 countries during a 6-year period. The study participants were aged 18-65 years, had a disease duration of less than 5 years at enrollment (median duration, 1 year), and had class II (mild generalized disease) to class IV (severe generalized disease) myasthenia gravis. These patients were randomly assigned to undergo thymectomy and receive standard prednisone therapy (66 participants) or to receive standard prednisone alone (60 participants).

Thymectomy was performed using a median sternotomy “with the goal of an en bloc resection of all mediastinal tissue that could anatomically contain gross or microscopic thymus.”

At follow-up, time-weighted average scores on the Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis scale were significantly lower by 2.85 points, indicating improved clinical status, in the thymectomy group than in the control group. Time-weighted average prednisone dose also was significantly lower, at an average alternate-day dose of 44 mg in the thymectomy group and 60 mg in the control group, Dr. Wolfe and his associates said (N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602489).

On a measure of treatment-related complications, scores favored thymectomy with regard to the number of patients with symptoms, the total number of symptoms, and the distress level related to symptoms throughout the study period. Fewer patients in the thymectomy group required hospitalization for exacerbations of myasthenia gravis (9% vs. 37%), and the mean cumulative number of hospital days was lower with thymectomy (8.4 vs. 19.2).

In addition, scores on the Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living scale favored thymectomy (2.24 vs. 3.41). Fewer patients in the thymectomy group required azathioprine (17% vs. 0.48%). And the percentage of patients who reported having minimal manifestations of the disease at 3 years was significantly higher with thymectomy (67%) than with prednisone alone (47%).

This study was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Muscular Dystrophy Association, and the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America and received no commercial support. Dr. Wolfe reported ties to Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Alpha Cancer Technologies, Argenx, Baxalta, CSL Behring, Grifols, and UCB, and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Thymectomy improved 3-year clinical outcomes and proved superior to medical therapy for mild to severe nonthymomatous myasthenia gravis, according to a report published online Aug. 11 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Compared with standard prednisone therapy, thymectomy plus prednisone decreased the number and severity of symptoms, allowed the lowering of steroid doses, decreased the number and length of hospitalizations for disease exacerbations, reduced the need for immunosuppressive agents, and improved health-related quality of life in an international, randomized clinical trial, said Gil I. Wolfe, MD, of the department of neurology, State University of New York at Buffalo and his associates.

Until now, thymectomy was known to be beneficial in some cases of myasthenia gravis “but with widely varying rates of clinical improvement or remission.” And the success of immunotherapy has raised the question of whether an invasive surgery is necessary. Data from randomized, controlled studies have been sparse.

Moreover, thymectomy rarely causes adverse effects, but “the procedure can cost up to $80,000 and can be associated with operative complications that need to be weighed against benefits.” In comparison, medical therapy with glucocorticoids and other immunosuppressive agents is less invasive but is definitely associated with adverse events, including some that are life threatening, and negatively impacts quality of life, the investigators said.

To address the lack of randomized controlled trial data, they assessed 3-year outcomes in 126 patients treated at 67 medical centers in 18 countries during a 6-year period. The study participants were aged 18-65 years, had a disease duration of less than 5 years at enrollment (median duration, 1 year), and had class II (mild generalized disease) to class IV (severe generalized disease) myasthenia gravis. These patients were randomly assigned to undergo thymectomy and receive standard prednisone therapy (66 participants) or to receive standard prednisone alone (60 participants).

Thymectomy was performed using a median sternotomy “with the goal of an en bloc resection of all mediastinal tissue that could anatomically contain gross or microscopic thymus.”

At follow-up, time-weighted average scores on the Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis scale were significantly lower by 2.85 points, indicating improved clinical status, in the thymectomy group than in the control group. Time-weighted average prednisone dose also was significantly lower, at an average alternate-day dose of 44 mg in the thymectomy group and 60 mg in the control group, Dr. Wolfe and his associates said (N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602489).

On a measure of treatment-related complications, scores favored thymectomy with regard to the number of patients with symptoms, the total number of symptoms, and the distress level related to symptoms throughout the study period. Fewer patients in the thymectomy group required hospitalization for exacerbations of myasthenia gravis (9% vs. 37%), and the mean cumulative number of hospital days was lower with thymectomy (8.4 vs. 19.2).

In addition, scores on the Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living scale favored thymectomy (2.24 vs. 3.41). Fewer patients in the thymectomy group required azathioprine (17% vs. 0.48%). And the percentage of patients who reported having minimal manifestations of the disease at 3 years was significantly higher with thymectomy (67%) than with prednisone alone (47%).

This study was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Muscular Dystrophy Association, and the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America and received no commercial support. Dr. Wolfe reported ties to Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Alpha Cancer Technologies, Argenx, Baxalta, CSL Behring, Grifols, and UCB, and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Thymectomy improved 3-year clinical outcomes and was superior to medical therapy for mild to severe nonthymomatous myasthenia gravis.

Major finding: Scores on the Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis scale were significantly lower by 2.85 points, indicating improved clinical status, in the thymectomy group than in the control group.

Data source: An international, randomized, medication-controlled trial involving 126 patients at 67 medical centers.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Muscular Dystrophy Association, and the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America and received no commercial support. Dr. Wolfe reported ties to Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Alpha Cancer Technologies, Argenx, Baxalta, CSL Behring, Grifols, and UCB, and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Choosing the transaxillary or supraclavicular approach for neurogenic TOS

The transaxillary approach has its advantages

I began my vascular fellowship at UCLA on July 1, 1986 – the previous day I was a chief surgery resident running a VA general surgery service where my last emergency case that evening was an abdominal peroneal resection for perforated rectal cancer! I was delighted to begin my fellowship, and learned that on Tuesdays I would be operating with Herb Machleder, MD – the expert on thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) who perfected the transaxillary approach. I remembered his service from when I was an intern holding the patient arm up by cradling it my arms while he and the fellow removed the rib and identified each structure—subclavius tendon, subclavian vein, anterior scalene muscle, subclavian artery brachial plexus and any other abnormal band or structure present. The rib was removed in entirety to ensure an excellent outcome and to prevent any possibility of recurrence from scarring to the brachial plexus to a portion of retained rib. Dr. Machleder then went on to design a rib retractor to better support the arm and afford superb visibility.

