User login

What is the future of para-aortic lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer?

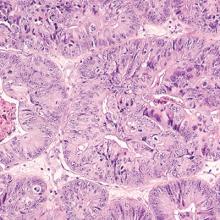

A landmark study of advanced endometrial cancer, GOG 258, was published in the New England Journal of Medicine this summer.1 This clinical trial compared the use of carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy with a combination of chemotherapy with external beam radiation, exploring the notion of “more is better.” The results of the trial revealed that the “more” (chemotherapy with external beam radiation) was no better than chemotherapy alone with respect to overall survival. These results have challenged a creeping dogma in gynecologic oncology, which has seen many providers embrace combination therapy, particularly for patients with stage III (node-positive) endometrial cancer, a group of patients who made up approximately three-quarters of GOG 258’s study population. Many have been left searching for justification of their early adoption of combination therapy before the results of a trial such as this were available. For me it also raised a slightly different question: In the light of these results, what IS the role of para-aortic lymphadenectomy in the staging of endometrial cancers? If radiation to the nodal basins is no longer part of adjuvant therapy, then

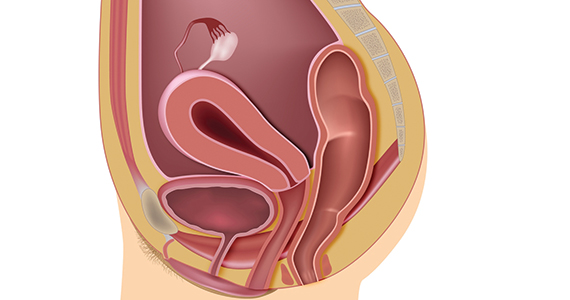

It was in the 1980s that the removal of clinically normal para-aortic lymph nodes (those residing between the renal and proximal common iliac vessels) became a part of surgical staging. This practice was endorsed by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) and the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) surgical committee in response to findings that 11% of women with clinical stage I endometrial cancer had microscopic lymph node metastases which were discovered only with routine pathologic evaluation of these tissues. Among those with pelvic lymph node metastases (stage IIIC disease), approximately one-third also harbored disease in para-aortic nodal regions.2 Among all patients with endometrial cancer, including those with low-grade disease, only a small fraction (approximately 2%) have isolated para-aortic lymph nodes (positive para-aortic nodes, but negative pelvic nodes). However, among patients with deeply invasive higher-grade tumors, the likelihood of discovering isolated para-aortic metastases is higher at approximately 16%.3 Therefore, the dominant pattern of lymph node metastases and lymphatic dissemination of endometrial cancer appears to be via the parametrial channels laterally towards the pelvic basins, and then sequentially to the para-aortic regions. The direct lymphatic pathway to the para-aortic basins from the uterine fundus through the adnexal lymphatics misses the pelvic regions altogether and may seen logical, but actually is observed fairly infrequently.4

Over the subsequent decades, there have been debates and schools of thought regarding what is the optimal degree of lymphatic dissection for endometrial cancer staging. Some advocated for full pelvic and infrarenal para-aortic nodal dissections in all patients, including even those in the lowest risk for metastases. Others advocated for a more limited, inframesenteric para-aortic nodal dissection, although the origins of such a distinction appear to be largely arbitrary. The inferior mesenteric artery is not a physiologic landmark for lymphatic pathways, and approximately half of para-aortic metastases are located above the level of the inferior mesenteric artery. This limited sampling may have been preferred because of relative ease of dissection rather than diagnostic or therapeutic efficacy.

As the population became more obese, making para-aortic nodal dissections less feasible, and laparoscopic staging became accepted as the standard of care in endometrial cancer staging, there was a further push towards limiting the scope of lymphadenectomy. Selective algorithms, such as the so-called “Mayo clinic criteria,” were widely adopted. In this approach, gynecologic oncologists perform full pelvic and infrarenal para-aortic lymphadenectomies but only in the presence of a high-risk uterine feature such as tumor size greater than 2 cm, deep myometrial invasion, or grade 3 histology.3 While this reduced the number of para-aortic dissections being performed, it did not eliminate them, as approximately 40% of patients with endometrial cancer meet at least one of those criteria.

At this same time, we learned something else critical about the benefits, or lack thereof, of lymphadenectomy. Two landmark surgical-staging trials were published in 2009 which randomly assigned women to hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy or hysterectomy alone, and found no survival benefit for lymphadenectomy.5,6 While these trial results initially were met with noisy backlash, particularly from those who had legitimate concerns regarding study design and conclusions that reach beyond the scope of this column, ultimately their findings (that there is no therapeutic benefit to surgically removing clinically normal lymph nodes) has become largely accepted. The subsequent findings of the Laparoscopic Approach to Cancer of the Endometrium (LACE) trial further support this, as there was no difference in survival found between patients who were randomly assigned to laparoscopic versus open staging for endometrial cancer, even despite a significantly lower rate of lymphadenectomy among the laparoscopic arm.7

SLN biopsy, in which the specific nodes which drain the uterus are selectively removed, represents the most recent development in lymph node assessment for endometrial cancer. On average, only three lymph nodes are removed per patient, and para-aortic nodes infrequently are removed, because it is rare that lymphatic pathways drain directly into the aortic basins after cervical injection. Yet despite this more limited dissection of lymph nodes, especially para-aortic, with SLN biopsy, surgeons still observe similar rates of IIIC disease, compared with full lymphadenectomy, suggesting that the presence or absence of lymphatic metastases still is able to be adequately determined. SLN biopsy misses only 3% of lymphatic disease.8 What is of particular interest to practitioners of the SLN approach is that “atypical” pathways are discovered approximately 20% of the time, and nodes are harvested from locations such as the presacral space or medial to the internal iliac vessels. These nodes are in locations previously overlooked by even the most comprehensive pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy. Therefore, while the para-aortic nodes may not be systematically removed with SLN biopsy, new and arguably more relevant regions are interrogated, which might explain its equivalent diagnostic virtue.

With this evolution in surgical-staging practice, what we have come to recognize is that the role of lymph node assessment is predominantly, if not exclusively, diagnostic. It can help us determine which patients are at risk for distant relapse and therefore candidates for systemic therapy (chemotherapy), versus those whose risk is predominantly of local relapse and can be adequately treated with local therapies alone, such as vaginal radiation. This brings us to the results of GOG 258. If defining the specific and complete extent of lymph node metastases (as if that was ever truly what surgeons were doing) is no longer necessary to guide the prescription and extent of external beam radiation, then lymph node dissection need only inform us of whether or not there are nodal metastases, not specifically the location of those nodal metastases. The prescription of chemotherapy is the same whether the disease is limited to the pelvic nodes or also includes the para-aortic nodes. While GOG 258 discovered more para-aortic failures among the chemotherapy-alone group, suggesting there may be some therapeutic role of radiation in preventing this, it should be noted that these para-aortic relapses did not negatively impact relapse-free survival, and these patients still can presumably be salvaged with external beam radiation to the site of para-aortic relapse.

It would seem logical that the results of GOG 258 further limit the potential role of para-aortic lymphadenectomy in women with clinical stage I disease. Perhaps para-aortic dissection can be limited to women who are at highest risk for isolated para-aortic disease, such as those with deeply invasive high-grade tumors not successfully mapped with the highly targeted sentinel node biopsy technique? Most clinicians look forward to an era in which we no longer rely on crude dissections of disease-free tissue just to prove they are disease free, but instead can utilize more sophisticated diagnostic methods to recognize disseminated disease.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jun 13;380(24):2317-26.

2. Cancer. 1987 Oct 15;60(8 Suppl):2035-41.

3. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109(1):11-8.

4. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019 Mar;29(3):613-21.

5. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Dec 3;100(23):1707-16.

