User login

Leadless pacemaker matches conventional transvenous outcomes

ORLANDO – A leadless transcatheter pacemaker rivals conventional transvenous pacemakers in terms of pacing capture and major complications, according to data presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The prospective multicenter study involved 725 patients requiring ventricular pacing, of whom 719 were successful implanted with the leadless Micra Transcatheter Pacemaking System and followed for 6 months.

Of the 297 patients included in the primary efficacy analysis, 98.3% showed a 6-month pacing capture threshold of no greater than 2.0 V, with a mean pacing capture threshold at implantation of 0.63 V and 0.54 V at 6 months.

The leadless device also was associated with half the incidence of major complications, compared with data from a historical control cohort (4% vs. 7.4%; hazard ratio, 0.49; P = .001), as well as fewer hospitalizations and fewer system revisions due to complications.

“Complications that lead to death or that required invasive revision, termination of therapy, or hospitalization or extension of hospitalization occurred in 4% of the patients; this finding is in line with recent reports of transvenous systems and was significantly lower than the rate in the control group,” wrote Dr. Dwight Reynolds of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and coauthors (N Engl J Med. Nov 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511643).

The study was supported by Micra manufacturer Medtronic. Most authors reported personal fees, grants, and advisory board positions from private industry, including Medtronic. Two authors are Medtronic employees.

Pacemaker leads are the “Achilles’ heel” of pacing and defibrillation systems, so a self-contained, leadless pacemaker that can be placed directly into the heart is an appealing prospect.

Although newer devices such as this one can be used only for single-chamber ventricular pacing and therefore will have limited usefulness for the majority of pacemaker recipients, these encouraging short-term results show the promise of leadless pacing.

Dr. Mark S. Link is with the cardiac arrhythmia service at Tufts Medical Center, Boston. These comments were taken from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2015, Nov 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1513625). No conflicts of interest were declared.

Pacemaker leads are the “Achilles’ heel” of pacing and defibrillation systems, so a self-contained, leadless pacemaker that can be placed directly into the heart is an appealing prospect.

Although newer devices such as this one can be used only for single-chamber ventricular pacing and therefore will have limited usefulness for the majority of pacemaker recipients, these encouraging short-term results show the promise of leadless pacing.

Dr. Mark S. Link is with the cardiac arrhythmia service at Tufts Medical Center, Boston. These comments were taken from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2015, Nov 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1513625). No conflicts of interest were declared.

Pacemaker leads are the “Achilles’ heel” of pacing and defibrillation systems, so a self-contained, leadless pacemaker that can be placed directly into the heart is an appealing prospect.

Although newer devices such as this one can be used only for single-chamber ventricular pacing and therefore will have limited usefulness for the majority of pacemaker recipients, these encouraging short-term results show the promise of leadless pacing.

Dr. Mark S. Link is with the cardiac arrhythmia service at Tufts Medical Center, Boston. These comments were taken from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2015, Nov 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1513625). No conflicts of interest were declared.

ORLANDO – A leadless transcatheter pacemaker rivals conventional transvenous pacemakers in terms of pacing capture and major complications, according to data presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The prospective multicenter study involved 725 patients requiring ventricular pacing, of whom 719 were successful implanted with the leadless Micra Transcatheter Pacemaking System and followed for 6 months.

Of the 297 patients included in the primary efficacy analysis, 98.3% showed a 6-month pacing capture threshold of no greater than 2.0 V, with a mean pacing capture threshold at implantation of 0.63 V and 0.54 V at 6 months.

The leadless device also was associated with half the incidence of major complications, compared with data from a historical control cohort (4% vs. 7.4%; hazard ratio, 0.49; P = .001), as well as fewer hospitalizations and fewer system revisions due to complications.

“Complications that lead to death or that required invasive revision, termination of therapy, or hospitalization or extension of hospitalization occurred in 4% of the patients; this finding is in line with recent reports of transvenous systems and was significantly lower than the rate in the control group,” wrote Dr. Dwight Reynolds of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and coauthors (N Engl J Med. Nov 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511643).

The study was supported by Micra manufacturer Medtronic. Most authors reported personal fees, grants, and advisory board positions from private industry, including Medtronic. Two authors are Medtronic employees.

ORLANDO – A leadless transcatheter pacemaker rivals conventional transvenous pacemakers in terms of pacing capture and major complications, according to data presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The prospective multicenter study involved 725 patients requiring ventricular pacing, of whom 719 were successful implanted with the leadless Micra Transcatheter Pacemaking System and followed for 6 months.

Of the 297 patients included in the primary efficacy analysis, 98.3% showed a 6-month pacing capture threshold of no greater than 2.0 V, with a mean pacing capture threshold at implantation of 0.63 V and 0.54 V at 6 months.

The leadless device also was associated with half the incidence of major complications, compared with data from a historical control cohort (4% vs. 7.4%; hazard ratio, 0.49; P = .001), as well as fewer hospitalizations and fewer system revisions due to complications.

“Complications that lead to death or that required invasive revision, termination of therapy, or hospitalization or extension of hospitalization occurred in 4% of the patients; this finding is in line with recent reports of transvenous systems and was significantly lower than the rate in the control group,” wrote Dr. Dwight Reynolds of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and coauthors (N Engl J Med. Nov 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511643).

The study was supported by Micra manufacturer Medtronic. Most authors reported personal fees, grants, and advisory board positions from private industry, including Medtronic. Two authors are Medtronic employees.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: A leadless transcatheter pacemaker has shown similar outcomes in terms of pacing capture and major complications to conventional transvenous pacemakers.

Major finding:A leadless transcatheter pacemaker achieved a 6-month pacing capture threshold no greater than 2.0 V in 98.3% of patients.

Data source: A prospective multicenter study involving 725 patients requiring ventricular pacing.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Micra manufacturer Medtronic. Most authors reported personal fees, grants, and advisory board positions from private industry, including Medtronic. Two authors are Medtronic employees.

AHA: Mixed results for mitral valve replacement vs. repair

Patients undergoing mitral valve replacement had a lower risk of regurgitation and heart failure–related adverse events at 2 years than those undergoing valve repair, according to the results of a trial presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The results of the trial appear to associate mitral valve replacement with clinical advantages over mitral valve repair after 2 years of follow-up. However, replacement held no significant advantages over repair in the primary endpoint of left ventricular end-systolic volume index (LVESVI) or in overall survival, said Dr. Daniel Goldstein of the department of cardiothoracic surgery at Montefiore Medical Center, New York.

In the trial conducted by the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network (CTSN), 251 patients with chronic severe ischemic mitral regurgitation were randomly assigned to undergo surgical repair of the mitral valve or to receive a mitral valve replacement with a prosthetic and procedure selected at the discretion of the surgeon.

In addition to the primary endpoint of LVESVI, the two approaches were also compared for survival, regurgitation recurrence, and heart failure events.

At 2 years, the mean change from baseline in LVESVI, a measure of remodeling, did not differ significantly between the repair and replacement arms (–9.0 vs. –6.5 mL/m2, respectively). In addition, although the 2-year mortality rate was numerically lower in the repair arm relative to the replacement arm (19% vs. 23.2%, respectively), it was also not statistically different (P = .39).

However, the rate of recurrence of moderate or severe mitral regurgitation favored replacement over repair and was significant (3.8% vs. 58.8%, respectively; P less than .001). In addition, the rate of cardiovascular readmissions was significantly lower in the replacement group (P = .01).

For those in the repair group, there were significant trends for more serious adverse events related to heart failure (P = .05) and for a lower quality of life improvement (P = .07) on the Minnesota Living With Heart Failure questionnaire. There were no significant differences in rates of all serious adverse events or overall readmissions.

All of the differences between groups observed at 2 years amplify differences previously reported after 12 months (N Engl J Med. 2014 Jan 2;370[1]:23-32). For example, the difference in the rate of moderate to severe regurgitation favoring replacement over repair was already significant at that time (2.3% vs. 32.6%, respectively; P less than .001), even though the mortality rates were then, as now, numerically lower in the repair group versus the replacement group (14.3% vs. 17.6%, respectively; P = .45).

