User login

Predictors of HA1c Goal Attainment in Patients Treated With Insulin at a VA Pharmacist-Managed Insulin Clinic (FULL)

Showing up to appointments and adherence to treatment recommendations correlated with glycemic goal attainment for patients.

About 30.3 million Americans (9.4%) have diabetes mellitus (DM).1 Veterans are disproportionately affected—about 1 in 4 of those who receive US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) care have DM.2 The consequences of uncontrolled DM include microvascular complications (eg, retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy) and macrovascular complications (eg, cardiovascular disease).

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends achieving a goal hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level of < 7% to prevent these complications. However, a goal of < 8% HbA1c may be more appropriate for certain patients when a more strict goal may be impractical or have the potential to cause harm.3 Furthermore, guidelines developed by the VA and the US Department of Defense suggest a target HbA1c range of 7.0% to 8.5% for patients with established microvascular or macrovascular disease, comorbid conditions, or a life expectancy of 5 to 10 years.4

Despite the existence of evidence showing the importance of glycemic control in preventing morbidity and mortality associated with DM, many patients have inadequate glycemic control. Diabetes mellitus is the seventh leading cause of death in the US. Moreover, DM is a known risk factor for heart disease, stroke, and kidney disease, which are the first, fifth, and ninth leading causes of death in the US, respectively.5

Because DM management requires ongoing and comprehensive maintenance and monitoring, the ADA supports a collaborative, multidisciplinary, and patient-centered approach to delivery of care.3 Collaborative teams involving pharmacists have been shown to improve outcomes and cost savings for chronic diseases, including DM.6-12 In 1995, the VA launched a national policy providing clinical pharmacists with prescribing privileges that would aid in the provision of coordinated medication management for patients with chronic illnesses.13 The policy created a framework for collaborative drug therapy management (CDTM) models, which grants pharmacists the ability to perform patient assessments, order laboratory tests, and modify medications within a scope of practice.

Since the initiation of these services, several examples of successful DM management services using clinical pharmacists within the VA exist in the literature.14-16 However, even with intensive chronic disease and drug therapy management, not all patients who enroll in these services successfully reach clinical goals. Although these pharmacist-driven services seem to demonstrate overall benefit and cost savings to veteran patients and the VA system, little published data exist to help determine patient behaviors that are associated with glycemic goal attainment when using these services.

At the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center in (CMCVAMC) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where this study was performed, primary care providers may refer patients with uncontrolled DM to the pharmacist disease state management (DSM) clinic. The clinic is a form of a CDTM and receives numerous referrals per year, with many patients discharged for successfully meeting glycemic targets.

However, a percentage of patients fail to attain glycemic goals despite involvement in this clinic. We observed specific patient behaviors that delayed glycemic goal attainment. This study examined whether these behaviors correlated with prolonged glycemic goal attainment. The purpose of this study was to identify patient behaviors that led to glycemic goal attainment in insulin-treated patients referred to this pharmacist DSM clinic.

Methods

This study was performed as a single-center retrospective chart review. The protocol and data collection documents were approved by the CMCVAMC Institutional Review Board. It included patients referred to a pharmacist-led DSM clinic for insulin titration/optimization from January 1, 2011 through December 31, 2012. Data were collected through June 30, 2013, to allow for 6 months after the last referral date of December 31, 2012.

This study included patients who were on insulin therapy at the time of pharmacy consult, who attended at least 3 consecutive pharmacy DSM clinic visits, and had an HbA1c ≥ 8% at the time of initial clinic consult. Patients who failed to have 3 consecutive pharmacy DSM clinic visits, were insulin-naïve at the time of referral, aged ≥ 90, lacked at least 1 follow-up HbA1c result while enrolled in the clinic, or had HbA1c < 8% were excluded.

Among the patients who met eligibility criteria, charts within the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) were reviewed in a chronologic order within the respective study time frame. A convenience sample of 100 patients were enrolled in each treatment arm: the goal-attained arm or the goal-not-attained arm.

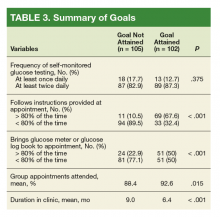

The primary study variable was HbA1c goal attainment, which was defined in this investigation as at least 1 HbA1c reading of < 8% while enrolled in the DSM clinic during the review period. Secondary variables included specific patient factors such as optimal frequency of self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) testing, adherence to pharmacist’s instructions for changes to glucose-lowering medications, adherence to bringing glucose meter/glucose log book to clinic appointments, and percentage of visits attended. Definitions for each variable are provided in Table 1.

We hypothesized that patients who were more adherent to treatment plans, regularly attend clinic visits, and appropriately monitor their glucose levels were more likely to meet their glycemic goals.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate descriptive statistics described the individual variables/predictors of HbA1c goal attainment. As the study’s purpose was to identify patient factors and characteristics associated with HbA1c goal attainment, a logistic regression model framework was used for all covariates to evaluate each measured variable’s independent association with HbA1c. The univariate tests were used to compare patient characteristics between the 2 study groups: Pearson chi-square test was used for nominal data, and a paired t test (for normally distributed data) or Wilcoxon rank sum test (for non-normally distributed data) was used for continuous variables. Variables having a P value < .2 underwent a multivariate analysis stepwise logistic regression model to identify patient factors and characteristics associated with HbA1c goal attainment. A Fisher exact test was used to determine gender effect on HbA1c goal attainment, categoric variables were analyzed using Pearson chi-square test, and an unpaired t test was used for continuous data. The backward elimination approach to inclusion of variables in the model was used to build the most parsimonious and best-fitting model, and the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit tests was used to assess model fit. Data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS, version 18.0 (Armonk, NY).

Results

Five hundred eighty-four patient records were reviewed, and 207 patients met inclusion criteria: 102 patient records were reviewed for the goal-attained arm, and 105 patient records for the goal-not-attained arm. Most patients were excluded from the analysis due to not having 3 consecutive visits during the specified period or having an HbA1c of < 8% at the time of referral to the pharmacist DSM clinic.

The patients in this study had type 2 diabetes for about 11 years, were overwhelmingly male (99%), were aged about 61 years, and were taking on average 13 medications at the time of referral to the pharmacist DSM clinic. Mean HbA1c at time of enrollment was slightly higher in the goal-not-attained arm vs goal-attained arm (10.7% vs 10.2%, respectively), but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .066). A little more than half the patients in both study arms were on basal + prandial insulin regimens (Table 2).

Patients who attained their goal HbA1cwere more likely to bring their glucose meter/glucose log book to at least 80% of their appointments (P < .001). Additionally, this same cohort followed insulin dosing instructions at least 80% of the time (P < .001).

Five variables were included in the multivariate analysis because they had a P value ≤ .2 in univariate analyses: (1) patient adherence to instructions (P < .001); (2) duration in clinic (P < .001); (3) patient bringingglucose meter or glucose log to appointments (P < .001); (4) percentage of scheduled appointments patient attended (P = .015); and (5) baseline HbA1c (P = .066).

Discussion

The development and constant modification of clinical practicing guidelines has made DM treatment a focus and priority.3,4 Additionally, the collaborative approach to health care and creation of VA pharmacist-driven services have demonstrated successful patient outcomes.6-16 Despite these efforts, further insight is needed to improve the management of DM. Our study identified specific behavioral factors that correlated to veteran patients to attaining their HbA1c goal of < 8% within a VA pharmacist DSM clinic. Additionally, it highlighted factors that contributed to patients not achieving their glycemic goals.

Our univariate analysis showed behaviors such as showing up for appointments and following directions regimens to correlate with glycemic goal attainment. However, following directions was the only behavioral factor that correlated to glycemic goal attainment in our multivariate analysis. Additionally, our findings indicated that factors for HbA1c goal attainment included patients who brought their glucose meter/glucose log book and attended clinic appointments at least 80% of the time, respectively.

These findings can help further refine the process for identifying patients who are most likely to achieve glycemic goals when referred to pharmacist DSM clinics or to any DM treatment program. Assessment of a patient’s motivation and ability to attend clinic appointments, bring their glucose meter/glucose log book, and to follow instructions provided at these appointments are reasonable screening questions to ask before referring that patient to a diabetes care program or service. Currently, this is not performed during the consult process to the pharmacist DSM clinic at the respective VA.