6. Lancet. 2009 Jan 10;373(9658):125-36.

7. JAMA. 2017 Mar 28;317(12):1224-33.

8. Lancet Oncol. 2017 Mar;18(3):384-92.

A landmark study of advanced endometrial cancer, GOG 258, was published in the New England Journal of Medicine this summer.1 This clinical trial compared the use of carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy with a combination of chemotherapy with external beam radiation, exploring the notion of “more is better.” The results of the trial revealed that the “more” (chemotherapy with external beam radiation) was no better than chemotherapy alone with respect to overall survival. These results have challenged a creeping dogma in gynecologic oncology, which has seen many providers embrace combination therapy, particularly for patients with stage III (node-positive) endometrial cancer, a group of patients who made up approximately three-quarters of GOG 258’s study population. Many have been left searching for justification of their early adoption of combination therapy before the results of a trial such as this were available. For me it also raised a slightly different question: In the light of these results, what IS the role of para-aortic lymphadenectomy in the staging of endometrial cancers? If radiation to the nodal basins is no longer part of adjuvant therapy, then

It was in the 1980s that the removal of clinically normal para-aortic lymph nodes (those residing between the renal and proximal common iliac vessels) became a part of surgical staging. This practice was endorsed by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) and the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) surgical committee in response to findings that 11% of women with clinical stage I endometrial cancer had microscopic lymph node metastases which were discovered only with routine pathologic evaluation of these tissues. Among those with pelvic lymph node metastases (stage IIIC disease), approximately one-third also harbored disease in para-aortic nodal regions.2 Among all patients with endometrial cancer, including those with low-grade disease, only a small fraction (approximately 2%) have isolated para-aortic lymph nodes (positive para-aortic nodes, but negative pelvic nodes). However, among patients with deeply invasive higher-grade tumors, the likelihood of discovering isolated para-aortic metastases is higher at approximately 16%.3 Therefore, the dominant pattern of lymph node metastases and lymphatic dissemination of endometrial cancer appears to be via the parametrial channels laterally towards the pelvic basins, and then sequentially to the para-aortic regions. The direct lymphatic pathway to the para-aortic basins from the uterine fundus through the adnexal lymphatics misses the pelvic regions altogether and may seen logical, but actually is observed fairly infrequently.4

Over the subsequent decades, there have been debates and schools of thought regarding what is the optimal degree of lymphatic dissection for endometrial cancer staging. Some advocated for full pelvic and infrarenal para-aortic nodal dissections in all patients, including even those in the lowest risk for metastases. Others advocated for a more limited, inframesenteric para-aortic nodal dissection, although the origins of such a distinction appear to be largely arbitrary. The inferior mesenteric artery is not a physiologic landmark for lymphatic pathways, and approximately half of para-aortic metastases are located above the level of the inferior mesenteric artery. This limited sampling may have been preferred because of relative ease of dissection rather than diagnostic or therapeutic efficacy.

As the population became more obese, making para-aortic nodal dissections less feasible, and laparoscopic staging became accepted as the standard of care in endometrial cancer staging, there was a further push towards limiting the scope of lymphadenectomy. Selective algorithms, such as the so-called “Mayo clinic criteria,” were widely adopted. In this approach, gynecologic oncologists perform full pelvic and infrarenal para-aortic lymphadenectomies but only in the presence of a high-risk uterine feature such as tumor size greater than 2 cm, deep myometrial invasion, or grade 3 histology.3 While this reduced the number of para-aortic dissections being performed, it did not eliminate them, as approximately 40% of patients with endometrial cancer meet at least one of those criteria.

At this same time, we learned something else critical about the benefits, or lack thereof, of lymphadenectomy. Two landmark surgical-staging trials were published in 2009 which randomly assigned women to hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy or hysterectomy alone, and found no survival benefit for lymphadenectomy.5,6 While these trial results initially were met with noisy backlash, particularly from those who had legitimate concerns regarding study design and conclusions that reach beyond the scope of this column, ultimately their findings (that there is no therapeutic benefit to surgically removing clinically normal lymph nodes) has become largely accepted. The subsequent findings of the Laparoscopic Approach to Cancer of the Endometrium (LACE) trial further support this, as there was no difference in survival found between patients who were randomly assigned to laparoscopic versus open staging for endometrial cancer, even despite a significantly lower rate of lymphadenectomy among the laparoscopic arm.7

SLN biopsy, in which the specific nodes which drain the uterus are selectively removed, represents the most recent development in lymph node assessment for endometrial cancer. On average, only three lymph nodes are removed per patient, and para-aortic nodes infrequently are removed, because it is rare that lymphatic pathways drain directly into the aortic basins after cervical injection. Yet despite this more limited dissection of lymph nodes, especially para-aortic, with SLN biopsy, surgeons still observe similar rates of IIIC disease, compared with full lymphadenectomy, suggesting that the presence or absence of lymphatic metastases still is able to be adequately determined. SLN biopsy misses only 3% of lymphatic disease.8 What is of particular interest to practitioners of the SLN approach is that “atypical” pathways are discovered approximately 20% of the time, and nodes are harvested from locations such as the presacral space or medial to the internal iliac vessels. These nodes are in locations previously overlooked by even the most comprehensive pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy. Therefore, while the para-aortic nodes may not be systematically removed with SLN biopsy, new and arguably more relevant regions are interrogated, which might explain its equivalent diagnostic virtue.

With this evolution in surgical-staging practice, what we have come to recognize is that the role of lymph node assessment is predominantly, if not exclusively, diagnostic. It can help us determine which patients are at risk for distant relapse and therefore candidates for systemic therapy (chemotherapy), versus those whose risk is predominantly of local relapse and can be adequately treated with local therapies alone, such as vaginal radiation. This brings us to the results of GOG 258. If defining the specific and complete extent of lymph node metastases (as if that was ever truly what surgeons were doing) is no longer necessary to guide the prescription and extent of external beam radiation, then lymph node dissection need only inform us of whether or not there are nodal metastases, not specifically the location of those nodal metastases. The prescription of chemotherapy is the same whether the disease is limited to the pelvic nodes or also includes the para-aortic nodes. While GOG 258 discovered more para-aortic failures among the chemotherapy-alone group, suggesting there may be some therapeutic role of radiation in preventing this, it should be noted that these para-aortic relapses did not negatively impact relapse-free survival, and these patients still can presumably be salvaged with external beam radiation to the site of para-aortic relapse.

It would seem logical that the results of GOG 258 further limit the potential role of para-aortic lymphadenectomy in women with clinical stage I disease. Perhaps para-aortic dissection can be limited to women who are at highest risk for isolated para-aortic disease, such as those with deeply invasive high-grade tumors not successfully mapped with the highly targeted sentinel node biopsy technique? Most clinicians look forward to an era in which we no longer rely on crude dissections of disease-free tissue just to prove they are disease free, but instead can utilize more sophisticated diagnostic methods to recognize disseminated disease.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jun 13;380(24):2317-26.

2. Cancer. 1987 Oct 15;60(8 Suppl):2035-41.

3. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109(1):11-8.

4. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019 Mar;29(3):613-21.

5. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Dec 3;100(23):1707-16.