As I began my career, I included transaxillary first rib resection as part of my practice for all forms of TOS, except when we needed to replace the subclavian artery because of an aneurysm or thrombosis. In those instances, we would employ the supraclavicular approach with an infraclavicular incision when necessary. In my 5 years as chief of the division of vascular surgery at UCLA (1998-2003), we saw many patients with TOS thanks to the legacy and practice of Dr. Machleder. We performed approximately 300 such operations between three of us and saw probably three to four times as many patients in clinic who did not need surgery to treat their TOS or other conditions.

When I arrived at Johns Hopkins as department chair in 2003, a robust thoracic outlet program did not exist there, so we began one. By the time I left in 2014, we were seeing 5-7 new patients per week and were operating on 125 per year, of which half were neurogenic. Ying Wei Lum, MD, and Maggie Arnold, MD, are continuing that practice at Johns Hopkins today.

The most important point about the “approach” for neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome is whether or not you should operate. At Johns Hopkins, we only operated on about a third of those who presented to us with neurogenic symptoms, as 60%-70% will get better with a thoracic outlet–focused physical therapy regimen. We developed a protocol for this, which we actually handed to the patients as the prescription as they came from all over for our opinion on their conditions. We are doing the same at UC Davis.

We have published a great deal about patients who do not do as well with the surgical approach to neurogenic TOS. These patients include those over the age of 40 and those who have had symptoms for more than 10 years, as they tend to be quite debilitated and never quite recover fully from the operation.1 A scalene block with lidocaine can predict success in patients with the operation, and I use it in older patients or those with multiple complaints.2 At UC Davis, our pain service can perform the block with ultrasound guidance, which is easier for the patient.

Other patients who do not do well with the surgical approach to neurogenic TOS include those with other comorbidities such as cervical spine disease and shoulder abnormalities or injuries, as well as those with a severe dependence on pain medication due to such medical issues as complex pain syndrome or myofasciitis caused by comorbid diseases.3

These patients cannot adequately perform the requisite postoperative physical therapy to completely improve, and some can take up to a year to get range of motion and strength back. We also found that patients who smoke get recurrent disease due to scarring.

At both UC Davis and Johns Hopkins, we created a YouTube video for patients to educate them on the procedure and expected results. The need for postoperative physical therapy should be emphasized in all patients. Some require more therapy than others, which means taking time off from work to focus on the therapy and not performing other activities until the pain and discomfort are gone and strength is back. In another study we performed, we found that if patients did improve the first year, they were more likely to stay symptom free over many years.

While we were doing a transaxillary rib resection case at UC Davis, my team, which includes my partner Misty Humphries, MD, created a list of the top 10 reasons that the transaxillary approach is preferred for neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome:

1. The scar is less noticeable and painful for the patient than the scar in the supraclavicular fossa, allowing the patient to start physical therapy 2 weeks after surgery.

2. The Machleder retractor makes visualization easy and stable, and allows all members of the team to see the anatomy.

3. The brachial plexus does not have to be retracted and is out of harm’s way, so no temporary palsies are seen in the postoperative period.

4. The subclavius tendon can be seen in entirety and the anterior portion of the rib is easy to completely remove.

5. The subclavian vein can be seen in entirety and defines the anterior portion of the dissection.

6. Once the anterior scalenectomy muscle is cut, the subclavian artery naturally retracts cephalad and is no longer near the rib when it is to be removed.

7. The posterior portion of the rib can be completely removed by readjusting the retraction and a second cut can be done safely with either the rib cutter or the first rib rongeur. It is essential to remove the rib posteriorly behind the nerve root so the arm is adducted and the nerve does not come in contact with the remaining rib, as we feel that leads to increased recurrences.

8. Two operating surgeons can address the rib from their side of the table and completely resect the rib, depending on the patient’s soft bony anatomy, by angling the instruments from either side.

9. Even large muscular or obese patients can be safely approached from the axilla utilizing the Machleder retractor and a lighted retractor.

10. The transaxillary approach can be taught through the teaching video we have made and through the ability for both surgeons to see because of the retractor.

Some of my favorite memories as a vascular surgeon were operating on Tuesdays with Dr. Machleder – similar to Tuesdays with Morrie.4 Not only did we remove ribs safely and completely, but he also taught me philosophy of surgery and of life. I hope I am doing the same with my team as we remove ribs now on Thursday – “Thursdays with Freischlag” – at UC Davis.

Dr. Freischlag is vice chancellor for human health sciences and dean of the school of medicine at the University of California, Davis. She had no relevant disclosures.

References

1. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55(5):1370-5.

2. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2009;11(2):176-83.

3. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56(4):1061-7.

Use a supraclavicular approach: My way is best!

The best sense we have of the pathophysiology of neurogenic (NTOS) is that the scalene triangle is “too tight” with regard to what it contains – the brachial plexus and the subclavian artery. Whether this is due to the triangle being too small or the nerves being “too large” (inflammation) is unknown. Supporting the former theory are observations that the anterior scalene muscle is frequently inflamed and/or chronically injured.1 but others have suggested that the first rib is abnormally located or elevated.2 In addition, some have suggested that inflammatory tissue surrounding the plexus contributes to the process, at least for chronic cases.3

Given the fact that at least two of the three parts of the triangle, plus tissue surrounding the plexus itself, have all been implicated in the disease process, why not choose an approach that allows correction of all potential causes? The transaxillary approach has been used for decades for this condition, but can only decompress the base of the triangle (first rib) and, to varying degrees, only part of the anterior scalene. It does not allow thorough exploration of the nerves. The supraclavicular approach (and the supraclavicular half of paraclavicular excision) addresses these concerns. First, the anterior scalene muscle is essentially entirely removed. With proper technique it is completely visible from the scalene tubercle to its origin at the spine. This approach also allows removal of all muscular and associated tissue medially, completely clearing the parietal pleura at the apex of the lung, at least theoretically reducing the chances of scar tissue arising from residual tissue here.

Second, although no research has yet implicated the middle scalene (scalenus medius, which does not translate perfectly), many patients have impressively bulky musculature at this site. The middle scalene is also completely resected while approaching the first rib; perhaps removing this as well contributes to the excellent results we see today.