Additionally, our findings show that patients who met goal did so, on average, within 6 months of referral to the pharmacist DSM clinic. This finding may have occurred because patients who successfully reach HbA1c goal in 2 consecutive checks are discharged from the clinic. Patients who do not meet this goal continue with the clinic, thus increasing their duration of enrollment in this service. This finding could help clinical pharmacists estimate how long patients will be followed by the service, thus allowing for a more accurate estimation of workload and clinic capacity. Additionally, this finding provides insight if the patient should remain in clinic or be transferred to another program. Our findings aligned with previous studies showing the link between patient behaviors and glycemic goal attainment.17-19

Limitations

This study has a few notable limitations. First, it is limited to 1 VA medical center, so our findings may not be extrapolated easily to other institutions of the Veterans Health Administration. Ideally, future studies centered on identifying factors that lead to successful glycemic goal attainment would be helpful from multiple VA institutions. This would encourage more factors to be identified and trends to be strengthened. Ultimately, this would allow for more global changes to the consult process from primary care to pharmacist DSM clinics nationally vs at a local VA institution. Additionally, this study was limited to a specific retrospective time frame, therefore limiting its ability to identify trends. This study also relied on some subjective factors, such as the patient’s self-report of properly following the clinic instructions. Another limitation was that our investigation was not designed to characterize the specific pharmacist’s interventions that improved glycemic control. Future studies would benefit from the inclusion of specific interventions and their effect on glycemic goal attainment.

Conclusion

This retrospective study offers insight to specific patient behavioral factors that correlate with glycemic goal attainment in a VA pharmacist DSM clinic. Behavioral factors linked to HbA1c goal attainment of < 8% included appointment keeping, bringing glucose meter/glucose log book at least 80% of the time to these appointments, and following clinic instructions. This investigation also found that patients who attain glycemic goals generally do so within 6 months of enrollment. Furthermore, this study provided insight that following the clinic instructions a majority of the time strongly contributes to glycemic goal attainment. We believe that an assessment of patients’ behaviors prior to referrals to diabetes management programs will yield useful information about possible barriers to glycemic goal attainment.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed September 25, 2018.

2. Gaspar JL, Dahlke ME, Kasper B. Efficacy of patient aligned care team pharmacist service in reaching diabetes and hyperlipidemia treatment goals. Fed Pract. 2015;32(11):42-47.

3. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2017. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(suppl 1):S6-S135.

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus in primary care. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/diabetes/VADoDDMCPGFinal508.pdf. Published April 2017. Accessed September 7, 2018.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Deaths: leading causes for 2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;65(5):1-96.

6. Nigro SC, Garwood CL, Berlie H, et al. Clinical pharmacists as key members of the patient-centered medical home: an opinion statement of the Ambulatory Care Practice and Research Network of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(1):96-108.

7. Smith M, Bates DW, Bodenheimer T, et al. Why pharmacists belong in the medical home. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):906-913.

8. Chisholm-Burns MA, Kim Lee J, Spivey CA, et al. US Pharmacists’ effect as team members on patient care. Med Care. 2010;48(10):923-933.

9. Wubben DP, Vivian EM. Effects of pharmacist outpatient interventions on adults with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(4):421-436.

10. Touchette DR, Doloresco F, Suda KJ, et al. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacy services: 2006-2010. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(8):771-793.

11. Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving patient and health system outcomes through advanced pharmacy practice. A report of the U.S. Surgeon General. American College of Clinical Pharmacy. https://www.accp.com/docs/positions/misc/Improving_Patient_and_Health_System_Outcomes.pdf. Published December 2011. Accessed September 10, 2018.

12. Isetts BJ, Schondelmeyer SW, Artz MB, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of medication therapy management services: the Minnesota experience. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2008;48(2):203-211.

13. Ourth H, Groppi J, Morreale AP, Quicci-Roberts K. Clinical pharmacist prescribing activities in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(18):1406-1415.

14. Taveira TH, Friedmann PD, Cohen LB, et al. Pharmacist-led group medical appointment model in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36(1):109-117.

15. Edwards KL, Hadley RL, Baby N, Yeary JC, Chastain LM, Brown CD. Utilizing clinical pharmacy specialists to address access to care barriers in the veteran population for the management of diabetes. J Pharm Pract. 2017;30(4):412-418.

16. Cripps RJ, Gourley ES, Johnson W, et al. An evaluation of diabetes-related measures of control after 6 months of clinical pharmacy specialist intervention. J Pharm Prac. 2011;24(3):332-338.

17. Jones H, Edwards L, Vallis TM, et al; Diabetes Stages of Change (DiSC) Study. Changes in diabetes self-care behaviors make a difference in glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):732-737.

18. Schetman JM, Schorling JB, Voss JD. Appointment adherence and disparities in outcomes among patients with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1685-1687.

19. Rhee, MK, Slocum W, Zeimer DC, et al. Patient adherence improves glycemic control. Diabetes Educ. 2005;31(2):240-250.

Showing up to appointments and adherence to treatment recommendations correlated with glycemic goal attainment for patients.

Showing up to appointments and adherence to treatment recommendations correlated with glycemic goal attainment for patients.

About 30.3 million Americans (9.4%) have diabetes mellitus (DM).1 Veterans are disproportionately affected—about 1 in 4 of those who receive US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) care have DM.2 The consequences of uncontrolled DM include microvascular complications (eg, retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy) and macrovascular complications (eg, cardiovascular disease).

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends achieving a goal hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level of < 7% to prevent these complications. However, a goal of < 8% HbA1c may be more appropriate for certain patients when a more strict goal may be impractical or have the potential to cause harm.3 Furthermore, guidelines developed by the VA and the US Department of Defense suggest a target HbA1c range of 7.0% to 8.5% for patients with established microvascular or macrovascular disease, comorbid conditions, or a life expectancy of 5 to 10 years.4

Despite the existence of evidence showing the importance of glycemic control in preventing morbidity and mortality associated with DM, many patients have inadequate glycemic control. Diabetes mellitus is the seventh leading cause of death in the US. Moreover, DM is a known risk factor for heart disease, stroke, and kidney disease, which are the first, fifth, and ninth leading causes of death in the US, respectively.5

Because DM management requires ongoing and comprehensive maintenance and monitoring, the ADA supports a collaborative, multidisciplinary, and patient-centered approach to delivery of care.3 Collaborative teams involving pharmacists have been shown to improve outcomes and cost savings for chronic diseases, including DM.6-12 In 1995, the VA launched a national policy providing clinical pharmacists with prescribing privileges that would aid in the provision of coordinated medication management for patients with chronic illnesses.13 The policy created a framework for collaborative drug therapy management (CDTM) models, which grants pharmacists the ability to perform patient assessments, order laboratory tests, and modify medications within a scope of practice.

Since the initiation of these services, several examples of successful DM management services using clinical pharmacists within the VA exist in the literature.14-16 However, even with intensive chronic disease and drug therapy management, not all patients who enroll in these services successfully reach clinical goals. Although these pharmacist-driven services seem to demonstrate overall benefit and cost savings to veteran patients and the VA system, little published data exist to help determine patient behaviors that are associated with glycemic goal attainment when using these services.

At the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center in (CMCVAMC) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where this study was performed, primary care providers may refer patients with uncontrolled DM to the pharmacist disease state management (DSM) clinic. The clinic is a form of a CDTM and receives numerous referrals per year, with many patients discharged for successfully meeting glycemic targets.

However, a percentage of patients fail to attain glycemic goals despite involvement in this clinic. We observed specific patient behaviors that delayed glycemic goal attainment. This study examined whether these behaviors correlated with prolonged glycemic goal attainment. The purpose of this study was to identify patient behaviors that led to glycemic goal attainment in insulin-treated patients referred to this pharmacist DSM clinic.

Methods

This study was performed as a single-center retrospective chart review. The protocol and data collection documents were approved by the CMCVAMC Institutional Review Board. It included patients referred to a pharmacist-led DSM clinic for insulin titration/optimization from January 1, 2011 through December 31, 2012. Data were collected through June 30, 2013, to allow for 6 months after the last referral date of December 31, 2012.

This study included patients who were on insulin therapy at the time of pharmacy consult, who attended at least 3 consecutive pharmacy DSM clinic visits, and had an HbA1c ≥ 8% at the time of initial clinic consult. Patients who failed to have 3 consecutive pharmacy DSM clinic visits, were insulin-naïve at the time of referral, aged ≥ 90, lacked at least 1 follow-up HbA1c result while enrolled in the clinic, or had HbA1c < 8% were excluded.

Among the patients who met eligibility criteria, charts within the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) were reviewed in a chronologic order within the respective study time frame. A convenience sample of 100 patients were enrolled in each treatment arm: the goal-attained arm or the goal-not-attained arm.

The primary study variable was HbA1c goal attainment, which was defined in this investigation as at least 1 HbA1c reading of < 8% while enrolled in the DSM clinic during the review period. Secondary variables included specific patient factors such as optimal frequency of self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) testing, adherence to pharmacist’s instructions for changes to glucose-lowering medications, adherence to bringing glucose meter/glucose log book to clinic appointments, and percentage of visits attended. Definitions for each variable are provided in Table 1.

