User login

Disaster Preparedness in Dermatology Residency Programs

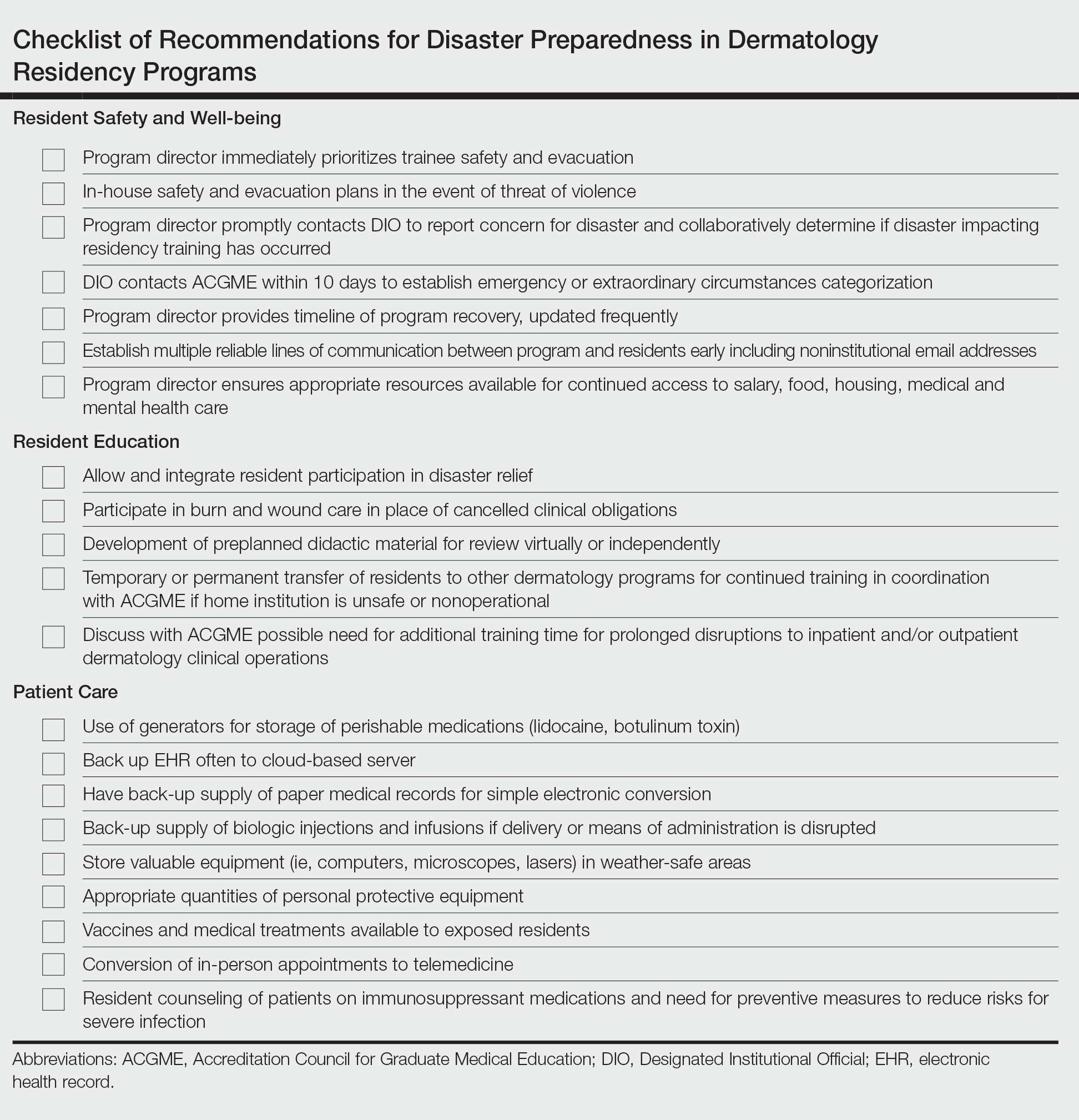

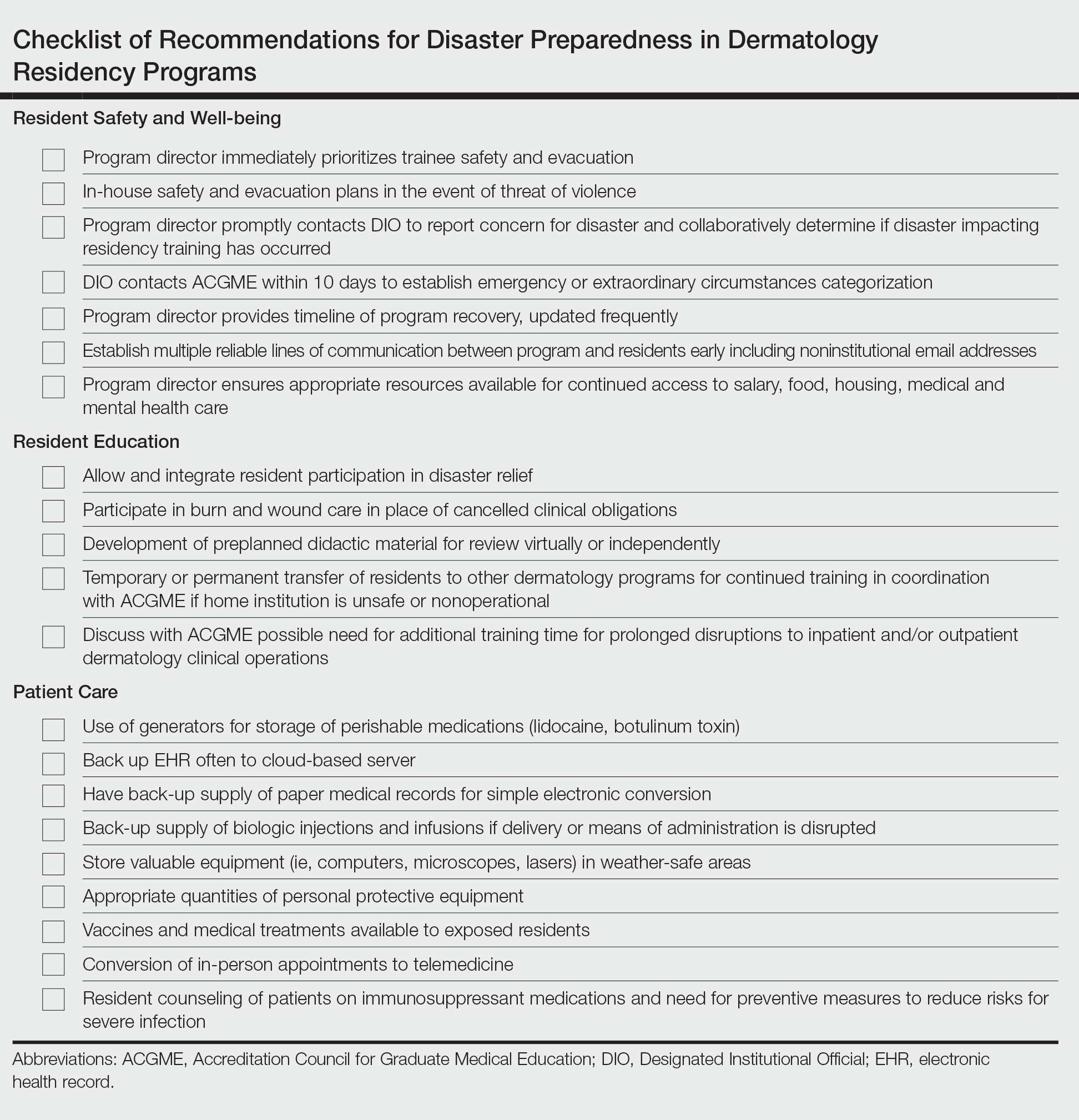

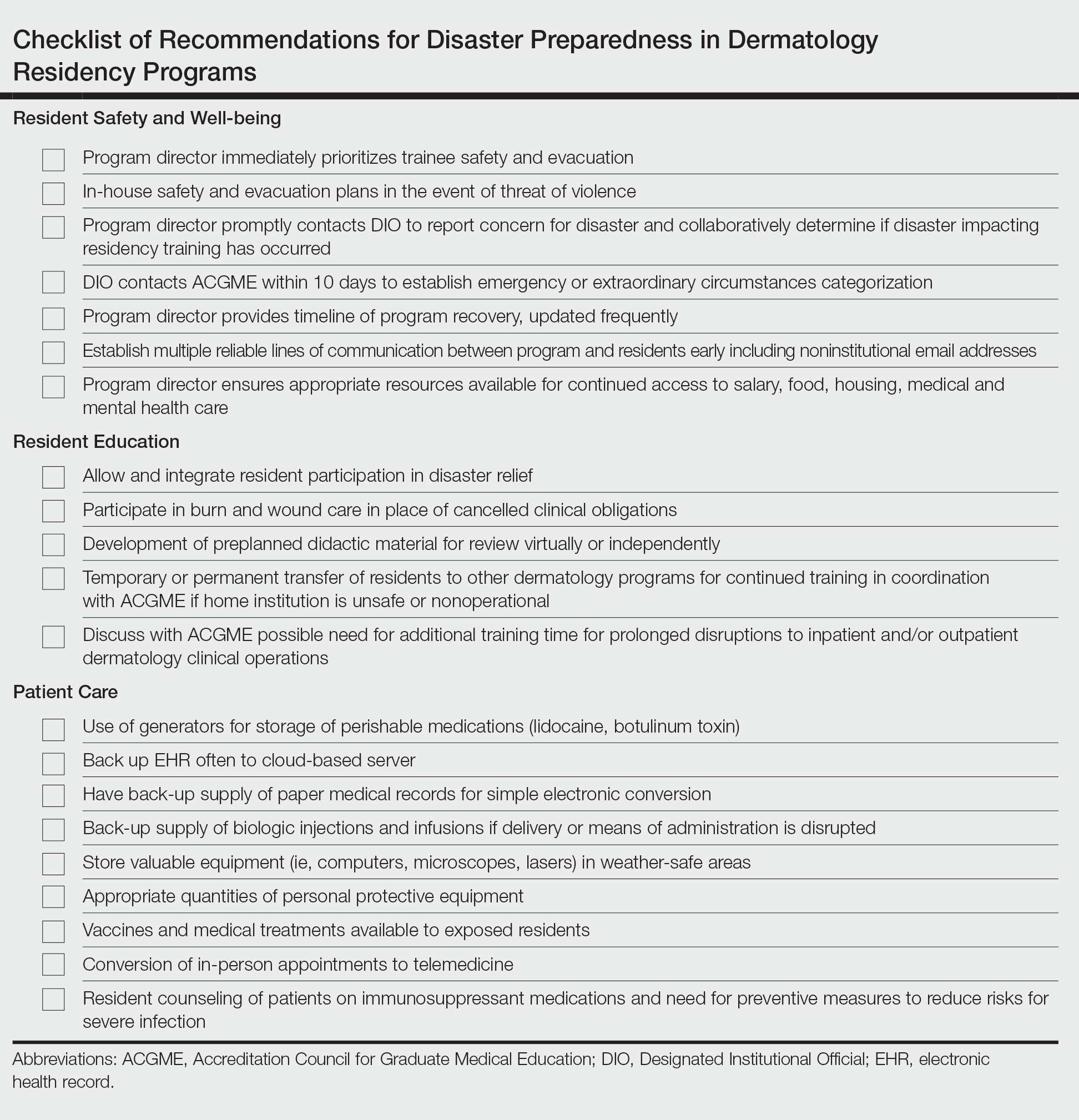

In an age of changing climate and emerging global pandemics, the ability of residency programs to prepare for and adapt to potential disasters may be paramount in preserving the training of physicians. The current literature regarding residency program disaster preparedness, which focuses predominantly on hurricanes and COVID-19,1-8 is lacking in recommendations specific to dermatology residency programs. Likewise, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) guidelines9 do not address dermatology-specific concerns in disaster preparedness or response. Herein, we propose recommendations to mitigate the impact of various types of disasters on dermatology residency programs and their trainees with regard to resident safety and wellness, resident education, and patient care (Table).

Resident Safety and Wellness

Role of the Program Director—The role of the program director is critical, serving as a figure of structure and reassurance.4,7,10 Once concern of disaster arises, the program director should contact the Designated Institutional Official (DIO) to express concerns about possible disruptions to resident training. The DIO should then contact the ACGME within 10 days to report the disaster and submit a request for emergency (eg, pandemic) or extraordinary circumstances (eg, natural disaster) categorization.4,9 Program directors should promptly prepare plans for program reconfiguration and resident transfers in alignment with ACGME requirements to maintain evaluation and completion of core competencies of training during disasters.9 Program directors should prioritize the safety of trainees during the immediate threat with clear guidelines on sheltering, evacuations, or quarantines; a timeline of program recovery based on communication with residents, faculty, and administration should then be established.10,11

Communication—Establishing a strong line of communication between program directors and residents is paramount. Collection of emergency noninstitutional contact information, establishment of a centralized website for information dissemination, use of noninstitutional email and proxy servers outside of the location of impact, social media updates, on-site use of 2-way radios, and program-wide conference calls when possible should be strongly considered as part of the disaster response.2-4,12,13

Resident Accommodations and Mental Health—If training is disrupted, residents should be reassured of continued access to salary, housing, food, or other resources as necessary.3,4,11 There should be clear contingency plans if residents need to leave the program for extended periods of time due to injury, illness, or personal circumstances. Although relevant in all types of disasters, resident mental health and response to trauma also must be addressed. Access to counseling, morale-building opportunities (eg, resident social events), and screening for depression or posttraumatic stress disorder may help promote well-being among residents following traumatic events.14

Resident Education

Participation in Disaster Relief—Residents may seek to aid in the disaster response, which may prove challenging in the setting of programs with high patient volume.4 In coordination with the ACGME and graduate medical education governing bodies, program directors should consider how residents may fulfill dermatology training requirements in conjunction with disaster relief efforts, such as working in an inpatient setting or providing wound care.10

Continued Didactic Education—The use of online learning and conference calls for continuing the dermatology curriculum is an efficient means to maintaining resident education when meeting in person poses risks to residents.15 Projections of microscopy images, clinical photographs, or other instructional materials allow for continued instruction on resident examination, histopathology, and diagnostic skills.

Continued Clinical Training—If the home institution cannot support the operation of dermatology clinics, residents should be guaranteed continued training at other institutions. Agreements with other dermatology programs, community hospitals, or private dermatology practices should be established in advance, with consideration given to the number of residents a program can support, funding transfers, and credentialing requirements.2,4,5