6. Lancet. 2009 Jan 10;373(9658):125-36.

7. JAMA. 2017 Mar 28;317(12):1224-33.

8. Lancet Oncol. 2017 Mar;18(3):384-92.

A landmark study of advanced endometrial cancer, GOG 258, was published in the New England Journal of Medicine this summer.1 This clinical trial compared the use of carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy with a combination of chemotherapy with external beam radiation, exploring the notion of “more is better.” The results of the trial revealed that the “more” (chemotherapy with external beam radiation) was no better than chemotherapy alone with respect to overall survival. These results have challenged a creeping dogma in gynecologic oncology, which has seen many providers embrace combination therapy, particularly for patients with stage III (node-positive) endometrial cancer, a group of patients who made up approximately three-quarters of GOG 258’s study population. Many have been left searching for justification of their early adoption of combination therapy before the results of a trial such as this were available. For me it also raised a slightly different question: In the light of these results, what IS the role of para-aortic lymphadenectomy in the staging of endometrial cancers? If radiation to the nodal basins is no longer part of adjuvant therapy, then

It was in the 1980s that the removal of clinically normal para-aortic lymph nodes (those residing between the renal and proximal common iliac vessels) became a part of surgical staging. This practice was endorsed by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) and the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) surgical committee in response to findings that 11% of women with clinical stage I endometrial cancer had microscopic lymph node metastases which were discovered only with routine pathologic evaluation of these tissues. Among those with pelvic lymph node metastases (stage IIIC disease), approximately one-third also harbored disease in para-aortic nodal regions.2 Among all patients with endometrial cancer, including those with low-grade disease, only a small fraction (approximately 2%) have isolated para-aortic lymph nodes (positive para-aortic nodes, but negative pelvic nodes). However, among patients with deeply invasive higher-grade tumors, the likelihood of discovering isolated para-aortic metastases is higher at approximately 16%.3 Therefore, the dominant pattern of lymph node metastases and lymphatic dissemination of endometrial cancer appears to be via the parametrial channels laterally towards the pelvic basins, and then sequentially to the para-aortic regions. The direct lymphatic pathway to the para-aortic basins from the uterine fundus through the adnexal lymphatics misses the pelvic regions altogether and may seen logical, but actually is observed fairly infrequently.4

Over the subsequent decades, there have been debates and schools of thought regarding what is the optimal degree of lymphatic dissection for endometrial cancer staging. Some advocated for full pelvic and infrarenal para-aortic nodal dissections in all patients, including even those in the lowest risk for metastases. Others advocated for a more limited, inframesenteric para-aortic nodal dissection, although the origins of such a distinction appear to be largely arbitrary. The inferior mesenteric artery is not a physiologic landmark for lymphatic pathways, and approximately half of para-aortic metastases are located above the level of the inferior mesenteric artery. This limited sampling may have been preferred because of relative ease of dissection rather than diagnostic or therapeutic efficacy.

As the population became more obese, making para-aortic nodal dissections less feasible, and laparoscopic staging became accepted as the standard of care in endometrial cancer staging, there was a further push towards limiting the scope of lymphadenectomy. Selective algorithms, such as the so-called “Mayo clinic criteria,” were widely adopted. In this approach, gynecologic oncologists perform full pelvic and infrarenal para-aortic lymphadenectomies but only in the presence of a high-risk uterine feature such as tumor size greater than 2 cm, deep myometrial invasion, or grade 3 histology.3 While this reduced the number of para-aortic dissections being performed, it did not eliminate them, as approximately 40% of patients with endometrial cancer meet at least one of those criteria.

At this same time, we learned something else critical about the benefits, or lack thereof, of lymphadenectomy. Two landmark surgical-staging trials were published in 2009 which randomly assigned women to hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy or hysterectomy alone, and found no survival benefit for lymphadenectomy.5,6 While these trial results initially were met with noisy backlash, particularly from those who had legitimate concerns regarding study design and conclusions that reach beyond the scope of this column, ultimately their findings (that there is no therapeutic benefit to surgically removing clinically normal lymph nodes) has become largely accepted. The subsequent findings of the Laparoscopic Approach to Cancer of the Endometrium (LACE) trial further support this, as there was no difference in survival found between patients who were randomly assigned to laparoscopic versus open staging for endometrial cancer, even despite a significantly lower rate of lymphadenectomy among the laparoscopic arm.7

SLN biopsy, in which the specific nodes which drain the uterus are selectively removed, represents the most recent development in lymph node assessment for endometrial cancer. On average, only three lymph nodes are removed per patient, and para-aortic nodes infrequently are removed, because it is rare that lymphatic pathways drain directly into the aortic basins after cervical injection. Yet despite this more limited dissection of lymph nodes, especially para-aortic, with SLN biopsy, surgeons still observe similar rates of IIIC disease, compared with full lymphadenectomy, suggesting that the presence or absence of lymphatic metastases still is able to be adequately determined. SLN biopsy misses only 3% of lymphatic disease.8 What is of particular interest to practitioners of the SLN approach is that “atypical” pathways are discovered approximately 20% of the time, and nodes are harvested from locations such as the presacral space or medial to the internal iliac vessels. These nodes are in locations previously overlooked by even the most comprehensive pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy. Therefore, while the para-aortic nodes may not be systematically removed with SLN biopsy, new and arguably more relevant regions are interrogated, which might explain its equivalent diagnostic virtue.

With this evolution in surgical-staging practice, what we have come to recognize is that the role of lymph node assessment is predominantly, if not exclusively, diagnostic. It can help us determine which patients are at risk for distant relapse and therefore candidates for systemic therapy (chemotherapy), versus those whose risk is predominantly of local relapse and can be adequately treated with local therapies alone, such as vaginal radiation. This brings us to the results of GOG 258. If defining the specific and complete extent of lymph node metastases (as if that was ever truly what surgeons were doing) is no longer necessary to guide the prescription and extent of external beam radiation, then lymph node dissection need only inform us of whether or not there are nodal metastases, not specifically the location of those nodal metastases. The prescription of chemotherapy is the same whether the disease is limited to the pelvic nodes or also includes the para-aortic nodes. While GOG 258 discovered more para-aortic failures among the chemotherapy-alone group, suggesting there may be some therapeutic role of radiation in preventing this, it should be noted that these para-aortic relapses did not negatively impact relapse-free survival, and these patients still can presumably be salvaged with external beam radiation to the site of para-aortic relapse.

It would seem logical that the results of GOG 258 further limit the potential role of para-aortic lymphadenectomy in women with clinical stage I disease. Perhaps para-aortic dissection can be limited to women who are at highest risk for isolated para-aortic disease, such as those with deeply invasive high-grade tumors not successfully mapped with the highly targeted sentinel node biopsy technique? Most clinicians look forward to an era in which we no longer rely on crude dissections of disease-free tissue just to prove they are disease free, but instead can utilize more sophisticated diagnostic methods to recognize disseminated disease.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jun 13;380(24):2317-26.

2. Cancer. 1987 Oct 15;60(8 Suppl):2035-41.

3. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109(1):11-8.

4. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019 Mar;29(3):613-21.

5. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Dec 3;100(23):1707-16.

6. Lancet. 2009 Jan 10;373(9658):125-36.

7. JAMA. 2017 Mar 28;317(12):1224-33.

8. Lancet Oncol. 2017 Mar;18(3):384-92.

Ovarian cancer diagnosed and treated earlier under ACA

CHICAGO – , according to a comparison of National Cancer Database surveys from 2006-2009 and 2011-2014.

During the post-Affordable Care Act (ACA) years of 2011-2014, compared with the pre-ACA years of 2004-2009, a treatment group of women aged 21-64 years with ovarian cancer was more likely to be diagnosed at an early stage, compared with a control group of women aged 65 years and older (difference-in-differences [DD]=1.7%), Anna Jo Smith, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Also, the ACA was associated with more women aged 21-64 receiving treatment within 30 days of diagnosis (DD = 1.6%), said Dr. Smith, a 4th-year resident at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Among women with public insurance, the ACA was associated with even greater improvement in early-stage diagnosis and treatment within 30 days in the treatment group vs. the controls (DD = 2.5% for each), she said, noting that the improvements were seen across race, income, and education groups.

The findings are based on pre-ACA surveys from 35,842 women aged 21-64 years and 28,895 women aged 65 years, and from post-ACA surveys from 37,145 women and 30,604 women in those age groups, respectively, and were adjusted for patient race, living in a rural area, area-level household income and education level, Charlson comorbidity score, distance traveled for care, Census region, and care at an academic center.

The 2010 ACA expanded access to insurance and care for many Americans, and the objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of that access on women with ovarian cancer, Dr. Smith explained.

“Under the 2010 Affordable Care Act, women with ovarian cancer were more likely to be diagnosed at an early stage and receive treatment within 30 days of diagnosis,” she said. “As stage and treatment are the major determinants of survival advantage, these gains under the ACA may have long-term impacts on the survival, health, and well-being of women with ovarian cancer.”

Dr. Smith reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Smith A et al., ASCO 2019. Abstract LBA5563.

