User login

In epilepsy, brain-responsive stimulation passes long-term tests

Two new long-term studies, one an extension trial and the other an analysis of real-world experience, show that Both studies showed that the benefit from the devices increased over time.

That accruing benefit may be because of improved protocols as clinicians gain experience with the device or because of network remodeling that occurs over time as seizures are controlled. “I think it’s both,” said Martha Morrell, MD, a clinical professor of neurology at Stanford (Calif.) University and chief medical officer at NeuroPace, the company that has marketed the device since it gained FDA approval in 2013.

In both studies, the slope of improvement over time was similar, but the real-world study showed greater improvement at the beginning of treatment. “I think the slopes represent physiological changes, but the fact that [the real-world study] starts with better outcomes is, I think, directly attributable to learning. When the long-term study was started in 2004, this had never been done before, and we had to make a highly educated guess about what we should do, and the initial stimulatory parameters were programmed in a way that’s very similar to what was used for movement disorders,” Dr. Morrell said in an interview.

The long-term treatment study appeared online July 20 in the journal Neurology, while the real-world analysis was published July 13 in Epilepsia.

An alternative option

Medications can effectively treat some seizures, but 30%-40% of patients must turn to other options for control. Surgery can sometimes be curative, but is not suitable for some patients. Other stimulation devices include vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), which sends pulses from a chest implant to the vagus nerve, reducing epileptic attacks through an unknown mechanism. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) places electrodes that deliver stimulation to the anterior nucleus of the thalamus, which can spread initially localized seizures.

The RNS device consists of a neurostimulator implanted cranially and connected to leads that are placed based on the individual patient’s seizure focus or foci. It also continuously monitors brain activity and delivers stimulation only when its signal suggests the beginning of a seizure.

That capacity for recording is a key benefit because the information can be stored and analyzed, according to Vikram Rao, MD, PhD, a coinvestigator in the real-world trial and an associate professor and the epilepsy division chief at the University of California, San Francisco, which was one of the trial centers. “You know more precisely than we previously did how many seizures a patient is having. Many of our patients are not able to quantify their seizures with perfect accuracy, so we’re better quantifying their seizure burden,” Dr. Rao said in an interview.

The ability to monitor patients can also improve clinical management. Dr. Morrell recounted an elderly patient who for many years has driven 5 hours for appointments. Recently she was able to review his data from the RNS System remotely. She determined that he was doing fine and, after a telephone consultation, told him he didn’t need to come in for a scheduled visit.

Real-world analysis

In the real-world analysis, researchers led by Babak Razavi, PhD, and Casey Halpern, MD, at Stanford University conducted a chart review of 150 patients at eight centers who underwent treatment with the RNS system between 2013 and 2018. All patients were followed at least 1 year, with a mean of 2.3 years. Patients had a median of 7.7 disabling seizures per month. The mean value was 52 and the numbers ranged from 0.1 to 3,000. A total of 60% had abnormal brain MRI findings.

At 1 year, subjects achieved a mean 67% decrease in seizure frequency (interquartile range, 50%-94%). At 2 years, that grew to 77%; at 3 or more years, 84%. There was no significant difference in seizure reduction at 1 year according to age, age at epilepsy onset, duration of epilepsy, location of seizure foci, presence of brain MRI abnormalities, prior intracranial monitoring, prior epilepsy surgery, or prior VNS treatment. When patients who underwent a resection at the time of RNS placement were excluded, the results were similar. There were no significant differences in outcome by center.

A total of 11.3% of patients experienced a device-related serious adverse event, and 4% developed infections. The rate of infection was not significantly different between patients who had the neurostimulator and leads implanted alone (3.0%) and patients who had intracranial EEG diagnostic monitoring (ICM) electrodes removed at the same time (6.1%; P = .38).

Although about one-third of the patients who started the long-term study dropped out before completion, most were because the participants moved away from treatment centers, according to Dr. Morrell, and other evidence points squarely to patient satisfaction. “At the end of the battery’s longevity, the neurostimulator needs to be replaced. It’s an outpatient, 45-minute procedure. Over 90% of patients chose to have it replaced. It’s not the answer for everybody, but the substantial majority of patients choose to continue,” she said.

Extension trial

The open-label extension trial, led by Dileep Nair, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation and Dr. Morrell, followed 230 of the 256 patients who participated in 2-year phase 3 study or feasibility studies, extending device usage to 9 years. A total of 162 completed follow-up (mean, 7.5 years). The median reduction of seizure frequency was 58% at the end of year 3, and 75% by year 9 (P < .0001; Wilcoxon signed rank). Although patient population enrichment could have explained this observation, other analyses confirmed that the improvement was real.

Nearly 75% had at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency; 35% had a 90% or greater reduction in seizure frequency. Some patients (18.4%) had at least a full year with no seizures, and 62% who had a 1-year seizure-free period experienced no seizures at the latest follow-up. Overall, 21% had no seizures in the last 6 months of follow-up.

For those with a seizure-free period of more than 1 year, the average duration was 3.2 years (range, 1.04-9.6 years). There was no difference in response among patients based on previous antiseizure medication use or previous epilepsy surgery, VNS treatment, or intracranial monitoring, and there were no differences by patient age at enrollment, age of seizure onset, brain imaging abnormality, seizure onset locality, or number of foci.

The researchers noted improvement in overall Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory–89 scores at 1 year (mean, +3.2; P < .0001), which continued through year 9 (mean, +1.9; P < .05). Improvements were also seen in epilepsy targeted (mean, +4.5; P < .001) and cognitive domains (mean, +2.5; P = .005). Risk of infection was 4.1% per procedure, and 12.1% of subjects overall experienced a serious device-related implant infection. Of 35 infections, 16 led to device removal.

The extension study was funded by NeuroPace. NeuroPace supported data entry and institutional review board submission for the real-world trial. Dr. Morrell owns stock and is an employee of NeuroPace. Dr Rao has received support from and/or consulted for NeuroPace.

SOURCE: Nair DR et al. Neurology. 2020 Jul 20. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010154. Razavi B et al. Epilepsia. 2020 Jul 13. doi: 10.1111/epi.16593.

Two new long-term studies, one an extension trial and the other an analysis of real-world experience, show that Both studies showed that the benefit from the devices increased over time.

That accruing benefit may be because of improved protocols as clinicians gain experience with the device or because of network remodeling that occurs over time as seizures are controlled. “I think it’s both,” said Martha Morrell, MD, a clinical professor of neurology at Stanford (Calif.) University and chief medical officer at NeuroPace, the company that has marketed the device since it gained FDA approval in 2013.

In both studies, the slope of improvement over time was similar, but the real-world study showed greater improvement at the beginning of treatment. “I think the slopes represent physiological changes, but the fact that [the real-world study] starts with better outcomes is, I think, directly attributable to learning. When the long-term study was started in 2004, this had never been done before, and we had to make a highly educated guess about what we should do, and the initial stimulatory parameters were programmed in a way that’s very similar to what was used for movement disorders,” Dr. Morrell said in an interview.

The long-term treatment study appeared online July 20 in the journal Neurology, while the real-world analysis was published July 13 in Epilepsia.

An alternative option

Medications can effectively treat some seizures, but 30%-40% of patients must turn to other options for control. Surgery can sometimes be curative, but is not suitable for some patients. Other stimulation devices include vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), which sends pulses from a chest implant to the vagus nerve, reducing epileptic attacks through an unknown mechanism. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) places electrodes that deliver stimulation to the anterior nucleus of the thalamus, which can spread initially localized seizures.

The RNS device consists of a neurostimulator implanted cranially and connected to leads that are placed based on the individual patient’s seizure focus or foci. It also continuously monitors brain activity and delivers stimulation only when its signal suggests the beginning of a seizure.

That capacity for recording is a key benefit because the information can be stored and analyzed, according to Vikram Rao, MD, PhD, a coinvestigator in the real-world trial and an associate professor and the epilepsy division chief at the University of California, San Francisco, which was one of the trial centers. “You know more precisely than we previously did how many seizures a patient is having. Many of our patients are not able to quantify their seizures with perfect accuracy, so we’re better quantifying their seizure burden,” Dr. Rao said in an interview.

The ability to monitor patients can also improve clinical management. Dr. Morrell recounted an elderly patient who for many years has driven 5 hours for appointments. Recently she was able to review his data from the RNS System remotely. She determined that he was doing fine and, after a telephone consultation, told him he didn’t need to come in for a scheduled visit.

