User login

Painful lesion on lower lip

The FP recognized this as a probable squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) arising in a burn, known as a Marjolin ulcer.

The combination of the burn and the location on the lower lip made it extremely likely that this lesion was an SCC. The FP suggested the patient get a biopsy and have surgery for treatment. Unfortunately, the patient lived in poverty with no health insurance, financial means, running water, or electricity and stated that she could not afford any medical treatment. Her local hospital required cash payments, and she did not believe they would help her without funding and hoped that the medical mission team could help her. The FP was saddened by this news, but suggested that she do her best to access treatment in the near future. The FP did not have access to a pathologist (even if he could do the biopsy). Ultimately, the patient would need an experienced surgeon to excise this SCC.

With close to 1 billion people living in extreme poverty in the world, this is one sad example of a person that likely went without medical care for a serious, but treatable, illness.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized this as a probable squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) arising in a burn, known as a Marjolin ulcer.

The combination of the burn and the location on the lower lip made it extremely likely that this lesion was an SCC. The FP suggested the patient get a biopsy and have surgery for treatment. Unfortunately, the patient lived in poverty with no health insurance, financial means, running water, or electricity and stated that she could not afford any medical treatment. Her local hospital required cash payments, and she did not believe they would help her without funding and hoped that the medical mission team could help her. The FP was saddened by this news, but suggested that she do her best to access treatment in the near future. The FP did not have access to a pathologist (even if he could do the biopsy). Ultimately, the patient would need an experienced surgeon to excise this SCC.

With close to 1 billion people living in extreme poverty in the world, this is one sad example of a person that likely went without medical care for a serious, but treatable, illness.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized this as a probable squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) arising in a burn, known as a Marjolin ulcer.

The combination of the burn and the location on the lower lip made it extremely likely that this lesion was an SCC. The FP suggested the patient get a biopsy and have surgery for treatment. Unfortunately, the patient lived in poverty with no health insurance, financial means, running water, or electricity and stated that she could not afford any medical treatment. Her local hospital required cash payments, and she did not believe they would help her without funding and hoped that the medical mission team could help her. The FP was saddened by this news, but suggested that she do her best to access treatment in the near future. The FP did not have access to a pathologist (even if he could do the biopsy). Ultimately, the patient would need an experienced surgeon to excise this SCC.

With close to 1 billion people living in extreme poverty in the world, this is one sad example of a person that likely went without medical care for a serious, but treatable, illness.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Identifying Melanoma With Dermoscopy

Identifying Melanoma With Dermoscopy: 7- Point Checklist

Fungal failure

Two months ago I met Ed, still working at age 71. “My life’s ambition,” he said, “has been to help high school science teachers do their jobs better.”

“How’s it going?” I asked.

Ed sighed. “I’m still at it,” he said. “Let’s just say we’re not there yet.”

I too, dear colleagues, have had a life’s ambition, secret until right now:

Alas, like Ed’s, my work is not yet done.

I get reminders of this all the time, but last week the evidence got so overwhelming that I had to take a breath to settle down. And a nip. Ten cases. In 24 hours.

1. A 66-year-old woman energetically smeared econazole cream twice daily for weeks for an itchy, lichenified rash on both dorsal feet and ankles. Switched to betamethasone. Cleared in 5 days.

2. A 48-year-old woman with scaly patches on both legs. No response to terbinafine cream, then to ketoconazole cream, then to oral fluconazole. Cleared promptly on triamcinolone.

3. A 26-year-old with an erosive vulvar rash lasting month, unresponsive to Nystatin. After 5 days on a steroid, it was gone.

4. A 45-year-old man with lots of dermatoheliosis and idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis on arms and legs. No luck with topical selenium sulfide for tinea versicolor.

5. A 42-year-old nurse treated for weeks with topical antifungals. She came in with globs of fungus cream sealed in with Tegaderm (to prevent spread). Her roommates wanted to cancel her lease. Cleared of both rash and Tegaderm in 1 week. Now allowed to touch doorknobs.

6. A 27-year-old man with 8 weeks of lichenified patches all over his torso. Antifungal creams not working. Steroids do!

7. A 25-year-old recent émigré from India, where he was treated for his itchy groin rash with a succession of antifungal creams. He cannot sleep. (Imagine the plane trip from Delhi!) Has lichenified inguinal folds and scrotum. Cleared in 1 week with a topical steroid.

8. A 22-year-old woman with widespread atopic dermatitis. No response to antifungals. She had a rash at age 2 that was called “allergy to shampoo.” Clears promptly on a steroid.

9. A 22-year-old man being treated for a scaly, bilateral periocular rash with oral cephalexin. Clears promptly on a weak topical steroid.

10. A 29-year-old woman who has been suffering for months with “sensitivity” of her vulvar skin that has been diagnosed and treated as “a yeast infection,” in the absence of any rash or discharge. Her only visible finding is inverse psoriasis in the gluteal cleft. Guess what clears her up?

And so it goes, and so it has gone, week after week, year after year, decade after decade. Medicine scales Olympus: genomics, immunotherapy, stereotactic surgery. Meantime, the it’s-not-a-fungus problem seems impervious to both education and even to daily observation as obvious as it is ineffective: If a supposed fungus does not respond to antifungal treatment, then it must be a very bad fungus. If it doesn’t respond to yet another antifungal cream, then it must be terrible fungus. Reconsidering that it may not be a fungus at all seems to demand a mental paradigm shift whose achievement will have to await a more discerning generation.

In the meantime, patients not only don’t get better, but they feel defiled and dirty. They avoid human contact, intimate and otherwise, and do a lot of superfluous and expensive cleaning of house and wardrobe. If you doubt this, ask them. If you think I overstate, spend a day with me.

Early in my career I inherited the once-yearly dermatology slot at Medical Grand Rounds at the local community hospital. I spoke about cutaneous fungus, with emphasis on the fact that lots of round rashes are nummular eczema rather than fungus, as well as what it means to patients to be told they are “fungal.”

I didn’t get much direct feedback, but the chief of medicine sprang into action. He canceled the dermatology slot. Not medical enough, I guess.

Ed tells me that many high school science teachers don’t know much science. They teach it because they thought they might like to, or because there was an opening. After Ed hangs up his cleats, there will be plenty of his work left to be done.

But then, there always is.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

Two months ago I met Ed, still working at age 71. “My life’s ambition,” he said, “has been to help high school science teachers do their jobs better.”

“How’s it going?” I asked.

Ed sighed. “I’m still at it,” he said. “Let’s just say we’re not there yet.”

I too, dear colleagues, have had a life’s ambition, secret until right now:

Alas, like Ed’s, my work is not yet done.

I get reminders of this all the time, but last week the evidence got so overwhelming that I had to take a breath to settle down. And a nip. Ten cases. In 24 hours.

1. A 66-year-old woman energetically smeared econazole cream twice daily for weeks for an itchy, lichenified rash on both dorsal feet and ankles. Switched to betamethasone. Cleared in 5 days.

2. A 48-year-old woman with scaly patches on both legs. No response to terbinafine cream, then to ketoconazole cream, then to oral fluconazole. Cleared promptly on triamcinolone.

3. A 26-year-old with an erosive vulvar rash lasting month, unresponsive to Nystatin. After 5 days on a steroid, it was gone.

4. A 45-year-old man with lots of dermatoheliosis and idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis on arms and legs. No luck with topical selenium sulfide for tinea versicolor.

5. A 42-year-old nurse treated for weeks with topical antifungals. She came in with globs of fungus cream sealed in with Tegaderm (to prevent spread). Her roommates wanted to cancel her lease. Cleared of both rash and Tegaderm in 1 week. Now allowed to touch doorknobs.

6. A 27-year-old man with 8 weeks of lichenified patches all over his torso. Antifungal creams not working. Steroids do!

7. A 25-year-old recent émigré from India, where he was treated for his itchy groin rash with a succession of antifungal creams. He cannot sleep. (Imagine the plane trip from Delhi!) Has lichenified inguinal folds and scrotum. Cleared in 1 week with a topical steroid.

8. A 22-year-old woman with widespread atopic dermatitis. No response to antifungals. She had a rash at age 2 that was called “allergy to shampoo.” Clears promptly on a steroid.

9. A 22-year-old man being treated for a scaly, bilateral periocular rash with oral cephalexin. Clears promptly on a weak topical steroid.

10. A 29-year-old woman who has been suffering for months with “sensitivity” of her vulvar skin that has been diagnosed and treated as “a yeast infection,” in the absence of any rash or discharge. Her only visible finding is inverse psoriasis in the gluteal cleft. Guess what clears her up?

