User login

Sweet Syndrome With Marked Eosinophilic Infiltrate

To the Editor:

Sweet syndrome (SS), also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is an uncommon inflammatory skin disorder characterized by sudden onset of fever, leukocytosis, neutrophilia, and tender erythematous papules or plaques or both. Skin biopsy usually reveals extensive infiltration of neutrophils into the epidermis and dermis.1-3 Although rare, cases of eosinophil-rich SS have been reported in patients with drug-induced and malignancy-associated SS.4,5 We report a case of a patient with classical SS with dermal eosinophilic infiltration.

An 80-year-old Hispanic man presented with abrupt onset of a rash on the posterior scalp, left ear, back, and hands of 5 days’ duration. The lesions were painful and had progressed to the point of impairing hand grip. The patient’s medical history included a reported common cold the week prior, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension, for which he took metoprolol, simvastatin, aspirin, and clopidogrel. He denied oral lesions and medication changes. He was afebrile and did not experience dietary changes, weight loss, or fatigue. He recently returned from travel to the Dominican Republic.

Physical examination revealed tender, well demarcated, pink to violaceous, pseudovesicular papules and plaques on the palms and dorsal hands (Figure 1), the posterior scalp, left ear, proximal left arm, and back. Pink, juicy, targetoid papules were also found on the scalp, back, and left arm. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy. Laboratory test results revealed an elevated white blood cell count (11,500/µL [reference range, 3800-10,800/µL]), absolute neutrophil count (8073/µL [reference range, 1500–7800/µL]), and eosinophil count (610/µL [reference range, 15–500/µL]). These results indicated leukocytosis with neutrophilia and mild eosinophilia. The patient also was anemic (hemoglobin, 11.5 g/dL [reference range, 13.2–17.1 g/dL]; hematocrit, 35.1% [reference range, 38.5%–50%]). Urine testing revealed altered renal function (serum creatinine, 2.42 mg/dL [reference range, 0.7–1.1 mg/dL]; blood urea nitrogen, 34 mg/dL [reference range, 7–25 mg/dL]; glomerular filtration rate, 4 mL/min/1.73 m2 (reference range, ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2]), suggesting stage 4 chronic kidney disease. Urinalysis showed mild hematuria and proteinuria.

