User login

COVID-19 prompts ‘lifesaving’ policy change for opioid addiction

In the face of the US COVID-19 pandemic, the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has announced policy changes to allow some patients in opioid treatment programs (OTP) to take home their medication.

According to the agency, states may request “blanket exceptions” for all stable patients in an OTP to receive a 28-day supply of take-home doses of medications such as methadone and buprenorphine, which are used to treat opioid use disorder (OUD).

States may request up to 14 days of take-home medication for patients who are less stable but who can, in the judgment of OTP clinicians, safely handle this level of take-home medication.

“SAMHSA recognizes the evolving issues surrounding COVID-19 and the emerging needs OTPs continue to face,” the agency writes in its updated guidance.

“SAMHSA affirms its commitment to supporting OTPs in any way possible during this time. As such, we are expanding our previous guidance to provide increased flexibility,” the agency said.

A ‘Lifesaving’ Decision

Commenting on the SAMHSA policy change, Richard Saitz, MD, professor and chair of the department of community health sciences, Boston University School of Public Health, said, the policy “is not only a good idea, it is critical and lifesaving.”

“This approach had to be done now. With the reduction in face-to-face visits, patients with opioid use disorder need a way to access treatment. If they cannot get opioid agonists, they would withdraw and return to illicit opioid use and high overdose risk and it would be cruel,” said Saitz.

“It is possible that there will be some diversion and some risk of overdose or misuse, but even for less stable patients the benefit likely far outweighs the risk,” he told Medscape Medical News.

Saitz believes policy changes like this should have been made before a crisis.

“Honestly, this is perhaps a silver lining of the crisis” and could lead to permanent change in how OUD is treated in the US, he said.

“Just like we are learning what can be done without a medical in-person visit, we will learn that it is perfectly fine to treat patients with addiction more like we treat patients with other chronic diseases who take medication that has risks and benefits,” Saitz said.

in cases when a patient is quarantined because of coronavirus.

Typically, only licensed practitioners can dispense or administer OUD medications to patients, but during the COVID-19 crisis, treatment program staff members, law enforcement officers, and national guard personnel will be allowed to deliver OUD medications to an approved “lockbox” at the patient’s doorstep. The change applies only while the coronavirus public health emergency lasts.

“This is also an excellent idea,” Saitz said.

ASAM Also Responds

In addition, the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) released a focused update to its National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder (NPG).

The update is “especially critical in the context of the ongoing COVID-19 emergency, which threatens to curtail patient access to evidence-based treatment,” the organization said in a news release. The new document updates the 2015 NPG. It includes 13 new recommendations and major revisions to 35 existing recommendations.

One new recommendation states that comprehensive assessment of a patient is critical for treatment planning, but completing all assessments should not delay or preclude initiating pharmacotherapy for OUD. Another new recommendation states that there is no recommended time limit for pharmacotherapy.

ASAM continues to recommend that patients’ psychosocial needs be assessed and psychosocial treatment offered. However, if patients can’t access psychosocial treatment because they are in isolation or have other risk factors that preclude external interactions, clinicians should not delay initiation of medication for the treatment of addiction.

Expanding the use of telemedicine might also be appropriate for many patients, ASAM announced.

They note that the NPG is the first to address in a single document all medications currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat OUD and opioid withdrawal, including all available buprenorphine formulations.

“All of the updated recommendations are designed to both improve the quality and consistency of care and reduce barriers to access to care for Americans living with OUD. The updated recommendations aim to support initiation of buprenorphine treatment in the emergency department and other urgent care settings,” the society said in the release.

“In addition, [the recommendations] provide greater flexibility on dosing during the initiation of buprenorphine treatment and for initiation of buprenorphine at home (which is also an important change in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis).”

The full document is available online.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the face of the US COVID-19 pandemic, the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has announced policy changes to allow some patients in opioid treatment programs (OTP) to take home their medication.

According to the agency, states may request “blanket exceptions” for all stable patients in an OTP to receive a 28-day supply of take-home doses of medications such as methadone and buprenorphine, which are used to treat opioid use disorder (OUD).

States may request up to 14 days of take-home medication for patients who are less stable but who can, in the judgment of OTP clinicians, safely handle this level of take-home medication.

“SAMHSA recognizes the evolving issues surrounding COVID-19 and the emerging needs OTPs continue to face,” the agency writes in its updated guidance.

“SAMHSA affirms its commitment to supporting OTPs in any way possible during this time. As such, we are expanding our previous guidance to provide increased flexibility,” the agency said.

A ‘Lifesaving’ Decision

Commenting on the SAMHSA policy change, Richard Saitz, MD, professor and chair of the department of community health sciences, Boston University School of Public Health, said, the policy “is not only a good idea, it is critical and lifesaving.”

“This approach had to be done now. With the reduction in face-to-face visits, patients with opioid use disorder need a way to access treatment. If they cannot get opioid agonists, they would withdraw and return to illicit opioid use and high overdose risk and it would be cruel,” said Saitz.

“It is possible that there will be some diversion and some risk of overdose or misuse, but even for less stable patients the benefit likely far outweighs the risk,” he told Medscape Medical News.

Saitz believes policy changes like this should have been made before a crisis.

“Honestly, this is perhaps a silver lining of the crisis” and could lead to permanent change in how OUD is treated in the US, he said.

“Just like we are learning what can be done without a medical in-person visit, we will learn that it is perfectly fine to treat patients with addiction more like we treat patients with other chronic diseases who take medication that has risks and benefits,” Saitz said.

in cases when a patient is quarantined because of coronavirus.

Typically, only licensed practitioners can dispense or administer OUD medications to patients, but during the COVID-19 crisis, treatment program staff members, law enforcement officers, and national guard personnel will be allowed to deliver OUD medications to an approved “lockbox” at the patient’s doorstep. The change applies only while the coronavirus public health emergency lasts.

“This is also an excellent idea,” Saitz said.

ASAM Also Responds

In addition, the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) released a focused update to its National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder (NPG).

The update is “especially critical in the context of the ongoing COVID-19 emergency, which threatens to curtail patient access to evidence-based treatment,” the organization said in a news release. The new document updates the 2015 NPG. It includes 13 new recommendations and major revisions to 35 existing recommendations.

One new recommendation states that comprehensive assessment of a patient is critical for treatment planning, but completing all assessments should not delay or preclude initiating pharmacotherapy for OUD. Another new recommendation states that there is no recommended time limit for pharmacotherapy.

ASAM continues to recommend that patients’ psychosocial needs be assessed and psychosocial treatment offered. However, if patients can’t access psychosocial treatment because they are in isolation or have other risk factors that preclude external interactions, clinicians should not delay initiation of medication for the treatment of addiction.

Expanding the use of telemedicine might also be appropriate for many patients, ASAM announced.

They note that the NPG is the first to address in a single document all medications currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat OUD and opioid withdrawal, including all available buprenorphine formulations.

“All of the updated recommendations are designed to both improve the quality and consistency of care and reduce barriers to access to care for Americans living with OUD. The updated recommendations aim to support initiation of buprenorphine treatment in the emergency department and other urgent care settings,” the society said in the release.

“In addition, [the recommendations] provide greater flexibility on dosing during the initiation of buprenorphine treatment and for initiation of buprenorphine at home (which is also an important change in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis).”

The full document is available online.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the face of the US COVID-19 pandemic, the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has announced policy changes to allow some patients in opioid treatment programs (OTP) to take home their medication.

According to the agency, states may request “blanket exceptions” for all stable patients in an OTP to receive a 28-day supply of take-home doses of medications such as methadone and buprenorphine, which are used to treat opioid use disorder (OUD).

States may request up to 14 days of take-home medication for patients who are less stable but who can, in the judgment of OTP clinicians, safely handle this level of take-home medication.

“SAMHSA recognizes the evolving issues surrounding COVID-19 and the emerging needs OTPs continue to face,” the agency writes in its updated guidance.

“SAMHSA affirms its commitment to supporting OTPs in any way possible during this time. As such, we are expanding our previous guidance to provide increased flexibility,” the agency said.

A ‘Lifesaving’ Decision

Commenting on the SAMHSA policy change, Richard Saitz, MD, professor and chair of the department of community health sciences, Boston University School of Public Health, said, the policy “is not only a good idea, it is critical and lifesaving.”