And so it goes, and so it has gone, week after week, year after year, decade after decade. Medicine scales Olympus: genomics, immunotherapy, stereotactic surgery. Meantime, the it’s-not-a-fungus problem seems impervious to both education and even to daily observation as obvious as it is ineffective: If a supposed fungus does not respond to antifungal treatment, then it must be a very bad fungus. If it doesn’t respond to yet another antifungal cream, then it must be terrible fungus. Reconsidering that it may not be a fungus at all seems to demand a mental paradigm shift whose achievement will have to await a more discerning generation.

In the meantime, patients not only don’t get better, but they feel defiled and dirty. They avoid human contact, intimate and otherwise, and do a lot of superfluous and expensive cleaning of house and wardrobe. If you doubt this, ask them. If you think I overstate, spend a day with me.

Early in my career I inherited the once-yearly dermatology slot at Medical Grand Rounds at the local community hospital. I spoke about cutaneous fungus, with emphasis on the fact that lots of round rashes are nummular eczema rather than fungus, as well as what it means to patients to be told they are “fungal.”

I didn’t get much direct feedback, but the chief of medicine sprang into action. He canceled the dermatology slot. Not medical enough, I guess.

Ed tells me that many high school science teachers don’t know much science. They teach it because they thought they might like to, or because there was an opening. After Ed hangs up his cleats, there will be plenty of his work left to be done.

But then, there always is.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

Two months ago I met Ed, still working at age 71. “My life’s ambition,” he said, “has been to help high school science teachers do their jobs better.”

“How’s it going?” I asked.

Ed sighed. “I’m still at it,” he said. “Let’s just say we’re not there yet.”

I too, dear colleagues, have had a life’s ambition, secret until right now:

Alas, like Ed’s, my work is not yet done.

I get reminders of this all the time, but last week the evidence got so overwhelming that I had to take a breath to settle down. And a nip. Ten cases. In 24 hours.

1. A 66-year-old woman energetically smeared econazole cream twice daily for weeks for an itchy, lichenified rash on both dorsal feet and ankles. Switched to betamethasone. Cleared in 5 days.

2. A 48-year-old woman with scaly patches on both legs. No response to terbinafine cream, then to ketoconazole cream, then to oral fluconazole. Cleared promptly on triamcinolone.

3. A 26-year-old with an erosive vulvar rash lasting month, unresponsive to Nystatin. After 5 days on a steroid, it was gone.

4. A 45-year-old man with lots of dermatoheliosis and idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis on arms and legs. No luck with topical selenium sulfide for tinea versicolor.

5. A 42-year-old nurse treated for weeks with topical antifungals. She came in with globs of fungus cream sealed in with Tegaderm (to prevent spread). Her roommates wanted to cancel her lease. Cleared of both rash and Tegaderm in 1 week. Now allowed to touch doorknobs.

6. A 27-year-old man with 8 weeks of lichenified patches all over his torso. Antifungal creams not working. Steroids do!

7. A 25-year-old recent émigré from India, where he was treated for his itchy groin rash with a succession of antifungal creams. He cannot sleep. (Imagine the plane trip from Delhi!) Has lichenified inguinal folds and scrotum. Cleared in 1 week with a topical steroid.

8. A 22-year-old woman with widespread atopic dermatitis. No response to antifungals. She had a rash at age 2 that was called “allergy to shampoo.” Clears promptly on a steroid.

9. A 22-year-old man being treated for a scaly, bilateral periocular rash with oral cephalexin. Clears promptly on a weak topical steroid.

10. A 29-year-old woman who has been suffering for months with “sensitivity” of her vulvar skin that has been diagnosed and treated as “a yeast infection,” in the absence of any rash or discharge. Her only visible finding is inverse psoriasis in the gluteal cleft. Guess what clears her up?

And so it goes, and so it has gone, week after week, year after year, decade after decade. Medicine scales Olympus: genomics, immunotherapy, stereotactic surgery. Meantime, the it’s-not-a-fungus problem seems impervious to both education and even to daily observation as obvious as it is ineffective: If a supposed fungus does not respond to antifungal treatment, then it must be a very bad fungus. If it doesn’t respond to yet another antifungal cream, then it must be terrible fungus. Reconsidering that it may not be a fungus at all seems to demand a mental paradigm shift whose achievement will have to await a more discerning generation.

In the meantime, patients not only don’t get better, but they feel defiled and dirty. They avoid human contact, intimate and otherwise, and do a lot of superfluous and expensive cleaning of house and wardrobe. If you doubt this, ask them. If you think I overstate, spend a day with me.

Early in my career I inherited the once-yearly dermatology slot at Medical Grand Rounds at the local community hospital. I spoke about cutaneous fungus, with emphasis on the fact that lots of round rashes are nummular eczema rather than fungus, as well as what it means to patients to be told they are “fungal.”

I didn’t get much direct feedback, but the chief of medicine sprang into action. He canceled the dermatology slot. Not medical enough, I guess.

Ed tells me that many high school science teachers don’t know much science. They teach it because they thought they might like to, or because there was an opening. After Ed hangs up his cleats, there will be plenty of his work left to be done.

But then, there always is.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

Jakinib explosion for RA: Where do they fit in clinical practice?

CHICAGO – A measure of clarity regarding how the emerging class of oral Janus kinase inhibitors might fit into clinical practice for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis was supplied by a fusillade of five consecutive strongly positive phase 3 trials presented during a single session at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The session featured three randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trials of the Janus kinase inhibitor (JAKi) upadacitinib in more than 3,200 participants in three different clinical scenarios, known as the SELECT-COMPARE, SELECT-EARLY, and SELECT-MONOTHERAPY trials, along with two Japanese phase 3 trials of peficitinib, a JAK1 and -3 inhibitor, in a total of more than 1,000 rheumatoid arthritis patients.

Upadacitinib

SELECT-COMPARE: Roy M. Fleischmann, MD, presented the findings of this trial in which 1,629 patients with active RA inadequately responsive to methotrexate were randomized 2:2:1 to 26 weeks of once-daily oral upadacitinib at 15 mg, placebo, or 40 mg of adalimumab (Humira) by subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks, all on top of background stable doses of methotrexate.

Upadacitinib, a JAK1 selective agent, was the clear winner, trouncing placebo, unsurprisingly, but more importantly also proving statistically superior to adalimumab – the current go-to drug in patients with an insufficient response to methotrexate – in terms of across-the-board improvement in RA signs and symptoms, quality-of-life measures, and physical function. This result, coupled with the similarly positive findings of a trial of oral baricitinib (Olumiant) versus adalimumab in inadequate responders to methotrexate alone, and a third positive trial of oral tofacitinib (Xeljanz), have altered Dr. Fleischmann’s treatment philosophy.

“I think that these studies have changed the treatment paradigm. And I think if access – that is, costs – were the same, given a choice, if it were me, I would actually use a JAK inhibitor before I would use adalimumab, based on the results of these multiple studies in different populations,” said Dr. Fleischmann, a rheumatologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

The two coprimary endpoints in SELECT-COMPARE were the week 12 American College of Rheumatology–defined 20% level of response (ACR 20) and a 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP). The ACR 20 response rate was 70.5% with upadacitinib 15 mg, significantly better than the 63% rate with adalimumab and the 36.4% rate with placebo. Similarly, the ACR 50 rate at 12 weeks was 45.2% with upadacitinib versus 29.1% with adalimumab, and ACR 70 rates were 24.9% and 13.5%, respectively.

“These are not small differences,” the rheumatologist observed. “That ACR 70 rate is almost doubled with upadacitinib.”

The rate for DAS28-CRP less than 2.6 at week 12 was 28.7% with upadacitinib, compared with 18% with adalimumab.

Improvements in pain scores and the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index were also significantly greater with the JAKi, both at weeks 12 and 26.

As in the other two SELECT phase 3 trials presented at the meeting, the response to upadacitinib was quick: The JAKi was superior to placebo on the efficacy endpoints by week 2, and superior to adalimumab by week 4.

The week-12 Boolean remission rate, a stringent measure, was 9.8% in the upadacitinib group, more than twice the 4% rate with adalimumab. At week 26, the rates were 18.1% and 9.8%, respectively, a finding Dr. Fleischmann deemed “very impressive.”

Radiographic disease progression as measured by change in modified total Sharp score (mTSS) at week 26 was 0.92 with placebo, 0.24 with upadacitinib, and slightly better at 0.1 with adalimumab. Adalimumab was also slightly better than baricitinib by this metric in a separate randomized trial. But that’s not a deal breaker for Dr. Fleischmann.

“It’s a 0.1–Sharp unit difference over 6 months. So by the time a patient would be able to tell the difference clinically, if my calculation is correct they’ll be 712 years old,” he quipped.