Dr. Goldstein reported no relevant financial relationships.

Patients undergoing mitral valve replacement had a lower risk of regurgitation and heart failure–related adverse events at 2 years than those undergoing valve repair, according to the results of a trial presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The results of the trial appear to associate mitral valve replacement with clinical advantages over mitral valve repair after 2 years of follow-up. However, replacement held no significant advantages over repair in the primary endpoint of left ventricular end-systolic volume index (LVESVI) or in overall survival, said Dr. Daniel Goldstein of the department of cardiothoracic surgery at Montefiore Medical Center, New York.

In the trial conducted by the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network (CTSN), 251 patients with chronic severe ischemic mitral regurgitation were randomly assigned to undergo surgical repair of the mitral valve or to receive a mitral valve replacement with a prosthetic and procedure selected at the discretion of the surgeon.

In addition to the primary endpoint of LVESVI, the two approaches were also compared for survival, regurgitation recurrence, and heart failure events.

At 2 years, the mean change from baseline in LVESVI, a measure of remodeling, did not differ significantly between the repair and replacement arms (–9.0 vs. –6.5 mL/m2, respectively). In addition, although the 2-year mortality rate was numerically lower in the repair arm relative to the replacement arm (19% vs. 23.2%, respectively), it was also not statistically different (P = .39).

However, the rate of recurrence of moderate or severe mitral regurgitation favored replacement over repair and was significant (3.8% vs. 58.8%, respectively; P less than .001). In addition, the rate of cardiovascular readmissions was significantly lower in the replacement group (P = .01).

For those in the repair group, there were significant trends for more serious adverse events related to heart failure (P = .05) and for a lower quality of life improvement (P = .07) on the Minnesota Living With Heart Failure questionnaire. There were no significant differences in rates of all serious adverse events or overall readmissions.

All of the differences between groups observed at 2 years amplify differences previously reported after 12 months (N Engl J Med. 2014 Jan 2;370[1]:23-32). For example, the difference in the rate of moderate to severe regurgitation favoring replacement over repair was already significant at that time (2.3% vs. 32.6%, respectively; P less than .001), even though the mortality rates were then, as now, numerically lower in the repair group versus the replacement group (14.3% vs. 17.6%, respectively; P = .45).

Dr. Goldstein reported no relevant financial relationships.

Patients undergoing mitral valve replacement had a lower risk of regurgitation and heart failure–related adverse events at 2 years than those undergoing valve repair, according to the results of a trial presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The results of the trial appear to associate mitral valve replacement with clinical advantages over mitral valve repair after 2 years of follow-up. However, replacement held no significant advantages over repair in the primary endpoint of left ventricular end-systolic volume index (LVESVI) or in overall survival, said Dr. Daniel Goldstein of the department of cardiothoracic surgery at Montefiore Medical Center, New York.

In the trial conducted by the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network (CTSN), 251 patients with chronic severe ischemic mitral regurgitation were randomly assigned to undergo surgical repair of the mitral valve or to receive a mitral valve replacement with a prosthetic and procedure selected at the discretion of the surgeon.

In addition to the primary endpoint of LVESVI, the two approaches were also compared for survival, regurgitation recurrence, and heart failure events.

At 2 years, the mean change from baseline in LVESVI, a measure of remodeling, did not differ significantly between the repair and replacement arms (–9.0 vs. –6.5 mL/m2, respectively). In addition, although the 2-year mortality rate was numerically lower in the repair arm relative to the replacement arm (19% vs. 23.2%, respectively), it was also not statistically different (P = .39).

However, the rate of recurrence of moderate or severe mitral regurgitation favored replacement over repair and was significant (3.8% vs. 58.8%, respectively; P less than .001). In addition, the rate of cardiovascular readmissions was significantly lower in the replacement group (P = .01).

For those in the repair group, there were significant trends for more serious adverse events related to heart failure (P = .05) and for a lower quality of life improvement (P = .07) on the Minnesota Living With Heart Failure questionnaire. There were no significant differences in rates of all serious adverse events or overall readmissions.

All of the differences between groups observed at 2 years amplify differences previously reported after 12 months (N Engl J Med. 2014 Jan 2;370[1]:23-32). For example, the difference in the rate of moderate to severe regurgitation favoring replacement over repair was already significant at that time (2.3% vs. 32.6%, respectively; P less than .001), even though the mortality rates were then, as now, numerically lower in the repair group versus the replacement group (14.3% vs. 17.6%, respectively; P = .45).

Dr. Goldstein reported no relevant financial relationships.

FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Mitral valve replacement reduced regurgitation better than valve repair, but it didn’t significantly improve left ventricular function or survival.

Major finding: In patients with severe ischemic mitral regurgitation, regurgitation occurred more frequently after mitral valve repair than after valve replacement (58.8% vs. 3.8%; P less than .001), but left ventricular end-systolic volume indexes and survival rates were not significantly different.

Data source: A randomized, multicenter trial with 251 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Goldstein reported no relevant financial relationships.

FDA finds long-term clopidogrel does not increase death or cancer risks

Long-term use of the blood-thinning agent clopidogrel did not alter the risk of death in people with heart disease or at risk of developing heart disease, nor did the drug appear to affect cancer risk, according to a statement from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The FDA’s meta-analysis looked at results from 12 trials enrolling a total of 56,799 patients to evaluate the effect of long-term clopidogrel use on all-cause mortality. The incidence of all-cause mortality was 6.7% for the long-term clopidogrel plus aspirin arm and 6.6% for the comparator, resulting in a Mantel Haenszel Risk Difference (MH RD) of 0.04% (95% confidence interval, –0.35%-0.44%).

“The results indicate that long-term (12 months or longer) dual-antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin do not appear to change the overall risk of death, compared with short-term (6 months or less) clopidogrel and aspirin, or aspirin alone,” the agency said in its statement.

The FDA also conducted a meta-analysis looking at nine of these trials (n = 45,374) that had enrolled patients with coronary artery disease or patients at risk of CAD. This also suggested no difference in the risk of all-cause mortality (MH RD –0.07%; 95% CI, –0.43%- 0.29%).

The meta-analysis included results from the Dual-Antiplatelet Therapy Trial (DAPT), whose results included a worrisome safety signal for extended use of clopidogrel (N Engl J Med 2014; 371:2155-66). Patients in the DAPT underwent percutaneous coronary intervention and placement of a drug-eluting stent, after which they received 1 year of clopidogrel or prasugrel plus aspirin. About 1,000 patients were then randomized to 18 additional months of one of the dual-antiplatelet therapies or to aspirin plus placebo. Extended (30-month) use of clopidogrel plus aspirin was associated with a significantly increased risk of death (2.2% for 30 months vs. 1.5% for 12 months), whereas no increased risk was seen for prasugrel plus aspirin. A higher risk of death was mainly due to noncardiovascular causes, including cancer and trauma.

The DAPT did not show an increased risk of cancer-related adverse events related to treatment duration. However, the FDA performed two meta-analyses of other trials, with about 40,000 patients included in each analysis, to determine whether a signal could be found for either cancer-related adverse events or cancer-related death. Neither revealed an increased risk related to long-term clopidogrel use.

Long-term use of the blood-thinning agent clopidogrel did not alter the risk of death in people with heart disease or at risk of developing heart disease, nor did the drug appear to affect cancer risk, according to a statement from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The FDA’s meta-analysis looked at results from 12 trials enrolling a total of 56,799 patients to evaluate the effect of long-term clopidogrel use on all-cause mortality. The incidence of all-cause mortality was 6.7% for the long-term clopidogrel plus aspirin arm and 6.6% for the comparator, resulting in a Mantel Haenszel Risk Difference (MH RD) of 0.04% (95% confidence interval, –0.35%-0.44%).