“This approach had to be done now. With the reduction in face-to-face visits, patients with opioid use disorder need a way to access treatment. If they cannot get opioid agonists, they would withdraw and return to illicit opioid use and high overdose risk and it would be cruel,” said Saitz.

“It is possible that there will be some diversion and some risk of overdose or misuse, but even for less stable patients the benefit likely far outweighs the risk,” he told Medscape Medical News.

Saitz believes policy changes like this should have been made before a crisis.

“Honestly, this is perhaps a silver lining of the crisis” and could lead to permanent change in how OUD is treated in the US, he said.

“Just like we are learning what can be done without a medical in-person visit, we will learn that it is perfectly fine to treat patients with addiction more like we treat patients with other chronic diseases who take medication that has risks and benefits,” Saitz said.

in cases when a patient is quarantined because of coronavirus.

Typically, only licensed practitioners can dispense or administer OUD medications to patients, but during the COVID-19 crisis, treatment program staff members, law enforcement officers, and national guard personnel will be allowed to deliver OUD medications to an approved “lockbox” at the patient’s doorstep. The change applies only while the coronavirus public health emergency lasts.

“This is also an excellent idea,” Saitz said.

ASAM Also Responds

In addition, the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) released a focused update to its National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder (NPG).

The update is “especially critical in the context of the ongoing COVID-19 emergency, which threatens to curtail patient access to evidence-based treatment,” the organization said in a news release. The new document updates the 2015 NPG. It includes 13 new recommendations and major revisions to 35 existing recommendations.

One new recommendation states that comprehensive assessment of a patient is critical for treatment planning, but completing all assessments should not delay or preclude initiating pharmacotherapy for OUD. Another new recommendation states that there is no recommended time limit for pharmacotherapy.

ASAM continues to recommend that patients’ psychosocial needs be assessed and psychosocial treatment offered. However, if patients can’t access psychosocial treatment because they are in isolation or have other risk factors that preclude external interactions, clinicians should not delay initiation of medication for the treatment of addiction.

Expanding the use of telemedicine might also be appropriate for many patients, ASAM announced.

They note that the NPG is the first to address in a single document all medications currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat OUD and opioid withdrawal, including all available buprenorphine formulations.

“All of the updated recommendations are designed to both improve the quality and consistency of care and reduce barriers to access to care for Americans living with OUD. The updated recommendations aim to support initiation of buprenorphine treatment in the emergency department and other urgent care settings,” the society said in the release.

“In addition, [the recommendations] provide greater flexibility on dosing during the initiation of buprenorphine treatment and for initiation of buprenorphine at home (which is also an important change in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis).”

The full document is available online.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinicians petition government for national quarantine

Clinicians across the United States are petitioning the federal government to follow the lead of South Korea, China, and other nations by imposing an immediate nationwide quarantine to slow the inevitable spread of COVID-19. Without federal action, the creators say, their lives and the lives of their colleagues, patients, and families are being put at increased risk.

In addition to the quarantine, the petition, posted on the website Change.org, calls on U.S. leaders to institute emergency production and distribution of personal protective equipment for healthcare workers and to rapidly increase access to testing.

The petition – which garnered more than 40,000 signatures in just 12 hours and as of this writing was approaching 94,000 – was started by an apolitical Facebook group to focus attention on what members see as the most critical issues for clinicians: slowing the spread of the virus through a coast-to-coast quarantine, protection of medical personnel with adequate supplies of essential equipment, and widespread testing.

“We started this group last Friday out of the realization that clinicians needed information about the outbreak and weren’t getting it,” said coadministrator Jessica McIntyre, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Elliot Hospital in Manchester, N.H.

“We wanted to get ahead of it and connect with people before we were in the trenches experiencing it and to see what other programs were doing. From a local perspective, it has been really hard to see what people are doing in other states, especially when the protocols in our own states are changing every single day as we collect more information,” she said in an interview.

The Horse Has Bolted

A family medicine physician in Illinois helped launch the Facebook group. She asked that her name not be used but said in an interview that earlier actions may have prevented or at least delayed the need for the more draconian measures that her group is recommending.

“Clearly South Korea is one of the superstars as far as response has gone, but the concern we have in the United States is that we’re well beyond that point – we needed to be testing people over a month ago, in the hope of preventing a quarantine,” she said in an interview.

According to National Public Radio, as of March 13, South Korea had conducted 3,600 tests per million population, compared with five per million in the United States.

“I think the most concerning part is to see where Italy is now and where we are in comparison. Our ICUs have not yet overflowed, but I think we’re definitely looking at that in the next few weeks – hopefully longer, but I suspect that it will happen shortly,” she continued.

She cited work by Harvard University biostatistician Xihong Lin, PhD, that shows that when health authorities in Wuhan, China – widely cited as the epicenter of the global pandemic – cordoned off the city, the infection rate dropped from one person infecting 3.8 others to one infecting 1.25, thereby significantly slowing the rate of transmission.

“This is absolutely what we need to be doing,” she said.

Real News

Within 3 days of its creation, the online group had accrued more than 80,000 members with advanced medical training, including MDs, DOs, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and certified registered nurse anesthetists.

“A lot of us were already very busy with our day-to-day work outside of COVID-19, and I think a lot of us felt unsure about where to get the best information,” said coadministrator David Janssen, MD, a family medicine physician in group practice in Sioux Center, Iowa,

“If you turn on the TV, there’s a lot of politicizing of the issue, and there’s a lot of good information, but also a lot of bad information. When health care providers talk to other health care providers, that’s often how we get our information and how we learn,” he said in an interview.

The COVID-19 U.S. Physicians/APP Facebook group includes 20 volunteer moderators who handle hundreds of posts per hour from persons seeking information on the novel coronavirus, what to tell patients, and how to protect themselves.

“It’s been wonderful to see how providers have been helping other providers sort through issues. Teaching hospitals have their hands on the latest research, but a lot of people like myself are at small community hospitals, critical-access hospitals, where we may have a lot of questions but don’t necessarily have the answers readily available to us,” Dr. Janssen said.

Dr. Janssen said that his community of about 8,000 residents initially had only four COVID-19 testing kits, or one for every 2,000 people. The situation has since improved, and more tests are now available, he added.

Dr. McIntyre, Dr. Janssen, and the Illinois family physician have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinicians across the United States are petitioning the federal government to follow the lead of South Korea, China, and other nations by imposing an immediate nationwide quarantine to slow the inevitable spread of COVID-19. Without federal action, the creators say, their lives and the lives of their colleagues, patients, and families are being put at increased risk.

In addition to the quarantine, the petition, posted on the website Change.org, calls on U.S. leaders to institute emergency production and distribution of personal protective equipment for healthcare workers and to rapidly increase access to testing.

The petition – which garnered more than 40,000 signatures in just 12 hours and as of this writing was approaching 94,000 – was started by an apolitical Facebook group to focus attention on what members see as the most critical issues for clinicians: slowing the spread of the virus through a coast-to-coast quarantine, protection of medical personnel with adequate supplies of essential equipment, and widespread testing.

“We started this group last Friday out of the realization that clinicians needed information about the outbreak and weren’t getting it,” said coadministrator Jessica McIntyre, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Elliot Hospital in Manchester, N.H.

“We wanted to get ahead of it and connect with people before we were in the trenches experiencing it and to see what other programs were doing. From a local perspective, it has been really hard to see what people are doing in other states, especially when the protocols in our own states are changing every single day as we collect more information,” she said in an interview.

The Horse Has Bolted

A family medicine physician in Illinois helped launch the Facebook group. She asked that her name not be used but said in an interview that earlier actions may have prevented or at least delayed the need for the more draconian measures that her group is recommending.

“Clearly South Korea is one of the superstars as far as response has gone, but the concern we have in the United States is that we’re well beyond that point – we needed to be testing people over a month ago, in the hope of preventing a quarantine,” she said in an interview.

According to National Public Radio, as of March 13, South Korea had conducted 3,600 tests per million population, compared with five per million in the United States.

“I think the most concerning part is to see where Italy is now and where we are in comparison. Our ICUs have not yet overflowed, but I think we’re definitely looking at that in the next few weeks – hopefully longer, but I suspect that it will happen shortly,” she continued.

She cited work by Harvard University biostatistician Xihong Lin, PhD, that shows that when health authorities in Wuhan, China – widely cited as the epicenter of the global pandemic – cordoned off the city, the infection rate dropped from one person infecting 3.8 others to one infecting 1.25, thereby significantly slowing the rate of transmission.