Third, the entire portion of the rib involved in NTOS (and the entire rib altogether if a paraclavicular approach is used) is very easily removed using this approach, as are any cervical ribs or Roos bands. Everything is seen, and everything can be evaluated and resected. Finally, many consider full neurolysis of the brachial plexus in this area an important part of the procedure. This is based on low-grade evidence only,3 but in the author’s experience, the incidence of improvement or cure seems to be higher, and recurrence rates lower, than with less-complete operations.

Parenthetically, related to this issue is that of visualization and education. The primary goal is ensuring the best outcome for the patient. Visualization is, by far, best if a supraclavicular approach is used. This is beneficial clinically by ensuring the most complete decompression of the nerves and avoidance of complications, but also is extremely helpful with regard to educating residents and fellows, learning the anatomy, identifying aberrant structures, and so on. Even with the best techniques (including a head- or retractor-mounted camera), no one can see what’s going on during a transaxillary approach except for the operator.

If the supraclavicular approach allows better access to and removal of all the potentially involved components causing NTOS, why doesn’t everyone use it? One answer is that the potential complication rate may be higher. Both the long thoracic and phrenic nerves are very much more at risk using this approach than using the transaxillary approach, and, on the left side, the risk of thoracic duct injury is higher. It must be conceded that published results, in general, do not show significant differences in outcomes between the two approaches.4 However, many would interpret this as a type II error, combined with the “fuzziness” of diagnosis and evaluation of outcomes this field has labored under. However, the opposite interpretation should be considered – there are no definitive data showing any higher complication rate between the two approaches. This debate likely is answerable in the same fashion as many other such debates in our field – someone who is good at the transaxillary approach will do a better job than someone who is not, and someone who is good at the supraclavicular approach will do a better job than someone who is not.

Is a prospective trial indicated? In theory, yes. However, the relative rarity of this condition, the fact that most surgeons follow almost exclusively one or the other technique, and the categorical nature of the outcome variable make such a trial relatively impractical. Pending this, the best suggestion is obviously to pick the best TOS surgeon you can find and have him or her fix the problem in the way they are most experienced!

Dr. Illig is professor of surgery and director, division of vascular surgery, and associate chair, faculty development and mentoring, University of South Florida, Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa, Fla. He had no relevant disclosures.

References

2. Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. London: Springer 2013; 319-21.

The transaxillary approach has its advantages

I began my vascular fellowship at UCLA on July 1, 1986 – the previous day I was a chief surgery resident running a VA general surgery service where my last emergency case that evening was an abdominal peroneal resection for perforated rectal cancer! I was delighted to begin my fellowship, and learned that on Tuesdays I would be operating with Herb Machleder, MD – the expert on thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) who perfected the transaxillary approach. I remembered his service from when I was an intern holding the patient arm up by cradling it my arms while he and the fellow removed the rib and identified each structure—subclavius tendon, subclavian vein, anterior scalene muscle, subclavian artery brachial plexus and any other abnormal band or structure present. The rib was removed in entirety to ensure an excellent outcome and to prevent any possibility of recurrence from scarring to the brachial plexus to a portion of retained rib. Dr. Machleder then went on to design a rib retractor to better support the arm and afford superb visibility.

As I began my career, I included transaxillary first rib resection as part of my practice for all forms of TOS, except when we needed to replace the subclavian artery because of an aneurysm or thrombosis. In those instances, we would employ the supraclavicular approach with an infraclavicular incision when necessary. In my 5 years as chief of the division of vascular surgery at UCLA (1998-2003), we saw many patients with TOS thanks to the legacy and practice of Dr. Machleder. We performed approximately 300 such operations between three of us and saw probably three to four times as many patients in clinic who did not need surgery to treat their TOS or other conditions.

When I arrived at Johns Hopkins as department chair in 2003, a robust thoracic outlet program did not exist there, so we began one. By the time I left in 2014, we were seeing 5-7 new patients per week and were operating on 125 per year, of which half were neurogenic. Ying Wei Lum, MD, and Maggie Arnold, MD, are continuing that practice at Johns Hopkins today.

The most important point about the “approach” for neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome is whether or not you should operate. At Johns Hopkins, we only operated on about a third of those who presented to us with neurogenic symptoms, as 60%-70% will get better with a thoracic outlet–focused physical therapy regimen. We developed a protocol for this, which we actually handed to the patients as the prescription as they came from all over for our opinion on their conditions. We are doing the same at UC Davis.

We have published a great deal about patients who do not do as well with the surgical approach to neurogenic TOS. These patients include those over the age of 40 and those who have had symptoms for more than 10 years, as they tend to be quite debilitated and never quite recover fully from the operation.1 A scalene block with lidocaine can predict success in patients with the operation, and I use it in older patients or those with multiple complaints.2 At UC Davis, our pain service can perform the block with ultrasound guidance, which is easier for the patient.

Other patients who do not do well with the surgical approach to neurogenic TOS include those with other comorbidities such as cervical spine disease and shoulder abnormalities or injuries, as well as those with a severe dependence on pain medication due to such medical issues as complex pain syndrome or myofasciitis caused by comorbid diseases.3

These patients cannot adequately perform the requisite postoperative physical therapy to completely improve, and some can take up to a year to get range of motion and strength back. We also found that patients who smoke get recurrent disease due to scarring.

At both UC Davis and Johns Hopkins, we created a YouTube video for patients to educate them on the procedure and expected results. The need for postoperative physical therapy should be emphasized in all patients. Some require more therapy than others, which means taking time off from work to focus on the therapy and not performing other activities until the pain and discomfort are gone and strength is back. In another study we performed, we found that if patients did improve the first year, they were more likely to stay symptom free over many years.

While we were doing a transaxillary rib resection case at UC Davis, my team, which includes my partner Misty Humphries, MD, created a list of the top 10 reasons that the transaxillary approach is preferred for neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome:

1. The scar is less noticeable and painful for the patient than the scar in the supraclavicular fossa, allowing the patient to start physical therapy 2 weeks after surgery.

2. The Machleder retractor makes visualization easy and stable, and allows all members of the team to see the anatomy.

3. The brachial plexus does not have to be retracted and is out of harm’s way, so no temporary palsies are seen in the postoperative period.

