User login

Doc accused of killing 14 patients in the ICU: Upcoming trial notes patient safety lapses

On Dec. 5, 2017, Danny Mollette, age 74, was brought to the emergency department of Mount Carmel West Medical Center in Columbus, Ohio, in critical condition. Staff inserted a breathing tube and sent him to the intensive care unit.

Mr. Mollette, who had diabetes, previously had been hospitalized for treatment of a gangrenous foot. When he arrived in the ICU, he was suffering from acute renal failure and low blood pressure, and had had two heart stoppages, according to a 2020 Ohio Board of Pharmacy report. He was placed under the care of William Husel, DO, the sole physician on duty in the ICU during the overnight shift.

Around 9:00 p.m., Dr. Husel discussed Mr. Mollette’s “grim prognosis” with family members at the patient’s bedside. He advised them that Mr. Mollette had “minutes to live” and asked, “How would you want him to take his last breath: on the ventilator or without these machines?”

In less than an hour, Mr. Mollette was dead. Some said that what happened in his case was similar to what happened with 34 other ICU patients at Mount Carmel West and Mount Carmel St. Ann’s in Westerville, Ohio, from 2014 through 2018 – all under Dr. Husel’s care.

Like Mr. Mollette, most of these gravely ill patients died minutes after receiving a single, unusually large intravenous dose of the powerful opioid fentanyl – often combined with a dose of one or more other painkillers or sedatives like hydromorphone – and being withdrawn from the ventilator. These deaths all occurred following a procedure called palliative extubation, the removal of the endotracheal tube in patients who are expected to die.

Mount Carmel fired Dr. Husel in December 2018 following an investigation that concluded that the opioid dosages he used were “significantly excessive and potentially fatal,” and “went beyond providing comfort.” His Ohio medical license was suspended. In February 2022, he is scheduled to go on trial in Columbus on 14 counts of murder.*

Hanging over the murder case against Dr. Husel is the question of how Mount Carmel, a 136-year-old Catholic hospital owned by the giant Trinity Health system, allowed this pattern of care to continue for so many patients over 4 years, and why numerous registered nurses and hospital pharmacists went along with Dr. Husel’s actions. Nearly two dozen RNs and two pharmacists involved in these cases have faced disciplinary action, mostly license suspension.

“The first time a patient died on a very high dose, someone should have flagged this,” said Lewis Nelson, MD, chair of emergency medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark. “As soon as I see it the second time or 27th time, it doesn’t seem okay. There was a breakdown in oversight to allow this to continue. The hospital didn’t have guardrails in place.”

The Franklin County (Ohio) Prosecuting Attorney’s Office faces two big challenges in trying Dr. Husel for murder. The prosecutors must prove that the drugs Dr. Husel ordered are what directly caused these critically ill patients to die, and that he intended to kill them.

Federal and state agencies have cited the hospital system for faults in its patient safety systems and culture that were exposed by the Husel cases. An outside medical expert, Robert Powers, MD, a professor of emergency medicine at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, testified in one of the dozens of wrongful death lawsuits against Mount Carmel and Dr. Husel that there was no record of anyone supervising Dr. Husel or monitoring his care.

There also are questions about why Mount Carmel administrators and physician leaders did not find out about Dr. Husel’s criminal record as a young man before hiring and credentialing him, even though the Ohio Medical Board had obtained that record. As a college freshman in West Virginia in 1994, Dr. Husel and a friend allegedly stole car stereos, and after a classmate reported their behavior, they built a pipe bomb they planned to plant under the classmate’s car, according to court records.

Dr. Husel pleaded guilty in 1996 to a federal misdemeanor for improperly storing explosive materials, and he received a 6-month sentence followed by supervision. He did not disclose that criminal conviction on his application for medical liability insurance as part of his Mount Carmel employment application, attorneys representing the families of his deceased patients say.

A Mount Carmel spokeswoman said the hospital only checks a physician applicant’s background record for the previous 10 years.

“I think [the credentialing process] should have been more careful and more comprehensive than it was,” Robert Powers testified in a September 2020 deposition. “This guy was a bomber and a thief. You don’t hire bombers and thieves to take care of patients.”

Mount Carmel and Trinity leaders say they knew nothing about Dr. Husel’s palliative extubation practices until a staffer reported Dr. Husel’s high-dose fentanyl orders in October 2018. However, three more Husel patients died under similar circumstances before he was removed from patient care in November 2018.

Mount Carmel and Trinity already have settled a number of wrongful death lawsuits filed by the families of Dr. Husel’s patients for nearly $20 million, with many more suits pending. The Mount Carmel CEO, the chief clinical officer, other physician, nursing, and pharmacy leaders, as well as dozens of nurses and pharmacists have been terminated or entered into retirement.

“What happened is tragic and unacceptable,” the Mount Carmel spokeswoman said in a written statement. “We have made a number of changes designed to prevent this from ever happening again. … Our new hospital leadership team is committed to patient safety and will take immediate action whenever patient safety is at issue.”

In January 2019, Mount Carmel’s then-CEO Ed Lamb acknowledged that “processes in place were not sufficient to prevent these actions from happening.” Mr. Lamb later said Mount Carmel was investigating whether five of the ICU patients who died under Dr. Husel’s care could have been treated and survived. Mr. Lamb stepped down in June 2019.

Before performing a palliative extubation, physicians commonly administer opioids and/or sedatives to ease pain and discomfort, and spare family members from witnessing their loved one gasping for breath. But most medical experts say the fentanyl doses Dr. Husel ordered – 500-2,000 mcg – were five to 20 times larger than doses normally used in palliative extubation. Such doses, they say, would quickly kill most patients – except those with high opioid tolerance – by stopping their breathing.

Physicians say they typically give much smaller doses of fentanyl or morphine, then administer more as needed if they observe the patient experiencing pain or distress. Mount Carmel’s 2016 guidelines for IV administration of fentanyl specified a dosage range of 50-100 mcg for relieving pain, and its 2018 guidelines reduced that to 25-50 mcg.

“If I perform a painful procedure, I might give 100 or 150 micrograms of fentanyl, or 500 or 600 for open heart surgery,” said Dr. Nelson of Rutgers, who also practices medical toxicology and addiction medicine. “But you’ll be intubated and monitored carefully. Without having a tube in your airway to help you breathe, those doses will kill you.”**

Mount Carmel West hired Dr. Husel in 2013 to work the late-night shift in its ICU. It was his first job as a full-fledged physician, after completing a residency and fellowship in critical care medicine at Cleveland Clinic. A good-looking and charismatic former high school basketball star, he was a hard worker and was popular with the ICU nurses and staff, who looked to him as a teacher and mentor, according to depositions of nurses and Ohio Board of Nursing reports.

In 2014, Dr. Husel was chosen by his hospital colleagues as physician of the year. He was again nominated in 2018. Before October 2018, there were no complaints about his care, according to the deposition of Larry Swanner, MD, Mount Carmel’s former vice president of medical affairs, who was fired in 2019.

“Dr. Husel is so knowledgeable that we would try to soak up as much knowledge as we could,” said Jason Schulze, RN, in a July 2020 deposition. Mr. Schulze’s license was suspended, however, that suspension was stayed for a minimum period of two years. This was in connection with his care of one of Dr. Husel’s ICU patients, 44-year-old Troy Allison, who died 3 minutes after Mr. Schulze administered a 1,000-microgram dose of fentanyl ordered by Dr. Husel in July 2018.

Dr. Husel’s winning personality and seeming expertise in the use of pain drugs, combined with his training at the prestigious Cleveland Clinic, may have lulled other hospital staff into going along with his decisions.

“They’re thinking, the guy’s likable and he must know what he’s doing,” said Michael Cohen, RPh, founder and president emeritus of the Institute for Safe Medication Practices. “But you can’t get fooled by that. You need a policy in place for what to do if pharmacists or nurses disagree with an order, and you need to have practice simulations so people know how to handle these situations.”

Dr. Husel’s criminal defense attorney, Jose Baez, said Dr. Husel’s treatment of all these palliative extubation patients, including his prescribed dosages of fentanyl and other drugs, was completely appropriate. “Dr. Husel practiced medicine with compassion, and never wanted to see any of his patients suffer, nor their family,” Mr. Baez said.

Most medical and pharmacy experts sharply disagree. “I’m a pharmacist, and I’ve never seen anything like those kinds of doses,” Mr. Cohen said. “Something strange was going on there.”

Complicating these issues, eight nurses and a pharmacist have sued Mount Carmel and Trinity for wrongful termination and defamation in connection with the Husel allegations. They strongly defend Dr. Husel’s and their care as compassionate and appropriate. Beyond that, they argue that the changes Mount Carmel and Trinity made to ICU procedures to prevent such situations from happening again are potentially harmful to patient care.

“None of the nurses ever thought that Dr. Husel did anything to harm his patients or do anything other than provide comfort care during a very difficult time,” said Robert Landy, a New York attorney who’s representing the plaintiffs in the federal wrongful termination suit. “The real harm came in January 2019, when there were substantial policy changes that were detrimental to patient care and safety.”

Many of these patient deaths occurred during a period when the Mount Carmel system and Trinity were in the process of closing the old Mount Carmel West hospital, located in the low-income, inner-city neighborhood of Columbus, and opening a new hospital in the affluent suburb of Grove City, Ohio.

“They were done with this old, worn-out, inner-city hospital and its patient base and wanted a brand-new sparkling object in the suburbs,” said Gerry Leeseberg, a Columbus attorney who is representing 17 families of patients who died under Dr. Husel’s care. “They may have directed less energy, attention, and resources to the inner-city hospital.”