“This is absolutely what we need to be doing,” she said.

Real News

Within 3 days of its creation, the online group had accrued more than 80,000 members with advanced medical training, including MDs, DOs, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and certified registered nurse anesthetists.

“A lot of us were already very busy with our day-to-day work outside of COVID-19, and I think a lot of us felt unsure about where to get the best information,” said coadministrator David Janssen, MD, a family medicine physician in group practice in Sioux Center, Iowa,

“If you turn on the TV, there’s a lot of politicizing of the issue, and there’s a lot of good information, but also a lot of bad information. When health care providers talk to other health care providers, that’s often how we get our information and how we learn,” he said in an interview.

The COVID-19 U.S. Physicians/APP Facebook group includes 20 volunteer moderators who handle hundreds of posts per hour from persons seeking information on the novel coronavirus, what to tell patients, and how to protect themselves.

“It’s been wonderful to see how providers have been helping other providers sort through issues. Teaching hospitals have their hands on the latest research, but a lot of people like myself are at small community hospitals, critical-access hospitals, where we may have a lot of questions but don’t necessarily have the answers readily available to us,” Dr. Janssen said.

Dr. Janssen said that his community of about 8,000 residents initially had only four COVID-19 testing kits, or one for every 2,000 people. The situation has since improved, and more tests are now available, he added.

Dr. McIntyre, Dr. Janssen, and the Illinois family physician have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinicians across the United States are petitioning the federal government to follow the lead of South Korea, China, and other nations by imposing an immediate nationwide quarantine to slow the inevitable spread of COVID-19. Without federal action, the creators say, their lives and the lives of their colleagues, patients, and families are being put at increased risk.

In addition to the quarantine, the petition, posted on the website Change.org, calls on U.S. leaders to institute emergency production and distribution of personal protective equipment for healthcare workers and to rapidly increase access to testing.

The petition – which garnered more than 40,000 signatures in just 12 hours and as of this writing was approaching 94,000 – was started by an apolitical Facebook group to focus attention on what members see as the most critical issues for clinicians: slowing the spread of the virus through a coast-to-coast quarantine, protection of medical personnel with adequate supplies of essential equipment, and widespread testing.

“We started this group last Friday out of the realization that clinicians needed information about the outbreak and weren’t getting it,” said coadministrator Jessica McIntyre, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Elliot Hospital in Manchester, N.H.

“We wanted to get ahead of it and connect with people before we were in the trenches experiencing it and to see what other programs were doing. From a local perspective, it has been really hard to see what people are doing in other states, especially when the protocols in our own states are changing every single day as we collect more information,” she said in an interview.

The Horse Has Bolted

A family medicine physician in Illinois helped launch the Facebook group. She asked that her name not be used but said in an interview that earlier actions may have prevented or at least delayed the need for the more draconian measures that her group is recommending.

“Clearly South Korea is one of the superstars as far as response has gone, but the concern we have in the United States is that we’re well beyond that point – we needed to be testing people over a month ago, in the hope of preventing a quarantine,” she said in an interview.

According to National Public Radio, as of March 13, South Korea had conducted 3,600 tests per million population, compared with five per million in the United States.

“I think the most concerning part is to see where Italy is now and where we are in comparison. Our ICUs have not yet overflowed, but I think we’re definitely looking at that in the next few weeks – hopefully longer, but I suspect that it will happen shortly,” she continued.

She cited work by Harvard University biostatistician Xihong Lin, PhD, that shows that when health authorities in Wuhan, China – widely cited as the epicenter of the global pandemic – cordoned off the city, the infection rate dropped from one person infecting 3.8 others to one infecting 1.25, thereby significantly slowing the rate of transmission.

“This is absolutely what we need to be doing,” she said.

Real News

Within 3 days of its creation, the online group had accrued more than 80,000 members with advanced medical training, including MDs, DOs, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and certified registered nurse anesthetists.

“A lot of us were already very busy with our day-to-day work outside of COVID-19, and I think a lot of us felt unsure about where to get the best information,” said coadministrator David Janssen, MD, a family medicine physician in group practice in Sioux Center, Iowa,

“If you turn on the TV, there’s a lot of politicizing of the issue, and there’s a lot of good information, but also a lot of bad information. When health care providers talk to other health care providers, that’s often how we get our information and how we learn,” he said in an interview.

The COVID-19 U.S. Physicians/APP Facebook group includes 20 volunteer moderators who handle hundreds of posts per hour from persons seeking information on the novel coronavirus, what to tell patients, and how to protect themselves.

“It’s been wonderful to see how providers have been helping other providers sort through issues. Teaching hospitals have their hands on the latest research, but a lot of people like myself are at small community hospitals, critical-access hospitals, where we may have a lot of questions but don’t necessarily have the answers readily available to us,” Dr. Janssen said.

Dr. Janssen said that his community of about 8,000 residents initially had only four COVID-19 testing kits, or one for every 2,000 people. The situation has since improved, and more tests are now available, he added.

Dr. McIntyre, Dr. Janssen, and the Illinois family physician have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The apology in medicine—yes, no, or maybe?

This is the third and final article in a series focusing on malpractice, liability, and reform. In the first article, we looked at the background on malpractice and reasons malpractice rates have been so high—including large verdicts and lawsuit-prone physicians. In the second article we considered recent experience and developments in malpractice exposure, who is sued and why. Finally, in this third article, we focus on apologies, apology laws, and liability.

“I’m sorry”

In childhood we are all taught the basic courtesies: “please” and “thank you,” and “I’m sorry,” when harm has occurred. Should we as adult health care providers fear the consequences of apologizing? Apologies are a way for clinicians to express empathy; they also serve as a tool to reduce medical malpractice claims.1

Apologies, ethics, and care

The American Medical Association takes the position that a physician has an ethical duty to disclose a harmful error to a patient.2,3 Indeed this approach has been an impetus for states to enact apology laws, which we discuss below. As pointed out in this 2013 article title, “Dealing with a medical mistake: Should physicians apologize to patients?”,4 the legal benefits of any apology are an issue. It is a controversial area in medicine still today, including in obstetrics and gynecology.

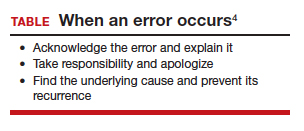

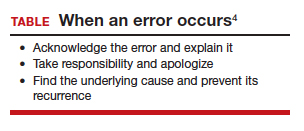

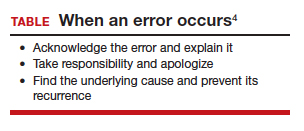

“Ethical codes for both M.D.s and D.O.s suggest providers should display honesty and empathy following adverse events and errors.”1,3,5 In addition, the American Medical Association states, “a physician should at all times deal honestly and openly with patients.”2 Concerns about liability that may result from truthful disclosure should not affect the physician’s honesty (TABLE). Increasingly, the law has sided with that principle through apology laws.

Some patients sue to get answers to the “What happened?” and “Why did it happen?” questions.6 They also sometimes are motivated by a desire to help ensure that the same injury does not happen to others. Silence on the part of the clinician may be seen as a lack of sympathy or remorse and patients may fear that other patients will be harmed.1

The relationship between physician and patient involves vulnerability and requires trust. When an injury occurs, the relationship can be injured as well. Barriers to apology in part reflect “the culture of medicine” as well as the “inherent psychological difficulties in facing one’s mistakes and apologizing for them.” However, apology by the provider may result in “effective resolution of disputes related to medical error.”7

The patient’s perspective is critical to this type of outcome, of course. A study from the United Kingdom noted that one-third of patients who experience a medical error have a desire to receive an apology or explanation. Furthermore, patients need assurance that a plan of action to prevent such a future occurrence is in place.8 Surveys reflect that patients desire, or even expect, the physician to acknowledge an error.9 We will see that there is evidence that some kinds of apologies tend to diminish blame and make the injured patient less likely to pursue litigation.10 For instance, Dahan and colleagues completed a study that highlights the “act of apology,” which can be seen as a “language art.”11 Medical schools have recognized the importance of the apology and now incorporate training focused on error disclosure and provision of apologies into the curriculum.12

Continue to: Legal issues and medical apologies...

Legal issues and medical apologies

From a legal standpoint, traditionally, an apology from a physician to a patient could be used against a physician in a medical liability (malpractice) case as proof of negligence.

