User login

Pandemic prompts spike in eating disorder hospitalization for adolescents

Hospital admission for children with eating disorders approximately tripled during the COVID-19 pandemic, based on data from 85 patients.

Eating disorders are common among adolescents and often require hospital admission for nutritional restoration, according to May Shum of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the volume of hospital admissions for adolescents with eating disorders has increased, the researchers wrote in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. This increase may be driven both by interruptions in medical care and increased psychological distress, but data on changes in patient characteristics and hospitalization course are lacking, they said.

The researchers reviewed charts from patients with eating disorders admitted to a single center between Jan. 1, 2017, and June 30, 2021. The majority of the patients were female (90.6%), and White (78.8%), had restrictive eating behaviors (97.2%), and had private insurance (80.0%).

Overall, the number of monthly admissions increased from 1.4 before the onset of the pandemic to 3.6 during the pandemic (P < .001).

Length of stay increased significantly from before to during pandemic cases (12.8 days vs. 17.3 days, P = .04) and age younger than 13 years was significantly associated with a longer length of stay (P < .001).

The number of patients for whom psychotropic medications were initiated or changed increased significantly (12.5% vs. 28.3%, P = .04); as did the proportion of patients discharged to partial hospitalization, residential, or inpatient psychiatric treatment rather than discharged home with outpatient therapy (56.2% vs. 75.0%, P = .04).

No significant differences were noted in demographics, comorbidities, admission parameters, EKG abnormalities, electrolyte repletion, or tube feeding.

The study findings were limited by the use of data from a single center. However, the results suggest an increase in severity of hospital admissions that have implications for use of hospital resources, the researchers said.

“In addition to an increase in hospital admissions for eating disorder management during the pandemic, longer inpatient stays of younger children with higher acuity at discharge is an added strain on hospital resources and warrants attention,” they concluded.

Considerations for younger patients

The current study is especially important at this time, Margaret Thew, DNP, FNP-BC, medical director of the department of adolescent medicine at Children’s Wisconsin in Milwaukee, said in an interview. “There have been reports of the rising numbers in eating disorders, but until research has been conducted, we cannot quantify the volumes,” said Ms. Thew, who was not involved in the study. “There have been many reports of the rise in mental health issues during the pandemic, so it seems accurate that the rate of eating disorders would rise,” she said. “Additionally, from a clinical perspective there seemed to be many younger-age patients with eating disorders presenting to the inpatient units who seemed sicker,” she noted.

Ms. Thew said she was not surprised by the study findings. “Working with adolescents with eating disorders we saw the increased numbers of both hospitalizations and outpatient referrals during the pandemic,” said Ms. Thew. “Length of stay was higher across the nation regarding admissions for concerns of eating disorders. These patients are sicker and fewer went home after medical stabilization,” she emphasized.

“Clinicians should be more aware of the rise in patients presenting with eating disorders at younger ages to their clinics and provide early interventions to prevent severe illness and medical instability,” said Ms. Thew. Clinicians also should be more proactive in managing younger children and adolescents who express mood disorders, disordered eating, or weight loss, given the significant rise in eating disorders and mental health concerns, she said.

Additional research is needed to continue following the rate of eating disorders into 2022, said Ms. Thew. More research is needed on early interventions and recognition of eating disorders for preteens and teens to prevent severe illness, as is research on how the younger patient with an eating disorder may present differently to the primary care doctor or emergency department, she said.

“We may need to study treatment of the younger population, as they may not do as well with admissions into behavioral health facilities,” Ms. Thew added.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Ms. Thew had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

Hospital admission for children with eating disorders approximately tripled during the COVID-19 pandemic, based on data from 85 patients.

Eating disorders are common among adolescents and often require hospital admission for nutritional restoration, according to May Shum of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the volume of hospital admissions for adolescents with eating disorders has increased, the researchers wrote in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. This increase may be driven both by interruptions in medical care and increased psychological distress, but data on changes in patient characteristics and hospitalization course are lacking, they said.

The researchers reviewed charts from patients with eating disorders admitted to a single center between Jan. 1, 2017, and June 30, 2021. The majority of the patients were female (90.6%), and White (78.8%), had restrictive eating behaviors (97.2%), and had private insurance (80.0%).

Overall, the number of monthly admissions increased from 1.4 before the onset of the pandemic to 3.6 during the pandemic (P < .001).

Length of stay increased significantly from before to during pandemic cases (12.8 days vs. 17.3 days, P = .04) and age younger than 13 years was significantly associated with a longer length of stay (P < .001).

The number of patients for whom psychotropic medications were initiated or changed increased significantly (12.5% vs. 28.3%, P = .04); as did the proportion of patients discharged to partial hospitalization, residential, or inpatient psychiatric treatment rather than discharged home with outpatient therapy (56.2% vs. 75.0%, P = .04).

No significant differences were noted in demographics, comorbidities, admission parameters, EKG abnormalities, electrolyte repletion, or tube feeding.

The study findings were limited by the use of data from a single center. However, the results suggest an increase in severity of hospital admissions that have implications for use of hospital resources, the researchers said.

“In addition to an increase in hospital admissions for eating disorder management during the pandemic, longer inpatient stays of younger children with higher acuity at discharge is an added strain on hospital resources and warrants attention,” they concluded.

Considerations for younger patients

The current study is especially important at this time, Margaret Thew, DNP, FNP-BC, medical director of the department of adolescent medicine at Children’s Wisconsin in Milwaukee, said in an interview. “There have been reports of the rising numbers in eating disorders, but until research has been conducted, we cannot quantify the volumes,” said Ms. Thew, who was not involved in the study. “There have been many reports of the rise in mental health issues during the pandemic, so it seems accurate that the rate of eating disorders would rise,” she said. “Additionally, from a clinical perspective there seemed to be many younger-age patients with eating disorders presenting to the inpatient units who seemed sicker,” she noted.

Ms. Thew said she was not surprised by the study findings. “Working with adolescents with eating disorders we saw the increased numbers of both hospitalizations and outpatient referrals during the pandemic,” said Ms. Thew. “Length of stay was higher across the nation regarding admissions for concerns of eating disorders. These patients are sicker and fewer went home after medical stabilization,” she emphasized.

“Clinicians should be more aware of the rise in patients presenting with eating disorders at younger ages to their clinics and provide early interventions to prevent severe illness and medical instability,” said Ms. Thew. Clinicians also should be more proactive in managing younger children and adolescents who express mood disorders, disordered eating, or weight loss, given the significant rise in eating disorders and mental health concerns, she said.

Additional research is needed to continue following the rate of eating disorders into 2022, said Ms. Thew. More research is needed on early interventions and recognition of eating disorders for preteens and teens to prevent severe illness, as is research on how the younger patient with an eating disorder may present differently to the primary care doctor or emergency department, she said.

“We may need to study treatment of the younger population, as they may not do as well with admissions into behavioral health facilities,” Ms. Thew added.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Ms. Thew had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

Hospital admission for children with eating disorders approximately tripled during the COVID-19 pandemic, based on data from 85 patients.

Eating disorders are common among adolescents and often require hospital admission for nutritional restoration, according to May Shum of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the volume of hospital admissions for adolescents with eating disorders has increased, the researchers wrote in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. This increase may be driven both by interruptions in medical care and increased psychological distress, but data on changes in patient characteristics and hospitalization course are lacking, they said.

The researchers reviewed charts from patients with eating disorders admitted to a single center between Jan. 1, 2017, and June 30, 2021. The majority of the patients were female (90.6%), and White (78.8%), had restrictive eating behaviors (97.2%), and had private insurance (80.0%).

Overall, the number of monthly admissions increased from 1.4 before the onset of the pandemic to 3.6 during the pandemic (P < .001).

Length of stay increased significantly from before to during pandemic cases (12.8 days vs. 17.3 days, P = .04) and age younger than 13 years was significantly associated with a longer length of stay (P < .001).

The number of patients for whom psychotropic medications were initiated or changed increased significantly (12.5% vs. 28.3%, P = .04); as did the proportion of patients discharged to partial hospitalization, residential, or inpatient psychiatric treatment rather than discharged home with outpatient therapy (56.2% vs. 75.0%, P = .04).

No significant differences were noted in demographics, comorbidities, admission parameters, EKG abnormalities, electrolyte repletion, or tube feeding.

The study findings were limited by the use of data from a single center. However, the results suggest an increase in severity of hospital admissions that have implications for use of hospital resources, the researchers said.

“In addition to an increase in hospital admissions for eating disorder management during the pandemic, longer inpatient stays of younger children with higher acuity at discharge is an added strain on hospital resources and warrants attention,” they concluded.

Considerations for younger patients

The current study is especially important at this time, Margaret Thew, DNP, FNP-BC, medical director of the department of adolescent medicine at Children’s Wisconsin in Milwaukee, said in an interview. “There have been reports of the rising numbers in eating disorders, but until research has been conducted, we cannot quantify the volumes,” said Ms. Thew, who was not involved in the study. “There have been many reports of the rise in mental health issues during the pandemic, so it seems accurate that the rate of eating disorders would rise,” she said. “Additionally, from a clinical perspective there seemed to be many younger-age patients with eating disorders presenting to the inpatient units who seemed sicker,” she noted.

Ms. Thew said she was not surprised by the study findings. “Working with adolescents with eating disorders we saw the increased numbers of both hospitalizations and outpatient referrals during the pandemic,” said Ms. Thew. “Length of stay was higher across the nation regarding admissions for concerns of eating disorders. These patients are sicker and fewer went home after medical stabilization,” she emphasized.

“Clinicians should be more aware of the rise in patients presenting with eating disorders at younger ages to their clinics and provide early interventions to prevent severe illness and medical instability,” said Ms. Thew. Clinicians also should be more proactive in managing younger children and adolescents who express mood disorders, disordered eating, or weight loss, given the significant rise in eating disorders and mental health concerns, she said.