The case of Danny Mollette illustrates the multiple issues with Mount Carmel’s patient safety system.

First, there was no evidence in the record that Mr. Mollette was in pain or lacked the ability to breathe on his own prior to Dr. Husel’s palliative extubation. He had received no pain medications in the hospital that day, according to the report of an Ohio Board of Nursing examiner in a licensure discipline action brought against nurse Jacob Deemer for his care of Mr. Mollette and two other ICU patients who died. Mr. Deemer said Dr. Husel told him that the patient had to be in pain given his condition.

After consulting with Mr. Mollette’s family at the bedside, Dr. Husel ordered Mr. Deemer to administer 1,000 mcg of fentanyl, followed by 2 mg of hydromorphone, and 4 mg of midzolam, a sedative. Mr. Deemer withdrew the drugs from the Pyxis dispensing cabinet, overriding the pharmacist preapproval system. He said Dr. Husel told him the pharmacist had said, “It is okay.”

Actually, according to the pharmacy board report, the pharmacist, Gregory White, wrote in the medical record system that he did not agree to the fentanyl order. But his dissent came as the drugs were being administered, the breathing tube was being removed, and the patient was about to die. Mr. White was later disciplined by the Ohio Board of Pharmacy for failing to inform his supervisors about the incident and preventing the use of those high drug dosages in the cases of Mr. Mollette and two subsequent Husel patients.

Then there are questions about whether the families of Mr. Mollette and other Husel patients were fully and accurately informed about their loved ones’ conditions before agreeing to the palliative extubation. Mr. Mollette’s son, Brian, told reporters in July 2019 that Dr. Husel “said my father’s organs were shutting down and he was brain damaged. In hindsight, we felt kind of rushed to make that decision.”

Plaintiff attorneys bringing civil wrongful death cases against Mount Carmel and Dr. Husel must overcome hurdles similar to those faced by prosecutors in the murder case against Dr. Husel. Even if the patients were likely to die from their underlying conditions, did the drugs hasten their deaths, and by how much? In the civil cases, there’s the additional question of how much a few more hours or days or weeks of life are worth in terms of monetary damages.

Another challenge in bringing both the criminal and civil cases is that physicians and other medical providers have certain legal protections for administering drugs to patients for the purpose of relieving pain and suffering, even if the drugs hasten the patients’ deaths – as long the intent was not to cause death and the drugs were properly used. This is known as the double-effect principle. In contrast, intentional killing to relieve pain and suffering is called euthanasia, and that’s illegal in the United States.

“There is no evidence that medication played any part in the death of any of these patients,” said Mr. Landy, who’s representing the nurses and pharmacists in the wrongful termination suit. “The only evidence we have is that higher dosages of opioids following extubation extend life, not shorten it.”

Dr. Husel, as well as the nurses and pharmacists who have faced licensure actions, claim their actions were legally shielded by the double-effect principle. But the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the Ohio Board of Nursing, and Ohio Board of Pharmacy haven’t accepted that defense. Instead, they have cited Mount Carmel, Dr. Husel, and the nurses and pharmacists for numerous patient safety violations, including administering excessive dosages of fentanyl and other drugs.

Among those violations is that many of Dr. Husel’s drug orders were given verbally instead of through the standard process of entering the orders into the electronic health record. He and the nurses on duty skipped the standard nonemergency process of getting preapproval from the pharmacist on duty. Instead, they used the override function on Mount Carmel’s automated Pyxis system to withdraw the drugs from the cabinet and avoid pharmacist review. In many cases, there was no retrospective review of the appropriateness of the orders by a pharmacist after the drugs were administered, which is required.

After threatening to cut off Medicare and Medicaid payments to Mount Carmel, CMS in June 2019 accepted the hospital’s correction plan, which restricted use of verbal drug orders and prohibited Pyxis system overrides for opioids except in life-threatening emergencies. The Ohio Board of Pharmacy hit Mount Carmel with $477,000 in fines and costs for pharmacy rules violations.

Under the agreement with CMS, Mount Carmel physicians must receive permission from a physician executive to order painkilling drugs that exceed hospital-set dosage parameters for palliative ventilator withdrawal. In addition, pharmacists must immediately report concerns about drug-prescribing safety up the hospital pharmacy chain of command.

“We have trained staff to ensure they feel empowered to speak up when appropriate,” the Mount Carmel spokeswoman said. “Staff members have multiple avenues for elevating a complaint or concern.”

Dr. Husel’s high dosages of fentanyl and other painkillers were well-known among the ICU nurses and pharmacists, who rarely – if ever – questioned those dosages, and went along with his standard use of verbal orders and overrides of the Pyxis system, according to depositions of nurses and pharmacists in the wrongful death lawsuits.

But the Mount Carmel nurses and pharmacists had a professional responsibility to question such dosages and demand evidence from the medical literature to support their use, according to hearing examiners at the nursing and pharmacy boards, who meted out licensure actions to providers working with Dr. Husel.

Nursing board hearing examiner Jack Decker emphasized those responsibilities in his November 30, 2020, report on nurse Deemer’s actions regarding three patients who died under Dr. Husel’s care in 2017 and 2018. Mr. Deemer’s license was suspended, however, that suspension was stayed for a minimum period of three years. Mr. Decker wrote that the ICU nurses had a professional responsibility to question Dr. Husel and, if necessary, refuse to carry out the doctor’s order and report their concerns to managers.

“Challenging a physician’s order is a difficult step even under ideal circumstances,” wrote Mr. Decker, who called Mount Carmel West’s ICU a “dysfunctional” environment. “But,” he noted, “when Mr. Deemer signed on to become a nurse, he enlisted to use his own critical thinking skills to serve as a patient protector and advocate. … Clearly, Mr. Deemer trusted Dr. Husel. But Dr. Husel was not to be trusted.”

While patient safety experts say these cases reveal that Mount Carmel had a flawed system and culture that did not train and empower staff to report safety concerns up the chain of command, they acknowledged that this could have happened at many U.S. hospitals.

“Sadly, I’m not sure it’s all that uncommon,” said Dr. Nelson of Rutgers. “Nurses and pharmacists have historically been afraid to raise concerns about physicians. We’ve been trying to break down barriers, but it’s a natural human instinct to play your role in the hierarchy.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Corrections 2/1/22: An earlier version of this article misstated (*) the number of murder counts and (**) Dr. Nelson's area of practice.

This article was updated 2/2/22 to reflect the fact that the license suspensions of Mr. Deemer and Mr. Schulze were stayed.

On Dec. 5, 2017, Danny Mollette, age 74, was brought to the emergency department of Mount Carmel West Medical Center in Columbus, Ohio, in critical condition. Staff inserted a breathing tube and sent him to the intensive care unit.

Mr. Mollette, who had diabetes, previously had been hospitalized for treatment of a gangrenous foot. When he arrived in the ICU, he was suffering from acute renal failure and low blood pressure, and had had two heart stoppages, according to a 2020 Ohio Board of Pharmacy report. He was placed under the care of William Husel, DO, the sole physician on duty in the ICU during the overnight shift.

Around 9:00 p.m., Dr. Husel discussed Mr. Mollette’s “grim prognosis” with family members at the patient’s bedside. He advised them that Mr. Mollette had “minutes to live” and asked, “How would you want him to take his last breath: on the ventilator or without these machines?”

In less than an hour, Mr. Mollette was dead. Some said that what happened in his case was similar to what happened with 34 other ICU patients at Mount Carmel West and Mount Carmel St. Ann’s in Westerville, Ohio, from 2014 through 2018 – all under Dr. Husel’s care.

Like Mr. Mollette, most of these gravely ill patients died minutes after receiving a single, unusually large intravenous dose of the powerful opioid fentanyl – often combined with a dose of one or more other painkillers or sedatives like hydromorphone – and being withdrawn from the ventilator. These deaths all occurred following a procedure called palliative extubation, the removal of the endotracheal tube in patients who are expected to die.

Mount Carmel fired Dr. Husel in December 2018 following an investigation that concluded that the opioid dosages he used were “significantly excessive and potentially fatal,” and “went beyond providing comfort.” His Ohio medical license was suspended. In February 2022, he is scheduled to go on trial in Columbus on 14 counts of murder.*

Hanging over the murder case against Dr. Husel is the question of how Mount Carmel, a 136-year-old Catholic hospital owned by the giant Trinity Health system, allowed this pattern of care to continue for so many patients over 4 years, and why numerous registered nurses and hospital pharmacists went along with Dr. Husel’s actions. Nearly two dozen RNs and two pharmacists involved in these cases have faced disciplinary action, mostly license suspension.

“The first time a patient died on a very high dose, someone should have flagged this,” said Lewis Nelson, MD, chair of emergency medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark. “As soon as I see it the second time or 27th time, it doesn’t seem okay. There was a breakdown in oversight to allow this to continue. The hospital didn’t have guardrails in place.”

The Franklin County (Ohio) Prosecuting Attorney’s Office faces two big challenges in trying Dr. Husel for murder. The prosecutors must prove that the drugs Dr. Husel ordered are what directly caused these critically ill patients to die, and that he intended to kill them.

Federal and state agencies have cited the hospital system for faults in its patient safety systems and culture that were exposed by the Husel cases. An outside medical expert, Robert Powers, MD, a professor of emergency medicine at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, testified in one of the dozens of wrongful death lawsuits against Mount Carmel and Dr. Husel that there was no record of anyone supervising Dr. Husel or monitoring his care.

