User login

Residential HCV program improves veterans’ diagnosis and care

Integrating comprehensive and collaborative hepatitis C virus (HCV) care within a Veterans Affairs residential treatment program can substantially increase diagnosis and treatment of HCV-infected veterans with substance use disorder (SUD), according to the results of an evaluation study for the period from December 2014 to April 2018.

A total of 97.5% (582/597) of patient admissions to the program were screened for HCV infection, and 12.7% (74/582) of the cases were confirmed to be HCV positive. All of the positive cases were sent to an infectious disease (ID) clinic for further evaluation and, if appropriate, to begin HCV pharmacotherapy, according to the report, published in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment.

Of the HCV-positive cases, 78.4% (58/74) received pharmacotherapy, with a sustained virologic response rate of 82.8% (48/58), wrote Mary Jane Burton, MD, of the G.V. (Sonny) Montgomery VA Medical Center, Jackson, Miss., and her colleagues.

As part of the program, all veterans admitted to the SUD residential program were offered screening for HCV. Veterans with negative screening results received education about how to remain HCV negative via handouts and veterans who screened positive received brief supportive counseling and were referred to the ID clinic via a consult. Veterans confirmed to have chronic HCV infection receive education and evaluation in the HCV clinic while they attend the residential SUD program. Treatment for HCV is instituted as early as feasible and prescribing is in accordance with VA guidelines (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2018), with the goal of initiating pharmacotherapy treatment for HCV while the veteran is still in the residential program, according to the researchers.

Following discharge from the program, veterans on HCV treatment are scheduled for follow-up every 2 weeks in the HCV treatment clinic for the remainder of their pharmacotherapy, the researchers added.

Patient-level barriers to HCV treatment among the SUD population include reduced health literacy, low health care utilization, comorbid mental health conditions, and poor social support, according to the literature. Because multidisciplinary approaches to HCV treatment that mitigate these barriers have been shown to increase treatment uptake among these patients, the VA program was initiated, the researchers stated. Dr. Burton and her colleagues reported that 18.9% (14/74) of the HCV-positive cases were newly diagnosed and would have likely gone undetected without this program (J Substance Abuse Treatment. 2019;98:9-14).

“We have demonstrated that integrating a comprehensive HCV screening, education, referral, and treatment program within residential SUD treatment is feasible and effective in diagnosing previously unrecognized HCV infections, transitioning veterans into HCV care, and promoting treatment initiation,” the researchers concluded.

The Department of Veterans Affairs and the VA Center for Innovation supported the study. Dr. Burton reported research support from Merck Sharpe & Dohme.

Integrating comprehensive and collaborative hepatitis C virus (HCV) care within a Veterans Affairs residential treatment program can substantially increase diagnosis and treatment of HCV-infected veterans with substance use disorder (SUD), according to the results of an evaluation study for the period from December 2014 to April 2018.

A total of 97.5% (582/597) of patient admissions to the program were screened for HCV infection, and 12.7% (74/582) of the cases were confirmed to be HCV positive. All of the positive cases were sent to an infectious disease (ID) clinic for further evaluation and, if appropriate, to begin HCV pharmacotherapy, according to the report, published in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment.

Of the HCV-positive cases, 78.4% (58/74) received pharmacotherapy, with a sustained virologic response rate of 82.8% (48/58), wrote Mary Jane Burton, MD, of the G.V. (Sonny) Montgomery VA Medical Center, Jackson, Miss., and her colleagues.

As part of the program, all veterans admitted to the SUD residential program were offered screening for HCV. Veterans with negative screening results received education about how to remain HCV negative via handouts and veterans who screened positive received brief supportive counseling and were referred to the ID clinic via a consult. Veterans confirmed to have chronic HCV infection receive education and evaluation in the HCV clinic while they attend the residential SUD program. Treatment for HCV is instituted as early as feasible and prescribing is in accordance with VA guidelines (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2018), with the goal of initiating pharmacotherapy treatment for HCV while the veteran is still in the residential program, according to the researchers.

Following discharge from the program, veterans on HCV treatment are scheduled for follow-up every 2 weeks in the HCV treatment clinic for the remainder of their pharmacotherapy, the researchers added.

Patient-level barriers to HCV treatment among the SUD population include reduced health literacy, low health care utilization, comorbid mental health conditions, and poor social support, according to the literature. Because multidisciplinary approaches to HCV treatment that mitigate these barriers have been shown to increase treatment uptake among these patients, the VA program was initiated, the researchers stated. Dr. Burton and her colleagues reported that 18.9% (14/74) of the HCV-positive cases were newly diagnosed and would have likely gone undetected without this program (J Substance Abuse Treatment. 2019;98:9-14).

“We have demonstrated that integrating a comprehensive HCV screening, education, referral, and treatment program within residential SUD treatment is feasible and effective in diagnosing previously unrecognized HCV infections, transitioning veterans into HCV care, and promoting treatment initiation,” the researchers concluded.

The Department of Veterans Affairs and the VA Center for Innovation supported the study. Dr. Burton reported research support from Merck Sharpe & Dohme.

Integrating comprehensive and collaborative hepatitis C virus (HCV) care within a Veterans Affairs residential treatment program can substantially increase diagnosis and treatment of HCV-infected veterans with substance use disorder (SUD), according to the results of an evaluation study for the period from December 2014 to April 2018.

A total of 97.5% (582/597) of patient admissions to the program were screened for HCV infection, and 12.7% (74/582) of the cases were confirmed to be HCV positive. All of the positive cases were sent to an infectious disease (ID) clinic for further evaluation and, if appropriate, to begin HCV pharmacotherapy, according to the report, published in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment.

Of the HCV-positive cases, 78.4% (58/74) received pharmacotherapy, with a sustained virologic response rate of 82.8% (48/58), wrote Mary Jane Burton, MD, of the G.V. (Sonny) Montgomery VA Medical Center, Jackson, Miss., and her colleagues.

As part of the program, all veterans admitted to the SUD residential program were offered screening for HCV. Veterans with negative screening results received education about how to remain HCV negative via handouts and veterans who screened positive received brief supportive counseling and were referred to the ID clinic via a consult. Veterans confirmed to have chronic HCV infection receive education and evaluation in the HCV clinic while they attend the residential SUD program. Treatment for HCV is instituted as early as feasible and prescribing is in accordance with VA guidelines (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2018), with the goal of initiating pharmacotherapy treatment for HCV while the veteran is still in the residential program, according to the researchers.

Following discharge from the program, veterans on HCV treatment are scheduled for follow-up every 2 weeks in the HCV treatment clinic for the remainder of their pharmacotherapy, the researchers added.

Patient-level barriers to HCV treatment among the SUD population include reduced health literacy, low health care utilization, comorbid mental health conditions, and poor social support, according to the literature. Because multidisciplinary approaches to HCV treatment that mitigate these barriers have been shown to increase treatment uptake among these patients, the VA program was initiated, the researchers stated. Dr. Burton and her colleagues reported that 18.9% (14/74) of the HCV-positive cases were newly diagnosed and would have likely gone undetected without this program (J Substance Abuse Treatment. 2019;98:9-14).

“We have demonstrated that integrating a comprehensive HCV screening, education, referral, and treatment program within residential SUD treatment is feasible and effective in diagnosing previously unrecognized HCV infections, transitioning veterans into HCV care, and promoting treatment initiation,” the researchers concluded.

The Department of Veterans Affairs and the VA Center for Innovation supported the study. Dr. Burton reported research support from Merck Sharpe & Dohme.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE TREATMENT

Drug-pricing policies find new momentum as ‘a 2020 thing’

The next presidential primary contests are more than a year away.

“This is a 2020 thing,” said Peter B. Bach, MD, who directs the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York and tracks drug-pricing policy.

Spurred on by midterm election results that showed health care to be a deciding issue, lawmakers – some of whom have already launched presidential-run exploratory committees – are pushing a bevy of new proposals and approaches.