Prolonged Disruptions—Nonessential departments of medical institutions may cease to function during war or mass casualty disasters, and it may be unsafe to send dermatology residents to other institutions or clinical areas. If the threat is prolonged, programs may need to consider allowing current residents a longer duration of training despite potential overlap with incoming dermatology residents.7

Patient Care

Disruptions to Clinic Operations—Regarding threats of violence, dangerous exposures, or natural disasters, there should be clear guidelines on sheltering in the clinical setting or stabilizing patients during a procedure.11 Equipment used by residents such as laptops, microscopes, and treatment devices (eg, lasers) should be stored in weather-safe locations that would not be notably impacted by moisture or structural damage to the clinic building. If electricity or internet access are compromised, paper medical records should be available to residents to continue clinical operations. Electronic health records used by residents should regularly be backed up on remote servers or cloud storage to allow continued access to patient health information if on-site servers are not functional.12 If disruptions are prolonged, residency program administration should coordinate with the institution to ensure there is adequate supply and storage of medications (eg, lidocaine, botulinum toxin) as well as a continued means of delivering biologic medications to patients and an ability to obtain laboratory or dermatopathology services.

In-Person Appointments vs Telemedicine—There are benefits to both residency training and patient care when physicians are able to perform in-person examinations, biopsies, and in-office treatments.16 Programs should ensure an adequate supply of personal protective equipment to continue in-office appointments, vaccinations, and medical care if a resident or other members of the team are exposed to an infectious disease.7 If in-person appointments are limited or impossible, telemedicine capabilities may still allow residents to meet program requirements.7,10,15 However, reduced patient volume due to decreased elective visits or procedures may complicate the fulfillment of clinical requirements, which may need to be adjusted in the wake of a disaster.7

Use of Immunosuppressive Therapies—Residency programs should address the risks of prescribing immunosuppressive therapies (eg, biologics) during an infectious threat with their residents and encourage trainees to counsel patients on the importance of preventative measures to reduce risks for severe infection.17

Final Thoughts

- Davis W. Hurricane Katrina: the challenge to graduate medical education. Ochsner J. 2006;6:39.

- Cefalu CA, Schwartz RS. Salvaging a geriatric medicine academic program in disaster mode—the LSU training program post-Katrina.J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:590-596.

- Ayyala R. Lessons from Katrina: a program director’s perspective. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1425-1426.

- Wiese JG. Leadership in graduate medical education: eleven steps instrumental in recovering residency programs after a disaster. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336:168-173.

- Griffies WS. Post-Katrina stabilization of the LSU/Ochsner Psychiatry Residency Program: caveats for disaster preparedness. Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33:418-422.

- Kearns DG, Chat VS, Uppal S, et al. Applying to dermatology residency during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1214-1215.

- Matthews JB, Blair PG, Ellison EC, et al. Checklist framework for surgical education disaster plans. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;233:557-563.

- Litchman GH, Marson JW, Rigel DS. The continuing impact of COVID-19 on dermatology practice: office workflow, economics, and future implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:576-579.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Sponsoring institution emergency categorization. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/covid-19/sponsoring-institution-emergency-categorization/

- Li YM, Galimberti F, Abrouk M, et al. US dermatology resident responses about the COVID-19 pandemic: results from a nationwide survey. South Med J. 2020;113:462-465.

- Newman B, Gallion C. Hurricane Harvey: firsthand perspectives for disaster preparedness in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2019;94:1267-1269.