There also are questions about why Mount Carmel administrators and physician leaders did not find out about Dr. Husel’s criminal record as a young man before hiring and credentialing him, even though the Ohio Medical Board had obtained that record. As a college freshman in West Virginia in 1994, Dr. Husel and a friend allegedly stole car stereos, and after a classmate reported their behavior, they built a pipe bomb they planned to plant under the classmate’s car, according to court records.

Dr. Husel pleaded guilty in 1996 to a federal misdemeanor for improperly storing explosive materials, and he received a 6-month sentence followed by supervision. He did not disclose that criminal conviction on his application for medical liability insurance as part of his Mount Carmel employment application, attorneys representing the families of his deceased patients say.

A Mount Carmel spokeswoman said the hospital only checks a physician applicant’s background record for the previous 10 years.

“I think [the credentialing process] should have been more careful and more comprehensive than it was,” Robert Powers testified in a September 2020 deposition. “This guy was a bomber and a thief. You don’t hire bombers and thieves to take care of patients.”

Mount Carmel and Trinity leaders say they knew nothing about Dr. Husel’s palliative extubation practices until a staffer reported Dr. Husel’s high-dose fentanyl orders in October 2018. However, three more Husel patients died under similar circumstances before he was removed from patient care in November 2018.

Mount Carmel and Trinity already have settled a number of wrongful death lawsuits filed by the families of Dr. Husel’s patients for nearly $20 million, with many more suits pending. The Mount Carmel CEO, the chief clinical officer, other physician, nursing, and pharmacy leaders, as well as dozens of nurses and pharmacists have been terminated or entered into retirement.

“What happened is tragic and unacceptable,” the Mount Carmel spokeswoman said in a written statement. “We have made a number of changes designed to prevent this from ever happening again. … Our new hospital leadership team is committed to patient safety and will take immediate action whenever patient safety is at issue.”

In January 2019, Mount Carmel’s then-CEO Ed Lamb acknowledged that “processes in place were not sufficient to prevent these actions from happening.” Mr. Lamb later said Mount Carmel was investigating whether five of the ICU patients who died under Dr. Husel’s care could have been treated and survived. Mr. Lamb stepped down in June 2019.

Before performing a palliative extubation, physicians commonly administer opioids and/or sedatives to ease pain and discomfort, and spare family members from witnessing their loved one gasping for breath. But most medical experts say the fentanyl doses Dr. Husel ordered – 500-2,000 mcg – were five to 20 times larger than doses normally used in palliative extubation. Such doses, they say, would quickly kill most patients – except those with high opioid tolerance – by stopping their breathing.

Physicians say they typically give much smaller doses of fentanyl or morphine, then administer more as needed if they observe the patient experiencing pain or distress. Mount Carmel’s 2016 guidelines for IV administration of fentanyl specified a dosage range of 50-100 mcg for relieving pain, and its 2018 guidelines reduced that to 25-50 mcg.

“If I perform a painful procedure, I might give 100 or 150 micrograms of fentanyl, or 500 or 600 for open heart surgery,” said Dr. Nelson of Rutgers, who also practices medical toxicology and addiction medicine. “But you’ll be intubated and monitored carefully. Without having a tube in your airway to help you breathe, those doses will kill you.”**

Mount Carmel West hired Dr. Husel in 2013 to work the late-night shift in its ICU. It was his first job as a full-fledged physician, after completing a residency and fellowship in critical care medicine at Cleveland Clinic. A good-looking and charismatic former high school basketball star, he was a hard worker and was popular with the ICU nurses and staff, who looked to him as a teacher and mentor, according to depositions of nurses and Ohio Board of Nursing reports.

In 2014, Dr. Husel was chosen by his hospital colleagues as physician of the year. He was again nominated in 2018. Before October 2018, there were no complaints about his care, according to the deposition of Larry Swanner, MD, Mount Carmel’s former vice president of medical affairs, who was fired in 2019.

“Dr. Husel is so knowledgeable that we would try to soak up as much knowledge as we could,” said Jason Schulze, RN, in a July 2020 deposition. Mr. Schulze’s license was suspended, however, that suspension was stayed for a minimum period of two years. This was in connection with his care of one of Dr. Husel’s ICU patients, 44-year-old Troy Allison, who died 3 minutes after Mr. Schulze administered a 1,000-microgram dose of fentanyl ordered by Dr. Husel in July 2018.

Dr. Husel’s winning personality and seeming expertise in the use of pain drugs, combined with his training at the prestigious Cleveland Clinic, may have lulled other hospital staff into going along with his decisions.

“They’re thinking, the guy’s likable and he must know what he’s doing,” said Michael Cohen, RPh, founder and president emeritus of the Institute for Safe Medication Practices. “But you can’t get fooled by that. You need a policy in place for what to do if pharmacists or nurses disagree with an order, and you need to have practice simulations so people know how to handle these situations.”

Dr. Husel’s criminal defense attorney, Jose Baez, said Dr. Husel’s treatment of all these palliative extubation patients, including his prescribed dosages of fentanyl and other drugs, was completely appropriate. “Dr. Husel practiced medicine with compassion, and never wanted to see any of his patients suffer, nor their family,” Mr. Baez said.

Most medical and pharmacy experts sharply disagree. “I’m a pharmacist, and I’ve never seen anything like those kinds of doses,” Mr. Cohen said. “Something strange was going on there.”

Complicating these issues, eight nurses and a pharmacist have sued Mount Carmel and Trinity for wrongful termination and defamation in connection with the Husel allegations. They strongly defend Dr. Husel’s and their care as compassionate and appropriate. Beyond that, they argue that the changes Mount Carmel and Trinity made to ICU procedures to prevent such situations from happening again are potentially harmful to patient care.

“None of the nurses ever thought that Dr. Husel did anything to harm his patients or do anything other than provide comfort care during a very difficult time,” said Robert Landy, a New York attorney who’s representing the plaintiffs in the federal wrongful termination suit. “The real harm came in January 2019, when there were substantial policy changes that were detrimental to patient care and safety.”

Many of these patient deaths occurred during a period when the Mount Carmel system and Trinity were in the process of closing the old Mount Carmel West hospital, located in the low-income, inner-city neighborhood of Columbus, and opening a new hospital in the affluent suburb of Grove City, Ohio.

“They were done with this old, worn-out, inner-city hospital and its patient base and wanted a brand-new sparkling object in the suburbs,” said Gerry Leeseberg, a Columbus attorney who is representing 17 families of patients who died under Dr. Husel’s care. “They may have directed less energy, attention, and resources to the inner-city hospital.”

The case of Danny Mollette illustrates the multiple issues with Mount Carmel’s patient safety system.

First, there was no evidence in the record that Mr. Mollette was in pain or lacked the ability to breathe on his own prior to Dr. Husel’s palliative extubation. He had received no pain medications in the hospital that day, according to the report of an Ohio Board of Nursing examiner in a licensure discipline action brought against nurse Jacob Deemer for his care of Mr. Mollette and two other ICU patients who died. Mr. Deemer said Dr. Husel told him that the patient had to be in pain given his condition.

After consulting with Mr. Mollette’s family at the bedside, Dr. Husel ordered Mr. Deemer to administer 1,000 mcg of fentanyl, followed by 2 mg of hydromorphone, and 4 mg of midzolam, a sedative. Mr. Deemer withdrew the drugs from the Pyxis dispensing cabinet, overriding the pharmacist preapproval system. He said Dr. Husel told him the pharmacist had said, “It is okay.”

Actually, according to the pharmacy board report, the pharmacist, Gregory White, wrote in the medical record system that he did not agree to the fentanyl order. But his dissent came as the drugs were being administered, the breathing tube was being removed, and the patient was about to die. Mr. White was later disciplined by the Ohio Board of Pharmacy for failing to inform his supervisors about the incident and preventing the use of those high drug dosages in the cases of Mr. Mollette and two subsequent Husel patients.

Then there are questions about whether the families of Mr. Mollette and other Husel patients were fully and accurately informed about their loved ones’ conditions before agreeing to the palliative extubation. Mr. Mollette’s son, Brian, told reporters in July 2019 that Dr. Husel “said my father’s organs were shutting down and he was brain damaged. In hindsight, we felt kind of rushed to make that decision.”

Plaintiff attorneys bringing civil wrongful death cases against Mount Carmel and Dr. Husel must overcome hurdles similar to those faced by prosecutors in the murder case against Dr. Husel. Even if the patients were likely to die from their underlying conditions, did the drugs hasten their deaths, and by how much? In the civil cases, there’s the additional question of how much a few more hours or days or weeks of life are worth in terms of monetary damages.

Another challenge in bringing both the criminal and civil cases is that physicians and other medical providers have certain legal protections for administering drugs to patients for the purpose of relieving pain and suffering, even if the drugs hasten the patients’ deaths – as long the intent was not to cause death and the drugs were properly used. This is known as the double-effect principle. In contrast, intentional killing to relieve pain and suffering is called euthanasia, and that’s illegal in the United States.

“There is no evidence that medication played any part in the death of any of these patients,” said Mr. Landy, who’s representing the nurses and pharmacists in the wrongful termination suit. “The only evidence we have is that higher dosages of opioids following extubation extend life, not shorten it.”

Dr. Husel, as well as the nurses and pharmacists who have faced licensure actions, claim their actions were legally shielded by the double-effect principle. But the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the Ohio Board of Nursing, and Ohio Board of Pharmacy haven’t accepted that defense. Instead, they have cited Mount Carmel, Dr. Husel, and the nurses and pharmacists for numerous patient safety violations, including administering excessive dosages of fentanyl and other drugs.

