User login

How Safe is Anti–IL-6 Therapy During Pregnancy?

TOPLINE:

The maternal and neonatal outcomes in pregnant women treated with anti–interleukin (IL)-6 therapy for COVID-19 are largely favorable, with transient neonatal cytopenia observed in around one third of the babies being the only possible adverse outcome that could be related to anti–IL-6 therapy.

METHODOLOGY:

- Despite guidance, very few pregnant women with COVID-19 are offered evidence-based therapies such as anti–IL-6 due to concerns regarding fetal safety in later pregnancy.

- In this retrospective study, researchers evaluated maternal and neonatal outcomes in 25 pregnant women with COVID-19 (mean age at admission, 33 years) treated with anti–IL-6 (tocilizumab or sarilumab) at two tertiary hospitals in London.

- Most women (n = 16) received anti–IL-6 in the third trimester of pregnancy, whereas nine received it during the second trimester.

- Maternal and neonatal outcomes were assessed through medical record reviews and maternal medicine networks, with follow-up for 12 months.

- The women included in the study constituted a high-risk population with severe COVID-19; 24 required level two or three critical care. All women were receiving at least three concomitant medications due to their critical illness.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 24 of 25 women treated with IL-6 receptor antibodies survived until hospital discharge.

- The sole death occurred in a woman with severe COVID-19 pneumonitis who later developed myocarditis and cardiac arrest. The physicians believed that these complications were more likely due to severe COVID-19 rather than anti–IL-6 therapy.

- All pregnancies resulted in live births; however, 16 babies had to be delivered preterm due to COVID-19 complications.

- Transient cytopenia was observed in 6 of 19 babies in whom a full blood count was performed. All the six babies were premature, with cytopenia resolving within 7 days in four babies; one baby died from complications associated with extreme prematurity.

IN PRACTICE:

“Although the authors found mild, transitory cytopenia in some (6 of 19) exposed infants, most had been delivered prematurely due to progressive COVID-19–related morbidity, and distinguishing drug effects from similar prematurity-related effects is difficult,” wrote Steven L. Clark, MD, from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, in an accompanying editorial.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Melanie Nana, MRCP, from the Department of Obstetric Medicine, St Thomas’ Hospital, London, England. It was published online in The Lancet Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was retrospective in design, which may have introduced bias. The small sample size of 25 women may have limited the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the study did not include a control group, which made it difficult to attribute outcomes solely to anti–IL-6 therapy. The lack of long-term follow-up data on the neonates also limited the understanding of potential long-term effects.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not receive any funding. Some authors, including the lead author, received speaker fees, grants, or consultancy fees from academic institutions or pharmaceutical companies or had other ties with various sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The maternal and neonatal outcomes in pregnant women treated with anti–interleukin (IL)-6 therapy for COVID-19 are largely favorable, with transient neonatal cytopenia observed in around one third of the babies being the only possible adverse outcome that could be related to anti–IL-6 therapy.

METHODOLOGY:

- Despite guidance, very few pregnant women with COVID-19 are offered evidence-based therapies such as anti–IL-6 due to concerns regarding fetal safety in later pregnancy.

- In this retrospective study, researchers evaluated maternal and neonatal outcomes in 25 pregnant women with COVID-19 (mean age at admission, 33 years) treated with anti–IL-6 (tocilizumab or sarilumab) at two tertiary hospitals in London.

- Most women (n = 16) received anti–IL-6 in the third trimester of pregnancy, whereas nine received it during the second trimester.

- Maternal and neonatal outcomes were assessed through medical record reviews and maternal medicine networks, with follow-up for 12 months.

- The women included in the study constituted a high-risk population with severe COVID-19; 24 required level two or three critical care. All women were receiving at least three concomitant medications due to their critical illness.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 24 of 25 women treated with IL-6 receptor antibodies survived until hospital discharge.

- The sole death occurred in a woman with severe COVID-19 pneumonitis who later developed myocarditis and cardiac arrest. The physicians believed that these complications were more likely due to severe COVID-19 rather than anti–IL-6 therapy.

- All pregnancies resulted in live births; however, 16 babies had to be delivered preterm due to COVID-19 complications.

- Transient cytopenia was observed in 6 of 19 babies in whom a full blood count was performed. All the six babies were premature, with cytopenia resolving within 7 days in four babies; one baby died from complications associated with extreme prematurity.

IN PRACTICE:

“Although the authors found mild, transitory cytopenia in some (6 of 19) exposed infants, most had been delivered prematurely due to progressive COVID-19–related morbidity, and distinguishing drug effects from similar prematurity-related effects is difficult,” wrote Steven L. Clark, MD, from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, in an accompanying editorial.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Melanie Nana, MRCP, from the Department of Obstetric Medicine, St Thomas’ Hospital, London, England. It was published online in The Lancet Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was retrospective in design, which may have introduced bias. The small sample size of 25 women may have limited the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the study did not include a control group, which made it difficult to attribute outcomes solely to anti–IL-6 therapy. The lack of long-term follow-up data on the neonates also limited the understanding of potential long-term effects.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not receive any funding. Some authors, including the lead author, received speaker fees, grants, or consultancy fees from academic institutions or pharmaceutical companies or had other ties with various sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The maternal and neonatal outcomes in pregnant women treated with anti–interleukin (IL)-6 therapy for COVID-19 are largely favorable, with transient neonatal cytopenia observed in around one third of the babies being the only possible adverse outcome that could be related to anti–IL-6 therapy.

METHODOLOGY:

- Despite guidance, very few pregnant women with COVID-19 are offered evidence-based therapies such as anti–IL-6 due to concerns regarding fetal safety in later pregnancy.

- In this retrospective study, researchers evaluated maternal and neonatal outcomes in 25 pregnant women with COVID-19 (mean age at admission, 33 years) treated with anti–IL-6 (tocilizumab or sarilumab) at two tertiary hospitals in London.

- Most women (n = 16) received anti–IL-6 in the third trimester of pregnancy, whereas nine received it during the second trimester.

- Maternal and neonatal outcomes were assessed through medical record reviews and maternal medicine networks, with follow-up for 12 months.

- The women included in the study constituted a high-risk population with severe COVID-19; 24 required level two or three critical care. All women were receiving at least three concomitant medications due to their critical illness.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 24 of 25 women treated with IL-6 receptor antibodies survived until hospital discharge.

- The sole death occurred in a woman with severe COVID-19 pneumonitis who later developed myocarditis and cardiac arrest. The physicians believed that these complications were more likely due to severe COVID-19 rather than anti–IL-6 therapy.

- All pregnancies resulted in live births; however, 16 babies had to be delivered preterm due to COVID-19 complications.

- Transient cytopenia was observed in 6 of 19 babies in whom a full blood count was performed. All the six babies were premature, with cytopenia resolving within 7 days in four babies; one baby died from complications associated with extreme prematurity.

IN PRACTICE:

“Although the authors found mild, transitory cytopenia in some (6 of 19) exposed infants, most had been delivered prematurely due to progressive COVID-19–related morbidity, and distinguishing drug effects from similar prematurity-related effects is difficult,” wrote Steven L. Clark, MD, from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, in an accompanying editorial.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Melanie Nana, MRCP, from the Department of Obstetric Medicine, St Thomas’ Hospital, London, England. It was published online in The Lancet Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was retrospective in design, which may have introduced bias. The small sample size of 25 women may have limited the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the study did not include a control group, which made it difficult to attribute outcomes solely to anti–IL-6 therapy. The lack of long-term follow-up data on the neonates also limited the understanding of potential long-term effects.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not receive any funding. Some authors, including the lead author, received speaker fees, grants, or consultancy fees from academic institutions or pharmaceutical companies or had other ties with various sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Saxophone Penis: A Forgotten Manifestation of Hidradenitis Suppurativa

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a multifactorial chronic inflammatory skin disease affecting 1% to 4% of Europeans. It is characterized by recurrent inflamed nodules, abscesses, and sinus tracts in intertriginous regions.1 The genital area is affected in 11% of cases2 and usually is connected to severe forms of HS in both men and women.3 The prevalence of HS-associated genital lymphedema remains unknown.

Saxophone penis is a specific penile malformation characterized by a saxophone shape due to inflammation of the major penile lymphatic vessels that cause fibrosis of the surrounding connective tissue. Poor blood flow further causes contracture and distortion of the penile axis.4 Saxophone penis also has been associated with primary lymphedema, lymphogranuloma venereum, filariasis,5 and administration of paraffin injections.6 We describe 3 men with HS who presented with saxophone penis.

A 33-year-old man with Hurley stage III HS presented with a medical history of groin lesions and progressive penoscrotal edema of 13 years’ duration. He had a body mass index (BMI) of 37, no family history of HS or comorbidities, and a 15-year history of smoking 20 cigarettes per day. After repeated surgical drainage of the HS lesions as well as antibiotic treatment with clindamycin 600 mg/d and rifampicin 600 mg/d, the patient was kept on a maintenance therapy with adalimumab 40 mg/wk. Due to lack of response, treatment was discontinued at week 16. Clindamycin and rifampicin 300 mg were immediately reintroduced with no benefit on the genital lesions. The patient underwent genital reconstruction, including penile degloving, scrotoplasty, infrapubic fat pad removal, and perineoplasty (Figure 1). The patient currently is not undergoing any therapies.