Serious infection rates through 26 weeks were similar in the upadacitinib and adalimumab study arms, with both being higher than placebo. Venous thromboembolism occurred in one patient on placebo, two on upadacitinib, and three on adalimumab.

SELECT-EARLY: This trial involved 947 methotrexate-naive patients with moderately to severely active RA deemed at baseline to be at high risk for disease progression. They were randomized to upadacitinib at 15 or 30 mg once daily or to methotrexate monotherapy. The markers utilized for high-risk disease were positive serology, an elevated CRP, and/or erosions at baseline, explained Ronald van Vollenhoven, MD, PhD, professor of rheumatology at the University of Amsterdam.

The coprimary endpoints were the week 12 ACR 50 and DAS28-CRP-less-than-2.6 response rates. ACR 50 was achieved in 28.3% of patients on methotrexate, 52.1% on the lower dose of upadacitinib, and 56.4% on upadacitinib 30 mg. The corresponding week 24 rates were 33.4%, 60.3%, and 65.6%.

The week 12 DAS28-CRP-less-than-2.6 rates were 13.7%, 35.6%, and 40.8%. By week 24, the rates had improved to 18.5%, 48.3%, and 50%.

Other functional, clinical, and quality-of-life endpoints followed suit. There was no radiographic progression over the course of 24 weeks in 77.7% of patients on methotrexate, 87.5% on upadacitinib 15 mg, and 89.3% on the JAKi at 30 mg.

The safety profile of upadacitinib was generally similar to that of methotrexate. Decreases in hemoglobin and neutrophils were more common in the high-dose upadacitinib group, while increased transaminase levels and reduced lymphocytes occurred more often with methotrexate.

Asked if the SELECT-EARLY results will lead to a change in the major guidelines for treatment of early RA, Dr. van Vollenhoven replied: “The advent of JAKis is changing the treatment of RA. Right now the positioning of JAKis is a big point of discussion: Should they be second or third or even fourth line? But it’s clear that methotrexate stands undisputed as the first-line treatment for RA in clinical practice. That has to do in part with lots and lots of experience, the fact that some patients do well with methotrexate, the convenience, but also the pricing.”

The goal in SELECT-EARLY was to test an individualized approach in which JAKis, which are clearly more effective than methotrexate, might be reserved as first-line therapy for the subgroup of patients with compelling markers for worse prognosis, and who are therefore less likely to turn out to be methotrexate responders.

“The markers we used aren’t good enough yet to engage in individualized treatment with a very specific drug, but we’re all trying very hard to find out who needs which treatment at which point in time,” the rheumatologist said.

SELECT-MONOTHERAPY: This trial randomized 648 patients with active RA and insufficient response to methotrexate to double-blind monotherapy with once-daily upadacitinib at 15 or 30 mg or to continued methotrexate.

Once again, upadacitinib achieved all of its primary and secondary endpoints. The week 14 ACR 20 rates for methotrexate and low- and high-dose upadacitinib were 41.2%, 67.7%, and 71.2%, respectively, with DAS28-CRP-less-than-or-equal-to-3.2 rates of 19.4%, 44.7%, and 53%. Remission as defined by a Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score of 2.8 or less was achieved in 1% of patients on methotrexate, 15% on upadacitinib 15 mg, and nearly 20% with upadacitinib 30 mg, reported Josef S. Smolen, MD, professor of medicine and chairman of rheumatology at the Medical University of Vienna.

Peficitinib

Yoshiya Tanaka, MD, PhD, professor and chairman of the department of internal medicine at the University of Occupational and Environmental Health in Kitakyushu, Japan, presented the findings of two pivotal phase 3, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trials of peficitinib at 100 or 150 mg once daily in 1,025 Asian patients with active RA insufficiently responsive to methotrexate or other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Both studies were positive for all the key endpoints. Based upon these results, the drug’s developer, Astellas Pharma, has filed for Japanese regulatory approval of peficitinib.

Which oral JAKi to use?

Some audience members, numbed by the parade of positive results, asked the investigators for guidance as to which JAKi to choose, and when.

“The upadacitinib dataset mirrors the two approved oral JAKis. The data all look very similar,” said Stanley B. Cohen, MD, codirector of the division of rheumatology at Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas and a former ACR president. “All the JAKis are effective; the safety profiles are similar. Can you help clinicians know what differentiates them? Why should I choose one or the other?”

Dr. Tanaka replied that, although much gets made of the between-agent differences in selectivity for JAK1, 2, and/or 3 inhibition, “In the human body we cannot see much difference in safety and efficacy.”

If indeed such differences exist, head-to-head randomized trials will be required to ferret them out, noted Dr. Fleischmann.

Dr. Smolen indicated rheumatologists ought to rejoice in the looming prospect of a fistful of JAKis to choose from.

“I always wondered which beta-blocker to use, and I always wondered which cholesterol-lowering drug to use, and which NSAID to use – and interestingly enough, one NSAID will work in you but not in me, and another will work in me but not in you. So I think we should be pleased that we will have several oral JAKis to choose from,” he said.

Dr. Fleischmann got in the final word: “The answer to your question is the way we always answer it in the office. It’s access. Whichever one has the best access for the patient is the one you would select.”

The SELECT trials were sponsored by AbbVie, and all the upadacitinib investigators reported receiving research funds from and serving as paid consultants to that company and numerous others. Dr. Tanaka reported receiving research grants from and serving as a paid consultant to Astellas Pharma and close to a dozen other pharmaceutical companies.

CHICAGO – A measure of clarity regarding how the emerging class of oral Janus kinase inhibitors might fit into clinical practice for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis was supplied by a fusillade of five consecutive strongly positive phase 3 trials presented during a single session at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The session featured three randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trials of the Janus kinase inhibitor (JAKi) upadacitinib in more than 3,200 participants in three different clinical scenarios, known as the SELECT-COMPARE, SELECT-EARLY, and SELECT-MONOTHERAPY trials, along with two Japanese phase 3 trials of peficitinib, a JAK1 and -3 inhibitor, in a total of more than 1,000 rheumatoid arthritis patients.

Upadacitinib

SELECT-COMPARE: Roy M. Fleischmann, MD, presented the findings of this trial in which 1,629 patients with active RA inadequately responsive to methotrexate were randomized 2:2:1 to 26 weeks of once-daily oral upadacitinib at 15 mg, placebo, or 40 mg of adalimumab (Humira) by subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks, all on top of background stable doses of methotrexate.

Upadacitinib, a JAK1 selective agent, was the clear winner, trouncing placebo, unsurprisingly, but more importantly also proving statistically superior to adalimumab – the current go-to drug in patients with an insufficient response to methotrexate – in terms of across-the-board improvement in RA signs and symptoms, quality-of-life measures, and physical function. This result, coupled with the similarly positive findings of a trial of oral baricitinib (Olumiant) versus adalimumab in inadequate responders to methotrexate alone, and a third positive trial of oral tofacitinib (Xeljanz), have altered Dr. Fleischmann’s treatment philosophy.

“I think that these studies have changed the treatment paradigm. And I think if access – that is, costs – were the same, given a choice, if it were me, I would actually use a JAK inhibitor before I would use adalimumab, based on the results of these multiple studies in different populations,” said Dr. Fleischmann, a rheumatologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

The two coprimary endpoints in SELECT-COMPARE were the week 12 American College of Rheumatology–defined 20% level of response (ACR 20) and a 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP). The ACR 20 response rate was 70.5% with upadacitinib 15 mg, significantly better than the 63% rate with adalimumab and the 36.4% rate with placebo. Similarly, the ACR 50 rate at 12 weeks was 45.2% with upadacitinib versus 29.1% with adalimumab, and ACR 70 rates were 24.9% and 13.5%, respectively.

“These are not small differences,” the rheumatologist observed. “That ACR 70 rate is almost doubled with upadacitinib.”

The rate for DAS28-CRP less than 2.6 at week 12 was 28.7% with upadacitinib, compared with 18% with adalimumab.

Improvements in pain scores and the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index were also significantly greater with the JAKi, both at weeks 12 and 26.

As in the other two SELECT phase 3 trials presented at the meeting, the response to upadacitinib was quick: The JAKi was superior to placebo on the efficacy endpoints by week 2, and superior to adalimumab by week 4.

The week-12 Boolean remission rate, a stringent measure, was 9.8% in the upadacitinib group, more than twice the 4% rate with adalimumab. At week 26, the rates were 18.1% and 9.8%, respectively, a finding Dr. Fleischmann deemed “very impressive.”