Additional research is needed to continue following the rate of eating disorders into 2022, said Ms. Thew. More research is needed on early interventions and recognition of eating disorders for preteens and teens to prevent severe illness, as is research on how the younger patient with an eating disorder may present differently to the primary care doctor or emergency department, she said.

“We may need to study treatment of the younger population, as they may not do as well with admissions into behavioral health facilities,” Ms. Thew added.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Ms. Thew had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

FROM PAS 2022

Mental illness tied to COVID-19 breakthrough infection

“Psychiatric disorders remained significantly associated with incident breakthrough infections above and beyond sociodemographic and medical factors, suggesting that mental health is important to consider in conjunction with other risk factors,” wrote the investigators, led by Aoife O’Donovan, PhD, University of California, San Francisco.

Individuals with psychiatric disorders “should be prioritized for booster vaccinations and other critical preventive efforts, including increased SARS-CoV-2 screening, public health campaigns, or COVID-19 discussions during clinical care,” they added.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Elderly most vulnerable

The researchers reviewed the records of 263,697 veterans who were fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

Just over a half (51.4%) had one or more psychiatric diagnoses within the last 5 years and 14.8% developed breakthrough COVID-19 infections, confirmed by a positive SARS-CoV-2 test.

Psychiatric diagnoses among the veterans included depression, posttraumatic stress, anxiety, adjustment disorder, substance use disorder, bipolar disorder, psychosis, ADHD, dissociation, and eating disorders.

In the overall sample, a history of any psychiatric disorder was associated with a 7% higher incidence of breakthrough COVID-19 infection in models adjusted for potential confounders (adjusted relative risk, 1.07; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.09) and a 3% higher incidence in models additionally adjusted for underlying medical comorbidities and smoking (aRR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.01-1.05).

Most psychiatric disorders were associated with a higher incidence of breakthrough infection, with the highest relative risk observed for substance use disorders (aRR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.12 -1.21) and adjustment disorder (aRR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.10-1.16) in fully adjusted models.

Older vaccinated veterans with psychiatric illnesses appear to be most vulnerable to COVID-19 reinfection.

In veterans aged 65 and older, all psychiatric disorders were associated with an increased incidence of breakthrough infection, with increases in the incidence rate ranging from 3% to 24% in fully adjusted models.

In the younger veterans, in contrast, only anxiety, adjustment, and substance use disorders were associated with an increased incidence of breakthrough infection in fully adjusted models.

Psychotic disorders were associated with a 10% lower incidence of breakthrough infection among younger veterans, perhaps because of greater social isolation, the researchers said.

Risky behavior or impaired immunity?

“Although some of the larger observed effect sizes are compelling at an individual level, even the relatively modest effect sizes may have a large effect at the population level when considering the high prevalence of psychiatric disorders and the global reach and scale of the pandemic,” Dr. O’Donovan and colleagues wrote.

They noted that psychiatric disorders, including depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorders, have been associated with impaired cellular immunity and blunted response to vaccines. Therefore, it’s possible that those with psychiatric disorders have poorer responses to COVID-19 vaccination.

It’s also possible that immunity following vaccination wanes more quickly or more strongly in people with psychiatric disorders and they could have less protection against new variants, they added.

Patients with psychiatric disorders could be more apt to engage in risky behaviors for contracting COVID-19, which could also increase the risk for breakthrough infection, they said.

The study was supported by a UCSF Department of Psychiatry Rapid Award and UCSF Faculty Resource Fund Award. Dr. O’Donovan reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Psychiatric disorders remained significantly associated with incident breakthrough infections above and beyond sociodemographic and medical factors, suggesting that mental health is important to consider in conjunction with other risk factors,” wrote the investigators, led by Aoife O’Donovan, PhD, University of California, San Francisco.

Individuals with psychiatric disorders “should be prioritized for booster vaccinations and other critical preventive efforts, including increased SARS-CoV-2 screening, public health campaigns, or COVID-19 discussions during clinical care,” they added.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Elderly most vulnerable

The researchers reviewed the records of 263,697 veterans who were fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

Just over a half (51.4%) had one or more psychiatric diagnoses within the last 5 years and 14.8% developed breakthrough COVID-19 infections, confirmed by a positive SARS-CoV-2 test.

Psychiatric diagnoses among the veterans included depression, posttraumatic stress, anxiety, adjustment disorder, substance use disorder, bipolar disorder, psychosis, ADHD, dissociation, and eating disorders.

In the overall sample, a history of any psychiatric disorder was associated with a 7% higher incidence of breakthrough COVID-19 infection in models adjusted for potential confounders (adjusted relative risk, 1.07; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.09) and a 3% higher incidence in models additionally adjusted for underlying medical comorbidities and smoking (aRR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.01-1.05).

Most psychiatric disorders were associated with a higher incidence of breakthrough infection, with the highest relative risk observed for substance use disorders (aRR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.12 -1.21) and adjustment disorder (aRR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.10-1.16) in fully adjusted models.

Older vaccinated veterans with psychiatric illnesses appear to be most vulnerable to COVID-19 reinfection.

In veterans aged 65 and older, all psychiatric disorders were associated with an increased incidence of breakthrough infection, with increases in the incidence rate ranging from 3% to 24% in fully adjusted models.

In the younger veterans, in contrast, only anxiety, adjustment, and substance use disorders were associated with an increased incidence of breakthrough infection in fully adjusted models.

Psychotic disorders were associated with a 10% lower incidence of breakthrough infection among younger veterans, perhaps because of greater social isolation, the researchers said.

Risky behavior or impaired immunity?

“Although some of the larger observed effect sizes are compelling at an individual level, even the relatively modest effect sizes may have a large effect at the population level when considering the high prevalence of psychiatric disorders and the global reach and scale of the pandemic,” Dr. O’Donovan and colleagues wrote.

They noted that psychiatric disorders, including depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorders, have been associated with impaired cellular immunity and blunted response to vaccines. Therefore, it’s possible that those with psychiatric disorders have poorer responses to COVID-19 vaccination.

It’s also possible that immunity following vaccination wanes more quickly or more strongly in people with psychiatric disorders and they could have less protection against new variants, they added.

Patients with psychiatric disorders could be more apt to engage in risky behaviors for contracting COVID-19, which could also increase the risk for breakthrough infection, they said.

The study was supported by a UCSF Department of Psychiatry Rapid Award and UCSF Faculty Resource Fund Award. Dr. O’Donovan reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Psychiatric disorders remained significantly associated with incident breakthrough infections above and beyond sociodemographic and medical factors, suggesting that mental health is important to consider in conjunction with other risk factors,” wrote the investigators, led by Aoife O’Donovan, PhD, University of California, San Francisco.

Individuals with psychiatric disorders “should be prioritized for booster vaccinations and other critical preventive efforts, including increased SARS-CoV-2 screening, public health campaigns, or COVID-19 discussions during clinical care,” they added.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Elderly most vulnerable

The researchers reviewed the records of 263,697 veterans who were fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

Just over a half (51.4%) had one or more psychiatric diagnoses within the last 5 years and 14.8% developed breakthrough COVID-19 infections, confirmed by a positive SARS-CoV-2 test.

Psychiatric diagnoses among the veterans included depression, posttraumatic stress, anxiety, adjustment disorder, substance use disorder, bipolar disorder, psychosis, ADHD, dissociation, and eating disorders.

In the overall sample, a history of any psychiatric disorder was associated with a 7% higher incidence of breakthrough COVID-19 infection in models adjusted for potential confounders (adjusted relative risk, 1.07; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.09) and a 3% higher incidence in models additionally adjusted for underlying medical comorbidities and smoking (aRR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.01-1.05).

Most psychiatric disorders were associated with a higher incidence of breakthrough infection, with the highest relative risk observed for substance use disorders (aRR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.12 -1.21) and adjustment disorder (aRR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.10-1.16) in fully adjusted models.

Older vaccinated veterans with psychiatric illnesses appear to be most vulnerable to COVID-19 reinfection.

In veterans aged 65 and older, all psychiatric disorders were associated with an increased incidence of breakthrough infection, with increases in the incidence rate ranging from 3% to 24% in fully adjusted models.

In the younger veterans, in contrast, only anxiety, adjustment, and substance use disorders were associated with an increased incidence of breakthrough infection in fully adjusted models.

Psychotic disorders were associated with a 10% lower incidence of breakthrough infection among younger veterans, perhaps because of greater social isolation, the researchers said.

Risky behavior or impaired immunity?

“Although some of the larger observed effect sizes are compelling at an individual level, even the relatively modest effect sizes may have a large effect at the population level when considering the high prevalence of psychiatric disorders and the global reach and scale of the pandemic,” Dr. O’Donovan and colleagues wrote.

They noted that psychiatric disorders, including depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorders, have been associated with impaired cellular immunity and blunted response to vaccines. Therefore, it’s possible that those with psychiatric disorders have poorer responses to COVID-19 vaccination.

It’s also possible that immunity following vaccination wanes more quickly or more strongly in people with psychiatric disorders and they could have less protection against new variants, they added.

Patients with psychiatric disorders could be more apt to engage in risky behaviors for contracting COVID-19, which could also increase the risk for breakthrough infection, they said.

The study was supported by a UCSF Department of Psychiatry Rapid Award and UCSF Faculty Resource Fund Award. Dr. O’Donovan reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

First comprehensive guidelines for managing anorexia in pregnancy

The first comprehensive guidelines to manage pregnant women with anorexia nervosa (AN) have been released.

Pregnant women with AN are at greater risk of poor outcomes, including stillbirth, underweight infant, or pre-term birth, yet there are no clear guidelines on the management of the condition.

“Anorexia in pregnancy has been an overlooked area of clinical care, as many believed only women in remission become pregnant, and it is clear that is not the case,” lead author Megan Galbally, MBBS, PhD, professor and director, Centre of Women’s and Children’s Mental Health at Monash University School of Clinical Sciences, Melbourne, told this news organization.