4. The subclavius tendon can be seen in entirety and the anterior portion of the rib is easy to completely remove.

5. The subclavian vein can be seen in entirety and defines the anterior portion of the dissection.

6. Once the anterior scalenectomy muscle is cut, the subclavian artery naturally retracts cephalad and is no longer near the rib when it is to be removed.

7. The posterior portion of the rib can be completely removed by readjusting the retraction and a second cut can be done safely with either the rib cutter or the first rib rongeur. It is essential to remove the rib posteriorly behind the nerve root so the arm is adducted and the nerve does not come in contact with the remaining rib, as we feel that leads to increased recurrences.

8. Two operating surgeons can address the rib from their side of the table and completely resect the rib, depending on the patient’s soft bony anatomy, by angling the instruments from either side.

9. Even large muscular or obese patients can be safely approached from the axilla utilizing the Machleder retractor and a lighted retractor.

10. The transaxillary approach can be taught through the teaching video we have made and through the ability for both surgeons to see because of the retractor.

Some of my favorite memories as a vascular surgeon were operating on Tuesdays with Dr. Machleder – similar to Tuesdays with Morrie.4 Not only did we remove ribs safely and completely, but he also taught me philosophy of surgery and of life. I hope I am doing the same with my team as we remove ribs now on Thursday – “Thursdays with Freischlag” – at UC Davis.

Dr. Freischlag is vice chancellor for human health sciences and dean of the school of medicine at the University of California, Davis. She had no relevant disclosures.

References

1. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55(5):1370-5.

2. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2009;11(2):176-83.

3. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56(4):1061-7.

Use a supraclavicular approach: My way is best!

The best sense we have of the pathophysiology of neurogenic (NTOS) is that the scalene triangle is “too tight” with regard to what it contains – the brachial plexus and the subclavian artery. Whether this is due to the triangle being too small or the nerves being “too large” (inflammation) is unknown. Supporting the former theory are observations that the anterior scalene muscle is frequently inflamed and/or chronically injured.1 but others have suggested that the first rib is abnormally located or elevated.2 In addition, some have suggested that inflammatory tissue surrounding the plexus contributes to the process, at least for chronic cases.3

Given the fact that at least two of the three parts of the triangle, plus tissue surrounding the plexus itself, have all been implicated in the disease process, why not choose an approach that allows correction of all potential causes? The transaxillary approach has been used for decades for this condition, but can only decompress the base of the triangle (first rib) and, to varying degrees, only part of the anterior scalene. It does not allow thorough exploration of the nerves. The supraclavicular approach (and the supraclavicular half of paraclavicular excision) addresses these concerns. First, the anterior scalene muscle is essentially entirely removed. With proper technique it is completely visible from the scalene tubercle to its origin at the spine. This approach also allows removal of all muscular and associated tissue medially, completely clearing the parietal pleura at the apex of the lung, at least theoretically reducing the chances of scar tissue arising from residual tissue here.

Second, although no research has yet implicated the middle scalene (scalenus medius, which does not translate perfectly), many patients have impressively bulky musculature at this site. The middle scalene is also completely resected while approaching the first rib; perhaps removing this as well contributes to the excellent results we see today.

Third, the entire portion of the rib involved in NTOS (and the entire rib altogether if a paraclavicular approach is used) is very easily removed using this approach, as are any cervical ribs or Roos bands. Everything is seen, and everything can be evaluated and resected. Finally, many consider full neurolysis of the brachial plexus in this area an important part of the procedure. This is based on low-grade evidence only,3 but in the author’s experience, the incidence of improvement or cure seems to be higher, and recurrence rates lower, than with less-complete operations.

Parenthetically, related to this issue is that of visualization and education. The primary goal is ensuring the best outcome for the patient. Visualization is, by far, best if a supraclavicular approach is used. This is beneficial clinically by ensuring the most complete decompression of the nerves and avoidance of complications, but also is extremely helpful with regard to educating residents and fellows, learning the anatomy, identifying aberrant structures, and so on. Even with the best techniques (including a head- or retractor-mounted camera), no one can see what’s going on during a transaxillary approach except for the operator.

If the supraclavicular approach allows better access to and removal of all the potentially involved components causing NTOS, why doesn’t everyone use it? One answer is that the potential complication rate may be higher. Both the long thoracic and phrenic nerves are very much more at risk using this approach than using the transaxillary approach, and, on the left side, the risk of thoracic duct injury is higher. It must be conceded that published results, in general, do not show significant differences in outcomes between the two approaches.4 However, many would interpret this as a type II error, combined with the “fuzziness” of diagnosis and evaluation of outcomes this field has labored under. However, the opposite interpretation should be considered – there are no definitive data showing any higher complication rate between the two approaches. This debate likely is answerable in the same fashion as many other such debates in our field – someone who is good at the transaxillary approach will do a better job than someone who is not, and someone who is good at the supraclavicular approach will do a better job than someone who is not.

Is a prospective trial indicated? In theory, yes. However, the relative rarity of this condition, the fact that most surgeons follow almost exclusively one or the other technique, and the categorical nature of the outcome variable make such a trial relatively impractical. Pending this, the best suggestion is obviously to pick the best TOS surgeon you can find and have him or her fix the problem in the way they are most experienced!

Dr. Illig is professor of surgery and director, division of vascular surgery, and associate chair, faculty development and mentoring, University of South Florida, Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa, Fla. He had no relevant disclosures.

References

2. Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. London: Springer 2013; 319-21.

The transaxillary approach has its advantages

I began my vascular fellowship at UCLA on July 1, 1986 – the previous day I was a chief surgery resident running a VA general surgery service where my last emergency case that evening was an abdominal peroneal resection for perforated rectal cancer! I was delighted to begin my fellowship, and learned that on Tuesdays I would be operating with Herb Machleder, MD – the expert on thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) who perfected the transaxillary approach. I remembered his service from when I was an intern holding the patient arm up by cradling it my arms while he and the fellow removed the rib and identified each structure—subclavius tendon, subclavian vein, anterior scalene muscle, subclavian artery brachial plexus and any other abnormal band or structure present. The rib was removed in entirety to ensure an excellent outcome and to prevent any possibility of recurrence from scarring to the brachial plexus to a portion of retained rib. Dr. Machleder then went on to design a rib retractor to better support the arm and afford superb visibility.