Statements of interest. Such out-of-court statements ordinarily would be “hearsay” and excluded from evidence; there is, however, an exception to this hearsay rule that allows “confessions” or “statements against interest” to be admissible against the party making the statement. The theory is that when a statement is harmful to the person making it, the person likely thought that it was true, and the statement should be admissible at trial. We do not generally go around confessing to things that are not true. Following an auto crash, if one driver jumps out of the car saying, “I am so sorry I hit you. I was using my cell phone and did not see you stop,” the statement is against the interest of the driver and could be used in court.

As a matter of general legal principle, the same issue can arise in medical practice. Suppose a physician says, “I am so sorry for your injury. We made a mistake in interpreting the data from the monitors.” That sounds a lot like not just an apology but a statement against interest. Malpractice cases generally are based on the claim that a “doctor failed to do what a reasonable provider in the same specialty would have done in a similar situation.”13 An apology may be little more than general sympathy (“I’m sorry to tell you that we have not cured the infection. Unfortunately, that will mean more time in the hospital.”), but it can include a confession of error (“I’m sorry we got the x-ray backward and removed the wrong kidney.”). In the latter kind of apology, courts traditionally have found a “statement against interest.”

The legal consequence of a statement against interest is that the statement may be admitted in court. Such statements do not automatically establish negligence, but they can be powerful evidence when presented to a jury.

Courts have struggled with medical apologies. General sympathy or feelings of regret or compassion do not generally rise to the level of an admission that the physician did not use reasonable care under the circumstances and ordinarily are not admissible. (For further details, we refer you to the case of Cobbs v. Grant.14 Even if a physician said to the patient that he “blamed himself for [the patient] being back in the hospital for a second time,…the statement signifies compassion, or at most, a feeling of remorse, for plaintiff’s ordeal.”) On the other hand, in cases in which a physician in an apology referred to a “careless” mistake or even a “negligent” mistake, courts have allowed it admitted at trial as a statement against interest. (A 1946 case, Woronka v. Sewall, is an example.15 In that case, the physician said to the patient, “My God, what a mess…she had a very hard delivery, and it was a burning shame to get [an injury] on top of it, and it was because of negligence when they were upstairs.”) Some of these cases come down to the provider’s use of a single word: fault, careless, or negligence.

The ambiguity over the legal place of medical apologies in medicine led attorneys to urge medical providers to avoid statements that might even remotely be taken as statements against interest, including real apologies. The confusion over the admissibility of medical apologies led state legislatures to adopt apology laws. These laws essentially limit what statements against interest may be introduced in professional liability cases when a provider has issued a responsibility or apologized.

Continue to: Apology statutes...

Apology statutes

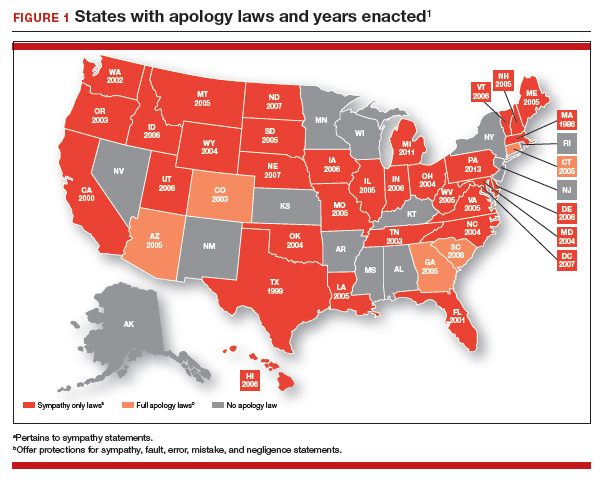

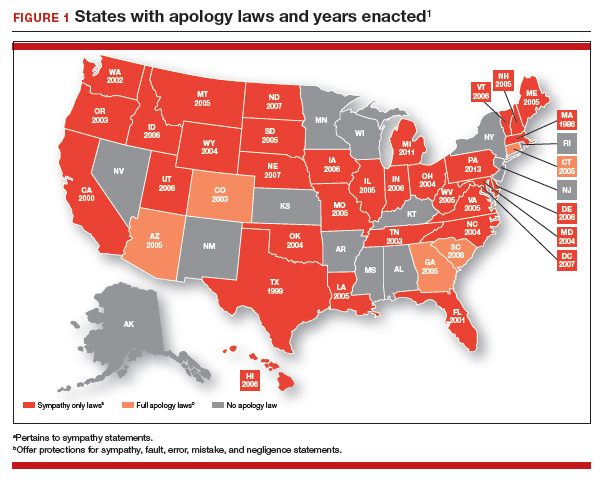

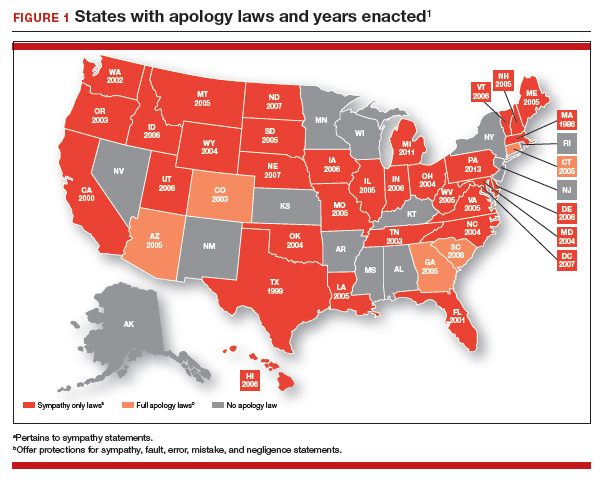

Massachusetts was the first state to enact an apology law—in 1986.1 As of 2019, a clear majority of states have some form of apology statute. “Apology laws are gaining traction,” was the first sentence in a 2012 review on the subject by Saitta and colleagues.3 Only a few (5 states) have “strong” statutes that have broad protection for statements of fault, error, and negligence, as well as sympathy. The other 33 states have statutes that only protect against statements of sympathy.4,16 FIGURE 1 is a US map showing the apology laws by state.1

Do apology statutes and apologies reduce liability?

The positive aspects of apology include personal, psychological, and emotional benefits to both the one apologizing and the one receiving the apology. It also may have financial benefits to health care providers.4 The assumption has been, and there has been some evidence for the proposition, that apologies reduce the possibility of malpractice claims. That is one of the reasons that institutions may have formal apology policies. Indeed, there is evidence that apologies reduce financial awards to patients, as manifest in the states of Pennsylvania and Kentucky.4 Apologies appear to reduce patient anger and can open the door to better communication with the provider. There is evidence that some kinds of apologies tend to diminish blame and make the injured patient less likely to pursue litigation.10 The conclusion from these studies might be that honest and open communication serves to decrease the incidence of medical malpractice lawsuit initiation and that honesty is the best policy.

It is important to note the difference, however, between apologies (or institutional apology policies) and apology laws. There is some evidence that apology and institutional apology policies may reduce malpractice claims or losses.17,18 On the other hand, the studies of apology laws have not found that these laws have much impact on malpractice rates. An especially good and thorough study of the effect of apology laws nationwide, using insurance claims data, essentially found little net effect of the apology laws.19,20 One other study could find no evidence that apology statutes reduce defensive medicine (so no reduction in provider concerns over liability).21

It should be noted that most studies on medical apology and its effects on malpractice claims generally have looked at the narrow or limited apology statutes (that do not cover expressions of fault or negligence). Few states have the broader statutes, and it is possible that those broader statutes would be more effective in reducing liability. Removing the disincentives to medical apologies is a good thing, but in and of itself it is probably not a liability game changer.

Continue to: Institutional policy and apology...