Real-world analysis

In the real-world analysis, researchers led by Babak Razavi, PhD, and Casey Halpern, MD, at Stanford University conducted a chart review of 150 patients at eight centers who underwent treatment with the RNS system between 2013 and 2018. All patients were followed at least 1 year, with a mean of 2.3 years. Patients had a median of 7.7 disabling seizures per month. The mean value was 52 and the numbers ranged from 0.1 to 3,000. A total of 60% had abnormal brain MRI findings.

At 1 year, subjects achieved a mean 67% decrease in seizure frequency (interquartile range, 50%-94%). At 2 years, that grew to 77%; at 3 or more years, 84%. There was no significant difference in seizure reduction at 1 year according to age, age at epilepsy onset, duration of epilepsy, location of seizure foci, presence of brain MRI abnormalities, prior intracranial monitoring, prior epilepsy surgery, or prior VNS treatment. When patients who underwent a resection at the time of RNS placement were excluded, the results were similar. There were no significant differences in outcome by center.

A total of 11.3% of patients experienced a device-related serious adverse event, and 4% developed infections. The rate of infection was not significantly different between patients who had the neurostimulator and leads implanted alone (3.0%) and patients who had intracranial EEG diagnostic monitoring (ICM) electrodes removed at the same time (6.1%; P = .38).

Although about one-third of the patients who started the long-term study dropped out before completion, most were because the participants moved away from treatment centers, according to Dr. Morrell, and other evidence points squarely to patient satisfaction. “At the end of the battery’s longevity, the neurostimulator needs to be replaced. It’s an outpatient, 45-minute procedure. Over 90% of patients chose to have it replaced. It’s not the answer for everybody, but the substantial majority of patients choose to continue,” she said.

Extension trial

The open-label extension trial, led by Dileep Nair, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation and Dr. Morrell, followed 230 of the 256 patients who participated in 2-year phase 3 study or feasibility studies, extending device usage to 9 years. A total of 162 completed follow-up (mean, 7.5 years). The median reduction of seizure frequency was 58% at the end of year 3, and 75% by year 9 (P < .0001; Wilcoxon signed rank). Although patient population enrichment could have explained this observation, other analyses confirmed that the improvement was real.

Nearly 75% had at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency; 35% had a 90% or greater reduction in seizure frequency. Some patients (18.4%) had at least a full year with no seizures, and 62% who had a 1-year seizure-free period experienced no seizures at the latest follow-up. Overall, 21% had no seizures in the last 6 months of follow-up.

For those with a seizure-free period of more than 1 year, the average duration was 3.2 years (range, 1.04-9.6 years). There was no difference in response among patients based on previous antiseizure medication use or previous epilepsy surgery, VNS treatment, or intracranial monitoring, and there were no differences by patient age at enrollment, age of seizure onset, brain imaging abnormality, seizure onset locality, or number of foci.

The researchers noted improvement in overall Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory–89 scores at 1 year (mean, +3.2; P < .0001), which continued through year 9 (mean, +1.9; P < .05). Improvements were also seen in epilepsy targeted (mean, +4.5; P < .001) and cognitive domains (mean, +2.5; P = .005). Risk of infection was 4.1% per procedure, and 12.1% of subjects overall experienced a serious device-related implant infection. Of 35 infections, 16 led to device removal.

The extension study was funded by NeuroPace. NeuroPace supported data entry and institutional review board submission for the real-world trial. Dr. Morrell owns stock and is an employee of NeuroPace. Dr Rao has received support from and/or consulted for NeuroPace.

SOURCE: Nair DR et al. Neurology. 2020 Jul 20. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010154. Razavi B et al. Epilepsia. 2020 Jul 13. doi: 10.1111/epi.16593.

Two new long-term studies, one an extension trial and the other an analysis of real-world experience, show that Both studies showed that the benefit from the devices increased over time.

That accruing benefit may be because of improved protocols as clinicians gain experience with the device or because of network remodeling that occurs over time as seizures are controlled. “I think it’s both,” said Martha Morrell, MD, a clinical professor of neurology at Stanford (Calif.) University and chief medical officer at NeuroPace, the company that has marketed the device since it gained FDA approval in 2013.

In both studies, the slope of improvement over time was similar, but the real-world study showed greater improvement at the beginning of treatment. “I think the slopes represent physiological changes, but the fact that [the real-world study] starts with better outcomes is, I think, directly attributable to learning. When the long-term study was started in 2004, this had never been done before, and we had to make a highly educated guess about what we should do, and the initial stimulatory parameters were programmed in a way that’s very similar to what was used for movement disorders,” Dr. Morrell said in an interview.

The long-term treatment study appeared online July 20 in the journal Neurology, while the real-world analysis was published July 13 in Epilepsia.

An alternative option

Medications can effectively treat some seizures, but 30%-40% of patients must turn to other options for control. Surgery can sometimes be curative, but is not suitable for some patients. Other stimulation devices include vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), which sends pulses from a chest implant to the vagus nerve, reducing epileptic attacks through an unknown mechanism. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) places electrodes that deliver stimulation to the anterior nucleus of the thalamus, which can spread initially localized seizures.

The RNS device consists of a neurostimulator implanted cranially and connected to leads that are placed based on the individual patient’s seizure focus or foci. It also continuously monitors brain activity and delivers stimulation only when its signal suggests the beginning of a seizure.

That capacity for recording is a key benefit because the information can be stored and analyzed, according to Vikram Rao, MD, PhD, a coinvestigator in the real-world trial and an associate professor and the epilepsy division chief at the University of California, San Francisco, which was one of the trial centers. “You know more precisely than we previously did how many seizures a patient is having. Many of our patients are not able to quantify their seizures with perfect accuracy, so we’re better quantifying their seizure burden,” Dr. Rao said in an interview.

The ability to monitor patients can also improve clinical management. Dr. Morrell recounted an elderly patient who for many years has driven 5 hours for appointments. Recently she was able to review his data from the RNS System remotely. She determined that he was doing fine and, after a telephone consultation, told him he didn’t need to come in for a scheduled visit.

Real-world analysis

In the real-world analysis, researchers led by Babak Razavi, PhD, and Casey Halpern, MD, at Stanford University conducted a chart review of 150 patients at eight centers who underwent treatment with the RNS system between 2013 and 2018. All patients were followed at least 1 year, with a mean of 2.3 years. Patients had a median of 7.7 disabling seizures per month. The mean value was 52 and the numbers ranged from 0.1 to 3,000. A total of 60% had abnormal brain MRI findings.

At 1 year, subjects achieved a mean 67% decrease in seizure frequency (interquartile range, 50%-94%). At 2 years, that grew to 77%; at 3 or more years, 84%. There was no significant difference in seizure reduction at 1 year according to age, age at epilepsy onset, duration of epilepsy, location of seizure foci, presence of brain MRI abnormalities, prior intracranial monitoring, prior epilepsy surgery, or prior VNS treatment. When patients who underwent a resection at the time of RNS placement were excluded, the results were similar. There were no significant differences in outcome by center.

A total of 11.3% of patients experienced a device-related serious adverse event, and 4% developed infections. The rate of infection was not significantly different between patients who had the neurostimulator and leads implanted alone (3.0%) and patients who had intracranial EEG diagnostic monitoring (ICM) electrodes removed at the same time (6.1%; P = .38).

Although about one-third of the patients who started the long-term study dropped out before completion, most were because the participants moved away from treatment centers, according to Dr. Morrell, and other evidence points squarely to patient satisfaction. “At the end of the battery’s longevity, the neurostimulator needs to be replaced. It’s an outpatient, 45-minute procedure. Over 90% of patients chose to have it replaced. It’s not the answer for everybody, but the substantial majority of patients choose to continue,” she said.

Extension trial

The open-label extension trial, led by Dileep Nair, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation and Dr. Morrell, followed 230 of the 256 patients who participated in 2-year phase 3 study or feasibility studies, extending device usage to 9 years. A total of 162 completed follow-up (mean, 7.5 years). The median reduction of seizure frequency was 58% at the end of year 3, and 75% by year 9 (P < .0001; Wilcoxon signed rank). Although patient population enrichment could have explained this observation, other analyses confirmed that the improvement was real.

Nearly 75% had at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency; 35% had a 90% or greater reduction in seizure frequency. Some patients (18.4%) had at least a full year with no seizures, and 62% who had a 1-year seizure-free period experienced no seizures at the latest follow-up. Overall, 21% had no seizures in the last 6 months of follow-up.