Among those violations is that many of Dr. Husel’s drug orders were given verbally instead of through the standard process of entering the orders into the electronic health record. He and the nurses on duty skipped the standard nonemergency process of getting preapproval from the pharmacist on duty. Instead, they used the override function on Mount Carmel’s automated Pyxis system to withdraw the drugs from the cabinet and avoid pharmacist review. In many cases, there was no retrospective review of the appropriateness of the orders by a pharmacist after the drugs were administered, which is required.

After threatening to cut off Medicare and Medicaid payments to Mount Carmel, CMS in June 2019 accepted the hospital’s correction plan, which restricted use of verbal drug orders and prohibited Pyxis system overrides for opioids except in life-threatening emergencies. The Ohio Board of Pharmacy hit Mount Carmel with $477,000 in fines and costs for pharmacy rules violations.

Under the agreement with CMS, Mount Carmel physicians must receive permission from a physician executive to order painkilling drugs that exceed hospital-set dosage parameters for palliative ventilator withdrawal. In addition, pharmacists must immediately report concerns about drug-prescribing safety up the hospital pharmacy chain of command.

“We have trained staff to ensure they feel empowered to speak up when appropriate,” the Mount Carmel spokeswoman said. “Staff members have multiple avenues for elevating a complaint or concern.”

Dr. Husel’s high dosages of fentanyl and other painkillers were well-known among the ICU nurses and pharmacists, who rarely – if ever – questioned those dosages, and went along with his standard use of verbal orders and overrides of the Pyxis system, according to depositions of nurses and pharmacists in the wrongful death lawsuits.

But the Mount Carmel nurses and pharmacists had a professional responsibility to question such dosages and demand evidence from the medical literature to support their use, according to hearing examiners at the nursing and pharmacy boards, who meted out licensure actions to providers working with Dr. Husel.

Nursing board hearing examiner Jack Decker emphasized those responsibilities in his November 30, 2020, report on nurse Deemer’s actions regarding three patients who died under Dr. Husel’s care in 2017 and 2018. Mr. Deemer’s license was suspended, however, that suspension was stayed for a minimum period of three years. Mr. Decker wrote that the ICU nurses had a professional responsibility to question Dr. Husel and, if necessary, refuse to carry out the doctor’s order and report their concerns to managers.

“Challenging a physician’s order is a difficult step even under ideal circumstances,” wrote Mr. Decker, who called Mount Carmel West’s ICU a “dysfunctional” environment. “But,” he noted, “when Mr. Deemer signed on to become a nurse, he enlisted to use his own critical thinking skills to serve as a patient protector and advocate. … Clearly, Mr. Deemer trusted Dr. Husel. But Dr. Husel was not to be trusted.”

While patient safety experts say these cases reveal that Mount Carmel had a flawed system and culture that did not train and empower staff to report safety concerns up the chain of command, they acknowledged that this could have happened at many U.S. hospitals.

“Sadly, I’m not sure it’s all that uncommon,” said Dr. Nelson of Rutgers. “Nurses and pharmacists have historically been afraid to raise concerns about physicians. We’ve been trying to break down barriers, but it’s a natural human instinct to play your role in the hierarchy.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Corrections 2/1/22: An earlier version of this article misstated (*) the number of murder counts and (**) Dr. Nelson's area of practice.

This article was updated 2/2/22 to reflect the fact that the license suspensions of Mr. Deemer and Mr. Schulze were stayed.

On Dec. 5, 2017, Danny Mollette, age 74, was brought to the emergency department of Mount Carmel West Medical Center in Columbus, Ohio, in critical condition. Staff inserted a breathing tube and sent him to the intensive care unit.

Mr. Mollette, who had diabetes, previously had been hospitalized for treatment of a gangrenous foot. When he arrived in the ICU, he was suffering from acute renal failure and low blood pressure, and had had two heart stoppages, according to a 2020 Ohio Board of Pharmacy report. He was placed under the care of William Husel, DO, the sole physician on duty in the ICU during the overnight shift.

Around 9:00 p.m., Dr. Husel discussed Mr. Mollette’s “grim prognosis” with family members at the patient’s bedside. He advised them that Mr. Mollette had “minutes to live” and asked, “How would you want him to take his last breath: on the ventilator or without these machines?”

In less than an hour, Mr. Mollette was dead. Some said that what happened in his case was similar to what happened with 34 other ICU patients at Mount Carmel West and Mount Carmel St. Ann’s in Westerville, Ohio, from 2014 through 2018 – all under Dr. Husel’s care.

Like Mr. Mollette, most of these gravely ill patients died minutes after receiving a single, unusually large intravenous dose of the powerful opioid fentanyl – often combined with a dose of one or more other painkillers or sedatives like hydromorphone – and being withdrawn from the ventilator. These deaths all occurred following a procedure called palliative extubation, the removal of the endotracheal tube in patients who are expected to die.

Mount Carmel fired Dr. Husel in December 2018 following an investigation that concluded that the opioid dosages he used were “significantly excessive and potentially fatal,” and “went beyond providing comfort.” His Ohio medical license was suspended. In February 2022, he is scheduled to go on trial in Columbus on 14 counts of murder.*

Hanging over the murder case against Dr. Husel is the question of how Mount Carmel, a 136-year-old Catholic hospital owned by the giant Trinity Health system, allowed this pattern of care to continue for so many patients over 4 years, and why numerous registered nurses and hospital pharmacists went along with Dr. Husel’s actions. Nearly two dozen RNs and two pharmacists involved in these cases have faced disciplinary action, mostly license suspension.

“The first time a patient died on a very high dose, someone should have flagged this,” said Lewis Nelson, MD, chair of emergency medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark. “As soon as I see it the second time or 27th time, it doesn’t seem okay. There was a breakdown in oversight to allow this to continue. The hospital didn’t have guardrails in place.”

The Franklin County (Ohio) Prosecuting Attorney’s Office faces two big challenges in trying Dr. Husel for murder. The prosecutors must prove that the drugs Dr. Husel ordered are what directly caused these critically ill patients to die, and that he intended to kill them.

Federal and state agencies have cited the hospital system for faults in its patient safety systems and culture that were exposed by the Husel cases. An outside medical expert, Robert Powers, MD, a professor of emergency medicine at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, testified in one of the dozens of wrongful death lawsuits against Mount Carmel and Dr. Husel that there was no record of anyone supervising Dr. Husel or monitoring his care.

There also are questions about why Mount Carmel administrators and physician leaders did not find out about Dr. Husel’s criminal record as a young man before hiring and credentialing him, even though the Ohio Medical Board had obtained that record. As a college freshman in West Virginia in 1994, Dr. Husel and a friend allegedly stole car stereos, and after a classmate reported their behavior, they built a pipe bomb they planned to plant under the classmate’s car, according to court records.

Dr. Husel pleaded guilty in 1996 to a federal misdemeanor for improperly storing explosive materials, and he received a 6-month sentence followed by supervision. He did not disclose that criminal conviction on his application for medical liability insurance as part of his Mount Carmel employment application, attorneys representing the families of his deceased patients say.

A Mount Carmel spokeswoman said the hospital only checks a physician applicant’s background record for the previous 10 years.

“I think [the credentialing process] should have been more careful and more comprehensive than it was,” Robert Powers testified in a September 2020 deposition. “This guy was a bomber and a thief. You don’t hire bombers and thieves to take care of patients.”

Mount Carmel and Trinity leaders say they knew nothing about Dr. Husel’s palliative extubation practices until a staffer reported Dr. Husel’s high-dose fentanyl orders in October 2018. However, three more Husel patients died under similar circumstances before he was removed from patient care in November 2018.

Mount Carmel and Trinity already have settled a number of wrongful death lawsuits filed by the families of Dr. Husel’s patients for nearly $20 million, with many more suits pending. The Mount Carmel CEO, the chief clinical officer, other physician, nursing, and pharmacy leaders, as well as dozens of nurses and pharmacists have been terminated or entered into retirement.

“What happened is tragic and unacceptable,” the Mount Carmel spokeswoman said in a written statement. “We have made a number of changes designed to prevent this from ever happening again. … Our new hospital leadership team is committed to patient safety and will take immediate action whenever patient safety is at issue.”

In January 2019, Mount Carmel’s then-CEO Ed Lamb acknowledged that “processes in place were not sufficient to prevent these actions from happening.” Mr. Lamb later said Mount Carmel was investigating whether five of the ICU patients who died under Dr. Husel’s care could have been treated and survived. Mr. Lamb stepped down in June 2019.

Before performing a palliative extubation, physicians commonly administer opioids and/or sedatives to ease pain and discomfort, and spare family members from witnessing their loved one gasping for breath. But most medical experts say the fentanyl doses Dr. Husel ordered – 500-2,000 mcg – were five to 20 times larger than doses normally used in palliative extubation. Such doses, they say, would quickly kill most patients – except those with high opioid tolerance – by stopping their breathing.

Physicians say they typically give much smaller doses of fentanyl or morphine, then administer more as needed if they observe the patient experiencing pain or distress. Mount Carmel’s 2016 guidelines for IV administration of fentanyl specified a dosage range of 50-100 mcg for relieving pain, and its 2018 guidelines reduced that to 25-50 mcg.

“If I perform a painful procedure, I might give 100 or 150 micrograms of fentanyl, or 500 or 600 for open heart surgery,” said Dr. Nelson of Rutgers, who also practices medical toxicology and addiction medicine. “But you’ll be intubated and monitored carefully. Without having a tube in your airway to help you breathe, those doses will kill you.”**

Mount Carmel West hired Dr. Husel in 2013 to work the late-night shift in its ICU. It was his first job as a full-fledged physician, after completing a residency and fellowship in critical care medicine at Cleveland Clinic. A good-looking and charismatic former high school basketball star, he was a hard worker and was popular with the ICU nurses and staff, who looked to him as a teacher and mentor, according to depositions of nurses and Ohio Board of Nursing reports.