Few if any of those ideas will likely make it to the president’s desk. Nevertheless, Senate Democrats eyeing higher office and seeking street cred in the debate are devising more innovative and aggressive strategies to take on Big Pharma.

“Democrats feel as if they’re really able to experiment,” said Rachel Sachs, an associate law professor at Washington University, St. Louis, who tracks drug-pricing laws.

Some Republicans are also proposing drug-pricing reform, although experts say their approaches are generally less dramatic.

Here are some of the ideas either introduced in legislation or that senators’ offices confirmed they are considering:

- Make a public option for generic drugs. The government could manufacture generics (directly or through a private contractor) if there is a shortage or aren’t enough competitors to keep prices down. This comes from a bill put forth by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-Ill.).

- Let Medicare negotiate drug prices. This idea has many backers – what differs is the method of enforcement. Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) has suggested that if the company and the government can’t reach an agreement, the government could take away the company’s patent rights. A proposal from Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Rep. Elijah Cummings (D-Md.) would address stalled negotiations by letting Medicare pay the lowest amount among: Medicaid’s best price, the highest price a single federal purchaser pays or the median price paid for a specific drug in Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom.

- Pay what they do abroad. Legislation from Mr. Sanders and Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.) would require companies to price their drugs no higher than the median of what’s charged in Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom. If manufacturers fail to comply, other companies could get the rights to make those drugs, too.

- Penalize price gouging. This would target manufacturers who raise drug prices more than 30% in 5 years. Punishments could include requiring the company to reimburse those who paid the elevated price, forcing the drug maker to lower its price, or charging a penalty up to three times what a company received from boosting the price. Backers include senators Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.), Kamala Harris (D-Calif.), Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.), and Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.).

- Import drugs. A Sanders-Cummings bill would let patients, wholesalers, and pharmacies import drugs from abroad – starting with Canada, and leaving the door open for some other countries. Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) and Ms. Klobuchar have a separate bill that is specific to patients getting medicine from Canada alone.

- Abolish “pay for delay.” From Mr. Grassley and Ms. Klobuchar, this legislation would tackle deals in which a branded drugmaker pays off a generic one to keep a competing product from coming to market.

This flurry of proposed lawmaking could add momentum to one of the few policy areas in which conventional Washington wisdom suggests House Democrats, Senate Republicans, and the White House may be able to find common ground.

“Everything is up in the air and anything is possible,” said Walid Gellad, MD, codirector of the Center for Pharmaceutical Policy and Prescribing at the University of Pittsburgh. “There are things that can happen that maybe weren’t going to happen before.”

And there’s political pressure. Polls consistently suggest voters have a strong appetite for action. As a candidate, President Trump vowed to make drug prices a top priority. In recent months, the administration has taken steps in this direction, like testing changes to Medicare that might reduce out-of-pocket drug costs. But Congress has been relatively quiet, especially when it comes to challenging the pharmaceutical industry, which remains one of Capitol Hill’s most potent lobbying forces.

One aspect of prescription drug pricing that could see bipartisan action is insulin prices, which have skyrocketed, stoking widespread outcry, and could be a target for bipartisan work. Ms. Warren’s legislation singles out the drug as one the government could produce, and Mr. Cummings has already called in major insulin manufacturers for a drug-pricing hearing later this month. In addition, Rep. Diana DeGette (D-Colo.), the new chair of the House Energy and Commerce Oversight and Investigations Subcommittee, has listed prescription drug pricing as a high priority for her panel. As cochair of the Congressional Diabetes Caucus, Ms. DeGette worked with Rep. Tom Reed (R-N.Y.) to produce a report on the high cost of insulin.

To be sure, some of the concepts, such as drug importation and bolstering development of generic drugs, have been around a long time. But some of the legislation at hand suggests a new kind of thinking.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) has labeled drug pricing a top priority, and the pharmaceutical industry has been bracing for a fight with the new Democratic majority.

Meanwhile, in the GOP-controlled Senate, two powerful lawmakers – Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) and Mr. Grassley – have indicated they want to use their influence to tackle the issue. Mr. Alexander, who chairs the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, has said cutting health care costs, including drug prices, will be high on his panel’s to-do list this Congress. Mr. Grassley runs the Finance Committee, which oversees pricing issues for Medicare and Medicaid.

“The solution to high drug prices is not just having the government spending more money. ... You need to look at prices,” Dr. Gellad said. “These proposals deal with price. They all directly affect price.”

Given the drug industry’s full-throated opposition to virtually any pricing legislation, Ms. Sachs said, “it is not at all surprising to me to see the Democrats start exploring some of these more radical proposals.”

Still, though, Senate staffers almost uniformly argued that the drug-pricing issue requires more than one single piece of legislation.

For instance, the price-gouging penalty spearheaded by Mr. Blumenthal doesn’t stop drugs from having high initial list prices. Letting Medicare negotiate doesn’t mean people covered by other plans will necessarily see the same savings. Empowering the government to produce competing drugs doesn’t promise to keep prices down long term and doesn’t guarantee that patients will see those savings.

“We need to use every tool available to bring down drug prices and improve competition,” said an aide in Ms. Warren’s office.

KHN’s coverage of prescription drug development, costs and pricing is supported in part by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

The next presidential primary contests are more than a year away.

“This is a 2020 thing,” said Peter B. Bach, MD, who directs the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York and tracks drug-pricing policy.

Spurred on by midterm election results that showed health care to be a deciding issue, lawmakers – some of whom have already launched presidential-run exploratory committees – are pushing a bevy of new proposals and approaches.

Few if any of those ideas will likely make it to the president’s desk. Nevertheless, Senate Democrats eyeing higher office and seeking street cred in the debate are devising more innovative and aggressive strategies to take on Big Pharma.

“Democrats feel as if they’re really able to experiment,” said Rachel Sachs, an associate law professor at Washington University, St. Louis, who tracks drug-pricing laws.

Some Republicans are also proposing drug-pricing reform, although experts say their approaches are generally less dramatic.

Here are some of the ideas either introduced in legislation or that senators’ offices confirmed they are considering:

- Make a public option for generic drugs. The government could manufacture generics (directly or through a private contractor) if there is a shortage or aren’t enough competitors to keep prices down. This comes from a bill put forth by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-Ill.).

- Let Medicare negotiate drug prices. This idea has many backers – what differs is the method of enforcement. Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) has suggested that if the company and the government can’t reach an agreement, the government could take away the company’s patent rights. A proposal from Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Rep. Elijah Cummings (D-Md.) would address stalled negotiations by letting Medicare pay the lowest amount among: Medicaid’s best price, the highest price a single federal purchaser pays or the median price paid for a specific drug in Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom.

- Pay what they do abroad. Legislation from Mr. Sanders and Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.) would require companies to price their drugs no higher than the median of what’s charged in Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom. If manufacturers fail to comply, other companies could get the rights to make those drugs, too.

- Penalize price gouging. This would target manufacturers who raise drug prices more than 30% in 5 years. Punishments could include requiring the company to reimburse those who paid the elevated price, forcing the drug maker to lower its price, or charging a penalty up to three times what a company received from boosting the price. Backers include senators Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.), Kamala Harris (D-Calif.), Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.), and Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.).

- Import drugs. A Sanders-Cummings bill would let patients, wholesalers, and pharmacies import drugs from abroad – starting with Canada, and leaving the door open for some other countries. Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) and Ms. Klobuchar have a separate bill that is specific to patients getting medicine from Canada alone.

- Abolish “pay for delay.” From Mr. Grassley and Ms. Klobuchar, this legislation would tackle deals in which a branded drugmaker pays off a generic one to keep a competing product from coming to market.

This flurry of proposed lawmaking could add momentum to one of the few policy areas in which conventional Washington wisdom suggests House Democrats, Senate Republicans, and the White House may be able to find common ground.

“Everything is up in the air and anything is possible,” said Walid Gellad, MD, codirector of the Center for Pharmaceutical Policy and Prescribing at the University of Pittsburgh. “There are things that can happen that maybe weren’t going to happen before.”