Institutional policy and apology

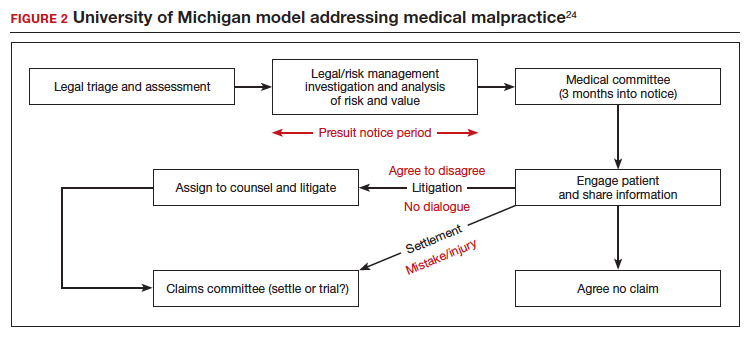

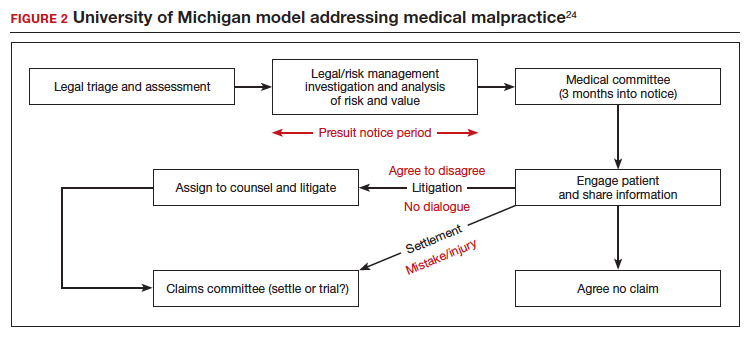

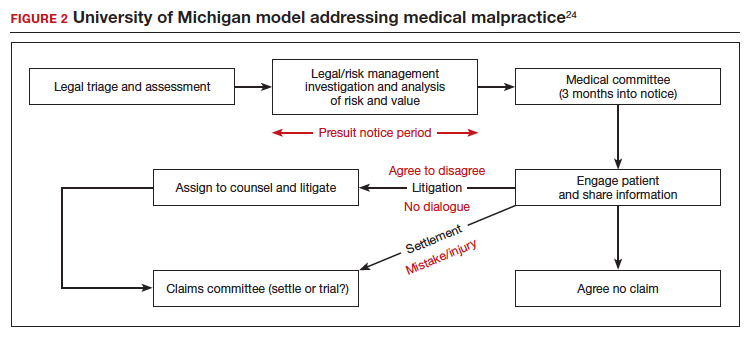

Some institutions have established an “inclusion of apology” strategy for medical errors. These policies appear to have a meaningful effect on reducing medical malpractice costs. These programs commonly include a proactive investigation, disclosure of error, and apologies. Such policies have been studied at the University of Michigan and the Veterans Affairs (VA) Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky. The University of Michigan program resulted in a 60% reduction in compensation costs for medical errors.22 It also cut litigation costs by half.23 The review of the Kentucky VA program also was positive.17 FIGURE 2 illustrates the key features of the Michigan program.24

Conclusions: Effective apologies

Our conclusions, first, are that apologies are important from all perspectives: ethical, medical, and legal. On the other hand, all of the attention given in recent years to apology statutes may have been misplaced, at least if they were intended to be malpractice reform.17

Institutional apology and response programs are likely successful because they are thoughtfully put together, generally based on the best understanding of how injured patients respond to apologies and what it takes to be sincere, and communicate that sincerity, in the apology. What is an effective apology?, “The acceptance of responsibility for having caused harm.” It may, for example, mean accepting some financial responsibility for the harm. It is also important that the apology is conveyed in such a way that it includes an element of self-critical expression.25 Although there are many formulations of the elements of an effective apology, one example is, “(1) acknowledging and accepting responsibility for the offense; (2) expressing remorse with forbearance, sincerity, and honesty; (3) explaining the understanding of the offense; and (4) willingness to make reparations.”26

At the other extreme is a medical professional, after a bad event, trying to engage in a half-hearted, awkward, or insincere apology on an ad hoc and poorly planned basis. Worse still, “when victims perceive apologies to be insincere and designed simply to cool them off, they react with more rather than less indignation.”27 Of course, the “forced apology” may be the worst of all. An instance of this was addressed in a New Zealand study in which providers were “forced” to provide a written apology to a couple (Mr. and Mrs. B) and a separate written apology to Baby B when there was failure to discuss vitamin K administration during the antenatal period when it was indicated.28 Rather than emphasizing required apology in such a case, which can seem hollow and disingenuous, emphasis was placed on the apology providing a “positive-physiological” effect for those harmed, and on strategies that “nurture the development of the moral maturity required for authentic apology.”

The great advantage of institutional or practice-wide policies is that they can be developed in the calm of planning, with good foresight and careful consideration. This is much different from having to come up with some approach in the heat of something having gone wrong. Ultimately, however, apologies are not about liability. They are about caring for, respecting, and communicating with those who are harmed. Apologizing is often the right and professional thing to do.

- Afrassiab Z. Why mediation & “sorry” make sense: apology statutes as a catalyst for change in medical malpractice. J Dispute Resolutions. 2019.

- AMA Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. AMA code of medical ethics’ opinions on patient safety. Virtual Mentor. 2011;13:626-628.

- Saitta N, Hodge SD. Efficacy of a physician’s words of empathy: an overview of state apology laws. J Am Osteopath Assn. 2012;112:302-306.

- Dealing with a medical mistake: Should physicians apologize to patients? Med Economics. November 10, 2013.

- AOA code of ethics. American Osteopathic Association website. http://www.osteopathic.org/inside-aoa/about /leadershipPages/aos-code-of-ethics.aspx. Accessed January 15, 2020.

- You had me at “I’m sorry”: the impact of physicians’ apologies on medical malpractice litigation. Natl Law Review. November 6, 2018. https://www.natlawreview.com /article/you-had-me-i-m-sorry-impact-physicians-apologiesmedical-malpractice-litigation. Accessed February 6, 2020.

- Robbennolt JK. Apologies and medical error. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:376-382.

- Bismark MM. The power of apology. N Z Med J. 2009;122:96-106.

- Witman AB, Park DM, Hardin SB. How do patients want physicians to handle mistakes? A survey of internal medicine patients in an academic setting. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2565-2569.

- Lawthers AG, Localio AR, Laird NM, et al. Physicians’ perceptions of the risk of being sued. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1992;17:463-482.

- Dahan S, Ducard D, Caeymaex L. Apology in cases of medical error disclosure: thoughts based on a preliminary study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181854.

- Halbach JL, Sullivan LL. Teaching medical students about medical errors and patient safety: evaluation of a required curriculum. Acad Med. 2005;80:600-606.

- Nussbaum L. Trial and error: legislating ADR for medical malpractice reform. 2017. Scholarly Works. https://scholars .law.unlv.edu/facpub/1011. Accessed February 7, 2020.

- Cobbs v. Grant, 8 Cal. 3d 229, 104 Cal. Rptr. 505, 502 P.2d 1 (1972).

- Woronka v. Sewall, 320 Mass. 362, 69 N.E.2d 581 (1946).

- Wei M. Doctors, apologies and the law: an analysis and critique of apology law. J Health Law. 2007;40:107-159.

- Kraman SS, Hamm G. Risk management: extreme honesty may be the best policy. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:963-967.

- Liebman CB, Hyman CS. Medical error disclosure, mediation skills, and malpractice litigation: a demonstration project in Pennsylvania. 2005. https://perma.cc/7257-99GU. Accessed February 7, 2020.

- McMichael BJ, Van Horn RL, Viscusi WK. “Sorry” is never enough: how state apology laws fail to reduce medical malpractice liability risk. Stanford Law Rev. 2019;71:341-409.

- Ho B, Liu E. What’s an apology worth? Decomposing the effect of apologies on medical malpractice payments using state apology laws. J Empirical Legal Studies. 2011;8:179-199.

- McMichael BJ. The failure of sorry: an empirical evaluation of apology laws, health care, and medical malpractice. Lewis & Clark Law Rev. 2017. https://law.lclark.edu/live/files/27734- lcb224article3mcmichaelpdf. Accessed February 7, 2020.

- Kachalia A, Kaufman SR, Boothman R, et al. Liability claims and costs before and after implementation of a medical error disclosure program. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:213-221.

- Boothman RC, Blackwell AC, Campbell DA Jr, et al. A better approach to medical malpractice claims? The University of Michigan experience. J Health Life Sci Law. 2009;2:125-159.

- The Michigan model: Medical malpractice and patient safety at Michigan Medicine. University of Michigan website. https:// www.uofmhealth.org/michigan-model-medical-malpracticeand-patient-safety-umhs#summary. Accessed February 7, 2020.

- Mastroianni AC, Mello MM, Sommer S, et al. The flaws in state ‘apology’ and ‘disclosure’ laws dilute their intended impact on malpractice suits. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:1611-1619.