Radiographic disease progression as measured by change in modified total Sharp score (mTSS) at week 26 was 0.92 with placebo, 0.24 with upadacitinib, and slightly better at 0.1 with adalimumab. Adalimumab was also slightly better than baricitinib by this metric in a separate randomized trial. But that’s not a deal breaker for Dr. Fleischmann.

“It’s a 0.1–Sharp unit difference over 6 months. So by the time a patient would be able to tell the difference clinically, if my calculation is correct they’ll be 712 years old,” he quipped.

Serious infection rates through 26 weeks were similar in the upadacitinib and adalimumab study arms, with both being higher than placebo. Venous thromboembolism occurred in one patient on placebo, two on upadacitinib, and three on adalimumab.

SELECT-EARLY: This trial involved 947 methotrexate-naive patients with moderately to severely active RA deemed at baseline to be at high risk for disease progression. They were randomized to upadacitinib at 15 or 30 mg once daily or to methotrexate monotherapy. The markers utilized for high-risk disease were positive serology, an elevated CRP, and/or erosions at baseline, explained Ronald van Vollenhoven, MD, PhD, professor of rheumatology at the University of Amsterdam.

The coprimary endpoints were the week 12 ACR 50 and DAS28-CRP-less-than-2.6 response rates. ACR 50 was achieved in 28.3% of patients on methotrexate, 52.1% on the lower dose of upadacitinib, and 56.4% on upadacitinib 30 mg. The corresponding week 24 rates were 33.4%, 60.3%, and 65.6%.

The week 12 DAS28-CRP-less-than-2.6 rates were 13.7%, 35.6%, and 40.8%. By week 24, the rates had improved to 18.5%, 48.3%, and 50%.

Other functional, clinical, and quality-of-life endpoints followed suit. There was no radiographic progression over the course of 24 weeks in 77.7% of patients on methotrexate, 87.5% on upadacitinib 15 mg, and 89.3% on the JAKi at 30 mg.

The safety profile of upadacitinib was generally similar to that of methotrexate. Decreases in hemoglobin and neutrophils were more common in the high-dose upadacitinib group, while increased transaminase levels and reduced lymphocytes occurred more often with methotrexate.

Asked if the SELECT-EARLY results will lead to a change in the major guidelines for treatment of early RA, Dr. van Vollenhoven replied: “The advent of JAKis is changing the treatment of RA. Right now the positioning of JAKis is a big point of discussion: Should they be second or third or even fourth line? But it’s clear that methotrexate stands undisputed as the first-line treatment for RA in clinical practice. That has to do in part with lots and lots of experience, the fact that some patients do well with methotrexate, the convenience, but also the pricing.”

The goal in SELECT-EARLY was to test an individualized approach in which JAKis, which are clearly more effective than methotrexate, might be reserved as first-line therapy for the subgroup of patients with compelling markers for worse prognosis, and who are therefore less likely to turn out to be methotrexate responders.

“The markers we used aren’t good enough yet to engage in individualized treatment with a very specific drug, but we’re all trying very hard to find out who needs which treatment at which point in time,” the rheumatologist said.

SELECT-MONOTHERAPY: This trial randomized 648 patients with active RA and insufficient response to methotrexate to double-blind monotherapy with once-daily upadacitinib at 15 or 30 mg or to continued methotrexate.

Once again, upadacitinib achieved all of its primary and secondary endpoints. The week 14 ACR 20 rates for methotrexate and low- and high-dose upadacitinib were 41.2%, 67.7%, and 71.2%, respectively, with DAS28-CRP-less-than-or-equal-to-3.2 rates of 19.4%, 44.7%, and 53%. Remission as defined by a Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score of 2.8 or less was achieved in 1% of patients on methotrexate, 15% on upadacitinib 15 mg, and nearly 20% with upadacitinib 30 mg, reported Josef S. Smolen, MD, professor of medicine and chairman of rheumatology at the Medical University of Vienna.

Peficitinib

Yoshiya Tanaka, MD, PhD, professor and chairman of the department of internal medicine at the University of Occupational and Environmental Health in Kitakyushu, Japan, presented the findings of two pivotal phase 3, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trials of peficitinib at 100 or 150 mg once daily in 1,025 Asian patients with active RA insufficiently responsive to methotrexate or other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Both studies were positive for all the key endpoints. Based upon these results, the drug’s developer, Astellas Pharma, has filed for Japanese regulatory approval of peficitinib.

Which oral JAKi to use?

Some audience members, numbed by the parade of positive results, asked the investigators for guidance as to which JAKi to choose, and when.

“The upadacitinib dataset mirrors the two approved oral JAKis. The data all look very similar,” said Stanley B. Cohen, MD, codirector of the division of rheumatology at Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas and a former ACR president. “All the JAKis are effective; the safety profiles are similar. Can you help clinicians know what differentiates them? Why should I choose one or the other?”

Dr. Tanaka replied that, although much gets made of the between-agent differences in selectivity for JAK1, 2, and/or 3 inhibition, “In the human body we cannot see much difference in safety and efficacy.”

If indeed such differences exist, head-to-head randomized trials will be required to ferret them out, noted Dr. Fleischmann.

Dr. Smolen indicated rheumatologists ought to rejoice in the looming prospect of a fistful of JAKis to choose from.

“I always wondered which beta-blocker to use, and I always wondered which cholesterol-lowering drug to use, and which NSAID to use – and interestingly enough, one NSAID will work in you but not in me, and another will work in me but not in you. So I think we should be pleased that we will have several oral JAKis to choose from,” he said.

Dr. Fleischmann got in the final word: “The answer to your question is the way we always answer it in the office. It’s access. Whichever one has the best access for the patient is the one you would select.”

The SELECT trials were sponsored by AbbVie, and all the upadacitinib investigators reported receiving research funds from and serving as paid consultants to that company and numerous others. Dr. Tanaka reported receiving research grants from and serving as a paid consultant to Astellas Pharma and close to a dozen other pharmaceutical companies.

CHICAGO – A measure of clarity regarding how the emerging class of oral Janus kinase inhibitors might fit into clinical practice for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis was supplied by a fusillade of five consecutive strongly positive phase 3 trials presented during a single session at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The session featured three randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trials of the Janus kinase inhibitor (JAKi) upadacitinib in more than 3,200 participants in three different clinical scenarios, known as the SELECT-COMPARE, SELECT-EARLY, and SELECT-MONOTHERAPY trials, along with two Japanese phase 3 trials of peficitinib, a JAK1 and -3 inhibitor, in a total of more than 1,000 rheumatoid arthritis patients.

Upadacitinib

SELECT-COMPARE: Roy M. Fleischmann, MD, presented the findings of this trial in which 1,629 patients with active RA inadequately responsive to methotrexate were randomized 2:2:1 to 26 weeks of once-daily oral upadacitinib at 15 mg, placebo, or 40 mg of adalimumab (Humira) by subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks, all on top of background stable doses of methotrexate.

Upadacitinib, a JAK1 selective agent, was the clear winner, trouncing placebo, unsurprisingly, but more importantly also proving statistically superior to adalimumab – the current go-to drug in patients with an insufficient response to methotrexate – in terms of across-the-board improvement in RA signs and symptoms, quality-of-life measures, and physical function. This result, coupled with the similarly positive findings of a trial of oral baricitinib (Olumiant) versus adalimumab in inadequate responders to methotrexate alone, and a third positive trial of oral tofacitinib (Xeljanz), have altered Dr. Fleischmann’s treatment philosophy.

“I think that these studies have changed the treatment paradigm. And I think if access – that is, costs – were the same, given a choice, if it were me, I would actually use a JAK inhibitor before I would use adalimumab, based on the results of these multiple studies in different populations,” said Dr. Fleischmann, a rheumatologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

The two coprimary endpoints in SELECT-COMPARE were the week 12 American College of Rheumatology–defined 20% level of response (ACR 20) and a 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP). The ACR 20 response rate was 70.5% with upadacitinib 15 mg, significantly better than the 63% rate with adalimumab and the 36.4% rate with placebo. Similarly, the ACR 50 rate at 12 weeks was 45.2% with upadacitinib versus 29.1% with adalimumab, and ACR 70 rates were 24.9% and 13.5%, respectively.

“These are not small differences,” the rheumatologist observed. “That ACR 70 rate is almost doubled with upadacitinib.”

The rate for DAS28-CRP less than 2.6 at week 12 was 28.7% with upadacitinib, compared with 18% with adalimumab.

Improvements in pain scores and the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index were also significantly greater with the JAKi, both at weeks 12 and 26.

As in the other two SELECT phase 3 trials presented at the meeting, the response to upadacitinib was quick: The JAKi was superior to placebo on the efficacy endpoints by week 2, and superior to adalimumab by week 4.