And there’s political pressure. Polls consistently suggest voters have a strong appetite for action. As a candidate, President Trump vowed to make drug prices a top priority. In recent months, the administration has taken steps in this direction, like testing changes to Medicare that might reduce out-of-pocket drug costs. But Congress has been relatively quiet, especially when it comes to challenging the pharmaceutical industry, which remains one of Capitol Hill’s most potent lobbying forces.

One aspect of prescription drug pricing that could see bipartisan action is insulin prices, which have skyrocketed, stoking widespread outcry, and could be a target for bipartisan work. Ms. Warren’s legislation singles out the drug as one the government could produce, and Mr. Cummings has already called in major insulin manufacturers for a drug-pricing hearing later this month. In addition, Rep. Diana DeGette (D-Colo.), the new chair of the House Energy and Commerce Oversight and Investigations Subcommittee, has listed prescription drug pricing as a high priority for her panel. As cochair of the Congressional Diabetes Caucus, Ms. DeGette worked with Rep. Tom Reed (R-N.Y.) to produce a report on the high cost of insulin.

To be sure, some of the concepts, such as drug importation and bolstering development of generic drugs, have been around a long time. But some of the legislation at hand suggests a new kind of thinking.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) has labeled drug pricing a top priority, and the pharmaceutical industry has been bracing for a fight with the new Democratic majority.

Meanwhile, in the GOP-controlled Senate, two powerful lawmakers – Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) and Mr. Grassley – have indicated they want to use their influence to tackle the issue. Mr. Alexander, who chairs the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, has said cutting health care costs, including drug prices, will be high on his panel’s to-do list this Congress. Mr. Grassley runs the Finance Committee, which oversees pricing issues for Medicare and Medicaid.

“The solution to high drug prices is not just having the government spending more money. ... You need to look at prices,” Dr. Gellad said. “These proposals deal with price. They all directly affect price.”

Given the drug industry’s full-throated opposition to virtually any pricing legislation, Ms. Sachs said, “it is not at all surprising to me to see the Democrats start exploring some of these more radical proposals.”

Still, though, Senate staffers almost uniformly argued that the drug-pricing issue requires more than one single piece of legislation.

For instance, the price-gouging penalty spearheaded by Mr. Blumenthal doesn’t stop drugs from having high initial list prices. Letting Medicare negotiate doesn’t mean people covered by other plans will necessarily see the same savings. Empowering the government to produce competing drugs doesn’t promise to keep prices down long term and doesn’t guarantee that patients will see those savings.

“We need to use every tool available to bring down drug prices and improve competition,” said an aide in Ms. Warren’s office.

KHN’s coverage of prescription drug development, costs and pricing is supported in part by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

The next presidential primary contests are more than a year away.

“This is a 2020 thing,” said Peter B. Bach, MD, who directs the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York and tracks drug-pricing policy.

Spurred on by midterm election results that showed health care to be a deciding issue, lawmakers – some of whom have already launched presidential-run exploratory committees – are pushing a bevy of new proposals and approaches.

Few if any of those ideas will likely make it to the president’s desk. Nevertheless, Senate Democrats eyeing higher office and seeking street cred in the debate are devising more innovative and aggressive strategies to take on Big Pharma.

“Democrats feel as if they’re really able to experiment,” said Rachel Sachs, an associate law professor at Washington University, St. Louis, who tracks drug-pricing laws.

Some Republicans are also proposing drug-pricing reform, although experts say their approaches are generally less dramatic.

Here are some of the ideas either introduced in legislation or that senators’ offices confirmed they are considering:

- Make a public option for generic drugs. The government could manufacture generics (directly or through a private contractor) if there is a shortage or aren’t enough competitors to keep prices down. This comes from a bill put forth by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-Ill.).

- Let Medicare negotiate drug prices. This idea has many backers – what differs is the method of enforcement. Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) has suggested that if the company and the government can’t reach an agreement, the government could take away the company’s patent rights. A proposal from Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Rep. Elijah Cummings (D-Md.) would address stalled negotiations by letting Medicare pay the lowest amount among: Medicaid’s best price, the highest price a single federal purchaser pays or the median price paid for a specific drug in Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom.

- Pay what they do abroad. Legislation from Mr. Sanders and Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.) would require companies to price their drugs no higher than the median of what’s charged in Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom. If manufacturers fail to comply, other companies could get the rights to make those drugs, too.

- Penalize price gouging. This would target manufacturers who raise drug prices more than 30% in 5 years. Punishments could include requiring the company to reimburse those who paid the elevated price, forcing the drug maker to lower its price, or charging a penalty up to three times what a company received from boosting the price. Backers include senators Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.), Kamala Harris (D-Calif.), Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.), and Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.).

- Import drugs. A Sanders-Cummings bill would let patients, wholesalers, and pharmacies import drugs from abroad – starting with Canada, and leaving the door open for some other countries. Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) and Ms. Klobuchar have a separate bill that is specific to patients getting medicine from Canada alone.

- Abolish “pay for delay.” From Mr. Grassley and Ms. Klobuchar, this legislation would tackle deals in which a branded drugmaker pays off a generic one to keep a competing product from coming to market.

This flurry of proposed lawmaking could add momentum to one of the few policy areas in which conventional Washington wisdom suggests House Democrats, Senate Republicans, and the White House may be able to find common ground.

“Everything is up in the air and anything is possible,” said Walid Gellad, MD, codirector of the Center for Pharmaceutical Policy and Prescribing at the University of Pittsburgh. “There are things that can happen that maybe weren’t going to happen before.”

And there’s political pressure. Polls consistently suggest voters have a strong appetite for action. As a candidate, President Trump vowed to make drug prices a top priority. In recent months, the administration has taken steps in this direction, like testing changes to Medicare that might reduce out-of-pocket drug costs. But Congress has been relatively quiet, especially when it comes to challenging the pharmaceutical industry, which remains one of Capitol Hill’s most potent lobbying forces.

One aspect of prescription drug pricing that could see bipartisan action is insulin prices, which have skyrocketed, stoking widespread outcry, and could be a target for bipartisan work. Ms. Warren’s legislation singles out the drug as one the government could produce, and Mr. Cummings has already called in major insulin manufacturers for a drug-pricing hearing later this month. In addition, Rep. Diana DeGette (D-Colo.), the new chair of the House Energy and Commerce Oversight and Investigations Subcommittee, has listed prescription drug pricing as a high priority for her panel. As cochair of the Congressional Diabetes Caucus, Ms. DeGette worked with Rep. Tom Reed (R-N.Y.) to produce a report on the high cost of insulin.

To be sure, some of the concepts, such as drug importation and bolstering development of generic drugs, have been around a long time. But some of the legislation at hand suggests a new kind of thinking.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) has labeled drug pricing a top priority, and the pharmaceutical industry has been bracing for a fight with the new Democratic majority.

Meanwhile, in the GOP-controlled Senate, two powerful lawmakers – Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) and Mr. Grassley – have indicated they want to use their influence to tackle the issue. Mr. Alexander, who chairs the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, has said cutting health care costs, including drug prices, will be high on his panel’s to-do list this Congress. Mr. Grassley runs the Finance Committee, which oversees pricing issues for Medicare and Medicaid.

“The solution to high drug prices is not just having the government spending more money. ... You need to look at prices,” Dr. Gellad said. “These proposals deal with price. They all directly affect price.”

Given the drug industry’s full-throated opposition to virtually any pricing legislation, Ms. Sachs said, “it is not at all surprising to me to see the Democrats start exploring some of these more radical proposals.”

Still, though, Senate staffers almost uniformly argued that the drug-pricing issue requires more than one single piece of legislation.

For instance, the price-gouging penalty spearheaded by Mr. Blumenthal doesn’t stop drugs from having high initial list prices. Letting Medicare negotiate doesn’t mean people covered by other plans will necessarily see the same savings. Empowering the government to produce competing drugs doesn’t promise to keep prices down long term and doesn’t guarantee that patients will see those savings.