“There are great opportunities to support women in their mental health and give them and their babies a healthier start to parenthood and life,” said Dr. Galbally.

“For instance, reducing the likelihood of prematurity or low birth weight at birth that can be associated with anorexia in pregnancy has extraordinary benefits for that child for lifelong health and well-being,” she added.

The guidelines were published online in Lancet Psychiatry.

Spike in cases

Dr. Galbally noted that during her 20 years of working in perinatal mental health within tertiary maternity services, she only ever saw an occasional pregnant woman with current AN.

In contrast, over the last 3 to 4 years, there has been a “steep increase in women presenting in pregnancy with very low body mass index (BMI) and current anorexia nervosa requiring treatment in pregnancy,” Dr. Galbally said.

Despite the complexity of managing AN in pregnancy, few studies are available to guide care. In a systematic literature review, the researchers identified only eight studies that addressed the management of AN in pregnancy. These studies were case studies or case reports examining narrow aspects of management.

Digging deeper, the researchers conducted a state-of-the-art research review in relevant disciplines and areas of expertise for managing anorexia nervosa in pregnancy. They synthesized their findings into “recommendations and principles” for multidisciplinary care of pregnant women with AN.

The researchers note that AN in pregnancy is associated with increased risks of pregnancy complications and poorer outcomes for infants, and measures such as BMI are less accurate in pregnancy for assessing severity or change in anorexia nervosa.

Anorexia affects pregnancy and neonatal outcomes through low calorie intake, nutritional and vitamin deficiencies, stress, fasting, low body mass, and poor placentation and uteroplacental function.

The authors note that managing AN in pregnancy requires multidisciplinary care that considers the substantial physiological changes for women and requirements for monitoring fetal growth and development.

At a minimum, they recommend monitoring the following:

- Sodium, potassium, magnesium, phosphate, and chloride concentration

- Iron status, vitamin D and bone mineral density, blood sugar concentration (fasting or random), and A1c

- Liver function (including bilirubin, aspartate transaminase, alanine aminotransferase, and gamma-glutamyl transferase) and bone marrow function (including full blood examination, white cell count, neutrophil count, platelets, and hemoglobin)

- Inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate)

- Cardiac function (electrocardiogram and echocardiogram)

- Blood pressure and heart rate (lying and standing) and body temperature

“There are considerable risks for women and their unborn child in managing moderate to severe AN in pregnancy,” said Dr. Galbally.

“While we have provided some recommendations, it still requires considerable adaptation to individual presentations and circumstances, and this is best done with a maternity service that manages other high-risk pregnancies such as through maternal-fetal medicine teams,” she said.

“While this area of clinical care can be new to high-risk pregnancy teams, it is clearly important that high-risk pregnancy services and mental health work together to improve care for women with anorexia in pregnancy,” Dr. Galbally added.

A nightmare, a dream come true

Reached for comment, Kamryn T. Eddy, PhD, co-director, Eating Disorders Clinical and Research Program, Massachusetts General Hospital, said, “for many with anorexia nervosa, pregnancy realizes their greatest nightmare and dream come true, both at once.”

“The physical demands of pregnancy can be taxing, and for those with anorexia nervosa, closer clinical management makes sense and may help to support patients who are at risk for return to or worsening of symptoms with the increased nutritional needs and weight gain that occur in pregnancy,” Dr. Eddy, associate professor, department of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, told this news organization.

“At the same time, the desire to have a child can be a strong motivator for patients to make the changes needed to recover, and for some, the transition to mother can also help in recovery by broadening the range of things that influence their self-worth,” Dr. Eddy added.

This research had no specific funding. Dr. Galbally and Dr. Eddy report no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The first comprehensive guidelines to manage pregnant women with anorexia nervosa (AN) have been released.

Pregnant women with AN are at greater risk of poor outcomes, including stillbirth, underweight infant, or pre-term birth, yet there are no clear guidelines on the management of the condition.

“Anorexia in pregnancy has been an overlooked area of clinical care, as many believed only women in remission become pregnant, and it is clear that is not the case,” lead author Megan Galbally, MBBS, PhD, professor and director, Centre of Women’s and Children’s Mental Health at Monash University School of Clinical Sciences, Melbourne, told this news organization.

“There are great opportunities to support women in their mental health and give them and their babies a healthier start to parenthood and life,” said Dr. Galbally.

“For instance, reducing the likelihood of prematurity or low birth weight at birth that can be associated with anorexia in pregnancy has extraordinary benefits for that child for lifelong health and well-being,” she added.

The guidelines were published online in Lancet Psychiatry.

Spike in cases

Dr. Galbally noted that during her 20 years of working in perinatal mental health within tertiary maternity services, she only ever saw an occasional pregnant woman with current AN.

In contrast, over the last 3 to 4 years, there has been a “steep increase in women presenting in pregnancy with very low body mass index (BMI) and current anorexia nervosa requiring treatment in pregnancy,” Dr. Galbally said.

Despite the complexity of managing AN in pregnancy, few studies are available to guide care. In a systematic literature review, the researchers identified only eight studies that addressed the management of AN in pregnancy. These studies were case studies or case reports examining narrow aspects of management.

Digging deeper, the researchers conducted a state-of-the-art research review in relevant disciplines and areas of expertise for managing anorexia nervosa in pregnancy. They synthesized their findings into “recommendations and principles” for multidisciplinary care of pregnant women with AN.

The researchers note that AN in pregnancy is associated with increased risks of pregnancy complications and poorer outcomes for infants, and measures such as BMI are less accurate in pregnancy for assessing severity or change in anorexia nervosa.

Anorexia affects pregnancy and neonatal outcomes through low calorie intake, nutritional and vitamin deficiencies, stress, fasting, low body mass, and poor placentation and uteroplacental function.

The authors note that managing AN in pregnancy requires multidisciplinary care that considers the substantial physiological changes for women and requirements for monitoring fetal growth and development.

At a minimum, they recommend monitoring the following:

- Sodium, potassium, magnesium, phosphate, and chloride concentration

- Iron status, vitamin D and bone mineral density, blood sugar concentration (fasting or random), and A1c

- Liver function (including bilirubin, aspartate transaminase, alanine aminotransferase, and gamma-glutamyl transferase) and bone marrow function (including full blood examination, white cell count, neutrophil count, platelets, and hemoglobin)

- Inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate)

- Cardiac function (electrocardiogram and echocardiogram)

- Blood pressure and heart rate (lying and standing) and body temperature

“There are considerable risks for women and their unborn child in managing moderate to severe AN in pregnancy,” said Dr. Galbally.

“While we have provided some recommendations, it still requires considerable adaptation to individual presentations and circumstances, and this is best done with a maternity service that manages other high-risk pregnancies such as through maternal-fetal medicine teams,” she said.

“While this area of clinical care can be new to high-risk pregnancy teams, it is clearly important that high-risk pregnancy services and mental health work together to improve care for women with anorexia in pregnancy,” Dr. Galbally added.

A nightmare, a dream come true

Reached for comment, Kamryn T. Eddy, PhD, co-director, Eating Disorders Clinical and Research Program, Massachusetts General Hospital, said, “for many with anorexia nervosa, pregnancy realizes their greatest nightmare and dream come true, both at once.”

“The physical demands of pregnancy can be taxing, and for those with anorexia nervosa, closer clinical management makes sense and may help to support patients who are at risk for return to or worsening of symptoms with the increased nutritional needs and weight gain that occur in pregnancy,” Dr. Eddy, associate professor, department of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, told this news organization.

“At the same time, the desire to have a child can be a strong motivator for patients to make the changes needed to recover, and for some, the transition to mother can also help in recovery by broadening the range of things that influence their self-worth,” Dr. Eddy added.

This research had no specific funding. Dr. Galbally and Dr. Eddy report no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The first comprehensive guidelines to manage pregnant women with anorexia nervosa (AN) have been released.

Pregnant women with AN are at greater risk of poor outcomes, including stillbirth, underweight infant, or pre-term birth, yet there are no clear guidelines on the management of the condition.

“Anorexia in pregnancy has been an overlooked area of clinical care, as many believed only women in remission become pregnant, and it is clear that is not the case,” lead author Megan Galbally, MBBS, PhD, professor and director, Centre of Women’s and Children’s Mental Health at Monash University School of Clinical Sciences, Melbourne, told this news organization.

“There are great opportunities to support women in their mental health and give them and their babies a healthier start to parenthood and life,” said Dr. Galbally.

“For instance, reducing the likelihood of prematurity or low birth weight at birth that can be associated with anorexia in pregnancy has extraordinary benefits for that child for lifelong health and well-being,” she added.

The guidelines were published online in Lancet Psychiatry.

Spike in cases

Dr. Galbally noted that during her 20 years of working in perinatal mental health within tertiary maternity services, she only ever saw an occasional pregnant woman with current AN.

In contrast, over the last 3 to 4 years, there has been a “steep increase in women presenting in pregnancy with very low body mass index (BMI) and current anorexia nervosa requiring treatment in pregnancy,” Dr. Galbally said.

Despite the complexity of managing AN in pregnancy, few studies are available to guide care. In a systematic literature review, the researchers identified only eight studies that addressed the management of AN in pregnancy. These studies were case studies or case reports examining narrow aspects of management.

Digging deeper, the researchers conducted a state-of-the-art research review in relevant disciplines and areas of expertise for managing anorexia nervosa in pregnancy. They synthesized their findings into “recommendations and principles” for multidisciplinary care of pregnant women with AN.

The researchers note that AN in pregnancy is associated with increased risks of pregnancy complications and poorer outcomes for infants, and measures such as BMI are less accurate in pregnancy for assessing severity or change in anorexia nervosa.

Anorexia affects pregnancy and neonatal outcomes through low calorie intake, nutritional and vitamin deficiencies, stress, fasting, low body mass, and poor placentation and uteroplacental function.