We hypothesized that patients who were more adherent to treatment plans, regularly attend clinic visits, and appropriately monitor their glucose levels were more likely to meet their glycemic goals.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate descriptive statistics described the individual variables/predictors of HbA1c goal attainment. As the study’s purpose was to identify patient factors and characteristics associated with HbA1c goal attainment, a logistic regression model framework was used for all covariates to evaluate each measured variable’s independent association with HbA1c. The univariate tests were used to compare patient characteristics between the 2 study groups: Pearson chi-square test was used for nominal data, and a paired t test (for normally distributed data) or Wilcoxon rank sum test (for non-normally distributed data) was used for continuous variables. Variables having a P value < .2 underwent a multivariate analysis stepwise logistic regression model to identify patient factors and characteristics associated with HbA1c goal attainment. A Fisher exact test was used to determine gender effect on HbA1c goal attainment, categoric variables were analyzed using Pearson chi-square test, and an unpaired t test was used for continuous data. The backward elimination approach to inclusion of variables in the model was used to build the most parsimonious and best-fitting model, and the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit tests was used to assess model fit. Data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS, version 18.0 (Armonk, NY).

Results

Five hundred eighty-four patient records were reviewed, and 207 patients met inclusion criteria: 102 patient records were reviewed for the goal-attained arm, and 105 patient records for the goal-not-attained arm. Most patients were excluded from the analysis due to not having 3 consecutive visits during the specified period or having an HbA1c of < 8% at the time of referral to the pharmacist DSM clinic.

The patients in this study had type 2 diabetes for about 11 years, were overwhelmingly male (99%), were aged about 61 years, and were taking on average 13 medications at the time of referral to the pharmacist DSM clinic. Mean HbA1c at time of enrollment was slightly higher in the goal-not-attained arm vs goal-attained arm (10.7% vs 10.2%, respectively), but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .066). A little more than half the patients in both study arms were on basal + prandial insulin regimens (Table 2).

Patients who attained their goal HbA1cwere more likely to bring their glucose meter/glucose log book to at least 80% of their appointments (P < .001). Additionally, this same cohort followed insulin dosing instructions at least 80% of the time (P < .001).

Five variables were included in the multivariate analysis because they had a P value ≤ .2 in univariate analyses: (1) patient adherence to instructions (P < .001); (2) duration in clinic (P < .001); (3) patient bringingglucose meter or glucose log to appointments (P < .001); (4) percentage of scheduled appointments patient attended (P = .015); and (5) baseline HbA1c (P = .066).

Discussion

The development and constant modification of clinical practicing guidelines has made DM treatment a focus and priority.3,4 Additionally, the collaborative approach to health care and creation of VA pharmacist-driven services have demonstrated successful patient outcomes.6-16 Despite these efforts, further insight is needed to improve the management of DM. Our study identified specific behavioral factors that correlated to veteran patients to attaining their HbA1c goal of < 8% within a VA pharmacist DSM clinic. Additionally, it highlighted factors that contributed to patients not achieving their glycemic goals.

Our univariate analysis showed behaviors such as showing up for appointments and following directions regimens to correlate with glycemic goal attainment. However, following directions was the only behavioral factor that correlated to glycemic goal attainment in our multivariate analysis. Additionally, our findings indicated that factors for HbA1c goal attainment included patients who brought their glucose meter/glucose log book and attended clinic appointments at least 80% of the time, respectively.

These findings can help further refine the process for identifying patients who are most likely to achieve glycemic goals when referred to pharmacist DSM clinics or to any DM treatment program. Assessment of a patient’s motivation and ability to attend clinic appointments, bring their glucose meter/glucose log book, and to follow instructions provided at these appointments are reasonable screening questions to ask before referring that patient to a diabetes care program or service. Currently, this is not performed during the consult process to the pharmacist DSM clinic at the respective VA.

Additionally, our findings show that patients who met goal did so, on average, within 6 months of referral to the pharmacist DSM clinic. This finding may have occurred because patients who successfully reach HbA1c goal in 2 consecutive checks are discharged from the clinic. Patients who do not meet this goal continue with the clinic, thus increasing their duration of enrollment in this service. This finding could help clinical pharmacists estimate how long patients will be followed by the service, thus allowing for a more accurate estimation of workload and clinic capacity. Additionally, this finding provides insight if the patient should remain in clinic or be transferred to another program. Our findings aligned with previous studies showing the link between patient behaviors and glycemic goal attainment.17-19

Limitations

This study has a few notable limitations. First, it is limited to 1 VA medical center, so our findings may not be extrapolated easily to other institutions of the Veterans Health Administration. Ideally, future studies centered on identifying factors that lead to successful glycemic goal attainment would be helpful from multiple VA institutions. This would encourage more factors to be identified and trends to be strengthened. Ultimately, this would allow for more global changes to the consult process from primary care to pharmacist DSM clinics nationally vs at a local VA institution. Additionally, this study was limited to a specific retrospective time frame, therefore limiting its ability to identify trends. This study also relied on some subjective factors, such as the patient’s self-report of properly following the clinic instructions. Another limitation was that our investigation was not designed to characterize the specific pharmacist’s interventions that improved glycemic control. Future studies would benefit from the inclusion of specific interventions and their effect on glycemic goal attainment.

Conclusion

This retrospective study offers insight to specific patient behavioral factors that correlate with glycemic goal attainment in a VA pharmacist DSM clinic. Behavioral factors linked to HbA1c goal attainment of < 8% included appointment keeping, bringing glucose meter/glucose log book at least 80% of the time to these appointments, and following clinic instructions. This investigation also found that patients who attain glycemic goals generally do so within 6 months of enrollment. Furthermore, this study provided insight that following the clinic instructions a majority of the time strongly contributes to glycemic goal attainment. We believe that an assessment of patients’ behaviors prior to referrals to diabetes management programs will yield useful information about possible barriers to glycemic goal attainment.

About 30.3 million Americans (9.4%) have diabetes mellitus (DM).1 Veterans are disproportionately affected—about 1 in 4 of those who receive US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) care have DM.2 The consequences of uncontrolled DM include microvascular complications (eg, retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy) and macrovascular complications (eg, cardiovascular disease).

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends achieving a goal hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level of < 7% to prevent these complications. However, a goal of < 8% HbA1c may be more appropriate for certain patients when a more strict goal may be impractical or have the potential to cause harm.3 Furthermore, guidelines developed by the VA and the US Department of Defense suggest a target HbA1c range of 7.0% to 8.5% for patients with established microvascular or macrovascular disease, comorbid conditions, or a life expectancy of 5 to 10 years.4

Despite the existence of evidence showing the importance of glycemic control in preventing morbidity and mortality associated with DM, many patients have inadequate glycemic control. Diabetes mellitus is the seventh leading cause of death in the US. Moreover, DM is a known risk factor for heart disease, stroke, and kidney disease, which are the first, fifth, and ninth leading causes of death in the US, respectively.5

Because DM management requires ongoing and comprehensive maintenance and monitoring, the ADA supports a collaborative, multidisciplinary, and patient-centered approach to delivery of care.3 Collaborative teams involving pharmacists have been shown to improve outcomes and cost savings for chronic diseases, including DM.6-12 In 1995, the VA launched a national policy providing clinical pharmacists with prescribing privileges that would aid in the provision of coordinated medication management for patients with chronic illnesses.13 The policy created a framework for collaborative drug therapy management (CDTM) models, which grants pharmacists the ability to perform patient assessments, order laboratory tests, and modify medications within a scope of practice.

Since the initiation of these services, several examples of successful DM management services using clinical pharmacists within the VA exist in the literature.14-16 However, even with intensive chronic disease and drug therapy management, not all patients who enroll in these services successfully reach clinical goals. Although these pharmacist-driven services seem to demonstrate overall benefit and cost savings to veteran patients and the VA system, little published data exist to help determine patient behaviors that are associated with glycemic goal attainment when using these services.

At the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center in (CMCVAMC) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where this study was performed, primary care providers may refer patients with uncontrolled DM to the pharmacist disease state management (DSM) clinic. The clinic is a form of a CDTM and receives numerous referrals per year, with many patients discharged for successfully meeting glycemic targets.

However, a percentage of patients fail to attain glycemic goals despite involvement in this clinic. We observed specific patient behaviors that delayed glycemic goal attainment. This study examined whether these behaviors correlated with prolonged glycemic goal attainment. The purpose of this study was to identify patient behaviors that led to glycemic goal attainment in insulin-treated patients referred to this pharmacist DSM clinic.

Methods

This study was performed as a single-center retrospective chart review. The protocol and data collection documents were approved by the CMCVAMC Institutional Review Board. It included patients referred to a pharmacist-led DSM clinic for insulin titration/optimization from January 1, 2011 through December 31, 2012. Data were collected through June 30, 2013, to allow for 6 months after the last referral date of December 31, 2012.

This study included patients who were on insulin therapy at the time of pharmacy consult, who attended at least 3 consecutive pharmacy DSM clinic visits, and had an HbA1c ≥ 8% at the time of initial clinic consult. Patients who failed to have 3 consecutive pharmacy DSM clinic visits, were insulin-naïve at the time of referral, aged ≥ 90, lacked at least 1 follow-up HbA1c result while enrolled in the clinic, or had HbA1c < 8% were excluded.