- Pero CD, Pou AM, Arriaga MA, et al. Post-Katrina: study in crisis-related program adaptability. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:394-397.

- Hattaway R, Singh N, Rais-Bahrami S, et al. Adaptations of dermatology residency programs to changes in medical education amid the COVID-19 pandemic: virtual opportunities and social media. SKIN. 2021;5:94-100.

- Hillier K, Paskaradevan J, Wilkes JK, et al. Disaster plans: resident involvement and well-being during Hurricane Harvey. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11:129-131.

- Samimi S, Choi J, Rosman IS, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:609-618.

- Bastola M, Locatis C, Fontelo P. Diagnostic reliability of in-person versus remote dermatology: a meta-analysis. Telemed J E Health. 2021;27:247-250.

- Bashyam AM, Feldman SR. Should patients stop their biologic treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic? J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:317-318.

In an age of changing climate and emerging global pandemics, the ability of residency programs to prepare for and adapt to potential disasters may be paramount in preserving the training of physicians. The current literature regarding residency program disaster preparedness, which focuses predominantly on hurricanes and COVID-19,1-8 is lacking in recommendations specific to dermatology residency programs. Likewise, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) guidelines9 do not address dermatology-specific concerns in disaster preparedness or response. Herein, we propose recommendations to mitigate the impact of various types of disasters on dermatology residency programs and their trainees with regard to resident safety and wellness, resident education, and patient care (Table).

Resident Safety and Wellness

Role of the Program Director—The role of the program director is critical, serving as a figure of structure and reassurance.4,7,10 Once concern of disaster arises, the program director should contact the Designated Institutional Official (DIO) to express concerns about possible disruptions to resident training. The DIO should then contact the ACGME within 10 days to report the disaster and submit a request for emergency (eg, pandemic) or extraordinary circumstances (eg, natural disaster) categorization.4,9 Program directors should promptly prepare plans for program reconfiguration and resident transfers in alignment with ACGME requirements to maintain evaluation and completion of core competencies of training during disasters.9 Program directors should prioritize the safety of trainees during the immediate threat with clear guidelines on sheltering, evacuations, or quarantines; a timeline of program recovery based on communication with residents, faculty, and administration should then be established.10,11

Communication—Establishing a strong line of communication between program directors and residents is paramount. Collection of emergency noninstitutional contact information, establishment of a centralized website for information dissemination, use of noninstitutional email and proxy servers outside of the location of impact, social media updates, on-site use of 2-way radios, and program-wide conference calls when possible should be strongly considered as part of the disaster response.2-4,12,13

Resident Accommodations and Mental Health—If training is disrupted, residents should be reassured of continued access to salary, housing, food, or other resources as necessary.3,4,11 There should be clear contingency plans if residents need to leave the program for extended periods of time due to injury, illness, or personal circumstances. Although relevant in all types of disasters, resident mental health and response to trauma also must be addressed. Access to counseling, morale-building opportunities (eg, resident social events), and screening for depression or posttraumatic stress disorder may help promote well-being among residents following traumatic events.14

Resident Education

Participation in Disaster Relief—Residents may seek to aid in the disaster response, which may prove challenging in the setting of programs with high patient volume.4 In coordination with the ACGME and graduate medical education governing bodies, program directors should consider how residents may fulfill dermatology training requirements in conjunction with disaster relief efforts, such as working in an inpatient setting or providing wound care.10

Continued Didactic Education—The use of online learning and conference calls for continuing the dermatology curriculum is an efficient means to maintaining resident education when meeting in person poses risks to residents.15 Projections of microscopy images, clinical photographs, or other instructional materials allow for continued instruction on resident examination, histopathology, and diagnostic skills.

Continued Clinical Training—If the home institution cannot support the operation of dermatology clinics, residents should be guaranteed continued training at other institutions. Agreements with other dermatology programs, community hospitals, or private dermatology practices should be established in advance, with consideration given to the number of residents a program can support, funding transfers, and credentialing requirements.2,4,5

Prolonged Disruptions—Nonessential departments of medical institutions may cease to function during war or mass casualty disasters, and it may be unsafe to send dermatology residents to other institutions or clinical areas. If the threat is prolonged, programs may need to consider allowing current residents a longer duration of training despite potential overlap with incoming dermatology residents.7

Patient Care

Disruptions to Clinic Operations—Regarding threats of violence, dangerous exposures, or natural disasters, there should be clear guidelines on sheltering in the clinical setting or stabilizing patients during a procedure.11 Equipment used by residents such as laptops, microscopes, and treatment devices (eg, lasers) should be stored in weather-safe locations that would not be notably impacted by moisture or structural damage to the clinic building. If electricity or internet access are compromised, paper medical records should be available to residents to continue clinical operations. Electronic health records used by residents should regularly be backed up on remote servers or cloud storage to allow continued access to patient health information if on-site servers are not functional.12 If disruptions are prolonged, residency program administration should coordinate with the institution to ensure there is adequate supply and storage of medications (eg, lidocaine, botulinum toxin) as well as a continued means of delivering biologic medications to patients and an ability to obtain laboratory or dermatopathology services.

In-Person Appointments vs Telemedicine—There are benefits to both residency training and patient care when physicians are able to perform in-person examinations, biopsies, and in-office treatments.16 Programs should ensure an adequate supply of personal protective equipment to continue in-office appointments, vaccinations, and medical care if a resident or other members of the team are exposed to an infectious disease.7 If in-person appointments are limited or impossible, telemedicine capabilities may still allow residents to meet program requirements.7,10,15 However, reduced patient volume due to decreased elective visits or procedures may complicate the fulfillment of clinical requirements, which may need to be adjusted in the wake of a disaster.7

Use of Immunosuppressive Therapies—Residency programs should address the risks of prescribing immunosuppressive therapies (eg, biologics) during an infectious threat with their residents and encourage trainees to counsel patients on the importance of preventative measures to reduce risks for severe infection.17

Final Thoughts

In an age of changing climate and emerging global pandemics, the ability of residency programs to prepare for and adapt to potential disasters may be paramount in preserving the training of physicians. The current literature regarding residency program disaster preparedness, which focuses predominantly on hurricanes and COVID-19,1-8 is lacking in recommendations specific to dermatology residency programs. Likewise, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) guidelines9 do not address dermatology-specific concerns in disaster preparedness or response. Herein, we propose recommendations to mitigate the impact of various types of disasters on dermatology residency programs and their trainees with regard to resident safety and wellness, resident education, and patient care (Table).

Resident Safety and Wellness

Role of the Program Director—The role of the program director is critical, serving as a figure of structure and reassurance.4,7,10 Once concern of disaster arises, the program director should contact the Designated Institutional Official (DIO) to express concerns about possible disruptions to resident training. The DIO should then contact the ACGME within 10 days to report the disaster and submit a request for emergency (eg, pandemic) or extraordinary circumstances (eg, natural disaster) categorization.4,9 Program directors should promptly prepare plans for program reconfiguration and resident transfers in alignment with ACGME requirements to maintain evaluation and completion of core competencies of training during disasters.9 Program directors should prioritize the safety of trainees during the immediate threat with clear guidelines on sheltering, evacuations, or quarantines; a timeline of program recovery based on communication with residents, faculty, and administration should then be established.10,11

Communication—Establishing a strong line of communication between program directors and residents is paramount. Collection of emergency noninstitutional contact information, establishment of a centralized website for information dissemination, use of noninstitutional email and proxy servers outside of the location of impact, social media updates, on-site use of 2-way radios, and program-wide conference calls when possible should be strongly considered as part of the disaster response.2-4,12,13

Resident Accommodations and Mental Health—If training is disrupted, residents should be reassured of continued access to salary, housing, food, or other resources as necessary.3,4,11 There should be clear contingency plans if residents need to leave the program for extended periods of time due to injury, illness, or personal circumstances. Although relevant in all types of disasters, resident mental health and response to trauma also must be addressed. Access to counseling, morale-building opportunities (eg, resident social events), and screening for depression or posttraumatic stress disorder may help promote well-being among residents following traumatic events.14

Resident Education

Participation in Disaster Relief—Residents may seek to aid in the disaster response, which may prove challenging in the setting of programs with high patient volume.4 In coordination with the ACGME and graduate medical education governing bodies, program directors should consider how residents may fulfill dermatology training requirements in conjunction with disaster relief efforts, such as working in an inpatient setting or providing wound care.10

Continued Didactic Education—The use of online learning and conference calls for continuing the dermatology curriculum is an efficient means to maintaining resident education when meeting in person poses risks to residents.15 Projections of microscopy images, clinical photographs, or other instructional materials allow for continued instruction on resident examination, histopathology, and diagnostic skills.