In 2014, Dr. Husel was chosen by his hospital colleagues as physician of the year. He was again nominated in 2018. Before October 2018, there were no complaints about his care, according to the deposition of Larry Swanner, MD, Mount Carmel’s former vice president of medical affairs, who was fired in 2019.

“Dr. Husel is so knowledgeable that we would try to soak up as much knowledge as we could,” said Jason Schulze, RN, in a July 2020 deposition. Mr. Schulze’s license was suspended, however, that suspension was stayed for a minimum period of two years. This was in connection with his care of one of Dr. Husel’s ICU patients, 44-year-old Troy Allison, who died 3 minutes after Mr. Schulze administered a 1,000-microgram dose of fentanyl ordered by Dr. Husel in July 2018.

Dr. Husel’s winning personality and seeming expertise in the use of pain drugs, combined with his training at the prestigious Cleveland Clinic, may have lulled other hospital staff into going along with his decisions.

“They’re thinking, the guy’s likable and he must know what he’s doing,” said Michael Cohen, RPh, founder and president emeritus of the Institute for Safe Medication Practices. “But you can’t get fooled by that. You need a policy in place for what to do if pharmacists or nurses disagree with an order, and you need to have practice simulations so people know how to handle these situations.”

Dr. Husel’s criminal defense attorney, Jose Baez, said Dr. Husel’s treatment of all these palliative extubation patients, including his prescribed dosages of fentanyl and other drugs, was completely appropriate. “Dr. Husel practiced medicine with compassion, and never wanted to see any of his patients suffer, nor their family,” Mr. Baez said.

Most medical and pharmacy experts sharply disagree. “I’m a pharmacist, and I’ve never seen anything like those kinds of doses,” Mr. Cohen said. “Something strange was going on there.”

Complicating these issues, eight nurses and a pharmacist have sued Mount Carmel and Trinity for wrongful termination and defamation in connection with the Husel allegations. They strongly defend Dr. Husel’s and their care as compassionate and appropriate. Beyond that, they argue that the changes Mount Carmel and Trinity made to ICU procedures to prevent such situations from happening again are potentially harmful to patient care.

“None of the nurses ever thought that Dr. Husel did anything to harm his patients or do anything other than provide comfort care during a very difficult time,” said Robert Landy, a New York attorney who’s representing the plaintiffs in the federal wrongful termination suit. “The real harm came in January 2019, when there were substantial policy changes that were detrimental to patient care and safety.”

Many of these patient deaths occurred during a period when the Mount Carmel system and Trinity were in the process of closing the old Mount Carmel West hospital, located in the low-income, inner-city neighborhood of Columbus, and opening a new hospital in the affluent suburb of Grove City, Ohio.

“They were done with this old, worn-out, inner-city hospital and its patient base and wanted a brand-new sparkling object in the suburbs,” said Gerry Leeseberg, a Columbus attorney who is representing 17 families of patients who died under Dr. Husel’s care. “They may have directed less energy, attention, and resources to the inner-city hospital.”

The case of Danny Mollette illustrates the multiple issues with Mount Carmel’s patient safety system.

First, there was no evidence in the record that Mr. Mollette was in pain or lacked the ability to breathe on his own prior to Dr. Husel’s palliative extubation. He had received no pain medications in the hospital that day, according to the report of an Ohio Board of Nursing examiner in a licensure discipline action brought against nurse Jacob Deemer for his care of Mr. Mollette and two other ICU patients who died. Mr. Deemer said Dr. Husel told him that the patient had to be in pain given his condition.

After consulting with Mr. Mollette’s family at the bedside, Dr. Husel ordered Mr. Deemer to administer 1,000 mcg of fentanyl, followed by 2 mg of hydromorphone, and 4 mg of midzolam, a sedative. Mr. Deemer withdrew the drugs from the Pyxis dispensing cabinet, overriding the pharmacist preapproval system. He said Dr. Husel told him the pharmacist had said, “It is okay.”

Actually, according to the pharmacy board report, the pharmacist, Gregory White, wrote in the medical record system that he did not agree to the fentanyl order. But his dissent came as the drugs were being administered, the breathing tube was being removed, and the patient was about to die. Mr. White was later disciplined by the Ohio Board of Pharmacy for failing to inform his supervisors about the incident and preventing the use of those high drug dosages in the cases of Mr. Mollette and two subsequent Husel patients.

Then there are questions about whether the families of Mr. Mollette and other Husel patients were fully and accurately informed about their loved ones’ conditions before agreeing to the palliative extubation. Mr. Mollette’s son, Brian, told reporters in July 2019 that Dr. Husel “said my father’s organs were shutting down and he was brain damaged. In hindsight, we felt kind of rushed to make that decision.”

Plaintiff attorneys bringing civil wrongful death cases against Mount Carmel and Dr. Husel must overcome hurdles similar to those faced by prosecutors in the murder case against Dr. Husel. Even if the patients were likely to die from their underlying conditions, did the drugs hasten their deaths, and by how much? In the civil cases, there’s the additional question of how much a few more hours or days or weeks of life are worth in terms of monetary damages.

Another challenge in bringing both the criminal and civil cases is that physicians and other medical providers have certain legal protections for administering drugs to patients for the purpose of relieving pain and suffering, even if the drugs hasten the patients’ deaths – as long the intent was not to cause death and the drugs were properly used. This is known as the double-effect principle. In contrast, intentional killing to relieve pain and suffering is called euthanasia, and that’s illegal in the United States.

“There is no evidence that medication played any part in the death of any of these patients,” said Mr. Landy, who’s representing the nurses and pharmacists in the wrongful termination suit. “The only evidence we have is that higher dosages of opioids following extubation extend life, not shorten it.”

Dr. Husel, as well as the nurses and pharmacists who have faced licensure actions, claim their actions were legally shielded by the double-effect principle. But the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the Ohio Board of Nursing, and Ohio Board of Pharmacy haven’t accepted that defense. Instead, they have cited Mount Carmel, Dr. Husel, and the nurses and pharmacists for numerous patient safety violations, including administering excessive dosages of fentanyl and other drugs.

Among those violations is that many of Dr. Husel’s drug orders were given verbally instead of through the standard process of entering the orders into the electronic health record. He and the nurses on duty skipped the standard nonemergency process of getting preapproval from the pharmacist on duty. Instead, they used the override function on Mount Carmel’s automated Pyxis system to withdraw the drugs from the cabinet and avoid pharmacist review. In many cases, there was no retrospective review of the appropriateness of the orders by a pharmacist after the drugs were administered, which is required.

After threatening to cut off Medicare and Medicaid payments to Mount Carmel, CMS in June 2019 accepted the hospital’s correction plan, which restricted use of verbal drug orders and prohibited Pyxis system overrides for opioids except in life-threatening emergencies. The Ohio Board of Pharmacy hit Mount Carmel with $477,000 in fines and costs for pharmacy rules violations.

Under the agreement with CMS, Mount Carmel physicians must receive permission from a physician executive to order painkilling drugs that exceed hospital-set dosage parameters for palliative ventilator withdrawal. In addition, pharmacists must immediately report concerns about drug-prescribing safety up the hospital pharmacy chain of command.

“We have trained staff to ensure they feel empowered to speak up when appropriate,” the Mount Carmel spokeswoman said. “Staff members have multiple avenues for elevating a complaint or concern.”

Dr. Husel’s high dosages of fentanyl and other painkillers were well-known among the ICU nurses and pharmacists, who rarely – if ever – questioned those dosages, and went along with his standard use of verbal orders and overrides of the Pyxis system, according to depositions of nurses and pharmacists in the wrongful death lawsuits.

But the Mount Carmel nurses and pharmacists had a professional responsibility to question such dosages and demand evidence from the medical literature to support their use, according to hearing examiners at the nursing and pharmacy boards, who meted out licensure actions to providers working with Dr. Husel.

Nursing board hearing examiner Jack Decker emphasized those responsibilities in his November 30, 2020, report on nurse Deemer’s actions regarding three patients who died under Dr. Husel’s care in 2017 and 2018. Mr. Deemer’s license was suspended, however, that suspension was stayed for a minimum period of three years. Mr. Decker wrote that the ICU nurses had a professional responsibility to question Dr. Husel and, if necessary, refuse to carry out the doctor’s order and report their concerns to managers.

“Challenging a physician’s order is a difficult step even under ideal circumstances,” wrote Mr. Decker, who called Mount Carmel West’s ICU a “dysfunctional” environment. “But,” he noted, “when Mr. Deemer signed on to become a nurse, he enlisted to use his own critical thinking skills to serve as a patient protector and advocate. … Clearly, Mr. Deemer trusted Dr. Husel. But Dr. Husel was not to be trusted.”

While patient safety experts say these cases reveal that Mount Carmel had a flawed system and culture that did not train and empower staff to report safety concerns up the chain of command, they acknowledged that this could have happened at many U.S. hospitals.

“Sadly, I’m not sure it’s all that uncommon,” said Dr. Nelson of Rutgers. “Nurses and pharmacists have historically been afraid to raise concerns about physicians. We’ve been trying to break down barriers, but it’s a natural human instinct to play your role in the hierarchy.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Corrections 2/1/22: An earlier version of this article misstated (*) the number of murder counts and (**) Dr. Nelson's area of practice.

This article was updated 2/2/22 to reflect the fact that the license suspensions of Mr. Deemer and Mr. Schulze were stayed.

