User login

Can an app guide cancer treatment decisions during the pandemic?

Deciding which cancer patients need immediate treatment and who can safely wait is an uncomfortable assessment for cancer clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In early April, as the COVID-19 surge was bearing down on New York City, those treatment decisions were “a juggling act every single day,” Jonathan Yang, MD, PhD, a radiation oncologist from New York’s Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, told Medscape Medical News.

Eventually, a glut of guidelines, recommendations, and expert opinions aimed at helping oncologists emerged. The tools help navigate the complicated risk-benefit analysis of their patient’s risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2 and delaying therapy.

Now, a new tool, which appears to be the first of its kind, quantifies that risk-benefit analysis. But its presence immediately raises the question: can it help?

Three-Tier Systems Are Not Very Sophisticated

OncCOVID, a free tool that was launched May 26 by the University of Michigan, allows physicians to individualize risk estimates for delaying treatment of up to 25 early- to late-stage cancers. It includes more than 45 patient characteristics, such as age, location, cancer type, cancer stage, treatment plan, underlying medical conditions, and proposed length of delay in care.

Combining these personal details with data from the National Cancer Institute’s SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) registry and the National Cancer Database, the Michigan app then estimates a patient’s 5- or 10-year survival with immediate vs delayed treatment and weighs that against their risk for COVID-19 using data from the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center.

“We thought, isn’t it better to at least provide some evidence-based quantification, rather than a back-of-the-envelope three-tier system that is just sort of ‘made up’?“ explained one of the developers, Daniel Spratt, MD, associate professor of radiation oncology at Michigan Medicine.

Spratt explained that almost every organization, professional society, and government has created something like a three-tier system. Tier 1 represents urgent cases and patients who need immediate treatment. For tier 2, treatment can be delayed weeks or a month, and with tier 3, it can be delayed until the pandemic is over or it’s deemed safe.

“[This system] sounds good at first glance, but in cancer, we’re always talking about personalized medicine, and it’s mind-blowing that these tier systems are only based on urgency and prognosis,” he told Medscape Medical News.

Spratt offered an example. Consider a patient with a very aggressive brain tumor ― that patient is in tier 1 and should undergo treatment immediately. But will the treatment actually help? And how helpful would the procedure be if, say, the patient is 80 years old and, if infected, would have a 30% to 50% chance of dying from the coronavirus?

“If the model says this guy has a 5% harm and this one has 30% harm, you can use that to help prioritize,” summarized Spratt.

The app can generate risk estimates for patients living anywhere in the world and has already been accessed by people from 37 countries. However, Spratt cautions that it is primarily “designed and calibrated for the US.

“The estimates are based on very large US registries, and though it’s probably somewhat similar across much of the world, there’s probably certain cancer types that are more region specific ― especially something like stomach cancer or certain types of head and neck cancer in parts of Asia, for example,” he said.

Although the app’s COVID-19 data are specific to the county level in the United States, elsewhere in the world, it is only country specific.

“We’re using the best data we have for coronavirus, but everyone knows we still have large data gaps,” he acknowledged.

How Accurate?

Asked to comment on the app, Richard Bleicher, MD, leader of the Breast Cancer Program at Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, praised the effort and the goal but had some concerns.

“Several questions arise, most important of which is, How accurate is this, and how has this been validated, if at all ― especially as it is too soon to see the outcomes of patients affected in this pandemic?” he told Medscape Medical News.

“We are imposing delays on a broad scale because of the coronavirus, and we are getting continuously changing data as we test more patients. But both situations are novel and may not be accurately represented by the data being pulled, because the datasets use patients from a few years ago, and confounders in these datasets may not apply to this situation,” Bleicher continued.

Although acknowledging the “value in delineating the risk of dying from cancer vs the risk of dying from the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic,” Bleicher urged caution in using the tool to make individual patient decisions.

“We need to remember that the best of modeling ... can be wildly inaccurate and needs to be validated using patients having the circumstances in question. ... This won’t be possible until long after the pandemic is completed, and so the model’s accuracy remains unknown.”

That sentiment was echoed by Giampaolo Bianchini, MD, head of the Breast Cancer Group, Department of Medical Oncology, Ospedale San Raffaele, in Milan, Italy.

“Arbitrarily postponing and modifying treatment strategies including surgery, radiation therapy, and medical therapy without properly balancing the risk/benefit ratio may lead to significantly worse cancer-related outcomes, which largely exceed the actual risks for COVID,” he wrote in an email.

“The OncCOVID app is a remarkable attempt to fill the gap between perception and estimation,” he said. The app provides side by side the COVID-19 risk estimation and the consequences of arbitrary deviation from the standard of care, observed Bianchini.

However, he pointed out weaknesses, including the fact that the “data generated in literature are not always of high quality and do not take into consideration relevant characteristics of the disease and treatment benefit. It should for sure be used, but then also interpreted with caution.”

Another Italian group responded more positively.

“In our opinion, it could be a useful tool for clinicians,” wrote colleagues Alessio Cortelinni and Giampiero Porzio, both medical oncologists at San Salvatore Hospital and the University of L’Aquila, in Italy. “This Web app might assist clinicians in balancing the risk/benefit ratio of being treated and/or access to the outpatient cancer center for each kind of patient (both early and advanced stages), in order to make a more tailored counseling,” they wrote in an email. “Importantly, the Web app might help those clinicians who work ‘alone,’ in peripheral centers, without resources, colleagues, and multidisciplinary tumor boards on whom they can rely.”

Bleicher, who was involved in the COVID-19 Breast Cancer Consortium’s recommendations for prioritizing breast cancer treatment, summarized that the app “may end up being close or accurate, but we won’t know except in hindsight.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Deciding which cancer patients need immediate treatment and who can safely wait is an uncomfortable assessment for cancer clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In early April, as the COVID-19 surge was bearing down on New York City, those treatment decisions were “a juggling act every single day,” Jonathan Yang, MD, PhD, a radiation oncologist from New York’s Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, told Medscape Medical News.

Eventually, a glut of guidelines, recommendations, and expert opinions aimed at helping oncologists emerged. The tools help navigate the complicated risk-benefit analysis of their patient’s risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2 and delaying therapy.

Now, a new tool, which appears to be the first of its kind, quantifies that risk-benefit analysis. But its presence immediately raises the question: can it help?

Three-Tier Systems Are Not Very Sophisticated

OncCOVID, a free tool that was launched May 26 by the University of Michigan, allows physicians to individualize risk estimates for delaying treatment of up to 25 early- to late-stage cancers. It includes more than 45 patient characteristics, such as age, location, cancer type, cancer stage, treatment plan, underlying medical conditions, and proposed length of delay in care.

Combining these personal details with data from the National Cancer Institute’s SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) registry and the National Cancer Database, the Michigan app then estimates a patient’s 5- or 10-year survival with immediate vs delayed treatment and weighs that against their risk for COVID-19 using data from the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center.

“We thought, isn’t it better to at least provide some evidence-based quantification, rather than a back-of-the-envelope three-tier system that is just sort of ‘made up’?“ explained one of the developers, Daniel Spratt, MD, associate professor of radiation oncology at Michigan Medicine.

Spratt explained that almost every organization, professional society, and government has created something like a three-tier system. Tier 1 represents urgent cases and patients who need immediate treatment. For tier 2, treatment can be delayed weeks or a month, and with tier 3, it can be delayed until the pandemic is over or it’s deemed safe.

“[This system] sounds good at first glance, but in cancer, we’re always talking about personalized medicine, and it’s mind-blowing that these tier systems are only based on urgency and prognosis,” he told Medscape Medical News.

Spratt offered an example. Consider a patient with a very aggressive brain tumor ― that patient is in tier 1 and should undergo treatment immediately. But will the treatment actually help? And how helpful would the procedure be if, say, the patient is 80 years old and, if infected, would have a 30% to 50% chance of dying from the coronavirus?

“If the model says this guy has a 5% harm and this one has 30% harm, you can use that to help prioritize,” summarized Spratt.

The app can generate risk estimates for patients living anywhere in the world and has already been accessed by people from 37 countries. However, Spratt cautions that it is primarily “designed and calibrated for the US.

“The estimates are based on very large US registries, and though it’s probably somewhat similar across much of the world, there’s probably certain cancer types that are more region specific ― especially something like stomach cancer or certain types of head and neck cancer in parts of Asia, for example,” he said.

Although the app’s COVID-19 data are specific to the county level in the United States, elsewhere in the world, it is only country specific.