The week-12 Boolean remission rate, a stringent measure, was 9.8% in the upadacitinib group, more than twice the 4% rate with adalimumab. At week 26, the rates were 18.1% and 9.8%, respectively, a finding Dr. Fleischmann deemed “very impressive.”

Radiographic disease progression as measured by change in modified total Sharp score (mTSS) at week 26 was 0.92 with placebo, 0.24 with upadacitinib, and slightly better at 0.1 with adalimumab. Adalimumab was also slightly better than baricitinib by this metric in a separate randomized trial. But that’s not a deal breaker for Dr. Fleischmann.

“It’s a 0.1–Sharp unit difference over 6 months. So by the time a patient would be able to tell the difference clinically, if my calculation is correct they’ll be 712 years old,” he quipped.

Serious infection rates through 26 weeks were similar in the upadacitinib and adalimumab study arms, with both being higher than placebo. Venous thromboembolism occurred in one patient on placebo, two on upadacitinib, and three on adalimumab.

SELECT-EARLY: This trial involved 947 methotrexate-naive patients with moderately to severely active RA deemed at baseline to be at high risk for disease progression. They were randomized to upadacitinib at 15 or 30 mg once daily or to methotrexate monotherapy. The markers utilized for high-risk disease were positive serology, an elevated CRP, and/or erosions at baseline, explained Ronald van Vollenhoven, MD, PhD, professor of rheumatology at the University of Amsterdam.

The coprimary endpoints were the week 12 ACR 50 and DAS28-CRP-less-than-2.6 response rates. ACR 50 was achieved in 28.3% of patients on methotrexate, 52.1% on the lower dose of upadacitinib, and 56.4% on upadacitinib 30 mg. The corresponding week 24 rates were 33.4%, 60.3%, and 65.6%.

The week 12 DAS28-CRP-less-than-2.6 rates were 13.7%, 35.6%, and 40.8%. By week 24, the rates had improved to 18.5%, 48.3%, and 50%.

Other functional, clinical, and quality-of-life endpoints followed suit. There was no radiographic progression over the course of 24 weeks in 77.7% of patients on methotrexate, 87.5% on upadacitinib 15 mg, and 89.3% on the JAKi at 30 mg.

The safety profile of upadacitinib was generally similar to that of methotrexate. Decreases in hemoglobin and neutrophils were more common in the high-dose upadacitinib group, while increased transaminase levels and reduced lymphocytes occurred more often with methotrexate.

Asked if the SELECT-EARLY results will lead to a change in the major guidelines for treatment of early RA, Dr. van Vollenhoven replied: “The advent of JAKis is changing the treatment of RA. Right now the positioning of JAKis is a big point of discussion: Should they be second or third or even fourth line? But it’s clear that methotrexate stands undisputed as the first-line treatment for RA in clinical practice. That has to do in part with lots and lots of experience, the fact that some patients do well with methotrexate, the convenience, but also the pricing.”

The goal in SELECT-EARLY was to test an individualized approach in which JAKis, which are clearly more effective than methotrexate, might be reserved as first-line therapy for the subgroup of patients with compelling markers for worse prognosis, and who are therefore less likely to turn out to be methotrexate responders.

“The markers we used aren’t good enough yet to engage in individualized treatment with a very specific drug, but we’re all trying very hard to find out who needs which treatment at which point in time,” the rheumatologist said.

SELECT-MONOTHERAPY: This trial randomized 648 patients with active RA and insufficient response to methotrexate to double-blind monotherapy with once-daily upadacitinib at 15 or 30 mg or to continued methotrexate.

Once again, upadacitinib achieved all of its primary and secondary endpoints. The week 14 ACR 20 rates for methotrexate and low- and high-dose upadacitinib were 41.2%, 67.7%, and 71.2%, respectively, with DAS28-CRP-less-than-or-equal-to-3.2 rates of 19.4%, 44.7%, and 53%. Remission as defined by a Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score of 2.8 or less was achieved in 1% of patients on methotrexate, 15% on upadacitinib 15 mg, and nearly 20% with upadacitinib 30 mg, reported Josef S. Smolen, MD, professor of medicine and chairman of rheumatology at the Medical University of Vienna.

Peficitinib

Yoshiya Tanaka, MD, PhD, professor and chairman of the department of internal medicine at the University of Occupational and Environmental Health in Kitakyushu, Japan, presented the findings of two pivotal phase 3, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trials of peficitinib at 100 or 150 mg once daily in 1,025 Asian patients with active RA insufficiently responsive to methotrexate or other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Both studies were positive for all the key endpoints. Based upon these results, the drug’s developer, Astellas Pharma, has filed for Japanese regulatory approval of peficitinib.

Which oral JAKi to use?

Some audience members, numbed by the parade of positive results, asked the investigators for guidance as to which JAKi to choose, and when.

“The upadacitinib dataset mirrors the two approved oral JAKis. The data all look very similar,” said Stanley B. Cohen, MD, codirector of the division of rheumatology at Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas and a former ACR president. “All the JAKis are effective; the safety profiles are similar. Can you help clinicians know what differentiates them? Why should I choose one or the other?”

Dr. Tanaka replied that, although much gets made of the between-agent differences in selectivity for JAK1, 2, and/or 3 inhibition, “In the human body we cannot see much difference in safety and efficacy.”

If indeed such differences exist, head-to-head randomized trials will be required to ferret them out, noted Dr. Fleischmann.

Dr. Smolen indicated rheumatologists ought to rejoice in the looming prospect of a fistful of JAKis to choose from.

“I always wondered which beta-blocker to use, and I always wondered which cholesterol-lowering drug to use, and which NSAID to use – and interestingly enough, one NSAID will work in you but not in me, and another will work in me but not in you. So I think we should be pleased that we will have several oral JAKis to choose from,” he said.

Dr. Fleischmann got in the final word: “The answer to your question is the way we always answer it in the office. It’s access. Whichever one has the best access for the patient is the one you would select.”

The SELECT trials were sponsored by AbbVie, and all the upadacitinib investigators reported receiving research funds from and serving as paid consultants to that company and numerous others. Dr. Tanaka reported receiving research grants from and serving as a paid consultant to Astellas Pharma and close to a dozen other pharmaceutical companies.

REPORTING FROM THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Growth on right hand

The FP recognized that this could be a wart but was concerned that it might be a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) related to HPV and sun exposure.

He performed a shave biopsy and the pathology report indicated it was an SCC in situ. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) At the follow-up visit, the FP reviewed the patient’s treatment options, which included topical 5% fluorouracil, topical imiquimod, and surgical excision. He also explained that the topical treatments were off label, so these options might have a lower success rate than the surgery.

The patient chose to have the surgery, even though he’d be out of work while the excision site was healing. The FP provided counseling about sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreens when exposed to the sun. He also referred the patient to a dermatologist who had extensive experience doing skin cancer surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

The new third edition will be available in January 2019: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/.

You can also get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized that this could be a wart but was concerned that it might be a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) related to HPV and sun exposure.

He performed a shave biopsy and the pathology report indicated it was an SCC in situ. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) At the follow-up visit, the FP reviewed the patient’s treatment options, which included topical 5% fluorouracil, topical imiquimod, and surgical excision. He also explained that the topical treatments were off label, so these options might have a lower success rate than the surgery.

The patient chose to have the surgery, even though he’d be out of work while the excision site was healing. The FP provided counseling about sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreens when exposed to the sun. He also referred the patient to a dermatologist who had extensive experience doing skin cancer surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

The new third edition will be available in January 2019: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/.

You can also get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized that this could be a wart but was concerned that it might be a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) related to HPV and sun exposure.

He performed a shave biopsy and the pathology report indicated it was an SCC in situ. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) At the follow-up visit, the FP reviewed the patient’s treatment options, which included topical 5% fluorouracil, topical imiquimod, and surgical excision. He also explained that the topical treatments were off label, so these options might have a lower success rate than the surgery.

The patient chose to have the surgery, even though he’d be out of work while the excision site was healing. The FP provided counseling about sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreens when exposed to the sun. He also referred the patient to a dermatologist who had extensive experience doing skin cancer surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

The new third edition will be available in January 2019: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/.

You can also get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Atopic dermatitis associated with increased suicidality

Patients with atopic dermatitis might face up to a 44% increased risk of suicidal ideation and are 36% more likely to attempt suicide than those without the disorder, a large meta-analysis has determined.

The analysis, which included data from studies published as far back as 1945, also found some correlation of increased suicide risk and increasing disease severity, although the numbers were small, Jeena K. Sandhu and her colleagues reported in JAMA Dermatology.

Both physical and psychological factors could be involved in the link, wrote Ms. Sandhu, a medical student at the University of Missouri–Kansas City, and her coauthors.