A 55-year-old man presented with Hurley stage II HS of 33 years’ duration. He had a BMI of 52; a history of hypertension, hyperuricemia, severe hip and knee osteoarthritis, and orchiopexy in childhood; a smoking history of 40 cigarettes per day; and an alcohol consumption history of 200 mL per day since 18 years of age. He had radical excision of axillary lesions 8 years prior. One year later, he was treated with concomitant clindamycin and rifampicin 300 mg twice daily for 3 months with no desirable effects. Adalimumab 40 mg/wk was initiated. After 12 weeks of treatment, he experienced 80% improvement in all areas except the genital region. He continued adalimumab for 3 years with good clinical response in all HS-affected sites except the genital region.

A 66-year-old man presented with Hurley stage III HS of 37 years’ duration. He had a smoking history of 10 cigarettes per day for 30 years, a BMI of 24.6, and a medical history of long-standing hypertension and hypothyroidism. A 3-month course of clindamycin and rifampicin 600 mg/d was ineffective; adalimumab 40 mg/wk was initiated. All affected areas improved, except for the saxophone penis. He continues his fifth year of therapy with adalimumab (Figure 2).

Hidradenitis suppurativa is associated with chronic pain, purulent malodor, and scarring with structural deformity. Repetitive inflammation causes fibrosis, scar formation, and soft-tissue destruction of lymphatic vessels, leading to lymphedema; primary lymphedema of the genitals in men has been reported to result in a saxophone penis.4

The only approved biologic treatments for moderate to severe HS are the tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor adalimumab and anti-IL-17 secukinumab.1 All 3 of our patients with HS were treated with adalimumab with reasonable success; however, the penile condition remained refractory, which we speculate may be due to adalimumab’s ability to control only active inflammatory lesions but not scars or fibrotic tissue.7 Higher adalimumab dosages were unlikely to be beneficial for their penile condition; some improvements have been reported following fluoroquinolone therapy. To our knowledge, there is no effective medical treatment for saxophone penis. However, surgery showed good results in one of our patients. Among our 3 adalimumab-treated patients, only 1 patient had corrective surgery that resulted in improvement in the penile deformity, further confirming adalimumab’s limited role in genital lymphedema.7 Extensive resection of the lymphedematous tissue, scrotoplasty, and Charles procedure are treatment options.8

Genital lymphedema has been associated with lymphangiectasia, lymphangioma circumscriptum, infections, and neoplasms such as lymphangiosarcoma and squamous cell carcinoma.9 Our patients reported discomfort, hygiene issues, and swelling. One patient reported micturition, and 2 patients reported sexual dysfunction.

Saxophone penis remains a disabling sequela of HS. Early diagnosis and treatment of HS may help prevent development of this condition.

- Lee EY, Alhusayen R, Lansang P, et al. What is hidradenitis suppurativa? Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:114-120.

- Fertitta L, Hotz C, Wolkenstein P, et al. Efficacy and satisfaction of surgical treatment for hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:839-845.

- Micieli R, Alavi A. Lymphedema in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review of published literature. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1471-1480.

- Maatouk I, Moutran R. Saxophone penis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:802.

- Koley S, Mandal RK. Saxophone penis after unilateral inguinal bubo of lymphogranuloma venereum. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2013;34:149-151.

- D’Antuono A, Lambertini M, Gaspari V, et al. Visual dermatology: self-induced chronic saxophone penis due to paraffin injections. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:330.

- Musumeci ML, Scilletta A, Sorci F, et al. Genital lymphedema associated with hidradenitis suppurativa unresponsive to adalimumab treatment. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:326-328.

- Jain V, Singh S, Garge S, et al. Saxophone penis due to primary lymphoedema. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2009;14:230-231.

- Moosbrugger EA, Mutasim DF. Hidradenitis suppurativa complicated by severe lymphedema and lymphangiectasias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1223-1224.

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a multifactorial chronic inflammatory skin disease affecting 1% to 4% of Europeans. It is characterized by recurrent inflamed nodules, abscesses, and sinus tracts in intertriginous regions.1 The genital area is affected in 11% of cases2 and usually is connected to severe forms of HS in both men and women.3 The prevalence of HS-associated genital lymphedema remains unknown.

Saxophone penis is a specific penile malformation characterized by a saxophone shape due to inflammation of the major penile lymphatic vessels that cause fibrosis of the surrounding connective tissue. Poor blood flow further causes contracture and distortion of the penile axis.4 Saxophone penis also has been associated with primary lymphedema, lymphogranuloma venereum, filariasis,5 and administration of paraffin injections.6 We describe 3 men with HS who presented with saxophone penis.

A 33-year-old man with Hurley stage III HS presented with a medical history of groin lesions and progressive penoscrotal edema of 13 years’ duration. He had a body mass index (BMI) of 37, no family history of HS or comorbidities, and a 15-year history of smoking 20 cigarettes per day. After repeated surgical drainage of the HS lesions as well as antibiotic treatment with clindamycin 600 mg/d and rifampicin 600 mg/d, the patient was kept on a maintenance therapy with adalimumab 40 mg/wk. Due to lack of response, treatment was discontinued at week 16. Clindamycin and rifampicin 300 mg were immediately reintroduced with no benefit on the genital lesions. The patient underwent genital reconstruction, including penile degloving, scrotoplasty, infrapubic fat pad removal, and perineoplasty (Figure 1). The patient currently is not undergoing any therapies.

A 55-year-old man presented with Hurley stage II HS of 33 years’ duration. He had a BMI of 52; a history of hypertension, hyperuricemia, severe hip and knee osteoarthritis, and orchiopexy in childhood; a smoking history of 40 cigarettes per day; and an alcohol consumption history of 200 mL per day since 18 years of age. He had radical excision of axillary lesions 8 years prior. One year later, he was treated with concomitant clindamycin and rifampicin 300 mg twice daily for 3 months with no desirable effects. Adalimumab 40 mg/wk was initiated. After 12 weeks of treatment, he experienced 80% improvement in all areas except the genital region. He continued adalimumab for 3 years with good clinical response in all HS-affected sites except the genital region.

A 66-year-old man presented with Hurley stage III HS of 37 years’ duration. He had a smoking history of 10 cigarettes per day for 30 years, a BMI of 24.6, and a medical history of long-standing hypertension and hypothyroidism. A 3-month course of clindamycin and rifampicin 600 mg/d was ineffective; adalimumab 40 mg/wk was initiated. All affected areas improved, except for the saxophone penis. He continues his fifth year of therapy with adalimumab (Figure 2).

Hidradenitis suppurativa is associated with chronic pain, purulent malodor, and scarring with structural deformity. Repetitive inflammation causes fibrosis, scar formation, and soft-tissue destruction of lymphatic vessels, leading to lymphedema; primary lymphedema of the genitals in men has been reported to result in a saxophone penis.4

The only approved biologic treatments for moderate to severe HS are the tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor adalimumab and anti-IL-17 secukinumab.1 All 3 of our patients with HS were treated with adalimumab with reasonable success; however, the penile condition remained refractory, which we speculate may be due to adalimumab’s ability to control only active inflammatory lesions but not scars or fibrotic tissue.7 Higher adalimumab dosages were unlikely to be beneficial for their penile condition; some improvements have been reported following fluoroquinolone therapy. To our knowledge, there is no effective medical treatment for saxophone penis. However, surgery showed good results in one of our patients. Among our 3 adalimumab-treated patients, only 1 patient had corrective surgery that resulted in improvement in the penile deformity, further confirming adalimumab’s limited role in genital lymphedema.7 Extensive resection of the lymphedematous tissue, scrotoplasty, and Charles procedure are treatment options.8

Genital lymphedema has been associated with lymphangiectasia, lymphangioma circumscriptum, infections, and neoplasms such as lymphangiosarcoma and squamous cell carcinoma.9 Our patients reported discomfort, hygiene issues, and swelling. One patient reported micturition, and 2 patients reported sexual dysfunction.

Saxophone penis remains a disabling sequela of HS. Early diagnosis and treatment of HS may help prevent development of this condition.

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a multifactorial chronic inflammatory skin disease affecting 1% to 4% of Europeans. It is characterized by recurrent inflamed nodules, abscesses, and sinus tracts in intertriginous regions.1 The genital area is affected in 11% of cases2 and usually is connected to severe forms of HS in both men and women.3 The prevalence of HS-associated genital lymphedema remains unknown.

Saxophone penis is a specific penile malformation characterized by a saxophone shape due to inflammation of the major penile lymphatic vessels that cause fibrosis of the surrounding connective tissue. Poor blood flow further causes contracture and distortion of the penile axis.4 Saxophone penis also has been associated with primary lymphedema, lymphogranuloma venereum, filariasis,5 and administration of paraffin injections.6 We describe 3 men with HS who presented with saxophone penis.