“We’re using the best data we have for coronavirus, but everyone knows we still have large data gaps,” he acknowledged.

How Accurate?

Asked to comment on the app, Richard Bleicher, MD, leader of the Breast Cancer Program at Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, praised the effort and the goal but had some concerns.

“Several questions arise, most important of which is, How accurate is this, and how has this been validated, if at all ― especially as it is too soon to see the outcomes of patients affected in this pandemic?” he told Medscape Medical News.

“We are imposing delays on a broad scale because of the coronavirus, and we are getting continuously changing data as we test more patients. But both situations are novel and may not be accurately represented by the data being pulled, because the datasets use patients from a few years ago, and confounders in these datasets may not apply to this situation,” Bleicher continued.

Although acknowledging the “value in delineating the risk of dying from cancer vs the risk of dying from the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic,” Bleicher urged caution in using the tool to make individual patient decisions.

“We need to remember that the best of modeling ... can be wildly inaccurate and needs to be validated using patients having the circumstances in question. ... This won’t be possible until long after the pandemic is completed, and so the model’s accuracy remains unknown.”

That sentiment was echoed by Giampaolo Bianchini, MD, head of the Breast Cancer Group, Department of Medical Oncology, Ospedale San Raffaele, in Milan, Italy.

“Arbitrarily postponing and modifying treatment strategies including surgery, radiation therapy, and medical therapy without properly balancing the risk/benefit ratio may lead to significantly worse cancer-related outcomes, which largely exceed the actual risks for COVID,” he wrote in an email.

“The OncCOVID app is a remarkable attempt to fill the gap between perception and estimation,” he said. The app provides side by side the COVID-19 risk estimation and the consequences of arbitrary deviation from the standard of care, observed Bianchini.

However, he pointed out weaknesses, including the fact that the “data generated in literature are not always of high quality and do not take into consideration relevant characteristics of the disease and treatment benefit. It should for sure be used, but then also interpreted with caution.”

Another Italian group responded more positively.

“In our opinion, it could be a useful tool for clinicians,” wrote colleagues Alessio Cortelinni and Giampiero Porzio, both medical oncologists at San Salvatore Hospital and the University of L’Aquila, in Italy. “This Web app might assist clinicians in balancing the risk/benefit ratio of being treated and/or access to the outpatient cancer center for each kind of patient (both early and advanced stages), in order to make a more tailored counseling,” they wrote in an email. “Importantly, the Web app might help those clinicians who work ‘alone,’ in peripheral centers, without resources, colleagues, and multidisciplinary tumor boards on whom they can rely.”

Bleicher, who was involved in the COVID-19 Breast Cancer Consortium’s recommendations for prioritizing breast cancer treatment, summarized that the app “may end up being close or accurate, but we won’t know except in hindsight.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Deciding which cancer patients need immediate treatment and who can safely wait is an uncomfortable assessment for cancer clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In early April, as the COVID-19 surge was bearing down on New York City, those treatment decisions were “a juggling act every single day,” Jonathan Yang, MD, PhD, a radiation oncologist from New York’s Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, told Medscape Medical News.

Eventually, a glut of guidelines, recommendations, and expert opinions aimed at helping oncologists emerged. The tools help navigate the complicated risk-benefit analysis of their patient’s risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2 and delaying therapy.

Now, a new tool, which appears to be the first of its kind, quantifies that risk-benefit analysis. But its presence immediately raises the question: can it help?

Three-Tier Systems Are Not Very Sophisticated

OncCOVID, a free tool that was launched May 26 by the University of Michigan, allows physicians to individualize risk estimates for delaying treatment of up to 25 early- to late-stage cancers. It includes more than 45 patient characteristics, such as age, location, cancer type, cancer stage, treatment plan, underlying medical conditions, and proposed length of delay in care.

Combining these personal details with data from the National Cancer Institute’s SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) registry and the National Cancer Database, the Michigan app then estimates a patient’s 5- or 10-year survival with immediate vs delayed treatment and weighs that against their risk for COVID-19 using data from the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center.

“We thought, isn’t it better to at least provide some evidence-based quantification, rather than a back-of-the-envelope three-tier system that is just sort of ‘made up’?“ explained one of the developers, Daniel Spratt, MD, associate professor of radiation oncology at Michigan Medicine.

Spratt explained that almost every organization, professional society, and government has created something like a three-tier system. Tier 1 represents urgent cases and patients who need immediate treatment. For tier 2, treatment can be delayed weeks or a month, and with tier 3, it can be delayed until the pandemic is over or it’s deemed safe.

“[This system] sounds good at first glance, but in cancer, we’re always talking about personalized medicine, and it’s mind-blowing that these tier systems are only based on urgency and prognosis,” he told Medscape Medical News.

Spratt offered an example. Consider a patient with a very aggressive brain tumor ― that patient is in tier 1 and should undergo treatment immediately. But will the treatment actually help? And how helpful would the procedure be if, say, the patient is 80 years old and, if infected, would have a 30% to 50% chance of dying from the coronavirus?

“If the model says this guy has a 5% harm and this one has 30% harm, you can use that to help prioritize,” summarized Spratt.

The app can generate risk estimates for patients living anywhere in the world and has already been accessed by people from 37 countries. However, Spratt cautions that it is primarily “designed and calibrated for the US.

“The estimates are based on very large US registries, and though it’s probably somewhat similar across much of the world, there’s probably certain cancer types that are more region specific ― especially something like stomach cancer or certain types of head and neck cancer in parts of Asia, for example,” he said.

Although the app’s COVID-19 data are specific to the county level in the United States, elsewhere in the world, it is only country specific.

“We’re using the best data we have for coronavirus, but everyone knows we still have large data gaps,” he acknowledged.

How Accurate?

Asked to comment on the app, Richard Bleicher, MD, leader of the Breast Cancer Program at Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, praised the effort and the goal but had some concerns.

“Several questions arise, most important of which is, How accurate is this, and how has this been validated, if at all ― especially as it is too soon to see the outcomes of patients affected in this pandemic?” he told Medscape Medical News.

“We are imposing delays on a broad scale because of the coronavirus, and we are getting continuously changing data as we test more patients. But both situations are novel and may not be accurately represented by the data being pulled, because the datasets use patients from a few years ago, and confounders in these datasets may not apply to this situation,” Bleicher continued.

Although acknowledging the “value in delineating the risk of dying from cancer vs the risk of dying from the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic,” Bleicher urged caution in using the tool to make individual patient decisions.

“We need to remember that the best of modeling ... can be wildly inaccurate and needs to be validated using patients having the circumstances in question. ... This won’t be possible until long after the pandemic is completed, and so the model’s accuracy remains unknown.”

That sentiment was echoed by Giampaolo Bianchini, MD, head of the Breast Cancer Group, Department of Medical Oncology, Ospedale San Raffaele, in Milan, Italy.

“Arbitrarily postponing and modifying treatment strategies including surgery, radiation therapy, and medical therapy without properly balancing the risk/benefit ratio may lead to significantly worse cancer-related outcomes, which largely exceed the actual risks for COVID,” he wrote in an email.

“The OncCOVID app is a remarkable attempt to fill the gap between perception and estimation,” he said. The app provides side by side the COVID-19 risk estimation and the consequences of arbitrary deviation from the standard of care, observed Bianchini.

However, he pointed out weaknesses, including the fact that the “data generated in literature are not always of high quality and do not take into consideration relevant characteristics of the disease and treatment benefit. It should for sure be used, but then also interpreted with caution.”

Another Italian group responded more positively.

“In our opinion, it could be a useful tool for clinicians,” wrote colleagues Alessio Cortelinni and Giampiero Porzio, both medical oncologists at San Salvatore Hospital and the University of L’Aquila, in Italy. “This Web app might assist clinicians in balancing the risk/benefit ratio of being treated and/or access to the outpatient cancer center for each kind of patient (both early and advanced stages), in order to make a more tailored counseling,” they wrote in an email. “Importantly, the Web app might help those clinicians who work ‘alone,’ in peripheral centers, without resources, colleagues, and multidisciplinary tumor boards on whom they can rely.”

Bleicher, who was involved in the COVID-19 Breast Cancer Consortium’s recommendations for prioritizing breast cancer treatment, summarized that the app “may end up being close or accurate, but we won’t know except in hindsight.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘A good and peaceful death’: Cancer hospice during the pandemic

Lillie Shockney, RN, MAS, a two-time breast cancer survivor and adjunct professor at Johns Hopkins School of Nursing in Baltimore, Maryland, mourns the many losses that her patients with advanced cancer now face in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. But in the void of the usual support networks and treatment plans, she sees the resurgence of something that has recently been crowded out: hospice.