“Atopic dermatitis is associated with multiple physical comorbidities, such as asthma, allergic rhinitis, metabolic syndrome, and sleep disturbances, which all contribute to the overall physical burden of the disease. Many patients also have a profound psychosocial burden. Because of the visibility of the disease, patients may experience shame, embarrassment, and stigmatization,” they wrote.

But the disease also is associated with high levels of proinflammatory cytokines, and those proteins have been isolated in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients who have attempted suicide, the investigators noted. “Treatments targeting cytokines, such as interleukin-4 and interleukin-13, have been shown to decrease symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients with atopic dermatitis.”

The investigators plumbed several databases of medical literature, searching for studies that mentioned both atopic dermatitis (AD) and suicide, suicidal ideation, or suicidal behavior. They found 15 studies, published from 1945 to May 2018. Most (13) were cross sectional; the remainder were cohort studies. Together, they comprised a total of 4.7 million subjects, 310,681 of whom had AD. The analysis looked at risks in three areas: suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicides.

Of the studies, 11 investigated suicidal ideation. Pooled data determined that patients with AD were a significant 44% more likely to experience suicidal ideation than those without the disease.

Three studies mentioned suicide attempts and had complete data for pooling. Taken together, they showed a significant 36% increased risk of attempted suicide among patients with AD, compared with those without the disorder.

Two studies investigated the prevalence of completed suicides among patients. One did report a significantly increased risk of 40%, compared with the control group, but it failed to report the number of suicides in the control group. The other study found no increased risk of completed suicides in patients with either mild or moderate to severe disease, compared with controls.

Two studies involved only pediatric patients. One, conducted in Korea, found a significant 23% increased risk of suicidal ideation and a 31% increased risk of attempted suicide. The other failed to find any increased risks in the overall analysis, but did find small increases in the risks of ideation and attempt in girls with AD, compared with healthy controls.

the team concluded. “Dermatology providers may use several tools to screen patients for suicidality. Asking patients about suicidal ideation with a question may be integrated into a patient visit. If a patient screens positive for suicidality, the dermatology provider should send a referral to the patient’s primary care or mental health provider for follow-up care. If the patient reports an orchestrated plan to commit suicide, this patient should be urgently referred to the emergency department for further assessment.”

Ms. Sandhu reported no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Sandhu JK et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Dec 12. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4566.

Patients with atopic dermatitis might face up to a 44% increased risk of suicidal ideation and are 36% more likely to attempt suicide than those without the disorder, a large meta-analysis has determined.

The analysis, which included data from studies published as far back as 1945, also found some correlation of increased suicide risk and increasing disease severity, although the numbers were small, Jeena K. Sandhu and her colleagues reported in JAMA Dermatology.

Both physical and psychological factors could be involved in the link, wrote Ms. Sandhu, a medical student at the University of Missouri–Kansas City, and her coauthors.

“Atopic dermatitis is associated with multiple physical comorbidities, such as asthma, allergic rhinitis, metabolic syndrome, and sleep disturbances, which all contribute to the overall physical burden of the disease. Many patients also have a profound psychosocial burden. Because of the visibility of the disease, patients may experience shame, embarrassment, and stigmatization,” they wrote.

But the disease also is associated with high levels of proinflammatory cytokines, and those proteins have been isolated in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients who have attempted suicide, the investigators noted. “Treatments targeting cytokines, such as interleukin-4 and interleukin-13, have been shown to decrease symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients with atopic dermatitis.”

The investigators plumbed several databases of medical literature, searching for studies that mentioned both atopic dermatitis (AD) and suicide, suicidal ideation, or suicidal behavior. They found 15 studies, published from 1945 to May 2018. Most (13) were cross sectional; the remainder were cohort studies. Together, they comprised a total of 4.7 million subjects, 310,681 of whom had AD. The analysis looked at risks in three areas: suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicides.

Of the studies, 11 investigated suicidal ideation. Pooled data determined that patients with AD were a significant 44% more likely to experience suicidal ideation than those without the disease.

Three studies mentioned suicide attempts and had complete data for pooling. Taken together, they showed a significant 36% increased risk of attempted suicide among patients with AD, compared with those without the disorder.

Two studies investigated the prevalence of completed suicides among patients. One did report a significantly increased risk of 40%, compared with the control group, but it failed to report the number of suicides in the control group. The other study found no increased risk of completed suicides in patients with either mild or moderate to severe disease, compared with controls.

Two studies involved only pediatric patients. One, conducted in Korea, found a significant 23% increased risk of suicidal ideation and a 31% increased risk of attempted suicide. The other failed to find any increased risks in the overall analysis, but did find small increases in the risks of ideation and attempt in girls with AD, compared with healthy controls.

the team concluded. “Dermatology providers may use several tools to screen patients for suicidality. Asking patients about suicidal ideation with a question may be integrated into a patient visit. If a patient screens positive for suicidality, the dermatology provider should send a referral to the patient’s primary care or mental health provider for follow-up care. If the patient reports an orchestrated plan to commit suicide, this patient should be urgently referred to the emergency department for further assessment.”

Ms. Sandhu reported no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Sandhu JK et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Dec 12. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4566.

Patients with atopic dermatitis might face up to a 44% increased risk of suicidal ideation and are 36% more likely to attempt suicide than those without the disorder, a large meta-analysis has determined.

The analysis, which included data from studies published as far back as 1945, also found some correlation of increased suicide risk and increasing disease severity, although the numbers were small, Jeena K. Sandhu and her colleagues reported in JAMA Dermatology.

Both physical and psychological factors could be involved in the link, wrote Ms. Sandhu, a medical student at the University of Missouri–Kansas City, and her coauthors.

“Atopic dermatitis is associated with multiple physical comorbidities, such as asthma, allergic rhinitis, metabolic syndrome, and sleep disturbances, which all contribute to the overall physical burden of the disease. Many patients also have a profound psychosocial burden. Because of the visibility of the disease, patients may experience shame, embarrassment, and stigmatization,” they wrote.

But the disease also is associated with high levels of proinflammatory cytokines, and those proteins have been isolated in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients who have attempted suicide, the investigators noted. “Treatments targeting cytokines, such as interleukin-4 and interleukin-13, have been shown to decrease symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients with atopic dermatitis.”

The investigators plumbed several databases of medical literature, searching for studies that mentioned both atopic dermatitis (AD) and suicide, suicidal ideation, or suicidal behavior. They found 15 studies, published from 1945 to May 2018. Most (13) were cross sectional; the remainder were cohort studies. Together, they comprised a total of 4.7 million subjects, 310,681 of whom had AD. The analysis looked at risks in three areas: suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicides.

Of the studies, 11 investigated suicidal ideation. Pooled data determined that patients with AD were a significant 44% more likely to experience suicidal ideation than those without the disease.

Three studies mentioned suicide attempts and had complete data for pooling. Taken together, they showed a significant 36% increased risk of attempted suicide among patients with AD, compared with those without the disorder.

Two studies investigated the prevalence of completed suicides among patients. One did report a significantly increased risk of 40%, compared with the control group, but it failed to report the number of suicides in the control group. The other study found no increased risk of completed suicides in patients with either mild or moderate to severe disease, compared with controls.

Two studies involved only pediatric patients. One, conducted in Korea, found a significant 23% increased risk of suicidal ideation and a 31% increased risk of attempted suicide. The other failed to find any increased risks in the overall analysis, but did find small increases in the risks of ideation and attempt in girls with AD, compared with healthy controls.

the team concluded. “Dermatology providers may use several tools to screen patients for suicidality. Asking patients about suicidal ideation with a question may be integrated into a patient visit. If a patient screens positive for suicidality, the dermatology provider should send a referral to the patient’s primary care or mental health provider for follow-up care. If the patient reports an orchestrated plan to commit suicide, this patient should be urgently referred to the emergency department for further assessment.”

Ms. Sandhu reported no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Sandhu JK et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Dec 12. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4566.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts seem to be more common among people with atopic dermatitis than those without the disease.

Major finding: Patients were 44% more likely to have suicidal ideation and 36% more likely to attempt suicide.

Study details: The meta-analysis comprised 15 studies with a total of 4.7 million participants, 310,681 of whom had the disease.

Disclosures: Ms. Sandhu reported no financial disclosures.

Source: Sandhu JK et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Dec 12. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4566.

Wart on scalp

The FP had seen many recalcitrant warts before, but rather than repeat the cryotherapy, he performed a shave biopsy to get a definitive diagnosis. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The biopsy revealed a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

This lesion may have started with a wart, as human papillomavirus (HPV) is both the cause of warts and a risk factor for cutaneous SCC. The FP referred the patient to a Mohs surgeon for complete excision of the SCC. He also provided counseling about sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreens when exposed to the sun.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

The new third edition will be available in January 2019: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/.

