User login

The Long, Controversial Search for a ‘Cancer Microbiome’

Last year, the controversy heightened when experts questioned a high-profile study — a 2020 analysis claiming that the tumors of 33 different cancers had their own unique microbiomes — on whether the “signature” of these bacterial compositions could help diagnose cancer.

The incident renewed the spotlight on “tumor microbiomes” because of the bold claims of the original paper and the strongly worded refutations of those claims. The broader field has focused primarily on ways the body’s microbiome interacts with cancers and cancer treatment.

This controversy has highlighted the challenges of making headway in a field where researchers may not even have the tools yet to puzzle-out the wide-ranging implications the microbiome holds for cancer diagnosis and treatment.

But it is also part of a provocative question within that larger field: whether tumors in the body, far from the natural microbiome in the gut, have their own thriving communities of bacteria, viruses, and fungi. And, if they do, how do those tumor microbiomes affect the development and progression of the cancer and the effectiveness of cancer therapies?

Cancer Controversy

The evidence is undeniable that some microbes can directly cause certain cancers and that the human gut microbiome can influence the effectiveness of certain therapies. Beyond that established science, however, the research has raised as many questions as answers about what we do and don’t know about microbiota and cancer.

The only confirmed microbiomes are on the skin and in the gut, mouth, and vagina, which are all areas with an easy direct route for bacteria to enter and grow in or on the body. A series of papers in recent years have suggested that other internal organs, and tumors within them, may have their own microbiomes.

“Whether microbes exist in tumors of internal organs beyond body surfaces exposed to the environment is a different matter,” said Ivan Vujkovic-Cvijin, PhD, an assistant professor of biomedical sciences and gastroenterology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, whose lab studies how human gut microbes affect inflammatory diseases. “We’ve only recently had the tools to study that question on a molecular level, and the reported results have been conflicting.”

For example, research allegedly identified microbiota in the human placenta nearly one decade ago. But subsequent research contradicted those claims and showed that the source of the “placental microbiome” was actually contamination. Subsequent similar studies for other parts of the body faced the same scrutiny and, often, eventual debunking.

“Most likely, our immune system has undergone selective pressure to eliminate everything that crosses the gut barrier because there’s not much benefit to the body to have bacteria run amok in our internal organs,” Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said. “That can only disrupt the functioning of our tissues, to have an external organism living inside them.”

The controversy that erupted last summer, surrounding research from the lab of Rob Knight, PhD, at the University of California, San Diego, centered on a slightly different but related question: Could tumors harbor their own microbiomes?

This news organization spoke with two of the authors who published a paper contesting Dr. Knight’s findings: Steven Salzberg, PhD, a professor of biomedical engineering at John Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, and Abraham Gihawi, PhD, a research fellow at Norwich Medical School at the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom.

Dr. Salzberg described two major problems with Dr. Knight’s study.

“What they found were false positives because of contamination in the database and flaws in their methods,” Dr. Salzberg said. “I can’t prove there’s no cancer microbiome, but I can say the cancer microbiomes that they reported don’t exist because the species they were finding aren’t there.”

Dr. Knight disagrees with Dr. Salzberg’s findings, noting that Dr. Salzberg and his co-authors did not examine the publicly available databases used in his study. In a written response, he said that his team’s examination of the database revealed that less than 1% of the microbial genomes overlapped with human ones and that removing them did not change their findings.

Dr. Knight also noted that his team could still “distinguish cancer types by their microbiome” even after running their analysis without the technique that Dr. Salzberg found fault with.

Dr. Salzberg said that the database linked above is not the one Dr. Knight’s study used, however. “The primary database in their study was never made public (it’s too large, they said), and it has/had about 69,000 genomes,” Dr. Salzberg said by email. “But even if we did, this is irrelevant. He’s trying to distract from the primary errors in their study,” which Dr. Salzberg said Dr. Knight’s team has not addressed.

The critiques Dr. Salzberg raised have been leveled at other studies investigating microbiomes specifically within tumors and independent of the body’s microbiome.

For example, a 2019 study in Nature described a fungal microbiome in pancreatic cancer that a Nature paper 4 years later directly contradicted, citing flaws that invalidated the original findings. A different 2019 study in Cell examined pancreatic tumor microbiota and patient outcomes, but it’s unclear whether the microorganisms moved from the gut to the pancreas or “constitute a durably colonized community that lives inside the tumor,” which remains a matter of debate, Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said.

A 2020 study in Science suggested diverse microbial communities in seven tumor types, but those findings were similarly called into question. That study stated that “bacteria were first detected in human tumors more than 100 years ago” and that “bacteria are well-known residents in human tumors,” but Dr. Salzberg considers those statements misleading.

It’s true that bacteria and viruses have been detected in tumors because “there’s very good evidence that an acute infection caused by a very small number of viruses and bacteria can cause a tumor,” Dr. Salzberg said. Human papillomavirus, for example, can cause six different types of cancer. Inflammation and ulcers caused by Helicobacter pylori may progress to stomach cancer, and Fusobacterium nucleatum and Enterococcus faecalis have been shown to contribute to colorectal cancer. Those examples differ from a microbiome; this “a community of bacteria and possibly other microscopic bugs, like fungi, that are happily living in the tumor” the same way microbes reside in our guts, he said.

Dr. Knight said that many bacteria his team identified “have been confirmed independently in subsequent work.” He acknowledged, however, that more research is needed.

Several of the contested studies above were among a lengthy list that Dr. Knight provided, noting that most of the disagreements “have two sides to them, and critiques from one particular group does not immediately invalidate a reported finding.”

Yet, many of the papers Dr. Knight listed are precisely the types that skeptics like Dr. Salzberg believe are too flawed to draw reliable conclusions.

“I think many agree that microbes may exist within tumors that are exposed to the environment, like tumors of the skin, gut, and mouth,” Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said. It’s less clear, however, whether tumors further from the body’s microbiome harbor any microbes or where they came from if they do. Microbial signals in organs elsewhere in the body become faint quickly, he said.

Underdeveloped Technology

Though Dr. Salzberg said that the concept of a tumor microbiome is “implausible” because there’s no easy route for bacteria to reach internal organs, it’s unclear whether scientists have the technology yet to adequately answer this question.

For one thing, samples in these types of studies are typically “ultra-low biomass samples, where the signal — the amount of microbes in the sample — is so low that it’s comparable to how much would be expected to be found in reagents and environmental contamination through processing,” Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin explained. Many polymerases used to amplify a DNA signal, for example, are made in bacteria and may retain trace amounts identified in these studies.

Dr. Knight agreed that low biomass is a challenge in this field but is not an unsurmountable one.

Another challenge is that study samples, as with Dr. Knight’s work, were collected during routine surgeries without the intent to find a microbial signal. Simply using a scalpel to cut through the skin means cutting through a layer of bacteria, and surgery rooms are not designed to eliminate all bacteria. Some work has even shown there is a “hospital microbiome,” so “you can easily have that creep into your signal and mistake it for tumor-resident bacteria,” Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said.

Dr. Knight asserted that the samples are taken under sterile conditions, but other researchers do not think the level of sterility necessary for completely clean samples is possible.

“Just because it’s in your sample doesn’t mean it was in your tumor,” Dr. Gihawi said.

Even if scientists can retrieve a reliable sample without contamination, analyzing it requires comparing the genetic material to existing databases of microbial genomes. Yet, contamination and misclassification of genetic sequences can be problems in those reference genomes too, Dr. Gihawi explained.

Machine learning algorithms have a role in interpreting data, but “we need to be careful of what we use them for,” he added.

“These techniques are in their infancy, and we’re starting to chase them down, which is why we need to move microbiome research in a way that can be used clinically,” Dr. Gihawi said.