The pandemic has forced patients and their physicians to reassess the risk/benefit balance of continuing or embarking on yet another cancer treatment.

“It’s one of the pearls that we will get out of this nightmare,” said Ms. Shockney, who recently retired as administrative director of the cancer survivorship programs at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“Physicians have been taught to treat the disease – so as long as there’s a treatment they give another treatment,” she told Medscape Medical News during a Zoom call from her home. “But for some patients with advanced disease, those treatments were making them very sick, so they were trading longevity over quality of life.”

Of course, longevity has never been a guarantee with cancer treatment, and even less so now, with the risk of COVID-19.

“This is going to bring them to some hard discussions,” says Brenda Nevidjon, RN, MSN, chief executive officer at the Oncology Nursing Society.

“We’ve known for a long time that there are patients who are on third- and fourth-round treatment options that have very little evidence of prolonging life or quality of life,” she told Medscape Medical News. “Do we bring these people out of their home to a setting where there could be a fair number of COVID-positive patients? Do we expose them to that?”

Across the world, these dilemmas are pushing cancer specialists to initiate discussions of hospice sooner with patients who have advanced disease, and with more clarity than before.

One of the reasons such conversations have often been avoided is that the concept of hospice is generally misunderstood, said Ms. Shockney.

“Patients think ‘you’re giving up on me, you’ve abandoned me’, but hospice is all about preserving the remainder of their quality of life and letting them have time with family and time to fulfill those elements of experiencing a good and peaceful death,” she said.

Indeed, hospice is “a benefit meant for somebody with at least a 6-month horizon,” agrees Ms. Nevidjon. Yet the average length of hospice in the United States is just 5 days. “It’s at the very, very end, and yet for some of these patients the 6 months they could get in hospice might be a better quality of life than the 4 months on another whole plan of chemotherapy. I can’t imagine that on the backside of this pandemic we will not have learned and we won’t start to change practices around initiating more of these conversations.”

Silver lining of this pandemic?

It’s too early into the pandemic to have hard data on whether hospice uptake has increased, but “it’s encouraging to hear that hospice is being discussed and offered sooner as an alternative to that third- or fourth-round chemo,” said Lori Bishop, MHA, RN, vice president of palliative and advanced care at the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization.

“I agree that improving informed-decision discussions and timely access to hospice is a silver lining of the pandemic,” she told Medscape Medical News.

But she points out that today’s hospice looks quite different than it did before the pandemic, with the immediate and very obvious difference being telehealth, which was not widely utilized previously.

In March, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services expanded telehealth options for hospice providers, something that Ms. Bishop and other hospice providers hope will remain in place after the pandemic passes.

“Telehealth visits are offered to replace some in-home visits both to minimize risk of exposure to COVID-19 and reduce the drain on personal protective equipment,” Bishop explained.

“In-patient hospice programs are also finding unique ways to provide support and connect patients to their loved ones: visitors are allowed but limited to one or two. Music and pet therapy are being provided through the window or virtually and devices such as iPads are being used to help patients connect with loved ones,” she said.

Telehealth links patients out of loneliness, but the one thing it cannot do is provide the comfort of touch – an important part of any hospice program.

“Hand-holding ... I miss that a lot,” says Ms. Shockney, her eyes filling with tears. “When you take somebody’s hand, you don’t even have to speak; that connection, and eye contact, is all you need to help that person emotionally heal.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Lillie Shockney, RN, MAS, a two-time breast cancer survivor and adjunct professor at Johns Hopkins School of Nursing in Baltimore, Maryland, mourns the many losses that her patients with advanced cancer now face in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. But in the void of the usual support networks and treatment plans, she sees the resurgence of something that has recently been crowded out: hospice.

The pandemic has forced patients and their physicians to reassess the risk/benefit balance of continuing or embarking on yet another cancer treatment.

“It’s one of the pearls that we will get out of this nightmare,” said Ms. Shockney, who recently retired as administrative director of the cancer survivorship programs at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“Physicians have been taught to treat the disease – so as long as there’s a treatment they give another treatment,” she told Medscape Medical News during a Zoom call from her home. “But for some patients with advanced disease, those treatments were making them very sick, so they were trading longevity over quality of life.”

Of course, longevity has never been a guarantee with cancer treatment, and even less so now, with the risk of COVID-19.

“This is going to bring them to some hard discussions,” says Brenda Nevidjon, RN, MSN, chief executive officer at the Oncology Nursing Society.

“We’ve known for a long time that there are patients who are on third- and fourth-round treatment options that have very little evidence of prolonging life or quality of life,” she told Medscape Medical News. “Do we bring these people out of their home to a setting where there could be a fair number of COVID-positive patients? Do we expose them to that?”

Across the world, these dilemmas are pushing cancer specialists to initiate discussions of hospice sooner with patients who have advanced disease, and with more clarity than before.

One of the reasons such conversations have often been avoided is that the concept of hospice is generally misunderstood, said Ms. Shockney.

“Patients think ‘you’re giving up on me, you’ve abandoned me’, but hospice is all about preserving the remainder of their quality of life and letting them have time with family and time to fulfill those elements of experiencing a good and peaceful death,” she said.

Indeed, hospice is “a benefit meant for somebody with at least a 6-month horizon,” agrees Ms. Nevidjon. Yet the average length of hospice in the United States is just 5 days. “It’s at the very, very end, and yet for some of these patients the 6 months they could get in hospice might be a better quality of life than the 4 months on another whole plan of chemotherapy. I can’t imagine that on the backside of this pandemic we will not have learned and we won’t start to change practices around initiating more of these conversations.”

Silver lining of this pandemic?

It’s too early into the pandemic to have hard data on whether hospice uptake has increased, but “it’s encouraging to hear that hospice is being discussed and offered sooner as an alternative to that third- or fourth-round chemo,” said Lori Bishop, MHA, RN, vice president of palliative and advanced care at the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization.

“I agree that improving informed-decision discussions and timely access to hospice is a silver lining of the pandemic,” she told Medscape Medical News.

But she points out that today’s hospice looks quite different than it did before the pandemic, with the immediate and very obvious difference being telehealth, which was not widely utilized previously.

In March, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services expanded telehealth options for hospice providers, something that Ms. Bishop and other hospice providers hope will remain in place after the pandemic passes.

“Telehealth visits are offered to replace some in-home visits both to minimize risk of exposure to COVID-19 and reduce the drain on personal protective equipment,” Bishop explained.

“In-patient hospice programs are also finding unique ways to provide support and connect patients to their loved ones: visitors are allowed but limited to one or two. Music and pet therapy are being provided through the window or virtually and devices such as iPads are being used to help patients connect with loved ones,” she said.

Telehealth links patients out of loneliness, but the one thing it cannot do is provide the comfort of touch – an important part of any hospice program.

“Hand-holding ... I miss that a lot,” says Ms. Shockney, her eyes filling with tears. “When you take somebody’s hand, you don’t even have to speak; that connection, and eye contact, is all you need to help that person emotionally heal.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Lillie Shockney, RN, MAS, a two-time breast cancer survivor and adjunct professor at Johns Hopkins School of Nursing in Baltimore, Maryland, mourns the many losses that her patients with advanced cancer now face in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. But in the void of the usual support networks and treatment plans, she sees the resurgence of something that has recently been crowded out: hospice.

The pandemic has forced patients and their physicians to reassess the risk/benefit balance of continuing or embarking on yet another cancer treatment.

“It’s one of the pearls that we will get out of this nightmare,” said Ms. Shockney, who recently retired as administrative director of the cancer survivorship programs at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“Physicians have been taught to treat the disease – so as long as there’s a treatment they give another treatment,” she told Medscape Medical News during a Zoom call from her home. “But for some patients with advanced disease, those treatments were making them very sick, so they were trading longevity over quality of life.”

Of course, longevity has never been a guarantee with cancer treatment, and even less so now, with the risk of COVID-19.

“This is going to bring them to some hard discussions,” says Brenda Nevidjon, RN, MSN, chief executive officer at the Oncology Nursing Society.

“We’ve known for a long time that there are patients who are on third- and fourth-round treatment options that have very little evidence of prolonging life or quality of life,” she told Medscape Medical News. “Do we bring these people out of their home to a setting where there could be a fair number of COVID-positive patients? Do we expose them to that?”

Across the world, these dilemmas are pushing cancer specialists to initiate discussions of hospice sooner with patients who have advanced disease, and with more clarity than before.

