User login

Mandatory reporting laws

Question: You are moonlighting in the emergency department and have just finished treating a 5-year-old boy with an apparent Colles’ fracture, who was accompanied by his mother with bruises on her face. Her exam revealed additional bruises over her abdominal wall. The mother said they accidentally tripped and fell down the stairs, and spontaneously denied any acts of violence in the family.

Given this scenario, which of the following is best?

A. You suspect both child and spousal abuse, but lack sufficient evidence to report the incident.

B. Failure to report based on reasonable suspicion alone may amount to a criminal offense punishable by possible imprisonment.

C. You may face a potential malpractice lawsuit if subsequent injuries caused by abuse could have been prevented had you reported.

D. Mandatory reporting laws apply not only to abuse of children and spouses, but also of the elderly and other vulnerable adults.

E. All are correct except A.

Answer: E. All doctors, especially those working in emergency departments, treat injuries on a regular basis. Accidents probably account for the majority of these injuries, but the most pernicious are those caused by willful abuse or neglect. Such conduct, believed to be widespread and underrecognized, victimizes children, women, the elderly, and other vulnerable groups.

Mandatory reporting laws arose from the need to identify and prevent these activities that cause serious harm and loss of lives. Physicians and other health care workers are in a prime position to diagnose or raise the suspicion of abuse and neglect. This article focuses on laws that mandate physician reporting of such behavior. Not addressed are other reportable situations such as certain infectious diseases, gunshot wounds, threats to third parties, and so on.

Child abuse

The best-known example of a mandatory reporting law relates to child abuse, which is broadly defined as when a parent or caretaker emotionally, physically, or sexually abuses, neglects, or abandons a child. Child abuse laws are intended to protect children from serious harm without abridging parental discipline of their children.

Cases of child abuse are pervasive; four or five children are tragically killed by abuse or neglect every day, and each year, some 6 million children are reported as victims of child abuse. Henry Kempe’s studies on the “battered child syndrome” in 1962 served to underscore the physician’s role in exposing child maltreatment, and 1973 saw the enactment of the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, which set standards for mandatory reporting as a condition for federal funding.

All U.S. states have statutes identifying persons who are required to report suspected child maltreatment to an appropriate agency, such as child protective services. Reasonable suspicion, without need for proof, is sufficient to trigger the mandatory reporting duty. A summary of the general reporting requirements, as well as each state’s key statutory features, are available at Child Welfare Information Gateway.1

Bruises, fractures, and burns are recurring examples of injuries resulting from child abuse, but there are many others, including severe emotional harm, which is an important consequence. Clues to abuse include a child’s fearful and anxious demeanor, wearing clothes to hide injuries, and inappropriate sexual conduct.2 The perpetrators and/or complicit parties typically blame an innocent home accident for the victim’s injuries to mislead the health care provider.

Elder abuse

Elder abuse is broadly construed to include physical, sexual, and psychological abuse, as well as financial exploitation and caregiver neglect.3 It is a serious problem in the United States, estimated in 2008 to affect 1 in 10 elders. The figure is likely an underestimate, because many elderly victims are afraid or unwilling to lodge a complaint against the abuser whom they love and may depend upon.4

The law, which protects the “elderly” (e.g., those aged 62 years or older in Hawaii), may also be extended to other younger vulnerable adults, who because of an impairment, are unable to 1) communicate or make responsible decisions to manage one’s own care or resources, 2) carry out or arrange for essential activities of daily living, or 3) protect one’s self from abuse.5

The law mandates reporting where there is reason to believe abuse has occurred or the vulnerable adult is in danger of abuse if immediate action is not taken. Reporting statutes for elder abuse vary somewhat on the identity of mandated reporters (health care providers are always included), the victim’s mental capacity, dwelling place (home or in an assisted-living facility), and type of purported activity that warrants reporting.

Domestic violence

As defined by the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, “Domestic violence is the willful intimidation, physical assault, battery, sexual assault, and/or other abusive behavior as part of a systematic pattern of power and control perpetrated by one intimate partner against another. ... The frequency and severity of domestic violence can vary dramatically; however, the one constant component of domestic violence is one partner’s consistent efforts to maintain power and control over the other.”6 Domestic violence is said to have reached epidemic proportions, with one in four women experiencing it at some point in her life.

Virtually all states mandate the reporting of domestic violence by health care providers if there is a reasonable suspicion that observed patient injuries are the result of physical abuse.7 California, for example, requires the provider to call local law enforcement as soon as possible or to send in a written report within 48 hours.

There may be exceptions to required reporting, as when an adult victim withholds consent but accepts victim referral services. State laws encourage but do not always require that the health care provider inform the patient about the report, but federal law dictates otherwise unless this puts the patient at risk. Hawaii’s domestic violence laws were originally enacted to deter spousal abuse, but they now also protect other household members.8

Any individual who assumes a duty or responsibility pursuant to all of these reporting laws is immunized from criminal or civil liability. On the other hand, a mandated reporter who knowingly fails to report an incident or who willfully prevents another person from reporting such an incident commits a criminal offence.

In the case of a physician, there is the added risk of a malpractice lawsuit based on “violation of statute” (breach of a legal duty), should another injury occur down the road that was arguably preventable by his or her failure to report.

Experts generally believe that mandatory reporting laws are important in identifying child maltreatment. However, it has been asserted that despite a 5-decade history of mandatory reporting, no clear endpoints attest to the efficacy of this approach, and it is argued that no data exist to demonstrate that incremental increases in reporting have contributed to child safety.

Particularly challenging are attempts at impact comparisons between states with different policies. A number of countries, including the United Kingdom, do not have mandatory reporting laws and regulate reporting by professional societies.9

In addition, some critics of mandatory reporting raise concerns surrounding law enforcement showing up at the victim’s house to question the family about abuse, or to make an arrest or issue warnings. They posit that when the behavior of an abuser is under scrutiny, this can paradoxically create a potentially more dangerous environment for the patient-victim, whom the perpetrator now considers to have betrayed his or her trust. Others bemoan that revealing patient confidences violates the physician’s ethical code.

However, the intolerable incidence of violence against the vulnerable has properly made mandatory reporting the law of the land. Although the criminal penalty is currently light for failure to report, there is a move toward increasing its severity. Hawaii, for example, recently introduced Senate Bill 2477 that makes nonreporting by those required to do so a Class C felony punishable by up to 5 years in prison. The offense currently is a petty misdemeanor punishable by up to 30 days in jail.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. Child Welfare Information Gateway (2016). Mandatory reporters of child abuse and neglect. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau. Available at www.childwelfare.gov; email: [email protected]; phone: 800-394-3366.

2. Available at www.childwelfare.gov/topics/can.

3. Available at www.justice.gov/elderjustice/elder-justice-statutes-0.

4. Available at www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/elderabuse/index.html.

5. Hawaii Revised Statutes, Sec. 346-222, 346-224, 346-250, 412:3-114.5.

6. Available at ncadv.org.

7. Ann Emerg Med. 2002 Jan;39(1):56-60.

8. Hawaii Revised Statutes, Sec. 709-906.

9. Pediatrics. 2017 Apr;139(4). pii: e20163511.

Question: You are moonlighting in the emergency department and have just finished treating a 5-year-old boy with an apparent Colles’ fracture, who was accompanied by his mother with bruises on her face. Her exam revealed additional bruises over her abdominal wall. The mother said they accidentally tripped and fell down the stairs, and spontaneously denied any acts of violence in the family.

Given this scenario, which of the following is best?

A. You suspect both child and spousal abuse, but lack sufficient evidence to report the incident.

B. Failure to report based on reasonable suspicion alone may amount to a criminal offense punishable by possible imprisonment.

C. You may face a potential malpractice lawsuit if subsequent injuries caused by abuse could have been prevented had you reported.