Among the patients who met eligibility criteria, charts within the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) were reviewed in a chronologic order within the respective study time frame. A convenience sample of 100 patients were enrolled in each treatment arm: the goal-attained arm or the goal-not-attained arm.

The primary study variable was HbA1c goal attainment, which was defined in this investigation as at least 1 HbA1c reading of < 8% while enrolled in the DSM clinic during the review period. Secondary variables included specific patient factors such as optimal frequency of self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) testing, adherence to pharmacist’s instructions for changes to glucose-lowering medications, adherence to bringing glucose meter/glucose log book to clinic appointments, and percentage of visits attended. Definitions for each variable are provided in Table 1.

We hypothesized that patients who were more adherent to treatment plans, regularly attend clinic visits, and appropriately monitor their glucose levels were more likely to meet their glycemic goals.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate descriptive statistics described the individual variables/predictors of HbA1c goal attainment. As the study’s purpose was to identify patient factors and characteristics associated with HbA1c goal attainment, a logistic regression model framework was used for all covariates to evaluate each measured variable’s independent association with HbA1c. The univariate tests were used to compare patient characteristics between the 2 study groups: Pearson chi-square test was used for nominal data, and a paired t test (for normally distributed data) or Wilcoxon rank sum test (for non-normally distributed data) was used for continuous variables. Variables having a P value < .2 underwent a multivariate analysis stepwise logistic regression model to identify patient factors and characteristics associated with HbA1c goal attainment. A Fisher exact test was used to determine gender effect on HbA1c goal attainment, categoric variables were analyzed using Pearson chi-square test, and an unpaired t test was used for continuous data. The backward elimination approach to inclusion of variables in the model was used to build the most parsimonious and best-fitting model, and the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit tests was used to assess model fit. Data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS, version 18.0 (Armonk, NY).

Results

Five hundred eighty-four patient records were reviewed, and 207 patients met inclusion criteria: 102 patient records were reviewed for the goal-attained arm, and 105 patient records for the goal-not-attained arm. Most patients were excluded from the analysis due to not having 3 consecutive visits during the specified period or having an HbA1c of < 8% at the time of referral to the pharmacist DSM clinic.

The patients in this study had type 2 diabetes for about 11 years, were overwhelmingly male (99%), were aged about 61 years, and were taking on average 13 medications at the time of referral to the pharmacist DSM clinic. Mean HbA1c at time of enrollment was slightly higher in the goal-not-attained arm vs goal-attained arm (10.7% vs 10.2%, respectively), but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .066). A little more than half the patients in both study arms were on basal + prandial insulin regimens (Table 2).

Patients who attained their goal HbA1cwere more likely to bring their glucose meter/glucose log book to at least 80% of their appointments (P < .001). Additionally, this same cohort followed insulin dosing instructions at least 80% of the time (P < .001).

Five variables were included in the multivariate analysis because they had a P value ≤ .2 in univariate analyses: (1) patient adherence to instructions (P < .001); (2) duration in clinic (P < .001); (3) patient bringingglucose meter or glucose log to appointments (P < .001); (4) percentage of scheduled appointments patient attended (P = .015); and (5) baseline HbA1c (P = .066).

Discussion

The development and constant modification of clinical practicing guidelines has made DM treatment a focus and priority.3,4 Additionally, the collaborative approach to health care and creation of VA pharmacist-driven services have demonstrated successful patient outcomes.6-16 Despite these efforts, further insight is needed to improve the management of DM. Our study identified specific behavioral factors that correlated to veteran patients to attaining their HbA1c goal of < 8% within a VA pharmacist DSM clinic. Additionally, it highlighted factors that contributed to patients not achieving their glycemic goals.

Our univariate analysis showed behaviors such as showing up for appointments and following directions regimens to correlate with glycemic goal attainment. However, following directions was the only behavioral factor that correlated to glycemic goal attainment in our multivariate analysis. Additionally, our findings indicated that factors for HbA1c goal attainment included patients who brought their glucose meter/glucose log book and attended clinic appointments at least 80% of the time, respectively.

These findings can help further refine the process for identifying patients who are most likely to achieve glycemic goals when referred to pharmacist DSM clinics or to any DM treatment program. Assessment of a patient’s motivation and ability to attend clinic appointments, bring their glucose meter/glucose log book, and to follow instructions provided at these appointments are reasonable screening questions to ask before referring that patient to a diabetes care program or service. Currently, this is not performed during the consult process to the pharmacist DSM clinic at the respective VA.

Additionally, our findings show that patients who met goal did so, on average, within 6 months of referral to the pharmacist DSM clinic. This finding may have occurred because patients who successfully reach HbA1c goal in 2 consecutive checks are discharged from the clinic. Patients who do not meet this goal continue with the clinic, thus increasing their duration of enrollment in this service. This finding could help clinical pharmacists estimate how long patients will be followed by the service, thus allowing for a more accurate estimation of workload and clinic capacity. Additionally, this finding provides insight if the patient should remain in clinic or be transferred to another program. Our findings aligned with previous studies showing the link between patient behaviors and glycemic goal attainment.17-19

Limitations

This study has a few notable limitations. First, it is limited to 1 VA medical center, so our findings may not be extrapolated easily to other institutions of the Veterans Health Administration. Ideally, future studies centered on identifying factors that lead to successful glycemic goal attainment would be helpful from multiple VA institutions. This would encourage more factors to be identified and trends to be strengthened. Ultimately, this would allow for more global changes to the consult process from primary care to pharmacist DSM clinics nationally vs at a local VA institution. Additionally, this study was limited to a specific retrospective time frame, therefore limiting its ability to identify trends. This study also relied on some subjective factors, such as the patient’s self-report of properly following the clinic instructions. Another limitation was that our investigation was not designed to characterize the specific pharmacist’s interventions that improved glycemic control. Future studies would benefit from the inclusion of specific interventions and their effect on glycemic goal attainment.

Conclusion

This retrospective study offers insight to specific patient behavioral factors that correlate with glycemic goal attainment in a VA pharmacist DSM clinic. Behavioral factors linked to HbA1c goal attainment of < 8% included appointment keeping, bringing glucose meter/glucose log book at least 80% of the time to these appointments, and following clinic instructions. This investigation also found that patients who attain glycemic goals generally do so within 6 months of enrollment. Furthermore, this study provided insight that following the clinic instructions a majority of the time strongly contributes to glycemic goal attainment. We believe that an assessment of patients’ behaviors prior to referrals to diabetes management programs will yield useful information about possible barriers to glycemic goal attainment.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed September 25, 2018.

2. Gaspar JL, Dahlke ME, Kasper B. Efficacy of patient aligned care team pharmacist service in reaching diabetes and hyperlipidemia treatment goals. Fed Pract. 2015;32(11):42-47.

3. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2017. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(suppl 1):S6-S135.

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus in primary care. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/diabetes/VADoDDMCPGFinal508.pdf. Published April 2017. Accessed September 7, 2018.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Deaths: leading causes for 2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;65(5):1-96.

6. Nigro SC, Garwood CL, Berlie H, et al. Clinical pharmacists as key members of the patient-centered medical home: an opinion statement of the Ambulatory Care Practice and Research Network of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(1):96-108.

7. Smith M, Bates DW, Bodenheimer T, et al. Why pharmacists belong in the medical home. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):906-913.

8. Chisholm-Burns MA, Kim Lee J, Spivey CA, et al. US Pharmacists’ effect as team members on patient care. Med Care. 2010;48(10):923-933.

9. Wubben DP, Vivian EM. Effects of pharmacist outpatient interventions on adults with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(4):421-436.

10. Touchette DR, Doloresco F, Suda KJ, et al. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacy services: 2006-2010. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(8):771-793.

11. Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving patient and health system outcomes through advanced pharmacy practice. A report of the U.S. Surgeon General. American College of Clinical Pharmacy. https://www.accp.com/docs/positions/misc/Improving_Patient_and_Health_System_Outcomes.pdf. Published December 2011. Accessed September 10, 2018.

12. Isetts BJ, Schondelmeyer SW, Artz MB, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of medication therapy management services: the Minnesota experience. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2008;48(2):203-211.

13. Ourth H, Groppi J, Morreale AP, Quicci-Roberts K. Clinical pharmacist prescribing activities in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(18):1406-1415.

14. Taveira TH, Friedmann PD, Cohen LB, et al. Pharmacist-led group medical appointment model in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36(1):109-117.

15. Edwards KL, Hadley RL, Baby N, Yeary JC, Chastain LM, Brown CD. Utilizing clinical pharmacy specialists to address access to care barriers in the veteran population for the management of diabetes. J Pharm Pract. 2017;30(4):412-418.

16. Cripps RJ, Gourley ES, Johnson W, et al. An evaluation of diabetes-related measures of control after 6 months of clinical pharmacy specialist intervention. J Pharm Prac. 2011;24(3):332-338.

17. Jones H, Edwards L, Vallis TM, et al; Diabetes Stages of Change (DiSC) Study. Changes in diabetes self-care behaviors make a difference in glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):732-737.