One of the reasons such conversations have often been avoided is that the concept of hospice is generally misunderstood, said Ms. Shockney.

“Patients think ‘you’re giving up on me, you’ve abandoned me’, but hospice is all about preserving the remainder of their quality of life and letting them have time with family and time to fulfill those elements of experiencing a good and peaceful death,” she said.

Indeed, hospice is “a benefit meant for somebody with at least a 6-month horizon,” agrees Ms. Nevidjon. Yet the average length of hospice in the United States is just 5 days. “It’s at the very, very end, and yet for some of these patients the 6 months they could get in hospice might be a better quality of life than the 4 months on another whole plan of chemotherapy. I can’t imagine that on the backside of this pandemic we will not have learned and we won’t start to change practices around initiating more of these conversations.”

Silver lining of this pandemic?

It’s too early into the pandemic to have hard data on whether hospice uptake has increased, but “it’s encouraging to hear that hospice is being discussed and offered sooner as an alternative to that third- or fourth-round chemo,” said Lori Bishop, MHA, RN, vice president of palliative and advanced care at the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization.

“I agree that improving informed-decision discussions and timely access to hospice is a silver lining of the pandemic,” she told Medscape Medical News.

But she points out that today’s hospice looks quite different than it did before the pandemic, with the immediate and very obvious difference being telehealth, which was not widely utilized previously.

In March, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services expanded telehealth options for hospice providers, something that Ms. Bishop and other hospice providers hope will remain in place after the pandemic passes.

“Telehealth visits are offered to replace some in-home visits both to minimize risk of exposure to COVID-19 and reduce the drain on personal protective equipment,” Bishop explained.

“In-patient hospice programs are also finding unique ways to provide support and connect patients to their loved ones: visitors are allowed but limited to one or two. Music and pet therapy are being provided through the window or virtually and devices such as iPads are being used to help patients connect with loved ones,” she said.

Telehealth links patients out of loneliness, but the one thing it cannot do is provide the comfort of touch – an important part of any hospice program.

“Hand-holding ... I miss that a lot,” says Ms. Shockney, her eyes filling with tears. “When you take somebody’s hand, you don’t even have to speak; that connection, and eye contact, is all you need to help that person emotionally heal.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Germline testing in advanced cancer can lead to targeted treatment

The study involved 11,974 patients with various tumor types. All the patients underwent germline genetic testing from 2015 to 2019 at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York, using the next-generation sequencing panel MSK-IMPACT.

This testing showed that 17.1% of patients had variants in cancer predisposition genes, and 7.1%-8.6% had variants that could potentially be targeted.

“Of course, these numbers are not static,” commented lead author Zsofia K. Stadler, MD, a medical oncologist at MSKCC. “And with the emergence of novel targeted treatments with new FDA indications, the therapeutic actionability of germline variants is likely to increase over time.

“Our study demonstrates the first comprehensive assessment of the clinical utility of germline alterations for therapeutic actionability in a population of patients with advanced cancer,” she added.

Dr. Stadler presented the study results during a virtual scientific program of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2020.

Testing for somatic mutations is evolving as the standard of care in many cancer types, and somatic genomic testing is rapidly becoming an integral part of the regimen for patients with advanced disease. Some studies suggest that 9%-11% of patients harbor actionable genetic alterations, as determined on the basis of tumor profiling.

“The take-home message from this is that now, more than ever before, germline testing is indicated for the selection of cancer treatment,” said Erin Wysong Hofstatter, MD, from Yale University, New Haven, Conn., in a Highlights of the Day session.

An emerging indication for germline testing is the selection of treatment in the advanced setting, she noted. “And it is important to know your test. Remember that tumor sequencing is not a substitute for comprehensive germline testing.”

Implications in cancer treatment

For their study, Dr. Stadler and colleagues reviewed the medical records of patients with likely pathogenic/pathogenic germline (LP/P) alterations in genes that had known therapeutic targets so as to identify germline-targeted treatment either in a clinical or research setting.

“Since 2015, patients undergoing MSK-IMPACT may also choose to provide additional consent for secondary germline genetic analysis, wherein up to 88 genes known to be associated with cancer predisposition are analyzed,” she said. “Likely pathogenic and pathogenic germline alterations identified are disclosed to the patient and treating physician via the Clinical Genetic Service.”

A total of 2043 (17.1%) patients who harbored LP/P variants in a cancer predisposition gene were identified. Of these, 11% of patients harbored pathogenic alterations in high or moderate penetrance cancer predisposition genes. When the analysis was limited to genes with targeted therapeutic actionability, or what the authors defined as tier 1 and tier 2 genes, 7.1% of patients (n = 849) harbored a targetable pathogenic germline alteration.

BRCA alterations accounted for half (52%) of the findings, and 20% were associated with Lynch syndrome.

The tier 2 genes, which included PALB2, ATM, RAD51C, and RAD51D, accounted for about a quarter of the findings. Dr. Hofstatter noted that, using strict criteria, 7.1% of patients (n = 849) were found to harbor a pathogenic alteration and a targetable gene. Using less stringent criteria, additional tier 3 genes and additional genes associated with DNA homologous recombination repair brought the number up to 8.6% (n = 1,003).

Therapeutic action

For determining therapeutic actionability, the strict criteria were used; 593 patients (4.95%) with recurrent or metastatic disease were identified. For these patients, consideration of a targeted therapy, either as part of standard care or as part of an investigation or research protocol, was important.

Of this group, 44% received therapy targeting the germline alteration. Regarding specific genes, 50% of BRCA1/2 carriers and 58% of Lynch syndrome patients received targeted treatment. With respect to tier 2 genes, 40% of patients with PALB2, 19% with ATM, and 37% with RAD51C or 51D received a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor.

Among patients with a BRCA1/2 mutation who received a PARP inhibitor, 55.1% had breast or ovarian cancer, and 44.8% had other tumor types, including pancreas, prostate, bile duct, gastric cancers. These patients received the drug in a research setting.

For patients with PALB2 alterations who received PARP inhibitors, 53.3% had breast or pancreas cancer, and 46.7% had cancer of the prostate, ovary, or an unknown primary.

Looking ahead

The discussant for the paper, Funda Meric-Bernstam, MD, chair of the Department of Investigational Cancer Therapeutics at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, pointed out that most of the BRCA-positive patients had cancers traditionally associated with the mutation. “There were no patients with PTEN mutations treated, and interestingly, no patients with NF1 were treated,” she said. “But actionability is evolving, as the MEK inhibitor selumitinib was recently approved for NF1.”

Some questions remain unanswered, she noted, such as: “What percentage of patients undergoing tumor-normal testing signed a germline protocol?” and “Does the population introduce a bias – such as younger patients, family history, and so on?”

It is also unknown what percentage of germline alterations were known in comparison with those identified through tumor/normal testing. Also of importance is the fact that in this study, the results of germline testing were delivered in an academic setting, she emphasized. “What if they were delivered elsewhere? What would be the impact of identifying these alterations in an environment with less access to trials?

“But to be fair, it is not easy to seek the germline mutations,” Dr. Meric-Bernstam continued. “These studies were done under institutional review board protocols, and it is important to note that most profiling is done as standard of care without consenting and soliciting patient preference on the return of germline results.”

An infrastructure is needed to return/counsel/offer cascade testing, and “analyses need to be facilitated to ensure that findings can be acted upon in a timely fashion,” she added.

The study was supported by MSKCC internal funding. Dr. Stadler reported relationships (institutional) with Adverum, Alimera Sciences, Allergan, Biomarin, Fortress Biotech, Genentech/Roche, Novartis, Optos, Regeneron, Regenxbio, and Spark Therapeutics. Dr. Meric-Bernstram reported relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study involved 11,974 patients with various tumor types. All the patients underwent germline genetic testing from 2015 to 2019 at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York, using the next-generation sequencing panel MSK-IMPACT.

This testing showed that 17.1% of patients had variants in cancer predisposition genes, and 7.1%-8.6% had variants that could potentially be targeted.

“Of course, these numbers are not static,” commented lead author Zsofia K. Stadler, MD, a medical oncologist at MSKCC. “And with the emergence of novel targeted treatments with new FDA indications, the therapeutic actionability of germline variants is likely to increase over time.

“Our study demonstrates the first comprehensive assessment of the clinical utility of germline alterations for therapeutic actionability in a population of patients with advanced cancer,” she added.

Dr. Stadler presented the study results during a virtual scientific program of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2020.