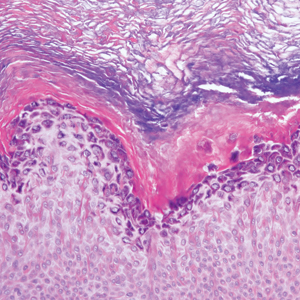

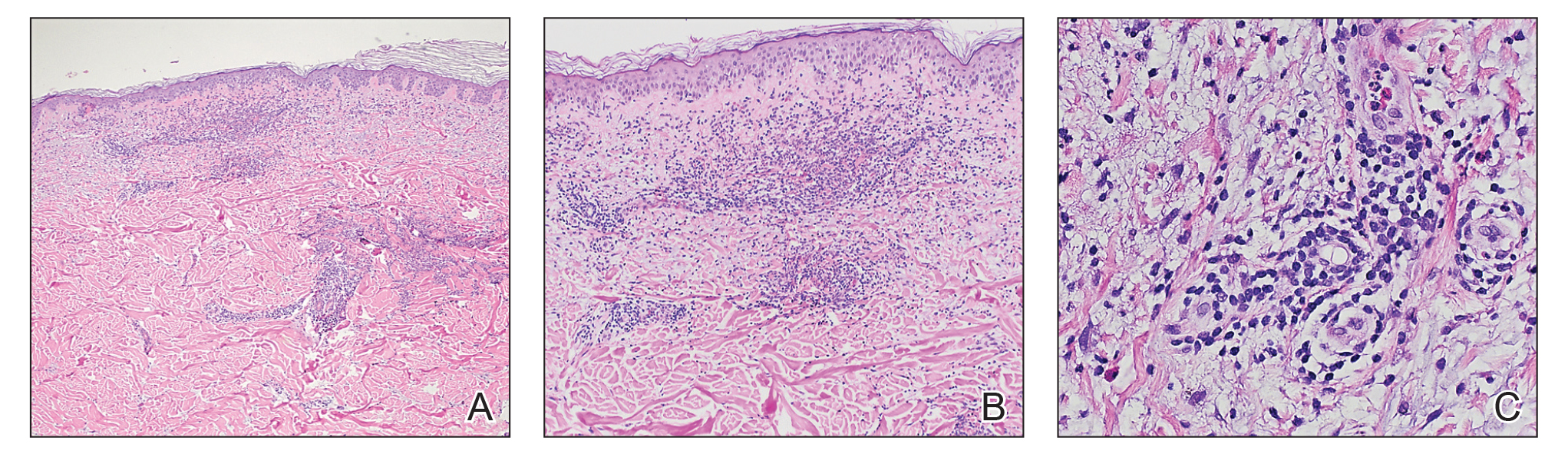

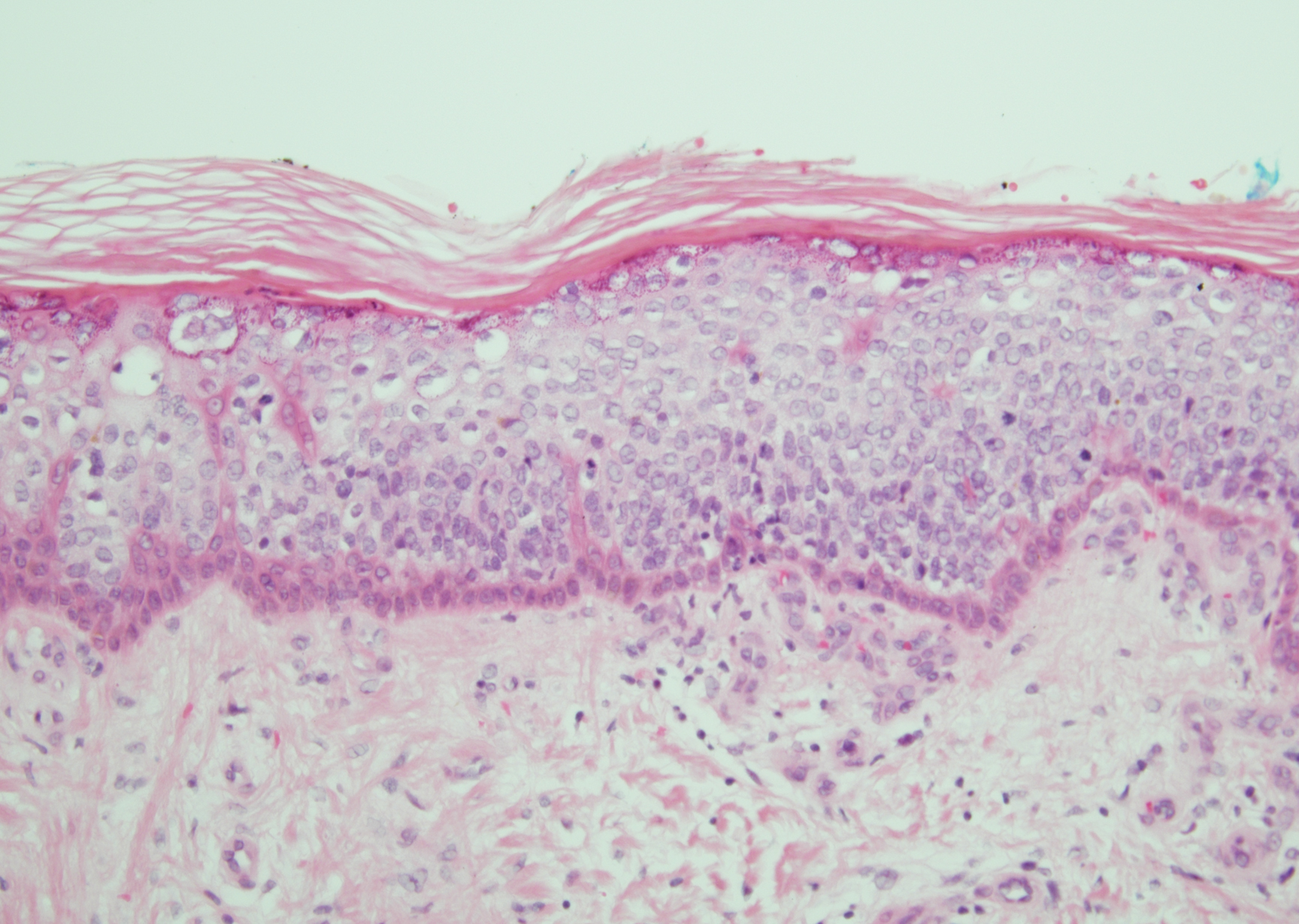

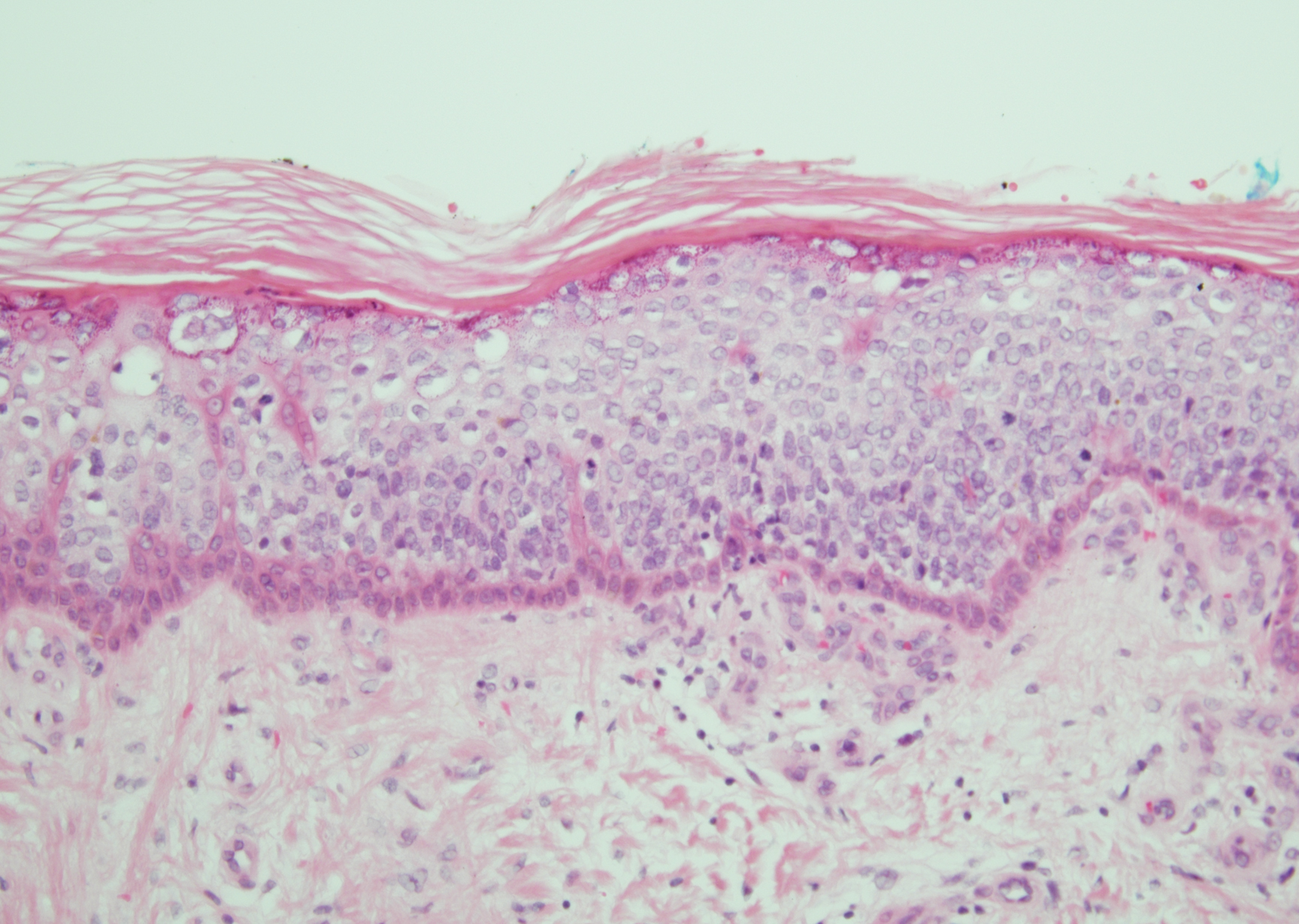

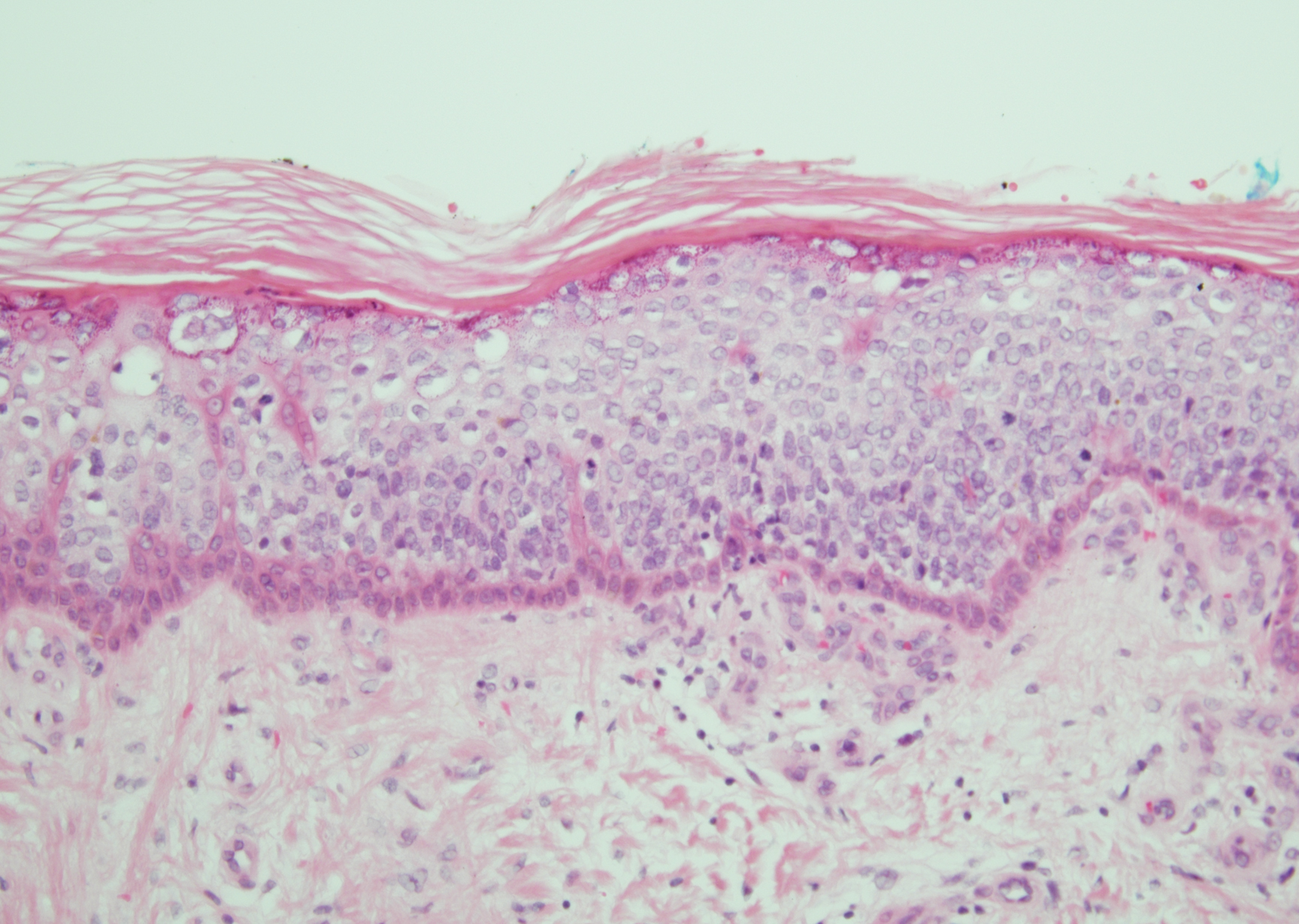

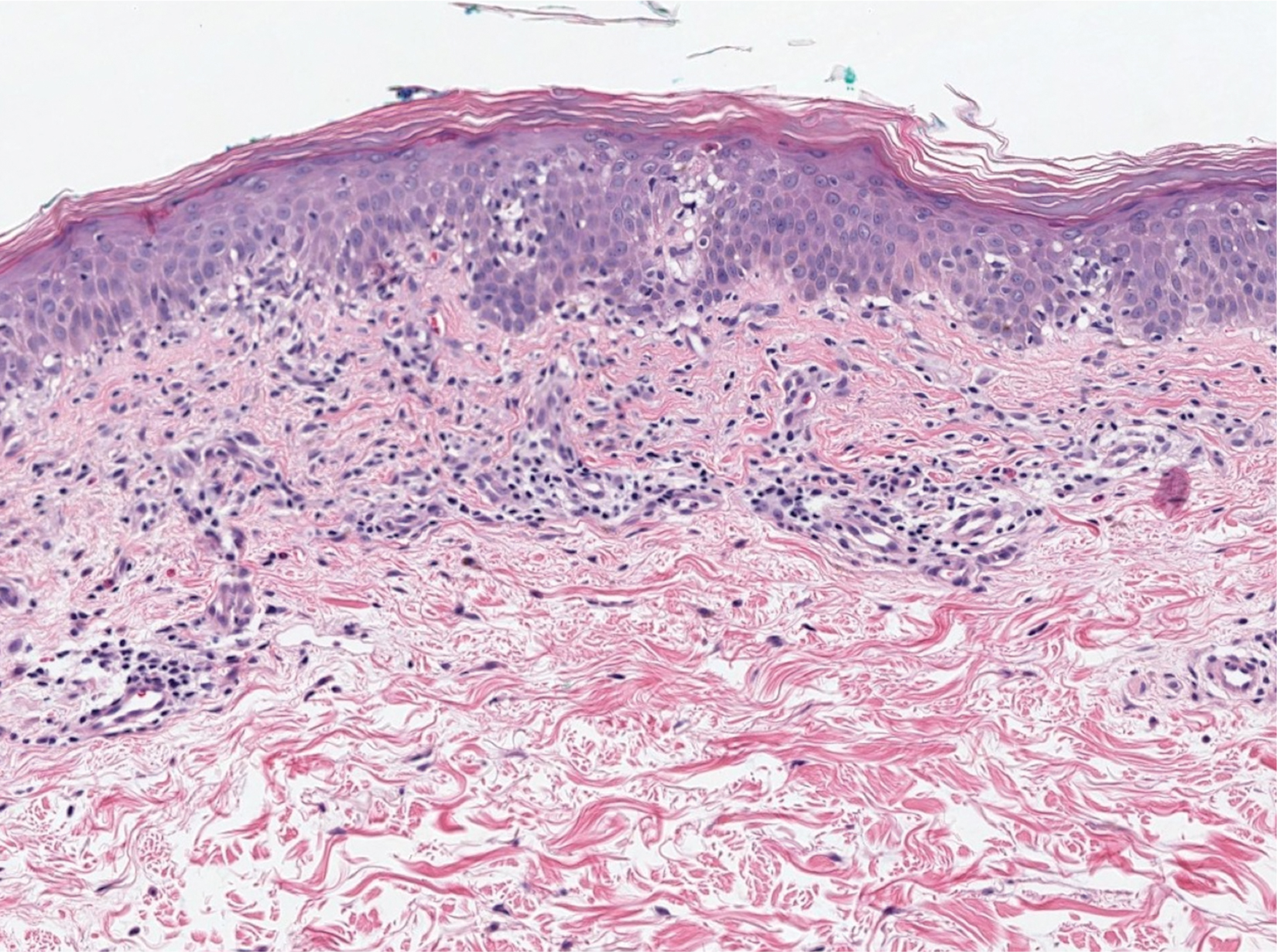

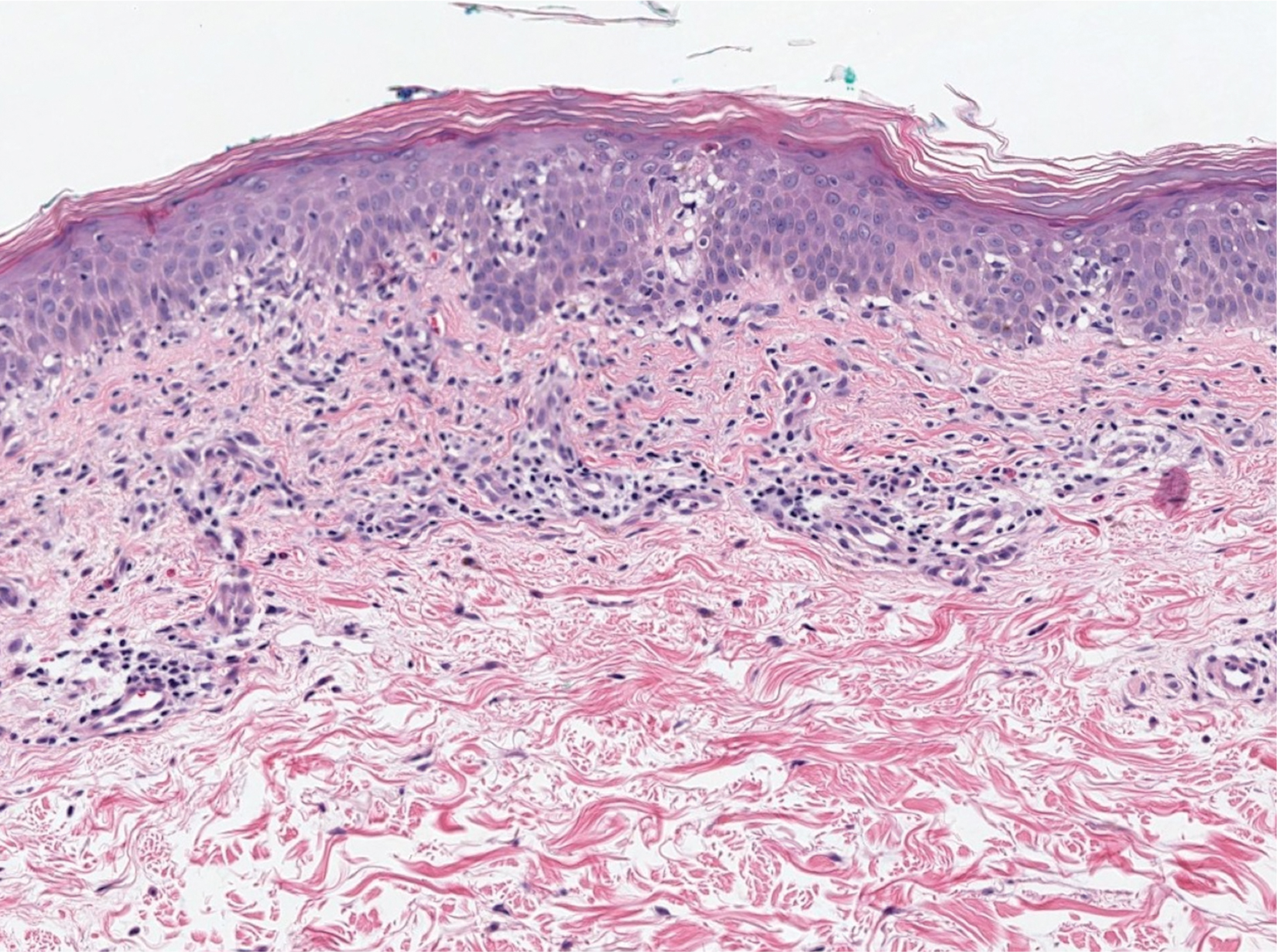

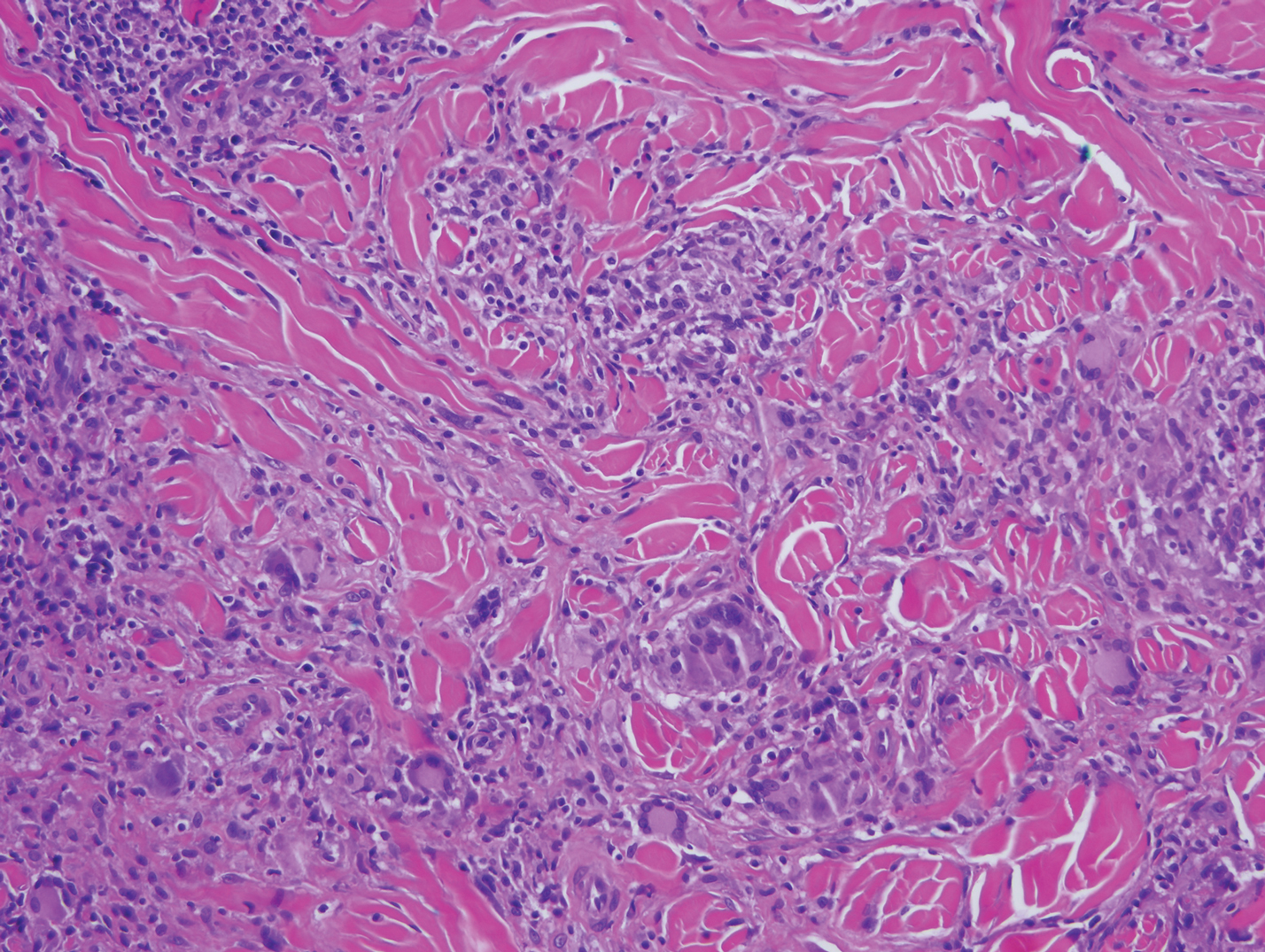

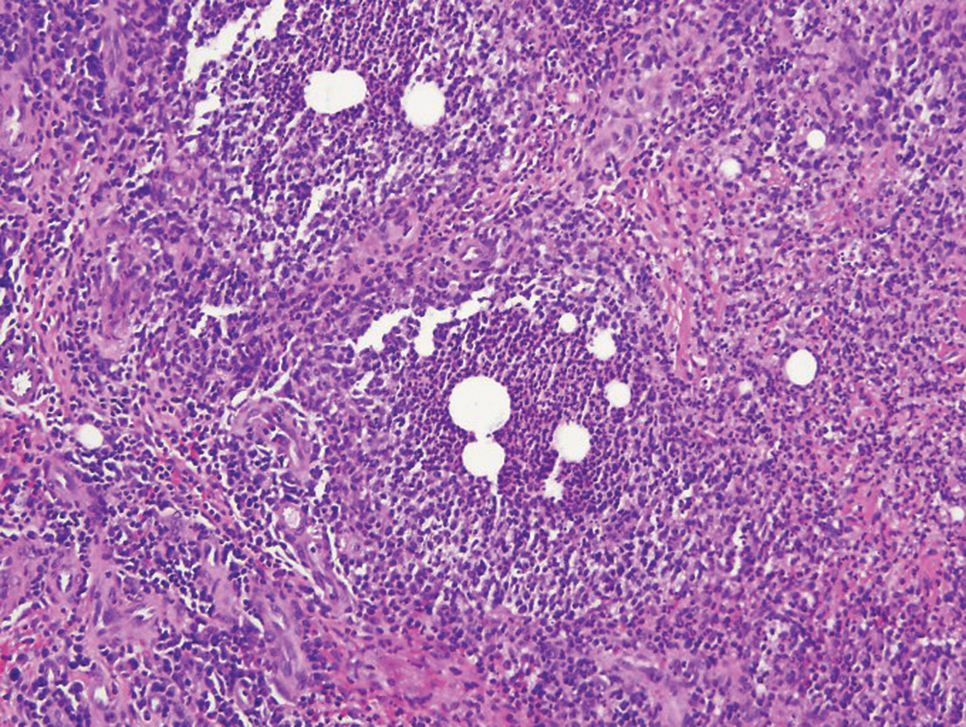

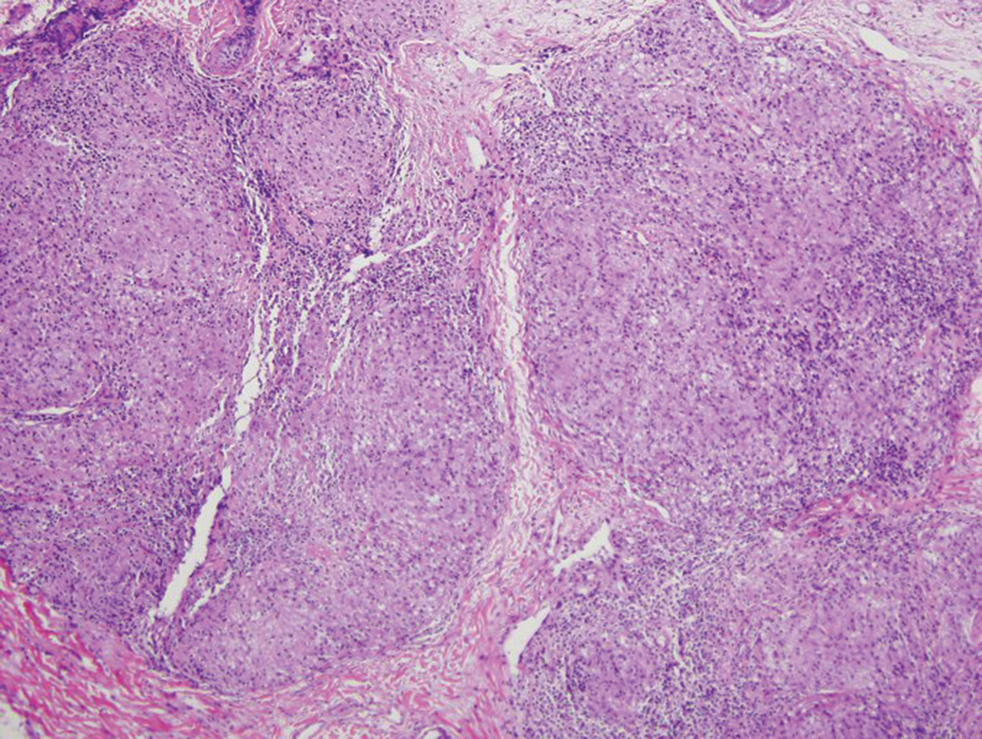

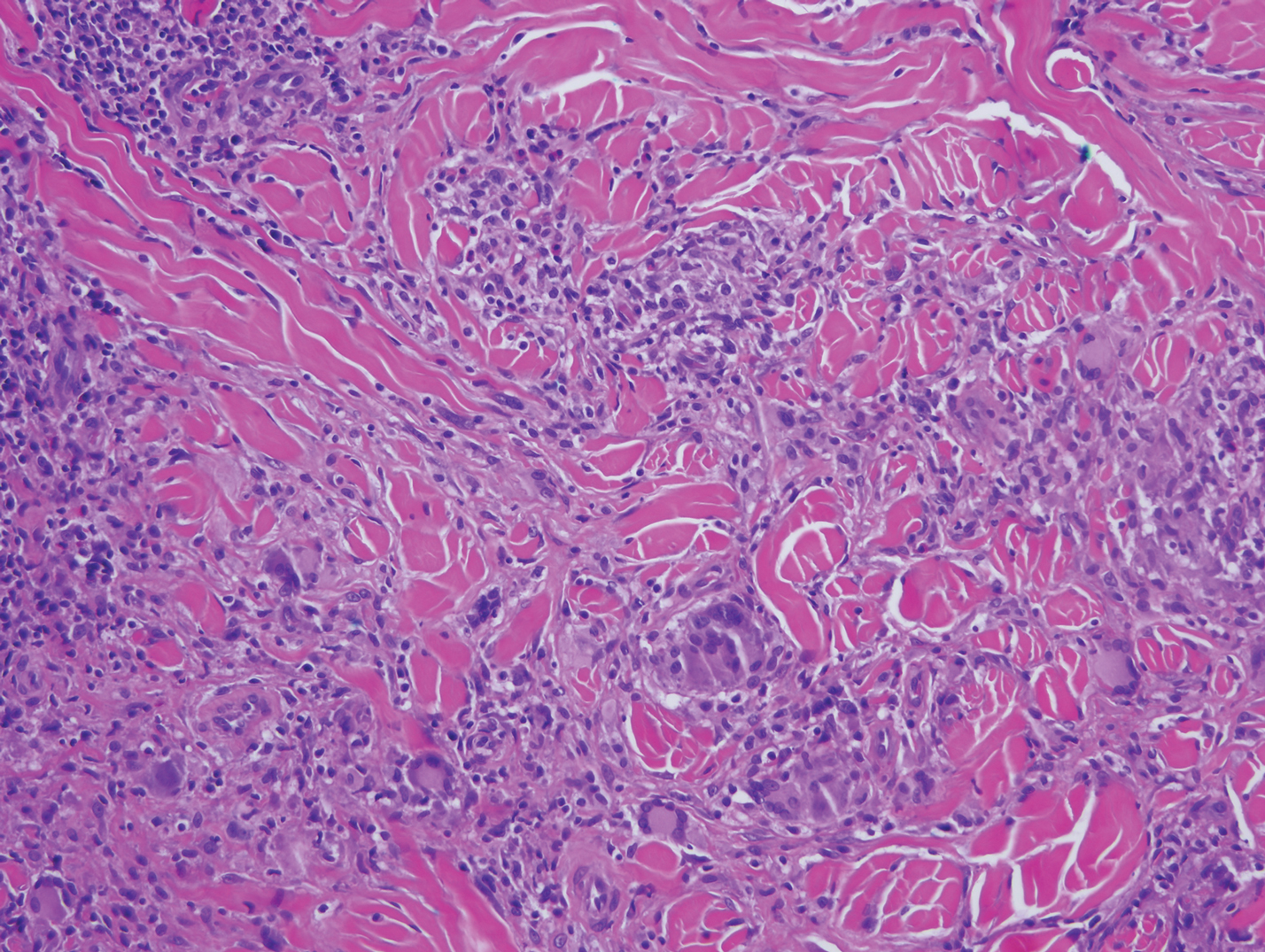

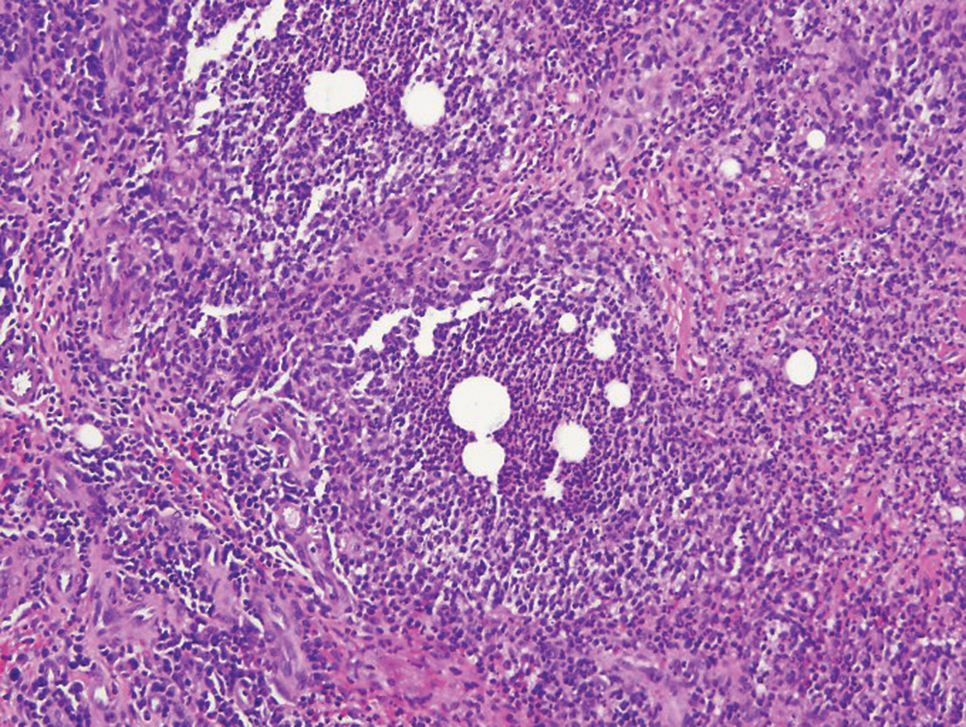

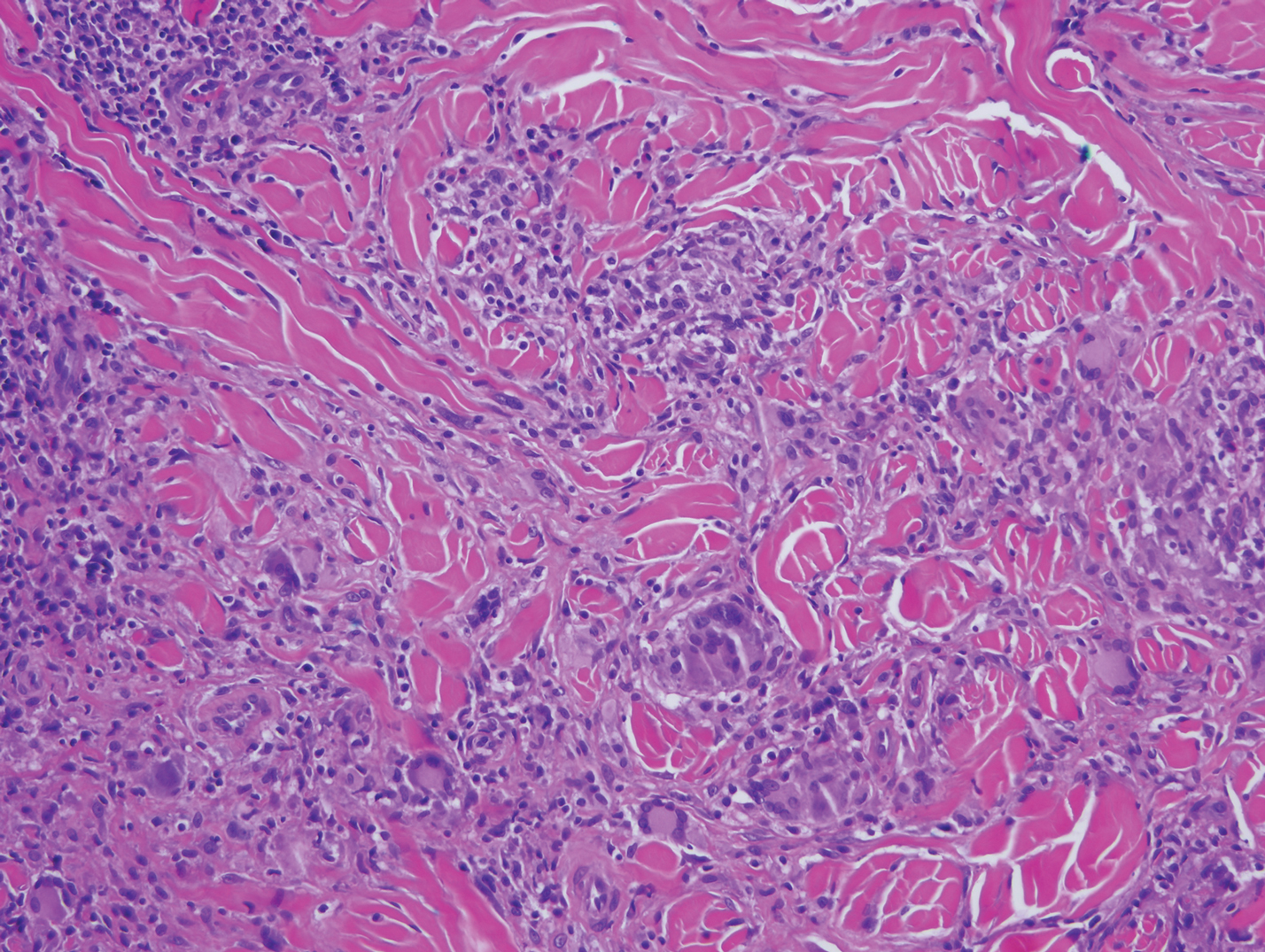

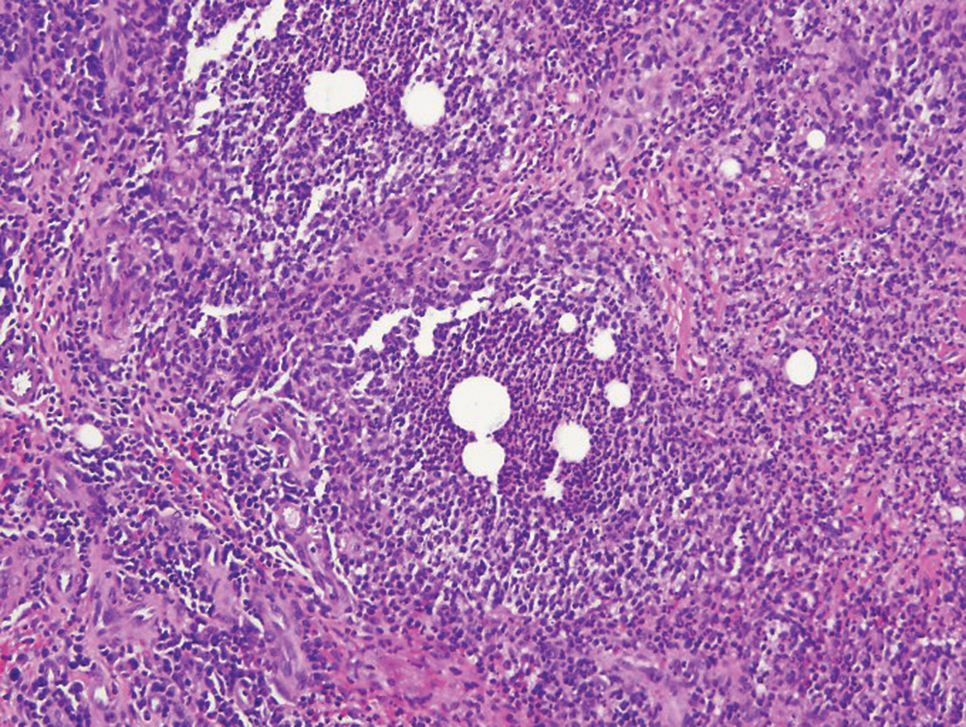

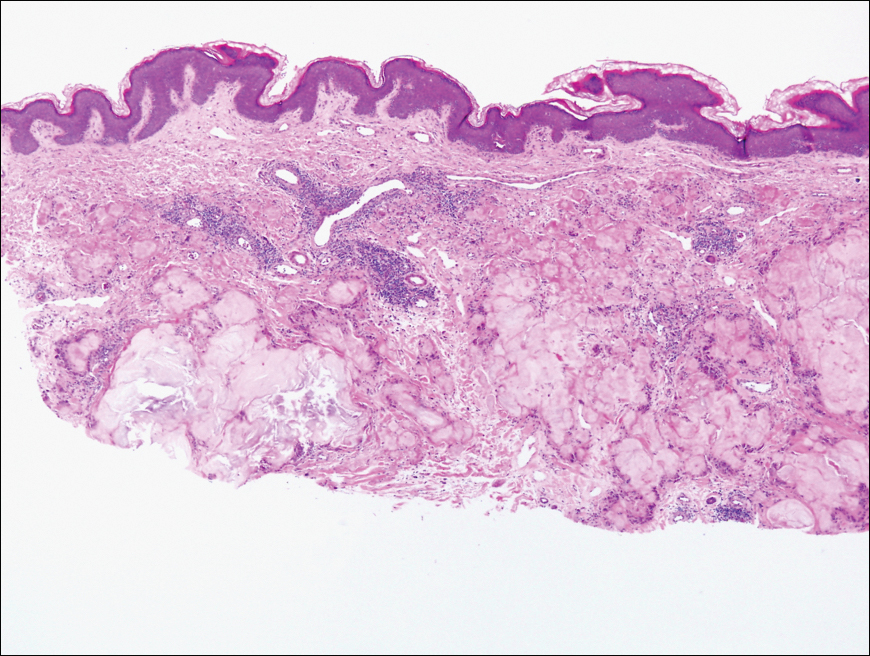

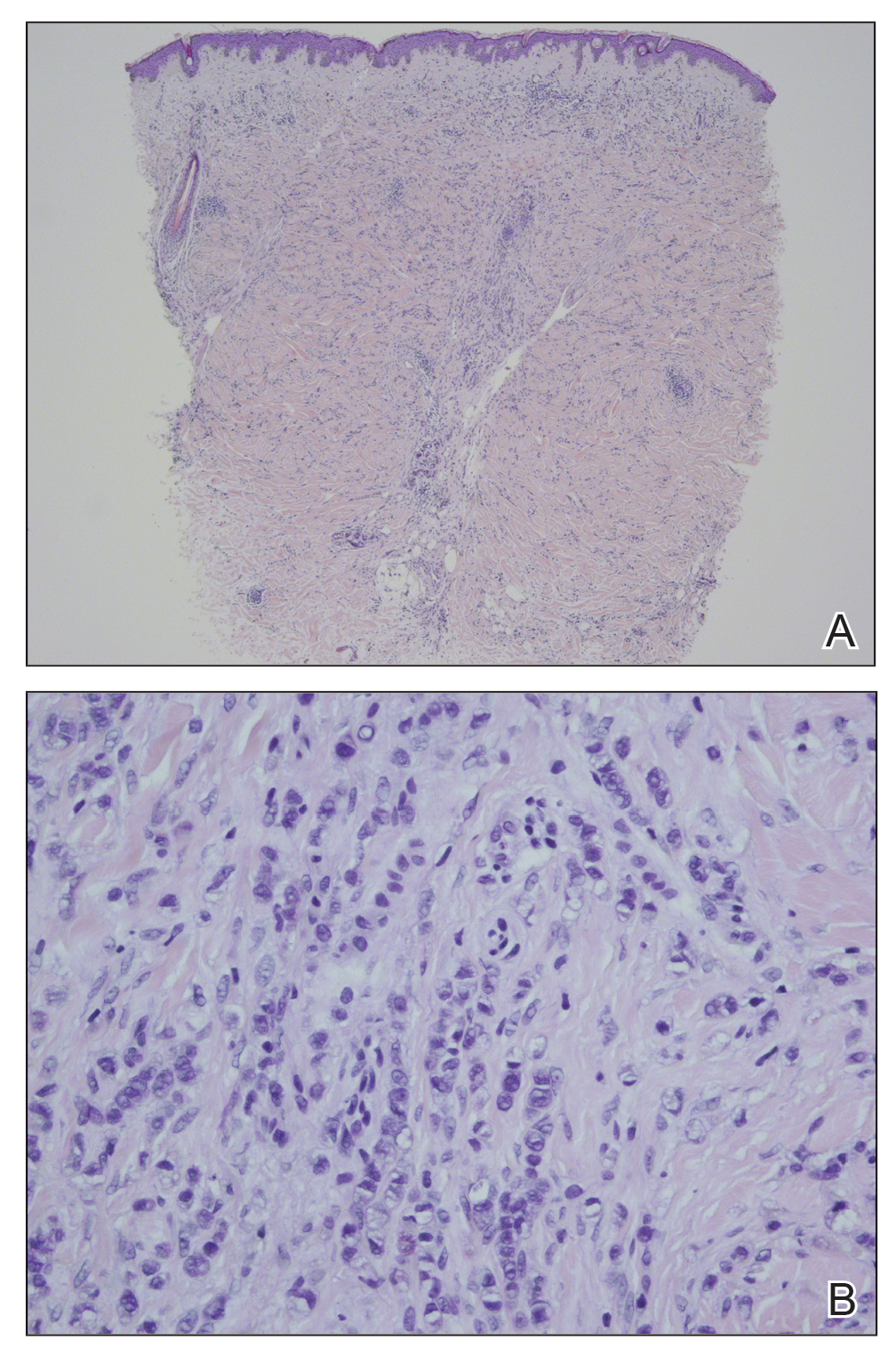

Histopathology of biopsies taken from plaques on the left arm and lower back revealed a dense neutrophilic infiltrate with numerous scattered eosinophils in the dermis. Some neutrophils were intact; others were fragmented without evidence of vasculitis. A subtle subepidermal edema also was noted (Figure 2). A diagnosis of SS was made.

Initial treatment included prednisone (40 mg daily, tapered by 5 mg every 3 days) and erythromycin (500 mg 4 times daily) for 7 days because of suspected Mycoplasma infection. The rash resolved in 1 week. No recurrence was noted during 4 months of follow-up. The white blood cell count returned to within reference range (8400/µL), ruling out the possibility of a smoldering myeloid process.

Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis was first described in a case series of 8 women by Sweet6 in 1964. Patients typically present first with fever, which can precede cutaneous symptoms for days or weeks. Skin lesions generally are asymmetric and located on the face, neck, and upper extremities. Lesions can be described as painful, purple to red papules, plaques, or nodules. Sweet syndrome can present as 3 subtypes based on cause7: (1) classical SS, also known as idiopathic SS, can be preceded by an upper respiratory tract or gastrointestinal tract infection or vaccination, or can be pregnancy associated2; (2) drug-induced SS usually follows use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, or other causative drugs including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, nitrofurantoin, quinolones, oral contraceptives, furosemide, hydralazine, diazepam, clozapine, abacavir, imatinib, bortezomib, azathioprine, and celecoxib2,3,8; and (3) malignancy-associated SS can occur as a paraneoplastic syndrome and generally is associated with hematologic malignancy or a solid tumor.1,9

In our patient, the observed clinical and histological findings were consistent with a diagnosis of SS,2,10 specifically tender erythematous plaques of sudden onset, fast response to systemic corticosteroid therapy, a dermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and leukocytosis greater than 8000/µL with more than 70% neutrophils. He also exhibited targetoid lesions, which have been reported in 7% to 12% of SS patients.10,11

The predominant cells involved in the dermis of SS lesions are mature neutrophils; however, eosinophils have been observed in small numbers within dermal infiltrates in skin lesions of patients with either classical SS or drug-induced dermatosis.2 In 2 studies of cases of SS (N=73 and N=31), eosinophils were reported in 35% and 41% of skin biopsies, respectively.4,5 Nevertheless, cases with dense eosinophilic infiltrates are rare. Furthermore, Masuda et al12 reported a case of eosinophil-rich SS in a 29-year-old woman after treatment of an upper respiratory tract infection with an antibiotic, and Soon et al13 described an eosinophil-rich case of SS in the setting of new-onset enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma.

Our patient was considered to have classical SS because he had an episode of an upper respiratory tract infection 1 week prior to onset of clinical manifestations. The histologic finding of numerous eosinophils in our case was unusual for idiopathic SS. This finding might suggest a drug hypersensitivity reaction, but the lack of any change in the patient’s long-term medication list and the lack of any other episodes made a diagnosis of drug-induced SS less likely in our patient.

Eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy is a rare cutaneous condition in which nodules, pruritic papules, and vesicles arise in patients with a hematologic malignancy, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia and mantle cell lymphoma,13 in which a deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and numerous eosinophils are observed. Malignancy was ruled out in our patient because of the lack of characteristic abnormalities in blood testing, the fast response to corticosteroid therapy, and the lack of recurrence posttreatment or additional systemic concerns.

The typical pathology findings of SS consist of mature neutrophils found in the dermis without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Eosinophil-rich infiltration, however rare, has been reported in SS. This report highlights a case of classical SS with a particularly dense eosinophilic infiltrate, which could be mistaken for other eosinophilic dermatoses. Dermatologists should be aware of the possibility of marked eosinophilic infiltration in all subtypes of this disorder.

- Herbert-Cohen D, Jour G, Saul T. Sweet’s syndrome. J Emerg Med. 2015;49:e95-e97.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Villarreal-Villarreal CD, Ocampo-Candiani J, Villarreal-Martínez A. Sweet syndrome: a review and update. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:369-378.

- Rochael MC, Pantaleão L, Vilar EA, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: study of 73 cases, emphasizing histopathological findings. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:702-707.

- Ratzinger G, Burgdorf W, Zelger BG, et al. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: a histopathologic study of 31 cases with review of literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:125-133.

- Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: a review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:761-778.

- Polimeni G, Cardillo R, Garaffo E, et al. Allopurinol-induced Sweet’s syndrome. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2016;29:329-332.

- Paydas S. Sweet’s syndrome: a revisit for hematologists and oncologists. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;86:85-95.

- Amouri M, Masmoudi A, Ammar M, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: a retrospective study of 90 cases from a tertiary care center. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1033-1039.

- Marcoval J, Martín-Callizo C, Valentí-Medina F, et al. Sweet syndrome: long-term follow-up of 138 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:741-746.

- Masuda T, Abe Y, Arata J, et al. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome) associated with extreme infiltration of eosinophils. J Dermatol. 1994;21:341-346.

- Soon CW, Kirsch IR, Connolly AJ, et al. Eosinophil-rich acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis in a patient with enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma, type 1. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:704-708.

To the Editor:

Sweet syndrome (SS), also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is an uncommon inflammatory skin disorder characterized by sudden onset of fever, leukocytosis, neutrophilia, and tender erythematous papules or plaques or both. Skin biopsy usually reveals extensive infiltration of neutrophils into the epidermis and dermis.1-3 Although rare, cases of eosinophil-rich SS have been reported in patients with drug-induced and malignancy-associated SS.4,5 We report a case of a patient with classical SS with dermal eosinophilic infiltration.

An 80-year-old Hispanic man presented with abrupt onset of a rash on the posterior scalp, left ear, back, and hands of 5 days’ duration. The lesions were painful and had progressed to the point of impairing hand grip. The patient’s medical history included a reported common cold the week prior, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension, for which he took metoprolol, simvastatin, aspirin, and clopidogrel. He denied oral lesions and medication changes. He was afebrile and did not experience dietary changes, weight loss, or fatigue. He recently returned from travel to the Dominican Republic.

Physical examination revealed tender, well demarcated, pink to violaceous, pseudovesicular papules and plaques on the palms and dorsal hands (Figure 1), the posterior scalp, left ear, proximal left arm, and back. Pink, juicy, targetoid papules were also found on the scalp, back, and left arm. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy. Laboratory test results revealed an elevated white blood cell count (11,500/µL [reference range, 3800-10,800/µL]), absolute neutrophil count (8073/µL [reference range, 1500–7800/µL]), and eosinophil count (610/µL [reference range, 15–500/µL]). These results indicated leukocytosis with neutrophilia and mild eosinophilia. The patient also was anemic (hemoglobin, 11.5 g/dL [reference range, 13.2–17.1 g/dL]; hematocrit, 35.1% [reference range, 38.5%–50%]). Urine testing revealed altered renal function (serum creatinine, 2.42 mg/dL [reference range, 0.7–1.1 mg/dL]; blood urea nitrogen, 34 mg/dL [reference range, 7–25 mg/dL]; glomerular filtration rate, 4 mL/min/1.73 m2 (reference range, ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2]), suggesting stage 4 chronic kidney disease. Urinalysis showed mild hematuria and proteinuria.

Histopathology of biopsies taken from plaques on the left arm and lower back revealed a dense neutrophilic infiltrate with numerous scattered eosinophils in the dermis. Some neutrophils were intact; others were fragmented without evidence of vasculitis. A subtle subepidermal edema also was noted (Figure 2). A diagnosis of SS was made.

Initial treatment included prednisone (40 mg daily, tapered by 5 mg every 3 days) and erythromycin (500 mg 4 times daily) for 7 days because of suspected Mycoplasma infection. The rash resolved in 1 week. No recurrence was noted during 4 months of follow-up. The white blood cell count returned to within reference range (8400/µL), ruling out the possibility of a smoldering myeloid process.

Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis was first described in a case series of 8 women by Sweet6 in 1964. Patients typically present first with fever, which can precede cutaneous symptoms for days or weeks. Skin lesions generally are asymmetric and located on the face, neck, and upper extremities. Lesions can be described as painful, purple to red papules, plaques, or nodules. Sweet syndrome can present as 3 subtypes based on cause7: (1) classical SS, also known as idiopathic SS, can be preceded by an upper respiratory tract or gastrointestinal tract infection or vaccination, or can be pregnancy associated2; (2) drug-induced SS usually follows use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, or other causative drugs including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, nitrofurantoin, quinolones, oral contraceptives, furosemide, hydralazine, diazepam, clozapine, abacavir, imatinib, bortezomib, azathioprine, and celecoxib2,3,8; and (3) malignancy-associated SS can occur as a paraneoplastic syndrome and generally is associated with hematologic malignancy or a solid tumor.1,9

In our patient, the observed clinical and histological findings were consistent with a diagnosis of SS,2,10 specifically tender erythematous plaques of sudden onset, fast response to systemic corticosteroid therapy, a dermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and leukocytosis greater than 8000/µL with more than 70% neutrophils. He also exhibited targetoid lesions, which have been reported in 7% to 12% of SS patients.10,11

The predominant cells involved in the dermis of SS lesions are mature neutrophils; however, eosinophils have been observed in small numbers within dermal infiltrates in skin lesions of patients with either classical SS or drug-induced dermatosis.2 In 2 studies of cases of SS (N=73 and N=31), eosinophils were reported in 35% and 41% of skin biopsies, respectively.4,5 Nevertheless, cases with dense eosinophilic infiltrates are rare. Furthermore, Masuda et al12 reported a case of eosinophil-rich SS in a 29-year-old woman after treatment of an upper respiratory tract infection with an antibiotic, and Soon et al13 described an eosinophil-rich case of SS in the setting of new-onset enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma.

Our patient was considered to have classical SS because he had an episode of an upper respiratory tract infection 1 week prior to onset of clinical manifestations. The histologic finding of numerous eosinophils in our case was unusual for idiopathic SS. This finding might suggest a drug hypersensitivity reaction, but the lack of any change in the patient’s long-term medication list and the lack of any other episodes made a diagnosis of drug-induced SS less likely in our patient.

Eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy is a rare cutaneous condition in which nodules, pruritic papules, and vesicles arise in patients with a hematologic malignancy, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia and mantle cell lymphoma,13 in which a deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and numerous eosinophils are observed. Malignancy was ruled out in our patient because of the lack of characteristic abnormalities in blood testing, the fast response to corticosteroid therapy, and the lack of recurrence posttreatment or additional systemic concerns.

The typical pathology findings of SS consist of mature neutrophils found in the dermis without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Eosinophil-rich infiltration, however rare, has been reported in SS. This report highlights a case of classical SS with a particularly dense eosinophilic infiltrate, which could be mistaken for other eosinophilic dermatoses. Dermatologists should be aware of the possibility of marked eosinophilic infiltration in all subtypes of this disorder.

To the Editor:

Sweet syndrome (SS), also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is an uncommon inflammatory skin disorder characterized by sudden onset of fever, leukocytosis, neutrophilia, and tender erythematous papules or plaques or both. Skin biopsy usually reveals extensive infiltration of neutrophils into the epidermis and dermis.1-3 Although rare, cases of eosinophil-rich SS have been reported in patients with drug-induced and malignancy-associated SS.4,5 We report a case of a patient with classical SS with dermal eosinophilic infiltration.

An 80-year-old Hispanic man presented with abrupt onset of a rash on the posterior scalp, left ear, back, and hands of 5 days’ duration. The lesions were painful and had progressed to the point of impairing hand grip. The patient’s medical history included a reported common cold the week prior, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension, for which he took metoprolol, simvastatin, aspirin, and clopidogrel. He denied oral lesions and medication changes. He was afebrile and did not experience dietary changes, weight loss, or fatigue. He recently returned from travel to the Dominican Republic.

Physical examination revealed tender, well demarcated, pink to violaceous, pseudovesicular papules and plaques on the palms and dorsal hands (Figure 1), the posterior scalp, left ear, proximal left arm, and back. Pink, juicy, targetoid papules were also found on the scalp, back, and left arm. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy. Laboratory test results revealed an elevated white blood cell count (11,500/µL [reference range, 3800-10,800/µL]), absolute neutrophil count (8073/µL [reference range, 1500–7800/µL]), and eosinophil count (610/µL [reference range, 15–500/µL]). These results indicated leukocytosis with neutrophilia and mild eosinophilia. The patient also was anemic (hemoglobin, 11.5 g/dL [reference range, 13.2–17.1 g/dL]; hematocrit, 35.1% [reference range, 38.5%–50%]). Urine testing revealed altered renal function (serum creatinine, 2.42 mg/dL [reference range, 0.7–1.1 mg/dL]; blood urea nitrogen, 34 mg/dL [reference range, 7–25 mg/dL]; glomerular filtration rate, 4 mL/min/1.73 m2 (reference range, ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2]), suggesting stage 4 chronic kidney disease. Urinalysis showed mild hematuria and proteinuria.

Histopathology of biopsies taken from plaques on the left arm and lower back revealed a dense neutrophilic infiltrate with numerous scattered eosinophils in the dermis. Some neutrophils were intact; others were fragmented without evidence of vasculitis. A subtle subepidermal edema also was noted (Figure 2). A diagnosis of SS was made.

Initial treatment included prednisone (40 mg daily, tapered by 5 mg every 3 days) and erythromycin (500 mg 4 times daily) for 7 days because of suspected Mycoplasma infection. The rash resolved in 1 week. No recurrence was noted during 4 months of follow-up. The white blood cell count returned to within reference range (8400/µL), ruling out the possibility of a smoldering myeloid process.

Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis was first described in a case series of 8 women by Sweet6 in 1964. Patients typically present first with fever, which can precede cutaneous symptoms for days or weeks. Skin lesions generally are asymmetric and located on the face, neck, and upper extremities. Lesions can be described as painful, purple to red papules, plaques, or nodules. Sweet syndrome can present as 3 subtypes based on cause7: (1) classical SS, also known as idiopathic SS, can be preceded by an upper respiratory tract or gastrointestinal tract infection or vaccination, or can be pregnancy associated2; (2) drug-induced SS usually follows use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, or other causative drugs including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, nitrofurantoin, quinolones, oral contraceptives, furosemide, hydralazine, diazepam, clozapine, abacavir, imatinib, bortezomib, azathioprine, and celecoxib2,3,8; and (3) malignancy-associated SS can occur as a paraneoplastic syndrome and generally is associated with hematologic malignancy or a solid tumor.1,9

In our patient, the observed clinical and histological findings were consistent with a diagnosis of SS,2,10 specifically tender erythematous plaques of sudden onset, fast response to systemic corticosteroid therapy, a dermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and leukocytosis greater than 8000/µL with more than 70% neutrophils. He also exhibited targetoid lesions, which have been reported in 7% to 12% of SS patients.10,11

The predominant cells involved in the dermis of SS lesions are mature neutrophils; however, eosinophils have been observed in small numbers within dermal infiltrates in skin lesions of patients with either classical SS or drug-induced dermatosis.2 In 2 studies of cases of SS (N=73 and N=31), eosinophils were reported in 35% and 41% of skin biopsies, respectively.4,5 Nevertheless, cases with dense eosinophilic infiltrates are rare. Furthermore, Masuda et al12 reported a case of eosinophil-rich SS in a 29-year-old woman after treatment of an upper respiratory tract infection with an antibiotic, and Soon et al13 described an eosinophil-rich case of SS in the setting of new-onset enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma.

Our patient was considered to have classical SS because he had an episode of an upper respiratory tract infection 1 week prior to onset of clinical manifestations. The histologic finding of numerous eosinophils in our case was unusual for idiopathic SS. This finding might suggest a drug hypersensitivity reaction, but the lack of any change in the patient’s long-term medication list and the lack of any other episodes made a diagnosis of drug-induced SS less likely in our patient.

Eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy is a rare cutaneous condition in which nodules, pruritic papules, and vesicles arise in patients with a hematologic malignancy, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia and mantle cell lymphoma,13 in which a deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and numerous eosinophils are observed. Malignancy was ruled out in our patient because of the lack of characteristic abnormalities in blood testing, the fast response to corticosteroid therapy, and the lack of recurrence posttreatment or additional systemic concerns.

The typical pathology findings of SS consist of mature neutrophils found in the dermis without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Eosinophil-rich infiltration, however rare, has been reported in SS. This report highlights a case of classical SS with a particularly dense eosinophilic infiltrate, which could be mistaken for other eosinophilic dermatoses. Dermatologists should be aware of the possibility of marked eosinophilic infiltration in all subtypes of this disorder.

- Herbert-Cohen D, Jour G, Saul T. Sweet’s syndrome. J Emerg Med. 2015;49:e95-e97.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Villarreal-Villarreal CD, Ocampo-Candiani J, Villarreal-Martínez A. Sweet syndrome: a review and update. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:369-378.

- Rochael MC, Pantaleão L, Vilar EA, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: study of 73 cases, emphasizing histopathological findings. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:702-707.

- Ratzinger G, Burgdorf W, Zelger BG, et al. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: a histopathologic study of 31 cases with review of literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:125-133.

- Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: a review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:761-778.

- Polimeni G, Cardillo R, Garaffo E, et al. Allopurinol-induced Sweet’s syndrome. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2016;29:329-332.

- Paydas S. Sweet’s syndrome: a revisit for hematologists and oncologists. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;86:85-95.

- Amouri M, Masmoudi A, Ammar M, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: a retrospective study of 90 cases from a tertiary care center. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1033-1039.

- Marcoval J, Martín-Callizo C, Valentí-Medina F, et al. Sweet syndrome: long-term follow-up of 138 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:741-746.

- Masuda T, Abe Y, Arata J, et al. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome) associated with extreme infiltration of eosinophils. J Dermatol. 1994;21:341-346.

- Soon CW, Kirsch IR, Connolly AJ, et al. Eosinophil-rich acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis in a patient with enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma, type 1. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:704-708.

- Herbert-Cohen D, Jour G, Saul T. Sweet’s syndrome. J Emerg Med. 2015;49:e95-e97.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Villarreal-Villarreal CD, Ocampo-Candiani J, Villarreal-Martínez A. Sweet syndrome: a review and update. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:369-378.

- Rochael MC, Pantaleão L, Vilar EA, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: study of 73 cases, emphasizing histopathological findings. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:702-707.

- Ratzinger G, Burgdorf W, Zelger BG, et al. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: a histopathologic study of 31 cases with review of literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:125-133.

- Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: a review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:761-778.

- Polimeni G, Cardillo R, Garaffo E, et al. Allopurinol-induced Sweet’s syndrome. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2016;29:329-332.

- Paydas S. Sweet’s syndrome: a revisit for hematologists and oncologists. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;86:85-95.

- Amouri M, Masmoudi A, Ammar M, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: a retrospective study of 90 cases from a tertiary care center. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1033-1039.

- Marcoval J, Martín-Callizo C, Valentí-Medina F, et al. Sweet syndrome: long-term follow-up of 138 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:741-746.

- Masuda T, Abe Y, Arata J, et al. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome) associated with extreme infiltration of eosinophils. J Dermatol. 1994;21:341-346.

- Soon CW, Kirsch IR, Connolly AJ, et al. Eosinophil-rich acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis in a patient with enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma, type 1. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:704-708.

Practice Points

- This report highlights a case of classical Sweet syndrome (SS) with a particularly dense eosinophilic infiltrate, which could be mistaken for other eosinophilic dermatoses.

- Dermatologists should be aware of the possibility of marked eosinophilic infiltration in all subtypes of SS.