“We need to use every tool available to bring down drug prices and improve competition,” said an aide in Ms. Warren’s office.

KHN’s coverage of prescription drug development, costs and pricing is supported in part by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Survey: Americans support Medicare for all

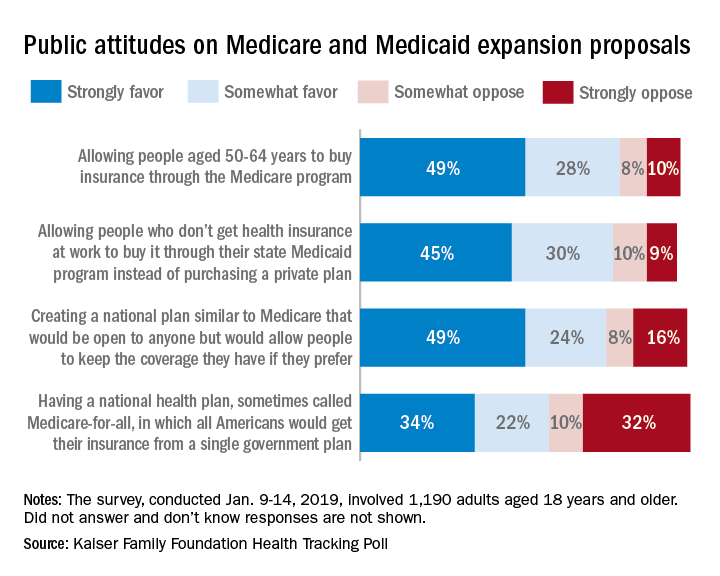

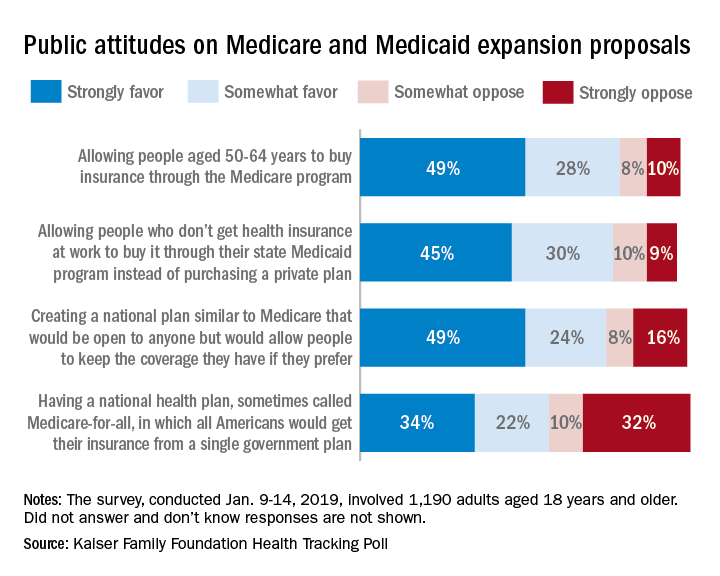

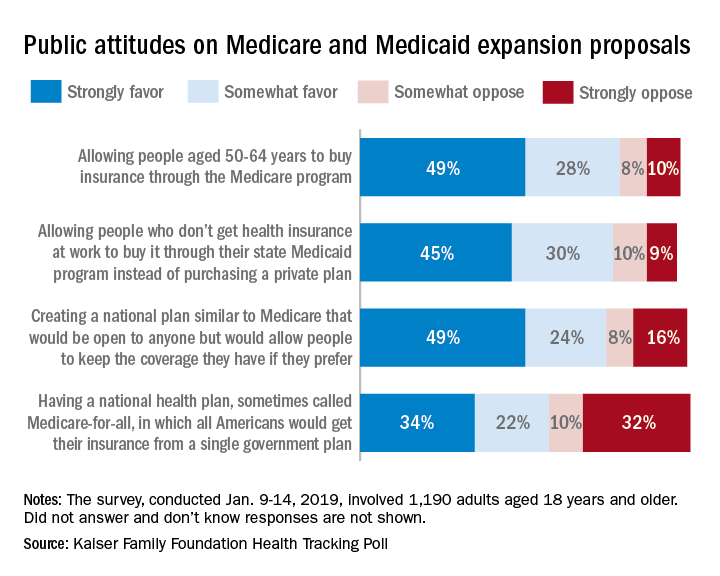

A majority of Americans support the concept of Medicare for all, but “larger majorities favor more incremental changes to the health care system,” according to a new survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Support for a Medicare-for-all health care system came in at 56% (strongly favor, 34%; somewhat favor, 22%) among the 1,190 respondents to the latest KFF Health Tracking Poll, which was conducted Jan. 9-14, 2019. That support came largely from Democrats, 81% of whom favored the plan, compared with only 23% of Republicans, the Kaiser investigators said Jan. 23.

A Medicare buy-in plan for Americans aged 50-64 years also was highly popular, receiving support from 77% of all respondents – 85% of Democrats, 75% of Independents, and 69% of Republicans. Support by party identification was similar for a proposal to enable all those who don’t have employer-based insurance to get coverage through state Medicaid programs, which received 75% support overall, they reported.

Just behind those proposals at 74% support was a federally administered health plan that would be open to anyone but would allow people to keep the coverage they have. It was the most popular proposal among Democrats (91%) but did not garner a majority among Republicans (47%), the investigators said.

Support for the Medicare-for-all plan varied considerably, depending on number of arguments presented to respondents. When told that such a proposal would guarantee insurance as a right for all Americans, 71% favored it, and when they heard that it would eliminate health insurance premiums and reduce out-of-pockets costs, 67% of respondents expressed support. Favorable responses, however, were in the minority when people were told that Medicare-for-all would eliminate private health insurance companies (37%), threaten the current Medicare program (32%), and lead to some delayed medical tests and treatments (26%), according to the Kaiser report.

A majority of Americans support the concept of Medicare for all, but “larger majorities favor more incremental changes to the health care system,” according to a new survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Support for a Medicare-for-all health care system came in at 56% (strongly favor, 34%; somewhat favor, 22%) among the 1,190 respondents to the latest KFF Health Tracking Poll, which was conducted Jan. 9-14, 2019. That support came largely from Democrats, 81% of whom favored the plan, compared with only 23% of Republicans, the Kaiser investigators said Jan. 23.

A Medicare buy-in plan for Americans aged 50-64 years also was highly popular, receiving support from 77% of all respondents – 85% of Democrats, 75% of Independents, and 69% of Republicans. Support by party identification was similar for a proposal to enable all those who don’t have employer-based insurance to get coverage through state Medicaid programs, which received 75% support overall, they reported.

Just behind those proposals at 74% support was a federally administered health plan that would be open to anyone but would allow people to keep the coverage they have. It was the most popular proposal among Democrats (91%) but did not garner a majority among Republicans (47%), the investigators said.

Support for the Medicare-for-all plan varied considerably, depending on number of arguments presented to respondents. When told that such a proposal would guarantee insurance as a right for all Americans, 71% favored it, and when they heard that it would eliminate health insurance premiums and reduce out-of-pockets costs, 67% of respondents expressed support. Favorable responses, however, were in the minority when people were told that Medicare-for-all would eliminate private health insurance companies (37%), threaten the current Medicare program (32%), and lead to some delayed medical tests and treatments (26%), according to the Kaiser report.

A majority of Americans support the concept of Medicare for all, but “larger majorities favor more incremental changes to the health care system,” according to a new survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Support for a Medicare-for-all health care system came in at 56% (strongly favor, 34%; somewhat favor, 22%) among the 1,190 respondents to the latest KFF Health Tracking Poll, which was conducted Jan. 9-14, 2019. That support came largely from Democrats, 81% of whom favored the plan, compared with only 23% of Republicans, the Kaiser investigators said Jan. 23.