“The results indicate that long-term (12 months or longer) dual-antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin do not appear to change the overall risk of death, compared with short-term (6 months or less) clopidogrel and aspirin, or aspirin alone,” the agency said in its statement.

The FDA also conducted a meta-analysis looking at nine of these trials (n = 45,374) that had enrolled patients with coronary artery disease or patients at risk of CAD. This also suggested no difference in the risk of all-cause mortality (MH RD –0.07%; 95% CI, –0.43%- 0.29%).

The meta-analysis included results from the Dual-Antiplatelet Therapy Trial (DAPT), whose results included a worrisome safety signal for extended use of clopidogrel (N Engl J Med 2014; 371:2155-66). Patients in the DAPT underwent percutaneous coronary intervention and placement of a drug-eluting stent, after which they received 1 year of clopidogrel or prasugrel plus aspirin. About 1,000 patients were then randomized to 18 additional months of one of the dual-antiplatelet therapies or to aspirin plus placebo. Extended (30-month) use of clopidogrel plus aspirin was associated with a significantly increased risk of death (2.2% for 30 months vs. 1.5% for 12 months), whereas no increased risk was seen for prasugrel plus aspirin. A higher risk of death was mainly due to noncardiovascular causes, including cancer and trauma.

The DAPT did not show an increased risk of cancer-related adverse events related to treatment duration. However, the FDA performed two meta-analyses of other trials, with about 40,000 patients included in each analysis, to determine whether a signal could be found for either cancer-related adverse events or cancer-related death. Neither revealed an increased risk related to long-term clopidogrel use.

Long-term use of the blood-thinning agent clopidogrel did not alter the risk of death in people with heart disease or at risk of developing heart disease, nor did the drug appear to affect cancer risk, according to a statement from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The FDA’s meta-analysis looked at results from 12 trials enrolling a total of 56,799 patients to evaluate the effect of long-term clopidogrel use on all-cause mortality. The incidence of all-cause mortality was 6.7% for the long-term clopidogrel plus aspirin arm and 6.6% for the comparator, resulting in a Mantel Haenszel Risk Difference (MH RD) of 0.04% (95% confidence interval, –0.35%-0.44%).

“The results indicate that long-term (12 months or longer) dual-antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin do not appear to change the overall risk of death, compared with short-term (6 months or less) clopidogrel and aspirin, or aspirin alone,” the agency said in its statement.

The FDA also conducted a meta-analysis looking at nine of these trials (n = 45,374) that had enrolled patients with coronary artery disease or patients at risk of CAD. This also suggested no difference in the risk of all-cause mortality (MH RD –0.07%; 95% CI, –0.43%- 0.29%).

The meta-analysis included results from the Dual-Antiplatelet Therapy Trial (DAPT), whose results included a worrisome safety signal for extended use of clopidogrel (N Engl J Med 2014; 371:2155-66). Patients in the DAPT underwent percutaneous coronary intervention and placement of a drug-eluting stent, after which they received 1 year of clopidogrel or prasugrel plus aspirin. About 1,000 patients were then randomized to 18 additional months of one of the dual-antiplatelet therapies or to aspirin plus placebo. Extended (30-month) use of clopidogrel plus aspirin was associated with a significantly increased risk of death (2.2% for 30 months vs. 1.5% for 12 months), whereas no increased risk was seen for prasugrel plus aspirin. A higher risk of death was mainly due to noncardiovascular causes, including cancer and trauma.

The DAPT did not show an increased risk of cancer-related adverse events related to treatment duration. However, the FDA performed two meta-analyses of other trials, with about 40,000 patients included in each analysis, to determine whether a signal could be found for either cancer-related adverse events or cancer-related death. Neither revealed an increased risk related to long-term clopidogrel use.

Conservative management for AR safe at 10 years

Whether to operate on patients with severe aortic regurgitation (AR) before or after symptoms appear has been a point of controversy among cardiothoracic surgeons, but a recent study has found that patients who have early surgery may not fare any better for up to 10 years than those who opt for a more conservative “watchful waiting” course of care.

Investigators from Belgium reported results from an analysis of 160 patients in the November issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2015;150:1100-08). “In asymptomatic severe AR, delaying surgery until the onset of class I/IIa operative triggers is safe, supporting current guidelines,” said Dr. Christophe de Meester and colleagues at the Catholic University of Louvain and St. Luc University Clinic in Brussels.

The goal of the study was to evaluate long-term outcomes and incidence of cardiac complications in patients with severe AR who did not have any signs and symptoms that called for surgery, and who either had surgery early on or entered conservative management and eventually had an operation when signs and symptoms did appear.

The study found that close follow-up and monitoring of patients with severe AR was a cornerstone of successful conservative management. “We found that survival was similar between the two groups,” Dr. De Meester and coauthors said. “Better survival was nonetheless observed in conservatively managed patients with regular as opposed to no or a looser follow-up.”

The most recent European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines and American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines state that symptomatic severe AR is a class I indication for surgery regardless of left ventricular (LV) systolic function.

However, Dr. De Meester and colleagues said, the timing of that surgery is not so clear-cut. Earlier studies have shown that surgery could be delayed for patients with minimal symptoms, but more recent evidence has suggested the opposite, according to the study. Two factors favor surgery before symptoms arise – poor aortic valve repair outcomes in patients with symptoms of heart failure and long-standing severe AR, which eventually leads to LV dysfunction.

Yet, the latest ESC guidelines have been “reluctant” to make a strong case for early surgery before symptoms of LV dysfunction appear, and the AHA/ACC guidelines call for surgery only when symptoms of LV dysfunction or LV dilatation develop, Dr. de Meester and his coauthors said.

In the past, the risks of aortic valve replacement were too high to consider early surgery, the study authors said. “However, with the advent of aortic valve repair, operative mortality and long-term outcomes have improved to such an extent that early surgery has become a plausible option for patients.”

But the risk of these patients developing symptoms for surgery was nonetheless low over 10 years, the study found: 7.4% for developing severe LV dilatation; 0.6% for becoming symptomatic; and 0.9% for developing LV dysfunction. Overall, the rate of adverse events in the study population was 9.9% at 10 years.

In the study, 69 patients were initially managed conservatively, 49 of whom were in the watchful waiting group that visited a cardiologist at least annually and another 20 considered an “irregular follow-up subgroup.” Among the watchful waiting group, 31 developed symptoms for surgery (only two declined surgery). Watchful waiting patients had five- and 10-year survival of 100% and 95%, respectively, compared with 90% and 79% among those who had irregular follow-up.

Overall, the conservatively managed group had outcomes better than or equal to the early surgery group. Ten-year cardiovascular survival was 96% in both groups, whereas event-free survival was 92% at 10 years in the conservatively managed group vs. 81% in the early surgery group.

The study was supported by the Belgium National Fund for Scientific Research. The authors had no conflicts to disclose.

The design of the Belgium study “challenges” existing treatment guidelines for asymptomatic chronic aortic insufficiency in two ways, Dr. Leora Balsam and Dr. Abe deAndra Jr., both of the New York University-Langone Medical Center, write in their commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1108-10): first, by making aortic valve repair the preferred surgical treatment in the study and, secondly, by offering surgery to both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients.

“In the era of evidence-based medicine,” Dr. Balsam and Dr. deAndra wrote, “there remains a need for research and innovation even in areas where guidelines exist.”

While many authors have described aortic valve repair as an alternative to aortic valve replacement for chronic severe aortic insufficiency, Dr. Balsam and Dr. deAndra explained that the term aortic valve repair “encompasses a wide array of techniques,” among them valve-sparing aortic root replacement, subcommissural annuloplasty and “myriad” leaf resection, plication, and reconstruction techniques. Because of mounting reports of excellent results with aortic valve repair techniques, growing ranks of cardiothoracic surgeons have advocated for repair as an early intervention for aortic valve problems. But the question remains: “Have we identified the optimal triggers for intervention for aortic insufficiency?” they asked. “The answer is probably no, and that newer technology and diagnostic studies will better discriminate between patients that can benefit from intervention and those that will not.”