Solitary Papule on the Shoulder

The Diagnosis: Dermatofibroma With Sebaceous Induction

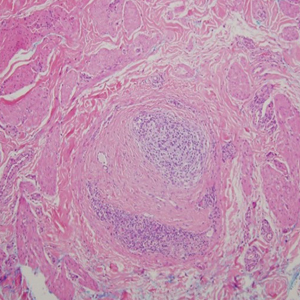

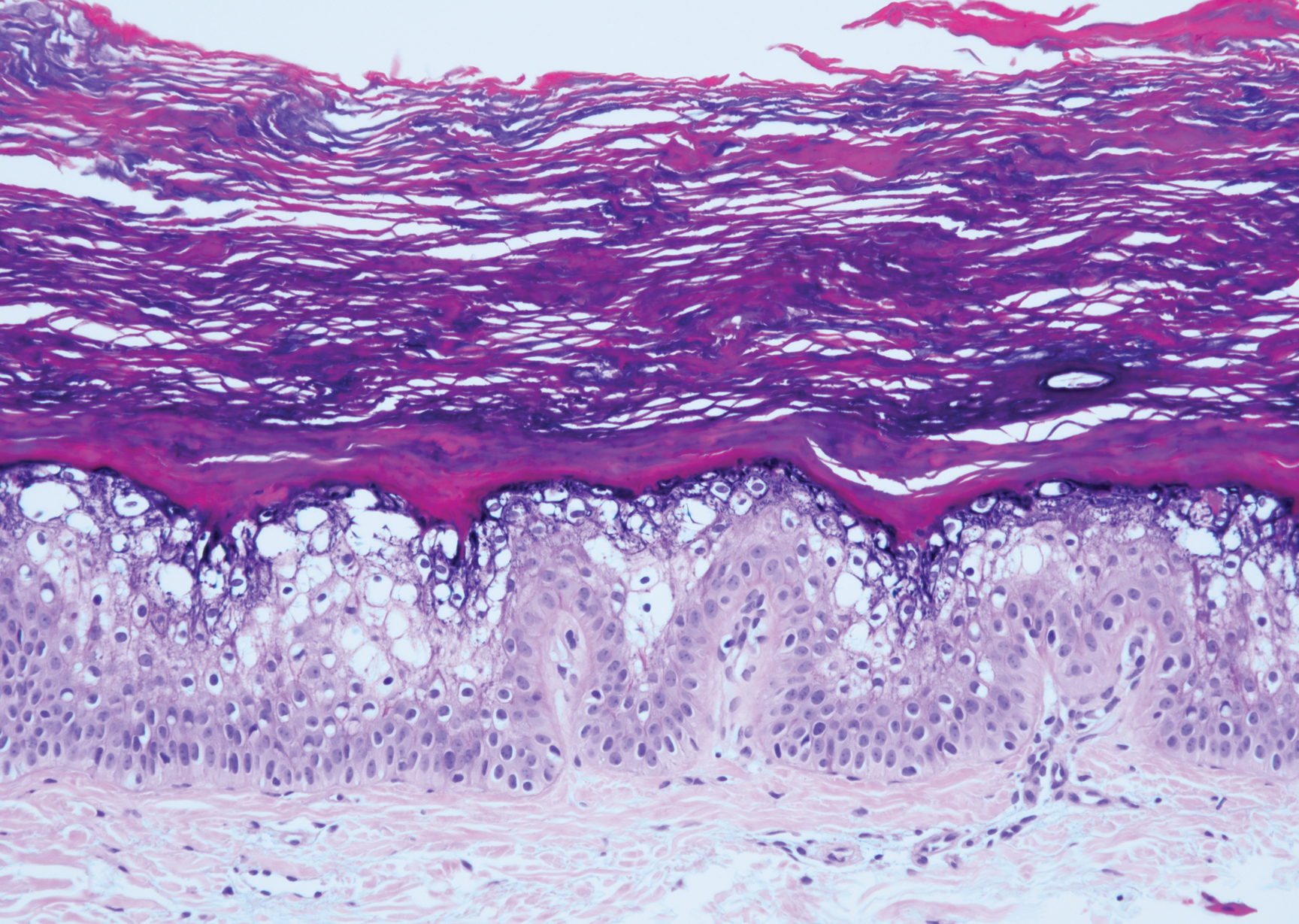

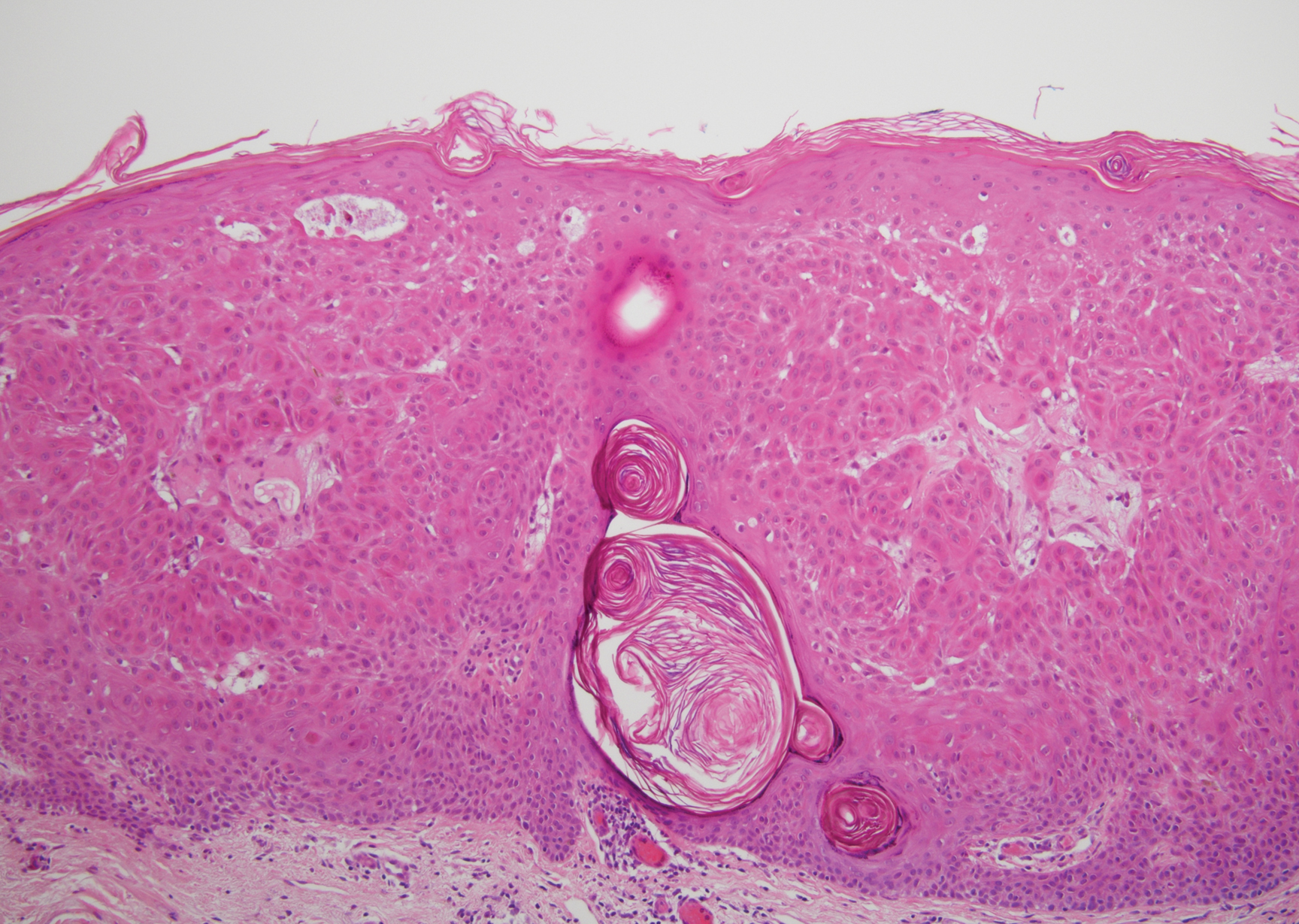

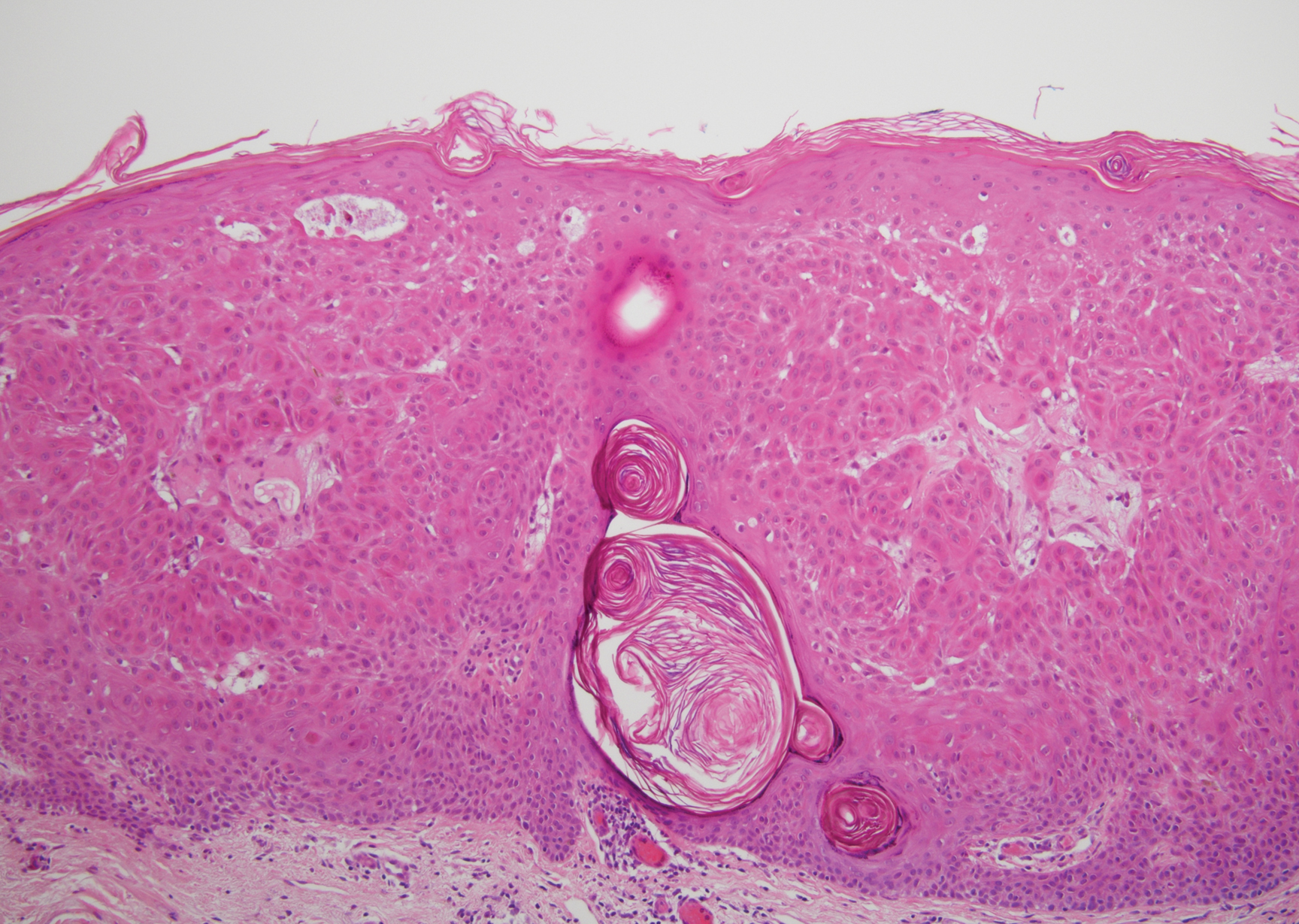

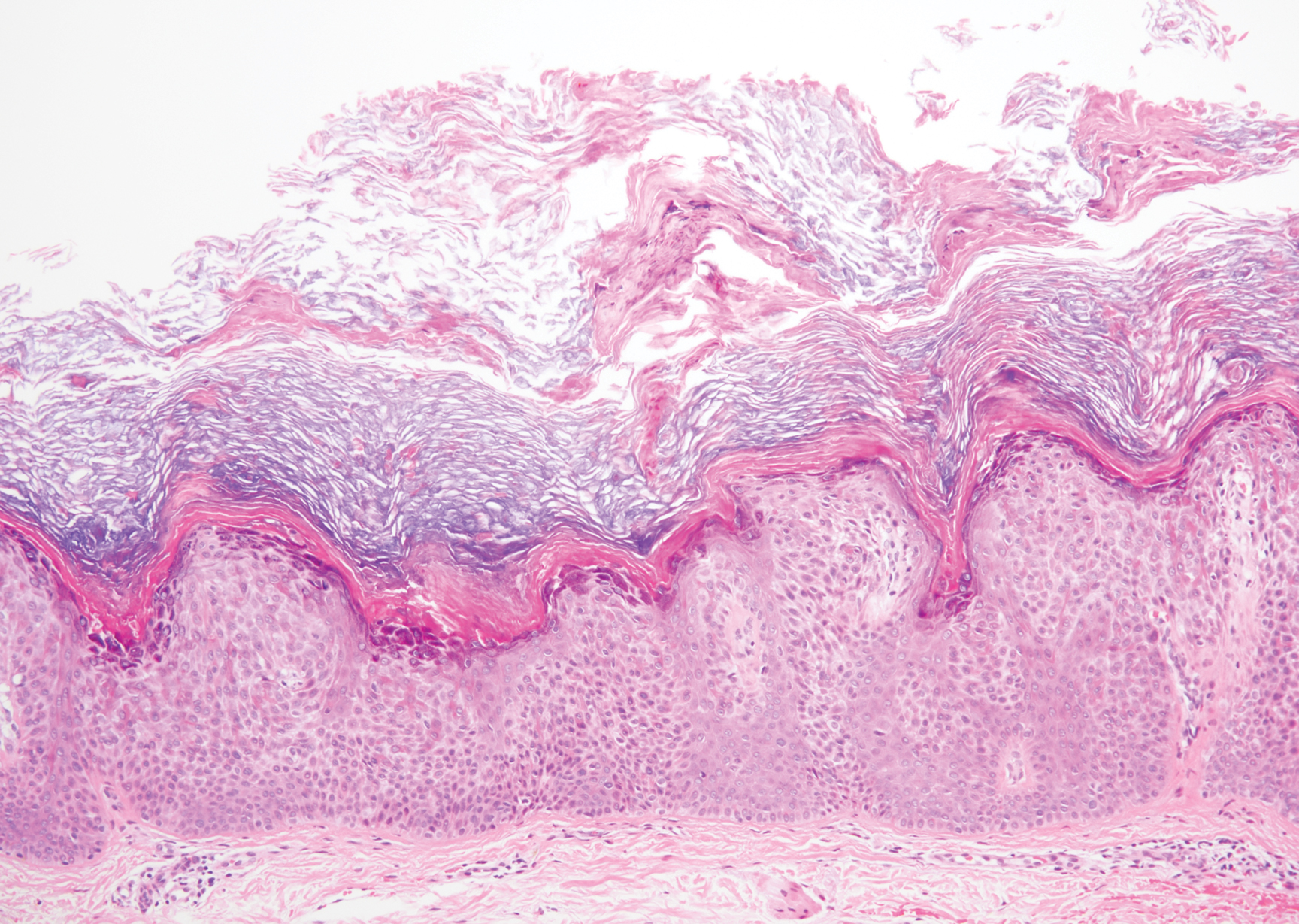

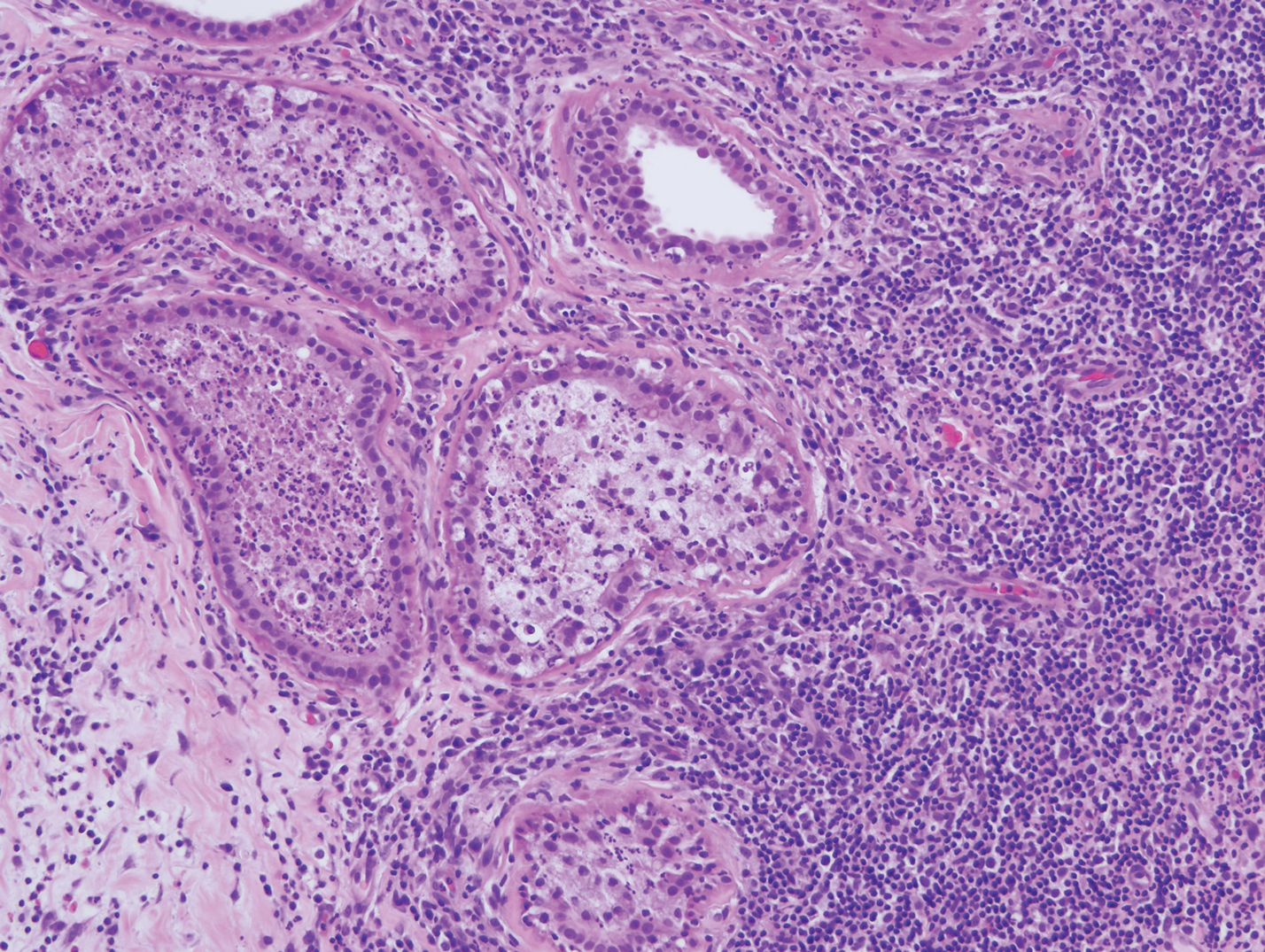

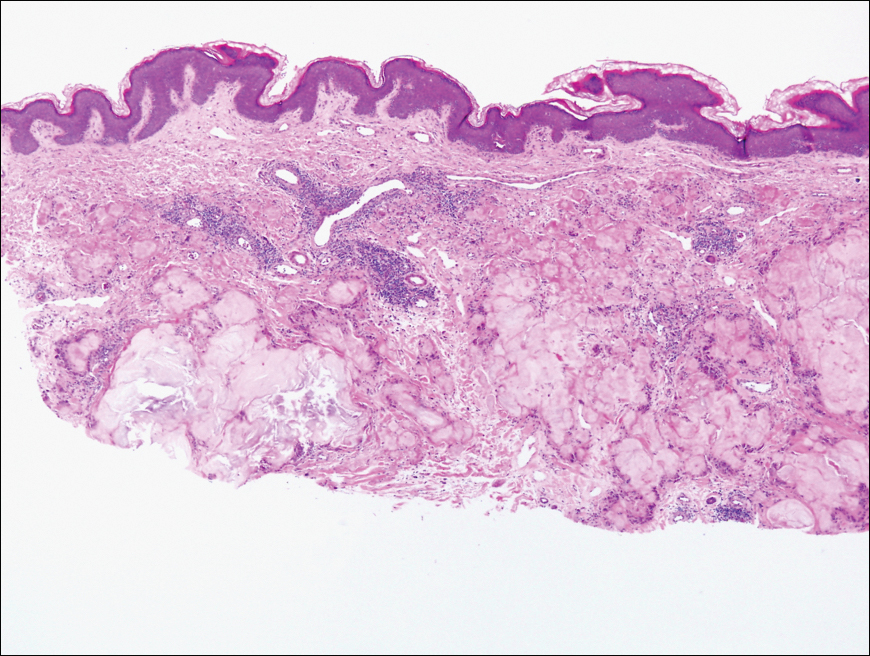

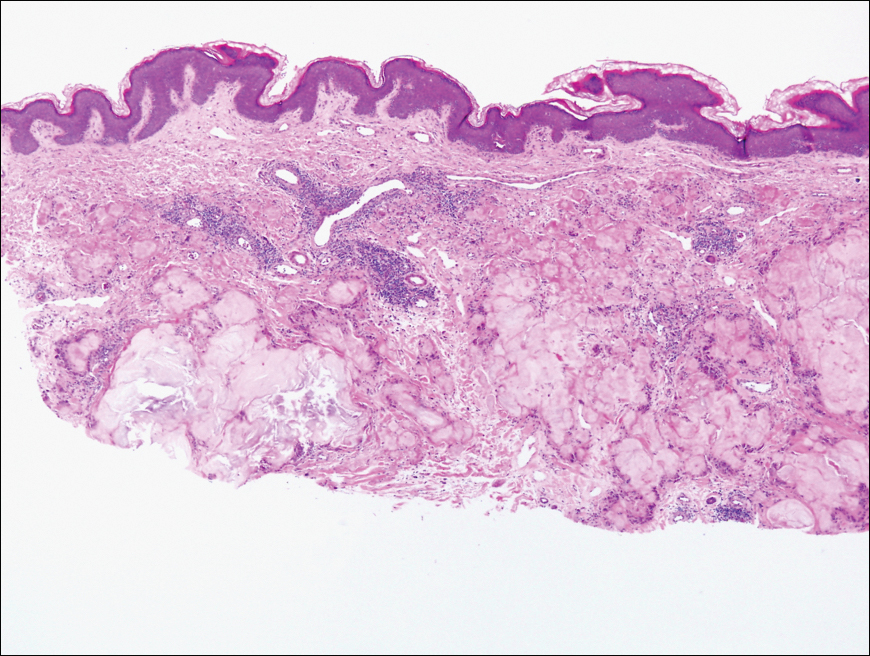

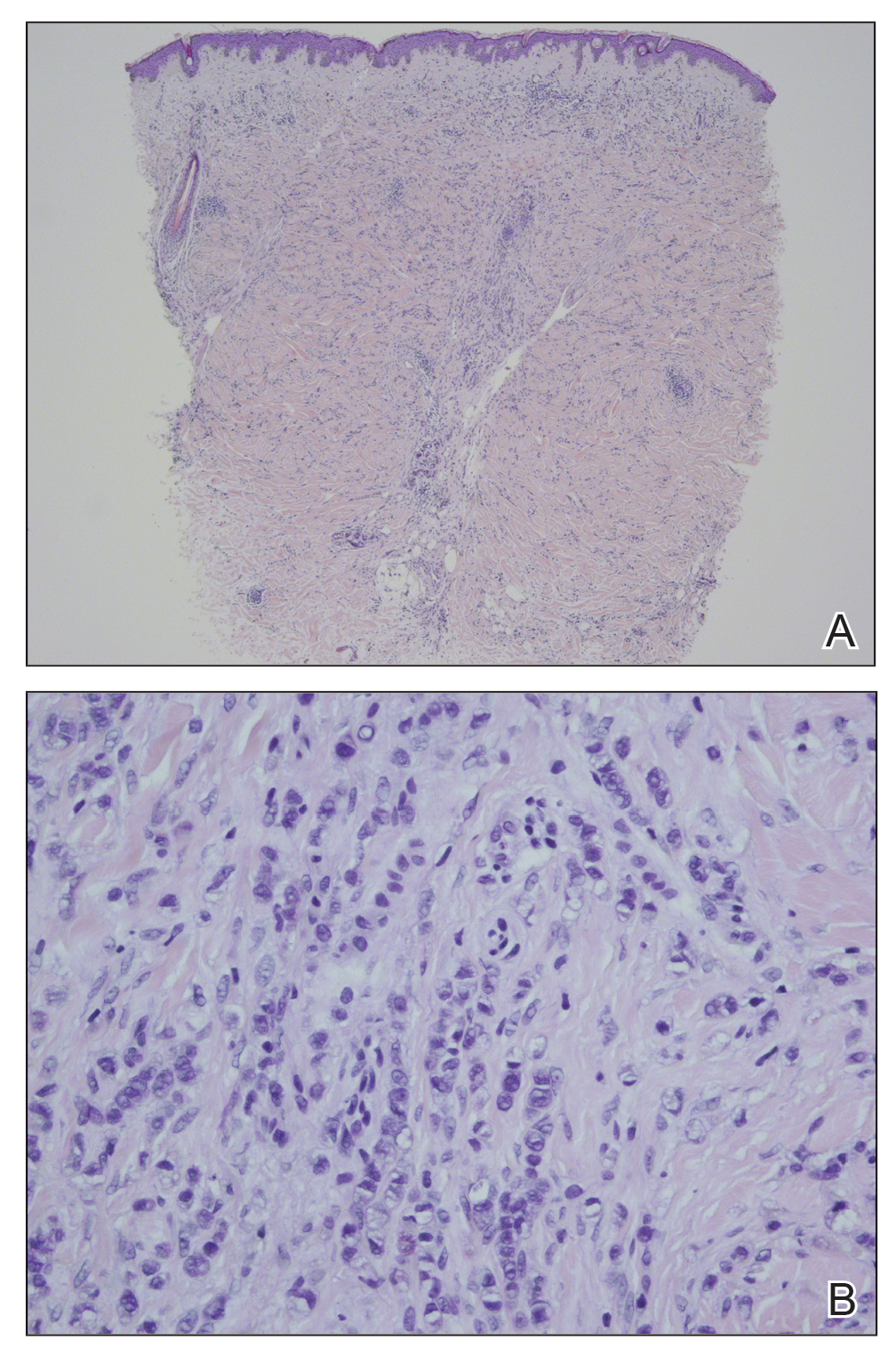

The biopsy of the lesion revealed a fibrohistiocytic dermal pattern with overlying benign epidermal and sebaceous hyperplasia with a proliferation of fibroblasts in the dermis. Other sections revealed hyperplastic sebaceous glands of the superficial and mid dermis. These findings were suggestive of a dermatofibroma (DF) that had induced epidermal and sebaceous hyperplasia.

Dermatofibromas are common benign fibrous soft tissue growths that account for approximately 3% of dermatopathology specimens.1 The etiology of DFs is unknown; however, they are thought to arise from sites of prior trauma or arthropod bites. Multiple or eruptive DFs have been reported in patients with lupus and atopic dermatitis.2 They commonly appear as round firm nodules measuring less than 1 cm in diameter on the extremities of young adults. Eruptive dermatofibromas also have been reported in human immunodeficiency virus-positive and immunosuppressed patients.3,4 On physical examination, gently pinching the lesion causes a downward movement known as the "dimple sign." If left undisturbed, DFs persist but may undergo partial regression, especially in the center; they also may be excised if symptomatic.

The clinical differential for this papule included a scar and sebaceous hyperplasia. The lack of history of skin cancer or prior procedure made a scar less likely. Sebaceous glands are less prominent on the shoulders, making sebaceous hyperplasia less likely, though dermoscopy showed pale yellow lobules. Sebaceous adenomas most commonly are seen on the head or neck and present as a flesh-colored papule. Sebaceous induction by DFs is rare but has been reported in the literature.5,6

The histology of DFs is described as a nodular proliferation of spindle-shaped fibroblasts and myofibroblasts with short intersecting fascicles. A predilection for sebaceous induction from an underlying DF on the shoulder has been reported.5 Sebaceous differentiation has been reported in 16% to 31.6% of DFs.5,6 Seborrheic keratosis-like epidermal hyperplasia frequently has been seen in DFs with sebaceous induction in comparison to DFs without sebaceous induction.5 Immunohistochemical stains are important to help differentiate DF from dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, especially when approaching the subcutis. Dermatofibromas stain positive for factor XIIIa and negative for CD34, whereas dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans stain negative for factor XIIIa and positive for CD34.7 Dermatofibromas also demonstrate positive immunostaining for vimentin, stromelysin 3,8 muscle-specific actin, and CD68.

- Rahbari H, Mehregan AH. Adnexal displacement and regression in association with histiocytoma (dermatofibroma). J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:94-102.

- Yazici AC, Baz K, Ikizoglu G, et al. Familial eruptive dermatofibromas in atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:90-92.

- Kanitakis J, Carbonnel E, Delmonte S, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient with HIV infection: case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:54-56.

- Zaccaria E, Rebora A, Rongioletti F. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas and immunosuppression: report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:723-727.

- Zeidi M, North JP. Sebaceous induction in dermatofibroma: a common feature of dermatofibromas on the shoulder. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:400-405.

- Shuweiter M, Böer A. Spectrum of follicular and sebaceous differentiation induced by dermatofibroma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:778.

- Abenoza P, Lillemoe T. CD34 and factor XIIIa in the differential diagnosis of dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:429-434.

- Kim HJ, Lee JY, Kim SH, et al. Stromelysin-3 expression in the differential diagnosis of dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: comparison with factor XIIIa and CD34. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:319-324.

The Diagnosis: Dermatofibroma With Sebaceous Induction

The biopsy of the lesion revealed a fibrohistiocytic dermal pattern with overlying benign epidermal and sebaceous hyperplasia with a proliferation of fibroblasts in the dermis. Other sections revealed hyperplastic sebaceous glands of the superficial and mid dermis. These findings were suggestive of a dermatofibroma (DF) that had induced epidermal and sebaceous hyperplasia.

Dermatofibromas are common benign fibrous soft tissue growths that account for approximately 3% of dermatopathology specimens.1 The etiology of DFs is unknown; however, they are thought to arise from sites of prior trauma or arthropod bites. Multiple or eruptive DFs have been reported in patients with lupus and atopic dermatitis.2 They commonly appear as round firm nodules measuring less than 1 cm in diameter on the extremities of young adults. Eruptive dermatofibromas also have been reported in human immunodeficiency virus-positive and immunosuppressed patients.3,4 On physical examination, gently pinching the lesion causes a downward movement known as the "dimple sign." If left undisturbed, DFs persist but may undergo partial regression, especially in the center; they also may be excised if symptomatic.

The clinical differential for this papule included a scar and sebaceous hyperplasia. The lack of history of skin cancer or prior procedure made a scar less likely. Sebaceous glands are less prominent on the shoulders, making sebaceous hyperplasia less likely, though dermoscopy showed pale yellow lobules. Sebaceous adenomas most commonly are seen on the head or neck and present as a flesh-colored papule. Sebaceous induction by DFs is rare but has been reported in the literature.5,6

The histology of DFs is described as a nodular proliferation of spindle-shaped fibroblasts and myofibroblasts with short intersecting fascicles. A predilection for sebaceous induction from an underlying DF on the shoulder has been reported.5 Sebaceous differentiation has been reported in 16% to 31.6% of DFs.5,6 Seborrheic keratosis-like epidermal hyperplasia frequently has been seen in DFs with sebaceous induction in comparison to DFs without sebaceous induction.5 Immunohistochemical stains are important to help differentiate DF from dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, especially when approaching the subcutis. Dermatofibromas stain positive for factor XIIIa and negative for CD34, whereas dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans stain negative for factor XIIIa and positive for CD34.7 Dermatofibromas also demonstrate positive immunostaining for vimentin, stromelysin 3,8 muscle-specific actin, and CD68.

The Diagnosis: Dermatofibroma With Sebaceous Induction

The biopsy of the lesion revealed a fibrohistiocytic dermal pattern with overlying benign epidermal and sebaceous hyperplasia with a proliferation of fibroblasts in the dermis. Other sections revealed hyperplastic sebaceous glands of the superficial and mid dermis. These findings were suggestive of a dermatofibroma (DF) that had induced epidermal and sebaceous hyperplasia.

Dermatofibromas are common benign fibrous soft tissue growths that account for approximately 3% of dermatopathology specimens.1 The etiology of DFs is unknown; however, they are thought to arise from sites of prior trauma or arthropod bites. Multiple or eruptive DFs have been reported in patients with lupus and atopic dermatitis.2 They commonly appear as round firm nodules measuring less than 1 cm in diameter on the extremities of young adults. Eruptive dermatofibromas also have been reported in human immunodeficiency virus-positive and immunosuppressed patients.3,4 On physical examination, gently pinching the lesion causes a downward movement known as the "dimple sign." If left undisturbed, DFs persist but may undergo partial regression, especially in the center; they also may be excised if symptomatic.