The authors note that managing AN in pregnancy requires multidisciplinary care that considers the substantial physiological changes for women and requirements for monitoring fetal growth and development.

At a minimum, they recommend monitoring the following:

- Sodium, potassium, magnesium, phosphate, and chloride concentration

- Iron status, vitamin D and bone mineral density, blood sugar concentration (fasting or random), and A1c

- Liver function (including bilirubin, aspartate transaminase, alanine aminotransferase, and gamma-glutamyl transferase) and bone marrow function (including full blood examination, white cell count, neutrophil count, platelets, and hemoglobin)

- Inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate)

- Cardiac function (electrocardiogram and echocardiogram)

- Blood pressure and heart rate (lying and standing) and body temperature

“There are considerable risks for women and their unborn child in managing moderate to severe AN in pregnancy,” said Dr. Galbally.

“While we have provided some recommendations, it still requires considerable adaptation to individual presentations and circumstances, and this is best done with a maternity service that manages other high-risk pregnancies such as through maternal-fetal medicine teams,” she said.

“While this area of clinical care can be new to high-risk pregnancy teams, it is clearly important that high-risk pregnancy services and mental health work together to improve care for women with anorexia in pregnancy,” Dr. Galbally added.

A nightmare, a dream come true

Reached for comment, Kamryn T. Eddy, PhD, co-director, Eating Disorders Clinical and Research Program, Massachusetts General Hospital, said, “for many with anorexia nervosa, pregnancy realizes their greatest nightmare and dream come true, both at once.”

“The physical demands of pregnancy can be taxing, and for those with anorexia nervosa, closer clinical management makes sense and may help to support patients who are at risk for return to or worsening of symptoms with the increased nutritional needs and weight gain that occur in pregnancy,” Dr. Eddy, associate professor, department of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, told this news organization.

“At the same time, the desire to have a child can be a strong motivator for patients to make the changes needed to recover, and for some, the transition to mother can also help in recovery by broadening the range of things that influence their self-worth,” Dr. Eddy added.

This research had no specific funding. Dr. Galbally and Dr. Eddy report no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Food for thought: Dangerous weight loss in an older adult

CASE Fixated on health and nutrition

At the insistence of her daughter, Ms. L, age 75, presents to the emergency department (ED) for self-neglect and severe weight loss, with a body mass index (BMI) of 13.5 kg/m2 (normal: 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2). When asked why she is in the ED, Ms. L says she doesn’t know. She attributes her significant weight loss (approximately 20 pounds in the last few months) to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). She constantly worries about her esophagus. She had been diagnosed with esophageal dysphagia 7 years ago after undergoing radiofrequency ablation for esophageal cancer. Ms. L fixates on the negative effects certain foods and ingredients might have on her stomach and esophagus.

Following transfer from the ED, Ms. L is involuntarily admitted to our inpatient unit. Although she acknowledges weight loss, she minimizes the severity of her illness and indicates she would like to gain weight, but only by eating healthy foods she is comfortable with, including kale, quinoa, and vegetables. Ms. L says that she has always been interested in “healthful foods” and that she “loves sugar,” but “it’s bad for you,” mentioning that “sugar fuels cancer.” She has daily thoughts about sugar causing cancer. Ms. L also mentions that she stopped eating flour, sugar, fried food, and oils because those foods affect her “stomach acid” and cause “pimples on my face and weight loss.” While in the inpatient unit, Ms. L requests a special diet and demands to know the origin and ingredients of the foods she is offered. She emphasizes that her esophageal cancer diagnosis and dysphagia exacerbate worries that certain foods cause cancer, and wants to continue her diet restrictions. Nonetheless, she says she wants to get healthy, and denies an intense fear of gaining weight or feeling fat.

HISTORY Multiple psychiatric diagnoses

Ms. L lives alone and enjoys spending time with her grandchildren, visiting museums, and listening to classical music. However, her family, social workers, and records from a previous psychiatric hospitalization reveal that Ms. L has a history of psychiatric illness and fears regarding certain types of foods for much of her adult life. Ms. L’s family also described a range of compulsive behaviors, including shoplifting, hoarding art, multiple plastic surgeries, and phases where Ms. L ate only frozen yogurt without sugar.

Ms. L’s daughter reported that Ms. L had seen a psychologist in the late 1990s for depression and had been diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the early 2000s. In 2006, during a depressive episode after her divorce, Ms. L had a suicide attempt with pills and alcohol, and was hospitalized. Records from that stay described a history of mood dysregulation with fears regarding food and nutrition. Ms. L was treated with aripiprazole 5 mg/d. A trial of trazodone 25 mg/d did not have any effect. When discharged, she was receiving lamotrigine 100 mg/d. However, her daughter believes she stopped taking all psychiatric medications shortly after discharge.

Her daughter says that in the past 2 years, Ms. L has seen multiple doctors for treatment of somatic gastrointestinal (GI) complaints. A 2018 note from a social worker indicated that Ms. L endorsed taking >80 supplements per day and constantly researched nutrition online. In the months leading to her current hospitalization, Ms. L suffered from severe self-neglect and fear regarding foods she felt were not healthy for her. She had stopped leaving her apartment.

Continue to: EVALUATION Poor insight, normal lab results...

EVALUATION Poor insight, normal lab results

During her evaluation, Ms. L appears cachectic and frail. She has a heavily constricted affect and is guarded, dismissive, and vague. Although her thought processes are linear and goal-directed, her insight into her condition is extremely poor and she appears surprised when clinicians inform her that her self-neglect would lead to death. Instead, Ms. L insists she is eating healthily and demonstrates severe anxiety in relation to her GI symptoms.

Ms. L is oriented to person, place, and time. She scores 27/30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, indicating normal cognition. She denies any depressive symptoms or suicidal intent. She does not appear to be internally preoccupied and denies having auditory or visual hallucinations or manic symptoms.

A neurologic examination reveals that her cranial nerves are normal, and cerebellar function, strength, and sensory testing are intact. Her gait is steady and she walks without a walker. Despite her severely low BMI and recent history of self-neglect, Ms. L’s laboratory results are remarkably normal and show no liver, metabolic, or electrolyte abnormalities, no signs of infection, and normal vitamin B12 levels. She has slightly elevated creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels, but a normal glomerular filtration rate.

Her medical history is significant for squamous cell esophageal cancer, treated with radiofrequency ablation. Although Ms. L is constantly worried about the recurrence of cancer, pathology reports demonstrate no esophageal dysplasia. However, she does show evidence of an approximately 1 cm × 1 cm mild, noncircumferential esophageal stenosis, likely resulting from radiofrequency ablation.

[polldaddy:11079394]