18. Schetman JM, Schorling JB, Voss JD. Appointment adherence and disparities in outcomes among patients with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1685-1687.

19. Rhee, MK, Slocum W, Zeimer DC, et al. Patient adherence improves glycemic control. Diabetes Educ. 2005;31(2):240-250.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed September 25, 2018.

2. Gaspar JL, Dahlke ME, Kasper B. Efficacy of patient aligned care team pharmacist service in reaching diabetes and hyperlipidemia treatment goals. Fed Pract. 2015;32(11):42-47.

3. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2017. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(suppl 1):S6-S135.

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus in primary care. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/diabetes/VADoDDMCPGFinal508.pdf. Published April 2017. Accessed September 7, 2018.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Deaths: leading causes for 2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;65(5):1-96.

6. Nigro SC, Garwood CL, Berlie H, et al. Clinical pharmacists as key members of the patient-centered medical home: an opinion statement of the Ambulatory Care Practice and Research Network of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(1):96-108.

7. Smith M, Bates DW, Bodenheimer T, et al. Why pharmacists belong in the medical home. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):906-913.

8. Chisholm-Burns MA, Kim Lee J, Spivey CA, et al. US Pharmacists’ effect as team members on patient care. Med Care. 2010;48(10):923-933.

9. Wubben DP, Vivian EM. Effects of pharmacist outpatient interventions on adults with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(4):421-436.

10. Touchette DR, Doloresco F, Suda KJ, et al. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacy services: 2006-2010. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(8):771-793.

11. Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving patient and health system outcomes through advanced pharmacy practice. A report of the U.S. Surgeon General. American College of Clinical Pharmacy. https://www.accp.com/docs/positions/misc/Improving_Patient_and_Health_System_Outcomes.pdf. Published December 2011. Accessed September 10, 2018.

12. Isetts BJ, Schondelmeyer SW, Artz MB, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of medication therapy management services: the Minnesota experience. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2008;48(2):203-211.

13. Ourth H, Groppi J, Morreale AP, Quicci-Roberts K. Clinical pharmacist prescribing activities in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(18):1406-1415.

14. Taveira TH, Friedmann PD, Cohen LB, et al. Pharmacist-led group medical appointment model in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36(1):109-117.

15. Edwards KL, Hadley RL, Baby N, Yeary JC, Chastain LM, Brown CD. Utilizing clinical pharmacy specialists to address access to care barriers in the veteran population for the management of diabetes. J Pharm Pract. 2017;30(4):412-418.

16. Cripps RJ, Gourley ES, Johnson W, et al. An evaluation of diabetes-related measures of control after 6 months of clinical pharmacy specialist intervention. J Pharm Prac. 2011;24(3):332-338.

17. Jones H, Edwards L, Vallis TM, et al; Diabetes Stages of Change (DiSC) Study. Changes in diabetes self-care behaviors make a difference in glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):732-737.

18. Schetman JM, Schorling JB, Voss JD. Appointment adherence and disparities in outcomes among patients with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1685-1687.

19. Rhee, MK, Slocum W, Zeimer DC, et al. Patient adherence improves glycemic control. Diabetes Educ. 2005;31(2):240-250.

New model for CKD risk draws on clinical, demographic factors

Data from more than 5 million individuals has been used to develop an equation for predicting the risk of incident chronic kidney disease (CKD) in people with or without diabetes, according to a presentation at Kidney Week 2019, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

In a paper published simultaneously online in JAMA, researchers reported the outcome of an individual-level data analysis of 34 multinational cohorts involving 5,222,711 individuals – including 781,627 with diabetes – from 28 countries as part of the Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium.

“An equation for kidney failure risk may help improve care for patients with established CKD, but relatively little work has been performed to develop predictive tools to identify those at increased risk of developing CKD – defined by reduced eGFR [estimated glomerular filtration rate], despite the high lifetime risk of CKD – which is estimated to be 59.1% in the United States,” wrote Robert G. Nelson, MD, PhD, from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases in Phoenix and colleagues.

Over a mean follow-up of 4 years, 15% of individuals without diabetes and 40% of individuals with diabetes developed incident chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR below 60 mL/min per 1.73m2.

The key risk factors were older age, female sex, black race, hypertension, history of cardiovascular disease, lower eGFR values, and higher urine albumin to creatinine ratio. Smoking was also significantly associated with reduced eGFR but only in cohorts without diabetes. In cohorts with diabetes, elevated hemoglobin A1c and the presence and type of diabetes medication were also significantly associated with reduced eGFR.

Using this information, the researchers developed a prediction model built from weighted-average hazard ratios and validated it in nine external validation cohorts of 18 study populations involving a total of 2,253,540 individuals. They found that in 16 of the 18 study populations, the slope of observed to predicted risk ranged from 0.80 to 1.25.

Moreover, in the cohorts without diabetes, the risk equations had a median C-statistic for the 5-year predicted probability of 0.845 (interquartile range, 0.789-0.890) and of 0.801 (IQR, 0.750-0.819) in the cohorts with diabetes, the investigators reported.

“Several models have been developed for estimating the risk of prevalent and incident CKD and end-stage kidney disease, but even those with good discriminative performance have not always performed well for cohorts of people outside the original derivation cohort,” the authors wrote. They argued that their model “demonstrated high discrimination and variable calibration in diverse populations.”

However, they stressed that further study was needed to determine if use of the equations would actually lead to improvements in clinical care and patient outcomes. In an accompanying editorial, Sri Lekha Tummalapalli, MD, and Michelle M. Estrella, MD, of the Kidney Health Research Collaborative at the University of California, San Francisco, said the study and its focus on primary, rather than secondary, prevention of kidney disease is a critical step toward reducing the burden of that disease, especially given that an estimated 37 million people in the United States have chronic kidney disease.

It is also important, they added, that primary prevention of kidney disease is tailored to the individual patient’s risk because risk prediction and screening strategies are unlikely to improve outcomes if they are not paired with effective individualized interventions, such as lifestyle modification or management of blood pressure.

These risk equations could be more holistic by integrating the prediction of both elevated albuminuria and reduced eGFR because more than 40% of individuals with chronic kidney disease have increased albuminuria without reduced eGFR, they noted (JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17378).

The study and CKD Prognosis Consortium were supported by the U.S. National Kidney Foundation and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One author was supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation. Nine authors declared grants, consultancies, and other support from the private sector and research organizations. No other conflicts of interest were declared. Dr. Tummalapalli and Dr. Estrella reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Nelson R et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17379.

Data from more than 5 million individuals has been used to develop an equation for predicting the risk of incident chronic kidney disease (CKD) in people with or without diabetes, according to a presentation at Kidney Week 2019, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

In a paper published simultaneously online in JAMA, researchers reported the outcome of an individual-level data analysis of 34 multinational cohorts involving 5,222,711 individuals – including 781,627 with diabetes – from 28 countries as part of the Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium.

“An equation for kidney failure risk may help improve care for patients with established CKD, but relatively little work has been performed to develop predictive tools to identify those at increased risk of developing CKD – defined by reduced eGFR [estimated glomerular filtration rate], despite the high lifetime risk of CKD – which is estimated to be 59.1% in the United States,” wrote Robert G. Nelson, MD, PhD, from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases in Phoenix and colleagues.

Over a mean follow-up of 4 years, 15% of individuals without diabetes and 40% of individuals with diabetes developed incident chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR below 60 mL/min per 1.73m2.

The key risk factors were older age, female sex, black race, hypertension, history of cardiovascular disease, lower eGFR values, and higher urine albumin to creatinine ratio. Smoking was also significantly associated with reduced eGFR but only in cohorts without diabetes. In cohorts with diabetes, elevated hemoglobin A1c and the presence and type of diabetes medication were also significantly associated with reduced eGFR.

Using this information, the researchers developed a prediction model built from weighted-average hazard ratios and validated it in nine external validation cohorts of 18 study populations involving a total of 2,253,540 individuals. They found that in 16 of the 18 study populations, the slope of observed to predicted risk ranged from 0.80 to 1.25.

Moreover, in the cohorts without diabetes, the risk equations had a median C-statistic for the 5-year predicted probability of 0.845 (interquartile range, 0.789-0.890) and of 0.801 (IQR, 0.750-0.819) in the cohorts with diabetes, the investigators reported.

“Several models have been developed for estimating the risk of prevalent and incident CKD and end-stage kidney disease, but even those with good discriminative performance have not always performed well for cohorts of people outside the original derivation cohort,” the authors wrote. They argued that their model “demonstrated high discrimination and variable calibration in diverse populations.”

However, they stressed that further study was needed to determine if use of the equations would actually lead to improvements in clinical care and patient outcomes. In an accompanying editorial, Sri Lekha Tummalapalli, MD, and Michelle M. Estrella, MD, of the Kidney Health Research Collaborative at the University of California, San Francisco, said the study and its focus on primary, rather than secondary, prevention of kidney disease is a critical step toward reducing the burden of that disease, especially given that an estimated 37 million people in the United States have chronic kidney disease.