- Davis ER. I’m sorry I’m scared of litigation: evaluating the effectiveness of apology laws. Forum: Tennessee Student Legal J. 2016;3. https://trace.tennessee.edu/forum/vol3/iss1/4/. Accessed February 7, 2020.

- Miller DT. Disrespect and the experience of injustice. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:527-553.

- McLennan S, Walker S, Rich LE. Should health care providers be forced to apologise after things go wrong? J Bioeth Inq. 2014;11:431-435

This is the third and final article in a series focusing on malpractice, liability, and reform. In the first article, we looked at the background on malpractice and reasons malpractice rates have been so high—including large verdicts and lawsuit-prone physicians. In the second article we considered recent experience and developments in malpractice exposure, who is sued and why. Finally, in this third article, we focus on apologies, apology laws, and liability.

“I’m sorry”

In childhood we are all taught the basic courtesies: “please” and “thank you,” and “I’m sorry,” when harm has occurred. Should we as adult health care providers fear the consequences of apologizing? Apologies are a way for clinicians to express empathy; they also serve as a tool to reduce medical malpractice claims.1

Apologies, ethics, and care

The American Medical Association takes the position that a physician has an ethical duty to disclose a harmful error to a patient.2,3 Indeed this approach has been an impetus for states to enact apology laws, which we discuss below. As pointed out in this 2013 article title, “Dealing with a medical mistake: Should physicians apologize to patients?”,4 the legal benefits of any apology are an issue. It is a controversial area in medicine still today, including in obstetrics and gynecology.

“Ethical codes for both M.D.s and D.O.s suggest providers should display honesty and empathy following adverse events and errors.”1,3,5 In addition, the American Medical Association states, “a physician should at all times deal honestly and openly with patients.”2 Concerns about liability that may result from truthful disclosure should not affect the physician’s honesty (TABLE). Increasingly, the law has sided with that principle through apology laws.

Some patients sue to get answers to the “What happened?” and “Why did it happen?” questions.6 They also sometimes are motivated by a desire to help ensure that the same injury does not happen to others. Silence on the part of the clinician may be seen as a lack of sympathy or remorse and patients may fear that other patients will be harmed.1

The relationship between physician and patient involves vulnerability and requires trust. When an injury occurs, the relationship can be injured as well. Barriers to apology in part reflect “the culture of medicine” as well as the “inherent psychological difficulties in facing one’s mistakes and apologizing for them.” However, apology by the provider may result in “effective resolution of disputes related to medical error.”7

The patient’s perspective is critical to this type of outcome, of course. A study from the United Kingdom noted that one-third of patients who experience a medical error have a desire to receive an apology or explanation. Furthermore, patients need assurance that a plan of action to prevent such a future occurrence is in place.8 Surveys reflect that patients desire, or even expect, the physician to acknowledge an error.9 We will see that there is evidence that some kinds of apologies tend to diminish blame and make the injured patient less likely to pursue litigation.10 For instance, Dahan and colleagues completed a study that highlights the “act of apology,” which can be seen as a “language art.”11 Medical schools have recognized the importance of the apology and now incorporate training focused on error disclosure and provision of apologies into the curriculum.12

Continue to: Legal issues and medical apologies...

Legal issues and medical apologies

From a legal standpoint, traditionally, an apology from a physician to a patient could be used against a physician in a medical liability (malpractice) case as proof of negligence.

Statements of interest. Such out-of-court statements ordinarily would be “hearsay” and excluded from evidence; there is, however, an exception to this hearsay rule that allows “confessions” or “statements against interest” to be admissible against the party making the statement. The theory is that when a statement is harmful to the person making it, the person likely thought that it was true, and the statement should be admissible at trial. We do not generally go around confessing to things that are not true. Following an auto crash, if one driver jumps out of the car saying, “I am so sorry I hit you. I was using my cell phone and did not see you stop,” the statement is against the interest of the driver and could be used in court.

As a matter of general legal principle, the same issue can arise in medical practice. Suppose a physician says, “I am so sorry for your injury. We made a mistake in interpreting the data from the monitors.” That sounds a lot like not just an apology but a statement against interest. Malpractice cases generally are based on the claim that a “doctor failed to do what a reasonable provider in the same specialty would have done in a similar situation.”13 An apology may be little more than general sympathy (“I’m sorry to tell you that we have not cured the infection. Unfortunately, that will mean more time in the hospital.”), but it can include a confession of error (“I’m sorry we got the x-ray backward and removed the wrong kidney.”). In the latter kind of apology, courts traditionally have found a “statement against interest.”

The legal consequence of a statement against interest is that the statement may be admitted in court. Such statements do not automatically establish negligence, but they can be powerful evidence when presented to a jury.

Courts have struggled with medical apologies. General sympathy or feelings of regret or compassion do not generally rise to the level of an admission that the physician did not use reasonable care under the circumstances and ordinarily are not admissible. (For further details, we refer you to the case of Cobbs v. Grant.14 Even if a physician said to the patient that he “blamed himself for [the patient] being back in the hospital for a second time,…the statement signifies compassion, or at most, a feeling of remorse, for plaintiff’s ordeal.”) On the other hand, in cases in which a physician in an apology referred to a “careless” mistake or even a “negligent” mistake, courts have allowed it admitted at trial as a statement against interest. (A 1946 case, Woronka v. Sewall, is an example.15 In that case, the physician said to the patient, “My God, what a mess…she had a very hard delivery, and it was a burning shame to get [an injury] on top of it, and it was because of negligence when they were upstairs.”) Some of these cases come down to the provider’s use of a single word: fault, careless, or negligence.

The ambiguity over the legal place of medical apologies in medicine led attorneys to urge medical providers to avoid statements that might even remotely be taken as statements against interest, including real apologies. The confusion over the admissibility of medical apologies led state legislatures to adopt apology laws. These laws essentially limit what statements against interest may be introduced in professional liability cases when a provider has issued a responsibility or apologized.

Continue to: Apology statutes...

Apology statutes

Massachusetts was the first state to enact an apology law—in 1986.1 As of 2019, a clear majority of states have some form of apology statute. “Apology laws are gaining traction,” was the first sentence in a 2012 review on the subject by Saitta and colleagues.3 Only a few (5 states) have “strong” statutes that have broad protection for statements of fault, error, and negligence, as well as sympathy. The other 33 states have statutes that only protect against statements of sympathy.4,16 FIGURE 1 is a US map showing the apology laws by state.1

Do apology statutes and apologies reduce liability?

The positive aspects of apology include personal, psychological, and emotional benefits to both the one apologizing and the one receiving the apology. It also may have financial benefits to health care providers.4 The assumption has been, and there has been some evidence for the proposition, that apologies reduce the possibility of malpractice claims. That is one of the reasons that institutions may have formal apology policies. Indeed, there is evidence that apologies reduce financial awards to patients, as manifest in the states of Pennsylvania and Kentucky.4 Apologies appear to reduce patient anger and can open the door to better communication with the provider. There is evidence that some kinds of apologies tend to diminish blame and make the injured patient less likely to pursue litigation.10 The conclusion from these studies might be that honest and open communication serves to decrease the incidence of medical malpractice lawsuit initiation and that honesty is the best policy.

It is important to note the difference, however, between apologies (or institutional apology policies) and apology laws. There is some evidence that apology and institutional apology policies may reduce malpractice claims or losses.17,18 On the other hand, the studies of apology laws have not found that these laws have much impact on malpractice rates. An especially good and thorough study of the effect of apology laws nationwide, using insurance claims data, essentially found little net effect of the apology laws.19,20 One other study could find no evidence that apology statutes reduce defensive medicine (so no reduction in provider concerns over liability).21

It should be noted that most studies on medical apology and its effects on malpractice claims generally have looked at the narrow or limited apology statutes (that do not cover expressions of fault or negligence). Few states have the broader statutes, and it is possible that those broader statutes would be more effective in reducing liability. Removing the disincentives to medical apologies is a good thing, but in and of itself it is probably not a liability game changer.

Continue to: Institutional policy and apology...