The authors’ observations

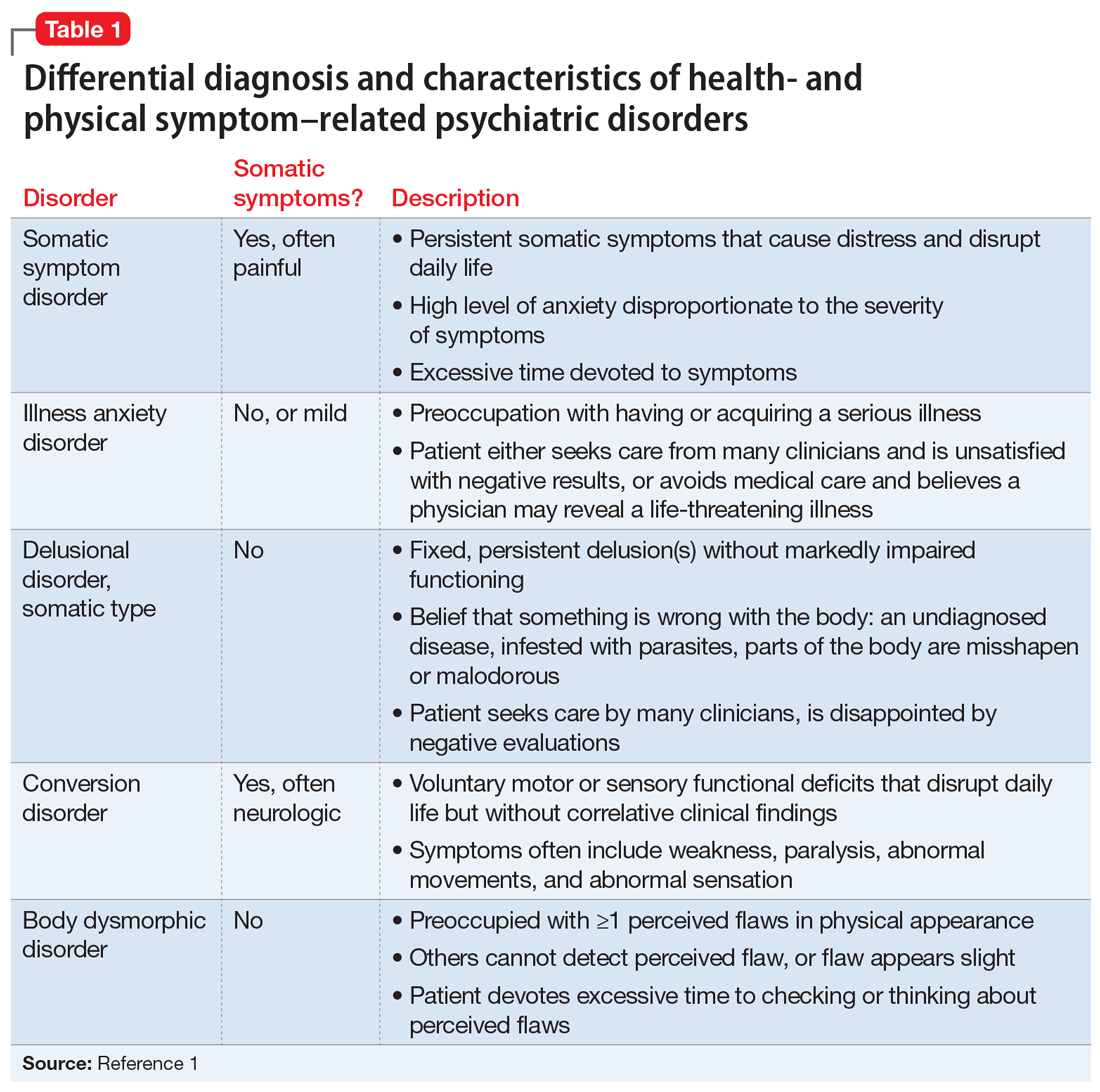

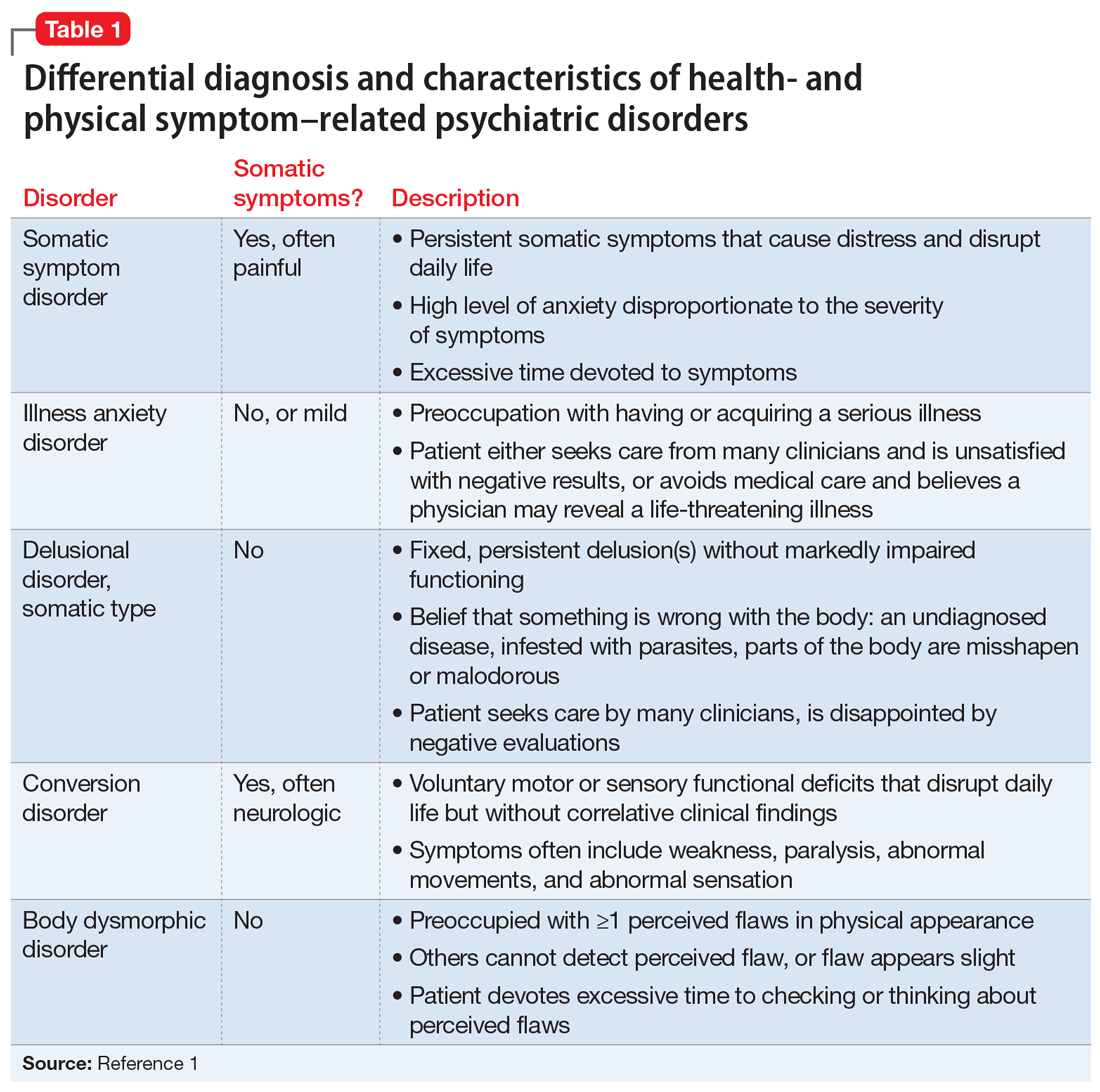

Several health- and physical symptom-related psychiatric disorders have overlapping features, which can complicate the differential diagnosis (Table 11). Ms. L presented to the ED with a severely low BMI of 13.5 kg/m2, obsessions regarding specific types of food, and preoccupations regarding her esophagus. Despite her extensive psychiatric history (including intense fears regarding food), we ruled out a primary psychotic disorder because she did not describe auditory or visual hallucinations and never appeared internally preoccupied. While her BMI and persistent minimization of the extent of her disease meet criteria for anorexia nervosa, she denied body dysmorphia and did not have any fear of gaining weight.

A central element of Ms. L’s presentation was her anxiety regarding how certain types of foods impact her health as well as her anxieties regarding her esophagus. While Ms. L was in remission from esophageal cancer and had a diagnosis of esophageal dysphagia, these preoccupations and obsessions regarding how certain types of foods affect her esophagus drove her to self-neglect and thus represent pathologic thought processes out of proportion to her symptoms. Illness anxiety disorder was considered because Ms. L met many of its criteria: preoccupation with having a serious illness, disproportionate preoccupation with somatic symptoms if they are present, extreme anxiety over health, and performance of health-related behaviors.1 However, illness anxiety disorder is a diagnosis of exclusion, and 1 criterion is that these symptoms cannot be explained by another mental disorder. We felt other diagnoses better fit Ms. L’s condition and ruled out illness anxiety disorder.

Ms. L’s long history of food and non-food–related obsessions and compulsions that interrupted her ability to perform daily activities were strongly suggestive for OCD. Additionally, her intense preoccupation, high level of anxiety, amount of time and energy spent seeking care for her esophagus and GERD symptoms, and the resulting significant disruption of daily life, met criteria for somatic symptom disorder (SSD). However, we did not believe that a diagnosis of OCD and SSD alone explained the entirety of Ms. L’s clinical picture. Despite ruling out anorexia nervosa, Ms. L nonetheless demonstrated disordered eating.