Influence on Cancer Treatment Outcomes

Again, however, the question of whether microbiomes exist within tumors is only one slice of the much larger field looking at microbiomes and cancer, including its influence on cancer treatment outcomes. Although much remains to be learned, less controversy exists over the thousands of studies in the past two decades that have gradually revealed how the body’s microbiome can affect both the course of a cancer and the effectiveness of different treatments.

The growing research showing the importance of the gut microbiome in cancer treatments is not surprising given its role in immunity more broadly. Because the human immune system must recognize and defend against microbes, the microbiome helps train it, Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said.

Some bacteria can escape the gut — a phenomenon called bacterial translocation — and may aid in fighting tumors. To grow large enough to be seen on imaging, tumors need to evolve several abilities, such as growing enough vascularization to receive blood flow and shutting down local immune responses.

“Any added boost, like immunotherapy, has a chance of breaking through that immune forcefield and killing the tumor cells,” Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said. Escaped gut bacteria may provide that boost.

“There’s a lot of evidence that depletion of the gut microbiome impairs immunotherapy and chemotherapy. The thinking behind some of those studies is that gut microbes can cross the gut barrier and when they do, they activate the immune system,” he said.

In mice engineered to have sterile guts, for example, the lack of bacteria results in less effective immune systems, Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin pointed out. A host of research has shown that antibiotic exposure during and even 6 months before immunotherapy dramatically reduces survival rates. “That’s pretty convincing to me that gut microbes are important,” he said.

Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin cautioned that there continues to be controversy on understanding which bacteria are important for response to immunotherapy. “The field is still in its infancy in terms of understanding which bacteria are most important for these effects,” he said.

Dr. Knight suggested that escaped bacteria may be the genesis of the ones that he and other researchers believe exist in tumors. “Because tumor microbes must come from somewhere, it is to be expected that some of those microbes will be co-opted from body-site specific commensals.”

It’s also possible that metabolites released from gut bacteria escape the gut and could theoretically affect distant tumor growth, Dr. Gihawi said. The most promising avenue of research in this area is metabolites being used as biomarkers, added Dr. Gihawi, whose lab published research on a link between bacteria detected in men’s urine and a more aggressive subset of prostate cancers. But that research is not far enough along to develop lab tests for clinical use, he noted.

No Consensus Yet

Even before the controversy erupted around Dr. Knight’s research, he co-founded the company Micronoma to develop cancer tests based on his microbe findings. The company has raised $17.5 million from private investors as of August 2023 and received the US Food and Drug Administration’s Breakthrough Device designation, allowing the firm to fast-track clinical trials testing the technology. The recent critiques have not changed the company’s plans.

It’s safe to say that scientists will continue to research and debate the possibility of tumor microbiomes until a consensus emerges.

“The field is evolving and studies testing the reproducibility of tumor-resident microbial signals are essential for developing our understanding in this area,” Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said.

Even if that path ultimately leads nowhere, as Dr. Salzberg expects, research into microbiomes and cancer has plenty of other directions to go.

“I’m actually quite an optimist,” Dr. Gihawi said. “I think there’s a lot of scope for some really good research here, especially in the sites where we know there is a strong microbiome, such as the gastrointestinal tract.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Last year, the controversy heightened when experts questioned a high-profile study — a 2020 analysis claiming that the tumors of 33 different cancers had their own unique microbiomes — on whether the “signature” of these bacterial compositions could help diagnose cancer.

The incident renewed the spotlight on “tumor microbiomes” because of the bold claims of the original paper and the strongly worded refutations of those claims. The broader field has focused primarily on ways the body’s microbiome interacts with cancers and cancer treatment.

This controversy has highlighted the challenges of making headway in a field where researchers may not even have the tools yet to puzzle-out the wide-ranging implications the microbiome holds for cancer diagnosis and treatment.

But it is also part of a provocative question within that larger field: whether tumors in the body, far from the natural microbiome in the gut, have their own thriving communities of bacteria, viruses, and fungi. And, if they do, how do those tumor microbiomes affect the development and progression of the cancer and the effectiveness of cancer therapies?

Cancer Controversy

The evidence is undeniable that some microbes can directly cause certain cancers and that the human gut microbiome can influence the effectiveness of certain therapies. Beyond that established science, however, the research has raised as many questions as answers about what we do and don’t know about microbiota and cancer.

The only confirmed microbiomes are on the skin and in the gut, mouth, and vagina, which are all areas with an easy direct route for bacteria to enter and grow in or on the body. A series of papers in recent years have suggested that other internal organs, and tumors within them, may have their own microbiomes.

“Whether microbes exist in tumors of internal organs beyond body surfaces exposed to the environment is a different matter,” said Ivan Vujkovic-Cvijin, PhD, an assistant professor of biomedical sciences and gastroenterology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, whose lab studies how human gut microbes affect inflammatory diseases. “We’ve only recently had the tools to study that question on a molecular level, and the reported results have been conflicting.”

For example, research allegedly identified microbiota in the human placenta nearly one decade ago. But subsequent research contradicted those claims and showed that the source of the “placental microbiome” was actually contamination. Subsequent similar studies for other parts of the body faced the same scrutiny and, often, eventual debunking.

“Most likely, our immune system has undergone selective pressure to eliminate everything that crosses the gut barrier because there’s not much benefit to the body to have bacteria run amok in our internal organs,” Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said. “That can only disrupt the functioning of our tissues, to have an external organism living inside them.”

The controversy that erupted last summer, surrounding research from the lab of Rob Knight, PhD, at the University of California, San Diego, centered on a slightly different but related question: Could tumors harbor their own microbiomes?

This news organization spoke with two of the authors who published a paper contesting Dr. Knight’s findings: Steven Salzberg, PhD, a professor of biomedical engineering at John Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, and Abraham Gihawi, PhD, a research fellow at Norwich Medical School at the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom.

Dr. Salzberg described two major problems with Dr. Knight’s study.

“What they found were false positives because of contamination in the database and flaws in their methods,” Dr. Salzberg said. “I can’t prove there’s no cancer microbiome, but I can say the cancer microbiomes that they reported don’t exist because the species they were finding aren’t there.”

Dr. Knight disagrees with Dr. Salzberg’s findings, noting that Dr. Salzberg and his co-authors did not examine the publicly available databases used in his study. In a written response, he said that his team’s examination of the database revealed that less than 1% of the microbial genomes overlapped with human ones and that removing them did not change their findings.

Dr. Knight also noted that his team could still “distinguish cancer types by their microbiome” even after running their analysis without the technique that Dr. Salzberg found fault with.

Dr. Salzberg said that the database linked above is not the one Dr. Knight’s study used, however. “The primary database in their study was never made public (it’s too large, they said), and it has/had about 69,000 genomes,” Dr. Salzberg said by email. “But even if we did, this is irrelevant. He’s trying to distract from the primary errors in their study,” which Dr. Salzberg said Dr. Knight’s team has not addressed.

The critiques Dr. Salzberg raised have been leveled at other studies investigating microbiomes specifically within tumors and independent of the body’s microbiome.

For example, a 2019 study in Nature described a fungal microbiome in pancreatic cancer that a Nature paper 4 years later directly contradicted, citing flaws that invalidated the original findings. A different 2019 study in Cell examined pancreatic tumor microbiota and patient outcomes, but it’s unclear whether the microorganisms moved from the gut to the pancreas or “constitute a durably colonized community that lives inside the tumor,” which remains a matter of debate, Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said.

A 2020 study in Science suggested diverse microbial communities in seven tumor types, but those findings were similarly called into question. That study stated that “bacteria were first detected in human tumors more than 100 years ago” and that “bacteria are well-known residents in human tumors,” but Dr. Salzberg considers those statements misleading.