CHICAGO – , according to a comparison of National Cancer Database surveys from 2006-2009 and 2011-2014.

During the post-Affordable Care Act (ACA) years of 2011-2014, compared with the pre-ACA years of 2004-2009, a treatment group of women aged 21-64 years with ovarian cancer was more likely to be diagnosed at an early stage, compared with a control group of women aged 65 years and older (difference-in-differences [DD]=1.7%), Anna Jo Smith, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Also, the ACA was associated with more women aged 21-64 receiving treatment within 30 days of diagnosis (DD = 1.6%), said Dr. Smith, a 4th-year resident at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Among women with public insurance, the ACA was associated with even greater improvement in early-stage diagnosis and treatment within 30 days in the treatment group vs. the controls (DD = 2.5% for each), she said, noting that the improvements were seen across race, income, and education groups.

The findings are based on pre-ACA surveys from 35,842 women aged 21-64 years and 28,895 women aged 65 years, and from post-ACA surveys from 37,145 women and 30,604 women in those age groups, respectively, and were adjusted for patient race, living in a rural area, area-level household income and education level, Charlson comorbidity score, distance traveled for care, Census region, and care at an academic center.

The 2010 ACA expanded access to insurance and care for many Americans, and the objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of that access on women with ovarian cancer, Dr. Smith explained.

“Under the 2010 Affordable Care Act, women with ovarian cancer were more likely to be diagnosed at an early stage and receive treatment within 30 days of diagnosis,” she said. “As stage and treatment are the major determinants of survival advantage, these gains under the ACA may have long-term impacts on the survival, health, and well-being of women with ovarian cancer.”

Dr. Smith reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Smith A et al., ASCO 2019. Abstract LBA5563.

CHICAGO – , according to a comparison of National Cancer Database surveys from 2006-2009 and 2011-2014.

During the post-Affordable Care Act (ACA) years of 2011-2014, compared with the pre-ACA years of 2004-2009, a treatment group of women aged 21-64 years with ovarian cancer was more likely to be diagnosed at an early stage, compared with a control group of women aged 65 years and older (difference-in-differences [DD]=1.7%), Anna Jo Smith, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Also, the ACA was associated with more women aged 21-64 receiving treatment within 30 days of diagnosis (DD = 1.6%), said Dr. Smith, a 4th-year resident at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Among women with public insurance, the ACA was associated with even greater improvement in early-stage diagnosis and treatment within 30 days in the treatment group vs. the controls (DD = 2.5% for each), she said, noting that the improvements were seen across race, income, and education groups.

The findings are based on pre-ACA surveys from 35,842 women aged 21-64 years and 28,895 women aged 65 years, and from post-ACA surveys from 37,145 women and 30,604 women in those age groups, respectively, and were adjusted for patient race, living in a rural area, area-level household income and education level, Charlson comorbidity score, distance traveled for care, Census region, and care at an academic center.

The 2010 ACA expanded access to insurance and care for many Americans, and the objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of that access on women with ovarian cancer, Dr. Smith explained.

“Under the 2010 Affordable Care Act, women with ovarian cancer were more likely to be diagnosed at an early stage and receive treatment within 30 days of diagnosis,” she said. “As stage and treatment are the major determinants of survival advantage, these gains under the ACA may have long-term impacts on the survival, health, and well-being of women with ovarian cancer.”

Dr. Smith reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Smith A et al., ASCO 2019. Abstract LBA5563.

REPORTING FROM ASCO 2019

Vaginal microbiota composition linked to ovarian cancer risk

Women with epithelial ovarian cancer or BRCA1 mutational status were more likely to present with a community type O cervicovaginal microbiota relative to age-matched controls, according to a case-control analysis.

The results suggest that the composition of the cervicovaginal microbiome may have a key role in ovarian carcinogenesis. In addition, dysbiosis could be an important risk factor in women at high risk for the disease.

“Our aim was to establish whether women with, or at risk of developing, ovarian cancer have an imbalanced cervicovaginal microbiome,” wrote Nuno R Nené, PhD, of University College London, and colleagues. Their report is in The Lancet Oncology.

The researchers conducted a case-control study of adult females located in five European countries. Study participants were divided into two sets that consisted of 176 females with ovarian cancer and 109 females with a BRCA1 mutation, but without a diagnosis of ovarian cancer.

The two sets were matched with a combination of healthy controls and others with benign gynecologic disorders. Each cohort was split into females younger than 50 years and those over age 50.

In the analysis, females younger than 50 years with ovarian cancer were more likely to have a community type O microbiota relative to age-matched controls (adjusted odds ratio, 2.80; P = .020).

In the BRCA set, women with a BRCA1 mutation who were younger than 50 years were also more likely to present with a community type O microbiota than were wild type age-matched controls (adjusted odds ratio, 2.79; P = .012).

“In both sets, we noted that the younger the participants, the stronger the association between community type O microbiota and ovarian cancer or BRCA1 mutation status,” the researchers wrote.

They acknowledged that a key limitation of the study was the homogenous patient population. Since the vaginal microbiome can vary based on ethnicity, the generalizability of the results may be limited.

“Our findings warrant further detailed analyses of the vaginal microbiome, especially in high-risk women,” they concluded.

The study was funded by the EU’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme, the EU’s Horizon 2020 European Research Council Programme, and The Eve Appeal. The authors reported financial affiliations with Eurofins, AstraZeneca, Biocad, Clovis, Pharmamar, Roche, Takeda, and Tesaro.

SOURCE: Nené NR et al. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jul 9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30340-7.

One question that remains from the current study is whether the human microbiota is an important factor in the pathogenesis and development of ovarian cancer.

Currently, there has been no evidence directly linking the composition of the human microbiota to ovarian cancer. As a result, causation has yet to be established by means of randomized studies, since the majority of completed studies have been cross-sectional in nature. As a highly heterogeneous condition, several factors may be involved, including a variety of host reproductive, genetic, microbiota, and lifestyle considerations.

While various mechanisms have been proposed, other less familiar causes could also be implicated. For example, Dr. Nené and colleagues found an association between BRCA1 mutation carriers younger than 50 years of age and the presence of community type O microbiota, while only 10%-15% of females with incident ovarian cancers exhibit this mutation. These findings accentuate the complexities of ovarian cancer pathophysiology.

Despite the suggested benefits of probiotic therapy, there remains a call for systems biology strategies in ovarian cancer research. In a similar manner, the human microbiota needs to be considered in future research.

Hans Verstraelen, MD, MPH, PhD, is affiliated with Ghent University and the Ghent University Hospital in Belgium. Dr. Verstraelen reported no competing interests. These comments are adapted from his editorial (Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jul 9. doi: 10.1016/ S1470-2045[19]30340-7 ).

One question that remains from the current study is whether the human microbiota is an important factor in the pathogenesis and development of ovarian cancer.

Currently, there has been no evidence directly linking the composition of the human microbiota to ovarian cancer. As a result, causation has yet to be established by means of randomized studies, since the majority of completed studies have been cross-sectional in nature. As a highly heterogeneous condition, several factors may be involved, including a variety of host reproductive, genetic, microbiota, and lifestyle considerations.

While various mechanisms have been proposed, other less familiar causes could also be implicated. For example, Dr. Nené and colleagues found an association between BRCA1 mutation carriers younger than 50 years of age and the presence of community type O microbiota, while only 10%-15% of females with incident ovarian cancers exhibit this mutation. These findings accentuate the complexities of ovarian cancer pathophysiology.

Despite the suggested benefits of probiotic therapy, there remains a call for systems biology strategies in ovarian cancer research. In a similar manner, the human microbiota needs to be considered in future research.

Hans Verstraelen, MD, MPH, PhD, is affiliated with Ghent University and the Ghent University Hospital in Belgium. Dr. Verstraelen reported no competing interests. These comments are adapted from his editorial (Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jul 9. doi: 10.1016/ S1470-2045[19]30340-7 ).

One question that remains from the current study is whether the human microbiota is an important factor in the pathogenesis and development of ovarian cancer.