As I began my career, I included transaxillary first rib resection as part of my practice for all forms of TOS, except when we needed to replace the subclavian artery because of an aneurysm or thrombosis. In those instances, we would employ the supraclavicular approach with an infraclavicular incision when necessary. In my 5 years as chief of the division of vascular surgery at UCLA (1998-2003), we saw many patients with TOS thanks to the legacy and practice of Dr. Machleder. We performed approximately 300 such operations between three of us and saw probably three to four times as many patients in clinic who did not need surgery to treat their TOS or other conditions.

When I arrived at Johns Hopkins as department chair in 2003, a robust thoracic outlet program did not exist there, so we began one. By the time I left in 2014, we were seeing 5-7 new patients per week and were operating on 125 per year, of which half were neurogenic. Ying Wei Lum, MD, and Maggie Arnold, MD, are continuing that practice at Johns Hopkins today.

The most important point about the “approach” for neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome is whether or not you should operate. At Johns Hopkins, we only operated on about a third of those who presented to us with neurogenic symptoms, as 60%-70% will get better with a thoracic outlet–focused physical therapy regimen. We developed a protocol for this, which we actually handed to the patients as the prescription as they came from all over for our opinion on their conditions. We are doing the same at UC Davis.

We have published a great deal about patients who do not do as well with the surgical approach to neurogenic TOS. These patients include those over the age of 40 and those who have had symptoms for more than 10 years, as they tend to be quite debilitated and never quite recover fully from the operation.1 A scalene block with lidocaine can predict success in patients with the operation, and I use it in older patients or those with multiple complaints.2 At UC Davis, our pain service can perform the block with ultrasound guidance, which is easier for the patient.

Other patients who do not do well with the surgical approach to neurogenic TOS include those with other comorbidities such as cervical spine disease and shoulder abnormalities or injuries, as well as those with a severe dependence on pain medication due to such medical issues as complex pain syndrome or myofasciitis caused by comorbid diseases.3

These patients cannot adequately perform the requisite postoperative physical therapy to completely improve, and some can take up to a year to get range of motion and strength back. We also found that patients who smoke get recurrent disease due to scarring.

At both UC Davis and Johns Hopkins, we created a YouTube video for patients to educate them on the procedure and expected results. The need for postoperative physical therapy should be emphasized in all patients. Some require more therapy than others, which means taking time off from work to focus on the therapy and not performing other activities until the pain and discomfort are gone and strength is back. In another study we performed, we found that if patients did improve the first year, they were more likely to stay symptom free over many years.

While we were doing a transaxillary rib resection case at UC Davis, my team, which includes my partner Misty Humphries, MD, created a list of the top 10 reasons that the transaxillary approach is preferred for neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome:

1. The scar is less noticeable and painful for the patient than the scar in the supraclavicular fossa, allowing the patient to start physical therapy 2 weeks after surgery.

2. The Machleder retractor makes visualization easy and stable, and allows all members of the team to see the anatomy.

3. The brachial plexus does not have to be retracted and is out of harm’s way, so no temporary palsies are seen in the postoperative period.

4. The subclavius tendon can be seen in entirety and the anterior portion of the rib is easy to completely remove.

5. The subclavian vein can be seen in entirety and defines the anterior portion of the dissection.

6. Once the anterior scalenectomy muscle is cut, the subclavian artery naturally retracts cephalad and is no longer near the rib when it is to be removed.

7. The posterior portion of the rib can be completely removed by readjusting the retraction and a second cut can be done safely with either the rib cutter or the first rib rongeur. It is essential to remove the rib posteriorly behind the nerve root so the arm is adducted and the nerve does not come in contact with the remaining rib, as we feel that leads to increased recurrences.

8. Two operating surgeons can address the rib from their side of the table and completely resect the rib, depending on the patient’s soft bony anatomy, by angling the instruments from either side.

9. Even large muscular or obese patients can be safely approached from the axilla utilizing the Machleder retractor and a lighted retractor.

10. The transaxillary approach can be taught through the teaching video we have made and through the ability for both surgeons to see because of the retractor.

Some of my favorite memories as a vascular surgeon were operating on Tuesdays with Dr. Machleder – similar to Tuesdays with Morrie.4 Not only did we remove ribs safely and completely, but he also taught me philosophy of surgery and of life. I hope I am doing the same with my team as we remove ribs now on Thursday – “Thursdays with Freischlag” – at UC Davis.

Dr. Freischlag is vice chancellor for human health sciences and dean of the school of medicine at the University of California, Davis. She had no relevant disclosures.

References

1. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55(5):1370-5.

2. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2009;11(2):176-83.

3. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56(4):1061-7.

Use a supraclavicular approach: My way is best!

The best sense we have of the pathophysiology of neurogenic (NTOS) is that the scalene triangle is “too tight” with regard to what it contains – the brachial plexus and the subclavian artery. Whether this is due to the triangle being too small or the nerves being “too large” (inflammation) is unknown. Supporting the former theory are observations that the anterior scalene muscle is frequently inflamed and/or chronically injured.1 but others have suggested that the first rib is abnormally located or elevated.2 In addition, some have suggested that inflammatory tissue surrounding the plexus contributes to the process, at least for chronic cases.3

Given the fact that at least two of the three parts of the triangle, plus tissue surrounding the plexus itself, have all been implicated in the disease process, why not choose an approach that allows correction of all potential causes? The transaxillary approach has been used for decades for this condition, but can only decompress the base of the triangle (first rib) and, to varying degrees, only part of the anterior scalene. It does not allow thorough exploration of the nerves. The supraclavicular approach (and the supraclavicular half of paraclavicular excision) addresses these concerns. First, the anterior scalene muscle is essentially entirely removed. With proper technique it is completely visible from the scalene tubercle to its origin at the spine. This approach also allows removal of all muscular and associated tissue medially, completely clearing the parietal pleura at the apex of the lung, at least theoretically reducing the chances of scar tissue arising from residual tissue here.

Second, although no research has yet implicated the middle scalene (scalenus medius, which does not translate perfectly), many patients have impressively bulky musculature at this site. The middle scalene is also completely resected while approaching the first rib; perhaps removing this as well contributes to the excellent results we see today.