D. Mandatory reporting laws apply not only to abuse of children and spouses, but also of the elderly and other vulnerable adults.

E. All are correct except A.

Answer: E. All doctors, especially those working in emergency departments, treat injuries on a regular basis. Accidents probably account for the majority of these injuries, but the most pernicious are those caused by willful abuse or neglect. Such conduct, believed to be widespread and underrecognized, victimizes children, women, the elderly, and other vulnerable groups.

Mandatory reporting laws arose from the need to identify and prevent these activities that cause serious harm and loss of lives. Physicians and other health care workers are in a prime position to diagnose or raise the suspicion of abuse and neglect. This article focuses on laws that mandate physician reporting of such behavior. Not addressed are other reportable situations such as certain infectious diseases, gunshot wounds, threats to third parties, and so on.

Child abuse

The best-known example of a mandatory reporting law relates to child abuse, which is broadly defined as when a parent or caretaker emotionally, physically, or sexually abuses, neglects, or abandons a child. Child abuse laws are intended to protect children from serious harm without abridging parental discipline of their children.

Cases of child abuse are pervasive; four or five children are tragically killed by abuse or neglect every day, and each year, some 6 million children are reported as victims of child abuse. Henry Kempe’s studies on the “battered child syndrome” in 1962 served to underscore the physician’s role in exposing child maltreatment, and 1973 saw the enactment of the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, which set standards for mandatory reporting as a condition for federal funding.

All U.S. states have statutes identifying persons who are required to report suspected child maltreatment to an appropriate agency, such as child protective services. Reasonable suspicion, without need for proof, is sufficient to trigger the mandatory reporting duty. A summary of the general reporting requirements, as well as each state’s key statutory features, are available at Child Welfare Information Gateway.1

Bruises, fractures, and burns are recurring examples of injuries resulting from child abuse, but there are many others, including severe emotional harm, which is an important consequence. Clues to abuse include a child’s fearful and anxious demeanor, wearing clothes to hide injuries, and inappropriate sexual conduct.2 The perpetrators and/or complicit parties typically blame an innocent home accident for the victim’s injuries to mislead the health care provider.

Elder abuse

Elder abuse is broadly construed to include physical, sexual, and psychological abuse, as well as financial exploitation and caregiver neglect.3 It is a serious problem in the United States, estimated in 2008 to affect 1 in 10 elders. The figure is likely an underestimate, because many elderly victims are afraid or unwilling to lodge a complaint against the abuser whom they love and may depend upon.4

The law, which protects the “elderly” (e.g., those aged 62 years or older in Hawaii), may also be extended to other younger vulnerable adults, who because of an impairment, are unable to 1) communicate or make responsible decisions to manage one’s own care or resources, 2) carry out or arrange for essential activities of daily living, or 3) protect one’s self from abuse.5

The law mandates reporting where there is reason to believe abuse has occurred or the vulnerable adult is in danger of abuse if immediate action is not taken. Reporting statutes for elder abuse vary somewhat on the identity of mandated reporters (health care providers are always included), the victim’s mental capacity, dwelling place (home or in an assisted-living facility), and type of purported activity that warrants reporting.

Domestic violence

As defined by the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, “Domestic violence is the willful intimidation, physical assault, battery, sexual assault, and/or other abusive behavior as part of a systematic pattern of power and control perpetrated by one intimate partner against another. ... The frequency and severity of domestic violence can vary dramatically; however, the one constant component of domestic violence is one partner’s consistent efforts to maintain power and control over the other.”6 Domestic violence is said to have reached epidemic proportions, with one in four women experiencing it at some point in her life.

Virtually all states mandate the reporting of domestic violence by health care providers if there is a reasonable suspicion that observed patient injuries are the result of physical abuse.7 California, for example, requires the provider to call local law enforcement as soon as possible or to send in a written report within 48 hours.

There may be exceptions to required reporting, as when an adult victim withholds consent but accepts victim referral services. State laws encourage but do not always require that the health care provider inform the patient about the report, but federal law dictates otherwise unless this puts the patient at risk. Hawaii’s domestic violence laws were originally enacted to deter spousal abuse, but they now also protect other household members.8

Any individual who assumes a duty or responsibility pursuant to all of these reporting laws is immunized from criminal or civil liability. On the other hand, a mandated reporter who knowingly fails to report an incident or who willfully prevents another person from reporting such an incident commits a criminal offence.

In the case of a physician, there is the added risk of a malpractice lawsuit based on “violation of statute” (breach of a legal duty), should another injury occur down the road that was arguably preventable by his or her failure to report.

Experts generally believe that mandatory reporting laws are important in identifying child maltreatment. However, it has been asserted that despite a 5-decade history of mandatory reporting, no clear endpoints attest to the efficacy of this approach, and it is argued that no data exist to demonstrate that incremental increases in reporting have contributed to child safety.

Particularly challenging are attempts at impact comparisons between states with different policies. A number of countries, including the United Kingdom, do not have mandatory reporting laws and regulate reporting by professional societies.9

In addition, some critics of mandatory reporting raise concerns surrounding law enforcement showing up at the victim’s house to question the family about abuse, or to make an arrest or issue warnings. They posit that when the behavior of an abuser is under scrutiny, this can paradoxically create a potentially more dangerous environment for the patient-victim, whom the perpetrator now considers to have betrayed his or her trust. Others bemoan that revealing patient confidences violates the physician’s ethical code.

However, the intolerable incidence of violence against the vulnerable has properly made mandatory reporting the law of the land. Although the criminal penalty is currently light for failure to report, there is a move toward increasing its severity. Hawaii, for example, recently introduced Senate Bill 2477 that makes nonreporting by those required to do so a Class C felony punishable by up to 5 years in prison. The offense currently is a petty misdemeanor punishable by up to 30 days in jail.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. Child Welfare Information Gateway (2016). Mandatory reporters of child abuse and neglect. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau. Available at www.childwelfare.gov; email: [email protected]; phone: 800-394-3366.

2. Available at www.childwelfare.gov/topics/can.

3. Available at www.justice.gov/elderjustice/elder-justice-statutes-0.

4. Available at www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/elderabuse/index.html.

5. Hawaii Revised Statutes, Sec. 346-222, 346-224, 346-250, 412:3-114.5.

6. Available at ncadv.org.

7. Ann Emerg Med. 2002 Jan;39(1):56-60.

8. Hawaii Revised Statutes, Sec. 709-906.

9. Pediatrics. 2017 Apr;139(4). pii: e20163511.

Question: You are moonlighting in the emergency department and have just finished treating a 5-year-old boy with an apparent Colles’ fracture, who was accompanied by his mother with bruises on her face. Her exam revealed additional bruises over her abdominal wall. The mother said they accidentally tripped and fell down the stairs, and spontaneously denied any acts of violence in the family.

Given this scenario, which of the following is best?

A. You suspect both child and spousal abuse, but lack sufficient evidence to report the incident.

B. Failure to report based on reasonable suspicion alone may amount to a criminal offense punishable by possible imprisonment.

C. You may face a potential malpractice lawsuit if subsequent injuries caused by abuse could have been prevented had you reported.

D. Mandatory reporting laws apply not only to abuse of children and spouses, but also of the elderly and other vulnerable adults.

E. All are correct except A.

Answer: E. All doctors, especially those working in emergency departments, treat injuries on a regular basis. Accidents probably account for the majority of these injuries, but the most pernicious are those caused by willful abuse or neglect. Such conduct, believed to be widespread and underrecognized, victimizes children, women, the elderly, and other vulnerable groups.

Mandatory reporting laws arose from the need to identify and prevent these activities that cause serious harm and loss of lives. Physicians and other health care workers are in a prime position to diagnose or raise the suspicion of abuse and neglect. This article focuses on laws that mandate physician reporting of such behavior. Not addressed are other reportable situations such as certain infectious diseases, gunshot wounds, threats to third parties, and so on.