Currently, there has been no evidence directly linking the composition of the human microbiota to ovarian cancer. As a result, causation has yet to be established by means of randomized studies, since the majority of completed studies have been cross-sectional in nature. As a highly heterogeneous condition, several factors may be involved, including a variety of host reproductive, genetic, microbiota, and lifestyle considerations.

While various mechanisms have been proposed, other less familiar causes could also be implicated. For example, Dr. Nené and colleagues found an association between BRCA1 mutation carriers younger than 50 years of age and the presence of community type O microbiota, while only 10%-15% of females with incident ovarian cancers exhibit this mutation. These findings accentuate the complexities of ovarian cancer pathophysiology.

Despite the suggested benefits of probiotic therapy, there remains a call for systems biology strategies in ovarian cancer research. In a similar manner, the human microbiota needs to be considered in future research.

Hans Verstraelen, MD, MPH, PhD, is affiliated with Ghent University and the Ghent University Hospital in Belgium. Dr. Verstraelen reported no competing interests. These comments are adapted from his editorial (Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jul 9. doi: 10.1016/ S1470-2045[19]30340-7 ).

Women with epithelial ovarian cancer or BRCA1 mutational status were more likely to present with a community type O cervicovaginal microbiota relative to age-matched controls, according to a case-control analysis.

The results suggest that the composition of the cervicovaginal microbiome may have a key role in ovarian carcinogenesis. In addition, dysbiosis could be an important risk factor in women at high risk for the disease.

“Our aim was to establish whether women with, or at risk of developing, ovarian cancer have an imbalanced cervicovaginal microbiome,” wrote Nuno R Nené, PhD, of University College London, and colleagues. Their report is in The Lancet Oncology.

The researchers conducted a case-control study of adult females located in five European countries. Study participants were divided into two sets that consisted of 176 females with ovarian cancer and 109 females with a BRCA1 mutation, but without a diagnosis of ovarian cancer.

The two sets were matched with a combination of healthy controls and others with benign gynecologic disorders. Each cohort was split into females younger than 50 years and those over age 50.

In the analysis, females younger than 50 years with ovarian cancer were more likely to have a community type O microbiota relative to age-matched controls (adjusted odds ratio, 2.80; P = .020).

In the BRCA set, women with a BRCA1 mutation who were younger than 50 years were also more likely to present with a community type O microbiota than were wild type age-matched controls (adjusted odds ratio, 2.79; P = .012).

“In both sets, we noted that the younger the participants, the stronger the association between community type O microbiota and ovarian cancer or BRCA1 mutation status,” the researchers wrote.

They acknowledged that a key limitation of the study was the homogenous patient population. Since the vaginal microbiome can vary based on ethnicity, the generalizability of the results may be limited.

“Our findings warrant further detailed analyses of the vaginal microbiome, especially in high-risk women,” they concluded.

The study was funded by the EU’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme, the EU’s Horizon 2020 European Research Council Programme, and The Eve Appeal. The authors reported financial affiliations with Eurofins, AstraZeneca, Biocad, Clovis, Pharmamar, Roche, Takeda, and Tesaro.

SOURCE: Nené NR et al. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jul 9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30340-7.

Women with epithelial ovarian cancer or BRCA1 mutational status were more likely to present with a community type O cervicovaginal microbiota relative to age-matched controls, according to a case-control analysis.

The results suggest that the composition of the cervicovaginal microbiome may have a key role in ovarian carcinogenesis. In addition, dysbiosis could be an important risk factor in women at high risk for the disease.

“Our aim was to establish whether women with, or at risk of developing, ovarian cancer have an imbalanced cervicovaginal microbiome,” wrote Nuno R Nené, PhD, of University College London, and colleagues. Their report is in The Lancet Oncology.

The researchers conducted a case-control study of adult females located in five European countries. Study participants were divided into two sets that consisted of 176 females with ovarian cancer and 109 females with a BRCA1 mutation, but without a diagnosis of ovarian cancer.

The two sets were matched with a combination of healthy controls and others with benign gynecologic disorders. Each cohort was split into females younger than 50 years and those over age 50.

In the analysis, females younger than 50 years with ovarian cancer were more likely to have a community type O microbiota relative to age-matched controls (adjusted odds ratio, 2.80; P = .020).

In the BRCA set, women with a BRCA1 mutation who were younger than 50 years were also more likely to present with a community type O microbiota than were wild type age-matched controls (adjusted odds ratio, 2.79; P = .012).

“In both sets, we noted that the younger the participants, the stronger the association between community type O microbiota and ovarian cancer or BRCA1 mutation status,” the researchers wrote.

They acknowledged that a key limitation of the study was the homogenous patient population. Since the vaginal microbiome can vary based on ethnicity, the generalizability of the results may be limited.

“Our findings warrant further detailed analyses of the vaginal microbiome, especially in high-risk women,” they concluded.

The study was funded by the EU’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme, the EU’s Horizon 2020 European Research Council Programme, and The Eve Appeal. The authors reported financial affiliations with Eurofins, AstraZeneca, Biocad, Clovis, Pharmamar, Roche, Takeda, and Tesaro.

SOURCE: Nené NR et al. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jul 9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30340-7.

Gaps in patient-provider survivorship communication persist

There has been little to no recent improvement in the large share of cancer patients who are not receiving detailed information about survivorship care, suggests a nationally representative cross-sectional survey.

In 2006, the Institute of Medicine issued a seminal report recommending survivorship care planning to address the special needs of this patient population, noted the investigators, led by Ashish Rai, PhD, American Cancer Society, Framingham, Mass. Other organizations have since issued guidelines and policies in this area.

For the study, Dr. Rai and colleagues analyzed data from 2,266 survivors who completed the 2011 or 2016 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey – Experiences with Cancer questionnaire. Survivors were asked whether any clinician had ever discussed various aspects of survivorship care; responses were dichotomized as having had detailed discussion versus not (brief or no discussion, or not remembering).

Between 2011 and 2016, there was minimal change in the percentage of survivors who reported not receiving detailed information on follow-up care (from 35.1% to 35.4%), late or long-term adverse effects (from 54.2% to 55.5%), lifestyle recommendations (from 58.9% to 57.8%), and emotional or social needs (from 69.2% to 68.2%), the investigators wrote. Their report is in Journal of Oncology Practice.

When analyses were restricted to only those survivors who had received cancer-directed treatment within 3 years of the survey, findings were essentially the same.

About one-quarter of survivors reported having detailed discussions about all four topics in both 2011 (24.4%) and 2016 (21.9%).

In 2016, nearly half of survivors, 47.6%, reported not having detailed discussions with their providers about a summary of their cancer treatments. (This question was not asked in 2011.)

“Despite national efforts and organizations promoting survivorship care planning and highlighting the need for improved quality of survivorship care delivery, clear gaps in quality of communication between survivors of cancer and providers persist,” Dr. Rai and colleagues said.

“Continued efforts are needed to promote communication about survivorship issues, including implementation and evaluation of targeted interventions in key survivorship care areas,” they recommended. “These interventions may consist of furnishing guidance on optimal ways to identify and address survivors’ communication needs, streamlining the flow of information across provider types, ensuring better integration of primary care providers with the survivorship care paradigm, and augmenting the use of health information technology for collection and dissemination of information across the cancer control continuum.”

Dr. Rai did not disclose any relevant conflicts of interest. The study did not receive specific funding.

SOURCE: Rai A et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019 July 2. doi: 10.1200/JOP.19.00157.

There has been little to no recent improvement in the large share of cancer patients who are not receiving detailed information about survivorship care, suggests a nationally representative cross-sectional survey.

In 2006, the Institute of Medicine issued a seminal report recommending survivorship care planning to address the special needs of this patient population, noted the investigators, led by Ashish Rai, PhD, American Cancer Society, Framingham, Mass. Other organizations have since issued guidelines and policies in this area.