Third, the entire portion of the rib involved in NTOS (and the entire rib altogether if a paraclavicular approach is used) is very easily removed using this approach, as are any cervical ribs or Roos bands. Everything is seen, and everything can be evaluated and resected. Finally, many consider full neurolysis of the brachial plexus in this area an important part of the procedure. This is based on low-grade evidence only,3 but in the author’s experience, the incidence of improvement or cure seems to be higher, and recurrence rates lower, than with less-complete operations.

Parenthetically, related to this issue is that of visualization and education. The primary goal is ensuring the best outcome for the patient. Visualization is, by far, best if a supraclavicular approach is used. This is beneficial clinically by ensuring the most complete decompression of the nerves and avoidance of complications, but also is extremely helpful with regard to educating residents and fellows, learning the anatomy, identifying aberrant structures, and so on. Even with the best techniques (including a head- or retractor-mounted camera), no one can see what’s going on during a transaxillary approach except for the operator.

If the supraclavicular approach allows better access to and removal of all the potentially involved components causing NTOS, why doesn’t everyone use it? One answer is that the potential complication rate may be higher. Both the long thoracic and phrenic nerves are very much more at risk using this approach than using the transaxillary approach, and, on the left side, the risk of thoracic duct injury is higher. It must be conceded that published results, in general, do not show significant differences in outcomes between the two approaches.4 However, many would interpret this as a type II error, combined with the “fuzziness” of diagnosis and evaluation of outcomes this field has labored under. However, the opposite interpretation should be considered – there are no definitive data showing any higher complication rate between the two approaches. This debate likely is answerable in the same fashion as many other such debates in our field – someone who is good at the transaxillary approach will do a better job than someone who is not, and someone who is good at the supraclavicular approach will do a better job than someone who is not.

Is a prospective trial indicated? In theory, yes. However, the relative rarity of this condition, the fact that most surgeons follow almost exclusively one or the other technique, and the categorical nature of the outcome variable make such a trial relatively impractical. Pending this, the best suggestion is obviously to pick the best TOS surgeon you can find and have him or her fix the problem in the way they are most experienced!

Dr. Illig is professor of surgery and director, division of vascular surgery, and associate chair, faculty development and mentoring, University of South Florida, Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa, Fla. He had no relevant disclosures.

References

2. Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. London: Springer 2013; 319-21.

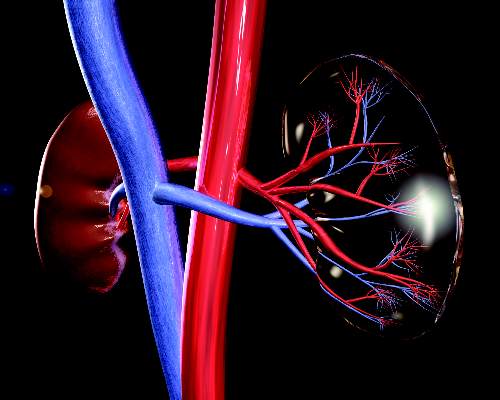

AAN recommends against routine closure of patent foramen ovale for secondary stroke prevention

An updated practice advisory from the American Academy of Neurology does not recommend the routine use of catheter-based closure of patent foramen ovale in patients with a history of cryptogenic ischemic stroke.

“Because of the limitations of the efficacy evidence and the potential for serious adverse effects, we judge the risk-benefit trade-offs of PFO [patent foramen ovale] closure by either the STARFlex or AMPLATZER PFO Occluder to be uncertain,” wrote Steven Messé, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates. “In rare circumstances, such as recurrent strokes despite adequate medical therapy with no other mechanism identified, clinicians may offer the AMPLATZER PFO Occluder if it is available,” they noted.

They also supported antiplatelet agents over anticoagulants unless patients have another indication for blood thinners, noting “the uncertainty surrounding the benefit of anticoagulation in the setting of PFO, and anticoagulation’s well-known harm profile.”

PFO affects about one in four individuals overall and up to half of cryptogenic stroke patients. The previous (2004) version of this practice advisory cited insufficient evidence to guide optimal therapy for secondary stroke prevention in these patients (Neurology. 2004;Apr 13;62[7]:1042-50). To update the guideline, Dr. Messé and his associates searched the literature for relevant randomized studies, excluding transient ischemic attacks when feasible because of their subjective nature, and focusing on intention-to-treat analyses to reduce bias (Neurology. 2016 Jul 27;doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002961).

Among 809 initial articles, 5 were considered relevant – a randomized, open-label, multicenter study of the STARFlex device (CLOSURE I), two randomized, controlled trials of the AMPLATZER PFO Occluder (PC Trial and RESPECT), and two randomized studies of warfarin versus aspirin in cryptogenic stroke patients, the experts said.

Percutaneous PFO closure with the STARFlex device did not appear to prevent secondary stroke, compared with medical therapy alone, based on a small positive estimated difference in risk of about 0.1%, and a 95% confidence interval that crossed zero (–2.2% to 2.0%). In contrast, the AMPLATZER PFO Occluder decreased the risk of secondary stroke by about 1.7% (95% CI, –3.2% to –0.2%), but upped the risk of procedural complications by more than 3%, and also slightly increased the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation (1.6%; 95% CI, 0.1% to 3.2%).

Efficacy data were insufficient to clearly support anticoagulants over antiplatelet therapy for recurrent stroke prevention, the experts concluded. Compared with antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulation was associated with a 2% increase in risk of recurrent stroke, but the 95% confidence interval for this estimate was wide and crossed zero. “In the absence of another indication for anticoagulation, clinicians may routinely offer antiplatelet medications instead of anticoagulation to patients with cryptogenic stroke and PFO,” they wrote. “In rare circumstances, such as stroke that recurs while a patient is undergoing antiplatelet therapy, clinicians may offer anticoagulation to patients with cryptogenic stroke and PFO.”

Their strongest recommendation was to counsel patients who are considering percutaneous PFO closure “that having a PFO is common; it occurs in about 1 in 4 people; it is impossible to determine with certainty whether their PFOs caused their strokes or TIAs; the effectiveness of the procedure for reducing stroke risk remains uncertain; and the procedure is associated with relatively uncommon, yet potentially serious, complications.”