Child abuse

The best-known example of a mandatory reporting law relates to child abuse, which is broadly defined as when a parent or caretaker emotionally, physically, or sexually abuses, neglects, or abandons a child. Child abuse laws are intended to protect children from serious harm without abridging parental discipline of their children.

Cases of child abuse are pervasive; four or five children are tragically killed by abuse or neglect every day, and each year, some 6 million children are reported as victims of child abuse. Henry Kempe’s studies on the “battered child syndrome” in 1962 served to underscore the physician’s role in exposing child maltreatment, and 1973 saw the enactment of the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, which set standards for mandatory reporting as a condition for federal funding.

All U.S. states have statutes identifying persons who are required to report suspected child maltreatment to an appropriate agency, such as child protective services. Reasonable suspicion, without need for proof, is sufficient to trigger the mandatory reporting duty. A summary of the general reporting requirements, as well as each state’s key statutory features, are available at Child Welfare Information Gateway.1

Bruises, fractures, and burns are recurring examples of injuries resulting from child abuse, but there are many others, including severe emotional harm, which is an important consequence. Clues to abuse include a child’s fearful and anxious demeanor, wearing clothes to hide injuries, and inappropriate sexual conduct.2 The perpetrators and/or complicit parties typically blame an innocent home accident for the victim’s injuries to mislead the health care provider.

Elder abuse

Elder abuse is broadly construed to include physical, sexual, and psychological abuse, as well as financial exploitation and caregiver neglect.3 It is a serious problem in the United States, estimated in 2008 to affect 1 in 10 elders. The figure is likely an underestimate, because many elderly victims are afraid or unwilling to lodge a complaint against the abuser whom they love and may depend upon.4

The law, which protects the “elderly” (e.g., those aged 62 years or older in Hawaii), may also be extended to other younger vulnerable adults, who because of an impairment, are unable to 1) communicate or make responsible decisions to manage one’s own care or resources, 2) carry out or arrange for essential activities of daily living, or 3) protect one’s self from abuse.5

The law mandates reporting where there is reason to believe abuse has occurred or the vulnerable adult is in danger of abuse if immediate action is not taken. Reporting statutes for elder abuse vary somewhat on the identity of mandated reporters (health care providers are always included), the victim’s mental capacity, dwelling place (home or in an assisted-living facility), and type of purported activity that warrants reporting.

Domestic violence

As defined by the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, “Domestic violence is the willful intimidation, physical assault, battery, sexual assault, and/or other abusive behavior as part of a systematic pattern of power and control perpetrated by one intimate partner against another. ... The frequency and severity of domestic violence can vary dramatically; however, the one constant component of domestic violence is one partner’s consistent efforts to maintain power and control over the other.”6 Domestic violence is said to have reached epidemic proportions, with one in four women experiencing it at some point in her life.

Virtually all states mandate the reporting of domestic violence by health care providers if there is a reasonable suspicion that observed patient injuries are the result of physical abuse.7 California, for example, requires the provider to call local law enforcement as soon as possible or to send in a written report within 48 hours.

There may be exceptions to required reporting, as when an adult victim withholds consent but accepts victim referral services. State laws encourage but do not always require that the health care provider inform the patient about the report, but federal law dictates otherwise unless this puts the patient at risk. Hawaii’s domestic violence laws were originally enacted to deter spousal abuse, but they now also protect other household members.8

Any individual who assumes a duty or responsibility pursuant to all of these reporting laws is immunized from criminal or civil liability. On the other hand, a mandated reporter who knowingly fails to report an incident or who willfully prevents another person from reporting such an incident commits a criminal offence.

In the case of a physician, there is the added risk of a malpractice lawsuit based on “violation of statute” (breach of a legal duty), should another injury occur down the road that was arguably preventable by his or her failure to report.

Experts generally believe that mandatory reporting laws are important in identifying child maltreatment. However, it has been asserted that despite a 5-decade history of mandatory reporting, no clear endpoints attest to the efficacy of this approach, and it is argued that no data exist to demonstrate that incremental increases in reporting have contributed to child safety.

Particularly challenging are attempts at impact comparisons between states with different policies. A number of countries, including the United Kingdom, do not have mandatory reporting laws and regulate reporting by professional societies.9

In addition, some critics of mandatory reporting raise concerns surrounding law enforcement showing up at the victim’s house to question the family about abuse, or to make an arrest or issue warnings. They posit that when the behavior of an abuser is under scrutiny, this can paradoxically create a potentially more dangerous environment for the patient-victim, whom the perpetrator now considers to have betrayed his or her trust. Others bemoan that revealing patient confidences violates the physician’s ethical code.

However, the intolerable incidence of violence against the vulnerable has properly made mandatory reporting the law of the land. Although the criminal penalty is currently light for failure to report, there is a move toward increasing its severity. Hawaii, for example, recently introduced Senate Bill 2477 that makes nonreporting by those required to do so a Class C felony punishable by up to 5 years in prison. The offense currently is a petty misdemeanor punishable by up to 30 days in jail.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. Child Welfare Information Gateway (2016). Mandatory reporters of child abuse and neglect. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau. Available at www.childwelfare.gov; email: [email protected]; phone: 800-394-3366.

2. Available at www.childwelfare.gov/topics/can.

3. Available at www.justice.gov/elderjustice/elder-justice-statutes-0.

4. Available at www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/elderabuse/index.html.

5. Hawaii Revised Statutes, Sec. 346-222, 346-224, 346-250, 412:3-114.5.

6. Available at ncadv.org.

7. Ann Emerg Med. 2002 Jan;39(1):56-60.

8. Hawaii Revised Statutes, Sec. 709-906.

9. Pediatrics. 2017 Apr;139(4). pii: e20163511.

Rural suicidality and resilience

Overall U.S. life expectancy decreased from 78.7 years to 78.6 years from 2016 to 2017. Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention noted that, along with drug overdose deaths, suicide also drove the decrease in average lifespan over that time period. Addressing suicide in rural communities presents unique challenges.

Dr. Bonham is vice chair of community behavioral health in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Dr. Kriechman is a child, adolescent and family psychiatrist at the university, where he serves as principal investigator on ASPYR – Alliance-building for Suicide Prevention & Youth Resilience.

You can hear more on resilience and suicide from the MDedge Psychcast in these past episodes:

- Find the MDedge Psychcast where ever you listen:

Overall U.S. life expectancy decreased from 78.7 years to 78.6 years from 2016 to 2017. Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention noted that, along with drug overdose deaths, suicide also drove the decrease in average lifespan over that time period. Addressing suicide in rural communities presents unique challenges.

Dr. Bonham is vice chair of community behavioral health in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Dr. Kriechman is a child, adolescent and family psychiatrist at the university, where he serves as principal investigator on ASPYR – Alliance-building for Suicide Prevention & Youth Resilience.

You can hear more on resilience and suicide from the MDedge Psychcast in these past episodes:

- Find the MDedge Psychcast where ever you listen:

Overall U.S. life expectancy decreased from 78.7 years to 78.6 years from 2016 to 2017. Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention noted that, along with drug overdose deaths, suicide also drove the decrease in average lifespan over that time period. Addressing suicide in rural communities presents unique challenges.

Dr. Bonham is vice chair of community behavioral health in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Dr. Kriechman is a child, adolescent and family psychiatrist at the university, where he serves as principal investigator on ASPYR – Alliance-building for Suicide Prevention & Youth Resilience.

You can hear more on resilience and suicide from the MDedge Psychcast in these past episodes:

- Find the MDedge Psychcast where ever you listen:

Courts block Trump from eroding contraceptive mandate

Federal judges have blocked the Trump administration from weakening the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate in two separate orders that bar the President from letting more entities claim exemptions.