It’s true that bacteria and viruses have been detected in tumors because “there’s very good evidence that an acute infection caused by a very small number of viruses and bacteria can cause a tumor,” Dr. Salzberg said. Human papillomavirus, for example, can cause six different types of cancer. Inflammation and ulcers caused by Helicobacter pylori may progress to stomach cancer, and Fusobacterium nucleatum and Enterococcus faecalis have been shown to contribute to colorectal cancer. Those examples differ from a microbiome; this “a community of bacteria and possibly other microscopic bugs, like fungi, that are happily living in the tumor” the same way microbes reside in our guts, he said.

Dr. Knight said that many bacteria his team identified “have been confirmed independently in subsequent work.” He acknowledged, however, that more research is needed.

Several of the contested studies above were among a lengthy list that Dr. Knight provided, noting that most of the disagreements “have two sides to them, and critiques from one particular group does not immediately invalidate a reported finding.”

Yet, many of the papers Dr. Knight listed are precisely the types that skeptics like Dr. Salzberg believe are too flawed to draw reliable conclusions.

“I think many agree that microbes may exist within tumors that are exposed to the environment, like tumors of the skin, gut, and mouth,” Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said. It’s less clear, however, whether tumors further from the body’s microbiome harbor any microbes or where they came from if they do. Microbial signals in organs elsewhere in the body become faint quickly, he said.

Underdeveloped Technology

Though Dr. Salzberg said that the concept of a tumor microbiome is “implausible” because there’s no easy route for bacteria to reach internal organs, it’s unclear whether scientists have the technology yet to adequately answer this question.

For one thing, samples in these types of studies are typically “ultra-low biomass samples, where the signal — the amount of microbes in the sample — is so low that it’s comparable to how much would be expected to be found in reagents and environmental contamination through processing,” Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin explained. Many polymerases used to amplify a DNA signal, for example, are made in bacteria and may retain trace amounts identified in these studies.

Dr. Knight agreed that low biomass is a challenge in this field but is not an unsurmountable one.

Another challenge is that study samples, as with Dr. Knight’s work, were collected during routine surgeries without the intent to find a microbial signal. Simply using a scalpel to cut through the skin means cutting through a layer of bacteria, and surgery rooms are not designed to eliminate all bacteria. Some work has even shown there is a “hospital microbiome,” so “you can easily have that creep into your signal and mistake it for tumor-resident bacteria,” Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said.

Dr. Knight asserted that the samples are taken under sterile conditions, but other researchers do not think the level of sterility necessary for completely clean samples is possible.

“Just because it’s in your sample doesn’t mean it was in your tumor,” Dr. Gihawi said.

Even if scientists can retrieve a reliable sample without contamination, analyzing it requires comparing the genetic material to existing databases of microbial genomes. Yet, contamination and misclassification of genetic sequences can be problems in those reference genomes too, Dr. Gihawi explained.

Machine learning algorithms have a role in interpreting data, but “we need to be careful of what we use them for,” he added.

“These techniques are in their infancy, and we’re starting to chase them down, which is why we need to move microbiome research in a way that can be used clinically,” Dr. Gihawi said.

Influence on Cancer Treatment Outcomes

Again, however, the question of whether microbiomes exist within tumors is only one slice of the much larger field looking at microbiomes and cancer, including its influence on cancer treatment outcomes. Although much remains to be learned, less controversy exists over the thousands of studies in the past two decades that have gradually revealed how the body’s microbiome can affect both the course of a cancer and the effectiveness of different treatments.

The growing research showing the importance of the gut microbiome in cancer treatments is not surprising given its role in immunity more broadly. Because the human immune system must recognize and defend against microbes, the microbiome helps train it, Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said.

Some bacteria can escape the gut — a phenomenon called bacterial translocation — and may aid in fighting tumors. To grow large enough to be seen on imaging, tumors need to evolve several abilities, such as growing enough vascularization to receive blood flow and shutting down local immune responses.

“Any added boost, like immunotherapy, has a chance of breaking through that immune forcefield and killing the tumor cells,” Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said. Escaped gut bacteria may provide that boost.

“There’s a lot of evidence that depletion of the gut microbiome impairs immunotherapy and chemotherapy. The thinking behind some of those studies is that gut microbes can cross the gut barrier and when they do, they activate the immune system,” he said.

In mice engineered to have sterile guts, for example, the lack of bacteria results in less effective immune systems, Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin pointed out. A host of research has shown that antibiotic exposure during and even 6 months before immunotherapy dramatically reduces survival rates. “That’s pretty convincing to me that gut microbes are important,” he said.

Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin cautioned that there continues to be controversy on understanding which bacteria are important for response to immunotherapy. “The field is still in its infancy in terms of understanding which bacteria are most important for these effects,” he said.

Dr. Knight suggested that escaped bacteria may be the genesis of the ones that he and other researchers believe exist in tumors. “Because tumor microbes must come from somewhere, it is to be expected that some of those microbes will be co-opted from body-site specific commensals.”

It’s also possible that metabolites released from gut bacteria escape the gut and could theoretically affect distant tumor growth, Dr. Gihawi said. The most promising avenue of research in this area is metabolites being used as biomarkers, added Dr. Gihawi, whose lab published research on a link between bacteria detected in men’s urine and a more aggressive subset of prostate cancers. But that research is not far enough along to develop lab tests for clinical use, he noted.

No Consensus Yet

Even before the controversy erupted around Dr. Knight’s research, he co-founded the company Micronoma to develop cancer tests based on his microbe findings. The company has raised $17.5 million from private investors as of August 2023 and received the US Food and Drug Administration’s Breakthrough Device designation, allowing the firm to fast-track clinical trials testing the technology. The recent critiques have not changed the company’s plans.

It’s safe to say that scientists will continue to research and debate the possibility of tumor microbiomes until a consensus emerges.

“The field is evolving and studies testing the reproducibility of tumor-resident microbial signals are essential for developing our understanding in this area,” Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said.

Even if that path ultimately leads nowhere, as Dr. Salzberg expects, research into microbiomes and cancer has plenty of other directions to go.

“I’m actually quite an optimist,” Dr. Gihawi said. “I think there’s a lot of scope for some really good research here, especially in the sites where we know there is a strong microbiome, such as the gastrointestinal tract.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Last year, the controversy heightened when experts questioned a high-profile study — a 2020 analysis claiming that the tumors of 33 different cancers had their own unique microbiomes — on whether the “signature” of these bacterial compositions could help diagnose cancer.

The incident renewed the spotlight on “tumor microbiomes” because of the bold claims of the original paper and the strongly worded refutations of those claims. The broader field has focused primarily on ways the body’s microbiome interacts with cancers and cancer treatment.

This controversy has highlighted the challenges of making headway in a field where researchers may not even have the tools yet to puzzle-out the wide-ranging implications the microbiome holds for cancer diagnosis and treatment.

But it is also part of a provocative question within that larger field: whether tumors in the body, far from the natural microbiome in the gut, have their own thriving communities of bacteria, viruses, and fungi. And, if they do, how do those tumor microbiomes affect the development and progression of the cancer and the effectiveness of cancer therapies?

Cancer Controversy

The evidence is undeniable that some microbes can directly cause certain cancers and that the human gut microbiome can influence the effectiveness of certain therapies. Beyond that established science, however, the research has raised as many questions as answers about what we do and don’t know about microbiota and cancer.

The only confirmed microbiomes are on the skin and in the gut, mouth, and vagina, which are all areas with an easy direct route for bacteria to enter and grow in or on the body. A series of papers in recent years have suggested that other internal organs, and tumors within them, may have their own microbiomes.

“Whether microbes exist in tumors of internal organs beyond body surfaces exposed to the environment is a different matter,” said Ivan Vujkovic-Cvijin, PhD, an assistant professor of biomedical sciences and gastroenterology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, whose lab studies how human gut microbes affect inflammatory diseases. “We’ve only recently had the tools to study that question on a molecular level, and the reported results have been conflicting.”