The practice advisory was supported by the American Academy of Neurology. Dr. Messé disclosed ties to GlaxoSmithKline and WL Gore & Associates and has been an investigator for the REDUCE and CLOSURE-I trials. Five of his coauthors have been investigators for RESPECT, CLOSURE-I, and REDUCE, have been editors for Neurology, and have received compensation from Genentech, Pfizer, Gilead Sciences, and other pharmaceutical companies. One coauthor had no disclosures.

An updated practice advisory from the American Academy of Neurology does not recommend the routine use of catheter-based closure of patent foramen ovale in patients with a history of cryptogenic ischemic stroke.

“Because of the limitations of the efficacy evidence and the potential for serious adverse effects, we judge the risk-benefit trade-offs of PFO [patent foramen ovale] closure by either the STARFlex or AMPLATZER PFO Occluder to be uncertain,” wrote Steven Messé, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates. “In rare circumstances, such as recurrent strokes despite adequate medical therapy with no other mechanism identified, clinicians may offer the AMPLATZER PFO Occluder if it is available,” they noted.

They also supported antiplatelet agents over anticoagulants unless patients have another indication for blood thinners, noting “the uncertainty surrounding the benefit of anticoagulation in the setting of PFO, and anticoagulation’s well-known harm profile.”

PFO affects about one in four individuals overall and up to half of cryptogenic stroke patients. The previous (2004) version of this practice advisory cited insufficient evidence to guide optimal therapy for secondary stroke prevention in these patients (Neurology. 2004;Apr 13;62[7]:1042-50). To update the guideline, Dr. Messé and his associates searched the literature for relevant randomized studies, excluding transient ischemic attacks when feasible because of their subjective nature, and focusing on intention-to-treat analyses to reduce bias (Neurology. 2016 Jul 27;doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002961).

Among 809 initial articles, 5 were considered relevant – a randomized, open-label, multicenter study of the STARFlex device (CLOSURE I), two randomized, controlled trials of the AMPLATZER PFO Occluder (PC Trial and RESPECT), and two randomized studies of warfarin versus aspirin in cryptogenic stroke patients, the experts said.

Percutaneous PFO closure with the STARFlex device did not appear to prevent secondary stroke, compared with medical therapy alone, based on a small positive estimated difference in risk of about 0.1%, and a 95% confidence interval that crossed zero (–2.2% to 2.0%). In contrast, the AMPLATZER PFO Occluder decreased the risk of secondary stroke by about 1.7% (95% CI, –3.2% to –0.2%), but upped the risk of procedural complications by more than 3%, and also slightly increased the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation (1.6%; 95% CI, 0.1% to 3.2%).

Efficacy data were insufficient to clearly support anticoagulants over antiplatelet therapy for recurrent stroke prevention, the experts concluded. Compared with antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulation was associated with a 2% increase in risk of recurrent stroke, but the 95% confidence interval for this estimate was wide and crossed zero. “In the absence of another indication for anticoagulation, clinicians may routinely offer antiplatelet medications instead of anticoagulation to patients with cryptogenic stroke and PFO,” they wrote. “In rare circumstances, such as stroke that recurs while a patient is undergoing antiplatelet therapy, clinicians may offer anticoagulation to patients with cryptogenic stroke and PFO.”

Their strongest recommendation was to counsel patients who are considering percutaneous PFO closure “that having a PFO is common; it occurs in about 1 in 4 people; it is impossible to determine with certainty whether their PFOs caused their strokes or TIAs; the effectiveness of the procedure for reducing stroke risk remains uncertain; and the procedure is associated with relatively uncommon, yet potentially serious, complications.”

The practice advisory was supported by the American Academy of Neurology. Dr. Messé disclosed ties to GlaxoSmithKline and WL Gore & Associates and has been an investigator for the REDUCE and CLOSURE-I trials. Five of his coauthors have been investigators for RESPECT, CLOSURE-I, and REDUCE, have been editors for Neurology, and have received compensation from Genentech, Pfizer, Gilead Sciences, and other pharmaceutical companies. One coauthor had no disclosures.

An updated practice advisory from the American Academy of Neurology does not recommend the routine use of catheter-based closure of patent foramen ovale in patients with a history of cryptogenic ischemic stroke.

“Because of the limitations of the efficacy evidence and the potential for serious adverse effects, we judge the risk-benefit trade-offs of PFO [patent foramen ovale] closure by either the STARFlex or AMPLATZER PFO Occluder to be uncertain,” wrote Steven Messé, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates. “In rare circumstances, such as recurrent strokes despite adequate medical therapy with no other mechanism identified, clinicians may offer the AMPLATZER PFO Occluder if it is available,” they noted.

They also supported antiplatelet agents over anticoagulants unless patients have another indication for blood thinners, noting “the uncertainty surrounding the benefit of anticoagulation in the setting of PFO, and anticoagulation’s well-known harm profile.”

PFO affects about one in four individuals overall and up to half of cryptogenic stroke patients. The previous (2004) version of this practice advisory cited insufficient evidence to guide optimal therapy for secondary stroke prevention in these patients (Neurology. 2004;Apr 13;62[7]:1042-50). To update the guideline, Dr. Messé and his associates searched the literature for relevant randomized studies, excluding transient ischemic attacks when feasible because of their subjective nature, and focusing on intention-to-treat analyses to reduce bias (Neurology. 2016 Jul 27;doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002961).

Among 809 initial articles, 5 were considered relevant – a randomized, open-label, multicenter study of the STARFlex device (CLOSURE I), two randomized, controlled trials of the AMPLATZER PFO Occluder (PC Trial and RESPECT), and two randomized studies of warfarin versus aspirin in cryptogenic stroke patients, the experts said.

Percutaneous PFO closure with the STARFlex device did not appear to prevent secondary stroke, compared with medical therapy alone, based on a small positive estimated difference in risk of about 0.1%, and a 95% confidence interval that crossed zero (–2.2% to 2.0%). In contrast, the AMPLATZER PFO Occluder decreased the risk of secondary stroke by about 1.7% (95% CI, –3.2% to –0.2%), but upped the risk of procedural complications by more than 3%, and also slightly increased the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation (1.6%; 95% CI, 0.1% to 3.2%).