It is also important, they added, that primary prevention of kidney disease is tailored to the individual patient’s risk because risk prediction and screening strategies are unlikely to improve outcomes if they are not paired with effective individualized interventions, such as lifestyle modification or management of blood pressure.

These risk equations could be more holistic by integrating the prediction of both elevated albuminuria and reduced eGFR because more than 40% of individuals with chronic kidney disease have increased albuminuria without reduced eGFR, they noted (JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17378).

The study and CKD Prognosis Consortium were supported by the U.S. National Kidney Foundation and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One author was supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation. Nine authors declared grants, consultancies, and other support from the private sector and research organizations. No other conflicts of interest were declared. Dr. Tummalapalli and Dr. Estrella reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Nelson R et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17379.

Data from more than 5 million individuals has been used to develop an equation for predicting the risk of incident chronic kidney disease (CKD) in people with or without diabetes, according to a presentation at Kidney Week 2019, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

In a paper published simultaneously online in JAMA, researchers reported the outcome of an individual-level data analysis of 34 multinational cohorts involving 5,222,711 individuals – including 781,627 with diabetes – from 28 countries as part of the Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium.

“An equation for kidney failure risk may help improve care for patients with established CKD, but relatively little work has been performed to develop predictive tools to identify those at increased risk of developing CKD – defined by reduced eGFR [estimated glomerular filtration rate], despite the high lifetime risk of CKD – which is estimated to be 59.1% in the United States,” wrote Robert G. Nelson, MD, PhD, from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases in Phoenix and colleagues.

Over a mean follow-up of 4 years, 15% of individuals without diabetes and 40% of individuals with diabetes developed incident chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR below 60 mL/min per 1.73m2.

The key risk factors were older age, female sex, black race, hypertension, history of cardiovascular disease, lower eGFR values, and higher urine albumin to creatinine ratio. Smoking was also significantly associated with reduced eGFR but only in cohorts without diabetes. In cohorts with diabetes, elevated hemoglobin A1c and the presence and type of diabetes medication were also significantly associated with reduced eGFR.

Using this information, the researchers developed a prediction model built from weighted-average hazard ratios and validated it in nine external validation cohorts of 18 study populations involving a total of 2,253,540 individuals. They found that in 16 of the 18 study populations, the slope of observed to predicted risk ranged from 0.80 to 1.25.

Moreover, in the cohorts without diabetes, the risk equations had a median C-statistic for the 5-year predicted probability of 0.845 (interquartile range, 0.789-0.890) and of 0.801 (IQR, 0.750-0.819) in the cohorts with diabetes, the investigators reported.

“Several models have been developed for estimating the risk of prevalent and incident CKD and end-stage kidney disease, but even those with good discriminative performance have not always performed well for cohorts of people outside the original derivation cohort,” the authors wrote. They argued that their model “demonstrated high discrimination and variable calibration in diverse populations.”

However, they stressed that further study was needed to determine if use of the equations would actually lead to improvements in clinical care and patient outcomes. In an accompanying editorial, Sri Lekha Tummalapalli, MD, and Michelle M. Estrella, MD, of the Kidney Health Research Collaborative at the University of California, San Francisco, said the study and its focus on primary, rather than secondary, prevention of kidney disease is a critical step toward reducing the burden of that disease, especially given that an estimated 37 million people in the United States have chronic kidney disease.

It is also important, they added, that primary prevention of kidney disease is tailored to the individual patient’s risk because risk prediction and screening strategies are unlikely to improve outcomes if they are not paired with effective individualized interventions, such as lifestyle modification or management of blood pressure.

These risk equations could be more holistic by integrating the prediction of both elevated albuminuria and reduced eGFR because more than 40% of individuals with chronic kidney disease have increased albuminuria without reduced eGFR, they noted (JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17378).

The study and CKD Prognosis Consortium were supported by the U.S. National Kidney Foundation and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One author was supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation. Nine authors declared grants, consultancies, and other support from the private sector and research organizations. No other conflicts of interest were declared. Dr. Tummalapalli and Dr. Estrella reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Nelson R et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17379.

REPORTING FROM KIDNEY WEEK 2019

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In the cohorts without diabetes, the risk equations had a median C-statistic for the 5-year predicted probability of 0.845 (interquartile range, 0.789-0.890), and of 0.801 (IQR, 0.750-0.819) in the cohorts with diabetes,

Study details: Analysis of cohort data from 5,222,711 individuals, including 781,627 with diabetes.

Disclosures: The study and CKD Prognosis Consortium were supported by the U.S. National Kidney Foundation and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One author was supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation. Nine authors declared grants, consultancies, and other support from the private sector and research organizations. No other conflicts of interest were declared. Dr. Tummalapalli and Dr. Estrella reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Nelson R et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17379.

Vitamin D, omega-3 fatty acids do not preserve kidney function in type 2 diabetes

A new study has found that neither vitamin D nor omega-3 fatty acids are significantly more beneficial than placebo for prevention and treatment of chronic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes, according to Ian H. de Boer, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and coauthors.

Findings of the study were presented at Kidney Week 2019, sponsored the American Society of Nephrology, and published simultaneously in JAMA.

To determine the benefits of either vitamin D or omega-3 fatty acids in regard to kidney function, the researchers conducted a randomized clinical trial of 1,312 patients with type 2 diabetes. The trial was designed to accompany the Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial (VITAL), which enrolled 25,871 patients to test the two supplements in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Participants in this study – known as VITAL–Diabetic Kidney Disease, designed as an ancillary to VITAL – were assigned to one of four groups: vitamin D plus omega-3 fatty acids (n = 370), vitamin D plus placebo (n = 333), omega-3 fatty acids plus placebo (n = 289), or both placebos (n = 320). The goal was to assess changes in in glomerular filtration rate estimated from serum creatinine and cystatin C (eGFR) after 5 years.

Of the initial 1,312 participants, 934 (71%) finished the study. At 5-year follow-up, patients taking vitamin D had a mean change in eGFR of −12.3 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (95% confidence interval, −13.4 to −11.2), compared with −13.1 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, −14.2 to −11.9) with placebo. Patients taking omega-3 fatty acids had a mean eGFR change of −12.2 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, −13.3 to −11.1), compared with −13.1 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, −14.2 to −12.0) with placebo.

The authors noted that the modest number of measurements collected per participant limited the evaluation and analyses. In addition, the study focused broadly on the type 2 diabetes population and not on subgroups, “who may derive more benefit from the study interventions.”

In an accompanying editorial, authors Anika Lucas, MD and Myles Wolf, MD, of Duke University in Durham, N.C., said multiple clinical trials, including this latest study from de Boer and colleagues on kidney function, have failed to reinforce the previously reported benefits of vitamin D.

“The VITAL-DKD study population had nearly normal mean 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels at baseline, leaving open the question of whether the results would have differed had recruitment been restricted to patients with moderate or severe vitamin D deficiency,” they wrote (JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17302).

Nevertheless, it seems safe to conclude that the previous associations between vitamin D deficiency and adverse health were “driven by unmeasured residual confounding or reverse causality.

“Without certainty about the ideal approach to vitamin D treatment in advanced CKD, a randomized trial that compared cholecalciferol, exogenous 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and an activated vitamin D analogue vs. placebo could definitively lay to rest multiple remaining questions in the area,” they suggested.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases funded the study. The authors reported numerous potential conflicts of interest, including receiving grants, consulting fees, and equipment and supplies from various pharmaceutical companies and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Wolf reported having served as a consultant for Akebia, AMAG, Amgen, Ardelyx, Diasorin, and Pharmacosmos. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: de Boer IH et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17380.

A new study has found that neither vitamin D nor omega-3 fatty acids are significantly more beneficial than placebo for prevention and treatment of chronic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes, according to Ian H. de Boer, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and coauthors.

Findings of the study were presented at Kidney Week 2019, sponsored the American Society of Nephrology, and published simultaneously in JAMA.

To determine the benefits of either vitamin D or omega-3 fatty acids in regard to kidney function, the researchers conducted a randomized clinical trial of 1,312 patients with type 2 diabetes. The trial was designed to accompany the Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial (VITAL), which enrolled 25,871 patients to test the two supplements in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Participants in this study – known as VITAL–Diabetic Kidney Disease, designed as an ancillary to VITAL – were assigned to one of four groups: vitamin D plus omega-3 fatty acids (n = 370), vitamin D plus placebo (n = 333), omega-3 fatty acids plus placebo (n = 289), or both placebos (n = 320). The goal was to assess changes in in glomerular filtration rate estimated from serum creatinine and cystatin C (eGFR) after 5 years.

Of the initial 1,312 participants, 934 (71%) finished the study. At 5-year follow-up, patients taking vitamin D had a mean change in eGFR of −12.3 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (95% confidence interval, −13.4 to −11.2), compared with −13.1 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, −14.2 to −11.9) with placebo. Patients taking omega-3 fatty acids had a mean eGFR change of −12.2 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, −13.3 to −11.1), compared with −13.1 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, −14.2 to −12.0) with placebo.