On Jan. 14, U.S. District Court Judge Wendy Beetlestone for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania issued a temporary nationwide ban on two rules that would have allowed an expanded group of employers and insurers to object to providing contraception coverage on either religious or moral grounds. The regulations, announced Nov. 7, 2018, were scheduled to take effect Jan. 14. The day before, U.S. District Judge Haywood Gilliam for the Northern District of California issued a similar temporary ban, but his order applied only to the 13 plaintiff states in the case, plus the District of Columbia.

While Pennsylvania and New Jersey are the only plaintiffs in the Judge Beetlestone case, she wrote that a nationwide injunction is required to protect numerous citizens from losing contraceptive coverage and resulting in “significant, direct, and proprietary harm” to states in the form of increased state-funded contraceptive services and increased costs associated with unintended pregnancies. Judge Gilliam provided similar reasoning in his Jan. 13 order, writing that the 13 plaintiff states have proven that rules promulgated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services would cause women to lose employer-sponsored contraceptive coverage, resulting in economic harm to the states.

California Attorney General Xavier Becerra, a plaintiff in the second case, said Judge Gilliam’s ruling will stop the Trump administration from denying millions of women and families access to co-pay birth control guaranteed by the Affordable Care Act.

“The law couldn’t be clearer – employers have no business interfering in women’s health care decisions,” Mr. Becerra said in the statement. “[The] court ruling stops another attempt by the Trump administration to trample on women’s access to basic reproductive care.”

At press time, the Trump administration officials had responded publicly to the court orders. The administration previously said the new policies would “better balance the government’s interest in promoting coverage for contraceptive and sterilization services with the government’s interests in providing conscience protections for entities with sincerely held moral convictions.” HHS estimated that the rules would affect no more than 200 employers.

Mark Rienzi, president of the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, a legal institute that defends religious freedoms, expressed disappointment at the court orders. Becket represents the Little Sisters of the Poor, an organization that has been fighting for several years for an exemption to the contraceptive mandate.

“Government bureaucrats should not be allowed to threaten the rights of the Little Sisters of the Poor to serve according to their Catholic beliefs,” Mr. Rienzi said in a statement. “Now the nuns are forced to keep fighting this unnecessary lawsuit to protect their ability to focus on caring for the poor. We are confident these decisions will be overturned.”

The ACA initially required all employers to cover birth control for employees with no copayments, except for group health plans of religious employers, which were deemed exempt. Those religious employers were primarily churches and other houses of worship. After a number of complaints and legal challenges, the Obama administration created a workaround for nonprofit religious employers to opt out of the mandate.

However, critics argued the process itself was a violation of their religious freedom. The issue led to the case of Zubik v. Burwell, a legal challenge over the mandate exemption that went before the U.S. Supreme Court in March 2016. The issue was never resolved. In May 2016, the Supreme Court vacated the lower court rulings related to Zubik v. Burwell and remanded the case back to the four appeals courts that had originally ruled on the issue.

The Trump administration then announced new rules aimed at broadening exemptions to the ACA’s contraceptive mandate to entities that object to services covered by the mandate on the basis of sincerely held religious beliefs. A second rule would protect nonprofit organizations and small businesses that have nonreligious moral convictions that oppose services covered by the mandate. The religious and moral exemptions would apply to institutions of education, issuers, and individuals, but not to governmental entities.

Thirteen states and the District of Columbia then sued the Trump administration over the rules as well as Pennsylvania and New Jersey in a separate case.

The nationwide ban against the rules will remain in effect while the cases continue through the court system.

Federal judges have blocked the Trump administration from weakening the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate in two separate orders that bar the President from letting more entities claim exemptions.

On Jan. 14, U.S. District Court Judge Wendy Beetlestone for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania issued a temporary nationwide ban on two rules that would have allowed an expanded group of employers and insurers to object to providing contraception coverage on either religious or moral grounds. The regulations, announced Nov. 7, 2018, were scheduled to take effect Jan. 14. The day before, U.S. District Judge Haywood Gilliam for the Northern District of California issued a similar temporary ban, but his order applied only to the 13 plaintiff states in the case, plus the District of Columbia.

While Pennsylvania and New Jersey are the only plaintiffs in the Judge Beetlestone case, she wrote that a nationwide injunction is required to protect numerous citizens from losing contraceptive coverage and resulting in “significant, direct, and proprietary harm” to states in the form of increased state-funded contraceptive services and increased costs associated with unintended pregnancies. Judge Gilliam provided similar reasoning in his Jan. 13 order, writing that the 13 plaintiff states have proven that rules promulgated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services would cause women to lose employer-sponsored contraceptive coverage, resulting in economic harm to the states.

California Attorney General Xavier Becerra, a plaintiff in the second case, said Judge Gilliam’s ruling will stop the Trump administration from denying millions of women and families access to co-pay birth control guaranteed by the Affordable Care Act.

“The law couldn’t be clearer – employers have no business interfering in women’s health care decisions,” Mr. Becerra said in the statement. “[The] court ruling stops another attempt by the Trump administration to trample on women’s access to basic reproductive care.”

At press time, the Trump administration officials had responded publicly to the court orders. The administration previously said the new policies would “better balance the government’s interest in promoting coverage for contraceptive and sterilization services with the government’s interests in providing conscience protections for entities with sincerely held moral convictions.” HHS estimated that the rules would affect no more than 200 employers.

Mark Rienzi, president of the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, a legal institute that defends religious freedoms, expressed disappointment at the court orders. Becket represents the Little Sisters of the Poor, an organization that has been fighting for several years for an exemption to the contraceptive mandate.

“Government bureaucrats should not be allowed to threaten the rights of the Little Sisters of the Poor to serve according to their Catholic beliefs,” Mr. Rienzi said in a statement. “Now the nuns are forced to keep fighting this unnecessary lawsuit to protect their ability to focus on caring for the poor. We are confident these decisions will be overturned.”

The ACA initially required all employers to cover birth control for employees with no copayments, except for group health plans of religious employers, which were deemed exempt. Those religious employers were primarily churches and other houses of worship. After a number of complaints and legal challenges, the Obama administration created a workaround for nonprofit religious employers to opt out of the mandate.

However, critics argued the process itself was a violation of their religious freedom. The issue led to the case of Zubik v. Burwell, a legal challenge over the mandate exemption that went before the U.S. Supreme Court in March 2016. The issue was never resolved. In May 2016, the Supreme Court vacated the lower court rulings related to Zubik v. Burwell and remanded the case back to the four appeals courts that had originally ruled on the issue.

The Trump administration then announced new rules aimed at broadening exemptions to the ACA’s contraceptive mandate to entities that object to services covered by the mandate on the basis of sincerely held religious beliefs. A second rule would protect nonprofit organizations and small businesses that have nonreligious moral convictions that oppose services covered by the mandate. The religious and moral exemptions would apply to institutions of education, issuers, and individuals, but not to governmental entities.

Thirteen states and the District of Columbia then sued the Trump administration over the rules as well as Pennsylvania and New Jersey in a separate case.

The nationwide ban against the rules will remain in effect while the cases continue through the court system.

Federal judges have blocked the Trump administration from weakening the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate in two separate orders that bar the President from letting more entities claim exemptions.

On Jan. 14, U.S. District Court Judge Wendy Beetlestone for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania issued a temporary nationwide ban on two rules that would have allowed an expanded group of employers and insurers to object to providing contraception coverage on either religious or moral grounds. The regulations, announced Nov. 7, 2018, were scheduled to take effect Jan. 14. The day before, U.S. District Judge Haywood Gilliam for the Northern District of California issued a similar temporary ban, but his order applied only to the 13 plaintiff states in the case, plus the District of Columbia.