Easing dementia caregiver burden, addressing interpersonal violence

The number of people with dementia globally is expected to reach 74.7 million by 2030 and 131.5 million by 2050.1 Because dementia is progressive, many patients will exhibit severe symptoms termed behavioral crises. Deteriorating interpersonal conduct and escalating antisocial acts result in an acquired sociopathy.2 Increasing cognitive impairment causes these patients to misunderstand intimate care and perceive it as a threat, often resulting in outbursts of violence against their caregivers.3

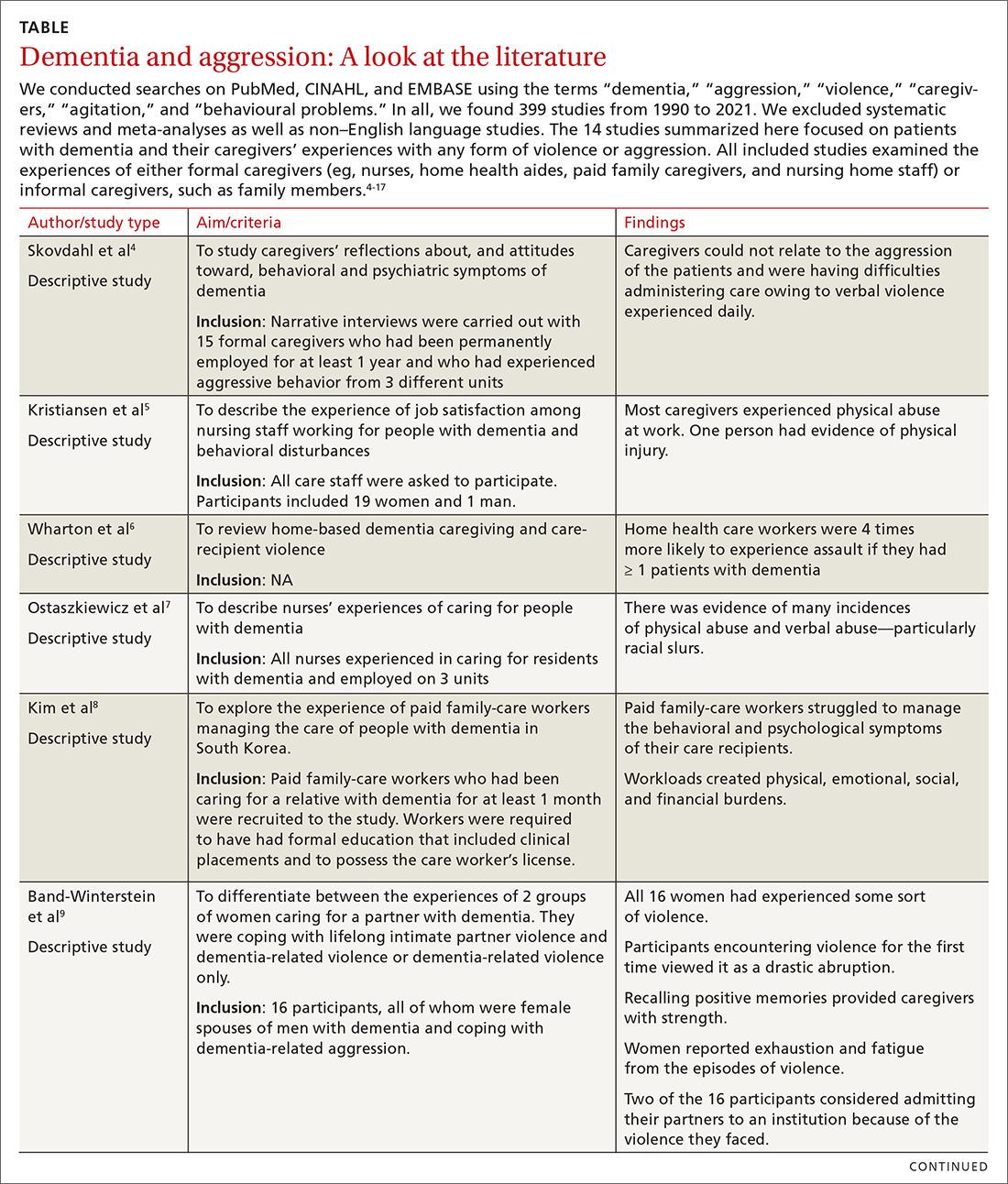

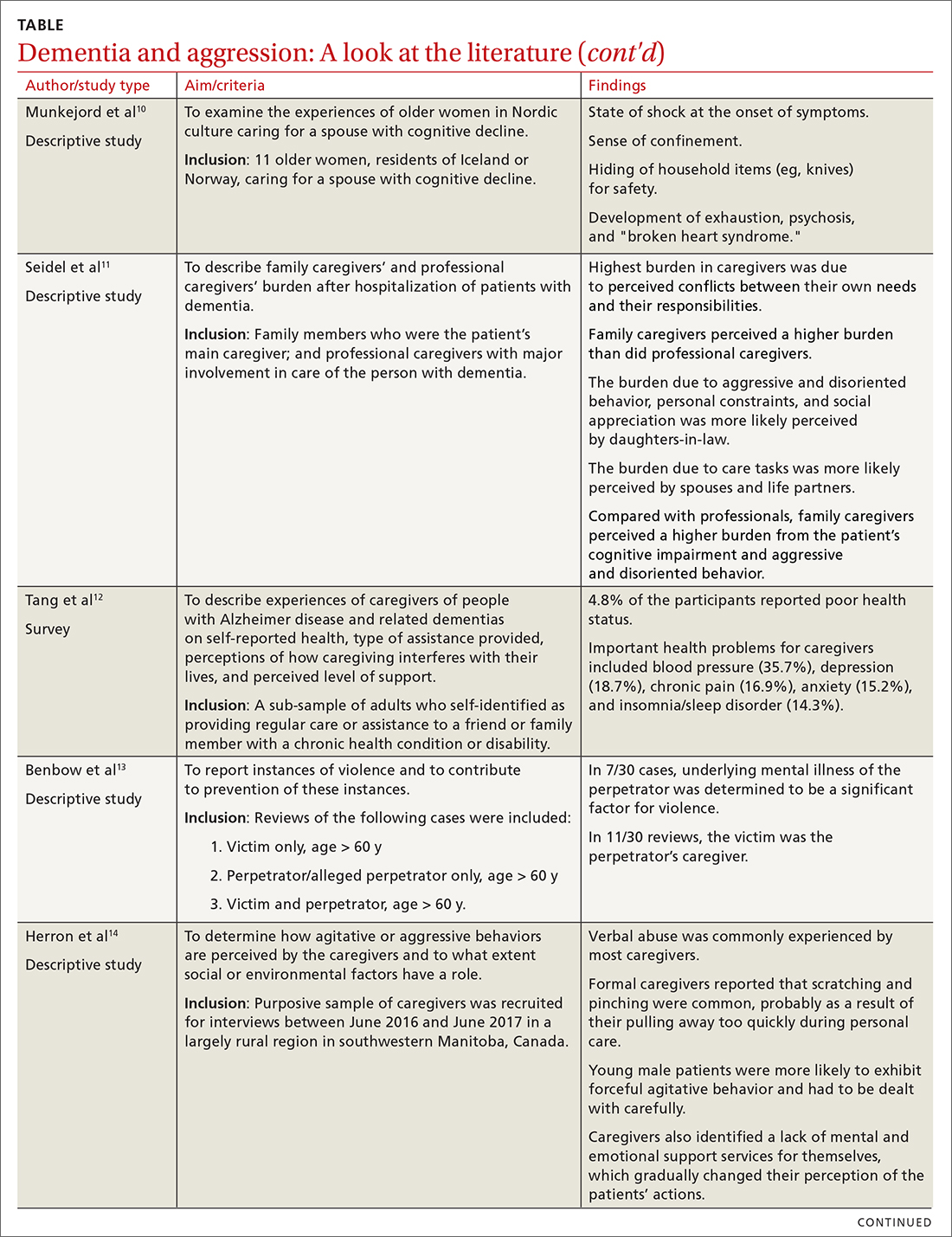

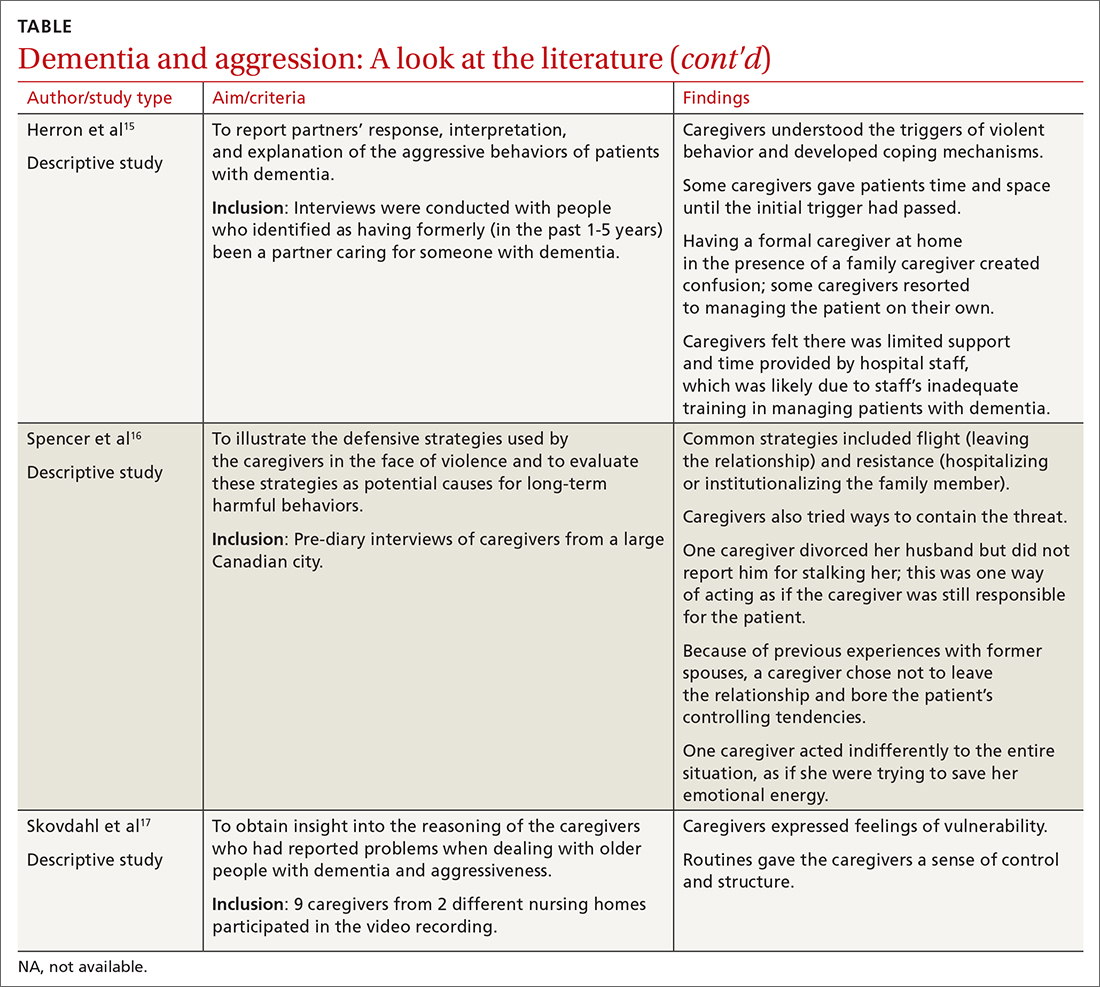

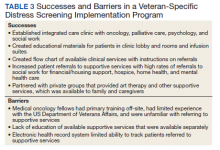

Available studies (TABLE4-17) make evident the incidence of interpersonal violence experienced by caregivers secondary to aggressive acts by patients with dementia. This violence ranges from verbal abuse, including racial slurs, to physical abuse—sometimes resulting in significant physical injury. Aggressive behavior by patients with dementia, resulting in violence towards their caregivers or partners, stems from progressive cognitive decline, which can make optimal care difficult. Such episodes may also impair the psychological and physical well-being of caregivers, increasing their risk of depression, anxiety, and even post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).18 The extent of the impact is also determined by the interpretation of the abuse by the caregivers themselves. One study suggested that the perception of aggressive or violent behavior as “normal” by a caregiver reduced the overall negative effect of the interactions.7Our review emphasizes the unintended burden that can fall to caregivers of patients with dementia. We also address the role of primary care providers (PCPs) in identifying these instances of violence and intervening appropriately by providing safety strategies, education, resources, and support.

CASE

A 67-year-old man with a medical history of PTSD with depression, type 2 diabetes, alcohol use disorder/dependence, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea was brought to his PCP by his wife. She said he had recently been unable to keep appointment times, pay bills, or take his usual medications, venlafaxine and bupropion. She also said his PTSD symptoms had worsened. He was sleeping 12 to 14 hours per day and was increasingly irritable. The patient denied any concerns or changes in his behavior.

The PCP administered a Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) examination to screen for cognitive impairment.19 The patient scored 14/30 (less than 20 is indicative of dementia). He was unable to complete a simple math problem, recall any items from a list of 5, count in reverse, draw a clock correctly, or recall a full story. Throughout the exam, the patient demonstrated minimal effort and was often only able to complete a task after further prompting by the examiner.

A computed tomography scan of the head revealed no signs of hemorrhage or damage. Thyroid-stimulating hormone levels and vitamin B12 levels were normal. A rapid plasma reagin test result was negative. The patient was given a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Donepezil was added to the patient’s medications, starting at 5 mg and then increased to 10 mg. His wife began to assist him with his tasks of daily living. His mood improved, and his wife noted he began to remember his appointments and take his medications with assistance.

However, the patient’s irritability continued to escalate. He grew paranoid and accused his wife of mismanaging their money. This pattern steadily worsened over the course of 6 months. The situation escalated until one day the patient’s wife called a mental health hotline reporting that her husband was holding her hostage and threatening to kill her with a gun. He told her, “I can do something to you, and they won’t even find a fingernail. It doesn’t have to be with a gun either.” She was counseled to try to stay calm to avoid aggravating the situation and to go to a safe place and stay there until help arrived.

His memory had worsened to the point that he could not recall any events from the previous 2 years. He was paranoid about anyone entering his home and would not allow his deteriorating roof to be repaired or his yard to be maintained. He did not shower for weeks at a time. He slept holding a rifle and accused his wife of embezzlement.

Continue to: The patient was evaluated...

The patient was evaluated by another specialist, who assessed his SLUMS score to be 18/30. He increased the patient’s donepezil dose, initiated a bupropion taper, and added sertraline to the regimen. The PCP spoke to the patient’s wife regarding options for her safety including leaving the home, hiding firearms, and calling the police in cases of interpersonal violence. The wife said she did not want to pursue these options. She expressed worry that he might be harmed if he was uncooperative with the police and said there was no one except her to take care of him.

Caregivers struggle to care for their loved ones