A Medicare buy-in plan for Americans aged 50-64 years also was highly popular, receiving support from 77% of all respondents – 85% of Democrats, 75% of Independents, and 69% of Republicans. Support by party identification was similar for a proposal to enable all those who don’t have employer-based insurance to get coverage through state Medicaid programs, which received 75% support overall, they reported.

Just behind those proposals at 74% support was a federally administered health plan that would be open to anyone but would allow people to keep the coverage they have. It was the most popular proposal among Democrats (91%) but did not garner a majority among Republicans (47%), the investigators said.

Support for the Medicare-for-all plan varied considerably, depending on number of arguments presented to respondents. When told that such a proposal would guarantee insurance as a right for all Americans, 71% favored it, and when they heard that it would eliminate health insurance premiums and reduce out-of-pockets costs, 67% of respondents expressed support. Favorable responses, however, were in the minority when people were told that Medicare-for-all would eliminate private health insurance companies (37%), threaten the current Medicare program (32%), and lead to some delayed medical tests and treatments (26%), according to the Kaiser report.

Trump zeroes in on surprise medical bills in White House chat with patients, experts

President Trump on Jan. 23 instructed administration officials to investigate how to prevent surprise medical bills, broadening his focus on drug prices to include other issues of price transparency in health care.

several attendees said.

“The pricing is hurting patients, and we’ve stopped a lot of it, but we’re going to stop all of it,” Mr. Trump said during a roundtable discussion when reporters were briefly allowed into the otherwise closed-door meeting.

David Silverstein, the founder of a Colorado-based nonprofit called Broken Healthcare who attended, said Mr. Trump struck an aggressive tone, calling for a solution with “the biggest teeth you can find.”

“Reading the tea leaves, I think there’s big change coming,” Mr. Silverstein said.

Surprise billing, or the practice of charging patients for care that is more expensive than anticipated or not covered by their insurance, has received a flood of attention in the past year, particularly as Kaiser Health News and other news organizations have undertaken investigations into patients’ most outrageous medical bills.

Attendees said each of 10 invited guests – among them patients as well as doctors with their own stories of unexpected bills – was given an opportunity to talk, though Mr. Trump did not stay to hear all of their stories during the roughly hour-long gathering.

The group included Paul Davis, a retired doctor from Findlay, Ohio, whose family’s experience with a $17,850 bill for a simple urine test was detailed in a KHN-NPR “Bill of the Month” feature last year.

Mr. Davis’ daughter, Elizabeth Moreno, was a college student in Texas when she had spinal surgery to remedy debilitating back pain. After the surgery, she was asked to provide a urine sample and later received a bill from an out-of-network lab in Houston that tested it. Experts said such tests rarely cost more than $200, not nearly what the lab charged Ms. Moreno and her insurance company. But fearing damage to his daughter’s credit, Mr. Davis paid the lab $5,000 and filed a complaint with the Texas attorney general’s office, alleging “price gouging of staggering proportions.”

Mr. Davis said White House officials made it clear that price transparency is a “high priority” for Trump, and while they did not see eye to eye on every subject, he said he was struck by their sincerity.

“These people seemed earnest in wanting to do something constructive to fix this,” Mr. Davis said.

Dr. Martin Makary, a surgeon and health policy expert at Johns Hopkins University who has written about transparency in health care and attended the meeting, said it was a good opportunity for the White House to hear firsthand about a serious and widespread issue.

“This is how most of America lives, and [Americans are] getting hammered,” he said.

Mr. Trump has often railed against high prescription drug prices but has said less about other problems with the nation’s health care system. In October, shortly before the midterm elections, he unveiled a proposal to tie the price Medicare pays for some drugs to the prices paid for the same drugs overseas, for example.

Mr. Trump, Mr. Azar, and Mr. Acosta said efforts to control costs in health care were yielding positive results, discussing in particular the expansion of association health plans and the new requirement that hospitals post their list prices online. The president also took credit for the recent increase in generic drug approvals, which he said would help lower drug prices.

Discussing the partial government shutdown, Mr. Trump said Americans “want to see what we’re doing, like today we lowered prescription drug prices, first time in 50 years,” according to a White House pool report.

Mr. Trump appeared to be referring to a recent claim by the White House Council of Economic Advisers that prescription drug prices fell last year.

However, as STAT pointed out in a recent fact check, the report from which that claim was gleaned said “growth in relative drug prices has slowed since January 2017,” not that there was an overall decrease in prices.

Annual increases in overall drug spending have leveled off as pharmaceutical companies have released fewer blockbuster drugs; patents have expired on brand-name drugs; and the waning effect of a spike driven by the release of astronomically expensive drugs to treat hepatitis C. Drugmakers are also wary of increasing their prices in the midst of growing political pressure.

Since Democrats seized control of the House of Representatives this month, party leaders have rushed to announce investigations and schedule hearings dealing with health care, focusing in particular on drug costs and protections for those with preexisting conditions.

Recently, the House Oversight Committee announced a “sweeping” investigation into drug prices, pointing to an AARP report saying the vast majority of brand-name drugs had more than doubled in price between 2005 and 2017.

KHN correspondents Shefali Luthra and Jay Hancock contributed to this report. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

President Trump on Jan. 23 instructed administration officials to investigate how to prevent surprise medical bills, broadening his focus on drug prices to include other issues of price transparency in health care.

several attendees said.

“The pricing is hurting patients, and we’ve stopped a lot of it, but we’re going to stop all of it,” Mr. Trump said during a roundtable discussion when reporters were briefly allowed into the otherwise closed-door meeting.

David Silverstein, the founder of a Colorado-based nonprofit called Broken Healthcare who attended, said Mr. Trump struck an aggressive tone, calling for a solution with “the biggest teeth you can find.”

“Reading the tea leaves, I think there’s big change coming,” Mr. Silverstein said.

Surprise billing, or the practice of charging patients for care that is more expensive than anticipated or not covered by their insurance, has received a flood of attention in the past year, particularly as Kaiser Health News and other news organizations have undertaken investigations into patients’ most outrageous medical bills.

Attendees said each of 10 invited guests – among them patients as well as doctors with their own stories of unexpected bills – was given an opportunity to talk, though Mr. Trump did not stay to hear all of their stories during the roughly hour-long gathering.

The group included Paul Davis, a retired doctor from Findlay, Ohio, whose family’s experience with a $17,850 bill for a simple urine test was detailed in a KHN-NPR “Bill of the Month” feature last year.

Mr. Davis’ daughter, Elizabeth Moreno, was a college student in Texas when she had spinal surgery to remedy debilitating back pain. After the surgery, she was asked to provide a urine sample and later received a bill from an out-of-network lab in Houston that tested it. Experts said such tests rarely cost more than $200, not nearly what the lab charged Ms. Moreno and her insurance company. But fearing damage to his daughter’s credit, Mr. Davis paid the lab $5,000 and filed a complaint with the Texas attorney general’s office, alleging “price gouging of staggering proportions.”

Mr. Davis said White House officials made it clear that price transparency is a “high priority” for Trump, and while they did not see eye to eye on every subject, he said he was struck by their sincerity.

“These people seemed earnest in wanting to do something constructive to fix this,” Mr. Davis said.

Dr. Martin Makary, a surgeon and health policy expert at Johns Hopkins University who has written about transparency in health care and attended the meeting, said it was a good opportunity for the White House to hear firsthand about a serious and widespread issue.

“This is how most of America lives, and [Americans are] getting hammered,” he said.

Mr. Trump has often railed against high prescription drug prices but has said less about other problems with the nation’s health care system. In October, shortly before the midterm elections, he unveiled a proposal to tie the price Medicare pays for some drugs to the prices paid for the same drugs overseas, for example.

Mr. Trump, Mr. Azar, and Mr. Acosta said efforts to control costs in health care were yielding positive results, discussing in particular the expansion of association health plans and the new requirement that hospitals post their list prices online. The president also took credit for the recent increase in generic drug approvals, which he said would help lower drug prices.