Continued Clinical Training—If the home institution cannot support the operation of dermatology clinics, residents should be guaranteed continued training at other institutions. Agreements with other dermatology programs, community hospitals, or private dermatology practices should be established in advance, with consideration given to the number of residents a program can support, funding transfers, and credentialing requirements.2,4,5

Prolonged Disruptions—Nonessential departments of medical institutions may cease to function during war or mass casualty disasters, and it may be unsafe to send dermatology residents to other institutions or clinical areas. If the threat is prolonged, programs may need to consider allowing current residents a longer duration of training despite potential overlap with incoming dermatology residents.7

Patient Care

Disruptions to Clinic Operations—Regarding threats of violence, dangerous exposures, or natural disasters, there should be clear guidelines on sheltering in the clinical setting or stabilizing patients during a procedure.11 Equipment used by residents such as laptops, microscopes, and treatment devices (eg, lasers) should be stored in weather-safe locations that would not be notably impacted by moisture or structural damage to the clinic building. If electricity or internet access are compromised, paper medical records should be available to residents to continue clinical operations. Electronic health records used by residents should regularly be backed up on remote servers or cloud storage to allow continued access to patient health information if on-site servers are not functional.12 If disruptions are prolonged, residency program administration should coordinate with the institution to ensure there is adequate supply and storage of medications (eg, lidocaine, botulinum toxin) as well as a continued means of delivering biologic medications to patients and an ability to obtain laboratory or dermatopathology services.

In-Person Appointments vs Telemedicine—There are benefits to both residency training and patient care when physicians are able to perform in-person examinations, biopsies, and in-office treatments.16 Programs should ensure an adequate supply of personal protective equipment to continue in-office appointments, vaccinations, and medical care if a resident or other members of the team are exposed to an infectious disease.7 If in-person appointments are limited or impossible, telemedicine capabilities may still allow residents to meet program requirements.7,10,15 However, reduced patient volume due to decreased elective visits or procedures may complicate the fulfillment of clinical requirements, which may need to be adjusted in the wake of a disaster.7

Use of Immunosuppressive Therapies—Residency programs should address the risks of prescribing immunosuppressive therapies (eg, biologics) during an infectious threat with their residents and encourage trainees to counsel patients on the importance of preventative measures to reduce risks for severe infection.17

Final Thoughts

- Davis W. Hurricane Katrina: the challenge to graduate medical education. Ochsner J. 2006;6:39.

- Cefalu CA, Schwartz RS. Salvaging a geriatric medicine academic program in disaster mode—the LSU training program post-Katrina.J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:590-596.

- Ayyala R. Lessons from Katrina: a program director’s perspective. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1425-1426.

- Wiese JG. Leadership in graduate medical education: eleven steps instrumental in recovering residency programs after a disaster. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336:168-173.

- Griffies WS. Post-Katrina stabilization of the LSU/Ochsner Psychiatry Residency Program: caveats for disaster preparedness. Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33:418-422.

- Kearns DG, Chat VS, Uppal S, et al. Applying to dermatology residency during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1214-1215.

- Matthews JB, Blair PG, Ellison EC, et al. Checklist framework for surgical education disaster plans. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;233:557-563.

- Litchman GH, Marson JW, Rigel DS. The continuing impact of COVID-19 on dermatology practice: office workflow, economics, and future implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:576-579.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Sponsoring institution emergency categorization. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/covid-19/sponsoring-institution-emergency-categorization/

- Li YM, Galimberti F, Abrouk M, et al. US dermatology resident responses about the COVID-19 pandemic: results from a nationwide survey. South Med J. 2020;113:462-465.

- Newman B, Gallion C. Hurricane Harvey: firsthand perspectives for disaster preparedness in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2019;94:1267-1269.

- Pero CD, Pou AM, Arriaga MA, et al. Post-Katrina: study in crisis-related program adaptability. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:394-397.

- Hattaway R, Singh N, Rais-Bahrami S, et al. Adaptations of dermatology residency programs to changes in medical education amid the COVID-19 pandemic: virtual opportunities and social media. SKIN. 2021;5:94-100.

- Hillier K, Paskaradevan J, Wilkes JK, et al. Disaster plans: resident involvement and well-being during Hurricane Harvey. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11:129-131.

- Samimi S, Choi J, Rosman IS, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:609-618.

- Bastola M, Locatis C, Fontelo P. Diagnostic reliability of in-person versus remote dermatology: a meta-analysis. Telemed J E Health. 2021;27:247-250.

- Bashyam AM, Feldman SR. Should patients stop their biologic treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic? J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:317-318.

- Davis W. Hurricane Katrina: the challenge to graduate medical education. Ochsner J. 2006;6:39.

- Cefalu CA, Schwartz RS. Salvaging a geriatric medicine academic program in disaster mode—the LSU training program post-Katrina.J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:590-596.

- Ayyala R. Lessons from Katrina: a program director’s perspective. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1425-1426.

- Wiese JG. Leadership in graduate medical education: eleven steps instrumental in recovering residency programs after a disaster. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336:168-173.

- Griffies WS. Post-Katrina stabilization of the LSU/Ochsner Psychiatry Residency Program: caveats for disaster preparedness. Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33:418-422.

- Kearns DG, Chat VS, Uppal S, et al. Applying to dermatology residency during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1214-1215.

- Matthews JB, Blair PG, Ellison EC, et al. Checklist framework for surgical education disaster plans. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;233:557-563.

- Litchman GH, Marson JW, Rigel DS. The continuing impact of COVID-19 on dermatology practice: office workflow, economics, and future implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:576-579.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Sponsoring institution emergency categorization. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/covid-19/sponsoring-institution-emergency-categorization/

- Li YM, Galimberti F, Abrouk M, et al. US dermatology resident responses about the COVID-19 pandemic: results from a nationwide survey. South Med J. 2020;113:462-465.

- Newman B, Gallion C. Hurricane Harvey: firsthand perspectives for disaster preparedness in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2019;94:1267-1269.

- Pero CD, Pou AM, Arriaga MA, et al. Post-Katrina: study in crisis-related program adaptability. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:394-397.

- Hattaway R, Singh N, Rais-Bahrami S, et al. Adaptations of dermatology residency programs to changes in medical education amid the COVID-19 pandemic: virtual opportunities and social media. SKIN. 2021;5:94-100.

- Hillier K, Paskaradevan J, Wilkes JK, et al. Disaster plans: resident involvement and well-being during Hurricane Harvey. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11:129-131.

- Samimi S, Choi J, Rosman IS, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:609-618.

- Bastola M, Locatis C, Fontelo P. Diagnostic reliability of in-person versus remote dermatology: a meta-analysis. Telemed J E Health. 2021;27:247-250.

- Bashyam AM, Feldman SR. Should patients stop their biologic treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic? J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:317-318.

Practice Points

- Dermatology residency programs should prioritize the development of disaster preparedness plans prior to the onset of disasters.

- Comprehensive disaster preparedness addresses many possible disruptions to dermatology resident training and clinic operations, including natural and manmade disasters and threats of widespread infectious disease.

- Safety being paramount, dermatology residency programs may be tasked with maintaining resident wellness, continuing resident education—potentially in unconventional ways—and adapting clinical operations to continue patient care.

Man with COVID finally tests negative after 411 days

according to experts in the United Kingdom.

The man was treated with a mixture of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies, King’s College London said in a news release.

The man, 59, tested positive in December 2020 and tested negative in January 2022. He had a weakened immune system because of a previous kidney transplant. He received three doses of vaccine and his symptoms lessened, but he kept testing positive for COVID.

To find out if the man had a persistent infection or had been infected several times, doctors did a genetic analysis of the virus.

“This revealed that the patient’s infection was a persistent infection with an early COVID variant – a variation of the original Wuhan variant that was dominant in the United Kingdom in the later months of 2020. Analysis found the patient’s virus had multiple mutations since he was first infected,” King’s College said.

The doctors treated him with a Regeneron treatment that is no longer widely used because it’s not effective against newer COVID variants.

“Some new variants of the virus are resistant to all the antibody treatments available in the United Kingdom and Europe. Some people with weakened immune systems are still at risk of severe illness and becoming persistently infected. We are still working to understand the best way to protect and treat them,” Luke Snell, MD, from the King’s College School of Immunology & Microbial Sciences, said in the news release.

This is one of the longest known cases of COVID infection. Another man in England was infected with COVID for 505 days before his death, which King’s College said was the longest known COVID infection.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to experts in the United Kingdom.

The man was treated with a mixture of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies, King’s College London said in a news release.

The man, 59, tested positive in December 2020 and tested negative in January 2022. He had a weakened immune system because of a previous kidney transplant. He received three doses of vaccine and his symptoms lessened, but he kept testing positive for COVID.

To find out if the man had a persistent infection or had been infected several times, doctors did a genetic analysis of the virus.

“This revealed that the patient’s infection was a persistent infection with an early COVID variant – a variation of the original Wuhan variant that was dominant in the United Kingdom in the later months of 2020. Analysis found the patient’s virus had multiple mutations since he was first infected,” King’s College said.

The doctors treated him with a Regeneron treatment that is no longer widely used because it’s not effective against newer COVID variants.

“Some new variants of the virus are resistant to all the antibody treatments available in the United Kingdom and Europe. Some people with weakened immune systems are still at risk of severe illness and becoming persistently infected. We are still working to understand the best way to protect and treat them,” Luke Snell, MD, from the King’s College School of Immunology & Microbial Sciences, said in the news release.