Dr. Balsam and Dr. deAndra had no disclosures.

The design of the Belgium study “challenges” existing treatment guidelines for asymptomatic chronic aortic insufficiency in two ways, Dr. Leora Balsam and Dr. Abe deAndra Jr., both of the New York University-Langone Medical Center, write in their commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1108-10): first, by making aortic valve repair the preferred surgical treatment in the study and, secondly, by offering surgery to both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients.

“In the era of evidence-based medicine,” Dr. Balsam and Dr. deAndra wrote, “there remains a need for research and innovation even in areas where guidelines exist.”

While many authors have described aortic valve repair as an alternative to aortic valve replacement for chronic severe aortic insufficiency, Dr. Balsam and Dr. deAndra explained that the term aortic valve repair “encompasses a wide array of techniques,” among them valve-sparing aortic root replacement, subcommissural annuloplasty and “myriad” leaf resection, plication, and reconstruction techniques. Because of mounting reports of excellent results with aortic valve repair techniques, growing ranks of cardiothoracic surgeons have advocated for repair as an early intervention for aortic valve problems. But the question remains: “Have we identified the optimal triggers for intervention for aortic insufficiency?” they asked. “The answer is probably no, and that newer technology and diagnostic studies will better discriminate between patients that can benefit from intervention and those that will not.”

Dr. Balsam and Dr. deAndra had no disclosures.

The design of the Belgium study “challenges” existing treatment guidelines for asymptomatic chronic aortic insufficiency in two ways, Dr. Leora Balsam and Dr. Abe deAndra Jr., both of the New York University-Langone Medical Center, write in their commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1108-10): first, by making aortic valve repair the preferred surgical treatment in the study and, secondly, by offering surgery to both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients.

“In the era of evidence-based medicine,” Dr. Balsam and Dr. deAndra wrote, “there remains a need for research and innovation even in areas where guidelines exist.”

While many authors have described aortic valve repair as an alternative to aortic valve replacement for chronic severe aortic insufficiency, Dr. Balsam and Dr. deAndra explained that the term aortic valve repair “encompasses a wide array of techniques,” among them valve-sparing aortic root replacement, subcommissural annuloplasty and “myriad” leaf resection, plication, and reconstruction techniques. Because of mounting reports of excellent results with aortic valve repair techniques, growing ranks of cardiothoracic surgeons have advocated for repair as an early intervention for aortic valve problems. But the question remains: “Have we identified the optimal triggers for intervention for aortic insufficiency?” they asked. “The answer is probably no, and that newer technology and diagnostic studies will better discriminate between patients that can benefit from intervention and those that will not.”

Dr. Balsam and Dr. deAndra had no disclosures.

Whether to operate on patients with severe aortic regurgitation (AR) before or after symptoms appear has been a point of controversy among cardiothoracic surgeons, but a recent study has found that patients who have early surgery may not fare any better for up to 10 years than those who opt for a more conservative “watchful waiting” course of care.

Investigators from Belgium reported results from an analysis of 160 patients in the November issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2015;150:1100-08). “In asymptomatic severe AR, delaying surgery until the onset of class I/IIa operative triggers is safe, supporting current guidelines,” said Dr. Christophe de Meester and colleagues at the Catholic University of Louvain and St. Luc University Clinic in Brussels.

The goal of the study was to evaluate long-term outcomes and incidence of cardiac complications in patients with severe AR who did not have any signs and symptoms that called for surgery, and who either had surgery early on or entered conservative management and eventually had an operation when signs and symptoms did appear.

The study found that close follow-up and monitoring of patients with severe AR was a cornerstone of successful conservative management. “We found that survival was similar between the two groups,” Dr. De Meester and coauthors said. “Better survival was nonetheless observed in conservatively managed patients with regular as opposed to no or a looser follow-up.”

The most recent European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines and American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines state that symptomatic severe AR is a class I indication for surgery regardless of left ventricular (LV) systolic function.

However, Dr. De Meester and colleagues said, the timing of that surgery is not so clear-cut. Earlier studies have shown that surgery could be delayed for patients with minimal symptoms, but more recent evidence has suggested the opposite, according to the study. Two factors favor surgery before symptoms arise – poor aortic valve repair outcomes in patients with symptoms of heart failure and long-standing severe AR, which eventually leads to LV dysfunction.

Yet, the latest ESC guidelines have been “reluctant” to make a strong case for early surgery before symptoms of LV dysfunction appear, and the AHA/ACC guidelines call for surgery only when symptoms of LV dysfunction or LV dilatation develop, Dr. de Meester and his coauthors said.

In the past, the risks of aortic valve replacement were too high to consider early surgery, the study authors said. “However, with the advent of aortic valve repair, operative mortality and long-term outcomes have improved to such an extent that early surgery has become a plausible option for patients.”

But the risk of these patients developing symptoms for surgery was nonetheless low over 10 years, the study found: 7.4% for developing severe LV dilatation; 0.6% for becoming symptomatic; and 0.9% for developing LV dysfunction. Overall, the rate of adverse events in the study population was 9.9% at 10 years.

In the study, 69 patients were initially managed conservatively, 49 of whom were in the watchful waiting group that visited a cardiologist at least annually and another 20 considered an “irregular follow-up subgroup.” Among the watchful waiting group, 31 developed symptoms for surgery (only two declined surgery). Watchful waiting patients had five- and 10-year survival of 100% and 95%, respectively, compared with 90% and 79% among those who had irregular follow-up.

Overall, the conservatively managed group had outcomes better than or equal to the early surgery group. Ten-year cardiovascular survival was 96% in both groups, whereas event-free survival was 92% at 10 years in the conservatively managed group vs. 81% in the early surgery group.

The study was supported by the Belgium National Fund for Scientific Research. The authors had no conflicts to disclose.

Whether to operate on patients with severe aortic regurgitation (AR) before or after symptoms appear has been a point of controversy among cardiothoracic surgeons, but a recent study has found that patients who have early surgery may not fare any better for up to 10 years than those who opt for a more conservative “watchful waiting” course of care.

Investigators from Belgium reported results from an analysis of 160 patients in the November issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2015;150:1100-08). “In asymptomatic severe AR, delaying surgery until the onset of class I/IIa operative triggers is safe, supporting current guidelines,” said Dr. Christophe de Meester and colleagues at the Catholic University of Louvain and St. Luc University Clinic in Brussels.

The goal of the study was to evaluate long-term outcomes and incidence of cardiac complications in patients with severe AR who did not have any signs and symptoms that called for surgery, and who either had surgery early on or entered conservative management and eventually had an operation when signs and symptoms did appear.

The study found that close follow-up and monitoring of patients with severe AR was a cornerstone of successful conservative management. “We found that survival was similar between the two groups,” Dr. De Meester and coauthors said. “Better survival was nonetheless observed in conservatively managed patients with regular as opposed to no or a looser follow-up.”

The most recent European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines and American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines state that symptomatic severe AR is a class I indication for surgery regardless of left ventricular (LV) systolic function.

However, Dr. De Meester and colleagues said, the timing of that surgery is not so clear-cut. Earlier studies have shown that surgery could be delayed for patients with minimal symptoms, but more recent evidence has suggested the opposite, according to the study. Two factors favor surgery before symptoms arise – poor aortic valve repair outcomes in patients with symptoms of heart failure and long-standing severe AR, which eventually leads to LV dysfunction.

Yet, the latest ESC guidelines have been “reluctant” to make a strong case for early surgery before symptoms of LV dysfunction appear, and the AHA/ACC guidelines call for surgery only when symptoms of LV dysfunction or LV dilatation develop, Dr. de Meester and his coauthors said.

In the past, the risks of aortic valve replacement were too high to consider early surgery, the study authors said. “However, with the advent of aortic valve repair, operative mortality and long-term outcomes have improved to such an extent that early surgery has become a plausible option for patients.”