Testing for somatic mutations is evolving as the standard of care in many cancer types, and somatic genomic testing is rapidly becoming an integral part of the regimen for patients with advanced disease. Some studies suggest that 9%-11% of patients harbor actionable genetic alterations, as determined on the basis of tumor profiling.

“The take-home message from this is that now, more than ever before, germline testing is indicated for the selection of cancer treatment,” said Erin Wysong Hofstatter, MD, from Yale University, New Haven, Conn., in a Highlights of the Day session.

An emerging indication for germline testing is the selection of treatment in the advanced setting, she noted. “And it is important to know your test. Remember that tumor sequencing is not a substitute for comprehensive germline testing.”

Implications in cancer treatment

For their study, Dr. Stadler and colleagues reviewed the medical records of patients with likely pathogenic/pathogenic germline (LP/P) alterations in genes that had known therapeutic targets so as to identify germline-targeted treatment either in a clinical or research setting.

“Since 2015, patients undergoing MSK-IMPACT may also choose to provide additional consent for secondary germline genetic analysis, wherein up to 88 genes known to be associated with cancer predisposition are analyzed,” she said. “Likely pathogenic and pathogenic germline alterations identified are disclosed to the patient and treating physician via the Clinical Genetic Service.”

A total of 2043 (17.1%) patients who harbored LP/P variants in a cancer predisposition gene were identified. Of these, 11% of patients harbored pathogenic alterations in high or moderate penetrance cancer predisposition genes. When the analysis was limited to genes with targeted therapeutic actionability, or what the authors defined as tier 1 and tier 2 genes, 7.1% of patients (n = 849) harbored a targetable pathogenic germline alteration.

BRCA alterations accounted for half (52%) of the findings, and 20% were associated with Lynch syndrome.

The tier 2 genes, which included PALB2, ATM, RAD51C, and RAD51D, accounted for about a quarter of the findings. Dr. Hofstatter noted that, using strict criteria, 7.1% of patients (n = 849) were found to harbor a pathogenic alteration and a targetable gene. Using less stringent criteria, additional tier 3 genes and additional genes associated with DNA homologous recombination repair brought the number up to 8.6% (n = 1,003).

Therapeutic action

For determining therapeutic actionability, the strict criteria were used; 593 patients (4.95%) with recurrent or metastatic disease were identified. For these patients, consideration of a targeted therapy, either as part of standard care or as part of an investigation or research protocol, was important.

Of this group, 44% received therapy targeting the germline alteration. Regarding specific genes, 50% of BRCA1/2 carriers and 58% of Lynch syndrome patients received targeted treatment. With respect to tier 2 genes, 40% of patients with PALB2, 19% with ATM, and 37% with RAD51C or 51D received a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor.

Among patients with a BRCA1/2 mutation who received a PARP inhibitor, 55.1% had breast or ovarian cancer, and 44.8% had other tumor types, including pancreas, prostate, bile duct, gastric cancers. These patients received the drug in a research setting.

For patients with PALB2 alterations who received PARP inhibitors, 53.3% had breast or pancreas cancer, and 46.7% had cancer of the prostate, ovary, or an unknown primary.

Looking ahead

The discussant for the paper, Funda Meric-Bernstam, MD, chair of the Department of Investigational Cancer Therapeutics at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, pointed out that most of the BRCA-positive patients had cancers traditionally associated with the mutation. “There were no patients with PTEN mutations treated, and interestingly, no patients with NF1 were treated,” she said. “But actionability is evolving, as the MEK inhibitor selumitinib was recently approved for NF1.”

Some questions remain unanswered, she noted, such as: “What percentage of patients undergoing tumor-normal testing signed a germline protocol?” and “Does the population introduce a bias – such as younger patients, family history, and so on?”

It is also unknown what percentage of germline alterations were known in comparison with those identified through tumor/normal testing. Also of importance is the fact that in this study, the results of germline testing were delivered in an academic setting, she emphasized. “What if they were delivered elsewhere? What would be the impact of identifying these alterations in an environment with less access to trials?

“But to be fair, it is not easy to seek the germline mutations,” Dr. Meric-Bernstam continued. “These studies were done under institutional review board protocols, and it is important to note that most profiling is done as standard of care without consenting and soliciting patient preference on the return of germline results.”

An infrastructure is needed to return/counsel/offer cascade testing, and “analyses need to be facilitated to ensure that findings can be acted upon in a timely fashion,” she added.

The study was supported by MSKCC internal funding. Dr. Stadler reported relationships (institutional) with Adverum, Alimera Sciences, Allergan, Biomarin, Fortress Biotech, Genentech/Roche, Novartis, Optos, Regeneron, Regenxbio, and Spark Therapeutics. Dr. Meric-Bernstram reported relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study involved 11,974 patients with various tumor types. All the patients underwent germline genetic testing from 2015 to 2019 at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York, using the next-generation sequencing panel MSK-IMPACT.

This testing showed that 17.1% of patients had variants in cancer predisposition genes, and 7.1%-8.6% had variants that could potentially be targeted.

“Of course, these numbers are not static,” commented lead author Zsofia K. Stadler, MD, a medical oncologist at MSKCC. “And with the emergence of novel targeted treatments with new FDA indications, the therapeutic actionability of germline variants is likely to increase over time.

“Our study demonstrates the first comprehensive assessment of the clinical utility of germline alterations for therapeutic actionability in a population of patients with advanced cancer,” she added.

Dr. Stadler presented the study results during a virtual scientific program of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2020.

Testing for somatic mutations is evolving as the standard of care in many cancer types, and somatic genomic testing is rapidly becoming an integral part of the regimen for patients with advanced disease. Some studies suggest that 9%-11% of patients harbor actionable genetic alterations, as determined on the basis of tumor profiling.

“The take-home message from this is that now, more than ever before, germline testing is indicated for the selection of cancer treatment,” said Erin Wysong Hofstatter, MD, from Yale University, New Haven, Conn., in a Highlights of the Day session.

An emerging indication for germline testing is the selection of treatment in the advanced setting, she noted. “And it is important to know your test. Remember that tumor sequencing is not a substitute for comprehensive germline testing.”

Implications in cancer treatment

For their study, Dr. Stadler and colleagues reviewed the medical records of patients with likely pathogenic/pathogenic germline (LP/P) alterations in genes that had known therapeutic targets so as to identify germline-targeted treatment either in a clinical or research setting.

“Since 2015, patients undergoing MSK-IMPACT may also choose to provide additional consent for secondary germline genetic analysis, wherein up to 88 genes known to be associated with cancer predisposition are analyzed,” she said. “Likely pathogenic and pathogenic germline alterations identified are disclosed to the patient and treating physician via the Clinical Genetic Service.”

A total of 2043 (17.1%) patients who harbored LP/P variants in a cancer predisposition gene were identified. Of these, 11% of patients harbored pathogenic alterations in high or moderate penetrance cancer predisposition genes. When the analysis was limited to genes with targeted therapeutic actionability, or what the authors defined as tier 1 and tier 2 genes, 7.1% of patients (n = 849) harbored a targetable pathogenic germline alteration.

BRCA alterations accounted for half (52%) of the findings, and 20% were associated with Lynch syndrome.

The tier 2 genes, which included PALB2, ATM, RAD51C, and RAD51D, accounted for about a quarter of the findings. Dr. Hofstatter noted that, using strict criteria, 7.1% of patients (n = 849) were found to harbor a pathogenic alteration and a targetable gene. Using less stringent criteria, additional tier 3 genes and additional genes associated with DNA homologous recombination repair brought the number up to 8.6% (n = 1,003).

Therapeutic action

For determining therapeutic actionability, the strict criteria were used; 593 patients (4.95%) with recurrent or metastatic disease were identified. For these patients, consideration of a targeted therapy, either as part of standard care or as part of an investigation or research protocol, was important.

Of this group, 44% received therapy targeting the germline alteration. Regarding specific genes, 50% of BRCA1/2 carriers and 58% of Lynch syndrome patients received targeted treatment. With respect to tier 2 genes, 40% of patients with PALB2, 19% with ATM, and 37% with RAD51C or 51D received a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor.

Among patients with a BRCA1/2 mutation who received a PARP inhibitor, 55.1% had breast or ovarian cancer, and 44.8% had other tumor types, including pancreas, prostate, bile duct, gastric cancers. These patients received the drug in a research setting.

For patients with PALB2 alterations who received PARP inhibitors, 53.3% had breast or pancreas cancer, and 46.7% had cancer of the prostate, ovary, or an unknown primary.