The clinical differential for this papule included a scar and sebaceous hyperplasia. The lack of history of skin cancer or prior procedure made a scar less likely. Sebaceous glands are less prominent on the shoulders, making sebaceous hyperplasia less likely, though dermoscopy showed pale yellow lobules. Sebaceous adenomas most commonly are seen on the head or neck and present as a flesh-colored papule. Sebaceous induction by DFs is rare but has been reported in the literature.5,6

The histology of DFs is described as a nodular proliferation of spindle-shaped fibroblasts and myofibroblasts with short intersecting fascicles. A predilection for sebaceous induction from an underlying DF on the shoulder has been reported.5 Sebaceous differentiation has been reported in 16% to 31.6% of DFs.5,6 Seborrheic keratosis-like epidermal hyperplasia frequently has been seen in DFs with sebaceous induction in comparison to DFs without sebaceous induction.5 Immunohistochemical stains are important to help differentiate DF from dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, especially when approaching the subcutis. Dermatofibromas stain positive for factor XIIIa and negative for CD34, whereas dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans stain negative for factor XIIIa and positive for CD34.7 Dermatofibromas also demonstrate positive immunostaining for vimentin, stromelysin 3,8 muscle-specific actin, and CD68.

- Rahbari H, Mehregan AH. Adnexal displacement and regression in association with histiocytoma (dermatofibroma). J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:94-102.

- Yazici AC, Baz K, Ikizoglu G, et al. Familial eruptive dermatofibromas in atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:90-92.

- Kanitakis J, Carbonnel E, Delmonte S, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient with HIV infection: case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:54-56.

- Zaccaria E, Rebora A, Rongioletti F. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas and immunosuppression: report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:723-727.

- Zeidi M, North JP. Sebaceous induction in dermatofibroma: a common feature of dermatofibromas on the shoulder. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:400-405.

- Shuweiter M, Böer A. Spectrum of follicular and sebaceous differentiation induced by dermatofibroma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:778.

- Abenoza P, Lillemoe T. CD34 and factor XIIIa in the differential diagnosis of dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:429-434.

- Kim HJ, Lee JY, Kim SH, et al. Stromelysin-3 expression in the differential diagnosis of dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: comparison with factor XIIIa and CD34. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:319-324.

- Rahbari H, Mehregan AH. Adnexal displacement and regression in association with histiocytoma (dermatofibroma). J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:94-102.

- Yazici AC, Baz K, Ikizoglu G, et al. Familial eruptive dermatofibromas in atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:90-92.

- Kanitakis J, Carbonnel E, Delmonte S, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient with HIV infection: case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:54-56.

- Zaccaria E, Rebora A, Rongioletti F. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas and immunosuppression: report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:723-727.

- Zeidi M, North JP. Sebaceous induction in dermatofibroma: a common feature of dermatofibromas on the shoulder. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:400-405.

- Shuweiter M, Böer A. Spectrum of follicular and sebaceous differentiation induced by dermatofibroma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:778.

- Abenoza P, Lillemoe T. CD34 and factor XIIIa in the differential diagnosis of dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:429-434.

- Kim HJ, Lee JY, Kim SH, et al. Stromelysin-3 expression in the differential diagnosis of dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: comparison with factor XIIIa and CD34. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:319-324.

A 64-year-old man presented to dermatology for a full-body skin examination. He had no history of skin cancer. Physical examination revealed an asymptomatic, 4-mm, yellowish pink papule on the left posterior shoulder (top). Dermoscopy revealed yellow globules (bottom). The patient was unsure of the duration of the lesion and denied any prior trauma or medical procedure to the area. Subsequently, a shave biopsy was performed.

Keratotic Papule on the Abdomen

The Diagnosis: Hypergranulotic Dyscornification

Hypergranulotic dyscornification (HD) is a rarely reported reaction pattern present in benign solitary keratoses with only few reports to date. It may be an underrecognized reaction pattern based on the paucity of reported cases as well as the histologic similarities to other entities. It has been hypothesized that this pattern reflects an underlying keratin mutation or disorder of keratinization.1

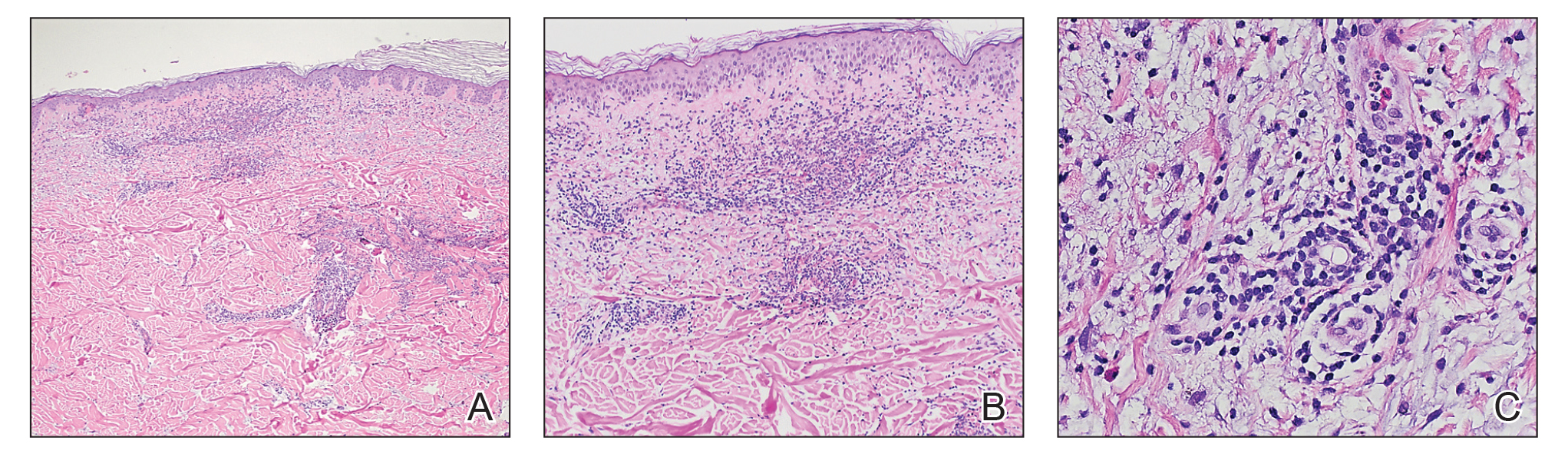

Clinically, HD most commonly presents as a waxy, tan-colored, solitary keratosis generally found on the lower limbs, trunk, or back in individuals aged 20 to 60 years.1,2 Histopathology shows marked hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and clumped basophilic keratohyalin granules within the corneocytes with digitated epidermal hyperplasia. There is abnormal cornification across the entire lesion with papillomatosis and marked hypergranulosis.3 There often are homogeneous orthokeratotic mounds of large, dull, eosinophilic-staining anucleate keratinocytes that are sharply demarcated from the thickened granular layer.1,2 Within the spinous, granular, and corneal layers, there is a pale, gray-staining, basophilic, cytoplasmic substance intercellularly.1

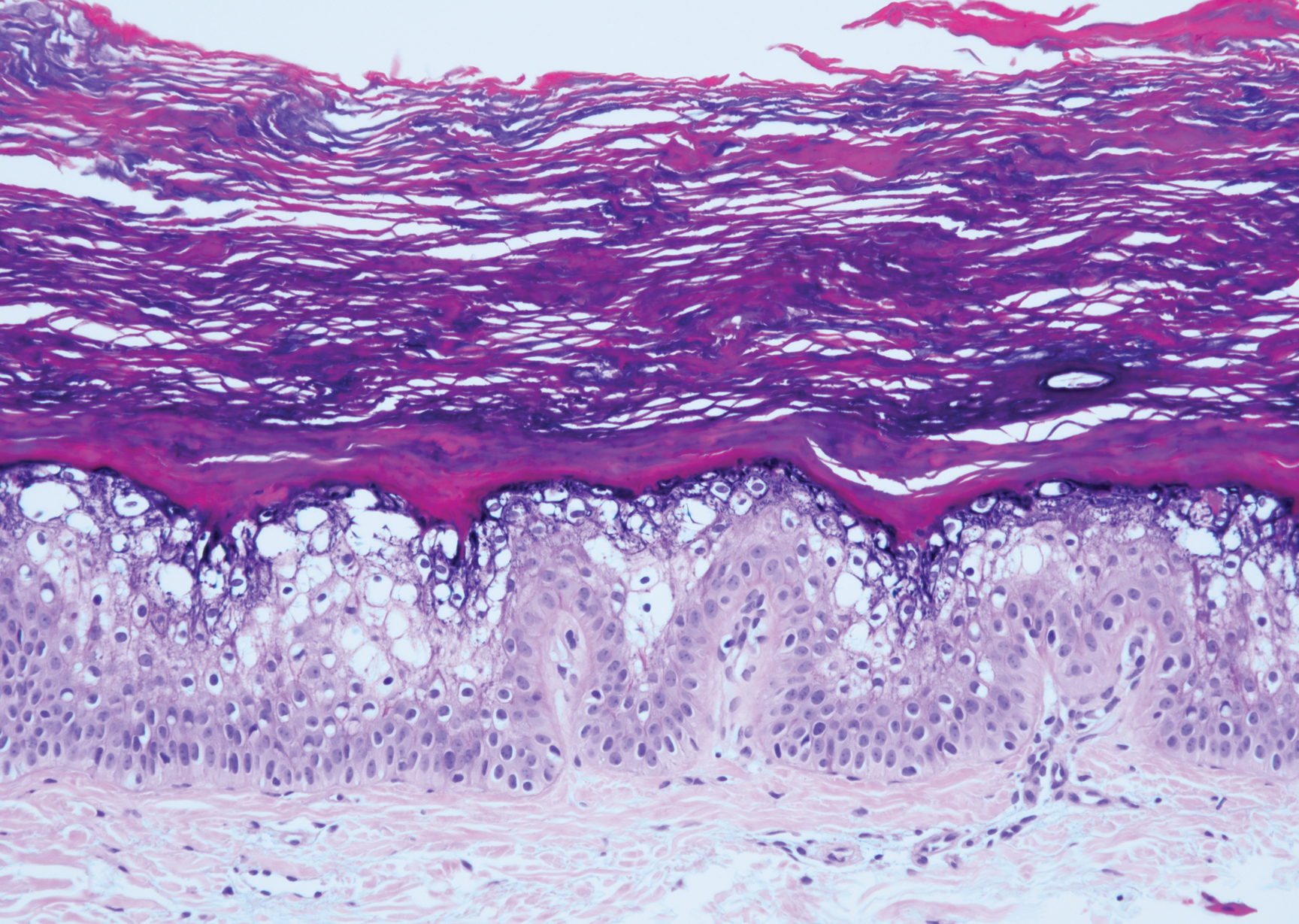

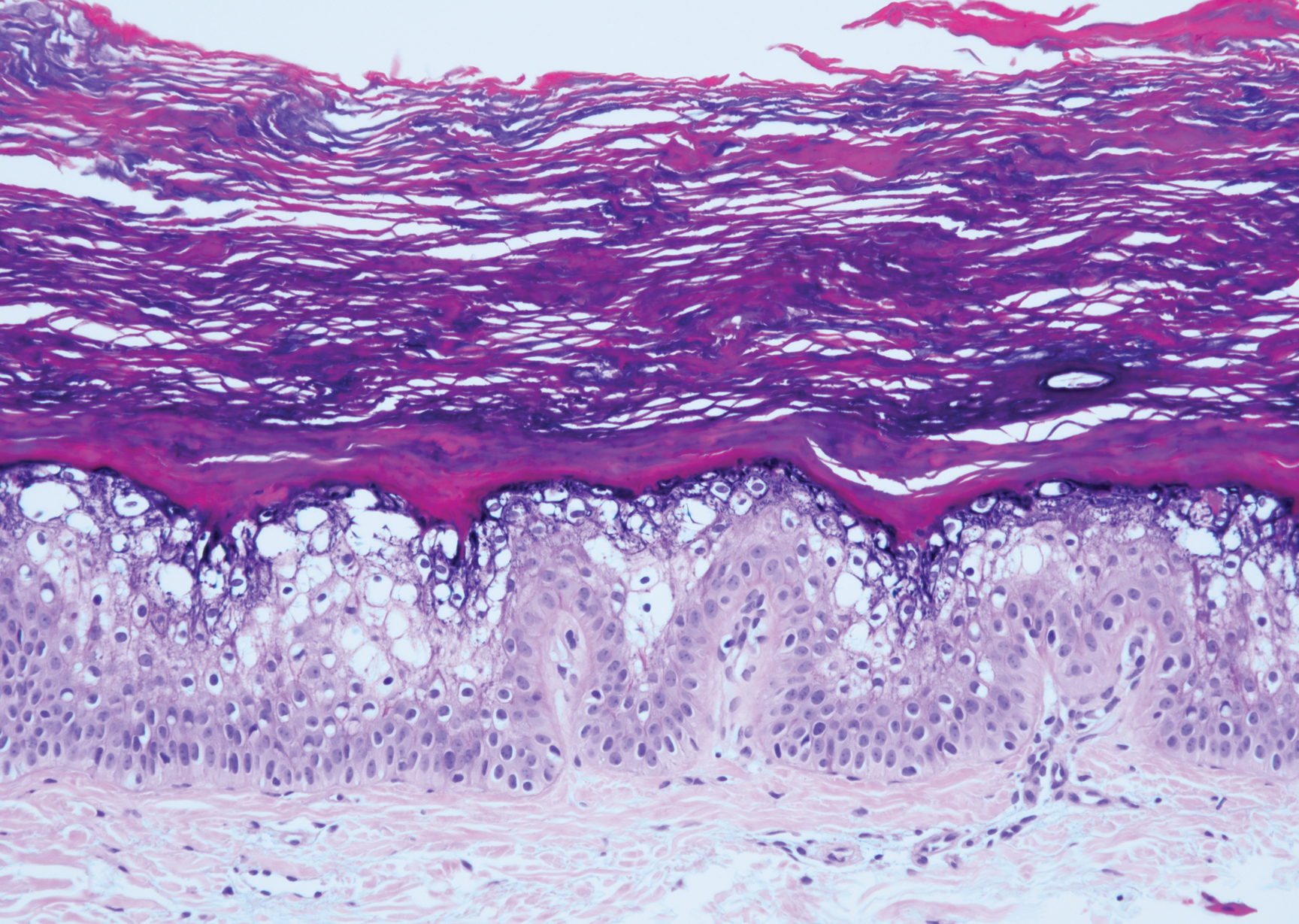

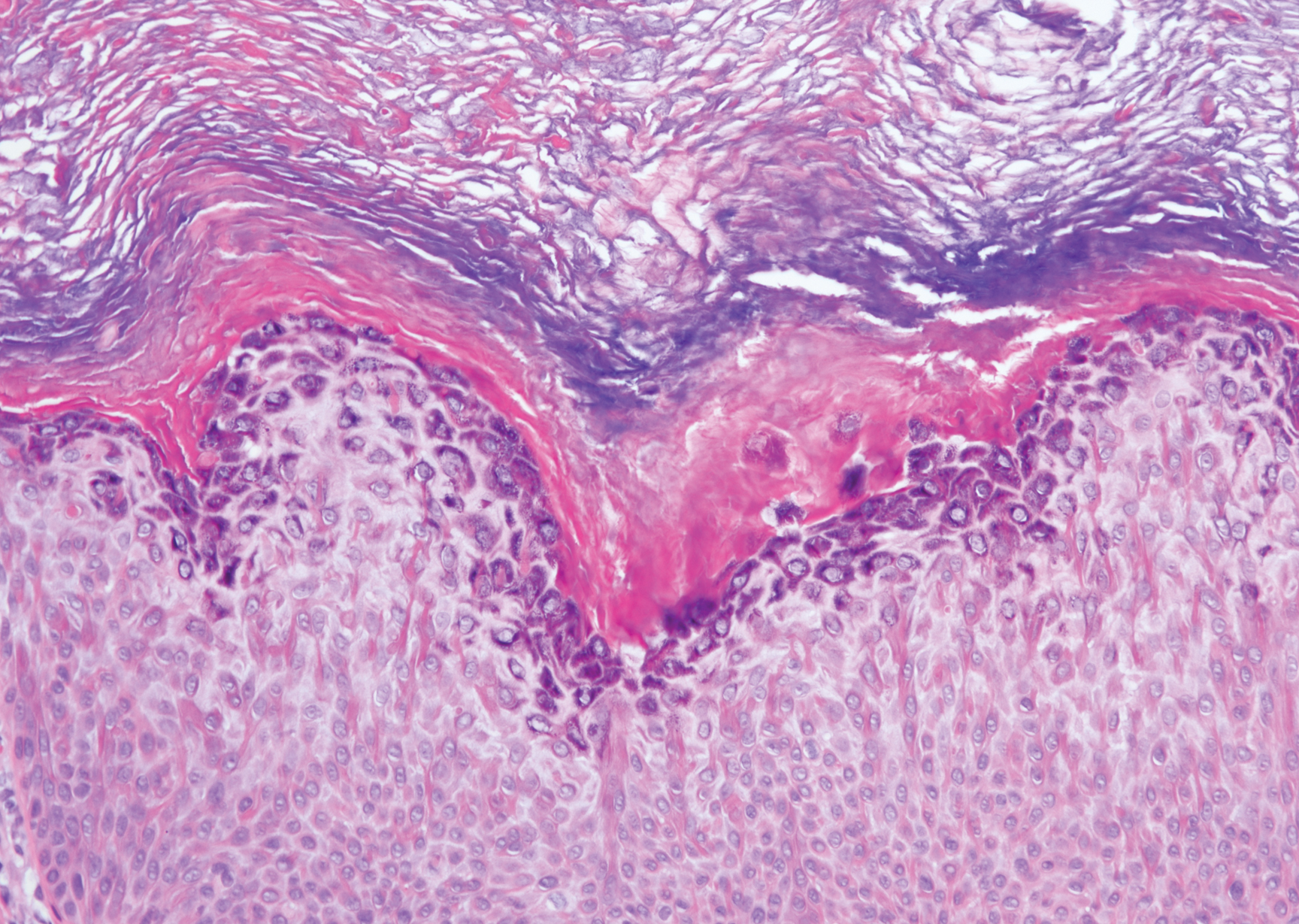

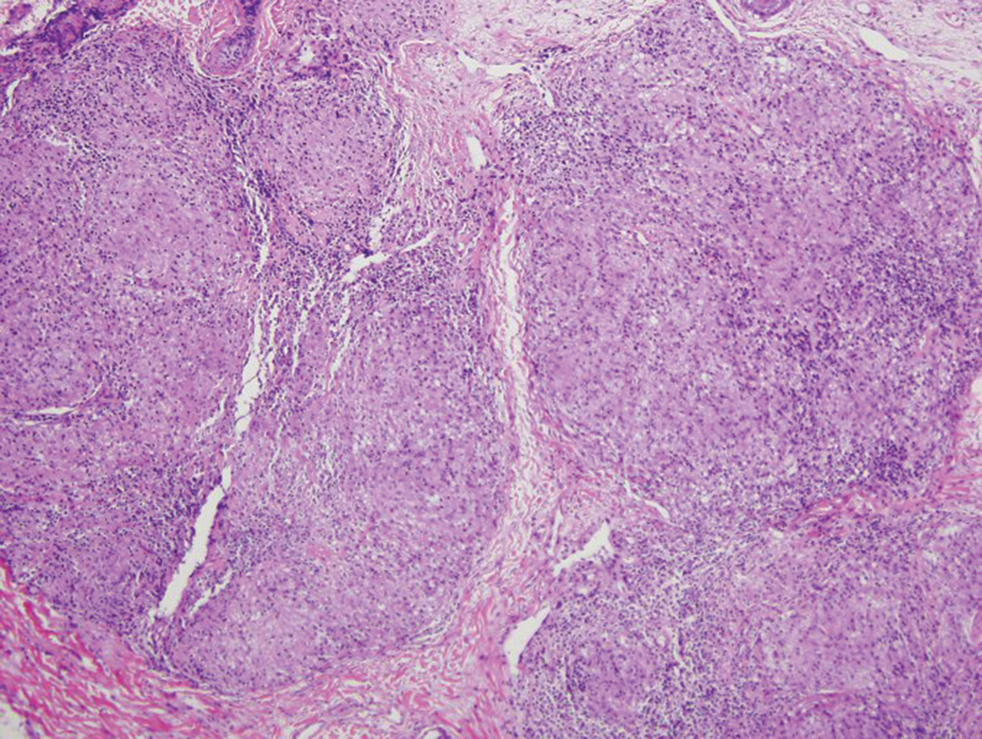

Histopathologically, HD may be mistaken for several other entities both benign and malignant.1 Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis can be a genetic disorder, an incidental finding in a variety of skin conditions, or an isolated lesion.4 The genetic syndrome, caused by mutation in keratins 1 or 10, clinically presents with hyperkeratosis, erosions, blisters, and thickening of the epidermis, often with a corrugated appearance. Epidermal nevi findings often are seen in conjunction with histologic changes of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis caused by mutation. Solitary lesions also can resemble seborrheic keratosis or verruca. In all examples of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, the histopathologic findings are identical.4 The granular layer is thickened, and coarse keratohyalin granules aggregate in the suprabasal cells.5 There is acantholysis with perinuclear vacuolization in the spinous and granular layers with characteristic pale cytoplasmic areas devoid of keratin filaments (Figure 1). The basal layer may be hyperproliferative.5