But the risk of these patients developing symptoms for surgery was nonetheless low over 10 years, the study found: 7.4% for developing severe LV dilatation; 0.6% for becoming symptomatic; and 0.9% for developing LV dysfunction. Overall, the rate of adverse events in the study population was 9.9% at 10 years.

In the study, 69 patients were initially managed conservatively, 49 of whom were in the watchful waiting group that visited a cardiologist at least annually and another 20 considered an “irregular follow-up subgroup.” Among the watchful waiting group, 31 developed symptoms for surgery (only two declined surgery). Watchful waiting patients had five- and 10-year survival of 100% and 95%, respectively, compared with 90% and 79% among those who had irregular follow-up.

Overall, the conservatively managed group had outcomes better than or equal to the early surgery group. Ten-year cardiovascular survival was 96% in both groups, whereas event-free survival was 92% at 10 years in the conservatively managed group vs. 81% in the early surgery group.

The study was supported by the Belgium National Fund for Scientific Research. The authors had no conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Delaying surgery until the onset of symptoms of aortic insufficiency is safe, in support of current clinical guidelines.

Major finding: Ten-year cardiovascular survival was equal among conservatively managed and early-surgery groups, but event free survival was 92% at 10 years in the conservatively managed group vs. 81% in the early surgery group.

Data source: Analysis of 160 consecutive asymptomatic patients with severe aortic regurgitation who were assigned to either conservative management or early surgery and followed up for a median of 7.2 years.

Disclosures: The Belgium National Fund of Scientific Research supported the study. The authors had no disclosures.

Does LVAD inhibit cardio protection?

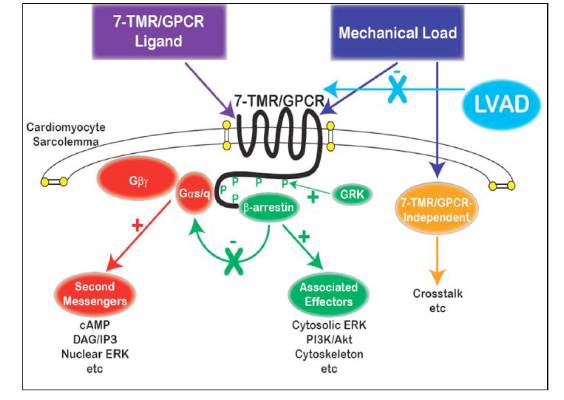

Placement of a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) after a heart attack has been found to suppress certain cellular signaling pathways that protect coronary tissue, but at the same time LVAD placement seemed to help normalize other protective properties in areas of the heart closest to the infarcted region, investigators reported in a recent study.

The findings could have implications in determining the best method for unloading and other medical therapies in the aftermath of a heart attack, Dr. Keshava Rajagopal of the University of Texas, Houston, and associates reported in the November issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2015;150:1332-41).

To study the effect of LVAD on cardiac tissue, the investigators induced myocardial infarction in sheep and then placed the animals on LVAD support for 2 weeks. After 10 more weeks of observation, the investigators harvested and analyzed the myocardial specimens. The principal goal of the study was to investigate how heart attack and subsequent short-term mechanical support of the left ventricle can influence signaling controlled by the protein beta-arrestin.

They found that an infarction of myocardial tissue caused activation of the beta-arrestin protein that regulates cellular pathways that can benefit cardiac cells. At the same time, LVAD support inhibited beta-arrestin activation, specifically in regulating pathways of two cardioprotective proteins: Akt, also called protein kinase B (PKB), and, to a lesser extent, ERK-1 and -2.

They also found that MI resulted in regional activation of load-induced signaling of cardiac G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) via G proteins.

“These studies demonstrate that small platform catheter-based LVAD support exerts suppressive effects on cardioprotective beta-arrestin–mediated signal transduction, while normalizing the signaling networks of G-alpha-q–coupled cardiac GPCRS in the MI-adjacent zone,” Dr. Rajagopal and colleagues said.

They acknowledged that further studies are needed to better understand the roles that specific GPCRs in beta-arrestin–regulated signaling play in left ventricle dysfunction after a heart attack and to help define the optimal timing for LVAD based on signaling and genetic markers along with standard LV functional endpoints.

The authors had no disclosures.

The University of Maryland investigators in this study have joined the ranks of other investigators who have begun to unravel the consequences of mechanical unloading at the cellular level as well as its effect on the heart’s ability to handle calcium after infarction, Dr. William Hiesinger and Dr. Pavan Atluri of the University of Pennsylvania wrote in their invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1342-3).

“More broadly, these investigations are building the foundation of what will likely be the best platform for an efficacious bridge to recovery: multimodal therapy utilizing the titration of mechanical myocardial unloading,” they said. Dr. Hiesinger and Dr. Atluri commented on the limitations of the University of Maryland study, namely its small sample size and narrow scope. “This is, however, reflective more of the amazing complexity of the biologic and mechanical interactions between the heart and VAD and the need for further investigations of this kind than the quality of the research,” they said.

Understanding the molecular basis and metabolic function cardiac dysfunction after a heart attack is in the “nascent stages,” and even less is known about the effect ventricular loading has on these pathways, Dr. Hiesinger and Dr. Atluri said. “This study offers a concrete platform for both specific treatment and further study,” they wrote.

The University of Maryland investigators in this study have joined the ranks of other investigators who have begun to unravel the consequences of mechanical unloading at the cellular level as well as its effect on the heart’s ability to handle calcium after infarction, Dr. William Hiesinger and Dr. Pavan Atluri of the University of Pennsylvania wrote in their invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1342-3).

“More broadly, these investigations are building the foundation of what will likely be the best platform for an efficacious bridge to recovery: multimodal therapy utilizing the titration of mechanical myocardial unloading,” they said. Dr. Hiesinger and Dr. Atluri commented on the limitations of the University of Maryland study, namely its small sample size and narrow scope. “This is, however, reflective more of the amazing complexity of the biologic and mechanical interactions between the heart and VAD and the need for further investigations of this kind than the quality of the research,” they said.

Understanding the molecular basis and metabolic function cardiac dysfunction after a heart attack is in the “nascent stages,” and even less is known about the effect ventricular loading has on these pathways, Dr. Hiesinger and Dr. Atluri said. “This study offers a concrete platform for both specific treatment and further study,” they wrote.

The University of Maryland investigators in this study have joined the ranks of other investigators who have begun to unravel the consequences of mechanical unloading at the cellular level as well as its effect on the heart’s ability to handle calcium after infarction, Dr. William Hiesinger and Dr. Pavan Atluri of the University of Pennsylvania wrote in their invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1342-3).

“More broadly, these investigations are building the foundation of what will likely be the best platform for an efficacious bridge to recovery: multimodal therapy utilizing the titration of mechanical myocardial unloading,” they said. Dr. Hiesinger and Dr. Atluri commented on the limitations of the University of Maryland study, namely its small sample size and narrow scope. “This is, however, reflective more of the amazing complexity of the biologic and mechanical interactions between the heart and VAD and the need for further investigations of this kind than the quality of the research,” they said.

Understanding the molecular basis and metabolic function cardiac dysfunction after a heart attack is in the “nascent stages,” and even less is known about the effect ventricular loading has on these pathways, Dr. Hiesinger and Dr. Atluri said. “This study offers a concrete platform for both specific treatment and further study,” they wrote.

Placement of a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) after a heart attack has been found to suppress certain cellular signaling pathways that protect coronary tissue, but at the same time LVAD placement seemed to help normalize other protective properties in areas of the heart closest to the infarcted region, investigators reported in a recent study.

The findings could have implications in determining the best method for unloading and other medical therapies in the aftermath of a heart attack, Dr. Keshava Rajagopal of the University of Texas, Houston, and associates reported in the November issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2015;150:1332-41).