Looking ahead

The discussant for the paper, Funda Meric-Bernstam, MD, chair of the Department of Investigational Cancer Therapeutics at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, pointed out that most of the BRCA-positive patients had cancers traditionally associated with the mutation. “There were no patients with PTEN mutations treated, and interestingly, no patients with NF1 were treated,” she said. “But actionability is evolving, as the MEK inhibitor selumitinib was recently approved for NF1.”

Some questions remain unanswered, she noted, such as: “What percentage of patients undergoing tumor-normal testing signed a germline protocol?” and “Does the population introduce a bias – such as younger patients, family history, and so on?”

It is also unknown what percentage of germline alterations were known in comparison with those identified through tumor/normal testing. Also of importance is the fact that in this study, the results of germline testing were delivered in an academic setting, she emphasized. “What if they were delivered elsewhere? What would be the impact of identifying these alterations in an environment with less access to trials?

“But to be fair, it is not easy to seek the germline mutations,” Dr. Meric-Bernstam continued. “These studies were done under institutional review board protocols, and it is important to note that most profiling is done as standard of care without consenting and soliciting patient preference on the return of germline results.”

An infrastructure is needed to return/counsel/offer cascade testing, and “analyses need to be facilitated to ensure that findings can be acted upon in a timely fashion,” she added.

The study was supported by MSKCC internal funding. Dr. Stadler reported relationships (institutional) with Adverum, Alimera Sciences, Allergan, Biomarin, Fortress Biotech, Genentech/Roche, Novartis, Optos, Regeneron, Regenxbio, and Spark Therapeutics. Dr. Meric-Bernstram reported relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ASCO 2020

Incidence of CNS tumors appears lower in Chinese children

, results of a population-based study suggest.

Adjusted incidence rates of CNS tumors were significantly higher among children from the U.S. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database than among children from a cancer registry in Hong Kong.

Anthony P. Y. Liu, MBBS, MMedSc, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn., and colleagues reported these findings in JCO Global Oncology.

The Hong Kong cohort originally included 526 patients, but only 508 of them were included in the comparison with the SEER patients. The SEER cohorts included 447 patients of API descent and 5,047 patients of all ethnicities.

In all cohorts, patients were younger than 18 years of age and had been diagnosed with a primary CNS tumor during 1999-2016.

Results

Age-, sex-, and study period–adjusted incidence rates of CNS tumors were significantly higher in the SEER cohorts than in the Hong Kong cohort (P < .001). The adjusted incidence rates were:

- 2.51 per 100,000 children in the Hong Kong cohort.

- 3.26 per 100,000 children among APIs in the SEER cohort.

- 4.10 per 100,000 children among all ethnicities in the SEER cohort.

Incidence rates of most tumor types were significantly lower in the Hong Kong cohort than in the entire SEER cohort. This includes choroid plexus tumors (0.08 vs. 0.16; P = .045), ependymomas (0.18 vs. 0.31; P = .005), and glial and neuronal tumors (0.94 vs. 2.61; P < .001). However, incidence rates of germ cell tumors were significantly higher in the Hong Kong cohort (0.57 vs. 0.24; P < .001).

For the most part, there were no significant differences in incidence by histology between the Hong Kong cohort and the API SEER cohort. The exception was glial and neuronal tumors, for which the incidence rate was lower in the Hong Kong cohort than in the API SEER cohort (0.94 vs. 1.74; P < .001).

The 5-year overall survival rate was significantly lower in the Hong Kong cohort than in the API and entire SEER cohorts – 66.8% , 75.3%, and 78.7%, respectively (P < .001). This appears to be driven by inferior survival among Hong Kong patients with glial and neuronal tumors. For other tumor types, there were no significant differences in survival across the cohorts.

Interpretation

“Dr. Liu and colleagues have conducted a very nice epidemiological study, and their results suggest that the incidence of pediatric brain tumors is much lower in Hong Kong compared to the incidence in the United States,” noted Eric Bouffet, MD, of the University of Toronto.

“These results are intriguing, and it is clear that large epidemiological studies are needed to better understand the impact of ethnic, genetic, and socio-environmental factors linked to the incidence of childhood cancer, and in particular childhood brain tumors,” Dr. Bouffet added.

“My suspicion is that the lower incidence of brain tumors in Hong Kong may relate to the omission of patients who did not have a biopsy from the dataset,” said David Ziegler, MD, PhD, of the University of New South Wales in Kensington, Australia.

Dr. Liu and colleagues acknowledged that this study had limitations. The Hong Kong data do not represent the entire Chinese population, the SEER registry represents only 34.6% of the U.S. population, and the SEER registry has substandard ancestry designation for APIs. In addition, neither dataset included information on disease progression/recurrence or treatment details.

The study was supported by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities and the Children’s Cancer Foundation, Hong Kong. Study authors disclosed relationships with MSD Oncology, Genentech, and Kazia Pharmaceutical.

Dr. Ziegler reported having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Bouffet disclosed relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb and Roche.

SOURCE: Liu APY et al. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020 May 11. doi: 10.1200/JGO.19.00378.

, results of a population-based study suggest.

Adjusted incidence rates of CNS tumors were significantly higher among children from the U.S. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database than among children from a cancer registry in Hong Kong.

Anthony P. Y. Liu, MBBS, MMedSc, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn., and colleagues reported these findings in JCO Global Oncology.

The Hong Kong cohort originally included 526 patients, but only 508 of them were included in the comparison with the SEER patients. The SEER cohorts included 447 patients of API descent and 5,047 patients of all ethnicities.

In all cohorts, patients were younger than 18 years of age and had been diagnosed with a primary CNS tumor during 1999-2016.

Results

Age-, sex-, and study period–adjusted incidence rates of CNS tumors were significantly higher in the SEER cohorts than in the Hong Kong cohort (P < .001). The adjusted incidence rates were:

- 2.51 per 100,000 children in the Hong Kong cohort.

- 3.26 per 100,000 children among APIs in the SEER cohort.

- 4.10 per 100,000 children among all ethnicities in the SEER cohort.

Incidence rates of most tumor types were significantly lower in the Hong Kong cohort than in the entire SEER cohort. This includes choroid plexus tumors (0.08 vs. 0.16; P = .045), ependymomas (0.18 vs. 0.31; P = .005), and glial and neuronal tumors (0.94 vs. 2.61; P < .001). However, incidence rates of germ cell tumors were significantly higher in the Hong Kong cohort (0.57 vs. 0.24; P < .001).

For the most part, there were no significant differences in incidence by histology between the Hong Kong cohort and the API SEER cohort. The exception was glial and neuronal tumors, for which the incidence rate was lower in the Hong Kong cohort than in the API SEER cohort (0.94 vs. 1.74; P < .001).

The 5-year overall survival rate was significantly lower in the Hong Kong cohort than in the API and entire SEER cohorts – 66.8% , 75.3%, and 78.7%, respectively (P < .001). This appears to be driven by inferior survival among Hong Kong patients with glial and neuronal tumors. For other tumor types, there were no significant differences in survival across the cohorts.

Interpretation

“Dr. Liu and colleagues have conducted a very nice epidemiological study, and their results suggest that the incidence of pediatric brain tumors is much lower in Hong Kong compared to the incidence in the United States,” noted Eric Bouffet, MD, of the University of Toronto.

“These results are intriguing, and it is clear that large epidemiological studies are needed to better understand the impact of ethnic, genetic, and socio-environmental factors linked to the incidence of childhood cancer, and in particular childhood brain tumors,” Dr. Bouffet added.

“My suspicion is that the lower incidence of brain tumors in Hong Kong may relate to the omission of patients who did not have a biopsy from the dataset,” said David Ziegler, MD, PhD, of the University of New South Wales in Kensington, Australia.

Dr. Liu and colleagues acknowledged that this study had limitations. The Hong Kong data do not represent the entire Chinese population, the SEER registry represents only 34.6% of the U.S. population, and the SEER registry has substandard ancestry designation for APIs. In addition, neither dataset included information on disease progression/recurrence or treatment details.

The study was supported by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities and the Children’s Cancer Foundation, Hong Kong. Study authors disclosed relationships with MSD Oncology, Genentech, and Kazia Pharmaceutical.

Dr. Ziegler reported having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Bouffet disclosed relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb and Roche.

SOURCE: Liu APY et al. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020 May 11. doi: 10.1200/JGO.19.00378.

, results of a population-based study suggest.

Adjusted incidence rates of CNS tumors were significantly higher among children from the U.S. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database than among children from a cancer registry in Hong Kong.

Anthony P. Y. Liu, MBBS, MMedSc, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn., and colleagues reported these findings in JCO Global Oncology.