The authors noted that the modest number of measurements collected per participant limited the evaluation and analyses. In addition, the study focused broadly on the type 2 diabetes population and not on subgroups, “who may derive more benefit from the study interventions.”

In an accompanying editorial, authors Anika Lucas, MD and Myles Wolf, MD, of Duke University in Durham, N.C., said multiple clinical trials, including this latest study from de Boer and colleagues on kidney function, have failed to reinforce the previously reported benefits of vitamin D.

“The VITAL-DKD study population had nearly normal mean 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels at baseline, leaving open the question of whether the results would have differed had recruitment been restricted to patients with moderate or severe vitamin D deficiency,” they wrote (JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17302).

Nevertheless, it seems safe to conclude that the previous associations between vitamin D deficiency and adverse health were “driven by unmeasured residual confounding or reverse causality.

“Without certainty about the ideal approach to vitamin D treatment in advanced CKD, a randomized trial that compared cholecalciferol, exogenous 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and an activated vitamin D analogue vs. placebo could definitively lay to rest multiple remaining questions in the area,” they suggested.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases funded the study. The authors reported numerous potential conflicts of interest, including receiving grants, consulting fees, and equipment and supplies from various pharmaceutical companies and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Wolf reported having served as a consultant for Akebia, AMAG, Amgen, Ardelyx, Diasorin, and Pharmacosmos. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: de Boer IH et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17380.

A new study has found that neither vitamin D nor omega-3 fatty acids are significantly more beneficial than placebo for prevention and treatment of chronic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes, according to Ian H. de Boer, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and coauthors.

Findings of the study were presented at Kidney Week 2019, sponsored the American Society of Nephrology, and published simultaneously in JAMA.

To determine the benefits of either vitamin D or omega-3 fatty acids in regard to kidney function, the researchers conducted a randomized clinical trial of 1,312 patients with type 2 diabetes. The trial was designed to accompany the Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial (VITAL), which enrolled 25,871 patients to test the two supplements in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Participants in this study – known as VITAL–Diabetic Kidney Disease, designed as an ancillary to VITAL – were assigned to one of four groups: vitamin D plus omega-3 fatty acids (n = 370), vitamin D plus placebo (n = 333), omega-3 fatty acids plus placebo (n = 289), or both placebos (n = 320). The goal was to assess changes in in glomerular filtration rate estimated from serum creatinine and cystatin C (eGFR) after 5 years.

Of the initial 1,312 participants, 934 (71%) finished the study. At 5-year follow-up, patients taking vitamin D had a mean change in eGFR of −12.3 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (95% confidence interval, −13.4 to −11.2), compared with −13.1 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, −14.2 to −11.9) with placebo. Patients taking omega-3 fatty acids had a mean eGFR change of −12.2 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, −13.3 to −11.1), compared with −13.1 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, −14.2 to −12.0) with placebo.

The authors noted that the modest number of measurements collected per participant limited the evaluation and analyses. In addition, the study focused broadly on the type 2 diabetes population and not on subgroups, “who may derive more benefit from the study interventions.”

In an accompanying editorial, authors Anika Lucas, MD and Myles Wolf, MD, of Duke University in Durham, N.C., said multiple clinical trials, including this latest study from de Boer and colleagues on kidney function, have failed to reinforce the previously reported benefits of vitamin D.

“The VITAL-DKD study population had nearly normal mean 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels at baseline, leaving open the question of whether the results would have differed had recruitment been restricted to patients with moderate or severe vitamin D deficiency,” they wrote (JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17302).

Nevertheless, it seems safe to conclude that the previous associations between vitamin D deficiency and adverse health were “driven by unmeasured residual confounding or reverse causality.

“Without certainty about the ideal approach to vitamin D treatment in advanced CKD, a randomized trial that compared cholecalciferol, exogenous 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and an activated vitamin D analogue vs. placebo could definitively lay to rest multiple remaining questions in the area,” they suggested.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases funded the study. The authors reported numerous potential conflicts of interest, including receiving grants, consulting fees, and equipment and supplies from various pharmaceutical companies and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Wolf reported having served as a consultant for Akebia, AMAG, Amgen, Ardelyx, Diasorin, and Pharmacosmos. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: de Boer IH et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17380.

FROM KIDNEY WEEK 2019

Key clinical point:

Major finding: At 5-year follow-up, patients taking vitamin D had a mean change in eGFR of −12.3 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, −13.4 to −11.2), compared with −13.1 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, −14.2 to −11.9) with placebo.

Study details: A randomized clinical trial of 1,312 adults with type 2 diabetes.

Disclosures: The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases funded the study. The authors reported numerous potential conflicts of interest, including receiving grants, consulting fees, and equipment and supplies from various pharmaceutical companies and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Wolf reported having served as a consultant for Akebia, AMAG, Amgen, Ardelyx, Diasorin, and Pharmacosmos. No other disclosures were reported.

Source: de Boer IH et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17380.