For example, research allegedly identified microbiota in the human placenta nearly one decade ago. But subsequent research contradicted those claims and showed that the source of the “placental microbiome” was actually contamination. Subsequent similar studies for other parts of the body faced the same scrutiny and, often, eventual debunking.

“Most likely, our immune system has undergone selective pressure to eliminate everything that crosses the gut barrier because there’s not much benefit to the body to have bacteria run amok in our internal organs,” Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said. “That can only disrupt the functioning of our tissues, to have an external organism living inside them.”

The controversy that erupted last summer, surrounding research from the lab of Rob Knight, PhD, at the University of California, San Diego, centered on a slightly different but related question: Could tumors harbor their own microbiomes?

This news organization spoke with two of the authors who published a paper contesting Dr. Knight’s findings: Steven Salzberg, PhD, a professor of biomedical engineering at John Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, and Abraham Gihawi, PhD, a research fellow at Norwich Medical School at the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom.

Dr. Salzberg described two major problems with Dr. Knight’s study.

“What they found were false positives because of contamination in the database and flaws in their methods,” Dr. Salzberg said. “I can’t prove there’s no cancer microbiome, but I can say the cancer microbiomes that they reported don’t exist because the species they were finding aren’t there.”

Dr. Knight disagrees with Dr. Salzberg’s findings, noting that Dr. Salzberg and his co-authors did not examine the publicly available databases used in his study. In a written response, he said that his team’s examination of the database revealed that less than 1% of the microbial genomes overlapped with human ones and that removing them did not change their findings.

Dr. Knight also noted that his team could still “distinguish cancer types by their microbiome” even after running their analysis without the technique that Dr. Salzberg found fault with.

Dr. Salzberg said that the database linked above is not the one Dr. Knight’s study used, however. “The primary database in their study was never made public (it’s too large, they said), and it has/had about 69,000 genomes,” Dr. Salzberg said by email. “But even if we did, this is irrelevant. He’s trying to distract from the primary errors in their study,” which Dr. Salzberg said Dr. Knight’s team has not addressed.

The critiques Dr. Salzberg raised have been leveled at other studies investigating microbiomes specifically within tumors and independent of the body’s microbiome.

For example, a 2019 study in Nature described a fungal microbiome in pancreatic cancer that a Nature paper 4 years later directly contradicted, citing flaws that invalidated the original findings. A different 2019 study in Cell examined pancreatic tumor microbiota and patient outcomes, but it’s unclear whether the microorganisms moved from the gut to the pancreas or “constitute a durably colonized community that lives inside the tumor,” which remains a matter of debate, Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said.

A 2020 study in Science suggested diverse microbial communities in seven tumor types, but those findings were similarly called into question. That study stated that “bacteria were first detected in human tumors more than 100 years ago” and that “bacteria are well-known residents in human tumors,” but Dr. Salzberg considers those statements misleading.

It’s true that bacteria and viruses have been detected in tumors because “there’s very good evidence that an acute infection caused by a very small number of viruses and bacteria can cause a tumor,” Dr. Salzberg said. Human papillomavirus, for example, can cause six different types of cancer. Inflammation and ulcers caused by Helicobacter pylori may progress to stomach cancer, and Fusobacterium nucleatum and Enterococcus faecalis have been shown to contribute to colorectal cancer. Those examples differ from a microbiome; this “a community of bacteria and possibly other microscopic bugs, like fungi, that are happily living in the tumor” the same way microbes reside in our guts, he said.

Dr. Knight said that many bacteria his team identified “have been confirmed independently in subsequent work.” He acknowledged, however, that more research is needed.

Several of the contested studies above were among a lengthy list that Dr. Knight provided, noting that most of the disagreements “have two sides to them, and critiques from one particular group does not immediately invalidate a reported finding.”

Yet, many of the papers Dr. Knight listed are precisely the types that skeptics like Dr. Salzberg believe are too flawed to draw reliable conclusions.

“I think many agree that microbes may exist within tumors that are exposed to the environment, like tumors of the skin, gut, and mouth,” Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said. It’s less clear, however, whether tumors further from the body’s microbiome harbor any microbes or where they came from if they do. Microbial signals in organs elsewhere in the body become faint quickly, he said.

Underdeveloped Technology

Though Dr. Salzberg said that the concept of a tumor microbiome is “implausible” because there’s no easy route for bacteria to reach internal organs, it’s unclear whether scientists have the technology yet to adequately answer this question.

For one thing, samples in these types of studies are typically “ultra-low biomass samples, where the signal — the amount of microbes in the sample — is so low that it’s comparable to how much would be expected to be found in reagents and environmental contamination through processing,” Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin explained. Many polymerases used to amplify a DNA signal, for example, are made in bacteria and may retain trace amounts identified in these studies.

Dr. Knight agreed that low biomass is a challenge in this field but is not an unsurmountable one.

Another challenge is that study samples, as with Dr. Knight’s work, were collected during routine surgeries without the intent to find a microbial signal. Simply using a scalpel to cut through the skin means cutting through a layer of bacteria, and surgery rooms are not designed to eliminate all bacteria. Some work has even shown there is a “hospital microbiome,” so “you can easily have that creep into your signal and mistake it for tumor-resident bacteria,” Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said.

Dr. Knight asserted that the samples are taken under sterile conditions, but other researchers do not think the level of sterility necessary for completely clean samples is possible.

“Just because it’s in your sample doesn’t mean it was in your tumor,” Dr. Gihawi said.

Even if scientists can retrieve a reliable sample without contamination, analyzing it requires comparing the genetic material to existing databases of microbial genomes. Yet, contamination and misclassification of genetic sequences can be problems in those reference genomes too, Dr. Gihawi explained.

Machine learning algorithms have a role in interpreting data, but “we need to be careful of what we use them for,” he added.

“These techniques are in their infancy, and we’re starting to chase them down, which is why we need to move microbiome research in a way that can be used clinically,” Dr. Gihawi said.

Influence on Cancer Treatment Outcomes

Again, however, the question of whether microbiomes exist within tumors is only one slice of the much larger field looking at microbiomes and cancer, including its influence on cancer treatment outcomes. Although much remains to be learned, less controversy exists over the thousands of studies in the past two decades that have gradually revealed how the body’s microbiome can affect both the course of a cancer and the effectiveness of different treatments.

The growing research showing the importance of the gut microbiome in cancer treatments is not surprising given its role in immunity more broadly. Because the human immune system must recognize and defend against microbes, the microbiome helps train it, Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said.

Some bacteria can escape the gut — a phenomenon called bacterial translocation — and may aid in fighting tumors. To grow large enough to be seen on imaging, tumors need to evolve several abilities, such as growing enough vascularization to receive blood flow and shutting down local immune responses.

“Any added boost, like immunotherapy, has a chance of breaking through that immune forcefield and killing the tumor cells,” Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said. Escaped gut bacteria may provide that boost.

“There’s a lot of evidence that depletion of the gut microbiome impairs immunotherapy and chemotherapy. The thinking behind some of those studies is that gut microbes can cross the gut barrier and when they do, they activate the immune system,” he said.

In mice engineered to have sterile guts, for example, the lack of bacteria results in less effective immune systems, Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin pointed out. A host of research has shown that antibiotic exposure during and even 6 months before immunotherapy dramatically reduces survival rates. “That’s pretty convincing to me that gut microbes are important,” he said.

Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin cautioned that there continues to be controversy on understanding which bacteria are important for response to immunotherapy. “The field is still in its infancy in terms of understanding which bacteria are most important for these effects,” he said.