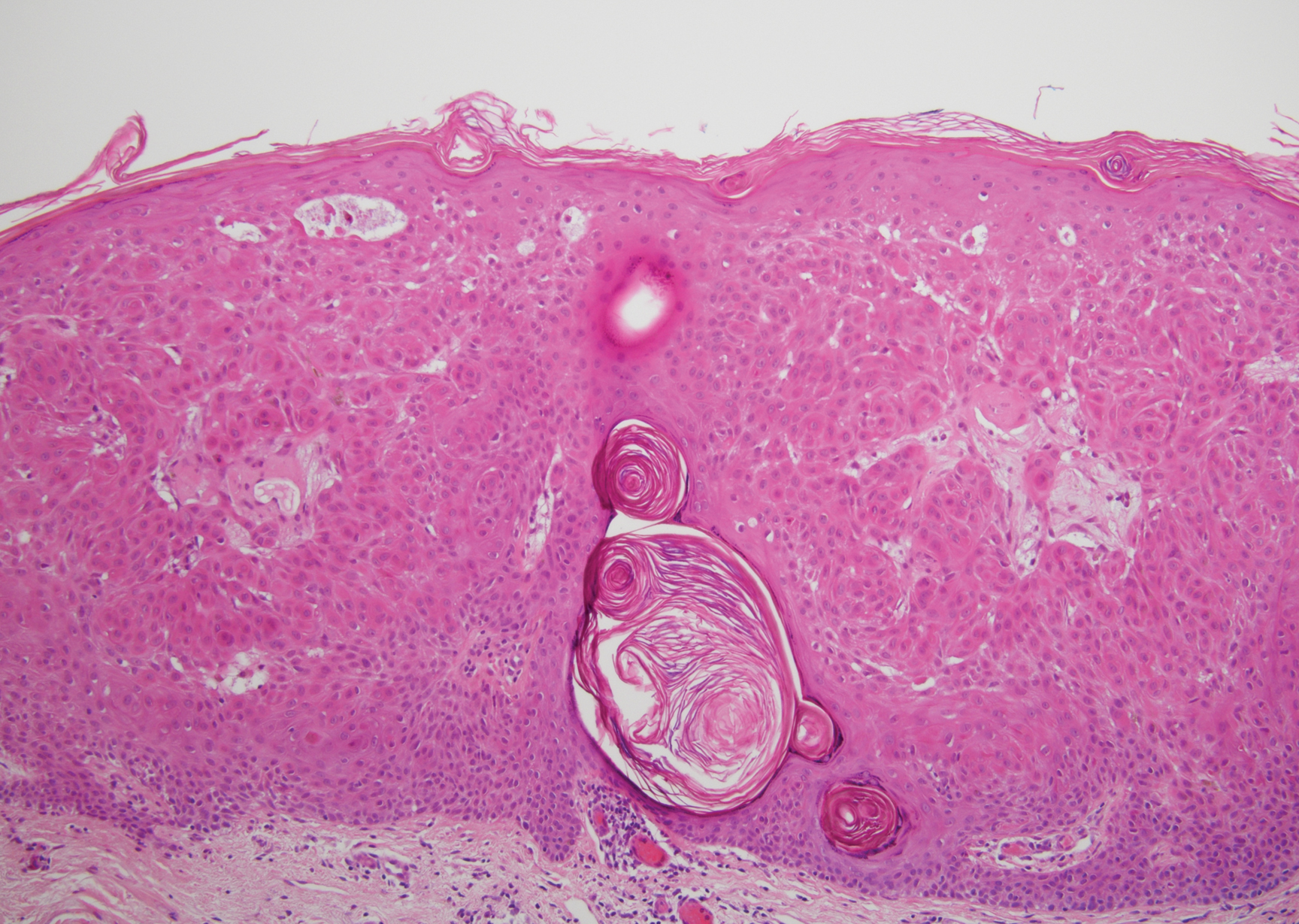

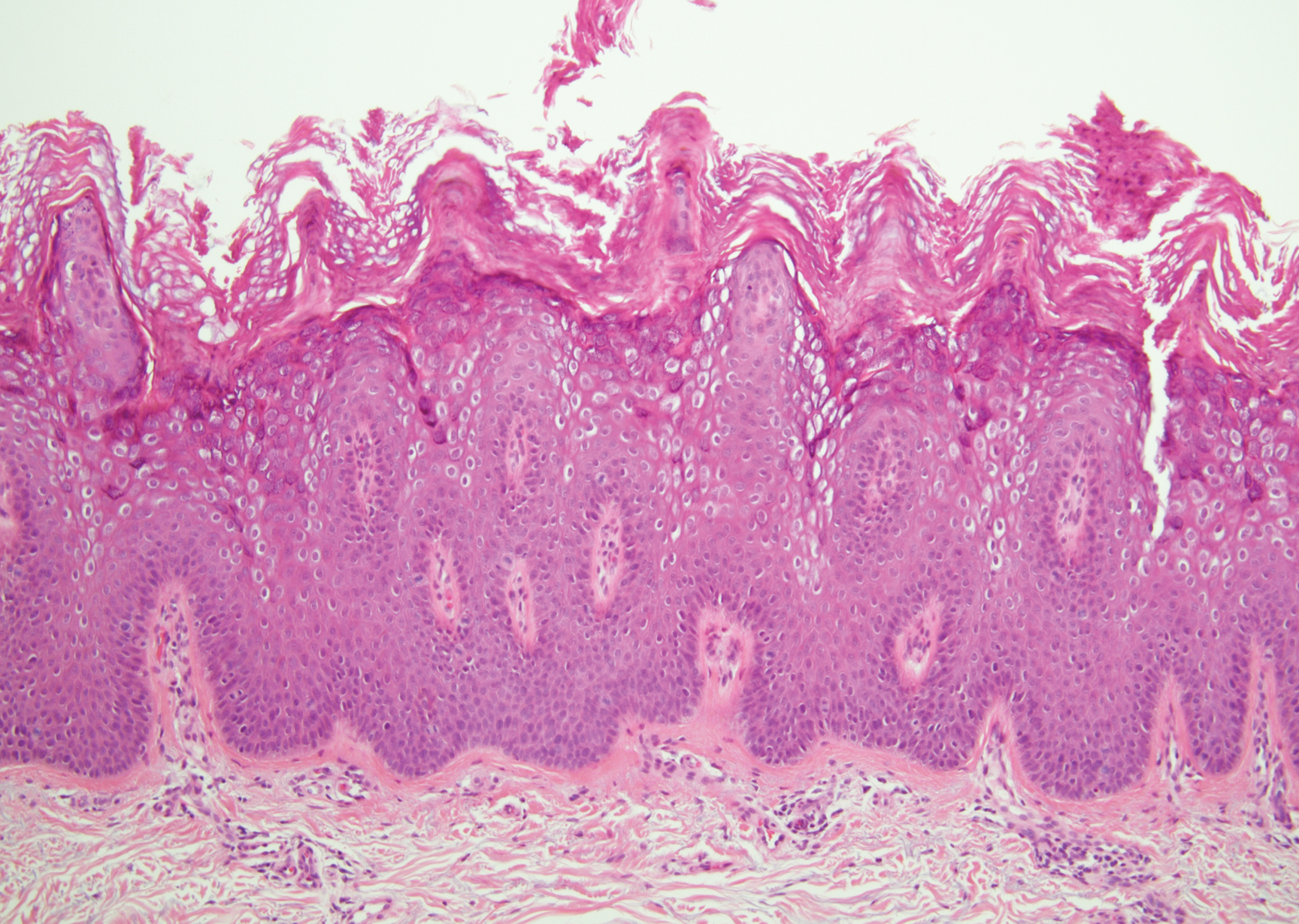

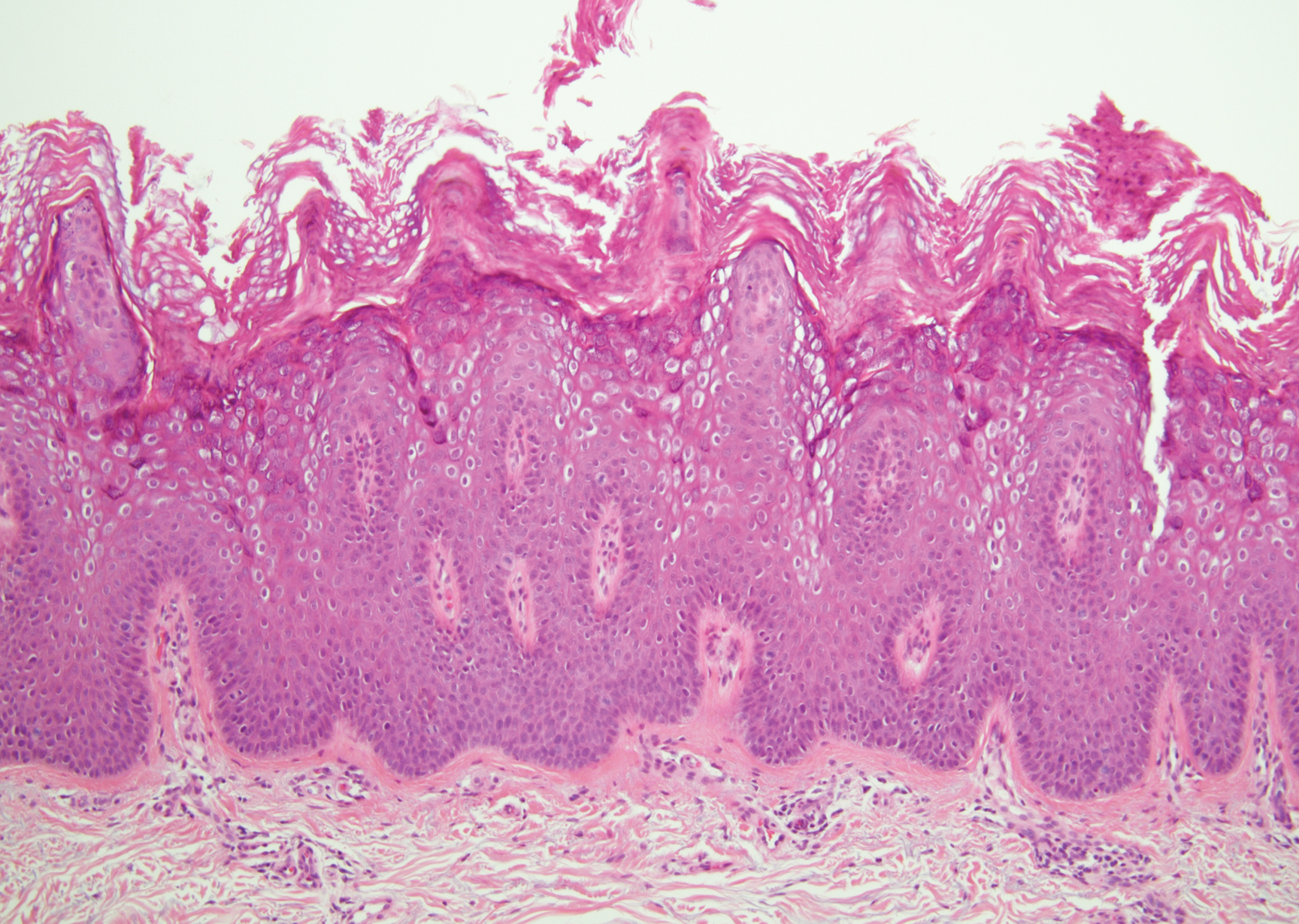

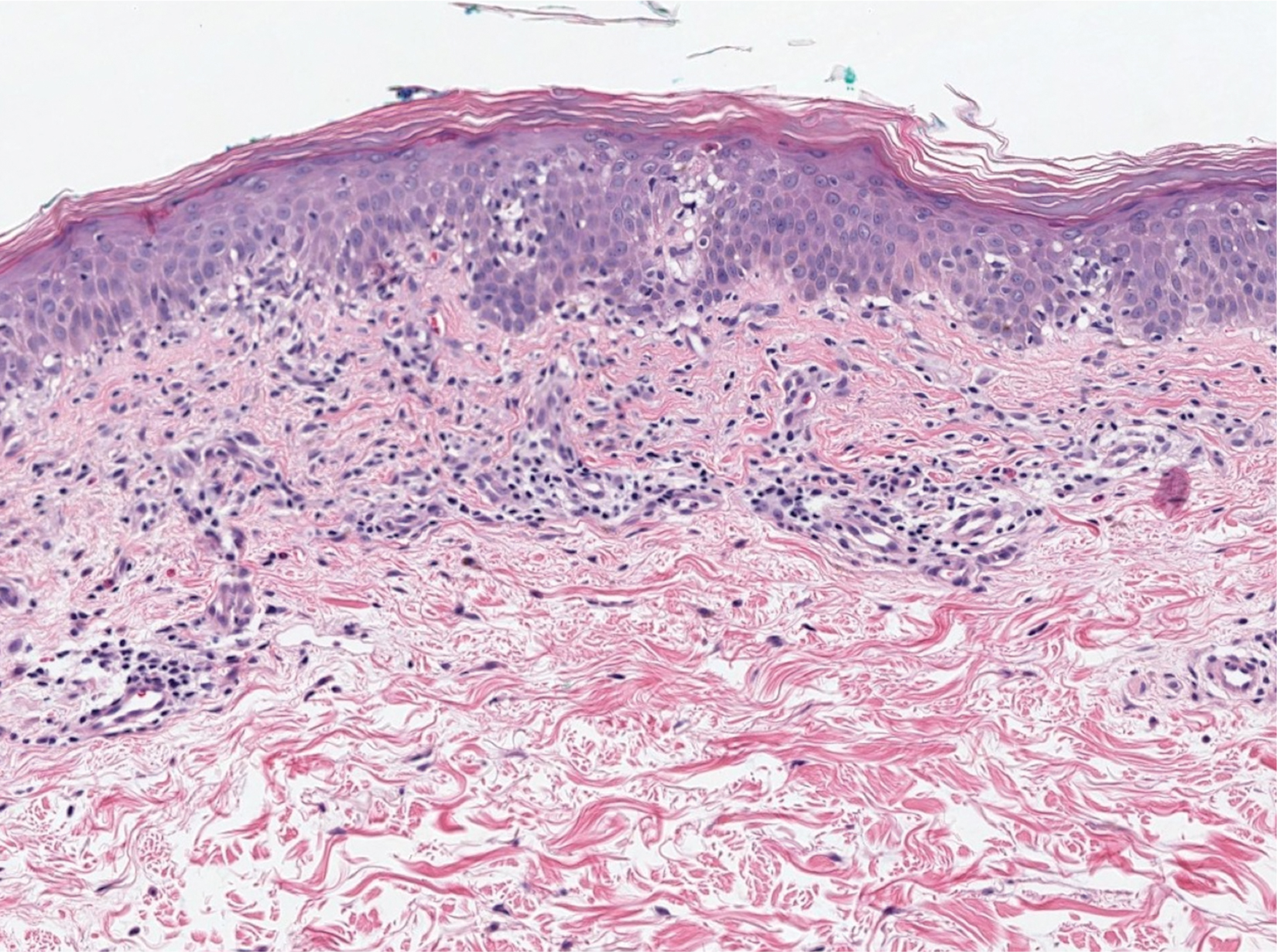

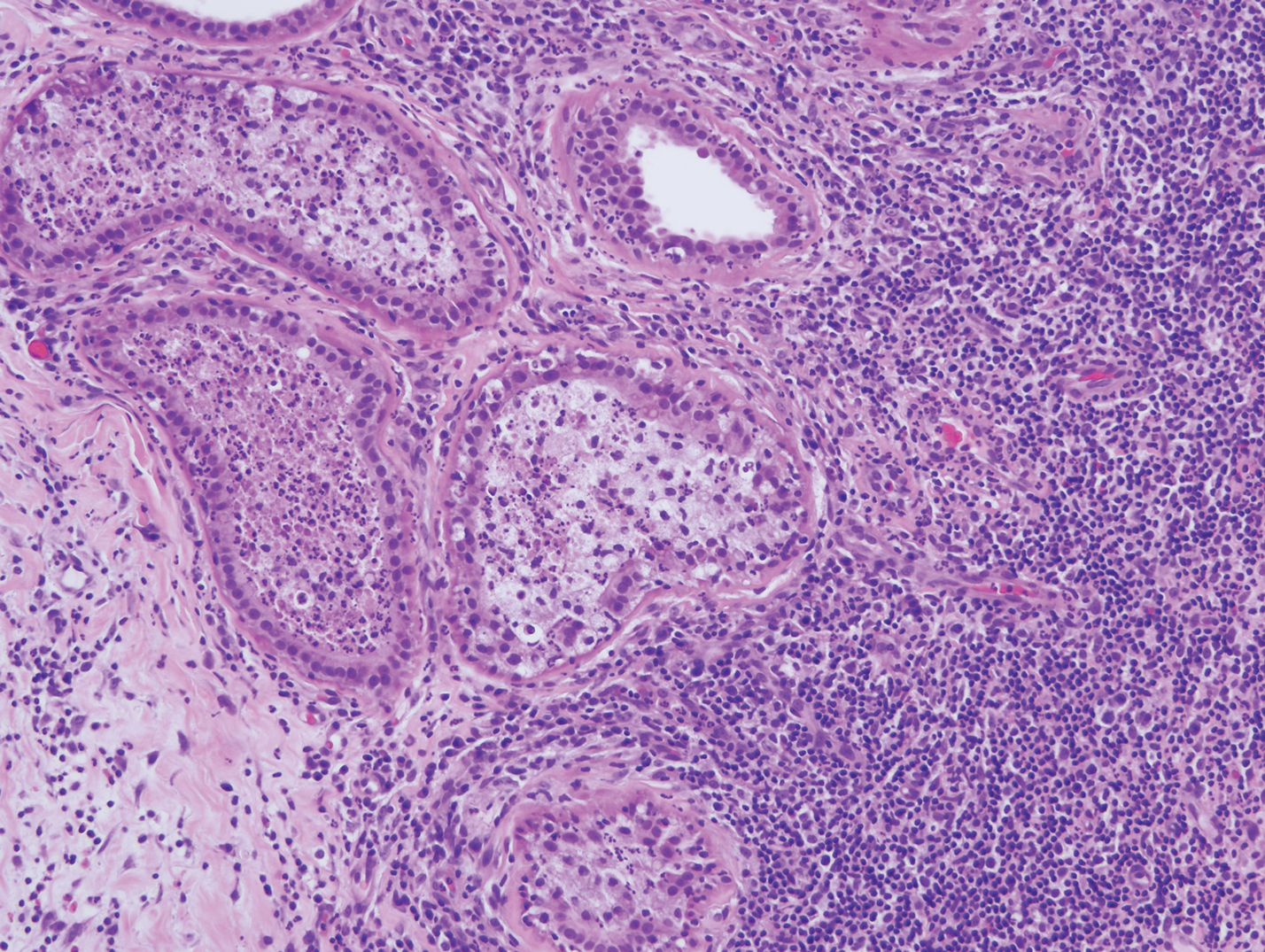

Irritated seborrheic keratosis presents as an exophytic, waxy, dark, sharply demarcated plaque with a stuck-on appearance.6 There is visible keratinization with comedolike openings, fissures and ridges, and scale; it also can contain milialike cysts. Histopathologically there is papillomatosis with prominent rete ridges, often including keratin pseudohorn cysts and squamous eddies. Enlarged capillaries can be seen in the dermal papillae. There is normal cytology with benign sheets of basaloid cells (Figure 2).7 Activating mutation in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 leads to the growth and thickness of the epidermis that has been identified in these benign lesions.8

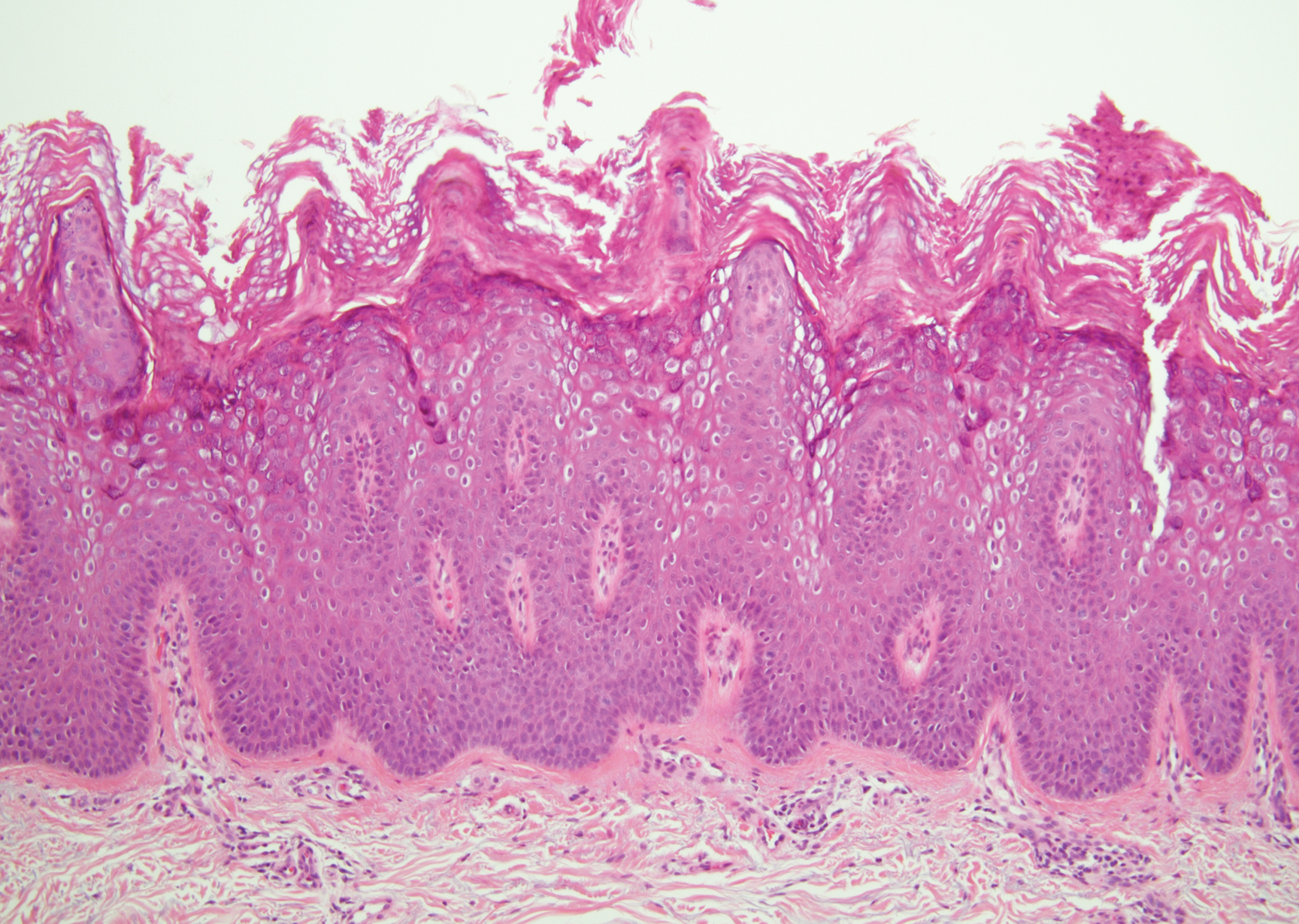

Verruca plana appears as a flesh-colored or reddish, warty, flat-topped papule that often forms clusters. Histopathologically it shows prominent hypergranulosis, thickened stratum spinosum, and vacuolized keratinocytes.9 The nuclei demonstrate a characteristic cytopathic effect of the virion, blurring the nuclear chromatin due to viral particle accumulation, known as koilocytes (Figure 3). The cause is the double-stranded DNA human papillomavirus types 2, 3, and 10.10

Bowen disease is a form of squamous cell carcinoma in situ characterized by an enlarging, well-demarcated, erythematous plaque with an irregular border and crusting or scaling. Histopathology reveals pleomorphic epidermal keratinization that becomes incorporated in the stratum corneum as parakeratotic nuclei. There is acanthosis, elongation of the rete ridges, and disorganized keratinocytes with atypia.11 The granular and spinous layers show an atypical honeycomb pattern with atypical cellular morphology (Figure 4).12 Bowen disease is a malignant lesion commonly found in older adults on sun-exposed skin that can evolve into invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

- Roy SF, Ko CJ, Moeckel GW, et al. Hypergranulotic dyscornification: 30 cases of a striking epithelial reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:742-747.

- Dohse L, Elston D, Lountzis N, et al. Benign hypergranulotic keratosis with dyscornification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:AB52.

- Reichel M. Hypergranulotic dyscornification. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:21-24.

- Kumar P, Kumar R, Kumar Mandal RK, et al. Systematized linear epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:21248.

- Peter Rout D, Nair A, Gupta A, et al. Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis: clinical update. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:333-344.

- Ingraffea A. Benign skin neoplasms. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2013;21:21-32.

- Braun R. Dermoscopy of pigmented seborrheic keratosis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1556.

- Duperret EK, Oh SJ, McNeal A, et al. Activating FGFR3 mutations cause mild hyperplasia in human skin, but are insufficient to drive benign or malignant skin tumors. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:1551-1559.

- Liu H, Chen S, Zhang F, et al. Seborrheic keratosis or verruca plana? a pilot study with confocal laser scanning microscopy. Skin Res Technol. 2010;16:408-412.

- Prieto-Granada CN, Lobo AZC, Mihm MC. Skin infections. In: Kradin RL, ed. Diagnostic Pathology of Infectious Disease. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:519-616.

- DeCoste R, Moss P, Boutilier R, et al. Bowen disease with invasive mucin-secreting sweat gland differentiation: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:425-430.

- Ulrich M, Kanitakis J, González S, et al. Evaluation of Bowen disease by in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2011;166:451-453.