Discussing the partial government shutdown, Mr. Trump said Americans “want to see what we’re doing, like today we lowered prescription drug prices, first time in 50 years,” according to a White House pool report.

Mr. Trump appeared to be referring to a recent claim by the White House Council of Economic Advisers that prescription drug prices fell last year.

However, as STAT pointed out in a recent fact check, the report from which that claim was gleaned said “growth in relative drug prices has slowed since January 2017,” not that there was an overall decrease in prices.

Annual increases in overall drug spending have leveled off as pharmaceutical companies have released fewer blockbuster drugs; patents have expired on brand-name drugs; and the waning effect of a spike driven by the release of astronomically expensive drugs to treat hepatitis C. Drugmakers are also wary of increasing their prices in the midst of growing political pressure.

Since Democrats seized control of the House of Representatives this month, party leaders have rushed to announce investigations and schedule hearings dealing with health care, focusing in particular on drug costs and protections for those with preexisting conditions.

Recently, the House Oversight Committee announced a “sweeping” investigation into drug prices, pointing to an AARP report saying the vast majority of brand-name drugs had more than doubled in price between 2005 and 2017.

KHN correspondents Shefali Luthra and Jay Hancock contributed to this report. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

President Trump on Jan. 23 instructed administration officials to investigate how to prevent surprise medical bills, broadening his focus on drug prices to include other issues of price transparency in health care.

several attendees said.

“The pricing is hurting patients, and we’ve stopped a lot of it, but we’re going to stop all of it,” Mr. Trump said during a roundtable discussion when reporters were briefly allowed into the otherwise closed-door meeting.

David Silverstein, the founder of a Colorado-based nonprofit called Broken Healthcare who attended, said Mr. Trump struck an aggressive tone, calling for a solution with “the biggest teeth you can find.”

“Reading the tea leaves, I think there’s big change coming,” Mr. Silverstein said.

Surprise billing, or the practice of charging patients for care that is more expensive than anticipated or not covered by their insurance, has received a flood of attention in the past year, particularly as Kaiser Health News and other news organizations have undertaken investigations into patients’ most outrageous medical bills.

Attendees said each of 10 invited guests – among them patients as well as doctors with their own stories of unexpected bills – was given an opportunity to talk, though Mr. Trump did not stay to hear all of their stories during the roughly hour-long gathering.

The group included Paul Davis, a retired doctor from Findlay, Ohio, whose family’s experience with a $17,850 bill for a simple urine test was detailed in a KHN-NPR “Bill of the Month” feature last year.

Mr. Davis’ daughter, Elizabeth Moreno, was a college student in Texas when she had spinal surgery to remedy debilitating back pain. After the surgery, she was asked to provide a urine sample and later received a bill from an out-of-network lab in Houston that tested it. Experts said such tests rarely cost more than $200, not nearly what the lab charged Ms. Moreno and her insurance company. But fearing damage to his daughter’s credit, Mr. Davis paid the lab $5,000 and filed a complaint with the Texas attorney general’s office, alleging “price gouging of staggering proportions.”

Mr. Davis said White House officials made it clear that price transparency is a “high priority” for Trump, and while they did not see eye to eye on every subject, he said he was struck by their sincerity.

“These people seemed earnest in wanting to do something constructive to fix this,” Mr. Davis said.

Dr. Martin Makary, a surgeon and health policy expert at Johns Hopkins University who has written about transparency in health care and attended the meeting, said it was a good opportunity for the White House to hear firsthand about a serious and widespread issue.

“This is how most of America lives, and [Americans are] getting hammered,” he said.

Mr. Trump has often railed against high prescription drug prices but has said less about other problems with the nation’s health care system. In October, shortly before the midterm elections, he unveiled a proposal to tie the price Medicare pays for some drugs to the prices paid for the same drugs overseas, for example.

Mr. Trump, Mr. Azar, and Mr. Acosta said efforts to control costs in health care were yielding positive results, discussing in particular the expansion of association health plans and the new requirement that hospitals post their list prices online. The president also took credit for the recent increase in generic drug approvals, which he said would help lower drug prices.

Discussing the partial government shutdown, Mr. Trump said Americans “want to see what we’re doing, like today we lowered prescription drug prices, first time in 50 years,” according to a White House pool report.

Mr. Trump appeared to be referring to a recent claim by the White House Council of Economic Advisers that prescription drug prices fell last year.

However, as STAT pointed out in a recent fact check, the report from which that claim was gleaned said “growth in relative drug prices has slowed since January 2017,” not that there was an overall decrease in prices.

Annual increases in overall drug spending have leveled off as pharmaceutical companies have released fewer blockbuster drugs; patents have expired on brand-name drugs; and the waning effect of a spike driven by the release of astronomically expensive drugs to treat hepatitis C. Drugmakers are also wary of increasing their prices in the midst of growing political pressure.

Since Democrats seized control of the House of Representatives this month, party leaders have rushed to announce investigations and schedule hearings dealing with health care, focusing in particular on drug costs and protections for those with preexisting conditions.

Recently, the House Oversight Committee announced a “sweeping” investigation into drug prices, pointing to an AARP report saying the vast majority of brand-name drugs had more than doubled in price between 2005 and 2017.

KHN correspondents Shefali Luthra and Jay Hancock contributed to this report. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Violence against women: Gail Robinson

Dr. Robinson is professor of psychiatry and obstetrics/gynecology and professor of equality, gender, and population at the University of Toronto. She’s also chair of GAP’s Committee on Gender & Mental Health. In this episode, Dr. Robinson delves into strategies for interacting with survivors of violence, the roots of the “Me Too” movement, as well as rising rates of maternal mortality in the United States.

Amazon

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Dr. Robinson is professor of psychiatry and obstetrics/gynecology and professor of equality, gender, and population at the University of Toronto. She’s also chair of GAP’s Committee on Gender & Mental Health. In this episode, Dr. Robinson delves into strategies for interacting with survivors of violence, the roots of the “Me Too” movement, as well as rising rates of maternal mortality in the United States.

Amazon

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Dr. Robinson is professor of psychiatry and obstetrics/gynecology and professor of equality, gender, and population at the University of Toronto. She’s also chair of GAP’s Committee on Gender & Mental Health. In this episode, Dr. Robinson delves into strategies for interacting with survivors of violence, the roots of the “Me Too” movement, as well as rising rates of maternal mortality in the United States.

Amazon

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Intimate partner violence, guns, and the ObGyn

On the afternoon of November 19, 2018, Dr. Tamara O’Neal was shot and killed by her ex-fiancé outside Mercy Hospital and Medical Center in Chicago, Illinois. After killing Dr. O’Neal, the gunman ran into the hospital where he exchanged gunfire with police, killing a pharmacy resident and a police officer, before he was killed by police.1

This horrific encounter between a woman and her former partner begs for a conversation about intimate partner violence (IPV). A data brief of The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey was published in November 2018. According to this report, 30.6% of women experienced physical violence by an intimate partner in 2015, with 21.4% of women experiencing severe physical violence. In addition, 31.0% of men experienced physical violence by an intimate partner in 2015; 14.9% of men experienced severe physical violence.2

Intimate partner violence is “our lane”

The shooting at Mercy Hospital occurred amongst a backdrop of controversy between the National Rifle Association (NRA) and the medical community. On November 7, 2018, the NRA tweeted that doctors should “stay in their lane” with regard to gun control after a position paper from the American College of Physicians on reducing firearm deaths and injuries was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.3 Doctors from every field and from all over the country responded through social media by stating that treating bullet wounds and caring for those affected by gun violence was “their lane.”4

It is time for us as a community to recognize that gun violence affects us all. The majority of mass shooters have a history of IPV and often target their current or prior partner during the shooting.5 At this intersection of IPV and gun control, the physician has a unique role. We not only treat those affected by gun violence and advocate for better gun control but we also have a duty to screen our patients for IPV. Part of the sacred patient-physician relationship is being present for our patients when they need us most. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that ObGyns screen patients for IPV at regular intervals and recognizes that it may take several conversations before a patient discloses her history of IPV.6 Additionally, given the increased risk of gun injuries and death, it behooves us to also screen for gun safety in the home.