For those with a seizure-free period of more than 1 year, the average duration was 3.2 years (range, 1.04-9.6 years). There was no difference in response among patients based on previous antiseizure medication use or previous epilepsy surgery, VNS treatment, or intracranial monitoring, and there were no differences by patient age at enrollment, age of seizure onset, brain imaging abnormality, seizure onset locality, or number of foci.

The researchers noted improvement in overall Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory–89 scores at 1 year (mean, +3.2; P < .0001), which continued through year 9 (mean, +1.9; P < .05). Improvements were also seen in epilepsy targeted (mean, +4.5; P < .001) and cognitive domains (mean, +2.5; P = .005). Risk of infection was 4.1% per procedure, and 12.1% of subjects overall experienced a serious device-related implant infection. Of 35 infections, 16 led to device removal.

The extension study was funded by NeuroPace. NeuroPace supported data entry and institutional review board submission for the real-world trial. Dr. Morrell owns stock and is an employee of NeuroPace. Dr Rao has received support from and/or consulted for NeuroPace.

SOURCE: Nair DR et al. Neurology. 2020 Jul 20. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010154. Razavi B et al. Epilepsia. 2020 Jul 13. doi: 10.1111/epi.16593.

FROM EPILEPSIA AND FROM NEUROLOGY

Psychiatrists report rare case of woman who thinks she’s a chicken

LEUVEN, Belgium — A 54-year-old woman has suffered the delusion of thinking she is a chicken for 24 hours. This very rare condition, known as zoanthropy, in which people think they are an animal is often not recognised, say researchers from the University of Leuven.

Zoanthropy can include people believing they are, or behaving like, any kind of animal: from a dog, to a lion or tiger, crocodile, snake, or bee.

It’s important to recognise this as a potential symptom of something serious, say the researchers in the July issue of the Belgian Journal of Psychiatry, Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie.

“Additional investigations with brain imaging and electroencephalogram are therefore advised,” say the authors.

Psychiatrists Need to Be Aware That Clinical Zoanthropy Exists

In their paper, they describe the case of the woman who briefly thought she was a chicken, which was followed by her having a generalized epileptic seizure.

“Clinically, we saw a lady who perspired profusely, trembled, blew up her cheeks, and ... seemed to imitate a chicken, [making noises] like clucking, cackling, and crowing like a rooster,” they say.

“After about 10 minutes she seemed to tighten her muscles for a few seconds, her face turned red and for a short time she didn’t react. These symptoms repeated themselves at intervals of a few minutes [and her] consciousness was fluctuating,” with the patient “disoriented in time and space.”

Lead author Dr Athena Beckers of University Psychiatric Centre, KU Leuven, Belgium, said in an interview with MediQuality: “With only 56 case descriptions in the medical literature from 1850 to the present day, the condition is rare. It amounts to about one description every 3 years.

“We suspect, however, that the delusion is not always noticed: the patient shows bizarre behaviour or makes animal sounds, it is probably often catalogued under the general term ‘psychosis’.”

Dr Beckers adds that it is important that the symptoms are recognised, because of the possible underlying causes which can include epilepsy. So this might require a different or complementary treatment “with, for example, antiepileptic drugs”.

“I myself have only seen this type of delusion once, but I ... heard anecdotal stories from other patients whose family member, for example with schizophrenia, sometimes thought he was a cow [during] ... a psychosis.

“After the publication of my article I was also contacted by someone who told me they had experienced the same thing 30 years ago – he thought he was a chicken.

“I think it’s a good thing that we psychiatrists are aware of the fact that clinical zoanthropy exists and may require additional research,” she observed.

Fortunately, this woman’s experience ended well. After about one year of disability, the patient was able to return to work progressively. Her mood remained stable and there were no more psychotic symptoms or any indication of epileptic episodes.

Such Delusions Are Rare

Dr Georges Otte, a recently retired neuropsychiatrist who formerly worked at Ghent University, Belgium, gave his thoughts to Mediquality: “The interface between neurology and psychiatry ... is a fertile meadow on which many crops thrive. But it is in the darkest corners of psychosis that one finds the most bizarre and also rarest excesses.”

There are a number of delusions of identity, said Dr Otte.

These include Cotard’s syndrome, a rare condition marked by the false belief that the person or their body parts are dead, dying, or don’t exist, or Capgras delusion, where the affected person believes that a spouse or close family member has been replaced with an imposter. Delusions can also occur as a result of substance abuse, for example after using psilocybin (magic mushrooms), he added.

“Delusions in which patients are convinced of ‘shape shifting’ (man to animal) are quite rare,” Dr Otte observed.

“In the literature we know that lycanthropy [a person thinks he or she is turning into a werewolf],” has been reported, and has “apparently inspired many authors of horror stories,” he added.

“But it’s not every day that as a psychiatrist, you will encounter such an extreme psychotic depersonalization as someone turning into a chicken.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

LEUVEN, Belgium — A 54-year-old woman has suffered the delusion of thinking she is a chicken for 24 hours. This very rare condition, known as zoanthropy, in which people think they are an animal is often not recognised, say researchers from the University of Leuven.

Zoanthropy can include people believing they are, or behaving like, any kind of animal: from a dog, to a lion or tiger, crocodile, snake, or bee.

It’s important to recognise this as a potential symptom of something serious, say the researchers in the July issue of the Belgian Journal of Psychiatry, Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie.

“Additional investigations with brain imaging and electroencephalogram are therefore advised,” say the authors.

Psychiatrists Need to Be Aware That Clinical Zoanthropy Exists

In their paper, they describe the case of the woman who briefly thought she was a chicken, which was followed by her having a generalized epileptic seizure.

“Clinically, we saw a lady who perspired profusely, trembled, blew up her cheeks, and ... seemed to imitate a chicken, [making noises] like clucking, cackling, and crowing like a rooster,” they say.

“After about 10 minutes she seemed to tighten her muscles for a few seconds, her face turned red and for a short time she didn’t react. These symptoms repeated themselves at intervals of a few minutes [and her] consciousness was fluctuating,” with the patient “disoriented in time and space.”

Lead author Dr Athena Beckers of University Psychiatric Centre, KU Leuven, Belgium, said in an interview with MediQuality: “With only 56 case descriptions in the medical literature from 1850 to the present day, the condition is rare. It amounts to about one description every 3 years.

“We suspect, however, that the delusion is not always noticed: the patient shows bizarre behaviour or makes animal sounds, it is probably often catalogued under the general term ‘psychosis’.”

Dr Beckers adds that it is important that the symptoms are recognised, because of the possible underlying causes which can include epilepsy. So this might require a different or complementary treatment “with, for example, antiepileptic drugs”.

“I myself have only seen this type of delusion once, but I ... heard anecdotal stories from other patients whose family member, for example with schizophrenia, sometimes thought he was a cow [during] ... a psychosis.

“After the publication of my article I was also contacted by someone who told me they had experienced the same thing 30 years ago – he thought he was a chicken.

“I think it’s a good thing that we psychiatrists are aware of the fact that clinical zoanthropy exists and may require additional research,” she observed.

Fortunately, this woman’s experience ended well. After about one year of disability, the patient was able to return to work progressively. Her mood remained stable and there were no more psychotic symptoms or any indication of epileptic episodes.

Such Delusions Are Rare

Dr Georges Otte, a recently retired neuropsychiatrist who formerly worked at Ghent University, Belgium, gave his thoughts to Mediquality: “The interface between neurology and psychiatry ... is a fertile meadow on which many crops thrive. But it is in the darkest corners of psychosis that one finds the most bizarre and also rarest excesses.”

There are a number of delusions of identity, said Dr Otte.

These include Cotard’s syndrome, a rare condition marked by the false belief that the person or their body parts are dead, dying, or don’t exist, or Capgras delusion, where the affected person believes that a spouse or close family member has been replaced with an imposter. Delusions can also occur as a result of substance abuse, for example after using psilocybin (magic mushrooms), he added.

“Delusions in which patients are convinced of ‘shape shifting’ (man to animal) are quite rare,” Dr Otte observed.

“In the literature we know that lycanthropy [a person thinks he or she is turning into a werewolf],” has been reported, and has “apparently inspired many authors of horror stories,” he added.