This is one of the longest known cases of COVID infection. Another man in England was infected with COVID for 505 days before his death, which King’s College said was the longest known COVID infection.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to experts in the United Kingdom.

The man was treated with a mixture of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies, King’s College London said in a news release.

The man, 59, tested positive in December 2020 and tested negative in January 2022. He had a weakened immune system because of a previous kidney transplant. He received three doses of vaccine and his symptoms lessened, but he kept testing positive for COVID.

To find out if the man had a persistent infection or had been infected several times, doctors did a genetic analysis of the virus.

“This revealed that the patient’s infection was a persistent infection with an early COVID variant – a variation of the original Wuhan variant that was dominant in the United Kingdom in the later months of 2020. Analysis found the patient’s virus had multiple mutations since he was first infected,” King’s College said.

The doctors treated him with a Regeneron treatment that is no longer widely used because it’s not effective against newer COVID variants.

“Some new variants of the virus are resistant to all the antibody treatments available in the United Kingdom and Europe. Some people with weakened immune systems are still at risk of severe illness and becoming persistently infected. We are still working to understand the best way to protect and treat them,” Luke Snell, MD, from the King’s College School of Immunology & Microbial Sciences, said in the news release.

This is one of the longest known cases of COVID infection. Another man in England was infected with COVID for 505 days before his death, which King’s College said was the longest known COVID infection.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

COVID bivalent booster better vs. recent Omicron subvariants: Pfizer

the company reported on Nov. 4, supporting calls by public health officials for eligible people to get this booster before a potential COVID-19 surge this winter.

The company’s ongoing phase 2/3 study of their Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 bivalent – which targets both the virus’ original strain and the two subvariants – shows that the vaccine offered the strongest protection in people older than 55 years.

One month after receiving a 30-mcg booster with the bivalent vaccine, those older than 55 had four times more neutralizing antibodies against these Omicron subvariants, compared with people who received the original monovalent vaccine as a booster in the study.

Researchers compared the geometric mean titer (GMT) levels of these antibodies in three groups before and 1 month after boosting. The 36 people older than 55 years in the released study findings had an GMT level of 896 with the bivalent booster, a level 13 times higher than before this immunization.

For the 38 adults ages 18-55 in the study, the GMT level increased to 606 at 1 month after the bivalent booster, an increase of almost 10-fold, compared with baseline. In a comparator group of 40 people receiving the original vaccine as a fourth dose, the GMT level was 236, or threefold higher than before their booster shot.

The newly released data is “very encouraging and consistent now with three studies all showing a substantial 3-4 fold increased level of neutralizing antibodies versus BA.5 as compared with the original booster,” said Eric Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif., and editor-in-chief of Medscape Medical News.

Pfizer and BioNTech announced the updated findings in a Nov. 4 press release.

A booster dose of the BA.4/BA.5-adapted bivalent vaccine is authorized for emergency use by the Food and Drug Administration for ages 5 years and older. The safety and tolerability profile of the Pfizer/BioNTech bivalent booster remains favorable and similar to the original COVID-19 vaccine, the company reported.

Until recently, the BA.5 Omicron variant was the dominant strain in the United States, but is now getting elbowed out by the subvariants BQ.1.1, BQ.1, and BA.4.6, which together make up almost 45% of the circulating virus.

Some skepticism

“It is important to note that these data are press-release level, which does not allow a view of the data totality,” Hana El Sahly, MD, professor of molecular virology and microbiology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in an interview.

“For example, there may be significant differences between the groups, and the release mentions at least one difference that is of importance: the interval since the last vaccination which often affects the response to subsequent boosting,” she said.

Dr. El Sahly added that the findings are not surprising. “In the short term, a variant-specific vaccine produces a higher level of antibody against the variant in the vaccine than the vaccines based on the ancestral strains.”

More researcher results are warranted. “These data do not indicate that these differences between the two vaccines translate into a meaningful clinical benefit at a population level,” Dr. El Sahly said.

An uncertain winter ahead

“As we head into the holiday season, we hope these updated data will encourage people to seek out a COVID-19 bivalent booster as soon as they are eligible in order to maintain high levels of protection against the widely circulating Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 sublineages,” Albert Bourla, Pfizer chairman and CEO, stated in the release.

The updated data from the Pfizer/BioNTech study are “all the more reason to get a booster, with added protection also versus BQ.1.1, which will soon become dominant in the U.S.,” Dr. Topol predicted.

It is unclear when the next surge will happen, as COVID-19 does not always follow a seasonal pattern, at least not yet, Dr. El Sahly said. “Regardless, it is reasonable to recommend additional vaccine doses to immunocompromised and frail or older persons. More importantly, influenza vaccination and being up to date on pneumococcal vaccines are highly recommended as soon as feasible, given the early and intense flu season.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

the company reported on Nov. 4, supporting calls by public health officials for eligible people to get this booster before a potential COVID-19 surge this winter.

The company’s ongoing phase 2/3 study of their Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 bivalent – which targets both the virus’ original strain and the two subvariants – shows that the vaccine offered the strongest protection in people older than 55 years.

One month after receiving a 30-mcg booster with the bivalent vaccine, those older than 55 had four times more neutralizing antibodies against these Omicron subvariants, compared with people who received the original monovalent vaccine as a booster in the study.

Researchers compared the geometric mean titer (GMT) levels of these antibodies in three groups before and 1 month after boosting. The 36 people older than 55 years in the released study findings had an GMT level of 896 with the bivalent booster, a level 13 times higher than before this immunization.

For the 38 adults ages 18-55 in the study, the GMT level increased to 606 at 1 month after the bivalent booster, an increase of almost 10-fold, compared with baseline. In a comparator group of 40 people receiving the original vaccine as a fourth dose, the GMT level was 236, or threefold higher than before their booster shot.

The newly released data is “very encouraging and consistent now with three studies all showing a substantial 3-4 fold increased level of neutralizing antibodies versus BA.5 as compared with the original booster,” said Eric Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif., and editor-in-chief of Medscape Medical News.

Pfizer and BioNTech announced the updated findings in a Nov. 4 press release.

A booster dose of the BA.4/BA.5-adapted bivalent vaccine is authorized for emergency use by the Food and Drug Administration for ages 5 years and older. The safety and tolerability profile of the Pfizer/BioNTech bivalent booster remains favorable and similar to the original COVID-19 vaccine, the company reported.

Until recently, the BA.5 Omicron variant was the dominant strain in the United States, but is now getting elbowed out by the subvariants BQ.1.1, BQ.1, and BA.4.6, which together make up almost 45% of the circulating virus.

Some skepticism

“It is important to note that these data are press-release level, which does not allow a view of the data totality,” Hana El Sahly, MD, professor of molecular virology and microbiology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in an interview.

“For example, there may be significant differences between the groups, and the release mentions at least one difference that is of importance: the interval since the last vaccination which often affects the response to subsequent boosting,” she said.

Dr. El Sahly added that the findings are not surprising. “In the short term, a variant-specific vaccine produces a higher level of antibody against the variant in the vaccine than the vaccines based on the ancestral strains.”

More researcher results are warranted. “These data do not indicate that these differences between the two vaccines translate into a meaningful clinical benefit at a population level,” Dr. El Sahly said.

An uncertain winter ahead

“As we head into the holiday season, we hope these updated data will encourage people to seek out a COVID-19 bivalent booster as soon as they are eligible in order to maintain high levels of protection against the widely circulating Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 sublineages,” Albert Bourla, Pfizer chairman and CEO, stated in the release.

The updated data from the Pfizer/BioNTech study are “all the more reason to get a booster, with added protection also versus BQ.1.1, which will soon become dominant in the U.S.,” Dr. Topol predicted.

It is unclear when the next surge will happen, as COVID-19 does not always follow a seasonal pattern, at least not yet, Dr. El Sahly said. “Regardless, it is reasonable to recommend additional vaccine doses to immunocompromised and frail or older persons. More importantly, influenza vaccination and being up to date on pneumococcal vaccines are highly recommended as soon as feasible, given the early and intense flu season.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

the company reported on Nov. 4, supporting calls by public health officials for eligible people to get this booster before a potential COVID-19 surge this winter.

The company’s ongoing phase 2/3 study of their Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 bivalent – which targets both the virus’ original strain and the two subvariants – shows that the vaccine offered the strongest protection in people older than 55 years.

One month after receiving a 30-mcg booster with the bivalent vaccine, those older than 55 had four times more neutralizing antibodies against these Omicron subvariants, compared with people who received the original monovalent vaccine as a booster in the study.

Researchers compared the geometric mean titer (GMT) levels of these antibodies in three groups before and 1 month after boosting. The 36 people older than 55 years in the released study findings had an GMT level of 896 with the bivalent booster, a level 13 times higher than before this immunization.

For the 38 adults ages 18-55 in the study, the GMT level increased to 606 at 1 month after the bivalent booster, an increase of almost 10-fold, compared with baseline. In a comparator group of 40 people receiving the original vaccine as a fourth dose, the GMT level was 236, or threefold higher than before their booster shot.