Dr. Knight suggested that escaped bacteria may be the genesis of the ones that he and other researchers believe exist in tumors. “Because tumor microbes must come from somewhere, it is to be expected that some of those microbes will be co-opted from body-site specific commensals.”

It’s also possible that metabolites released from gut bacteria escape the gut and could theoretically affect distant tumor growth, Dr. Gihawi said. The most promising avenue of research in this area is metabolites being used as biomarkers, added Dr. Gihawi, whose lab published research on a link between bacteria detected in men’s urine and a more aggressive subset of prostate cancers. But that research is not far enough along to develop lab tests for clinical use, he noted.

No Consensus Yet

Even before the controversy erupted around Dr. Knight’s research, he co-founded the company Micronoma to develop cancer tests based on his microbe findings. The company has raised $17.5 million from private investors as of August 2023 and received the US Food and Drug Administration’s Breakthrough Device designation, allowing the firm to fast-track clinical trials testing the technology. The recent critiques have not changed the company’s plans.

It’s safe to say that scientists will continue to research and debate the possibility of tumor microbiomes until a consensus emerges.

“The field is evolving and studies testing the reproducibility of tumor-resident microbial signals are essential for developing our understanding in this area,” Dr. Vujkovic-Cvijin said.

Even if that path ultimately leads nowhere, as Dr. Salzberg expects, research into microbiomes and cancer has plenty of other directions to go.

“I’m actually quite an optimist,” Dr. Gihawi said. “I think there’s a lot of scope for some really good research here, especially in the sites where we know there is a strong microbiome, such as the gastrointestinal tract.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Late-Stage Incidence Rates Support CRC Screening From Age 45

, a cross-sectional study of stage-stratified CRC found.

It is well known that CRC is becoming more prevalent generally in the under 50-year population, but stage-related analyses have not been done.

Staging analysis in this age group is important, however, as an increasing burden of advance-staged disease would provide further evidence for earlier screening initiation, wrote Eric M. Montminy, MD, a gastroenterologist at John H. Stroger Hospital of County Cook, Chicago, Illinois, and colleagues in JAMA Network Open.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has recommended that average-risk screening begin at 45 years of age, as do the American Gastroenterological Association and other GI societies, although the American College of Physicians last year published clinical guidance recommending 50 years as the age to start screening for CRC for patients with average risk.

“Patients aged 46-49 may become confused on which guideline to follow, similar to confusion occurring with prior breast cancer screening changes,” Dr. Montminy said in an interview. “We wanted to demonstrate incidence rates with stage stratification to help clarify the incidence trends in this age group. Stage stratification is a key because it provides insight into the relationship between time and cancer incidence, ie, is screening finding early cancer or not?”

A 2020 study in JAMA Network Open demonstrated a 46.1% increase in CRC incidence rates (IRs) in persons aged 49-50 years. This steep increase is consistent with the presence of a large preexisting and undetected case burden.

“Our results demonstrate that adults aged 46-49 years, who are between now-conflicting guidelines on whether to start screening at age 45 or 50 years, have an increasing burden of more advanced-stage CRC and thus may be at an increased risk if screening is not initiated at age 45 years,” Dr. Montminy’s group wrote.

Using incidence data per 100,000 population from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry, the investigators observed the following IRs for early-onset CRC in the age group of 46-49 years:

- Distant adenocarcinoma IRs increased faster than other stages: annual percentage change (APC), 2.2 (95% CI, 1.8-2.6).

- Regional IRs also significantly increased: APC, 1.3 (95% CI, 0.8-1.7).

- Absolute regional IRs of CRC in the age bracket of 46-49 years are similar to total pancreatic cancer IRs in all ages and all stages combined (13.2 of 100,000) over similar years. When distant IRs for CRC are included with regional IRs, those for IRs for CRC are double those for pancreatic cancer of all stages combined.

- The only decrease was seen in localized IRs: APC, -0.6 (95% CI, -1 to -0.2).

“My best advice for clinicians is to provide the facts from the data to patients so they can make an informed health decision,” Dr. Montminy said. “This includes taking an appropriate personal and family history and having the patient factor this aspect into their decision on when and how they want to perform colon cancer screening.”

His institution adheres to the USPSTF recommendation of initiation of CRC screening at age 45 years.

Findings From 2000 to 2020

During 2000-2020 period, 26,887 CRCs were diagnosed in adults aged 46-49 years (54.5% in men).

As of 2020, the localized adenocarcinoma IR decreased to 7.7 of 100,000, but regional adenocarcinoma IR increased to 13.4 of 100,000 and distant adenocarcinoma IR increased to 9.0 of 100,000.

Regional adenocarcinoma IR remained the highest of all stages in 2000-2020. From 2014 to 2020, distant IRs became similar to localized IRs, except in 2017 when distant IRs were significantly higher than localized.

Why the CRC Uptick?

“It remains an enigma at this time as to why we’re seeing this shift,” Dr. Montminy said, noting that etiologies from the colonic microbiome to cellphones have been postulated. “To date, no theory has substantially provided causality. But whatever the source is, it is affecting Western countries in unison with data demonstrating a birth cohort effect as well,” he added. “We additionally know, based on the current epidemiologic data, that current screening practices are failing, and a unified discussion must occur in order to prevent young patients from developing advanced colon cancer.”

Offering his perspective on the findings, Joshua Meyer, MD, vice chair of translational research in the Department of Radiation Oncology at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, said the findings reinforce the practice of offering screening to average-risk individuals starting at age 45 years, the threshold at his institution. “There are previously published data demonstrating an increase in advanced stage at the time of screening initiation, and these data support that,” said Dr. Meyer, who was not involved in the present analysis.

More research needs to be done, he continued, not just on optimal age but also on the effect of multiple other factors impacting risk. “These may include family history and genetic risk as well as the role of blood- and stool-based screening assays in an integrated strategy to screen for colorectal cancer.”

There are multiple screening tests, and while colonoscopy, the gold standard, is very safe, it is not completely without risks, Dr. Meyer added. “And the question of the appropriate allocation of limited societal resources continues to be discussed on a broader level and largely explains the difference between the two guidelines.”

This study received no specific funding. Co-author Jordan J. Karlitz, MD, reported personal fees from GRAIL (senior medical director) and an equity position from Gastro Girl/GI On Demand outside f the submitted work. Dr. Meyer disclosed no conflicts of interest relevant to his comments.

, a cross-sectional study of stage-stratified CRC found.

It is well known that CRC is becoming more prevalent generally in the under 50-year population, but stage-related analyses have not been done.

Staging analysis in this age group is important, however, as an increasing burden of advance-staged disease would provide further evidence for earlier screening initiation, wrote Eric M. Montminy, MD, a gastroenterologist at John H. Stroger Hospital of County Cook, Chicago, Illinois, and colleagues in JAMA Network Open.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has recommended that average-risk screening begin at 45 years of age, as do the American Gastroenterological Association and other GI societies, although the American College of Physicians last year published clinical guidance recommending 50 years as the age to start screening for CRC for patients with average risk.

“Patients aged 46-49 may become confused on which guideline to follow, similar to confusion occurring with prior breast cancer screening changes,” Dr. Montminy said in an interview. “We wanted to demonstrate incidence rates with stage stratification to help clarify the incidence trends in this age group. Stage stratification is a key because it provides insight into the relationship between time and cancer incidence, ie, is screening finding early cancer or not?”

A 2020 study in JAMA Network Open demonstrated a 46.1% increase in CRC incidence rates (IRs) in persons aged 49-50 years. This steep increase is consistent with the presence of a large preexisting and undetected case burden.

“Our results demonstrate that adults aged 46-49 years, who are between now-conflicting guidelines on whether to start screening at age 45 or 50 years, have an increasing burden of more advanced-stage CRC and thus may be at an increased risk if screening is not initiated at age 45 years,” Dr. Montminy’s group wrote.