“But it’s not every day that as a psychiatrist, you will encounter such an extreme psychotic depersonalization as someone turning into a chicken.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

LEUVEN, Belgium — A 54-year-old woman has suffered the delusion of thinking she is a chicken for 24 hours. This very rare condition, known as zoanthropy, in which people think they are an animal is often not recognised, say researchers from the University of Leuven.

Zoanthropy can include people believing they are, or behaving like, any kind of animal: from a dog, to a lion or tiger, crocodile, snake, or bee.

It’s important to recognise this as a potential symptom of something serious, say the researchers in the July issue of the Belgian Journal of Psychiatry, Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie.

“Additional investigations with brain imaging and electroencephalogram are therefore advised,” say the authors.

Psychiatrists Need to Be Aware That Clinical Zoanthropy Exists

In their paper, they describe the case of the woman who briefly thought she was a chicken, which was followed by her having a generalized epileptic seizure.

“Clinically, we saw a lady who perspired profusely, trembled, blew up her cheeks, and ... seemed to imitate a chicken, [making noises] like clucking, cackling, and crowing like a rooster,” they say.

“After about 10 minutes she seemed to tighten her muscles for a few seconds, her face turned red and for a short time she didn’t react. These symptoms repeated themselves at intervals of a few minutes [and her] consciousness was fluctuating,” with the patient “disoriented in time and space.”

Lead author Dr Athena Beckers of University Psychiatric Centre, KU Leuven, Belgium, said in an interview with MediQuality: “With only 56 case descriptions in the medical literature from 1850 to the present day, the condition is rare. It amounts to about one description every 3 years.

“We suspect, however, that the delusion is not always noticed: the patient shows bizarre behaviour or makes animal sounds, it is probably often catalogued under the general term ‘psychosis’.”

Dr Beckers adds that it is important that the symptoms are recognised, because of the possible underlying causes which can include epilepsy. So this might require a different or complementary treatment “with, for example, antiepileptic drugs”.

“I myself have only seen this type of delusion once, but I ... heard anecdotal stories from other patients whose family member, for example with schizophrenia, sometimes thought he was a cow [during] ... a psychosis.

“After the publication of my article I was also contacted by someone who told me they had experienced the same thing 30 years ago – he thought he was a chicken.

“I think it’s a good thing that we psychiatrists are aware of the fact that clinical zoanthropy exists and may require additional research,” she observed.

Fortunately, this woman’s experience ended well. After about one year of disability, the patient was able to return to work progressively. Her mood remained stable and there were no more psychotic symptoms or any indication of epileptic episodes.

Such Delusions Are Rare

Dr Georges Otte, a recently retired neuropsychiatrist who formerly worked at Ghent University, Belgium, gave his thoughts to Mediquality: “The interface between neurology and psychiatry ... is a fertile meadow on which many crops thrive. But it is in the darkest corners of psychosis that one finds the most bizarre and also rarest excesses.”

There are a number of delusions of identity, said Dr Otte.

These include Cotard’s syndrome, a rare condition marked by the false belief that the person or their body parts are dead, dying, or don’t exist, or Capgras delusion, where the affected person believes that a spouse or close family member has been replaced with an imposter. Delusions can also occur as a result of substance abuse, for example after using psilocybin (magic mushrooms), he added.

“Delusions in which patients are convinced of ‘shape shifting’ (man to animal) are quite rare,” Dr Otte observed.

“In the literature we know that lycanthropy [a person thinks he or she is turning into a werewolf],” has been reported, and has “apparently inspired many authors of horror stories,” he added.

“But it’s not every day that as a psychiatrist, you will encounter such an extreme psychotic depersonalization as someone turning into a chicken.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Move over supplements, here come medical foods

As the Food and Drug Administration focuses on other issues, companies, both big and small, are looking to boost physician and consumer interest in their “medical foods” – products that fall somewhere between drugs and supplements and promise to mitigate symptoms, or even address underlying pathologies, of a range of diseases.

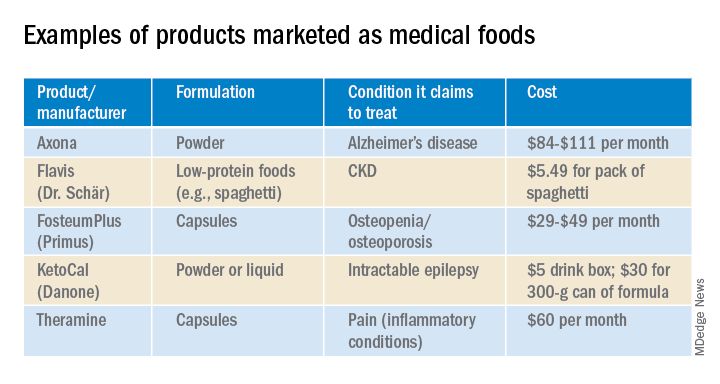

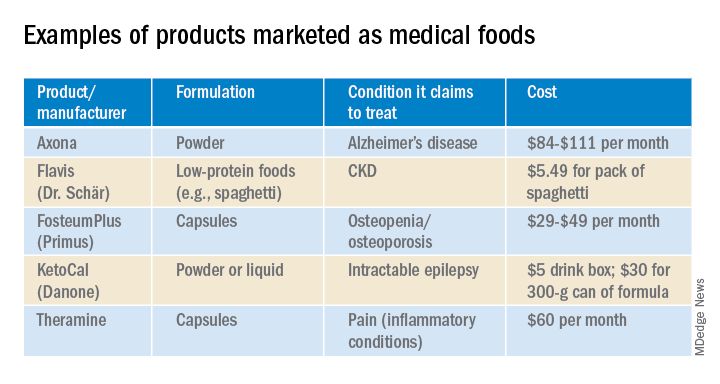

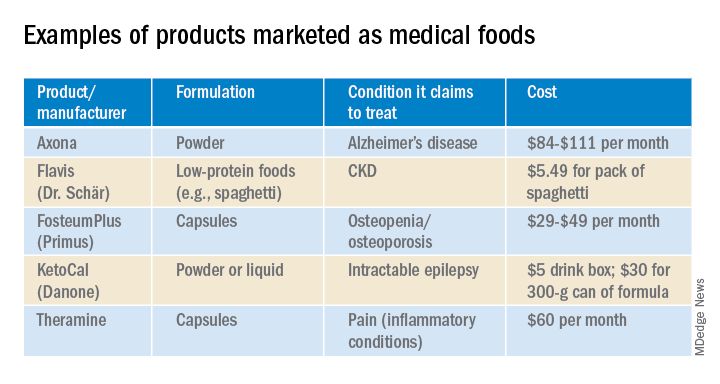

Manufacturers now market an array of medical foods, ranging from powders and capsules for Alzheimer disease to low-protein spaghetti for chronic kidney disease (CKD). The FDA has not been completely absent; it takes a narrow view of what medical conditions qualify for treatment with food products and has warned some manufacturers that their misbranded products are acting more like unapproved drugs.

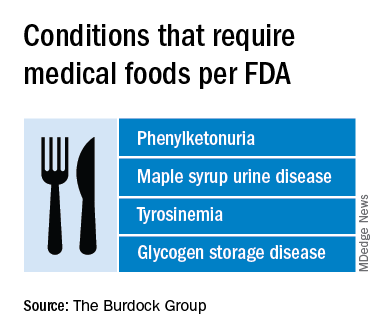

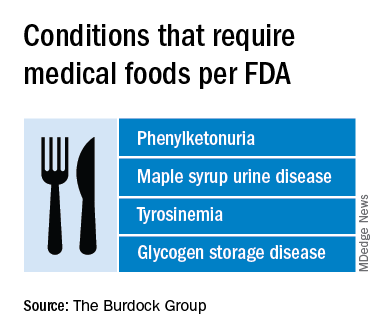

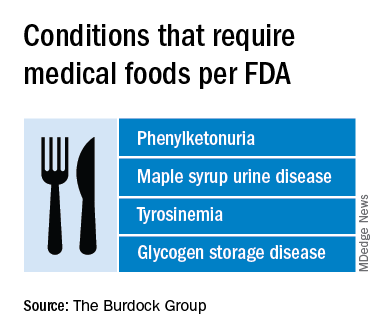

By the FDA’s definition, medical food is limited to products that provide crucial therapy for patients with inborn errors of metabolism (IEM). An example is specialized baby formula for infants with phenylketonuria. Unlike supplements, medical foods are supposed to be used under the supervision of a physician. This has prompted some sales reps to turn up in the clinic, and most manufacturers have online approval forms for doctors to sign. Manufacturers, advisers, and regulators were interviewed for a closer look at this burgeoning industry.