Ask patients about IPV, and ask again

The shooting at Mercy Hospital was a stark reminder that IPV can affect any of us. With nearly one-third of women and more than one-quarter of men experiencing IPV in their lifetime, action must be taken. The first step is to routinely screen patients for IPV, offering support and community resources. (see “Screening for intimate partner violence). The second step is to work to decrease the access perpetrators of IPV have to weapons with which to enact violence—through legislation, community engagement, and using our physician voices.

States that have passed legislation that prohibits persons with active restraining orders or a history of IPV or domestic violence from possessing firearms has seen a decrease in IPV firearm homicide rates.7 These policies can make a profound impact on the safety of our patients. Women who are in violent relationships are 5 times more likely to die if their partner has access to a firearm.5

Continue to: #BreakTheCycle...

#BreakTheCycle

The 116th Congress convened in January. We have an opportunity to make real gun legislation reform and work to keep our communities and our patients at risk for IPV safer. Tweet your representatives with #BreakTheCycle, and be on the lookout for important legislation to enact real change.

To sign the open letter from American Healthcare Professionals to the NRA regarding their recent comments and our medical experiences with gun violence, click here. Currently, there are more than 41,000 signatures.

There are numerous verified screening tools available to assess for intimate partner violence (IPV) for both pregnant and nonpregnant patients. Many recommended tools are accessible on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv/ipvandsvscreening.pdf. In our office, the tool most commonly used is a 3-part question assessing domestic violence and IPV. It is important to recognize IPV can affect everyone—all races and religions regardless of socioeconomic background, sexual orientation, and pregnancy status. All patients deserve screening for IPV, and it should never be assumed a patient is not at risk. During an annual gynecology visit for return and new patients or a new obstetric intake visit, we use the following script obtained from ACOG’s Committee Opinion 518 on IPV1 :

Because violence is so common in many women’s lives and because there is help available for women being abused, I now ask every patient about domestic violence:

1. Within the past year (or since you have become pregnant) have you been hit, slapped, kicked, or otherwise physically hurt by someone?

2. Are you in a relationship with a person who threatens or physically hurts you?

3. Has anyone forced you to have sexual activities that made you feel uncomfortable?

If a patient screens positive, we assess their immediate safety. If a social worker is readily available, we arrange an urgent meeting with the patient. If offices do not have immediate access to this service, online information can be provided to patients, including the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence (https://nnedv.org/) and a toll-free number to the National Domestic Violence Hotline: 1-800-799-7233. Additionally, we ask patients about any history of verbal, physical, or sexual violence with prior partners, family members, acquaintances, coworkers, etc. Although the patient might not be at immediate risk, prior experiences with abuse can cause fear and anxiety around gynecologic and obstetric exams. Acknowledging this history can help the clinician adjust his or her physical exam and support the patient during, what may be, a triggering experience.

As an additional resource, Dr. Katherine Hicks-Courant, a resident at Tufts Medical Center, in Boston, Massachusetts, created a tool kit for providers working with pregnant patients with a history of sexual assault. It can be accessed without login online under the Junior Fellow Initiative Toolkit section at http://www.acog.org.

References

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 518: intimate partner violence. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:412-417.

If you, or someone you know, needs help, please call The National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Buckley M, Gorner J, Greene M. “Chicago hospital shooting: Young cop, doctor, pharmacy resident and gunman die in Mercy Hospital attack. Chicago Tribune. Nov. 20, 2018.

2. Smith SG, Zhang X, Basile KC, et al. The National Intimate Partner

and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2015 data brief – updated release. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; November 2018.

3. Butkus R, Doherty R, Bornstein SS; for the Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. Reducing firearm injuries and deaths in the United States: a position paper from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:704-707.

4. Papenfuss M. NRA Tweets Warning to Anti-Gun Doctors: ‘Stay In Your Lane’. The Huffington Post. November 8, 2018.

5. Everytown for Gun Safety website. Mass Shootings in the United States: 2009–2016. Available at https://everytownresearch.org/reports/mass-shootings-analysis/. Accessed January 17, 2019.

6. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 518: intimate partner violence. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(2 pt 1):412-417. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/Intimate-Partner-Violence.

7. Zeoli AM, McCourt A, Buggs S, et al. Analysis of the strength of legal firearms restrictions for perpetrators of domestic violence and their associations with intimate partner homicide. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187:2365-2371.

On the afternoon of November 19, 2018, Dr. Tamara O’Neal was shot and killed by her ex-fiancé outside Mercy Hospital and Medical Center in Chicago, Illinois. After killing Dr. O’Neal, the gunman ran into the hospital where he exchanged gunfire with police, killing a pharmacy resident and a police officer, before he was killed by police.1

This horrific encounter between a woman and her former partner begs for a conversation about intimate partner violence (IPV). A data brief of The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey was published in November 2018. According to this report, 30.6% of women experienced physical violence by an intimate partner in 2015, with 21.4% of women experiencing severe physical violence. In addition, 31.0% of men experienced physical violence by an intimate partner in 2015; 14.9% of men experienced severe physical violence.2

Intimate partner violence is “our lane”

The shooting at Mercy Hospital occurred amongst a backdrop of controversy between the National Rifle Association (NRA) and the medical community. On November 7, 2018, the NRA tweeted that doctors should “stay in their lane” with regard to gun control after a position paper from the American College of Physicians on reducing firearm deaths and injuries was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.3 Doctors from every field and from all over the country responded through social media by stating that treating bullet wounds and caring for those affected by gun violence was “their lane.”4

It is time for us as a community to recognize that gun violence affects us all. The majority of mass shooters have a history of IPV and often target their current or prior partner during the shooting.5 At this intersection of IPV and gun control, the physician has a unique role. We not only treat those affected by gun violence and advocate for better gun control but we also have a duty to screen our patients for IPV. Part of the sacred patient-physician relationship is being present for our patients when they need us most. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that ObGyns screen patients for IPV at regular intervals and recognizes that it may take several conversations before a patient discloses her history of IPV.6 Additionally, given the increased risk of gun injuries and death, it behooves us to also screen for gun safety in the home.

Ask patients about IPV, and ask again

The shooting at Mercy Hospital was a stark reminder that IPV can affect any of us. With nearly one-third of women and more than one-quarter of men experiencing IPV in their lifetime, action must be taken. The first step is to routinely screen patients for IPV, offering support and community resources. (see “Screening for intimate partner violence). The second step is to work to decrease the access perpetrators of IPV have to weapons with which to enact violence—through legislation, community engagement, and using our physician voices.

States that have passed legislation that prohibits persons with active restraining orders or a history of IPV or domestic violence from possessing firearms has seen a decrease in IPV firearm homicide rates.7 These policies can make a profound impact on the safety of our patients. Women who are in violent relationships are 5 times more likely to die if their partner has access to a firearm.5

Continue to: #BreakTheCycle...

#BreakTheCycle

The 116th Congress convened in January. We have an opportunity to make real gun legislation reform and work to keep our communities and our patients at risk for IPV safer. Tweet your representatives with #BreakTheCycle, and be on the lookout for important legislation to enact real change.

To sign the open letter from American Healthcare Professionals to the NRA regarding their recent comments and our medical experiences with gun violence, click here. Currently, there are more than 41,000 signatures.

There are numerous verified screening tools available to assess for intimate partner violence (IPV) for both pregnant and nonpregnant patients. Many recommended tools are accessible on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv/ipvandsvscreening.pdf. In our office, the tool most commonly used is a 3-part question assessing domestic violence and IPV. It is important to recognize IPV can affect everyone—all races and religions regardless of socioeconomic background, sexual orientation, and pregnancy status. All patients deserve screening for IPV, and it should never be assumed a patient is not at risk. During an annual gynecology visit for return and new patients or a new obstetric intake visit, we use the following script obtained from ACOG’s Committee Opinion 518 on IPV1 :

Because violence is so common in many women’s lives and because there is help available for women being abused, I now ask every patient about domestic violence:

1. Within the past year (or since you have become pregnant) have you been hit, slapped, kicked, or otherwise physically hurt by someone?