To study the effect of LVAD on cardiac tissue, the investigators induced myocardial infarction in sheep and then placed the animals on LVAD support for 2 weeks. After 10 more weeks of observation, the investigators harvested and analyzed the myocardial specimens. The principal goal of the study was to investigate how heart attack and subsequent short-term mechanical support of the left ventricle can influence signaling controlled by the protein beta-arrestin.

They found that an infarction of myocardial tissue caused activation of the beta-arrestin protein that regulates cellular pathways that can benefit cardiac cells. At the same time, LVAD support inhibited beta-arrestin activation, specifically in regulating pathways of two cardioprotective proteins: Akt, also called protein kinase B (PKB), and, to a lesser extent, ERK-1 and -2.

They also found that MI resulted in regional activation of load-induced signaling of cardiac G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) via G proteins.

“These studies demonstrate that small platform catheter-based LVAD support exerts suppressive effects on cardioprotective beta-arrestin–mediated signal transduction, while normalizing the signaling networks of G-alpha-q–coupled cardiac GPCRS in the MI-adjacent zone,” Dr. Rajagopal and colleagues said.

They acknowledged that further studies are needed to better understand the roles that specific GPCRs in beta-arrestin–regulated signaling play in left ventricle dysfunction after a heart attack and to help define the optimal timing for LVAD based on signaling and genetic markers along with standard LV functional endpoints.

The authors had no disclosures.

Placement of a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) after a heart attack has been found to suppress certain cellular signaling pathways that protect coronary tissue, but at the same time LVAD placement seemed to help normalize other protective properties in areas of the heart closest to the infarcted region, investigators reported in a recent study.

The findings could have implications in determining the best method for unloading and other medical therapies in the aftermath of a heart attack, Dr. Keshava Rajagopal of the University of Texas, Houston, and associates reported in the November issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2015;150:1332-41).

To study the effect of LVAD on cardiac tissue, the investigators induced myocardial infarction in sheep and then placed the animals on LVAD support for 2 weeks. After 10 more weeks of observation, the investigators harvested and analyzed the myocardial specimens. The principal goal of the study was to investigate how heart attack and subsequent short-term mechanical support of the left ventricle can influence signaling controlled by the protein beta-arrestin.

They found that an infarction of myocardial tissue caused activation of the beta-arrestin protein that regulates cellular pathways that can benefit cardiac cells. At the same time, LVAD support inhibited beta-arrestin activation, specifically in regulating pathways of two cardioprotective proteins: Akt, also called protein kinase B (PKB), and, to a lesser extent, ERK-1 and -2.

They also found that MI resulted in regional activation of load-induced signaling of cardiac G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) via G proteins.

“These studies demonstrate that small platform catheter-based LVAD support exerts suppressive effects on cardioprotective beta-arrestin–mediated signal transduction, while normalizing the signaling networks of G-alpha-q–coupled cardiac GPCRS in the MI-adjacent zone,” Dr. Rajagopal and colleagues said.

They acknowledged that further studies are needed to better understand the roles that specific GPCRs in beta-arrestin–regulated signaling play in left ventricle dysfunction after a heart attack and to help define the optimal timing for LVAD based on signaling and genetic markers along with standard LV functional endpoints.

The authors had no disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Left ventricular assist device (LVAD) support inhibits pathologic responses to mechanical loading but also can inhibit adaptive responses after myocardial infarction.

Major finding: LVAD support inhibited cardioprotective beta-arrestin–mediated signaling, but net benefits of normalization of load-induced G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling were observed in the MI-adjacent zone.

Data source: Sheep were induced with myocardial infarction and then placed on LVAD support for 2 weeks and observed for a total of 12 weeks. Then myocardial specimens were harvested and analyzed.

Disclosures: The study authors had no relationships to disclose.

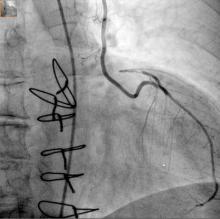

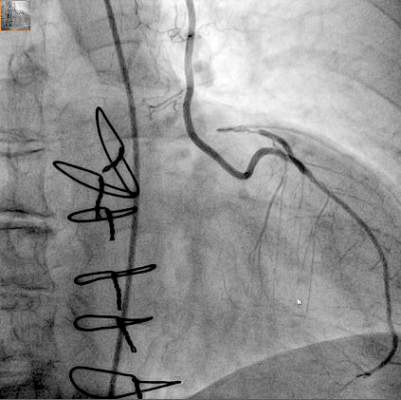

Hybrid revascularization shows promise, but there are concerns

A hybrid coronary revascularization procedure that combines off-pump left internal mammary artery (LIMA) grafting with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) showed good results at 1 year after surgery, but nonetheless showed a rate of adverse events that may raise questions about the procedure.

In a study published in the November issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, a team of investigators from Aarhus University Hospital in Denmark reported high rates of graft patency and low rates of death and stroke with the procedure 1 year after a series of 100 operations (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1181-6).

“The high left internal mammary artery graft patency rate and low risk of death and stroke at 1 year seem promising for the long-term outcome of this revascularization strategy,” said Dr. Ivy Susanne Modrau and colleagues.

The single-center study evaluated 1-year clinical and angiographic results of 100 consecutive trial patients with multivessel disease who had the hybrid procedure between October 2010 and February 2012. “The rationale of hybrid coronary revascularization is to achieve the survival benefits of the LIMA to LAD (left anterior descending artery) graft with reduced invasiveness to minimize postprocedural discomfort and morbidity, in particular the risk of stroke,” Dr. Modrau and colleagues said.

The study used the LIMA to LAD graft performed off-pump through a reversed J-hemisternotomy “We chose this technique because of its excellent exposure of the heart, technical ease, low risk of complicating chronic pain, and applicability in virtually all patients,” Dr. Modrau said. Eighty-nine patients had surgery prior to PCI and 11 had PCI prior to surgery.

The primary endpoint was rate of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCE), the composite of all-cause death, stroke, myocardial infarction, and repeat revascularization by PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting at 1 year. Secondary endpoints included individual components and status of stent and graft patency on angiography.

Overall, 20 patients met the 1-year primary endpoint of MACCE. One patient died, one other had a stroke, and three had heart attacks. Sixteen patients had repeat revascularization procedures, eight performed during the index hospitalization. Graft patency was 98% after 1 year.

Dr. Modrau and coauthors noted the MACCE rate of 20% “was higher than expected,” and certainly higher than results in the SYNTAX study (17.8% in the PCI group and 12.4% in the coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG] group) (Euro. Intervention. 2015;10:e1-e6). One possible reason the Danish investigators cited for higher than expected MACCE rates was that they may be attributed to the learning curve involved with LIMA grafting and the use of early angiography possibly revealing “clinically silent LIMA graft dysfunction due to technical errors.”

The number of repeat revascularizations in the study was more in line with the SYNTAX study: 7% in the Aarhus University study and 6% in the SYNTAX CABG group. However, a meta-analysis of six studies with 1,190 patients reported 1-year repeat revascularization rates of 3.8% after a hybrid procedure and 1.4% after CABG (Am Heart J. 2014;167:585-92).

Ultimately, the safety and efficacy of the hybrid revascularization approach will require long-term follow-up data and head-to-head comparison with conventional CABG and PCI in clinical trials. “Meanwhile, LIMA patency, the cornerstone of surgical revascularization, may be used as a surrogate endpoint for long-term survival after HCR,” Dr. Modrau and coauthors said.

They reported having no disclosures.

Hybrid revascularization procedures are “still not ready for prime time,” Dr. Carlos Mestres of Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1028-9).

The study illuminates two key points of concern, Dr. Mestres said: the “unexpectedly high” 20% rate of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCE); and the in-hospital revascularization rate that was significantly higher than the 1% after CABG that the authors reported in their own institution. That calls into question the reason the investigators would change their own department strategy away from conventional CABG, where they had optimal results, he said.