A 33-year-old man with Hurley stage III HS presented with a medical history of groin lesions and progressive penoscrotal edema of 13 years’ duration. He had a body mass index (BMI) of 37, no family history of HS or comorbidities, and a 15-year history of smoking 20 cigarettes per day. After repeated surgical drainage of the HS lesions as well as antibiotic treatment with clindamycin 600 mg/d and rifampicin 600 mg/d, the patient was kept on a maintenance therapy with adalimumab 40 mg/wk. Due to lack of response, treatment was discontinued at week 16. Clindamycin and rifampicin 300 mg were immediately reintroduced with no benefit on the genital lesions. The patient underwent genital reconstruction, including penile degloving, scrotoplasty, infrapubic fat pad removal, and perineoplasty (Figure 1). The patient currently is not undergoing any therapies.

A 55-year-old man presented with Hurley stage II HS of 33 years’ duration. He had a BMI of 52; a history of hypertension, hyperuricemia, severe hip and knee osteoarthritis, and orchiopexy in childhood; a smoking history of 40 cigarettes per day; and an alcohol consumption history of 200 mL per day since 18 years of age. He had radical excision of axillary lesions 8 years prior. One year later, he was treated with concomitant clindamycin and rifampicin 300 mg twice daily for 3 months with no desirable effects. Adalimumab 40 mg/wk was initiated. After 12 weeks of treatment, he experienced 80% improvement in all areas except the genital region. He continued adalimumab for 3 years with good clinical response in all HS-affected sites except the genital region.

A 66-year-old man presented with Hurley stage III HS of 37 years’ duration. He had a smoking history of 10 cigarettes per day for 30 years, a BMI of 24.6, and a medical history of long-standing hypertension and hypothyroidism. A 3-month course of clindamycin and rifampicin 600 mg/d was ineffective; adalimumab 40 mg/wk was initiated. All affected areas improved, except for the saxophone penis. He continues his fifth year of therapy with adalimumab (Figure 2).

Hidradenitis suppurativa is associated with chronic pain, purulent malodor, and scarring with structural deformity. Repetitive inflammation causes fibrosis, scar formation, and soft-tissue destruction of lymphatic vessels, leading to lymphedema; primary lymphedema of the genitals in men has been reported to result in a saxophone penis.4

The only approved biologic treatments for moderate to severe HS are the tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor adalimumab and anti-IL-17 secukinumab.1 All 3 of our patients with HS were treated with adalimumab with reasonable success; however, the penile condition remained refractory, which we speculate may be due to adalimumab’s ability to control only active inflammatory lesions but not scars or fibrotic tissue.7 Higher adalimumab dosages were unlikely to be beneficial for their penile condition; some improvements have been reported following fluoroquinolone therapy. To our knowledge, there is no effective medical treatment for saxophone penis. However, surgery showed good results in one of our patients. Among our 3 adalimumab-treated patients, only 1 patient had corrective surgery that resulted in improvement in the penile deformity, further confirming adalimumab’s limited role in genital lymphedema.7 Extensive resection of the lymphedematous tissue, scrotoplasty, and Charles procedure are treatment options.8

Genital lymphedema has been associated with lymphangiectasia, lymphangioma circumscriptum, infections, and neoplasms such as lymphangiosarcoma and squamous cell carcinoma.9 Our patients reported discomfort, hygiene issues, and swelling. One patient reported micturition, and 2 patients reported sexual dysfunction.

Saxophone penis remains a disabling sequela of HS. Early diagnosis and treatment of HS may help prevent development of this condition.

- Lee EY, Alhusayen R, Lansang P, et al. What is hidradenitis suppurativa? Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:114-120.

- Fertitta L, Hotz C, Wolkenstein P, et al. Efficacy and satisfaction of surgical treatment for hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:839-845.

- Micieli R, Alavi A. Lymphedema in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review of published literature. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1471-1480.

- Maatouk I, Moutran R. Saxophone penis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:802.

- Koley S, Mandal RK. Saxophone penis after unilateral inguinal bubo of lymphogranuloma venereum. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2013;34:149-151.

- D’Antuono A, Lambertini M, Gaspari V, et al. Visual dermatology: self-induced chronic saxophone penis due to paraffin injections. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:330.

- Musumeci ML, Scilletta A, Sorci F, et al. Genital lymphedema associated with hidradenitis suppurativa unresponsive to adalimumab treatment. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:326-328.

- Jain V, Singh S, Garge S, et al. Saxophone penis due to primary lymphoedema. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2009;14:230-231.

- Moosbrugger EA, Mutasim DF. Hidradenitis suppurativa complicated by severe lymphedema and lymphangiectasias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1223-1224.

- Lee EY, Alhusayen R, Lansang P, et al. What is hidradenitis suppurativa? Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:114-120.

- Fertitta L, Hotz C, Wolkenstein P, et al. Efficacy and satisfaction of surgical treatment for hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:839-845.

- Micieli R, Alavi A. Lymphedema in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review of published literature. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1471-1480.

- Maatouk I, Moutran R. Saxophone penis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:802.

- Koley S, Mandal RK. Saxophone penis after unilateral inguinal bubo of lymphogranuloma venereum. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2013;34:149-151.

- D’Antuono A, Lambertini M, Gaspari V, et al. Visual dermatology: self-induced chronic saxophone penis due to paraffin injections. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:330.

- Musumeci ML, Scilletta A, Sorci F, et al. Genital lymphedema associated with hidradenitis suppurativa unresponsive to adalimumab treatment. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:326-328.

- Jain V, Singh S, Garge S, et al. Saxophone penis due to primary lymphoedema. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2009;14:230-231.

- Moosbrugger EA, Mutasim DF. Hidradenitis suppurativa complicated by severe lymphedema and lymphangiectasias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1223-1224.

Practice Points

- Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a multifactorial chronic inflammatory skin disease.

- Saxophone penis is a specific penile malformation characterized by a saxophone shape due to inflammation.

- Repetitive inflammation within the context of HS may cause structural deformity of the penis, resulting in a saxophone penis.

- Early diagnosis and treatment of HS may help prevent development of this condition.