While Pennsylvania and New Jersey are the only plaintiffs in the Judge Beetlestone case, she wrote that a nationwide injunction is required to protect numerous citizens from losing contraceptive coverage and resulting in “significant, direct, and proprietary harm” to states in the form of increased state-funded contraceptive services and increased costs associated with unintended pregnancies. Judge Gilliam provided similar reasoning in his Jan. 13 order, writing that the 13 plaintiff states have proven that rules promulgated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services would cause women to lose employer-sponsored contraceptive coverage, resulting in economic harm to the states.

California Attorney General Xavier Becerra, a plaintiff in the second case, said Judge Gilliam’s ruling will stop the Trump administration from denying millions of women and families access to co-pay birth control guaranteed by the Affordable Care Act.

“The law couldn’t be clearer – employers have no business interfering in women’s health care decisions,” Mr. Becerra said in the statement. “[The] court ruling stops another attempt by the Trump administration to trample on women’s access to basic reproductive care.”

At press time, the Trump administration officials had responded publicly to the court orders. The administration previously said the new policies would “better balance the government’s interest in promoting coverage for contraceptive and sterilization services with the government’s interests in providing conscience protections for entities with sincerely held moral convictions.” HHS estimated that the rules would affect no more than 200 employers.

Mark Rienzi, president of the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, a legal institute that defends religious freedoms, expressed disappointment at the court orders. Becket represents the Little Sisters of the Poor, an organization that has been fighting for several years for an exemption to the contraceptive mandate.

“Government bureaucrats should not be allowed to threaten the rights of the Little Sisters of the Poor to serve according to their Catholic beliefs,” Mr. Rienzi said in a statement. “Now the nuns are forced to keep fighting this unnecessary lawsuit to protect their ability to focus on caring for the poor. We are confident these decisions will be overturned.”

The ACA initially required all employers to cover birth control for employees with no copayments, except for group health plans of religious employers, which were deemed exempt. Those religious employers were primarily churches and other houses of worship. After a number of complaints and legal challenges, the Obama administration created a workaround for nonprofit religious employers to opt out of the mandate.

However, critics argued the process itself was a violation of their religious freedom. The issue led to the case of Zubik v. Burwell, a legal challenge over the mandate exemption that went before the U.S. Supreme Court in March 2016. The issue was never resolved. In May 2016, the Supreme Court vacated the lower court rulings related to Zubik v. Burwell and remanded the case back to the four appeals courts that had originally ruled on the issue.

The Trump administration then announced new rules aimed at broadening exemptions to the ACA’s contraceptive mandate to entities that object to services covered by the mandate on the basis of sincerely held religious beliefs. A second rule would protect nonprofit organizations and small businesses that have nonreligious moral convictions that oppose services covered by the mandate. The religious and moral exemptions would apply to institutions of education, issuers, and individuals, but not to governmental entities.

Thirteen states and the District of Columbia then sued the Trump administration over the rules as well as Pennsylvania and New Jersey in a separate case.

The nationwide ban against the rules will remain in effect while the cases continue through the court system.

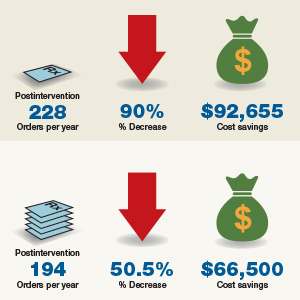

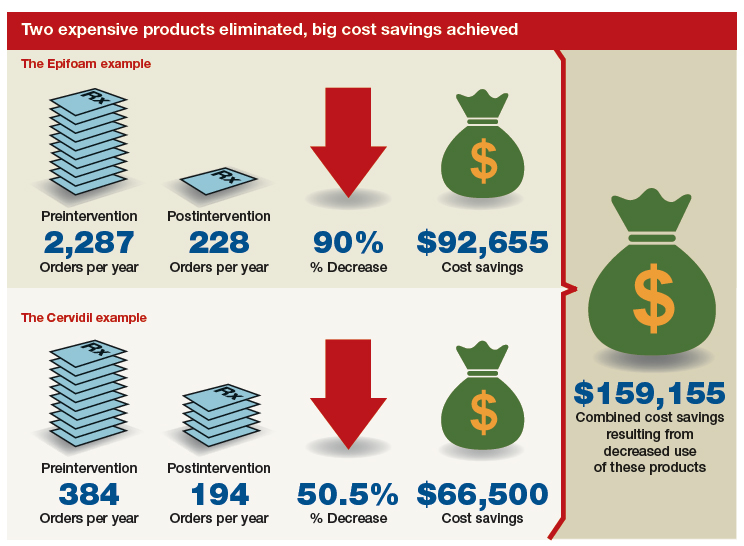

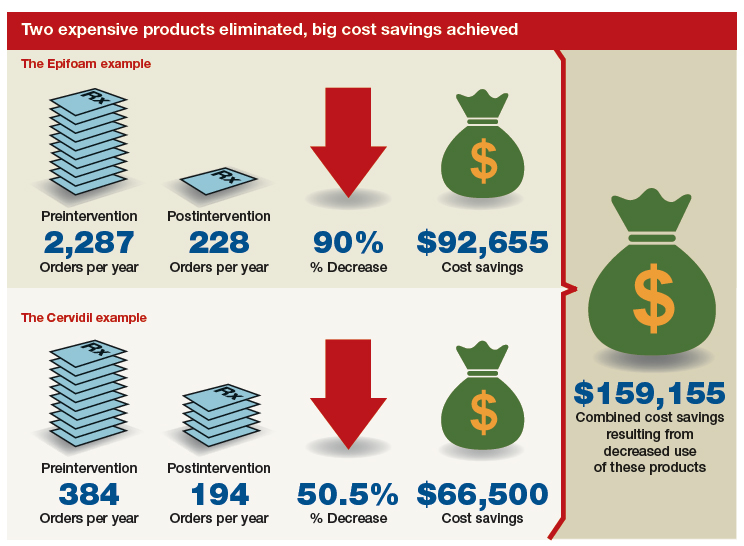

New or existing drugs? Both fuel price inflation

Inflation in existing drugs’ prices and the debut of new drugs are both contributing to the overall rising costs of pharmaceuticals.

.

For oral and injectable specialty drugs, costs increased 20.6% and 12.5%, respectively, with 71.1% and 52.4% attributable to new drugs. Costs of oral and injectable generic drugs grew by 4.4% and 7.3%, also driven by entrants into the market.

Researchers looked at monthly wholesale acquisition costs of 24,877 National Drug Codes for oral drugs and 3,049 injectable drugs from 2005 to 2016. They compared them with pharmacy claims from the UPMC Health Plan, which offers insurance products to more than 3.2 million members across the spectrum of private and public arenas.

“Our analyses yielded three main findings,” explained Inmaculada Hernandez, PharmD, PhD, University of Pittsburgh, and her colleagues in a report published in the January 2019 issue of Health Affairs.

“First, costs increased considerably faster than inflation across all drug classes, and increases were highest for oral specialty drugs and lowest for oral generics,” Dr. Hernandez and her colleagues wrote.

“Second, rising costs of brand-name drugs were driven by inflation in the prices of widely used existing drugs,” they added. A combination of new products and price inflation in existing drugs drove the rising costs of specialty drugs, with new drugs accounting for a larger share of the price increases.

Third, “existing generics tended to decrease the average cost of generic drugs,” Dr. Hernandez noted. However, new generic products cost more than those already on the market, which fueled the annual increases in average costs.

The authors noted that their estimates demonstrate the role of inflation on pharmaceutical cost increases and support policy efforts to control that inflation.

“In the current value-based landscape, increasing drug costs attributable to new products can sometimes be justified on the basis of improved outcomes,” Dr. Hernandez and colleagues stated. “However, rising costs due to inflation do not reflect improved value for patients.”