The newly released data is “very encouraging and consistent now with three studies all showing a substantial 3-4 fold increased level of neutralizing antibodies versus BA.5 as compared with the original booster,” said Eric Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif., and editor-in-chief of Medscape Medical News.

Pfizer and BioNTech announced the updated findings in a Nov. 4 press release.

A booster dose of the BA.4/BA.5-adapted bivalent vaccine is authorized for emergency use by the Food and Drug Administration for ages 5 years and older. The safety and tolerability profile of the Pfizer/BioNTech bivalent booster remains favorable and similar to the original COVID-19 vaccine, the company reported.

Until recently, the BA.5 Omicron variant was the dominant strain in the United States, but is now getting elbowed out by the subvariants BQ.1.1, BQ.1, and BA.4.6, which together make up almost 45% of the circulating virus.

Some skepticism

“It is important to note that these data are press-release level, which does not allow a view of the data totality,” Hana El Sahly, MD, professor of molecular virology and microbiology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in an interview.

“For example, there may be significant differences between the groups, and the release mentions at least one difference that is of importance: the interval since the last vaccination which often affects the response to subsequent boosting,” she said.

Dr. El Sahly added that the findings are not surprising. “In the short term, a variant-specific vaccine produces a higher level of antibody against the variant in the vaccine than the vaccines based on the ancestral strains.”

More researcher results are warranted. “These data do not indicate that these differences between the two vaccines translate into a meaningful clinical benefit at a population level,” Dr. El Sahly said.

An uncertain winter ahead

“As we head into the holiday season, we hope these updated data will encourage people to seek out a COVID-19 bivalent booster as soon as they are eligible in order to maintain high levels of protection against the widely circulating Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 sublineages,” Albert Bourla, Pfizer chairman and CEO, stated in the release.

The updated data from the Pfizer/BioNTech study are “all the more reason to get a booster, with added protection also versus BQ.1.1, which will soon become dominant in the U.S.,” Dr. Topol predicted.

It is unclear when the next surge will happen, as COVID-19 does not always follow a seasonal pattern, at least not yet, Dr. El Sahly said. “Regardless, it is reasonable to recommend additional vaccine doses to immunocompromised and frail or older persons. More importantly, influenza vaccination and being up to date on pneumococcal vaccines are highly recommended as soon as feasible, given the early and intense flu season.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Working while sick: Why doctors don’t stay home when ill

The reasons are likely as varied as, “you weren’t feeling bad enough to miss work,” “you couldn’t afford to miss pay,” “you had too many patients to see,” or “too much work to do.”

In Medscape’s Employed Physicians Report: Loving the Focus, Hating the Bureaucracy, 61% of physicians reported that they sometimes or often come to work sick. Only 2% of respondents said they never come to work unwell.

Medscape wanted to know more about how often you call in sick, how often you come to work feeling unwell, what symptoms you have, and the dogma of your workplace culture regarding sick days. Not to mention the brutal ethos that starts in medical school, in which calling in sick shows weakness or is unacceptable.

So, we polled 2,347 physicians in the United States and abroad and asked them about their sniffling, sneezing, cold, flu, and fever symptoms, and, of course, COVID. Results were split about 50-50 among male and female physicians. The poll ran from Sept. 28 through Oct. 11.

Coming to work sick

It’s no surprise that the majority of physicians who were polled (85%) have come to work sick in 2022. In the last prepandemic year (2019), about 70% came to work feeling sick one to five times, and 13% worked while sick six to ten times.

When asked about the symptoms that they’ve previously come to work with, 48% of U.S. physicians said multiple symptoms. They gave high marks for runny nose, cough, congestion, and sore throat. Only 27% have worked with a fever, 22% have worked with other symptoms, and 7% have worked with both strep throat and COVID.

“My workplace, especially in the COVID years, accommodates persons who honestly do not feel well enough to report. Sooner or later, everyone covers for someone else who has to be out,” says Kenneth Abbott, MD, an oncologist in Maryland.

The culture of working while sick

Why doctors come to work when they’re sick is complicated. The overwhelming majority of U.S. respondents cited professional obligations; 73% noted that they feel a professional obligation to their patients, and 72% feel a professional obligation to their co-workers. Half of the polled U.S. physicians said they didn’t feel bad enough to stay home, while 48% said they had too much work to do to stay home.

Some 45% said the expectation at their workplace is to come to work unless seriously ill; 43% had too many patients to see; and 18% didn’t think they were contagious when they headed to work sick. Unfortunately, 15% chose to work while sick because otherwise they would lose pay.

In light of these responses, it’s not surprising that 93% reported they’d seen other medical professionals working when sick.

“My schedule is almost always booked weeks in advance. If someone misses or has to cancel their appointment, they typically have 2-4 weeks to wait to get back in. If I was sick and a full day of patients (or God forbid more than a day) had to be canceled because I called in, it’s so much more work when I return,” says Caitlin Briggs, MD, a psychiatrist in Lexington, Ky.

Doctors’ workplace sick day policy

Most employees’ benefits allow at least a few sick days, but doctors who treat society’s ill patients don’t seem to stay home from work when they’re suffering. So, we asked physicians, official policy aside, whether they thought going to work sick was expected in their workplace. The majority (76%) said yes, while 24% said no.

“Unless I’m dying or extremely contagious, I usually work. At least now, I have the telehealth option. Not saying any of this is right, but it’s the reality we deal with and the choice we must make,” says Dr. Briggs.

Additionally, 58% of polled physicians said their workplace did not have a clearly defined policy against coming to work sick, while 20% said theirs did, and 22% weren’t sure.

“The first thing I heard on the subject as a medical student was that sick people come to the hospital, so if you’re sick, then you come to the hospital too ... to work. If you can’t work, then you will be admitted. Another aphorism was from Churchill, that ‘most of the world’s work is done by people who don’t feel very well,’ ” says Paul Andreason, MD, a psychiatrist in Bethesda, Md.

Working in the time of COVID

Working while ill during ordinary times is one thing, but what about working in the time of COVID? Has the pandemic changed the culture of coming to work sick because medical facilities, such as doctor’s offices and hospitals, don’t want their staff coming in when they have COVID?

Surprisingly, when we asked physicians whether the pandemic has made it more or less acceptable to come to work sick, only 61% thought COVID has made it less acceptable to work while sick, while 16% thought it made it more acceptable, and 23% said there’s no change.

“I draw the line at fevers/chills, feeling like you’ve just been run over, or significant enteritis,” says Dr. Abbott. “Also, if I have to take palliative meds that interfere with alertness, I’m not doing my patients any favors.”

While a minority of physicians may call in sick, most still suffer through their sneezing, coughing, chills, and fever while seeing patients as usual.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The reasons are likely as varied as, “you weren’t feeling bad enough to miss work,” “you couldn’t afford to miss pay,” “you had too many patients to see,” or “too much work to do.”

In Medscape’s Employed Physicians Report: Loving the Focus, Hating the Bureaucracy, 61% of physicians reported that they sometimes or often come to work sick. Only 2% of respondents said they never come to work unwell.

Medscape wanted to know more about how often you call in sick, how often you come to work feeling unwell, what symptoms you have, and the dogma of your workplace culture regarding sick days. Not to mention the brutal ethos that starts in medical school, in which calling in sick shows weakness or is unacceptable.

So, we polled 2,347 physicians in the United States and abroad and asked them about their sniffling, sneezing, cold, flu, and fever symptoms, and, of course, COVID. Results were split about 50-50 among male and female physicians. The poll ran from Sept. 28 through Oct. 11.

Coming to work sick

It’s no surprise that the majority of physicians who were polled (85%) have come to work sick in 2022. In the last prepandemic year (2019), about 70% came to work feeling sick one to five times, and 13% worked while sick six to ten times.

When asked about the symptoms that they’ve previously come to work with, 48% of U.S. physicians said multiple symptoms. They gave high marks for runny nose, cough, congestion, and sore throat. Only 27% have worked with a fever, 22% have worked with other symptoms, and 7% have worked with both strep throat and COVID.

“My workplace, especially in the COVID years, accommodates persons who honestly do not feel well enough to report. Sooner or later, everyone covers for someone else who has to be out,” says Kenneth Abbott, MD, an oncologist in Maryland.

The culture of working while sick

Why doctors come to work when they’re sick is complicated. The overwhelming majority of U.S. respondents cited professional obligations; 73% noted that they feel a professional obligation to their patients, and 72% feel a professional obligation to their co-workers. Half of the polled U.S. physicians said they didn’t feel bad enough to stay home, while 48% said they had too much work to do to stay home.

Some 45% said the expectation at their workplace is to come to work unless seriously ill; 43% had too many patients to see; and 18% didn’t think they were contagious when they headed to work sick. Unfortunately, 15% chose to work while sick because otherwise they would lose pay.

In light of these responses, it’s not surprising that 93% reported they’d seen other medical professionals working when sick.

“My schedule is almost always booked weeks in advance. If someone misses or has to cancel their appointment, they typically have 2-4 weeks to wait to get back in. If I was sick and a full day of patients (or God forbid more than a day) had to be canceled because I called in, it’s so much more work when I return,” says Caitlin Briggs, MD, a psychiatrist in Lexington, Ky.