Painful Anal Lesions in a Patient With HIV

The Diagnosis: Condyloma Latum

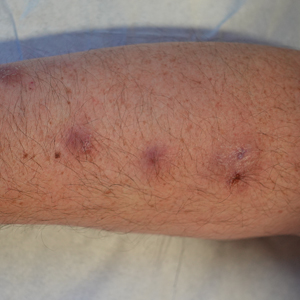

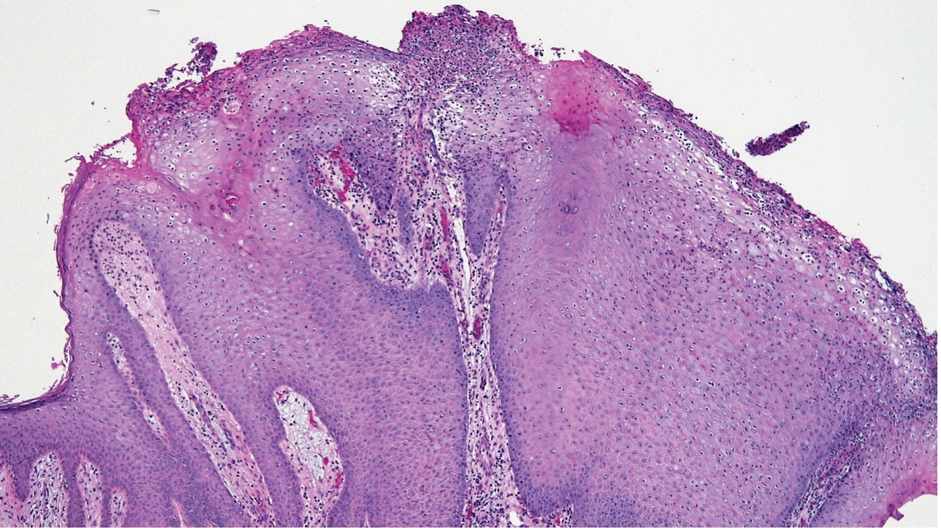

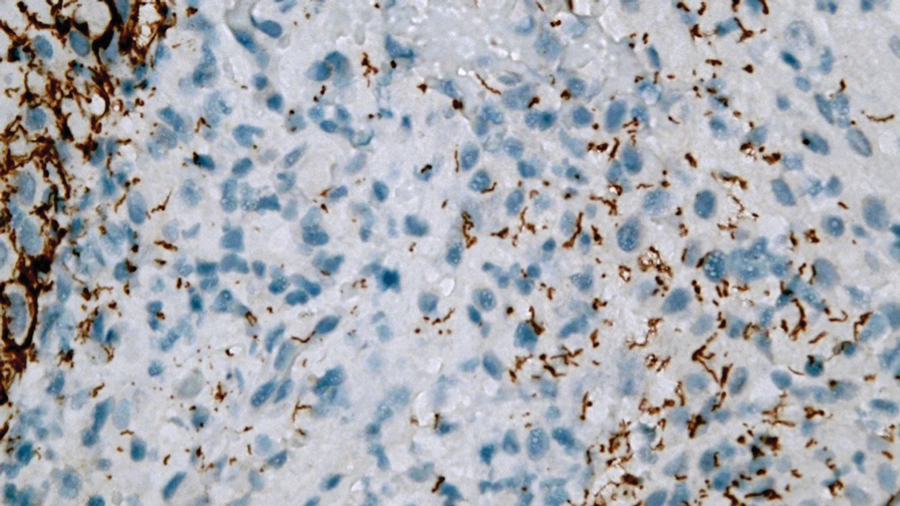

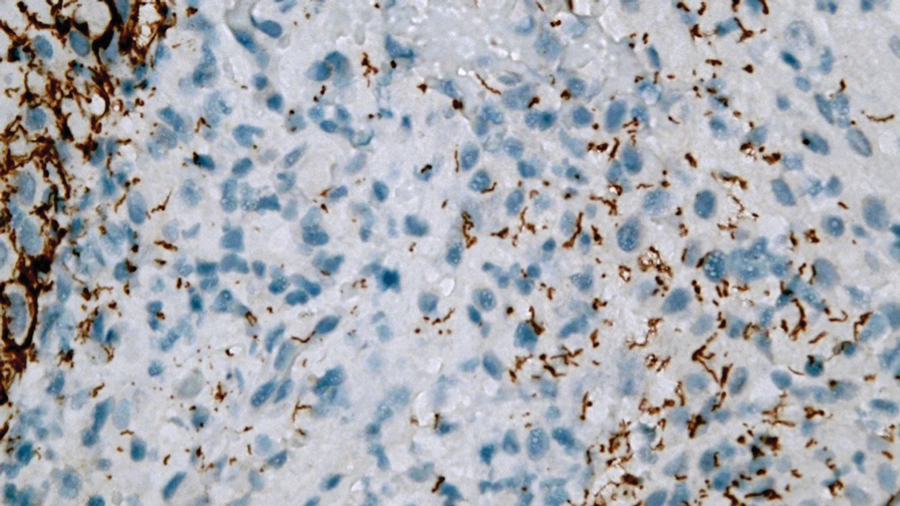

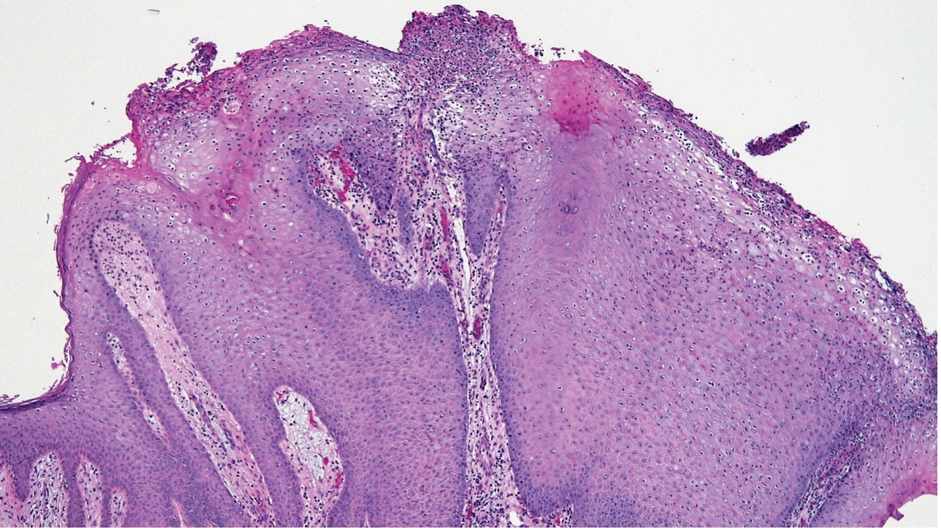

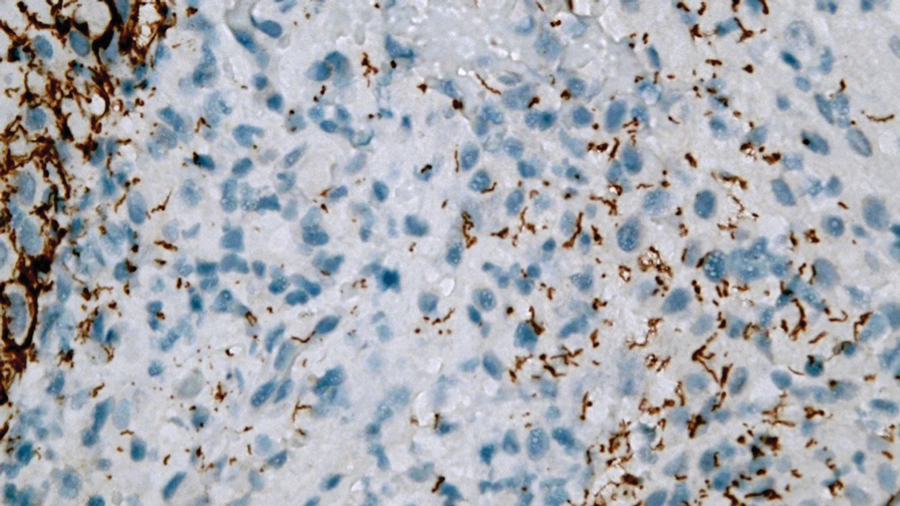

Laboratory test results were notable for a rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:512, a positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination test, negative rectal nucleic acid amplification tests for gonorrhea and chlamydia, and a negative herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction. A VDRL test of cerebrospinal fluid from a lumbar puncture was negative. Histopathology of the punch biopsy sample revealed marked verrucous epidermal hyperplasia without keratinocytic atypia and with mixed inflammation (Figure 1), while immunohistochemical staining showed numerus T pallidum organisms (Figure 2). A diagnosis of condyloma latum was made based on the laboratory, lumbar puncture, and punch biopsy results. Due to a penicillin allergy, the patient was treated with oral doxycycline for 14 days. On follow-up at day 12 of therapy, he reported cessation of rectal pain, and resolution of anal lesions was noted on physical examination.

Condylomata lata are highly infectious cutaneous lesions that can manifest during secondary syphilis.1 They typically are described as white or gray, raised, flatappearing plaques and occur in moist areas or skin folds including the anus, scrotum, and vulva. However, these lesions also have been reported in the axillae, umbilicus, nasolabial folds, and other anatomic areas.1,2 The lesions can be painful and often manifest in multiples, especially in patients living with HIV.3

Condylomata lata can have a verrucous appearance and may mimic other anogenital lesions, such as condylomata acuminata, genital herpes, and malignant tumors, leading to an initial misdiagnosis.1,2 Condylomata lata should always be included in the differential when evaluating anogenital lesions. Other conditions in the differential diagnosis include psoriasis, typically manifesting as erythematous plaques with silver scale, and molluscum contagiosum, appearing as small umbilicated papules on physical examination.

Condylomata lata have been reported to occur in 6% to 23% of patients with secondary syphilis.1 Although secondary syphilis more typically manifests with a diffuse maculopapular rash, condylomata lata may be the sole dermatologic manifestation.4

Histopathology of condylomata lata consists of epithelial hyperplasia as well as lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrates. It is diagnosed by serologic testing as well as immunohistochemical staining or dark-field microscopy.

First-line treatment of secondary syphilis is a single dose of benzathine penicillin G administered intramuscularly.5 However, a 14-day course of oral doxycycline can be used in patients with a penicillin allergy. When compliance and follow-up cannot be guaranteed, penicillin desensitization and treatment with benzathine penicillin G is recommended. Clinical evaluation and repeat serologic testing should be performed at 6 and 12 months follow-up, or more frequently if clinically indicated.5

- Pourang A, Fung MA, Tartar D, et al. Condyloma lata in secondary syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;10:18-21. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.01.025

- Liu Z, Wang L, Zhang G, et al. Warty mucosal lesions: oral condyloma lata of secondary syphilis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:277. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.191129

- Rompalo AM, Joesoef MR, O’Donnell JA, et al; Syphilis and HIV Study Group. Clinical manifestations of early syphilis by HIV status and gender: results of the syphilis and HIV study. Sex Transm Dis.2001;28:158-165.

- Kumar P, Das A, Mondal A. Secondary syphilis: an unusual presentation. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2017;38:98-99. doi:10.4103/0253-7184.194318

- Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:1-187. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7004a1

The Diagnosis: Condyloma Latum

Laboratory test results were notable for a rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:512, a positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination test, negative rectal nucleic acid amplification tests for gonorrhea and chlamydia, and a negative herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction. A VDRL test of cerebrospinal fluid from a lumbar puncture was negative. Histopathology of the punch biopsy sample revealed marked verrucous epidermal hyperplasia without keratinocytic atypia and with mixed inflammation (Figure 1), while immunohistochemical staining showed numerus T pallidum organisms (Figure 2). A diagnosis of condyloma latum was made based on the laboratory, lumbar puncture, and punch biopsy results. Due to a penicillin allergy, the patient was treated with oral doxycycline for 14 days. On follow-up at day 12 of therapy, he reported cessation of rectal pain, and resolution of anal lesions was noted on physical examination.