The Hong Kong cohort originally included 526 patients, but only 508 of them were included in the comparison with the SEER patients. The SEER cohorts included 447 patients of API descent and 5,047 patients of all ethnicities.

In all cohorts, patients were younger than 18 years of age and had been diagnosed with a primary CNS tumor during 1999-2016.

Results

Age-, sex-, and study period–adjusted incidence rates of CNS tumors were significantly higher in the SEER cohorts than in the Hong Kong cohort (P < .001). The adjusted incidence rates were:

- 2.51 per 100,000 children in the Hong Kong cohort.

- 3.26 per 100,000 children among APIs in the SEER cohort.

- 4.10 per 100,000 children among all ethnicities in the SEER cohort.

Incidence rates of most tumor types were significantly lower in the Hong Kong cohort than in the entire SEER cohort. This includes choroid plexus tumors (0.08 vs. 0.16; P = .045), ependymomas (0.18 vs. 0.31; P = .005), and glial and neuronal tumors (0.94 vs. 2.61; P < .001). However, incidence rates of germ cell tumors were significantly higher in the Hong Kong cohort (0.57 vs. 0.24; P < .001).

For the most part, there were no significant differences in incidence by histology between the Hong Kong cohort and the API SEER cohort. The exception was glial and neuronal tumors, for which the incidence rate was lower in the Hong Kong cohort than in the API SEER cohort (0.94 vs. 1.74; P < .001).

The 5-year overall survival rate was significantly lower in the Hong Kong cohort than in the API and entire SEER cohorts – 66.8% , 75.3%, and 78.7%, respectively (P < .001). This appears to be driven by inferior survival among Hong Kong patients with glial and neuronal tumors. For other tumor types, there were no significant differences in survival across the cohorts.

Interpretation

“Dr. Liu and colleagues have conducted a very nice epidemiological study, and their results suggest that the incidence of pediatric brain tumors is much lower in Hong Kong compared to the incidence in the United States,” noted Eric Bouffet, MD, of the University of Toronto.

“These results are intriguing, and it is clear that large epidemiological studies are needed to better understand the impact of ethnic, genetic, and socio-environmental factors linked to the incidence of childhood cancer, and in particular childhood brain tumors,” Dr. Bouffet added.

“My suspicion is that the lower incidence of brain tumors in Hong Kong may relate to the omission of patients who did not have a biopsy from the dataset,” said David Ziegler, MD, PhD, of the University of New South Wales in Kensington, Australia.

Dr. Liu and colleagues acknowledged that this study had limitations. The Hong Kong data do not represent the entire Chinese population, the SEER registry represents only 34.6% of the U.S. population, and the SEER registry has substandard ancestry designation for APIs. In addition, neither dataset included information on disease progression/recurrence or treatment details.

The study was supported by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities and the Children’s Cancer Foundation, Hong Kong. Study authors disclosed relationships with MSD Oncology, Genentech, and Kazia Pharmaceutical.

Dr. Ziegler reported having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Bouffet disclosed relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb and Roche.

SOURCE: Liu APY et al. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020 May 11. doi: 10.1200/JGO.19.00378.

FROM JCO GLOBAL ONCOLOGY

Novel penclomedine shows promise for some AYAs with CNS cancers

according to phase 1/2 clinical trial findings.

The trial included 15 patients, aged 15-39 years, with measurable cancer involving the CNS who were treated with the agent 4-Demethyl-4-cholesteryloxycarbonylpenclomedine (DM-CHOC-PEN).

Two of these patients were “in their 59th month of survival and doing well” as of April, when the data were presented at the AACR virtual meeting I.

One of the patients with long-term survival benefit had non–small cell lung cancer, and one had astrocytoma, Lee Roy Morgan, MD, PhD, chief executive officer of Dekk-Tec Inc., New Orleans, reported during a poster presentation.

Patients with glioblastoma, however, “did not do well,” said Dr. Morgan, an adjunct professor at Tulane University in New Orleans. He noted that none of the five glioblastoma patients experienced a long-term response.

Safety

Study subjects were treated with the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of DM-CHOC-PEN as identified in an earlier study. Patients with liver involvement received 75 mg/m2, and those without liver involvement received up to 98.7 mg/m2. Dosing was by 3-hour intravenous administration once every 21 days as lab tests and subject status allowed.

DM-CHOC-PEN was generally well tolerated. One patient experienced grade 2 vasogenic edema, and another experienced seizures. Both were secondary to tumor swelling, and both resolved with tumor regression.

No grade 3 toxicities occurred at the MTD, and “no renal, hematological, hepatic, or pulmonary toxicities were noted using the MTD in this trial,” Dr. Morgan said.

Mechanism

DM-CHOC-PEN is a polychlorinated pyridine with a cholesteryl carbonate attachment that induces lipophilicity, which potentiates the drug’s penetration of the blood-brain barrier and its entry into the brain and brain cancers, Dr. Morgan explained.

He added that DM-CHOC-PEN is a bis-alkylator that binds to DNA’s cytosine/guanine nucleotides. The agent does not require hepatic activation, it crosses the blood-brain barrier intact, and accumulates in CNS tumors but not normal CNS tissue, he said.

Further, it “is not a substrate for [p-glycoprotein] transport; thus, it doesn’t easily get out of the brain,” Dr. Morgan said. He noted that DM-CHOC-PEN can be used with other agents, such as temozolomide and bis-chloroethylnitrosourea, because of the difference in mechanisms of action.

This study was supported by Louisiana state grants, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Small Business Innovation Research program. Dr. Morgan reported having no disclosures, but he is chief executive officer of Dekk-Tec Inc., which is developing DM-CHOC-PEN.

SOURCE: Morgan L et al. AACR 2020, Abstract CT181.

according to phase 1/2 clinical trial findings.

The trial included 15 patients, aged 15-39 years, with measurable cancer involving the CNS who were treated with the agent 4-Demethyl-4-cholesteryloxycarbonylpenclomedine (DM-CHOC-PEN).

Two of these patients were “in their 59th month of survival and doing well” as of April, when the data were presented at the AACR virtual meeting I.

One of the patients with long-term survival benefit had non–small cell lung cancer, and one had astrocytoma, Lee Roy Morgan, MD, PhD, chief executive officer of Dekk-Tec Inc., New Orleans, reported during a poster presentation.

Patients with glioblastoma, however, “did not do well,” said Dr. Morgan, an adjunct professor at Tulane University in New Orleans. He noted that none of the five glioblastoma patients experienced a long-term response.

Safety

Study subjects were treated with the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of DM-CHOC-PEN as identified in an earlier study. Patients with liver involvement received 75 mg/m2, and those without liver involvement received up to 98.7 mg/m2. Dosing was by 3-hour intravenous administration once every 21 days as lab tests and subject status allowed.

DM-CHOC-PEN was generally well tolerated. One patient experienced grade 2 vasogenic edema, and another experienced seizures. Both were secondary to tumor swelling, and both resolved with tumor regression.

No grade 3 toxicities occurred at the MTD, and “no renal, hematological, hepatic, or pulmonary toxicities were noted using the MTD in this trial,” Dr. Morgan said.

Mechanism

DM-CHOC-PEN is a polychlorinated pyridine with a cholesteryl carbonate attachment that induces lipophilicity, which potentiates the drug’s penetration of the blood-brain barrier and its entry into the brain and brain cancers, Dr. Morgan explained.

He added that DM-CHOC-PEN is a bis-alkylator that binds to DNA’s cytosine/guanine nucleotides. The agent does not require hepatic activation, it crosses the blood-brain barrier intact, and accumulates in CNS tumors but not normal CNS tissue, he said.

Further, it “is not a substrate for [p-glycoprotein] transport; thus, it doesn’t easily get out of the brain,” Dr. Morgan said. He noted that DM-CHOC-PEN can be used with other agents, such as temozolomide and bis-chloroethylnitrosourea, because of the difference in mechanisms of action.

This study was supported by Louisiana state grants, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Small Business Innovation Research program. Dr. Morgan reported having no disclosures, but he is chief executive officer of Dekk-Tec Inc., which is developing DM-CHOC-PEN.

SOURCE: Morgan L et al. AACR 2020, Abstract CT181.

according to phase 1/2 clinical trial findings.

The trial included 15 patients, aged 15-39 years, with measurable cancer involving the CNS who were treated with the agent 4-Demethyl-4-cholesteryloxycarbonylpenclomedine (DM-CHOC-PEN).