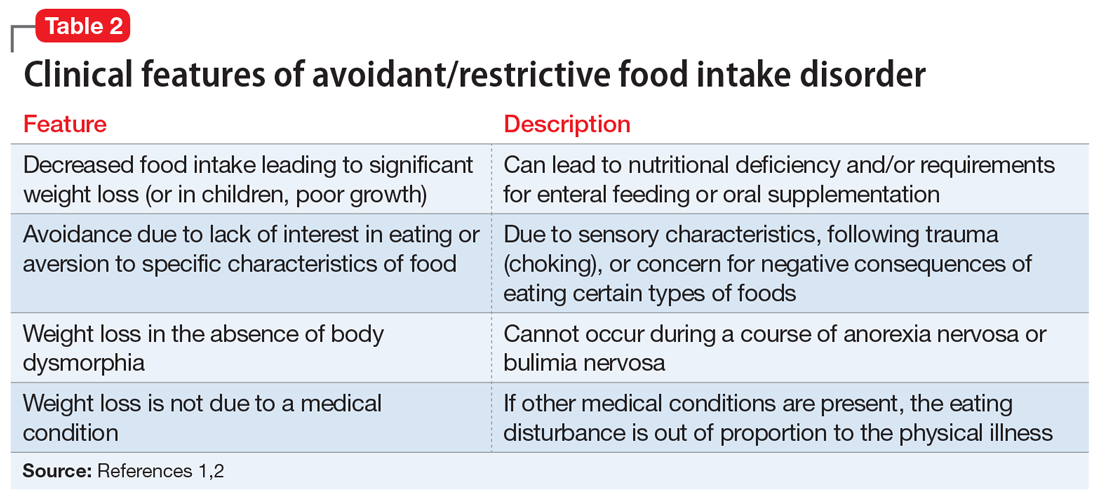

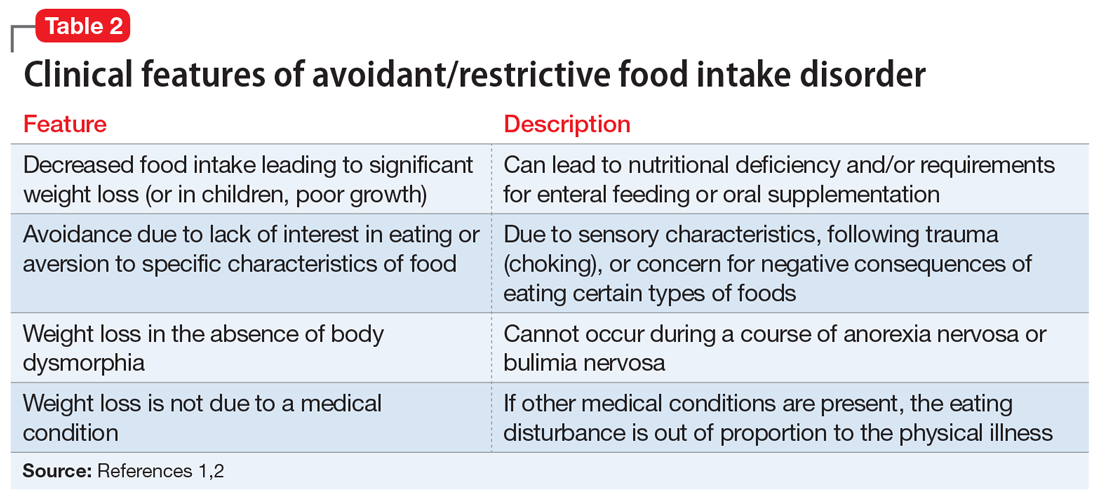

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is an eating disorder in which patients restrict their diet and do not meet nutritional needs for any number of reasons, do not experience body dysmorphia, and do not fear weight gain.1 A common feature of ARFID is a fear of negative consequences from eating specific types of food.2 Table 21,2 summarizes additional clinical features of ARFID. Although ARFID is typically diagnosed in children and adolescents, particularly in individuals with autism with heightened sensory sensitivities, ARFID is also common among adult patients with GI disorders.3 In a retrospective chart review of 410 adults ages 18 to 90 (73% women) referred to a neurogastroenterology care center, 6.3% met the full criteria for ARFID and 17.3% had clinically significant avoidant or restrictive eating behaviors. Among patients with ARFID symptoms, 93% stated that a fear of GI symptoms was the driver of their avoidant or restrictive eating behaviors.2 Patients with GI diseases often develop dietary control and avoidance coping mechanisms to alleviate their symptoms.4 These strategies can exacerbate health anxieties and have a detrimental effect on mental health.5 Patients with GI disorders have a high degree of comorbidity with affective disorders, including anxiety disorders.6 These trends may arise from hypervigilance and the need to gain control over physical symptoms.7 Feeling a need for control, actions driven by anxiety and fear, and the need for compensatory behaviors are cardinal features of OCD and eating disorders.8 Multiple studies have demonstrated comorbidities between irritable bowel syndrome and eating disorders,9 SSD,10 and OCD.11 Taken together with observations that ARFID is also found in patients with GI disorders,2 these findings demonstrate that patients with a history of GI disease are at high risk of developing extreme health anxieties and behavioral coping strategies that can lead to disordered eating.

The rise in “healthy” eating materials online—particularly on social media—has created an atmosphere in which misinformation regarding diet and health is common and widespread. For patients with OCD and a predisposition to health anxiety, such as Ms. L, searching online for nutrition information and healthy living habits can exacerbate food-related anxieties and can lead to a pathological drive for purity and health.12Although not included in DSM-5, orthorexia nervosa was identified in 1997 as a proposed eating disorder best characterized as an obsession with healthy eating with associated restrictive behaviors.13 Patients with this disorder are rarely focused on losing weight, and orthorexic eating behaviors have been associated with both SSD and OCD.12,14 As in Ms. L’s case, patients with orthorexia nervosa demonstrate intrusive obsessions with nutrition, spend excessive amount of time researching nutrition, and fixate on food quality.12 Throughout Ms. L’s hospitalization, even as her food-related magical thinking symptoms improved, she constantly informed her care team that she had been “eating healthily” even though she was severely cachectic. Patients with SSD and OCD prone to health anxieties are at risk of developing pathologic food beliefs and dangerous eating behaviors. These patients may benefit from psychoeducation regarding nutrition and media literacy, which are components of effective eating disorder programs.15

[polldaddy:11079399]

Continue to: The authors' observations...

The authors’ observations

How do we approach the pharmacologic treatment of patients with co-occurring eating, somatic symptom, and anxiety disorders? Olanzapine facilitates recovery in children and adolescents with ARFID by promoting eating and weight gain, and decreasing symptoms of depression and anxiety.16 Patients with orthorexia nervosa also may benefit from treatment with olanzapine, which has decreased food-related fixations, magical thinking, and delusions regarding food.17 Further, orthorexic patients with ARFID have also been shown to respond to SSRIs due to those agents’ efficacy for treating intrusive thoughts, obsessions, and preoccupations from OCD and SSD.18,19 Thus, treating Ms. L’s symptoms with olanzapine and fluoxetine targeted the intersection of several diagnoses on our differential. Olanzapine’s propensity to cause weight gain is favorable in this population, particularly patients such as Ms. L, who do not exhibit body dysmorphia or fear of gaining weight.

OUTCOME Weight gain and fewer fears

Ms. L is prescribed olanzapine 5 mg/d and fluoxetine 20 mg/d. She gains 20.6 pounds in 4 weeks. Importantly, she endorses fewer fears related to foods and expands her palate to include foods she previously considered to be unhealthy, including white bread and farm-raised salmon. Further, she spends less time thinking about food and says she has less anxiety regarding the recurrence of GI symptoms.

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Murray HB, Bailey AP, Keshishian AC. Prevalence and characteristics of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in adult neurogastroenterology patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):1995-2002.e1.

3. Görmez A, Kılıç A, Kırpınar İ. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: an adult case responding to cognitive behavioral therapy. Clinical Case Studies. 2018;17(6):443-452.

4. Reed-Knight B, Squires M, Chitkara DK, et al. Adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome report increased eating-associated symptoms, changes in dietary composition, and altered eating behaviors: a pilot comparison study to healthy adolescents. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28(12):1915-1920.

5. Melchior C, Desprez C, Riachi G, et al. Anxiety and depression profile is associated with eating disorders in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Front Psychiatry. 2020;10:928.

6. Mayer EA, Craske M, Naliboff BD. Depression, anxiety, and the gastrointestinal system. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62 Suppl 8:28-37.

7. Abraham S, Kellow J. Exploring eating disorder quality of life and functional gastrointestinal disorders among eating disorder patients. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70(4):372-377.

8. Swinbourne JM, Touyz SW. The co-morbidity of eating disorders and anxiety disorders: a review. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2007;15(4):253-274.

9. Perkins SJ, Keville S, Schmidt U, et al. Eating disorders and irritable bowel syndrome: is there a link? J Psychosom Res. 2005;59(2):57-64.

10. Hausteiner-Wiehle C, Henningsen P. Irritable bowel syndrome: relations with functional, mental, and somatoform disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(2):6024-6030.

11. Masand PS, Keuthen NJ, Gupta S, et al. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in obsessive-compulsive disorder. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(1):21-25.

12. Koven NS, Abry AW. The clinical basis of orthorexia nervosa: emerging perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:385-394.

13. Bratman S. Health food junkie. Yoga Journal. 1997;136:42-50.

14. Barthels F, Müller R, Schüth T, et al. Orthorexic eating behavior in patients with somatoform disorders. Eat Weight Disord. 2021;26(1):135-143.

15. Ciao AC, Loth K, Neumark-Sztainer D. Preventing eating disorder pathology: common and unique features of successful eating disorders prevention programs. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(7):453.

16. Brewerton TD, D’Agostino M. Adjunctive use of olanzapine in the treatment of avoidant restrictive food intake disorder in children and adolescents in an eating disorders program. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(10):920-922.

17. Moroze RM, Dunn TM, Craig Holland J, et al. Microthinking about micronutrients: a case of transition from obsessions about healthy eating to near-fatal “orthorexia nervosa” and proposed diagnostic criteria. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(4):397-403.

18. Spettigue W, Norris ML, Santos A, et al. Treatment of children and adolescents with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: a case series examining the feasibility of family therapy and adjunctive treatments. J Eat Disord. 2018;6:20.

19. Niedzielski A, Kaźmierczak-Wojtaś N. Prevalence of Orthorexia Nervosa and Its Diagnostic Tools-A Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5488. Published 2021 May 20. doi:10.3390/ijerph18105488 Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa and its diagnostic tools-a literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5488.

CASE Fixated on health and nutrition

At the insistence of her daughter, Ms. L, age 75, presents to the emergency department (ED) for self-neglect and severe weight loss, with a body mass index (BMI) of 13.5 kg/m2 (normal: 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2). When asked why she is in the ED, Ms. L says she doesn’t know. She attributes her significant weight loss (approximately 20 pounds in the last few months) to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). She constantly worries about her esophagus. She had been diagnosed with esophageal dysphagia 7 years ago after undergoing radiofrequency ablation for esophageal cancer. Ms. L fixates on the negative effects certain foods and ingredients might have on her stomach and esophagus.

Following transfer from the ED, Ms. L is involuntarily admitted to our inpatient unit. Although she acknowledges weight loss, she minimizes the severity of her illness and indicates she would like to gain weight, but only by eating healthy foods she is comfortable with, including kale, quinoa, and vegetables. Ms. L says that she has always been interested in “healthful foods” and that she “loves sugar,” but “it’s bad for you,” mentioning that “sugar fuels cancer.” She has daily thoughts about sugar causing cancer. Ms. L also mentions that she stopped eating flour, sugar, fried food, and oils because those foods affect her “stomach acid” and cause “pimples on my face and weight loss.” While in the inpatient unit, Ms. L requests a special diet and demands to know the origin and ingredients of the foods she is offered. She emphasizes that her esophageal cancer diagnosis and dysphagia exacerbate worries that certain foods cause cancer, and wants to continue her diet restrictions. Nonetheless, she says she wants to get healthy, and denies an intense fear of gaining weight or feeling fat.

HISTORY Multiple psychiatric diagnoses

Ms. L lives alone and enjoys spending time with her grandchildren, visiting museums, and listening to classical music. However, her family, social workers, and records from a previous psychiatric hospitalization reveal that Ms. L has a history of psychiatric illness and fears regarding certain types of foods for much of her adult life. Ms. L’s family also described a range of compulsive behaviors, including shoplifting, hoarding art, multiple plastic surgeries, and phases where Ms. L ate only frozen yogurt without sugar.

Ms. L’s daughter reported that Ms. L had seen a psychologist in the late 1990s for depression and had been diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the early 2000s. In 2006, during a depressive episode after her divorce, Ms. L had a suicide attempt with pills and alcohol, and was hospitalized. Records from that stay described a history of mood dysregulation with fears regarding food and nutrition. Ms. L was treated with aripiprazole 5 mg/d. A trial of trazodone 25 mg/d did not have any effect. When discharged, she was receiving lamotrigine 100 mg/d. However, her daughter believes she stopped taking all psychiatric medications shortly after discharge.

Her daughter says that in the past 2 years, Ms. L has seen multiple doctors for treatment of somatic gastrointestinal (GI) complaints. A 2018 note from a social worker indicated that Ms. L endorsed taking >80 supplements per day and constantly researched nutrition online. In the months leading to her current hospitalization, Ms. L suffered from severe self-neglect and fear regarding foods she felt were not healthy for her. She had stopped leaving her apartment.