The market

The global market for medical foods – about $18 billion in 2019 – is expected to grow steadily in the near future. It is drawing more interest, especially in Europe, where medical foods are more accepted by physicians and consumers, Meghan Donnelly, MS, RDN, said in an interview. She is a registered dietitian who conducts physician outreach in the United States for Flavis, a division of Dr. Schär. That company, based in northern Italy, started out targeting IEMs but now also sells gluten-free foods for celiac disease and low-protein foods for CKD.

It is still a niche market in the United States – and isn’t likely to ever approach the size of the supplement market, according to Marcus Charuvastra, the managing director of Targeted Medical Pharma, which markets Theramine capsules for pain management, among many other products. But it could still be a big win for a manufacturer if they get a small slice of a big market, such as for Alzheimer disease.

Defining medical food

According to an update of the Orphan Drug Act in 1988, a medical food is “a food which is formulated to be consumed or administered enterally under the supervision of a physician and which is intended for the specific dietary management of a disease or condition for which distinctive nutritional requirements, based on recognized scientific principles, are established by medical evaluation.” The FDA issued regulations to accompany that law in 1993 but has since only issued a guidance document that is not legally binding.

Medical foods are not drugs and they are not supplements (the latter are intended only for healthy people). The FDA doesn’t require formal approval of a medical food, but, by law, the ingredients must be generally recognized as safe, and manufacturers must follow good manufacturing practices. However, the agency has taken a narrow view of what conditions require medical foods.

Policing medical foods hasn’t been a priority for the FDA, which is why there has been a proliferation of products that don’t meet the FDA’s view of the statutory definition of medical foods, according to Miriam Guggenheim, a food and drug law attorney in Washington, D.C. The FDA usually takes enforcement action when it sees a risk to the public’s health.

The agency’s stance has led to confusion – among manufacturers, physicians, consumers, and even regulators – making the market a kind of Wild West, according to Paul Hyman, a Washington, D.C.–based attorney who has represented medical food companies.

George A. Burdock, PhD, an Orlando-based regulatory consultant who has worked with medical food makers, believes the FDA will be forced to expand their narrow definition. He foresees a reconsideration of many medical food products in light of an October 2019 White House executive order prohibiting federal agencies from issuing guidance in lieu of rules.

Manufacturers and the FDA differ

One example of a product about which regulators and manufacturers differ is Theramine, which is described as “specially designed to supply the nervous system with the fuel it needs to meet the altered metabolic requirements of chronic pain and inflammatory disorders.”

It is not considered a medical food by the FDA, and the company has had numerous discussions with the agency about their diverging views, according to Mr. Charuvastra. “We’ve had our warning letters and we’ve had our sit downs, and we just had an inspection.”

Targeted Medical Pharma continues to market its products as medical foods but steers away from making any claims that they are like drugs, he said.

Confusion about medical foods has been exposed in the California Workers’ Compensation System by Leslie Wilson, PhD, and colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco. They found that physicians regularly wrote medical food prescriptions for non–FDA-approved uses and that the system reimbursed the majority of the products at a cost of $15.5 million from 2011 to 2013. More than half of these prescriptions were for Theramine.

Dr. Wilson reported that, for most products, no evidence supported effectiveness, and they were frequently mislabeled – for all 36 that were studied, submissions for reimbursement were made using a National Drug Code, an impossibility because medical foods are not drugs, and 14 were labeled “Rx only.”

Big-name companies joining in

The FDA does not keep a list of approved medical foods or manufacturers. Both small businesses and big food companies like Danone, Nestlé, and Abbott are players. Most products are sold online.

In the United States, Danone’s Nutricia division sells formulas and low-protein foods for IEMs. They also sell Ketocal, a powder or ready-to-drink liquid that is pitched as a balanced medical food to simplify and optimize the ketogenic diet for children with intractable epilepsy. Yet the FDA does not include epilepsy among the conditions that medical foods can treat.

Nestlé sells traditional medical foods for IEMs and also markets a range of what it calls nutritional therapies for such conditions as irritable bowel syndrome and dysphagia.

Nestlé is a minority shareholder in Axona, a product originally developed by Accera (Cerecin as of 2018). Jacquelyn Campo, senior director of global communications at Nestlé Health Sciences, said that the company is not actively involved in the operations management of Cerecin. However, on its website, Nestlé touts Axona, which is only available in the United States, as a “medical food” that “is intended for the clinical dietary management of mild to moderate Alzheimer disease.” The Axona site claims that the main ingredient, caprylic triglyceride, is broken down into ketones that provide fuel to treat cerebral hypometabolism, a precursor to Alzheimer disease. In a 2009 study, daily dosing of a preliminary formulation was associated with improved cognitive performance compared with placebo in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease.

In 2013, the FDA warned Accera that it was misbranding Axona as a medical food and that the therapeutic claims the company was making would make the product an unapproved drug. Ms. Campo said Nestlé is aware of the agency’s warning, but added, “to our knowledge, Cerecin provided answers to the issues raised by the FDA.”

With the goal of getting drug approval, Accera went on to test a tweaked formulation in a 400-patient randomized, placebo-controlled trial called NOURISH AD that ultimately failed. Nevertheless, Axona is still marketed as a medical food. It costs about $100 for a month’s supply.

Repeated requests for comment from Cerecin were not answered. Danielle Schor, an FDA spokesperson, said the agency will not discuss the status of individual products.

More disputes and insurance coverage

Mary Ann DeMarco, executive director of sales and marketing for the Scottsdale, Ariz.–based medical food maker Primus Pharmaceuticals, said the company believes its products fit within the FDA’s medical foods rubric.

These include Fosteum Plus capsules, which it markets “for the clinical dietary management of the metabolic processes of osteopenia and osteoporosis.” The capsules contain a combination of genistein, zinc, calcium, phosphate, vitamin K2, and vitamin D. As proof of effectiveness, the company cites clinical data on some of the ingredients – not the product itself.

Primus has run afoul of the FDA before when it similarly positioned another product, called Limbrel, as a medical food for osteoarthritis. From 2007 to 2017, the FDA received 194 adverse event reports associated with Limbrel, including reports of drug-induced liver injury, pancreatitis, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. In December 2017, the agency urged Primus to recall Limbrel, a move that it said was “necessary to protect the public health and welfare.” Primus withdrew the product but laid out a defense of Limbrel on a devoted website.

The FDA would not comment any further, said Ms. Schor. Ms. DeMarco said that Primus is working with the FDA to bring Limbrel back to market.

A lack of insurance coverage – even for approved medical foods for IEMs – has frustrated advocates, parents, and manufacturers. They are putting their weight behind the Medical Nutrition Equity Act, which would mandate public and private payer coverage of medical foods for IEMs and digestive conditions such as Crohn disease. That 2019 House bill has 56 cosponsors; there is no Senate companion bill.

“If you can get reimbursement, it really makes the market,” for Primus and the other manufacturers, Mr. Hyman said.

Primus Pharmaceuticals has launched its own campaign, Cover My Medical Foods, to enlist consumers and others to the cause.

Partnering with advocates

Although its low-protein breads, pastas, and baking products are not considered medical foods by the FDA, Dr. Schär is marketing them as such in the United States. They are trying to make a mark in CKD, according to Ms. Donnelly. She added that Dr. Schär has been successful in Europe, where nutrition therapy is more integrated in the health care system.

In 2019, Flavis and the National Kidney Foundation joined forces to raise awareness of nutritional interventions and to build enthusiasm for the Flavis products. The partnership has now ended, mostly because Flavis could no longer afford it, according to Ms. Donnelly.

“Information on diet and nutrition is the most requested subject matter from the NKF,” said Anthony Gucciardo, senior vice president of strategic partnerships at the foundation. The partnership “has never been necessarily about promoting their products per se; it’s promoting a healthy diet and really a diet specific for CKD.”

The NKF developed cobranded materials on low-protein foods for physicians and a teaching tool they could use with patients. Consumers could access nutrition information and a discount on Flavis products on a dedicated webpage. The foundation didn’t describe the low-protein products as medical foods, said Mr. Gucciardo, even if Flavis promoted them as such.

In patients with CKD, dietary management can help prevent the progression to end-stage renal disease. Although Medicare covers medical nutrition therapy – in which patients receive personalized assessments and dietary advice – uptake is abysmally low, according to a 2018 study.