The researchers noted that the data are limited by the lack of rebate information, which is generally proprietary. Thus, “the contribution of existing drugs may have been lower than we estimated,” they noted. In addition, “because the magnitude of rebates has increased in the past decade, our findings likely overestimated cost increases for brand-name drugs.” The researchers also didn’t examine the effect of drugs transitioning from brand to generic offerings.

The authors provided no disclosures.

SOURCE: Hernandez I et al. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019 Jan 2019. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05147.

Inflation in existing drugs’ prices and the debut of new drugs are both contributing to the overall rising costs of pharmaceuticals.

.

For oral and injectable specialty drugs, costs increased 20.6% and 12.5%, respectively, with 71.1% and 52.4% attributable to new drugs. Costs of oral and injectable generic drugs grew by 4.4% and 7.3%, also driven by entrants into the market.

Researchers looked at monthly wholesale acquisition costs of 24,877 National Drug Codes for oral drugs and 3,049 injectable drugs from 2005 to 2016. They compared them with pharmacy claims from the UPMC Health Plan, which offers insurance products to more than 3.2 million members across the spectrum of private and public arenas.

“Our analyses yielded three main findings,” explained Inmaculada Hernandez, PharmD, PhD, University of Pittsburgh, and her colleagues in a report published in the January 2019 issue of Health Affairs.

“First, costs increased considerably faster than inflation across all drug classes, and increases were highest for oral specialty drugs and lowest for oral generics,” Dr. Hernandez and her colleagues wrote.

“Second, rising costs of brand-name drugs were driven by inflation in the prices of widely used existing drugs,” they added. A combination of new products and price inflation in existing drugs drove the rising costs of specialty drugs, with new drugs accounting for a larger share of the price increases.

Third, “existing generics tended to decrease the average cost of generic drugs,” Dr. Hernandez noted. However, new generic products cost more than those already on the market, which fueled the annual increases in average costs.

The authors noted that their estimates demonstrate the role of inflation on pharmaceutical cost increases and support policy efforts to control that inflation.

“In the current value-based landscape, increasing drug costs attributable to new products can sometimes be justified on the basis of improved outcomes,” Dr. Hernandez and colleagues stated. “However, rising costs due to inflation do not reflect improved value for patients.”

The researchers noted that the data are limited by the lack of rebate information, which is generally proprietary. Thus, “the contribution of existing drugs may have been lower than we estimated,” they noted. In addition, “because the magnitude of rebates has increased in the past decade, our findings likely overestimated cost increases for brand-name drugs.” The researchers also didn’t examine the effect of drugs transitioning from brand to generic offerings.

The authors provided no disclosures.

SOURCE: Hernandez I et al. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019 Jan 2019. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05147.

Inflation in existing drugs’ prices and the debut of new drugs are both contributing to the overall rising costs of pharmaceuticals.

.

For oral and injectable specialty drugs, costs increased 20.6% and 12.5%, respectively, with 71.1% and 52.4% attributable to new drugs. Costs of oral and injectable generic drugs grew by 4.4% and 7.3%, also driven by entrants into the market.

Researchers looked at monthly wholesale acquisition costs of 24,877 National Drug Codes for oral drugs and 3,049 injectable drugs from 2005 to 2016. They compared them with pharmacy claims from the UPMC Health Plan, which offers insurance products to more than 3.2 million members across the spectrum of private and public arenas.

“Our analyses yielded three main findings,” explained Inmaculada Hernandez, PharmD, PhD, University of Pittsburgh, and her colleagues in a report published in the January 2019 issue of Health Affairs.

“First, costs increased considerably faster than inflation across all drug classes, and increases were highest for oral specialty drugs and lowest for oral generics,” Dr. Hernandez and her colleagues wrote.

“Second, rising costs of brand-name drugs were driven by inflation in the prices of widely used existing drugs,” they added. A combination of new products and price inflation in existing drugs drove the rising costs of specialty drugs, with new drugs accounting for a larger share of the price increases.

Third, “existing generics tended to decrease the average cost of generic drugs,” Dr. Hernandez noted. However, new generic products cost more than those already on the market, which fueled the annual increases in average costs.

The authors noted that their estimates demonstrate the role of inflation on pharmaceutical cost increases and support policy efforts to control that inflation.

“In the current value-based landscape, increasing drug costs attributable to new products can sometimes be justified on the basis of improved outcomes,” Dr. Hernandez and colleagues stated. “However, rising costs due to inflation do not reflect improved value for patients.”

The researchers noted that the data are limited by the lack of rebate information, which is generally proprietary. Thus, “the contribution of existing drugs may have been lower than we estimated,” they noted. In addition, “because the magnitude of rebates has increased in the past decade, our findings likely overestimated cost increases for brand-name drugs.” The researchers also didn’t examine the effect of drugs transitioning from brand to generic offerings.

The authors provided no disclosures.

SOURCE: Hernandez I et al. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019 Jan 2019. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05147.

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS

Key clinical point: Price inflation in existing drugs and new product introductions are driving increases in pharmaceutical costs.

Major finding: 71% of oral specialty drug price increases during 2005-2019 are attributable to new products.

Study details: Researchers analyzed the wholesale acquisition prices of 24,877 oral drugs and 3,049 injectable drugs and compared them with pharmacy claims across all public and private insurance products offered by the UPMC Health Plan.

Disclosures: The authors provided no disclosures.

Source: Hernandez I et al. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019 Jan. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05147.

Deep sleep decreases, Alzheimer’s increases

Also today, physician groups are pushing back on Part B of the drug reimbursement proposal, dabigatran matches aspirin for second stroke prevention, and reassurance for pregnancy in atopic dermatitis.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, physician groups are pushing back on Part B of the drug reimbursement proposal, dabigatran matches aspirin for second stroke prevention, and reassurance for pregnancy in atopic dermatitis.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, physician groups are pushing back on Part B of the drug reimbursement proposal, dabigatran matches aspirin for second stroke prevention, and reassurance for pregnancy in atopic dermatitis.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Meeting 21st Century Public Health Needs: Public Health Partnerships at the Uniformed Services University

The Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USU) was established by Congress in 1972 under the Uniformed Services Health Professions Revitalization Act. The only medical school administered by the federal government, “America’s Medical School” as it is affectionately known, has a mission to educate, train, and comprehensively prepare uniformed services health professionals to support the US military and public health system.

The USU School of Medicine (SOM) matriculates about 170 students each year. Although the majority of the medical students receive commissions in the US Army, Navy, or Air Force and serve as military physicians in the Department of Defense (DoD), a small number of students each year are commissioned as officers in the US Public Health Service Commissioned Corps (PHS). The PHS is a uniformed service within the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) whose officers serve nationwide in more than 30 government agencies. However, unlike its sister DoD services, the PHS does not participate in the Health Professions Scholarship Program, so admission to USU represents the only direct accession to the PHS Commissioned Corps for prospective physicians.

Beginning with the first graduating class, more than 160 PHS physician officers have now been trained under agreements with PHS agencies and SOM, and numerous others have received training and experience from the other academic programs and research centers within USU. Ten of those graduates achieved the rank of Rear Admiral, the general officer or “flag” position of the PHS.

The benefits of the partnerships between USU, PHS, and the agencies served by PHS to public health outcomes are many. Specifically, investment in PHS students at the SOM has served to ease disparities experienced by American Indians and Alaskan Natives (AI/AN), combat the shortage of primary care physicians (PCPs), generate exceptional clinical researchers, and train health care professionals to be prepared and ready to respond to emerging threats to public health.

Addressing Health Care Disparities Experienced by AI/AN

Through numerous treaties, laws, court cases, and Executive Orders—and most recently reaffirmed by the reauthorization of the Indian Health Care Improvement Act as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010)–the US federal government holds responsibility for the provision of medical services to AI/AN. The Indian Health Service (IHS) is the principal federal provider of health care services for the AI/AN population. The mission of the IHS is to raise the physical, mental, social, and spiritual health of the AI/AN population to the highest level. It seeks to accomplish this mission by assuring that comprehensive, culturally acceptable personal and public health services are available and accessible to all AI/AN people.