Institutional policy and apology

Some institutions have established an “inclusion of apology” strategy for medical errors. These policies appear to have a meaningful effect on reducing medical malpractice costs. These programs commonly include a proactive investigation, disclosure of error, and apologies. Such policies have been studied at the University of Michigan and the Veterans Affairs (VA) Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky. The University of Michigan program resulted in a 60% reduction in compensation costs for medical errors.22 It also cut litigation costs by half.23 The review of the Kentucky VA program also was positive.17 FIGURE 2 illustrates the key features of the Michigan program.24

Conclusions: Effective apologies

Our conclusions, first, are that apologies are important from all perspectives: ethical, medical, and legal. On the other hand, all of the attention given in recent years to apology statutes may have been misplaced, at least if they were intended to be malpractice reform.17

Institutional apology and response programs are likely successful because they are thoughtfully put together, generally based on the best understanding of how injured patients respond to apologies and what it takes to be sincere, and communicate that sincerity, in the apology. What is an effective apology?, “The acceptance of responsibility for having caused harm.” It may, for example, mean accepting some financial responsibility for the harm. It is also important that the apology is conveyed in such a way that it includes an element of self-critical expression.25 Although there are many formulations of the elements of an effective apology, one example is, “(1) acknowledging and accepting responsibility for the offense; (2) expressing remorse with forbearance, sincerity, and honesty; (3) explaining the understanding of the offense; and (4) willingness to make reparations.”26

At the other extreme is a medical professional, after a bad event, trying to engage in a half-hearted, awkward, or insincere apology on an ad hoc and poorly planned basis. Worse still, “when victims perceive apologies to be insincere and designed simply to cool them off, they react with more rather than less indignation.”27 Of course, the “forced apology” may be the worst of all. An instance of this was addressed in a New Zealand study in which providers were “forced” to provide a written apology to a couple (Mr. and Mrs. B) and a separate written apology to Baby B when there was failure to discuss vitamin K administration during the antenatal period when it was indicated.28 Rather than emphasizing required apology in such a case, which can seem hollow and disingenuous, emphasis was placed on the apology providing a “positive-physiological” effect for those harmed, and on strategies that “nurture the development of the moral maturity required for authentic apology.”

The great advantage of institutional or practice-wide policies is that they can be developed in the calm of planning, with good foresight and careful consideration. This is much different from having to come up with some approach in the heat of something having gone wrong. Ultimately, however, apologies are not about liability. They are about caring for, respecting, and communicating with those who are harmed. Apologizing is often the right and professional thing to do.

This is the third and final article in a series focusing on malpractice, liability, and reform. In the first article, we looked at the background on malpractice and reasons malpractice rates have been so high—including large verdicts and lawsuit-prone physicians. In the second article we considered recent experience and developments in malpractice exposure, who is sued and why. Finally, in this third article, we focus on apologies, apology laws, and liability.

“I’m sorry”

In childhood we are all taught the basic courtesies: “please” and “thank you,” and “I’m sorry,” when harm has occurred. Should we as adult health care providers fear the consequences of apologizing? Apologies are a way for clinicians to express empathy; they also serve as a tool to reduce medical malpractice claims.1

Apologies, ethics, and care

The American Medical Association takes the position that a physician has an ethical duty to disclose a harmful error to a patient.2,3 Indeed this approach has been an impetus for states to enact apology laws, which we discuss below. As pointed out in this 2013 article title, “Dealing with a medical mistake: Should physicians apologize to patients?”,4 the legal benefits of any apology are an issue. It is a controversial area in medicine still today, including in obstetrics and gynecology.

“Ethical codes for both M.D.s and D.O.s suggest providers should display honesty and empathy following adverse events and errors.”1,3,5 In addition, the American Medical Association states, “a physician should at all times deal honestly and openly with patients.”2 Concerns about liability that may result from truthful disclosure should not affect the physician’s honesty (TABLE). Increasingly, the law has sided with that principle through apology laws.

Some patients sue to get answers to the “What happened?” and “Why did it happen?” questions.6 They also sometimes are motivated by a desire to help ensure that the same injury does not happen to others. Silence on the part of the clinician may be seen as a lack of sympathy or remorse and patients may fear that other patients will be harmed.1

The relationship between physician and patient involves vulnerability and requires trust. When an injury occurs, the relationship can be injured as well. Barriers to apology in part reflect “the culture of medicine” as well as the “inherent psychological difficulties in facing one’s mistakes and apologizing for them.” However, apology by the provider may result in “effective resolution of disputes related to medical error.”7

The patient’s perspective is critical to this type of outcome, of course. A study from the United Kingdom noted that one-third of patients who experience a medical error have a desire to receive an apology or explanation. Furthermore, patients need assurance that a plan of action to prevent such a future occurrence is in place.8 Surveys reflect that patients desire, or even expect, the physician to acknowledge an error.9 We will see that there is evidence that some kinds of apologies tend to diminish blame and make the injured patient less likely to pursue litigation.10 For instance, Dahan and colleagues completed a study that highlights the “act of apology,” which can be seen as a “language art.”11 Medical schools have recognized the importance of the apology and now incorporate training focused on error disclosure and provision of apologies into the curriculum.12

Continue to: Legal issues and medical apologies...

Legal issues and medical apologies

From a legal standpoint, traditionally, an apology from a physician to a patient could be used against a physician in a medical liability (malpractice) case as proof of negligence.

Statements of interest. Such out-of-court statements ordinarily would be “hearsay” and excluded from evidence; there is, however, an exception to this hearsay rule that allows “confessions” or “statements against interest” to be admissible against the party making the statement. The theory is that when a statement is harmful to the person making it, the person likely thought that it was true, and the statement should be admissible at trial. We do not generally go around confessing to things that are not true. Following an auto crash, if one driver jumps out of the car saying, “I am so sorry I hit you. I was using my cell phone and did not see you stop,” the statement is against the interest of the driver and could be used in court.

As a matter of general legal principle, the same issue can arise in medical practice. Suppose a physician says, “I am so sorry for your injury. We made a mistake in interpreting the data from the monitors.” That sounds a lot like not just an apology but a statement against interest. Malpractice cases generally are based on the claim that a “doctor failed to do what a reasonable provider in the same specialty would have done in a similar situation.”13 An apology may be little more than general sympathy (“I’m sorry to tell you that we have not cured the infection. Unfortunately, that will mean more time in the hospital.”), but it can include a confession of error (“I’m sorry we got the x-ray backward and removed the wrong kidney.”). In the latter kind of apology, courts traditionally have found a “statement against interest.”

The legal consequence of a statement against interest is that the statement may be admitted in court. Such statements do not automatically establish negligence, but they can be powerful evidence when presented to a jury.

Courts have struggled with medical apologies. General sympathy or feelings of regret or compassion do not generally rise to the level of an admission that the physician did not use reasonable care under the circumstances and ordinarily are not admissible. (For further details, we refer you to the case of Cobbs v. Grant.14 Even if a physician said to the patient that he “blamed himself for [the patient] being back in the hospital for a second time,…the statement signifies compassion, or at most, a feeling of remorse, for plaintiff’s ordeal.”) On the other hand, in cases in which a physician in an apology referred to a “careless” mistake or even a “negligent” mistake, courts have allowed it admitted at trial as a statement against interest. (A 1946 case, Woronka v. Sewall, is an example.15 In that case, the physician said to the patient, “My God, what a mess…she had a very hard delivery, and it was a burning shame to get [an injury] on top of it, and it was because of negligence when they were upstairs.”) Some of these cases come down to the provider’s use of a single word: fault, careless, or negligence.

The ambiguity over the legal place of medical apologies in medicine led attorneys to urge medical providers to avoid statements that might even remotely be taken as statements against interest, including real apologies. The confusion over the admissibility of medical apologies led state legislatures to adopt apology laws. These laws essentially limit what statements against interest may be introduced in professional liability cases when a provider has issued a responsibility or apologized.

Continue to: Apology statutes...

Apology statutes

Massachusetts was the first state to enact an apology law—in 1986.1 As of 2019, a clear majority of states have some form of apology statute. “Apology laws are gaining traction,” was the first sentence in a 2012 review on the subject by Saitta and colleagues.3 Only a few (5 states) have “strong” statutes that have broad protection for statements of fault, error, and negligence, as well as sympathy. The other 33 states have statutes that only protect against statements of sympathy.4,16 FIGURE 1 is a US map showing the apology laws by state.1

Do apology statutes and apologies reduce liability?

The positive aspects of apology include personal, psychological, and emotional benefits to both the one apologizing and the one receiving the apology. It also may have financial benefits to health care providers.4 The assumption has been, and there has been some evidence for the proposition, that apologies reduce the possibility of malpractice claims. That is one of the reasons that institutions may have formal apology policies. Indeed, there is evidence that apologies reduce financial awards to patients, as manifest in the states of Pennsylvania and Kentucky.4 Apologies appear to reduce patient anger and can open the door to better communication with the provider. There is evidence that some kinds of apologies tend to diminish blame and make the injured patient less likely to pursue litigation.10 The conclusion from these studies might be that honest and open communication serves to decrease the incidence of medical malpractice lawsuit initiation and that honesty is the best policy.