Dr. Burdock thinks low-protein foods for CKD do meet the FDA’s criteria for a medical food but that the agency might not necessarily agree with him. The FDA would not comment.

Physician beware

When it comes to medical foods, the FDA has often looked the other way because the ingredients may already have been proven safe and the danger to an individual or to the public’s health is relatively low, according to Dr. Burdock and Mr. Hyman.

However, if the agency “feels that a medical food will prevent people from seeking medical care or there is potential to defraud the public, it is justified in taking action against the company,” said Dr. Burdock.

According to Dr. Wilson, the pharmacist who reported on the inappropriate medical food prescriptions in the California system, the FDA could help by creating a list of approved medical foods. Physicians should take time to learn about the difference between medical foods and supplements, she said, adding that they should also not hesitate to “question the veracity of the claims for them.”

Ms. Guggenheim believed doctors need to know that, for the most part, these are not FDA-approved products. She emphasized the importance of evaluating the products and looking at the data of their impact on a disease or condition.

“Many of these companies strongly believe that the products work and help people, so clinicians need to be very data driven,” she said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

As the Food and Drug Administration focuses on other issues, companies, both big and small, are looking to boost physician and consumer interest in their “medical foods” – products that fall somewhere between drugs and supplements and promise to mitigate symptoms, or even address underlying pathologies, of a range of diseases.

Manufacturers now market an array of medical foods, ranging from powders and capsules for Alzheimer disease to low-protein spaghetti for chronic kidney disease (CKD). The FDA has not been completely absent; it takes a narrow view of what medical conditions qualify for treatment with food products and has warned some manufacturers that their misbranded products are acting more like unapproved drugs.

By the FDA’s definition, medical food is limited to products that provide crucial therapy for patients with inborn errors of metabolism (IEM). An example is specialized baby formula for infants with phenylketonuria. Unlike supplements, medical foods are supposed to be used under the supervision of a physician. This has prompted some sales reps to turn up in the clinic, and most manufacturers have online approval forms for doctors to sign. Manufacturers, advisers, and regulators were interviewed for a closer look at this burgeoning industry.

The market

The global market for medical foods – about $18 billion in 2019 – is expected to grow steadily in the near future. It is drawing more interest, especially in Europe, where medical foods are more accepted by physicians and consumers, Meghan Donnelly, MS, RDN, said in an interview. She is a registered dietitian who conducts physician outreach in the United States for Flavis, a division of Dr. Schär. That company, based in northern Italy, started out targeting IEMs but now also sells gluten-free foods for celiac disease and low-protein foods for CKD.

It is still a niche market in the United States – and isn’t likely to ever approach the size of the supplement market, according to Marcus Charuvastra, the managing director of Targeted Medical Pharma, which markets Theramine capsules for pain management, among many other products. But it could still be a big win for a manufacturer if they get a small slice of a big market, such as for Alzheimer disease.

Defining medical food

According to an update of the Orphan Drug Act in 1988, a medical food is “a food which is formulated to be consumed or administered enterally under the supervision of a physician and which is intended for the specific dietary management of a disease or condition for which distinctive nutritional requirements, based on recognized scientific principles, are established by medical evaluation.” The FDA issued regulations to accompany that law in 1993 but has since only issued a guidance document that is not legally binding.

Medical foods are not drugs and they are not supplements (the latter are intended only for healthy people). The FDA doesn’t require formal approval of a medical food, but, by law, the ingredients must be generally recognized as safe, and manufacturers must follow good manufacturing practices. However, the agency has taken a narrow view of what conditions require medical foods.

Policing medical foods hasn’t been a priority for the FDA, which is why there has been a proliferation of products that don’t meet the FDA’s view of the statutory definition of medical foods, according to Miriam Guggenheim, a food and drug law attorney in Washington, D.C. The FDA usually takes enforcement action when it sees a risk to the public’s health.

The agency’s stance has led to confusion – among manufacturers, physicians, consumers, and even regulators – making the market a kind of Wild West, according to Paul Hyman, a Washington, D.C.–based attorney who has represented medical food companies.

George A. Burdock, PhD, an Orlando-based regulatory consultant who has worked with medical food makers, believes the FDA will be forced to expand their narrow definition. He foresees a reconsideration of many medical food products in light of an October 2019 White House executive order prohibiting federal agencies from issuing guidance in lieu of rules.

Manufacturers and the FDA differ

One example of a product about which regulators and manufacturers differ is Theramine, which is described as “specially designed to supply the nervous system with the fuel it needs to meet the altered metabolic requirements of chronic pain and inflammatory disorders.”

It is not considered a medical food by the FDA, and the company has had numerous discussions with the agency about their diverging views, according to Mr. Charuvastra. “We’ve had our warning letters and we’ve had our sit downs, and we just had an inspection.”

Targeted Medical Pharma continues to market its products as medical foods but steers away from making any claims that they are like drugs, he said.

Confusion about medical foods has been exposed in the California Workers’ Compensation System by Leslie Wilson, PhD, and colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco. They found that physicians regularly wrote medical food prescriptions for non–FDA-approved uses and that the system reimbursed the majority of the products at a cost of $15.5 million from 2011 to 2013. More than half of these prescriptions were for Theramine.

Dr. Wilson reported that, for most products, no evidence supported effectiveness, and they were frequently mislabeled – for all 36 that were studied, submissions for reimbursement were made using a National Drug Code, an impossibility because medical foods are not drugs, and 14 were labeled “Rx only.”

Big-name companies joining in

The FDA does not keep a list of approved medical foods or manufacturers. Both small businesses and big food companies like Danone, Nestlé, and Abbott are players. Most products are sold online.

In the United States, Danone’s Nutricia division sells formulas and low-protein foods for IEMs. They also sell Ketocal, a powder or ready-to-drink liquid that is pitched as a balanced medical food to simplify and optimize the ketogenic diet for children with intractable epilepsy. Yet the FDA does not include epilepsy among the conditions that medical foods can treat.

Nestlé sells traditional medical foods for IEMs and also markets a range of what it calls nutritional therapies for such conditions as irritable bowel syndrome and dysphagia.

Nestlé is a minority shareholder in Axona, a product originally developed by Accera (Cerecin as of 2018). Jacquelyn Campo, senior director of global communications at Nestlé Health Sciences, said that the company is not actively involved in the operations management of Cerecin. However, on its website, Nestlé touts Axona, which is only available in the United States, as a “medical food” that “is intended for the clinical dietary management of mild to moderate Alzheimer disease.” The Axona site claims that the main ingredient, caprylic triglyceride, is broken down into ketones that provide fuel to treat cerebral hypometabolism, a precursor to Alzheimer disease. In a 2009 study, daily dosing of a preliminary formulation was associated with improved cognitive performance compared with placebo in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease.

In 2013, the FDA warned Accera that it was misbranding Axona as a medical food and that the therapeutic claims the company was making would make the product an unapproved drug. Ms. Campo said Nestlé is aware of the agency’s warning, but added, “to our knowledge, Cerecin provided answers to the issues raised by the FDA.”

With the goal of getting drug approval, Accera went on to test a tweaked formulation in a 400-patient randomized, placebo-controlled trial called NOURISH AD that ultimately failed. Nevertheless, Axona is still marketed as a medical food. It costs about $100 for a month’s supply.

Repeated requests for comment from Cerecin were not answered. Danielle Schor, an FDA spokesperson, said the agency will not discuss the status of individual products.

More disputes and insurance coverage

Mary Ann DeMarco, executive director of sales and marketing for the Scottsdale, Ariz.–based medical food maker Primus Pharmaceuticals, said the company believes its products fit within the FDA’s medical foods rubric.

These include Fosteum Plus capsules, which it markets “for the clinical dietary management of the metabolic processes of osteopenia and osteoporosis.” The capsules contain a combination of genistein, zinc, calcium, phosphate, vitamin K2, and vitamin D. As proof of effectiveness, the company cites clinical data on some of the ingredients – not the product itself.

Primus has run afoul of the FDA before when it similarly positioned another product, called Limbrel, as a medical food for osteoarthritis. From 2007 to 2017, the FDA received 194 adverse event reports associated with Limbrel, including reports of drug-induced liver injury, pancreatitis, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. In December 2017, the agency urged Primus to recall Limbrel, a move that it said was “necessary to protect the public health and welfare.” Primus withdrew the product but laid out a defense of Limbrel on a devoted website.