Condylomata lata are highly infectious cutaneous lesions that can manifest during secondary syphilis.1 They typically are described as white or gray, raised, flatappearing plaques and occur in moist areas or skin folds including the anus, scrotum, and vulva. However, these lesions also have been reported in the axillae, umbilicus, nasolabial folds, and other anatomic areas.1,2 The lesions can be painful and often manifest in multiples, especially in patients living with HIV.3

Condylomata lata can have a verrucous appearance and may mimic other anogenital lesions, such as condylomata acuminata, genital herpes, and malignant tumors, leading to an initial misdiagnosis.1,2 Condylomata lata should always be included in the differential when evaluating anogenital lesions. Other conditions in the differential diagnosis include psoriasis, typically manifesting as erythematous plaques with silver scale, and molluscum contagiosum, appearing as small umbilicated papules on physical examination.

Condylomata lata have been reported to occur in 6% to 23% of patients with secondary syphilis.1 Although secondary syphilis more typically manifests with a diffuse maculopapular rash, condylomata lata may be the sole dermatologic manifestation.4

Histopathology of condylomata lata consists of epithelial hyperplasia as well as lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrates. It is diagnosed by serologic testing as well as immunohistochemical staining or dark-field microscopy.

First-line treatment of secondary syphilis is a single dose of benzathine penicillin G administered intramuscularly.5 However, a 14-day course of oral doxycycline can be used in patients with a penicillin allergy. When compliance and follow-up cannot be guaranteed, penicillin desensitization and treatment with benzathine penicillin G is recommended. Clinical evaluation and repeat serologic testing should be performed at 6 and 12 months follow-up, or more frequently if clinically indicated.5

The Diagnosis: Condyloma Latum

Laboratory test results were notable for a rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:512, a positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination test, negative rectal nucleic acid amplification tests for gonorrhea and chlamydia, and a negative herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction. A VDRL test of cerebrospinal fluid from a lumbar puncture was negative. Histopathology of the punch biopsy sample revealed marked verrucous epidermal hyperplasia without keratinocytic atypia and with mixed inflammation (Figure 1), while immunohistochemical staining showed numerus T pallidum organisms (Figure 2). A diagnosis of condyloma latum was made based on the laboratory, lumbar puncture, and punch biopsy results. Due to a penicillin allergy, the patient was treated with oral doxycycline for 14 days. On follow-up at day 12 of therapy, he reported cessation of rectal pain, and resolution of anal lesions was noted on physical examination.

Condylomata lata are highly infectious cutaneous lesions that can manifest during secondary syphilis.1 They typically are described as white or gray, raised, flatappearing plaques and occur in moist areas or skin folds including the anus, scrotum, and vulva. However, these lesions also have been reported in the axillae, umbilicus, nasolabial folds, and other anatomic areas.1,2 The lesions can be painful and often manifest in multiples, especially in patients living with HIV.3

Condylomata lata can have a verrucous appearance and may mimic other anogenital lesions, such as condylomata acuminata, genital herpes, and malignant tumors, leading to an initial misdiagnosis.1,2 Condylomata lata should always be included in the differential when evaluating anogenital lesions. Other conditions in the differential diagnosis include psoriasis, typically manifesting as erythematous plaques with silver scale, and molluscum contagiosum, appearing as small umbilicated papules on physical examination.

Condylomata lata have been reported to occur in 6% to 23% of patients with secondary syphilis.1 Although secondary syphilis more typically manifests with a diffuse maculopapular rash, condylomata lata may be the sole dermatologic manifestation.4

Histopathology of condylomata lata consists of epithelial hyperplasia as well as lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrates. It is diagnosed by serologic testing as well as immunohistochemical staining or dark-field microscopy.

First-line treatment of secondary syphilis is a single dose of benzathine penicillin G administered intramuscularly.5 However, a 14-day course of oral doxycycline can be used in patients with a penicillin allergy. When compliance and follow-up cannot be guaranteed, penicillin desensitization and treatment with benzathine penicillin G is recommended. Clinical evaluation and repeat serologic testing should be performed at 6 and 12 months follow-up, or more frequently if clinically indicated.5

- Pourang A, Fung MA, Tartar D, et al. Condyloma lata in secondary syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;10:18-21. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.01.025

- Liu Z, Wang L, Zhang G, et al. Warty mucosal lesions: oral condyloma lata of secondary syphilis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:277. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.191129

- Rompalo AM, Joesoef MR, O’Donnell JA, et al; Syphilis and HIV Study Group. Clinical manifestations of early syphilis by HIV status and gender: results of the syphilis and HIV study. Sex Transm Dis.2001;28:158-165.

- Kumar P, Das A, Mondal A. Secondary syphilis: an unusual presentation. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2017;38:98-99. doi:10.4103/0253-7184.194318

- Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:1-187. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7004a1

- Pourang A, Fung MA, Tartar D, et al. Condyloma lata in secondary syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;10:18-21. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.01.025

- Liu Z, Wang L, Zhang G, et al. Warty mucosal lesions: oral condyloma lata of secondary syphilis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:277. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.191129

- Rompalo AM, Joesoef MR, O’Donnell JA, et al; Syphilis and HIV Study Group. Clinical manifestations of early syphilis by HIV status and gender: results of the syphilis and HIV study. Sex Transm Dis.2001;28:158-165.

- Kumar P, Das A, Mondal A. Secondary syphilis: an unusual presentation. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2017;38:98-99. doi:10.4103/0253-7184.194318

- Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:1-187. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7004a1

A 24-year-old man presented to the emergency department with rectal pain and lesions of 3 weeks’ duration that were progressively worsening. He had a medical history of poorly controlled HIV, cerebral toxoplasmosis, and genital herpes, as well as a social history of sexual activity with other men.

He had been diagnosed with HIV 7 years prior and had been off therapy until 1 year prior to the current presentation, when he was hospitalized with encephalopathy (CD4 count, <50 cells/mm3). A diagnosis of cerebral toxoplasmosis was made, and he began a treatment regimen of sulfadiazine, pyrimethamine, and leucovorin, as well as bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide. Since then, the patient admitted to difficulty with medication adherence.

Rapid plasma reagin, gonorrhea, and chlamydia testing were negative during a routine workup 6 months prior to the current presentation. He initially presented to an urgent care clinic for evaluation of the rectal pain and lesions and was treated empirically with topical podofilox. He presented to the emergency department 1 week later (3 weeks after symptom onset) with anal warts and apparent vesicular lesions. Empiric treatment with oral valacyclovir was prescribed.

Despite these treatments, the rectal pain became severe—especially upon sitting, defecation, and physical exertion—prompting further evaluation. Physical examination revealed soft, flat-topped, moist-appearing, gray plaques with minimal surrounding erythema at the anus. Laboratory test results demonstrated a CD4 count of 161 cells/mm3 and an HIV viral load of 137 copies/mL.

Identifying, Treating Lyme Disease in Primary Care

Geographic spread of the ticks that most often cause Lyme disease in the United States and a rise in incidence of bites, resulting in 476,000 new US cases a year, have increased the chances that physicians who have never encountered a patient with Lyme disease will see their first cases.

“It’s increasing in areas where it was not seen before,” Steven E. Schutzer, MD, with the Department of Medicine, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, said in an interview. Dr. Schutzer coauthored a report on diagnosing and treating Lyme disease with Patricia K. Coyle, MD, Department of Neurology, Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York.

The report, a Curbside Consult published in New England Journal of Medicine Evidence, comes amid high season for Lyme disease. Bites from an ixodid (hard shield) tick — almost always the source of the disease in the United States — are most common from April through October.

Identifying the Bite

About 70%-90% of the time, Lyme disease will be signaled by erythema migrans (EM) or lesion expanding from the tick bite site, the authors wrote. The “classic” presentation looks like a bullseye, but most of the time the skin will show a variation of that, the authors noted.

“The presence of EM is considered the best clinical diagnostic marker for Lyme disease,” they wrote.

Other dermatologic conditions, however, can complicate diagnosis: “EM mimickers include contact dermatitis, other arthropod bites, fixed drug eruptions, granuloma annulare, cellulitis, dermatophytosis, and systemic lupus erythematosus,” they wrote.

Testing Steps

“The current recommendation is to do two-step testing almost simultaneously,” Dr. Schutzer said in an interview. The first, he said, is an ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay)-type test and the second one, used for years, has been a pictoral view of a Western immunoblot showing which antigens of the Lyme bacteria, Borrelia burgdorferi, the antibodies are reacting to.