For the study, Dr. Rai and colleagues analyzed data from 2,266 survivors who completed the 2011 or 2016 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey – Experiences with Cancer questionnaire. Survivors were asked whether any clinician had ever discussed various aspects of survivorship care; responses were dichotomized as having had detailed discussion versus not (brief or no discussion, or not remembering).

Between 2011 and 2016, there was minimal change in the percentage of survivors who reported not receiving detailed information on follow-up care (from 35.1% to 35.4%), late or long-term adverse effects (from 54.2% to 55.5%), lifestyle recommendations (from 58.9% to 57.8%), and emotional or social needs (from 69.2% to 68.2%), the investigators wrote. Their report is in Journal of Oncology Practice.

When analyses were restricted to only those survivors who had received cancer-directed treatment within 3 years of the survey, findings were essentially the same.

About one-quarter of survivors reported having detailed discussions about all four topics in both 2011 (24.4%) and 2016 (21.9%).

In 2016, nearly half of survivors, 47.6%, reported not having detailed discussions with their providers about a summary of their cancer treatments. (This question was not asked in 2011.)

“Despite national efforts and organizations promoting survivorship care planning and highlighting the need for improved quality of survivorship care delivery, clear gaps in quality of communication between survivors of cancer and providers persist,” Dr. Rai and colleagues said.

“Continued efforts are needed to promote communication about survivorship issues, including implementation and evaluation of targeted interventions in key survivorship care areas,” they recommended. “These interventions may consist of furnishing guidance on optimal ways to identify and address survivors’ communication needs, streamlining the flow of information across provider types, ensuring better integration of primary care providers with the survivorship care paradigm, and augmenting the use of health information technology for collection and dissemination of information across the cancer control continuum.”

Dr. Rai did not disclose any relevant conflicts of interest. The study did not receive specific funding.

SOURCE: Rai A et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019 July 2. doi: 10.1200/JOP.19.00157.

There has been little to no recent improvement in the large share of cancer patients who are not receiving detailed information about survivorship care, suggests a nationally representative cross-sectional survey.

In 2006, the Institute of Medicine issued a seminal report recommending survivorship care planning to address the special needs of this patient population, noted the investigators, led by Ashish Rai, PhD, American Cancer Society, Framingham, Mass. Other organizations have since issued guidelines and policies in this area.

For the study, Dr. Rai and colleagues analyzed data from 2,266 survivors who completed the 2011 or 2016 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey – Experiences with Cancer questionnaire. Survivors were asked whether any clinician had ever discussed various aspects of survivorship care; responses were dichotomized as having had detailed discussion versus not (brief or no discussion, or not remembering).

Between 2011 and 2016, there was minimal change in the percentage of survivors who reported not receiving detailed information on follow-up care (from 35.1% to 35.4%), late or long-term adverse effects (from 54.2% to 55.5%), lifestyle recommendations (from 58.9% to 57.8%), and emotional or social needs (from 69.2% to 68.2%), the investigators wrote. Their report is in Journal of Oncology Practice.

When analyses were restricted to only those survivors who had received cancer-directed treatment within 3 years of the survey, findings were essentially the same.

About one-quarter of survivors reported having detailed discussions about all four topics in both 2011 (24.4%) and 2016 (21.9%).

In 2016, nearly half of survivors, 47.6%, reported not having detailed discussions with their providers about a summary of their cancer treatments. (This question was not asked in 2011.)

“Despite national efforts and organizations promoting survivorship care planning and highlighting the need for improved quality of survivorship care delivery, clear gaps in quality of communication between survivors of cancer and providers persist,” Dr. Rai and colleagues said.

“Continued efforts are needed to promote communication about survivorship issues, including implementation and evaluation of targeted interventions in key survivorship care areas,” they recommended. “These interventions may consist of furnishing guidance on optimal ways to identify and address survivors’ communication needs, streamlining the flow of information across provider types, ensuring better integration of primary care providers with the survivorship care paradigm, and augmenting the use of health information technology for collection and dissemination of information across the cancer control continuum.”

Dr. Rai did not disclose any relevant conflicts of interest. The study did not receive specific funding.

SOURCE: Rai A et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019 July 2. doi: 10.1200/JOP.19.00157.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY PRACTICE

Abnormal uterine bleeding: When can you forgo biopsy?

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Ultrasound is a reasonable first step for the evaluation of postmenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding and endometrial thickness up to 5 mm, according to James Shwayder, MD, JD.

About a third of such patients presenting with abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) will have an endometrial polyp or submucous myoma, Dr. Shwayder explained during a presentation at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

However, recurrent bleeding warrants further work-up, he said.

The 5-mm value is based on a number of studies, which, in sum, show that the negative predictive value for cancer for endometrial thickness less than 4 mm is greater than 99%, said Dr. Shwayder, chief of the division of gynecology and director of the fellowship in advanced endoscopy obstetrics, gynecology, and women’s health at the University of Louisville (Ky.).

“In fact ... the risk of cancer is 1 in 917,” he added. “That’s pretty good ... that’s a great screening tool.”

The question is whether one can feel comfortable foregoing biopsy in such cases, he said, describing a 61-year-old patient with a 3.9-mm endometrium and AUB for 3 days, 3 weeks prior to her visit.

There are two possibilities: The patient will either have no further bleeding, or she will continue to bleed, he said, noting that a 2003 Swedish study provides some guidance in the case of continued bleeding (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:401-8).

The investigators initially looked at histology associated with endometrial thickness in 394 postmenopausal women referred for AUB between 1987 and 1990. Both transvaginal ultrasound and dilatation and curettage were performed, and the findings were correlated.

“But they had the rare opportunity to take patients who had benign evaluations and bring them back 10 years later,” Dr. Shwayder said. “What they found was that, regardless of the endometrial thickness, if it was benign initially and they did not bleed over that 10-year period, no one had cancer.”

However, among the patients followed for 10 years who had recurrent bleeding, 10% had cancer and 12% had hyperplasia. Thus, deciding against a biopsy in this case is supported by good data; if the patient doesn’t bleed, she has an “incredibly low risk of cancer,” he said.

“If they bleed again, you’ve gotta work ‘em up,” he stressed. “Don’t continue to say, ‘Well, let me repeat the ultrasound and see if it’s thinner or thicker.’ No. They need to be evaluated.”

Keep in mind that if a biopsy is performed as the first step, the chances of the results coming back as tissue insufficient for diagnosis (TIFD) are increased, and a repeat biopsy will be necessary because of the inconclusive findings, Dr. Shwayder said. It helps to warn a patient in advance that their thin endometrium makes it highly likely that a repeat biopsy will be necessary, as 90% come back as TIFD or atrophy.

Importantly, though, ACOG says endometrial sampling should be performed first line in patients over age 45 years with AUB.

“I’ll be honest – I use ultrasound in these patients because of the fact that a third will have some sort of structural defect, and the focal abnormalities are things we’re not going to be able to pick up with a straight biopsy, but we have to be cognizant that the college recommends biopsy in this population,” Dr. Shwayder said.

Asymptomatic endometrial thickening

Postmenopausal women are increasingly being referred for asymptomatic endometrial thickening that is found incidentally during an unrelated evaluation, Dr. Shwayder said, noting that evidence to date on how to approach such cases is conflicting.

Although ACOG is working on a recommendation, none is currently available, he said.

However, a 2001 study comparing 123 asymptomatic patients with 90 symptomatic patients, all with an endometrial thickness of greater than 10 mm, found no prognostic advantage to screening versus waiting until bleeding occurred, he noted (Euro J Cancer. 2001;37:64-71).

Overall, 13% of the patients had cancer, 50% had polyps, and 17% had hyperplasia.

“But what they emphasized was ... the length [of time] the patients complained of abnormal uterine bleeding. If it was less than 8 weeks ... there was no statistical difference in outcome, but if it was over 8 weeks there was a statistically significant difference in the grade of disease – a prognostic advantage for those patients who were screened versus symptomatic.”