Using incidence data per 100,000 population from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry, the investigators observed the following IRs for early-onset CRC in the age group of 46-49 years:

- Distant adenocarcinoma IRs increased faster than other stages: annual percentage change (APC), 2.2 (95% CI, 1.8-2.6).

- Regional IRs also significantly increased: APC, 1.3 (95% CI, 0.8-1.7).

- Absolute regional IRs of CRC in the age bracket of 46-49 years are similar to total pancreatic cancer IRs in all ages and all stages combined (13.2 of 100,000) over similar years. When distant IRs for CRC are included with regional IRs, those for IRs for CRC are double those for pancreatic cancer of all stages combined.

- The only decrease was seen in localized IRs: APC, -0.6 (95% CI, -1 to -0.2).

“My best advice for clinicians is to provide the facts from the data to patients so they can make an informed health decision,” Dr. Montminy said. “This includes taking an appropriate personal and family history and having the patient factor this aspect into their decision on when and how they want to perform colon cancer screening.”

His institution adheres to the USPSTF recommendation of initiation of CRC screening at age 45 years.

Findings From 2000 to 2020

During 2000-2020 period, 26,887 CRCs were diagnosed in adults aged 46-49 years (54.5% in men).

As of 2020, the localized adenocarcinoma IR decreased to 7.7 of 100,000, but regional adenocarcinoma IR increased to 13.4 of 100,000 and distant adenocarcinoma IR increased to 9.0 of 100,000.

Regional adenocarcinoma IR remained the highest of all stages in 2000-2020. From 2014 to 2020, distant IRs became similar to localized IRs, except in 2017 when distant IRs were significantly higher than localized.

Why the CRC Uptick?

“It remains an enigma at this time as to why we’re seeing this shift,” Dr. Montminy said, noting that etiologies from the colonic microbiome to cellphones have been postulated. “To date, no theory has substantially provided causality. But whatever the source is, it is affecting Western countries in unison with data demonstrating a birth cohort effect as well,” he added. “We additionally know, based on the current epidemiologic data, that current screening practices are failing, and a unified discussion must occur in order to prevent young patients from developing advanced colon cancer.”

Offering his perspective on the findings, Joshua Meyer, MD, vice chair of translational research in the Department of Radiation Oncology at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, said the findings reinforce the practice of offering screening to average-risk individuals starting at age 45 years, the threshold at his institution. “There are previously published data demonstrating an increase in advanced stage at the time of screening initiation, and these data support that,” said Dr. Meyer, who was not involved in the present analysis.

More research needs to be done, he continued, not just on optimal age but also on the effect of multiple other factors impacting risk. “These may include family history and genetic risk as well as the role of blood- and stool-based screening assays in an integrated strategy to screen for colorectal cancer.”

There are multiple screening tests, and while colonoscopy, the gold standard, is very safe, it is not completely without risks, Dr. Meyer added. “And the question of the appropriate allocation of limited societal resources continues to be discussed on a broader level and largely explains the difference between the two guidelines.”

This study received no specific funding. Co-author Jordan J. Karlitz, MD, reported personal fees from GRAIL (senior medical director) and an equity position from Gastro Girl/GI On Demand outside f the submitted work. Dr. Meyer disclosed no conflicts of interest relevant to his comments.

, a cross-sectional study of stage-stratified CRC found.

It is well known that CRC is becoming more prevalent generally in the under 50-year population, but stage-related analyses have not been done.

Staging analysis in this age group is important, however, as an increasing burden of advance-staged disease would provide further evidence for earlier screening initiation, wrote Eric M. Montminy, MD, a gastroenterologist at John H. Stroger Hospital of County Cook, Chicago, Illinois, and colleagues in JAMA Network Open.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has recommended that average-risk screening begin at 45 years of age, as do the American Gastroenterological Association and other GI societies, although the American College of Physicians last year published clinical guidance recommending 50 years as the age to start screening for CRC for patients with average risk.

“Patients aged 46-49 may become confused on which guideline to follow, similar to confusion occurring with prior breast cancer screening changes,” Dr. Montminy said in an interview. “We wanted to demonstrate incidence rates with stage stratification to help clarify the incidence trends in this age group. Stage stratification is a key because it provides insight into the relationship between time and cancer incidence, ie, is screening finding early cancer or not?”

A 2020 study in JAMA Network Open demonstrated a 46.1% increase in CRC incidence rates (IRs) in persons aged 49-50 years. This steep increase is consistent with the presence of a large preexisting and undetected case burden.

“Our results demonstrate that adults aged 46-49 years, who are between now-conflicting guidelines on whether to start screening at age 45 or 50 years, have an increasing burden of more advanced-stage CRC and thus may be at an increased risk if screening is not initiated at age 45 years,” Dr. Montminy’s group wrote.

Using incidence data per 100,000 population from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry, the investigators observed the following IRs for early-onset CRC in the age group of 46-49 years:

- Distant adenocarcinoma IRs increased faster than other stages: annual percentage change (APC), 2.2 (95% CI, 1.8-2.6).

- Regional IRs also significantly increased: APC, 1.3 (95% CI, 0.8-1.7).

- Absolute regional IRs of CRC in the age bracket of 46-49 years are similar to total pancreatic cancer IRs in all ages and all stages combined (13.2 of 100,000) over similar years. When distant IRs for CRC are included with regional IRs, those for IRs for CRC are double those for pancreatic cancer of all stages combined.

- The only decrease was seen in localized IRs: APC, -0.6 (95% CI, -1 to -0.2).

“My best advice for clinicians is to provide the facts from the data to patients so they can make an informed health decision,” Dr. Montminy said. “This includes taking an appropriate personal and family history and having the patient factor this aspect into their decision on when and how they want to perform colon cancer screening.”

His institution adheres to the USPSTF recommendation of initiation of CRC screening at age 45 years.

Findings From 2000 to 2020

During 2000-2020 period, 26,887 CRCs were diagnosed in adults aged 46-49 years (54.5% in men).

As of 2020, the localized adenocarcinoma IR decreased to 7.7 of 100,000, but regional adenocarcinoma IR increased to 13.4 of 100,000 and distant adenocarcinoma IR increased to 9.0 of 100,000.

Regional adenocarcinoma IR remained the highest of all stages in 2000-2020. From 2014 to 2020, distant IRs became similar to localized IRs, except in 2017 when distant IRs were significantly higher than localized.

Why the CRC Uptick?

“It remains an enigma at this time as to why we’re seeing this shift,” Dr. Montminy said, noting that etiologies from the colonic microbiome to cellphones have been postulated. “To date, no theory has substantially provided causality. But whatever the source is, it is affecting Western countries in unison with data demonstrating a birth cohort effect as well,” he added. “We additionally know, based on the current epidemiologic data, that current screening practices are failing, and a unified discussion must occur in order to prevent young patients from developing advanced colon cancer.”

Offering his perspective on the findings, Joshua Meyer, MD, vice chair of translational research in the Department of Radiation Oncology at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, said the findings reinforce the practice of offering screening to average-risk individuals starting at age 45 years, the threshold at his institution. “There are previously published data demonstrating an increase in advanced stage at the time of screening initiation, and these data support that,” said Dr. Meyer, who was not involved in the present analysis.

More research needs to be done, he continued, not just on optimal age but also on the effect of multiple other factors impacting risk. “These may include family history and genetic risk as well as the role of blood- and stool-based screening assays in an integrated strategy to screen for colorectal cancer.”

There are multiple screening tests, and while colonoscopy, the gold standard, is very safe, it is not completely without risks, Dr. Meyer added. “And the question of the appropriate allocation of limited societal resources continues to be discussed on a broader level and largely explains the difference between the two guidelines.”