You can also get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP had seen many recalcitrant warts before, but rather than repeat the cryotherapy, he performed a shave biopsy to get a definitive diagnosis. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The biopsy revealed a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

This lesion may have started with a wart, as human papillomavirus (HPV) is both the cause of warts and a risk factor for cutaneous SCC. The FP referred the patient to a Mohs surgeon for complete excision of the SCC. He also provided counseling about sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreens when exposed to the sun.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

The new third edition will be available in January 2019: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/.

You can also get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP had seen many recalcitrant warts before, but rather than repeat the cryotherapy, he performed a shave biopsy to get a definitive diagnosis. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The biopsy revealed a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

This lesion may have started with a wart, as human papillomavirus (HPV) is both the cause of warts and a risk factor for cutaneous SCC. The FP referred the patient to a Mohs surgeon for complete excision of the SCC. He also provided counseling about sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreens when exposed to the sun.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

The new third edition will be available in January 2019: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/.

You can also get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

How I Became a Derm Guru (And How You Can, Too)

Many years ago, when I was still in primary care (internal medicine), I thought I knew a bit about the practice of medicine. I was totally comfortable in the hospital (in those days, we saw our own patients twice a day in the hospital), including the ER, the OR, even obstetrics. MIs, shootings, stab wounds, renal failure—I would never say I had mastered them, but I was comfortable with most of what I saw. Deliveries, assisting with C-sections, performing lumbar punctures, performing and interpreting exercise tolerance tests, performing flexible sigmoidoscopies—no problem.

But the one thing that nearly always stopped me in my tracks was … you guessed it: dermatology complaints. Rashes, lesions, or any other skin complaint the least bit out of the ordinary were completely baffling to me. I still remember that feeling after all these years (and I still occasionally experience it!).

I felt like saying to those patients: What in the world would make you think I’d have any idea what that is? But of course, I couldn’t say that, so I’d mumble something, throw some cream at it, then quickly change the subject. Mind you, this was in a setting where a derm referral from us would take 4 to 6 months. And in case you’re wondering, the other providers in my department were as bad at derm as I was.

Long story short, it got to the point that I would scan my schedule every morning, praying I wouldn’t see the word “rash” or “skin.” But, of course, they still came—often just as my hand touched the doorknob to leave: “Oh, by the way, what about this …?” You get the picture. Many of you, if not most, live that picture.

I finally got up the nerve to go to our dermatology department to ask if I could follow one of the docs while he saw patients. Little did I know that practically every provider in the building had already done the same, and had been dismissed with words that essentially meant, “You? A mere PA? You can’t get there from here. Just send ’em to us.”

For a short time, I bought that line—but in the meantime, my patients were not getting the care they needed. So, driven in part by anger at the notion that a mere PA was simply unable to learn dermatology, I bought a decent textbook, Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas of Dermatology, and started reading it. I also started collecting all the derm articles I could find in the journals, and read about those cases.

I won’t bore you with the grimy details, but what I did differently was work at learning derm (what a concept!). I started going to derm conferences, bought a good camera and started taking pictures with it, and continued to buy books (this was in the pre-computer days of the ’80s) and actually read them.

Continue to: And a funny thing happened...

And a funny thing happened: The more I read, the more diagnoses I recognized on my patients. My colleagues and the clinic schedulers took note of this and began sending me their problem cases. Even the derm department, beleaguered as usual by huge backlogs of patients, started sending patients to me. By 1985, even though I was in the internal medicine department, I had transitioned to doing derm fulltime. And that’s what I’ve been doing since.

Around 1992, I discovered that I was one of 6 dermatology PAs in this country. Last time I checked, our numbers were approaching 4,000. So, yes, derm is indeed difficult, but rocket science it isn’t.

Being the pedantic sort that I am, and finding that whole experience so enlightening, I resolved to make it my mission to foster the use of PAs in dermatology—part of which involves the education of those PAs, by means of taking students but also by writing articles (several hundred at last count) and lecturing at conferences and at PA programs. Nearing retirement, I only practice two days a week, but I write and publish at least 5 clinical articles a month, all of which are based on real cases: my cases, using my photos, doing new research on each case. This keeps my knowledge fresh and my 75-year-old mind sharp, helps ward off burnout, and, most importantly, saves lives while reducing patient discomfort.

What follows are 10 dermatology pearls that I have gleaned along the way. My apologies to my former students and attendees at my lectures who’ve heard all this before:

1 If the treatment for your diagnosis isn’t working, consider another diagnosis. Here’s an example (Figure 1): A man in his 50s was sent to dermatology for psoriasis that wasn’t responding to a biologic. Was it really psoriasis? A KOH prep quickly showed it to be tinea corporis, which cleared completely with a month’s worth of oral terbinafine (250 mg qid).

Continue to: #2...

2 The correct diagnosis dictates correct treatment. This may sound obvious, but in primary care, the emphasis is often on “let’s try this” or “let’s try that,” an understandable approach to a symptomatic patient with an uncertain diagnosis. But by the time he finally gets to dermatology, the patient has tried a whole bag full of prescription and OTC products given for numerous, totally different diagnoses. A better approach might be to expedite an urgent referral to dermatology, when possible.

3 Cutaneous fungal infections (ie, dermatophytosis) are vastly overdiagnosed, especially by novices. If you truly suspect it, ask about a potential source; one doesn’t acquire a fungal infection out of thin air. It must come from a person, animal, or occasionally, the soil. It also helps if the victim has been rendered susceptible by the injudicious use of steroids. Better yet, find the fungus with a microscopic examination (KOH prep) or culture. Finally, remember, not everything round and scaly is fungal (see Figure 2).

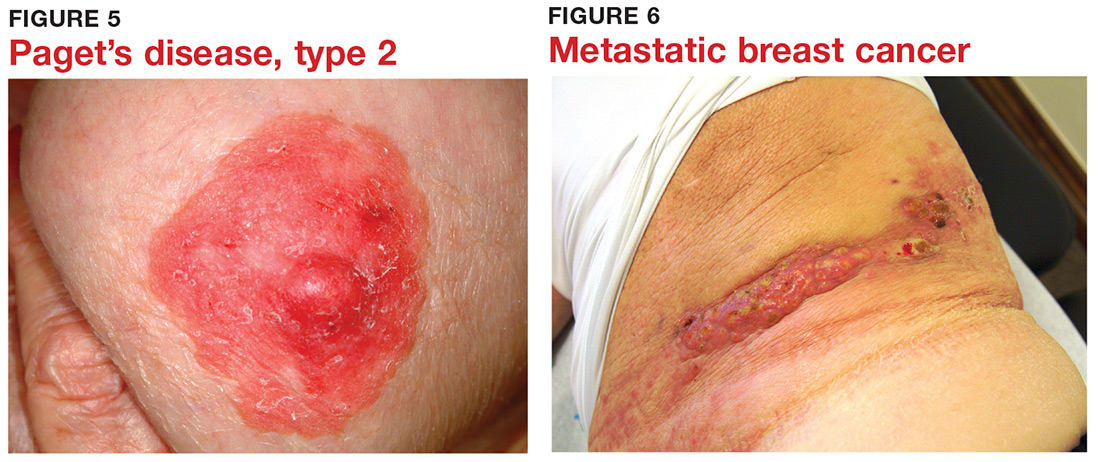

4 Remember these ancient words of wisdom regarding skin complaints: (a) A diagnosis is seldom made if not entertained, (b) you won’t entertain it if you’ve never heard of it, (c) you will not see it if you’re not looking for it, and (d) even if you did see it, you would not “see” it because you’re not looking for it. Dermatology is far deeper and wider than most imagine it to be. The trick is to expose yourself to as many different diagnoses as possible, by reading and attending lectures, ahead of the possible sighting. Figures 3 and 4 offer examples of common conditions that are seldom recognized outside dermatology.