Efficacy data were insufficient to clearly support anticoagulants over antiplatelet therapy for recurrent stroke prevention, the experts concluded. Compared with antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulation was associated with a 2% increase in risk of recurrent stroke, but the 95% confidence interval for this estimate was wide and crossed zero. “In the absence of another indication for anticoagulation, clinicians may routinely offer antiplatelet medications instead of anticoagulation to patients with cryptogenic stroke and PFO,” they wrote. “In rare circumstances, such as stroke that recurs while a patient is undergoing antiplatelet therapy, clinicians may offer anticoagulation to patients with cryptogenic stroke and PFO.”

Their strongest recommendation was to counsel patients who are considering percutaneous PFO closure “that having a PFO is common; it occurs in about 1 in 4 people; it is impossible to determine with certainty whether their PFOs caused their strokes or TIAs; the effectiveness of the procedure for reducing stroke risk remains uncertain; and the procedure is associated with relatively uncommon, yet potentially serious, complications.”

The practice advisory was supported by the American Academy of Neurology. Dr. Messé disclosed ties to GlaxoSmithKline and WL Gore & Associates and has been an investigator for the REDUCE and CLOSURE-I trials. Five of his coauthors have been investigators for RESPECT, CLOSURE-I, and REDUCE, have been editors for Neurology, and have received compensation from Genentech, Pfizer, Gilead Sciences, and other pharmaceutical companies. One coauthor had no disclosures.

FROM NEUROLOGY

CMS proposes bundled payments for AMI, CABG

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is proposing new bundled payment models for acute myocardial infarction and coronary artery bypass grafting, and a separate payment to incentivize the use of cardiac rehabilitation.

As part of the proposal, CMS also is developing a pathway that would allow the bundle to be recognized as an advanced alternative payment model under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act and qualify the physicians and clinicians being paid through the model for the 5% incentive payment.

The proposed bundled payment model would place patient care accountability for 90 days after discharge on the hospital where acute myocardial infarction care or coronary artery bypass grafting occurred. Beginning July 1, 2017, hospitals in 98 randomly selected metropolitan statistical areas would be placed under this model and monitored for a 5-year period to test whether the model leads to improved outcomes and generates cost savings.

The proposed rule can be seen here and an advanced notice is expected to be published on the Federal Register website on July 26. CMS will be accepting comments on the proposal for 60 days following official publication in the Federal Register.

“In 2014, more than 200,000 Medicare beneficiaries were hospitalized for heart attack treatment or underwent bypass surgery, costing Medicare over $6 billion. But the cost of treating patients varied by 50% across hospitals, and the share of patients readmitted to the hospitals within 30 days varied by more than 50%. And patient experience also varies,” CMS Acting Principal Deputy Administrator and Chief Medical Officer Patrick Conway, MD, said during a July 25 press teleconference introducing the proposal. “In some cases, hospitals, doctors, and rehabilitation facilities work together to support a patient from heart attack or surgery all the way through recovery. But in other cases, coordination breaks down, especially when a patient leaves the hospital. By structuring a payment around a patient’s total experience of care, bundled payments support better care coordination and ultimately better outcomes for patients.”

The hospital would be paid a fixed target price for each care episode, with hospitals delivering higher-quality care receiving a higher target price. The hospital would either keep the savings achieved or, if the costs exceeded the target pricing, have to repay Medicare the difference.

Target prices will be based on historical cost data beginning with hospitalization and extending out 90 days following discharge and adjusted based on the complexity of treatment required. For the 18 months of the program (July 1, 2017, through Dec. 31, 2018) target prices would be based on a blend of two-thirds participant-specific data and one-third regional data. In the third performance year (2019), the mix would move to one-third participant data and two-thirds regional data. Beginning in 2020, only regional data would be used to set target prices.

For heart attacks, the following quality measures are being proposed: Hospital 30-day, all-cause, risk-standardized mortality following acute myocardial infarction hospitalization; excess days in acute care after hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction; Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey scores; and voluntary hybrid hospital 30-day, all-cause, risk-standardized mortality eMeasure data submission.

For bypass surgery, the quality measures will be the hospital 30-day all-cause, risk-standardized mortality rate following coronary artery bypass graft; and HCAHPS survey scores.

“CMS’s evaluation ... will examine quality during the episode period, after the episode period ends, and for longer durations such as 1-year mortality rates,” the agency said in a fact sheet describing the proposal. “CMS will examine outcomes and patient experience measures such as mortality, readmissions, complications, and other clinically relevant outcomes.”

Separately, the agency is proposing to test a cardiac rehabilitation incentive payment. The two-part cardiac rehabilitation incentive payment would be paid retrospectively based on the total cardiac rehabilitation use of beneficiaries attributable to participant hospitals.

“Currently, only 15% of heart attack patients receive cardiac rehabilitation, even though completing a rehabilitation program can lower the risk of the second heart attack or death,” Dr. Conway said. “Patients who receive cardiac rehabilitation are assigned a team of health care professionals such as cardiologists, dietitians, and physical therapists who help the patient to recover and regain cardiovascular fitness.”

The initial payment would be $25 per cardiac rehabilitation service for each of the first 11 services paid for by Medicare during the 90-day care period for a heart attack or bypass surgery. After 11 services, the payment would increase to $175 during the care period.

The number of sessions would be limited to two 1-hour sessions per day up to 36 sessions over up to 36 weeks, with the option for an additional 36 sessions over an extended period if approved by the local Medicare contractor. Intensive cardiac rehabilitation program sessions would be limited to 72 1-hour sessions, up to six sessions per day, over 18 weeks.

While officials from the American College of Cardiology said that the organization supports the concepts of value-based care, “it is important that bundled care models be carried out in such a way that clinicians are given the time and tools to truly impact patient care in the best ways possible. Changes in payment structures in health care can pose significant challenges to clinicians and must be driven by clinical practices that improve patient outcomes,” ACC President Richard A. Chazal, MD, said in a statement. “We are optimistic that CMS will listen to comments, incorporate feedback from clinicians, and provide ample time for implementation of these new payment models. Our ultimate goal is to improve patient care and to improve heart health.”