Instances of personal violence lead to shock, astonishment, heartbreak, and fear. Anticipation of a recurrence of violence causes many partners and caregivers to feel exhausted, because there is minimal hope for any chance of improvement. There are a few exceptions, however, as our case will show. In addition to emotional exhaustion, there is also a never-ending sense of self-doubt, leading many caregivers to question their ability to handle their family member.20,21 Over time, this leads to caregiver burnout, leaving them unable to understand their family member’s aggression. The sudden loss of caregiver control in dealing with the patient may also result in the family member exhibiting behavioral changes reflecting emotional trauma. For caregivers who do not live with the patient, they may choose to make fewer or shorter visits—or not visit at all—because they fear being abused.7,22

Caregivers of patients with dementia often feel helpless and powerless once abrupt and drastic changes in personality lead to some form of interpersonal violence. Additionally, caregivers with a poor health status are more likely to have lower physical function and experience greater caregiving stress overall.23 Other factors increasing stress are longer years of caregiving and the severity of a patient’s dementia and functional impairment.23

Interventions to reduce caregiver burden

Many studies have assessed the role of different interventions to reduce caregiver burden, such as teaching them problem-solving skills, increasing their knowledge of dementia, recommending social resources, providing emotional support, changing caregiver perceptions of the care situation, introducing coping strategies, relying on strengths and experiences in caregiving, help-seeking, and engaging in activity programs.24-28 For Hispanic caregivers, a structured and self-paced online telenovela format has been effective in improving care and relieving caregiver stress.29 Online positive emotion regulators helped in significantly improving quality of life and physical health in the caregivers.30 In this last intervention, caregivers had 6 online sessions with a facilitator who taught them emotional regulation skills that included: noticing positive events, capitalizing on them, and feeling gratitude; practicing mindfulness; doing a positive reappraisal; acknowledging personal strengths and setting attainable goals; and performing acts of kindness. Empowerment programs have also shown significant improvement in the well-being of caregivers.31

Caregivers may reject support.

Continue to: These practical tips can help

These practical tips can help

Based on our review of the literature, we recommend offering the following supports to caregivers:

- Counsel caregivers early on in a patient’s dementia that behavior changes are likely and may be unpredictable. Explain that dementia can involve changes to personality and behavior as well as memory difficulties.33,34

- Describe resources for support, such as day programs for senior adults, insurance coverage for caregiver respite programs, and the Alzheimer’s Association (www.alz.org/). Encourage caregivers to seek general medical and mental health care for themselves. Caregivers should have opportunities and support to discuss their experiences and to be appropriately trained for the challenge of caring for a family member with dementia.35

- Encourage disclosure about abrupt changes in the patient’s behavior. This invites families to discuss issues with you and may make them more comfortable with such conversations.

- Involve ancillary services (eg, social worker) to plan for a higher level of care well in advance of it becoming necessary.

- Discuss safety strategies for the caregiver, including when it is appropriate to alter a patient’s set routines such as bedtimes and mealtimes.33,34

- Discuss when and how to involve law enforcement, if necessary.33,34 Emphasize the importance of removing firearms from the home as a safety measure. Although federal laws do not explicitly prohibit possession of arms by patients with neurologic damage, a few states mention “organic brain syndrome” or “dementia” as conditions prohibiting use or possession of firearms.36

- Suggest, as feasible, nonpharmacologic aids for the patient such as massage therapy, animal-assisted therapy, personalized interventions, music therapy, and light therapy.37 Prescribe medications to the patient to aid in behavior modification when appropriate.

- Screen caregivers and family members for signs of interpersonal violence. Take notice of changes in caregiver behavior or irregularity in attending follow-up appointments.

CASE

Over the next month, the patient’s symptoms further deteriorated. His PCP recommended hospitalization, but the patient and his wife declined. Magnetic resonance imaging of the patient’s brain revealed severe confluent and patchy regions of white matter and T2 signal hyperintensity, consistent with chronic microvascular ischemic disease. An old, small, left parietal lobe infarct was also noted.

One month later, the patient presented to the emergency department. His symptoms were largely unchanged, but his wife indicated that she could no longer live at home due to burnout. The patient’s medications were adjusted, but he was not admitted for inpatient care. His wife said they needed help at home, but the patient opposed the idea any time that it was mentioned.