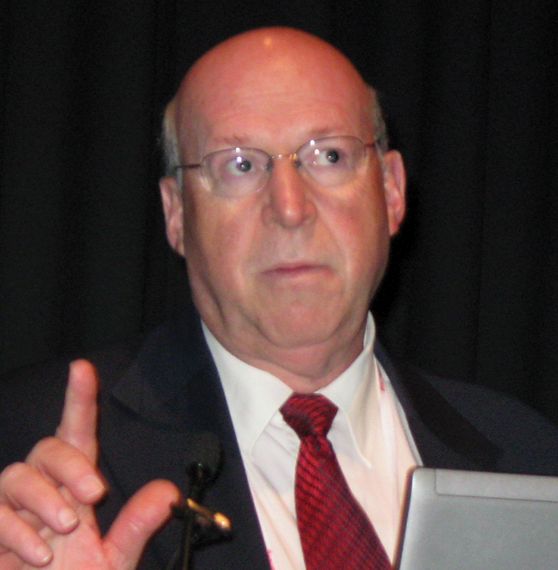

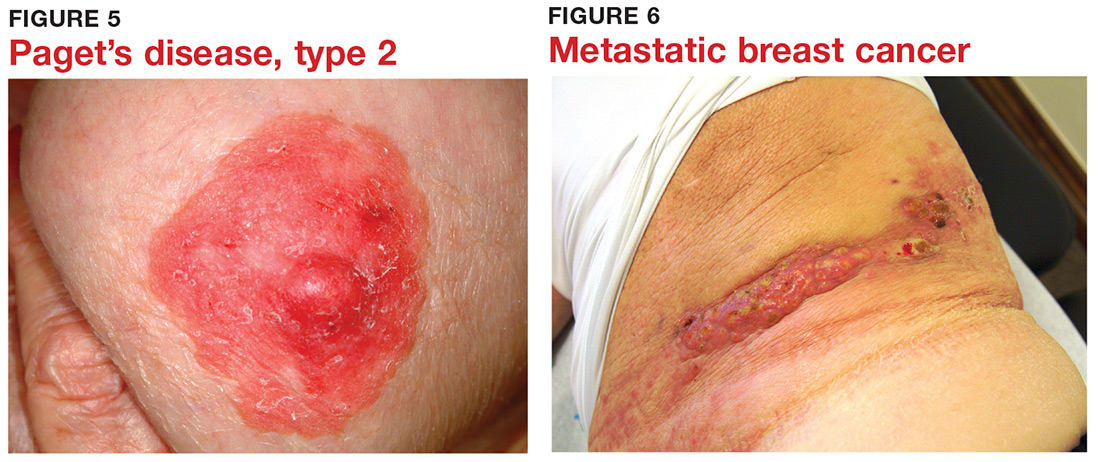

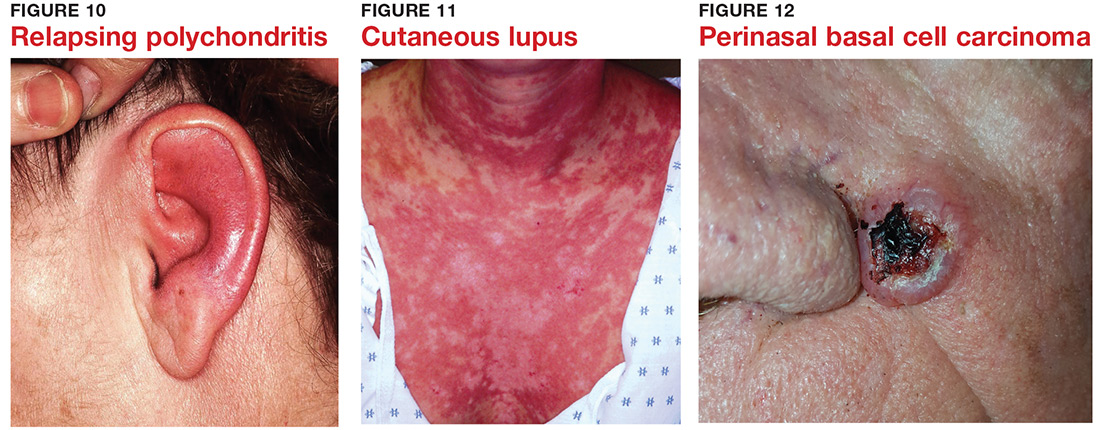

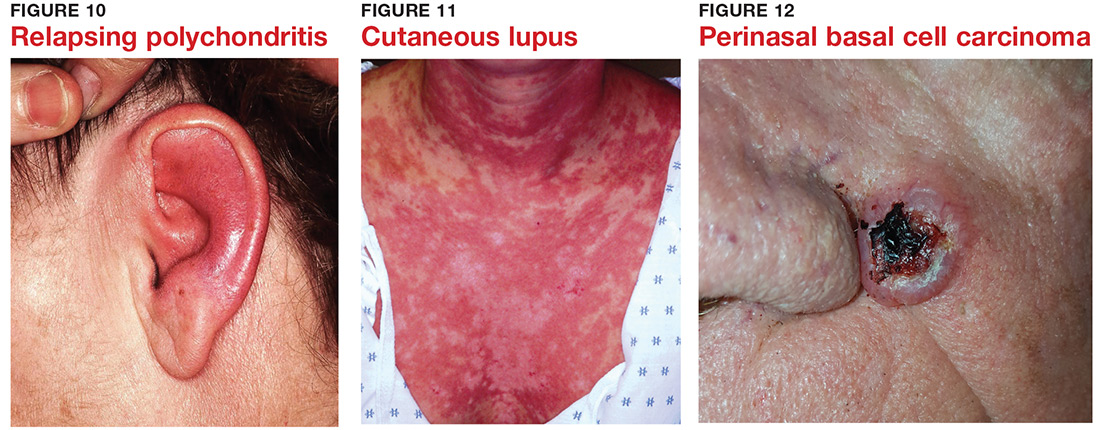

5 Skin cancer can present as a rash. Examples abound, such as mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease (Figure 5), mycosis fungoides, metastatic breast cancer (Figure 6), and superficial basal cell carcinoma. A biopsy is usually required to diagnose these, but you wouldn’t think to do that if you’d never heard of the condition.

6 Melanoma doesn’t typically arise from a mole or other pre-existing lesion. Far more often, it arises “de novo,” out of nothing. So, in general, we’re not worried about “moles” (nevi) unless there’s a history of change (see Figure 7).

Continue to: #7...

7 When looking for skin cancer, pay as much attention to the owner as to the lesion. The most common skin cancers—basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma—usually occur on sun-damaged, fair-skinned, blue-eyed older patients. Though there are certainly exceptions to this paradigm, it pays to be generally suspicious of any odd lesion seen on these patients (Figure 8).

8 It’s practically impossible to overstate the role of atopy when evaluating pediatric skin complaints. These children—20% of all newborns!—are born with thin, dry, sensitive, overreactive skin that is prone to eczema and urticaria. They will also have a marked tendency to develop seasonal allergies, allergic rhinitis, and asthma. Parents find it difficult to accept the genetic basis for atopic dermatitis (Figure 9), preferring instead to blame everything on laundry detergent or food. Education (of oneself first!) is the key.

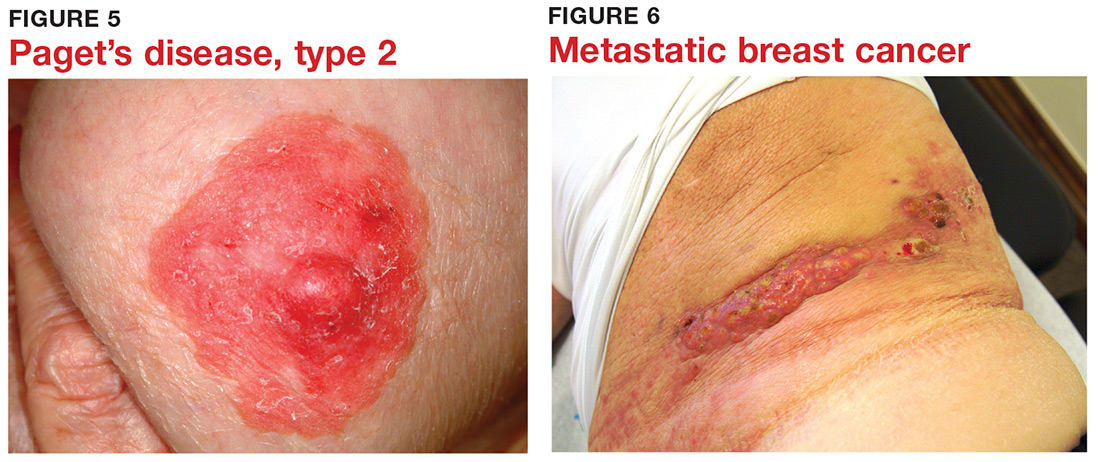

9 “Infections” are not always what they seem

10 Overcome your fear of steroids by educating yourself about their safe use. Glucocorticoids (eg, triamcinolone, prednisone, betamethasone) are extremely useful in treating common derm conditions. We see patients every day who are so frightened of steroids, they won’t even consider using them because some well-meaning medical provider scared them to death. The proper use of these miraculous products could easily be the subject of an entire article. For now, I’ll advise you to read about their safe use in any number of dermatology texts (including online publications).