However, the pictoral view is subjective and some of the antigens could be cross-reactive. So the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) “has been allowing newer substitutes like a second ELISA-like assay that often uses more recombinant, less cross-reactive antigen targets,” he said. The authors advised that, “The second-tier test should not be performed alone without the first tier.”

Dr. Schutzer advised physicians to check with the lab they plan to use before sending samples.

“If you’re a practicing physician and you know you’re using a particular laboratory, you should familiarize yourself with them, talking to one of the clinical pathologists involved in advance to know what the limitations are.” Take the time to talk with the person overseeing the test and get tips on how they want the sample transported and how the cases should be reported, he said.

If the patient has neurological symptoms, he said, before treating talk with a neurologist who can advise whether, for instance, a spinal tap is in order or whether an emergency department visit is appropriate.

“If you just start proceeding you may mess up the diagnostic signs that could show up in a lab test. Don’t be hesitant to ask for extra input from colleagues,” Dr. Schutzer said.

Suspicion in Endemic Areas

On Long Island, New York, where Lyme disease is endemic, internist Ian Storch, DO, said he sees “a few cases a season.

“We have a lot of people over the summer going to the Hamptons and areas out east for the weekend and tick bites are not uncommon,” he said. “People panic.”

He said one thing it’s important to tell patients is that the tick has to be on the skin for 48-72 hours to transmit the disease. If individuals were in a wooded area and were fine before they got there and the tick was attached for less than 2 days, “they’re usually fine.”

Another issue, Dr. Storch said, is patients sometimes want to get tested for Lyme disease immediately after a tick bite. But the antibody test doesn’t turn positive for weeks, he noted, and you can get a false-negative result. “If you’re worried and you really want to test, you need to wait 6 weeks to do the blood test.”

In his region, he said that although a tick bite is a red flag, he may also suspect Lyme disease when a patient presents with otherwise unexplained joint pain, weakness, lethargy, or fever. “In our area, those are things that would make you test for Lyme.”

He also urged consideration of Lyme in this new age of long COVID. Weakness, fatigue, and lethargy are also classic symptoms of long COVID, he noted. “Keep Lyme disease in your differential because there is a lot of overlap with chronic Lyme disease,” Dr. Storch said.

Discerning Lyme from Southern Tick–Associated Rash Illness

Bonnie M. Word, MD, director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic in Texas, where Lyme disease is not endemic, said Lyme disease “will not and should not be on the initial differential diagnosis for those residing in nonendemic areas unless a history of travel to an endemic area is obtained.”

She noted the typical EM rash may not be as distinct or easy to discern on black and brown skin. In addition, she said, EM may have many variations in presentation, such as a crusted center or faint borders, which could lead to a delay in diagnosis and treatment. She suggested consulting the CDC guidance on Lyme disease rashes.

Another challenge in diagnosis, she said, is the patient who presents with what appears to be a classic EM lesion but does not live in a Lyme-endemic area. In Texas, Southern Tick–Associated Rash Illness (STARI) may present with a similar lesion, she said.

“It is transmitted by the Lone Star Tick, which is found in the southeast and south-central US,” Dr. Word said. “However, its habitat is moving northward and westerly,” she said.

Adding Lyme disease to the differential diagnosis is reasonable, she said, if a patient presents with neurologic symptoms “such as a facial palsy, meningitis, radiculitis, and carditis if in addition to their symptoms there is evidence of an epidemiologic link to a Lyme-endemic region.”

She noted that a detailed travel history is important as “Lyme is also endemic in Eastern Canada, Europe, states of the former Soviet Union, China, Mongolia, and Japan.”

Primary care physicians play a critical role in evaluating, diagnosing, and treating most cases of early Lyme disease, thus limiting the number of people who will develop disseminated or late Lyme disease, she said. “The two latter manifestations are most often treated by infectious disease, neurology, or rheumatology specialists.”

Treatment*

Treatment is tailored to the clinical situation, Dr. Schutzer and Dr. Coyle write. A watch-and-wait approach may be appropriate in an asymptomatic but concerned person, even in an endemic area if the person has no known tick bite and no EM lesion.

If there is high risk of an infected ixodid tick bite in a high-incidence area and the tick was attached for at least 36 hours but less than 72 hours, one dose of doxycycline has been recommended as prophylaxis.

When a diagnosis of early nondisseminated Lyme disease is made after observation of an EM lesion, oral antibiotics are typically used to treat for 10 to 14 days. Suggested oral antibiotics and doses are 100 mg of doxycycline twice a day, 500 mg of amoxicillin three times a day, or 500 mg of cefuroxime twice a day, the authors write.

Dr. Schutzer said he hopes the paper serves as a refresher for those physicians who regularly see Lyme disease cases and also helps those newly included in the disease’s spreading regions.

“The earlier you diagnose it, the earlier you can treat it and the better the chance for a favorable outcome,” he said.

Dr. Schutzer, Dr. Coyle, Dr. Storch, and Dr. Word reported no relevant financial relationships.

*This story was updated on August, 2, 2024.

Geographic spread of the ticks that most often cause Lyme disease in the United States and a rise in incidence of bites, resulting in 476,000 new US cases a year, have increased the chances that physicians who have never encountered a patient with Lyme disease will see their first cases.

“It’s increasing in areas where it was not seen before,” Steven E. Schutzer, MD, with the Department of Medicine, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, said in an interview. Dr. Schutzer coauthored a report on diagnosing and treating Lyme disease with Patricia K. Coyle, MD, Department of Neurology, Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York.

The report, a Curbside Consult published in New England Journal of Medicine Evidence, comes amid high season for Lyme disease. Bites from an ixodid (hard shield) tick — almost always the source of the disease in the United States — are most common from April through October.

Identifying the Bite

About 70%-90% of the time, Lyme disease will be signaled by erythema migrans (EM) or lesion expanding from the tick bite site, the authors wrote. The “classic” presentation looks like a bullseye, but most of the time the skin will show a variation of that, the authors noted.

“The presence of EM is considered the best clinical diagnostic marker for Lyme disease,” they wrote.

Other dermatologic conditions, however, can complicate diagnosis: “EM mimickers include contact dermatitis, other arthropod bites, fixed drug eruptions, granuloma annulare, cellulitis, dermatophytosis, and systemic lupus erythematosus,” they wrote.

Testing Steps

“The current recommendation is to do two-step testing almost simultaneously,” Dr. Schutzer said in an interview. The first, he said, is an ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay)-type test and the second one, used for years, has been a pictoral view of a Western immunoblot showing which antigens of the Lyme bacteria, Borrelia burgdorferi, the antibodies are reacting to.

However, the pictoral view is subjective and some of the antigens could be cross-reactive. So the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) “has been allowing newer substitutes like a second ELISA-like assay that often uses more recombinant, less cross-reactive antigen targets,” he said. The authors advised that, “The second-tier test should not be performed alone without the first tier.”

Dr. Schutzer advised physicians to check with the lab they plan to use before sending samples.

“If you’re a practicing physician and you know you’re using a particular laboratory, you should familiarize yourself with them, talking to one of the clinical pathologists involved in advance to know what the limitations are.” Take the time to talk with the person overseeing the test and get tips on how they want the sample transported and how the cases should be reported, he said.

If the patient has neurological symptoms, he said, before treating talk with a neurologist who can advise whether, for instance, a spinal tap is in order or whether an emergency department visit is appropriate.

“If you just start proceeding you may mess up the diagnostic signs that could show up in a lab test. Don’t be hesitant to ask for extra input from colleagues,” Dr. Schutzer said.

Suspicion in Endemic Areas

On Long Island, New York, where Lyme disease is endemic, internist Ian Storch, DO, said he sees “a few cases a season.

“We have a lot of people over the summer going to the Hamptons and areas out east for the weekend and tick bites are not uncommon,” he said. “People panic.”

He said one thing it’s important to tell patients is that the tick has to be on the skin for 48-72 hours to transmit the disease. If individuals were in a wooded area and were fine before they got there and the tick was attached for less than 2 days, “they’re usually fine.”

Another issue, Dr. Storch said, is patients sometimes want to get tested for Lyme disease immediately after a tick bite. But the antibody test doesn’t turn positive for weeks, he noted, and you can get a false-negative result. “If you’re worried and you really want to test, you need to wait 6 weeks to do the blood test.”

In his region, he said that although a tick bite is a red flag, he may also suspect Lyme disease when a patient presents with otherwise unexplained joint pain, weakness, lethargy, or fever. “In our area, those are things that would make you test for Lyme.”

He also urged consideration of Lyme in this new age of long COVID. Weakness, fatigue, and lethargy are also classic symptoms of long COVID, he noted. “Keep Lyme disease in your differential because there is a lot of overlap with chronic Lyme disease,” Dr. Storch said.

Discerning Lyme from Southern Tick–Associated Rash Illness

Bonnie M. Word, MD, director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic in Texas, where Lyme disease is not endemic, said Lyme disease “will not and should not be on the initial differential diagnosis for those residing in nonendemic areas unless a history of travel to an endemic area is obtained.”