Continue to: EVALUATION Poor insight, normal lab results...

EVALUATION Poor insight, normal lab results

During her evaluation, Ms. L appears cachectic and frail. She has a heavily constricted affect and is guarded, dismissive, and vague. Although her thought processes are linear and goal-directed, her insight into her condition is extremely poor and she appears surprised when clinicians inform her that her self-neglect would lead to death. Instead, Ms. L insists she is eating healthily and demonstrates severe anxiety in relation to her GI symptoms.

Ms. L is oriented to person, place, and time. She scores 27/30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, indicating normal cognition. She denies any depressive symptoms or suicidal intent. She does not appear to be internally preoccupied and denies having auditory or visual hallucinations or manic symptoms.

A neurologic examination reveals that her cranial nerves are normal, and cerebellar function, strength, and sensory testing are intact. Her gait is steady and she walks without a walker. Despite her severely low BMI and recent history of self-neglect, Ms. L’s laboratory results are remarkably normal and show no liver, metabolic, or electrolyte abnormalities, no signs of infection, and normal vitamin B12 levels. She has slightly elevated creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels, but a normal glomerular filtration rate.

Her medical history is significant for squamous cell esophageal cancer, treated with radiofrequency ablation. Although Ms. L is constantly worried about the recurrence of cancer, pathology reports demonstrate no esophageal dysplasia. However, she does show evidence of an approximately 1 cm × 1 cm mild, noncircumferential esophageal stenosis, likely resulting from radiofrequency ablation.

[polldaddy:11079394]

The authors’ observations

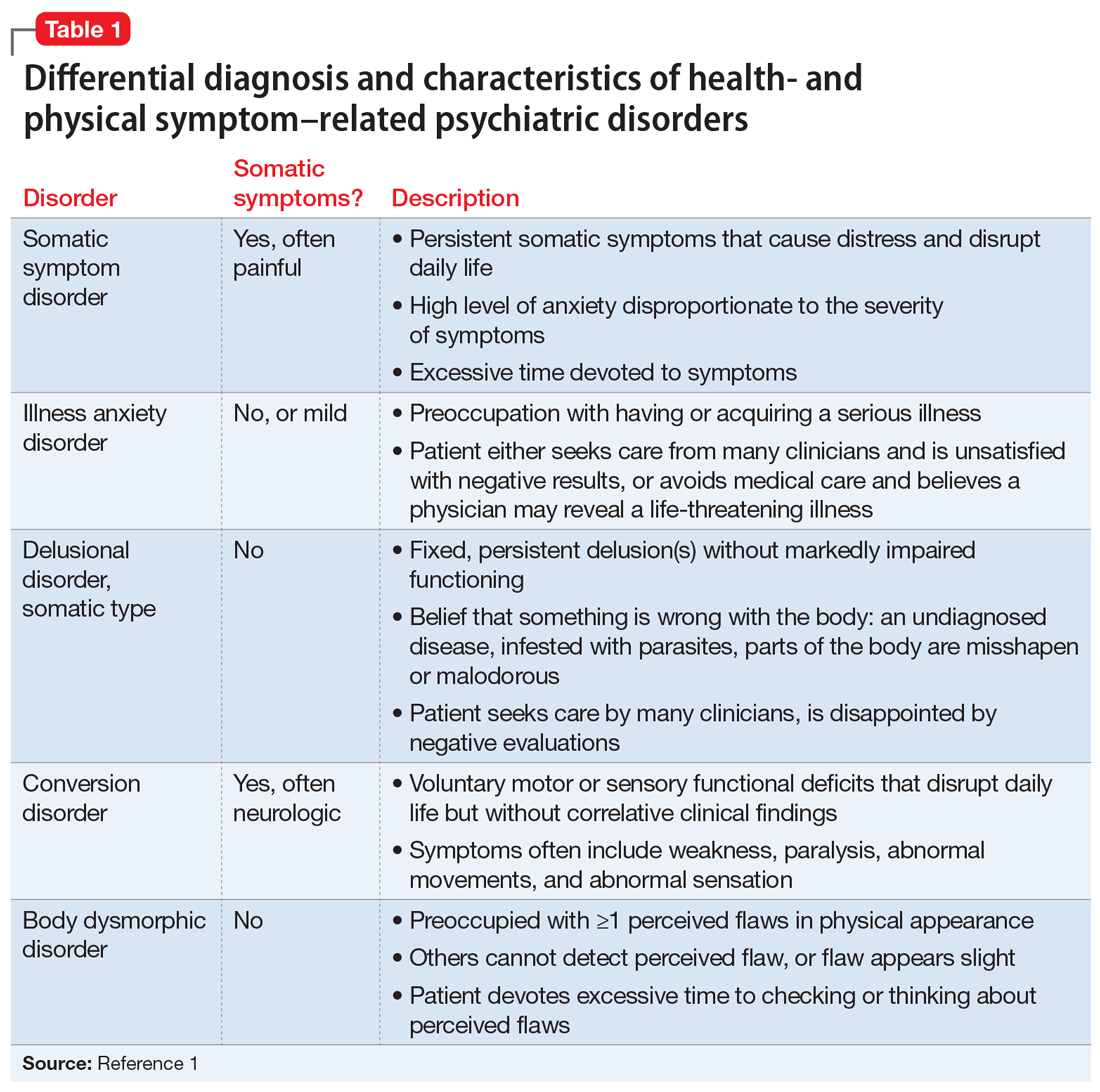

Several health- and physical symptom-related psychiatric disorders have overlapping features, which can complicate the differential diagnosis (Table 11). Ms. L presented to the ED with a severely low BMI of 13.5 kg/m2, obsessions regarding specific types of food, and preoccupations regarding her esophagus. Despite her extensive psychiatric history (including intense fears regarding food), we ruled out a primary psychotic disorder because she did not describe auditory or visual hallucinations and never appeared internally preoccupied. While her BMI and persistent minimization of the extent of her disease meet criteria for anorexia nervosa, she denied body dysmorphia and did not have any fear of gaining weight.

A central element of Ms. L’s presentation was her anxiety regarding how certain types of foods impact her health as well as her anxieties regarding her esophagus. While Ms. L was in remission from esophageal cancer and had a diagnosis of esophageal dysphagia, these preoccupations and obsessions regarding how certain types of foods affect her esophagus drove her to self-neglect and thus represent pathologic thought processes out of proportion to her symptoms. Illness anxiety disorder was considered because Ms. L met many of its criteria: preoccupation with having a serious illness, disproportionate preoccupation with somatic symptoms if they are present, extreme anxiety over health, and performance of health-related behaviors.1 However, illness anxiety disorder is a diagnosis of exclusion, and 1 criterion is that these symptoms cannot be explained by another mental disorder. We felt other diagnoses better fit Ms. L’s condition and ruled out illness anxiety disorder.

Ms. L’s long history of food and non-food–related obsessions and compulsions that interrupted her ability to perform daily activities were strongly suggestive for OCD. Additionally, her intense preoccupation, high level of anxiety, amount of time and energy spent seeking care for her esophagus and GERD symptoms, and the resulting significant disruption of daily life, met criteria for somatic symptom disorder (SSD). However, we did not believe that a diagnosis of OCD and SSD alone explained the entirety of Ms. L’s clinical picture. Despite ruling out anorexia nervosa, Ms. L nonetheless demonstrated disordered eating.

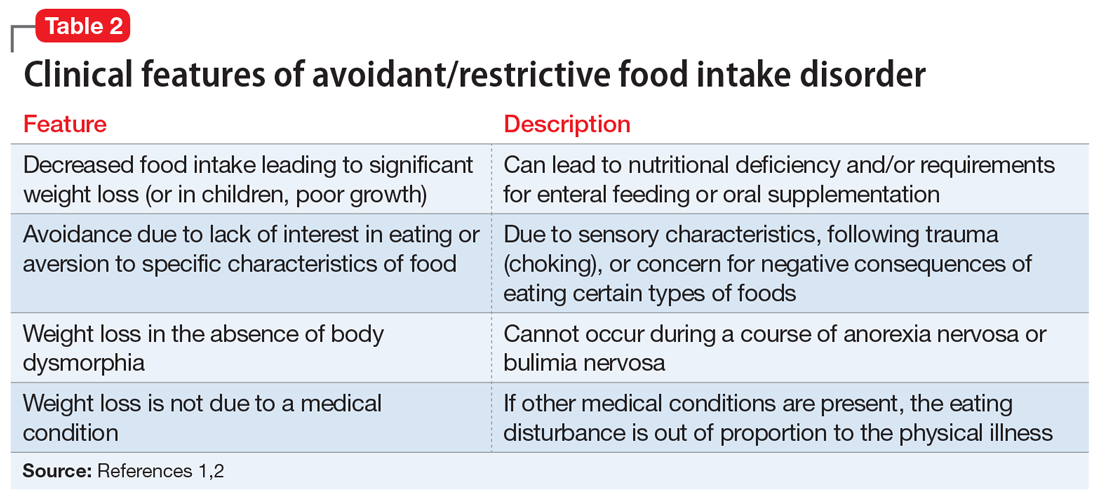

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is an eating disorder in which patients restrict their diet and do not meet nutritional needs for any number of reasons, do not experience body dysmorphia, and do not fear weight gain.1 A common feature of ARFID is a fear of negative consequences from eating specific types of food.2 Table 21,2 summarizes additional clinical features of ARFID. Although ARFID is typically diagnosed in children and adolescents, particularly in individuals with autism with heightened sensory sensitivities, ARFID is also common among adult patients with GI disorders.3 In a retrospective chart review of 410 adults ages 18 to 90 (73% women) referred to a neurogastroenterology care center, 6.3% met the full criteria for ARFID and 17.3% had clinically significant avoidant or restrictive eating behaviors. Among patients with ARFID symptoms, 93% stated that a fear of GI symptoms was the driver of their avoidant or restrictive eating behaviors.2 Patients with GI diseases often develop dietary control and avoidance coping mechanisms to alleviate their symptoms.4 These strategies can exacerbate health anxieties and have a detrimental effect on mental health.5 Patients with GI disorders have a high degree of comorbidity with affective disorders, including anxiety disorders.6 These trends may arise from hypervigilance and the need to gain control over physical symptoms.7 Feeling a need for control, actions driven by anxiety and fear, and the need for compensatory behaviors are cardinal features of OCD and eating disorders.8 Multiple studies have demonstrated comorbidities between irritable bowel syndrome and eating disorders,9 SSD,10 and OCD.11 Taken together with observations that ARFID is also found in patients with GI disorders,2 these findings demonstrate that patients with a history of GI disease are at high risk of developing extreme health anxieties and behavioral coping strategies that can lead to disordered eating.