This study received no specific funding. Co-author Jordan J. Karlitz, MD, reported personal fees from GRAIL (senior medical director) and an equity position from Gastro Girl/GI On Demand outside f the submitted work. Dr. Meyer disclosed no conflicts of interest relevant to his comments.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Improving Fecal Immunochemical Test Collection for Colorectal Cancer Screening During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third-most common cancer worldwide and accounts for almost 11% of all cancer diagnoses, with > 1.9 million cases reported globally.1,2 CRC is the second-most deadly cancer, responsible for about 935,000 deaths.1 Over the past several decades, a steady decline in CRC incidence and mortality has been reported in developed countries, including the US.3,4 From 2008 through 2017, an annual reduction of 3% in CRC death rates was reported in individuals aged ≥ 65 years.5 This decline can mainly be attributed to improvements made in health systems and advancements in CRC screening programs.3,5

US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends CRC screening in individuals aged 45 to 75 years. USPSTF recommends direct visualization tests, such as colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy for CRC screening.6 Although colonoscopy is commonly used for CRC screening, it is an invasive procedure that requires bowel preparation and sedation, and has the potential risk of colonic perforation, bleeding, and infection. Additionally, social determinants—such as health care costs, missed work, and geographic location (eg, rural communities)—may limit colonoscopy utilization.7 As a result, other cost-effective, noninvasive tests such as high-sensitivity guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) and fecal immunochemical test (FIT) are also used for CRC screening. These tests detect occult blood in the stool of individuals who may be at risk for CRC, helping direct them to colonoscopy if they screen positive.8

The gFOBT relies on simple oxidation and requires a stool sample to detect the presence of the heme component of blood.9 If heme is present in the stool sample, it will enable the oxidation of guaiac to form a blue-colored dye when added to hydrogen peroxide. It is important to note that the oxidation component of this test may lead to false-positive results, as it may detect dietary hemoglobin present in red meat. Medications or foods that have peroxidase properties may also result in a false-positive gFOBT result. Additionally, false-negative results may be caused by antioxidants, which may interfere with the oxidation of guaiac.

FIT uses antibodies, which bind to the intact globin component of human hemoglobin.9 The quantity of bound antibody-hemoglobin complex is detected and measured by a variety of automated quantitative techniques. This testing strategy eliminates the need for food or medication restrictions and the subjective visual assessment of change in color, as required for the gFOBT.9 A 2016 meta-analysis found that FIT performed better compared with gFOBT in terms of specificity, positivity rate, number needed to scope, and number needed to screen.8 The FIT screening method has also been found to have greater adherence rates, which is likely due to fewer stool sampling requirements and the lack of medication or dietary restrictions, compared with gFOBT.7,8

The COVID-19 pandemic had a drastic impact on CRC preventive care services. In March 2020, elective colonoscopies were temporarily ceased across the country and the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) deferred all elective surgeries and medical procedures, including screening and surveillance colonoscopies. In line with these recommendations, elective colonoscopies were temporarily ceased across the country.10 The National Cancer Institute’s Population-Based Research to Optimize the Screening Process consortium reported that CRC screening rates decreased by 82% across the US in 2020.11 Public health measures are likely the main reason for this decline, but other factors may include a lack of resource availability in outpatient settings and public fear of the pandemic.10

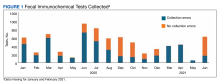

The James A. Haley Veterans Affairs Hospital (JAHVAH) in Tampa, Florida, encouraged the use of FIT in place of colonoscopies to avoid delaying preventive services. The initiative to continue CRC screening methods via FIT was scrutinized when laboratory personnel reported that in fiscal year (FY) 2020, 62% of the FIT kits that patients returned to the laboratory were missing information or had other errors (Figure 1). These improperly returned FIT kits led to delayed processing, canceled orders, increased staff workload, and more costs for FIT repetition.

Research shows many patients often fail to adhere to the instructions for proper FIT sample collection and return. Wang and colleagues reported that of 4916 FIT samples returned to the laboratory, 971 (20%) had collection errors, and 910 (94%) of those samples were missing a sample collection date.12 The sample collection date is important because hemoglobin degradation occurs over time, which may create false-negative FIT results. Although studies have found that sample return times of ≤ 10 days are not associated with a decrease in FIT positive rates, it is recommended to mail completed FITs within 24 hours of sample collection.13

Because remote screening methods like FIT were preferred during the COVID-19 pandemic, we conducted a quality improvement (QI) project to address FIT inefficiency. The aim of this initiative was to determine the root cause behind incorrectly returned FIT kits and to increase correctly collected and testable FIT kits upon initial laboratory arrival by at least 20% by the second quarter of FY 2021.

Quality Improvement Project

This QI project was conducted from July 2020 to June 2021 at the JAHVAH, which provides primary care and specialty health services to veterans in central and south Florida. The QI was designed based on the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) model of health care improvement. The QI team consisted of physicians, nurses, administrative staff, and laboratory personnel. A SIPOC (Suppliers, Input, Process, Output, Customers) map was initially designed to help clarify the different groups involved in the process of FIT kit distribution and return. This map helped the team decide who should be involved in the solution process.

The QI team performed a root cause analysis using a fishbone diagram and identified the reasons FIT kits were returned to the laboratory with errors that prevented processing. The team brainstormed potential change ideas and created an impact vs effort chart to increase the number of correctly returned and testable FIT kits upon initial arrival at the laboratory by at least 20% by the second quarter of FY 2021. We identified strengths and prioritized change ideas to improve the number of testable and correctly returned FIT kits to the hospital laboratory. These ideas included centralizing FIT kit dispersal to a new administrative group, building redundant patient reminders on kit completion and giving patients more accessible places for kit return.

Patients included in the study were adults aged 50 to 75 years seen at the JAHVAH outpatient clinic who were asked to undergo FIT CRC screening. FIT orders for other facilities were excluded. The primary endpoint of this project was to improve the number of correctly returned FITs. The number of correct and incorrect returned FITs were measured from July 2020 to June 2021. FITs returned with errors were categorized by the type of error, including: no order on file in the electronic health record (EHR), canceled test, expired test, unable to identify test, missing information, and missing collection date.

We attempted to calculate costs of FITs that were returned to the laboratory but could not be analyzed and were discarded. In FY 2020, 1568 FITs were discarded. Each FIT cost about $7.80 to process for an annualized expense of $12,230 for discarded FITs.

Root Cause Analysis

Root causes were obtained by making a fishbone diagram. From this diagram, an impact vs effort chart was created to form and prioritize ideas for our PDSA cycles. Data about correctly and incorrectly returned kits were collected monthly from laboratory personnel, then analyzed by the QI team using run charts to look for change in frequency and patterns.

To improve this process, a swim lane chart for FIT processing was assembled and later used to make a comprehensive fishbone diagram to establish the 6 main root cause errors: missing FIT EHR order, cancelled FIT EHR order, expired stool specimen, partial patient identifiers, no patient identifiers, and no stool collection date. Pareto and run charts were superimposed with the laboratory data. The most common cause of incorrectly returned FITs was no collection date.

PDSA Cycles

Beginning in January 2021, PDSA cycles from the ideas in the impact vs effort chart were used. Organization and implementation of the project occurred from July 2020 to April 2021. The team reassessed the data in April 2021 to evaluate progress after PDSA initiation. The mean rate of missing collection date dropped from 24% in FY 2020 prior to PDSA cycles to 14% in April 2021; however, the number of incorrectly returned kits was similar to the baseline level. When reviewing this discrepancy, the QI team found that although the missing collection date rate had improved, the rate of FITs with not enough information had increased from 5% in FY 2020 to 67% in April 2021 (Figure 2). After discussing with laboratory personnel, it was determined that the EHR order was missing when the process pathway changed. Our PDSA initiative changed the process pathway and different individuals were responsible for FIT dispersal. The error was quickly addressed with the help of clinical and administrative staff; a 30-day follow-up on June 21, 2021, revealed that only 9% of the patients had sent back kits with not enough information.