The FDA would not comment any further, said Ms. Schor. Ms. DeMarco said that Primus is working with the FDA to bring Limbrel back to market.

A lack of insurance coverage – even for approved medical foods for IEMs – has frustrated advocates, parents, and manufacturers. They are putting their weight behind the Medical Nutrition Equity Act, which would mandate public and private payer coverage of medical foods for IEMs and digestive conditions such as Crohn disease. That 2019 House bill has 56 cosponsors; there is no Senate companion bill.

“If you can get reimbursement, it really makes the market,” for Primus and the other manufacturers, Mr. Hyman said.

Primus Pharmaceuticals has launched its own campaign, Cover My Medical Foods, to enlist consumers and others to the cause.

Partnering with advocates

Although its low-protein breads, pastas, and baking products are not considered medical foods by the FDA, Dr. Schär is marketing them as such in the United States. They are trying to make a mark in CKD, according to Ms. Donnelly. She added that Dr. Schär has been successful in Europe, where nutrition therapy is more integrated in the health care system.

In 2019, Flavis and the National Kidney Foundation joined forces to raise awareness of nutritional interventions and to build enthusiasm for the Flavis products. The partnership has now ended, mostly because Flavis could no longer afford it, according to Ms. Donnelly.

“Information on diet and nutrition is the most requested subject matter from the NKF,” said Anthony Gucciardo, senior vice president of strategic partnerships at the foundation. The partnership “has never been necessarily about promoting their products per se; it’s promoting a healthy diet and really a diet specific for CKD.”

The NKF developed cobranded materials on low-protein foods for physicians and a teaching tool they could use with patients. Consumers could access nutrition information and a discount on Flavis products on a dedicated webpage. The foundation didn’t describe the low-protein products as medical foods, said Mr. Gucciardo, even if Flavis promoted them as such.

In patients with CKD, dietary management can help prevent the progression to end-stage renal disease. Although Medicare covers medical nutrition therapy – in which patients receive personalized assessments and dietary advice – uptake is abysmally low, according to a 2018 study.

Dr. Burdock thinks low-protein foods for CKD do meet the FDA’s criteria for a medical food but that the agency might not necessarily agree with him. The FDA would not comment.

Physician beware

When it comes to medical foods, the FDA has often looked the other way because the ingredients may already have been proven safe and the danger to an individual or to the public’s health is relatively low, according to Dr. Burdock and Mr. Hyman.

However, if the agency “feels that a medical food will prevent people from seeking medical care or there is potential to defraud the public, it is justified in taking action against the company,” said Dr. Burdock.

According to Dr. Wilson, the pharmacist who reported on the inappropriate medical food prescriptions in the California system, the FDA could help by creating a list of approved medical foods. Physicians should take time to learn about the difference between medical foods and supplements, she said, adding that they should also not hesitate to “question the veracity of the claims for them.”

Ms. Guggenheim believed doctors need to know that, for the most part, these are not FDA-approved products. She emphasized the importance of evaluating the products and looking at the data of their impact on a disease or condition.

“Many of these companies strongly believe that the products work and help people, so clinicians need to be very data driven,” she said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

As the Food and Drug Administration focuses on other issues, companies, both big and small, are looking to boost physician and consumer interest in their “medical foods” – products that fall somewhere between drugs and supplements and promise to mitigate symptoms, or even address underlying pathologies, of a range of diseases.

Manufacturers now market an array of medical foods, ranging from powders and capsules for Alzheimer disease to low-protein spaghetti for chronic kidney disease (CKD). The FDA has not been completely absent; it takes a narrow view of what medical conditions qualify for treatment with food products and has warned some manufacturers that their misbranded products are acting more like unapproved drugs.

By the FDA’s definition, medical food is limited to products that provide crucial therapy for patients with inborn errors of metabolism (IEM). An example is specialized baby formula for infants with phenylketonuria. Unlike supplements, medical foods are supposed to be used under the supervision of a physician. This has prompted some sales reps to turn up in the clinic, and most manufacturers have online approval forms for doctors to sign. Manufacturers, advisers, and regulators were interviewed for a closer look at this burgeoning industry.

The market

The global market for medical foods – about $18 billion in 2019 – is expected to grow steadily in the near future. It is drawing more interest, especially in Europe, where medical foods are more accepted by physicians and consumers, Meghan Donnelly, MS, RDN, said in an interview. She is a registered dietitian who conducts physician outreach in the United States for Flavis, a division of Dr. Schär. That company, based in northern Italy, started out targeting IEMs but now also sells gluten-free foods for celiac disease and low-protein foods for CKD.

It is still a niche market in the United States – and isn’t likely to ever approach the size of the supplement market, according to Marcus Charuvastra, the managing director of Targeted Medical Pharma, which markets Theramine capsules for pain management, among many other products. But it could still be a big win for a manufacturer if they get a small slice of a big market, such as for Alzheimer disease.

Defining medical food

According to an update of the Orphan Drug Act in 1988, a medical food is “a food which is formulated to be consumed or administered enterally under the supervision of a physician and which is intended for the specific dietary management of a disease or condition for which distinctive nutritional requirements, based on recognized scientific principles, are established by medical evaluation.” The FDA issued regulations to accompany that law in 1993 but has since only issued a guidance document that is not legally binding.

Medical foods are not drugs and they are not supplements (the latter are intended only for healthy people). The FDA doesn’t require formal approval of a medical food, but, by law, the ingredients must be generally recognized as safe, and manufacturers must follow good manufacturing practices. However, the agency has taken a narrow view of what conditions require medical foods.

Policing medical foods hasn’t been a priority for the FDA, which is why there has been a proliferation of products that don’t meet the FDA’s view of the statutory definition of medical foods, according to Miriam Guggenheim, a food and drug law attorney in Washington, D.C. The FDA usually takes enforcement action when it sees a risk to the public’s health.

The agency’s stance has led to confusion – among manufacturers, physicians, consumers, and even regulators – making the market a kind of Wild West, according to Paul Hyman, a Washington, D.C.–based attorney who has represented medical food companies.

George A. Burdock, PhD, an Orlando-based regulatory consultant who has worked with medical food makers, believes the FDA will be forced to expand their narrow definition. He foresees a reconsideration of many medical food products in light of an October 2019 White House executive order prohibiting federal agencies from issuing guidance in lieu of rules.

Manufacturers and the FDA differ

One example of a product about which regulators and manufacturers differ is Theramine, which is described as “specially designed to supply the nervous system with the fuel it needs to meet the altered metabolic requirements of chronic pain and inflammatory disorders.”

It is not considered a medical food by the FDA, and the company has had numerous discussions with the agency about their diverging views, according to Mr. Charuvastra. “We’ve had our warning letters and we’ve had our sit downs, and we just had an inspection.”

Targeted Medical Pharma continues to market its products as medical foods but steers away from making any claims that they are like drugs, he said.

Confusion about medical foods has been exposed in the California Workers’ Compensation System by Leslie Wilson, PhD, and colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco. They found that physicians regularly wrote medical food prescriptions for non–FDA-approved uses and that the system reimbursed the majority of the products at a cost of $15.5 million from 2011 to 2013. More than half of these prescriptions were for Theramine.

Dr. Wilson reported that, for most products, no evidence supported effectiveness, and they were frequently mislabeled – for all 36 that were studied, submissions for reimbursement were made using a National Drug Code, an impossibility because medical foods are not drugs, and 14 were labeled “Rx only.”

Big-name companies joining in

The FDA does not keep a list of approved medical foods or manufacturers. Both small businesses and big food companies like Danone, Nestlé, and Abbott are players. Most products are sold online.

In the United States, Danone’s Nutricia division sells formulas and low-protein foods for IEMs. They also sell Ketocal, a powder or ready-to-drink liquid that is pitched as a balanced medical food to simplify and optimize the ketogenic diet for children with intractable epilepsy. Yet the FDA does not include epilepsy among the conditions that medical foods can treat.

Nestlé sells traditional medical foods for IEMs and also markets a range of what it calls nutritional therapies for such conditions as irritable bowel syndrome and dysphagia.