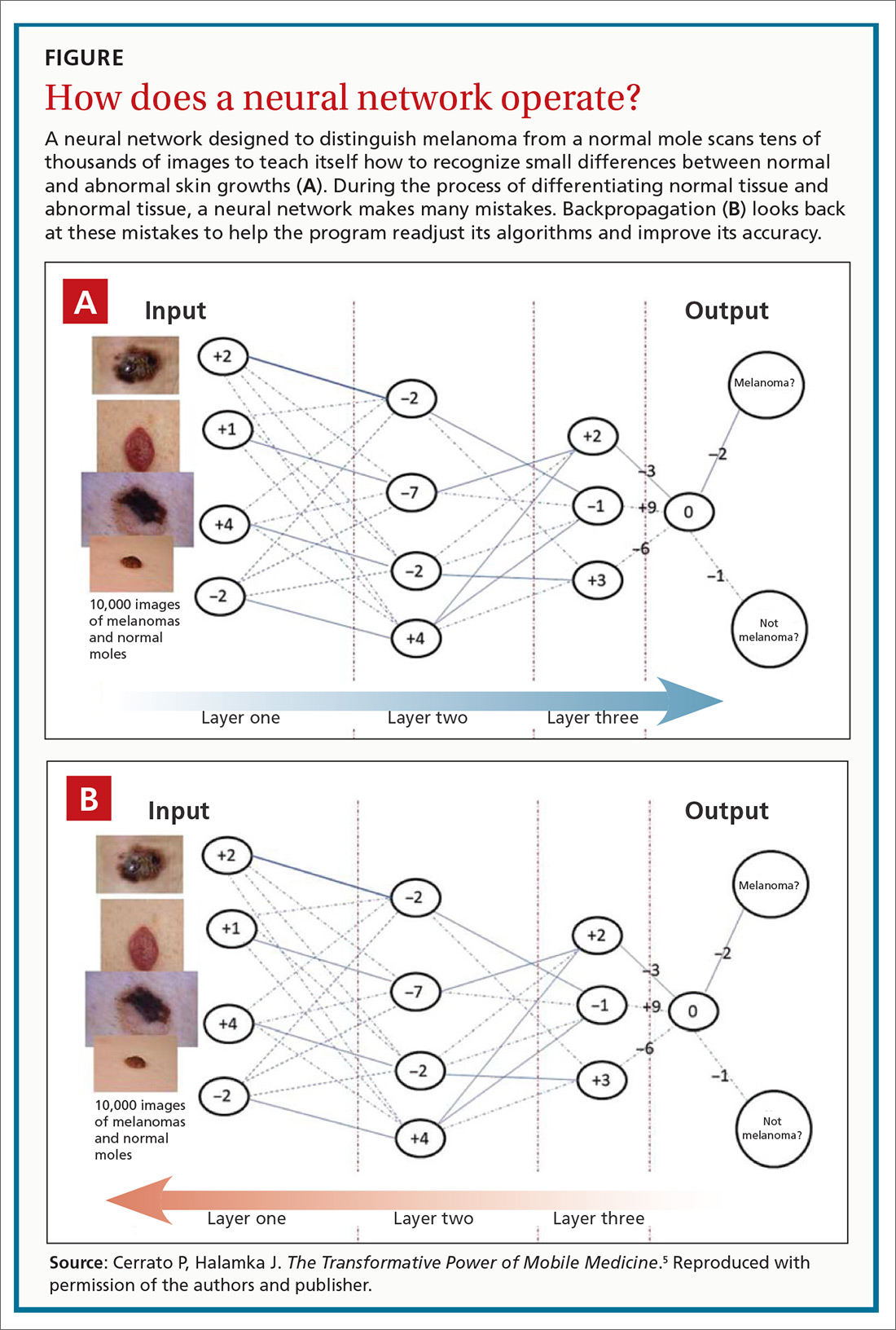

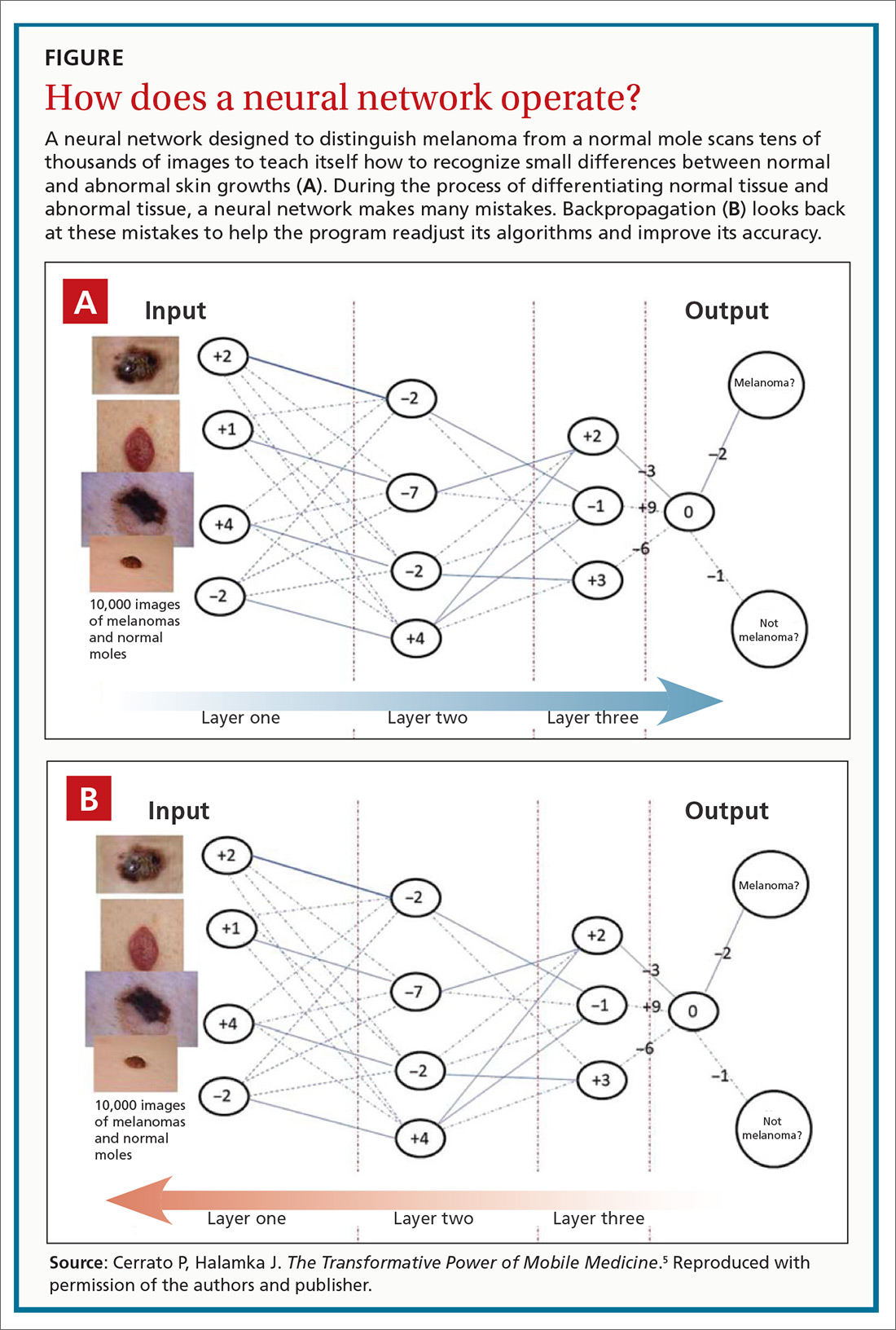

It’s time to get to know AI

This month’s cover story on artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning provides a glimpse into the future of medical care. The article’s title, “An FP’s guide to AI-enabled clinical decision support” points to the fact that practical and useful applications of AI and machine learning are making inroads into medicine. However, other industries are far ahead of medicine when it comes to AI.

For example, I met with a financial advisor last week, and our discussion included a display of the likelihood that my wife and I would have sufficient funds in our retirement account based on a Monte Carlo simulation using 500 trials! In other words, our advisor used a huge database of financial information, analyzed that data with a sophisticated statistical technique, and applied the results to our personal situation. (No, we won’t run out of money—with 99% certainty.)

So as physicians, how can we further increase our certainty in the diagnoses we make and the guidance we offer our patients?

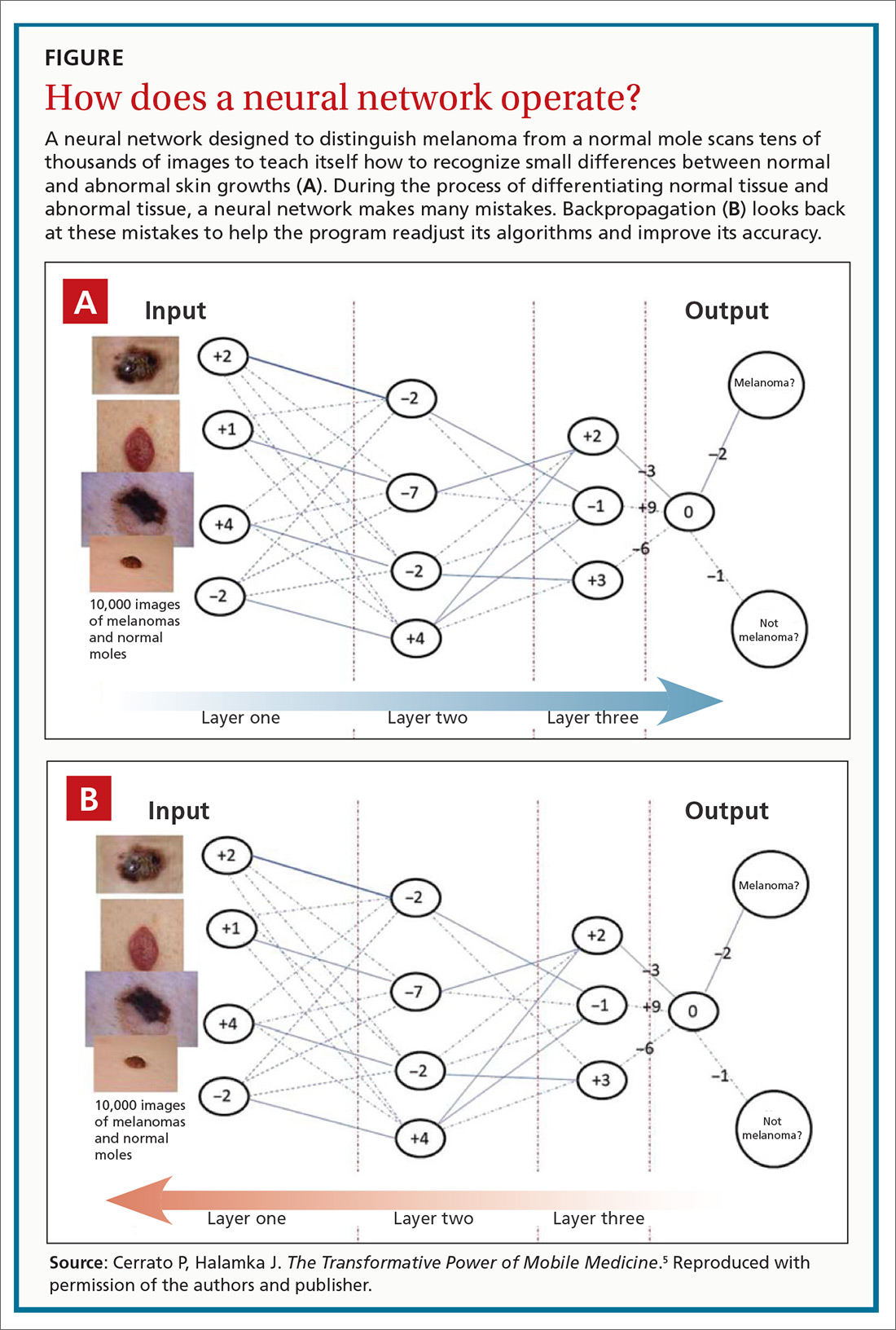

Halamka and Cerrato provide some insights. They discuss 2 clinical applications of AI and machine learning that are ready to use in primary care: screening for diabetic retinopathy and risk assessment for colon cancer. The first is an example of using AI for diagnosis and the second for risk assessment; both are core functions of primary care clinicians. These tools were developed with very sophisticated computer programs, but they are not unlike a plethora of clinical decision aids already widely used in primary care for diagnosis and risk assessment, such as the Ottawa Ankle Rules, the Gail Model for breast cancer risk, the FRAX tool for osteoporosis-related fracture risk, the ASCVD Risk Calculator for cardiovascular risk, and the CHA2DS2-VASC score for prediction of thrombosis and bleeding risk from anticoagulation therapy.