After troubleshooting, the team achieved a sustainable increase in the number of correctly returned FIT kits from an average of 38% before the project to 72% after 30-day follow-up.

Discussion

Proper collection and return of FIT samples are vital for process efficiency for both physicians and patients. This initiative aimed to improve the rate of correctly returned FIT kits by 20%, but its final numbers showed an improvement of 33.6%. Operational benefits from this project included early detection of CRC, improved laboratory workflow, decreased FIT kit waste, and increased patient satisfaction.

The multipronged PDSA cycle attempted to increase the rate of correctly returned FIT kits. We improved kit comprehension and laboratory accessibility, and instituted redundant return reminders for patients. We also centralized a new process pathway for FIT distribution and educated physicians and support staff. Sampling and FIT return may seem like a simple procedure, but the FIT can be cumbersome for patients and directions can be confusing. Therefore, to maximize screening participation, it is essential to minimize confusion in the collection and return of a FIT sample.14,15

This QI initiative was presented at Grand Rounds at the University of South Florida in June 2021 and has since been shared with other VA hospitals. It was also presented at the American College of Gastroenterology Conference in 2021.

Limitations

This study was a single-center QI project and focused mostly on FIT kit return rates. To fully address CRC screening, it is important to ensure that individuals with a positive screen are appropriately followed up with a colonoscopy. Although follow-up was not in the scope of this project, it is key to CRC screening in general and should be the subject of future research.

Conclusions

FIT is a useful method for CRC screening that can be particularly helpful when in-person visits are limited, as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. This increase in demand for FITs during the pandemic revealed process deficiencies and gave JAHVAH an opportunity to improve workflow. Through the aid of a multidisciplinary team, the process to complete and return FITs improved and surpassed the goal of 20% improvement. Our goal is to continue to fine-tune the workflow and troubleshoot the system as needed.

1. Sawicki T, Ruszkowska M, Danielewicz A, Niedz′wiedzka E, Arłukowicz T, Przybyłowicz KE. A review of colorectal cancer in terms of epidemiology, risk factors, development, symptoms and diagnosis. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(9):2025. Published 2021 Apr 22. doi:10.3390/cancers13092025

2. Rawla P, Sunkara T, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Prz Gastroenterol. 2019;14(2):89-103. doi:10.5114/pg.2018.81072

3. Yang DX, Gross CP, Soulos PR, Yu JB. Estimating the magnitude of colorectal cancers prevented during the era of screening: 1976 to 2009. Cancer. 2014;120(18):2893-2901. doi:10.1002/cncr.28794

4. Naishadham D, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Siegel R, Cokkinides V, Jemal A. State disparities in colorectal cancer mortality patterns in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(7):1296-1302. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0250

5. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(3):145-164. doi:10.3322/caac.21601

6. US Preventive Services Task Force, Davidson KW, Barry MJ, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third-most common cancer worldwide and accounts for almost 11% of all cancer diagnoses, with > 1.9 million cases reported globally.1,2 CRC is the second-most deadly cancer, responsible for about 935,000 deaths.1 Over the past several decades, a steady decline in CRC incidence and mortality has been reported in developed countries, including the US.3,4 From 2008 through 2017, an annual reduction of 3% in CRC death rates was reported in individuals aged ≥ 65 years.5 This decline can mainly be attributed to improvements made in health systems and advancements in CRC screening programs.3,5

US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends CRC screening in individuals aged 45 to 75 years. USPSTF recommends direct visualization tests, such as colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy for CRC screening.6 Although colonoscopy is commonly used for CRC screening, it is an invasive procedure that requires bowel preparation and sedation, and has the potential risk of colonic perforation, bleeding, and infection. Additionally, social determinants—such as health care costs, missed work, and geographic location (eg, rural communities)—may limit colonoscopy utilization.7 As a result, other cost-effective, noninvasive tests such as high-sensitivity guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) and fecal immunochemical test (FIT) are also used for CRC screening. These tests detect occult blood in the stool of individuals who may be at risk for CRC, helping direct them to colonoscopy if they screen positive.8

The gFOBT relies on simple oxidation and requires a stool sample to detect the presence of the heme component of blood.9 If heme is present in the stool sample, it will enable the oxidation of guaiac to form a blue-colored dye when added to hydrogen peroxide. It is important to note that the oxidation component of this test may lead to false-positive results, as it may detect dietary hemoglobin present in red meat. Medications or foods that have peroxidase properties may also result in a false-positive gFOBT result. Additionally, false-negative results may be caused by antioxidants, which may interfere with the oxidation of guaiac.

FIT uses antibodies, which bind to the intact globin component of human hemoglobin.9 The quantity of bound antibody-hemoglobin complex is detected and measured by a variety of automated quantitative techniques. This testing strategy eliminates the need for food or medication restrictions and the subjective visual assessment of change in color, as required for the gFOBT.9 A 2016 meta-analysis found that FIT performed better compared with gFOBT in terms of specificity, positivity rate, number needed to scope, and number needed to screen.8 The FIT screening method has also been found to have greater adherence rates, which is likely due to fewer stool sampling requirements and the lack of medication or dietary restrictions, compared with gFOBT.7,8

The COVID-19 pandemic had a drastic impact on CRC preventive care services. In March 2020, elective colonoscopies were temporarily ceased across the country and the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) deferred all elective surgeries and medical procedures, including screening and surveillance colonoscopies. In line with these recommendations, elective colonoscopies were temporarily ceased across the country.10 The National Cancer Institute’s Population-Based Research to Optimize the Screening Process consortium reported that CRC screening rates decreased by 82% across the US in 2020.11 Public health measures are likely the main reason for this decline, but other factors may include a lack of resource availability in outpatient settings and public fear of the pandemic.10

The James A. Haley Veterans Affairs Hospital (JAHVAH) in Tampa, Florida, encouraged the use of FIT in place of colonoscopies to avoid delaying preventive services. The initiative to continue CRC screening methods via FIT was scrutinized when laboratory personnel reported that in fiscal year (FY) 2020, 62% of the FIT kits that patients returned to the laboratory were missing information or had other errors (Figure 1). These improperly returned FIT kits led to delayed processing, canceled orders, increased staff workload, and more costs for FIT repetition.

Research shows many patients often fail to adhere to the instructions for proper FIT sample collection and return. Wang and colleagues reported that of 4916 FIT samples returned to the laboratory, 971 (20%) had collection errors, and 910 (94%) of those samples were missing a sample collection date.12 The sample collection date is important because hemoglobin degradation occurs over time, which may create false-negative FIT results. Although studies have found that sample return times of ≤ 10 days are not associated with a decrease in FIT positive rates, it is recommended to mail completed FITs within 24 hours of sample collection.13

Because remote screening methods like FIT were preferred during the COVID-19 pandemic, we conducted a quality improvement (QI) project to address FIT inefficiency. The aim of this initiative was to determine the root cause behind incorrectly returned FIT kits and to increase correctly collected and testable FIT kits upon initial laboratory arrival by at least 20% by the second quarter of FY 2021.

Quality Improvement Project

This QI project was conducted from July 2020 to June 2021 at the JAHVAH, which provides primary care and specialty health services to veterans in central and south Florida. The QI was designed based on the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) model of health care improvement. The QI team consisted of physicians, nurses, administrative staff, and laboratory personnel. A SIPOC (Suppliers, Input, Process, Output, Customers) map was initially designed to help clarify the different groups involved in the process of FIT kit distribution and return. This map helped the team decide who should be involved in the solution process.