Agency partnerships at USU, like the one between the school and IHS, sponsor medical students to become PHS physicians who can combat health disparities, especially those experienced by AI/AN. AI/AN continue to be subjected to disparities in health status across a wide array of chronic conditions, with significantly higher mortality rates than those of white populations.1 These trends are driven by multifactorial etiologies, including social determinants of health,2 obesity and the metabolic syndrome,3 high rates of tobacco and alcohol use,4 and limited access to medical care.5

Recruitment and retention of health care providers (HCPs) has long been a challenge for the IHS.6 Despite many attractive factors, providing care in a setting of otherwise limited resources and the relative remoteness of most facilities may prove to be deterring factors to prospective applicants. Furthermore, promotion of quality providers to administrative roles and high turnover rates of contractors or temporary staff contribute to poor continuity of care in certain locations. Consequently, efforts are under way to increase provider retention and continuity of care for patients.

This effort is augmented by training officers for a career of service to the IHS within the PHS. After completion of medical school and a residency in primary care, IHS-sponsored graduates from USU serve as officers in the PHS, stationed at an IHS-designated high-priority site for 10 years.7 However, many stay with the IHS for much longer, like IHS Chief Medical Officer, RADM Michael Toedt (USU 1995). In fact, nearly all the officers commissioned in the past 20 years are still on active duty. Within the IHS, physicians focus on community-oriented practice and improving the health of small-town and rural residents at tribal or federally operated clinics and community hospitals. In addition to performing clinical duties, graduates frequently become leaders within the IHS, advocating for systemwide improvements, performing practice-based research, and improving the overall well-being of AI/AN communities.

Combating the PCP Shortage

It has been well documented that primary care is essential for the prevention and control of chronic disease.8 However, fewer US medical school graduates are choosing to practice in primary care specialties, and the number of PCPs is forecasted to be insufficient for the needs of the American population in the coming years.9,10 This deficit is predicted to be especially pronounced in rural and underserved communities.11

Training PHS officers at the USU can fill this growing need by cultivating PCPs committed to a career of service in areas of high need. PHS medical students who are sponsored to attend USU by the IHS select from 1 of 7 approved primary care residencies: emergency medicine, family medicine, general pediatrics, general internal medicine, general psychiatry, obstetrics/gynecology, and general surgery.7 PHS students are permitted to train at military or civilian graduate medical education programs; permission to pursue combination programs is granted on a case-by-case basis, with consideration for the needs of the agency. Previously, such authorizations have included internal medicine/pediatrics, internal medicine/psychiatry, and family medicine/preventive medicine. This requirement, understood at the time of matriculation, selects for students who are passionate about primary care and are willing to live and practice in rural, underserved areas during their 10-year service commitment to the agency.

During medical school, USU students participate in numerous training activities that prepare doctors for practice in isolated or resource-poor settings, including point-of-care ultrasonography and field exercises in stabilization and transport of critically ill patients. The motto of the SOM, “Learning to Care for Those in Harm’s Way,” thereby applies not only to battlefield medicine, but to those who practice medicine in austere environments of all kinds.

Generating Clinical Researchers

Although IHS currently funds most PHS students, sponsorship also is available through the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), one of the institutes of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland. Students selected for this competitive program complete a residency in either internal medicine or pediatrics, then complete an NIH-sponsored fellowship in either infectious diseases or allergy and immunology. Similar to their IHS counterparts, they incur a debt of service—10 years in the PHS Commissioned Corps; however, their service obligation is served at NIH. This track supports the creation of the next generation of clinical researchers and physician-scientists, critical in this time of ever-increasing threats to public health and national security, like emerging infectious diseases and bioterrorism.

Emergency Response Preparations

Combined training with experts from DoD and HHS prepares junior medical officers to serve as leaders in responding to large-scale emergencies and disasters. According to a memorandum of December 11, 1981, then Surgeon General C. Everett Koop described the importance of this skill set, saying that USU students are “ready for instant mobilization to meet military [needs] and [respond to] national disasters.” He continued, “Students are taught the necessary leadership and management skills to command medical units and organizations in the delivery of health services...They are exposed to the problems of dealing with national medical emergencies such as floods, earthquakes, and mass immigrations to this country.”12 Fittingly, physician graduates of USU have recently led disaster response efforts for Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria and Typhoon Yutu.

Traditional medical school didactic coursework is supplemented by lectures on disaster response, emergency preparedness, and global health engagement. As training progresses, students translate their knowledge into action with practical fieldwork exercises in mass casualty triage, erection of field hospitals using preventive medicine principles, and containment of infectious disease outbreaks among displaced persons—under the close observation and guidance of military and public health subject matter experts from across the country. Medical students complete their clinical training at military treatment facilities around the country and have elective clerkship opportunities in operational medicine nationally and internationally. PHS graduates of USU are well prepared to interface with their military colleagues, building effective joint mission capacity.

Additional Training Opportunities

In addition to the 4-year, tuition-free MD program, the university offers 7 graduate degree programs in public health and residency programs in preventive medicine specialty areas. Continuing education opportunities and graduate certificates are available in global health, tropical medicine and hygiene, travelers’ health, international and domestic disaster response, and other fields of interest to any public health professional, military or civilian. Many programs are available to federal or uniformed service members at no cost, some incur a degree of service commitment. Furthermore, the university is home to multiple research centers, including the National Center for Disaster Medicine and Public Health, which strive to improve public health through research efforts and education.

Conclusion

Though the emerging public health needs of the nation are both varied and daunting, the USU/PHS partnership trains providers that will heed the call and face the modern public health needs head-on. USU remains an important source for commissioning PHS physicians and producing career officers. The unique training provided at USU educates and enables PHS physicians to ease disparities experienced by AI/AN, combat the shortage of PCPs, generate exceptional clinical researchers, and be prepared and ready to respond to emerging threats to public health.

1. Espey DK, Jim MA, Cobb N, et al. Leading causes of death and all-cause mortality in American Indians and Alaska natives. Am J Public Health . 2014;104(S3):S303-S311.

2. Kunitz SJ, Veazie M, Henderson JA. Historical trends and regional differences in all-cause and amenable mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives since 1950. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6)(suppl 3):S268-S277.

3. Sinclair KA, Bogart A, Buchwald D, Henderson JA. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and associated risk factors in Northern Plains and Southwest American Indians. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(1):118-120.

4. Cobb N, Espey D, King J. Health behaviors and risk factors among American Indians and Alaska Natives, 2000–2010. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6)(suppl 3):S481-S489.

5. Warne D, Frizzell LB. American Indian health policy: historical trends and contemporary issues. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6)(suppl 3):S263-S267.

6. Noren J, Kindig D, Sprenger A. Challenges to Native American health care. Public Health Rep. 1998;113(1):22-23.

7. Indian Health Services. Follow Your Path: The Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Participant Program Guide. https://www.ihs.gov/careeropps/includes/themes/responsive2017/display_objects/documents/USUHS-IHS-Participant-Program-Guide.pdf. Published October 2015. Accessed August 16, 2018.

8. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q . 2005;83(3):457-502.

9. Health Resources and Services Administration. Projecting the supply and demand for primary care practitioners through 2020. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/health-workforce-analysis/primary-care-2020. Accessed December 14, 2018.

10. Dill MJ, Salsberg ES. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections through 2025. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/The%20Complexities%20of%20Physician%20Supply.pdf. Published November 2008. Accessed December 14, 2018.