The overall 5-year disease-free survival was 86% for asymptomatic versus 77% for symptomatic patients; for those with bleeding for less than 8 weeks, it was 98% versus 83%, respectively. The differences were not statistically different. However, for those with bleeding for 8-16 weeks it was 90% versus 74%, and for those with bleeding for more than 16 weeks it was 69% versus 62%, respectively, and those differences were statistically significant.

The problem is that many patients put off coming in for a long time, which means they are in a category with a worse prognosis when they do come in, Dr. Shwayder said. That’s not to say everyone should be screened, but there is no prognostic advantage to screening asymptomatic patients versus symptomatic patients who had bleeding for less than 8 weeks.

“It’s a little clarification, but I think an important one,” he noted.

Another study of 1,607 patients with endometrial thickening, including 233 who were asymptomatic and 1,374 who were symptomatic, found a lower rate of deep invasion with stage 1 disease, but no difference in the rate of more advanced disease, and no association with a more favorable outcome between the groups. (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219[2]:183e1-6).

Additionally, a study of 42 asymptomatic patients, 95 symptomatic patients with bleeding for less than 3 months, and 83 symptomatic patients with bleeding for more than 3 months showed a nonsignificant trend toward poorer 5-year survival in patients with a longer history of bleeding prior to surgery (Arch Gynecol Obstet 2013;288:1361-4).

“So now the question becomes how thick is too thick [and whether there is] some threshold where we ought to be evaluating patients and some threshold where we’re not,” he said.

The risk of malignancy among symptomatic postmenopausal women with an endometrial thickness greater than 5 mm is 7.3%, and the risk is similar at 6.7% in asymptomatic patients with an endometrial thickness of 11 mm or greater, according to a 2004 study by Smith-Bindman et al. (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;24:558-65).

“So the thought process here is that if a patient is asymptomatic, but the endometrium is over 11 mm, maybe we ought to evaluate that patient, because her risk of cancer is equivalent to that of someone who presents with postmenopausal bleeding and has an endometrium greater than 5 mm,” he explained.

In fact, a practice guideline from the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada recommends that women with endometrial thickness over 11 mm and other risk factors for cancer – such as obesity, hypertension, or late menopause – should be referred to a gynecologist for investigation, Dr. Shwayder said, adding that he also considers increased vascularity, heterogeneity in the endometrium, and fluid seen on a scan as cause for further evaluation.

“But endometrial sampling without bleeding should not be routinely performed,” he said. “So don’t routinely [sample] but based on risk factors and ultrasound findings, you may want to consider evaluating these patients further.”

Dr. Shwayder is a consultant for GE Ultrasound.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Ultrasound is a reasonable first step for the evaluation of postmenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding and endometrial thickness up to 5 mm, according to James Shwayder, MD, JD.

About a third of such patients presenting with abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) will have an endometrial polyp or submucous myoma, Dr. Shwayder explained during a presentation at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

However, recurrent bleeding warrants further work-up, he said.

The 5-mm value is based on a number of studies, which, in sum, show that the negative predictive value for cancer for endometrial thickness less than 4 mm is greater than 99%, said Dr. Shwayder, chief of the division of gynecology and director of the fellowship in advanced endoscopy obstetrics, gynecology, and women’s health at the University of Louisville (Ky.).

“In fact ... the risk of cancer is 1 in 917,” he added. “That’s pretty good ... that’s a great screening tool.”

The question is whether one can feel comfortable foregoing biopsy in such cases, he said, describing a 61-year-old patient with a 3.9-mm endometrium and AUB for 3 days, 3 weeks prior to her visit.

There are two possibilities: The patient will either have no further bleeding, or she will continue to bleed, he said, noting that a 2003 Swedish study provides some guidance in the case of continued bleeding (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:401-8).

The investigators initially looked at histology associated with endometrial thickness in 394 postmenopausal women referred for AUB between 1987 and 1990. Both transvaginal ultrasound and dilatation and curettage were performed, and the findings were correlated.

“But they had the rare opportunity to take patients who had benign evaluations and bring them back 10 years later,” Dr. Shwayder said. “What they found was that, regardless of the endometrial thickness, if it was benign initially and they did not bleed over that 10-year period, no one had cancer.”

However, among the patients followed for 10 years who had recurrent bleeding, 10% had cancer and 12% had hyperplasia. Thus, deciding against a biopsy in this case is supported by good data; if the patient doesn’t bleed, she has an “incredibly low risk of cancer,” he said.

“If they bleed again, you’ve gotta work ‘em up,” he stressed. “Don’t continue to say, ‘Well, let me repeat the ultrasound and see if it’s thinner or thicker.’ No. They need to be evaluated.”

Keep in mind that if a biopsy is performed as the first step, the chances of the results coming back as tissue insufficient for diagnosis (TIFD) are increased, and a repeat biopsy will be necessary because of the inconclusive findings, Dr. Shwayder said. It helps to warn a patient in advance that their thin endometrium makes it highly likely that a repeat biopsy will be necessary, as 90% come back as TIFD or atrophy.

Importantly, though, ACOG says endometrial sampling should be performed first line in patients over age 45 years with AUB.

“I’ll be honest – I use ultrasound in these patients because of the fact that a third will have some sort of structural defect, and the focal abnormalities are things we’re not going to be able to pick up with a straight biopsy, but we have to be cognizant that the college recommends biopsy in this population,” Dr. Shwayder said.

Asymptomatic endometrial thickening

Postmenopausal women are increasingly being referred for asymptomatic endometrial thickening that is found incidentally during an unrelated evaluation, Dr. Shwayder said, noting that evidence to date on how to approach such cases is conflicting.

Although ACOG is working on a recommendation, none is currently available, he said.

However, a 2001 study comparing 123 asymptomatic patients with 90 symptomatic patients, all with an endometrial thickness of greater than 10 mm, found no prognostic advantage to screening versus waiting until bleeding occurred, he noted (Euro J Cancer. 2001;37:64-71).

Overall, 13% of the patients had cancer, 50% had polyps, and 17% had hyperplasia.

“But what they emphasized was ... the length [of time] the patients complained of abnormal uterine bleeding. If it was less than 8 weeks ... there was no statistical difference in outcome, but if it was over 8 weeks there was a statistically significant difference in the grade of disease – a prognostic advantage for those patients who were screened versus symptomatic.”

The overall 5-year disease-free survival was 86% for asymptomatic versus 77% for symptomatic patients; for those with bleeding for less than 8 weeks, it was 98% versus 83%, respectively. The differences were not statistically different. However, for those with bleeding for 8-16 weeks it was 90% versus 74%, and for those with bleeding for more than 16 weeks it was 69% versus 62%, respectively, and those differences were statistically significant.

The problem is that many patients put off coming in for a long time, which means they are in a category with a worse prognosis when they do come in, Dr. Shwayder said. That’s not to say everyone should be screened, but there is no prognostic advantage to screening asymptomatic patients versus symptomatic patients who had bleeding for less than 8 weeks.

“It’s a little clarification, but I think an important one,” he noted.

Another study of 1,607 patients with endometrial thickening, including 233 who were asymptomatic and 1,374 who were symptomatic, found a lower rate of deep invasion with stage 1 disease, but no difference in the rate of more advanced disease, and no association with a more favorable outcome between the groups. (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219[2]:183e1-6).

Additionally, a study of 42 asymptomatic patients, 95 symptomatic patients with bleeding for less than 3 months, and 83 symptomatic patients with bleeding for more than 3 months showed a nonsignificant trend toward poorer 5-year survival in patients with a longer history of bleeding prior to surgery (Arch Gynecol Obstet 2013;288:1361-4).

“So now the question becomes how thick is too thick [and whether there is] some threshold where we ought to be evaluating patients and some threshold where we’re not,” he said.

The risk of malignancy among symptomatic postmenopausal women with an endometrial thickness greater than 5 mm is 7.3%, and the risk is similar at 6.7% in asymptomatic patients with an endometrial thickness of 11 mm or greater, according to a 2004 study by Smith-Bindman et al. (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;24:558-65).