The Diagnosis: Hypergranulotic Dyscornification

Hypergranulotic dyscornification (HD) is a rarely reported reaction pattern present in benign solitary keratoses with only few reports to date. It may be an underrecognized reaction pattern based on the paucity of reported cases as well as the histologic similarities to other entities. It has been hypothesized that this pattern reflects an underlying keratin mutation or disorder of keratinization.1

Clinically, HD most commonly presents as a waxy, tan-colored, solitary keratosis generally found on the lower limbs, trunk, or back in individuals aged 20 to 60 years.1,2 Histopathology shows marked hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and clumped basophilic keratohyalin granules within the corneocytes with digitated epidermal hyperplasia. There is abnormal cornification across the entire lesion with papillomatosis and marked hypergranulosis.3 There often are homogeneous orthokeratotic mounds of large, dull, eosinophilic-staining anucleate keratinocytes that are sharply demarcated from the thickened granular layer.1,2 Within the spinous, granular, and corneal layers, there is a pale, gray-staining, basophilic, cytoplasmic substance intercellularly.1

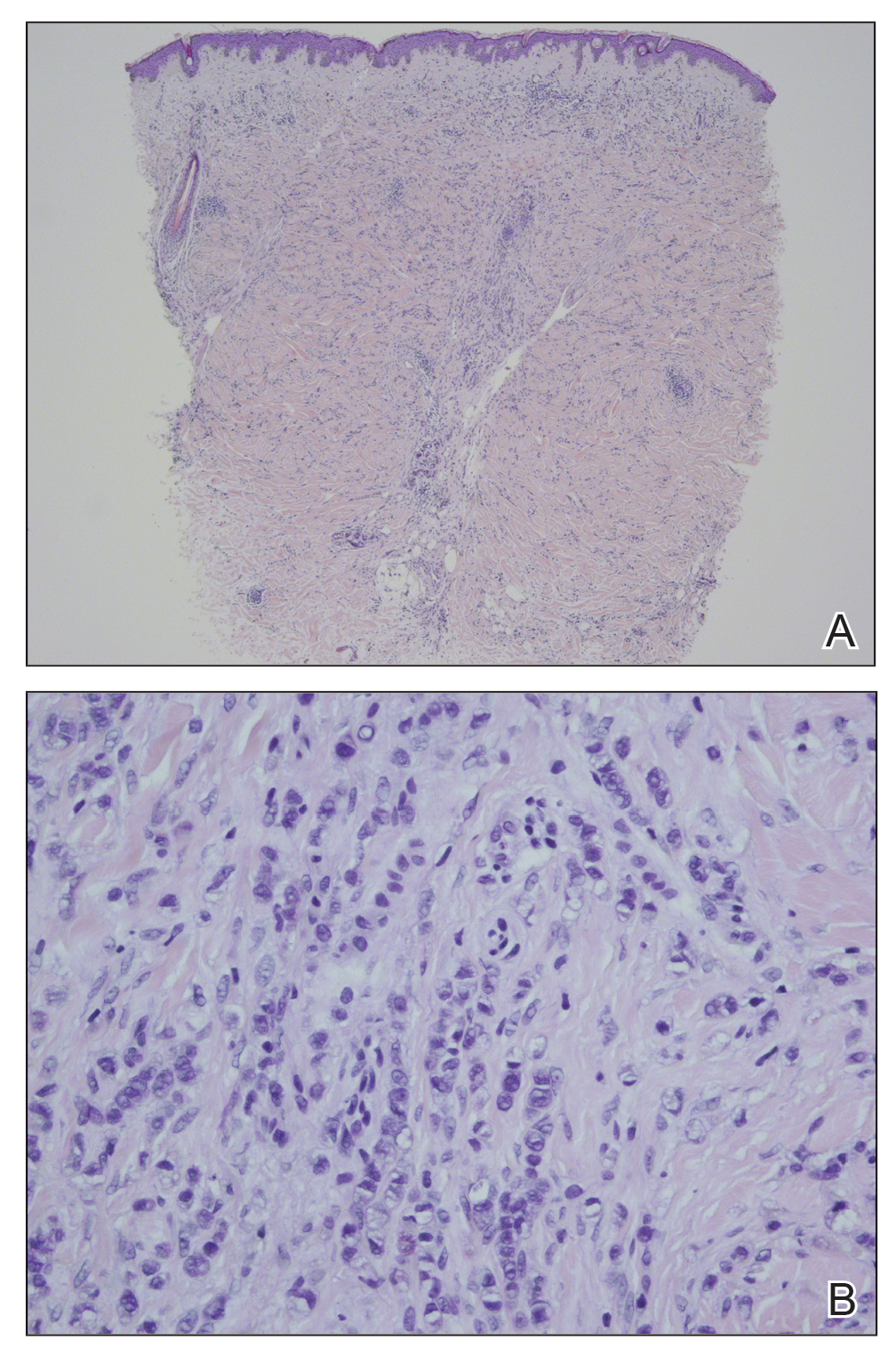

Histopathologically, HD may be mistaken for several other entities both benign and malignant.1 Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis can be a genetic disorder, an incidental finding in a variety of skin conditions, or an isolated lesion.4 The genetic syndrome, caused by mutation in keratins 1 or 10, clinically presents with hyperkeratosis, erosions, blisters, and thickening of the epidermis, often with a corrugated appearance. Epidermal nevi findings often are seen in conjunction with histologic changes of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis caused by mutation. Solitary lesions also can resemble seborrheic keratosis or verruca. In all examples of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, the histopathologic findings are identical.4 The granular layer is thickened, and coarse keratohyalin granules aggregate in the suprabasal cells.5 There is acantholysis with perinuclear vacuolization in the spinous and granular layers with characteristic pale cytoplasmic areas devoid of keratin filaments (Figure 1). The basal layer may be hyperproliferative.5

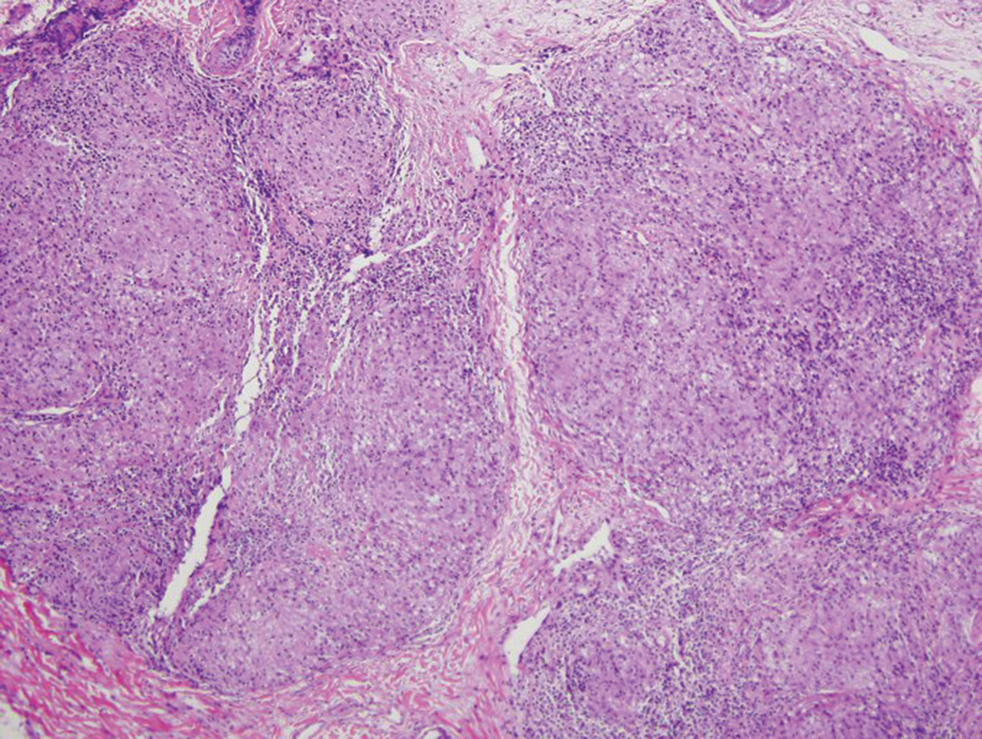

Irritated seborrheic keratosis presents as an exophytic, waxy, dark, sharply demarcated plaque with a stuck-on appearance.6 There is visible keratinization with comedolike openings, fissures and ridges, and scale; it also can contain milialike cysts. Histopathologically there is papillomatosis with prominent rete ridges, often including keratin pseudohorn cysts and squamous eddies. Enlarged capillaries can be seen in the dermal papillae. There is normal cytology with benign sheets of basaloid cells (Figure 2).7 Activating mutation in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 leads to the growth and thickness of the epidermis that has been identified in these benign lesions.8

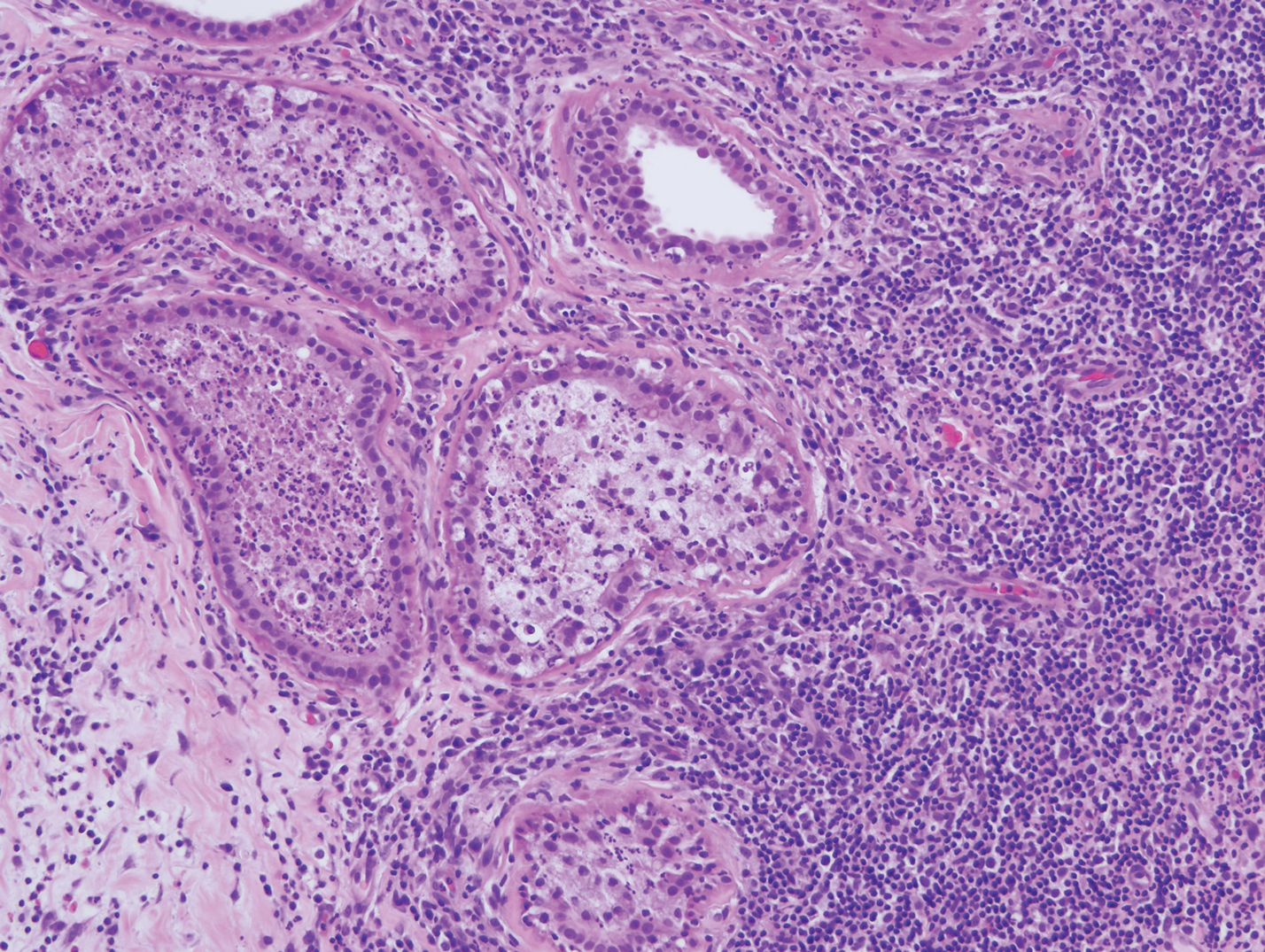

Verruca plana appears as a flesh-colored or reddish, warty, flat-topped papule that often forms clusters. Histopathologically it shows prominent hypergranulosis, thickened stratum spinosum, and vacuolized keratinocytes.9 The nuclei demonstrate a characteristic cytopathic effect of the virion, blurring the nuclear chromatin due to viral particle accumulation, known as koilocytes (Figure 3). The cause is the double-stranded DNA human papillomavirus types 2, 3, and 10.10

Bowen disease is a form of squamous cell carcinoma in situ characterized by an enlarging, well-demarcated, erythematous plaque with an irregular border and crusting or scaling. Histopathology reveals pleomorphic epidermal keratinization that becomes incorporated in the stratum corneum as parakeratotic nuclei. There is acanthosis, elongation of the rete ridges, and disorganized keratinocytes with atypia.11 The granular and spinous layers show an atypical honeycomb pattern with atypical cellular morphology (Figure 4).12 Bowen disease is a malignant lesion commonly found in older adults on sun-exposed skin that can evolve into invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

The Diagnosis: Hypergranulotic Dyscornification

Hypergranulotic dyscornification (HD) is a rarely reported reaction pattern present in benign solitary keratoses with only few reports to date. It may be an underrecognized reaction pattern based on the paucity of reported cases as well as the histologic similarities to other entities. It has been hypothesized that this pattern reflects an underlying keratin mutation or disorder of keratinization.1

Clinically, HD most commonly presents as a waxy, tan-colored, solitary keratosis generally found on the lower limbs, trunk, or back in individuals aged 20 to 60 years.1,2 Histopathology shows marked hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and clumped basophilic keratohyalin granules within the corneocytes with digitated epidermal hyperplasia. There is abnormal cornification across the entire lesion with papillomatosis and marked hypergranulosis.3 There often are homogeneous orthokeratotic mounds of large, dull, eosinophilic-staining anucleate keratinocytes that are sharply demarcated from the thickened granular layer.1,2 Within the spinous, granular, and corneal layers, there is a pale, gray-staining, basophilic, cytoplasmic substance intercellularly.1

Histopathologically, HD may be mistaken for several other entities both benign and malignant.1 Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis can be a genetic disorder, an incidental finding in a variety of skin conditions, or an isolated lesion.4 The genetic syndrome, caused by mutation in keratins 1 or 10, clinically presents with hyperkeratosis, erosions, blisters, and thickening of the epidermis, often with a corrugated appearance. Epidermal nevi findings often are seen in conjunction with histologic changes of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis caused by mutation. Solitary lesions also can resemble seborrheic keratosis or verruca. In all examples of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, the histopathologic findings are identical.4 The granular layer is thickened, and coarse keratohyalin granules aggregate in the suprabasal cells.5 There is acantholysis with perinuclear vacuolization in the spinous and granular layers with characteristic pale cytoplasmic areas devoid of keratin filaments (Figure 1). The basal layer may be hyperproliferative.5

Irritated seborrheic keratosis presents as an exophytic, waxy, dark, sharply demarcated plaque with a stuck-on appearance.6 There is visible keratinization with comedolike openings, fissures and ridges, and scale; it also can contain milialike cysts. Histopathologically there is papillomatosis with prominent rete ridges, often including keratin pseudohorn cysts and squamous eddies. Enlarged capillaries can be seen in the dermal papillae. There is normal cytology with benign sheets of basaloid cells (Figure 2).7 Activating mutation in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 leads to the growth and thickness of the epidermis that has been identified in these benign lesions.8

Verruca plana appears as a flesh-colored or reddish, warty, flat-topped papule that often forms clusters. Histopathologically it shows prominent hypergranulosis, thickened stratum spinosum, and vacuolized keratinocytes.9 The nuclei demonstrate a characteristic cytopathic effect of the virion, blurring the nuclear chromatin due to viral particle accumulation, known as koilocytes (Figure 3). The cause is the double-stranded DNA human papillomavirus types 2, 3, and 10.10

Bowen disease is a form of squamous cell carcinoma in situ characterized by an enlarging, well-demarcated, erythematous plaque with an irregular border and crusting or scaling. Histopathology reveals pleomorphic epidermal keratinization that becomes incorporated in the stratum corneum as parakeratotic nuclei. There is acanthosis, elongation of the rete ridges, and disorganized keratinocytes with atypia.11 The granular and spinous layers show an atypical honeycomb pattern with atypical cellular morphology (Figure 4).12 Bowen disease is a malignant lesion commonly found in older adults on sun-exposed skin that can evolve into invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

- Roy SF, Ko CJ, Moeckel GW, et al. Hypergranulotic dyscornification: 30 cases of a striking epithelial reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:742-747.

- Dohse L, Elston D, Lountzis N, et al. Benign hypergranulotic keratosis with dyscornification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:AB52.

- Reichel M. Hypergranulotic dyscornification. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:21-24.

- Kumar P, Kumar R, Kumar Mandal RK, et al. Systematized linear epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:21248.

- Peter Rout D, Nair A, Gupta A, et al. Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis: clinical update. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:333-344.

- Ingraffea A. Benign skin neoplasms. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2013;21:21-32.

- Braun R. Dermoscopy of pigmented seborrheic keratosis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1556.

- Duperret EK, Oh SJ, McNeal A, et al. Activating FGFR3 mutations cause mild hyperplasia in human skin, but are insufficient to drive benign or malignant skin tumors. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:1551-1559.

- Liu H, Chen S, Zhang F, et al. Seborrheic keratosis or verruca plana? a pilot study with confocal laser scanning microscopy. Skin Res Technol. 2010;16:408-412.

- Prieto-Granada CN, Lobo AZC, Mihm MC. Skin infections. In: Kradin RL, ed. Diagnostic Pathology of Infectious Disease. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:519-616.

- DeCoste R, Moss P, Boutilier R, et al. Bowen disease with invasive mucin-secreting sweat gland differentiation: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:425-430.

- Ulrich M, Kanitakis J, González S, et al. Evaluation of Bowen disease by in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2011;166:451-453.

- Roy SF, Ko CJ, Moeckel GW, et al. Hypergranulotic dyscornification: 30 cases of a striking epithelial reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:742-747.

- Dohse L, Elston D, Lountzis N, et al. Benign hypergranulotic keratosis with dyscornification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:AB52.

- Reichel M. Hypergranulotic dyscornification. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:21-24.

- Kumar P, Kumar R, Kumar Mandal RK, et al. Systematized linear epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:21248.

- Peter Rout D, Nair A, Gupta A, et al. Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis: clinical update. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:333-344.

- Ingraffea A. Benign skin neoplasms. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2013;21:21-32.

- Braun R. Dermoscopy of pigmented seborrheic keratosis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1556.

- Duperret EK, Oh SJ, McNeal A, et al. Activating FGFR3 mutations cause mild hyperplasia in human skin, but are insufficient to drive benign or malignant skin tumors. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:1551-1559.

- Liu H, Chen S, Zhang F, et al. Seborrheic keratosis or verruca plana? a pilot study with confocal laser scanning microscopy. Skin Res Technol. 2010;16:408-412.

- Prieto-Granada CN, Lobo AZC, Mihm MC. Skin infections. In: Kradin RL, ed. Diagnostic Pathology of Infectious Disease. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:519-616.

- DeCoste R, Moss P, Boutilier R, et al. Bowen disease with invasive mucin-secreting sweat gland differentiation: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:425-430.

- Ulrich M, Kanitakis J, González S, et al. Evaluation of Bowen disease by in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2011;166:451-453.

A 59-year-old woman with a history of basal cell carcinoma, uterine and ovarian cancer, and verrucae presented with an asymptomatic 3-mm lesion on the left side of the lower abdomen. Physical examination revealed a waxy, tan-colored, solitary keratosis. A shave biopsy was performed. Histopathology showed hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, papillomatosis, and marked hypergranulosis with pale gray cytoplasm of the spinous-layer keratinocytes.

Pseudoepitheliomatous Hyperplasia Arising From Purple Tattoo Pigment

To the Editor:

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (PEH) is an uncommon type of reactive epidermal proliferation that can occur from a variety of causes, including an underlying infection, inflammation, neoplastic condition, or trauma induced from tattooing.1 Diagnosis can be challenging and requires clinicopathologic correlation, as PEH can mimic malignancy on histopathology.2-4 Histologically, PEH shows irregular hyperplasia of the epidermis and adnexal epithelium, elongation of the rete ridges, and extension of the reactive proliferation into the dermis. Absence of cytologic atypia is key to the diagnosis of PEH, helping to distinguish it from squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthoma. Clinically, patients typically present with well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques or nodules in reactive areas, which can be symptomatically pruritic.

A 48-year-old woman presented with scaly and crusted verrucous plaques of 2 months’ duration that were isolated to the areas of purple pigment within a tattoo on the right lower leg. The patient reported pruritus in the affected areas that occurred immediately after obtaining the tattoo, which was her first and only tattoo. She denied any pertinent medical history, including an absence of immunosuppression and autoimmune or chronic inflammatory diseases.