11. Wilson N, Couper I, De Vries E, Reid S, Fish T, Marais B. A critical review of interventions to redress the inequitable distribution of healthcare professionals to rural and remote areas. Rural Remote Health . 2009;9(2):1060.

12. Department of Health and Human Services. Memorandum. Continued PHS Participation at USUHS. https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/ps/access/QQBBZV.pdf. Published December 11, 1981. Accessed December 14, 2018.

The Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USU) was established by Congress in 1972 under the Uniformed Services Health Professions Revitalization Act. The only medical school administered by the federal government, “America’s Medical School” as it is affectionately known, has a mission to educate, train, and comprehensively prepare uniformed services health professionals to support the US military and public health system.

The USU School of Medicine (SOM) matriculates about 170 students each year. Although the majority of the medical students receive commissions in the US Army, Navy, or Air Force and serve as military physicians in the Department of Defense (DoD), a small number of students each year are commissioned as officers in the US Public Health Service Commissioned Corps (PHS). The PHS is a uniformed service within the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) whose officers serve nationwide in more than 30 government agencies. However, unlike its sister DoD services, the PHS does not participate in the Health Professions Scholarship Program, so admission to USU represents the only direct accession to the PHS Commissioned Corps for prospective physicians.

Beginning with the first graduating class, more than 160 PHS physician officers have now been trained under agreements with PHS agencies and SOM, and numerous others have received training and experience from the other academic programs and research centers within USU. Ten of those graduates achieved the rank of Rear Admiral, the general officer or “flag” position of the PHS.

The benefits of the partnerships between USU, PHS, and the agencies served by PHS to public health outcomes are many. Specifically, investment in PHS students at the SOM has served to ease disparities experienced by American Indians and Alaskan Natives (AI/AN), combat the shortage of primary care physicians (PCPs), generate exceptional clinical researchers, and train health care professionals to be prepared and ready to respond to emerging threats to public health.

Addressing Health Care Disparities Experienced by AI/AN

Through numerous treaties, laws, court cases, and Executive Orders—and most recently reaffirmed by the reauthorization of the Indian Health Care Improvement Act as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010)–the US federal government holds responsibility for the provision of medical services to AI/AN. The Indian Health Service (IHS) is the principal federal provider of health care services for the AI/AN population. The mission of the IHS is to raise the physical, mental, social, and spiritual health of the AI/AN population to the highest level. It seeks to accomplish this mission by assuring that comprehensive, culturally acceptable personal and public health services are available and accessible to all AI/AN people.

Agency partnerships at USU, like the one between the school and IHS, sponsor medical students to become PHS physicians who can combat health disparities, especially those experienced by AI/AN. AI/AN continue to be subjected to disparities in health status across a wide array of chronic conditions, with significantly higher mortality rates than those of white populations.1 These trends are driven by multifactorial etiologies, including social determinants of health,2 obesity and the metabolic syndrome,3 high rates of tobacco and alcohol use,4 and limited access to medical care.5

Recruitment and retention of health care providers (HCPs) has long been a challenge for the IHS.6 Despite many attractive factors, providing care in a setting of otherwise limited resources and the relative remoteness of most facilities may prove to be deterring factors to prospective applicants. Furthermore, promotion of quality providers to administrative roles and high turnover rates of contractors or temporary staff contribute to poor continuity of care in certain locations. Consequently, efforts are under way to increase provider retention and continuity of care for patients.

This effort is augmented by training officers for a career of service to the IHS within the PHS. After completion of medical school and a residency in primary care, IHS-sponsored graduates from USU serve as officers in the PHS, stationed at an IHS-designated high-priority site for 10 years.7 However, many stay with the IHS for much longer, like IHS Chief Medical Officer, RADM Michael Toedt (USU 1995). In fact, nearly all the officers commissioned in the past 20 years are still on active duty. Within the IHS, physicians focus on community-oriented practice and improving the health of small-town and rural residents at tribal or federally operated clinics and community hospitals. In addition to performing clinical duties, graduates frequently become leaders within the IHS, advocating for systemwide improvements, performing practice-based research, and improving the overall well-being of AI/AN communities.

Combating the PCP Shortage

It has been well documented that primary care is essential for the prevention and control of chronic disease.8 However, fewer US medical school graduates are choosing to practice in primary care specialties, and the number of PCPs is forecasted to be insufficient for the needs of the American population in the coming years.9,10 This deficit is predicted to be especially pronounced in rural and underserved communities.11

Training PHS officers at the USU can fill this growing need by cultivating PCPs committed to a career of service in areas of high need. PHS medical students who are sponsored to attend USU by the IHS select from 1 of 7 approved primary care residencies: emergency medicine, family medicine, general pediatrics, general internal medicine, general psychiatry, obstetrics/gynecology, and general surgery.7 PHS students are permitted to train at military or civilian graduate medical education programs; permission to pursue combination programs is granted on a case-by-case basis, with consideration for the needs of the agency. Previously, such authorizations have included internal medicine/pediatrics, internal medicine/psychiatry, and family medicine/preventive medicine. This requirement, understood at the time of matriculation, selects for students who are passionate about primary care and are willing to live and practice in rural, underserved areas during their 10-year service commitment to the agency.

During medical school, USU students participate in numerous training activities that prepare doctors for practice in isolated or resource-poor settings, including point-of-care ultrasonography and field exercises in stabilization and transport of critically ill patients. The motto of the SOM, “Learning to Care for Those in Harm’s Way,” thereby applies not only to battlefield medicine, but to those who practice medicine in austere environments of all kinds.

Generating Clinical Researchers

Although IHS currently funds most PHS students, sponsorship also is available through the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), one of the institutes of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland. Students selected for this competitive program complete a residency in either internal medicine or pediatrics, then complete an NIH-sponsored fellowship in either infectious diseases or allergy and immunology. Similar to their IHS counterparts, they incur a debt of service—10 years in the PHS Commissioned Corps; however, their service obligation is served at NIH. This track supports the creation of the next generation of clinical researchers and physician-scientists, critical in this time of ever-increasing threats to public health and national security, like emerging infectious diseases and bioterrorism.

Emergency Response Preparations

Combined training with experts from DoD and HHS prepares junior medical officers to serve as leaders in responding to large-scale emergencies and disasters. According to a memorandum of December 11, 1981, then Surgeon General C. Everett Koop described the importance of this skill set, saying that USU students are “ready for instant mobilization to meet military [needs] and [respond to] national disasters.” He continued, “Students are taught the necessary leadership and management skills to command medical units and organizations in the delivery of health services...They are exposed to the problems of dealing with national medical emergencies such as floods, earthquakes, and mass immigrations to this country.”12 Fittingly, physician graduates of USU have recently led disaster response efforts for Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria and Typhoon Yutu.

Traditional medical school didactic coursework is supplemented by lectures on disaster response, emergency preparedness, and global health engagement. As training progresses, students translate their knowledge into action with practical fieldwork exercises in mass casualty triage, erection of field hospitals using preventive medicine principles, and containment of infectious disease outbreaks among displaced persons—under the close observation and guidance of military and public health subject matter experts from across the country. Medical students complete their clinical training at military treatment facilities around the country and have elective clerkship opportunities in operational medicine nationally and internationally. PHS graduates of USU are well prepared to interface with their military colleagues, building effective joint mission capacity.

Additional Training Opportunities

In addition to the 4-year, tuition-free MD program, the university offers 7 graduate degree programs in public health and residency programs in preventive medicine specialty areas. Continuing education opportunities and graduate certificates are available in global health, tropical medicine and hygiene, travelers’ health, international and domestic disaster response, and other fields of interest to any public health professional, military or civilian. Many programs are available to federal or uniformed service members at no cost, some incur a degree of service commitment. Furthermore, the university is home to multiple research centers, including the National Center for Disaster Medicine and Public Health, which strive to improve public health through research efforts and education.

Conclusion