Doctors’ workplace sick day policy

Most employees’ benefits allow at least a few sick days, but doctors who treat society’s ill patients don’t seem to stay home from work when they’re suffering. So, we asked physicians, official policy aside, whether they thought going to work sick was expected in their workplace. The majority (76%) said yes, while 24% said no.

“Unless I’m dying or extremely contagious, I usually work. At least now, I have the telehealth option. Not saying any of this is right, but it’s the reality we deal with and the choice we must make,” says Dr. Briggs.

Additionally, 58% of polled physicians said their workplace did not have a clearly defined policy against coming to work sick, while 20% said theirs did, and 22% weren’t sure.

“The first thing I heard on the subject as a medical student was that sick people come to the hospital, so if you’re sick, then you come to the hospital too ... to work. If you can’t work, then you will be admitted. Another aphorism was from Churchill, that ‘most of the world’s work is done by people who don’t feel very well,’ ” says Paul Andreason, MD, a psychiatrist in Bethesda, Md.

Working in the time of COVID

Working while ill during ordinary times is one thing, but what about working in the time of COVID? Has the pandemic changed the culture of coming to work sick because medical facilities, such as doctor’s offices and hospitals, don’t want their staff coming in when they have COVID?

Surprisingly, when we asked physicians whether the pandemic has made it more or less acceptable to come to work sick, only 61% thought COVID has made it less acceptable to work while sick, while 16% thought it made it more acceptable, and 23% said there’s no change.

“I draw the line at fevers/chills, feeling like you’ve just been run over, or significant enteritis,” says Dr. Abbott. “Also, if I have to take palliative meds that interfere with alertness, I’m not doing my patients any favors.”

While a minority of physicians may call in sick, most still suffer through their sneezing, coughing, chills, and fever while seeing patients as usual.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The reasons are likely as varied as, “you weren’t feeling bad enough to miss work,” “you couldn’t afford to miss pay,” “you had too many patients to see,” or “too much work to do.”

In Medscape’s Employed Physicians Report: Loving the Focus, Hating the Bureaucracy, 61% of physicians reported that they sometimes or often come to work sick. Only 2% of respondents said they never come to work unwell.

Medscape wanted to know more about how often you call in sick, how often you come to work feeling unwell, what symptoms you have, and the dogma of your workplace culture regarding sick days. Not to mention the brutal ethos that starts in medical school, in which calling in sick shows weakness or is unacceptable.

So, we polled 2,347 physicians in the United States and abroad and asked them about their sniffling, sneezing, cold, flu, and fever symptoms, and, of course, COVID. Results were split about 50-50 among male and female physicians. The poll ran from Sept. 28 through Oct. 11.

Coming to work sick

It’s no surprise that the majority of physicians who were polled (85%) have come to work sick in 2022. In the last prepandemic year (2019), about 70% came to work feeling sick one to five times, and 13% worked while sick six to ten times.

When asked about the symptoms that they’ve previously come to work with, 48% of U.S. physicians said multiple symptoms. They gave high marks for runny nose, cough, congestion, and sore throat. Only 27% have worked with a fever, 22% have worked with other symptoms, and 7% have worked with both strep throat and COVID.

“My workplace, especially in the COVID years, accommodates persons who honestly do not feel well enough to report. Sooner or later, everyone covers for someone else who has to be out,” says Kenneth Abbott, MD, an oncologist in Maryland.

The culture of working while sick

Why doctors come to work when they’re sick is complicated. The overwhelming majority of U.S. respondents cited professional obligations; 73% noted that they feel a professional obligation to their patients, and 72% feel a professional obligation to their co-workers. Half of the polled U.S. physicians said they didn’t feel bad enough to stay home, while 48% said they had too much work to do to stay home.

Some 45% said the expectation at their workplace is to come to work unless seriously ill; 43% had too many patients to see; and 18% didn’t think they were contagious when they headed to work sick. Unfortunately, 15% chose to work while sick because otherwise they would lose pay.

In light of these responses, it’s not surprising that 93% reported they’d seen other medical professionals working when sick.

“My schedule is almost always booked weeks in advance. If someone misses or has to cancel their appointment, they typically have 2-4 weeks to wait to get back in. If I was sick and a full day of patients (or God forbid more than a day) had to be canceled because I called in, it’s so much more work when I return,” says Caitlin Briggs, MD, a psychiatrist in Lexington, Ky.

Doctors’ workplace sick day policy

Most employees’ benefits allow at least a few sick days, but doctors who treat society’s ill patients don’t seem to stay home from work when they’re suffering. So, we asked physicians, official policy aside, whether they thought going to work sick was expected in their workplace. The majority (76%) said yes, while 24% said no.

“Unless I’m dying or extremely contagious, I usually work. At least now, I have the telehealth option. Not saying any of this is right, but it’s the reality we deal with and the choice we must make,” says Dr. Briggs.

Additionally, 58% of polled physicians said their workplace did not have a clearly defined policy against coming to work sick, while 20% said theirs did, and 22% weren’t sure.

“The first thing I heard on the subject as a medical student was that sick people come to the hospital, so if you’re sick, then you come to the hospital too ... to work. If you can’t work, then you will be admitted. Another aphorism was from Churchill, that ‘most of the world’s work is done by people who don’t feel very well,’ ” says Paul Andreason, MD, a psychiatrist in Bethesda, Md.

Working in the time of COVID

Working while ill during ordinary times is one thing, but what about working in the time of COVID? Has the pandemic changed the culture of coming to work sick because medical facilities, such as doctor’s offices and hospitals, don’t want their staff coming in when they have COVID?

Surprisingly, when we asked physicians whether the pandemic has made it more or less acceptable to come to work sick, only 61% thought COVID has made it less acceptable to work while sick, while 16% thought it made it more acceptable, and 23% said there’s no change.

“I draw the line at fevers/chills, feeling like you’ve just been run over, or significant enteritis,” says Dr. Abbott. “Also, if I have to take palliative meds that interfere with alertness, I’m not doing my patients any favors.”

While a minority of physicians may call in sick, most still suffer through their sneezing, coughing, chills, and fever while seeing patients as usual.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mid-October flulike illness cases higher than past 5 years

Outpatient visits for influenzalike illness (ILI), which includes influenza, SARS-CoV-2, and RSV, were higher after 3 weeks than for any of the previous five flu seasons: 3.3% of visits reported through the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network involved ILI as of Oct. 22. The highest comparable rate in the previous 5 years was the 1.9% recorded in late October of 2021, shortly after the definition of ILI was changed to also include illnesses other than influenza.

This season’s higher flu activity is in contrast to the previous two, which were unusually mild. The change, however, is not unexpected, as William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease expert and professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University, recently told CNN.

“Here we are in the middle of October – not the middle of November – we’re already seeing scattered influenza cases, even hospitalized influenza cases, around the country,” he said. “So we know that this virus is now spreading out in the community already. It’s gathering speed already. It looks to me to be about a month early.”

One indication of the mildness of the previous two flu seasons was the number of deaths, both pediatric and overall. Influenza-associated pediatric deaths had averaged about 110 per season over the previous eight seasons, compared with just 1 for 2020-2021 and 43 in 2021-2022. Overall flu deaths never reached 1% of all weekly deaths for either season, well below baseline levels for the flu, which range from 5.5% to 6.8%, CDC data show.

Other indicators of early severity

This season’s early rise in viral activity also can be seen in hospitalizations. The cumulative rate of flu-related admissions was 1.5 per 100,000 population as of Oct. 22, higher than the rate observed in the comparable week of previous seasons going back to 2010-2011, according to the CDC’s Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network.

A look at state reports of ILI outpatient visit rates shows that the District of Columbia and South Carolina are already in the very high range of the CDC’s severity scale, while 11 states are in the high range. Again going back to 2010-2011, no jurisdiction has ever been in the very high range this early in the season, based on data from the Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network.

Outpatient visits for influenzalike illness (ILI), which includes influenza, SARS-CoV-2, and RSV, were higher after 3 weeks than for any of the previous five flu seasons: 3.3% of visits reported through the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network involved ILI as of Oct. 22. The highest comparable rate in the previous 5 years was the 1.9% recorded in late October of 2021, shortly after the definition of ILI was changed to also include illnesses other than influenza.

This season’s higher flu activity is in contrast to the previous two, which were unusually mild. The change, however, is not unexpected, as William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease expert and professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University, recently told CNN.

“Here we are in the middle of October – not the middle of November – we’re already seeing scattered influenza cases, even hospitalized influenza cases, around the country,” he said. “So we know that this virus is now spreading out in the community already. It’s gathering speed already. It looks to me to be about a month early.”

One indication of the mildness of the previous two flu seasons was the number of deaths, both pediatric and overall. Influenza-associated pediatric deaths had averaged about 110 per season over the previous eight seasons, compared with just 1 for 2020-2021 and 43 in 2021-2022. Overall flu deaths never reached 1% of all weekly deaths for either season, well below baseline levels for the flu, which range from 5.5% to 6.8%, CDC data show.