Two of these patients were “in their 59th month of survival and doing well” as of April, when the data were presented at the AACR virtual meeting I.

One of the patients with long-term survival benefit had non–small cell lung cancer, and one had astrocytoma, Lee Roy Morgan, MD, PhD, chief executive officer of Dekk-Tec Inc., New Orleans, reported during a poster presentation.

Patients with glioblastoma, however, “did not do well,” said Dr. Morgan, an adjunct professor at Tulane University in New Orleans. He noted that none of the five glioblastoma patients experienced a long-term response.

Safety

Study subjects were treated with the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of DM-CHOC-PEN as identified in an earlier study. Patients with liver involvement received 75 mg/m2, and those without liver involvement received up to 98.7 mg/m2. Dosing was by 3-hour intravenous administration once every 21 days as lab tests and subject status allowed.

DM-CHOC-PEN was generally well tolerated. One patient experienced grade 2 vasogenic edema, and another experienced seizures. Both were secondary to tumor swelling, and both resolved with tumor regression.

No grade 3 toxicities occurred at the MTD, and “no renal, hematological, hepatic, or pulmonary toxicities were noted using the MTD in this trial,” Dr. Morgan said.

Mechanism

DM-CHOC-PEN is a polychlorinated pyridine with a cholesteryl carbonate attachment that induces lipophilicity, which potentiates the drug’s penetration of the blood-brain barrier and its entry into the brain and brain cancers, Dr. Morgan explained.

He added that DM-CHOC-PEN is a bis-alkylator that binds to DNA’s cytosine/guanine nucleotides. The agent does not require hepatic activation, it crosses the blood-brain barrier intact, and accumulates in CNS tumors but not normal CNS tissue, he said.

Further, it “is not a substrate for [p-glycoprotein] transport; thus, it doesn’t easily get out of the brain,” Dr. Morgan said. He noted that DM-CHOC-PEN can be used with other agents, such as temozolomide and bis-chloroethylnitrosourea, because of the difference in mechanisms of action.

This study was supported by Louisiana state grants, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Small Business Innovation Research program. Dr. Morgan reported having no disclosures, but he is chief executive officer of Dekk-Tec Inc., which is developing DM-CHOC-PEN.

SOURCE: Morgan L et al. AACR 2020, Abstract CT181.

FROM AACR 2020

Oncologists’ income and satisfaction are up

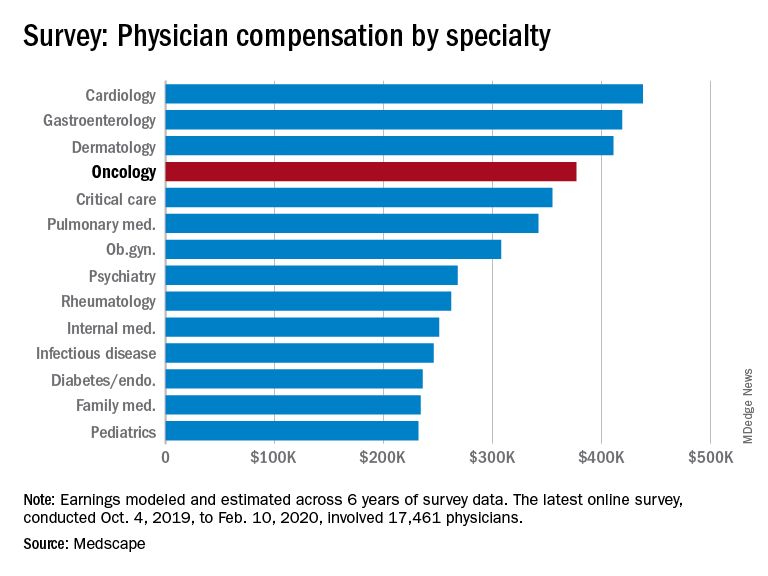

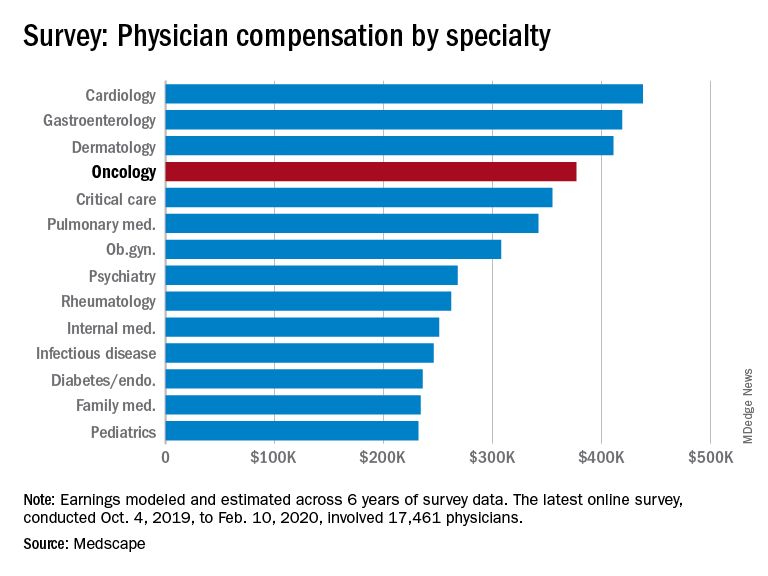

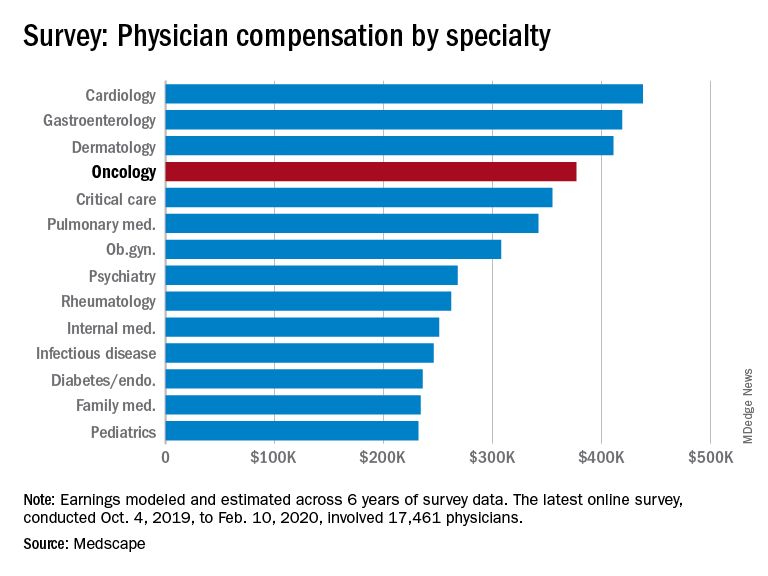

Oncologists continue to rank above the middle range for all specialties in annual compensation for physicians, according to findings from the newly released Medscape Oncologist Compensation Report 2020.

The average earnings for oncologists who participated in the survey was $377,000, which was a 5% increase from the $359,000 reported for 2018.

Just over two-thirds (67%) of oncologists reported that they felt that they were fairly compensated, which is quite a jump from 53% last year.

In addition, oncologists appear to be very satisfied with their profession. Similar to last year’s findings, 84% said they would choose medicine again, and 96% said they would choose the specialty of oncology again.

Earning in top third of all specialties

The average annual earnings reported by oncologists put this specialty in eleventh place among 29 specialties. Orthopedic specialists remain at the head of the list, with estimated earnings of $511,000, followed by plastic surgeons ($479,000), otolaryngologists ($455,000), and cardiologists ($438,000), according to Medscape’s compensation report, which included responses from 17,461 physicians in over 30 specialties.

At the bottom of the estimated earnings list were public health and preventive medicine doctors and pediatricians. For both specialties, the reported annual earnings was $232,000. Family medicine specialists were only marginally higher at $234,000.

Radiologists ($427,000), gastroenterologists ($419,000), and urologists ($417,000) all reported higher earnings than oncologists, whereas neurologists, at $280,000, rheumatologists, at $262,000, and internal medicine physicians, at $251,000, earned less.

The report also found that gender disparities in income persist, with male oncologists earning 17% more than their female colleagues. The gender gap in oncology is somewhat less than that seen for all specialties combined, in which men earned 31% more than women, similar to last year’s figure of 33%.

Male oncologists reported spending 38.8 hours per week seeing patients, compared with 34.9 hours reported by female oncologists. This could be a factor contributing to the gender pay disparity. Overall, the average amount of time seeing patients was 37.9 hours per week.

Frustrations with paperwork and denied claims