The rise in “healthy” eating materials online—particularly on social media—has created an atmosphere in which misinformation regarding diet and health is common and widespread. For patients with OCD and a predisposition to health anxiety, such as Ms. L, searching online for nutrition information and healthy living habits can exacerbate food-related anxieties and can lead to a pathological drive for purity and health.12Although not included in DSM-5, orthorexia nervosa was identified in 1997 as a proposed eating disorder best characterized as an obsession with healthy eating with associated restrictive behaviors.13 Patients with this disorder are rarely focused on losing weight, and orthorexic eating behaviors have been associated with both SSD and OCD.12,14 As in Ms. L’s case, patients with orthorexia nervosa demonstrate intrusive obsessions with nutrition, spend excessive amount of time researching nutrition, and fixate on food quality.12 Throughout Ms. L’s hospitalization, even as her food-related magical thinking symptoms improved, she constantly informed her care team that she had been “eating healthily” even though she was severely cachectic. Patients with SSD and OCD prone to health anxieties are at risk of developing pathologic food beliefs and dangerous eating behaviors. These patients may benefit from psychoeducation regarding nutrition and media literacy, which are components of effective eating disorder programs.15

[polldaddy:11079399]

Continue to: The authors' observations...

The authors’ observations

How do we approach the pharmacologic treatment of patients with co-occurring eating, somatic symptom, and anxiety disorders? Olanzapine facilitates recovery in children and adolescents with ARFID by promoting eating and weight gain, and decreasing symptoms of depression and anxiety.16 Patients with orthorexia nervosa also may benefit from treatment with olanzapine, which has decreased food-related fixations, magical thinking, and delusions regarding food.17 Further, orthorexic patients with ARFID have also been shown to respond to SSRIs due to those agents’ efficacy for treating intrusive thoughts, obsessions, and preoccupations from OCD and SSD.18,19 Thus, treating Ms. L’s symptoms with olanzapine and fluoxetine targeted the intersection of several diagnoses on our differential. Olanzapine’s propensity to cause weight gain is favorable in this population, particularly patients such as Ms. L, who do not exhibit body dysmorphia or fear of gaining weight.

OUTCOME Weight gain and fewer fears

Ms. L is prescribed olanzapine 5 mg/d and fluoxetine 20 mg/d. She gains 20.6 pounds in 4 weeks. Importantly, she endorses fewer fears related to foods and expands her palate to include foods she previously considered to be unhealthy, including white bread and farm-raised salmon. Further, she spends less time thinking about food and says she has less anxiety regarding the recurrence of GI symptoms.

CASE Fixated on health and nutrition

At the insistence of her daughter, Ms. L, age 75, presents to the emergency department (ED) for self-neglect and severe weight loss, with a body mass index (BMI) of 13.5 kg/m2 (normal: 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2). When asked why she is in the ED, Ms. L says she doesn’t know. She attributes her significant weight loss (approximately 20 pounds in the last few months) to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). She constantly worries about her esophagus. She had been diagnosed with esophageal dysphagia 7 years ago after undergoing radiofrequency ablation for esophageal cancer. Ms. L fixates on the negative effects certain foods and ingredients might have on her stomach and esophagus.

Following transfer from the ED, Ms. L is involuntarily admitted to our inpatient unit. Although she acknowledges weight loss, she minimizes the severity of her illness and indicates she would like to gain weight, but only by eating healthy foods she is comfortable with, including kale, quinoa, and vegetables. Ms. L says that she has always been interested in “healthful foods” and that she “loves sugar,” but “it’s bad for you,” mentioning that “sugar fuels cancer.” She has daily thoughts about sugar causing cancer. Ms. L also mentions that she stopped eating flour, sugar, fried food, and oils because those foods affect her “stomach acid” and cause “pimples on my face and weight loss.” While in the inpatient unit, Ms. L requests a special diet and demands to know the origin and ingredients of the foods she is offered. She emphasizes that her esophageal cancer diagnosis and dysphagia exacerbate worries that certain foods cause cancer, and wants to continue her diet restrictions. Nonetheless, she says she wants to get healthy, and denies an intense fear of gaining weight or feeling fat.

HISTORY Multiple psychiatric diagnoses

Ms. L lives alone and enjoys spending time with her grandchildren, visiting museums, and listening to classical music. However, her family, social workers, and records from a previous psychiatric hospitalization reveal that Ms. L has a history of psychiatric illness and fears regarding certain types of foods for much of her adult life. Ms. L’s family also described a range of compulsive behaviors, including shoplifting, hoarding art, multiple plastic surgeries, and phases where Ms. L ate only frozen yogurt without sugar.

Ms. L’s daughter reported that Ms. L had seen a psychologist in the late 1990s for depression and had been diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the early 2000s. In 2006, during a depressive episode after her divorce, Ms. L had a suicide attempt with pills and alcohol, and was hospitalized. Records from that stay described a history of mood dysregulation with fears regarding food and nutrition. Ms. L was treated with aripiprazole 5 mg/d. A trial of trazodone 25 mg/d did not have any effect. When discharged, she was receiving lamotrigine 100 mg/d. However, her daughter believes she stopped taking all psychiatric medications shortly after discharge.

Her daughter says that in the past 2 years, Ms. L has seen multiple doctors for treatment of somatic gastrointestinal (GI) complaints. A 2018 note from a social worker indicated that Ms. L endorsed taking >80 supplements per day and constantly researched nutrition online. In the months leading to her current hospitalization, Ms. L suffered from severe self-neglect and fear regarding foods she felt were not healthy for her. She had stopped leaving her apartment.

Continue to: EVALUATION Poor insight, normal lab results...

EVALUATION Poor insight, normal lab results

During her evaluation, Ms. L appears cachectic and frail. She has a heavily constricted affect and is guarded, dismissive, and vague. Although her thought processes are linear and goal-directed, her insight into her condition is extremely poor and she appears surprised when clinicians inform her that her self-neglect would lead to death. Instead, Ms. L insists she is eating healthily and demonstrates severe anxiety in relation to her GI symptoms.

Ms. L is oriented to person, place, and time. She scores 27/30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, indicating normal cognition. She denies any depressive symptoms or suicidal intent. She does not appear to be internally preoccupied and denies having auditory or visual hallucinations or manic symptoms.

A neurologic examination reveals that her cranial nerves are normal, and cerebellar function, strength, and sensory testing are intact. Her gait is steady and she walks without a walker. Despite her severely low BMI and recent history of self-neglect, Ms. L’s laboratory results are remarkably normal and show no liver, metabolic, or electrolyte abnormalities, no signs of infection, and normal vitamin B12 levels. She has slightly elevated creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels, but a normal glomerular filtration rate.

Her medical history is significant for squamous cell esophageal cancer, treated with radiofrequency ablation. Although Ms. L is constantly worried about the recurrence of cancer, pathology reports demonstrate no esophageal dysplasia. However, she does show evidence of an approximately 1 cm × 1 cm mild, noncircumferential esophageal stenosis, likely resulting from radiofrequency ablation.

[polldaddy:11079394]

The authors’ observations

Several health- and physical symptom-related psychiatric disorders have overlapping features, which can complicate the differential diagnosis (Table 11). Ms. L presented to the ED with a severely low BMI of 13.5 kg/m2, obsessions regarding specific types of food, and preoccupations regarding her esophagus. Despite her extensive psychiatric history (including intense fears regarding food), we ruled out a primary psychotic disorder because she did not describe auditory or visual hallucinations and never appeared internally preoccupied. While her BMI and persistent minimization of the extent of her disease meet criteria for anorexia nervosa, she denied body dysmorphia and did not have any fear of gaining weight.

A central element of Ms. L’s presentation was her anxiety regarding how certain types of foods impact her health as well as her anxieties regarding her esophagus. While Ms. L was in remission from esophageal cancer and had a diagnosis of esophageal dysphagia, these preoccupations and obsessions regarding how certain types of foods affect her esophagus drove her to self-neglect and thus represent pathologic thought processes out of proportion to her symptoms. Illness anxiety disorder was considered because Ms. L met many of its criteria: preoccupation with having a serious illness, disproportionate preoccupation with somatic symptoms if they are present, extreme anxiety over health, and performance of health-related behaviors.1 However, illness anxiety disorder is a diagnosis of exclusion, and 1 criterion is that these symptoms cannot be explained by another mental disorder. We felt other diagnoses better fit Ms. L’s condition and ruled out illness anxiety disorder.

Ms. L’s long history of food and non-food–related obsessions and compulsions that interrupted her ability to perform daily activities were strongly suggestive for OCD. Additionally, her intense preoccupation, high level of anxiety, amount of time and energy spent seeking care for her esophagus and GERD symptoms, and the resulting significant disruption of daily life, met criteria for somatic symptom disorder (SSD). However, we did not believe that a diagnosis of OCD and SSD alone explained the entirety of Ms. L’s clinical picture. Despite ruling out anorexia nervosa, Ms. L nonetheless demonstrated disordered eating.