Nestlé is a minority shareholder in Axona, a product originally developed by Accera (Cerecin as of 2018). Jacquelyn Campo, senior director of global communications at Nestlé Health Sciences, said that the company is not actively involved in the operations management of Cerecin. However, on its website, Nestlé touts Axona, which is only available in the United States, as a “medical food” that “is intended for the clinical dietary management of mild to moderate Alzheimer disease.” The Axona site claims that the main ingredient, caprylic triglyceride, is broken down into ketones that provide fuel to treat cerebral hypometabolism, a precursor to Alzheimer disease. In a 2009 study, daily dosing of a preliminary formulation was associated with improved cognitive performance compared with placebo in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease.

In 2013, the FDA warned Accera that it was misbranding Axona as a medical food and that the therapeutic claims the company was making would make the product an unapproved drug. Ms. Campo said Nestlé is aware of the agency’s warning, but added, “to our knowledge, Cerecin provided answers to the issues raised by the FDA.”

With the goal of getting drug approval, Accera went on to test a tweaked formulation in a 400-patient randomized, placebo-controlled trial called NOURISH AD that ultimately failed. Nevertheless, Axona is still marketed as a medical food. It costs about $100 for a month’s supply.

Repeated requests for comment from Cerecin were not answered. Danielle Schor, an FDA spokesperson, said the agency will not discuss the status of individual products.

More disputes and insurance coverage

Mary Ann DeMarco, executive director of sales and marketing for the Scottsdale, Ariz.–based medical food maker Primus Pharmaceuticals, said the company believes its products fit within the FDA’s medical foods rubric.

These include Fosteum Plus capsules, which it markets “for the clinical dietary management of the metabolic processes of osteopenia and osteoporosis.” The capsules contain a combination of genistein, zinc, calcium, phosphate, vitamin K2, and vitamin D. As proof of effectiveness, the company cites clinical data on some of the ingredients – not the product itself.

Primus has run afoul of the FDA before when it similarly positioned another product, called Limbrel, as a medical food for osteoarthritis. From 2007 to 2017, the FDA received 194 adverse event reports associated with Limbrel, including reports of drug-induced liver injury, pancreatitis, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. In December 2017, the agency urged Primus to recall Limbrel, a move that it said was “necessary to protect the public health and welfare.” Primus withdrew the product but laid out a defense of Limbrel on a devoted website.

The FDA would not comment any further, said Ms. Schor. Ms. DeMarco said that Primus is working with the FDA to bring Limbrel back to market.

A lack of insurance coverage – even for approved medical foods for IEMs – has frustrated advocates, parents, and manufacturers. They are putting their weight behind the Medical Nutrition Equity Act, which would mandate public and private payer coverage of medical foods for IEMs and digestive conditions such as Crohn disease. That 2019 House bill has 56 cosponsors; there is no Senate companion bill.

“If you can get reimbursement, it really makes the market,” for Primus and the other manufacturers, Mr. Hyman said.

Primus Pharmaceuticals has launched its own campaign, Cover My Medical Foods, to enlist consumers and others to the cause.

Partnering with advocates

Although its low-protein breads, pastas, and baking products are not considered medical foods by the FDA, Dr. Schär is marketing them as such in the United States. They are trying to make a mark in CKD, according to Ms. Donnelly. She added that Dr. Schär has been successful in Europe, where nutrition therapy is more integrated in the health care system.

In 2019, Flavis and the National Kidney Foundation joined forces to raise awareness of nutritional interventions and to build enthusiasm for the Flavis products. The partnership has now ended, mostly because Flavis could no longer afford it, according to Ms. Donnelly.

“Information on diet and nutrition is the most requested subject matter from the NKF,” said Anthony Gucciardo, senior vice president of strategic partnerships at the foundation. The partnership “has never been necessarily about promoting their products per se; it’s promoting a healthy diet and really a diet specific for CKD.”

The NKF developed cobranded materials on low-protein foods for physicians and a teaching tool they could use with patients. Consumers could access nutrition information and a discount on Flavis products on a dedicated webpage. The foundation didn’t describe the low-protein products as medical foods, said Mr. Gucciardo, even if Flavis promoted them as such.

In patients with CKD, dietary management can help prevent the progression to end-stage renal disease. Although Medicare covers medical nutrition therapy – in which patients receive personalized assessments and dietary advice – uptake is abysmally low, according to a 2018 study.

Dr. Burdock thinks low-protein foods for CKD do meet the FDA’s criteria for a medical food but that the agency might not necessarily agree with him. The FDA would not comment.

Physician beware

When it comes to medical foods, the FDA has often looked the other way because the ingredients may already have been proven safe and the danger to an individual or to the public’s health is relatively low, according to Dr. Burdock and Mr. Hyman.

However, if the agency “feels that a medical food will prevent people from seeking medical care or there is potential to defraud the public, it is justified in taking action against the company,” said Dr. Burdock.

According to Dr. Wilson, the pharmacist who reported on the inappropriate medical food prescriptions in the California system, the FDA could help by creating a list of approved medical foods. Physicians should take time to learn about the difference between medical foods and supplements, she said, adding that they should also not hesitate to “question the veracity of the claims for them.”

Ms. Guggenheim believed doctors need to know that, for the most part, these are not FDA-approved products. She emphasized the importance of evaluating the products and looking at the data of their impact on a disease or condition.

“Many of these companies strongly believe that the products work and help people, so clinicians need to be very data driven,” she said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Epilepsy after TBI linked to worse 12-month outcomes

findings from an analysis of a large, prospective database suggest. “We found that patients essentially have a 10-times greater risk of developing posttraumatic epilepsy and seizures at 12 months [post injury] if the presenting Glasgow Coma Scale GCS) is less than 8,” said lead author John F. Burke, MD, PhD, University of California, San Francisco, in presenting the findings as part of the virtual annual meeting of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons.

Assessing risk factors

While posttraumatic epilepsy represents an estimated 20% of all cases of symptomatic epilepsy, many questions remain on those most at risk and on the long-term effects of posttraumatic epilepsy on TBI outcomes. To probe those issues, Dr. Burke and colleagues turned to the multicenter TRACK-TBI database, which has prospective, longitudinal data on more than 2,700 patients with traumatic brain injuries and is considered the largest source of prospective data on posttraumatic epilepsy.

Using the criteria of no previous epilepsy and having 12 months of follow-up, the team identified 1,493 patients with TBI. In addition, investigators identified 182 orthopedic controls (included and prospectively followed because they have injuries but not specifically head trauma) and 210 controls who are friends of the patients and who do not have injuries but allow researchers to control for socioeconomic and environmental factors.

Of the 1,493 patients with TBI, 41 (2.7%) were determined to have posttraumatic epilepsy, assessed according to a National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke epilepsy screening questionnaire, which is designed to identify patients with posttraumatic epilepsy symptoms. There were no reports of epilepsy symptoms using the screening tool among the controls. Dr. Burke noted that the 2.7% was in agreement with historical reports.

In comparing patients with TBI who did and did not have posttraumatic epilepsy, no differences were observed in the groups in terms of gender, although there was a trend toward younger age among those with PTE (mean age, 35.4 years with posttraumatic injury vs. 41.5 without; P = .05).

A major risk factor for the development of posttraumatic epilepsy was presenting GCS scores. Among those with scores of less than 8, indicative of severe injury, the rate of posttraumatic epilepsy was 6% at 6 months and 12.5% at 12 months. In contrast, those with TBI presenting with GCS scores between 13 and 15, indicative of minor injury, had an incidence of posttraumatic epilepsy of 0.9% at 6 months and 1.4% at 12 months.

Imaging findings in the two groups showed that hemorrhage detected on CT imaging was associated with a significantly higher risk for posttraumatic epilepsy (P < .001).

“The main takeaway is that any hemorrhage in the brain is a major risk factor for developing seizures,” Dr. Burke said. “Whether it is subdural, epidural blood, subarachnoid or contusion, any blood confers a very [high] risk for developing seizures.”

Posttraumatic epilepsy was linked to poorer longer-term outcomes even for patients with lesser injury: Among those with TBI and GCS of 13-15, the mean Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended (GOSE) score at 12 months among those without posttraumatic epilepsy was 7, indicative of a good recovery with minor defects, whereas the mean GOSE score for those with PTE was 4.6, indicative of moderate to severe disability (P < .001).

“It was surprising to us that PTE-positive patients had a very significant decrease in GOSE, compared to PTE-negative patients,” Dr. Burke said. “There was a nearly 2-point drop in the GOSE and that was extremely significant.”

A multivariate analysis showed there was still a significant independent risk for a poor GOSE score with posttraumatic epilepsy after controlling for GCS score, head CT findings, and age (P < .001).