Dr. Mestres also said the Danish investigators’ conclusion that the study results seemed promising for long-term outcomes of the hybrid procedure “are to be carefully dissected.”

He commended the investigators for collecting angiographic data at 1 year, but said that 1 year of follow-up “is simply not enough” to credibly compare staged procedures with CABG.

Dr. Mestres had no disclosures.

Hybrid revascularization procedures are “still not ready for prime time,” Dr. Carlos Mestres of Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1028-9).

The study illuminates two key points of concern, Dr. Mestres said: the “unexpectedly high” 20% rate of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCE); and the in-hospital revascularization rate that was significantly higher than the 1% after CABG that the authors reported in their own institution. That calls into question the reason the investigators would change their own department strategy away from conventional CABG, where they had optimal results, he said.

Dr. Mestres also said the Danish investigators’ conclusion that the study results seemed promising for long-term outcomes of the hybrid procedure “are to be carefully dissected.”

He commended the investigators for collecting angiographic data at 1 year, but said that 1 year of follow-up “is simply not enough” to credibly compare staged procedures with CABG.

Dr. Mestres had no disclosures.

Hybrid revascularization procedures are “still not ready for prime time,” Dr. Carlos Mestres of Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1028-9).

The study illuminates two key points of concern, Dr. Mestres said: the “unexpectedly high” 20% rate of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCE); and the in-hospital revascularization rate that was significantly higher than the 1% after CABG that the authors reported in their own institution. That calls into question the reason the investigators would change their own department strategy away from conventional CABG, where they had optimal results, he said.

Dr. Mestres also said the Danish investigators’ conclusion that the study results seemed promising for long-term outcomes of the hybrid procedure “are to be carefully dissected.”

He commended the investigators for collecting angiographic data at 1 year, but said that 1 year of follow-up “is simply not enough” to credibly compare staged procedures with CABG.

Dr. Mestres had no disclosures.

A hybrid coronary revascularization procedure that combines off-pump left internal mammary artery (LIMA) grafting with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) showed good results at 1 year after surgery, but nonetheless showed a rate of adverse events that may raise questions about the procedure.

In a study published in the November issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, a team of investigators from Aarhus University Hospital in Denmark reported high rates of graft patency and low rates of death and stroke with the procedure 1 year after a series of 100 operations (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1181-6).

“The high left internal mammary artery graft patency rate and low risk of death and stroke at 1 year seem promising for the long-term outcome of this revascularization strategy,” said Dr. Ivy Susanne Modrau and colleagues.

The single-center study evaluated 1-year clinical and angiographic results of 100 consecutive trial patients with multivessel disease who had the hybrid procedure between October 2010 and February 2012. “The rationale of hybrid coronary revascularization is to achieve the survival benefits of the LIMA to LAD (left anterior descending artery) graft with reduced invasiveness to minimize postprocedural discomfort and morbidity, in particular the risk of stroke,” Dr. Modrau and colleagues said.

The study used the LIMA to LAD graft performed off-pump through a reversed J-hemisternotomy “We chose this technique because of its excellent exposure of the heart, technical ease, low risk of complicating chronic pain, and applicability in virtually all patients,” Dr. Modrau said. Eighty-nine patients had surgery prior to PCI and 11 had PCI prior to surgery.

The primary endpoint was rate of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCE), the composite of all-cause death, stroke, myocardial infarction, and repeat revascularization by PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting at 1 year. Secondary endpoints included individual components and status of stent and graft patency on angiography.

Overall, 20 patients met the 1-year primary endpoint of MACCE. One patient died, one other had a stroke, and three had heart attacks. Sixteen patients had repeat revascularization procedures, eight performed during the index hospitalization. Graft patency was 98% after 1 year.

Dr. Modrau and coauthors noted the MACCE rate of 20% “was higher than expected,” and certainly higher than results in the SYNTAX study (17.8% in the PCI group and 12.4% in the coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG] group) (Euro. Intervention. 2015;10:e1-e6). One possible reason the Danish investigators cited for higher than expected MACCE rates was that they may be attributed to the learning curve involved with LIMA grafting and the use of early angiography possibly revealing “clinically silent LIMA graft dysfunction due to technical errors.”

The number of repeat revascularizations in the study was more in line with the SYNTAX study: 7% in the Aarhus University study and 6% in the SYNTAX CABG group. However, a meta-analysis of six studies with 1,190 patients reported 1-year repeat revascularization rates of 3.8% after a hybrid procedure and 1.4% after CABG (Am Heart J. 2014;167:585-92).

Ultimately, the safety and efficacy of the hybrid revascularization approach will require long-term follow-up data and head-to-head comparison with conventional CABG and PCI in clinical trials. “Meanwhile, LIMA patency, the cornerstone of surgical revascularization, may be used as a surrogate endpoint for long-term survival after HCR,” Dr. Modrau and coauthors said.

They reported having no disclosures.

A hybrid coronary revascularization procedure that combines off-pump left internal mammary artery (LIMA) grafting with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) showed good results at 1 year after surgery, but nonetheless showed a rate of adverse events that may raise questions about the procedure.

In a study published in the November issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, a team of investigators from Aarhus University Hospital in Denmark reported high rates of graft patency and low rates of death and stroke with the procedure 1 year after a series of 100 operations (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1181-6).

“The high left internal mammary artery graft patency rate and low risk of death and stroke at 1 year seem promising for the long-term outcome of this revascularization strategy,” said Dr. Ivy Susanne Modrau and colleagues.

The single-center study evaluated 1-year clinical and angiographic results of 100 consecutive trial patients with multivessel disease who had the hybrid procedure between October 2010 and February 2012. “The rationale of hybrid coronary revascularization is to achieve the survival benefits of the LIMA to LAD (left anterior descending artery) graft with reduced invasiveness to minimize postprocedural discomfort and morbidity, in particular the risk of stroke,” Dr. Modrau and colleagues said.

The study used the LIMA to LAD graft performed off-pump through a reversed J-hemisternotomy “We chose this technique because of its excellent exposure of the heart, technical ease, low risk of complicating chronic pain, and applicability in virtually all patients,” Dr. Modrau said. Eighty-nine patients had surgery prior to PCI and 11 had PCI prior to surgery.

The primary endpoint was rate of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCE), the composite of all-cause death, stroke, myocardial infarction, and repeat revascularization by PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting at 1 year. Secondary endpoints included individual components and status of stent and graft patency on angiography.

Overall, 20 patients met the 1-year primary endpoint of MACCE. One patient died, one other had a stroke, and three had heart attacks. Sixteen patients had repeat revascularization procedures, eight performed during the index hospitalization. Graft patency was 98% after 1 year.

Dr. Modrau and coauthors noted the MACCE rate of 20% “was higher than expected,” and certainly higher than results in the SYNTAX study (17.8% in the PCI group and 12.4% in the coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG] group) (Euro. Intervention. 2015;10:e1-e6). One possible reason the Danish investigators cited for higher than expected MACCE rates was that they may be attributed to the learning curve involved with LIMA grafting and the use of early angiography possibly revealing “clinically silent LIMA graft dysfunction due to technical errors.”

The number of repeat revascularizations in the study was more in line with the SYNTAX study: 7% in the Aarhus University study and 6% in the SYNTAX CABG group. However, a meta-analysis of six studies with 1,190 patients reported 1-year repeat revascularization rates of 3.8% after a hybrid procedure and 1.4% after CABG (Am Heart J. 2014;167:585-92).

Ultimately, the safety and efficacy of the hybrid revascularization approach will require long-term follow-up data and head-to-head comparison with conventional CABG and PCI in clinical trials. “Meanwhile, LIMA patency, the cornerstone of surgical revascularization, may be used as a surrogate endpoint for long-term survival after HCR,” Dr. Modrau and coauthors said.

They reported having no disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point:High 1-year left internal mammary artery (LIMA) graft patency and low risk of death and stroke seem promising for long-term outcome after HCR.