2. Are you in a relationship with a person who threatens or physically hurts you?

3. Has anyone forced you to have sexual activities that made you feel uncomfortable?

If a patient screens positive, we assess their immediate safety. If a social worker is readily available, we arrange an urgent meeting with the patient. If offices do not have immediate access to this service, online information can be provided to patients, including the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence (https://nnedv.org/) and a toll-free number to the National Domestic Violence Hotline: 1-800-799-7233. Additionally, we ask patients about any history of verbal, physical, or sexual violence with prior partners, family members, acquaintances, coworkers, etc. Although the patient might not be at immediate risk, prior experiences with abuse can cause fear and anxiety around gynecologic and obstetric exams. Acknowledging this history can help the clinician adjust his or her physical exam and support the patient during, what may be, a triggering experience.

As an additional resource, Dr. Katherine Hicks-Courant, a resident at Tufts Medical Center, in Boston, Massachusetts, created a tool kit for providers working with pregnant patients with a history of sexual assault. It can be accessed without login online under the Junior Fellow Initiative Toolkit section at http://www.acog.org.

References

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 518: intimate partner violence. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:412-417.

If you, or someone you know, needs help, please call The National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

On the afternoon of November 19, 2018, Dr. Tamara O’Neal was shot and killed by her ex-fiancé outside Mercy Hospital and Medical Center in Chicago, Illinois. After killing Dr. O’Neal, the gunman ran into the hospital where he exchanged gunfire with police, killing a pharmacy resident and a police officer, before he was killed by police.1

This horrific encounter between a woman and her former partner begs for a conversation about intimate partner violence (IPV). A data brief of The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey was published in November 2018. According to this report, 30.6% of women experienced physical violence by an intimate partner in 2015, with 21.4% of women experiencing severe physical violence. In addition, 31.0% of men experienced physical violence by an intimate partner in 2015; 14.9% of men experienced severe physical violence.2

Intimate partner violence is “our lane”

The shooting at Mercy Hospital occurred amongst a backdrop of controversy between the National Rifle Association (NRA) and the medical community. On November 7, 2018, the NRA tweeted that doctors should “stay in their lane” with regard to gun control after a position paper from the American College of Physicians on reducing firearm deaths and injuries was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.3 Doctors from every field and from all over the country responded through social media by stating that treating bullet wounds and caring for those affected by gun violence was “their lane.”4

It is time for us as a community to recognize that gun violence affects us all. The majority of mass shooters have a history of IPV and often target their current or prior partner during the shooting.5 At this intersection of IPV and gun control, the physician has a unique role. We not only treat those affected by gun violence and advocate for better gun control but we also have a duty to screen our patients for IPV. Part of the sacred patient-physician relationship is being present for our patients when they need us most. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that ObGyns screen patients for IPV at regular intervals and recognizes that it may take several conversations before a patient discloses her history of IPV.6 Additionally, given the increased risk of gun injuries and death, it behooves us to also screen for gun safety in the home.

Ask patients about IPV, and ask again

The shooting at Mercy Hospital was a stark reminder that IPV can affect any of us. With nearly one-third of women and more than one-quarter of men experiencing IPV in their lifetime, action must be taken. The first step is to routinely screen patients for IPV, offering support and community resources. (see “Screening for intimate partner violence). The second step is to work to decrease the access perpetrators of IPV have to weapons with which to enact violence—through legislation, community engagement, and using our physician voices.

States that have passed legislation that prohibits persons with active restraining orders or a history of IPV or domestic violence from possessing firearms has seen a decrease in IPV firearm homicide rates.7 These policies can make a profound impact on the safety of our patients. Women who are in violent relationships are 5 times more likely to die if their partner has access to a firearm.5

Continue to: #BreakTheCycle...

#BreakTheCycle

The 116th Congress convened in January. We have an opportunity to make real gun legislation reform and work to keep our communities and our patients at risk for IPV safer. Tweet your representatives with #BreakTheCycle, and be on the lookout for important legislation to enact real change.

To sign the open letter from American Healthcare Professionals to the NRA regarding their recent comments and our medical experiences with gun violence, click here. Currently, there are more than 41,000 signatures.

There are numerous verified screening tools available to assess for intimate partner violence (IPV) for both pregnant and nonpregnant patients. Many recommended tools are accessible on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv/ipvandsvscreening.pdf. In our office, the tool most commonly used is a 3-part question assessing domestic violence and IPV. It is important to recognize IPV can affect everyone—all races and religions regardless of socioeconomic background, sexual orientation, and pregnancy status. All patients deserve screening for IPV, and it should never be assumed a patient is not at risk. During an annual gynecology visit for return and new patients or a new obstetric intake visit, we use the following script obtained from ACOG’s Committee Opinion 518 on IPV1 :

Because violence is so common in many women’s lives and because there is help available for women being abused, I now ask every patient about domestic violence:

1. Within the past year (or since you have become pregnant) have you been hit, slapped, kicked, or otherwise physically hurt by someone?

2. Are you in a relationship with a person who threatens or physically hurts you?

3. Has anyone forced you to have sexual activities that made you feel uncomfortable?

If a patient screens positive, we assess their immediate safety. If a social worker is readily available, we arrange an urgent meeting with the patient. If offices do not have immediate access to this service, online information can be provided to patients, including the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence (https://nnedv.org/) and a toll-free number to the National Domestic Violence Hotline: 1-800-799-7233. Additionally, we ask patients about any history of verbal, physical, or sexual violence with prior partners, family members, acquaintances, coworkers, etc. Although the patient might not be at immediate risk, prior experiences with abuse can cause fear and anxiety around gynecologic and obstetric exams. Acknowledging this history can help the clinician adjust his or her physical exam and support the patient during, what may be, a triggering experience.

As an additional resource, Dr. Katherine Hicks-Courant, a resident at Tufts Medical Center, in Boston, Massachusetts, created a tool kit for providers working with pregnant patients with a history of sexual assault. It can be accessed without login online under the Junior Fellow Initiative Toolkit section at http://www.acog.org.

References

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 518: intimate partner violence. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:412-417.

If you, or someone you know, needs help, please call The National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Buckley M, Gorner J, Greene M. “Chicago hospital shooting: Young cop, doctor, pharmacy resident and gunman die in Mercy Hospital attack. Chicago Tribune. Nov. 20, 2018.

2. Smith SG, Zhang X, Basile KC, et al. The National Intimate Partner

and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2015 data brief – updated release. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; November 2018.

3. Butkus R, Doherty R, Bornstein SS; for the Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. Reducing firearm injuries and deaths in the United States: a position paper from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:704-707.

4. Papenfuss M. NRA Tweets Warning to Anti-Gun Doctors: ‘Stay In Your Lane’. The Huffington Post. November 8, 2018.

5. Everytown for Gun Safety website. Mass Shootings in the United States: 2009–2016. Available at https://everytownresearch.org/reports/mass-shootings-analysis/. Accessed January 17, 2019.

6. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 518: intimate partner violence. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(2 pt 1):412-417. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/Intimate-Partner-Violence.

7. Zeoli AM, McCourt A, Buggs S, et al. Analysis of the strength of legal firearms restrictions for perpetrators of domestic violence and their associations with intimate partner homicide. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187:2365-2371.

1. Buckley M, Gorner J, Greene M. “Chicago hospital shooting: Young cop, doctor, pharmacy resident and gunman die in Mercy Hospital attack. Chicago Tribune. Nov. 20, 2018.

2. Smith SG, Zhang X, Basile KC, et al. The National Intimate Partner