“So the thought process here is that if a patient is asymptomatic, but the endometrium is over 11 mm, maybe we ought to evaluate that patient, because her risk of cancer is equivalent to that of someone who presents with postmenopausal bleeding and has an endometrium greater than 5 mm,” he explained.

In fact, a practice guideline from the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada recommends that women with endometrial thickness over 11 mm and other risk factors for cancer – such as obesity, hypertension, or late menopause – should be referred to a gynecologist for investigation, Dr. Shwayder said, adding that he also considers increased vascularity, heterogeneity in the endometrium, and fluid seen on a scan as cause for further evaluation.

“But endometrial sampling without bleeding should not be routinely performed,” he said. “So don’t routinely [sample] but based on risk factors and ultrasound findings, you may want to consider evaluating these patients further.”

Dr. Shwayder is a consultant for GE Ultrasound.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Ultrasound is a reasonable first step for the evaluation of postmenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding and endometrial thickness up to 5 mm, according to James Shwayder, MD, JD.

About a third of such patients presenting with abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) will have an endometrial polyp or submucous myoma, Dr. Shwayder explained during a presentation at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

However, recurrent bleeding warrants further work-up, he said.

The 5-mm value is based on a number of studies, which, in sum, show that the negative predictive value for cancer for endometrial thickness less than 4 mm is greater than 99%, said Dr. Shwayder, chief of the division of gynecology and director of the fellowship in advanced endoscopy obstetrics, gynecology, and women’s health at the University of Louisville (Ky.).

“In fact ... the risk of cancer is 1 in 917,” he added. “That’s pretty good ... that’s a great screening tool.”

The question is whether one can feel comfortable foregoing biopsy in such cases, he said, describing a 61-year-old patient with a 3.9-mm endometrium and AUB for 3 days, 3 weeks prior to her visit.

There are two possibilities: The patient will either have no further bleeding, or she will continue to bleed, he said, noting that a 2003 Swedish study provides some guidance in the case of continued bleeding (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:401-8).

The investigators initially looked at histology associated with endometrial thickness in 394 postmenopausal women referred for AUB between 1987 and 1990. Both transvaginal ultrasound and dilatation and curettage were performed, and the findings were correlated.

“But they had the rare opportunity to take patients who had benign evaluations and bring them back 10 years later,” Dr. Shwayder said. “What they found was that, regardless of the endometrial thickness, if it was benign initially and they did not bleed over that 10-year period, no one had cancer.”

However, among the patients followed for 10 years who had recurrent bleeding, 10% had cancer and 12% had hyperplasia. Thus, deciding against a biopsy in this case is supported by good data; if the patient doesn’t bleed, she has an “incredibly low risk of cancer,” he said.

“If they bleed again, you’ve gotta work ‘em up,” he stressed. “Don’t continue to say, ‘Well, let me repeat the ultrasound and see if it’s thinner or thicker.’ No. They need to be evaluated.”

Keep in mind that if a biopsy is performed as the first step, the chances of the results coming back as tissue insufficient for diagnosis (TIFD) are increased, and a repeat biopsy will be necessary because of the inconclusive findings, Dr. Shwayder said. It helps to warn a patient in advance that their thin endometrium makes it highly likely that a repeat biopsy will be necessary, as 90% come back as TIFD or atrophy.

Importantly, though, ACOG says endometrial sampling should be performed first line in patients over age 45 years with AUB.

“I’ll be honest – I use ultrasound in these patients because of the fact that a third will have some sort of structural defect, and the focal abnormalities are things we’re not going to be able to pick up with a straight biopsy, but we have to be cognizant that the college recommends biopsy in this population,” Dr. Shwayder said.

Asymptomatic endometrial thickening

Postmenopausal women are increasingly being referred for asymptomatic endometrial thickening that is found incidentally during an unrelated evaluation, Dr. Shwayder said, noting that evidence to date on how to approach such cases is conflicting.

Although ACOG is working on a recommendation, none is currently available, he said.

However, a 2001 study comparing 123 asymptomatic patients with 90 symptomatic patients, all with an endometrial thickness of greater than 10 mm, found no prognostic advantage to screening versus waiting until bleeding occurred, he noted (Euro J Cancer. 2001;37:64-71).

Overall, 13% of the patients had cancer, 50% had polyps, and 17% had hyperplasia.

“But what they emphasized was ... the length [of time] the patients complained of abnormal uterine bleeding. If it was less than 8 weeks ... there was no statistical difference in outcome, but if it was over 8 weeks there was a statistically significant difference in the grade of disease – a prognostic advantage for those patients who were screened versus symptomatic.”

The overall 5-year disease-free survival was 86% for asymptomatic versus 77% for symptomatic patients; for those with bleeding for less than 8 weeks, it was 98% versus 83%, respectively. The differences were not statistically different. However, for those with bleeding for 8-16 weeks it was 90% versus 74%, and for those with bleeding for more than 16 weeks it was 69% versus 62%, respectively, and those differences were statistically significant.

The problem is that many patients put off coming in for a long time, which means they are in a category with a worse prognosis when they do come in, Dr. Shwayder said. That’s not to say everyone should be screened, but there is no prognostic advantage to screening asymptomatic patients versus symptomatic patients who had bleeding for less than 8 weeks.

“It’s a little clarification, but I think an important one,” he noted.

Another study of 1,607 patients with endometrial thickening, including 233 who were asymptomatic and 1,374 who were symptomatic, found a lower rate of deep invasion with stage 1 disease, but no difference in the rate of more advanced disease, and no association with a more favorable outcome between the groups. (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219[2]:183e1-6).

Additionally, a study of 42 asymptomatic patients, 95 symptomatic patients with bleeding for less than 3 months, and 83 symptomatic patients with bleeding for more than 3 months showed a nonsignificant trend toward poorer 5-year survival in patients with a longer history of bleeding prior to surgery (Arch Gynecol Obstet 2013;288:1361-4).

“So now the question becomes how thick is too thick [and whether there is] some threshold where we ought to be evaluating patients and some threshold where we’re not,” he said.

The risk of malignancy among symptomatic postmenopausal women with an endometrial thickness greater than 5 mm is 7.3%, and the risk is similar at 6.7% in asymptomatic patients with an endometrial thickness of 11 mm or greater, according to a 2004 study by Smith-Bindman et al. (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;24:558-65).

“So the thought process here is that if a patient is asymptomatic, but the endometrium is over 11 mm, maybe we ought to evaluate that patient, because her risk of cancer is equivalent to that of someone who presents with postmenopausal bleeding and has an endometrium greater than 5 mm,” he explained.

In fact, a practice guideline from the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada recommends that women with endometrial thickness over 11 mm and other risk factors for cancer – such as obesity, hypertension, or late menopause – should be referred to a gynecologist for investigation, Dr. Shwayder said, adding that he also considers increased vascularity, heterogeneity in the endometrium, and fluid seen on a scan as cause for further evaluation.

“But endometrial sampling without bleeding should not be routinely performed,” he said. “So don’t routinely [sample] but based on risk factors and ultrasound findings, you may want to consider evaluating these patients further.”

Dr. Shwayder is a consultant for GE Ultrasound.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ACOG 2019

FDA approves bevacizumab-bvzr for several cancers

The Food and Drug Administration has approved bevacizumab-bvzr (Zirabev) – a biosimilar to bevacizumab (Avastin) – for the treatment of five cancers: metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC); unresectable, locally advanced, recurrent or metastatic non-squamous non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC); recurrent glioblastoma; metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC); and persistent, recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer.

Approval was based on “review of a comprehensive data package which demonstrated biosimilarity of [bevacizumab-bvzr] to the reference product,” Pfizer said in a statement announcing the approval.

Bevacizumab-bvzr is the second bevacizumab biosimilar to be approved, following approval of Amgen’s bevacizumab-awwb (Mvasi) in 2017.

Warnings and precautions with the biosimilars, as with bevacizumab, include serious and sometimes fatal gastrointestinal perforation, surgery and wound healing complications, and sometimes serious and fatal hemorrhage.