A few weeks later, the patient presented for outpatient follow-up. He was delusional, believing that the government was compelling citizens to take sertraline in order to harm their mental health. He had also begun viewing online pornography in front of his wife and attempting to remove all of his money from the bank. He was prescribed aripiprazole 15 mg, and his symptoms began to improve. Soon after, however, he threatened to kill his grandson, then took all his Lasix pills (a 7-day supply) simultaneously. The patient denied that this was a suicide attempt.

Over the course of the next month, the patient began to report hearing voices. A neuropsychological evaluation confirmed a diagnosis of dementia with psychiatric symptoms due to neurologic injury. The patient was referred to a geriatric psychiatrist and continued to be managed medically. He was assigned a multidisciplinary team comprising palliative care, social work, and care management to assist in his care and provide support to the family. His behavior improved.

Continue to: At the time of this publication...

At the time of this publication, the patient’s irritability and paranoia had subsided and he had made no further threats to his family. He has allowed a home health aide into the house and has agreed to have his roof repaired. His wife still lives with him and assists him with activities of daily living.

Interprofessional teams are key

Caregiver burnout increases the risk of patient neglect or abuse, as individuals who have been the targets of aggressive behavior are more likely to leave demented patients unattended.8,16,23 Although tools are available to screen caregivers for depression and burnout, an important step forward would be to develop an interprofessional team to aid in identifying and closely following high-risk patient–caregiver groups. This continual and varied assessment of psychosocial stressors could help prevent the development of violent interactions. These teams would allow integration with the primary health care system by frequent and effective shared communication of knowledge, development of goals, and shared decision-making.38 Setting expectations, providing support, and discussing safety strategies can improve the health and welfare of caregivers and patients with dementia alike.

CORRESPONDENCE

Abu Baker Sheikh, MD, MSC 10-5550, 1 University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131; [email protected].

1. Wu YT, Beiser AS, Breteler MMB, et al. The changing prevalence and incidence of dementia over time - current evidence. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:327-339.

2. Cipriani G, Borin G, Vedovello M, et al. Sociopathic behavior and dementia. Acta Neurol Belg. 2013;113:111-115.

3. Cipriani G, Lucetti C, Danti S, et al. Violent and criminal manifestations in dementia patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16:541-549.

4. Skovdahl K, Kihlgren AL, Kihlgren M. Different attitudes when handling aggressive behaviour in dementia—narratives from two caregiver groups. Aging Ment Health. 2003;7:277-286.

5. Kristiansen L, Hellzén O, Asplund K. Swedish assistant nurses’ experiences of job satisfaction when caring for persons suffering from dementia and behavioural disturbances. An interview study. Int J Qualitat Stud Health Well-being. 2006;1:245-256.

6. Wharton TC, Ford BK. What is known about dementia care recipient violence and aggression against caregivers? J Gerontol Soc Work. 2014;57:460-477.

7. Ostaszkiewicz J, Lakhan P, O’Connell B, et al. Ongoing challenges responding to behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62:506-516.

8. Kim J, De Bellis AM, Xiao LD. The experience of paid family-care workers of people with dementia in South Korea. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2018;12:34-41.

9. Band-Winterstein T, Avieli H. Women coping with a partner’s dementia-related violence: a qualitative study. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2019; 51:368-379.

10. Munkejord MC, Stefansdottir OA, Sveinbjarnardottir EK. Who cares for the carer? The suffering, struggles and unmet needs of older women caring for husbands living with cognitive decline. Int Pract Devel J. 2020;10:1-11.

11. Seidel D, Thyrian JR. Burden of caring for people with dementia - comparing family caregivers and professional caregivers. A descriptive study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019;12:655-663.

12. Tang W, Friedman DB, Kannaley K, et al. Experiences of caregivers by care recipient’s health condition: a study of caregivers for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias versus other chronic conditions. Geriatr Nurs. 2019;40:181-184.

13. Benbow SM, Bhattacharyya S, Kingston P. Older adults and violence: an analysis of domestic homicide reviews in England involving adults over 60 years of age. Ageing Soc. 2018;39:1097-1121.

14. Herron RV, Wrathall MA. Putting responsive behaviours in place: examining how formal and informal carers understand the actions of people with dementia. Soc Sci Med. 2018;204:9-15.

15. Herron RV, Rosenberg MW. Responding to aggression and reactive behaviours in the home. Dementia (London). 2019;18:1328-1340.

16. Spencer D, Funk LM, Herron RV, et al. Fear, defensive strategies and caring for cognitively impaired family members. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2019;62:67-85.

17. Skovdahl K, Kihlgren AL, Kihlgren M. Dementia and aggressiveness: stimulated recall interviews with caregivers after video-recorded interactions. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:515-525.

18. Needham I, Abderhalden C, Halfens RJ, et al. Non-somatic effects of patient aggression on nurses: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49:283-296.

19. Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, et al. The Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) Examination for detecting mild cognitive impairment and dementia is more sensitive than the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) - a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psych. 2006;14:900-910.

20. Janzen S, Zecevic AA, Kloseck M, et al. Managing agitation using nonpharmacological interventions for seniors with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28:524-532.

21. Zeller A, Dassen T, Kok G, et al. Nursing home caregivers’ explanations for and coping strategies with residents’ aggression: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:2469-2478.

22. Alzheimer’s Society. Fix dementia care: homecare. Accessed December 28, 2021. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/migrate/downloads/fix_dementia_care_homecare_report.pdf

23. von Känel R, Mausbach BT, Dimsdale JE, et al. Refining caregiver vulnerability for clinical practice: determinants of self-rated health in spousal dementia caregivers. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:18.

24. Chen HM, Huang MF, Yeh YC, et al. Effectiveness of coping strategies intervention on caregiver burden among caregivers of elderly patients with dementia. Psychogeriatrics. 2015; 15:20-25.

25. Wawrziczny E, Larochette C, Papo D, et al. A customized intervention for dementia caregivers: a quasi-experimental design. J Aging Health. 2019;31:1172-1195.

26. Gitlin LN, Piersol CV, Hodgson N, et al. Reducing neuropsychiatric symptoms in persons with dementia and associated burden in family caregivers using tailored activities: Design and methods of a randomized clinical trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;49:92-102.

27. de Oliveira AM, Radanovic M, Homem de Mello PC, et al. An intervention to reduce neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiver burden in dementia: preliminary results from a randomized trial of the tailored activity program-outpatient version. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34:1301-1307.

28. Livingston G, Barber J, Rapaport P, et al. Clinical effectiveness of a manual based coping strategy programme (START, STrAtegies for RelaTives) in promoting the mental health of carers of family members with dementia: pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347:f6276.

29. Kajiyama B, Fernandez G, Carter EA, et al. Helping Hispanic dementia caregivers cope with stress using technology-based resources. Clin Gerontol. 2018;41:209-216.

30. Moskowitz JT, Cheung EO, Snowberg KE, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a facilitated online positive emotion regulation intervention for dementia caregivers. Health Psychol. 2019;38:391-402.

31. Yoon HK, Kim GS. An empowerment program for family caregivers of people with dementia. Public Health Nurs. 2020;37:222-233.

32. Zwingmann I, Dreier-Wolfgramm A, Esser A, et al. Why do family dementia caregivers reject caregiver support services? Analyzing types of rejection and associated health-impairments in a cluster-randomized controlled intervention trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:121.

33. Nybakken S, Strandås M, Bondas T. Caregivers’ perceptions of aggressive behaviour in nursing home residents living with dementia: A meta-ethnography. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:2713-2726.

34. Nakaishi L, Moss H, Weinstein M, et al. Exploring workplace violence among home care workers in a consumer-driven home health care program. Workplace Health Saf. 2013;61:441-450.

35. Medical Advisory Secretariat. Caregiver- and patient-directed interventions for dementia: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2008;8:1-98.

36. Betz ME, McCourt AD, Vernick JS, et al. Firearms and dementia: clinical considerations. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:47-49.

37. Leng M, Zhao Y, Wang Z. Comparative efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions on agitation in people with dementia: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;102:103489.

38. Morgan S, Pullon S, McKinlay E. Observation of interprofessional collaborative practice in primary care teams: an integrative literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:1217-1230.

The number of people with dementia globally is expected to reach 74.7 million by 2030 and 131.5 million by 2050.1 Because dementia is progressive, many patients will exhibit severe symptoms termed behavioral crises. Deteriorating interpersonal conduct and escalating antisocial acts result in an acquired sociopathy.2 Increasing cognitive impairment causes these patients to misunderstand intimate care and perceive it as a threat, often resulting in outbursts of violence against their caregivers.3

Available studies (TABLE4-17) make evident the incidence of interpersonal violence experienced by caregivers secondary to aggressive acts by patients with dementia. This violence ranges from verbal abuse, including racial slurs, to physical abuse—sometimes resulting in significant physical injury. Aggressive behavior by patients with dementia, resulting in violence towards their caregivers or partners, stems from progressive cognitive decline, which can make optimal care difficult. Such episodes may also impair the psychological and physical well-being of caregivers, increasing their risk of depression, anxiety, and even post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).18 The extent of the impact is also determined by the interpretation of the abuse by the caregivers themselves. One study suggested that the perception of aggressive or violent behavior as “normal” by a caregiver reduced the overall negative effect of the interactions.7Our review emphasizes the unintended burden that can fall to caregivers of patients with dementia. We also address the role of primary care providers (PCPs) in identifying these instances of violence and intervening appropriately by providing safety strategies, education, resources, and support.

CASE