It is important to note the difference, however, between apologies (or institutional apology policies) and apology laws. There is some evidence that apology and institutional apology policies may reduce malpractice claims or losses.17,18 On the other hand, the studies of apology laws have not found that these laws have much impact on malpractice rates. An especially good and thorough study of the effect of apology laws nationwide, using insurance claims data, essentially found little net effect of the apology laws.19,20 One other study could find no evidence that apology statutes reduce defensive medicine (so no reduction in provider concerns over liability).21

It should be noted that most studies on medical apology and its effects on malpractice claims generally have looked at the narrow or limited apology statutes (that do not cover expressions of fault or negligence). Few states have the broader statutes, and it is possible that those broader statutes would be more effective in reducing liability. Removing the disincentives to medical apologies is a good thing, but in and of itself it is probably not a liability game changer.

Continue to: Institutional policy and apology...

Institutional policy and apology

Some institutions have established an “inclusion of apology” strategy for medical errors. These policies appear to have a meaningful effect on reducing medical malpractice costs. These programs commonly include a proactive investigation, disclosure of error, and apologies. Such policies have been studied at the University of Michigan and the Veterans Affairs (VA) Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky. The University of Michigan program resulted in a 60% reduction in compensation costs for medical errors.22 It also cut litigation costs by half.23 The review of the Kentucky VA program also was positive.17 FIGURE 2 illustrates the key features of the Michigan program.24

Conclusions: Effective apologies

Our conclusions, first, are that apologies are important from all perspectives: ethical, medical, and legal. On the other hand, all of the attention given in recent years to apology statutes may have been misplaced, at least if they were intended to be malpractice reform.17

Institutional apology and response programs are likely successful because they are thoughtfully put together, generally based on the best understanding of how injured patients respond to apologies and what it takes to be sincere, and communicate that sincerity, in the apology. What is an effective apology?, “The acceptance of responsibility for having caused harm.” It may, for example, mean accepting some financial responsibility for the harm. It is also important that the apology is conveyed in such a way that it includes an element of self-critical expression.25 Although there are many formulations of the elements of an effective apology, one example is, “(1) acknowledging and accepting responsibility for the offense; (2) expressing remorse with forbearance, sincerity, and honesty; (3) explaining the understanding of the offense; and (4) willingness to make reparations.”26

At the other extreme is a medical professional, after a bad event, trying to engage in a half-hearted, awkward, or insincere apology on an ad hoc and poorly planned basis. Worse still, “when victims perceive apologies to be insincere and designed simply to cool them off, they react with more rather than less indignation.”27 Of course, the “forced apology” may be the worst of all. An instance of this was addressed in a New Zealand study in which providers were “forced” to provide a written apology to a couple (Mr. and Mrs. B) and a separate written apology to Baby B when there was failure to discuss vitamin K administration during the antenatal period when it was indicated.28 Rather than emphasizing required apology in such a case, which can seem hollow and disingenuous, emphasis was placed on the apology providing a “positive-physiological” effect for those harmed, and on strategies that “nurture the development of the moral maturity required for authentic apology.”

The great advantage of institutional or practice-wide policies is that they can be developed in the calm of planning, with good foresight and careful consideration. This is much different from having to come up with some approach in the heat of something having gone wrong. Ultimately, however, apologies are not about liability. They are about caring for, respecting, and communicating with those who are harmed. Apologizing is often the right and professional thing to do.

- Afrassiab Z. Why mediation & “sorry” make sense: apology statutes as a catalyst for change in medical malpractice. J Dispute Resolutions. 2019.

- AMA Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. AMA code of medical ethics’ opinions on patient safety. Virtual Mentor. 2011;13:626-628.

- Saitta N, Hodge SD. Efficacy of a physician’s words of empathy: an overview of state apology laws. J Am Osteopath Assn. 2012;112:302-306.

- Dealing with a medical mistake: Should physicians apologize to patients? Med Economics. November 10, 2013.

- AOA code of ethics. American Osteopathic Association website. http://www.osteopathic.org/inside-aoa/about /leadershipPages/aos-code-of-ethics.aspx. Accessed January 15, 2020.

- You had me at “I’m sorry”: the impact of physicians’ apologies on medical malpractice litigation. Natl Law Review. November 6, 2018. https://www.natlawreview.com /article/you-had-me-i-m-sorry-impact-physicians-apologiesmedical-malpractice-litigation. Accessed February 6, 2020.

- Robbennolt JK. Apologies and medical error. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:376-382.

- Bismark MM. The power of apology. N Z Med J. 2009;122:96-106.

- Witman AB, Park DM, Hardin SB. How do patients want physicians to handle mistakes? A survey of internal medicine patients in an academic setting. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2565-2569.

- Lawthers AG, Localio AR, Laird NM, et al. Physicians’ perceptions of the risk of being sued. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1992;17:463-482.

- Dahan S, Ducard D, Caeymaex L. Apology in cases of medical error disclosure: thoughts based on a preliminary study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181854.

- Halbach JL, Sullivan LL. Teaching medical students about medical errors and patient safety: evaluation of a required curriculum. Acad Med. 2005;80:600-606.

- Nussbaum L. Trial and error: legislating ADR for medical malpractice reform. 2017. Scholarly Works. https://scholars .law.unlv.edu/facpub/1011. Accessed February 7, 2020.

- Cobbs v. Grant, 8 Cal. 3d 229, 104 Cal. Rptr. 505, 502 P.2d 1 (1972).

- Woronka v. Sewall, 320 Mass. 362, 69 N.E.2d 581 (1946).

- Wei M. Doctors, apologies and the law: an analysis and critique of apology law. J Health Law. 2007;40:107-159.

- Kraman SS, Hamm G. Risk management: extreme honesty may be the best policy. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:963-967.

- Liebman CB, Hyman CS. Medical error disclosure, mediation skills, and malpractice litigation: a demonstration project in Pennsylvania. 2005. https://perma.cc/7257-99GU. Accessed February 7, 2020.

- McMichael BJ, Van Horn RL, Viscusi WK. “Sorry” is never enough: how state apology laws fail to reduce medical malpractice liability risk. Stanford Law Rev. 2019;71:341-409.

- Ho B, Liu E. What’s an apology worth? Decomposing the effect of apologies on medical malpractice payments using state apology laws. J Empirical Legal Studies. 2011;8:179-199.

- McMichael BJ. The failure of sorry: an empirical evaluation of apology laws, health care, and medical malpractice. Lewis & Clark Law Rev. 2017. https://law.lclark.edu/live/files/27734- lcb224article3mcmichaelpdf. Accessed February 7, 2020.

- Kachalia A, Kaufman SR, Boothman R, et al. Liability claims and costs before and after implementation of a medical error disclosure program. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:213-221.

- Boothman RC, Blackwell AC, Campbell DA Jr, et al. A better approach to medical malpractice claims? The University of Michigan experience. J Health Life Sci Law. 2009;2:125-159.

- The Michigan model: Medical malpractice and patient safety at Michigan Medicine. University of Michigan website. https:// www.uofmhealth.org/michigan-model-medical-malpracticeand-patient-safety-umhs#summary. Accessed February 7, 2020.

- Mastroianni AC, Mello MM, Sommer S, et al. The flaws in state ‘apology’ and ‘disclosure’ laws dilute their intended impact on malpractice suits. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:1611-1619.

- Davis ER. I’m sorry I’m scared of litigation: evaluating the effectiveness of apology laws. Forum: Tennessee Student Legal J. 2016;3. https://trace.tennessee.edu/forum/vol3/iss1/4/. Accessed February 7, 2020.

- Miller DT. Disrespect and the experience of injustice. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:527-553.

- McLennan S, Walker S, Rich LE. Should health care providers be forced to apologise after things go wrong? J Bioeth Inq. 2014;11:431-435

- Afrassiab Z. Why mediation & “sorry” make sense: apology statutes as a catalyst for change in medical malpractice. J Dispute Resolutions. 2019.

- AMA Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. AMA code of medical ethics’ opinions on patient safety. Virtual Mentor. 2011;13:626-628.