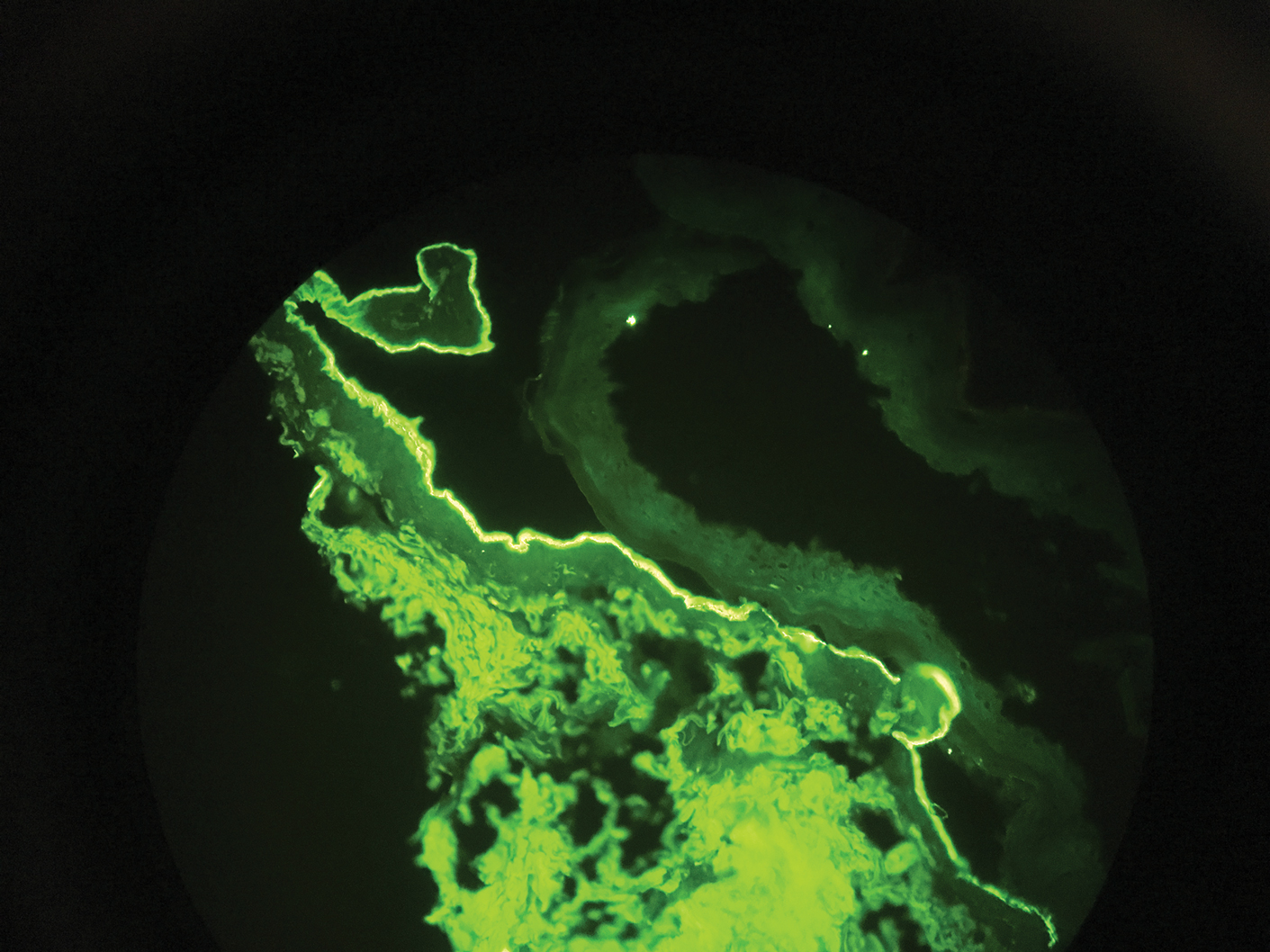

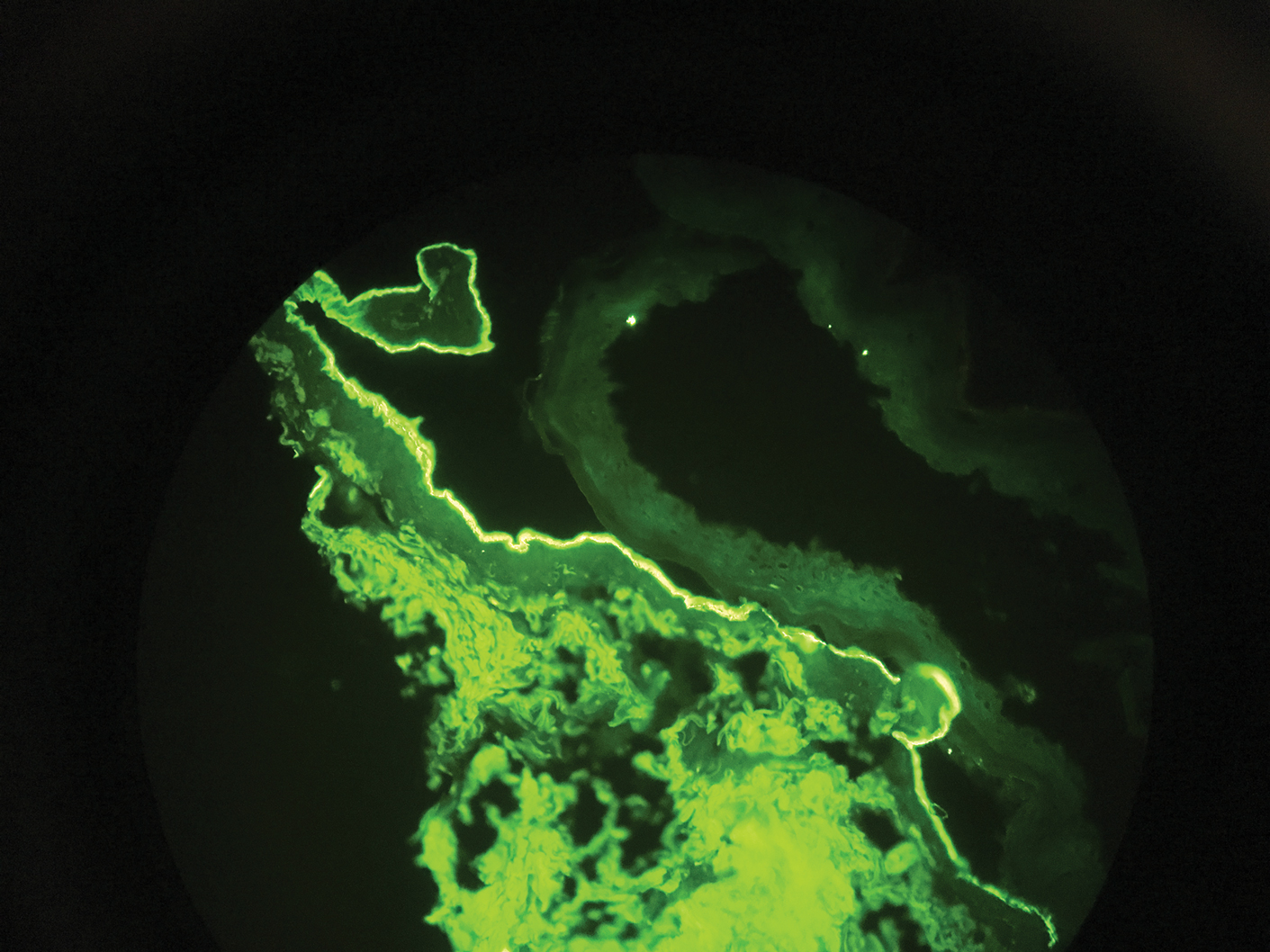

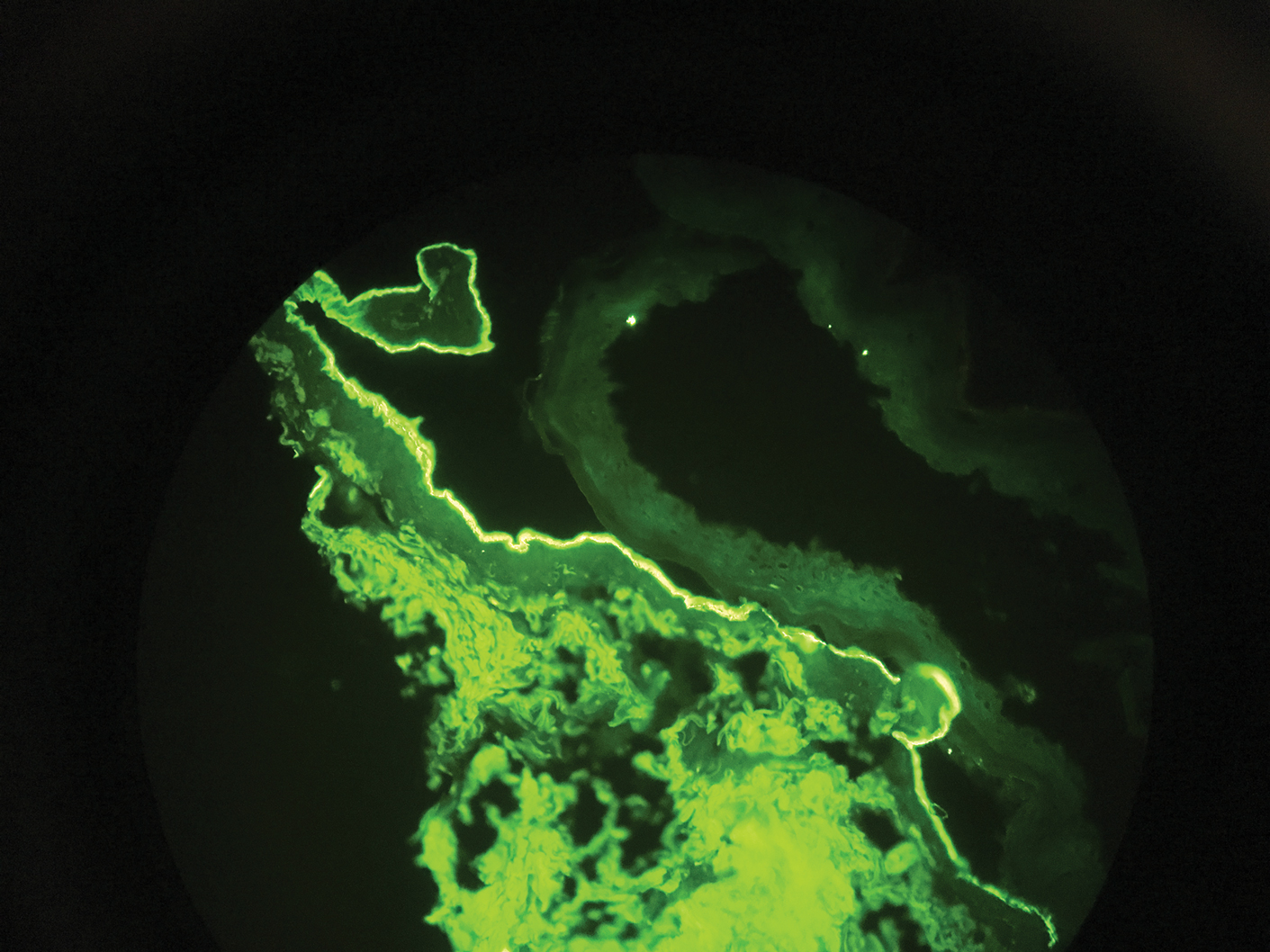

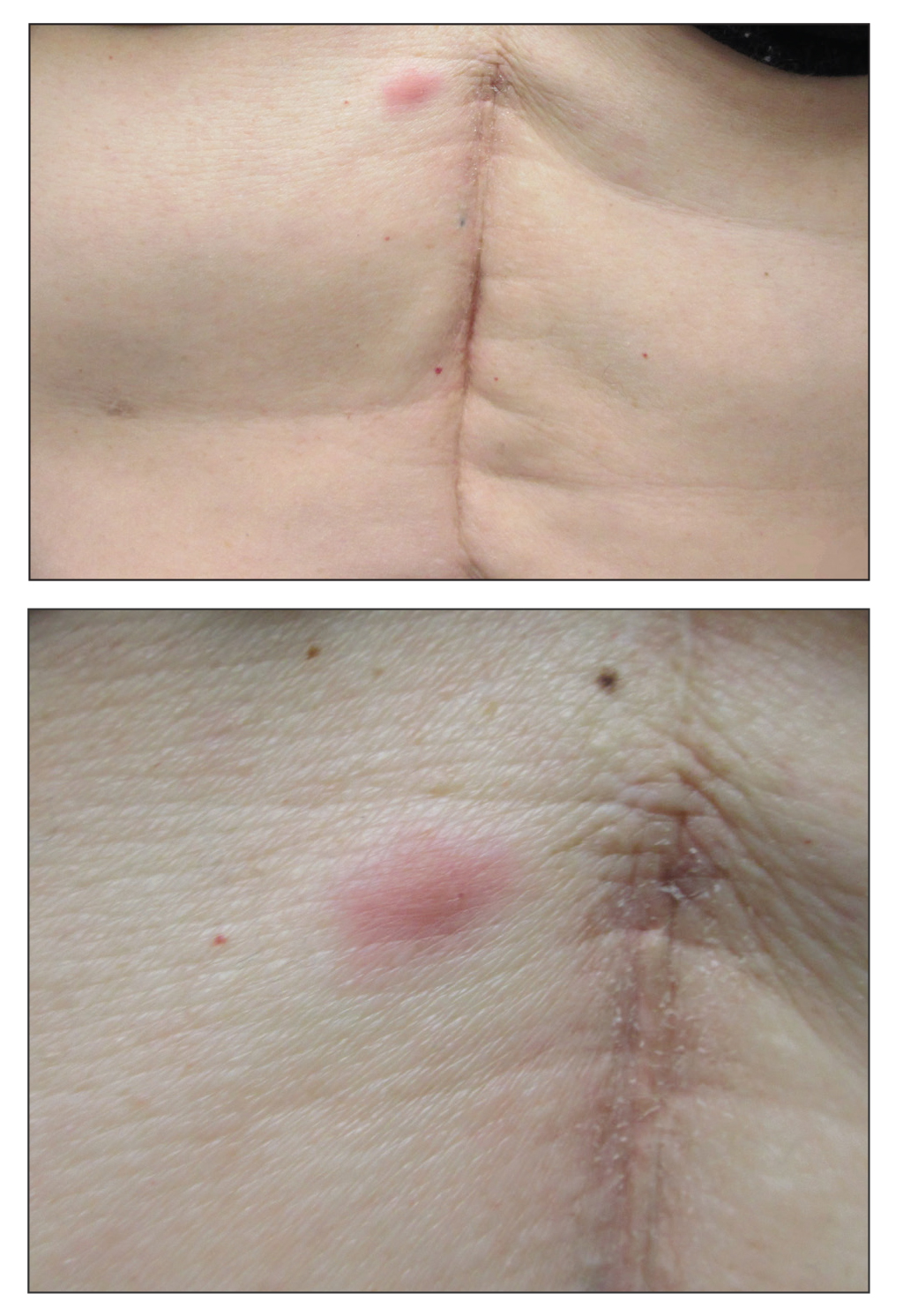

Physical examination revealed scaly and crusted plaques isolated to areas of purple tattoo pigment (Figure 1). Areas of red, green, black, and blue pigmentation within the tattoo were uninvolved. With the initial suspicion of allergic contact dermatitis, two 6-mm punch biopsies were taken from adjacent linear plaques on the right leg for histology and tissue culture. Histopathologic evaluation revealed dermal tattoo pigment with overlying PEH and was negative for signs of infection (Figure 2). Infectious stains such as periodic acid–Schiff, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, and Gram stains were performed and found to be negative. In addition, culture for mycobacteria came back negative. Prurigo was on the differential; however, histopathologic changes were more compatible with a PEH reaction to the tattoo.

Upon diagnosis, the patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% under occlusion for 1 month without reported improvement. The patient subsequently elected to undergo treatment with intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL to all areas of PEH, except the areas immediately surrounding the healing biopsy sites. Twice-daily application of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% to all affected areas also was initiated. At follow-up 1 month later, she reported symptomatic relief of pruritus with a notable reduction in the thickness of the plaques in all treated areas (Figure 3). A second course of intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL was performed. No additional plaques appeared during the treatment course, and the patient reported high satisfaction with the final result that was achieved.

An increase in the popularity of tattooing has led to more reports of various tattoo skin reactions.4-6 The differential diagnosis is broad for tattoo reactions and includes granulomatous inflammation, sarcoidosis, psoriasis (Köbner phenomenon), allergic contact dermatitis, lichen planus, morphealike reactions, squamous cell carcinoma, and keratoacanthoma,5 which makes clinicopathologic correlation essential for accurate diagnosis. Our case demonstrated the characteristic epithelial hyperplasia in the absence of cytologic atypia. In addition, the presence of mixed dermal inflammation histologically was noted in our patient.

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia development from a tattoo in areas of both mercury-based and non–mercury-based red pigment is a known association.7-9 Balfour et al10 also reported a case of PEH occurring secondary to manganese-based purple pigment. Because few cases have been reported, the epidemiology for PEH currently is unknown. Treatment of this condition primarily is anecdotal, with prior cases showing success with topical or intralesional steroids.5,7 As with any steroid-based treatment, we recommend less aggressive treatments initially with close follow-up and adaptation as needed to minimize adverse effects such as unwanted atrophy. Some success has been reported with the use of the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser in the setting of a PEH tattoo reaction.5 Similar to other tattoo reactions, surgical removal can be considered with failure of more conservative treatment methods and focal involvement.

We report an unusual case of PEH occurring secondary to purple tattoo pigment. Our report also demonstrates the clinical and symptomatic improvement of PEH that can be achieved through the use of intralesional corticosteroid therapy. Our patient represents a case of PEH reactive to tattooing with purple ink. Further research to elucidate the precise pathogenesis of PEH tattoo reactions would be helpful in identifying high-risk patients and determining the most efficacious treatments.

- Meani RE, Nixon RL, O’Keefe R, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia secondary to allergic contact dermatitis to Grevillea Robyn Gordon. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E8-E10.

- Chakrabarti S, Chakrabarti P, Agrawal D, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a clinical entity mistaken for squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:232.

- Kluger N. Issues with keratoacanthoma, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and squamous cell carcinoma within tattoos: a clinical point of view. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;37:812-813.

- Zayour M, Lazova R. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:112-126.

- Bassi A, Campolmi P, Cannarozzo G, et al. Tattoo-associated skin reaction: the importance of an early diagnosis and proper treatment [published online July 23, 2014]. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:354608.

- Serup J. Diagnostic tools for doctors’ evaluation of tattoo complications. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2017;52:42-57.

- Kazlouskaya V, Junkins-Hopkins JM. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia in a red pigment tattoo: a separate entity or hypertrophic lichen planus-like reaction? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:48-52.

- Kluger N, Durand L, Minier-Thoumin C, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous epidermal hyperplasia in tattoos: report of three cases. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:337-340.

- Cui W, McGregor DH, Stark SP, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia—an unusual reaction following tattoo: report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:743-745.

- Balfour E, Olhoffer I, Leffell D, et al. Massive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: an unusual reaction to a tattoo. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:338-340.

To the Editor:

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (PEH) is an uncommon type of reactive epidermal proliferation that can occur from a variety of causes, including an underlying infection, inflammation, neoplastic condition, or trauma induced from tattooing.1 Diagnosis can be challenging and requires clinicopathologic correlation, as PEH can mimic malignancy on histopathology.2-4 Histologically, PEH shows irregular hyperplasia of the epidermis and adnexal epithelium, elongation of the rete ridges, and extension of the reactive proliferation into the dermis. Absence of cytologic atypia is key to the diagnosis of PEH, helping to distinguish it from squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthoma. Clinically, patients typically present with well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques or nodules in reactive areas, which can be symptomatically pruritic.

A 48-year-old woman presented with scaly and crusted verrucous plaques of 2 months’ duration that were isolated to the areas of purple pigment within a tattoo on the right lower leg. The patient reported pruritus in the affected areas that occurred immediately after obtaining the tattoo, which was her first and only tattoo. She denied any pertinent medical history, including an absence of immunosuppression and autoimmune or chronic inflammatory diseases.

Physical examination revealed scaly and crusted plaques isolated to areas of purple tattoo pigment (Figure 1). Areas of red, green, black, and blue pigmentation within the tattoo were uninvolved. With the initial suspicion of allergic contact dermatitis, two 6-mm punch biopsies were taken from adjacent linear plaques on the right leg for histology and tissue culture. Histopathologic evaluation revealed dermal tattoo pigment with overlying PEH and was negative for signs of infection (Figure 2). Infectious stains such as periodic acid–Schiff, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, and Gram stains were performed and found to be negative. In addition, culture for mycobacteria came back negative. Prurigo was on the differential; however, histopathologic changes were more compatible with a PEH reaction to the tattoo.

Upon diagnosis, the patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% under occlusion for 1 month without reported improvement. The patient subsequently elected to undergo treatment with intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL to all areas of PEH, except the areas immediately surrounding the healing biopsy sites. Twice-daily application of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% to all affected areas also was initiated. At follow-up 1 month later, she reported symptomatic relief of pruritus with a notable reduction in the thickness of the plaques in all treated areas (Figure 3). A second course of intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL was performed. No additional plaques appeared during the treatment course, and the patient reported high satisfaction with the final result that was achieved.

An increase in the popularity of tattooing has led to more reports of various tattoo skin reactions.4-6 The differential diagnosis is broad for tattoo reactions and includes granulomatous inflammation, sarcoidosis, psoriasis (Köbner phenomenon), allergic contact dermatitis, lichen planus, morphealike reactions, squamous cell carcinoma, and keratoacanthoma,5 which makes clinicopathologic correlation essential for accurate diagnosis. Our case demonstrated the characteristic epithelial hyperplasia in the absence of cytologic atypia. In addition, the presence of mixed dermal inflammation histologically was noted in our patient.

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia development from a tattoo in areas of both mercury-based and non–mercury-based red pigment is a known association.7-9 Balfour et al10 also reported a case of PEH occurring secondary to manganese-based purple pigment. Because few cases have been reported, the epidemiology for PEH currently is unknown. Treatment of this condition primarily is anecdotal, with prior cases showing success with topical or intralesional steroids.5,7 As with any steroid-based treatment, we recommend less aggressive treatments initially with close follow-up and adaptation as needed to minimize adverse effects such as unwanted atrophy. Some success has been reported with the use of the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser in the setting of a PEH tattoo reaction.5 Similar to other tattoo reactions, surgical removal can be considered with failure of more conservative treatment methods and focal involvement.

We report an unusual case of PEH occurring secondary to purple tattoo pigment. Our report also demonstrates the clinical and symptomatic improvement of PEH that can be achieved through the use of intralesional corticosteroid therapy. Our patient represents a case of PEH reactive to tattooing with purple ink. Further research to elucidate the precise pathogenesis of PEH tattoo reactions would be helpful in identifying high-risk patients and determining the most efficacious treatments.

To the Editor:

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (PEH) is an uncommon type of reactive epidermal proliferation that can occur from a variety of causes, including an underlying infection, inflammation, neoplastic condition, or trauma induced from tattooing.1 Diagnosis can be challenging and requires clinicopathologic correlation, as PEH can mimic malignancy on histopathology.2-4 Histologically, PEH shows irregular hyperplasia of the epidermis and adnexal epithelium, elongation of the rete ridges, and extension of the reactive proliferation into the dermis. Absence of cytologic atypia is key to the diagnosis of PEH, helping to distinguish it from squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthoma. Clinically, patients typically present with well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques or nodules in reactive areas, which can be symptomatically pruritic.

A 48-year-old woman presented with scaly and crusted verrucous plaques of 2 months’ duration that were isolated to the areas of purple pigment within a tattoo on the right lower leg. The patient reported pruritus in the affected areas that occurred immediately after obtaining the tattoo, which was her first and only tattoo. She denied any pertinent medical history, including an absence of immunosuppression and autoimmune or chronic inflammatory diseases.

Physical examination revealed scaly and crusted plaques isolated to areas of purple tattoo pigment (Figure 1). Areas of red, green, black, and blue pigmentation within the tattoo were uninvolved. With the initial suspicion of allergic contact dermatitis, two 6-mm punch biopsies were taken from adjacent linear plaques on the right leg for histology and tissue culture. Histopathologic evaluation revealed dermal tattoo pigment with overlying PEH and was negative for signs of infection (Figure 2). Infectious stains such as periodic acid–Schiff, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, and Gram stains were performed and found to be negative. In addition, culture for mycobacteria came back negative. Prurigo was on the differential; however, histopathologic changes were more compatible with a PEH reaction to the tattoo.

Upon diagnosis, the patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% under occlusion for 1 month without reported improvement. The patient subsequently elected to undergo treatment with intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL to all areas of PEH, except the areas immediately surrounding the healing biopsy sites. Twice-daily application of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% to all affected areas also was initiated. At follow-up 1 month later, she reported symptomatic relief of pruritus with a notable reduction in the thickness of the plaques in all treated areas (Figure 3). A second course of intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL was performed. No additional plaques appeared during the treatment course, and the patient reported high satisfaction with the final result that was achieved.

An increase in the popularity of tattooing has led to more reports of various tattoo skin reactions.4-6 The differential diagnosis is broad for tattoo reactions and includes granulomatous inflammation, sarcoidosis, psoriasis (Köbner phenomenon), allergic contact dermatitis, lichen planus, morphealike reactions, squamous cell carcinoma, and keratoacanthoma,5 which makes clinicopathologic correlation essential for accurate diagnosis. Our case demonstrated the characteristic epithelial hyperplasia in the absence of cytologic atypia. In addition, the presence of mixed dermal inflammation histologically was noted in our patient.

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia development from a tattoo in areas of both mercury-based and non–mercury-based red pigment is a known association.7-9 Balfour et al10 also reported a case of PEH occurring secondary to manganese-based purple pigment. Because few cases have been reported, the epidemiology for PEH currently is unknown. Treatment of this condition primarily is anecdotal, with prior cases showing success with topical or intralesional steroids.5,7 As with any steroid-based treatment, we recommend less aggressive treatments initially with close follow-up and adaptation as needed to minimize adverse effects such as unwanted atrophy. Some success has been reported with the use of the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser in the setting of a PEH tattoo reaction.5 Similar to other tattoo reactions, surgical removal can be considered with failure of more conservative treatment methods and focal involvement.

We report an unusual case of PEH occurring secondary to purple tattoo pigment. Our report also demonstrates the clinical and symptomatic improvement of PEH that can be achieved through the use of intralesional corticosteroid therapy. Our patient represents a case of PEH reactive to tattooing with purple ink. Further research to elucidate the precise pathogenesis of PEH tattoo reactions would be helpful in identifying high-risk patients and determining the most efficacious treatments.

- Meani RE, Nixon RL, O’Keefe R, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia secondary to allergic contact dermatitis to Grevillea Robyn Gordon. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E8-E10.

- Chakrabarti S, Chakrabarti P, Agrawal D, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a clinical entity mistaken for squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:232.

- Kluger N. Issues with keratoacanthoma, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and squamous cell carcinoma within tattoos: a clinical point of view. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;37:812-813.

- Zayour M, Lazova R. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:112-126.

- Bassi A, Campolmi P, Cannarozzo G, et al. Tattoo-associated skin reaction: the importance of an early diagnosis and proper treatment [published online July 23, 2014]. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:354608.

- Serup J. Diagnostic tools for doctors’ evaluation of tattoo complications. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2017;52:42-57.

- Kazlouskaya V, Junkins-Hopkins JM. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia in a red pigment tattoo: a separate entity or hypertrophic lichen planus-like reaction? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:48-52.

- Kluger N, Durand L, Minier-Thoumin C, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous epidermal hyperplasia in tattoos: report of three cases. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:337-340.

- Cui W, McGregor DH, Stark SP, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia—an unusual reaction following tattoo: report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:743-745.

- Balfour E, Olhoffer I, Leffell D, et al. Massive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: an unusual reaction to a tattoo. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:338-340.

- Meani RE, Nixon RL, O’Keefe R, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia secondary to allergic contact dermatitis to Grevillea Robyn Gordon. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E8-E10.

- Chakrabarti S, Chakrabarti P, Agrawal D, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a clinical entity mistaken for squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:232.

- Kluger N. Issues with keratoacanthoma, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and squamous cell carcinoma within tattoos: a clinical point of view. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;37:812-813.

- Zayour M, Lazova R. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:112-126.

- Bassi A, Campolmi P, Cannarozzo G, et al. Tattoo-associated skin reaction: the importance of an early diagnosis and proper treatment [published online July 23, 2014]. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:354608.

- Serup J. Diagnostic tools for doctors’ evaluation of tattoo complications. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2017;52:42-57.

- Kazlouskaya V, Junkins-Hopkins JM. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia in a red pigment tattoo: a separate entity or hypertrophic lichen planus-like reaction? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:48-52.

- Kluger N, Durand L, Minier-Thoumin C, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous epidermal hyperplasia in tattoos: report of three cases. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:337-340.

- Cui W, McGregor DH, Stark SP, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia—an unusual reaction following tattoo: report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:743-745.

- Balfour E, Olhoffer I, Leffell D, et al. Massive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: an unusual reaction to a tattoo. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:338-340.

Practice Points

- Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (PEH) is a rare benign condition that can arise in response to multiple underlying triggers such as tattoo pigment.

- Histopathologic evaluation is essential for diagnosis and shows characteristic hyperplasia of the epidermis.

- Clinicians should consider intralesional steroids in the treatment of PEH once atypical mycobacterial and deep fungal infections have been ruled out.

Pruritic Eruption With Skinfold Sparing

The Diagnosis: Papuloerythroderma of Ofuji

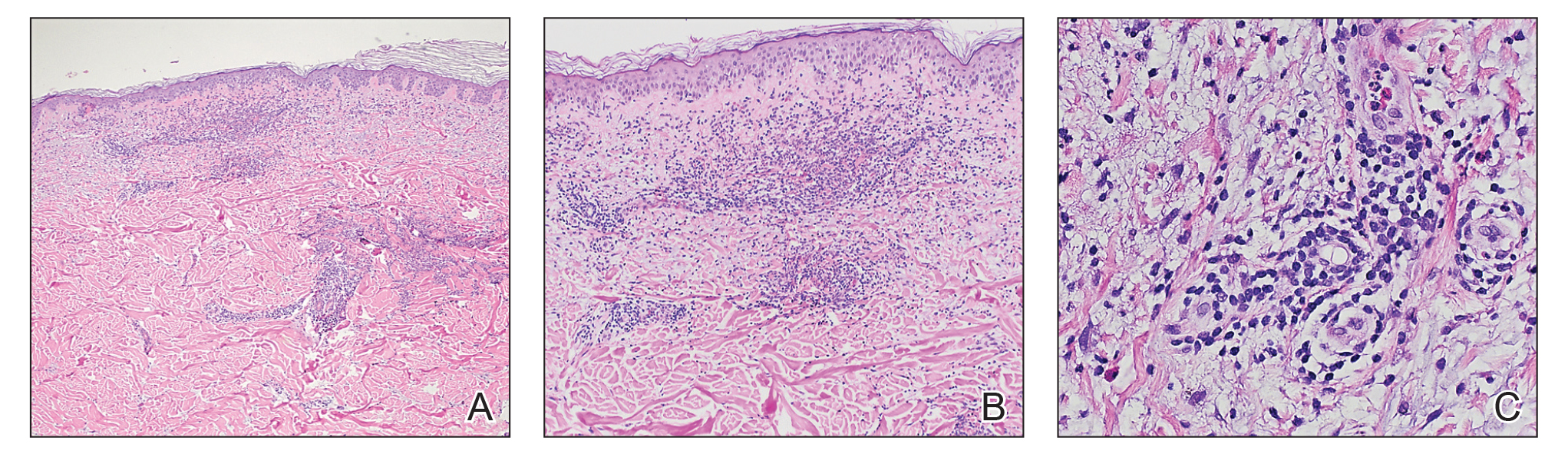

The patient presented with a characteristic finding of skinfold sparing, known as the "deck-chair sign" (Figure 1).1 A repeat biopsy at our institution revealed a dermal perivascular and bandlike infiltrate with lymphocytes and occasional eosinophils (Figure 2). The epidermis showed mild spongiosis, lymphocytic exocytosis, and rare necrotic keratinocytes. A T-cell gene rearrangement assay was negative for a monoclonal population of T lymphocytes. Based on the clinical and histologic features, the diagnosis was most consistent with papuloerythroderma of Ofuji (PEO); however, a lymphoproliferative disorder needed to be excluded. Further workup included a peripheral smear, complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, IgE level, and hepatitis panel; all were normal, except for an elevated serum IgE level. Human immunodeficiency virus and age-appropriate malignancy screening were negative. The patient was prescribed betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05% twice daily, which resulted in near-complete resolution of the rash and marked improvement in pruritus.

In 1984, PEO was described as an entity of generalized pruritic erythroderma characterized by flat-topped, red to brown, coalescing papules with sparing of the skinfolds, later coined the deck-chair sign.1,2 Papuloerythroderma of Ofuji commonly presents in elderly Asian males with a male to female ratio of 4:1.3 Papuloerythroderma of Ofuji is a T cell-mediated skin disease; however, the etiology of the signature rash remains unclear. One explanation includes circulating factors in the skin that elicit an inflammatory response, which does not occur in areas of external pressure.3 The deck-chair sign may occur more frequently in elderly individuals due to increased skin laxity, which creates crease lines that are spared from rubbing and excoriations.4