She noted the typical EM rash may not be as distinct or easy to discern on black and brown skin. In addition, she said, EM may have many variations in presentation, such as a crusted center or faint borders, which could lead to a delay in diagnosis and treatment. She suggested consulting the CDC guidance on Lyme disease rashes.

Another challenge in diagnosis, she said, is the patient who presents with what appears to be a classic EM lesion but does not live in a Lyme-endemic area. In Texas, Southern Tick–Associated Rash Illness (STARI) may present with a similar lesion, she said.

“It is transmitted by the Lone Star Tick, which is found in the southeast and south-central US,” Dr. Word said. “However, its habitat is moving northward and westerly,” she said.

Adding Lyme disease to the differential diagnosis is reasonable, she said, if a patient presents with neurologic symptoms “such as a facial palsy, meningitis, radiculitis, and carditis if in addition to their symptoms there is evidence of an epidemiologic link to a Lyme-endemic region.”

She noted that a detailed travel history is important as “Lyme is also endemic in Eastern Canada, Europe, states of the former Soviet Union, China, Mongolia, and Japan.”

Primary care physicians play a critical role in evaluating, diagnosing, and treating most cases of early Lyme disease, thus limiting the number of people who will develop disseminated or late Lyme disease, she said. “The two latter manifestations are most often treated by infectious disease, neurology, or rheumatology specialists.”

Treatment*

Treatment is tailored to the clinical situation, Dr. Schutzer and Dr. Coyle write. A watch-and-wait approach may be appropriate in an asymptomatic but concerned person, even in an endemic area if the person has no known tick bite and no EM lesion.

If there is high risk of an infected ixodid tick bite in a high-incidence area and the tick was attached for at least 36 hours but less than 72 hours, one dose of doxycycline has been recommended as prophylaxis.

When a diagnosis of early nondisseminated Lyme disease is made after observation of an EM lesion, oral antibiotics are typically used to treat for 10 to 14 days. Suggested oral antibiotics and doses are 100 mg of doxycycline twice a day, 500 mg of amoxicillin three times a day, or 500 mg of cefuroxime twice a day, the authors write.

Dr. Schutzer said he hopes the paper serves as a refresher for those physicians who regularly see Lyme disease cases and also helps those newly included in the disease’s spreading regions.

“The earlier you diagnose it, the earlier you can treat it and the better the chance for a favorable outcome,” he said.

Dr. Schutzer, Dr. Coyle, Dr. Storch, and Dr. Word reported no relevant financial relationships.

*This story was updated on August, 2, 2024.

Geographic spread of the ticks that most often cause Lyme disease in the United States and a rise in incidence of bites, resulting in 476,000 new US cases a year, have increased the chances that physicians who have never encountered a patient with Lyme disease will see their first cases.

“It’s increasing in areas where it was not seen before,” Steven E. Schutzer, MD, with the Department of Medicine, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, said in an interview. Dr. Schutzer coauthored a report on diagnosing and treating Lyme disease with Patricia K. Coyle, MD, Department of Neurology, Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York.

The report, a Curbside Consult published in New England Journal of Medicine Evidence, comes amid high season for Lyme disease. Bites from an ixodid (hard shield) tick — almost always the source of the disease in the United States — are most common from April through October.

Identifying the Bite

About 70%-90% of the time, Lyme disease will be signaled by erythema migrans (EM) or lesion expanding from the tick bite site, the authors wrote. The “classic” presentation looks like a bullseye, but most of the time the skin will show a variation of that, the authors noted.

“The presence of EM is considered the best clinical diagnostic marker for Lyme disease,” they wrote.

Other dermatologic conditions, however, can complicate diagnosis: “EM mimickers include contact dermatitis, other arthropod bites, fixed drug eruptions, granuloma annulare, cellulitis, dermatophytosis, and systemic lupus erythematosus,” they wrote.

Testing Steps

“The current recommendation is to do two-step testing almost simultaneously,” Dr. Schutzer said in an interview. The first, he said, is an ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay)-type test and the second one, used for years, has been a pictoral view of a Western immunoblot showing which antigens of the Lyme bacteria, Borrelia burgdorferi, the antibodies are reacting to.

However, the pictoral view is subjective and some of the antigens could be cross-reactive. So the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) “has been allowing newer substitutes like a second ELISA-like assay that often uses more recombinant, less cross-reactive antigen targets,” he said. The authors advised that, “The second-tier test should not be performed alone without the first tier.”

Dr. Schutzer advised physicians to check with the lab they plan to use before sending samples.

“If you’re a practicing physician and you know you’re using a particular laboratory, you should familiarize yourself with them, talking to one of the clinical pathologists involved in advance to know what the limitations are.” Take the time to talk with the person overseeing the test and get tips on how they want the sample transported and how the cases should be reported, he said.

If the patient has neurological symptoms, he said, before treating talk with a neurologist who can advise whether, for instance, a spinal tap is in order or whether an emergency department visit is appropriate.

“If you just start proceeding you may mess up the diagnostic signs that could show up in a lab test. Don’t be hesitant to ask for extra input from colleagues,” Dr. Schutzer said.

Suspicion in Endemic Areas

On Long Island, New York, where Lyme disease is endemic, internist Ian Storch, DO, said he sees “a few cases a season.

“We have a lot of people over the summer going to the Hamptons and areas out east for the weekend and tick bites are not uncommon,” he said. “People panic.”

He said one thing it’s important to tell patients is that the tick has to be on the skin for 48-72 hours to transmit the disease. If individuals were in a wooded area and were fine before they got there and the tick was attached for less than 2 days, “they’re usually fine.”

Another issue, Dr. Storch said, is patients sometimes want to get tested for Lyme disease immediately after a tick bite. But the antibody test doesn’t turn positive for weeks, he noted, and you can get a false-negative result. “If you’re worried and you really want to test, you need to wait 6 weeks to do the blood test.”

In his region, he said that although a tick bite is a red flag, he may also suspect Lyme disease when a patient presents with otherwise unexplained joint pain, weakness, lethargy, or fever. “In our area, those are things that would make you test for Lyme.”

He also urged consideration of Lyme in this new age of long COVID. Weakness, fatigue, and lethargy are also classic symptoms of long COVID, he noted. “Keep Lyme disease in your differential because there is a lot of overlap with chronic Lyme disease,” Dr. Storch said.

Discerning Lyme from Southern Tick–Associated Rash Illness

Bonnie M. Word, MD, director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic in Texas, where Lyme disease is not endemic, said Lyme disease “will not and should not be on the initial differential diagnosis for those residing in nonendemic areas unless a history of travel to an endemic area is obtained.”

She noted the typical EM rash may not be as distinct or easy to discern on black and brown skin. In addition, she said, EM may have many variations in presentation, such as a crusted center or faint borders, which could lead to a delay in diagnosis and treatment. She suggested consulting the CDC guidance on Lyme disease rashes.

Another challenge in diagnosis, she said, is the patient who presents with what appears to be a classic EM lesion but does not live in a Lyme-endemic area. In Texas, Southern Tick–Associated Rash Illness (STARI) may present with a similar lesion, she said.

“It is transmitted by the Lone Star Tick, which is found in the southeast and south-central US,” Dr. Word said. “However, its habitat is moving northward and westerly,” she said.

Adding Lyme disease to the differential diagnosis is reasonable, she said, if a patient presents with neurologic symptoms “such as a facial palsy, meningitis, radiculitis, and carditis if in addition to their symptoms there is evidence of an epidemiologic link to a Lyme-endemic region.”

She noted that a detailed travel history is important as “Lyme is also endemic in Eastern Canada, Europe, states of the former Soviet Union, China, Mongolia, and Japan.”

Primary care physicians play a critical role in evaluating, diagnosing, and treating most cases of early Lyme disease, thus limiting the number of people who will develop disseminated or late Lyme disease, she said. “The two latter manifestations are most often treated by infectious disease, neurology, or rheumatology specialists.”

Treatment*

Treatment is tailored to the clinical situation, Dr. Schutzer and Dr. Coyle write. A watch-and-wait approach may be appropriate in an asymptomatic but concerned person, even in an endemic area if the person has no known tick bite and no EM lesion.

If there is high risk of an infected ixodid tick bite in a high-incidence area and the tick was attached for at least 36 hours but less than 72 hours, one dose of doxycycline has been recommended as prophylaxis.

When a diagnosis of early nondisseminated Lyme disease is made after observation of an EM lesion, oral antibiotics are typically used to treat for 10 to 14 days. Suggested oral antibiotics and doses are 100 mg of doxycycline twice a day, 500 mg of amoxicillin three times a day, or 500 mg of cefuroxime twice a day, the authors write.

Dr. Schutzer said he hopes the paper serves as a refresher for those physicians who regularly see Lyme disease cases and also helps those newly included in the disease’s spreading regions.

“The earlier you diagnose it, the earlier you can treat it and the better the chance for a favorable outcome,” he said.

Dr. Schutzer, Dr. Coyle, Dr. Storch, and Dr. Word reported no relevant financial relationships.