Other indicators of early severity

This season’s early rise in viral activity also can be seen in hospitalizations. The cumulative rate of flu-related admissions was 1.5 per 100,000 population as of Oct. 22, higher than the rate observed in the comparable week of previous seasons going back to 2010-2011, according to the CDC’s Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network.

A look at state reports of ILI outpatient visit rates shows that the District of Columbia and South Carolina are already in the very high range of the CDC’s severity scale, while 11 states are in the high range. Again going back to 2010-2011, no jurisdiction has ever been in the very high range this early in the season, based on data from the Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network.

Outpatient visits for influenzalike illness (ILI), which includes influenza, SARS-CoV-2, and RSV, were higher after 3 weeks than for any of the previous five flu seasons: 3.3% of visits reported through the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network involved ILI as of Oct. 22. The highest comparable rate in the previous 5 years was the 1.9% recorded in late October of 2021, shortly after the definition of ILI was changed to also include illnesses other than influenza.

This season’s higher flu activity is in contrast to the previous two, which were unusually mild. The change, however, is not unexpected, as William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease expert and professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University, recently told CNN.

“Here we are in the middle of October – not the middle of November – we’re already seeing scattered influenza cases, even hospitalized influenza cases, around the country,” he said. “So we know that this virus is now spreading out in the community already. It’s gathering speed already. It looks to me to be about a month early.”

One indication of the mildness of the previous two flu seasons was the number of deaths, both pediatric and overall. Influenza-associated pediatric deaths had averaged about 110 per season over the previous eight seasons, compared with just 1 for 2020-2021 and 43 in 2021-2022. Overall flu deaths never reached 1% of all weekly deaths for either season, well below baseline levels for the flu, which range from 5.5% to 6.8%, CDC data show.

Other indicators of early severity

This season’s early rise in viral activity also can be seen in hospitalizations. The cumulative rate of flu-related admissions was 1.5 per 100,000 population as of Oct. 22, higher than the rate observed in the comparable week of previous seasons going back to 2010-2011, according to the CDC’s Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network.

A look at state reports of ILI outpatient visit rates shows that the District of Columbia and South Carolina are already in the very high range of the CDC’s severity scale, while 11 states are in the high range. Again going back to 2010-2011, no jurisdiction has ever been in the very high range this early in the season, based on data from the Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network.

You and the skeptical patient: Who’s the doctor here?

“I spoke to him on many occasions about the dangers of COVID, but he just didn’t believe me,” said Dr. Hood, an internist in Lexington, Ky. “He just didn’t give me enough time to help him. He waited to let me know he was ill with COVID and took days to pick up the medicine. Unfortunately, he then passed away.”

The rise of the skeptical patient

It can be extremely frustrating for doctors when patients question or disbelieve their physician’s medical advice and explanations. And many physicians resent the amount of time they spend trying to explain or make their case, especially during a busy day. But patients’ skepticism about the validity of some treatments seems to be increasing.

“Patients are now more likely to have their own medical explanation for their complaint than they used to, and that can be bad for their health,” Dr. Hood said.

Dr. Hood sees medical cynicism as part of Americans’ growing distrust of experts, leveraged by easy access to the internet. “When people Google, they tend to look for support of their opinions, rather than arrive at a fully educated decision.”

Only about half of patients believe their physicians “provide fair and accurate treatment information all or most of the time,” according to a 2019 survey by the Pew Research Center.

Patients’ distrust has become more obvious during the COVID-19 pandemic, said John Schumann, MD, an internist with Oak Street Health, a practice with more than 500 physicians and other providers in 20 states, treating almost exclusively Medicare patients.

“The skeptics became more entrenched during the pandemic,” said Dr. Schumann, who is based in Tulsa, Okla. “They may think the COVID vaccines were approved too quickly, or believe the pandemic itself is a hoax.”

“There’s a lot of antiscience rhetoric now,” Dr. Schumann added. “I’d say about half of my patients are comfortable with science-based decisions and the other half are not.”

What are patients mistrustful about?

Patients’ suspicions of certain therapies began long before the pandemic. In dermatology, for example, some patients refuse to take topical steroids, said Steven R. Feldman, MD, a dermatologist in Winston-Salem, N.C.

“Their distrust is usually based on anecdotal stories they read about,” he noted. “Patients in other specialties are dead set against vaccinations.”

In addition to refusing treatments and inoculations, some patients ask for questionable regimens mentioned in the news. “Some patients have demanded hydroxychloroquine or Noromectin, drugs that are unproven in the treatment of COVID,” Dr. Schumann said. “We refuse to prescribe them.”

Dr. Hood said patients’ reluctance to follow medical advice can often be based on cost. “I have a patient who was more willing to save $20 than to save his life. But when the progression of his test results fit my predictions, he became more willing to take treatments. I had to wait for the opportune moment to convince him.”

Many naysayer patients keep their views to themselves, and physicians may be unaware that the patients are stonewalling. A 2006 study estimated that about 10%-16% of primary care patients actively resist medical authority.

Dr. Schumann cited patients who don’t want to hear an upsetting diagnosis. “Some patients might refuse to take a biopsy to see if they have cancer because they don’t want to know,” he said. “In many cases, they simply won’t get the biopsy and won’t tell the doctor that they didn’t.”

Sometimes skeptics’ arguments have merit

Some patients’ concerns can be valid, such as when they refuse to go on statins, said Zain Hakeem, DO, a physician in Austin, Tex.

“In some cases, I feel that statins are not necessary,” he said. “The science on statins for primary prevention is not strong, although they should be used for exceedingly high-risk patients.”

Certain patients, especially those with chronic conditions, do a great deal of research, using legitimate sources on the Web, and their research is well supported.

However, these patients can be overconfident in their conclusions. Several studies have shown that with just a little experience, people can replace beginners’ caution with a false sense of competence.

For example, “Patients may not weigh the risks correctly,” Dr. Hakeem said. “They can be more concerned about the risk of having their colon perforated during a colonoscopy, while the risk of cancer if they don’t have a colonoscopy is much higher.”

Some highly successful people may be more likely to trust their own medical instincts. When Steve Jobs, the founder of Apple, was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2003, he put off surgery for 9 months while he tried to cure his disease with a vegan diet, acupuncture, herbs, bowel cleansings, and other remedies he read about. He died in 2011. Some experts believe that delay hastened his death.

Of course, not all physicians’ diagnoses or treatments are correct. One study indicated doctors’ diagnostic error rate could be as high as 15%. And just as patients can be overconfident in their conclusions, so can doctors. Another study found that physicians’ stated confidence in their diagnosis was only slightly affected by the inaccuracy of that diagnosis or the difficulty of the case.

Best ways to deal with cynical patients

Patients’ skepticism can frustrate doctors, reduce the efficiency of care delivery, and interfere with recovery. What can doctors do to deal with these problems?

1. Build the patient’s trust in you. “Getting patients to adhere to your advice involves making sure they feel they have a caring doctor whom they trust,” Dr. Feldman said.

“I want to show patients that I am entirely focused on them,” he added. “For example, I may rush to the door of the exam room from my last appointment, but I open the door very slowly and deliberately, because I want the patient to see that I won’t hurry with them.”

2. Spend time with the patient. Familiarity builds trust. Dr. Schumann said doctors at Oak Street Health see their patients an average of six to eight times a year, an unusually high number. “The more patients see their physicians, the more likely they are to trust them.”

3. Keep up to date. “I make sure I’m up to date with the literature, and I try to present a truthful message,” Dr. Hood said. “For instance, my research showed that inflammation played a strong role in developing complications from COVID, so I wrote a detailed treatment protocol aimed at the inflammation and the immune response, which has been very effective.”

4. Confront patients tactfully. Patients who do research on the Web don’t want to be scolded, Dr. Feldman said. In fact, he praises them, even if he doesn’t agree with their findings. “I might say: ‘What a relief to finally find patients who’ve taken the time to educate themselves before coming here.’ ”

Dr. Feldman is careful not to dispute patients’ conclusions. “Debating the issues is not an effective approach to get patients to trust you. The last thing you want to tell a patient is: ‘Listen to me! I’m an expert.’ People just dig in.”

However, it does help to give patients feedback. “I’m a big fan of patients arguing with me,” Dr. Hakeem said. “It means you can straighten out misunderstandings and improve decision-making.”

5. Explain your reasoning. “You need to communicate clearly and show them your thinking,” Dr. Hood said. “For instance, I’ll explain why a patient has a strong risk for heart attack.”

6. Acknowledge uncertainties. “The doctor may present the science as far more certain than it is,” Dr. Hakeem said. “If you don’t acknowledge the uncertainties, you could break the patient’s trust in you.”

7. Don’t use a lot of numbers. “Data is not a good tool to convince patients,” Dr. Feldman said. “The human brain isn’t designed to work that way.”

If you want to use numbers to show clinical risk, Dr. Hakeem advisd using natural frequencies, such as 10 out of 10,000, which is less confusing to the patient than the equivalent percentage of 0.1%.