Major finding: At 1 year, 98% of patients had patent LIMA grafts but the 20% rate of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events was “higher than expected.”

Data source: Prospective single arm clinical feasibility study including 100 consecutive patients with multivessel disease undergoing staged hybrid coronary revascularization.

Disclosures: The study authors had no disclosures.

Stem cell benefits endure 3 years in infants

Infants with congenital heart disease, specifically left heart syndrome, who had cardiac stem-cell therapy after surgery showed improved cardiac and brain function after 3 years when compared with infants who had standard therapy, according to latest results from a clinical trial of progenitor cell infusion in infants.

The prospective, controlled study, published in the November issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2015;150[5]:1198-1208), involved 14 infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS). Dr. Suguru Tarui and colleagues at Okayama University Hospital in Japan infused seven infants with intracoronary cardiosphere-derived cells (CDCs) 1 month after they had two- or three-stage palliative surgery. Seven controls had standard care alone. The trial is known TICAP (Three-year follow-up of the Transcoronary Infusion of Cardiac Progenitor Cells in Patients With Single-Ventricle Physiology) (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT01273857).

Infants born with HLHS are known to have poor prognoses. HLHS has been associated with the highest mortality of all congenital heart lesions (Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2015;18[1]:2-6).

The Okayama investigators conducted TICAP in 2011 and demonstrated the feasibility and safety of the intracoronary delivery of CDCs in infants with HLHS after staged procedures. The latest report looks at the secondary outcome of cardiac function through 36 months of follow-up, and is the first clinical trial to report on the mid-term results of cardiac progenitor therapy in congenital heart disease.

“CDC infusion could improve right ventricular function from 3 through 36 months of observation,” Dr. Tarui and colleagues said. “Patients treated by CDCs showed an increase in somatic growth and reduced heart failure status in mid-term follow-up.”

Upon entry into the study, all subjects were of similar age, body weight, and risk profiles. After 36 months, the CDC group showed no complications and significantly improved right ventricular injection fraction compared with controls. As a result, the CDC group had reduced brain natriuretic peptide levels, lower rates of unplanned catheterizations, and higher weight for age. No adverse events occurred in the CDC group, while two patients in the control group had complications (one developed heart failure, another developed enteropathy).

The investigators looked at predictors of cardiac functional efficacy in the CDC group and determined that younger age was associated with greater improvement of right ventricular ejection fraction, as measured on echocardiography. The lower weight-for-age Z score and reduced ejection fraction at the time of infusion may be predictors of cardiac function improvements at 3 years.

“This therapeutic strategy may merit somatic growth enhancement and reduce the incidence of heart failure,” Dr. Tarui and coauthors said.

They noted a number of limitations of their small clinical trial. The study was nonrandomized, and the cardiac interventions were not blinded, among others. “Larger phase II studies focusing on changes in cardiac function, myocardial fibrosis, and quality of life and clinical event rates are warranted to confirm these effects of CDC administration in patients with single ventricular physiology,” they said.

The government of Japan through its ministries of Health, Labor and Welfare, and Education, Culture Sports, Science and Technology provided funding for the study, as did the Research Foundation of Okayama University Hospital. The authors had no disclosures.

The benefits of stem cell treatments for cardiac function beyond the initial follow-up period have “remained an unanswered question,” Dr. Sunjay Kaushal of University of Maryland, Baltimore, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150[5]:1209-11). “The 3-year follow-up data from the TICAP trial, therefore, offers one of the first opportunities to examine the durability of the outcomes found in stem cell-treated patients,” Dr. Kaushal said.

While TICAP provides clues into independent predictors of success with stem cell treatments, the small study population of seven patients makes it difficult to confirm those predictors, he said. “Multivariate analysis of results from future trials with larger sample size will be needed to verify these preliminary findings,” he noted.

Nonetheless, the study adds to the emerging evidence that younger, sicker patients may respond better to stem cell infusion, a concept Dr. Kaushal termed “intriguing.”

“Meanwhile, the TICAP trial and its three-year follow-up should garner enthusiasm for stem cell therapy, and establish the basis for non-ischemic ventricular dysfunction in pediatric patients as an emerging indication for stem cell therapy,” he said.

The benefits of stem cell treatments for cardiac function beyond the initial follow-up period have “remained an unanswered question,” Dr. Sunjay Kaushal of University of Maryland, Baltimore, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150[5]:1209-11). “The 3-year follow-up data from the TICAP trial, therefore, offers one of the first opportunities to examine the durability of the outcomes found in stem cell-treated patients,” Dr. Kaushal said.

While TICAP provides clues into independent predictors of success with stem cell treatments, the small study population of seven patients makes it difficult to confirm those predictors, he said. “Multivariate analysis of results from future trials with larger sample size will be needed to verify these preliminary findings,” he noted.

Nonetheless, the study adds to the emerging evidence that younger, sicker patients may respond better to stem cell infusion, a concept Dr. Kaushal termed “intriguing.”

“Meanwhile, the TICAP trial and its three-year follow-up should garner enthusiasm for stem cell therapy, and establish the basis for non-ischemic ventricular dysfunction in pediatric patients as an emerging indication for stem cell therapy,” he said.

The benefits of stem cell treatments for cardiac function beyond the initial follow-up period have “remained an unanswered question,” Dr. Sunjay Kaushal of University of Maryland, Baltimore, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150[5]:1209-11). “The 3-year follow-up data from the TICAP trial, therefore, offers one of the first opportunities to examine the durability of the outcomes found in stem cell-treated patients,” Dr. Kaushal said.

While TICAP provides clues into independent predictors of success with stem cell treatments, the small study population of seven patients makes it difficult to confirm those predictors, he said. “Multivariate analysis of results from future trials with larger sample size will be needed to verify these preliminary findings,” he noted.

Nonetheless, the study adds to the emerging evidence that younger, sicker patients may respond better to stem cell infusion, a concept Dr. Kaushal termed “intriguing.”

“Meanwhile, the TICAP trial and its three-year follow-up should garner enthusiasm for stem cell therapy, and establish the basis for non-ischemic ventricular dysfunction in pediatric patients as an emerging indication for stem cell therapy,” he said.

Infants with congenital heart disease, specifically left heart syndrome, who had cardiac stem-cell therapy after surgery showed improved cardiac and brain function after 3 years when compared with infants who had standard therapy, according to latest results from a clinical trial of progenitor cell infusion in infants.

The prospective, controlled study, published in the November issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2015;150[5]:1198-1208), involved 14 infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS). Dr. Suguru Tarui and colleagues at Okayama University Hospital in Japan infused seven infants with intracoronary cardiosphere-derived cells (CDCs) 1 month after they had two- or three-stage palliative surgery. Seven controls had standard care alone. The trial is known TICAP (Three-year follow-up of the Transcoronary Infusion of Cardiac Progenitor Cells in Patients With Single-Ventricle Physiology) (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT01273857).

Infants born with HLHS are known to have poor prognoses. HLHS has been associated with the highest mortality of all congenital heart lesions (Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2015;18[1]:2-6).

The Okayama investigators conducted TICAP in 2011 and demonstrated the feasibility and safety of the intracoronary delivery of CDCs in infants with HLHS after staged procedures. The latest report looks at the secondary outcome of cardiac function through 36 months of follow-up, and is the first clinical trial to report on the mid-term results of cardiac progenitor therapy in congenital heart disease.

“CDC infusion could improve right ventricular function from 3 through 36 months of observation,” Dr. Tarui and colleagues said. “Patients treated by CDCs showed an increase in somatic growth and reduced heart failure status in mid-term follow-up.”

Upon entry into the study, all subjects were of similar age, body weight, and risk profiles. After 36 months, the CDC group showed no complications and significantly improved right ventricular injection fraction compared with controls. As a result, the CDC group had reduced brain natriuretic peptide levels, lower rates of unplanned catheterizations, and higher weight for age. No adverse events occurred in the CDC group, while two patients in the control group had complications (one developed heart failure, another developed enteropathy).