*This story was updated on August, 2, 2024.

Shortage of Blood Bottles Could Disrupt Care

Hospitals and laboratories across the United States are grappling with a shortage of Becton Dickinson BACTEC blood culture bottles that threatens to extend at least until September.

In a health advisory, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) warned that the critical shortage could lead to “delays in diagnosis, misdiagnosis, or other challenges” in the management of patients with infectious diseases.

Healthcare providers, laboratories, healthcare facility administrators, and state, tribal, local, and territorial health departments affected by the shortage “should immediately begin to assess their situations and develop plans and options to mitigate the potential impact,” according to the health advisory.

What to Do

To reduce the impact of the shortage, facilities are urged to:

- Determine the type of blood culture bottles they have

- Optimize the use of blood cultures at their facility

- Take steps to prevent blood culture contamination

- Ensure that the appropriate volume of blood is collected for culture

- Assess alternate options for blood cultures

- Work with a nearby facility or send samples to another laboratory

Health departments are advised to contact hospitals and laboratories in their jurisdictions to determine whether the shortage will affect them. Health departments are also encouraged to educate others on the supply shortage, optimal use of blood cultures, and mechanisms for reporting supply chain shortages or interruptions to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), as well as to help with communication between laboratories and facilities willing to assist others in need.

To further assist affected providers, the CDC, in collaboration with the Infectious Diseases Society of America, hosted a webinar with speakers from Johns Hopkins University, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Vanderbilt University, who shared what their institutions are doing to cope with the shortage and protect patients.

Why It Happened

In June, Becton Dickinson warned its customers that they may experience “intermittent delays” in the supply of some BACTEC blood culture media over the coming months because of reduced availability of plastic bottles from its supplier.

In a July 22 update, the company said the supplier issues were “more complex” than originally communicated and it is taking steps to “resolve this challenge as quickly as possible.”

In July, the FDA published a letter to healthcare providers acknowledging the supply disruptions and recommended strategies to preserve the supply for patients at highest risk.

Becton Dickinson has promised an update by September to this “dynamic and evolving situation.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Hospitals and laboratories across the United States are grappling with a shortage of Becton Dickinson BACTEC blood culture bottles that threatens to extend at least until September.

In a health advisory, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) warned that the critical shortage could lead to “delays in diagnosis, misdiagnosis, or other challenges” in the management of patients with infectious diseases.

Healthcare providers, laboratories, healthcare facility administrators, and state, tribal, local, and territorial health departments affected by the shortage “should immediately begin to assess their situations and develop plans and options to mitigate the potential impact,” according to the health advisory.

What to Do

To reduce the impact of the shortage, facilities are urged to:

- Determine the type of blood culture bottles they have

- Optimize the use of blood cultures at their facility

- Take steps to prevent blood culture contamination

- Ensure that the appropriate volume of blood is collected for culture

- Assess alternate options for blood cultures

- Work with a nearby facility or send samples to another laboratory

Health departments are advised to contact hospitals and laboratories in their jurisdictions to determine whether the shortage will affect them. Health departments are also encouraged to educate others on the supply shortage, optimal use of blood cultures, and mechanisms for reporting supply chain shortages or interruptions to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), as well as to help with communication between laboratories and facilities willing to assist others in need.

To further assist affected providers, the CDC, in collaboration with the Infectious Diseases Society of America, hosted a webinar with speakers from Johns Hopkins University, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Vanderbilt University, who shared what their institutions are doing to cope with the shortage and protect patients.

Why It Happened

In June, Becton Dickinson warned its customers that they may experience “intermittent delays” in the supply of some BACTEC blood culture media over the coming months because of reduced availability of plastic bottles from its supplier.

In a July 22 update, the company said the supplier issues were “more complex” than originally communicated and it is taking steps to “resolve this challenge as quickly as possible.”

In July, the FDA published a letter to healthcare providers acknowledging the supply disruptions and recommended strategies to preserve the supply for patients at highest risk.

Becton Dickinson has promised an update by September to this “dynamic and evolving situation.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Hospitals and laboratories across the United States are grappling with a shortage of Becton Dickinson BACTEC blood culture bottles that threatens to extend at least until September.

In a health advisory, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) warned that the critical shortage could lead to “delays in diagnosis, misdiagnosis, or other challenges” in the management of patients with infectious diseases.

Healthcare providers, laboratories, healthcare facility administrators, and state, tribal, local, and territorial health departments affected by the shortage “should immediately begin to assess their situations and develop plans and options to mitigate the potential impact,” according to the health advisory.

What to Do

To reduce the impact of the shortage, facilities are urged to:

- Determine the type of blood culture bottles they have

- Optimize the use of blood cultures at their facility

- Take steps to prevent blood culture contamination

- Ensure that the appropriate volume of blood is collected for culture

- Assess alternate options for blood cultures

- Work with a nearby facility or send samples to another laboratory

Health departments are advised to contact hospitals and laboratories in their jurisdictions to determine whether the shortage will affect them. Health departments are also encouraged to educate others on the supply shortage, optimal use of blood cultures, and mechanisms for reporting supply chain shortages or interruptions to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), as well as to help with communication between laboratories and facilities willing to assist others in need.

To further assist affected providers, the CDC, in collaboration with the Infectious Diseases Society of America, hosted a webinar with speakers from Johns Hopkins University, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Vanderbilt University, who shared what their institutions are doing to cope with the shortage and protect patients.

Why It Happened

In June, Becton Dickinson warned its customers that they may experience “intermittent delays” in the supply of some BACTEC blood culture media over the coming months because of reduced availability of plastic bottles from its supplier.

In a July 22 update, the company said the supplier issues were “more complex” than originally communicated and it is taking steps to “resolve this challenge as quickly as possible.”

In July, the FDA published a letter to healthcare providers acknowledging the supply disruptions and recommended strategies to preserve the supply for patients at highest risk.

Becton Dickinson has promised an update by September to this “dynamic and evolving situation.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Doesn’t Fit Anything I Trained for’: Committee Examines Treatment for Chronic Illness After Lyme Disease

WASHINGTON — Advancing treatment for what has been variably called chronic Lyme and posttreatment Lyme disease (PTLD) is under the eyes of a National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) committee of experts for the first time — a year after the NASEM shone a spotlight on the need to accelerate research on chronic illnesses that follow known or suspected infections.

The committee will not make recommendations on specific approaches to diagnosis and treatment when it issues a report in early 2025 but will instead present “consensus findings” on treatment for chronic illness associated with Lyme disease, including recommendations for advancing treatment.

It’s an area void of the US Food and Drug Administration–approved therapies, void of any consensus on the off-label use of medications, and without any current standard of care or proven mechanisms and pathophysiology, said John Aucott, MD, director of the Johns Hopkins Medicine Lyme Disease Clinical Research Center, Baltimore, one of the invited speakers at a public meeting held by the NASEM in Washington, DC.

“The best way to look at this illness is not from the silos of infectious disease or the silos of rheumatology; you have to look across disciplines,” Dr. Aucott, also associate professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology, told the committee. “The story doesn’t fit anything I trained for in my infectious disease fellowship. Even today, I’d posit that PTLD is like an island — it’s still not connected to a lot of the mainstream of medicine.”

Rhisa Parera, who wrote and directed a 2021 documentary, Your Labs Are Normal, was one of several invited speakers who amplified the patient voice. Starting around age 7, she had pain in her knees, spine, and hips and vivid nightmares. In high school, she developed gastrointestinal issues, and in college, she developed debilitating neurologic symptoms.

Depression was her eventual diagnosis after having seen “every specialist in the book,” she said. At age 29, she received a positive western blot test and a Lyme disease diagnosis, at which point “I was prescribed 4 weeks of doxycycline and left in the dark,” the 34-year-old Black patient told the committee. Her health improved only after she began working with an “LLMD,” or Lyme-literate medical doctor (a term used in the patient community), while she lived with her mother and did not work, she said.

“I don’t share my Lyme disease history with other doctors. It’s pointless when you have those who will laugh at you, say you’re fine if you were treated, or just deny the disease completely,” Ms. Parera said. “We need this to be taught in medical school. It’s a literal emergency.”

Incidence and Potential Mechanisms

Limited research has suggested that 10%-20% of patients with Lyme disease develop persistent symptoms after standard antibiotic treatment advised by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), Dr. Aucott said. (On its web page on chronic symptoms, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention presents a more conservative range of 5%-10%.)

His own prospective cohort study at Johns Hopkins, published in 2022, found that 13.7% of 234 patients with prior Lyme disease met symptom and functional impact criteria for PTLD, compared with 4.1% of 49 participants without a history of Lyme disease — a statistically significant difference that he said should “put to rest” the question of “is it real?”

PTLD is the research case definition proposed by the IDSA in 2006; it requires that patients have prior documented Lyme disease, no other specific comorbidities, and specific symptoms (fatigue, widespread musculoskeletal pain, and/or cognitive difficulties) causing significant functional impact at least 6 months from their initial diagnosis and treatment.